Project Gutenberg's Motor Matt's Queer Find, by Stanley R. Matthews

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most

other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions

whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of

the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at

www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have

to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook.

Title: Motor Matt's Queer Find

or, The Secret of The Iron Chest

Author: Stanley R. Matthews

Release Date: March 19, 2015 [EBook #48524]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK MOTOR MATT'S QUEER FIND ***

Produced by David Edwards, Demian Katz and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (Images

courtesy of the Digital Library@Villanova University

(http://digital.library.villanova.edu/))

|

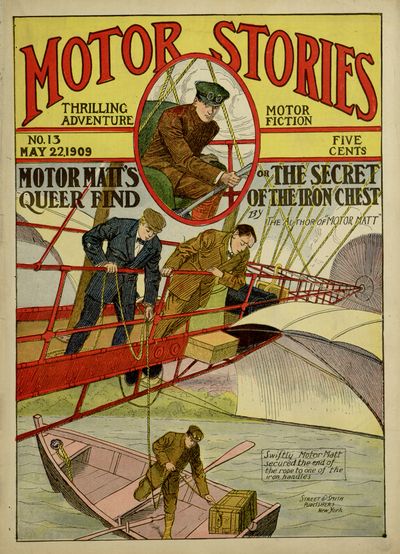

THRILLING ADVENTURE |

MOTOR FICTION |

|

NO. 13 MAY 22, 1909. |

FIVE CENTS |

|

MOTOR MATT'S QUEER FIND |

or THE SECRET OF THE IRON CHEST |

|

By The Author of "MOTOR MATT"

Street & Smith

Publishers New York |

| MOTOR STORIES | |

| THRILLING ADVENTURE | MOTOR FICTION |

Issued Weekly. By subscription $2.50 per year. Entered according to Act of Congress in the year 1909, in the Office of the Librarian of Congress, Washington, D. C., by Street & Smith, 79-89 Seventh Avenue, New York, N. Y.

| No. 13. | NEW YORK, May 22, 1909. | Price Five Cents. |

MOTOR MATT'S QUEER FIND;

OR,

THE SECRET OF THE IRON CHEST.

By the author of "MOTOR MATT."

CHAPTER I. THE HUT BY THE BAYOU.

CHAPTER II. YAMOUSA.

CHAPTER III. THE ATTACK ON THE CAR.

CHAPTER IV. SMOKE PICTURES.

CHAPTER V. A QUEER FIND.

CHAPTER VI. FOUL PLAY.

CHAPTER VII. DRIED FROGS—AND LUCK.

CHAPTER VIII. THE PLOTTERS.

CHAPTER IX. THE HEAD OF OBBONEY.

CHAPTER X. ON THE TRAIL.

CHAPTER XI. A BLACK MYSTERY.

CHAPTER XII. AT CLOSE QUARTERS.

CHAPTER XIII. THREE IN A TRAP.

CHAPTER XIV. AN ASTOUNDING SITUATION.

CHAPTER XV. THE TREASURE.

CHAPTER XVI. DIAMONDS GALORE.

THE MASKED LIGHT.

Motor Matt, a lad who is at home with every variety of motor, and whose never-failing nerve serves to carry him through difficulties that would daunt any ordinary young fellow. Because of his daring as a racer with bicycle, motor-cycle and automobile he is known as "Mile-a-minute Matt." Motor-boats, air ships and submarines come naturally in his line, and consequently he lives in an atmosphere of adventure in following up his "hobby."

Carl Pretzel, a cheerful and rollicking German boy, stout of frame as well as of heart, who is led by a fortunate accident to link his fortunes with those of Motor Matt.

Dick Ferral, a young sea dog from Canada, with all a sailor's superstitions, but in spite of all that a royal chum, ready to stand by the friend of his choice through thick and thin.

Townsend, a wealthy though eccentric gentleman, who owns a remarkable submarine boat on which our friends have seen various adventures in the past.

Whistler,

Jurgens,

Bangs,

} a trio of rogues bent upon gaining possession of a prize. Yamousa, the hideous voodoo woman of the Louisiana swamps.

THE HUT BY THE BAYOU.

"Lisden, vonce, you fellers! I t'ink I hear someding."

Carl Pretzel turned back from the forward rail of the Hawk, gave his chums, Motor Matt and Dick Ferral, a warning look, and then leaned out over the side of the air ship, his eyes on the earth below.

The Hawk was sweeping over the tongue of land between Lake Pontchartrain and Lake Borgne, bound for New Orleans by way of the Lower Mississippi.

Night was coming on, and the boys in the air ship had been looking anxiously for a place in which to effect a landing. Interminable stretches of cypress and live oak covered the low ground beneath them, and there did not seem to be a gap anywhere in the dense growth.

"You must have bells in your ears, mate," said Dick, in response to Carl's announcement that he had heard "something." "Dowse me if I heard any noise."

"Listen, pards, both of you," called Matt from his seat among the levers. "If you can hear a voice, down there, it will be a pretty sure sign that we're close to a clearing. We've done enough flying for to-day, and these Louisiana air currents are so changeable I don't want to do any night traveling. If you——"

"Dere it vas some more!" cried Carl excitedly. "You hear him dot time, Tick?"

"Aye, matey," answered Dick, "I heard a voice, fair enough. It was a sort of screech, as though a woman might have piped up—or a panther."

"Where away was it?" asked Matt.

"Two points off the starboard bow, Matt."

Matt shifted the rudder, thus altering the course of the Hawk; he also depressed the horizontal plane and threw the air ship closer to the tree tops.

"It's getting so blooming dark, down there among the trees," observed Dick, "that it's hard to see anything, but I believe I can make out a bit of a river, and an arm of it like a bayou."

"Yah, so helup me," put in Carl, "I can see dot meinseluf, I bed you. Und dere iss a light like a fire, vich geds prighter und prighter as ve go aheadt. Vat you t'ink is dot anyvay, Tick?"

Before Dick could answer, the cry that had already claimed their attention was wafted up from below, this time so clear and distinct that there was no mistaking it.

"A moi! a moi!"

It was a screech, as Dick had said, and resembled greatly the yell of some wild animal; nevertheless, the call was plainly human, for it was broken into words.

"French lingo, or I'm a Fiji!" averred Dick. "It's the same as some one calling for help. And a woman, too. No man could make a sound like that."

As if to prove Dick's words, the cry was repeated, but the words were English, now, and not French.

"Help! Help!"

"Py chiminy grickets!" gasped Carl. "Dere iss someding going on vat means drouple for der laty."

"We've got to land," declared Matt, "and see what's the matter. Can you find a place?"

Both Dick and Carl were leaning over the forward rail and staring ahead and downward.

Suddenly the tree tops broke away and a heap of blazing wood could be seen. The fire had been kindled on a cleared stretch of bayou bank, and not far from it was a log hovel. But there was no one in sight, either near the fire or around the hut.

The two boys on the lookout announced their discoveries to Motor Matt.

"We'll come down on the bayou bank," said Matt. "Give me directions, Dick."

The young Canadian, watching sharply below, called their bearings to Matt, and the Hawk was safely manœuvred to the surface of the ground. The calls for aid had ceased, an ominous silence reigning in the vicinity of the fire and the hut while the boys got out their mooring ropes and secured the Hawk to nearby trees.

"Where's the woman in distress?" queried Dick, coming around the front end of the car and joining Matt and Carl. "She was making plenty of noise, a while ago, but she's quiet enough now."

"She may be in the hut," said Matt. "You stay here and watch the air ship, Dick, while Carl and I take a look through the shanty."

Matt pulled a blazing pine knot from the fire, and, with this to light the way, started toward the hut. Carl dropped in at his side and they proceeded onward together. Suddenly Carl drew to a halt and laid a hand on Matt's arm.

"I tell you someding, Matt," said the Dutch boy, "und dot iss, I don'd like dis pitzness. Br-r-r! I haf some greepy feelings all droo me."

Carl could be as brave as a lion when brought company front with any danger he could understand, but he was so full of superstition that if a black cat crossed the road in front of him he was at once thrown into a panic.

"Nonsense!" exclaimed Matt. "We're here to help some one who is in trouble, and we don't want to get scared at our own shadows."

"Der blace itseluf iss enough to make my shkin ged oop und valk all ofer me mit coldt feet; and den, for vy don'd we hear dat foice some more?"

There was a sort of weirdness about the place, and no mistake. The great live oaks, uncannily festooned with Spanish moss, completely inclosed the little clearing, bending about it in a half circle and coming down to the very edge of the bayou. The fact that there was a fire, of course, proved that human beings had been in the clearing, even if they were not there now. But there was something ghostly about the fire, and while it threw flickering shadows across the clearing it seemed only to make the darkness deeper in the depths of the wood.

