The Commonwealth of Massachusetts.

A REPORT

UPON

The Mollusk Fisheries

OF

MASSACHUSETTS.

BOSTON:

WRIGHT & POTTER PRINTING CO., STATE PRINTERS,

18 Post Office Square.

1909.

The Project Gutenberg EBook of A Report upon the Mollusk Fisheries of Massachusetts, by Commissioners on Fisheries and Game This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook. Title: A Report upon the Mollusk Fisheries of Massachusetts Author: Commissioners on Fisheries and Game Release Date: February 8, 2015 [EBook #48195] Language: English Character set encoding: ASCII *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK REPORT--MOLLUSK FISHERIES MASSACHUSETTS *** Produced by Richard Tonsing, Sandra Eder and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

The cover image was created by the transcriber and is placed in the public domain.

BOSTON:

WRIGHT & POTTER PRINTING CO., STATE PRINTERS,

18 Post Office Square.

1909.

Approved by

The State Board of Publication.

Commissioners on Fisheries and Game,

State House, Boston, Jan. 15, 1909.

To the Honorable Senate and House of Representatives.

We herewith transmit a special report upon the mollusk fisheries of Massachusetts, as ordered by chapter 49, Resolves of 1905, relative to scallops; chapter 73, Resolves of 1905, relative to oysters; chapter 78, Resolves of 1905, relative to quahaugs; and chapter 93, Resolves of 1905, relative to clams.

Respectfully submitted,

G. W. FIELD,

Chairman.

The Commonwealth of Massachusetts.

Report on the Mollusk Fisheries of Massachusetts.

Introduction.

The Shellfisheries of Massachusetts: Their Present Condition and Extent.

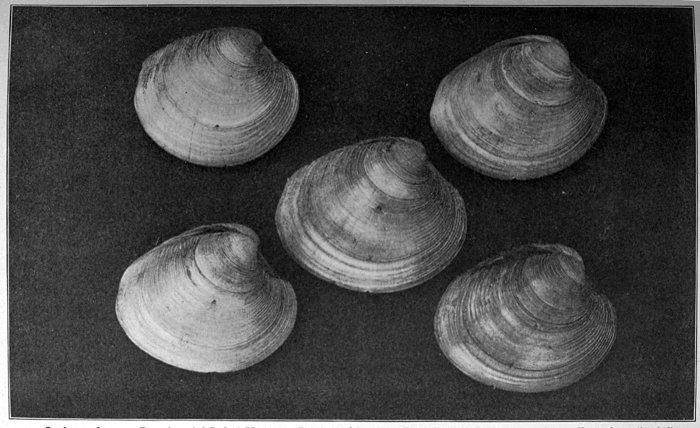

Quahaug (Venus mercenaria).

Scallop (Pecten irradians).

Oyster (Ostrea Virginiana).

Clam (Mya arenaria).

Index.

Transcriber's Notes

REPORT ON THE MOLLUSK FISHERIES OF MASSACHUSETTS.

The general plan of the work was outlined by the chairman of the Commission on Fisheries and Game, who has given attention to such details as checking up scientific data, editing, revising, and confirming results, reports, etc. The work has been under the direct charge and personal supervision of the biologist to the commission, Mr. D. L. Belding. The able services of Prof. J. L. Kellogg of Williams College were early enlisted, and many valuable results which we are able to offer are the direct outcome of the practical application of the minute details discovered by Professor Kellogg in his careful study and original investigations of the anatomy and life histories of the lamellibranch mollusks.

Of the other workers who, under the direction of Mr. Belding, have contributed directly, special mention should be made of Mr. J. R. Stevenson of Williams College, W. G. Vinal of Harvard University, F. C. Lane of Boston University, A. A. Perkins of Ipswich and C. L. Savery of Marion. Those who have for a briefer time been identified with the work are R. L. Buffum, W. H. Gates and K. B. Coulter of Williams College, and Anson Handy of Harvard University.

In addition to the results here given, much valuable knowledge has been acquired, particularly upon the life histories of the scallop and of the quahaug, and the practical application of this knowledge to the pursuit of sea farming. It is hoped that the commission will later be enabled to publish these results.

The present report is limited to a statement of the condition of the shellfish in each section of our coast, and to consideration of practical methods for securing increased opportunities[Pg 4] for food and livelihood by better utilization of naturally productive lands under water. Since the chief purpose of legislative action under which this work was undertaken was to ascertain how the best economic results could be secured, we have thought it wise to embody the results of our investigation in a plan which is suggested as a basis for appropriate legislation for making possible a suitable system of shellfish cultivation similar to that which already exists in Rhode Island, Connecticut and many other coast States, and which has been carried on for more than two thousand years on the shores of the Mediterranean Sea.

The following tentative outlines are offered, and it is intended to subject each topic to an unprejudiced examination and discussion:—

The Purpose.—The proposed system of shellfish culture aims to develop the latent wealth of the tidal waters, to increase the output of tidal flats already productive, and to make possible the reclamation of large portions of the waste shore areas of our Commonwealth. It is further designed to foster dependent and allied industries; to extend the shellfish market, both wholesale and retail; to multiply opportunities for the transient visitors and shore cottagers to fish for clams and quahaugs for family use, and to ensure fishermen a reliable source of bait supply; to increase the earnings of the shore fishermen, and to furnish work to thousands of unemployed; to increase the value of shore property; to add to the taxable property of the shore towns and cities of the State; to secure to all the citizens of the State a proper return from an unutilized State asset; to furnish the consuming public with a greater quantity of sea food of guaranteed purity; and in every way, both in the utilization of present and in the creation of new resources to build up and develop the fast-declining shellfish industries of the Commonwealth.

Private v. Public Ownership of Tidal Flats.—The first difficulty confronting this proposed system is the too frequently accepted fallacy that all lands between the tide marks now are[Pg 5] and should be held in common by the inhabitants of the shore communities, to the exclusion of citizens from other sections of the State,—an assumption which is directly contrary to the more ancient law, supported by decisions of the highest courts, that the right of taking shellfish is a public right, freely open to any inhabitant of the State. Such unwarranted assumption of exclusive rights in the shellfisheries by individuals, corporations or towns sacrifices the rights of the majority. The disastrous effect of this policy is plainly demonstrated in the history of the rise and decline of the shellfisheries of Massachusetts.

Secondly, this fallacious assumption is contrary to the fundamental principles of all economic doctrines. It may be safely affirmed that the individual ownership of property has proved not only a success but even is a necessary condition of progress, and has in fact at length become the foundation of all society. It inevitably follows that if the system is justifiable in the case of farm lands it is equally justifiable in the case of the tidal flats, for the same principle is involved in each. It is therefore fair to assume that if private ownership of farm land has proved to be for the best interests of human progress, so private ownership of the tidal flats will also be a benefit to the public.

It is not our purpose to discuss the underlying principle involved in private ownership of property,—it is simply our purpose to call attention to two facts: (1) if individual control of real estate is just, private ownership of tidal flats and waters is likewise just; (2) that individual control of such areas is the only practical system yet devised capable of checking the alarming decline in the shellfisheries and of developing them to a normal state of productiveness, and rendering unnecessary an annually increasing mass of restrictive legislation.

The Present System.—The present system of controlling the shellfisheries is based on the communal ownership of the tidal flats. Ownership by the Commonwealth has degenerated into a system of town control, whereby every coast community has entire jurisdiction over its shellfisheries, to the practical exclusion of citizens of all other towns. Thus at the present time the mollusk fisheries of Massachusetts are divided into a number of separate and disorganized units, which are incapable[Pg 6] of working together for the best interests of the towns or of the public. This communistic system is distinctly unsound, and is in direct opposition to the principles of social and economic development. The man who advocates keeping farm lands untilled and in common, for the sake of the few wild blackberries they might produce, would be considered mentally unbalanced; but it is precisely this system which holds sway over our relatively richer sea gardens. With no thought of seed time, but only of harvest, the fertile tidal flats are yearly divested of their fast-decreasing output by reckless and ruthless exploitation, and valuable territories when once exhausted are allowed to become barren. All hopes for the morrow are sacrificed to the clamorous demands of the present. The more the supply decreases, the more insistent becomes the demand; and the greater the demand, the more relentless grows the campaign of spoliation. The entire shore front of the Commonwealth is scoured and combed by irresponsible aliens and by exemplars of the "submerged tenth" who are now but despoilers, but who if opportunity were present might become cultivators of the flats rather than devastators. The thoughtful fisherman, who would control the industry in a measure, is under present conditions overruled by his selfish or short-sighted fellow workers, and is of necessity forced to join their ranks by the clinching argument that if the shellfisheries are to be ruined anyway, he might as well have his share as long as they last. The theory of public ownership of shellfisheries has been weighed in the balance and found wanting. The necessity for some radical change in the present system is becoming more and more apparent, and a system of private control, with certain modifications, is the logical result.

Need of Reform.—The shellfish supply of Massachusetts is steadily declining. So extensive is this decline that it is unnecessary to mention the abundant proofs of almost complete exhaustion in certain localities and of failing output in others. While the apparent cause of this decrease is overfishing and unsystematic digging, the real cause can be readily traced to the present defective system of town control, which has made possible, through inefficiency and neglect, the deplorable condition of this important industry. Unless the de[Pg 7]cline is at once checked, within a very few years our valuable shellfisheries will be exhausted to the point of commercial extinction. The legislation of former years, essentially restrictive and prohibitory in character, has unfortunately been constructed on a false economic basis. Its aim has been to protect these industries by restricting the demand rather than by increasing the supply. What the future requires is not merely protective or restrictive legislation, but rather constructive laws for developing the shellfisheries. The system of shellfish culture here presented appears to be the only practical method for improving the condition of these industries in such a way as to protect all vested interests of both private and public rights, and at the same time to make possible adequate utilization of the natural productive capacity.

In brief, the proposed system of shellfish culture is based upon a system of leases to individuals. These leases should be divided into two classes: (1) those covering the territory between the tide lines, and consisting of small areas, from 1 to 2 acres; (2) the territory below low-water mark, comprised of two classes of grants, which differ only in size and distance from the shore,—the smaller (a), from 1 to 5 acres, to include the shore waters, small bays and inlets, and the larger (b), of unrestricted size, to be given in the deeper and more exposed waters. The owners of all grants shall be permitted to plant and grow all species of shellfish, and shall have exclusive control of the fisheries area covered by such lease. The large and more exposed grants, which cannot be economically worked without considerable capital, should be available for companies; while the smaller holdings, for which but small capital is required, are restricted to the use of the individual shore fishermen. For the tidal flats and shore waters but one-half of the whole territory in any one township shall be leased, the other half still remaining public property.

Success of this System.—The system of private control by leased grants is by no means a new and untried theory. In actual operation for many years in this and other States, in spite of lack of protection and other drawbacks which would be eliminated from a perfected system, it has proved an unqualified success. The rapid depletion and even extermination[Pg 8] of the native oyster beds necessitated legislative consideration, and for years the oyster industry above and below low-water mark in this and other States has been dealt with by a similar system. The plan here suggested would be but a direct extension of a well-tested principle towards the cultivation of other species of mollusks. The financial value to the fishermen of such a step has been proved beyond all question in this State during the past three years by the demonstrations of the Massachusetts department of fisheries and game. These experiments have proved that tidal flats, with small outlay of capital and labor, will yield, acre for acre, a far more valuable harvest than any upland garden.

This system has the further element of success by being based on individual effort, in contrast to the present communal regulation of shellfisheries. In all business individual initiative and effort furnish the keynote of success, and the future wellfare of the shellfisheries depends upon the application of this principle.

Nature cannot without the aid and co-operation of man repair the ill-advised, untimely and exhaustive inroads made in her resources. This is shown in the thousands of acres of good farm lands made unproductive by unwise treatment, and by the wasteful destruction of our forests. It is as strikingly shown in the decline of our shellfisheries. The fisherman exhausts the wealth of the flats by destroying both young and adults, and returns nothing. The result is decrease and ultimate extermination. The farmer prepares his land carefully and intelligently, plants his seed and in due time reaps a harvest. If the fisherman could have similar rights over the tidal areas, he could with far less labor and capital and with far greater certainty year by year reap a continuous harvest at all seasons. The success of the leasing system in other States, notably Louisiana, Rhode Island and others, is definite and conspicuous.

