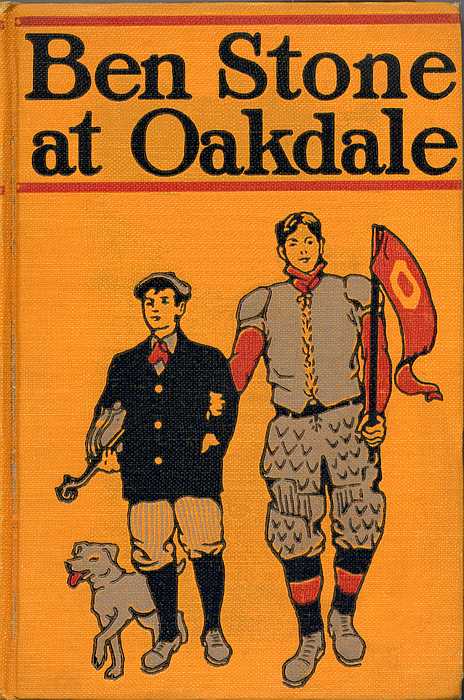

Book cover

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook.

Title: Ben Stone at Oakdale

Author: Morgan Scott

Release Date: February 17, 2015 [eBook #48277]

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK BEN STONE AT OAKDALE***

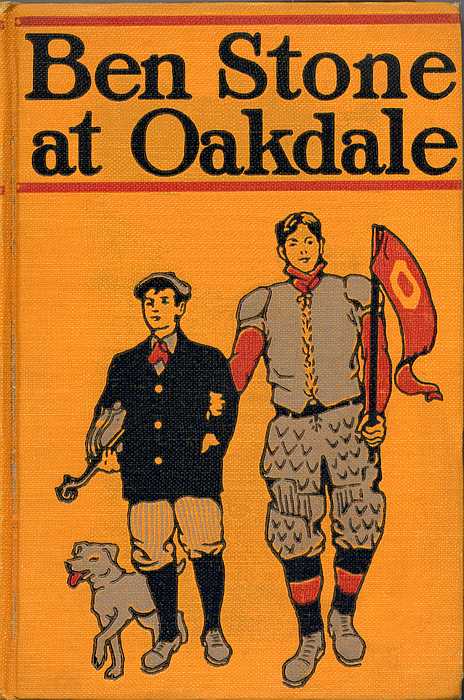

Book cover

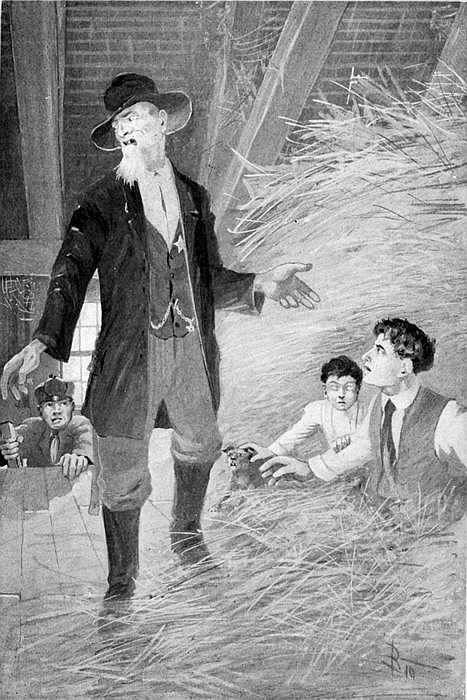

“HERE THEY BE!”—PAGE 260.

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I. | Ben Stone | 5 |

| II. | The Pariah | 16 |

| III. | One Ray of Light | 26 |

| IV. | A Brave Heart | 40 |

| V. | One More Chance | 49 |

| VI. | Into the Shadows | 61 |

| VII. | A Desperate Encounter | 71 |

| VIII. | A Rift | 83 |

| IX. | Proffered Friendship | 96 |

| X. | Stone’s Story | 105 |

| XI. | On the Threshold | 118 |

| XII. | The Skies Brighten | 127 |

| XIII. | Hayden’s Demand | 135 |

| XIV. | The Bone of Contention | 142 |

| XV. | The Fellow Who Wouldn’t Yield | 152 |

| XVI. | Stone’s Defiance | 162 |

| XVII. | An Armed Truce | 170 |

| XVIII. | The Game | 179 |

| XIX. | Between the Halves | 190 |

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| XX. | One Who Was True | 198 |

| XXI. | A Surprising Meeting | 209 |

| XXII. | A Sympathetic Soul | 218 |

| XXIII. | The Blind Fugitive | 228 |

| XXIV. | Clouds Gather Again | 235 |

| XXV. | Flight | 247 |

| XXVI. | The Arrest | 256 |

| XXVII. | The Darkest Hour | 265 |

| XXVIII. | On Trial | 280 |

| XXIX. | Sleuth’s Clever Work | 296 |

| XXX. | Clear Skies | 309 |

As he was leaving the academy on the afternoon of his third day at school in Oakdale, Ben Stone was stopped by Roger Eliot, the captain of the football team. Roger was a big, sturdy chap, singularly grave for a boy of his years; and he could not be called handsome, save when he laughed, which was seldom. Laughter always transformed his features until they became remarkably attractive.

Compared with Ben, however, Roger appeared decidedly comely, for the new boy was painfully plain and uncouth. He was solid and stocky, with thick shoulders and rather big limbs, having a freckled face and reddish hair. He had a somewhat large nose, although this alone would not have been detrimental to his appearance. It was his square jaw, firm-shut mouth, and seemingly sullen manner that had prevented any of the boys of the school from seeking his acquaintance up to this point. Half of his left ear was gone, as if it had been slashed off with some sharp instrument.

Since coming to Oakdale Ben had seemed to shun the boys at the school, seeking to make no acquaintances, and he was somewhat surprised when the captain of the eleven addressed him. Roger, however, was not long in making his purpose clear; he took from his pocket and unfolded a long paper, on which were written many names in two extended columns.

“Your name is Stone, I believe?” he said inquiringly.

“Yes, sir,” answered Ben.

“Well, Stone, as you are one of us, you must be interested in the success of the football team. All the fellows are, you know. We must have a coach this year if we expect to beat Wyndham, and a coach costs money. Everybody is giving something. You see, they have put down against their names the sums they are willing to give. Give us a lift, and make it as generous as possible.”

He extended the subscription paper toward the stocky boy, who, however, made no move to take it.

Several of the boys, some of them in football clothes, for there was to be practice immediately after school, had paused in a little group a short distance from the academy steps and were watching to note the result of Roger’s appeal to the new scholar.

Ben saw them and knew why they were waiting there. A slow flush overspread his face, and a look of mingled shame and defiance filled his brownish eyes. Involuntarily he glanced down at his homespun clothes and thick boots. In every way he was the poorest-dressed boy in the school.

“You’ll have to excuse me,” he said, in a low tone, without looking up. “I can’t give anything.”

Roger Eliot showed surprise and disappointment, but he did not immediately give over the effort.

“Why, of course you’ll give something,” he declared, as if there could be no doubt on that point. “Every one does. Every one I’ve asked so far has; if you refuse, you’ll be the first. Of course, if you can’t afford to give much——”

“I can’t afford to give a cent,” interrupted Ben grimly, almost repellantly.

Roger slowly refolded the paper, looking the other over closely. He took note of the fellow’s well-worn clothes and poverty-touched appearance, and with dawning comprehension he began to understand the meaning of the flush on Ben’s cheeks. Instead of being offended, he found himself sorry for the new boy.

“Oh, all right!” he said, in a manner that surprised and relieved Stone. “You know your own business, and I’m sure you’d like to give something.”

These words, together with Eliot’s almost friendly way, broke down the barrier of resentment which had risen unbidden in the heart of the stocky lad, who suddenly exclaimed:

“Indeed I would! I’m powerful sorry I can’t. Perhaps—by an’ by—if I find I’m going to get through all right—perhaps I’ll be able to give something. I will if I can, I promise you that.”

“Well, now, that’s the right stuff,” nodded Roger heartily. “I like that. Perhaps you can help us out in another way. You’re built for a good line man, and we may be able to make use of you. All the candidates are coming out to-day. Do you play?”

“I have—a little,” answered Ben; “but that was some time ago. I don’t know much about the game, and I don’t believe I’d be any good now. I’m all out of practice.”

“Never you mind that,” said the captain of the team. “Lots of the fellows who are coming out for practice have never played at all, and don’t know anything about it. We need a good lot of material for the coach to work up and weed out when we get him, so you just come along over to the field.”

Almost before Ben realized what was happening, Roger had him by the arm and was marching him off. They joined the others, and Roger introduced him to “Chipper” Cooper, Sile Crane, Billy Piper, and the rest. He noticed in particular the three named, as each was characteristic in his appearance to a distinct degree.

