This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook.

Title: Red Belts

Author: Hugh Pendexter

Release Date: February 9, 2015 [eBook #48219]

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK RED BELTS***

| Note: | Images of the original pages are available through Internet Archive. See https://archive.org/details/redbelts00pend |

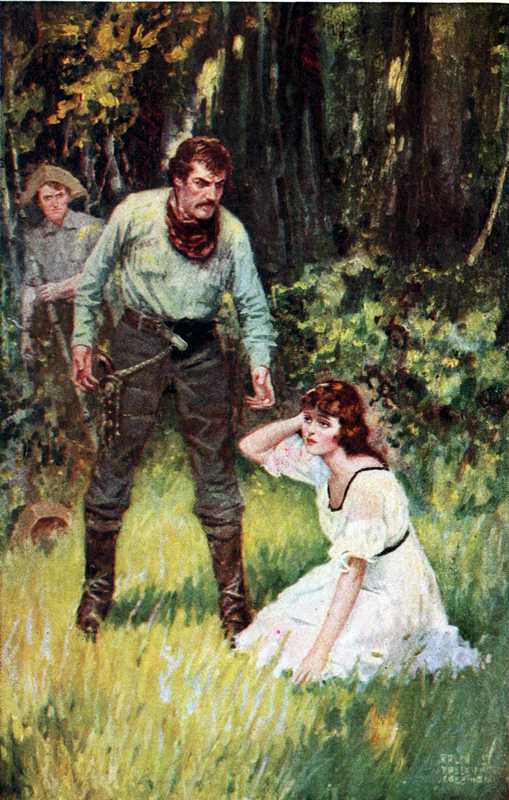

“On the ground lay Elsie Tonpit, hurled there by a bandit,

a huge brute of a man, bending over her.”

RED BELTS BY HUGH PENDEXTER FRONTISPIECE BY RALPH PALLEN COLEMAN GARDEN CITY NEW YORK DOUBLEDAY, PAGE & COMPANY 1920

In 1784 North Carolina’s share of the national debt was a ninth, or about five millions of dollars—a prodigious sum for a commonwealth just emerging from a colonial chrysalis to raise. Yet North Carolina was more fortunate than some of her sister débutantes into Statehood, in that she possessed some twenty-nine million acres of virgin country beyond the Alleghanies. This noble realm, from which the State of Tennessee was to be fashioned, had been won by confiscation and the rifles of the over-mountain settlers and had cost North Carolina neither blood nor money.

The republic was too young to have developed coalescence. A man might be a New Yorker, a New Englander, a Virginian and so on, but as yet seldom an American. The majority of the Northern representatives to the national Congress believed the Union was full grown, geographically; that it covered too much territory already. To all such narrow visions the Alleghanies appealed as being the natural western boundary. These conservatives insisted the future of the country was to be found on the seaboard.

Charles III of Spain heartily approved of this policy of restriction and set in motion his mighty machinery to prevent further expansion of the United States. He knew the stimuli for restoring his kingdom to a world plane could be found only in his American possessions.

As a result of those sturdy adventurers, crossing the mountains to plunge into the unknown, carried with them scant encouragement from their home States or the central Government. In truth, the national Congress was quite powerless to protect its citizens. And this, perhaps, because the new States had not yet fully evolved above the plan of Colonial kinship. It was to be many years before the rights of States gave way to the rights of the nation. The States were often at odds with one another and would stand shoulder to shoulder only in face of a general and overwhelming peril.

Spain, powerful, rapacious and cunning, stalked its prey beyond the mountains. She dreamed of a new world empire, with the capital at New Orleans, and her ambitions formed a sombre back-curtain before which Creek and Cherokee warriors—some twenty thousand fighting men—manœuvred to stop the white settlers straggling over the Alleghanies. These logical enemies of the newcomers were augmented by white renegades, a general miscellany of outlaws, who took toll in blood and treasure with a ferocity that had nothing to learn from the red men.

So the over-mountain men had at their backs the indifference of the seaboard.

Confronting them were ambuscades and torture. But there was one factor which all the onslaughts of insidious intrigue and bloody violence could not eliminate from the equation—the spirit of the people. The soul of the freeman could not be bought with foreign gold or consumed at the stake. Men died back on the seaboard, and their deaths had only a biological significance, but men were dying over the mountains whose deaths will exert an influence for human betterment so long as these United States of America shall exist.

The fires of suffering, kindled on the western slopes of the Alleghanies to sweep after the sun, contained the alchemy of the spiritual and were to burn out the dross. From their clean ashes a national spirit was to spring up, the harbinger of a mighty people following a flag of many stars, another incontestable proof that materiality can never satisfy the soul of man.

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I. | From Over the Mountains | 3 |

| II. | The Dead are Dangerous | 27 |

| III. | The Price of a Jug of Whisky | 43 |

| IV. | For Watauga and America | 68 |

| V. | The Ancient Law | 86 |

| VI. | On the White Path | 106 |

| VII. | In the Maw of the Forest | 125 |

| VIII. | The Emperor of the Creeks | 142 |

| IX. | Polcher’s Little Ruse | 174 |

| X. | Through the Neck of the Bottle | 197 |

| XI. | Sevier Offers the Red Ax | 210 |

| XII. | Tonpit Changes His Plans | 226 |

| XIII. | The Sentence of the Wilderness | 237 |

With its sixty cabins and new log court-house Jonesboro was the metropolis of the Watauga country. The settlers on the Holston and Nolichucky as a rule lived on isolated farms, often entirely surrounded by the mighty forest. Outside the tiny communities along these three rivers the Western country was held by red men, wild beasts and beastly white renegades. There were no printing-presses, and it required thirty days for a backwoods horseman, familiar with the difficult mountain trails, to make the State capital five hundred miles away.

The Watauga region contained reckless and lawless men, and anarchy would have reigned if not for the summary justice occasionally worked by the backwoods tribunals. North Carolina did not seem vitally concerned about her children over the mountains. Perhaps “step-children” would more nearly describe the relationship, with the mother State playing the rôle of an indifferent dame.

On a July morning in 1784 the usual bustle and indolence of Jonesboro were in evidence. Men came and went in their linsey trousers and buckskin hunting-shirts, some for the fields, some for the chase. A group of idlers, scorning toil, lounged before the long log tavern kept by Polcher, quarter-blood Cherokee and whispered to be an agent of the great Creek chief, McGillivray.

The loungers were orderly enough, as a rule, almost secretive in their bearing. Plotting mischief to be carried out under the protection of night, honest men said. Polcher seemed to have complete control of this class, and more than one seriously minded settler in passing scowled blackly at the silent group.

On this particular morning, however, Lon Hester was disturbing the sinister quiet of the tavern with his boisterous manners and veiled prophecies. He held an unsavoury reputation for being strangely welcome among hostile Cherokees, even free to come and go among the “Chickamaugas”—renegade Cherokees, who under Dragging Canoe had withdrawn to the lower Tennessee to wage implacable war against the whites.

Polcher followed him anxiously from bar to door and back again, endeavouring to confine his loose tongue to eulogies on the rye whisky and the peach and apple brandy. The other habitues saw the tavern-keeper was deeply worried at Hester’s babblings, yet he seemed to lack the courage to exert any radical restraint.

“Got Polcher all fussed up,” whispered one with a broad grin.

“He carries it too far,” growled another.

Hester, reckless from drink, sensed his host’s uneasiness and took malicious delight in increasing it. Each time he came to the door and Polcher followed at his heels, his hands twisting nervously in the folds of his soiled apron, he would wink knowingly at his mates and say enough to cause the tavern-keeper to tremble with apprehension.

This baiting of the publican continued for nearly an hour, and then Hester’s drunken humour took a new slant. Reaching the door, he wheeled on Polcher and viciously demanded:

“What ye trailin’ me for? Think I’m only seven years old? Or be ye ’fraid ye won’t git yer pay?”

“Now, now, Lon! Is that the way to talk to your old friend?” soothed Polcher, fluttering a hand down the other’s sleeve. “There’s some fried chicken and some bear meat inside, all steaming hot and waiting for you.” Then, dropping his voice and attempting to placate the perverse temper of the man by adopting a confidential tone, he whispered, “And there’s things only you and me ought to talk about. You haven’t reported a word yet of all that Red Hajason must have said.”

With a raucous laugh Hester openly jeered him, crying:

“It’s ye’n me, eh? When I quit here, it was ‘Ye do this’ an’ ‘Ye do that.’ Now we must keep things away from the boys, eh? ——! When I git ready to talk to ye, I’ll let ye know. An’, when I bring my talk to ye, mebbe it won’t be me that’ll be takin’ the orders.”

