Every attempt has been made to replicate the original as printed. Some typographical errors have been corrected; a list follows the text. Contents. |

Prison Hulks at Portsmouth

Old hulks of English warships were first used as prisons when the American War of Independence closed the shores of the colonies to the convict-exile and rendered some additional prison space in England immediately necessary. Used as prisons of war: many American prisoners were confined there after the War of 1812,—loathsome places of durance from which escape was difficult. They were also used for temporary detention of prisoners sentenced to penal servitude in the colonies over seas.

ENGLISH DEBTOR’S PRISONS AND PRISONS

OF WAR

FRENCH WAR PRISONS

AMERICAN WAR PRISONS

WITH REFERENCES TO THOSE OF

OTHER LANDS

by

MAJOR ARTHUR GRIFFITHS

Late Inspector of Prisons in Great Britain

Author of

“The Mysteries of Police and Crime

“Fifty Years of Public Service,” etc.

![]()

THE GROLIER SOCIETY

EDITION NATIONALE

Limited to one thousand registered and numbered sets.

NUMBER 307.

THE word prison connotes crime; a place of punishment and detention where misdeeds are expiated and penalties enforced. A certain sense of shame attaches to all who have been committed to durance; for according to the old law, the “natural inherent right of liberty cannot be surrendered or forfeited unless by the commission of some great or atrocious crime.” This doctrine was coeval in one country at least, England, with the foundation of the constitution. Yet the seclusion and detention of individuals who had done no wrong, was long the rule in most civilised countries, and many prisons, which are to all intents and purposes non-criminal, have existed and been constantly filled with unfortunate persons guilty of no real offence against the law.

Of these there have been two principal classes: The debtors—those who had become bound to others for the repayment of moneys lent or goods purchased—and the prisoners of war,—combatants captured in the field whom the conqueror was entitled to hold in diminution of his enemy’s strength while hostilities continued. In both cases the right exercised is that of the strongest and in neither is it defensible, nor has it been always carried out fairly or humanely. The full acceptance of the principle, however, has called many large prisons into being which have gained great notoriety, and a description of them and the methods pursued forms the contents of this volume.

The British, essentially a commercial people, sought very early to control the relations between debtor and creditor, and ancient practice greatly favoured the latter. Every assistance was given him for the recovery of what was due him. His right to it was so amply acknowledged that the law went farther and decreed that the debtor who could not pay in cash was liable in person, so his services were attached to work out the debt and he was adjudged a serf or slave to the master he could not otherwise satisfy. The principle was derived from the Mosaic law by which the defaulter might be sold into bondage with his family, his wife and his wage-earning children. It was the same in ancient Greece and Rome, where the creditor had a claim to the person of his debtor. Solon abrogated this procedure, but it long held in Rome under very barbarous conditions. When judgment was pronounced there against a debtor, he was allowed thirty days to liquidate, but if at the end of that period he was still unable to pay, he was handed over to his creditor, who might keep him in chains for sixty days and make public exposure of him proclaiming his failure, with permission finally to sell him or put him to death. There were no public prisons for debtors in old Rome and the creditor acted as his own gaoler until milder methods ruled that the right of private imprisonment was intolerable. Nor was it permissible in feudal times, when men were continually called upon to bear arms for their lord and their valid effective strength would have been reduced by locking them up in gaol.

Imprisonment for debt had its origin in the wish to foster and protect trade. The creditor was permitted when he had proved his debt to recoup himself by laying his debtor by the heels. Yet in England the practice was held by jurists to be an undoubted invasion of the “Bill of Rights.” It was distinctly laid down that no court of justice, whether at common law or statute law, possessed the power to deprive an individual of his personal liberty for anything less than serious and atrocious crime. Still the right was usurped and exercised by specious means. Sellon says in his “Practice,” “They obtained jurisdiction by a mere fiction over actions of debt, detinue and causes of a like nature.” The judgment pronounced in English courts against a debtor was merely to the effect that he should pay the debt and costs, and it was incidental thereto that “if he does not pay an execution will issue against his property.” But no mention of imprisonment was included in the judgment, for which there was, in fact, no authority.

This immunity from personal arrest remained in force in England long after Magna Charta, but a change was introduced by a statute generally known as that of “Marlbridge,” which enacted as a remedy against absconding bailiffs and stewards that if any went off with the rents they had collected for their employers, their bodies might be attached when caught and they themselves held to serve to make good the loss. A second statute called that of “Acton Burnell” (11th Edward I), allowed merchants to arrest their debtors for acknowledged breaches of contract. The practice was excused by the plea that traders were very constantly foreigners and very likely to run out of the kingdom. As time passed the chicanery of the law was further called in to protect the creditor and the debtors’ offence was held to be a fraudulent act, a delictum or offence injurious to the plaintiff or a contempt of the court originally moved to recover the debt. The rule then was that the creditor should make a sworn affidavit against his debtor and that the court should summons him to appear and answer the claim. If he neglected to attend, the disobedience justified a presumption against him and the sheriff was ordered to distrain his goods so as to force him to come into court. If this procedure also failed, the defendant’s conduct was construed into contumacy and a writ of capias was issued for the seizure of his person.

Herein there was clearly a great stretch of power and an unlawful interference with personal liberty, yet the procedure was acquiesced in on account of its general convenience. Still the public suffered in its broad interests and the debtor was undoubtedly damnified and afterward horribly ill-used. When the arrest was made, too often arbitrarily, he was hurried off to gaol where he might be kept in durance almost indefinitely with small hope of enlargement. He was in much worse case than the prisoner charged with a crime, for no proper provision was made for his support and maintenance. While the supposed lawbreaker got the county allowance, such as it was, the debtor might starve. The latter was no doubt entitled to claim his “groats,” fourpence per diem, from his creditor, who was slow to pay, and did so only under compulsion enforced by legal process, a costly matter generally beyond the means of the insolvent and necessitous debtor. To die within the walls was easier than to obtain release, even if he could show that he had been wrongfully locked up. It cost money to prove that he did not owe the debt; a suit at law must be begun and carried through, and legal process was an expensive undertaking wholly beyond his means. This was so well understood that a recognised and not uncommon form of charity was the donation and bequest of moneys for the assistance of poor debtors.

Many are the painful details of the misusage of debtors, and of the power given to one class of the community to oppress the other. The laws relating to debtor and creditor in England were for centuries unsound, illogical and unequal, and productive of untold misery to enormous numbers of innocent people. The great debtors’ prisons of England will live in history rivalling in their callous neglect and distinctly inhuman treatment the more notorious receptacles used by high-handed and cruel tyrants for the coercion of their helpless subjects. The irresponsible despotic ruler who cast all who offended him into dark dungeons and hermetically closed oubliettes, condemning them to a lingering and acutely painful death, was no worse than the callous judge who, enmeshed by complex, senseless machinery, consigned harmless people to gaol for unlimited terms and under the most irksome conditions, because unable to meet the smallest and not always the most righteous pecuniary demands. It was not until John Howard laid bare the secrets of the prison houses that the whole story was revealed or the unjust sufferings of the debtor class fully realised.

The status of military prisons the world over has been an indictment upon humanity. In England, the Hulks and Dartmoor; in France, Verdun and Bitche; in Russia, Peter and Paul and the Schlüsselburg; in the United States, Libby Prison, Andersonville and Fort Delaware are sad examples of the cruelties of war. Idleness, starvation and homesickness conspired to make the wretched captives prefer death or daring escape to indefinite torture.

