The Project Gutenberg EBook of Christmastide, by William Sandys

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most

other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions

whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of

the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at

www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have

to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook.

Title: Christmastide

Its History, Festivities, and Carols

Author: William Sandys

Release Date: January 13, 2015 [EBook #47956]

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK CHRISTMASTIDE ***

Produced by Heather Clark, Emmy and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was

produced from images generously made available by The

Internet Archive)Music transcribed by Linda Cantoni.

LONDON:

JOHN RUSSELL SMITH,

SOHO SQUARE.

London: Printed by E. TUCKER, Perry’s Place, Oxford Street.

TO

WYNN ELLIS, ESQUIRE,

High Sheriff of Hertfordshire,

THE FOLLOWING WORK

IS GRATEFULLY INSCRIBED, AS A SMALL TRIBUTE

OF RESPECT FOR HIS PUBLIC, AND

ESTEEM FOR HIS PRIVATE

CHARACTER.

Lithographs. | |

| PAGE | |

| Play before Queen Elizabeth | frontispiece |

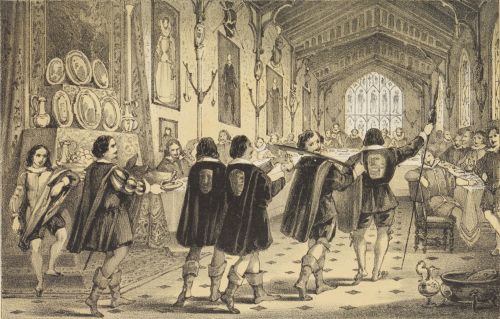

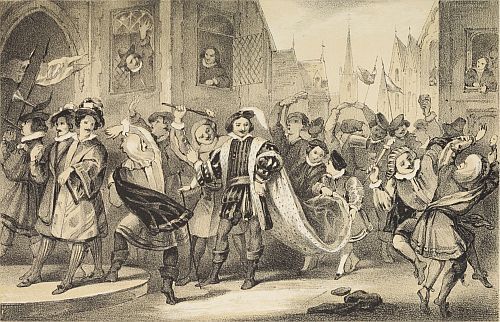

| Ushering in the Boar’s Head | 30 |

| Pageant before Henry the Eighth | 66 |

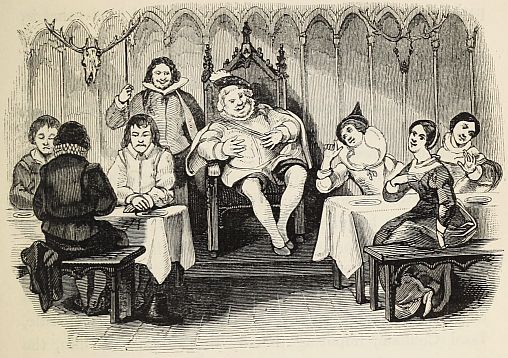

| Lord of Misrule, G. Ferrers | 86 |

| New Year’s Gifts to Queen Elizabeth | 100 |

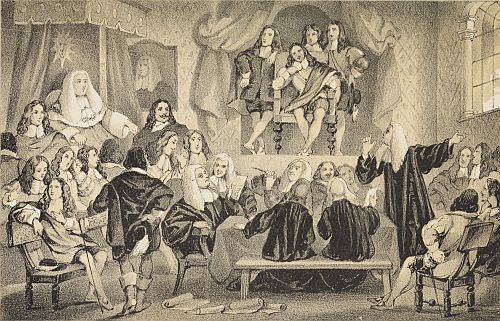

| Temple Revels, temp. Charles the Second | 130 |

| The Wassail Bowl | 134 |

| Old Christmas Festivities | 142 |

| The Christmas Tree | 152 |

Vignettes. | |

| CHAP. | |

| 1 Edward the First’s Offering at the Epiphany | 1 |

| 2 Froissart’s Christmas Log | 23 |

| 3 Merry Carol | 45 |

| 4 Archie returning his Christmas Gift | 63 |

| 5 Teonge’s Twelfth Night at Sea | 85 |

| 6 Charles the Second gambling at Christmas | 103 |

| 7 Pepys’ Wassail Bowl | 127 |

| 8 Modern Christmas Plays | 145 |

| 9 Three Kings offering | 159 |

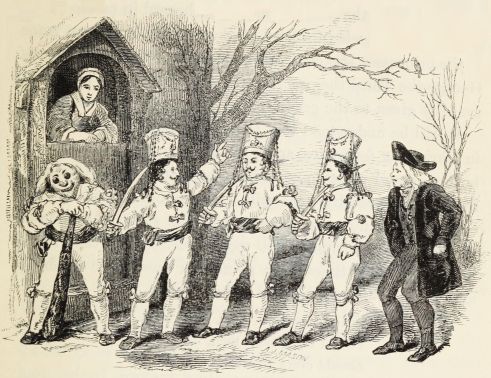

| 10 Carol Singers of old | 173 |

| 11 Decorating with Evergreens | 199 |

| Carols | 215 |

| A Mock Play | 292 |

| Christmas Play of St. George and the Dragon, as represented in the West of England | 298 |

