We and Our Neighbors:

OR,

THE RECORDS OF AN UNFASHIONABLE STREET.

(Sequel to "My Wife and I.")

A NOVEL.

By HARRIET BEECHER STOWE.

Author of "Uncle Tom's Cabin," "My Wife and I," etc.

With Illustrations.

NEW YORK:

J. B. FORD & COMPANY.

COPYRIGHT A.D. 1875

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

|---|---|---|

| I.— | The Other Side of the Street | 7 |

| II.— | How WE Begin Life | 23 |

| III.— | The Family Dictator at Work | 30 |

| IV.— | Eva to Harry's Mother | 42 |

| V.— | Aunt Maria Rouses a Tempest in a Teapot | 52 |

| VI.— | The Settling of the Waters | 69 |

| VII.— | Letters and Air-Castles | 78 |

| VIII.— | The Vanderheyden Fortress Taken | 86 |

| IX.— | Jim and Alice | 95 |

| X.— | Mr. St. John | 103 |

| XI.— | Aunt Maria Clears her Conscience | 115 |

| XII.— | "Why Can't They Let Us Alone?" | 131 |

| XIII.— | Our "Evening" Projected | 144 |

| XIV.— | Mr. St. John is Outargued | 152 |

| XV.— | Getting Ready to Begin | 160 |

| XVI.— | The Minister's Visit | 173 |

| XVII.— | Our First Thursday | 178 [Pg iv] |

| XVIII.— | Raking up the Fire | 192 |

| XIX.— | A Lost Sheep | 197 |

| XX.— | Eva to Harry's Mother | 201 |

| XXI.— | Bolton and St. John | 207 |

| XXII.— | Bolton to Caroline | 214 |

| XXIII.— | The Sisters of St. Barnabas | 221 |

| XXIV.— | Eva to Harry's Mother | 227 |

| XXV.— | Aunt Maria Endeavors to Set Matters Right | 232 |

| XXVI.— | She Stood Outside the Gate | 243 |

| XXVII.— | Rough Handling of Sore Nerves | 253 |

| XXVIII.— | Reason and Unreason | 262 |

| XXIX.— | Aunt Maria Frees her Mind | 270 |

| XXX.— | A Dinner on Washing Day | 274 |

| XXXI.— | What They Talked About | 285 |

| XXXII.— | A Mistress Without a Maid | 296 |

| XXXIII.— | A Four-footed Prodigal | 307 |

| XXXIV.— | Going to the Bad | 317 |

| XXXV.— | A Soul in Peril | 328 |

| XXXVI.— | Love in Christmas Greens | 339 |

| XXXVII.— | Thereafter? | 350 |

| XXXVIII.— | "We Must be Cautious" | 357 |

| XXXIX.— | Says She to her Neighbor—What? | 365 |

| XL.— | The Engagement Announced | 369 |

| XLI.— | Letter from Eva to Harry's Mother | 375[Pg v] |

| XLII.— | Jim's Fortunes | 387 |

| XLIII.— | A Midnight Caucus over the Coals | 399 |

| XLIV.— | Fluctuations | 407 |

| XLV.— | The Valley of the Shadow | 414 |

| XLVI.— | What They all Said About It | 418 |

| XLVII.— | "In the Forgiveness of Sins" | 430 |

| XLVIII.— | The Pearl Cross | 439 |

| XLIX.— | The Unprotected Female | 448 |

| L.— | Eva to Harry's Mother | 461 |

| LI.— | The Hour and the Woman | 465 |

| LII.— | Eva's Consultations | 469 |

| LIII.— | Wedding Presents | 474 |

| LIV.— | Married and A' | 478 |

| I.— | New Neighbors | Frontispiece. |

| "'Who can have taken the Ferguses' house, sister?' said a brisk little old lady, peeping through the window blinds." | ||

| PAGE | ||

| II.— | Talking it Over | 73 |

| "Come now, Puss, out with it. Why that anxious brow? What domestic catastrophe?" | ||

| III.— | The Domestic Artist | 131 |

| "A spray of ivy that was stretching towards the window had been drawn back and was forced to wreathe itself around a picture." | ||

| IV.— | Wickedness, or Misery? | 197 |

| "Bolton laid his hand on her shoulder, and, looking down on her, said: 'Poor child, have you no mother?'" | ||

| V.— | Confidences | 287 |

| "In due course followed an introduction to 'my wife,' whose photograph Mr. Selby wore dutifully in his coat-pocket." | ||

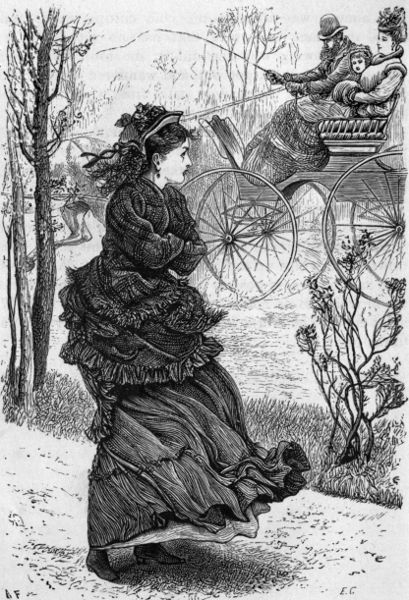

| VI.— | Going to the Bad | 327 |

| "The sweet-faced woman calls the attention of her husband. He frowns, whips up the horse, and is gone.... Bitterness possesses Maggie's soul.... Why not go to the bad?" | ||

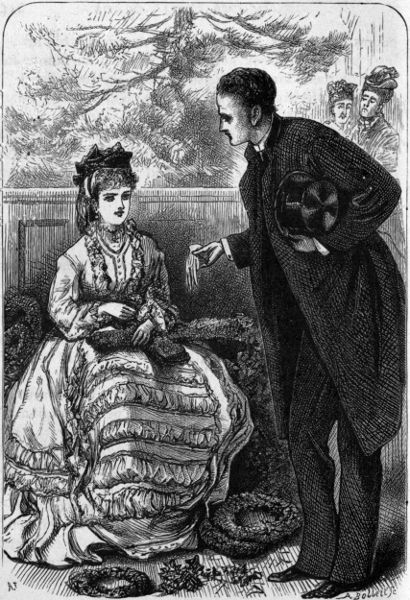

| VII.— | Skirmishing | 341 |

| "'I like your work,' he said, 'better than you do mine.' 'I didn't say that I didn't like yours,' said Angie, coloring." | ||

| VIII.— | A Midnight Caucus | 400 |

| "'There, now he's off,' said Eva ... then, leaning back, she began taking out hair-pins and shaking down curls and untying ribbons as a preface to a wholly free conversation." | ||

"Who can have taken the Ferguses' house, sister?" said a brisk little old lady, peeping through the window blinds. "It's taken! Just come here and look! There's a cart at the door."

"You don't say so!" said Miss Dorcas, her elder sister, flying across the room to the window blinds, behind which Mrs. Betsey sat discreetly ensconced with her knitting work. "Where? Jack, get down, sir!" This last remark was addressed to a rough-coated Dandie Dinmont terrier, who had been winking in a half doze on a cushion at Miss Dorcas's feet. On the first suggestion that there was something to be looked at across the street, Jack had ticked briskly across the room, and now stood on his hind legs on an old embroidered chair, peering through the slats as industriously as if his opinion had been requested. "Get down, sir!" persisted Miss Dorcas. But Jack only winked contumaciously at Mrs. Betsey, whom he justly considered in the light of an ally, planted his toe nails more firmly in the embroidered chair-bottom, and stuck his nose further between the slats, while Mrs. Betsey took up for him, as he knew she would.

"Do let the dog alone, Dorcas! He wants to see as much as anybody."

"Now, Betsey, how am I ever to teach Jack not to[Pg 8] jump on these chairs if you will always take his part? Besides, next we shall know, he'll be barking through the window blinds," said Miss Dorcas.

Mrs. Betsey replied to the expostulation by making a sudden diversion of subject. "Oh, look, look!" she called, "that must be she," as a face with radiant, dark eyes, framed in an aureole of bright golden hair, appeared in the doorway of the house across the street. "She's a pretty creature, anyway—much prettier than poor dear Mrs. Fergus."

"Henderson, you say the name is?" said Miss Dorcas.

"Yes. Simons, the provision man at the corner, told me that the house had been bought by a young editor, or something of that sort, named Henderson—somebody that writes for the papers. He married Van Arsdel's daughter."

