| INTRODUCTION | Page 11 | |

| CHAPTER I | Page 17 | |

| THE EXTRAORDINARY AND INITIAL CLIENT OF A | ||

| YOUNG LAWYER WITHOUT PREVIOUS PRACTICE | ||

| CHAPTER II | Page 39 | |

| THE REMARKABLE BEHAVIOR OF THE LAWYER'S | ||

| SECOND CLIENT | ||

| CHAPTER III | Page 51 | |

| THE HORRIFIC EPISODE IN THE COURSE OF WHICH | ||

| THE LAWYER OBTAINED A THIRD CLIENT | ||

| CHAPTER IV | Page 67 | |

| IN WHICH IS RELATED THE REMARKABLE BEQUEST | ||

| OF THE LAWYER'S FOURTH CLIENT | ||

| CHAPTER V | Page 81 | |

| THE CONCLUSION OF THE STORY OF THE YOUNG | ||

| LAWYER AND HIS FOUR CLIENTS | ||

| CONCLUSION | Page 97 |

| "Upon the last stage of their journey they stopped for dinner at a tavern" | frontispiece |

| "Bidding his companions to await his return,.... he followed his interlocutor" | facing page 26 |

| The somewhat peculiar pastime of our hero's second client | facing page 44 |

| "You next!" | facing page 58 |

| "It was at this juncture ... that an apologetic knock fell upon the door" | facing page 68 |

| "The negro advanced to the portmanteau, ... and displayed the contents to his master" | facing page 90 |

In the year 1807 New York was grown to be a city of no small pretension to an extremely cosmopolitan cast of society. Being a seaport of considerable importance and of great conveniency to foreign immigration, it had even before this become a favorite haven for itinerant visitors from European countries, who for reasons best known to themselves did not find it to fit their inclinations to remain at home. These people, being received into the society of the most exclusive and particular fashion of the town, soon lent to the community a tone characteristic of the manners and customs of European centres of civilization.

Could the reader have been introduced into our American city at this period of its history, he might easily have flattered himself that he was in London or Paris. Or could he have stood upon Courtlandt Street corner, and have beheld young gentlemen of style dressed in the latest English mode or the young ladies gay with red hats and red shawls worn à la Française[12] passing in review upon their evening promenade, he might have believed himself to have been transported into a community composed of both those European cities. Madame Bouchard, the mantua-maker upon Courtlandt Street, vied in public favor with Mrs. Toole, the English woman, whose shop upon Broadway had for so long been the particular emporium of fashionable feminine adornment. Fashionable bucks, who could afford to do so, drank nothing but Imperial champagne at Dodge's; and young ladies who aspired to the highest flash of ton made it a point to converse in French from the boxes of the theatres between the acts of Mr. Cooper's performances. Monsieur Duport taught dancing to young people of quality at twenty-five dollars a quarter, and the French waltz and the English contra-dance divided the favor of the most récherché assemblies.

So much as this has been told with a certain particularity that the author may better invite the confidence of the discerning reader; for otherwise it might cause him some misgivings to accept with entire assurity the fact that a deposed East India Rajah should secretly have maintained his court in an otherwise unoccupied house on Broadway, and it might shock his sense of the credible to accept the[13] statement that an Oriental Potentate should have been able successfully to pursue his vengeance against the authors of his undoing in so unexpected a situation as the town of New York afforded.

It is with so much a preface as this that the author invites his reader to embark with him upon the following narrative, which, though it may at times appear a little strange and out of the ordinary course of events, may yet lead the thoughtful mind to consider how easy it is for the innocent to become entangled in a fate which in no wise concerns him, and for the discreet to become enveloped in a network of circumstances which he himself has had no part in framing.

Accordingly, while the frivolous may easily read this serious story for the sake of entertainment, the sober and more sedate reader will doubtless carry away with him the moral of the discourse which the author would earnestly point out for his consideration.

There was at this period in the town of New York a number of young gentlemen possessed of very lively spirits and pretty ingenious tastes for folly. These gay rattlers about the town had gathered themselves together into a society known as the "Bluebird Club," in which they pledged themselves not only to eat a supper of oysters and to drink as considerable a quantity of rum punch as possible, but subsequently to perform all manner of extraordinary acts of folly. This assemblage of rakes, though it possessed no fixed place of meeting, usually resorted to an oyster-house of no good repute situate upon Front Street, maintained by a negro crimp by name Bram Gunn, whither it gathered once a month during the period that oysters were in season.

Because of many questions of police jurisprudence that had arisen, it was deemed necessary by the members of the Bluebird Club to conceal their individual[18] identities as far as possible from the recognition of those who might otherwise know them. Accordingly, it was customary for those who attended the assemblies of the club to assume for the occasion some such masquerade or disguise as the rag-fairs of the junk-shops or the disused wardrobes of the theatres might afford them.

The organizer of this society and its leading spirit, at the time of which we speak, was a young gentleman by name Nathaniel Griscombe. He was nominally an attorney-at-law; but, though fairly entitled by admission to practise his profession at the bar of justice, he had so far had such small encouragement therein that he had as yet found nothing whatever to do but sit at his office window and amuse himself with his own thoughts and speculations, with such an occasional entertainment as might be offered by the transit across that frame of vision of one or more of those females of lighter tastes and inclinations who by the men of the town were denominated "does." He was regarded by those who knew him as possessed of a superior wit, and he was noted as a professional fulminator of what was then popularly known as "whim-whams." It was also reputed that he could consume more spirituous liquors, without a perceptible effect upon his equilibrium, than any man of his age about the town.

Such extravagances as he indulged in entirely hid from the view of his acquaintances and of the town the fact that he was a young gentleman of no uncommon parts. Indeed, had fortune offered him opportunities in proportion to his abilities instead of neglecting him so entirely, he might have been earning the applause of those in his profession who possessed the respect of the community instead of evaporating his time with such entirely shallow companions as those young bucks and rattlers with whom he elected to consort. Having, however, a prodigious amount of idle time upon his hands, and being of a disposition that would desire the applause even of the vain and foolish rather than no applause at all, he yielded himself with only an occasional qualm of conscience to the indulgence of such follies and escapades as afforded excitement and interest for the moment to his extremely volatile spirits and active temperament.

Upon a particular night this young gentleman wended his way to a meeting of the Bluebird Club, arm in arm with three fellow-members. Each was clad in a most extravagant and ridiculous masquerade. One was adorned with a long night-gown covered over with yellow moons, a mask with a prodigious nose and spectacles, and a wig of cotton-wool. Another wore[20] the black costume of an astrologer, his face blackened, and a tall steeple-crowned hat made of black paste-board upon his head. Our young gentleman of the law had clad himself in the loose cotton blouse and drawers of a clown. Upon his head he wore an extraordinary cocked hat with a rosette and ribbons of green, yellow, and red; and, to further conceal his identity, he had chalked his face, and had painted red circles in vermilion around his eyes and mouth. In these costumes our three wild bucks made their way to the meeting-place of the Bluebird Club, shouting, singing, and by their pungent jests exciting alternate emotions of amusement and irritation in all those whom they passed. Arriving at the meeting-place of their society, they found gathered an unusually large assembly, consisting of four or five and twenty other young gentlemen, all like themselves bent upon the execution of whims and follies, and all alike disguised in extravagant and outrageous costumes.

With many absurd ceremonies, which were supposed to be of a secret nature, and a multitude of performances which rather befitted a cage of monkeys than a gathering of rational human beings, but which so well sufficed to tickle their sense of wit that continued roars and peals of laughter greeted each performance, the initiatory formalities were concluded;[21] and a supper of stewed oysters, cucumber pickles, water biscuit, and rum punch, was attacked with a heartiness of appetite which did credit alike to the easy consciences and the hearty stomachs of those who partook thereof. Nor did the mirth of the club at all diminish with the progress of the repast. Rather did their sense of the ludicrous become more keen and volatile as each new glass of rum punch was consumed. A look, a word, a grimace, was enough to cast the whole assembly into convulsions of laughter, from which some could hardly recover before spasms of cachinnations would seize upon them again.

