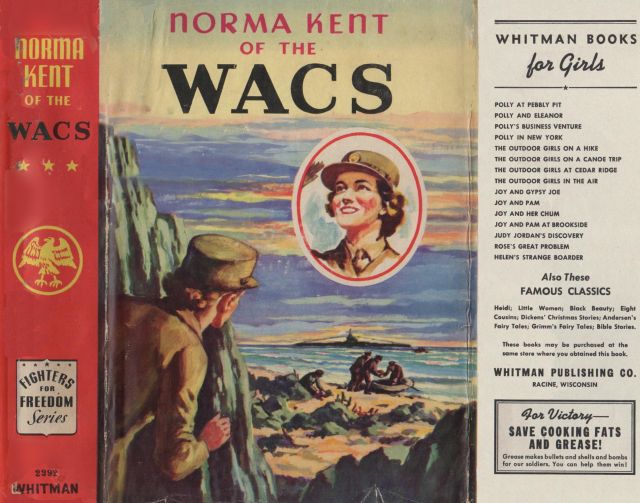

The Project Gutenberg EBook of Norma Kent of the WACS, by Roy J. Snell This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org/license Title: Norma Kent of the WACS Author: Roy J. Snell Illustrator: Hedwig Jo Meixner Release Date: March 29, 2015 [EBook #48599] Language: English Character set encoding: UTF-8 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK NORMA KENT OF THE WACS *** Produced by Stephen Hutcheson, Carolyn Jablonski, Rod Crawford, Dave Morgan and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

FIGHTERS

for

FREEDOM

Series

| PAGE | ||

| I | Mrs. Hobby’s Horses | 9 |

| II | The Test That Told | 15 |

| III | Interceptor Control | 24 |

| IV | A Light in the Night | 33 |

| V | Spy Complex | 41 |

| VI | A Startling Adventure | 50 |

| VII | A Hand in the Dark | 58 |

| VIII | Rosa Almost Flies | 68 |

| IX | Something Special | 78 |

| X | I’m Afraid | 84 |

| XI | Two Against Two | 91 |

| XII | Harbor Bells | 102 |

| XIII | A Wolf in WAC’s Clothing | 113 |

| XIV | Pale Hands | 122 |

| XV | Spotters in the Night | 131 |

| XVI | The Vanishing Print | 137 |

| XVII | Those Bad Gremlins | 146 |

| XVIII | Sudden Panic | 157 |

| XIX | A Battle in the Night | 167 |

| XX | Patsy Watches Three Shadows | 178 |

| XXI | Night for a Spy Story | 186 |

| XXII | Flight of the Black Pigeon | 196 |

| XXIII | Rosa Flies the Seagull | 208 |

| XXIV | The Decoy Beacon | 220 |

| XXV | The Masterpiece | 232 |

| XXVI | A Sub—On the Spot | 238 |

The Girl on the Cot Next to Hers Whispered Something

Norma Kent stirred uneasily. Her army cot creaked.

“You’ll have to lie still,” she told herself sternly. “You’ll keep the other girls awake.”

Even as she thought this, the girl on the cot next to her own half rose to whisper:

“We’re Mrs. Hobby’s horses now.”

“That’s the girl called Betty,” Norma thought as she barely suppressed a disturbing laugh.

“Shish,” she managed to whisper. Then all was silent where, row on row, fifty girls were sleeping. Fifty! And Norma had spoken to barely half a dozen of them! It was all very strange.

Strange and exciting. Yes, it had surely been all that. They had all been jumpy, nervous as colts, on the train from Chicago. If they were walking down the aisle and the train tipped, they had laughed loudly. They had been high-pitched, nervous laughs. And why not? Had they not launched themselves on a new and striking adventure?

As Norma recalled all this she suddenly started, then rose silently on one shoulder. She had caught a flash of light where no light was supposed to be.

“A flash of light,” she whispered silently. At the same instant she caught the gleam of light once more. This time she located it—at the head of the cot by the nearest window.

“Rosa Rosetti!” she thought, with a start. She did not know the girl, barely recalled her name. She had a beaming smile, yet beyond doubt was foreign-born.

“What would you do if you suspected that someone was a spy?” That question had, not twenty-four hours before, been put to her by a very important person. She had answered as best she could. Had her answer been the correct one? Her reply had been:

“Nothing. At least, not at once.”

Now she settled back in her place. The flash of light from the head of Rosa Rosetti’s cot did not shine again. Nor did Norma Kent fall asleep at once.

“A flash of light in the night,” she was thinking. “How very unimportant!”

And yet, as her thoughts drifted back to her childhood days not so long ago—she was barely twenty-one now and just out of college—she recalled a story told by her father, a World War veteran. The story dealt with a stranger in an American uniform who, claiming to be lost from his outfit, had found refuge in their billet for the night.

“That night,” her father had said, “flashes of light were noticed at the window of our attic lodging. And that night, too, our village was bombed.”

“Suppose we are bombed tonight?” the girl thought. Then she laughed silently, for she was lodged deep in the heart of Iowa, at old Fort Des Moines.

As the name drifted through her dreamy thoughts, it gave her a start. She was fully awake again, for the full weight of the tremendous move she had made came crashing back upon her.

“I’m a WAC,” she whispered, “a WAC! I’m in the Army now!”

Yes, that was it. She was a member of the Woman’s Army Corps. So, too, were all the girls sleeping so peacefully there. Here at Fort Des Moines in four short weeks they would receive their basic training. And then—“I may drive a truck,” she thought with a thrill, “or operate an army short-wave set, or help watch for enemy planes along the seacoast, or—” she caught her breath, “I may be sent overseas.” North Africa, the Solomons, the bleak shores of Alaska—all these and more drifted before her mind’s eye.

“Come what may,” she whispered, “I am ready!”

She might have fallen asleep then had not a cot less than ten feet from her given out a low creak as a tall, strong girl, who had caught her eye from the first, sat straight up in her bed to whisper three words.

The words were whispered in a foreign tongue. Norma was mildly shocked at hearing them whispered here in the night.

“She was talking in her sleep,” Norma assured herself as the girl settled quietly back in her place. Then it came to her with the force of a blow. “She too might be a spy!”

“What nonsense!” she chided herself. “How jittery I am tonight! I’ll go to sleep. And here’s hoping I don’t dream.”

She did fall asleep, and she did not dream.

From some place very, very far away, a bugle was blowing and someone seemed to sing, “I can’t get ’em up, I can’t get ’em up. I can’t get ’em up in the morning.” Then an alarm clock went off with a bang and Norma, the WAC recruit, was awake.

Her feet hit the floor with a slap and she was putting on her clothes before she knew it. A race to the washroom, a hasty hair-do, a dash of color to her cheeks and, twenty minutes later, together with thirty other raw recruits, she lined up for Assembly.

It was bitter cold. A sharp wind was blowing. A bleak dawn was showing in the east. Norma shivered in spite of her thick tweed coat. She looked at the slender girl next to her and was ashamed. The girl’s lips were blue. Her thin and threadbare coat flapped in the breeze. She wanted to wrap this girl inside her coat, but did not. This would be quite unsoldierlike. So she stood at rigid attention. But out of the corner of her mouth she said:

“It won’t be long now. Those soldier suits we’ll wear are grand.”

“It wo-won’t be-be long!” the girl replied cheerfully through chattering teeth.

Norma permitted herself one quick flashing look to right and left. To her right, beyond the slender girl, stood the tall girl who had whispered so strangely in her sleep. Wrapped in a long black fur coat she stood primly at attention. There was something about this girl’s prim indifference to those about her that irritated Norma.

She turned to the left to find herself looking into a pair of smiling blue eyes. The girl said never a word but her bright smile spoke volumes. This girl’s dress, short squirrelskin coat, heavy skirt, neat shoes, and small hat spoke both of taste and money. Beyond this girl stood the little Italian who flashed a light at night. She stood, lips parted, eyes shining, sturdy young body erect, very sure of herself and unafraid.

“Whatever happens, I’m going to like her a lot, and that can’t be helped,” Norma assured herself.

Five minutes later they were all back in the barracks making up their bunks and preparing for a busy day ahead.

“Bedding down Mrs. Hobby’s horses,” said a laughing voice.

“Say! What does that mean?” Norma demanded, looking up from her work into a pair of laughing blue eyes.

“Don’t you know?” asked the other girl, as she sat down on her cot.

“I don’t. That’s a fact,” Norma admitted.

“Well, I’ll tell you. But first,” the other girl put out a hand, “my name’s Betty Gale. Something tells me that we’ve both just finished college and that we’re likely to be pals in this great adventure until death or some Lady Major does us part.”

“You’re right in the first count,” Norma laughed. “And I hope you are in the second. My name is Norma Kent.”