"What, the Van Arsdels that failed last spring? One of our mushroom New York aristocracy—up to-day and down to-morrow!" commented Miss Dorcas, with an air of superiority. "Poor things!"

"A very imprudent marriage, I don't doubt," sighed Mrs. Betsey. "These upstart modern families never bring up their girls to do anything."

"She seems to be putting her hand to the plough, though," said Miss Dorcas. "See, she actually is lifting out that package herself! Upon my word, a very pretty creature. I think we must take her up."

"The Ferguses were nice," said Mrs. Betsey, "though he was only a newspaper man, and she was a nobody; but she really did quite answer the purpose for a neighbor—not, of course, one of our sort exactly, but a very respectable, lady-like little body."

"Well," said Miss Dorcas, reflectively, "I always said it doesn't do to carry exclusiveness too far. Poor dear Papa was quite a democrat. He often said that he had[Pg 9] seen quite good manners and real refinement in people of the most ordinary origin."

"And, to be sure," said Mrs. Betsey, "if one is to be too particular, one doesn't get anybody to associate with. The fact is, the good old families we used to visit have either died off or moved off up into the new streets, and one does like to have somebody to speak to."

"Look there, Betsey, do you suppose that's Mr. Henderson that's coming down the street?" said Miss Dorcas.

"Dear me!" said Mrs. Betsey, in an anxious flutter. "Why, there are two of them—they are both taking hold to lift out that bureau—see there! Now she's put her head out of the chamber window there, and is speaking to them. What a pretty color her hair is!"

At this moment the horse on the other side of the street started prematurely, for some reason best known to himself, and the bureau came down with a thud; and Jack, who considered his opinion as now called for, barked frantically through the blinds.

Miss Dorcas seized his muzzle energetically and endeavored to hold his jaws together, but he still barked in a smothered and convulsive manner; whereat the good lady swept him, vi et armis, from his perch, and disciplined him vigorously, forcing him to retire to his cushion in a distant corner, where he still persistently barked.

"Oh, poor doggie!" sighed Mrs. Betsey. "Dorcas, how can you?"

"How can I?" said Miss Dorcas, in martial tones. "Betsey Ann Benthusen, this dog would grow up a perfect pest of this neighborhood if I left him to you. He must learn not to get up and bark through those blinds. It isn't so much matter now the windows are shut, but the habit is the thing. Who wants to have a dog firing a fusillade when your visitors come up the front[Pg 10] steps—barking-enough-to-split-one's-head-open," added Miss Dorcas, turning upon the culprit, with a severe staccato designed to tell upon his conscience.

Jack bowed his head and rolled his great soft eyes at her through a silvery thicket of hair.

"You are a very naughty dog," she added, impressively.

Jack sat up on his haunches and waved his front paws in a deprecating manner to Miss Dorcas, and the good lady laughed and said, cheerily, "Well, well, Jacky, be a good dog now, and we'll be friends."

And Jacky wagged his tail in the most demonstrative manner, and frisked with triumphant assurance of restored favor. It was the usual end of disciplinary struggles with him. Miss Dorcas sat down to a bit of worsted work on which she had been busy when her attention was first called to the window.

Mrs. Betsey, however, with her nose close to the window blinds, continued to announce the state of things over the way in short jets of communication.

"There! the gentlemen are both gone in—and there! the cart has driven off. Now, they've shut the front door," etc.

After this came a pause of a few moments, in which both sisters worked in silence.

"I wonder, now, which of those two was the husband," said Mrs. Betsey at last, in a slow reflective tone, as if she had been maturely considering the subject.

In the mean time it had occurred to Miss Dorcas that this species of minute inquisition into the affairs of neighbors over the way was rather a compromising of her dignity, and she broke out suddenly from a high moral perch on her unconscious sister.

"Betsey," she said, with severe gravity, "I really suppose it's no concern of ours what goes on over at the[Pg 11] other house. Poor dear Papa used to say if there was anything that was unworthy a true lady it was a disposition to gossip. Our neighbors' affairs are nothing to us. I think it is Mrs. Chapone who says, 'A well-regulated mind will repress curiosity.' Perhaps, Betsey, it would be well to go on with our daily reading."

Mrs. Betsey, as a younger sister, had been accustomed to these sudden pullings-up of the moral check-rein from Miss Dorcas, and received them as meekly as a well-bitted pony. She rose immediately, and, laying down her knitting work, turned to the book-case. It appears that the good souls were diversifying their leisure hours by reading for the fifth or sixth time that enlivening poem, Young's Night Thoughts. So, taking down a volume from the book-shelves and opening to a mark, Mrs. Betsey commenced a sonorous expostulation to Alonzo on the value of time. The good lady's manner of rendering poetry was in a high-pitched falsetto, with inflections of a marvelous nature, rising in the earnest parts almost to a howl. In her youth she had been held to possess a talent for elocution, and had been much commended by the amateurs of her times as a reader of almost professional merit. The decay of her vocal organs had been so gradual and gentle that neither sister had perceived the change of quality in her voice, or the nervous tricks of manner which had grown upon her, till her rendering of poetry resembled a preternatural hoot. Miss Dorcas beat time with her needle and listened complacently to the mournful adjurations, while Jack, crouching himself with his nose on his forepaws, winked very hard and surveyed Miss Betsey with an uneasy excitement, giving from time to time low growls as her voice rose in emphatic places; and finally, as if even a dog's patience could stand it no longer, he chorused a startling point with a sharp yelp!

"There!" said Mrs. Betsey, throwing down the book. "What is the reason Jack never likes me to read poetry?"

Jack sprang forward as the book was thrown down, and running to Mrs. Betsey, jumped into her lap and endeavored to kiss her in a most tumultuous and excited manner, as an expression of his immense relief.

"There! there! Jacky, good fellow—down, down! Why, how odd it is! I can't think what excites him so in my reading," said Mrs. Betsey. "It must be something that he notices in my intonations," she added, innocently.

The two sisters we have been looking in upon are worthy of a word of introduction. There are in every growing city old houses that stand as breakwaters in the tide of modern improvement, and may be held as fortresses in which the past entrenches itself against the never-ceasing encroachments of the present. The house in which the conversation just recorded has taken place was one of these. It was a fragment of ancient primitive New York known as the old Vanderheyden house, only waiting the death of old Miss Dorcas Vanderheyden and her sister, Mrs. Betsey Benthusen, to be pulled down and made into city lots and squares.

Time was when the Vanderheyden house was the country seat of old Jacob Vanderheyden, a thriving Dutch merchant, who lived there with somewhat foreign ideas of style and stateliness.

Parks and gardens and waving trees had encircled it, but the city limits had gained upon it through three generations; squares and streets had been opened through its grounds, till now the house itself and the garden-patch in the rear was all that remained of the ancient domain. Innumerable schemes of land speculators had attacked the old place; offers had been insidiously made to the proprietors which would have[Pg 13] put them in possession of dazzling wealth, but they gallantly maintained their position. It is true their income in ready money was but scanty, and their taxes had, year by year, grown higher as the value of the land increased. Modern New York, so to speak, foamed and chafed like a great red dragon before the old house, waiting to make a mouthful of it, but the ancient princesses within bravely held their own and refused to parley or capitulate.

Their life was wholly in the past, with a generation whose bones had long rested under respectable tombstones. Their grandfather on their mother's side had been a signer of the Declaration of Independence; their grandfather on the paternal side was a Dutch merchant of some standing in early New York, a friend and correspondent of Alexander Hamilton's and a co-worker with him in those financial schemes by which the treasury of the young republic of America was first placed on a solid basis. Old Jacob did good service in negotiating loans in Holland, and did not omit to avail himself of the golden opportunities which the handling of a nation's wealth presents. He grew rich and great in the land, and was implicitly revered in his own family as being one of the nurses and founders of the American Republic. In the ancient Dutch secretary which stood in the corner of the sitting-room where our old ladies spent their time were many letters from noted names of a century or so back—papers yellow with age, but whose contents were all alive with the foam and fresh turbulence of what was then the existing life of the period.

Mrs. Betsey Benthusen was a younger sister and a widow. She had been a beauty in her girlhood, and so much younger than her sister that Miss Dorcas felt all the pride and interest of a mother in her success, in her lovers, in her marriage; and when that marriage proved a[Pg 14] miserable failure, uniting her to a man who wasted her fortune and neglected her person, and broke her heart, Miss Dorcas received her back to her strong arms and made a home and a refuge where the poor woman could gather up and piece together, in some broken fashion, the remains of her life as one mends a broken Sèvres china tea cup.