The extravagance and uproar had become deafening, when at their height the door of the room in which the assembly sat at their obstreperous repast was suddenly flung open, and a portentously tall and mysterious figure, clad entirely in black, entered the apartment, and stood regarding the furious scene of folly in masquerade, if not with amazement, at least with a perfectly silent observation. The figure that thus so suddenly appeared was wrapped in a long rich cloak of a dark and heavy material, the face being entirely hidden by a mask hung with long black silk fringe. This apparition stood for a considerable time unobserved by our young racketers, who were too far engrossed in their own follies to take notice of anything[22] else; but presently one, and then another, and then all of the individual members became aware of his presence. This acknowledgment of the advent of the stranger was indicated by a redoubled outburst of uproar, composed of shouts, whistles, and cat-calls; and, supposing nothing else than that the new-comer was one of their members, they began freely to bestow upon him such part of the evening's entertainment as had not been consumed in a shower of cucumber pickles and water biscuit that fairly rained upon him like a storm of hail.

Any one less determined upon a purpose than the stranger could hardly have stood his ground. As it was, he made no pretence of defending himself from the attack, but submitted to the assault of the Bluebird Club with so much dignity of demeanor that, what with the richness of his attire, so different from their tinsel foppery, and what with the silence of his observation,—his eyeballs now closing into darkness and now shining whitely beneath the ebony shadow of his mask,—it began to dawn upon the brains even of our half-tipsy buffoons that here was something of a different purpose from their intemperate madness and frenzy of folly.

By little and little the uproar in the room diminished, until at last all fell fairly silent, and sat returning[23] the gaze of the visitor, if not with a growing respect, at least with an increasing curiosity as to the purpose of the presence that had thus unexpectedly introduced itself upon their absurd and senseless performances. Whereupon, being able now to make himself heard, the stranger in a commanding voice demanded to know which of the company present was the attorney-at-law, Nathaniel Griscombe.

It may be imagined that our young lawyer was somewhat surprised and sobered by this inquiry. Rising from his seat, he replied to the challenge that he was the individual whom the other named; and then, suspecting that it might be the intention of the stranger to put a hoax upon him, he added that, if the visitor was up to any whim-whams or bit of hoax, he, Nathaniel Griscombe, was a rattler himself, and knew perfectly well exactly what o'clock it was.

The stranger, without any immediate reply, regarded our young gentleman for a considerable time in silence. But, if he experienced any emotion of surprise or amusement at the sight of his white and bepainted face and the extraordinary attire that the youthful attorney presented to him, he made no betrayal of his sentiment. "Sir," said he, with perfect seriousness, "so far from jesting or desiring to jest, I assure you that I at this moment am more serious[24] than I suppose you have ever been in all of your life. I have been looking for you everywhere, and have gone from place to place, misdirected by every one from whom I requested knowledge. I have stood at the door for a considerable time, knocking; but, finding myself not heard because of the noise you have been making, and not choosing to wait all night for permission to enter, I came in without being bidden, to find you, at last, in this company of apes and buffoons. My purpose in coming here, I must inform you, is of so serious a nature that, were it governed by other circumstances, I would at once withdraw and leave you in peace to the continuation of your folly. But you will perhaps be surprised when I assure you that it is with the utmost satisfaction I discover you in such a place as this, and so surrounded and engaged as you are."

At these words, spoken with perfect sobriety and every appearance of candor, our young gentleman presented, it must be confessed, a rather silly face. "Upon my word," he said with as easy a laugh as he could assume for the occasion, "I am very well pleased that my present surroundings afford you satisfaction. I can only say, however, that I am glad you are not likely to come to me as a client; for your respect for my parts could hardly be augmented by finding me so engaged."

"As to that," returned the stranger, with unrelaxed sobriety, "you will no doubt be additionally surprised to learn that I do indeed come to you as a client to his attorney."

"Then, indeed, sir," cried our young gentleman, who began again sagely to suspect that a hoax was being put upon him, "you have my word of honor that I am at a loss to guess why you are satisfied to find me indulging in such folly and intemperance as that which you discovered when you favored us with this unexpected visit."

"As to that," said the stranger, "I can easily enlighten you. The nature of the business in which I would employ you is of such a sort as to demand the attention of one not only possessed of spirit and courage and an entire command of unoccupied time, but also of one possessed of other and very different qualifications. To this end I have made diligent inquiries; and I have conceived the opinion that you are a man not only possessed of considerable parts, but of an honesty sufficient to carry you through so delicate and dangerous a commission as that with which I have to intrust you."

At these words, our young gentleman knew not what face to assume; nor could he yet tell whether to regard the whole affair as a hoax or as the beginning[26] of a more serious adventure. "Upon my word, sir," he cried, "you pique my curiosity. But, if I am to believe what you tell me, I must be better assured of your truth. I am, as you may well believe, too knowing a bird to be caught by chaff."

"Indeed," said the other, "you yourself can alone prove the sincerity of my words; nor would it in the least remove the doubts that you entertain of my sincerity, should I inform you that the business upon which you will be employed concerns the possible murder of my own self. If, however, you are the man of mettle I suppose you to be, you have only to accompany me in the conveyance that awaits below, and you can then and there satisfy yourself as to whether I have spoken with veracity or with dis-ingenuousness."

By this time, as may be believed, the assembly of young bucks had fallen entirely silent; nor could our young attorney compose himself to any frame of mind to digest the credibility of that which he heard. "I protest," he cried at last, "the more you tell me, the more my belief is increased that you have a purpose to make me the victim of a jest. Nevertheless, if what you have just said is offered as a challenge, you shall find me your man; for I declare that I am not afraid to accompany you or any other man, wherever you may choose to conduct."

"BIDDING HIS COMPANIONS TO AWAIT HIS RETURN ... HE FOLLOWED HIS INTERLOCUTOR"

Thereupon, bidding his companions to await his return, he arose, and, removing his cocked hat with its parti-colored ribbons from its peg upon the wall where it hung, he followed his interlocutor down the staircase to the street below.

Here he discovered a very handsome cabriolet with red wheels, into which, at the bidding of his companion, our young gentleman stepped, the other following him and closing the door with a crash. Thereupon the driver instantly whipped up his horses, and drove away at an extremely rapid rate of speed.

The curtains of the window had been closed, so that our young lawyer was entirely at a loss as to whither he was being conveyed, excepting that the cabriolet continued rattling over the stony streets, and that it turned several corners at an undiminished rate of speed. Nor did his companion speak a word until the vehicle was drawn up to the sidewalk with a suddenness that nearly precipitated our hero from his seat. Almost instantly the door was opened, and the attorney, following his conductor, stepped out upon the sidewalk at what appeared to be the back gate of a considerable garden that partly enclosed the back buildings of a large and imposing edifice standing at a little distance, its outlines nearly lost in the obscurity of the night beyond.

What with the many turnings of the conveyance that had brought him thither, and what with the fruitless surmises and speculations as to his destination, Griscombe was as entirely at a loss to tell whither he had been fetched or what was the situation of the building he now beheld as he would have been, had he been transported into another world. Nor did his companion give him time for surmises or suppositions; for, drawing forth from his breeches pocket a key, he opened the gate, and immediately introduced our hero through a dark and wind-swept garden and by the back door into the kitchen of the residence, which was illuminated by the light of a single candle.

