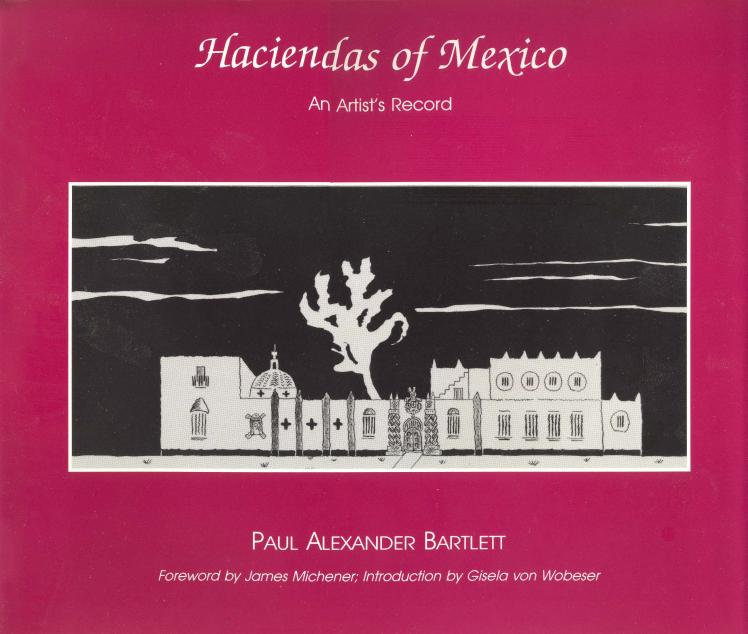

Front dust jacket cover

The Haciendas of Mexico

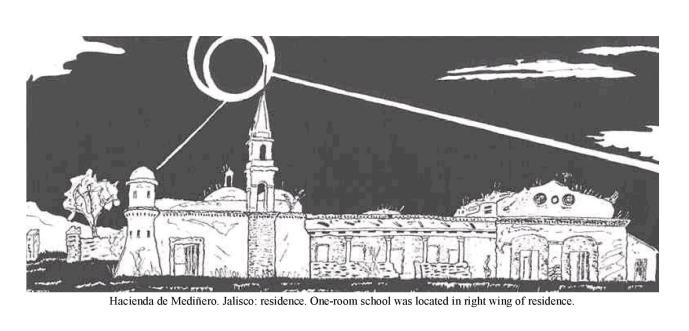

Hacienda de Mediñero. Jalisco: residence. One-room school was located in right wing of residence.

An Artist's Record

PAUL ALEXANDER BARTLETT

Foreword by James A. Michener

Introduction by Gisela von Wobeser

UNIVERSITY PRESS OF COLORADO

Copyright © 1990 by the University Press of Colorado, Niwot, CO 80544

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

First Edition

The University Press of Colorado is a cooperative publishing enterprise supported, in part, by Adams State College, Colorado State University, Fort Lewis College, Mesa State College, Metropolitan State College, University of Colorado, University of Northern Colorado, University of Southern Colorado, and Western State College.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials.

ANSI Z39.48-1984

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Bartlett, Paul Alexander.

The haciendas of Mexico: an artist's record/Paul Alexander Bartlett; foreword by James A. Michener, Introduction by Gisela von Wobeser.—1st ed. p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references.

ISBN 0-807801-205-x (alk. paper)

1. Bartlett, Paul Alexander. 2. Haciendas in art. 3. Haciendas—Mexico—Pictorial works. I. Title.

N6537.B2264A4 1989 728.8'0972—dc20 89-24922

Manufactured in the United States of America

*********

2015 PROJECT GUTENBERG EDITION

The Haciendas of Mexico: An Artist's Record, a copyrighted work, originally published by the University Press of Colorado, is now out-of-print. The University Press of Colorado has released all rights to the book to the author's literary executor, Steven James Bartlett, who has decided to make the book available as an open access publication, freely available to readers through Project Gutenberg under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-NoDerivs license, which allows anyone to distribute this work without changes to its content, provided that both the author and the original URL from which this work was obtained are mentioned, that the contents of this work are not used for commercial purposes or profit, and that this work will not be used without the copyright holder's written permission in derivative works (i.e., you may not alter, transform, or build upon this work without such permission). The full legal statement of this license may be found at:

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode

Dedicated to my son, Steven,

who was my compañero on many hacienda trips.

This book would not exist without his help.

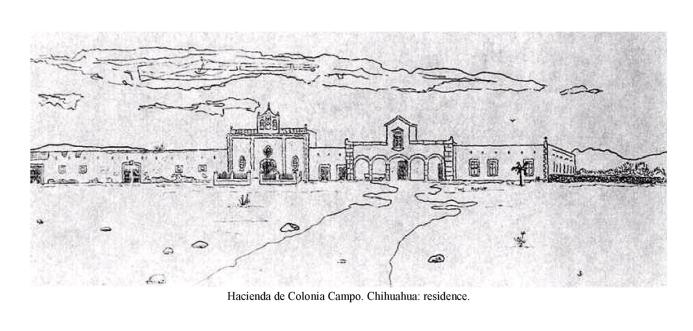

Hacienda de Colonia Campo. Chihuahua: residence.

Contents

Foreword

by James A. Michener

Introduction

by Gisela von Wobeser

II. Through the Eyes of Hacienda Visitors

III. Hacienda Life

IV. Fiestas

V. Education

VI. The Revolution

VII. Mexico Since the Revolution

Hacienda de Mediñero, Jalisco: residence. One-room school was located in right wing of residence.

Hacienda de Colonia Campo, Chihuahua: residence.

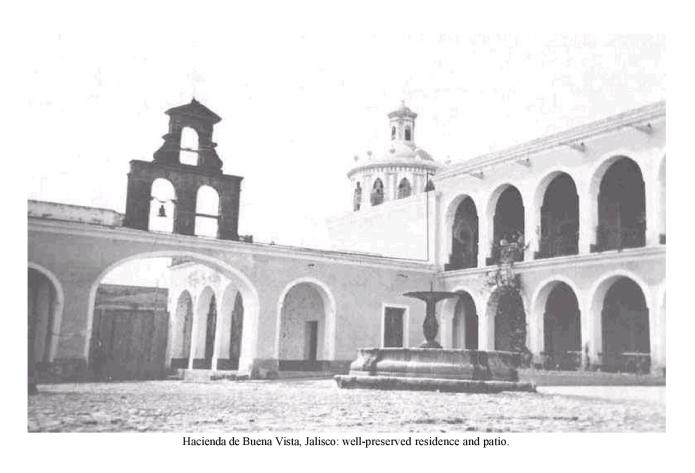

Hacienda de Buena Vista, Jalisco: well-preserved residence and patio.

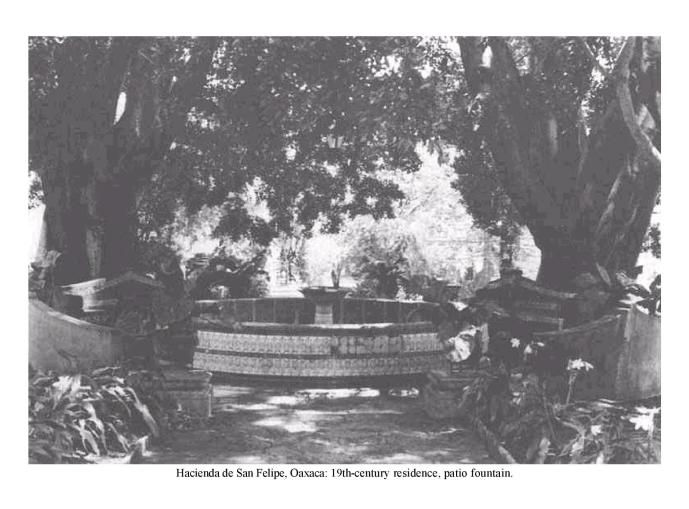

Hacienda de San Felipe, Oaxaca: 19th-century residence, patio fountain.

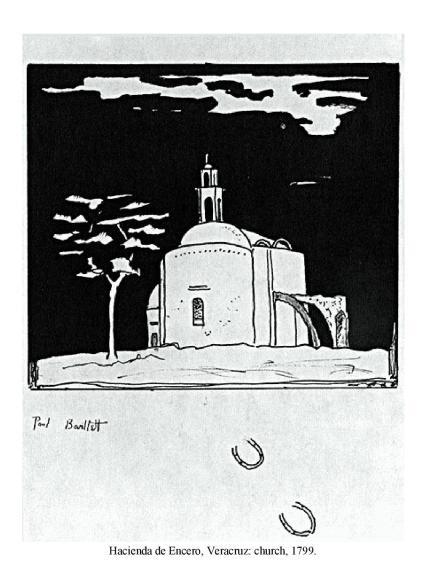

Hacienda de Encero, Veracruz: church, 1799.

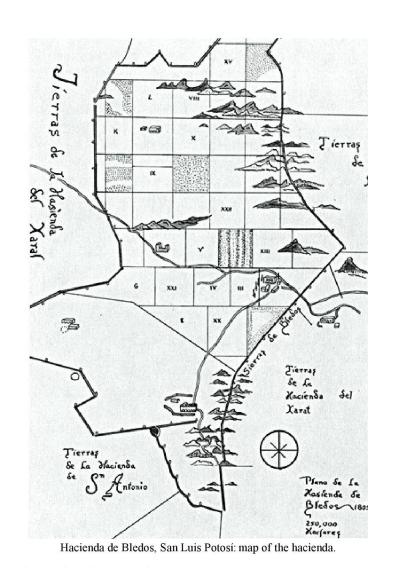

Hacienda de Bledos, San Luis Potosí: map of the hacienda.

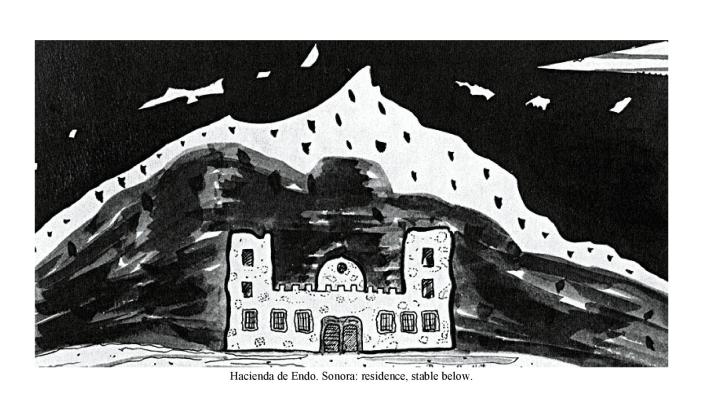

Hacienda de Endo, Sonora: residence, stable below.

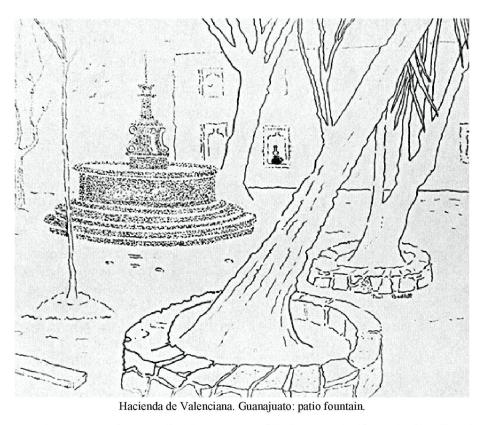

Hacienda de Valenciana, Guanajuato: patio fountain.

Hacienda de Valenciana, Guanajuato: figure on 1788 church wall.

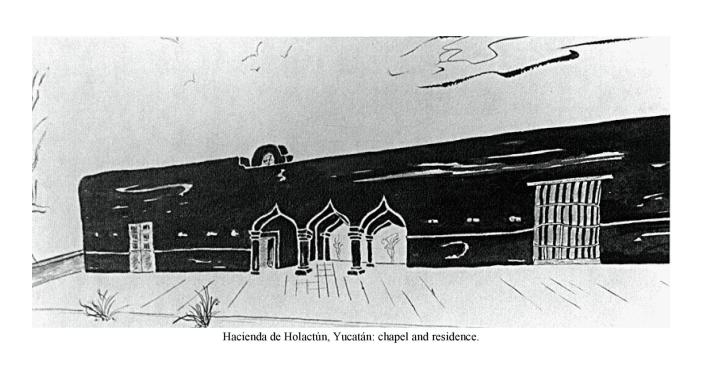

Hacienda de Holactún, Yucatán: chapel and residence.

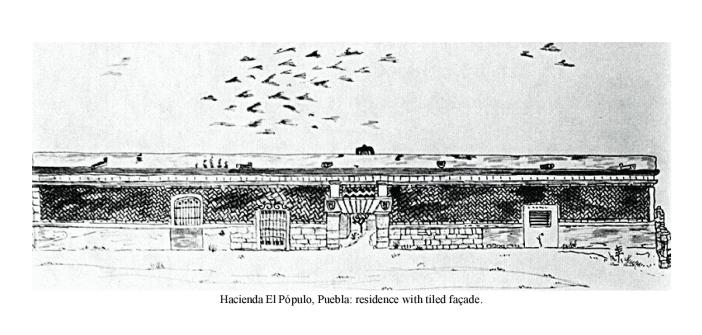

Hacienda El Pópulo, Puebla: residence with tiled façade.

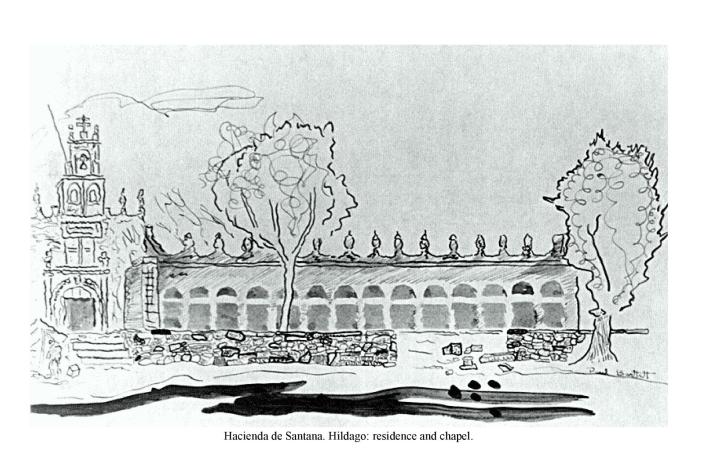

Hacienda de Santana, Hildago: residence and chapel.

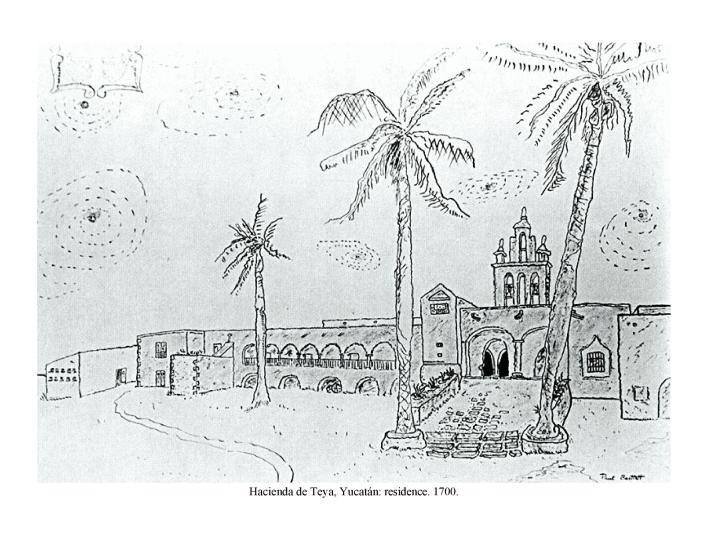

Hacienda de Teya, Yucatán: residence, 1700.

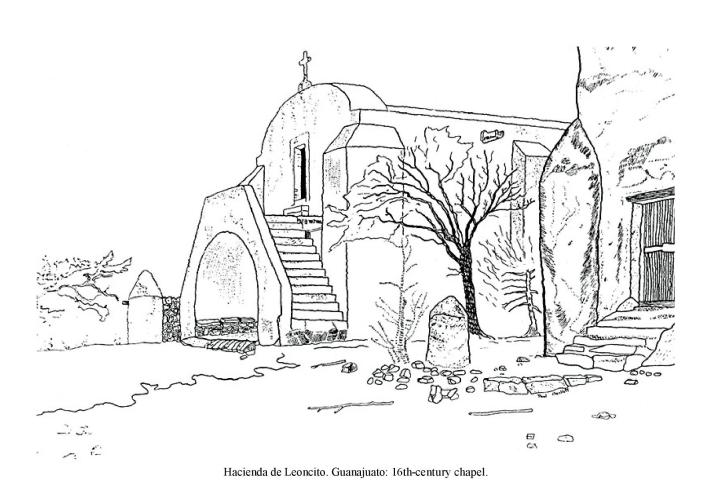

Hacienda de Leoncito, Guanajuato: 16th-century chapel.

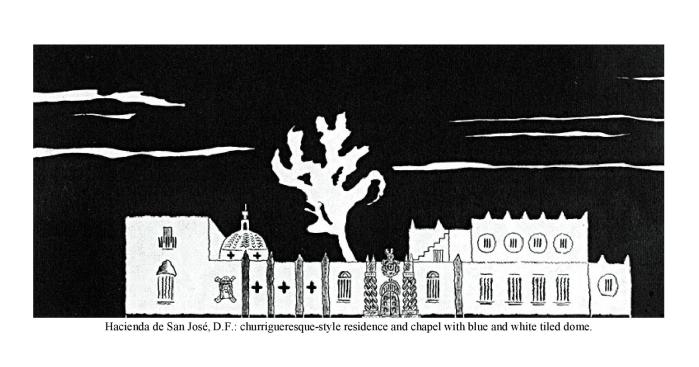

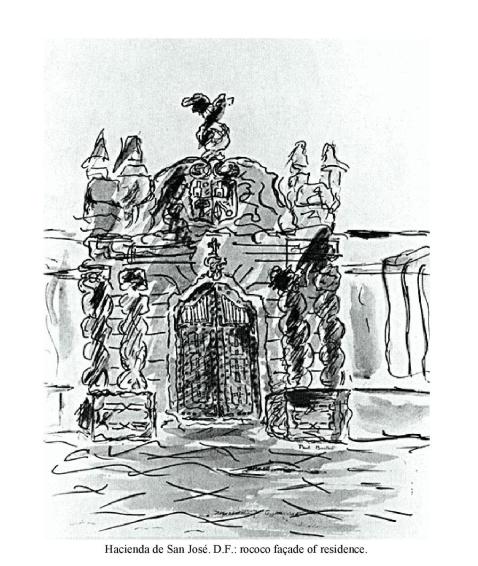

Hacienda de San José, D.F.: rococo façade of residence.

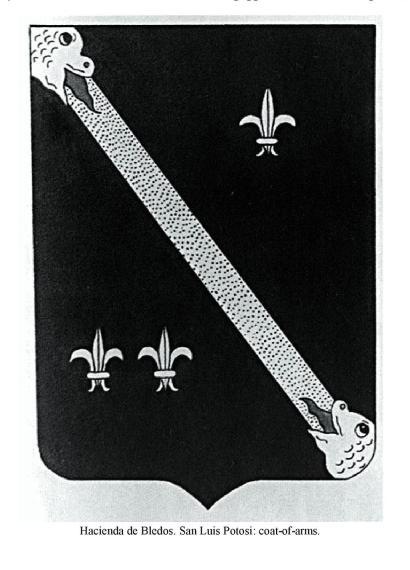

Hacienda de Bledos, San Luis Potosí: coat-of-arms.

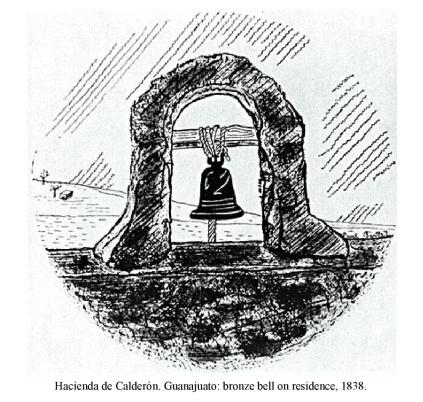

Hacienda de Calderón, Guanajuato: bronze bell on residence, 1838.

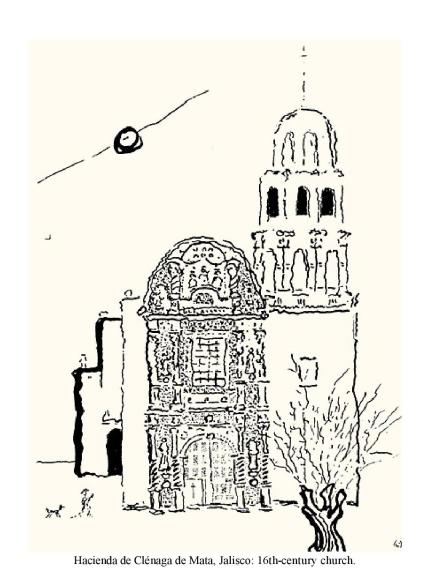

Hacienda de Ciénega de Mata, Jalisco: 16th-century church

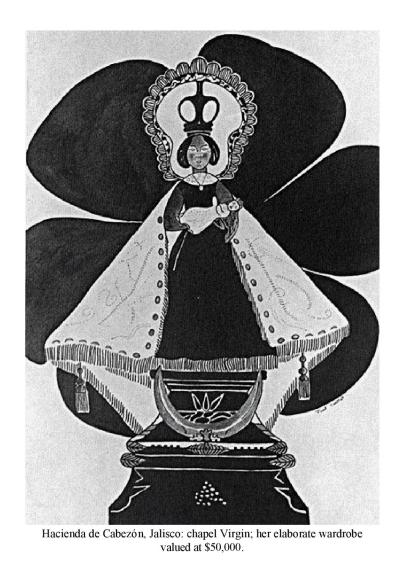

Hacienda de Cabezón, Jalisco: chapel Virgin; her elaborate wardrobe valued at $50,000.