Cooper was a jolly chap, with mischievous eyes and a crooked nose. He had the habit of propounding ancient conundrums and cracking stale jokes. Crane was a long, lank, awkward country boy, who spoke ungrammatically, in a drawling, nasal voice. Piper, who was addressed as “Sleuth” by his companions, was a washed-out, colorless fellow, having an affected manner of keenness and sagacity, which were qualities he did not seem to possess to any great degree.

They passed down the gravel walk to the street, and crossed over to the gymnasium, which stood on the shore of the lake, close behind the fenced field that served for both a football and baseball ground.

The gymnasium was a big, one-story frame building, that had once been used as a bowling alley in the village. The man who built it and attempted to run it had failed to find business profitable, and in time it was purchased at a low price by Urian Eliot, Roger’s father, who moved it to its present location and pledged it to the academy as long as the scholars should continue to use it as a gymnasium.

Inside this building Ben was introduced to many more boys, a large number of whom had prepared or were making ready for football practice. There was Charley Tuttle, called “Chub” for short, a roly-poly, round-faced, laughing chap, who was munching peanuts; Tim Davis, nicknamed “Spotty,” even more freckled than Ben, thin-legged, sly-faced, and minus the two front teeth of his upper jaw; Sam Rollins, a big, hulking, low-browed fellow, who lost no opportunity to bully smaller boys, generally known as “Hunk”; Berlin Barker, a cold blond, rather good-looking, but proud and distant in his bearing; and others who did not impress the new boy at all with their personalities.

Few of these fellows gave Ben any attention after nodding or speaking to him when introduced. They were all busily engaged in discussing football matters and prospects. Stone heard some of this talk in the big dressing-room, where Eliot took him. The captain of the eleven opened a locker, from which he drew a lot of football clothing.

“I have my regular suit here, Stone,” he said; “and here are some other things, a lot of truck from which you can pick out a rig, I think. Take those pants and that jersey. Here are stockings and shoes. My shoes ought to fit you; I’m sure the rest of the stuff is all right.”

Ben started to object, but Roger was in earnest and would not listen to objections. As he was getting into the outfit provided by Eliot, Ben lent his ear to the conversation of the boys.

“We’ve got to beat Wyndham this year,” said one. “She buried us last year, and expects to do so again. Why, they have a regular Harvard man for a coach over there.”

“Beat her!” cried another. “You bet we will! Wait till we get our coach. I say, captain, how are you making it, gathering the needful?”

“First rate,” answered Roger, who was lacing his sleeveless jacket. “I’ll raise it all right, if I have to tackle every man, woman and child in town with that paper.”

“That’s the stuff!” whooped Chipper Cooper. “Being captain of a great football team, you are naturally a good man to tackle people. Rah! rah! rah! Cooper!” Then he skipped out of the dressing-room, barely escaping a shoe that was hurled at him.

“Bern’s home,” said a boy who was fussing over a head harness. “Came on the forenoon train with his folks. I saw him as I came by. Told him there’d be practice to-night, and he said he’d be over.”

“He’s a corking half-back,” observed a fellow who wore shin guards. “As long as we won’t have Roger with us next year, I’ll bet anything Bern is elected captain of the team.”

“Come on, fellows,” called Eliot, who had finished dressing in amazingly quick time. “Come on, Stone. We want to do as much as we can to-night.”

They trooped out of the gymnasium, Ben with them. A pleasant feeling of comradery and friendliness with these boys was growing upon him. He was a fellow who yearned for friends, yet, unfortunately, his personality was such that he failed to win them. He was beginning to imbibe the spirit of goodfellowship which seemed to prevail among the boys, and he found it more than agreeable.

Fortune had not dealt kindly with him in the past, and his nature had been soured by her heavy blows. He had come to Oakdale for the purpose of getting such an education as it was possible for him to obtain, and he had also come with the firm determination to keep to himself and seek no friends; for in the past he had found that such seeking was worse than useless.

But now circumstances and Roger Eliot had drawn him in with these fellows, and he longed to be one of them, longed to establish himself on a friendly footing with them, so that they would laugh and joke with him, and call him by his first name, and be free and easy with him, as they were among themselves.

“Why can’t I do it?” he asked himself, as he came out into the mellow afternoon sunshine. “I can! I will! They know nothing about the past, and they will never know.”

Never had the world looked more beautiful to him than it did as he passed, with his schoolmates about him, through the gate and onto the football field. Never had the sky seemed so blue and the sunshine so glorious. He drank in the clear, fresh air with his nostrils, and beneath his feet the springy turf was delightfully soft and yet pleasantly firm. Before him the door to a new and better life seemed flung wide and inviting.

There were some boys already on the field, kicking and passing a football. One of these—tall, handsome, supple and graceful—was hailed joyously as “Bern.” This chap turned and walked to meet them.

Suddenly Ben Stone stood still in his tracks, his face gone pale in an instant, for he was face to face with fate and a boy who knew his past.

The other boy saw him and halted, staring at him, astonishment and incredulity on his face. In that moment he was speechless with the surprise of this meeting.

Ben returned the look, but there was in his eyes the expression sometimes seen in those of a hunted animal.

The boys at a distance continued kicking the football about and pursuing it, but those nearer paused and watched the two lads, seeming to realize in a moment that something was wrong.

It was Roger Eliot who broke the silence. “What’s the matter, Hayden?” he asked. “Do you know Stone?”

The parted lips of Bernard Hayden were suddenly closed and curved in a sneer. When they parted again, a short, unpleasant laugh came from them.

“Do I know him!” he exclaimed, with the utmost disdain. “I should say I do! What’s he doing here?”

“He’s attending the academy. He looks to me like he might have good stuff in him, so I asked him out for practice.”

“Good stuff!” cried Hayden scornfully. “Good stuff in that fellow? Well, it’s plain that you don’t know him, Eliot!”

The boys drew nearer and gathered about, eager to hear what was to follow, seeing immediately that something unusual was transpiring.

Not a word came from Ben Stone’s lips, but the sickly pallor still clung to his uncomely face, and in his bosom his heart lay like a leaden weight. He had heard the boys in the gymnasium talking of “Bern,” but not for an instant had he fancied they were speaking of Bernard Hayden, his bitterest enemy, whom he felt had brought on him the great trouble and disgrace of his life.

He had come from the gymnasium and onto the football field feeling his heart exulting with a new-found pleasure in life; and now this boy, whom he had believed so far away, whom he had hoped never again to see, rose before him to push aside the happiness almost within his grasp. The shock of it had robbed him of his self-assertion and reliance, and he felt himself cowering weakly, with an overpowering dread upon him.

Roger Eliot was disturbed, and his curiosity was aroused. The other boys were curious, too, and they pressed still nearer, that they might not miss a word. It was Eliot who asked:

“How do you happen to know him, Hayden?”

“He lived in Farmington, where I came from when we moved here—before he ran away,” was the answer.

“Before he ran away?” echoed Roger.

“Yes; to escape being sent to the reformatory.”

Some of the boys muttered, “Oh!” and “Ah!” and one of them said, “He looks it!” Those close to Stone drew off a bit, as if there was contamination in the air. Immediately they regarded him with disdain and aversion, and he looked in vain for one sympathetic face. Even Roger Eliot’s grave features had hardened, and he made no effort to conceal his displeasure.

Sudden rage and desperation seemed to swell Ben’s heart to the point of bursting. The pallor left his face; it flushed, and from crimson it turned to purple. He felt a fearful desire to leap upon his enemy, throttle him, strike him down, trample out his life, and silence him forever. His eyes glared, and the expression on his face was so terrible that one or two of the boys muttered their alarm and drew off yet farther.

“He’s going to fight!” whispered Spotty Davis, the words coming with a whistling sound through his missing teeth.

Ben heard this, and immediately another change came upon him. His hands, which had been clenched and half-lifted, opened and fell at his sides. He bowed his head, and his air was that of utter dejection and hopelessness.

Bern Hayden observed every change, and now he laughed shortly, cuttingly. “You see, he doesn’t deny it, Eliot,” he said. “He can’t deny it. If he did, I could produce proof. You’d need only to ask my father.”

“I’m sorry to hear this,” said the captain of the eleven, although to Ben it seemed there was no regret in his voice. “Of course we don’t want such a fellow on the team.”

“I should say not! If you took him, you couldn’t keep me. I wouldn’t play on the same team with the son of a jail-bird.”

“What’s that?” cried Roger. “Do you mean to say his father——”

“Why, you’ve all heard of old Abner Stone, who was sent to prison for counterfeiting, and who was shot while trying to escape.”

“Was that his father?”

“That was his father. Oh, he comes of a fine family! And he has the gall to come here among decent fellows—to try to attend the academy here! Wait till my father hears of this! He’ll have something to say about it. Father was going to send him to the reformatory once, and he may do it yet.”

