This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook.

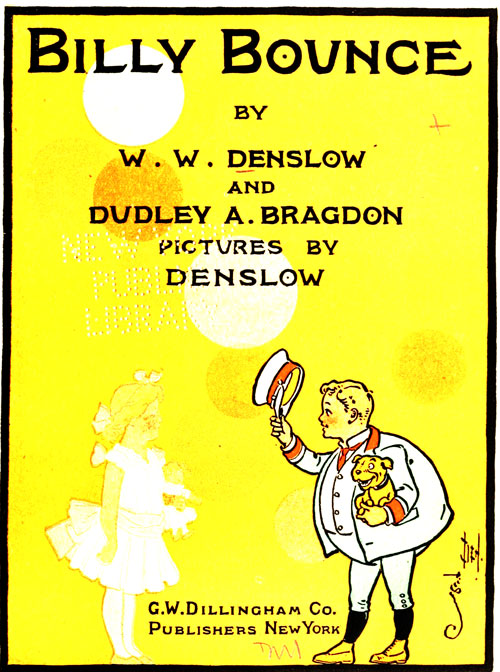

Title: Billy Bounce

Author: W. W. (William Wallace) Denslow and Dudley A Bragdon

Release Date: March 20, 2015 [eBook #48537]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK BILLY BOUNCE***

| Note: | Images of the original pages are available through Internet Archive. See https://archive.org/details/billybounce00dens |

The Near Astronomer.

Barker.

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I. | DARK PLOT OF NICKEL PLATE, THE POLISHED VILLAIN | 9 |

| II. | A JUMP TO SHAMVILLE | 22 |

| III. | BILLY IS CAPTURED BY TOMATO | 34 |

| IV. | ADVENTURES IN EGGS-AGGERATION | 47 |

| V. | PEASE PORRIDGE HOT | 63 |

| VI. | BLIND MAN'S BUFF | 77 |

| VII. | THE WISHING BOTTLE | 88 |

| VIII. | GAMMON AND SPINACH | 97 |

| IX. | IN SILLY LAND | 110 |

| X. | SEA URCHIN AND NE'ER DO EEL | 124 |

| XI. | IN DERBY TOWN | 138 |

| XII. | O'FUDGE | 152 |

| XIII. | BILLY PLAYS A TRICK ON BOREAS | 167 |

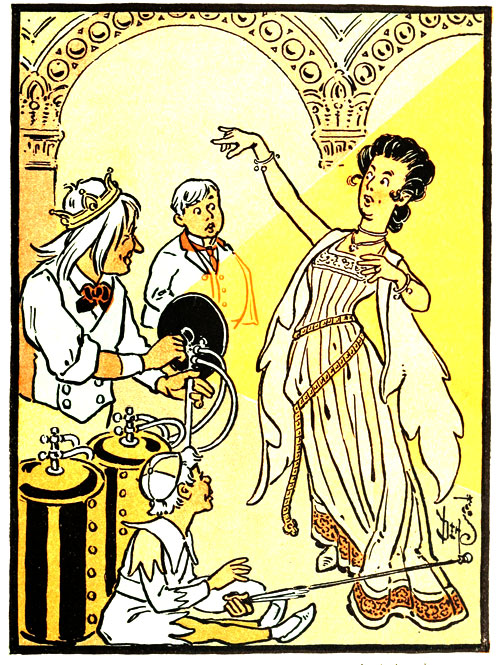

| XIV. | KING CALCIUM AND STERRY OPTICAN | 181 |

| XV. | BILLY MEETS GLUCOSE | 195 |

| XVI. | IN SPOOKVILLE | 210 |

| XVII. | IN THE VOLCANO OF VOCIFEROUS | 221 |

| XVIII. | THE ELUSIVE BRIDGE | 236 |

| XIX. | IN THE DARK, NEVER WAS | 247 |

| XX. | THE WINDOW OF FEAR | 257 |

| XXI. | IN THE QUEEN BEE PALACE | 267 |

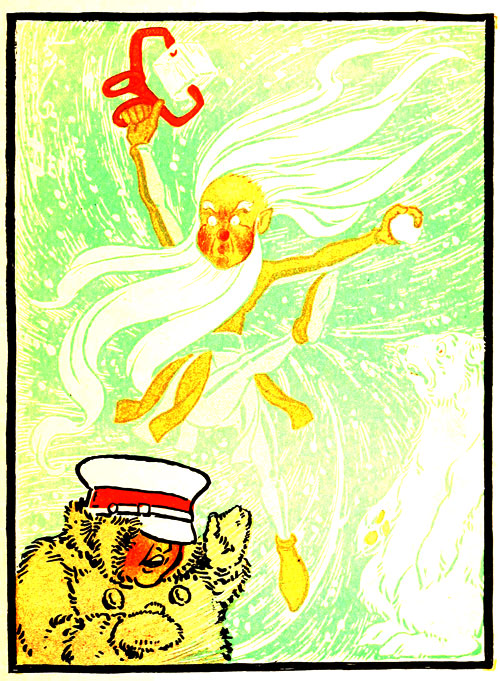

Col. Solemncholly.

| "Why it is, a large fried egg," said Billy, excitedly.— | Page 47....Frontispiece |

| PAGE | |

| "I can't tell you where Bogie Man lives, it's against the rules." | 14 |

| "Now," said Mr. Gas, "be careful not to sit on the ceiling." | 17 |

| "Come, now, don't give me any of your tomato sauce." | 39 |

| Billy never wanted for plenty to eat. | 64 |

| "He-he-ho-ho, oh! what a joke," cried the Scally Wags. | 82 |

| "That's my black cat-o-nine tails," said the old woman. | 90 |

| The Night Mare and the Dream Food Sprites. | 101 |

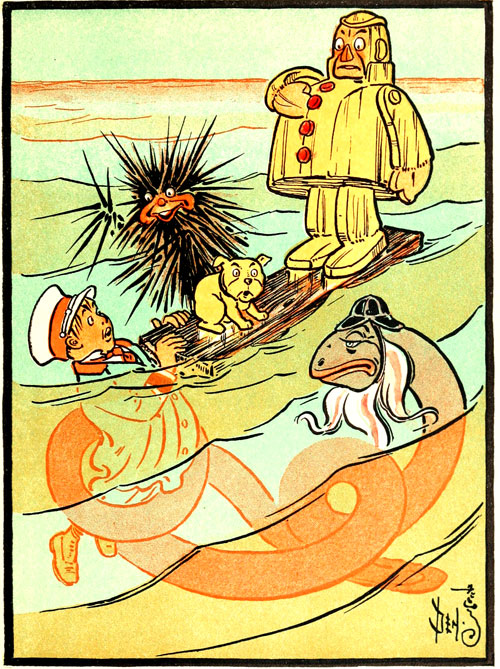

| "Get off, you're sinking us," cried Billy. | 134 |

| He saw flying to meet him several shaggy bears. | 141 |

| "Talking about me, were you?" said Boreas, arriving in a swirl of snow. | 172 |

| "Me feyther," cried she, in a tragic voice, "the light, the light." | 187 |

| "Come up to the house and spend an unpleasant evening." | 217 |

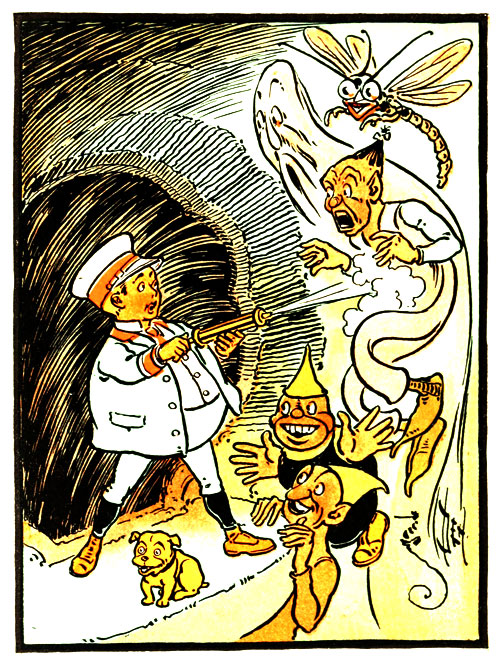

| Billy shot a blast of hot air from his pump full in Bumbus's face. | 263 |

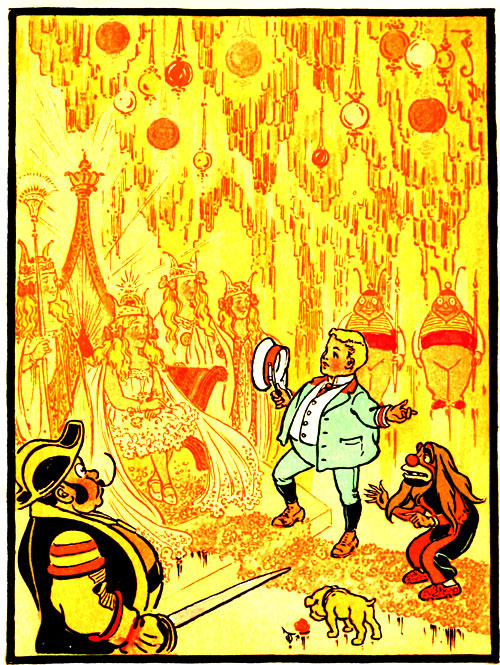

| "Allow me to present Bogie Man." | 271 |

Billy and the Ace of Spades.

Drone.

OUR PURPOSE.—Fun for the "children between the ages of one and one hundred."

AND INCIDENTALLY—the elimination of deceit and gore in the telling: two elements that enter, we think, too vitally into the construction of most fairy tales.

AS TO THE MORAL.—That is not obtrusive. But if we can suggest to the children that fear alone can harm them through life's journey; and to silly nurses and thoughtless parents that the serious use of ghost stories, Bogie Men and Bugbears of all kinds for the sheer purpose of frightening or making a child mind is positively wicked; we will admit that the tale has a moral.

Nickel Plate, the polished Villain, sat in his office in the North South corner of the first straight turning to the left of the Castle in Plotville.

"Gadzooks," exclaimed he with a heavy frown, "likewise Pish Tush! Methinks I grow rusty—it is indeed a sad world when a real villain is reduced to chewing his moustache and biting his lips instead of feasting on the fat of the land."

So saying he rose from his chair, smote himself heavily on the chest, carefully twirled his long black moustache and paced dejectedly up and down and across the room.

"I wonder," he began, when ting-a-ling-a-ling the telephone rang.

