POMANDER WALK

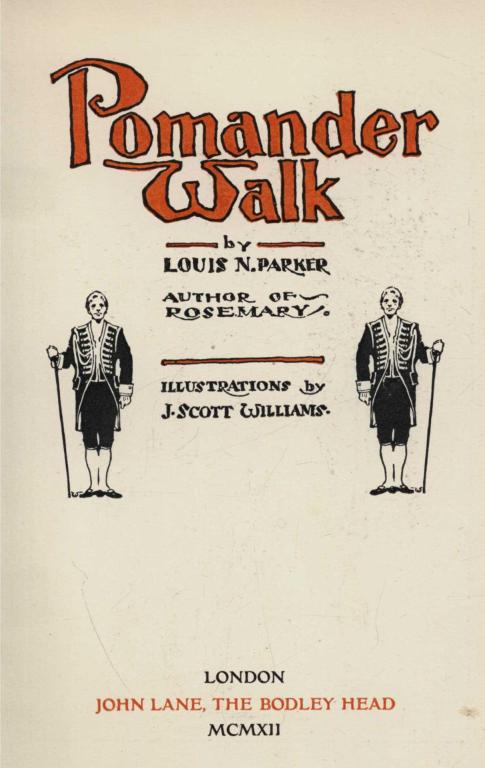

Pomander

Walk

by

LOUIS N. PARKER

AUTHOR OF

ROSEMARY

ILLUSTRATIONS by

J. SCOTT WILLIAMS

LONDON

JOHN LANE, THE BODLEY HEAD

MCMXII

THE UNIVERSITY PRESS, CAMBRIDGE, U.S.A.

TO

GEORGE C. TYLER

FOR VALOUR

Contents

CHAPTER

I. Concerning the Walk in General

II. How Sir Peter Antrobus and Jerome Brooke-Hoskyn, Esquire, Smoked a Pipe Together

III. Concerning Number Four and Who Lived in It

IV. Concerning a Mysterious Lady and an Elderly Beau

V. Concerning What You Have All Been Waiting For

VI. In which Pomander Walk is not Quite Itself

VII. Showing How History Repeats Itself

VIII. Concerning a Great Conspiracy

IX. In which Old Lovers Meet, and the Conspiracy Comes to a Head

X. In Which the Mysterious Lady Reappears and Helps Jack to Vanish

XI. Pomander Walk Takes a Dish of Tea

XII. In which the Old Conspiracy is Triumphant and a New Conspiracy is Hatched

XIII. In which Admiral Sir Peter Antrobus is More Determined Than Ever to Fire the Little Brass Gun

XIV. In which Miss Barbara Pennymint Hears the Nightingale and the Lamps are Lighted

XV. Showing How the Roundabout Road Leads Back to the Starting Point

Illustrations

Marjolaine . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Frontispiece

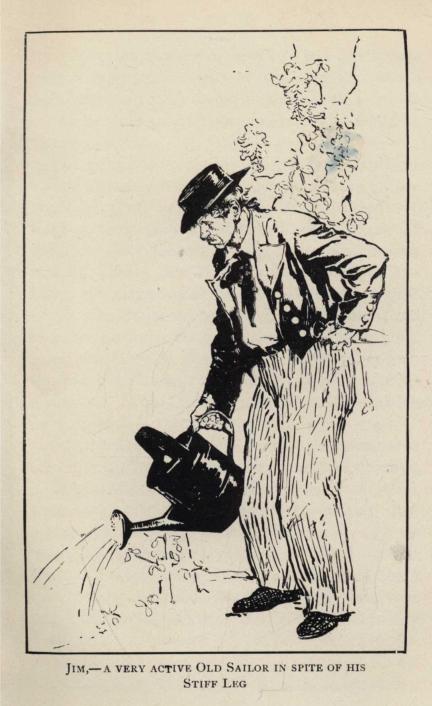

Jim—a very active old sailor in spite of his stiff leg

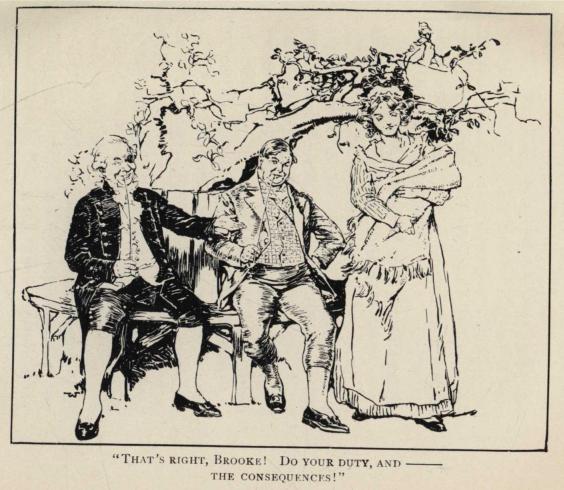

"That's right, Brooke! Do your duty, and —— the consequences!"

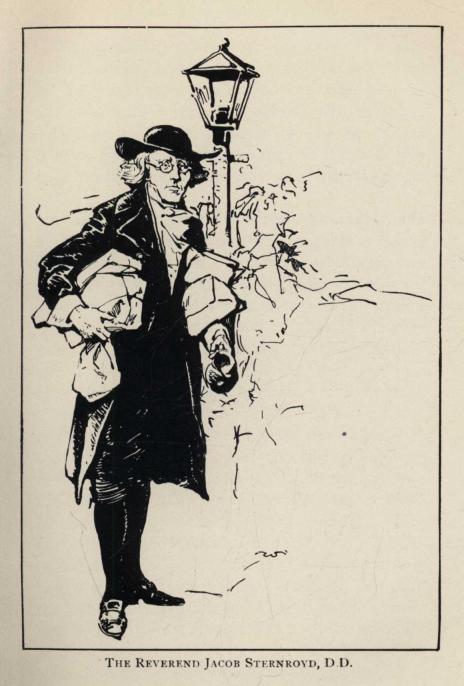

The Reverend Jacob Sternroyd, D.D.

Mr. Jerome Brooke-Hoskyn at his ease

"Let us sit quite still and think hard whether we'd like to meet again"

"She placed her arm very tenderly over her shoulders and gently called her by name"

"It's enough to give a body the fantoddles—as my poor dear mother used to say"

He started off like an alarm clock

He seized him by the sleeve, and dragged him, bewildered and protesting, to the Gazebo

As the sun came out, out came Mr. Jerome Brooke-Hoskyn, as resplendent as the sun

The Eyesore seized the animal by the scruff of his neck and hurled him into the river

Then he resumed. "Brooke," says he, "Brooke, my Boy"—just like that

"Peter!" he cried, scandalised

CHAPTER I

CONCERNING THE WALK IN GENERAL

It lies out Chiswick way, not far from Horace Walpole's house where later Miss Pinkerton conducted her Academy for Young Ladies. It is still there, although it was actually built in 1710; but London has gradually stretched its tentacles towards it, and they will soon absorb it. Where Marjolaine and Jack made love, there will be a row of blatant shops, and Sir Peter's house will be replaced by a flaring gin-palace. It has fallen from its high estate nowadays; and Mrs. Poskett's prophecy has come true: one of its dainty houses—I think it is the one in which the Misses Pennymint lived—is now indeed occupied by a person who earns a precarious living with a mangle.

Even in the days I am writing about, it was old—ninety-five years old—and had seen many ups and downs; for I am writing of events that took place in 1805: the year of Trafalgar; the year of Nelson's death.

At that time it was a charming, quaint little crescent of six very small red-brick houses, close to the Thames, facing due south, and with a beautiful view across the river.

Why it was called Pomander Walk is more than I can tell you. There is a tradition that the builder had inherited a beautiful gold pomander of Venetian filigree and that the word struck him as being pretty and having an old-world flavour about it. It certainly conferred a sort of quiet dignity on the crescent; almost too much dignity, indeed, at first, for it seemed to make the letting of the houses difficult. Common people fought shy of it, because of the name, yet the houses were so small that wealthy folk—the Quality—wouldn't look at them. Ultimately, however, they were occupied by gentlefolk in reduced circumstances; people who had an eye for the picturesque, people who sought retirement; and the owner was happy.

In 1805 it had grown mellow with age. The red bricks of which it was built had lost the crudeness of their original colour and had acquired a delicious tone restful to the eye. Pomander Walk was, in fact, one of the prettiest nooks near London. It stood—and stands—on a little plot of ground projecting into the river. At the upper end it was cut off from the rest of the parish of Chiswick by Pomander Creek, which ran a long way inland and formed a sort of refuge for lazy barges, one of which was generally lying there with its great brown sail hanging loose to dry. Chiswick Parish Church was only a little way across the creek, but in order to get to it you had to walk very nearly a mile to the first bridge, and I am afraid Sir Peter Antrobus too often made that an excuse for not attending more than two services on a Sunday.

The little houses were built in the sober and staid style introduced during the reign of Her Gracious Majesty Queen Anne (now deceased). The architect had taken a slily humorous delight in making them miniature copies of much more pretentious town mansions. Each little house had its elaborate door with a shell-shaped lintel; each had its miniature front-garden, divided from the road-way by elaborate iron railings; and each had an ornate iron gate with link-extinguisher complete. You might have thought the houses were meant to be inhabited by very small Dukes, so stately were they in their tiny way. The ground-floor sitting-rooms all had bow-windows, and in each bow-window the occupants displayed their dearest treasures, generally under a glass globe. A glance at these would almost have been enough to tell you what manner of people their owners were. In the first, at the top corner of the crescent, stood the model of a man-of-war. The second displayed a silver cup with the arms of the City of London carefully turned outward for the passer-by to admire respectfully; the third showed a stuffed canary; the fourth was empty—I will tell you why later; the fifth presented a pinchbeck snuff-box, and in the sixth there was an untidy pile of old books.