"It may be, Carl," said Matt, "that the woman who was calling for help has become unconscious. That makes it all the more necessary for us to find her as quick as we can. Come on!"

Waving his torch, Matt hurried along toward the hut. The door was open, and the torch glare struck whitely against some object suspended over it.

"Vatt iss dot ofer der door, eh?" asked Carl excitedly. "Py shinks, it iss some pones! It iss a skeleton oof someding! Whoosh! Dis iss gedding on my nerfs like anyding."

The young motorist whirled on his Dutch chum.

"You go back to the air ship, Carl," said he, "and send Dick here. Your nerves are troubling you so much that you're not of much help."

Carl was only too ready to go back to the Hawk. With a mumbled apology for himself, he turned and hurried away. When Dick came up, a moment later, Matt was looking at the object over the door of the hovel.

"What is it, matey?" queried Dick.

"It looks like the skull of a cat, or a dog," answered Matt.

"Then I suppose it was put up there to bring luck. People around here must be a jolly lot."

"We'll see what's inside," and Matt, holding his torch high, passed through the door.

The hut contained but one room. There was a fireplace in one end, and over a bed of coals a kettle was hanging. A "shake-down" on the floor, in one corner, was covered with ragged blankets. But the strangest feature of the place was this: The whole under part of the thatched roof, and every crevice of the walls, was hung with rags, feathers, bones of cats, alligator teeth, and a thousand other objects, equally curious.

"Well, strike me lucky!" mumbled Dick. "This is a rummy old place we've got into. Between you and me and the mainmast, old ship, I'd just about as soon give it a good offing. But where's the woman that wanted help?"

The question was hardly out of Dick's mouth before it was answered by another screeching, "A moi! a moi!"

The call did not come from anywhere about the hut, but from outside and somewhere in the timber.

"This way, Dick!" shouted Matt, and rushed out of the hut.

"A moi! a moi!"

The call was again repeated, and the two boys, guiding themselves by the call, flung up the slight slope and darted in among the trees.

"Careful, matey!" panted Dick, from close behind his comrade. "There's no telling what sort of a jolly mess we're running into. Better dowse that light—it'll be safer; besides, I can see the gleam of a lantern ahead, there, through the trees."

"I just caught a sight of that myself, Dick," answered Matt, in a low voice. "Your suggestion about the torch is good," and Matt dropped the blazing fagot and crushed out the fire with his foot. "Now, then," he finished, "we'll go on, and go quietly."

A dozen yards, perhaps, brought the boys to a spot from which they could behold a scene that caused their pulses to leap.

An old crone was bound to a cypress stump, and beside her stood a man with a lithe switch.

The hag was swarthy, and her kinky hair was white. Evidently she was a mulatto. The man at her side was white. The moment Matt's eyes rested on him, the young motorist gripped Dick's arm with tense fingers.

"That man!" whispered Matt excitedly; "do you recognize him, Dick?"

"Whistler, or I'm a Hottentot!" gasped Dick.

For a moment, blank amazement held the two boys spellbound. Then, as Whistler lifted the switch and brought it viciously down on the old woman's shoulders, the spell was broken and the two boys started forward.

"Will you tell?" demanded Whistler, pausing after the blow.

"A moi! a moi!" screeched the woman.

"You can call till you're blue in the face," went on Whistler savagely, "and you'll not bring anybody. I'll find out from you what I want to know, Yamousa, or I'll flay you alive. Will you tell?"

At that moment, Matt and Dick broke into the lantern light. The lantern was suspended from the broken limb of a tree, and the glow was so faint that the boys had not been seen until they were close upon the man and the woman.

Whistler, with an oath of consternation, jumped backward. The next moment, he had whirled his gad and brought it down on the lantern. A crash followed, and Stygian blackness shrouded the spot. A sound of running feet, fading away in the timber, came to the boys' ears.

"Never mind Whistler, Dick," said Matt; "let's look after the woman."

YAMOUSA.

No sound had come from the woman since the two boys had reached the scene. Groping their way to her, they found that she had become unconscious and was drooping heavily in the cords that held her bound to the stump.

"Of all the things that ever happened to us, mate," remarked Dick, "this captures the prize. We get cast away on a little turtle back in the Bahamas, and Lat Jurgens and this old hunks, Whistler, come to the island in Nemo, Jr.'s submarine. We capture the pair and leave 'em roped in our tent; then we capture the submarine. Later we send ashore for Jurgens and Whistler and the landing party reports that they have vanished. Now, dropping down here in answer to a cry of distress, we find Whistler giving an old woman a taste of the cat. Whistler, of all men! I'm fair dazed with it all."[A]

[A] For an account of the adventures of Motor Matt and his friends in helping Archibald Townsend, otherwise Captain Nemo, Jr., recover his stolen submarine from Jurgens and his rascally followers, see No. 12 of the Motor Stories, "Motor Matt's Peril; or, Cast Away in the Bahamas."

"So am I," said Matt, "but we'll not let that bother us now. This old woman has been brutally treated, and has fainted away. We must get her to the hut and see what we can do to revive her."

"Right-o," agreed Dick. "I've my sheath knife handy and I'll cut her loose from that stump in a brace of shakes."

Matt held the limp form upright while Dick severed the cords; then, picking the woman up, they carried her through the woods, back to the clearing, and laid her on the ragged blankets in the hut.

"I think I saw a candle on the shelf over the fireplace, Dick," said Matt. "Better light it."

Dick found the candle. It was a tallow dip stuck in an old tin candlestick. With the light in his hand, he walked to the old woman's side and bent downward.

The face of the woman was scarred and hideous. There were big gold earrings pulling down the lobes of her ears, and another large ring pierced her nose and fell down over her upper lip. Her cheeks were hollow, and the yellow skin resembled parchment. Her clothing was a motley garb of patched rags. Two claw-like hands, with finger nails an inch long, lay on the blankets beside her.

Matt lifted his eyes to Dick's with a shudder.

"She's not what you'd call Cinderella, exactly," grinned Dick, "and I don't think her beauty will ever prove fatal."

"Anyhow," said Matt, "she's a woman and needs help. That's enough for us to know."

A tin water pail stood on a bench, and there was a gourd dipper hanging over it. Matt filled the gourd and returned and dashed the water in the old woman's face.

The effect was magical. With a screech that caused the boys to start backward in consternation, the old woman sat up suddenly and glared about her, with eyes like coals. Abruptly her attention fixed itself on the boys and she began to croon in a harsh, mumbling voice:

She exploded the last word like the crack of a revolver, lifting and aiming her fingers as she might have done with a weapon.

"Avast, there, old lady!" cried Dick. "We're friends of yours. Can't you understand that?"

"American?" shrilled the woman, rising slowly to her feet.

"Yes," said Matt.

"Where is ze man zat take me from my home and beat me wiz ze stick?" she demanded, crouching like a cat, while her talon-like hands clawed the air angrily.

"He ran away," answered Matt. "We cut you loose from the stump and brought you here. Do you know that man?"

The old woman staggered to the fireplace and stirred up the coals under the kettle; then she turned back, took the candle out of Dick's hand and studied his face. From Dick she turned to Matt, giving him a similar scrutiny.

Her eyes were bright and fiery—age had not seemed to dim them. As she turned from Matt, the hag gave a croaking laugh.

"I guess we'd better send the 'blue peter' to the masthead, old ship," said Dick, "trip anchor and slant away. This don't look like a comfortable berth, to me."

"You not go 'way yet," cried the woman, whirling about. "You are ze good boys, you help Yamousa, ze Obeah woman, and by gar, Yamousa help you! Sit on ze bench."

She waved one hand toward the bench on which the water pail was standing. Dick, heeding a significant look from Matt, followed to the bench and sat down.

"Do you know that man who was beating you?" asked Matt, again, determined if possible to get a little information about Whistler.

"Oui, I know heem!" answered the woman, with a spitting snarl. "One time he work on ze sugar plantation near ze bayou, and he come many time to see Yamousa and have her tell him ze t'ings he do not know. He come now from ze Bahamas and ask about ze iron chest, and where zis Townsend take heem. But Yamousa, she no tell. For why Yamousa no tell, eh? Well, she see zat Whistler haf ze bad heart. Whistler try to beat her, make her tell; zen ze American boys come and drive heem away. How you get here, eh?"

"We came in an air ship," Matt answered.

"Sacre tonnere! I know zat you come—I seen him in ze smoke."

Yamousa had said things which had aroused the intense curiosity of the two boys. Whistler had tried to force her into telling him the whereabouts of an "iron chest." That iron chest had been found in a sea cavern of an uninhabited island among the Bahamas, had been taken aboard Townsend's submarine, and had been in the submarine when Matt and his chums turned the boat over to her owner on the Florida coast. Townsend had taken the chest to New Orleans, and Jurgens and Whistler were eager to recover it.