| Index to Carols | 303 |

| Index to principal matters | 305 |

| Index of References | 306 |

Music. | |

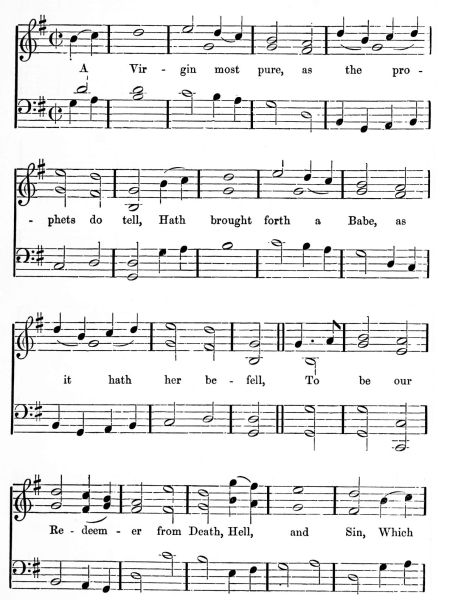

| A Virgin most pure | 313 |

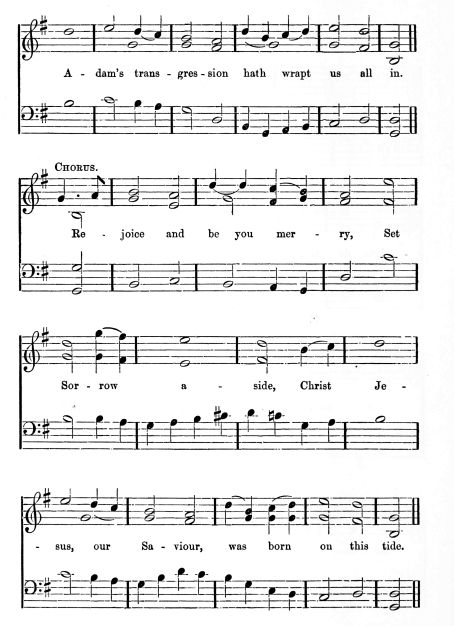

| A Child this day is born | 315 |

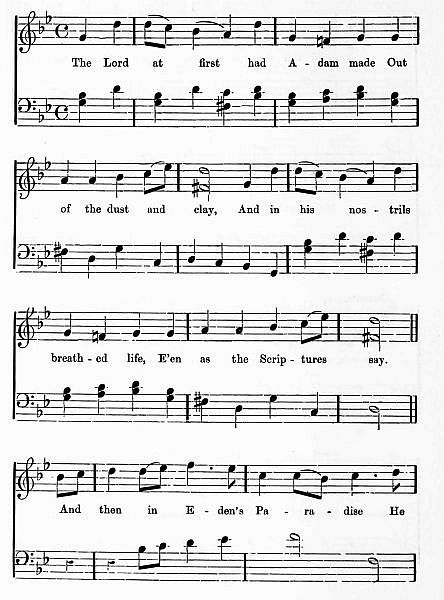

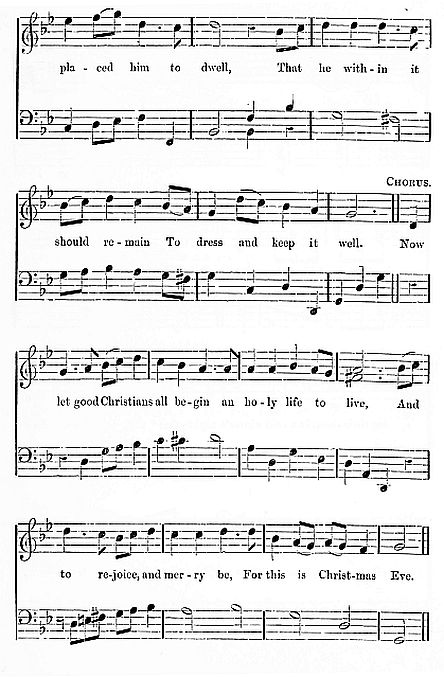

| The Lord at first had Adam made | 316 |

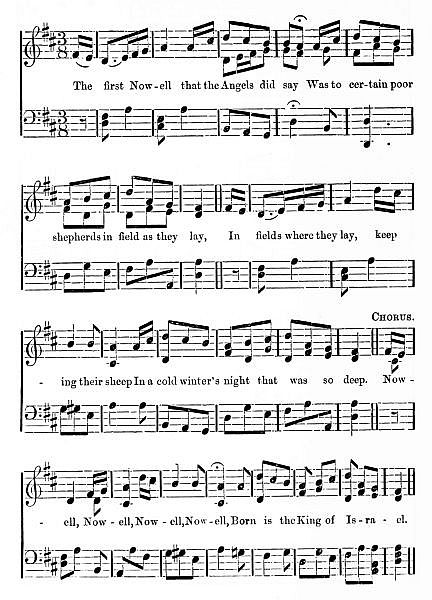

| The first Nowell | 318 |

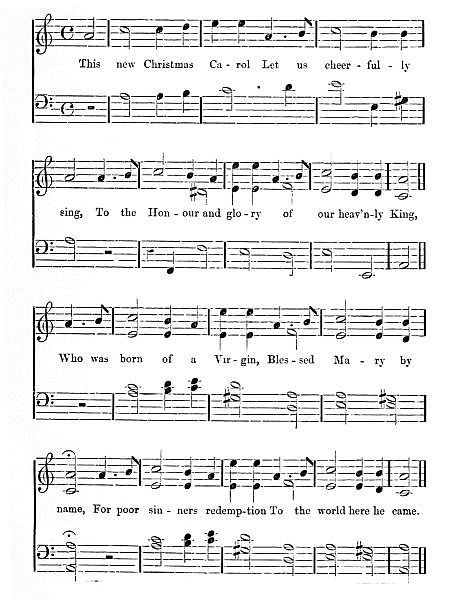

| This New Christmas Carol | 319 |

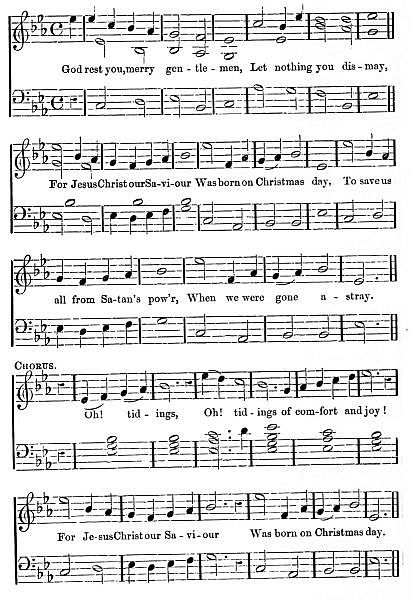

| God rest you, merry gentlemen | 320 |

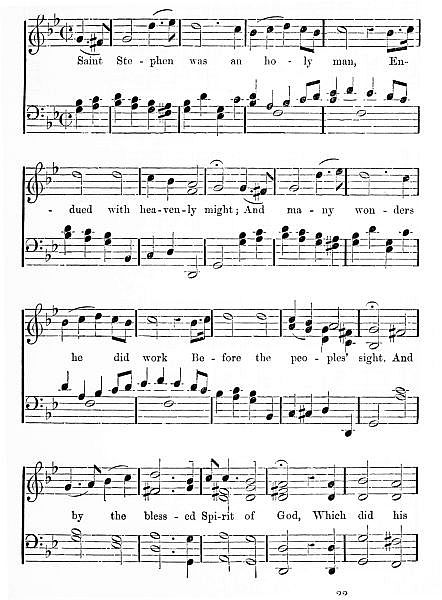

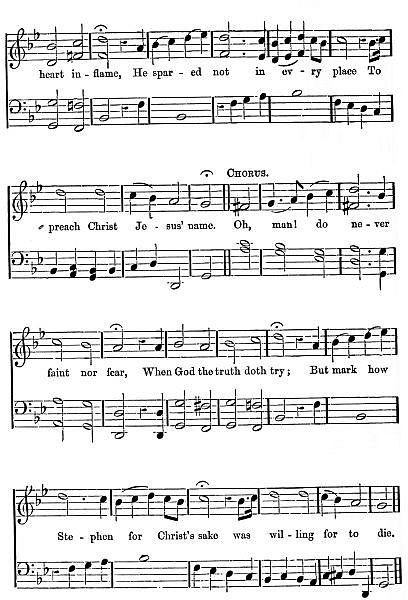

| St. Stephen | 321 |

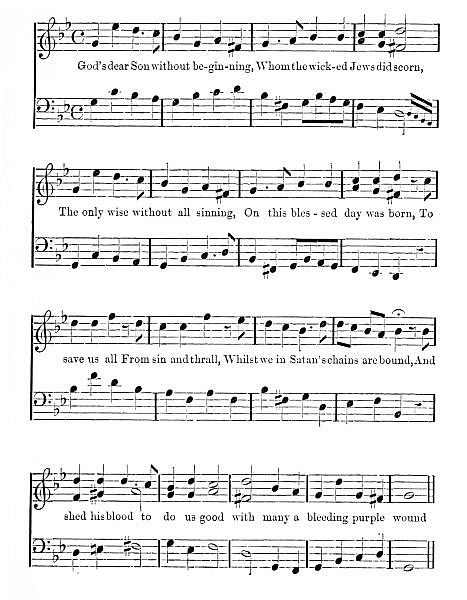

| God’s dear Son | 323 |

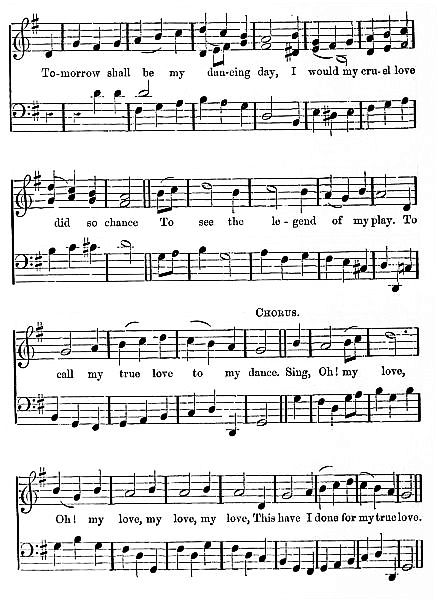

| To-morrow shall be my dancing-day | 324 |

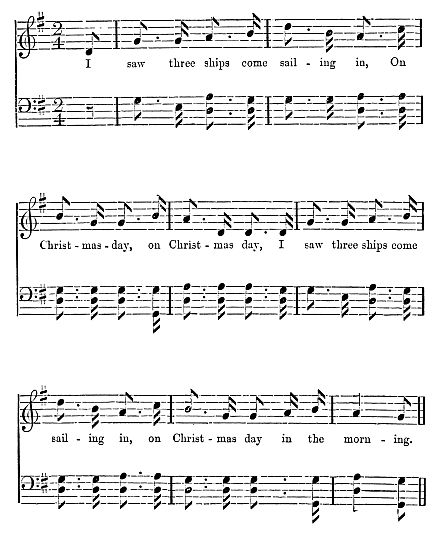

| I saw three ships | 325 |

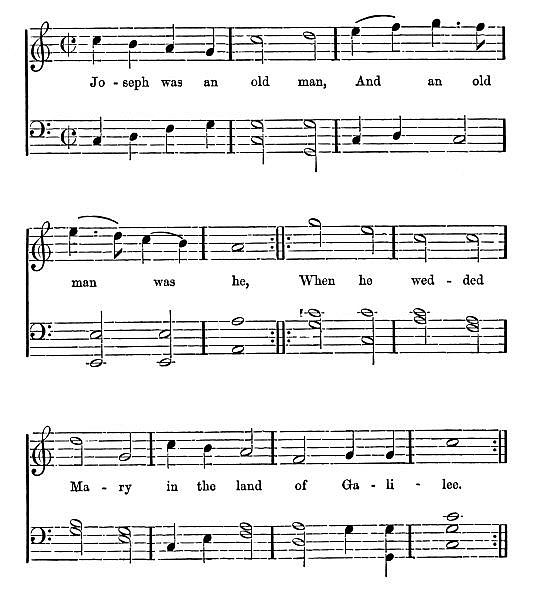

| Joseph was an old man | 326 |

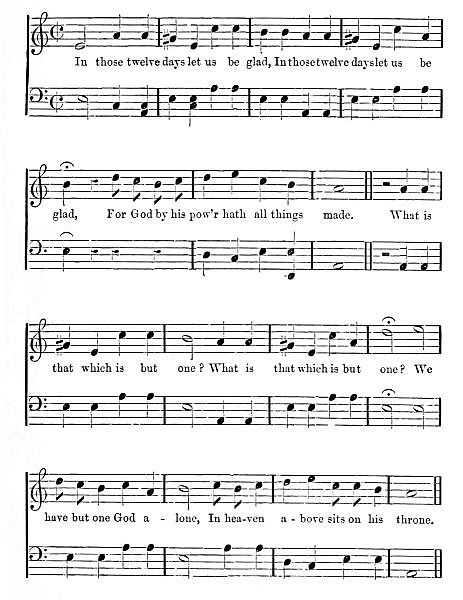

| In those twelve days | 327 |

IT would not be consistent with the proposed character of this work to enlarge on the Christian dispensation, as connected with the sacred feast of Christmas; to show Christianity as old as the Creation; that the fall of man naturally involved his punishment; and hence the vicarious sacrifice of our Saviour to redeem us from sin and death. These are subjects to be entered on by those who have had opportunities, if not of thinking more, at least of reading more, relative to them, than the writer of these pages, whose leisure hours are few, and whose endeavour will be to give, in as popular and interesting a manner as his abilities will enable him, some[2] information respecting the mode of keeping this Holy Feast, particularly in England, in the olden times, and in the middle ages.

The Nativity is hailed by Christians of all denominations, as the dawn of our salvation; the harbinger of the day-spring on high; that promise of futurity, where care, sin, and sorrow enter not, where friends long severed shall meet to part no more; no pride, no jealousy, no self (that besetting sin of the world) intruding. Well, then, may we observe it with gratitude for the unbounded mercy vouchsafed to us; for the fulfilment of the promise pronounced in the beginning of the world, releasing us from the dominion of Satan. A promise which even the Pagans did not lose sight of, although they confused its import, as a glimmering of it may be traced through their corrupted traditions and superstitious ceremonies.

Has the early dream of youth faded away purposeless?—the ambition of manhood proved vanity of vanities? Have riches made themselves wings and flown away? or, has fame, just within the grasp, burst like a bubble? Have the friends, the companions of youth, one by one fallen off from thy converse; or the prop of advancing age been removed, leaving thee weak and struggling with the cares of life; or, has “the desire of thine eyes” been taken from thee at a stroke? Under these and other trials, the Christian looks to the anniversary of the Nativity (that rainbow of Christianity) as the commemoration of the birth of the Blessed Redeemer, who will give rest to the weary, and receive in his eternal kingdom all those who truly trust in him. And well may His name be called, “Wonderful, Counsellor, the Mighty God, the Everlasting Father, the Prince of Peace!”

