The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Pansy Magazine, August 1886, by Various This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook. Title: The Pansy Magazine, August 1886 Author: Various Editor: Pansy (Mrs. G. R. (Isabella) Alden) Release Date: January 1, 2015 [EBook #47834] Language: English Character set encoding: UTF-8 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE PANSY MAGAZINE, AUGUST 1886 *** Produced by Emmy, Juliet Sutherland and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

|

GOLD MEDAL, PARIS, 1878.

BAKER'S Breakfast Cocoa. Warranted absolutely pure Cocoa, from which the excess of Oil has been removed. It has three times the strength of Cocoa mixed with Starch, Arrowroot or Sugar, and is therefore far more economical, costing less than one cent a cup. It is delicious, nourishing, strengthening, easily digested, and admirably adapted for invalids as well as for persons in health.

——————

Sold by Grocers everywhere. ——————

W. BAKER & CO., Dorchester, Mass.

|

|

GOLD MEDAL, PARIS, 1878.

BAKER'S Vanilla Chocolate, Like all our chocolates, is prepared

with the greatest care, and

consists of a superior quality of

cocoa and sugar, flavored with

pure vanilla bean. Served as a

drink, or eaten dry as confectionery,

it is a delicious article,

and is highly recommended by

tourists.

——————

Sold by Grocers everywhere. ——————

W. BAKER & CO., Dorchester, Mass.

|

| A warm iron passed over the back of these PAPERS TRANSFERS the Pattern to a Fabric. Designs in Crewels, Embroidery, Braiding, and Initial Letters. New book bound in cloth, showing all Briggs & Co.'s latest Patterns, sent on receipt of 25 cents. Use Briggs & Co.'s Silk Crewels and Filling Silk, specially shaded for these patterns.

104 Franklin St.,

New York. Retail by the leading Zephyr Wool Stores. |

Greatest inducements ever offered. Now's your time to get up orders for our celebrated Teas and Coffees and secure a beautiful Gold Band or Moss Rose China Tea Set, or Handsome Decorated Gold Band Moss Rose Dinner Set, or Gold Band Moss Decorated Toilet Set. For full particulars address

It has been the positive means of saving many lives where no other food would be retained. Its basis is Sugar of Milk, the most important element of mothers' milk.

It contains no unchanged starch and no Cane Sugar, and therefore does not cause sour stomach, irritation, or irregular bowels.

It is the Most Nourishing, the Most Palatable, the Most Economical, of all Prepared Foods.

Sold by Druggists—25 cts., 50 cts., $1.00. Send for pamphlet giving important medical opinions on the nutrition of Infants and Invalids.

$3 Printing Press

We will send six copies of "The Household Primer," "Household Receipt Book," and "Household Game Book," to every subscriber who will agree to distribute all but one of each among friends.

Every person sending us their own and one new subscription to The Pansy before Sept. 1st, will receive the two copies one year for $1.75. The remittance must be made to us direct and not through an agent.

CANDY! | Send one, two, three or five dollars for a retail box, by express, of the best Candies in the World, put up in handsome boxes. All strictly pure. Suitable for presents. Try it once. Address

C. F. GUNTHER, Confectioner, 78 Madison Street, Chicago. |

“You see,” said Satie, telling it to the band, “her heart was just full yesterday, and she told it all out to me. I do not believe anyone would have got it out of her at any other time. It seems that she has a small annuity, which, with the work she can do, makes her very comfortable; but this interest money comes hard, especially as she has less work this summer than usual. Now I thought that if we could pay the interest, perhaps she would get on, and another year she may get more work.”

“That would be a good thing to do,” said Lou Brandt, “but it would be better if we could pay the mortgage, then there would be no interest.”

“Pay the mortgage!” exclaimed two or three at once in tones which indicated that they thought Lou had taken leave of her wits.

“Why not? It is only seventy-five dollars, and it is a great pity if twenty-five boys and girls cannot raise that amount! Satie told me about the trouble, last night, and when father came home I asked him about it and he said that the interest would not help matters, for the mortgage will be due this fall, and Major Grimes means to foreclose if it is not paid up. Granny has lived in that little house forty years; if she were turned out now, she would not know what to do. She has not a relative in the world.”

“Let’s do it! We can get the money, somehow, I know!” said one of the boys. “I suppose Major Grimes thinks he will get the cottage into his own hands, for little or nothing, but we will show him the Industry Band mean business!”

“If we cannot raise the money in two months I am sure we can find somebody who will advance it and hold the mortgage as security until we can pay it,” said Lou.

“O Lou! what a business head you have on your shoulders!” said John Baker.

“Well, let’s proceed directly to business, and see if there are not others with equally good heads. We will meet Thursday afternoon at four o’clock and bring in our pledges. We can each think it over between now and then and decide how much we can give right out of our own pocket money.”

To this plan all agreed; then they separated.

Annie Williams was the youngest member of the band. She had not much money of her own, and this plan which Lou proposed, presented serious difficulties to the child. Just a few days before, she had spent her last penny, and she did not know how she was to get any money to give toward this fund. That night she added to her evening prayer this petition: “Dear Jesus, if thou would’st have me do something to help poor Mrs. Frink out of her trouble, wilt thou show me the way? If I can earn any money, please tell me where the work is for me to do.” Then she went to bed, content to leave it all with Jesus.

When they met according to appointment on Thursday afternoon, Lou who was treasurer of the band was ready with book and pencil to put down the names and pledges. Tom Mason was there, money in hand. “I can give three dollars; I sold some ducks yesterday, and father gave me a dollar for doing the meanest job on the farm.”

“What is that?” asked one of the boys.

“As if you didn’t know that there is nothing a boy hates like picking up stones all day!”

Another could give a dollar and fifty cents, another, two dollars; and the girls, when were they ever behind in giving? Laura Kline had concluded to wear her last year’s hat, and give what a new one would cost. Nell Blake had agreed to wash the breakfast dishes for a month, so that her mother could do more of the family sewing, and the money saved was to be hers, to give to the fund. Lou Brandt said, “Well, I think I have taken the hardest job of you all; I have agreed not to use a single slang phrase for a whole year, and I am to have five dollars a month! I will give the money for the first two months towards paying off the mortgage, and if we do not raise it all in that time perhaps I will give another month’s pay.”

“But suppose you fail?” said Satie Howe. “I think you will have to give security.”

“Agreed!” said Lou laughingly, and as she spoke she took off her heavy gold bracelets which had been her last birthday present, and laid them beside Tom’s three dollars. They all laughed and Satie said, “Well, Lou, I guess we can trust you to redeem those!”

When Annie Williams’ name was called she said, “I do not know how much I can give. I am sure to have something, but I have not found out yet how much He wants me to give.”

“Who wants you to give?” asked Lou.

“Why, Jesus; I asked him, but he has not told me yet.” The girls were hushed and awed; how many of them had thought to ask Jesus about it! Lou laid down her pencil and her voice trembled with emotion as she said,

“Girls, boys, we have made a mistake! We have begun wrong! Let us pray about this too!” Dropping upon her knees, while the others followed her example, Lou’s voice led them in a prayer for God’s direction in this matter which they had been considering, and for his blessing upon all their efforts as well.

“That was what they call ‘a new departure,’” said Tom Mason. Another boy remarked,

“It is queer that with so many of us belonging to the church, we should have band meetings without an opening and closing prayer! but that little mouse stirred us up, so that I reckon we shall do better after this.”

Annie Williams came to the next meeting with a bright face; when her name was called she walked over to the treasurer and laid down a bit of paper which read after the usual form of bank checks: “Pay to the order of Annie Williams five dollars;” and was signed “John Williams.”

“Papa showed me how to write on the back—‘endorse it,’ he called it,” and turning the paper over she brought to view, “Pay to the order of Louise Brandt. Annie Williams.” And she added, “Papa said if you took that to any bank they would give you the money, only you would have to put your name under mine.”

“What business women we are getting to be!” said Tom Mason.

“Do you want to hear about it?” asked Annie when the laugh at Tom’s remark subsided.

“Of course we do!” said Lou.

