A MONTHLY SERIAL

FORTY ILLUSTRATIONS BY COLOR PHOTOGRAPHY

A GUIDE IN THE STUDY OF NATURE

Two Volumes a Year

VOLUME VII.

January, 1900, to May, 1900

EDITED BY C. C. MARBLE

CHICAGO

A. W. MUMFORD, Publisher

203 Michigan Ave.

1900

COPYRIGHT, 1900

BY

A. W. Mumford

ILLUSTRATED BY COLOR PHOTOGRAPHY.

THIS miniature of Rallus elegans or king rail, is found throughout the whole of temperate North America as far as the British Provinces, south to Guatemala and Cuba, and winters almost to the northern limit of its range. A specimen was sent by Major Bendire to the National Museum from Walla Walla, Wash., which was taken Jan. 16, 1879, when the snow was more than a foot deep. Other names of the species are: Lesser clapper rail, little red rail, and fresh-water mud hen. The male and female are like small king rails, are streaked with dark-brown and yellowish olive above, have reddish chestnut wing coverts, are plain brown on top of head and back of neck, have a white eyebrow, white throat, breast and sides bright rufous; the flanks, wing linings and under tail coverts are broadly barred with dark brown and white; eyes red.

The name of this rail is not as appropriate to-day as it was when Virginia included nearly all of the territory east of the Mississippi. It is not a local bird, but nests from New York, Ohio, and Illinois northward. Short of wing, with a feeble, fluttering flight when flushed from the marsh, into which it quickly drops again, as if incapable of going farther, it is said this small bird can nevertheless migrate immense distances. One small straggler from a flock going southward, according to Neltje Blanchan, fell exhausted on the deck of a vessel off the Long Island coast nearly a hundred miles at sea.

The rail frequents marshes and boggy swamps. The nest is built in a tuft of weeds or grasses close to the water, is compact and slightly hollowed. The eggs are cream or buff, sparsely spotted with reddish-brown and obscure lilac, from 1.20 to 1.28 inches long to .90 to .93 broad. The number in a set varies from six to twelve. The eggs are hatched in June.

The Virginia rail is almost exclusively a fresh-water bird. It is not averse to salt water, but even near the sea it is likely to find out those spots in the bay where fresh-water springs bubble up rather than the brackish. These springs particularly abound in Hempstead and Great South Bay on the south coast of Long Island. Brewster says the voice of the Virginia rail, when heard at a distance of only a few yards, has a vibrating, almost unearthly quality, and seems to issue from the ground directly beneath the feet. The female, when anxious about her eggs or young, calls ki ki-ki in low tones and kiu, much like a flicker. The young of both sexes in autumn give, when startled, a short, explosive kep or kik, closely similar to that of the Carolina rail.

There is said to be more of individual variation in this species than in any of the larger, scarcely two examples being closely alike. The chin and throat may be distinctly white, or the cinnamon may extend forward entirely to the bill. This species is found in almost any place where it can find suitable food. Nelson says: "I have often flushed it in thickets when looking for woodcock, as well as from the midst of large marshes. It arrives the first of May and departs in October; nests along the borders of prairie sloughs and marshes, depositing from eight to fourteen eggs. The nest may often be discovered at a distance by the appearance of the surrounding grass, the blades of which are in many cases interwoven over the nest, apparently to shield the bird from the fierce rays of the sun, which are felt with redoubled force on the marshes. The nests are sometimes built on a solitary tussock of grass, growing in the water, but not often. The usual position is in the soft, dense grass growing close to the edge of the slough, and rarely in grass over eight inches high. The nest is a thick, matted platform of marsh grasses, with a medium-sized depression for the eggs."

Some of the rails have such poor wings that it has been believed by some unthinking people that they turn to frogs in the fall instead of migrating—a theory parallel with that which formerly held that swallows hibernate in the mud of shallow ponds.

|

||

| FROM COL. F. KAEMPFER. A. W. MUMFORD, PUBLISHER, CHICAGO |

VIRGINIA RAIL. ⅝ Life-size. |

COPYRIGHT 1900, BY NATURE STUDY PUB. CO., CHICAGO. |

W. E. WATT, A.M.

IT is a remarkable thing in the history of the United States that, when the iron shackles were about to fall from the bondman, he was caught by a cotton fiber and held for nearly a century longer. We were about to emancipate the slaves a century ago when Eli Whitney invented the cotton gin, multiplied cotton production by two hundred, and made slavery profitable throughout the South. The South Carolina legislature gave Whitney $50,000 and cotton became king and controlled our commerce and politics.

Eight bags of cotton went out of Charleston for Liverpool in 1784. Now about six million bales go annually, and we keep three million bales for our own use. So two-thirds of our cotton goes to England. The cotton we ship sells for more than all our flour. Cotton is still king.

In our civil war we came very near being thrown into conflict with England by an entanglement of the same fiber which caught the black man. One of the greatest industries of England in 1861-5 was cotton manufacture, and when we, by our blockade system, closed the southern ports so cotton could not be carried out, we nearly shut down all the works in that country where cotton was made up. That meant hard times to many towns and suffering to many families. That is why so many Englishmen said we ought to be satisfied to cut our country in two and let the people of the Confederacy have their way.

Cotton is a world-wide product. It grows in all warm countries everywhere, sometimes as a tree and sometimes as a shrub. It is usually spoken of as a plant. There was cotton grown in Chicago last year. Not in a hot house, but in a back yard with very little attention. A little girl got some seed, planted it, and had some fine bolls in the fall. It is a pretty plant, and was cultivated in China nearly a thousand years ago as a garden plant.

Herodotus tells us that the clothing worn by the men in Xerxes' army was made of cotton. Their cotton goods attracted wide attention wherever they marched. Columbus found the natives of the West Indies clothed in cotton. Cotton goods is not only wide spread, but very ancient. Cloth was made from this plant in China twenty-one hundred years ago. At the coronation of the emperor, 502 A.D., the robe of state which he wore was made of cotton, and all China wondered at the glory of his apparel.

More capital is used and more labor employed in the manufacture and distribution of cotton than of any other manufactured product. There is one industry in Chicago which out-ranks cotton. It is the live-stock business. More money is spent for meat and live-stock products than for cotton, taking the whole country together. But cotton ranks first as a manufacture.

We spend more for meat than for cotton goods, and more for cotton goods than for wheat and flour. The hog and cotton seed have a peculiar commercial relation to each other. The oils produced from them are so nearly alike that lard makers use cotton seed oil to cheapen their output. A large part of what is sold as pure leaf lard comes from the cotton plant.

A hundred years ago a good spinner used to make four miles of thread in a day. This was cut into eight skeins. Now one man can do the work of a thousand spinners because of machinery. One gin does to-day what it took a thousand workers to do then. Five men are employed in the running of one gin, so the gin alone makes one man equal to two hundred. Because one workman cleans two hundred times as much cotton since Whitney's time as before, cotton-raising has become a broad industry. The reason more cotton was not raised in the olden times is that it could not be used. Now we can use as much cotton as we can possibly raise.

At first there was strong opposition to these improvements in machinery [Pg 6] because the workmen felt their occupation would be taken away. But the cotton workers are to be congratulated, for there are four times as many men working in the cotton industries as there were a hundred years ago, and yarn thread is produced at less than one-tenth the cost while the workmen are all better paid for their labor.

James Hargreaves invented the spinning jenny in 1767. He was an illiterate man, and yet his machinery has not been materially improved upon. The poor fellow was mobbed by the infuriated workmen who saw that their labor was apparently to be taken from them by machinery. He was nearly killed. He sold out his invention and died in poverty. He received nothing from the government nor from the business world for his great invention. But after his death his daughter received a bounty.

Two years after the jenny, in 1769, Richard Arkwright invented the spinning frame. He was a barber by trade, but through the appreciation of crazy old George III., he was struck upon the shoulder with a sword and rose Sir Richard Arkwright. He amassed a great fortune from his invention. His spinning frame and Hargreaves' spinning jenny each needed the other to perfect its work. The jenny made yarn which was not smooth and hard. So it was used only for woof, and could not be stretched for warping. The result of the two inventions was a strong, even thread which was better for all purposes than any which had been made before.