“I’ve got some old apple brandy you never tasted,” murmured Polcher, trying to decoy him inside.

“Ye’re a master hand to keep things to yerself,” retorted Hester, readjusting a long feather in his hat. “But mebbe, now I’ve made this last trip, the brandy will be ’bout the only thing ye can hoot ’bout as bein’ all yer own.”

Several of the group grinned broadly, finding only enjoyment in the scene.

The majority, however, eyed the reckless speaker askance. They knew his runaway tongue might easily involve them all in a most unwholesome fashion. Polcher’s saturnine face suddenly became all Indian in its malevolent expression, but by a mighty effort he controlled himself and turned back into the tavern.

Hester glanced after him and laughed sneeringly. As he missed the expected applause from his mates, his mirth vanished, and dull rage filled his bloodshot eyes as he stared at the silent men and saw by their downcast gaze that he was rebuked. Standing with hands on his hips, he wagged his head until the feather in his hat fell over one ear. In the heraldry of the border the cock’s feather advertised his prowess as a man-beater, insignia he would retain until a better man bested him in the rough-and-tumble style of fighting that had left him cock-of-the-walk.

“What’s the matter with ye all?” he growled, thrusting out his under lip. “Don’t like my talk, eh? Ye’re lowin’ I oughter be takin’ orders from that sand-hiller in there? Well, I reckon I’m ’bout done takin’ any lip from him. Ye’ll find it’s me what will be givin’ orders along the Watauga mighty soon if—”

“For Gawd’s sake, Lonny, stop!” gasped a white-bearded man.

“Who’ll stop me?” roared Hester, leaping from the doorway and catching the speaker by the throat. “Mebbe ye ’low it’s ye who’ll do the stoppin’, Amos Thatch, with yer sly tricks at forest-runnin’. Who ye workin’ for, anyhow? Who gives ye orders? —— yer old hide, I reckon ye’re tryin’ to carry watter on both shoulders.”

“Don’t, Lonny!” gasped Thatch, but making no effort to escape or resent the cruel clutch on his throat. “Ye’re funnin’, I know. Ye know I’m workin’ same’s ye be.”

“Workin’ same as ye be, eh? Ye old rip! Fiddlin’ round in the same class that ye be, eh?”

“Don’t choke me! Let’s go inside an’ have a drink. Too many ears round here. Too near the court-house.”

With a wild laugh Hester threw him aside and derisively mocked:

“Too near the court-house, is it? Who cares for the court-house?”

And he grimaced mockingly at the figure of a man busily writing at a rough table by the open window. Then, believing he must justify his display of independence, he turned to the group and with drunken gravity declared:

“The time’s past, boys, when we have to hide an’ snoop round. There’s a big change comin’, an’ them that’s got the nerve will come out on top. The time’s past when court-houses can skeer us into walkin’ light when we feel like walkin’ heavy. I know. I’ve got news that’ll—”

“Now, shut up!” gritted Polcher, darting out the door and whipping a butcher-knife from under his apron. “Another word and I’ll slit your throat and be thanked by our masters.”

As Hester felt the knife prick the skin over his Adam’s apple, his jaw sagged in terror. Sobered by the assault, he realized he had gone too far. Instantly the loungers crowded about him to prevent outsiders from witnessing the tableau. Old Thatch whispered:

“He’s dirty drunk. ‘Nolichucky Jack’ must ’a’ heard some of it. I seen him stop writing and cock his ear.”

“To —— with Chucky Jack!” Hester feebly defied. “I ain’t said nothin’.”

“If you had finished what you’d begun, you’d never said anything more,” hissed Polcher. “You can drink your skin full every hour in the day, and that’s all right. But you’ve got to keep your trap closed. I’ve tried soft means, and now I’m going to rip your insides out if you don’t keep shut.”

Hester glanced down at his own bony hands and the long finger-nails, pared to points for the express purpose of scooping out an opponent’s eyes, then shifted his gaze to the grim faces of his companions. He read nothing but indorsement for Polcher.

“I can’t fight a whole crowd,” he jerkily admitted.

“You don’t have to fight none of us,” warned Polcher, lowering the knife and hiding it under his apron. “All you’ve got to do is to fight yourself, to keep your tongue from wagging. You say you’ve brought something. Is it for me?”

“No, it ain’t for ye,” sullenly retorted Hester, his small eyes glowing murderously.

“Then keep it for the right man. Don’t go to peddling it to Chucky Jack and all his friends,” said Polcher.

Glimpsing a stranger swinging down the brown trail that answered for the settlement’s one street, he motioned with his head for the men to pass inside. To mollify the bully he added—

“You understand, Lon, it’s yourself as much as it’s us you’ll be hurting by too much talk.”

“It’s that last drink of that——peach brandy,” mumbled Hester. “I’ll stick to rye after this. I can carry that.”

“Now you’re talking like a man of sense,” warmly approved Polcher, clapping him heartily on the shoulder. “Lord, what fools we all be at times when we git too much licker in. The boss combed me once till I thought he was going to kill me just because I got to speaking too free. Now let’s join the boys and try that rye.”

Outwardly amiable again, Hester followed him indoors; deep in his heart murder was sprouting. He knew Polcher wished to pacify him, and this knowledge only fanned his fury higher. And he knew Polcher had lied in confessing to babbling, for the tavern-keeper’s taciturnity, even when he drank, was that of his Indian ancestors.

The whisky was passed, Polcher jovially proclaiming it was his treat in honour of Hester’s return from somewhere after a month’s absence. Hester tossed off his portion without a word, now determined not to open his lips again except in monosyllables. Old Thatch sought to arouse him to a playful mood with a chuckling reminder of some deviltry he had played on a new settler over on the Holston. But even pride in his evil exploits could not induce Hester to emerge from his brooding meditations.

For the first time since he had won the right to wear the cock’s feather he had been backed down—and, at that, in the presence of the rough men he had domineered by his brutality. Of course it was the knife that had done it, he told himself, and yet he knew it was something besides the knife. If Old Thatch had held a knife at his throat, he would have laughed at him. No, it wasn’t that; it was the discovery that there dwelt in Polcher’s obsequious form a man he had never suspected. The knowledge enraged while subduing him. He recalled former insolences to the tavern-keeper, his treatment of him as if he were a humble servitor.

It was humiliating to know that, while he was sincere in his behaviour, Polcher had played a part, had tricked him. He knew that Polcher would gladly have him resume the rôle of bully, swear at him and treat him with disdain. He had no doubt but that Polcher would meekly submit to such browbeating. But never again could he play the bully with Polcher, and all this just because he understood how Polcher had fooled him by submitting in the past. This was gall to his little soul. The man he had looked down upon with contempt had been his master all along.

His smouldering rage was all the more acute because he had believed he had been the selected agent in mighty affairs; whereas, he had acted simply as a messenger. On entering the settlement early that morning he had smiled derisively at beholding the tavern and the usual group before the door. He had supposed himself miles above them in the secrets of the great game about to be played. Now his self-sufficiency was pricked and had deflated like a punctured bladder.

Being of cheap fibre, Hester had but one mental resource to fall back upon: the burning lust to re-establish himself in his own self-respect by killing Polcher. He had been grossly deceived. He had been permitted to believe—nay, even encouraged to believe—the breed was only the vintner to the elect. It was while wallowing in the depths of this black mood that the sunlight was blocked from the doorway by the arrival of the stranger Polcher had glimpsed up the trail.

The newcomer paused and waited for the sunshine to leave his eyes before entering the long and dimly lighted room. His hunting-shirt was fringed and tasseled and encircled by a bead-embroidered belt. From this hung a war-ax, severe in design and bespeaking English make. His long dark hair was topped with a cap of mink-skin. In his hand he carried the small-bore rifle of the Kentuckians. The loungers drew aside to both ends of the bar, leaving an open space for him. He took in the room and its occupants with one wide, sweeping glance; hesitated, then advanced.

It maddened Hester to observe how servilely Polcher leaned forward to take the stranger’s order. The other men, seemingly intent on their drink, quickly summed up the newcomer. A forest-ranger fresh from Kentucky. He stood nearly six feet in his moccasins and carried his head high as his grey eyes ranged deliberately over the two groups before returning to meet the bland gaze of Polcher.

In a drawling voice he informed—

“A little whisky.”

“You’ve travelled far, sir,” genially observed Polcher, his Indian blood prompting him to deduce a long, hard trail from the stained and worn garments. “That beadwork is Shawnee, I take it.”

