THE

REV. S. BARING-GOULD

SIXTEEN VOLUMES

VOLUME THE THIRD

BY THE

REV. S. BARING-GOULD, M.A.

New Edition in 16 Volumes

Revised with Introduction and Additional Lives of

English Martyrs, Cornish and Welsh Saints,

and a full Index to the Entire Work

ILLUSTRATED BY OVER 400 ENGRAVINGS

VOLUME THE THIRD

March

LONDON

JOHN C. NIMMO

14 KING WILLIAM STREET, STRAND

MDCCCXCVII

Printed by Ballantyne, Hanson & Co.

At the Ballantyne Press

ix

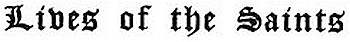

| The Annunciation | Frontispiece |

| After Francia, in the Church of S. John Lateran, Rome. | |

| S. David | to face p. 10 |

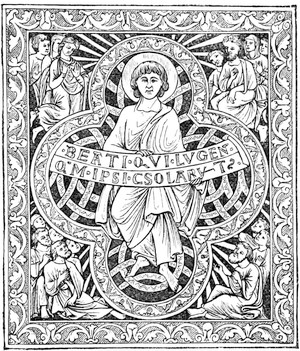

| S. Rudesind | " 18 |

| After Cahier. | |

| Lichfield Cathedral (see p. 23) | on p. 20 |

| S. Chad | to face p. 24 |

| S. Kunegund, Empress of Germany | " 52 |

| Forms of Mitre | on p. 54 |

| S. Casimir, Prince of Poland | to face p. 60 |

| After Cahier. | |

| Group of Angels | on p. 62 |

| Marriage of the Virgin | " 89 |

| After a Bas-Relief by Orcagna. | |

| S. Thomas Aquinas | to face p. 128 |

| After Cahier. | |

| S. John of God | " 168 |

| After Cahier.x | |

| Jesus Christ, in the Character of a Pilgrim, accepting the Hospitality of two Dominicans | on p. 171 |

| From a Fresco by Fra Angelico at Florence. | |

| S. Gregory of Nyssa | to face p. 172 |

| After a Picture by Dominichino at Rome. | |

| S. Gregory of Nyssa (with square Nimbus) | " 174 |

| After Cahier. | |

| Cathedral—Modena | " 182 |

| From Stoughton's "Italian Reformers." | |

| Hatred and Malice | on p. 202 |

| Symbolic Carving at the Abbey of S. Denis. | |

| Deceitfulness and Vanity | " 211 |

| Symbolic Carving at the Abbey of S. Denis. | |

| S. Gregory the Great | to face p. 226 |

| After Cahier. | |

| Mass of S. Gregory | " 238 |

| Pusillanimity | on p. 240 |

| Symbolic Carving at the Abbey of S. Denis. | |

| Slothfulness and Gluttony | " 265 |

| Symbolic Carving at the Abbey of S. Denis. | |

| SS. Joseph and Nicodemus anointing the Body of Christ | to face p. 282 |

| From an old Painting. | |

| S. Patrick | " 288 |

| After Cahier. | |

| S. Gertrude of Nivelles | " 306 |

| After Cahier.xi | |

| Portion of a Monstrance | on p. 311 |

| Murder of S. Edward | to face p. 324 |

| S. Joseph, Husband of the Blessed Virgin Mary | " 326 |

| From the Vienna Missal. | |

| Death of S. Joseph | " 328 |

| S. Cuthbert reasoning with the Monks | " 342 |

| Death of S. Cuthbert | " 342 |

| S. Cuthbert in his Hermit's Cell | " 344 |

| S. Benedict | " 388 |

| After Cahier. | |

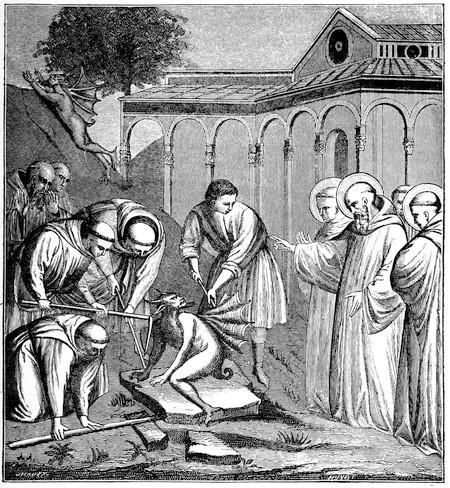

| S. Benedict exorcising an Evil Spirit which had interrupted the Workmen employed in building a Chapel | " 392 |

| From a Fresco, by Spinelli d'Arezzo, in the Church of San Miniato, near Florence. | |

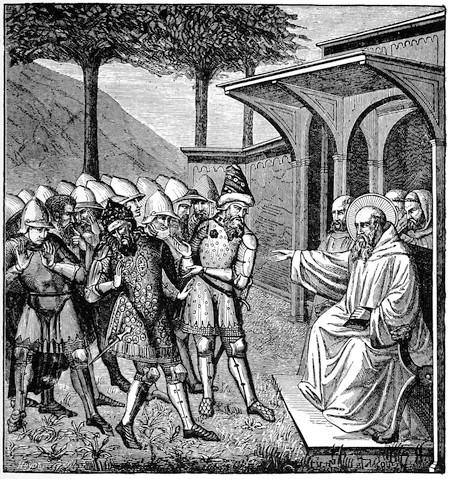

| S. Benedict reproving Totila, and predicting his Death | " 400 |

| From a Fresco, painted by Spinelli d'Arezzo, in the Church of San Miniato, near Florence. | |

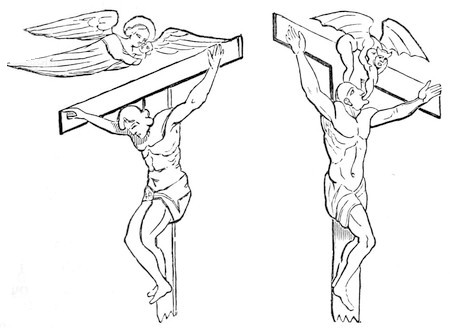

| The Two Thieves (see p. 456): S. Dimas Penitent, with Angel bearing his happy Soul to Paradise; the Impenitent, with Demon dragging forth his unwilling Soul | on p. 443 |

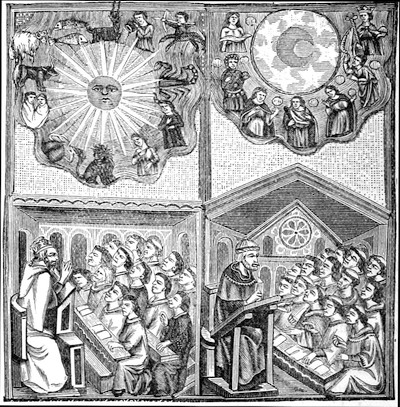

| The Heavenly Messenger | to face p. 450 |

| "The Angel Gabriel was sent from God unto a city of Galilee, named Nazareth, to a virgin espoused to a man whose name was Joseph, of the house of David; and the virgin's name was Mary."xii | |

| The Annunciation | to face p. 452 |

| After Israel van Mecken, in the Museum at Munich. | |

| The Annunciation | " 454 |

| After a Picture in the Museum at Madrid(?) | |

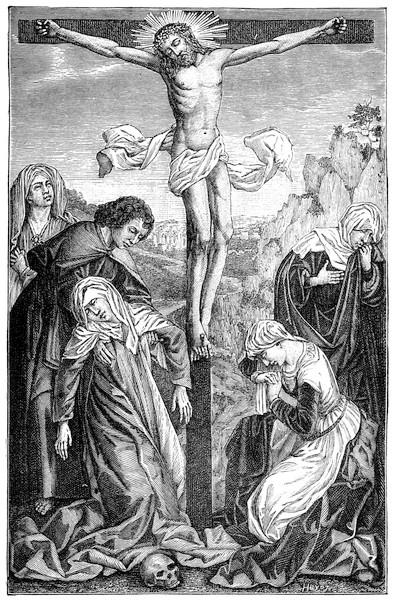

| Memorial of the Crucifixion | " 456 |

| After a Picture by Roger van der Weyden, in the Museum at Madrid. | |

| "Fortitude" | on p. 481 |

| "Hope" | " 490 |

| S. Amadeus of Savoy | to face p. 512 |

| After Cahier. |

1

Lives of the Saints

S. Hesychius, B.M. at Carteja, in Spain, 1st cent.

S. Eudocia, M. at Heliopolis, in Phœnicia, 2nd cent.

S. Antonina, M. at Nicæa, 4th cent.

S. Domnina, V.H. in Syria, circ. A.D. 460.

S. Simplicius, Abp. of Bourges, circ. A.D. 480.

S. David, Abp. of Menevia, in Wales, A.D. 544.

S. Herculanius, B.M. at Perugia, A.D. 547.

S. Albinus, B. of Angers, circ. A.D. 549.

S. Marnon, B. in Scotland.

S. Siward, Ab. of S. Calais, in France, A.D. 687.

S. Swibert, B. Ap. of the Frisians, A.D. 713.

S. Monan, Archd. of S. Andrews, in Scotland, circ. A.D. 874.

S. Leo, M. Abp. of Rouen and Ap. of Bayonne, circ. A.D. 900.

S. Leo Luke, Ab. of Muletta, in Calabria, circ. A.D. 900.

S. Rudesind, B. of Dumium, in Portugal, A.D. 977.

B. Roger, Abp. of Bourges, A.D. 1368.

B. Bonavita, C. Blacksmith of Lugo, in Italy, A.D. 1375.

(1ST CENT.)