"Hello," said he. "Yes, this is Nickel Plate—[10] Oh! good morning, Mr. Bogie Man—Sh-h-h—Don't speak so loudly. Some one may see you.—No—Bumbus has not returned with Honey Girl—I'm sorry, sir, but I expect him every minute. I'll let you know as soon as I can. Oh! yes, he is to substitute Glucose for Honey Girl and return here for further villainous orders. Oh! a—excuse me, but can you help me with a little loan of—hello—hello—pshaw he's rung off. Central—ting-a-ling-a-ling—Central, won't you give me Bogie Man again, please—what! he's left orders not to connect us again—well!—good-bye."

"Now then what am I to do? I have just one nickel to my name and I can't spend that. If Bumbus has failed I don't know what we shall do. A fine state of affairs for a man with an ossified conscience and a good digestion—ha-a-a, what is that?"

"Buzz-z-z," came a sound through the open window.

"Is that Bumbus?" called Nickel Plate in a loud whisper.

"I be," answered Bumbus, climbing over the sill and darting to a chair.

"Why didn't you come in by the door?—you know how paneful a window is to me."

"When is a cow?" said Bumbus, perching himself on the back of his chair and fanning himself with his foot.

"Sometimes, I think—" began Nickel Plate, angrily.

"Wrong answer; besides it's not strictly true," said Bumbus, turning his large eyes here and there as he viewed his master.

"A truce to foolishness," said Nickel Plate, "what news—but wait—" and taking two wads of cotton out of his pocket he stuffed them in two cracks in the wall—"walls have ears—we will stop them up—proceed."

"Honey Girl has disappeared," whispered Bumbus.

"Gone! and her golden comb?"

"She has taken it with her."

"Gone," growled Nickel Plate—"but wait, I am not angry enough for a real villain"; lighting a match he quickly swallowed it. "Ha, ha! now I am indeed a fire eater. Gadzooks, varlet! and how did she escape us?"

Bumbus hung his head. "Alas, sir, with much[12] care did I carry Glucose to the Palace of the Queen Bee to substitute her for Honey Girl—dressed to look exactly like her, even to a gold-plated comb. I had bribed Drone, the sentry, to admit us in the dead of night. Creeping softly through the corridors of the Castle, with Glucose in my arms, I came to the door of Honey Girl. I opened the door and crept quietly into the room; all was still. I reached the dainty couch and found—"

"Yes," said Nickel Plate excitedly.

"I found it empty; Honey Girl had fled."

"Sweet Honey Girl! alas, have we lost you? also which is more important, the reward for the abduction—but revenge, revenge!" hissed Nickel Plate.

"What did you do with Glucose?"

"Glucose has gone back to her work in the factory," said Bumbus, "but will come back to us whenever we wish."

"Enough," said Nickel Plate, "Bogie Man must know of this at once. I will telephone him—but no, he has stopped the connection. Will you take the message?"

"Sir, you forget."

"Too true, I need you here: a messenger." So saying Nickel Plate rang the messenger call and sat down to write the note of explanation to Bogie Man.

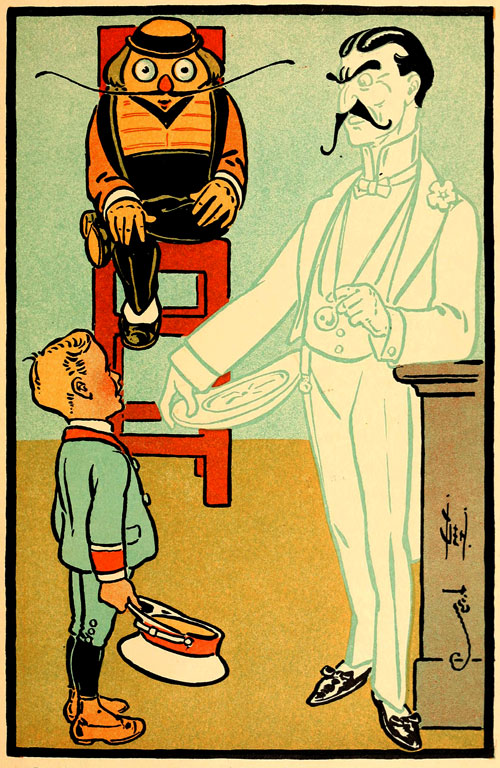

"Rat-a-tat-tat" came a knock on the door.

"Come in," said Nickel Plate in a deep bass voice, the one he kept for strangers.

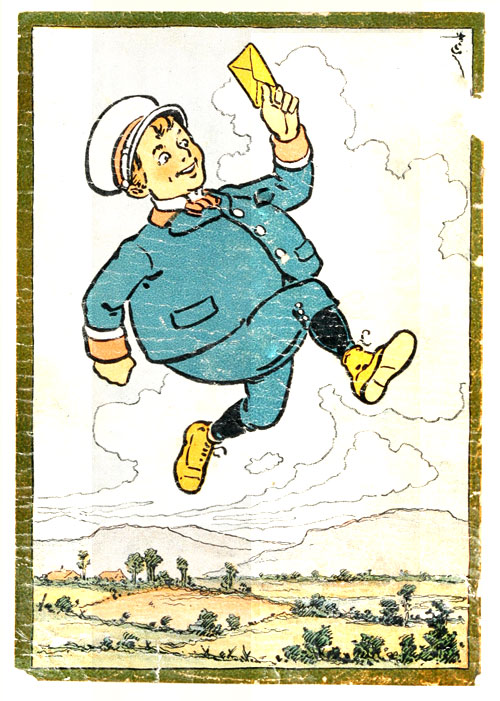

The door popped open and in ran—yes, he really ran—a messenger boy. And such a messenger boy, such bright, quick eyes, such a clean face and hands, not even a high water line on his neck and wrists, such twinkling feet and such a well brushed uniform! Why you would hardly believe he was a messenger boy if you saw him, he was such an active little fellow.

"Did you ring, sir?" said Billy Bounce.

"Sh-h-h, not so loud," whispered Nickel Plate mysteriously—the whisper he kept for strangers. "Yes, I rang."

"Very well, sir, I am here."

"Ah-h," hummed Bumbus. "Are you here, are you there, do you really truly know it? Have a care, have a care."

"Excuse me, sir," said Billy bewildered, "I don't think I understand you."

"Neither do I," said Bumbus. "Nobody does. I'm a mystery."

"Mr. who?" said Billy.

"Mr. Bumbus of course."

"Oh! I thought you said Mr. E."

"Don't be silly, boy," interrupted Nickel Plate.

"Bumbus, be quiet."

"I be," said Bumbus.

"Can you read?" whispered Nickel Plate.

"Yes, sir."

"That's good. Then perhaps you know where Bogie Man lives."

"No, sir, but if you'll tell me I can find his house," said Billy, hoping it wasn't the real Bogie Man he meant.

"That would be telling," said Nickel Plate.

"But, sir, I don't know where to find him."

"Did you ever see such a lazy boy?" hummed Bumbus. "Lazy bones, lazy bones, climb up a tree and shake down some doughnuts and peanuts to me."

"But really," said Nickel Plate frowning, "really you know I can't tell you where Bogie Man lives; it's against the rules."

"I can't tell you where Bogie Man lives, it's against the rules."—Page 14.

"Then, sir," said Billy, his head in a whirl, "I don't see how I can deliver your message."

"That's your lookout. You're a messenger boy, aren't you?"

"Yes, sir."

"And your duty is to carry messages wherever they are sent?"

"Yes, sir, but—"

"There, I can't argue with you any more. You will have to take the message—good day," said Nickel Plate handing Billy the note.

"But, sir—"

Bumbus jumped off his chair and slowly revolved around Billy, humming—

As he sang this, Bumbus circled closer and closer to Billy until finally he touched him,[16] digging him in the ribs and giving him gentle pushes toward the door. Suddenly Billy found himself outside of the room with the door slammed in his face.

"Well," said Billy staring at the note in his hand, "I'm glad I'm out of that room anyway." Then looking up at the door he read painted in bold, black letters on the glass "Nickel Plate, Polished Villain. Short and long orders in all kinds of villainy promptly executed. Abductions a specialty." And lower down in smaller letters, "I. B. Bumbus, Assistant Villain, office hours between 3 o'clock."

"What am I to do with this note? It is addressed to Bogie Man, In-The-Dark, Never Was. If I don't deliver the message I'll be discharged, and if I do deliver it—but how can I—oh pshaw! I know, I'm asleep—ouch!" for he had given himself a sharp nip in the calf of his leg to wake himself.

But there was the note still in his hand, and there in front of him stood the building he had just left.

"I'm awake, that's certain, and—I beg your pardon, sir—" for he had bumped into a little [17]old gentleman who was hurrying in the opposite direction.

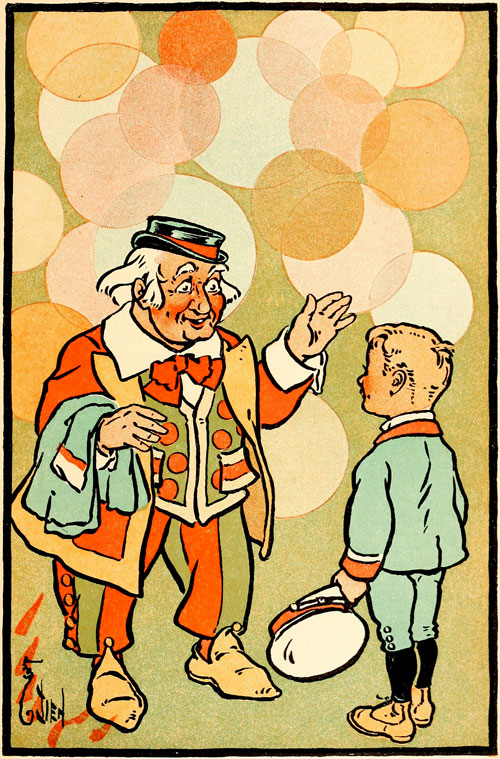

"Now," said Mr. Gas, "be careful not to sit on the ceiling."—Page 17.

"It's Mr. Gas, the balloon maker," cried Billy, joyfully; "perhaps you can help me; it's a good thing I ran into you."

"Humph!" said Mr. Gas, with his hands on his stomach, "it's not a very good thing for me that you ran into me, but I'm glad to see you."

"I am sorry, Mr. Gas, but I'm really in very serious trouble," said Billy, with a sigh.

Mr. Gas smiled. "I might have known you didn't know the way to Bogie Man's house."

"Why," said Billy, in surprise, "how did you know—"

"Gift horses can't be choosers, which means, don't ask any questions," said Mr. Gas, pinching Billy's ear; "but come along to my house, and I'll help you."