“It was once worn by a Shawnee,” grimly replied the stranger. “Lost my horse a few miles back and had to hoof it afoot.”

“Virginy-born,” murmured Polcher.

“Yes, I’m from old Virginy,” proudly retorted the stranger, tossing up his head. “A mighty fine State.”

“Quite a number of ye Virginians seem keen to git clear of her mighty fine State an’ come down here to squat on North Car’lina land,” spoke up Hester, his insolent half-closed eyes advertising mischief.

The newcomer slowly turned and eyed him curiously and smiled faintly as he noted the cock’s feather. And he quietly reminded:

“The first settlers on the Watauga were Virginians. When they came here fourteen years ago, they reckoned they was on soil owned by Virginy. I don’t reckon North Car’lina lost anything by their mistake.” He threw off his drink and proceeded to deliver himself of the sting he had held in reserve. “From what I hear, the Sand-hillers didn’t care to come over the mountains and face the Indians till after the Virginians had made the country safe.”

The two groups of men shifted nervously. Hester’s eyes flew open in amazement, then half-closed in satisfaction.

“The——they had to wait for Virginy to blaze a trail!” he growled, slowly straightening up his long form and tipping his hat and its belligerent feather down over one eye. “An’ where was ye, mister, when the first brave Virginians kindly come over here to make things safe for North Car’lina?”

“I was eleven years old, shooting squirrels in Virginy,” chuckled the stranger.

“An’ wearin’ a Shawnee belt! Who give it to ye?”

“The warrior who was through with it when I got through with him. It happened up on the Ohio,” was the smiling response. “Anything else you’d like to ask?”

“Killed a Injun, eh?” jeered Hester. “That’s easy to tell. Sure ye ain’t the feller that licked the Iroquois all to thunder? No one here to prove ye didn’t, ye know.”

Toying with his empty glass, the stranger again surveyed Hester, much as if the bully were some strange kind of insect. He grimaced in disgust as he observed the long, pointed finger-nails. “One thing’s certain,” he drawled, “you never fought no Iroquois, or they’d have them talons and that hair of yours made into a necklace for some squaw to wear. Just what is your fighting record, anyway?”

“I ain’t never been licked yet by anything on two kickers atween here an’ the French Broad,” bellowed Hester, slouching forward, his hands held half open before him. Then he flapped his arms and gave the sharp challenge of a gamecock. “I’m Lon Hester, what trims ’em down when they’re too big an’ pulls ’em out when they’re too short.” And again he sounded his chanticleer’s note.

“I’m Kirk Jackson, from the Shawnee country, and I reckon it’s high time your comb was out,” was the even retort.

“Just a minute, gentlemen,” purred Polcher, with a wink at Hester. “Fun’s fun, but, when you’re armed with deadly weapons, you might carry a joke too far. Before you start fooling, let’s put all weapons one side.”

Jackson’s brows contracted, but, as Hester promptly threw a knife and pistol on the bar, the Virginian reluctantly stood his rifle against the wall and hung his belt on it. It was obvious he was regretting the situation. Hester read in it a sign of cowardice and crowed exultingly. For a moment Jackson stood with his gaze directed through the open door. Hester believed he contemplated bolting and edged forward to intercept him. What had attracted Jackson’s gaze, however, was the slim figure of a girl on horseback, and, as he stared, she turned and glanced toward the tavern, and his grey eyes lighted up with delighted recognition.

“Take yer last peep on natur’, ’cause I’m goin’ to have both of ’em,” warned Hester, hitching forward stiff-legged, his hands held wide for a blinding gouge.

“You dirty dog!” gritted Jackson, his soul boiling with fury at the brutality of the threat.

With a spring Hester leaped forward, his right hand hooking murderously close to the grey eyes. Jackson gave ground and found himself with his back dangerously close to the group at the end of the room. He could feel the men stiffening behind him, and he believed they would play foul if Hester needed assistance. As Hester made his second rush, Jackson worked with both elbows and knocked two men away from his back, sending one reeling against the wall, the other against the bar.

Then he leaped high, his legs working like scissors, feinting with his left foot and planting the right under the bully’s chin, smashing the long teeth through the protruding tongue and hurling him an inert mass against the base of the bar.

“No kickin’!” yelled Old Thatch, pulling a knife.

“You played foul!” roared Polcher, his suave mask dropping and leaving his dark face openly hideous. “Shut that door, boys!”

The men at the upper end of the bar rushed to the door and not only closed it but appropriated Jackson’s rifle and belt. There was a stir behind him, and Jackson leaped to the end of the bar just vacated by the men. Here he wheeled and snatched a five-gallon jug of brandy from the bar and swung it high above his head. Then planting a foot on Hester’s chest he warned:

“The first move made means I’ll brain this dog at my feet and then damage the rest of you as much as I can.”

Polcher and his henchmen stood motionless, wrathfully regarding the man at bay.

“You broke the rules by kicking,” said Polcher.

“Rules, you miserable liar and scoundrel!” hissed Jackson. Then in a loud voice, “Open that door and stand clear, or I’ll smash this punkin at my feet and rush you.”

“One minute!” softly said Polcher. And he whipped a long pistol from under the bar and levelled it at Jackson. “You set that jug on the bar and do it soft-like. You’ve played foul with my friend. He’s going to have a fair shake at you.”

“Just let me git at him!” sobbed Hester from the floor. “That’s all I ask, boys.”

“Before you can move that jug an inch, I’ll shoot your head off,” warned Polcher. “Put the jug down and step to the middle of the floor. No one will meddle while Mr. Hester has a fair chance.”

“Fair chance? You low-down murderers! Shoot and be——!”

“I’ll count three—then I’ll shoot. There’s witnesses here to say you come in drunk and hellin’ for a row and got it. One—two—”

“Drop that pistol, Polcher!” called a voice at the window.

The tavern-keeper glanced about and paled as he beheld the muzzle of a long rifle creep in over the sill and bear upon him.

“If you’d said three, it would have been your last word on earth.”

Polcher lowered his weapon but protested:

“Look here, Sevier, this stranger has assaulted one of my patrons. I propose to see they fight it out man-fashion.”

“A man-fashion fight is a bit beyond your imagination,” was the grim reply. “Have that door opened and see the stranger’s rifle is stood outside. Be quick!”

Polcher nodded to Old Thatch, who threw back the door and passed the rifle and the belt. Jackson tingled with a fresh shock as he glimpsed a slim brown hand receiving the weapons. Then Sevier commanded:

“Now, young man, come out. If you want to be murdered, there’s a rare chance for you anywhere along the border without entering this hell-hole. Remember, Polcher, you’re a dead man if a hand is raised against this guest of yours.”

Jackson sprang through the door and closed it after him. The girl he had seen passing the tavern at the inception of the brawl was waiting for him.

“Elsie!” he whispered, relieving her of his weapons. “I’ve just come from Charlotte, where I went to find you.”

She was as fair as he was dark, and her blue eyes glistened as he addressed her. Then she sighed, and an expression of sadness overclouded her small face.

“I saw you for a second,” she faltered. “It seemed impossible it could be you. I knew you would have trouble when I saw them close the door. I left my horse and called Mr. Sevier. Kirk, I’m glad to see you—and I’m sorry you came.”

John Sevier, or Chucky Jack, as he was commonly called after the Nolichucky River he lived on, stepped round the corner of the tavern before Jackson could reply to the girl’s contradictory statement and brusquely called out:

“Come along, Miss Tonpit. And you, sir; this is no place for an honest man to linger in.”

“I owe you thanks. I’ll try to thank you later,” said Jackson. “I find Miss Tonpit is an old acquaintance—an old friend—I’ll walk home with her.”

The girl cast a swift glance at Sevier and faintly shook her head. Sevier tucked his arm through Jackson’s and quietly insisted:

“You must come with me now; Miss Tonpit is perfectly safe—perfectly safe.”

To Jackson’s amazement the girl flushed, then turned pale and ran to where her horse was tied to a tree.

“—— it, man! Virginians don’t leave such matters to chance,” cried Jackson, tugging to release his arm. “The young lady should be escorted home. This seems to be a desperate community.”

“I, too, am a Virginian,” Sevier calmly reminded, tightening his hold en the other’s arm. “And I know the community better than you do.” There was a peculiar hardness in his voice as he added, “Miss Tonpit is perfectly safe in any part of the Watauga settlements at any time of day or night, providing her identity is known.”

Jackson stared savagely into Sevier’s face and hoarsely demanded—

“Just what do you mean by that?”

“Nothing to her hurt, God bless her!” was the ready response. “But this is no place to talk. If there was an ounce of courage to go with the ton of hate back in the tavern, we’d both be riddled with bullets before this. Step over to the court-house where we can talk.”