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| Introduction | 5 | |

| I. | The Fleet Prison | 15 |

| II. | Abuses at the Fleet | 39 |

| III. | Famous Dwellers in the Fleet | 76 |

| IV. | The King’s Bench Prison | 100 |

| V. | Life in the King’s Bench | 127 |

| VI. | English Prisons of War | 154 |

| VII. | The Hulks | 179 |

| VIII. | American Prisoners in England | 199 |

| IX. | French War Prisons | 231 |

| X. | Later Records | 258 |

| XI. | American War Prisons | 287 |

| Prison Hulks at Portsmouth | Frontispiece |

| The Fleet Beggar | Page 28 |

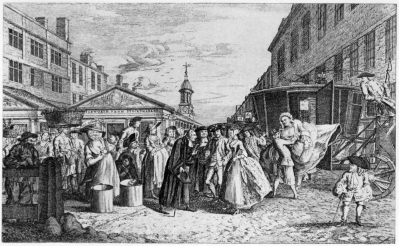

| A Fleet Wedding | “ 68 |

| Princetown Prison | “ 164 |

The great debtors’ prisons of England notorious for their callous neglect and inhuman treatment—Denounced by John Howard, the philanthropist—The Fleet, the King’s Bench and the Marshalsea—Origin of the Fleet—Early government—Closely connected with religious and political persecution—Bishop Hooper—Account of the Fleet at the beginning of the seventeenth century—Charges of cruelty brought against Warden Alexander Harris—Charitable bequests—Fees extorted—Prices charged for chamber-rent—Deplorable state of the prison.

THE three principal prisons in London in the fourteenth century were the Fleet, the King’s Bench and the Marshalsea, but Newgate took precedence in interest because identified with its earliest history. All have their peculiar histories full of interesting associations, replete with memories of famous inmates and striking incidents, and all are worthy of detailed description. All alike received prisoners for debt and on occasion, more heinous offenders, especially in the earlier years of their existence. The old King’s Bench was the peculiar prison for the Court of that name, but it also took debtors committed by the Court of Exchequer and the Court of Common Pleas. The Marshalsea Court, so called from having been originally under the control of the Knight Marshal of the Royal Household, was at first intended to settle differences between the lesser servants of the palace, and had its own judge, counsel and attorneys, but none except members of Clifford’s Inn were permitted to practise in this court. The jurisdiction of this court extended twelve miles round Whitehall, excluding the city of London. It also served the Admiralty Court and received prisoners charged with piracy.

The Fleet prison took its name from the little stream long stigmatised as the “Fleet[1] Ditch,” the open sewer or water-way which rose in the eastern ridge of Hampstead Hill, flowed by “Oldbourne” or Holborn under four bridges to discharge into the Thames on the west side of Blackfriars bridge. As time passed this ditch, after being deepened once or twice to allow for water traffic, became more and more pestilential and was at length filled up and arched over, becoming then the site of Fleet Market in what is now known as Farringdon Street, on which the main gates of the prison opened. The building was of great antiquity and is first mentioned in authentic records about A. D. 1197. A deed of that date granted it to the safe keeping of one Nathaniel de Leveland and his son Robert, in conjunction with the King’s Houses at Westminster. It is stated that the Fleet prison had been the inheritance of the Levelands since the time of the Norman Conquest. Four years later this same Robert de Leveland petitioned King John for leave to hand over the wardenship of the Fleet to Simon Fitz-Robert, archdeacon of Wells, while he, Leveland, proceeded with the crusaders to the Holy Land. He returned very shortly afterward, as appears from a grant of moneys made him by the City of London in 1205, his salary for guardianship of the prison. His wife Margaret was also granted an allowance as keeper of the Westminster Royal Houses.

Many entries in the records show that in those early days the Fleet was a place of detention for offenders of all sorts as well as of ordinary debtors, and especially of defaulters owing money to the King’s Exchequer. The Chamberlain of Chester in the reign of Edward I was imprisoned in the Fleet for a year on account of a debt to the King. A similar case was that of the sheriffs of Nottingham and Derby, who were detained in 1347 for sums owing to the Exchequer in the reign of Edward III; another, that of William de Hedersete, who was answerable for great “arrears to our lord the King,” through a deceased partner who had died insolvent. The Fleet received debtors for the Court of Chancery, and was essentially the King’s prison to which were committed all who came under his displeasure or failed in their obligations and payments. When one Guy de Codemore was ordered into exile and did not leave the country, forthwith he was thrown into the Fleet. French prisoners of war taken in the capture of Harfleur, in 1423, were brought to the Fleet. When Sir Geoffrey Poole of Hampshire fell out with a neighbour, the Lord Privy Seal summoned him to appear before him and committed him to the Fleet until the King’s (Henry VIII) further pleasure should be known. Lady Poole won her husband’s pardon this time, but Sir Geoffrey was again in trouble the very next year for assaulting the parson of Pacton in the county of Sussex.

In these troublous times various offenders found themselves in the Fleet. It was a place of penitence for young gentlemen who misbehaved, such as the son and heir of Sir Mathew Browne of Surrey who, with his servants, was guilty of arson in a wood; a printer who sold seditious books was committed to it in 1541; the riotous servants of a gentleman of the Privy Chamber were laid by the heels in the Fleet. Smugglers and all who infringed the Customs’ laws were committed to the prison as debtors to the King. A ship master of Southampton who was “privately conveying five packets of wool to Flanders without a license” was arrested and sent to the Fleet, the wool being seized and the captain fined half the value of his ship. It was made a place for the detention of state prisoners, for when Cowley, the Master of the Rolls in Ireland, was under examination in 1541 he was lodged in the Fleet until the King himself should come to London. This was the fate of the illustrious knight, Sir John Falstaff, when he bearded the Lord Chief Justice, as Shakespeare tells us in “Henry IV”:—

Poets, dramatists and pamphleteers were from time to time cast into the Fleet, and it was christened by Pope the “Haunt of the Muses.” Among the first was Lord Surrey and among the latter Nash, author of the satirical play “The Isle of Dogs.” Wycherley, the wit and dramatist, who married the Countess of Drogheda, languished for seven years as a debtor in the Fleet, and Sir Richard Baker, author of the famous “Chronicles,” wrote them as a means of subsistence when an impecunious debtor there, where he died. Francis Sandford, author of the “Genealogical History,” also died in the prison in 1693. James Howell, who wrote the delightful “Familiar Letters” during the troublous times of the Civil War, was a tenant of the Fleet prison in the years 1643 to 1647. In one of his letters dated from the Fleet in 1643, he describes his arrest one morning betimes, by five men armed with “swords, pistols and bills,” who took him to gaol where, as he says, “as far as I can tell I must lie at dead anchor a long time unless some gentle gale blow thence to launch me out.” He consoles himself, however, with the thought that all Englishmen being islanders, are, in effect, prisoners.

The Fleet was arbitrarily used by Sir Richard Empson in the reign of Henry VII, when that overbearing law officer was indicted for committing to it, without process, persons accused of murder and high crimes. Cardinal Wolsey was charged with a like invasion of the liberty of the subject, “by his power and might contrary to right,” in the case of a Sir John Stanley who had taken possession of a farm illegally. This man would not yield but preferred to turn monk in Westminster monastery, where he died.

Other prisoners were committed to the Fleet for political misdemeanours and severely dealt with by the ruling powers. It was an offence to marry the sister of Lady Jane Grey and for this imprisonment was adjudged to Edward Seymour, Earl of Hertford. Dr. Donne, who married Sir George More’s daughter without his knowledge, was laid by the heels; the penalty of durance overtook Sir Robert Killigrew for entering into conversation with Sir Thomas Overbury, when returning from a visit to Sir Walter Raleigh, then a prisoner in the Tower. James I, when overmuch importuned by the Countess of Dorset, who broke into the Privy Council Chamber, sent her to the Fleet, and Lucius Carey, Lord Falkland, was imprisoned for sending a challenge.

Many painful memories hang about the old Fleet prison in connection with the religious and political persecutions of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. It was crowded with the martyrs to intolerance in the reign of the bigoted Queen Mary and the victims Elizabeth sacrificed in the way of reprisals when she came to the throne. The Protestant party had been in the ascendant under Edward VI and the old religion had been sharply attacked, so that many eminent Catholic bishops burned at the stake,—Cranmer, Latimer, Ridley, and the pious Hooper, whose chief offence was that being a priest, he had married a wife. He was now Bishop of Worcester but he had been in the Fleet before, imprisoned by his own friends for refusing to wear vestments on the occasion of his consecration. He was soon set free but came again to the Fleet on his way to the stake.