“You know I staid a long time out at uncle John’s last spring; one day uncle brought in a little lamb and said ‘See here, Annie, if you will save this lamb’s life you may have it. The poor thing’s mother will not own it, and unless you feed it it will die.’ Aunt Mary showed me how to feed it, and it grew; and before I came away it was a big lamb. I used to feed it with a spoon out of a bowl, and I grew real fond of it. The other day uncle John wrote to me that he was going to sell all his flock, and that he was sorry, but he thought he must sell my lamb too. He is going to Florida next winter, and there would be no one at the farm who could take care of it, so he sent me five dollars! You can’t think how glad I was; I knew right away that Jesus had answered my prayer.”

I cannot describe all the ways by which the money came in, but you will not be surprised when I tell you that when the money on the mortgage came due, the “Industry Band” were ready to become the purchasers, and that Grandma Frink was made the happiest woman in the village of Danvers.

Faye Huntington.

Hosanna: Blessed is the King of Israel that cometh in the name of the lord.

And I, if I be lifted up from the earth, will draw all men unto me.

If ye know these things, happy are ye if ye do them.

Wherefore let him that thinketh he standeth, take heed lest he fall.

Let not your heart be troubled; ye believe in God, believe also in me.

“HERE is another chance to fit my story to two of your verses,” said Grandma, and all the young Burtons looked glad.

“It was the summer I was twelve,” said Grandma, “and I spent it at Grandfather Holland’s. He was a minister, you know. We used to have very pleasant Sunday evenings, talking over the sermon, and reciting the catechism; there wasn’t any Sunday-school in those days; not in our part of the country.

“One night we had the story of Jesus washing the disciples’ feet. Cousin Mercy said she didn’t see how he could do it; to think of his washing Judas’ feet, too! She thought it was wonderful!

“I said it was wonderful, but I could see how he could do it, and in a sense like to do it; that it showed how truly noble he was, and that I should like a chance to treat an enemy kindly, because I thought it would be a splendid thing to do. But I added, rather mournfully, that I did not suppose I should ever have an enemy. Grandfather did not make much reply; he only smiled on me, a curious sort of smile, and repeated this third verse of yours: ‘If ye know these things, happy are ye if ye do them.’

“Then what did cousin Stephen do, but repeat, with his eyes fixed on me, this next verse: ‘Let him that thinketh he standeth, take heed lest he fall.’

“I felt my cheeks grow red. I wished I could have a chance to show Steenie how truly noble I was; for I saw he didn’t believe it.

“The very next week something happened which made me think of those two verses again.

“I went to the little village school, while I was at grandfather’s; and Priscilla Howe went too. Priscilla was a bound girl whom my grandfather was bringing up.”

“Bound!” exclaimed little Sarah, in startled tone; Grandma had to stop and explain to her what that meant. Then she continued her story.

“I didn’t like Priscilla very well; I hardly knew why; she was a still, cold, little thing, a trifle sullen, perhaps; at least I thought so, and I didn’t have much to do with her. On Wednesday afternoons we had an exercise in school which I always liked.

“The afternoon before, the teacher would read to us a certain article, generally a description of something; a great meeting, maybe, or a fire, or a storm; we were to take what notes we pleased, while the reading was going on. Then the next day we were to bring in our written account of that same thing; using as few words, and as short ones, as we could, to get in all the facts; and the scholar who brought in the best paper, with the fewest mistakes in spelling, and punctuation, wore home the medal for composition. Now I had a good memory, and it seemed to come natural to me to write out things; so I liked this exercise. But poor Priscilla hated it; she could not remember half a dozen things in the article; and couldn’t express them. Tuesday evening grandfather let me sit in his study while I wrote out my exercise. The story was a very nice one, and I felt sure of getting the medal.

“The next morning, when I went to get ready for school, my exercise was nowhere to be found; I made a great noise about it, and every one in the house helped me look; but the exercise was gone. I tried to get time to write another, but I couldn’t, and I missed the medal of course; and cried bitterly. The next day I found the exercise; where, do you think?”

“Where?” asked all the Burtons at once, in tones of eager interest and sympathy.

“Down in the bottom of Priscilla’s mending basket, all torn into little tiny bits, less than half an inch square!”

You should have heard the murmur of indignation which ran through the audience then!

“I can’t tell you how I felt,” said Grandma. “I went down to the sitting-room where the family were gathered, but I was too angry to trust my voice to tell the story. They were all busy, and I crept into a corner with my dark little face, and kept still. My cousin Mercy was [317] at the piano. I ought to tell you about that piano, children,” said Grandma, breaking from her story. “It was the only one in that part of the world; pianos were scarcer in those days than they are now; and Mercy’s was a great curiosity; it had been sent to her by a rich uncle, who went away off to foreign parts and made a fortune.

“It would look very queer and old-fashioned to you, but it was a great wonder and delight to me.

“Mercy called me to come and sing a hymn, but dear me! I couldn’t have sung if they had promised me a piano of my own for doing it. Just then, my aunt Martha, who was grandfather’s housekeeper, said, as she looked from the window, ‘There comes Priscilla with three lighted candles in her hands; how often I have told that child not to carry three candles at once! Run, Ruthie dear, and open the door for her; she will burn herself, or set the house on fire.’

“But ‘Ruthie’ did not run. I sat as still as a stone. ‘Ruth!’ said my grandfather, astonished, while my cousin Stephen laid aside his book, and went toward the door: ‘I can’t open doors for her!’ I burst forth; ‘not if she burns herself up! She tore my exercise into little bits, and I hate her!’

“Children, don’t you feel ashamed of your Grandma? Was ever such a wicked and at the same time silly little burst of rage? It ended with a perfect flood of tears. Grandfather was a wise man, and felt that this was no time for explanations, but as I hurried from the room, I heard cousin Stephen’s mocking voice saying: ‘Let him that thinketh he standeth, take heed lest he fall.’

“It dried my tears in a minute, that verse did. All the Sunday evening talk, and my boastful words, came back to me, and I just hated myself, as I sat in my own little room in the dark, and went over the whole thing. How angry I had been with Priscilla; and yet, only three days before, I had wanted an enemy, that I might show everybody how noble I was! After awhile I cried again; but I don’t think there was any anger in those tears. I did feel so ashamed, and so disappointed in myself. To think that the Lord Jesus could wash the feet of Judas, and I could not open a door for a little girl who had torn my paper! I did want to be a good girl, and follow my Saviour’s example; and it seemed so dreadful to have failed!

“It was a very meek and miserable little girl who stole around to grandfather’s side that evening, in answer to his gentle call. In a low voice, and with a few tears dropping quietly, I told him the whole sad story; and I can seem to hear his voice yet, as he said, sorrowfully, after a few minutes: ‘Yes poor little girl; you are learning how much easier it is to resolve, than to do. ”If ye know these things, happy are ye if ye do them,“ the Saviour said.’

“Mercy was at the piano again, touching the keys softly; she began to sing in a low voice:

Arise, my soul, arise;

Shake off thy guilty fears;

The bleeding sacrifice

In my behalf appears;

Before the throne my surety stands,

My name is graven on his hands—

“‘Yes,’ said my grandfather, and he placed his dear old hand on my head, ‘little Ruth must try again; He knows all about it, and will forgive her; it was because He knew she couldn’t be gentle, and forgiving, and loving, all alone, that He came down here, and lived, and died.’

“I’ve never forgotten it, children; but I can tell you one thing; it was a long time before I did any more boasting. It was a long time before cousin Stephen could see me, without beginning, ‘Let him that thinketh,’ and laughing a little.”

There was silence in the audience for a few minutes after Grandma’s voice ceased; then Ralph made his speech: “Well, I think Priscilla was a bad, wicked girl; and ought to have been punished.”

Pansy.

“They are,” replied Emma Copeland, her companion; “they belong to a German family that have moved into the little house back of Mr. Swift’s.”

“Do you know anything about them?”

Emma smiled; she had been waiting for this question. She knew that sooner or later Miss Vinton would find them out and would want to know all about them, not from curiosity, but from a desire and purpose to aid, if in any way they needed help that she could give.

“The family consists of the father and mother and these two children, besides the baby. The baby is sick, and I think they are quite poor. The children sell flowers; you remember there is a garden attached to that house. They go past every morning with baskets of flowers which they take to town. The father means to raise fruit and vegetables, but as this is the beginning, they are poorly prepared for sickness.”

“I see!” replied Miss Vinton thoughtfully. Presently she said, “Emma, I think you will have to go out upon an errand for me.”

