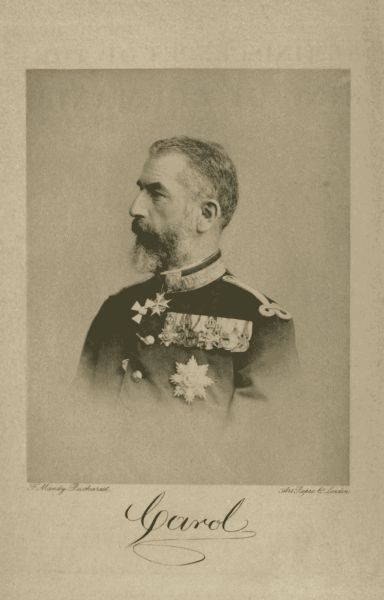

F. Mándy Bucharest. Art Repro Co. London.

Carol

Project Gutenberg's Reminiscences of the King of Roumania, by Mite Kremnitz This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook. Title: Reminiscences of the King of Roumania Author: Mite Kremnitz Editor: Sidney Whitman Release Date: March 17, 2015 [EBook #48509] Language: English Character set encoding: UTF-8 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK REMINISCENCES--KING OF ROUMANIA *** Produced by David Edwards, Julia Neufeld and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

F. Mándy Bucharest. Art Repro Co. London.

Carol

REMINISCENCES OF THE

KING OF ROUMANIA

EDITED FROM THE ORIGINAL WITH

AN INTRODUCTION BY

SIDNEY WHITMAN

WITH PORTRAIT

AUTHORIZED EDITION

NEW YORK AND LONDON

HARPER & BROTHERS

1899

| PAGE. | ||

| INTRODUCTION | vii | |

| I. | THE PRINCIPALITIES OF MOLDAVIA AND WALLACHIA | 1 |

| II. | THE SUMMONS TO THE THRONE | 11 |

| III. | STORM AND STRESS | 32 |

| IV. | MARRIAGE AND HOME LIFE | 83 |

| V. | FINANCIAL TROUBLES | 129 |

| VI. | THE JEWISH QUESTION | 143 |

| VII. | PEACEFUL DEVELOPMENT | 155 |

| VIII. | THREATENING CLOUDS | 218 |

| IX. | THE ARMY | 250 |

| X. | THE WAR WITH TURKEY | 265 |

| XI. | THE BERLIN CONGRESS AND AFTER | 311 |

| EPILOGUE | 355 |

Goethe (West-Oestlicher Divan).

It is said to have been a chance occasion which gave the first impetus towards the compilation of the German original[1] from which these "Reminiscences of the King of Roumania have been re-edited and abridged." One day an enterprising man of letters applied to one who had followed the King's career for years with vivid interest: "The public of a country extending from the Alps to the ocean is eager to know something about Roumania and her Hohenzollern ruler." The King, without whose consent little or nothing could have been done, thought the matter over carefully; in fact, he weighed it in his mind for several years before coming to a final decision.[viii] At first his natural antipathy to being talked about—even in praise (to criticism he had ever been indifferent)—made him reluctant to provide printed matter for public comment. On the other hand, he had long been most anxious that Roumania should attract more public attention than the world had hitherto bestowed on her. In an age of universal trade competition and self-advertisement, for a country to be talked about possibly meant attracting capitalists and opening up markets: things which might add materially to her prosperity. With such possibilities in view, the King's own personal taste or scruples were of secondary moment to him. So the idea first suggested by a stranger gradually took shape in his mind, and with it the desire to see placed before his own subjects a truthful record of what had been achieved in Roumania in his own time. By these means he hoped to give his people an instructive synopsis of the difficulties which had been successfully overcome in the task of creating practical institutions out of chaos.

As so often happens in such cases, the work grew beyond the limits originally entertained. But the task was no easy one, and involved the labour of several years. However, the result achieved is well worth the trouble, for it is an historical document of exceptional political interest, containing, among other material, important letters from Prince Bismarck, the Emperor[ix] William, the Emperor Frederick, the Czar of Russia, Queen Victoria, and Napoleon III. It is, in fact, a piece of work which a politician must consult unless he is to remain in the dark concerning much of moment in the political history of our time, and particularly in the history of the Eastern Question. "The Reminiscences of the King of Roumania" constitute an important page in the story of European progress. Nor is this all. They also contain a study in self-revelation which, so far as it belongs to a regal character, is absolutely unique in its completeness—even in an age so rich in sensational memoirs as our own.

The subject-matter deals with a period of over twenty-five years in the life of a young European nation, in the course of which she gained her independence and strove successfully to retain it, whilst more than trebling her resources in peaceful work. In this eventful period greater changes have taken place in the balance of power in Europe than in many preceding centuries. A republic has replaced a monarchy in France, and also on the other side of the Atlantic, in Brazil, since the days when a young captain of a Prussian guard regiment, a scion of the House of Hohenzollern, set himself single-handed the Sisyphean task of establishing a constitutional representative monarchy on a soil where hitherto periodical conspiracies and revolts had run riot luxuriously. Just here, however, our democratic[x] age has witnessed the realisation of the problem treated by Macchiavelli in "Il Principe"—the self-education of a prince.

To-day, the man who thirty-three years ago came down the Danube as a perfect stranger—practically alone, without tried councillors or adherents—is to all intents and purposes the omnipotent ruler of a country which owes its independence and present position entirely to his statesmanship. Nor can there be much doubt that but for him Roumania and the Lower Danube might be now little more than a name to the rest of Europe—as, indeed, they were in the past.

King Charles of Roumania is the second son of the late Prince Charles Anthony[2] of Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen: the elder South German Roman Catholic branch of the House of Hohenzollern, of which the German Emperor is the chief. Until the year 1849 the Hohenzollern-Sigmaringens, whose dominions are situated between Württemberg and Baden, near the spot where the Danube rises in the Black Forest, possessed full sovereign rights as the head of one of the independent principalities of the German Confederation. These sovereign rights of his[xi] own and his descendants Prince Charles Anthony formally and voluntarily ceded to Prussia on December 7, 1849. Of him we are credibly informed:

"Prince Charles Anthony lives in the history of the German people as a man of liberal thought and high character, who of his own free will gave up his sovereign prerogative for the sake of the cause of German Unity. His memory is green in the hearts of his children as the ideal of a father, who—for all his strictness and discipline—was not feared, but ever loved and honoured, by his family. He was always the best friend and adviser of his grown-up sons." His letters to his son Charles, which are frequently quoted in the present memoir, fully bear out this testimony to the Prince's intimate, almost ideal, relationship with his children, as also to the magnanimity with which he is universally credited.

Of the King's mother—Princess Josephine of Baden—we learn: "Princess Josephine was deeply religious without being in the least bigoted. Her unselfishness earned for her the love and devotion of all those who knew her. As a wife and a mother her life was one of exceptional harmony and happiness. The great deference which King Charles has always shown to the other sex has its source in the veneration which he felt for his mother."

Prince Charles was born on April 20, 1839,[xii] at the ancestral castle of the Hohenzollerns at Sigmaringen on the Danube, then ruled over by his grandfather, the reigning Prince Charles of Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen. The castle was not in those days the treasury of art and history which it is at the present day. The grandfatherly régime was of a patriarchal, almost despotic kind: every detail of household affairs was regulated with a view to strict economy. Though, perhaps, unpleasant at times, all this proved to be invaluable training for the young Prince, whose ultimate destiny it was to rule over one of the most extravagant peoples in Europe. Punctuality was strictly enforced: at nine o'clock the old Prince wound up his watch as a sign that the day was over, and at ten darkness and silence reigned supreme over the household.