Miss Dorcas was by nature of a fiery, energetic temperament, intense and original—precisely the one to be a contemner of customs and proprieties; but a very severe and rigid education had imposed on her every yoke of the most ancient and straitest-laced decorum. She had been nurtured only in such savory treatises as Dr. Gregory's Legacy to his Daughters, Mrs. Chapone's Letters, Miss Hannah More's Coelebs in Search of a Wife, Watts On the Mind, and other good books by which our great grandmothers had their lives all laid out for them in exact squares and parallelograms, and were taught exactly what to think and do in all possible emergencies.

But, as often happens, the original nature of Miss Dorcas was apt to break out here and there, all the more vivaciously for repression, in a sort of natural geyser: and so, though rigidly proper in the main, she was apt to fall into delightful spasms of naturalness.

Notwithstanding all the remarks of Mrs. Chapone and Dr. Watts about gossip, she still had a hearty and innocent interest in the pretty young housekeeper that was building a nest opposite to her, and a little quite harmless curiosity in what was going on over the way.

A great deal of good sermonizing, by the by, is expended on gossip, which is denounced as one of the seven deadly sins of society; but, after all, gossip has its better side: if not a Christian grace, it certainly is one of those weeds which show a good warm soil.

The kindly heart, that really cares for everything human[Pg 15] it meets, inclines toward gossip, in a good way. Just as a morning glory throws out tendrils, and climbs up and peeps cheerily into your window, so a kindly gossip can't help watching the opening and shutting of your blinds and the curling smoke from your chimney. And so, too, after all the high morality of Miss Dorcas, the energetic turning of her sister to the paths of propriety, and the passage from Young's Night Thoughts, with its ponderous solemnity, she was at heart kindly musing upon the possible fortunes of the pretty young creature across the street, and was as fresh and ready to take up the next bit of information about her house as a brisk hen is to discuss the latest bit of crumb thrown from a window.

Miss Dorcas had been brought up by her father in diligent study of the old approved English classics. The book-case of the sitting-room presented in gilded order old editions of the Rambler, the Tattler, and the Spectator, the poems of Pope, and Dryden, and Milton, and Shakespeare, and Miss Dorcas and her sister were well versed in them all. And in view of the whole of our modern literature, we must say that their studies might have been much worse directed.

Their father had unfortunately been born too early to enjoy Walter Scott. There is an age when a man cannot receive a new author or a new idea. Like a lilac bush which has made its terminal buds, he has grown all he can in this life, and there is no use in trying to force him into a new growth. Jacob Vanderheyden died considering Scott's novels as the flimsy trash of the modern school, while his daughters hid them under their pillows, and found them all the more delightful from the vague sensation of sinfulness which was connected with their admiration. Walter Scott was their most modern landmark; youth and bloom and heedlessness and impropriety[Pg 16] were all delightfully mixed up with their reminiscences of him—and now, here they were still living in an age which has shelved Walter Scott among the classics, and reads Dickens and Thackeray and Anthony Trollope.

Miss Dorcas had been stranded, now and then, on one of these "trashy moderns"—had sat up all night surreptitiously reading Nicholas Nickleby, and had hidden the book from Mrs. Betsey lest her young mind should be carried away, until she discovered, by an accidental remark, that Mrs. Betsey had committed the same delightful impropriety while off on a visit to a distant relative. When the discovery became mutual, from time to time other works of the same author crept into the house in cheap pamphlet editions, and the perusal of them was apologized for by Miss Dorcas to Mrs. Betsey, as being well enough, now and then, to see what people were reading in these trashy times. Ah, what is fame! Are not Dickens and Thackeray and Trollope on their inevitable way to the same dusty high shelf in the library, where they will be praised and not read by the forthcoming jeunesse of the future?

If the minds of the ancient sisters were a museum of by-gone ideas, and literature, and tastes, the old Vanderheyden house was no less a museum of by-gone furniture. The very smell of the house was ghostly with past suggestion. Every article of household gear in it had grown old together with all the rest, standing always in the same spot, subjected to the same minute daily dusting and the same semi-annual house-cleaning.

Carlyle has a dissertation on the "talent for annihilating rubbish." This was a talent that the respectable Miss Dorcas had none of. Carlyle thinks it a fine thing to have; but we think the lack of it may come from very respectable qualities. In Miss Dorcas it came from a vivid imagination of the possible future uses to which[Pg 17] every decayed or broken household article might be put. The pitcher without nose or handle was fine china, and might yet be exactly the thing for something, and so it went carefully on some high perch of preservation, dismembered; the half of a broken pair of snuffers certainly looked too good to throw away—possibly it might be the exact thing needed to perfect some invention. Miss Dorcas vaguely remembered legends of inventors who had laid hold on such chance adaptations at the very critical point of their contrivances, and so the half snuffers waited years for their opportunity. The upper shelves of the closets in the Vanderheyden house were a perfect crowded mustering ground for the incurables and incapables of household belongings. One might fancy them a Hotel des Invalides of things wounded and fractured in the general battle of life. There were blades of knives without handles, and handles without blades; there were ancient tea-pots that leaked—but might be mended, and doubtless would be of some good in a future day; there were cracked plates and tea-cups; there were china dish-covers without dishes to match; a coffee-mill that wouldn't grind, and shears that wouldn't cut, and snuffers that wouldn't snuff—in short, every species of decayed utility.

Miss Dorcas had in the days of her youth been blest with a brother of an active, inventive turn of mind; the secret crypts and recesses of the closets bore marks of his unfinished projections. There were all the wheels and weights and other internal confusions of a clock, which he had pulled to pieces with a view of introducing an improvement into the machinery, which never was introduced; but the wheels and weights were treasured up with pious care, waiting for somebody to put them together again. All this array of litter was fated to come down from its secret recesses, its deep, dark closets, its high[Pg 18] shelves and perches, on two solemn days of the year devoted to house-cleaning, when Miss Dorcas, like a good general, looked them over and reviewed them, expatiated on their probable capabilities, and resisted gallantly any suggestions of Black Dinah, the cook and maid of all work, or Mrs. Betsey, that some order ought to be taken to rid the house of them.

"Dear me, Dorcas," Mrs. Betsey would say, "what is the use of keeping such a clutter and litter of things that nothing can be done with and that never can be used?"

"Betsey Ann Benthusen," would be the reply, "you always were a careless little thing. You never understood any more about housekeeping than a canary bird—not a bit." In Miss Dorcas's view, Mrs. Betsey, with her snow white curls and her caps, was still a frivolous young creature, not fit to be trusted with a serious opinion on the nicer points of household management. "Now, who knows, Betsey, but some time we may meet some poor worthy young man who may be struggling along as an inventor and may like to have these wheels and weights! I'm sure brother Dick said they were wonderfully well made."

"Well, but, Dorcas, all those cracked cups and broken pitchers; I do think they are dreadful!"

"Now, Betsey, hush up! I've heard of a kind of new cement that they are manufacturing in London, that makes old china better than new; and when they get it over here I'm going to mend these all up. You wouldn't have me throw away family china, would you?"

The word "family china" was a settler, for both Mrs. Betsey and Miss Dorcas and old Dinah were united in one fundamental article of faith: that "the Family" was a solemn, venerable and awe-inspiring reality. What, or why, or how it was, no mortal could say.

Old Jacob Vanderheyden, the grandfather, had been[Pg 19] in his day busy among famous and influential men, and had even been to Europe as a sort of attaché to the first American diplomatic corps. He had been also a thriving merchant, and got to himself houses, and lands, and gold and silver. Jacob Vanderheyden, the father, had inherited substance and kept up the good name of the family, and increased and strengthened its connections. But his son and heir, Dick Vanderheyden, Miss Dorcas's elder brother, had seemed to have no gifts but those of dispersing; and had muddled away the family fortune in all sorts of speculations and adventures as fast as his father and grandfather had made it. The sisters had been left with an income much abridged by the imprudence of the brother and the spendthrift dissipation of Mrs. Betsey's husband; they were forsaken by the retreating waves of rank and fashion; their house, instead of being a center of good society, was encompassed by those ordinary buildings devoted to purposes of trade whose presence is deemed incompatible with genteel residence. And yet, through it all, their confidence in the rank and position of their family continued unabated. The old house, with every bit of old queer furniture in it, the old window curtains, the old tea-cups and saucers, the old bedspreads and towels, all had a sacredness such as pertained to no modern things. Like the daughter of Zion in sacred song, Miss Dorcas "took pleasure in their dust and favored the stones thereof." The old blue willow-patterned china, with mandarins standing in impossible places, and bridges and pagodas growing up, as the world was made, out of nothing, was to Miss Dorcas consecrated porcelain—even its broken fragments were impregnated with the sacred flavor of ancient gentility.

