Transcriber’s Notes

Cover created by Transcriber, using an illustration from the original book, and placed in the Public Domain.

The original book did not have a Table of Contents or a List of Illustrations. Those have been added by Transcriber, using the content of the original book, and placed in the Public Domain.

Punctuation, hyphenation, and spelling were made consistent when a predominant preference was found in this book; otherwise they were not changed.

Simple typographical errors were corrected; ambiguous hyphens at the ends of lines were retained.

The Western Front

The Somme Battlefield

Trench Scenery

The Upper Hand

The British Navy and the Western Front

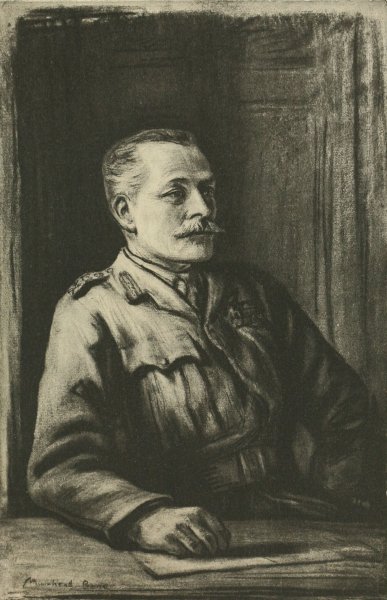

| I | General Sir Douglas Haig |

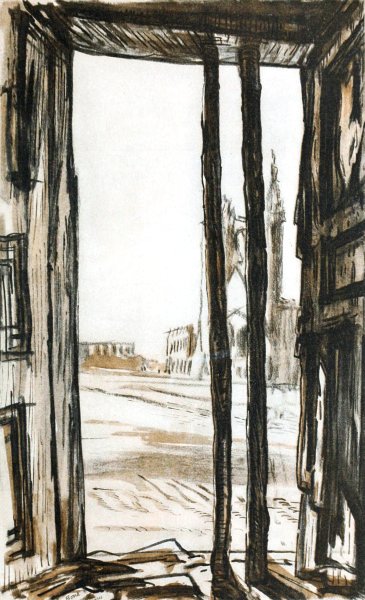

| II | Grand’place And Ruins Of The Cloth Hall, Ypres |

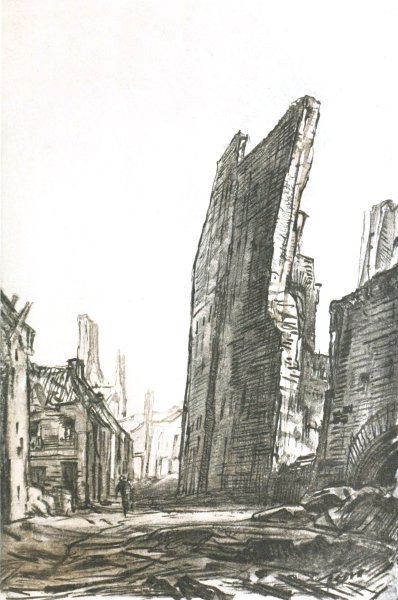

| III | A Street In Ypres |

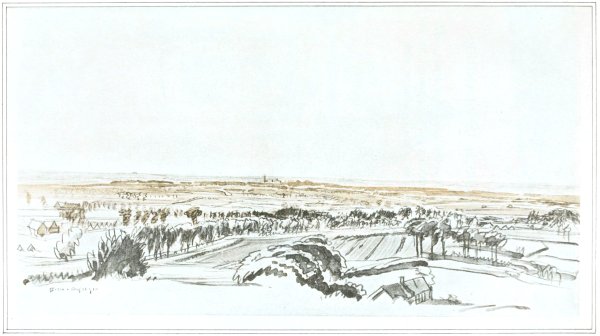

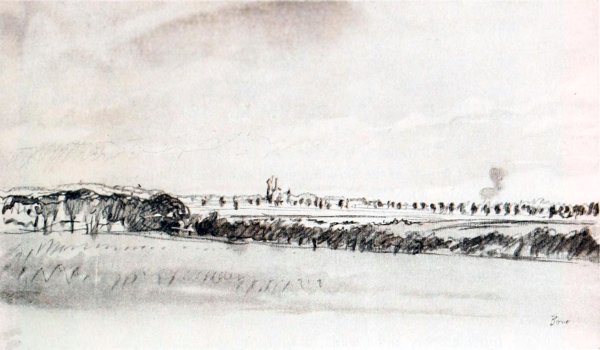

| IV | Distant View Of Ypres |

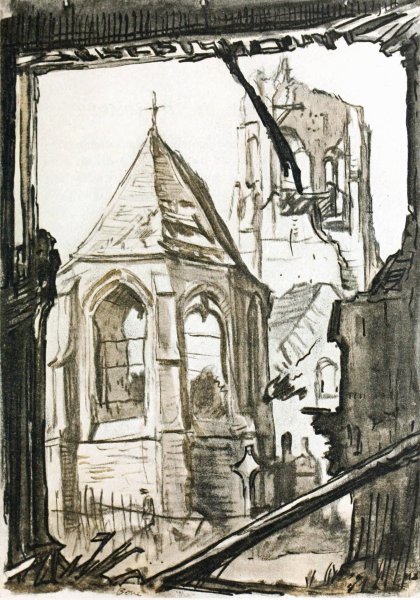

| V | A Village Church In Flanders |

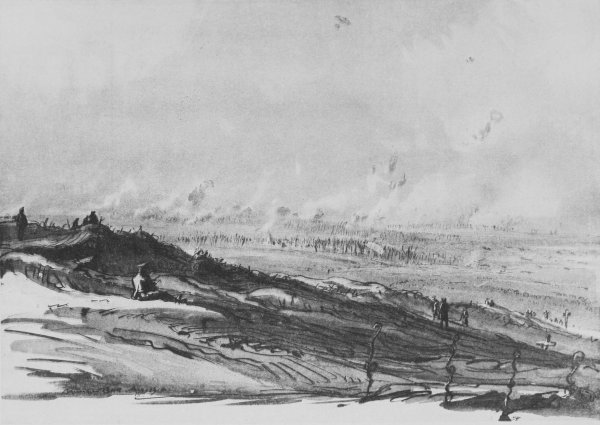

| VI | The Battle Of The Somme |

| VII | “Tanks” |

| VIII | Ruined German Trenches, Near Contalmaison |

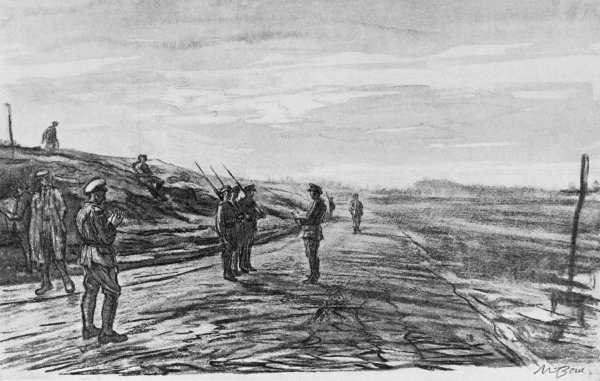

| IX | The Night Picket |

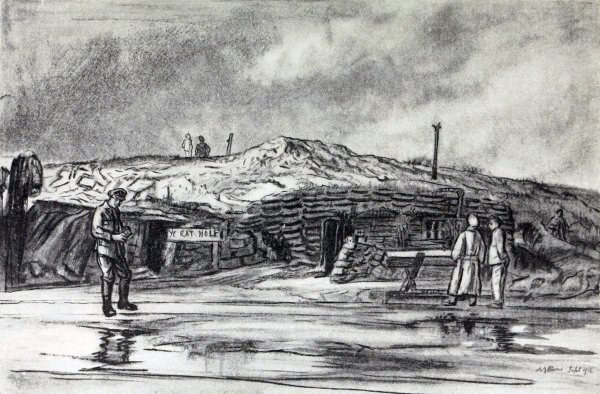

| X | Dug-outs |

| XI | Gordon Highlanders: Officers’ Mess |

| XII | Waiting For The Wounded |

| XIII | The Happy Warrior |

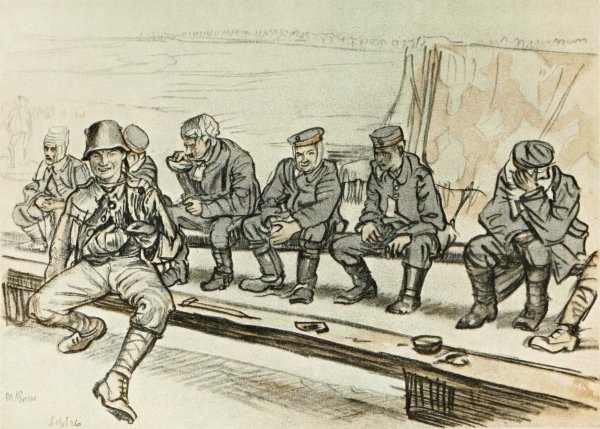

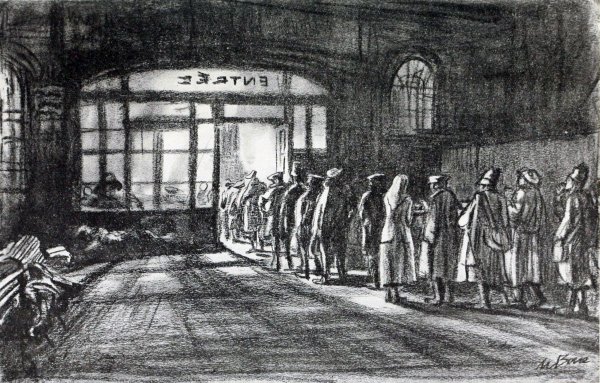

| XV | At A Base Station |

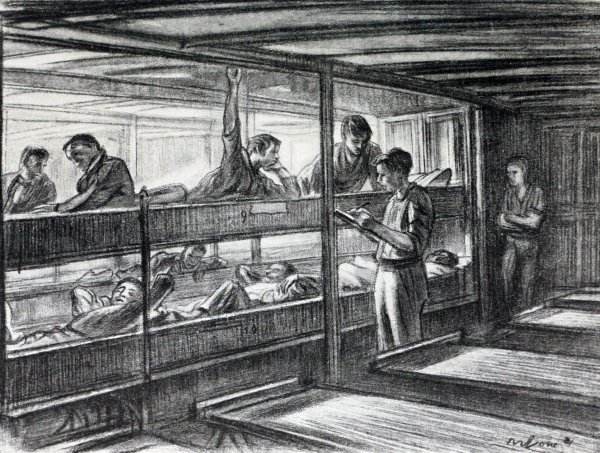

| XVI | On A Hospital Ship |

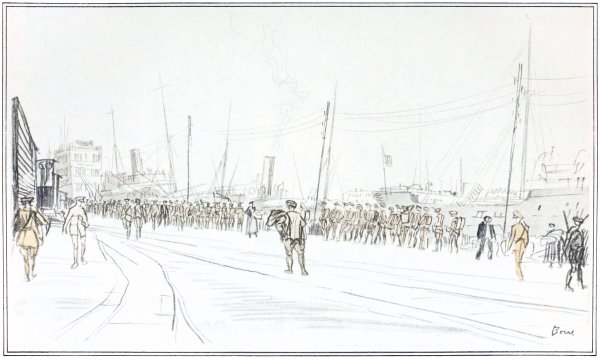

| XVII | Disembarked Troops Waiting To March Off |

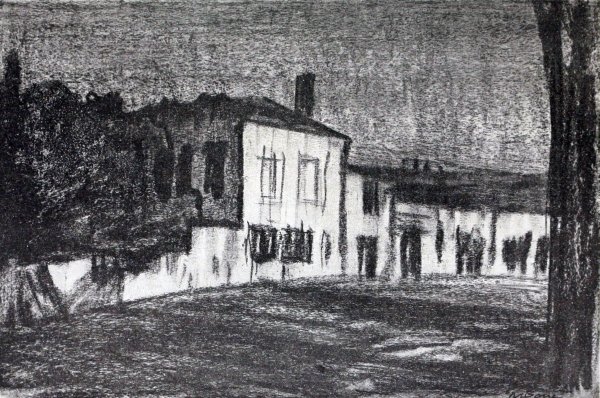

| XVIII | Soldiers’ Billets—moonlight |

| XIX | A Gun Hospital |

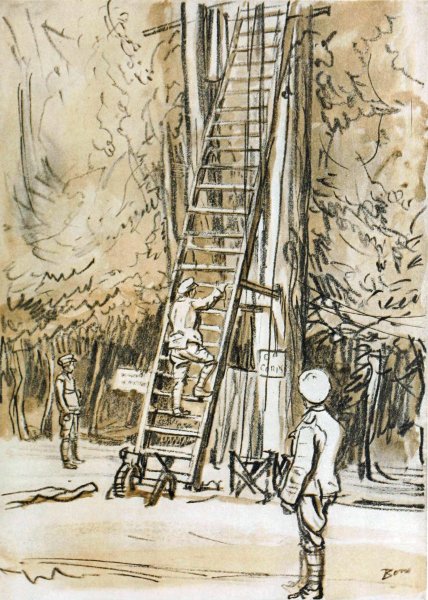

| XX | An Observation Post |

| THE SOMME BATTLEFIELD | |

| XXI | Amiens Cathedral |

| XXII | The Virgin Of Montauban |

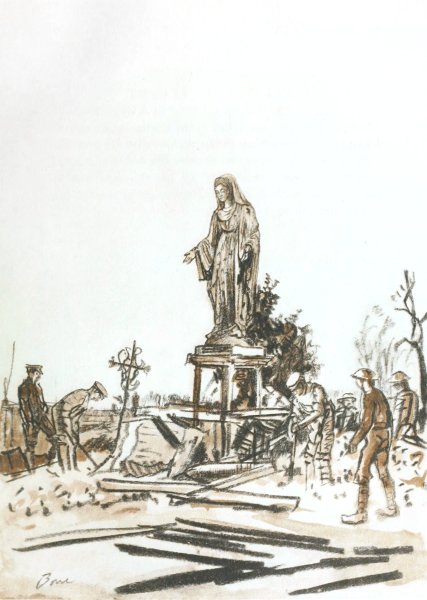

| XXIII | A Sketch In Albert |

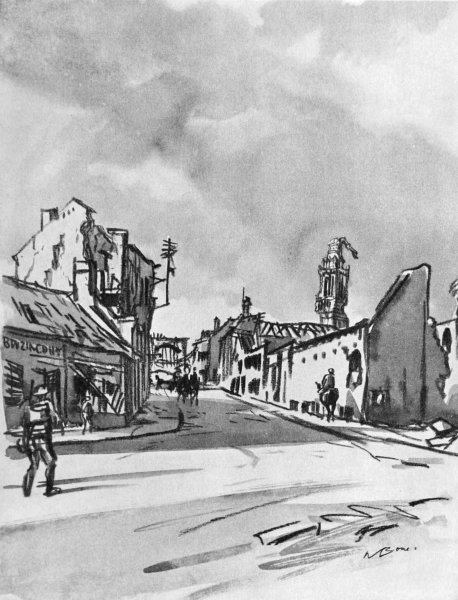

| XXIV | Taking The Wounded On Board |

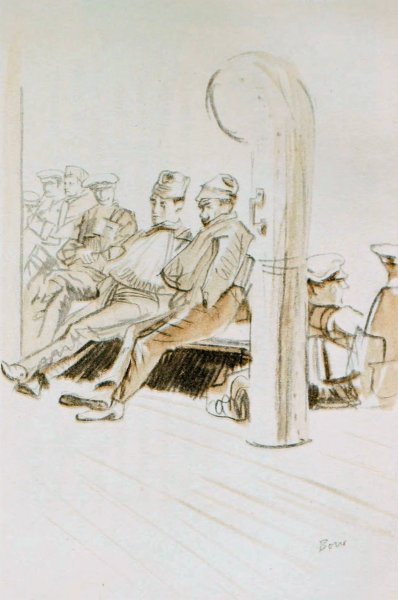

| XXV | “Walking Wounded” Sleeping On Deck |

| XXVI | (a and b) |

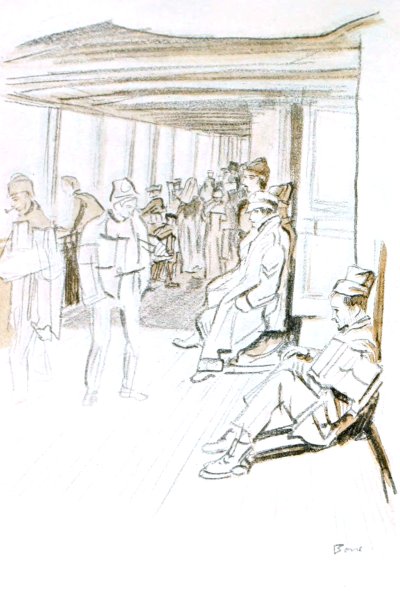

| “Walking Wounded” On A Hospital Ship | |

| “Walking Wounded” On A Hospital Ship | |

| XXVII | (a and b) |

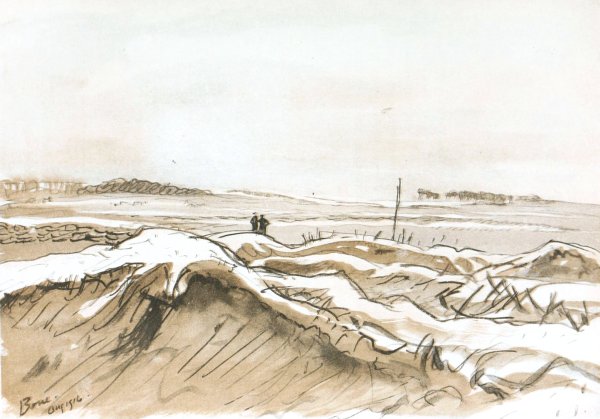

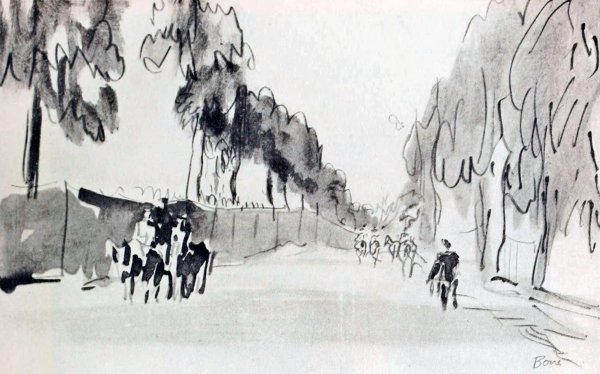

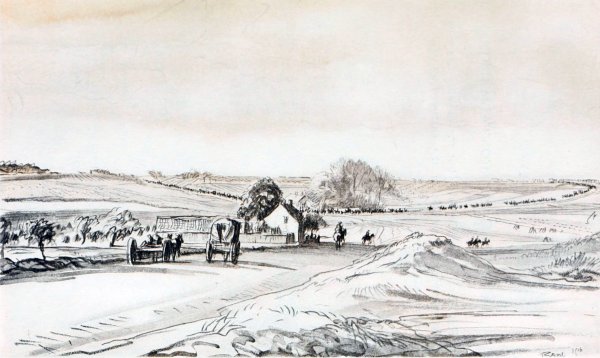

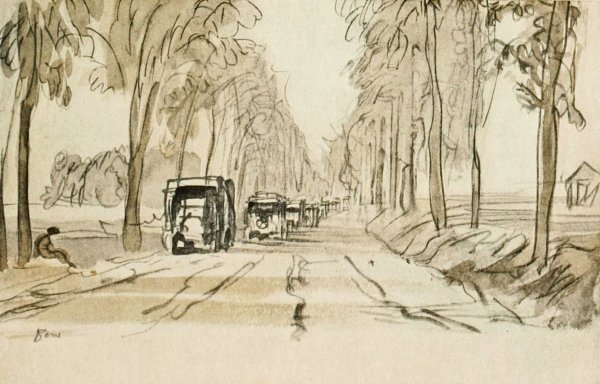

| A Main Approach To The British Front | |

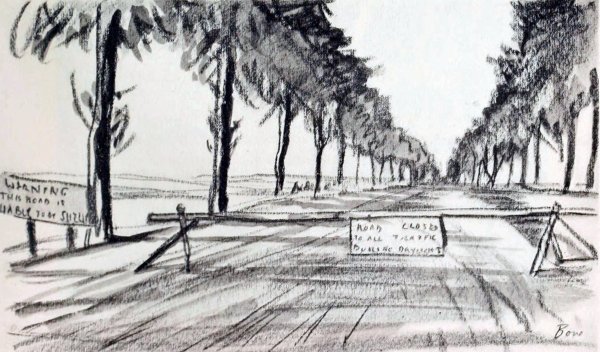

| “Road Liable To Be Shelled” | |

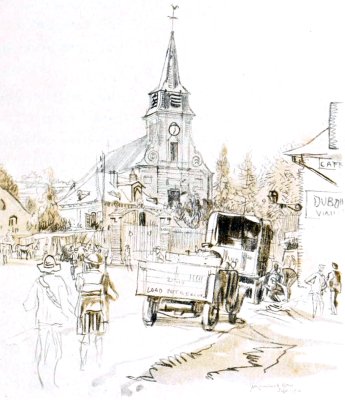

| XXVIII | Trouble On The Road |

| XXIX | British Troops On The March To The Somme |

| XXX | A Sketch At Contalmaison |

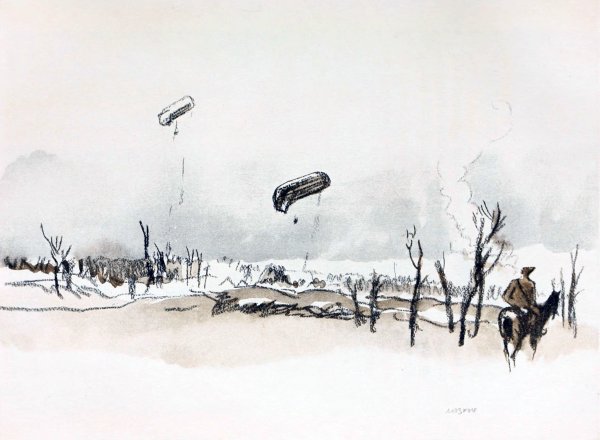

| XXXI | On The Somme: Sausage Balloons |

| XXXII | A Wrecked Aeroplane Near Albert |

| XXXIII | A Mess Of The Royal Flying Corps |

| XXXIV | Watching Our Artillery Fire On Trones Wood From Montauban |

| XXXV | (a and b) |

| In The Regained Territory | |

| XXXVI | A V.a.d. Rest Station |

| XXXVII | A Gateway At Arras |

| XXXVIII | Outside Arras, Near The German Lines |

