Project Gutenberg's Oliver Twist, Vol. I (of 3), by Charles Dickens This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook. Title: Oliver Twist, Vol. I (of 3) Author: Charles Dickens Illustrator: George Cruikshank Release Date: December 4, 2014 [EBook #47529] Language: English Character set encoding: UTF-8 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK OLIVER TWIST, VOL. I (OF 3) *** Produced by The Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

NEW WORK BY “BOZ.”

———

BARNABY RUDGE:

BY “BOZ.”

Which will be published forthwith in Bentley’s Miscellany.

LONDON:

PRINTED BY SAMUEL BENTLEY,

Dorset Street, Fleet Street.

Among other public buildings in a certain town which for many reasons it will be prudent to refrain from mentioning, and to which I will assign no fictitious name, it boasts of one which is common to most towns, great or small, to wit, a workhouse; and in this workhouse was born, on a day and date which I need not take upon myself to repeat, inasmuch as it can be of no possible consequence to the reader, in this stage of the business at all events, the item of mortality whose name is prefixed to the head of this chapter. For a[2] long time after he was ushered into this world of sorrow and trouble, by the parish surgeon, it remained a matter of considerable doubt whether the child would survive to bear any name at all; in which case it is somewhat more than probable that these memoirs would never have appeared, or, if they had, being comprised within a couple of pages, that they would have possessed the inestimable merit of being the most concise and faithful specimen of biography extant in the literature of any age or country. Although I am not disposed to maintain that the being born in a workhouse is in itself the most fortunate and enviable circumstance that can possibly befal a human being, I do mean to say that in this particular instance it was the best thing for Oliver Twist that could by possibility have occurred. The fact is, that there was considerable difficulty in inducing Oliver to take upon himself the office of respiration,—a troublesome practice, but one which custom has rendered necessary to our easy existence,—and for some time he lay gasping on a little[3] flock mattress, rather unequally poised between this world and the next, the balance being decidedly in favour of the latter. Now, if during this brief period, Oliver had been surrounded by careful grandmothers, anxious aunts, experienced nurses, and doctors of profound wisdom, he would most inevitably and indubitably have been killed in no time. There being nobody by, however, but a pauper old woman, who was rendered rather misty by an unwonted allowance of beer, and a parish surgeon who did such matters by contract, Oliver and nature fought out the point between them. The result was, that, after a few struggles, Oliver breathed, sneezed, and proceeded to advertise to the inmates of the workhouse the fact of a new burden having been imposed upon the parish, by setting up as loud a cry as could reasonably have been expected from a male infant who had not been possessed of that very useful appendage, a voice, for a much longer space of time than three minutes and a quarter.

As Oliver gave this first proof of the[4] free and proper action of his lungs, the patchwork coverlet which was carelessly flung over the iron bedstead, rustled; the pale face of a young female was raised feebly from the pillow; and a faint voice imperfectly articulated the words, “Let me see the child, and die.”

The surgeon had been sitting with his face turned towards the fire, giving the palms of his hands a warm and a rub alternately; but as the young woman spoke, he rose, and advancing to the bed’s head, said, with more kindness than might have been expected of him—

“Oh, you must not talk about dying yet.”

“Lor bless her dear heart, no!” interposed the nurse, hastily depositing in her pocket a green glass bottle, the contents of which she had been tasting in a corner with evident satisfaction. “Lor bless her dear heart, when she has lived as long as I have, sir, and had thirteen children of her own, and all on ’em dead except two, and them in the wurkus with me, she’ll know better than to take on in that way, bless her dear heart! Think what it is to be a mother, there’s a dear young lamb, do.”

Apparently this consolatory perspective of a mother’s prospects failed in producing its due effect. The patient shook her head, and stretched out her hand towards the child.

The surgeon deposited it in her arms. She imprinted her cold white lips passionately on its forehead, passed her hands over her face, gazed wildly round, shuddered, fell back—and died. They chafed her breast, hands, and temples; but the blood had frozen for ever. They talked of hope and comfort. They had been strangers too long.

“It’s all over, Mrs. Thingummy,” said the surgeon at last.

“Ah, poor dear, so it is!” said the nurse, picking up the cork of the green bottle which had fallen out on the pillow as she stooped to take up the child. “Poor dear!”

