Transcriber's Note

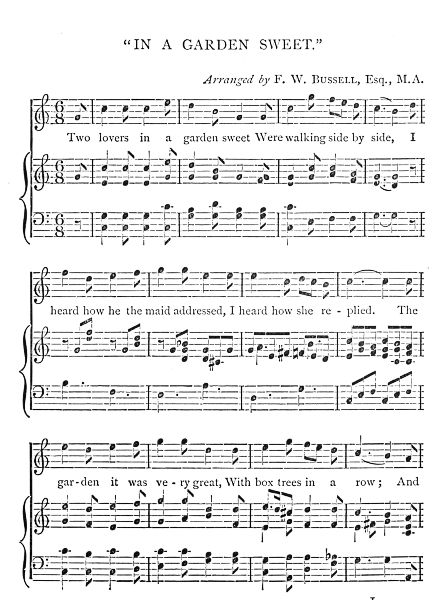

In the html version of this e-book, Midi, PDF, and MusicXML files have been provided for the songs. To hear a song, click on the [Listen] link. To view a song in sheet-music form, click on the [PDF] link. To view MusicXML code for a song, click on the [MusicXML] link. All lyrics are set forth in text below the music images.

BY THE SAME AUTHOR.

HISTORIC ODDITIES AND STRANGE EVENTS.

Demy 8vo, 10s. 6d.[Just published.

ARMINELL: A Social Romance.

3 vols., crown 8vo. [Now ready.

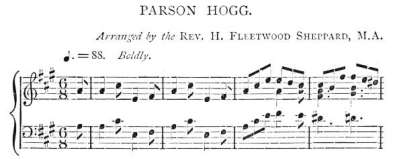

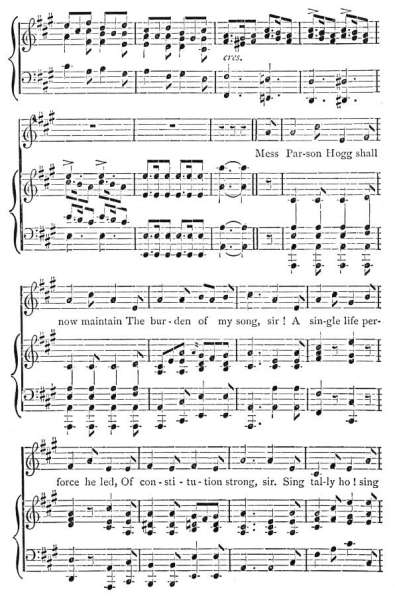

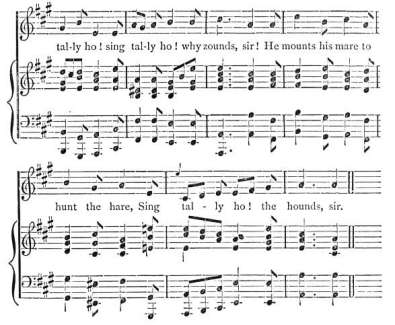

SONGS OF THE WEST; Ballads and Songs of the Peasantry of Devon and Cornwall, with their Traditional Melodies, by Rev. S. Baring Gould, M.A., and Rev. H. Fleetwood Sheppard, M.A., arranged for voice and pianoforte. Parts I. and II., 3s. each, net. Parts III. and IV. in-preparation.

STRANGE SURVIVALS AND POPULAR SUPERSTITIONS.

[In Preparation.

YORKSHIRE ODDITIES.

New and Cheaper Edition. [In the Press.

OLD COUNTRY LIFE.

BY

S. BARING GOULD, M.A.,

AUTHOR OF

"MEHALAH," "JOHN HERRING," ETC.

WITH ILLUSTRATIONS

BY W. PARKINSON, F. D. BEDFORD, AND F. MASEY.

LONDON:

METHUEN AND CO., 18, BURY STREET, W.C.

Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott Company.

1890.

[The right of reproduction is reserved.]

Richard Clay & Sons, Limited,

London & Bungay.