Roger’s mind seemed made up now. “You know where my locker is, Stone,” he said. “You can leave there the stuff I loaned you.”

For a moment it seemed that the accused boy was about to speak. He lifted his head once more and looked around, but the disdainful and repellant faces he saw about him checked the words, and he turned despairingly away. As he walked slowly toward the gate, he heard the hateful voice of Bern Hayden saying:

“Better watch him, Eliot; he may steal those things.”

The world had been bright and beautiful and flooded with sunshine a short time before; now it was dark and cold and gloomy, and the sun was sunk behind a heavy cloud. Even the trees outside the gate seemed to shrink from him, and the wind came and whispered his shame amid the leaves. Like one in a trance, he stumbled into the deserted gymnasium and sat alone and wretched on Roger Eliot’s locker, fumbling numbly at the knotted shoestrings.

“It’s all over!” he whispered to himself. “There is no chance for me! I’ll have to give up!”

After this he sat quite still, staring straight ahead before him with eyes that saw nothing. Full five minutes he spent in this manner. The sound of boyish voices calling faintly one to another on the football field broke the painful spell.

They were out there enjoying their sport and football practice, while Ben found himself alone, shunned, scorned, outcast. He seemed to see them gather about Hayden while Bern told the whole shameful story of the disgrace of the boy he hated. The whole story?—no, Ben knew his enemy would not tell it all. There were some things—one in particular—he would conveniently forget to mention; but he would not fail to paint in blackest colors the character of the lad he despised.

Once Ben partly started up, thinking to hasten back to the field and defend his reputation against the attacks of his enemy; but almost immediately he sank down with a groan, well knowing such an effort on his part would be worse than useless. He was a stranger in Oakdale, unknown and friendless, while Hayden was well known there, and apparently popular among the boys. To go out there and face Hayden would earn for the accused lad only jeers and scorn and greater humiliation.

“It’s all up with me here,” muttered the wretched fellow, still fumbling with his shoestrings and making no progress. “I can’t stay in the school; I’ll have to leave. If I’d known—if I’d even dreamed Hayden was here—I’d never come. I’ve never heard anything from Farmington since the night I ran away. I supposed Hayden was living there still. How does it happen that he is here? It was just my miserable fortune to find him here, that’s all! I was born under an unlucky star.”

All his beautiful castles had crumbled to ruins. He was bowed beneath the weight of his despair and hopelessness. Then, of a sudden, fear seized him and held him fast.

Bern Hayden had told the boys on the football field that once his father was ready to send Stone to the reformatory, which was true. To escape this fate, Ben had fled in the night from Farmington, the place of his birth. Nearly two years had passed, but he believed Lemuel Hayden to be a persistent and vindictive man; and, having found the fugitive, that man might reattempt to carry out his once-baffled purpose.

Ben thrust his thick middle finger beneath the shoestrings and snapped them with a jerk. He almost tore off Eliot’s football clothes and flung himself into his own shabby garments.

“I won’t stay and be sent to the reform school!” he panted. “I’d always feel the brand of it upon me. If others who did not know me could not see the brand, I’d feel it, just as I feel——” He lifted his hand, and his fingers touched his mutilated left ear.

A few moments later he left the gymnasium, walking out hurriedly, that feeling of fear still accompanying him. Passing the corner of the high board fence that surrounded the football field, his eyes involuntarily sought the open gate, through which he saw for a moment, as he hastened along, a bunch of boys bent over and packed together, saw a sudden movement as the football was passed, and then beheld them rush forward a short distance. They were practicing certain plays and formations. Among them he caught a glimpse of the supple figure of Bern Hayden.

“I’d be there now, only for you!” was Ben’s bitter thought, as he hastened down the road.

Behind him, far beyond Turkey Hill, the black clouds lay banked in the west. They had smothered the sun, which could show its face no more until another day. The woods were dark and still, while harsh shadows were creeping nearer from the distant pastures where cowbells tinkled. In the grass by the roadside crickets cried lonesomely.

It was not cold, but Ben shivered and drew his poor coat about him. Besides the fear of being sent to a reformatory, the one thought that crushed him was that he was doomed forever to be unlike other boys, to have no friends, no companions—to be a pariah.

As he passed, he looked up at the academy, set far back in its yard of many maple trees, and saw that the great white door was closed, as if shut upon him forever. The leaden windows stared at him with silent disapproval; a sudden wind came and swung the half-open gate to the yard, which closed with a click, making it seem that an unseen hand had thrust it tight against him and held it barred.

Farther along the street stood a square, old-fashioned, story-and-a-half house, with a more modern ell and shed adjoining, and a wretched sagging barn, that lurched on its foundations, and was only kept from toppling farther, and possibly falling, by long, crude timber props, set against its side. The front yard of the house was enclosed by a straggling picket fence. As well as the fence, the weather-washed buildings, with loose clapboards here and there, stood greatly in want of paint and repairs.

This was the home of Mrs. Jones, a widow with three children to support, and here Ben had found a bare, scantily-furnished room that was within his means. The widow regarded as of material assistance in her battle against poverty the rent money of seventy-five cents a week, which her roomer had agreed to pay in advance.

For all of her misfortune and the constant strain of her toil to keep the wolf from the door and a roof over the heads of herself and her children, Mrs. Jones was singularly happy and cheerful. It is true the wounds of the battle had left scars, but they were healed or hidden by this strong-hearted woman, who seldom referred to them save in a buoyant manner.

Jimmy Jones, a puny, pale-faced child of eight, permanently lamed by hip disease, which made one leg shorter than the other, was hanging on the rickety gate, as usual, and seemed to be waiting Ben’s appearance, hobbling out to meet him when he came along the road.

“You’re awful late,” cried the lame lad, in a thin, high-pitched voice, which attested his affliction and weakness. “I’ve been watchin’. I saw lots of other fellers go by, but then I waited an’ waited, an’ you didn’t come.”

A lump rose in Ben’s throat, and into his chilled heart crept a faint glow. Here was some one who took an interest in him, some one who did not regard him with aversion and scorn, even though it was only a poor little cripple.

Jimmy Jones had reminded Ben of his own blind brother, Jerry, which had led him to seek to make friends with the lame boy, and to talk with him in a manner that quickly won the confidence of the child. This was his reward; in this time when his heart was sore and heavy with the belief that he was detested of all the world, Jimmy watched and waited for him at the gate, and came limping toward him with a cheery greeting.

Ben stooped and caught up the tiny chap, who was pitifully light, swinging him to a comfortable position on his bent left arm.

“So you were watching for me, were you, Jimmy?” he said, in a wonderfully soft voice for him. “That was fine of you, and I won’t forget it.”

“Yep, I waited. What made you so late? I wanted to tell you, I set that box-trap you fixed for me so it would work, an’ what do you think I ketched? Bet you can’t guess.”

“A squirrel,” hazarded Ben.

“Nope, a cat!” laughed the little fellow, and Ben whistled in pretended great surprise. “But I let her go. We don’t want no cats; we got enough now. But that jest shows the trap will work all right now, an’ I’ll have a squirrel next, I bet y’u.”

“Sure you will,” agreed Ben, as he passed through the gate and caught a glimpse of the buxom widow, who, hearing voices, had hastened from the kitchen to peer out. “You’ll be a great trapper, Jimmy; not a doubt of it.”

“Say, if I ketch a squirrel, will you help me make a cage for him?” asked Jimmy eagerly.

“I don’t know,” answered Ben soberly. “If I can, I will; but——”

“Course you ken! Didn’t you fix the trap? I expect you know how to make ev’ry kind of thing like that.”

“If I have a chance to make it, I will,” promised Ben, as he gently placed the boy on the steps and forced to his face a smile that robbed it in a remarkable way of its uncomeliness.

“I don’t s’pose we ken begin now?”

“It’s too late to-night, and I’m in a hurry. We’ll have to put it off, Jimmy.”

The smile vanished from his face the moment he passed round the corner of the house on his way to the back door. “Poor little Jimmy!” he thought. “I can’t help you make your squirrel-cage, as I’m not going to stay here long enough to do it.”

He ascended the narrow, uncarpeted stairs to his small, uncarpeted room over the kitchen, where a loose board rattled beneath his feet, and the dull light from a single window showed him the old-fashioned, low-posted, corded bedstead—with its straw tick, coarse sheets and patchwork quilt—pushed back beneath the sloping rafters of the roof.

Besides the bed, there was in the room for furniture a broken-backed rocking-chair; a small table with a split top, on which stood a common kerosene hand-lamp; a dingy white earthen water pitcher and bowl—the former with a circular piece broken out of its nose—sitting on a washstand, made of a long box stood on one end, with a muslin curtain hanging in front of it. His trunk was pushed into a corner of the room opposite the bed.