“You needn’t mind sending up to me, if the child cries, nurse,” said the surgeon, putting on his gloves with great deliberation. “It’s very likely it will be troublesome. Give it a little gruel if it is.” He put on his hat, and, pausing by the bed-side on his way to the door, added[6] “She was a good-looking girl, too; where did she come from?”

“She was brought here last night,” replied the old woman, “by the overseer’s order. She was found lying in the street;—she had walked some distance, for her shoes were worn to pieces; but where she came from, or where she was going to, nobody knows.”

The surgeon leant over the body, and raised the left hand. “The old story,” he said, shaking his head: “no wedding-ring, I see. Ah! good night!”

The medical gentleman walked away to dinner; and the nurse, having once more applied herself to the green bottle, sat down on a low chair before the fire, and proceeded to dress the infant.

And what an excellent example of the power of dress young Oliver Twist was! Wrapped in the blanket which had hitherto formed his only covering, he might have been the child of a nobleman or a beggar;—it would have been hard for the haughtiest stranger to have fixed his station in society. But now that he was enveloped[7] in the old calico robes, which had grown yellow in the same service, he was badged and ticketed, and fell into his place at once—a parish child—the orphan of a workhouse—the humble half-starved drudge—to be cuffed and buffeted through the world, despised by all, and pitied by none.

Oliver cried lustily. If he could have known that he was an orphan, left to the tender mercies of churchwardens and overseers, perhaps he would have cried the louder.

For the next eight or ten months, Oliver was the victim of a systematic course of treachery and deception—he was brought up by hand. The hungry and destitute situation of the infant orphan was duly reported by the workhouse authorities to the parish authorities. The parish authorities inquired with dignity of the workhouse authorities, whether there was no female then domiciled in “the house” who was in a situation to impart to Oliver Twist the consolation and nourishment of which he stood in need. The workhouse authorities replied with humility that there was not. Upon this, the parish authorities magnanimously and humanely resolved, that Oliver should be “farmed,”[9] or, in other words, that he should be despatched to a branch-workhouse some three miles off, where twenty or thirty other juvenile offenders against the poor-laws rolled about the floor all day, without the inconvenience of too much food or too much clothing, under the parental superintendence of an elderly female who received the culprits at and for the consideration of sevenpence-halfpenny per small head per week. Sevenpence-halfpenny’s worth per week is a good round diet for a child; a great deal may be got for sevenpence-halfpenny—quite enough to overload its stomach, and make it uncomfortable. The elderly female was a woman of wisdom and experience; she knew what was good for children, and she had a very accurate perception of what was good for herself. So, she appropriated the greater part of the weekly stipend to her own use, and consigned the rising parochial generation to even a shorter allowance than was originally provided for them; thereby finding in the lowest depth a deeper still, and proving herself a very great experimental philosopher.

Everybody knows the story of another experimental philosopher, who had a great theory about a horse being able to live without eating, and who demonstrated it so well, that he got his own horse down to a straw a day, and would most unquestionably have rendered him a very spirited and rampacious animal upon nothing at all, if he had not died, just four-and-twenty hours before he was to have had his first comfortable bait of air. Unfortunately for the experimental philosophy of the female to whose protecting care Oliver Twist was delivered over, a similar result usually attended the operation of her system; for at the very moment when a child had contrived to exist upon the smallest possible portion of the weakest possible food, it did perversely happen in eight and a half cases out of ten, either that it sickened from want and cold, or fell into the fire from neglect, or got smothered by accident; in any one of which cases, the miserable little being was usually summoned into another world, and there gathered to the fathers which it had never known in this.

Occasionally, when there was some more than usually interesting inquest upon a parish child who had been overlooked in turning up a bedstead, or inadvertently scalded to death when there happened to be a washing, though the latter accident was very scarce,—anything approaching to a washing being of rare occurrence in the farm,—the jury would take it into their heads to ask troublesome questions, or the parishioners would rebelliously affix their signatures to a remonstrance: but these impertinences were speedily checked by the evidence of the surgeon, and the testimony of the beadle; the former of whom had always opened the body and found nothing inside (which was very probable indeed), and the latter of whom invariably swore whatever the parish wanted, which was very self-devotional. Besides, the board made periodical pilgrimages to the farm, and always sent the beadle the day before, to say they were going. The children were neat and clean to behold, when they went; and what more would the people have?