What the chest contained, no one knew. A man who called himself simply the "Man from Cape Town" had given Townsend a chart and secured his promise to find the chest, carry it to New Orleans, and open it in the presence of a woman whom the Cape Town man claimed was his daughter. These two were then to divide the contents between them.

The fact that Whistler, and presumably Jurgens, as well, still had designs on the chest, was surprising information for Matt and Dick. The three boys were proceeding to New Orleans in the Hawk, in response to a request from Townsend; and it might easily chance that the business which had led Townsend to call Motor Matt and his friends to New Orleans was to cross the evil designs of Jurgens and Whistler.

"Do you know anything about that iron chest, Yamousa?" inquired Matt.

"Not now, but I find heem out," replied the old woman. "By gar, I find out anyt'ing zat ees wanted to be known."

"You say you knew that we were coming?"

"Oui."

"I can't understand how you discovered that. We didn't know ourselves we were coming until we got a telegram at Palm Beach, Florida, yesterday."

"I tell by ze smoke," repeated the woman; "I read heem in ze smoke."

"What sort of a place is this, anyhow?" muttered Dick to Matt uncomfortably. "Is the old lady a fortune teller? I never took much stock in that sort of thing, you know."

"Yamousa ees ze Obeah woman," chirped the hag, her ears having evidently been sharp enough to overhear what Dick had said: "I am ze voodoo queen. I know t'ings ozzers don't know, an' ze people come from ever'where to see Yamousa—from New Orleans, oui, and from Algiers, Plaquemine, St. Bernard—all up and down ze river an' ze coast—zey all come to haf Yamousa tell zem t'ings zat zey don't know. I tell you ze same. You are my franes—mes amis—an', I do planty mooch for you. Where is ze ozzer of you? In ze smoke I see t'ree, all in ze flying boat zat come to Bayou Yamousa."

"She means Carl," muttered Dick, "and how the old Harry she knew anything about him is a fair dazer."

"In ze smoke I see heem," replied the hag, again catching Dick's words.

"I think I'm beginning to see through this a little, Dick," said Matt. "In some way, Jurgens and Whistler got off that island in the Bahamas and——"

"Zey hide in a cave till you go 'way," broke in Yamousa, "an' zen zey come out an' bymby ze boat come from ze Great Bahama an' pick zem off. Oui, hé, zey ees bot' ver' bad an' haf ze bad heart."

"How did you find that out, Yamousa?" asked Matt.

"Not in ze smoke, not zat, non. Whistler tell me."

Yamousa's knowledge, which, for the most part, seemed to be derived from unusual sources, filled Matt and Dick with growing bewilderment.

"Sink me," muttered Dick, "but my nerves are beginning to bother me. Go on, though, matey. What about Whistler?"

"Why, he's still after the iron chest, he and Jurgens. They got away from that turtle back in the Bahamas, landed in this vicinity, and Whistler came here to get this voodoo priestess to tell him where he could locate the chest."

"All my eye and Betty Martin, that! Just as though Yamousa could tell him!"

"Anyhow, Whistler must have thought so or he wouldn't be here. We saw and heard enough to convince us that what Yamousa said about his designs was true. We got here in time to drive him off and——"

Just there occurred a startling interruption. A frantic yell came from the clearing—a yell that was plainly given by Carl.

"More trouble!" boomed Dick, leaping from the bench, "and it's Carl that's flying distress signals now."

Matt did not reply, but he led the way to the door and through it into the dying glow of the fire on the bayou bank.

THE ATTACK ON THE CAR.

Carl was having a fight. Matt and Dick were able to discover that much as they rushed from the house. And the fight was against hopeless odds, for at least a dozen men could be seen in the faint glow of the fire. They were pressing around the car, and Carl, standing in Matt's chair, was laying about him with a long-handled wrench, keeping the attacking force temporarily at bay.

"Keelhaul me!" cried Ferral, as he raced after Motor Matt. "What does that gang mean by making a dead-set at the Hawk? They're negroes, the lot of them!"

"There's one white man, Dick!" answered Matt. "Whistler is there. He must have recognized us in the woods and he's setting the negroes on to smash the air ship, or else capture it."

"The confounded swab! He'll not find it so easy, I warrant you."

Whistler, leaving the negroes to get the better of Carl, was working at one of the mooring ropes. This made it look as though he was trying to steal the air ship rather than to destroy it.

Carl, sweeping his makeshift weapon in a fierce circle about him and now and then bowling over a negro who came too close, caught sight of his two chums hustling for the scene.

"Hoop-a-la!" Carl bellowed. "Here comes my bards, und now you fellers vas going to ged more as you t'ought. Dere vill be doings now, und don'd forged dot! Slide indo der scrimmage, Matt, you und Tick! It vas going to be some hot vones, I dell you dose."

Just then the wrench hit a negro and knocked him off his feet.

"Dot vas me," yelped Carl, "und I gif you some sambles oof vat you vas to oxpect! I peen der olt Missouri Rifer, py shinks, und ven I shvell my banks den it vas dime peoples took to der hills! I vas der orichinal Pengal diger, fresh from der chungle und looking to gopple oop vatefer geds in my vay! Ach, vat a habbiness! Sooch a pooty fighdt vat it iss!"

It was perhaps a sad thing, yet nevertheless true, that Carl Pretzel loved a fist fight better than he loved a square meal; and that was saying a good deal—for Carl.

While he was fighting it was his custom to waste a good deal of valuable breath boasting about his own prowess and taunting his foes. Just now he was the old Missouri River and the original Bengal tiger, both rolled into one. But he had hardly finished introducing himself to the negroes before one of them hit him with a stone. The wrench dropped from Carl's hand and he turned a back somersault over the rail of the car. Before he could get up, half a dozen husky negroes had piled on top of him and he was helpless and unable to make a move.

Matt and Dick, bearing down with all speed upon Whistler, saw their chum as he tumbled out of the car. They could not do anything for Carl at that moment, however, as Whistler had straightened erect and flung a hand to his hip.

The boys knew what that motion meant. Whistler was a desperate man, and as quick to use a revolver, when he had one, as he was to use his fists when he hadn't.

"Land on him—before he can shoot!"

As Dick yelled the words, Matt cleared the distance separating him from Whistler with a wild leap. His body struck Whistler's squarely, and with a terrific impact. Both went down and rolled over and over on the ground.

The revolver, which Whistler had just drawn from his pocket, fell from his hand. Dick saw it and was less than a second in grabbing it up.

"We've drawn Whistler's fangs, mate," he shouted to Matt, who had regained his feet. "He'll not trouble us, and this piece of cold steel will give the negroes something to think about. Break away, there!" and Dick, flourishing the weapon, jumped for the crowd that had laid hold of Carl.

The negroes, from what Matt could see of them, appeared to be laborers from some neighboring plantation. Nearly all of them were big and powerful, but ran to brute strength rather than to science.

The attack on the car, there was no doubt, had been engineered by Whistler. He recognized in Matt and his friends a source of peril, and by capturing the Hawk and injuring one or more of the boys, he would be able to reduce the peril to a minimum.

It had been strange, indeed, that the boys should have encountered their old enemy there on the bank of that Louisiana bayou. But Whistler, either acting for himself or in conjunction with Jurgens, was scheming to regain possession of the iron chest. Inasmuch as the chest was presumably still in the hands of Townsend, the man whom Matt and his friends were going to New Orleans to meet, there was a reason for Whistler and the boys being in that part of the country at the same time. So their meeting was not such a remarkable coincidence, after all.

The sight of the revolver threw the blacks into a panic. Those who had captured Carl sprang away from him and retreated warily toward the edge of the timber. At the same time, the others began to draw back from the car.

"Go for 'em, you cowards!" yelled Whistler, scrambling to his feet. "You're getting a dollar apiece, all around, for this, but by thunder you've got to earn it."

"Keep away from this air ship," shouted Matt sternly, posting himself near the end of the car. "The man who lays a hand on the Hawk does so at his own peril."

"Never mind him!" bawled Whistler, "Sail into 'em with stones if you can't do any better."

Stones could be used at fairly long range, and the negroes, screened by the shadows of the timber, began at once to act upon Whistler's suggestion. Missiles, large and small, began raining down upon the boys, banging against the car, slapping into the silken envelope of the gas bag, and menacing the motor. Something would have to be done, and quickly, or disaster would overtake the Hawk.

"Stay with the Hawk, Carl!" shouted Matt. "This way, Dick! We've got to scatter those fellows into the timber or they'll put a hole in the gas bag or do some damage to the motor."