With no more illumination than this latter could afford, the stranger thence led the way through the dark but richly furnished spaces of a silent and sleeping house of palatial dimensions, until at the further extremity of the building he finally conducted our young lawyer into a large and nobly appointed library. Here a lingering fire of coals still burned in the marble fireplace, diffusing a grateful warmth throughout the apartment, at the same time lending a soft and ruddy illumination by means of which our hero was able with but little difficulty to distinguish the stateliness and profusion of his surroundings. The heavy and luxuriant folds of rich and heavy tapestry sheltered[29] the windows; soft and luxuriant rugs of Oriental pattern lay spread in quantities upon the floor; the walls were hung with paintings glowing with color and of the most exquisite outlines; beautifully bound books crowded the cases that surrounded the room, and the marble mantel glistened with ormolu and crystal adornments.

Meantime his conductor, having lit a quantity of wax candles upon the mantel-shelf, and having laid aside the mask that for all this while had concealed his identity, turned at last to our hero a face whose lineaments, though extremely handsome, were as pale as wax and furrowed with the lines of a most consuming care. A quantity of hair as black as ebony curled about his alabaster forehead, and he fixed upon his visitor a pair of large and sombre eyes whose piercing brilliancy betrayed an illimitable anxiety of soul. Beautiful, however, as was the countenance presented to the observer, there was in the hardness of its lines and the thin and compressed nervousness of the lips a stern relentlessness of expression that the smouldering and sinister fire which glowed in the eyes alone might be needed to enflame into a conflagration of rage and of cruelty.

Having motioned Griscombe to a soft and luxuriant seat upon the other side of the fire, himself leaning[30] with an elegant ease against the mantel-shelf, this strange and singular being composed himself as though with a considerable effort, and addressed to his listener the following extraordinary discourse, without any preface whatever:—

"You will doubtless be considerably surprised," he said, "to learn that you behold before you one who feels well assured that he is already condemned to an unknown death that shall visit him perhaps within the course of a day or two—perhaps within the course of a few hours. I know perfectly well that you may be inclined even to doubt the truth of so extraordinary a statement or to question the entire sanity of one who propounds so startling a statement. Nor can I even enter into such an account of my miserable circumstances as shall convince you at once of my truthfulness and of my sanity, without involving you also in the danger in which I lie entrapped. Should you be the recipient of my confidence, certain death would probably await you, as I believe it awaits me; and you would thus be prevented from carrying out the important commission that I am now about to impose upon you."

It may be rather imagined than described into what a state of amazement, not to say stupefaction, our hero was cast by so extraordinary a prologue.[31] He sat, sunk into a perfectly inert silence, gazing at the singular and tragic being before him, without possessing, as it were, the power of making a single movement. At another time his absurd and preposterous figure, with its bedaubed and bepainted countenance, might, in its expression of solemn seriousness, have appeared infinitely ludicrous. As it was, the profound tragedy of the scene was only accented by the grotesqueness of his outlandish presentment. Without seeming to observe his silence, but fetching a profound sigh that appeared to come from the very bottom of his heart, the speaker presently resumed his address as follows: "But, though I may not relate to you all the circumstances of my dreadful fate, I may at least tell you this much,—that I and another were engaged in a political revolution in Industan, in the course of which a powerful and implacable Oriental ruler was overthrown from power. Knowing to what an extent I had incurred his resentment, I thought to escape his vengeance in this remote country. I find, however, he has discovered me; and I have already received a warning that my life is in imminent danger. My brother, who was the companion of my machinations, as he was the partaker of my rewards, is hidden in a remoter part of this country; and it is my intention not only to[32] transmit through you a warning to him of his extreme danger and of my own miserable fate, but also to have you carry a portion of that treasure which was my reward, and which I do not choose to have fall into the hands of my enemies.

"I may, sir, be unable to convince you of my sincerity by the use of such empty words as those which I am obliged to use; but what your ears may disbelieve, your eyes may at least convince you of."

As he concluded, he smote his hands together sharply two or three times in succession, whereupon a door near to where he stood was, as though in echo, immediately opened by a waiting attendant, who, with a silent footfall, entered the apartment. This new personage upon the scene possessed an Oriental cast of countenance, which was further enhanced by his extraordinary costume, his head being surmounted by a turban, and his figure clad in a long garment of dark embroidered silk. In one hand he bore a casket about the bigness of a hat-box, bound about with bands of steel of prodigious strength, and studded with polished brass nails. In the other he carried a small tray with a leathern bag upon it. Without betraying the slightest signs of curiosity or surprise at Griscombe's extraordinary figure, but with a deportment of the utmost seriousness, he placed[33] both of these objects upon the table beside our hero, and then, with a profound obeisance to the gentleman beside the fireplace, withdrew as silently and as suddenly as he had entered.

"In yonder bag," said the gentleman, immediately resuming his colloquy, "are one hundred pieces of gold, valued at twenty dollars each. Such part of this as you find necessary, you are to expend in executing the commission with which I shall presently intrust you: the residue you are to retain as a fee for your services. This strong box you are immediately to convey to your lodgings in my cabriolet (which waits for you below at the back gate), devoting to its safety the most extraordinary care; for it contains a priceless treasure. If by nine o'clock to-morrow morning you receive no word from me, you will know that I am no longer in the world of the living, and that the vengeance that has followed so relentlessly upon my footsteps has at last overtaken me. In that case you are immediately and with all despatch to convey this box to Bordentown in the State of New Jersey, and are to deliver it to the person designated upon the address attached to the handle. He is my brother; and his name, as you will discover, is Mr. Michael Desmond. Upon the opposite side of the ferry at Paulus Hook you will find a post-chaise[34] awaiting its passenger. This I have provided for myself in case I am able to escape the dangers which overhang me. Should I not be so fortunate as to accomplish an escape, you are to take my place in the conveyance, and to pursue your commission, stopping neither day nor night until it is accomplished. My brother I make the legatee of the greater part of that wealth (the price, if you please, of treachery and of blood) which has proved the source of my own undoing. Behold! You shall see it for yourself!"

As he spoke, our young lawyer's extraordinary client stepped briskly to the box, applied a key to the lock, and lifted the lid. Within was a considerable mass of closely packed lamb's-wool, which—as Griscombe, consumed by a fever of curiosity, arose to observe—the speaker deftly removed, displaying to the young lawyer's dazzled and bewildered gaze a sight that well-nigh bereft him of what reason he had remaining after his late most incredible interview. Reposing upon a second mass of lamb's wool, hollowed out as though to receive its precious contents, was a double handful of precious stones of inconceivable size and brilliancy, which, in the light of the candles that had been lit, shed forth a thousand dazzling sparks of infinite variety of flaming colors. It was but a glance: the next moment the lamb's wool[35] was replaced, the lid was clapped down again, the key turned, and Griscombe's bedazzled sight returned once more to the objects about him.

"And now, my dear sir," resumed his interlocutor, "whether or not you believe my story, you will, I am sure, perceive how important is the commission I intrust to your keeping, and how well I am inclined to pay you for all of your trouble. I trust, therefore, you will consider me to be lacking neither in courtesy nor in hospitality if I beg you to withdraw, and to return to your own house. So great is my threatened danger that I dare not even accompany you to my cabriolet that is awaiting you where we left it; but in lieu of myself I shall send with you an attendant who is altogether attached to my interests, and who will serve as a guard until you and your charge are safely ensconced in your lodgings."

Thereupon he once more clapped his hands together. Again the same mysterious attendant, who had before replied to the summons, appeared in instant response, and, in obedience to elaborate directions delivered in a foreign tongue, of which the young lawyer understood not a single iota, bowed to our hero, and indicated that he was prepared to accompany him upon his return.

With this concludes the first chapter of our narrative, with only this to add, that our hero—under the escort of his singular attendant—arrived safely at home, where he hid his treasure casket under the bed, in the remotest corner of the room, until he could otherwise dispose of it.