His own account of this second confinement is to be found in Fox’s Book of Martyrs. “On the first of September, 1553, I was committed unto the Fleet from Richmond, to have the liberty of the prison, and within five days after I had paid for my liberty five pounds sterling to the warden for fees, who immediately upon the payment thereof complained unto Stephen Gardiner, Bishop of Winchester, and so I was committed to close prison one quarter of a year in the lower chamber of the Fleet and used very extremely. Then by the means of a good gentleman, I had liberty to come down to dinner and supper; not suffered to speak to any of my friends, but as soon as dinner and supper were done to repair to my chamber again. Notwithstanding ... the warden and his wife picked quarrels with me and complained untruly of me to their great friend the Bishop of Winchester.

“After one quarter of a year and somewhat more, Babington, the warden, and his wife fell out with me for the wicked mass; and thereupon the warden resorted to the bishop and obtained to put me in the ward, where I have continued a long time, having nothing appointed to me for my bed but a little pad of straw and a rotten covering with a tick and a few feathers to lie on, the chamber being vile and stinking, until by God’s means good people sent me bedding. On one side of the prison is the stink and filth of the house and on the other side the town ditch (the Fleet ditch) so that the evil smells have affected me with sundry diseases. During which time I have been sick and the doors, bars, hasps and chains being all closed and made fast upon me, I have mourned, called and cried for help, but the warden when he hath known me many times ready to die, and when the poor men of the ward have called to help me, hath commanded the doors to be kept fast and charged that none of his men should come at me saying, ‘Let him alone, it were a good riddance of him.’ ”

Yet the sums extorted from the poor bishop were as high as for a peer of the realm. A lord, spiritual or temporal, paid the sum of five pounds as “fyne” for liberty of the house and irons on first coming in. It was a graduated scale, each item according to rank ranging from ten pounds for an archbishop, duke or duchess, to twenty-five shillings for an esquire. The rates were proportionate and laid upon everything: fees for dismission, for entering the obligation and to everyone concerned in the administration, porter, “jayler,” chamberlain, charge for commons or board and for “coyne.” When these fees were not promptly paid the wretched prisoner was “left to lye in the common prison without ‘bedd’ or ‘dyete,’ subject to the discomfort of low companions and the dangers of distemper.”

Bishop Hooper sums up his griefs thus: “I have suffered imprisonment almost eighteen months. My goods, living, friends and comfort taken from me; the Queen [Mary] owing me by first account eighty pounds or more, she hath put me in prison and giveth nothing to find me; neither is there any suffered to come at me whereby I might have relief. I am with a wicked man and woman [the warden and his wife] so that I see no remedy (save God’s help) but I shall be cast away in prison before I come to judgment. But I commit my just cause to God whose will be done whether it be life or death.” It was death, and as he esteemed it, a glorious death, that of being burnt at the stake after some more months in confinement, during which he was frequently examined and called upon to recant. He was sent down for execution to Gloucester, of which diocese he had been bishop before his translation to Worcester. He was burned alive at a slow fire and suffered exceeding torment, but bore it with the splendid endurance vouchsafed to so many victims to savage laws that counted difference in religious belief an abominable crime.

We have an authentic account of the interior of the prison early in the seventeenth century, in the volume published by the Camden Society, entitled the “Æconomy of the Fleete” by Alexander Harris, at one time warden there. Charges were brought against him by a number of his prisoners, of oppression and ill-usage and he is at great pains to make his defence. The prison, as he describes it, was no doubt identically the same as that of earlier date. It consisted of “six great rooms and a courtyard with Tower chambers and Bolton’s ward,” the strongest part of the prison. There was a further sub-division. One ward of the Tower chambers was appropriated to females exclusively; another was called the “Twopenny” ward from the price charged; a third the “Beggars’ ” ward in which nothing was demanded and nothing given. At a lower level was the Dungeon, a receptacle for refractory prisoners where they were kept in irons and confined in the stocks.

The inmates one and all were entirely at the mercy of the warden, who inherited his office, or purchased it, and looked to recoup himself by the fees he extorted from his prisoners. The place was a sort of sorry hotel kept by a brutal and rapacious landlord, as a life tenant, with a keen eye to profit, and who gave his lodgers nothing, exacting payment often exorbitant for even light and air and the barest necessaries. The English law was so neglectful and inhuman that it made no regular provision for the imprisoned debtor. A fiction existed that the creditor was bound to contribute four pence daily to provide him with food, but, as has been said, as late as 1843 this payment of the “groat” was not punctually made, if at all, and could only be enforced by slow process of law at a cost prohibitory to the penniless prisoner, and he was thrown on his own resources, to starve if without friends or private means, or in the extreme case to drag out a miserable existence from the doles of the charitable. Great numbers of hapless folk in the passing ages were detained for five and twenty, thirty and even forty years, on account of debts of a few pounds, grown out of a first pitifully small sum and largely increased by arbitrary charges for fees and maintenance, which but for unjust arrest and detention would never have existed. Thousands died of hope deferred or slow starvation and with them suffered those naturally dependent upon them. It was a calculation well within the mark that every debtor was saddled with two dependents for whom he was the stay and breadwinner. Some figures are given by John Howard when, later, he began his self-sacrificing philanthropic labours, and may be quoted here to show how numerous were the innocent victims of the iniquitous and remorseless legal system in force:

“I have found,” he writes in 1777,[2] “by carefully examining sundry gaols, that upon an average two dependents (by which I mean wives and children only) may be assigned to each man (debtor) in prison. My computation is confirmed by the account which we have from the Benevolent Society at the Thatched House, October 9th, 1777. Since its institution in 1772 there were yearly about 3,980 discharged debtors who had 2,193 wives and 6,288 children.” From this he reasoned that as there was a total of debtors in England and Wales of 4,084, the dependents would be twice that number.

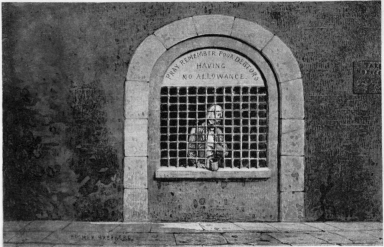

The sufferings entailed upon poor debtors and their families appealed forcibly to good people and produced much spontaneous assistance. Societies were formed having considerable sums at their disposal to be expended in the relief of poor debtors by the payment of and legal extinction of small debts. Other sums were subscribed, granted or bequeathed with the direct intention of purveying to the daily crying needs of the imprisoned, as moneys held in trust to be expended on bread and improved dietaries for those who would otherwise starve. These allowances survived to a comparatively recent date, and when the state assumed control of all British prisons in 1878, a long list still existed and was absorbed by the Charity Commissioners. These poor creatures were active on their own behalf and collected funds by begging openly in the public streets. This was practised by the so-called “Running Box;” a prisoner ran about the streets adjacent, carrying a box which he shook constantly, rattling its contents and imploring alms from passers by for the poor prisoners in the Fleet. There was also the prison gate or “grating,” which at the Fleet was a window barred, behind which always sat an emaciated debtor rattling his money box and ever chanting dolorously his appeal, “Pray remember the poor prisoners who have no allowance.” The practice was universal and in Salisbury it went the length in 1774—as Howard says—of exhibiting two Crown debtors at the door of the County Gaol, who offered articles manufactured in the prison for sale. Hard by the outer gate was a row of staples fixed in the walls and through the rings was run a chain, to each end of which was padlocked a “Common Side” debtor appealing to the passers by. At Salisbury there was a custom of sending out felons to roam the city in quest of alms; two were chained together, one carrying a money box, the other a sack or basket for food.

No debtor was allowed to benefit by the funds thus obtained until they had been formally sworn at the “grate,” to the effect that they were not worth five pounds in the world. After this they were entitled to a share in the contents of the collection box and to participate in the donations and bequests of the charitable souls who compassionated their poverty-stricken, hardly-used brethren.