| XXXIX | Watching German Prisoners |

| XL | On The Somme: “Mud” |

| TRENCH SCENERY | |

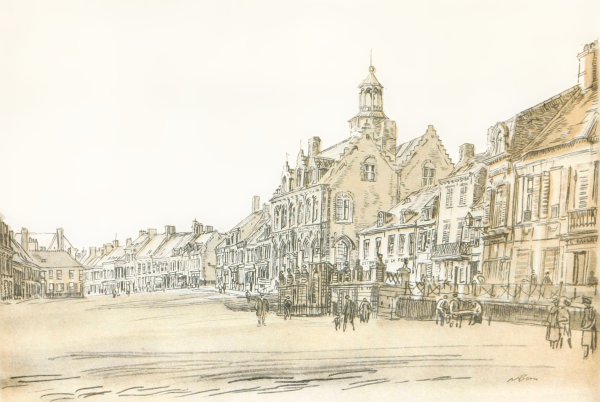

| XLI | Cassel |

| XLII | A Line Of Tanks |

| XLIII | A Kitchen In The Field |

| XLIV | The Gun Pit: Hardening The Steel |

| XLV | The Gun Pit: A Gun Jacket Entering The Oil Tank |

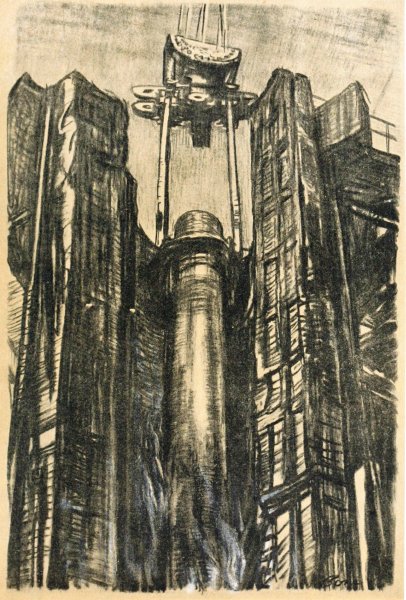

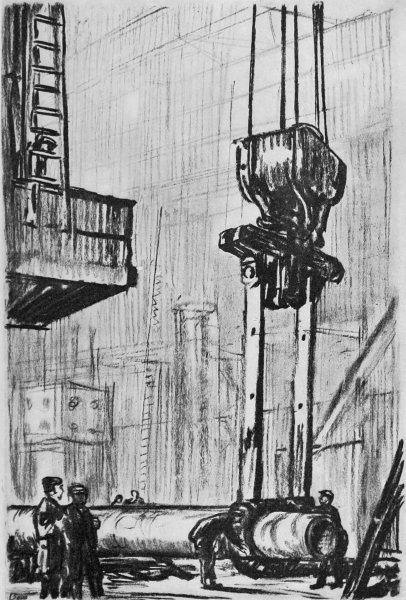

| XLVI | The Gun Pit: The Great Clutches Of The Crane |

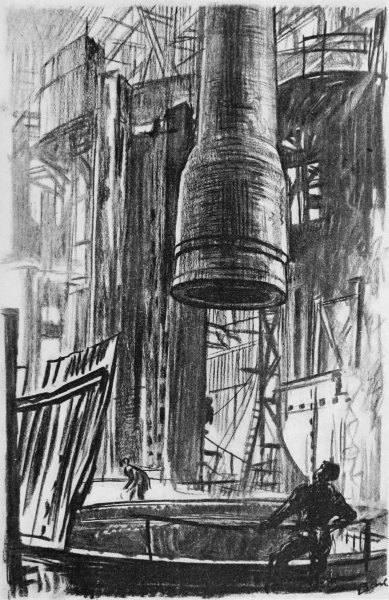

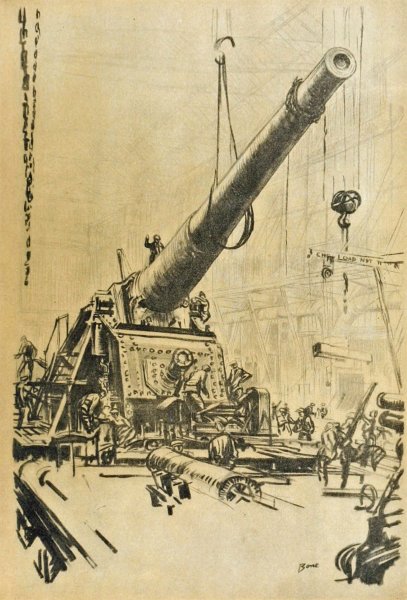

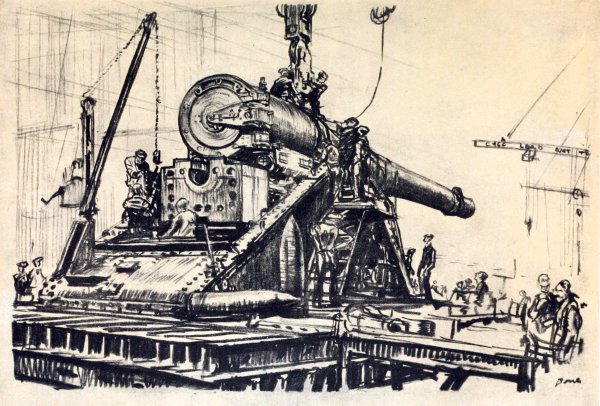

| XLVII | Mounting A Great Gun |

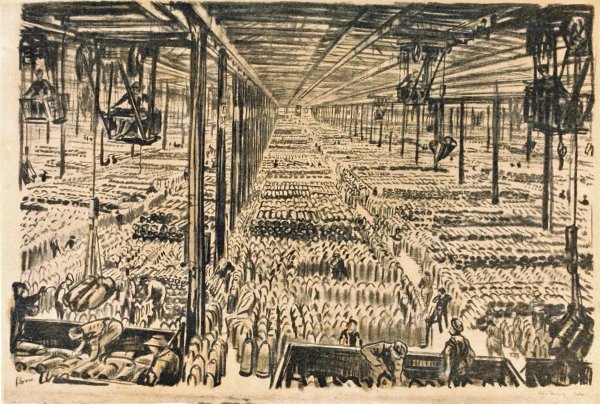

| XLVIII | “The Hall Of The Million Shells” |

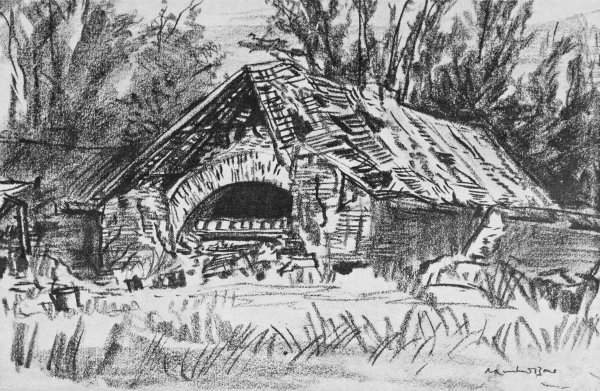

| XLIX | The Ruined Tower Of Bécordel-bécourt |

| L | Embarking The Wounded |

| LI | (a and b) |

| Mont St. Eloi | |

| Ruins Of Mametz | |

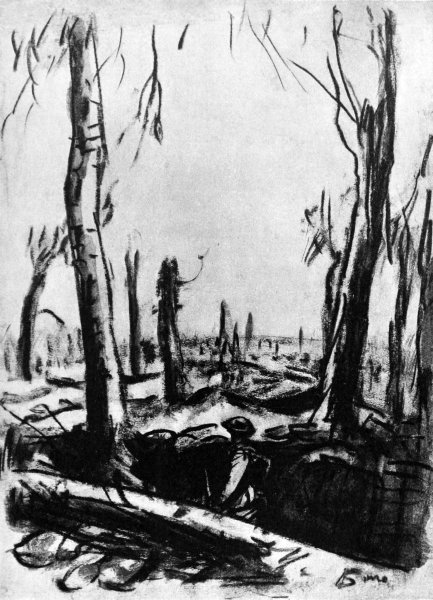

| LII | Ruined Trenches In Mametz Wood |

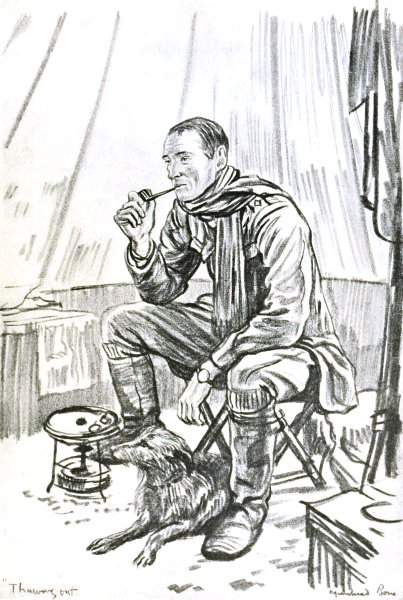

| LIII | “Thawing Out” |

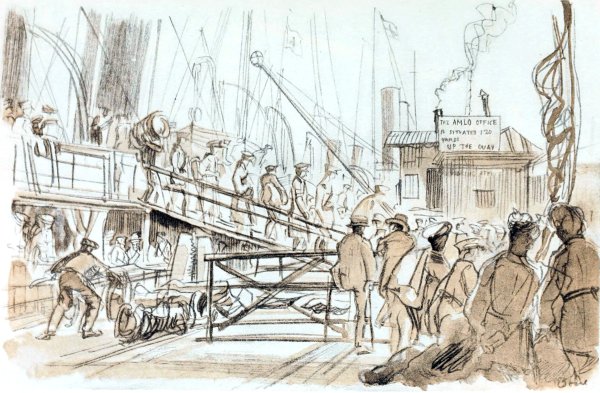

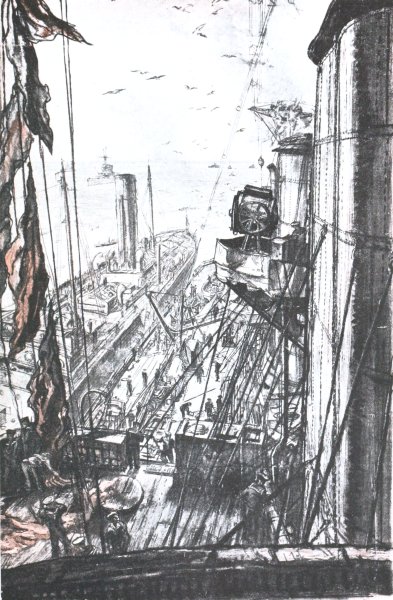

| LIV | Disembarking |

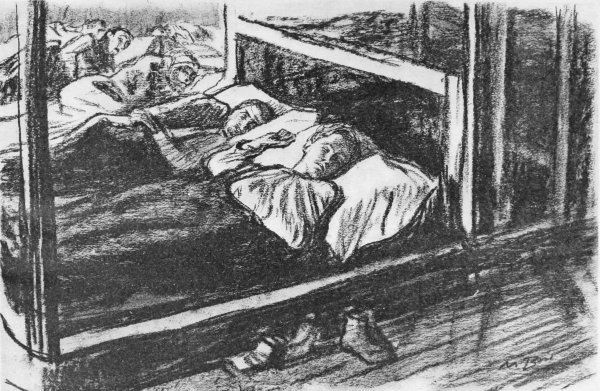

| LV | Sleeping Wounded From The Somme |

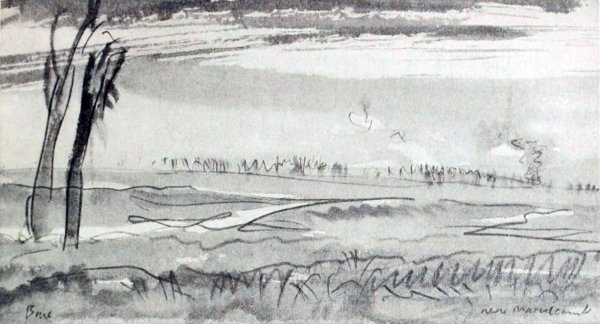

| LVI | Distant Amiens |

| LVII | Scottish Soldiers In A French Barn |

| LVIII | Welsh Soldiers |

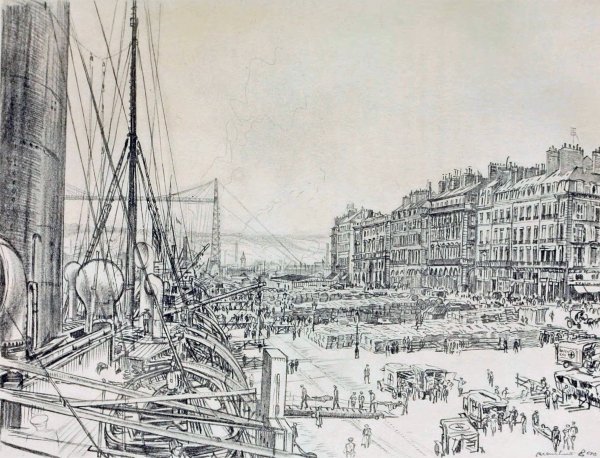

| LIX | A British Red Cross Depot At Boulogne |

| LX | Indian Cavalry |

| THE UPPER HAND | |

| LXI | Mounting A Great Gun |

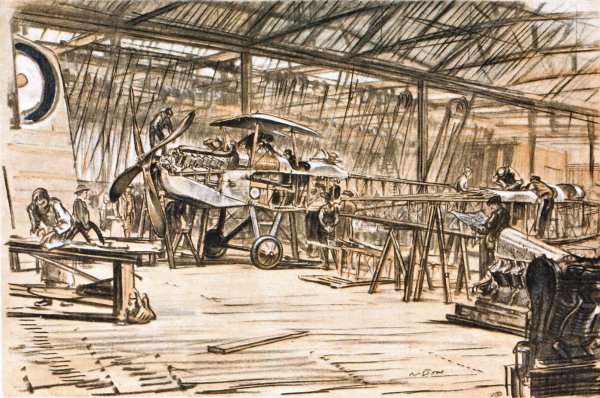

| LXII | Erecting Aeroplanes |

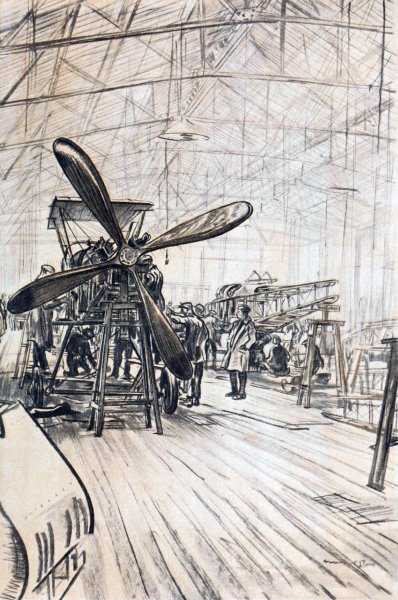

| LXIII | An Aeroplane On The Stocks |

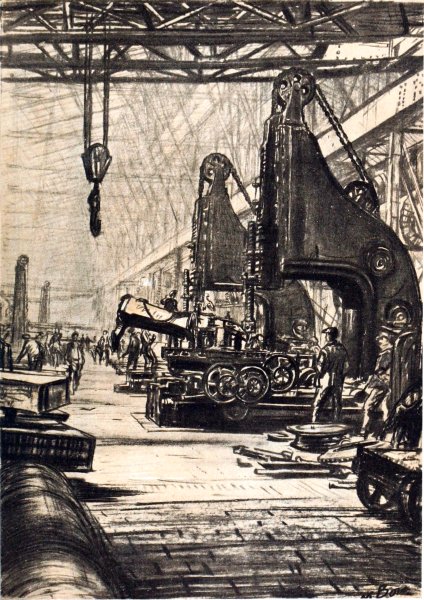

| LXIV | The Giant Slotters |

| LXV | Night Work On The Breech Of A Great Gun |

| LXVI | The Howitzer Shop |

| LXVII | The Night Shift Working On A Big Gun |

| LXVIII | Some Great Guns |

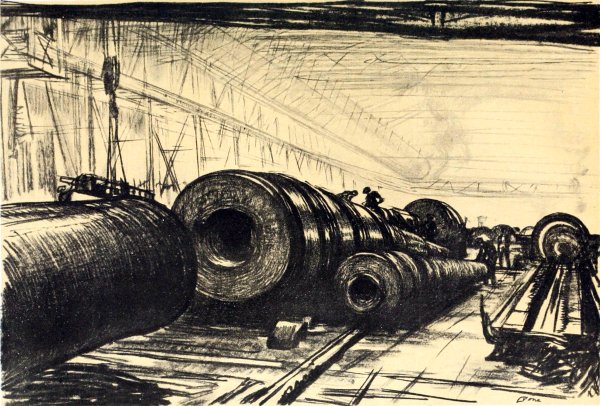

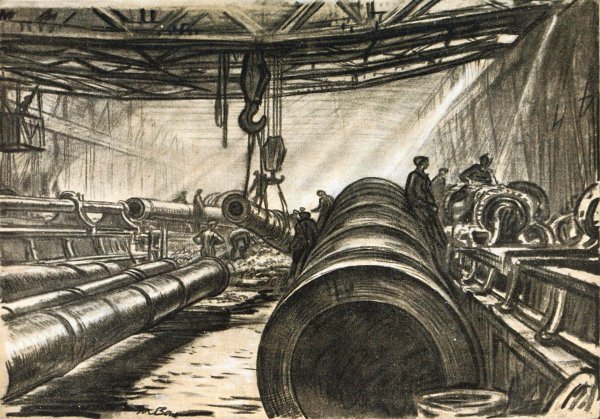

| LXIX | Moving Heavy Gun Tubes |

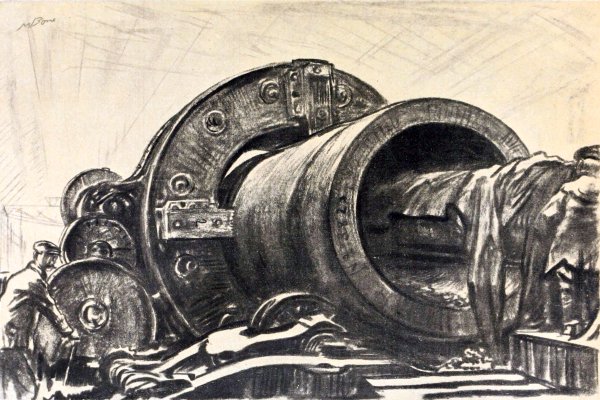

| LXX | A Coring Machine At Work On A Big Gun Tube |

| LXXI | Ruins Near Arras |

| LXXII | On The Somme: In The Old No Man’s Land |

| LXXIII | (a and b) |

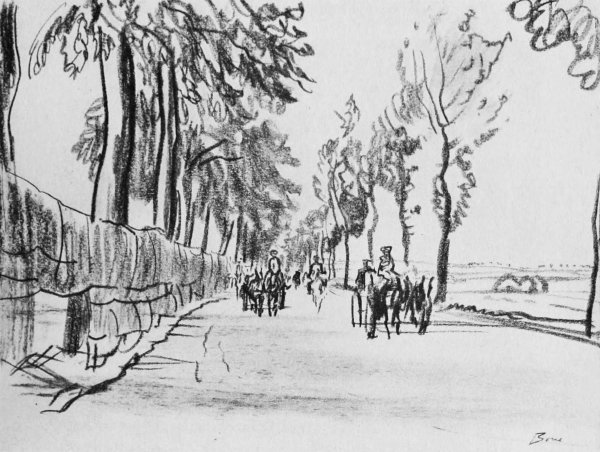

| A Road Near The Front | |

| A Train Of Lorries | |

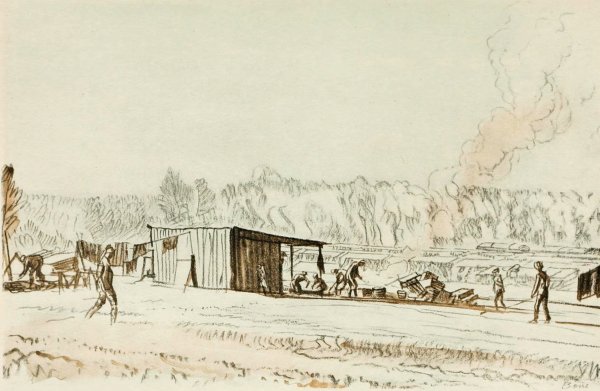

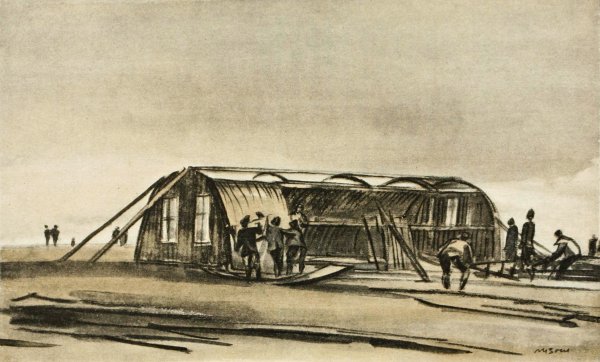

| LXXIV | On The Somme. R.f.c. Men Building Their Winter Hut |

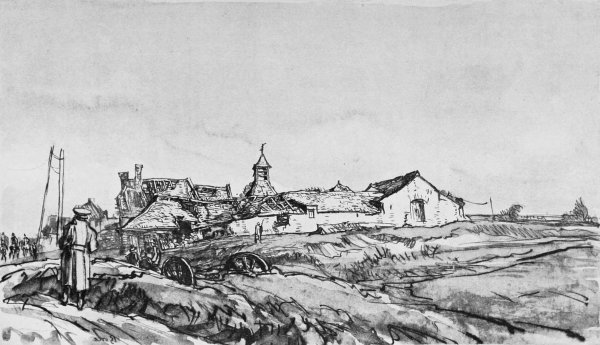

| LXXV | Maricourt: The Ruins Of The Village |

| LXXVI | On The Somme, Near Mametz |

| LXXVII | A Market Place. Transport Resting |

| LXXVIII | (a and b) |

| The “Blighty Boat” And A Hospital Ship | |

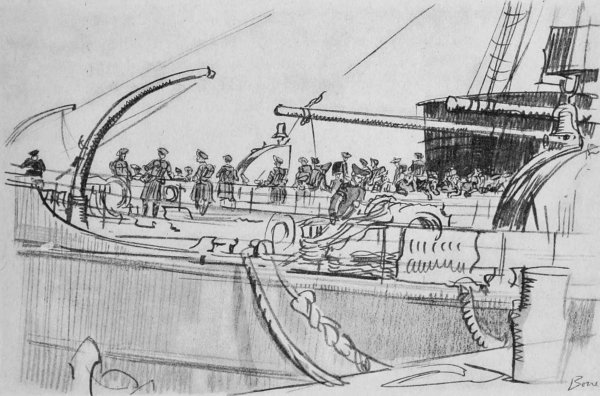

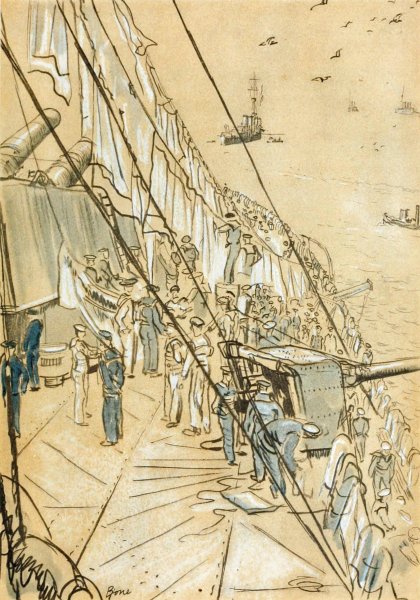

| Scottish Troops On A Troopship | |

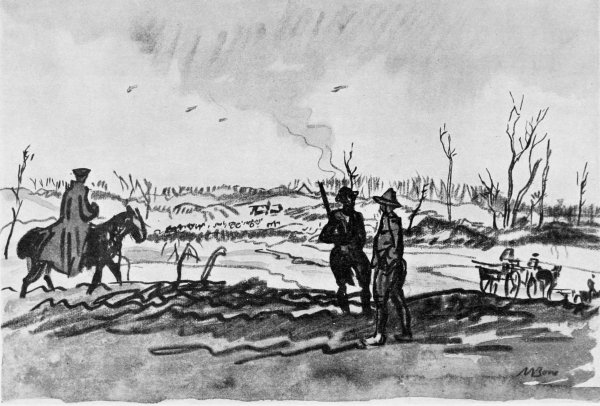

| LXXIX | Troops Returning From The Ancre |

| LXXX | A Hospital Ship At A Base |

| THE BRITISH NAVY AND THE WESTERN FRONT | |

| LXXXI | “Oiling”: A Battleship Taking In Oil Fuel At Sea |

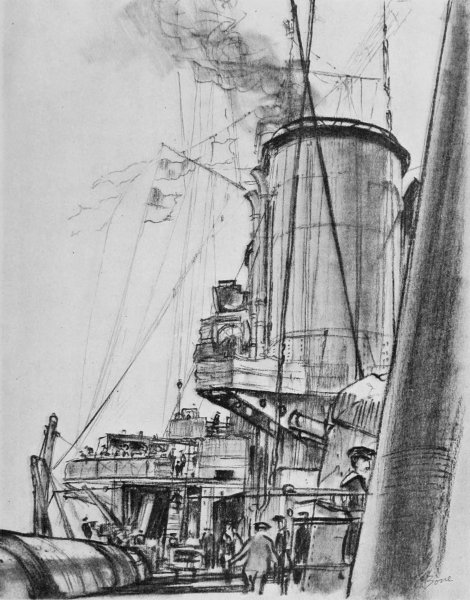

| LXXXII | On A Battle-cruiser (H.m.s. “Lion”) |

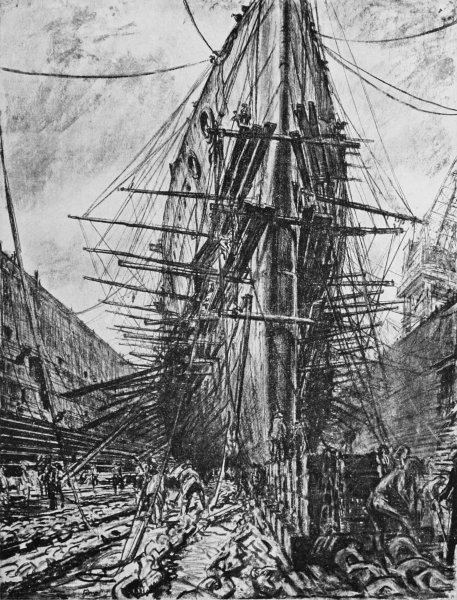

| LXXXIII | H.m.s. “Lion” In Dry Dock |

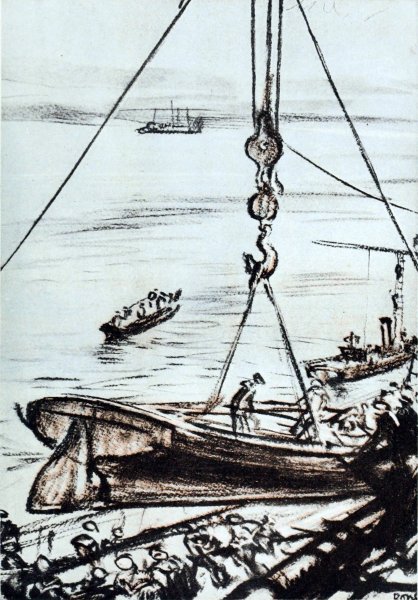