The Obstacles to this Proposed System.—Before the proposed system of titles to shellfish ground can be put in actual operation, it is absolutely necessary to have all rights and special privileges pertaining to shore areas revested in State control by repeal of certain laws. In this centralization of author[Pg 9]ity four main factors must be carefully considered: (1) communal rights to fisheries in tidal areas, as in the colonial beach law of 1641-47; (2) the theory, practice and results of town supervision and control; (3) the rights of riparian owners; (4) the rights of the fishermen and of all other inhabitants of the State. So important are all four that it is necessary to discuss each in turn.

(1) Communal Fishery Rights of the Public.—The fundamental principle upon which the shellfish laws of the State are founded is the so-called beach or free fishing right of the public. While in other States shore property extends only to mean high water, in Massachusetts, Maine and Virginia, the earliest States to enact colonial laws, the riparian property holders own to mean low-water mark. But by specific exception and according to further provisions of this same ancient law the right of fishing (which includes the shellfisheries) below high-water mark is free to any inhabitant of the Commonwealth. The act reads as follows:—

Section 2. Every inhabitant who is an householder shall have free fishing and fowling in any great ponds, bays, coves and rivers, so far as the sea ebbs and flows within the precincts of the town where they dwell, unless the freemen of the same town or the General Court have otherwise appropriated them.

It is necessary that some change be made in this law, which at present offers no protection to the planters. Its repeal is by no means necessary, as the matter can be adjusted by merely adding "except for the taking of mollusks from the areas set apart and leased for the cultivation of mollusks."

(2) Results of Town Administration of Mollusk Fisheries.—All authority to control mollusk privileges was originally vested in the State. The towns, as the ancient statutes will show, derived this authority from the higher State authority, developed their systems of local regulations or by-laws only with the State permission, and even now they enjoy the fruits of these concessions solely with the active consent of the Legislature. Thus the State has ever been, and is at present, the source of town control. The towns have no rights of supervision and control over shellfisheries except as derived from the General Court.[Pg 10] The State gave them this authority in the beginning. It follows, therefore, that the Legislature can withdraw this delegated authority at any time when it is convinced that it is for the benefit of the State so to do. To those few who are directly profiting at the expense of the many, this resumption of authority by the State may seem at first sight a high-handed proceeding, but a brief survey of the facts will prove it to be justly warranted and eminently desirable. The present system of town control has had a sufficient trial. It is in its very essentials an un-business-like proceeding. A large number of towns acting in this matter as disorganized units working independently of one another could not in the nature of things evolve any co-ordinated and unified system which would be to the advantage of all. The problems involved are too complicated, requiring both broad and special knowledge, which cannot be acquired in a short term of experience. Lastly, the temptations of local politics have been found to be too insistent to guarantee completely fair allotment of valuable privileges.

The Legislature has not only acted unwisely in allowing the towns in this respect thus to mismanage their affairs, but it has not fulfilled its duty to the Commonwealth as a whole. The Legislature has unwittingly delegated valuable sources of wealth and revenue, the fruits of which should have been enjoyed at least in some degree, directly or indirectly, by all citizens of the Commonwealth alike as well as by those of the coast towns. Many of the coast cities and towns have dealt with this opportunity very unwisely, and few have developed or even maintained unimpaired this extremely valuable asset of the State. It cannot be too strongly emphasized that such important sources of wealth as the shellfisheries are not the property of the coast towns alone; they are the property of the whole Commonwealth, and the whole Commonwealth should share in these benefits. In allowing these valuable resources to be mismanaged and dissipated by the shore towns, the Legislature has done a great injury to all the inland communities, and, indeed, even to those very coast towns for whose benefit such legislation was enacted. The Legislature was not justified, in the first place, in granting jurisdiction over these important industries belonging equally to the whole Commonwealth and to the coast towns.[Pg 11] It was but an experiment. Inasmuch as these towns have grossly mismanaged the trust placed in them, the Legislature is doubly under the obligation to take advantage of the knowledge gained by this experimental delegation of the State authority to cities and towns. The completely obvious obligation of the Legislature is to remove what is either tacitly or frankly acknowledged by many city and town authorities to be an impossible burden upon the city or town, and to restore to State officers the general administrative control and supervision of the public rights in the shellfisheries.

(3) Riparian Ownership does not include Exclusive Fishing Rights.—The third objection is that in the assumption of State control is involved the much-discussed and vaguely understood question of riparian ownership. To make plain the conditions relative to the fisheries, including the shellfisheries on the tidal flats, it should be borne in mind that in only four States, Virginia and Maryland, Massachusetts and Maine, does the title of the riparian owner extend to low-water mark, but in these States the right of fishing, fowling and boating are specifically mentioned as not included in the title. Under the existing laws owners of seashore property in Massachusetts possess certain rights (though perhaps not in all cases clearly defined) over the tidal areas within 100 rods of the mean high-water mark. As the proposed system of shellfish grants deals with this territory between high and low water marks, it is necessary to see in what manner, if any, the rights at present possessed by riparian owners would be impaired by the leasing of certain rights of fishing. While the riparian owner has in a measure authority over the territory which borders his upland, there are certain specific limitations to this authority. He does not have exclusive rights of hunting, boating and fishing between the tide lines on his own property, but participates in these rights equally with every citizen of this Commonwealth. The courts have distinctly held that shellfish are fish, and that a man may fish—i.e., dig clams—on the tidal flats adjoining the shore without the consent of the riparian owner.

(4) Rights of the Fishermen and of All Citizens.—The fishermen as a class are best located to benefit most from an opportunity to lease exclusive fishing rights, whether they chance[Pg 12] to be riparian owners or not, though every other citizen of this Commonwealth who so desired would not be excluded from an opportunity to secure a similar lease. The personnel of the fisher class has vastly changed in the past decade. There are to-day two distinct types: The permanent resident, usually native born, bound to a definite locality by ties of home and kin and of long association,—a most useful type of citizen. Contrasted with this is the other, a more rapidly increasing class,—foreign born, unnaturalized, nomadic, a humble soldier of fortune, a hanger-on in the outskirts of urban civilization, eking out an existence by selling or eating the shellfish from the public fishing grounds. Too ignorant to appreciate the importance of sanitary precaution, the alien clammer haunts the proscribed territory polluted by sewage, and does much to keep the dangerous typhoid germ in active circulation in the community.

The public mollusk fisheries only foster such types of non-producers, and prevent them from becoming desirable citizens. The best class of fishermen and citizens has no advantage over the worst, but is practically compelled to engage in the same sort of petty buccaneering and wilfully destructive digging, in order to prevent that portion and privilege of fishing which the law says shall belong to every householder and freeman of the Commonwealth from being appropriated by these humble freebooters, who are at once the annoyance, the terror and the despair of cottagers and shore dwellers.

All these conditions would be almost completely corrected by the lease of the flats to individuals, thus removing from the fishermen stultifying competition and compelling these irresponsible wandering aliens to acquire definite location. But most particularly a system of leasing would permit each person to profit according to his industry, perseverance, thrift and foresight.

The Grants.—As previously stated, the grants should be made into two divisions: (1) including suitable areas between the high and low water marks; (2) territory below mean low-water mark. The privilege of planting and growing all shellfish should be given for both classes of grants. Class 1 would be primarily for the planting of clams, with additional[Pg 13] rights over oysters and quahaugs; class 2 would be primarily for the planting of quahaugs and oysters, with possible rights over clams and scallops.

The grants should be leased for a limited period of years, with the privilege of renewal provided the owner had fulfilled the stipulated requirements of the lease. In order, however, that these leases should not degenerate into deeds, to be handed down from father to son, it might be necessary to assign a maximum time limit during which a man might remain in control of any particular lease. This would be merely fair play to all concerned, for it would not be just to allow one man to monopolize a particularly fine piece of property, while his equally deserving neighbor had land of far less productive value. In connection with this clause should follow some provisions for payment of the value of improvements. Should there be more than one claimant for lease of any particular area, some principle of selection, such as priority of application, highest bid, etc., should be established.

That there may be no holding of grants for purposes other than those stipulated in the agreement, there should be a certain cultural standard of excellence to be decided upon relative to the use made of the granted areas. A clause of this kind is necessary in order to keep the system in a proper state of efficiency, and to insure the development of the shellfish industries.

All taxes on the capital invested in these grants and taxes upon the income should go to the town in which the leasehold is situated. In addition, there should be a just and equable revenue assessed by the State on every grant, as rent for the same. This rent should be apportioned according to a fixed scale in determining the relative values of the grants, and should be paid annually, under penalty of forfeiture. The revenue might be divided into two parts: one part to go to the State department having the control of the shellfisheries, for the maintenance of a survey, control and protection of property on leased areas, and other work; the second part to go to the town treasury of the community in which the grant is located, to be expended under the direction and control of responsible State officials in restocking barren flats and otherwise develop[Pg 14]ing the shellfish upon its unleased territory which is open for free public use.

Grants to be Nontransferable.—These grants, while designed for the use of all citizens of the Commonwealth, should be made especially available for the poor man with little capital. In order to assure the poor man of the enjoyment of his privilege, it is necessary to guard against the possibility of undue monopolization. Leases must, therefore, be strictly nontransferable. Neither should areas be rented to another individual under any consideration whatever. Every grant must be for the benefit of its individual owner. He should be at liberty to hire laborers to assist him in working his grant, but not to transfer it in any way. Any attempt on his part to do so should not only immediately result in the forfeiture of his grant, but should also subject him to a heavy penalty.

Survey.—In order to guard against confusion and to maintain an orderly system, an accurate survey of all granted areas should be made. The ranges of every grant should be determined and recorded. The plots should be numbered and properly staked or buoyed, and a record of the same, giving the name of the owner, yearly rental and value, should be kept on file at the proper town and State offices. The same system which is now in operation in the oyster industry of other States should be applied to all the mollusk fisheries of Massachusetts.

Administration.—The department of the State government under whose jurisdiction this system of leases may come should be indued with full authority, properly defined, to supervise the grants, furnish them with adequate protection by the employment of State or town police, oversee the survey, allot the grants, and to exercise such other powers as may be necessary to develop the system, remedy its defects and strengthen its efficiency.

Protection of Property and of the Rights granted by the Lease.—No system of shellfish grants is possible without absolute protection. The lessee must be permitted to cultivate his grant free from outside interference, and thus, with reasonably good fortune, he can enjoy the fruits of his labors. This protection, which is the greatest and most vital need of the[Pg 15] entire system, and the foundation upon which depends its whole success, must be insured by proper legislation rigorously enforced, and accompanied by severe penalties.

Leasing of the Grants.—Every citizen of the Commonwealth is entitled to participate in this system, but for obvious reasons an inhabitant of any coast town should be given first choice of grants within the boundary of his particular town. The first grants might be given by allotment, but after the system had become well established, they could be issued in the order of their application.

Water Pollution.—The sanitary condition of the marketed shellfish taken from contaminated waters is not only at present to some extent endangering the public health, but is placing an undeserved stigma upon a most reputable and valuable source of food supply for the public. The public should demand laws closing, after proper scientific investigation, these polluted areas, and conferring the power to thoroughly enforce such laws. The danger arising from contamination should be reduced to a minimum by prescribing some definite regulations for transferring shellfish from these polluted waters to places free from contamination, where the shellfish may in brief season be rendered fit for the market.

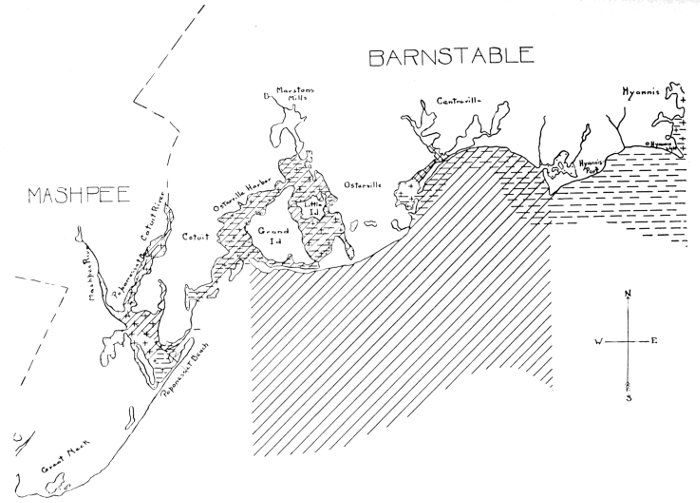

It should be unlawful to use any brand, label or other device for designation, intended to give the impression that certain oysters offered for sale were grown at specified places, e.g., Cotuit, Wellfleet, Wareham, etc., unless such oysters were actually planted, grown or cultivated within the towns or waters designated, for a period of at least three months immediately previous to the date of marketing. Furthermore, there should be appointed proper inspectors, whose duties would be to guarantee by certificates, labels and stamps the purity of shellfish placed upon the market, and likewise have the power of enforcing severe penalties on violators.