As he spoke, Matt flung away in the direction of the timber line. With a whoop, Dick followed him. Before Matt had got half way to the timber, he was struck in the shoulder and knocked down. Half stunned, and with his whole right side feeling as though it was paralyzed, he rose to his knees.

Dick had fared little better. A rock, thrown by one of the black men, had hit the revolver he was carrying and knocked it from his hand. The weapon flew off somewhere in the darkness, and while the stones continued to hail through the air, Dick went down on all fours and tried to locate the six-shooter.

"Now you've got 'em!" came the voice of Whistler. "They've lost the gun and are all but done for. Rush 'em!"

The negroes, considering that they were only receiving a dollar each for helping Whistler, were putting a lot of vim and ginger into the one-sided combat.

Giving vent to exultant yells, they rushed from the timber and, in a few minutes more, would have overwhelmed[Pg 6] Matt and his friends by sheer force of numbers. But the unexpected happened.

From the door of the hut came old Yamousa, her tattered garments flying about her as she ran. Over her head she held a gleaming white skull—either of a cat or a dog—and the picture she made, gliding through the firelight, was enough to awe the fiercest of the superstitious blacks.

"Stop!" she screeched. "Zis ees somet'ing I will not have. Zese boys are my franes—mes amis—an' I will not haf zem hurt. You hear? T'row one more stone an' Yamousa puts obi on ze lot of you, ev'ry las' one. How do you like zat, you niggers? How you like ze evil eye on you?"

Instantly the headlong rush of the blacks was stopped. Halting in trepidation, they drew together, hands drooping at their sides and every ounce of hostility oozing out at their finger tips.

The boys were amazed at the old woman's power. Under the spell of their superstition, the negroes were held as by iron chains.

"Don't let the old hag fool you!" shouted Whistler. "She can't hurt you as much as those white boys can if you leave 'em alone. They came out of the sky in their bird ship, and if you don't capture them they'll put something worse than the evil eye upon you. Never mind Yamousa!"

A murmuring went up from the blacks and they began to move undecidedly.

Hissing like an enraged wild cat, Yamousa flung herself forward and laid the skull she was carrying in the forward end of the car, just where the firelight would show it to the eyes of the black men.

"Ze white man talk," she screamed, tossing her arms, "an' what he say ees nozzing. You know what Yamousa can do—how she can spoil ze luck an' bring ze long sickness. Zis air ship ees under ze protection of Obboney. Touch heem if you dare! An' zeese white boys are my franes—hurt zem an' you hurt me. Shall I put ze spell on you? Spik!"

Lifting herself to her full height, Yamousa raised her skinny arms and waved her talon-like hands. A yell of fear went up from the blacks. To a man they fell on their knees, imploring the Obeah woman not to work any evil spells.

Whistler raged and fumed, but all to no purpose. The negroes were completely dominated by Yamousa and would not listen to him.

"Zis white man who gif you ze dollar apiece to do zis what you try," went on Yamousa, "come to Yamousa's place zis night, drag her to ze stump in ze wood, tie her zere an' beat her wiz ze stick——"

Roars of consternation went up from the blacks.

"Zese white boys save Yamousa," the hag went on, "an' now you come an' try to keel zem an' take zeir bird ship! Sacre tonnere! Me, I put obi on zat white man wiz ze black heart! You catch heem, bring heem to me, give heem blow for blow zat he struck Yamousa, an' I gif you each ze lucky charm. Zat ees better zan a dollar each, eh?"

By then the blacks were completely under Yamousa's influence. As she finished, they sprang up and made a rush for Whistler. That worthy, understanding well how cleverly he had been worsted, took to his heels and fled into the timber, the blacks whooping and yelling, and pushing him hard.

"You all right now," said Yamousa, turning to the boys with a cackling laugh. "Come back in ze house while I show you somet'ing in ze smoke."

"I don'd vant to shtay py der Hawk mit dot t'ing!" whooped Carl, pointing to the white skull. "My nerfs iss vorse as dey vas, a heap! Don'd leaf me alone, bards!"

"You go on with Matt, Carl," said Dick, "and I'll stay and watch the air ship. I guess there's not much danger now, anyhow. Yamousa has got the negroes under her thumb in handsome style, and Whistler will have his hands so full looking after himself that he won't be able to try any games with the air ship."

Carl was not in love with the idea of going into the house; still, he liked it better than staying out in the open all by himself. A supernatural twist had been given to the course of events and Carl was anything but easy in his mind. When Matt followed Yamousa back toward the hut, Carl took hold of his arm and kept close beside him.

SMOKE PICTURES.

"Sit on ze bench," said Yamousa, when they were all in the house again, pointing to the bench where Matt and Dick had rested themselves a little while before.

Carl made it a point to keep a grip on Matt, and he walked with him to the bench and snuggled up close to his side when they sat down. The Dutch boy's eyes were almost popping from his head. The queer assortment of odds and ends with which the roof and walls were decorated cast over him a baneful spell, and he was beginning to wish that he had stayed with the car.

Yamousa hobbled back and forth, getting together materials for the work she had in prospect. First, she took an earthen jar from one corner of the room and set it down in front of the boys. As she moved across the floor with the jar she sang the Creole song which Matt had already heard, finishing by aiming her finger at Carl and shrieking out the final "boum!"

Carl gave a howl of consternation, his feet went into the air, and he would have tumbled from the bench if Matt had not held him.

"Donnervetter!" gasped Carl huskily. "I dradder be some odder place as here. Vat's der madder mit der olt laty? She gifs me some cholts."

"Don't be afraid," whispered Matt. "She has proved herself a friend of ours."

"Yah, meppy, aber I don'd vant her to boint her finger ad me like dot some more."

Yamousa got a small box from a cupboard and emptied a brownish powder out of it into the jar; then, with a pair of tongs, she removed a live coal from the fireplace and dropped it into the jar with the powder.

A wisp of smoke floated upward, accompanied by a sizzling noise. The noise increased until it resembled the buzzing of a swarm of bees, and the smoke spread out until it filled all that part of the room, growing denser every moment.

In and out through the vapor, stumbling around the jar in a sort of dance, moved Yamousa, tossing her arms and crooning a chant.

The boys stared breathlessly. Yamousa's candle was on the other side of the room, glowing like a coal through the vapor.

Suddenly figures began to take shape in the smoke, the filmy fog thickening in places and decreasing in others as though some invisible hand was moulding the black haze into a scene en silhouette.

By degrees the picture perfected itself until, at last, it lay clearly before the boys.

They saw a broad river on which a small boat was floating. There was no one in the boat, but on the stern thwart, in plain view and unmistakable, was Townsend's iron chest.

The boat and the chest heaved and rolled on the waves, and the oars in the oarlocks played up and down on the surface of the water.

Then, as the two boys watched, scarcely breathing, so great was their interest and excitement, a vague shape came gliding over the river out of the distance. Presently the shape resolved itself into the form of the air ship. The Hawk glided low and halted hoveringly over the boat.

There were three passengers in the air ship's car, and Matt and Carl had no difficulty in recognizing themselves and Ferral. A rope was thrown downward by Ferral, and Matt could be seen climbing over the rail and descending the rope.

On reaching the boat, Matt made the rope secure to the iron handles of the chest and Carl and Dick laid back on the rope and drew the chest upward.

The moving picture had proceeded thus far when Carl, overcome by the uncanny nature of the whole proceeding, lifted a hair-raising yell, hurled himself from the seat, and bolted for the door.

The frenzied shout seemed to destroy the spell. The smoke billowed shapelessly into a blank fog, and Matt darted from the house after Carl.

Dick, startled by the Dutch boy's shout, had run toward the cabin, meeting Carl a few yards from the air ship.

"Der olt laty vas der teufel," Carl was excitedly explaining to Dick. "She makes moofing bictures, py shinks, oudt oof nodding but shmoke. Ve see der air ship, und meinseluf, und you, und Modor Matt, und ve vas doing some t'ings vat I don'd know und vat ain'd peen done, yah, so helup me. Led's ged avay from here, mitoudt losing some more time."

Carl was in a nervous condition, and while he talked he jumped up and down and flourished his arms. When he was through, he made a bolt for the Hawk, but Matt was close enough to catch hold of him.

"Don't get excited, Carl," said Matt. "Calm yourself down."

"How I vas going to do dot," exploded Carl, "ven I see der hocus-pocus dot olt laty make mit us? Himmelblitzen! She iss some relations mit der Olt Nick, und oof ve know ven ve vas vell off ve vill pull oudt oof here righdt avay."

"Chuck it, Carl!" said Dick. "I guess there ain't anything going to hurt you. Give me a line on this, Matt. I can't overhaul Carl's talk and get much sense out of it."

Matt proceeded to describe what had taken place in the hut. Dick listened with wide eyes.

