|

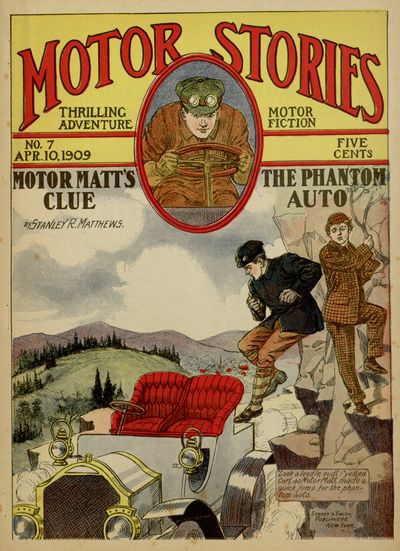

THRILLING ADVENTURE |

MOTOR FICTION |

|

NO. 7 APR. 10, 1909. |

FIVE CENTS |

|

MOTOR MATT'S CLUE |

THE PHANTOM AUTO |

| By Stanley R. Matthews. |

Street & Smith, Publishers, New York. |

| MOTOR STORIES | |

| THRILLING ADVENTURE | MOTOR FICTION |

Issued Weekly. By subscription $2.50 per year. Entered according to Act of Congress in the year 1909, in the Office of the Librarian of Congress, Washington, D. C., by Street & Smith, 79-89 Seventh Avenue, New York, N. Y.

| No. 7. | NEW YORK, April 10, 1909. | Price Five Cents. |

Motor Matt's Clue;

OR,

THE PHANTOM AUTO.

By the author of "MOTOR MATT."

CHAPTER I. A NIGHT MYSTERY.

CHAPTER II. DICK FERRAL.

CHAPTER III. LA VITA PLACE.

CHAPTER IV. THE HOUSE OF WONDER.

CHAPTER V. SERCOMB.

CHAPTER VI. THE PHANTOM AUTO AGAIN.

CHAPTER VII. SURROUNDED BY ENEMIES.

CHAPTER VIII. THE KETTLE CONTINUES TO BOIL.

CHAPTER IX. ORDERED AWAY.

CHAPTER X. A NEW PLAN.

CHAPTER XI. A DARING LEAP.

CHAPTER XII. DESPERATE VILLAINY.

CHAPTER XIII. TIPPOO.

CHAPTER XIV. IN THE NICK OF TIME.

CHAPTER XV. A STARTLING INTERRUPTION.

CHAPTER XVI. THE PRICE OF TREACHERY.

CHAPTER XVII. THE LUCK OF DICK FERRAL.

BILL, THE BOUND BOY.

A WINTER STORY OF COLORADO.

Matt King, concerning whom there has always been a mystery—a lad of splendid athletic abilities, and never-failing nerve, who has won for himself, among the boys of the Western town, the popular name of "Mile-a-minute Matt."

Carl Pretzel, a cheerful and rollicking German lad, who is led by a fortunate accident to hook up with Motor Matt in double harness.

Uncle Jack, a wealthy Englishman, with ways and means of his own for accomplishing things, who leads a hermit's life in the wilds of New Mexico.

Dick Ferral, a Canadian boy and a favorite of Uncle Jack; has served his time in the King's navy, and bobs up in New Mexico where he falls into plots and counter-plots, and comes near losing his life.

Ralph Sercomb, a cousin of Dick Ferral, and whose sly, treacherous nature is responsible for Dick's troubles.

Joe Mings,

Harry Packard,

Balt Finn,} three unscrupulous friends of Sercomb, all motor-drivers, and who come from Denver to help Sercomb in his nefarious plans.

A NIGHT MYSTERY.

"Oh, py shiminy! Look at dere, vonce! Vat it iss, Matt? Br-r-r! I feel like I vould t'row some fits righdt on der shpot! It's a shpook, you bed you!"

A strange event was going forward, there under the moon and stars of that New Mexico night. The wagon-road followed the base of a clifflike bank, and at the outer edge of the road there was a precipitous fall into Stygian darkness.

A second road entered the first through a narrow gully. A few yards beyond the point where the thoroughfares joined an automobile was halted, its twin acetylene lamps gleaming like the eyes of some fabled monster in the semigloom.

Two boys were on the front seat of the automobile, and one of them had leaned over and gripped the arm of the lad who had his hands on the steering-wheel. The eyes of the two in the car were staring ahead.

What the boys saw was sufficiently startling, in all truth.

Out of the gully, directly in advance of them, had rolled a white automobile—springing ghostlike out of the darkness as it came under the glare of the acetylene lights.

The white car was a runabout, with two seats in front and an abnormally high deck behind. It carried no lamps, moved with weird silence, and, strangest of all, there was no one in either seat! Yet, with no hand on the steering-wheel, the white car made the dangerous turn out of the gully into the main road with the utmost ease, and was now continuing on between the foot of the cliff and the brink of the chasm with a steadiness that was—well, almost hair-raising.

Motor Matt, who had been piloting the Red Flier slowly and carefully along that dangerous course, had cut off the power and thrown on the brake the instant the white car leaped into sight. As he gazed at the receding auto, and noted the conditions under which it was moving, a gasp escaped his lips.

"That beats anything I ever heard of, Carl!" he muttered.

"It vas a shpook pubble!" clamored Carl Pretzel. "I don'd like dot, py shinks. Durn aroundt, or pack oop,[Pg 2] or do somet'ing else to ged oudt oof der vay. Shpooks iss pad pitzness, und schust vy dit it habben don't make no odds aboudt der tifference. Ged avay, Matt, und ged avay kevick! Py Chorge! I vas so vorked oop as I can't dell."

Carl released Matt's arm, pulled a big red handkerchief out of his pocket and wiped the perspiration from his face. He was having a chill and perspiring at the same time; and his mop of towlike hair was trying to stand on end.

Matt started the Red Flier. There was gas enough in the cylinders to take the spark, so that it was not necessary to get out and use the crank.

To turn around on such a road was out of the question, even if Matt had desired to do so—which he did not. Nor did he reverse the engine and back away, but started along in the trail of the white car.

"Vat you vas doing, anyvay?" cried Carl.

"I'm going to follow up that phantom auto and see if I can find what controls it."

"You vas grazy, Matt! Meppy ve ged kilt oof ve ged too nosey mit dot machine. It don'd pay to dake some chances in a case like dose. I know vat I know, und dot's all aboudt it. Go pack pefore der shpook pubble hits us und knock us py der cliff ofer!"

Carl was excited. He believed in "spooks" and Motor Matt didn't, and that was all the difference between them.

"Don't lose your nerve, Carl——"

"It vas gone alretty!" groaned Carl, crouching in his seat, hanging on with both hands and staring ahead with popping eyes.

"Nothing's going to happen," went on Matt. "There's no such thing as ghosts, Carl."

"Don'd I know ven I see vone?" quavered Carl. "You t'ink I vas plind, Matt. Dot pubble moofs mitoudt nopody to make it go like vat it does; und it don'd hit der rocks or go ofer der cliff. Donnervetter! I vish I vas somevere else, py grickets. Ach! I vas so colt like ice, und I sveat; und my teet' raddle so dot I don't hardly peen aple to shpeak anyt'ing."

"We've seen the Red Flier moving along without anybody aboard, Carl," said Matt, in an attempt to quiet his chum's fears.

"Yah, so," answered Carl, "aber der Ret Flier vas moofing along some shdraighdt roads, und der veel vas tied mit ropes so dot she keeps a shdraighdt course. Aber dot shpook pubble don'd haf nopody on, und der veel ain'd tied, und yet she go on und on like anyding. Ach, I peen as goot as a deadt Dutchman, I know dot."

While the boys were thus arguing matters the Red Flier was trailing the phantom auto. The white machine, still controlled in some mysterious manner, glided safely along the treacherous trail. It was beyond the glow of the acetylene lights, but the moonlight brought it out of the gloom like a white blur.

In advance of the runabout Matt saw a place where the road curved around the face of the cliff. The phantom auto melted around the curve.

Hardly had it vanished when a loud yell was wafted back to the ears of the boys.

Carl nearly jumped out of his seat, and a frightened whoop escaped his lips.

"Ach, du lieber!" he wailed. "Ve vas goners, Matt, ve vas bot' goners. I can't t'ink oof nodding, nod efen my brayers! Vat vas dot? I bed you it vas der teufel gedding retty to chump on us. Whoosh! I never had some feelings like dis yet."

"Don't be foolish, Carl," said Matt. "There was no spook back of that yell, but real flesh and blood. Keep a stiff upper lip and we'll find out all about it."

Just then the Red Flier rounded the turn. A long, straightaway course lay ahead of the boys, lighted brightly by the lamps and, farther on, by the moon and stars. But the phantom auto had vanished!