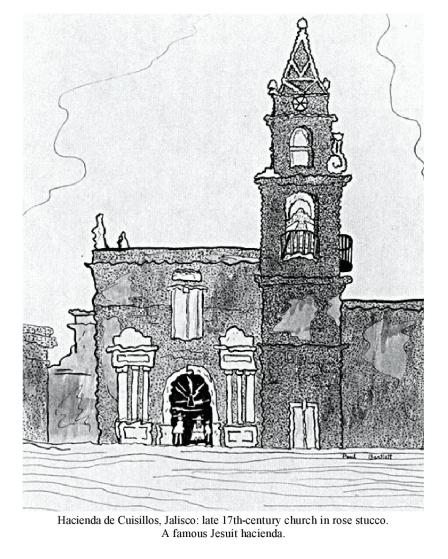

Hacienda de Cuisillos, Jalisco: late 17th-century church in rose stucco. A famous Jesuit hacienda.

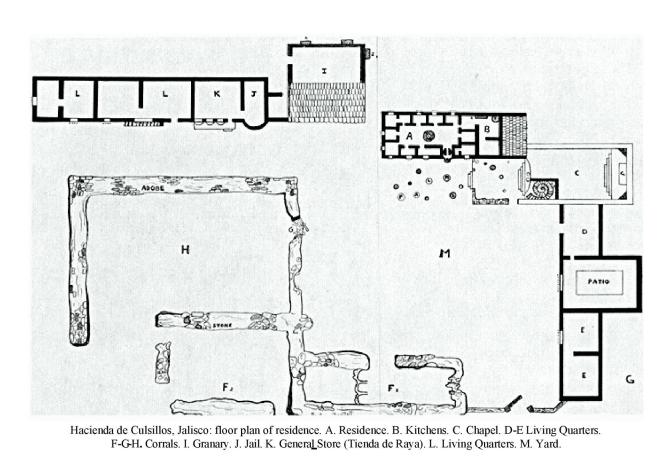

Hacienda de Cuisillos, Jalisco: floor plan of residence.

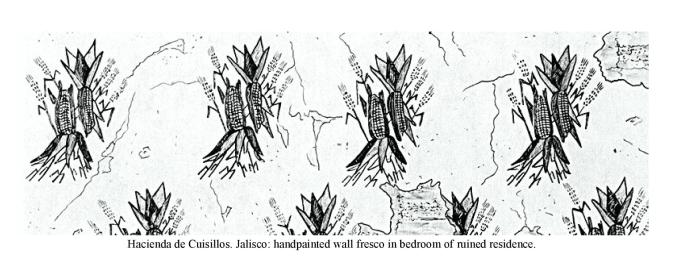

Hacienda de Cuisillos, Jalisco: handpainted wall fresco in bedroom of ruined residence.

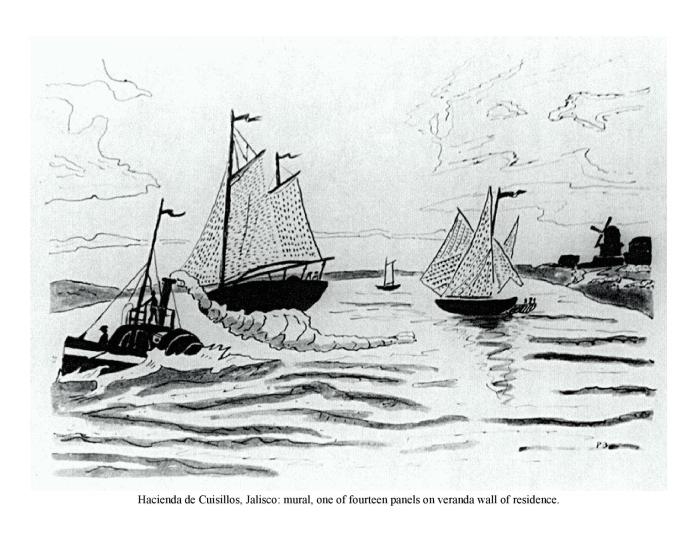

Hacienda de Cuisillos, Jalisco: mural, one of fourteen panels on veranda wall of residence.

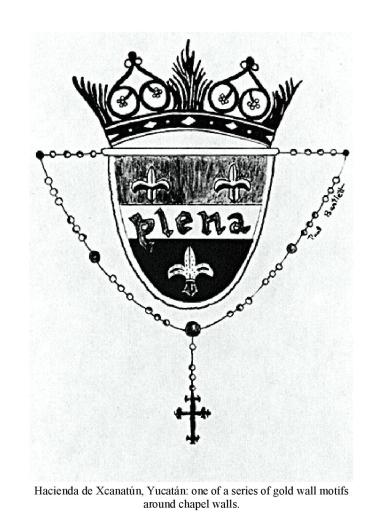

Hacienda de Xcanatún, Yucatán: one of a series of gold wall motifs around chapel walls.

Hacienda de San José Huejotzingo, Puebla: florentine armor in residence.

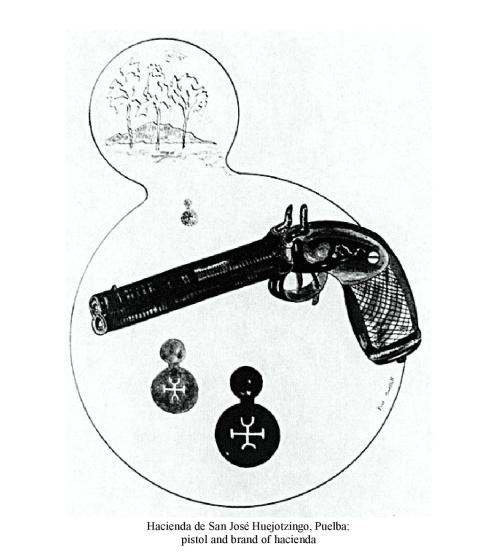

Hacienda de San José Huejotzingo, Puebla: pistol and brand of hacienda.

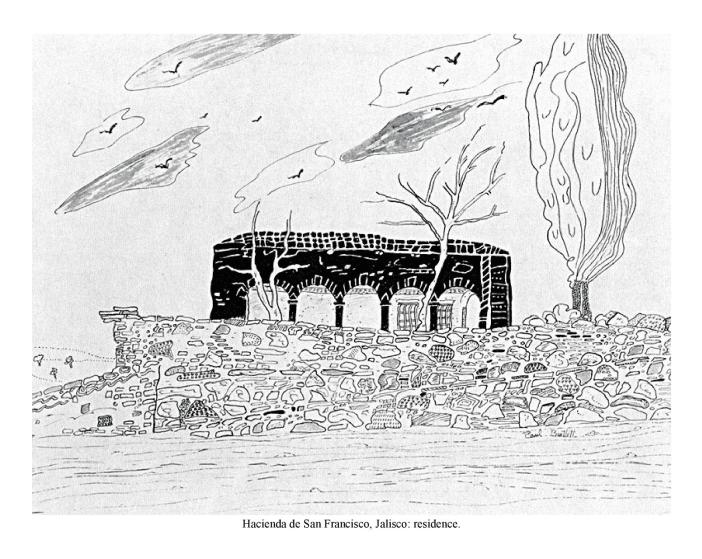

Hacienda de San Francisco, Jalisco: residence.

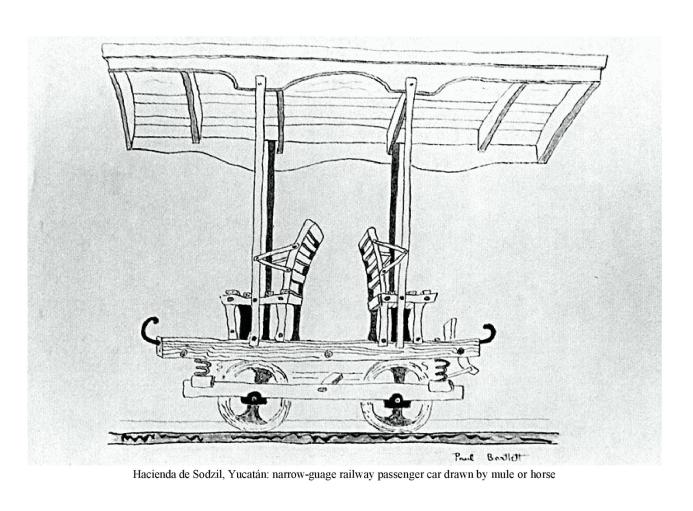

Hacienda de Sodzil, Yucatán: narrow-gauge railway passenger car drawn by mule or horse.

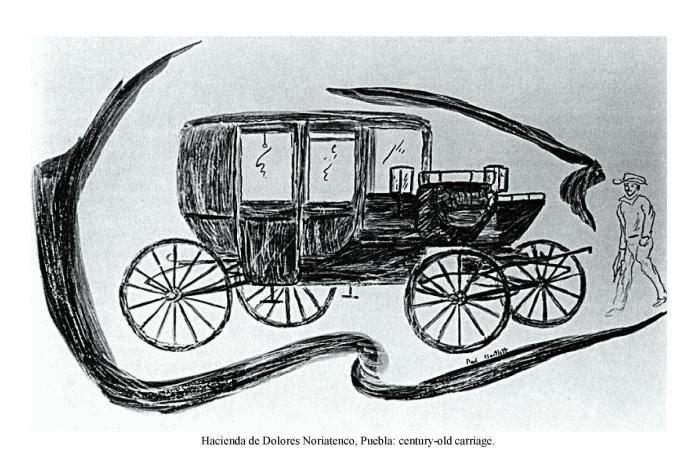

Hacienda de Dolores Noriatenco, Puebla: century-old carriage.

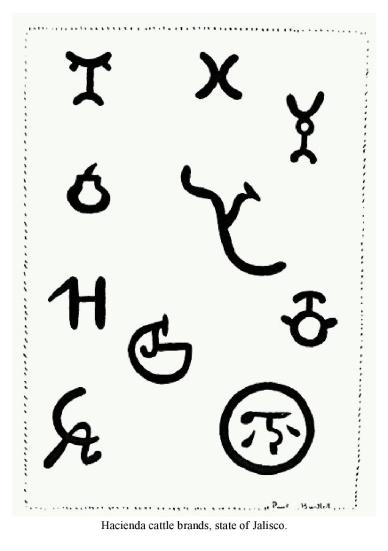

Hacienda cattle brands, state of Jalisco.

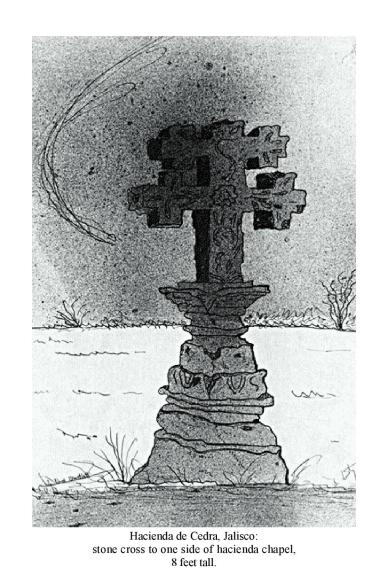

Hacienda de Cedra, Jalisco: stone cross to one side of hacienda chapel, 8 feet tall.

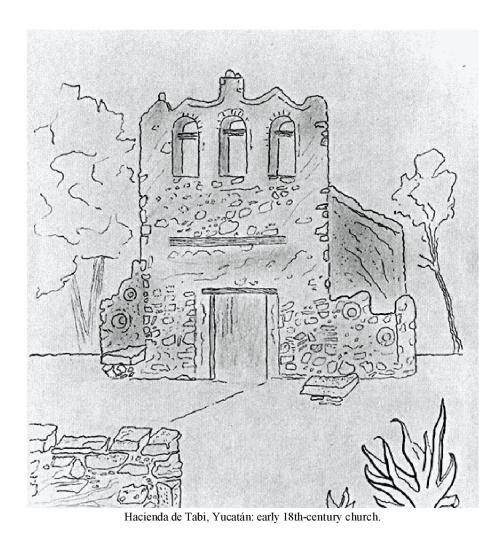

Hacienda de Tabi, Yucatán: early 18th-century church.

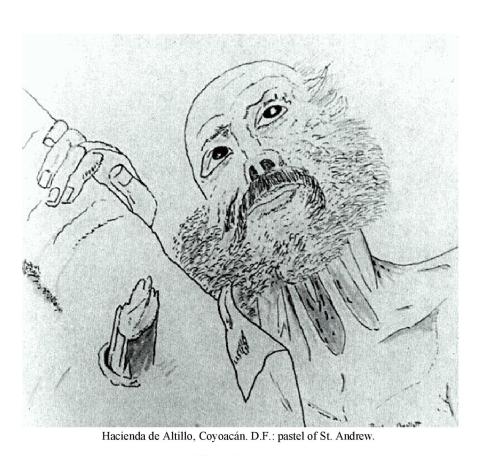

Hacienda de Altillo, Coyoacán, D.F.: pastel of St. Andrew.

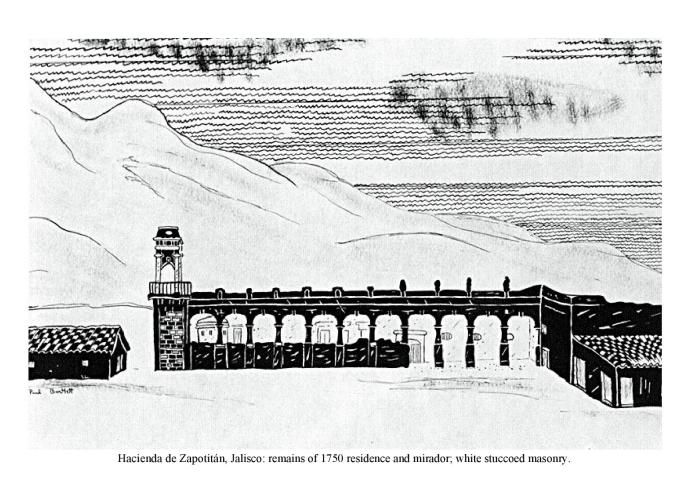

Hacienda de Zapotitán, Jalisco: remains of 1750 residence and mirador, white stuccoed masonry.

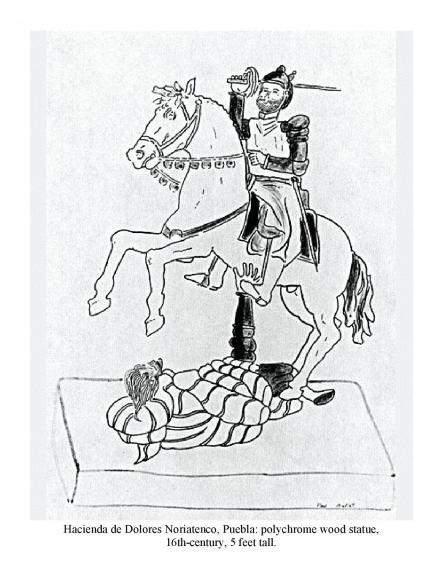

Hacienda de Dolores Noriatenco, Puebla: polychrome wood statue, 16th century, 5 feet tall.

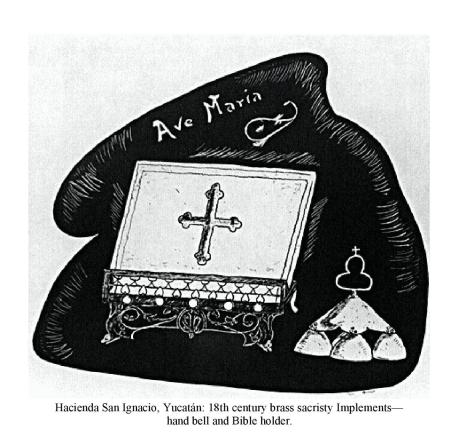

Hacienda San Ignacio, Yucatán: 18th century brass sacristy implements—handbell and Bible holder.

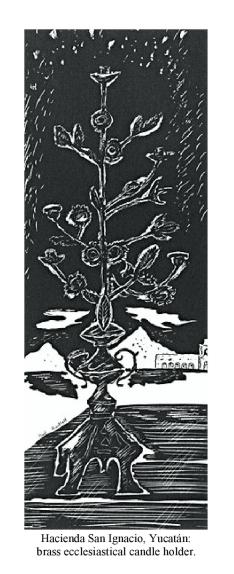

Hacienda San Ignacio, Yucatán: brass ecclesiastical candle holder.

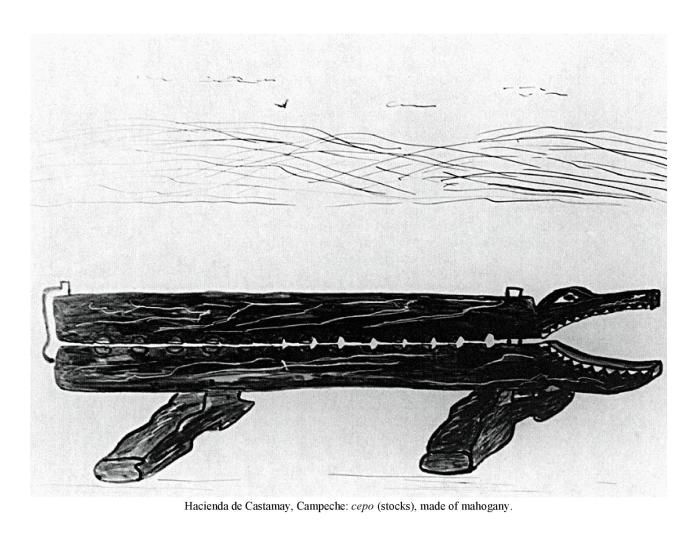

Hacienda de Castamay, Campeche: cepo (stocks), made of mahogany.

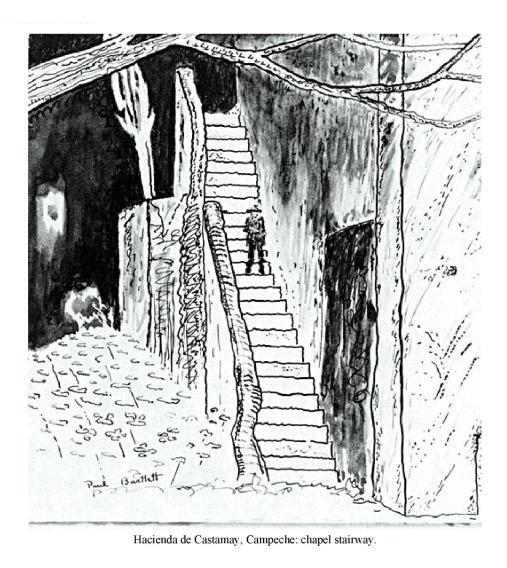

Hacienda de Castamay, Campeche: chapel stairway.

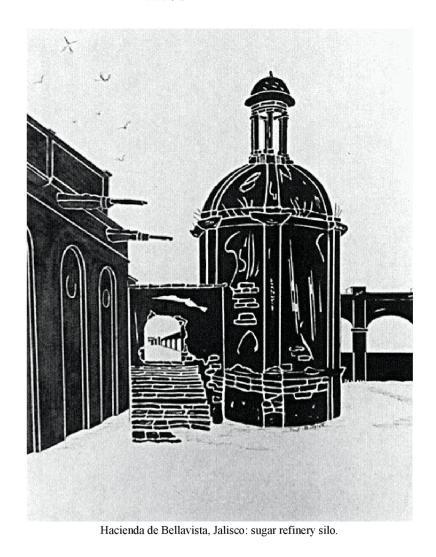

Hacienda de Bellavista, Jalisco: sugar refinery silo.

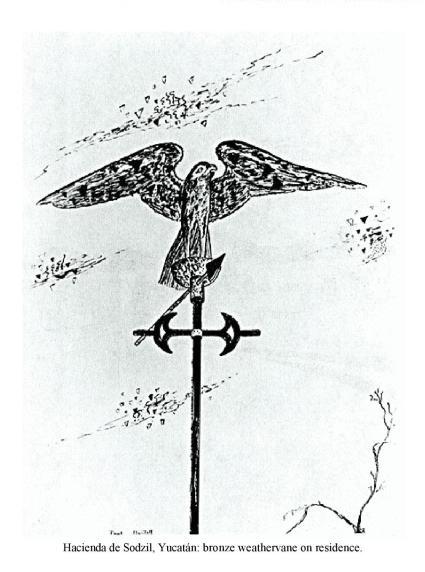

Hacienda de Sodzil, Yucatán: bronze weathervane on residence.