As the ingenuous reader may readily imagine, what little remained of that night was passed with no great ease or repose by our hero. But little slumber visited his eyelids, and that little so disturbed by vivid and diabolical visions of terror that he had better have remained awake than to have fallen into so portentous a sleep. In a succession of monstrous images he continually beheld his client distorted by the most grotesque and fantastic pangs of dissolution; as continually he was haunted by visions of the journey he was about to undertake; and such phantoms were always accompanied by corresponding dreams of the strong box of treasure.

In one of these tremendous visions he beheld himself searching in a deep bed of sliding sand for the jewels which had been lost from the overturned casket, while a dreadful form leaned out of the window of the post-chaise upon the bank above, shrieking to him to hasten or it would immediately perish.

It was from this portentous dream that he awoke to find the early winter daylight struggling through the window-shades, and to an immediate realization of the strange and inexplicable commission that awaited him.

Nor was it until in the gray of the morning he had again viewed the bag of gold and the casket of treasure, that he could feel entirely assured that what had befallen him the night before was not an hallucination, such as those that had pursued him throughout the troubled sleep from which he had just aroused himself. It appeared to him incredible that such strange occurrences could really have happened to him, and it was above an hour before he could compose his mind to accept that which had occurred.

Finding himself at the end of that time in no small degree exhausted by the several instances of extreme excitement through which he had just passed, and discovering that he was now assailed by a sharp and vehement appetite, he determined to visit an oyster-bay at the neighboring Oswego Market, where, so long as he had been able to obtain the necessary credit, he had been in the habit of taking an occasional meal. To this end, having extracted a piece of gold from the leathern bag, and having carefully hidden the rest in a drawer of his bureau, he sallied forth in quest of that[41] with which to satisfy his appetite, carrying with him, for the sake of safe keeping, the treasure casket of jewels.

Having satisfied the immediate pangs of his appetite by a breakfast of unusual elaborateness, and having nearly overwhelmed the keeper of the oyster-bay with the proffer of a double eagle of gold, from which he was requested to extract payment for the entertainment he had just received, he returned home refreshed in body and in mind, with renewed courage and possessed by a keen and vehement desire to follow out to its end the adventure upon which he now found himself embarked.

Entering that bare and half-furnished apartment which he designated his office and which opened into his bedroom beyond, he discovered a stranger to be seated in a chair beside the desk, as though awaiting his coming. As our hero entered, this stranger arose with a profound salutation, and presented to our hero's view a person singularly tall and slender, a face of coppery yellow, straight hair, a hooked beak of a nose, and eyes of piercing blackness. He was clad with the utmost care in clothes of the latest cut of fashion. His linen was of immaculate whiteness, and the plaited frill of his shirt front exhibited the nicest and most elaborate laundry-work imaginable. In short, his costume[42] was that of the most exquisite dandy. His countenance—the singularity of its appearance enhanced by a pair of gold ear-rings in his ears—was that of a remote foreigner of unknown nationality.

Without giving our lawyer time for further observation, the stranger, in the most excellent and well-chosen English, and with hardly a touch of foreign accent, addressed him as follows:—

"You behold," said he, "one who has come to you offering himself as a client, whom, though you may find his business to be of a singular nature, you will also find to be extremely inclined to profit you well in the relations which he seeks to establish with you."

"Sir," replied Griscombe, with no little importance of tone, "you come to me at a time of extreme inconveniency. It is now after half-past seven, and at nine o'clock I may be obliged to undertake a commission of importance beyond anything of which you can perhaps conceive. A journey of the utmost tragic importance lies before me; and this box, which you behold in my hands, belongs to a wealthy and liberal client, whose behests must in no wise be denied."

"I am convinced," replied the stranger, in accents of the most extreme and deferential courtesy, "that your time must indeed be greatly in demand if you cannot afford to bestow a little of it upon myself. I am in a[43] position to be perfectly well able to indulge every whim that seizes me; and just now it is my whim to become your client, and to purchase of you a considerable portion of your valuable time."

At these words it began to occur to Griscombe that the eccentric being before him was, perhaps, better worth his attention than he had at first supposed. Accordingly, excusing himself for a moment, upon the plea that he had to dispose of his present charge, he entered his bedroom, and deposited the jewel-casket where he had before hidden it,—under his bed, and in the remotest corner of the room. Having thus left it in safety, he returned again to the office, where his second client was patiently awaiting his return.

So soon as Griscombe had composed himself to listen, the other resumed his discourse as follows: "I am," said he, "as I before told you, perfectly well able to pay for every whim that seizes me. That I may convince you of this, I herewith offer you a fee which I feel well assured is equal to any you may have received in your life before. Behold, in this bag are a hundred pieces of gold, valued at twenty dollars each; and, if that is not sufficient, I am fully prepared to increase your fee to any reasonable extent."

At these words Griscombe knew not whether his ears deceived him nor whether he or this new-found[44] client were mad or sane. Nor could he at all accredit the truth of what he heard, until the stranger, opening the mouth of the bag, poured forth upon the table a great heap of jingling gold money. "You will," resumed his new-found client, with perfect composedness of manner, "be, no doubt, considerably surprised to learn the nature of the duty which I shall call upon you to perform. It is that you play me a game of jack-straws."

Here he allowed for a moment or two of pause, and then continued: "You have doubtless observed that I am a foreigner. By way of explanation of this whim of mine, I may inform you that I am an East Indian of considerable importance in my own country. Being extravagantly wealthy and possessing a prodigious amount of unoccupied time, I have passed a great part of it in practising and playing the game to which I now invite you to participate; and by and by I became so inordinately fond of the pastime that I now find it impossible entirely to cease indulging in it. In this country I find every one either to be too busily engaged to take part in it, or too lacking in the patience to pursue it to a consummation. Learning that you are favored with ample leisure to pursue your every whim, I was encouraged to visit you, and to invite you to participate [45]with me in my recreation. Since beholding you, I am consumed with such an appetite to test your skill that I am entirely willing to pay very handsomely for the privilege of indulging myself. See, I have brought with me the implements of my favorite pastime."

THE SOMEWHAT PECULIAR PASTIME OF OUR HERO'S SECOND CLIENT

As he concluded, the stranger drew forth from a pocket in his coat a cylindrical box of ebony, carved into the most exquisite Oriental design. Unscrewing the lid of this receptacle, and tilting downward the box itself, he spilled out upon the table a set of ivory jack-straws of so marvellous a sort that Griscombe, in his wildest imaginings, could never have believed possible. Some of the straws were plain sticks of polished ivory: others were ornamented with heads or figures of wrought gold set with precious stones. Each of them was different from the other,—this a gryphon, that a serpent with distended crest, this a yawning tiger with diamond eyes, that an idol's head with a ruby tongue thrust from its gaping jaws.

The stranger either did not observe or did not choose to remark upon the extreme surprise that possessed his attorney. Offering his opponent a golden hook with a pearl handle, he invited him to open the game, into which he himself entered with every appearance of the most entire satisfaction and enjoyment.

In spite of his not infrequent indulgences, Griscombe was favored with extreme steadiness of nerve; and, though a casual acquaintance would never have accredited him with it, he possessed at once patience and perseverance to an extraordinary degree. But neither patience nor perseverance or steadiness of nerve was any match for the infinite skill and dexterity with which the stranger played his game. Griscombe was but a child in his hands, and the jack-straw player dallied with him as a cat dallies with a mouse. At the end of each round the stranger politely assured his opponent that he played naturally a very excellent game, and that in time and by practice he might eventually hope to become no inconsiderable adept at the sport. But these courteous expressions only declared to Griscombe how inadequate was his play, and at each repetition merely served to incite him to fresh endeavors.

At the end of an hour the stranger declared his appetite for the amusement to be satisfied; and, gathering up his jack-straws and replacing them in the ebony box, he thanked our hero most courteously for the entertainment he had offered him. Thereupon, resuming his cloak and hat which he had laid aside at the beginning of the game, he delivered a bow of the profoundest depth, and departed without[47] another word, leaving the pile of gold pieces upon the table behind him, as though they were not worth any further attention.