Matt was astounded, and brought the Red Flier to a halt once more. With a high wall of rock on one side of the road, and an abyss on the other, where could the white car have gone?

"Ach, chiminy!" chattered Carl. "Poof, und avay she goes. Der pubble vas snuffed oudt, und schust meldet indo der moonpeams. Dis vas a hoodoo pitzness, all righdt. Ve ged der douple-gross pooty soon, I bed you someding for nodding!"

"But that yell——"

"Der teufel make him! Id don'd vas nodding but der shpook feller, saying in der shpook languge, 'Ah, ha, I ged you pooty kevick!' I vish dot I hat vings so I could fly avay mit meinseluf."

Matt got down from the car and started to walk forward. Carl let off a yell and scrambled after him.

"Don'd leaf me, Matt! It vas goot to be mit somepody ad sooch a dime. Misery lofes gompany, und dot's vat I need."

"Come on, then," laughed Matt.

"Vere you go, hey?"

"I'm going to see if I can discover what became of that car."

"It vent oop on der moonpeams," averred Carl earnestly. "You can look, und look, und dot's all der goot it vill do. Dake it from me, Matt, dot ve don'd vas——"

"Ahoy, up there!"

The words seem to come from nowhere—or, rather, from everywhere, which was equivalent to the same thing.

Carl gave a roar and tried to push himself into the face of the cliff.

"Vat I tell you, hey?" he groaned. "Dere it vas again. Matt, more und vorse dan der odder dime. Righdt here iss vere ve kick some puckets; yah, leedle Carl Pretzel und Modor Matt King vill be viped oudt like a sponge mit a slate."

"Keep still, Carl!" called Matt. "There's no ghost back of that voice. Listen a minute."

Turning in the road, Matt lifted his head.

"Hello!" he called.

"Hello, yourself!" came the muffled but distinct response.

The voice seemed to float out of the blackness of the chasm, and Matt stepped closer to the edge.

"Who are you?" he asked.

"My name'll be M-u-d, Mud, if you don't man a line an' give me a boost out of this."

"Where are you?"

"Down the wall, hanging like a lizard to a piece of scrub. Can't you tell by my talk where I am? From the looks, I'm about a fathom down; but I'll be all the way down if you don't get a move on. Shake yourself together, mate, and be lively!"

Carl's fear, as this conversation proceeded, was gradually lost in curiosity. The voice from over the brink[Pg 3] had a very human ring to it, and the Dutch boy was beginning to feel easier in his mind.

"Get the rope out of the tonneau, Carl," called Matt. "Hurry up!"

"Bully!" came from below, the person on the wall evidently hearing Matt's order to Carl. "That's the game, matey. If you've got a rope, reeve a bowline in the end and toss it over. I'm a swab if I don't think it's up to you to do it, too. I wouldn't have slid over the edge if your white devil-wagon hadn't made me dodge out of the way. How'd it—Wow!"

The voice below broke off with a startled whoop.

"What's the matter?" called Matt.

"The bush pulled out a little," was the answer, "and I thought I was gone. Rush things up there, will you?"

At that moment Carl came with the rope, and Matt, standing above the place where he supposed the unseen speaker to be, allowed the noosed end to slide down to him.

"I've got it!" cried the voice. "Are you ready to lay on?"

"Catch hold, Carl," said Matt, "and brace yourself. All ready," he shouted, when he and Carl were planted firmly with the rope in their hands.

"Then here goes!"

The rope grew taut under a suddenly imposed weight, and Matt and Carl laid back on it and hauled in.

DICK FERRAL.

A young fellow of seventeen or eighteen crawled over the brink of the chasm and sat on the rocks to breathe himself. The lamps of the Red Flier shone full on him, so that Matt and Carl were easily able to take his sizing.

He wore a flannel shirt, cowboy-hat and high-heeled boots. His trousers were tucked in his boot-tops. His bronzed face was clean-cut, and he had clear, steady eyes.

"Wouldn't that just naturally rattle your spurs?" he asked, looking Matt and Carl over as he talked. "I thought you fellows had put a stamp on that rope and were sending it by mail. It seemed like a good while coming, but maybe that was because I was hangin' to a twig and three leaves with the skin of my teeth." He swerved his eyes to the Red Flier. "You've lit your candles," he added, "since you scared me out of a year's growth by flashin' around that bend. If you'd had the lights going then, I guess I could have crowded up against the cliff instead of makin' a jump t'other way and going over the edge."

"You vas wrong mit dot," said Carl. "It vasn't us vat come along und knocked you py der gulch."

"That's the truth," added Matt, noting the stranger's startled expression. "We were following that other automobile, and stopped when we heard you yell."

Without a word the rescued youth got up and went back to give the Red Flier a closer inspection. When he returned, he seemed entirely satisfied that he had made a mistake.

"I did slip my hawser on that first idea, and no mistake," said he. "As I went over, I saw out of the clew of my eye that the other flugee was white. Yours is bigger, and painted different. What are your names, mates?"

Matt introduced himself and Carl.

"I'm Dick Ferral," went on the other, shaking hands heartily, "and when I'm at home, which is about once in six years, I let go the anchor in Hamilton, Ontario. I'm a sailor, most of the time, but for the last six months I've been punching cattle in the Texas Panhandle. A crimp annexed my money, back there in Lamy, and I'm rolling along toward an old ranch my uncle used to own, called La Vita Place. It can't be far from here, if I'm not off my bearings. Where are you bound, mates, in that steam hooker?"

"Santa Fé," answered Matt.

"Own that craft?" and Dick Ferral nodded toward the car.

"No; it belongs to a man named Tomlinson, who lives in Denver. Carl and I brought it to Albuquerque for him. When we got there, we found a line from him asking us to bring the car on to Santa Fé. If we got there in two weeks he said it would be time enough, so we're jogging along and taking things easy."

"If you've got plenty of time, I shouldn't think you'd want to do any cruising in waters like these, unless you had daylight to steer by."

"We'd have reached the next town before sunset," Matt answered, "if we hadn't had trouble with a tire."

"It was a good thing for me you were behind your schedule, and happened along just after I turned a handspring over the cliff. If you hadn't, Davy Jones would have had me by this time. But what became of that other craft? I didn't have much time to look at it, for it came foaming along full and by, at a forty-knot gait, but as I slid over the rock I couldn't see a soul aboard."

"No more dere vasn't," said Carl earnestly. "Dot vas a shpook pubble, Verral. You see him, und ve see him, aber he don'd vas dere; nodding, nodding at all only schust moonshine!"

"Well, well, well!" Ferral cast an odd glance at Motor Matt. "That old flugee was a sort of Flying Dutchman, hey?"

"I don'd know somet'ing about dot," answered Carl, shaking his head gruesomely, "aber I bed you it vas a shpook."

"There wasn't any one on the car," put in Matt, "and it's a mystery how it traveled this road like it did. It came out of a gully, farther back around the bend, right ahead of us. We followed it, and when we had come around that turn it had vanished."

"What you say takes me all aback, messmates," said Ferral. "I'm no believer in ghost-stories, but this one of yours stacks up nearer the real thing in that line than any I ever heard. Say," and Ferral seemed to have a sudden idea, "if you fellows want a berth for the night, why not put in at La Vita Place?"

"Sure, Matt, vy nod?" urged Carl.

"How far is it, Ferral?" asked Matt.

"It can't be far from here, although I'm a bit off soundings on this part of the chart. I've never been to Uncle Jack's before—and shame on me to say it—and likely I wouldn't be going there now if the old gentleman hadn't dropped off, leaving things in a bally mix. They say I'm to get my whack from the estate, if a will can be found, although I don't know why anything should come to me. I've always been a rover, and Uncle Jack didn't like it. My cousin, Ralph Sercomb—I never liked[Pg 4] him and wouldn't trust him the length of a lead line—stands to win his pile by the same will. Ralph is at the ranch, and, I suppose, waitin' for me with open arms and a knife up his sleeve."

"When did your uncle die?" inquired Matt.

"As near as I can find out, he just simply vanished. All he left was a line saying he was tired of living alone, that he never could get me to give up my roaming and come and stay with him, and that while Ralph came often and did what he could to cheer him up, he had always had a soft place in his heart for me, and missed me. He said, too, in that last writing of his, that when he was found his will would be found with him, and that he hoped Ralph and I would stay at the ranch until the will turned up. That's what came to me, down in the Texas Panhandle, from a lawyer in Lamy. As soon as I got that I felt like a swab. Here I've been knockin' around the world ever since I was ten, Uncle Jack wanting me all the time and me holding back. Now I'm coming to the ranch like a pirate. Anyhow, that's the way it looks. If Uncle Jack was alive he'd say, 'You couldn't come just to see me, Dick, but now that I'm gone, and have left you something, you're quick enough to show up.'"

