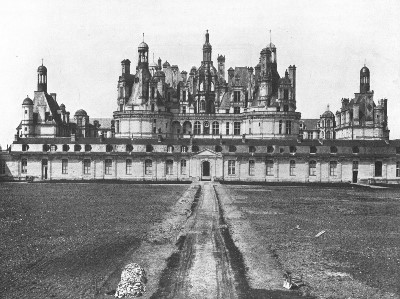

| PLATE LXXV | CHAMBORD: SOUTHERN FAÇADE |

THE BROCHURE SERIES

|

THE |

||

| 1900. | OCTOBER | No. 10. |

The Château of Chambord is one of the most unique palaces of the Renaissance in existence. "It is," writes Jules Loiseleur, "the Versailles of the feudal monarchy; and was to the Château of Blois, that central residence of the Valois, what Versailles was to the Tuilleries,—the country-seat of royalty. Tapestries from Arras, Venetian mirrors, curiously sculptured chests, crystal chandeliers, massive silver furniture, and miracles of all the arts, were amassed in this palace during eight reigns, and dispersed in a single day by the breath of the Revolution.

"It has often been asked why Francis I., to whom the banks of the Loire presented many marvelous sites, selected such a wild and forsaken spot in the midst of arid plains for the erection of the strange building which he planned. His peculiar choice has been attributed to his passion for the chase and also because of the memory of his amours with the beautiful Comtesse de Thoury, whom he had visited in that neighborhood before he ascended the throne. Independently of these motives, which no doubt counted in his selection, perhaps the very wildness of the place and its distance from the Loire, which reminded him too much of the cares of royalty, was a determining reason. Kings, like private individuals, and even more than they, experience the need at times of burying themselves, and therefore make a hidden and far-away nest where they may be their own masters and live to please themselves. Moreover, Chambord, with its countless rooms, its secret stairways, and its subterranean passages, seems to have been built for one who, tired of the blaze of royal glory, sought here for shadow and mystery. At the same time when he was rearing Chambord in the heart of the uncultivated plains of the Sologne, Francis I. built in the midst of the Blois de Boulogne a château, where, from time to time, he shut himself up with learned men and artists, and to which the courtiers, who were positively forbidden there, gave the name of Madrid, in memory of the prison in which their master had suffered. But Chambord, like Madrid, was not a prison; it was a retreat.

"That sentiment of peculiar charm which is attached to the situation of Chambord will be felt by every artist who visits this strange creation. At the end of a long avenue of poplars breaking through thin underbrush you see, little by little, peeping and mounting upward from the earth, a fairy building, which, rising in the midst of arid sand and heath, produces the most striking and unexpected effect. A jinnee of the Orient, a poet has said, must have stolen it from the country of sunshine to hide it in the country of fog for the amours of a handsome prince. The park in which it is situated is twenty square miles in area, and is surrounded by twenty miles of walls."

Francis I. had passed his early years at Cognac, at Amboise or Romorantin, and when he first saw Chambord it was only an old feudal manor house built by the Counts of Blois. There has been much question as to who the architect he employed to transform it really was, and the honor of having designed the splendid residence has been claimed for several of the Italian artists, who early in the sixteenth century came to seek patronage in France. It seems well established today, however, that Chambord was neither the work of Primaticcio, with whose name it is tempting to associate any building of this king's, nor of Vignola, nor of Il Rosso, all of whom have left some trace of their sojourn in France, for the methods of contemporary Italian architecture were totally different; but as M. de la Saussaye, the author of a very complete and concise history of the building, proves, it was due to the skill of that fertile local school of art and architecture around Tours and Blois, and more particularly to a comparatively obscure genius, whose name is also mentioned in connection with Amboise and Blois, one Pierre le Nepveu, known also as Pierre Trinqueau, who is designated in the papers which preserve in some degree the history of the origin of the edifice as the maistre de l'œuvre de maçonnerie. "Behind this modest title apparently," writes Mr. Henry James, "we must recognize one of the most original talents of the French Renaissance; and it is a proof of the vigor of the artistic life of that period that, brilliant production being everywhere abundant, an artist of so high a value should not have been treated by his contemporaries as a celebrity. We manage things very differently today."

Although Le Nepveu was the chief architect, Cousin, Bontemps, Goujon, Pilon and other noted artists were engaged in the decoration of Chambord. Many changes in the structure were afterwards carried out, especially by Louis XIV. and by Marshal Saxe, to whom that monarch presented it in 1749. From 1725 to 1733 Stanislaus Leszczynski, the ex-king of Poland, who spent the greater part of his life in being elected and in being ousted from his throne, dwelt at Chambord. During the Revolution the palace was as far as possible despoiled of every vestige of its royal origin, and the apartments to which upwards of two centuries had contributed a treasure of decoration and furniture were swept bare. In 1791 an odd proposal was made to the French Government by a company of English Quakers, who had conceived the bold idea of establishing in the palace a manufacture of some peaceful commodity not today recorded. Napoleon I. presented Chambord to Marshal Berthier, from whose widow it was purchased in 1821 for the sum of £61,000 raised by national subscription on behalf of the Duke of Bordeaux, formerly Comte de Chambord.