Parliament imposed a fine of $2,500 for sending American cotton cloth to England, and another for exporting machinery to America. Massachusetts at once gave a bonus of $2,500, and afterwards $10,000 to encourage the introduction of cotton machinery. Francis Cabot Lowell was an American inventor. He brought the business of weaving cotton cloth to this country. There had been some small attempts before his time, but he introduced it extensively and profitably. He established a cotton factory in Massachusetts in 1810, and was very successful. In that year he was in England, dealing with makers of cotton goods. The idea occurred to him that it would be more profitable to make the goods on his side of the water where the cotton was raised. He acted promptly. Lowell, Massachusetts, is named after him, and stands as a monument to his good judgment and inventive genius.

Three years after he had established the manufacture of cotton goods in this country, he invented the famous power loom. That was a great step in advance. It has done more for the industry than anything since the days of Hargreaves and Arkwright. By the use of power these looms set the spindles running at a remarkable rate of speed. Twenty years ago the world wondered at the velocity of our spindles, 5,000 revolutions in one minute. But it has kept on wondering ever since, and the speed of spindles has constantly increased as if there could be no limit. 15,000 revolutions are now common.

In Great Britain there are 45,000,000 spindles running at a wondrous rate, and 17,000,000 are running in America. With cheaper labor and more extended experience, they are doing more of it across the water than we. For our consumption we make all the coarse grades, but all the fine cottons are imported. They get large quantities of cotton now in India. Egypt also is a great cotton country, producing the best cotton grown with the one exception of our famous sea island cotton. Her crop is worth $48,000,000 annually. England has hunted the world over for cotton and good cotton ground, and while we were engaged in war she was increasing her endeavors in this direction with much earnestness.

If you will notice the contents of a boll of cotton you will be surprised to find that the fiber is not the main thing there. The seed is far heavier than the fiber, and it really occupies more space when the two are crowded into their closest possible limits. You can press the cotton down upon the seed till the whole is but little larger than the seed.

The fiber clings to the seed with great firmness, and you find it difficult to tear them from each other. There [Pg 7] is no wonder it was such a slow process to separate them in the good old days. The Yankee, Eli Whitney, went to Georgia to teach school, but by the time he arrived there the school was taken by another, and he was out of employment. That was a happy misfortune for him and for the country.

He was a nailer, a cane maker, and a worker in wood and metal. A Yankee nailer cannot be idle in a strange land. The expression, "as busy as a nailer," is a good one. Whitney looked about him to see what was the popular demand in his line. He found the greatest difficulty the southern people had to contend with was the separating of cotton from its seed. He went at the business of inventing a machine to do the work for them.

He placed a saw in a slit in a table so that cotton could be pushed against its teeth as it revolved. The teeth caught into the fiber and pulled it away from the seeds. As the seeds were too large to pass through the slit in the table they flew away as the fiber let go its hold upon them, and Whitney soon found he had solved the problem.

This is the first step in what may be called the manufacture of cotton fabrics. In another article we shall examine all the various sorts of textiles that are made from this interesting fiber, and speak of their manufacture, treatment, sale, and use.

Under Whitney's gin the bulky seeds soon began to pile up astonishingly, and it became customary to remove the gins as the piles of this useless seed accumulated. It was left to rot upon the ground in these heaps just as it fell from the gin. Another ingenious Yankee saw there was a great deal of material going to waste in these piles, and he experimented to see what could be done with the seed.

It was found to be very good for use on ground that had become poor by exhaustive farming. An excellent fertilizer is made from it. The cake is used for feed for cattle to great advantage. Dairymen regulate the quality and color of the milk they get from their cows by varying the amount of oil cake given in their food. The oil extracted from this seed is used in the arts. It is not equal to linseed oil for painters' use, but it is a great substance for use in mixing in with better oils to make them go farther. In other words, it is largely used for the purposes of adulterating other oils. Not only is it used in making lard, but it is now sold on its own merits for cooking purposes.

Two days out of New York we sighted the black smoke of a great steamer. At sea everybody is on the lookout for vessels and much interested in the passengers that may be on the craft casually met. So we kept watch of the horizon and were glad to see that a big one was coming our way. She was headed so nearly towards us that we hoped to get a good view of the many passengers that might be expected on so large a ship. When she was near enough to show some of her side, she looked rusty and ill kept. We wondered what the fare must be for a ride across the water on such a cheap-looking monster. As she came nearer we saw there were no passengers. "What is she?" "What does she carry?" The first mate told us she was a tank steamer, running between the United States and Belgium, carrying 4,200 tons of cotton-seed oil at a trip.

CHARLES CRISTADORO.

OUT in the garden where the western sun flooded the nasturtiums along the garden wall, a large yellow and black-bodied spider made his lair. The driving rain of the night before had so torn and disarranged his web that he had set about building himself a new one lower down. Already he had spun and placed the spokes or bars of his gigantic web and was now making the circles to complete his geometric diagram.

From his tail he exuded a white, sticky substance, which, when stretched, instantly became dry. As he stepped from one spoke to another he would spin out his web and, stretching the spoke towards the preceding one, bring the fresh-spun web in contact with it and then exude upon the jointure an atom of fresh web, which immediately cemented the two parts, when the spoke settled back into place, pulling the cross web straight and taut. The process of house-building continued uninterruptedly, every movement of the spider producing some result. No useless steps were taken, and as the work progressed the uniformity of the work was simply amazing; every square, every cross piece, was placed exactly in the same relative position as to distance, etc. A micrometer seemingly would not have shown the deviation of .000001 of an inch between any two of the squares.

When the web was three-fourths finished a lusty grasshopper went blundering up against one of the yet uncovered spokes of the web and escaped. The spider noticed this and visibly increased his efforts and sped from spoke to spoke, trailing his never ending film of silky web behind him. At last the trap was set and, hastening to the center, he quickly covered the point with web after web, until he had a smooth, solid floor with an opening that allowed the tenant to occupy either side of the house at will. The spot was well selected, the hoppers in the heat of the day finding the heavy shade of the broad nasturtium leaves particularly grateful.

Our friend the spider had not long to wait for his breakfast, for presto!—a great, brown-winged hopper flew right into the net. Before he could, with his strong wings and powerful legs, tear the silken gossamer asunder and free himself, like lightning our spider was upon him. In the flash of an eye the grasshopper was actually enshrouded in a sheet of white film of web, and with the utmost rapidity was rolled over and over by the spider, which used its long legs with the utmost dexterity. Wound in his graveyard suit of white silk, the grasshopper became absolutely helpless. His broad wings and sinewy legs were now useless. The spider retreated to the center of the web and watched the throes of his prey. By much effort the hopper loosed one leg and was bidding fair to kick the net to shreds when the spider made another sally and, putting a fresh coating of sticky web around him, rolled him over once or twice more and left him.

In a few moments, when all was over, the spider attacked his prey and began his breakfast. Before his meal was well under way, a second hopper flew into the parlor of the spider and, leaving his meal, the agile creature soon had hopper number two securely and safely ensnared. No experienced football tackle ever downed his opponent with any such skill or celerity as the spider displayed as he rolled over and bundled up into a helpless web-covered roll the foolish and careless hopper.

|

||

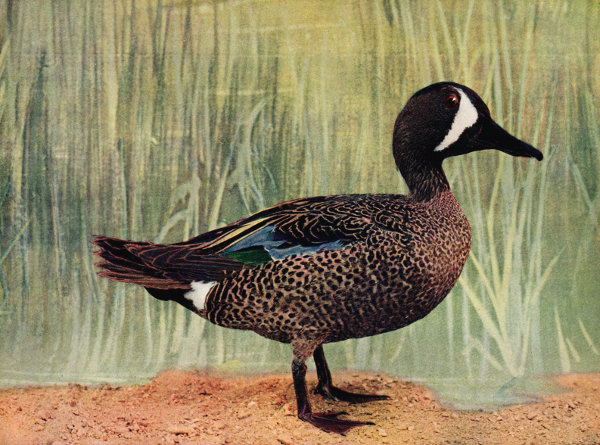

| FROM COL. F. NUSSBAUMER & SON. A. W. MUMFORD, PUBLISHER, CHICAGO. |

BLUE WINGED TEAL. ½ Life-size. |

COPYRIGHT 1900, BY NATURE STUDY PUB. CO., CHICAGO. |

SO many names have been applied to this duck that much confusion exists in the minds of many as to which to distinguish it by. A few of them are blue-winged; white-face, or white-faced teal; summer teal, and cerceta comun (Mexico.) It inhabits North America in general, but chiefly the eastern provinces; north to Alaska, south in winter throughout West Indies, Central America, and northern South America as far as Ecuador. It is accidental in Europe.