Prince Charles was a delicate child, and was considered so throughout his early manhood, though in reality his health and bodily powers left little to be desired. The first happy years of his childhood were passed at Sigmaringen and the summer residences of Inzigkofen and Krauchenwies. This peaceful life was broken by a visit in 1846 to his maternal grandmother, the Grand Duchess Stéphanie of Baden. On this occasion Prince Charles attracted the attention and interest of Mme. Hortense Cornu, the intimate friend and confidant of Prince Louis Napoleon—later Napoleon III.

It cannot be said that the young Prince progressed very rapidly in his studies; but though he learned slowly, his memory proved most retentive. His naturally independent and strong character, moreover, prevented him from adopting outside opinions too readily, and this trait he retained in after years. For though as King of Roumania he is ever willing to listen to the opinion of others, the decision invariably remains in his own hands.

An exciting period supervened for the little South German Principality with the year 1848, when the revolutionary wave forced the old Prince to abdicate in favour of his son Prince Charles Anthony. Owing to the action of a "Committee of Public Safety," the Hohenzollern family quitted Sigmaringen on September 27. This the children used to call the "first flight" in contradistinction to the "second," some seven months later. Though Prince Charles Anthony succeeded in gaining the upper hand over the revolutionary movement of '48, the trouble commenced again in 1849 owing to the insurrection in the Grand Duchy of Baden. As soon as order had been completely restored, Prince Charles Anthony carried out his long-cherished plan of transferring the sovereignty of the Hohenzollern Principality to the King of Prussia, and in a farewell speech he declared his sole reason to be "the desire to promote the unity, greatness, and power[xiv] of the German people." The family settled first at Neisse in Prussian Silesia, then at Düsseldorf, as Prince Charles Anthony was appointed to the command of the Fourteenth Military Division, while Prince Charles Anthony, and later on also his brother Friedrich, were settled with their tutor in Dresden, where Prince Charles spent seven years.

Before joining his parents at Düsseldorf, Prince Charles successfully passed his ensign's examination, though he was entitled as a Prince of the House of Hohenzollern to claim his commission without submitting to this test. As a reward for his success he was permitted to make a tour through Switzerland and Upper Italy before being placed under his previously appointed military governor, Captain von Hagens. This officer was a man in every way fitted to instruct and prepare the young Prince for his career by developing his powers of initiative and independence of action. In accordance with his expressed wish, he was gazetted Second Lieutenant in the Prussian Artillery of the Guard, but was not required to join his corps until his studies were completed. A thorough knowledge of the practical part of his profession was acquired at the fortress of Jülich, followed, after a visit to the celebrated Krupp Works at Essen, by a course of instruction at Berlin.

The betrothal of his sister, Princess Stéphanie,[xv] to King Pedro V. of Portugal, in the autumn of 1857, was followed by her marriage by proxy at Berlin on April 29, 1858, whilst another important family event occurred in November of the same year. William, Prince of Prussia (afterwards King William I., who had assumed the regency during the illness of his brother the King, Frederick William IV.), appointed Prince Charles Anthony, of Hohenzollern, to the Presidency of the Prussian Ministry. His son Charles developed the greatest interest in politics, and at that time unconsciously acquired a fund of diplomatic knowledge and experience which was to stand him in good stead in his future career.

In the midst of the gaieties of Berlin the Prince was deeply affected by the melancholy news of the death of his sister Stéphanie on July 17, 1859. Two years later the marriage of his brother Leopold to the Infanta Antoinette of Portugal afforded him a welcome opportunity of visiting the last resting-place of his dearly loved sister near Lisbon. On his return from his journey, Prince Charles requested to be transferred to an Hussar Regiment, as the artillery did not appear at that time to take that place in public estimation to which it was entitled. This application, however, was postponed until his return from a long tour through the South of France, Algiers, Gibraltar, Spain, and Paris. After a short stay at the University of Bonn, Prince Charles again[xvi] resumed military duty as First Lieutenant in the Second Dragoon Guards stationed at Berlin, where he speedily regained the position he had formerly held in the society of the capital. The Royal Family, especially the Crown Prince, welcomed their South German relative most warmly, and the friendship thus created was subsequently more than equal to the test of time and separation.

A second visit to the Imperial Court of France in 1863, this time at the invitation of Napoleon III., was intended by the latter to culminate in a betrothal to a Princess of his House, but the project fell through, as the proposed conditions did not find favour with the King of Prussia. Prince Charles was forced to content himself with the consolation offered by King William, that he would soon forget the fair lady amidst the scenes of war (in Denmark). As orderly officer to his friend the Crown Prince of Prussia, Prince Charles took part in the siege and assault of the Düppel entrenchments, the capture of Fridericia, and the invasion of Jütland. The experience he gained of war and camp-life during this period was of inestimable benefit to the young soldier, who was afterwards called upon to achieve the independence of Roumania on the battlefields of Bulgaria.

The war of 1864 having come to an end, Prince Charles returned to the somewhat dreary monotony[xvii] of garrison life in Berlin. This not unnaturally soon gave rise to a feeling of ennui and a consequent longing on his part for more absorbing work than that of mere subordinate military routine. Nothing then indicated, however, that in a short time he would step from such comparative obscurity to the wide field of European politics by the acceptance of a hazardous, though pre-eminently honourable, position of the utmost importance in Eastern Europe—the throne of the United Principalities of Wallachia and Moldavia, which, thanks to his untiring exertions and devotion to duty, are now known as the Kingdom of Roumania.

In starting on his adventurous, not to say perilous, experiment, Prince Charles already possessed plenty of valuable capital to draw upon. In the first place, few princes to whose lot it has fallen to sway the destinies of a nation have received an early training so well adapted to their future vocation, or have been so auspiciously endowed by nature with qualities which in this instance may fairly be said to have been directly inherited from his parents. His early and most impressionable years had been passed in the bosom of an ideally happy and plain-living family, and this in itself was one of the strongest[xviii] of guarantees for harmonious development and for future happiness in life. Both his father and mother had earnestly striven to instil into their children the difference between the outward aspect and the true inwardness of things—the very essence of training for princes no less than for those of humbler rank. Also we find the following significant reference to the Prince and his feelings on the threshold of his career:

"The stiff and antiquated 'Junker' spirit which in those days was so prevalent in Prussia and Berlin, and more particularly at the Prussian Court, was most repugnant to him. His nature was too simple, too genuine, for him to take kindly to this hollow assumption, this clinging to old-fashioned empty formula. His training had been too truly aristocratic for him not to be deeply imbued with simplicity and spontaneity in all his impulses. His instincts taught him to value the inwardness of things above their outward appearance."

Nor was it long before he had ample opportunity of putting these precepts into practice. Neither as Prince nor as King has the Sovereign of Roumania ever permitted prosecution for personal attacks upon himself. The crime of lèse majesté has no existence—or, to say the least, is in permanent abeyance—in Roumania.

Anti-dynastic newspapers have for years persisted in their attacks upon the King, his policy,[xix] and his person—sometimes in the most audacious manner. Although his Ministers have from time to time strenuously urged his Majesty to authorise the prosecution of these offenders, he has never consented to this course. He even refused to prosecute those who attacked his consort, holding that the Queen is part of himself, and, like himself, must be above taking notice of insults, and must bear the penalty of being misunderstood, or even calumniated, and trust confidently to the unerring justice of time for vindication.

The King's equable temperament has enabled him to take an even higher flight. For let us not forget that it is possible to be lenient, even forgiving, in the face of calumny, and yet to suffer agonies of torture in the task of repressing our wounded feelings. King Charles is said to have read many scurrilous pamphlets and papers directed against him and his dynasty—for singularly atrocious examples have been ready to his hand—and to have been able sometimes even to discover a fund of humour in the more fantastic perversions of truth which they contained.

Speaking of one of the most outrageous personal attacks ever perpetrated upon him, he is reported to have said that such things could not touch or affect him—that he stood beyond their reach. Here the words employed by Goethe regarding his deceased friend Schiller might well be applied:

His absolute indifference towards calumny is doubtless due to his conviction that time will do him justice—that a ruler must take his own course, and that the final estimate is always that of posterity.