In front of the crescent lay a delightful lawn, always admirably kept. Jim, Sir Peter Antrobus's man, mowed it regularly every Saturday afternoon. This lawn was protected on the river-side by a chain hanging from white posts. You never saw posts so white as those were, for every Saturday evening Jim—a very active old sailor in spite of his stiff leg—gave them a fresh coat of paint; he even went so far as to paint the chain as well.

In the lower corner of the lawn, and facing the bend of the river, stood what the inhabitants of the Walk called the Gazebo, a little shelter formed by a well-trimmed boxwood hedge, in which was a rustic seat. Sir Peter Antrobus and Mr. Brooke-Hoskyn would sit there on warm summer evenings and discuss the news of the day—or, let me rather say—the news of the day before yesterday; for the only journal they saw was a three days old "Globe" which Sir Peter's cousin sent him when he had done with it, and when he thought of it.

The great charm of the Gazebo was that it was sufficiently removed from the houses to ensure strict privacy: the ladies of the Walk, who shared fully in their sex's attribute of curiosity, could neither see nor hear what went on in its seclusion, and Sir Peter, who thought he was a woman-hater, was all the more fond of it on that account. In his own house he really could not talk at his ease, for his voice had, by long struggles against gales, acquired a tremendous carrying power; the party-wall was very thin, and his next-door neighbour, Mrs. Poskett, was—or, at least, so he imagined—always listening.

But the pride of the Walk was a great elm-tree standing in the centre of the lawn, and shading it delightfully. A very ancient tree, much older than the Walk: indeed, the crescent had, in a manner of speaking, been built round it. At its base Jim—there was really no limit to the things Jim could do—had built a comfortable seat which encircled its trunk, and this seat was the special prerogative of the ladies of the Walk when it was not occupied by Mr. Brooke-Hoskyn's numerous progeny.

I think I have told you all that is necessary about the external features of the Walk. You must see it with sympathetic eyes, if you are not to laugh at it: a little crescent of six very small old red-brick houses; in front of them, six tiny gardens full at all seasons of the year of bright old-fashioned flowers; then the highly ornamental railings and stately gates; then a red-brick pavement, or side-walk; then a broad path; and then the lawn, the elm-tree, and the Gazebo. Beyond this, the Thames, bearing great brown barges up to Richmond or down to Chelsea, according to the state of the tide; and the Parish Church of Chiswick, half buried in the foliage of stately trees, as a fitting background.

You could not find a quieter, more peaceful, or more forgotten spot near London in a month's search; for the only way into the Walk was along a very narrow path by the side of Pomander Creek: a path the children of Chiswick had been sternly forbidden to use, and which even their elders only attempted when they were more than usually sober, for fear of falling into the creek. So, although the Walk was nominally open to the public, it was not a thoroughfare, as you had to go out the same way as you went in. Strangers very seldom found their way to its precincts, and to all intents and purposes the lawn and the Gazebo had grown to be the private property of the inhabitants. As their rooms were extremely small, they made the lawn a sort of common drawing-room, where they entertained each other in a modest way with a dish of tea. After Mr. Basil Pringle and Madame Lachesnais and her daughter had come to live in the Walk there would even be music on the lawn. Madame would bring out her harp, Mr. Pringle his violin, and Marjolaine would sing quaint old French ditties.

I pity the unhappy stranger who stumbled into the Walk on such an occasion. The music would stop dead. Teacups would hang suspended half-way to expectant lips, and all eyes would be turned on the intruder with a stare which, if he had any marrow, would infallibly freeze it. Then to see Sir Peter throw his chest out, march up to the stranger and ask him what he wanted in a voice which masked a volcanic rage under courteous tones, was to behold a thing never to be forgotten. All the stranger could do was to stammer an apology and beat a retreat; but for days the memory of the unknown danger he had escaped would haunt him.

Sir Peter Antrobus—Admiral Sir Peter Antrobus—was not a person to be trifled with, I assure you. In the first place, he lived in the corner house as you entered the Walk. This gave him a sort of prescriptive right to sovereignty. You must also consider that he was an Admiral and that his gallantry had earned him a knighthood. He was, indeed, the only specimen of actual nobility the Walk had to show, though Mr. Brooke-Hoskyn could, by much pressure, be induced to admit, that if everyone had his rights and if lawyers were not such scoundrels, he himself—but he always broke off there and left you wondering what degree of the peerage he had claims to. But Sir Peter was undoubtedly a knight, and his title gave him the pas in all the Walk's social functions. Not only that, but the Walk looked up to him as its natural leader and adviser. None of the inhabitants would ever dream of making any little improvements to their houses without having first consulted the Admiral. It was he who determined when the lawn needed mowing, the Gazebo trimming, and it was he who fixed the date for painting the wood-work and railings of the houses. Also, he chose the colour: a good, useful green; and anyone who had dared depart from the precise shade chosen by him, would have heard of it. He was to all intents and purposes an autocrat, and the Walk trembled at his nod. His rule was very gentle, however. He kept his one remaining eye steadily fixed on the Walk; but although it wore a threatening frown and could flash in fury, the expression lurking in its depth was one of affection. He loved the Walk with all his heart; he was proud of it with all his soul. His one ambition was to keep it as spick and span as his own quarterdeck had been. I think, indeed, he confused it in his mind to some extent with that quarterdeck, for in his little garden he had erected the model of a mast, on which he hoisted the Union Jack with his own hands regularly at sunrise, and as regularly struck it at sunset. And once, when the Regent had gone by in the Royal barge on his way to Richmond, he had come out in gala uniform, and dipped it in a Royal salute in the finest style. The Admiral was salt from head to foot and right through. He used to call himself a piece of salt junk: for he had been at sea ever since he was a lad of ten. His bravery and high spirits had cleared the road for him at a time when the sea was a path of glory for British mariners, and his culminating recollection was the battle of Copenhagen, in which he had taken part with Nelson. His only cause for complaint was that he had been put on half-pay too early. Was not a man of sixty, hale, hearty, and in the full possession of all his faculties, worth two whipper-snappers of thirty? And did the loss of an eye disqualify him? Could he not spy the enemy as quickly with one eye as with two? As a matter of fact, you could only use one eye with a spy-glass, and so, what was the good of the other? Answer him that! Very well, then.

But these outbursts only came in moments of great depression; generally after his monthly excursion into town to draw his pay. On these occasions it was his habit to visit the coffee-houses where sea-captains of his own standing congregated; in the afternoon he would dine with a few cronies at the Hummums; later, he might take a taste of the newest play at Covent Garden—he maintained that the Drama, like the Navy, was going to the dogs—and after the play there usually followed a jorum of punch and a church-warden pipe in some hostelry where glees were sung. Then, in the small hours, he would be lifted into an old, ramshackle shay, by the faithful Jim; Jim would be lifted beside him, and together they would steer a devious course towards Chiswick, where the village constable was on the look-out for them, and would pilot them along the perilous Creek, unlock the door for them, and deposit them safely in the passage. What happened after that, which saw the other to bed, or whether either of them ever got beyond the foot of the stairs, it were the height of indiscretion to enquire. An English gentleman's house is his castle, and if an English gentleman is too tired to go upstairs that is nobody's business but his own.

The Walk was always aware of these excursions, and on the mornings following upon them it had become the rule to make as little noise as possible, so as not to disturb the Admiral's repose. When he ultimately woke on such mornings it was small wonder he took a jaundiced view of life, prophesied the immediate stranding of His Majesty's entire Fleet owing to puerile navigation, and was, generally, in his least amiable and least hopeful mood. Small wonder, also, that he railed against a purblind and imbecile government for putting a seasoned officer on the shelf. A headache modifies one's outlook, and, as Mrs. Poskett was fond of saying, one should be especially considerate with a man, more especially a sailor-man, the day after he had drawn his pay—most especially a sailor-man who, at the mature age of sixty, was still a bachelor.

If Sir Peter was a bachelor, that was not Mrs. Poskett's fault. She herself had only narrowly missed belonging to the minor nobility. Alderman Poskett, her deceased husband, had died just as he was ripe for the Shrievalty, and, sure enough, the year he would have been Sheriff the King had dined with the Lord Mayor, and Poskett would infallibly have received a knighthood, had he been alive. Mrs. Poskett felt, in a confused way, that she had been badly used, and that the Walk would only be stretching ordinary courtesy very slightly by addressing her as Lady Poskett. Unfortunately this never occurred to the Walk, and as Mrs. Poskett was determined to achieve the title somehow, she had cast her eyes on Sir Peter. The latter, however, had not been a handsome midshipman, and a still handsomer Captain, without acquiring considerable experience in the wiles of the sex, and, so far, Mrs. Poskett's blandishments had met with only negative success. Mrs. Poskett lived next door to the Admiral, and to her great distress there was a sort of subdued feud between them; a feud she could do nothing to abate. Could she be expected to get rid of Sempronius, for the sake of Sir Peter? In the first place, it is not so easy to get rid of a long-haired, yellow Persian cat. Once, in a fit of desperation at the failure of her siege on the Admiral's affections, she had put Sempronius in a market-basket, and she and Abigail—her little maid, fresh from a Charity School—had carried him quite half a mile and let him loose, after a tragic farewell, in the middle of a cabbage-field. But when they got home disconsolate, there was Sempronius washing his face in front of the fire as if nothing had happened. After that there was never again any question of getting rid of him. If the Admiral really feared for the safety of his thrush, why did n't he get rid of the thrush? Only once had Sempronius been found sitting on the roof of the osier cage, and extending a soft paw downwards through its bars; the thrush was singing blithely all the time, and you could see by the expression on Sempronius's face that his only feeling was one of admiration for the song. But the Admiral had taken on amazingly, had stormed and sworn, and promised to throw Sempronius into the river if he ever caught him at such games again.