"Keelhaul me if I ever heard anything like that before!" he exclaimed, when Matt had finished. "It sounds like a yarn for the marines. You two must have been hypnotized and imagined you saw all that. Fakirs in India do stunts of that sort, but they only make people think they see such things; they don't really see them."

"I know ven I see somet'ing, you bed my life," fluttered Carl, "und I see der air ship, und you and Matt und meinseluf in der shmoke, und ve do t'ings schust so natural like life. It don'd vas some treams, I tell you dot. Oof——"

Carl was interrupted by a shrill cry from the hut door.

"Come once more an' see ze smoke picture! Come queek!"

"Nod me!" and Carl galloped on toward the air ship.

"We'd better go, Dick," said Matt.

"Do you think Carl will try to unmoor the Hawk?" returned Dick, with a hurried look in the direction Carl had gone.

"No, he won't do that."

Matt and Dick thereupon retraced their course to the hut. Yamousa had vanished from the door and the boys groped their way through the stifling, pungent vapor to the bench.

The smoke picture had already been formed and showed the interior of a room with stone walls. On the floor of the room lay a man, bound hand and foot and, to all appearances, a prisoner. He had gray hair and mustache, and his features, although vague and indistinct, were easily recognized.

"Townsend!" whispered Matt.

"Aye!" returned Dick, "Townsend, as I live!"

The stone chamber faded into the front of a building, and along the front was a sign, the lettering of which could easily be read: "M. Crenelette, Antiques."

This second picture faded and Yamousa laid a piece of board over the top of the jar. Slowly the air cleared and the old woman stepped close to the bench, shaking her withered head until the gold rings in her ears and nose danced glimmeringly.

"You know ze man in ze stone room?" she asked.

"Yes," replied Matt, in a stifled voice.

"Ah, ha! Zat will be in New Orleans. Me, I live zere one time. Ze front of ze buildings you see has ze stone chamber in ze basement. Eet ees in Royal Street, on ze French side of Canal. You look an' you fin' ze sign, zen you get ze white-haired man away from ze enemies. Go 'way an' sleep; zen, in ze morning, I gif you breakfus, an' you go on to ze big city an' safe your frane. Bo' soir, mes amis! Sleep an' do not fear."

Without answer, Matt and Dick stumbled out of the house, full of wonder and bewilderment.

"Strike me lucky!" breathed Dick. "This is the first time anything like that ever crossed my hawse. The question is, is there anything in it, or is it all a fake?"

"I don't take much stock in wonder-workers like Yamousa," answered Matt, "because they usually prey upon the ignorant and the superstitious. I haven't the least[Pg 8] notion how she make the pictures. That part of it is strange enough, and maybe, as you say, she only hypnotizes us and causes us to think we see something that isn't really in the smoke at all. But I don't see how those pictures can really mean anything, and I'm going to bunk down in the car and get some sleep."

Matt tried to persuade himself that the smoke pictures of Yamousa were merely a trick, but somehow the idea that there might be something in them clung to his mind. Although his thoughts kept him unsettled and restless for a time, yet he finally fell asleep.

There was no sleep for Carl, however. He found the revolver that had been knocked out of Dick's hand by the flying stone. The mechanism had been damaged and the weapon was useless, but nevertheless Carl felt safer with it, and placed himself on guard.

Dick, like Matt, was able to get some rest, and the night passed uneventfully. It was only when morning dawned that anything of an unusual nature occurred.

A shout from Carl brought Matt and Dick to their feet. Carl had retreated until he was standing midway between the air ship and the edge of the clearing, his fearful eyes on Yamousa, who was crouching at the side of the car.

"Queek!" cried Yamousa, "hurry away. Your enemies come—I see zem in ze smoke—an' zey come close. Leesen!"

She held up one talon-like finger in token of silence. From somewhere, off in the timber, could be heard faint sounds as of some one approaching through the undergrowth.

In another moment the boys were actively at work casting off the ropes.

"Take zis," said Yamousa, handing Matt something wrapped in a piece of newspaper. "It will breeng you ze luck. You haf helped Yamousa, an' Yamousa she try to help you. But hurry; zere ees no time to lose."

Carl, gathering courage from the prospect of an early departure from that ill-omened spot, ran forward and helped Dick with the ropes.

Matt laid the small parcel Yamousa handed to him in the bottom of the car and immediately got the engine to going. The woman, meanwhile, with an apprehensive look over her shoulder, had started toward the timber.

As Dick and Carl leaped into the car, Yamousa gave a screech of warning and pointed toward the other side of the cleared space.

One look in that direction was enough for Matt. Half a dozen white men had hurried into sight. Whistler was in the lead.

"Let 'er go, matey!" yelled Dick. "They'll be on us in half a minute."

Matt, with a twist of a lever, threw the power into the machinery and the Hawk took the push and glided upward.

A QUEER FIND.

Had the boys been a minute later in casting loose, there would certainly have been trouble—and perhaps they would not have been able to get away at all.

Whistler, who was well in advance of the others, strained every nerve to reach the car, but the Hawk was well in the air before he reached the spot where it had been moored. Neither he, nor any of those with him, seemed to be armed. No shots were fired, and Whistler shook his fist upward and shouted maledictions.

"Py chiminy," whooped Carl, "ve'll led him vistle some. He ought to be good at dot."

Swiftly the clearing vanished behind the Hawk, and the tops of the trees soon hid it entirely.

Carl drew a long breath.

"I vas nefer so habby ofer anyt'ing as I vas to ged avay from dot blace," he averred. "Der olt voman vas pad meticine, und ve vas lucky dot ve vas aple to ged avay ad all."

"Avast there, matey!" answered Dick. "Yamousa tried to be a friend of ours."

"I don'd like friendts vat iss so spookish," went on Carl, kicking the cat's skull off the front of the car and watching it tumble into the green tree tops below. "Dere iss all kindts oof drouples come oof sooch pitzness."

"She said she looked into the smoke and saw Whistler and those other fellows coming," muttered Dick.

"Meppy she dit, und meppy she saw dem, or heard dem."

"If she saw Whistler and his outfit in a smoke picture," went on Dick, "and then came to warn us, it not only proves that she means well, but that there's something in that smoke business."

Matt smiled a little.

"We'd better forget all that happened last night, pards," said he. "We can't make head or tail out of it, anyhow, and I don't believe in worrying over things you can't understand. We helped Yamousa; and Yamousa, in her own way, has tried to befriend us. Suppose we let it go at that and sponge out the occult part of it? The biggest, and possibly the most amazing discovery we made, was that Whistler got clear of the Bahamas and seems to have got this far on the trail of the iron chest. If Whistler is on the trail, no doubt Lat Jurgens is, also. Perhaps Townsend knew about this when he telegraphed us to come to New Orleans."

"I hope nothing has happened to Townsend," murmured Dick, his mind reverting to the smoke picture he had seen.

"There you go again," laughed Matt. "You're still thinking of what Yamousa showed us, and imagining there may be something in it. Cut it out, Dick. If there's anything in the picture we'll know it before long. Dip into the ration bag and get out some breakfast—I'm nearly starved."

While Dick held to the post of lookout, Carl drew on the food supply and all hands ate a cold breakfast.

After the meal the boys passed an hour discussing Jurgens and Whistler, their designs on the iron chest, and the way they had probably escaped from the sand key in the Bahamas. For the most part, the discussion led nowhere. The boys could make guesses, but unless they were to put their faith in what Yamousa told them, their talk could bring them to nothing definite.

The conversation was interrupted by Dick.

"Mississippi, ho!" he cried. "The river's dead ahead, mates, and hard under our forefoot."

"Good!" exclaimed Matt. "We'll follow the river to New Orleans."

"Where we going to keep der air ship when we reach der city?" inquired Carl.

This was always a conundrum to the boys. The Hawk was so big and unwieldy, and withal so easily damaged, that to stow it away where it would be safe from wind and storm was a difficult problem.

"We might anchor the Hawk on some scow in the river," suggested Dick, "and then put the canvas cover over her. If we find we're going to stay in New Orleans long, it might pay to build a roof over the scow."

"That would cost too much," objected Matt. "It would take a mighty high roof to clear the top of the gas bag, and a mighty big one to cover it. Why not berth her on one of the docks? The docks are high, they're roofed, and there's always a watchman in charge."

"Right-o!" said Dick. "You've tagged on to the right rope, old ship. We'll use the docks. Stuyvesant Dock will about suit us. I was in this port once on the old Billy Ruffin. We coaled over in Algiers, and some of us had shore leaves. A great town, that, and——"

Carl, who had been leaning over the rail, went limp and white all of a sudden and looked around with staring eyes.

"What's the matter with you, mate?" demanded Dick, startled by the Dutch boy's manner. "Sick?"