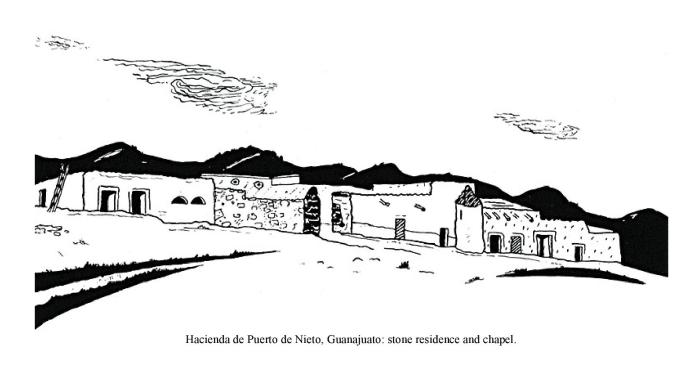

Hacienda de Puerto de Nieto, Guanajuato: stone residence and chapel.

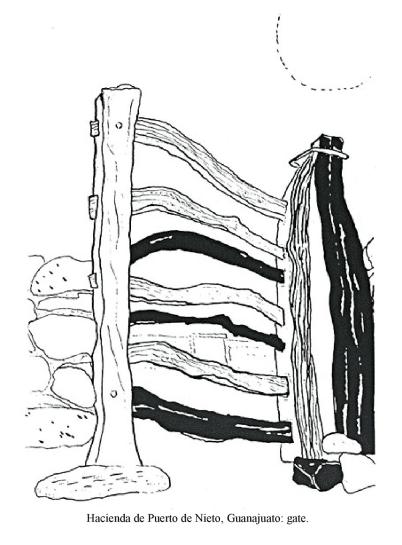

Hacienda de Puerto de Nieto, Guanajuato: gate.

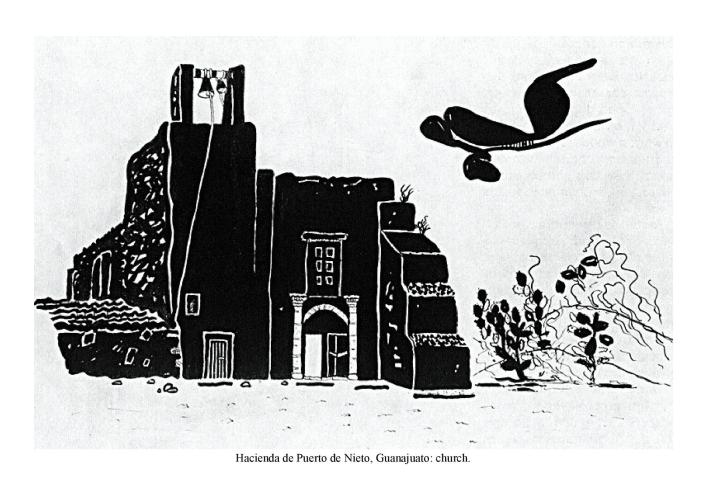

Hacienda de Puerto de Nieto, Guanajuato: church.

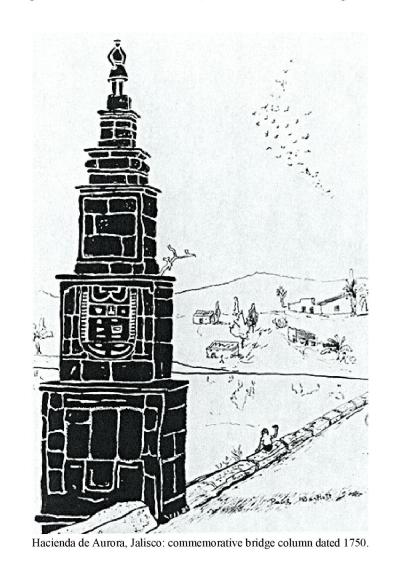

Hacienda de Aurora, Jalisco: commemorative bridge column dated 1750.

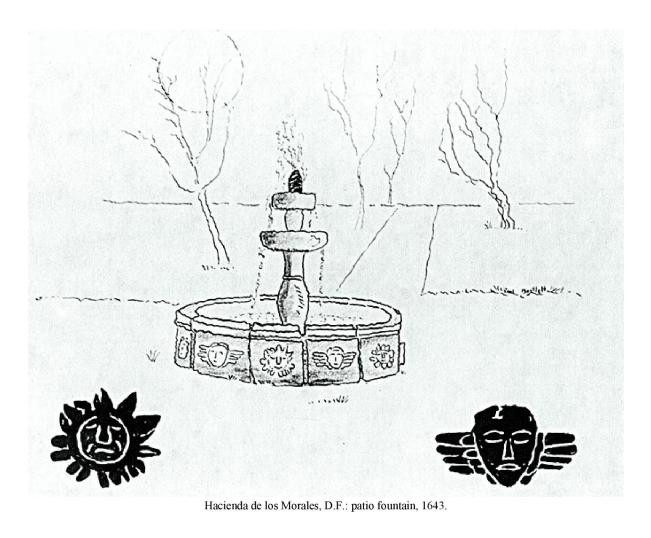

Hacienda de los Morales, D.F.: patio fountain, 1643.

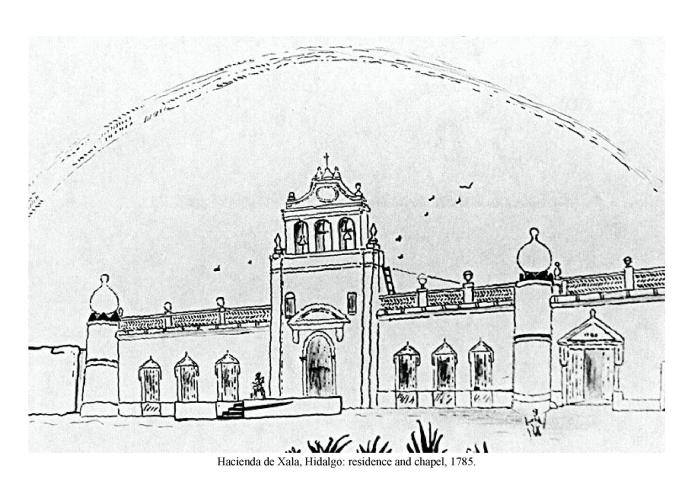

Hacienda de Xala, Hidalgo: residence and chapel, 1785.

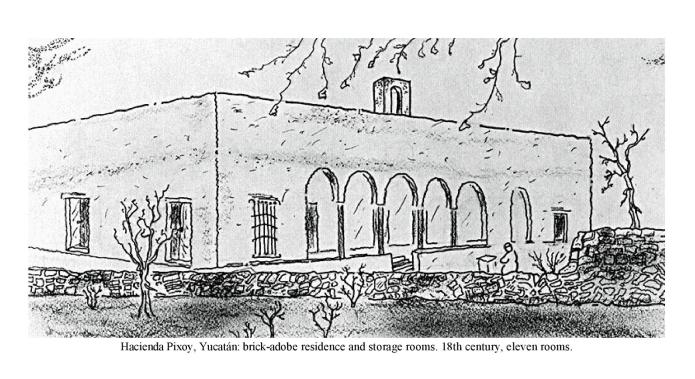

Hacienda Pixoy, Yucatán: brick-adobe residence and storage rooms. 18th century, eleven rooms.

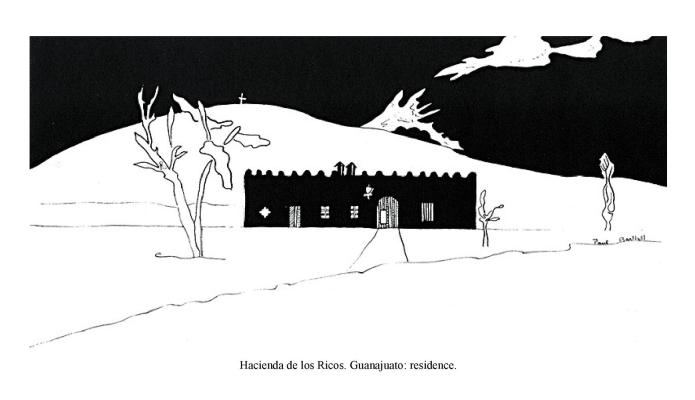

Hacienda de los Ricos, Guanajuato: residence.

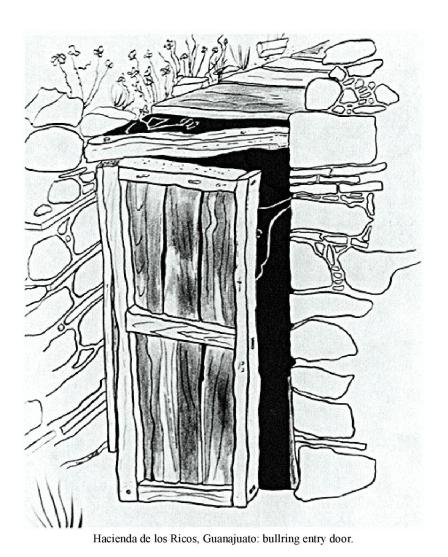

Hacienda de los Ricos, Guanajuato: bullring entry door.

Hacienda de Yaxche, Yucatán: Virgin, 14 inches high, 17th century.

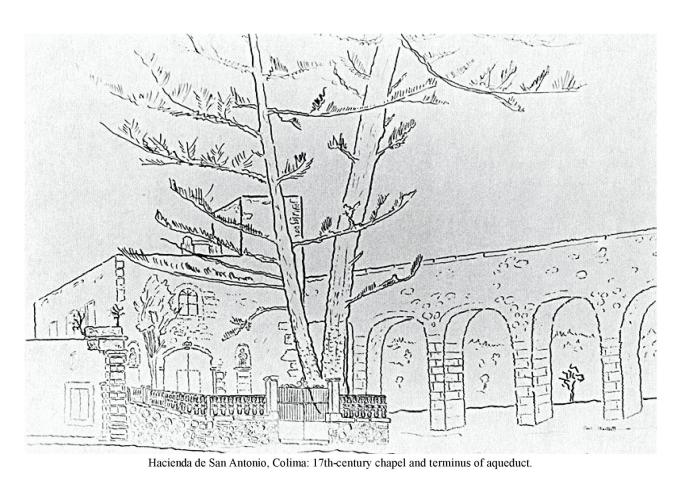

Hacienda de San Antonio, Colima: 17th-century chapel and terminus of aqueduct.

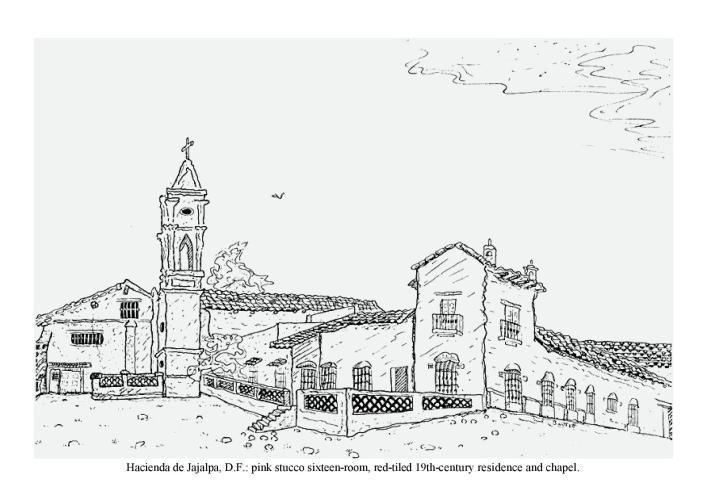

Hacienda de Jajalpa, D.F.: pink stucco sixteen-room, red-tiled 19th-century residence and chapel.

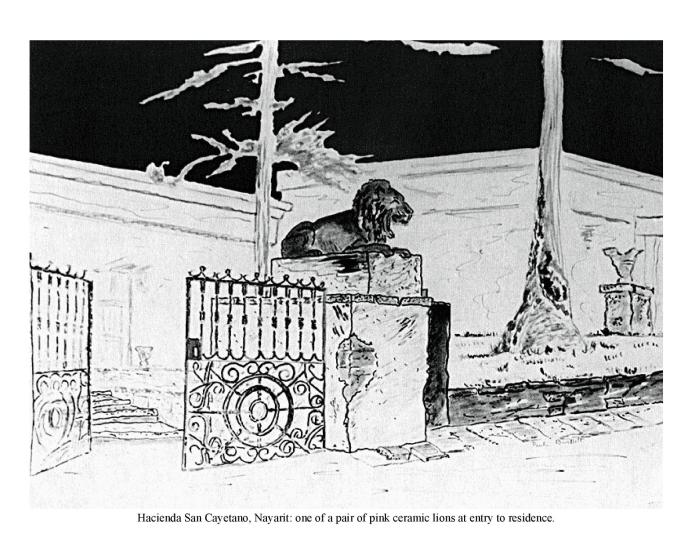

Hacienda San Cayetano, Nayarit: one of a pair of pink ceramic lions at entry to residence.

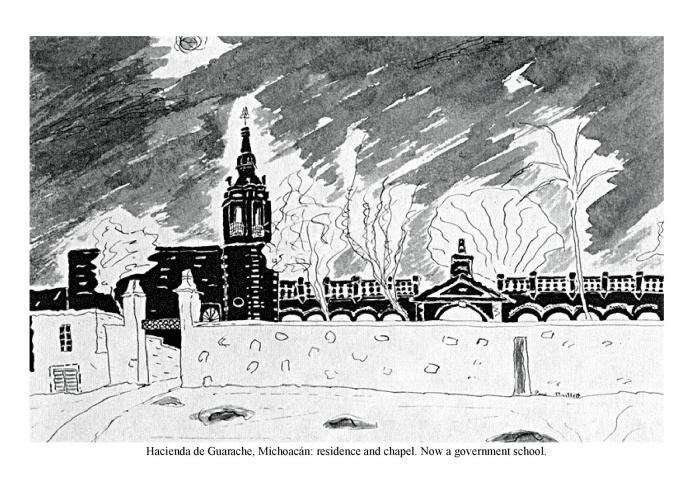

Hacienda de Guarache, Michoacán: residence and chapel. Now a government school.

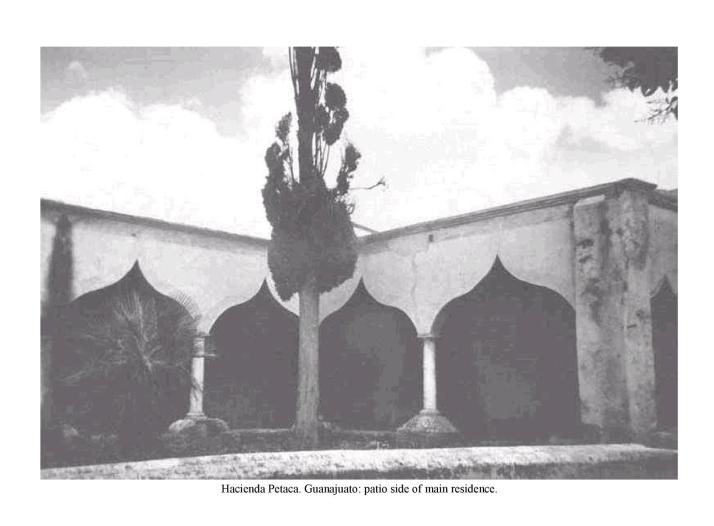

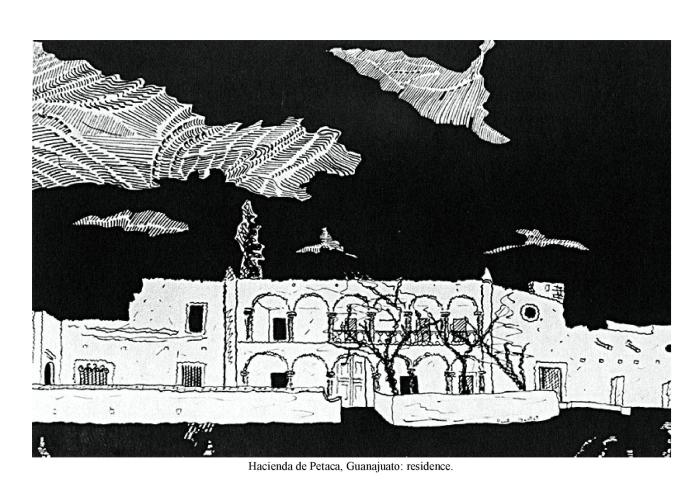

Hacienda de Petaca, Guanajuato: residence.

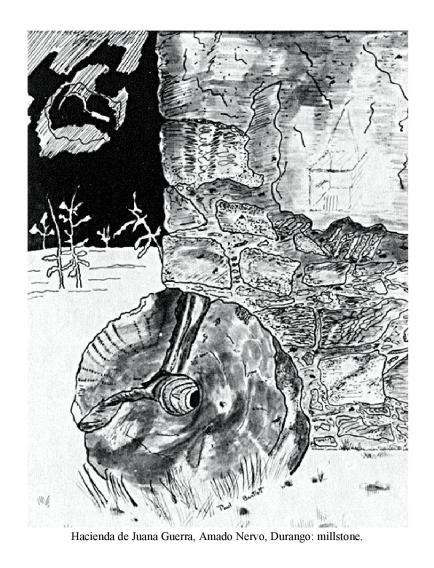

Hacienda de Juana Guerra, Amado Nervo, Durango: millstone.

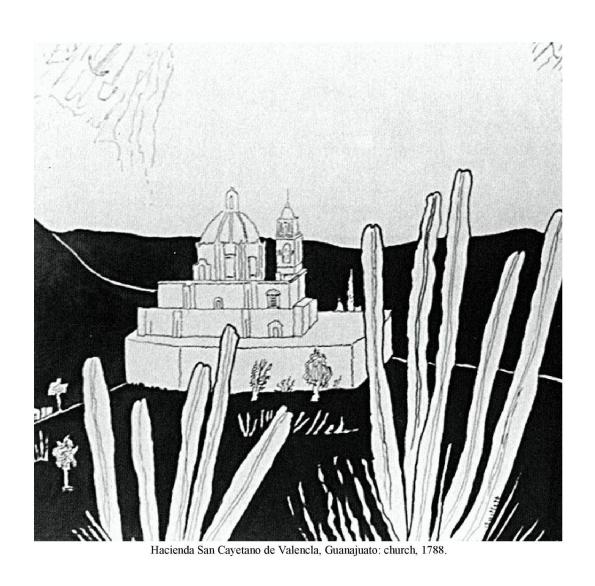

Hacienda San Cayetano de Valencia, Guanajuato: church, 1788.

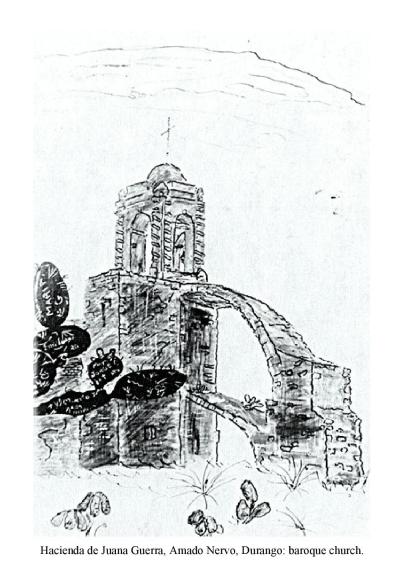

Hacienda de Juana Guerra, Amado Nervo, Durango: baroque church.

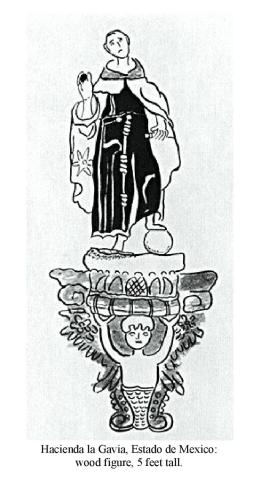

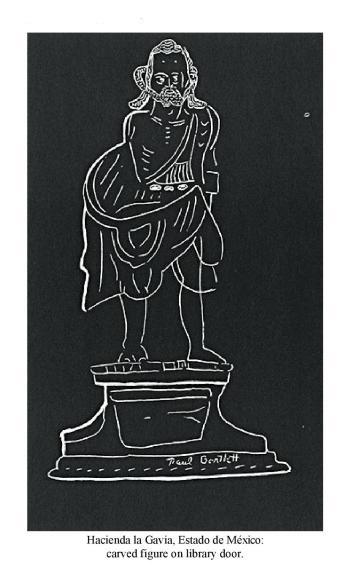

Hacienda la Gavia, Estado de México: wood figure, 5 feet tall.

Hacienda de Cocoyoc, Morelos: 16th-century chapel.