| CHAP. | PAGE | |

| I. | Old County Families | 1 |

| II. | The Last Squire | 28 |

| III. | Country Houses | 53 |

| IV. | The Old Garden | 93 |

| V. | The Country Parson | 116 |

| VI. | The Hunting Parson | 146 |

| VII. | Country Dances | 174 |

| VIII. | Old Roads | 198 |

| IX. | Family Portraits | 219 |

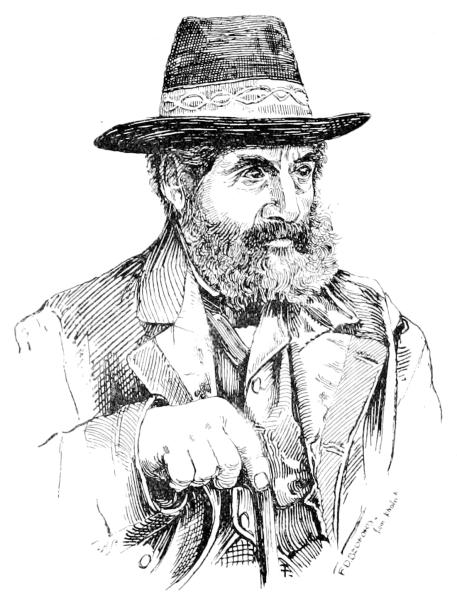

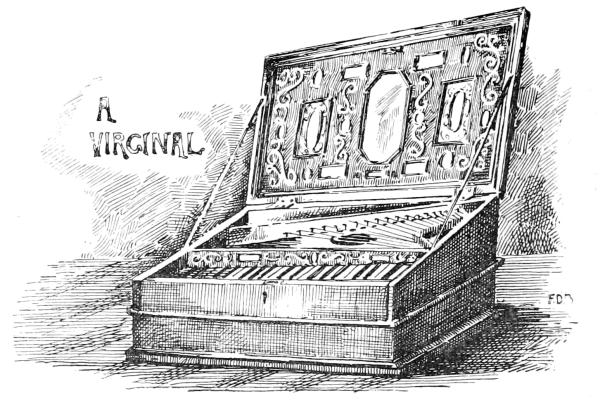

| X. | The Village Musician | 239 |

| XI. | The Village Bard | 259 |

| XII. | Old Servants | 284 |

| XIII. | The Hunt | 315 |

| XIV. | The County Town | 334 |

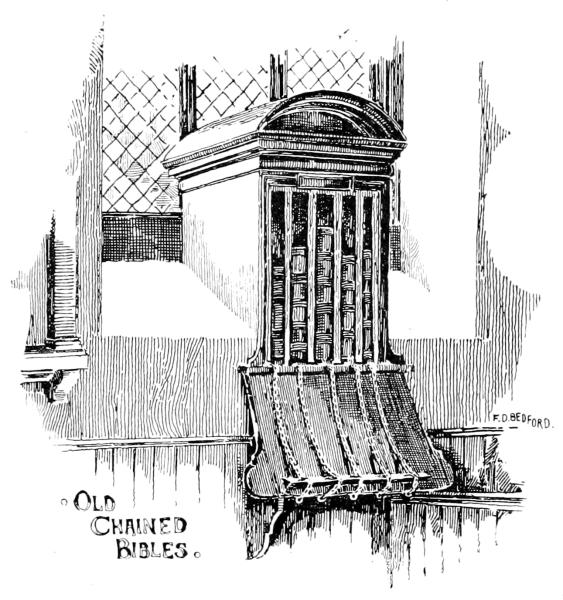

| Head and tail pieces to each chapter by F. D. Bedford. | ||

| PAGE | ||

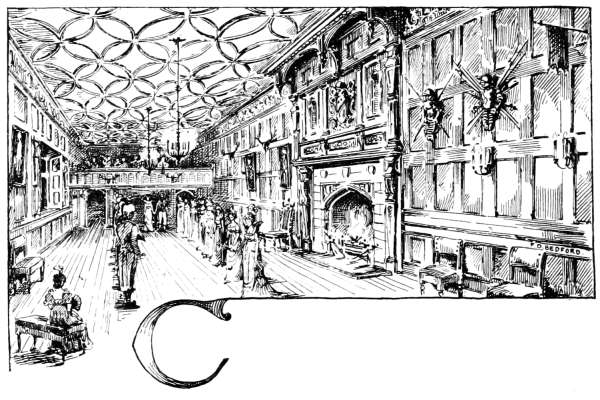

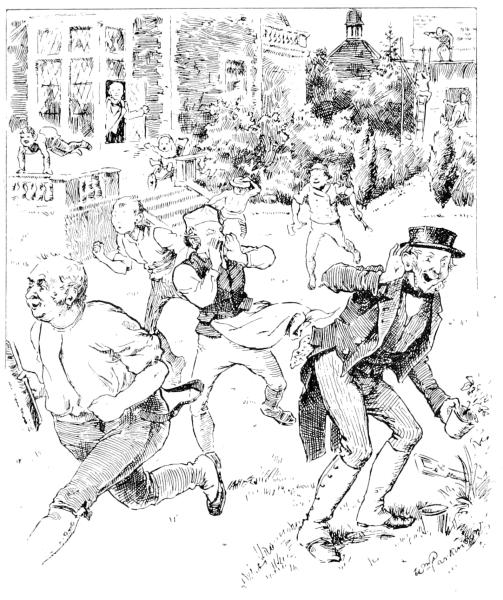

| Country Dance—Frontispiece | W. Parkinson | |

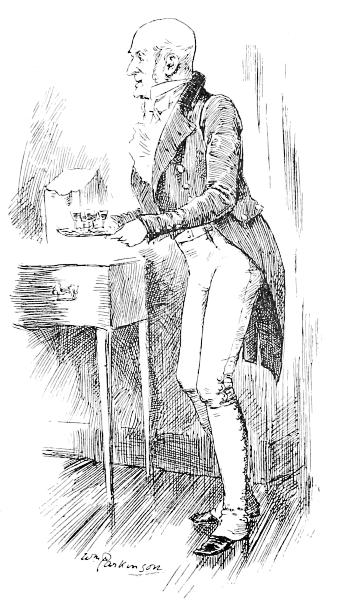

| Old Dames with their Factotum Butler | "" | 5 |

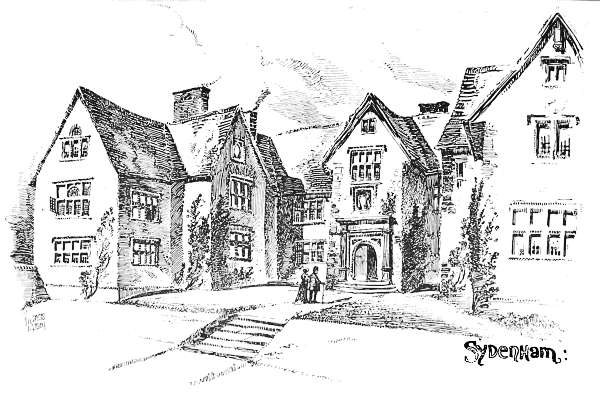

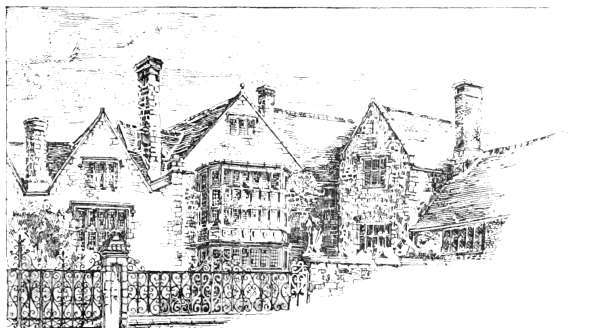

| Sydenham House, Devon | F. Masey | 7 |

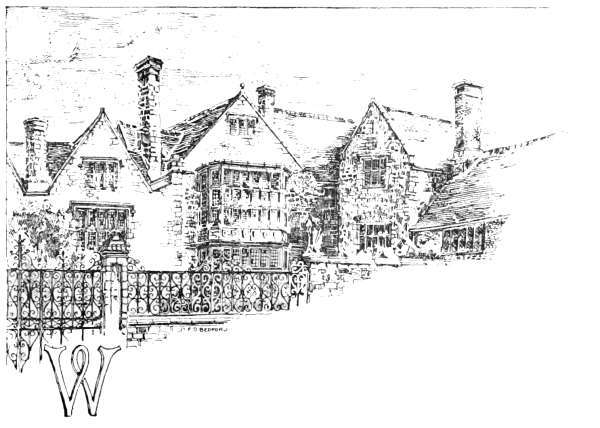

| Wortham—An Empty Shell | "" | 24 |

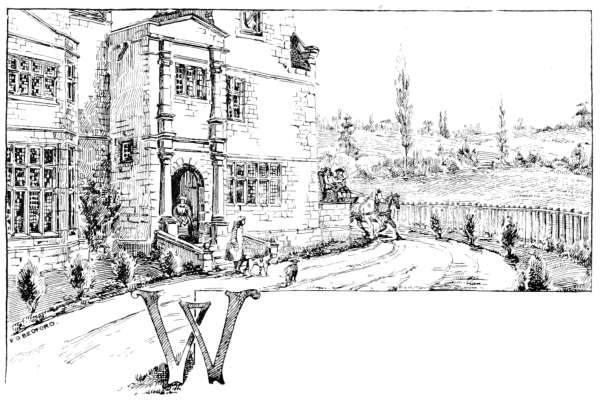

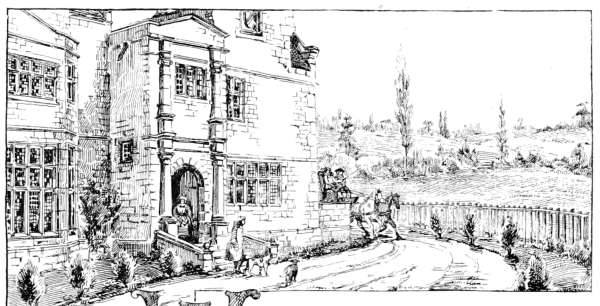

| Grimstone | "" | 29 |

| Madame Grym | W. Parkinson | 33 |

| Gryms, A Group of | From painting | 36 |

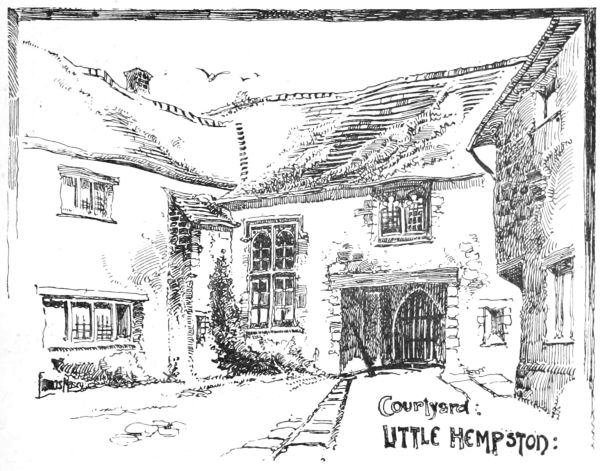

| Courtyard, Little Hempston | F. Masey | 57 |

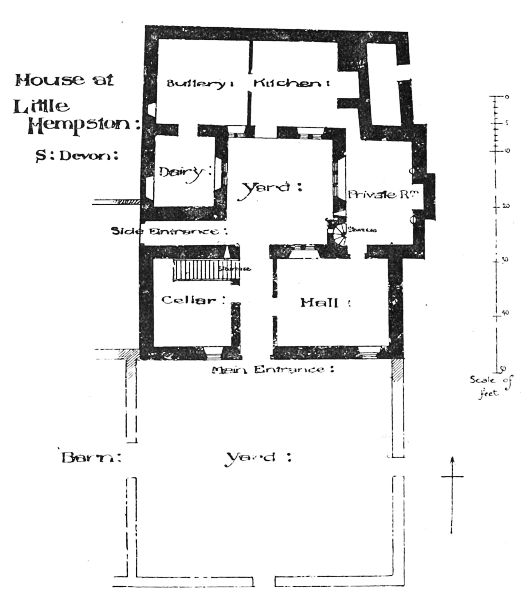

| House at Little Hempston | "" | 58 |

| Willsworthy | F. B. Bond | 59 |

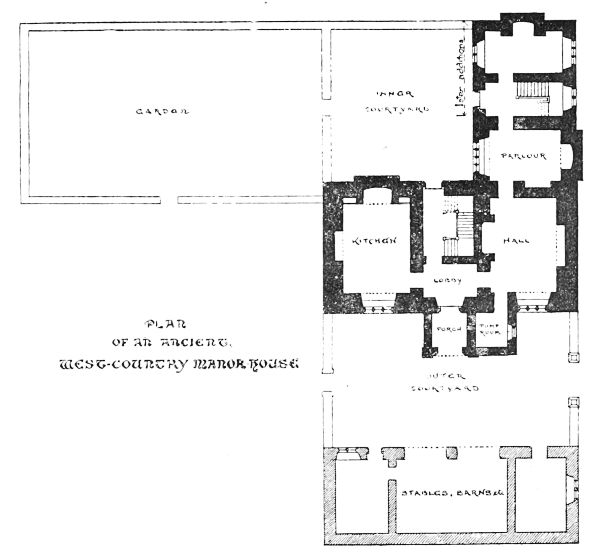

| ""Plan | "" | 60 |

| Kew Palace | F. Masey | 63 |

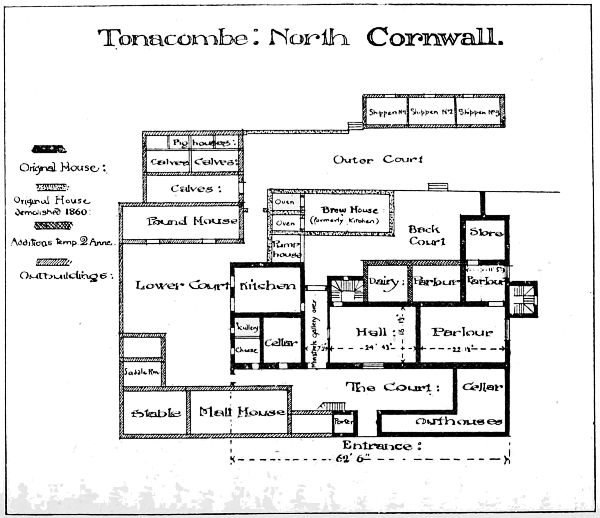

| Tonacombe, North Cornwall | "" | 68 |

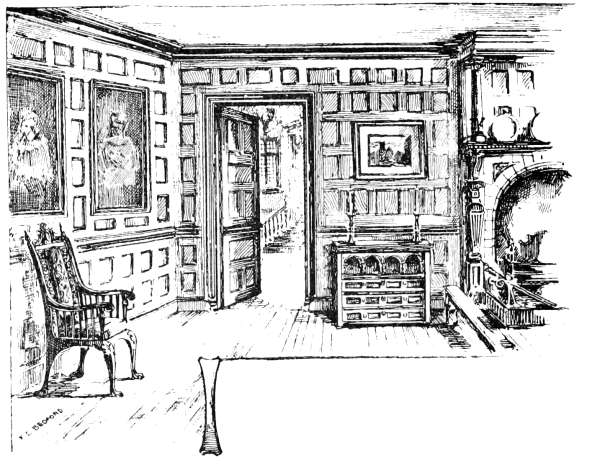

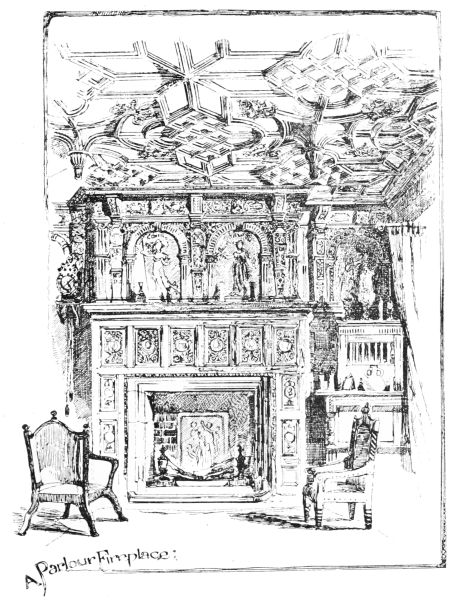

| A Parlour Fireplace | F. B. Bond | 73 |

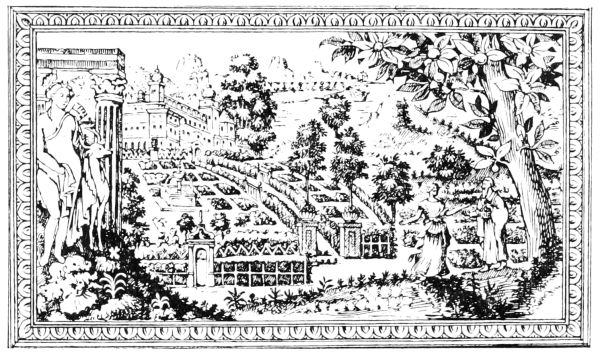

| Garden from Tapestry | "" | 98 |