It cannot be expected that this system of farming would produce any very extraordinary or luxuriant crop. Oliver Twist’s ninth birth-day found him a pale thin child, somewhat diminutive in stature, and decidedly small in circumference. But nature or inheritance had implanted a good sturdy spirit in Oliver’s breast: it had had plenty of room to expand, thanks to the spare diet of the establishment; and perhaps to this circumstance may be attributed his having any ninth birth-day at all. Be this as it may, however, it was his ninth birth-day; and he was keeping it in the coal-cellar with a select party of two other young gentlemen, who, after participating with him in a sound threshing, had been locked up therein for atrociously presuming to be hungry, when Mrs. Mann, the good lady of the house, was unexpectedly startled by the apparition of Mr. Bumble the beadle striving to undo the wicket of the garden-gate.

“Goodness gracious! is that you, Mr. Bumble, sir?” said Mrs. Mann, thrusting her head out of the window in well-affected ecstasies of[13] joy. “(Susan, take Oliver and them two brats up stairs, and wash ’em directly.)—My heart alive! Mr. Bumble, how glad I am to see you, sure-ly!”

Now Mr. Bumble was a fat man, and a choleric one; so, instead of responding to this open-hearted salutation in a kindred spirit, he gave the little wicket a tremendous shake, and then bestowed upon it a kick which could have emanated from no leg but a beadle’s.

“Lor, only think,” said Mrs. Mann, running out,—for the three boys had been removed by this time,—“only think of that! That I should have forgotten that the gate was bolted on the inside, on account of them dear children! Walk in, sir; walk in, pray, Mr. Bumble, do sir.”

Although this invitation was accompanied with a curtsey that might have softened the heart of a churchwarden, it by no means mollified the beadle.

“Do you think this respectful or proper conduct, Mrs. Mann,” inquired Mr. Bumble, grasping his cane,—“to keep the parish officers[14] a-waiting at your garden-gate, when they come here upon porochial business connected with the porochial orphans? Are you aware, Mrs. Mann, that you are, as I may say, a porochial delegate, and a stipendiary?”

“I’m sure, Mr. Bumble, that I was only a-telling one or two of the dear children as is so fond of you, that it was you a-coming,” replied Mrs. Mann with great humility.

Mr. Bumble had a great idea of his oratorical powers and his importance. He had displayed the one, and vindicated the other. He relaxed.

“Well, well, Mrs. Mann,” he replied in a calmer tone; “it may be as you say; it may be. Lead the way in, Mrs. Mann, for I come on business, and have got something to say.”

Mrs. Mann ushered the beadle into a small parlour with a brick floor: placed a seat for him, and officiously deposited his cocked hat and cane on the table before him. Mr. Bumble wiped from his forehead the perspiration which his walk had engendered, glanced complacently[15] at the cocked hat, and smiled. Yes, he smiled: beadles are but men, and Mr. Bumble smiled.

“Now don’t you be offended at what I’m a-going to say,” observed Mrs. Mann, with captivating sweetness. “You’ve had a long walk, you know, or I wouldn’t mention it. Now will you take a little drop of something, Mr. Bumble?”

“Not a drop—not a drop,” said Mr. Bumble, waving his right hand in a dignified, but still placid manner.

“I think you will,” said Mrs. Mann, who had noticed the tone of the refusal, and the gesture that had accompanied it. “Just a leetle drop, with a little cold water, and a lump of sugar.”

Mr. Bumble coughed.

“Now, just a little drop,” said Mrs. Mann persuasively.

“What is it?” inquired the beadle.

“Why, it’s what I’m obliged to keep a little of in the house, to put in the blessed infants’ Daffy when they ain’t well, Mr. Bumble,”[16] replied Mrs. Mann as she opened a corner cupboard, and took down a bottle and glass. “It’s gin.”

“Do you give the children Daffy, Mrs. Mann?” inquired Bumble, following with his eyes the interesting process of mixing.

“Ah, bless ’em, that I do, dear as it is,” replied the nurse. “I couldn’t see ’em suffer before my very eyes, you know, sir.”

“No,” said Mr. Bumble approvingly; “no, you could not. You are a humane woman, Mrs. Mann.”—(Here she set down the glass.)—“I shall take an early opportunity of mentioning it to the board, Mrs. Mann.”—(He drew it towards him.)—“You feel as a mother, Mrs. Mann.”—(He stirred the gin and water.)—“I—I drink your health with cheerfulness, Mrs. Mann;”—and he swallowed half of it.