[Spanish Martyrologies. Not in the Roman.]

Hesychius is traditionally said to have been one of seven apostles sent by S. Peter into Spain. He is supposed to have preached in the neighbourhood of Gibraltar, and to have made Carteja, or Carcesia, the modern Algeziras, his head-quarters. Nothing authentic is known of this mission, or of his labours and martyrdom.

2

(2ND1 CENT.)

[Greek Menæa, and Roman Martyrology. This saint does not occur in any of the ancient Latin Martyrologies. Her name was inserted in the Roman Martyrology by Baronius. She is called Eudoxia or Eudocia. Authority:—An ancient Greek Life which, however, from its using the word homo-ousios, and calling the Prætor, Count, proves to be later than the times of Constantine. The story has a foundation of fact, no doubt; but a large amount of addition to it has been made of fabulous matter, to convert it into a religious romance.]

There was a Samaritan woman named Eudocia, of great beauty, who lived as a harlot, in the city of Heliopolis, in Phœnicia. She had amassed much wealth by her shameful mode of life, and she thought only of how she might gratify the lust of the flesh, the lust of the eye, and the pride of life. But the word of God is like a hammer that breaketh the rocks in pieces.

There was a monk, named Germanus, passing through the city, and he lodged with an acquaintance next door to the house of Eudocia. And in the middle of the night he arose, as was his wont, and sang his Psalms, and, opening a book began, by the light of his lamp, to read a spiritual lecture with a loud voice. And this happened to be its subject,—the coming of Jesus Christ on the clouds of heaven to judge all men according to their works, when they that have done well shall enter into life, and they that have done evil shall be cast into eternal fire. Now, it fell out that there was only a lath and plaster wall between the room where the monk was and that in which Eudocia lay. And when he began to sing she awoke, wondering, and listened, annoyed at first at the disturbance, but afterwards interested and alarmed. Then, when she heard him read3 the sentence of God on sinners, she was filled with remorse for the past, present shame, and fear for the future. And when morning dawned, she sent for the monk, and she asked him if that was true which he had read during the night. He answered that it was so. Then looking round, and wondering at the costly furniture and luxuries that abounded, he said simply, "What a rich man thy husband must be!" Then she reddened with shame, and said, in a low voice, "I have many lovers, but no husband." "Oh, my daughter," cried Germanus, "Would'st thou rather be poor now, and live in joy and glory hereafter, or be wealthy now and perish miserably in everlasting death?" Then Eudocia said, "How hard thy God must be to hate riches." "God forbid," exclaimed the monk, "it is not riches that He abhors, but goods unjustly gotten." Then he declared to her in order what she must do and believe to be saved. "And first, send for a priest of the city who may give thee proper instruction, that thou mayest be baptized, for baptism is the beginning and the foundation of the whole Christian life. And now, prepare thyself with fasting and prayer."

So Eudocia bade her servants close the house, as though she had gone into her country villa, and should any one come to the door, refuse him admission. And she sent for a priest, and when he came she said, "Oh, sir! I am a grievous sinner, a sea of guilt." "Be of good cheer, my daughter," was his salutation. "The sea of guilt may be changed into a port of salvation, and the waves tossing with passion sink into an ineffable calm." Then he instructed her on the nature of repentance, and bade her wear a mean dress, putting away her trinkets and silk gown, and fast for seven days; and he diligently taught her what she must believe and do. And before he went on his way, Germanus visited her once again, to confirm the good work that was begun in her. Then she asked him why he lived4 in the desert, and in the practice of severe mortification. "Oh, my daughter," he said; "We monks labour incessantly to cleanse from every spot of sin the garments of our souls." And she said, "I have now fasted and eaten nothing for seven days. And I will declare to thee what befel me last night. In my exhaustion I sank into a trance, and saw, and lo! an angel took me by the hand, and led me into Heaven, where was unspeakable light, and there I saw the blessed ones in white, with shining faces, and all their countenances lit up as I approached, and they came running towards me, and greeted me, even me, as a sister. Then there came up a shadow, horrible and black, and it shrieked, saying, 'This woman is mine. I have used her to destroy many, she has worked for me as a bond slave, and shall she be saved? I, for one little disobedience, was cast out of heaven, and here is this beast, steeped from head to foot in pollution, admitted to the company of the elect! Have done with this; take them all, scrape all the rascals and harlots on earth together, and admit them into your society. I will off into my Hell, and grovel there in fire for ever.' And then I heard a voice from the ineffable light answer and say, 'God willeth not the death of a sinner, but rather that he should be converted and live.' And after that the angel took me by the hand and led me home again, and saying to me, 'There is joy in heaven over one sinner that repenteth,' signed me thrice with the cross, and vanished."

Then Germanus rejoiced, and bade Eudocia be of good courage, and continue in the good path she had elected to walk in.

Now, when the time of her preparation was over, Eudocia was baptized by the bishop, Theodotus, and when the sacrament of illumination had been administered, she went home and made an inventory of all that she had, and5 sent it to the bishop. And when Theodotus had looked at it he went to her house, and said, "What is this little book that thou hast sent me?" And she answered, "This is the list of all my precious things, which I pray thy holiness to order the steward of the Church to receive of me, and distribute, as seemeth fitting, to those that have need." Then the bishop did as he was desired, and the Church treasurer came, and collected, and disposed of all her costly things. It may interest some to know what these were. Besides money, and jewels, and pearls, of which there was great store, he carried off two hundred and seventy-five boxes of silk dresses, and four hundred and ten chests of linen, one hundred and sixty boxes of gowns embroidered with gold, one hundred and fifty cases of dresses with jewelled work, one hundred and twenty-three large chests of various garments, twelve boxes of musk, thirty-three of Indian storax, a large number of silver vessels, several silk curtains ornamented with gold bullion, satin curtains, and many other things too numerous to mention.2

Now, as soon as all her valuables had been distributed to the most needy, Eudocia, still in her white baptismal robe, departed into the desert to a convent of thirty nuns directed by Germanus, the monk, who had been the means of converting her. And never did she change the colour or character of her garment till her dying day; only in winter she put over it a sackcloth gown to her ankles, and a hooded cloak of the same material.

Thirteen months after her admission, the superior of the convent died, and Germanus appointed the penitent Eudocia to be superior in her room.

There was a young man, who had been a lover of Eudocia,6 who was greatly vexed at her conversion, and resolved, partly out of passion, and partly out of love of adventure, to seek her out in her seclusion, and entice her back into the world of pleasure. To accomplish his object he assumed a monastic habit, and went to the convent, and tapped at the door. The portress partly opened the window, and, peeping through it, asked who was there. Then the man answered, after the manner of monks, "I am a sinner, and seek to communicate in your prayers and benedictions." Then the sister answered, "Thou art mistaken in coming here. No men are admitted into the house. But go on thy way, and thou wilt find a monastery governed by the blessed Germanus; he will take thee in." Then she shut the window in his face.

The young man, whose name was Philostratus, made his way to the monastery of Germanus, and he found the old man sitting in the porch, reading. He fell at his feet, and declared himself a sinner, who desired to amend his life. Germanus looked hard at him, and a certain wantonness of the eye made him hesitate about receiving him. "We are all old men here," said he; "and are not the proper advisers and guides of a hot-headed, fire-blooded youth. Go elsewhere my son, and get a director who is nearer thine age." "My father!" exclaimed the dissembler, "How cans't thou reject me, after that thou hast received Eudocia. She has passed through the fires of temptation such as assail youth, and could well advise me. Let her give me some counsel, and I will go my way strengthened thereby."

Germanus had acted somewhat injudiciously in appointing a reclaimed harlot to be superior of a sisterhood after only thirteen months' probation; he now committed another indiscretion in allowing the strange monk ingress into the convent. But he was guileless himself, and thought no evil of another, so he listened to the petition of Philostratus,7 and calling to him the monk who offered the incense in the convent, and was, therefore, allowed to enter it, bade him take with him the stranger, and give him audience of the superior. So Philostratus was led back to the convent, and the door was opened, and he was admitted into the room of Eudocia, some of the sisters standing afar off, according to the rule of the house, to witness the meeting, though out of hearing of the conversation. Then Philostratus looked at the sordid room, and the horsehair cover thrown over the pallet bed, and the haggard cheeks and sunken eyes of his former mistress, and he burst forth into entreaties that she would leave this wretched life of constant self-watching and self-denial, and return to the gaiety of city life, smart gowns, and pearl necklaces, costly feasts, and obsequious admirers. "All Heliopolis awaits thee," he urged, "ready once more to lavish on thee its gold and its adulation; return once more to the raptures and liberty of a life of pleasure."