"N-o-o," gurgled Carl, "I vas vat you call flappergasted—so astoundet mit vat I see dot I can't shpeak. Look ofer der site, und see vat you see py der rifer. Ach, du lieber! I don'd know vat to t'ink."

Matt had already swerved the Hawk into an upstream course. The murky waters of the Mississippi lay no more than a hundred feet below, and the light, variable winds were helping rather than retarding the air ship.

Matt and Dick both cast downward looks over the guard rail, and what they saw caused them to straighten erect and stare at each other in amazement. For a moment or two, neither could speak.

Ahead of them drifting downstream with the current was a skiff. Although there were oars over the skiff's sides, trailing in the water, the boat was empty.

In the stern sheets, however, was the iron chest!

The boys had seen that particular iron chest so many times that they were perfectly familiar with its appearance.

During the interval that passed while the lads were staring at each other, before the mental eyes of all of them floated that smoke picture seen the evening before in Yamousa's hut.

"Der olt Nick has somet'ing to do mit dot," muttered Carl, drawing one hand over his puzzled eyes.

"It's the queerest find I ever heard of!" stuttered Dick. "From the way you described that first smoke picture to me, Matt, this event is fitting into it in a way that takes my breath."

"It—it might be a coincidence," mumbled Matt, hardly knowing what to believe, now that he was face to face with such a reality.

"Coincidence nothing!" averred Dick bluntly. "Yamousa has powers we never dreamed of. She may be a clairvoyant, or something like that."

"I never took much stock in clairvoyants," demurred Matt.

"Well, anyhow, there's the chest. In some manner it's got away from Townsend."

"Exactly," said Matt, throwing aside the uncanny feeling that had come over him. "No matter how we happened to make this queer find, nor how little we understand the manner in which we made it, our duty is clear. We've got to recover the chest, find Townsend, and turn it over to him."

"Stand by, then, to go aboard the skiff," called Dick. "Port your helm, Matt. I'll do the conning for you."

"Keep away!" shouted Carl. "Don'd go near dot poat und don'd fool mit dot safe. It's pad meticine! Eferyt'ing iss pad meticine vat has anyt'ing to do mit dot olt laty. Ach, blitzen, I vish ve hatn't seen dot poat!"

But Matt and Dick knew what their duty was and paid little heed to Carl's protests.

Guided by Dick, Matt brought the Hawk within a dozen feet of the boat, cut off the power, and the air ship hovered in the air, motionless save for the slight influence of the wind. Dick tossed a rope over the side. Matt, leaving his seat among the levers, prepared to get over the rail and lower himself into the boat.

"Hadn't I better go, matey?" queried Dick. "I'm used to sliding up and down ropes and backstays."

"You and Carl stay here and make ready to hoist the safe aboard," replied Matt. "I'm a pretty fair hand at rope climbing."

Probably none of the boys thought, at that moment, how closely they were copying the smoke pictures shown Matt and Carl by Yamousa. That smoke scene seemed to have depicted the event with the sureness of fate.

Matt dropped over the side quickly, in order to get into the boat before the Hawk should drift away from it. He succeeded in carrying out his design and, still clinging to the rope, stepped from the gunwale of the skiff to one of the midship thwarts and then into the stern.

There was nothing in the boat to show who the occupant had been. A bailing tin lay in the bottom, but there was absolutely nothing else in the skiff apart from the iron chest.

"Work quickly, old ship!" Ferral called down. "The wind is freshening and we'll be blown away from you if you don't hustle."

Swiftly, Motor Matt secured the end of the rope to one of the iron handles.

"Haul away," said he, stepping back.

Carl and Dick seized the rope and began to pull. The chest rose slowly into the air; and then, when it was lifted about half way, one of the sudden gusts of wind which the Hawk had been encountering all along the Gulf coast struck the air ship, and she leaped sideways nearly to the shore of the river.

Carl and Dick secured the rope frantically. While the chest continued to swing below the car, Dick jumped into the levers and got the propeller going. This gave him a better command of the air ship and he attempted to manœuvre the craft back and into Matt's vicinity.

Again and again he tried, but, as the wind was now high and shifting quickly from one quarter to another, no success attended his efforts.

"Take the chest aboard," Matt cried, standing up in the skiff and making a trumpet of his hands, "and go on to town. Berth the Hawk on one of the docks, if you can, and, if you can't, make a landing farther inland. I'll follow you."

There was nothing else to be done, and Matt watched the Hawk bear away up the river, Dick at the motor and Carl heaving in the chest by slow degrees.

FOUL PLAY.

Matt was greatly worried over the way that experience with the boat and the chest had worked out. Dick knew enough about handling the air ship to be able to look after her in ordinary weather, but those shifting air currents had bothered even Matt. It was so easy for some little thing to go wrong and either wreck or cause irreparable damage to an air ship. In that respect, an air ship was totally unlike any other craft.

But there had been no other way out of the dilemma and Matt, facing the situation with all the grace he could muster, dropped on the midship thwart, seized the oars, and headed the skiff upstream.

Fortune favored him a little, for a lugger from the oyster beds came lurching up the river, all sails set and bound for the landing. Matt hailed the lugger and the oysterman took him aboard.

He said nothing to the lugger's crew as to how he had happened to be in the skiff. Had he done that, one explanation would have led to another and it would have been necessary to speak of the iron chest—a subject which it was well enough to keep in the background.

When the lugger tied up at the landing, Matt left the skiff with her crew and went ashore. His object now was to find Carl, Dick, and the Hawk, and he made his way along the river front in the direction of Canal Street. He could see nothing of the Hawk in the air, but along the wharves he encountered several groups of roustabouts who were talking excitedly about the "flying machine" that had recently passed over the town.

By making inquiries, he learned that the Hawk had settled earthward in the vicinity of the Stuyvesant Docks. Instructions were given him as to the best way for finding the docks, and he hurried on.

Fully three hours had passed since the chest had been recovered and the Hawk and Matt had parted company. A good many things could happen in three hours, and Matt continued to feel worried.

As he was passing the Morgan Line Docks he saw Dick bearing down on him. The look of elation in Dick's face was indirect evidence that all was right with the Hawk.

"Hooray!" shouted the Canadian. "You were so long turning up, matey, that I was afraid something had happened to you. I hope we won't ever again part company like we did down there on the river. Confound this Louisiana wind, anyhow! It never blows twice from the same direction, seems like. You didn't row all the way to town against the current?"

"If I had, Dick," answered Matt, "I couldn't have got here before night. A lugger picked me up. Where's the Hawk?"

"Safely berthed on the big dock. I gave the dock watchman a five-dollar note to look after her and keep curious people away. We've stretched a rope around the air ship and no one can get within a dozen feet of her. She's as snug as possible, and there couldn't be a better place for her. Why, the dock's better than that old balloon house in South Chicago!"

"Where's Carl?"

"He went away with Bangs, and——"

"Bangs? Who's Bangs?"

"Why, he introduced himself to Carl and me as soon as we got the Hawk moored. He's a friend of Townsend's and has been hanging out on the levee looking for us ever since Townsend sent that telegram asking us to come. He was there by Townsend's orders, and was to tell us where to berth the Hawk and where to go our selves."

"I should think Townsend would have been there to meet us," observed Matt.

"Oh, that's all right—Bangs explained that point. Townsend is full of business, these days, and asked Bangs as a favor to watch for us."

"What did you do with the iron chest?"

"Bangs and Carl took it away in an express wagon. As soon as Carl delivers the chest to Townsend, he's coming back to the docks. I told him that, by that time, you'd probably be there, and that we could all go up to see Townsend. Bangs said that Carl would surely get back to the docks by noon."

As Dick finished speaking, the noon whistles took up their clamor.

"Did Bangs identify himself in any way?" asked Matt.

"Why, no," answered Dick, puzzled. "It was identification enough, I thought, to have him meet us, tell us all about Townsend, and say Townsend had sent him to watch for us."

"That might be a yarn, Dick, with not a particle of truth in it."

"But he was on the levee——"

"Everybody up and down the river front could see the Hawk, so you were known to be coming. Well, maybe everything is all right. Carl went with Bangs and the chest, anyhow. He'll see that the chest is properly delivered."

"Bangs insisted on either Carl or me going with him to see Townsend," pursued Dick, "and that gives the whole business a straight look. If there was anything crooked about Bangs he wouldn't have wanted any one to go with the chest, see?"

Dick was so honest himself that he was rarely looking for treachery in others. Matt made no response to what he had just said, but turned the subject, as they walked together in the direction of the Stuyvesant Docks.

"Did you have any trouble making a landing, Dick?" he asked.