| LXXXIV | On A Battleship: Lowering A Boat From The Main Derrick |

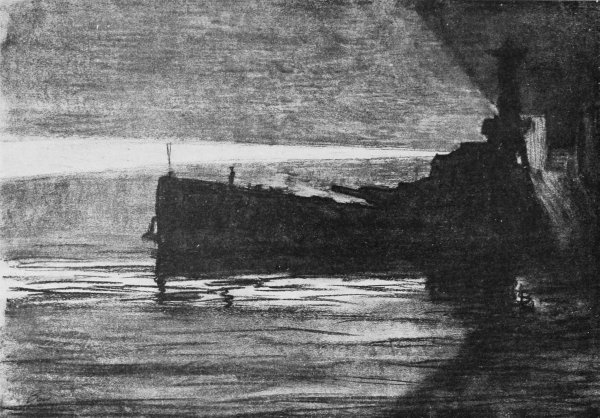

| LXXXV | Approaching A Battleship At Night |

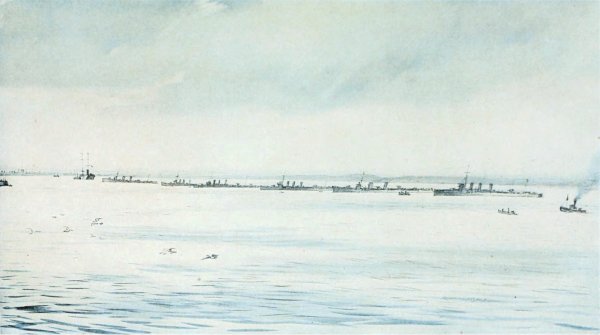

| LXXXVI | A Line Of Destroyers |

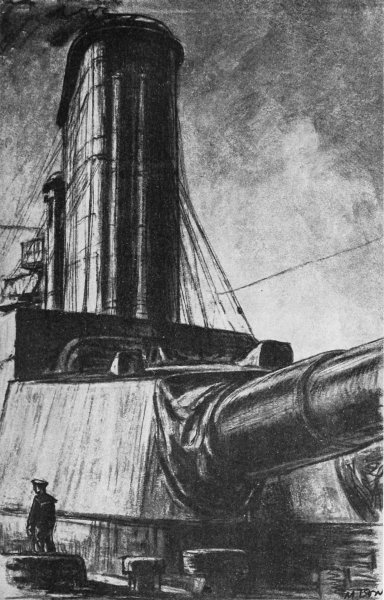

| LXXXVII | On A Battleship: A Gun Turret |

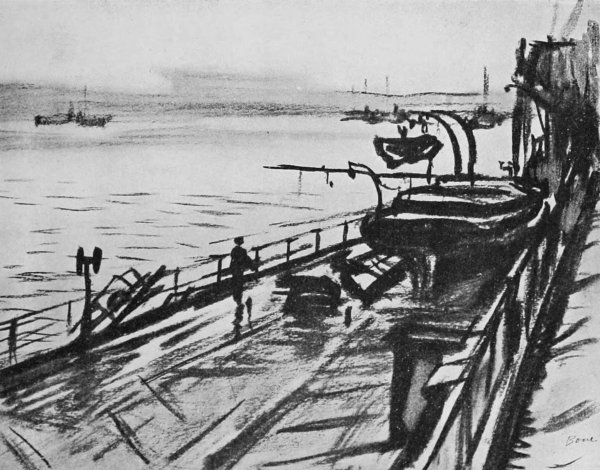

| LXXXVIII | On A Battleship In The Forth |

| XXXIX | (a and b) |

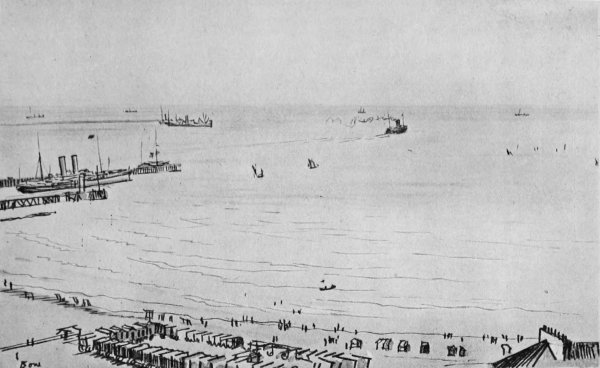

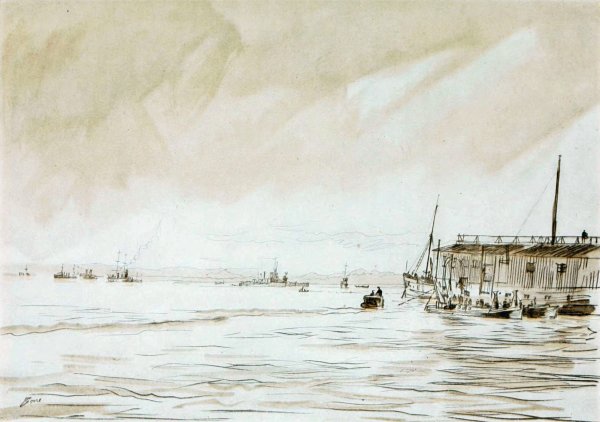

| A Fleet Seascape | |

| The Crew At A Small Gun On A Battleship | |

| XC | The Fo’c’sle Of A Battleship |

| XCI | On A Battleship: The After Deck |

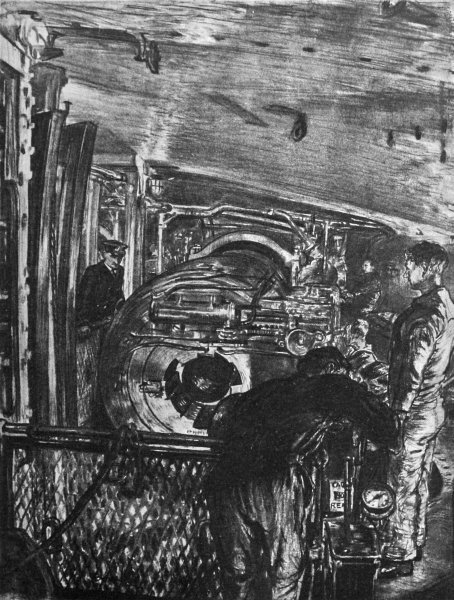

| XCII | Inside The Turret |

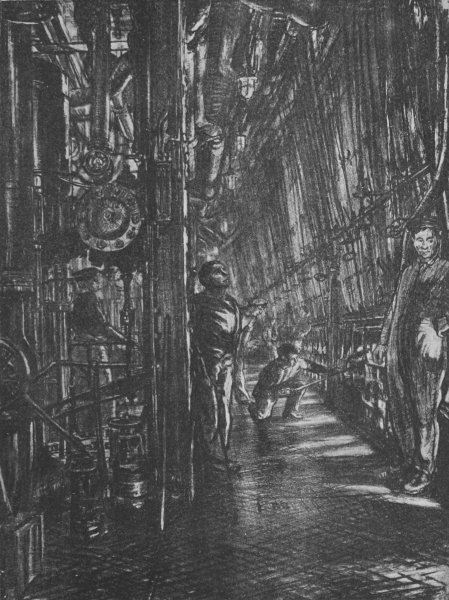

| XCIII | A Boiler Room On A Battleship |

| XCIV | (a and b) |

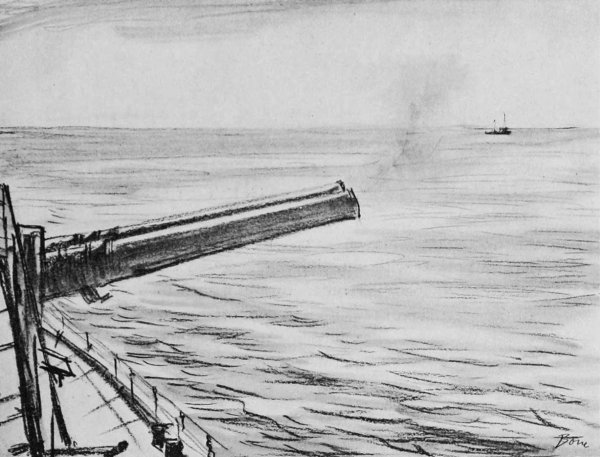

| Practice Firing: Big Guns On A Battleship | |

| On A Battleship: Sunset After A Wet Day | |

| XCV | On A Battleship: Airing Blankets |

| XCVI | Captain Cyril Fuller |

| XCVII | The Fleet’s Post Office |

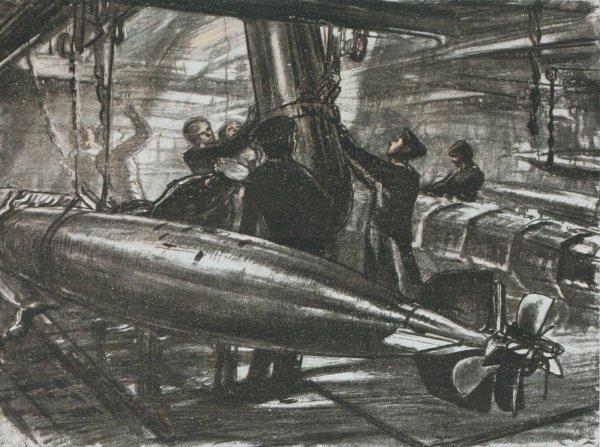

| XCVIII | In The Submerged Torpedo Flat Of A Battleship |

| XCIX | Sailors On A Battleship Making Munitions For The Army |

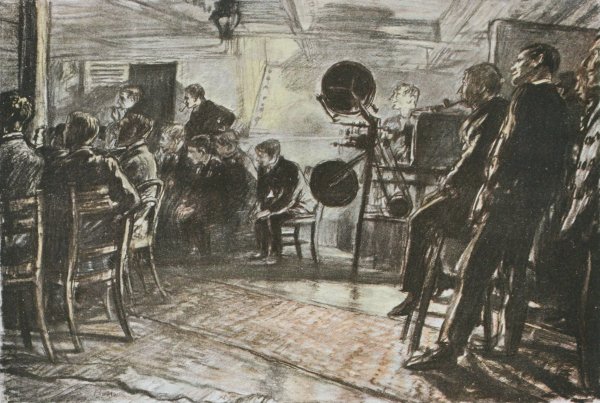

| C | The Cinema On A Battleship |

DRAWINGS BY

MUIRHEAD BONE

WITH AN INTRODUCTION BY

GENERAL SIR DOUGLAS HAIG

G.C.B., G.C.V.O., K.C.I.E., A.D.C.

PUBLISHED BY AUTHORITY OF THE WAR OFFICE

FROM THE OFFICES OF “COUNTRY LIFE,” LTD.,

20, TAVISTOCK STREET, COVENT GARDEN, LONDON

MCMXVII

I have been asked to write a foreword to Mr. Muirhead Bone’s drawings. This I am glad to do, as they illustrate admirably the daily life of the troops under my command.

The conditions under which we live in France are so different from those to which people at home are accustomed, that no pen, however skilful, can explain them without the aid of the pencil.

The destruction caused by war, the wide areas of devastation, the vast mechanical agencies essential in war, both for transport and the offensive, the masses of supplies required, and the wonderful cheerfulness and indomitable courage of the soldiers under varying climatic conditions, are worthy subjects for the artist who aims at recording for all time the spirit of the age in which he has lived.

It has been said that the portrait and the picture are invaluable aids to the right reading of history. From this point of view I welcome, on behalf of the Army that I have the honour to command, this series of drawings, as a permanent record in pencil of the duties which our soldiers have been called upon to perform, and the quality and manner of its performance.

General Headquarters,

November, 1916

The British line in France and Belgium runs through country of three kinds, and each kind is like a part of England. Between the Somme and Arras a British soldier often feels that he has not quite left the place of his training on Salisbury Plain. The main roads may be different, with their endless rows of sentinel trees, and the farms are mostly clustered into villages, where they turn their backs to the streets. More of the land, too, is tilled. But the ground has the same large and gentle undulation; and these great rollers are made, as in Wiltshire, of pure chalk coated with only a little brown clay. There are the same wide prospects, the same lack of streams and ponds, the same ledges and curious carvings of the soil; and journeys on foot seem long, as they do on our downs, because so much of the road before you is visible while you march.