Another part of the room, which served as a wardrobe, or was intended for that purpose, was set off by a calico curtain. The kitchen chimney ran up through one end of the room and served to heat it a little—a very little.

Such a room as this was the best Ben Stone could afford to pay for from his meager savings. He had been satisfied, and had thought it would do him very well; for Mrs. Jones had genially assured him that on evenings when the weather became colder he would be welcome to sit and study by the open fire in the sitting-room, a concession for which he had been duly grateful.

But now he would need it no more; his hopes, his plans, his dreams were ended. He sat down dumbly on the broken chair, his hard, square hands lying helpless in his lap. The shadows of the dingy little chamber crept upon him from the corners; and the shadows of his life hovered thick about him.

Finally he became aware of the smell of cooking, which came to him from below, and slowly the consciousness that he was hungry grew upon him. It did not matter; he told himself so. There was in his heart a greater hunger that might never be satisfied.

It had grown quite dark and he struck a light, after which he pulled out his small battered trunk and lifted the lid. Then, in a mechanical manner, he began packing it with his few belongings.

At last the craving of his stomach became so insistent that he took down a square tin box from a shelf behind the calico curtain and opened it on the little table. It had been full when he came on Monday, but now there was left only the end of a stale loaf of bread and a few crumbs of cheese. These, however, were better than nothing, and he was about to make the best use of them, when there sounded a step outside his door, followed by a knock that gave him a start.

Had it come so soon? Would they give him no more time? Well, then, he must meet them; and, with his face gray and set, he opened the door.

With a long, nicked, blue platter, that served as a tray, Mrs. Jones stood outside and beamed upon him. On the tray were a knife, a fork, pewter spoons, and dishes of food, from one of which—a steaming bowl—came a most delightful odor.

“Land sakes!” said the widow. “Them stairs is awful in the dark, an’ I didn’t darst bring a lamp; I hed my han’s full. I brought y’u somethin’ hot to eat; I hope y’u don’t mind. It ain’t right for a big, growin’ youngster like you to be alwus a-eatin’ cold vittles, ’specially when he’s studyin’ hard. It’s bad f’r the dejesshun; an’ Joel—my late departed—he alwus had somethin’ the matter with his dejesshun. It kep’ him from workin’ reg’ler an’ kinder sp’iled his prospects, poor man! an’ left me in straightened circumstances when he passed away. But I ain’t a-repinin’ or complainin’; there is lots in this world a heap wuss off’n I be, an’ I’m satisfied that I’ve got a great deal to be thankful f’r. If I’d thought, I’d a-brought up somethin’ f’r a tablecloth, but mebbe you can git along.”

She had entered while talking, bringing with her, besides the odor of food, another odor of soapsuds, which clung to her from her constant labor at the washtubs, where, with hard, backaching toil, she uncomplainingly scrubbed out a subsistence. For Mrs. Jones took in washings, and in Oakdale there was not another whose clothes were so white and spotless, and whose work was done so faithfully.

Ben was so taken aback that he stood speechless in the middle of the floor, watching her as she arranged the dishes on the table.

“There’s some beef stew,” she said, depositing the steaming bowl. “An’ here’s hot bread an’ butter, an’ some doughnuts I fried to-day. Joel alwus uster say my doughnuts was the best he ever tasted, an’ he did eat a monst’rus pile of ’em. I don’t think they was the best thing in the world f’r his dejesshun, either. Mis’ Collins give me some apples this mornin’, an’ I made a new apple pie. I thought y’u might like to try it, though it ain’t very good, an’ I brought y’u up a piece. An’ here’s a glass of milk. Jimmy he likes milk, an’ I hev to keep it in the house f’r him. He don’t eat much, nohow. I saw you with Jimmy when you come in, an’ I noticed you looked kinder tired an’ pale, an’ I says to myself, ‘What that boy needs is a good hot supper.’ Jimmy he’s bin talkin’ about you all day, an’ how y’u fixed his squirrel trap. Now, you jest set right up here, an’ fall to.”

She had arranged the dishes and placed the old chair at the table, after which, as had become habitual with her on rising from the wash-tub, she wiped her hands on her apron and rested them on her hips, her arms akimbo. She was smiling at him in such a healthy, motherly manner, that her whole face seemed to glow like the genial face of the sun when it appears after a dark and cloudy day.

To say that Ben was touched, would be to fail utterly in expressing the smallest degree of his feelings, yet he was a silent, undemonstrative fellow, and now he groped in vain for satisfactory words with which to thank the widow. Unattractive and uncomely he was, beyond question, but now his unspeakable gratitude to this kind woman so softened and transformed his face that, could they have seen him, those who fancied they knew him well would have been astonished at the change.

“Mrs. Jones,” he faltered, “I—I—how can I——”

“Now you set right down, an’ let the victuals stop y’ur mouth,” she laughed. “You’ve bin good to my Jimmy, an’ I don’t forgit nobody who’s good to him. I’d asked y’u down to supper with us, but you’re so kinder backward an’ diffident, that I thought p’raps y’u wouldn’t come, an’ Mamie said she knowed y’u wouldn’t.”

Ben felt certain that back of this was Mamie’s dislike for him, which something told him had developed in her the moment she first saw him. She was the older daughter, a strong, healthy girl of seventeen, who never helped her mother about the work, who dressed in such cheap finery as she could obtain by hook or crook, who took music lessons on a rented melodeon paid for out of her mother’s hard earnings, who felt herself to be a lady unfortunately born out of her sphere, and who was unquestionably ashamed of her surviving parent and her brother and sister.

“Set right down,” persisted Mrs. Jones, as she took hold of him and pushed him into the chair. “I want to see y’u eatin’. That’s Mamie!” she exclaimed, her face lighting with pride, as the sound of the melodeon came from a distant part of the house. “She’s gittin’ so she can play real fine. She don’t seem to keer much f’r books an’ study, but I’m sartin she’ll become a great musician if she keeps on. If Sadie was only more like her; but Sadie she keeps havin’ them chills. I think she took ’em of her father, f’r when he warn’t ailin’ with his dejesshun he was shakin’ with a chill, an’ between one thing an’ t’other, he had a hard time of it. It ain’t to be wondered at that he died with debt piled up and a mortgage on the place; but I don’t want you to think I’m complainin’, an’ if the good Lord lets me keep my health an’ strength, I’ll pay up ev’ry dollar somehow. How is the stew?”

“It—it’s splendid!” declared Ben, who had begun to eat; and truly nothing had ever before seemed to taste so good.

As he ate, the widow continued to talk in the same strain, strong-hearted, hopeful, cheerful, for all of the ill-fortune that had attended her, and for all of the mighty load on her shoulders. He began to perceive that there was something heroic in this woman, and his admiration for her grew, while in his heart her thoughtful kindness had planted the seed of affection.

The warm bread was white and light and delicious, and somehow the smell of the melting butter upon it made him think vaguely of green fields and wild flowers and strawberries. Then the doughnuts—such doughnuts as they were! Ben could well understand how the “late departed” must have fairly reveled in his wife’s doughnuts; and, if such perfect productions of the culinary art could produce the result, it was fully comprehensible why Mr. Jones’ “dejesshun” had been damaged.

But the pie was the crowning triumph. The crust was so flaky that it seemed to melt in the boy’s mouth, and the apple filling had a taste and flavor that had been imparted to it in some magical manner by the genius of the woman who seemed to bestow something sweet and wholesome upon the very atmosphere about her.

With her entrance into that room, she had brought a ray of light that was growing stronger and stronger. He felt it shining upon him; he felt it warming his chilled soul and driving the shadows from his gloomy heart; he felt it giving him new courage to face the world and fight against fate—fight until he conquered.

“There,” said the widow, when Ben finished eating and sat back, flushing as he realized he had left not a morsel before him, “now I know y’u feel better. It jest done me good to see you eat. It sort of reminded me of the way Joel used to stow victuals away. He was a marster hand to eat, but it never seemed to do him no good. Even when he was in purty good health, which was seldom, he never could eat all he wanted to without feelin’ oppressed arterwards an’ havin’ to lay down and rest. He was a good one at restin’,” she added, with a slight whimsical touch.

Once more Ben tried to find words to express his thanks, and once more Mrs. Jones checked him.

“It ain’t been no trouble,” was her declaration, “an’ it was wuth a good deal to me to see you enjoy it so. What’re y’u doin’ with your trunk pulled out this way?”

This question reminded him again of his determination to leave Oakdale directly; and, knowing the good woman had regarded the room as engaged by him for the time of the fall term of school, and also feeling that to leave her thus and so deprive her of the rent money she expected to receive for weeks to come would be a poor return for her kindness, he hesitated in confusion and reluctance to tell her the truth.

“What’s the matter?” she asked, noting his manner. “Has anything happened? I noticed you was pale, an’ didn’t look jest well, when you come in. Is there anything wrong?”