“Swell,” said Betty Gale. “Now—about Mrs. Hobby’s Horses.”

“Mrs. Hobby’s Horses.” Betty laughed. “That’s really no great secret. Perhaps you didn’t notice it, but we’ve been sleeping in a stable.”

“A stable!” Norma stared. “A stable with polished floors?”

“Oh, they fixed them up, of course. But the row of buildings to which this belongs was all stables only a short while ago.”

“For horses?”

“Why not?” Betty laughed again. “Fort Des Moines has always been a cavalry post.”

“Oh! And I suppose it was from these very stables that cavalry horsemen rode thundering away to fight the Indians.”

“Absolutely!”

“How romantic!” Norma exclaimed. “But I still don’t see what that’s got to do with hobby horses.”

“I didn’t say hobby horses. I said they called us Mrs. Hobby’s horses. Don’t you see?” Betty’s voice dropped. “Mrs. Hobby is director of the Corps. And they say she’s a wonder. All of us raw recruits must spend a week in these stables before we go to live in Boom Town. So you see, they call us Mrs. Hobby’s horses.”

“But Boom Town? Where’s that?” Norma demanded.

“Oh! Come on!” Betty exclaimed. “You want to know too much too soon. Let’s get our bunks made. We have a lot of things to do this day. One of them is to eat breakfast. That cold air made me hungry. Let’s get going.”

A short time later they found themselves caught in a brown stream of WACs pouring toward a long, low building. Once inside they were greeted with the glorious odor of frying bacon, brewing coffee, and all that goes with a big delicious breakfast.

And was it big! In this mess hall twenty-five hundred girls were being served.

As she joined the long line that moved rapidly forward Norma was all but overcome by the feeling that she was part of something mammoth and wonderful.

“It’s big!” she exclaimed.

“Biggest thing in all the world.” Betty pressed her arm. “We’re in the Army now!”

Yes, they were in the Army. And this was Army food. On their sectional trays, oatmeal, toast and bacon were piled.

Their cups were a marvel to behold. Half an inch thick, big as a pint jar, and entirely void of handles, they presented a real problem. But Norma mastered the art of an Army coffee drinker in one stride. So too did Millie, the girl from a department store.

“Boy!” Millie giggled, balancing her cup in one hand. “Now let the Japs come! I’ll get one of them and never even nick this cup! Honest,” she confided, “I think this is going to be fun.”

“Fun, and lots of work,” was Norma’s reply.

“Oh! Work!” Millie sobered. “Lead me to it! It can’t be worse than Shield’s Bargain Basement during the Christmas rush. It’s ‘Can you find me this?’ or ‘Can you give me that?’ and ‘Miss Martin, do this,’ and ‘Miss Martin, do that,’ hours and hours on end. Bad air, cross customers, bossy floorwalkers. And for what? I ask you? Sixteen dollars a week!”

“Could you live on that?” Norma asked in surprise.

“No, but I did,” Millie giggled. “But honest, I think this will be a lot better.”

“It’s not so much a matter of it being better or worse,” Norma replied soberly, “as it is of what we have to give. This is war, you know. Our war!”

“Yes, I know.” The little salesgirl, it seems, had a serious side to her nature. “I’ve thought about that, too. In the city where they examined us they said I might do library work. I sold books, you know, and I know an awful lot about them. And I can cook, too,” she added hopefully.

“They have a cooking and baking school,” Betty encouraged. “They teach you how to cook in a mess hall and out of doors for a few people and a great many. Perhaps for a thousand people at a time. And you do it all in the baggage car of a special train.”

“Ee-magine little me cooking for a thousand people!” Millie wilted like an unwatered flower. “Honest, girls, I’m just scared stiff! I couldn’t go back! I just couldn’t! I’d rather die! And today they give us our special interviews and everything.”

“You’ll make it all right,” Betty assured her. “Just drink the rest of your coffee. That will pep you up.”

Once again Millie lifted her huge army cup. “Here’s to us all,” she laughed.

At that they clinked their cups and drank to their day that had just begun.

Mid-afternoon found Norma sitting at the end of a row of girls, waiting her turn at a private interview. In twenty-five open booths twenty-five interviewers sat smilingly asking questions in low tones of twenty-five new recruits, and carefully writing down the answers. In her row as she sat waiting her turn Norma saw Lena, the tall, strong girl who whispered strangely in the night, Rosa, who had flashed a light, Betty, Millie, and a few others.

As she waited—just waited—she began to be a little afraid. The interviewers were smiling, but after all, those were serious smiles. She could not hear the questions. She could guess them. These interviewers were asking, “What can you do? What would you like most to do? What else can you do?”

All of a sudden Norma realized that she had never done a real day’s work in all her life. She had always gone to school. Oh, yes! She could cook, just a little. But so little!

“I guess,” she thought, “that I’m what they call a typical American college girl, not a bad student, and not too good, fairly good at tennis and basketball. I’ve got brown hair and eyes, and I’m not too tall nor yet too short.” She laughed in spite of herself. “A good fellow, and all that. But,” she sobered, “what can I do? What do I want to do? What else can I do?”

She had felt a little sorry for the shopgirl, Millie. Now she envied her. Millie knew all about books and she could really cook. At this very moment, smiling with fresh-born confidence, Millie was stepping into a booth for her trial-by-words. And she, Norma Kent, a college graduate, sat there shivering in her boots! Surely this was a strange world.

The booth that Millie had entered was wide open. Norma could see all but hear nothing of what went on. At first she was interested in watching the smiles and frowns that played across Millie’s frank and mobile face. Of a sudden her interest was caught and held by the examiner. Tall, slim, looking very much the soldier in her neatly pressed uniform that bore a lieutenant’s bar on its shoulder, this examiner seemed just what Norma hoped in time to become—a real soldier.

“She’s not too young—perhaps thirty,” the girl told herself. “And she’s wearing some sort of medal pinned to her breast. Say! That’s strange!”

And indeed it was strange. The Woman’s Army Corps was as yet very young. Only a few had gone overseas and none, as far as she knew, had either won honors or returned to America.

“She’s keen,” she whispered to the girl next to her.

“Who?” The girl stared.

“That examiner,” Nonna nodded toward the booth.

“Oh! Oh sure!” The other girl resumed polishing her nails.

“All the same she is,” Norma told herself. “And I’d like to know her.”

As Millie, the shopgirl, at last rose from her place, a happy smile played about her lips.

“She made it,” Norma said aloud. “And am I glad!” She smiled at Millie as she passed.

Lena, the “night whisperer” was next to enter the vacated booth. As the interviewer began her task her body appeared to stiffen.

“On her guard,” Norma thought. “I wonder why.”

On the officer’s face there was still a smile, but somehow it was a different sort of smile.

And the tall girl? She too seemed rather strange. She appeared always on her guard. “As if she were speaking a piece and feared she might forget,” was Norma’s thought.

Still, in the end all must have gone well for, as she passed her on the way out, the tall girl flashed Norma a look that said plainer than words. “See? That’s how you do it.”

Whatever may have been Norma’s reactions to this they were quickly lost, for suddenly she realized that the black eyes of the examining officer were upon her and that her name was being called. Her time had come. Swallowing hard, she rose to step into the booth.

“You are Norma Kent,” said the examiner, flashing her a friendly smile. “And your home is—”

“Greenvale, Illinois,” was the prompt reply. The date of her birth, when she entered and left grade school, high school, and college, and other details followed.

“And now,” said the examiner, leaning forward, “what can you do?”

“I—I really don’t know,” the girl faltered. “I’ve never worked at anything.”

“Ah! So you’ve never worked? Can you cook?”

“Not very well.”

“I see.” The examiner studied Norma’s face.

“How many in your family?”

“Just father and I.”

“And your father? What does he do?”

“He’s with the Telephone Company, in charge of a wide territory—equipment and all that.”

“Hmm.” The examiner studied her report. “Just two of you. You should be great pals.”

“Oh—we are!” Norma’s eyes shone. “You see,” she exclaimed, “Dad was in the other World War. I’ve always loved him for that. He was in France.”

“France,” said the examiner, with a quick intake of breath. Norma did not at all understand. “What a lovely land to die for.”

“Dad lost his right arm,” Norma stated in a matter-of-fact tone. “That’s why he can’t go back this time, and—and that’s why he wants me to go.”

“Would you like to go overseas?” The examiner’s eyes shone with a strange new light.

“I’d love to!” the girl whispered hoarsely. “But what could I do?”

“Oh! Loads of things.” The examiner made a record on her sheet. “Your father must have driven about a great deal looking things over in his present occupation.”

“Of course.”

“Did you ever go with him?”

“Oh! Many, many times!”

“Did you ever assist him?”