“But, Miss Tonpit? She lives near here? I shall have a chance to see her again?”

And Jackson held back and gazed after the girl, who was now cantering up the trail towards the foot-hills.

“Every opportunity, I should say,” assured Sevier, leading the way into the court-house. “Now suppose you give an account of yourself. I’m sort of a justice of the peace here. We’re hungry for honest men, God knows. I believe you’ll fit in with the court-house crowd rather than with the tavern crowd.”

“But Elsie? Miss Tonpit?”

“Your story first,” Sevier insisted, seating himself at the table and motioning Jackson to a stool fashioned from a solid block of cedar.

Jackson surrendered and rapidly narrated:

“I’m Kirk Jackson, Virginian. I met the Tonpits in Charlotte a little over a year ago and fell in love with Miss Elsie. I must confess my suit didn’t progress as I had hoped. I think her father was opposed. I can’t blame him. Major Tonpit’s daughter can look higher than a forest-ranger. Anyway, I went back to the Ohio country, where I had served under George Rogers Clark. I’m just back from there. Absence had renewed my courage.

“I hurried back to Charlotte and learned the major had moved over the mountains. My informant didn’t know whether he had made his new home in the Watauga district or on the Holston. I saw and recognized her just as that brute in the tavern was preparing to tear my eyes out. Now tell me what you meant by saying she is safe anywhere hereabouts, providing her identity is known.”

Sevier drummed the table and frowned. Then he explained:

“John Tonpit, according to all indications, holds the whip-hand over these scoundrels here. They serve him, I believe.”

“Good heavens!” Jackson weakly exclaimed. “Major Tonpit, proud to arrogance—having truck with those scoundrels?”

And he wondered if this were the girl’s reason for pronouncing his quest of her as hopeless. Then he rallied with the buoyancy of youth. If the only barrier between them was some sinister business of her father’s, he would overcome it, although great be her pride.

“Can’t you tell me something more definite?”

Sevier tapped a document on the table and replied:

“This is a petition I’m about to send to Governor Martin. North Carolina is dumping criminals and trash upon us, and we’re asking for a superior court to handle their cases. The Creeks, under Alexander McGillivray, are working day and night to get the Cherokees to join them in a decisive war against all settlers on the Watauga, the Holston and the French Broad. The petition asks for power to raise militia and for officers to lead the men.”

“But how does Major Tonpit come into this?” broke in Jackson. “Tavern brawlers and hostile red men!”

“I’m coming to that, if there is any that. The Creeks have made a secret treaty with Spain. McGillivray pledges twenty thousand warriors towards exterminating the Western settlements.”

“But you can’t know that for a fact.”

“You’ve been away the last year. You’re out of touch with affairs. The treaty was signed at Pensacola, June first, by McGillivray on behalf of the Creek Nation and by Don Estephan Miro, Governor of West Florida and Louisiana, on behalf of Spain.”

Jackson was nonplussed by this intelligence. He gazed in silence at the man across the table, whose words were building a mighty barrier between him and the girl. Sevier’s handsome face softened in sympathy. He was a tall, fair-skinned man with an erect carriage, and his slender figure well set off the hunting-shirt he invariably wore. Eager and impulsive by nature, he was now holding himself in restraint because he knew his revelations were so many blows at the young ranger’s happiness.

“The major fits into all this. Spain and the Creeks?” Jackson faintly asked.

“So I firmly believe. There is one flaw in the chain—the Cherokees. For, while McGillivray has pledged twenty thousand braves, his Creeks can’t furnish any such a number of fighting men. There are a few thousand Seminoles he can get, but unless he lines up the Cherokee Nation he has promised more warriors than he can call to the war-path. One of the principal chiefs of the Cherokees, Old Tassel, is holding off. He controls three thousand warriors. He wants his lands back, but he wants to get them by peaceful measures.

“Major Tonpit has great influence with Old Tassel. Could he swing him for a war against us, not only would his three thousand fighting men be added to McGillivray’s total, but the rest of the Cherokee Nation, now hesitating, would gladly rush in. Major Tonpit may supply the link to complete the chain. It will be the weakest link in the chain, yet absolutely necessary for McGillivray’s success.”

“Tonpit a schemer for Spain!” gasped Jackson.

Sevier frowned, then shrugged his shoulders and corrected:

“Scarcely a schemer. He isn’t cold-blooded enough for that. For a schemer you need a man of Polcher’s cool mind. Tonpit is flattered by attentions from royalty. He loves royalty. His head is in the clouds of personal ambition. He sees himself a dictator of a mighty province reaching from the Alleghanies to the Mississippi. If put in as royal governor he would rule supreme, he believes.

“I became suspicious when he gave up his comfortable home in Charlotte and went to the State capital and then came out here and made his home. Since being here, he has informed Governor Martin that the Indians are friendly and desire peace but that our settlers persist in stealing their lands and abusing them. This has won him the friendship of Old Tassel. Every talk Tassel has sent to the governor has been carried by Tonpit.”

“That’s bad!” cried Jackson. “But I can’t make myself believe he deliberately plots for Spain. Even in the national Congress men are expressing different views as to what shall be done with the region west of the mountains.”

“True. And Major Tonpit takes the views of Charles III.”

“But he may be friendly with Old Tassel and yet not be working with the Creeks,” persisted Jackson, trying to find something favourable to say in behalf of Elsie’s father.

“I know he is hand in glove with McGillivray,” solemnly declared Sevier. “I know McGillivray looks on him as a man of insane ambitions but lacking balance. I know McGillivray even now is holding back from war only because he is not quite satisfied that Tonpit will live up to his agreements. It isn’t the major’s heart or courage he doubts, but his lack of balance. Once he gets what he believes to be a firm hold on Tonpit, you’ll see things begin to hum along the Holston and the Watauga.”

Jackson shifted the trend of conversation, seeking to find a weak spot in Sevier’s hypothesis.

“After all, McGillivray’s probably over-rated. I never saw an Indian yet who could plan a campaign and stick to it,” he hopefully said.

Sevier smiled ruefully.

“You don’t know Alexander McGillivray, who calls himself ‘Emperor’ of the Creek Nation. His father was Lachlan McGillivray, a Scotch trader. His half-breed mother was of a powerful family of the Hutalgalgi, or Wind clan. Her father was a French officer. McGillivray was educated at Charleston and studied Latin and Greek as well as the usual branches. He’s a partner in the firm of Panton, Forbes and Leslie in Pensacola. Naturally that firm has a monopoly of the Creek trade. He’s shrewd as a Scotchman, has the polish of a Frenchman and is more cunning than any of his Indians. He is an educated gentleman according to English standards. He lives up to his title of ‘Emperor.’ I must say this for him: he’s kind to captives and honestly tries to do away with the usual Indian cruelties.

“Now to return to my petition to show where we fit in. It’s Old Tassel’s deadly fear of the Watauga riflemen as much as his desire for peace that is holding him back. And, if he should die, his three thousand warriors would flock to McGillivray at once. The renegade Cherokees, who call themselves Chickamaugas, are impatient to take the path. As things are turning out, my riflemen aren’t enough. They’ve served without pay. The new settlers demand pay. We must have power to raise and equip militia.”

“I begin to understand,” Jackson sadly admitted. “This Polcher? He must be active in anything evil.”

“He’s cunning. His tavern is where messages are brought and relayed on. If word comes to Tonpit, it is left at the tavern and sent secretly. Look here, young man! Perhaps I’ve talked more freely than I should. You’re in love with Miss Elsie, and you’d be a fool if you weren’t. But that naturally makes you wish to see things that exonerate the major. Wander round and see and hear for yourself. In a few days, maybe, I’ll feel like telling you something else. Only remember this: Elsie Tonpit hasn’t a better friend west of the Alleghanies than John Sevier. By heavens! I’m a better friend to her than her father is!”

He clamped his lips together and began rereading the petition.

Jackson studied the strong visage with new interest. Sevier’s face reminded him strongly of Washington’s in its Anglo-Saxon lines of determination. But there was also a certain mobility of expression, a mirroring of emotions, which came from his French blood. He was a Virginian, and the young ranger had heard his fame echoing up and down the lonely Ohio. As Nolichucky Jack—usually clipped to Chucky Jack—his name was reputed to be worth a thousand rifles when he took the field against the red men.

But it puzzled Jackson to understand how this man, a gentleman born and bred, could have left the solid comforts of his home at Newmarket in the beautiful valley of the Shenandoah, thrust behind him positive assurances of great political advancement, cast off the social prominence he so naturally graced and bring his Bonnie Kate to the lonely country of the Nolichucky.