By D. L. Belding, assisted by F. C. Lane.

Dr. George W. Field, Chairman, Commission on Fisheries and Game.

Sir:—I herewith submit the following report upon the present extent and condition of the shellfish industries of Massachusetts. The following biological survey was made in connection with the work done under chapters 49, 73, 78 and 93, Resolves of 1905, and chapter 74, Resolves of 1906. The statistics and survey records which furnish the basis of the report were obtained by D. L. Belding and F. C. Lane.

Respectfully submitted,

David L. Belding,

Biologist.

When money was first appropriated in 1905 for a three-year investigation of the life, habits and methods of culture of the clam, quahaug, oyster and scallop, provision was made for a survey of the present productive and nonproductive areas suitable for the cultivation of these four shellfish. The following report embodies the results of this survey.

A. Method of Work.—In making this survey two objects were in view, which permit the grouping of the work under two main heads:—

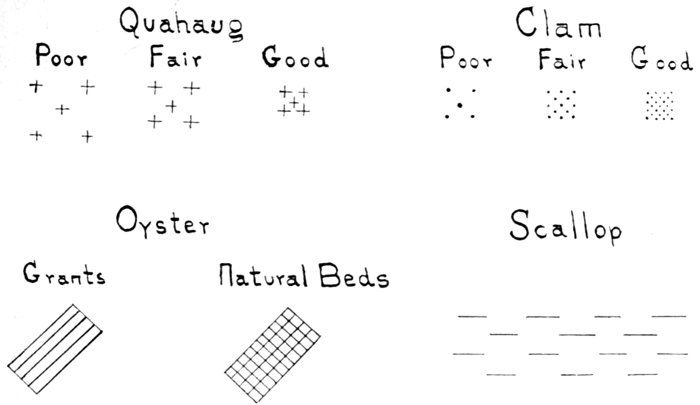

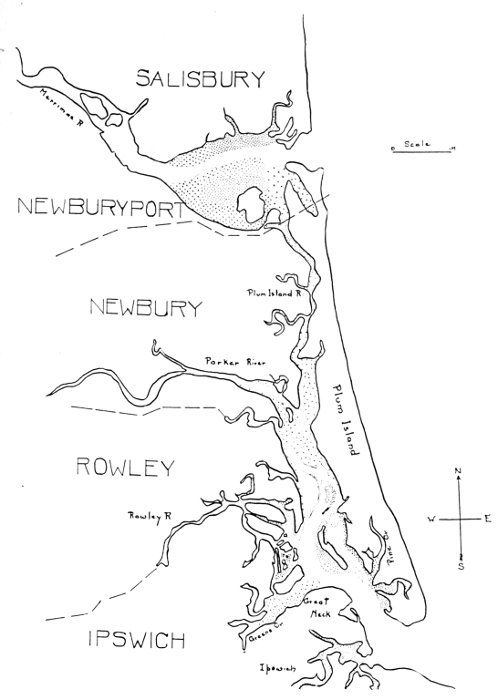

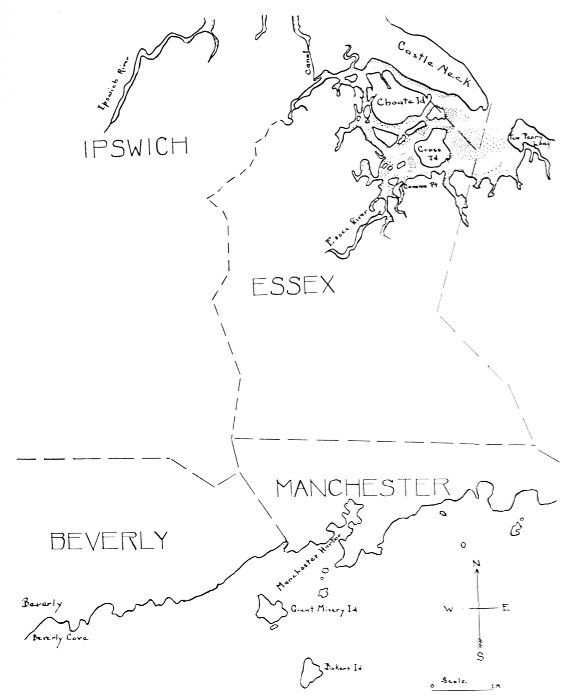

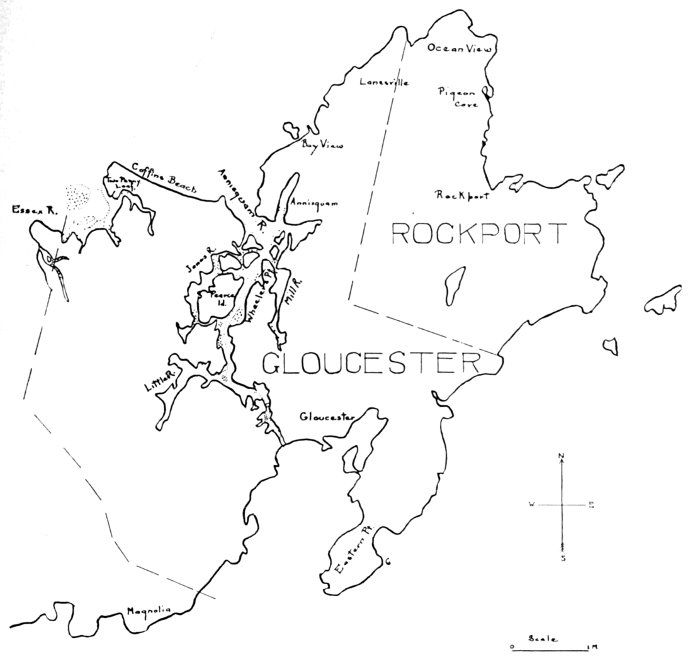

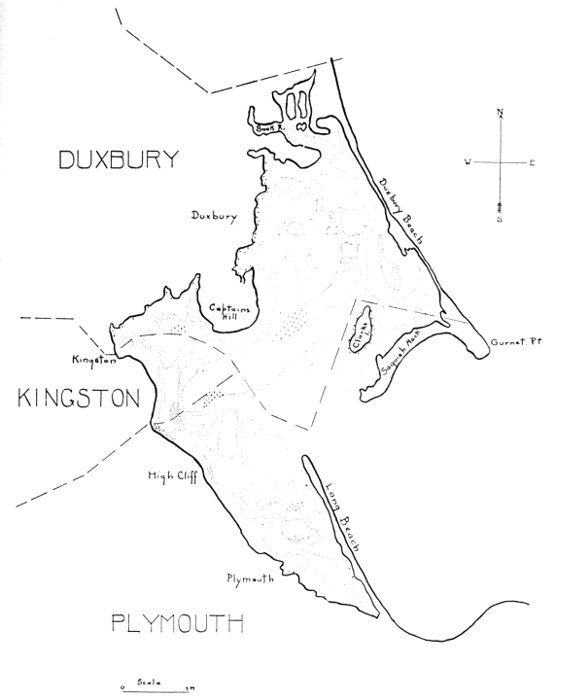

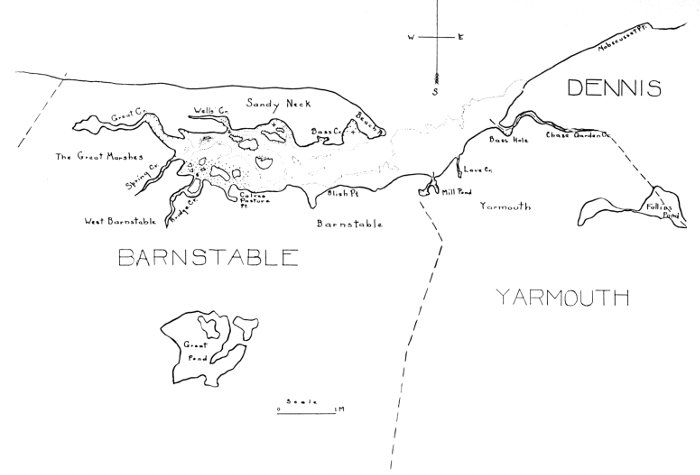

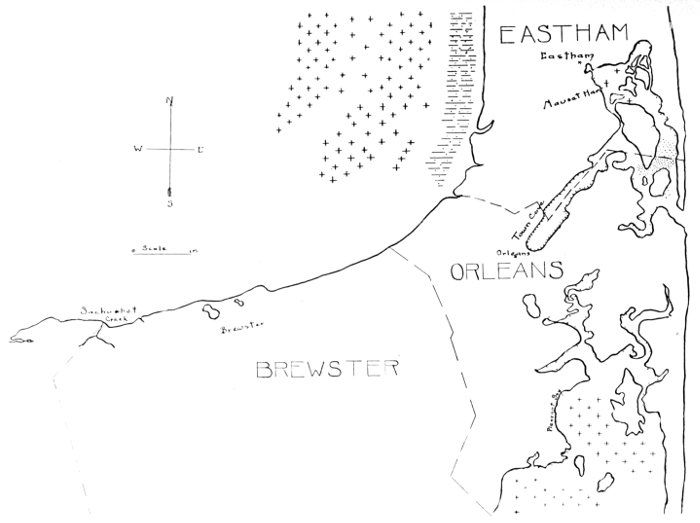

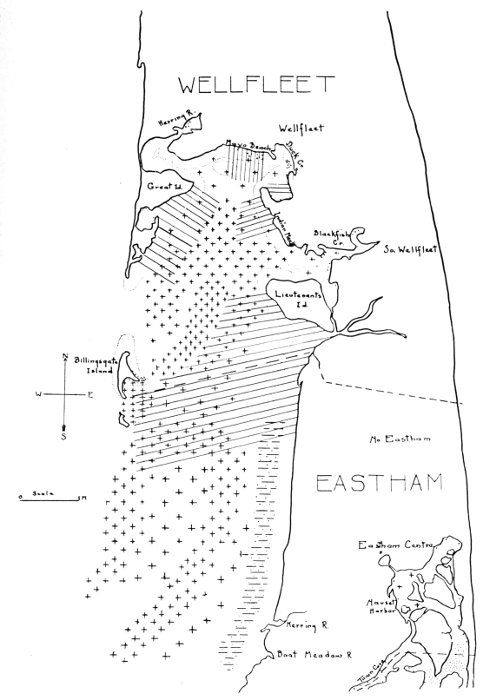

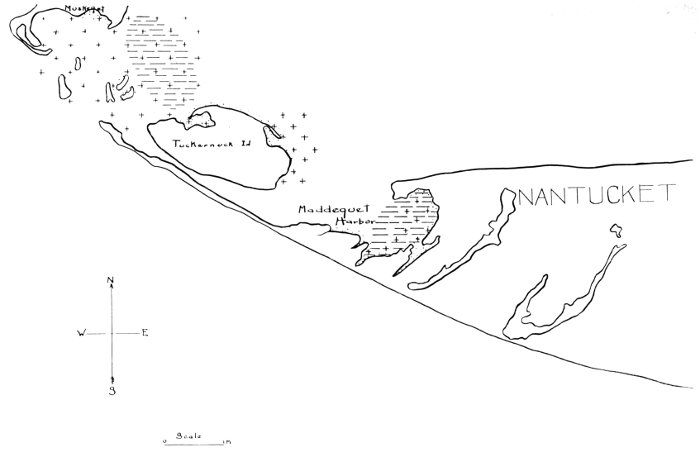

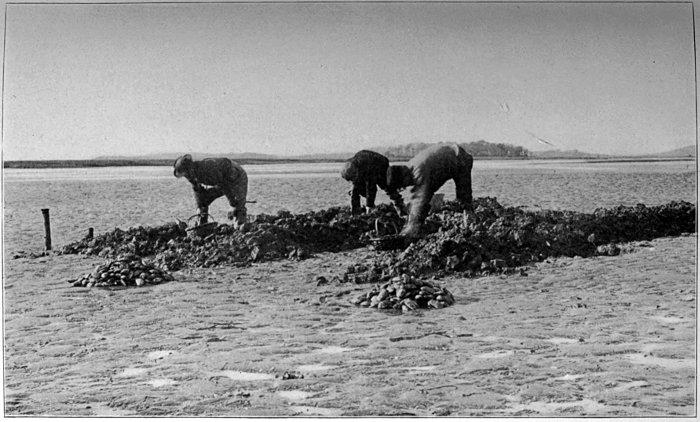

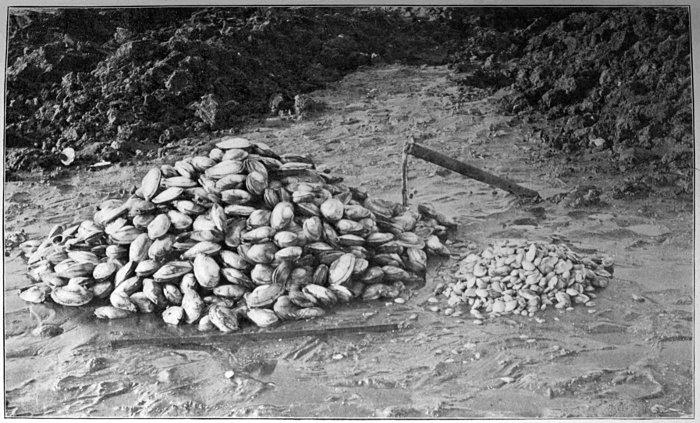

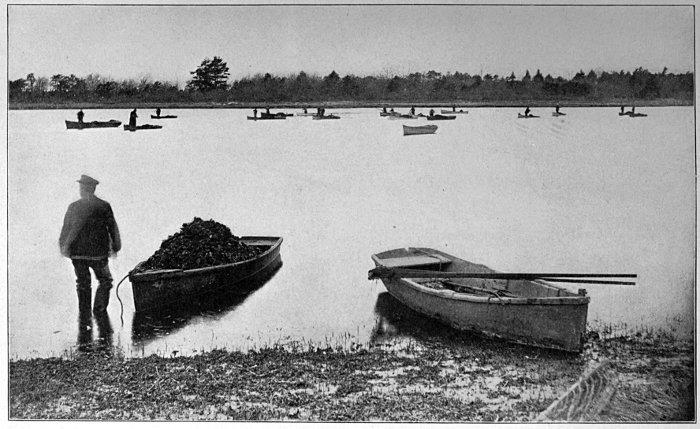

(1) A survey of the productive and nonproductive shellfish areas of the State was undertaken, showing by charts the location, extent and abundance of each of the four shellfish, as well as the biological conditions of the waters and soils of the areas along the entire coast which could be made more productive under proper cultural methods. Wherever possible, information as to the production of certain areas was obtained from the shellfishermen as a supplement to the survey work.

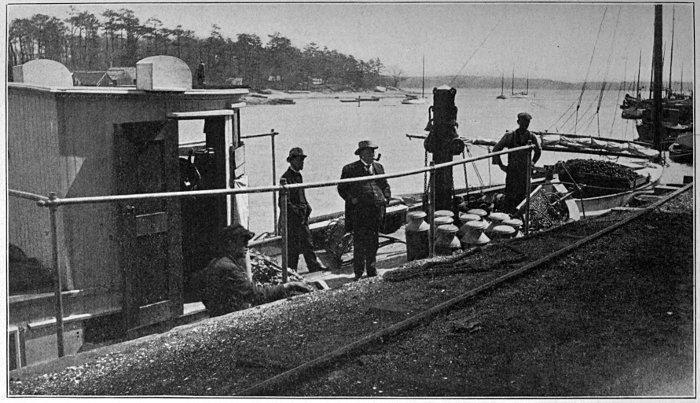

(2) Statistical records of the four shellfish industries were formulated, showing their value and extent as regards (a) production, (b) capital invested, (c) men employed. Data for these records were obtained from town records, from market reports and from the dealers and shellfishermen, both by personal interviews and by tabulated forms of printed questions. Owing to the present chaotic condition of the shellfisheries, it has been impossible to obtain absolutely exact data. The statistics that have been obtained are to all purposes correct, and are the most exact figures ever published on the subject.

B. Value of the Survey.—Before any reform measures of practical value can be advanced, accurate and comprehensive knowledge of the present shellfish situation in Massachusetts is absolutely essential.[Pg 17] Up to this time there have been only vague and inaccurate conjectures as to the value of the shellfisheries, and even the fisherman, outside his own district, has little knowledge of their extent and their economic possibilities. The consumer has far less knowledge. For the first time this problem of the Massachusetts shellfisheries has been approached from the point of view of the economic biologist. This survey is intended to present a concise yet detailed account of the present status of the shellfisheries of Massachusetts, and is therefore the first step towards the preservation of our shellfisheries by providing a workable basis for the restocking of the barren and unproductive areas. It is hoped that it will be of interest both to the fishermen and consumers.