“Down to the Rutgers?” asked Emma.

“Yes; your German will enable you to understand enough to find out their needs. Who is their physician, do you know?”

“I saw Doctor Prince pass this morning, perhaps he was going there.”

“There he is coming up the street now!” exclaimed Miss Vinton; “Emma, ask him to come in for a moment, if he is not in too much haste.”

He came in smiling, saying without being questioned, “You want to know about the Rutgers, I suppose?” he understood Miss Vinton.

“Yes; do they need anything that I can supply?”

“So far as I can judge they would do very well if it were not for this sickness. If you can send comforts for the sick child, it would[319] help. I would suggest the loan of a cot-bed, a soft pillow, and something in the way of a child’s wrapper, besides nourishing, easily digested food. Milk, beef extract—you know what to send?”

“Do you think the child will get well?”

“There is no reason why, with proper care and plenty of nourishing food, the child should not recover. If the family could be relieved so that the mother could give her whole time to the care of the child all would be well, so far as I can see.”

“I understand. I will see what I can do.”

Then the doctor bowed himself out, and as he went down street he said within himself, “I declare! to look at that girl and know what her sufferings are, one would feel that if any one could be excused for letting other people take care of themselves she would be the one. Yet she does more to help the poor, and smooth the beds of the sick and suffering than any other five women in this whole town! The Rutgers will find their path brightening, I am thinking!”

This was a true prophecy. Emma Copeland knew just how to carry out the wishes of her friend, and before noon the sick child lay in a clean white wrapper upon a fresh cot-bed. A little stand stood near with a white napkin spread upon it and a tray with a cup of beef tea, a glass of milk, a tiny saucer of nourishing jelly, a silver spoon on the tray, another beside the glass of medicine, and the mother had been made to understand that she was to give her whole time to the care of her sick child. A loaf of bread, and a piece of meat, and other things from the Vinton larder emphasized this injunction. The children, Carl and Gretchen, moved softly about; Conrad himself peeped in now and then to look upon the little one lying now so comfortably in the white bed, going back to his work with a lighter heart, saying in his native tongue, “God bless the kind lady!” One morning a visitor said to May Vinton:

“I am afraid you trouble yourself too much about other people. I hear you have taken up a poor German family. Why do you not let the authorities take care of the town’s poor?”

“Well, I am egotistical enough to think that I can do some things better than the authorities! They do not give sympathy, nor advice; and this is what some people need most of all. Then again Christ was not speaking of the public authorities when he said, ‘Inasmuch as ye have done it unto one of the least of these ye have done it unto me.’ Besides a little help to these people, such as we would give to any friend in the time of sickness, does not degrade them in their own eyes nor in the estimation of their neighbors, as help from a public charity might. They only needed tiding over a deep place, now they will do well enough.”

And so they did. A few weeks later the cot-bed was again in its place in Mrs. Vinton’s store-room. The sick child was every day putting on flesh and strength. The mother could now care for her household, and the whole family rejoiced, with hearts full of love and gratitude to their new friend. Carl and Gretchen came now and then to visit Miss Vinton, always bringing some little token. The children were shy little things, but it was a great treat to them to go into that handsome room and talk with its fair, though suffering occupant. In their gratitude they treasured every word she uttered, and carried away many useful lessons.

One day, long afterward, when Gretchen had grown to be a young lady and Carl was studying in the High School, some one remarked, “How that family have risen in the world! It is only a few years since they came here, poor and friendless, now they have a home and circle of friends. There’s the Ketlers who came over at the same time. They have not prospered nearly so well; the children have grown up in comparative ignorance. I do not understand what has made the difference.”

“I can explain it,” said another, “there’s an influence going out from that front corner room of the Vinton homestead which has power to revolutionize hearts and lives and to build up families; when the Rutgers first came they fell under that influence, and it is this which has made the difference. I suppose a small sum would cover all the money Miss Vinton expended for the family, but there is a great deal in doing things at the right time and in giving your money and sympathy when most needed.”

“But there must be something back of what we see,” said the first speaker.

“Yes; a consecrated life lies behind the work.”

Faye Huntington.

By Pansy.

“Can’t you raise a few more teaspoons somewhere?” “Give us another plate,” or, “More doughnuts needed;” and Nettie flew hither and thither, washed cups, rinsed spoons, said, “What did I do with that towel?” or, “Where in the world is the bread knife?” or, “Oh! I smell the coffee! maybe it is boiling over,” and was conscious of nothing but weariness and relief when the last cup of coffee was drank, and the last teaspoon washed.

But with the next morning’s sunshine she knew the opening was a success. She counted the gains with eager joy, assuring Jerry that they could have twice as much gingerbread next time.

“And you’ll need it,” said Norm. “I had to tell half a dozen boys that there wasn’t a crumb left. I felt sorry for ’em, too; they were boarding-house fellows who never get anything decent to eat.”

Already Norm had apparently forgotten that he was one who used frequently to make a similar complaint.

There was a rarely sweet smile on Nettie’s face, not born of the chink in the factory bag which she had made for the money; it grew from the thought that she need not hide the bag now, and tremble lest it should be taken to the saloon to pay for whiskey. What a little time ago it was that she had feared that! What a changed world it was!

“But there won’t be such a crowd again,” she said as they were putting the room in order, “that was the first night.”

“Humph!” said that wise woman Susie with a significant toss of her head; “last night you said we mustn’t expect anybody because it was the first night.”

Then “the firm” had a hearty laugh at Nettie’s expense and set to work preparing for evening.

I am not going to tell you the story of that summer and fall. It was beautiful; as any of the Deckers will tell you with eager eyes and voluble voice if you call on them, and start the subject.

The business grew and grew, and exceeded their most sanguine expectations. Mr. Decker interested himself in it most heartily, and brought often an old acquaintance to get a cup of coffee. “Make it good and strong,” he would say to Nettie in an earnest whisper. “He’s thirsty, and I brought him here instead of going for beer. I wish the room was larger, and I’d get others to come.”

In time, and indeed in a very short space of time, this grew to be the crying need of the firm: “If we only had more room, and more dishes!” There was a certain long, low building which had once been used as a boarding-house for the factory hands, before that institution grew large and moved into new quarters, and which was not now in use. At this building Jerry and Nettie, and for that matter, Norm, looked with longing eyes. They named it “Our Rooms,” and hardly ever passed, that they did not suggest some improvement in it which could be easily made, and which would make it just the thing for their business. They knew just what sort of curtains they would have at the the windows, just what furnishings in front and back rooms, just how many lamps would be needed. “We will have a hanging lamp over the centre table,” said Jerry. “One of those new-fashioned things which shine and give a bright light, almost like gas; and lots of books and papers for the boys to read.”

“But where would we get the books and papers?” would Nettie say, with an anxious business face, as though the room, and the table, and the hanging lamp, were arranged for,[323] and the last-mentioned articles all that were needed to complete the list.

“Oh! they would gather, little by little. I know some people who would donate great piles of them if we had a place to put them. For that matter, as it is, father is going to send us some picture-papers, a great bundle of them; send them by express, and we must have a table to put them on.”

So the plans grew, but constantly they looked at the long, low building and said what a nice place it would be.

One morning Jerry came across the yard with a grave face. “What do you think?” he said, the moment he caught sight of Nettie. “They have gone and rented our rooms for a horrid old saloon; whiskey in front, and gambling in the back part! Isn’t it a shame that they have got ahead of us in that kind of way?”

“Oh dear me!” said Nettie, drawing out each word to twice its usual length, and sitting down on a corner of the woodbox with hands clasped over the dish towel, and for the moment a look on her face as though all was lost.

But it was the very same day that Jerry appeared again, his face beaming. This time it was hard to make Nettie hear, for Mrs. Decker was washing, and mingling with the rapid rub-a-dub of the clothes was the sizzle of ham in the spider, and the bubble of a kettle which was bent on boiling over, and making the half-distracted housekeeper all the trouble it could. Yet his news was too good to keep; and he shouted above the din: “I say, Nettie, the man has backed out! Our rooms are not rented, after all.”

“Goody!” said Nettie, and she smiled on the kettle in a way to make it think she did not care if everything in it boiled over on the floor; whereupon it calmed down, of course, and behaved itself.