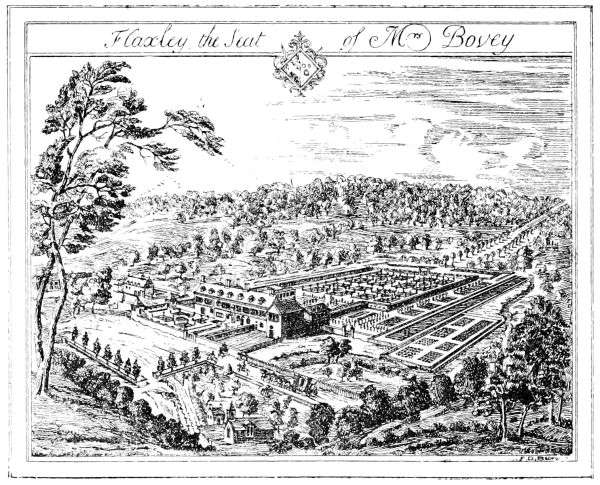

| Flaxley, from a print of 1714 | F. D. Bedford | 100 |

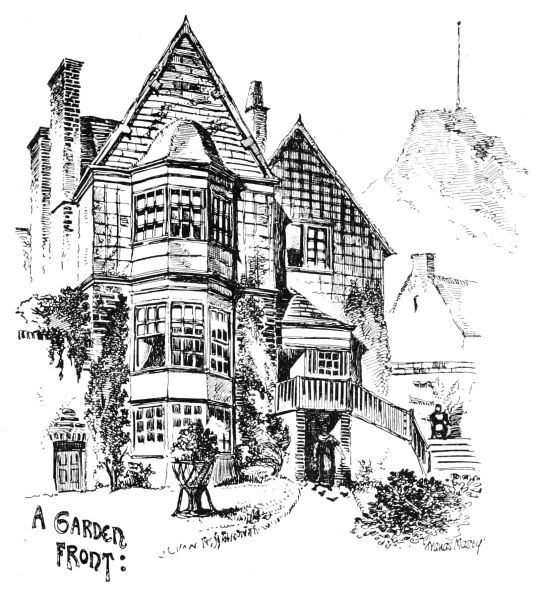

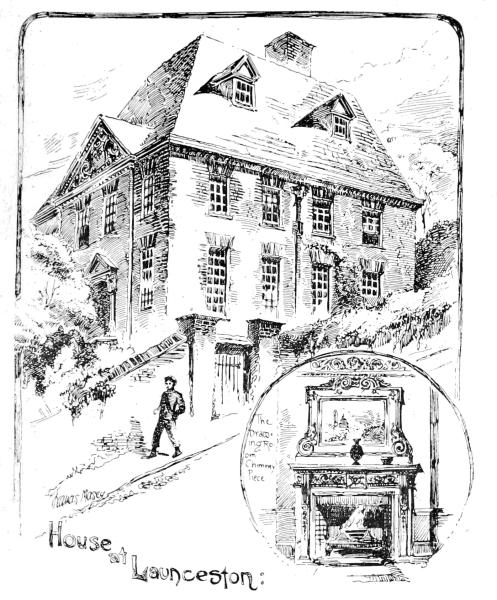

| A Town House Garden Front, Launceston | F. Masey | 107 |

| Old Country Parsonage, Bratton-Clovelly | F. D. Bedford | 121 |

| """ Parson in Cassock | W. Parkinson | 133 |

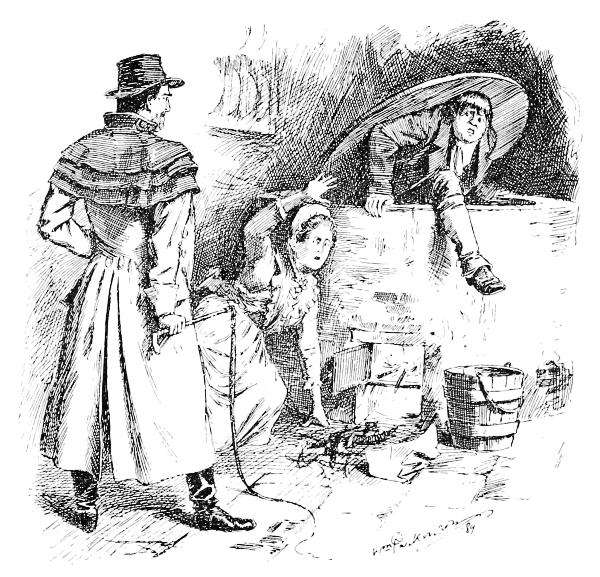

| Parson Chowne and Sally's Young Man | "" | 164 |

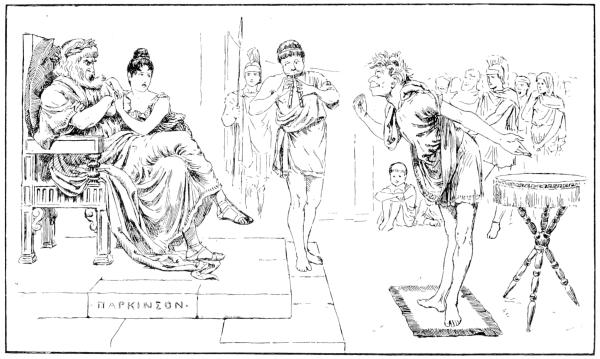

| Hippoclides before Clisthenes | "" | 175 |

| Minuet being Danced | W. Parkinson | 196 |

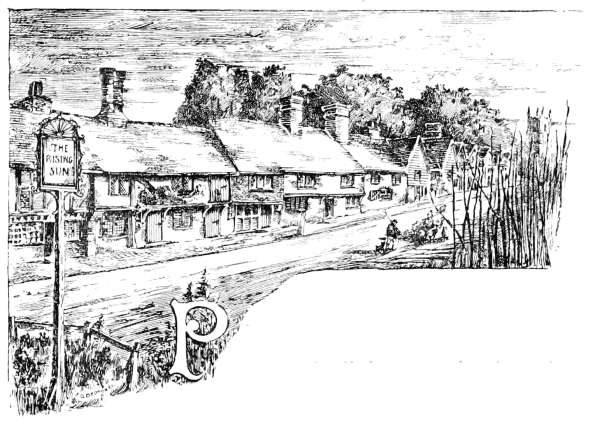

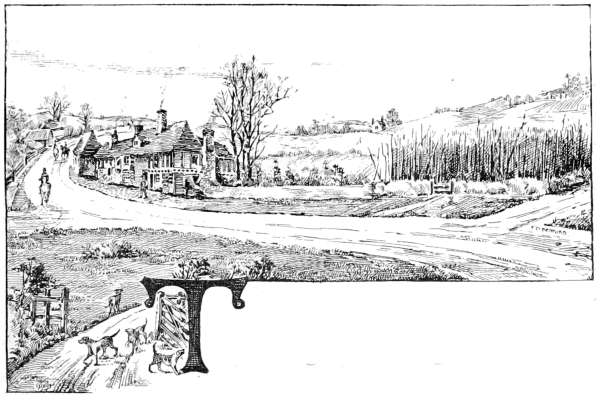

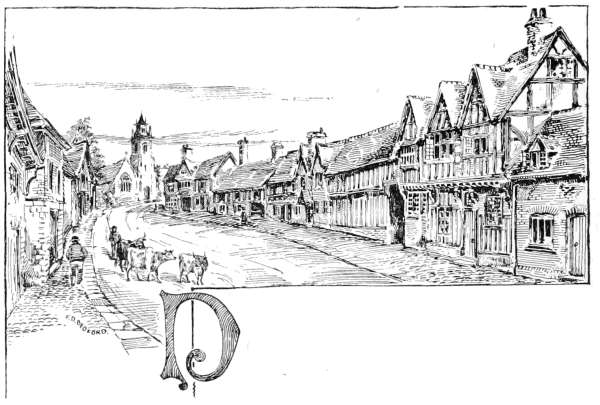

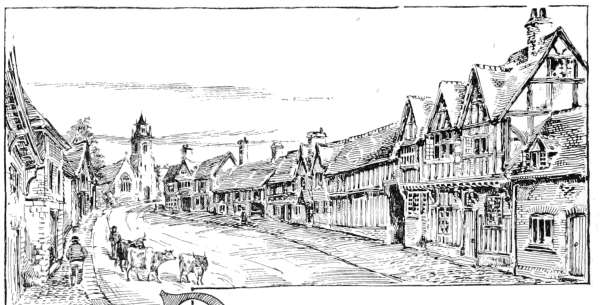

| Packman's Way | F. D. Bedford | 204 |

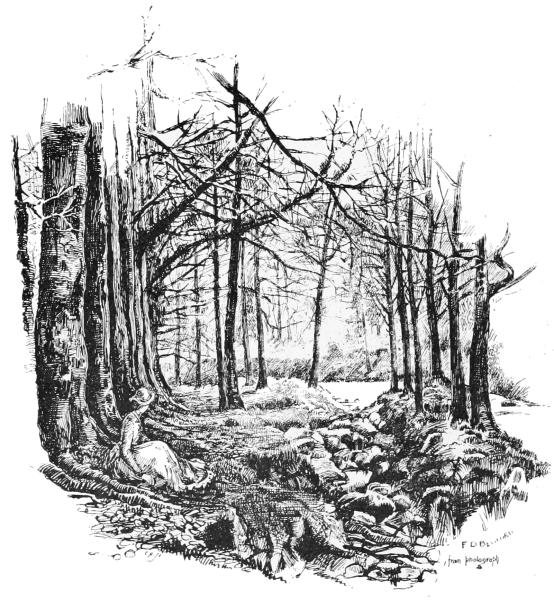

| By the Road-side | "" | 207 |

| An Old Travelling Carriage | F. Masey | 214 |

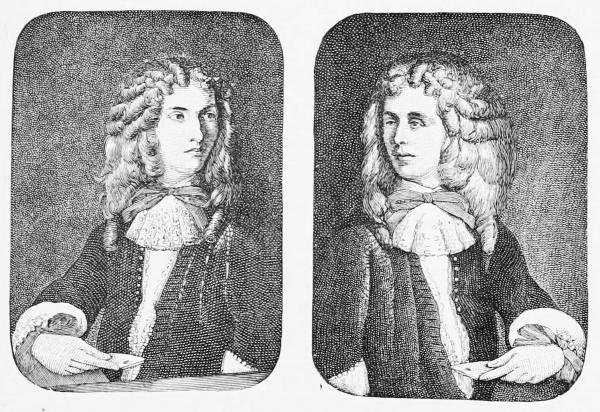

| Sir Edward, a.d. 1668 | J. D. Cooper | 227 |

| N. a.d. 1888 | "" | 227 |

| Lady Northcote | F. D. Bedford | 232 |

| Lady Young | "" | 232 |

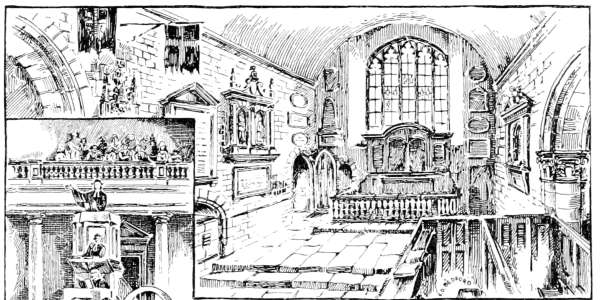

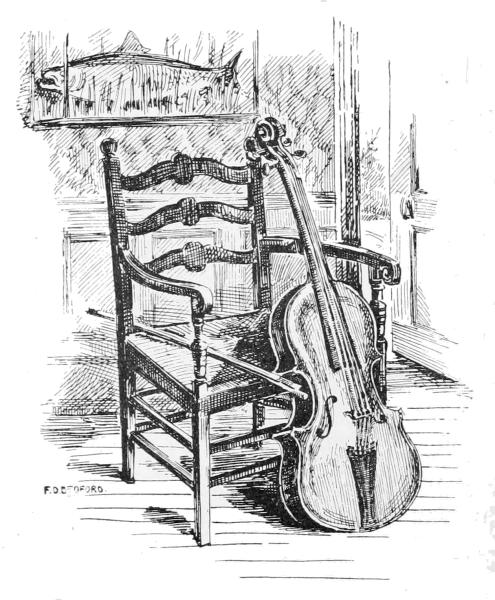

| Old Church Orchestra | W. Parkinson | 243 |

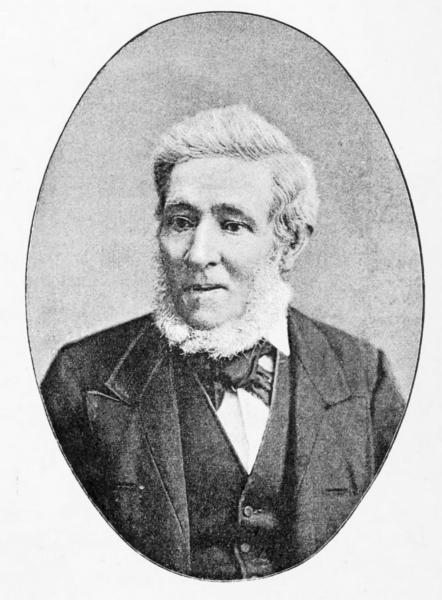

| James Olver | From photo | 257 |

| John Helmore | F. D. Bedford | 278 |

| Richard Hard | "" | 279 |

| The Old Butler | W. Parkinson | 285 |

| The Hunt Passing | "" | 316 |

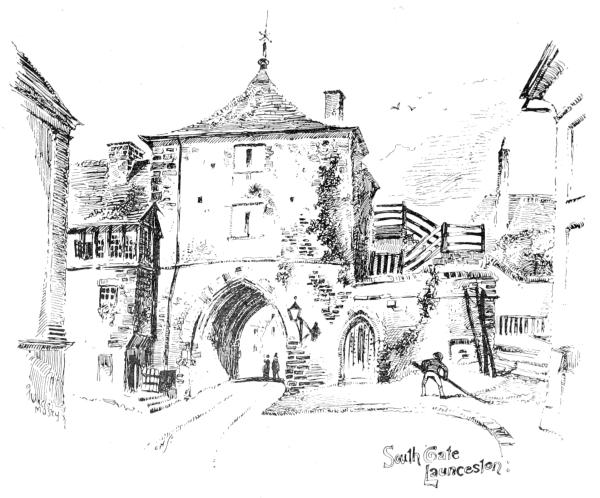

| South Gate, Launceston | F. Masey | 335 |

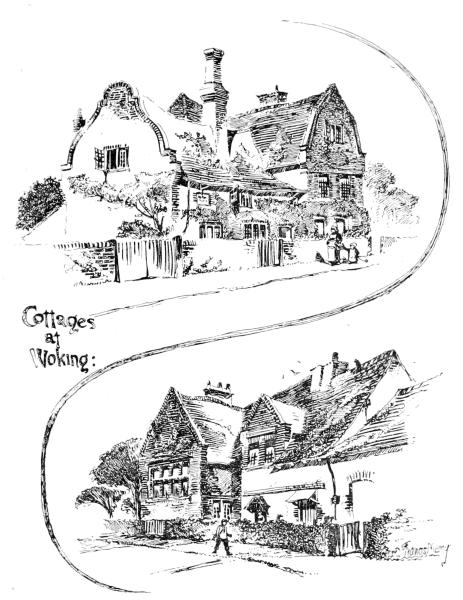

| Cottages at Woking | "" | 339 |

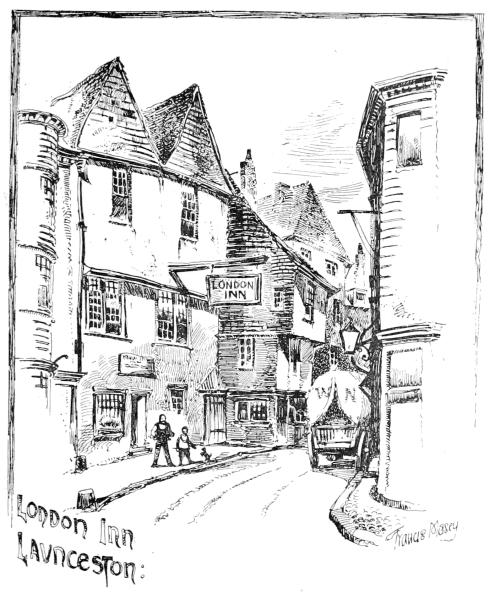

| London Inn, Launceston | "" | 343 |

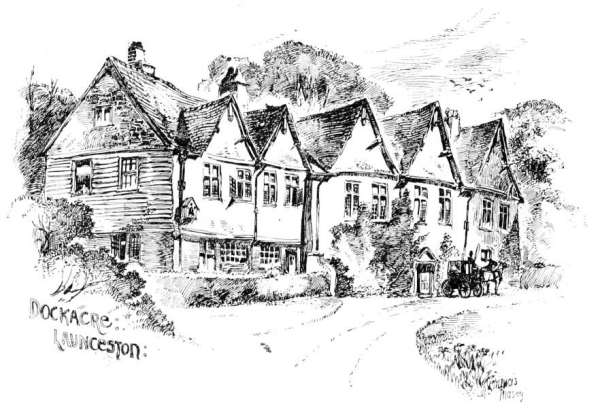

| Dockacre, " | "" | 349 |

| House at Launceston | "" | 353 |

| Old Cart, Slate Quarry, Lew Trenchard | F. D. Bedford | 358 |

OLD COUNTRY LIFE.

