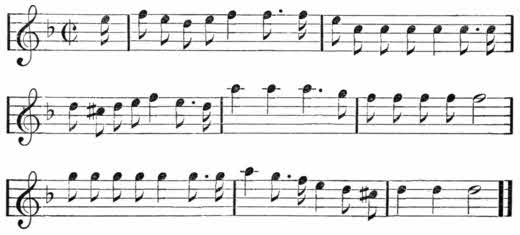

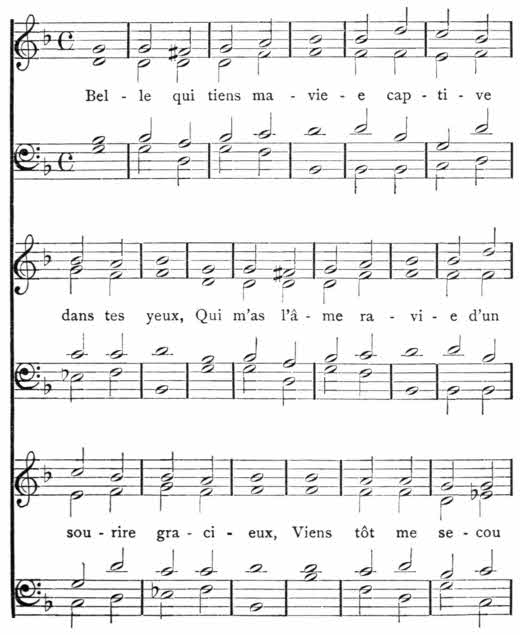

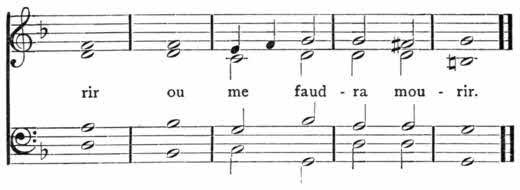

The web browser version of this book contains links to Midi, PDF, and MusicXML files for the music scores on pages 94 and 319-320.

Additional Transcriber's Notes are at the end.

Sir Christopher

A Romance of a Maryland

Manor in 1644

BY

MAUD WILDER GOODWIN

Author of "The Head of a Hundred," "White Aprons,"

"The Colonial Cavalier," etc.

Illustrated by

HOWARD PYLE, AND OTHER ARTISTS

Boston

Little, Brown, and Company

1901

Copyright, 1901,

By Little, Brown, and Company.

All rights reserved

Entered at Stationers' Hall

UNIVERSITY PRESS · JOHN WILSON

AND SON · CAMBRIDGE, U. S. A.

TO

BLANCHE WILDER BELLAMY

AND

FREDERICK PUTNAM BELLAMY

On a bluff of the Maryland coast stand a church, a school, a huddle of gravestones, and an obelisk raised to the memory of Leonard Calvert. These alone mark the site of St. Mary's, once the capital of the Palatinate.

It is near this little town, about the middle of the seventeenth century, that my story begins, among the feuds then raging between Catholic and Protestant, Cavalier and Roundhead, Marylander and Virginian. The Virginians of that day were but a generation removed from the pioneers who suffered in the massacre of 1622; and the sons and daughters of those early settlers whose lives were traced in "The Head of a Hundred"[A] appear in the present romance.

The adventures of Romney Huntoon, of the Brents, and, most of all, of Christopher Neville and Elinor Calvert, furnish the material of my story; but I venture to hope that the reader will feel beneath the incidents and adventures that throbbing of the human heart which has chiefly interested me.

[A]Published 1895.

| Chapter | Page | |

| I. | Robin Hood's Barn | 1 |

| II. | St. Gabriel's and St. Inigo's | 16 |

| III. | Blessing and Banning | 34 |

| IV. | The Lord of the Manor | 49 |

| V. | Peggy | 72 |

| VI. | The King's Arms | 90 |

| VII. | In good Green Wood | 108 |

| VIII. | A Clue | 130 |

| IX. | A Requiem Mass | 144 |

| X. | The Ordeal by Touch | 159 |

| XI. | The Greater Love | 172 |

| XII. | How Lovers are Convinced | 180 |

| XIII. | A Change of Venue | 196 |

| XIV. | In which Fate takes the Helm | 215 |

| XV. | Digitus Dei | 223 |

| XVI. | Life or Death | 240 |

| XVII. | Romney | 256 |

| XVIII. | The Emerald Tag | 274 |

| XIX. | The Rolling Year | 292 |

| [x]XX. | A Birthnight Ball | 309 |

| XXI. | A Rooted Sorrow | 334 |

| XXII. | Candlemas Eve | 354 |

| XXIII. | "Hey for St. Mary's, and Wives for us All!" | 370 |

| XXIV. | The Calvert Motto | 392 |

| "'Let me go to him!' she shrieked, in her anguish of soul" | Frontispiece | |

| From a drawing by Howard Pyle | ||

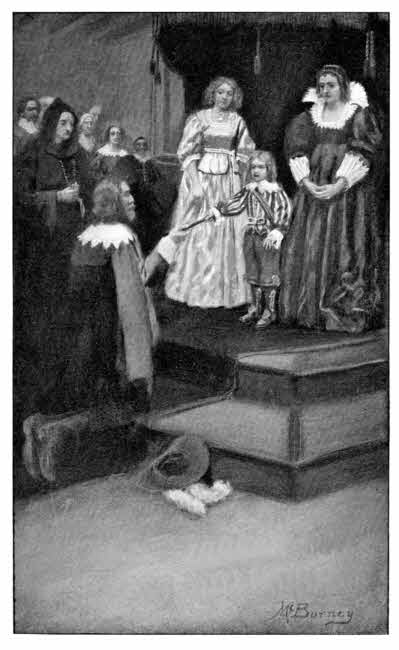

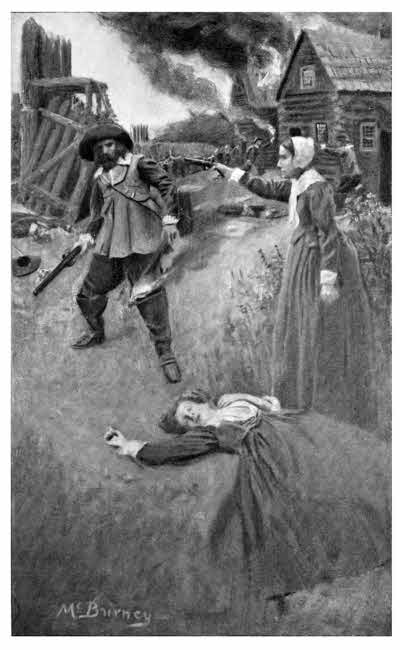

| "Stretch out thy rod, Cecil" | Page | 58 |

| From a drawing by James E. McBurney | ||

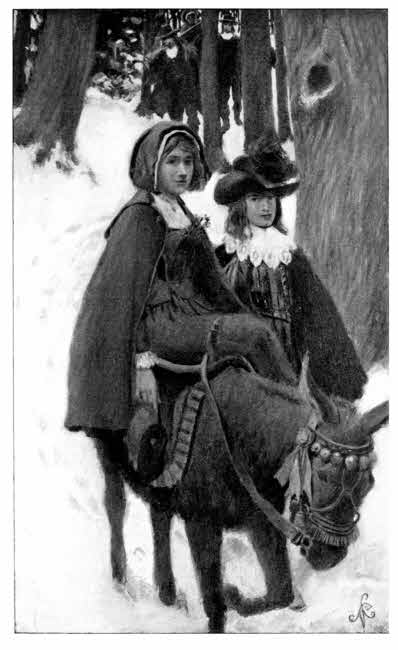

| "You are quite a courtier, Master Huntoon" | " | 116 |

| From a drawing by S. M. Palmer | ||

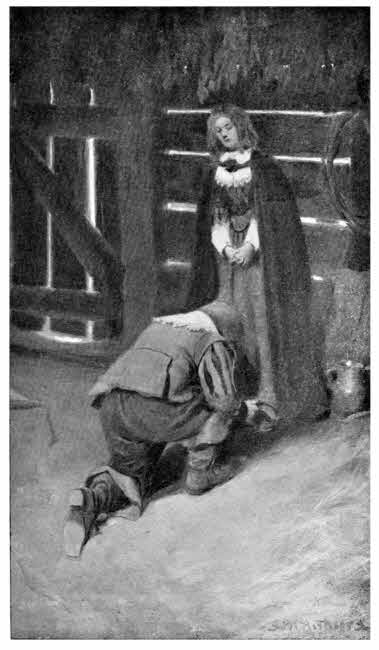

| "This is love indeed" | " | 194 |

| From a drawing by S. M. Arthurs | ||

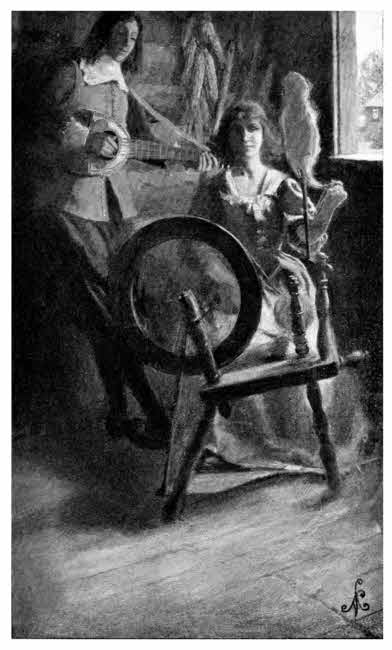

| "He sang to the music of his lute, and she to the accompaniment of her whirring wheel" | " | 301 |

| From a drawing by S. M. Palmer | ||

| "As it is, I am satisfied. Go!" | " | 390 |

| From a drawing by James E. McBurney | ||

SIR CHRISTOPHER

Through the January twilight a sail-boat steered its course by the light of a fire which blazed high in the throat of the chimney at St. Gabriel's Manor. Within the hall, circled by the light from the fire, a Danish hound stretched its lazy length on the floor, and, pillowing his head against the dog's body, lay a boy eight or nine years old.

