Yours faithfully

Charles Wesley Emerson

PSYCHO VOX

OR

The Emerson System of Voice Culture.

BY

CHARLES WESLEY EMERSON.

Founder of the Emerson College of Oratory,

Boston, Mass.

EMERSON PUBLISHING COMPANY

MILLIS, MASS.

1923

Copyright, 1897.

By Charles Wesley Emerson.

“When a man lives with God, his

voice shall be as sweet as the murmur of

the brook and the rustle of the corn.”

PSYCHO VOX.

It is true in nature, in both organic and inorganic matter, that sound reports the quality of substance, that is, the quality of the sound indicates the quality of the object which produces it. This is very apparent in the animal kingdom. The naturalist knows by the tone of the bird’s voice what kind of bird it is. The hunter knows by the voice of a wild animal heard in the distance whether it is carniverous or herbiverous; for in the voice of the former he hears something which is savage, something which tears, while in the latter he hears the softer tones of the milder animal.

In this treatise I shall consider the human voice as the natural reporter of the individual, his character, and his physical and mental states. I am not considering the individual in any narrow sense, but in the sense of his entire being—body and mind.

Modern research shows that the mind affects all parts of the body,—the brain most immediately. I would not be understood, however, to imply that the brain thinks, or that any part of the body thinks; but that the soul uses the body in this world as a medium through which to manifest its thoughts, emotions, and purposes. One of nature’s laws is expression. What is inmost shall be outermost. What is spoken in secret “shall be proclaimed upon the housetops.” This law is never supplanted, never circumscribed, it always was, is, and ever will be constant in its action.

The mind expresses its degree of development through the vocal mechanism. As the individual rises in development, more thought is expressed in his voice. The voice of a baby has little mind in it; it reports little more than physical sensations. If its physical sensations are agreeable, the “coo” tells it more clearly than words could. As the mind continues to develop, one power after another manifests itself in the voice until we hear thought, affection, and choice speaking in unmistakable tones.

The voice is educated through inducing right states of mind while using it. Mont Blanc rises shoulder to shoulder with other mountains; then, towering above them, its brow pierces the clouds. One speaking while inspired with a sense of its sublimity need not be told not to speak on a high pitch, for he will feel no impulse so to do. Education means to draw out; therefore all true education is from within. If there ever was an age of the world in which this needed to be said, it is to-day. Materialism has spread all over the civilized world, influencing men in religion and in education. I admit that man is influenced by environment, but it must be remembered that man is not confined to material environment alone, his immediate environment is Spirit. Man learns not only from without, but from within; not through sense merely, but through soul.

Singing is heart speaking to heart; inward life speaking to inward life. The power of moving the feelings is the power by which the world is governed. A person may possess reason, but reason must speak in the form of feeling before it becomes effective in influencing others. Elementally considered, the singing and the speaking voices are one. Good teaching for the one is good teaching for the other. The first step in educating the voice is to teach the pupil to think in sounds. The voice is capable of expressing every mental activity—intellectual as well as emotional. The voice rarely fails to reveal the lower order of feelings, as physical pleasure or pain; it can also reveal the higher realm of feelings,—benevolence, love of truth for its own sake, love of good, sympathy with all conscious being, hope, faith, and all spiritual perceptions.

The mind must be trained to the perception of beautiful vocal sounds; it must hold these sounds as ideals while practising with the voice. It is at this point that the chief difficulty in vocal culture arises, viz., that of keeping the mind constantly and exclusively concentrated upon its ideals. If a person holds the right ideal steadily before his mind while properly practising, repetition will cause this ideal to take dominating possession of the tones, and thus shape them to itself and become incarnated in them.

I once heard a most interesting conversation between two gentlemen, one of whom was a Russian violinist. A young Italian had been entertaining a company by playing upon a violin. The Russian asked to see the instrument, and said to a gentleman sitting near, “This is a very old violin—probably a hundred years old.” The other replied, “I suppose it must be very valuable, then, for we are told that the longer a violin is played upon the better it becomes.” “Ah, my friend,” continued the Russian, “that all depends upon what kind of music has been played upon it. The tone of this violin indicates to my mind that it has deteriorated in value in consequence of its having been compelled to discourse music of an inferior quality.”

What a revelation in nature! The molecules that compose the wood of a violin can be marshalled into harmony by the music played upon it! If in the mind of the violinist there is melody and harmony of a high order, it finds its way through his fingers into the bow that touches the strings, and all the molecules of the resounding wood waltz into harmonious forms. What a spectacle for the eye of reason to see all these molecules begin to form into line and step out to the concord of sweet sounds born of the mind of the musician!

If this principle is true of the violin, is it not pre-eminently true of the vocal organism which was designed by its infinite Creator for the especial purpose of responding to the activities of the mind that inhabits it? As the mind thinks mystery, grandeur, or solemnity, the vocalized breath is shaped into corresponding forms of expression. In the throat is a beautiful instrument, made by Him who made the soul to require such an organ for its expression.

It is a fatal mistake to consider the voice as something separate from the man. The true voice is the soul incarnated in tone.

The mission of the voice is to communicate to others what is in the soul of each. The eyes of no two persons receive the same rays of light. All men know more than one man, because each person has his own individual point from which to view life and the world. If we listen not to the report of others, our lives will contain but little truth. A person with a grand intellect lies as open to the thoughts of others as the placid lake to the stars which it nightly reflects. Narrow minds will entertain only those thoughts which come to them through some channel in favor of which they maintain a prejudice. The receptive mind will “prove all things” by entertaining all things, and then “hold fast that which is good.”

This power to communicate thought through sound is beautiful and mysterious. A person listening to an orchestral composition often finds that the thoughts awakened in him correspond to those which inspired the composer.

I know that Beethoven believed in God’s government on earth, because once while listening to one of his compositions, which no words accompanied, visions arose before my mind. I saw the early condition of this world; I heard a sound as if a thousand wild animals were tearing each other into fragments with snarls, and yells, and fierce cries. The blood was flowing, and their eyes were shooting fire. I next saw men tearing each other as the beasts had done before. I saw the glitter of arms and the coats of mail; I saw the onset and heard the shock of the charge. I saw men fall, and then there went up a groan of agony which finally merged into a cry toward heaven for help. It was a universal prayer of suffering humanity. Then there came a voice to which all heaven seemed to contribute, a voice that was helpful, a voice of forgiveness, a voice that seemed to soothe the cry of agony, and fully answer the prayer. Old things had passed away, and behold, all things had become new. There was a new heaven and a new earth wherein dwelt righteousness. Human beings I saw, not as “trees walking,” but as gods crowned with love, glory, and immortality.

It was then I was made to realize what the apostle meant when he said he was caught up into heaven and saw things unlawful to utter,—not against the laws of man, but above the laws of language. The composition of Beethoven made me think what words could not tell.

In the poem, “Aux Italiens,” Owen Meredith describes the power exerted upon the minds of others through a composition of Verdi when rendered by Mario.

Of all the operas that Verdi wrote,

The best, to my taste, is the Trovatore;

And Mario could soothe with a tenor note

The souls in purgatory.

The moon on the tower slept soft as snow,

And who was not thrilled in the strangest way,

As we heard him sing, while the gas burned low,

“Non ti scordar di me!”

The Emperor there, in his box of state,

Looked grave, as if he had just then seen

The red flag wave from the city gate,

Where his eagles in bronze had been.

There was something in the voice of the singer which caused the Emperor’s mind to see the red flag standing where “his eagles in bronze had been.”

The Empress, too, had a tear in her eye.

You’d have said that her fancy had gone back again

For one moment under the old blue sky

To the old, glad life in Spain.

The tones of Mario caused the Empress to see her early home; and the chief character in the poem to see his first love, and to even smell the flower he had seen her wear.

Meanwhile, I was thinking of my first love,

As I had not been thinking of aught for years,

Till over my eyes there began to move

Something that felt like tears.

. . . . . . . . . .

For I thought of her grave below the hill,

Which the sentinel cypress tree stands over,

And I thought,—“Were she only living still,

How I could forgive her and love her!”

And I swear, as I thought of her thus, in that hour,

And of how, after all, old things were best,

That I smelt the smell of that jasmin-flower

Which she used to wear in her breast.

An orator, by his tones as well as by his words, causes definite mental activities to take possession of his audience, thus influencing them with the action of their own minds. The language of tone is the language of the spheres, it is the language of the invisible world, it is the language of the angels.

The soul knows what tones to employ for the purpose of communicating its own activities to other souls. The impulse of the soul constructs the form of the tone which communicates its thought to the audience. There is no such thing as true voice which soul has not formed. The proper study of the voice is a study of the manifestations of the soul. Life is rich and valuable if we live from the interior. Life is disappointing, life is the blasting of all highest hopes, life is the shatterer and annihilator of all ideals, if we live not from the soul.

“In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God.” “All things were made by Him; and without Him was not anything made that was made.” Think what an estimate the Bible puts upon the “Word!” The Word, which is the fruition of the soul in manifestation, is used as a symbol of the relation of Jesus Christ to the Father. The Word is represented as being the Truth, the Life, the Creative Energy, and the Being of God Himself. Man’s word, when he lives truly, is but an expression, a moving out upon the world, and upon the hearts of others, of the love, the truth, the worship of his soul.

True words, then, are not sounds separate from the spirit; they are the incarnated soul. I would never teach voice, I would never teach oratory, if words were not, in their true nature, Divine things, if they were not forms of the spirit and of the soul!

The human voice is that sound, caused by the vibration of the vocal cords in the larynx and reinforced by the resonant chambers, which reports the physical and mental states of man.

Voice is caused by the contraction of the muscles of expiration, which brings sufficient pressure upon the lungs to drive the air from them out between the vocal cords, thus causing their edges to vibrate, thereby throwing the column of breath into such rapid vibration as to produce sound.

Larynx, (Including Vocal Cords),

Lungs,

Muscles of Respiration.