“Oh, yes! Of course! It was all great fun. He had big charts showing every center, every phone. I helped him mark down each new installation.”

“Ah!” the examiner breathed.

“Yes, and we had a grand little shop in the basement where we worked things out—lots of new things.” Norma’s eyes shone. “There were many rural centers where the switchboards were in stores. When a number was called a light shone on the board. But that wasn’t enough. The storekeeper couldn’t always see the light.”

“And what did you do about it?”

“We fixed up a new board, just Dad and I. Put a tiny bell on every line.”

“I see. The light flashed, the bell rang, and then the storekeeper really knew all about it?”

“Yes. But the light sometimes failed, so we put on bells with different tones. Each line spoke for itself.” Norma laughed. “We called it the musical switchboard.”

“And you say you’ve never worked?” The examiner laughed.

“That! Why, that was just fun!”

“Perhaps it was. The best work in the world is the kind we can think of as fun. All that time you were fitting yourself for two of our most important departments—Communication and Interceptor Control.”

“Can—can you really use me?” Norma was close to tears.

“Can we? Oh! My child!” The examiner all but embraced her. “We’ll make a major out of you! See if we don’t!”

Norma was not long in discovering the reason for that last surprising outburst of her examiner. When at last the report was finished, they looked up to find the row of chairs empty.

“Well!” the examiner breathed. “That’s all for today. This,” she added, “is not my regular work. My training was finished many weeks ago. I have been away from the Fort for some time doing a—well” she hesitated—“a rather special sort of work. Now I’m back for a brief spell. They were shorthanded here.”

“So you’ve been helping out?”

“That’s it.” The examiner rose. Norma too stood. “We all have one great purpose. Each of us must do what she can wherever she is.”

“To bring this terrible war to an end,” Norma added.

“You’re right again,” the other smiled.

“Whew!” she exclaimed after looking Norma over from head to toe. “You certainly do look fit.”

“I should,” Norma grinned. “Our college has put us through some training, I can tell you. We marched five miles bare-legged in shorts, with the snow blowing across the field!”

“Climbed fences. I’ll bet.” The examiner smiled.

“Yes, and walls too. We did gym work and took corrective exercises.”

“Grand! They were preparing you for—”

“Just anything.”

“That’s swell. My name is Warren.” The officer put out a hand. “Lieutenant Rita Warren, to be exact. I’m going up to Boom Town. Want to go along?”

“I’d love to!”

“Right! Then come. Let’s go.” Swinging into the regulation thirty-inch stride, Lieutenant Warren marched out of the hall with her recruit and along the snow-lined path.

“That Interceptor Control sounds intriguing,” Norma said as they marched over the crusted snow.

“Oh, it is! It really is!” Lieutenant Warren’s face glowed. “The most interesting work in the world. I’ll tell you a little about it. But don’t let me tell you too much.”

“I’ll flash the red light.” Norma laughed, as she asked, “How much is too much?”

Lieutenant Warren did not answer, instead, she said, “We are stationed along the seacoast.”

“Just any seacoast?”

“Any coast of America. There are a number of us in each group. We take over some small hotel. The hotel is run just for us.”

“Must be grand!”

“Oh, it is! But we don’t have much time to think of that. We have work to do. Plenty of it. You see, along every coast there are thousands and thousands of volunteer watchers. They are there day and night.”

“Watching for enemy planes?”

“Yes, that’s it, and for possible enemy landings.”

“But none have come?”

“Not yet. But let us relax our vigil—then see what happens! If an aircraft carrier stole in close in the fog and sent over fifty bombing planes, hundreds—perhaps thousands would die. That must never happen.”

“No! Never!” Norma’s hand clenched hard.

“That’s the why of the Interceptor Control.”

“Do the WACs help with the watching?”

“In a way, yes. But not out on the sandbanks and rocky shores.”

“That’s done by volunteers?”

“Yes. The WAC works inside. There’s plenty to be done if an enemy plane is sighted. Just plenty.

“This,” she said, changing the subject, “is Boom Town. Six months ago it was open country.”

Norma looked up, then stared. So interested had she become in their talk that she had failed to note that they were now passing before a long row of new red brick buildings.

“This,” She Said, Changing the Subject, “Is Boom Town.”

“The two-story ones are barracks,” her companion explained. “Some of the one-story buildings are Company Headquarters, some are mess halls, and some day rooms.”

“Day rooms?” Norma was puzzled.

“Day rooms that you mostly visit at night,” Lieutenant Warren laughed. “Lights in the barracks are out at nine-thirty. Most of the girls prefer to retire then. When you’ve been here three days you’ll know why.

“Some hardy souls wish to stay up another hour, so they retire to the day room to lounge in easy chairs, write letters, read, or play cards. Bed check is at ten-forty-five. You’d better be in bed by then or you’ll get a black mark.”

“Every night?” Norma asked in surprise.

“From Saturday noon to Sunday night is all your own. You’ll learn about that later.”

For a moment they walked on in silence. It was Norma who broke that silence.

“Can you tell me a little of what the WACs of the Interceptor Control do?”

“A little is right,” was the quick reply. “Much of it is a deep, deep secret. You’d love it all, I know.

“But listen. This is how it works,” she went on. “Some high school girl is watching from a cliff. There are many girl watchers, and how faithful they are!”

“This girl hears a plane in the dark. It’s off shore. She rushes to a phone and calls a number. A WAC at the switchboard replies.”

“And then?” Norma whispered.

“Then the girl on the cliff says: ‘One single. High. Off five miles. Going south.’

“The WAC knows from the spot on the switchboard where the girl is. She reports the call. Another girl locates the spot on a chart. A third WAC reports to three men. One of these men represents the Army, one the Navy, and one the Civil Aeronautics Authority. These men consult their records. Perhaps they discover that no plane belonging to any of their organizations is supposed to be on that spot.”

“And then they send out a fighting plane,” Norma suggested.

“Not yet. Perhaps that girl watcher heard a vacuum sweeper instead of a plane, so they wait.”

“And?”

“Then, perhaps two minutes later, there comes a flash from another watcher—this time a fisherman’s wife.

“Flash! One single. High. Going south. Very fast.”

“‘Three hundred miles an hour,’ someone says. Then a fighter plane goes up. And soon, if it’s really an attack, the sky will be filled with fighter planes.”

“Lives saved—many lives saved by the WACs,” Norma enthused.

“We shall have done our part,” Lieutenant Warren replied modestly. “And that is all our country expects from any of us.”

“Lieutenant,” Norma asked suddenly in a low tone, “did you notice anything unusual about the two girls who went into your booth just ahead of me?”

“Why no—let me see,”—the lieutenant paused to consider. “One was rather short and chunky—of Italian stock. And the other—”

“Tall, strong—and, well—rather silent.”

“Yes. Now I recall her. No—nothing very unusual. Quite different in character, but capable, I’d say. They’ll fit in. Of course, they’re both of foreign extraction The tall girl’s parents were German-born. She’s an American, as we all are. She was raised by her uncle. Something unusual, did you say? Why did you ask that?” She fixed her dark eyes on Norma’s puzzled face.

“Nothing, I guess. No real reason at all. I—I’m sorry I asked. I wouldn’t hurt anyone—not for all the world.”

“Of course you wouldn’t, my dear.” The Lieutenant pressed her arm.

Lieutenant Warren seemed fairly bursting in her enthusiasm for the Interceptor Control. She told Norma more, much more, as they marched along. Then suddenly, as if waking from a trance, she stopped dead in her tracks to exclaim softly:

“Oh! What have I been telling you? I shouldn’t have breathed a word of that! It’s so hard not to talk about a thing that’s got a grip on your very soul. Promise me you won’t breathe a word of it!”

“I promise,” Norma said quietly. “I’m sure I know how important it is.”

“Do you know?” some sprite might have whispered. Soon enough the girl was to learn.

“Come on in here,” the Lieutenant said a moment later. “I must pick up a suit I’ve had pressed.”

The air in the large room they entered was heavy with steam. “On this side,” said the Lieutenant, pushing a door open a crack, “is the beauty parlor. Some young reporters have made fun of it. As if it were a crime for a soldier to look well!

“Those girls working in there,” she said as she closed the door, “are civilians. They come over from the city every day. Sometimes they worry me.”

“Worry you?” Norma was puzzled.

“Yes. You see, they’re not checked.”

“Checked?” Norma stared.

“Their records, you know. After all, this is an Army camp and, as such, is just packed with secrets. We send out a thousand freshly trained WACs a week. One of these days we’ll be sending a trainload all at once. Where are they going? Are they being sent overseas? Will they be secretaries to commanding officers? What other important tasks will they perform? Our enemy would like to know all this and much more. And these hairdressers just come and go. Who are they? No one knows.”