“And now about business,” said the beadle, taking out a leathern pocket-book. “The child that was half-baptized Oliver Twist, is nine year old to-day.”

“Bless him!” interposed Mrs. Mann, inflaming her left eye with the corner of her apron.

“And notwithstanding a offered reward of ten pound, which was afterwards increased to twenty pound,—notwithstanding the most superlative, and, I may say, supernat’ral exertions on the part of this parish,” said Bumble, “we have never been able to discover who is his father, or what is his mother’s settlement, name, or condition.”

Mrs. Mann raised her hands in astonishment; but added, after a moment’s reflection, “How comes he to have any name at all, then?”

The beadle drew himself up with great pride, and said, “I inwented it.”

“You, Mr. Bumble!”

“I, Mrs. Mann. We name our foundlins in alphabetical order. The last was a S,—Swubble, I named him. This was a T,—Twist, I named him. The next one as comes will be Unwin, and the next Vilkins[18]. I have got names ready made to the end of the alphabet, and all the way through it again, when we come to Z.”

“Why, you’re quite a literary character, sir!” said Mrs. Mann.

“Well, well,” said the beadle, evidently gratified with the compliment; “perhaps I may be—perhaps I may be, Mrs. Mann.” He finished the gin and water, and added, “Oliver being now too old to remain here, the Board have determined to have him back into the house, and I have come out myself to take him there,—so let me see him at once.”

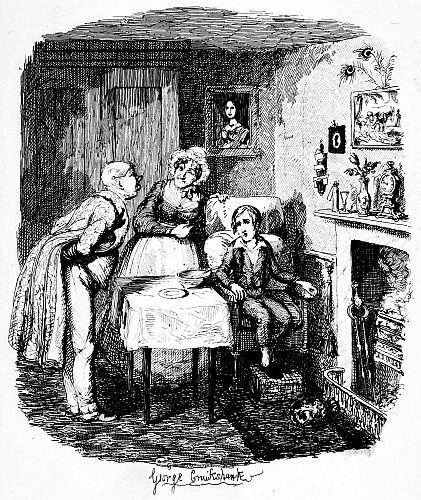

“I’ll fetch him directly,” said Mrs. Mann, leaving the room for that purpose. And Oliver, having by this time had as much of the outer coat of dirt, which encrusted his face and hands, removed, as could be scrubbed off in one washing, was led into the room by his benevolent protectress.

“Make a bow to the gentleman, Oliver,” said Mrs. Mann.

Oliver made a bow, which was divided between[19] the beadle on the chair and the cocked-hat on the table.

“Will you go along with me, Oliver?” said Mr. Bumble in a majestic voice.

Oliver was about to say that he would go along with anybody with great readiness, when, glancing upwards, he caught sight of Mrs. Mann, who had got behind the beadle’s chair, and was shaking her fist at him with a furious countenance. He took the hint at once, for the fist had been too often impressed upon his body not to be deeply impressed upon his recollection.

“Will she go with me?” inquired poor Oliver.

“No, she can’t,” replied Mr. Bumble; “but she’ll come and see you sometimes.”

This was no very great consolation to the child; but, young as he was, he had sense enough to make a feint of feeling great regret at going away. It was no very difficult matter for the boy to call the tears into his eyes. Hunger and recent ill-usage are great assistants if you want to cry; and Oliver cried very[20] naturally indeed. Mrs. Mann gave him a thousand embraces, and, what Oliver wanted a great deal more, a piece of bread and butter, lest he should seem too hungry when he got to the workhouse. With the slice of bread in his hand, and the little brown-cloth parish cap upon his head, Oliver was then led away by Mr. Bumble from the wretched home where one kind word or look had never lighted the gloom of his infant years. And yet he burst into an agony of childish grief as the cottage-gate closed after him. Wretched as were the little companions in misery he was leaving behind, they were the only friends he had ever known; and a sense of his loneliness in the great wide world sank into the child’s heart for the first time.