The season of Christmas, however, was not only set apart[3] for sacred observance, but soon became a season of feasting and revelry; so much so, that even our sumptuary laws have recognised it, and exempted it from their operation. When Edward the Third, in his tenth year, endeavoured to restrain his subjects from over luxury in their meals, stating that the middle classes sought to imitate the great in this respect, and thus impoverished themselves, and became the less able to assist their liege lord, he forbade more than two courses, and two sorts of meat in each, to any person, except in the great feasts of the year, namely, “La veile et le jour de Noël, le jour de Saint Estiephne, le jour del an renoef (New Year’s Day), les jours de la Tiphaynei et de la Purification de Nostre Dame,” &c.

A cheerful and hospitable observance of this festival being quite consistent with the reverence due to it, let us—after having as our first duty repaired to the house of our Lord, to return humble thanks for the inestimable benefits now conferred—while preparing to enter into our own enjoyments, enable, as far as in our power, our dependants and poorer brethren, to participate in the earthly comforts, as they do in the heavenly blessings of the season. Remember the days of darkness will come, and who can say how soon, how suddenly? and if long and late to some, yet will they surely come, when the daughters of music are laid low, then the remembrance of a kindly act of charity to our neighbour will soothe the careworn brow, and smooth the restless pillow of disease. “Go,” then, “your way; eat the fat and drink the sweet, and send portions unto them for whom nothing is prepared: for this day is holy unto our Lord.”

A great similarity exists in the observances of the return of the seasons, and of other general festivals throughout the[4] world; and indeed the rites and ceremonies of the various pagan religions have, to a great extent, the marks of a common origin; and the study of popular antiquities involves researches into the early history of mankind, and their religious ceremonies.

Immediately after the deluge, the religion of Noah and his family was pure; but a century had scarcely elapsed before it became perverted among some of his descendants. That stupendous pagan temple, the Tower of Babel, was built, and the confusion of tongues, and dispersion of mankind, followed. As the waves of population receded farther from the centre, the systems of religion—except with the chosen people—got more and more debased, and mingled with allegories and symbols. But still, even the most corrupt preserved many allusions to the fall of man, and his redemption; to the deluge, and the deliverance by the ark; and to a future state. Thus, whether in China, Egypt, India, Africa, Scandinavia, in the rites of Vitzliputzli in Mexico, and of Pacha Camac, in Peru, among the Magi, the Brahmins, the Chaldæans, the Gymnosophists, and the Druids, the same leading features may be traced. It has even been supposed, that amongst a chosen race of the priests, some traditionary knowledge of the true religion prevailed, which they kept carefully concealed from the uninitiated.

One of the greatest festivals was that in celebration of the return of the sun; which, at the winter solstice, began gradually to regain power, the year commenced anew, and the season was hailed with rejoicings and thanksgivings. The Saxons, and other northern nations, kept a feast on the 25th of December, in honour of Thor, and called it the Mother-Night, as the parent of other nights; also Mid-Winter. It[5] was likewise called Gule, Gwyl, Yule, or Iul, and half a dozen similar names, respecting the meaning of which learned antiquaries differ: Gebelin and others stating they convey the idea of revolution or wheel; while others, equally learned, consider the meaning to be festival, or holy-day. Gwyl in Welsh, and Geol in Saxon, both signify a holy-day; and as Yule, or I-ol, also signifies ale, an indispensable accompaniment of Saxon and British feasts, they were probably convertible terms. The word Yule may be found in many of our ancient metrical romances, and some of the old mysteries, as applied to Christmas, and is still so used in Scotland, and parts of England. The word Gala would seem to have a similar derivation. The curious in these matters may, however, refer to the learned Hickes’s two folios, Gebelin’s nine quartos, and Du Cange’s ten folios, and other smaller works, and satisfy their cravings after knowledge.

The feast of the birth of Mithras was held by the Romans on the 25th of December, in commemoration of the return of the sun; but the most important heathen festival, at this period of the year, was the Saturnalia, a word which has since become proverbial for high-jinks, and all manner of wild revelry. The origin seems to be unknown, but to have been previous to the foundation of Rome, and to have had some reference to the happy state of freedom and equality in the golden age of Saturn, whenever that era of dreams existed; for, when we go back to the olden times, no matter how far, we find the archæologists of that age still looking back on their older times: and so we are handed back, not knowing where to stop, until we stumble against the Tower of Babel, or are stopped by the prow of the Ark, and then decline going any farther.

The Greeks, Mexicans, Persians, and other great nations of antiquity, including of course the Chinese, who always surpassed any other country, had similar festivals. During the Saturnalia among the Romans, which lasted for about a week from the 17th of December, not only were masters and slaves on an equality, but the former had to attend on the latter, who were allowed to ridicule them. Towards the end of the feast a king or ruler was chosen, who was invested with considerable powers, and may be supposed to be intimately connected with our Lord of Misrule, or Twelfth Night King,—presents also were mutually given, and public places decked with shrubs and flowers. The birth of our Saviour thus took place at that time of the year, already marked by some of the most distinguished feasts. And why should it not have been so? We know that, at whatever period of the year it took place, it would have been, for Christians, “The Feast of Feasts;” and it is surely no derogation to imagine, that it was appointed at this time as the fulfilment of all feasts, and the culmination of festivals. The rising of the Christian Sun absorbed in its rays the lesser lights of early traditions, and it has continued to illuminate us with its blended brilliancy. Abercrombie, in his work on the Intellectual Powers, has some able remarks on the value of an unbroken series of traditional testimony or rites, especially as applicable to Christianity. “If the events, particularly, are of a very uncommon character, these rites remove any feeling of uncertainty which attaches to traditional testimony, when it has been transmitted through a long period of time, and, consequently, through a great number of individuals. They carry us back, in one unbroken series, to the period of the events themselves, and to the individuals who were witnesses of[7] them. The most important application of the principle, in the manner now referred to, is in those observances of religion which are intended to commemorate the events connected with the revelation of the Christian faith. The importance of this mode of transmission has not been sufficiently attended to by those who have urged the insufficiency of human testimony, to establish the course of events which are at variance with the common course of nature.”

During the Commonwealth, some of the Puritan party endeavoured to show that the 25th of December was not really the Birth of our Saviour, but that it took place at a different time of the year. Thomas Mockett, in ‘Christmas, the Christian’s Grand Feast,’ has collected the principal statements corroborative of this view—arguments they cannot be called; and after all, his conclusion is nothing more than, be the 25th of December the right day or not, Christians were not bound to keep it as a feast, because the supreme authority of the land, and ordinances of both Houses of Parliament, had directed otherwise. Parliament, however, cannot control the day of the Nativity, though it can do a great deal; having, on one occasion, according to tradition, nearly passed an act against the growth of poetry (an enactment perhaps not much wanted at present), though this was said to have been a clerical error; and, at another time, after inflicting a punishment of fourteen years’ transportation, gave half to the king and half to the informer; this, as may be supposed, was subsequently repealed. If, however, it is safe to say anything against Parliament, even of two hundred years since, without fear of the pains and penalties of contempt, it might be presumed that, like the patient in the ‘Diary of a Physician,’ they had “turned heads.” Dr. Thomas[8] Warmstry, in ‘The Vindication of the Solemnity of the Nativity of Christ,’ published three years previous to Mockett’s tract, gives satisfactory replies to the objections made by the Puritans, and seems to have embodied the arguments against them, considering it sufficient for us that the Church has appointed the 25th of December for our great feast.

Whether the Apostles celebrated this day, although probable, is not capable of proof; but Clemens Romanus, about the year 70, when some of them were still living, directs the Nativity to be observed on the 25th of December. From his time to that of Bernard, the last of the Fathers, A.D. 1120, the feast is mentioned in an unbroken series; a tract, called ‘Festorum Metropolis,’ 1652, naming thirty-nine Fathers, who have referred to it, including Ignatius, Cyprian, Athanasius, Gregory Nazianzen, Ambrosius, Chrysostom, Augustine, and Bede; besides historians and more modern divines. ‘The Feast of Feasts,’ 1644, also contains many particulars of the celebration during the earlier centuries of Christianity. About the middle of the fourth century, the feasting was carried to excess, as may have been the case occasionally in later times; and Gregory Nazianzen wars against such feasting, and dancing, and crowning the doors, so that the temporal rejoicing seems to have taken the place of the spiritual thanksgiving. In the same age there occurred one of those acts of brutality, which throughout all ages have disgraced humanity. The Christians having assembled in the Temple at Nicomedia, in Bithynia, to celebrate the Nativity, Dioclesian, the tyrant, had it inclosed, and set on fire, when about 20,000 persons are said to have perished; the number, however, appears large.

The early Christians, of the eastern and western Churches,[9] slightly differed in the day on which they celebrated this feast: the Easterns keeping it, together with the Baptism, on the 6th of January, calling it the Epiphany; while the Westerns, from the first, kept it on the 25th of December; but in the fourth century the Easterns changed their festival of the Nativity to the same day, thus agreeing with the Westerns. The Christian epoch was, it is said, first introduced into chronology about the year 523, and was first established in this country by Bede. New Year’s Day was not observed by the early Christians as the Feast of the Circumcision, but (excepting by some more zealous persons, who kept it as a fast) with feasting, songs, dances, interchange of presents, &c., in honour of the new year; though the bishops and elders tried to check these proceedings, which were probably founded in some measure on the Roman feast of the double-faced Janus, held by them on this day. According to Brady, the first mention of it, as a Christian festival, was in 487; and it is only to be traced from the end of the eleventh century, under the title of the Circumcision; and was not generally so kept until included in our liturgy, in 1550; although, from early times, Christmas Day, the Nativity, and Twelfth Day, were the three great days of Christmas-tide. Referring to the probability, that the feasting on New Year’s Day might have been derived from the feast of Janus, it must be observed, that some of the early Christians, finding the heathens strongly attached to their ancient rites and customs, which made it difficult to abolish them (at least until after a considerable lapse of time), took advantage of this feeling, and engrafted the Christian feasts on those of the heathen, first modifying and purifying them. The practice may have been wrong, but the fact was so. Thus, Gregory[10] Thaumaturgus, bishop of Neocæsarea, who died in 265, instituted festivals in honour of certain Saints and Martyrs, in substitution of those of the heathens, and directed Christmas to be kept with joy and feasting, and sports, to replace the Bacchanalia and Saturnalia. Pagan temples were converted into Christian churches; the statues of the heathen deities were converted into Christian saints; and papal Rome preserved, under other names, many relics of heathen Rome. The Pantheon was converted into a Romish church, and Jupiter changed to St. Peter.

