LEAFLET NO. 59

LEAFLET NO. 59

HINTS ON WOLF AND COYOTE TRAPPING

By Stanley P. Young, Principal Biologist, in Charge Division of Predatory-Animal and Rodent Control, Bureau of Biological Survey

Issued July, 1930

HE RANGE of coyotes and wolves in the United States to-day is confined mainly to the immense area west of the Mississippi River. Wolves, however, have been so materially reduced in numbers west of the one-hundredth meridian that except for those drifting into the United States from the northern States of Mexico, they are the cause of little concern. The areas now most heavily infested with wolves are in Alaska, eastern Texas, Oklahoma, Arkansas, Missouri, Wisconsin, Minnesota, and Michigan. A few r of these animals are found also in northern Louisiana and eastward along the Gulf coastal area into Mississippi. Coyotes, on the other hand, exist in all the Western States, as well as in the Mid-Western States above listed as inhabited by wolves. They have also been reported in Orleans County, N. Y., and in southeastern Alabama where introduced.

Coyotes and wolves make serious inroads on the stocks of sheep and lambs, cattle, pigs, and poultry, as well as on the wild game mammals and the ground-nesting and insectivorous birds of the country. Wherever these predatory animals occur in large numbers, they are a source of worry and loss to stockmen, farmers, and sportsmen because of their destructiveness to wild and domestic animals. The coyote is by far the most persistent of the predators of the western range country; and moreover, it is a further menace because it is a carrier of rabies, or hydrophobia. This disease was prevalent in Nevada, California, Utah, Idaho, and eastern Oregon in 1916 and 1917, and later in Washington and in southern Colorado. Since this widespread outbreak, sporadic cases of rabid coyotes have occurred each year in the Western States. The coyote has also been found to be a carrier of tularemia, a disease of wild rabbits and other rodents that is transmissible and sometimes fatal to human beings.

Much of the country inhabited by coyotes and wolves is purely agricultural and contains vast grazing areas, and a large percentage of the food of the animals of those areas consists of the mutton, beef, pork, and poultry produced by the stockman and farmer, and the wild game that needs to be conserved. It is a matter of great importance, therefore, to the Nation’s livestock-producing sections, as well as to the conservationist’s plan of game protection or game propagation, that coyotes and wolves be controlled in areas where they are destructive. Trapping has been found to be one of the most effective methods of capturing these animals.

Every wild animal possesses some form of defense against danger or harm to itself. With wolves and coyotes this is shown in their acute sense of smell, alert hearing, and keen eyesight. To trap these animals successfully, one must work to defeat these highly developed senses when placing traps, and success in doing so will come only with a full knowledge of the habits of the two predators and after repeated experiments with trap sets. Of the two animals, possibly the wolf is the more difficult to» 3 « trap. It is cunning, and as it matures from the yearling stage to the adult its cleverness at times becomes uncanny. Individual coyotes also possess this trait, particularly old animals that have been persistently hunted and trapped with crude methods.

The steel trap, in sizes 3 and 4 for coyotes and sizes 4K and 14 for wolves (114 in Alaska), is recommended for capturing these large predators. Steel traps have been used in this country by many generations of trappers, and although deemed by many persons to be inhumane, no better or more practical device has yet been invented to take their place.

On the open range coyotes and wolves have what are commonly referred to as “scent posts,” or places where they come to urinate. The animals usually establish these posts along their runways on stubble of range grasses, on bushes, or possibly on some old bleached-out carcasses. Where ground conditions are right for good tracking, these scent posts may be detected from the toenail scratches on the ground made by the animals after they have urinated. This habit of having scent posts and of scratching is similar to that noted in dogs. As wolves and coyotes pass over their travel ways, they generally stop at these posts, invariably voiding fresh urine and occasionally excreta also.

Finding these scent posts is of prime importance, for it is at such points that traps should be set. If such posts 'can not be found, then one can be readily established, if the travel way of the coyote or wolf has been definitely ascertained, by dropping scent of the kind to be described later on a few clusters of weeds, spears of grass, or stubble of low brush. The trap should then be set at this point. Any number of such scent stations can thus be placed along a determined wolf or coyote travel way.

Time consumed in finding a wolf or coyote scent post is well spent, for the success of a trap set depends upon its location. Coyotes and wolves can not be caught unless traps are set and concealed where the animals will step into them. If traps are placed where the animals are not accustomed to stop on their travel ways, the chances are that they will pass them by on the run. Even if a wolf or a coyote should detect the scent, the fact that it is in an unnatural place may arouse the suspicion of the animal and cause it to become shy and make a detour. Often the fresh tracks of shod horses along wolf and coyote runways are sufficient to cause the predators to leave the trail for some distance. A lone wolf is much more cautious than a pack of wolves running together.