A little north of Arras there begins, almost at a turn of the road, a black country, where men of the South Lancashires feel at home and grant that the landscape has some of the points of Wigan. It is the region of Loos and Vermelles and Bully Grenay, most of it level ground on which the only eminences are the refuse-heaps of coal mines. Across this level the eye feels its way from one well-known stack of pit-head buildings and winding machinery to another. They are, to an English eye, strangely lofty and stand out like lighthouses over a sea. The villages near their feet are commonly “model” or “garden,” with all the houses built well, as parts of one plan. As in Lancashire, farming and mining go on side by side, and in August the corn is grey with a mixture of blown dusts from collieries and from the road.

The next change is not abrupt, like the first; but it is as great. Near Ypres you are on the sands, though yet twenty miles from the sea. Here you have a sense of being in a place still alive but pensioned off by nature after its work was done. You feel it at Rye and Winchelsea, at Ravenna, and at any place which the sea has once made great and then abandoned. The wide Ypres landscape drawn by Mr. Bone was all mellow on sunny days at the end of July with the warm brown and yellow of many good crops. Almost up to the British front it was farmed minutely and intensely; in spring I had seen a man ploughing a field where a German shell, on the average, dropped every day. But all this countryside has the brooding quietude of a sort of honourable old age, dignity and pensiveness and comfort behind its natural rampart of sand dunes, but not the stir of life at full pressure.

Into this vari-coloured belt of landscape, some ninety miles long, and into its cities and villages, the war has brought strange violences of effort and several different degrees of desolation. Some villages are dead5 and buried, like Pozières, where you must dig to find where a house stood. There are cities dead, but with their bones still above ground: Ypres is one—many walls stand where they did, but grass is growing among the broken stones and bits of stained glass on the floor of the Cloth Hall, and at noon a visitor’s footsteps ring and echo in the empty streets like those of a belated wayfarer in midnight Oxford. “How doth the city sit desolate that once was full of people!” Again, there are towns like Arras, whose flesh, though torn, has life in it still, and seems to feel a new wound from each shell, though there be no man there to be hit. These are the broader differences between one part of the front and another. In any one place there are minor caprices of destruction or survival. Mr. Bone has drawn the top of the Albert Church tower, a building that was ugly when it was whole, but now is famous for its impending figure of the Virgin, knocked by artillery fire into a singular diving attitude, with the Child in her outstretched hands. Of the two or three buildings unharmed in Arras one is the oldest house in the town and another was Robespierre’s birthplace.