I WONDER whether the day will ever dawn on England when our country houses will be as deserted as are those in France and Germany? If so, that will be a sad day for England. I judge from Germany. There, after the Thirty Years' War, the nobles and gentry[2] set-to to build themselves mansions in place of the castles that had been burnt or battered down. In them they lived till the great convulsion that shook Europe and upset existing conditions social as well as political. Napoleon overran Germany, and the nobles and gentry had not recovered their losses during that terrible period before the State took advantage of their condition to transfer the land to the peasantry. This was not done everywhere, but it was so to a large extent in the south. Money was advanced to the farmers to buy out their landlords, and the impoverished nobility were in most cases glad to sell. They disposed of the bulk of their land, retaining in some cases the ancestral nest, and that only. No doubt that the results were good in one way—but where is a good unmixed? The qualifying evil is considerable in this case.

The gentry or nobility—the terms are the same on the Continent—went to live in the towns. They could no longer afford to inhabit their country mansions. They acquired a taste for town life, its conveniences, its distractions, its amusements; they ceased to feel interest in country pursuits; they only visited their mansions for about eight weeks in the year, for the Sommer-frische. Those who could not afford to furnish[3] two houses, carted that amount of furniture which was absolutely necessary to their country houses for the holiday, and that concluded, carted it back to town again. This state of things continues. Whilst the family is in residence at the Schloss it lives economically; it is there for a little holiday; it does not concern itself with the peasants, the sick, the suffering, the necessitous. It is there—pour s'amuser. The consequence is that the Schloss is without a civilizing influence, without moral force in the place. The country folk have little interest in the family, and the family concerns itself less with the people.

Not only so, but it brings little money into the place. It employs no labour. It is there not to keep open house, but to shut up the purse. In former days the landlord exacted his rents, but then he lived in the midst of his tenants, and the money that came in as rent went out as wage, and in payment for butter, eggs, meat, oats, and hay. The money collected out of a place returned to it again. It is so in many country places in England now where squire and parson live on the land.

In Germany the peasant has stepped out of obligation to the landlord into bondage to the Jew, who receives, but spends nothing. In France the[4] condition is much the same; the great house is a ruin, and so, very generally, is the family that occupies and owns it, if it still lingers on in it.

I remember a stately château of the time of Louis XIV., tenanted by two charming old ladies of the ancienne noblesse, with grand historic names—the last leaves that fluttered on a great family tree, with roots in the remote past; and they fluttered sere to their fall. They walked out every evening in the park attended by their factotum, an old serving-man, who was butler, coachman, gardener, and major-domo. They kept but one female servant, who was cook, lady's-maid, laundress, and house-maid. The old ladies are dead now, and the roof of the château has fallen in. They had no money to spend on the house or in the village, and never was there a village that more needed the circulation in it of a little coin.

Great houses, with us, are only tenanted by their owners when the London season is over; but that is for a good deal longer than the German Sommer-frische; and when the family does come down, it is as rain on a fleece of wool and as the drops that water the earth. It fills the house with guests, and consumes nearly all the market produce of the parish; and at[5] that season, as the people of the place know, money begins to circulate.

It is not, however, my intention to speak of the[6] great mansions of the nobility, but of those of the squirearchy, who are in residence on their estates all the year round.

These houses are elements of considerable blessing to the country. The families of the squires are always in the midst of the people, know the history, and wants, and infirmities of every one. They care for the good of the district. The ladies look after the girls; the squire attends to the condition of the roads and bridges; money is freely spent in the district, and a considerable amount of culture and moral restraint is acquired by those in the classes below, in the farm-houses and the cottages. Such only who have been in parishes that have been for generations squireless, and also in those where a resident family has been planted for centuries, can appreciate the difference in general tone among the people.

Should the time come when the county family will be taken away, then the parish will feel for some time like a mouth from which a molar has been drawn—there will be a vacancy that will cause unrest and discomfort. The molar does not grind and champ to sustain itself alone, but the entire body to which it belongs, and it is much the same with the country squire.

In the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries there were far more resident gentry in the country than there are at present. The number began to dwindle in the eighteenth century. The registers of parishes are instructive in this respect. In a parish there may have been but a single manor, nevertheless there were in it some three or four gentle families, of as good blood as the lord of the manor, inhabiting bartons. Let us take a parish or two as examples. Ugborough in South Devon has valuable registers dating from 1538. In the sixteenth century we find in them the names of the following families, all of gentle blood, occupying good houses—the Spealts, the Prideaux, the Stures, the Fowels, the Drakes, the Glass family, the Wolcombes, the Fountaynes, the Heles, the Crokers, the Percivals. In the seventeenth century occur the Edgcumbes, the Spoores, the Stures, the Glass family again, the Hillerdons, Crokers, Coolings, Heles, Collings, Kempthornes, the Fowells, Williams, Strodes, Fords, Prideaux, Stures, Furlongs, Reynolds, Hurrells, Fownes, Copplestons, and Saverys. In the eighteenth century there are only the Saverys and Prideaux; by the middle of the nineteenth these are gone. The grand old mansion of the Fowells that passed to the Savery family is in Chancery, deserted[10] save by a caretaker, falling to ruins. What other mansions there were in the place are now farm-houses.

Let us take another parish—Staverton. That had in it the grand mansion, Barkington, of the Rowes, who owned other estates in the same parish, in which were settled junior branches of the same family. All have vanished, root and branch. The Woolstones had a noble estate there. They are represented now by a clergyman in the neighbourhood. The Prestons were estated there also; they are gone, and their place knoweth them no more. My own family had two good houses there, Coombe and Pridhamsleigh, from the beginning of the sixteenth century. Both were sold at the end of last century. The Worths of Worth had estates and a house there, and have only a fine monument in the church to testify that they ever lived and died there. In another book I have mentioned the instance of Bratton-Clovelly, where were the Coryndons, Burnabys, Ellacots of Ellacot, Langfords of Langford, Calmadys, Willoughbys, Incledons—all gone, and not one of their houses remaining intact.

The country gentry in those days were not very wealthy. They lived very much on the produce of the home farm, and their younger sons went into[11] trade, and their daughters, without any sense of degradation, married yeomen.

In South Devon, at Slapton, lived in state the Amerideths, deriving from Welsh princes. Griffith Amerideth was the first to settle in Devon; he was a tailor and draper in Exeter, and died in 1559. He married a daughter of a very good family, and his son married the eldest daughter of Lewis Fortescue, one of the Barons of the Exchequer, and his grandchildren married into the Fortescue, Rolle and Loveys families, all of greatest position and fortune in the West.

It has been claimed for the Glanvilles that they are of Norman extraction; they, however, became tanners at Whitchurch, where their tan-pits remain to this day, though their mansion has lost all trace of antiquity. Chief Justice Glanville, who came from this house, and died in 1600, gave it splendour, yet his brother and nephew were not ashamed of the tan-pits, and even allowed a daughter of the house to marry a Tavistock blacksmith, and entered him as "faber" in the pedigree they enrolled with the heralds. The Courtenays of Molland married their daughters to farmers in the place. When, a few years ago, the late Earl of Devon visited Molland, he met a hale[12] old yeoman there named Moggridge. He held out his hand to him; "Cousin," said he, "jump into the carriage with me, and let us have a drive together; we have not met for one hundred and eighty years." When the Woolstones of Staverton registered their pedigree, they considered that there was nothing to be ashamed of to enter one daughter as married to a "clothier," another to an "agricola"—a yeoman.

It was quite another matter when one of the sons or daughters was guilty of misconduct; then he or she was struck out of the pedigree. I know of one or two little domestic scandals to which the registers bear witness, and I know that in such cases those who have stained the family name have not been recorded in the heralds' book. But that Joan who married a blacksmith, or Nicolas who was an armourer in London should be cancelled—God forbid!

My own conviction is, confirmed by a very close study of parochial registers, that some of the very best blood in England is to be found among the tradesmen of our county towns.

I know a little china and glass shop in the market-place of a small country town. The name over the shop is peculiar, but I know that it is one of[13] considerable antiquity. In the reign of Henry VII. a Jewish refugee settled in Cornwall. His son, a barber-surgeon, prospered, and became Mayor of Liskeard. His children married well, mostly with families of county position, and a son settled in the little town I speak of, where he married one of the honourable family of Edgecumbe. And now the lineal descendant of this man, in the male line, keeps a little china shop. I know—what perhaps he does not—his arms, crest, and motto, to which he has just claim.

Let us take another instance. When the lands of the Abbey of Tavistock were made over to the Russell family, on one of the largest farms or estates that belonged to the Abbey was seated a family that had been for a long time hereditary tenants under the Abbot. In the same position they continued, only under the Russells. In the reign of Elizabeth or of James I. they built themselves a handsome residence, with hall and mullioned windows, and laid out the grounds, and dug fish-ponds about this mansion. They also acquired lands of their own; amongst other estates a house that had belonged to the Speccots. They produced a sheriff of the county in the eighteenth century. As late as 1820 they were[14] seated in their grand old mansion. Then—how I cannot tell—there came a collapse. They lost the house and lands they had held since the thirteenth century; the Duke of Bedford pulled down the house, and the family is now represented by a surgeon, a hairdresser, and a hatter. The coat of arms borne by this family is found in every book of heraldry, it is so remarkable—a woman's breast distilling milk.

Sir Bernard Burke, in his Vicissitudes of Families, tells the pathetic tale of the fall of the great baronial family of Conyers. The elder line became extinct in 1731, when the baronetcy fell to Ralph Conyers, Chester-le-street, a glazier, whose father, John, was grandson of the first Baronet. Sir Ralph intermarried with Jane Blackiston, the eventual heiress of the Blackistons of Shieldun, a family not less ancient. His eldest son, Sir Blackiston Conyers, the heir of two ancient houses, derived from them little more than his name. He went into the navy, where he reached the rank of lieutenant, and became on leaving the navy collector of the port of Newcastle. He died without a son, and his title and property went to his nephew, Sir George, whose mother was a lady of Lord Cathcart's family. In three years this young fellow squandered the property and died, leaving[15] the barren title to his uncle, Thomas Conyers, who, after an unsuccessful attempt at a humble business, in his seventy-second year was residing as a pauper in the workhouse of Chester-le-Street.

Mr. Surtees bestirred himself in his favour, collected a little subscription, which enabled the old baronet to leave the workhouse. This was in 1810, and he died soon after, leaving three daughters married to labouring men in the little town of Chester-le-Street.

I have already mentioned the Coryndons of Bratton-Clovelly. It was a family not of splendour but of antiquity.

In 1620, when they registered their pedigree, they began with one Roger Coryndon, "who cam out of the Easterne parts and lived at Bratton neere 200 yeares since." There they remained till the beginning of this century, the property passing through the hands of a John Coryndon, barber of Exeter; a Thomas Coryndon, a tailor there; and George Coryndon, a wheelwright in Plymouth dockyard in 1748, whose son in a title-deed signs himself "gentleman," as he was perfectly justified in doing.

A family may be ruined by extravagance, but it is not always through ruin that the representatives it a family are to be found in humble or comparatively[16] humble circumstances; but that the junior members of a gentle family went into trade. The occasion of that irruption of false pride relative to "soiling the hands with trade," was the great change that ensued after Queen Anne's reign. When the trade of the country grew, great fortunes were made in business, at the same time that the landed gentry had become impoverished, first through their losses in the Civil War, then by the extravagance of the period of the Restoration, together with drinking and gambling. Vast numbers of estates changed hands, passed away from the old aristocracy into the possession of men who had amassed fortunes in trade, and it was among the children of these rich retired tradesmen that there sprang up such a contempt for whatever savoured of the shop and the counting-house. I know a horse that had been wont to draw an apple-cart for an itinerant vendor of fruit. He had several admirable points about him, indications that showed he was qualified to make a good carriage-horse. He was bought by a dealer, and sold to a squire. Then he was groomed, put into silvered harness, and became a favourite with the ladies as a docile beast to drive in a low carriage. One day as his mistress was taking out a friend in the trap, she told her the story of the horse. At the[17] word "apple-cart" back went the ears of the brute, and he kicked the carriage to pieces. After this it was quite sufficient to visit the stable and to mention "apple-cart" to set the horse kicking. Which story may be applied to what has been said about the nouveaux-riches of Queen Anne's time and trade.