Since that day Mrs. Poskett had felt that she had a very uphill task before her; but she had set herself to work to become Lady Antrobus with increased determination. She was heartily encouraged in this by Miss Ruth Pennymint, who lived in the third house from the top corner—lived there with her much younger sister, Miss Barbara.

Miss Ruth, elderly and kind hearted, was an inveterate matchmaker. As she explained to her bosom friend, Mrs. Brooke-Hoskyn, "My dear," she said, "I've lived three years with a tragic instance of what comes of blighted affections; and I'll take precious good care nobody else's affections get blighted if I can help it." To which Mrs. Brooke-Hoskyn replied, "And well I understand your meaning, Ruth; for if Mr. Brooke-Hoskyn had n't asked me to marry him, what I should ha' done I don't know." Whereupon the two ladies, for no obvious reason, wept together and were greatly comforted.

It seems that Miss Barbara had years ago been more or less affianced to a Lieutenant in the Navy. Not a young lieutenant, an elderly lieutenant with several characteristics which were doubtful recommendations. But time had softened the image of the gallant tar in Miss Barbara's recollection, and the more it receded, the more romantic it had become, until now she was, not so much in love with her recollections of him, as with what she could remember of the ideal she had set up in her own mind.

In the flesh, Lieutenant Charles—no one had ever heard his surname—had been a very short, puffy man, with a completely bald head. His language was interlarded with expletives, suitable, perhaps, to intercourse with rough sailors in a gale, but devastating on shore in the company of ladies. Personally, I am not at all certain he had ever actually proposed to Miss Barbara. I don't believe he knew how.

The two ladies were living near the Docks at the time, with their father, who was something in linseed; and I have no doubt Lieutenant Charles found the old man's Port-wine agreeable and liked to bask in Miss Barbara's pretty smiles. For Miss Barbara was very pretty indeed; a bonny, plump little thing, by nature all mirth and laughter. She did not so much walk as hop like a little bird. She was altogether like a bird. Her father had always called her his dicky-bird. She kissed just as a bird pecks, and when she spoke or laughed, it was exactly like the twitter of birds settling down to sleep at sunset.

Whether she had ever really been in love with the lieutenant is another question I must leave unanswered. It is only barely conceivable. To be sure, girls do fall in love with the most improbable men: even short and puffy ones; and perhaps the lieutenant's strange oaths bewitched her in some inexplicable way. The only evidence of practical romance I can bring forward, is that the lieutenant did undoubtedly present Miss Barbara on one of his home-comings from distant parts with a grey parrot with a red tail. To be sure, he may have found the bird an intolerable nuisance; but this is an ill-natured suggestion. Whether this gift was intended as a hint, whether the parrot was meant as a dove and harbinger of a coming proposal, or whether it was an economical return for much liquid refreshment, the world will never know, for the same night the lieutenant's inglorious career came to an equally inglorious end.

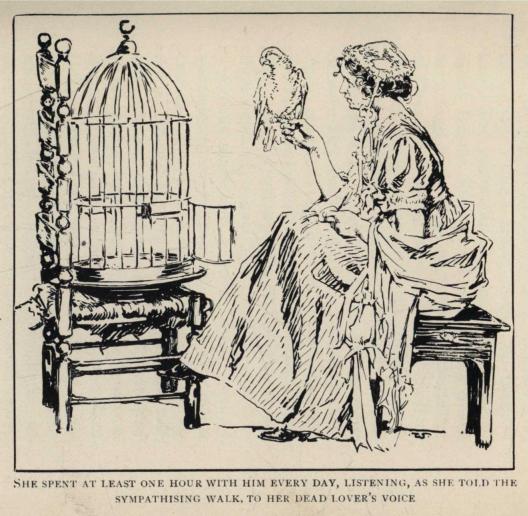

This combination of what might, with a little violence, be construed as a lover's gift with the tragic loss of the lover, was the turning-point in Miss Barbara's life. Henceforth she convinced herself that she had been engaged to marry Charles, and she vowed herself to perpetual spinsterhood and the care of the parrot.

The care of the parrot was no such easy matter. The bird had made a long journey in the lieutenant's cabin, and had acquired all the lieutenant's most picturesque expressions. He was not, therefore, a bird you could admit into general society with any feeling of comfort, for although he was generally sulky in the presence of strangers, he would occasionally, and when you least expected them, rap out a string of uncomplimentary references to their personal appearance, and consign them, body and soul, to unmentionable localities, with a clearness of utterance which left no doubt as to his meaning.

When Papa Pennymint died, it was found that linseed had not been a commodity for which the demand had been sufficient to build up anything approaching a fortune. As a matter of fact, the old man had died just in time to avoid bankruptcy, and the two ladies had been obliged to sell their pretty home and to take refuge in Pomander Walk, out of reach of the genteel friends who had known them in the days of their prosperity. Of course the bird had come with them; but he had not left his language behind, and Barbara was forced to keep him shut up in the little back parlour, out of earshot. There she spent at least one hour with him every day, listening, as she told the sympathising Walk, to her dead lover's voice; and it was this constant companionship with the loquacious bird which had fostered and developed in her mind the legend of her unhappy love.

As a detail, I may as well add here that Barbara had christened the parrot Doctor Johnson, in honour of the mighty lexicographer, about whom she knew nothing except that an engraved portrait of him used to hang in what her father called his study, and that when she asked him who the original was and what he had done, he said, "Oh, I don't know. Seems he talked a lot." The parrot talked a lot, and so he was called Doctor Johnson. I should very much have liked to hear the observations the Giant of Fleet Street would have made, had he lived long enough to be aware of the compliment.

How the Misses Pennymint made both ends meet was a never-ending subject of discussion between Mrs. Poskett and Mrs. Brooke-Hoskyn. They regretfully came to the conclusion that the two ladies positively worked for their living. This was a serious aspersion on the Walk—but there was a worse one.

A little while ago a young man—well, a youngish man—with one shoulder a little higher than the other, had come to live with the Pennymints. At first they let it be understood that he was a distant cousin come on a visit; but when weeks passed and then months, he could no longer be described as a visitor, and the Walk had to face the fact that not only did the Misses Pennymint work for their living, but that they also kept a lodger. At first the Walk was consoled with the idea that at any rate he looked like a gentleman, and might possibly be one. But lately it had been discovered that he was a mere common fiddler, and played every evening in the orchestra at Vauxhall Gardens. Yet, in spite of his ungentlemanly profession, the man did, undoubtedly, behave like a gentleman. Moreover, it was very difficult to tax the Misses Pennymint with their ungenteel goings-on; because there was not an inhabitant of the Walk who had not experienced some kindness at their hands.

I hope I have conveyed the impression of a quiet and contented little community. I am sorry to have to add that there was one fly in the amber of their content. In the early spring of 1805 a mysterious figure had suddenly appeared in the Walk. A fisherman. A gaunt creature in an indescribable slouch hat: the sort of hat you do not pick up when you see it lying in the road; his bony form was encased in a long, nondescript linen garment, something like a carter's smock-frock. This had once been white, but was now of every shade of brown. It had enormous pockets, bulging with unthinkable contents. One morning the Walk had awakened to find him sitting at the corner where Pomander Creek empties into the Thames; sitting on an old box, with a dreadful tin vessel full of worms at his side; sitting fishing. The Walk rubbed its eyes and wondered what the Admiral would say. When the Admiral came out of his house he stopped aghast. Then he gathered himself together for a mighty effort. But it came to nothing: you cannot argue with a man who refuses to argue back. The fisherman met Sir Peter's first onslaught with a curt "Public thoroughfare," and then definitely closed his lips. Sir Peter raked him fore and aft, but never got another syllable out of him. Ultimately he retired baffled and beaten. Henceforward the fisherman came to his pitch every day, except Sunday. The Walk grew accustomed, if not reconciled, to his presence by slow degrees. They spoke of him among themselves as the Eyesore.

CHAPTER II

HOW SIR PETER ANTROBUS AND JEROME BROOKE-HOSKYN,

ESQUIRE, SMOKED A PIPE TOGETHER

On Saturday afternoon, May 25, 1805, Pomander Walk was looking its very best. The sun transfigured the old houses; the elm rustled in the river-breeze; the Admiral's thrush was singing wistfully; Mrs. Poskett's cat, Sempronius, was seated in her little front garden, wistfully listening to the bird's song; the Eyesore was patiently wasting worms on discriminating fish who knew a hook when they saw it; and Sir Peter Antrobus and Mr. Brooke-Hoskyn, both in their shirt-sleeves, were finishing a game of quoits.

"A ringer!" shouted Sir Peter, whose quoit had fallen fairly over the peg. Then he hurried up to the quoits, and, measuring their respective distances from it with a huge bandana handkerchief, added, "One maiden to you, Brooke! Game all! Peeled, by Jehoshaphat!"

Mr. Brooke-Hoskyn flicked the dust off his waistcoat with magnificent indifference. The Admiral produced a boatswain's whistle, and in answer to a blast, his man, Jim, appeared at an upstair window. "Ay, ay, Admiral!"