But she had chosen that better part which was not to be taken away from her, and she resisted all his persuasion, and dismissed him, startled, humbled, and resolved to lead a better life.

So far the story of Eudocia is natural and devoid of improbabilities. But the Greek writer was not content to leave it thus deficient in marvels, and he has added several chapters of fanciful adventures, as insipid as they are untrue; and the contrast they make with the earlier portion of the history, and of the final chapter, points them out as an interpolation. In this interpolation Eudocia converts "King" Aurelian at Heliopolis, and appears before the governor, Diogenes, armed only with a particle of the Holy Eucharist, which she bears in her bosom. The king orders her to be stripped, and when she has been divested of her clothes, till the Host is exposed, then the B. Sacrament is8 suddenly transmuted into a blazing fire, which consumes the governor and all the bystanders, and an angel veils modestly the naked shoulders and bosom of Eudocia.

The sudden extinction of a governor could hardly have been passed over by profane history had it really occurred, and, therefore, the falsifier of the Acts found it advisable to revive him. Accordingly, Eudocia is represented as taking the charred corpses by the hand and restoring them instantly to perfect soundness.

But putting aside this absurd story, which is to be found repeated ad nauseam in almost all the forged and falsified Greek Acts of martyrdoms, with slight variations, we pass to the last chapter of the Life, which simply narrates the execution, by the sword, of Eudocia in her convent, by order of Valerius, the governor, without any sermons, inflated declamations, and theological disquisitions, such as usually accompany corrupted, interpolated acts, and are an invariable feature in forgeries.

(4TH CENT.)

[Greek Menæa, and Menologium of the Emperor Basil. Inserted in the Roman Martyrology by Baronius. Authority:—The account in the Menologium.]

Antonina is said to have lived in the city of Nicæa, in the reign of Maxentius. On account of her refusal to offer incense to the gods she was stripped of her clothes, hung up, and her sides torn with rakes. Then she was thrust into a sack, or earthen vessel (it is uncertain which), and was drowned in a lake near the city. A head and body are shown at Bologna as those of S. Antonina, "but whether of this one or of another we are not able to divine," say the9 Bollandists. A curious instance of the facility with which some forgeries may be detected is connected with S. Antonina. Canisius published an edition of the Greek Menologium in the 16th century; in it occurred a mistake. S. Antonina was stated to have suffered at Cæa, a misprint for Nicæa. Shortly after, the Jesuit, Hieronymus Romanus de Higuera, forged a chronicle of Flavius Dexter, Bishop of Barcelona, in the 4th century. He had seen the Menologium of Canisius, and, as there was a Ceija in Spain, he inserted S. Antonina in his Spanish Chronicle as having suffered there, and this blunder was partly the means of the detection of the forgery.

(ABOUT A.D. 460.)

[Greek Menologium. Authority:—Theodoret.]

Theodoret, after relating the virtues of S. Maro the hermit, (Feb. 14th) goes on to tell of a holy virgin, named Domnina, who lived in a small shed, and attended prayers in the Church at cock-crow. She was emaciated with continuous fasting; she neither looked at any one, nor suffered her own face to be seen. Whenever she took the hand of Theodoret, the bishop, to kiss it, he drew it away moistened with her tears. She spent her time, when not engaged in prayer, in ministering to the necessities of travellers.

10

(A.D. 544.)

[Roman, Irish, Scotch, and ancient Anglican Martyrologies. His festival was celebrated in England with rulers of the choir, and nine lessons. Pope Callixtus II. ordered him to be venerated throughout the Christian world. There are no very ancient accounts of S. David, The oldest is a life existing in MS. at Utrecht, which was not known to Usher or Colgan. Usher cites Ricimer, Giraldus, and John of Tynemouth, a Durham priest, who collected the Acts of the English, Scottish, Welsh, and Irish Saints, and who lived in 1360. Ricimer was Bishop of S. David's about 1085, and died about 1096. His life of S. David seems to have been the foundation of all subsequent biographies of that saint. Several MSS. of this life are extant; and a portion of it containing matter not found in the life of the same saint by Giraldus Cambrensis, was printed by Wharton in the Anglia Sacra. Giraldus Cambrensis wrote his life of S. David about 1177. S. Kentigern (d. 590) mentions S. David, and there are numerous allusions to him in the lives of contemporary Welsh and Irish saints.]

S. David, or Dewi, as the Welsh call him, was born about 446, at Mynyw, which was named S. David's after him. His father was Sandde, son of Ceredig, who was the son of Cunedda, the great conqueror of N. Wales. His mother's name was Nôn; she was the daughter of Gynyr of Caergawch. Giraldus says he was baptized at Porth Clais by Alveas, Bishop of Munster, "who by divine providence had arrived at that time from Ireland." The same author says he was brought up at "Henmenen," which is probably the Roman station Menapia.

S. David was educated under Iltyt at Caerworgon. He was afterward ordained priest, and studied the Scriptures for ten years with Paulinus at Ty-gwyn-ar Dâf, or Whitland, in Caermarthenshire. He then retired for prayer and study to the Vale of Ewias, where he raised a chapel, and a cell on the site now occupied by Llanthony Abbey. The river Honddu furnished him with drink, the mountain pastures with meadow-leek for food. His legendary history states11 that he was advised by an angel to move from under the shadow of the Black Mountains to the vale of Rhos, and to found a monastery at Mynyw, his birth place.

He built a monastery on the boggy land which forms nearly the lowest point of that basin-shaped glen: on, or near its site stands the present Cathedral of S. David. He practised the same rigorous austerities as before. Water was his only drink, and he rigorously abstained from animal food. He devoted himself wholly to prayer, study, and to the training of his disciples. He, like many other abbots at that time, was promoted to the episcopate. A wild legend makes him to have started on a pilgrimage to Jerusalem, and to have received consecration at the hands of the patriarch John III. This tale was invented by some British monk to show that the Welsh bishops traced their succession to the oldest, if not the most powerful, of the patriarchates. Except when compelled by unavoidable necessity he kept aloof from all temporal concerns. He was reluctant even to attend the Synod of Brefi. This was convened by Dubricius about 519 at Llandewi Brefi, in Cardiganshire, to suppress the Pelagian heresy, which was once more raising its head. The synod was composed of bishops, abbots, and religious of different orders, together with princes and laymen. Giraldus says, "When many discourses had been delivered in public, and were ineffectual to reclaim the Pelagians from their error, at length Paulinus, a bishop with whom David had studied in his youth, very earnestly entreated that the holy, discreet, and eloquent man might be sent for. Messengers were therefore despatched to desire his attendance: but their importunity was unavailing with the holy man, he being so fully and intently given up to contemplation, that urgent necessity alone could induce him to pay any regard to temporal or secular concerns. At last two holy men,12 Daniel and Dubricius, persuaded him to come. After his arrival, such was the grace and eloquence with which he spoke, that he silenced the opponents, and they were utterly vanquished. But Father David, by common consent of all, whether clergy or laity, (Dubricius having resigned in his favour), was elected primate of the Cambrian Church." Dubricius retired to the Isle of Bardsey.

A beautiful yet wild legend tells us:—"While S. David's speech continued, a snow white dove descending from heaven sat upon his shoulders; and moreover the earth on which he stood raised itself under him till it became a hill, from whence his voice was heard like a trumpet, and was understood by all, both near and far off: on the top of which hill a church was afterwards built, and remains to this day."

S. David at first strenuously declined the primacy; at last he accepted it on the condition that he was to be allowed to transfer the archiepiscopal chair from the busy city of Caerleon upon the Usk—the former capital of Britannia Secunda—to the quiet retreat of Mynyw. Arthur, the famous king, and Pendragon, who is said to have been a nephew of our saint, assented to this. Doubtless the advances westward which the heathen English were making, filled S. David with dread lest the seat of the primacy should one day fall into their hands. So he thought it prudent to remove it to the iron-bound shores of Pembroke, where the English could not so easily land.

After his elevation, S. David, in spite of his retiring disposition, proved a vigorous and hard-working prelate. He occasionally resided at Caerleon, and in 529 he convened a synod, which exterminated the Pelagian heresy, and was in consequence named "The Synod of Victory." It ratified the canons and decrees of Brefi, as well as a code of rules which he had drawn up for the regulation of13 the British Church, a copy of which remained in the Cathedral of S. David's until it was lost in an incursion of pirates. Giraldus says, "In his times, in Cambria, the Church of God flourished exceedingly, and ripened with much fruit every day. Monasteries were built everywhere; many congregations of the faithful of various orders were collected to celebrate with fervent devotion the Sacrifice of Christ. But to all of them Father David, as if placed on a lofty eminence, was a mirror and pattern of life. He informed them by words, and he instructed them by example; as a preacher he was most powerful through his eloquence, but more so in his works. He was a doctrine to his hearers, a guide to the religious, a light to the poor, a support to the orphans, a protection to widows, a father to the fatherless, a rule to monks, and a path to seculars, being made all things to all men that he might bring all to God."

He founded several churches and monasteries. It is also generally agreed that Wales was first divided into dioceses in his time.