One who for years has lived in close contact with the Roumanian royal family gives the following sympathetic and yet obviously sincere description of the personal impression the King creates:

"King Charles had attained his fiftieth year when I saw him for the first time. There is, perhaps, no other stage of life at which a man is so truly his full self as just this particular age. The physical development of a man of fifty is long completed, whereas on the other hand he has not yet suffered any diminution of strength or elasticity. His spiritual individuality is also ripe and complete, in so far as any full, deep nature can ever be said to have completed its development. It is only consonant with that true nobility which precludes every effect borrowed or based on calculation, that the first impression the King makes upon the stranger is not a striking one: he is too distinguished to attract attention; too genuine to create an effect[xxi] for the eye of the many. An artist might admire the handsome features; but the King lacks the tall figure, the impressive mien which is the attribute of the hero of romance, and which excites the enthusiasm of the crowd. On the other hand, his slender figure of medium height is elegant and well knit; his gait is energetic and graceful. His sea-blue eyes, which lie deep beneath strong black eyebrows—meeting right across his aquiline nose—now and then take a restless roving expression. They are those of an eagle, a trite comparison which has often been made before. Moreover, their keenness and their great reach of sight justifies an affinity with the king of birds."

It is not generally known—but it is true, nevertheless—that the King of Roumania is half French by descent. His grandmother on his father's side was a Princess Murat, and his maternal grandmother, as already mentioned, was a French lady well known to history as Stéphanie Beauharnais, the adopted daughter of the first Napoleon, and later, by her marriage, Princess Stéphanie of Baden. It is to this combination in his ancestry that people have been wont to ascribe some of the marked characteristics of the King. His personal appearance—notably the fine clear-cut profile—undoubtedly recalls the typical features of the old French nobility. Also the slight, symmetrical, and graceful figure is rather French Beauharnais than German Hohenzollern.[xxii] His gift for repartee—l'esprit du moment, as it is so aptly styled—is decidedly French; and perhaps not less so his sanguine temperament, which has stood him in such good stead, and encouraged him not to lose heart in the midst of his greatest troubles, particularly years ago, when his subjects did not know and value him as they do now. An abnormal capacity for work and an absolute indifference towards every form of material enjoyment—or gratification of the senses—have also singularly fitted him for what posterity will probably deem to have been King Charles's most striking vocation: that of the politician. And his success as a politician is all the more remarkable, since his youthful training as well as his early tastes were almost exclusively those of the Prussian soldier. He even lacked the study of law and bureaucratic administration, which are commonly held to be the necessary groundwork of a political career. Yet not an atom of German dreaminess is to be detected in him; nor aught of roughness: little of the insensible hardness of iron; but rather something of the fine temper of steel—the elasticity of a well-forged blade—which, though it will show the slightest breath of damp, and bend at times, yet flies back rigid to the straight line. Thus I am assured is King Charles as a politician—not to be swayed or tampered with by influences of any kind, the sober moderation of an[xxiii] independent judgment has, in fact, never deserted him. It is also owing to a felicitous temperament that he has always been able to encounter opposition—even bitter enmity—without feeling its effect in a way common to average mankind.

He had to begin by acquiring the difficult art of "taking people," and this—as the King himself admits—he only acquired gradually. However, he possessed an inborn genius for the business of ruler. By nature he is a practical realist whose insatiable appetite for facts, faits politiques, crowds out most other interests. So he quickly profited by experience, which, added to an independence of judgment which he always possessed, has made him an opportunist whose opportunity always means the welfare of his country. In dealing with public questions he endeavours to start with the Gladstonian open mind: i.e., by having no fixed opinion of his own. He listens to all—forms his own opinion in doing so—and invariably finishes by impressing and influencing others. He even indirectly manipulates public opinion by constantly seeing and conversing with a vast number of people. For in Roumania there is no class favouritism so far as access to the monarch is concerned. Anybody may be presented at Court, and on any Sunday afternoon all are at liberty to call and see the King even without the formality of an audience paper to fix an appointment.

Personal favouritism has never existed under him. In fact, so thoroughly has he realised and carried into practice what he considers to be his duty of personal impartiality, that he once vouchsafed the following justification of an apparent harshness: that a ruler must take up one and drop another as the interests of the country require. In other words, he must not allow personal feeling to sway him—whereas in private life he should never forsake a friend. And yet withal King Charles is anxiously intent upon avoiding personal responsibility—not from timidity, but from an idea that it is irreconcilable with the dignity of a constitutional king to put himself forward in this way. Thus not "Le Roi le veut," but rather "I hold it to be in the public interest that such and such a thing should be done" is his habitual form of speech in council with his Ministers.

One of the King's favourite aphorisms is singularly suggestive in our talkative age: "It is not so much by what a prince does as by what he says that he makes enemies!" Like all men of true genius—or what the Germans call "geniale Naturen"—King Charles is of simple, unaffected nature;[3] without a taint of the histrionic in his composition, yet gifted with great reserve force[xxv] of self-repression, and rare powers of discernment and well-balanced judgment.

With all the pride of a Hohenzoller, a sentiment which he never relinquishes, and which, indeed, is a constant spur to regulate his conduct by a high standard, he yet holds that nobody should let a servant do for him what he can do for himself. Also, he has ever felt an unaffected liking for people of humble station who lead useful lives, and have raised themselves honestly by their own merit. In fact, the man who works—however lowly his sphere of life—is nearer to his sympathies than one whose position gives him an excuse for laziness. He instinctively dislikes the "loafer," whatever his birth. He admits as little that exalted position is an excuse for a useless life as that it should be put forward to excuse deviation from the principles of traditional morality. And in this respect his own life, which has been singularly marked by what the German language terms "Sittenreinheit," "purity of morals," offers an impressive justification for his intolerance upon this one particular point.

It is said to be King Charles's earnest conviction that the maxims he has striven to put into practice[xxvi] are the only possible ones upon which a monarchy on a democratic basis can hope to exist in our time. But here he is obviously attempting to award to principle what, in this instance at least, must be largely due to the intuitive gifts of an extraordinary personality. Maxims are all very well so far as they go, but they did not go the whole length of the way. Did not even Immanuel Kant himself admit that, during a long experience as a tutor, he had never been able to put those precepts successfully into practice upon which his work on "Pädagogik" is founded? Also many of the difficulties successfully encountered by the King of Roumania have been of such a nature as cut-and-dry application of precepts or maxims would never have sufficed to vanquish. Among these may be cited the acute crises which from time to time have been the product of bitter party-warfare in Roumania. Thus, during the Franco-German War, when the sympathies of the Roumanian people were with the French to a man, his position was one of extreme difficulty. The spiteful enmity he encountered in those days taxed his endurance to its utmost limits, and even called forth a threat of abdication. A weaker man would have left his post. Again, in 1888, when a peasant rising brought about by party intrigues seemed to threaten the results of many years' labour, even experienced statesmen hinted that the Hohenzollern dynasty might not last another six[xxvii] months. The King was advised to use force and fire upon the rioters. This he declined to do. He simply dismissed the Ministry from office, and called the Opposition into power, and subsequent events proved that his decision was the right one. But by far the greatest crisis of his reign, and at the same time the greatest test of his nerve and political sagacity, was furnished by the singularly difficult situation of Roumania during the Russo-Turkish War of 1877: here, indeed, the very existence of Roumania was at stake. The situation may be read between the lines in the present volume.