When Pope Gregory sent over St. Augustin to convert Saxon England, he directed him to accommodate the ceremonies of the Christian worship as much as possible to those of the heathen, that the people might not be too much startled at the change; and, in particular, he advised him to allow the Christian converts, on certain festivals, to kill and eat a great number of oxen, to the glory of God, as they had formerly done to the honour of the devil. St. Augustin, it appears, baptized no fewer than 10,000 persons on the Christmas day next after his landing in 596, and permitted, in pursuance of his instructions, the usual feasting of the inhabitants, allowing them to erect booths for their own refreshment, instead of sacrificing to their idols,—objecting only to their joining in their dances with their pagan neighbours. Thus several of the pagan observances became incorporated with the early Christian festivals; and to such an extent, that frequent endeavours were made, by different Councils, to suppress or modify them; as, in 589, the songs and dances, at the festivals of Saints, were prohibited by the Council of Toledo, and by that of Chalon, on the Saone, in 650. In after times, the clergy still found it frequently requisite to[11] connect the remnants of pagan idolatry with Christianity, in consequence of the difficulty they found in suppressing it. So, likewise, on the introduction of the Protestant religion, some of the Roman Catholic ceremonies, in a modified state, were preserved; and thus were continued some of the pagan observances. In this manner may many superstitious customs, still remaining at our great feasts, and in our games and amusements, be accounted for.

The practice of decorating churches and houses with evergreens, branches, and flowers, is of very early date. The Jews used them at their Feast of Tabernacles, and the heathens in several of their ceremonies, and they were adopted by the Christians. Our Saviour Himself permitted branches to be used as a token of rejoicing, upon His triumphal entry to Jerusalem. It was natural, therefore, that at Christmas time, when His Birth, and the fulfilment of the promise to fallen man, were celebrated, that this symbol of rejoicing should be resorted to. Some of the early Councils, however, considering the practice somewhat savoured of paganism, endeavoured to abolish it; and, in 610, it was enacted, that it was not lawful to begirt or adorn houses with laurel, or green boughs, for all this practice savours of paganism. In the earlier carols the holly and the ivy are mentioned, where the ivy, however, is generally treated as a foil to the holly, and not considered appropriate to festive purposes.

“Holly and Ivy made a great party,

Who should have the mastery

In lands where they go.

Then spake Holly, I am friske and jolly,

I will have the mastery

In lands where they go.”

But in after times it was one of the plants in regular use. Stowe mentions holme, ivy, and bays, and gives an account of a great storm on Candlemas Day, 1444, which rooted up a standard tree, in Cornhill, nailed full of holme and ivy for Christmas, an accident that by some was attributed to the evil spirit. Old Tusser’s direction is “Get ivye and hull (holly) woman deck up thine house.” The misletoe—how could Shakespeare call it the “baleful misletoe?”—was an object of veneration among our pagan ancestors in very early times, and as it is probable it was the golden branch referred to by Virgil, in his description of the descent to the lower regions, it may be assumed to have been used in the religious ceremonies of the Greeks and Romans. His branch appears to have been the misletoe of the oak, now of great rarity, though it is found on many other trees. It was held sacred by the Druids and Celtic nations, who attribute to it valuable medicinal qualities, calling it allheal and guidhel, and they preferred, if not selected exclusively, the misletoe of the oak. Vallancey says it was held sacred because the berries as well as the leaves grow in clusters of three united to one stalk, and they had a veneration for the number three; his observation, however, is incorrect as to the leaves, which are in pairs only. The Gothic nations also attached extraordinary qualities to it, and it was the cause of the death of their deity Balder. For Friga, when she adjured all the other plants, and the animals, birds, metals, earth, fire, water, reptiles, diseases, and poison, not to do him any hurt, unfortunately neglected to exact any pledge from the misletoe, considering it too weak and feeble to hurt him, and despising it perhaps because it had no establishment of its own, but lived upon other plants. When the gods, then, in their great assembly,[13] amused themselves by throwing darts and other missiles at him, which all fell harmless, Loke, moved with envy, joined them in the shape of an old woman, and persuaded Hoder, who was blind, to throw a branch of misletoe, and guided his hand for the purpose; when Balder, being pierced through by it, fell dead. The Druids celebrated a grand festival on the annual cutting of the misletoe, which was held on the sixth day of the moon nearest their new year. Many ceremonies were observed, the officiating Druid being clad in white, with a golden sickle, and received the plant in a white cloth. These ceremonies kept alive the superstitious feelings of the people, to whom no doubt the Druids were in the habit of dispensing the plant at a high price; and as late as the seventeenth century, peculiar efficacy was attached to it, and a piece hung round the neck was considered as a safeguard against witches. In modern times it has a tendency to lead us towards witches of a more attractive nature; for, as is well known, if one can by favour or cunning induce a fair one to come under the misletoe he is entitled to a salute, at the same time he should wish her a happy new year, and present her with one of the berries for good luck; each bough, therefore, is only laden with a limited number of kisses, which should be well considered in selecting one. In some places people try lots by the crackling of the leaves and berries in the fire.

From the pagan Saturnalia and Lupercalia probably were derived those extraordinary but gross, and as we should now consider them, profane observances, the Feast of Asses and the Feast of Fools, with other similar burlesque festivals. In the early ages of Christianity, there were practices at the beginning of the year of men going about dressed in female attire or in[14] skins of beasts, causing occasionally much vice and debauchery; but the regular Feast of Asses and Feast of Fools were not apparently fully established until the ninth or tenth century; a period when it was considered a sufficient qualification for a priest, if he could read the Gospels and understand the Lord’s Prayer. All sorts of buffooneries and abominations were permitted at these representations; mock anthems and services were sung; an ass, covered with rich priestly robes, was gravely conducted to the choir, and provided from time to time with drink and provender, the inferior clergy, choristers, and people dancing round him and imitating his braying; while all sorts of impurities were committed, even at the holy altar. A hymn was sung, commencing—

Orientis partibus

Adventavit asinus;

Pulcher et fortissimus,

Sarcinis aptissimus.

Hez, Sire Asnes, car chantez;

Belle bouche rechignez;

Vous aurez du foin assez.

Et de l’avoine à planter.

Lentus erat pedibus,

Nisi foret baculus,

Et cum in clunibus

Pungeret aeuleus.

and after several verses in this strain, finishing with—

Hez va! hez va! hez va, hez!

Bialx Sire Asnes car allez;

Belle bouche car chantez.

On the mock mass being completed, the officiating priest[15] turned to the people and said, “Ite missa est,” and brayed three times, to which they responded by crying or braying out, Hinham, Hinham, Hinham. This festival is said to have been in commemoration of the flight to Egypt; but there was one kept at Rouen in honour of Balaam’s ass, where the performers, if they may be so called, walked in procession on Christmas Day, representing the prophets and others, as David, Moses, Balaam, Virgil, &c., just as General Wolfe may now be seen as a party in the Christmas play of St. George and the Dragon. Many attempts were made from the twelfth to the end of the sixteenth century to suppress these licentious abuses of sacred things; and although by that time they were abolished in the churches, yet they were continued by the laity, and our modern mummers probably have their origin from them. A pupil of Gassandi, writing to him as late as 1645, mentions having seen in the church at Aix, the Feast of Innocents (which was of a similar nature) kept by the lay brethren and servants in the church, dressed in ragged sacerdotal ornaments, with books reversed, having large spectacles, with rinds of scooped oranges instead of glasses. Louis the Twelfth, in the early part of the sixteenth century, ordered the representation of the gambol of the ‘Prince des Sots’ and the ‘Mère sotte,’ in which, according to a note to Rabelais, liv. i, c. 2, ed. 1823, Julius the Second and the Court of Rome were represented. This was about the time probably when the principality of Chauny wishing to have some swans (cignes) for the waters ornamenting their town, unluckily wrote to Paris for some cinges (singe being then written with a c), and in due time received a wagonful of apes. They could, therefore, have readily proffered their[16] scribe as the prince des sots, excepting that it takes a wise man to make a good fool. At Angers, there was an old custom called Aquilanneuf, or Guilanleu, where young persons went round to churches and houses on the first of the year, to collect contributions, nominally to purchase wax in honour of the Virgin, or the patron of the church, crying out, Au gui menez Rollet Follet, tiri liri mainte du blanc et point du bis; they had a chief called Roi Follet, and spent their money in feasting and debauchery. An order was made by the synod there, in 1595, which stopped the practice in the churches, but another, in 1668, was necessary to modify and restrain it altogether.

Feasts of this description were not much in vogue in England, though they were introduced, as we find them prohibited at Lincoln, by Bishop Grosthead, in the time of Henry the Third; but towards the end of the following century they were probably abolished. There are traces of the fool’s dance, where the dancers were clad in fool’s habits, in the reign of Edward the Third. A full account of these strange observances may be found in Ducange, and in Du Tilliot’s Mémoires de la Fête des Foux.

Christianity was introduced among the Britons at a very early period, but there are no records, that can be considered authentic, of their mode of keeping the feast of the Nativity, though it was doubtless observed as one of their highest festivals. Some of the druidical ceremonies might have been embodied, and even the use of the mysterious misletoe then adopted, the aid of the bards called in, and ale and mead quaffed in abundance. The great and veritable King Arthur, according to the ballad of the “Marriage of Sir Gawaine,”—

“......a royale Christmasse kept,

With mirth and princelye cheare;

To him repaired many a knighte,

That came both farre and neare.”