Ferral turned away and looked down into the blackness of the gulch. He faced about, presently, and went on:

"But it wasn't Uncle Jack's money that brought me. Now, when it's too late, I'm trying to do the right thing—and to make up for what I ought to have done and didn't do in the past. A fellow like me is thoughtless. He never understands where he's failed in his duty till a blow like this brings it home to him. He's the only relative Ralph and I had left, and I've acted like a misbemannered Sou'wegian.

"When I went to sea, I shipped from Halifax on the Billy Ruffian, as we called her, although she's down on the navy list as the Bellerophon. From there I was transferred to the South African station, and the transferring went on and on till my time was out, and I found myself down in British Honduras. Left there to come across the Gulf of Galveston, and worked my way up into the Texas Panhandle, where I navigated the Staked Plains on a cow-horse. Had six months of that, when along came the lawyer's letter, and I tripped anchor and bore away for here. As I told you, a crimp did me out of my roll in Lamy. He claimed to be a fellow Canuck in distress, and I was going with him to his hotel to see what I could do to help him out. He led me into a dark street, and somebody hit me from behind and I went down and out with a slumber-song. Then I got up and laid a course for Uncle Jack's. If you'll go with me the rest of the way, I'll like it, and you might just as well stop over at La Vita Place and make a fresh start for Santa Fé in the morning."

"We'll do it," answered Matt, who was liking Dick Ferral more and more as he talked.

"Dot's der shtuff!" chirped Carl. "Oof you got somet'ing to eat at der ranch, und a ped to shleep on, ve vill ged along fine."

"I guess we can find all that at the place, although I don't think the ranch amounts to much. Uncle Jack was queer—not unhinged, mind you, only just a bit different from ordinary people. He never did a thing in quite the same way some one else would do it. When he left England, a dozen years ago, he stopped with us a while in Hamilton, and then came on here and bought an old Mexican casa. He wanted to get away from folks, he said, but I guess he got tired of it; if he hadn't, he wouldn't have been so dead set on having me with him after my parents died. The bulk of his money is across the water. But hang his money! It's Uncle Jack himself I'm thinking about, now."

"We'll get into the car," said Matt, "and go on a hunt for La Vita Place."

Matt stepped to the crank. As he bent over it, Carl gave a frightened shout.

"Look vonce!" he quavered, pointing along the road with a shaking finger. "Dere iss some more oof der shpooks!"

Matt started up and whirled around. Perhaps a hundred feet from where the three boys were standing, a dim figure could be seen, silvered uncannily by the moonlight.

"Great guns, Carl!" muttered Matt. "Your nerves must be in pretty bad shape. That's a man, and he's been walking toward us while we were talking."

"Vy don'd he come on some more, den?" asked Carl. "Vat iss he shtandin' shdill mit himseluf for? Vy don'd he shpeak oudt und say somet'ing?"

"Hello!" called Ferral. "How far is it to La Vita Place, pilgrim?"

The form did not answer, but continued to stand rigid and erect in the moonlight.

"Ve'd pedder ged oudt oof dis so kevick as ve can," faltered Carl, crouching back under the shadow of the car. "I don'd like der looks oof dot feller."

"Let's get closer to him, Ferral," suggested Matt, starting along the road at a run.

"It's main queer the way he's actin', and no mistake," muttered Ferral, starting after Matt.

Matt was about half-way to the motionless figure, when it melted slowly into the black shadow of the cliff. On reaching the place where the figure had stood, it was nowhere to be seen.

"What do you think of that, Ferral?" Matt asked in bewilderment.

Ferral did not reply. His eyes were bright and staring, and he leaned against the rock wall and drew a dazed hand across his brows.

LA VITA PLACE.

"I'm all ahoo, and that's the truth of it," muttered Ferral. "This is the greatest place for seein' things, and then losin' track of 'em, that I ever got into. There was certainly a man standing right there where you are, wasn't there?"

"That's the way it looked to me," answered Matt. "It can't be that we were all fooled. Imagination might have played hob with one of us, but it couldn't with all three."

Ferral peered around him then looked over the shelf into the gulch, and up toward the top of the cliff.

"Well, sink me, if this ain't the queerest business I ever ran into! Some one must be hoaxin' us."

"Why should any one do that?" asked Matt. "What have they got to gain by such foolishness?"

"I'm over my head. There's no use staying here, though, overhaulin' our jaw-tackle. Let's go on to the ranch."

"That's the ticket! If what we've seen and can't understand means anything to us, it's bound to come out."

They started back.

"Are you on good terms with your cousin, Ralph Sercomb?" Matt asked, as they walked along.

"The last time I saw him was six years ago, when I came to Hamilton to settle up my father's estate. Ralph was there, and I licked him. I can't remember what it was for, but I did it proper. He was always more or less of a sneak, but he's got one of these angel-faces, and to take his sizing offhand no one would ever think he'd do anything wrong."

"Does he live in Hamilton?"

"No, in Denver. His mother and my mother were Uncle Jack's sisters. Last I heard of Ralph he was driving a racing-automobile for a manufacturing firm—a little in your line, I guess, eh?"

By that time the two boys had got back to the machine. Carl was up in front, imagining all sorts of things.

"I peen hearing funny noises," he remarked, as Matt "turned over" the engine and then got up in the driver's seat, "und dey keep chabbering, 'Don'd go on, go pack, go pack,' schust like dot. I t'ink meppy ve pedder go pack, Matt."

"We can't go back, Carl," returned Matt, starting the machine as soon as Ferral had climbed into the tonneau. "We couldn't turn around in this road even if we wanted to."

"Vell, hurry oop und ged avay from dis shpooky blace. Der kevicker vat ve do dot, der pedder off ve vas. I got some feelings dot dere is drouple aheadt. Dot shpook plew indo nodding ven you come oop mit it, hey?"

"The man vanished mysteriously—that's the size of it. If it was daylight, we might be able to figure out how he got away so suddenly."

Under Motor Matt's skilful guidance the Red Flier ran purring along the dangerous road. Half a mile brought the car and its passengers to the end of the cliff and the chasm, and they whirled out into level country, covered with brush and trees.

"There's a light ahead, mates!" announced Ferral, leaning over the back of the front seat, and pointing. "It's on the port side, too, and that agrees with the instructions I got on leaving Lamy. That's La Vita Place, all right enough, and Ralph's at home if that light is any indication."

Owing to the fact that the house was almost screened from the road by trees and bushes, it was impossible for the boys to see much of it. The single light winked at them through a gap in the tree-branches, and was evidently shining from an up-stairs window.

"While you're routing out your cousin and telling him he has company for the night, Ferral," said Matt, turning from the road, "Carl and I will look for a place to leave the car."

"Aye, aye, pard," assented Ferral, jumping out. "There must be a barn or something, I should think. Go around toward the back of the house."

There was a blind road leading through the dark grove toward the rear of the place. The car's lamps shot a gleam ahead and Matt pushed onward carefully. When he and Carl came opposite the side of the house, they heard voices, somewhere within the building, talking loudly. They could not distinguish what was said, as the intervening wall of the building smothered the words.

"Ve don't vas der only gompany vat dey haf do-nighdt, Matt," remarked Carl, in a tone of huge relief. "It feels goot to be so glose py so many real peoples afder dot shpook pitzness."

"I didn't think you believed in ghosts, Carl," laughed Matt.

"Vell, a feller vas a fool ven he don'd pelieve vat he sees, ain'd he?"

"That depends on how he looks at what he sees."

This was too deep for Carl, and before he could frame an answer, Matt brought the Red Flier to a halt in front of a small stone barn.

The barn had a wide door, and Matt got out, took the tail lamp and went forward to investigate. Opening one of the double doors, he stepped inside.

The barn was a crude affair, the stones having been laid up without mortar. The roof consisted of a thatch of poles and boughs, overlaid with earth.

There was plenty of room in the structure, however, for the machine, and there were no horses in the place to damage it.

While Carl opened both doors, Matt ran the Red Flier into its temporary garage. Just as they had closed the doors and were about to start for the house, Ferral ran up to them out of the darkness.

"Here's a go!" he exclaimed. "I pounded on the front door till I was blue in the face, and no one showed up."

"There's some one in the house, all right," declared Matt. "Carl and I heard them."

"Sure ve dit," struck in Carl, "so blain as anyt'ing. Und dare vas a lighdt, Verral—ve all saw der lighdt."

"Well, there's no noise inside the house now, and no light, either," replied the perplexed Ferral. "What sort of a blooming place is it? As soon as I began pounding on the door, the voices died out and the light vanished from the window."

"Are you positive this is La Vita Place?" asked Matt, with a sudden thought that they might have made a mistake.