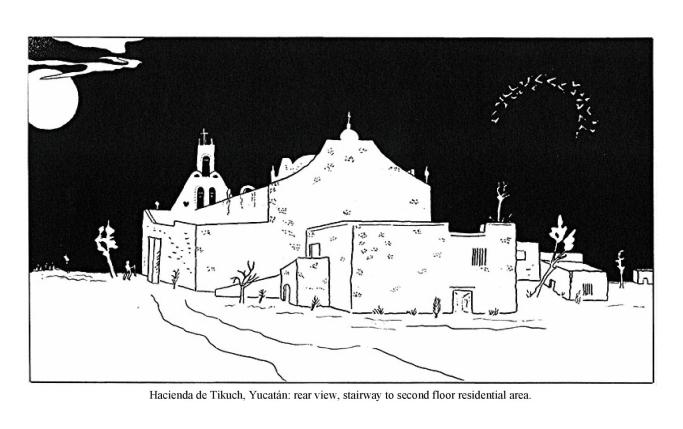

Hacienda de Tikuch, Yucatán: rear view, stairway to second floor residential area

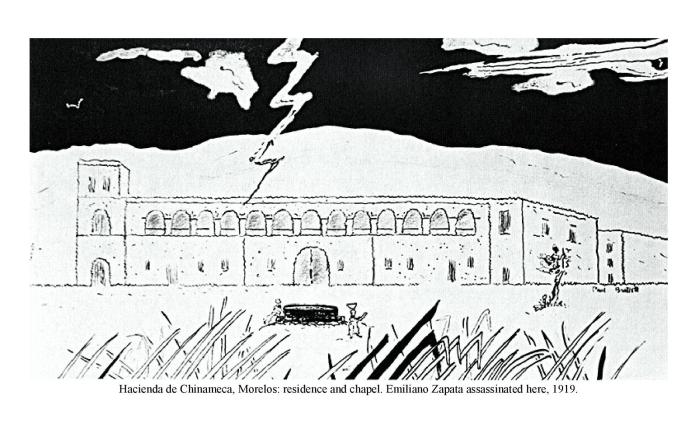

Hacienda de Chinameca, Morelos: residence and chapel. Emiliano Zapata assassinated here, 1919.

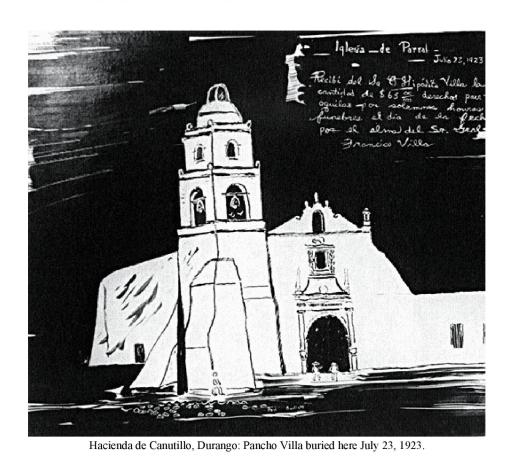

Hacienda de Canutillo, Durango: Pancho Villa buried here July 23, 1923.

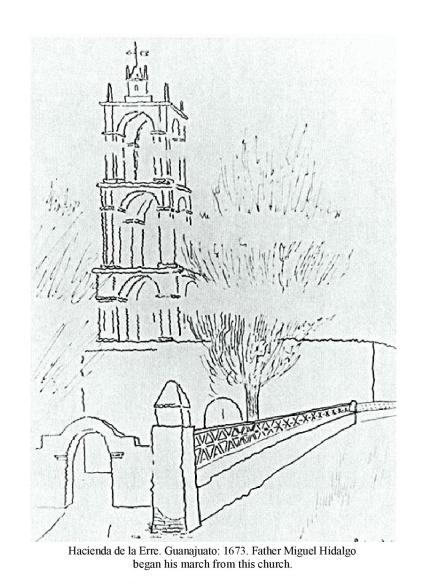

Hacienda de la Erre, Guanajuato: 1673. Father Miguel Hidalgo began his march from this church.

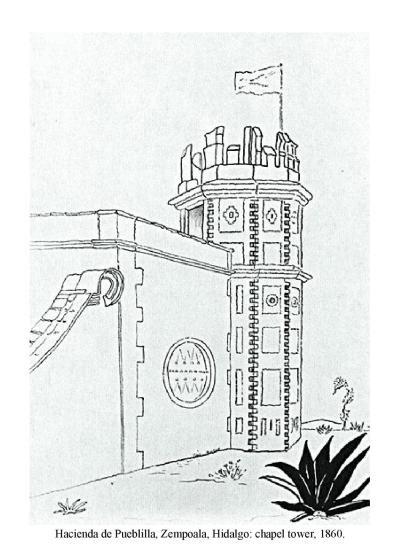

Hacienda de Pueblilla, Zempoala, Hidalgo: chapel tower, 1860.

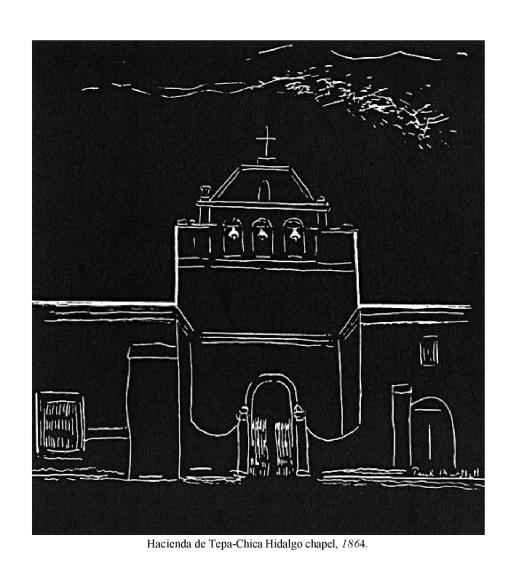

Hacienda de Tepa-Chica, Hidalgo: chapel, 1864.

Hacienda la Gavia, Estado de México: carved figure on library door.

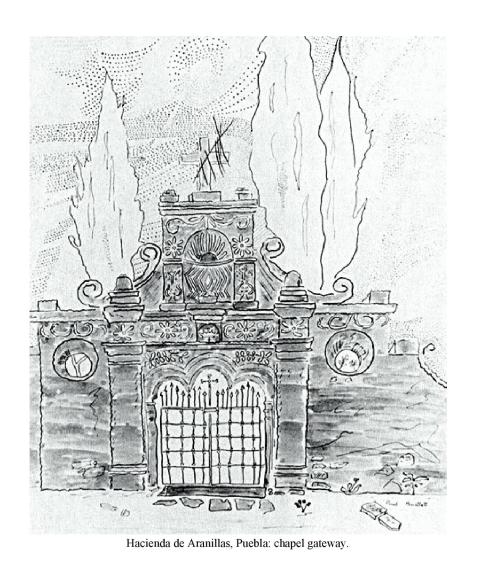

Hacienda de Arenillas, Puebla: chapel gateway.

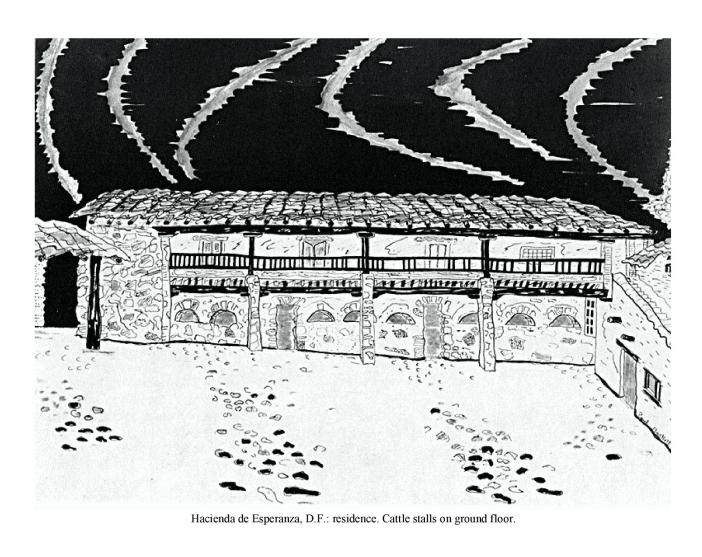

Hacienda de Esperanza, D.F.: residence. Cattle stalls on ground floor.

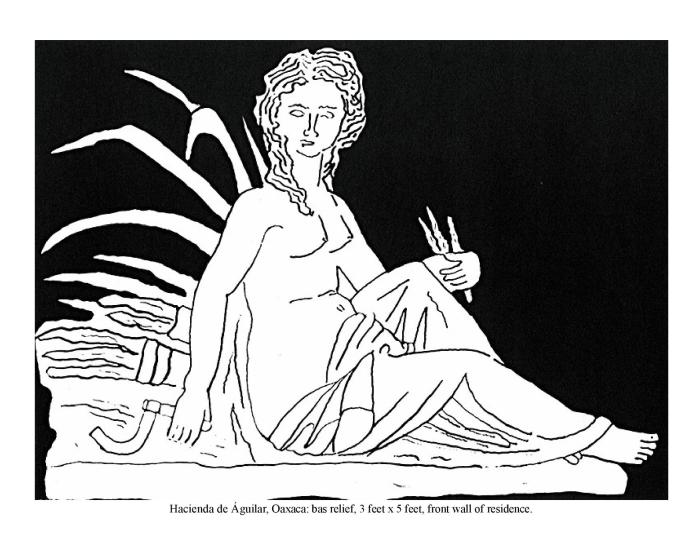

Hacienda de Águilar, Oaxaca: bas relief, 3 feet x 5 feet, front wall of residence.

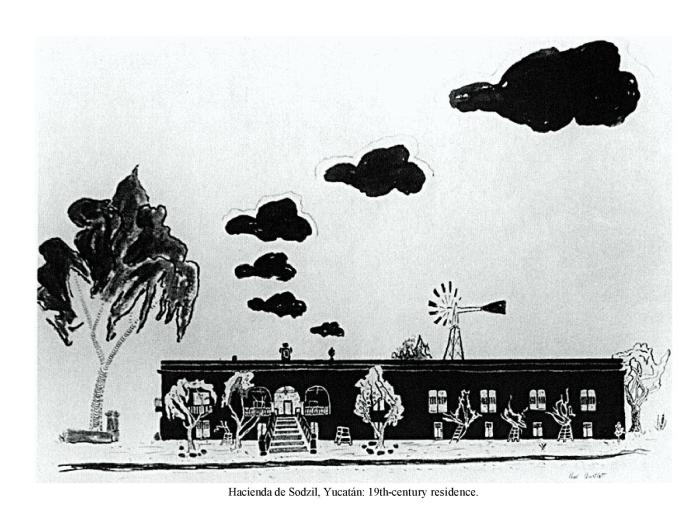

Hacienda de Sodzil, Yucatán: 19th-century residence.

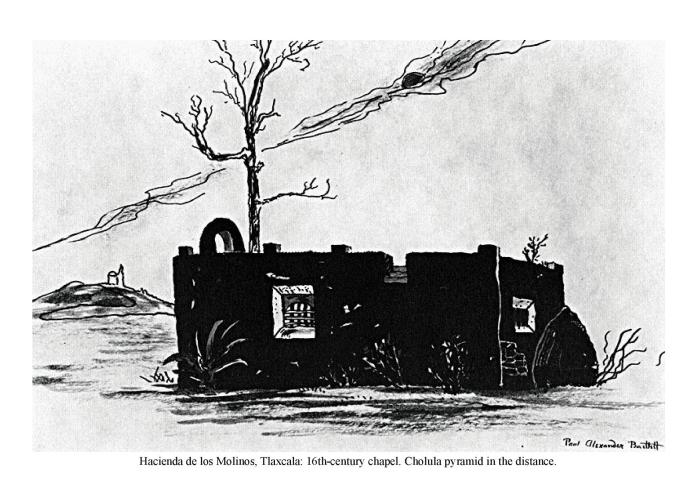

Hacienda de los Molinos, Tlaxcala: 16th-century chapel. Cholula pyramid in the distance.

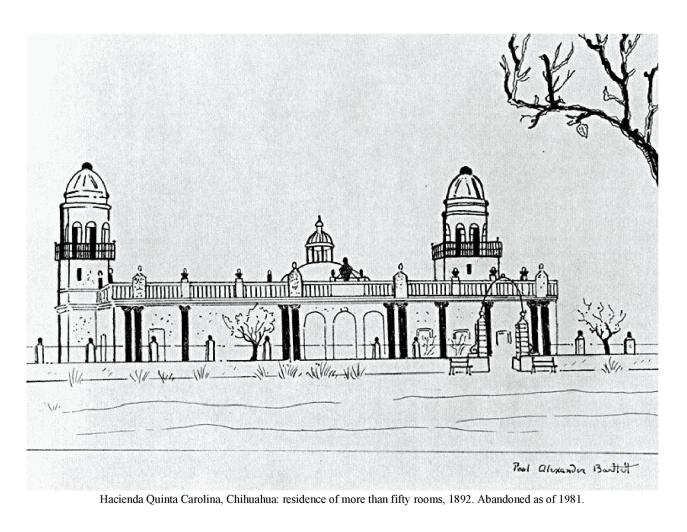

Hacienda Quinta Carolina, Chihuahua: residence of more than fifty rooms, 1892. Abandoned as of 1981.

Hacienda de Caleturia, Puebla: silver door knocker.

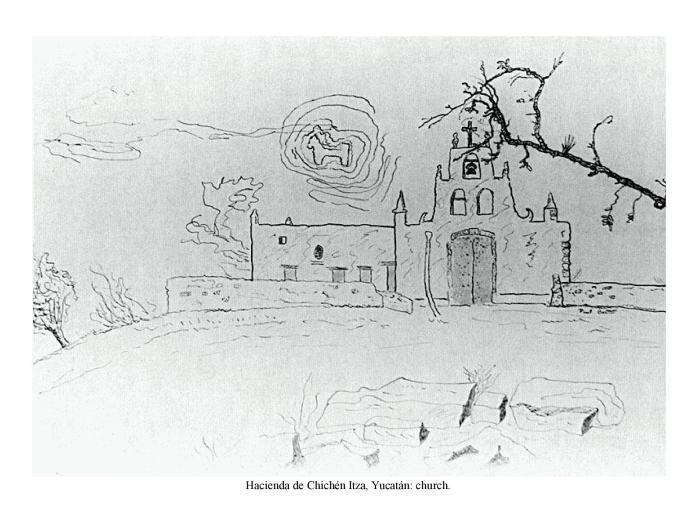

Hacienda de Chichén Itza, Yucatán: church.

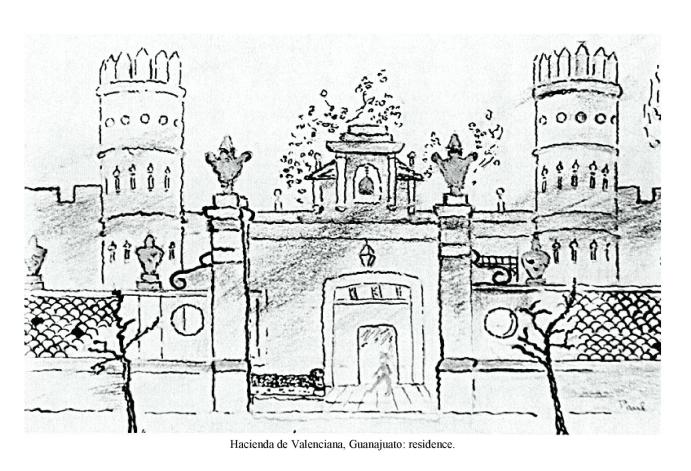

Hacienda de Valenciana, Guanajuato: residence.

Hacienda cattle brands from various states in Mexico appear at the beginning of each chapter.

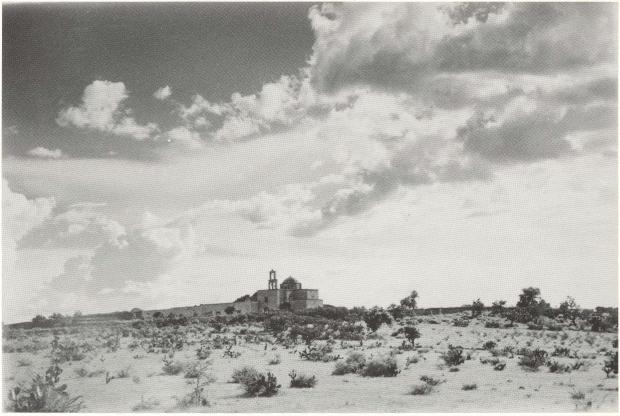

Hacienda Castillo, Jalisco: 18th-century landscape view typical of many haciendas.

Hacienda de Buena Vista, Jalisco: well-preserved residence and patio.

Hacienda de San Felipe, Oaxaca: 19th-century residence, patio fountain.

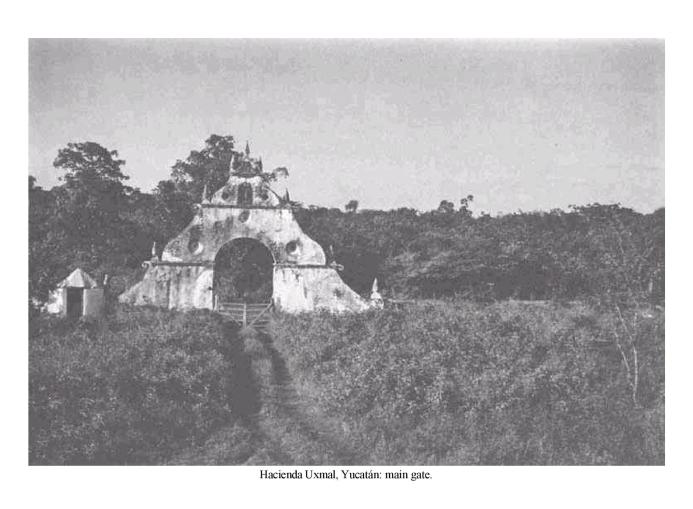

Hacienda Uxmal, Yucatán: main gate.

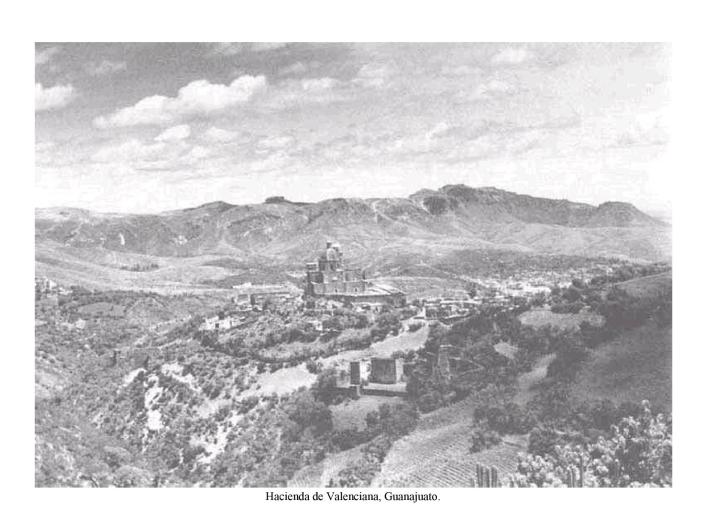

Hacienda de Valenciana, Guanajuato.

Hacienda Petaca, Guanajuato: patio side of main residence.

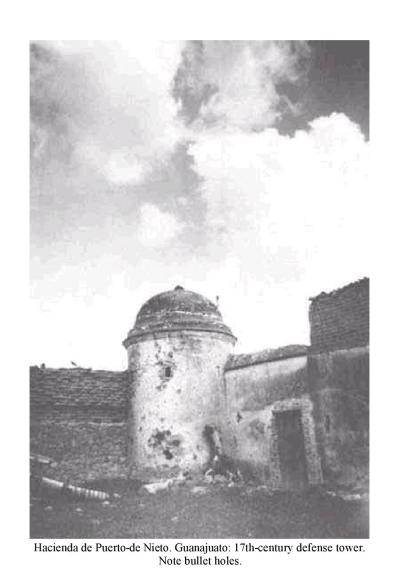

Hacienda de Puerto de Nieto, Guanajuato: 17th-century defense tower. Note bullet holes.

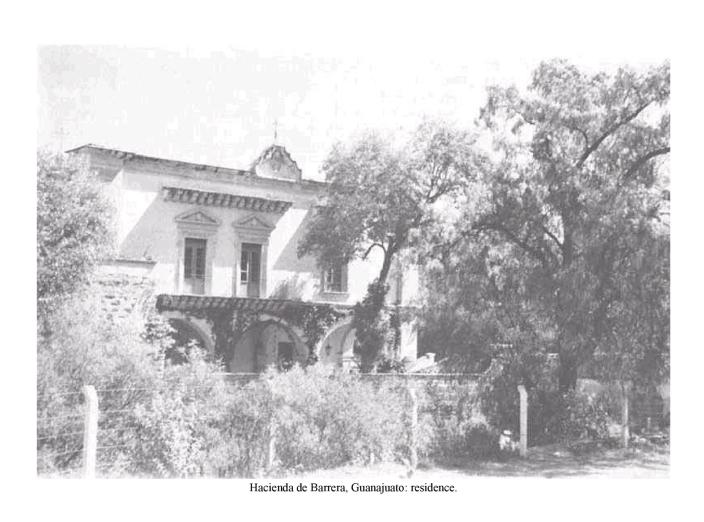

Hacienda de Barrera, Guanajuato: residence.

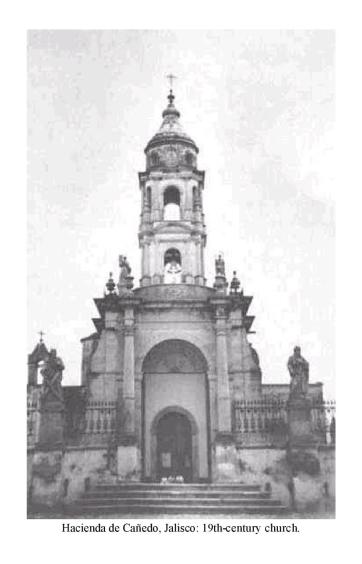

Hacienda de Cañedo, Jalisco: 19th-century church.