He was a plain laddie, with a freckled nose, a wide mouth, and round apple cheeks over which flaxen curls tumbled in confusion. His big eyes, the redeeming feature of the face, were just now fixed upon the shadows cast by the motion of his joined hands on the wall. At length the lips parted over a row of baby teeth with a gap in the centre, through which the little tongue showed blood-red, as the boy laughed long and loud.

"Thee, Knut!" he lisped, with that occasional slip of the letter s which was a lingering trick of babyhood and cost him much shame,[2] "is not that broad-shouldered shadow like Couthin Giles? And the tall one,—why, 'tis the very image of Father Mohl! And the short one ith Couthin Mary. Look how she bows as she goes before the father! And what a fine cowl I have made of my kerchief!"

Unconscious of observation as the boy was, he was being closely watched from two directions. In the shadow of the settle by the fire sat a tonsured priest, holding before him a breviary over the top of which he was contemplating the boy on the floor; opposite the priest, on the landing of the stairs, a woman leaned on the balustrade, following with absorbed interest every movement of the chubby hands, and every expression of the childish face, which bore a burlesqued resemblance to her own. After a moment the woman gathered her skirts closer about her and stealing down the winding stair, crept up behind the boy and clasped both hands playfully over his eyes.

"Who is it?" she asked gaily.

"Mother!" cried the child, wrenching himself free only to jump up and throw himself into the arms outstretched to receive him. "Didst fancy I was like to mithtake thy hands?" he asked. "No, faith! Father Mohl's hands are long and cold, and Couthin Mary's fingers are stiff and hard, no more like to thine than a potato to a puff-ball."

"Hush, Cecil! Hush, little ingrate!" whispered[3] the mother, clapping her hands this time over his lips. "I would not thy Cousin Mary heard that speech for a silver crown." Nevertheless, she smiled.

Elinor Calvert, as she stood there with one hand on her son's shoulder and the other bending back his face, looked like some sunshiny goddess. Her dress well became her height. She wore a long petticoat of figured damask, beneath a robe of green stuff. Her bodice, long and pointed, fitted the figure closely, and the flowing sleeves of green silk fell back from round white arms. Around her neck was a string of pearls, bearing a heart-shaped miniature set also in pearls, and held to the left side of her bodice by a brooch of diamonds. Her figure was tall, and crowned by a head nobly proportioned and upheld by a white pillar of throat. Her features were heavily moulded, especially the lips and chin. The golden hair which swept her brow softened its marked width, yet the impression conveyed by the face might have been cold had it not been for the softness of the eyes under their fringe of dark lashes.

In spite of the flashes of gaiety which marked her intercourse with her son, the prevailing expression of Mistress Calvert's face was sad. Rumor said that there was enough to account for this in the story of her brief married life in[4] England, for Churchill Calvert was a spendthrift and a gambler, who died leaving his widow with her little son a year old, and no other support than the income of a slender dowry.

In those dark days of her early widowhood Elinor received a letter from her husband's kinsman, Lord Baltimore.

"I know your pride too well," he wrote, "to offer you any help; but you must not deny my right to provide for my godson. Money with me is scarce, but land is plenty, and I offer you in Cecil's name a grant of seven thousand acres in Maryland. It is covered with virgin forest. Like the old outlaw you must needs store your grain in caves and stable your horses and cattle under the trees; wherefore I shall counsel Cecil to name his manor Robin Hood's Barn. Should you be willing to remove thither, make up your mind speedily, for at the sailing of a ship now in harbor, our cousins the Brents start for the new world, and would rejoice to have you and Cecil in their keeping."

Baltimore was right in foreseeing the struggle in Elinor's mind between pride and love for her child; but he was also right in predicting that love would triumph, and Elinor thanked him and Heaven daily for this asylum, where her boy could grow up safe from the temptations of London which had wrecked his father's life.

As she bent over Cecil to-night, her heart was full of contending emotions. She and her boy were safely sheltered under the roof of her dear cousin, Mary Brent, Cecil would soon be old enough to take possession of the manor at Cecil Point, the future was apparently bright with promise; yet she was conscious of some unsatisfied hunger of the heart, and, deeper than that, of a sense of some impending grief; but she was a woman of shaken nerves easily sunk in melancholy.

"Hark!" cried Cecil, suddenly pulling himself away from his mother's arms,—"I hear the sound of footsteps outside." At the same moment Mary Brent came slipping down the stairs.

"Elinor," she said with a little nervousness, "Giles was expecting a friend to-night."

"Ah?" said Elinor, indifferently.

"Yes; 'tis a pity he was called to St. Mary's in such haste, for the friend comes on business."

"Perchance he may tarry till Giles returns."

"I hope so,—but, Elinor,—this business concerns thee."

"Me!"

"Ay, the new-comer is one who would fain have a lease of the manor at Cecil Point."

"Robin Hood's Barn? Now, Mary, have I not told thee and Giles that I would hear of no such plan? I am a woman of affairs and can well[6] manage till Cecil is old enough to take control. Another six months we shall rest under your roof,—then, dear cousin, we must be gone to our own."

Mary Brent laid her hand upon the younger woman's arm.

"Vex me not, Elinor," she said, "by speaking so. Let it be settled that this is your home. 'Tis not kind to talk of leaving me. Besides, you could not live upon your lands without an arm to protect you, stout enough for defence and for toil."

"We will hire laborers."

"Common laborers are not enough. There must be a man with head to direct as well as hands to work."

Cecil, who had stood by an eager listener, suddenly stripped up the sleeve of his jerkin and bared his arm.

"Feel that!" he cried, doubling his elbow till the muscle stood out. Mary Brent laughed as she laid her hand upon it.

"Truly, 'tis a pretty muscle. Yet will it be better for a few more years of growth. Say, Elinor, wilt thou take this man for thy tenant? Giles has left the lease already drawn for thee, as Cecil's guardian, to sign when thou hast settled terms with the man. Giles says he is as fine a fellow as hath yet set foot in Maryland. He is[7] a gentleman, moreover, and hath a title, having been knighted for gallant service in that ill-fated Cadiz expedition some years since."

"Who is the man?"

"Neville is his name, Sir Christopher Neville."

"Christopher Neville!" repeated Elinor, slowly, but the shuffling of snow-covered feet upon the stepping-stones outside put an end to further speech. Knut began to bark.

"Give over barking, thou naughty dog! Hie away to the kitchen and make way for thy betters!" said Mary Brent, making a feint at taking down a stick from over the fireplace. The dog continued barking, and Cecil began to laugh.

"Hush, Cecil," said his mother; "where are thy manners? Make haste to open the door!"

Cecil ran to the door and flinging it wide let in a great gust of wind. The light from within fell upon a man wrapped in a heavy cloak and wearing a broad-brimmed cavalier hat with plumes at the side.

"Come in, good thir!" cried Cecil, "before you are frozen stiff;" and he led the way to the fire, before which Mary Brent stood with outstretched hand of welcome.

"My brother Giles is called to St. Mary's; but he left a welcome for you, and bade us keep you without fail till his return."

The new-comer bowed low above Mistress[8] Brent's hand. He was a tall, plain man, approaching middle age, with keen eyes, and dents in his face as if Time had nicked it with his sickle. Around his firm-set mouth, hovered a smile that had summered and wintered many disappointments.

"Elinor, let me make Sir Christopher Neville known to thee! My cousin, Elinor Calvert, Sir Christopher, the mistress of Cecil Point."

With this, Elinor, who had stood still as a statue, moved slowly forward and held out her hand. Neville kissed it.

The priest who had sat in the shadow of the settle, a silent observer of the scene before him, rose, now that all eyes were turned toward the stranger, and glided quietly out at the further doorway, murmuring, "Suscipiat Dominus sacrificium de manibus meis ad laudem et gloriam nominis sui!"

"Come, Cecil!" said Mary Brent. "Let us make ready the hot posset. I have the ale on the fire a-heating and the milk and sugar and spices ready, and with a sippet of bread 'tis wonderful sustaining. Sir Christopher, you will find its sting comforting after your long journey."

As she drew the child after her she whispered to Elinor, "To business, Cousin! Tell him he may have the manor for the clearing of the land and half the harvest!"

The door closed behind her. Elinor Calvert and Christopher Neville stood looking at each other across the width of the fireplace. A long silence followed, broken at last by Elinor's impulsive speech.

"Why art thou come hither?"

"Maryland is free to all."

"Why dost thou seek to become my tenant?"