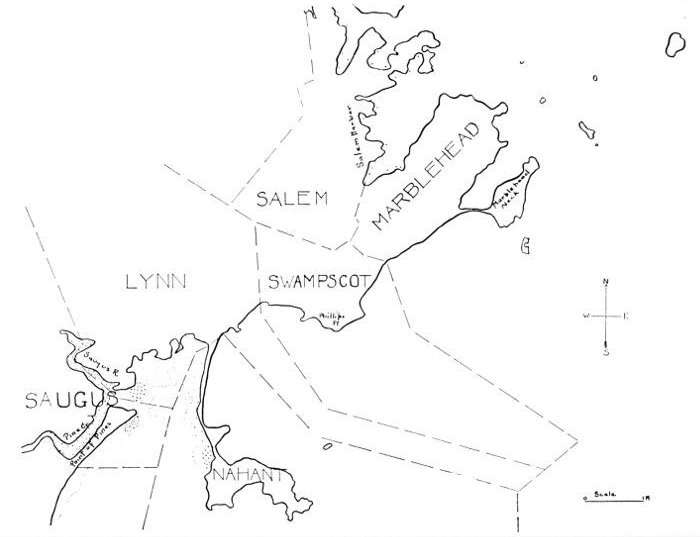

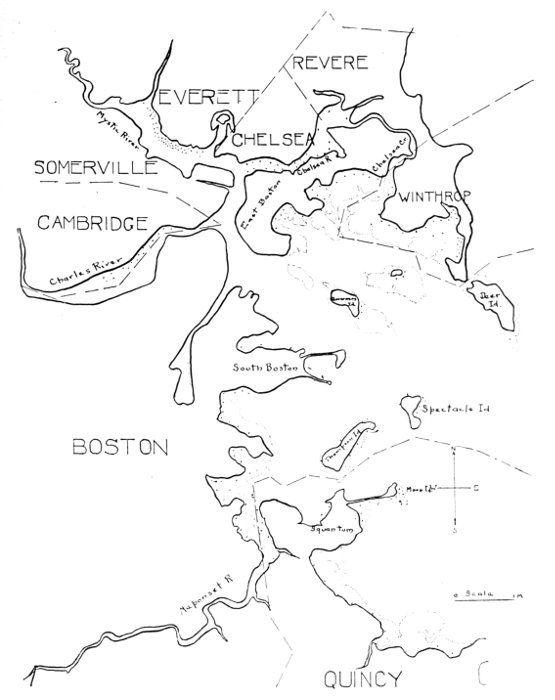

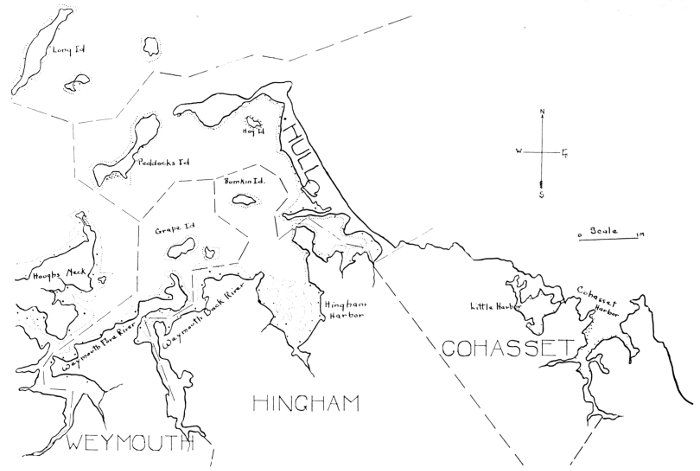

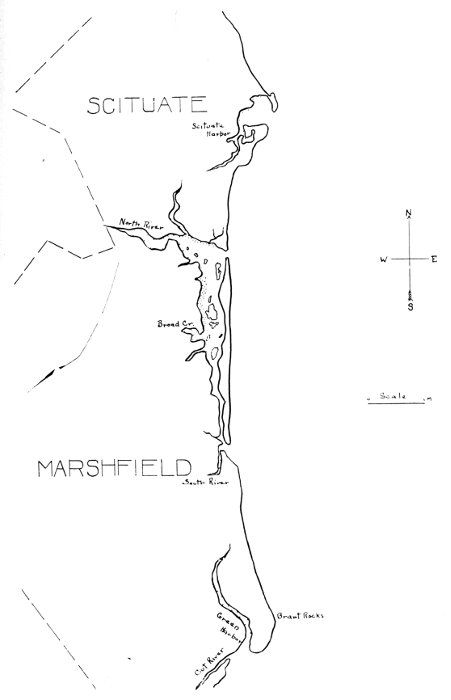

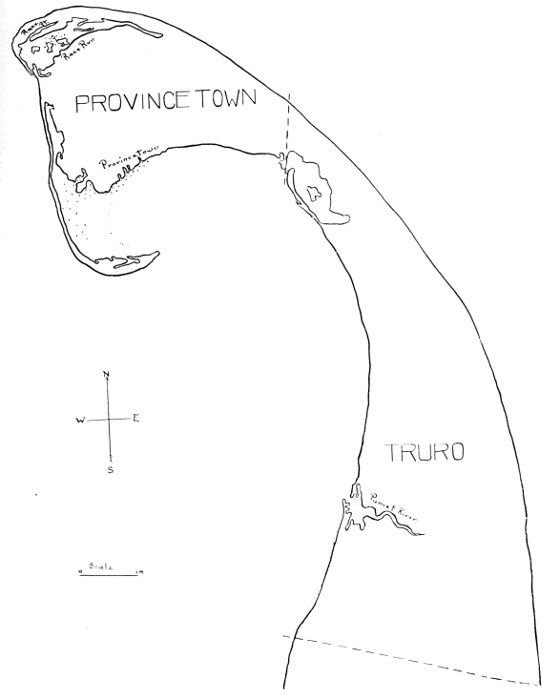

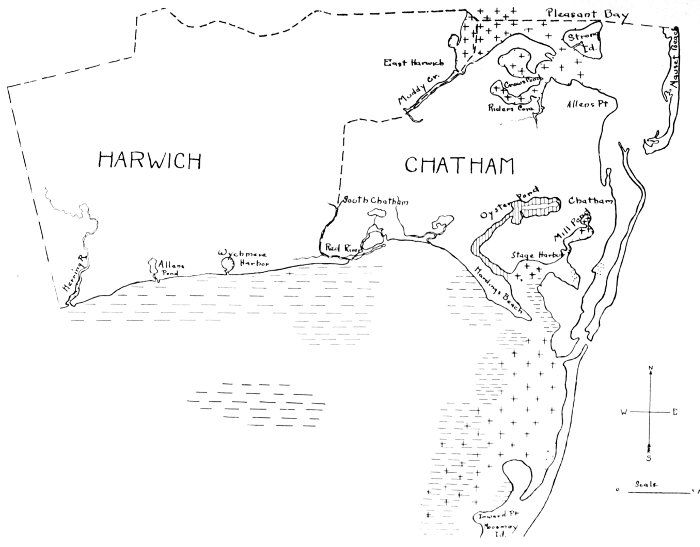

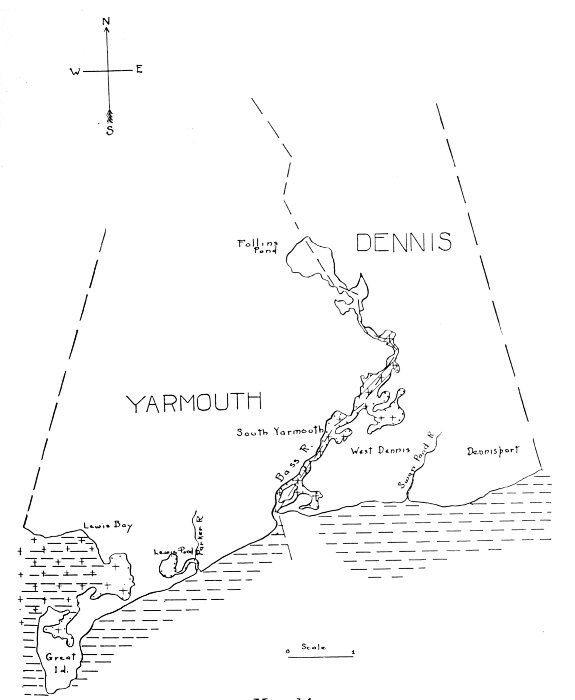

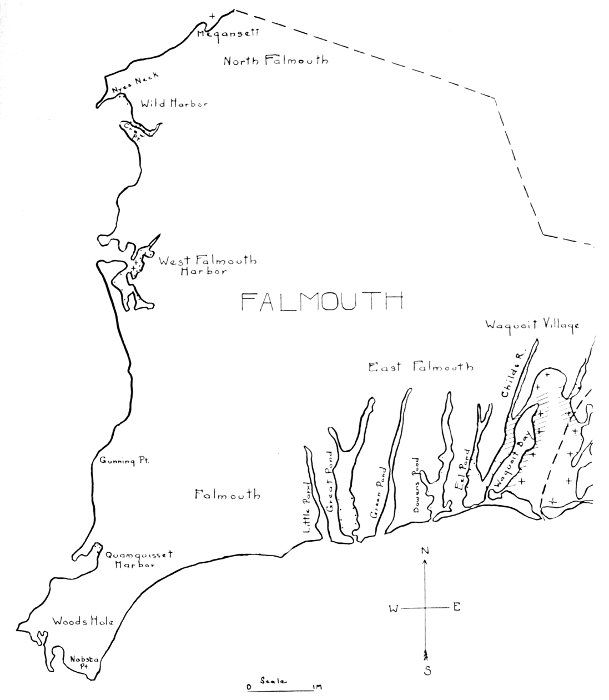

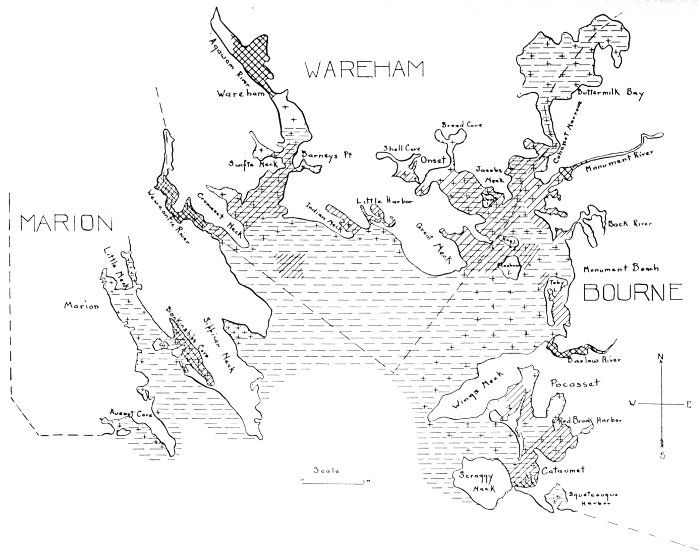

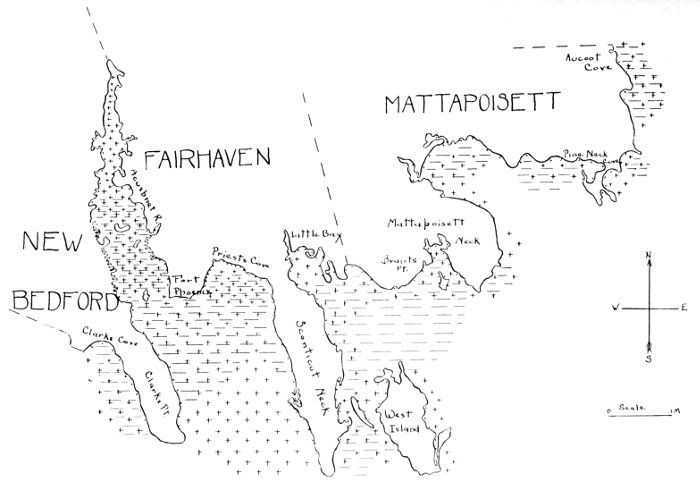

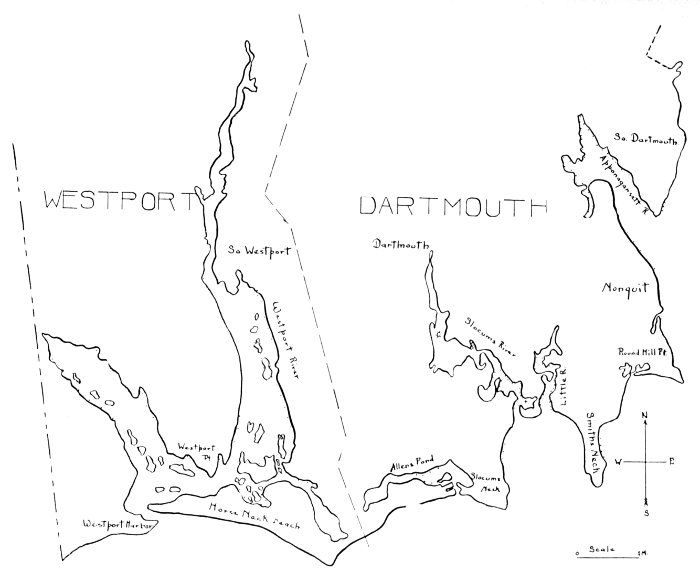

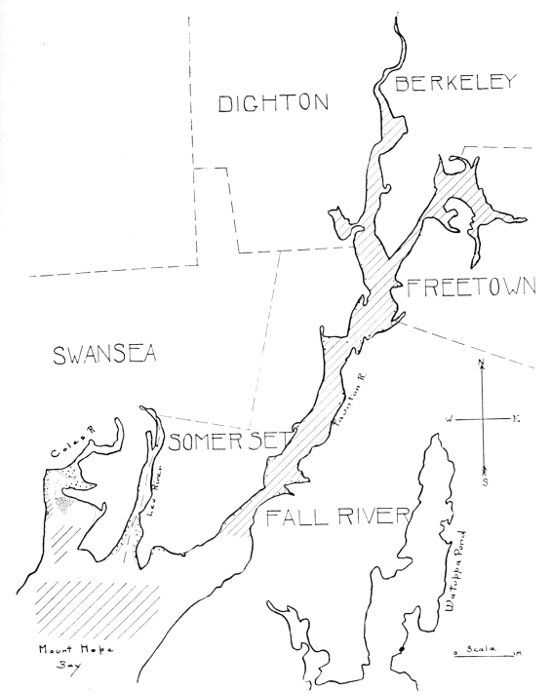

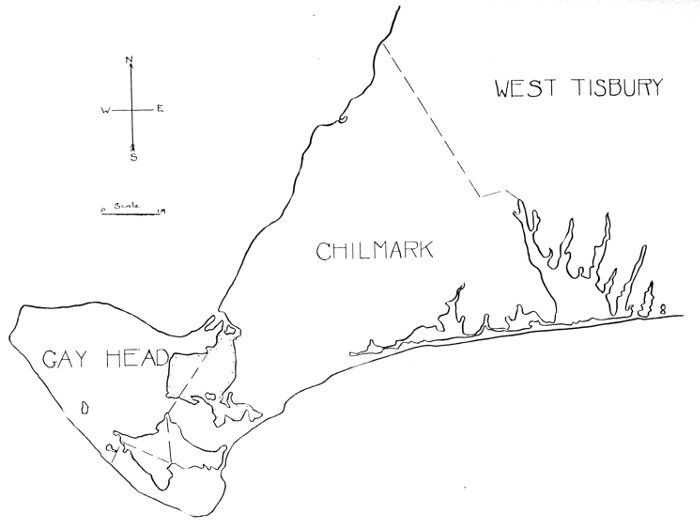

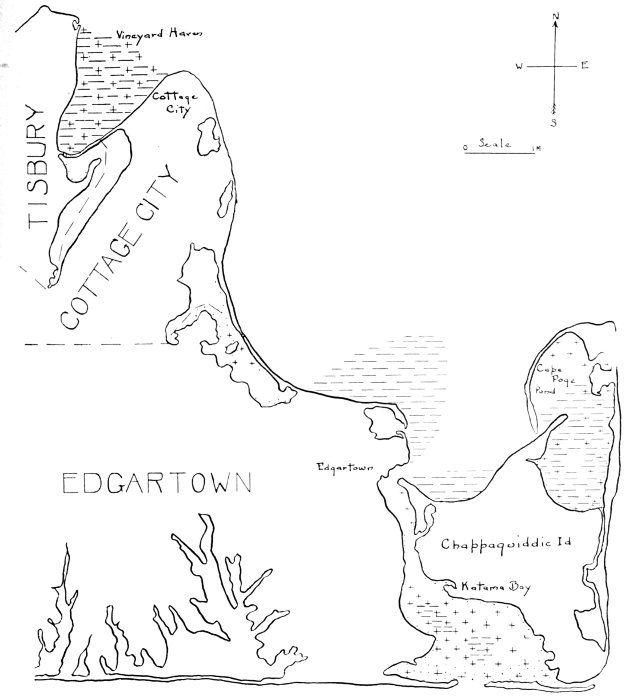

