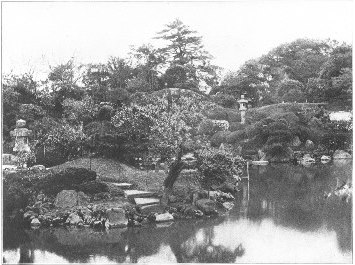

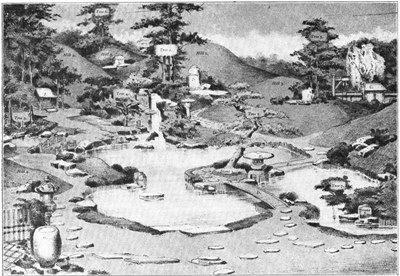

| PLATE XI | DAIMIO'S GARDEN AT SHINJIKU |

THE BROCHURE SERIES

|

THE |

||

| 1900. | FEBRUARY | No. 2. |

The Japanese garden is not a flower garden, neither is it made for the purpose of cultivating plants. In nine cases out of ten there is nothing in it resembling a flower-bed. Some gardens may contain scarcely a sprig of green; some (although these are exceptional) have nothing green at all and consist entirely of rocks, pebbles and sand. Neither does the Japanese garden require any fixed allowance of space; it may cover one or many acres, it may be only ten feet square; it may, in extreme cases, be much less, and be contained in a curiously shaped, shallow, carved box set in a veranda, in which are created tiny hills, microscopic ponds and rivulets spanned by tiny humped bridges, while queer wee plants represent trees, and curiously formed pebbles stand for rocks. But on whatever scale, all true Japanese gardening is landscape gardening; that is to say, it is a living model of an actual Japanese landscape.

But, though modelled upon an actual landscape, the Japanese garden is far more than a mere naturalistic imitation. To the artist every natural view may be said to convey, in its varying aspects, some particular mental impression or mood, such as the impression of peacefulness, of wildness, of solitude, or of desolation; and the Japanese gardener intends not only to present in his model the features of the veritable landscape, but also to make it express, even more saliently than the original, a dominant sentimental mood, so that it may become not only a picture, but a poem. In other words, a Japanese garden of the best type is, like any true work of art, the representation of nature as expressed through an individual artistic temperament.

