Book cover

| Note: | Images of the original pages are available through Internet Archive. See https://archive.org/details/motorrangersclou00west |

Book cover

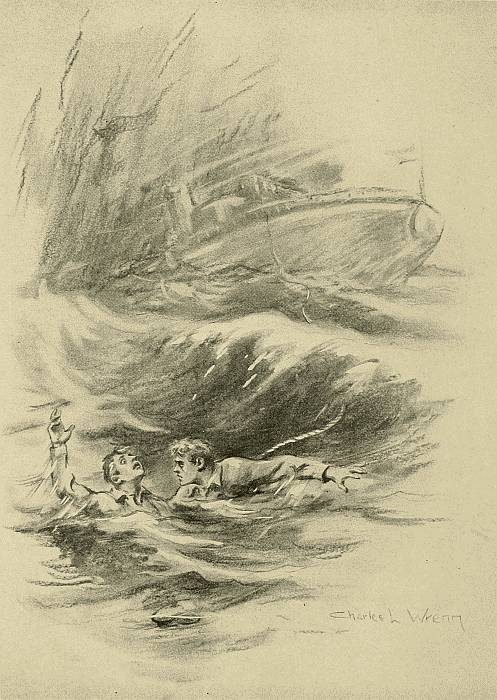

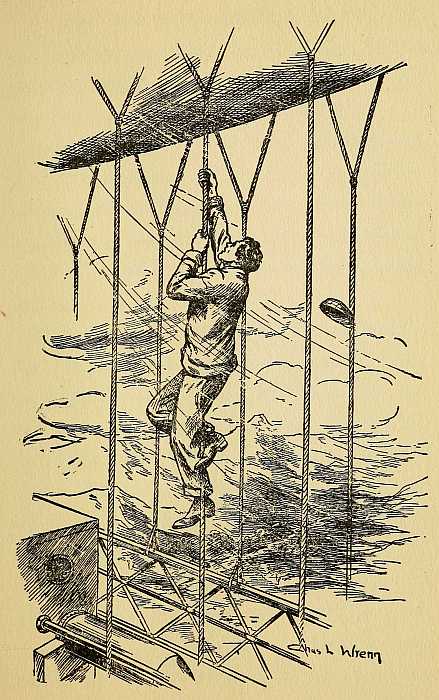

In a flash Nat’s strong arm was about him.—Page 22

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I. | The Magnetic Island | 5 |

| II. | Nat to the Rescue | 17 |

| III. | The Islands Vanish | 27 |

| IV. | Professor Grigg and Mr. Tubbs | 37 |

| V. | Trouble with a Hat | 47 |

| VI. | “What Would You Say to a Voyage in the Air?” | 55 |

| VII. | A Strange Sail Appears | 63 |

| VIII. | Trapped by Two Rascals | 71 |

| IX. | Some Strategy | 80 |

| X. | “Ding-Dong” and a Gun | 88 |

| XI. | Captain Lawless Tries Trickery | 99 |

| XII. | “Good Work, Manuello!” | 108 |

| XIII. | South American Justice | 120 |

| XIV. | Off on Their Strange Voyage | 130 |

| XV. | A Signal that Meant “Danger” | 140 |

| XVI. | Indians? | 148 |

| XVII. | A Queer Sort of Gun | 156 |

| XVIII. | What It Did | 166 |

| XIX. | An Involuntary Passenger | 177 |

| XX. | “All Our Lives Depend on It” | 187 |

| XXI. | “Feathered Aeroplanes” | 199 |

| XXII. | A Serious Accident | 211 |

| XXIII. | Overboard!—1950 Feet Up! | 223 |

| XXIV. | The City of a Vanished Race | 231 |

| XXV. | A Strange Adventure | 246 |

| XXVI. | Saved from the Sun Gods | 257 |

| XXVII. | “Did We Dream It All?” | 268 |

“What do you make of the weather, Nat?”

Joe Hartley turned to Nat Trevor as he spoke, and scanned the face of the young leader of the adventure-seeking Motor Rangers with some anxiety.

But the stout and placid Joe’s unwonted look of apprehension found no reflection on the firm countenance of Nat Trevor, who stood as steadily at the wheel of the Nomad as if that sixty-foot, gasolene-driven craft was not, to use Joe’s phrase of a few moments before, pitching and tumbling “like a bucking broncho.”

“It does look pretty ugly for a fact, Joe,” rejoined Nat, after he had scrutinized the horizon on every side.

“And this is a part of the Pacific where we were warned before we left the Marquesas that we must look out for squalls,” returned Joe, still looking worried.

“Oh, well, the Nomad has weathered many a good hard blow, not to mention those waterspouts,” commented Nat. “I guess she’ll last through whatever is to come.”

At this moment a third boyish countenance was suddenly protruded from a hatchway leading to the Nomad’s engine-room.

“S-s-s-s-say, y-y-y-you chaps,” sputtered our old acquaintance, William—otherwise and more frequently Ding-Dong—Bell, “w-w-what’s in the w-w-w-wind?”

“A bit of a storm, I guess, Ding-Dong,” returned Nat, watching his steering carefully, so as to send the Nomad sliding easily over the long, oily swells, “but don’t you mind, old chap. She’ll stand it, never fear. How are your engines running?”

“L-l-l-like a d-d-d-dollar w-w-watch,” returned Ding-dong, with a note of pride in his tones.

“Good. Now if only we were farther to seaward of that island yonder, I’d feel easier,” commented Nat.

“Say, Nat,” struck in Joe, as Ding-dong dived below once more, “it seems to me we are a long time passing that island.”

“I agree with you, Joe. That is what made me ask Ding-dong about his engines. At the pace they are turning up, we should have left it behind us long ago, yet there it is, still on our starboard bow.”

“And we are getting closer in to it all the time, you’ll notice,” rejoined Joe.

“There must be some powerful currents hereabouts,” said Nat, looking for the first time a little bit troubled. “There’s something queer about that island, anyhow. I can’t find it on the chart. According to that, this part of the mid-south Pacific is absolutely free from islands or rocks.”

“Hullo,” cried Joe suddenly, “that’s odd! Look, Nat, the island isn’t really one island at all. It’s two of them.”

This paradoxical speech was really a correct explanation of the case, as it now appeared. The Nomad had, by this time, made some little progress over the rising sea, and as the bit of land “opened out,” it could be seen that there were, as Joe had said, two islands, with a narrow channel running in between them.

“Phew!” whistled Nat. “This complicates the situation. To make matters worse——” He stopped short.

“Well?” demanded Joe.

“Never mind,” replied Nat; and then in an undertone he added to himself: “I may be wrong, but I’ll bet the hole out of a doughnut that we are being dragged round toward that passage.”

That such was actually the case, he realized to his dismay an instant later. Head the Nomad’s bow round as he would, some invisible force still dragged her in toward the two islands. It soon became apparent, too, that the narrow channel was, in reality, more in the nature of a cleft between the two masses of land. Its walls were steep and sheer and formed of grayish rock. It could now be seen that the water in this abyss was boiling and bubbling as if in a caldron.

Nat and Joe exchanged glances of dismay. It was no longer possible to disguise the fact that they were momentarily being sucked, as though by invisible yet resistless forces, toward this ominous looking chasm.

The three youths had set out for the California coast, on which was their home, some days before, from the Marquesas group of islands, where they had had some surprising adventures. What these were will be found set down in the third volume of this series, “The Motor Rangers on Blue Water.” It may be said here, briefly, that their experiences in the South Seas had included the routing of a rascally band, who had made a headquarters on one of the Marquesas Group, and the discovering of the rightful owner of some valuable sapphires which had come into their possession in a truly remarkable way.

Of how they acquired these sapphires, and of the adventures and perils through which they passed before they gained full possession, details will be found in the second volume of the Motor Ranger Series, namely, “The Motor Rangers Through the Sierras.” In that volume, we followed our youthful and enterprising heroes through the great Sierra range, and learned of their clever flouting of the schemes of the same band of rascals whom they re-encountered in the South Seas. Among other feats, they located and caused the destruction of the hitherto secret fortress of Colonel Morello, a notorious outlaw. This earned them his undying enmity, which he was not slow to display. In this volume, too, it was related how the lads found, in a miner’s abandoned hut, the wonderful sapphires.

It now remains, only briefly, to sketch the earlier experiences of the three lads, to give our readers a grasp of their characters. In the first volume of this series, then, which was called “The Motor Rangers’ Lost Mine,” the three lads set out for Lower California on a mission which was to involve them in unlooked-for complications.

This errand grew out of Nat’s employment as automobile expert by Mr. Montagu Pomery, the “Lumber King,” as the papers called him, who made his winter home at Santa Barbara. Nat, who lived with his mother, was, at that time, very poor, and much depended on his situation with the millionaire, in charge of his several cars. But Ed Dayton, who considered that Nat had superseded him in the place, made trouble for him. Aided by Donald Pomery, the lumber king’s son, a weak, unprincipled youth, he hatched up a plot, which, for a time, put Nat under a cloud. But Mr. Pomery himself proved Nat’s firm friend.