"The usual. Here, under the elm. And look lively."

"Ay, ay, sir!"

Jim disappeared like a Jack-in-the-box. "We must play it off," said Sir Peter.

But Mr. Brooke-Hoskyn protested. "Another time, Sir Peter. It is very warm, and my eye is out."

"So 's mine," cried the Admiral, with a guffaw; "but I see straight, what?"

It was a matter of principle with Mr. Brooke-Hoskyn never to take the slightest notice of the Admiral's jokes. Sir Peter might be the autocrat of the Walk, although Mr. Brooke-Hoskyn had his own views even on that point; but he himself was the acknowledged wit and man of fashion, and from that position nothing should shake him. He had spied Miss Ruth Pennymint working in her open bow-window, and Mrs. Poskett busy with her flowers. Assuming his grandest manner, he said warningly: "Should we not resume our habiliments? The fair are observing us."

"Gobblessmysoul!" cried Sir Peter, shocked at being discovered in undress. They hastily helped each other into their coats, which were lying on the bench under the elm. Meanwhile, Jim had brought out a tray with two pewters, two long clay pipes, a jar of tobacco and a lighted candle, and had placed it on the bench. From the open upstair window of the Pennymint's house came the strains of a violin: one passage, played over and over again, with varying degrees of success.

"Wish Mr. Pringle would stop his infernal scraping," growled the Admiral.

Mr. Brooke-Hoskyn shrugged his shoulders with condescending pity. "Poor fellow! What a way of earning his living!"

Sir Peter turned to the quarter from which the music came, and, making a speaking-trumpet of his hands, roared, "Mr. Pringle! Mr. Pringle, ahoy!"

A hideous wrong note, as if the player had been scared out of his wits, was the answer, and Basil Pringle appeared at the window. "I beg your pardon, Admiral; I was engrossed."

"Join us under the elm, what?"

"With pleasure. I 'll just put away my Strad."

As Basil retired Sir Peter turned to Mr. Brooke-Hoskyn. "His what?"

"His Stradivarius," answered the latter, and as that obviously conveyed no meaning, "his violin."

"Oh! His fiddle! Why could n't he say so?—Jim!"

"Ay, ay, sir!"

"Another pewter."

"Ay, ay, sir." Jim hobbled off into the Admiral's house and Sir Peter and Mr. Brooke-Hoskyn stood, facing each other, each grasping his pewter of foaming ale.

"Well!" cried Sir Peter, "The King!"

But Mr. Brooke-Hoskyn was not to be put off with so curt a toast. Planting his feet firmly together, and throwing his chest out, he boomed in a formal and stately manner, "His Most Gracious Majesty, King George the Third, God bless him!"

The Admiral eyed him curiously for a moment, and seemed about to speak, but thought better of it; and for an appreciable time the faces of both gentlemen were hidden. When they came to light again it was with a great sigh of satisfaction, and they both settled down on the bench for quiet enjoyment.

"Now!" cried Sir Peter, "a pipe of tobacco with you, Mr. Brooke-Hoskyn?"

"Delighted!"

"St. Vincent. Prime stuff: and—in your ear—smuggled!"

"No!—reely?"

The two men leant over the candle and lighted their pipes with artistic care.

"Was you at a banquet again last night, Brooke?" asked the Admiral, during this process.

"Yes—yes," replied the other, with splendid indifference. "The Guildhall. All the hote tonn."

"Lucky dog," said Sir Peter, smacking his lips: "turtle, eh?"

With the air of a man jaded by too much enjoyment Mr. Brooke-Hoskyn condescended to enlarge. "As usual. Believe me, personally I should much prefer seclusion and meditation in the company of poets and philosophers, or dallying with Selina; but my friends are good enough to insist. Only last night," with a side glance to watch the effect he was producing, "Fox—my good friend, the Right Honourable Charles James Fox—said, 'Brooke, my boy'—just like that—'Brooke, my boy, what would our banquets be without you?'"

Sir Peter was deeply impressed. He felt himself in touch with the great world. "Gobblessmysoul!" he cried. "What's your average?"

"I am sorry to say, I usually have to wrench myself away from my precious Selina four nights a week."

"Think o' that, now!—By the way, how is she?"

Mr. Brooke-Hoskyn turned his lack-lustre eyes fondly towards his house. "Selina? Cheerful, sir. Selina is faint but pursuing. We have now been in the holy state of matrimony five years, and never a word of complaint has fallen from the dear soul's lips."

"Re-markable! And all that time Pomander Walk has seen scarcely anything of her."

"She has been much occupied—much occupied," put in Mr. Brooke-Hoskyn, with a deprecatory flourish of his pipe. And, as if in corroboration of his statement, the door of his house opened and a pretty maidservant came out, carrying a year-old baby in her arms. "Chck! chck!" said Mr. Brooke-Hoskyn.

"Four olive-branches in five years!" cried Sir Peter, instinctively sidling away from the baby.

"Of the female sex," explained Mr. Brooke-Hoskyn: "all of the female sex. This is Number Four. Chck! chck!"

Mrs. Poskett, attracted by the baby, had hastily come out of her door carrying her cat, Sempronius, in her arms, and was beckoning to the maid.

"And another coming!" roared the Admiral. "That's right, Brooke! Do your duty, and damn the consequences!—But let's have a boy next time," he went on, heedless of Mr. Brooke-Hoskyn's frantic signals, "let 's have a boy, and make a sailor of him!—Gobblessmysoul!" For Mrs. Poskett, having dropped the cat in the garden, had come up to the tree, and was simpering with pretty modesty.

"Good afternoon, gentlemen," said she. "Oh—don't put your pipes away, please. I have been well trained. Alderman Poskett smoked even indoors. May I sit down?" She planted herself between the two men. "Now, go on talking, just as though I was n't here."

There was an awkward pause. Fortunately at this moment Jim created a diversion by bringing the third pewter. To his amazement Mrs. Poskett promptly seized it. "For me? How thoughtful of you!" she cried; and while Sir Peter and Mr. Brooke-Hoskyn looked on too much astonished to speak, she drained it as to the manner born.

"Jim, another," grunted the Admiral.

But Mrs. Poskett protested. "Oh, no, I could n't! Reely and posivitely I could n't!"

"We was expecting Mr. Pringle, ma'am," said the Admiral, stiffly.

But the hint was entirely lost. "Ah, poor Mr. Pringle! Poor fellow! An unhappy life, I fear; and him with one shoulder higher than the other. Not that you notice it much when you look at him sideways. There. I was rather alarmed when he arrived a month ago. Can't be too careful, and me a lone woman. A musician, you know. One never knows what their morals may be."

"Hoho!" shouted Sir Peter, "he's quiet enough—except when he 's making a noise!"

Mrs. Poskett looked puzzled. She never could see a joke.

Mr. Brooke-Hoskyn received it with his customary stony stare and at once broke in. "He is some sort of cousin to the Misses Pennymint, I am told?"

"Yes," said Mrs. Poskett, with a sniff, "we are told. But who knows?—I fear—" she sank her voice to a mysterious whisper—"I fear he is—hush!—a lodger!"

Mr. Brooke-Hoskyn was genuinely shocked. "You don't say so!"

The Admiral began to grow uncomfortable. He hated tittle-tattle. "Where's that cat of yours, ma'am?" he cried, with sudden suspicion.

"Sempronius? The dear thing is so happy. He 's in the front garden, listening to your dear thrush."

"By Jehoshaphat!" cried the Admiral, half rising.

"Oh, don't be alarmed! Sempronius adores him. He would n't touch a hair of his head."

"I warn you, ma'am," growled Sir Peter, reluctantly sinking back into his seat, "if he does, I 'll wing him." From which you might gather the speakers thought that thrushes had hair and cats wings.

Now Basil Pringle, who had carefully laid his famous Strad in its case and covered it with a magnificent silk handkerchief, joined the little group under the elm. He was—apart from a very slight malformation of one shoulder—a good-looking fellow. He had the musician's pensive face, and a pair of very tender brown eyes, and his hands were the true violinist's hands, with long and lissome fingers. Jim hobbled up at the same time with a fresh pewter of ale.

"Ah, Mr. Pringle," said the Admiral, hospitably, "here 's your pewter."

But Basil waved it away. "Good afternoon, Mrs. Poskett—Gentlemen. Thank you, Admiral, but I 'm sure you 'll excuse me. I have a long night's work."

Jim was ready for the occasion. He hobbled back quicker than he had come, and drained the pewter at one draught under the very nose of the Eyesore.

"Fiddling at Vauxhall?" asked the Admiral.

"As usual, Sir Peter. It is a gala night. Fireworks."

Mrs. Poskett gave a little scream of delight.

"Fireworks! Oh, ravishing!"

"And Mrs. Poole is to sing; and Incledon."

Up jumped the Admiral, slapping his thigh. "Incledon! Then, by gum, I must be there! He was a sailor, y' know. I remember him in '85, on the Raisonable. Lord Hervey, and Pigot and Hughes—they 'd have him up to sing glees together!—Lord! Did ye ever hear him sing:

'A health to the Captain and officers too,And all who belong to the jovial crewOn board of the Arethusa'?"

Now, the Admiral's voice was an admirable substitute for a fog-horn, but as a vehicle for a ballad, it left much to be desired. Mr. Brooke-Hoskyn writhed in melodramatic agony, and even Mrs. Poskett winced. Basil tried to turn the enthusiast's thoughts into a gentler channel by interpolating that to-night Incledon was to sing "Tom Bowling." At once the Admiral's face took on an expression of the tenderest pathos. "Tom Bowling?—Ah!" and he was off again, in a roar he intended for a mere sentimental whisper

"Here, a sheer hulk, lies poor Tom Bowling—"

This was too much for Jim's feelings, never more receptive to melodious sorrow than when he had just absorbed a pint of ale, and he joined his master in a sympathetic howl.