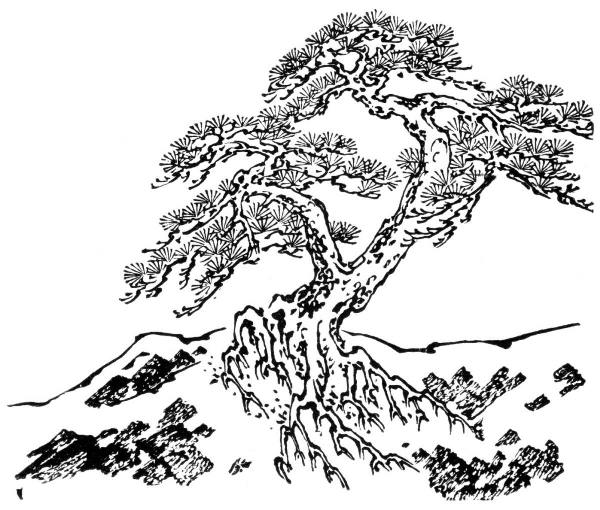

Through long accumulation of traditional methods, the representation of natural features in a garden model has come to be a highly conventional expression, like all Japanese art; and the Japanese garden bears somewhat the same relation to an actual landscape that a painting of a view of Fuji-yama by the wonderful Hokusai does to the actual scene—it is a representation based upon actual and natural forms, but so modified to accord with accepted canons of Japanese art, so full of mysterious symbolism only to be understood by the initiated, so expressed, in a word, in terms of the national artistic conventions, that it costs the Western mind long study to learn to appreciate its full beauty and significance. Suppose, to take a specific example, that in the actual landscape upon which the Japanese gardener chose to model his design, a pine tree grew upon the side of a hill. Upon the side of the corresponding artificial hill in his garden he would therefore plant a pine, but he would not clip and trim its branches to imitate the shape of the original, but rather, satisfied that by so placing it he had gone far enough toward the imitation of nature, he would clip his garden pine to make it correspond, as closely as circumstances might permit, with a conventional ideal pine tree shape (such a typical ideal pine tree is shown in the little drawing on page 25), a shape recognized as the model for a beautiful pine by the artistic conventions of Japan for centuries, and one familiar to every Japanese of any pretensions to culture whatsoever. And, as there are recognized ideal pine tree shapes, there are also ideal mountain shapes, ideal lake shapes, ideal water-fall shapes, ideal stone shapes, and innumerable other such ideal shapes.

In like manner in working out his design the gardener must take cognizance of a multitude of religious and ethical conventions. The flow of his streams must, for instance, follow certain cardinal directions; in the number and disposition of his principal rocks he must symbolize the nine spirits of the Buddhist pantheon. Some tree and stone combinations are regarded as fortunate, and should be introduced if possible; while other combinations are considered unlucky, and are to be as carefully avoided.

| MODEL PINE TREE |

But endless and complex and bewildering to the western mind as are the rules and formulæ, æsthetic, symbolistic and religious, by which the Japanese landscape gardener is bound, it is apparent that most of them were originally based upon purely picturesque considerations, and that the earliest practitioners of this very ancient art, finding that certain types of arrangement, certain contrasts of mass or line, led to harmonious results, formulated their discoveries into rules, much as the rules of composition are formulated for us today in modern artistic treatises. Moreover, as Japanese gardening was at first, and for many years, practised only as a sacred art and by the priests of certain religious cults, it was but natural that they should impart to these laws which they had discovered symbolic and religious attributes. To preserve the arts in their purity, and to prevent the vulgar from transgressing æsthetic laws, combinations productive of beauty were represented as auspicious, and endowed with moral significance, while inharmonious arrangements were condemned as unlucky or inauspicious. It is one of the cardinal principles of Japanese philosophy, for example, that the inanimate objects of the universe are endowed with male or female attributes, and that from a proper blending of the two sex essences springs all the harmony, good fortune and beauty in this world. When, therefore, two contrasting shapes, colors, or masses, such as those of the sturdy pine tree and the graceful willow, were found conducive of a pleasing combination, they were named respectively male and female, and it became almost a religious observance to thereafter place them together in their attributed sex relations.

It will be apparent, therefore, that with an art of such antiquity, originally practised as a religious ceremony, and in a country in which inherited tradition has such binding force, that there should have grown up around the craft of landscape gardening, a code of the most complex laws, rules, symbolism, formulæ and superstitions, which the artistic gardener is bound to learn and to implicitly obey.

And yet it must not be considered that the art of the Japanese gardener has, through the accumulation of its limiting rules, become a mere science, or that its practice is only a mechanical expression of pre-established artistic conventions. On the contrary, the landscape gardener must be, first of all, a student and lover of nature, for his art is founded on nature; he must be next a poet, in order to appreciate and re-express in his garden the moods of nature, and he must thereafter be a lifelong student of his craft, that he may design in accordance with its established principles. But the very number of these precepts makes a wide range of choice among them possible; and in almost every instance, even the most apparently superstitious and fanciful of them will be found, upon examination, to make in some way for beauty in the final result. To those who can understand it, moreover, the mystical symbolism of a Japanese garden design is an added source of pleasure, just as a knowledge of symphonic form makes a symphony more enjoyable to the musician.

"After having learned," writes Mr. Lafacdio Hearn, "something about the Japanese manner of arranging flowers, one can thereafter consider European ideas of floral decoration only as vulgarities. Somewhat in the same way, and for similar reasons, after having learned what a Japanese garden is, I can remember our costliest and most elaborate gardens at home only as ignorant displays of what wealth can accomplish in the creation of incongruities that violate nature."