“But have we been checked?”

“Have you been checked?” the Lieutenant whispered. “Oh, my dear! The F.B.I. knows all about you. Your fingerprints are in Washington. Your life from the time you were born has been checked and double-checked.”

“So none of us could possibly turn out to be spies?” Norma breathed a sigh of relief.

“I wouldn’t quite say that,” her companion replied thoughtfully. “But it would be very difficult.”

“Oh!” Norma exclaimed, fussing at her hair. “Do you suppose I could possibly get my hair set?”

“I can’t see why not. This is a slack hour.”

“I’m going to try it!” the girl exclaimed. “Tomorrow I’ll be getting my uniform, won’t I?”

“Yes, you will.”

“Then my cap must be fitted properly.”

“Try it, and good luck.” The Lieutenant held out a hand. “It’s been a pleasure to talk to you.”

“Oh!” Norma exclaimed. “I want to see you many, many times!”

“My visit here at this time is short. But in the future. Here’s hoping.”

“In the future. Here’s hoping,” Norma whispered to herself as she passed through the door.

On entering the small, crowded beauty parlor Norma found only one vacant chair. She looked at the girl standing behind the chair. “Spanish,” Norma thought. And yet her eyes were set at a slant like those of an Oriental. For all this she was decidedly not an Oriental.

“Oh, well.” Norma thought, “she looks capable. It will soon be time for rattling those trays again. And do I need to get my fingers wrapped round one of those mugs of strong coffee! Boy! Has this been a day!”

“Hair set,” she said, as she settled back in her chair.

Without a word the girl went to work. She was half finished before she spoke. Then in the most casual manner she said:

“Lieutenant Warren is a friend of yours?”

Norma was surprised. The door had been opened only a little way, and for a space of seconds, yet this girl had seen. “Yes,” was her noncommittal reply.

“It is always quite fine to have an officer for a friend. She can help you, tell you things, and guide you,” suggested the hairdresser.

“Yes—I—I suppose so,” Norma murmured.

“She told you about the Interceptor Control?” The girl’s whisper invited confidence.

At once Norma was on her guard. “We talked about Boom Town,” she replied evenly. “It’s interesting. Built so quickly, and all that. Yet it looks warm and cozy.”

“Boom Town. Oh! Yes, it’s quite grand.” These words were spoken without enthusiasm.

After that they talked about trivial things—clothes, shampoos, and the weather. Twice the strange girl led back to the Interceptor Control. Twice Norma led her away again.

“Now why would she, a hairdresser, want to talk about Interceptor Control?” she asked herself.

As she left the chair she was not a little surprised to see the tall recruit, Lena, waiting to take her place. More surprising was the fact that as Lena’s eyes met the hairdresser’s, there appeared to pass between them an instant flash of recognition.

“And Lena hasn’t been on the grounds a whole day!” she thought with a start.

“Spies!” her mind registered as she left the building. Then she threw back her head and laughed. “Spies in the heart of America!” she whispered. “In a woman’s camp! I’m getting a spy complex—seeing ghosts under the bed! What’s the matter with me?”

That evening, not wishing to retire at the “lights out” signal, she sought out the day room that is used at night, and found it.

It was a comfortable place, that day room. Half underground, it was not subject to draft. A large round stove gave off a genial glow and plenty of heat. A large cushioned lounging chair awaited her.

Only one other girl was in the room. “Lena, the one who whispers in the night,” Norma thought. “Guess she’s asleep.”

Lena was not asleep, for as Norma sank into her chair, she opened one eye and drawled:

“Had a good day, didn’t you?”

“Just fine!” was the smiling reply.

“Hobnobbing with the brass hats.” Was there a suggestion of a sneer on Lena’s face?

If it was there Norma chose to ignore it. “There don’t seem to be any brass hats around this place,” she replied, good-naturedly.

“Oh! Aren’t there?” the girl exclaimed. “You just wait and—” At that the girl caught herself. “Well,” she finished lamely, “I’ll admit I’ve been treated fine.”

“Tomorrow we get measured for our uniforms,” she added.

“Your uniform should need very little fitting.” Norma could not help admiring the girl’s look of perfect fitness and form as she stood up.

“I didn’t get it sitting ’round,” Lena laughed. “I’m going out for some air and a look at the moon. You’re rather a perfect thirty-six yourself,” she said over her shoulder as she marched toward the door.

Norma wondered in a vague sort of way how Lena had got her training. She knew about her own. It hadn’t been easy.

After a time she began wondering about the moon. Seeing it shine over the stables, the barracks and mess halls would be a pleasant experience. She wasn’t dressed for the outdoors, so she stepped to the window and looked up. She did not see the moon. Instead, her eyes fell upon two shadowy figures. One was Lena. The other, too, was a girl.

“Just another raw recruit,” she thought.

But then the girl turned so the light of a distant lamp was on her face. She was the girl who had done Norma’s hair that afternoon.

“Should have been back in the city hours ago,” she told herself.

It all seemed very strange to her. Where had Lena known this girl before? Or had she? Why were they together now? Only time could tell, and perhaps time wouldn’t.

She was just thinking of retiring when Lena again entered the room. Seating herself before the fire she held out her hands to warm them. For some time neither girl spoke. At last leaning far over and speaking in a hoarse whisper Lena said:

“You know that little Italian girl?”

“Rosa?”

“Yes.”

“What about Rosa?”

“I think she’s a spy. I saw her flashing a light in the night. Her cot is by the window, you know,” came in Lena’s insinuating whisper.

“Oh! Do you really think so?” There was little encouragement in Norma’s tone. “Who’s a spy?” These words were on her lips. She did not say them. Nor, having said them, could she have given the answer.

Two days later found them all in uniform. And did they look grand!

“Oh! Millie!” Norma exclaimed. “You look like a million dollars!”

“Do I? Then I’m glad.” Millie beamed. “I was afraid I’d still look like a salesgirl.”

“How does a salesgirl look?” Betty asked.

“Oh, sort of dumb.” At that they both laughed.

“It’s the grandest outfit I ever had!” Millie exclaimed. “Such a soft, warm woolen suit. And such tailoring! And my coat! Oh gee! I feel like Christmas morning!”

“The shoes weren’t marked down to two dollars and thirty-nine cents either!” said Betty. “I’ve had a lot of fine shoes, but none better than these.”

That afternoon a corporal formed them into a squad—Norma, Betty, Lena, Millie, Rosa and five other girls. Then they began to drill.

“One! Two! Left! Right! Left! Right,” the corporal called. “Squad right! Squad left! March! March! Doublequick! March!”

Some of the girls found it difficult to keep in step and maintain that thirty-inch stride. But not Norma. The whole manual of drill was an old story to her.

Soon they were joined by other squads. Then, eager that her squad might look its best, when the Lieutenant who had taken them over was not near, Norma began calling in a hoarse whisper the counts and changes. “Left! Right! Left! Right! Squad right! March! Double quick!” They drilled until many a girl was ready to cry “quits.”

When they broke ranks Lieutenant Drury singled out Norma’s squad.

“Say!” she exclaimed. “You girls are wonderful! Been practicing behind the stable or somewhere?”

“It’s her,” Millie nodded toward Norma. “She keeps us going.”

“That’s swell. How come?” The Lieutenant turned to Norma.

“I knew it all before I was five years old,” Norma laughed. “My father was an officer in the last war, and I am his only boy. He started drilling me when I was a mere tot. I liked it, so we kept it up. That’s all there is to it.”

“Well,” the Lieutenant laughed, “I guess there are many of us who are our fathers’ only sons. And by the grace of God we’ll make them mighty proud of us before this old war is done!”

That night in a corner of the day room Norma had a little time all by herself. Her father was home all alone now. The chair she had occupied by the fire for so long was empty now, and would be for a long time.

“But I wouldn’t go back,” she told herself, biting her lip. “Not for worlds!”

And he would not want her back. She recalled his parting words at the train. “Norma,”—his voice had been husky. “For a long time I wanted a son. Now I’m proud to have a daughter to give for the defense of my country. Get in there, girl, and fight! Perhaps you’ll not be carrying a gun, but you’ll be taking a fighting man’s place. And I’m sure you’ll help show those fine boys how a girl can live like a soldier and die like one, if need be.”

“I’ll be back,” she had whispered, “when the war is won.”

That night Lena may have whispered in her sleep. She may even have gone out to talk with her hairdresser. If so, Norma knew nothing of it. She was too weary for that. She retired early. She did, however, remain awake long enough to twice catch the gleam of light from Rosa’s cot. She liked the little Italian girl, but—

Once again she recalled one question asked her back there in Chicago. She had been given a final examination before her induction into the service. One of the women in that examining group, she had been told, was a psychologist. In the back of her mind all during the examination she had asked herself, “Which one is she?”