Jackson’s material mind had taught him that one fought Indians because one must, not from choice. A beautiful and devoted wife and ample fortune appealed to the young ranger as being the goal in life. It never entered his process of reasoning that Destiny transplants men to obtain results, just as Nature supplies seeds with methods of locomotion so that new regions may be fructified. The vital incentive for Jackson’s admiration for the man was not his sacrifices but rather his knowledge that Chucky Jack had invented a new style of forest-fighting.

He could not know that in his lifetime a certain Corsican would utilize the same tactics in overrunning Europe: namely, the hurling of a small force with irresistible momentum and the achieving of greater results thereby than by the leisurely employment of large bodies of soldiery. The border already rang with the victories of Chucky Jack, who was to fight thirty-odd battles with the red men and never suffer a defeat; whose coming to the Watauga country marked the passing of defensive warfare and instituted the offensive.

“Yes, it’s natural that you should try to think leniently of Major Tonpit,” murmured Sevier without raising his eyes from the petition.

Jackson flushed and coldly replied:

“I am a Virginian, first and last. I have nothing to do with the Spanish King.”

“We soon must begin to call ourselves Americans—if we wouldn’t bend the knee to Spain,” gently corrected Sevier with a whimsical smile.

“Of course,” agreed Jackson. “We’re all Americans now. But first we are Virginians, I take it.”

Sevier rose and stood at the window and stared thoughtfully across the valley and spoke as one repeating articles of faith in the privacy of his chamber:

“Virginians when we were colonials, but now Americans first and last—if this republic is to endure. If this union of States is to last, we must forget our former identity; we must be merged in one compact body and be known as Americans. Well, well. It will all come some day, please God!”

He broke off and leaned from the window and called out:

“Ho, Major Hubbard! Step here a minute.”

Jackson saw a tall figure in forest dress turn in the trail leading to the woods. As the man came toward the court-house, he beheld a dark, gloomy face, a countenance he could never imagine as being lighted with a smile. Hubbard came up to the window, and Sevier said:

“Mr. Jackson, step here, please. Meet Major James Hubbard. Major, this is Kirk Jackson, fresh from the Shawnee country and come to live with us.”

Hubbard’s face glowed with passion, and he clutched Jackson’s hand fiercely and cried:

“The Shawnees! I envy you your chance, sir.”

Sevier gently nudged Jackson to stand aside and, leaning from the window, muttered:

“Major, times are ticklish. Any little break will mean ruin to many cabins. Remember!”

Hubbard made some reply inaudible to Jackson. In a freer tone Sevier asked—

“What is the latest news?”

“That —— mixed-blood, John Watts, and his Chickamaugas have gone to water. They’ll be raiding the French Broad and Holston next.”

Sevier pursed his lips musingly and said:

“We must have more men, more arms and money. North Carolina must act on my petition.”

Hubbard laughed harshly and sneered:

“Why should they give money when you’ve always been ready to foot the bills? Ask them for money, and they’ll tell you that the Indians—curse them, curse them—are friendly and much abused. And they’ll leave you to pay the shot.”

“I can’t pay again. I’ve spent my all,” Sevier quietly answered. “But I’m hopeful the State will show common sense. North Carolina must realize we’re no longer able to handle the criminals pouring over the mountains without courts; that we’re unable to stand off the Creek Nation once the Cherokees join it. Old Tassel can’t always hold his three thousand in check.”

“His chiefs rebel. Many of his young warriors are stealing away to go to water and follow Watts,” was the gloomy response.

A few words more and Hubbard returned to the trail and struck off for the forest. Sevier stood and looked after him uneasily. Wheeling about, his face betrayed his anxiety and prompted Jackson to ask:

“What’s the matter with him? Any relation to Hubbard, the Injun-killer, we heard about up on the Ohio?”

“He is the killer. He’s killed more Cherokees than any other three men on the border. His family was wiped out by Shawnees back in Virginia. You can’t make him believe any Indian should be allowed to live. And he worries me. Now he’s off to scout the forest. It only needs the killing of an Indian or so to explode the powder under our feet. Huh! I wish he had not gone.”

“He had news?”

“Nothing more than we’ve suspected for a year. John Watts is always ready to take the path. He’s the shrewdest of the Cherokee leaders. If Old Tassel loses his grip or should decide that peace doesn’t pay—”

His French blood found expression in an outward gesture of the hands as he dropped down at the table.

Toying with the petition and speaking his thoughts aloud, he ran on:

“But Major Hubbard wants war. He’s inclined to look on the dark side of things. Tush! The State by this time realizes what we’ve won for her without an ounce of help. Pure selfishness will compel the Legislature to send us the necessary aid. Ha! There’s news, by heavens! The Cherokees must have struck!”

It was the distant clatter of flying hoofs. Sevier dropped through the window with Jackson at his heels. Polcher and his henchmen were piling from the tavern and staring toward the mountains. Some one was riding at top speed from the east.

Although the rider might be bringing the fate of a continent, Jackson’s first interest was in a man and woman cantering up the trail from the opposite direction. Instead of watching for the furious rider, he had eyes only for the two. The man was tall and gaunt and of haughty bearing, his sharp, cold face swinging from side to side as if he were the master riding among slaves. The girl was his daughter, Elsie Tonpit. The young Virginian forgot the approaching messenger and ran toward the couple, his heart beating tumultuously.

To his glad surprise Tonpit greeted him with a shadowy smile and stretched out a hand in welcome. The girl, however, betrayed symptoms of alarm instead of being pleased by her father’s attempt at cordiality. She even sought to evade the fond gaze of her lover and glanced apprehensively toward the court-house. Jackson knew in a moment that she felt shame for what she believed Sevier had told him.

“When Elsie informed me you were in Jonesboro, Mr. Jackson, I set out to find you,” Tonpit now delighted the young man by saying.

“I have to thank her and Sevier for rescuing me from a ridiculous position,” he blurted out and then bit his tongue for having uttered the words.

“Ha! How is that?” coldly demanded Tonpit, but with his gaze seeking a glimpse of the rider, now well among the cabins.

“The men in the tavern were taking advantage of their numbers,” quickly spoke up the girl. “The man called Hester was the ringleader, I should say.”

“This is the first time you’ve said anything about it,” murmured her father, his eyes now lighting as they focussed on the bobbing figure of the horseman.

“It only needed Mr. Sevier’s command to relieve Mr. Jackson of any embarrassment,” she awkwardly explained.

Tonpit’s thin visage grew cold with hate.

“I and my friends refuse to be beholden to this man Sevier,” he harshly warned.

And, touching spur to his mount, he beckoned the girl to follow him and darted toward the tavern. With one backward glance she rode after him.

Jackson ran forward, as did Sevier, as the rider reined in before the tavern door and wearily dismounted. From all quarters came the settlers and their families. Polcher brought out a pitcher of brandy, and the messenger drank deeply. Then jumping on a horse-block he waved a paper in his hand and cried out—

“For Chucky Jack!”

“Here!” called Sevier from the edge of the crowd.

The missive was tossed into his outstretched hand. As he was breaking the seal, the messenger drew a deep breath, waved his arms for silence and shouted—

“North Carolina has ceded us to the central Government to pay for her part of the war debt!”

With a low word for his daughter to follow him Tonpit backed his horse clear from the crowd and spurred away. For sixty seconds the astounded gathering remained motionless. Sevier stared incredulously at the message, while his neighbours gazed stupidly at the dusty messenger. All felt as if they had been abandoned in the wilderness without shelter or means of self-defence. True, the over-mountain men had always fought their own way and financed their own campaigns, yet in the back of their minds was ever the thought that, should a crisis come, the mother State must aid them.

That a crisis was imminent was evidenced by Chucky Jack’s open mention of his petition for soldiers. Chucky Jack was worth many riflemen and had whipped the Indians many times. All the more proof that the settlements must be in desperate straits when he was impelled to beseech help. And of a sudden they were disowned; there was no mother State, no slumbering asset they could call to life.

Sevier had not talked much about the possibility of Creeks and Cherokees uniting, but the petition, coupled with whispered rumours seeping through the cabins, now brought morbid speculations. How many Indians would come and when, were the questions more than one man and woman asked themselves. Who would go to hold the line on the French Broad so that the red raiders might not penetrate to the Watauga?

Jackson watched Tonpit ride hastily away, followed by Elsie, and he fancied he beheld elation in the man’s hard visage and sorrow in the girl’s gentle face. It was quite a coincidence, too, that Major Tonpit should ride forth just in time to learn the momentous news—unless he had been expecting it and came purposely to hear it. His prompt return home gave colour to the suspicion.