Owing to Mrs. Pomery’s interference, the millionaire was compelled to discharge Nat, but he almost immediately re-employed him on the confidential mission of which we have spoken. This was to visit Lower California and investigate conditions on his timber claims there. Much rare and valuable wood had been going astray, and Mr. Pomery suspected his superintendent, Diego Velasco. He lacked proof, however, and Nat he selected as a bright, trustworthy lad, who could carry out an investigation painstakingly.

Nat recalled that his dead father had been interested, in his youth, in a rich mine in Lower California, and the prospect of the trip, therefore, had a double fascination for him. Mr. Pomery provided an automobile, equipped in elaborate fashion, for the long trip, much of which was to be made through desert country. With Mr. Pomery’s permission, Nat invited his two chums, Joe Hartley, son of a well-to-do department store keeper, and William Bell, the stammering lad, to accompany him. The latter’s mother and the former’s father at first demurred considerably to the trip, but at last they gave their consent. Nat, for his part, had some trouble winning his mother over. But soon all was arranged, and they set out. How they discovered the Lost Mine, and Nat became rich, was all told in that book, together with many other adventures that befell them. The reader is now in a position to understand our chief characters, sturdy, intelligent Nat Trevor, with his curly black hair and dancing blue eyes; stout, red-faced Joe Hartley, always good-natured, though inclined to be a bit nervous, and Ding-dong Bell, the cheery, stuttering lad, whose eccentricities of speech provided much amusement for his companions.

The day on which this story opens was the seventh since their departure from the Marquesas on their return voyage to the Pacific Coast. They had left behind them their fellow adventurers, some of whom wished to return by steamer, while others were anxious to continue their travels in the fascinating South Seas. So far, smiling skies and sunny seas had been encountered. But this particular day had dawned with a smoky, red horizon, through which the rising sun blazed like a red-hot copper ball.

It had been oppressively hot—torrid, in fact. But although the air was motionless and heavy, the sea was far from being calm. It heaved with a swell that tossed the Nomad almost on her beam-ends at times. That some peculiar kind of tropical storm, or typhoon, was approaching, Nat felt small doubt. A glance at the barometer showed that that instrument had fallen with incredible rapidity. A candle, held in the thick, murky air, would have flamed straight skyward without a flicker.

Dinner was eaten without a change being observable in the weather conditions, and, on coming on deck to relieve Joe at the wheel while he went below to eat, Nat sighted the bit of land toward which they were now being drawn like a needle to a lodestone. In the meantime the weather had been growing more and more extraordinary. The copperish sky had deepened in color till a panoply of angry purple overspread the heaving sea. The sun glared weakly through the cloud curtains as through a fog. But still there had come no wind.

Hardly had the two lads on the bridge of the Nomad realized that they were inexorably being drawn toward the two islands, however, when from far off to the southwest there came a low, moaning sound. It seemed almost animal in character; like the lowing of an angry bull, in fact, was the comparison that occurred to Nat. The sound increased in violence momentarily, while the sky from purple changed to black, and a blast like that from an open oven door fanned their faces. Through this awe-inspiring twilight the Nomad continued her inexplicable advance toward the two islands.

“Here it comes!” shouted Joe suddenly, as, from the same quarter as that from which the wind had proceeded, there came a sudden, angry roar.

“Hold tight for your life!” flung back Nat over his shoulder, gripping his steering wheel with every ounce of strength he possessed.

And thus began hours of stress and turmoil, which the Motor Rangers were ever to remember as one of the most soul-racking experiences of their young lives.

“Wow! This is the worst ever!”

Joe was clinging tightly to the bridge of the Nomad.

Spray, flying like dust through the dense mid-afternoon twilight, stung his face. The wind whipped out his garments stiff, as if they had been made of metal, and half choked the words back down his throat.

Nat made no reply. He clung grimly to his wheel, striving with might and main to head the Nomad into the furious waves. Ding-dong Bell had emerged on deck an instant before, but had been promptly ordered below again.

“Keep your engines doused with oil; give them plenty of gasolene, and stand by for signals,” had been the young captain’s orders.

Below, beside his shining, laboring engines, Ding-dong was valorously striving to carry those orders out. But the strain on the motors was as great as they had ever been called upon to bear, even in the memorable encounter with the waterspouts.

Besides heading into the storm, Nat was “bucking” the strange current that set toward the island chasm. But powerfully as the Nomad’s propeller churned the driving seas, the unseen tide was more powerful still.

“Nat, we’re bound to be drawn into that gorge within a few minutes, unless——”

“Unless a miracle happens.”

Joe’s comment and Nat’s rejoinder were both shouted above the storm. Their voices sounded feeble as whispers amid the fury of the conflicting elements.

Hardly a hundred yards now separated the storm-battered Nomad from the towering walls and boiling waters of the chasm. Inevitably, unless the miracle of which Nat had spoken occurred, they must, in a few moments, be laboring in the midst of that ominous-looking place. While the thought was still pulsating through their minds, and their hearts beat high with apprehension, the dreaded thing happened.

The Nomad was suddenly caught, as if by hands bent on causing her dissolution, and hurtled straight into the cleft between the islands. Nat, hardly conscious of what he was about, directed her course so that the craft was not instantaneously dashed to bits against the side of the cliffs. Joe, too alarmed to utter a word, simply clung tight to the rail. Below, in the engine-room, Ding-dong Bell was thrown from his feet and smashed up against a steel stanchion.

The blow knocked him senseless. And so, with her engineer unconscious, another member of her crew almost useless from fright, and only one guiding spirit on board her, the Nomad hastened forward into what seemed certain annihilation.

Within the cleft it was black as night. The angry seas that boiled and gnashed between the steep walls, for an instant completely hid the Nomad from view. But presently she gallantly emerged, fighting like a live thing for her life.

The wind, compressed within those narrow confines, blew with a force and fury almost incredible except to those who have passed through a South Pacific storm. It would have been impossible to cry out and make one’s voice heard. The most powerful shout would not have been audible a foot away. The situation of the Motor Rangers appeared to be almost desperate.

“Can she last out? Can she possibly stand this terrific battering?”

Such were the thoughts that galloped through Nat’s excited brain. He rang the electric signal for “more power,” but no response came from the engine-room, where Ding-dong lay senseless beside his motors.

Then he turned about to look for Joe. Now that his eyes had grown used to the darkness it was possible to see—as one sees on a night when the moon is obscured by heavy clouds. The young captain’s heart leaped into his mouth as his eyes pierced the obscurity.

Except for himself, the bridge was empty of life.

Joe Hartley had vanished!

“Swept overboard!” shot through Nat’s brain.

At the same instant he caught a cry:

“Help! Help!”

It appeared to come from far astern.

“Joe!” shouted Nat into the darkness.

“Help!” came the cry again. It was closer this time.

A coil of light but strong rope was looped to the bridge in front of Nat. Without an instant’s hesitation, he tied one end of it about his waist. He had reached a desperate determination. If he got a chance, he had made up his mind to save Joe Hartley if it were humanly possible. The other end of the coil he knew was made fast to the bridge rail, so that a final testing of the knot about his waist was all that was necessary to put his daring scheme into execution. But first Nat fixed the wheel by means of the metal grips provided for that purpose.

Then, with every nerve a-quiver, every muscle flexed, he waited for another summons. Suddenly it came.

“Help, Nat! I——”

A smother of foam swept glimmering past the Nomad. It was luminous with phosphorescence. Amidst the greenish, ghastly glare, was plainly perceptible a darker spot. It was a human head.

“Hold on, Joe! I’ll be with you!” shouted Nat, and then, without hesitation, he mounted the bridge rail at the port side and plunged into the mass of spume.

Fortunately for those interested in the adventures of the Motor Rangers, at that instant a freak of the current spun Joe’s body about and flung him, like a bit of driftwood, toward the side of the Nomad. In a flash Nat’s strong arm was about him. It was just in time, too, for Joe, who had been swept from the bridge unseen when the Nomad encountered the angry maze of cross currents and tide rips, was almost exhausted.

In this condition he was not in full possession of his ordinary presence of mind. He clung to Nat desperately, with a grip that threatened to pull both rescuer and rescued under water together.

Nat, battling with the sharp, angry waves, as choppy and angular as giant fangs, had all he could do without struggling with Joe. Again and again he tried to break the other’s grip, but without avail. The hold of a drowning man or boy is the most tenacious known. It is almost impossible to loosen it.

“Joe, you must let go of me!” gasped out Nat.

But Joe only clung in a more leech-like fashion. What with the other lad’s dead weight clinging to him, and the conditions against which he was laboring, Nat, strong as he was, felt his strength being rapidly sapped.