When a little lady with keen dark eyes had leaned forward to ask: “If you suspected that one of your companions was a spy, what would you do?”—a flash came to her. “She’s the psychologist.”

She had thought the question over, then replied slowly, “If I saw her setting a fire or stealing papers I’d report her at once.”

“But if not?” the little lady had insisted.

“If I merely suspected that she was a spy, I’d wait and watch, that’s all,” had been her whole reply.

In the eyes of her examiners she had read approval. That’s what she was doing now—watching and waiting.

“All the same,” she told herself now, “I’m going to ask Rosa why she flashes that light at night.”

The next day three things happened. Norma saw her favorite Lieutenant. She asked Rosa a question and received a surprising reply, and Millie, the shopgirl who was in the Army now, led them all in an amusing adventure that might not have turned out so well.

In the afternoon they drilled as a squad, as a platoon, and as a company. It was a hard workout, but to Norma it was a thrilling adventure.

“All this is the real thing!” she exclaimed once.

“I’ll say it is!” Betty laughed. “These new shoes are burning up my feet!”

“It’s the real McCoy, all the same,” Norma insisted. “It’s what I’ve been training for all my life! My father thought it was just for fun, for after all, I was a girl.”

“How little he knew!” Betty replied soberly.

Marching and drilling were not hard for Norma. She had time to think of other things. She began studying the ancient fort, and the atmosphere that hung about it like a cloud.

She had begun to love the place, and at times found herself wishing that she might remain here for a long time.

“Four weeks seem terribly short,” she told Betty.

“It may be much longer,” Betty suggested. “You might join the motor transport school and learn to drive a truck in a convoy.”

“Yes, and I might not,” was her reply.

“Or attend the bakers’ and cooks’ school,” Betty suggested.

“Not that either.”

“Well then,” Betty exclaimed, “since you’re so awfully good at this drilling stuff, perhaps they’d let you attend the officers’ training school.”

“Hmm.” she murmured. “Now you’re talking! Maybe. I don’t know.”

On that particular day, as a bright winter sun shone down on the long parade ground, Norma thought only of the old fort and what it stood for.

It was quite ancient, but just how old, she could not tell. Always a lover of horses, she tried to picture the parade ground in those old days when a thousand, perhaps two thousand men, all mounted on glorious cavalry horses, came riding down that stretch of green.

“Dignified officers in the lead—band playing and horses prancing! What a picture!” she murmured.

On each side of the parade ground were rows of red brick buildings. On the right side had been the homes of officers. Now these were occupied by the officers of the school.

On the opposite side were barracks occupied by officer candidates in training.

“That’s where I’d be training,” she thought with a little thrill, “if I applied for entrance and was accepted.”

On bright, warm days, she had been told, the whole school, six thousand strong, assembled on the parade ground and marched down the field. “That,” she thought, “would be glorious!” She hoped that they would have fine weather before she went away.

It was after drill was over that a rather strange thing happened. There was, she had discovered, an air of grim, serious determination about this place that was almost depressing. You seldom heard a laugh. There was always the tramp-tramp of feet.

Even now, when her squad of ten had been put on their own, and they were headed for the Service Club for a bottle of coke or a cup of hot chocolate, they were still going tramp-tramp, in regular file.

“It’s a little bit too much!” she thought.

Just at that moment a shrill voice cried out sharply:

“Left! Right! One! Two! One! Two.” She recognized that voice. It was Millie, the shopgirl!

For a space of seconds they kept up the steady tramp, tramp, tramp. Then, with a burst of laughter, they all took up the chant: “One! Two!”

They kept this up to the very door of the Club. Then, all of a sudden, the chant ended with a low escape of breath. There in front of the Club stood a captain of the WACs.

As they filed past, the girls saluted, and the captain gravely returned their salute.

“Wasn’t that terrible!” Millie whispered, gripping Norma’s arm. “And I started it! Do—do you suppose they’ll put me in the guardhouse?”

“I don’t know,” Norma hesitated. “No—not the guardhouse. No WAC is ever put in there. I guess it wasn’t so bad. We were just letting off steam, that was all.” Truth was, she didn’t know the answer. Of one thing she was sure—she for one felt better for this little bit of gaiety.

The Service Club had a cheerful atmosphere about it. Straight ahead, as they entered, they saw at the back of a fairly large lounging room, a fire in a large open fireplace. From the right, where chairs stood about small tables, came the pleasant odor of hot coffee and chocolate.

As Norma turned to the right she caught the eye of Lieutenant Warren. She was seated alone at a table, sipping coffee. At once she motioned to Norma to come sit across from her. With some hesitation, Norma joined her.

“What will you have? It’s on me,” the Lieutenant smiled.

“That coffee smells just right,” was the reply.

“Doughnuts—a sweet roll, or cookies?”

“A—a sweet roll. But please let me get them!”

“No! No! Permit me!” Lieutenant Warren was away.

“That training you received at college was fine,” the Lieutenant said when they were seated. “Grand stuff. I only wish all colleges went in for it. And they will. Our quota now is a hundred and fifty thousand. It will be a half million before you know it.”

“But Lieutenant Warren!” Norma’s brow puckered. “We’re not to carry guns, are we?”

“No. That’s not contemplated.”

“Then why all this drilling?”

“We’re going in for hard things—driving trucks, carrying messages on motorcycles, repairing radios, cars, airplanes. We’re to take the places of soldiers so they can carry guns and fight. We’ve got to be hard—hard as nails.”

“I—I see.”

“That’s not all.” The Lieutenant’s eyes shone. “Learning to drill properly is learning to obey orders. That’s necessary. If I say to you, ‘Take this message down that road where the bullets are flying,’ you’ve jolly well got to do it.”

“I—I see,” Norma repeated.

“You don’t mind this drilling, do you?”

“I love it!” This time Norma’s eyes shone.

“I thought so. And you know a great deal about it—perhaps more than most of us.”

“Per—perhaps,” the girl agreed, hesitatingly.

“With your permission, I am going to suggest that you be given a company to drill.”

“Oh! Oh, please! No!” Norma held up a hand.

“Wait.” The tone was low. “You saw me examining recruits?”

“Yes.”

“I was the only officer doing that work.”

“I—I didn’t notice.”

“All the same it was true. Why do you think I did it?”

“Because you wished to serve,” Norma replied in a low voice. “But with me it would be a step up too soon.”

“We are in a war. A step up or down does not matter. All that matters is that we should be prepared for that step. You are well prepared. You won’t refuse?”

“I won’t refuse,” the girl answered solemnly.

“Lieutenant,” Norma said in a low tone a moment later, “when I had my interview they asked me what I’d do if I suspected someone of being a spy. Why did they ask me that?”

“The psychologist was taking your measure. That was a problem question. The answer would give her a slant on your general character.”

“Then they don’t expect to find a spy among the WACs?”

“It’s not impossible for a spy to join our ranks, but certainly not easy. You filled out a questionnaire that told every place you had lived and when, every school you attended, and when.”

“And if I had been working, I would have had to tell how long and when, why I quit, and all the rest. All the same,” Norma spoke slowly, guardedly,—“spies have gotten into every sort of place, so—”

“So you think we have a spy?” The Lieutenant’s voice was low. “Anything you’d like to tell me?”

“No. Not—not yet.”

“Okay. Let’s skip it. But just one thing. We all need to be careful about members of our organization who are children of the foreign-born. It’s easy to do them an injustice. Too easy. They form a large group in our population. Take that little Italian girl over there. She’s an attractive young lady.”

“That’s true,” Norma agreed.

“And that big girl—Lena. Her parents are foreign-born. What a truck driver she’d make!”

“Yes—Oh yes. Sure she would.”

The Lieutenant gave Norma a short, sharp look.

Nothing more was said. A moment later Millie stood by their table. There was a worried look on the shopgirl’s face.

“Wasn’t that terrible?” She did not smile.

“What’s so terrible?” The Lieutenant smiled.

“What we did a little while ago,” said Millie.

“Want to tell me about it?” the Lieutenant asked.

Millie dropped into a chair to tell the story of their hilarious march.

“Now,” she exclaimed at the end, “It was I who started it. What will they do to me?”

“Nothing,” was the instant response, quite as quickly rewarded by a golden smile.

“You were on your own,” the Lieutenant explained. “We want you to be happy. When an army loses its sense of humor it begins losing battles.”

“I—I’m so glad,” Millie exclaimed.

“But let me tell you.” The Lieutenant held up a warning hand. “There are other times and places. Take Inspection as an example. When you line up by your cots for inspection be sure there are no wrinkles in your blanket; that your locker is in order and open; that your shoes, towel, washcloth and laundry bag are in place. And above all, look straight ahead. Don’t smile. Don’t frown. Just look—and don’t move a muscle—not even if a fly gets inside your glasses or a bee stings you.”