“Yes, Mrs. Jones,” he forced himself to say; “everything is wrong with me.”

“At the academy? Why,” she exclaimed, as he nodded in answer to her question, “I thought y’u passed the exammernation all right? Didn’t y’u?”

“It’s not that; but I must leave school just the same.”

“Land of goodness! Do tell! It can’t be possible!” Mrs. Jones was completely astounded and quite shocked.

“It is not because I have failed in any of the requirements of the school,” Ben hastened to say. “I can’t explain just why it is, Mrs. Jones. It’s a long story, and I don’t wish to tell it. But I have an enemy in the school. I didn’t know he was here; I saw him for the first time to-day.”

This explanation did not satisfy her. “Why,” she said, “I was thinkin’ y’u told me when y’u took this room that you didn’t know a livin’ soul in this place.”

“I did tell you so, and I thought at the time that it was the truth; but since then I have found out I was mistaken. There is one fellow in the school whom I know—and he knows me! He will make it impossible for me to attend school here.”

“I don’t see how,” said the widow, greatly puzzled. “How can anybody make y’u leave the school if y’u don’t want to?”

“He hates me—he and his father, too. I am sure his father is a man of influence here.”

“Now I don’t want to be curi’s an’ pry inter nobody’s affairs,” declared the widow; “but I do think you’d better trust me an’ tell me about this business. I don’t b’lieve you ever done no great wrong or bad thing to make y’u afraid of nobody. Anybody that can be good an’ kind to a little lame boy, same as you’ve been to my Jimmy, ain’t bad.”

“Perhaps if you knew all about it you would change your opinion of me,” said the boy a trifle huskily, for he was affected by her confidence in him.

She shook her head. “No I wouldn’t. I b’lieve you’re makin’ a mountain out of er molehill. You’re deescouraged, that’s what’s the matter. But somehow you don’t look like a boy that’s easy deescouraged an’ quick to give up. Now, you jest tell me who your enemy is. You ain’t got no mother here to advise y’u, an’ perhaps I can help y’u some.”

Her insistent kindness prevailed upon him, and he yielded.

“My enemy’s name is Bernard Hayden,” he said.

“Land! You don’t tell! Why, he’s the son of Lemuel Hayden, who come here an’ bought the limestone quarries over south of th’ lake. He ain’t been here a year yet, but he’s built buildin’s an’ run a branch railroad from the main road to the quarries, an’ set things hummin’ in great shape. Next to Urian Eliot, who owns ’most all the mill business in the place, he’s said to be the richest man in town.”

“I knew it!” cried Ben; “I knew he would be a man of influence here. I knew him in Farmington, the place where I was born. Mrs. Jones, if I do not leave the school and Oakdale at once, Lemuel Hayden will try to make me do so.”

He could not bring himself to disclose to her his fear that Mr. Hayden might again seek to commit him to the State Reformatory. That secret was the shame of his soul, and when he was gone from Oakdale he was certain it would be a secret no longer. Already Bern Hayden had told the boys on the football field, and in a small place gossip of such nature flies quickly.

“Now let me talk to you a little,” said Mrs. Jones, sitting down on the trunk, which threatened to collapse beneath her weight. “I stick to it that I don’t b’lieve you ever done northing very bad, an’ if you’re poor that ain’t your fault. You’ve got a right to have an eddercation, jest the same as Lemuel Hayden’s boy has. Jest because, mebbe, you got inter some foolish boy scrape an’ got this Hayden boy down on you, be y’u goin’ to let him keep y’u from gittin’ an eddercation, to make a man of y’u, an’ take you through the world?

“As I said before, you don’t look like a boy to be scart or driv easy, an’ I shall be disapp’inted in you if y’u are. I ain’t goin’ to pry inter the affair; if y’u want to tell me about it some time, y’u can. But I’m goin’ to advise y’u to stay right here in this school an’ hold your head up. Joel, my late departed, he alwus said it warn’t no disgrace to be poor. That passage in the Bible that says it’s harder f’r a rich man to enter the kingdom of heaven then f’r a camel to pass through the eye of a needle, alwus was a great conserlation to Joel.

“An’ there’s rich people in this very town that should be ashamed to hold their heads up, knowin’, as ev’rybody does, how they come by their riches; but to-day I’d ruther be a-earnin’ my daily bread by sweatin’ at the wash-tub than to be in their shoes an’ have on my mind what they must have on their minds. Ev’ry day I live I thank the Lord that he’s been so good to me an’ let me have so many pleasures an’ enjoyments.”

Here she paused a moment to take breath, having digressed without intending to do so; and once more Ben found himself wondering at her splendid courage and the cheerful heart she maintained in spite of troubles and afflictions that might well have crushed and broken the spirit of an ordinary woman. She laughed in the face of misfortune, and she positively refused to be trampled on by bitter fate.

She was right in thinking Ben was not a weak boy nor one to be easily frightened; but had she known that over him hung the dark, chilling shadow of the reformatory, she could not have wondered at the course he had contemplated pursuing, and she might have hesitated about so freely giving him advice. Knowing nothing of this, however, she continued to urge him to reconsider his determination to give up school and leave Oakdale.

“Now promise me that you’ll stay till y’u have to leave school,” she entreated. “An’ I don’t b’lieve you’ll have to at all.”

“Mrs. Jones, I’ll think it over,” he said. “I have almost decided to take your advice and stay, no matter what comes.”

“That’s what I like to hear!” she laughed, rising from the trunk. “Don’t you never back down an’ run f’r nobody nor northin’. If Joel hed had more of the stand-up-an’-stick-to-it sperrit, I’m sartin it would ‘a’ been better f’r us all—but I ain’t complainin’, I ain’t complainin’.

“Goodness! I’ve been spendin’ a lot of time here when I’ve jest got loads of things to do before I can git a blessed wink of sleep this night. I’ve got to go. But you jest make up your mind to stick, enermies or no enermies. Good night.”

She had gathered up the dishes and was going. Ben held the lamp, to light her down the stairs, calling a grateful good night after her.

For two hours, at least, he walked the floor of that poor little room, fighting the inward battle with himself. Finally he paused, his hands clenched and his head thrown back. His square jaw seemed squarer and firmer than ever, and the determination on his plain face transfigured it.

“I am going to stay, Bernard Hayden!” he said quietly, as if speaking face to face with his enemy. “Whatever happens, I’ll not show the white feather. Do your worst!” He felt better when he had fully settled on this resolution.

Opening his window, he looked out on the quiet village that seemed winking sleepily and dreamily with its twinkling lights. Even as he lifted his eyes toward the overcast sky, the pure white moon burst through a widening rift and poured its light like a benediction upon the silent world. Still with his face upturned, his lips moving slightly, the boy knelt at the window, and the hush and peace of the night filled his heart.

Although he was certain he would be compelled to undergo an unpleasant ordeal at school the following day, he did not falter or hesitate. With determination in his heart, and his face grimly set, he turned in at the gate shortly after the ringing of the first bell, and walked up the path.

Several boys in a group near the academy steps saw him approaching. He distinctly heard one of them say, “Here he comes now”; and then a hush fell upon them as they watched him draw near. In spite of himself, he could not refrain from giving them a resentful and defiant glance. In return they looked on him in silent scorn, and he felt that not one of them held an atom of sympathy in his heart.

In the coat-room, where he went to hang his hat, he found Roger Eliot, who saw him, but did not speak. Ben’s lips parted, but Roger’s manner chilled him to silence, and he said nothing.

Bernard Hayden looked in. “Hey, Roger,” he called. “I want to see you a moment.” Then his eyes fell on Ben, and his proud lips curled a bit.

“All right, Bern,” said Eliot, walking out. Hayden took his arm, and they turned toward the outer door, talking in low tones.

As Ben entered the big lower room, a little gathering of girls just inside the door suddenly stopped chattering, looked at him in a frightened way, and hastily drew aside, one or two of them uttering low exclamations. His freckled face flushed, but it suddenly grew white as he saw a tall, spare man, who was talking earnestly with Professor Richardson, near the latter’s desk.

The tall man was Lemuel Hayden, and Ben knew what had brought him to the academy that morning.

The principal saw Ben come in, and said something that caused Mr. Hayden to turn and look toward the unfortunate boy, who, chilled and apprehensive, was seeking his seat. Ben felt those cold gray eyes upon him, and suddenly his soul seemed to quiver with anger. A sense of injustice and wrong seized him, filling him with a desire to confront his enemies and defend himself as best he could.

“No use!” an inward voice seemed to whisper. “They are too powerful. Who will believe your word against that of Lemuel Hayden?”

Mr. Hayden was a man who had placed fifty years of his life behind him, and his appearance and manner seemed to indicate that during the greater number of those years his stern will had dominated the acts and enforced the obedience of nearly every one who chance to have dealings with him. His shaved upper lip exposed a firm, hard, almost cruel, mouth. His carefully trimmed whiskers, like his hair, were liberally besprinkled with gray.