In the fields, as you near the front line, you note an ascending scale of desolation. It is most clear on the battlefield of the Somme. First you pass across two or three miles of land on which so many shells fall, or used to fall, that it has not been tilled for two years. It is a waste, but a green waste, where not trodden brown by horses and men. It is gay in summer with poppies, convolvolus and cornflowers. Among the thistles and coarse grass you see self-sown shoots of the old crops, of beet, mustard and corn. Beyond this zone of land merely thrown idle you reach the ultimate desert where nothing but men and rats can live. Here even the weeds have been rooted up and buried by shells, the houses are ground down to brick-dust and lime and mixed with the earth, which is constantly turned up and turned up again by more shells and kept loose and soft. The trees, broken half-way up their trunks and stripped of leaves and branches, look curiously haggard and sinister.

It is hoped that Mr. Bone’s drawings will give a new insight into the spirit in which the battle of freedom is being fought. An artist does not merely draw ruined churches and houses, guards and lorries, doctors and wounded men. It is for him to make us see something more than we do even when we see all these with our own eyes—to make visible by his art the staunchness and patience, the faithful absorption in the next duty, the humour and human decency and good nature—all the strains of character and emotion that go to make up the temper of Britain at war.

G.H.Q., France,

November, 1916

The gaunt emptiness of Ypres is expressed in this drawing, done from the doorway of a ruined church in a neighbouring square. The grass has grown long this summer on the Grand’Place and is creeping up over the heaps of ruins. The only continuous sound in Ypres is that of birds, which sing in it as if it were country.

In the distance is seen what remains of the Cloth Hall. On the right a wall long left unsupported is bending to its fall. The crash of such a fall is one of the few sounds that now break the silence of Ypres, where the visitor starts at the noise of a distant footfall in the grass-grown streets.

The Ypres salient is here seen from a knoll some six miles south-west of the city, which is marked, near the centre of the drawing, by the dominant ruin of the cathedral. The German front line is on the heights beyond, Hooge being a little to the spectator’s right of the city and Zillebeke slightly more to the right again. Dickebusch lies about half way between the eye and Ypres. The fields in sight are covered with crops, varied by good woodland. To a visitor coming from the Somme battlefield the landscape looks rich and almost peaceful.

All round this church there is the quiet of a desert. The drawing was made from within a house opposite; the fall of its entire front provided an extensive window view.

An exciting moment in the fighting for the summit ridge of the battlefield in August, 1916. All the British guns have just burst into action and our infantry are advancing unseen in the cloud of smoke on the sky-line. The puffs of smoke high in the air are from bursting shrapnel. The battle is seen from King George’s Hill, near the old German front line, taken on July 1st, 1916. Below, among the ravaged trees, are the ruins of Mametz; beyond them, Mametz Wood; beyond it, again, the wood of Bazentin-le-Petit.

In this fine drawing Mr. Bone has seen the “Tank” in its major aspect, as a grim and daunting engine of war.

The drawing shows a former German front-line trench reduced by our artillery fire, before an advance, to a mass of capricious looking irregularities in the ground. The German barbed wire entanglements are seen destroyed by our shell fire to open the way for our attacking troops.

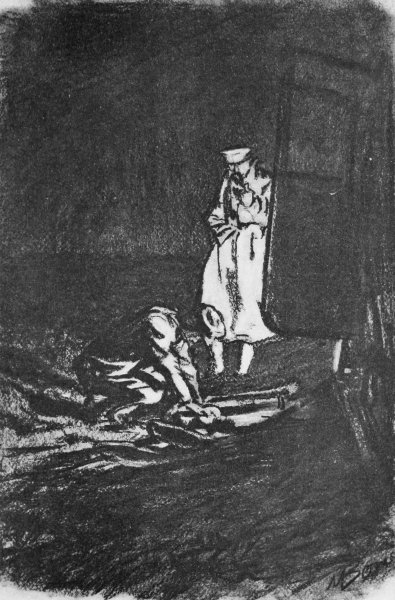

The hour is Retreat and a Sergeant-Major is inspecting the three men for duty at a one-man post during the coming night. Each man in turn will do two hours’ duty, followed by four hours’ rest. The fine austere drawing of the sunset, the wide waste spaces, the intent men mounting picket and the men off duty strolling at ease, is imbued with the spirit of the region just behind our front.

A small hamlet of sand-bagged dug-outs a little behind the front line, seen during a passing lift of the clouds at the end of a wet day. Many dug-outs, like the one on the left, bear such names as “The Rat Hole,” “It,” “Some Dug-out, believe ma,” “The Old Curiosity Shop” and “The Ritz.” On the right, a shelf in the outer wall of sand-bags is decorated with flowers in pots.

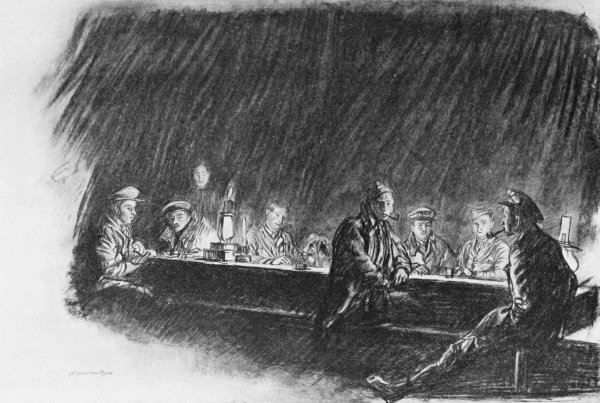

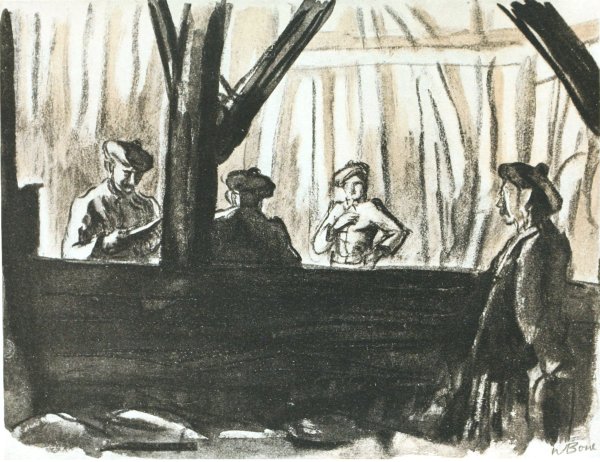

In the bare dancing hall of a village inn behind the Somme Front. The artist has found means to interpret with the utmost sympathy and power the extraordinary romantic quality that there often is about a Highland mess in France, created by the rude setting, the primitive half light amidst cavernous gloom, and the spectator’s sense of an enveloping world of strange dangers and adventures.

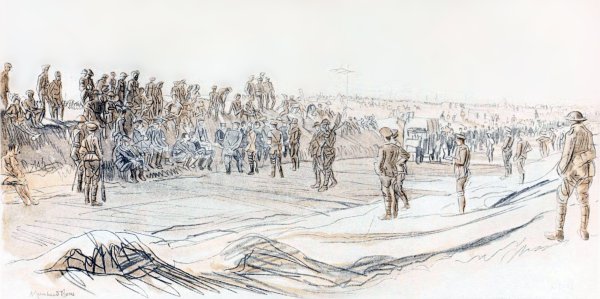

A British advance has just begun, and the surgeons of a Divisional Collecting Station near the Somme are awaiting the arrival of the first laden stretcher-bearers. In a few minutes the three officers will be at work, perhaps for twenty-four hours on end. At one Casualty Clearing Station a distinguished surgeon performed, without resting, nineteen difficult operations, each lasting more than an hour, in cases of severe abdominal wounds, where delay would have meant the loss of life. In almost every case the man was saved. Another surgeon operated for thirty-six hours without relief. Such devotion is not exceptional in the R.A.M.C.

The place is a field dressing station. The wounded Grenadier Guardsman in the foreground on the left, wearing a German helmet and eating bread and jam, had brought in as prisoner the German who is sitting on the right with his hand to his face. The Guardsman indicated the German to the artist, and said, “Won’t you draw my pal here, too, Sir? He and me had a turn-up this morning when we took their trench, and he jabbed me in the arm and I jabbed him in the eye, and we’re the best of friends.” Other Germans are sitting in attitudes characteristic of newly-made prisoners.

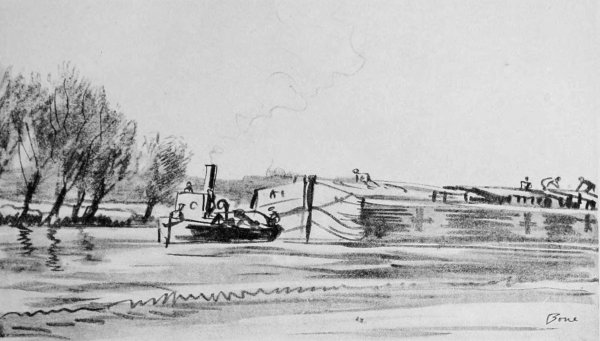

Many wounded or sick soldiers, British and French, are brought by river or canal from near the front to near a base hospital or the sea. The motion is easy, the men have good air and quiet; any who are well enough to be on deck have pleasant and changeful surroundings to look at. The English have fitted up for this purpose many of the large, square-built and bluff-bowed—almost box-like—French canal boats. They are towed, in pairs, by small tugs. The French Red Cross uses barges driven by engines placed aft.

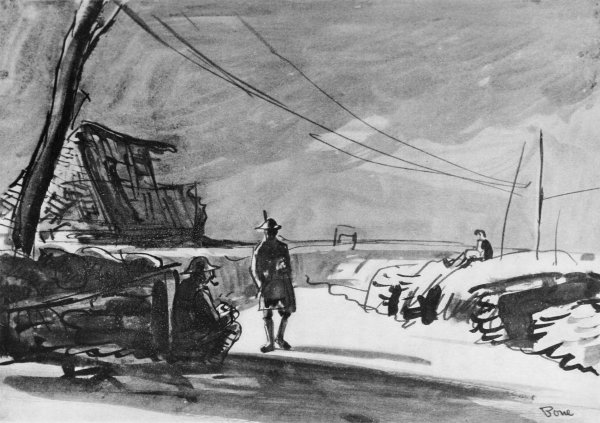

A midnight scene at a base railway station. Train-loads of “walking wounded” on their way to England are met at any hour of the day or night by V.A.D. workers who offer the men hot tea or cocoa, and bread and butter. The quality of the food, and the manner of the gift, give extraordinary pleasure to the tired men.

The boat here is an old one; in newer boats the accommodation is finer, but the drawing shows the ordinary mode of bedding the patients in double tiers of continuous bunks. At some point in the passage an R.A.M.C. orderly asks every patient to what part of “Blighty” he belongs, and an effort is made to send him to a hospital near his home. The orderly’s approach, as he makes his rounds, is always eagerly awaited throughout the ship by the wounded men.

An every-day scene at the French ports where our men land. Whatever may come after, there are few moments so thrilling to an untravelled soldier of the New Army as those in which he awaits the order to march off into the unknown, with all the strange events of war before him.

The unusually comfortable quarters of a Company in reserve while other Companies of its Battalion are in the firing and support trenches, two or three miles further up. Reserve billets are more often under ground, sometimes in the cellars of ruined houses. A thick covering of ruins above gives complete security against shell fire.

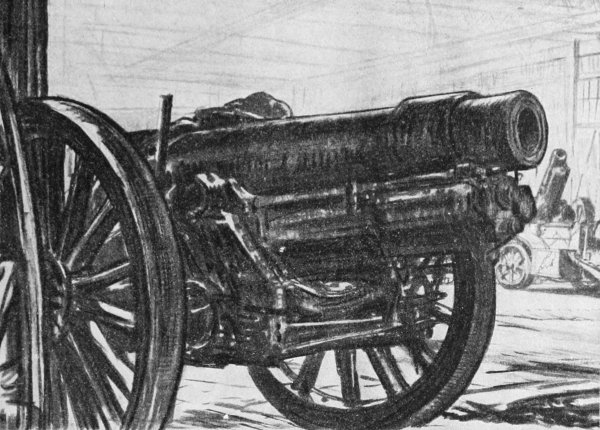

Many wounded or worn guns, of all calibres, are brought back for treatment to “hospitals” which do not fly the Red Cross. Here are a few invalided “heavies.” The gun on the extreme right is the first British 9.2 that came to France. Like most of our heavy guns she has been christened by her crew and bears the punning inscription, “Lizzie, Somme Strafer.”

The lower part of the first of the ladders leading up to an artillery observation post in the top of a tall tree. It commanded a large part of the Somme battlefield until the summit ridge was won; every detail of several successful British advances could be watched from the tree-top. The battle has now left it far in the rear, and it is disused.

The main Anglo-German battlefield of 1916 is a little range of chalk down or blunt hill. It is ten miles long and seven miles wide, and its watershed runs from north-west to south-east—from near Thiepval, above the small river Ancre, to Combles, four miles to the north of the canalised Somme. This summit ridge is not quite 500 feet high—about as high as the Hog’s Back in Surrey. The south-western slope of the range is rather steeper and more broken up into terraces and lateral ridges and defiles than the north-eastern slope. There is no real escarpment, but enough difference to make the south-western slope the harder to attack.

Small as this ridge is, it is the highest ground, in these parts, between the Belgian plain and the main plain of Northern France. It is crossed at right angles by one great road, the famous French Route Nationale that runs nearly dead straight from Rouen, through Amiens, to Valenciennes, and so leads on to Brussels by Mons. On the battlefield, between Albert and Bapaume, it reaches the highest point above the sea in all its long course, at a spot where a heap of powdered brick and masonry, forty yards off to the north, marks the site of the Windmill of48 Pozières, one of those solitary buildings to which, like Falfemont Farm and the Abbey at Eaucourt, the war has brought death and immortality.

From this road, at one point or another, you can see most of the places that were made famous in 1916. A mile and a half from Albert, as you go out north-eastward, you spy in a hollow below you a whitish sprinkling of mixed mud, brick-dust and lime, the remains of La Boisselle, on the right of the road. On its left a second grey patch is the site of Ovillers. Beyond La Boisselle Contalmaison is just out of sight behind a shoulder of hill. Nearly all the most hard-fought woods are in sight—High Wood on the sky-line, and Delville Wood larger on its right, and then in succession, with sharp intervals of bareness between them, the woods of Bazentin, Mametz and Fricourt. Above them and more distant are the dense trees that have Maricourt and the French troops at their feet, and, high on their right, the thin file of trees shading the road that runs from Albert, past Carnoy and Cléry, to Peronne. You walk on for three miles and may not observe that you have passed through Pozières, so similar are raw chalk and builder’s lime, raw clay and powdered brick, when weeds grow thick over both. But the great road—strangely declined into a rough field track—begins to fall away before you, and new prospects to open—Courcelette and Martinpuich almost at your feet, and straight beyond them the church and town hall of Bapaume at the end of the long avenue of roadside trees. Looking left you see, two miles away, the western end of the summit ridge, the last point upon it from which the Germans were driven; so that, even after the fall of Thiepval, a shell would sometimes come from the Schwaben Redoubt to remind unwary walkers at Pozières Windmill that enemy eyes still watched the lost ground.

Among the wreckage of the countryside you can detect the traces of old standing comfort and rustic wealth. The many wayside windmills show you how much corn was grown. In size and plan they are curiously like the mighty stone dovecotes of Fifeshire. Almost as frequent as ruined windmills are ruined sugar refineries, standing a little detached in the fields, like the one at Courcelette, for which armies fought as they fought for the neighbouring windmill. Beet was the next crop to grain. There were little industries, too, like the making of buttons for shirts at Fricourt, where you see by the road small refuse49 heaps of old oyster shells with many round holes where the little discs have been cut cleanly out of the mother-of-pearl, though all other trace of the factories has vanished. Each village commune had its wood, with certain rights for the members of the commune to take timber; Fricourt Wood at the doors of Fricourt, Mametz Wood rather far from Mametz, as there was no good wood nearer. All these woods were well fenced and kept up, like patches of hedged cover dotted over a park. It was a good country to live in, and good men came from it. The French Army Corps that drew on these villages for recruits has won honour beyond all other French Corps in the battle of the Somme.