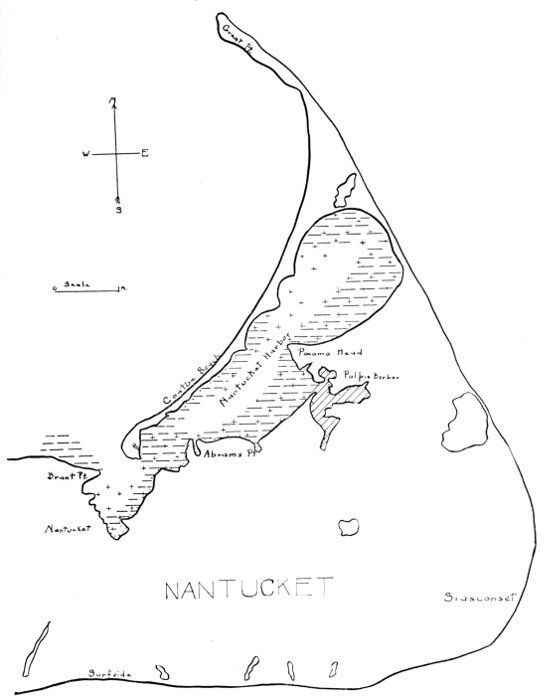

C. Presentation of the Report.—The first part of the report presents the general results of the survey, i.e., the present condition of the shellfisheries, while the second part deals directly with details of the survey. The report is divided into four parts, each shellfish being considered separately. Under each is grouped (1) the industry as a whole; (2) a statistical summary of the industry for the whole State; (3) the towns of the State and their individual industries. A series of charts showing the shellfish areas of the State makes clear the description of the survey.