This, though ancient, is certainly of a date long subsequent to the far-famed hero; but it ought to be taken as authority, for, according to the modern progress of antiquarianism, the farther off we live from any given time or history, the more we know about it; the old Babylonians, Greeks, Romans, and Mediævals, knowing nothing respecting themselves and their next door neighbours, while we are as familiar as if we had been born and bred with them. By the same rule of remoteness, the modern chronicler, Whistlecraft (Frere), should be taken as authority, for the particulars of the ancient Christmas feast, on which he humorously thus dilates:—

“They served up salmon, venison, and wild boars,

By hundreds, and by dozens, and by scores,

Hogsheads of honey, kilderkins of mustard,

Muttons, and fatted beeves, and bacon swine,

Herons and bitterns, peacocks, swan, and bustard,

Teal, mallard, pigeons, widgeons, and, in fine,

Plum-puddings, pancakes, apple-pies, and custard,

And therewithal they drank good Gascon wine,

With mead, and ale, and cider of our own,

For porter, punch, and negus were not known.”

After the conversion of the Anglo-Saxons to Christianity, Easter, Whitsuntide, and Christmas, were kept as solemn festivals; the kings living at those times in great state, wearing their crowns, receiving company on a large scale, and[18] treating them with great hospitality. The Wittenagemots were also then held, and important affairs of church and state discussed. Knowing the affection of the early Saxons for their ale and mead, and that quaffing these from the skulls of their enemies, while feasting from the great boar Scrymer, was—notwithstanding the apparent sameness of the amusement—one of their anticipated joys in a future state, we can readily imagine that excesses frequently took place at these festivals. The wassail bowl, of which the skull of an enemy would thus appear to have formed their beau idéal, is said to have been introduced by them. Rowena, the fair daughter of Hengist, presenting the British king, Vortigern, with a bowl of wine, and saluting him with “Lord King Wass-heil;” to which he answered, as he was directed, “Drinc heile,” and saluted her then after his fashion, being much smitten with her charms. The purpose of father and daughter was obtained; the king married the fair cup-bearer, and the Saxons obtained what they required of him. This is said to have been the first wassail in this land; but, as it is evident that the form of salutation was previously known, the custom must have been much older among the Saxons; and, indeed, in one of the histories, a knight, who acts as a sort of interpreter between Rowena and the king, explains it to be an old custom among them. By some accounts, however, the Britons are said themselves to have had their wassail bowl, or lamb’s wool—La Mas Ubhal, or day of apple fruit—as far back as the third century, made of ale, sugar (whatever their sugar was), toast and roasted crabbs, hissing in the bowl; to which, in later times, nutmeg was added. The followers of Odin and Thor drank largely in honour of their pagan deities; and, when converted, still continued their[19] potations, but in honour of the Virgin Mary, the Apostles, and Saints; and the early missionaries were obliged to submit to this substitution, being unable to abolish the practice, which afterwards degenerated into drinking healths of other people, to the great detriment of our own. Strange! that even from the earliest ages, the cup-bearer should be one of the principal officers in the royal presence, and that some of the high families take their name from a similar office.

The feast of Christmas was kept in the same state on the Continent, and the bishops were accustomed to send their eulogies—Visitationis Scripta—on the Nativity, to kings, queens, and others of the blood royal. But it is foreign to the purpose of this work to refer to the customs abroad, unless it may be necessary to do so slightly, for the purpose of illustration. It may be mentioned, however, that at this festival, in 800, Charlemagne received from the pope, Leo the Third, the crown of Emperor, and was hailed as the pious Augustus the Great, and pacific Emperor of the Romans.

Alfred, as might be expected from his fine character, reverently observed the festival. On one occasion he gave to the celebrated Asser, by way of gift, an abbey, in Wiltshire, supposed to have been Amesbury; another, at Barnwell, in Somersetshire; a rich silk pall, and as much incense as a strong man could carry on his shoulder,—a truly princely New Year’s gift. He directed Christmas to be kept for twelve days; so that now, if not at an earlier date, the length of the feast was defined, and the name, probably, of Twelfth-day given to the last day of it; though, in the old Runic festivals, among the ancient Danes, it appears to have been more correctly called the thirteenth day, a name which would sound[20] uncouth to our modern ears: Who would eat any thirteenth cake? Alfred was commemorating this festival, with his army, at Chippenham, in 878, when he was surprised by Guthrum, and his Danes, and compelled to fly and conceal himself in the Isle of Athelney, his power fading away for a time, even like that of a twelfth-night king. Something similar happened a century before, when Offa, king of Mercia, about the year 790, was completing Offa’s dyke. The Welsh, despising the solemnity of the time, broke through, and slew many of Offa’s soldiers, who were enjoying their Christmas. The Danish kings kept the feast much in the same manner as the Saxons; and there is a story told of Canute, who had many good qualities about him, which shows the rudeness of the times, even in the royal circle, though such a scene may even now be realized in Oriental courts. While this monarch was celebrating his Christmas in London, A.D. 1017, Edric, earl of Mercia, who had treacherously betrayed and deserted Ethelred and Edmund Ironside, boasted of his services to Canute, who turned to Eric, earl of Northumberland, exclaiming, “Then let him receive his deserts, that he may not betray us, as he betrayed Ethelred and Edmund.” The Norwegian immediately cut him down with his battle-axe, and his body was thrown from a window into the Thames. Such speedy justice would rather astonish a drawing-room now-a-days.

Dancing seems then, even as at present, to have been a favourite Christmas amusement, and certainly in one instance was carried to an extreme. Several young persons were dancing and singing together on Christmas Eve, 1012, in a churchyard, and disturbed one Robert, a priest, who was performing mass in the church. He entreated them in vain[21] to desist: the more he begged the more they danced, and, we may conclude, showed him some of their best entrechâts and capers. What would, in modern times, have been a case for the police, was then a subject for the solemn interference of the powers of the church. Robert, as they would not cease dancing, as the next best thing, prayed that they might dance without ceasing. So they continued without intermission, for a whole year, feeling neither heat nor cold, hunger nor thirst, weariness nor decay of apparel; but the ground on which they performed not having the same miraculous support, gradually wore away under them, till at last they were sunk in it up to the middle, still dancing as vehemently as ever. Sir Roger de Coverley, danced down the whole length of the Crystal Palace, would have been nothing to this. A brother of one of the girls took her by the arm, endeavouring to bring her away; the limb, however, came off in his hand, like Dr. Faustus’s leg, in the hand of the countryman, but the girl never stopped her dancing, or missed a single step in consequence. At the end of the year Bishop Hubert came to the place, when the dancing ceased, and he gave the party absolution. Some of them died immediately after, and the remainder, after a profound sleep of three days and three nights, went about the country to publish the miracle.

It was at Christmas, 1065, that Westminster Abbey was consecrated, in the presence of Queen Edgitha, and a great number of nobles and priests, Edward the Confessor being himself too ill to attend; and indeed he died on the 5th of January, 1066, and was buried in the Abbey on the following day; his tomb there, and his name of the Confessor, given him by the priests, having caused him probably to be better known than any particular merits of his own deserve.

A great change was now about to take place in the government of our country: William of Normandy claimed it as his of right against Harold; and, having power to support his claim, in the space of a few months became King of England, placing his Norman followers in the high places of the land.

THE Anglo-Norman kings introduced increased splendour at this festival, as they did on all other occasions; the king wearing his crown and robes of state, and the prelates and nobles attending, with great pomp and ceremony, to partake of the feast provided by their monarch, and to receive from him presents, as marks of his royal favour; returning, probably, more than an equivalent. William the Conqueror, was crowned on Christmas day, 1066.

“On Christmas day in solemne sort,

Then was he crowned here,

By Albert, Archbishop of Yorke,

With many a noble peere.”

There was some disturbance during the ceremony, owing to the turbulence or misconception of his Norman followers, who, as well as their master, were disposed to rule with a rod of iron. William gave a striking proof of how little his nature was capable of understanding “good will towards men,” when he kept his Christmas at York, in 1069, with the usual festivities, and afterwards gave directions to devastate the country between York and Durham; thus consigning 100,000 people to death, by cold, hunger, fire, and sword. Well, perhaps some of us are William the Conquerors in heart; what else is a bully at school, or a bully in society, or, yet more, a bully in domestic life? Who can count the misery caused by one selfish, one imperious tyrant, whose victims dare not, or will not, complain; the crouching child, the trembling, submissive, broken-hearted, yet even still the loving wife? Oh! woman,—woman, how few amongst us are able to appreciate you! We see you fair and accomplished; we find you loving and affectionate; we know you virtuous and faithful; but, can we estimate your truthfulness, your negation of self, your purity of thought? Partakers of our joys, but partners indeed in our sorrows; how many a weary heart of man, crushed by the pressure of worldly cares and trials, have you not saved, and brought to the contemplation of better things! “She openeth her mouth with wisdom; and in her tongue is the law of kindness.”

It would be easy to give a list of the different places where our monarchs kept their Christmasses, from the time of the Conquest, in nearly, if not quite, an unbroken series; but as this would be scarcely as amusing as a few pages in a well conducted dictionary, it will no doubt be considered to have been wisely omitted. It may be stated, in general terms,[25] that the earlier kings occasionally passed Christmas in Normandy, and that some of the principal towns favoured, besides London and Westminster, appear to have been, Windsor, York, Winchester, Norwich, Worcester, Gloucester, Oxford, Eltham, and Canterbury; and in the time of the Tudors, Greenwich. Some examples of marked or distinguished Christmasses will be given in the following pages.

In 1085, William, who was fond of magnificence, kept his Christmas with great state at Gloucester, which was a favourite place with him and his son William. He was either in a particular good humour, or wished to perform what he might think an act of grace, and compensate the severity with which he treated his conquered, or rather semi-conquered new subjects, by showing favour to his own countrymen;—a sort of liberal disposition of public gifts to family friends, that may be seen occasionally even in modern times—so he gave bishoprics to three of his chaplains, namely, that of London to Maurice, of Thetford to William, and of Chester to Robert. There is a somewhat strange regulation among the constitutions of Archbishop Lanfranc for the government of the monks of his cathedral, which contain numerous injunctions respecting washing and combing, and other matters that would now surprise even a well-regulated boys’ school. On Christmas Eve they are directed to comb their heads before they washed their hands, while at other times they were to wash first, and comb afterwards. We do not see the philosophy of this curious distinction.