Luckily, so intense had been the heat, the lads wore only light tropical trousers and sleeveless undershirts. Had they been incumbered with ordinary clothes, they could not have survived a quarter of the time that Nat and Joe did.

Nat began hauling in on his line, but with Joe gripping him so tightly, it was too much of a task.

“Joe, I hate to do it,” he said at length, “but I must, old fellow, I must!”

With these words, Nat did what he would have done with anybody else when first he realized the conditions. He struck Joe a blow on the head that completely robbed him of his senses. The lad’s vise-like grip relaxed. Under these circumstances, Nat could handle him easily.

By strong, rapid, over-hand motions, he hauled himself and his burden closer and closer to the side of the Nomad. At last they reached it. And now came the most difficult part of Nat’s enterprise. He had to get back on board, and, more than that, to get Joe there, too.

The Nomad was rolling and plunging till she was almost rail under at every roll. A sudden lurch of extra violence gave Nat his opportunity. It brought the bridge rail within reach of his free hand. He grasped it with a tenacious grip. But the next instant he was almost flung back into the sea again, as the little craft righted, and the lad, with his unconscious burden, was carried high above the boiling waters.

But Nat’s muscles had been trained to nickel steel suppleness and strength. He managed to hold on somehow, and the next roll to port of the Nomad gave him an opportunity to get one foot on the edge of the bridge. Thus he clung till the next wild roll in the opposite direction was over.

Then exerting a reserve force he had never before had occasion to bring into play, the young captain drew up Joe’s limp form and bundled it bodily within the bridge railings. This done, he clambered over himself. But he felt queer and dizzy. He could hardly keep his feet, even though he hung on to the rail. His head spun like a teetotum.

“I—why, what’s the matter with me? I—I believe I’m going to——”

Nat did not conclude his sentence in words. Instead, he enacted it by giving a crazy plunge backward and collapsing in a heap, almost alongside the unconscious Joe.

Nat sat upright with a strange singing sound in his ears. It was insufferably hot. He fairly panted as he opened his eyes. The sweat ran off him in rivulets. For an instant recollection paused, and then rushed back in an overwhelming flood.

“We were in that channel between those two queer islands,” mused Nat; “and we—gracious, where are the islands?”

He had staggered dizzily to his feet and was looking about him. He knew he could not have lain senseless very long, for his garments were still wet, despite the intense heat. But the islands were nowhere to be seen.

It was still partially dark, a murky twilight replacing the former deeper blackness. But an indefinable change had taken place, somehow, in the atmosphere. Nat drew in his breath with difficulty. It seemed to scorch his lungs.

He glanced over the side of the craft and then drew back with an alarmed cry. The water all about them was bubbling and eddying furiously. A shower of spray from one of the miniature waterspouts struck Nat in the face. It was this that caused his exclamation and made him step back hastily, just as if, in fact, he had been struck a blow in the face.

The water was boiling hot!

Where it had spattered on the lad’s skin it had instantly raised blisters.

“Well, we certainly have landed in a surprising sort of fix this time,” muttered Nat to himself.

He bent over Joe. The lad had not yet regained his senses. But he was breathing heavily, and this stilled a dreaded fear, which, for a moment had almost caused Nat’s heart to stop beating.

“This air is suffocating,” gasped Nat presently. “It smells like it does when they are fumigating a room.”

He ran his tongue around his dry mouth in an effort to moisten it, for it felt parched and cracked. The reek of sulphur in the air, too, caused his throat to contract and his nose and eyes to tingle unmercifully.

But this stench also told Nat something. It furnished him with a partial explanation of the extraordinary occurrences that, as it seemed, were not yet over.

“This whole disturbance is volcanic,” reasoned the boy. “That is the cause of this awful sulphur smell. But that doesn’t account altogether for the sudden disappearance of those islands. I wonder——” But here he broke off his meditations.

Joe was plainly in need of immediate attention, and Nat devoted his efforts to trying to raise the recumbent lad. He wanted to get him below to the cabin, where there was a well-stocked medicine chest and a supply of reasonably cool water.

But, weakened as he was, Nat couldn’t accomplish the task.

“What’s the matter with me, anyhow?” he asked himself half angrily. “This sulphur stuff must have knocked all my senses out of my head. Where’s Ding-dong, I wonder?”

He rang the engine-room call sharply. But there was no response. No Ding-dong appeared.

“Maybe the signal is out of whack,” muttered Nat, who had noticed some time before that the engine had stopped running. “Guess I’ll go below and see what’s the matter.”

It was the work of an instant to reach the hatchway leading below, and dive into the engine room. What met Nat’s eyes there made him jump almost as violently as he had when the boiling water struck him.

“Great Scott!” he exclaimed, as his gaze fell on the unconscious engineer, “if this isn’t worse and more of it. Poor Ding-dong is knocked out, too; cut on the head. It doesn’t seem to be a bad gash, but it has deprived him of his senses. Well, if this isn’t a fine kettle of fish! In the midst of a boiling sea with two unconscious chaps on my hands!”

Ding-dong stirred and moved uneasily as Nat examined his wound.

“Let me be!” he muttered peevishly; “lemme be.”

“That’s just what I’m not going to do,” rejoined Nat cheerfully.

On the wall of the engine room was a tap leading from the drinking water tanks of the craft. Nat saturated his handkerchief under this faucet and bathed Ding-dong’s wound. Then he applied the water plentifully to the lad’s face, and, opening his shirt, doused him with it.

Under this treatment, the unconscious lad sat up and opened his eyes.

“Hullo, Nat!” he exclaimed, like one awakening from a long sleep. “What’s up? What on earth has happened? Where are we? What makes it so hot?”

As usual, under strong excitement, Ding-dong forgot to stutter, as Joe termed it.

“I can only answer two of your questions,” replied Nat. “‘What’s up’ is that poor Joe is lying senseless on the bridge. He was washed overboard in that chasm. You’ve got to try to help me get him to the cabin. ‘What on earth has happened,’ is this: We have, apparently, passed through the chasm, and the islands have vanished in some mysterious fashion, although we can’t be far from where they were. The sea all about us is boiling hot, and I guess we are in the very core of some strange volcanic disturbance or other.”

“Cc-c-c-crickets!” sputtered Ding-dong, rising dizzily but pluckily to his feet, “we do seem to run into some mighty queer adventures, don’t we? Come on. I’ll give you a hand with poor old Joe. But, by the way, what have you been doing all this time?”

“Oh, I-I-guess I went to sleep for a while, too,” responded Nat, rather confusedly, and without mentioning his heroic rescue of Joe from the waters of the rift.

He was spared answering further questions, for it required their united strength to carry Joe to the cabin. Ordinarily, this would not have been so, but the heat was so terrific that it had sapped the strength of both boys till they had but half of their accustomed energy and vim.

Joe was laid on a locker and restoratives applied. Presently he was able to sit up, and then out came the story of Nat’s rescue. The lad colored brilliantly as Joe and Ding-dong both poured out their praise unstintedly.

“But, say,” exclaimed Joe, rubbing his head and looking suddenly bewildered, “I’ve got an awful bump here. I guess I must have hit my head before your brave——”

“I hit it for you to keep you quiet,” burst out Nat; “and if you don’t shut up now, I’ll bust it again.”

Going on deck, the three lads found that it had grown lighter. But the water still boiled about them furiously. Clouds of sulphurous steam arose from it, making them cough and choke.

In the brighter light they had quite an extensive view of their surroundings. But, of the islands, not a trace appeared. They had vanished as if they had been the fabric of a dream.

“By George! I have it!” cried Joe suddenly. “Those islands were of volcanic origin. Didn’t you notice how bare and bleak they were? I’ll bet that in this disturbance, whatever it is, they have subsided as suddenly as they arose.”

“Such cases are not uncommon,” rejoined Nat. “Only last year, Captain Rose, of the missionary schooner Galilee, of San Francisco, reported seeing an island of some extent arise and then vanish again before his very eyes.”

“W-w-w-well,” sputtered Ding-dong, with a grin and a return to his old manner, “w-w-w-we can r-r-r-report the same thing; but as t-t-this isn’t a go-go-gospel schooner maybe nobody w-w-w-will believe us.”

“My suggestion is, that we get the engines going and get out of this without delay,” said Nat.

“Here, too,” agreed Joe Hartley. “There’s nothing to hang about here for.”

An examination of the engines showed that, in falling, Ding-dong had shut off the gasolene supply valve, and had thus stopped the motors. This was soon remedied and the motors set going again. As the Nomad cut her way through the boiling sea where lately the twin islands had stood, they all felt like raising a fervent prayer of thanks to Providence for their wonderful deliverance.

“I’ve often heard of such things on the Pacific, but I never expected to live through one,” was Nat’s comment.

“Nor I,” was Joe’s rejoinder; “and I don’t know that I should care to repeat the experience. But hullo!” he broke off suddenly, “what’s that? No, not over there; off this way!”