The King, by virtue of a convention, had allowed the Russians to march through Roumania, but the latter had declined an acceptable alliance which the Roumanians wished for. When things in Bulgaria went badly with the Russians, they wanted to call upon some bodies of Roumanian troops which were stationed on the banks of the Danube. The King, or, as he was then, Prince Charles, with the instinct of the soldier—and in this case, moreover, of the far-sighted politician—was burning to let Roumania take her share in the struggle. But he was determined that she should only enter the fray—if at all—as an independent belligerent power. So he held back—and held back again, risking the grave danger which might accrue to Roumania, and above all to himself, from ultimate Russian resentment. In the meantime, the Russians were[xxviii] defeated in the battles round Plevna; still he held back; not with a point-blank refusal, but with a dilatory evasiveness which drove the Russians nearly frantic. For, during those terrible months of July and August 1877, in which their soldiers were dying like flies, they could see the whole Roumanian army standing ready mobilised, but motionless, a few hours away to the north, on the Danube—immovable in the face of all Muscovite appeals for assistance. At last the Russians were obliged to accept Prince Charles's conditions, to agree to allow him the independent command of all Roumanian troops, and to place a large corps of Russian troops besides under his orders. Then, indeed, the former Prussian lieutenant started within twenty-four hours, after playing the Russians at their own game for four months, and beating them at it to boot. Had Russia refused his demands, not a single Roumanian would have entered upon that struggle in the subsequent course of which their Sovereign covered himself with renown. It was no part of his business as the ruler of Roumania to seek military glory per se, although the instinct for such was strong within the Hohenzoller. Also on the 11th September, the battle of Grivitza—which was fought against his advice—saw him at his post, and sixteen thousand Russians and Roumanians[4] were killed and wounded under his[xxix] command, probably a greater number slain in open battle in one day than England has lost in all her wars since the Crimea! Surely there was something of the heroic here; and yet it could hardly weigh as an achievement when compared with those Fabian tactics which preceded it, and the execution of which, until the psychological moment came, called for nerves of steel. Hardly ever has la politique dilatoire—of which Prince Bismarck was such a master in his dealings with Benedetti—had an apter exponent than King Charles on this eventful occasion. And its results, although afterwards curtailed by the decision of the Berlin Congress, secured the independence of Roumania and its creation as a kingdom.

King Charles is peculiarly German in his passionate love of nature. At Sinaja—his summer residence—he looks after his trees with the same solicitude which filled his great countryman, Prince Bismarck. He spends his holidays by preference amid romantic scenery—at Abbazia, on the blue Adriatic, or in Switzerland. He visits Ragatz nearly every year, and thoroughly enjoys his stay among the bluff Swiss burghers. It is impossible for him to conceal his identity there; but he does his best to avoid the dreaded royalty-hunting tourist[xxx] of certain nationalities, and finds an endless fund of amusement in the rough politeness of the inhabitants, with their customary greeting: "Herr König, beehren Sie uns bald wieder"—"Mr. King, pray honour us again with your visit."

He also loves to roam at will unknown among the venerable buildings of towns, such as Vienna and Munich, to look at the picture and art galleries, and gather ideas of the way to obtain for his own people some of those treasures of culture which he admires in the great centres of civilisation. He has even, at great personal sacrifice, collected quite a respectable gallery of pictures at Bucharest and Sinaja.

If I have dwelt somewhat at length upon the King's personal characteristics and his political methods, it has been in order to assist the reader to appreciate what kind of man he is, and so the more readily to understand cause and effect in estimating how the apparently impossible grew into an accomplished fact. This seemed to be all the more necessary as the "Reminiscences" themselves—far more of a diary than a "Life"—are conceived in a spirit of rarely dispassionate impartiality. The letters, in particular, addressed to the King by his father—whilst they afford us a sympathetic insight into a charming relationship between father and son—do credit to the fearless spirit of the latter in publishing them; and the frankness[xxxi] with which the most painful situations are placed on record can scarcely fail to elicit the sympathy and respect of the reader. In fact, the book contains passages which it would trouble the self-love of many a man to publish. This it is, however, which stamps it with the invaluable hall-mark of veracity, whilst, at the same time, it leaves the reader full liberty to form his own judgment.

SIDNEY WHITMAN.

REMINISCENCES OF THE KING OF ROUMANIA

After the conquest of the Balkan Peninsula by the Turks, who were intent on extending the Ottoman Empire even to the north of the Danube, there was little left for the Roumanian Principalities of Moldavia and Wallachia, deserted and abandoned to their fate by the neighbouring Christian States, except to make the best possible terms with the victorious followers of the Crescent. Each Principality, therefore, concluded separate conventions with the Sublime Porte, by means of which they aimed at domestic independence in return for the payment of tribute and military service. These conventions or capitulations were not infrequently violated by the Turks as well as by the Roumanian Hospodars or Princes.[2] Though the rulers of Bucharest and Jassy were appointed and dismissed at the pleasure of the Grand Seignior, the very existence of the Principalities was due solely to the provisions of the treaties above mentioned, by virtue of which they escaped incorporation in the Ottoman Empire; nor were the nobility of Moldavia and Wallachia forced to follow the example of their equals in Bosnia and Herzegovina in embracing Islam, in order to maintain their power over the Christian population. Still the Principalities of the Danube did not entirely escape the ruin and misery which befell Bulgaria and Roumelia; but, since the forms and outward appearance of administrative independence remained, it was yet possible that the Roumanian patriot might develop his country socially and politically without threatening the immediate interests of the Turkish Empire south of the Danube.

Chief amongst the difficulties which beset the regeneration of Roumania was the rule of the Phanariotes,[5] to whom the Porte had practically handed over the territories of the Lower Danube. The dignity of Hospodar[6] was confined to members of the great Phanariot families, who oppressed[3] and misruled the whole country, whilst the Greek nobles in their train not only monopolised all offices and dignities, but even poisoned the national spirit by their corrupt system. Even to-day Roumania suffers from the after-effects of Levantine misrule, which blunted the public conscience and confused all moral conceptions.

Since the end of the eighteenth century the Danubian Principalities have attracted the unenviable notice of Russia, whose objective, Constantinople, is covered by them. In less than a century, from 1768 to 1854, these unfortunate countries suffered no less than six Russian occupations, and as many reconquests by the Turks. It speaks highly for the national spirit of the Roumanians that they should have borne the miseries entailed by these wars without relapsing into abject callousness and apathy; and that, on the contrary, the memory of their former national independence should have continued to gather fresh life, and that their wish to shake off the yoke of their bondage, be it Russian or Turkish, should have grown stronger with the lapse of time. The Hospodars, appointed by the Russians, were hindered in every way by the Turks in their task of awakening the national spirit and preparing the way for the regeneration of their enslaved people. Besides this, many of these Hospodars were prejudiced against the introduction of reforms which could only endanger their own interests and positions. They were,[4] therefore, far more disposed to seek the protection of foreign States than to rely upon the innate strength of the people they governed. Such were the causes that hindered the development of the moral and material resources of the Roumanian nation.

The ideas from time to time conceived by the rulers of Russia for the unification of the Principalities were based solely on selfish aims and considerations. Thus, for instance, a letter dated September 10, 1782, from Catherine II., who gave the Russian Empire its present shape and direction, to the Emperor Joseph II., shows clearly that the state then proposed, consisting of Wallachia, Moldavia and Bessarabia, was to be merely a Russian outpost, governed by a Russian nominee, against the Ottoman Empire. Even in this century (1834) Russia would have been prepared to further the unification of the Principalities, if only they and the other Great Powers had declared themselves content to accept a ruler drawn from the Imperial House of Russia, or some closely allied prince. As, however, this was not the case, the Russian project was laid aside in favour of a policy of suppressing the national spirit by means of the Czars influence as protector. The Sublime Porte, on the other hand, was straining every nerve to maintain the prevailing state of affairs. And finally, Austria, the third neighbour of the Principalities, hesitated[5] between its desire to gain possession of the mouths of the Danube by annexing Wallachia and Moldavia, and its disinclination to increase the number of its Roumanian subjects by four or five millions, and thereby to strengthen those incompatible elements beyond the limits of prudence. At the same time Austria looked upon the interior development of Roumania with an even more unfavourable eye than Russia, and it seemed as though Moldavia and Wallachia, in spite of the ever increasing desire of their inhabitants for union and for the development of their resources, so long restrained, were condemned to remain for ever in their lamentable condition by the jealousy of their three powerful neighbours.