A detailed list of the benefactors and their gifts will be found in Howard’s “State of Prisons” (1784), and some are curious enough and may be quoted, such as the bequest known as “Eleanor Gwynne’s bread,” which gave the debtors in Ludgate every eighth week five shillings’ worth of penny loaves, and the gift of Mrs. Elizabeth Mission, the yearly income of two hundred pounds, three per cent. annuities for free bread and coals. A mysterious gift was sent for years to the Wood Street Compter, “nine stone of beef and fourteen quartern loaves,” but its origin was kept secret until at the death of Princess Caroline its royal origin was displayed, and the alms was continued by the order of George III during his life. Mr. Allnutt, who was for many years a prisoner in the Marshalsea for debt, came in for a good estate while incarcerated and at his death he left one hundred pounds a year to be applied to the release of poor debtors. In the Southwark County Gaol, once known as the

The Fleet Beggar

From the painting by Hosmer Shepherd

At the barred window at the gate of the Fleet prison, it was the custom for an emaciated debtor to sit, rattling his money-box and imploring alms. English law made no regular provision for the imprisoned debtors. The creditor was supposed to contribute fourpence daily to provide him with food, but this was rarely made and could only be enforced by process of law.

White Lion Prison, there were sixteen legacies and donations, all applied to the relief of debtors, and “Nell” Gwynne also bequeathed a sum to be expended in loaves for Common Side debtors.

Returning to the misgovernment of Warden Harris, and the malfeasances laid to his charge, one of the most serious against him was that he allowed two prisoners, well-known to be bitter enemies and constantly quarrelling, to consort together in the same cell or room, that called the Tower chamber, where one fell suddenly upon the other and stabbed him so that he presently died. The story told is much confused. It was not clear who was the aggressor and whether or not the fatal blow was struck in self-defence. The two prisoners in question were a Sir John Whitebrook, against whom the warden had a grievance (no less than that Whitebrook had murderously assaulted him), and the other was one Boughton, of whose hostile feelings toward Whitebrook the warden astutely availed himself.

It was stated that Whitebrook was held a close prisoner by the order of two courts, but that he became violently disturbed, and breaking out went to the warden’s study, where he found Harris in his gown writing. A talk ensued as to the quality of the lodging provided and the charge for the chamber-rent, and as the warden was using the pomice-box to dry his writing, Sir John Whitebrook struck him on the head with the sharp end of a hammer, inflicting four wounds upon his skull and other bruises, before the warden could close with him. Then the assailant was thrown on his back and the hammer taken from him so that the warden might easily have beaten out his brains, “but that he was neither wrathful nor daunted.” When the servants came upon the scene, Whitebrook was seized by the butler but yet contrived to take out a stiletto and use it fiercely. The warden’s deputy was stabbed through the hand and the porter or doorkeeper of the house would have been killed but the stiletto did not enter. After this the furious creature was carried in irons to Bolton’s ward.

This affray was part of a settled plan of mutinous disturbance in which some three score prisoners had combined to break up the strongest wards and the massive doors of the Tower chamber. At that time Whitebrook and Boughton agreed amicably and the malcontents set themselves to “bar out” the warden from the prison and refused all persuasions of the officials to “unlock” the chambers even at the request of the Lord Chancellor, the Lord Chief Justice and the Sergeant at Arms, but they yielded to the Clerk of the Council when sent from the Lords. Whitebrook was still insubordinate and refused the chamber offered him but seized upon five others which they “again fortified,” so that the warden “had no command in that part of the prison.” The authority of the officials was at last vindicated and the turbulent prisoners were removed into the common prison, where Boughton and Whitebrook came together and, after a suspension of hostilities for some months, the fatal quarrel with the results described took place.

Another serious allegation was that a prisoner, who was in possession of a large sum in cash, was robbed of it with the connivance of the warden. A man named Coppin was supposed to have fifty-one pounds concealed in his bed and orders were issued to remove him to another room and keep him close while the turnkeys rifled his bed and carried off his treasure. The answer given was that Coppin was known for six years past to be quite impecunious and unable “to pay the warden one penny for meate, drink, lodgings or attendance.” It was proved by the evidence of other prisoners that when Coppin was transferred from the Tower Chamber into Bolton’s ward, he took his bedding with him and that he never complained of having lost “one penny or any other thing.”

There were many more charges against the warden, Alexander Harris, which he answered speciously and sometimes denied categorically. He was accused of breaking into prisoners’ rooms, forcing the locks of their trunks, seizing their goods and cash and applying them to his own use; but he replied that Peck, the particular complainant, although worth money, never paid a sou and when set free left the Fleet deeply in the warden’s debt, having occupied a good room for eight years, for which he paid not one penny. He was a debtor whom a small sum would discharge, but “he never paid any man.” Peck’s children were known thieves, who sought shelter in the Fleet until the gallows got one and the other died a natural death. Peck himself “purloyned the goods of his fellow-prisoners and by force, with knife drawn, took away the bedding of a dead room-mate from the mother who claimed it. Peck with his accomplices came into the gaoler’s lodge and thrust him out, with his aged wife, and in resisting grievously bruised the gaoler, offering to stabb the man that was under the gaoler.”

For these foul abuses Peck was moved to Newgate by order of the Lord Chief Justice, where he lay for a long time not daring to open his trunks, for they were full of stolen goods; but the warden called in neighbours and with the help of some prisoners forced them and inventoried the contents. The warden of the Fleet found more than enough to satisfy his debt for eight years’ lodging and fees. Peck’s remaining property consisted of only three blankets, two pillows, “an ould covering of darnex” and two bolsters.

Harris was also accused of impounding the moneys paid as fees to the servant who went as escort with prisoners allowed to go at large for the day. This curious custom obtained in the Fleet, from the earliest to the latest times, of permitting a prisoner on payment of a fee to go at large in the city and even into the country if accompanied by a “baston” or tipstaff. When the practice began it was understood that no prisoner was meant to go further than to Westminster or to his counsel, but by degrees custom enlarged their walks all over London and indeed far beyond it. In all cases the warden was always responsible for his prisoner and if he escaped was mulcted to the amount of his debt. Permission to go abroad was always preceded by the prisoner or his friends giving security for the amount due. The extent to which this privilege was conceded is seen by the fact that twenty officers were on the staff of the prison for the purpose of providing the requisite escorts. The warden estimated that he paid out to them some eighty pounds a year, which at twenty pence a day would account for about a thousand absences, or an average of ten days annually to say a hundred prisoners, who could afford the luxury of an “exeat.” The warden’s risk was great, for there were times when the aggregate of the debts owed by the inmates of the Fleet amounted to two hundred thousand pounds, besides the State obligations or sums owing to the king. The warden’s emoluments were necessarily large to cover this liability, and often exceeded two thousand pounds a year.

Residence beyond the prison within the “Rules,” was another form of privilege. “The liberty of the rules and the ‘day rules’ of the Fleet may be traced,” says Mr. Timbs, “to the time of Richard II, when prisoners were allowed to go at large by bail, or with a ‘baston’ (tipstaff), for nights and days together. This license was paid at eightpence per day and twelvepence for his keeper that shall be with him. These were day rules. However they were confirmed by a rule of court during the reign of James I. The rules wherein prisoners were allowed to lodge were enlarged in 1824, so as to include the churches of St. Bride’s and St. Martin’s, Ludgate; New Bridge Street, Blackfriars to the Thames; Dorset Street and Salisbury Square; and part of Fleet Street, Ludgate Hill and Ludgate Street, to the entrance of St. Paul’s Churchyard, the Old Bailey and the lanes, courts, etc., in the vicinity of the above; the extreme circumference of the liberty being about a mile and a half. Those requiring the ‘rules’ had to provide sureties for their punctual reappearance and keeping within the boundaries, and to pay a percentage on the amount of debts for which they were detained, which also entitled them to the liberty of the day rules, enabling them during term or the sitting of the courts of Westminster, to go abroad during the day, to transact or to arrange their affairs, etc. The Fleet and the Queen’s Bench were the only prisons in the Kingdom to which these privileges had for centuries been attached.”

The withholding discharge from those entitled by law to go at large until all fees and duties were satisfied, an act amounting to false imprisonment, was a frequent complaint against the warden, as against all gaolers in the old days. This was answered by the plea that it was a general rule to detain out-going prisoners until they had satisfied all just dues, and the imposition of these dues was defended as having been lawfully originated by Act of Parliament, custom or toleration of the State and judges of courts. The warden was charged too with making imprisonment more grievous by keeping prisoners too close, “chaining, manacling and bolting them with irons,” and this for months and years without order, warrant or law; but he pleaded that such treatment was the necessary restraint of dangerous prisoners, “badd” debtors for great sums, perjurers, “forgerors,” conspirators and such like censured persons by whom the warden or his servants may be “out-done or slain” through violence to his person or office, or whose cause was almost ready for hearing by the Star Chamber.