The young Virginian shifted his attention to Chucky Jack. Sevier perused the message for the second time, crumpled it into a ball as if to hurl it from him, thought better of it and tucked it inside his buckskin shirt and called to the assemblage:

“Women and men of the Watauga, North Carolina will have none of us. We’re shoved through the door and told to shift for ourselves. To be exact, we’re told to look to the central Government for protection. And, as you know, the ink is scarcely dry on the petition I was about to send to the Legislature, asking for courts and militia.

“Without consulting one of the twenty-five thousand settlers on this side of the mountains, North Carolina chooses to pay her share of the national debt by the simple process of ceding us to Congress. She proposes to pay her debts with lands we won by rifle and ax. The act was passed by the Legislature a month ago, and for thirty days, while the messenger was bringing the news, we have been set off from North Carolina.

“During those thirty days our plight has been as serious as it is now, only, not knowing the truth, we worried but little. This fact should teach us that we can care for ourselves during the next thirty days, and so on, until there is no danger from the Indians along our border. So I ask you to be of brave heart and to remember the Watauga people always have had to hoe their own row. Please God we can keep on.

“A year or two ago this message would have worried me none. I could send out the call, and my old friends would respond overnight, as fast as horseflesh could fetch them. If an Indian war comes now, it will be more serious than what we’ve experienced in the past but nothing that our rifles can not blast away. I still can count on my friends and old companions-in-arms. Of the newcomers who have come to us in such numbers I am not so sure.”

And he paused to dart a lightning glance at Polcher and his cronies pressed about the tavern door.

“The national Congress oughter help us,” piped up an old man.

“It would be glad to. But the national Government, while empowered to levy armies, can not compel a single State to furnish a soldier,” Sevier reminded. “The national Government can do only what the States will permit it to do. Last year several hundred soldiers stormed the very doors of Congress and demanded their over-due pay, and Congress was unable to escape the mob’s demands. There will come a time when our Congress will have the power to protect its citizens in this, or in any other, land. But not now.”

“If not now, then by the Eternal, men of Watauga, there is one power that can defend us!” cried Polcher from the tavern doorway. “And we have only to ask to be freed from either Creek or Cherokee.”

“Aye! Aye! Spain looks after its own!” cried another of the tavern coterie.

“So does the devil!” thundered Sevier, enraged at Polcher’s making the Creek menace common property. “We’ll get nothing from Spain only as we pay dearly for it. And remember, there can be no danger from the Creeks except as Spain sets the mischief afoot. All who would be free and live in security follow me to the court-house. Messengers must be sent out; delegates must be elected and called here.”

“What’s yer plan?” hooted a tavern fellow.

“My plan is to form a Government of our own and to be admitted into the Union as a separate State!” retorted Sevier in a ringing voice.

The decent element raised a hoarse cheer, and faces heretofore gloomy became inspired. Polcher quickly warned:

“Vermont’s been trying to be admitted ever since 1776. We can’t stand on air, neither one thing nor another. Spain will protect us and give us justice. If she should fail, we could turn to and drive her into the gulf!”

“The time to drive her into the gulf is before you slip on her yoke!” shouted Sevier. “And, if we’re able to do that same thing, why seek her protection? To the court-house!”

The women gathered in knots to discuss the startling news. The men followed their old leader. Jackson remained outside the court-house, watching the scene. His experience with Kentuckians on the Ohio had taught him the feeble central Government was powerless to function in a crisis like this—and this because the thirteen States retained the mental attitude of the thirteen colonies.

Polcher’s advocacy of accepting the protection of Spain was not painfully repugnant to Jackson, no more than it was to some others west of the mountains, who believed themselves forsaken and left to shape their own destiny. When it hurt, it hurt pride, not a national spirit. He repudiated the idea because of an instinctive dislike to domination by any foreign power. His sense of Americanism was not shocked as Sevier’s was, for the union Polcher openly urged, and which John Tonpit was suspected of secretly promoting, simply meant a political affiliation and not the death of national ideals, the seeds of which were scarcely sown.

Jackson, however, firmly opposed the project, for his forebears had come to America to escape overlords. Then again common sense told him the law of compensation would decree that Spain’s protégés must pay Spain’s price.

Being in this frame of mind, he saw no reason why he should not play his luck by accepting Tonpit’s courteous demeanour at full face-value and profit by it to the extent of wooing his daughter. His last meeting with Tonpit before going to the Ohio country convinced him his suit was frowned upon. Now, with the father’s smile still soothing him, with a vivid picture of Elsie’s shy, backward glance, he had small liking for the court-house and its jumble of loud-voiced phillipics against Spain and North Carolina. The situation was localized in his estimation. And yet he hesitated, his loyalty to Sevier, whom he had known for only a few hours, holding him back.

Polcher came from the tavern with Lon Hester, and Jackson thrust his thumbs into his belt and strode toward them, thinking it timely to conclude the morning’s one-sided argument. But Polcher said some hurried words to the bully, who turned and hastened down the trail, while the tavern-keeper himself affected to ignore the truculent ranger and strolled toward the court-house. Jackson turned to follow him, only to behold the people pouring from the building. There came staccato commands, and a score of men flew to their horses and rode away.

The Virginian breathed in relief. It was not necessary for him to choose between love and duty. Chucky Jack had rushed matters through with his characteristic energy, and the messengers were off to arrange for the election of delegates. The tavern-keeper, too, was no longer visible, and with nothing to detain him Jackson took the trail to the south, his heart as light as his moccasined feet.

What recked youth in love-time even if the fate of the Anglo-Saxon race in America were at stake! Ever thus does youth help shape the course of political evolution, help win a world without realizing the achievement, and only ask in the midst of astounding events that the heart of a simple maid be won.

The dalliance of the young man’s thoughts blinded him, and his feet followed the rough path unguided by his eyes. Some premonition that she was near was what finally awakened him from his smiling reverie. He halted and threw back his head with a jerk. Tonpit’s commodious cabin stood in from the trail, surrounded by clumps of cedar and bass-wood. Within ten feet of the ranger stood Elsie.

Jackson reddened with confusion. He knew he had been smiling as he came down the trail, and the restrained merriment tugging the corners of her mouth proclaimed her a witness to his deportment. He felt as sheepish as if she had detected him making faces at himself in a mirror.

“Elsie, I’ve come all the way from the Ohio to win the privilege of calling you sweetheart,” he hurriedly greeted.

She cast an apprehensive glance toward the house.

“I like you, Kirk. You know how much,” she wistfully began. “My father—”

“He seemed glad to see me,” he completed as she hesitated.

And he gained her side and took her hands in his.

“He is glad to see few men,” she warned. “He loves me, but to others he’s cold.”

“Politics,” assured Jackson. “Big men always have political bees swarming through their heads. I wouldn’t give a beaver’s pelt for all the political power they can develop in this whole country. I’m a free man, and you’re a free maid, and your politician is a slave. And you must love me, dear.”

“And I’m a free maid, and I must,” she quoted, drawing him out of range of the cabin.

“Elsie, not another step till I know,” he whispered. “I asked myself every step from the falls of the Ohio, but now, you must—please!”

“Then I must if I must,” she murmured, dancing ahead toward a natural arbour.

“Wait!” he cried. “I bring a belt from the Ohio to the dearest little girl in the world. It shows a white road leading to a little cabin, which shall be the happiest home in all the col—I mean the States.”

She seated herself on a log and he kneeled by her side. She remained silent, her eyes averted to hide her glorious confusion.

“I’ve brought my talk,” he whispered. “What does the wonderful little woman say to it? Does she pick up the belt, the white wampum, the one road leading to the cabin?”

“I like your talk,” she confessed. “Oh, I like it more than you can ever know, Kirk. But my father—he won’t let me pick your belt up.”

“I’m not asking your father to marry me,” he reminded.

“Don’t speak in that voice,” she whimpered, wilting against him. “Kirk, dear! I’m miserable. Ever since coming over the mountains I’ve sensed poison in the air.”

He patted her hair and waited for her to continue.

“It’s something I can’t understand. It’s something that keeps my father up all night, walking his room. And yet, when I go to him, it’s to always find him strangely exalted.”

“Politics,” he belittled. “What has that to do with our love?”

She lifted her head and revealed eyes round with fear and warned:

“But it does! It concerns our happiness deeply. Not that he has said anything. Not that his love for me ever changes—”

“Good Lord! Love for you—change?” he gasped.