“Jeepers!” Millie exclaimed. “This is some woman’s army!”

That evening, by some strange chance, Norma found herself in the day room with Rosa, alone.

“It’s my chance.” she told herself with a sharp intake of breath. “Now I’ll ask her.”

“Rosa,” she said quietly, “why do you flash a light by the window at night?”

“Oh!” Rosa exclaimed sharply. “Does it show?” Her face was flushed.

“Yes. Just a little.” Norma was trying to make it easy. “But why should you do it at all?”

“I don’t like to tell you.” Rosa backed away. “You’ll laugh at me.”

“Rosa, I’ll never laugh at you about anything.”

“Honest?” Rosa’s dark eyes searched her face.

“Honest. Never! Never!”

“All right, then. I’ll tell you. My mother didn’t want me to join up. She believes much in prayer. She gave me a book of prayers and said: ‘Read one prayer every night.’ I have read one prayer every night. But it was dark, so I hid a small flashlight in my bed. Now you can laugh.” Rosa turned away.

“Rosa,”—Norma put an arm about her—“I think that’s wonderful! But Rosa, your mother did not say ‘Read a prayer in bed.’”

“No, she did not say that.”

“Rosa, we are forbidden a light in the barracks after nine-thirty, so why don’t you come down here to read your prayer?”

“Thank you! Thank you so very much. I shall do that.” Instantly Rosa was away after her book.

Long after Rosa had read her prayer and left the room, Norma sat staring at the fire. In that fire she read many questions. Would she be asked to drill a company? Should she ask for the privilege of entering officers’ training? Had Rosa told the truth? And Lena? What of Lena and the strange girl in the beauty parlor?

At Fort Des Moines the WACs are on their own from Saturday noon until Sunday night. Needless to say, over at the mess hall, in the barracks, and on the field there was much talk among the new recruits about how these hours were to be spent.

“What do you do?” Norma asked a tall, slender girl from Massachusetts who had been in training for three weeks.

“Well,” the girl drawled, “the first week I went dashing off to Des Moines, rented a room at a nice hotel, ate oysters on the half-shell, Boston baked beans, brown bread and all the things I wanted, and had a grand time all by myself. But now,” she added, “I just get some books from the library, settle down in a big chair at the Service Club and loaf.”

“But isn’t Des Moines interesting?” Norma asked in surprise.

“Sure it is,” a bright-eyed girl from Texas exclaimed. “Beth is just lazy, that’s all. Des Moines is a nice big overgrown town, all full of nice, friendly people. It has the grandest eating spots! Yes, and halls where you can dance—really nice places.”

“And boys to dance with! Umm!” exclaimed a girl from Indiana. “There are soldiers and sailors who come in from their camps and all sorts of college boys.”

“A nice big, overgrown town, all full of nice friendly people.” Norma recalled these words later. Truth was, she found herself a little homesick. At that moment she would have loved a good romp with her dog Spark, and after that a quiet talk with her dad.

“I know what I’ll do!” she thought. “And I won’t tell a soul! They’d laugh at me.”

Betty, who more than any girl at camp had begun to seem Norma’s chum, had decided to stay in camp. When the day came, Norma too remained until four o’clock. Part of the time she spent having her hair washed and set. It was no accident that she took the chair of the Spanish hairdresser who served her before.

“I’ll bring up the subject of the Interceptor Control. If she asks questions I’ll tell her things I read in that little book called ‘The Battle of Britain.’ Anything that’s been published. Then perhaps I’ll string her a little.”

The hairdresser fell for the bait. Norma loaded her up with commonly known facts, then drew pictures from her fertile imagination. In the end she was hearing planes at unbelievable distances.

“But why are you so interested in all this?” she asked at last.

The girl shot her a swift look. “Oh! Miss Kent!” she exclaimed—there was a shrill note in her voice—“It is all so very interesting! Everything you WACs do is thrilling! It is a great organization!”

“Yes,” Norma agreed. “It is one of the big things that has come out of the war.”

To herself she was recalling Lieutenant Warren’s words:

“These girls worry me a little. Their records have not been checked.”

Then again she remembered how her own record had been checked to the last detail. “The examiners do not take your word for a thing,” she had been told. “The F.B.I. questionnaire you filled out is checked and double-checked by men who know. Even your fingerprints are sent to Washington.”

All this she knew was true. And yet the girls in the beauty parlor were not checked. “That tall girl, Lena, could tell this hairdresser anything—just anything at all. If she became the secretary to a colonel she could report anything to this hairdresser.”

“But Lena—” it came to her with the force of a blow—“Lena’s record has been checked. Her fingerprints were sent to Washington.”

“What a silly young fool you are!” she chided herself as a short time later she took the car to Des Moines. But she was not even sure of that.

Arrived at the heart of the city she looked up a long street to see a tall, inviting brick hotel standing on a hill.

And Yet the Girls in the Beauty Parlor Were Not Checked

After walking and climbing for fifteen minutes she found herself entering a long room filled with lounge chairs and lined on two walls by tall glass cases. The contents of these cases surprised her, for in them were more kinds of mounted fish than she had ever seen.

“Oh!” she exclaimed. “Am I in the wrong place? Is this a museum?”

“No, Miss.” the smiling bellboy who took her bag replied. “This hotel was once owned by a very rich man who collected fish. He’s dead now.”

“But his collection lives on.” She wondered vaguely what would live on when she was gone.

The first thing she did when she had been shown to a neat and comfortable room was strange. Opening her bag, she took out a cardboard folder tied with a ribbon. From this folder she selected a dozen pictures. These she proceeded to thumbtack, one by one, to the wall directly under a mellow light.

After that, without further unpacking, she dropped into a chair and sat for a long time looking at those pictures through moist eyelashes.

The house with the broad lawn and tall shade trees about it was her home. The tall, distinguished looking man with one empty sleeve was her dad. The picture done in color was her college chum. And the grinning young man in the uniform of a private was Bill—just plain Bill.

There were other pictures but these were the ones that counted most. They had adorned the walls of her room at college for a long time. When you bunk in a stable—even a glorious, glorified stable—with a hundred other girls, you don’t thumbtack your pictures to the wall. It isn’t allowed. Besides, it would be silly.

Norma wanted to see her pictures in their proper setting. Now she was seeing them.

“Norma, you’re a silly goose,” she told herself aloud. Then she wondered whether she had spoken the truth. Sometimes one drops into a new world too hastily. It does one good to take a look back.

It was Bill who had started her thinking of the WACs. She and Bill were grand good friends, that’s all. No diamond ring—no talk of wedding bells—just friends.

All the same, when Bill came to the school all togged up in a new uniform, she had felt a big tug at her heart strings.

“Oh! Bill!” she had cried. “You look like a million!”

“And I feel like a millionaire,” was Bill’s reply. “Army life is the berries, and regarding the Japs, all I’ve got to say is they’d better look out!”

“Getting pretty good with a Tommy gun, Bill?” she laughed.

“And how!” was his prompt reply.

They found a log down among the willows at the edge of the campus, and there Bill, in his big, boisterous way, told her all about the Army.

“Oh, Bill!” she exclaimed when he had finished. “You make it sound so wonderful! I wish they’d let girls join.”

“They do!” Bill stopped grinning. “Ever heard of the WACs?”

“Yes, I—” she paused. Yes, she had heard of them. That was about all.

“Bill, I’ll really look into this.”

“You’d better. They’re a grand outfit. And boy! Are they going places!”

“I’ll be seein’ you,” she said to Bill as their hands clasped in farewell.

“In the Army?”

“I shouldn’t wonder.”

“Hot diggity! That’s the stuff!” He gave her hand a big squeeze, and was gone.

“And now I’m here, Bill,” she said to the picture on the wall. “I’m in the Army now. But, oh, Bill! I do hope our companies will some time march in the same parade!”

After an hour with her pictures, Norma felt herself ready for one more week of drilling, police duty, study, and all that went on from dawn till dark at old Fort Des Moines.

After a hearty meal eaten in a big bright cafeteria where all the people seemed carefree and gay, she stepped out to see the lights of Des Moines at night.

Thrills she had experienced more than once came to her from exploring a strange city at night. Certainly exploring a city of friendly people, many of whom smiled at her in a kindly way as she marched along in her spick-and-span uniform, could not be dangerous.

For an hour she prowled the streets alone. Past dark public buildings that loomed at her from the night, down narrow dark streets where taxi drivers and workers sat or stood before narrow lunch counters, she wandered. And then back to the broad street where lights were bright and the throngs were gay.

A feeling of utter loneliness drove her once again into the shadows. And there she met with a startling adventure.