“That’s the boy,” Ben distinctly heard him say. Then Prof. Richardson said something in a low voice, and once more they fell to talking earnestly in subdued tones.

Ben sat down and waited, feeling certain that the very worst must happen. After a few moments, he heard the principal say:

“I shall give the matter my immediate attention, Mr. Hayden. It is very unfortunate, and I may be compelled to take your advice.”

The second bell was ringing as Lemuel Hayden passed down the center aisle and out of the academy. In passing, he looked at Ben, and his lips were pressed together above the edge of his whiskers until his mouth formed a thin, hard line.

Boys and girls came trooping in and sought their seats. Ben paid no attention to any of them, although he was sure that many eyed him closely. His deskmate, however, a little chap by the name of Walker, found an opportunity amid the bustle and movement of the scholars to lean toward Ben and whisper:

“My! I bet you’re going to get it! Look out!”

Ben paid no heed. His nerves were strained, and he waited in grim silence the coming crash, fully believing it was Prof. Richardson’s purpose to open the forenoon session in the regular manner and then denounce him before the assembled scholars.

When the opening exercises were over, Ben’s heart strained and quivered in the conviction that the trying moment had come. He was surprised and temporarily relieved when the first class was called in regular order and a few of the lower room scholars left to join a class in the upper room.

After a short time, however, he concluded that the time of trial had simply been postponed, and this conviction brought upon him a sort of slow torture that was hard to bear. He tried to study, but could not fix his mind on his book. His eyes might stare dully at the page, and his lips might keep repeating words printed there, but his thoughts persistently dwelt on the desperate strait into which he had fallen, and he speculated on the probable course that would be pursued by Lemuel Hayden.

His fancy pictured Mr. Hayden as hastening from the academy to consult with the town authorities and inform them about the dangerous character who had boldly entered the village for the purpose of attending school there. Ben felt that Mr. Hayden’s words would create a profound impression, and he was certain the man would then demand that the “dangerous character” of whom he spoke should be taken into custody at once and sent without delay to the State Reformatory.

The tortured lad further pictured Mr. Hayden and the authorities as making out certain papers and placing them in the hands of the village constable, urging him at the same time to do his duty without delay.

The boy fell to listening for the footsteps of Mr. Hayden and the constable at the door. Once he started and turned, but the door opened to admit returning scholars who had been to a recitation in the upper room.

Suddenly Ben heard his name sharply called by the principal, and he started to his feet with the conviction that at last the moment had arrived and that Prof. Richardson was about to arraign him before the school. Instead of that, his class in arithmetic had been called and was already on the front seats. He hastened down the aisle and joined the class.

Knowing he was wholly unprepared in the day’s lesson, he inwardly prayed that he might not be called to the blackboard. He was chosen, however, as one of five pupils to work problems on the board and demonstrate them to the rest of the class.

When the others had finished and taken their seats, he still remained before the board, chalk in hand, an unprepossessing figure as he frowned hopelessly over his task. At last, seeing the boy had failed, the principal told him to be seated. Although his face was burning and he was shamed by his failure, he could not repress a glance of defiance at some of his slyly-grinning classmates.

Prof. Richardson did not reprove him, but dismissed him with the rest of the class when the successful ones had demonstrated their problems.

“He thinks I won’t be here much longer, and so it’s not worth while bothering with me,” concluded Ben.

The forenoon wore away. At intermission Ben did not leave his seat, not caring to mingle with the boys and give them an opportunity to insult or anger him.

As the mid-day hour approached, the boy’s suspense grew greater, for he was still confident that he was not to escape. Thinking Prof. Richardson meant to speak of his case before dismissing the scholars at noon, his dread of the ordeal grew as the short hand of the clock behind the desk drew nearer and nearer to twelve.

Finally the hands of the clock stood upright, one over the other. Prof. Richardson closed his desk and locked it, after which he turned and faced the scholars. His eyes found Ben Stone and stopped. The time had come!

“Stone,” said the professor quietly, without a trace of harshness or reproof, “I should like to have you remain after the others are dismissed. I wish to speak with you.”

For a moment a feeling of relief flashed over Ben like an electric shock. So it was to be done privately, and not before the whole school! He was grateful for that much consideration for his feelings. When they were by themselves in that big, empty room, with no one else to hear, the professor would tell him quietly but firmly that it was quite out of the question to permit a boy of his bad reputation to remain in the school. He would be directed to leave the academy, never to return.

With many backward glances at the lad who remained behind, the scholars filed out. The door had closed behind the last of them when Ben was told to come down to the principal’s desk. There was no accusation, nothing but kindness, in Prof. Richardson’s eyes, as he looked on the boy who stood before him.

“Stone,” he said, in that same self-contained tone of voice, “I find it necessary to speak of an unpleasant matter relative to yourself. You came here to this school as a stranger, and it has ever been my practice to judge a boy by his acts and to estimate his character by what he proves himself to be. This is the course I should have pursued in your case, but this morning there came to me a gentleman who is well known in this town and highly respected, who knew you well before settling in Oakdale, and he told me many disagreeable things about you. I cannot doubt that he spoke the truth. He seemed to regard you as a rather dangerous and vicious character, and he expressed a belief that it was not proper for you to associate with the scholars here. I am not, however, one who thinks there is no chance of reform for a boy or man who has done wrong, and I think it is a fatal mistake to turn a cold shoulder on the repentant wrongdoer. I have given some thought to this matter, Stone, and I have decided to give you a chance, just the same as any other boy, to prove yourself here at this school.”

Ben was quivering from head to feet. In his heart new hope and new life leaped. Still in some doubt, he faltered:

“Then you—you are not going to—to expel me, sir?”

“Not until I am satisfied that you deserve it; not until by some act that comes under my observation you convince me that you are not earnestly seeking to reform—that you are not worthy to remain in the school.”

“Oh, thank you—thank you!” choked the boy, and that was all he could say. His voice broke, and he saw the kind face of the professor through a blurring mist.

“I hope I am not making a mistake in this, Stone,” that same soothing voice went on. “I hope you will try to prove to me that I am not.”

“I will, sir—I will!” Ben eagerly promised.

“That is all I ask of you. If you have a vicious disposition, try to overcome it; if you have a violent temper, seek to control it. Learn to be your own master, which is the great lesson that every one must learn in case he wishes to become honored and respected and successful in life. Prove to every one that you regret any mistakes of your past, and that you may be thoroughly trusted in the future. In this manner you will rise above your mistakes and above yourself. I don’t think I need say anything more to you, but remember that I shall watch you with anxiety and with hope. That is all.”

Ben felt that he could have seized the professor’s hand and kissed it, but he knew he would quite break down, and the thought of such weakness shamed him. All he did was to again huskily exclaim:

“Thank you, sir—thank you!”

The September air seemed again filled with mellow sweetness as he hurried in happy relief from the academy. With the touch of a passing breeze, the maple trees of the yard waved their hands gayly to him, and in the distance beyond the football field Lake Woodrim dimpled and laughed in the golden sunshine.

“One chance more!” he exultantly murmured. “One chance more, and I’ll make the most of it.”

As he hastened from the yard and turned down the street, he saw several boys assembled beneath a tree in a fence-corner near the roadside. They were laughing loudly at something that was taking place there. On the outskirts of the little gathering he saw the thin-legged figure of Spotty Davis, who was smoking a cigarette and grinning as he peered over the heads of those in front of him.

Ben would have hurried past, but he suddenly stopped in his tracks, checked by the shrill, protesting voice of a child in distress. At the sound of that voice, he turned quickly toward the boys beneath the tree and forced his way among them, pushing some of them unceremoniously aside.

What he saw caused a fierce look to come to his face and his freckled cheeks to flush; for in the midst of the group was Hunk Rollins, a look of vicious pleasure on his face, holding little Jimmy Jones by the ear, which he was twisting with brutal pleasure, showing his ugly teeth as he laughed at the tortured lad’s cries and pleadings.

“Oh, that don’t hurt any!” the bullying fellow declared, as he gave another twist. “What makes ye holler? It’s only fun, and you’ll like it when you get used to it.”

A moment later Ben reached the spot and sent the tormentor reeling with a savage thrust, at the same time snatching the sobbing cripple from him.

“You miserable coward!” he cried, hoarse with anger.

The cripple gave a cry and clung to him. “Don’t let him hurt me any more, Ben!” he pleaded. “He’s pulled my hair an’ my nose, an’ ’most twisted my ear off. I was comin’ to meet you to tell you I ketched a squirrel in the trap.”

In sullen silence the watching boys had fallen back. Ben was facing Hunk Rollins, and in his eyes there was a look that made the bully hesitate.

“Now you’ll see a fight,” said one of the group, in an awed tone. “Hunk will give it to him.”