Geoffrey of Monmouth states that he died in his monastery at Mynyw i.e., S. David's, where he was honourably buried by order of Maelgwn Gwynedd. This event is recorded by him as if it happened soon after the death of Arthur, who died 542. According to the computations of Archbishop Usher, S. David died 544, aged 82. The Bollandists agree with Usher on the date of his death, but they put his birth back as far as 446, so that according to their calculation he lived to the age of 98.

Numerous legends have gathered round the history of S. David. Thus an angel is said to have foretold his birth thirty years before to his father in a dream. "On the morrow, said the angelic voice, thou wilt slay a stag by a river side, and wild find three gifts there, to wit, the stag, a14 fish, and a honeycomb. Thou shalt give part of these to the son who shall be born thirty years hence. The honeycomb proclaims his honied wisdom, the fish, his life on bread and water, the stag his dominion over the old serpent." The mention of the stag doubtless arose from the old fancy that that animal kills serpents by trampling on them: thus did David trample the Pelagian heresy under foot. When S. Patrick settled in the vale of Rhos, a voice bade him depart, for it was reserved for the abode of a child who should be born thirty years after.

At his baptism, S. David splashed some water on to the blind eyes of the bishop who was baptizing him, and restored their power of sight. His schoolfellows at "Henmenen" saw a dove teaching him, and singing hymns with him. After studying with Paulinus, he journeyed to Glastonbury. He was intending to dedicate afresh the church which had been re-built, when the Lord appeared to him in a dream, and told him that He had already dedicated it: as a sign that He had spoken unto him He pierced the saint's hand with His fingers. So our saint contented himself with building a Lady Chapel at the east end. He is said to have founded twelve monasteries on this journey. He returned to Wales, and then established a monastery at Mynyw, which was soon filled with monks and disciples. They worked hard with their own hands in the fields; they harnessed themselves to the plough instead of using oxen for that purpose; they tended bees that they might have some honey to give to the sick and the poor. The bees became so attached to one monk, Modemnoc, that they followed him on board ship when he was about to set sail for Ireland. He returned to the monastery and made several attempts to embark unobserved by his winged friends; but all his efforts failed. So at last he asked S. David's leave to take them with him; the saint blessed15 the bees, and bade them depart in peace, and be fruitful and multiply in their new home. Thus Ireland, where bees had been hitherto unable to live, was enriched by their honey.

He opened many fountains in dry places, healed many brackish streams, raised many dead to life, and had many visions of God and of Angels. In one of these visions he was warned that he should depart, March 1st. Thenceforth he was more zealous in the discharge of his duty: on the Sunday before his death he preached a sermon to the assembled people, and after consecrating and receiving the Lord's Body, he was seized with a sudden pain: then turning to the people he said, "Brethren, persevere in the things which ye have heard of me: on the third day hence I go the way of my fathers." On that day, while the clergy were singing the Matin Office, he had a vision of his Lord; then, exulting in spirit, he exclaimed, "Raise me after Thee." With these words he breathed his last.

He was canonized by Pope Callixtus II., A.D. 1120; who is also said to have granted an indulgence to all those who made a pilgrimage to his shrine. Three kings of England—William the Conqueror, Henry II., and Edward I.—are said to have undertaken the journey, which when twice repeated was deemed equal to one pilgrimage to Rome; whence arose this saying:—

"Roma semel quantum, dat bis Menevia tantum."

A noble English matron, Elswida, in the reign of Edgar, transferred his relics, probably in 964, from S. David's to Glastonbury.

S. David's plain but empty shrine stands now in the choir of S. David's Cathedral to the north of Edward Tudor's altar tomb.

16

(ABOUT A.D. 549.)

[S. Albinus seems to have enjoyed an amount of popularity as a saint which it is difficult to account for. Besides receiving great veneration at Angers, where his feast is a double, and in Brittany, where it is a semi-double, in Gnesen, in Poland, it was observed as a double. His name appears in most Martyrologies, as those of Usuardus, Hrabanus, Wandelbert, &c. Authority:—His life written by Fortunatus, a priest, his contemporary.]

S. Albinus, or S. Aubin, as he is called in France, belonged to an ancient family at Vannes, in Brittany. He embraced the religious life in the abbey of Cincillac, called afterwards Tintillant, near Angers. At the age of thirty-five, in the year 504, he was chosen abbot, and twenty-five years afterwards, bishop of Angers. In the 3rd Council of Orleans, in 538, he caused the thirtieth canon of the Epaone to be revived, which declared excommunication to those who contracted marriage within the first or second degree of consanguinity. His life is singularly devoid of incident which could mark it off from that of many another abbot and bishop, and it is therefore difficult to account for his undoubted popularity in France in ancient times.

(A.D. 713.)

[Ado, Usuardus, Molanus, Belgian, and Cologne Martyrologies, Gallican and Roman Martyrologies. Authorities:—Bede, lib. V. C. 12; and the life of S. Willibrod. There exists a forged life of S. Swibert, under the name of Marcellinus, which was composed in the 15th century, and which is undeserving of attention. S. Swibert is called the Elder to17 distinguish him from S. Swibert, B. of Verden, in Westphalia, in 807. (April 30); there was also another Swibert about 750, abbot in Cumberland, mentioned by Bede. Many writers have confounded together S. Swibert the Elder, and S. Swibert the Younger.]

S. Swibert was a Northumbrian monk who had been trained under S. Egbert, whom he accompanied to Ireland. Egbert desired greatly the conversion of Friesland, but was unable himself to attempt it, and his zeal communicated itself to his disciple Swibert, and when S. Willibrord sailed in 690 for that country, Swibert, at Egbert's desire, accompanied him. They landed at the mouth of the Rhine, at Katwyck, and Willibrord established his head quarters at Utrecht. Two years before, Pepin l'Herstall had conquered Radbod, king of Frisia, and had obliged him to ask peace, and abandon to the mayor of the palace his most important possessions, amongst others the whole basin between the Meuse and the Rhine, where stand now the town of Leyden, Delft, Gouda, Brill, and Dortrecht, as well as the city of Utrecht.

Finding it difficult to make headway against the superstitions of paganism, Willibrord appealed to the authority of Pepin, who sent Willibrord to Rome to receive mission and benediction for his work from the Holy See. On his return, success declared for the apostles, and four years after, Pepin sent Willibrord again to Rome with letters praying the pope to ordain him bishop to the nation he had converted. Pope Sergius consecrated him in 696, and Willibrord fixed his see at Utrecht, of which he was the first bishop. In the meantime, Swibert had been labouring in Hither Friesland, or the southern part of Holland, the northern part of Brabant, and the counties of Guelders and Cleves, with great success. In 697, Swibert was in England, probably in quest of fellow-helpers for the harvest, for the fields were white thereto, and he received episcopal18 consecration from the hands of S. Wilfred of York, then in banishment from his see. Swibert, invested with this sacred character, returned to his flock, and committing them to the care of S. Willibrord, penetrated further up the Rhine, and preached to the Boructarii, a people living below Cologne, with success. But the Saxons invading the country, swept away his work, and he retired into the islet of Kaiserwerth in the Rhine, which Pepin had given him, where he founded a monastery, which flourished for many ages, till it was converted into a collegiate church of secular canons.

His relics were found in 1626, at Kaiserwerth, in a silver shrine, and there are preserved and venerated.

(A.D. 874.)

[Aberdeen Breviary.]

S. Adrian, bishop of S. Andrews, trained the holy man from his childhood, and appointed him to be his archdeacon. He afterwards sent him to preach the Gospel in the island of May, at the mouth of the Frith of Forth; he then went into Fife. The Church suffered severely from the incursions of the Northmen who ravaged the coasts, burning churches and monasteries, robbing them of their sacred vessels, and carrying off the unfortunate people captive. S. Monan is said by Butler to have been martyred by these invaders, but this is inaccurate. There is no evidence that he died any other than a peaceful death. He was buried at Inverny.

19

(ABOUT A.D. 900.)

[Gallican Martyrology; on this day at Bayonne. By Saussaye and Ferrarius on March 3rd. Authority:—Two lives of no great antiquity, one written shortly after 1293.]

Leo, Gervase, and Philip, were the three sons of pious parents in the North of France; Leo was elected to be archbishop of Rouen, but resigned his government of the diocese into the hands of vicars, and betook himself with his two brothers to Bayonne, where Christianity had made but small progress, much heathen superstition remained, and a colony of Moors had settled there. He was well received, and succeeded in making many converts, but was killed by some pirates who had lived in the town, but had been ejected by the citizens on account of their nefarious deeds. According to the legend, a spring of water bubbled up where S. Leo fell, and he arose and carried his head to the place where he had last been preaching.

He is represented in Art, at Bayonne, where he is greatly venerated, as a bishop, holding his head in his hands.

(A.D. 977.)

[Spanish and Benedictine Martyrologies. Office with twelve lections in the Coimbra Breviary. His translation is observed on Sept. 1st. Authority:—A life by Brother Stephen of Cella-nuova, about 1180.]