The Japanese artist who is called upon to design a new garden will first examine the site, and confer with his patron regarding its proposed size and character. If the site be large, and already furnished with natural hills, trees and water, the gardener will, of course, take advantage of these features. If it possess none of them, he will inquire the amount of money that can be placed at his disposal for the construction of artificial hills, lakes and the like; and this amount of money will also determine another important point, namely, the degree of elaboration with which the whole is to be treated. For all works of Japanese art whatsoever are rigorously divided into three styles, the "rough" style, the "finished" style and the "intermediate" style; and the adoption of any one style governs the degree of elaboration to which any part of the design may be carried. If the "rough" style is chosen, even the smallest accessory detail—a rustic well, or a stone lantern—must be rude to harmonize; if the "finished" style, no detail that does not correspond can be admitted,—a restriction greatly conducive to harmony, and one to which the almost invariable congruity and unity of Japanese compositions is due.

Knowing, then, the size and character of the site, and his patrons' wishes as to expense and elaboration, the landscape gardener will next choose the model landscape, or landscapes, upon which he is to base his design. He will find them divided by convention into two classes: those representing "Hill Gardens" and "Flat Gardens." (There is a third class, the "Tea Garden," but as this is of a separate genus altogether, it will be considered later.)

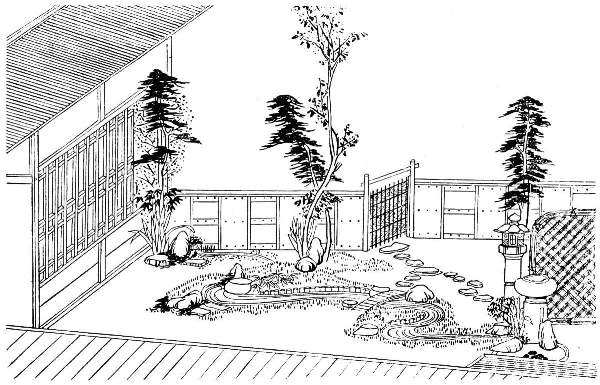

Showing some important features of arrangement close to a dwelling,—the water basin with its rock-hidden drain, the lantern, with its fire-box partially concealed by the trained branches of the pine tree.]

The "Hill Garden" class is the more elaborate of the two, and that best adapted for large gardens, and for those where the natural site is undulating, or where money can be spent in artificial grading. The "Hill Garden" has many different species, such, for instance, as the "Rocky-ocean" style, which represents in general an inlet of the sea surrounded by high cliffs, the shores spread with white sea-sand, scattered with sea rocks and grown upon with pine trees trained to look as if bent and distorted with the sea wind; or the "Wide-river" style, showing a spreading stream issuing from behind a hill and running into a lake; or the "Reed-marsh" style, in which the hills are low, rounded sand dunes bordering a heath or moor in which lies a marshy pool overgrown with rushes; and many other such "styles," all well recognized, all carefully discriminated and all modelled upon actual landscapes. In any case, however, the true "Hill Garden" must present, in combination, mountain or hill, and water scenery.

If on the contrary the site be small and flat, and the garden is to be less elaborate, the "Flat" style is usually chosen. The "Flat Garden" is generally supposed to represent either the floor of a mountain valley, a moor, a rural scene, or the like; and as in the case of "Hill Gardens," there are a number of well recognized and classical examples.