The use of irons was justified by “ancient continuance” and custom throughout the Kingdom which many “now in the Fleet do by suffering in other prisons know to be true.” The fact that a fine was paid to be freed from them “proveth the use,” said the warden, “and there be some knights now prisoners that did wear irons for thirty years past for misdemeanours after they had been fined to be freed from them in the Fleet.” In support of this use of irons the opinion of the Master of the Rolls, given twenty-three years previously, is quoted; that if abridged the discipline of the house would be subverted. “The warden protested that he did never show spleen or passion in the putting irons on prisoners for private revenge, not even when several, who were in execution for great sums, had run away and escaped and the warden was compelled to pay their debts.”

The warden indignantly denied the charge of starving “close prisoners” (those kept close), declaring it to be “fabulous and false and to have no colour;” for food was supplied although no payment was made, and in one case, when a prisoner “faigned himself sick” from starvation, the doctor saw in the window the most part of a roasted pullet, left from the meal before. This complaint of being starved drove a certain prisoner to break out, behaving himself rather as a “Bedlam frantic than a gentleman” and with others seeking “for revenge” to the utter dislike and grief of all in the prison, “with steel chisel, mallets and hammers cut all the stone work of the door of the Tower Chamber into which the bolts and locks did shut, so that no door could be shut upon eighteen prisoners of great weight.”

The exactions of the warden for chamber-rent were the cause of bitter complaint; the order was that no man should pay more than one shilling and threepence weekly for a room with bed and bedding, yet the price demanded was eight shillings, ten, even twenty, per week without bedding. The warden answered that many of his prisoners desired to have more ease than ordinary, and sought lodgings in the warden’s own house and would not lie in the prison. Better accommodation must be paid for at a higher rate, if they paid at all, but “the misery is that none will pay at all, but stand upon it they should pay nothing, which is contrary to right, custom and usage.” Yet these defaulters also brought friends, wives, children and servants which were no prisoners, to share their quarters and still would pay nothing for the privilege. On the whole it was quite a mistake to suppose that the warden’s rents “yielded a mass of benefit each year, whereof the contrary doth appear, for prisoners are not the best payers and some lie there many years and die without paying and others lie many years and then become insolvent.”

It was pleaded that where in old time no rent was charged on the Common Side, the warden Harris demanded it as if for a private chamber, and even for the dungeon as well. The answer was that the Common Side was the king’s ancient prison where for “many hundred years men were imprisoned there only” and they were not exempt from payment. In the part called the Tower Chamber there were eight bedsteads by which the warden had made seventy-one pounds by the year. In one ward, called the “Twopenny,” the inmates paid twopence a night; only in the “Beggars’ ” ward did prisoners pay nothing and receive nothing. In this last the insolvent debtor was forced to fend for himself; he was dependent upon chance charity for food, fire, clothing, bedding. Many hundreds succumbed to starvation and cold and died like dogs upon rotten straw, their nakedness barely covered by foul scanty rags. Rarely the degraded and neglected lodgers were suffered to go in search of water to cleanse the ward, but these as a rule were always filthily dirty.

The state of affairs was horrible within the gaol. No order was kept. Prisoners quarrelled and fought continually, many ranged the wards and corridors howling like lunatics all through the night and blowing horns, so that sleep was impossible to the sick and sorrowful. The lowest women entered freely, thieves took refuge there and thus avoided arrest; stolen goods were hidden in secure corners and never discovered. The prisoners went about armed and used swords and daggers freely in brawls and fights amongst themselves or in attacking the officers and servants of the gaol.

The Fleet, the appointed prison of the Star Chamber—Trial and conviction of Prynne and of “Freeborn” John Lilburne—Horrors in the Fleet and other debtors’ prisons reported by Moses Pitt—House of Commons Committee 1696—Ill treatment of Jacob Mendez Solas, a Portuguese prisoner—Shameful malpractices of Huggins and Bambridge—Case of Captain Mackpheadris and of Captain David Sinclair—Committal of Huggins and Bambridge to Newgate—Their trial and verdict of not guilty—Hogarth’s great picture of the Fleet Committee—Howard’s visitation in 1774—Social evils—Increase of Fleet marriages—Fleet parsons and their practices—Passing of the Marriage Act and abuses abolished.

THE Fleet was the appointed prison for the victims of the Star Chamber from the time of Elizabeth until toward the end of the reign of Charles I. It was essentially the King’s Prison to which State offenders might be committed, and to which debtors to the king on so confessing themselves might claim transfer from anywhere in the provinces if they preferred to be imprisoned in the capital. The Star Chamber, that oppressive, half-secret and wholly irresponsible tribunal, was accustomed to send to it all persons who fell under its displeasure; and this view is further confirmed by the circumstance, that whilst during the reign of Charles I we find it frequently used in this way, we do not notice any suggestion that the practice was then a new one. The two most interesting cases that belong to this part of the history of the Fleet are those of Prynne and Lilburne.

The trial of Prynne in the Star Chamber should be forever memorable as an example of the reckless disregard for law, justice, common sense and humanity which can be exhibited by high-handed judges. The following extracts will give a sufficient idea of the course of the trial and the mode of determining the sentence:—

“For the book” (the “Histriomastix” wherein he castigated the court and society severely), said Richardson, the Lord Chief Justice, “I hold it a most scandalous, infamous libel on the king’s majesty, a most pious and religious king; on the queen’s majesty, a most excellent and gracious queen, such a one as this kingdom never enjoyed the like and I think the earth never had a better,” etc. Then followed quotations from Prynne’s book, full of “outrageous opinions” on plays and players and dancing and then the first part of the sentence: “Mr. Prynne, I must now come to my sentence; I am very sorry, for I have known you long, but now I must utterly forsake you for I find that you have forsaken God” (the whole tenor of Prynne’s book was to lead men, in his way, to draw nearer to God) “ ... and forsaken all goodness. Therefore, Mr. Prynne, I shall proceed to my censure wherein I agree with my Lord Cottington: first for the burning of your book in as disgraceful manner as may be, whether in Cheapside or St. Paul’s Churchyard.... And because Mr. Prynne is of Lincoln’s Inn, and that his profession may not sustain disgrace by his punishment, I do think it fit, with my Lord Cottington, that he be put from the Bar and degraded in the University and I leave it to my lords, the lords bishop, to see that done; and for the pillory I hold it just and equal though there were no statute for it. In the case of all such crime it may be done by the discretion of the Court, so I do agree to that too. I fine him £5,000 and I know he is as well able to pay £5,000 as one-half of one thousand; and perpetual imprisonment. I do think fit for him to be restrained from writing—neither to have pen, ink nor paper—yet let him have some pretty prayer book to pray God to forgive him his sins, but to write, in good faith, I would never have him. For, Mr. Prynne, I do judge you by your book an insolent spirit and one that did think by this book to have got the name of a reformer, to set up the puritan or separatist faction.”

Sir Edward Coke followed, and among other things said: “Mr. Prynne, I do declare you to be a schism-maker in the Church, a sedition-sower in the Commonwealth, a wolf in sheep’s clothing; in a word omnium malorium nequissimus. I shall fine him £10,000, which is more than he is worth and less than he deserveth. I will not set him at liberty no more than a plagued man or a mad dog, who though he cannot bite will foam. He is so far from being a sociable soul that he is not a rational soul; he is fit to live in dens with such beasts of prey as wolves and tigers like himself, therefore do I condemn him to perpetual imprisonment as those monsters that are no longer fit to live among men, nor see light. Now for corporal punishment, my Lords, I shall burn him in the forehead and slit him in the nose.... I should be loth he should escape with his ears, for he may get a periwig which he now so much inveighs against and so hide them or force his conscience to make use of his unlovely love locks on both sides.”