The Blessed Rudesind was the son of a Count Gutierre da Mendenez, in Gallicia. His mother is said to have had a foretoken of the sanctity of the child that was about to be given her, whilst praying in the Church of S. Salvador on Mount Corduba. When the child was born, she desired20 to have him baptised in the church, but as there was no font there, one had to be brought up the hill in a cart. The cart broke down, says the popular legend, however, the font continued its journey without it. The child grew up to be a good man, and he was appointed to the bishopric of Dumium, a see which has ceased to exist. His kinsman, Sisnand, bishop of Compostella, was a scandal to the Church, "spending all his time in sports, excesses, and vanities, and paying no attention to his duties." Wherefore, at the request of the king, Sancho, and the nobles and people, Rudesind undertook the government of it, and Sancho put Sisnand in prison. During the absence of the king against the Moors, the Normans invaded Gallicia, whereupon the bishop called together an army, marched against them, and drove them back to their ships, and then turned his arms against the Moors, and routed them. On the death of Sancho, Sisnand escaped from prison, attacked Rudesind on Christmas night, whilst engaged with the canons in the sacred offices, and threatened him, sword in hand, unless he resigned the see. Rudesind at once laid aside his office, and retired into a monastery, where he assumed the habit, and after some years was chosen abbot.

21

SS. Martyrs, under the Emperor Alexander at Rome, circ. A.D. 219.

SS. Jovinus and Basileus, MM. at Rome, circ. A.D. 258.

SS. Ducius, B.M., Absalom, Largius, Herolus, Primitius, and Januarius, MM. at Cæsarea in Cappadocia.

SS. Paul, Heraclius, Secundola, Januaria, and Luciosa, MM. in the Port of Rome.

S. Simplicius, Pope of Rome, A.D. 483.

S. Joavan, P. at S. Paul de Leon, 6th. cent.

SS. Martyrs, under the Lombards, in Italy, circ. A.D. 579.

S. Ceadda, or Chad, B. of Lichfield, A.D. 672.

S. Willeich, P. at Keiser-werdt, on the Rhine, circ. A.D. 726.

B. Charles the Good, M., Count of Flanders, A.D. 1127.

(CIRC. A.D. 219.)

Nearly all the Latin Martyrologies commemorate these martyrs, without giving their names. Baronius added to the Roman Martyrology, that they suffered under Ulpian the præfect; this was a conjecture of his, for Ulpian was bitterly hostile to the Christians, and it was under him that S. Martina (Jan. 1st) suffered. Alexander himself, only seventeen when he came to the throne, was of mild disposition, and the reins of government were in the hands of his mother Mamæa, who, with the approbation of the senate, chose sixteen of the wisest and most virtuous senators as a council of state, and at the head of this placed the learned Ulpian, a prudent governor, and severe disciplinarian, who could not brook that certain citizens should worship God in any way than that of the established religion, and looked on Christianity as a dangerous political element in the state, which demanded extirpation.

22

(A.D. 483.)

[Roman Martyrology. Authorities:—Evagrius, Hist. Eccl., and his own letters.]

S. Simplicius was born at Tivoli, and succeeded S. Hilary in the papal throne, in 468. He strongly resisted the Emperor Leo, who desired to elevate the patriarch of Constantinople to the second rank in the Church, above the patriarchs of Antioch and Alexandria. He was also engaged in controversy with Acacius of Constantinople concerning the appointment of Peter Mongus to the see of Alexandria. After having governed the Church in most difficult and stormy times, Simplicius died on March 2nd, in the year 483; and was buried in S. Peter's.

(6TH CENT.)

[Venerated in Brittany. Authorities:—A Life by Albert Le Grand, and the lections of the Church of S. Paul de Léon. Albert Le Grand wrote his life in 1623, from old MSS. histories and legends preserved at Léon in his time.]

This saint was an Irishman by birth, and nephew of S. Paul de Léon. He studied with his uncle in Britain, and then returned to Ireland, but hearing that S. Paul had gone into Brittany, he departed for that country, and after having passed his noviciate in the monastery of Llanaterenecan, under S. Judulus, he departed to Léon, and received priest's orders from his uncle, who appointed him to the isle of Baz. He is patron of two parishes in the diocese of S. Paul de Léon.

23

(CIRC. A.D. 579.)

[Roman Martyrology. Authority:—The Dialogues of S. Gregory the Great, lib. iii.]

The Lombards in their ravages of the North of Italy put to death forty husbandmen, who refused to eat meats they had offered to their idols, and about four hundred who refused to pay reverence to the head of a goat, which they regarded with a peculiar veneration.

(A.D. 672.)

[Roman, Anglican, Scottish, and Irish Martyrologies. Authorities:—A life is given by Bede, lib. 3, cap. 23, 24, 28; Lib. 4, cap. 2, 3, also in a MS. printed in the Monasticon, and a Metrical Life attributed to Robert of Gloucester.]

S. Chad or Ceadda was, perhaps, the youngest of the four brothers, Cedd, Cynebil, and Celin, all of whom were eminent priests. Our saint has sometimes been confounded with his brother Cedd, bishop among the East Saxons, whose life was related on January 7th. We know neither the date nor the place of his birth. It is certain he was an Angle, and a native of Northumbria, and that he flourished in the 7th century, though Dempster wishes to claim him as a Scottish, and Colgan as an Irish, saint. The date 620 A.D. has been suggested as the probable time of Chad's birth.

Bede tells us that S. Chad was a pupil of Aidan. That bishop required the young men who studied with him to spend much time in reading Holy Writ, and to learn by heart large portions of the Psalter, which they would require in their devotions.

24

At the death of Aidan, in 651, he went to Ireland, which was then full of men of learning and piety. The ravages of the Teutonic hordes on the continent had driven thither many illustrious foreigners. Then Ireland was fulfilling the mission ascribed to the Celtic race, that of supplying the link between Latin and Teutonic civilization. S. Chad, while in Ireland, made the acquaintance of Egbert, who was afterwards abbot of Iona.

Cedd had, at the request of Ethelwald, King of Deira, established a monastery at Lastingham, in Yorkshire. It stood just on the edge of that wide expanse of moorland which extends thirty miles inland from the coast.

Bishop Cedd returned thither from his diocese of London many years after, at a time when a plague was raging. He caught it, and whilst lying on his death-bed, bequeathed the care of the monastery to his brother, Chad, who was still in Ireland.

S. Chad, on his return, ruled the monastery with great care and prudence, and received all who sought his hospitality with kindness and humility. One day a stranger arrived at the gate, praying to be received into the brotherhood. This was Owini, lately steward of Queen Ethelreda. Tradition relates that as he pursued his toilsome journey from the fens which surrounded the abbey of Ethelreda into Yorkshire, the pilgrim erected crosses by the roadside to guide any burdened souls who might hereafter seek the same haven of rest. While quietly keeping the strict rule of S. Columba at Lastingham, our saint was summoned to the episcopate by King Oswy, of Northumbria.

But we must go back a little in our history. When the decision of the council or parliament, held at Whitby, in 664, was adverse to the Keltic rite, Cedd renounced the customs of Lindisfarne, but Colman, bishop of Lindisfarne, obstinately holding to them, withdrew from Northumbria25 into Scotland with all those who were willing to follow him. Tuda succeeded him in the pontificate of Northumbria, but died soon after.

"In the meanwhile," says Bede, "King Alchfrid (of Deira) sent Wilfrid the priest to the king of the Gauls, to have him consecrated bishop for himself and his subjects. Now he sent him to be ordained to Agilbert, of whom we said above that he left Britain, and was made bishop of the city of Paris. Wilfrid was consecrated, A.D. 665, by him with great pomp; many bishops coming together for that purpose in a village belonging to the king (Clothair III. of Neustria) called Compiegne. While he was still making some stay abroad, after his ordination, king Oswy, following the example of his son, sent to Kent a holy man of modest character, sufficiently well read in the Scriptures, and diligently carrying out into practice what he had learnt from the Scriptures, to be ordained bishop of the Church at York. Now this was a priest named Ceadda (Chad), brother of the most reverend prelate Cedd, of whom we have made frequent mention, and abbot of the monastery called Lastingham. The king also sent with him his own priest, Eadhed by name, who was afterwards, in the reign of Egfrid, made bishop of the Church of Ripon. But when they arrived in Kent, they found that Archbishop Deusdedit had departed this life, and that no other prelate was as yet appointed in his place. Whereupon they turned aside to the province of the West Saxons, where Wini was bishop, and by him the above-mentioned person was consecrated bishop; two bishops of the British nation, who kept Easter Sunday according to canonical custom from the 14th to the 20th day of the moon, being associated with him; for at that time there was no other bishop in all Britain canonically ordained, except Wini.

"Chad then, being consecrated a bishop, began at once26 to devote himself to ecclesiastical truth and to chastity; to apply himself to the practice of humility, continence, and study; to travel about, not on horseback, but after the manner of the apostles, on foot, to preach the gospel in the towns, the open country, cottages, villages, and castles; for he was one of the disciples of Aidan, and endeavoured to instruct his hearers by the same actions and behaviour, according to his master's example and that of his own brother Cedd. Wilfrid also, who had already been made a bishop, coming into Britain, A.D. 666, in like manner by his doctrine brought into the English Church many rules of Catholic observance. Whence it came to pass that the Catholic institutions daily gained strength, and all the Scots that dwelt in England either conformed to these or returned into their own country."