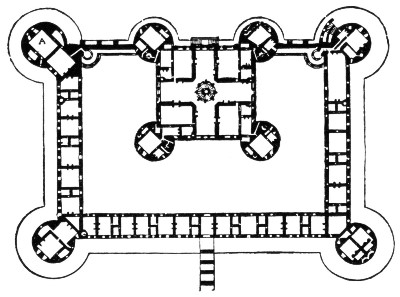

The Château, only the north part of which is completed, consists of two square blocks, the larger of which, five hundred and twelve feet long by three hundred and eighty-five feet broad, encloses the smaller in such a way, that the northern façade of the one forms the centre of the northern façade of the other. The corners of each block terminate in massive round towers, with conical roofs crowned by lanterns, so that four of these towers appear in the principal façade. In plan it will be seen that Chambord resembles the typical French château; with the habitation of the seigneur and his family in the centre, and this habitation enclosed on three sides by a court, while like most feudal dwellings, the central donjon shares one of its sides with the exterior of the whole. The central part is adorned with an unexampled profusion of dormer-windows, turrets, carved chimneys and pinnacles, besides innumerable mouldings and sculptures, above all of which rises the double lantern of the tower containing the principal staircase.

"It is a forest of campaniles, chimneys, sky-lights, domes and towers, in lace-work and open-work, twisted according to a caprice which excludes neither harmony nor unity," writes M. Loiseleur. "The beautiful open-work tower of the large staircase dominates the entire mass of pinnacles and steeples, and bathes in the blue sky its colossal fleur-de-lis, the last point of the highest pinnacle among pinnacles, the highest crown among all crowns.

"We must take Chambord for what it is, an ancient Gothic château dressed out in great measure according to the fashion of the Renaissance. In no other place is the transition from one style to another revealed in a way so impressive and naïve; nowhere else does the brilliant butterfly of the Renaissance show itself more deeply imprisoned in the heavy Gothic chrysalis. Chambord, by its plan which is essentially French and feudal, and by its enclosure flanked with towers, and by the breadth of its heavy mass, slavishly recalls the mediæval manoirs. By its lavish profusion of ornamentation it suggests the creations of the sixteenth century as far as the beginning of the roofs; it is Gothic as far as the platform; and it belongs to the Renaissance when it comes to the roof itself. It may be compared to a rude French knight of the fourteenth century, who wears on his cuirass some fine Italian embroideries, and on his head the plumed felt of Francis I.,—assuredly an incongruous costume, but one not without character."

"With a sympathetic denial of any extreme over-technical admiration," writes Mr. Cook in his Old Touraine, "Viollet le Duc gives just that intelligible account of the Château which is a compromise between the unmeaning adulation of its contemporary critics and the ignorance of the casual traveller. 'Chambord,' says he, 'must be taken for what it is; for an attempt of the architect to reconcile the methods of two opposite principles,—to unite in one building the fortified castle of the Middle Ages and the pleasure-palace of the sixteenth century.' Granted that the attempt was an absurd one, it must be remembered that the Renaissance was but just beginning in France; Gothic art seemed out of date, yet none other had established itself to take its place. In literature, in morals, as in architecture, this particular phase in the civilization of the time was evident, and if only this transition period is realized in all its meanings, with all the 'monstrous and inform' characteristics that were inevitably a part of it, the mystery of this strange sixteenth century in France is half explained."

| PLAN OF THE CHÂTEAU OF CHAMBORD |

"At Chambord," writes Mrs. Pattison, in her Renaissance of Art in France, "which was building in 1526, the stories are, it is true, forcibly indicated, but the whole building is pulled together in Gothic fashion by the towers of the corps de logis, and by those which flank the pavilions or wings which stretch out on either side of the main body. In a building of the size of Chambord the result of this treatment is hardly satisfactory, for the lines of the wings to right and left of the main body seem to droop away from the heavy towers on either side. Inside the court, however, the unpleasant effect, even at Chambord, disappears, for the apparent length of the wings is greatly abbreviated by the effect of the two spiral staircases which run up outside the building at the internal angles on opposite sides.