Miss Dorcas's own private and personal closets, drawers, and baskets were squirrel's-nests of all sorts of memorials of the past. There were pieces of every[Pg 20] gown she had ever worn, of all her sister's gowns, and of the mortal habiliments of many and many a one beside who had long passed beyond the need of earthly garments. Bits of wedding robes of brides who had long been turned to dust; fragments of tarnished gold lace from old court dresses; faded, crumpled, artificial flowers, once worn on the head of beauty; gauzes and tissues, old and wrinkled, that had once set off the triumphs of the gay—all mingled in her crypts and drawers and trunks, and each had its story. Each, held in her withered hand, brought back to memory the thread of some romance warm with the color and flavor of a life long passed away.

Then there were collections, saving and medicinal; for Miss Dorcas had in great force that divine instinct of womanhood that makes her perceptive of the healing power inherent in all things. Never an orange or an apple was pared on her premises when the peeling was not carefully garnered—dried on newspaper, and neatly stored away in paper bags for sick-room uses.

There were closets smelling of elderblow, catnip, feverfew, and dried rose leaves, which grew in a bit of old garden soil back of the house; a spot sorely retrenched and cut down from the ample proportions it used to have, as little by little had been sold off, but still retaining a few growing things, in which Miss Dorcas delighted. The lilacs that once were bushes there had grown gaunt and high, and looked in at the chamber windows with an antique and grandfatherly air, quite of a piece with everything else about the old Vanderheyden house.

The ancient sisters had few outlets into the society of modern New York. Now and then, a stray visit came from some elderly person who still remembered the Vanderheydens, and perhaps about once a year they went to[Pg 21] the expense of a carriage to return the call, and rolled up into the new part of the town like shadows of the past. But generally their path of life led within the narrow limits of the house. Old Dinah, the sole black servant remaining, was the last remnant of a former retinue of negro servants held by old Jacob when New York was a slave State and a tribe of black retainers was one of the ostentations of wealth. All were gone now, and only Dinah remained, devoted to the relics of the old family, clinging with a cat-like attachment to the old place.

She was like many of her race, a jolly-hearted, pig-headed, giggling, faithful old creature, who said "Yes'm" to Miss Dorcas and took her own way about most matters; and Miss Dorcas, satisfied that her way was not on the whole a bad one in the ultimate results, winked at her free handling of orders, and consented to accept her, as we do Nature, for what could be got out of her.

"They are going to have mince-pie and broiled chicken for dinner over there," said Mrs. Betsey, when the two ladies were seated at their own dinner-table that day.

"How in the world did you know that?" asked Miss Dorcas.

"Well! Dinah met their girl in at the provision store and struck up an acquaintance, and went in to help her put up a bedstead, and so she stopped a while in the kitchen. The tall gentleman with black hair is the husband—I thought all the while he was," said Mrs. Betsey. "The other one is a Mr. Fellows, a great friend of theirs, Mary says——"

"Mary!—who is Mary?" said Miss Dorcas.

"Why, Mary McArthur, their girl—they only keep one, but she has a little daughter about eight years old to help. I wish we had a little girl, or something that one[Pg 22] might train for a waiter to answer door-bells and do little things."

"Our door-bells don't call for much attention, and a little girl is nothing but a plague," interposed Miss Dorcas.

"Dinah has quite fallen in love with Mrs. Henderson," said Mrs. Betsey; "she says that she is the handsomest, pleasantest-spoken lady she's seen for a great while."

"We'll call upon her when they get well settled," said Miss Dorcas, definitively.

Miss Dorcas settled this with the air of a princess. She felt that such a meritorious little person as the one over the way ought to be encouraged by people of good old families.

Our readers will observe that Miss Dorcas listened without remonstrance and with some appearance of interest to the items about minced pie and broiled chicken; but high moral propriety, as we all know, is a very cold, windy height, and if a person is planted on it once or twice a day, it is as much as ought to be demanded of human weakness.

For the rest of the time one should be allowed, like Miss Dorcas, to repose upon one's laurels. And, after all, it is interesting, when life is moving in a very stagnant current, even to know what your neighbor has for dinner!

(Letter from Eva Henderson to Isabelle Courtney.)

My Dear Belle: Well, here we are, Harry and I, all settled down to housekeeping quite like old folks. All is about done but the last things,—those little touches, and improvements, and alterations that go off into airy perspective. I believe it was Carlyle that talked about an "infinite shoe-black" whom all the world could not quite satisfy so but that there would always be a next thing in the distance. Well, perhaps it's going to be so in housekeeping, and I shall turn out an infinite housekeeper; for I find this little, low-studded, unfashionable home of ours, far off in a tabooed street, has kept all my energies brisk and busy for a month past, and still there are more worlds to conquer. Visions of certain brackets and lambrequins that are to adorn my spare chamber visit my pillow nightly, while Harry is placidly sleeping the sleep of the just. I have been unable to attain to them because I have been so busy with my parlor ivies and my Ward's case of ferns, and some perfectly seraphic hanging baskets, gorgeous with flowering nasturtiums that are now blooming in my windows. There is a dear little Quaker dove of a woman living in the next house to ours who is a perfect witch at gardening—a good kind of witch, you understand, one who could make a broomstick bud and blossom if she undertook it—and she has been my teacher and exemplar in these matters. Her parlor is a perfect bower, a drab dove's nest wreathed round with vines and all a-bloom with geraniums;[Pg 24] and mine is coming on to look just like it. So you see all this has kept me ever so busy.

Then there are the family accounts to keep. You may think that isn't much for our little concern, but you would be amazed to find how much there is in it. You see, I have all my life concerned myself only with figures of speech and never gave a thought about figures of arithmetic or troubled my head as to where money came from, or went to; and when I married Harry I had a general idea that we were going to live with delightful economy. But it is astonishing how much all our simplicity costs, after all. My account-book is giving me a world of new ideas, and some pretty serious ones too.

Harry, you see, leaves every thing to me. He has to be off to his office by seven o'clock every morning, and I am head marshal of the commisariat department—committee of one on supplies, and all that—and it takes up a good deal of my time.

You would laugh, Belle, to see me with my matronly airs and graces going my daily walk to the provision-store at the corner, which is kept by a tall, black-browed lugubrious man, with rough hair and a stiff stubby beard, who surveys me with a severe gravity over the counter, as if he wasn't sure that my designs were quite honest.

"Mr. Quackenboss," I say, with my sweetest smile, "have you any nice butter?"

He looks out of the window, drums on the counter, and answers "Yes," in a tone of great reserve.

"I should like to look at some," I say, undiscouraged.

"It's down cellar," he replies, gloomily chewing a bit of chip and casting sinister glances at me.

"Well," I say, cheerfully, "shall I go down there and look at it?"

"How much do you want?" he asks, suspiciously.

"That depends on how well I like it," say I.

"I s'pose I could get up a cask," he says in a ruminating tone; and now he calls his partner, a cheerful, fat, roly-poly little cockney Englishman, who flings his h's round in the most generous and reckless style. His alert manner seems to say that he would get up forty casks a minute and throw them all at my feet, if it would give me any pleasure.

So the butter-cask is got up and opened, and my severe friend stands looking down on it and me as if he would say, "This also is vanity."

"I should like to taste it," I say, "if I had something to try it with."

He scoops up a portion on his dirty thumbnail and seems to hold it reflectively, as if a doubt was arising in his mind of the propriety of this mode of offering it to me.

And now my cockney friend interposes with a clean knife. I taste the butter and find it excellent, and give a generous order which delights his honest soul; and as he weighs it out he throws in, gratis, the information that his little woman has tried it, and he was sure I would like it, for she is the tidiest little woman and the best judge of butter; that they came from Yorkshire, where the pastures round were so sweet with a-many violets and cowslips—in fact, my little cockney friend strays off into a kind of pastoral that makes the little grocery store quite poetic.

I call my two grocers familiarly Tragedy and Comedy, and make Harry a good deal of fun by recounting my adventures with them. I have many speculations about Tragedy. He is a married man, as I learn, and I can't help wondering what Mrs. Quackenboss thinks of him. Does he ever shave—or does she kiss him in the rough—or has she given up kissing him at all? How did he act when he was in love?—if ever he was in love—and what did he say to the lady to induce her to marry[Pg 26] him? How did he look when he did it? It really makes me shudder to think of such a mournful ghoul coming back to the domestic circle at night. I should think the little "Quacks" would all run and hide. But a truce to scandalizing my neighbor—he may be better than I am, after all!