Many skilled writers have tried to describe the aghast look of these fields where the battle had passed over them. But every new visitor says the same thing—that they had not succeeded; no eloquence has yet conveyed the disquieting strangeness of the portent. You can enumerate many ugly and queer freaks of the destroying powers—the villages not only planed off the face of the earth but rooted out of it, house by house, like bits of old teeth; the thin brakes of black stumps that used to be woods, the old graveyards wrecked like kicked ant-heaps, the tilth so disembowelled by shells that most of the good upper mould created by centuries of the work of worms and men is buried out of sight and the unwrought primeval subsoil lies on the top; the sowing of the whole ground with a new kind of dragon’s teeth—unexploded shells that the plough may yet detonate, and bombs that may let themselves off if their safety pins rust away sooner than the springs within. But no piling up of sinister detail can express the sombre and malign quality of the battlefield landscape as a whole. “It makes a goblin of the sun”—or it might if it were not peopled in every part with beings so reassuringly and engagingly human, sane and reconstructive as British soldiers.

G. H. Q., France.

January, 1917.

The “Parthenon of Gothic Architecture” is seen in this exquisitely delicate and sensitive drawing from the south-east, with the lovely rose window of the south transept partly in view on the left. The wooden spire, which Ruskin called “the pretty caprice of a village carpenter,” looks finer in the drawing than in the original, the relative flimsiness of the material being less apparent. Nothing is lost by the intervention of the foreground houses, as the façade of the south transept, like the famous west front and the choir stalls, is sheathed with sand-bags to a height of thirty or forty feet for protection against German bombs. Patrolling French aeroplanes are seen in the sky.

An image which strangely escaped destruction during the time when the village of Montauban, now utterly erased, was being shelled successively by British and German guns. By a similar caprice of fate the Virgin of Carency, now enshrined in a little chapel in the French military cemetery at Villers-aux-Bois, received only some shot wounds when the village was destroyed during the French advance towards Lens in 1915.

Albert, as a whole, is wrecked to the degree shown in this drawing. The building in the middle distance, on the right of the road, with its roof timbers exposed, is a wrecked factory, and many hundreds of bicycles and sewing machines now make an extraordinary tangle of twisted and broken metal in its basement.

Wounded men from the Somme, ordered to England by the Medical Officer commanding the General or Stationary Hospital in which each man has been a patient, are being put on board a hospital ship at the base. In the centre of the foreground is seen the timber framework of the ship’s large red cross of electric lights. With this, and a tier of some sixty green lights running from stem to stern, a hospital ship at night is a beautiful as well as unmistakeable object at sea.

The best place to sleep, on a summer night in a full hospital ship, for a man whose wound is not grave enough to cause serious “shock” and consequent need of much artificial warming.

This drawing was done in the warm early autumn of 1916. All “walking wounded” wear lifebelts, if their injuries permit, during the Channel crossing, and each “stretcher case” has a lifebelt under his pillow, if not on. The necessity for this, in a war with Germany, has been proved by the fate of too many of our hospital ships.

The deck of a British hospital ship is one of the most cheerful places in the world. Every man is at rest after toil, is about to see friends after separation, can smoke when he likes, and has in every other man on board a companion with whom endless reminiscences can be exchanged, and perhaps the merits and demerits of the Ypres salient, or the most advantageous use of “tanks,” warmly debated, as is the custom of privates of the New Army. Silent or vocal, a great beatitude fills the vessel.

The canvas screen on the left marks a place where the road had been under enemy observation. A “sausage,” or stationary observation balloon, is seen above the road. “Sausages” are not pretty. They exhibit, at various stages of inflation, the various shapes taken by a maggot partly uncurled. But the work done from them, besides being always disagreeable and often risky, is extremely valuable.

A stretch of high-road which was under enemy observation when drawn. Such roads are, of course, only used with due caution. The whole drawing is remarkably instinct with the artist’s sense of a malign invisible presence—a “terror that walketh by noonday”—infesting the sunny vacant length of the forbidden road.

War has its tyre troubles, as peace has. In this case the lack of a spare wheel, and the consequent necessity for changing an inner tube, had the compensation of giving the artist time to make the drawing.

A typical Picardy landscape behind the frontal zone of destruction. The crescent-shaped line of troops and transport on the road is a small fraction of a Division moving up to take its place in the front line.

The place is Contalmaison, but the drawing has caught the spirit of the whole of the shattered country-side recaptured this year.

A typical winter scene on the Somme battlefield. The nearer “sausage,” or captive observation balloon, is being run out to its proper height for work, by unwinding its cable from a reel on the ground. The further balloon is already moored high enough and its observer, alone in the small hanging cage, is at work with his map, telescope and telephone.

A casualty in the R.F.C. The smashed biplane and the retreating stretcher party on the right explain themselves. On the left, Albert church, to the right of a tall factory chimney, is seen in the distance.

The Officers’ mess at the most advanced station of the Royal Flying Corps on the Somme front. The great tent was designed as an aeroplane hangar. An R.F.C. mess usually has an atmosphere of its own. There is more variety of apparel than at other messes; there are more dogs; personal mascots abound, and in many ways there is more expression of individual choice or peculiarity than elsewhere—corresponding, perhaps, to the more individual character of a flying officer’s work and responsibilities and to the temperament which leads to success in flying. The officers are drawn from all sorts of regiments, and each continues to wear his regimental badge. It is winter, and the second figure from the left is wearing a fur jacket.

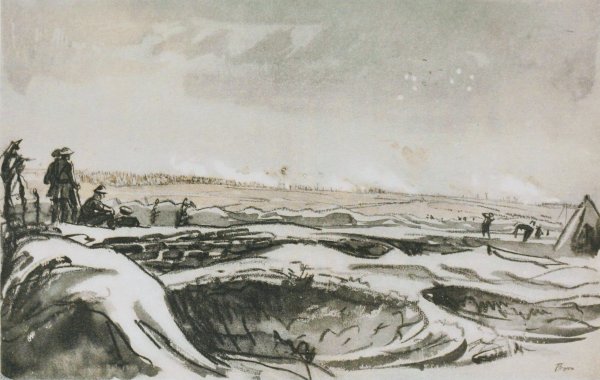

The drawing expresses well the singular aspect of the parts of the battlefield where artillery fire was heavy and where the conical holes made in the ground by high explosive shells were consequently close together. At a later stage these separate pock-marks overlap, like the pits in confluent small-pox, and the whole of the shelled ground becomes soft and loose, as though raked deeply but unevenly. In the distance the detached higher puffs of smoke from bursting shrapnel are distinguishable from the rising clouds of smoke from high-explosive shells.

Both the places drawn were in German hands until July. The first drawing is of a cemetery found behind the old German front line near Fricourt. There were many imperfectly marked German graves near these. They have since been marked, as many thousands of hurriedly made British graves have been, with wooden crosses and metal inscriptions by our Graves’ Registration and Inquiries Units.

The second drawing, with a helmeted sentry at the sand-bagged entrance to a dug-out, conveys the sinister air of a village destroyed, but not quite effaced, by shell-fire.

At a base railway station in France. Between the arrivals of hospital trains from the front the V.A.D. workers occupy themselves in the “dispensary” in rolling bandages or preparing hot cocoa and other food for the wounded or sick men who will pass through the station.

A few hundred yards from this gate the Anglo-French treaty of peace was signed after Agincourt. Part of the city’s later history is written in the curious and beautiful Spanish architecture of its chief squares. It is now in the middle stage of destruction: almost every building is shattered or injured, but enough is standing to make the empty city seem still sensitive, in its very stones, under the enemy’s random shellfire.

At Arras the Germans always seem very near you. In fact they are. No other famous town in the Allies’ hands has a German front trench in its suburbs; nowhere do the two front trenches come so close to each other. The result is a subtle quality of apprehensiveness in the atmosphere of the silent empty city. It seems like someone standing on tiptoe, peering and listening, in a solitary place, for some vague unseen danger, or like a horse nervously pricking its ears, you cannot tell why. This tingle of uncanny dread has been conveyed with remarkable success in this figureless but haunted landscape.

British soldiers watching recently captured Germans on their way down from the front to an Army Corps “cage.” Until removed to the base our prisoners are well housed in huts or tents in a kind of compound fenced with barbed wire and placed well outside the range of their friends’ artillery. There are no attempts at escape. Our men, behind the front line, always watch the arrival of new prisoners with silent curiosity. Those of our soldiers who have themselves fought with the Germans, and captured them, usually befriend them with cigarettes and drinks from water-bottles.

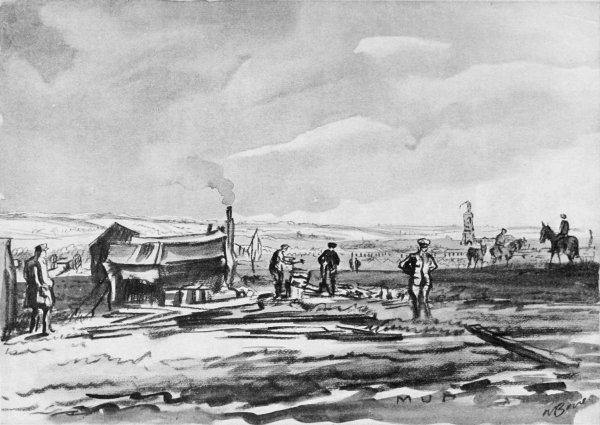

At a camp, near Albert, whose Church, with the image knocked awry, is seen to the right. With the permission of the officer on the left some soldiers are fishing in the mud for such fragments of old timber, boxes and tins as may be of use to them in their field housekeeping, though they are not worth collecting for deposit at the official Salvage Dumps.

In one of these drawings Mr. Bone gives a rousing glimpse of trench life at a moment of action. These are its moments of transfiguration, when all the glow of courage, that has been banked down and husbanded through months of waiting and guarding, bursts, at a word of command, into flame. The rest of trench life is work, contrivance and observation. It has been called monotonous. But, for any man who has not lost the heart of a boy, it has the relish of an endlessly changeful outdoor adventure, a game with the earth and the weather, as well as with the more official enemy.

No two points in an Allied front trench are wholly alike. Certain general patterns there are, but no facsimiles. Each traverse or bay has a look of its own; it is personal and expresses, as Robinson Crusoe’s stockade might have done, the nature of some man or men making shift, each after his kind, to put up what they could, in the shortest time, between their bodies and danger. A German firing trench is less various. In it you seem to see the minds of a few large and able contractors; in ours the minds of thousands of good campers-out. To put it in another way, the German trench has, in some measure, the quality of a long street built, well enough, to a single design; ours possesses the charm of a92 strip of coast or a long country lane, where nature or man has made every indentation and turn a surprise, and each farmer has made gates and hedges to his own mind.

The line goes through wonderful places and charges them with singular thrills of romance. It has made windmills famous as forts, and brought herons into the suburbs of cities. In one place it runs across water and land so intermixed that the sentries of both armies are upon little islands crowned with breast-works like grouse butts; you see them, when the winter evening falls, standing immobile, waist-deep in mist, each man about forty yards from his enemy. Men have stood there, turn by turn, for two years and a half, moving softly and whispering as if in a church, till the shyest of wildfowl have learnt to treat the surrounding marsh as their own, and the only sound is of wild duck and snipe astir between the muzzles of two nations’ loaded rifles, snipe safe among the snipers. At more than one place the two front lines converge until each sentry knows that he is within a gentle bomb’s throw of the enemy. Out of the firing trench, at one of these places, you walk on tiptoe along a short sap that halves this short distance, and from its end you look up at a small heap of rubble—a couple of cart-loads—and know that some German is cautiously listening, like you, on its further side.

Those are the cramped and contorted parts of the front. A few miles away it will straighten and loose itself out; you see it run free, in great, easy curves, up the slopes of wide moorlands, the two front lines drawn apart almost three hundred yards. Each is a double band of colour; the white ribbon of its dug chalk and the broader rust-brown ribbon of its tangled wire stand out clear against the shabby velveteen grey of the heath. Here there is less of thrill and more of ease in trench life; by day the sentries peer, hour by hour, into the baffling mist that is woven across their sight by our own and the enemy’s wire; it is like trying to see through low and leafless, but thick, undergrowth. By night the wire makes, to the sentry’s eye, a middle stratum of opaque dark grey, between the full blackness of the earth below it and the more penetrable obscurity of the night air above. But the darkness is never trusted for long. All night each army is sending up rocket-like lights to burst and hang like arc lamps in the air over the firing trench of the other. From a commanding point you can see, at any moment of any night, scores of these ascending rockets, each like a line drawn on the dark with a pencil of flame, arching over to intersect each other near the zenith of their flight, incessantly tracing and re-tracing the lines of a Gothic nave over all No Man’s Land, from the Alps to the sea. All night, too, there93 is a kind of pulse of light in the sky, along the whole front, from the flash of guns. From the trenches the flash itself can seldom be seen, but the sky winks and winks from moment to moment with the spread and contraction of a trembling radiance like summer lightning.

At most parts of the line a man in the front trench is cut off from landscape. To look at a tree behind the enemy’s lines may be to give a mark to a sniper hidden in its boughs. By day you see the upper half of the dome of the sky, and, through loopholes, a few yards of rough earth or chalk, then the nebulous wire and, through its thin places, perhaps a few uniforms, blue, grey or brown, lying beyond, among the coarse grass and weeds. At night you see all the stars well, and on moonlight nights, if you walk the trench softly, you can watch strange friezes sharply silhouetted on the sky line of the parapet, the wars and loves of capering rats, “flouting the ivory moon.” Whole choirs of larks may be heard: neither cannon nor small arms seem to alarm them; and most of the ground has its own hawk to quarter it daily.

To men put on this short allowance of natural sights and sounds it is an extraordinary pleasure to find in the rear of their trench a clean rivulet, such as often occurs in chalk land, where the surface water filters rapidly in and comes out at the bases of slopes like so many crystal springs. But the greatest of all trench delights is the re-discovery, every year, of the sun. Some day in March it is suddenly found to have a miraculous warmth, and everybody off duty comes out like the bees and stands about in the trench, sunning his head and shoulders in the tepid rays and adoring—quite inarticulately—and feeling that all’s well with the world. A winter in trenches revives, in us children of civilisation, a pre-Promethean rapture of love for the sun; and the dark nights, in which not a match must be struck, makes us, at any rate, think more highly than ever we did of the moon, which halves the strain of the soldier on guard, and of the stars which guide him back overland to his billet, at a relief, to sleep in Elysium. So, for a man who has all his senses alive and unjaded, the hard and bare life has its compensations. It makes him do without many things; but it also quickens delight in the things which are at the base of all the rest, and without which there could not have been the incomparable adventure and spectacle of life on the earth.

G. H. Q., France.

February, 1917.

Cassel has no great part in this war. But it has endured ancient sieges; three notable battles have taken its name since 1070; the last of them led to the annexation of Cassel to France in 1678 and gave her a town finely set on a hill amidst lowlands, and equally good to look at and look from. The many windmills about it give Cassel an air of liveliness as you approach, and this cheerful effect is maintained on reaching the main square, drawn by Mr. Bone, with its lightsome spaciousness and comfortable, well-proportioned houses. The eyes of passing Scottish soldiers find a familiar look in the “step” gables of many of Cassel’s roofs. One is seen on the right.

Thanks to the imaginative power of the artist, the “Tank” is here seen not as the British soldier sees it—a friendly giant with lovably droll tricks of gait and gesture—but as it must look to a threatened enemy, the very embodiment of momentum irresistibly grinding its way towards its prey. In the presence of “tanks” as here drawn—though there is no trace of exaggeration in the drawing—the spectator is as a crushed worm and, in fact, finds there is more force in that phrase than he knew.

One of the improvements in our field organisation since the early part of the war is the more general provision of hot meals for the men in the front trenches. From cookhouses like the one shown in the drawing, or from travelling field kitchens, the hot stew and tea are brought up the communication trench in dixies, two to a platoon, each dixie being slung from a pole carried on two men’s shoulders. The cooks work under shell fire and many have been killed.