“I say it hasn’t, you silly. But after the messenger came and we were riding home, he asked me if I would make a sacrifice for him. He didn’t say what but gave me to understand it would be only for a short time. Now I’ll make any sacrifice for my father, only—”

She persisted in her silence, and he gravely prompted—

“Go on, sweetheart.”

“Only I must know it will help him.”

“Tell me what he asked you to do and let me be the judge.”

“He’s asked nothing as yet. I think he plans to tell me tonight. He said something about my understanding everything tonight. Since then he’s been in his room, whistling and singing. Never in my life have I heard him whistle or sing before. And, do you know, he has a beautiful voice—and I never knew it before.”

“When a man can sing and whistle, he can’t be planning to ask much of a sacrifice of his daughter.”

“Oh, I’m not fearing what he may ask. He’s been a good father to me. I must be perfectly loyal to him in my heart. I only wish he didn’t have men come to see him—that is, certain kind of men.”

She gave him an odd look, then, forgetting the house was hidden by the trees, she gazed over his shoulder. He was quick to detect the glint of alarm in her eyes and asked—

“Who’s with him now?”

“Nay, you must not ask me. That would mean I was spying on him. Doubtless I’m very silly. I shall know all tonight. Tomorrow, if we should meet alone, I’ll perhaps be able to tell you.”

“We certainly shall meet alone,” he promised. “But why wait till tomorrow? Why not this afternoon or tonight? I sha’n’t sleep a wink if I have to wait till tomorrow. Why not here?”

“Oh, I couldn’t, Kirk,” she protested. In the next breath she filled him with ecstasy by declaring, “And yet I will if possible. Tonight—come when the moon is clearing the forest, two hours before midnight. He always goes to his room at that hour. I shall be here on the hour and will wait for you, but you mustn’t wait for me. I shall come promptly or not at all.”

“But if I come and you’re not here—” he began complaining.

“Hush, silly. I’ll leave a note on this very log. Don’t wait if I’m not here. Don’t wait if the note is not here. It will simply mean I couldn’t leave the house without disturbing him.”

“Why couldn’t I call at the house?”

“Oh, no! Not at the house,” she hurriedly cried. “Promise?”

“Very well. I’ll come as far as this arbour.”

“Now, don’t be ugly. Some time you can come to a house and know you’ll always find me—”

“You darling!” he softly exulted.

She lifted her head from his shoulder and touched a finger to his lips. A voice was calling her name.

“It’s father,” she warned, unwarrantably alarmed her lover thought.

He made to walk a bit with her, but she gently pushed him back into the arbour. Then, giving him her lips, she ran to the house.

He should have walked the skies as he returned to the settlement, but somehow complete happiness was held in abeyance until he could learn what it was that Tonpit was to ask of his daughter. His peace of mind could not return until he had seen her again and learned the truth. He had worried none while with her, for joy had destroyed perspective and dulled imagination. He had actually lived in the present, taking toll of each delicious minute. Now he was recalling her father’s reputation as a man of mystery.

Back east, before his last trip to the Shawnee country, he had heard strange remarks concerning John Tonpit. Here in Jonesboro the talk was resumed. He could remember when Tonpit was counted a poor man, but now he seemed to be above want. The sordid fact angered him by persisting in invading his speculations. John Sevier had the right of it in saying Tonpit was engaged in a conspiracy—no doubt about that. But it was left for the girl herself to hint that she might be involved in his wretched schemes.

“—— his beastly ambitions!” growled Jackson, turning from the trail and throwing himself under a clump of willows.

He lighted his pipe and smoked it empty before recovering any of his natural optimism. After all, he told himself, a father could not be unnatural with his only child. Tonpit’s mode of address, even when talking to Elsie, was harsh. That characteristic induced one to attach undue significance to his simplest statements. The girl had permitted his solemn assertions to carry too much weight. She had confused the austere vehicle of his spoken thoughts with the simple meaning of his words.

“He’s a queer one,” Jackson admitted as he stowed his pipe preparatory to resuming his walk back to the settlement. “I can imagine the poor child being thrown into a panic by his cold voice announcing it’s going to rain tomorrow.”

He chuckled a bit at this caricature of the maid’s awe, then fell back under the willows as the long shadow of a man fell across the sunlight within a few feet of him. Walking noiselessly, the stealthy figure of Lon Hester swung by.

For a moment Jackson was tempted to accost him and conclude the little argument started in the tavern. But his impulse vanished because of wonderment at the bully’s presence at this end of the settlement. The tavern was his proper habitat. Again he saw Polcher whispering in the bully’s ear and saw the latter set out afoot with the purposeful step of one going on an important errand. Linked up to this recollection was the girl’s statement that her father had a visitor whom she was unwilling to name.

“But it couldn’t have been the tavern brawler,” muttered Jackson, rising and softly following Hester. “Still, Polcher was giving the lout some orders and sent him somewhere. And Sevier says Polcher is a deep one. Polcher showed he was for the Spanish alliance after the messenger came. He and Tonpit have the same fancy, it seems. But Tonpit was there and heard as much as Polcher did. What could happen that needed a message and a messenger? Sevier says all messages are brought to the tavern.

“Almost appears as if the affair was ripe for a sudden blow somewhere, for something decisive to happen—and Tonpit was singing and whistling. Good Lord! What with being thrown off by North Carolina and not yet accepted by the Union, it certainly isn’t any time for the settlers to take on fresh troubles. Reckon I’ve been selfish. I’ll see Chucky Jack and tell him what little I know.”

Making a detour so as to escape the notice of the tavern loungers, Jackson approached the court-house from the east side of the settlement. The town was ominously calm. Small groups of men were quietly talking, and all carried their rifles. As they talked, they looked much at the court-house, where through the windows Sevier could be seen pacing back and forth, his hands clasped behind him, his head bowed. He was one man who carried the entire load of the settlement’s troubles. He was idolized by the men, and there was none who would think of intruding in this his great hour of anxiety.

“Reckon, if Chucky Jack can’t fix things up for us, there ain’t no fixing to be done,” one man spoke up and said to Jackson.

“He’s a great man,” heartily retorted Jackson. “I talked with him this morning for the first time. My name is Kirk Jackson, just returned from the Ohio.”

“My name’s Stetson. My cabin is on t’other side of the court-house. Seen you with him this morning. You’ll eat with us today. Where’s your horse?”

“Broke a leg a few miles out. Had to shoot him,” the ranger sadly informed.

“Shoo! That’s tough. I’ve got several. Help yourself any time. I’ll tell the woman.”

“It’s a —— of a Government that leaves us folks to shift for ourselves,” spoke up another settler, catching Jackson’s eye.

“Seeing how you’ve always shifted for yourselves, I reckon you ain’t worse off than you’ve always been,” smiled Jackson. “And I reckon Jack Sevier’s enough help for one settlement to have. The Indians are awfully scared of him.”

“That’s ’cause they know he won’t wait to fight behind logs,” Stetson broke in eagerly and with great pride. “They know that every time they make a raid he’ll lead us straight into their country for a hundred miles or so and rip —— out of their villages. Nothing takes the fighting guts out of a Injun so much as to hear—while burning a few cabins—that Chucky Jack is back in their towns burning up all their corn. He’s thinking up things now.”

Jackson had halted his advance on the court-house because of the respectful aloofness of the settlers. But now came one who ignored the black frowns, an Indian. He was a Cherokee, and his path was to the court-house.

Suddenly a woman’s shrill voice called from a cabin:

“The murderin’ spy! He’s come to see how we took the bad news!”

“There’s more of his kidney back in the woods!” shouted a man.

The Indian continued his advance. The various groups of men thinned out and formed a half-circle behind him so as to block his threat. The Indian halted and, still gazing at the court-house, threw back his head and sounded the wolf-howl, wa-ya. With muttered imprecations a score of rifles were brought to bear on him, while several men ran back to the forest to scout for a hidden foe. But the signal was intended only for Sevier, who now appeared at the window. A glance took in the situation, the erect form of the red man and the half-circle of menacing rifles. Leaning from the window, Sevier shouted:

“Put down those guns! I’ll answer for the Cherokee!” Then to the savage, “The Tall Runner is welcome.”

Without a glance behind him, the Indian made for the door. Sevier sighted Jackson and beckoned for him to enter.

Sevier was alone in the long room. He motioned for Jackson to remain in the background and, addressing the Indian, said:

“Tall Runner, of the Aniwaya people, is welcome. What talk does the warrior of the Wolf clan bring to me?”