"There was a big freight boat alongside the docks and she blanketed us against the wind. If it hadn't been for the freighter, Carl and I might have had more than we could attend to. We just grazed the steamer's stacks, ducked under the dock roof, and rounded to as neat as you please. We were lucky rather than skillful, you see, for it would have been an easy matter to smash the Hawk into smithereens."

The boys continued on along the levee, and on every hand the queer craft that had dropped out of the sky was the topic of conversation. Not many people were allowed on the dock where the Hawk was moored, but there were a few curious ones clustered around the guard rope and surveying the craft.

Carl Pretzel, however, was not in evidence.

"He's probably been delayed," suggested Dick. "We'll just hang around and wait for him."

While they were waiting, the watchman came up to them.

"It's none o' my business," said he, "and I reckon you'll think I haven't any call buttin' in, but that feller[Pg 11] that drove away with your friend, in the express wagon, hasn't got a very good character in this town."

"Is that straight?" queried Dick.

"Straight as a plumb-line. He's as crooked as a dog's hind leg. Proctor used to run a boat on the river, but he took to drinkin' an turned 'shady,' an' now he's not much better than a loafer. I'd have told you before, only I supposed you knew what you was doin' an' that you wouldn't thank me to interfere. I heard Proctor say, though, that your friend would sure be back here by noon. Well, it's noon, an' he ain't here. That's why I'm talkin' now."

"Proctor?" cried Dick. "Why, he said his name was Bangs."

"He's been known to change his name before now, so I ain't surprised at that. But his real name is Proctor."

The watchman went on about his business, and Matt and Dick withdrew by themselves in no very easy frame of mind.

"Dowse me!" growled Dick. "Can't Carl and I be away from you for a few hours, old ship, without making fools of ourselves? But Bangs told such a straight yarn——"

"If a trap was laid, Dick," interposed Matt, "it was a clever one and I don't see how you could avoid dropping into it. It's a pretty safe guess, I think, that there has been foul play. This fellow Proctor, or Bangs, wanted the iron chest and laid his plans to get it."

"But how could he lay his plans?" muttered Dick. "Sink me if I can understand that part of it. First off, he couldn't have known we had the iron chest, seeing that we fished it out of that skiff so recently."

Matt listened thoughtfully. He was trying to figure the matter out in his own mind, but it was a difficult problem.

"Then, again," continued Dick, "Bangs was here watching for us. If he wasn't a friend of Townsend's how could he have known we were coming?"

"From what we knew of Archibald Townsend," answered Matt, "we can bank on his being honest and square. If that's the case, he'd hardly have a friend like Bangs, would he? And certainly, if he knew Bangs, he'd hardly trust him to meet us, as Bangs told you he had done."

"I'm a swab," growled Dick, with profound self-reproach, "and Carl's a swab. We've dropped into a tangle of foul play, and it don't make it any brighter because we can't understand where Bangs got the information that enabled him to carry out his plot. I had an idea that I wouldn't let Bangs touch that iron chest until you got here, but he told such a straight story that I was argued out of my original intention. Oh, keelhaul me!"

Dick fumbled in his pocket for a handkerchief. When he drew it out, a bit of crumpled newspaper came with it.

"Ah," muttered Dick, picking up the bit of paper, "maybe Carl will have some luck. He unwrapped that little parcel Yamousa gave you as we were leaving the bayou. What do you think we found in it?"

"A rabbit's foot?"

"No, a dried frog! Carl, before he started away in the express wagon, put the frog in his pocket. He said he'd try it out before he turned it over to you. If we're right in thinking that Bangs is playing a treacherous game, then Carl will have plenty of chance to find out what the charm is good for."

"We've got to be doing something, Dick," said Matt. "We can't hang around and wait for the dried frog to help Carl."

"We might slant away and look up that expressman," returned Dick. "He could probably tell us where he took Carl, and Bangs, and the box."

"A good tip!" exclaimed Matt. "We'll go on a still hunt for the expressman."

After reassuring himself that the Hawk would be safely looked after by the watchman, Matt and Dick left the docks and began hunting for the man who had been hired by Bangs to take the iron chest into the town.

DRIED FROGS—AND LUCK.

Mr. Bangs had a very dark complexion, black hair, black eyes, and a ropy black mustache. His face had a puffed, unhealthy look—probably due to dissipation—and his walk was a sort of slumping process which proved, beyond the power of words, that he was dead to ambition and lost to hope. In the worst sense of the term, he had ceased to live for himself and was living for others—a mere tool for the unscrupulous whenever there was a dollar to be turned.

And yet there was something very plausible about Bangs. He had an engaging way with him, whenever he desired to put it forward, and he used it to the limit when accosting Dick and Carl on the docks.

Carl, no less than Dick, believed firmly that everything was all right, and that Bangs was really the friend of Townsend and had been sent to the levee to watch for the air ship. It pleased the Dutch boy to think that he was to go with Bangs and the iron chest, and he was delighted with the dried frog amulet, which Matt had seemed to forget about since leaving the bayou.

Of course Carl believed in charms. Having a wholesome regard for Yamousa's powers, it was natural for him to have abundant faith in the dried frog. Stowing the relic away in his pocket, he mounted the express wagon with the utmost confidence, waved his hand to Dick, and then rolled away with Bangs, the expressman, and the iron chest.

Carl's "luck" began the moment the express wagon turned into Canal Street. The old, square stone flagging, in that part of town, was deeply worn. The front wheel of the wagon on Carl's side plunged into a rut, and Carl fell forward on the backs of the mules and then rolled down under their heels.

The hind heels of a mule are dangerous objects to tamper with, and in less than half a second the expressman's team got very busy.

Carl distinctly remembered pitching over upon the backs of the mules, and he had a hazy recollection of slipping down inside the pole, but after that he drew a blank. When he opened his eyes and looked around, he was sitting up in the street, supported by Bangs. The expressman was picking up his hat, and a crowd was gathering.

"It was a right smart of a jolt," grinned one of the bystanders.

"Don't you-all know it's bad business t' tampah with the south end of a mu-el goin' no'th?" asked another.

"Vas it an eart'quake?" inquired Carl, mechanically taking his hat. "Der puildings vas shdill shdanding on der shtreet, und nodding vas dorn oop mooch, aber somet'ing must haf habbened."

"You done drapped on de mu-els," said the colored proprietor of the express wagon. "Dey's gentle, an' dey'll eat oats off'n de back of a choo-choo engyne, but dey won't stan' fo' no meddlin' wid dey feet."

"Hurt?" inquired Bangs, helping Carl erect.

"Vell," answered Carl, feeling himself all over, "dere don'd vas any vone blace vere I feel der vorst, but dere iss a goneness all ofer me, oop und down und sideways. Oof I hat a gun," he finished, his temper rising, "I vould go on a mule hunt."

Carl slapped the dust from his clothes and climbed back into the wagon. Before he gripped the seat with both hands, he transferred the dried frog from the left-hand pocket of his coat to the right-hand pocket.

"Meppy I ditn't put it in der righdt blace," he thought.

The express wagon turned from Canal Street into Royal, and from Royal into St. Peter, halting before a dingy building, with iron balconies, not far from Congo Square.

A mulatto woman sat in the doorway of the building with a basket of pralines in front of her on the walk. Carl took one handle of the chest, and Bangs the other. The chest, being of iron, was heavy. Somebody had spilled a pitcher of milk on the sidewalk and Carl's foot slipped as he crossed the wet spot. His end of the chest dropped, barking one of his shins and landing on the toes of one of his feet.

Carl gave a yell of pain and toppled over, sitting down with a good deal of force in the basket of pralines. The praline vendor had been knitting, but she sprang up, when she saw the destruction the Dutch boy was causing to her stock in trade, and tried to make a pin cushion of him with her knitting needles.

Bangs rushed to the rescue, and Carl, after placating the woman with a silver dollar, once more picked up his end of the chest and limped after Bangs.

The doorway through which they passed led them into a narrow, ill-smelling corridor, open to the sky and filled with rubbish. Out of the rubbish grew a number of untrimmed and uncared-for oleander bushes.

"Now," remarked Bangs, not unkindly, "you can sit down here and rest. I'll have the creole gentleman who lives here help me up to Townsend's room with the chest; then I'll tell Townsend about you, and he'll come down and give you a hearty greeting."

"Mebby I pedder go mit der chest?" objected Carl.

A look of pained surprise crossed Bangs' face.

"You don't think for a moment, my dear friend," said he, "that I'm trying to deceive you? I merely wish to announce your coming to my friend Townsend so that he'll come down here personally and give you welcome."

"Ach, vell go aheadt," muttered Carl, dropping down on a box near a clump of oleanders and nursing his foot.