"Chambord is, indeed, throughout truly typical of the earlier stage of the new Renaissance movement. In the general arrangement, in the ordonnance, late Gothic caprice and fantastic love of the unforeseen rule triumphant. The older portions of the Château, the seemingly irregular assemblages of half Oriental turrets and spires, are debased Gothic, full of audacious disregard of all outward seeming of order. The architect, instead of seeking to bring home to the eye the general law, the plan on which the whole is grouped, has wilfully obscured and concealed it beneath the obviousness of the wild and daring conceits heaped above.

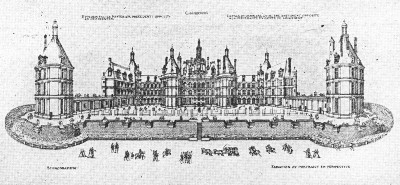

| VIEW OF CHAMBORD (1576) | ENGRAVING FROM DU CERCEAU |

"But even at Chambord the mark is set which promises other days. It is the transition moment; Gothic fancy may wildly distribute ornament and obscure design, but the ornament which it distributes is Gothic no longer. The obscæna which haunt the cathedrals of the middle ages, which infest the earlier towers of Amboise, and linger defilingly about Gaillon, are banished. In their place come faint foliated traceries and arabesques in low relief, enriching every surface, disturbing none, moving with melodious adaptation of subtle line, winding, falling, rising in sympathy with every swiftly ascending shaft or hollowing curve.

"It is not now possible to approach Chambord carrying in our eyes a vision of the great Renaissance palace, as engraved by Du Cerceau in his Plus excellens Bâtimens de la France. Burdened by the weighty labors of Louis XIV., weakened by eight improving years at the hands of Stanislaus Leszczynski, mutilated by Marshal Saxe, the Chambord which we now go out from Blois to visit is not the Chambord of Francis I. The broad foundations and heaving arches which rose proudly out of the waters of the moat no longer impress the eye. The truncated mass squats ignobly upon the turf, the waters of the moat are gone; gone are the deep embankments crowned with pierced balustrades; gone is the no-longer-needed bridge with its guardian lions. All the outlying work which gave the actual building space and dignity has vanished, and we enter directly from the park outside to what was once but the inner court of the Château.

"It is not until we stand within this inner court—until we have passed through the lines of building which enclose it on the western side, and which show the unmistakable signs of stupid and brutal destruction, that we can believe again in the departed glories of Chambord. Lippomano, ambassador from Venice to France in the reign of Henry III., turned out of his way to visit Chambord. 'On the 21st,' he says, 'we made a slight detour in order to visit the Château of Chambord, or, more strictly speaking, the palace commenced by Francis I., and truly worthy of this great prince. I have seen many magnificent buildings in the course of my life, but never anything more beautiful or more rich. They say that the piles for the foundations of the Château in this marshy ground have alone cost 300,000 francs. The effect is very good on all sides. The number of the rooms is as remarkable as their size, and indeed space was not wanting to the architect, since the wall that surrounds the park is seven leagues in length. The park itself is full of forests, of lakes, of streams, of pasture-land, and of hunting-grounds, and in the centre rises the Château with its gilt battlements, with its wings covered in with lead, with its pavilions, its towers and its corridors, even as the romancers describe to us the abode of Morgana or of Alcinoüs. More than half remains to be done, and I doubt it will ever be finished, for the kingdom is completely exhausted by war. We left much marvelling, or rather let us say thunderstruck.'

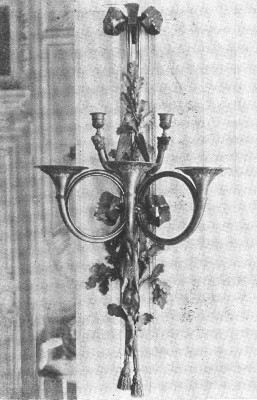

"To destroy the character of Chambord from the outside was not difficult. It was not easy to tame the rude defiance of Vincennes, or give facility to the reserved and guarded approaches of Gaillon. Solid rectangular towers, heavy machicolations, and ponderous drawbridges offer a stubborn resistance to schemes of ruthless innovation; but Chambord was no fortress, it was a country house. The very site is motived by no other reason than the pleasures of the chase. The battlements of Gaillon gave back the echoes of the trumpet, but the galleries of Chambord resounded with the huntsman's bugle.

"The construction of these galleries in itself points to the rapid progress of social change. There are not only such as may be called covered passages communicating from the spiral staircases with the rooms on each story; galleries which have their special cause in actual need and daily use; but the roofs of the range of one-storied buildings which connect the side wings on the north and south, and which run along the western front, are finished up from the cornice with a balustrade, and turned into a promenade for courtiers.