I ought to tell you that some of my essays in provisioning my garrison might justly excite his contempt—they have been rather appalling to my good Mary McArthur. You know I had been used to seeing about a ten-pound sirloin of beef on Papa's table, and the first day I went into the shop I assumed an air of easy wisdom as if I had been a housekeeper all my life, and ordered just such a cut as I had seen Mamma get, with all sorts of vegetables to match, and walked home with composed dignity. When Mary saw it she threw up her hands and gave an exclamation of horror—"Miss Eva!" she said, "when will we get all this eaten up?" And verily that beef pursued us through the week most like a ghost. We had it hot, and we had it cold; we had it stewed and hashed, and made soup of it; we sliced it and we minced it, and I ate a great deal more than was good for me on purpose to "save it." Towards the close of the week Harry civilly suggested (he never finds fault with anything I do, but he merely suggested) whether it wouldn't be better to have a little variety in our table arrangements; and then I came out with the whole story, and we had a good laugh together about it. Since then I have come down to taking lessons of Mary, and I say to her, "How much of this, and that, had I better get?" and between us we make it go quite nicely.

Speaking of neighbors, my dear blessed Aunt Maria, whom I suppose you remember, has almost broken her heart about Papa's failing and my marrying Harry and, finally, our coming to live on an unfashionable street—which[Pg 27] in her view is equal to falling out of heaven into some very suspicious region of limbo. She almost quarreled with us both because, having got married contrary to her will, we would also insist on going to housekeeping and having a whole house to ourselves on a back street instead of having one little, stuffy room on the back side of a fashionable boarding house. Well, I made all up with her at last. If you will have your own way, and persist in it, people have to make up with you. You thus get to be like the sun and moon which, though they often behave very inconveniently, you have to make the best of; and so Aunt Maria has concluded to make the best of Harry and me. It came about in this wise: I went and sat with her the last time she had a sick headache, and kissed her, and bathed her head, and told her I wanted to be a good girl and did really love her, though I couldn't always take her advice now I was a married woman; and so we made it up.

But the trouble is that now she wants to show me how to run this poor little unfashionable boat so as to make a good show with the rest of them, and I don't want to learn. It's easier to keep out of the regatta. My card-receiver is full of most desirable names of people who have come in their fashionable carriages and coupés, and they have "oh'd" and "ah'd" in my little parlors, and declared they were "quite sweet," and "so odd," and "so different, you know;" but, for all that, I don't think I shall try to keep up all this gay circle of acquaintances. Carriage-hire costs money; and when paid for by the hour, one asks whether the acquaintances are worth it. But there are some real noble-hearted people that I mean to keep. The Van Astrachans, for instance. Mrs. Van Astrachan is a solid lump of goodness and motherliness, and that sweet Mrs. Harry Endicott is most lovable. You remember Harry Endicott, I[Pg 28] suppose, and what a trump card he was thought to be among the girls, one time when you were visiting us, and afterwards all that scandal about him and that pretty little Mrs. John Seymour? She is dead now, I hear, and he has married this pretty Rose Ferguson, a friend of hers; and since his wife has taken him in hand, he has turned out to be a noble fellow. They live up on Madison avenue quite handsomely. They are among the "real folks" Mrs. Whitney tells about, and I think I must keep them. The Elmores I don't care much for. They are a frivolous, fast set, and what's the use? Sophie and her husband, my old friend Wat Sydney, I keep mainly because she won't give me up. She is one of the clinging sort, and is devoted to me. They have a perfect palace up by the park—it is quite a show-house, and is, I understand, to be furnished by Harter. So, you see, it's like a friendship between princess and peasant.

Now, I foresee future conflicts with Aunt Maria in all these possibilities. She is a nice woman, and bent on securing what she thinks my interest, but I can't help seeing that she is somewhat

"A shade that follows wealth and fame."

The success of my card-receiver delights her, and not to improve such opportunities would be, in her view, to bury one's talent in a napkin. Yet, after all, I differ. I can't help seeing that intimacies between people with a hundred thousand a year and people of our modest means will be full of perplexities.

And then I say, Why not try to find all the neighborliness I can on my own street? In a country village, one finds a deal in one's neighbors, simply because one must. They are there; they are all one has, and human nature is always interesting, if one takes it right side out. Next door is the gentle Quakeress I told you of. She is[Pg 29] nobody in the gay world, but as full of sweetness and loving kindness as heart could desire. Then right across the way are two antiquated old ladies, very old, very precise, and very funny, who have come in state and called on me; bringing with them the most lovely, tyrannical little terrier, who behaved like a small-sized fiend and shocked them dreadfully. I spy worlds of interest in their company if once I can rub the stiffness out of our acquaintance, and then I hope to get the run of the delightfully queer old house.

Then there are our set—Jim Fellows, and Bolton, and my sister Alice, and the girls—in and out all the time. We sha'n't want for society. So if Aunt Maria puts me up for a career in the gay world I shall hang heavy on her hands.

I haven't much independence myself, but it is no longer I, it is We. Eva Van Arsdel alone was anybody's property; Mamma talked her one way, her sister Ida another way, and Aunt Maria a third; and among them all her own little way was hard to find. But now Harry and I have formed a firm and compact We, which is a fortress into which we retreat from all the world. I tell them all, We don't think so, and We don't do so. Isn't that nice? When will you come and see us?

Ever your loving

From the foregoing letter our readers may have conjectured that the natural self-appointed ruler of the fortunes of the Van Arsdel family was "Aunt Maria," or Mrs. Maria Wouvermans.

That is to say, this lady had always considered such to be her mission, and had acted upon this supposition up to the time that Mr. Van Arsdel's failure made shipwreck of the fortunes of the family.

Aunt Maria had, so to speak, reveled in the fortune and position of the Van Arsdels. She had dictated the expenditures of their princely income; she had projected parties and entertainments; she had supervised lists of guests to be invited; she had ordered dresses and carriages and equipages, and hired and dismissed servants at her sovereign will and pleasure. Nominally, to be sure, Mrs. Van Arsdel attended to all these matters; but really Aunt Maria was the power behind the throne. Mrs. Van Arsdel was a pretty, graceful, self-indulgent woman, who loved ease and hated trouble—a natural climbing plant who took kindly to any bean-pole in her neighborhood, and Aunt Maria was her bean-pole. Mrs. Van Arsdel's wealth, her station, her éclat, her blooming daughters, all climbed up, so to speak, on Aunt Maria, and hung their flowery clusters around her, to her praise and glory. Besides all this, there were very solid and appreciable advantages in the wealth and station of the Van Arsdel family as related to the worldly enjoyment of Mrs. Maria Wouvermans. Being a widow, connected with an old[Pg 31] rich family, and with but a small fortune of her own and many necessities of society upon her, Mrs. Wouvermans had found her own means in several ways supplemented and carried out by the redundant means of her sister. Mrs. Wouvermans lived in a moderate house on Murray Hill, within comfortable proximity to the more showy palaces of the New York nobility. She had old furniture, old silver, camel's hair shawls and jewelry sufficient to content her heart, but her yearly income was far below her soul's desires, and necessitated more economy than she liked. While the Van Arsdels were in full tide of success she felt less the confinement of these limits. What need for her to keep a carriage when a carriage and horses were always at her command for the asking—and even without asking, as not infrequently came to be the case? Then, the Van Arsdel parties and hospitalities relieved her from all expensive obligations of society. She returned the civilities of her friends by invitations to her sister's parties and receptions; and it is an exceedingly convenient thing to have all the glory of hospitality and none of the trouble—to have convenient friends to entertain for you any person or persons with whom you may be desirous of keeping up amicable relations. On the whole, Mrs Wouvermans was probably sincere in the professions, to which Mr. Van Arsdel used to listen with a quiet amused smile, that "she really enjoyed Nelly's fortune more than if it were her own."

"Haven't a doubt of it," he used to say, with a twinkle of his eye which he never further explained.

Mr. Van Arsdel's failure had nearly broken Aunt Maria's heart. In fact, the dear lady took the matter more sorely than the good man himself.