She had rounded a corner and was walking slowly north, admiring the sight of the moon shining over the jagged line of rooftops, when suddenly two figures emerged from a narrow alley to turn in ahead of her.

“Been taking a short cut,” she thought.

The steady swinging stride of the taller of the two girls, as they marched on before her, suggested that she might be a WAC.

“But she’s wearing civilian clothes,” she told herself in surprise.

The two shadowy figures seemed vaguely familiar. Because of this she followed them. They had gone two blocks when all of a sudden the taller of the two turned her head half about. The moonlight painted her features in sharp outline.

“It’s Lena!” she whispered. “Lena, in civilian clothes!” What did it mean? Had this girl been found out and dismissed from the service?

As if the question had been put directly to her, the shorter of the two girls paused and looked back. Just in time Norma dodged into the shadows.

An inaudible gasp escaped her lips. The other girl was the one from the beauty parlor at the Fort.

As the two girls resumed their march, Norma followed them, without thinking too much about the reason or possible consequence.

At the next corner they turned west on a dark street. Here, on both sides, were auto repair shops and cheap second-hand stores.

Scarcely had Norma rounded this corner when the two girls swung through a door to disappear into a shop that was almost completely dark.

Acting purely on impulse. Norma caught the door before it had completely closed. Pushing it a little farther open she slipped inside and then allowed it to close noiselessly.

At the same instant a thought struck her all in a heap. Lena had a perfect right to dress in civilian clothes on her day off. All WACs have. She, Norma, had chosen to wear her uniform.

“In a way it is a sort of protection,” she had said to Betty.

“Yes, like a nun’s cape and veil,” Betty had laughed.

“Is it a protection?” Norma asked herself now. At first the place seemed completely dark. Then she caught a gleam of light at the far end of the room. She began hearing low voices. The two girls were back there. Someone was with them.

“What a goose I am,” Norma thought. “Lena has a right to dress as she pleases. Nothing unusual has happened. That other girl probably has a friend who works here. They have come here to meet him. I’ll just slip out of the door.”

But she couldn’t. Not just yet. The door was closed and locked. Just a little frightened, she felt for some sort of bolt or spring lock that could be released. There was none.

For the first time in her life she was seized with a feeling very near to panic. She wanted to dash to the heavily shaded windows and pound on them for help. She wanted to scream. And yet she did not dare. Perhaps those people did not know she was there.

“And after all, why should I be afraid?” she asked herself. “This is some sort of a repair shop.” That faint light from the back brought out the looming bulks of cars and trucks. “There’s no law against going into a repair shop, even at night.”

All of a sudden she realized that it was not fear of those who enforce the law that inspired her with fear, but those who hated the law.

“Spies,” she whispered softly.

But were there spies in this city? Perhaps. Who could tell? Spies were everywhere.

Once again she tried the latch, lifting it up and down, pulling at the door without a sound. It was no use. Some mysterious type of lock held the door fast shut.

In the hope of finding a smaller door, she began gliding along the wall. All at once she bumped into something that toppled over to fall with a loud bang.

Like a wild bird in a cage she flew to the door to try the latch with all her strength.

“Who’s there?” came in a hoarse voice.

She neither moved nor spoke.

A minute passed—two—three minutes—or was it an hour? Her heart was beating painfully. She had the sense of someone approaching, yet she neither heard nor saw a moving thing.

Then suddenly she did see it—a groping hand. The flash of light cutting through a spot beside a windowshade revealed it.

A scream was on her lips. And yet she did not scream.

And then the hand gripped her arm.

“What are you doing here?” a voice growled.

She tried to speak, but no words came.

“Oh! You are one of them.” The voice changed suddenly. Now it was low, apologetic. “You are one of them lady soldiers. A WAC they call them, don’t they?”

“Yes. Yes. That’s what I am.” She formed the words but could not say them.

There was no need, for the man went on, “You were perhaps looking for the WAC garage. It is not here. That is another place. You came in—the door locked itself. Is it not so?”

“Yes! Yes! That is it,” she whispered. Lena must not hear her voice or see her face.

“I shall unlock the door. This is all too bad,” said the man who had gripped her arm.

By some magic the door was opened and she stepped out into the night. The light of a car illuminated the man’s face for a second. Then the door slammed shut.

“I’ll know that face if I see it again,” she told herself. She wondered if after all Lena had seen her face—and if she had, what then?

Ten minutes later, panting a little, she entered the hotel, called for her key, then dashed up two flights of stairs to her room.

Having locked and bolted the door, she sank into the chair before her array of pictures.

“Oh, Bill!” she whispered, “I wish I hadn’t come.” She was thinking not alone of Des Moines, but Fort Des Moines, the Army, and all the rest. She was wishing desperately that she might be back with her dad and her dog Spark.

After that she sat looking at her father’s picture. From his square shoulders and his twinkling gray eyes she drew strength. She seemed to feel again his hand on her shoulder as he said in his slow calm voice, “You’re the only boy I’ve got. Thank God they’re giving you a chance. I know you’ll do your duty as a good soldier.”

“No,” she whispered, “I’m not sorry. I’m glad.”

One thing she decided before she fell asleep in that big comfortable bed. This was that she would cease playing the part of an F.B.I. agent and start being a real WAC.

“I’ll put this Lena business out of my life,” she whispered. “This is the end of it forever and ever.”

Did some sprite whisper, “Oh, no, sister! No you won’t!” If so, it was all lost on her, for she had fallen fast asleep. But if there was a sprite hovering about and he did say that, he would have spoken the truth. There are some things that just won’t be put out of our lives.

When she awoke the sun was shining in her window. It was Sunday morning. But she was not thinking of that. Instead, a question had popped into her head. How had that man known she was a WAC? He had not seen her. The place had been completely dark. There could be but one answer—by the sense of feeling. He had gripped her arm. He had recognized the feel of her soft wool WAC uniform. And how had he come to know the feel of fine wool? Here too there could be but one answer—Lena. It was strange.

On the following Monday Norma was asked to take charge of the drilling of her company.

“I realize that this is an unusual request,” the officer in charge said soberly. “But this is an unusual war, and ours an unusual organization. For that reason we must perform unusual tasks.

“We are short of officers. The Army camps are constantly calling for more and more of our workers. They go out in small groups. An officer goes with each group. So now you see how it is.” She smiled. “What do you say?”

“I—I’ll try it.” Norma agreed.

She undertook the task with fear and trembling. It was not so much that she distrusted her own ability. She had been well trained. But how would the other girls take it?

“Some of them are thirty years old. One is a grandmother,” she said to Betty, as she broke the news. “And I am barely old enough to vote.”

“It’s not age that counts,” Betty replied in a tone that carried conviction. “It’s ability and experience. Go in there, old pal, and win. This is war. We all must do our best. And you can bet I’ll be right in there rooting for you.”

“Then—thanks! Oh, thanks!” Norma replied huskily.

All the same, when the time came for her first order: “Company, attention!” her throat was dry and her heart was in her mouth.

There was a surprised look on many faces as they turned about to line up. There was a smile or two, but they were not unkind smiles.

Then a thing happened that broke the tension. An officer of the old school, her father had drilled her in an unusual way. When as a child she stood at attention, he would call: “Hup, two, three.”

Now, in her excitement she called to her company:

“Hup, two, three!”

Then suddenly realizing what she had done, she laughed. And they all laughed with her. The ice was broken.

“Mark time! One! Two! One! Two! March.”

Feet came down with an even thud—thud—and crunch—crunch on the frozen path. The march was on.

Oddly enough, at the first rest period one of the older members said:

“Why not ‘Hup, two, three,’ for us?”

“Sure. That’s the way the soldiers get it. And we’re in the Army now.”

“They’ll call us the Hup company,” someone laughed.

“That will be swell,” exclaimed another. “And that’s what we’ll be, the ‘Hup an’ comin’ Company’.”

And so it came to be.

For two hours Norma put them through their paces. Only once did her attention waver. That was when Lena gave her a long, searching look. “She knows about that night,” she told herself, and all but lost a step.

When at last the tired marchers were once more on their own, many of the girls came forward to congratulate her and tell her how well she had done.

“They are won over. Just wonderful!” Tears of gratitude stood in Norma’s eyes as she reported to her superior.

“These came here for just one purpose,” the Lieutenant said.

“To help win the war.”

“Yes. That’s it. To hasten the end of this terrible affair and to help bring their brothers, sweethearts, and friends back home again.

“So how could they fail to do their best or refuse to respond to the orders of any leader? But you, my child,”—she placed a hand on Norma’s shoulder—“you have real officer’s blood coursing through your veins.”

Norma thanked her, then marched away.

“She spoke wiser than she knew,” Norma thought with a smile. She had not told her that her father had been an officer in the other World War.