At length came the February Revolution of 1848 in Paris, the effects of which were felt even in far Roumania. An insurrection arose in Moldavia: the Hospodar was forced to abdicate; and a Provisional Government, the Lieutenance Princière,[7] was formed at Bucharest, and proceeded to frame a constitution embodying the freedom of the Press, the abolition of serfdom and all the privileges of the nobility. The earlier state of affairs was, however, restored on September 25 of the same year by the combined action of the Russians and the Turks, with the[6] result that the Principalities for a time lost even the last remnants of their former independence, and the power of the Hospodars was hedged in with such narrow restrictions by the Treaty of Balta Liman (May 1, 1849) that they could undertake no initiative without the sanction of the Russian and Turkish commissaries, under whose control they were placed.

The Crimean War brought with it emancipation from the Russian protectorate, but although the situation was now improving, much was still necessary before the Roumanians could regain their domestic independence. A French protector had taken the place of the Russian. The pressure, it is true, was by no means so severe, nor was it felt so directly as formerly, yet the country perforce suffered no inconsiderable damage, both moral and material, from the half-voluntary, half-compulsory compliance with the wishes of the French ruler. Napoleon wished to elevate Roumania, the "Latin sister nation," into a French dependency, and thereby to make France the decisive factor in the Oriental question. A willing tool was found in the person of the new Hospodar of the now united Principalities, and thenceforth everything was modelled upon French pattern.

An international Commission assembled in Bucharest in 1857, together with a Divan convoked by an Imperial Firman for Moldavia and[7] Wallachia, to consider the question of the future position of the Danubian Principalities. The deliberations of these two bodies, however, resulted in nothing, as neither the Sublime Porte nor the Great Powers were inclined to agree to the programme submitted to them, the main features of which were: the union of the two Principalities as a neutral, autonomous state under the hereditary sovereignty of a prince of a European dynasty, and the introduction of a constitution. A conference held at Paris, on the other hand, decided that each Principality should elect a native Hospodar, subject to the Sultan's confirmation.

The desire for national unity had, however, become so strong that the newly elected legislative bodies of both countries rebelled against the decision of the Great Powers, and elected Colonel Alexander Kusa as their ruler in 1859. Personal union was thus achieved, though the election of a foreign prince had, for the time being, to be abandoned. Still Prince Kusa was required to pledge his word to abdicate should an opportunity arrive for the closer union of the two countries under the rule of a foreign prince.

Guided by the advice of the Great Powers, the Sultan confirmed the election of Prince Kusa, but by means of two Firmans, a diplomatic sleight of hand, by which the fait accompli of the irregular union remained undisturbed, albeit unrecognised.[8] Formal sanction to the union was not conceded by the Sublime Porte until 1861. Prince Kusa, whose private life was by no means above reproach, endeavoured to fulfil in public the patriotic ambition of furthering his people's progress. But Roumania at that period was not prepared for the purely parliamentary form of government it had assumed, and the well-meant reforms initiated by the Prince and the Chamber achieved no immediate result. Prince Kusa, therefore, felt himself compelled to abolish the Election Laws by a coup d'état, and to frame a new one, which obtained the sanction of the Sublime Porte, and eventually the approval of the majority of the nation.

The increased liberty of action gained by the Prince was utilised to the full in formulating a series of necessary and excellent reforms; he failed, however, to place the budget on a satisfactory footing, and the finances remained in the same unfavourable condition as before, whilst several of his measures were directly opposed to the interests of certain factions and classes of the population. In addition to these difficulties, scandals arose which were based only too firmly upon the extremely lax life which Prince Kusa led, and a conspiracy was formed for his overthrow which found a ready support throughout the land. The Palace at Bucharest was surprised on the night of February 22, 1866, by a band of[9] armed men, who forced the Prince to abdicate and quit the country. This accomplished, the leaders of the various parties assembled and formed a Provisional Government under the Lieutenance Princière, or regency, which consisted of General N. Golesku, Colonel Haralambi and Lascar Catargiu.

The Chamber at once proceeded to elect a new ruler, and their first choice fell upon the Count of Flanders, the younger brother of the King of Belgium. Napoleon III., however, who was then still able to play the arbitrator in the affairs of Europe, hinted that the Count would be better advised to decline the proffered crown. The Emperor's wish was acceded to, and, although the Provisional Government for a time appeared to persist in the election of the Count of Flanders, Roumania was ultimately forced to look for a candidate whose election would not be opposed by any of the Great Powers.

The choice was difficult, if not impossible; for the Paris Conference, which had reassembled in the meantime, had decided against the union of the Principalities; and, unless Roumania could attain its object semi-officially by the favour of the Great Powers, the position was hopeless.

It was, indeed, a serious, not to say alarming, situation; for a war between Prussia and Austria for the hegemony of Germany was imminent, and threatened to lead to further complications in the[10] East. If the election were delayed until after the outbreak of hostilities, one of the belligerent parties was certain to reject the candidate whose election the other approved, whilst Russia would take advantage of the interregnum to stir up the whole of Roumania, especially Moldavia, against the union; for anything that might tend to impede the Russian advance upon Constantinople could not fail to evoke the most lively hostility in St. Petersburg. It was, therefore, upon France and her Emperor that all the hopes of the Roumanians reposed: with Napoleon on their side everything was possible, without him nothing.

The leading Roumanian statesmen were well aware of the difficulties in the way, and eventually fixed upon Prince Charles of Hohenzollern as their candidate, for he was related to both the French and Prussian dynasties, upon whose goodwill and support he might confidently reckon. It was of the utmost importance, therefore, to move him to accept their offer at once, and to obtain the sanction of the nation by a plébiscite.

The Roumanian delegate, Joan Bratianu, arrived at Düsseldorf on Good Friday 1866, to lay the offer of the Roumanian people before Prince Charles and his father. In an audience granted by the latter on the following day, March 31, Bratianu announced the intention of the Lieutenance Princière, inspired by Napoleon III., to advance Prince Charles Anthony's second son, Charles, as a candidate for the throne of the Principalities. Bratianu succeeded in obtaining a private interview with Prince Charles the same evening, in order to acquaint the latter with the political situation, and to point out the danger which must inevitably be incurred if the present Provisional Government remained in power. Prince Charles replied that he possessed courage enough to accept the offer, but feared that he was not equal to the task, adding that nothing was known of the intentions of the King of Prussia, without whose permission, as chief of the family, he could[12] not take so important a step. He therefore declined for the moment to give any definite answer to the proposals of the Roumanian Government. Bratianu returned to Paris, after promising to take no immediate steps in the matter. Prince Charles Anthony without delay addressed a memorial regarding this offer to the King of Prussia, and clearly defined the circumstances which had led to his taking this step. A similar communication was forwarded to the President of the Prussian Ministry.

A few days later Prince Charles arrived in Berlin, and at once visited the King, the Crown Prince, and Prince Frederick Charles, as he reported in a letter to his father:

"The King made no mention of the Roumanian question at the interview, but the Crown Prince, on the other hand, entered into a minute discussion with me, and did not appear to be at all against the idea. The only thing that displeased him was that the candidature was inspired by France, as he feared that the latter might demand a rectification of the frontier from Prussia in return for this good office. I replied that I did not consider that the Emperor Napoleon had thought of such a bargain, but had been induced to take the initiative in this matter by family feeling rather than by any selfish consideration. The Crown Prince, moreover, considered it a great honour that[13] so difficult a task had been offered to a member of the House of Hohenzollern. Prince Frederick Charles also at once started upon a minute discussion of the Roumanian question. He seemed to be intimately acquainted with the issue, and volunteered the opinion that I was intended for better things than to rule tributary Principalities: he therefore advised me to decline the offer."