He pointed excitedly to a small black object, which, in the now clear atmosphere, was visible at the distance of about a mile to the southeast of them.

“It’s a boat,” announced Nat, after a brief scrutiny of the strange object.

“So it is. What on earth can it be doing out here? Wait a jiffy, I’ll go below and get the glasses.”

Joe, now fully recovered, dived into the after cabin and soon reappeared with a pair of powerful binoculars.

Nat focused them on the distant object, which, by this time, was visible, even to the naked eye, and reported it to be a small boat, painted white, and looking like a ship’s dinghy, or small lifeboat.

Excitement ran high on board the Nomad when Nat proclaimed that he was almost certain he had seen an arm wave from the small craft.

“I couldn’t be quite sure, though,” he admitted. “Here, Joe, you take a look.”

The chubby-faced Joe now bent the glasses on the object of their scrutiny.

He gazed intently for a minute, and then uttered a shout.

“By ginger, Nat, you’re right!” he exclaimed. “There is someone on board. There must be something the matter with them, though, for they seem to be collapsed in a kind of bundle on the thwarts.”

“We must make all speed to their aid,” said Nat, signaling for more power. “Poor fellows, if they have been adrift in all that flare-up, they must be about dead.”

“I should say so,” agreed Joe.

As they neared the boat, Nat began blowing long blasts on the electric whistle, to let the occupants know that aid was at hand. In response, a figure upreared itself in the drifting craft, waved feebly once or twice, and then subsided in a limp-looking heap.

“I reckon we’re only just about in time,” said Nat grimly, coaxing another knot out of the Nomad.

As they drew alongside the boat, they saw that not one but two persons occupied it. The one who had signaled them from a distance proved to be a short, stocky little man, with a crop of brilliant red hair and a pair of twinkling blue eyes. The merry flash in those optics had not been dulled, even by the terrible ordeal through which, it was apparent, he and his companion had passed.

“Hullo, shipmates! Glad to see you!” he chirruped, grinning up at the boys on the bridge with a look of intense good humor.

His white duck clothes were scorched, and his rubicund hair, on close inspection, proved to be singed, but nothing appeared capable of downing his amiability.

His companion was of a different character entirely. He was dressed in duck trousers and black alpaca coat. White canvas shoes adorned his extremely large feet. But it was his face that attracted the boys’ attention. It was large, round and learned looking, with a thin-lipped mouth cutting the lower part of it like a gash. Above this, a huge, bony nose protruded, across which was perched a pair of big, horn-rimmed spectacles. A crop of sparse gray locks crowned his high forehead and was scattered sparingly over his large, but well-shaped head, which was bare.

“God bless my soul, George Washington Tubbs, but I’ve lost my hat again!” he exclaimed to his companion, as the Nomad drew alongside.

“We’d have lost more than that, I fancy, if it hadn’t been for this here craft,” observed George Washington Tubbs, with a wink at the boys. “We’d have been a pair of buckwheat cakes, well browned, professor, when they found us.”

“I wish I could find my hat,” muttered the spectacled individual in a contemplative tone, peering about under the seats.

“It was blown off when the island busted up,” rejoined Mr. Tubbs. “But we’re keeping these gentlemen waiting. I presume,” he went on, addressing the boys, “that it is your intention to rescue us?”

Nat could hardly keep from laughing. His first impression was that they had encountered a pair of harmless lunatics. But something in the manner of both men precluded this idea almost as soon as it was formed.

“Won’t you come aboard?” he said politely.

It seemed as inadequate a remark as Stanley’s famous one to Livingston in the wilds of Africa; but, for the life of him, Nat couldn’t have found other words.

“Thanks; yes, we will,” responded Mr. Tubbs, with decisive briskness. “Oh, by the way! Don’t move! Don’t stir! Just as you are, till I tell you!”

Nat’s suspicions of lunacy began to revive.

Mr. Tubbs bent swiftly, and picked up what looked like a large camera from the bottom of the boat. Only it was unlike any camera the boys had ever seen. It was a varnished wooden box, with a big handle at the side. Mr. Tubbs gravely set it up on its tripod and began turning the handle rapidly.

“Now, you can move about! Let’s get action now!” he shouted, waving his free hand.

“This will be a dandy film!” he continued, addressing the world at large. “Gallant rescue of Professor Thaddeus Grigg and an obscure individual named Tubbs, following the disappearance of the volcanic isles.”

In good-natured acquiescence to Mr. Tubbs’ orders, the boys began bustling about. Ding-dong Bell, who had come on deck when he got the signal to stop his engines, was particularly active.

“Now, then, professor,” admonished Mr. Tubbs, “up with you.”

“Without my hat?” moaned the professor; but he nevertheless clambered over the side of the Nomad, the boys helping him, while Mr. Tubbs kept up a running fire of directions.

“Keep in the picture, please. Look around now, professor. Fine! Good! Great!”

These last exclamations came like a series of pistol shots, and seemingly proclaimed that the speaker was well satisfied with the pictures he had made. The professor being on board, Mr. Tubbs followed him, the boys helping him up with his machine, and with a box which, so he informed them, contained extra films.

Professor Grigg, as the red-headed, moving-picture man had called him, was too much exhausted to remain on deck, but retired to the cabin escorted by Ding-dong. As he went he was still murmuring lamentations over his hat.

“It’s his weakness,” explained Mr. Tubbs, who seemed to be in no wise the worse for his experience, “he’s lost ten hats since we left ’Frisco in the Tropic Bird.”

The name instantly recalled to Nat an item he had read in the papers some months before, concerning the setting forth on a mysterious expedition of Professor Grigg of the Smithsonian Institute and one George Washington Tubbs, a moving-picture photographer of some fame. The object of the expedition had been kept a secret, and the newspapermen could elicit no information concerning it. It had been rumored, however, that its purpose was to record the volcanic phenomena of the South Pacific.

“Is—is that the Professor Grigg?” asked Nat, in rather an awestruck tone.

“It is,” responded Mr. Tubbs, “and this is the Mr. Tubbs. I’ve taken moving pictures of the Russo-Japanese war, of the coronation, of the Delhi Durbar, of the fleet on battle practice, of—of everything, in fact. I’ve been up in balloons, down in submarines, sat on the cowcatchers of locomotives, in the seats of racing automobiles, hung by my eyebrows from the steel work of new skyscrapers; but I’ll be jiggered if this isn’t the first time I ever took a moving picture of an island being swallowed up alive—oh, just like you’d swallow an oyster.”

“Then the island was swallowed?” asked Joe, with wide-open eyes.

“Swallowed? I should say so. And with a dose of boiling water, too. But I got my pictures! I got my pictures!” concluded Mr. Tubbs triumphantly.

“But where’s your schooner? How did you come to be drifting about in an open boat?” inquired Nat.

“Ah, as Mr. Kipling says, ‘that’s another story,’” said Mr. Tubbs. “I guess I’ll have to leave that part of it to the professor. But—hullo, here he comes now. I guess he’s feeling better already. Possibly he’ll tell you the story for himself.”

“I shall be very glad to,” said the professor, who, after partaking of some stimulants from the Nomad’s medicine chest, already felt, as he said, “much revived.”

“You see in us, young men,” he continued, “the sole members of the volcanic phenomena expedition of the Smithsonian Institute and the British Royal Geographical Society, who adhered to the duty before them. Would you care to hear how we came to be adrift as you found us?”

“Would we?” came in concert from the boys.

“Then I——” began the professor, and then broke off and felt his bare head. “Can—can any one lend me a hat?” he asked.

He was speedily furnished with a peaked yachting cap belonging to Nat. It sat oddly, almost comically, on his large head, but none of the boys was inclined to laugh at the professor just then. They were far too interested in hearing what the eccentric man had to tell about the voyage of the Tropic Bird.

“We sailed from San Francisco, as you no doubt know from the papers,” said the professor, “without the object of our mission being divulged. There is no harm in telling it now.

“It had been ascertained that a certain phase of the sun spots would be reached on this present day. As you are perhaps aware, it has long been a theory of scientific men that there was some intimate relation between that phenomenon and the volcanic disturbances and earthquakes that occur in these seas from time to time.”

“I think that we learned something like that in physics,” said Nat, nodding.

“In physic?” chuckled Joe, but was frowned down.

The professor went on:

“It was my duty, assigned to me by the Smithsonian Institute and the British Royal Geographical Society, working in concert, to investigate such a disturbance and make elaborate reports thereon. At my suggestion, it was also decided to engage a moving-picture operator to take photos of the whole scene, which must prove of inestimable benefit to scientific knowledge. The Tropic Bird was chartered to convey the expedition, and Mr. Tubbs was placed under contract to take the pictorial record of the scene, if we were fortunate enough to encounter one.

“We cruised about for some time, awaiting the exact condition of the sun spots which would indicate that a phenomenon of the kind I was in search of was about to be demonstrated. Some days ago my observations showed me that the desired condition was at hand. As fortune would have it, on that very day we sighted these islands—or rather those islands, for they have completely vanished as I predicted they would.