These abominable barbarities were all inflicted in public, the branding, the mutilation, the loss of ears, and afterwards poor Prynne, stout and unyielding to the last, was remanded to the Fleet where his friends on visiting him found him “serene in spirit and still cheerfully patient.” His chief persecutor had been Archbishop Laud who was present in Court throughout, and this fact was remembered against the cruel prelate when later he was himself arraigned and sentenced to death. Prynne was a second time tried and sentenced to lose the hacked remnant of his ears.

A second victim of the Star Chamber’s intolerance of criticism was John Lilburne, “Freeborn John,” who refused to incriminate himself, standing on his rights as a freeborn Englishman. His alleged offence (with his printer Wharton) was the publication of libellous and seditious books, called “News from Ipswich.” They were both remanded to the Fleet for the present, but on the 13th February (1638) were again brought up and pressed to reconsider their determination. Still inflexible, they were sent back to the Fleet under a fine of £500 each and with an addition in Lilburne’s case of a remarkable punishment. Foiled in their attempt to break men’s spirits by fines, imprisonments, brandings, slitting of noses, etc., another degrading punishment was now borrowed from the felon-code,—whipping. “To the end,” runs the sentence, “that others may be the more deterred from daring to offend in the like manner hereafter, the court hath further ordered and decreed that the said John Lilburne shall be whipt through the street from the Prison of the Fleet unto the pillory, to be erected at such time and in such place as this court shall hold fit; and that both he and Wharton shall be set in the said pillory and from thence returned to the Fleet.” The pillory was placed between Westminster Hall gate and the Star Chamber and Lilburne was whipped from the prison thither “smartly.” Rushworth says, “Whilst he was whipt at the cart and stood in the pillory, he uttered many bold speeches against tyranny of bishops, etc., and when his head was in the hole of the pillory he scattered sundry copies of pamphlets (said to be seditious) and tossed them among the people, taking them out of his pocket.” The Star Chamber Council was sitting at the time and was informed of this last-mentioned incident; when, consistent in their acts, they ordered him to be gagged immediately, which was done. Lilburne then stamped with his feet, and the people understood his meaning well enough,—that he would speak if he were able. This was not all. At the same sitting of the Council an order was made directing that Lilburne should be “laid alone with irons on his hands and legs in the wards of the Fleet, where the basest and meanest sort of prisoners” were, with other regulations in a similar spirit. This punishment also was carried into effect for a time, but ultimately brought to a summary conclusion through an accident in the prison. “Lilburne,” says Rushworth, “having for some time endured close imprisonment, lying with double irons on his feet and hands and laid in the inner wards of the prison, there happened a fire in the prison of the Fleet, near to the place where he was prisoner, which gave a jealousy that Lilburne, in his fury and anguish, was desperate and had set the Fleet Prison on fire, not regarding himself to be burnt with it; whereupon the inhabitants without the Fleet (the street then not being five or six yards over from the prison door) and the prisoners all cried, ‘Release Lilburne or we shall all be burnt!’ and thereupon they ran headlong and made the warden remove him out of his hold, and the fire was quenched and he remained a prisoner in a place where he had some more air.” He continued in prison till November the 3d, 1640, when the Long Parliament began and then he was released and immediately applied to the House of Lords for redress, who granted it in the most satisfactory manner, not merely declaring his sentence and punishment most unjust and illegal, but ordering the erasure of the proceedings from the files of all courts of justice, “as unfit to continue on record.” On the breaking out of the Civil War, Lilburne fought bravely, we need not say on which side. Freeborn John was one of the most impracticable as well as courageous of enthusiasts (Marten said of him, if there were none living but himself, John would be against Lilburne, and Lilburne against John); and the Parliament pleased him little better than the King; so he wrote against them too, and was banished upon pain of death if he returned. But Freeborn John would and did return, and was immediately arraigned at the Old Bailey, where he was publicly acquitted, “which for joy occasioned a great acclamation of the people present.” He died a Quaker and was buried in Moorfields, four thousand citizens and other persons honouring his remains by following them to the grave.

Atrocities continued to be perpetrated in the Fleet after the Restoration and the inmates endured grievous ill-treatment. Some of these were set forth in the reign of William III in a quaint book printed and published in 1691 by one Moses Pitt, entitled, “The Cry of the Oppressed,” being a true and tragical account of the unparalleled sufferings of multitudes of poor imprisoned debtors in most of the gaols of England under the tyranny of the gaolers and other oppressors. A chief item was the relation of “some of the barbarities of Richard Manlove, Esq., the present warden of the Fleet, who has lately been found guilty of oppression and extortion by a jury of twelve men.”

The said warden “locked up till opened by the worthy Mr. Justice Lutwyche three score gentlemen and others for non-payment of exclusive chamber rent, where was a noisome House of Office near their lodgings, not allowing the king’s beds, but forcing them to procure beds or lie on the ground: and keeping men dead amongst them for pretended dues till they infected others.”

“Again Richard Brocas, Esq., was carried down thither for not paying excessive chamber-rent and his wife and servants denied to bring him victuals or physic; and when he died the jury summoned, could not but find his death occasioned by cruelty and they were dismissed by contrivance with the coroner; and when he was buried, a new jury summoned, he taken up again and an inquisition returned contrary to law; and Sir John Pettus of Suffolk, baronet, for not paying extorting dues, was forced into a little room (now the warden’s coachman’s lodgings) who being a learned studious person for want of those necessaries, he melancholy died and was kept many days above ground; his friends being denied his body till they paid the warden’s pretended dues.”

“Sir William Ducy, Baronet, was kept by the warden in his coach house till he was drawn out with ropes, being so offensive, that none could come near him. Symon Edolph, Esq., seventy-eight years of age, the son of Sir Thomas Edolph of Kent, for not paying forty two pounds demanded of him, when he profered thirty pounds, which was for a little room about twelve foot square, after the rate of six shillings per week, besides payment of the chamberlain, was dragged down to the wards in the hard weather and there not allowed a bed but must have lain on the ground had he not (at his own charge) procured one.” “Walter Cowdrey, gaoler of Winchester, for about two or three months’ chamber rent, was kept above ground till it caused a sickness in the next room, and his friends denied to take his body without paying extorting fees. By which may be perceived the inhumanity of this gaoler, not only to gentlemen but one of his own trade and calling. Sir George Putsay, sergeant at law, dying of dropsie; and being a very great fat man, was kept (for extorting fees) till a judge’s warrant was procured for his delivery. Moses Pitt of London, bookseller, being committed prisoner to the Fleet, April the 20th 1689, lodged on the gentleman’s side in a chamber which the warden values at eight shillings per week, though of right it’s but two shillings and fourpence, the rest being exaction (and the said Moses Pitt at the time of writing of this has two chambers within the rules of the Kings-Bench for one shilling three pence per week, twice as good as the said chamber), he the said Pitt continued in the said chamber from the said 20th of April 1689 to the 26th of August 1690 which was seventy weeks and three days, in which time the said Pitt had paid the warden his commitment fee, two pounds four shillings and sixpence, where as there is but fourpence due: Pitt also paid him fourteen shillings for two day-writs, and was to pay him eight shillings and fourpence at the going out of the gate, (every prisoner there in execution pays eleven shillings and twopence a day when he goes abroad about his business) but the said warden kept his said fourteen shillings and would not let him go out of the gates of the prison by which the said Pitt lost his tryals, which was many thousand pounds damage to him.” This Moses Pitt was once a rich man and his printing works were established in a large house called “the theatre” in Westminster, which he rented from Dr. Fell, Bishop of Oxford, and where in the reign of Charles II he brought out an atlas in twelve folio volumes and a great quantity of Bibles, Testaments and prayer books reducing their price by more than half which he claimed, “did at that time great good, Popery being likely to overwhelm us.” Mr. Pitt embarked upon extensive building speculations in Westminster and erected a great house in Duke Street which he let to the noted Judge Jeffreys, but failed to secure a clear title to the property. Then his creditors came down upon him and he became involved in a mesh of borrowings and their attendant lawsuits which landed him at length in the Fleet prison. His hardships led him to prepare his book denouncing the evils of imprisonment for debt; and to obtain facts he addressed a circular to sixty-five provincial prisons. The result was a “small book as full of tragedies as pages; which were not enacted in foreign nations among Turks and infidels, Papists and Idolaters, but in this country by our own countrymen”—such tragedies as no age or country can parallel.