Nor was it until he had fairly gone that Griscombe—with a shock that set every nerve tingling—recalled his precious chest and that inestimable treasure that had been deposited in his care, and which for all this time had been left unprotected and almost unthought of. At the recollection of this his heart seemed to stand still within him, and his ears began to hum and buzz, and a cold sweat stood out upon every pore of his body. For upon the instant it occurred to him that maybe this polite stranger with his marvellous jack-straws was merely a rook seeking to divert his attention while a confederate carried away the treasure box from the room beyond. With weak and trembling joints, and yet with hurried steps, he ran into the next room, and, falling upon his knees, gazed under the bed; and it was with a feeling of relief that well-nigh burst his heart that he discovered the object of his solicitude reposing exactly where he had placed it.

With a heart as light as a feather and with a rebound of excessive joy and delight at the thought of the additional fee of a thousand dollars he had just earned with such extreme ease and in so extraordinary[48] a manner, he set himself in haste to dress for the journey that lay before him, finding it exceedingly difficult, in the lightness of heart that now possessed him, to direct a proper sobriety of attention to the possibly tragic fate that had maybe befallen his first unfortunate client since he had beheld him the night before.

With this concludes the second stage of our narrative, excepting to add that, when nine o'clock came, bringing no signs of his client, Griscombe crossed the ferry to Paulus Hook, where he found the post-chaise awaiting his arrival, exactly as his client had foretold. Entering this vehicle, our young lawyer immediately began that journey which he pursued with all diligence, stopping neither day nor night till he had arrived at his destination.

Our hero arrived at Bordentown early upon a clear and frosty winter morning with entire safety and success, and with no greater adventures befalling him than usually occur to the traveller in a private conveyance upon so considerable a journey. Nor had he the least difficulty in discovering Mr. Michael Desmond's address, that gentleman dwelling in one of the most palatial of those abodes that lend such an air of aristocratic distinction to the town.

Immediately, in reply to his request to see the master of the house, he was shown into the reception-room, where Mr. Desmond presently appeared, presenting to his astonished sight a person so exactly and minutely resembling his brother that, had Griscombe not known it to be otherwise, he would have believed them to have been the same individual.

The remarkable resemblance, however, did not extend deeper than the lineaments of the features; for,[52] whereas the countenance of the first Mr. Desmond had been overclouded by an expression of the most sombre melancholy and the most overwhelming anxiety, the face of this gentleman beamed with courteous hospitality and generous welcome.

He still held in his hand the card which Griscombe had sent in to him by the servant; and, as he advanced with a smile of extreme cordiality illuminating his face, he cried, "I cannot, my dear Mr. Griscombe, be too much delighted that you have favored me with so early a call, since it will give me the pleasure of having you to breakfast and of introducing you to my daughter. I see from what you have written me upon your card that you come upon important business from my brother; but, before satisfying my curiosity upon that point, I shall insist that you first appease the craving of what must be a very hearty appetite after so long a journey."

Nor would he accept any refusal of his invitation, but, with polite determination, put aside every effort that Griscombe made to explain the pressing and tragic nature of his mission. "Nay," he cried, as Griscombe continued to urge upon him the importance of his affair, "I insist that you say no more at present. I am perfectly well aware with what an extreme degree of exaggeration a young lawyer regards[53] a commission that may very easily wait for breakfast. I am determined that you first satisfy your appetite, and then your sense of duty."

And so, protesting and insisting, he led our reluctant hero by the hand until he at last introduced him into a spacious and sunlit dining-room, rendered additionally cheerful by a large fire of cedar logs that crackled in the marble fireplace. Here a table spread with snowy napery and sparkling with crystal and silver was prepared for an ample breakfast; and, as they entered, the slender and graceful figure of a young lady, clad entirely in white, arose from where she sat at the head of the board behind the tea-urn. In response to her father's introduction, she replied to our young gentleman's profound bow with all the ease and dignity of deportment imaginable.

At that time Miss Arabella Desmond was one of the most perfect beauties in the United States. With a figure of rounded yet slender contour, she bore herself with an ease and grace of deportment that at once charmed and delighted the beholder. Her features presented the most exquisite delicacy of outline, and the rich abundance of her raven tresses matched in their color the dark and lustrous eyes, whose liquid brilliancy was ineffably enhanced by the ivory delicacy of her complexion. Add, if you please,[54] to those graces of person a wit at once subtle and alert and an address as amiable as it was entertaining, and you shall possess an image—imperfect, to be sure—of that famous beauty whose hermit-like seclusion from the world and whose mysterious personality had now for above two years been a matter of wonder and of speculation to the elegant society of Bordentown, that would gladly have received so admirable an addition into its fold.

Griscombe, as may be supposed, had all this while maintained a close hold upon his precious treasure-casket. He had placed it beneath his chair as he took his seat at the table; and what with the consciousness thereof, and of the interview with his host concerning his brother's probable fate, he discovered himself to be the victim of a singular embarrassment, and strangely at a loss for words wherewith to commend his wit to the easy and affable beauty. It was in vain that he endeavored to display the aptness of dialogue which he was entirely conscious he possessed. He was aware only of an unwonted constraint; and, accordingly, it was with a singular commixture of relief and regret that, at the invitation of Mr. Desmond, he at last quitted the table, and followed his host toward the study, mentally declaring to himself that, should the opportunity again offer, Miss Desmond[55] should discover him to be not so lacking in brilliancy as she must have supposed from their first interview. Nor was it until he found himself in the study, face to face with the father, the strong box of treasure upon the table between them, that he was able to fetch himself entirely back to the seriousness and complexity of the business which rested upon him. Beginning at the beginning, however, he presently found that he was recovering entire command of himself, and presently, in clear and lucid phrases, was reciting every circumstance that had befallen him from the time of his absurd and preposterous masquerade at the supper of the Bluebird Club to the moment when his present host had met him in the reception-room.

As he progressed in his discourse, a dark and sombre shadow of extraordinary gloom gathered deeper and deeper upon the hitherto smiling countenance of Mr. Desmond. By little and little the color left his cheek; and an expression of the profoundest anxiety overspread his face, causing him to resemble to a still more extraordinary degree his unfortunate brother. As our young lawyer concluded his narrative, the other arose, and began walking up and down the narrow spaces of the room, betraying every appearance of an infinite perturbation of spirit, suppressed[56] by an iron will and an implacable determination.

"My dear Mr. Griscombe," he said at last, stopping in front of the fireplace, "I shall not attempt to conceal from you my apprehensions regarding the fate of my unfortunate brother. I fear that he is no more, and that a tragic fate has overtaken him. That, however, is now past and gone. It is irremediable, and the question that at present lies upon us is that of my own danger. Tell me, do you suppose it likely that the agents who pursued my brother have any knowledge of my being established in this place?"

"That I cannot tell you," said Griscombe, "unless, indeed, the mysterious jack-straw player who penetrated into my office may have been in search of such information. I confess I cannot account in any other way for his coming to me."

"It may be so," said Mr. Desmond, thoughtfully. "At any rate, I shall immediately quit this place where I now live, and shall seek for an asylum in some still more retired and undiscoverable locality. Meantime let us examine into the safety of the treasure which you have so faithfully transported thither."

And, as he concluded his speech, he arose, and crossing the room to a handsome mahogany escritoire, and opening a secret drawer therein, brought[57] thence a small steel key, the fellow to that with which his unfortunate brother had once before opened the casket in Griscombe's presence. This he applied to the lock, gave it a turn, and threw back the lid.