This is Bede's account of the consecration of Wilfrid and Chad. At that time the diocese of York comprised the whole of Northumbria, including the south of Scotland. Under Oswald the see of Lindisfarne—the Iona of the Anglo-Saxons—was founded, containing within its jurisdiction the kingdom of Bernicia, until the establishment by Theodore of another see at Hexham. The writer of Wilfrid's life tells us that he objected to being consecrated by the English bishops, inasmuch as they were converts to the Scottish calculation regarding the celebration of Easter, or had received consecration from those who were of that opinion. Though Wini, who had been consecrated in Gaul, cannot be placed in either of these classes, yet Wilfrid knew he would summon to assist him two bishops who belonged to one of them; hence his preference for Gaul. Wilfrid's delay in Gaul, perhaps, excited the King's suspicions that he, like his friend Agilbert, was seeking a mitre there; or it may be that the king, influenced by the Scottish party (who could not forgive Wilfrid for the victory he27 gained over them at Whitby), consented to the election of Chad to the see.

Chad has been severely censured for accepting the bishopric under these circumstances. It may be, however, that he, stirred by sorrow at seeing the diocese left without a head, and doubting too, perhaps, whether Wilfrid would return, adopted this course, which may be condemned as uncanonical.

S. Chad is commemorated in some Breviaries as an archbishop. But he was only a bishop, for that dignity had fallen into abeyance from the time that Paulinus fled into Kent. But though no suffragans acknowledged Chad as their superior, he had ample scope for the most abundant energy. We have given above Bede's account of his untiring labours; let us now hear that of the metrical Life attributed to Robert of Gloucester.

He endeavoured earnestly, night and day, when he had thither come,

To guard well holy Church, and to uphold Christendom.

He went into all his bishopric, and preacht full fast,

Much of that folk, through his word, to God their hearts cast,

All afoot he travelled about, nor kept he any state,

Rich man though he was made he reckoned there of little great.

The Archbishop of York had not him used to go

To preach about on his feet, nor another none the mo,

They ride upon their palfreys, lest they should spurn their toe,

But riches and worldly state doth to holy Church woe.

Theodore, the new archbishop of Canterbury, arrived in England in A.D. 669. "Soon after," says Bede, "he visited the whole island, wherever the tribes of the Angles dwelt, for he was willingly entertained and heard by all persons; and everywhere he taught the right rule of life, and the canonical custom of celebrating Easter. He was the first archbishop whom all the English Church obeyed."

Visiting Northumbria, he charged Chad with not being duly consecrated. The saint replied with great humility,28 "If thou knowest that I have not duly received the episcopate, I willingly resign the office, for I never thought myself worthy of it; but, though unworthy, I consented to undertake it for obedience sake." Theodore hearing his humble answer, said that he should not resign the episcopate, but he himself completed his ordination again after the Roman manner. He probably advised Chad to resign his see to Wilfrid, for we next hear of our saint in retirement at Lastingham.

In 669, Jaruman, bishop of the Mercians, died. King Wulfhere asked Theodore to send them a bishop. The archbishop did not wish to consecrate a fresh one, so he begged King Oswy to let Chad, who was then at Lastingham, be their bishop. Theodore knowing that it was Chad's custom to go about the work of the gospel on foot, rather than on horseback, bade our saint ride whenever he had a long journey to perform, but, finding Chad unwilling to comply, the archbishop with his own hands lifted him on horseback, for he thought him a holy man, and obliged him to ride wherever he had need to go.

Though Chad was bishop of Lindisfarne for so short a time, he left his mark on the affections of the people, for we find that at least one chantry was dedicated in his name at York Minster. Soon after his election to the bishopric of the Mercians, he set out for Repton in Derbyshire, where Diuma, the first bishop of the Mercians, had established his see.

Whether our saint desired a more central position for the episcopal see, or was influenced by the wish to do honour to a spot enriched with the blood of martyrs, Bede does not tell us, but Chad established the Mercian see at Lichfield, then called Licetfield, or the Field of the Dead, where one thousand British Christians are said to have been put to death.

29

His new diocese was not much less in extent than that of Northumbria. It comprised seventeen counties, and stretched from the banks of the Severn to the shores of the German Ocean. Theodore, years afterwards, detached from it the sees of Worcester, Leicester, Lindesey (in Lincolnshire), and Hereford. Though it was far beyond the power of one man to administer it effectually, yet Bede witnesses that "Chad took care to administer the same with great rectitude of life, according to the example of the ancients. King Wulfhere also gave him land of fifty families to build a monastery at the place called Ad Barve, i.e., 'At the wood,' in the province of Lindesey, wherein monks of the regular life instituted by him continue to this day." "Ad Barve" is conjectured by Smith, of Durham, to be Barton-on-Humber, where there is still standing a very ancient church, admitted by Rickman to be partly Saxon, dedicated to S. Peter.

After fixing his see at Lichfield, Bede tells us "he built himself a habitation not far from the Church, wherein he was wont to pray and read with seven or eight of the brethren, as often as he had any spare time from the labour and ministry of the Word. When he had most gloriously governed the Church in that province two years and a half, in the dispensation of the Most High Judge, there came round the time of which Ecclesiastes speaks. "There is a time to cast stones, and a time to gather them together," for a deadly sickness sent from heaven came upon that place, to transfer, by the death of the flesh, the living stones of the Church from their earthly abodes to the heavenly building. And after many of the Church of that most reverend prelate had been taken out of the flesh, his hour also drew near wherein he was to pass out of this world to our Lord. It happened that one day, Owini, a monk of great merit, the same that left his worldly30 mistress to become a subject of the heavenly king, at Lastingham, was busy labouring alone near the oratory, where the bishop was praying, the other monks having gone to the Church, this monk, I say, heard the voice of persons singing most sweetly, and rejoicing, and appearing to descend from heaven. He heard the voice approaching from the south-east, till it came to the roof of the oratory, where the bishop was, and entering therein, filled the same and all about it. After a time he perceived the same song of joy ascend from the oratory, and return heavenwards the same way it came, with inexpressible sweetness. Presently the bishop opened the window of the oratory, and, making a noise with his hand, ordered him to ask the seven brethren who were in the church, to come to him at once. When they were come, he first admonished them to preserve the virtue of peace among themselves, and towards all the faithful, also to practise indefatigably the rules of regular discipline, which they had either been taught by him or seen him observe, or had noticed in the words or actions of the former fathers. Then he added that the day of his death was at hand: 'For,' said he, 'that amiable guest who was wont to visit our brethren, has vouchsafed to come to me also to-day, and to call me out of this world. Return, therefore, to the church, and speak to the brethren, that they in their prayers recommend my passage to the Lord, and that they be careful to provide for their own, the hour whereof is uncertain, by watching, prayer, and good works.' When they, receiving his blessing, had gone away in sorrow, Owini returned alone, and casting himself on the ground prayed the bishop to tell him what that song of joy was which he heard coming to the oratory. The bishop, bidding him conceal what he had heard till after his death, said, 'They were angelic spirits, who came to call me to my heavenly reward, which I have always longed after, and31 they promised they would return seven days' hence, and take me away with them.' His languishing sickness increasing daily, on the seventh day, when he had prepared for death by receiving the Body and Blood of our Lord, his soul being delivered from the prison of the body, the angels, as may justly be believed, attending him, he departed to the joys of heaven.

"It is no wonder that he joyfully beheld the day of his death, or rather the day of our Lord, which he had always anxiously looked for till it came; for notwithstanding his many merits of continence, humility, teaching, prayer, voluntary poverty, and other virtues, he was so full of the fear of God, so mindful of his last end in all his actions, that, as I was informed by one of the brothers, who instructed me in divinity, and who had been bred in his monastery, whose name was Trumhere, if it happened that there blew a strong gust of wind, when he was reading or doing anything else, he at once called upon God for mercy, and begged it might be extended to all mankind. If it blew stronger, he, prostrating himself, prayed more earnestly. But if it proved a violent storm of wind or rain, or of thunder and lightning, he would pray and repeat Psalms in the church till the weather became calm. Being asked by his followers why he did so, he answered, 'Have ye not read,—'The Lord also thundered in the heavens, and the Highest gave forth His voice; yea, He sent out his arrows and scattered them, and he shot out lightnings and discomfited them.' For the Lord moves the air, raises the winds, darts lightning, and thunders from heaven to excite the inhabitants of the earth to fear Him; to put them in mind of the future judgment; to dispel their pride and vanquish their boldness, by bringing into their thoughts that dreadful time when, the heavens and the earth being in a flame, He will come in the clouds with great power and majesty, to32 judge the quick and the dead. Wherefore it behoves us to answer His heavenly admonition with due fear and love.'

"Chad died on the second of March, and was first buried by S. Mary's Church, but afterwards, when the Church of the most Holy Prince of the Apostles, Peter, was built, his bones were translated into it. In both which places as a testimony of his virtue, frequent miraculous cures are wont to be wrought. The place of the sepulchre is a wooden monument, made like a little house covered, having a hole in the wall, through which those that go thither for devotion usually put in their hand and take out some of the dust, which they put into water and give to sick cattle or men to drink, upon which they are presently eased of their infirmity and restored to health."