William Rufus, the weak and profligate successor of the Conqueror, kept the Christmas in state, like his father, and Henry the First followed their example; even in 1105, which was “annus valde calamitosus,” wherein he raised[26] many tributes, he still kept his Christmas in state, at Windsor. In 1116, he kept it at St. Albans, when the celebrated monastery there was consecrated. In the Christmas 1126-7, which was held at Windsor, anticipating the struggle for the crown that would take place after his death, he assembled all the principal clergy and nobles (David, king of Scots, being also present), and caused them to swear that they would maintain England and Normandy for his daughter, the Empress Matilda, after his death. In these early times, however, a few oaths, more or less, were of little consequence; the “time whereof the memory of man runneth not to the contrary” was of very short date; a week sometimes making a man to forget utterly what he might previously have sworn to; and the vicar of Bray would have been by no means a reprehensible character.

King Stephen, after his accession, wore his crown and robes of state like the former kings, and kept his Christmas at London; but about the fifth year of his reign, the internal wars and tumults became and continued of such magnitude, that during the remainder of this troubled reign, the celebration of festivals was laid aside.

Henry the Second renewed the celebration of Christmas with great splendour, and with plays and masques; and the lord of Misrule appears to have been known at this time, if not at a much earlier date. In 1171, he celebrated the feast at Dublin, in a large wooden house erected for the purpose, and entertained several of the Irish chieftains, as well as the principal men of his own court and army; the Irish were much surprised at the great plenty and variety of provisions, and were especially amused at the English eating cranes; however, after a very short hesitation they joined readily in[27] the feasting themselves, and history does not say that any ill effects followed. Cranes continued to be favourites at Christmas and aristocratic feasts for some time; at the celebrated and often quoted enthronisation banquet of Archbishop Nevil, in the time of Edward the Fourth, there were no less than 204 of these birds. There were some strange dishes, however, in vogue in the time of Henry the Second, as far as the names, whatever the actual merits of the compounds might have been. Dillegrout, karumpie, and maupigyrnun, may have far surpassed some of our grand sounding modern dishes, where the reality sadly disappoints the ear. This dillegrout also was rather an important dish, as the tenant of the manor of Addington, in Surrey, held it by service of making a mess of dillegrout on the day of the coronation. Fancy the anxiety on this ceremony, not only for the excellence of the dish, but that it shall not be proclaimed a failure, and thus risk the possession of the manor, and some more favoured tenant being put in possession, on the tenure of providing a plum-pudding every Christmas, or something similar, like the celebrated King George’s pudding, still tendered to visitors at the Isle of Portland. This dillegrout, too, required some little skill to make it well, being compounded of almond milk, the brawn of capons, sugar and spices, chicken parboiled and chopped, and was called, also, ‘le mess de gyron,’ or, if there was fat with it, it was termed maupigyrnun.

At Christmas, 1176, Roderick, king of Connaught, kept court with Henry at Windsor, and in 1183, Henry kept the feast at Caen, in Normandy, and there wished his son Henry (who died not long afterwards) to receive homage from his brothers; but the impetuous Richard would not consent, the[28] “merry” Christmas was, therefore, sadly interrupted, and fresh family feuds arose; they had previously been but too frequent, Henry’s life having been much embittered by the conduct of his sons.

When Richard himself came to the throne, he gave a splendid entertainment during Christmas, 1190, at Sicily, when on his way to the Crusades, inviting every one in the united English and French armies of the degree of a gentleman, and giving each a suitable present, according to his rank. Notwithstanding, however, the romance of Richard Cœur de Lion affirms that—

“Christmas is a time full honest,

Kyng Richard it honoured with gret feste;”

and an antiquary of course ought to consider these romances of equal authenticity with the old chronicles; yet one cannot help thinking that during Richard’s short reign, his captivity and his absence from his kingdom must have interfered with his Christmas celebrations; in fact, he, of the lion-heart, seems to have been more ornamental than useful in the pages of history.

John celebrated the feast pretty regularly, but seems occasionally to have selected a city or town for the purpose, where some great personage was allowed to provide for the entertainment; as, for instance, the celebrated Hubert de Burgh, at Canterbury, in 1203. In 1213, he kept his Christmas at Windsor with great festivity, and gave many presents. He was accustomed to make a present to his chancellor, every Christmas, of two marks of gold, according to ancient custom, no doubt by way of New Year’s gift, and gave him half that value at Easter and Whitsuntide. In[29] 1214, he was keeping his Christmas at Worcester, when he was informed of the resolution of the barons to withdraw their allegiance, unless their claims were attended to. This information being ill-suited for the festivities then in progress, the king departed suddenly and shut himself up in the Temple; but the barons went to him on the Epiphany of 1215 with their demands, to which he promised a satisfactory answer at the ensuing Easter. The dissensions between himself and his barons, ending in Magna Charta, are well-known matters of history. In the following year the chief barons of the realm were under sentence of excommunication, and the city of London was under an interdict; but the citizens disregarded this, kept open their churches, rang their bells, enjoyed their turtle and whitebait (whatever the turtle and whitebait of that time might have been), drank their hippocras, ale, mead, and claret or clarré, and celebrated their Christmas with unusual festivity. The English had long been celebrated for their pre-eminence in drinking; as Iago says, “your Dane, your German, and your swag-bellied Hollander, are nothing to your English.” They probably inherited the talent from the Saxons, for their kings had their wine, mead, cyder, ale, pigment, and morat, to which their Norman successors added claret or clarré, garhiofilac, and hippocras. Morat was made from honey and mulberries; claret, pigment, hippocras, and garhiofilac (so called from the girofle or cloves contained in it), were different preparations of wine mixed with honey and spices, no doubt very palatable; and hippocras particularly was indispensable at all the great feasts. Garhiofilac was probably made of white wine, and claret of red wine, as there is an order of Henry the Third in existence, directing the keepers of his wines at York, to deliver to[30] Robert de Monte Pessulano two tuns of white wine to make garhiofilac, and one tun of red wine to make claret for him at the ensuing Christmas, as he used to do in former years. These sheriffs were very useful persons in those times, and performed many offices for our olden monarchs that would somewhat surprise a modern high sheriff to perform now, when he is only called upon to attend to the higher duties of his office, and becomes officially one of the first men in his county. Henry the Third, in his twenty-sixth year, directed the sheriff of Gloucester, to cause twenty salmons to be bought for the king, and put into pies against Christmas; and the sheriff of Sussex to buy ten brawns with the heads, ten peacocks, and other provisions for the same feast.

In his thirty-ninth year, the French king, having sent over as a present to Henry (whether as a New Year’s gift or not does not exactly appear) an elephant—“a beast most strange and wonderfull to the English people, sith most seldome or never any of that kind had beene seene before that time,”—the sheriffs of London were commanded to build a house for the same, forty feet long and twenty feet broad, and to find necessaries for himself and keeper.

The boar’s head just referred to was the most distinguished of the Christmas dishes, and there are several old carols remaining in honour of it.

“At the begynnyng of the mete,

Of a borys hed ye schal hete,

And in the mustard ye shal wete;

And ye shal syngyn or ye gon.”

The dish itself, though the “chief service in this land,” and of very ancient dignity—probably as old as the Saxons,—was[31] not confined to Christmas; for, in 1170, when King Henry the Second had his son Henry crowned in his own lifetime, he himself, to do him honour, brought up the boar’s head with trumpets before it, “according to the manner.” It continued the principal entry at all grand feasts, and was frequently ornamented. At the coronation feast of Henry the Sixth there were boars’ heads in “castellys of golde and enamell.” By Henry the Eighth’s time it had become an established Christmas dish, and we find it ushered in at this season to his daughter the Princess Mary, with all the usual ceremonies, and no doubt to the table of the monarch himself, who was not likely to dispense with so royal a dish; and so to the time of Queen Elizabeth, and the revels in the Inns of Court in her time, when at the Inner Temple a fair and large boar’s head was served on a silver platter, with minstrelsy. At the time of the celebrated Christmas dinner, at Oxford, in 1607, the first mess was a boar’s head, carried by the tallest of the guard, having a green scarf and an empty scabbard, preceded by two huntsmen, one carrying a boar spear and the other a drawn faucion, and two pages carrying mustard, which seems to have been as indispensable as the head itself. A carol was sung on the occasion, in the burden of which all joined. Queen’s College, Oxford, was also celebrated for its custom of bringing in the boar’s head with its old carol. Even in the present day, though brawn, in most cases, is considered as a sort of substitute, the boar’s head with lemon in his mouth may be seen, though rarely, and when met with, may be safely recommended as a dainty; but some of the soi-disant boars’ heads seen at Christmas in a pompous state of whiskerless obesity, may without disparagement take Lady Constance’s words literally and “hang a calf skin on[32] their recreant limbs.” Brawn is probably as old as boar’s head; but the inventor of such an arrangement of hogsflesh must have been a genius, and would have been a patentee in our days, and probably have formed a joint-stock brawn association. We have just observed it in the time of Henry the Third, and the ‘begging frere,’ in ‘Chaucer’s Sompnoure’s Tales,’ says, “geve us of your braun, if ye have any,” and it may be found in most of the coronation and grand feasts; even in the coronation feast of Katharine, queen to Henry the Fifth, in 1421, brawn and mustard appear, though the feast was intended to be strictly a fish dinner, and with this exception and a little confectionary, really was so, comprising, with other marine delicacies, “fresh sturgion with welks,” and “porperous rosted,” the whole bill of fare, however, would match even the ministerial whitebait dinner. This is not the only instance where brawn was ranked with fish; for when Calais was taken, there was a large quantity there; so the French, guessing it to be some dainty, tried every means of cooking it; they roasted it, boiled it, baked it, but all in vain, till some imaginative mind suggested a trial au naturel, when its merits were discovered. But now came the question, in what class of the animal creation should it be placed? The monks tasted and admired: “Ha! ha!” said they, “capital fish!” and immediately placed it on their list of fast-day provisions. The Jews were somewhat puzzled, but a committee of taste, of the most experienced elders, decided that it certainly was not any preparation from impure swine, and included it in their list of clean animals.