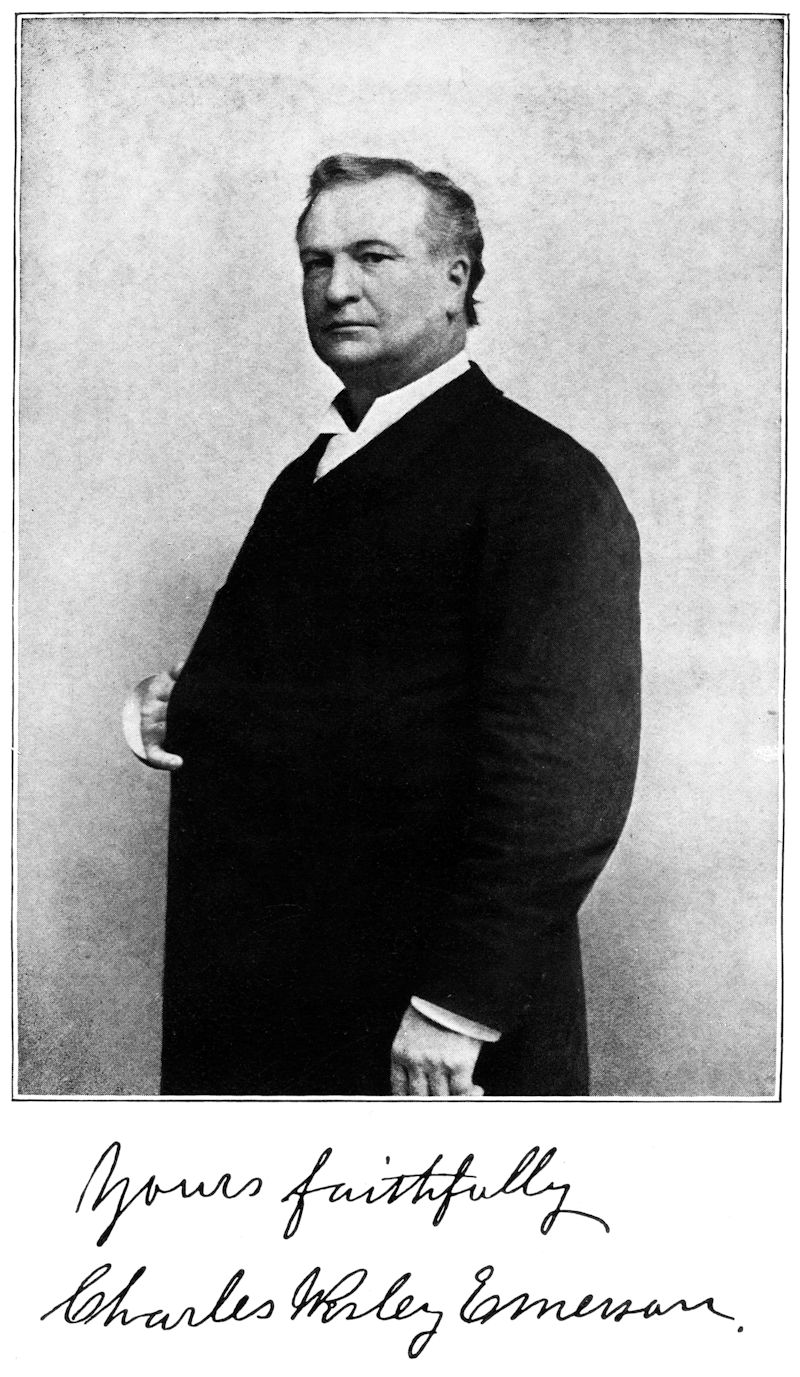

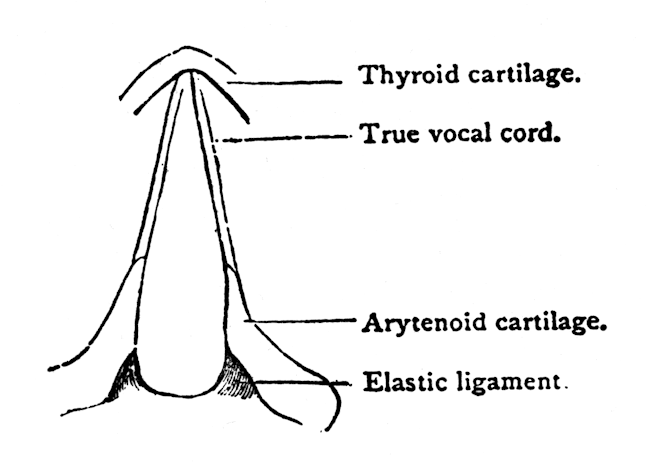

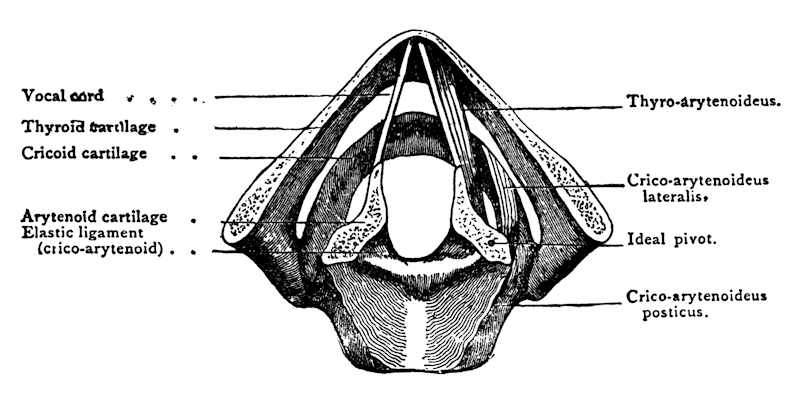

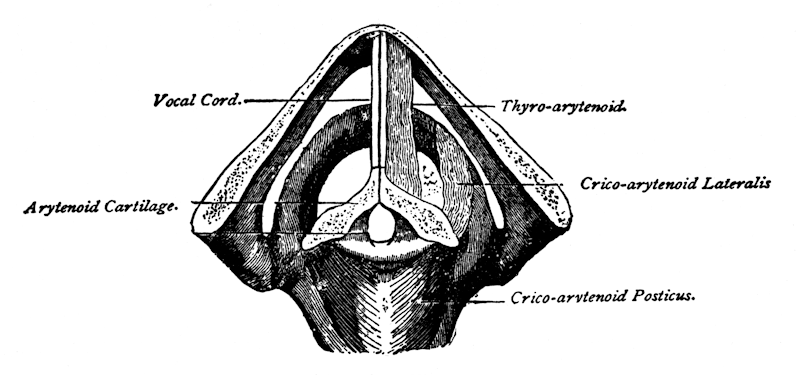

The larynx is the principal organ of voice. It is situated in the front of the neck, and forms the prominence sometimes called “Adam’s apple”; it also forms a part of the anterior boundary of the pharynx. At the upper part it has the form of a triangular box, with one angle directly in front. It is composed of nine cartilages moved by muscles, and lined with mucous membrane. Six of its cartilages are in pairs; three are single. The three single cartilages are the thyroid, cricoid, and epiglottis; the three pairs are the arytenoid, cuneiform, and cornicula laryngis. The larynx is sometimes called a music-box; from it proceeds the sound called voice.

SIDE VIEW OF THE LARYNX AND TWO RINGS OF THE TRACHEA.

Across the larynx are stretched the true vocal cords.

SHAPE OF THE GLOTTIS WHEN AT REST.

THE GLOTTIS DILATED.

GLOTTIS, CLOSED, AND MUSCLES CLOSING IT.

Each cord consists of a band of yellow tissue, covered by mucous membrane.

By means of the action of the muscles of the larynx that connect with the cartilages which enter into its structure, the vocal cords are so adjusted that when the muscles of expiration force the air, which is compressed in the lungs, out between these cords, their edges are set in vibration. This is the beginning of the sound which we call voice, but before it is heard in speech or song it is reinforced by the chambers of resonance.[1]

|

For the function of the false, or superior vocal cords, see pp. 68-71, Physical Culture. |

The various degrees of pitch in the compass of the voice depend upon the rate of vibration of the vocal cords. This rate of vibration, the pressure of breath being the same, is caused by the different degrees of tension of the vocal cords. If the vocal cords are drawn thin and short, the pitch will be high; as the tension diminishes, the pitch will be lower. The greater the number of vibrations to the second, the higher will be the pitch. A sound consisting of sixteen vibrations to the second produces the lowest pitch that has been recognized by the human ear as sound; while more than 38,000 vibrations per second have not been heard.

The lowest rate of vibration on record of any voice is about forty-four vibrations per second, while the highest rate in any voice on record is a little over nineteen hundred.

Different degrees of loudness of voice are caused by different degrees of amplitude of the waves of vibration.

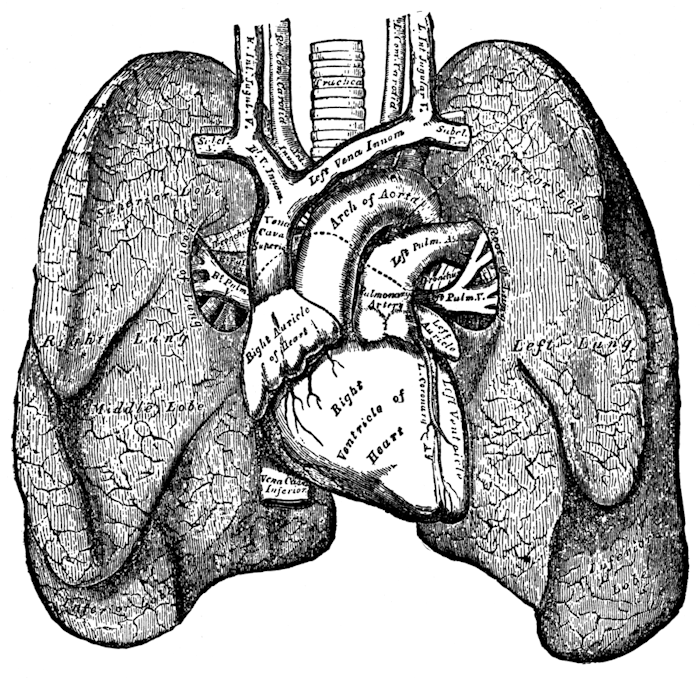

The two lungs are the essential organs of respiration; the right lung has three lobes, the left, two. The base of each lung rests upon the convex surface of the diaphragm.

FRONT VIEW OF THE HEART AND LUNGS, AND LARGE BLOOD-VESSELS.

The root of each lung is formed by the bronchus and blood-vessels, which enter the lung a little above the middle of its inner surface, and connect it to the heart and trachea. With the exception of the root, the surface of each lung is free and moves in the cavity of the thorax. The bronchus is one of two tubes which arise from the bifurcation of the trachea. It conducts the air from the trachea to either lung. The bronchial tubes are sub-divisions, or ramifications, of the bronchus and terminate in the air-cells.

Inasmuch as voice is vocalized breath, it is important to give attention to respiration.

The principal muscles used in the ordinary movements of inspiration are:—

| I. | Diaphragm. | |

| II. | Levatores costarum. | |

| III. | External intercostals. | |

The principal muscles used in expiration are:—

| I. | Internal intercostals | ||

| with the infracostals. | |||

| II. | Triangularis sterni. | ||

| { Transversalis. | |||

| III. | Abdominal muscles | { Rectus. | |

| { Internal oblique. | |||

| { External oblique. | |||

There are many accessory muscles which aid in violent respiratory movements, both inspiratory and expiratory. All the muscles which elevate the scapula may act through it upon the ribs; the three scalene muscles act directly upon the first rib.

The principal muscles of inspiration may be assisted by the

| I. | Serratus posticus superior. | |

| II. | Serratus magnus. | |

| III. | Pectoralis major. | |

| IV. | Pectoralis minor. | |

The principal muscles of expiration may be aided by the following muscles:—

| I. | Serratus posticus inferior, | |

| II. | Longissimus dorsi, | |

| III. | Sacro lumbalis, | |

and all the muscles which tend to depress the ribs.

THE DIAPHRAGM.

The diaphragm separates the cavity of the thorax from the cavity of the abdomen, and constitutes the floor for the heart and lungs to rest upon, and also a close-fitting cover for the contents of the abdomen. Therefore it is evident that the moving of the diaphragm moves the organs which are immediately above and those below it. In reposeful breathing the enlargement of the cavity of the chest is chiefly accomplished by the contraction of the diaphragm. As it contracts it presses upon the abdominal viscera. The abdominal muscles antagonize the diaphragm by pressing back the abdominal viscera, thus causing its ascent as soon as the diaphragm has become relaxed.