Having, then, determined that the garden is to be of one of these types, and having also determined the degree of elaboration with which it is to be treated, the gardener will next proceed to fix the scale upon which it is to be constructed,—and this scale (a most important factor) is decided by the size of the garden area, and the number of features which must be introduced into the scene; for it is clear that if the site be large, and one in which natural hills or large bodies of water are already present, the scale will be a normal one; whereas if a whole valley, with hills, a river, a water-fall, a lake and a wooded slope is to be presented in a space of some fifty or sixty square yards, the scale of the whole must be miniature. But whatever scale is adopted, every tree, every rock, every pool, every accessory detail must be made exactly to correspond to it. A hill that might in a large garden be a natural elevation of considerable size, with full sized trees planted upon it, might in a smaller one modelled after the same design, be only a hillock, planted with dwarfed trees or shrubs; or in a still smaller area become only a clump of thick-leaved bushes trimmed to resemble a hill-shape, or even a large boulder flanked by tiny shrubs. So skilfully and completely do Japanese gardeners carry out any scale that they have determined upon, however, that Mr. Hearn describes a garden of not much above thirty yards square, that when viewed through a window from which the garden alone was visible, seemed to be really an actual and natural landscape seen from a distance,—a perfect illusion.

Having determined upon the natural model and the scale for it, the gardener will begin by imitating on the given site the main natural land conformations of his original, building hills or grading slopes, excavating lake basins and cutting river channels. These natural features he will next proceed to elaborate, and it is in this process of elaboration that he must most carefully observe all those complex laws and conventions to which we have before alluded.

Showing some characteristic garden accessories,—stepping-stones, a lantern, a common variety of bamboo fence. The lantern and plum tree conventionally mark the approach to a little shrine reached through a Shinto archway by means of a row of stepping-stones.]

Almost every Japanese garden, be it hilly or flat, large or small, rough or elaborate, must be made to contain, in some form, water, rocks and vegetation, as well as such architectural accessories as bridges, pagodas, lanterns, water-basins, stepping-stones and boundary fences or hedges.

Water may be made to present the sea, lakes, rivers, brooks, water-falls, springs, or combinations of them. It is not, of course, possible to imitate the open sea with any degree of realism; and when a coast scene is presented, it is customary to fashion the body of water as an ocean inlet, the supposed juncture with the sea being hidden by a cliff or hill. Lake scenes are much more common. There are six "classical" shapes into which lake forms are divided, some of them more formal for use near buildings, others more natural for use in wilder landscapes. It is an axiom that every lake, or pool, or stream represented must have both its source and outlet indicated. Sometimes the inflow is indicated by a stream issuing from behind a hillock which conceals its artificial source, sometimes a deep pool of clear water may suggest a spring, sometimes a water-fall (at least ten individual and distinct forms of water-fall are recognized as admissible into a properly planned garden) supplies the water; but water showing no inflow or outlet is termed "dead" water, and is regarded with the contempt bestowed upon all shams and falsities in art.

In cases where it is impossible to introduce actual water into a garden its presence is often imitated by areas of smooth or rippled sand, the banks of the sand bed treated to simulate the banks of a natural lake or stream, and islands and bridges introduced to further the illusion.

Extreme importance is attached to the use in gardens of natural stones, rocks and boulders; and some teachers of the craft go so far as to maintain that they constitute the skeleton of the design, and that their proper disposition and selection should receive the primary consideration. In large gardens there may be as many as one hundred and thirty-eight principal rocks and stones, each having its special name and function; but in smaller ones as few as five rocks will often suffice. Whatever the style of landscape composition, three stones, the "Guardian Stone," the "Stone of Worship," and the "Stone of the Two Deities" must never be dispensed with, their absence being regarded as inauspicious. On the same principle there are certain stone forms which are considered unlucky, and are therefore invariably avoided.

The raised parts of a Japanese garden are supposed to represent the nearer eminences or distant mountains of natural scenery, and the stones which adorn them are intended to imitate either minor undulations and peaks, or rocks or boulders on their slopes. In like manner there are no less than twenty "water" stones, which have their places in lake and river scenery, as well as nine varieties of "cascade" stones alone. There are also sixteen stones which have their functions solely in the adornment of islands.