The following telegram, published in the Press, was handed to Prince Charles as he was sitting with his comrades at the regimental mess-table:

"Bucharest, 13th April.

"The Lieutenance Princière and Ministry have announced the candidature of Prince Charles of Hohenzollern as Prince of Roumania, under the title of Charles I., by means of placards at the street corners; it is rumoured that the Prince will arrive here shortly. The populace appeared delighted by the news."

The Prince at once visited Colonel von Rauch, who had been entrusted with the delivery of Prince Charles Anthony's memorial to the King, and learnt that an answer would be sent on April 16. The following report was despatched to Prince Charles Anthony by his messenger on the 14th: "I was commanded to attend their Majesties at the Soirée Musicale yesterday evening. The King took me into a side room[14] and expressed himself as follows: 'I have not yet replied to the Prince, because I am still waiting for news from Paris, as the Porte has declared its intention of recalling its ambassador from the Conference if the election of a foreign prince is discussed.

"'Should the protecting States have regard to this declaration of the Porte, the election of a Hohenzollern prince would be rendered impossible; on the other hand, should the majority decide for a foreign prince, and the coming Chamber in Bucharest follow their example, the whole matter would enter upon a new phase. However, that I may not keep the Prince waiting, I shall express my opinions shortly as to the future acceptance or refusal of the Roumanian crown.'"

The King of Prussia forwarded the following autograph letter to the young Hohenzollern prince early the next morning:

"Your father has, no doubt, imparted to you the enclosed (telegram from Bratianu). You will remain quite passive. Great obstacles have arisen, as Russia and the Porte are so far opposed to a foreign prince.

"WILLIAM."

The telegram ran thus:

"Five million Roumanians proclaim Prince Charles, the son of your Royal Highness, as their sovereign. Every church is open, and the voice of[15] the clergy rises with that of the people in prayer to the Eternal, that their Elected may be blessed and rendered worthy of his ancestors and the trust reposed in him by the whole nation.

"J. C. BRATIANU."

The long expected reply from the Prussian monarch arrived at Düsseldorf on April 16. After discussing the probable moral and material bonds of union which would unite Prussia and Roumania in the event of the offer being accepted, the King continued:

"The question is whether the position of your son and his descendants would really be as favourable as might otherwise be expected? For the present the ruler of Roumania will continue as a vassal of the Porte. Is this a dignified and acceptable position for a Hohenzollern? And though it may be expected that in future this position will be exchanged for that of an independent sovereignty, still the date of the realisation of this aim is very remote, and will probably be preceded by political convulsions through which the ruler of the Danubian Principalities might perhaps be unable to retain his position! With such an outlook, are not the present position and prospects of your son happier than the life which is offered him?

"Even in the event of my consenting to the[16] election of one of your sons to the throne of Roumania, is there any guarantee that this elective sovereignty, even if it becomes hereditary, will remain faithful to him who is now chosen? The past of these countries shows the contrary; and the experience of other States, ancient and well established, as well as newly created and elective empires, shows how uncertain such structures are in our times.

"But, above all, we must take into consideration the attitude of the Powers represented at the Paris Conference to this question of election. Two questions still remain undecided: (a) Is there to be an union or not? (b) Is there to be a foreign Prince or not?

"Russia and the Porte are against the union, but it appears that England will join the majority, and if she decides for the union the Porte will be obliged to submit.

"In the same way both the former States are opposed to the election of a foreign Prince as the ruler of the Danubian Principalities. I have mentioned this attitude of the Porte, and yesterday we received a message from Russia to say that it was not disposed to agree to the project of your son's election, and that it will demand a resumption of the Conference. All these events prevent the hope of a simple solution. I must therefore urge you to consider these matters again. Even should Russia, against its will of course, consent[17] to the election of a foreign Prince, it is to be expected that intrigue after intrigue will take place in Roumania between Russia and Austria. And since Austria will more willingly vote for such an election, Roumania would be forced to rely upon her as against Russia, and so the newly created country with its dynasty would be on the side of the chief opponent of Prussia, though the latter is to provide the Prince!

"You will gather from what I have said that, from dynastic and political considerations, I do not consider this important question quite as couleur de rose as you do. In any case we must await the news which the next few days will bring us from Bucharest, St. Petersburg, and Constantinople, and we must see whether the Paris Conference will reassemble immediately.

"Your faithful Cousin and Friend,

"WILLIAM."

"P.S.—A note received to-day from the French Ambassador proves that the Emperor Napoleon is favourably inclined to the plan. This is very important. The position will only be tenable if Russia agrees, as she is influential in Roumania on account of her professing the same religion and owing to her geographical proximity and old associations. These constitute an influence against which a new Prince in a weak and divided country would not be able to contend for any[18] length of time. If you are desirous of prosecuting this affair your son must, above all things, gain the consent of Russia. It is true that up to now the prospect of success is remote...."

Prince Charles Anthony replied, assuring the King that, although the examples of such enterprises in Greece and Mexico had proved disastrous, yet the complications which might arise from Roumania were not likely to affect the prestige of Prussia, and he therefore begged his Majesty not to refuse his consent so long as there was a chance of arranging the matter. A most important interview then took place between Count Bismarck and Prince Charles at the Berlin residence of the former, who was at that time confined to his house by illness.

Bismarck opened the conversation with the words: "I have requested your Serene Highness to visit me, not in order to converse with you as a statesman, but quite openly and freely as a friend and an adviser, if I may use the expression. You have been unanimously elected by a nation to rule over them; obey the summons. Proceed at once to the country, to the government of which you have been called!"

Prince Charles replied that this course was out of the question, unless the King gave his permission, although he felt quite equal to the task.

"All the more reason," replied the Count. "In this case you have no need for the direct permission of the King. Ask the King for leave—leave to travel abroad. The King (I know him well) will not be slow to understand, and to see through your intention. You will, moreover, remove the decision out of his hands, a most welcome relief to him, as he is politically tied down. Once abroad, you resign your commission and proceed to Paris, where you will ask the Emperor for a private interview. You might then lay your intentions before Napoleon, with the request that he will interest himself in your affairs and promote them amongst the Powers. In my opinion this is the only method of tackling the matter, if your Serene Highness thinks at all of accepting the crown in question. On the other hand, should this question come before the Paris Conference, it will not take months merely, but even years to settle. The two Powers most interested—Russia and the Porte—will protest emphatically against your election; France, England, and Italy will be on your side, whilst Austria will make every endeavour to ruin your candidature. From Austria there is, however, not much to fear, as I propose to give her occupation for some time to come!... As regards us, Prussia is placed in the most difficult position of all: on account of her political and geographical situation she has always held aloof from the Eastern Question and[20] has only striven to make her voice heard in the Council of the Powers. In this particular case, however, I, as Prussian Minister, should have to decide against you, however hard it would be for me, for at the present moment I must not come to a rupture with Russia, nor pledge our State interest for the sake of family interest. By independent action on the part of your Highness the King would escape this painful dilemma; and, although he cannot give his consent as head of the family, I am convinced that he will not be against this idea, which I would willingly communicate to him if he would do me the honour of visiting me here. When once your Serene Highness is in Roumania the question would soon be solved; for when Europe is confronted by a fait accompli the interested Powers will, it is true, protest, but the protest will be only on paper, and the fact cannot be undone!"

The Prince then pointed out that Russia and Turkey might adopt offensive measures, but Bismarck denied this possibility: "The most disastrous contingencies, especially for Russia, might result from forcible measures. I advise your Serene Highness to write an autograph letter to the Czar of Russia before your departure, saying that you see in Russia your most powerful protector, and that with Russia you hope some day to solve the Eastern Question. A matrimonial[21] alliance also might be mooted, which would give you great support in Russia."