As the diaphragm contracts, the air rushes through the nostrils or mouth to fill the lungs. By lifting the ribs the thorax can be sufficiently enlarged to meet ordinary demands for breath; therefore the lungs would not immediately suffer if the diaphragm was not contracted. The principal sufferers in such a case would be the stomach, liver, and intestines, for without this exercise which the contraction of the diaphragm gives them they would not as vigorously perform their functions.

It is taught in many works on physiology that men inhale by means of the contraction of the diaphragm chiefly, while in adult women the diaphragm is exercised little, if any, during respiration. This statement was first given in early physiologies without due warrant from close observation. This idea, having once found its way into a standard work, has continued in successive works until now. This theory is of such vital interest to all that the authority for it should be carefully examined. It is a fact that more women than men breathe wholly by means of elevating and lowering the ribs; it is also a well-observed fact that the healthiest women and the healthiest men breathe alike, with no movement of the upper part of the chest during reposeful respiration. It is only when an unusual amount of air is required that the healthiest men and women ever move the upper part of the chest during respiration; then the diaphragm is exercised vigorously, and the movements of the ribs take place only for the purpose of enlarging the cavity of the thorax beyond what it is possible for the diaphragm alone to accomplish. During the last twenty-five years I have cured hundreds of people, both men and women, of dyspepsia and its attendant weaknesses by teaching them how to exercise the diaphragm in respiration, and in the production of tone. To say nothing of the incorrect way in which women breathe, I find that a majority of men breathe improperly.

The shape of the diaphragm, when it is relaxed, resembles an open umbrella. When the diaphragm is flattened by contraction it no longer retains its dome-like shape, and thus gives greater depth to the thorax.

During expiration of breath the diaphragm is fully relaxed, while during the production of tone it should be somewhat contracted. In the proper adjustment of the diaphragm and abdominal muscles during voice production, the diaphragm by its contraction resists, to some extent, the pressure caused by the contraction of the abdominal muscles, and thus only gradually yields to the force brought against it by the contraction of these muscles, in consequence of which a firm and steady support is given to the voice.

The question is often asked, “Should one breathe through the nose or through the mouth?” Nature has so constructed the organs of respiration and determined their action that a person in health breathes through the nose, while a person in ill health often breathes through the mouth. By “breathing through the nose,” of course, is meant reposeful breathing. In extraordinary breathing some persons are obliged to breathe through the mouth, but this is always an indication of exhaustion or weakness. Every person should, if possible, maintain the habit of breathing through the nose.

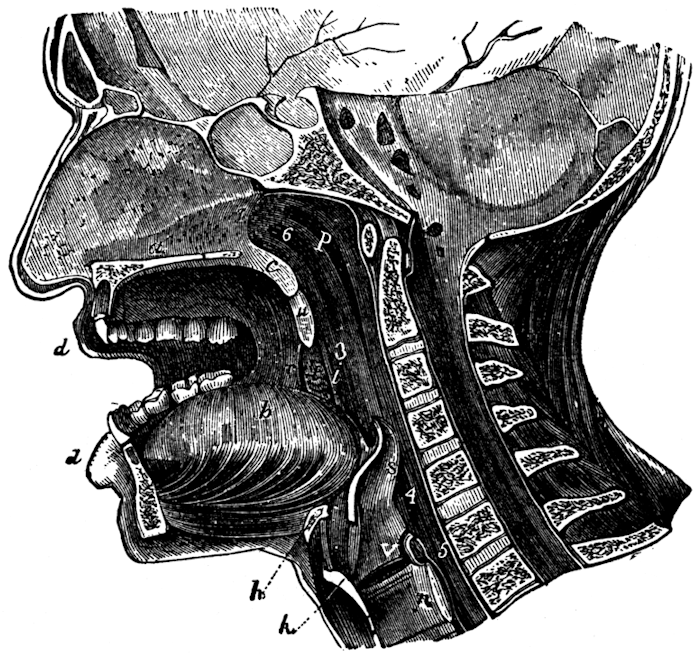

Median Section of Mouth, Nose, Pharynx, and Larynx:—a, septum of nose; below it, section of hard palate; b, tongue; c, section of velum pendulum palati; d, d, lips; u, uvula; r, anterior arch or pillar of fauces; i, posterior arch; t, tonsil; p, pharynx; h, hyoid bone; k, thyroid cartilage; n, crycoid cartilage; s, epiglottis; v, glottis; 1, posterior opening of nares; 3, isthmus faucium; 4, superior opening of larynx; 5, passage into œsophagus; 6, mouth of right Eustachian tube.

The organs that reinforce voice are its resonant chambers, viz.:—

Nares,

Mouth,

Pharynx,

Trachea.

Resonance means resounding or sounding again, and is caused by means of the air conveying the vibrations of one substance to another substance. This is familiarly illustrated in the echo.

There are two classes of resonant chambers; one class is comparatively fixed, and consists of the nares and trachea; the other class may, for convenience, be termed the transient forms of resonance. [2]A transient resonant chamber is one that is formed on the instant for a particular purpose, and may be broken as quickly.

Elements of speech are formed by producing a succession of definitely formed but transient molds of resonance.

The pharynx is for the purpose of reinforcing the tone, giving it projection and some assistance in proper direction. All the other transient resonant molds are for the purpose of producing elements of speech.

|

See Tyndall on sound, page 227. |

The nares are the cavities in the head extending through the nose to the pharynx. The walls of the nares are smooth, and, with their turbinated bones, suggest the inside of a sea-shell.

The pharynx is a membranous sac. It has seven openings, the two posterior nares, the two Eustachian tubes, the larynx, the œsophagus, and the isthmus faucium, which is the opening into the mouth.

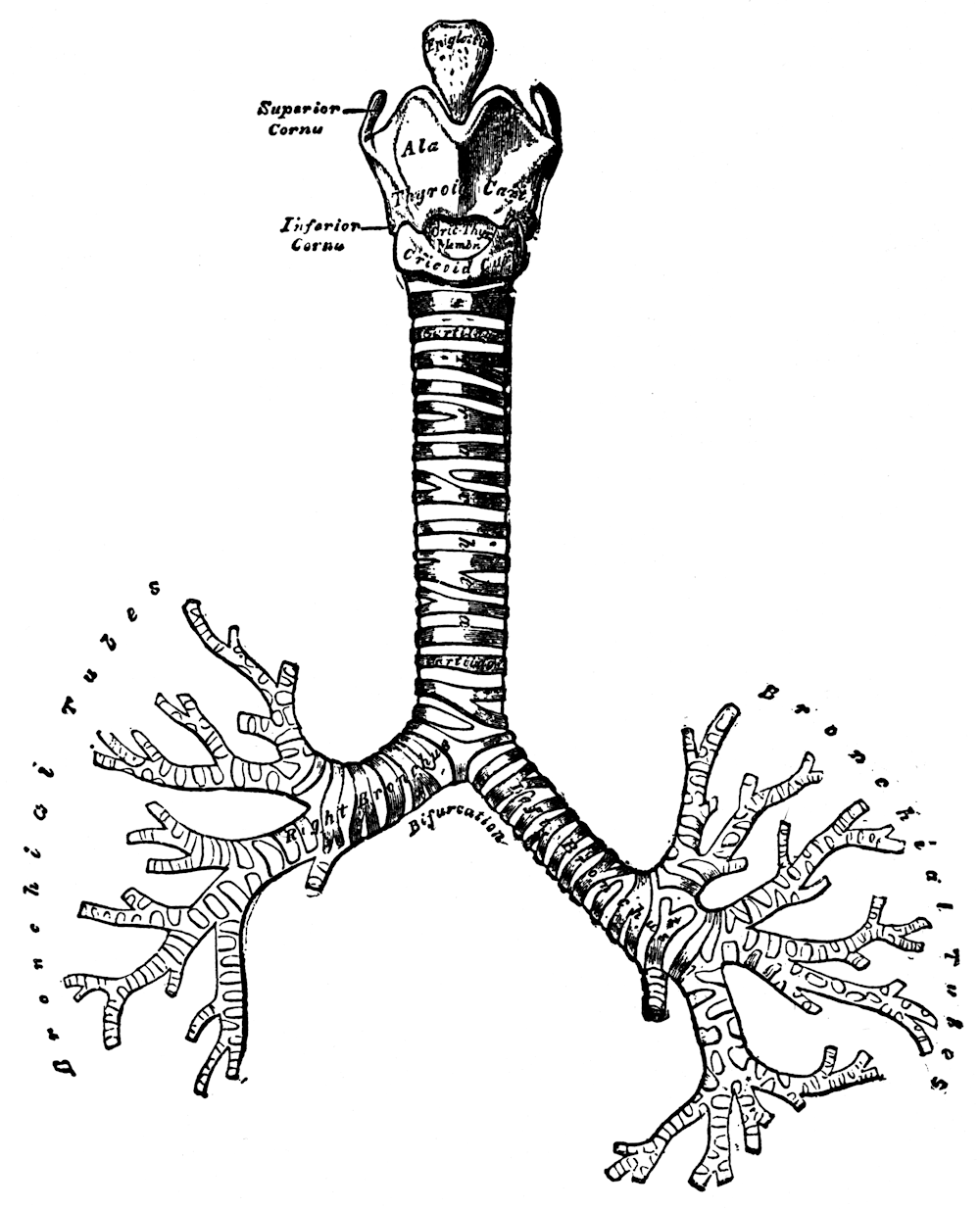

LARYNX, TRACHEA, AND BRONCHI.

The trachea, or windpipe, is a cylindrical tube extending from the lower part of the larynx to where it divides into the bronchi. The interior surface is firm and beautiful.

Lips,

Upper gum,

Hard palate,

Soft palate,

Tongue,

Nares.

Although the quality of the voice produced by the vocal cords of the human being cannot be distinguished from that produced by the vocal cords of the lower animals the organs which resound it give it a distinct quality.

No one of these agents alone molds the tone, but their proper relation to each other constitutes resonant molds as definite as those into which melted ore is cast to give it form and stamp. This proper relationship cannot be secured by exercising the organs in any strictly mechanical way, but only by forming definite ideal tones in the mind and exercising the voice while these ideal tones are firmly fixed as steady objects of thought. If these mental objects drop from the mind at any time during the vocal practice, no mechanical ingenuity can possibly take their places in rightly affecting the voice.

Later in this work, I shall more fully elaborate this point.

Many years of observation and study have convinced me that the voice exerts a powerful effect upon the whole physical system. It either builds up the body, sustains its power and adds to its health, or it devitalizes the body and brings a dangerous strain upon the entire system.

The voice cannot be a reporter of the person, mental and physical, without holding the most delicate relations to mind and body. The exercise of the voice subtly and vitally affects the organs that promote health and give life. I could give many illustrations showing that the wrong use of the voice has injured health, and that its right use has promoted health; but if the principles involved in this chapter are fully understood, I need not relate incidents to prove that the voice is a life-giver or a death-dealer, depending entirely upon how it is used.

The Greeks were taught the right use of the voice as a part of their physical, intellectual, and moral culture. In modern times we have neglected voice culture to a very great extent, and have suffered much ill health in consequence.