The blue-winged teal is stated to be probably the most numerous of our smaller ducks, and, though by far the larger number occur only during the migrations, individuals may be found at all times of the year under favorable circumstances of locality and weather. The bulk of the species, says Ridgway, winters in the Gulf states and southward, while the breeding-range is difficult to make out, owing to the fact that it is not gregarious during the nesting-season, but occurs scatteringly in isolated localities where it is most likely to escape observation.

The flight of this duck, according to "Water Birds of North America," is fully as swift as that of the passenger pigeon. "When advancing against a stiff breeze it shows alternately its upper and lower surface. During its flight it utters a soft, lisping note, which it also emits when apprehensive of danger. It swims buoyantly, and when in a flock so closely together that the individuals nearly touch each other. In consequence of this habit hunters are able to make a frightful havoc among these birds on their first appearance in the fall, when they are easily approached. Audubon saw as many as eighty-four killed by a single discharge of a double-barreled gun.

"It may readily be kept in confinement, soon becomes very docile, feeds readily on coarse corn meal, and might easily be domesticated. Prof. Kumlein, however, has made several unsuccessful attempts to raise this duck by placing its eggs under a domestic hen. He informs me that this species is the latest duck to arrive in the spring." It nests on the ground among the reeds and coarse herbage, generally near the water, but its nest has been met with at least half a mile from the nearest water, though always on low land. The nest is merely an accumulation of reeds and rushes lined in the middle with down and feathers. This duck prefers the dryer marshes near streams. The nests are generally well lined with down, and when the female leaves the nest she always covers her eggs with down, and draws the grass, of which the outside of the nest is composed, over the top. Prof. Kumlein does not think that she ever lays more than twelve eggs. These are of a clear ivory white. They range from 1.80 to 1.95 inches in length and 1.25 to 1.35 in breadth.

The male whistles and the female "quacks."

The food of the blue-wing is chiefly vegetable matter, and its flesh is tender and excellent. It may be known by its small size, blue wings, and narrow bill.

Mr. Fred Mather, for many years superintendent of the State Fish Hatchery of Cold Spring Harbor, Long Island, domesticated the mallard and black duck, bred wood ducks, green and blue-winged teal, pin-tails, and other wild fowl. He made a distinction between breeding and domestication. He does not believe that blue-winged teal can be domesticated as the mallard and black duck can, i. e., to be allowed their liberty to go and come like domestic ducks.

The hind toe of this family of ducks is without a flap or lobe, and the front of the foot is furnished with transverse scales, which are the two features of these birds which have led scientists to separate them into a distinct sub-family. They do not dive for their food, but nibble at the aquatic plants they live among; or, with head immersed and tail in air, "probe the bottom of shallow waters for small mollusks, crustaceans, and roots of plants." The bill acts as a sieve.

NELL KIMBERLY MC ELHONE.

I BEG your pardon, my dear," said Mr. Flicker, "but you are quite mistaken. That is not a tree stump."

"Excuse me," said Mrs. Flicker gently, "but I still believe it is."

Now if they had been the sparrows, or the robins, or the red-winged blackbirds, they would have gone on chattering and contradicting until they came to using claws and bills, and many feathers would have been shed; but they were the quiet, well-bred Flickers, and so they stopped just here, and once more critically regarded the object in question.

"Whoever heard of a stump, old and gray and moss-covered, appearing in one night?" said Mr. Flicker, after a pause. "I have seen more of the world than you have, my dear, and I do assure you it would take centuries to make a stump like that." Let it be here recorded that in this Mr. Flicker was perfectly correct.

"Well, then," reasoned Mrs. Flicker, "if it is not a stump, what is it?"

Mr. Flicker looked very wise. He turned his head first to one side and then the other—flashing his beautiful scarlet crescent in the sunlight. Then he sidled nearer to his wife and darting his head down to her, whispered, "It is a person."

The timid Mrs. Flicker drew back into the nest in horror, and it was some moments before she felt like putting her head out of the door again. In the meantime she had quieted down to the thoughtful little flicker she really was, and had gathered together her reasoning powers. So out came the pretty fawn-colored head and again the argument began.

Though still quivering a little from the fright, Mrs. Flicker said, in the firm tones of conviction, "No, Mr. Flicker, that is not a person. Persons move about with awkward motions. Persons make terrible sounds with their bills. Persons have straight, ugly wings without feathers—not made to fly with, but just to carry burdens instead of carrying them in their bills. Persons wear colors that nature disapproves. Persons point things at us that make a horrible sound and sometimes kill. Persons cannot keep still. That is not a person."

Mr. Flicker was greatly impressed, and stood like a statue, gazing at what his wife called a gray stump. She went back to ponder the matter over her eggs.

The sprightly little warblers and goldfinches flashed in and out through the bushes that grew thickly together on a small island opposite Mr. Flicker's nest; the orioles called to one another in the orchard back of him; the catbirds performed their ever-varying tricks in the cherry tree near by; Mr. Water Wagtail came and splashed about on the shore of the creek, and Mr. Kingfisher perched on a stump in the water, watching for a dainty morsel, and still Mr. Flicker sat regarding his new puzzle. He paid no attention to any of his neighbors—but for that matter he seldom did, for the flickers are aristocratic bird-folk, and mingle very little with their kind. But on this day he was particularly oblivious, so greatly occupied was he with the gray stump.

Once or twice he had detected a slight motion on the part of the stump; a rustle, a change of position, a faint sign of life—just enough to make his little bird-heart thump, but not enough to warrant flight in so discreet a bird. But at last there began a quiet bending, bending of the stump; it was very slow, but none the less certain, and Mr. Flicker waited with throbbing heart, till he saw two large, round, glassy eyes pointed full at him, then, with a quick note of warning for his little wife, he rose in the air with a whirr, and the golden wings shimmered away in the sunlight overhead.

Mrs. Flicker peeped cautiously forth, [Pg 13] and, with her unerring bird instinct, sought first of all the gray stump which, alas, was not quite a stump after all, and was indeed the cause of the danger. She saw the terrible instrument still pointed at her husband, and her heart fluttered wildly; but there was no report, and she watched him till she could only see the occasional flash of the gold-lined wings and the white spot on his back; and then behold, the stump was once more a stump, and Mrs. Flicker returned to her eggs.

When Mr. Flicker came back, he flew past his house without once swerving, and disappeared in a pine tree on the edge of the orchard, and a conclave of cedar waxwings in the next tree discussed his tactics enthusiastically. The cedar waxwings were also interested in the gray stump—but afraid of it? Oh no, not they! Care sits lightly on the cedar waxwing's topknot, and he never takes his dangers seriously.

A series of deceiving and circuitous flights finally landed Mr. Flicker at his own door, and he perched himself in his hiding-place of leaves and watched the gray stump with an air of settled gloom.

However, a bird is a bird, even though it be a serious flicker, and before many minutes he and his wife were chatting happily again. Mrs. Flicker even asserted boldly that if she had not her eggs to look after, she would certainly investigate this thing; and then Mr. Flicker began to preen his feathers as if in preparation for the undertaking, but really to gain time and get up his courage, when, "Take care! Take care!" came notes of warning from the catbirds; and the stump suddenly lengthened itself like a telescope and walked away, with its two-eyed instrument under its arm. Mr. and Mrs. Flicker watched it gather a spray of late apple blossoms, saw it climb the fence and disappear down the road.

"I beg your pardon," said polite little Mrs. Flicker to her husband. "I was wrong; it is not a stump. But," she added coaxingly, "it really is more like a stump than a person, now isn't it? And I should not be afraid of it again."