“We landed, and found the islands to be of distinctly volcanic origin, and, seemingly, of recent formation. At any rate, they are not charted.”

Nat nodded.

“Of course there was no trace of habitation. But a few creepers and shrubs of rapid growth had taken root in the clefts of the lava-like rock, of which the islands were composed. I saw at once that it was here, if anywhere, that a seismic disturbance would result, in all probability, providing the conditions were favorable. That night, on our return to the ship, the captain of it waited on me.

“After much beating about the bush, he informed me that his crew was aware of my belief that the islands would be the center of a volcanic disturbance, and that they refused to remain in the vicinity. He denied being alarmed himself, however. I succeeded in calming the crew’s fears, and we remained at anchor off the islands for some days. At last, signs of the storm which broke to-day began to make themselves manifest on my instruments. I realized that the great moment was at hand.

“I warned Mr. Tubbs, here—a most valuable assistant—to be ready at any moment. I was confident that with the breaking of the storm the islands would vanish. But nothing was said to the crew. Quite early to-day Mr. Tubbs and I embarked in that small boat and lay off the islands. I was certain that the storm would be magnetic in character, and would break with great fury.”

“However did your boat live through it?” asked Nat.

“She is fitted with air chambers, and specially built to weather any storm,” was the reply. “But to resume: The cowardly captain, when he saw the storm coming up, sounded a signal for us to return on board. When we did not, he hoisted sail and made off, leaving us to our fate. The storm broke, and there was a spectacle of appalling magnificence. Mr. Tubbs behaved with the greatest heroism throughout.”

Here Mr. Tubbs blushed as red as his own hair, and waved a deprecatory hand.

“I guess it was watching you kept me from feeling scared,” he declared, addressing the professor; “but anyhow, I got my pictures.”

“We have some faint idea of what the storm was,” put in Nat; “but can you explain something to us?” and he described to the professor the manner in which the Nomad had been drawn toward the volcanic islands.

“Pure magnetism,” declared the scientist, “a common feature of such storms.”

“But our craft is of wood,” declared Nat.

“Yes, but your engines, being metallic, of course, overcame that resistance. You are fortunate, indeed, not to have been drawn down when the islands vanished. It was a terrific sight.”

Nat explained that during that period they were all unconscious and then went on to tell of the experiences through which they had passed.

“Oh, why wasn’t I on board your craft?” moaned Mr. Tubbs, as he concluded. “What a picture that chasm would have made! It’s the opportunity of a lifetime gone.”

The boys could hardly keep from smiling over his enthusiasm; but Nat struck in with:

“It’s an opportunity I don’t want to encounter again,” an opinion with which everybody but Mr. Tubbs—even the professor—concurred.

“And now,” said the man of science suddenly, “I don’t wish to alarm you, young men, but it is possible that there may be some reflex action exerted by this storm. In other words, there may be a mild recurrence of it. In my opinion we had better get as far away from this spot as possible.”

The others agreed with him. Ding-dong dived below to his engines. Nat took his station on the bridge.

“By the way, what about the boat?” asked Nat suddenly, referring to the craft from which they had rescued the scientist and his assistant.

“Unless you want it, we will let it drift,” said the professor. “It is too large for you to hoist conveniently, and it would impede your speed if you towed it.”

And so it was arranged to leave the boat behind, but Mr. Tubbs took a series of pictures of it as the Nomad sped away. The professor also waved the craft, in which they had weathered so much, a farewell. But, when doing so, in some manner the peak of his borrowed cap slipped from between his fingers. The headpiece went whirling overboard, and fell into the sea with a splash.

“God bless my soul, I’ve lost my hat!” he exclaimed for the second time that day, as the catastrophe happened.

“He’ll use up every hat on board. You see if he don’t,” confided Mr. Tubbs to Nat, while the professor gazed fondly at the spot where the cap had vanished.

After breakfast the next morning, the professor appeared on the bridge with Nat when the latter took his daily observation, a practice which was, of course, in addition to the regular “shooting the sun,” which took place at noon. The man of science had already made a deep impression on the lad. He was eccentric to a degree; but in common with many men of ability, this was a characteristic that in no way appeared to affect his scientific ability. The evening before he had entertained all hands with fascinating tales of his experiences in various parts of the world. Already everybody felt the same respect for Professor Grigg as was manifest in the manner of the irrepressible Tubbs.

Nat operated his instruments and then noted the result on a pad, to be entered later in the log book. The professor peered over his shoulder as he jotted down his figures.

“Pardon me,” he observed, “but you are a hundredth part of a degree out of the way on that last observation.”

For an instant Nat felt nettled. He colored up and faced round on the scientist. But Professor Grigg’s bland look disarmed him.

“Is that so, professor?” he asked. “How is that?”

“Let me test your instruments,” was the reply. “It is impossible to tell without that.”

Nat handed the various instruments over to his learned companion. The professor scrutinized them narrowly.

“I think,” he said finally, “that the magnetic influences of yesterday’s storm have deflected all of them.”

“Of course,” agreed Nat. “How stupid of me not to have thought of that! Is it possible to adjust them?”

“I will try to do so,” said Professor Grigg, and, placing a sextant to his eye, he began twisting and adjusting a small set screw.

Several times he lowered the instrument, and, taking out a fountain pen and a loose-leaf notebook, wrote down his readings. Nat watched him with some fascination. There is always a pleasure to a clever lad in watching a man doing something which he is perfectly competent to do. The professor, the instant he laid his hands on the instruments, impressed Nat as possessing the latter quality to a degree.

“Just as I thought,” said the professor finally, “your instruments have been deflected. But we will set them right at noon. A few simple adjustments, that is all. But I find that you have kept them in wonderful shape, considering your rough and trying experiences.”

“We have always tried to,” said Nat. “We knew how much depended on them.”

“And yet,” mused the professor, with his eyes fixed intently on Nat, as the lad stood at the wheel, “without the ability to understand them, those instruments would be worthless. Conradini, the Italian explorer, learned that.”

“At the expense of his life,” put in Nat. “The lesson was lost.”

“Ah, you have heard of Conradini?” asked the professor, in seeming surprise.

“I have read of him in that pamphlet on aerial exploration issued by the Italian Royal Society,” was the reply.

The professor readjusted his glasses. In his astonishment, he almost lost his latest piece of headgear—loaned him by Ding-dong. It was a not too reputable-looking Scotch tam o’shanter.

“You have a knowledge that surprises me in one so young,” he declared at last. “You take an interest in exploration, then?”

“That was the object of the Motor Rangers, when first we founded them,” declared Nat. “I think,” he added, with a twinkle in his eye, “that we’ve had our fair share of adventure.”

“From what you have told me of your enterprises, I agree with you,” assented the professor warmly. “But you have not told me yet of the future.”

“How do you mean?” asked Nat.

“I mean, what plans have you ahead of you? What do you intend to do next?”

The question came bluntly. Nat answered it with equal frankness.

“I really don’t know,” he said. “As you are aware, though, our course is now laid for Santa Barbara.”

“So you said last night, when you kindly offered us a passage home,” said the professor.

He paused for an instant, and Nat swung the Nomad’s bow around a trifle more to the south.

“Have you no plans for further adventurous cruises or auto trips?” pursued the man of science.

Nat laughed.

“I guess we’ve had our fill of adventure for a time,” he said; “that cleft between the volcanic islands nearly proved our Waterloo.”

“Nonsense; such lads as you could not live without adventure,” admonished the professor, making a frantic grab at his hat, as a vagrant wind gave it a puff that set it rakishly sidewise above one ear. “Do you mean to say that you feel like settling down to humdrum life now, after all you have seen and endured?”

“I guess we all feel like taking a rest,” said Nat. “We have had a fairly strenuous time of it lately.”

“Granted. But it has put you into condition to weather further times of stress and trial. Ever since we had that talk last night about the Motor Rangers, and what they have accomplished, it has been in my mind to broach a proposition to you.”

“To us?” temporized Nat. “I don’t see where we could be of any use to Professor Thaddeus Grigg, the most noted scientist of investigation of this age.”

The professor raised a deprecatory hand.

“As if you had not been of the highest service to me and to my companion already,” he exclaimed. “Had it not been for you, we might have—oh, well, let us not talk about it. That coward of a captain——”

He broke off abruptly. Nat waited for him to resume speaking.

“What I wanted to approach you about was this,” resumed the professor, after a minute. “From the moment I met you, you appeared to me to be self-reliant, enterprising boys, who mixed coolness and common sense with courage. Such being the case, you are just the combination I have been seeking for, to carry out a project which awaits me on my return to America. It is a scheme involving danger, excitement and rich rewards.”

He paused impressively. In spite of himself, Nat’s eyes began to dance, his pulse to beat a bit faster. Adventure was as the breath of life to the young leader of the Motor Rangers, and, to tell the truth, he had faced the prospect of a life of inactivity with mixed feelings.