We have told the life of S. Chad in the reverent language of Bede, who, as he says, had some of the details direct from those who had studied under the saint. Though his episcopate was short, it was abundantly esteemed by the warm-hearted Mercians, for thirty-one churches are dedicated in his honour, all in the midland counties, and either in or near the ancient diocese of Lichfield. The first church ever built in Shrewsbury was named after him, and when the old building fell, in the year 1788, an ancient wooden figure of the patron escaped destruction, which is still preserved in the new church. The carver has represented him in his pontifical robes and a mitre, with a book in his right hand, and a pastoral staff in his left.

His well is shown at Lichfield. There was one in London called Chad's Well, the water of which was sold to valetudinarians at sixpence a glass. Doubtless, from the miracles alleged to have been wrought by mixing a little dust from his shrine with water, he got the character of patron saint of medicinal springs. At Chadshunt there was an oratory and well bearing his name. The priest received as much33 as £16 a-year from the offerings of pilgrims. Chadwell—one source of the New River—is, perhaps, a corruption for S. Chad's Well.

No writings of our saint have survived, but in Lichfield Cathedral library there is a MS. of the 7th century in Anglo-Saxon character, containing the Gospels of S. Matthew, S. Mark, and part of S. Luke, which is known by the name of Chad's Gospel.

Among the Bodleian MSS. there is an Anglo-Saxon homily for S. Chad's day, written in the Middle Anglian dialect, which stretched from Lichfield to Peterborough.

His relics were translated from the wooden shrine to the cathedral, when it was rebuilt by Bishop Roger, in honour of SS. Mary and Chad. In 1296, Walter Langton was raised to the see of Lichfield. He built the Lady Chapel, and there erected a beautiful shrine, at the enormous cost of £2,000, to receive the relics of S. Chad. This was spared by Henry VIII.

His emblem in the Clog Almanacks is a branch. Perhaps this was suggested by the Gospel, viz., S. John v., formerly read on the Feast of his Translation, which speaks of the fruitful branches of the vine. This translation was formerly celebrated with great pomp at Lichfield, on August 2nd.

As long as the virtues of chastity, humility, and a forsaking all for Christ's sake are esteemed among men, the name of the apostle of the Mercians ought not to be forgotten.

A beautiful legend formerly inscribed beneath the cloister windows of Peterborough, recorded the conversion of King Wulfhere's sons, Wulfade and Rufine, by S. Chad, and their murder by their father, for he had turned heathen again in spite of the entreaties of Queen Ermenild:—

34

The legend goes on to say that Rufine was baptized also by the saint. The king's steward, Werbode (who had been rebuked by the two princes for seeking the hand of their sister, Werburga), told Wulfere of their becoming Christians, and that they were then praying in S. Chad's oratory. The king took horse thither at once, and slew them both with his own hand. Stung with remorse, he fell ill, and was counselled by his queen to ask Chad to shrive him. As a penance the saint told him to build several abbeys, and amongst the number he completed Peterborough Minster, which his father had begun. This legend is told with very full and touching details in a Latin version printed in the Monasticon.3

The Latin version is this. King Wulfere, son of Penda the Strenuous, had been baptized many years before by B. Finan, and promised at the font, and again when he wedded35 Ermenilda, of the royal house of Kent, to destroy all the idols in his realm. He neglected to do so, and let his three sons, Wulfade, Rufine, and Kenred remain unbaptized. His beauteous daughter, Werburga, had been dedicated to Christ as a virgin by the Queen; yet, when Werbode, his chief councillor, and the chief supporter of idolatry in the realm, sought her hand in marriage, the king consented. The queen, Ermenilda, however, sharply rebuked him for his presumption. The brothers threatened him with their sore vengeance if he again preferred his low-born suit to their sister. Their disdainful words cost them dear.

While Chad was praying by a fountain near his cell, a hart, with quivering limbs and panting breath, leaped into the cooling stream. Pitying its distress, the saint covered him with boughs, then placing a rope round its neck, he let it graze in the forest. Wulfade came up, heated in the chase, and asked where the beast had gone. The saint replied, "Am I keeper of the hart? Yet, through the ministry of the hart I have become the guide of thy salvation. The hart bathing in the fountain foreshoweth to thee the laver of baptism, as the text says: As the hart panteth after the water-brooks, so panteth my soul after thee, O God."

Many other things did the saint set forth about the ministry of dumb animals to the faithful. The dove from the ark told that the waters were dried up.

The young prince replied, "The things you tell me would be more likely to work faith in me if the hart you have taught to wander in the forest with the rope round its neck were to appear in answer to your prayers." The saint prostrated himself in prayer, and lo! the hart burst from the thicket. The saint exclaimed, "All things are possible to him that believeth. Hear then, and believe the faith of Christ." The saint instructed him, and baptized him. The36 next day he received the Eucharist, and went home, and told his brother Rufine that he had become a Christian. The other said, "I have long wished for baptism; I will seek holy Chad." The brothers set out together. Rufine espying the hart with the cord round its neck, gave hot chase; the animal made for the saint's cell, and leaped into the fountain as before. Rufine saw a venerable man praying near. He said, "Art thou, my lord, father Chad, guide of my brother Wulfade to salvation?" He answered, "I am." The prince earnestly desiring baptism, Chad baptized him, Wulfade holding him at the font, after the manner taught by holy Church.

Then they departed, but returned daily to him. Werbode stealthily spied their ways and doings, and told their father that they had become Christians, and were then worshipping in Chad's oratory, adding that their conversion would alienate his subjects. The king set out in anger for the cell, the queen sending Werbode before to tell the princes of his approach, that they might hide. But Werbode only looked in at the window of the oratory, and saw them praying earnestly. He returned to the king, and told him that his sons were obstinate in their purpose of worshipping Christ. The king, pale with anger, rushed towards the oratory. He threatened them with his vengeance for breaking the laws of the land by becoming Christians, and bade them renounce Christ. Wulfade replied, "They did not want to break the laws, and that the king himself once professed the faith which now he renounced. They wished to retain his fatherly affection, but no tortures could turn them from Christ." The king rushed furiously upon him, and cut off his head. His brother, Rufine, fled, but his father pursued him, and gave him a mortal wound. Thus these two departed to celestial glory. Werbode was smitten with madness when they returned to the castle and told the37 murder in the ears of all. The queen buried her sons honourably in one stone tomb, and withdrew with her daughter, Werburga, to the monastery at Sheppey, and then to that of Ely.

The king, overcome with remorse, fell dangerously ill. The queen counselled him to seek out Chad, and confess to him. Wulfere took her advice, and starting one morning with his thanes, as if to follow the chase, his attendants got scattered from him, and he was left alone. Soon he espied the meek hart with the rope round its neck; he followed its track gladly, till he came to Chad's cell. The king, approaching the oratory, espied the saint saying mass; he dared not enter till he had been shriven. When the canon began, so great a light shone through the apertures in the wall, that priest and sacrifice were covered with such splendour that the king was nearly blinded by it, for it was brighter than that of the natural sun.

The saint knew what the king wanted, so when the office was ended he hastily put off his vestments, and, thinking to lay them upon the appointed place, unwittingly hung them upon a sunbeam, for the natural sun was now streaming through the window. He found the king prostrate before the door; raising him up he heard the penitent's confession, and enjoined him as a penance, to root out idolatry, and to found monasteries.4 He then motioned to the king that he should enter the oratory and pray. Wulfere, chancing to lift up his eyes, with wonder saw the vestments hanging on the sunbeam. He rose from his knees, and, drawing near, placed his own gloves and baldric upon the beam, but they immediately fell to the ground. The king understood by this that Chad was beloved by the Sun of Righteousness, since the natural sun paid him such homage.

38

(A.D. 1127.)

[Hermann Greven and Molanus in their additions to Usuardus, Galesinius, Canisius, Saussaye, and the Belgian Martyrologies. Authorities:—A life by a contemporary, Walter, archdeacon of Thèrouanne, another life by Gualbert of Bruges, written about two years after the death of the count, and another by Suger, abbot of S. Denys, d. 1151.]

Charles the Good, Count of Flanders, the son of S. Canute, King of Denmark, and Adelheid,5 daughter of Robert the Frisian, was taken to Bruges after the martyrdom of his father, (see Jan. 19th), and received a careful education from Robert II., Count of Flanders, his uncle on his mother's side, who trained him to be a good knight, 'without fear and without reproach,' and at the same time to be a good Christian. Charles distinguished himself by his bravery in the Holy Land, and in the war carried on by his uncle against the English, and after the death of Baldwin VII., who succeeded his father, Robert II., in 1111, and died without issue, he was declared his successor by acclamation of the nobility and people, in accordance with the dying wish of his uncle. His elevation was not, however, acceptable to every party in the state, and his government, which began in the midst of plots, was brought to a close by one.

He was married to Margaret de Clermont, sister of the Bishop of Tournai, and of the royal blood of France.