It has often struck observers that wherever an important county family has resided for many generations, there are to be found among the poor many families bearing the same name, and it is rashly concluded that these are scions of the ancient stock.

It does so happen sometimes that these cottagers represent the old family, but only very rarely. Representatives are far more likely to be found as yeomen or tradesmen. The bearing of the name is no guarantee to filiation, even irregular; for it was by no means infrequent for servants to bear their masters' names; and the cottagers bearing the proud names of Courtenay, Berkley, Percy, Devereux, probably have not one drop of the noble blood of these families in their veins. But this is a subject to which I will return when speaking about old servants.

Now let us consider what was the origin of our county families.

Some have been estated, lords of manors, for many[18] centuries, but these are few and far between. Then comes a whole class of men who worked themselves up from being yeomen, small owners into great owners, by thrift and moderation. I know some cases of small holders of land, who have held their little properties for three or four centuries, but who have never advanced in the social scale. Others have added field to field, have taken advantage of the improvidence of their neighbours, and have bought them out. Then they have risen to become gentry. But the most numerous class is that of the well-to-do merchants, who have bought lands and founded families. In my own county of Devon this is the history of the origin of a considerable number of those families which claimed a right to bear arms, and proved their pedigrees before the heralds at the beginning of the seventeenth century. Dartmouth, Totnes, Exeter, Bideford, Barnstaple—all the great commercial centres—saw the building up of county families. The same process which began in the reign of Elizabeth has continued to this day, and will continue so long as the possession of a country house and of acres proves attractive; and may it long so continue, for what else does this mean than the bringing of money into country places, and not of[19] money only, but of intelligence, culture, and good fellowship?

One of the most extraordinary phenomena of social history in our land is the way in which the landed aristocracy have become extinct in the male line; how families of note have disappeared, as though engulfed like Korah and his company. Recklessness of living and ruin will not account for this. It is not that they have parted with their acres that surprises us, but the way in which the families have disappeared, as if snuffed out altogether.

It is feasible—I do not say easy—to trace a family of quite ordinary position with certainty through many generations. Whoever had any property made a will, or, if he neglected to make a will, had an administration of his effects taken by the next of kin after his death; and will or administration tell us about the man and where he lived. Then we refer to the parish registers, and with their assistance get some more information. There are other means by which additional matter may be acquired. Thus it is quite possible to draw a pedigree—a genuine, well-authenticated one—of almost any tradesman's or yeoman's family from the time of Elizabeth.

Now Lieutenant-Colonel Vivian has spent infinite[20] pains in tracing the genealogies of those families in the West of England which bore arms, and were accounted gentle at the beginning of the seventeenth century down to the present day. For this purpose he has searched all the wills extant relative to Devon and Cornwall, and most of the parish registers in these counties. Consequently, we can take his conclusions as being as reliable as they can well be made.

In the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries the heralds made periodical visitations of the counties, and noted down the pedigrees of the gentle families, enrolled such as had a right to bear arms, and disqualified as ignobiles such as had assumed the position and arms of a gentleman without legitimate title.

In the county of Devon there were visitations by the heralds in 1531, 1564, 1572, and 1620, this last was the final visitation made. Now in the lists then drawn up appear fourteen gentle families under letter A, forty-seven under B, sixty-three under C.

Of the fourteen whose names began with A, the Aclands alone remain. Of the forty-seven whose names began with B, only five remain. Of the sixty-three under C, fifty-eight are gone. Some few linger on, represented in the female line, but such are not included, though the descendants may have taken the ancient name.

How are we to account for this amazing extinction? The families were prolific, but apparently those most prolific most rapidly exhausted their vitality.

The Arscotts go back to the beginning of the reign of Henry VI., and spread over the north of Devon. John Arscott of Arscott, who died in 1563, had eight sons. His eldest son Humphry had indeed but two, but of these, the eldest and heir had two, and the second had six; yet in 1634 the estates devolved on a daughter.

John Arscott in 1563 had three brothers. Of these the next, Thomas, married a Bligh in 1551, and had four sons. Of these the descendants of one alone can be traced to a certain Roseclear Arscott of Holsworthy, who left four sons; all these died without issue. The son and heir is buried at Whitchurch, near Tavistock, with the laconic entry—"Charles Arscott, gent., of age, but not worth £300; buried 23 March, 1704-5."

The third of the four—of whom John Arscott was the eldest—was Richard, who left four sons. Of these the second, Humphry, was the father of seven, and Tristram, the eldest, of two. Tristram's family died out in the male line in 1620. Of the seven sons of Humphry all traces have disappeared. The[22] fourth was John Arscott of Tetcott, he, like his elder brothers, a man of good estate. His family became extinct in the male line in 1788.

The Crymes family, of Buckland Monachorum, was vastly prolific. William Crymes, who died in 1621, had nine sons; of these, as far as is known, only three married—William, Lewis, and Ferdinando. William left but one son; Lewis had a son who died in infancy, and that son only; Ferdinando had a son of the same name, whose only son died within a year of his birth. Ellis Crymes, the son of William, and inheritor of the estate, married twice, and had by his first wife, a daughter of Sir Francis Drake, as many as ten sons; by his second wife he had six more. Of the ten first only eight had children; and of the offspring of the second batch of six not a single grandchild male lived. In two generations after this prolific Ellis with his sixteen sons, the whole family disappears. I do not say that it is absolutely blotted out of the land of the living, but it is no longer represented in the county, nor can it be traced further.

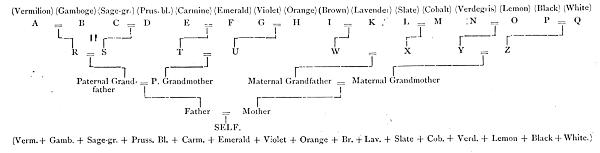

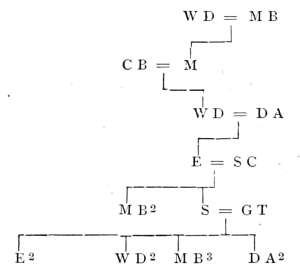

I can give an excellent example in my own family, as I have taken great pains to trace all the ramifications. In the Visitation of 1620, John Gould of Coombe in Staverton is represented as father of seven[23] sons; and Prince, who wrote his Worthies of Devon, published in 1701, in mentioning the family, comments on its great expansion; yet of all these sons, who, one would have supposed, would have half peopled the county, but a single male lineal representative remains, and he is over fifty, and unmarried.

The Heles were one of the most widely-spread and deeply-rooted families in the West of England. At an assize in Exeter in 1660, when Matthew Hele was high-sheriff, the entire grand-jury, numbering about twenty, was all composed of men of substance and quality, and all bearing the name of Hele. Where are they now? Vanished, root and branch.

Where are the Dynhams, once holding many lordships in Devon? Gone, leaving an empty shell—their old manor-house of Wortham—to show where they had been.

In the seventeenth century John Bridgeman, Bishop of Chester, father of Sir Orlando Bridgeman, and ancestor of the Earl of Bradford, bought the fine old mansion, Great Levers, that had at one time belonged to the Lever family, then had passed to the Ashtons. He reglazed his hall window, that was in four compartments, with coats of arms. In the first light he inserted the armorial bearings of the[24] Levers, with the motto "Olim" (Formerly); in the next the arms of the Ashtons, with the legend, "Heri" (Yesterday); then his own, with the text, "Hodie" (To-day); and he left the fourth and last compartment without a blazoning, but with the motto, "Cras, nescio cujus" (Whose to-morrow, I know not).

Possibly one reason for the extinction, or apparent extinction, of the squirarchal families is, that the[25] junior branches did not keep up their connexion with the main family trunk, and so in time all reminiscence of cousinship disappeared; and yet, this is not so likely to have occurred in former times, when families held together in a clannish fashion, as at present.

When Charles, thirteenth Duke of Norfolk, had completed his restoration of Arundel Castle, he proposed to entertain all the descendants of his ancestor, Jock of Norfolk, who fell at Bosworth, but gave up the intention on finding that he would have to invite upwards of six thousand persons.

In the reign of James I., Lord Montague desired leave of the king to cut off the entail of some land that had been given to his ancestor, Sir Edward Montague, chief justice in the reign of Henry VIII., with remainder to the Crown; and he showed the king that it was most unlikely that it ever would revert to the Crown, as at that time there were alive four thousand persons derived from the body of Sir Edward, who died in 1556. In this case the noble race of Montague has lasted, and holds the Earldom of Sandwich, and the Dukedom and Earldom of Manchester. The name of Montague now borne by the holder of the Barony of Rokeby is an assumption, the proper family name being Robinson.

"When King James came into England," says Ward in his Diary, "he was feasted at Boughton by Sir Edward Montague, and his six sons brought up the six first dishes. Three of them were lords, and three more knights."

Fuller in his Worthies records that "Hester Sandys, the wife of Sir Thomas Temple, of Stowe, Bart., had four sons and nine daughters, which lived to be married, and so exceedingly multiplied, that she saw seven hundred extracted from her body," yet—what became of the Temples? The estate of Stowe passed out of the male line with Hester, second daughter of Sir Richard Temple, who married Richard Grenville, and she was created Countess Temple with limitation to the heirs male of her body. There is at present a (Sir) Grenville Louis John Temple, great-great-grandson to (Sir) John Temple, who in 1786 assumed the baronetcy conferred upon Sir Thomas Temple of Stowe in 1611. This (Sir) John, who was born at Boston, in the United States, assumed the baronetcy on the receipt of a letter from the then Marquis of Buckingham, informing him of the death of Sir Richard Temple in 1786; but the heirship has not been proved, and there exists a doubt whether the claim can be substantiated.[1]

Innocent XIII. (1721-4) boasted that he had nine uncles, eight brothers, four nephews, and seven grandnephews. He thought, and others thought with him, that the Conti family was safe to spread and flourish. Yet, a century later, and not a Conti remained.

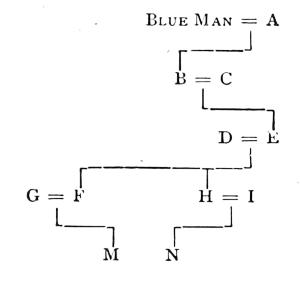

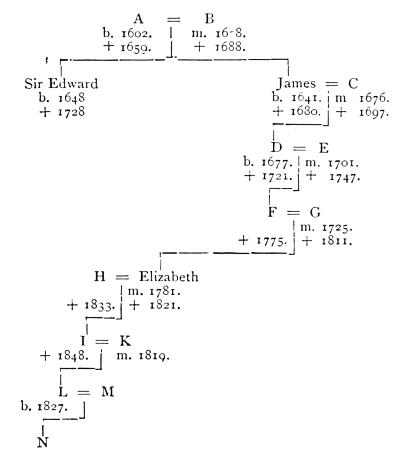

In the following chapter I will tell the story of the extinction of a family that was of consequence and wealth in the West of England, owning a good deal of land at one time. The story is not a little curious, and as all the particulars are known to me, I am able to relate it with some minuteness. It affords a picture of a condition of social life sufficiently surprising, and at a period by no means remote.

IN a certain wild and picturesque region of the west, which commands a noble prospect of Dartmoor, in a small but antique mansion, which we will call Grimstone, lived for generations a family called Grym. This family rose to consequence after the last heralds'[29] visitation, consequently did not belong to the aboriginal gentry of the county. It produced a chancellor, and an Archbishop of Canterbury.

The family mansion is still standing, with granite mullioned windows and quaint projecting porch, over which is a parvise. A pair of carved stone gate-posts give access to the turf plot in front of the house. The mighty kitchen with three fireplaces shows that the Gryms were a hospitable race, who would on high days feed a large number of guests, and the ample cellars show that they did more than feed them. I cannot recall any library in the house, unless, perhaps, the porch-room were intended for books; if so, it continued to be intended for them only.

The first man of note in the family who lived at Grimstone was Brigadier John Grym of the Guards, born in 1699, a fine man and a gallant soldier. He had one son, of the same name as himself, a man amiable, weakly in mind, and of no moral force and decision of character. His father and mother were a little uneasy about him because he was so infirm of purpose; they put their heads together, and concluded that the best thing to do for him was to marry him to a woman who had in abundance those qualities in which their son was deficient. Now there lived[32] about four miles off, in a similar quaint old mansion, a young lady of very remarkable decision of character. She was poor, and one of a large family. She at once accepted the offer made her in John Grym's name by the Brigadier and his wife, and became Madame John Grym, and on the death of the Brigadier, Madame Grym, and despotic reigning queen of Grimstone, who took the reins of government into her firm hands, and never let them out of them. The saying goes, when woman drives she drives to the devil, and madame did not prove an exception.

The marriage had taken place in 1794; the husband died six years later, but madame survived till 1835. Throughout the minority of her eldest son John, that is to say, for sixteen or seventeen years, she had the entire, uncontrolled management of the property, and she managed pretty well in that time to ruin the estate.