When Miss Melissa Moore, school teacher, returned to Manhattan after her summer vacation, she confided to a fellow-teacher that she had made seventy new acquaintances, and that she loved them all. Now Miss Melissa Moore, in her wildest dreams, never thought of herself as being beautiful, being a plain, honest person; she even knew that her bird-hunting costume—the short gray skirt and gray flannel shirt-waist and gray felt hat, whose brim hung disconsolately over her glasses, with no color at all to brighten her—was not becoming, but if she had dreamed that Mrs. Flicker had called her an old gray moss-covered stump, she would, being only human, have cut her once and forever, and her list of new acquaintances would have numbered sixty-nine.

THE geographical distribution of this member of the blackbird family is western North America to the Pacific Ocean, east to Wisconsin, Illinois, Kansas, and Texas. The bird is accidental in the Atlantic states. It is found generally distributed on the prairies in all favorable localities from Texas to Illinois. It is a common bird in the West, collecting in colonies to breed in marshy places anywhere in its general range, often in company with the red-winged blackbird. The nests are usually placed in the midst of large marshes, attached to the tall flags and grasses. Davie says they are generally large, light, but thick-brimmed, made of interwoven grasses and sedges impacted together. The eggs are from two to six in number, but the usual number is four. Their ground color is dull grayish-white, in some grayish-green, profusely covered with small blotches and specks of drab, purplish-brown and umber. The average size is 1.12 × .75.

Mr. Nelson says that the yellow-headed blackbird is a very common resident of Cook County, Ill., in large marshes. It arrives the first of May and commences nesting the last of that month. Owing to the restricted localities inhabited by it, it is but slightly known among farmers; even those living near the marshes think it an uncommon bird. The only difference in the habits of the male and female is the slightly greater shyness of the former. Colonies nest in rushes in the Calumet marshes, are bold and interesting, and adults are sometimes seen on the ground along country roads some distance from water.

The food of these birds during the nesting season is worms and grubs, which are fed each day to the young birds by the hundreds. In this way they help protect the crops of the farmer. In the autumn, when the young can fly as well as their parents, they collect in large flocks and start on their southern journey. At this time young and old travel together. Many of them are killed by hawks, which often follow a flock for days, dashing into their midst whenever they see a chance to capture one.

The blackbirds are alike in general characteristics. They all walk and get most of their food on the ground. In spring, when large flocks are roaming in all directions, one may easily be confused by them. Miss Merriam says that with a little care they will easily be distinguished. The crow blackbirds may be known by their large size and long tails. The male cowbird may be told at a glance, she says, by his chocolate-colored head, the red-wing by his epaulettes, and, we may add, the yellow-headed by the brilliant yellow of his whole head and neck, "as if he had plunged up to his shoulders in a keg of yellow paint, while the rest of his attire is shining black." He utters a loud, shrill whistle, quite unlike any sound produced by his kinsmen.

|

||

| FROM COL. F. NUSSBAUMER & SON. A. W. MUMFORD, PUBLISHER, CHICAGO. |

YELLOW-HEADED BLACK BIRD. ⅔ Life-size. |

COPYRIGHT 1900, BY NATURE STUDY PUB. CO., CHICAGO. |

E. K. M.

THE little readers of Birds and All Nature will not have much respect for me, I am afraid, after reading what Mr. Wood Thrush said of my family in the last number of the magazine.

Probably you don't recollect it. Well, he said that my cousin, Mr. Red-Wing Blackbird, was often found in the company of Mr. Cowbird, and that Mr. Cowbird was a very disreputable creature, being no better than an outcast and a tramp.

Humph! Just as though birds, like boys and girls, are to be judged by the company they keep. Why, I associate with Mr. Cowbird, too; he is a distant relative of mine, and certainly nobody who looks at my picture can call me disreputable. See what a glossy black coat I wear and what a fine yellow collar and hat. We are only free in our manners, that is all, helping ourselves liberally to the grain planted by our dear friend, Mr. Farmer.

I am not lazy, either, like my relative, Mr. Cowbird, for I build a new house every spring, locating it among the tall flags and grasses in a nice damp piece of marshland.

Though I am a blackbird, I'm not found from the Atlantic to the Pacific, as Mr. Red-Wing is and others of our tribe. For that reason you can't call me common, you know. But, then, our manners and customs are about the same. We do not hop like other birds, but walk very much as you do, putting one foot before the other, a bit awkwardly, perhaps, but I am sure with considerable dignity. Indeed, my mate says but for cocking my head on one side when strutting on the ground one might take me for a bishop—in feathers—I have such a solemn, serious air, as though burdened with a sense of my own importance.

Like the generality of birds, I find a warm climate in winter conducive to my health, so in November I leave the north and hie me to the south, returning about the first of May, not so early as my cousin, Mr. Red-Wing, and the other common members of the blackbird family. They, like some visitors, welcome or unwelcome, usually come early and stay late.

It strikes me, for that reason, the blackbird family should be considered of some importance, even if they do associate with Mr. Cowbird, tramp that he is, for when the first flocks of blackbirds are seen sailing overhead, like leaves blown by the wind against the sky, you know that spring is near, no matter how cold or chill the weather may be. Crowds and crowds of us are then seen circling and wheeling above our last year's nesting-place, talking and laughing like little children and making just as much noise.

Con-cur-ee is the only song we know, but we utter that in different tones, so that our mates consider it very pleasing, and so may you.

OLIVE SCHREINER.

... And now we turn to nature. All these years we have lived beside her, and we have never seen her; now we open our eyes and look at her.

The rocks have been to us a blur of brown; we bend over them, and the disorganized masses dissolve into a many-colored, many-shaped, carefully [Pg 18] arranged form of existence. Here masses of rainbow-tinted crystals, half-fused together; there bands of smooth gray methodically overlying each other. This rock here is covered with a delicate silvery tracery in some mineral, resembling leaves and branches; there on the flat stone, on which we so often have sat to weep and pray, we look down, and see it covered with the fossil footprints of great birds, and the beautiful skeleton of a fish. We have often tried to picture in our mind what the fossilized remains of creatures must be like, and all the while we sat on them. We have been so blinded by thinking and feeling that we have never seen the world.

The flat plain has been to us a reach of monotonous red. We look at it, and every handful of sand starts into life. That wonderful people, the ants, we learn to know; see them make war and peace, play and work, and build their huge palaces. And that smaller people we make acquaintance with, who live in the flowers. The citto flower had been for us a mere blur of yellow; we find its heart composed of a hundred perfect flowers, the homes of the tiny black people with red stripes, who moved in and out in that little yellow city. Every bluebell has its inhabitant. Every day the karroo (plain) shows up a new wonder sleeping in its teeming bosom. On our way we pause and stand to see the ground-spider make its trap, bury itself in the sand, and then wait for the falling in of its enemy. Farther on walks a horned beetle, and near him starts open the door of a spider, who peeps out carefully, and quickly puts it down again. On a karroo-bush a green fly is laying her silver eggs. We carry them home, and see the shells pierced, the spotted grub come out, turn to a green fly, and flit away. We are not satisfied with what nature shows us, and will see something for ourselves. Under the white hen we put a dozen eggs, and break one daily to see the white spot wax into the chicken. We are not excited or enthusiastic about it; but a man is not to lay his throat open, he must think of something. So we plant seeds in rows on our dam-wall, and pull one up daily to see how it goes with them. Alladeen buried her wonderful stone, and a golden palace sprang up at her feet. We do far more. We put a brown seed in the earth, and a living thing starts out, starts upward—why, no more than Alladeen can we say—starts upward, and does not desist till it is higher than our heads, sparkling with dew in the early morning, glittering with yellow blossoms, shaking brown seeds with little embryo souls on to the ground. We look at it solemnly, from the time it consists of two leaves peeping above the ground and a soft white root, till we have to raise our faces to look at it; but we find no reason for that upward starting.