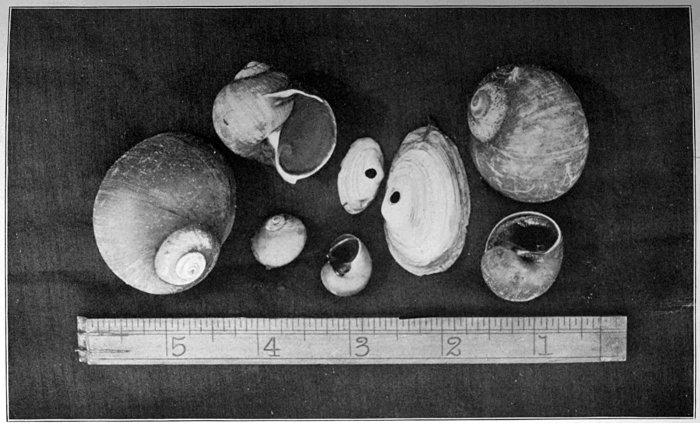

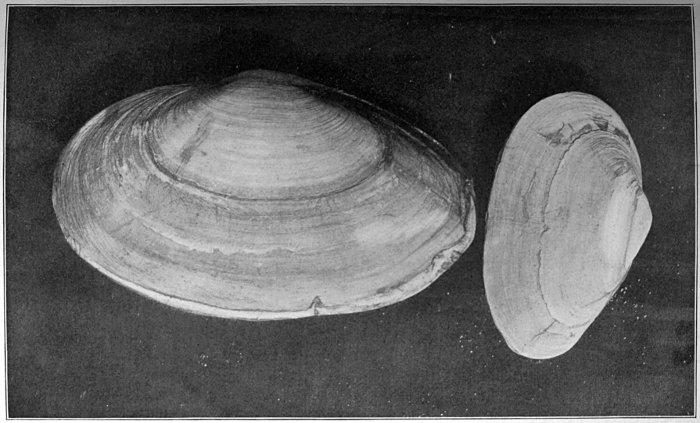

Geographical Situation.—The peculiar geographical situation of Massachusetts renders possible the production of the four edible shellfish—clam, oyster, quahaug and scallop,—in great abundance. Cape Cod forms the dividing line between the northern and the southern fauna, which furnish the coast of Massachusetts with a diversity of molluscan life. Zoölogically, the Massachusetts coast is the point where the habitats of the northern (the soft clam, Mya arenaria) and the southern clam (the quahaug, hard clam or little neck, Venus mercenaria) overlap. Nature has favored Massachusetts with a coast indented with bays, estuaries and inlets which are especially adapted for the growth of marine food mollusks.

Former Natural Abundance.—If we compare the natural shellfish areas of to-day with those of former years, we find a great change. All four shellfish formerly throve in large numbers in the numerous bays and indentations of our coast line. The area between tide marks was formerly inhabited by quantities of soft clams, and the muddy patches just below low-water mark produced great numbers of quahaugs. In the estuaries were extensive natural oyster beds. On our shoals it was possible to gather many thousand bushels of scallops. Now thousands of acres once productive lie barren, and we have but a remnant of the former abundant yield.

Historical Wastefulness.—History tells us that the Pilgrims at Plymouth "sucked the abundance of the seas" and found health and wealth. But between the lines of history we can read a tale of wastefulness and prodigality with hardly a parallel, and to-day we find the natural heritage of the shellfisheries almost totally wasted through the careless indifference of our forefathers. Prof. James L. Kellogg, in[Pg 18] the introduction to his "Notes on Marine Food Mollusks of Louisiana," gives the following excellent account of the exploiting of natural resources:—

As one looks over the record of the settling of this country, and notes how a continent was reclaimed from a state of nature, he can hardly fail to be impressed with the reckless wastefulness of his ancestors in their use of the treasures which nature, through eons of time, had been collecting. In thousands of cases, natural resources, which, carefully conserved, would have provided comfort and even luxury for generations of men, have been dissipated and destroyed with no substantial benefit to any one. They scattered our inheritance. Such knowledge dulls a feeling of gratitude that may be due to them for their many beneficent acts,—though the truth probably is that few of them ever had a thought of their descendants. Men seldom seem to have a weighty sense of responsibility toward others than those who immediately follow them. The history of the prodigality of our ancestors since their occupation of this great continent has not fully been written,—and it should be, in such a way that the present generation might know it; for sometimes it seems as if the present generation were as criminally careless of the natural resources that remain to it as were any of those that are gone. Perhaps it is hardly that. We have learned some wisdom from the past, because our attention has recently been drawn to the fact of the annihilation of several former sources of subsistence. Rapidly in America, in recent years, the struggle to obtain support for a family has become more severe to the wage earner. In thirty years the increasing fierceness of competition has resulted in a revolution of business methods. In every profession and in every line of business only the most capable are able to obtain what the mediocre received for their honest labor in the last generation.

But it is easier to condemn the past for its failures than to recognize and condemn those of our own generation. The average man really has a blind and unreasoning faith in his own time, and to laud only its successes is to be applauded as an optimist. In the present stage of our national life we certainly have no room for the pessimist, who is merely a dyspeptic faultfinder; nor for the optimist, who blinds his eyes to our faults and mistakes, and so fails to read their priceless lessons. Instead, our intelligence, as a race, has reached that degree of development which should give it the courage to consider "things as they are."

Considering things as they are, we must admit that we are not realizing our obligations to future generations in many of the ways in which we are misusing our natural resources. This waste is often deliberate, though usually due to the notion that nature's supplies, especially of living organisms, are limitless. The waste of 70 or 80 per cent, in lumbering the Oregon "big trees," and the clean sweep of the Louisiana pine, now in progress, is deliberately calculated destruction for present gain,—and the future may take care of itself. In making millionaires of a very few men, most of whom are still living, a large part of the lower peninsula of Michigan was made a hopeless desert. To "cut and come again" is not a part of the moral codes of such men. It seems to mean sacrifice; and yet they are woefully mistaken, even in that.

But most often, no doubt, the extinction of useful animals and plants,[Pg 19] that we have so often witnessed, has been due to the ignorant assumption that, under any circumstances, the supply would last forever. This idea seems especially to prevail concerning marine food animals. The fact that the sea is vast might naturally give the impression that its inhabitants are numberless.... But when a natural food supply nears complete annihilation, men begin to think of the necessity of a method of artificial culture.[1]

Present Unimproved Resources.—In spite of the wastefulness of former generations, many areas can again be made to produce the normal yield if proper and adequate measures are promptly taken to restore to the flats, estuaries and bays of Massachusetts their normal productive capacity. In spite of the fact that some of the natural beds have entirely disappeared, either "fished out" or buried under the débris of civilization, and others are in imminent danger of becoming exhausted, Massachusetts still possesses a sufficient natural supply to restock most of these barren areas.

Possibilities of Development.—Opportunities for development are alluring. The shellfisheries could be increased, in these days of rapid transit and marketing facilities, into industries which would furnish steady employment for thousands of men and women, both directly and indirectly, resulting in a product valued at a minimum of $3,000,000 annually, with possibilities of indefinite expansion. At present the idea of marine farming attracts popular attention. The conditions are parallel to agriculture, except that in the case of marine farming the crops are more certain,—i.e., are not subject to so many fatalities. The experiments of the Department of Fisheries and Game for the past three years have proved that cultivation of shellfish offers great inducements and profit to both individuals and towns. When the present waste areas are again made productive, the value of the annual catch should be increased tenfold.

Statistical Summary of the Shellfisheries for 1907.

| Name of Mollusk. | Production. | Area in Acres. | Capital invested. | Men employed. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bushels. | Value. | ||||

| Clam, | 153,865 | $150,440 | 5,111 | $18,142 | 1,361 |

| Oyster, | 161,182 | 176,142 | 2,400 | 268,702 | 159 |

| Quahaug, | 144,044 | 194,687 | 28,090 | 94,260 | 745 |

| Scallop, | 103,000 | 164,436 | 30,900 | 121,753 | 647 |

| Total, | 562,091 | $685,705 | 66,501 | $502,857 | 2,912 |

In the above table the areas for the scallop, clam and quahaug are only approximate. The scallop and quahaug fisheries cover nearly the same areas, and employ to a great extent the same men and capital.

Annual Yields (in Bushels) of the Shellfisheries of Massachusetts since 1879, from United States Fish Commission Reports.

| Year. | Clam. | Quahaug. | Oyster. | Scallop. | Totals. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1879, | 158,621 | 11,050 | 36,000 | 10,542 | 216,218 |

| 1887, | 230,659 | 35,540 | 43,183 | 41,964 | 351,346 |

| 1888, | 243,777 | 26,165 | 45,631 | 26,168 | 341,741 |

| 1898, | 147,095 | 63,817 | 101,225 | 128,863 | 441,000 |

| 1902, | 227,941 | 106,818 | 103,386 | 66,150 | 504,295 |

| 1905, | 217,519 | 166,526 | 112,580 | 43,872 | 540,497 |

| 1907,[2] | 153,865 | 144,044 | 161,182 | 103,000 | 562,091 |

Massachusetts fishermen to-day receive an annual income of $685,705 from the shellfisheries, which approximately cover a productive area of 40,000 acres. Under the present methods of production, the average value per acre is only $17; each acre, if properly farmed, should furnish an annual production of at least $100, or six times the present yield. The shellfish areas of Massachusetts which are at present utilized are giving almost a minimum production, instead of the enormous yield which they are capable of furnishing. All that is necessary to procure the maximum yield is the application of systematic cultural methods, instead of relying on an impoverished natural supply. Not only are the productive areas furnishing far less than they are capable of producing, but also Massachusetts possesses 6,000 acres of barren flats, which should become, under the proper cultural methods, as valuable as the productive areas. (This has been experimentally demonstrated by the commission.) While it is possible to develop, through cultural methods, these latent natural resources, it will take years to bring them to a high degree of development. It can be partially accomplished, at least, in the next few years, and the present production increased several times, as nature responds to the slightest intelligent effort of man, and gives large returns.

A. Is there a Decline?

(1) So obvious is the general decline of the shellfisheries that almost every one is aware, through the increasing prices and difficulty of supplying the demand, that the natural supply is becoming exhausted.

(2) Statistical figures of the shellfish production not only show a decline, but conceal a rapid diminution of the supply.

(3) Production statistics alone should never be taken as typifying the real conditions of an industry, as such figures are often extremely deceiving. For instance:—

(4) The increased prices, stimulated by an increasing demand, have caused a greater number of men, equipped with the best modern implements, to swell the production by overworking shellfish areas which in reality are not one-fourth so productive as they were ten years ago.

While the general decline of the shellfisheries is a matter of public knowledge, specific illustrations of this decline have been lacking. The present report calls attention to actual facts as proofs of the decline of each shellfishery, by a comparison of the present conditions in various localities with the conditions of 1879. The only past record of Massachusetts shellfisheries of any importance is found in the report of the United States Fish Commission for 1883, and, although this is very limited, it is sufficient to furnish many examples of the extinction or decline of the shellfisheries in certain localities.

In a general consideration of the shellfisheries, it is noticeable that in certain localities the extinction of the industry has been total, in others only partial, while others have remained unchanged or have even improved. This last class is found either where the natural advantages are so great that the resources have not been exploited, or where men have, through wise laws and cultural methods (as in the oyster industry), preserved and built up the shellfisheries.

1879 v. 1907.—In comparing the present condition of the shellfisheries with that of 1879, it will be seen that many changes have taken place. Even twenty-five years ago inroads were being made upon the natural supply; from that time to the present can be traced a steady decline. During the past five years the production has been augmented by additional men, who have entered into the business under the attraction of higher prices, and the extension of the quahaug and oyster fisheries. Though the annual catch is greater, a disproportionately greater amount of time, labor and capital is required to secure an equal quantity of shellfish.

| 1907. | 1879. | Gain. | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Production (bushels), | 562,991 | 264,818 | 297,273 |

| Men, | 2,912 | 910 | 2,092 |

| Capital, | $502,857 | $165,000 | $337,857 |

| Area (acres), | 66,501 | 66,501 | — |

The following instances illustrate specific decline in the various natural shellfisheries:—

(1) Oyster industry, natural beds: Wareham, Marion, Bourne, Wellfleet, Charles River.

(2) Sea clam industry: Dennis, Chatham, Nantucket.

(3) Scallop industry: Buzzards Bay and north side of Cape Cod (Barnstable).