"Now," said Mr. Gas, when they had entered the shop where he made all the toy balloons for all the little boys and girls in all the world, "be careful not to sit on the ceiling, because if you do you'll burst some of my balloons."

Billy laughed. "Sit on the ceiling; why, how could I?"

"Wait and see," said Mr. Gas; "nothing is impossible to your Fairy Godfather."

"Are you my Fairy Godfather?" asked Billy, opening his eyes very, very wide.

"On Sundays and week days I am; the rest of the time I'm not."

"But what other days are there?" said Billy.

"Strong days of course. I thought you knew Geography," said Mr. Gas huffily.

"Yes, sir, I suppose so," said Billy afraid to ask any more questions.

"Now then, put on this suit," said the balloon maker, producing what looked like a big rubber bag.

"Yes, sir, but—"

"Of course it's wrong side out. How can I get the right side inside unless the wrong side is outside of the inside of the outside of the inside of your outside clothes. Anybody who can count his chickens before they are hatched ought to know that."

Billy gasped and proceeded to pull the suit on over his messenger boy's uniform.

"Stand on your head."

Billy knew how to do this. He had practiced it often enough against fences when he should have been delivering messages.

Taking one of Billy's trouser legs in each hand, Mr. Gas gave a quick jerk and Billy found himself standing on his feet with the rubber suit inside of his uniform.

"There," said Mr. Gas, "that's done—the next thing is to blow you up."

"Oh! Mr. Gas, please don't do that," said Billy, thinking of gunpowder and things.

"With a hot air pump—stand quiet," chug-chug-ff-chug-ff-squee-e went the pump and there stood Billy like a great round butter ball. His uniform fitted as close and snug on the rubber suit as the skin on an onion. For that was a peculiar property of the rubber suit; any clothes, loose, tight or otherwise were bound to fit over it.

"Thank you sir," said Billy looking down and trying to see his foot, "but—"

"Here's the hot air pump; put it in your pocket.—Now—be careful, don't jump or you'll bump your head. You're ready now to hunt Bogie Man."

"How am I to get there?"

"Jump there of course," replied Mr. Gas. "When you get outside the door all you have to do is to jump into the air; that will carry you out of town. Then keep on jumping till you get there. That's simple, isn't it?"

"But can't you tell me in which direction to jump?" asked Billy.

"Jump up, of course; if you jump down you'll dent the sidewalk."

"But shall I jump North or East or South or West, sir?"

"Exactly; just follow those directions and you will be sure to arrive; but wait, before you start I'll give you Barker, my little dog."

"What kind of a dog is he?" asked Billy.

"A full-blooded, yellow cur. He won the Booby prize at the last dog show."

"Thank you, sir; but won't you keep him for me until I get back?"

"Don't jump to conclusions, Billy, it strains the suit; Barker will help you when you want shade or shelter by night or day."

"Isn't he rather a small dog for me to get[21] under?" asked Billy, looking at the tiny animal Mr. Gas held out to him.

Mr. Gas stamped his foot. "More questions—listen: when night or rain comes on, drop to the ground, dig a little hole, hold Barker's nose over it and pinch his tail to make him bark. Shovel in the dirt, and of course you will have planted his bark. Well, you know what is planted must grow, so up will come the bark and the boughs, and you can shelter yourself all night beneath the singing tree."

Billy took the dog and started out of the door. "Thank you; is that all, sir?"

"Of course not," said Mr. Gas.

"Yes, sir."

"Good-bye."

"Good-bye?" asked Billy, in surprise, "I thought you said—"

"Yes, that's it; we had to say good-bye before it could be all."

"Oh! good-bye," said Billy, and going outside took a great big jump up into the air.

Up, up, up, went Billy when he took his leap into the air.

Way above the house tops, past the city, over green fields, hills and valleys, crossing brooks and rivers that looked like little threads of silver so far below were they, until he thought he never would alight.

Finally things began to get larger and larger and larger on the earth, and he knew he was floating gently down, down, down. It was just like going down from the twenty-first story in a very slow, very comfortable elevator.

Plump, and Billy was on the ground. Before him stood a city. This seemed strange, for he knew he hadn't seen it until his feet touched Mother Earth.

"Excuse me, sir," said Billy, to a tall, thin, rusty coated man who was looking intently at the heavens through a long hollow tube open at both ends.

"Oh! you're here, are you?" said the man, lowering the tube and looking at Billy. "I've been waiting for you to come down."

"Yes, sir," said Billy; "excuse me, but what city is this?"

"Shamville. So you are a meteor."

"No, sir, I'm a messenger," said Billy.

"Pardon me, but you are a meteor, by right of discovery, and I ought to know, for I'm a near Astronomer."

"A near what?"

"Not a near what, but a near Astronomer; with my near telescope I have nearly discovered hundreds of nearly new stars," said the man, looking very, very wise.

"Oh! I see," said Billy, smiling. "Well sir, you may be a near astronomer, but in this case you are not near right."

"Well, you're a near meteor and that will do well enough in Shamville."

By this time they had entered the city.

"Who is that long haired, greasy gentleman writing on his cuff?" asked Billy.

"You must meet him. He is our village near poet," answered the star-gazer, impressively. "Allow me, Mr. Never Print, to introduce my latest discovery, Billy Bounce, a near meteor."

Mr. Never Print stopped writing, and after rolling his eyes and carefully disarranging his hair, said: "How beautiful a thing is a fried oyster! Have you read my latest near book?"

"No, sir," said Billy.

"Ah! such is near fame," said the poet, untying his cravat. "Art is long, but a toothless dog does not bite."

"Sir," said Billy, "I didn't quite catch your meaning?"

The Near Poet.

"The near meaning, you mean; like all great near poets, my meaning is hidden. Perhaps you will understand this better: The little flower, like a beefsteak, reminds[25] us that a gentle answer comes home to roost."

Billy was so bewildered by this that he leaned against a wall, or rather, he leaned on what looked like a wall. As the near astronomer helped him to his feet he said:

"Be careful of the near walls. They're just painted canvas, you know, and are not meant to lean against."

"Thank you," said Billy; "is there anything here that is not an imitation?"

"Oh, no!" answered the astronomer, "this is Shamville; but I assure you we're all just as good as the original."

"Well, I must be off," said Billy, "I must deliver this note to Bogie Man."

"To whom?"

"To Bogie Man. Can you tell me how to get there?"

"Oh, my goodness! Oh, my gracious! What have I done, what have I done?" cried the astronomer, beating himself over the head with his near telescope.

"I don't know sir, I'm sure," said Billy; "from what I've seen I shouldn't think you had ever done anything."

"Hear him! hear him!" screamed the astronomer, then calling to the people on the streets: "Come near-artist, come near-actor, come near everybody, we have in our midst one who would expose us to the people who really do things."

With fearful cries the entire population made one dash for Billy, who, forgetting that all he had to do was to jump, tried to run. In his big suit he found this almost impossible and soon he was surrounded by an excited mob.

"Roast him at the steak," cried the butcher, still holding in his hands the papier mache chicken he had been selling when the call came.

"Splendid," said, the near poet.

"Boil him in oil," suggested the near artist.

"What is it, forgery?" asked the blacksmith.

"Put him in a cell," said the merchant.

Billy saw that he was in a tight place and must act quickly. No one had as yet taken hold of him, they were all too excited to think of that; but he knew a near policeman was even then trying to edge through the crowd and something must be done. Just then the[27] near astronomer put out a hand to seize Billy's collar—quick as a wink Billy reached up and pushed the star gazer's plug hat right down over his eyes.

"You can't see stars this time at any rate," said Billy, and then was surprised to find himself rising, rising, rising off of the ground.

In hitting he had jumped up to reach the star gazer's hat and of course up he went.

"Good-bye," called Billy, to the astonished crowd, "I had forgotten that you couldn't do any more than nearly catch me or I should not have been frightened."

And the last Billy ever saw of Shamville was a great sea of big round eyes and wide open mouths.

"I wonder whether this is the beginning or the end of my adventures," said Billy to himself. "I hope it is the last because I really want to deliver this note to Bogie Man as soon as I can. They will think it strange at the office if I'm gone longer than a week delivering one message."

"My goodness, can that be a cyclone?" For just ahead of him Billy saw a great cloud[28] from which came a hum-m-m—Buzz-z-z-z. "Why, it's a swarm of bees and they are carrying something. I do hope they won't sting me."

By this time Billy had met them and of course, as he couldn't steer himself in the air, the bees had to get out of the way.

"Hum-m," said a big old fat bee, clearing his throat, "what sort of a beetle are you?"

"I'm—I'm a boy," said Billy, very, very politely, because he saw that the soldier bees had fixed sting bayonets.

"I've never heard of a beetle boy—stop a minute, I want to look at you."

"I'm sorry, sir," said Billy, "but I can't."

General Merchandise.

"We'll soon fix that," shouted the old bee general. "Ho! guard, seize him."

And in a twinkling Billy found himself in[29] the grasp of the bees. Now of course as soon as Billy stopped moving forward he had to drop to earth, so down, down, down he went, with the excited bee soldiers clinging to him and flapping their wings in a vain endeavor to keep him and themselves up in the air. And almost on top of them dropped the fussy old Bee General.

"Now see what you've done, Beetle Boy," said he. "What do you mean by interfering with the Queen's Own Yellow Jackets on the public fly-ways?"

Before Billy could answer a sweet girlish voice said:

"What is the matter, General Merchandise?"

"We've caught a fly-wayman or something equally wicked, Princess Honey Girl," said the General, gravely saluting.

"Indeed Miss," said Billy, kneeling (as well as he could in his suit) before the beautiful, golden haired maiden, who had stepped out of her Palanquin and stood looking at him, "indeed Miss, I'm not any of the things this bee gentleman calls me—I'm just a messenger boy."

"There now, what did I tell you?" shouted[30] the General. "Just a minute ago he said he was a Beetle Boy. Ho, guard—oh! that's so, you've already ho—d."

"I beg your pardon, sir, but you were the one that said I was a Beetle Boy."

"Don't contradict," said General Merchandise. "Why didn't you tell me you weren't, then?"

"That would be contradicting, sir," said Billy, laughing in spite of his fears.

"General," said the Princess, "let me speak."

"If you will promise not to talk," said the General, bowing.

"First then, soldiers, take your hands off Mr. Messenger Boy."

"Billy Bounce is my name, Princess," murmured Billy.

"Ha," growled the General, half to himself, "another name, eh!"

"Silence, General; I can't forget that my Aunt Queen Bee—"

"She's not an ant, she's a bee," said the General, sulkily.