A fowl drowns itself in our dam. We take it out, and open it on the bank, and kneel, looking at it. Above are the organs divided by delicate tissues; below are the intestines artistically curved in a spiral form, and each tier covered by a delicate network of blood-vessels standing out red against the faint blue background. Each branch of the blood-vessels is comprised of a trunk, bifurcating into the most delicate hair-like threads, symmetrically arranged.... Of that same exact shape and outline is our thorn-tree seen against the sky in mid-winter; of that shape also is delicate metallic tracery between our rocks; in that exact path does our water flow when without a furrow we lead it from the dam; so shaped are the antlers of the horned beetle. How are these things related that such deep union should exist between them all? Is it chance? Or, are they not all the fine branches of one trunk, whose sap flows through us all?

... And so it comes to pass, in time, that the earth ceases for us to be a weltering chaos. We walk in the great hall of life, looking up and around reverentially. Nothing is despicable—all is meaning—full; nothing is small—all is part of a whole, whose beginning and end we know not. The life that throbs in us is a pulsation from it; too mighty for our comprehension, not too small.—Story of an African Farm.

ANNE WAKELY JACKSON.

DURING the late autumn days, when the summer chorus has dispersed, and only a few winter soloists remain to cheer us, one is more than ever impressed by the wonderful carrying power of bird notes. Many of these notes are not at all loud; and yet we hear them very distinctly at a comparatively long distance from their source.

The ear that is trained to listen will distinguish a bird's note above a great variety of loud and distracting noises. This is due, not to the loudness of the note, but to the quality of its tone.

We all know by experience, though few of us, alas, profit by it that when we wish to make ourselves heard, it is not always necessary to raise our voices, but only to use a different quality of tone.

Thus, some singers, when you hear them in a small room, seem to completely fill it with sound, while if they sing in a large hall, they can scarcely be heard at all beyond a certain distance. Their voices lack carrying power, and their notes apparently escape almost directly after leaving their mouths.

It is this carrying quality, which can be cultivated to a large extent in the human voice, that we find in bird notes. They produce their notes in a perfectly natural way. They do not, like us, have to be trained and taught to sing naturally.

I believe that nearly every human voice has some sweet or agreeable quality in it. If the owner would but use that part, instead of inflicting the harsh or strident or shrill part upon the unfortunate listener, what a musical world we should live in! No discordant voices! Think of it!

To go back to the birds. Here is an example of the penetrating quality of tone they possess. One morning I was busily engaged in the back part of the house, when my ear caught the sound of a bird's note, and I determined to follow it up.

It led me to the front part of the house, out of the front door, down the walk, across the street, and into a neighbor's yard where I found my "caller," a white-breasted nut-hatch, carefully searching the bark of a tall soft maple. His note did not sound particularly loud when I stood there near him. Yet I had heard it with perfect distinctness in the rear of the house.

What a penetrating quality there is in the high, faint "skreeking" of the brown creeper, and in the metallic "pip" of the hairy woodpecker.

The birds could teach us many a lesson on "voice production," if we would but listen to them.

The person who has never learned to listen, misses much of the beauty of life. For him "that hath ears to hear," when he goes abroad, the air is full of subtle music. Not merely the music of the birds, but other voices of nature as well; the wind in the trees, the rustle of leaves.

The unthinking person walks along the street, seeing nothing, hearing nothing. What does he miss? Many things. He misses yon tall tree, which suggests such strength, such enduring majesty. He misses the beautiful leaf that lies in his path, a marvel of exquisitely blended coloring. He misses the delicate tracery of slender twigs and branches, with their background of blue sky or gray cloud. He misses the voices of his feathered friends who would gladly cheer him on his way. If he thinks of nature at all, he is apt to think her beauties have departed with the summer. Not so. If you love nature, she will never withhold some part of her beauty from you, no matter how cold or windy or rainy the day may be. If you see no beauty it is not because it is entirely lacking, but because you are blind to it.

The love of nature is a great gift, a gift that is within the reach of all of us. Let us, then, cultivate this gift, and we shall find beauty and harmony and peace, such as we never dreamed of before. Our lives will become better and nobler for the contact with nature, and we shall be brought into a closer understanding of nature's God.

A FALL EXPERIENCE.

ELLA F. MOSBY.

IT was October 8, and many birds had gone on their long journey to tropical lands. The fog hung thick like a white blanket between the trees, and obscured all distant objects, such as mountain ranges or winding rivers, from view. My home was in Lynchburg, on the James River, and consequently in the line of the "birds' highway," and I was standing beside the window on the lookout for migrants, when, to my surprise, there alighted in the tree beside me a female scarlet tanager in olive-green and dusky yellow, with her soft, innocent eyes looking with gentle confidence around her. In a few minutes the trees around her were ringing with chip cheer! chip cheer! from a large flock of tanagers that had evidently lost their way in the fog, and descended near the ground to make observations. During the morning three different waves of migrating tanagers passed, flying slowly and so low that it was easy to see and recognize them.

The next day it was again thickly foggy. As I glanced out at the window I saw another tanager, sitting motionless on a bough. From ten to three wave after wave, in even greater numbers than the day before, passed. Frequently there were from three to nine tanagers perched in full view, occasionally calling chip cheer! but usually quietly resting or eating insects, of which the trees were full. I heard one crunching a hard-shelled bit in his strong beak. The scarlet of summer was not to be seen in the fall plumage of green and yellow, but the books are misleading when they speak of the male as "dull," or "like the female." It is true he is green above and yellow underneath, but where her wings are darker or "fuscous," his wings and tail are a glossy, velvety black, and instead of her dull yellow, his breast is a shining and vivid lemon-yellow, so that he is almost as beautiful as in his black and scarlet. In such large flocks I saw every phase of varying yellow or green in the immature males and females, one of the latter seeming a soft olive all over, slightly greener above and slightly more yellow below. Even in the spring, when our woods ring with the joyous calls and songs of both varieties, I have never seen half the number of tanagers together.

I was interested in noticing how many of our migrating birds gathered in unusually large flocks. The oven birds and the mocking-birds were seen in large numbers before they left, for many, if not most of the latter, do go farther South in cold weather. I heard one of the mocking-birds singing the most exquisite song, but softened almost to a whisper, as if singing in a dream a farewell to the trees he knew so well. He sang in this way for quite a long while, the rest of the flock flying excitedly to and fro. I also saw a large flock of chebecs instead of the one or two scattered migrants I was accustomed to see in the fall. The gay-colored sapsuckers came to us in large flocks—they spend the winter with us—filling the trees around us.

For the first time, too, I had an experience of the caprices of migrating warblers. The blackpolls and pine-warblers, so numerous last year, had evidently chosen another route to the tropics, nor were the magnolia and the chestnut-sided to be seen. But the Cape May warblers, usually rare, were very numerous, and remained long—from September 20 to October 18. This might probably be explained by the abundant supply of food, for the unusual warmth of the season had not only awakened the fruit trees and lilacs, the kalmia and other wild flowers, to a second period of blooming, but had filled the air with immense swarms of tiny insects. Everywhere glittered and danced myriads of winged creatures, and the trees offered a plentiful table for our insect-loving warblers.

|

||

| FROM COL. F. NUSSBAUMER & SON. A. W. MUMFORD, PUBLISHER, CHICAGO. |

. BLACK SQUIRREL. 5/13 Life-size. |

COPYRIGHT 1900, BY NATURE STUDY PUB. CO., CHICAGO. |

The squirrels are found in all parts of the globe except Australia, where, however, there is a far worse pest of the agriculturist, the abundant rabbit. All the varieties, according to the authorities, correspond so closely in form, structure, habits and character that it is sufficient to describe the common squirrel and its habits, in order to gain sufficient knowledge of the whole tribe. The body of the true squirrel is elongated, tail long, and its fur evenly parted lengthwise along the upper surface. The eyes are large and prominent, the ears may be either small or large, scantily covered with hair or are furnished with tufts. The fore-legs are shorter than the rear. The fore-paws have four toes and one thumb, the hind-paws have five toes.

The time to see the squirrels is in the early morning when they come to the ground to feed, and in the woods large numbers may be seen frisking about on the branches or chasing up and down the trunks. If alarmed the squirrel springs up a tree with extraordinary activity and hides behind a branch. This trick often enables it to escape its enemy the hawk, and by constantly slipping behind the large branches frequently tires it out. The daring and activity of the little animal is remarkable. When pursued it leaps from branch to branch, or from tree to tree, altering its direction while in the air by means of its tail, which acts as a rudder.