Great wisdom is exhibited in the construction of the human lungs. In the arrangement of the air cells, the greatest possible amount of surface is presented in order that the air may freely enter the blood. The lungs are largely made up of blood vessels, bronchial tubes, and air cells. When a person breathes, the oxygen, entering the lungs through the trachea and the bronchial tubes, penetrates the thin walls of these cells and passes at once into the blood. When the blood enters the lungs it is dark in color, but when it leaves the lungs it is of a light vermilion hue. The oxygen which has been taken into the lungs has wrought this change. So wonderful is this element of nature that some have called it life. If there is an elixir of life in the material world surely it is oxygen, for it has to do minutely and intimately with every power of the human body. The more a person breathes this oxygen as it is mixed in the common air, the more life and power he possesses.

It is essential to perfect health that every avenue to the lungs should be kept open and free, and that the air cells should be kept clear, for if the walls of the cells thicken, oxygen cannot penetrate them. If these cells are not properly filled during respiration, the walls thicken, and substances collect in the cells. If any trouble occurs in the air cells, except for traumatic reasons, it will first be found in the apexes of the lungs. In the production of tone, whether on a low, high, or medium pitch, the vocal cords are drawn so closely together that the air cannot immediately escape from the lungs; therefore, unable to get out readily, it is pressed up into the apexes of the lungs by the expiratory muscles, filling the air cells to the utmost, thus keeping them clear and their walls thin and healthy. In correct singing or speaking, the apexes of the lungs are filled with air. Tubercule seeks devitalized tissue for its development. Therefore tuberculosis usually begins in the apexes of the lungs because they are not kept clear and healthy through proper respiration and vocal exercise. Voice was given to man to make him strong and expressive, to give him life and power.

The stomach is the principal organ of digestion. Out of the nutriment taken into it all the tissues of the body are renewed. It lies under the diaphragm, and is held in place by the abdominal muscles. The stomach is moved during respiration, descending with every inspiration, and rising with every expiration.

In addition to this exercise during the production of tone, the stomach is held firmly between the diaphragm and abdominal muscles. At the close of the tone the muscles which thus hold the stomach relax.

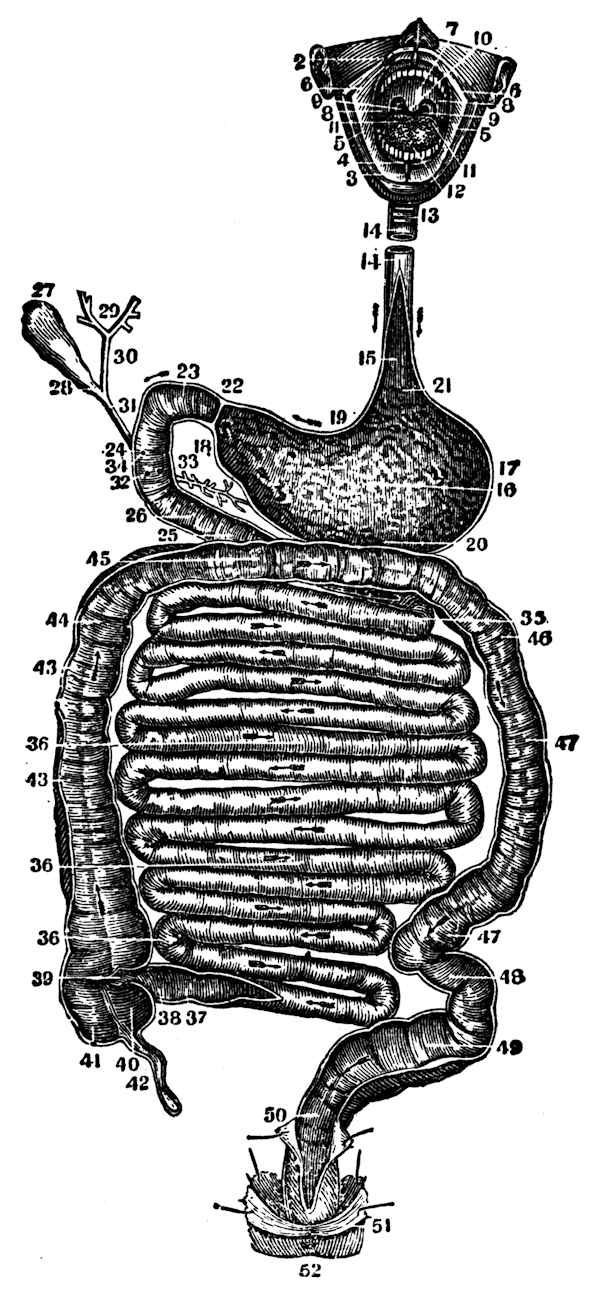

A view of the Organs of Digestion, opened in nearly their whole length; a portion of the œsophagus has been removed on account of want of space in the figure; the arrows indicate the course of substances along the canal: 1, the upper lip, turned off the mouth; 2, its frænum; 3, the lower lip, turned down; 4, its frænum; 5, 5, inside of the cheeks, covered by the lining membrane of the mouth; 6, points to the opening of the duct of Steno; 7, roof of the mouth; 8, lateral half-arches; 9, points to the tonsil; 10, velum pendulum palati; 11, surface of the tongue; 12, papillæ near its point; 13, a portion of the trachea; 14, the œsophagus; 15, its internal surface; 16, inside of the stomach; 17, its greater extremity or great cul-de-sac; 18, its lesser extremity or smaller cul-de-sac; 19, its lesser curvature; 20, its greater curvature; 21, the cardiac orifice; 22, the pyloric orifice; 23, upper portion of duodenum; 24, 25, the remainder of the duodenum; 26, its valvulæ conniventes; 27, the gall-bladder; 28, the cystic duct; 29, division of hepatic ducts in the liver; 30, hepatic duct; 31, ductus communis choledochus; 32, its opening into the duodenum; 33, ductus Wirsungii, or pancreatic duct; 34, its opening into the duodenum; 35, upper part of jejunum; 36, the ileum; 37, some of the valvulæ conniventes; 38, lower extremity of the ileum; 39, ileo-colic valve; 40, 41, cœcum, or caput coli; 42, appendicula vermiformis; 43, 44, ascending colon; 45, transverse colon; 46, 47, descending colon; 48, sigmoid flexure of the colon; 49, upper portion of the rectum; 50, its lower extremity; 51, portion of the levator-ani muscle; 52, the anus.

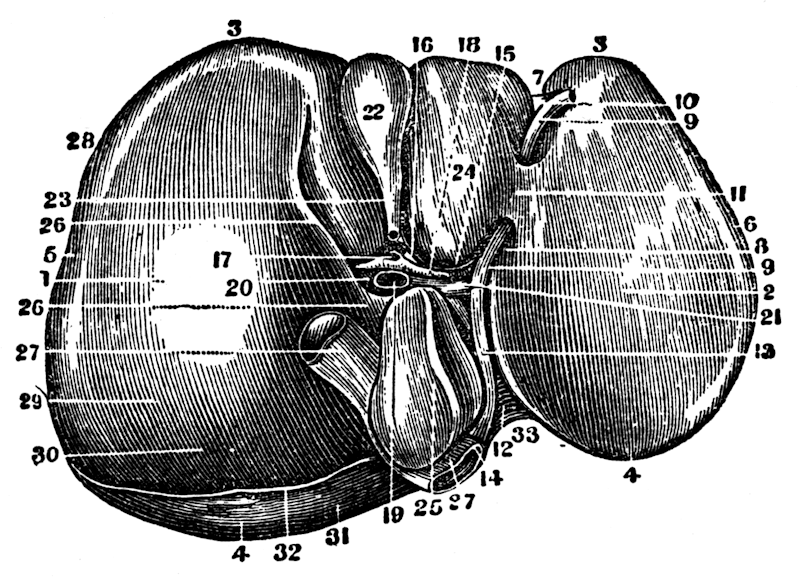

LIVER.

The inferior or concave surface of the liver, showing its subdivisions into

lobes: 1, center of the right lobe; 2, center of the left lobe; 3, its anterior,

inferior, or thin margin; 4, its posterior, thick, or diaphragmatic portion; 5,

the right extremity; 6, the left extremity; 7, the notch in the anterior margin;

8, the umbilical or longitudinal fissure; 9, the round ligament or remains of

the umbilical vein; 10, the portion of the suspensory ligament in connection

with the round ligament; 11, pons hepatis, or band of liver across the umbilical

fissure; 12, posterior end of longitudinal fissure; 13, 14, attachment of the

obliterated ductus venosus to the ascending vena cava; 15, transverse fissure;

16, section of the hepatic duct; 17, hepatic artery; 18, its branches; 19, vena

portarum; 20, its sinus, or division into right and left branches; 21, fibrous

remains of the ductus venosus; 22, gall-bladder; 23, its neck; 24, lobulus

quartus; 25, lobulus Spigelii; 26, lobulus caudatus; 27, inferior vena cava; 28,

curvature of liver to fit the ascending colon; 29, depression to fit the right

kidney; 30, upper portion of its right concave surface over the renal capsule;

31, portion of liver uncovered by the peritoneum; 32, inferior edge of the

coronary ligament in the liver; 33, depression made by the vertebral column.

The liver is a glandular organ, intended for the secretion of bile from the blood. It is situated under the diaphragm and partially over the stomach; therefore the exercises which produce pressure and relief upon the stomach, exert the same effect upon the liver. That the liver may properly perform its function it is necessary for it to be thus exercised. One cannot speak or sing well without moving the diaphragm, and when this is moved it moves nearly all the organs contained in the trunk of the body, and especially promotes the healthy activity of the lungs, stomach, liver, and intestines.

Mucous membrane lines all those passages by which the internal parts communicate with the exterior, and is continuous with the skin at the various orifices of the surface of the body. The mucous membrane, beginning with the lips, lines the mouth, throat, œsophagus, stomach, and in short, the entire alimentary canal. It also lines the nares, larynx, bronchial tubes, and air cells. It is one because unbroken. Its function is to secrete mucous for the purpose of preventing dryness.

Sympathetic relations exist throughout the whole human system, and especially between different parts of the same organ; if one part of the mucous membrane is injured, another part is as liable to suffer as that immediately injured. If congestion takes place in any part of this mucous membrane, it may cause congestion in some remote part of the membrane, without affecting the intervening parts. There is a certain common misuse of the voice which creates in the pharynx an irritation called “clergyman’s sore throat.” By the law of sympathy, this congestion is likely to be communicated from the pharynx to the mucous membrane of the stomach. It may also attack the mucous membrane of the bronchial tubes and through them affect the lungs.

Although this disease caused by the misuse of the voice is called “clergyman’s sore throat,” it is not confined to clergymen; it prevails to a considerable extent among school teachers, lawyers, and auctioneers. It is dangerous for one to enter upon any form of public speaking without having a sufficient knowledge of the voice to use his own correctly. This is true not merely because it gives power to speak more effectively, but because it enables one to preserve his own health, and thereby prolong his usefulness. “Clergyman’s sore throat” is caused by making too close a chamber of resonance in the pharynx while speaking. This is a confirmed habit with a very large number of persons; in fact, it might almost be said to be a prevailing difficulty, but it does not always cause a sore throat until the voice is more constantly used than it ordinarily is in private life.

A clergyman or others may for years have practised this habit without feeling the effect upon the throat; but as soon as they come to speak steadily for a half hour or more, and that, too, for the purpose of being heard in a large room, begin to realize a huskiness which soon develops into an irritation of the throat.