"Yet in spite of these marked indications of change the ancient spirit lingers. The unrestrained freedom of grotesque caprice finds expression everywhere, even in those later portions which belong to another reign. Pierre le Nepveu has left on all his work the imprint of profuse and fantastic force; the outlines of his cupolas strike the sky with an audacity which seems to defy the adverse criticism of those who moved within the limits of more cautious rule. Symmetrical balance, for which the masters of a succeeding era sought, and by which they strove to harmonize every portion of their design, obliged them to reject the aid of those varied resources which Le Nepveu shrewdly marshaled with a vigorous hand.

"Chambord is in truth a brilliant example of transition. The early Renaissance is there to be seen, taking on itself the burden beneath which the failing forces of the Gothic spirit had sunk. But the intention of the work is wholly foreign to the main direction taken by the new movement, and condemned, by its very nature, to remain, in spite of the wonderful genius lavished upon it, an unfruitful tour de force."

The interior of the palace is now but a great wilderness of hewn stone. The sixteenth century treasures of art which had adorned it were all stolen or destroyed in the Revolution, the spoliation being so complete that it was stripped of even the carved wainscots, panels, doors and shutters, and the four hundred and forty enormous apartments now give only the impression of a vast and comfortless barrack. In the original arrangement of the interior all ideas of practical defense were sacrificed to produce a pleasure palace, and it was furnished with innumerable secret stairways (there are thirteen great staircases, not to mention numberless smaller ones) isolated turrets and a hundred facilities for what the gallant Viollet le Duc calls "les intrigues secrètes de cette cour jeune et tout occupée de galanteries."

"On the whole," writes Mr. Henry James, "Chambord makes a great impression—there is a dignity in its desolation. It speaks with a muffled but audible voice of the vanished monarchy, which had been so strong, so splendid, but today has become a sort of fantastic vision. I thought, while I lingered there, of all the fine things that it takes to make up such a monarchy; and how one of them is a superfluity of mouldering empty palaces."

A Change in |

The attention of subscribers to The Brochure Series is again called to the fact that, beginning with the Seventh Volume, January, 1901, the magazine is to be enlarged, and that the subscription price will then be increased to $1.00 a year, and the price of single copies to ten cents each.

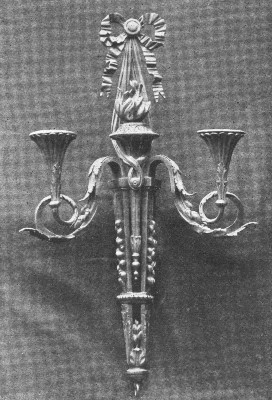

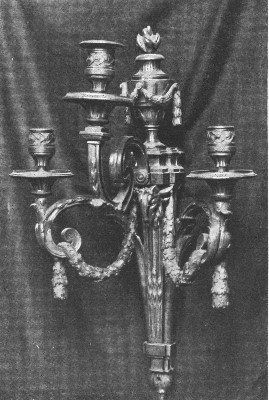

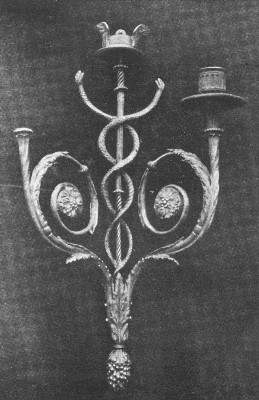

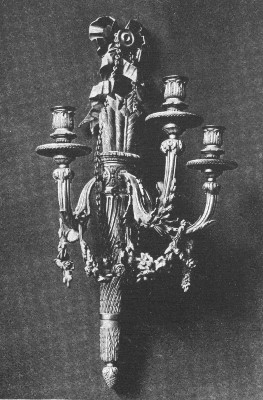

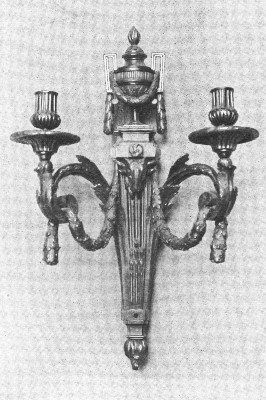

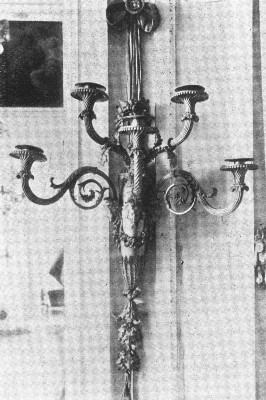

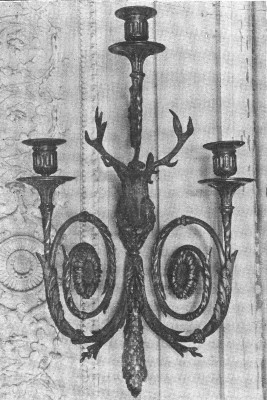

LOUIS XVI. SCONCES |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|