At the coronation of Henry the Seventh, a distinction was made between “brawne royall,” and “brawne,” the former probably being confined to the king’s table. Brawn and[33] mustard appear to be as inseparable as the boar’s head and mustard, and many directions respecting them may be found at early feasts. In the middle of the sixteenth century brawn is called a great piece of service, chiefly in Christmas time, but as it is somewhat hard of digestion, a draught of malvesie, bastard, or muscadell is usually drunk after it, where either of them is conveniently to be had.

“Even the two rundlets,

The two that was our hope, of muscadel,

(Better ne’er tongue tript over,) these two cannons,

To batter brawn withal, at Christmas, sir,—

Even these two lovely twins, the enemy

Had almost cut off clean.”

At the palace, and at the revels of the Inns of Court, it seems to have been a constant dish at a Christmas breakfast. Tusser prescribes it amongst his good things for Christmas, and it has so remained to the present time. The salmon recently mentioned, as having been ordered for the king, continued to be a favourite dish for this feast. Carew says—

“Lastly, the sammon, king of fish,

Fils with good cheare the Christmas dish.”

There used to be a superstition at Aberavon, in Monmouthshire, that every Christmas Day, in the morning, and then only, a large salmon exhibited himself in the adjoining river, and permitted himself to be handled and taken up, but it would have been the greatest impiety to have captured him. One would not wish to interfere with the integrity of this legend, by calling on the salmon some Christmas morning, for fear that he may have followed the tide of emigration, or may have been affected by free trade.

The salmon, however, is not the only living creature, besides man, that is supposed to venerate this season.

“Some say, that ever ’gainst that season comes

Wherein our Saviour’s birth is celebrated,

The bird of dawning singeth all night long:

And then, they say, no spirit can walk abroad;

The nights are wholesome; then no planets strike;

No fairy tales, nor witch hath power to charm,

So hallow’d and so gracious is the time.”

According to popular superstition the bees are heard to sing, and the labouring cattle may be seen to kneel, on this morning, in memory of the cattle in the manger, and the sheep to walk in procession, in commemoration of the glad tidings to the shepherds.

Howison, in his ‘Sketches of Upper Canada,’ mentions an interesting incident of his meeting an Indian at midnight, on Christmas Eve, during a beautiful moonlight, cautiously creeping along, and beckoning him to silence, who, in answer to his inquiries, said, “Me watch to see the deer kneel; this is Christmas night, and all the deer fall upon their knees to the Great Spirit, and look up.”

In our notice of Christmas wines, we must not omit malt-wine or ale, which may be considered, indeed, as our national beverage.

“The nut-brown ale, the nut-brown ale,

Puts downe all drinke when it is stale,”

or, as it has been classically rendered, alum si sit stalum. The Welsh who are still famous for their ale, had early laws regulating it, while the steward of the king’s household had as much of every cask of plain ale as he could reach with his[35] middle finger dipped into it; and as much of every cask of spiced ale as he could reach with the second joint of his middle finger. As millers are remarkable for the peculiarity of their thumbs, no doubt these stewards were gifted with peculiarly long middle fingers. Ale, or beer, was afterwards divided into single beer, or small ale, double beer, double-double beer, and dagger ale; there was, also, a choice kind, called March ale; and our early statute books contain several laws regulating the sale of ale, which was to be superintended by an ale-taster, and the terrors of the pillory and cucking-stool held over misdemeanants.

It maybe expected that “Christmas broached the mightiest ale,” and Christmas ale has, accordingly, been famous from the earliest times.—

“Bryng us in good ale, and bryng us in good ale,

For our blyssd Lady sake, bring us in good ale,”

is a very old wassailing cry, and the wandering musicians always expected a black jack of ale and a Christmas pye. A favourite draught, also, was spiced ale with a toast, stirred up with a sprig of rosemary,—“Mark you, sir, a pot of ale consists of four parts: imprimis, the ale, the toast, the ginger, and the nutmeg.” Mead, or metheglin, was another national drink, and here the steward was only allowed as far as he could reach in the cask with the first joint of his middle finger. That metheglin was so called from one Matthew Glinn, who had a large stock of bees that he wished to make profitable, must be considered more as a joke than a tradition.

Henry the Third generally kept his Christmasses with festivities. In 1230, there was a grand one at York, the[36] King of Scots being present; but four years afterwards he kept it at Gloucester, with only a small company, many of the nobles having left him in consequence of the great favour he was showing foreigners, to their injury. In 1241, he again offended them by placing the Pope’s legate, at the great dinner at Westminster Hall, in the place of honour, that is, the middle, he himself sitting on the right-hand, the Archbishop of York (the Archbishop of Canterbury being dead) on his left-hand, and then the prelates and nobles, according to rank. This etiquette, as to place at table, is certainly as old as the Egyptians, and many a wronged or neglected individual’s dinner has been spoilt, who has failed in getting such a place above the salt, or at the cross table, as he considered his merits entitled him to.

On one occasion, in his forty-second year, Henry rather took undue advantage of the custom of the season, and being distressed for money, required compulsory New Year’s Gifts from the Londoners. His wars frequently distressed him for money, and in 1254, his queen sent him, to Gascoigne, 500 marks from her own revenues, as a New Year’s Gift, toward the maintenance of them. In several instances, he kept his Christmasses at the expense of some of the great nobles, as Hubert de Burgh, and Peter, bishop of Winchester, who, in 1232, not only took all the expense upon himself, but gave the king and all his court festive garments; and, in another year, when Alexander, King of Scots, married his daughter Margaret, the Archbishop of York, where the feast was held, gave 600 fat oxen, which were all spent at one meal, and expended 4000 marks besides. This convenient practice saved the pocket of the sovereign, and gratified the ambition of the subject; but the great expense caused by such a favour,[37] must have been something like the costly present of an elephant, by an Eastern despot, to a subject. In his later years, the king laid aside hospitality very much.

The three Edwards kept the feast much as before, and Edward the First is said to have been the first king who kept any solemn feast at Bristol, holding his Christmas there in 1284. In his wardrobe accounts, there are some valuable particulars of the custom of the king at this time. In pursuance of ancient usage, he offered at the high altar, on the Epiphany, one golden florin, frankincense, and myrrh, in commemoration of the offering of the three kings; a custom carried down with some variation to the present day. In the same accounts, some of the New Year’s Gifts given to him are mentioned; among them, a large ewer set with pearls all over, with the arms of England, Flanders, and Barr, a present from the countess of Flanders; a comb and looking-glass of silver-gilt enamelled, and a bodkin of silver in a leathern case, from the countess of Barr; also, a pair of large knives of ebony and ivory, with studs of silver enamelled, given by the Lady Margaret, his daughter, duchess of Brabant.

The custom of giving New Year’s Gifts existed from the earliest period, and as Warmstry, in his ‘Vindication,’ says, may be “harmless provocations to Christian love, and mutuall testimonies thereof to good purpose, and never the worse because the heathens have them at the like times.” The Romans had their Xenia and Strenæ, during the Saturnalia, which were retained by the Christians, whence came the French term étrennes; a very ancient one, for in the old mystery, “Li Gieus de Robin et de Marion,” in the thirteenth century, Marion says, she will play, “aux jeux qu’on fait aux étrennes, entour la veille de Noël.” The Greek word strenæ, is translated[38] in our New Testament, delicacies; so that, whether delicacies were called strenæ because such gifts were generally of an elegant or graceful nature, or the New Year’s Gifts adopted a word previously applied to delicacies, seems immaterial, as the result is the same. These “diabolical New Year’s Gifts,” as some called them, were denounced by certain of the councils, as early as the beginning of the seventh century, though without effect. They were either in the nature of an offering from an inferior to his superior, who gave something in return, or an interchange of gifts between equals. Tenants were accustomed to give capons to their landlords at this season, and in old leases, a capon, at Christmas, is sometimes reserved as a sort of rent,—

“Yet must he haunt his greedy landlord’s hall,

With often presents at ech festivall;

With crammed capons ev’ry New Year’s morne.”

The practice of New Year’s Gifts is of great antiquity in this country. In the twelfth century, Jocelin of Brakelond, when about to make a gift to his abbot, refers to it, as being according to the custom of the English; and, in very early times, the nobility, and persons connected with the court, gave these New Year’s Gifts to the monarch, who gave in return presents of money, or of plate, the amount of which in time became quite a matter of regulation; and the messenger, bringing the gift, had, also, a handsome fee given him. How much kindly feeling is caused by the interchange of these gifts, and how much taste and fancy displayed at Fortnum and Mason’s, and other places, to tempt us to purchase for the gratification of our younger friends, and receive our reward in the contemplation of their unfeigned pleasure and amusement![39] Humorous and witty, as well as elegant, bon-bons and souvenirs, drawing the money from us like so many magnets; as Nasgeorgus says—

“These giftes the husband gives his wife,

And father eke the childe,

And maister on his men bestowes

The like, with favour milde.”