The drawing shows one of the most thrilling moments in the making of a great gun. The doors of the furnace have just been thrown back and the heated gun tube is about to be lifted by the giant pincers of the crane.

The gun jacket shown here has just been heated in the furnace and is about to plunge into its oil bath. The spectacle is always striking, especially at dusk, when the fierce glow of the huge mass of metal seems more brilliant than ever. The passage is made in a few seconds.

The figures in the foreground give a scale by which to judge the size and power of the crane that handles the heavier guns in the gun pit. The tube has now been lifted from the oil tank and waits to be carried back to the gun shop lathes.

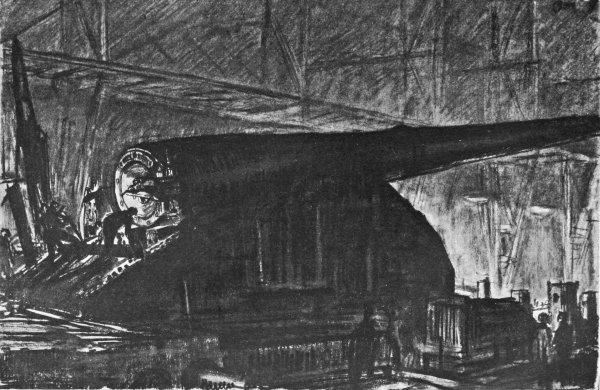

This is one of the largest guns. At such a scene as its mounting one is always struck by the contrast between the restless stir of the minute figures busy about it and the massive impassivity—for the present—of the thing they have created. “A great gun,” it has been said, “is so sheer.” In a gun shop it dwarfs everything round it and seems the embodiment, at the same time, of immobility and of menace.

A store containing loaded shells of every calibre. All the plant has been made since 1914, in answer to the challenge of German militarism. The railway trucks in the foreground are incessantly filled and refilled from the supplies pouring into the store for dispatch to the front. Women drive the cranes that gather up bunches of shells from any part of the building and lower them, with absolute precision, to their appointed places in the trucks. All handling of shells must be cautious and deliberate, but the work proceeds, without haste and without rest, at a remarkable speed.

The village of Bécordel-Bécourt is just on the Allies’ side of the front line as it was before the Battle of the Somme. It has, therefore, sustained only the German artillery fire, not that of both armies in turn. Hence the survival of this comparatively large fragment of the village church.

Owing to the low tide the “stretcher cases” or “lying wounded” had all to be carried underneath the pier to the level of the hospital ship. This meant very hard work for the stretcher bearers, and one is here seen resting a moment while the previous stretcher is being carefully taken aboard to be lowered by the lift from the deck to the large wards below.

In the left centre are the tall ruins of the large church of the monastery at Mont St. Eloi, a little hill about five miles north-west of Arras. The hill is a splendid viewpoint, commanding the Vimy Ridge, the German lines between Neuville St. Vaast and Thelus, the city of Arras itself, the wood of Souchez and the slopes of Notre Dame de Lorette. On the ground for many miles north and north-east of it the French fought with heroic determination in the advances which gained them Carency, Souchez and Notre Dame de Lorette in 1915.

Mametz must have been one of the pleasantest of the villages on the Somme battlefield. It was built on a gentle slope, facing south, a little way off the dusty main road from Albert to Peronne, and large, shady trees were intermingled with the houses. The drawing shows what was left of the village after its capture in the beginning of July. The tall fragment of the parish church stands in the centre of the drawing.

In this one drawing may be seen the face of all the hard-fought woods of the Somme battlefield—Mametz, Fricourt, Bazentin, Delville, Thiepval, Foureaux and St. Pierre Vaast. Everywhere in them all there is the same close network of half-filled trenches, the same bristle of ruined tree trunks, the same litter of the leavings of prolonged fighting at close quarters—bits of broken rifles and bayonets, perforated helmets, unexploded hand grenades, fragments of shell, displaced sand-bags, broken stretchers, boots not quite empty, and shreds of uniform and equipment.

It is always cold in an aeroplane in flight, but in winter the cold endured by airmen is often atrocious, however perfect their equipment. A pilot, who has just come down from his three hours of duty in the air, is here seen “thawing out” over a spirit stove in his tent. Like the thawing of meat taken from cold storage, the process requires some patience.

At a base port in France. Officers are disembarking from the upper deck. Many officers arrive under orders simply to “proceed overseas.” At the “A. M. L. O. Office” they receive, through the Assistant Military Landing Officer, exact orders where to go and what to do. The men on the lower deck disembark by a second gangway and the boat is cleared in a few minutes.

Every soldier on active service has more or less of deferred sleep, as well as deferred pay, due to him. If he be wounded he usually recovers a large instalment of both—the former during his first nights and days in hospital, the latter when he leaves the convalescent hospital for the ten days’ sick leave given to all wounded or sick men who have been sent to England for treatment.

As you walk southward from Amiens, across meadows and cornfields, the ground rises more gently than the immediate south bank of the Somme, on which the Cathedral and the City stand. Thus the city sinks gradually out of sight until nothing is left but the thin Cathedral spire, looking like the mast of a sunken ship. Mr. Bone’s drawing was done from a point, about a mile south of the city, at which the Cathedral roof, the tower of Saint Martin’s Church, and one or two factory chimneys are still unsubmerged.

A typical billet for troops on the march or enjoying a “Divisional rest” between two turns of duty in the trenches. An average-sized barn at a French farm will house about thirty men. If the straw be deep and the roof sound it makes better quarters than anything but a good bedroom. Its chief drawback in the men’s eyes is that smoking has to be forbidden because of the straw. In the winter evenings the men usually cross the farmyard to the kitchen, where they smoke and make friends with the farmer, and buy coffee, at a penny a bowl, from his wife.

Characteristic trench attitudes, two of the men with their heads well down, the cheek cuddling the small of the butt, while the N.C.O. beyond directs their fire, with his head a little free. There is just the same soldierly combination of “much care and valour” in the typical Welshman in France to-day as there was in Shakespeare’s Fluellen.

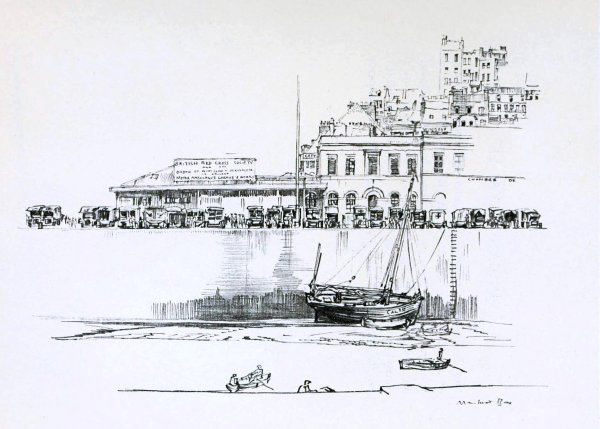

Dead low water in Boulogne Harbour, and a slack time for the motor ambulances parked on the quay above. The work of the R.A.M.C. inevitably comes in rushes, with lulls in between. The great thing is, when a rush comes, to treat every case with a rapidity exactly proportioned to its urgency, removing instantly to the base hospitals or to England every serious case which will be the better, or none the worse, for a slight delay in operation. To work this system perfectly there must always be in readiness, at every point where wounded are entrained or transhipped, a supply of ambulances equal to the maximum call.

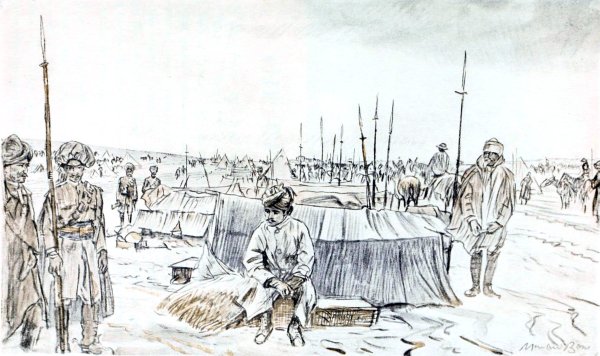

Our Indian Cavalry on the Somme were given a chance of showing their quality at the Bois de Foureaux on July 17th, 1916. They used it. Apart from other soldierly qualities, the grave dignity of their bearing impresses all foreign visitors to the battlefield. They always salute a passing officer as if they were Kings and he an Emperor.

In these better days it is no harm to speak of the time when the Marne had been won and yet our Army in France was within an inch of its life. The thread of its fate had frayed very thin; only one strand remained; at last, not even that—what had taken its place was a gallant sham, a last forlorn bluff, scarcely a hope. And then came the ancient reward of those who fight on without hope. Like a storm that had blown itself out, the strain was suddenly gone. The strong had not known all their strength, the weak had steadfastly hidden their weakness, and they had worn out the strong.

That extreme peril has never recurred. But there were months in 1915 when men in our trenches still felt that the upper hand was not theirs. What would happen was this. Once or twice in the day the Germans, after their meals, would spray a piece of our trench with trench-mortar bombs and rifle-grenades. As a rule they did not mean136 to attack, in the fuller sense. The piece was not an overture; it was complete in itself; a sort of isolated pas d’intimidation. Not many men on our side would be killed. But, while the shower went on, everyone on duty in our firing trench felt with crystal clearness that he was on the defensive. At each fresh discharge he would plaster himself upon the front wall of the trench and gaze upwards for the coming evil. If he saw the approaching waddle of a trench-mortar bomb, wagging its tail through the air, he would judge it like a catch in the long field, only with an ardent desire to miss it; and to this end he would jump round corners of trench and put solid angles of earth between him and the large muted sound like “pfloonk” that was to ensue. If what he heard was the thin hiss or spit of a rifle grenade, then he knew that it could not be seen, and he kept his head down and wondered how near the venomous little metallic smash of the burst would be. In any case he was bespattered, throughout the bombardment, with little falling bits of earth, warm metals and products of combustion; the tinkling of this hail on his helmet deepened his rueful sense of resemblance to a hen crouching under the lee of a hedge in bad weather. And, all this time, our own mortars and guns would be silent or—almost worse than silence itself—would reply with the mildness of Sterne’s patient ass. “Please do not shell our front trench. But, if you want to, you may,” so they seemed to be saying.

From these mortifications the men in the firing trench, and the gunners who had endured the sharper torment of not being able to help them, were saved by the women, whom Mr. Bone shows us working at home, arming their knights for battle in a sense more valid than any known to Froissart or Malory. There came a time, most moving and memorable to all who were then in our trenches, when any German attempt to gall them began to evoke new, heart-warming sounds. All the upper air, over the place where the pelted sentries were crouching, seemed to have come to life on our side. At last our own trench mortars were answering, not in a few grudged monosyllables, but volubly, out of the fulness of the dump. Higher up also, there rose arch over arch, as it were, of audible, reassuring protection—first the low-pitched bridges of sound traced by the whizz of our field guns, and then the vast rainbow curve of our heavier shells making wing, high over head, with a more august, leisurely waft that sounded divinely. It was a changed and137 cheered world to be living in. We had the upper hand now, and every woman turning a shell or driving a crane in England had helped us to have it.

We have it now still more securely. Since that time we have learnt the technique of attack—how to keep what we take and how to take what we want at no more than it need cost in lives. We have won, in hard fight, the best of all posts of observation—the sky, so that during the great engagements last year on the Somme there was not a German aeroplane to be seen in the air while ours were ranging everywhere over the battlefield, each with its eyes on the enemy’s lines and its voice at the ear of our guns. Our men and the gunners have now crossed bayonets so often that all the old awe in which Europe held the men of Sedan and Sadowa is gone; boys from Wiltshire and Worcestershire farms, recruits of a few months before, have chased Prussian guardsmen uphill out of their trenches and then held these ruined defences against all that those picked products of intensive military culture could do to regain them.

All this turning of tables has been brought about by one cause, in the sense that if that cause had been absent, the care and skill of the finest leaders, the daring of all our airmen, the staunchness of all our infantry would have been strength to no purpose. Munition workers have woven the curtain of smoke that our gunners now draw between our advancing troops and the eyes of their enemy. It is munitions that, thrown from our howitzers, make level roads through the tangles of wire on which, in the old days, the corpses of whole platoons of our men were hung up to rot and look, from far off, like washing put out to dry on thorned hedges. It is munitions that, when we attack, hold back the hostile supports behind a wall of falling bullets as hard to pass as Adam found the flaming sword at the gate. It is, then, not without reason that in this sheaf of drawings of the war on the Western front are included some drawings of guns and shells in the making. They are drawings of victory in the making, and of the saving of hundreds of thousands of British lives.

G.H.Q., France,

March, 1917

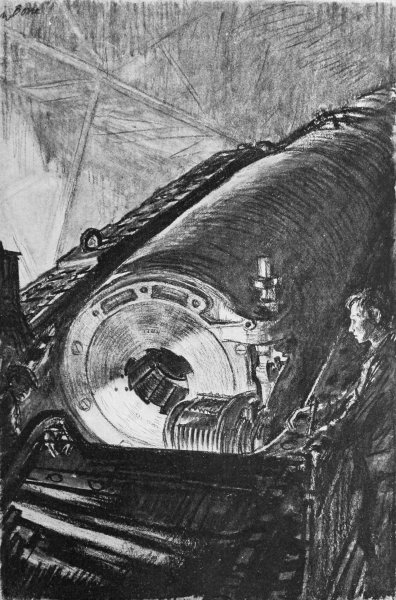

One of the largest guns viewed from the breech. However many large guns may have been turned out by the same men before, a glow of pride is always felt in a gun shop when one more masterpiece like this is ready at last to go out to its work in the field.

A great contrast to the scenes in the gun shop. Here everything is light and delicate, the bright, varnished wood curved to delicate shapes like violins, the women flitting with their needlecraft around the wide, dazzling planes and the brilliant pigmy engines shining like jewels—all seem gay and exhilarating after the sombre company of the guns. There is even a lightsome airiness about the thought that these delicate creations fly away from their makers’ hands when completed and do not burden any railway with their transit.

Another view of the same shop. Close to, the propeller seems a great thing, wonderfully subtle in its graceful curves.

These machines are among the largest of their kind. A row of them, jutting colossally forward like the heads of Egyptian sculptured lions, make an impressive feature in the spacious avenues of a great machine shop. The nearer machine is at work on part of a big gun mounting.

The breech is open: underneath it, hidden from sight, the mechanics are at work. Such a scene has a special appeal to those who loved the stories of Jules Verne in their youth. These largest of all guns seem as if they could fulfil the hopes of Verne’s sanguine President of the Gun Club and justify his fervid belief in ballistics as your only science.

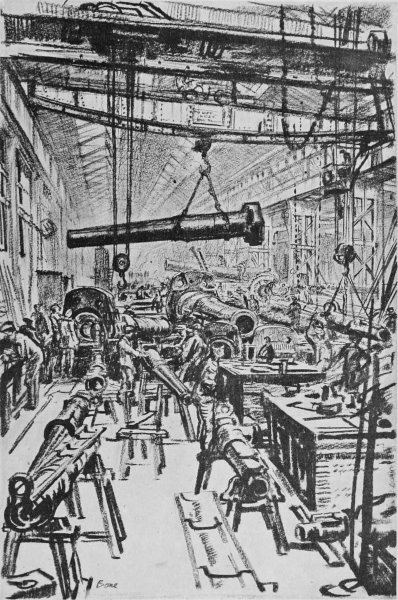

Howitzers of various calibres are in the background; in the foreground, guns of lighter types. Guns are like ships; each piece seems endowed with a personality which endears it to its creators. The soldiers to whose keeping they are sent feel a similar tenderness towards their own special charge. They express it by giving them fond names like “Saucy Sue,” “Sweet Seventeen,” “Jill Johnson,” “Our Lizzie,” and “’Ria.”

“A scene,” the artist writes, “so romantic in its mingling of grimness and mystery that one thinks with compunction of the long line of romantic artists whose lot it was not to have seen it!” The work on hand seems carried on by noiseless ghosts, so completely is the noise of their labours drowned by the incessant hum of machines.

A sketch in the heavy gun bay. The size of these unmounted guns may be judged by the figures at work near them.