Rollins had been astonished, but he knew what was expected of him, and he began to bluster fiercely, taking a step toward Stone, who did not retreat or move.

“Who are you calling a coward? Who are you pushing?” snarled the low-browed chap, scowling his blackest, and assuming his fiercest aspect, his huge hands clenched.

“You!” was the prompt answer. “No one but a coward and a brute would hurt a harmless little cripple.”

“You take care!” raged Hunk. “I won’t have you calling me names! I want you to understand that, too. Who are you? You’re nothing but the son of a jail-bird!”

“Go for him, Hunk!” urged Spotty Davis, his voice making a whistling sound through the space left by his missing teeth. “Soak him a good one!”

“I’ll soak him if he ever puts his hands on me again,” declared Rollins, who was desirous of maintaining his reputation, yet hesitated before that dangerous look on Stone’s face. “I don’t care to fight with no low fellow like him.”

“Hunk’s scared of him,” cried one of the boys, and then the others groaned in derision.

Stung by this, the bully roared, “I’ll show you!” and made a jump and a swinging blow at Ben. His arm was knocked aside, and Stone’s heavy fist landed with terrible violence on his chin, sending him to the ground in a twinkling.

The boys uttered exclamations of astonishment.

With his fists clenched and his uncomely face awesome to look upon, Ben Stone took one step and stood over Rollins, waiting for him to rise. It was thus that Prof. Richardson saw them as he pushed through the gathering of boys. Without pausing, he placed himself between them, and turned on Ben.

“It has not taken you very long, Stone,” he said, in a manner that made Ben shrink and shiver, “to demonstrate beyond question that what Mr. Hayden told me about you is true. I told you it is my custom to judge every boy by his acts and by what he proves himself to be. For all of your apparently sincere promise to me a short time ago, you have thus quickly shown your true character, and I shall act on what I have seen.”

“He hit me, sir,” Hunk hastened to explain, having risen to his feet. “He came right in here and pushed me, and then he hit me.”

Ben opened his lips to justify himself. “Professor, if you’ll let me explain——”

“I need no explanations; I have seen quite enough to satisfy me,” declared the professor coldly. “You have not reformed since the time when you made a vicious and brutal assault on Bernard Hayden.”

Involuntarily, Ben lifted an unsteady hand to his mutilated ear, as if that could somehow justify him for what had happened. His face was ashen, and the hopeless look of desperation was again in his eyes.

Upon the appearance of Prof. Richardson, many of the boys had lost no time in hurrying away; the others he now told to go home, at the same time turning his back on Ben. The miserable lad stood there and watched them depart, the academy principal walking with Rollins, who, in his own manner and to his own justification, was relating what had taken place beneath the tree.

As Ben stood thus gazing after them, he felt a hand touch his, and heard the voice of little Jimmy at his side.

“I’m sorry,” said the lame boy, “I’m awfully sorry if I got you into any trouble, Ben.”

“You’re not to blame,” was the husky assurance.

“Mebbe I hadn’t oughter come, but I wanted to tell y’u ’bout the squirrel I ketched. He’s jest the handsomest feller! Hunk Rollins he’s alwus plaguin’ an’ hurtin’ me when he gets a chance. My! but you did hit him hard!”

“Not half as hard as he ought to be hit!” exclaimed Ben, with such savageness that the lame lad was frightened.

With Jimmy clinging to his hand, they walked down the road together. The little cripple tried to cheer his companion by saying:

“You warn’t to blame; why didn’t you say you warn’t?”

“What good would it have done!” cried Ben bitterly. “The professor wouldn’t listen to me. I tried to tell him, but he stopped me. Everything and every one is against me, Jimmy. I have no friends and no chance.”

“I’m your friend,” protested the limping lad. “I think you’re jest the best feller I ever knew.”

To Jimmy’s surprise, Ben caught him up in his strong arms and squeezed him, laughing with a choking sound that was half a sob:

“I forgot you.”

“I know I don’t ’mount to much,” said the cripple, as he was lifted to Stone’s shoulder and carried there; “but I like you jest the same. I want you to see my squirrel. I’ve got him in an old bird cage. I’m goin’ to make a reg’ler cage for him, an’ I thought p’raps you’d show me how an’ help me some.”

Ben spent the greater part of the noon hour in the woodshed with little Jimmy, admiring the squirrel and explaining how a cage might be made. Mrs. Jones heard them talking and laughing, and peered out at them, her face beaming as she wiped her hands on her apron.

“Land!” she smiled; “Jimmy’s ’most crazy over that squirrel. You don’t s’pose it’ll die, do y’u?”

“Not if it can have a big cage with plenty of room to exercise,” answered Ben. “It’s a young one, and it seems to be getting tame already.”

“Well, I’m glad. Jimmy he’s jest silly over pets. But I tell him it ain’t right to keep the squirrel alwus shut up, an’ that he’d better let him go bimeby. Goodness! I can’t waste my time this way. I’ve got my han’s full to-day.”

Then she disappeared.

“Mother she thinks it ain’t jest right to keep a squirrel in a cage,” said the lame boy, with a slight cloud on his face. “What ju think, Ben?”

“Well,” said Ben, “it’s this way, Jimmy: Yesterday this little squirrel was frolicking in the woods, running up and down the trees and over the ground, playing with other squirrels and enjoying the open air and the sunshine. Now he’s confined in a cramped cage here in this dark old woodshed, taken from his companions and shut off from the sunshine and the big beautiful woods. Try to put yourself in his place, Jimmy. How would you like it if a great giant came along, captured you, carried you off where you could not see your mother or your friends, and shut you up in a narrow dungeon with iron bars?”

Jimmy sat quite still, watching the little captive vainly nosing at the wires in search of an opening by which he might get out. As he watched, the squirrel faced him and sat up straight, its beautiful tail erect, its tiny forefeet held limp.

“Oh, see, Ben—see!” whispered the lame lad. “He’s beggin’ jest like a dog; he’s askin’ me to let him go. I couldn’t keep him after that. I sha’n’t want no cage f’r him, Ben; I’m goin’ to let him go back to the woods to find the other squirrels he uster play with.”

Together they carried the cage out into the old grove back of the house, where Jimmy himself opened the door. For a moment or two the captive shrank back in doubt, but suddenly he whisked through the door and darted up a tree. Perched on a limb, he uttered a joyful, chittering cry.

“He’s laughing!” cried the lame boy, clapping his hands. “See how happy he is, Ben! I’m awful glad I didn’t keep him.”

The first bell was ringing as Ben turned toward the academy.

“Why, you ain’t had no dinner!” called Jimmy, suddenly aware of that fact.

“I didn’t want any,” truthfully declared Ben, as he vaulted a fence. “So long, Jimmy.” He waved his hand and hurried on.

He did not return to the academy, however. As the second bell began ringing, he paused on the edge of the deep, dark woods, which lay to the north of Turkey Hill. Looking back, he could see the academy, the lake and the village. The sound of the bell, mellowed by the distance, seemed full of sadness and disappointment. When it ceased, he turned and strode on, and the shadowy woods swallowed him.

All that long, silent afternoon, he wandered through the woods, the fields and the meadows. The cool shadows of the forest enfolded him, and the balsamic fragrance of spruce and pine and juniper soothed his troubled spirit. He sat on a decaying log, listening to the chatter of a squirrel, and hearing the occasional soft pat of the first-falling acorns. He noted the spots where Jack Frost had thus early begun his work of painting the leaves pink and crimson and gold. In a thicket he saw the scarlet gleam of hawthorne berries.

Beside Silver Brook, which ran down through the border of the woods, he paused to listen to the tinkle and gurgle of the water. There the blackberried moonseed clambered over the underbrush. When he crossed the brook and pushed on through this undergrowth, his feet and ankles were wet by water spilled from many hooded pitcher plants. Near the edge of the woods, with a sudden booming whir of wings that made his heart jump, a partridge flew up and went diving away into the deeper forest.

At the border of the woods, where meadow and marshland began, he discovered clusters of pale-blue asters mingling with masses of rose-purple blazing star. Before him he sent scurrying a flight of robins, driven from their feast of pigeon berries amid the wine-stained pokeweed leaves.

The sun leaned low to the west and the day drew toward a peaceful close. He seemed to forget for brief periods his misfortune and wretchedness, but he could not put his bitter thoughts aside for long, and whenever he tried to do so, they simply slunk in the background, to come swarming upon him again at the first opportunity. At best, it was a wretched afternoon he spent with them.

He had escaped facing disgrace and expulsion by declining to return to the academy that afternoon; but his trunk and clothes were at Mrs. Jones’ and he must get them, which led him, as night approached, to turn back toward the village.

On the southern slope of Turkey Hill he lingered, with the valley and the village below him. The sunshine gilded a church spire amid the oaks, and in its yard of maples he could see the roof and belfry of the academy.