But did she really want to become an officer of the WACs? She did not know.

After that the days glided by. Drill was not all there was to their training. Far from that. The Articles of War were read to them. They studied long hours learning what it meant to be a soldier. They studied military regulations. They took gas mask drill, first aid, and a score of other activities that were likely to fall to the lot of any WAC.

From time to time each girl was assigned to K. P.—Kitchen Police—peeling potatoes, washing dishes, scrubbing floors, dishing up food.

Betty, who was a real student, hated this, for on that day they were excused from study. But Millie, who found study difficult, wished that K. P. came five times a week.

Though Norma had sworn that the spy complex should not tempt her again, strange things happened, and always her mystery-loving mind would ask, “Why? Why?”

There was the time she went with the little Italian girl, Rosa, to visit the airport on their day off. Then, too, Betty more than once tempted her to start spy hunting all over again.

“I won’t!” she told herself. “I won’t! I just won’t!” Positive as she was at the time, Norma did not succeed long in keeping this resolution.

It was really Rosa’s strange and mysterious adventure at the airport that got her going all over again.

On the Saturday that Norma and Rosa went to visit the airfield they doffed their uniforms and put on their civies.

“All the same,” Norma said, “we’ll take along our identification cards, just in case—”

Airplanes, especially those flown by the Army Air Forces, had always interested Norma, so she was more than delighted when shortly after their arrival at the field, a flight of small, sleek fighter planes came winging in out of the blue.

“Look, Rosa!” Norma exclaimed. “Aren’t they wonderful! Like a flock of beautiful white pigeons!”

There was no need to say “Look” to the little Italian WAC. As if in a hypnotic trance, she stood with eyes glued on the flight of planes.

“See how they circle!” Norma herself was entranced. “This is like war. This is how they will come sweeping in after escorting a bomber squadron in Africa, or China, or who knows where. That’s the way they’ll look when we watch them beyond the seas.”

“Yes, this is war,” was all that Rosa said, as one by one the fighting planes taxied across the field into position.

Like a troop of boys the fliers came walking across the field.

“Bill is in flight training right now,” Norma said, all excited. “If only he were in that group!”

“Who’s Bill?” Rosa’s eyes left the planes for an instant.

“Oh, he’s just Bill.” Norma laughed. “But he’s not here.”

Always interested in any person in uniform, Norma moved closer to the joking, laughing group.

“How young they seem!” she said, half aloud. It shocked her to think that some day, perhaps not too far away, from the blue sky, shot out of his plane, Bill would come hurtling down, tumbling over and over like a stick thrown into the air crashing at last to earth.

“This is war,” she thought, with a shudder. “We WACs must do all in our power to make it end. And we will! Now we are a hundred and fifty thousand. Next it will be three hundred thousand—half a million—a million WACs marching away to win the war.”

Looking up, she allowed her eyes to sweep the field. It was an inspiring picture—the men, the planes, the flag floating in the breeze.

“Oh!” she whispered. “Oh! How I wish Dad were young again!”

And then, with a sudden start, she realized that Rosa was gone from her side.

“She’s vanished!” she thought, with a sudden sense of panic, as her eyes sought the girl in vain.

Just then, as if moving of its own will, one of the fighter planes began gliding toward the center of the field.

At once the quiet scene became one of action. A young pilot close to the plane made a running jump to grab the tail of the plane. He had just reached it when, in the midst of shouting and sound of rushing feet, the plane’s motor went silent, and the plane itself came to a sudden stop.

Norma was thunderstruck when, from the pilot’s seat of that plane, none other than her companion, Rosa, the little Italian WAC, was dragged out.

“Rosa! Rosa! You little dunce! Why did you do it?” she screamed as she raced forward.

By the time she reached the side of the plane Rosa was on the ground. A stalwart member of the Military Police had her by the arm, and was saying:

“Come along, sister. What’s wrong with you? Drunk? Or just plain nuts—or nothin’ at all?”

“It’s the guardhouse for her,” a second M. P. predicted loudly.

Realizing that for the moment nothing could be accomplished, Norma joined three grinning young pilots as they followed the M. P.’s and Rosa across the field.

“What’s the matter with that girl?” one of the pilots asked in a friendly tone.

“I don’t know,” was all Norma could say.

“She was with you, wasn’t she?” a second pilot asked.

Norma made no reply.

“She really had that plane going,” said the first pilot. “One minute more, and she’d have been right up in the sky.”

“And there’s secrets in those planes that nobody but us are supposed to know,” put in number three. “By George! Maybe she’s a spy!”

“Hush,” said Norma. “She’s no more a spy than you are. She’s a WAC.”

“A WAC!” the first pilot exclaimed. “Well I’ll be jiggered! And I suppose you’re one too?”

“Sure I am,” Norma agreed.

“Well, all I got to say is you’d look swell in any uniform,” was the final rejoinder.

Just then the flight commander, a very youthful-appearing major who had come across the field in long strides, caught up with the procession.

“Caught this girl trying to steal one of your planes,” said an M. P.

“Yes,” said the other. “We’re taking her to the guardhouse. C’mon, sister.” He gave the weeping Rosa a gentle push.

“Wait a minute. Not so fast. Those are our planes. I’m flight commander. Let the girl go. She won’t run away, will you, young lady?”

Rosa tried to speak, but no words came.

“Here’s a young lady who was with her,” said a pilot, moving Norma gently forward. “She says they’re both WACs.”

“WACs?” said the officer. “Hmm! Where are your uniforms?”

“We’re on leave.” Norma swallowed hard, then threw her shoulders back. “Saturday afternoon and Sunday we can wear what we please. And—and Major,” she stammered, “I don’t know why Rosa did it. I—I think the plane charmed her.”

“Charmed her! Hmm! Now let’s see.”

“She’s one of the best little WACs in our squadron,” said Norma, half in despair.

“And are you the squadron’s leader?”

“No, but I drill the entire company. And that’s not all!” Norma exclaimed, gathering courage from the major’s smiling eyes. “I’m the daughter of Major John M. Kent, who fought in the World War—”

“John M. Kent!” The major studied her face. “You do look like him. You’ve got his eyes.”

“Then you know him?” Norma exclaimed.

“Quite well. He’s a splendid man.”

“His eyes are not all I have,” said Norma. “I have his picture.” She fumbled in her billfold.

“Here—here it is.”

The officer studied the photograph, and, across the bottom of it, he read:

“To my beloved daughter Norma.”

“Norma,” he smiled. “That’s a pretty name for a pretty girl. So you’re a WAC? A chip off the old block. Shake.” He held out his hand. She seized it in a good, friendly grip.

“And here’s a picture of our squadron,” Norma said half a minute later. “There’s Rosa, right there, uniform and all. You know we wouldn’t do anything wrong. I guess Rosa just lost her head.”

“Yes, lost my head,” Rosa sobbed.

“All right, boys,” said the major. “You may let the young lady go. You can’t put a WAC in the guardhouse. It just isn’t being done, especially not here.”

To Norma he said: “If I’m here long enough I’m coming to visit your camp. Yours is a grand outfit. We’re going to need you all before this scrap is over.”

“Oh! Please do come!” Norma exclaimed. “I—I’ll get you the keys to Boom Town and to every other place in old Fort Des Moines!”

“Well, I’m jiggered!” exclaimed one of the pilots, as Norma and the still silently weeping Rosa hurried off the field.

Once she was safe on the streetcar and headed for the city, Rosa ceased her weeping, but every now and again Norma heard her whisper:

“Why did I do it? Oh why?”

What was back of all this? Hidden away in the little Italian girl’s mind were secrets. Norma would never be able to doubt that from this day on.

“I’d like to go exploring in that mind of yours,” she thought. That this type of exploring often leads to disaster she knew all too well. So, for the time being, she did not explore.

Arrived at the city, Norma at once sought out a restaurant with a little nook in the wall where lights were subdued and where delicious foods were served.

By the time they had gone all the way from soup to ice cream and were sipping good strong black tea, the little Italian girl’s eyes were shining once again.

“Was that after all so terrible?” she asked.

“Of course it was,” Norma replied instantly. The question surprised and shocked her.

“I did no harm to the plane.”

“You might have killed someone, wrecked the plane, or even flown away in it.”

“Oh, no, I—” For a space of seconds it seemed that Rosa was on the verge of revealing some important secret. “But—but I didn’t do any of those terrible things,” she ended lamely.

“The secret must wait,” Norma told herself. To Rosa she said: “There were secrets in that plane.”

“I didn’t want their secrets,” Rosa’s cheeks flushed.

“How could they know that?” Norma was a little provoked.

“You Might Have Wrecked the Plane,” Norma Replied

“I’m a WAC. When they knew that they saw it was all right.”