(4) Clam industry: Essex, Plymouth, Duxbury, Buzzards Bay, Annisquam, Wellfleet, Nantucket.

(5) Quahaug industry: Chatham, Buzzards Bay, Fall River district.

These are only a few of the more prominent cases. Similar cases will be found all along the coast of Massachusetts, and no one can deny that the natural supply is rapidly becoming exhausted, and that methods are needed to increase the production, or at least to save the little that remains.

B. Causes of the Decline.

I. An Increasing Demand.—The indirect cause of the decline of the shellfisheries is the increased demand. To-day more shellfish are consumed than ever before, and the demand is much greater each succeeding year. It is an economic principle that there must be an equilibrium between supply and demand. If the demand is increasing, either the supply has to increase to meet the demand, or the price of the commodity goes up and a new equilibrium is established. The supply must equal the demand of the market. This increasing demand has worked havoc with the shellfisheries. There was a time when the natural supply was of such abundance that the moderate demand of those early days could be met without injury to the fishery. Soon this limit was passed, and with a steadily increasing demand came a corresponding drain on the natural resources, which little by little started a decline, the result of which is to-day apparent.

The ill-advised policy of the past has been to check the demand by various devices, such as closed seasons, limited daily production, etc. These not only have proved without benefit to the fisherman, but also have hurt the consumer by the increased price. The demand can be checked by raising the price, but this tends towards a class distinction between the rich and the poor. The poor man should be able to enjoy "the bounties of the sea" as well as the rich. The policy of the future should be not to check the demand, but rather to increase the supply.

Several causes contribute to this demand, which has unlimited possibilities of expansion:—

(1) The popularity of shellfish as an article of diet is steadily increasing, not merely for its nutritive value, but for variety and change in diet. Fashionable fads, i.e., the "little neck" of the restaurants and hotels, contribute to the popularity of these shellfish.

(2) In the present age, transportation facilities and cold storage make possible shipments to all parts of the United States, and continually widen the market for sea foods.

(3) The influx of summer people to the seashore not only causes an additional summer demand, but also widens the popular knowledge of these edible mollusks.

(4) Advertising and more attractive methods of preserving and selling sea food by the dealers still further increase the demand.

II. Overfishing.—The immediate and direct cause of the decline is overfishing. Increased demand causes a severe drain upon the shellfish beds, which soon leads to overfishing. It is not merely the hard working of the beds, but the continuous unmethodical and indiscriminate fishing which has caused the total extermination of once flourishing beds in certain localities. Under present methods a bed is worked until all its natural recuperatory power is exhausted, and then it is thrust aside as worthless, a barren area. Prof. Jacob Reighard, in "Methods of Plankton Investigation in their Relation to Practical Problems,"[3] aptly sums up the situation in his opening paragraph:—

In this country the fisherman as a rule continues to fish in any locality until fishing in that locality has become unprofitable. He then moves his operations to new waters until these in turn are exhausted. He is apt to look upon each new body of water as inexhaustible, and rarely has occasion to ask himself whether it is possible to determine in advance the amount of fish that he may annually take from the water without soon depleting it.

In this way the shellfish beds have become exhausted through the indifference and lack of knowledge on the part of the fishing public. In colonial days the resources of the shellfisheries were apparently inexhaustible. The conviction that man could ever exhaust the resources of nature took firm hold of the Puritan mind, and even in the present generation many still cling to this illogical doctrine, although proof to the contrary can be seen on all sides. This idea has caused great harm to the shellfisheries, stimulating men to wreck certain localities by overfishing.

III. Pollution of Harbors and Estuaries and the Ill Effects upon Public Health through the Shellfisheries.—The unscientific disposal of sewage, sludge, garbage and factory waste may tend to rapidly fill up the harbor channels, as well as the areas where the currents are not so rapid.

Competent authorities scout the idea that Boston harbor is at present filling up to any considerable degree with sewage sludge, but the problem must be met in the not distant future. This sewage sludge upon entering salt or brackish water precipitates much more rapidly than in fresh water or upon land, and becomes relatively insoluble, hence the accumulation in harbors, e.g., Boston and New Bedford harbors and the estuaries of the Merrimac, Taunton and other rivers. This sludge, instead of undergoing the normal rapid oxidation and nitrification, as it does when exposed to the air on land, undergoes in the sea water a series of changes, mainly putrefactive, which results in the production of chemical substances which in solution may (1) drive away the fish[Pg 24] which in incredible quantities formerly resorted to that place; (2) impair the vitality and even kill whatever fish spawn or fry may be present; (3) check the growth of or completely destroy the microscopic plants and animals which serve as food for the young fish and shellfish; (4) by developing areas of oily film floating upon the surface of the water, enormous numbers of the surface-swimming larvæ of clams, quahaugs, scallops, oysters, mussels and other marine animals may be destroyed annually. But most serious of all is the fact that all the edible mollusks, notably the clam, quahaug, oyster and mussel, act as living filters, whose function is to remove from the water the bacteria and other microscopic plants and animals. Most of these microscopic organisms serve as food for the mollusk; and in instances where the mollusk is eaten raw or imperfectly cooked, man is liable to infection, if the bacillus of typhoid fever or other disease chances to be present in the mollusk. Though the chance of such infection is remote, it is nevertheless actually operative. Many typhoid epidemics in this country and abroad have been found to be directly referable to shellfish from sewage-polluted waters. For these reasons approximately 1,500 acres in Boston harbor and 700 acres in New Bedford harbor have become unsuitable for the growth of shellfish; and the State Board of Health, after investigation, decided that clams, oysters and quahaugs found within these areas are likely to be the direct cause of a dangerous epidemic of typhoid. For this reason the taking of these shellfish for any purpose was very properly prohibited; but at the last session of the Legislature a bill was passed which permitted the taking of such shellfish for bait, upon securing permits from the Board of Health, and providing heavy penalties for both buying and selling. As a matter of fact, however, it is well-nigh impracticable to properly enforce this law, for the reason that it is possible only in very rare instances to keep any one lot of clams known to have been dug under these conditions under surveillance from the time of digging until they are placed upon the hook as bait. Complete prevention of the taking of such shellfish is the only method by which the public health can be properly safeguarded. Even though in our opinion the annual financial loss to the public from the destruction of this public fishery by the dumping of city sewage into the water is not less than $400,000, the public health is of greater consequence, and should not be jeopardized, as is the fact under present conditions. Until such a time as the public realize that economic disposal of sewage must take place on land rather than in water, laws absolutely preventing any contact with the infected shellfish should be enforced without exception. In instances like these it is greatly to be deplored that but rarely under our system of government can legislation, which the best knowledge and common-sense demand for the public weal, be passed in its adequate and beneficial entirety, but is so frequently emasculated in the selfish interests of a few persons.

IV. Natural Agencies.—The above causes are given as they are obviously important, but by no means are they to be considered the only reasons. Geographic and climatic changes often explain the extinction of shellfish in certain localities.

Not only has this survey shown by specific examples the alarming but actual decline of the natural shellfish supply (in spite of deceptive production statistics), but it has brought to light numerous evils of various kinds. These abuses have developed gradually with the rise of the shellfisheries, until at the present day they cannot be overlooked or considered unimportant. So closely are these connected with the present status of our shellfishery that upon their abolition depends its future success or failure. Some need immediate attention; others will require attention later. After a thorough and competent investigation, remedies for the correction of each evil should be applied.

In the future Massachusetts will have to utilize all her wealth of natural resources, to keep her leading position among the other States of the Union. To do this she should turn to her sea fisheries, which have in the past made her rich, and hold forth prospects of greater wealth in the future. Untold possibilities of wealth rest with her shellfisheries, if obsolete methods and traditions can be cast aside. In any age of progress the ancient and worthless must be buried beneath the ruins of the past, while the newer and better take their place. There is no more flagrant example of obsolete methods and traditions holding in check the development of an industry than with the shellfisheries, and it is time that Massachusetts realized these limitations.

The shellfisheries of Massachusetts are in a chaotic state, both legally and economically. The finest natural facilities are wasted, and thousands of acres of profitable flats are allowed to lie barren merely for a lack of initiative on the part of the general public. This chaotic and unproductive state will exist until both the consumer and the fishermen alike understand the true condition of affairs, and realize that in the bays, estuaries and flats of Massachusetts lies as much or more wealth, acre for acre, as in the most productive market gardens.

In Rhode Island the clam and scallop fisheries have almost disappeared. Five or ten years from now the shellfisheries of Massachusetts will be in a similar condition, and beyond remedy. Now is the time for reform. The solution of the problem is simple. Shellfish farming is the only possible way in which Massachusetts can restore her natural supply to its former abundance.

I. The Shellfish Laws.—The first evils which demand attention are the existing shellfish laws. While these are supposed to wisely regulate the shellfisheries, in reality they do more harm than good, and are direct obstacles to any movement toward improving the natural re[Pg 26]sources. Before Massachusetts can take any steps toward cultivating her unproductive shellfish areas, it will be necessary to modify the worst of these laws.

A. Fishery Rights of the Public.—The fundamental principle upon which the shellfish laws of the State are founded is the so-called beach or free fishing rights of the public. While in other States property extends only to mean high water, in Massachusetts the property holders own to extreme low-water mark. Nevertheless, according to further provisions of this ancient law, the right of fishing (which includes the shellfisheries) below high-water mark is free to any inhabitant of the Commonwealth.

(1) Origin.—The first authentic record of this law is found under an act of Massachusetts, in 1641-47, by which every householder was allowed "free fishing and fowling" in any of the great ponds, bays, coves and rivers, as far "as the sea ebbs and flows," in their respective towns, unless "the freemen" or the General Court "had otherwise appropriated them." From this date the shellfisheries were declared to be forever the property of the whole people, i.e., the State, and have been for a long period open to any inhabitant of the State who wished to dig the shellfish for food or for bait.

(2) Early Benefits.—In the early days, when the natural supply was apparently inexhaustible and practically the entire population resided on or near the seacoast, it was just that all people should have common rights to the shore fisheries. As long as the natural supply was more than sufficient for the demand, no law could have been better adapted for the public good.

(3) Present Inadequacy.—Two hundred and fifty years have passed since this law was first made. The condition of the shellfisheries has changed. No longer do the flats of Massachusetts yield the enormous harvest of former years, but lie barren and unproductive. The law which once was a benefit to all has now become antiquated, and incapable of meeting the new conditions.

(4) Evil Effects.—If this law were merely antiquated, it could be laid aside unnoticed. On the contrary, as applied to the present conditions of the shellfisheries it not only checks any advancement, but works positive harm. From the mistaken comprehension of the so-called beach rights of the people, the general public throughout the State is forced to pay an exorbitant price for sea food, and the enterprising fishermen are deprived of a more profitable livelihood. The present law discriminates against the progressive majority of fishermen in order to benefit a small unprogressive element.

(5) Protection.—If shellfish farming is ever to be put on a paying basis, it is essential that the planter have absolute protection. No man is willing to invest capital and labor when protection cannot be guaranteed. What good does it do a man to plant a hundred bushels of clams, if the next person has a legal right to dig them? Since the[Pg 27] law absolutely refuses any protection to the shellfish culturist, Massachusetts can never restock her barren flats and re-establish her shellfisheries until this law is modified to meet the changed conditions.

(6) Who are the Objectors? Objectors to any new system are always found, and are not lacking in the case of shellfish culture. These would immediately raise the cry that the public is being deprived of its rights. To-day the public has fewer rights than ever. The present law causes class distinctions, and a few are benefited at the expense of the public. The industrious fisherman suffers because a few of the worthless, unenterprising class, who have no energy, do not wish others to succeed where they cannot. In every seacoast town in Massachusetts the more enlightened fishermen see clearly that the only way to preserve the shellfisheries is to cultivate the barren areas.

Hon. B. F. Wood, in his report of the shellfisheries of New York, in 1906, clearly states the case.[4]

There is, unfortunately, in some of the towns and villages upon our coast an unprogressive element, composed of those who prefer to reap where they have not sown; who rely upon what they term their "natural right" to rake where they may choose in the public waters. They deplete, but do not build up. They think because it may be possible to go out upon the waters for a few hours in the twenty-four (when the tide serves) and dig a half peck of shellfish, that it is sufficient reason why such lands should not be leased by the State to private planters. It might as well be said that it is wrong for the government to grant homestead farms to settlers, because a few blackberries might be plucked upon the lands by any who cared to look for them.