Mr. Van Arsdel was, in a small dry way, something of a philosopher. He was a silent man for the most part, but had his own shrewd comments on the essential worth[Pg 32] of men and things—particularly of men in the feminine gender. He had never checked his pretty wife in any of her aspirations, which he secretly valued at about their real value; he had never quarreled with Aunt Maria or interfered with her sway in his family within certain limits, because he had sense enough to see that she was the stronger of the two women, and that his wife could no more help yielding to her influence than a needle can help sticking to a magnet.

But the race of fashionable life, its outlays of health and strength, its expenditures for parties, and for dress and equipage, its rivalries, its gossip, its eager frivolities, were all matters of which he took quiet note, and which caused him often to ponder the words of the wise man of old, "What profit hath a man of all his labor and the vexation of his heart, wherein he hath labored under the sun?"

To Mr. Van Arsdel's eye the only profit of his labor and travail seemed to be the making of his wife frivolous, filling her with useless worries, training his daughters to be idle and self-indulgent, and his sons to be careless and reckless of expenditure. So when at last the crash came, there was a certain sense of relief in finding himself once more an honest man at the bottom of the hill, and he quietly resolved in his inmost soul that he never would climb again. He had settled up his affairs with a manly exactness that won the respect of all his creditors, and they had put him into a salaried position which insured a competence, and with this he resolved to be contented; his wife returned to the economical habits and virtues of her early life; his sons developed an amount of manliness and energy which was more than enough to compensate for what they had lost in worldly prospects. He enjoyed his small, quiet house and his reduced establishment as he never had done a more brilliant one, for[Pg 33] he felt that it was founded upon certainties and involved no risks. Mrs. Van Arsdel was a sweet-tempered, kindly woman, and his daughters had each and every one met the reverse in a way that showed the sterling quality which is often latent under gay and apparently thoughtless young womanhood.

Aunt Maria, however, settled it in her own mind, with the decision with which she usually settled her relatives' affairs, that this state of things would be only temporary.

"Of course," she said to her numerous acquaintances, "of course, Mr. Van Arsdel will go into business again—he is only waiting for a good opening—he'll be up again in a few years where he was before."

And to Mrs. Van Arsdel she said, "Nelly, you must keep him up—you mustn't hear of his sinking down and doing nothing"—doing nothing being his living contentedly on a comfortable salary and going without the "pomps and vanities." "Your husband, of course, will go into some operations to retrieve his fortunes, you know," she said. "What is he thinking of?"

"Well, really, Maria, I don't see as he has the least intention—he seems perfectly satisfied to live as we do."

"You must put him up to it, Nelly—depend upon it, he's in danger of sinking down and giving up; and he has splendid business talents. He should go to operating in stocks, you see. Why, men make fortunes in that way. Look at the Bubbleums, and the Flashes, they were all down two years ago, and now they're up higher than ever, and they did it all in stocks. Your husband would find plenty of men ready to go in with him and advance money to begin on. No man is more trusted. Why, Nelly, that man might die a millionaire as well as not, and you ought to put him up to it; it's a wife's business to keep her husband up."

"I have tried to, Maria; I have been just as cheerful[Pg 34] as I knew how to be, and I've retrenched and economized everywhere, as all the girls do—they are wonderful, those girls! To see them take hold so cheerfully and help about household matters, you never would dream that they had not been brought up to it; and they are so prudent about their clothes—so careful and saving. And then the boys are getting on so well. Tom has gone into surveying with a will, and is going out with Smithson's party to the Rocky Mountains, and Hal has just got a good situation in Boston——"

"Oh, yes, that is all very well; but, Nelly, that isn't what I mean. You know that when men fail in business they are apt to get blue and discouraged and give up enterprise, and so gradually sink down and lose their faculties. That's the way old Mr. Snodgrass did when he failed."

"But I don't think, Maria, that there is the least danger of my husband's losing his mind—or sinking down, as you call it. I never saw him more cheerful and seem to take more comfort of his life. Mr. Van Arsdel never did care for style—except as he thought it pleased me—and I believe he really likes the way we live now better than the way we did before; he says he has less care."

"And you are willing to sink down and be a nobody, and have no carriage, and rub round in omnibuses, and have to go to little mean private country board instead of going to Newport, when you might just as well get back the position that you had. Why, it's downright stupidity, Nelly!"

"As to mean country board," pleaded Mrs. Van Arsdel, "I don't know what you mean, Maria. We kept our old homestead up there in Vermont, and it's a very respectable place to spend our summer in."

"Yes, and what chances have the girls up there—where[Pg 35] nobody sees them but oxen? The girls ought to be considered. For their sakes you ought to put your husband up to do something. It's cruel to them, brought up with the expectations they have had, to have to give all up just as they are coming out. If there is any time that a mother must feel the want of money it is when she has daughters just beginning to go into society; and it is cruel towards young girls not to give them the means of dressing and doing a little as others do; and dress does cost so abominably, now-a-days; it's perfectly frightful—people cannot live creditably on what they used to."

"Yes, certainly, it is frightful to think of the requirements of society in these matters," said Mrs. Van Arsdel. "Now, when you and I were girls, Maria, you know we managed to appear well on a very little. We embroidered our own capes and collars, and wore white a good deal, and cleaned our own gloves, and cut and fitted our own dresses; but, then dress was not what it is now. Why, making a dress now is like rigging a man-of-war—it's so complicated—there are so many parts, and so much trimming."

"Oh, it's perfectly fearful," said Aunt Maria; "but, then, what is one to do? If one goes into society with people who have so much of all these things, why one must, at least, make some little approach to decent appearance. We must keep within sight of them. All I ask," she added, meekly, "is to be decent. I never expect to run into the extremes those Elmores do—the waste and the extravagance that there must be in that family! And there's Mrs. Wat Sydney coming out with the whole new set of her Paris dresses. I should like to know, for curiosity's sake, just what that woman has spent on her dresses!"

"Yes," said Mrs. Van Arsdel, warming with the subject, "you know she had all her wardrobe from Worth,[Pg 36] and Worth's dresses come to something. Why, Polly told me that the lace alone on some of those dresses would be a fortune."

"And just to think that Eva might have married Wat Sydney," said Aunt Maria. "It does seem as if things in this world fell out on purpose to try us!"

"Well, I suppose they do, and we ought to try and improve by them," said Mrs. Van Arsdel, who had some weak, gentle ideas of a moral purpose in existence, to which even the losses and trials of lace and embroidery might be made subservient. "After all," she added, "I don't know but we ought to be contented with Eva's position. Eva always was a peculiar child. Under all her sweetness and softness she has quite a will of her own; and, indeed, Harry is a good fellow, and doing well in his line. He makes a very good income, for a beginning, and he is rising every day in the literary world, and I don't see but that they have as good an opportunity to make their way in society as the Sydneys with all their money."

"Sophie Sydney is perfectly devoted to Eva," said Aunt Maria.

"And well she may be," answered Mrs. Van Arsdel, "in fact, Eva made that match; she actually turned him over to her. You remember how she gave her that prize croquet-pin that Sydney gave her, and how she talked to Sydney, and set him to thinking of Sophie—oh, pshaw! Sydney never would have married that girl in the world if it had not been for Eva."

"Well," said Aunt Maria, "it's as well to cultivate that intimacy. It will be a grand summer visiting place at their house in Newport, and we want visiting places for the girls. I have put two or three anchors out to the windward, in that respect. I am going to have the Stephenson girls at my house this winter, and your girls[Pg 37] must help show them New York, and cultivate them, and then there will be a nice visiting place for them at Judge Stephenson's next summer. You see the Judge lives within an easy drive of Newport, so that they can get over there, and see and be seen."

"I'm sure, Maria, it's good in you to be putting yourself out for my girls."

"Pshaw, Nelly, just as if your girls were not mine—they are all I have to live for. I can't stop any longer now, because I must catch the omnibus to go down to Eva's; I am going to spend the day with her."

"How nicely Eva gets along," said Mrs. Van Arsdel, with a little pardonable motherly pride; "that girl takes to housekeeping as if it came natural to her."

"Yes," said Aunt Maria; "you know I have had Eva a great deal under my own eye, first and last, and it shows that early training will tell." Aunt Maria picked up this crumb of self-glorification with an easy matter-of-fact air which was peculiarly aggravating to her sister.

In her own mind Mrs. Van Arsdel thought it a little too bad. "Maria always did take the credit of everything that turned out well in my family," she said to herself, "and blamed me for all that went wrong."

But she was too wary to murmur out loud, and bent her head to the yoke in silence.

"Eva needs a little showing and cautioning," said Aunt Maria; "that Mary of hers ought to be watched, and I shall tell her so—she mustn't leave everything to Mary."