So the weeks passed, and the enterprise grew and flourished. I hope you remember Mrs. Speckle? Very early in the autumn she sent every one of her chicks out into the world to toil for themselves and began business. Each morning a good-sized, yellow-tinted, warm, beautiful egg lay in the nest waiting for Jerry; and when he came, Mrs. Speckle cackled the news to him in the most interested way.

“She couldn’t do better if she were a regularly constituted member of the firm with a share in the profits,” said Jerry.

The egg was daily carried to Mrs. Farley’s, where there was an invalid daughter, who had a fancy for that warm, plump egg which came to her each morning, done up daintily in pink cotton, and laid in a box just large enough for it. But there came a morning which was a proud one to Nettie. Jerry had returned from Mrs. Farley’s with news. “The sick daughter is going South; she has an auntie who is to spend the winter in Florida, so they have decided to send her. They start to-morrow morning. Mrs. Farley said they would take our eggs all the same, and she wished Miss Helen could have them; but somebody else would have to eat them for her.”

Then Nettie, beaming with pleasure, “Jerry, I wish you would tell Mrs. Farley that we can’t spare them any more at present; I would have told you before, but I didn’t want to take the egg from Miss Helen; I want to buy them now, every other morning, for mother and father; mother thinks there is nothing nicer than a fresh egg, and I know father will be pleased.”

What satisfaction was in Nettie’s voice, what joy in her heart! Oh! they were poor, very poor, “miserably poor” Lorena Barstow called them, but they had already reached the point where Nettie felt justified in planning for a fresh egg apiece for father and mother, and knew that it could be paid for. So Mrs. Speckle began from that day to keep the results of her industry in the home circle, and grew more important because of that.

Almost every day now brought surprises. One of the largest of them was connected with Susie Decker. That young woman from the very first had shown a commendable interest in everything pertaining to the business. She patiently did errands for it, in all sorts of weather, and was always ready to dust shelves, arrange cookies without eating so much as a bite, and even wipe teaspoons, a task which she used to think beneath her. “If you can’t trust me with things that would smash,” she used to say with scornful gravity, to Nettie, “then you can’t expect me to be willing to wipe those tough spoons.”

But in these days, spoons were taken uncomplainingly. Susie had a business head, and was already learning to count pennies and add them to the five and ten cent pieces; and when Jerry said approvingly: “One of these days, she will be our treasurer,” the faintest shadow of a blush would appear on Susie’s face, but she always went on counting gravely, with an air of one who had not heard a word.

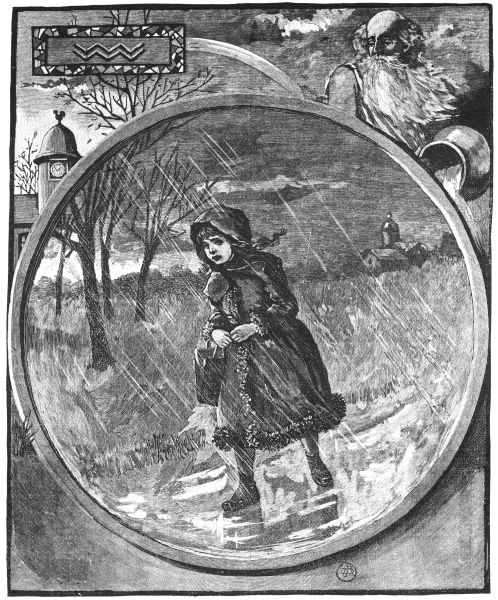

On a certain stormy, windy day, one of November’s worst, it was discovered late in the afternoon that the molasses jug was empty, and the boys had been promised some molasses candy that very evening.

“What shall we do?” asked Nettie, looking perplexed, and standing jug in hand in the middle of the room. “Jerry won’t be home in time to get it, and I can’t leave those cakes to bake themselves; mother, you don’t think you could see to them a little while till I run to the grocery, do you?”

Mrs. Decker shook her head, but spoke sympathetically: “I’d do it in a minute, child, or I’d go for the molasses, but these shirts are very particular; I never had such fine ones to iron before, and the irons are just right, and if I should have to leave the bosoms at the wrong minute to look at the cakes, why, it would spoil the bosoms; and on the other hand, if I left the cakes and saved the bosoms, why, they would be spoiled.”

This seemed logical reasoning. Susie, perched on a high chair in front of the table, was counting a large pile of pennies, putting them in heaps of twenty-five cents each. She waited until her fourth heap was complete, then looked up. “Why don’t you ask me to go?”

“Sure enough!” said Nettie, laughing, “I’d ‘ask’ you in a minute if it didn’t rain so hard; but it seems a pretty stormy day to send out a little chicken like you.”

“I’m not a chicken, and I’m not in the leastest bit afraid of rain; I can go as well as not if you only think so.”

“I don’t believe it will hurt her!” said Mrs. Decker, glancing doubtfully out at the sullen sky. “It doesn’t rain so hard as it did, and she has such a nice thick sack now.”

It was nice, made of heavy waterproof cloth, with a lovely woolly trimming going all around it. Susie liked that sack almost better than anything else in the world. Her mother had bought it second-hand of a woman whose little girl had outgrown it; the mother had washed all day and ironed another day to pay for it, and felt the liveliest delight in seeing Susie in the pretty garment.

The rain seemed to be quieting a little, so presently the young woman was robed in sack and waterproof bonnet with a cape, and started on her way.

Half-way to the grocery she met Jerry hastening home from school with a bag of books slung across his shoulder.

“Is it so late as that?” asked Susie in dismay. “Nettie thought you wouldn’t be at home in a good while; the candy won’t get done.”

“No, it is as early as this,” he answered laughing; “we were dismissed an hour earlier than usual this afternoon. Where are you going? after molasses? See here, suppose you give me the jug and you take my books and scud home. There is a big storm coming on; I think the wind is going to blow, and I’m afraid it will[325] twist you all up and pour the molasses over you. Then you’d be ever so sticky!”

Susie laughed and exchanged not unwillingly the heavy jug for the books. There had been quite wind enough since she started, and if there was to be more, she had no mind to brave it.

“If you hurry,” called Jerry, “I think you’ll get home before the next squall comes.” So she hurried; but Jerry was mistaken. The squall came with all its force, and poor small Susie was twisted and whirled and lost her breath almost, and panted and struggled on, and was only too thankful that she hadn’t the molasses jug.

Nearly opposite the Farley home, their side door suddenly opened and a pleasant voice called: “Little girl, come in here, and wait until the shower is over; you will be wet to the skin.”

It is true Susie did not believe that her waterproof sack could be wet through, but that dreadful wind so frightened her, twisting the trees as it did, that she was glad to obey the kind voice and rush into shelter.

“Why, it is Nettie’s sister, I do believe!” said Ermina Farley, helping her off with the dripping hood.

“You dear little mouse, what sent you out in such a storm?”

Miss Susie not liking the idea of being a mouse much more than she did being a chicken, answered with dignity, and becoming brevity.

“Molasses candy!” said Mrs. Farley, laughing, yet with an undertone of disapproval in her voice which keen-minded Susie heard and felt, “I shouldn’t think that was a necessity of life on such a day as this.”

“It is if you have promised it to some boys who don’t ever have anything nice only what they get at our house; and who save their pennies that they spend on beer, and cider, and cigars to get it.”

Wise Susie, indignation in every word, yet well controlled, and aware before she finished her sentence that she was deeply interesting her audience! How they questioned her? What was this? Who did it? Who thought of it? When did they begin it? Who came? How did they get the money to buy their things? Susie, thoroughly posted, thoroughly in sympathy with the entire movement, calm, collected, keen far beyond her years, answered clearly and well. Plainly she saw that this lady in a silken gown was interested.

“Well, if this isn’t a revelation!” said Mrs. Farley at last. “A young men’s Christian association not only, but an eating-house flourishing right in our midst and we knowing nothing about it. Did you know anything of it, daughter?”

“No, ma’am,” said Ermina. “But I knew that splendid Nettie was trying to do something for her brother; and that nice boy who used to bring eggs was helping her; it is just like them both. I don’t believe there is a nicer girl in town than Nettie Decker.”

Mrs. Farley seemed unable to give up the subject. She asked many questions as to how long the boys stayed, and what they did all the time.