Bangs gave a whistle. The creole gentleman, barefooted and wearing a red flannel shirt and tattered trousers, appeared in the courtyard from nowhere in particular, and he and Bangs passed a few words in French. The creole gentleman grinned a little and laid hold of one of the iron handles. Bangs took the other, and they carried the iron chest up a stairway to a gallery on the second floor.

Carl watched the two mount the stairs and pass around the gallery to a door; then the door opened and the two men and the iron chest disappeared. The creole gentleman did not show himself again, and if he left the room into which he had gone with Bangs he must have passed out by some other way than the gallery.

The moment Carl was by himself, he changed the dried frog to the breast pocket of his coat.

"I don'd got him in der righdt blace for luck," thought Carl. "Meppy dot iss pedder. Oof I lif long enough to ged der frog vere he ought to be, I bed you I haf some goot fortunes."

While Carl leaned back, and waited, there came a shrill cry from behind another clump of oleanders:

"Get out of here! Get out! Get out! Sic him, Tige!"

Carl, fearing the onslaught of a dog, snatched up a piece of wood and jumped to the top of the box. No dog came.

"Don'd you set some dogs on me!" he called. "I got as mooch righdt here as anypody. I vas vaiding for Misder Downsent. Who you vas, anyhow?"

"You're the limit!" came the shrill words. "Go soak your head! Police! Police!"

As the last word rang through the courtyard, Carl's cap was jerked off his head from behind. With an angry shout, he whirled just in time to see the branches shaking as the thief got away.

"I'm der limid, am I?" he muttered, crashing through the bushes. "Want me to go soak my headt, hey? Vell, py chiminy, I show you somet'ing."

When Carl got through the bushes the thief had disappeared, but a wild, rollicking laugh came from behind the other thicket of oleanders. Running in that direction he came upon a yellow-crested parrot chained to a perch. The parrot seemed to be getting a good deal of fun out of the situation, for he was lifting himself up and down and chuckling fiendishly.

"Vy," gasped Carl, a slow grin working its way over his face, "it vas a barrot! Pooty Poll! Sooch a nice pird vat it iss! Vant some crackers? Say somet'ing, vonce, und——"

Just at that moment, something hit Carl on the back of the head. Whirling away from the parrot, he looked upward. A black monkey was clinging to the ironwork of the gallery overhead. In one paw the monkey held Carl s cap, and with the other paw he was fishing bits of plaster out of the wall and throwing them downward.

"Und dere iss a monkey, too!" exclaimed Carl. "It looks like I vas in a menacherie. Say, you monk, gif me dot hat!"

"Sic 'im, Tige!" shrilled the parrot. "Police! police!"

The monkey chattered and flaunted the cap defiantly, at the same time getting ready to throw another piece of plaster.

"Nice leedle monk!" wheedled Carl. "Iss der leedle monkey hungry? Den come down und ged some peanuds vich I ain'd got! Pooty leedle monk! py shinks, I vill preak you in doo oof you don'd——"

Biff!

The piece of plaster came downward, straight as a die, and landed on Carl's chin. That was more than Carl's temper could stand, and he started up the stairway toward the gallery.

In order to get near the monkey he had to run around[Pg 13] the gallery, past the door through which the creole gentleman and Bangs had vanished with the chest.

There was a window, set in a sort of embrasure, beside the door, and one of the lights was broken out.

As Carl passed under the window, on his way around the gallery, he heard a voice that brought him to a gasping halt. All thoughts of his stolen cap, and the monkey, left his mind.

Staggering up against the balcony rail, he stood there blinking in stunned bewilderment.

"Vas I ashleep?" he whispered; "vas I treaming? I vonder oof I can pelief vat I hear, or——"

He broke off his words abruptly, turned and stepped to the wall. Here he paused just long enough to shift the dried frog from his coat to his trousers pocket, then, softly, climbed into the embrasure and peered through the broken pane of the window.

No, he had not been asleep, or dreaming.

He was peering into a room in which were two men, neither of whom was the creole gentleman.

One of the men was Bangs, and the other was—Lat Jurgens! Between them stood the iron chest.

THE PLOTTERS.

"You're a good one, Proctor!" Jurgens was saying, leaning over the chest and rubbing his hands. "This is the biggest piece of luck that ever came my way. Did Whistler have anything to do with it?"

"Whistler?" returned Bangs. "How could he have anything to do with it? He's not in town."

"I know that, but he went to see the voodoo woman to try and have her give him a line on the chest. He left yesterday, and here the chest drops into our hands. It looks to me as though old Yamousa had been giving us a helping hand."

"Bosh!" returned Bangs disgustedly, "Yamousa didn't have a thing to do with it. I was waiting for that air ship to come in, accordin' to that telegram Townsend sent to Motor Matt and which you found out about. It came, but there were only two boys in the car. They landed on Stuyvesant Dock, and they hadn't any more than got the craft secured before I was right there. I told 'em the yarn we had framed up—how Townsend was expecting them but was so busy he couldn't come, so had sent me." Bangs chuckled. "They swallowed the yarn, all right," he went on. "While I was talking I saw the iron chest in the car. Say, that almost took me off my feet. However did it happen to get into the hands of those boys?"

"Pass the ante, Proctor. Didn't they tell you?"

"Nary a word. They said Motor Matt would be along, in a little while, but that's all they told me about him. I suggested that one of them go with me to take the chest to Townsend, and the Dutch boy was the one who came. He's down in the courtyard now, waiting for Townsend to come and give him a welcome."

Bangs dropped into a chair as he finished and gave vent to a low laugh.

"Didn't they ask you how Townsend had come to get separated from the chest?" asked Jurgens.

"Yes."

"And what did you tell 'em?"

"The truth; that the chest had been stolen from Townsend. Even then the two boys wouldn't tell me where they had found the chest. I reckon Motor Matt, who seems to be pretty long-headed, must have warned them to keep mum."

Jurgens continued to chuckle and rub his hands.

"Blamed if things aren't coming our way better than I had imagined they would!" he exclaimed. "This is rich, and no mistake. And you say the Dutchman is down in the court?"

"That's it."

"Waiting for me to slip down and give him the glad hand?"

"That's what he's waiting for," guffawed Bangs.

"Well, I'll give him the hand, all right, but there'll be something in it. We've got to take care of him, in some way, until——"

Whatever Jurgens' plans were concerning Carl they did not appear. Fate, at that moment, hastened events toward a conclusion.

The square window, against which Carl was leaning and listening, was far from secure. In his interest and excitement, he bore rather harder upon the window than he intended. As a result, the window suddenly gave way and Carl fell crashing with it into the room.

Just how much the dried frog in Carl's pocket had to do with the mishap is for those versed in superstitious lore to answer. Ever since he had taken possession of the charm he had encountered a run of hard luck, but everything that had so far happened to him was trivial as compared with this final catastrophe.

Before he could get to his feet he had been pounced upon by Bangs and Jurgens, dragged clear of the broken glass and held firmly down on his back.

"He's not so much of a fool as you thought, Proctor!" growled Jurgens. "He was in the window, listening."

"Much good it'll do him!" grunted Bangs. "We've got the chest, and what he discovered won't do him any good."

"You bet it won't! Get a rope."

Bangs secured a rope from somewhere in the room and Carl was expeditiously lashed by the hands and feet.

"Himmelblitzen!" ground out Carl. "You vas a humpug, Pangs! You say you vas somet'ing, und you peen somet'ing else. Py chincher, oof I hat der use oof my handts I vould make you t'ink you vas hit mit some cyclones."

"Oh, come," laughed Bangs, "don't be so fierce. We've got you, and we've got the chest, and that pal of yours is away off on Stuyvesant Dock and hasn't the least notion where you are. Sing small, my fat kiskidee; it won't do you any good to take on."

"Vait, py chinks!" flamed Carl; "schust vait ondil Modor Matt findts oudt vat iss going on. Den, I bed you, someding vill habben. I don'd know nodding, und Tick he don'd know nodding eider; aber Matt—vell, dere iss a feller vat knows more as you. Look oudt for him, dot's all."

"Where is Motor Matt?" demanded Jurgens.

"Ask me," said Carl.

"That's what I'm doing."

"Veil, keep on; und ven I dell you somet'ing, schust led me know. Churgens, you vas a pad egg, und you[Pg 14] vill ged vat's coming by you vone oof dose tays. How you ged off dot islant in der Pahamas?

"Ask me," taunted Jurgens.

"Vat a frame-oop!" muttered Carl dejectedly. "Look here, vonce: Vere iss Downsent?"

"Ask me again," said Jurgens mockingly.

"How you steal dot chest from him?"

"I don't mind telling you that," grinned Jurgens. "The information can't possibly harm us, because we'll be out of the way long before you can tell any one; and I'd like to have Motor Matt, who's been bucking us ever since we first went on the trail of the chest, know just what we've done to his friend Townsend.