She was a litigious woman, always at strife with her neighbours, proud and ambitious. Her ambition was to extend the bounds of the property, but she had not the capital to dispose of to enable her to pay for the lands she purchased, and which were mortgaged to two-thirds of their value. She borrowed money at[33] five and six per cent., and bought property with it that rendered only three and a half.

She attended the parish vestries, where she made her will felt, and pursued with implacable animosity such farmers or landowners as did not submit to her dictation. She drove a pair of ponies herself, but[34] whilst driving had her mind so engaged in her schemes that she forgot to attend to the beasts; they sometimes ran away with her, upset her, and she was found on more than one occasion senseless by the roadside, and her carriage shattered hard by.

As her affairs became worse, more and more intricately involved, she began to be alarmed lest she should be arrested for debt. For security she had a house or pavilion erected in which to take refuge should the officers of the law come for her. This had a secret chamber, or well, made in the thickness of the walls, accessible from an upper loft through a trap-door. When she had received warning that she was being looked for, she fled to the loft. The trap was raised, and madame was lowered into the well on a carpet or sheet, then the trap was closed and covered with a mat. She had recourse to this place of concealment on several occasions, and the secret of the hiding-nest was not revealed till after her death.

The pavilion still stands, but has been converted into a barn, and all the internal arrangements have been altered.

When defeated in an action against a neighbour, on success in which she had greatly set her heart, she brought an action against the lawyer who had[35] conducted her case, charging him with having wilfully understated her claims, withheld evidence, and acted in collusion with the other side. She lost, of course, and being unable to pay costs, escaped to London; there she died. It is said that when the judgment was given against her the church bells were rung, so unpopular had she become.

In London she died, and her son, fearing lest her body should be arrested for debt, had her packed in bran, in a grand-piano case, and sent down by water to Plymouth, whence it was conveyed by waggon, as a piano, to Grimstone. The bill for the packing of madame in bran in a piano case is still extant. The waggoner who drove her in this case from Plymouth did not die till the other day.

At the time when she was in constant alarm of a warrant and execution, the portable plate of the house, to the weight of about fifty pounds, was daily intrusted to one of the labourers on the farm, who carried it about with him, and when at work put it in the hedge, and threw his jacket over it.

On one occasion, when the bailiffs were expected, she was afraid lest her gig should be taken, and before retiring into her well, she had it lifted by ropes and concealed under hay above the stable.

She left two sons, John, the elder, the heir to Grimstone, and Ralph, the younger. Both inherited the self-will, strength of character, and vindictiveness of the mother, but the younger assuredly in double measure. No sooner was she dead, than the brothers flew at each other's throats, or, to be more exact, Ralph flew at that of his more fortunate brother, if it can be called fortunate to inherit an encumbered estate, mortgaged almost to its value. Ralph instituted a[37] Chancery suit against John. The younger brother remained in the parish, residing in another house, and occasionally accompanied his brother John when out shooting, and they met in the hunting-field.

One day when they were out rabbiting together, Ralph's gun suddenly went off, and riddled his brother's beaver hat. John vowed that a deliberate attempt had been made on his life by his brother. He forbade him his house, and thenceforth would no more associate with him in field sports. Ralph before his mother's death had been put in a solicitor's office, but had been dismissed from it for falling on a fellow-clerk with a pistol and attempting to shoot him. John remembered this, and if he mistrusted his brother, it was not altogether without cause.

Now that he could no longer go to Grimstone, and found himself regarded askance by the neighbours, Ralph went up to town, where, having connexions in good position, he got introduced into society, and he made the acquaintance of a very charming girl with a small fortune at her own disposal, of six thousand pounds. He was a remarkably handsome young man, with flashing blue eyes, and bold, well-chiselled features, an erect bearing, and a brusque, haughty manner. It is perhaps hardly to be wondered at[38] that, with his personal good looks, and with his indomitable will, he should bear down all opposition on the part of the young lady's friends, and induce her to throw in her lot with him.

According to the marriage settlement, half the wife's fortune was to be at his disposal. It is almost unnecessary to say, that he managed to get rid of that within a twelvemonth. Thereupon ensued a series of persecutions as mean as they were cruel. His object was to force her to surrender the second three thousand pounds. He attempted to cajole her out of this, and when he failed by this means, he endeavoured to frighten her into submission. To do this he put a pistol under the pillow, and when she was asleep at his side, discharged the pistol over her head. Then he pretended that he had missed his mark, but assured her he would not fail another time.

She had, fortunately, sufficient resolution to resist intimidation. Whether she would have succumbed in the end we cannot say, but, luckily for her, he was arrested for costs in the Chancery suit against his brother, and was lodged in the prison of King's Bench, where he remained for seven years. Bethell, afterwards Lord Westbury, was counsel against him. Ralph Grym conducted his own case. Every now and[39] then he was brought from prison into court, as some fresh stage of the case was entered upon, and then returned to his detention. One day Bethell informed the judge that he moved for an "abatement," owing to the death of one of the parties involved in the suit. This was the first tidings Ralph Grym received of the decease of his brother-in-law, who with his brother John was party in the suit. His brother now abandoned the action, and Ralph was let out of King's Bench. He at once returned to the neighbourhood of Grimstone, and sent a message to his brother on the very first night of his return that he had a gun; that he was passionately fond of shooting; that for seven or eight years he had been debarred the pleasure; that his hand had become shaky; and that—in all human probability, when he was out shooting, should John come in sight, his gun would go off accidentally, and on this occasion not perforate the beaver.

John took the hint and remained indoors, whilst Ralph shot when and what he liked over his brother's grounds. But this was a condition of affairs so intolerable, that John deemed it expedient to come to terms with his brother, give him five hundred pounds, and pack him off to London.

Furnished with this sum, Ralph returned to town, and there set up livery stables. He was himself a first-rate rider, and he taught ladies riding, and conducted riding parties in Epping forest. He made money by purchasing good-looking horses that were faulty in one or two particulars, at some ten pounds or fifteen pounds, and as his horses were well turned out, and well bred, he had the credit of mounting his customers well. And he was not indisposed to sell some of these for very considerable sums.

Thus passed three or four years, the happiest in his life, and he might have continued his livery stables, had he not quarrelled with a groom and fought him. He was thrown, and dislocated his hip. This was badly set; it was a long job, and he was never again able to ride comfortably. His business went back, he lost his customers, and failed. Then, without a penny in his pocket, he returned to Devon, and to the neighbourhood of Grimstone, and lodged with the tenants on the estate.

Utterly ruined in means and in credit, he became a burden to his hosts. They declined to entertain him wholly and severally, so he slept in one farmhouse, and had his meals in one or another of the[41] neighbouring farms. His brother refused to see him, defied his threats, and denied him money.

This went on for some time. At length his hosts plainly informed him that he was no longer welcome. He was not an agreeable guest, was exacting, insolent, and violent. They met in consultation, sent round the hat, collected a small subvention; and then a gig was got ready, the money thrust into his hand, and he was mounted in the trap to be driven off to the nearest railway station, where he might take a ticket for London, or Jericho. The gig was at the door, and Ralph was settling himself into it, when a man, breathless and without a hat, arrived running from Grimstone, to say that John Grym, his brother, had suddenly fallen down dead. The trap that was to take Ralph away now conveyed him to the mansion of his ancestors, to take possession as heir, and he carried off with him the proceeds of the subscription among the tenants.

John had died without issue, and intestate. Ralph found in the house five hundred pounds in gold, a thousand pounds' worth of stock was on the farm, three hundred pounds' worth of wool was in store, and there was much family plate and some family jewels.

Ralph's character from this moment underwent a[42] change. When in town he had lived as a prodigal, and squandered his money as it came in, was freehanded and genial. In the year of Bloomsbury, when the Derby was run in snow, he won three thousand pounds by a bet, when he had not three-halfpence of his own. Next year he won on the turf fifteen hundred pounds; but money thus made slipped through his fingers. No sooner, however, was he squire of Grimstone than he became a miser, and that so suddenly, that he had to be sued in the County Court for the cheap calico he had ordered for a shroud for his brother. He became the hardest of landlords and the harshest of masters.

With his wife he was not reconciled. Repeated efforts were made by well-intentioned persons to re-unite them. He protested his willingness to receive her, but only on the condition that she made over to him the remaining three thousand pounds of her property. To this condition she had the wisdom not to accede. Before he was imprisoned she had borne him a daughter, whom we will call Rosalind. He made many attempts to get possession of the child, in the hopes of thereby extorting the money from the mother.

Before he became squire, Mrs. Grym lived in a[43] small house near Grimstone, on the interest of the three thousand pounds, of course in a very small way. On one occasion she was called to town, and was unable to take little Rosalind with her. She accordingly conveyed the child to the house of a neighbouring rector, and entreated that she might be kept there till her return, and be on no account surrendered to the father should he attempt to claim her.

A couple of Sundays after her departure, between ten and eleven in the morning, Ralph Grym appeared at the parsonage, and asked to see the rector. He was admitted, and after a little preliminary conversation, stated his desire to have an interview with his child, then aged five. This could not be refused. The little girl was introduced, and Ralph talked to her, and played with her.

In the meantime the bells for service were ringing. The bell changed to the last single toll, five minutes before divine worship began, and Mr. Grym made no signs of being in a hurry to depart.

The rector, obliged to attend to his sacred duties, drew his son aside, a boy of sixteen, and said to him, "Harry, keep your eye on Rosalind, and on no account suffer Mr. Grym to carry her off."

The boy accordingly remained at home.

"Well, young shaver," said Ralph, "what are you staying here for?"

"My father does not wish me to go to church this morning."

"Rosalind," said her father, "go, fetch your bonnet, and come a walk with me. I have some peppermints in my pocket."

The child, highly elated, got herself ready. Henry, the rector's son, also prepared to go out.

"Young shaver, we don't want you," said Ralph, rudely.

"My father ordered me to take a walk this morning, sir."

"There are two ways—I and Rosalind go one, and you the other," said Ralph.

"My father bade me on no account leave Rosalind."

Ralph growled and went on, the boy following. Mr. Grym led the way for six miles, and the child became utterly wearied. The father made every effort to shake off the boy. He swore at him, he threatened him, money he had not got to offer him; all was in vain. At last, when the little girl sat down exhausted, and began to cry, the father with an oath left her.

"That," said Henry, in after life, "was the first[45] time I had to do with Ralph Grym, and then I beat him."

Many years after he had again to stand as Rosalind's protector against Ralph, then striking at his child with a dead hand, and again he beat him.

After her mother's death Ralph invited his daughter to Grimstone, but only with the object of extorting from her the three thousand pounds she had inherited from her mother. When she refused to surrender this, he let her understand that her presence was irksome to him. He shifted the hour of dinner from seven to nine, then to ten, and finally gave orders that no dinner was to be served for a week. Still she did not go.

"I want your room, Rosalind," he said roughly; "I have a friend coming."

"The house is large, there are plenty of apartments; he shall have mine, I will move into another."

"I want all the rooms."

"I see you want to drive me away."

"I beg you will suit yourself as to the precise hour to-morrow when you leave."

Again, after some years, was Rosalind invited to Grimstone; but it was with the same object, never abandoned. On this occasion, when old Ralph found[46] that she was resolute not to surrender the three thousand pounds, he turned her out of doors at night, and she was forced to take refuge at the poor little village tavern. He never forgave her.

Squire Grym was rough to his tenants. One man, the village clerk, had a field of his, and Ralph suddenly demanded of him two pounds above the rent the man had hitherto paid. As he refused, Ralph abruptly produced a horse-pistol, presented it at the man's head, and said,

"Put down the extra two pounds, or I will blow your brains out."

The clerk was a sturdy fellow, and was undaunted. He looked the squire steadily in the eye, and answered—

"I reckon her (i. e. the pistol), though old and risty, won't miss, for if her does, I reckon your brains 'll make a purty mess on the carpet."

Ralph lowered the pistol with an oath, and said no more. He was a suspicious man, and fancied that all those about him conspired to rob him. When he bore a grudge against a man, or suspected him, he required some of his tenants to give evidence against the man; he himself prepared the story they were to swear to, and drilled them into the evidence they were[47] to give. The tenant who refused to do as he bid was never forgiven.

He was never able to keep a bailiff over a twelvemonth. When he died, at an age over eighty, in his vindictiveness against his daughter, because she had refused him the three thousand pounds, he left everything of which he was possessed to the bailiff then in his house. How the boy who had saved Rosalind from being carried off by her father many years before, and who was now a solicitor, came to her aid, and secured for her something out of the spoils, is history too recent to be told here.

Thus ended the family of Grym of Grimstone, and thus did the old house and old acres pass away into new hands.