The piercing and terrible shriek which instantly succeeded the action struck through Griscombe's brain like a dagger. The next moment he beheld his host stagger back, clutching at the empty air, and at last fall into a dishevelled heap into the arm-chair behind him, where he lay white and shrunken together as though shrivelled up to one-half his former size and bulk by a vision that had just blasted his sight.

So unexpected was this conclusion, and so terrifying, that Griscombe sat as though stupefied. At last he arose, hardly conscious of what he was doing, and the next moment found himself gazing down into the interior depths of the open casket, like one in a dream.

There before him he beheld a spectacle the most dreadful that ever he had beheld. His sight appeared to him to swim as though through a transparent fluid, his brain expanded with a fantastic volatility, and his soul fluttered, as it were, upon his lips. For there before him lay, entirely surrounded by lamb's wool as white as snow, a still, calm face, as transparent as[58] wax,—the immobile face of the first Mr. Desmond, now infinitely terrible in its image of eternal sleep. As though in a malign mockery, the now worthless jewels—about which the possessor had once been so infinitely concerned—had been poured out carelessly upon the motionless lineaments. A precious diamond, like a tear, reposed upon the transparent cheek, and a ruby of inestimable value clung to the pallid and sphinx-like lips. Across the forehead was stretched a fillet of linen; and upon it were inscribed in letters as black as ink the two ominous words—

How long Griscombe stood like one entranced, gazing at the dreadful spectacle before him, he could never tell; but, when at last he turned, it was to behold that Mr. Desmond had arisen from his seat, and that he was now clutching to the mantel-shelf as he stood leaning against it, his body heaving and his whole frame convulsed with the vehemence of the passion that racked every joint and bone. "God, man!" he cried at last in a hoarse and raucous voice, and without turning his face: "shut the box lid!"—and Griscombe obeyed with stiff and nerveless fingers that strangely disregarded the commands of his will.

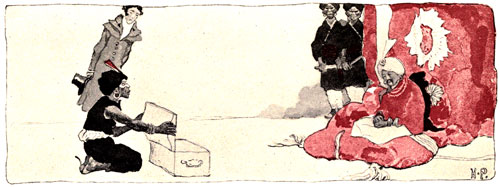

"YOU NEXT!"

At last the unhappy man, having regained some control over the emotions that convulsed him, and heaving a profound sigh as though from the bottom of his soul, turned once more, and exhibited to the young lawyer a countenance from which every vestige of color had departed, and in whose dull and leaden eyes and pinched and shrivelled features it was well-nigh impossible to recognize the genteel and complacent host of a few moments before. "You have," said he, in hollow tones, "just delivered to me my death-warrant. In how dreadful a form it was served upon me, you yourself have beheld. My sins have overtaken me, as my poor brother's have overtaken him. They may perhaps have been of an unusually heinous character; but how great is my punishment! I call upon you to declare, even if our hands were ensanguined with the blood of a prince of India, and if the spouse of an Oriental king were executed at our commands, and even if we were partakers in our reward as in our crime, is not the fate that has overtaken us altogether too enormous for our deserts?"

"As to that," cried Griscombe, "Heaven is your judge, and not I. As for me, I begin to perceive a glimmer of light through these mysteries that have been gathering about me during these last few days, and I declare to you that I will have no more concern[60] either in you or in your secrets. How is it possible," he exclaimed, "that I have come to be the partaker in the consequences of that rapine and of murder in which you and your brother were doubtless one time so guilty? No: I will have no more to do with you!"

"And would you," cried the other, "desert me in such extremity as this? Then at least have some pity upon my innocent daughter. We live a life in this place without a friend or an intimate,—almost, I may say, without an acquaintance. To whom am I to confide her in a time of such mortal danger as this? Am I to take her with me in my flight? And what if my fate overtakes me upon such a journey,—what, then, would become of her?"

Upon this plea Griscombe stood for awhile with downcast eyes, every shadow of expression banished from his countenance. As with an inner vision he beheld Miss Desmond as he had seen her but a little while before,—innocent, beautiful, radiantly unconscious of the doom that was about to fall upon the house—and his heart was wrung at the thought of such hideous misfortunes falling upon her sinless life. "Sir," he said at last, "your appeal has reached me. What is it you would have me to do? For your daughter's sake I will assist you in so far as my abilities may extend."

"I would have you," said the miserable man, "convey my daughter, upon your return to New York, in the post-chaise which brought you hither. With her I will send a quantity of jewels similar to those which you brought to me. These I will place in a strong box, and that again in a portmanteau of such a convenient size that you can easily take it into the post-chaise with you. These jewels comprise a large part of my fortune; and with them my daughter, should she be called upon to be separated forever from her unhappy father, can easily live in affluence and luxury. She, together with this treasure, you are to carry to a M. de Troinville, who has for a long while been the agent both of my brother and of myself, and who is under considerable obligation to us. With you I shall send to that gentleman a letter of full instruction; and, as soon as you have delivered that and my daughter into his hands, your responsibility shall be at an end, and you will have the satisfaction of knowing that you have relieved the anxiety of one who has probably only a day or maybe a few hours to live, and who would otherwise have found his last moments upon earth to have been blighted."

"So be it," said Griscombe, after a moment or two of consideration. "I accept the commission."

"Sir," said Mr. Desmond, "you have won the[62] eternal gratitude of the most miserable man upon the earth." And, as he spoke, he made as though he would have embraced our hero.

"Nay," said Griscombe, "I do not choose to accept your caresses. You owe me no gratitude; for, upon my word, I declare that what I do is only for the sake of your daughter, and that, except for her, I would leave you to a fate which in no wise concerns me, and which, from your own confession, you appear in no small degree to have merited. Prepare your letter to M. de Troinville; and in the mean time, by your leave, I will wait in some other apartment of your house than this."

"You are," said Mr. Desmond, "neither polite nor sympathetic. But let it pass. I find myself obliged to accept your services, however unwillingly they may have been offered."

Little remains to be said concerning this part of our narrative, excepting that about ten o'clock Griscombe was summoned to depart upon his return to New York, and that he found the post-chaise waiting in front of the house, with the young lady and the portmanteau already ensconced within. As our hero stepped into the conveyance, Mr. Desmond gave him the letter of introduction to M. de Troinville, and at[63] the same time thrust upon him a leathern bag containing a hundred pieces of gold valued at twenty dollars each, declaring that he had employed him as his attorney, and that this was his fee. Griscombe would gladly have rejected the stipend, could he have done so without betraying to the unconscious young lady the portentous nature of the affair that had overwhelmed them all. As it was, he found himself obliged, however unwillingly, to accept the gratuity thus thrust upon him.

Even if our hero had never again beheld Miss Desmond, he might easily have retained her in his memory for years afterward as a bright and radiant vision of that otherwise gloomy and portentous episode of his life. As it was, what with his having been intrusted with the guardianship of so beautiful a creature, what with his pity for her unconsciousness of the dreadful fate that had overtaken her father, and what with the necessity he was under of disguising from her the terrible events that had occurred, and of answering in kind the sallies of the innocent and entertaining gayety that burst from her continually during their journey,—what with all these, and the warmth and fragrant charm of her presence so close to him in the narrow confines of the post-chaise, his heart was possessed to its inmost fibres with so consuming an ardor of pity and tenderness that he could gladly have laid down his life for her sake.

It was at two o'clock of an afternoon upon the last stage of their journey that they stopped for a dinner at the tavern in Newark, N.J., almost, so to speak, in sight of their destination. It was excessively cold; and a light snow had begun to fall from the gray and leaden sky, giving promise of an early night. A cheerful fire of hickory wood burned in the fire-place, diffusing a grateful warmth throughout the apartment; and in the pleasure of its heat Miss Desmond yielded herself to an extreme relaxation of spirits. She rallied Griscombe upon the diffidence he had exhibited upon their first introduction. She congratulated him with a mock seriousness upon his approaching release from his duties as a squire of dames. Her father had given her to believe that he would follow her immediately to New York, accordingly, reminding Griscombe that the next day would be Christmas, she invited him to come to M. de Troinville's to dine with them. Nor could Griscombe listen to her innocent prattle without experiencing such an overmastering pity for her unconsciousness of the tragic fate that had overtaken her father and for her own hapless condition, that it was well-nigh impossible for him to answer her sallies with raillery of a like sort. However, he continued to act his part with such skill of performance that his[69] companion never once suspected with what effort he composed the words he uttered.