The man of the Wolf, the most powerful clan of the Cherokee Nation, permitted his gaze to kindle with admiration as he looked on Sevier. After a brief silence he began:

“I bring a talk from Old Tassel. He tells me to say to Tsan-usdi (Little John) that he is an old man. He says he is standing on slippery ground. He says his elder brother’s people are building houses in sight of Cherokee towns and that his young warriors grow nervous. He says the white people living south of the French Broad have no right there, and he asks his elder brother to take them away.”

Sevier waited for a minute, then replied:

“This is the talk I send back to Old Tassel. I will meet the Cherokee chiefs in a grand council and fix a place beyond which no settler shall go south of the French Broad and the Holston. Tell Old Tassel that, if he stands on slippery ground, it is because the Indians have wet the ground with the blood of white people, killed while travelling the Kentucky road and while hoeing their fields along the Watauga.

“As for the settlers who have made homes south of the French Broad, they can not now be removed, but, if the chiefs of the Nation will come to a council, we will agree they shall go no farther. The Cherokees know Tsan-usdi wants peace. But there can be no lasting peace so long as the Cherokee Nation listens to the evil whisperings of the Creeks and loads its guns with Spanish powder. Tell Old Tassel it was North Carolina that sent the settlers south of the French Broad, not Little John.”

The Indian remained silent for several minutes, then with a cunning gleam in his eyes continued:

“I will carry your talk to Old Tassel. Who sends the talk? Tsan-usdi or North Carolina? Or does Tsan-usdi speak for North Carolina?”

Sevier’s gaze hardened. He knew Old Tassel had learned of North Carolina’s act of cession. This would imply advance knowledge on the part of the chief. The messenger was sent with a colourless talk, his real errand being to learn how the settlers were reacting to the Cessions Act.

In a voice of thunder he warned:

“Brother of the Wolf, I am going to speak to you. Be wise and remember my words. Tell Old Tassel the talk comes from Little John and his three thousand riflemen. Tell him to forget that the settlements are no longer a part of North Carolina. Tell him he is to remember that the settlers never have had help from North Carolina and have always depended upon their own guns. Tell him our rifles shoot as straight and that our horses run as swiftly as they did a few moons ago. I will send for Old Tassel when I have my council talk ready.”

Tall Runner was somewhat abashed but did not offer to depart. He remained silent and motionless, staring furtively at the one white man the Cherokee Nation feared above all other men. For three centuries the Cherokees had made wars and treaties with the English, the Spanish, the French, the Americans, with Creeks, Catawbas, Shawnees and Iroquois, but in all their campaigns they had never shown so much respect, or fear, for any one individual as they had for John Sevier.

Sevier knew Tall Runner had something on his mind, something he had not intended to speak but was now tempted to divulge. Sternly, yet not unkindly, Sevier prompted:

“My brother of the Wolf has seen something on his way here, or has heard something. He thought at first to bury it deep in his head. Now his medicine commands him to tell it. The ears of Tsan-usdi are open; his heart is open. Does the Tall Runner speak?”

The Indian stood with eyes cast down as if irresolute; finally he lifted his head, succumbing to the personal magnetism of Sevier, a subtle influence that never failed to work on both friend and foe, and said:

“It is not in the talk I brought from our peace town of Echota. It is something I saw on the Great War-Path very near here. A dead man of the Ani-Kusa.”

Sevier’s hands gripped the edge of the table.

“A warrior from the upper Creek towns,” he repeated.

“He was a messenger,” was the laconic correction.

The borderer fully appreciated the grave results sure to follow the slaying of a messenger from McGillivray, Emperor of the Creek Nation. One faint hope remained, that the Creek had fallen by the hand of a Cherokee.

As if reading his thoughts, Tall Runner significantly added:

“The dead warrior was not scalped. He was shot by a white man hiding in ambush. I found where the white man kneeled and waited. I followed his trail back to the settlement. I found where his trail left the settlement and made for the woods.”

There was no doubt in the minds of either Sevier or Jackson as to the identity of the assassin. Major Hubbard, his heart rankling with fanatical hatred for all red men, had left the village for the forest, taking the direction the Cherokee would cover on returning home.

“When was the Creek killed?” quietly asked Sevier.

“The blood had dried.”

“Five hours ago,” muttered Sevier. Then aloud, “How do you know the Creek brought a message for me?”

“Who else would he bring a talk to?” shrewdly countered Tall Runner. “He carried no arms. He was a messenger. His moccasins were worn through because of haste. He had not stopped at any of our villages to get new moccasins. His talk was for the white men. Little John is their chief.”

“And by this time the news of his death is spreading,” Sevier gloomily mused.

“I threw boughs on the body. It may not be seen if Tsan-usdi goes and covers it with earth. If others find it, the word will travel as far as a red ax or a war-belt can travel.” Which was equivalent to saying that McGillivray would surely learn of the killing and seize upon it as pretext for declaring war upon the settlements.

Sevier walked to the window and back. When he halted before the Cherokee, his countenance was placid, and his voice was gentle as he directed:

“Go to Old Tassel and tell him my talk. That I will meet him and his head men and give them a talk; that I wish only for peace and will hold back the whites from going farther on Cherokee lands unless an Indian war makes me use all my riflemen in defending our cabins.”

Finding himself overlooked, Jackson reminded:

“I’m still here. If I’m in the way, I’ll get out. Of course I couldn’t help hearing your talk with the Cherokee.”

“Don’t go,” Sevier replied. “I’m worried about the dead Creek. Tall Runner says he was an Ani-Kusa, from the upper towns. He brought a message from McGillivray. There was no writing on his body, or Tall Runner would have found it and brought it here. That makes two mysteries.”

“I don’t understand,” Jackson confessed. “Two mysteries?”

“Who was to receive McGillivray’s message? Who did receive the message?”

“Isn’t it possible McGillivray is trying to treat with you; that some of the tavern crowd found it out and stole the message and killed the Indian?” Jackson put the query with much animation, the theory growing on him even as he spoke.

“No. McGillivray has spies at the State capital. He knew ahead what the Legislature intended doing before the Cessions Act was passed. He knows he couldn’t swing me into line with Spain. Believing that the Watauga settlements are disowned and helpless, it’s the tavern crowd he’d dicker with.”

“If Hubbard killed him, why didn’t he get the message?”

“I haven’t any doubt as to Hubbard’s killing him. He went in that direction in time to meet the Creek. He left us with blood in his thoughts, cursing all Indians and believing the Chickamaugas are taking the war-path. He saw the Creek and shot him. He never bothered to approach the body, much less to examine it. Either the Creek had delivered the message or it was found on his body by some white man before Tall Runner came along.”

“I saw Hester leave the tavern and go down the trail in that direction right after the messenger brought the news of the Cessions Act,” Jackson informed, his sense of duty overriding his disinclination to say anything that might compromise Tonpit.

“Ah! Hester never quits the tavern unless it’s on important business. But none of that gang would kill a messenger sent them by McGillivray. It’s through him that Spanish gold comes to them. Do you know where Hester went?”

Jackson was deeply embarrassed and felt himself slipping into deep water.

“I don’t know, but I believe he visited John Tonpit. He was afoot and didn’t plan to go far. A short time afterward I saw him coming up the trail. I didn’t see him go to or come from Tonpit’s house.”

“My boy, why not tell it all?” gravely encouraged Sevier.

Jackson made his decision under the compelling gaze of the steady blue eyes and briefly related his meeting Miss Elsie and his knowledge that her father was closeted with a visitor.

“That would explain much!” rapped out Sevier. “McGillivray sent a written message to Major Tonpit. The bearer managed to get it to the tavern. Polcher forwarded it to Tonpit by Hester. If the Creek had taken it direct to the major, he probably would now be alive. But the system is to send all messages to the tavern, where they are relayed without exciting suspicion. That Polcher is a deep one. He’s a natural conspirator. He loves underhanded methods. He must be an able man to hide his real self in the rôle of a tavern-keeper.

“Tonpit couldn’t do that. He’s insanely ambitious. He must always have a dignified part to play. Useful at a certain point when his dignity fits in, such as influencing some of our settlers to follow his lead, but incapable of continual plotting. He’s just a fool figurehead. Yes, I’m convinced Polcher is the more dangerous man of the two.”

Jackson hesitated and twisted nervously. His sympathies were entirely with the settlement. Although he had known Sevier for a few hours only, he was eager to serve him. Finally he blurted out:

“I expect to see Miss Elsie tonight. Naturally I don’t care to set her father against me, but, if I learn anything that’s all right for me to repeat, I’ll tell you.”

Leaning forward, Sevier swept his flaming gaze up and down the ranger’s trim form in mingled anger and scorn.