This finally develops into a congestion, and sooner or later into a cough, which results in the breaking down of the powers of the individual, and if it does not receive immediate and proper attention consumption may be the result. No medicine, however good, can give more than a temporary relief. So long as the cause (which is the misuse of the voice), remains, the difficulty must return. Sometimes “clergyman’s sore throat” is not introduced by huskiness; the first symptom observed is that of dryness or irritation. This is especially true if the voice is characterized by a metallic element. All these evils can be cured by proper vocal education, providing the patient does not wait too long.

The vocal organs may be said to be tools, and the nerves the workmen appointed to use them.

Nerves are whitish and elastic bundles of fibers, with their accompanying tissues. They transmit nervous impulses between nerve centers and various parts of the animal body.

“Nerves are composed of one or more (sometimes nearly a hundred) nerve fibers, each fiber forming a means of communication between two parts more or less distant from each other.”—Dutton.

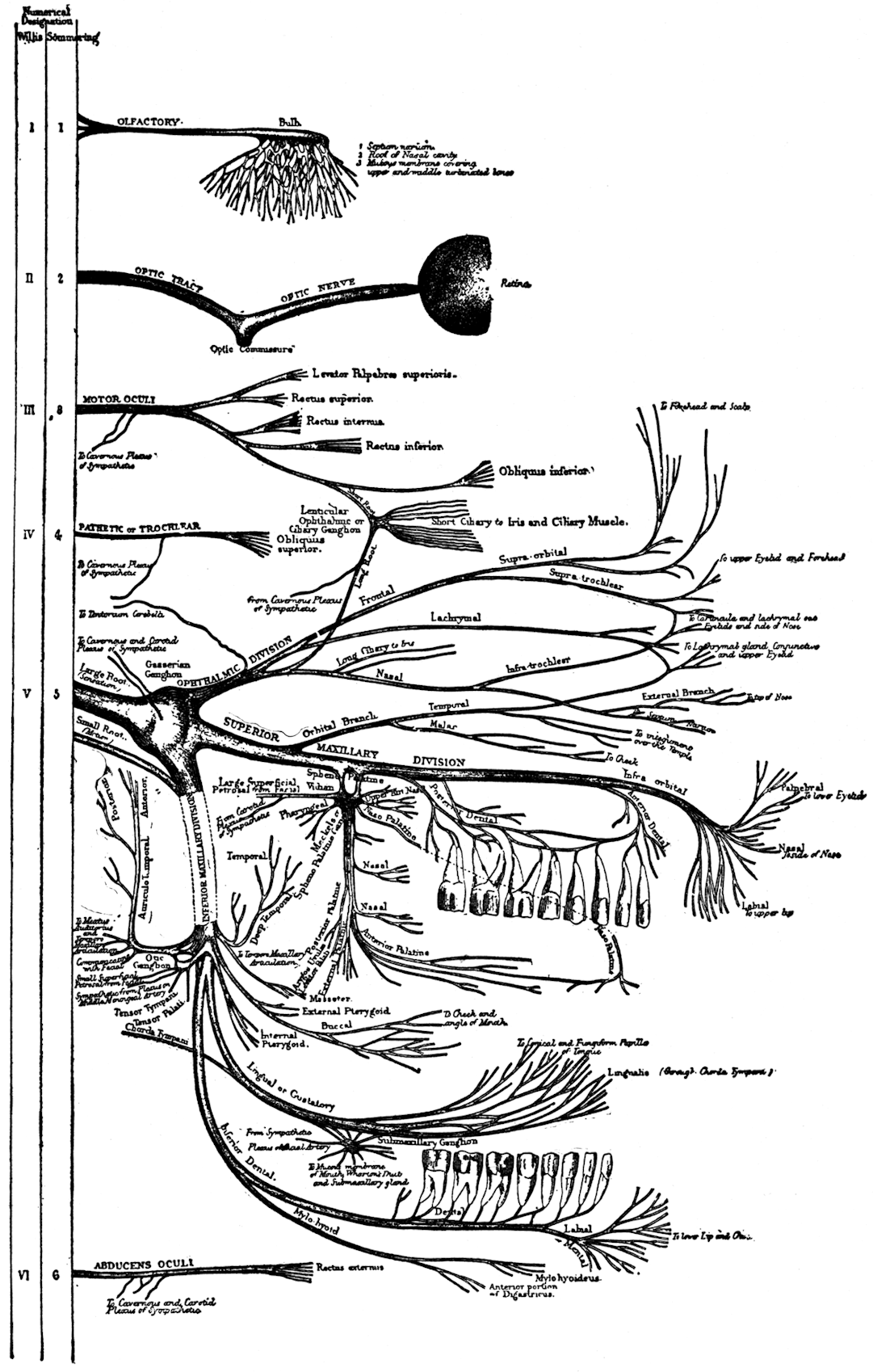

The brain is contained in the cranium, and may be said to be the controller of the entire nervous system. From it proceed twelve pairs of cranial nerves.

I. Olfactory, nerve of smell,—distributed in the mucous membrane of the nose.

II. Optic, nerve of sight,—distributes its branches to the eye ball.

III. Motor oculi,—motor of the eye.

IV. Patheticus,—assists in moving the eye.

V. Trigeminus,—nerve of sensation, motion, and taste.

VI. Abducens,—assists the movements of the eye.

VII. Facial (or nerve of expression),—moves the face, ear, palate, and tongue. By means of this nerve the tongue is directly connected with the brain, and receives its impulse of action therefrom.

VIII. Auditory,—nerve of hearing.

IX. Glosso-pharyngeal, nerve of sensation and taste,—it is distributed to the back of the tongue, middle ear, tonsils, and pharynx.

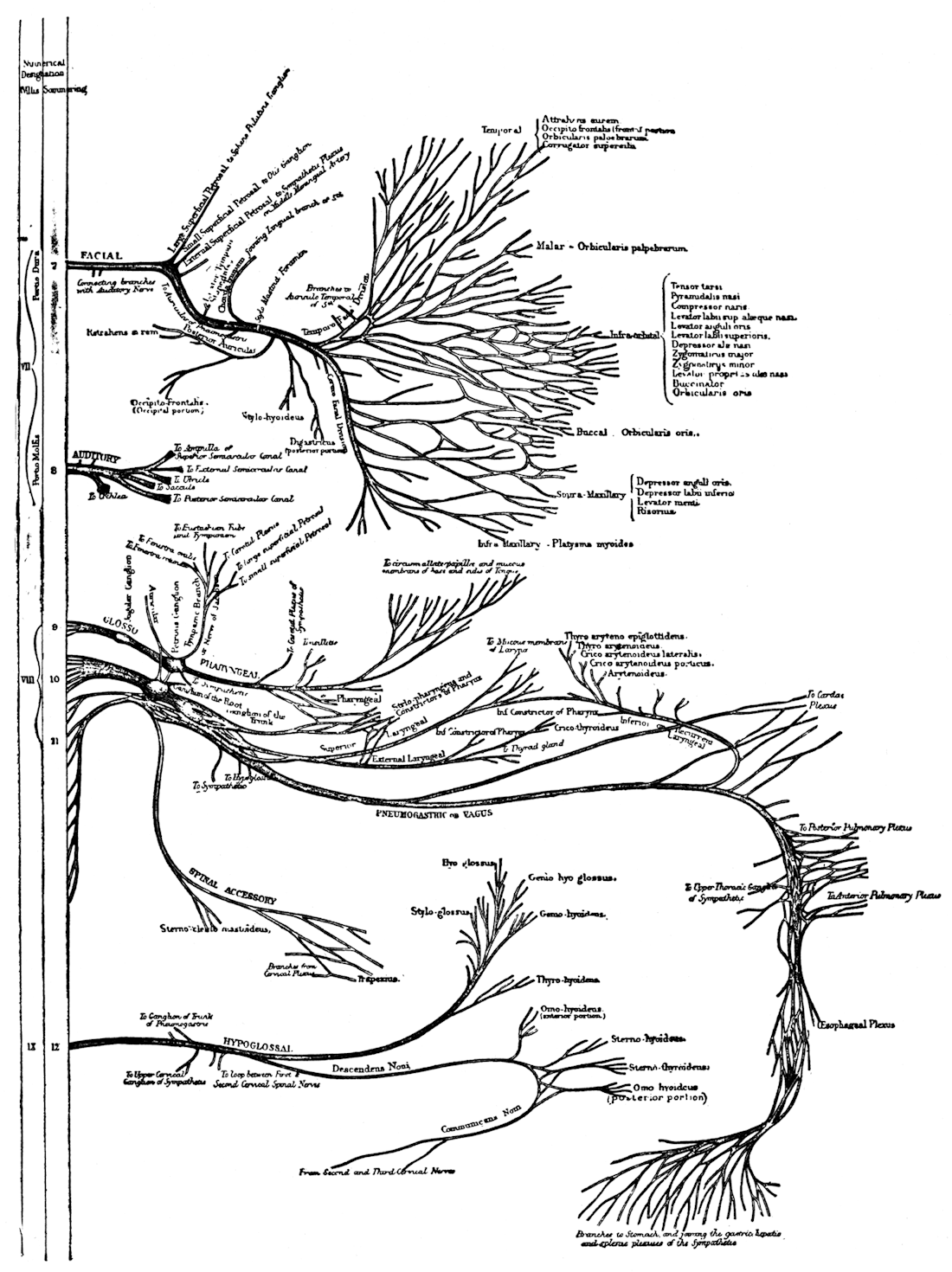

X. Pneumogastric,—the auriculo-laryngo-pharyngo-œsophago-tracheo-pulmono-cardio-gastro-hepatic nerve. It is a nerve of sensation and motion, probably receiving its motor influence from its spinal accessory.

XI. Spinal accessory furnishes motor power to the pneumogastric.

XII. Hypo-glossal,—motor of the tongue. It communicates with the pneumogastric and sympathetic nerves.

DIAGRAM OF THE FIRST SIX CRANIAL NERVES, WITH THEIR CHIEF BRANCHES OF DISTRIBUTION.

DIAGRAM OF THE LAST SIX CRANIAL NERVES, WITH THEIR CHIEF BRANCHES OF DISTRIBUTION.

My principal object in writing of the relation of the voice to the nervous system is to show anatomical and physiological reasons for denominating the voice the reporter of the states of mind.

We have before us the names of the nerves which connect the organs of speech with the organ of thought. Through some of the cranial nerves the mind immediately discharges its impulses upon certain organs, both consciously and subconsciously. This is illustrated by the motor occuli, patheticus, and abducens, which move the eye sometimes consciously and sometimes subconsciously. This shows that these nerves may, and often do, act upon the eye, without any conscious plan or purpose on the part of the individual.

The mind often manifests, through the cranial nerves, states of mind of which the person is unconscious. While consciousness is the power by which one knows his own states of mind, there is no proof that consciousness takes note of all one’s states of mind. The proof that it does not is found in the fact that people, through involuntary acts, often manifest mental activities of which they are unconscious. Spontaneous expression is truest.

The facial nerve causes the muscles of the face to portray the thoughts and feelings of the soul more truthfully than any artist could delineate them with pencil and brush. Before we can properly teach vocal culture and oratorical expression we must understand the principle of spontaneous manifestation by means of cranial nerves as distinct from purposeful forms of expression. The facial nerve not only acts as a motor of expression through the face, causing it to reveal thought and emotion, but acts in the same manner upon the tongue, causing it to form and modulate tones in song and speech.