Ferral himself had said that he had never been to the ranch before, and it was very possible he had gone wrong in following directions.

"Call me a lubber if I ain't," answered Ferral decidedly. "Come around front and I'll show you."

Together the three boys made their way back through the gloomy grove, turned the corner of the building and brought up at the front door. The house continued dark and silent.

Ferral scratched a match and held the flickering taper at arm's length over his head.

"Look at that printing above the door," said he.

There, plainly enough, were the rudely painted words, "La Vita Place."

"We're takin' our scope of cable this far, all right," observed Ferral, dropping the match and laying a hand on the door-knob, "and I guess I've got as good a right in Uncle Jack's house as anybody. Open up, I say!" he shouted, and shook the door vigorously.

No one answered. Not a sound could be heard inside the building.

Matt stepped back and ran his eye over the gloomy outline of the structure.

It was a two-story adobe, the windows small and deeply set in the thick walls. The window through which the light had been seen was now as dark as the others. This was as puzzling as any of the other events of the[Pg 6] night, but it could be explained. Those inside were not in a mood to receive callers; but, even if that was the case, why could not some one come to the door and say so?

"I'm going to get in," said Ferral decidedly, stepping back as though he would kick the door open.

"Wait a minute," suggested Matt, "and let's see if the kitchen door isn't unlocked."

"It isn't—I've tried it."

"How about the windows?"

"The lower ones are all fastened."

"Then I'll try one of the upper ones."

There was a tree close to the corner of the house with a branch swinging close to the window through which the boys had seen the light. Watched by Ferral and Carl, Matt climbed the tree and made his way carefully out along the branch. When opposite the window, he was able to step one foot on the deep sill and balance himself while lifting the sash.

"It's unlocked!" he called down softly. "I'll get inside and open the door."

"There's no telling what you'll find inside there," Ferral called back. "We'll all climb up and get in at the window, then look through the house together."

Carl was beginning to have "spooky" feelings again. Not wanting to be left alone by the front door, he insisted on being the next one to climb the tree. Matt, who had got into the house, reached out and gave his Dutch chum a helping hand. When Ferral came, they both gave him a lift, and all three were presently inside the up-stairs room.

"There's been somebody here, and not so very long ago," said Matt. "I smell tobacco smoke."

"It's t'ick enough to cut mit a knife," sniffed Carl.

"I'll strike a match and look for a lamp," said Ferral, "then we can see what we're doing."

As the little flame flickered up in his hands, the boys took in the dimensions of a small, square room. A table with four chairs around it stood in the center of the room, and on the table was a pack of cards, left, apparently, in the middle of the game. In the midst of the cards stood a lamp.

Ferral lighted the lamp.

"Four people were here," said he, picking up the lamp, "and it's an easy guess they can't be far away. We'll cruise around a little and see what we can find."

Opening the only door that led out of the room, Ferral stepped into the hall. Just as he did so, a sharp, incisive report echoed through the house. A crash of glass followed, and Ferral was blotted out in darkness.

THE HOUSE OF WONDER.

"Ferral!" cried Matt in trepidation.

"Aye, aye!" answered the voice of Ferral.

"Hurt?"

"Not a bit of it, matey. Strike me lucky, though, if I didn't have a tight squeak of it. The lamp-chimney was smashed and the light put out. If the bullet had gone a few inches lower, the lamp itself would have been knocked into smithereens and I'd have been fair covered with blazing oil. That flare-up proves the skulkers are still aboard." He lifted his voice. "Ahoy, there, you pirates! What're you running afoul o' me like that for? I've a right here, being Dick Ferral, of the old Billy Ruffian. Mr. Lawton's my uncle."

Silence fell with the last word. There were no sounds in the house, apart from the quiet, sharp breathing of the three boys. Outside the faint night wind soughed through the trees, making a sort of moan that was hard on the nerves.

Carl went groping for Matt, giving a grunt of satisfaction when he reached him and took a firm hold of his coat-tails.

"Ve pedder go py der vinder vonce again," suggested Carl, catching his breath, "make some shneaks py der pubble und ged apsent mit ourselufs. Ven pulleds come ad you from der tark it vas pedder dot you ain'd aroundt. Somepody don'd vant us here."

"I'm here because it's my duty," said Ferral, still in the hall, "and by the same token I've got to stay here and overhaul the whole blooming layout—but it ain't right to ring you in on such a rough deal. You and the Dutchman can up anchor and bear away, Matt, and I'll still be mighty obliged for your bowsing me off that piece of wall, and sorry, too, you couldn't be treated better under my uncle's roof."

"You're not going to cut loose from us like that, Ferral," replied Matt. "We'll stay with you till this queer affair straightens out more to your liking."

"But the danger——"

"Well, we've faced music of that kind before."

"Bully for you, old ship!" cried Ferral heartily. "I'll never forget it, either. Now, sink me, I'm going through this cabin from bulkhead to bulkhead, and if I can lay hands on that deacon-faced Sercomb, he'll tell me the why of this or I'll wring his neck for him."

Matt stepped resolutely into the hall and ranged himself at Ferral's side. Ferral was drawing a match over the wall. The gleam of light would make targets of the boys for their unseen enemies, but there would have to be light if the investigation was to be thorough.

No shot came.

"Either we've got the swabs on the run," muttered Ferral, "or I'm a point off. The lamp's out of commission, so I'll leave it here on the floor. We've got to find another."

"Be jeerful, be jeerful," mumbled Carl. "Efen dough ve ged shot fuller oof holes as some bepper-poxes it vas pedder dot ve be jeerful."

"Right-o," answered Ferral, moving off along the hall. "Only two rooms on this floor," he added, looking around; "we'll go into the other and try for a lamp we can use."

The door of the second room opened off the hall directly opposite the door of the first. The boys stepped in and found themselves in a bedroom. There was a rack of books on the wall, a trunk—open and contents scattered—carpet torn up and bed disarranged.

"Looks like a hurricane had bounced in here," remarked Ferral.

"Here's a candle," said Matt, and lifted the candlestick from the table and held it for Ferral to touch the match to the wick.

When the candle was alight, Ferral stepped to the table and looked at a portrait swinging from the wall. It was the portrait of a gray-haired man. A broad ribbon[Pg 7] crossed his breast and the insignia of some order hung against it. In spite of the surrounding perils, Ferral took off his hat.

"Uncle Jack," he murmured, his voice vibrant with feeling. "The warmest corner of my heart is set aside for his memory, mates. I wish I'd done more for his comfort when he was alive."

He turned away abruptly.

"But we can't lose time here. What have you got there, Matt?"

Matt had seen a sword swinging from the wall. Drawing the blade from its scabbard, he was holding it in his hand.

"I'd thought of borrowing this," said he, "until we see what's ahead."

"That's a regular jim-hickey of an idea!"

With one hand Ferral twitched at a lanyard about his neck and brought out a dirk.

"I might as well carry this, too," he added.

"Und vat vill I do some fighding mit?" asked Carl anxiously. "I don'd got anyt'ing more as a chack-knife."

"You stay behind and act as rear-guard, Carl," said Matt. "Dick and I will go ahead."

With sword and dirk in readiness for instant use, Matt and Ferral forged along the short hall to the stairs, peering carefully around them as they went. They did not see anything of their enemies and could not hear a sound apart from the noise they made themselves.

The flickering gleams of the candle showed a number of rich furnishings in the lower hall. The first story consisted of three rooms, parlor, library and kitchen. The parlor covered one side of the house, and was divided by a passage from the two rooms on the other side.

But in none of the rooms, nor the hall, was any of their lurking foes to be seen!

"Dis vas der plamedest t'ing vat efer habbened!" whispered Carl. "A rekular vonder-house! Noises, und lights, und pulleds, und nopody aroundt."

"Wait," warned Ferral, making for an open door that evidently led into the cellar, "we haven't looked through the hold yet. We'll go down and get closer to bilge-water! I warrant you we'll stir up the rats."

They descended a short flight of stairs into a rock-walled cellar. The cellar covered the entire lower part of the house, and was so high as to leave plenty of head-room.

On a shelf were a number of cobwebbed bottles, and in one corner was a bin of potatoes—but there were no enemies in the cellar.

"Shiver me!" muttered Ferral, peering dazedly at Matt through the flickering gleams of the candle. "How do you account for this?"

"The four people who were here," returned Matt, "must have got out while we were in your uncle's room. If they have gone to the barn and tampered with the Red Flier——"

This startling thought turned Motor Matt to the right about, and he raced back to the first floor. Carl and Ferral followed him swiftly.

There were only two outside doors to the house, one leading from the kitchen, and the other from the front hall.

Investigation showed that both of these doors were bolted on the inside.

All the lower windows were also securely fastened.

Ferral dropped down in a chair in the front hall and drew his hand across his forehead.