Mrs. Poskett was overcome. "Oh, don't, Sir Peter," she cried. "Alderman Poskett used to sing just like that. You could hear him a mile off, but you could never tell what the tune was." The tender recollection very nearly moved her to tears.

Sir Peter stopped his song abruptly, with a penitent, "Gobblessmysoul! I beg your pardon!"

Mr. Brooke-Hoskyn felt he had been out of the conversation long enough. He turned condescendingly to Basil. "Are we not to see the Misses Pennymint to-day?"

"They are very busy," replied the young violinist.

Mrs. Poskett saw her opportunity. "I saw Miss Ruth sewing at a ball-dress," she said; and then added with a meaning look at Mr. Brooke-Hoskyn, "I wonder which of them is going to a ball?"

Basil knew from experience what was coming. Mrs. Poskett continued, "I've seen them making wedding-dresses, and even," with pretty confusion, "even christening robes."

Mr. Brooke-Hoskyn turned to her with an outraged expression: "I trust you do not insinuate Pomander Walk harbours mantua-makers?"

"It harbours a poor, hunchback fiddler," remarked Basil, very quietly.

Sir Peter was getting red in the face. "The Misses Pennymint are estimable ladies, and we are fortunate to have them among us. Frequently when I have my periodical headaches—"

"Hum," said Mr. Brooke-Hoskyn.

"The result, sir, of voyages in unhealthy regions!—they have sent me their home-made lavender water. When you had your last fit of asthma, Mrs. Poskett, did n't they come and sit with you and give you treacle-posset? And when Mrs. Brooke-Hoskyn presented you with your fourth daughter, whose calves-foot jelly comforted her? We have nothing to do with their means of livelihood; we are, I am happy to say, like one family. What, Brooke?"

Thus appealed to, Mr. Brooke-Hoskyn could only assent: but he did so with a bad grace, and with a contemptuous glance at Basil. It was really too bad of Sir Peter to suggest that he, Jerome Brooke-Hoskyn, the Man of Fashion, the friend of the Right Honourable Charles James Fox, had anything in common with this shabby musician.

Mrs. Poskett bridled. "Do you include the French people at Number Four?" she said.

"They are not French, ma'am," retorted the Admiral, "and if they were, they couldn't help it."

Mrs. Poskett pointed with a giggle to the Eyesore, who was at that moment lovingly fixing one more worm on his hook. "Do you include the Eyesore?"

"No, I do not!" roared the Admiral, in a rage. "He doesn't live here. If England were under a proper government, he would be hanged for trespassing. I 've tried to remove him, as you know, but—ha!—it appears he has as much right here as any of us."

"After all," said Basil, soothingly, "he never moves from one spot."

"He never speaks to anybody," added Mrs. Poskett.

"He'd better not, ma'am!"

And Mr. Brooke-Hoskyn summed up with a laugh, "And I will do him the justice to say, he never catches a fish!"

Basil held up a warning hand, for the door of Number Four had just opened.

CHAPTER III

CONCERNING NUMBER FOUR AND WHO LIVED IN IT

If I had had to give an account of Number Four even six months before this story opens I should have been forced to admit it was a blot on the Walk. The people who occupied it had left without paying their rent, which was in itself a thing likely to cast discredit on the whole Walk. But they did worse than that. Just before leaving, they managed, on one plausible pretext or another, to wheedle sums of varying amounts out of almost all their neighbours. Out of every one of them, in fact, except the Reverend Jacob Sternroyd, D.D., who lived all alone in the sixth and last house, and about whom I shall have more to say by-and-by. For weeks the Walk remained hopeful of seeing its money back. Then came doubt, and lastly, a period of very bad temper during which everybody told everybody else they had said so all along, and if people had only listened to them—! The owner of the house, a very fat brewer at Brentford, put in a dreadful old Irishwoman as caretaker, and she would sit on the front door-steps—the actual door-steps, in the open, where the whole Walk could not avoid seeing her—and smoke a filthy short black pipe: a sight terrible to behold.

When remonstrated with, she retorted volubly in incomprehensible Milesian. The Admiral himself had attacked her.

"Now, my good woman, we can't have you smoking here."

The old woman looked up at him with bleary eyes, and puffed in his face.

"Did you hear what I said?"

"What for should I not hear, darlint?"

"You are not to smoke here!"

"Who says so?"

"I say so. If you don't go indoors, I 'll come and take the pipe out of your mouth."

"Will you so? You bring your ugly face inside that gate and see phwat I'll do to ye!"

"Do you know who I am?"

"Sure an' I do. Yer father sowld stinkin' fish on Dublin quay when I was ridin' in me carriage."

"You foul-mouthed old woman—!"

"Don't you 'ould woman' me, neither. You go to hell and watch ould Nick stirrin' up yer grandmother!"

No gentleman could hope to carry on a conversation on these lines with any success when all the windows of the Walk were open, and all the inhabitants listening behind the curtains. The Admiral went straight to the Brentford brewer, but the latter gave him no redress. He only asked whether the Admiral had taken the old lady's advice.

She was not only in herself an intolerable nuisance, but she prevented desirable tenants from taking the house. Whenever any candidate appeared she had an excruciating toothache; or she was doubled up with rheumatism; or she shook the whole house with a ghastly churchyard cough. The sympathy of the enquirer forced the information from her that she had been sprightly and well, a picture of a woman, till she came to Pomander Walk. Mind you, she was n't saying anything against the house. It was a good enough house; though, to be sure, the rats were something awful. Still, some people liked rats. In desperate cases she even went so far as to hint that the house was haunted. She was a foolish old woman, of course, but why did locked doors open of themselves? Doors she had locked with her own hands. They did say that the last tenant had hanged himself in the garret. And by that time the enquirer had given her half-a-crown, and had left her in the undisputed possession of her cutty-pipe on the doorstep.

This fertility of imagination led to her undoing, however. For upon hearing of it (from the Admiral, of course) the brewer sent his wife in the guise of an enquiring tenant, and subsequently turned the old woman out without any ceremony whatever.

But the Walk did not recover its self-respect for some time. The house was still undeniably empty. The windows got dirty; dead leaves covered the door-step; the paint peeled off the woodwork and the railings; some wretched boys threw a dead dog into the garden, where it lay hidden for days; and, besides, the old woman's suggestion that the house was haunted, left its poison behind. Presently Mr. Brooke-Hoskyn's nurse saw a face gibbering behind the window, and had hysterics; and next Miss Barbara Pennymint distinctly saw a hand beckoning to her from the same window and fled, shrieking, to her sister.

The Admiral pooh-poohed the whole thing and made elaborate arrangements to spend a night in the house with Jim. Jim expressed his delight at the prospect of such an adventure, and went about describing exactly what he would do to the ghost if he saw it; but he had very bad luck when the time came, with a sudden attack of sciatica which glued him to his bed. The curious thing was that however often the Admiral postponed the day for the undertaking, Jim's sciatica inevitably returned when the day came. So time slipped away. The Admiral said he would explore the mystery alone, but it slipped his memory.

So the house remained tenantless, and when the Walk was painted according to the Admiral's instructions, Number Four had to be passed over, and consequently looked more woe-begone than ever.

And the next thing the Walk knew was that it woke one morning to find strange men bringing loads of furniture, amongst which was a harp, a forte-piano, and a guitar-case, and that painters—not their own painters, but an entirely unknown lot—were at work scraping off the old paint.

The Admiral rushed out—I am shocked to say, in his slippers and shirt-sleeves—and was told that the house was let; let, without any sort of warning or notice; let, so to speak, over the heads of the Walk; over his own head. And the men could not tell him the name of the new tenant. All they knew was that it was a lady. A lady with a name they could n't pronounce. A foreign name. Foreign? Foreign?—Yes; French, by the sound of it.

This was beyond anything the Admiral or the Walk had ever had to cope with. However, the Admiral mastered his indignation and contented himself with giving the painters strict and minute instructions as to the precise shade of green they were to use so as to make the house uniform with the rest.

He had to go to London next day to draw his pay. We know the inevitable consequences of that excursion. The following morning he woke at midday in a very bad humour. The first thing he saw when he threw open his window, was Sempronius digging up his sweet peas; and the next was Number Four painted a creamy white.

I draw a veil.

It was no use appealing to the brewer. He said he had nothing to do with it; and when it was pointed out to him that the chaste uniformity of the Walk was ruined, he impertinently suggested that the entire Walk might get itself painted all over again, and painted sky-blue.

So the Admiral took his time, determined to give this malapert and intrusive foreign woman—she had now become a woman—a severe lesson.

A few days later the house was taken possession of by an elderly female servant—a stout and florid Bretonne, who went about, as Mrs. Poskett said, looking a figure of fun in her national costume.

Then began such a scrubbing and brushing and washing at Number Four as the Walk had never seen. The bolder spirits—not the Admiral: he reserved himself for the enemy-in-chief—Mrs. Poskett, and Mrs. Brooke-Hoskyn's nurse, made tentative approaches, but were repulsed with great slaughter: the Bretonne could not speak a word of English. When, however, she proceeded to tie a rope from the elm—the sacred Elm—-to the Gazebo, to hang rugs across it and beat them to the tune of "Malbroucq s'en va-t-en guerre" sung with immense gusto, Sir Peter was forced to attack her himself. He had picked up a smattering of French in the wars, and the Walk lined its window with eager faces to witness his victory.