"IT WAS AT THIS JUNCTURE ... THAT AN APOLOGETIC KNOCK FELL UPON THE DOOR"

It was at this juncture, fraught with such pathetic emotions to our hero, that an apologetic knock fell upon the door; and the next moment, as in answer to his own summons, a little old gentleman of extraordinary appearance entered the room. A long white beard half concealed his face, which was of a yellow-brown complexion, and entirely covered with a multitude of minute wrinkles. His eyes, piercing and black, sparkled like those of a serpent beneath his overhanging eyebrows.

"My dear young gentleman and my dear young lady," he began in a thin, high voice, "learning at the bar that you had a good fire in this room, I ventured to intrude myself upon you with perhaps as strange a request as you ever heard in all of your life."

At the very first appearance of the stranger—who, somehow, in his singularly Oriental appearance suggested the jack-straw player of a few days before—a strange presentiment of evil began to take possession of Griscombe's mind. Nor were his apprehensions lessened as the old gentleman, resuming his speech, continued as follows: "I am, as you may observe, my dear young gentleman and my dear young lady, extremely old; and I am obliged to confess to[70] the possession of certain follies of which I am now entirely unable to rid myself. Fortunately for myself, I am excessively rich, and so am perfectly well able to indulge those whims, however absurd, that have now grown altogether a part of my nature, and which, in one so old as myself, can never hope to be eradicated. Learning that you, my dear young gentleman, were an attorney-at-law, I determined to approach you as a client, and to purchase of you a small portion of your no doubt extremely valuable time." Upon this he drew from beneath his cloak a leathern purse full of money, which he set upon the table. "In this," he continued, "are a hundred pieces of gold valued at twenty dollars each. I offer it to you as a retaining fee, and I venture to say that few lawyers of your age have ever received so much at a time from a single client."

"And what," cried Griscombe, with a voice he could scarcely command,—"and what is it you desire of me?"

"I hardly know," said the old man, "how to prefer the extraordinary request that I have to offer. You must know that I am inordinately fond of the game of tit-tat-toe; and my object is to purchase one half-hour of your valuable time, my dear young gentleman, so that I may indulge myself in my favorite pastime."

At these extraordinary words, and at the entire seriousness of the speaker, the young lady burst into an irrepressible fit of laughter, which she found it altogether impossible to control. But upon Griscombe the effect was entirely different. Those vague and alarming suggestions that had already begun to take possession of him leaped at once into positive reality. He had for safety left the portmanteau with its precious contents in the adjoining bedroom, which he had just used as a dressing-chamber, and he instantly perceived, under the innocent request of the old gentleman with the white beard, the most sinister and malignant designs upon it. He sprung to his feet, as though stung by the lash of a fury. "You villain," he cried in a hoarse and straining voice, "I know what are your designs; and but for this young lady, and my desire to conceal from her your ominous purposes, I would fling you at once out of the window. Begone, lest I find it impossible to restrain myself!"

These words were uttered with a paroxysm of passion such as the young lady was entirely unable to account for. Never before had she beheld our hero exhibit anything but the utmost delicacy and gentleness of manner; and now, not in the least understanding the reason for his fury, she gazed upon him with[72] astonishment, in which terror was almost the entire component part. These emotions, however, gradually gave place to an increasing and generous indignation at what she considered the unmerited violence exhibited by a young man against another old enough to be his grandsire.

"Upon my word, Mr. Griscombe," she cried indignantly, "I profess I am entirely at a loss to understand your anger against this poor old gentleman. What, may I ask, is the reason of your excessive fury at so harmless a request as that which he has proffered?"

"Madame," exclaimed Griscombe, vehemently, "I cannot explain it to you."

"I confess," she cried with still more heat than before, "I cannot understand your violence, unless it is that you fear to appear ridiculous by indulging this poor old gentleman in his innocent whim." And then, upon our hero's continued silence, she added: "I could not have believed it possible that you could have exhibited so much impatience and anger at so slight a cause. My opinion of you is altogether altered from what it was; nor can I again recover my original favorable impression unless you offer such reparation as lies in your power by accepting the fee which has been so generously offered you, and by[73] sitting down and gratifying your client with the game of tit-tat-toe he has requested. Should you decline such reparation, I can, as I say, never entertain again for you the regard I have until now experienced."

"Indeed," said the old man, in a gentle voice, but with a smile in which Griscombe read the most malignant and sinister suggestion, "if the young gentleman apprehends any malevolent designs upon my part, he has only to declare what he suspects; and I will go directly away. If, however, he has nothing with which to accuse me, I, too, shall insist upon it that he, by way of a penance, shall indulge me with my little game."

Poor Griscombe stood overwhelmed with a multitude of emotions. One thing alone was clear to his mind: he must protect his innocent and precious charge from all knowledge of what had now doubtless befallen her unhappy father. It were better that those emissaries of evil that had beset him should fulfil their every purpose—even to the last—rather than that she should suffer. He must be dumb, and allow them to conclude their dreadful work. After all, he could easily inform M. de Troinville before the fatal portmanteau should be opened. "I will obey you if you command me, madame," he cried; "but pray, pray spare me this!" And, as he spoke, he fixed upon Miss[74] Desmond a look of such agonizing appeal that she could not but have been moved by it, had she not been blinded by her own imperiousness of purpose. As it was, she only hardened her face into a still more immovable expression of determination. Where-upon, finding her not to be shaken, our hero sank into rather than sat down upon the chair beside him.

The old gentleman with the beard, having thus gained his point, beamed with the utmost cheerfulness of expression, and, advancing with alacrity, pushed aside the dinner plates, and immediately assumed a position opposite his unwilling opponent, and between him and the door of the room where his precious portmanteau lay hidden. Having thus established himself, the old gentleman drew from a capacious pocket a sandalwood box inlaid with arabesque figures of gold and mother-of-pearl. Opening this box, he displayed, to the profound astonishment of at least one of his companions, an exquisitely wrought tablet of mother-of-pearl and gold, pierced with one-and-eighty holes arranged in a square of nine. Opening a slide in the side of the tablet, he thence emptied from a receptacle upon the table five curiously wrought pins of gold, and a like number of silver. Handing the five pins of the more precious metal to Griscombe and reserving for himself the five[75] pegs of silver, the old gentleman immediately explained to his listeners the simple process of the game upon which he proposed to embark. Each player in turn was to thrust a pin into a hole in the tablet, and he who could so far escape his opponent's interference as to arrange three of the five pins in a line should, upon each occurrence thereof, have scored a point in the game. Having completed these easy instructions, he immediately invited Griscombe to open the play, which he upon his part entered upon with every appearance of entire enjoyment and satisfaction.

At any time Griscombe would have been no match for the extraordinary skill of his opponent; but, as it was, he was so torn and distracted by a multitude of emotions that he occasionally knew not what he was doing or what he beheld. His imagination framed the most ominous images of what was going forward in the bedroom beyond; and he lost again and again, while at times his hands trembled so that he could hardly place the pin in its respective hole. Now and then his hearing, strung to an unnatural intensity of key, seemed to detect smothered sounds from the adjoining room; and at such times the ivory tablet appeared to vanish from his sight, and the sweat started from every pore.