"Silence, sir; you forget yourself. I say that I cannot forget that my Aunt Queen Bee, whose heir I am, bestowed the title of General Merchandise[31] upon you, because she set such store by you, but I cannot stand these interruptions."

"Pardon, your highness," said the General, humbly.

"Granted. Now, Billy Bounce, what have you to say for yourself?"

"Nothing, Princess," answered Billy, "except that I am carrying a message from Nickel Plate to Bogie Man and—"

"My bitter enemy," cried the Princess.

"Hum-m-m-m-m, I told you so," shouted the General. "Ho, guards, seize him!"

Billy found himself again seized, and very roughly this time; indeed, had it not been for the toughness of his rubber suit he would have surely been stung. But, nothing daunted, he said:

"Your enemies, Princess Honey Girl; then they are mine."

"What do you mean?" asked she, blushing.

"I mean," said Billy, earnestly, "that if I were not a messenger boy, who has to do his duty under any circumstances, and had I known that these were your enemies, I should not have carried their message."

"Then why do you?" said the General. "Give me the message and you shall be free."

"No," said Billy, "I cannot do that; I have undertaken to carry it, and my honor demands that I do so while I live."

"You are right," said the General; "then the best way out of the difficulty is to kill you."

"No," said the Princess, "that shall not be done."

"Thank you, Princess," whispered Billy, "you shall not regret it. Let me do my duty—let me carry the message. Then, when it is delivered, I shall be free to fight for you; indeed, when I am once in Bogie Man's Castle I shall be in the very best position to help you."

"Good," said the Princess.

"Good," said the General.

"Good," said all the soldiers.

"But why are Nickel Plate, Bumbus and Bogie Man your enemies?" asked Billy.

"Because they want to carry me far away from the Bee Palace and make me work in the factory," answered the Princess, sadly, "putting the wicked Glucose, who looks almost exactly like me, in my place in the castle."

"But why?" said Billy.

"I am Crown Princess, and if they can do away with me and substitute Glucose for me they will be in control of the Castle and the Bee Government and can make a corner in honey."

"Villains!" cried Billy, "but between us we will foil them."

"You will help me?" said the Princess, looking earnestly at him.

"I will, I promise you. But now I must be on my way."

"Good-bye, Billy Bounce; don't forget me," said the Princess.

"I will see you soon. Good-bye, Honey Girl," and, with a farewell wave to the Princess, the General, and all the soldier bees, Billy jumped up and away in further search of Bogie Man.

Billy had floated a long, long time through the sweet, soft air: indeed he was gently settling down to earth again, when he discovered that the jolly old red faced sun was rolling off to his bed in the far west.

"Well," said he to himself, "if Father Sun is going to turn in for the night, and I see him putting on his white cloud night cap, I expect it's about time for me to do the same."

"Bow-wow," came a faint bark from under his coat.

"Why, it's Barker," said Billy, reaching in and patting a warm little head. "I'd almost forgotten you, old doggie, and I thank you for reminding me of the Singing Tree."

In a twinkling Billy was on the ground and digging a hole in the soft earth.

"I hate to pinch your tail, old fellow," said Billy, "but it's really necessary you know," and holding Barker's nose over the hole he gave his tail a gentle tweak.

"Bow-wow-wow."

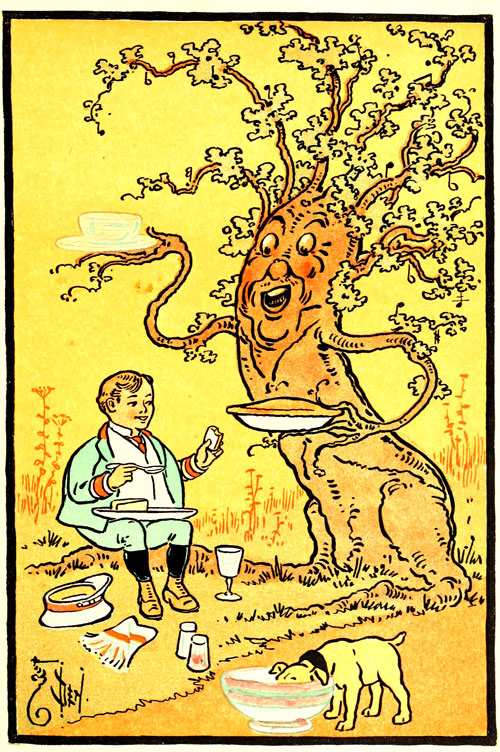

Quickly Billy shovelled in the earth, and lo and behold, quicker than I can tell you about it, there stood the Singing Tree, bowing and smiling.

Just as Billy was going to wish the tree a polite good evening, he saw Barker scampering after a little beam of sunlight that had crept in through the branches of the tree. "Barker, come here," called Billy, but he was too late.

"Snap—gulp," and Barker had swallowed the sunlight.

"I hope it won't make you sick, doggie," said Billy, looking at him anxiously.

But Barker wrinkled his nose at him in such a happy dog smile and wagged his stubby little tail so contentedly that Billy decided he was used to the diet and turned to the Singing Tree.

"Good evening," said Billy, "I hope you are well."

"Mi?-so-so," sang the tree, "pause and rest at my bass."

"Excuse me, sir, but what is your name?" said Billy; "you see I'd like to know how to address you."

"C. Octavious Minor," sang the tree. "But it's time you slept. I'll look sharp for accidental intruders and pitch into them with my staff if they bother us; good night."

Then he began to sing softly:

And when the tree got to this point in his song he stopped. For Billy was sound asleep with Barker snuggled up in his arms, while from his half-opened lips came a contented snore.

Billy was awakened in the morning by the singing tree tickling him gently on the nose with one of its branches.

"Up—up," it sang.

Barker thinking it was calling "up pup" jumped up, and ran madly around the tree for his morning's exercise. And then suddenly there was no tree. Barker didn't notice this at first, and circled around where the tree had been three times more before he discovered that it was gone.

Have you ever seen a dog look surprised and hurt and just a little bit ashamed? Well, that's the way Barker looked when Billy picked him up and stowed him away again in his jacket.

"Well, I must be off," said Billy to himself.

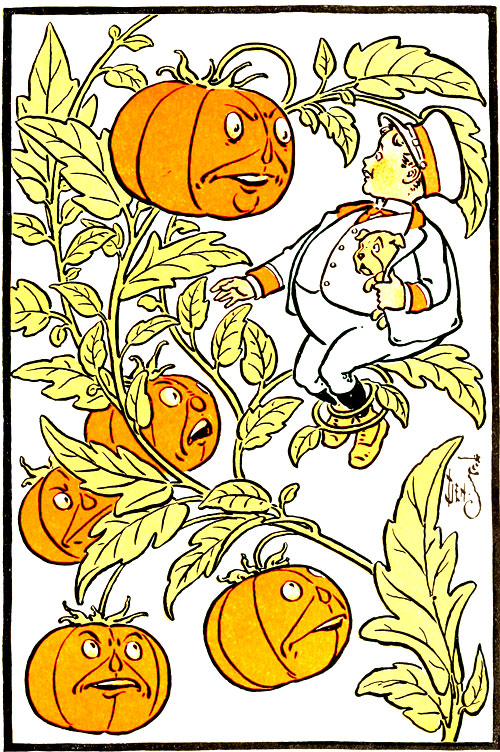

"Don't hurry," said a voice at his elbow.

Billy was so startled that he stepped back, caught his foot in a vine, and rolled over and over on the ground. There, where a minute before had been nothing at all, stood a great red Tomato leaning on its vine.

"It's—it's a fine morning, sir," said Billy.

"A vine morning you mean," said the Tomato sourly.

"I beg your pardon?" said Billy, because he hadn't quite understood the Tomato.

"Granted for just this once. But don't do it again."

"What?"

"Anything—great tin cans! how I hate boys."

"I'm sorry, sir," said Billy.

"No, you're not," grumbled the Tomato; "you say you are, but you're not; boys are never sorry."

"Why don't you like boys, sir? I'm sure"—and then he stopped. He was on the point of saying "boys like tomatoes" when he remembered that this might sound a little personal and thought better of it.

The Tomato did not notice this, however, and said, wiping a dew tear from his eye, "A boy threw my favourite sister at a cat last week and I have never been able to abide boys since; and, come to think of it, you look like that boy."

"Oh! no, sir, it wasn't I," said Billy, frightened. "I—I've only just come."

"Well, maybe not; goodness knows, though, [39]you're ugly enough. Where are you going?"

"Come, now, don't give me any of your tomato sauce."—Page 39.

"I'm taking a message to Bogie Man, sir; and—and I really must go at once. Good bye."

"Oh! ho! so you're the boy Bumbus warned me about last night. I guess you'll have to stay here," said the Tomato threateningly.

This made Billy angry. "I guess not," he said, and gave a great jump into the air.

"Not so fast, Mr. Rubber Ball, not so fast," said the Tomato in Billy's ear. And though Billy was many, many feet away from the ground, Tomato's vines had grown right up to him, while one of his tendrils had wound itself about his feet.

Not only that but hundreds of other tomatoes, not quite so large as the first one it is true, but large enough to frighten Billy, were shaking their heads at him threateningly.

But Billy plucked up his courage and said in a voice that was a wee bit shaky, "Come, now, don't give me any of your tomato sauce; if you're not careful I'll squash you."

"Even then I'd be some pumpkins," shouted the Tomato, nearly bursting with rage, "and as[40] everybody knows a well red tomato is not a greeny, I certainly should be able to catsup with a small boy."

"You ought to go on the stage," said Billy, trying to smile; "you really are very funny."

This seemed to mollify the Tomato. "Some of my family have gone on as soupers. What would you suggest for me, comedy or tragedy?"

"Comedy, by all means," answered Billy, settling himself more comfortably on a large leaf, because, of course, having stopped moving, he would have fallen had he had nothing to support him.

"I can recite," said the Tomato. "Don't you want to hear me?"

"I'd be delighted, only, you know, I'm late, and—"

"You will be the late lamented if you don't sit tight, my boy," said the Tomato, sourly. "Listen."

TOMATO'S RECITATION.

"Good," said Billy, "it really must be very funny indeed when it is well done," and pop he had jumped on Tomato's head, given a quick spring, and had sailed off before Tomato realized what he was up to.

"I'm glad Tomato recited; he was so out of breath when he finished that he couldn't[42] grow after me," said Billy to himself when he saw that he was safe from pursuit.

"I wonder what Honey Girl is doing today." And I fear that he was still thinking so hard about Honey Girl that he forgot to notice when he next dropped to the ground. Anyway, he was standing deep in thought when something tapped him on the shoulder.