Again note the nature of the hypo-glossal cranial nerve, which is not only a motor of the tongue, causing it to act spontaneously, but is distributed also to the muscles of the neck which are concerned in the movements of the larynx. The purpose of this distribution is probably to associate the action of the tongue with that of the larynx which is necessary for articulate speech. All the motions of the tongue are performed through the medium of these nerves.

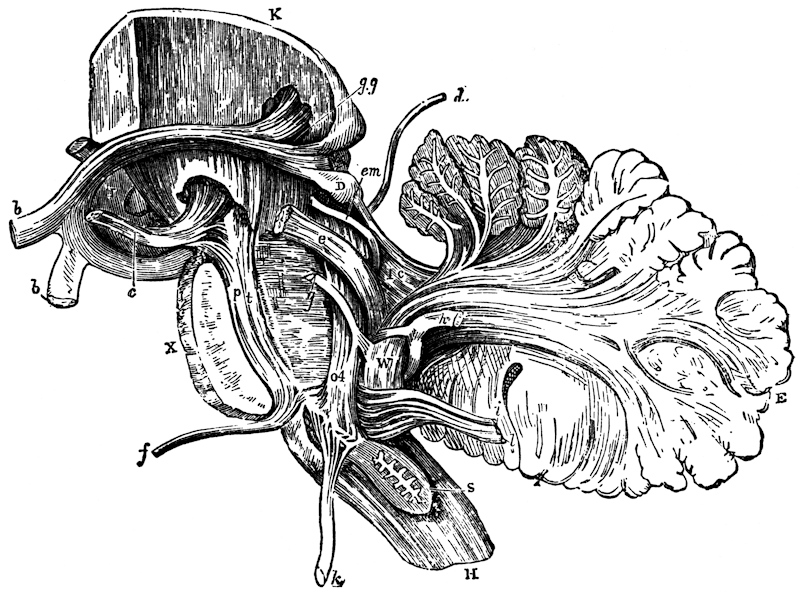

The drawing exhibits the cerebral connection of all the cerebral nerves except the first. It is from a sketch taken from two dissections of this part. D. Posterior optic tubercle. The generative bodies of the thalamus are just above it. E. Cerebellum. H. Spinal cord. I. Tuber cinereum. K. Optic thalamus divided perpendicularly. W. Corpus restiforme. X. Pons Varolii. b b. Optic nerves: this nerve is traced on the left side back beneath the optic thalamus and round the crus cerebri. It divides into four roots; the first (g g) plunges into the substance of the thalamus, the next runs over the external geniculate body and surface of the thalamus, the third goes to the anterior optic tubercle, the fourth runs to D, the testis or posterior optic tubercle. C. Third pair common oculo-muscular, arising by two roots like the spinal roots of the spinal nerves, the upper from the gray neurine of the locus niger, the lower from the continuation of the pyramidal columns in the crus cerebri and Pons Varolii, p t. d, Fourth pair, apparently arising from the inter-cerebral commissure (I c), but really plunging down to the olivary tract (o t) as it ascends to the optic tubercles. e m. Motor or non-ganglionic root of the fifth pair, arising from the posterior edge of the olivary tract. e. Sensory root of the fifth pair running down between the olivary tract and restiform body to the sensory tract. f. Sixth pair, or abducens, arising from the pyramidal tract. g. Seventh pair, facial nerve, or portio dura, arising by an anterior portion from the olivary tract and by a posterior portion from the cerebellic fibers of the anterior columns as they ascend on the corpus restiforme, W. h. Eighth pair, portio mollis, or auditory nerve, with its two roots embracing the restiform body. i. Ninth pair, or glosso-pharyngeal; and j. Tenth pair, or par vagum, plunging into the restiform ganglion. J J. Fibers of the optic nerve plunging into the thalamus; immediately below these letters is the corpus geniculatum externum. k. Eleventh pair, or lingual nerve; the olivary body has been nearly sliced off and turned out of its natural position; some of the filaments of the lingual nerve are traced into the deeper portion of the ganglion, which is left in its situation; others which are the highest are evidently connected with the pyramidal tract.

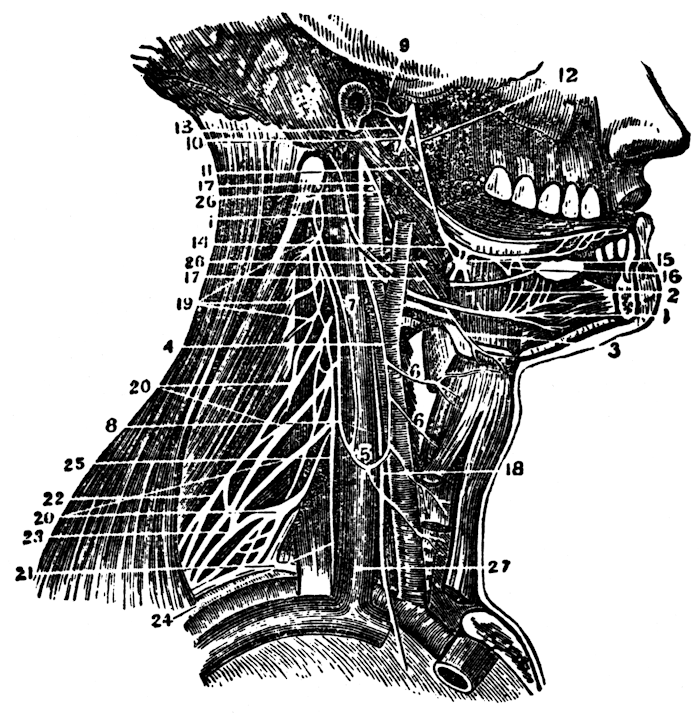

The course and distribution of the Hypoglossal or Ninth pair of nerves; the deep-seated nerves of the neck are also seen: 1, the hypoglossal nerve; 2, branches communicating with the gustatory nerve; 3, a branch to the origin of the hyoid muscles; 4, the descendens noni nerve; 5, the loop formed with the branch from the cervical nerves; 6, muscular branches to the depressor muscles of the larynx; 7, a filament from the second cervical nerve, and 8, a filament from the third cervical, uniting to form the communicating branch with the loop from the descendens noni; 9, the auricular nerve; 10, the inferior dental nerve; 11, its mylohyoidean branch; 12, the gustatory nerve; 13, the chorda tympani passing to the gustatory nerve; 14, the chorda tympani leaving the gustatory nerve to join the submaxillary ganglion; 15, the submaxillary ganglion; 16, filaments of communication with the lingual nerve; 17, the glosso-pharyngeal nerve; 18, the pneumogastric or par vagum nerve; 19, the three upper cervical nerves; 20, the four inferior cervical nerves; 21, the first dorsal nerve; 22, 23, the brachial plexus; 24, 25, the phrenic nerve; 26, the carotid artery; 27, the internal jugular vein.

The study of the functions of the cranial nerves convinces me that the state of mind which conceives a tone acts upon the organs of speech through the cranial nerves in a way to give vocal expression. In perfect expression the conception and the expression are absolutely synchronous.

In the production of a good tone there is an exact relation between pitch and resonance. This relation is provided for in nature and a disobedience to it brings an unpleasant quality into the voice. This is true in both speech and song, for the speaking and singing voices rest upon the same fundamental principles. Speech is one application or use of the voice, song is another. The voice of true speech is as melodic as the voice of song. There are, however, many persons who use their voices better when they sing than when they speak, while others use their voices better in speaking than in singing.

There is a difference between tone and noise. Voice is produced by a succession of vibrating waves of air. In a musical tone the waves are regular in their succession; in noise they are irregular.

Resonance, or echo, is produced by the universal law of reflex action which manifests itself in light, sound, etc. How interesting and delightful is the echo! It makes the mountains, like the morning stars, sing together for joy. Listen to a thunder storm among the mountains. There is a sudden explosion, then a silence, as the vibrating waves of mighty amplitude pass over the valley to wake the voice of the mountain beyond, which, standing like a sentinel on guard, speaks in thunder tones to the next, and that repeats the sublime echo until all the mountains join in the chorus, answering back to the heavens. This law of sympathy, undulating from mountain to mountain, so inspired the Greeks that they said the gods spoke to each other from mountain peak to mountain peak.

Every pitch in the human voice has its corresponding chamber of resonance, formed by the nares, by the trachea, by the pharynx, or by the mouth, and sometimes by more than one of these. The transient resonant chambers are formed by the adjustment of the lips, and by the relation of the tongue to the upper gum, the hard palate, the soft palate, and the pharynx. With the exception of the pharynx, these and the nasal forms constitute the resonant chambers which produce the different elements of speech in our language. The tone, though smooth when it leaves the vocal cords, may be made harsh by the transient resonant chambers. The nares resound different intervals of the scale in different portions of their length, never resounding two intervals in the same portion.

The cultivation of the voice is produced, first, through perfecting the forms of the transient chambers of resonance; second, through establishing perfect freedom and regularity in the action of the vocal cords; third, through developing the rhythmic impulses of the tone. No person ever speaks continuously in a perfect monotone; the pitch is constantly changing with the varying thoughts; as the pitch changes, the resonant chambers change the quality. Nature, unhindered, never reports the same quality on two different degrees of pitch. It is not that the individual, while speaking, intends to change the quality; but nature has so arranged the vocal organs and so determined the laws of acoustics, that unless the voice be interfered with by wrong mental determination, she herself changes the quality as the voice rises or falls.

It is a law of acoustics that a low pitch is resounded in a comparatively large resonant chamber; a high pitch in a comparatively small one. A simple and instructive experiment in illustration of this principle is this: Take a large bottle, strike a C tuning fork, hold it over the empty bottle, and no sound will be heard. The bottle does not respond, because the cavity is too large for the pitch of the fork. If water is poured into the bottle, the air column inside thereby being shortened until the proper sized chamber is formed, by then holding the high-pitched tuning fork over it, the sound of the fork will be resounded by the resonant chamber and the tone will burst forth quite loudly. Use any number of tuning forks, each on a different key, and a resonant chamber can thus be made which will resound each fork.

I once tried an experiment with two tuning forks which were fastened to sounding boxes and which had been tuned to exactly the same pitch. I struck one fork and stopping its vibration, the sound of the other, vibrating responsively, was distinctly heard. The same result was achieved when one of the tuning forks was placed in a remote part of the room. I also placed the fork upon the piano, struck it, and the string of the same pitch, in connection with its overtones, responded. In order that any resonant cavity may resound, the pitch that belongs to that cavity must be struck. Every room in a house, in consequence of its size, its form, and the material of which it is constructed, resounds to a certain pitch. Sometimes in the course of conversation the globe of a chandelier in the room resounds. This is because the pitch which is agreeable to its size, form, and substance is struck.

Overtones are tones above in pitch, but harmonic with the fundamental tone. They are caused by the vibration of the aliquot parts of a string as distinct from that of its whole length. These parts being shorter vibrate with greater rapidity, thereby giving a higher pitch than the fundamental note, though in perfect harmony with it. An overtone can be discovered by holding near one of the vibrating aliquot parts a chamber of the right size, form, and substance to reinforce the tone of one of these parts. This resonance would be loud enough to be distinguished from the fundamental tone.