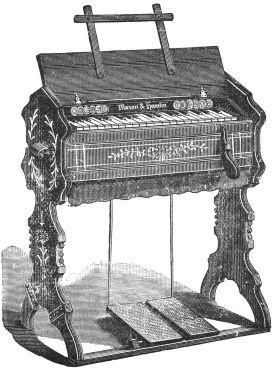

Susie explained: “Well, they eat, you know; and Norm doesn’t hurry them; he says they have to pitch the things down fast where they board, to keep them from freezing; and our room is warm, because we keep the kitchen door open, and the heat goes in; but we don’t know what we shall do when the weather gets real cold; and after they have eaten all the things they can pay for, they look at the pictures. Jerry’s father sends him picture papers, and Mr. Sherrill brings some, most every day. Miss Sherrill is coming Thanksgiving night to sing for them; and Nettie says if we only had an organ she would play beautiful music. We want to give them a treat for Thanksgiving; we mean to do it without any pay at all if we can; and father thinks we can, because he is working nights this week, and getting extra pay; and Jerry thinks there will be two chickens ready; and Nettie wishes we could have an organ for a little while, just for Norm, because he loves music so, but of course we can’t.”

Long before this sentence was finished, Ermina and her mother had exchanged glances which Susie, being intent on her story, did not see.

She was a wise little woman of business; what if Mrs. Farley should say: “Well, I will give you a chicken myself for the Thanksgiving[326] time, and a whole peck of apples!” then indeed, Susie believed that their joy would be complete; for Nettie had said, if they could only afford three chickens she believed that with a lot of crust she could make chicken pie enough for them each to have a large piece, hot; not all the boys, of course, but the seven or eight who worked in Norm’s shop and boarded at the dreary boarding-house; they would so like to give Norm a surprise for his birthday, and have a treat say at six o’clock for all of these; for this year Thanksgiving fell on Norm’s birthday. The storm held up after a little, and Susie, trudging home, a trifle disgusted with Mrs. Farley because she said not a word about the peck of apples or the other chicken, was met by Jerry coming in search of her. The molasses was boiling over, he told her, and so was her mother, with anxiety lest the wind had taken her, Susie, up in a tree, and had forgotten to bring her down again. He hurried her home between the squalls, and Susie quietly resolved to say not a word about all the things she had told at the Farley home. What if Nettie should think she hadn’t been womanly to talk so much about what they were doing! If there was one thing that this young woman had a horror of during these days, it was that Nettie would think she was not womanly. The desire, nay, the determination to be so, at all costs had well nigh cured her of her fits of rage and screaming, because in one of her calm moments Nettie had pointed out to her the fact that she never in her life heard a woman scream like that. Susie being a logical person, argued the rest of the matter out for herself, and resolved to scream and stamp her foot no more.

Great was the astonishment of the Decker family, next morning. Mrs. Farley herself came to call on them. She wanted some plain ironing done that afternoon. Yes, Mrs. Decker would do it and be glad to; it was a leisure afternoon with her. Mrs. Farley wanted something more! she wanted to know about the business in which Nettie and her young friend next door were engaged; and Susie listened breathlessly, for fear it would appear that she had told more than she ought. But Mrs. Farley kept her own counsel, only questioning Nettie closely, and at last she made a proposition that had well nigh been the ruin of the tin of cookies which Nettie was taking from the oven. She dropped the tin!

“Did you burn you, child?” asked Mrs. Decker, rushing forward.

“No, ma’am,” said Nettie, laughing, and trying not to laugh, and wanting to cry, and being too amazed to do so. “But I was so surprised and so almost scared, that they dropped.

“O Mrs. Farley, we have wanted that more than anything else in the world; ever since Mr. Sherrill saw how my brother Norman loved music, and said it might be the saving of him; Jerry and I have planned and planned, but we never thought of being able to do it for a long, long time.”

Yet all this joy was over an old, somewhat wheezy little house organ which stood in the second-story unused room of Mrs. Farley’s house, and which she had threatened to send to the city auction rooms to get out of the way.

She offered to lend it to Nettie for her “Rooms,” and Nettie’s gratitude was so great that the blood seemed inclined to leave her face entirely for a minute, then thought better of it and rolled over it in waves.

“Oh, let me open the round one!” cried Priscilla.

“No, I want to open that myself,” said Rose, “but I’ll let you open the other.”

“Well,” answered Priscilla pleasantly, “I will.”

So saying, she began to tear off the paper, but stopped at an exclamation from Rose.

“See! see! Priscilla, this is old gold satin!”

Sure enough. The round roll proved to be a banner, fastened to a slender brass rod, and finished with a fringe of bright little stars. There was a spray of blue forget-me-nots painted upon it, and as Rose held it up in the sunlight, both girls declared that it was very beautiful indeed.

“Isn’t aunt Alice lovely to send me this,” cried Rose, after they had examined it to their full satisfaction. “But I can’t see how it’s an answer to my letter.”

“Maybe this is the answer,” said Priscilla, taking up the other package. “See, it’s just sheets of paper, fastened together, and lots of writing on them.”

“Yes,” said Rose, “it’s a letter. Why, no it isn’t,” she added. “Oh goody! goody! it’s a story! aunt Alice does tell splendid stories, but I never thought of her writing one. Come, let’s read it.”

The pages of the paper were neatly fastened together, and every word was so plainly written that the two girls could easily read them.

Rose began as follows:

Long ago, in a small village whose cottages clustered upon a mountain slope, a great number of people had come together to celebrate a fair which was held each year for the benefit of that district.

Some had come to sell and some to buy, but many were there for pleasure only. Hucksters and villagers, peasants, and venders of trinkets, or of useful articles—all were there in bustling confusion.

Among the crowd had come a man whom no one could recollect having seen before, and yet he spoke to each whom he met, calling him by name. His manner was dignified, quiet and gentle, and he said that he came neither to buy nor sell, but that he had a wonderful cloak which he would give for the asking. He said, moreover, that it was the safeguard which all travellers wore who journeyed to the Pleasant Land.

Now this kingdom, as the people well knew, lay just beyond their own boundary, toward the setting of the sun; and indeed many of them had wished that they might sometime go thither, for they had heard wondrous reports of its beauty and of the happiness of its people. But they had been deterred from setting out by their affairs at home, and by certain sayings that had got abroad concerning the difficulties of the way. So when the stranger spoke thus, a large number of the people gathered around, and began to comment on the cloak, which hung upon the man’s arm and was of some soft woollen goods. It gave out too, a scent more delicate and sweet than the fragrance of any flower that blooms.

Their criticisms were various. One old peasant said that while he should like to own the cloak, he feared its elegance might excite the contempt of his neighbors, who heretofore had never seen him clothed in anything but coarse garments.

A woman at his elbow also had a voice in the matter.

“The opinion of the neighbors,” said she, “would have little weight with me. But such a cloak hanging from the shoulders would greatly hinder one when at work.”

“Yea, that it would,” answered another, “and work we must, if we would lay up dowries for our daughters, or buy a bit of land for our sons. We have none of us time to journey[331] towards that Western country,” she added reflectively.

Just then a youth wearing the heavy shoes and blouse of a workman drew near. After asking some questions, of the way that led to the Pleasant Land, he declared his intention of setting out that very hour, but added that he should have no need of the mantle, for he was young and sturdy and used to depending upon himself.

“Yet take the cloak!” urged the stranger, “for I have never known any traveller to reach the kingdom without one.”

The youth, however, shook his head, and, laughing lightly, waved his hand in farewell to the people.

He turned his face confidently toward the West, taking a narrow path that led over the mountain, and thence into a little valley.

It was a quiet, peaceful way bordered by grass of a tender green and by flowers whose delicacy showed that they were the blossoms of spring.

One end of the vale was almost shut in by the rocky walls of two high mountains, and the pass between them was barred by a massive gate. Toward this gate the narrow footpath tended. The youth still felt fresh and vigorous and it was not long ere he had reached the portal where at each hand he now beheld a sentinel.

“Few are the days of the journey,” said the first.

“And, alas! wearisome and profitless to him who weareth not the mantle of loving kindness,” said the second.

Immediately the great gate turned noiselessly on its hinges, and when it closed again the youth had entered what proved to be a busy city, with people of all descriptions hurrying along the streets. Two things were most noticeable: there was no one amid all the throng who did not carry a burden of some kind, and there was not one who had not something peculiar to himself which was an annoyance to all whom he met.