Travel ways of coyotes and wolves are confined to open and more or less broken country. In foraging for food over these runways the animals may use trails of cattle or sheep, canyons, old wood roads, dry washes, low saddles on watershed divides, or even highways in thinly settled areas. Any one of these places, or any combination of them, may be a wolf or coyote runway. Wolves have been known to cover a circuitous route of more than a hundred miles in an established runway. It is in such country that their scent posts should be looked for.

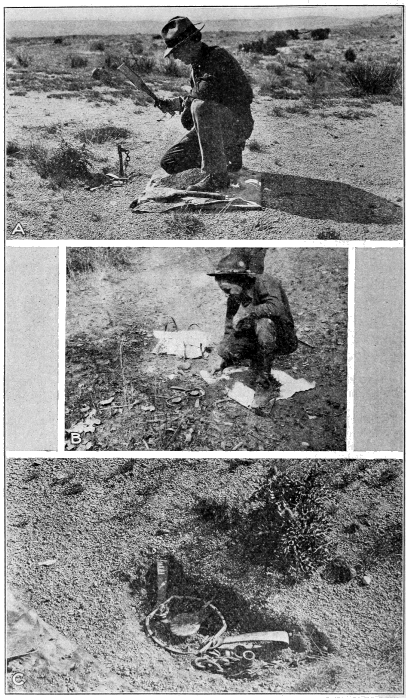

Figure 1.—First step in setting traps for wolves and coyotes. The stubble and woods near the traps are the scent post: A, Trap and stake in position, and “setting cloth”; B, doable trap set; C, trap set showing distance from scent post, and stake driven into ground

Places where carcasses of animals killed by wolves and coyotes or of animals that have died from natural causes have lain a long time offer excellent spots for setting traps, for wolves and coyotes often revisit these carcasses. It is always best to set the traps a few yards away from the carcasses at weeds, bunches of grass, or low stubble of bushes. Other good situations are at the intersection of two or more trails, around old bedding grounds of sheep, and at water holes on the open range. Ideal places for wolf or coyote traps are points 6 to 8 inches from the bases of low clusters of weeds or grasses along a trail used as a runway.

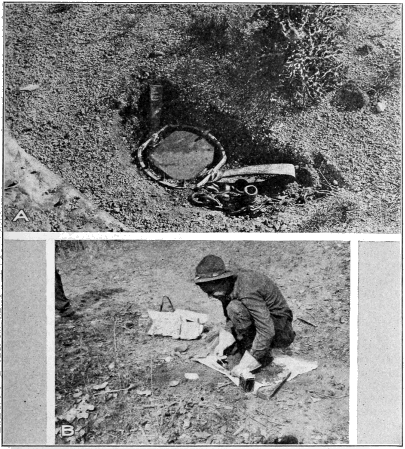

Figure 2.—Burying the traps: A, A shoulder of dirt should be built up around and under the pan as a foundation for the trap pad, which is shown in place; B, trap completely bedded, springs and jaws covered, and pan unobstructed, ready for trap pad to be put in place

Traps used should be clean, with no foreign odor. In making a set, a hole the length and width of the trap with jaws open is dug with a trowel, a sharpened piece of angle iron, or a prospector’s pick. While digging, the trapper stands or kneels on a “setting cloth,” about 3 feet square, made of canvas or of a piece of sheep or calf hide. If canvas is used, the human scent may be removed by previously burying it in an old manure pile. The livestock scent acquired in this process is usually » 6 « strong enough to counteract any scent later adhering to the setting cloth and likely to arouse suspicion. The dirt removed from the hole dug to bed the trap is placed on the setting cloth. The trap is then dropped into the hole and firmly bedded so as to rest perfectly level.

Instead of using digging tools, some hunters bed the trap where the ground is loose, as in sandy loam, by holding it at its base and with a circular motion working it slowly into the ground even with the surface and then removing the dirt from under the pan before placing the trap pad to be described later. An important advantage of this method is that there is less disturbance of the ground around the scent post than when tools are used, for the secret of setting a trap successfully is to leave the ground as natural as it was before the trap was concealed. A double trap set, as shown in Figure 1, B, may be used and is often preferred to a single set for coyotes.

The trap may be left unanchored or anchored. Either draghooks may be attached to a chain (preferably 6 feet long) fastened by a swivel to the trap base or to a spring, and all buried underneath, or a steel stake pin (fig. 1, A and C) may be used, attached by a swivel to a 6-foot chain fastened to the base or a spring of the trap. If a stake pin is used, it should be driven full length into the ground near the right-hand spring of the trap, with the trigger and pan directly toward the operator. Anchoring the trap is the preferred method, because animals caught are obtained without loss of time and because other animals are not driven out of their course by one of their kind dragging about a dangling, clanking trap, often the case where drag hooks are used.