"I have a fancy for the land at Cecil Point."

"Thy answers ring false. Tell me the real reason in a word."

"As well in one word as in a thousand, since the word is Thou."

The flush mounted to Elinor Calvert's brow and she stood playing with the tassels of her girdle, finding nothing to say in answer.

"Yes," Neville went on, "for thy sake I am come hither out of England. For thy sake I came this night that I might have speech of thee. For this reason I would fain be thy tenant, that I might add one strong arm for thy defence in the dangers which threaten."

"Thou art a friend indeed."

"Ay, a true friend, since thou wilt have me for naught beyond. It is ten years since I asked thee wouldst thou have me for a husband, and thou didst deny me, and wed Calvert. For four years I strove as an honest man should to put thee out of my mind. I was fain to believe I had[10] succeeded, when the news of thy freedom reached me; then the old love I had counted dead rose up stronger than ever, rose up out of the grave where I had laid it as in a trance, rose up and bade me never again cheat myself into the belief that I and it could be put asunder."

The man paused for breath, so shaken was he by the force of his passion.

Elinor Calvert looked at him in terror, unable to break by word or movement the spell under which he held her. He made a stride closer, and grasped her hand.

"What stands between us?" he asked, holding her eyes with his, those penetrating eyes that had the power to pierce all disguises, to rend all shams to tatters, "Norse een like grey goshawks." Most eyes only look—Neville's saw. The woman before him felt evasions impossible, subterfuges of no avail.

"Your faith," she answered.

"You cared a little for me, then, in the old days?"

"I did," she answered, like one in a trance bending to the will of the questioner. As she spoke she unconsciously laid her hand upon the diamond crescent at her breast.

His eyes followed her motion and he colored high, for he saw that it was the brooch he had sent her at her marriage. She saw that he saw,[11] and she too blushed, a painful blush that stained her face crimson and ran up to lose itself in the shadow of her hair.

"I know who have stood in the way of thy loving me; but let them no longer come between thee and me, or their tonsured heads shall answer for it to my sword."

Elinor frowned, and Neville saw that he was endangering his cause.

"Forgive my impetuous speech!" said he. "Forget that the words were spoken."

"I cannot."

If Elinor had told the whole truth she would have added, "I do not wish to."

"Then at least put them aside and deal with me in cold business terms as though we were the strangers thy cousins believe us to be. Wilt thou have me for thy tenant on shares—three quarters of the harvest to go to thee and one quarter to me?"

"Tenant of mine thou shalt never be. I could not be so unfair, to let thee give thy life for me and get nothing in return!"

"To let me do the thing I have set my heart on and get in return a sight of thee once in the year. That is to make one three-hundred-and sixty-fifth of every year blessed."

"My tenant," said Elinor, slowly, "thou canst not be."

Neville bent his head.

"But—"

"Blessed be but—! But what?"

"But—perhaps—Cecil's."

"Ay, that is better!" said Neville, smiling a little; "that will be best, for then there will be no favor on either side, and as the lad grows older he and I can deal together as man to man."

"Oh, it is such a relief to my mind!" sighed Elinor.

"And to mine," quoth Neville.

"It is not the same thing as being my tenant?"

"Not at all—quite different. And thou wilt come with Cecil to see how the land fares from time to time?"

"Why, that were but business."

"Truly to do aught else were treason to thy son's interest, and by and by when the house is built and the title of Robin Hood's Barn suits the manor no more, thou and he will come to visit me there?"

"That could not be—"

"No, I feared that was asking too much," Neville said humbly, "but at least thou wilt let me have the boy?"

"How good thou art!"

"Good!—I to thee? Shall I tell thee whose picture dwells in my soul by day and night,[13] Elinor?" There was a curious vibration in Neville's voice, as if memory were pulling out the stops of an organ.

"Ay, tell me," said Elinor, tremulously, in a voice scarce above a whisper.

"'Tis that of a girl in a robe of green like the one thou wearest this night—ay, and floating sleeves like thine, whereby she caught the name she bears in my heart."

A softness stole into Elinor's eyes and the flush of girlhood rose to her cheek.

"Ah," Neville went on. "Dost thou remember that day in the Somerset wood, and how I gave thee the name of Lady Greensleeves, and how I sang thee the dear old ballad, thou sitting on the stone wall and I leaning against the great chestnut-tree?"

"Nay, 'twas not a chestnut—'twas an oak, for I do recall the acorns that lay about thy feet as I listened with my eyes cast down."

"And I stood looking at thy lashes, scarce knowing whether I would have them lift or not, as they lay against the rose of thy cheek."

"How long ago it all was!" sighed Elinor.

"Yet when thou dost speak and look like that it seems but yesterday. Oh, my dearest—"

Neville, carried beyond his prudence, drew nearer and was about to fall upon his knees before her, when he saw the door open to admit[14] Mistress Brent, followed by a servant bearing a steaming bowl of posset.

How much of his speech had been overheard, he knew not. Manlike he found it hard to steer his bark in an instant from deep waters into the shallows of conversation; but Elinor took the helm and dashed into the safe channel.

"Mary, thou art come in good time to help me to argue terms with a too generous tenant."

Mary Brent came forward smiling, but a little bewildered.

Elinor took the goblets from the tray and filled them with the posset. "Drink!" she cried gaily. "Drink both of you to the prosperity of Cecil Manor, and I will drink a health to Cecil's tenant, Sir Christopher Neville."

With this, she swept a deep courtesy, and rising, clinked her goblet against Neville's.

At the same moment Cecil burst upon them from the stairs, his golden curls topped by Master Neville's brown cavalier hat, and the heavy cloak sweeping the floor after him as he walked.

"Good evening, madam!" he cried, sweeping off his hat before Mary Brent with a droll imitation of Neville's manner.

"Small boys," said Elinor, "wax bold as bed hour draws near. Ask pardon of Sir Christopher and be off to thy bed."

"Thou wilt come with me?"

"Not to-night, sweetheart; we have a guest—"

"Guest or no guest, I go not without thee," cried the child. "'Tis the first time since our coming thou didst ever deny me. I should lie awake and see bogies an thou didst not tuck in the counterpane about me with thine own hands."

"I pray thee," said Neville, under his breath, "grant the boy his wish. Let not his acquaintance and mine begin with misliking."

At this, Cecil, who till now had hung back and glowered at the stranger from behind his mother's skirts, came forward with the grace of the Calvert line, and stretching out his hand frankly to Neville, said: "I thank you, thir; I am glad you are come to stay with us." As his mother led him away to bed he turned on the landing and kissed his hand to the new-comer. Then, with a sudden relapse into the barbarism of childhood, he dropped on hands and knees and climbed the remaining stairs in that fashion—growling like a wolf as he went. Ten minutes later the group in the hall heard him chanting an evening hymn, and his voice had the high, unearthly sweetness, the clear, angelic note of those who stand before the Throne.

When Elinor returned from Cecil's bedside, Neville detected traces of weeping in the flush of her cheek and the heaviness of her eyelids; but her manner was gracious and marked by a gaiety which would have led one who did not know her well to believe that she was as light-hearted as the boy upstairs.

The candles on the supper-table shone on a strangely assorted group. At the head of the board sat Mistress Brent. She was a demure little lady, like a sleek white cat, full of domestic impulses, clinging to her hearthstone and purring away life, content to rub against the feet of those whom she counted her superiors. Her placid face beamed with joy at the thought that her roof was found worthy to shelter the holy Fathers from St. Inigo's. Yet, even as she rejoiced, she remembered with some misgivings a conversation she had held with her brother Giles before his setting out. "Mary," he had said, "it is[17] rumored throughout the province that thy house is headquarters for the Jesuits."

"Brother," she had answered, "my house is open to all who seek its shelter, and shall I shut its doors to the priests of our Holy Church?"

"There is no arguing with women," her brother had said, with a testy shrug of his shoulders. "Thou must needs turn every question of policy into an affair of pious sentiment. Baltimore is as good a Catholic as thou; but he is first of all an Englishman, and second, the ruler of this province, wherein he hath promised fair play to men of all creeds; and he will not have the reins of control wrenched from his hands by the Jesuits, who hold themselves free of the common law, and answerable to none but the tribunals of the Church."

"I know naught of questions of policy, Giles, as thou sayst; but while I have a roof over my head, I will take for the motto of my house the words of Scripture: 'Knock, and it shall be opened unto you.'"

When this motto is posted over the lintel there will never be a lack of footmarks on the threshold. Many were the guests who came to try the hospitality of St. Gabriel's Manor, and no visitors were more frequent than the Jesuits, those brave men who for the sake of their faith had crossed the sea, braved the perils of the wilderness, and[18] planted a mission near St. Mary's which they christened St. Inigo's.

On Mary Brent's right hand this evening sat one of these priests, Father White, whose shrewd eyes shone with love to God and man, whose heart yearned over the sinner as it bowed before the saint, and whose life was at the service of the order of Ignatius Loyola. His features were delicately cut, and the skin of a transparency which recalled the alabaster columns at San Marco with the light shining through them. So translucent to the soul behind seemed his fragile frame.

His mulatto servant, Francisco, stood at the back of his chair and ministered to his wants with loving care.