He tells the story of a Liverpool surgeon who was so reduced by poverty, neglect and hunger that he lived on the mice caught by his cat. When he sought redress he was beaten and put in irons. A debtor in Lincoln who sought restitution of a purse taken from him was “treated to a ride on the jailer’s coach;” in other words placed upon a hurdle and dragged about the prison yard with his head on the stones whereby he “became not altogether so well in his intellects as formerly.” One unfortunate wretch who dared to send out of the prison for food had the thumbscrews put on him and was chained by the neck on tip-toe against a wall. The frontispiece of this old book gives a quaint representation of the interior of the Fleet prison.

These complaints led to the appointment of a committee of the House of Commons in 1696 and a report of many great irregularities, chief among them that the warden will let the prison for the sum of £1,500 to a sub-tenant on the understanding that there would be some two thousand prisoners always in custody who would pay fees to the value of twice the rent. A second report, presumably from the same committee, disclosed a widespread system of discharges not by regular legal process but on the payment of bribes and it was unanimously agreed that the management of the Fleet was “very prejudicial to personal credit and a great grievance to the whole kingdom.”

No remedy was applied to these glaring evils, which, on the contrary, constantly increased until they culminated in the horrible scandals laid bare by the Parliamentary Committee appointed in 1727 to inquire into the conduct of the then deputy warden, the infamous Bambridge, who leased the governorship from the real warden, the no less notorious Huggins. The most shameful malpractices had been rife since the abolition of the Star Chamber which had reserved the place entirely for debtors and prisoners for contempt of the Courts of Chancery, Exchequer and Common Pleas. It seemed that whereas the fees ought to have ceased when the prison was limited in its uses, the warden had wielded an unwarrantable and arbitrary power in extorting them at more exorbitant rates, enforcing payment by loading the prisoners with irons “worse than if the Star Chamber was still existing.”

The course pursued in every case where the incoming prisoner possessed means, was much the same. On arrest he was first conveyed to a Sponging House, one of three attached to the Fleet, beyond the walls, all belonging to the warden and kept by one or other of his tipstaffs. Here the charges were so ruinous that the debtors aghast begged to be taken at once to the Fleet itself, where at least prices were regulated by rules. Transfer was refused until a heavy fee had been exacted and while the prisoner still demurred his bill in the Sponging House steadily grew in total. When at last he was removed into the Fleet he had been bled freely, in fees alone to the amount of some fifty odd pounds. Here fresh exactions were imposed and the debtor, refusing to submit to insatiable demands, was sent back to the Sponging House, where a virulent small-pox was raging at the time. The prisoner, unvaccinated in those days, and in terror of his life, implored the ruthless warden to again remove him but could obtain no mercy and presently, taking the fell disease, died of it, leaving his affairs in hopeless confusion and a wife with a family of young children to starve. This was the true story of Mr. Robert Castell, a gentleman and a scholar, by profession an architect, whose original liabilities had been small and whose ruin and death were to be laid at Bambridge’s door.

Another story of like complexion was that of the Portuguese Jacob Mendez Solas, animadverted upon by the Parliamentary committee. This hapless foreigner enlodging in the Fleet was one day called into the Gate House or lodge, where he was seized, fettered and removed to Corbett’s Sponging House, whence after weeks of detention he was carried back into the prison. Extortion had been the object of this procedure and as the Portuguese still resisted, his life was made intolerable to him. He was turned now into a dungeon, known as the “strong room of the Master’s Side,” which is thus described in the Committee’s report:—

“The place is a vault, like those in which the dead are interred, and wherein the bodies of persons dying in the said prison are usually deposited, till the coroner’s inquest hath passed upon them. It has no chimney nor fireplace, nor any light but what comes over the door, or through a hole of about eight inches square. It is neither paved nor boarded; and the rough bricks appear both on the sides and top, being neither wainscoted nor plastered. What adds to the dampness and stench of the place is its being built over the common shore and adjoining to the sink and dunghill, where all the nastiness of the prison is cast. In this miserable place the poor wretch was kept by the said Bambridge, manacled and shackled, for near two months. At length, on receiving five guineas from Mr. Kemp, a friend of Solas’s, Bambridge released the prisoner from his cruel confinement. But though his chains were taken off, his terror still remained, and the unhappy man was prevailed upon by that terror not only to labour gratis for the said Bambridge, but to swear also at random all that he hath required of him. And this committee themselves saw an instance of the deep impression his sufferings had made upon him; for, on his surmising, from something said, that Bambridge was to return again as warden of the Fleet, he fainted and the blood started out of his mouth and nose.”

The same report continued: “Captain John Mackpheadris, who was bred a merchant, is another melancholy instance of the cruel use the said Bambridge hath made of his assumed authority. Mackpheadris was a considerable trader, and in a very flourishing condition, until the year 1720, when, being bound for large sums to the Crown, for a person afterward ruined by the misfortunes of that year, he was undone. In June, 1727, he was prisoner in the Fleet, and although he had before paid his commitment fee, the like fee was extorted from him a second time; and he having furnished a room, Bambridge demanded an extravagant price for it, which he refused to pay, and urged that it was unlawful for a warden to demand extravagant rents, and offered to pay what was legally due. Notwithstanding which, the said Bambridge assisted by the said James Barnes and other accomplices, broke open his room and took away several things of great value, amongst others, the King’s Extent in aid of the prisoner (which was to have been returned in a few days, in order to procure the debt to the Crown, and the prisoner’s enlargement), which Bambridge still detains. Not content with this, Bambridge locked the prisoner out of his room and forced him to lie in the open yard called the ‘Bare.’ He sat quietly under his wrongs, and getting some poor materials, built a little hut, to protect himself as well as he could from the injuries of the weather. The said Bambridge, seeing his unconcernedness, said, ‘—— him! he is easy! I will put him into the strong room before to-morrow!’ and ordered Barnes to pull down his little hut, which was done accordingly. The poor prisoner, being in an ill state of health and the night rainy, was put to great distress. Some time after this he was (about eleven o’clock at night) assaulted by Bambridge, with several other persons, his accomplices, in a violent manner; and Bambridge, though the prisoner was unarmed, attacked him with his sword, but by good fortune was prevented from killing him; and several other persons coming out upon the noise, they carried Mackpheadris for safety into another gentleman’s room; soon after which Bambridge, coming with one Savage and several others, broke open the door, and Bambridge strove with his sword to kill the prisoner, but he again got away and hid himself in another room. The next morning the said Bambridge entered the prison with a detachment of soldiers and ordered the prisoner to be dragged to the lodge and ironed with great irons. On which he, desiring to know for what cause and by what authority he was to be so cruelly used, Bambridge replied, it was by his own authority, and —— him, he would do it and have his life. The prisoner desired that he might be carried before a magistrate, that he might know his crime before he was punished; but Bambridge refused, and put irons upon his legs which were too little, so that in forcing them on, his legs were like to have been broken and the torture was impossible to be endured. Upon which the prisoner complaining of the grievous pain and straitness of the irons, Bambridge answered that he did it on purpose to torture him. On which the prisoner replying that by the law of England no man ought to be tortured, Bambridge declared that he would do it first and answer for it afterwards; and caused him to be dragged away to the dungeon, where he lay without a bed, loaded with irons so close riveted that they kept him in continual torture and mortified his legs. After long application his irons were changed and a surgeon directed to dress his legs; but his lameness is not, nor can be, cured. He was kept in this miserable condition for three weeks, by which his sight is greatly prejudiced and in danger of being lost.

“The prisoner upon this usage, petitioned the judges; and after several meetings and a full hearing, the judges reprimanded Mr. Huggins and Bambridge and declared that a gaoler could not answer the ironing of a man before he be found guilty of a crime, but it being out of term, they could not give the prisoner any relief or satisfaction.”