Alas, the Bretonne now pretended not to understand the Admiral's French, and replied to all his remonstrances, commands, and objurgations, with "Bien, mon vieux!" while she banged more lustily on the rugs and covered the now apoplectic Admiral with layers of dust.

The Admiral promised his subjects—Mr. Brooke-Hoskyn, I am sorry to say, indulged in a cynical smile—that the very first hour the Frenchwoman came into residence—the very first hour, mind you—he would teach her her place.

The next day the house was ready for her, and the Walk could but shudder as it looked at it: it had become so un-English. The steps were as white as snow; the garden was trim and neat; the quiet cream paint was offensively cheerful; the brass knocker was a poem; the windows gleamed, positively gleamed, in the sun, and behind them were coquettish lace curtains. The crowning offence was that every window-sill was loaded with growing flowers. Mr. Pringle said the house standing in the midst of its prim neighbours reminded him of a laughing young girl surrounded by her maiden aunts; and Miss Ruth Pennymint told him he ought to know better than to say such things in the presence of ladies.

The Admiral himself as this story proceeds, shall tell you in his own words of the startling effect produced by the arrival of the new tenants. Suffice it to say that it was totally unexpected, and that the Walk was forced to readjust its views in every particular. At the point of time we have now reached, Madame Lachesnais and her daughter, Marjolaine, were the most popular inhabitants of the Walk, and nobody had anything but good to say of them.

Wherefore, when, as recorded in the previous chapter, Mr. Pringle held up a warning hand and said "Madame!" all turned expectantly.

It was quite a little procession that now issued from Number Four. First came Nanette, the servant, spick and span in her Bretonne dress, with a cap of dazzling whiteness. On her arm was a great market-basket. She was followed by Madame herself, a tall and graceful person no longer in the first bloom of youth, but, in spite of the traces of sorrow on her face, still beautiful. She was dressed in some quiet, grey material, for she was still in half-mourning for her late husband; her delicate throat and hands were set off by exquisite old lace. She moved with a sort of floating grace, very charming to watch. There was distinction and well-bred self-possession in every line. Behind her followed her daughter, Marjolaine, a charming girl of nineteen. There is no necessity for more particular description. A charming girl of nineteen is the loveliest thing on earth, and more need not be said.

The Admiral and Mr. Brooke-Hoskyn leaped to their feet as Madame appeared. Both threw their chests out and assumed their finest company manner, to such an extent, indeed, that Mrs. Poskett could not repress a contemptuous sniff.

Madame came graciously towards the group. "Ah! Good afternoon," she said, in a pleasant voice, with only the slightest trace of a French accent. "I am going marketing in Chiswick with Nanette. Nanette cannot speak a word of English, you know." Then she turned to her daughter. "Marjolaine, you may take your book under the tree, if our friends will have you." Marjolaine was talking to Mr. Basil Pringle. "It is nearly time for my singing-lesson, Maman."

"Ah, yes. Mr. Basil, I fear you find her very backward."

Basil could only murmur, "O no, Madame, I assure you—"

It was noticeable that everyone who spoke to Madame did so with a sense of subdued reverence.

Madame turned to Marjolaine. "Ask Miss Barbara to chaperone you, as I have to go out."

"Bien, Maman."

"You are to speak English, dear."

"Bien, Maman—O! I mean yes, mother!"

Sir Peter and Mr. Brooke-Hoskyn both sidled up to Madame, while Mrs. Poskett stood utterly neglected and looked on with the air of an injured saint.

"May I not offer you my escort?" said both gentlemen in one breath.

"O no!" laughed Madame. "I have Nanette. Nothing can happen to me while I have Nanette."

"As if anything ever could happen in Chiswick!" said Mrs. Poskett, a little spitefully.

Madame signalled to Nanette to lead the way, and followed her past the Eyesore and out of the Walk, convoyed by the gallant Admiral as far as the corner, where he stood looking after her an appreciable time.

Meanwhile Marjolaine had run up to the railings of Number Three where Miss Ruth Pennymint was sewing in the window.

"Miss Ruth," she cried, "is Barbara busy?"

Miss Ruth looked up from her work with a smile as she saw the eager young face. "She's closeted with Doctor Johnson."

"Will you ask her to come out when she's done?" and Marjolaine came back to the tree. Basil rose from his seat. "Pray don't move," said the young girl, prettily, "Barbara will be here in a moment. She is with Doctor Johnson."

Basil's face was very grave. It looked almost like the face of a man who finds himself in the presence of a great tragedy; or of one who knows he is fighting an insuperable obstacle. "Ah, yes," he sighed, "Doctor Johnson. Surely that is very pathetic." And he turned away and leant disconsolately against the railings, with his eyes fixed on the door of Number Three.

"Come and sit down, Missie, come and sit down," cried the Admiral, heartily.

Marjolaine accepted his invitation. "I used to be so afraid of you, Sir Peter!"

"Gobblessmysoul! Why?"

"You were so angry with us for painting our house white!"

"Hum," coughed the Admiral, looking guiltily at Mrs. Poskett and Mr. Brooke-Hoskyn. "Ah—hum!—the others were green, ye see. But it's an admirable contrast."

Mrs. Poskett sniffed. She had not forgotten the Admiral's ignominious surrender.

Now Miss Ruth and Miss Barbara came out of their house, hand in hand, as usual. Miss Ruth was, as we are aware, considerably older than her sister, and still treated her like a pet child. Barbara disengaged herself as soon as she caught sight of Marjolaine, rushed at her with bird-like hops, and pecked a little kiss off each cheek as a bird pecks at a cherry.

"Oh, Marjolaine, dearest!" she cried with enthusiasm, "Doctor Johnson has been most extraordinarily eloquent!" The two girls walked away together with their arms gracefully entwined around each other's waists. Ruth joined the others under the tree.

"Good afternoon," she said, "Dear Barbara!—She has just had her hour with the parrot. Her memories of Lieutenant Charles are at their liveliest."

Mr. Basil, who had never taken his eyes off Barbara, heaved a soul-rending sigh, and came up to Miss Ruth.

"Very unwholesome, I think," said Mrs. Poskett, sharply. Miss Ruth explained to Basil: "Lieutenant Charles was in His Majesty's Navy, you know, and dear Barbara was affianced to him."

"So I have heard," answered Basil, coldly. As a matter of fact, he had heard it on an average twice every day. Ruth went on relentlessly, "Unhappily he was abruptly removed from this earthly sphere."

Bare politeness forced Basil to show some interest. After all, Ruth was Barbara's sister. "I presume he fell in battle?"

"Say rather in single combat."

The Admiral with difficulty suppressed a guffaw. He whispered to Basil with a hoarse chuckle, "As a matter of fact he was knocked on the head outside a gin-shop."

"But," the unconscious Ruth went on, "he had bestowed a token of his affection on dear Barbara, in the shape of the remarkable bird you may have seen."

Basil had seen him often and had heard him constantly. For whenever the bird was left alone, he filled the air incessantly with ear-piercing shrieks.

"Doctor Johnson," continued Ruth, "named after the great Lexicographer in consideration of his astonishing fluency of speech. Doctor Johnson is Barbara's only consolation."

Basil suppressed a groan. The obstacle! The obstacle!

"Yes, dear," said Barbara, who had come up with Marjolaine. She spoke with pretty melancholy, but with a side-glance at Basil. "Yes, dear, he speaks with Charles's voice, and says the very things Charles used to say."

Basil moved away. This was almost more than he could bear.

"How lovely!" cried Marjolaine. "I wish I could hear him!"

"Ah, no!" Barbara's chubby face fell into the nearest approach to solemnity she could manage. "Not even you may share that melancholy joy. The things he says are too sacred."

Sir Peter had sidled up to Basil. "I tell you, sir, that bird's language would silence Billingsgate. The atmosphere of that room must be solid, sir—solid." Basil stared at him with amazed reproof, and the Admiral turned to Marjolaine. "Well, Missie, we all hope you 've grown to like the Walk?"

"I love it! And so does Maman."

The Admiral grew enthusiastic. He turned towards the houses glowing in the late sun. "It is a sheltered haven. Look at it! A haven of content! What says the poet? 'The world forgetting, by the world forgot.'"

All had turned with him. They were just an ordinary, every-day set of people. There was not a poet among them, if we except Basil, and yet the Walk, basking in the evening sun, touched some chord in each heart. The Admiral saw his flag drooping in the still air, and remembered his fighting days; Mrs. Poskett thought of Sempronius, and her tea-kettle simmering on the hob; Ruth was grateful for the shelter her little house had given her in her misfortune; Barbara thought of Doctor Johnson and—must I say it?—of Basil; Basil thought of Barbara; Mr. Brooke-Hoskyn thought of patient, unattractive Selina, and the four baby girls; Marjolaine, in her fresh girlhood, could only think of how pretty the flowers looked in the window.

Barbara exclaimed, "When the sunlight falls on it so, how lovely it is!"

Basil looked into her blue eyes, and murmured, "It reminds me of the music I am at work on."

"What is that?" cried Marjolaine. "It sounds beautiful—through the wall."

The musician's enthusiasm was kindled; he grew eloquent. "It is by a new German composer: a man called Beethoven. My old violin-master, Kreutzer, sent it me.—Ah! These new Germans! They are so complicated; so difficult. I am old-fashioned, you know. I had the honour of playing under Mr. Haydn at the Salomon concerts. Yes! and in the very first performance of his immortal Oratorio, 'The Creation,' at Worcester. So perhaps I am prejudiced. Yet this new music is very wonderful; very heart-searching." He stopped abruptly, realising he was talking to deaf ears. Sir Peter came to his rescue.