Opposite Father White sat Christopher Neville, and one at least of the company found him good to look upon, despite his square jaw and the sabre-cut over the left eye. But for the particularity of his dress he might have conveyed the impression of rude strength, but his black velvet doublet fitted close and gave elegance to the heavily built figure, and the shirt that broke out above the waist was adorned with hand-wrought ruffles of an exquisite fineness.

Notwithstanding his plainness, his personality carried conviction. The whole man made himself felt in the direct glance and the firm hand-clasp. His words, too, had a stirring quality. People[19] differed, disputed, denounced; but they always listened. He often roused antagonism, but seldom irritation. It is not those who oppose, but those who fail to comprehend, who exasperate, and Neville had above all the gift of comprehension. Yet with this intellectual perception was combined a singular imperviousness to social atmosphere. So that in his presence one had often the feeling of being a piece of china in a bull pasture; but, in his wildest assault, the slightest droop of the lip, the faintest appeal for sympathy reduced him to the gentleness of a lamb.

"I would he were of our communion," thought Father White, studying him.

Near Neville sat a younger priest, the same who had watched Elinor Calvert and her son from the shadow of the settle. His aspect was more humble than that of his superior. He bowed lower as he passed the crucifix rudely fastened to the chimney breast; his eyes were seldomer raised, and he mumbled more scraps of Latin over his food; but all this outward show of holiness failed to convince. It was like the smell of musk which hints of less desirable scents, to be overpowered rather than cleansed. His narrow gray eyes, cast down as they were, found opportunity to scrutinize Elinor Calvert closely as she sat by the side of Neville. Set a man, a priest, and a[20] woman to watch each other—the priest will catch the man; but the woman will catch the priest.

"Prithee try this wine, Father!" said Mary Brent to the venerable priest on her right, holding toward him a cup of sparkling red-brown wine. "'Tis made in our own press from the wild grapes that grow hereabout, and Giles has christened it 'St. Gabriel's Blessing.'"

"Tempt me not!" said Father White, smiling but pushing the goblet away. "I have not spent my life studying the Spiritual Experiences of Saint Ignatius without profiting by that holy man's injunction to regard the mouth as the portal of the soul. The wine industry is important, but I fear the effect of drinking on the natives. I have seen a chief take blasphemous swigs of the consecrated wine at the sacrament, and at a wedding half the tribe are drunken."

"Prithee, tell me more of these missions among the natives," Elinor said to Father Mohl, bending the full splendor of her glance upon him; "are they not fraught with deadly peril?"

"To the body, doubtless."

"'Twould be to the soul too if I were engaged in them, for I have such hatred of hardship that I should spend my time bewailing the task I had undertaken."

"Nay, daughter, for ere thou wert called to the[21] trial thou wouldst have faced the tests that do lead up to it as the via dolorosa to Calvary. Before we take the final vows we undergo three probations, the first devoted to the mind, and the last a year of penance and privation, that we may test our strength and learn to forego all that hampers our spiritual progress; this is called the school of the heart."

"Would there were such for a woman!"

"There is," said Neville from the other side; "but it is where she rules instead of being ruled."

Elinor turned and looked at him with that lack of comprehension which a woman knows how to assume when she understands everything. "He loves her," thought the priest; "but she only loves his love."

Yet, knowing how many matches have been brought about by this state of things, Father Mohl set himself to study Neville. He found him reserved in general, with the suavity and self-command of a man of the world, but outspoken under irritation.

"We must make him angry," thought the priest.

Seeing that Neville was a Protestant, he began relating the deeds wrought by priests.

"Do you recall, Father White," he said, "how the natives brought their chief to die in the mission house, and how Father Copley laid on him a[22] sacred bone, and how the sick man recovered, and went about praising God and the fathers?"

"I do remember it well," Father White answered.

"Yes," continued the younger priest, "and I recall how Brother Fisher found a native woman sick unto death. He instructed her in the catechism, laid a cross on her breast, and behold, the third day after, the woman rose entirely cured, and throwing a heavy bag over her shoulder walked a distance of four leagues."

"Wonderful! wonderful!" murmured Mary Brent.

Neville was irritated, and thought to turn Father Mohl's tales to ridicule. Whom the gods would destroy they first make droll.

"Did you ever hear of the miracle of the buttered whetstone?" he asked.

"Pray you tell it," said Father Mohl, with his ominous smile.

"Why, there was a friar once in London who did use to go often to the house of an old woman; but ever when he came she hid all the food in the house, having heard that friars and chickens never get enough."

If only Neville had looked at Elinor! but he steered as straight for destruction as any rudderless bark in a storm on a rocky coast.

"This day," he went on, "the friar asked the goodwife had she any meat."

"'Devil a taste!' she said.

"'Well,' quoth the friar, 'have you a whetstone?'

"'Yes.'

"'Marry, I'll eat that.'

"So when she had brought the whetstone, he bade her fetch a frying-pan, and when he had it, he set it on the fire and laid the whetstone in it.

"'Cock's body!' said the poor wife, 'you'll burn the pan!'

"'No! no!' quoth the friar; 'you shall see a miracle. It shall not burn at all if you bring me some eggs.'

"So she brought the eggs and he dropped them in the pan.

"'Quick!' cried he, 'some butter and milk, or pan and egg will both burn.'

"So she ran for the butter, and the friar took salt from the table and threw it into the pan with butter and eggs and milk, and when all was done he set the pan on the table, whetstone and all, and calling the woman, he bade her tell her friends how she had witnessed a miracle, and how a holy friar had made a good meal of a fried whetstone."

Father Mohl was now angered in his turn.[24] Priests, having surrendered the love of women, cling with double tenacity to their reverence.

"A merry tale, sir," said he, smoothly, "though better suited to the ale-house than the lady's table, and more meet for the ears of scoffers than of believers—Daughter," turning to Mary Brent, "you were amazed a moment since at the wonders God hath wrought through the hands of His chosen ones; but the judgments of the Lord are no less marvellous than His mercies. There was a Calvinist settled at Kent Fort who made sport over our holy observances."

Elinor Calvert colored and looked from under her eyelids at Neville. But he went on plying his knife and fork. "If he were angry," she said to herself, "he would not eat." But in this she mistook the nature of man, judging it by her own.

"Yes," continued Father Mohl, "although, thanks to our prayers, the wretch was rescued from drowning on the blessed day of Pentecost, yet he showed thanks neither to God nor to us. Coming upon a company offering their vows to the saints, he began impudently to jeer at these religious men, and flung back ribald jests as he pushed his boat from shore. The next morning his boat was found overturned in the Bay, and he was never heard of more."

Neville looked up. "I am glad," he said, "to[25] be able to supply a happier ending to your story. The man, as it happens, was picked up by an outward-bound ship, and is alive and well in England to-day."

"You knew the blasphemer, then?"

"I know the man of whom you speak—a fine fellow he is, and the foe of all liars and hypocrites."

"Ah, I forgot," answered Father Mohl, smoothly, "you are not one of us."

"Not I," cried Neville, hotly; "I have cast in my lot with honest men."

"Say no more," said Mohl, satisfied, "lest thou too blaspheme and die! Misereatur tui, Omnipotens Deus!" Having thus achieved the difficult task of giving offence and granting forgiveness at the same time, Father Mohl smiled and leaned back content.

Neville, on his side, was smiling too, thinking, poor fool, that the victory lay with him; but looking round he saw Elinor raise her wine cup to her lips, and looking closer he saw two tears rise in her eyes, swell over the lids, and slip into the wine cup. Instantly he cursed himself for a stupid brute. "Madam," he said, speaking low in Elinor's ear, so that she alone could hear him, "thou art wasteful. Cleopatra cast only one pearl into her wine-cup, and thou hast dropped two."

At the same moment a little white figure appeared in the doorway.

"May I come in for nutth?" asked a small voice.

"Cecil, for shame! Go back to bed this instant!" cried his mother; but Neville drew a stool between him and Mary Brent, and silently motioned to Cecil to come and occupy it.

"The child should be taught obedience through discipline," said Father Mohl, looking with raised eyebrows toward Elinor. Cecil cowered against the wall; but kept his eyes upon the coveted seat.

Neville crossed glances with the priest as men cross swords. "Or confidence through love—

"Cecil," he continued, "beg thy mother to heed the petition of a guest and let thee sit here by me for ten little minutes; I will bid thee eat nuts,—so shalt thou practise Father Mohl's precepts of obedience."

Elinor smiled, Neville put out his hand, a strong, nervous hand, and Cecil knew his cause was won.

"Lonely upstairs," he confided to Neville as he helped himself to nuts; "makes me think of bears."

"Bears come not into houses."

"They say not, but the dark looks like a big black one, big enough to swallow house and all. I do not like the dark, do you?"

"I did not when I was your age,—that's sure; but I have seen so many worse things since then—"

"What?"

"Myself, for instance."

"That's silly."

"I think it is."

"Do not say silly things! Mother sends me to bed when I do."

"Is it not silly to fear the dark?"

"Mayhap, but I lie still all of a tremble, and then I seem to hear a growl at the door, and then blood and flesh cannot stand it and I scream for Mother. Three or two timeth I scream, and she comes running."

"Wouldst have the bear eat thy mother?"

"Nay, but sure 'nuff he would not. The Dark Bear eateth only little boys."

"Oh, only little boys?"