This is a corner in the gun shop where heavy gun forgings of all sorts lie about, awaiting their turn on the machines. The overhead crane is lifting one of the guns. Many of these cranes are being driven by women.

The big gun tube is rotating slowly while the tool inside scoops out long shavings of the metal like cheese parings. The mounting heaps of the metal shavings are constantly cleared away. The iridescent colours of these shavings (showing the different temperings of the steel) present surprisingly beautiful effects to the eye, tired with the bewildering rotations of the immense gun tubes on their machines.

Landscape near Arras is like the biblical vine hanging over a wall—“All the archers have shot at her.” Injured, but not yet destroyed, the woods seem like creatures scared, as if the trees themselves were possessed with the disquiet of dryads crouching somewhere in hiding. Many different parts of the front have their own almost personal expression, but it is seldom one of fear. At and around Arras this expression of alarm is so curiously strong that, if he transgressed prose, the visitor might fancy the taut bulrushes were nature’s hair standing on end, and a slight stir in the poplars her shudder. By some means, which a layman cannot mark down, Mr. Bone has suffused his drawing with his own sense of the tragic queerness of this vacuous and unnerved landscape.

High ground near “King George’s Hill,” whence the King viewed the main battlefield of 1916; the drawing shows this in the distance. The foreground was won last July by the Manchesters. They found in No Man’s Land the bodies of many Frenchmen killed in earlier fighting, and buried them beside their own dead. Not all the bodies could be identified: Some of the crosses shown in the drawing bear such inscriptions as “In honoured Memory of Two Unknown French Soldiers, buried here.”

The canvas screen on the left remains from a time when this stretch of road was under enemy observation. The battle of the Somme has left it far behind the front. From a point just beyond the trees indicated upon the skyline on the right every detail of a part of the fighting on July 1st, 1916, could be seen.

Whether on the road between a rail-head and the front, or during a halt by the way, or at rest in their own park, the lorries of a Division keep their proper distance or interval from each other, like men on parade. If one falls lame it is taken in tow; if disabled past towing, it falls out and waits for a first-aid mobile workshop to come and repair it. The scene here is one of the two chief roads to the Somme front. In July and August, 1916, the procession of lorries along it was often unbroken for several miles. Field railways have much lightened its traffic since then.

To most English soldiers it is one of the compensations, and not of the hardships, of active service that they so often have to do work which is not their own trade nor a regular part of all soldiering. They find a flavour of the sport of peace-time camping-out in the work of making or finding their own shelter from the weather. Sometimes it is done, as here, with excellent materials, sometimes with hardly any at all, and the man who has built himself a rain-proof hut, for one, out of a few old biscuit tins, some sticks and a waste piece of corrugated iron enjoys a special thrill of triumphant ingenuity.

Near Maricourt the British line ended, and the French began, during the battle of the Somme. Blue and khaki were equally blended in the endless lines of traffic passing both ways through Maricourt and raising a barrage of dust all along the road to Bray-sur-Somme. At Maricourt crossroads there was a doubled post of military police, one man British and one French, ready with rebuke or instruction in either tongue. The place is now several miles behind the British front, and its old animation is gone. It and the woods near it are less completely destroyed than most of the neighbouring villages. Many walls are standing; even a few roofs remain.

The German front line, until July 1st, 1916, run a few yards on the spectator’s side of the two dismounted figures in the foreground. In the background are the bare poles of Mametz Wood. The nearest figure can be known for an Australian, by his hat.

After work the divisional motor transport lorries return methodically to their own parks. During long journeys they rest now and then, tucked into the right of the road or standing in a market place, while the men eat their haversack rations. Mixed with the lorries here are their seniors, the covered vans of French country carriers and, still older, the long, low, French farm wagons now drawn by horses, but built, as is shown by the very low pole, for draught oxen. In the market place there wait also the cars of British staff officers visiting the town. The handsome building in the background has its red-brick façade set off with alternating square bosses of white stone, on each side of the windows, after the custom of 17th and early 18th century builders.

Leaving a French base port. The artist has contrived to suggest in his drawing of the homeward hastening leave-boat the happy eagerness with which the eyes and minds of all on board are turned westward. The slower hospital ship is just leaving the harbour. There is no possibility of any honest failure to distinguish, by day or night, the black painted lightless transport from the hospital ship with its gleaming white and light-green paint and its festal-looking tiers and crosses of scores of brilliant green and red lamps.

There are some Scottish soldiers on all troopships. On this one there were no others. The Highlanders on the drawing have the good fortune to be on deck and also not to be crowded. On most troopships the men, if on deck, look, at a little distance, like a solid brown mass.

A unit coming back from the trenches to rest is unlike anything ever seen at home. Everyone is dead tired; everyone, though washed and shaved, has caked mud on his uniform; most of the men are stooping to get well under the weight of their packs and so ease the cut of the straps on their shoulders; cooks and a few footsore men trail behind the transport wagons and field kitchens, taking a tow with one hand. Odds and ends of light baggage are carried in little, almost toy-like hand-carts, the men pulling them by many ropes and pushing them from behind. Some men, perhaps, are wearing German helmets. Everyone’s face has a look of contented collapse, the restful reaction of senses and nerves relaxed after many days of strained attention and short sleep. The weary and happy procession serpentines slowly across the chalk downs, carried along by the rhythm of the swing it has learnt from months of route marching in England.

The ship’s large wooden Red Cross, to be illuminated at night with electric lights, is seen near the centre of the drawing.

Our Western front is a line that does not really end at the sea. If it did, then its left flank might be turned. But its real left flank is not there. It is somewhere far out on a line that runs north-west of Nieuport, through and beyond the North Sea. The British soldier in Belgium or France may not see much of the Navy itself. But every day brings him some proof that the Navy is holding its part of the line. His letters never go wrong, and he knows that, but for the Fleet, they would have to make their way to him like swimmers across a bay full of sharks. It is faith in the Navy that makes the men going on leave laugh when obeying the order to put on lifebelts on leaving harbour. In the soldier’s mind that long left flank of180 our line is not forgotten but rather written off, once for all, as unbreakable. He puts much the same sort of trust in the power of the Fleet as he puts in the affection of friends at home. To him it is one of the things that need never be feared for; it cannot fail.

This is not to say that soldiers underrate the hardness of the Navy’s task. A few sailors visit the front from time to time and hold curious arguments with the soldiers, each side being deeply convinced that the other has the harder time of it. The soldier’s imagination is struck by the large proportion of deaths among the casualties of naval war and by visions of night duty on vessels at sea in bad winter weather. What strikes the sailor, in presence of the imperfections of dug-outs, is the soldier’s hardship of not being able to “go below” into some small cubic space of warmth and dryness when action is over or a watch is through. When a naval officer, who visited the Somme front last summer, and saw a fight near Martinpuich, rejoined the ship that he commanded, he paraded his whole ship’s company and spent two hours in telling them what a rough time the soldiers had, and what fine work they were doing. The generosity of the praise made his soldier guide feel almost ashamed, remembering the almost instant fate of the “Cressy,” “Aboukir,” and “Hogue,” and the obedience of the “Theseus” to the heart-breaking order to abandon her sinking consort.

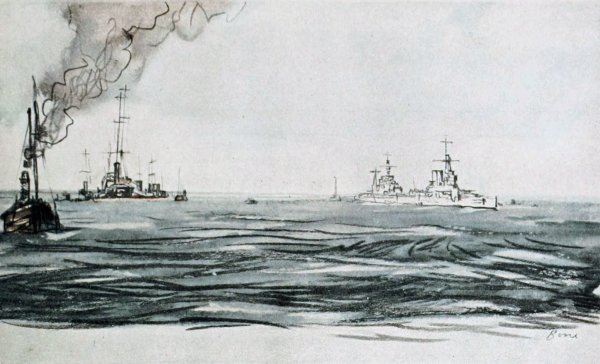

Few officers or men from the western front can visit the Fleet; but the winds of chance, which blow casualties and convalescents all about Great Britain, drop a few of them down in spots where the Fleet, as Mr. Bone draws it, is under their eyes. Drawings like those of “A Fleet Seascape” (LXXXIX) and “A Line of Destroyers” (LXXXVI) awake recollections of guard duty in a small Scotch fishing village; of the majestic seaward procession through the midsummer night, before the battle of Jutland; of the return from the fight, the destroyers streaming tranquilly back to their moorings under the hill, with the great searchlight wheeling to and fro along the sea outside them, like a sentry moving alertly on his post; a few wounded ships steaming in more sedately, or taking a tow, one with a couple of funnels knocked out of the straight, another with a field-dressing of bedding stuffed into a hole in her side, and the whole wound, apparently, smeared with red paint, as the surgeons smear flesh wounds with yellow; and then of the coming181 ashore, the men triumphant and happy, the officers learning with astonishment and indignation that people at home had heard more of losses than of the victory.

Mr. Bone’s drawings give an insight into the world of the Navy to which these random glimpses can add nothing. “H.M.S. ‘Lion’ in dry dock” (LXXXIII) is wonderful, technically—if a layman may judge—and in spirit. A whole aspect of modern naval life is lit up by “A boiler-room on a battleship” (XCIII). For, to the astonished landsman visiting a man-of-war, the sailors of to-day seem to work and eat and sleep in a variety of engineering laboratories, surrounded by countless wheels, handles, buttons and bells for the evocation or dismissal of the genies of steam, petrol and electricity. Nothing could be more unlike the lower decks of seventeenth and eighteenth century battleships as we imagine them. The only things which have not changed, from the days of Drake to those of Hawke, and from Nelson’s time to Beatty’s, are the hereditary instinct for the sea and the fine fighting temperament of officers and men.

G. H. Q., France,

April, 1917

Viewed from the bridge. A large oil “tanker” is alongside. Unseen, but very fast, the oil fuel is running into the battleship. How great a boon this new fuel is can be understood, at any rate partly, by those who have endured the coaling of a great ship in the old way. The scene shown in the drawing was animated by the changeful gleam of the gay signal flags flapping in the foreground and by the flashing of the wings of innumerable hungry gulls.

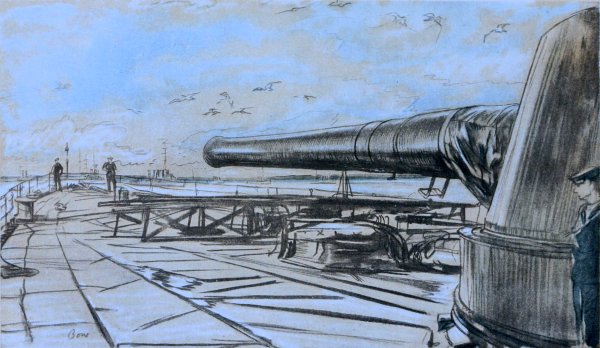

The ship’s funnel behind and the sailor’s figure on the left help to give the scale of the great gun.

The great hull we see here has seen more battling in the present war than any other of our “capital” ships. Officially “sunk” by the Germans, she will yet prove a troublesome ghost to them. In the foreground the dockyard workers are busily surveying the ship’s Gargantuan cables for weakened or damaged links.

The “Main Derrick” is a great crane and lifts a heavy boat like the one in the drawing, or an Admiral’s barge, out of the water and stows it on deck with the greatest ease.

A battleship revealed by the beam of its own searchlight. A big gun emerges in silhouette, as well as a sentry on duty. One feels considerable awe when threading one’s way in a small picket boat between the ships of the Fleet at night.

A line of destroyers at anchor. Seen from a distance, in this formation, a long line of destroyers looks curiously like a battalion drawn up in line of platoons in file, at a wide interval, and standing on the sea. It will be remembered that the battle of Jutland was as much a battle of destroyers as of any other type of warship.

Part of the deck of one of the most famous of British ships, cleared for action.

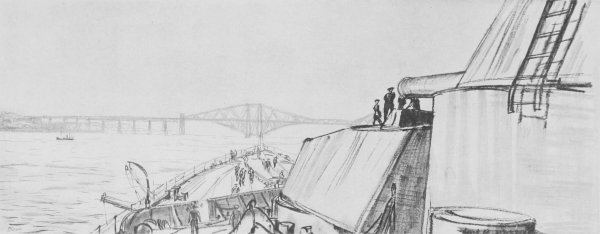

Britain has many beautiful estuaries, but the Forth has features like the distant Highland hills and its enormous Bridge which make it unique among our waterways. The Bridge makes even the largest warship seem a pigmy, yet one has a queer sensation when about to pass under it for the first time; one momentarily expects all the ship’s top hamper to be carried away—everything about the Bridge being on so big a scale that what is safely distant seems perilously close.

To the left a group of destroyers are gathered round a parent ship. To the right is the beginning of an imposing line of battleships.

From this point of view the shield partly hides the muzzle of the gun. The gun crew are listening to instructions. Note the “Navy Warm” worn by the figure in the middle: often, when the weather is “fine” from the landsman’s point of view, it is still bitterly cold on the North Sea. Two larger guns can be seen protruding from their turret in the deck below.

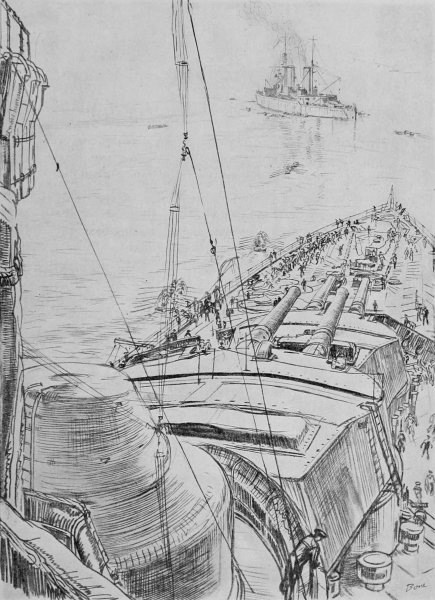

The crew of a Battleship at “General Drill” on a brisk spring morning is an exhilarating sight to the spectator posted at a quiet corner well out of the way. The band of the Marines plays, and the maximum of everything possible seems to be going on at once. In the sketch the ship’s boats have been launched and are making their way with steady stroke out to a neighbouring ship and back.

The delicate but firm precision of the drawing conveys aptly the general air of a man-of-war’s deck, where everything is intricate without confusion, and busy without fuss.

Interior of a Big Gun Turret on a Battleship, with the crew at their stations. The breech of the gun is open and looks gigantic in this confined space where every inch is made to serve some purpose. An officer is seen in the gangway between the twin guns, but of course the higher direction of the firing is transmitted from the “Fire control” station situated elsewhere.

The vessel is oil-driven, so the stoke-hold is robbed of its old terrors and is remarkably cool. The stokers seem few in proportion to the size of the place, but they are experts of a higher class than coal furnaces required.

Here the scale of the great guns is only given by the dwarfed rail beneath and by the long stretch of horizon which the funnels subtend. But no merely physical ratio can convey the impression of enormousness that a great naval gun makes on the imagination. By subtler technical means the artist has managed to transfuse this impression from his own imagination to that of the spectator of the drawing.

The sailor has much to bear from the weather, but at any rate he sees to extraordinary advantage the glories of sunset and the “incomparable pomp of dawn,” unsullied by the smoke of the land.

An unfamiliar aspect of a warship to the public, but, to Jack, it returns with unfailing regularity once a week. In the cramped space it requires careful management to keep all the great crew in health and comfort.

To the right is an old hulk which now serves as a sorting office for the Fleet’s Post. Around it there is at certain hours a busy scene, picket boats coming from the various ships to deliver or collect their mails.

Interior of the Chamber from which the torpedoes are fired. The torpedo in the foreground is partly engaged in the tube through which it will be fired. To the right is seen the exterior of another tube. The men are lowering, for stowage in safety, a trial torpedo which has been fired for a practice run and then re-captured.

This is Jack at his handiest, especially from the Army point of view. The party are using spare time to make “grommets” of rope-work to go round the bases of 9.2 shells. Not many people, even in the Army, know that the Army have come to look to the men of the Fleet for a great supply of these necessaries.

A relaxation immensely popular and quite easy for the handy men, who abound in the Navy, to equip and run. Being their own child, each ship takes a pride in its “pictures.” The operator in this case was the Chief Mechanician of the ship and the film the “Battle of the Ancre.” In the centre are a group of midshipmen, to the right a group of warrant officers. In the foreground will be observed the ever ready fire hose.