The vocal cords act in like manner with the string described, and produce fundamental tones and overtones. In the vocal mechanism which produces the human voice, the resonant chambers are so graded in size as to correspond exactly with the fundamental note and all its overtones; therefore, an overtone as distinct from the fundamental tone is never heard, but reveals its presence only by enriching the voice.

Freedom of tone is secured by the delicate adjustment and elasticity in the action of those parts which form the transient resonant molds. The hindrances to freedom of voice are produced by holding the vocal organs too rigid and close while forming these molds.

I have spoken of the deleterious effect upon the health caused by the misadjustment of the tongue in its relation to the pharynx, which results in “clergyman’s sore throat.” Another malformation of a resonant chamber is produced by holding a portion of the tongue too near the posterior portion of the roof of the mouth. A third is produced by holding the tongue too near the hard palate; a fourth by holding the tongue too near the front teeth. All these false adjustments are reported in throaty, rasping, and squeezed tones of the voice. The first object in the cultivation of the voice should be to establish habitual openness and freedom throughout the vocal aperture and this, too, by the shortest possible method. This method should consist, not in giving definite attention to first one portion of the vocal tube and then to another, but in securing a unified action of all the parts. By vocal practice, while holding the right mental concept, a clear and open passage from the vocal cords to the anterior portion of the nares can easily be secured.

The tone must be idealized with reference to place and form. The student should imagine the tone outside that resonant chamber of the nares most distant from the vocal cords. This will bring the consciousness outside that part of the nose which is between the eyes. The anterior portion of the nares is, so far as place and consequent resonance are concerned, the dominant center of the voice. My reason for calling this the dominant center of the voice is that when the tone is perfectly directed toward this chamber, all the resonant passages open freely through the entire nares, mouth, and pharynx to the vocal cords; and also the tongue has a tendency to relax its rigidity.

It is important, however, that the mind should not think of this locality as being in the nares, but outside, and think of it, too, as an ever expanding and luminous globe which moves in a forward and downward curve.

Beauty of voice is largely due to the fact that the vocal aperture is in the form of a curve. Unpleasant qualities in the voice are caused by the vocal column being made to move in angles instead of curves. That the voice may be shaped to the vocal aperture, it is necessary to hold in the mind a curve as an object of thought. Voice is in the mind before it is expressed in sound. The mental form precedes, causes and accompanies the physical form.

This curve should become a fixed mental object during all vocal practice, whether in speaking or in singing. Holding this object must become a habit so firmly established that the mind will ultimately act above consciousness in forming it. The vocal organs always react upon ideals held in the mind. Thus, if a flat object is held in the mind while using the voice, the tone tends to flatness; if a round one, it tends to roundness; if a narrow form, it tends to narrowness; if a contracting figure, it tends to contraction; if a free, elastic, expansive one, it tends to freedom, elasticity, and expansiveness. The figure of an expanding globe gives the voice the qualities last described. This figure, moving in the form of a curve, unites to the above qualities that of beauty, for the curve always awakens in the imagination the sense of the beautiful.

Tone is vocalized breath. It is observable that the higher order of animals usually begin their tones in the form of the nares resonance. When the cow lows for her young the tone is resounded in the nares before the mouth opens. The same thing is to be noticed in the mother horse calling to her young. She begins the tone with the nares resonance, and as the impulse increases she opens her mouth to let forth the whinnie so full of feeling. No animal excels the house cat in the correct use of the voice. She begins her tone as a nares resonance, and when her mouth opens, the tone which is moving in the right direction indicates that her vital energies are fully aroused. She acts upon the same principle that a man does in aiming a gun. He aims before he fires. Nature aims the tone before she gives the explosion. The mightiest of all voices is that of the lion. He distinctly guides his tone with the nares resonance. If he did not so direct it, the blast of tone which shakes the very earth would rend his throat.

Many people injure their throats by letting on a power of voice which is not properly guided. The only reason a person’s throat ever suffers from continued use of the voice is because the tone is not properly directed. Some public speakers after using their voices for an hour, or even half an hour, feel an irritation in their throats, but if their tones were properly directed, they could use their voices without injury as long as their general strength would permit. The moment the current of tone is turned from its proper direction, the voice is being injured.

All the muscles of respiration work in a harmonious manner with each other when the tone is properly directed; they work improperly together in a way to produce friction when the tone is not centered.

One prevailing difficulty with voices which are not perfectly educated is that the wrong quality is given for the pitch. Each interval of the scale requires a different resonant quality, and this necessitates a difference in the sizes of the resounding chambers. This difference is provided for in the graded sizes of the different portions of the nares, and in the pharynx and trachea. However, notwithstanding the freedom of the resonant chambers here mentioned, this proper quality of the voice would be interfered with in the speaking and singing words, or even elements of words, the freest of which are vowels, unless the transient chambers of resonance were perfectly formed. If words seem to interrupt and injure a singing tone, it is because the transient resonant chambers in which they are formed are not properly constructed.

The only way to perfect the forms of the transient resonant chambers is by holding the elements of speech in the mind as distinct objects of thought while speaking or singing them. Such is the natural service of the vocal organs to the mental concepts, that these mental objects will, through the cranial nerves which control the organs of speech, externalize themselves by producing exact molds of resonance. It takes time and practice to develop the power of holding the elements as distinct objects of thought; it takes still more time and practice to develop the power of holding these sounds as mental objects while the mind materializes them in the voice. This power, like all powers, grows in the ratio of repetition guided by continued mental concentration.

One should never attempt to locate the tone in any particular resonant chamber by saying, “Now I will practise for head resonance, or now I will practise for chest resonance.” I have known such attempts to result in much injury to the voice. If the direction of the tone is kept steadily toward the globe of light in front of the nares, while at the same time imagining this globe to move in a forward and downward curve, and if, in addition, the transient molds of resonance are perfectly formed, each interval of the scale will be resounded in its proper resonant chamber. The high notes will be resounded in the front part of the nares, then as the voice descends in pitch it will be resounded farther back in the nares, until the note is so low that the posterior part only can resound it; finally, as the pitch continues to grow lower, the nares cannot resound it at all. At this point the pharynx takes it up until the pitch becomes so low that the trachea, being larger than the pharynx, produces the resonance which is heard in the chest only. After the proper direction has been established, viz., toward the globe of light in front of the anterior portion of the nares, it should never be changed, for this direction keeps the nares, pharynx, and trachea open and free, so that each pitch of the voice will be resounded in that portion of the resonant chambers which by its size is suited to its pitch. What I have thus far said of the resonant chambers in the nares, pharynx, and trachea applies to the fundamental tone; but while the fundamental tone is resounding in the trachea, pharynx, or nares posteri, smaller portions of the nares and transient resonant chambers may be resounding the overtones, so that many resonant chambers may be resounding at the same time, thereby giving the richest possible quality to the tones of voice.

Exercise I.—While the lips are closed, give a nares tone represented by the letter m; then opening the mouth, without changing in any degree the character of the tone and not allowing any breath or voice to pass through the mouth, prolong the tone, holding before the mind the ideal concept for direction of tone previously described. The lips should be again closed just before the tone ceases. Repeat this on different intervals of the scale, ranging from a comparatively high pitch to a comparatively low one.

The reason the sound represented by m should be used in securing this freedom and direction of tone is because this letter best represents the tone which proper resonance of the nares produces. In vocal practice, one should begin on a comparatively high pitch and descend to a lower one, because the front of the nares resounds the high notes of the scale, and therefore assists in fixing consciousness of the direction of tone. Then, too, while using the voice, the mind should never hold as an object of thought the idea of going up to a tone, for the reflex action of such an idea upon the vocal organs is to produce a squeezed and strained effect. The mind should develop the consciousness of being higher than the note it would give, so as to feel as if descending upon a note, rather than trying to reach to its height. If this first exercise, which gives direction to the vocalized column of air, is practised on successive intervals of the scale, it will fix this direction as a habit. Hence, it is very important that there should be much repetition in descending and ascending the scale; otherwise, the voice might be open and resonant on some notes, while on others it would be constricted and forced, and consequently bring those false breaks into the voice which have been called registers. Registers are not natural to the voice, but created by its wrong use.

Exercise II.—Sing the sound represented by m-nom on the different intervals of the scale, commencing on a comparatively high pitch, descending and ascending a number of times. Begin the tone with the pure nares resonance as described in the previous exercise. Allow the sound which is represented by m-n to blend with the resonance which constitutes the vowel o, closing the lips before the tone ceases. In this exercise we blend the vowel o with the resonance in the front of the nares, thus directing the mind, which guides the vocal action, as far as possible from the throat, where it would cause constriction.

Exercise III.—To gain greater facility for uniting the free resonant elements of speech in a forward and downward curve, other words may be practised, viz., Most-men-want-poise-and-more-royal-margin.

Each word should first be sung separately on each note of the scale, repeating the word several times on each interval. With each repetition the mind should be concentrated upon the ideal form of the word, thus making the resonant mold more and more perfect.

A few words of explanation in regard to the vocal elements used will make the exercise more clearly understood.

M-O-S-T. The resonance in forming the s being near the teeth, and that forming t being a puff of breath at the point of the tongue, aid in fixing the attention of the mind upon the imagined curve.

M-E-N. The added resonant element in this word is e, which, by being joined to m on the one side and n on the other, will assist in directing the mind to the curve while giving the vowel e.

W-A-N-T. Here we have the aid of the letters n and t together with the position of the lips for w in assisting to join the vowel a, as heard in awe, to the expanding globe moving in the forward and downward curve.

P-O-I-S-E. In this word we are again aided in locating the resonance by the necessity of forming the sounds of p and z at the very front of the mouth.

A-N-D. Here the student has his chief assistance in the resonant element, represented by the letter n, and somewhat by the letter d, for bringing the attention of the mind to the globe in its relation to the curve while forming the resonant element represented by the letter a.

M-O-R-E. Here again the student has the assistance of the frontal nares element, represented by the letter m with the vowel o, which by this time he has joined with it. The new resonant element in this word is r. In forming this element there seems to be a prevailing tendency to constrict the throat, but now, by joining it with elements which have been associated in the mind with the expanding globe, this stricture is removed.

R-O-Y-A-L. The next word to be joined to this chain is r-o-y-a-l. Here we are depending upon previous practice in giving it the luminous curve tendency.

M-A-R-G-I-N. The new elements in this word are the sound of a as heard in far (ä), and the vocal element represented by g. The letter g represents an element, in forming which many people constrict the throat, giving what is called a “throaty” tone. Our object in using a, as heard in far, in this connection, is to introduce the largest and freest transient chamber of resonance which the organs of the mouth are capable of forming. The Italian ä has been much used in vocal practice, and it is a good element, providing it is not introduced too early in a student’s course of study, and if in its introduction it is always joined to the frontal nares mold as in ma. After practising upon the elements of speech described above, the student may practise them in the sentence form. Most men want poise and more royal margin. Repeat this exercise upon various intervals of the scale, beginning upon a comparatively high pitch, and descending to a comparatively low one.

By the practice of these exercises the student develops the ability to make each word and element of speech perfect without breaking the steady, sustained current of the tone.

Exercise IV. Sing ma-za-ska-a, commencing upon a comparatively high pitch, descending and ascending the scale.