"Ay, and he beginneth with their toes. Therefore I dare not kneel alone to say my Hail Maries. The Dark Bear is not like God, for God careth only for the heart. Thir Chrithtopher, why doth God care more for the heart than for the head and legs?"

"Come, Cecil," said Elinor's warning voice, "thou art chattering as loud as a tree-toad, and the ten minutes are more than passed. Run up and hide those cold toes of thine under the counterpane!"

"If I go, wilt thou come up after supper to see me?"

"If I can be spared."

"Nay, no ifs—ay or no?"

Father Mohl smiled, and his smile was not good to see.

"Is this the flower of that confidence through love which you so much admire, Sir Christopher?"

"No," answered Neville, "only the thorns on its stem; the blossoms are not yet out."

"Ay or no?" repeated the child, oblivious of the discussion going on around him.

"Oh, ay, and get thee gone!" cried his mother, thoroughly out of patience with the child and herself and every one else.

Cecil ran round to her seat, hugged her in a stifling embrace, and then pattered out of the room and up the stair, reassuring his timid little heart by saying aloud as he went, "Bearth come not into houtheth! Bearth come not into houtheth!"

Father Mohl sat with bent head, the enigmatic smile still playing round his lips. At length, making the sign of the cross, he spoke aside to Father White,—

"Have I leave to depart?"

"Go—and pax tibi!"

The company rose.

"Father, must thou be gone so soon?"[29] Mary Brent asked, with hospitable entreaty in her tones.

"I must, my daughter."

"This very night?"

"This very night."

"But the road to St. Mary's is dark and rough."

"Ay, but our feet are used to treading rough roads, and the moon will show the blazed path as clearly as the sun itself."

"Farewell," said Father White. "Bear my greetings to my brothers at St. Inigo's, and charge them that they cease not from their labors till I come."

When Father Mohl passed Neville, Sir Christopher, moved by a sudden compunction, held out his hand. "Hey for St. Mary's!" he exclaimed, with a note of cordiality which if a trifle forced was at least civil.

Father Mohl ignored the outstretched hand, and with his own grasped the crucifix at his breast. The sneer in his smile deepened, and one heard the breath of scorn in his nostrils as he answered, with a meaning glance at Elinor, "The latter part of the Marylanders' battle-cry were perchance honester. Why not make it 'Wives for us all'?"

This passed the bounds of patience, and Neville cast overboard that self-control which is the ballast[30] of the soul. His outstretched hand clenched itself into a fist.

"Sir!" he cried, very white about the lips, "if you wore a sword instead of a scapular, we might easily settle our affairs. But since your garb cries 'Sanctuary!' while your tongue doth cut and thrust rapier-like, I'll e'en grant you the victory in the war of words. Good-night, Sir Priest!"

For answer the father only folded his cloak about him and slipped out of the door as quietly as though he were to re-enter in an hour.

Father White followed Mistress Brent to the hall, from the window of which she strove to watch the retreating figure of Father Mohl. Neville thus found himself alone with Elinor Calvert once more. He regarded her with some anxiety, an anxiety justified by her bearing. The full round chin was held an inch higher than its wont, the nostrils were dilated and the eyelids half closed. A wise man would have been careful how he offered a vent for her scorn; but to her lover it seemed that any utterance would be better than this contemptuous silence.

"You are very angry—" ventured Neville, timidly.

"I have cause."

"—and ashamed of me."

"I have a right to be."

"Thank Heaven for that!"

"If you thank Heaven for the shame you cause you are like enough to spend your life on your knees."

"I deprecate your scorn, madam. Yet I cannot take back the saying."

"Make it good, then!"

"Why, so I will. None feel shame save when they feel responsibility. None feel responsibility for those who are neither kith nor kin save where they—"

"Where they what?" flashed Elinor, turning her great angry eyes full upon him.

"Save where they love, Mistress Calvert."

It was out now and Neville felt better. Elinor clenched her hands and began an angry retort, and then all of a sudden broke down, and bending her head over the back of the high oak chair, stood sobbing silently.

"I pray you be angry," pleaded Neville; "your wrath was hard to bear; but 'twas naught to this."

"Oh, yes," answered Elinor between her sobs, "it is much you care either for my anger or your grief, that the first proof you give of your boasted love is to offend those whom I hold in affection and reverence."

"'Twas he provoked me to it," answered Neville, sullenly, "with his tales of my friend[32] yonder, as honest a fellow as walks the earth. Is a man to sit still and listen in silence to a pack of lies told about his friend?"

"Say no more!" commanded Elinor. "I see a man is bound to bear all things for the man to whom he has professed friendship—nothing for the woman to whom he has professed love."

There was little logic in the argument, but it made its mark, for it was addressed not to the mind but to the heart.

"Forgive me!" cried Neville—which was by far the best thing he could have said.

If a woman has anything to forgive, the granting of pardon is a necessity. If she has nothing to forgive, it is a luxury.

"I do," she murmured.

"Perhaps I was rougher of manner than need was."

"Yet 'twas but nature."

"Yes, but nature must be held in check."

Thus did these inconsistent beings oppose each other, each taking the ground occupied a few minutes since by the other, and as hot for the defence as they had been but now for the attack.

Neville seized Elinor's hand and kissed it passionately; then snatching up his hat and cloak he exclaimed, "I will go after Mohl and make my peace. Henceforth I swear what is[33] dear to you shall be held at least beyond reproach by me."

Elinor turned upon him such a glance that he scarcely dared look upon her lest he be struck blind by the ecstasy of his own soul.

"At last!" he whispered as he passed out into the night.

Was it luck or fate that guided him ? Who shall say? Luck is the pebble on which the traveller trips and slides into quicksands or sands of gold. Fate is the cliff against which he leans, or dashes himself to death. Yet the pebble was once part of the cliff.

"Mother! Moth-er!"

It was Cecil's voice on the landing, and Cecil's white nightgowned figure hanging over the balustrade.

"Yes, Poppet, what is it?"

"Thou didtht not come upstairs as thou didtht promise when the nuts were served...."

"Dearest, I could not. I was in talk with Sir Christopher."

"But thou didtht promise, and how oft have I heard thee say, 'A promise is a promise'?"

Elinor started from her chair to go toward the stair; but Father White stayed her with uplifted finger.

"Let me deal with him," he said under his breath; "'tis time the lad learned the difference between the failure which is stuff o' the conscience, and that which is the fault of circumstances." Then aloud, "Cecil, wilt thou close thine eyes and come down to me when thou hast counted a hundred?"

"Ay, that will I."

"Without fail?"

"Why, surely! There is naught I would love better than toathting my toeth by the great fire."

"Very well, then; shut thine eyes and begin!"

Cecil counted faithfully to the stroke of a hundred, and then springing to his feet with a shout, started down the stair, but to his surprise the priest was nowhere to be seen. Cecil searched behind the settle and under the table as if one could fancy Father White's stately figure in such undignified hiding-place! At length the child gave up the search and called aloud,—

"Where art thou?"

"Here, in this little room," answered a muffled voice, and Cecil ran to the door only to find it securely fastened by a bolt within.

"Come in," cried the voice.

"I cannot; it ith bolted."

"But you promised—"

"But the door ith fatht."

"What of that? 'A promise is a promise.'"

By this time Cecil, perceiving that jest and lesson were both pointed at him, stood with quivering lip, ready at a single further word to burst into tears; but the kind father, flinging wide the door, caught him in his arms, saying, "We must not hold each other responsible, my boy, for[36] promises which God and man can make impossible of fulfilment. We must be gentle and charitable and easy to be entreated for forgiveness; and so good-night to mother, and I will lay thee again in thy trundle-bed."

"Has Sir Christopher Neville left us also?" asked Mary Brent, as Father White came down from Cecil's room and joined her and Elinor at the fire.

"He has."

"A strange man!" said Father White.

Elinor colored.

"Ay," answered Mary Brent; "I cannot make out why Giles hath taken such a liking to him. To me he seems proud and reserved, with something in his tone that suggests that he is turning the company into a jest. For myself I did not see anything droll in his story of the fried whetstone."

Elinor shrugged her shoulders.

"If every man were condemned that told a tale in which others could see nothing droll, we should need a Tyburn Hill here in Maryland."

"Ay, but what's the use of telling a droll story if it be not droll? I do not understand Sir Christopher."

"I don't think you do."

"I think I do."

It was Father White who spoke, and his[37] shrewd gray eyes were fixed upon Elinor, who turned to the fire without a word.

Mary Brent sat tapping her foot on the floor.

"'Tis strange he should have left without a word," she said at last.

"Never fear, Mary! We have not lost him. He is too large to be mislaid like a parcel. He did but go out to fulfil a behest of mine, and if Father White understands him, as he says he does, he will have divined that it was an errand of courtesy and good-will on which he set out."

A silence fell on the group. Then Father White, looking out, exclaimed: "'Tis a bitter night and the snow is falling again! No wonder the settlers grumble over such a winter in this land where they were promised all sunshine and flowers."

"Yes," said Mary Brent. "If the weather is to be like this, we might as well have settled on the bleak Massachusetts coast."

"It cannot last long. The natives all say they never knew such a season. They fear to go abroad at night, there are so many half-starved wild beasts prowling around."

Elinor rose and began to pace the floor uneasily.