But, in spite of all he suffered, he took care never to permit the young lady to perceive the agony under which he labored. The frequent mistakes of which he was guilty and the extreme inadequacy with which he played the game she attributed to mortification or to obstinacy. At last, at some more preposterous blunder, she could contain her patience no longer. "Why do you not place your pin in that hole, Mr. Griscombe?" she cried: "it will score you a point," And Griscombe, obeying, found the next instant that three of his pins stood in a line.

At that moment a faint whistle sounded from without; and the old gentleman, as though in answer to a signal, declared his desire for the game to be entirely appeased. Withdrawing the pins from the tablet, he replaced them in their receptacle, replaced the tablet itself in the box and shut the lid with a snap. "Madame," he said, "I should have played with you instead of with our young gentleman here; for, indeed, he exhibits no great aptitude for the game." Then addressing Griscombe with a double meaning that set every nerve of his victim to quivering, "Nevertheless, young sir," he observed, "you have afforded me a great deal of entertainment, and I protest that you have entirely earned the fee which you have pocketed." Thereupon he incontinently[77] departed, leaving the young lady and our hero to digest, each in his or her own way, the events that had just transpired.

So concludes this part of the narrative, with only this to add—that, had Griscombe had no one to think of but himself, he would at once have torn open the fatal travelling-case, and so have satisfied himself as to the nature of its contents. As it was, for the sake of his charge, who had in so short a time grown so infinitely dear to him, he would rather have had his right hand struck off than have betrayed his terrible apprehensions to her innocent ears. Accordingly, he still wrapped himself in his martyrdom of silence, though he would rather have sat facing a living adder than that ominous portmanteau upon the front seat of the post-chaise.

The snow, which had begun falling about noon, was, by the time the two travellers reached the ferry to New York, descending in such impenetrable sheets as entirely to conceal the further shore from Paulus Hook. Indeed, it required no little persuasion upon the part of our hero and the promise of a very heavy bribe to induce the negro ferryman to transport them across the river upon so forbidding a night. And so slow was their transit and so doubtful their course that the night was pretty far advanced before they reached New York.

The town lay perfectly silent, smothered in a blanket of soundless white, upon which the ceaseless clouds of snow fell noiselessly out of the inky sky above. Indeed, the drifts were become so deep that Griscombe entertained very considerable doubts as to how he should convey Miss Desmond and the now tragic contents of the portmanteau to their final destination.

Accordingly, it was with the feeling of the utmost relief that, upon quitting the ferry-boat, he was met by a negro, who told him that M. de Troinville had been already informed of their coming, and that, because of the storm, a conveyance had been waiting at the ferry-house ever since early in the evening to transport the young lady and her baggage to that gentleman's house.

A large coach was indeed in waiting, the driver, the horses, and the vehicle alike covered thickly with a coating of white. In this conveyance our hero, with the utmost solicitude, disposed the young lady, and at the same time ordered that the portmanteau should be deposited upon the front seat. Having thereupon distributed a liberal gratuity to those who had assisted him, he himself immediately entered, and closed the door; and instantly the driver cracked his whip, and the coach whirled away, with scarcely a sound, upon the muffled and velvet-like covering of the street, directing its course through the continually falling clouds of whiteness.

Nor could Griscombe so far penetrate the obscurity of the thickly falling snow as at all to tell whither they were being conveyed. Several corners were turned and a number of streets were traversed, the lamps whereof were entirely unable to pierce[83] the falling clouds of snow so as to declare the locality toward which the coach was being driven.

At length, however, after a rather protracted journeying, and to our hero's considerable relief, the carriage stopped at the sidewalk before a large and imposing edifice, altogether unlighted and as black as night. No other building was immediately near; and the mansion stood altogether alone, looking down upon the street in solitary state.

Almost instantly upon the arrival of the coach a number of servants appeared upon the sidewalk, as though they had been waiting in expectation of the coming of the travellers. Some of these opened the door of the conveyance, and assisted the young lady and our hero to alight; others took charge of the portmanteau, which they proceeded immediately to carry into the house; others, again, stood about as though waiting in attendance upon the new arrivals.

All these attentions were preferred with a singular assiduity and in such entire silence that Griscombe knew not whether most to admire the imposing extent of M. de Troinville's household or the extraordinary training of his attendants. Turning to one who appeared to be the upper servant, our hero commanded that the portmanteau be conveyed to some place of safety unopened, and carefully guarded, and[84] that he himself be immediately conducted to M. de Troinville for a private interview concerning business of the utmost importance. In reply the man to whom he spoke delivered an order in a foreign tongue, which Griscombe was entirely unable to understand, whereupon two attendants, as in obedience to his command, conducted him and the young lady up the steps and into a wide and imposing hallway, the front door whereof was instantly shut upon them.

It was but little wonder that Griscombe and Miss Desmond should have stood gazing about them altogether at a loss to understand in what manner of place they had arrived. For, however much they might have been surprised at any eccentricity of a French gentleman living entirely alone in bachelor quarters, what they beheld was the very last thing they might have expected.

The faint yellow light of a single lamp, suspended from the lofty ceiling by a chain, diffused a dim illumination throughout the space, and by its yellow glow Griscombe discovered, with no little surprise, that the hall was altogether unfurnished. Not a fragment of carpet lay upon the floor, not a chair, not a stick of furniture, relieved the bleak and barren space of wainscot about them; but all was a perfectly empty and barren desolation.

And, what was still more remarkable, the numerous attendants that had just before surrounded them and had introduced them into the house had disappeared as if by magic; and a dead and solemn silence reigned throughout the entire edifice, broken only by a single distant voice that, in a monotonous sing-song, inexpressive intonation, continued for a time a level discourse, which at last sank abruptly into an entire silence.

There was something so ominous and threatening in all the unexpectedness of these things that Griscombe felt his spirits becoming overshadowed by an overmastering sense of impending evil. It was only when he discovered that Miss Desmond was becoming perturbed by a similar emotion of dismay, and that she was clinging to him with an exceeding tenacity, that, by an effort of will, he overmastered his accumulating fears, and, in spite of the cloud of apprehension that threatened to overshadow him, regained command of his courage once more.

"What does this mean!" exclaimed Miss Desmond in a hurried and terrified whisper. "What strange place is this to which we have been brought?"

"Have courage," replied our hero, steadily, but in the same subdued tone. "You are in no danger. We have probably come to the wrong house, that is all.[86] Wait but a little while, and all will be explained." But, though our hero spoke with so much courage, his heart was exceedingly burdened with a sense of impending calamity; for he seemed to feel the network of circumstances that had been gathering about him for these few days past enwrapping both him and his ward in ever tightening meshes.

At that instant the figure of a man appeared emerging suddenly from out the gloom. He was tall and thin, and was clad in a long flowing robe of Oriental design. Desiring Griscombe and the young lady to follow him, and without waiting for any question or refusal, he turned, and immediately led the way up a broad uncarpeted stairway to the floor above.

Here a narrow thread of light outlined a door opening upon the landing, as though emitted from a considerable illumination within. This door, as they approached it, was suddenly flung open; and the next moment our hero found himself with his companion in an apartment flooded with such a dazzling brilliancy that, coming as he had from the obscurity without, he was for a time entirely blinded by the unusual radiance.

Little by little, however, his sight returned to him; and he discovered that he and the young lady were in a room of extraordinary dimensions, suffused with an oppressive warmth, heavy with perfume, and flaming[87] with a thousand radiant and variegated colors. Surrounding him and his companion on all sides was a multitude of attendants of a foreign aspect, all clad in extraordinarily rich and sumptuous costumes of an Oriental pattern.

Immediately upon his appearance with the young lady hanging upon his arm, this crowd of attendants parted, forming, as it were, a vista through which our hero and his companion could behold the farther extremity of the saloon.

It was thus that Griscombe first beheld him who, his instinct instantly told him, was the spider who had woven all this web of mystery in which he had become so singularly entangled.