There were other cases, that, for instance, of Captain David Sinclair, an old and distinguished officer whom hard fate and impecuniosity had consigned to a debtors’ prison. Bambridge was his enemy and openly declared that he would have Sinclair’s blood. On the king’s birthday, a jovial occasion, on which he thought to find the captain elated with wine, Bambridge entered his room and struck him with a cane. Then turning to the soldiers of the escort, who came armed with musket and bayonet, Bambridge ordered them to carry Sinclair to the strong room and to stab him if he made any resistance. Confinement in this dark, damp dungeon all but cost Sinclair his life; he lost the use of his limbs and his memory went; he was left for four days without food and had he not been removed he would certainly have died. An unfortunate Spanish merchant, Mr. John Holder, who was confined in the Common Side under Bambridge, was seized with a fatal illness from the miseries and privations he endured.

It was said in the report already quoted that Bambridge, when he manacled Solas, was the first to put a debtor in irons. This is manifestly erroneous as is seen in the account of the charges brought against warden Harris in 1620, for misusage of prisoners in the Fleet. But this brutal gaoler, Bambridge, was guilty of many and great enormities. He was proved to have defied writs of habeas corpus; to have stolen or misappropriated charitable bequests; to have bribed or terrified lawyers who came to champion ill-used prisoners. When Sir William Rich was behind-hand in his chamber-rent, Bambridge threatened to fire at him, slashed at him with a hanger, and struck him with a stick. Rich was then thrown into the strong room, heavily ironed, and kept there in close confinement accused of having attacked the warden with a shoemaker’s knife, which he did, but in self-defence.

Huggins and Bambridge, in their greedy desire to increase their emoluments, invented an astute device, that of allowing, even helping debtors to escape from custody, whom they presently rearrested, and having made them pay forfeit, pocketed the amounts. To facilitate this a false gate was broken through the prison wall, through which the fugitives were released with the co-operation of the warden, and thus the forfeit was exacted many times over.

The same means of exit was utilised by a smuggler, in custody for revenue fraud, who passed in and out on his own concerns, and to do business for Mr. Huggins. This man, by name Dumay, made frequent voyages to France, where he bought quantities of wine for Huggins and paid for them by bills drawn upon one of the tipstaffs, which when due were punctually met. Confidence was thus established and the traffic was greatly developed, but when an unusually large deal had been effected the tipstaff declined to accept the bill and the French wine merchant was swindled out of his goods and his money.

This inquiry of 1727 resulted in the committal of both Huggins and Bambridge to the gaol of Newgate, and their prosecution. A bill was introduced into Parliament to remove both men from their posts and to revise the management of the Fleet; but when these wretches were arraigned for their misdeeds the evidence was deemed insufficient and they escaped with a verdict of not guilty. The episode is especially interesting as having inspired Hogarth to paint the remarkable picture of the Fleet Prison Committee, which is said to have first brought the painter into fame. Speaking of this picture, Horace Walpole in his “Anecdotes of Painting” says: “The scene is the Committee; on the left are the instruments of torture. A prisoner in rags half starved appears before them. The poor man has a good countenance that adds to the interest. On the other hand is the inhuman gaoler. It is the very figure that Salvator Rosa would have drawn for Iago at the moment of detection,—villainy, fear and conscience are mixed on his yellow and livid countenance. His lips contracted by tremor, his legs step back as though thinking to make his escape—one hand is thrust precipitately into his bosom, the fingers of the other are catching uncertainly at his button-holes. If this was a portrait it is the most striking that ever was drawn; if not it is still finer.” There is no question that this is Bambridge, who lingered on for twenty years disgraced and despised and in the end committed suicide by cutting his throat.

We have two views of the interior of the Fleet and its general aspect from two eye witnesses at a later date than the exposure of Huggins and Bambridge. One is John Howard’s account of his visitation in 1774; the other a volume of verse “The Humours of the Fleet, an humorous and descriptive poem written by a gentleman of the College,” published in London in 1749. The author was the younger Dance, son of Mr. Dance, the architect, who rebuilt the gaol of Newgate after its destruction by the Lord George Gordon rioters in 1780. It is described as “The Prince of Prisons” standing “close by the borders of a slimy flood,” a structure in whose extended oblong boundaries are shops and sheds and stalls of all degrees, for the sale of everything from trinkets to pork and beans. The inmates are next described:

The first ceremony for the newcomer is to sit or stand for his portrait:

Then follows the description of the chamberlain “who settles the price of quarters; one pound six and light weekly for the best room, or as low as half a crown per month.”

and so on page after page illustrating the daily life, sorrows, dirt and rags; the sports—backgammon, Mississippi, portobello, racquets, billiards, fives; increasing drought quenched by gin; rough horseplay with newcomers who are borne to the pump and drenched, the whole presented in a picture crowded with the ragged, slipshod figures standing treat to the tipstaffs and one another. The poem concludes with the closing of the prison when

The cry is heard from half-past nine till the clock of St. Paul’s strikes ten, very like the familiar shout on shipboard “Any more for the shore.” The final “all told” was the signal to shut and lock the gate after which no person was permitted to pass either in or out.

The philanthropist’s inspection, naturally, was a more serious matter, and his account of what he found in the Fleet was a striking item in his general indictment of British prisons. The Fleet at that date held three hundred and twenty-four inmates in the “House” and one hundred resided within the “Rules.” The prison buildings were partly old and partly new, having been rebuilt a few years previous. It now consisted of a long house (198 feet) facing a narrow courtyard and having four stories or galleries with a basement or cellar floor called Bartholomew Fair, which was appropriated to the Common Side or the solvent pauper debtors. In the galleries the rooms opened on either side of a central passage, narrow and dark, with one window at each end. The rooms were for the most part 14½ feet in length by 12½ feet wide, and 9½ feet in height, all provided with fire-place and chimney, and lighted with one window. On the ground-floor or Hall Gallery were a chapel, a tap-room, a coffee-room and eighteen chambers for prisoners; on the first floor twenty-five rooms, on the second twenty-seven, with prisoners’ committee-room, the infirmary and a “dirty billiard table, kept by the prisoners who slept in that room.” This billiard table was open to outsiders, and Howard saw “several butchers and others from the market playing, who were admitted as at any public house. Besides the inconvenience to prisoners,” says Howard, “the frequenting a prison lessens the dread of being confined in one.” The gallery rooms on the top floor were reserved for Master’s Side debtors who paid the warden’s rent, nominally, at the rate of one shilling and three pence weekly, a price liable to be much increased. They fell to prisoners in succession, and when any became vacant it was taken by the first on the warden’s lists who had paid his full entrance fee. If all rooms were occupied, a newcomer must hire of some tenant a part of his room or shift as he could. The same practice obtained some fifty years later as described by Charles Dickens when telling of the imprisonment of Mr. Pickwick.

The discipline was very lax, due to the unrestrained admission of all classes, male and female, the latter often of very indifferent character. “Social evenings” were of common occurrence; on Monday nights a wine club, on Thursdays a beer club, each lasting until one or two in the morning. “I need not say,” remarks Howard, “how much riot these meetings occasioned, and how the sober prisoners are annoyed by them.” Master’s Side debtors, mostly well disposed, respectable people, were moved to maintain order and better government and formed themselves into a committee to establish rules and insist upon their observance. This committee was chosen every month and consisted of three members from every gallery, with a president and secretary. They met every Thursday in their own committee room and at other times when summoned by the cryer (the servant of the prison who called persons from within when a visitor came to see them), at command of the president or a majority of their own number. This committee raised contributions by assessment, heard complaints, determined disputes, advised fines and seized goods for payment. It claimed to speak the sense of the whole House. The president held the cash and the committee disposed of it. It appointed a scavenger who washed the galleries once a week, watered them and swept them daily, every morning before eight, and who swept the yards twice a week, and lit the lamps all over the House. The cryer’s fee for calling a prisoner to any stranger who visited the prison was one penny; from a complainant who desired that the committee might be brought together he got a fee of twopence. The tax levied on a newcomer, besides the two shillings for “garnish” to be spent in wine, was one shilling and sixpence to be appropriated for the use of the House. Distinction of rank was overlooked in the Fleet, for Common Side debtors were confined to their own apartments in Bartholomew Fair and were forbidden to associate with “the lawmakers.”