"But," continued Father White, "there are more reasons than those of climate for preferring Maryland to Massachusetts. How wouldst thou have prospered in a Puritan colony?"

"I trust even there I should have been true to Mother Church, and perchance converted some of the heretics from the error of their ways."

"Yet," interrupted Elinor, "they too are serving God in their own way."

Mary Brent shook her head. "I care not to talk of them. In truth had I known this Neville was a Protestant, I had never urged him for thy tenant at Robin Hood's Barn."

Elinor murmured something about "toleration."

"Toleration!" repeated her cousin scornfully. "I hate the word. He that tolerates any religion against his own is either a hypocrite or a backslider."

"Shall there be no liberty of conscience?"

"Ay, but liberty to think wrong is no liberty."

"These be deep matters, my daughters, and best left to the schoolmen," said Father White. "None doubt that Mistress Brent hath kept her fidelity unspotted to the Church. Let Elinor Calvert pattern after her kinswoman."

Thereafter Father White turned again to the subject of missions, and the two women listened till the hour-glass had been turned and the candles began to burn low in their sockets. At last Mary Brent grew somewhat impatient. If she had a vice it was excess of punctuality. She was willing to share her last crust with a stranger;[39] but he must be on hand when it came out of the oven. The hours for meals and especially for bedtime were scrupulously observed in her household, and to-night it irked her to be kept up thus beyond her usual hour for retiring.

Elinor, perceiving this and feeling some sense of responsibility for the cause, said at last,—

"I pray thee, Cousin, wait no longer the coming of Sir Christopher, whose errand has kept him beyond what I counted on, else I would not have given my consent. Father White and I will sit up to await his coming. Go thou to bed, and see that the counterpane is drawn high over Cecil, for the howling of the wind promises a cold night."

"Poor little one!" said Mary Brent, rising and evidently glad of an excuse for retiring, "I will see that he is tucked in warm and snug. Sir Christopher is to sleep next Father White. I have had his bed made with our new homespun sheets."

As Mistress Brent passed out of sight up the stairs, Elinor turned to Father White with tears standing in her eyes,—

"How good she is!" she murmured.

"Ay, a good woman—her price is above rubies. I pray that by her example and influence you may be held as true as she to your duties to God and His Holy Church."

Elinor stirred uneasily. The movement did not escape the priest's eye, accustomed to studying every symptom of the soul's troubles as a physician studies the signs of bodily tribulations.

"My daughter," he continued, "is your heart wholly at peace—firmly stayed upon the living rock?"

"No! no!" cried Elinor, "it is rather a boat tossed upon the waves at the mercy of every tempest that sweeps the waters."

"How strange!" said Father White, speaking softly as to a suffering child. "How strange that you thus of your own will are tossed about, and run the risk of being cast upon the rocks; yea, of perishing utterly in the whirlwind, when peace is waiting for you, to be had for the asking."

"I would I knew how to find it."

"Even as St. Peter found it when he too was in peril of deep waters, by calling upon the name of the Lord. Come, my daughter, come with me to the altar, that we may seek it together!"

Taking a candle from the table he rose and led the way to the recess at the end of the hall, which Mary Brent had piously fitted up as a chapel, where before the altar burned the undying lamp of devotion.

"Here," said the priest, "peace awaits the storm-tossed soul. It shall be thine. But first must thou throw overboard all sinful desires, all[41] guilty memories, all selfish wishes, and seek in simplicity of heart that peace of God which passeth understanding. Kneel, my daughter, at the confessional!"

So saying he seated himself in the great oaken chair, brought out of England. Elinor fell upon her knees beside it and poured out the grief and struggles of her tumultuous soul.

"Bless me, Father, because I have sinned." The voice trembled at first so that the words could scarcely be heard, but grew firmer as she went on in the familiar words: "I confess to Almighty God, to blessed Mary ever Virgin, to Michael the archangel, to blessed John the Baptist, to the holy apostles Peter and Paul, to all the saints, and to you, Father, that I have sinned exceedingly in thought, word, and deed, through my fault, through my fault, through my most grievous fault."

"Mea culpa, mea culpa, mea maxima culpa!" How the words ring down the ages laden with their burden of human penitence and remorse! Still, despite all the uses to which they have been wrested by hypocrisy and levity, they remain infinitely touching in the link they furnish, the bond of unity for the suffering, sin-laden souls of many races and many generations.

When Elinor had finished the list of offences whereof she wished to free her soul, and which[42] even to the sensitive conscience of Father White appeared over trivial for the emotion she had shown, the priest asked softly: "Is there nothing else? Examine well thine heart. Leave no dark sin untold to grow in the shadow and choke the fair flower of repentance."

"No, Father, I know of no other sin."

"Nor any unworthy wish?"

"Nor any unworthy wish."

"Nor any carnal affection threatening to draw thy soul away from the path of salvation?"

The shaft was shrewdly aimed. It struck home.

"Father, is it a sin to love?"

"It may be—a deadly sin."

"To love purely, with a high and unselfish devotion?"

"It may be."

"Prithee, tell me how, since God himself is love."

"There is indeed a Godlike love, stooping to the weakest, bending over the lowest, yearning most over the most unworthy, such as the love of the shepherd for his sheep, of the mother for her son, of the true priest for his flock; but let a woman beware how she brings to the altar such a love for her husband."

Elinor started.

"Yes," Father White went on tenderly, but as[43] one who must probe the wound that it may heal the sooner, "it is the nature of woman to look up. She will do it, and if she cannot raise the one she loves she will stoop to the dust herself, that from that abasement the man may still seem to stand above her."

"Father," cried Elinor, casting aside all concealment, "the man I love is not base."

"Do I know him?"

"You have seen him."

"This night?"

"This night."

"Can a man who knoweth not how to rule his own tongue rule a wife, and above all a wife like thee, aflame one instant, the next melted to tenderness, full of pity and long-suffering, yet quick of spirit and proud as Lucifer?"

Elinor was silent.

"A captious temper is a grievous fault, yet it may be mended—if he is of the true faith. But, oh, my daughter, tempt not thy fate by marrying an unbeliever! Faults thou mayst conquer; sins thou mayst forgive or win forgiveness for; but unbelief is a blight which fosters every vice and destroys every virtue. Root up this passion, though it seem to tear thy life with it. Think on thy boy! Durst thou expose him to the influence of such an example?"

"Father," said Elinor, tremulously, "I cannot[44] answer now—I must have time to think. Who knows but my love may draw him into the right path?"

The priest shook his head; but as he was about to answer, the stamping of feet was heard outside, and Father White dismissed his penitent with a wave of his hand.

"Go, my daughter. But as thou dost value thy soul and the soul of thy boy, entangle thyself no further till thou hast taken counsel once more with me. And may Almighty God be merciful unto thee, and, forgiving thee thy sins, bring thee to life everlasting!"

Elinor rose from her knees, and drawing aside the curtain passed out into the hall, while Father White tarried for the candles.

Neville came in at the outer door, bringing with him a gust of wind and cold. Knut rose from the hearth with a low growl and moved suspiciously toward the stranger, then, drawn by some magnetic attraction, he nosed about him and at last fawned upon him and rubbed against his legs, seeking a caress. Neville bent over and patted his head. "Good dog!" he said, "I would I had had you with me in the forest yonder. Belike I had not been so long in finding my way out. Ah, Mistress Calvert," he added, peering into the shadow from which gleamed the shimmer of Elinor's gown, "I am grieved to have kept the[45] household awake so late, and all for naught, since I failed as completely in the search for Father Mohl as though he had vanished like a spirit in the air."

"Yet of old you were a swift runner. I have seen you chase a hare across the fields at Frome and keep the pace."

"Ay, but that was over Somerset turf, and with the light of day to guide me."

"I am much disappointed—"

Neville felt the chill in Elinor's tone.

"Not more disappointed than I," he answered. "'Tis the elements must bear the blame. When I started out the moonlight shone full on the path, and I could see my way for a quarter of a mile, but even then the clouds were hanging round the moon like wolves about a sheep-fold. In half an hour she was swallowed up, and then, to confuse me the more, a light snow began falling, slowly at first, then faster and faster, till, what with the wind in my face and the snow on the path, I lost the trail somewhere near the cross-road. Before I knew it I was caught in a thicket of brush and briar, and when I had struggled out there was no hope of catching the priest."

Elinor looked closely at Neville. He was very white and breathing heavily.

"You are hurt," she exclaimed, moving toward him with quick sympathy. "See, your garments[46] are pulled this way and that as if you had struggled with worse foes than the wind."

"Only contact with a few brambles through which I forced my way back to the road I had lost."

"But your jerkin is torn—"

"Ay, caught on a stray branch which hung too low."

"And there is blood on your boots—yes, and on your hands. Oh, tell me what you have gone through while we sat here at our ease by the hearth!"

Neville drew near and spoke low: "For such sympathy I would have dared far more than I met. If you will have the story, it fell out thus. Having forgot to buckle on my sword as I went out, I found myself scantily armed with my short poniard. Yet did I never think of danger, till after I had turned about, and losing the blazed path, began to scan each branch I passed, for some token that might lead me straight.