After the contours of land and water and the principal rocks and stones have been arranged, the distribution of garden vegetation is considered; for the garden rocks form only the skeleton of the design and are only complete when embellished with vegetation.

| TYPICAL ARRANGEMENTS OF STONES WITH FOLIAGE |

In the grounds of the larger temples, avenues and groves of trees are planted with the same formality adopted in Western gardens, but in true landscape gardening such formal arrangements are never resorted to. Indeed it is an axiom that when several trees are planted together they should never be placed in rows, but always in open and irregular groups. The rules for planting the clumps are rigidly determined; and these clumps may be disposed in double, triple or quadruple combinations, while these combinations may be again [Pg 31]regrouped according to recognized rules based upon contrasts of form, line and color of foliage. Occasionally, when it is the designer's purpose to represent a natural forest or woodland, formulas are, of course, disregarded, and the trees are grouped together irregularly.

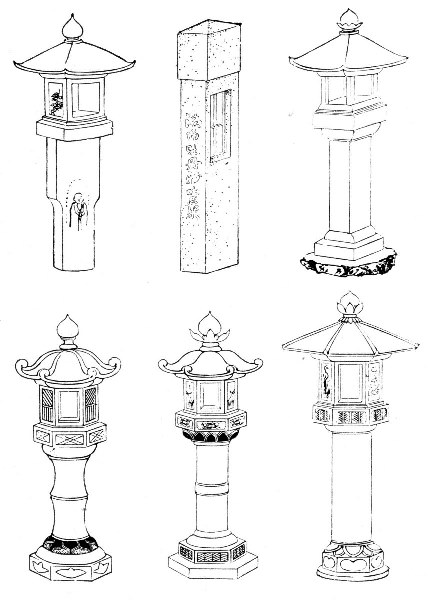

| TYPICAL VARIETIES OF GARDEN LANTERN |

The architectural accessories of the Japanese garden,—bridges, pagodas, lanterns, water-basins, wells and boundary fences or hedges, we have no space to consider in detail. It must suffice to say that their use is rather ornamental than to aid in the landscape imitation, and that they are generally placed in the foreground of the scene. There are many beautiful designs for each of them, and their use and disposition is formally regulated.

Important accessories in the Japanese garden are Stepping-Stones. Turf is not used in the open spaces, but these are spread with sand, either pounded smooth or raked into elaborate patterns. This sand, kept damp at all times, presents a cool and fresh surface, and to preserve its smoothness, which the marks of the Japanese wooden clogs would sadly mar, a pathway is invariably constructed across such areas with stones called "stepping-stones," or "flying stones" as they are occasionally termed, on account of the supposed resemblance in their composition to the order taken by a flight of birds. In the simpler and smaller gardens such stones form one of the principal features of the design. As nothing could be less artistic than a formal arrangement of stones at regular intervals, not to speak of the difficulty of keeping one's balance while walking upon them, the Japanese gardener therefore uses certain special stones and combinations having definite shapes and dimensions, the whole being arranged with a studied irregularity. The sketch on this page exhibits three typical arrangements. The left hand group shows stepping-stones as arranged to lead from a tea room. The centre group shows stepping-stones combined with a "pedestal stone" which marks the point from which a typical cross view in the garden is to be observed. The right hand group shows the stones near a veranda with a "shoe-removing" stone terminating the series.

| ARRANGEMENTS OF STEPPING-STONES |

A third main type of garden, neither "Flat" nor "Hilly," to which we have before referred, properly speaking, is called the "Tea Garden." "Tea Gardens" are used for the performance of the "tea ceremony," and to explain the principle of its design would require a preliminary explanation of the intricacies of that ceremony itself, to which an entire volume might easily be devoted. A most cursory indication of the principal use and requirements must here suffice.