"I don't know anything about your new-fangled fiddle-faddles; but, by Jehoshaphat, Pringle, play me a hornpipe, and I 'll dance till your arms drop off!"

He hummed the tune, and with amazing agility sketched a few steps, while Mr. Brooke-Hoskyn put up his quizzing glass and eyed him with a superior smile. "Oh!" laughed Marjolaine, clapping her hands, "you must teach me!"

"That I will, Missie! and the sooner the better."

Mrs. Poskett was furious. "No fool like an old fool," she whispered in Ruth's ear.

Barbara, who had been up to Mrs. Poskett's gate to stroke Sempronius, came running down with a little cry of horror. She pointed to the frouzy figure of the Eyesore. "Look! The Eyesore 's going to smoke!"

And, sure enough, after removing an indescribable handkerchief, a greasy newspaper, obviously containing his lunch, half an apple, a large piece of cheese, a huge pocket-knife, and a lump of coal he had picked up in the road, the Eyesore had dragged out a horrible little clay pipe and a dreadful little paper packet of tobacco. The Walk stood petrified. When the Eyesore smoked, everybody had to go indoors and shut their windows.

"His poisonous tobacco!" cried Ruth. "Can you not speak to him, Admiral?"

"I can, Madam, but he'll answer back."

"And then," said Mrs. Poskett somewhat tartly, "of course you are helpless."

"Not at all, ma'am. I hope I can swear with any man; but—the ladies!"

Mr. Brooke-Hoskyn had been observing the Eyesore. "Thank heaven," he whispered, "his pipe won't draw."

For the Eyesore was trying to blow through the stem, was knocking his pipe on the palm of his hand, was endeavouring to run a straw through it: all without success. Finally, in an access of rage, he tossed it aside and sullenly resumed his fishing. A sigh of relief went up from the whole Walk. They were saved.

Now a quaint figure came slowly round the corner. "Ah!" cried Basil, "here is our good Doctor Sternroyd!"

"With his books, as usual," added Mr. Brooke-Hoskyn. "What a brain!"

"Old dryasdust!" laughed Sir Peter. But pointing to the Doctor, Basil motioned them all to silence.

And, to be sure, the Doctor was worth looking at. He was dressed in the fashion of fifty years before. Indeed, I should doubt whether in all those fifty years he had had a new suit of clothes. On his head was a venerable hat of indefinite shape; under his left arm a great bundle of old books; under his right a venerable umbrella of generous proportions, which had once been green. Fortunately his coat had originally been snuff-coloured, so that the spilled snuff made no difference to it. His small-clothes were shabby; his lean shanks were encased in grey worsted stockings, and the great silver buckles on his shoes were tarnished.

At the present moment, however, it was not so much his appearance as his actions that arrested the Walk's attention. He had come in dreamily as usual with his lack-lustre eyes seeing nothing in spite of their great silver-rimmed spectacles. Suddenly his attention was attracted by something lying at his feet. He stopped, picked it up laboriously, and examined it minutely, pushing his spectacles over his forehead for the purpose.

"Bless the man!" cried Mrs. Poskett. "He 's picked up the Eyesore's filthy pipe!"

And now he was exhibiting all the symptoms of frantic joy. Utterly unconscious of the people watching him, he indulged in delighted chuckles, and his withered old legs quite independently of their master's volition executed a sort of grotesque dance. He looked very much like a crane that had caught a fish.

"But why the step-dance?" exclaimed Mr. Brooke-Hoskyn, with a laugh.

Sir Peter hailed him. "Doctor Sternroyd, ahoy!"

The Doctor looked from one to the other in genuine amazement. It was evident his mind had been wandering in some remote world.

"Dear me! Tut, tut!" he stammered. "I had not observed you!" Then, with a radiant face, "Ah, my friends, congratulate me!"

All gathered round him, and the Admiral asked, "What about, Doctor?"

"This," said the reverend gentleman, holding up the trophy. "This. A beautiful specimen of an early Elizabethan tobacco-pipe!"

It was with the greatest difficulty the Admiral restrained a great burst of laughter from the onlookers. Mr. Brooke-Hoskyn got as far as "That, sir? Why, that's—" when a tremendous dig from the Admiral's elbow deprived him of his wind, and sent him backward clucking like an infuriated turkey-cock.

"I do not wonder at your surprise," continued the antiquary. "Yes, Ladies and Gentlemen, they are sometimes found in the alluvial deposit of the Thames; but even my friend, the Archbishop of Canterbury, whose specialty they are, does not possess so perfect a specimen in his entire collection."

Again the Admiral was obliged to exercise all his authority in order to suppress unseemly mirth or explanations. Doctor Sternroyd went on with the tone of regret assumed by a man of learning in the presence of an ignorant and unappreciative audience. "Ah, you don't understand the value of these things. Out of this fragment it is possible to reconstruct an entire epoch. I see Sir Walter Raleigh's fleet bringing home the fragrant weed from the distant plantations; I see him enjoying its vapours in his pleasaunce at Sherborne; I see Drake solacing himself with it on board the Golden Hind. Yes, yes, I shall read a paper on it.—Ah! if only my dear wife, my beloved Araminta, were here now!" With mingled melancholy and triumph he drifted across the lawn and into his house—the last house of the crescent.

"Amazing!" said Mr. Brooke-Hoskyn; "but why would n't you let me tell him, Sir Peter?"

There was a wistful look on Sir Peter's face as he replied. "Ah, Brooke! We all live on our illusions. The more we believe, the happier we are!"

This was beyond Brooke; but Miss Ruth understood and sighed her assent.

CHAPTER IV

CONCERNING A MYSTERIOUS LADY, AND AN ELDERLY BEAU

This was evidently to be a memorable afternoon in the annals of Pomander Walk; for no sooner had it recovered from its mirth over the Doctor's antiquarian discovery than Jim, who had been training the sweet peas at the corner of the Admiral's house, shouted hoarsely:

"Admiral! Pirate in the offing!"

Such a startling announcement was well calculated to silence all laughter; and the imposing figure who now appeared round the corner certainly did nothing to encourage mirth: a very tall, very gaunt, very bony lady, severely but richly dressed; her face hidden in the remote recesses of a more than usually capacious poke bonnet. She was followed by an enormous footman carrying a gold-headed cane in one hand, while a fat pug reposed on his other arm. The Walk was paralysed and could only stare and gasp. Who was she? Where did she come from? Whom did she want?

She stopped and examined the Eyesore through her uplifted face-à-main, as if he had been some strange, unpleasant animal. "Fellow," she said, "is this Pomander Lane?" A shudder ran through the Walk. Pomander Lane, indeed!—The only answer the lady got from the Eyesore was that at that precise moment he found it agreeable to scratch his back. With an exclamation of disgust she turned from him only to find herself face to face with Jim. Now Jim was not pretty to look at.

"Fellow, is this Pomander Lane?" she repeated.

"You 've a-lost yer bearin's, mum," replied the old tar huskily and not too cordially.

"What savages!" muttered the Lady as she turned to Mr. Brooke-Hoskyn. "You! Is this Pomander Lane?"

Mr. Brooke-Hoskyn had laid himself out to fascinate her with his courtliest manner, but the "You!" with which she addressed him aroused the turkey-cock within him, and it was an icy and raging Brooke-Hoskyn who replied, "This, ma'am, is Pomander Walk!"

"Same thing," said the Lady contemptuously.

"Excuse me, ma'am—!" exclaimed Sir Peter hotly.

But she waved him aside and proceeded in a tone intended to be ingratiating, and therefore more offensive than any tone she could have chosen, "My good people"—imagine the Walk's feelings!—"I have undertaken to look after the morals of this part of your parish. I have made it my duty to give advice and distribute alms."

Morals—parish—advice—alms! Had the Walk ever heard such words uttered within its genteel precincts? The Lady turned to Ruth, who happened to be at her side. "Where are your children?"

Ruth stood aghast. She could only breathe indignantly, "I am a spinster."

"Are there no children?" said the Lady reproachfully.

Mr. Brooke-Hoskyn's nurse happened to pass at the moment on her way into the house. The Lady stopped her. "Ah, yes." Mrs. Poskett and the Admiral had sunk in helpless surprise on the bench under the elm. The Lady turned to them. "The father and mother, I suppose?"

Mrs. Poskett and the Admiral started apart, as if they had been shocked by a galvanic battery. Mrs. Poskett uttered an indignant scream; the Admiral could only gasp, "Gobblessmysoul!"

Mr. Brooke-Hoskyn, purple in the face, came clucking down. "This, ma'am, is my youngest. The youngest of four—at present."

The Lady looked him up and down. "I will give your wife instructions about their management—"

Mr. Brooke-Hoskyn danced with rage. "You'll—haha!—She'll teach Selina!—Hoho!—Oh, that's good!"

But the Lady had caught sight of Marjolaine, who with Barbara was standing by the Gazebo. Both young ladies, I regret to say, were laughing immoderately. Brushing the Admiral aside, she sailed imposingly across to them and addressed Marjolaine, who was by this time looking demure, and overdoing it.

"What do I see?" said the Lady severely, examining Marjolaine through her glasses. "Curls? At your age, curls? Fie!" Then shaking a lank finger at her, "Mind! your hair must be quite straight when next I come."