It is easily domesticated and is very amusing in its habits when suffered to go at large in a room or kept in a spacious cage, but when confined in a little box, especially in one of the cruel wheel cages, its energies and playfulness are quite lost. The ancient Greeks were fully aware of its attractive qualities, and we are indebted to them for its scientific name. That name signifies "he who is under the shadow of his tail," and everyone who knows the meaning of the Greek word sciurus "must involuntarily think of the lively little creature as it sits on the loftiest branches of the trees."

The favorite haunts of the squirrel are dry, shady forests. When fruits and nuts are ripe it visits the village [Pg 24] gardens. Where there are many pine cones it makes its permanent home, building one or more, usually in old nests of crows which it improves. If it does not intend to remain long it uses the nests of magpies, crows, or birds of prey, but the nest which it intends to serve as a permanent sleeping-place, a shelter against bad weather, or a nursery, is newly built. It is said that every squirrel has at least four nests; but nothing has been definitely proven on this score. Brehm says they also build in hollow trees; that the open-air nests usually lie in a fork close to the main trunk of the tree; the bottom is built like one of the larger bird nests while above there is a flat, conical roof after the manner of magpies' nests, close enough to be impenetrable to the rain. The main entrance is placed sideways, usually facing the east; a slightly smaller loop-hole for escape from its many enemies is found close to the trunk.

According to the season it eats fruit or seeds, buds, twigs, shells, berries, grain and mushrooms. The seeds, buds and young shoots of fir and pine trees probably form its principal food.

As soon as the animal is provided with food in abundance it lays by stores for later and less plenteous times, carrying to its storerooms nuts, grains and kernels, sometimes from a great distance. In the forests of southeastern Siberia the squirrels also store away mushrooms, and that in a very peculiar manner.

"They are so unselfish," says Radde, "that they do not think of hiding their supply of mushrooms, but pin them on the pine needles or in larch woods on the small twigs. There they leave the mushrooms to dry, and in times of scarcity of food these stores are of good service to some roaming individual of their kind."

L. WHITNEY WATKINS.

GRANVILLE OSBORNE.

AMONG the beautiful incidents of scripture none has become more familiar to old and young alike than that which relates how Noah "sent forth a dove from him to see if the waters were abated from off the face of the ground." We can imagine the timid messenger sent forth by Noah's hand from the open window of the ark. Over the vast surface of the waters it flew, in obedience to natural instincts, seeking a place of rest, but, as the narrative relates, "the dove found no rest for the sole of her foot, and she returned unto him into the ark, for the waters were on the face of the whole earth." With what an unerring flight the dove had returned to the only safe refuge, and how gently did Noah "put forth his hand" and "draw her in unto him," after the weary quest was over and the tired wings had only brought back a message of defeated hopes. After seven days had gone by Noah sent forth the dove again with longing expectancy that the flood might be receding. With swift flight the dove disappeared from view, and, high in air, sought amid the waste of waters, with its marvelous powers of sight, for any sign which told of safety and rest. At length it reached a refuge, the spot it sought, where the valleys once more began to show themselves above the depths. And in the evening, as Noah watched and waited at the open window of the ark, he saw afar off the glint of snowy wings against the golden sky, and "lo, the dove returned, bearing in her mouth an olive leaf plucked off, so Noah knew that the waters were abated from off the earth." The olive branch was a token that even the trees in the valleys were uncovered, and has been the type in all after ages of peace and rest. The Hebrew word "yonah" is the general name for the many varieties of doves and pigeons found in Bible lands. It is frequently used by the prophetic writers as a symbol of comparison. Both Isaiah and Ezekiel speak of doves that "fly as a cloud." In many of the wild valleys of Palestine the cliffs are full of caves, and there the wild pigeons build their nests and fly in flocks that truly are "like the clouds" in number. Again the same prophets speak of the "doves of the valleys, all of them mourning." This is peculiarly applicable to the turtle dove. Its low, sad plaint may be heard all day long at certain seasons in the olive groves and in the solitary and shady valleys amongst the mountains. These birds can never be tamed. Confined in a cage, they languish and die, but no sooner are they set at liberty than they "flee as a bird" to their mountains. David refers to their habits in this respect when his heart was sad within him: "O that I had wings like a dove, for then would I fly away and be at rest." Nahum alludes to a striking habit of the dove when he says: "And the maids of Hazzab shall lead her as with the voice of doves, tabering upon their breasts."

Hazzab was the queen of Nineveh, who was to be led by her maidens into captivity, mourning as doves do, and "tabering," or striking on their breasts, a common practice in that country.

David, in beautiful imagery, comforts those who mourn, saying: "Though ye have lain among the pots, ye shall be as the wings of a dove covered with silver and her feathers with yellow gold." A dove of Damascus is referred to whose feathers have the metallic luster of silver and the gleam of gold. They are small and kept in cages. Their note is very sad and the cooing kept up by night as well as by day.

To the millions who devoutly sing of the "Heavenly Dove" no other symbol either in or out of the Bible suggests so much precious instruction and spiritual comfort as this innocent bird—pure, gentle, meek, loving, faithful, the appropriate emblem of that "Holy Spirit" that descended from the open heavens upon our Lord at his baptism.

THIS is the smallest beast of prey, but so agile and courageous that it is regarded as a model of carnivorous animals. It dwells in fields, gardens, burrows, clefts of rock, under stones or wood piles, and roams around by day as well as by night. Its slender and attenuated shape enables it to enter and explore the habitations of the smallest animals, and, as it is a destroyer of rats, mice, and other noxious animals, it is useful and deserves protection. It is, however, hunted by many who do not appreciate its value.

The weasel attains a length of eight inches, including the tail. The body appears to be longer than it really is because the neck and head are of about the same circumference as the body. It is of the same thickness from head to tail.

This animal is found throughout Europe, Canada, and the northern portions of the United States. Plains, mountains, forests, populous districts, as well as the wilderness, are its home. It adapts itself to circumstances, and can find a suitable dwelling-place in any locality. It is found in barns, cellars, garrets, and similar retreats.

An observer says one who noiselessly approaches the hiding-place of a weasel may easily secure the pleasure of watching it. He may then hear a slight rustle of leaves and see a small, brown creature gliding along. As soon as it catches sight of a human being it stands on its hind legs to obtain a better view. "The idea of flight seldom enters this dwarf-like creature's head, but it looks at the world with a pair of bold eyes and assumes an attitude of defiance." Men have been attacked by it. A naturalist once saw a large bird swoop down on a field, pick up a small animal and fly upward with it. Suddenly the bird staggered in its flight, and then dropped to the ground dead. A weasel tripped merrily away. It had severed its enemy's neck with its teeth and thus escaped.

The weasel preys upon mice, house rats and water rats, moles, hares, rabbits, chickens, birds, lizards, snakes, frogs, fish, and crabs.

A litter of weasels numbers eight. The mother is very fond of the little blind creatures and nourishes them until long after they can see.

Buffon said this little animal was not capable of domestication, but as a matter of fact, when accustomed to people from childhood, it becomes very tame and attractive.

A lady tells the following anecdote of her pet weasel:

"If I pour some milk into my hand my tame weasel will drink a good deal, but if I do not pay it this compliment it will scarcely take a drop. When satisfied it generally goes to sleep. My chamber is the place of its residence and I have found a method of dispelling its strong odor by perfumes. By day it sleeps in a quilt, into which it gets by an unsewn place which it has discovered on the edge; during the night it is kept in a wired box or cage, which it always enters with reluctance and leaves with pleasure. If it be set at liberty before my time of rising, after a thousand playful little tricks, it gets into my bed and goes to sleep beside me. If I am up first it spends a full half-hour in caressing me, playing with my fingers like a little dog, jumping on my head and my neck with a lightness and elegance which I have never found in other animals. If I present my hands at the distance of three feet it jumps into them without ever missing. It exhibits great address and cunning to compass its ends, and seems to disobey certain prohibitions merely through caprice. In the midst of twenty people it distinguishes my voice, seeks me out and springs over all the others to come at me."