“Ah ha!” cried the youth, “I see how it is. If one wants to get through this crowd in any comfort he must use a sharp tongue, and elbows or fists to the best advantage.”

So saying, he set out again upon his way, but was soon met by a band of merry-makers, who seemed inclined to take up most of the path.

“Now for it!” said the youth to himself, and, setting his arms akimbo he attempted to push his way among them. But it was not without several hard blows that he escaped and passed on, so perfectly did the company imitate his manner and attempt to bar his way.

The next to claim his attention was a woman carrying a heavy basket—and more especially as the basket was set around with thorns.

“Let me but escape their sharp points,” cried the youth, “and I care little how hard they press her.”

The result of the encounter was some scratches to both travellers, which might have been saved if each had sought to spare his neighbor pain.

Thus it went from day to-day, sometimes with sharp words, occasionally with blows, but oftener a slight push from one passer to the other, until at last we must leave the youth to pursue his hopeless journey, while we return to the village whence he had set out.

Hazlett.

“I DON’T like grandma at all,” said Fred,

“I don’t like grandma at all,”

And he drew his face in a queer grimace;

The tears were ready to fall,

As he gave his kitten a loving hug,

And disturbed her nap on the soft, warm rug.

“Why, what has your grandma done?” I asked,

“To trouble the little boy?

O what has she done, the cruel one,

To scatter the smiles of joy?”

Through quivering lips the answer came,

“She—called—my—kitty—a—horrid—name.”

“She did? are you sure?” and I kissed the tears

Away from the eyelids wet.

“I can scarce believe that grandma would grieve

The feelings of either pet.

What did she say?” “Boo-hoo!” cried Fred,

“She—called—my—kitty—a—quadruped!”

—Selected.

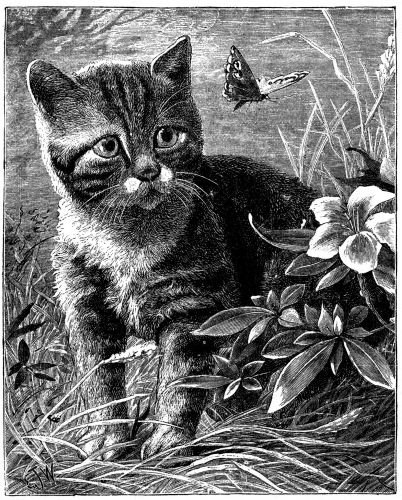

He belonged to a family which is quite small, I believe, though its members are very large, so that when he was but two or three months old, he was as large as many ordinary cats, while his mother was positively colossal!

The way I came to get Mozart was this: his mother, brothers and sisters, and he, were owned by my auntie May, and this same auntie was, once upon a time, about to move from her home in New York, to New Jersey. Knowing how I loved cats, when my mother was visiting her, she proposed that one of the kittens should be taken home to me. So, on the morning of my father and mother’s start, one was procured, and imprisoned in a willow basket which was tied with strong cord. Just as the good-bys were being said, when the basket was reposing in the bottom of the sleigh, and as the driver was raising his reins preparatory to the start, my uncle called out, “Don’t step on the kitten!” To which the driver responded, “It ain’t here!” and grinned broadly, as the disappointing animal jumped to the ground, and sped across the snow to the stable. There was no time to recapture him, for they were then almost afraid they would miss the train, and the sleigh-bells jingled as the sleigh ran down the hill to the depot, the occupants thereof looking curiously at the empty basket in the bottom. “How did he get out?” was the question; and became the question for discussion on the train, as all day my mother and father whizzed along from New York into Pennsylvania. The basket had been found to be just as securely tied as it was when the kitten[333] had first been placed therein, and the only explanation that could be given when my parents reached home was, that the kitten had been in the basket, and was not! Which explanation was, as you may not be surprised to hear, exceedingly unsatisfactory to me, for I dearly loved, and do dearly love all members of the feline kingdom. I never see one but I feel that I must stop and pat its soft fur.

But so far, instead of telling you how I did get Mozart, I have been telling you how I did not get him!

It was about a week after my father and mother had reached home, when, one morning, as we were seated at the breakfast table, the door-bell rang, and an expressman appeared, with a grin on his face that seemed literally to reach from one ear to the other! “’Ere’s a cat!” he exclaimed, and forthwith produced a box a foot or two square, the top of which was decorated, in good-sized letters, with this injunction:

“THIS SIDE UP WITH CARE!”

As the official brought it into the hall, the listeners and lookers-on heard a prolonged “Waa-a-a-a-a-a!” which seemed to echo and re-echo, and at last died away into silence.

“It is the kitten that we didn’t bring!” said my mother, while I ran for a hammer and chisel with which to open the box. When the operation was performed, there jumped out a large, yellow, cat-like kitten, which escaped as far as possible from us, as we tried to grasp it, repeating its mournful, yet decisive cry of—“Waa-a-a-a-a-a!”

Strange to say, he did not recognize us as friends, immediately, but preferred to wait until he formed a closer acquaintance before he was victimized by our embraces or pettings, so he was consigned to the cellar, where he spent much of his time. When we would try to get him up, unless we succeeded in finding him asleep, he would climb a beam, and with great agility elude our efforts to capture him.

Having heard many stories of cats returning to their former homes, and having had some experience in that line ourselves, we were careful to keep Mozart in the house, lest he should make his escape and be seen no more. If he did manage to get out of the kitchen door in a clandestine manner, a ridiculous procession was formed of the bareheaded members of our family, and no peace was given the poor animal, until, after racing around the yard once or twice, he surrendered to our clutches. Truly our anxious efforts to capture the unwilling prisoner must have been a ludicrous sight to any unsympathizing spectator.

We let Mozart sleep in the kitchen, and this gave him the chance he apparently coveted, of sleeping on the table, which he did so obstinately, that we were finally compelled to resort to the expedient of turning the table on its side every night, so that if he slept on it, it would have to be in direct resistance to the law of gravitation!

Mozart also showed a great desire to make the table his dining-room, though this freak was explained on the arrival of my auntie May, who said that he had eaten on an old table in the barn at home. He also probably slept there. But with us he was obliged to make his couch on some old pieces of carpeting.

I now remember that I have not yet given a thorough description of my hero, and as that is properly one of the first things to do in a sketch of this kind, I must hasten to it. Mozart was clothed with a stationary garment of brownish-yellow fur—I do not know whether the artists would call it chrome yellow, yellow ochre, Naples yellow, or what. This garment was at regular intervals striped with rings of a darker shade, and these went completely around his body.

These rings reached their abrupt termination at the tip of the wearer’s tail. It is quite proper to insert just here the fact that once upon a time one of them fell off, and was found, a little wad of dark yellow fur, on the floor of the dining-room.

Mozart had eyes of a rather uncertain color (a peculiarity of his family, which you perhaps have observed), but they were probably nearer the color of his fur than any other of which I think. His head was shapely, and his ears and caudal appendage were graceful. Thus endeth the description of his personal appearance.

The reason for naming Mozart as I did, will be obvious when I state that he had unmistakable musical talent. As I cannot conscientiously praise his voice, I will remain silent about it, simply saying that it was very expressive, and that is more than can be said of some of the so-called fine singers of this country. His vocal organs seemed exceedingly devoid of elasticity, for their use was always confined to the one syllable and note—“Waa-a-a-a-a-a!” differing only in pitch and the length of time it was prolonged.

This difficulty prevented us from always comprehending Mozart’s language, save by his accompanying gestures and actions, and by the surrounding circumstances. But I have said more about his voice than I intended. As I said before, he had unmistakable musical talent. If he had not a musical voice, he had a musical ear (two of them, indeed!) and would listen with rapturous delight to any music. If anyone was playing on my piano, he would come and sit by the side of it, and either listen intently or try to find out by his whiskers from whence the sound proceeded. But if, while he was making these investigations, the piano would play very loud for a moment, he would shrink away, much frightened by the noise. If it was a special friend of his who was playing, he would sometimes jump into the person’s lap, getting as near as possible to the keys. Any rational and unprejudiced persons giving heed to these statements, will believe what I said about Mozart’s ears, I am sure.