"I'll be box-hauled if I can twig this layout, at all!" he muttered. "Those fellows couldn't get out and leave those doors and windows locked on the inside."

"And they couldn't have got past us on the stairs and got out the way we came in," added Matt, equally nonplused. "We looked carefully as we came down from the upper floor, and the rascals must have been driven ahead of us. I'm knocked all of a heap, and that's a fact."

Carl cantered forward.

"Der shpooks vas blaying viggle-vaggle mit us," he averred in a stage whisper. "Led us say goot-by, bards, und shkin oudt. It vas pedder so, yah, so helup me."

"Are you getting cold feet, matey?" queried Ferral.

"I peen colt all ofer," admitted Carl, "efer since dot shpook pubble vented off indo nodding righdt vile ve look. Den der man-shpook meldet oudt, und dese oder shpooks faded. Yah, you bed my life, ve vill go oop in shmoke ourselufs oof ve shtay here long."

"Carl does a lot of foolish talking, Dick," spoke up Matt, "but he's as game as a hornet, for all that. Don't pay any attention to his spook talk. I saw a lantern in the kitchen, and a padlock and key lying on a shelf. While you two are trying to solve this riddle, I'm going out to the barn and get a lock and key on the Red Flier. I can't afford to let anything happen to that machine."

"I vill go mit you, Matt," said Carl.

"You stay here with Dick," Matt answered. "I'll not be gone more than a minute."

Hurrying into the kitchen he lighted the lantern; then, with the padlock and key in his pocket and the sword in his hand, he unbolted the kitchen door and made his way to the barn.

He listened intently as he went, but there was no sound in the gloomy grove save the hooting of an owl.

He found the Red Flier just as he and Carl had left it, and an examination of the barn proved that no one had taken refuge there. After putting the bolt upon the door and locking it—he already had the spark-plug in his pocket—he felt easier, and returned unmolested to the house.

While he was gone, Ferral and Carl had lighted a large lamp in the parlor and drawn the shades at the windows. They were seated comfortably in easy chairs, eating sandwiches of dried beef and bread.

"There's your snack, mate," cried Ferral, pointing to a plate on the table. "Better get on the outside of it. We may have a lively time, and it's just as well to prepare ourselves for whatever is going to happen."

Carl, now that the tension had eased a trifle and food was in sight, was feeling better.

"I guess ve got der whole ranch py ourselufs," he beamed, his mouth half-full of sandwich. "Ve schared dem odder fellers avay. Oof dey shday avay undil ve clear oudt, dot's all vat I ask."

"Who were the lubbers, and how did they slip their cables?" queried Ferral. "That's the point that's got me hooked. Do you think that white car, and that man we saw in the road, had anything to do with the swabs who were in here?"

Before Matt could answer, a rap fell on the front door and its echoes ran through the house. Carl jumped up in a panic.

"Blitzen and dunder!" he cried chokingly, struggling[Pg 8] with his last mouthful of sandwich and peering wildly at Matt and Dick, "dere's somet'ing else! Schust ven ve ged easy in our mindts, bang goes der front door! Now vat?"

"We'll see what," returned Ferral grimly, getting to his feet and starting for the hall.

Matt followed him, sword in hand, and ready for any emergency that might present itself.

SERCOMB.

The rapping on the door had grown to a vigorous thumping before Ferral and Matt reached the entrance. Quickly throwing the bolt, Ferral pulled the door open and a young man of twenty-one or two stepped in.

He was well built and muscular and had a smooth, harmless face. The face was so void of expression that, to Matt, it showed a lack of character.

Ferral was carrying the candle. Through its gleams, he and the newcomer stared at each other.

"Why—why," murmured the youth who had just entered, "can this be my cousin Dick?"

"You've taken my soundings all right, Sercomb," answered Ferral coolly. "Wasn't you expecting me?"

"Well, yes, in a way," and Sercomb's eyes roamed to Matt. "We got track of you down in Texas, and the lawyer said he'd sent word, but we didn't know whether you'd come or not."

"Where have you been, Sercomb?" and Matt saw Ferral's keen eyes studying the other's face.

Sercomb met the look calmly.

"I've been spending the evening at a neighbor's," he replied, "my nearest neighbor's—a mile away through the hills."

"Got out of an up-stairs window, didn't you?" asked Ferral caustically.

"What do you mean?" demanded Sercomb, a slight flush running into his face.

"Why, when you started to make that call you left all the lower windows fastened and both outside doors bolted on the inside."

"There's some mistake," answered Sercomb blankly. "When I went away I left the front door open. We don't go to the trouble of locking doors in this country, Dick."

"Well, these were locked when I got here. What's more, there were four men in a room up-stairs playing cards. Come, come, you grampus! Don't try to play fast and loose with me. How did you and the other three lubbers get out of the house? And why wouldn't you let me in when I rapped?"

"Look here," blustered Sercomb, "what do you take me for? You never liked me, and you're up to your old trick of suspecting me of something crooked whenever anything goes wrong. I was hoping you'd got over that. Uncle Jack was all cut up over the way you treated me, and he never could understand it. Now that he's dead and gone, I should think we might at least be friends."

"Dead and gone, is he," asked Ferral quickly. "How do you know?"

"Because I've found him—and the will."

Ferral was dazed, as though some one had struck him a blow in the face. Matt, who was watching Sercomb intently, thought he saw an exultant flash in his eyes as he spoke.

"The poor old chap," Sercomb went on, "was tucked away in a thicket of bushes, less than a stone's throw from the house. I don't know whether there was any foul play—I haven't been able to find his Hindu servant, Tippoo, yet, but there weren't any marks on the body. I laid Uncle Jack away in the grove, and I'll show you the place in the morning. The will was in his coat-pocket, and wrapped in a piece of oilskin. It was very sad, very sad," and Sercomb averted his face for a moment; "and to think that neither you nor I, Dick, was with him. But come into the other room. I'm tired and want to sit down and rest."

Ferral, like one in a dream, followed his cousin into the parlor. Sercomb was standing in front of Carl, apparently wondering where Ferral had picked up so many friends.

"Here, Ralph," said Ferral, suddenly rousing himself, "I'd forgot to introduce my friends," and he presented Matt and Carl. "What you've told me," he went on, "catches me up short and leaves me in stays. I heard that Uncle Jack had disappeared, but not that Davy Jones had got him."

For the moment, Ferral's feelings caused him to thrust aside his dislike of Sercomb.

"It's too confounded bad, and that's a fact," said Sercomb, throwing himself into a chair and lighting a cigarette. "I haven't been down to see the old chap for six months. Our firm had a machine in the endurance run from Chicago to Omaha, and I was busy with that, and in getting ready for a big race that's soon to be pulled off, so my hands were more than full. When I got the lawyer's letter, though, I broke away from everything and came on here."

"Why didn't the lawyer tell me Uncle Jack and the will had been found?" asked Ferral.

"That only happened two days ago. The lawyer wrote you the same time he wrote me."

"But I saw the lawyer in Lamy, day before yesterday——"

"He didn't know it, then."

"How does the will read, Ralph?"

"Everything was left to me, this place and all Uncle Jack's holdings in South African stock. Of course, you know, you've never come near him, Dick. If you had, the will might have read different."

"I don't care the fag-end of nothing about Uncle Jack's money; it was Uncle Jack himself I wanted to see. If this place is yours, Sercomb——" and Ferral broke off and started to get up.

"You and your friends are welcome to stay here all night," said Sercomb. "It's not much of a place, and I'm going to pack up the valuables, send them to Denver, and clear out."

"Going to keep up your racing?"

Sercomb smiled.

"Hardly; not with a mint of money like I've got now," he answered. "In a few months, I'm off for old England."

A brief silence followed, broken suddenly by Sercomb.

"But I'm bothered about the intruders you say were here when you came. They must have locked both doors on the inside."

"A rum go," said Ferral, "if strangers can come in and make free with a person's property like that."

"Tell me about it. This country is a good deal of a wilderness, you know, and strangers are likely to do anything."

Ferral said nothing concerning the phantom auto, nor about the man who had so mysteriously vanished on the cliff road; he confined himself strictly to what had happened in the house, and tipped Matt and Carl a wink to apprise them that they were to let it go at that.

Sercomb seemed greatly wrought up, and insisted on taking a lamp and making an investigation of the upper floor.

"They were thieves," Sercomb finally concluded. "They thought I had gone away for the night, and so they came in here and tore up Uncle Jack's bedroom like we see it. It was known that Uncle Jack had money, and it was just as well known that he had disappeared."

"If you knew all that yourself," said Ferral, "why didn't you lock up before you went visiting?"

"I was careless," admitted Sercomb, with apparent frankness. "The one thing that bothers me is the fact that you were shot at, Dick! A nice way for you to be treated in Uncle Jack's own house!"