After having made the true forms of the above-mentioned elements of speech habitual, the student may concentrate his practice upon the resonant form of a, as heard in far. Thus, this vocal element, being joined with the consonants m and z, is aided in making its most perfect resonant mold, while s, being forward to give the right direction, and k, being strongly projected by the pharynx resonant chamber, the ä is sent forward, like a ball from a gun, thereby developing projection of tone until at last the student may venture to practise upon ä alone.

While expressing these separate elements, each must be held in the mind as a luminous globe moving in the forward and downward curve. Repeat this exercise on different intervals of the scale. It may also be given in the form of arpeggios.

In practising these exercises, the student must be careful never to strain the voice either for the purpose of reaching a high or a low note. He should attempt to reach no pitch until it is perfectly easy for him to do so. He should practise most upon those notes which are easily within the compass of his voice, not continuing to repeat an element on the same interval of the scale, but changing at least one note with each successive repetition, that the voice may develop an evenness and the habit of reaching the resonant chamber which gives the right quality for the pitch.

It is obvious that the vocal exercises above described develop musical expressiveness both in song and speech. Rhythm is an act of the feelings more than it is of the intellect. The student should allow the feeling of rhythm to take full possession of him while he executes the musical variations. Rhythm causes the force of the voice to exert itself melodically. Were it not for rhythm, the tone would move forward in a sort of sameness in force. One can no more endure to listen to a voice that is not rhythmical in force than he can to one that is monotonous in pitch. The feelings are benumbed by monotony, while they rejoice in harmonious variety. Originally the word rhythm meant motion. Later it was used to express the relation of measure to motion. To-day the word meter and the word rhythm are sometimes used synonymously.

Rhythm is the name of the sense of relationship existing between duration and motion. Without rhythm there can be no real melody. In poetry the rhythm celebrates the exact relationship the thoughts sustain to each other. The rhythm creates a deeper interest, and consequently a deeper feeling, than would be created if this relationship were not celebrated by the regular recurrence of certain pleasing sounds. In prose composition the relationship between the thoughts may be as perfect, but this relationship, although expressed melodically, is not as rhythmically emphasized.

Thought in voice form always manifests itself rhythmically. In sculpture, painting and architecture, that which corresponds to rhythm in music and poetry is called symmetry. Symmetry involves proportion, and gives a feeling of life to these forms of art.

There are certain characteristics of voice which are denominated “qualities.” Among these are: Color, Form and Equilibrium. By color of voice I mean that quality which affects us when we hear it, just as color affects us when we see it; so that color as applied to voice is really the name of the feeling it produces, which is the same as that produced by color received through the sense of sight.

We judge of form of voice as we judge of color of voice, that is, by its effect upon the feelings. There are certain tones which affect us as certain forms do.

When we see objects in equilibrium, we speak of them as being well poised, or centered; they give us the feeling of certainty; right tones affect us in the same way. Other tones which lack center give us the same kind of mental pain which things do when we perceive they are not in equilibrium.

Color appeals to the feelings; form appeals to the intellect; equilibrium appeals to the will, so that color, form and equilibrium appeal to the mind as a unit.

Force (Energy),

Pitch,

Volume,

Time.

Each form possesses a distinct meaning and expresses definite states of mind.

Force indicates the degree of energy a particular thought arouses in an individual. Pitch includes slide or inflection, and indicates the feeling aroused by the thought. Volume indicates the condition of the will—whether it is perfectly free or struggling against difficulties. Time indicates the value the intellect places upon the thought. All forms of emphasis may be reduced to these four; and these four may be combined in an infinite variety of ways.

The state of mind which will project the tone is that of reciprocity, that is, concentrating the mind upon persons in a distant portion of the audience, as if receiving from them and giving to them, thus establishing a sympathy between the speaker and the hearer. This will project the tone without noise. The mental effort of a speaker should be to draw his audience nearer that they may hear, rather than to place his mind exclusively on sending his voice to a great distance. This effort to draw the hearers nearer will give the voice carrying quality without interfering with its naturalness and sympathy.

The doctrine of evolution is one of the latest, and if well understood, and looked at from a sufficiently high point of view, appears the grandest of all the revelations which science has given. The theory applied to organic being is substantially this: there is, potentially, in every organism a higher manifestation. Its evolution is secured by the relation of its organic tendency to its environment.

In taking a limited or superficial view of the doctrine of evolution, some have been led to look at matter as the only environment. It is this which has made the age materialistic. We are hardly aware of the extent to which this tendency to materialism biases and influences us in regard to religious and secular education. Those who have the most faith in God and His providence are scarcely conscious of how much they are affected by the prevailing thought that material environment alone shapes and influences the development of individuals and the destiny of the human race. If we recognize that the spirit of God is our most immediate environment, the study of evolution is safe.

This view is suggested even by the study of physical science. The scientist, in his analysis of matter, ascertains that it is divisible into molecules, and that nothing is an absolute solid. Each molecule has a sphere of its own, in which it acts separately, and, in a certain sense, independently of other molecules, and vibrates as freely as oscillates the pendulum of a clock. You say, “The pendulum of a clock has room to oscillate.” This is equally true of each molecule; it has room to vibrate without interfering with other molecules or preventing them from vibrating. All the molecules that compose a certain substance are rushing toward each other; but a sacred sphere encloses each, thereby establishing its eternal separateness. This revelation of science of the eternal separateness of molecules points to the silent sea of Thought which encloses every molecular island. What is this silent sea of thought but the presence of Deity? If He encloses every molecule, does He not surround the human soul? Is it unscientific to say, in the language of scripture, “In Him we live, and move, and have our being”? Whither shall I go to escape His presence? “If I ascend into heaven, Thou art there; if I make my bed in hell, behold, Thou art there. If I take the wings of the morning and dwell in the uppermost parts of the sea, even there Thy hand shall lead me and Thy right hand shall hold me.” If we take a sufficiently broad view, science itself will lead us up the shining way to where we shall recognize His presence on the throne of the universe.

If we follow this doctrine of evolution, step by step, it will lead us to perceive that God is in every fact of nature. Watch an acorn as it develops into the sturdy oak. No scientist will say that a material environment is its only condition of growth. He will say, “There is life in the acorn itself.” What is this life? Here the great scientist bows his head. The power of life in the acorn suggests to him the presence of the Infinite. Were it not for God’s purpose manifested in giving the acorn life, the germ could not develop under the influence of the moisture, the sunlight, and the earth. Its dominating environment, then, is the presence of Him who relates it to its material surroundings.

Without the Infinite Mind in the universe there could be no evolution. No man can be broadly and fully educated unless there is joined in his mind both the light of science and the light of revelation. Prophecy outruns science, and is the herald of truth. Science, no surer, and vastly slower, follows with its confirmations. The doctrine of evolution, studied in the light of divine revelation, becomes of great value to us.

We cannot understand the doctrine of the Evolution of Expression until we first see evolution written on the broad expanse of nature. The four volumes of the Evolution of Expression taught in this college represent the four principal steps in the unfolding of the powers of the orator. It has been said that poets are born, not made. This statement contains only a modicum of truth. We say such a one was born a poet because very early in life he seemed to show poetic feeling and to express his thoughts in poetic forms. All great poets, musicians, and orators have been educated; some may not have studied under masters, but all have applied themselves to the means of education which was within their reach.

The study of eloquence has been, to a great extent, a sealed book. It was observed that when the orator spoke on a lofty subject, his voice became grand, and was called “orotund”; when he spoke on common subjects, his voice became simple; this was called “pure tone”; when he spoke on subjects of mystery and sublimity, the voice became “aspirate orotund.” All these things were noted; and teachers of oratory said to their pupils, “As the orators used the orotund, aspirate, pure tone, etc., we will teach you these forms of voice.” When Webster spoke of the value of the Constitution of the United States, and used an orotund voice, as only a Webster could, was he thinking of his voice? No; he was thinking of convincing his hearers of the great value of the Union. Shall I affect people as did Webster by using these tones when reading a passage from his speech? No. The human soul says, “I will respond to anything genuine; but I can never be impressed, though I may be amused, by those who try to imitate the genuine.” Webster’s thoughts, like vast waves of the ocean, surged through his voice and formed themselves into tones clear, direct, incisive, and sublime.

I recognize but one power in education, and that is mind. When God created my body, He ordained that my soul should rule it. When He made the mouth, larynx, muscles of respiration, etc., He ordained that the soul should rule them. My soul, master; they, servants. The servant knows his rightful master’s commands, but the stranger he will not obey. The infinite God rules all worlds, and all parts of all worlds. As God is the master of the illimitable universe, so He has placed within man’s body, which is man’s little universe, a natural master—the soul. All its agents must be commanded and employed by the master within.

For many years there has been an attempt to reduce vocal culture to the conscious manipulation of the vocal organs. This was once my method of teaching; but I have changed entirely and most radically. I believe and have taught for many years that certain mental states produce definite effects upon the vocal organs. Our object in this college is to induce such states of mind as shall produce the desired effects in vocal expression. The mental states operate directly through the cranial nerves upon the vocal organs, and instantaneously change their activity.

In my early teaching I made an attempt to cultivate the voice by dealing directly with the vocal organs themselves, but later I discovered that certain states of mind caused all the vocal organs to act in right relations to each other for the production of different tones. I also found that certain states of mind affect and control all the muscles which aid in voice production. To ascertain what states of mind produce certain effects, and how to induce these states of mind, was my field of study for a number of years. At last I was rewarded by discovering what states of mind would induce the desired forms of expression, and also what methods to use to cause the right activities of mind which would, without fail, bring the proper tones of voice in expression. It devolves upon the teacher to know how to induce the states of mind which will produce the required action of the vocal organs, and through this the desired tone. Every day in our work here in the Evolution of Expression, we are obeying the true pedagogy of vocal technique. The methods by which we induce certain states of mind in a pupil are definite and technical. If I were writing for a teachers’ manual, I would tell the teacher how to induce in the pupil the proper states of mind; but my present purpose is simply to show that certain states of mind will produce definite effects in the voice.

One who watches the effects of this method of teaching, which depends for results upon inducing the required states of mind, will marvel at the results. Not only can more be accomplished in three months than could be accomplished by the old methods in three years, but results can be attained by this that could never be reached by any mechanical method.

We are now prepared to consider the Evolution of Expression, the study of which involves the technique employed in this college for the cultivation of the voice as well as oratorical expression.

The name of the first chapter in the first volume is Animation of Voice. This is the name of an effect, not a cause. A certain state of mind will produce Animation of Voice, therefore I work to induce in the pupils the right state of mind, which is as sure to manifest itself in Animation of Voice as a sufficient amount of excellent gunpowder set on fire in a good cannon is to discharge its contents.

The first physiological condition of the vocal organs in Animation of Voice is freedom. The second condition is nerve energy. If an elocutionist should be engaged in some public or private school to teach oratory and voice culture, he would probably be requested first to teach the boys to open their mouths. Every previous effort to do this having failed, an elocutionist is engaged for one hour a week to pry open the mouths of the boys. The elocutionist might begin by saying, “John, you do not open your mouth wide enough.” John tries, but fails. The teacher might go through the class in this way, but with no better success. At last comes recess, and the teacher, listening to the boys in the yard, hears John, who had the lockjaw in the schoolroom, telling the boys about some incident—his mouth fully open. The elocution teacher was outside of the boy; and the key that would unlock his jaw was inside of him. How stiff, hard, grinding, and throaty was his voice in the schoolroom, but now how open and free!