Unlike most of his sex, the second John Chrysostom Wolfgang Theophilus Mozart (for we had given him the full name of the great musician, calling him simply Mozart for short) seemed to take an interest in the art of sewing. I may record as a proof of this that when my aunt Julia would be sewing on her machine, my hero would jump up into the vacancy between her spinal column and the chair, and there remain until he was dismissed. If he had been allowed a longer time to stay there than was given him, he would, probably, not have left so soon, but as to that I cannot positively speak.

Before recording the following incident I will repeat the aforesaid statement that every word of this biographical sketch is strictly true, and unto that fact I will set my signature and seal, any time you wish. (Possibly that is one particular in which this differs from most biographical sketches.)

Mozart’s saucer from which he was in the habit of eating and drinking, stood out in the kitchen by the sink. On the day of which I speak, he came in and told in plaintive accents that something was the matter. As I have remarked heretofore, he always left us in uncertainty as to what, for a time, at least. When questioned, however, he earnestly smelled of his empty saucer, and then, jumping up on the sink, put his paw on the cold water faucet, and then, descending, repeated his summons for aid. The saucer was speedily filled with water, and he drank long and eagerly.

This same incident was repeated in every particular, at another time, with the faucet in the bath-room upstairs.

On one occasion Mr. Mozart did a most disgraceful thing—one that was enough to bring disrepute on any family—namely, he ran away. There were several cats living around our barn in those days, and whether he eloped with one of them or not, I never heard, but certain it was that he disappeared, and no trace of him could be found.

But after sin, remorse is sure to come, and conscience speaks earnestly to the sinner, so “in the stilly night,” when “slumber’s chains had bound” the inmates of our house, some of them were awakened by mournful and heart-rending sounds coming from the rear of the house. Under some circumstances, we might have thought we were being serenaded; one of the members of the household was despatched to the back door, to admit the runaway! The lost had returned! the prodigal had come home! And as he rested once more on his couch of carpeting, how sweet it must have smelled to him (in which respect he would have differed from us), and how soft it must have felt, because his conscience was at rest, and because he could once more sleep the sleep of the innocent! Some of his feline friends had returned to the door with him, and had uplifted their voices with his, but only the proper inhabitant of the house was admitted.

Paranete.

She was devotedly attached to her father, and the impression which the teachings of his beautiful, godly life made upon her childish mind was never effaced. Though he died when she was only nine years old, her recollections of him are said to have been remarkably vivid.

She could tell how he looked and talked and acted, things he said and did. Once coming upon him suddenly she found him engaged in prayer, and so lost in communion with God that he did not become conscious of her presence; and she afterwards said that she never forgot the scene, neither did its influence upon her cease while she lived. She was never strong, having inherited a nervous temperament along with a feeble constitution. Once when she was grown to womanhood she said, “I never knew what it was to feel well.”

At the age of twelve years she was very ill with a fever, so ill that the family thought the hour had come when they must part with Elizabeth. But she was spared, perhaps in answer to the mother’s prayers, for that mother recorded in her journal the circumstance of her illness and restoration with a comment upon God’s goodness in sparing the child, wondering whether it might be to the end that she would one day devote herself to the Saviour and do something for the honor of religion. And in the spring of the following year, this child of many prayers, publicly confessed her faith in Christ, and was enrolled among his people.

She grew to girlhood developing a lovely Christian character, also showing a marked talent in composition. She contributed when quite young to the Youth’s Companion. As she passed on through her girlhood into womanhood she became her mother’s faithful friend and assistant, thoughtful for her comfort, and also a tender sympathizing friend towards her brothers.

I want to copy for you a little bit of verse which she wrote for the Youth’s Companion, which I think will please some of our little folks.

What are little babies for?

Say! say! say!

Are they good-for-nothing things?

Nay! nay! nay!

Can they speak a single word?

Say! say! say!

Can they help their mother’s sew?

Nay! nay! nay!

Can they walk upon their feet?

Say! say! say!

Can they even hold themselves?

Nay! nay! nay!

What are little babies for?

Say! say! say!

Are they made for us to love?

Yea! yea! YEA!!!

A friend says of her: “Human nature seems to have been her favorite study. There seemed to be no one in whom she could not find something to interest her, none with whom there was not some point of sympathy.”

And now I wonder if you have guessed, or if you knew all the while that this remarkable woman was the author of some of your favorite books!

The Susy books! ah! your mothers will tell you that these books were their favorites as well as your own! Susy’s Six Birthdays was published thirty-three years ago, then followed the others of the series, and Flower of the Family, and Peterchen and Gretchen, and Tangle Thread, Silver Thread and Golden[336] Thread, besides many others, up to twenty-five volumes. The book which has been more widely read than any other of her works is probably “Stepping Heavenward.”

More than seventy thousand copies have been sold in this country, and the work has also been translated into the French and German languages.

Mrs. Prentiss’ books were all written after her marriage to Rev. George L. Prentiss, which occurred in 1845. Mr. Prentiss was the pastor of a church in New Bedford. Afterwards they lived in New York and, in the year 1866, they went to a quiet place among the Green Mountains to spend the summer, and so delighted were they with the beauties of Dorset that they made it their summer home, building a cottage there in which Mrs. Prentiss died about twelve years later.

It is impossible to give you any account of the varied scenes of her life in such a brief sketch. She was called to pass through many sorrows. The death of the father to which I have already referred; later the loss of her mother, sister, brother and children.

These bereavements came one after another, yet her Christian character only shone out the brighter.

“Though the death of her children tore with anguish the mother’s heart, she made no show of grief, and to the eye of the world her life soon appeared to move on as aforetime. Never again, however, was it exactly the same life. She had entered into the fellowship of Christ’s sufferings and the new experience wrought a great change in her whole being.” She was remarkably happy in the children spared to her, and in all her home life. A friend has written of her:

“I have ever regarded her as favored among women, blessed in doing her Master’s will and in testifying of Him, blessed in her home, in her friends, in her work and blessed in her death.”

Faye Huntington.

By Margaret Sidney.

He did have bestowed upon him, however, at the last moment, in various little rencontres with master and under teachers, several little pleasant attentions that made his heart thrill, and the warm blood mount his brown cheek.

“Allen, I must say I could give you a prize for loving the right, with all my heart.” This from the master, with that peculiar light in his gray eyes that seldom came; and because so seldom, was treasured deep by the one who brought it there. He went further: “My boy, I would give ten years of my life for such a son as you are.” They were in a side recitation room alone, and the master’s hand laid on the lad’s shoulder, no one saw, much less heard the words.

George Edward looked up quickly and gratefully.

“Good-by,” said the master. “If you want any help in vacation over a tough spot in any study, just drop me a hint of it.” There was a smile in the overworked face, that lighted up each hard line.

“Good-by, Allen,” said an under teacher regretfully, as George Edward ran down the passage, “I wish you were to be near me this summer; I shall miss you,” and Mr. Bryan put himself in the way of the boy’s advancement. “I want to thank you for your good influence in the class-room. For you have done more than the teacher sometimes,” he frankly added.

George Edward tried to protest, but it was no use. “Don’t be discouraged,” added the teacher kindly, “if prizes do not fall to you now; but keep on.”

“I should have liked to carry one home to father and mother,” said George Edward honestly.

“Of course; who of us does not?” assented Mr. Bryan. “Let me tell you though, my boy, that the prizes, though late often, that fall to industry and conscientious work, are better worth getting. Take that with you to think of this summer.”

The boys made loud protestations of regret, which goes without saying, at the necessary parting to come. How long the vacation seemed, looking from the standpoint of June. How impossible to wait till September before George Edward’s round countenance should burst upon them like a ray of sunshine, and his cheery voice call to some sport, in which they could see no hint of fun if he did not lead off. But all things are finally pronounced ended. So at last George Edward found himself at home, with the only prospect of enjoyment ahead of him, an invitation to visit at Uncle Frost’s.

“I’m sorry it’s all the outing we can give you this summer, my boy,” said Mother Allen soberly; “your father intended to take you if he went on the Maine trip, but Mr. Porter wanted the Western business done now, and that is altogether too expensive to be thought of.”

George Edward’s eyes glistened. That Western trip would have made a vacation beating every other boy’s that he had known. He broke out eagerly, “O mother—” then stopped. She looked pale and troubled.

“It’s a good enough place at Uncle Frost’s,” he finished indifferently; “when do I start?”