"Don't let that fret you, Sercomb. I've had belaying-pins and bullets heaved at me so many times that I don't mind so long as they go wide. We'll have a round with our jaw-tackle to-morrow. Just now, though, I and my mates are ready for a little shut-eye. Where do we berth?"

"Two of you can fix up Uncle Jack's bed and sleep there; the other can bunk down on the couch in the room where those four rascals were playing cards. I'll sleep down-stairs on the parlor davenport. Yes," Sercomb added, "it will be just as well to sleep over all this queer business, and do our talking in the morning. Good night, all of you."

Leaving the lamp for the boys, Sercomb went stumbling down-stairs.

"What do you think of Ralph Sercomb, Matt?" whispered Ferral, when Sercomb had left the stairs and could be heard moving around the parlor.

"I don't like his looks," answered Matt frankly, "nor the way he acts."

"Me, neider," put in Carl. "He vas a shly vone, und I bed you he talks crooked mit himseluf."

"That's the way I always sized him up," admitted Ferral, "and strikes me lucky if I think he's improved any since I saw him last. But he's got the will, and poor old Uncle Jack——"

Ferral's eyes wandered to the picture on the wall, and he shook his head sadly.

"I'd have a look at that will," said Matt, "and I'd get a lawyer to look at it."

"These lawyer-sharps, of course, will have their watch on deck, but I hate to quibble over the old chap's property when it's Uncle Jack himself I wanted to find. Anyhow, I got my whack, all right, to be cut off without a shilling; at the same time, Ralph got more than was his due. But I'm no kicker."

"If Sercomb drives a racing-car," went on Matt, "he must have skill and nerve."

"Nerve, aye! Cousin Ralph always had his locker full of that. But how shall we sleep? My head's all ahoo with what's happened, and I need sleep to clear away the fog. You and your mate take the bed, Matt, and I'll——"

"No, you don't," said Matt. "I'm for the couch in the other room."

Matt insisted on this, and finally had his way. He was not intending to sleep on the couch, but to go out to the barn and spend the night in the tonneau of the Red Flier. If Sercomb knew so much about automobiles, Matt felt that the touring-car would bear watching. He had no confidence in Sercomb, and felt sure that he was playing an underhand game of some kind.

Sitting down on the couch, Matt waited until the house was quiet, then went softly to the open window, climbed through, and made his way to the ground by means of the tree. Hardly had his feet struck solid earth, when he heard the front door drawn carefully open.

Sercomb stepped out and noiselessly closed the door behind him. Matt, intensely alive to the possibilities of the unexpected situation, drew back into the darker shadows of the tree-branches.

Sercomb, moving away a little from the house, gave a low whistle. A hoot, as of an owl, came instantly from the grove.

Sercomb started away rapidly in the direction from which the sound came.

Matt followed him, keeping carefully in the shadows.

THE PHANTOM AUTO AGAIN.

Sercomb did not follow the blind trail that led to the main road. He made for the road, but took his way along a foot-path that led through the grove.

It was not at all difficult for Matt to shadow him, and the young motorist was considerably surprised to see Sercomb gain the road at a point where a heavy touring-car had drawn up. The car was about the size of the Red Flier and, in the semidarkness, looked very much like it. But it had a top.

Three men were standing near the head of the machine, in the glow of the lamps. They were all fairly well dressed, quite young, and there was little of the ruffian about them.

They greeted Sercomb excitedly, and for several minutes all four of them engaged in a brisk conversation. Their voices were pitched in too low a tone, and Matt was too far away to hear what was said.

Undoubtedly, Matt reasoned, these three who had just come in the automobile had formed part of the number who had been in the up-stairs room. The fourth member of the party must have been Sercomb, himself.

But how had Sercomb and the other three got away? Their departure from the house was a mystery. And where had they kept their automobile while they were in the house? This was another mystery.

They were planning evil things of some sort, and against Dick Ferral.

Matt had a clue. It assured him that Sercomb had not told the truth when he said he knew nothing about the so-called intruders who had vanished from the house so strangely. Sercomb, by this stealthy meeting with the three in the road, proved to Matt that he knew all about the men.

From their earnest talk it was clear that they were plotting mischief. Wishing that he could overhear something of what was said, Matt began creeping carefully along the path. By getting a few yards nearer he was sure that he would be within ear-shot.

Just as he had nearly reached the coveted point for which he was making, and the mumble of talk was breaking up into an occasional word which he could distinguish, the conversation broke off with a chorus of excited exclamations.

Matt started up, at first fearing he had been seen, and that the four in the road were coming to capture him. But in this he was mistaken. All four of them, as a matter of fact, had started in his direction, but they abruptly halted and whirled around. Matt's heart jumped when he saw what it was that had claimed their attention.

It was the phantom auto!

The white runabout was wheeling swiftly along the road in the direction of the treacherous cliff trail. The streaming lights of the touring-car were full upon the ghostly runabout, showing the vacant seats distinctly. The weird spectacle was more than enough to fill the four men with momentary panic. They stood as though rooted to the ground, watching the runabout turn of its own accord from the road, pass the touring-car, and then come neatly back into the road again.

An oath broke from one of the men. Leaping to the touring-car he cranked up the machine quickly and hopped into the driver's seat. Two others jumped in behind him, one in front and the other behind, Sercomb being the only one who remained at the roadside.

Swiftly the touring-car was turned and headed in pursuit. Then, suddenly, there came the report of a firearm, shivering through the still air.

At first, Matt thought one of those in the touring-car had fired at the runabout; then, a moment more, he knew he was mistaken.

The shot had come from the runabout and had punctured one of the touring-car's front tires.

The big car limped and slewed until the power was cut off and it came to a halt. Those who were in the car piled out, sputtering and fuming, and Sercomb ran forward and joined them. Together, all four watched the white phantom whisk out of sight.

There followed a good deal of talking and gesticulating among Sercomb and the three with him. Finally one of them took off the tail lamp and all made an examination of the damaged tire.

A jack was got out and the forward wheel lifted.

From his actions, Sercomb was nervous and excited. He kept walking from the road, looking toward the house and listening. He fancied, no doubt, just as Matt did, that the sound of the shot might have awakened the sleepers in the house.

However, this did not seem to have been the case.

Leaving one of the men to tinker with the tire, Sercomb took the other two and led them off through the grove. They passed within a yard of where Matt was crouching in the bushes, but their plans, whatever they were, had been settled, and they were doing no talking.

Matt continued to dodge after Sercomb. The course he and the two with him were taking did not lead toward the house, but angled off through the grove on a line that would take them fully a hundred feet past the nearest wall of the adobe building.

Abreast of the house, at that point, there was a circular space, clear of timber and with only a patch of brush in the center. Matt, not daring to venture beyond the edge of the timber, stood and watched while Sercomb and his companions disappeared in the thicket.

Matt's position was such that he could see all around the little patch of bushes, and he watched for the three men to appear on the other side. They did not appear, and as minute after minute slipped away, Matt's amazement and curiosity increased.

The men had gone into that little thicket, and why had they not shown themselves again? What was there in that bunch of brush to attract them and keep them so long?

Matt concluded to investigate. There might be danger in doing that, as there would be three against him if he was discovered, but he knew he had only to raise his voice to bring Ferral and Carl.

This clue, which he had picked up so unexpectedly in the night, called upon him to make the most of it and, if possible, discover what Sercomb was up to.

Hastening across the cleared space, he came to the thicket without a challenge. Resolutely he plunged into the bushes—and the next moment the ground seemed to drop out from under him.

Throwing out his hands wildly he plunged downward, struck an incline and rolled over and over, finally coming to a jolting stop on hard earth, on his hands and knees.

The suddenness of his fall had bewildered him. He was bruised a little, but not otherwise hurt, and as his wits returned his curiosity came uppermost.

What sort of a place was he in?

His groping hands informed him that the incline he had rolled down was a rude stairway. A patch of starlight above revealed the opening into which he had stumbled.

Climbing the stairway, he reached a stone landing and lifted himself erect in the very center of the thicket. A flat slab, tilted upon its edge, showed how the hole was covered when not in use.

Matt drew a quick breath. The mysteries of La Vita Place were clearing a little.

Here, undoubtedly, was a passage communicating with the house. Sercomb and the other three men must have used it in making their strange escape from the up-stairs room, earlier in the night.

But why were Sercomb and his two companions going back through the passage?

Instinctively Matt's suspicions flew to Dick Ferral. Sercomb was planning some evil against him, and the two from the touring-car were there to help him carry it out.

Matt hesitated a moment, trying to decide whether he should go through the passage or reach the house by crossing the cleared place and entering the front door.

He decided upon the passage. The rascals had gone that way and would probably make their escape in the same manner.