In reply to a question as to the attitude of Prussia to a fait accompli, Bismarck declared: "We shall not be able to avoid recognising the fact and devoting our full interest to the matter. Your courageous resolve is therefore certain to be received here with applause."

The Prince then asked whether the Count advised him to accept the crown, or whether it would be better to let the matter drop.

"If I had not been in favour of the course proposed, I should not have permitted myself to express my views," was the reply. "I think the solution of the question by a fait accompli will be the luckiest and most honourable for you. And even if you do not succeed your position with regard to the House of Prussia would continue the same. You would remain here and be able to look back with pleasure to a coup with which you could never reproach yourself. But if you succeed, as I think you will, this solution would be of incalculable value to you; you have been elected unanimously by the vote of the nation in the fullest sense of the word; you follow this summons and thereby from the commencement earn the full confidence of the whole nation."

The Prince objected that he could not quite trust the plébiscite, because it had been effected so quickly, but Bismarck replied:

"The surest guarantee can be given you by the deputation which will shortly be sent to you, and which you must not receive on Prussian territory; moreover, I should place myself in communication with the Roumanian agent in Paris as soon as possible. I communicated this idea sous discrétion to the French Ambassador, Benedetti, after we had learnt that Napoleon wished to hear our views, and he declares that France will place a ship at your disposal to undertake the journey to Roumania from Marseilles, but I think it would be better to make use of the ordinary steamer in order to keep the matter quite secret."

As in duty bound, Prince Charles proceeded to the Royal Palace after this interview, to ascertain the King's views on the proposed course of action. His Majesty did not share Count Bismarck's view and thought that the Prince had better await the decision of the Paris Conference, although, even should this be favourable, it would still be unworthy a Prince of the House of Hohenzollern to place himself under the suzerainty of the Sultan! To this Prince Charles replied that, although he was ready to acknowledge the Turkish suzerainty for a time, he reserved to himself the task of freeing his country by force of arms, and of gaining perfect independence on the field of battle. The King gave the Prince leave to proceed to Düsseldorf, embraced him heartily, and bade him Godspeed!

Prince Bismarck sent for Colonel Rauch, who had played an important part in the negotiations with the King, and informed him on April 23 that the Paris Conference had decided by five votes to three that the Bucharest Chamber was to elect a native prince, and that France had declared that she would not tolerate forcible measures either on the part of Russia or of the Porte. The President of the Prussian Ministry then repeated the advice he had given to Prince Charles, viz., to accept the election at once, then proceed to Paris, and thence to Bucharest with the support of Napoleon, and to write at once to the Czar Alexander, hinting at the projected Russian marriage. If Russia was won, everything would be won, and the intervention by force of one or the other of the guaranteeing Powers would be no longer to be feared. As regards the consent of the King, which of course could not be given now, it would not be refused to a final fait accompli. Prince Charles must decide for himself whether he felt the power and decision to solve the problem in this straightforward fashion; but it must be understood that no other method offered any prospect, for the Powers would eventually agree upon a native prince, and the Roumanians must submit. "I spoke," he added, "to the Roumanian political agent in Paris, M. Balaceanu, in a similar strain yesterday evening, and laid stress upon the fact that the King cannot at present decide or accept the election of Prince[24] Charles, because political complications might be created thereby."

From Paris came the news that nothing would be more agreeable to the Emperor and his Government than to see Prince Charles on the throne of Roumania, but that nothing could be done in the face of the decision of the Conference, and that the Prince's project of a fait accompli was so adventurous that the Emperor could not promise his support. An interview was then arranged at the house of Baroness Franque in Ramersdorf, with M. Balaceanu, who declared that the intention of the Roumanian Government was to adhere to its choice, and, if necessary, to carry on the government under the name of Charles I. Roumania would allow herself neither to be bent nor broken.

Two days later, on April 29, Colonel von Rauch returned from Berlin with the royal answer to Prince Charles Anthony's second memorial, which contained a repetition of the King's objections to the acceptance of the offer, and still more to the fait accompli, which was so warmly urged from Paris. The "Memorial Diplomatique" of the 28th contained this suggestive phrase: "... l'initiative de la France n'a pour object que les faits à accomplir!"

Prince Charles Anthony received M. Bratianu and Dr. Davila on May 1 at Düsseldorf. They came to announce the arrival of the deputation with the verification of the plébiscite, and to[25] inquire whether or no Prince Charles intended to decline their offer definitely. It was then decided to telegraph in cipher to Bucharest that the Prince had decided to accept the offer, but only on condition that the King should give his consent.

In answer to a telegram from Prince Charles Anthony, the King of Prussia begged him to come to Berlin to discuss the question of the fait accompli. The result of the interview was that the King agreed to refrain from influencing the decision of Prince Charles directly and to permit the fait accompli to "take place." The Prince was to resign his commission as a Prussian officer after passing the Prussian frontier.

On the receipt of this news from Berlin, the Prince at once sent for MM. Balaceanu and Bratianu, and on their arrival informed them that he was prepared to set out for Roumania without delay. The question then arose as to which route was to be taken, since Prussia might declare war any day with Austria, whilst a sea journey viâ Marseilles or Genoa risked a possible detention at Constantinople. The Prince eventually decided on the shortest route, viâ Vienna-Basiasch; but this plan had to be reconsidered, as owing to an indiscretion the proposed itinerary became public.

The long expected mobilisation order of the Prussian Army was signed by the King on May 9, and Prince Charles in consequence received an order from his colonel to rejoin his regiment[26] at once, from which, however, he was exempted by the six weeks' leave granted by the King himself. Balaceanu urged the Prince by letter not to delay his departure, and reiterated his entreaties on behalf of the Roumanian people, who were anxiously awaiting the arrival of their chosen ruler.

The last day at home was Friday, May 11, 1866, and with it came the inevitable anguish of parting with his dearly loved parents. Repressing the emotions which might otherwise have betrayed the pregnant measure he had undertaken, Prince Charles, clad for the last time in the uniform of the Prussian Dragoons, rode down the avenue towards Benrath Castle, where his eldest brother resided and awaited him. Upon arriving there, he exchanged his uniform for mufti and proceeded to the station with his sister, Princess Marie, who accompanied him for the first few hours of his journey, and at Bonn the Prince joined Councillor von Werner, with whom the momentous journey was to be undertaken. Zurich was reached at two o'clock in the afternoon, when the travellers broke their journey for the first time in order to arrange the difficult question of passports. Von Werner telegraphed to a Swiss official, whom Prince Charles Anthony had already asked about the passes, to arrange a meeting at St. Gallen, but as the official was not at home at the time, a delay of twenty-four hours[27] occurred, which Prince Charles spent in writing to the Emperors of Russia and France and the Sultan of Turkey.

Baron von Mayenfisch and Lieutenant Linche, a Roumanian staff officer, who both joined the party in Zurich, set out independently, the former for Munich, the latter for Basiasch on the Danube. The Prince and Von Werner occupied themselves with erasing the marking of the Prince's linen and reducing the quantity of his baggage to indispensable limits. The following day (May 14) found the Prince and his companion at St. Gallen, where a passport was obtained for the former under the name of "Karl Hettingen," travelling on business to Odessa, and at the Prince's request a note was made on this document of the fact that Herr Hettingen wore spectacles. The acquisition of these passports, however, and the fact of his travelling second-class, were not alone sufficient to overcome all further difficulties and dangers, for on reaching Salzburg, on the Austro-Bavarian frontier, on the 16th, a customs official gruffly demanded the Prince's name, and he to his horror found that he had forgotten it. Luckily Von Werner, with great presence of mind, flung himself into the breach by insisting on paying duty for some cigars, and so diverted the intruder's attention, whilst the Prince refreshed his peccant memory with a glimpse at his passport. But this was not all, for scarcely had[28] this little manœuvre been successfully carried out than several officers of the "King of Belgium's" Regiment, with whom the Prince had served in 1864 in Denmark, entered the waiting-room and caused him no little misgiving lest he should be recognised. Here fortune, however, again favoured him, and all passed off well, the travellers continuing their journey as far as Vienna, which they found crowded with troops. Pressburg, Pest, Szegedin and Temesvar found them still caged in the dismal squalor of a dirty second-class carriage, and suffering much discomfort from an icy wind which chilled them to the bone. The tedious railway journey at length ended at Basiasch, from whence they were to proceed down stream by steamer. The mobilisation of the Austrian troops had, however, completely disorganised the river service, and a most unwelcome delay of two days took place at this unsavoury spot.