On the sea-banks, in the midst of the sand-hills, living by piracy, and by fishing, were colonies of Flemings. Furnes is the centre of this district. It was held by Clémence of Burgundy, the widow of Count Robert II., as her dowry. She had married one of her nieces to39 King Louis VI., another to William de Loo, Viscount of Ypres, son of Philip, her brother-in-law. Consequently there were several ambitious and powerful parties ready to lay claim to the County of Flanders, and wrest it from the hands of Charles.

The Flemings of the sea-coast rose, at the instigation of Clémence, and were secretly favoured by the King of France; whilst, at the same time, William de Loo asserted his claim.

The feudal nobles desired to profit by these circumstances, to increase their own power. One of them, Godfrey of Louvain, married the dowager countess, Clémence. The Counts of Hainault, Boulogne, S. Pol, and Hesdin, took arms. Clémence took Audenarde, the Count of S. Pol invaded West Flanders, but Charles fell suddenly on them with an army, subjugated De Loo, deprived S. Pol of his castle, and the countess of her dowry, dispersed the armed men of Hainault, Boulogne, and Coucy, and as Walter of Thérouanne says, "The land held its tongue before him." The king of France was the first to strike an alliance with him.

These successes excited the mistrust of the king of England and the emperor Henry V. The latter, under pretext of a war against the duke of Saxony, assembled an army in August 1124, crossed the Rhine, and marched towards Metz, threatening to destroy Rheims, where pope Callixtus II. had lately excommunicated him. In this imminent peril, all the vassals of the king rallied around Louis VI. "The noble Count of Flanders," says the abbot Suger, "brought with him ten thousand brave soldiers, and if there had been time, he would have brought thrice as many." In face of these preparations to resist his invasion the emperor withdrew to Utrecht. On his death, all eyes turned to Charles, and the imperial crown was offered him.40 He refused it, as he did also the crown of Jerusalem, offered him by the Christians in the Holy Land. He now devoted himself to the administration of his country with great zeal. He enacted wise laws, and laboured to make justice prevail in all the courts of judicature. Nevertheless a vague uneasiness prevailed amongst his subjects. The sea had overleaped the sand-hills, fires had broken out and consumed certain monasteries, and an eclipse of the sun gave prognostication of further evils. The winter of 1125 was of unparalleled severity; ice and snow prevailed till the end of March, and no sooner had the fields and woods begun to resume their verdant tints, than furious gales and a deluge of rain dissipated the hopes of the farmers. A dreadful famine ensued. "Some," says Gualbert, "perished before they could reach the towns and castles, where food was obtainable; others died in extending their hands for alms. In all our land the natural colour of the face had become exchanged for the pallor of death. Despair was general, for those who were not themselves in want sickened with grief at the sight of such miseries."

In these calamities the Count of Flanders exhibited more greatness than if he had reigned at Aachen, or at Jerusalem. He exempted the farmers from their taxes and rents, and required them to house and feed so many poor. At Ypres he distributed 1800 loaves in one day. He forbade the consumption of barley for the manufacture of beer, that it might be used for bread, and he ordered the immediate sowing of such vegetables as are of rapid growth. The ensuing winter was also severe, but with the spring the distress gave signs of alleviation, for the crops were abundant, and in the autumn plenty reigned once more. During the stress of famine, Charles learnt that Lambert, brother of Bertulf, dean of S. Donatus, at Bruges, had bought up all the grain of the monasteries of S. Winoc,41 S. Bertin, S. Peter, and S. Bavo, together with all the foreign corn that had been brought into the ports from the Baltic, and was keeping it back so as to sell it at an enormous profit. Charles sent for Lambert and the dean, and bitterly reproached them. The Count sent one of his councillors, Tankmar van Straten, to examine the granaries of these two men, and they were found to be filled to overflowing with stored-up grain. Tankmar offered a reasonable price for the store, but it was indignantly refused by the avaricious men. He, therefore, by the Count's orders, insisted on their receiving it, and opening the granaries, distributed the corn to the starving poor. This aroused the wrath of the brothers, who had powerful friends among the people of Furnes, and to avenge themselves, a project was formed to assassinate the prince. One day, as he was hearing mass in a chapel of the Cathedral of S. Donatus, at Bruges, one of the conspirators cut off his arm with a hatchet, and another clave his skull. His body was buried in the Church of S. Christopher, but was afterwards translated to the Cathedral of S. Donatus, where they remained till the period of the French Revolution, when the cathedral was levelled with the ground. The relics of the holy martyr were, however, preserved with respect, and on March 2nd, 1827, seven hundred years after the death of Charles, were solemnly replaced above an altar in the Church of S. Sauveur, now used as the cathedral. The day of his festival attracts a great concourse of the faithful; those afflicted with fever especially come from all quarters to cure themselves by drinking out of the skull of the Blessed Charles the Good.

42

SS. Marinus, M., and Asterius, C. at Cæsarea, circ. A.D. 260.

SS. Felix, Castus, Luciolus, Florian, Justus, and Others, MM.

in Africa.

SS. Emetherius and Chelidonius, MM. at Calahorra, in Spain.

SS. Basiliscus, Eutropius, and Cleonicus, MM. at Amasea and

Comana, in Pontus, circ. A.D. 308.

S. Camilla, V. R. at Ecoulives, near Auxerre, A.D. 437.

S. Nôn, W. in Wales, the Mother of S. David, circ. A.D. 460.

S. Winwaloe, Ab. of Landevenec, in Brittany, 6th cent.

S. Titian, B. of Brescia, circ. A.D. 526.

S. Calupanus, H. at Clermont, A.D. 576.

S. Kunegund, Empss. V., Wife and Wid., at Bamberg, circ. A.D. 1040.

(ABOUT A.D 260.)

[Usuardus, Ado, Notker, Bede, Wandelbert, and Roman Martyrologies. Authority:—Eusebius, Hist. Eccl. lib. vii. c. 15, 16.]

Peace being restored to the Church," writes Eusebius, "Marinus of Cæsarea, in Palestine, who was one of the army, distinguished for his military honours, and illustrious for his family and wealth, was beheaded for his confession of Christ, on the following occasion. There is a certain honour among the Romans, called the vine, which they who obtain are said to be centurions. A place becoming vacant, Marinus, by order of succession, was called to be promoted, but another, advancing to the tribunal, objected, saying that he was a Christian, and refused to sacrifice to the emperor, and therefore legally could not share in Roman honours; but that the office devolved on himself, the objector, who was second on the list. The judge, whose name was Achæus, roused at this, began first to question Marinus on his opinions; and when he saw that he was constant in affirming that he was a Christian, granted him three hours43 for reflection. But as soon as he came out of the judgment hall, Theotecnus, bishop of that place, coming to him, took him by the hand, and drawing him to the Church, placed him before the altar, raised his cloak a little, and pointing to the sword at his side, at the same time that he presented before him the book of the Holy Gospels, told him to choose which of the two he would retain. Without hesitation, Marinus extended his hand and took the book. 'Hold fast, then, hold fast to God,' said Theotecnus, 'and strengthened by him, mayest thou obtain what thou choosest. Go in peace.' Immediately on his return thence, a crier proclaimed before the prætorium that the appointed time had elapsed. Marinus then was arraigned, and after exhibiting a still greater fervour for the faith, was led away and made perfect by martyrdom."

"Mention is also made of the confidence of Asterius, a man of senatorial rank, in great favour with the emperors, and well known for his nobility and wealth. As he was present at the death of the above-mentioned martyr, taking up the corpse, he bore it on his shoulder in a splendid and costly dress, and covering it in a magnificent manner, gave it a decent burial."

Asterius is venerated by the Greeks on August 7th as a martyr, who suffered decollation, and Marinus is not mentioned by them. Eusebius says nothing of the martyrdom of Asterius, as he certainly would have done, had he died for Christ, for he says, "Many other facts are stated of this man by his friends, who are alive at present," and then he relates his counteracting by his prayers the drowning of a victim annually offered to the river Jordan. The Roman Martyrology, however, accepts the Greek tradition. "Asterius received the honour he rendered to the martyr, becoming himself a martyr;" but perhaps the word martyr is here to be taken in the sense frequently given to it44 anciently, of a confessor, or witness to Christ, not necessarily by losing his life for his testimony, but only by imperilling it.

(UNCERTAIN DATE.)

[Commemorated in the Mozarabic Missal and Breviary; the Evora and Toledo Breviaries, and as a double at Burgos and Leon; Martyrology of S. Jerome, those of Usuardus, Ado, Notker, and the Roman Martyrology. Authority:—A hymn of Prudentius, and Acts of no great antiquity, printed by Tamayus Salazar, and an Elogium by Gregory of Tours.]

These martyrs were put to death with the sword at Calahorra, in Navarre, on the Ebro. According to the hymn of Prudentius, and the story of Gregory of Tours, on their execution, the ring of one martyr, and the stole (orarium) of the other, were caught up in a cloud, and ascended into Heaven. Probably this legend contains a reminiscence of an incident such as the wind wafting away some of the martyrs' garments during the execution.

Relics at Calahorra.

(ABOUT A.D. 308.)