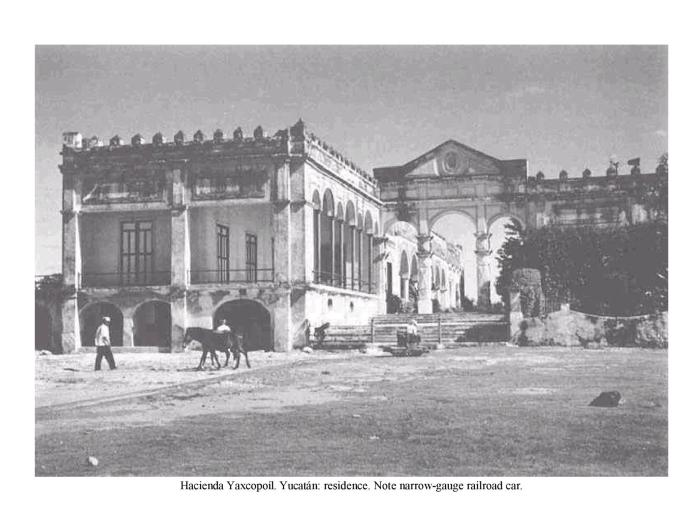

Hacienda Yaxcopoíl, Yucatán: residence. Note narrow-gauge rail-road car.

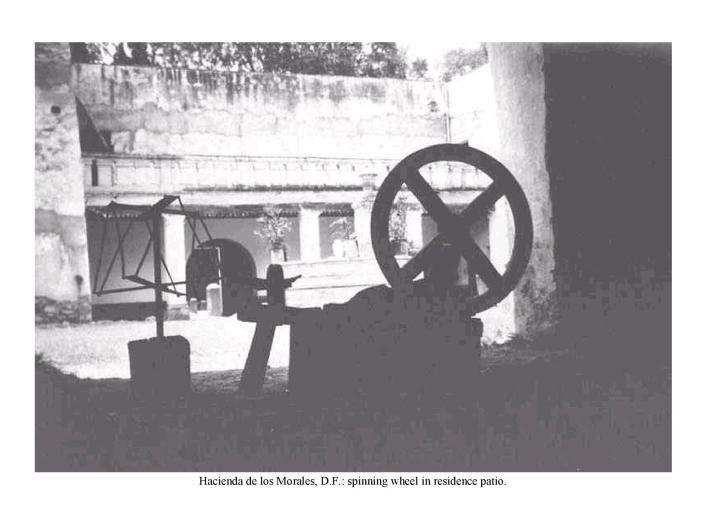

Hacienda de los Morales, D.F.: spinning wheel in residence patio.

Hacienda de Blanca, Oaxaca: patio.

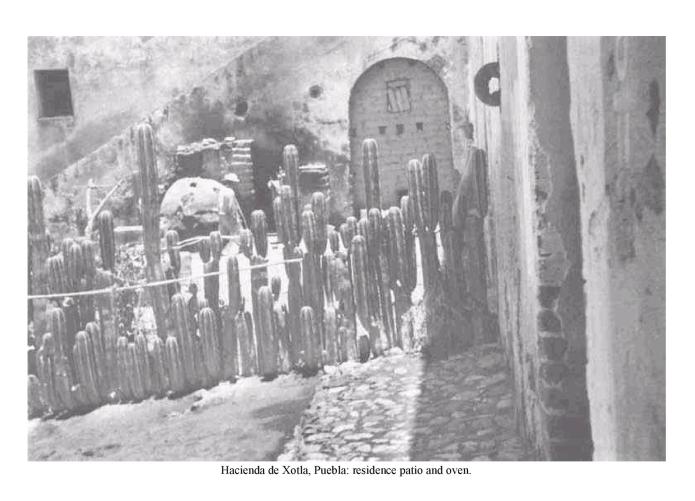

Hacienda de Xotla, Puebla: residence patio and oven.

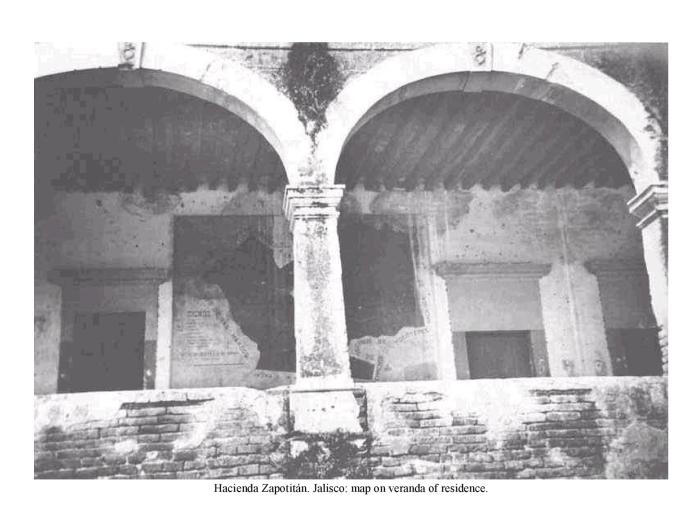

Hacienda Zapotitán, Jalisco: map on veranda of residence.

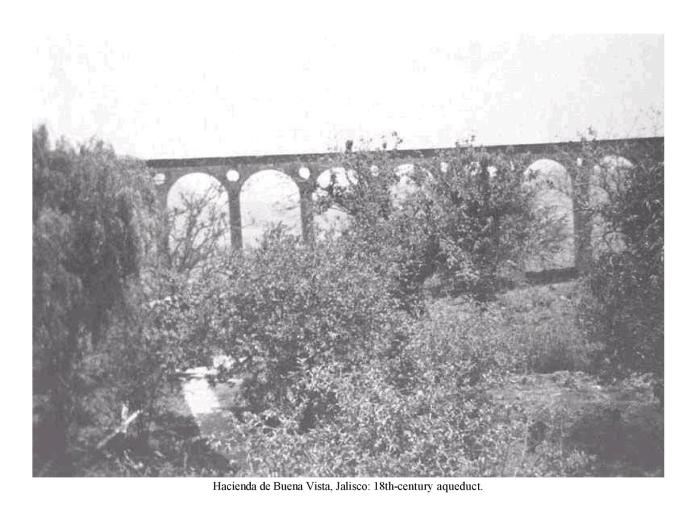

Hacienda de Buena Vista, Jalisco: 18th-century aqueduct.

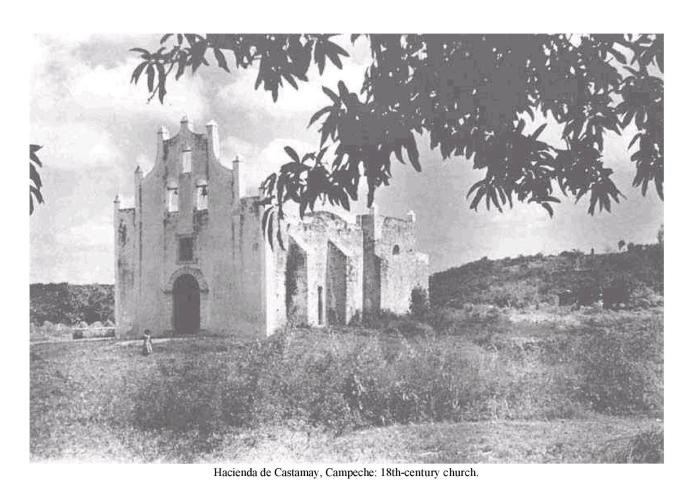

Hacienda de Castamay, Campeche: 18th-century church

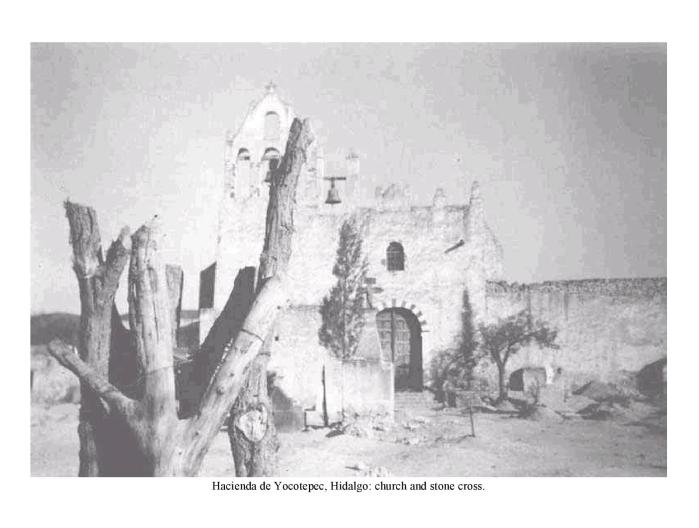

Hacienda de Yocotepec, Hidalgo: church and stone cross.

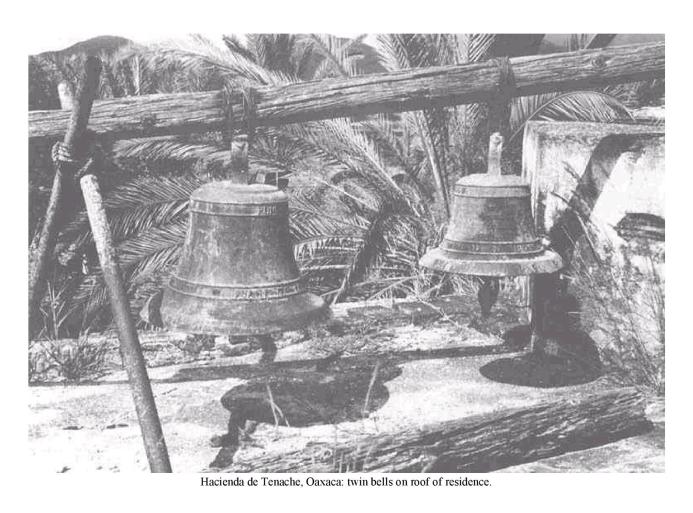

Hacienda de Tenache, Oaxaca: twin bells on roof of residence.

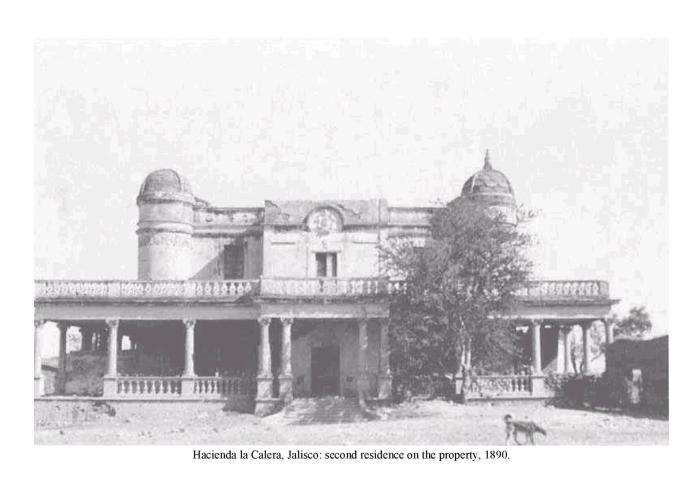

Hacienda la Calera, Jalisco: second residence on the property, 1890.

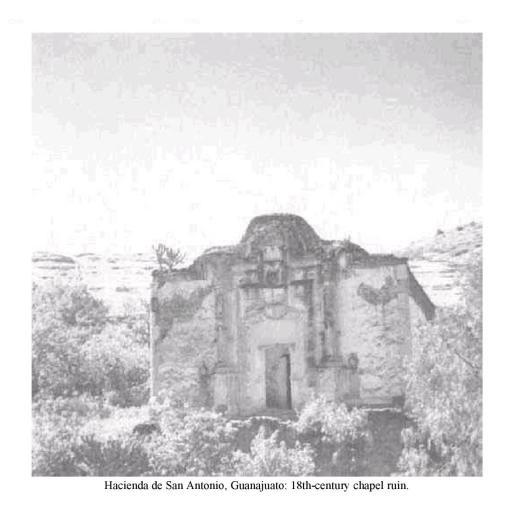

Hacienda de San Antonio, Guanajuato: 18th-century chapel ruin.

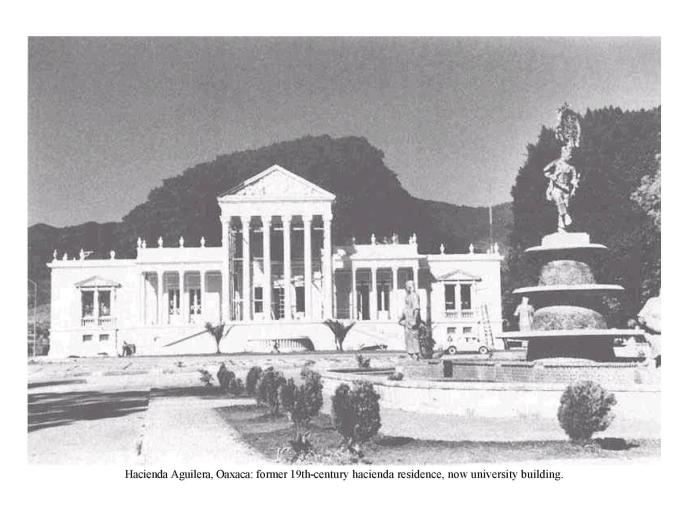

Hacienda Aguilera, Oaxaca: former 19th-century hacienda residence, now university building.

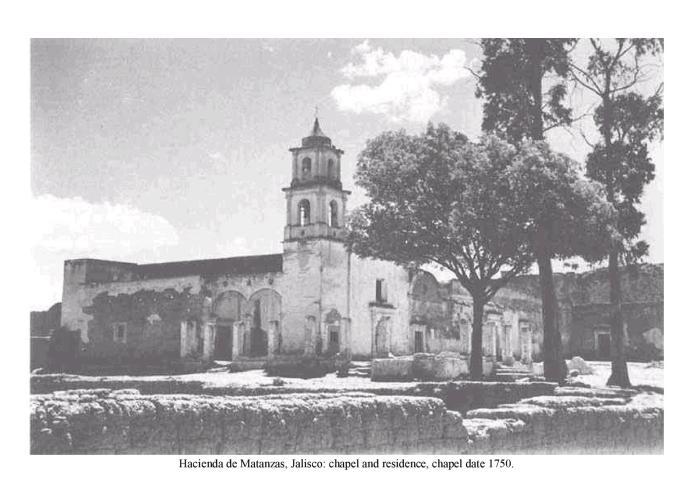

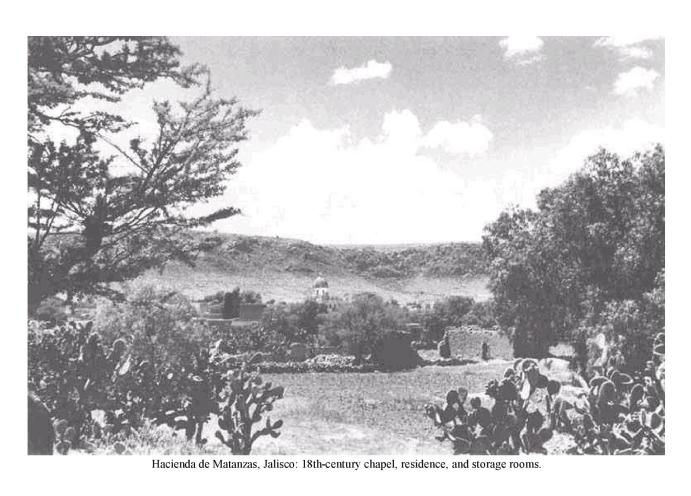

Hacienda de Matanzas, Jalisco: chapel and residence, chapel date 1750.

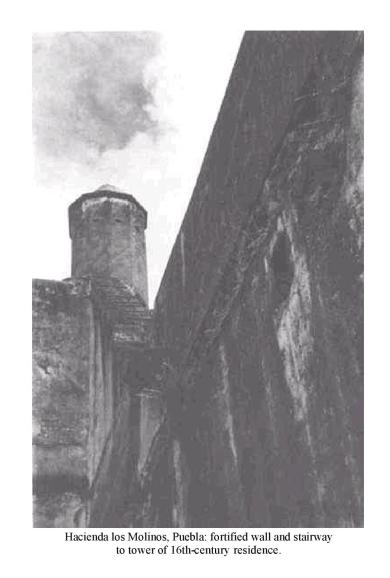

Hacienda los Molinos, Puebla: fortified wall and stairway to tower of 16th-century residence.

Hacienda de Matanzas, Jalisco: 18th-century chapel, residence,

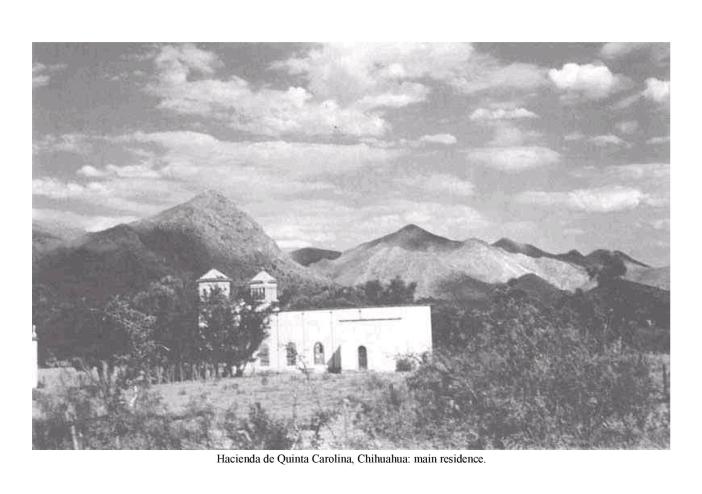

Hacienda Quinta Carolina, Chihuahua: main residence.

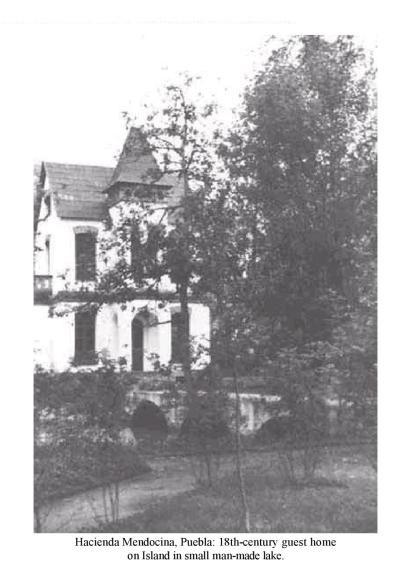

Hacienda Mendocina, Puebla: 18th-century guest home on island in small man-made lake.

James A. Michener

Distinguished Visiting Professor, University of Miami

I first became aware of the high artistic merit of Paul Bartlett's work on the classic haciendas of Old Mexico when I came upon an exhibition in Texas in 1968. His drawings, sketches, and photographs evoked so effectively the historic buildings I had known when working in Mexico that I wrote to the architect-artist to inform him of my pleasure.

Subsequently, I saw examples of his devotion to the great haciendas with their strong Mexican-Spanish coloration, and always I enjoyed his reminders of what life in colonial Mexico must have been like for the favored classes.

It is rewarding to renew my acquaintance with this remarkable body of work, for it is a reassuring example of what a lifetime of scholarship can accomplish.

The haciendas of Mexico have a special appeal for me. They represent a way of life that is now gone—some would say fortunately, since it was often a burdensome and cruel way of life for the peasant workers, a way of life that eventually motivated a revolution and the dissolution of the majority of hacienda landholdings.

Many haciendas can be reached only with difficulty by horse or by foot, by boat or motorcycle or jeep. Their isolation from the culture of Europe, three hundred years ago, impresses the mind with its severity. In their isolation, these estates recall the brave attempts of hacienda families to re-establish cultivated patterns of living in the New World, with fine china and crystal, grand pianos and chapel organs, ornate furnishings, paintings, and tapestries.

For my project, I received no financial rewards. Hence, I made repeated trips to Mexico, each funded by the modest savings accumulated in the United States between visits, with the hacienda project ever in mind.

My wife, Elizabeth encouraged my efforts. She was my mainstay, my constant friend and faithful companion. Our son, Steven, was born in Mexico and was raised in a world punctuated by hacienda visits; he was my compañero on many hacienda trips. The three of us usually returned to Mexico to stay for a year or two at a time.

To find out where haciendas were located in a particular area, I turned to local government officials, owners of village stores, the postman, or the peasant who delivered charcoal on his burro. Mostly, I found the haciendas on random trips, when their archways and rooftops appeared in the distance.

In 1941, when I began this project, few studies of the Mexican hacienda had been made. Only a handful of scholars had visited individual haciendas, and had gained first-hand familiarity with a limited number of them. To this day, with the possible exception of my own work, this is still true. And it is certain to remain true, since many of the haciendas I visited no longer exist. My own interest in that heritage was to re-create the special aura that my visits to more than three hundred haciendas had created. As an artist I felt an enduring affinity with a time that is no more, a heritage and tradition that may be recaptured only, I think, through the medium of art.