“Well, sir?” was all he said, however.

The scientist continued, with apparent irrelevance.

“You three lads, from what you have told me, have operated motor cars, motor boats, and endured much in both forms of transportation?” he asked.

Nat nodded.

“I guess we’ve had our share of the rough along with the smooth,” he said briefly, but he was listening closely.

“What would you say to trying a voyage in the air?” was the question that the man of science suddenly launched at him without the slightest warning.

Nat glanced up from his steering amazed. The scientist met the lad’s gaze firmly.

“Well?” he demanded.

“I—I—upon my word, I don’t know,” stammered Nat.

For once in his life, the young leader of the Motor Rangers was fairly taken aback.

“I am perfectly serious,” resumed Professor Grigg solemnly.

“The idea was such a new one that I admit it staggered me a bit,” explained Nat hastily.

“Suppose you summon your friends, and I will explain in more detail,” rejoined the professor.

Joe, who was polishing up the brass work and putting things to rights generally on the storm-battered craft, was nothing loath to obey Nat’s summons to the bridge. Ding-dong Bell announced that his engines were in good running order and could be left to themselves for a time. So it was not long before they all, including Mr. Tubbs, were grouped in interested attitudes about the man of science.

“As Mr. Tubbs knows,” said the professor, “it was our original plan to resume our voyage on the Tropic Bird, following our observations and picture making at the volcanic islands. Our destination was to be the coast of Chile. From there we were to go in search of a lost Inca city, which is described in documents recently discovered.”

“G-g-g-g-g-gee wer-w-w-w-whiz!” sputtered Ding-dong.

“Hush!” admonished Nat, who could hardly attend to his steering for interest. As for Joe Hartley, his eyes fairly bulged in his head.

“A lost Inca city,” he murmured. “Sounds good to me.”

“Is nothing known of the location of the place?” inquired Nat.

“Not except in a general way,” was the reply. “It is known to be situated on an island in the midst of a lake high up on an Andean plateau in Bolivia.”

“Like the one on Lake Titicaca in Peru,” said Nat.

“Ah, you have read of that?” said the professor approvingly. “Yes, from the documents which came into the possession of the institute as the gift of a traveler in Chile, it is probable that the ruins which I am commissioned to search for are very similar in character to those you have mentioned.”

“How are they to be reached?” asked Joe.

The professor smiled.

“From what we have been able to learn,” he said, “earthquakes have destroyed the roads formerly used, and there is no way of reaching the lake by land——”

“Then—then——” stammered Ding-dong helplessly.

“One must fly to them,” said the professor as calmly as if he were in a class-room. “Thanks to modern science, I believe it may be possible at last to obtain pictures and priceless relics of that forgotten civilization.”

“But where are you going to get an airship?” asked Nat, when he had recovered his breath.

As for Joe and Ding-dong, they regarded the professor in silent amazement. Mr. George Washington Tubbs merely grinned. Clearly, the idea was no startling novelty to him.

“That has been arranged for,” rejoined the professor. “A dirigible balloon of the most modern type is already at Santa Rosa, a small town on the Chilian coast. Before leaving the States, I took some lessons in operating such a craft; but really, that was hardly necessary, as Mr. Tubbs is a fairly expert operator of dirigibles, and has a knowledge of their construction and machinery.”

“Then all that you will have to do, when you reach this town, is to get the dirigible ready and then start the search for the lost city?” inquired Nat eagerly.

“That is all. It should not take long, either. The machine is packed in numbered sections. For security it has been labeled ‘Merchandise,’ and is in charge of the American consular agent, who alone knows what the boxes really contain.”

“Excuse me for saying so,” stuttered Joe; “but it sounds like—like a wonderful fairy tale.”

“It is one,” said the professor smilingly, “a fairy tale which, with the aid of you boys, I hope to make true.”

“With our assistance?” echoed Nat in an astonished tone.

“Yes. I really believe that it was Providence that threw me in the path of you boys. You are exactly the type of self-reliant, clever young Americans that I need for assistants in the work. Are you willing to charter the Nomad to me, land me on the South American coast, instead of in California, and give me your services, for a substantial compensation?”

“I—I beg your pardon,” Nat managed to choke out, “but the idea is so entirely new to us that I think we shall have to hold a consultation first.”

“Take your time,” said the professor airily; “take your time. It is characteristic of me to arrive at quick decisions, as Mr. Tubbs knows, and I don’t mind telling you that I shall be very disappointed if you don’t see your way to accommodate me. We are now almost on a straight course for the coast of South America. If, on the other hand, we landed in Santa Barbara, I should have to take steamer from San Francisco to South America, and I might arrive too late.”

“Why?” demanded Nat. “Is there any one else in search of the lost city?”

“My colleagues fear so,” was the rejoinder. “The documents passed through many hands before they reached scientific ones, and the treasures of the lost city, if they come up to all accounts, are enough to tempt any one to search for them for their intrinsic value alone.”

“Have you any idea who the men are who may prove your rivals?” asked Nat.

“I have—yes. But I do not wish to discuss that phase of the matter any more just now. Suppose you and your friends hold your consultation and then notify me of its result?”

“Very well,” agreed Nat.

Leaving the wheel in charge of the rubicund-headed Mr. Tubbs, who was a capable steersman—indeed, there didn’t seem to be much he couldn’t do—the boys withdrew to Ding-dong’s domain—to wit, the engine room.

They were below for about fifteen minutes.

When they reappeared, Nat’s face bore a radiant expression. He walked straight up to the scientist, who was gazing at the sea with an abstracted look as he studied the various forms of life that were visible in the clear water.

“Well?” he asked, facing around, clearly anxious for “the verdict.”

“Well,” repeated Nat with a smile, which was strangely at variance with his words, “I regret to report that we cannot undertake the commission you proposed——”

“What! You cannot? But I——”

“That is,” continued Nat, “for any compensation. But we will agree to land you and your companion at the port you desire, and further than that, we will, from that time, place ourselves under your orders in the hunt for the lost city.”

As Nat spoke these words, the dignified man of science actually capered about, and snapped his bony fingers in huge delight.

As for Mr. Tubbs, he gave a wild “Hurr-oo!” of delight.

“Hurrah for the Grigg’s expedition!” he cried.

“Three cheers!” ordered Nat, and they were given with a will. The echoes were still ringing out, when Nat gave a sharp exclamation, and pointed to the eastward.

“A strange sail!” he cried, as they all turned eager eyes on the distant speck of canvas.

“Why! why, that’s the Tropic Bird!” exclaimed the scientist in astonishment, as they drew nearer rapidly to the vessel Nat’s keen eyes had espied.

“It is, indeed,” reiterated Mr. Tubbs, his red hair seeming to bristle. “Oh, the cowardly pack of rascals! I’d just like to run alongside and give them a bit of my mind.”

“They deserve it, certainly,” admitted the professor; “but I think we had better ignore them.”

But as they came close enough to the schooner to perceive her clearly, they saw that she carried her ensign reversed. This is a signal of distress which there is no ignoring at sea, and is the universal sign of imperative need on the part of the craft displaying it.

“We must see what they want,” declared Nat, setting his wheel over and changing the course of the Motor Rangers’ vessel.

“Got any fresh water?” hailed a voice, as they came alongside.

The man who uttered the appeal was a powerfully built fellow, with a plentiful crop of black whiskers, which gave him a ferocious expression.

“That’s Captain Ralph Lawless,” whispered the professor to Nat.

At the same instant, the skipper of the Tropic Bird appeared to recognize the professor.

“Why, surely that’s Professor Grigg?” he cried out, apparently in great astonishment.

“Yes, it is, you cowardly rascal,” burst out the professor, his anger overmastering his usually placid disposition. “What do you mean by deserting us in the manner you did? We might have perished if it had not been for these brave lads and their vessel.”

“Well, I’m sorry,” muttered the man, as the Motor Rangers’ vessel drew in close alongside, “but I couldn’t help myself.”

“Couldn’t help yourself?” echoed the scientist, still angry. “How was that, pray?”

“Why, I felt my schooner being drawn in toward the islands. If I hadn’t ‘cut stick’ when I did, we’d all have been lost, and I don’t see how that would have helped you.”

This answer mollified the professor somewhat.

“So now you are in distress?” he said.

“Yes. We have run short of water. Can’t those kids let us have some?”

“You’ll have to ask ‘those kids,’ as you call them,” said the professor, with some disgust.

“How much do you want?” asked Nat, who felt less and less liking for the captain of the Tropic Bird.

“Oh, a few gallons will do. I know an island not more than a day’s sail from here, where I can refill my tanks.”

At this point, another man—a short, stout fellow, like the captain—came bustling up.

“Hullo, there, professor!” he hailed in an impudent voice. “So you came out all right, after all. Are you coming on board?”

“I am coming on board to get my things, Mr. Durkee,” was the response, “but I am not going to continue my voyage on the Tropic Bird.”