The next stage (fig. 2, A and B) is the careful burying of the trap and building up of a so-called shoulder around and under the pan. This should be so built that, when it is completed, the shape of the ground within the jaws of the trap represents an inverted cone, in order to give a foundation for the pan cover, commonly called the “trap pad.” The trap pad may be made of canvas, of old “slicker cloth,” or even of a piece of ordinary wire fly screen cut into the shape shown in Figure 2, A. The trap pad to be effective must contain no foreign odor that might arouse the suspicion of wolf or coyote.

In placing the trap pad over the pan and onto the shoulders of the dirt built up for carrying it, the utmost care must be taken to see that no rock, pebble, or dirt slips under the pan, which would prevent the trap from springing. With the trap pad in place (fig. 2, A), the entire trap is carefully covered with the remaining portion of earth on the setting cloth (fig. 3, B).

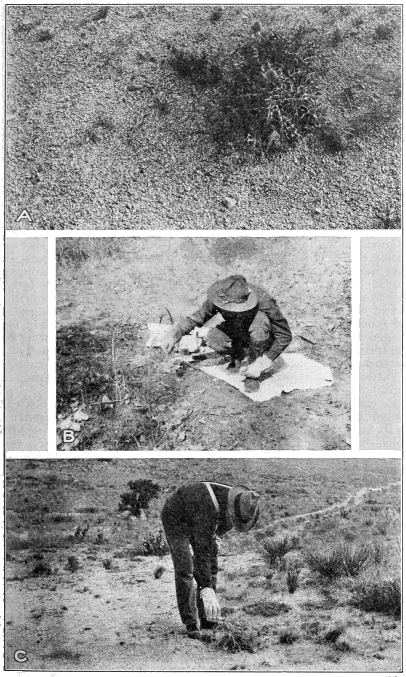

Cover traps at least half an inch deep with dry dust if possible. It is well to have the covered surface over the trap a little lower than the surrounding ground, for a wolf or a coyote is then less apt to scratch and expose the trap without springing it. Furthermore, the animal will throw more weight on a foot placed in a depression, and thus is more likely to be caught deeper on the foot and with a firmer grip. All surplus earth on the setting cloth not needed for covering the trap should be taken a good distance away and scattered evenly on the ground.

Figure 3.—Completed trap sets, with ground made to blend again with surroundings. The small stone in the foreground of A and the triangular stick in B serve to break the natural gait of the animal and cause it to step directly over it onto the pan of the trap; C, place the scent on side of brush or weed that is nearest the trap

A few drops of scent are now applied (fig. 3, C) to the weed, cluster of grass, or stubble used as the scent post. A scent tested and successfully used by Government hunters is made as follows:

Put into a bottle the urine and the gall of a wolf or a coyote, depending on which is to be trapped, and also the anal glands, which are situated under the skin on either side of the vent and resemble small pieces of bluish fat. If these glands can not be readily found, the whole anal parts may be used. To every 3 ounces of the mixture add 1 ounce of glycerin, to give it body and to prevent too rapid evaporation, and 1 grain of corrosive sublimate to keep it from spoiling.

Let the mixture stand several days, then shake well and scatter a few drops on weeds or ground 6 or 8 inches from the place where the trap is set. The farther from the travelway the trap is set, the more scent will be needed. A little of the scent should be rubbed on the trapper’s gloves and shoe soles to conceal the human odor.

If the animals become “wise” to this kind of scent, an effective fish scent may be prepared in the following way:

Grind the flesh of sturgeon, eels, trout, suckers, carp, or other oily variety of fish in a sausage mill, place in strong tin or iron cans, and leave in a warm place of even temperature to decompose thoroughly. Provide each can with a small vent to allow the escape of gas (otherwise there is danger of explosion), but screen the aperture with a fold of cloth to prevent flies depositing eggs, as the scent seems to lose much of its quality if many maggots develop. This scent may be used within 3 days after it is prepared, but it is more lasting and penetrating after a lapse of 30 days. It is also very attractive to livestock, and its use on heavily stocked ranges is not recommended, as cattle are attracted to such scent stations and will spring the traps.

An excellent system for a hunter to follow is to commence with a quantity of ground fish placed in large iron containers, similar to a milk can. As the original lot is used on the trap line, it should be replenished by adding more ground fresh fish. The addition from time to time of new material seems to improve the quality of the scent mixture.

Where no moisture has fallen, rescenting of scent posts need be done only every four or five days. In wet weather every third day is good practice. For dropping the scent it is best to use a 2 to 4 ounce shaker-corked bottle.

The actual trapping of a wolf or a coyote by the method here described occurs when the animal comes over its runway and is attracted to the “post” by the scent that has been dropped. In approaching the spot for a smell the animal invariably puts a foot on the concealed pan; the jaws are thus released and the foot is securely held. The place where a wolf or a coyote has thus been caught affords an excellent location for a reset after the animal has been removed from the trap. This is due to the natural scent dropped by the animal while in the trap.

It is advisable always to wear gloves while setting traps and to use them for no other purpose than for trap setting.

U. S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE: 1930

For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, Washington, D. C. Price 5 cents