Such is the story of the extinction of one family. Others have been snuffed out, or have snuffed themselves out, in other ways; strangely true it is, that of the multitudes of old county families that once lived in England, few remain on their paternal inheritance.

As I have told the story of the ruin of one family, I will conclude this chapter with that of the saving of another when trembling on the brink of ruin. Again I will give fictitious names. The St. Pierres were divided into two main branches, the one seated on a[48] considerable estate on the Dart, near Ashburton, the other on a modest property near the Tamar, on the Devonshire side. In 1736 died Edward St. Pierre, the last male representative of the elder branch, when he left his property to the representative of the junior, William Drake St. Pierre. This latter had an only son, Edward, and a daughter. He was married to a woman of considerable force of character. On his death in 1766, Edward, then aged twenty-six, came in for a very large property indeed; he was in the Dragoons, and a dare-devil, gambling fellow. He eloped with a married lady, and lived with her for some years. She died, and was buried at Bath Abbey. He never married, but continued his mad career till his death.

One day he had been gambling till late, and had lost every guinea he had about him. Then he rode off, put a black mask over his face, and waylaid the man who had won the money of him, and on his appearance challenged him to deliver. The man recognized him, and incautiously exclaimed, "Oh, Edward St. Pierre! I did not think this of you!"

"You know me, do you?" was the reply, and Edward St. Pierre shot him dead.

Now there had been a witness, a man who had seen Captain Edward take up his position, and who,[49] believing him to be a highwayman, had secreted himself, and waited his time to escape.

Edward St. Pierre was tried for the murder. Dunning of Ashburton, then a rising lawyer, was retained to defend him. It was essential to weaken or destroy the testimony of the witness. Dunning had recourse to an ingenious though dishonest device. The murder had been committed when the moon was full, or nearly full, so that in the brilliant white light every object was as clear as by day.

Dunning procured a pocket almanack, removed the sheet in which was the calendar of the month of the murder, and had it reprinted at the same press, or at all events with exactly similar type, altering the moons, so as to make no moon on the night in question.

On the day of trial he left this almanack in his great-coat pocket, hanging up in the ante-room of the court. The trial took place, and the witness gave his evidence.

"How could you be sure that the man on horseback was Captain St. Pierre?" asked the judge.

"My Lord, the full moon shone on him. I knew his horse; I knew his coat. Besides, when he had shot the other he took off his mask."

"The full moon was shining, do you say?"

"Yes, my Lord; I saw his face by the clear moonlight."

"Pass me a calendar. Who has got a calendar?" asked the judge.

At that time almanacks were not so plentiful as they are now. As it happened no one present had one. Then Dunning stood up, and said,—

"My Lord, I had one yesterday, and I put it, I think, in the pocket of my overcoat. If your Lordship will send an apparitor into the ante-room to search my pocket, it may there be found."

The calendar was produced—there was no moon. The evidence against the accused broke down, and he was acquitted.

This was considered at the time a clever move of Mr. Dunning; it occurred to no one that it was immoral. Captain St. Pierre had to pay Dunning heavily; in fact, he made over to him a portion of the estate in lieu of paying in cash, and later, when he became further involved, he sold the property to the Barings. Dunning was created Baron Ashburton, but the title became extinct with his son, who bequeathed his property to Alexander Baring, his first cousin, who was elevated to the peerage under the title of Baron[51] Ashburton, and the St. Pierre property now belongs to Lord Ashburton.

Captain Edward St. Pierre died in 1788, without issue, and his sister became his heir; but he had got rid of everything he could get rid of. Only the estate near the Tamar had been saved from sale by his mother taking it of him on a lease for ninety-nine years. She was residing on it when the news reached her that her good-for-nothing son was dead.

He had died at Shaldon, near Teignmouth, on the 29th June, and his last request was that he might be carried to Bath, and laid by the side of the woman he had wronged.

When his mother received the tidings of his death she was in uncertainty what to do. All the last night of June to the dawn of July 1, she sat in one tall-backed arm-chair, musing what to do with the rest of her life. Should she go to Bath, and spend the remainder of her days at cards, amusing herself? or should she devote it to a country life, and to repairing the shattered fortunes of the family?

When morning broke her mind was made up. She would adopt the nobler, the better cause; and she carried it out to the end. As each farm fell vacant in the parish she took it into her own hands,[52] and farmed it herself, and succeeded so well, that when the rival gentle family in the parish, owning a handsome barton there, fell into difficulties, she bought their estate, so as to make some amends for the loss of the Ashburton property. That the chair in which the old lady sat meets with respect ça va sans dire.

WHAT a feature in English scenery is the old country house! Compare the seat that has been occupied for many generations with the new mansion. The former with its embowering trees, its lawns and ancient oaks, its avenues of beech, the lofty, flaky Scotch pines in which the rooks build, and about which they wheel and caw;[54] and the latter with new plantations, the evidence everywhere present of hedges pulled down, manifest in the trees propped up on hunches of clay.

There is nothing so striking to the eye on a return to England from the Continent as the stateliness of our trees. I do not know of any trees in Europe to compare with ours. It is only with us that they are allowed to grow to advanced age, and die by inches; only with us are they given elbow-room to expand into the full plenitude of their growth. On the Continent every tree is known to the police, when it was planted, when it attains its maximum of growth; and then, down it comes.

Horace Walpole had no love of the country—indeed, he hated it, and regarded the months that he spent in Norfolk as intolerable. He laments in a letter to Sir Horace Mann (Oct. 3rd, 1743), that the country houses of the nobility and gentry of England are scattered about in the country, and are not moved up to town, where they would make streets of palaces, like those of the great people of Florence, and Genoa, and Bologna. "Think what London would be if the chief houses were in it, as in the cities of other countries, and not dispersed, like great rarity-plums in a vast pudding of country."

It is precisely because our most noble mansions are in the country, in a setting of their own, absolutely incomparable, of park and grove, that they are unsurpassed for loveliness anywhere. Framed in by pines and deciduous trees, copper beech and silver poplar, with shrubberies of azalea in every range of colour, from scarlet, through yellow to white, and rhododendrons full of bloom from early spring to midsummer, and double cherry, almond, medlar. Why, the very framing makes an ugly country house look sweet and homelike.

But beautiful as are the parks and grounds about our gentlemen's houses, they are but a remnant of what once was. We see in our old churches, in our mansions, that oak grew in profusion in England at one time, and reached sizes we cannot equal now. Great havoc was wrought with the woods and parks in the time of the Commonwealth and at the Restoration. The finest trees were cut down that ships might be built of them for the royal navy; the commissioners marked and took what trees they would. Thus in 1664 Pepys had to select trees in Clarendon Park, near Salisbury, which the Chancellor had bought of the Duke of Albemarle. Very angry the Chancellor was at having his park despoiled of[56] his best timber, and Pepys gives us in his Diary an amusing account of his trouble thereupon.

But to come to the houses themselves. Is there anything more sweet, peaceful, comfortable than the aspect of an old country house, of brick especially, with brown tiled roof and clustering chimneys backed by woods, with pleasure gardens at its side, and open lawn and park before it? No, its equal is to be found nowhere. The French château, the Italian palace, the German schloss are not to be spoken of in the same breath. Each has its charm, but there is a coldness and stiffness in the first, a turned-inwardness in the second, and a nakedness in the last that prevent us from associating with them the ideas of comfort and peace.

The true English country house is a product of comparatively late times, that is to say, from the reign of Henry VIII. onwards. Before that, the great nobles lived in castles, and the smaller gentry in houses of no great comfort and grandeur.

In the parish of Little Hempston, near Totnes, is a perfect mansion of the fourteenth century, probably the original manor-house of the Arundels, but given to the Church, when it became a parsonage. It is now used as a farm, and a very uncomfortable farm-house[57] it makes. As one of the best preserved houses of that period I know, it deserves a few words.

This house consists of three courts; one is a mere garden court, through which access was had to the main entrance; through this passed the way into the principal quadrangle. The third court was for stables and cattle-sheds. Now this house has but a single window in it looking outwards, and that is the great hall window, all the rest look inwards into the tiny quadrangle, which is almost like a well, never illumined by the sun, so small is it.

The hall had in it a brazier in the midst, which could never heat it, though the numbed fingers might be thawed at it. Adjoining the hall is the ladies' bower, a sitting-room dark as a vault, with indeed[59] a fireplace in it. These were the sole rooms that were occupied by day, the hall and the bower.

The Arundels had another place at Ebbfleet, near Stratton, which was no bigger, and only a little less gloomy; the windows were always made, for protection, to look into a court. It was not till after the Wars of the Roses that there was more light allowed into the chambers.

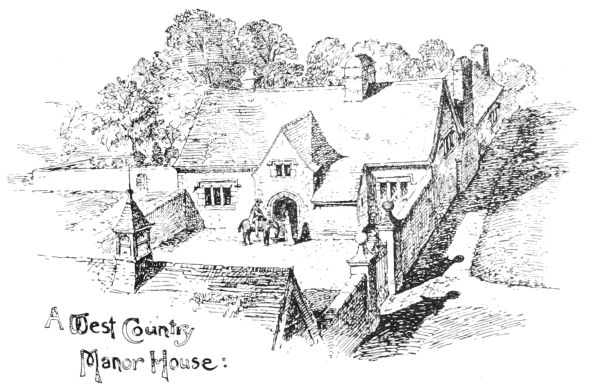

I give a sketch and plan of a manor-house still almost unaltered, called Willsworthy, in the parish of Peter Tavy in Devon. It is built entirely of granite. It has near it a ruined chapel, but what family occupied[60] it and when I do not know; it has not certainly been tenanted by gentlefolks since the reign of Henry VIII.

It was not till the Tudor period that the houses of our forefathers became comfortable and cheerful.

We should be wrong, however, if we supposed that in the Elizabethan period the windows were designed so much for looking out at as for letting the sun look in at. The old idea of a quadrangle was not[61] discarded, but it was modified. The quadrangle became a pleasant garden within walls; the destruction of the walls to afford vistas was the work of a later age.

The normal plan of a house till the reign of Elizabeth was the quadrangle; but then, in the more modest mansions, the house itself did not occupy more than a single side of the court, all the rest was taken up with barns and stables, and the windows of the house looked into this great stable-yard. On the side of Coxtor, above Tavistock, stands an interesting old yeoman's house, built of solid granite, which has remained in the possession of the same worthy family for many generations, and has remained unaltered. This house, in little, shows us the disposition of the old squire's mansion, for the yeoman copied the plan of the house of the lord of the manor. A granite doorway gives admission to the court, surrounded on all sides but the north by stabling. On the north side, raised above the yard by a flight of steps, is a small terrace laid out in flower-beds; into this court all the windows of the house look. We enter the porch, and find ourselves in the hall, with its great fireplace, its large south window, where sits the mistress at her needlework, as of old; and here is the high table, the[62] wall panelled and carved, where sit the yeoman and his family at meals, whilst the labourers sit below. This very simple yet interesting house is quite a fortress; it is walled up against the stormy gales that sweep the moor. It is a prison too, for it catches and holds captive the sunbeams that fall into the bright little court.

We are too ready to regard our forefathers as fools, but they knew a thing or two; they were well aware that in England, if we want flowers to blow early and freely, they must be sheltered.

It was not till the reign of Charles II. that the fancy came on English people to do away with nooks and corners, and to build oblong blocks of houses without projections anywhere.

The new Italian, or French château style, had its advantages, but its counterbalancing disadvantages. The main advantage was that the rooms were loftier than before; the walls, white and gold, were more cheerful at night; there may have been other advantages, but these are the only two that are conspicuous. The disadvantages were many. In the first place, no shelter was provided out of doors from the wind; no pleasant nooks, no sun-traps. The block of building, naked and alone, stood in the midst of a[65] park, and the wind whistled round it, and the rain drove against it. When the visitor arrived in bad weather, he was blown in at the door, and nearly blown through the hall. In our eagerness to make vistas, obtain extensive landscapes, we have levelled our enclosing walls. But what could have been a sweeter prospect from a hall or parlour window, than an enclosed garden full of flowers, with bees humming, butterflies flitting, and fruit-trees ripening their burdens against old red brick enclosing walls, tinted gorgeously with lichens?

There is at present a fashion for being blown about by the wind, so we unmuffle our mansions of their enclosing walls and hedges. But England is a land of wind. Nothing strikes an Englishman more, when living abroad, than the general stillness of the air. Look at the wonderful bulbous spires and cupolas to towers on the Continent;—marvellously picturesque they are. If examined, they are found to be very generally covered with the most delicate slate work, that folds in and out of the crinks and crannies, like chain mail. Such slating would not endure three winters in England; it would be torn adrift and scattered like autumn leaves before an equinoctial gale. We never had these bulbous spires in England,[66] because the climate would not permit of their construction. Our forefathers knew that this was a windy world of ours—

and they built their houses accordingly—to provide the greatest possible amount of shelter from the cold blasts of March, and from the driving rains of winter. The house originally consisted on the ground-floor of hall, parlour, kitchen, and entrance-porch and stairs. In later times the side wing was carried further back, and a second parlour was built, and the staircase erected between the parlours.