The captain looked rather dismayed at this.

“Oh, come now,” he said, “let bygones be bygones. I should be in a fine fix if I sailed home without you.”

“You ought to have thought of that when you deserted us in that cowardly fashion during the magnetic storm,” rejoined the professor.

The deck of the Nomad was almost on a level with the top of the schooner’s bulwarks, so it was easy for the professor to step from one craft to the other. He now did so, disdaining the proffered aid of Captain Lawless and his mate.

Mr. Tubbs joined him, and the two went immediately into the after-cabin of the schooner, where they had lived while on board.

While they were collecting their belongings, Nat and Joe filled a twenty-gallon keg with drinking water, and it was hoisted to the schooner’s deck. It was really more than they could spare, but Nat was a generous lad, and figured that, if necessary, they could go on short allowance till the South American coast was reached.

During the time that the boys were about this work, Captain Lawless and his mate had been holding a consultation in the lee of the deckhouse, just aft of the foremast.

“It’s going to make lots of trouble for us if we arrive in America without the professor or that chap Tubbs,” said the mate. “Besides that, too, we’ll have lost our chance of sharing in that hunt for a lost city. There ought to be enough loot in that to make us both rich.”

“That’s so,” agreed the captain. “If what those papers of the professor’s say is right, that place must be paved with gold, and when it rains it must drop diamonds.”

“Pretty near,” grinned the mate, in appreciation of his superior officer’s humor. “I wish I’d had time to go over the papers more thoroughly before that kid’s craft overhauled us. That was a good guess of yours that they’d pick up the old gent and that chap Tubbs, and the reversed ensign was a good way to get ’em to come alongside.”

“Well, now that we’ve gone this far, we may as well take the next step,” observed the captain.

“And what’s that?” asked the mate, with a peculiar glint coming into his little rat-like eyes.

“Why, fix it so that it won’t be possible for old Grigg to make trouble for us in the States.”

“How?”

“Simple enough. We can easily overpower those kids, and as for the professor and Tubbs, we’ll lock ’em in the cabin.”

“Say, cap, you are a schemer!” observed the mate, in rather sarcastic admiration, “and then I suppose we’ll sail for home and be arrested and imprisoned as pirates?”

“Not at all,” was the reply. “We don’t need to go home. South America’s good enough for me. It’s Chile that the old cove is headed for, ain’t it?”

“So his papers said.”

“All right, then. We’ll make the whole bunch prisoners, land ’em on an island some place, and then we’ll sail on to Chile ourselves, and have a try at finding this old lost city. By the way, did you make a tracing of that map you found in the professor’s desk?”

“Did I? Well, I should say so. I’ve got it in my pocketbook now. That’s likely to mean dollars and cents to us later on.”

“That’s so. Now then, you go and tell the crew what we are going to do. They won’t cut up rough about it, especially if they think there is money in it.”

“All right. I’m off. But see here, how are you going to do it? Those kids look pretty husky.”

“Bah! What can they do against eight of us? If they get too obstreperous, a tap on the head with a marlin-spike will soon quiet them.”

While the two worthies of the schooner were cold-bloodedly discussing their plans to save themselves from the consequences of their cowardly act and at the same time enrich themselves, Nat and Joe, blissfully ignorant of any such proceedings, had hoisted the water keg on board.

This done, they started aft toward the cabin to join the professor and Mr. Tubbs. They found the two companions below, busily packing up their possessions. But at the instant they entered, the professor looked up from his desk, where he was sorting papers, with a troubled expression.

“What is the matter, professor?” inquired Nat politely.

“Somebody has been tampering with my papers!” he exclaimed. “I had them arranged in a peculiar manner. And see, this lock has been forced. Oh, that rascal of a captain! If we were in a civilized port, I’d——”

The professor’s angry tirade was interrupted in a startling manner. The door at the head of the companionway stairs was slammed abruptly to.

Warned by some intuition which he could not have analyzed, Nat bounded to the stairway and strove to reopen the door. But it resisted his stoutest efforts.

“It’s locked!” he managed to gasp, as the truth burst upon him.

“And we have been trapped by those two rascals!” exclaimed the professor.

The first effect of a sudden and utterly unexpected disaster is, usually, to produce incredulity in its victims. It was so in this case.

“Nonsense,” spoke the professor, more sharply than was his wont, “I guess, after all, I am mistaken; it must be an accident.”

“If so, it’s a remarkable one,” said Nat grimly. “The bolt has been slid into a hasp on the outside.”

“Woof!” ejaculated Mr. Tubbs. “Then we are in the position of the mouse that wandered into a nice snug trap.”

“That’s the way it looks to me,” was Nat’s rejoinder. “What do you make of it, Joe?”

The stout lad had, by this time, joined Nat on the stairway. But their combined efforts failed to budge the door.

“It’s locked sure enough,” replied Joe. “Hush!”

“What’s up?”

“I thought I heard a sound of whispering on the outside.”

“So did I. That means there is some one out there listening to see how we are taking it. Let’s give the door a good pounding. Maybe we can make them give some explanation.”

The idea was voted a good one. The two lads shook and banged on the door with all the vigor they possessed.

They were rewarded by hearing a gruff voice growl out:

“Ain’t a bit of use your shaking that door. It’ll hold till we get good and ready to open it.”

“That’s Captain Lawless,” declared the professor.

He raised his voice.

“What do you mean by this outrage?” he loudly demanded.

“Now, perfusser, don’t get hot in the collar,” was the rough advice hurled back at him. “I knows what I’m doin’. You don’t think that I’m goin’ to stand trial before a maritime court just on your account, do you?”

“You precious rascal!” hailed Mr. Tubbs. “I’d like to have my hands on you for about five minutes.”

No rejoinder came this time. Evidently the skipper was not in a mood to bandy words. As a matter of fact, he was half beginning to regret his action in imprisoning the adventurers. To use the vernacular, he was rather apprehensive that he had “bitten off more than he could chew.”

“We’ve got to get out of this somehow.”

It was fifteen minutes later, after an interval devoted to a discussion of their situation, that the professor spoke.

“Agreed,” struck in Mr. Tubbs, “but how in the name of the immortal Abe Lincoln are we going to do it?”

“I’ve got an idea,” said Nat suddenly. “See that old lounge in the corner there?”

They nodded and waited for his next words.

“It’s old and rickety, but it’s made of stout timbers. What’s the matter with using that for a battering ram?”

“Excellent!” exclaimed the professor, catching his meaning. “But what are we going to do if we get out of here?”

“That’s a logical inquiry,” said Mr. Tubbs. “We haven’t got any weapons, and those rascals may be well armed. I know that the captain and the mate always carry revolvers. I’m not sure about the others, though.”

“Humph!” murmured Nat. “I hadn’t thought of that. Tell you what we can do, though. Let’s make a search of the cabin. Maybe we can find some pistols or other weapons in one of them.”

“A good idea,” agreed the professor; “we’ll start by examining the captain’s boudoir.”

They had hardly commenced their search of that worthy’s room, before a shout from Joe announced that he had made a discovery. It was nothing more nor less than a pistol in a case. On the wall, too, apparently as an ornament, hung an aged and rusty looking blunderbuss.

“Hurray!” cried Nat; “that’s something, anyhow. Professor, you take the pistol and I’ll——”

“If it’s all the same to you,” interrupted the man of science, “I had a good deal rather you boys took the weapons. I am short-sighted, and I know that my friend Tubbs is not over familiar with firearms——”

“Except in a shooting gallery at Coney Island,” put in Mr. Tubbs apologetically.

“Very well, sir,” said Nat. “Joe will take the blunderbuss and I’ll carry the pistol. Wonder if that old blunderbore is loaded, anyhow?”

“I’ve got an idea for testing it,” said Joe.

“What’s that?”

“Look here, why wouldn’t it be a good idea to place the muzzle of this ferocious weapon to the door at the point where we think the lock is located? If it is loaded, it’s pretty sure to have enough slugs in it to carry away the lock, and the rest we’ll have to chance to luck.”

“That’s a good suggestion, too. At any rate, it won’t do any harm to try it. We can’t be worse off, unless that rascally captain makes us walk the plank or something, and he wouldn’t dare to do that, I guess.”

“Let’s see if there aren’t some more shooting-irons lying round loose,” suggested Mr. Tubbs; “seems to me that mate always had some in his room.”

But a visit to the mate’s room resulted in the discovery of nothing more formidable than a pair of ancient cutlasses, hung crosswise on the wall. The professor and Mr. Tubbs helped themselves to these, the latter flourishing his in a truly awe-inspiring manner.

“How do you like the weapon?” asked Nat, who, despite the seriousness of their position, could not forbear smiling at the moving-picture man’s antics.

“Man alive!” rejoined Mr. Tubbs, “I only wish that it was possible to get a moving picture of ourselves going into action.”