"Peering about me with my poniard in hand to cut the boughs, I was aware of a rustling in the branches over my head as of something heavier than bird or fowl. I jumped aside. The creature sprang and missed me. My hope lay in a counter attack, and I in turn leaped upon her, and buried my poniard in her neck. She must have been made of something other than flesh[47] and blood, else she had fallen dead at my feet from that blow; but instead she made off at a bound, and with such speed that I had no chance to discover her species, though in the dark she looked about the size of a panther. The worst thing in the whole adventure was the loss of my knife. It has helped me through many a perilous place, and it goes hard with me to have lost it now. I suppose I may count this the best service it has done me. But why do I dwell at such length upon a trifle? I warrant there be few hunters who have passed a night in our wilderness without some such taste of the manners of wild beasts."

"Make not light of such an escape," murmured Elinor, breathlessly. "As for me, I will give thanks for thee upon my knees in my closet. Father White will show thee to thy chamber. 'Tis the one next his, and hath the distinction of owning a bed with sheets in place of a deerskin."

Neville gazed at Elinor with some disappointment. He did not appreciate that this was the way her quick wit chose to let him know that their conversation was overheard. As he looked up at her words, he saw Father White moving towards them. The candle in his hand shone upward and cast a light on his white hairs, which gave them the effect of a halo around his forehead. As he held up his fingers in token of[48] benediction to Elinor as she passed him, he seemed like some saint breathing serenity and heavenly joy.

Despite his lifetime prejudices Neville felt himself vaguely stirred by the half-unearthly vision of the saintly face framed in its snowy halo, and the dark robes fading into the blackness of the hall beyond.

"Bless me too, Father!" he murmured, "for I have sinned." The priest moved as if he were about to comply, then suddenly recalling himself, he dropped his half outstretched arm and asked:

"Is it the blessing of Holy Church you crave?"

"No, faith!" cried Neville, suddenly emancipated from the thrall of his first impression. "It was but the blessing of a good man I asked, which to my thinking should have some value, with the backing of any church or none; but since it must be bought with hypocrisy or begged on bended knee I will have none of it. Good-night, madam," he added, bowing low to Elinor; and helping himself to a candle from the table, he lighted it at the fire.

"Good-night, my daughter!" the priest echoed, and added softly: "Concede misericors Deus fragilitati nostræ præsidium!"

The morning sun streamed into the bedroom where Cecil slept on his low truckle-bed beside his mother's curtained couch. The brilliant rays tugged at the boy's eyelids and lifted them as suddenly as the ropes raise the curtain of a play-house, and indeed to this small observer it seemed that a perpetual comedy was being acted in the world for his special benefit. Better still, that it was his delightful privilege to play the part of Harlequin in this rare farce of life and to make the gravest grown-people the sport of his jests. The earliest manifestation of humor, in the individual as in the race, is the practical joke; so it was quite natural that as a fresh and delightful pleasantry it occurred to Cecil, instantly on waking, to creep over to his mother's bed and begin to tickle her ear with the tassel of the bed curtain. The mere occupation was pleasure enough, but the sensation rose to ecstasy as he watched the sleepy hand raised time after time to brush away the supposed[50] insect. At length the enjoyment grew too exquisite for repression, and at the cost of ruining its own existence burst out into a peal of laughter that roused the drowsy mother.

"Thou naughty implet! What hour o' the clock is it?"

"I know not the hour o' the clock; but o' the sun 'tis past rising time, and Couthin Mary is stirring already."

"Then we must be stirring too; but first sit thee down here on the edge of the bed and try to listen as if thou wert grown."

"I am, mother,—I am above thy waist."

"Ay," said Elinor, smiling, "but the question is, art thou up to my meaning? Hearken! Dost thou know what a tenant is?"

"Ay,—'tis a man who farms thy land, giving thee half and keeping three quarters for himthelf."

His mother laughed.

"Thou hast a good understanding for one so young, and the description is apt enough for most tenants; but how sayst thou of one who would give thee three quarters and keep only one for himself?"

"Why, 'twould not become a Calvert to drive such a bargain with such a poor fool."

"Thou art not far wrong. Share and share alike is fair dealing 'twixt land and labor, and[51] so let it be between thee and Sir Christopher Neville."

"Thir Chrithtopher Neville! The gentleman that came last night? Why, he ith no laborer. He cannot be in need to work for a living."

"Nay, Cecil, 'tis a labor of love."

"There, mother, I knew he liked me, for all thou saidst my borrowing of his sword and cloak did anger him. Every one likes me. Couthin Mary says so."

"Vain popinjay! thou art too credulous of flattery."

"Would Couthin Mary tell a lie?"

"Never mind that question now, but don thy best clothing for the ceremony of receiving the homage of thy tenant this morning."

"Hooray! Am I to wear my morocco shoes with the red satin roses?"

"Ay."

"And my thilver-broidered doublet?"

"Ay, little peacock."

"And my stockings with the clocks of gold? Oh, Mother, it makes me feel so grand! I like being lord of the manor. And Thir Chrithtopher Neville must kneel before me; and how if I tickle him on the neck when he bends, and make him laugh out before them all?"

"Cecil, if thou dost disgrace me by any of thy clownish pranks, thou and I will never be friends[52] more. And give thyself no airs either with this kind new friend. Say to thyself, when he bows before thee, that it is strength bending to weakness, and pride stooping that it may help the helpless."

"Do I stand on the platform at the end of the hall where Couthin Mary stands when her tenants come in?"

"Yes, with Cousin Mary and me beside thee."

"I hope Thir Chrithtopher trips on the step. But I like him, for all he hath the eyes of a hawk and the mouth of a mastiff."

"Well thou mayst like him! Friends like him are scarce enough anywhere, and most of all in this new land. Now run away and make haste lest we vex Cousin Mary by our tardiness, and so begin awry the day which should open with all good omens. But, Cecil, I have a gift for thee, something I gave thy father on our marriage. I did think to keep it till thou shouldst be of age; but on the whole I would rather thou hadst it to remember this day by."

So speaking, Elinor unlocked her jewel-chest of black oak bound with brass, and drew from within a pomander-box of gold, the under lid pierced with holes which permitted the fragrance to escape till it nearly filled the room with the mingled odor of rose attar and storax, civet and ambergris, the upper lid adorned with a miniature[53] of Elinor Calvert painted on ivory and set in pearls like the picture of Cecil which she wore at her breast. The artist had worked as one who loves his task, and the delicate tints of neck and arms shone half-veiled by the creamy lace that fell over them. In the golden curls a red rose nestled, and around the throat glistened a necklace of rubies.

"Mother!" exclaimed Cecil, "wert thou once as beautiful as that?"

Elinor smiled; but it was not quite a happy smile.

"Yes, once I was as fair as that, and in those days there were many to care whether I was fair or not. Now there be few either to know or care."

"Nay, to me thou art still fair, Mother, and there is another who thinks so too."

"Who is that?"

"Thir Chrithtopher. I saw him looking at you last night, and, Mother, dost not think, since he thinks to deal so generously with us, it would be a fine thing for me to give him this portrait of thee to bind the bargain?"

"Foolish baby, 'twill be time enough to think of that when he asks for it."

"Then if he asks for it, I may give it—"

"A safe promise truly," said Elinor, smiling this time with beaming eyes and cheeks, whose[54] rose flush matched the coloring of the ivory portrait. "Now hasten with thy dressing."

Cecil's head was so filled with thoughts of the pomander-box and his own greatness that his mother was fully dressed while he sat mooning over the lacing of his hose and breeches, and gazing with admiring fondness at the red roses on his holiday shoes.

Three times Cousin Mary had called to him to make haste, and when at last he entered the hall every one had finished eating, and he was sent in disgrace to take his breakfast in the buttery. This was too great a blow for his new-swollen pride, and he fell to howling lustily, while the tears flowed into his cup of milk and salted it with their brine. The day which an hour ago had been one glow of rose color all arranged as a background for the figure of Cecil Calvert in his velvet suit and gold-clocked stockings, had become a plain Thursday morning in which a little boy was crying into his milk in a bare buttery hung with pails and pans.

Suddenly he felt a strong arm thrown over his shoulder, and a kind voice said in his ear: "I have been late more than once, Cecil; but it will not do for pioneers, least of all for Little John or Robin Hood."

"Go away; I hate thee," answered the amiable child.

"Dost thou truly? and why?"

"Because were it not for thee I had not put on my best suit with the troublesome lacings, and but for that I had not been late, and but for that Couthin Mary had not been vexed, and but for that Mother had not punished me."

"I see clearly it is I am to blame; and now if thou hast finished thy bread and milk let us go and ask pardon for our—I mean my fault, and perhaps we shall be forgiven."

Hand in hand the Lord of the Manor and his tenant sought the hall.

As they walked along the corridor, Neville's face wore a characteristic smile. This smile of his seemed to begin in one corner of his mouth and ripple along without ever quite reaching the other, which, to tell the truth, would have required a goodly journey. There was a certain fascination in the smile; but one who would fathom its meaning must look for it, not in the lips at all, but in the pucker of the eyelids and the gray twinkle of the eyes and the chuckle that lay hid somewhere in the little creases that the years had drawn in diverging lines from the point where the lids met.

If Neville was amused he felt no need of proclaiming the fact. A sense of the ridiculous marks the noisy man, wit the talkative man; but humor and silence have a strange affinity, and a smile needs no interpreter to itself.