This, then, is an attempt to survey the story of the haciendas. It is not a treatise about their economic structure, their political influence, or their historical importance in the establishment of New Spain. Despite the meager records relating to the many individual haciendas, there are excellent studies of regional haciendas in Mexico. The reader will find references to them in the Bibliography.

The text was written to accompany a selection of my hacienda illustrations, including descriptions of hacienda life based on information received from personal contacts with hacienda families and caretakers who could still recall the old days. My impressions and commentary are offered to enable the reader to leave the twentieth century for a while and return to a period when the freshly colonized American continent witnessed the birth, the spread, and eventually the death of a unique way of life.

Finally, I wish to acknowledge my thanks to the many who helped my hacienda project to develop and grow through its many stages; among them: historians Frank Tannenbaum of Columbia University and Silvio Zavala of Mexico City; authors Ralph Roeder, Stuart Chase, and Russell Kirk; artist Roberto Montenegro; art directors Reginald Poland of the Atlanta Art Association, Herbert Friedmann of the Los Angeles County Museum, Donald Goodall of the University of Texas Art Gallery in Austin, the Reverend J. Pociask, S.J. of the DeSaisset Gallery at the University of Santa Clara, and Stella Benson of the Latin American library collections at the University of Texas in Austin; and art patron Huntington Hartford. I am especially grateful to my son, Steven, without whose help this book would have remained an unfinished project. I am also indebted to Dr. Fae Batten for her magnanimous effort, patience, and skill in preparing my photos for this book, and to Lowell Waxman, head librarian of the Claremont Branch of the San Diego Libraries for his tireless assistance in the department of references. In addition, I am thankful for the good friends and associates it has been my fortune to come across on the long journey over the years.

Hacienda Castillo, Jalisco: 18th-century landscape view typical of many haciendas.

This book contains reproductions of a selected number of illustrations and photographs, drawn from a collection of more than 300 original pen-and-ink illustrations and several hundred photographs, which now form part of the Benson Latin American Collection of the University of Texas in Austin. A collection of hacienda photographs, illustrations, and other materials is also maintained by the Western History Research Center of the University of Wyoming in Laramie.

Hacienda de Buena Vista, Jalisco: well-preserved residence and patio.

Gisela von Wobeser

Professor of History, Instituto de Investigaciones Históricas

Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, México, D.F.

Translated from the Spanish by

Steven J. Bartlett

Senior Research Professor, Oregon State University

The lifework of artist Paul Alexander Bartlett to retrieve the past of the Mexican hacienda has made this book possible. This volume contains a selection of his original pen-and-ink illustrations and photographs, realized over a period of some forty years, of more than three hundred haciendas.

Bartlett began his record during the 1940s. He made a series of visits to Mexico to sketch and photograph the hacienda buildings that had survived the Agrarian Reform. Many haciendas were inaccessibly located, at considerable distances from population centers. He traveled hundreds of miles on foot, on muleback, by train and by boat, climbed hills, and descended into canyons to find them.

The record that Bartlett has made represents an important chapter in Mexican history. Because the majority of hacienda structures have been subjected to severe and progressive deterioration, his study, in many cases, is the only trace that remains of the physical appearance of individual haciendas. His collection of illustrations and photographs is now in the custody of two institutions, the University of Texas at Austin, in the Benson Latin American Collection, and the University of Wyoming in Laramie, in the Western History Research Center [Now the American Heritage Center]. These two archives will be useful to scholars interested in the physical structure of the haciendas, their evolution and history, their economy, as well as in comparative studies. At the same time, this collection of materials makes it possible to study the characteristics of different types of haciendas. Above all, the contents of the two archives form an extremely valuable resource for the history of art and architecture.

Hacienda de San Felipe, Oaxaca: 19th-century residence, patio fountain.

Hacienda de Encero, Veracruz: church, 1799.

When Bartlett began his travels through the Mexican backcountry, the producing haciendas had largely disappeared. What he found were often remnants of an earlier existence during the Porfiriato, the period between 1877 and 1911. Many of the buildings he saw dated from this epoch, along with their interior decorations, water and irrigation systems, machinery, and farming tools. In addition to these haciendas, he also found vestiges of the first half of the nineteenth century and of the colonial era. These were mainly hacienda buildings, some of which had been rebuilt during the Porfiriato.

The disintegration of the haciendas began as a result of the Mexican Revolution, and it ended with the redistribution of their land during the Agrarian Reform. During the 1930s and 1940s, huge rural estates were fragmented and converted into ejidos or minifundios. Ejidos are tracts of land that are granted as communal property to rural towns. They are worked by members of the community, who benefit from the land's yield. Ejidal properties cannot be sold or transferred. The minifundios are small private pieces of property, amounting on the average to 100 hectares but varying according to the region of the country and type of soil. Between 1934 and 1940, approximately 17,900,000 hectares (44,230,900 acres) were redistributed, representing close to half of all tillable land. This repartitioning of the land has continued into the present, though its pace has been much slower.

As hacienda property was broken up, the hacienda owners, the hacendados, were left in possession of the hacienda buildings and the immediate land around them, the size of which was restricted by the limits that were set for these small properties. This meant that immense haciendas were reduced to very tiny ranches. Along with their land, the hacendados lost access to water, they lost their means of irrigation, machinery, and livestock.

Because of these measures, the hacienda system was annihilated. For the majority of the hacendados, the few acres left them turned out to be unproductive land, and their hardships were magnified by the instability and the violence that prevailed in the country. As a result, many hacienda buildings were abandoned or were destined for new purposes.

Only a few of the ex-haciendas remained in production. Some landowners took advantage of the limited property left to them to plant lucrative, high-yielding crops, while others augmented the size of their cultivated land by leasing adjoining land or by purchasing it under assumed names.

Hacienda de Bledos, San Luis Potosí: map of the hacienda.

When Bartlett began his hacienda visits in the 1940s, he found many of the hacienda buildings in ruins, exposed to the ravages of time and vandalism. Buildings had been converted into chicken coops, pigsties, public apartments, and machine shops. Others served as sources for construction materials, from which were scavenged rocks, bricks, beams, and tiles for the habitations of the local population. In some cases the destruction was total: All the hacienda's structures were removed, and only the name of the place alluded to the fact that an hacienda had ever existed there.

At other haciendas, buildings were adapted to new uses. They were transformed into hotels, resorts, government buildings, barracks, hospitals, restaurants, and schools. The exterior of the buildings were generally left intact; interiors were completely changed.

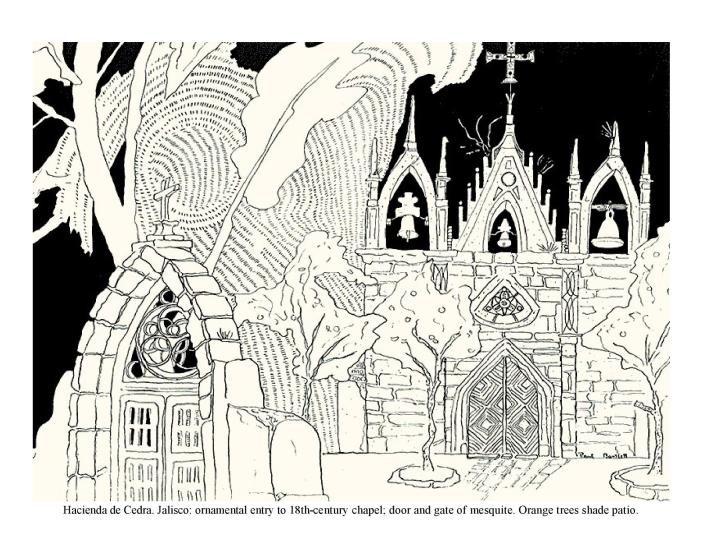

Hacienda de Cedra, Jalisco: ornamental entry to 18th-century chapel; door and gate of mesquite.

Orange trees shade patio.

Hacienda de Endo, Sonora: residence, stable below.

The best-preserved hacienda buildings were those that continued to function as country properties or vacation homes. In these, Bartlett often found furnishings and utensils from the epoch of Don Porfirio, surrounded by the old traditions of Mexican country life.

As an artist, Bartlett's attention was drawn foremost to the hacienda buildings themselves and to the works of art that they housed. The majority of his illustrations and photographs therefore depict the main group of hacienda buildings or certain buildings—for example, the main residence, the church, the patios, and work buildings. However, among his rich materials, one can also find a testimony to hacienda work and life: machinery, irrigation devices and structures, farm implements, mining equipment, warehouses, barns, corrals, and carriages, among others.

The history of the hacienda spans three centuries. The first haciendas appeared in New Spain toward the beginning of the seventeenth century, when demand for agricultural products increased and the prehispanic supply system crumbled. Farming received an impetus at the hands of Spaniards, and the small farms and livestock ranches, which dated from the sixteenth century, expanded their landholdings. Many new sources of water were tapped, and a resident labor force was developed. These steps encouraged production and supplied the regional as well as the continually growing metropolitan markets.

The increase in hacienda production and in the number of hacienda workers made it necessary to expand the sixteenth-century facilities, which, with the exception of those of the sugar plantations, had been very modest. In this way, a large number of buildings were constructed, buildings that were to be preserved as the core of many haciendas until the Porfiriato.

There were three principal types of haciendas. Grain haciendas were the most important because they were dedicated to the cultivation of the subsistence crops corn and wheat. In addition, beans, barley, lima beans, chiles, and other crops were planted. Grain haciendas were established mainly in the vicinity of the urban centers, which they supplied. The important areas of grain cultivation were Puebla, Atlixco, Toluca, Guadalajara, Oaxaca, and Michoacán. Livestock haciendas occupied a second level of importance. They raised cattle and horses, as well as goats and sheep. This type of hacienda tended to be located in more remote areas, in an attempt to prevent the livestock from invading cultivated fields. Sugar haciendas were located in tropical regions, where they could count on sufficient water for the cultivation of sugarcane. The most important sugar regions were Veracruz, Cuernavaca, Cuautla, and Michoacán.

Throughout the seventeenth century the haciendas grew in significance. They held much of the land and water resources, expanded their labor force, intensified their control over the market, and consolidated their territorial rights in accordance with composiciones de tierras. (The phrase composiciones de tierras belongs to the legal terminology of the time. It relates to a legal mechanism that was instituted by the Spanish Crown during the first half of the sixteenth century but which was applied mainly during the seventeenth century. It made it possible to legalize properties whose titles were not in order.) They sought to make improvements by constructing, for example, buildings, irrigation systems, roads, granaries, and shelters for livestock. Together, these made it possible to increase agricultural yields substantially. It was not an easy process, often involving transfers of hacienda property, severe indebtedness of their owners, and great difficulties in production.

Hacienda expansion proceeded throughout the following two centuries. Huge tracts of uncultivated land were transformed into farmland and impressive water distribution systems opened up new areas to irrigation. The population, constantly growing, demanded an ever greater quantity of food. Much land that had been devoted to the raising of livestock was turned over to cultivation, and the stock were gradually displaced until livestock haciendas came to be located mainly in the north of the country. However, this was not a period of unimpeded progress: there were severe periods of crisis, sharp fluctuations in production, a lack of continuity in the transmission of property, and frequent bankruptcies. Hacienda properties tended to be deeply mortgaged to ecclesiastical institutions and to individual lenders.

Hacienda Uxmal, Yucatán: main gate.

When dictator Porfirio Díaz assumed power in 1877, a boom period for the hacienda began. Historical circumstances were favorable, and the government offered all manner of facilities to the livestock and farm impresarios. The substantial increase in the country's population, as well as the strengthening international economy, created a great demand for farm and livestock products. The consumption of goods from the tropics, such as coffee, cacao, sugar, tobacco, and vanilla, grew considerably during this time both in Europe and in the United States. The same thing happened with certain basic materials, among them henequén, rubber, chicle, and ixtle. (Ixtle or istle is the name given to the hard fibers that are extracted from different plants of the genus agave, of which the most important are the maguey and the lechuguilla. They are raised mainly in northern Mexico.)

As a result of laws that secularized communal land and set aside fallow land, huge areas of cultivation and land suitable for farming were placed at the disposition of commercial agriculture. Supporting capital for the most part came from foreign sources—from the United States, France, and England. Labor came from the impoverished peasants, from town workers, and from indigenous groups, among them the Mayas and the Tarahumaras.

Large landed estates appeared and a powerful class of hacienda owners arose. It was during this period that it was possible to overcome some of the endemic problems that had beset the hacienda since its birth: instability, indebtedness, lack of capital, and scarce revenues. During the Porfiriato, the majority of the haciendas were highly productive and provided their owners with plentiful earnings. Yet, at the same time there were haciendas that had to face financial problems and fluctuations in production.

Frequently, hacendados participated in other areas of business, such as finance, commerce, and mining. Their privileged economic position permitted them to furnish their rural properties with great luxury and to sustain a life of affluence. Bartlett found hacienda residences with twenty bedrooms, salons for dancing, Japanese gardens, billiard rooms and music rooms, swimming pools, bullrings, and palisades. Bearing witness to the interior splendor of these mansions, there was fine furniture from Europe, carpeting from Persia, velvet draperies, chandeliers of cut crystal, and valuable oil paintings. There were haciendas that possessed chapels that rivaled the provincial churches in size, architecture, and decor. Of course not all haciendas were this elegant: most had much more rustic appointments; many were in decline, poorly maintained, furnished with the very barest minimum.

Bartlett captured and transmits to us today through his art the grand cultural richness that enfolds the hacienda, its diversity according to its moment in time, its location, and its type of production, and he accompanies these with a portrayal of hacienda life, customs, and its inherent style of thought. He is one of the pioneers in his field of study.

Sonora

1. Hacienda de Endo

Chihuahua

2. Hacienda de Colonia Campo

3. Hacienda Corralitos

4. Hacienda Quinta Carolina

Durango

5. Hacienda de Juana Guerra

6. Hacienda de Canutillo

Nayarit

7. Hacienda San Cayetano

San Luis Potosí

8. Hacienda de Castamay

Guanajuato

9. Hacienda de Valenciana

10. Hacienda de Leoncito

11. Hacienda de Calderón

12. Hacienda de Puerto de Nieto

13. Hacienda de los Ricos

14. Hacienda San Cayetano de Valencia

15. Hacienda de Petaca

16. Hacienda de la Erre

Jalisco

17. Hacienda de Medinero

18. Hacienda de Cedra

19. Hacienda de Ciénega de Mata

20. Hacienda de Cabezón

21. Hacienda de Cuisillos

22. Hacienda de Zapotitán

23. Hacienda de Bellavista

24. Hacienda de Aurora

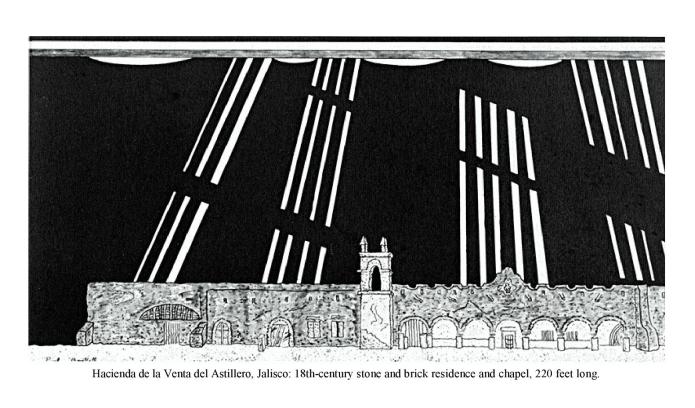

25. Hacienda de la Venta del Astillero

Hidalgo

26. Hacienda de Santana

27. Hacienda de Xala

28. Hacienda de Pueblilla

29. Hacienda de Tepa-Chica

Michoacán

30. Hacienda de Guarache

Colima

31. Hacienda de San Antonio

State of México

32. Hacienda de San José

33. Hacienda de Altillo

34. Hacienda de los Morales

35. Hacienda de Jajalpa

36. Hacienda la Gavia

37. Hacienda de Esperanza

Morelos

38. Hacienda de Cocoyoc

39. Hacienda de Chinameca

Tlaxcala

40. Hacienda de los Molinos

Puebla

41. Hacienda de Pópulo

42. Hacienda de San José Huejotzingo

43. Hacienda de Dolores Noriatenco

44. Hacienda de Arenillas

45. Hacienda de Caleturia

Veracruz

46. Hacienda de Encero

47. Hacienda Manga de Clavo

Oaxaca

48. Hacienda de Águilar

Campeche

49. Hacienda de Castamay

Yucatán

50. Hacienda de Holactún

51. Hacienda de Teya

52. Hacienda de Xcanatun

53. Hacienda de Sodzil

54. Hacienda de Tabi

55. Hacienda San Ignacio

56. Hacienda Pixoy

57. Hacienda Yaxche

58. Hacienda de Tikuch

59. Hacienda de Chichén Itza

Forty years ago, traveling by train in Mexico, I saw, in remote areas, what appeared to be miniature villages. I made sketches of them from the train and later visited some of the sites and learned they were ancient haciendas. Over the years since then, I have visited 330 haciendas and made the first art record of these estates. I traveled on horseback, on foot, by bus, train, car, truck, motorbike, and mule-drawn, narrow-gauge railway. I saw that haciendas had become mere place-names as they disintegrated or were bulldozed.

Walk into a handsome mansion and you find twenty or thirty empty rooms. To escape the revolution, the owner fled years earlier. Earthquakes, weather, and abandonment have riddled walls and floors. The residence stands roofless, windowless, doorless—constructed of stone, brick and adobe, or a combination of these. Church and chapel exist at every hacienda and they are still used by neighbors and peasants who may occupy the manor house. There are dates on bell skirts, on walls or beams of a storage bodega, on escutcheons, on archways; often they are carved in the mesquite floor of a chapel or church.

Hacienda de Valenciana, Guanajuato: patio fountain.

In the tropics, flame trees, bougainvillea, red-orange galeanas, lavender jacaranda, and yellow primavera flower among ruins. In northern areas, pine, tall eucalypti, mesquite, cedar, pepper, and chinaberry remain.

I sketched under the tropic sun, in corrals, in a bullring, under an Indian laurel; I poked through empty rooms.

As I sketched, burro trains passed, their sacks loaded with charcoal or corn; goat bells tapped as a herd grazed; ox teams hauled carts with wooden wheels; blackbirds crowded a treetop; a cowboy tipped his hat.

There was always courtesy. I drank pulque from a communal gourd; I shared pineapple grown in Tecomán; I was entertained at town houses of hacendados. On the estates there was silence from the days of the viceroys, the silence of padres, the silence of abandonment.

In the sixteenth century, following the Spanish invasion of Mexico between the years 1519 and 1521, the Spanish Crown granted enormous land areas to the conquerors and adventurers who came to the New World. Since this property belonged to the natives, the grants amounted to usurpation. Scattered throughout Mexico, from Yucatán to Sonora, the extensive holdings frequently included towns and villages. These grants of land were the origin of the haciendas, the rural estates.

During the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, Spanish immigrants sometimes passed themselves off as noblemen—camouflaging criminal or poverty-stricken backgrounds. Others, with a sack of cash or a pair of brawny shoulders, used the invasion as an opportunity to bluff their way and claim land and lives through the power of the sword. They remembered that dropping quicksilver into a mule's ear made the animal trot faster. Wealthy immigrants were able to purchase titles, and this arrangement was encouraged by the Crown since it benefited the treasury.

The hacendado (or his representative) employed or coerced native workers to build a residence, church or chapel, storage buildings, mills, dams, aqueducts, fences, and roads. He paid lip service to the Crown and whenever possible circumvented legalities. It was advantageous to sidestep the Crown since a letter or document took half a year to reach Spain. The employer was unable to communicate with the people who spoke Otomi, Coro, or Chichiméc. He was thwarted by new diseases, strange customs, tropical climate, and crop problems. Unlike the countries of Europe, Mexico was a corn culture, not a wheat culture. During his first years he learned that grain did better when planted in the most primitive manner, by stick and foot.

Hacienda de Valenciana, Guanajuato: figure on 1788 church wall.

Hacienda de Holactún, Yucatán: chapel and residence

Hacienda de San José, D.F.: churrigueresque-style residence and chapel with blue and white tiled dome.

Hacienda de Valenciana, Guanajuato.

Hacienda Petaca. Guanajuato: patio side of main residence.

Hacienda El Pópulo, Puebla: residence with tiled façade.

Hacienda de Santana. Hildago: residence and chapel.

Hacienda de Teya, Yucatán: residence. 1700.

Hacienda de Leoncito, Guanajuato: 16th-century chapel.

Hacienda de San José, D.F.: rococo façade of residence.

As rapidly as possible, the landowner, the hacendado, added to his holdings, buying or usurping acreage. An hacienda might consist of several thousand or several million acres. The terrain might be mountainous, semi-desert, coastal strips, forest or jungle, or a combination of topographical zones. There were cattle haciendas, sheep haciendas, mining haciendas, pulque/tequila haciendas; others produced henequén, grew coffee, sugarcane, corn, wheat. A few bred bulls for the bullring.

During the first century of the occupation, Fray Bartolomé de Las Casas, friend of the Indians, objected to the atrocities committed by the Spanish. Alfonso de Zorita, writing his "Brevíssima Relación," exposed Indian mistreatment. Burnouf, French agronomist, wrote Emperor Maximilian that the whip of the mayordomo (the hacendado's administrator) was destroying many lives. Regardless of objections through the years, the hacienda system prospered.