"Tea Gardens" are divided into outer and inner inclosures separated by a rustic fence. The outermost inclosure contains a main entrance gate, and behind this there is often a small building in which it is sometimes the custom to change the clothing before attending the ceremony. The outer inclosure also contains a picturesque open arbor, called the "Waiting Shed," which plays an important part in tea ceremonies, for here the guests adjourn at stated intervals to allow of fresh preparations being made in the tiny tea room. The tea room is entered from the garden through a low door, about two and one-half feet square, placed in the outer wall and raised two feet from the ground, through which the guests are obliged to pass in a bending posture indicative of humility and respect. The rustic well forms an important feature of the inner garden, as do the principal lantern and the water-basin. A portion of the inner inclosure of a "Tea Garden" in the Tamagawa, or Winding-river style, showing the stream, bridge, lantern, water-basin, and an arrangement of stones, including the indispensable "Guardian Stone," is represented in the drawing on this page. All these separate features are connected, according to very rigid principles, by stepping-stones which make meandering routes between them, and form the skeleton of the whole design.

| INNER INCLOSURE OF A TEA GARDEN, "TAMAGAWA" STYLE |

We can, perhaps, no better summarize this necessarily sketchy review of a complex subject, than by reproducing here, from Professor Conder's very elaborate monograph, "Landscape Gardening in Japan," (Tokio, 1893)—from which most of the information in this article has been derived, and to which the student of the subject is referred,—a figured model of an ordinary "Hill Garden" in the finished style. The numbers refer to the titles of the principal hills, stones, tree clumps and accessories, the positions of which are all relatively established by rule.

| FIGURED MODEL OF AN ORDINARY HILL GARDEN IN THE FINISHED STYLE |

| Hills: 1, Near Mountain. 2, Companion Mountain. 3, Mountain Spur. 4, Near Hill. 5, Distant Peak. Stones: 1, Guardian Stone. 2, Cliff Stone. 3, Worshipping Stone. 4, View Stone. 5, Waiting Stone. 6, "Moon-Shadow" Stone. 7, Cave Stone. 8, Seat of Honor Stone. 9, Pedestal Stone. 10, Idling Stone. Trees: 1, Principal Tree. 2, "View Perfecting" Tree. 3, Tree of Solitude. 4, Cascade-Screening Tree. 5, Tree of Setting Sun. 6, Distancing Pine. 7, Stretching Pine. Accessories: A, Garden Well. B, Lantern. C, Garden Gate. D, Boarded Bridge. E, Plank Bridge. F, Stone Bridge. G, Water Basin. H, Lantern, I, Garden Shrine. |

Hill 1 represents a mountain of considerable size in the middle distance, in front of which should be placed the cascade which feeds the lake; while Hills 2 and 3 are its companions, the depressions between them being planted with shrubs giving the idea of a sheltered dale. Hill 5 represents a distant peak in the perspective.

The model shows ten important stones. The "Guardian Stone," 1, representing the dedication stone of the garden, occupies the most central position in the background, and in this case forms the flank of the cliff over which the cascade pours. The broad flat "Worshipping Stone," 3, indicating the place for worship, is placed in the foreground, or some open space. The "Moon-Shadow Stone," 6, occupies an important position in the distant hollow between two hills and in front of the distant peak, its name implying the sense of indistinctness and mystery attached to it.

The term "tree" as used in the diagram often refers to an arrangement or clump of trees. The "Principal Tree," 1, is placed in the centre of the background, and is usually a large and striking specimen. The "View Perfecting Tree," 2, generally stands alone, and its shape is carefully trained to harmonize with the foreground accessories. The "Tree of [Pg 35]Solitude," 3, is a group to afford a shady resting place. The "Tree of the Setting Sun," 5, is planted in the western part of the garden to intercept the direct rays of the sunset. The titles of the other features in the model will probably be found self explanatory.

Errata. |

By an unfortunate misprint in the preceding issue of The Brochure Series, Prof. A. D. F. Hamlin, author of the article on the "Ten Most Beautiful Buildings in the United States," was announced as Professor of Architecture in "Cornell" University, instead of in "Columbia" University. Mr. Hamlin's correct title is: "Adjunct-Professor of Architecture, Columbia University."

In the same issue (page 15), it was stated that the terraces and approaches to the Capitol at Washington were the work of Mr. Edward Clark. This was an error: they were designed by Mr. Frederick Law Olmstead, and elaborated by Mr. Thomas Wisedell under Mr. Olmstead's supervision.