"Salute!" said a stern voice. Looking up Billy saw that he was surrounded by hundreds of grim-faced soldiers, dressed in uniforms of the very deepest indigo, and all wearing blue glasses. And such a thin, sad, hollow-cheeked, hollow-eyed officer as had tapped him on the shoulder! Billy could tell he was an officer because of the gun metal sword he carried and the epaulettes of crepe that he wore.

"Salute," said the officer again in a deep, sepulcheral tone.

"Yes, sir," said Billy, cracking his heels together and putting his hand up to his cap as he had seen soldiers do.

"That's not the proper salute. Take out your handkerchief and wipe your right eye," said the officer. "That's the proper salute for the Blues."

Billy did as he was told with a sinking heart. Everything seemed so changed by the Regiment of Blues. The sun had gone under a cloud, the wind whistled dismally, a frog croaked in a nearby pond, and all together Billy came near to wanting to use his handkerchief in earnest.

"So you think you are going to see Bogie Man."

"Yes, sir, I am."

"You're not, as sure as my name is Colonel Solemncholly."

"Excuse me, but I am," said Billy staunchly.

"I knew it, I knew it," said the Colonel, sadly. "He is too fat to give up easily—goodness, how I hate fat people—they laugh."

"Don't you ever laugh, sir?"

"I'd be court martialed if I did."

"But aren't you Commander?" asked Billy.

Private Tear.

"Yes, of the Blues, but you know we're the away-from-home guard of Bogie Man, and he is our real Commander."

"Oh! I see. Then you can tell me how to get to Never Was."

"Indeed not. We were sent out to stop you, and that reminds me—Corporal Punishment and Private Tear, seize this boy."

"Snap," went the whip in Corporal Punishment's hand, "Crack," it struck Private Tear on the shoulder, and snuffing and wiping his eyes, Private Tear stepped out of the ranks.

"Seize him and throw him in the Dumps," cried Colonel Solemncholly.

As the Colonel spoke the drums gave a long dismal roll and the band struck up a funeral march.

Corporal Punishment's whip was circling in the air preparatory to coming down on Billy's head, and Private Tear was getting ready to put his handkerchief over his eyes when Billy laughed. It wasn't because he felt like laughing at all, but because Barker in snuggling closer to him had tickled him in the ribs.

"Look out, he's armed!" cried Colonel Solemncholly, Corporal Punishment and Private Tear in one breath.

This gave Billy an idea, and he burst out into a loud laugh.

"Throw a wet blanket over him," commanded the Colonel. "Regiment, carry arms!"

At that the soldiers drew out their pocket-handkerchiefs, held them to their eyes, reversed their guns, and advanced boldly on Billy, while the band played the tune the old cow died on.

Billy continued to force his laugh, trying hard to think of some way out of his difficulty. He didn't like the idea of the wet blanket, and he couldn't jump or run because Corporal Punishment's whip was wound around his neck.

"Double quick!" cried the Colonel. "Catch him before the sun comes out."

Barker stirred uneasily in Billy's pocket.

"Saved!" cried Billy. "It's worth trying." And quickly taking Barker out of his pocket, he held him by his hind legs and gently thumped his little stomach.

"Plump," and out fell the bar of sunlight he had swallowed the night before. When it struck[46] the ground it burst into a million dancing, sparkling bits of golden sunshine, and presto! the Blues had disappeared, lock, stock and barrel.

And there stood Billy, in a glow of sunlight on the beautiful green grass, listening to the sweet notes of forest birds in the trees nearby.

"Now I know how to get rid of the Blues," sang Billy to himself, as he leapt into the air, "a good hearty laugh and a bit of sunshine will always disperse them."

"Hello!" cried Billy, "what's that ahead?"

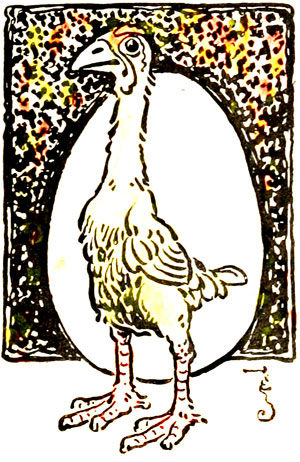

Far off on the horizon he saw a large white and gold thing sailing through the air. As he drew nearer he could see its wings gently flapping.

"It looks something like—why it is, a large fried egg," said he, excitedly.

"Good day, sir," for by this time they were side by side.

"It's not a good day, and I'm not sir, I'm White Wings," said the fried egg, curling up around the edges scornfully.

"Well, maybe you're not sir," said Billy, tartly, "but you're very surly."

"You wouldn't blame me if you knew how nearly I jumped out of the frying-pan into the fire this morning; you can see that I'm all of[48] a-tremble still, and all because Bogie Man sent an airless message to the Blue Hen's Chicken that I was to get up before breakfast and do sentry duty."

"What for?" asked Billy.

"To stop one Billy Bounce, alias Rubber Ball Boy, and take him prisoner to the town of Eggs-Aggeration. He's a very dangerous person."

"Why, I'm——" and then Billy stopped.

"Of course you are; I knew that as soon as I saw you," said White Wings, complacently.

"What did you know?"

"That you're——"

"What am I?"

"I don't know, but you said you were," said White Wings. "But wait a minute, I have a lineless picture of this Billy Bounce some place about me."

"You needn't trouble," said Billy. "I'm Billy Bounce."

"Yes, I know," answered White Wings, unblushingly, "it's impossible to deceive me."

"Well!" was all Billy could say, so disgusted was he with the barefaced fib.

"And here we are," said the Egg, as they dropped gently on the sidewalk in the town of Eggs-Aggeration. And such a grotesque town as it was. Not a straight street or house in it. The walls, a little distance away, went up and up so high that Billy could just barely see the roofs of the houses; but when he was standing next them he could almost reach their tops by standing on tiptoe. The streets looked miles long, but he knew he could almost come to their end in three steps and a jump.

"What an exaggeration," said Billy to himself; "why, of course, that's the reason they call it Eggs-Aggeration."

"Here's Billy Bounce," called White Wings, and out of their doors and windows trooped the inhabitants.

First came the Blue Hen's Chicken, and after her rolled eggs of all kinds and descriptions.

Blue Hen's Chicken.

"My goodness," said White Wings, "what a time I had with him, to be sure.[50] It was only after a fierce hand-to-egg struggle that I succeeded in capturing him."

"Why!" exclaimed Billy in surprise. "I——"

"Is he very strong?" interrupted the Blue Hen's Chicken.

"Strong," said White Wings, "Strong, I should say he was; much stronger than our oldest inhabitant."

"What are you going to do with me?" asked Billy, too disgusted to deny the story.

"Wait and see," chuckled the Chicken, "wait—wait—wait—wait—and see—bad luck—bad luck—bad luck."

"Serve him right for being a greedy boy," said Turkey Egg, angrily. "I know him, he's a bad lot—always eating, just gobble, gobble, gobble, all day long."

"That's not true," said Billy, "you know you don't know me."

"Never saw you in my life before," whispered Turkey Egg, "but don't mention that, if I want to get my witness fee I've got to say something, haven't I?"

"But you may be swearing my life away," said Billy.

"I never swear, but I'm sure you want to get away, don't you?"

"Yes, of course."

"Well, you want to take your life with you, don't you?"

"Yes."

"There you are, then; if your life is taken away it won't be here, and if it is not here you won't be here, and if you are not here you will be away," and Turkey Egg laughed heartily at his joke.

"You are the most heartless egg I ever knew," said Billy, in despair.

"Sh-h-h-h-h! now you've hit the truth," said Turkey Egg, confidentially; "years ago, when they thought I was going to turn out bad, they blew my heart out."

"Isn't he handsome," simpered little Miss Easter Egg, coloring up.

Billy pretended not to hear this, but it did his heart good to know that he had one friend in the city.

In the meantime Blue Hen's Chicken and the Official Candler, who was called Egg Judge, had been discussing what should be done with Billy.

"Bogie Man says he is to be kept in custardy for a thousand years," said Blue Hen's Chicken.

Little Miss Easter Egg.

"I know that's an exaggeration," said Billy; "why, I can't live that long."

"Of course not," answered the Official Candler; "and if you're not alive, what difference will it make whether it's a thousand years or ten thousand?"

"Come, come! We're wasting time," fussed the Blue Hen's Chicken. "To the Packing House jail with him."

"I'll stick to him," cried Al Bumen, the policeman, shaking his egg-beater at Billy fiercely; "come along now! There's no use trying to resist, for I have you egg-sactly where I want you."

And Billy, seeing that it was indeed useless to try to escape as things then were, went sulkily off, with Al Bumen's moist hand in his collar.

"Please take your sticky fingers off of my neck," said he; "I won't try to run."

"You promise?" asked Al Bumen.

"I do, cross my heart and hope to die," said Billy eagerly.

"Well, I don't believe you, I can't believe any body in Eggs-Aggeration."

Poor Billy hung his head in shame as he was led along the street like a common criminal. He tried two or three times to pull away, but Al Bumen's arm would stretch out like a rubber band and then "snap," Billy would bounce back like a return ball.

"There, now, what did I tell you," said Al Bumen, "that's the second time that you have tried to escape and you said you wouldn't."

"But you wouldn't take my word."

"Of course not, I have no use for your word, I have plenty of my own. And anyway, how could you keep your word if you gave it to me."

My, my, my, what a day it was for the[54] inhabitants of Eggs-Aggeration. They had seen Eggs beaten, and taken up by the Police, but never a boy. The Scramble Egg children tumbled along at Billy's side, shouting and rolling over and over in their glee. Mothers brought their little cradled Egg babies out to see him pass—even poor "Addle," the village egg idiot, made faces at him; only Billy felt sorry for him because he could see that he was cracked. But when some of the bad little street boys threw stones at him, even Al Bumen was angry—indeed, they barely missed his head two or three times.

"Stop it," he cried, "I know you every one, you are the Strictly boys."

"How do you know them?" asked Billy, for they looked like any other eggs to him.

"Do you think I can't recognize a fresh egg when I see him—oh! I know them—their mother thinks because they have had their names in the grocer's window that they can't turn out bad, but I've known some terrible ones in that family."

Billy felt almost relieved when they reached the jail. "In with you," said Al Bumen.[55] "By the way, have you ever had the Chicken Pox?"

"No, sir," said Billy.

"Well, you must be vaccinated at once; I wouldn't have you catch it and break out now that you are safely here."

"I warn you I shall try to," said Billy, in a temper.