"Oh, Mary lived years with me, and is the most devoted, faithful creature," said Mrs. Van Arsdel.

"Never mind—she needs watching. She's getting old now, and don't work as she used to, and if Eva don't look out she won't get half a woman's work out of her—these old servants always take liberties. I shall look into[Pg 38] things there. Eva is my girl; I sha'n't let anyone get around her;" and Aunt Maria arose to go forth. But if anybody supposes that two women engaged in a morning talk are going to stop when one of them rises to go, he knows very little of the ways of womankind. When they have risen, drawn up their shawls, and got ready to start, then is the time to call a new subject, and accordingly Aunt Maria, as she was going out the door, turned round and said: "Oh! there now! I almost forgot what I came for:—What are you going to do about the girls' party dresses?"

"Well, we shall get a dressmaker in the house. If we can get Silkriggs, we shall try her."

"Now, Nelly, look here, I have found a real treasure—the nicest little dressmaker, just set up, and who works cheap. Maria Meade told me about her. She showed me a suit that she had had made there in imitation of a Paris dress, with ever so much trimming, cross-folds bound on both edges, and twenty or thirty bows, all cut on the bias and bound, and box-plaiting with double quilling on each side all round the bottom, and going up the front—graduated, you know. There was waist, and overskirt, and a little sacque, and, will you believe me, she only asked fifteen dollars for making it all."

"You don't say so!"

"It's a fact. Why, it must have been a good week's work to make that dress, even with her sewing machine. Maria told me of her as a great secret, because she really works so well that if folks knew it she would be swamped with work, and then go to raising her price—that's what they all do when they can get a chance—but I've been to her and engaged her for you."

"I'm sure, Maria, I don't know what we should do if you were not always looking out for us."

"I don't know—I'm getting to be an old woman,"[Pg 39] said Aunt Maria. "I'm not what I was. But I consider your family as my appointed field of labor—just as our rector said last Sunday, we must do the duty next us. But tell the girls not to talk about this dressmaker. We shall want all she can do, and make pretty much our own terms with her. It's nice and convenient for Eva that she lives somewhere down in those out-of-the-way regions where she has chosen to set up. Well, good morning;" and Aunt Maria opened the house-door and stood upon the top of the steps, when a second postscript struck her mind.

"There now!" said she, "I was meaning to tell you that it is getting to be reported everywhere that Alice and Jim Fellows are engaged."

"Oh, well, of course there's nothing in it," said Mrs. Van Arsdel. "I don't think Alice would think of him for a moment. She likes him as a friend, that's all."

"I don't know, Nelly; you can't be too much on your guard. Alice is a splendid girl, and might have almost anybody. Between you and me—now, Nelly, you must be sure not to mention it—but Mr. Delafield has been very much struck with her."

"Oh, Maria, how can you? Why, his wife hasn't been dead a year!"

"Oh, pshaw! these widowers don't always govern their eyes by the almanac," said Aunt Maria, with a laugh. "Of course, John Delafield will marry again. I always knew that; and Alice would be a splendid woman to be at the head of his establishment. At any rate, at the little company the other night at his sister's, Mrs. Singleton's, you know, he was perfectly devoted to her, and I thought Mrs. Singleton seemed to like it."

"It would certainly be a fine position, if Alice can fancy him," said Mrs. Van Arsdel. "Seems to me he is rather querulous and dyspeptic, isn't he?"

"Oh; well, yes; his health is delicate; he needs a wife to take care of him."

"He's so yellow!" ruminated Mrs. Van Arsdel, ingenuously. "I never could bear thin, yellow men."

"Oh, come, don't you begin, Nelly—it's bad enough to have girls with their fancies. What we ought to look at are the solid excellences. What a pity that the marrying age always comes when girls have the least sense! John Delafield is a solid man, and if he should take a fancy to Alice, it would be a great piece of good luck. Alice ought to be careful, and not have these reports around, about her and Jim Fellows; it just keeps off advantageous offers. I shall talk to Alice the first time I get a chance."

"Oh, pray don't, Maria—I don't think it would do any good. Alice is very set in her way, and it might put her up to make something of it more than there is."

"Oh, never fear me," said Aunt Maria, nodding her head; "I understand Alice, and know just what needs to be said. I sha'n't do her any harm, you may be sure," and Aunt Maria, espying her omnibus afar, ran briskly down the steps, thus concluding the conference.

Now it happened that adjoining the parlor where this conversation had taken place was a little writing-cabinet which Mr. Van Arsdel often used for the purposes of letter-writing. On this morning, when his wife supposed him out as usual at his office, he had retired there to attend to some correspondence. The entrance was concealed by drapery, and so he had been an unintentional and unsuspected but much amused listener to Aunt Maria's adjurations to his wife on his behalf.

All through his subsequent labors of the pen, he might have been observed to pause from time to time and laugh to himself. The idea of lying as a quiet dead weight on the wheels of the progress of his energetic relation was[Pg 41] something vastly pleasing to the dry and secretive turn of his humor—and he rather liked it than otherwise.

"We shall see whether I am losing my faculties," he said to himself, as he gathered up his letters and departed.

My Dear Mother: Harry says I must do all the writing to you and keep you advised of all our affairs, because he is so driven with his editing and proofreading that letter-writing is often the most fatiguing thing he can do. It is like trying to run after one has become quite out of breath.

The fact is, dear mother, the demands of this New York newspaper life are terribly exhausting. It's a sort of red-hot atmosphere of hurry and competition. Magazines and newspapers jostle each other, and run races, neck and neck, and everybody connected with them is kept up to the very top of his speed, or he is thrown out of the course. You see, Bolton and Harry have between them the oversight of three papers—a monthly magazine for the grown folk, another for the children, and a weekly paper. Of course there are sub-editors, but they have the general responsibility, and so you see they are on the qui vive all the time to keep up; for there are other papers and magazines running against them, and the price of success seems to be eternal vigilance. What is exacted of an editor now-a-days seems to be a sort of general omniscience. He must keep the run of everything,—politics, science, religion, art, agriculture, general literature; the world is alive and moving everywhere, and he must know just what's going on and be able to have an opinion ready made and ready to go to press at any moment. He[Pg 43] must tell to a T just what they are doing in Ashantee and Dahomey, and what they don't do and ought to do in New York. He must be wise and instructive about currency and taxes and tariffs, and able to guide Congress; and then he must take care of the Church,—know just what the Old Catholics are up to, the last new kink of the Ritualists, and the right and wrong of all the free fights in the different denominations. It really makes my little head spin just to hear what they are getting up articles about. Bolton and Harry are kept on the chase, looking up men whose specialties lie in these lines to write for them. They have now in tow a Jewish Rabbi, who is going to do something about the Talmud, or Targums, or something of that sort; and a returned missionary from the Gaboon River, who entertained Du Chaillu and can speak authentically about the gorilla; and a lively young doctor who is devoting his life to the study of the brain and nervous system. Then there are all sorts of writing men and women sending pecks and bushels of articles to be printed, and getting furious if they are not printed, though the greater part of them are such hopeless trash that you only need to read four lines to know that they are good for nothing; but they all expect them to be re-mailed with explanations and criticisms, and the ladies sometimes write letters of wrath to Harry that are perfectly fearful.

Altogether there is a good deal of an imbroglio, and you see with it all how he comes to be glad that I have a turn for letter-writing and can keep you informed of how we of the interior go on. My business in it all is to keep a quiet, peaceable, restful home, where he shall always have the enjoyment of seeing beautiful things and find everything going on nicely without having to think why, or how, or wherefore; and, besides this, to do every[Pg 44] little odd and end for him that he is too tired or too busy to do; in short, I suppose some of the ambitious lady leaders of our time would call it playing second fiddle. Yes, that is it; but there must be second fiddles in an orchestra, and it's fortunate that I have precisely the talent for playing one, and my doctrine is that the second fiddle well played is quite as good as the first. What would the first be without it?