The weasel probably lives from eight to twelve years. It is easily caught in a trap, with bait of an egg, a small bird, or a mouse. No other animal is so fitly endowed for hunting mice.

|

||

| FROM COL. F. NUSSBAUMER & SON. A. W. MUMFORD, PUBLISHER, CHICAGO. |

WEASEL. ⅖ Life-size. |

COPYRIGHT 1900, BY NATURE STUDY PUB. CO., CHICAGO. |

In the attempt to check the rabbit pest in New Zealand, recourse has been had to the importation of natural enemies, such as ferrets, stoats, and weasels. In the Wairarapa district some 600 ferrets, 300 stoats and weasels, and 300 cats had been turned out previous to 1887. Between January, 1887, and June, 1888, contracts were made by the government for nearly 22,000 ferrets, and several thousand had previously been liberated on crown and private lands. Large numbers of stoats and weasels have also been liberated during the last fifteen years.

This host of predatory animals speedily brought about a decrease in the number of rabbits, but their work was not confined to rabbits, and soon game birds and other species were found to be diminishing. The stoat and the weasel are much more bloodthirsty than the ferret, and the widespread destruction is attributed to them rather than to the latter animal. Now that some of the native birds are threatened with extermination, it has been suggested to set aside an island along the New Zealand coast, where the more interesting indigenous species can be kept safe from their enemies and saved from complete extinction.

BIRDS are dependent on the elements as well as is man, and in the want of materials and the requirements in nest-building the birds are comparable to the lords of creation.

It is not a rare thing for a pair of robins to be badly handicapped in nesting-time by a lack of rain, for in May, and even in the showery month of April, there is occasionally a dry run of weather lasting for more than a week.

I have seen a pair of robins start a nest, and the dry weather would come on and stop operations, and the disconsolate pair would wait for the rain so that they could make mortar for their nest. Robins must have mud to use in the construction of their little home, and all the dry materials will avail them nothing unless there is a good stock of mortar on hand to cement the grass, rags, and other materials together.

On one occasion we supplied a pair of redbreasts with plenty of mortar by letting the hydrant run on the ground. The delighted robins immediately accepted the situation and gathered materials for the partially finished home, which was quickly completed and the four beautiful eggs deposited. We broke the law by letting the water run, but then we can excuse ourselves in behalf of the faithful birds by saying that "necessity knows no law."

The eave-swallows also require mortar for the construction of their nests, and they select quarters not very far removed from lakes, ponds, or streams. There is a neighborhood where the swallows used to build in great numbers, and the barns were well patronized by these little insect-feeders, rows of the gourd-shaped nests being seen beneath the eaves.

At last the pond in the section was drained, and all the swallows deserted that neighborhood. There are very few birds which are not more or less affected by civilization, and a study of this subject is most interesting.

Years ago the chimney swifts were in the habit of building their stick nests in the hollows of big trees, and even at the present day we may find nests in these old-time situations. As time passed the swifts found that the chimneys of men's houses offered better situations for nests, and so the reasoning birds adopted our city and village chimneys to the abandonment of the primitive habit of nesting in hollow trees.—Humane Alliance.

BIRDS THAT CARRY LIGHTS.

P. W. H.

"LIGHTNING BUGS" and other insects that carry lights are familiar in many parts of the country, but who ever heard of birds that carry lights? A strange story is told of the heron's powder patch which makes a two-candle light, which discloses a new idea in bird lore. A belated sportsman returning from a day's sport found himself late in the evening on the edge of a flat or marsh which bordered the path. The moon had not risen, and the darkness was so intense that he was obliged to move slowly and carefully. As he walked along, gun on shoulder, he thought he saw a number of lights, some moving, others stationary. As they were in the river bed, he knew that they could not be lanterns, and for some time he was puzzled; but, being of an inquisitive mind, he walked down to the water to investigate.

As the stream was a slow-running, shallow one, he had no difficulty in wading in, and soon convinced himself that the lights were not carried by men, and were either ignes fatui or from some cause unknown. To settle the apparent mystery he crept as close as he could, took careful aim and fired. At the discharge the lights disappeared, but, keeping his eye on the spot where they had been, he walked quickly to it and found, to his amazement, a night heron, upon whose breast gleamed the mysterious light.

"The sportsman told me of this incident," says a friend who knew him well, "and, while I had often heard of the light on the heron's breast, I never before could find anyone who had personally witnessed the phenomenon, consequently I propounded numerous questions. The observer saw the light distinctly; first at a distance of at least fifty yards, or one hundred and fifty feet. There were three lights upon each bird—one upon each side between the hips and tail, and one upon the breast.

"He saw the lights of at least four individuals, and was so interested that he observed them all carefully and, as to their intensity, stated to me that each light was the equivalent of two candles, so that when he aimed he could see the gun-sight against it.

"As to whether the bird had control of the light, he believed he did, as he saw the lights open and shut several times as he crawled toward the birds and he stopped when the light disappeared and crept on when it came again. The light did not endure long after the bird was shot, fading away almost immediately. In color the light was white and reminded the sportsman of phosphorescent wood.

"Stories of luminous birds have been related by sportsmen occasionally, but, so far as I know, exact facts and data have never before been obtained on this most interesting and somewhat sensational subject. A friend in Florida told we that he had distinctly seen a light moving about in a flock of cranes at night and became satisfied that the light was the breast of the bird. Another friend informed me that on entering a heron rookery at night he had distinctly observed lights moving about among the birds."

That herons have a peculiar possible light-producing apparatus is well known. These are called powder-down patches, and can be found by turning up the long feathers on the heron's breast, where will be found a patch of yellow, greasy material that sometimes drops off or fills the feathers in the form of a yellow powder. This powder is produced by the evident decomposition of the small feathers, producing just such a substance as one might expect would become phosphorescent, as there is little doubt that it does.

The cranes and herons are not the only birds having these oily lamps, if so we may term them. A Madagascar bird, called kirumbo, has a large patch [Pg 31] on each side of the rump. The bitterns have two pairs of patches; the true herons three, while the curious boat-bills have eight, which, if at times all luminous, would give the bird a most conspicuous, not to say spectral appearance at night.

Some years ago a party of explorers entered a large cave on the island of Trinidad that had hitherto been considered inaccessible. To their astonishment they found it filled with birds which darted about in the dark in such numbers that they struck the explorers and rendered their passage not only disagreeable, but dangerous. The birds proved to be night hawks, known as oil birds, and in great demand for the oil they contain, and it is barely possible that these birds are also light-givers. The powder-down patches of the oil bird are upon each side of the rump.

As to the use of such lights to a bird there has been much conjecture; but it is thought that it may be a lure to attract fishes. It is well known that fishes and various marine animals are attracted by light, and a heron standing motionless in the water, the light from its breast, if equal to two candles, would be plainly seen for a considerable distance by various kinds of fishes, which would undoubtedly approach within reach of the eagle eye and sharp bill of the heron and so fall victims to their curiosity. If this is a true solving of the mystery it is one of the most remarkable provisions of nature.

There is hardly a group of animals that does not include some light-givers of great beauty; but it is not generally known that some of the higher animals also produce light at times. Renninger, the naturalist, whose studies and observations of Paraguay are well known, tells a most remarkable story of his experience with the monkey known as Nyctipithithecus trivigatus. He was in complete darkness when he observed the phenomenon, which was a phosphorescent light gleaming from the eyes of the animal; not the light which appears in the eye of the cat, but shafts of phosphorescent light which were not only distinctly visible, but illumined objects a distance of six inches from the animal's eyes.

The subject is an interesting one and research among the various phenomena disclosed by naturalists may discover many other animals capable of strange illuminations.

NELLY HART WOODWORTH.

NOT the least interesting of my summer neighbors is a Quaker family named Chebec, the least fly-catchers.

They are little people, else they would not be least fly-catchers, plainly dressed, with olive shoulder-capes lined with yellow, wings finely barred with black and white and heads dark and mousy. The large eyes, circled with white, are as full of expression as a thrush's.

What is lacking in song is made up in an energy decidedly muscular, the originality of the note chebec, uttered with a jerk of the head or a launch into the air after some passing insect, never being confused with other bird voices.