"I give you leave to try, but it's useless to try to leave—you can thank your lucky stars you weren't put in the incubator instead of in here."

"The incubator?" asked Billy.

"Yes—the Orphan Asylum—it's a terribly hot place; an egg that goes in there never comes out the same," said Al Bumen, gravely.

"Oh, I know," said Billy; "it changes them into chicks."

"Yes—it's capital punishment; they either come out entirely bad or with fowl natures. It's enough to make one chicken-hearted to think of it."

Billy was shown into his cell and the door was locked. "Why—who are you?" said he, in surprise. For when his eyes got used to the darkness he discovered that he had a cell mate.

A shaven-headed, heavy-jawed egg yawned and sat up on the cake-of-ice cot he had been lying on.

"Me? I'm Boiled Egg."

"What—what have you done, sir?" said Billy, hoping it wasn't murder.

"That's the trouble," said Boiled Egg, sulkily; "I'm overdone—got into hot water last night and they arrested me for a hard character this morning. I believe the charge is salt and peppery."

"That's too bad," said Billy, sympathetically.

"It is that—but they'd better look out, or I'll turn into an Easter Egg and dye on their hands," said he, fiercely.

"Tap—tap—tap," came from the wall.

"What's that?" asked Billy.

"Oh! a couple of softies in the next cell."

"Who are they?"

"The Poachers—Ham Omelet found them trapping a rasher of bacon on his property and had them arrested—they've been put on toast and water for punishment. By the way, do you know what they have done with Nest Egg?"

"Who?" asked Billy.

"Nest Egg—the laundryman?"

"No, I've never heard of him; what has he done?"

"He was arrested for impersonating an egg," said Boiled Egg, "and it served him right, because he never could be served any other way, you know."

"Why?" asked Billy.

"Well, in the first place, he came here from China, and I tell you we Union eggs are all down on Chinese labor. What chance has an honest, hard-working egg against that sort of a fellow. I say, crack his head open, that's the only thing that should be done to him."

"Goodness! That ice makes it damp in here; I believe I'm taking cold—catch—choo—catch—choo," and Billy sneezed twice.

"Gehsundheit!" said a voice in his ear.

Gehsundheit

"Did you speak, Mr. Boiled Egg?" asked Billy, surprised.

"No; please be quiet and let me sleep," said Boiled Egg, sleepily.

"Gehsundheit!"

And this time Billy turned his head and saw a little snuff-colored fellow sitting on his shoulder, with the funniest little face he had ever seen. His eyes were puckered up, his nose wrinkled and his mouth open, so that he looked for all the world as if he were going to sneeze any minute. In his coat pocket he carried a very life-like stuffed rabbit.

"Who are you?" asked Billy.

"Gehsundheit!"

"And what is that?"

"A Cherman Count—and amateur presti-indigestion-tater, or magician—you haf called me—alreatty am I here."

"I didn't call you."

"Ogscuse me, but did you not schneeze?"

"Yes," said Billy.

"So—vas I right—ven you schneeze den does it call me. See, here are my orders from Mr. Gas." And, taking a paper out of Gehsundheit's[59] hand, Billy read "Gehsundheit, Draughty Castle, Germany; when Billy Bounce sneezes he needs your assistance—go to him at once. Signed by Mr. Gas."

"What luck," whispered Billy excitedly. "What luck—indeed I do need you."

"It is most well, I am here. Vat was your vish?"

"I want to get out," said Billy.

"Can you crawl through a keyhole?" asked Gehsundheit.

"Of course not—if I could I shouldn't need your help," said Billy, disdainfully.

"No; dat iss too bad, I can. Can you disappear?"

"Certainly not."

"Too bad—too bad. Let me think. Ah! I haf it, turn yourself into a fly," said Gehsundheit eagerly.

"But I can't. Can you?"

"No, but it would be so useful if you could. I am afraid times haf changed. Ven I vas a boy peeples could do so much magic. To-day it iss not so. I—I only am de greatest magician in vorld."

"But I thought you were here to help me," said Billy.

"I am, but if you will not follow my directions how can I?" said Gehsundheit, crossly.

"Then can you do nothing for me?"

"Sure can I—would you lend me your cap?"

"Yes," said Billy, handing him his cap and wondering what he was going to do with it.

Gehsundheit carefully took the rabbit out of his pocket and laying the cap over it made several passes with his hands. "Presto—chesto—besto—change!" and lifting up the cap and the rabbit with both hands made a quick turn and pulled the rabbit out of the cap.

"It iss wonderful, iss it not?" said Gehsundheit. "See I haf taken a rabbit from your cap."

"Is that all you can do for me," asked Billy in disgust.

"It's all the tricks I haf yet learned, but yes, I can lend you a pocket handkerchief."

"What good will that do?" asked Billy.

"Vy, if you haf caught cold you will need it," said Gehsundheit, pulling out a little handkerchief.

"Oh, go away and let me alone," said[61] Billy, thoroughly angry. "Much use you are."

And presto—Gehsundheit was gone.

"He's a nice one—gracious, but I'm hungry," and Billy hammered on the cell door.

"Do be still," said Boiled Egg. "Can't you see I'm trying to sleep?"

"But I'm hungry," said Billy.

"Hungry," exclaimed Boiled Egg, turning pale—"why, why, you don't mean to say you eat?"

"Indeed I do. I haven't had my breakfast yet, and I want some eggs."

"Help, help, help!" yelled the Egg, crouching down in a corner and pulling the cake of ice cot in front of him; "he wants to eat me. Help, help, help, help! he wants eggs."

"If you're not quiet I will eat you, sure enough," said Billy, angrily.

"He says he will eat me. Help, help, help!"

Rattle! went the key in the door; bang! it opened wide, and in ran Al Bumen and Yolk, the jailer.

"What's the matter here?" asked Al Bumen, in a fierce voice.

"I'm hungry, and I want some eggs for breakfast," said Billy, sullenly.

Out went Al Bumen, in a jiffy, and after him tumbled Yolk, leaving the door wide open and the keys behind them.

"This is my chance," cried Billy, and out he dashed after them. Far off, down the street, Billy saw Yolk and Al Bumen running as fast as their legs would carry them.

"Billy Bounce wants eggs to eat! Billy Bounce wants eggs to eat! Look out, everyone, he's loose! Help, help, help!" In a minute the town was in an uproar; mothers seized their children, and, carrying them inside, locked the doors and barricaded the windows.

Gray haired old eggs hobbled as fast as their legs would carry them to places of safety. Strong egg men fainted and were dragged indoors. In a minute Billy was the only living soul on the street.

"Now is my time," cried he. "Good-bye, eggs, some day I shall come back and eat you all up," and laughing heartily he jumped high into the air and sailed far, far away.

Billy sat under the Singing Tree. "Time for supper, isn't it, Mr. Tree?" he said; "I'm as hungry as a wolf."

Immediately the tree commenced to sing, "Pease porridge hot, pease porridge cold, pease porridge in the pot nine days old," and with a rustle of leaves it handed down three kinds of porridge. Billy chose some of the hot pease porridge and found it very good.

Then it sang, "Little fishey in the brook, papa caught it with a hook, mamma fried it in a pan and Billy ate it like a man," at the same time handing him a sizzling hot fish on a clean white platter. The fish was done to a turn and it's no wonder Billy left nothing but the bones.

Next came "Pat a cake, pat a cake, baker's man! so I will, master, as fast as I can; pat it and[64] prick it and mark it with B; put in the oven for Billy and me."

"There," said Billy, when that was finished, "I feel as though I'd had almost enough; but a little pie would——"

Billy never wanted for plenty to eat.—Page 64.

And sure enough, the tree sang "Little Jack Horner sat in a corner, eating a Xmas pie; he put in his thumb and he took out a plum and said what a good boy am I!"

Of course, one plum was gone, because Jack Horner had taken that, but there were plenty more left, and Billy ate to his heart's content.

So it was every night, and Billy never wanted for plenty to eat.

But this night he had had such a hearty meal that I fear it made him a bit restless in his sleep. At any rate, some time in the middle of the night he was awakened by a voice calling "Umberufen," and a tiny hand thumping him on the chest.

"Was-smatter?" asked Billy sleepily.

"Umberufen," said the voice.

"Oh!" said Billy, sitting up suddenly and upsetting a little old man with wooden pajamas and a nut-cracker face. "Who's Umberufen?"

"I am, and you called me out of a sound [65]sleep. I do think you mortals are the most inconsiderate people I ever met," said Umberufen angrily. "Now what do you want? Tell me quickly, because I want to get back to my sawdust bed."

"I didn't call you—I've been asleep myself."

"You did—there's no use trying to deceive me. I distinctly felt it when you touched wood—why," pointing at Billy's hand which rested on the trunk of the singing tree, "you're still touching wood. Now tell me you didn't call me."

Umberufen.

"What has my touching wood to do with you?" asked Billy.

"It calls me to you, worse luck—what a dull fat boy you are, to be sure," said Umberufen scornfully.

"How was I to know? I've not made any arrangement with you, I'm sure."

"Well, if you didn't, your Fairy Godfather did, and got me dirt cheap at that—ten cents a day and traveling expenses. But speak up, what do you want?"

"I want to go to sleep," said Billy crossly.

"But you were asleep," replied Umberufen.

"Yes, I was."

"Then if you were asleep, why did you call me to tell me you wanted to go to sleep?"

"It was an accident," said Billy. "I didn't want you, don't want you, and if you can't do anything but scold a fellow because you came when you weren't wanted, I don't ever want to see you again. Good-night." And Billy turned over in a huff and closed his eyes.

"But I can't go until I do something for you-those are my orders," said Umberufen sulkily. "You called me here and you've got to abide by the consequences."

"I don't care what you do. Well, then, stand on your head," said Billy.

"Zip"—and there stood little old Umberufen on his head. "Why didn't you say so sooner?" said he as he regained his feet. "I'd have been[67] home by this time—good-night," and he was gone.

When Billy woke in the morning he felt just a bit sleepy and cross, but after he and Barker had had a game of romps he felt better, and tucking the dog under his arm he jumped off into space singing gaily.

"My gracious, what a big sea shore this is!" exclaimed Billy, when he drifted down to earth again; "and how hot the sun is, but where is the water?"

And Billy stood wiping the perspiration from his brow, while Barker squirmed out of his arms and stood in Billy's shadow with his tongue lolling out.

"It seems to me the singing tree can help us here," said Billy.

Barker undoubtedly understood him, and thought it a splendid plan, for quick as a flash his little fore paws had dug a hole in the soft sand. He barked into it, kicked the sand in again with his hind legs, and he and Billy were soon sitting in the grateful shade of the tree.