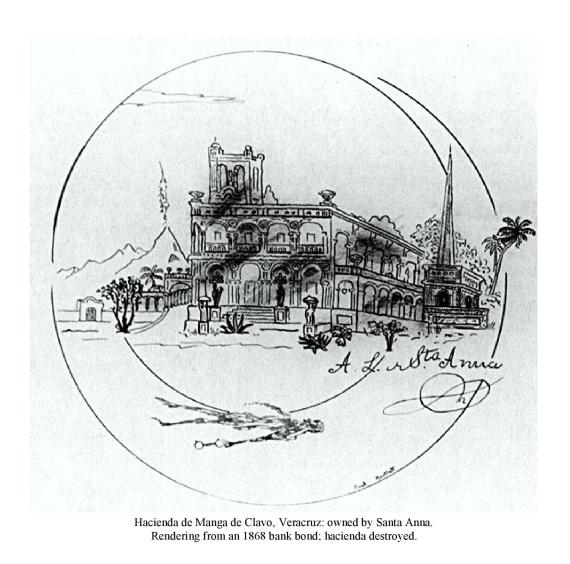

Counts, countesses, dukes and duchesses, crude invasionists, wealthy men, and religious orders owned estates. Some of the famous hacendados were Hernán Cortéz, Porfirio Díaz, Martín Ruiz de Zavala, General Santa Anna, and Pancho Villa (who was given his hacienda as a political bribe). Famous families owned estates: Terrazas, Rosa, Amor, Jaral, Ibarra, Echeverría, and Regla.

From the seventeenth to the nineteenth century, hacienda architecture varied: Where generation after generation owned the hacienda, in families of great wealth, façades were gothic, churrigueresque, plateresque, Islamic, baroque, rococo. The most widespread architectural style derived from the Roman. Most residences had their living quarters around an atrium, or patio. Grilled windows and massive wooden doors and shutters were common. Thousands of work-hours went into the carvings and embellishments—in gray, pink, or yellowish limestone. Hornacinas (niches) peppered a church or chapel façade.

Hacienda de Bledos, San Luis Potosí: coat-of-arms.

Hacienda de Puerto de Nieto, Guanajuato: 17th-century defense tower. Note bullet holes.

Each niche contained a saint or religious figure: It was tapestry in stone.

In the states of Puebla and Oaxaca, tiled façades ornamented the hacienda residences and lofty walls surrounded them. Church and chapel domes were also tiled. In the Sierras, haciendas were often built of logs and planed wood—rustic, two-story buildings with outside stairways. In the tropics, the usual residence was one story with ample verandas and deep-set doors and windows. Most buildings were roofed in cone-shaped, interlocking, or flat tiles.

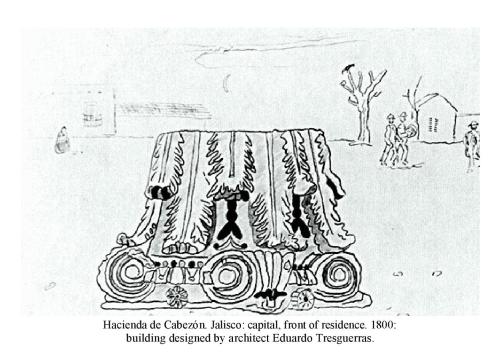

The majority of hacienda structures were skillfully mortared in stone block cantera (limestone) by rule-of-thumb. Professional architects like Francisco Eduardo de Tresguerras were seldom available. Instead, artisans were employed who used various styles learned from early ecclesiastical buildings.

Bitter rivalries between estates were part of the scene. Owners were on the alert for a bankrupt hacienda that could be purchased at a very low price. If extending landholdings meant violating the rights of a village or of an individual farmer or rancher, those rights were brushed aside, or contested legally.

Hacienda de Barrera, Guanajuato: residence.

To bolster his stature, the hacendado placed a baronial device on the façade of his residence or church: A coat-of-arms elevated his status. He also respected his skin, and against the threat of la intrusa (the intruder) he installed gun slots, grilled windows, studded doors, and armed his retainers. La intrusa was his Old World enemy. Now and then he raised a private army to repel difficult natives, belligerent hacendados, or revolutionaries. Thick-walled, ponderous buildings reflected his philosophy. They indicated his loneliness and his fear of death as well.

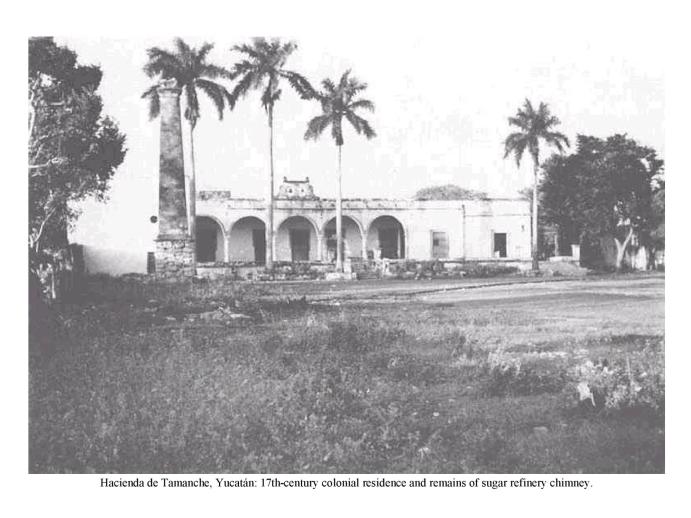

As life became less threatening in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, as roads improved and travel became safer and more comfortable, hacienda owners erected open structures: Residences appeared with multiple arches across the front, and tiled verandas led to the outdoors. Two-story homes, with balconies on the second floor became common. Eucalypti, jacaranda, chirimoya, and columnar cypress shaded a complex of buildings: church, residence, bodega. In the north country, a line of cottonwoods led to the gracious house, which was stuccoed pink or pale yellow. Farther south, a grove of palms graced the setting.

As time passed, viceroys, churchmen, lawyers, and teachers became more and more aware of the language barriers that existed throughout the country and that impeded progress. The Catholics, through their colegios (ecclesiastical schools) attempted to upgrade life. There were no public schools.

Among the ecclesiastical orders, the Jesuits were major hacienda owners. Their design-for-living began at 4:00 A.M. and ended at 7:00 P.M. At the most famous Jesuit hacienda, Santa Lucía, near Mexico City, slaves were purchased, bred, sold, or retained for work on the estate. There were no fiestas at Santa Lucía. For almost two hundred years the hacienda functioned to support the ecclesiastical schools of the order. The Colegio Máximo, in Mexico City, was the principal beneficiary. Until June 25, 1767, when all Jesuits were deported from Mexico, the estate prospered, selling wheat, corn, textiles, cattle, sheep, and slaves. Its economic influence extended as far as Guadalajara, Zapotlán, and Colima.

Schooling at the hacienda was largely disregarded. There were sixty foreign dialects to contend with. There were no dictionaries, no language bridges for the Zapotec, Coro, Méxica, and Nahuatl people. On the estates a priest or teacher, one who knew a little Latin, gave lessons in Spanish, arithmetic, Latin, and the catechism. Scholarly priests began linguistic studies of some tribes; they edited dictionaries, but these were never circulated. Some of their work has yet to be published.

Machismo was more meaningful to the average estate than education. The blacksmith from Barcelona, who now owned ninety thousand acres, was eager for compliant women. Sex life, for the invaders, for the colonist, was freer than in Europe. Since the men did not speak the Indian dialects, sex was a body language. Some were promiscuous and guilty of perversion. Priests and nuns were shocked by their animality and attempted to control their countrymen. Since most haciendas were remote and few women accompanied the settlers, isolation and power granted license.

The kindly man, the gentile man, looked for other ways to overcome loneliness, isolation, homesickness. Some, preferring the familiar life, returned to their homeland. By 1910, thousands of estates were scattered across the country. Mansions were located in the midst of maguey and henequén fields or were situated in lush valleys. Some faced the ocean; some were lost in acres of corn; miles of range country surrounded others; there were desert haciendas with the nearest neighbor fifty miles away; there were rain forest haciendas, mahogany haciendas. Many were regional landmarks.

Hacienda de Calderón, Guanajuato: bronze bell on residence, 1838.

Haciendas became an embodiment of time. They seemed to defy time, offering the illusion that a family could live there indefinitely.

Through the years there were notable visitors to the haciendas who have left us their impressions: Bishop Landa, Father Alonso Ponce, Gemelli Gareri, Samuel de Champlain, John Chilton, Mora y Escobar, Sieur Bully, Fathers Balalenque and Acosta, Thomas Gage ("clerical spy"), Don Ernesto de Icaza, Emperor Iturbide, Emperor Maximilian I, Baron von Humboldt, Madame Calderón de la Barca, James Stephens, and Frederick Catherwood, among others.

One of the most famous haciendas, in the state of Jalisco, is Ciénega de Mata, legalized by the Crown in 1697. Owned by the Rincón Gallardo family, it was a tract of eighty-seven estancias (ranches). According to Alfonso Rincón Gallardo, reminiscing about his father's estate, the residence was built during the sixteenth, seventeenth, and eighteenth centuries. It is a two-story building with twenty rooms and spans or arches across the front. The church is gray limestone, like the residence, with a baroque façade. An elaborate coat-of-arms embellishes the entry. Sculptured pink stone cantera saints and angels fill various niches. The octagonal dome and tower are richly carved.

Hacienda de Ciénega de Mata, Jalisco: 16th-century church.

Gallardo appreciated the life at Ciénega, the brandings, the roundups, sheep pasturing, shearings, and weanings. "I liked to ride with the cowboys," he wrote, "those extraordinary horsemen, pleasant companions, tanned by sun and wind, simple in tastes, frank, never tiring—the classic men of the great haciendas."

Recalling his life he tells us:

Every morning after breakfast, all of us—my father dressed in his charro outfit; my mother attired English style—would set out on horseback, riding about the hacienda's vast fields of corn and barley. After the midday meal, back at the house, we walked about the stables, the granaries, and over a small hill that lay nearby; and sometimes we played fronton or went out riding again. At night, after supper, we read or played games. In this tranquil, pleasant manner, life went on, broken only by the annual festival, an event celebrated on a grand scale with parades, banquets, horse races, cockfights, boxing matches, and, in the evening, a fantastic display of fireworks.

Brantz Mayer, secretary of the United States Legation in Mexico during 1841 and 1842, enjoyed a horseback visit to the Hacienda de San Nicolás, near Tetécala, in the state of Mexico. He admired the white buildings and the neatness of the estate: "The sugarcane fields were in capital order, the roads smooth, the fences maintained; cattle were under the care of herdsmen."

Hacienda de Cabezón, Jalisco: chapel Virgin; her elaborate wardrobe valued at $50,000.

The mayordomo was hospitable and accommodated Mayer and his party with comfortable rooms. Following dinner, Mayer walked among the hacienda's fields of sugarcane. He inspected the tienda de raya (the general store), and the hacienda's offices, kitchens, parlors, bedrooms, and an "immense corridor of arches filled with caged birds, hung with hammocks, where the family pass most of the long warm days of summer."

Hacienda de Cabezón, Jalisco: capital, front of residence.

1800: building designed by architect Eduardo Tresguerras.

At sunset the workers gathered under the arches of the residence and the administrator called the roll and each man replied with "Alabo a Dios" ("I praise God"). When all were dismissed they walked away singing a hymn to the Virgin.... That night a group of musicians played in a hut: violin, clarinet, flute, and drum.

In 1833, travelers Emma Undsay Squier and her husband were guests at a tequila hacienda, Ometusco, about an hour and a half by horseback from Mexico City. From the railroad station, the complex appeared like a "salmon-pink birthday cake in the shape of a walled fortress." The buildings were surrounded by fields of maguey. The Squiers entered the grounds through a large gateway where soldiers lounged. The walled patio was enormous and paved with stone. Burros trotted by, bearing casks of freshly collected agua miel (sap of the maguey).

Ometusco was the size of a village; the hacendado's home was a palace of many rooms, kitchens, winding stairways, patios, poultry yards, corrals. The largest patio, centered by a stone fountain, was planted with flowers, trees, and flowering vines. A tiny school had its own patio. The chapel was elaborate. Guests enjoyed a billiard room in the main house. Each bedroom had beds protected by mosquito netting. The dining room could seat seventy persons at a mahogany table. Inlaid buffets glittered with silver and glassware, seldom to be seen after the revolutionary period of 1910-1914.

Hacienda de Cuisillos, Jalisco: late 17th-century church in rose stucco. A famous Jesuit hacienda.

Hacienda de Cuisillos, Jalisco: floor plan of residence. A. Residence. B. Kitchens. C. Chapel. D-E. Living Quarters. F-G-H. Corrals. I. Granary. J. Jail. K. General Store (Tienda de Raya). L. Living Quarters. M. Yard.

Hacienda de Cuisillos, Jalisco: handpainted wall fresco in bedroom of ruined residence.

Hacienda de Cuisillos, Jalisco: mural, one of fourteen panels on veranda wall of residence.

By 1952, the renowned Hacienda Cabezón had become a mere casco (a shell). Located about 48 miles from Guadalajara, near Ameca, the residence was designed in 1780 by the famous architect Francisco Eduardo de Tresguerras. Now, grunting, shuffling pigs have squatters' rights to the fifteen rooms. The building is roofless; its handpainted bedroom walls are open to the weather, all that remains of the handsome structure, once the focal point of fifteen or twenty sitios (ranches), is the chapel, pewless, clean, its walls faded red, gold, and yellow. Swallows fly in and out of their nests in the gold curlicues of the reredos.

Cabezón has a single treasure: the Virgin of Candelaria, protected by a plate-glass case. Her face seems Andalusian. Colored scrolls, garlands, and angels frame her as she stands on a silver crescent moon, her figure the center of a gilded reredo. About 18 inches tall, she wears a white satin gown sewn with gold. A jeweled pearl crown rests on her hair, making her the perfect madonna. Close by, under the dark mesquite floor, members of the hacienda family are buried: Ignacio Cañedo de Valdivierlos (1836); Estanislao Cañedo (1887); Manuel Calixto Cañedo (1905).

According to a chiseled inscription, the floor was laid in 1858 and cost 166 pesos.

The land belonging to the famous ecclesiastical hacienda, Santa Lucía, was purchased by the Jesuits on December 4, 1576. Legally, the estate's area measured 18.8 square miles, an area populated by Otomi, Tepaneca, and Chichimeca Indians. At the time of its purchase it had 16,800 sheep, 1,400 goats, 125 brood mares and colts, 1 stallion, 1 saddle horse, 2 donkey mares, 2 donkey stallions, and 8 slaves.

During the 1580s, construction work was carried out on residences, offices, storage buildings, corrals, sheds, and quarters for the slaves. A chapel was built in 1592. The hacienda produced barley, oats, beans, wheat, corn, chickpeas, and livestock: cattle, sheep, goats, mules, and horses, in increasing numbers each year. Santa Lucía prospered for nearly two centuries.

Cuisillos is another Jalisco hacienda, a place of jacaranda, palms, eucalyptus, ash, and mesquite, near Cabezón. Horizon hills are often steel blue, and a low-lying volcano is often misty gray. Cuisillos, deeded in 1620, first belonged to Juan González de Apodaca, chief constable under Cortéz. During the sixteenth century it was one of the largest estates in Mexico and added substantial revenues to the Crown. Neoclassic, its casa principal (main house) and chapel form an L, and fronting the L is a grove of palms. The main house has thirty rooms, two tiled patios with a fountain in each; in the main patio there are fourteen fresco panels painted in 1910 of seascapes, landscapes, and scenes of women in the eighteenth century.

The grilled patio gate bears the renovation date 1910 and the hacienda brand and family monogram. All rooms are still roofed and floored. The house is putting up a valiant struggle. Its primitive kitchen has an igloo-shaped oven with a charcoal basket dangling from its chimney pipe. A corkscrew limestone stairway leads to the chapel tower where there are bronze bells whose skirt dates are 1895, 1895, 1896, and 1896; the fifth bell has no date. The chapel façade is ornate. The interior is simple: a small coro (choir gallery), with a small darkwood organ that is badly battered. The walls of the chapel are white and gold.

A neighboring hacienda is architecturally imposing. The Hacienda Cañedo has a church that would be outstanding in any city. The building, of yellow limestone, is baroque-Italianate. It towers above the surrounding structures and is amazing for its spire and its twelve stone apostles in the forecourt—8-foot carvings of limestone on stone pedestals—native craft at its finest.

The church interior is blue, white, and gold. Sedate. The black mesquite floor has a carved strip leading to the altar, and the words on the strip indicate when the floor was laid and what it cost. Altar and decorations are simple: brass candle holders, vases with paper flowers. There are solid-backed wooden pews in cedar. The room expresses spaciousness.

The residence, which adjoins the church, is a stone mansion with badly scaled walls. All rooms are vacant except the kitchen, a charcoal-blackened room with smudged clay pots and a row of cracked white plates in racks above a tiled stone stove. Around this casco are other buildings, storage rooms—all stone, all neglected. At one time, according to a wall sign, there was a biblioteca rural (rural library) in the complex.

In the state of Hidalgo, the Hacienda de San Francisco—a pulque estate—was refurbished in 1880. The twenty-room mansion stands in a giant field of maguey ringed by hills. Fifty carriages could park in front. Once there were twin swimming pools, a bullring, and fifty Japanese gardeners to maintain the gardens.

The residence has rooms around a flower-weed-garbage patio. The building is in a pseudo Arabian-Spanish style. On a wall there is a crank-style phone. There is electricity and a broken television antenna. A large sala (parlor) has a number of ornate tables, tufted velvet couches, and silk-damask chairs; imported brocaded drapes are fastened by gold sashes, all from France via train, ox cart, and tumpline. On the stairway leading to the roof, the hacienda workers killed the owner in 1910.

Occasionally there are guests, weekenders. Barefooted girls wearing braids serve among the antiques.

Hacienda de Cañedo, Jalisco: 19th-century church.

Far south, in Yucatán, Yaxcopoíl is a working henequén hacienda, a survivor of two centuries, still semi-successful economically. Located about forty miles from Mérida, on the Uxmal-Campeche highway, the residence forms a U. Residence, chapel, offices, and storage space are eighteenth-century structures. The main house has thirteen arches along its broad veranda and micro-chapel. This section of the complex is connected by an imposing pillared breezeway to the dining room, kitchen, and servants' quarters.

Hacienda de Xcanatún, Yucatán: one of a series of gold wall motifs around chapel walls.

The floor of the extensive patio between these buildings is paved with flagstone carved with Mayan glyphs and designs, appropriated from nearby ruins on the property. The residence is furnished in eighteenth and nineteenth-century styles with marble-topped tables, bronze and brass beds, dangling chain lamps with handpainted globes and shades, henequén hammocks, and tanned hides on tile floors. Bathroom fixtures are British and washbasins with silver faucets bear a porcelainized coat-of-arms.

There are reed chairs in the living room. Mediocre prints and a seventeenth-century religious canvas decorate the walls. The floor tiles are conventional in pattern; there are no rugs; the ceiling beams are stenciled in pastel floral designs. Double doors lead to the veranda. The dining room has a center table with a Tiffany-type lamp. In the office there are chairs, an oak desk, a handpress, and a bookcase.

In the micro-chapel, its wall decorated with gold and silver fleur-de-lys and pink roses, there is a large sixteenth-century canvas by an accomplished, anonymous artist: the descent from the cross, with eight or ten figures merging with the background. There are no chairs. The altar is small, insignificant. A white Seybold organ, a silver crucifix, a pair of silver candles on a side table complete the furnishings.

Behind the residence stands a theater with simple stone façade and pilaster figures of women representing spring, summer, autumn, and winter. A windmill spins behind a carved Mayan head perched on the roof line. The auditorium accommodates a couple of hundred people for movies and plays.

Hacienda de San José Huejotzingo, Puebla: florentine armor in residence.

The henequén production mill consists of a large open shed with a corrugated roof. There is a machine press for crushing the maguey leaves, which are hauled in by narrow-gauge flat cars, pulled by mules or Ford-engine. There are fence-like racks behind the mill for drying thousands of fibers at one time. Employees here work on salary; today there are no feudal restrictions.

Hacienda de San José Huejotzingo, Puebla: pistol and brand of hacienda

From the rooftop of the residence, Mayan ruins are visible as earthen mounds in the midst of maguey plantings. The seven mounds are an unexplored archaeological site.

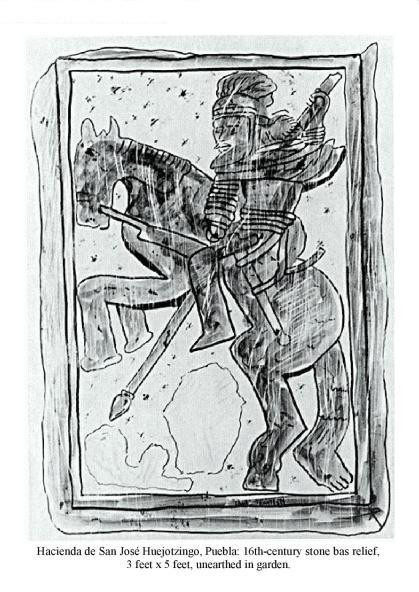

The imposing Hacienda San José Huejotzingo is near the city of Puebla in the state of Puebla. Its stark one-story red brick, white brick façade faces a lane of dying elm and willow. The residence measures 170 feet across the front. At each corner there is an ornamental tower. The house encloses two patios. Destroyed by revolutionaries, its chapel and storage areas are roofless, but the residential rooms have been reconditioned. They are filled with recuerdos (mementos): incunabula, antique firearms, a suit of Italian armor, oil paintings, Aztec figures, charro spurs, leather chests, colonial tables and chairs.