After all, in this great fuss about the men's sphere and the women's, isn't the women's ordinary work just as important and great in its way? For, you see, it's what the men with all their greatness can't do, for the life of them. I can go a good deal further in Harry's sphere than he can in mine. I can judge about the merits of a translation from the French, or criticise an article or story, a great deal better than he can settle the difference between the effect of tucking and inserting in a dress, or of cherry and solferino in curtains. Harry appreciates a room prettily got up as well as any man, but how to get it up—all the shades of color and niceties of arrangement, the thousand little differences and agreements that go to it—he can't comprehend. So this man and woman question is just like the quarrel between the mountain and the squirrel in Emerson's poem, where "Bun" talks to the mountain:

I am quite satisfied that, first and last, I shall crack a good many nuts for Harry. Not that I am satisfied with a mere culinary or housekeeping excellence, or even an artistic and poetic skill in making home lovely; I do want a sense of something noble and sacred in life—something[Pg 45] to satisfy a certain feeling of the heroic that always made me unhappy and disgusted with my aimless fashionable girl career. I always sympathized with Ida, and admired her because she had force enough to do something that she thought was going to make the world better. It is better to try and fail with such a purpose as hers than never to try at all; and in that point of view I sympathize with the whole woman movement, though I see no place for myself in it. But my religion, poor as it is, has always given this excitement to me: I never could see how one could profess to be a Christian at all and not live a heroic life—though I know I never have. When I hear in church of the "glorious company of the apostles," the "goodly fellowship of the prophets," the "noble army of martyrs," I have often such an uplift—and the tears come to my eyes, and then my life seems so poor and petty, so frittered away in trifles. Then the communion service of our church always impresses me as something so serious, so profound, that I have wondered how I dared go through with it; and it always made me melancholy and dissatisfied with myself. To offer one's soul and body and spirit to God a living sacrifice surely ought to mean something that should make one's life noble and heroic, yet somehow it didn't do so with mine.

It was one thing that drew me to Harry, that he seemed to me an earnest, religious man, and I told him when we were first engaged that he must be my guide; but he said no, we must go hand in hand, and guide each other, and together we would try to find the better way. Harry is very good to me in being willing to go with me to my church. I told him I was weak in religion at any rate, and all my associations with good and holy things were with my church, and I really felt afraid to trust myself without them. I have tried going to his sort of services with him, but these extemporaneous prayers[Pg 46] don't often help me. I find myself weighing and considering in my own mind whether that is what I really do feel or ask; and if one is judging or deciding one can't be praying at the same time. Now and then I hear a good man who so wraps me up in his sympathies, and breathes such a spirit of prayer as carries me without effort, and that is lovely; but it is so rare a gift! In general I long for the dear old prayers of my church, where my poor little naughty heart has learned the way and can go on with full consent without stopping to think.

So Harry and I have settled on attending an Episcopal mission church in our part of the city. Its worshipers are mostly among the poor, and Harry thinks we might do good by going there. Our rector is a young Mr. St. John, a man as devoted as any of the primitive Christians. I never saw anybody go into work for others with more entire self-sacrifice. He has some property, and he supports himself and pays about half the expenses of the mission besides. All this excites Harry's respect, and he is willing to do himself and have me do all we can to help him. Both Alice and I, and my younger sisters, Angelique and Marie, have taken classes in his mission school, and the girls help every week in a sewing-school, and, so far as practical work is concerned, everything moves beautifully. But then, Mr. St. John is very high church and very stringent in his notions, and Harry, who is ultra-liberal, says he is good, but narrow; and so when they are together I am quite nervous about them. I want Mr. St. John to appear well to Harry, and I want Harry to please Mr. St. John. Harry is æsthetic and likes the church services, and is ready to go as far as anybody could ask in the way of interesting and beautiful rites and ceremonies, and he likes antiquities and all that, and so to a certain extent they get on nicely; but come to the question of church[Pg 47] authority, and Lloyd Garrison and all the radicals are not more untamable. He gets quite wild, and frightens me lest dear Mr. St. John should think him an infidel. And, in fact, Harry has such a sort of latitudinarian way of hearing what all sorts of people have to say, and admitting bits of truth here and there in it, as sometimes makes me rather uneasy. He talks with these Darwinians and scientific men who have an easy sort of matter-of-course way of assuming that the Bible is nothing but an old curiosity-shop of by-gone literature, and is so tolerant in hearing all they have to say, that I quite burn to testify and stand up for my faith—if I knew enough to do it; but I really feel afraid to ask Mr. St. John to help me, because he is so set and solemn, and confines himself to announcing that thus and so is the voice of the church; and you see that don't help me to keep up my end with people that don't care for the church.

But, Mother dear, isn't there some end to toleration; ought we Christians to sit by and hear all that is dearest and most sacred to us spoken of as a by-gone superstition, and smile assent on the ground that everybody must be free to express his opinions in good society? Now, for instance, there is this young Dr. Campbell, whom Harry is in treaty with for articles on the brain and nervous system—a nice, charming, agreeable fellow, and a perfect enthusiast in science, and has got so far that love or hatred or inspiration or heroism or religion is nothing in his view but what he calls "cerebration"—he is so lost and absorbed in cerebration and molecules, and all that sort of thing, that you feel all the time he is observing you to get facts about some of his theories as they do the poor mice and butterflies they experiment with.

The other day he was talking, in his taking-for-granted, rapid way, about the absurdity of believing in prayer, when I stopped him squarely, and told him that[Pg 48] he ought not to talk in that way; that to destroy faith in prayer was taking away about all the comfort that poor, sorrowful, oppressed people had. I said it was just like going through a hospital and pulling all the pillows from under the sick people's heads because there might be a more perfect scientific invention by and by, and that I thought it was cruel and hard-hearted to do it. He looked really astonished, and asked me if I believed in prayer. I told him our Saviour had said, "Ask, and ye shall receive," and I believed it. He seemed quite astonished at my zeal, and said he didn't suppose any really cultivated people now-a-days believed those things. I told him I believed everything that Jesus Christ said, and thought he knew more than all the philosophers, and that he said we had a Father that loved us and cared for us, even to the hairs of our heads, and that I shouldn't have courage to live if I didn't believe that. Harry says I did right to speak up as I did. Dr. Campbell don't seem to be offended with me, for he comes here more than ever. He is an interesting fellow, full of life and enthusiasm in his profession, and I like to hear him talk.

But here I am, right in the debatable land between faith and no faith. On the part of a great many of the intelligent, good men whom Harry, for one reason or other, invites to our house, and wants me to be agreeable to, are all shades of opinion, of half faith, and no faith, and I don't wish to hush free conversation, or to be treated like a baby who will cry if they make too much noise; and then on the other hand is Mr. St. John—whom I regard with reverence on account of his holy, self-denying life—who stands so definitely entrenched within the limits of the church, and does not in his own mind ever admit a doubt of anything which the church has settled; and between them and Harry and all I don't know just what I ought to do.

I am sure, if there is a man in the world who means in all things to live the Christian life, it's Harry. There is no difference between him and Mr. St. John there. He is ready for any amount of self-sacrifice, and goes with Mr. St. John to the extent of his ability in his efforts to do good; and yet he really does not believe a great many things that Mr. St. John thinks are Christian doctrines. He says he believes only in the wheat, and not in the chaff, and that it is only the chaff that will be blown away in these modern discussions. With all this, I feel nervous and anxious, and sometimes wish I could go right into some good, safe, dark church, and pull down all the blinds, and shut all the doors, and keep out all the bustle of modern thinking, and pray, and meditate, and have a lovely, quiet time.

Mr. St. John lends me from time to time some of his ritualistic books; and they are so refined and scholarly, and yet so devout, that Harry and I are quite charmed with their tone; but I can't help seeing that, as Harry says, they lead right back into the Romish church—and by a way that seems enticingly beautiful. Sometimes I think it would be quite delightful to have a spiritual director who would save you all the trouble of deciding, and take your case in hand, and tell you exactly what to do at every step. Mr. St. John, I know, would be just the person to assume such a position. He is a natural school-master, and likes to control people, and, although he is so very gentle, I always feel that he is very stringent, and that if I once allowed him ascendancy he would make no allowances. I can feel the "main de fer" through the perfect gentlemanly polish of his exterior; but you see I know Harry never would go completely under his influence, and I shrink from anything that would divide me from my husband, and so I don't make any move in that direction.

You see, I write to you all about these matters, for my mamma is a sweet, good little woman who never troubles her head with anything in this line, and my god-mother, Aunt Maria, is a dear worldly old soul, whose heart is grieved within her because I care so little for the pomps and vanities. She takes it to heart that Harry and I have definitely resolved to give up party-going, and all that useless round of calling and dressing and visiting that is called "going into society," and she sometimes complicates matters by trying her forces to get me into those old grooves I was so tired of running in. I never pretend to talk to her of the deeper wants or reasons of my life, for it would be ludicrously impossible to make her understand. She is a person over whose mind never came the shadow of a doubt that she was right in her views of life; and I am not the person to evangelize her.