"Ah-h," said Billy, "this is what I call comfort."

"Comfort," said a voice on the other side[68] of the tree, "much you know about comfort." The voice was followed by the saddest-looking mortal that Billy had ever beheld. A regular sugar-loaf head—large at the jaws and small at the top, scrawny neck, sloping shoulders, and skinny legs. And such a face—weeping beady eyes, a long sharp nose and thin lips turned down at the corners.

"Who are you?" asked Billy sharply. "And what do you mean by coming up so suddenly?"

The Hermit.

"I'm a hermit, and this is my fast day, so I couldn't come slowly," said the man sadly.

"What is a fast day?" asked Billy.

"A day when you don't eat."

"Oh!" said Billy, "I thought you meant a day when time flies."

"No," said the man, wrapping his legs around and around each other, "no; if that were the case every day would be a fast day, because it's always fly time in this desert."

"You seem unhappy. Cheer up!"

"I can't cheer up. How is a fellow to cheer when he can't speak above a whisper?"

"I mean laugh," said Billy.

"Laugh," said the man wearily, "what's that?"

"Don't you know what a laugh is?" cried Billy, in surprise. "Why, this is a laugh: ha-ha-ha!"

"I don't see any sense in that," said the Hermit; "that's just a noise."

"Of course it's a noise. Come, now, I'll tell you a joke: When is a door not a door?" Of course it was very, very old, but so was the Hermit, and Billy wanted to start with the simplest joke he could think of.

"Quite impossible."

"No; when it's a-jar. Isn't that a good one?" said Billy. "Ha-ha-ha!"

"Oh, my! oh, me! what a terrible thing!" cried the man, bursting into tears. "Suppose all the[70] doors should be changed into jars, what would the poor people do?"

"But don't you see, that's the joke," said Billy; "a-jar means partly open."

"Yes, but if it were still a door how could it be a jar? It's got to be one or the other."

"Oh, pshaw!" said Billy, in disgust; "can't you see it's a joke. I think it's very funny."

"Oh! is that funny?" asked the Hermit.

"Of course."

"Then that's the reason it doesn't make me laugh. When I was a boy I broke my humerus and had to have my funny bone extracted, so I can't see anything funny."

"Poor fellow!" said Billy sympathetically. "What town is that over there?"

"Mirage town," said the Hermit; "but you can't reach it unless you fly."

"Why not?"

"It's built in the sky."

"In the sky? Is it on the road to Bogie Man's house?"

"Are you seeking Bogie Man? Oh, me! oh, my! Don't tell me you are seeking him."

"But I am," said Billy; "why not?"

"Because I've got to hold you if you are, and I'm so tired," said the Hermit, slowly reaching out his arms.

"Good-by," cried Billy, giving a jump and bounding out of his reach.

"Oh! please come back and tell me another joke, I haven't had a good cry for a week," called the Hermit, holding out his arms.

"Too late," Billy called back—"But when is a door not a door? when its a jar."

"Thank you," sobbed the Hermit, and the last Billy saw or heard of him he was murmuring, "When is a door a jar," and weeping bitterly.

In a twinkling Billy stood at the gates of Mirage Town. Far beneath him he could see the burning hot desert, while through the gates he could see cool, airy houses, beautiful streets shaded by great trees and far beyond soft, green meadows and sparkling brooks.

"My goodness, but I'm thirsty," said Billy to himself. "I wish the gate keeper would hurry and let me in," and again and again he knocked, but seemingly with no result.

Finally when his throat was parched and his tongue dry with thirst, he could stand it no longer.[72] He put his shoulder to the gates—open they swung, and Billy fell inside on his face. "Why, it was just like pushing clouds away," he exclaimed.

"But I'm in the sun here; I must cross to the other side."

So across the street he ran.

"Why this is strange, I was sure this was the shady side," he said in surprise. For when he got there the sun if anything was hotter than ever and the side he had left was cool, shady and inviting.

Billy shut his eyes. "I'm afraid this is sun-stroke," he said, "anyway I'll try again," and back he ran as hard as he could go. But when he got across it was the same thing as before.

"Come in and rest," called a voice from a house at his side; "you look hot and tired—come in and rest your face and hands."

"Thank you, I will," said Billy, gratefully, not noticing that the voice was just a wee bit derisive.

"This way," called the voice; "turn the knob and walk in—if you can."

"Oh! I can," said Billy, walking toward the door of the house he thought he heard the voice coming from.

"Not that way—I'm across the street," called the voice.

"Oh!" said Billy, politely, starting across again, "I beg your pardon—I thought——"

"Think again," said the voice; "are you coming in or not? I'm not over here, I'm over there."

"Where?"

"Back where you're coming from."

"I thought you said—" began Billy.

"It doesn't make any difference what I said, I didn't say it," answered the voice.

Billy began to lose his temper.

"Are you making fun of me—who are you anyway?"

"I'm Nothing Divided By Two."

"Why, that's nothing," said Billy.

"Wrong," answered the voice.

"Why?"

"Don't ask so many questions—are you coming in or not?"

"I think not," said Billy, "I can't spare the time."

"I suppose you think you'll have to get right on to Bogie Man's House."

"Yes."

"But you're not—you'll never get away from Mirage Town."

"Why not?" asked Billy,

"Because there is no such place."

"But I'm here."

"That's the trouble—you are in a town that doesn't exist, so of course, you are not in any place. And, if you'll tell me how you can leave a place where you're not I'll——"

"I'll show you," said Billy angrily, "I'll jump out," and he tried to jump.

"No use," said the voice laughing, "there's nothing under your feet—and you can't jump from nothing."

"Well, I'll get a drink of water from that brook and then you'll see," said Billy, "I'll go out by the gate I entered."

"Ha! ha! ha!" laughed the voice, "try and see."

Nothing daunted, however, Billy ran toward the brook—"Can't catch me—can't catch me," called the brook, "running boys can't catch running brooks."

"Indeed I will," and sure enough after a long hard run Billy reached the brook. "Now,"[75] said he exultingly, "now I've got you." Dipping his cap deep into the water he eagerly lifted it to his lips and found it—empty, while far off down the road ran the brook.

Billy came very near crying, he was so hot and thirsty and disappointed. But he swallowed the lump in his throat (which, being salty, made him thirstier than ever) and turned back again.

"The gates are all that's left," he said, bravely, "and I'll catch them, I'm sure." But it wasn't to be, for the farther and the harder he ran, the farther off the gates were. And finally he sank down, entirely out of breath.

"No water, no shade, no trees—why the Singing Tree, of course," he cried, delightedly. Out jumped Barker, scratch, scratch, scratch, bow-wow-wow, and, "Bing!" the topmost branches of the Singing Tree popped up and almost struck Billy in the face.

"Hello!" cried Billy, "where are your roots? I don't see anything but branches."

"Two miles below, where they ought to grow," sang the tree. "Come, hold on tight, you'll be all right."

And Billy seized the branch that held itself out to him.

"Hold on there, I want to speak to you," called the voice that had teased him so.

"I'll hold on," called Billy, "but I'll soon be out of your hearing."

Down grew the tree; shorter and shorter it grew, and sure enough, in a minute Billy was on solid ground and Mirage Town had disappeared from view.

Billy made an early start the next morning so that he could get away from the desert before the sun rose to its full height. And indeed the pink had just begun to appear in the East when he looked below him and saw once more trees and grass and streams of water.

"Thank goodness, I am clear of the burning desert at last," he said to himself—"Ugh!! though, here I am falling, and I know I'll be drenched passing through that cloud."

"Plump—squash," and he was in the cloud, "there—it wasn't so bad after all. Why there's Honey Girl's Palanquin." Sure enough he had alighted within a few feet of Honey Girl, General Merchandise and the Bee Soldiers all sound asleep.

"Who—o, who—o—who—o goes there?" cried a large owl, perched on the limb of a tree above the sleepers' heads.

"I'm not going, I'm coming," said Billy.

"Who—o—o—who—o—o—who—o—o are you?"

"Billy Bounce."

"That's not the right answer," cried General Merchandise, jumping to his feet, "you must say, a friend."

"A friend then," answered Billy.

"Not a friend then or now—just say a friend," said the General.

"A friend."

"That's right—advance and give the what-you-may-call-it."

"The what?" asked Billy.

"The counter sign I mean."

"I don't know it."

"Well I suppose I'll have to tell you, seeing it's you—it's Bogie Man," said the General.

"Bogie Man," repeated Billy.

"There, that's all over—now you may sit down."

"Thank you—but—but what has happened to the soldiers, they seem to have lost their arms—have you had a battle?"

"Oh! no—" answered the General proudly,[79] "that's my own idea, you've read of soldiers before a battle sleeping on their arms, haven't you?"

"Yes."

"Well, every night our soldiers take off their arms and sleep on them; of course, it was a little uncomfortable at first, but it's very military."

"Yes, I suppose so," said Billy, dubiously, "but who is that—a—gentleman up in the tree?"

"You mean the owl?"

"Yes-s, I thought he looked like an owl."

"That's our sentry—he does it very cheap by the night, because he says he has to stay awake anyway, and he might as well stay awake here and get paid for it," answered the General.

"How is Princess Honey Girl?"

"Well—very well, in fact, but a little nervous; you see Bumbus and the Scally Wags are on our trail and she feels uneasy."

"Bumbus!" cried Billy.

"Yes—he is a renegade bee you know, and it makes him very bitter against the Princess. You haven't seen anything of them lately, have you?"

"No, I have not. But who are the Scally Wags?"

"Oh! they're terrible fellows. I can't tell you what they look like for I've never seen them, but many a time I've read of their doings in 'The Morning Bee.'"

"Good morning, Billy Bounce," said Honey Girl, opening the curtains of her Palanquin. "General, isn't it time to sound the reveille?"

The Bee Bugler.

"Exactly, we must get our soldiers up bee-times," said the General, saluting. "Bugler." Up jumped a little bee, saluted, plucked a trumpet flower and gave the reveille.

And in a second the whole camp was buzzing with soldiers.

"There—how's that?" said the General proudly.

"Splendid," said Billy—then turning to the Princess, "I have thought of you many, many times since I last saw you, Princess Honey Girl."

"And I have thought of you, Billy Bounce: perhaps some day when this cruel war is over you can visit my Aunt and myself in the Bee Palace," said the Princess.

"Perhaps," said Billy, "and I don't believe that time is far distant, for when I once find Bogie Man I shall——"

"Buzz-z-z—There they are—There they are," called a voice—and looking up and away to the East Billy saw Bumbus and several objects that he knew at once for Scally Wags.