Hurrying down the steps he began making his way along a gallery. The passage was not wide, for he could stretch out his hands and touch either side. It ran straight, and Matt pushed rapidly through the gloom, trailing a hand along one wall.

He knew he had only a hundred feet to go before he should reach the house, but in his haste he covered the[Pg 11] distance before he realized it, and stumbled against a flight of steps.

While he was picking himself up, he heard a commotion from somewhere above—a wild scramble of feet, a thump of blows and an overturning of furniture. Above the hubbub sounded the voice of Carl.

"Vat's der madder mit you? Hoop-a-la! Take dot, oof you like or oof you don'd like, und dere's anoder! Matt! Come along for der fight fest! Vere you vas, Matt, vile der scrimmage iss going on! Verral! Iss dot you?"

Just then, as Matt began scrambling upward, a form came hurtling down.

"They're onto us, Joe!" panted a voice. "This way, old pal! Nothing doing to-night. Cut for it! I ran into something at the foot of the steps—look out for that!"

Matt, who had been thrown violently against the wall, heard forms dashing past him. Before he could interfere with them, they were well along the passage.

SURROUNDED BY ENEMIES.

Although the two men had got past Matt, nevertheless he followed them to the end of the passage, arriving just in time to see them disappear through the opening and close the aperture with the slab.

Only two went out. What had become of Sercomb? Had Ferral and Carl captured him—catching him red-handed and so unmasking his treachery?

In any event, Ferral and Carl had proven more than a match for the two miscreants who had stolen in upon them. Thankful that the affair had turned out so fortunately for his friends, although still mystified as to what Sercomb's purpose was, Matt groped his way back along the corridor and mounted the steps.

It was a long flight—much longer than the one at the other end of the passage—and, at the top, Matt was confronted by a blank wall. He ran his hands over it, and, in so doing, must have touched a spring, for a section of the wall slid back and a sudden glow of lamplight blinded him.

"Ach, du lieber!" came the astounded voice of Carl. "Dere vas Matt, py chincher! Vere you come from, hey?"

Matt stepped from the head of the steps into the room in which Ferral and Carl had been sleeping. The panel closed noiselessly behind him.

"Sink me!" muttered Ferral, stepping past Matt to run his hands over the wall. "A nice little trap-door in the wall, or I'm a Fiji!" He whirled around. "How does it come you stepped through it, messmate?"

"Where's Sercomb?" whispered Matt, peering around.

"What's he got to do with this?"

Just at that moment Sercomb's voice came up from below.

"What's going on up there? Anything happened, Dick?"

"Two men came in and made trouble for us!" shouted Matt. "Didn't you hear 'em run down the stairs?"

"No, I didn't hear anybody!" answered Sercomb.

"Take a look around, and we'll see what we can find up here."

During this brief colloquy, Ferral and Carl were staring at Matt in open-mouthed astonishment.

Matt whirled to Ferral.

"Not a word to Sercomb about that hole in the wall," he whispered. "Tell me quick, what happened in here?"

"I was sleeping full and by, forty knots," answered Ferral, in the same low tone, "when I felt myself grabbed. It was dark as Egypt, and I couldn't see a thing. I shouted to Carl, and we had it touch and go, here in the dark. My eye, but it was a scrimmage! Right in the midst of it the fellows we were fighting melted away. I had just got the glim to going when you stepped in on us."

"Wasn't Sercomb in the fight?"

"Why, no. He must have been down-stairs, sleeping like a log. He only just chirped—you heard him."

"Well, Sercomb came into this room with two other men, through that hole in the wall——"

"Is that right?" demanded Ferral, his face hardening.

"Yes, but don't say a word about it. Wait till we find out what his game is."

"How dit you know all dot, Matt?" queried Carl.

Briefly as he could Matt sketched his recent experiences. The astonishing recital left his two friends gasping.

"The old hunks!" breathed Ferral, scowling. "I can smoke his weather-roll, fast enough. What did I tell you about the soft-sawdering beggar?"

Matt stepped into the hall and listened. Apparently, Sercomb was not in the house. Coming back, he pulled his two friends close together so they could hear him without his speaking above a whisper.

"Sercomb has gone out to hurry up the repairs on the big car and get it out of the way. We can talk a little, but we've got to be wary. Don't let Sercomb know anything about this clue I've picked up. We're surrounded by enemies, Ferral, and you're the object of some sort of game they've got on. By lying low, perhaps we can get wise to it."

"Dot shpook auto has dook a hant in der pitzness," murmured Carl, flashing a fearful glance around. "I don'd like dot fery goot."

"This spook business will all be explained, Carl," said Matt, "and you'll find that flesh and blood is mixed up in the whole of it. That white runabout put a shot into one of the tires of that big touring-car, and no revolver ever went off without a human hand back of it. We know, too, how those men got away from that room where they were playing cards. They ran in here, got through the hole in the wall and went out by way of the tunnel. That shot that was fired at you, Dick, and put out the lamp, must have come from this room, just before Sercomb and the others dodged through the wall."

"Sercomb?" echoed Ferral.

"Sure! It's a cinch he was playing cards in that room with the three men. He came here from Denver, and he must have traveled in that big car and brought the others with him."

"Oh, he's the nice boy!" commented Ferral sarcastically. "A fine cousin, that swab is! That phantom flugee is mixing in the game. I wonder if Sercomb has anything to do with that?"

"No. When the phantom auto showed up in the road, Sercomb and all three of the others were scared nearly[Pg 12] out of their wits. I'll bet that was the first time Sercomb ever saw it. Besides, the bullet that pierced the tire of the big car came from the runabout. That wouldn't have happened if the runabout was here to help Sercomb's plans."

"Right-o. What kind of a bally old place is this, anyhow? Holes in the wall, tunnels, and all that—it fair dazes me. What could Uncle Jack have wanted of a secret passage?"

"Didn't you tell me that this was an old Mexican house, and that your uncle bought it?" asked Matt.

"That's how he got hold of the place, matey."

"Then it must have come into his hands like we find it. The Mexicans used to build queer houses; I found that out while I was down in Phœnix."

Matt turned away and took a look at the walls. They were wainscoted in cedar, all around. Every little way there were panels, and the entrance to the passage, which Matt had recently used, was by a panel.

"The walls of these adobe houses are always thick," went on Matt, "but these walls are even thicker than common. There's room in this wall for that stairway, and no one would ever suspect the wall is hollow, simply because it's made of adobe."

"How does the door work?" queried Ferral, stepping to the wainscoting and trying to manipulate the panel. "I'd like to know how to get the cover off the blooming hatch; the knowledge might come handy."

Along the wainscoting, about five feet from the floor, were arranged clothes-hooks. Matt, helping Ferral hunt for the secret spring that operated the panel, pulled on one of the hooks. Instantly the panel slid open, answering the pull on the hook with weird silence.

"Chiminy grickets!" murmured Carl, stepping back. "Dot looks like der vay to der infernal blace."

Ferral stepped forward as though he would pass through the opening, but Matt caught his arm and held him back.

"Don't go down there now, Ferral," said he. "When Sercomb comes we want him to find us here. He doesn't guess that I'm next to what he's done to-night, and none of his confederates know it. If we keep mum, the knowledge may do us a lot of good. If we try to face him down with it, we'll only show him our hands without accomplishing anything."

"The sneaking lubber!" growled Ferral. "Why, he berthed us in this room so he and his mates could sneak in on us while we were asleep. But," and here Ferral rubbed his chin perplexedly, "what did they want to do that for?"

"We'll find out," returned Matt, "if we play our cards right."

"You're the lad to discover things," said Ferral admiringly. "I never had a notion you were going to slip out of the house when you left us."

"And I never had a notion what I was going to drop into," said Matt, "I can promise you that. But it is a tip-top clue, and we'll be foolish if we don't use it for all it's worth."

"You've started off in handsome style! Your head-work makes me feel like a green hand and a lubber."

"Dot's Matt, Verral," declared Carl, puffing up like a turkey-cock. "He alvays does t'ings in hantsome shdyle, you bed you. He iss der lucky feller to tie to, dot's righdt. I know, pecause I haf tied to him meinseluf, und I haf peen hafing luck righdt along efer since, yah, so. Be jeerful, eferypody, und oof der shpooks leaf us alone, ve vill all come oudt oof der horn py der pig end. But vat makes Sercomb act like dot?"

"He wants Uncle Jack's property," scowled Ferral, "and I'll wager that's what he's working for."

"But how can he be working for it when he's already got it?" put in Matt. "He claims to have found your uncle, and to have secured the will."

"That's his speak-easy for it. He's a long-winded grampus, and can talk the length of the best bower, but that don't mean that there's any truth in all his wig-wagging."