The afternoon session was over by this time, and from that elevation Ben could look down on the fenced football field, where he beheld the boys already at practice. Once the still air brought their voices to him even from that distance. His heart swelled with a sense of injustice and wrong, until it seemed to fill his chest in a stifling manner.

Of course Bern Hayden was there with the boys who had so joyously hailed his return to Oakdale. But for Hayden he might also be there taking part in the practice, enjoying that for which his heart hungered, the friendly companionship of other lads.

The shadows were thickening and night was at hand as he crossed the fields and reached the road to the north of the academy. He hoped to avoid observation and reach Mrs. Jones’ house without encountering any one who knew him.

As he quickened his steps, he suddenly realized that he must pass the wretched little tumble-down home of Tige Fletcher, a dirty, crabbed, old recluse, who hated boys because he had been taunted and tormented by them, and who kept two fierce dogs, which were regarded as vicious and dangerous. Beyond Fletcher’s house there was a footpath from High street to the academy yard, and this was the course Ben wished to follow.

Knowing he might be set upon by the dogs, he looked about for a weapon of defense, finally discovering a thick, heavy, hardwood cudgel, about three feet in length. With this in his hand, he strode on, grimly determined to give the dogs more than they were looking for if they attacked him.

He was quite near the house when, on the opposite side, there suddenly burst forth a great uproar of barking, with which there immediately mingled a shrill scream of terror.

Unhesitatingly, Ben dashed forward, instinctively gripping his stout cudgel and holding it ready for use. The barking and the cry of fear had told him some one was in danger from Old Tige’s dogs.

Immediately on passing the corner of the house, he saw what was happening, and the spectacle brought his heart into his mouth. The dogs had rushed at a little girl, who, driven up against the fence, faced them with her blue eyes full of terror, and tried to drive them back by striking at them with her helpless hands.

Giving a shout to check the dogs and distract their attention from the girl, Ben rushed straight on. He saw one of the dogs leap against the child and knock her down. Then he was within reach, and he gave the animal a fearful blow with the club as it was snapping at the girl’s throat.

A moment later Ben found he had his hands full in defending himself, for the second dog, a huge brindle mastiff, having a protruding under-jaw and reddish eyes, leaped at his throat, his teeth gleaming. By a quick, side-stepping movement, the boy escaped, and with all his strength he struck the dog, knocking it down, and sending it rolling for a moment on the ground.

The first dog was a mongrel, but it was scarcely less ferocious and dangerous than the mastiff. Although Ben had seemed to strike hard enough to break the creature’s ribs, it recovered, and came at him, even as the mastiff was sent rolling. The yellow hair on the back of the dog’s neck bristled, and its eyes were filled with a fearful glare of rage.

The boy was not given time to swing his club for another telling blow, but was compelled to dodge as the dog sprang from the ground. His foot slipped a little, and he flung up his left arm as a shield. The teeth of the dog barely missed his elbow.

Quickly though Ben recovered and whirled, he was none too soon. This time, however, the mongrel was met by a well-directed blow on the nose, and the terrible pain of it took all the fight out of him and sent him slinking and howling away, with his tail curled between his legs.

The mastiff was not disposed of so quickly; for, although it had been knocked down by the first blow it received, it uttered a snarling roar, and again flung itself at the boy the moment it could regain its feet.

Against the fence the white-faced little girl crouched, uttering wild cries of fear, as, with terror-filled eyes, she watched the desperate encounter.

Knowing he would be torn, mangled, perhaps killed, if the teeth of the great dog ever fastened upon him, Ben fought for his very life. Three times he beat the creature down with his club, but for all this punishment the rage and fury of the animal increased, and it continued to return to the attack with vicious recklessness.

The boy set his teeth and did his best to make every blow count. Had his courage and nerve failed him for a moment, he must have been seized and dragged down by the frothing dog. He kept his wits about him, and his brain at work. Repeatedly he tried to hit the mastiff on the nose in the same manner as he had struck the mongrel, but for some moments, which seemed like hours, every attempt failed.

Once Ben’s heart leaped into his mouth, as his foot slipped again, but he recovered himself on the instant and was fully prepared for the big dog’s next charge.

At last he succeeded in delivering the blow on which he believed everything depended. Hit fairly on the nose by that club, which was wielded by a muscular young arm, the raging beast was checked and paralyzed for a moment.

Seizing the opportunity, Ben advanced and struck again, throwing into the effort every particle of strength and energy he could command. The dog dropped to the ground and lay still, its muscles twitching and its limbs stiffening; for that final blow had broken its neck.

Quivering and panting with the excitement and exertion of the struggle, Ben stood looking down at the body of the dog, giving no heed for the moment to the hoarse cries of rage which issued from the lips of Old Tige Fletcher, who was hobbling toward him with his stiff leg. Nor did he observe three boys who were coming along the path from the academy at a run, having been led to quicken their steps by the cries of the girl and the barking of the dogs.

Of the trio Roger Eliot was in the lead, and he was running fast, the sound of the frightened girl’s screams having filled him with the greatest alarm. He was followed closely by Chipper Cooper, while Chub Tuttle brought up the rear, panting like a porpoise, and scattering peanuts from his pockets at every jump.

These boys came in sight soon enough to witness the end of the encounter between Stone and the huge mastiff. They saw the dog beaten back several times, and Roger uttered a husky exclamation of satisfaction when Ben finally finished the fierce brute with a blow that left it quivering on the ground.

By that time Eliot’s eyes had discovered the girl as she crouched and cowered against the fence, and he knew instantly that it was in defense of her that Ben had faced and fought Fletcher’s dreaded dogs.

Even before reaching that point Roger’s heart had been filled with the greatest alarm and anxiety by the sounds coming to his ears; for he believed he recognized the voice of the child whose terrified cries mingled with the savage barking and snarling of the dogs. His little sister had a habit of meeting him on his way home after football practice, and he had warned her not to come too far on account of the danger of being attacked by Fletcher’s dogs. That his fear had been well-founded he saw the moment he discovered the child huddled against the fence, as it was, indeed, his sister.

“Amy!” he chokingly cried.

Reaching her, he caught her up and held her sobbing on his breast, while she clung to his neck with her trembling arms.

“Drat ye!” snarled Tige Fletcher, his face contorted with rage as he stumped forward, shaking his crooked cane at Ben Stone. “What hev ye done to my dorg? You’ve killed him!”

“I think I have,” was the undaunted answer; “at any rate, I meant to kill him.”

“I’ll hey ye ’rested!” shrilled the recluse. “That dorg was wuth a hundrud dollars, an’ I’ll make ye pay fer him, ur I’ll put ye in jail.”

Roger Eliot turned indignantly on the irate man.

“You’ll be lucky, Mr. Fletcher, if you escape being arrested and fined yourself,” he declared. “You knew your dogs were vicious, and you have been notified by the authorities to chain them up and never to let them loose unless they were muzzled. You’ll be fortunate to get off simply with the loss of a dog; my father is pretty sure to take this matter up when he hears what has happened. If your wretched dogs had bitten my sister—” Roger stopped, unable to find words to express himself.

The old man continued to splutter and snarl and flourish his cane, upon which Tuttle and Cooper made a pretense of skurrying around in great haste for rocks to pelt him with, and he beat a hasty retreat toward his wretched hovel.

“Don’t stone him, fellows,” advised Roger. “Let’s not give him a chance to say truthfully that we did that.”

“We oughter soak him,” said Chub, his round face expressive of the greatest indignation. “A man who keeps such ugly curs around him deserves to be soaked. Anyhow,” he added, poking the limp body of the mastiff, “there’s one dog gone.”

“Ain’t it a dog-gone shame!” chuckled Chipper, seizing the opportunity to make a pun.

Roger turned to Ben.

“Stone,” he said, in his kindly yet unemotional way, “I can’t thank you enough for your brave defense of my sister. How did it happen?”

Ben explained, telling how he had heard the barking of the dogs and the screams of Amy Eliot as chance led him to be passing Fletcher’s hut, whereupon he ran as quickly as possible to her assistance.

“It was a nervy thing to do,” nodded Roger, “and you may be sure I won’t forget it. I saw some of it, and the way you beat that big dog off and finished him was splendid.”

“Say, wasn’t it great!” chimed in Chub, actual admiration in his eyes as he surveyed Ben. “By jolly! you’re a dandy, Stone! Ain’t many fellers could have done it.”

“I won’t forget it,” repeated Roger, holding out his hand.

Ben flushed, hesitated, then accepted the proffered hand, receiving a hearty, thankful grip from Eliot.

Ben came down quietly through the grove behind the house, slipped round to the ell door and ascended to his bare room without being observed by any one about the place. It did not take him long again to draw out his battered trunk and pack it with his few possessions.

He then found before him an unpleasant duty from which he shrank; Mrs. Jones must again be told that he was going away.