"Princess, you must leave at once," he cried.

"Right again," said the General. "We can outfly them—Company, 'Tenshun!!!—fix stings—carry Palanquin—forward—fly!" and up and off went the whole company, the Princess waving good-bye to Billy.

Indeed he was so intent on watching her and waving to her that when he did come to himself and realized that it was time he got away, it was too late.

"Buzz-z-z—here's Billy Bounce," cried Bumbus, settling down at his side.

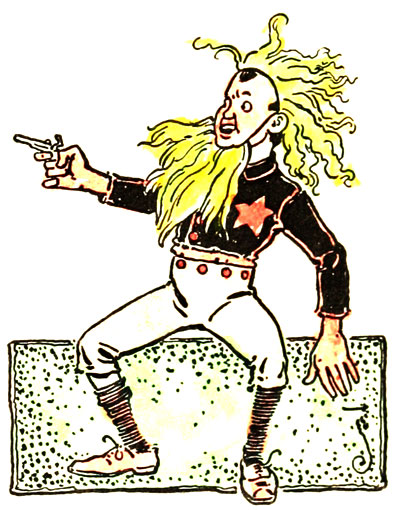

"He-he-ho-ho, oh! what a joke," cried the Scally Wags in one voice, tweaking his nose and his ears and pinching his legs.

And though the tweaks and the pinches hurt, Billy couldn't help laughing at the funny little figures. Such great flapping ears, such wide slits of mouths set in a continual grin, such long arms, such round, funny little stomachs and such gay parti-colored clothes.

"Well, boy," said Bumbus, poking him in the ribs, "what are you laughing at?"

"At your friends, the Scally Wags," said Billy.

"Bite him on the wrist," cried the head Scally Wag angrily.

"Bite me," laughed Billy, "why you haven't a full set of teeth between you." And it was true, for there was only one tooth to a Scally Wag.

"Be quiet," said Bumbus, "I'm thinking! Where's that note Nickel Plate gave you?"

Billy did not answer.

"Did you hear me?"

Billy nodded yes.

"He-he-ho-ho, oh! what a joke," cried the Scally Wags.—Page 82.

"Then why don't you answer? Come, speak up," cried Bumbus in a temper.

"I thought you said to be quiet, that you wanted to think," said Billy, looking very, very innocent.

"You'll pay for this," said Bumbus.

"What, the thought?" asked Billy. "You shouldn't sell it if it is the only one you have, you'll probably need it some time."

"Gr-r-r-r-r-r-r, buz-z-z-z-z," was all that Bumbus could answer, he was so angry.

"Leave him to me," said the head Scally Wag. "I'll joke him to death."

"Do your worst," said Bumbus, regaining his breath.

"No, I'll do my best. Here's a conundrum, little fat boy—but you mustn't answer it correctly."

"Why not?" said Billy.

"Oh! that's against the rules of the game; no wag, not even a Scally Wag expects his conundrums to be answered correctly."

"Why do you ask me then?"

"So that I can laugh at you for not knowing the answer."

"But that's nonsense," persisted Billy.

"Of course it is—we Scally Wags are all nonsense."

"Well, go ahead."

"What time will it be this time last week?"

"You mustn't say will it be, but was it."

"Have you ever heard this conundrum before?"

"No," said Billy.

"Well, you see I have—it's my conundrum and I guess I know what I ought to say."

"Then it will be the same time that it is now," answered Billy.

"Wrong—wrong again," said the head Scally Wag. "It will be a week earlier."

"Ha-ha-ho-ho-he-he, oh! what a joke," cried the Scally Wags again, tweaking, pinching and punching Billy.

"If you do that again I'll pitch into you," cried Billy angrily.

"There, that will do," interrupted Bumbus; then hummed,

"But that doesn't rhyme," said Billy.

"Of course not—why should it?" asked Bumbus.

"Wasn't it meant for a poem?"

"Certainly not; it was meant for the truth."

"But it's not the truth."

"I didn't say it was the truth," said Bumbus.

"You just said it was meant for the truth," said Billy.

"Yes, meant for the truth—it was just an imitation, so there's no more truth than poetry in it."

"It's my turn now," said the Head Scally Wag. "We couldn't joke him to death, so lets tickle him into little bits."

"Oh, don't!" cried Billy; "I'm ticklish."

"So much the better," said Bumbus. "But if you will give up the note we'll let you go."

"I can't do that," said Billy decidedly, "I've got to carry that to Bogie Man."

"Come on," cried the Scally Wags, and they swarmed over Billy digging their fingers in the spots where he should have been ticklish. But of course they didn't know that he had on his air suit, and the more they tickled the more serious Billy looked.

"No use," said the head Scally Wag, sinking down on the ground exhausted. "We would need a sledge-hammer to tickle that boy."

"Give him laughing gas," suggested Bumbus.

"Just the thing," cried the Scally Wags.

"Wait a minute," said Billy, "just let me have one little game before you give me the gas."

"As a last request?" asked Bumbus.

"Yes."

"Well what is it? speak quickly, for time is short and life is long you know."

"I want to play a game of blind man's buff," said Billy.

"That sounds reasonable," said Bumbus. "How do you play it?"

"First you must all tie your handkerchiefs over your eyes."

"Ha—ha—he—he—ho—ho—. Oh! what a joke," cried the Scally Wags, "we all carry pocket handkerchiefs."

"And then?" said Bumbus.

"Then," said Billy, "you all try to catch me."

"Is that all?" asked Bumbus.

"Yes."

"What fun—ha—ha—he—he—ho—ho," said the Scally Wags, "what a game to be sure."

Billy had some difficulty tying the handkerchiefs around the Scally Wags' heads on account of their enormous ears, but finally they were all blindfolded. Bumbus was tied up in a jiffy.

"Go," cried Billy, at the same time leaping into the air, and Bumbus and the Scally Wags all made a rush for the spot where he had stood.

"I've got him—I've got him," cried all the Scally Wags, hanging on to Bumbus. "I've got him," cried Bumbus, catching hold of a Scally Wag. And Billy laughed aloud to see them scrambling and pushing and jostling one another in their efforts to catch him.

Even when he was just a moving black speck on the horizon Bumbus and the Scally Wags were still struggling.

"I can't understand why Bumbus wanted to take that note away from me," Billy said to himself as he floated along. "First he and Nickel Plate employed me to carry it and now he tries to hinder me. Why of course—I know—he is aware that Princess Honey Girl has told me her story and fears that when once I do find Bogie Man I will vanquish him—so I shall, too. I wonder what the future will bring."

"Won't you have your fortune told sir?" and Billy looked up to see sailing along at his side a very old, very withered woman sitting on a broom.

"Why it's a witch," said Billy.

"I'm not a which, I'm a Was," said the old woman.

"Oh! I beg your pardon, ma'am," said Billy, "I saw that you were riding a broom."

"Well what of it—the broom's willing."

"I didn't mean it that way," began Billy.

"Oh! you mean you meant it any way. But this is not having your fortune told," interrupted the old woman. "Come right into the house."

And sure enough Billy discovered that he was standing in front of a little old house, as wrinkled and ugly and out of repair as the old woman.

"What town is this?" he asked.

"Superstitionburg—don't bump into the ladder."

"What is that for?"

"Oh! we all have ladders over our doors here for bad luck. Sit down and I'll get the cards and tell your fortune."

"Thank you," said Billy, "will it be true?"

"No, of course not. Ah—h! you have lately had serious trouble."

"That's true," said Billy.

"Then I've made a mistake. You will marry a tall, short, blonde dark complected man."

"Hold on," said Billy, "I'm a boy—how can I marry a man?"

"There I knew something was wrong. I have[90] the deck of cards that I tell ladies' fortunes with—shall I try it over again?"

"No, I think not," said Billy, "I must be going."

"Purr-r-r-r-r, Purr-r-r-r," and a great black, hump-backed cat with glaring green eyes and nine long black tails rubbed against his leg.

"Oh!" he cried, "what a large cat."

"Yes," said the old woman, "that's my black cat-o-nine tails. I'm very proud of him, he's the unluckiest cat of the entire thirteen in Superstitionburg."

"Unlucky?"

"Yes, the cats always sit thirteen at table for bad luck. As there never is more than enough for twelve and as he always gets his share he brings bad luck to one of the cats every meal. Isn't that nice?"

"But isn't that hard on the extra cat?"

"Oh! no they don't mind at all—it's so good for the digestion."

"Won't you have a cup of poison before you go?"

"Poison?" said Billy, edging toward the door.

"That's my black cat-o-nine tails," said the old woman.—Page 90.

"Yes. I have some lovely poison, I brewed it myself; do have some."

"No thank you, I—I really am not thirsty, and I must go."

"I don't see how you are going to get away now, the town guard knows you are here and is bound to arrest you if your eyes are not crossed."

"What have I done?" asked Billy.

"Nothing, only it's not bad luck to meet a straight-eyed person, and if you can't bring somebody bad luck you're not allowed in the city."

"But how do they know I am here?"

"Their noses are itching because a stranger has come to call. Their noses are very sensitive to strangers. It makes them such careful guards."

"Have they guns?" asked Billy.

"Oh! yes, they all have guns that are not loaded."

"Oh! well, then, they can't shoot me."

"I guess you don't know much about guns—because it is always guns that are not loaded that shoot people."

"That's so, I had forgotten," said Billy. "But as you are a witch, can't you——"

"I am a Was, remember."

"I mean as you are a Was—can't you help me?"

"I can lend you my invisible cloak," said the old woman, going to a closet and taking nothing out of it. "Here it is," handing Billy nothing at all very carefully.

"But where is it?" asked Billy.

"I just gave it to you."

"I don't see it."

"Of course not—it's invisible."

"Then if I put it on will it make me invisible?"

"Certainly not—it's the cloak that's invisible."

"Have you anything else?" asked Billy.

"Yes, I have the wishing bottle."

"Shall I be able to see that?"

"Oh! yes—here it is."

"Why that's hair dye, it says on the label."

"Sh-h—don't speak so loud—that's all it is, but you see it turns the hair so black that it almost makes it invisible. It's the best I can do for you. But don't tell anyone—it would ruin my reputation as a cuperess."

"A cuperess?" asked Billy.

"Yes, I cast charms."

"What kind?"

"All kinds but watch charms."

"I thought that was a sorceress."

"I used to be, but it's rude to drink poison out of a saucer now, and so I am a cuperess."

"Thank you very much for the wishing bottle," said Billy. "I don't know that I shall need it, but I'll take it anyway."

"Bad luck to you," called the old woman. "By the way where are you going now?"

"To Bogie Man's House," answered Billy.