It is not Chebec himself that commands my special admiration, but "Petite," his winsome little lady, with her rare gentleness and confidence. Our intimacy began when she was living on a long maple branch that nearly touched my chamber window, and she was dancing attendance upon four pure-white eggs when I became conscious of her neighborly intentions. She soon settled down into the most demure little matron, a regular stay-at-home, really grudging the time necessary for taking her meals. Later, when I "peeked in" at the nestlings, Petite only hugged them closer, nor did she leave until my hand was laid on her shoulder. We were soon fast friends. The most tempting morsels the neighborhood afforded were brought to her door, and, though she was unwearied in the family service, my efforts were [Pg 32] gratefully received, even anticipated. The following spring her choice of residence was a bough that hung over the door, coming to the end of the branch whenever I appeared in an effort to express her approval. For, you see, I had given her a quantity of strings and lace and cotton for her nest, and she was truly grateful!

Excess of splendor is always perilous. The work of art was no sooner completed than Robin Redbreast grew envious, rushed over and pulled out the finest strings, leaving the nest in so shaky a condition that the wind soon finished it.

Petite's feelings were deeply injured—she could not be induced to rebuild near her malicious neighbor.

To help her forget her troubles I gave her some yellow ravelings, much handsomer than those Robin had stolen.

Thoroughly consoled, she worked as fast as she possibly could until the last ray of light had faded. Knowing that Robin's impudence had delayed her spring's work, I did my best to supply her needs.

Altogether her patience was extreme. Occasionally she hinted gently that her time was precious or that I was keeping her waiting, as she hovered about my face or rested briefly upon my shoe, keeping a sharp lookout meanwhile upon the cloth I was raveling.

How she scampered off when it was ready, snatching it from my hand before it reached the ground!

The next day saw the new house completed—no ordinary affair, but a magnificent dwelling, yellow from foundation to rafter, with a long, fantastic fringe of the same floating from its rim and waving gracefully in every breeze.

Petite now became my attentive companion in my garden work, talking in subdued tones from the nearest branch as if she felt the seriousness of the occasion, circling in the air and alighting on the same bough in pretended alarm when I tried to touch her soft, delicate feathers.

May 3d of this present year she called softly from the orchard that she had arrived. For a few days she had little to say, wearied with the long journey and being broken of her rest, as must have been the case. She was not quite herself, either—really put on airs and kept at a distance; but when she began to think of housekeeping she was the same trusting darling that won my heart and gave me willing hands in her service.

We talked matters over on the piazza while she fluttered about my head, touched my hat with dainty feet, or poised before me to say in her own pretty way that it was quite time to be thinking of sitting. "What do you propose to do for me this year? How much help can I rely upon from you?" she asked as plainly as if she spoke English.

"Ah, Petite," I answered, "you must not demand too much. It is quite time the sweet peas were planted!" But words were useless; she coaxed, enticed, pleaded, until mine was a full and unconditioned surrender. "You deserve it, Petite, for your perseverance! You shall have the finest house that was ever seen in this section," I said, and with that promise we parted.

I found a quantity of jeweler's cotton, pink as a rosebud, soft and fluffy and light enough to satisfy the most fastidious bird architect. Small pieces were placed upon lawn and tree trunks, where Petite soon spied them; her first impulse was one of approval.

Not meaning to be rash in her judgment, her head was cocked cunningly on one side as she poised, eyeing them closely, until I feared that, dissatisfied, she would accuse me of breaking my promise.

When she seized one, cautiously, in her beak and sailed away with it trailing after her in the air my fears were over. As no harm attended its transfer to the orchard, where it was adjusted to her taste, her admiring mate left his fly-catching to help in the work, the cotton disappearing so rapidly there were signs of a corner in the market.

The nest, strengthened with a few strings, grew rapidly toward completion. To all appearance its unique beauty was a matter of congratulation, the builders regarding it from all sides with intense satisfaction.

|

||

| FROM KŒHLER'S MEDICINAL-PFLANZEN. | QUINCE. | CHICAGO: A. W. MUMFORD, PUBLISHER. |

Description of Plate.—A, flowering twig; B, fruit; 1, stipules; 2, flower in section; 3, stamen; 4, pollen; 5, style; 6, stigma; 7 and 8, fruit in sections; 9 and 10, seeds of one cell of the ovary; 11, seeds; 12, seed in sections.

BY DR. ALBERT SCHNEIDER,

Northwestern University School of Pharmacy.

THE quince is the pear-like fruit of a bush or small tree resembling the pear tree. The branches are spreading and of a grayish green or brownish green color. The leaves are simple, entire, ovate, with short petioles and distinct stipules. The lower surface of leaves and stipules as well as the young twigs and the sepals are densely covered with hair-cells producing a woolly appearance. The flowers develop in May and June and are usually solitary upon terminal branches. Calyx green with five foliaceous, serrate, reflexed lobes. Corolla of five separate ovate, rather large, pink petals. Stamens yellow, numerous (20); five styles and a five-celled ovary. The matured fruit is a pome. That is, the greater bulk consists of the thickened calyx enclosing the ovary. The form, size and color of the ripe fruit are shown in the illustration. Each cell of the ovary bears from six to fifteen seeds which resemble apple seeds very closely as to form and color.

The name Cydonia is derived from the name of the Greek city Cydon, now Canea, of Crete. The Cydonian apple of the Greeks was emblematic of fortune, love and fertility, and was dedicated to the goddess Aphrodite (Venus). It is a question whether Crete was the original home of the quince. Some authorities maintain that it found its way into Greece from upper Asia, Persia, or India. Wherever its first home may have been this plant was known in Greece 700 years B. C. From Greece the tree was introduced into Italy and Spain, from which countries it finally spread over central Europe. Charlemagne, Karl der Grosse—812, was largely instrumental in spreading the quince in Germany.

The ancient Greeks made extensive medicinal use of the fruit. On account of its astringency it has been used in dysentery, hemorrhage, and other conditions requiring an astringent substance. At present it is little used, the seeds excepted.

The pulp is fibrous and tough; it is not edible in the raw state on account of its acrid, astringent taste. As a whole it is a discouraging and disagreeable fruit in spite of its beautiful yellow color and pleasantly aromatic odor. Mixed with apples it makes excellent pies and tarts. A marmalade is made from the pulp, also a delicious jelly. It is stated that the word marmalade is derived from marmelo, the Portuguese name for quince.

The seeds are extensively used on account of the mucilage of the outer surface (epidermal cells). A decoction commonly known as mucilage of quince seed is much used as a demulcent in certain diseases—in erysipelas, inflammatory conditions of the eyes and in other affections where mucilaginous applications are found useful. The Mohammedans of India value the seeds very highly as a restorative and demulcent tonic. European physicians have used them with much success in dysentery. The mucilage is also one of the substances used by hair-dressers under the name of bandoline.

Chemically the mucilage is simply a modification of cellulose. Pereira considered it a special chemical substance which he designated cydonin. The seed, about 20 per cent. of which is mucilage, will make a sticky emulsion with forty times its weight of water. As to its physical properties it closely resembles gum arabic and agar. There are, however, simple tests by means of which it is possible to distinguish them. The seeds rubbed or crushed emit an odor resembling almonds, due to the presence of hydrocyanic acid.

Most of the quince seed of the market comes from southern Russia, southern [Pg 36] France and the Cape of Good Hope. It is cultivated in various temperate and subtropical countries.

The quince must not be confounded with the Indian "bael" fruit which is known in India as the Bengal quince. The Chinese quince is a species of pear. The Japanese quince is also a species of pear resembling the Chinese quince. It is a great garden favorite on account of its large scarlet or crimson flowers. The fruit, which is not edible in the raw state, resembles a small apple and is sometimes used for making a jelly. The Portugal quince differs from the ordinary variety by its more delicate coloring. It is, however, less productive than the common varieties.

DIAMONDS AND GOLD.

CECIL RHODES says: "So long as women are vain and men foolish there will be no diminution in the demand for diamonds." He ought to know, for he is called the "Diamond King."

Thirty years ago John O'Reilly found some children at a farm house in South Africa playing in the evening with some beautiful stones that had peculiar forms and brilliancy. He took the finest to town with him and found it was worth $500.

People swarmed into the country where little children had rough diamonds for playthings, and over $400,000,000 worth of these crystals has been taken from Africa.