"Now you're hitting the high gear without any lost motion," said Matt. "Between you and me and the spark-plug, Dick, I don't think he ever found your uncle; and, as for the will, if he really has it, and everything's left to him, what's all this underhand work for?"

A sudden thought came to Ferral.

"Say," he whispered hoarsely, "do you think that sneaking cur could have handed out any foul play to Uncle Jack? I hate to think it of him, but——"

"No," answered Matt gravely, "I don't think——"

He was interrupted by some one coming in at the front door, and stopped abruptly.

"There's Sercomb now," he whispered. "Let's hear what he's got to say for himself. Mind you don't let out anything about my clue. When you had your trouble, I ran in here from the other room and lent a hand."

"Are you up there?" came Sercomb's voice. "I can't find a soul about the place."

From the road the boys could hear the muffled pounding of a motor. And they knew, even as Sercomb spoke, that he was not telling the truth.

THE KETTLE CONTINUES TO BOIL.

Sercomb came up-stairs and stepped into the room. Daylight was just coming in through the windows, and the gray of the morning and the yellow of the lamplight gave Sercomb's face a ghastly look. Nevertheless, it was a frank and open face—as always.

"Now, Dick," cried Sercomb, "what in the world has been going on here? Do you mean to say that some one came into this room and attacked you?"

"That's the how of it, old ship," answered Ferral, repressing his real feelings admirably. "As near as we can figure out, there were two of them. It was so dark, though, we couldn't see our own fists, so there may have been more than two."

"Some of the gang who dropped in here while I was away, I'll bet," said Sercomb.

"I'm thinking the same thing, Ralph," returned Ferral, with a meaning look at Matt. "They were handy, too, but not handy enough. They left us all at once, and how they ever did it beats me. We boxed the compass for 'em, though, and when we'd worked around the card they thought they had enough—and ducked."

"Where did they go?"

"Didn't you hear them go out the front door?"

"Not I, Dick! If I had, I'd have taken a part in the scrimmage myself."

"You were slow hearing the racket, Ralph. It was all over when you piped up."

"I heard it quick enough, but I was sound asleep when it aroused me. Being a little bewildered, I went out into the kitchen."

Something like loathing swept over Matt as he watched Sercomb's face and listened to his smooth misstatement.

"Wonder how Uncle Jack managed to hang on in such a lawless country as this," said Ferral.

"No one ever bothered him. He was pretty well liked by the scattered settlers."

"Everybody liked the old chap! I thought no end of him myself."

"Too bad you didn't show it, Dick, while he was alive," said Sercomb.

There wasn't any sarcasm in his voice—only a dry, expressionless statement of what Ferral knew were the cold facts. Nevertheless, there was a gratuitous slur in the words. Ferral bristled at once, but a look from Matt caused him to curb his temper.

"Belay a bit on that, Ralph," said Ferral mildly. "I know it well without your say-so to round it off. From now on, though, I'll do my best to show Uncle Jack what I think of him."

Sercomb looked a little puzzled.

"His will shows everybody what he thought of you—at the last," said he.

It looked as though Sercomb was deliberately trying to force a quarrel, but Ferral, still with Matt's glances to admonish him, did not fall into the trap.

"I'll go down and get breakfast," observed Sercomb, after waiting in vain for a response from Ferral. "Some Denver friends are coming up from Lamy to make me a little visit, and we may be a bit crowded here. There are three of them."

It was a broad hint for Dick Ferral to take his two friends and leave, as soon after breakfast as he could make it convenient. Ferral fired up at that. Matt and Carl had served him well, and he was not the one to put up with any back-handed slaps from his cousin Ralph.

"By the seven holy spiritsails, Sercomb!" he cried, "I'll have you know that I and my friends have as much right under Uncle Jack's roof as you and yours. We'll be here to breakfast, and as long as we want to stay."

"Now, don't fly off at a tangent, Dick," returned Sercomb, with a distressed look. "I didn't mean anything like that, and why do you go out of your way to take me in any such fashion? I'll go down and get the meal for all of us—if you can put up with my cooking."

"Go and help, Carl," said Matt. "We don't want to make Mr. Sercomb any extra trouble. We won't be here very long, anyhow."

"Dot's me," said Carl, as cheerfully as he could.

He hated to be associated with Sercomb, but the idea of a meal always struck a mellow note in Carl's get-up.

"You understand, don't you, Mr. King?" said Sercomb, in a whining tone, turning to Matt and jerking his head toward Ferral.

"Perfectly," smiled Matt.

Carl and Sercomb went out. When they were going down the stairs Ferral shook his fist.

"Shamming the griffin!" he growled; "the putty-faced shark, I'd like to lay him on his beam-ends! Do you wonder I've had a grouch at him all these years, Matt?"

"No, I don't," said Matt frankly; "but stick it out. I've a hunch, Dick, that you're soon going to be done with your cousin for good and all. He's playing a game here that's going to get him into hot water."

Matt stretched himself out on the bed.

"I'm going to lie here," said he, "and you can talk to me. Carl will keep an eye on Sercomb. Tell me more about your uncle."

"He was no end of a toff in London," replied Ferral, taking a chair and casting a look at the portrait. "His wife died, and that broke him up; then his daughter died, and that was about the finish. He bucked up, though, and crossed the pond. When he was in Hamilton he said he wanted to go some place where there wasn't so many people. Then he came here."

"This last move of his," said Matt, "looks like a strange one to me."

"He was full of his crochets, Uncle Jack was, but there was always a good bit of sense down at the bottom of them. Sercomb would have gone down on his knees and licked his boots, knowing Uncle Jack had money, and nobody but him and me to leave it to. There's another cut to my jib, though. I wouldn't go around where he was because I was afraid he'd think the same of me. I've got a notion, Matt, and it just came to me."

"What is it?"

"I'll bet that, when Uncle Jack left, he hid that will, and that he signed it and left blank the place where his heir's name was to be. The one that was shrewd enough to find it, you know, could put in his own name."

"Why should he do that?"

"Just to see whether Sercomb or I was the smarter."

"But you overlook what your uncle said about being found wherever the will was discovered."

"Right-o. I'm always overlooking things. You see, I'm taken all aback with this game of Sercomb's. If I knew what his lay was, or what he's trying to accomplish, I'd have my turn-to in short order. Still, as you say, he's going to get his what-for no matter which way the wind blows."

"There's a lot of things happened that are mighty mysterious," mused Matt; "little by little, though, they're clearing up. That clue I hooked onto last night makes several things clear. Did Sercomb know you were coming?"

"The Lamy lawyer must have told him he'd found out where I was, and had written to me. One thing I did do, and that was to sling my fist to a letter for Uncle Jack, once a month, anyhow. So he knew I was down in the Panhandle."

"When you pounded on the door last night, Sercomb must have suspected it was you. If he hadn't, he'd have let you in."

"He'd have let me in anyhow, only he didn't want me to see those other three swabs. And then for him to play-off like he did, and say he was calling at a neighbor's! It would have done me a lot of good to blow the gaff, when he came in on us a spell ago, and let him understand just where he gets off."

"That wouldn't have helped any, and it might have spoiled our chances for finding out what he's up to."

What answer Ferral made to this Matt did not hear. The young motorist had put in a strenuous night, and he was worn out. Ferral's words died to a mumble, and before Matt knew it he was sound asleep.

Some one shook him, and he opened his eyes and started up.

"Dozed off, did I?" he laughed. "Sorry, old man, but[Pg 14] I didn't sleep any last night, you know. You were saying——"

An odor of boiling coffee and sizzling bacon floated up from down-stairs.

"What I was saying, mate," answered Ferral, "was some sort of a while ago. I've had my jaw-tackle stowed for an hour, letting you do the shut-eye trick. But now it's about mess-time, I reckon; and, anyhow, those friends of Sercomb's are here from Lamy. Listen!"

The chug of a motor on the low gear came to Matt. Getting up, he looked out of a window that commanded the front of the house.

A car was coming slowly along the blind trail from the road, following the same course the Red Flier had taken the night before.

As the automobile drew closer, Matt gave a startled exclamation.

"Some new kink in the yarn, Matt?" queried Ferral.

"I should say so!" answered Matt. "That's the same car that was in the road last night——"

"What?" demanded Ferral, grabbing Matt's arm.

"There's no doubt of it, Dick," said Matt; "and the three in the car are the same ones Sercomb met and talked with. Two of them, of course, are the handy-boys who blew in here and roughed things up with you and Carl."

The car came to a stop in front. Just then the front door opened and Sercomb rushed out.

"Hello, fellows!" he called. "Mighty glad to see you. Pile out and clean up for the grub-pile——"

Matt heard that much, and just then had to turn around to look after Ferral. With an angry growl, Ferral had broken away and started down the stairs.