In the dining room are tall ecclesiastical wooden candelabra, carved cedar chairs, monogrammed chests, pre-Columbian objects, colonial pottery, and old dishes. Modern Tonalá pottery ornaments a nineteenth-century buffet. Throughout the residence the floors are red tile.

The central patio has a 5-foot limestone statue of St. Joseph, carved in 1624. It stands near a wall tile that reads: Margarita Barrados, died June 3, 1871. A stone plaque of a conquistador on horseback, in primitive style, decorates another wall.

The property—a corn, wheat, and cattle estate dating from Cortesian days—is owned by Juan Matienzo, who has made a hobby of reconstructing his ancestral home. Few other haciendas have Popocatépetl's 18,000-foot peak looming behind.

Hacienda de San José Huejotzingo, Puebla: 16th-century stone bas relief, 3 feet x 5 feet, unearthed in garden.

Hacienda de San Francisco, Jalisco: residence.

Hacienda de Sodzil, Yucatán: narrow-gauge railway passenger car drawn by mule or horse

Hacienda Yaxcopoíl, Yucatán: residence. Note narrow-gauge railroad car.

Hacienda de los Morales, D.F.: spinning wheel in residence patio.

Hacienda de Bianca, Oaxaca: patio

San Martín Rinconada, a feudal hacienda, is halfway between Puebla and Jalapa on the Jalapa route. The buildings are enclosed in a compound. The protective walls, 30 feet high, are in good condition—mellowed by age. Extensive cornfields surround the compound, which is about one half-block square.

An intricate grilled gateway opens to a plateresque church. The church clock keeps time, and the stone sundial by the corral also keeps time, hacienda time. Behind the church, a windowless chapel, with double doors for light and air, contains five mauled wooden desks, dusty benches of adzed wood, and a cracked blackboard. This was once a school.

Outside the compound, facing the church, are adobe huts roofed with straw. They accommodated the workers, their poultry, pigs, and dogs. Perhaps one hundred people lived in the twenty huts. A shingle-roofed pozo (well) supplies water for horses, cattle, and people, spilling it into a 20-foot wooden trough. Gun slots in the compound walls slant toward the well and trough. Zapatistas and Carrancistas threatened the hacienda in 1914; they banged on the residence door and demanded beef and saddle horses but left the property undamaged.

Now empty, the bedrooms are papered in gold and white and are semi-frescoed overhead. A minute patio, facing several bedrooms, has a few shabby cypress. The sala has no furnishings.

Stained-glass windows, humble panes of colored glass, light the auditorium that seated one hundred people. Behind a plaster life-size Christ on the altar hangs a dark red velvet drape; nearby, on the same wall, is a tortured Christus. A pair of prayer wheels stands by the altar. Chandeliers are encased in white covers, carefully tied. There are stubby oak candelabra with fat candles that have dripped wax. A foxed, framed letter is dated 1742.

Life on an hacienda was basically agrarian, revolving around the care of livestock, poultry, planting, harvesting, crop storage, irrigation, and general maintenance. If the estate was located in an area that included tropical low-level land, mountainous terrain, and semi-desert, administration was complex. The thousands of acres had to be supervised on horseback. Weather was a daily concern. Keeping a competent work force was an ever-changing problem.

The personnel of an hacienda consisted of a mayordomo (the administrator), minor supervisors, field workers, cowhands, shepherds, blacksmiths, masons, saddlers, cobblers, carpenters, woodcutters, weavers, a stable boss and assistants, errand boys, a barber, a chandler, gardeners, dairymen, maids, butler, cooks, seamstresses, the manager of the tienda de raya, butchers, a priest, an organist, a teacher, a governess, and sometimes a doctor. The bigger the estate, the bigger the staff. All were responsible to the hacendado who lived on the hacienda or who was an absentee owner-administrator.

Hacienda de Dolores Noriatenco, Puebla: century-old carriage.

During the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, the haciendas became increasingly self-sufficient. Isolated as they were, they made every effort to provide for their own needs: water, food, carriages, wagons, carts, saddles, shoes, spurs, harnesses, clothing, linen. Equipment like saws, plows, pumps, pipe, guns, and machetes had to be "imported."

The hacendado, his family, and staff ate an early breakfast. Bells clanged for a Mass at 6:00 or 7:00 A.M. (before or after breakfast), depending on the weather. In most tropical regions, work commenced at dawn to escape the noon heat; during the summer, work was often suspended around midday and resumed late in the afternoon.

Hacienda cattle brands, state of Jalisco.

Each morning, the hacendado found his clothes laid out by his mozo (valet), perhaps his charro outfit, a shirt, socks, sombrero, pistol, boots, gloves, and quirt. His breakfast menu included fruit, eggs, meat dishes, beans, tortillas, or pan dulces (varied sweet rolls). The chef offered coffee, chocolate, tea, pulque, or beer. Cuban cigars were favored. Mounted on a well-groomed thoroughbred, riding western saddle, the hacendado checked crops, cattle, corrals, granary, irrigation project, and village laborers. He also conferred with village caciques (chiefs). During a lifetime the hacendado rode some 60,000 miles.

Hacienda de Cedra, Jalisco: stone cross to one side of hacienda chapel. 8 feet tall.

The hacendada looked after her staff, her maids, the governess, the tutor, she allocated tasks: sheets to be laundered, soap to be made, the purchase of manta for linen, clothes to be mended, skirts to be hemmed. If guests were expected, the dinner menu had to be carefully planned. Children, relatives, friends—they were all important. Supplies had to be brought to the hacienda from the nearest village or town: kerosene, salt, lamps, matches, drugs.

By 2:00 or 2:30 P.M., it was time to eat. At a kind of makeshift picnic, the workers shared their clay pots of hot beans or rice, their tortillas, and pulque. Sometimes there was meat with the rice or beans: chicken, pork, beef, goat. In season, there were zapotes, mangos, oranges, avocados, bananas, chirimoyas. Workers wore cast-offs: torn shirts, torn trousers, battered hats; the women were usually dressed in blue cotton dresses and blue and white rebozos. They ate in the fields, in the kitchen, in the corral and stables—sharing their food.

Hacienda de Tabi, Yucatán: early 18th-century church.

At the same hour, inside the big house, the hacendado, his family, and guests enjoyed a meal at the long table set with imported or hacienda linen, elegant china, cut glass, and Mexican and European silverware. Barefoot maids served. Perhaps the maids wore Tehuana or Yucatecan dresses. The butler may have worn white gloves. In the spacious, beamed, windowed room, cool in summer, warm in winter, the menu was varied:

Hors d'oeuvres

Soup

Sopa Seca (pasta, rice, etc.)

Beef, chicken, pork, lamb, venison—or

a combination of these (Turkey, rabbit,

quail, fish, when available)

Flan (custard), chongo (a milk and

syrup confection), cajeta (caramelized

goat's milk), cake—or fresh fruit and

cheese

Coffee, tea, wine, liquor, horchata

(a rice drink), jamaica (a tropical drink),

chocolate.

Wine and liquor were both domestic and imported. Both local and imported cheeses were served, as well as European delicacies like caviar, marmalades, jellies, mints, nuts, and bon-bons.

After dinner, the siesta called for relaxation, comfortable chairs, hammocks. A well-earned sense of ease took over. A few guests played pool or billiards, bridge, rummy, pinochle. At dusk, croquet was a favorite game. Some estates had a swimming pool or access to a river, lake, or ocean playa.

Hacienda de Altillo, Coyoacán, D.F.: pastel of St. Andrew.

Hacienda de Xotla, Puebla: residence patio and oven.

Hacienda Zapotitán, Jalisco: map on veranda of residence.

Hacienda de Buena Vista, Jalisco: 18th-century aqueduct.

Hacienda de Zapotitán, Jalisco: remains of 1750 residence and mirador; white stuccoed masonry.

At a Jesuit hacienda, a peasant who failed to attend Mass might be lashed; but the average hacienda was lenient about attendance. At evening Mass after a day's labor, the workers were glad to kneel or squat: the hour was a humble reward. Hymns were sung. Someone played the organ or piano.

Each chapel or church boasted an altar—a lace-covered table with paper flowers or a rococo gilded carving, with santos (saints) and angels in the gray niches. The Virgin or saint was the focal point. Stained-glass and onyx windows appeared in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Marble and onyx sometimes replaced mesquite or tiled floors. Some chapels and churches had pews, but in those without furniture the workers knelt. As for the hacienda family, they sat on cane chairs or worshipped behind a screened coro. There was a clear distance between them and the "unwashed."

Hacienda de Dolores Noriatenco, Puebla: polychrome wood statue, 16th-century, 5 feet tall.

Most services were conducted in Latin, a language disliked by the Indians because they considered it an affront to their integrity. Spanish was a tribulation and Latin was another. When they memorized songs in Latin or Spanish, they often mispronounced words intentionally.

Hacienda de Castamay, Campeche: 18th-century church.

Crucifixes were evident in most places of worship. The figure of Christ was sometimes pornographic in style, sometimes tragic. "Yerma," Federico Garcia Lorca's tragic evocation, was brought to life again and again.

Young people grew up seeing marriage distorted, warped by superstition and rigid conventions. They learned to admire martyrs. They learned that the body was unclean—putrefying. The bloody cross hung in countless minds. With a cross dangling at her throat, the señorita made confections: sugar skulls. "A Nun's Cry" was the name of a confection. Hacienda loneliness did strange things; it summoned duendes (spirits). In this remote place, the church bred intolerance—deep whispers of death and damnation.

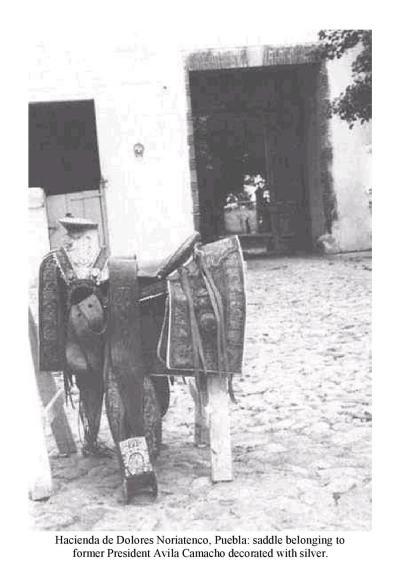

Hacienda de Dolores Noriatenco, Puebla: saddle belonging to former President Ávila Camacho decorated with silver.

Great art—when it could be found—added to extremism. St. Sebastian and his arrow-pierced body, Murillo and his forlorn madonnas, Caravaggio and his rebellious saints—each tilted the mind a little further askew. However, there was great music at some estates. Freighted by train, retransported in sections by ox cart, the London Broadway piano brought Bach, Händel, and Couperin to the señora's sala. Most haciendas had a sala cluttered with heirlooms: horsehair sofas, tapestry chairs, wicker rockers, a parotta table, an ormolu screen, an inlaid card table, brass spittoons, and a whatnot of oriental ivory carvings.

Hacienda San Ignacio, Yucatán: 18th century brass sacristy Implements—handbell and Bible holder.

Since most work was onerous and the hours long, with most workers undernourished and small-boned, the haciendas faced labor problems. Most man-hours went into agricultural jobs; in some areas where the water supply was critical, wells had to be dug and serviced, pipelines demanded upkeep. If an aqueduct supplied the estate, the canal, its outlets, and spans had to be maintained. In the fields—across thousands of acres—there was planting, weeding, harvesting, and shucking to be done. There were beans, peppers, and tomatoes to pick. Fences had to be repaired. The cycles continued, altered by rain or drought, by pests and soil failure.

The most capable agronomists were the Jesuits; their haciendas achieved the best production records. Their workers often were treated with a measure of consideration. The Jesuit conduct book called for respect. This 200-page bible of Instrucciónes, written in the sixteenth century, forbade the whip, ball and chain, and the pillory. Yet even so, Jesuit cruelty was evident. In Santa Lucía, administrators chained mill workers and left skeletons of men in chains in subterranean rooms. In 1767, the Jesuits were expelled from New Spain. By 1810, Augustinians, Carmelites, Dominicans, and Franciscans owned more than half of the nation's real estate.

As for slavery on the haciendas, when is a man a slave? He is a slave if he works in perpetual debt. If he cannot, under penalty of imprisonment and death, leave the hacienda and work elsewhere, he is a slave. From the days of the encomiendas (land grant estates) until 1910, workers were enslaved by the hacienda. A small hacienda kept ten or twelve black slaves. Since there were approximately eight thousand haciendas in 1910, the total of black slaves must have reached many thousands. A large hacienda kept one hundred to one hundred and fifty slaves, of all ages. There is no accurate count, but it is clear that black slavery played an important role in the hacienda system.

Hacienda San Ignacio, Yucatán: brass ecclesiastical candle holder.

Disharmony was common among the ethnic groups: negro, mulatto, mestizo, Creole, Zapotec, Méxica, Chichimeca, Yaqui. The mores of each group were affected by Spanish customs and demands. Ethnic problems existed at each estate to varying degrees. At the mining hacienda, the sugar refining hacienda, and the vast cattle properties, the worker was less valuable than the horse. Big jobs and big land grants minimized personalities; anonymity took over. At the mine holdings, workers grubbed for ore 1,000 feet below. They worked almost naked, without adequate food, drank contaminated water, climbed precarious ladders in shafts faintly lit. Men, women, and children were employed. In principle, they were to work for a few days and then return home, but they worked until they were ill or until they died. Overseers were unwilling to spare the workers. There was no medical care.

Hacienda de Castamay, Campeche: cepo (stocks), made of mahogany.

With their mining, sugar refinery, and cattle properties, the hacendados were proud of their affluence, evident in their elegant mansions, ornate churches, endowed schools, and hospitals. They lived like Carolingian kings as they traveled from one hacienda to another, attended by friends, relatives, and parasites. They were famed for their hospitality, hated for their cruelty, kowtowed to when they went abroad.

Rincón Gallardo offered his private army to the Spanish Crown should there be a need. It took the Gallardo family less than a century to create a principality with its own administration, castle, village, and subordinate haciendas.

Hacienda de Castamay, Campeche: chapel stairway.

Rincón Gallardo reminisced about his hacienda life:

I spent my vacations with friends at Tlalayote, near Apán, in the state of Hidalgo. There we rode in the morning; in the afternoon we hunted for pheasant, quail and rabbit, and, near Tultengo Lake, for ducks. Since there was no automobile we went everywhere on horseback.

I can remember returning late from a hunt, the stars our only guide, since the one we were supposed to use—Evaristo, our groom—had by then a headful of pulque and was in no shape to lead us home. But once back at Tlalayote's main house we handed over our game-bags to Miscaela, the magnificent cook, who prepared several of the birds and served us plentifully with great mugs of pulque brought in from the fermenting shed.

This rural life seemed yet another indication of the land's undying attraction. As a young man I learned to ride charro style, to throw a calf by its tail, to lasso on horseback and on foot, to drive a six-mule team, to break wild colts and calves, and use firearms of various kinds.

I enjoyed the brandings, the shearings, and the weanings, which include one of my favorite sports ... separating calves from their mothers.

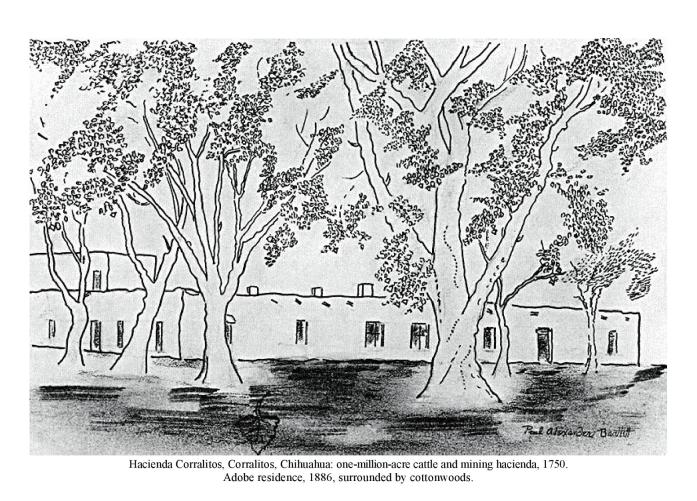

Hacienda Corralitos, Corralitos, Chihuahua: one-million-acre cattle and mining hacienda, 1750. Adobe residence, 1886, surrounded by cottonwoods.

But there were a few hacendados who disavowed the great estates: One of them said: "I'd rather have an attic in Paris than an hacienda."

Hacienda de Bellavista, Jalisco: sugar refinery silo.

Haciendas were the home of the fiesta. The first fiestas were held shortly after the Conquest. As the influence of Catholicism spread, fiestas increased in number—honoring a saint, commemorating a religious event, a holiday, a wedding. Generally, fiestas were initiated by the peasants and represented a communal expression. At an hacienda village someone had to collect funds, arrange for costumes, supervise church or chapel decorations, commission the fireworks, hire or borrow musicians, and arrange for food and drinks. If the hacendado hosted a fiesta, he might leave the details to his wife or the mayordomo. The priest and his assistant also managed fiestas.

People came on foot, by ox cart, palanquin, burro, mule, horse, wagon, and carriage—from distant haciendas and towns. For some four hundred years fiestas livened these feudal outposts that existed across the nation. Guests were often royalty or politically important: a viceroy, a duke, a governor, or church dignitary. Since travel was usually tedious and fatiguing, everything was done to make the festival memorable.

Hacienda de Yocotepec, Hidalgo: church and stone cross.

Sixteenth-century fiestas were announced by drums and the chirimía—a shrill flute from Aztec-Toltec-Mayan days. Dancers performed in front of the big house or danced in a patio or on the tiles of the church plaza. They wore harlequin-like costumes, feathered headdresses, conquest clothes, white trousers sashed with red, giant sombreros, masks; they flaunted wands, shields, spears, bows, and arrows. Ankle rattles hissed. Gourds thumped and rustled. Only male dancers participated.

In the far south, at estates in Chiapas, Yucatán, Quintana Roo, and Campeche, the marimba replaced the flute and drum. Sometimes six or eight musicians pounded out music simultaneously on four or five instruments.

Hacienda de Sodzil, Yucatán: bronze weathervane on residence.

In the north, on Sonoran and Chihuahuan haciendas, the violin was the chief instrument. Fashioned with no other tools than pieces of glass and a knife, it supplied basic rhythms, one or several instruments wailing for Yaqui and Tarahumaran dances.

Hacienda de Puerto de Nieto, Guanajuato: stone residence and chapel.

Flowers decked every fiesta. Gardenias were tossed into the fountains, carnations were woven into bell ropes, and rambler roses were spun around ox cart wheels and wagon wheels. Blossoms filled churches and chapels with fragrance, they crisscrossed patios on wires, they brightened roadside shrines.

Food and drink were plentiful: tortillas, beans, beans cooked with beef or chicken, pots and pots of beans, iron caldrons of soup, meat barbecued on spits, ox and goat, barrels of punch, buckets of pulque, barrels of beer, bottles of tequila, and, of course, cognac—for the gente de razón (gentry).

Hacienda de Puerto de Nieto, Guanajuato: gate.

In the big house, dinners were elaborate—the hacendado presiding. The menu offered Cochinita pibil (pork barbecued in banana leaves), squash blossom soup, quesadillas (tortilla turnovers stuffed with cheese and mushrooms), uchepos (corn mush steamed in husks), muk-bil pollo (chicken and pork tamale pie), tamales Veracruzanos (pork-filled tamales), and ate de guayaba (guava candy paste). For special guests, the chefs served more elaborate dishes: pheasant, quail, javelina, venison, dove, rabbit. There were no government restrictions on wild game. Fishermen contributed gallo (rooster fish), pardo trucha (trout), huachinango (red snapper), turtle, turtle eggs, lobster, and crab.

Hacienda de Puerto de Nieto, Guanajuato: church.

The guests gathered for cockfights. If it was summertime, a canopy shaded the pit. In the highlands a mozo swept aside pine needles and built a green fire to fight the mosquitoes. In the south, white awnings and striped parasols furnished shade. The cocks, which were uncaged at a pit, were named: Biba Manza, Panadero, Porfirio, Tigre, Mi General, and El Rayo. At a signal the birds flew at each other, their razor blades flashing. Bets were wagered ... a hundred ... a thousand ... five.

Hacienda de Aurora, Jalisco: commemorative bridge column dated 1750.

Hacienda de los Morales, D.F.: patio fountain, 1643.

Hacienda de Xala, Hidalgo: residence and chapel, 1785.

Hacienda de Tenache, Oaxaca: twin bells on roof of residence.

Hacienda la Calera, Jalisco: second residence on the property, 1890.

Hacienda Pixoy, Yucatán: brick-adobe residence and storage rooms. 18th century, eleven rooms.

Hacienda de los Ricos, Guanajuato: residence.

Hacienda de los Ricos, Guanajuato: bullring entry door.