There are some particulars in the wardrobe accounts of the New Year’s Gifts of Edward the Second, and also payments made to him to play at dice at Christmas; a custom existing probably long before his time, and certainly continued down to a comparatively recent period, gambling at the groom-porter’s having been observed as late as the time of George the Third. He also gave numerous gifts, being, as is well known, of extravagant and luxurious habits. In his eleventh year, especially, at Westminster, several knights received sumptuous presents of plate from him, and the king of the bean (Rex Fabæ) is mentioned as receiving handsome silver-gilt basins and ewers as New Year’s Gifts. Two of the kings of the bean named, are, Sir William de la Bech, and Thomas de Weston, squire of the king’s household. Edward kept several stately Christmasses, and one at Nottingham in 1324, with particular magnificence, glory, and resort of people. Even when a prisoner at Kenilworth in 1326-7, he kept up a degree of state, although his son, Edward the Third, then aged about sixteen years, was crowned on Christmas Day, 1326, the queen-mother keeping open court, with a great assembly of nobles, prelates, and burgesses, when it was decided to depose the father, whose melancholy fate is well known. Edward the Third became not only a great warrior, but, also,[40] in many respects, a great monarch, and his Christmasses, with other feasts, were held with much splendour. One at Wells, where there were many strange and sumptuous shows made to pleasure the king and his guests, is particularly mentioned; but that at Windsor, in 1343-4, is by far the most distinguished in history, as the king then renewed the Round Table, and instituted the celebrated Order of the Garter, making St. George the patron; whether from the circumstance of the countess of Salisbury having dropped her garter (whence the old Welsh tune took its name of Margaret has lost her garter), cannot now be distinctly proved; but we may as well leave the balance in favour of gallantry. Suffice it, that never has any order of knighthood enrolled such a succession of royal, brave, and world-renowned characters. In 1347 at Guildford, and 1348 at Ottford, in Kent, there were great revellings at Christmas. In the first of these years, there were provided for the amusements of the court, eighty-four tunics of buckram, of divers colours; forty-two visors of different likenesses; twenty-eight crests; fourteen coloured cloaks; fourteen dragons’ heads; fourteen white tunics; fourteen heads of peacocks, with wings; fourteen coloured tunics, with peacocks’ eyes; fourteen heads of swans, with wings; fourteen coloured tunics of linen; and fourteen tunics, coloured, with stars of gold and silver. In the following year, quadrupeds were in the ascendancy, instead of the feathered creation, and amongst the things mentioned in the wardrobe expenses are, twelve heads of men, surmounted by those of elephants; twelve of men, having heads of lions over them; twelve of men’s heads, having bats’ wings; and, twelve heads of wodewoses, or wildmen. A good pantomime decorator would have been invaluable in those days. On[41] New Year’s Eve 1358, Edward, with his gallant son, were in a different scene, fighting under the banners of Sir Walter de Mauny before the walls of Calais, which place the French thought had been betrayed to them; but the plot was counteracted, and they were defeated, and many French knights made captives, who were hospitably entertained by the English king on the following day, being New Year’s Day.

The mummeries, or disguises, just referred to, were known here as early as the time of Henry the Second, if not sooner, and may have been derived originally from the heathen custom of going about, on the kalends of January, in disguises, as wild beasts and cattle, and the sexes changing apparel. They were not confined to the diversions of the king and his nobles; but a ruder class was in vogue among the inferior orders, where, no doubt, abuses were occasionally introduced in consequence. Even now, our country geese or guise dancers are a remnant of the same custom, and, in some places, a horse’s head still accompanies these mummers. The pageants, in former times, of different guilds or trades, some of which still exist, and, at the Lord Mayor’s shows, had all probably a common origin, modified by circumstances; but, with respect to those of the city, I must refer to Mr. Fairholt’s account, printed for the Percy Society, where he has treated largely on the subject. Who knows how many juvenile citizens may not have been fired by ambition at the sight of these soul-stirring spectacles, to becoming common councilmen, aldermen, sheriffs, and lord-mayors themselves—to have at their beck, the copper-cased knights; the brazen trumpets; the prancing horses, bedecked with streamers; the marshalmen, in martial attire; gilded coach, with the sword of state looking out of window!—and then the charms of the dinner,[42] in all the magnificence of turtle-soup, barons of beef, champagne, venison, and minced pies, with Gog and Magog looking benignly on; though they must miss the times, when the Lord Mayor’s Fool used to jump into a huge bowl of Almayn custard.

Edward the Third gave and received New Year’s Gifts, as former kings; and we find an instance of presents given to Roger Trumpony and his companions, minstrels of the king, in the name of the king of the bean. He also made the usual oblations at the Epiphany.

The continental usages were, in many places, similar to our own; but, as before intimated, they will be but slightly noticed. Charles the Fifth, of France, for instance, in 1377, held the feast of Christmas, or Noël as it was called, at Cambray, “et là, fist ses sérimonies impériaulx, selon l’usage,” referring evidently to old customs; he also presented gold, incense, and myrrh, in three gilt cups. Not many years afterwards, the duke of Burgundy gave New Year’s Gifts of greater value than any one, and especially to all the nobles and knights of his household, to the value of 15,000 golden florins; but there was probably as much policy in this, as any real regard for the sacred festival.

Richard the Second was young when he came to the throne, extravagant, fond of luxury and magnificence, and the vagaries of fashion in dress were then, and for a long time after, unequalled; his dress, was “all jewels, from jasey to his diamond boots.” It is to be expected, therefore, that his Christmasses were kept in splendour, regardless of expense; and this appears to have been the case even to the close of his short and unfortunate reign; as, in 1399, there was a royal Christmas at Westminster, with justings and running at the tilt throughout,[43] and from twenty-six to twenty-eight oxen, with three hundred sheep, and fowls without number, were consumed every day. In the previous Christmas, at Lichfield where the Pope’s nuncio and several foreign gentlemen were present, there were spent two hundred tuns of wine, and two thousand oxen, with their appurtenances. It is to be assumed that the pudding was in proportion to the beef; so these, in point of feasting, must have been royal Christmasses indeed.

In the midst of all this grandeur, there was a want of cleanliness and comfort in the rush-strewn floors and imperfectly furnished rooms and tables, that would have been very evident to a modern guest; and the manners at table, even in good society, would rather shock our present fastidious habits. Chaucer, not long previously, in describing the prioresse, who appears to have been a well-bred and educated person for the time, proves the usual slovenliness of the domestic habits, by showing what she avoided—

“At mete was she wel ytaughte withalle;

She lette no morsel from hire lippes falle,

Ne wette hire fingres in hire sauce depe.

Wel coude she carie a morsel, and wel kepe,

Thatte no drope ne felle upon hire brest.

In curtesie was sette ful moche hire lest.

Hire over lippe wiped she so clene,

That in hire cuppe was no ferthing sene,

Of grese, whan she dronken hadde hire draught.”

or, according to the Roman de la Rose, from whence Chaucer took this account,—

“Et si doit si sagement boyre,

Que sur soy n’en espande goutte.”

It must be remembered, however, that there were no forks[44] in those days. The Boke of Curtasye of the same age, reprobates a practice that is even now scarcely obsolete, and may unexpectedly be seen in company, where it excites surprise, to say the least of it;—

“Clense not thi tethe at mete sittande,

With knyfe ne stre, styk ne wande.”

Richard also had his pageants, or disguisings, but instead of looking to the brute or feathered creation for models, we find, on one occasion, there is a charge for twenty-one linen coifs for counterfeiting men of the law, in the king’s play or diversion at Christmas, 1389. If the men of the law had been as plentiful as at present, there would have been no need of making any counterfeits, where a sufficient quantity of real ones might have been procured so cheap. The unfortunate Richard was murdered on Twelfth Day, 1400, a sad finish to all his Christmasses. At the same time, a plan was laid by the earls of Kent and Huntingdon (recently degraded from the dukedoms of Exeter and Surrey), with the earl of Salisbury and others, to gain access, under colour of a Christmas mumming, at Windsor, where Henry the Fourth and the princes were keeping the feast, and thus effect the restoration of Richard; but one of the conspirators, the earl of Rutland (degraded from duke of Aumarle), gave timely notice of it, in order, as it is said, to forestal his father, the duke of York, who had got some knowledge of the plot. Henry the Fourth kept his Christmas feasts in the usual style, and does not require any particular notice, which might tend to needless repetition.

THE wild course of Henry the Fifth, while Prince of Wales, and his brilliant but short career as king, are well known, and are immortalised by Shakespeare;—

“Never was such a sudden scholar made:

Never came reformation in a flood,

With such a heady current, scouring faults;”

his historical plays have probably supplied many with their principal knowledge of the early annals of our country, from King Lear downwards; and we must not quarrel with the dramatic fate of Cordelia, although her real story was more prosperous, as we have, consequently, some of the most[46] pathetic passages in the works of our immortal bard—that is, if such bard there ever was; for the overbearing mass of intellect, imagination, and beauty, presented to us under the name of Shakespeare, is such, that one almost considers the name a myth, and decides that, at least, the Seven Sages must have been engaged in its production. When his warlike avocations allowed him Henry the Fifth kept the feast with splendour; but his reign was nearly brought to a close at its outset, if we are to believe those historians who state that, when he was keeping the Christmas of 1413-14, at Eltham, there was a plot for seizing him and his three brothers, and the principal clergy, and killing them. As this plot was, however, attributed to the Lollards, some of whom were taken and executed, and rewards offered for Sir John Oldcastle, Lord Cobham, imputing thereby the attempts to him, the account must be taken with considerable allowance.

Even in the midst of the horrors of war Henry did not forget the Christian mercies of this tide; for during the siege of Rouen in his sixth year, and that city being in great extremity from hunger, he ceased hostilities on Christmas Day, and gave food to all his famishing enemies who would accept of it.

“Alle thay to have mete and drynke therto,

And, again, save condyte to come and to go.”

Something like this occurred, in 1428, at the siege of Orleans, “where the solemnities and festivities of Christmas gave a short interval of repose: the English lords requested of the French commanders, that they might have a night of minstrelsy with trumpets and clarions. They borrowed these musicians and instruments from the French, and Dunois and Suffolk also exchanged gifts.” In his eighth year, Henry,[47] with his queen, the “most fair” Katherine, sojourned at Paris during the feast, and “kept such solemn estate, so plentiful a house, so princely pastime, and gave so many gifts, that from all parts of France, noblemen and others resorted to his palace, to see his estate, and do him honour.” This was a stroke of policy to ingratiate himself with the French, and the French king at the same time kept his Christmas quietly.

Henry the Sixth, for the first few years of his troubled reign, was a mere child; though, in the tenth year of his reign, and the same of his age, having just previously received the homage of the French and Norman nobles at Paris, he celebrated the Feast with great solemnity at Rouen; a place where, not long after, some of those in high places of our country were to disgrace themselves by the cruel punishment of Joan of Arc. He seems afterwards to have kept his Christmas in the usual manner, until the disastrous wars of York and Lancaster, during which the fate of the monarch,—and, indeed, who, for the time being, was such monarch—depended on the predominance of the white or red rose.