Joan Bratianu arrived from Paris in time to accompany his future sovereign upon the last stage of his journey, but, as strict secrecy was still imperative, he was compelled to treat the Prince as a stranger. The Roumanian frontier was reached at last, and the boat lay alongside the quay of Turnu Severin. As the Prince was about to hurry on shore, the master of the steamboat stopped him to inquire why he should land here when he wanted to go to Odessa. The Prince replied that he only intended to spend a[29] few minutes on shore, and then hurried forward. As soon as he touched Roumanian soil, Bratianu, hat in hand, requested his Prince to step into one of the carriages waiting there. And as he did so he heard the captain's voice exclaim: "By God, that must be the Prince of Hohenzollern!"

After the despatch of a couple of telegrams to the Lieutenance Princière and the Government, the Prince and Bratianu set out for the capital in a carriage drawn by eight horses at a hand gallop, which never slackened its headlong pace throughout the ice-cold, misty night. At four o'clock they reached the river Jiu, but lost some time there, as the ferry was not in working order. At Krajowa, where the news of his arrival had brought together an enormous and enthusiastic multitude, a right royal welcome awaited the new Prince, and, escorted by two sections of Dorobanz Cavalry (Militia hussars), he reached the prettily decorated town of Slatina at noon, where a halt of a couple of hours was made before proceeding to Piteschti. En route the Prince overtook the 2nd Line Regiment marching on Bucharest, and was greeted by them with enthusiastic cheers. A numerous escort of cavaliers, amongst them Dr. Davila, met the Prince outside Piteschti, where yet another most enthusiastic reception was accorded him. General Golesku and Jon Ghika, the President of the Ministry, were presented to the Prince, who expressed his pleasure at greeting[30] the first members of the Government. The night was passed at Goleschti, where the Prince entered upon his duties by signing a decree pardoning the Metropolitan of Moldavia for his share in the Separatist riots of April 15. Prince Charles rose early the following morning to make all necessary arrangements for his triumphal entry into the capital, where the inhabitants were waiting impatiently to do him honour. The keys of the town were presented by the Burgomaster, who also addressed a speech to the new ruler. The procession then passed along the streets lined by soldiers of the Line and National Guard, until they reached a house outside which a guard of honour was posted. "What house is that?" asked the Prince in the innocence of his heart. "That is the Palace," replied General Golesku with embarrassment. Prince Charles thought he had misunderstood him, and asked: "Where is the Palace?" The General, still more embarrassed, pointed in silence to the one-storeyed building.

At length the procession halted at the Metropolie, the Cathedral of Bucharest, where the venerable Metropolitan received the Prince and tendered him the Cross and Bible to kiss. After hearing the Te Deum, the Prince, with his suite, proceeded to the Chamber, which stands exactly opposite the Metropolie. Here he took the oath to keep the laws, maintain the rights, and preserve[31] the integrity of Roumania.—"Jur de a pazi legile Romaniei, d'a mentine drepturile sale si integritateā teritoriului!"[8] Then, after replying in French to the address of the President of the Chamber, Prince Charles repaired with his suite to the Palace to refresh himself after the exertions of the day. The rooms, though small, proved to have been tastefully furnished by Parisian upholsterers during the government of Prince Kusa, but the view from the windows was primitive indeed; on the one side stood an insignificant guardhouse, whilst the other offered the national spectacle of a gipsy encampment with its herd of swine wallowing in the gutters of the main road—it could hardly be called a street. Such were the surroundings amongst which the adventurous Hohenzollern Prince commenced his new career!

The first Roumanian Ministry under the new régime was composed of members of all political parties, Conservatives and Liberals, Moldavians and Wallachians, Right, Centre, and Left. Lascar Catargui was appointed President of the Ministry, which, amongst others, included Joan Bratianu (Finance), Petre Mavrogheni (Foreign Affairs), General Prince[9] Jon Ghika (War), and Demeter Sturdza (Public Works).

The chief task of the new Government was to secure the recognition of their new ruler by the Powers, but the telegrams from the Roumanian agents abroad showed very plainly that the fait accompli was only the first step towards the desired end. The initiative of the Prince found favour, it is true, with Napoleon, but his Minister, Drouyn de L'Huys, regarded his action as an insult[33] to the Paris Conference, whilst the Sultan refused to receive the letter addressed to him by Prince Charles, and announced his intention of applying to the Conference for sanction to occupy the Principalities by armed force. To meet this possibility, the immediate mobilisation of the Roumanian Army was decided upon by the Cabinet, and the Prince seized an occasion for reviewing the troops on May 24. The Turkish protest against the election was submitted to the Conference on the following day, but the Powers decided that Turkey was not entitled to occupy Roumanian territory without the previous consent of the Powers, and also declared that they had broken off official communications with the Prince's Government. As the news from Constantinople became more and more threatening, a credit of eight million francs was voted by the Roumanian Chamber for warlike purposes, and orders were issued for the concentration of the frontier battalions and Dorobanz Cavalry. The former, however, mutinied and refused to leave their garrisons, whilst an inspection of the arsenal showed that there was scarcely enough powder in the magazines for more than a few rounds to each soldier.

The deputation sent to conciliate Russia met with a cold reception from Prince Gortchakoff, who complained that France had been consulted before the fait accompli. He further remonstrated[34] against the collection of Polish refugees on the Roumanian frontier. On the other hand, he did not appear averse from an alliance between Prince Charles and the Russian Imperial family. Bismarck received the members of the deputation with cordiality, and recommended them to assume an anti-Austrian attitude in the event of an insurrection in Hungary. In the meantime, the Paris Conference declined to appoint commissaries for the Principalities, as had been done formerly under the Hospodars, and practically decided to leave Roumania an open question.

The finances of the Principalities were completely disorganised, as the Public Treasury was empty, the floating debt amounted to close on seven millions sterling, and it seemed as though the year 1866 would indicate a deficit of another six millions. To complete the financial ruin of the country, a proposal to create paper money was set on foot, but was thrown out by the Chamber.

The chief measure laid before the Chamber was the draft of a new Constitution. The Prince insisted upon an Upper and a Lower House as well as upon an unconditional and absolute veto, whilst the Chamber wished to grant a merely suspensive veto, such as is exercised by the President of the United States of America. Owing in great part to the efforts of Prince Charles, the report of the Committee upon the[35] Constitution was presented on June 28, when a series of heated debates arose on the question of granting political rights to the Roumanian Jews. The excitement spread rapidly throughout Bucharest, and a riotous mob destroyed the newly erected synagogue. Thereupon, the unpopular sections of the Constitution were hastily abandoned by the Government in deference to the wishes of the Jews themselves. A better fate, however, befell the veto question, which was decided in favour of the Prince, and on July 11 the Constitution was unanimously passed through the Chamber by ninety-one votes.

On the following day the Prince proceeded, with the same ceremonies as before, to the Metropolie to attend the Te Deum before taking the oath to the new Constitution in the Chamber. He then seized the opportunity of reminding the representatives of the nation that Roumania's chief object must be to remain neutral and on good terms with the neighbouring Powers.