“No, it isn’t very pleasant,” said Mrs. Allen truthfully. “I’m sorry you couldn’t have gone into the country; but we can’t afford it unless I go and shut up the house, and I can’t do that, because grandma isn’t well, and must come here.”

“Never mind,” said George Edward, “there’s some fun in it, anyway. We’ll call it bully.”

“It will be a change,” said his mother, “and[339] that’s all you can say, and you’ll have a chance to learn something new, and see other people.”

“When does he want me to come?” asked George Edward, dashing at the letter again.

“Next week,” said Mrs. Allen.

“All right; I’ll put my traps together, and be off. Gainesburg is the cry now,” cried George Edward.

But for once the boy was in luck. Two days after Uncle Frost’s house had received him, Mrs. Allen was reading the following letter:

My Dear Mother:

Hurrah—hurrah—hurrah! Uncle Frost is a brick (beg pardon, mother)! He’s given me a royal, out-and-out invite to go to the White Mountains with the family. Expenses all thrown in, etc., etc. Start on Saturday. Telegraph “yes” please.

Your affectionate Son,

George Edward.

“Yes” was telegraphed over the hills on Thursday, and for two weeks our boy revelled in the bliss of mountain life, with quantities of fun, frolic and adventure thrown in by the way, to return all made over, to Uncle Frost’s, there to meet the ill news travelling fast over the electric wires:

“Your father died suddenly at St. Paul. Come at once.”

Had it come so soon? George Edward looked life in the face this vacation time, accepted his cross, bade good-by to all hopes of ever entering school or college life again, and thanked God for the situation in the drug store that the apothecary around the corner gave him.

His father’s affairs, well looked over, gave no hope of anything but the direst economy for the widow. As for the son, he must go to work, and at once.

“Now we will see if he holds out a saint,” one boy was mean enough to think, seeing George Edward hurry to his place of work every morning bright and early. Other eyes quite as sharp, though far from cruel, were on him. It was an awful ordeal for any boy to pass through; most of all, because of the commonplaceness of the sacrifice he was daily making. Had he marched up to the cannon’s mouth, and courted death to save his mother’s life, this would have been easy compared to the monotonous dead-level existence he was enduring. For to the active boy, alert for an excitement, wide awake for novelty, with every muscle crying out for exercise and change, the close confinement of the small store, and the routine work, were torture indeed. He began to show the effects of such a life, and in three weeks his mother was aghast to find that her boy had grown suddenly thin and pale.

“Why, George Edward,” she cried, “you can’t stay in that store.”

“I must,” said George Edward doggedly.

“But you will die,” cried poor Mrs. Allen, “then what shall I do?” And the tears began to come.

George Edward thought a bit. Then he said “There isn’t anything else, mother, only work on a farm. But it’s August now, who’d give me a chance at it, pray tell?”

“I shall try,” said his mother, rousing herself, “you will die where you are.” And she seized paper and pen and wrote the following:

A boy of sixteen who has just lost his father wishes a place to work on a farm for the remainder of the season. Only those persons of unexceptional references who wish such a farm hand not afraid to work, need apply to

Mrs. E. C. Allen,

—— ——

George Edward was in a fever of excitement, though he tried not to show it, all the next three days. His mother met with such poor success in her efforts to conceal her state of mind, that she went around the house, a bright spot in either cheek, scarcely able to set herself with calmness at any task. At last, on the evening of the third day, this letter was drawn from the post-office:

Respected Madam:

If your son really wants to work, send him on. Here’s a letter from my paster, maybe that will be satisfyin’. Three dollars a week an’ board. That’s what I pay. Yours to command,

Job Stevens,

Blueberry Hill.

The “paster’s” letter reading remarkably well, and a friend investigating the matter with thoroughness for Mrs. Allen, finding it all right, George Edward’s trunk was packed, and he at once dispatched for Blueberry Hill.

It was evening when he arrived there.

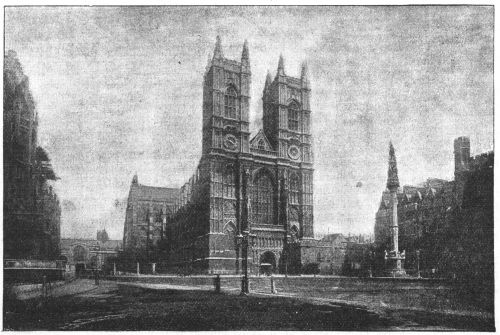

As the grand procession moved along the queen was very kind and gracious, and the poor came up to her carriage, with nosegays for her, and when any one wanted to speak to her, she would stop the carriage. The coronation took place at Westminster. The crown was placed upon her head amidst great shouting and rejoicing. Elizabeth placed a ring upon her own finger, to signify that she was espoused to the realm of England, and that ring she wore for forty years.

Elizabeth was a fine scholar, and in many respects her reign was prosperous, but she was very irritable, and did several things which have marred and stained her name.

Of course there is very much to learn about her which you must read yourself in history. You will there be told all about her troubles with the unfortunate Mary, Queen of Scots, who was her relative, and who after being a prisoner in Fotheringay Castle for many years, was executed.

She was very beautiful. It is thought that Elizabeth envied her remarkable beauty, which is a very wicked thing to do. Elizabeth, though homely, was very vain, and dearly loved compliments.

At one time there were many pictures of the queen circulated, much resembling her, and therefore not very handsome. So the queen issued a formal proclamation against them, forbidding the people to sell them, and stating that an artist would be employed to make a true picture of her. What a pity she did not realize that beauty of mind, kindness of heart, nobleness of character, and above all, the true Christian spirit, were much more to be desired than anything so frail and perishable as human beauty. Never, in any reign, has England known such pomp and splendor as in Elizabeth’s time. She was fond of parade. She once went to church[341] surrounded by a thousand men in armor, and drums and trumpets sounding.

You will read in her life about the Earl of Essex, who was a prime favorite with Elizabeth for a long time, but he offended her, and she caused him to be executed. She had once given him a ring, to be returned to her in case he ever needed her aid. When in prison he sent it, but it was intercepted. The queen got angry because the ring did not come, and therefore thought Essex was very proud. After his death, however, she learned about the ring, and was therefore thrown into deep distress, and soon pined away and died. She had about three thousand dresses at the time of her death, in her wardrobe. Her last words were, “Millions of worlds for an inch of time.”

She was buried in Westminster Abbey, where many of the great of England sleep in unbroken repose.

Ringwood.

After some years he was sent to Florence to preach. At first his plain and severe denunciations of the prevailing sins of the time repelled the people who preferred to go where they could hear more polished and less conscience-awakening sermons, and Savonarola mourned over his apparent failure to reach the hearts of the multitude[342] who were rushing on in the ways of sinful indulgence. But his soul was moved with zeal “for the redemption of the corrupt Florentines. He must, he would, stir them from their lethargy of sin.” He was convinced that he was in the line of duty, and the more indifferent his hearers were the more anxious he grew for their awakening. Actuated by this motive he suddenly found his voice and revealed his powers as an orator. God had shown him how to reach men’s hearts at last, and “he shook men’s souls by his predictions and brought them around him in panting, awestruck crowds;” then at the close of his denunciations of sin, his voice would sink into tender pleading and sweetly he would speak of the infinite love and mercy of God the Father.

After a time, St. Mark’s Church would not hold the crowds which came to hear him and he was invited to preach in the Cathedral. He was now acknowledged as a power in Florence, and the great Lorenzo de’ Medici who was then at the height of his fame as a ruler, was alarmed, and he sent a deputation of five of the leaders of the government to advise the monk to be more moderate in his preaching, hinting that trouble might follow a disregard of this advice. But the monk was unmoved. He replied, “Tell your master that although I am an humble stranger and he the city’s lord, yet I shall remain and he will depart.” He also declared that he owed his election to God, and not to Lorenzo, and to God alone would he render obedience.

Lorenzo was very angry, but he tried to silence the monk by bribery, but Savonarola would not be bribed nor driven. He continued to preach with great fervor, denouncing sin in high places as well as in low. You know that in those times corruption had crept into the Church of Christ, and it was against these sins of the Church that his most scathing denunciations were hurled. He had many followers, and he pushed his reforms in Church and State. His enemies grew more bitter and fiercer. Remonstrances from those in authority had no effect. He was offered a cardinal’s hat, but would not accept the conditions. He said, “I will have no hat but that of the martyr, red with mine own blood.”