The following is taken from the report of the Massachusetts Commissioners on Fisheries and Game for 1906:[5]—

There are at least four distinct classes within our Commonwealth, each of which either derive direct benefits from the mollusk fisheries of our coast, or are indirectly benefited by the products of the flats:—

(1) The general public,—the consumers, who ultimately pay the cost, who may either buy the joint product of the labor and capital invested in taking and distributing the shellfish from either natural or artificial beds, or who may dig shellfish for food or bait purposes for their own or family use.

(2) The capitalist, who seeks a productive investment for money or brains, or both. Under present laws, such are practically restricted to distribution of shellfish, except in the case of the oyster, where capital may be employed for production as well,—an obvious advantage both to capital and to the public.

(3) The fishermen, who, either as a permanent or temporary vocation, market the natural yield of the waters; or, as in the case of the shellfisheries, may with a little capital increase the natural yield and availability by cultivating an area of the tidal flats after the manner of a garden.

[Pg 28](4) The owners of the land adjacent to the flats, who are under the present laws often subjected to loss or annoyance, or even positive discomfort, by inability to safeguard their proper rights to a certain degree of freedom from intruders and from damage to bathing or boating facilities, which constitute a definite portion of the value of shore property.

All of these classes would be directly benefited by just laws, which would encourage and safeguard all well-advised projects for artificial cultivation of the tidal flats, and would deal justly and intelligently with the various coincident and conflicting rights of the fishermen, owners of shore property, bathers and other seekers of pleasure, recreation or profit, boatmen, and all others who hold public and private rights and concessions.

That any one class should claim exclusive "natural valid rights," over any other class, to the shellfish products of the shores, which the law states expressly are the property of "the people," is as absurd as to claim that any class had exclusive natural rights to wild strawberries, raspberries, cranberries or other wild fruits, and that therefore the land upon which these grew could not be used for the purpose of increasing the yield of these fruits. This becomes the more absurd from the fact that the wild fruits pass to the owner of the title of the land, while the shellfish are specifically exempted, and remain the property of the public.

The class most benefited by improved laws would be the fishermen, who would profit by better wages through the increased quantity of shellfish they could dig per hour, by a better market and by better prices, for the reason that the control of the output would secure regularity of supply. Moreover, when the market was unfavorable the shellfish could be kept in the beds with a reasonable certainty of finding them there when wanted, and with the added advantage of an increased volume by growth during the interval, together with the avoidance of cold-storage charges. Thus the diggers could be certain of securing a supply at almost any stage of the tide and in all but the most inclement weather, through a knowledge of "where to dig;" moreover, there would be a complete elimination of the reasoning which is now so prolific of ill feelings and so wasteful of the shellfish, viz., the incentive of "getting there ahead of the other fellow."

B. All the shellfish laws should be revised, to secure a unity and clearness which should render graft, unfairness and avoidable economic loss impossible, and be replaced with a code of fair, intelligent and forceful laws, which would not only permit the advancement of the shellfish industry through the individual efforts of the progressive shellfishermen, but also protect the rights of the general public.

C. The majority of the shellfish laws of the State are enacted by the individual towns. In 1880 the State first officially granted to each town the exclusive right to control and regulate its own shellfisheries, as provided under section 68 of chapter 91 of the Public Statutes. This was slightly modified by the Acts of 1889 and 1892 to read as follows (now section 85 of chapter 91 of the Revised Laws):—

Section 85. The mayor and aldermen of cities and the selectmen of towns, if so instructed by their cities and towns, may, except as provided in[Pg 29] the two preceding sections, control, regulate or prohibit the taking of eels, clams, quahaugs and scallops within the same; and may grant permits prescribing the times and methods of taking eels and such shellfish within such cities and towns and make such other regulations in regard to said fisheries as they may deem expedient. But an inhabitant of the commonwealth, without such permit, may take eels and the shellfish above-named for his own family use from the waters of his own or any other city or town, and may take from the waters of his own city or town any of such shellfish for bait, not exceeding three bushels, including shells, in any one day, subject to the general rules of the mayor and aldermen and selectmen, respectively, as to the times and methods of taking such fish. The provisions of this section shall not authorize the taking of fish in violation of the provisions of sections forty-four and forty-five. Whoever takes any eels or any of said shellfish without such permit, and in violation of the provisions of this section, shall forfeit not less than three nor more than fifty dollars.

Responsibility has thus been transferred from the State to the towns, and they alone, through their incompetence and neglect, are to blame for the decline of the shellfisheries. The town laws are miniature copies of the worst features of the State laws. While a few towns have succeeded in enacting fairly good laws, the majority have either passed no shellfish regulations at all, or made matters worse by unintelligent and harmful laws. It is time that a unified system of competent by-laws were enacted and enforced in every town.

The ill-advised features which characterize the present town laws are numerous, and are best considered under the following headings:—

(1) Unintelligent Laws.—One of the worst features of our town shellfish laws is their extreme unfitness. Numerous laws which are absolutely useless for the regulation and improvement of these industries have been made by towns, through men who knew nothing about the shellfisheries. These laws were made without any regard for the practical or biological conditions underlying the shellfish industry. It is to be expected that laws from such a source would often be ill-advised and unintelligent, but under the present system it cannot be avoided. Until sufficient knowledge of the habits and growth of shellfish is acquired by the authorities of State and town, Massachusetts can never expect to have intelligent and profitable shellfish laws. While the majority of these unintelligent laws do no harm, there are some that work hardship to the fishermen and are an injury to the shellfisheries.

(2) Unfairness; Town Politics.—Town politics offers many chances for unscrupulous discrimination in the shellfish laws. Here we find one class of fishermen benefiting by legislation at the expense of the other, as in the case of the quahaugers v. oystermen. In one town the oystermen will have the upper hand; in another, the quahaugers. In every case there is unfair discrimination, and a resultant financial loss to both parties. The waters of Massachusetts are large enough for both[Pg 30] industries, and every man should have a "square deal," which is frequently lacking under the present régime.

Besides party discrimination, there is discrimination against certain individuals, as illustrated in giving oyster grants. Town politics plays a distressing part here. Favoritism is repeatedly shown, and unfairness results. All this shows the unpopularity and impracticability of such regulations and the method of making them.

(3) Present Chaotic State.—The present town laws are in a chaotic condition, which it is almost impossible to simplify. No one knows the laws, there is merely a vague impression that such have existed. Even the selectmen themselves, often new to the office and unacquainted with the shellfisheries, know little about the accumulated shellfish laws of the past years, and find it impossible to comprehend them. The only remedy is to wipe out all the old and replace them with unified new laws.

(4) Unsystematic Laws.—The present laws are unsystematized. Each town has its own methods, good and bad, and the result is a heterogeneous mixture. Often there are two or three laws where one would definitely serve. To do absolute justice there should be a definite system, with laws elastic enough to satisfy the needs of all.

(5) Nonenforcement.—The worst feature of allowing town control of the shellfisheries is the nonenforcement of the laws already passed. We find in many towns that good by-laws have been made, but from inattention and lack of money these have never been enforced and have become practically nonexistent. The 1½-inch quahaug law of several towns is an instance of this. In but one town in the State, Edgartown, is any effort made to enforce this excellent town by-law, although several of the other towns have passed the same. The proper enforcement of laws is as important as the making, as a law might as well not be made if not properly enforced. The only way that this can be remedied is either to take the control completely out of the hands of the town, or else have a supervisory body which would force the town to look after violators.

Besides the town by-laws there are other evils which result from the present system of town control.

II. Lack of Protection in Oyster Industry.—In no case is the management by towns more inefficient and confusing than in the case of the oyster industry. As this subject will be taken up in the oyster report which follows, it is only necessary here to state that there is great need of a proper survey of grants, fair laws, systematic methods, etc. Protection is necessary for the success of any industry, and is especially needed for the oyster industry. The oyster industry of Massachusetts will never become important until adequate protection is guaranteed to the planters. Under the present system, uncertainty rather than protection is the result.

III. Town Jealousy.—The evil of town jealousy, whereby one[Pg 31] town forbids its shellfisheries to the inhabitant of neighboring towns, is to-day an important factor. It is fair that a town which improves its own shellfisheries should not be interfered with by a town which has allowed its shellfisheries to decline. While this is true perhaps of the clam, quahaug and oyster, it does not hold true of the scallop. The result of this close-fisted policy has resulted in the past in a great loss in the scallop industry. The town law in regard to scallops is all wrong. The scallop fisheries should be open to all the State, and no one town should "hog the fishing," and leave thousands of bushels to die from their dog-in-the-manger attitude.

IV. Sectional Jealousy.—Another evil, which in the past has been prominent, but is becoming less and less as the years go by, is the jealousy of the north shore v. the south shore, Cape Cod v. Cape Ann. In the past this has been a stumbling block against any advance, as any plan initiated on the south shore would be opposed from sheer prejudice by the north shore representatives, and vice versa. The cry of "entering wedge" has been raised again and again whenever any bill was introduced for the good of the shellfisheries by either party. Merely for political reasons good legislation has been defeated. However, the last few years have shown a decided change. The jealous feeling has in a large measure subsided; the shellfisheries need intelligent consideration, and all parties realize that united effort is necessary to insure the future of these industries.

V. Quahaugers v. Oystermen.—On the south shore the worst evil which at present exists is the interclass rivalry between the quahaugers and oystermen. This has caused much harm to both parties, through expensive lawsuits, economic loss, uncertainty of a livelihood, as well as retarding the proper development of both industries.

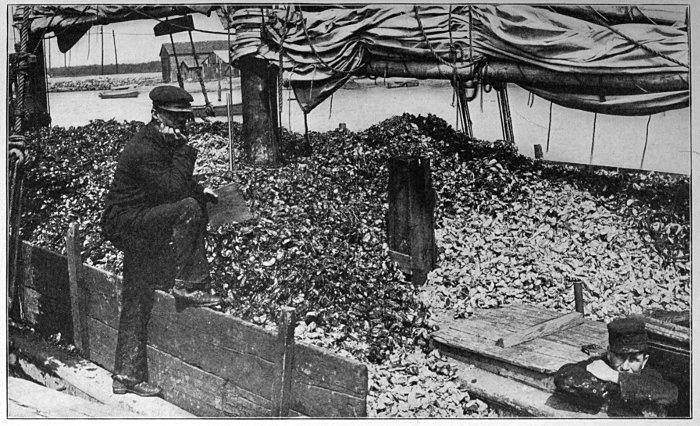

VI. Waste of Competition.—At the present day the utilization of waste products in all industries is becoming more and more important. In this age material which was considered useless by our forefathers is made to play its part in the economic world. Through science industrial waste of competition is being gradually reduced to a minimum, although in any business which deals with perishable commodities, such as fish, fruit, etc., there is bound to be a certain amount of loss.

Under the present system the shellfisheries suffer from the effects of waste resulting from competition. Both the fisherman and the consumer feel the effects of this, in different ways,—the fisherman through poor market returns, the consumer through poor service. As long as the shellfisheries are free to all, there is bound to be that scramble to get ahead of "the other fellow," which not only results in the destructive waste of the actual catch, but also causes a "glutted" market, which gives a low return to the fisherman. Thousands of dollars are thus lost each year by the fishermen, who are forced to keep shipping their shellfish, often to perish in the market, merely because the present system invites ruthless competition. The fishermen in this respect alone[Pg 32] should be the first to desire a new system, which would give to each a shellfish farm and the privilege of selecting his market.

VII. At the present moment there are two evils which demand attention, and which can be lessened by the passage of two simple laws:—

(1) During the past three years many thousands of bushels of quahaugs under 1½ inches have been shipped out of the State, merely passing into the hands of New York oystermen, who replanted, reaping in one year a harvest of at least five bushels to every one "bedded." Through the inactivity of town control, the incentive to get ahead of the other fellow and the ignorance that they are wasting their own substance have caused many quahaugers in the past to do this at many places.

The 1½-inch quahaug law has been for years a law for many towns in the State. It has been practically a dead letter in all but Edgartown, where it is enforced thoroughly. There should be a State law restricting the size of the quahaugs taken.