"Pray, Mistress Brent," said Neville, bowing before his hostess when they reached the hall, "wilt thou forgive me for being the cause that Master Cecil did put on his best suit with the troublesome lacings, whereby he was late to breakfast?"

Mary Brent, being a literal soul, replied, "Why, 'twas not thy fault at all."

"Then," said Neville, "let the offence become a fixed charge upon the estate, which I as tenant must assume, and whereupon I promise to give a breakfast party at Robin Hood's Barn to those here present on this date each year in remembrance of this day's delinquency.

"As for thee, Sir Landlord, I will give thee an Indian bow and arrows, that thou mayst play Little John, and when thou dost come a-hunting at Robin Hood's Barn, thou mayst work havoc at thy will among the heron and wild duck which I am told do specially abound on the shores of the bay.

"How say you, Mistress Brent, are the terms accepted, and are we ready for the ceremony of investiture?"

"I have already bidden in the household," said Mary Brent, and following on her words there came filing in a train of men and maid servants, white and black, all arrayed in holiday attire, till the lower part of the long room was filled.

"'Tis a stately ceremonial thou hast planned," said Elinor, smiling at her cousin.

"Well enough!" Mary Brent answered, veiling her satisfaction in deprecation, "since thou hast as yet no tenants, and canst not hold a court baron at Robin Hood's Barn. I would Giles and Leonard Calvert were here, for in truth 'tis as goodly a show as we have held."

The tenantry were gathered.

On the dais stood Cecil, his eyes dancing under the page-cut hair which fell like thatch over his forehead, and his curls tremulous with the excitement, which would not let him be still for an instant. Elinor stood beside him in a white dress with a golden girdle, and on the step knelt Neville.

Elinor found leisure to note the elegance of the jewelled buckles which he wore on his shoes, and that his collar was of Venice point. It pleased her that he had taken as much trouble to array himself for his investiture as he would have done for a court function.

Of what was Neville thinking as he knelt there on the step of the dais?

Was it of Cecil and his manor?

Not at all.

Of law and leases?

Still less.

Of what, then?

Why, of the tiny point of a lady's slipper under a white robe, a slipper that tempted him to bend a little lower still and kiss it. Would she feel it, he wondered? Would she chide him if she did? Men kissed the foot of a saint without blame. If the adorable is to be adored and the lovable to be loved, why was not the kissable to be kissed? Besides,—only a slipper!

He was in the hem-of-the-garment stage of his passion, and fancied himself humble in his desire.

"Stretch out thy rod, Cecil!" It was Elinor's voice that broke in on Neville's indecision.

The boy reached forth the stick of ebony tipped with silver which was Baltimore's gift to Mary Brent on her coming out of England. Neville grasped the other end, and smiling at Cecil, with a single upward glance at Elinor bending over him, he said,—

"Hear you, my lord, that I, Christopher Neville, shall be to you both true and faithful, and shall owe my fidelity to you for the land I hold of you, and lawfully shall do and perform such customs and services as my duty is to you, so help me God and all His saints."

"Amen!" said Father White.

"By the terms assigned I do promise to pay to you on taking possession of the manor at Cecil Point ten Indian arrows and a string of fish, and[59] thereafter, when the land shall be cleared, to yield you three quarters of the harvest yearly."

"Nay," interrupted Cecil, "'tis not the bond mother and I did agree upon; 'twas to be share and share alike. Saidst thou not so in bed this morning, Mother?"

Before Elinor could reply, Father White spoke as he stepped forward,—

"The case may be happily settled, my daughter, by the yielding of the quarter in dispute to the revenue at St. Inigo's for the benefit of Holy Church."

The mutinous blood rose in Neville's cheeks and his chin went out quarter of an inch; but he held his peace and looked toward Elinor, who also colored but spoke firmly,—

"Nay, Father, 'twere not well that the Church should profit by an injustice. What duty Cecil hath to the Church is for thee and me to settle later, but it must come from his share and not from Sir Christopher's. Now, Cecil, 'tis thy turn to make thy promise to thy tenant. Go on: 'I, Cecilius Calvert—'"

"Now, Mother," said the young landlord, shaking off the admonishing hand from his shoulder with a petulance for which a young Puritan would have been roundly punished, "if thou dost prompt me like that none will believe I know my part, and I have learned it as well as thou, thus:[60] I, Cecilius Calvert, do hereby accept thee, Chrithtopher Neville, as my tenant at Cecil Point, and promise to protect thee in thy rights to the extent of the law, and if need be by the aid of my sword."

Neville smiled in spite of himself at the words, and a ripple of laughter went round the circle of tenants as they noted the comparative size of protector and protected; but Cecil was too full of his new-fledged dignity to heed them. He called for the written deed and the candle and the wax, and on the oaken table he scrawled his name under those of his mother and Sir Christopher, and then taking off his signet ring—'twas his father's and a deal too wide for his chubby finger,—he pressed it firmly into the wax covering the seam of the folded paper, and then stood looking with admiration at the print of the crest; a ducal crown surmounted by two half-bannerets. "'Tis a pretty device, is it not, Thir Chrithtopher? I would you had as pretty a one. Mother, if Thir Chrithtopher Neville married thee would he bear the Calvert crest?"

If one could slay one's child and bring him to life again after an appropriate interval many of us might be tempted to infanticide. A great flame of anger and shame rose to Elinor's cheek; but Neville came to her assistance.

"Nay, little landlord," he said coolly, "no[61] husband of thy mother could bear thy crest. 'Tis for thee, as the only heir in this generation, to bear it worthily before the world. Mistress Brent, is the ceremony ended?"

"Ay, and most happily," said Mary, nervously, struggling between desire to laugh and cry; "let us have in the cake and wine."

The servants went out to fetch the great trays of oaken wood with rim and handles of silver which had been in the Brent family for generations. As they re-entered in procession,—for Mary Brent dearly loved form and ceremony, and kept it up even here in the wilderness,—a knock was heard at the iron-studded door.

Being flung open it revealed the figure of a man, a tall, slender man with Saxon flaxen hair and true blue eyes.

"Mistress Brent?" he said questioningly, looking from Mary to Elinor.

"I am she," said Mary, stepping forward and holding out her hand with even more than her usual warmth of hospitality. "Can I be of service to you?"

"The question is, rather, are you willing to allow my claim upon your far-famed hospitality?"

"I think it has never yet been denied any one."

"I believe it well, but perhaps no one ever yet claimed it who lay under such a shadow. If you consent in your goodness to shelter a[62] traveller, you must know that you are harboring the brother of Richard Ingle."

Mary Brent started, for her brother had confided to her Richard Ingle's treasonable speeches, and in her eyes treason ranked next to blasphemy among the unpardonable sins. For an instant she hesitated and half withdrew her hand, then stretching it out again she looked full at him and said,—

"'Twere a pity frank truth-telling like yours should cost you dear. Let me ask but one question, Do you hold with your brother in his treason?"

A pained look came into Ralph Ingle's eyes. "Lady," he said, "'tis a hard matter to hear or speak evil of one's brother—one's only brother." His lip trembled, but the voice rang clear and steady. "Yet when the time comes to choose between brotherly affection and one's duty to King and Commonwealth, the knot must be cut though the blood flows. So I told Richard yesterday, there on the deck of The Reformation, and hereafter we have sworn to forget that the same father called us both son."

"You speak like a true man," said Mary Brent, "and shall be taken at your word. You find us celebrating the tenancy of Sir Christopher Neville yonder, who is taking up land of Mistress Calvert and her son.

"Elinor, this is Master Ingle. Judge him on his deeds—not his name!"

Ingle swept the ground with the plumes of his hat before Elinor as he murmured,—

"Nay, rather judge me of your own gentleness, and let mercy temper the verdict."

Neville stood, looking coldly at the intruder. He was jealous, for he saw the light of a new interest dawning in Elinor Calvert's face, and he saw the hot, passionate light of love at first sight as clear as day in Ralph Ingle's eyes.

For the first time he was conscious with angry protest that he was growing old. His cast-down glance fell upon his grizzled mustachios, and he inwardly cursed the sign of age. "The conceited stripling!" he muttered, as he looked at the bowing golden curls. "I know I am not just. I have no ambition to be just. I hate him. Come, Cecil," he said, crossing over to where the child stood holding a wine cup in one hand and a distressingly large slice of fruit cake in the other, "thou and I have no larger part to play here than the cock in Hamlet."

"What part did he play?" asked Cecil, crowding his mouth with plums, while he held the remaining cake high above his head to escape Knut's jumping.

"Oh, the important office was his to announce the daybreak and put an end to the ghost's walking.[64] Do ghosts walk nowadays dost thou think, Cecil?"

"Sure."

"I think so too; I have seen them,—in fact, I feel sometimes as if I were one of them."

"Art thou really?" Cecil's eyes were round as saucers.

"Well, never mind that question just now. Perhaps I am—perhaps I am not; do thou drain thy wine, and let us be off outside to build a snow-man in the road."

Nothing loath, the child slipped his hand into the big, muscular one held out to him, and unobserved by the preoccupied group around the fire, they slipped out.

Ralph Ingle turned as they passed him. "I must watch that man," he thought. "He who takes a child by the hand takes the mother by the heart."

"Wait," said Cecil at the door. "I must doff my finery, for who knows when I may need it to receive another tenant?"