“Now then, Joe,” said Nat, when they had scoured the cabin unsuccessfully for any more weapons, “it’s time for you to try your stunt.”

Joe ascended the stairs and carefully placed the muzzle of the blunderbuss in position under the spot where he was certain the lock was situated.

“All ready?” asked Nat in a strained whisper.

“All right here,” responded Joe, his finger crooking on the rusty trigger.

“Then let her go!” came the command.

But before Joe could press the bit of steel which he hoped would discharge the gun, there came a startling interruption.

Bang!

Another gun had been fired outside. What could it mean?

“That’s the Nomad’s gun. They are attacking her and trying to make Ding-dong a prisoner!” cried Nat.

Bo-o-o-o-o-m!

The rusty throat of the old blunderbuss roared, and Joe was knocked clean off his feet by the accompanying “kick.”

At the same instant the door was blown into fragments, and a stentorian voice could be heard roaring out:

“Howling tornadoes! What’s that? A volcano?”

“Reckon somebody was taking a siesta on that door and old Mister Blunderbuss disturbed him,” grinned Nat, as he caught Joe in his arms.

“Forward!” yelled Mr. Tubbs, brandishing his cutlass in the manner made familiar by the heroes of naval pictures of the olden time.

The others caught the infection.

“Forward!” cried Nat, and, shoulder to shoulder, they plunged up the companionway, burst through the shattered doorway, and rushed pell-mell out upon the deck of the schooner.

All this time Ding-dong Bell had been making history in a fashion all his own. The lad had been below, pottering about his beloved engines, at the time that the others had gone aboard the schooner, and consequently was quite unaware of what had occurred till he emerged on deck and found that the Motor Rangers’ craft was deserted.

“Guess they’ve gone aboard the schooner,” thought the lad, and was preparing to follow, when a sailor, stationed at the latter vessel’s main shrouds, to which the Motor Rangers’ boat was made fast, stopped him.

“Stay where you are, young feller,” he ordered crisply.

It was at this moment that Ding-dong’s sharp eyes noticed a little group, consisting of the captain, the mate, and several of the sailors, standing aft by the cabin companionway.

“I want to join my friends,” exclaimed Ding-dong, forgetting to stutter in his righteous indignation at the fellow’s tone and manner.

“Guess your friends ain’t receiving company, except by permission of Captain Lawless,” was the reply given, with an impudent grin.

As the man spoke, he made a motion as if to grab Ding-dong, who was standing with one leg on board the Nomad and the other on the schooner’s bulwarks.

But Ding-dong was quite as quick in his actions as were his two chums. Moreover, he was a muscular lad, and his thews and sinews had been toughened to a steel-like fineness by his many adventures.

Consequently, as the sailor rushed at him, the lad merely caught the man’s outstretched arm, and, by a trick that he had learned from Nat, gave it a sudden twist.

“Ouch!” grunted the fellow, and, without making any more fuss, he writhed almost double and fell in a heap. But as he did so, Captain Lawless spied what was going forward. In the haste with which the plans to capture the Motor Rangers and their friends had been made, the fact of Ding-dong Bell’s existence had been temporarily forgotten by the rascally skipper and his mate. This sudden appearance, then, of one of the Motor Rangers, alive and intensely active, was very disconcerting to them.

“Confound you, boy; where did you spring from?” roared Lawless, as he dashed at Ding-dong like an angry bull.

“Fer-fer-f-from under a go-go-gooseberry bush,” sputtered Ding-dong, giving an agile backward jump, which brought him upon the deck of the Motor Rangers’ vessel.

At the same instant came a thunderous sound from the cabin door beneath, which, as we know, the imprisoned party were pounding and rapping.

The sound told Ding-dong the whole story as plainly as if it had been put into words.

“What have you done with my friends?” he demanded.

“Never you mind. Just throw up your hands and come on board this schooner or it will be the worse for you.”

“No, thank you,” parried Ding-dong, his speech quite distinct in his indignation and excitement, “I guess I know when I’m well off.”

“You brat, I don’t propose to be thwarted by such a whipper-snapper as you. Come on board at once, I say!”

“Not to-day, thank you. Call around to-morrow,” scoffed Ding-dong.

As he spoke, the lad rapidly made his way forward over the turtle back of the Nomad.

A sudden idea had come to him. On this turtle back was situated the rapid-firing gun which was a part of the craft’s equipment. Joe had been polishing it that morning, the cover was off and it looked ready for instant action.

With cat-like activity and swiftness, Ding-dong made for the implement of destruction. Reaching it, he took his stand on the small platform on which it stood.

Before the astonished Captain Lawless could scramble after the lad, Ding-dong had swung the gun on its swivel, and the captain found himself gazing straight into its formidable looking muzzle.

Ding-dong had his hand on the firing lever, and the rascally skipper went white as ashes as for an instant he thought the lad was going to discharge it.

“Don’t! Don’t shoot!” he begged abjectly.

“Then you get right back where you belong,” ordered Ding-dong.

Just then he noticed that several of the crew of the schooner were about to follow their captain on board.

“You fellows, too,” ordered the boy in a sharp, shrill voice, which nevertheless rang with determination.

“I’m ver-ver-very nervous,” he went on, “and at any mum-mum-moment I’m likely to give this lever a twist.”

“I’ll get even with you for this, my hearty,” muttered the nonplussed Captain Lawless, but nevertheless he scrambled back after his crew as Ding-dong gave his crisp command.

“Now, then,” cried the boy in a determined tone, “you let my friends out of that cabin, or I’ll have to indulge in some target practice with your schooner as the bull’s-eye.”

“Not much you won’t!” roared out Durkee, the mate.

As he spoke, the fellow whipped out a pistol and aimed it at Ding-dong.

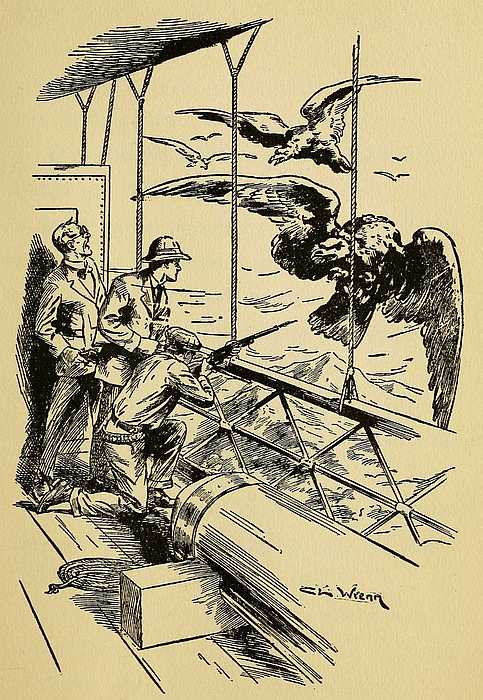

The lad depressed the breech of the gun and gave the lever a twist. Instantly a sputter of bullets flew forth. They lodged in the schooner’s spars and rigging, sending a shower of splinters all about.

At the same instant, the roar of the blunderbuss sounded from the cabin, and a fat sailor, who had been sitting on the door, bounded into the air. He was not hurt, but imagined that a mine had exploded beneath him.

As the adventurers rushed out of the cabin, they came face to face with a scene in which Ding-dong Bell was the dominating factor. The moral effect of the machine gun’s discharge had been tremendous. Palefaced and demoralized, Captain Lawless and his crew fled forward, where they huddled in a mass like so many frightened sheep.

“Say, professor!” hailed Lawless, “call that young gad-fly off. He’s done a hundred dollars’ worth of harm to my ship already. Call him off, do you hear?”

“It would serve you right if your schooner was sunk,” retorted the professor. “What did you mean by imprisoning us in that cabin?”

“It was just a joke,” pleaded Lawless, whose face was pallid. He paid no attention to the promptings of his mate, who was urging him, in an undertone, to “stand up to the lubbers.”

“We’ll give in, professor,” he went on in a shaky tone. “You’re welcome to take all your baggage and go, without us making any more trouble.

“How can we depend on you?” asked the professor.

“I’ll give you my word,” said the captain.

“A whole lot of dependence we could place on that,” scoffed Mr. Tubbs.

“Tell you what,” spoke Nat; “let’s make him lock all his sailors up in the forecastle. We can guard them, and then, in case of treachery, we’ll only have two to deal with.”

The professor delivered this ultimatum. Captain Lawless readily agreed to comply with it. The crew, sullen and muttering, was ordered below, and the forecastle hatch battened down. Joe was set to guard it, while the others helped in the work of transporting the baggage on board the Motor Rangers’ craft.

Of course Ding-dong Bell, who had really displayed the qualities of a capable general, came in for much warm congratulation. He took his honors modestly.

“I dud-dud-didn’t know it was lur-lur-loaded,” he protested, and, as a matter of fact, the lad had been as much astonished as any one at the tremendous fusillade that followed his manipulation of the machine-gun’s firing lever.