At Upcott, in Broadwood, in Devon, is a house that belonged to the Upcotts. The plan is much the same as that of Willsworthy, even ruder, though the house itself was finer. It had a porch, a hall, and a dairy and kitchen. The parlour is of Queen Anne's reign, and probably takes the place of one earlier on the same spot. The plan of Hurlditch is the same, a mansion of the important family of Speccot. There also the parlour is comparatively recent.

There was in a house previous to the reign of Henry VII. but one good room, and that was the[67] hall. It opened to the roof, and must have been cold enough in winter, and draughty at all times.

At Wortham, the fine mansion of the Dynhams, there was an arrangement, as far as I know, unique—two halls, one for winter with a fire-place in it, serving as a sort of lower story to the summer-hall, clear to the roof—thus one is superposed on the other.

Tonacombe, a mansion of the Leys and Kempthornes in Morwenstowe parish in Cornwall, is a singularly untouched house of a somewhat similar construction, but enlarged. Here there was the tiny entrance-court into which the hall looked; the hall itself being open to the roof, with its great fire-place, and the parlour panelled with oak. All other reception-rooms are later additions or alterations of offices into parlours.

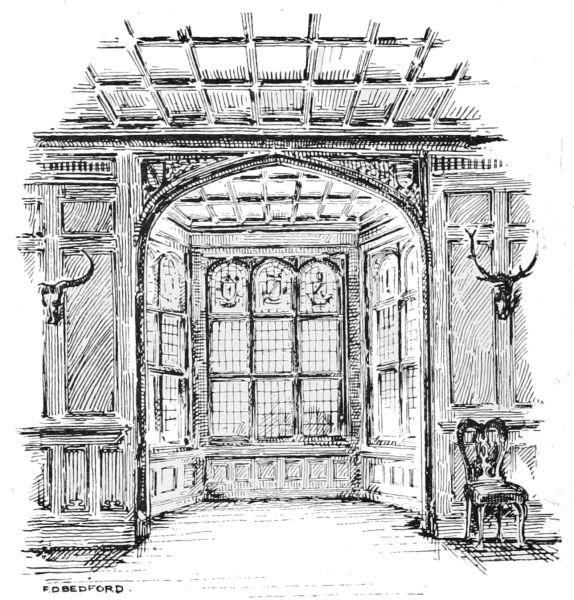

With the reign of the Tudors a great sense of security and an increase of wealth must have come to the country gentry, for they everywhere began to rebuild their houses, to give them more air and light, and completely shook off that fear which had possessed them previously of looking out into the world. Then came in an age of great windows. It would seem as though in the rebound they thought they could not have light enough. Certainly glass must[68] have been inexpensive in those days. It was the same in the churches; the huge perpendicular windows converted the sacred edifices into lanterns. The old halls open to the roof gave way to ceiled halls, and[69] the newel staircase in the wall—very inconvenient, impossible for the carrying up or down-stairs of large furniture—was discarded for the broad and stately staircase of oak.

It seems to me that the loss of shelter that ensued on the abandonment of the quadrangle, or of the E-shaped Elizabethan house, is not counterbalanced by the compactness of the square or the oblong block of the Queen Anne house. Moreover, the advantages internally were not so great as might be supposed, for, to light the very lofty room the windows were made narrow and tall; thus shaped they admitted far less sun than when they were broad and not tall.

Only one who, like myself, has the happiness to occupy a room with a six-light window, twelve feet wide and five feet high, through which the sun pours in and floods the whole room, whilst without the keen March wind is cutting, cold and cruel, can appreciate the blessedness of such a window, can tell the exhilarating effect it has on the spirits, how it lets the sun in, not only through the room, and on to one's book or paper, but into the very heart and soul as well.

A long upright narrow window does not answer the[70] purpose for which it was constructed. The light enters the room from the sky, not from the earth, therefore only through the upper portion of a window. The wide window gives us the greatest possible amount of light. If we were but to revert to the Elizabethan window, we would find a singular improvement in our health and spirits.

Our old country houses were, say modern masons, shockingly badly built. "Why, sir," said one to me, "do look here at this wall. It is three foot six thick—what waste of room!—and then only the facing is with mortar between the stones, all the rest of the stones are set in clay." I was engaged building my porch when the man said this. So I, convinced by his superior experience, apologized for my forbears, and bade him rebuild with mortar throughout. What was the result? That wall has been to me ever since a worry. The rain beats through it; every course of mortar serves as an aqueduct, and the driving rain against that wall traverses it as easily as if it were a sponge. Our old houses were dry within—dry as snuff. Now we cannot keep the wet out without cementing them externally. Those fools, our forefathers, by breaking the connexion prevented the water from penetrating.

Do any of my readers know the cosiness of an oak-panelled or of a tapestried room? There is nothing comparable to it for warmth. What the reader certainly does know is, that from a papered wall and from a plate-glass window there is ever a cold current of air setting inwards. He supposes that there is a draught creeping round the walls from the door, or that the window-frame does not fit; and he plugs, but cannot exclude the cold air. But the origin of the draught is in the room itself, and it is created by the fire. The wall is cold and the plate-glass is cold, and the heated atmosphere of the room is lowered in temperature against these cold surfaces, and returns in the direction of the fire as a chill draught. But when the room is lined with oak or with woven woollen tapestry, then the walls are warm, and they give back none of these chill recoil currents. The fire has not the double obligation laid on it of heating the air of the apartment and the walls.

In Germany and Russia during the winter double windows are set up in every room, and by this means a film of warm air is interposed between the heated atmosphere of the room and the external cold air. That our ancestors did not attempt,—plate-glass was[72] not known to them,—but they did what they could in the right direction. They covered the chill stone and plaster walls of the rooms with non-conducting materials.

The oak-panelled room was, it can hardly be denied, difficult to light at night, as the dark walls absorbed the candle rays. But that mattered little at a time when every one went to bed with the sun. When later hours were kept, then the oak panels were painted white. But now that we have mineral oils, not to mention gas and electric lighting, we may well scrape off the white paint and restore the dark oak. Then, for an evening, the sombre background has quite a marvellous effect in setting off the bright ladies' dresses, and showing off fresh pretty faces.

Before the reign of Elizabeth the staircase was not an important feature in the house. The hall reached to the roof, and the stairs were winding flights of stone steps in turrets, or in the thickness of the wall; when the fashion set in to ceil the halls low, then the staircase became a stately feature of the house. But it was more than a stately feature, it was the great ventilating shaft of the house; it was to the house what the tower is to the church, the chimney[75] by which the stale fumes might pass away. The great staircase window, made up of thousands of little pieces of glass set in lead, acted as a colander through which the outer air streamed in and the inner vitiated air escaped. Where there is a central quadrangle, this was in many cases glazed in; then a staircase led to a series of galleries about it, lighted from above, communicating with the several suites of apartments. Many of our old inns are thus constructed. The reader will remember the picture of the court of the White Hart in Pickwick, with the first introduction of Sam Weller. The central court serves as a ventilator to the house, and so does its dwindled representative, the well-staircase. Those fools, our forefathers, again, if they shut out the winds and gave shelter to their houses, made ample provision for internal ventilation.

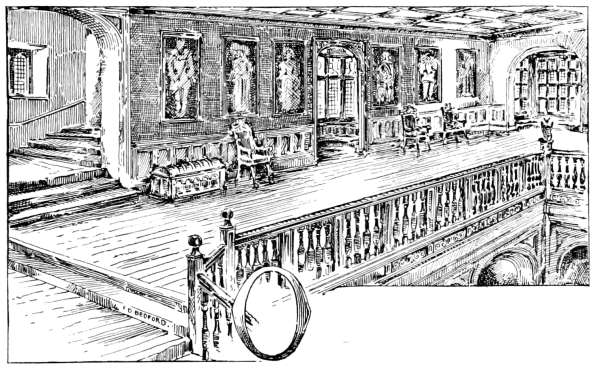

What a degraded, miserable feature of the house is the staircase now-a-days, with its steps seven inches instead of four, and the tread nine and a half inches instead of thirteen. It takes an effort to go up-stairs now, it is a scramble; it was an easy, a leisurely, and a dignified ascent formerly. Then again, our staircases are narrow—one of four feet is of quite a respectable width; but the old Elizabethan staircase measured[76] from six feet to eight feet wide. That of Blickling Hall, Norfolk is seven feet eight inches. There the ascent is single to the first landing; after that the stair branches off, one for the ascent, the other for the descent. The first ascent is of eight steps; then after the main landing, on each side eleven steps to the second landing; then nine more lead to the level of the upper storys and grand corridor. On such staircases as these furniture can be conveyed up and down without damage to the walls, or injury to the furniture. Architects who build modern narrow and steep staircases, forget that often a coffin has to be conveyed with its tenant down them; and this can be done neither with convenience nor dignity upon them.

But let us think of the staircase on a brighter occasion than a funeral. The grand old flight of steps with its landings, and with sometimes its bay-window with seats in it on one of the landings, how it lends itself to the exigencies of a sitting-out place at a ball. The window is filled with azaleas; the walls hung with full-length family portraits; the broad dark oak stairs are carpeted with crimson; a chandelier pendant from the moulded Elizabethan ceiling-drop sheds a soft golden light over the scene;[77] and on the landings, on the steps themselves, sit the dancers after the exertions of a waltz or a galop, enjoying the fresher air, and forming a picture of almost ideal charm. Then also it is that the ventilating advantages of the great staircase become most manifest. The dancing has been in the hall, which has become hot; the door on to the stairs is thrown open; there is a circulation of air at once, and in two minutes the atmosphere of the ball-room has renewed itself.

In the matter of sleeping arrangements we have certainly made an advance on those of our ancestors. I have already mentioned Upcott, which belonged to a family of that name that expired in the reign of Henry VII. The hall is small, but has a huge fire-place in it. In the window is a coat of arms, in stained glass, representing Upcott impaling an unknown coat, party per pale, argent and sable, three dexter hands couped at the wrist, counterchanged. Now this house has or had but a single bedroom. There may have been, and there probably was, a separate apartment for the squire and his wife, over the parlour, which was rebuilt later; but for all the rest of the household there existed but one large dormitory over the hall, in which slept the unmarried[78] ladies of the family, and the maid-servants, and where was the nursery for the babies. All the men of the family, gentle and serving, slept in the hall about the fire on the straw, and fern, and broom that littered the pavement.

That house is a very astonishing one to me, for it reveals a state of affairs singularly rude—at a comparatively late period. Things were improved in this particular later; bedrooms many were constructed, communicating with each other. At the head of the stairs slept the squire and his wife, and all the rooms tenanted by the rest of the household were accessible only through that. The females, daughters of the house and maid-servants, lay in rooms on one side, say the right, the maids in those most distant, reached through the apartments of the young ladies; those of the men lay on the left, the sons of the house nearest the chamber of the squire, the serving-men furthest off.

When the party in the house retired for the night, a file of damsels marched up-stairs, domestic servants first, passed through the room of their master and mistress, then through those of the young ladies, and were shut in at the end; next entered the daughters of the house to their several chambers,[79] the youngest lying near the room of the serving-maids, the eldest most outside, near that of her father and mother. That procession disposed of, a second mounted the stairs, consisting of the men of the house, the stable-boy first, and the son and heir last, and were disposed of similarly to the females, but on the opposite side of the staircase. Then, finally, the squire and his wife retired to roost in the chamber that commanded those of all the rest of the household. This arrangement still subsists in our old fashioned farm-houses.

Now may be understood the odd provision in a will proved in the Consistory Court of Canterbury in 1652 (Bowyer, f. 57)—"I give to my son Thomas the sole fee-simple and inheritance of my dwelling-house, and all my lands and hereditaments thereto belonging, to him and to his heirs for ever. And my will is, that Joan my daughter shall have free ingress, egress, and regress to the bedd in the chambre where she now lieth, so long as she continueth unmarried."

But to this arrangement followed another, more practical and convenient, that of having a grand corridor up-stairs, out of which opened the doors of the bedrooms; or, where there was a glazed-in quadrangle[80] with staircase and landings around it, there the doors of the bedrooms opened from these landings. The corridor was used as a room for dancing, or for music, or for games; it was the recreation place of the house on a rainy day. Being up-stairs, and away from library and parlours, the young people might skip, and play blind-man's buff, dance, and disturb no one; nor was there much furniture in these corridors to stand in the way and get knocked over.

This corridor is a feature of an old house so very dear to young folks, and so very advantageous to their health, that it is a pity in our modern houses we have got rid of it.