To the delight of the Walk Marjolaine made a pretty and submissive curtsey, and answered, "Yes, ma'am; but don't come again in a hurry. Give me lots and lots of time!"

Meanwhile Mrs. Poskett and Ruth had been urging the Admiral on. Now he approached the Lady in his quarter-deck manner, and said,

"Madam—hum—we give alms, and we do not take advice. You 're on the wrong tack. You 're out of your reckoning." Then, pointing grandly to the only entrance to the Walk, "That is your course for Pomander Lane."

"Yes," said Brooke-Hoskyn, with the same action, "That!"

"Yes," said all the ladies, pointing melodramatically to the corner, "That!"

"Jim," ordered the Admiral, "pilot the lady out."

"Ay, ay, sir."

The Lady eyed them all in turn through her face-à-main. "Very well," she said, with magnificent scorn. "I was told I should have difficulty here. I was told you only go to church twice on Sundays. I did not expect to find you so bad as you are. I shall come again. I am not so easily beaten. I shall certainly come again!"

In grim silence she gathered her skirts about her and departed as she had come, followed by the footman and the fat pug.

When she had turned the corner the Walk once more indulged in a burst of laughter.

"What a figure of fun!" cried Ruth.

"I gave here her sailing orders—what?" chuckled the Admiral.

And Mrs. Poskett gazed into his face with admiration.

"What a wonderful man you are, Sir Peter!"

When they had all recovered, Basil came to Marjolaine and eagerly reminded her it was high time for her singing-lesson.

Marjolaine appealed to Barbara: "Maman told me to ask you to come with me."

Barbara gave a little hop of delight, but Ruth exclaimed, "Shall I take your place, dear?"

"No, no," cried Barbara, almost as if she were in a fright, "I love to hear her." Barbara, Marjolaine, and Basil moved slowly towards Number Three, while Ruth approached Mrs. Poskett. "Will you come in and take a dish of tea?"

"No," replied Mrs. Poskett, "no, thank you," and then, with a giggle, "I'm going—you'll never guess!—I 'm going to comb my wig."

Seeing the ladies all strolling towards their houses the Admiral once more challenged Mr. Brooke-Hoskyn to play off the rubber at quoits. But he declined. "I think not, Sir Peter. Selina will be expecting me."

Mrs. Poskett stopped. "I wonder you can bear to leave her so much alone."

Mr. Brooke-Hoskyn felt the implied reproach. With a countenance full of woe, he replied, "It tears my heart-strings, ma'am; but she will have it so. 'Brooke,' she says—or 'Jerome,' as the case may be—'your place is in the fashionable world, among the hote tonn.' So I sacrifice my inclination to her pleasure."

"How unselfish of you!" said Ruth.

Mr. Brooke-Hoskyn continued more cheerfully. "She has many innocent pastimes. At the present moment the dear soul is joyously darning my socks."

By this time Mrs. Poskett and the other ladies were on their respective door-steps. Mrs. Poskett gave a startled cry and called the Admiral's attention to the corner of the Walk, where four men in livery had just deposited a sedan chair. "Company, Sir Peter!" she cried.

Sir Peter turned abruptly and examined the person who was with difficulty emerging from the sedan. "Eh?— Gobblessmysoul! Is it possible?— My old friend, Lord Otford!" He bustled up to the newcomer, shouting "Otford! Otford!"

Now the name had had a magical effect on Mr. Brooke-Hoskyn. At the sound of it the colour had all vanished from his fat cheeks, the strength seemed to have gone out of his legs, and his knees were knocking together. "Lord Otford, by all that's unlucky!" he exclaimed.

Mrs. Poskett had swept back to the elm. She happened to have a very becoming dress on, and she was determined the noble lord should see it. She caught sight of Mr. Brooke-Hoskyn's face. "What's the matter?"

Mr. Brooke-Hoskyn pulled himself together with a mighty effort. "Nothing, ma'am." Then with great dignity, "He and I differ in politics. There might be bloodshed." And while Mrs. Poskett exclaimed "Well, I never!" he had dashed into his house as a rabbit dashes into its burrow.

Mrs. Poskett sailed up to her house trying to catch his lordship's eye. I am afraid all the ladies were anxious to be noticed, for all lingered at their doors. A real, live lord was not an ordinary sight in Pomander Walk. And this one happened to be a handsome one; well set up, dressed in the height of fashion, yet quietly, as a gentleman should dress; and carrying his forty-five years as though they had been no more than thirty.

"You're looking well, Peter!" he exclaimed, still shaking the Admiral by the hand.

"My dear Jack! My dear old Jack!" cried the latter. "Here! come into the house!"

"No, no," laughed his friend, with a suspicious glance at the diminutive window. "Stuffy. No. Looks pleasant under the elm."

"Why, come along, then!" shouted the Admiral, dragging him towards the tree.

Lord Otford took off his hat to Mrs. Poskett with an elaborate bow. "I say, Peter, in clover, you rascal!"

"Dam fine woman—what?"

Here Lord Otford caught sight of Marjolaine just disappearing in the doorway of Number Three. He stopped short. "Ay, and pretty gel on door-step." Then, as if struck by a sudden thought, "By Jove!"

"Dainty little thing, eh?" said the Admiral with a chuckle.

"Yes," replied the nobleman, pensively. "Reminds me vaguely—" but he changed the subject. "Well! You're hale and hearty!"

"Nothing amiss with you, neither," laughed Sir Peter, sitting on the bench and drawing his friend down beside him. "I am glad to see you! Thought you was in Russia."

"Got home a month ago, Peter. Not married yet?"

"Peter Antrobus married? That's a good 'un." Up went the Admiral's finger to his nose. "No, my Lord. All women, yes. One woman, no!"

"Sure nobody can hear us?"

Sir Peter looked round cautiously. Save for the Eyesore, absorbed in his placid effort to catch fish, there was no sign of life in the Walk. Nobody was visible at the windows. From Number Three came the sound of a fresh young voice singing scales and arpeggios.

"Quite safe, Jack," said he.

"Peter, I want your help."

"Woman?" asked Sir Peter.

"Yes. Not my woman, though, this time. It's about my boy—Jack."

"Aha! Got into a mess? Chip of the old block—what?"

"No, no. Marriage."

"Gobblessmysoul! How old is he?"

"Twenty-five."

"Good Lord!"

"I want to see Jack settled. There 's the succession to think of."

"You talk as though you was a king."

"Well, so I am, in a small way. Think of the estate! I want Jack to take the reins."

"How can he, when he 's on the sea?"

"He's to retire as soon as he gets his Captaincy."

The Admiral jumped up. "Retire! Now! With Boney ready to gobble us up!"

Otford drew him down again. "Don't you see? With all this battle and bloodshed, now's the time for Jack to give me a grandson. He 's my only child, remember. Why, hang it, man, if he was to die without issue, the title and the estates would go to that infernal whig scoundrel, James Sayle."

"That won't do," Sir Peter assented, wisely nodding his head.

"Of course it won't. Now, there's old Wendover's gel—Caroline Thring."

The Admiral made a wry face. "Caroline Thring? I've heard of her. Never seen her: but heard of her. Eccentric party, ain't she? And did n't I hear there was an affair with Young Beauchamp?"

"That's fallen through. She's an estimable person."

"Ugh," said the Admiral.

"People call her eccentric," Lord Otford continued, hotly, "because she goes about doing good—distributing alms—"

The Admiral was about to exclaim, but Otford gave him no time. "You 're prejudiced, you old reprobate. Wendover 's willing, and there's nothing in the way. The estates join. She's sole heiress. Gad, sir, that alliance would make Jack the biggest man in the Three Kingdoms."

"Is Jack fond of her?"

"Does n't object to her. Hesitates. Says he don't want to marry at all. Says he has n't had his fling."

"Well—what's it all got to do with me?"

"Ever since Jack's been home on leave, he's done nothing but talk about you—"

"Good lad!" cried Sir Peter, slapping his thigh. "I loved him when he was a middy on board the Termagant."

"And he loves you. Coming to look you up. To-day, very likely. When he comes, refer to Caroline—carelessly. Say what a fine gel she is. Don't say a word about the estate. These young whipper-snappers have such high-and-mighty ideas about marrying for money. Refer to young Beauchamp. Say in your time young fellers did n't let other young fellers cut 'em out. See?"

"You 're a wily old fox, Jack. But, hark'ee! Sure he's not in love with anybody else?"

"He says he is n't. Oh, there may be a Spanish Senorita!—Gad! I should almost be ashamed of him if there wasn't!—But there's no—no—"

"No Lucy Pryor?" said the Admiral carelessly.

The name seemed to fall on Lord Otford like a blow. He sat quite still a moment, looking straight before him into who knows what memories. At last he said very sadly, "No. No Lucy Pryor."

The Admiral realised his own tactlessness. He took Lord Otford's hand. "I beg your pardon, Jack. I 'm sorry."

"It still hurts, Peter," said his Lordship with a wistful smile. "Like an old bullet.—Well! You 'll do what you can, eh?—I don't want you to overdo it. Just edge him in the right direction."

"Keep his eye in the wind, what?"

"That's it.—Well? Any new-comers in the Walk?"

"Yes," chuckled the Admiral, "two oil lamps. One in front of my house, and one in front of Sternroyd's. They wanted to give us their new-fangled, stinking gas, but the whole Walk mutinied."

"Very fine, but—"

"They 're only used when there's no moon."

"But I meant new people!"

"Oh! Ah! Yes!—" Then with a sort of smack of the lips indicative of the highest appreciation, "A French widow and her daughter."