Mr. Bumble walked on with long strides, and little Oliver, firmly grasping his gold-laced cuff, trotted beside him, inquiring at the end of every quarter of a mile whether they were “nearly there,” to which interrogations Mr. Bumble returned very brief and snappish replies;[21] for the temporary blandness which gin and water awakens in some bosoms had by this time evaporated, and he was once again a beadle.

Oliver had not been within the walls of the workhouse a quarter of an hour, and had scarcely completed the demolition of a second slice of bread, when Mr. Bumble, who had handed him over to the care of an old woman, returned, and, telling him it was a board night, informed him that the board had said he was to appear before it forthwith.

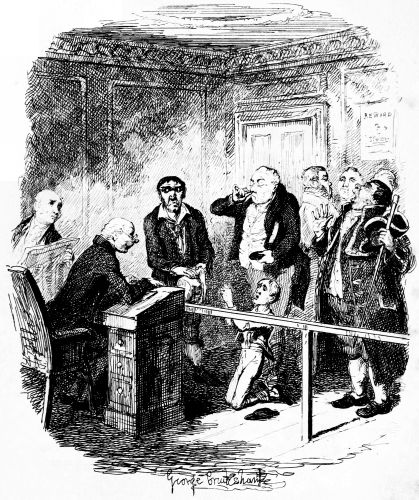

Not having a very clearly defined notion of what a live board was, Oliver was rather astounded by this intelligence, and was not quite certain whether he ought to laugh or cry. He had no time to think about the matter, however; for Mr. Bumble gave him a tap on the head with his cane to wake him up, and another on the back to make him lively, and bidding him follow, conducted him into a large whitewashed room where eight or ten fat gentlemen were sitting round a table, at[22] the top of which, seated in an arm-chair rather higher than the rest, was a particularly fat gentleman with a very round, red face.

“Bow to the board,” said Bumble. Oliver brushed away two or three tears that were lingering in his eyes, and seeing no board but the table, fortunately bowed to that.

“What’s your name, boy?” said the gentleman in the high chair.

Oliver was frightened at the sight of so many gentlemen, which made him tremble; and the beadle gave him another tap behind, which made him cry; and these two causes made him answer in a very low and hesitating voice; whereupon a gentleman in a white waistcoat said he was a fool, which was a capital way of raising his spirits, and putting him quite at his ease.

“Boy,” said the gentleman in the high chair, “listen to me. You know you’re an orphan, I suppose?”

“What’s that, sir?” inquired poor Oliver.

“The boy is a fool—I thought he was,” said the gentleman in the white waistcoat, in[23] a very decided tone. If one member of a class be blessed with an intuitive perception of others of the same race, the gentleman in the white waistcoat was unquestionably well qualified to pronounce an opinion on the matter.

“Hush!” said the gentleman who had spoken first. “You know you’ve got no father or mother, and that you are brought up by the parish, don’t you?”

“Yes, sir,” replied Oliver, weeping bitterly.

“What are you crying for?” inquired the gentleman in the white waistcoat. And to be sure it was very extraordinary. What could the boy be crying for?

“I hope you say your prayers every night,” said another gentleman in a gruff voice, “and pray for the people who feed you, and take care of you, like a Christian.”

“Yes, sir,” stammered the boy. The gentleman who spoke last was unconsciously right. It would have been very like a Christian, and a marvellously good Christian, too, if Oliver had prayed for the people who fed and took[24] care of him. But he hadn’t, because nobody had taught him.

“Well, you have come here to be educated, and taught a useful trade,” said the red-faced gentleman in the high chair.

“So you’ll begin to pick oakum to-morrow morning at six o’clock,” added the surly one in the white waistcoat.

For the combination of both these blessings in the one simple process of picking oakum, Oliver bowed low by the direction of the beadle, and was then hurried away to a large ward, where, on a rough hard bed, he sobbed himself to sleep. What a noble illustration of the tender laws of this favoured country!—they let the paupers go to sleep!

Poor Oliver! He little thought, as he lay sleeping in happy unconsciousness of all around him, that the board had that very day arrived at a decision which would exercise the most material influence over all his future fortunes. But they had. And this was it:—

The members of this board were very sage, deep, philosophical men; and when they came[25] to turn their attention to the workhouse, they found out at once, what ordinary folks would never have discovered—the poor people liked it! It was a regular place of public entertainment for the poorer classes—a tavern where there was nothing to pay—a public breakfast, dinner, tea, and supper all the year round—a brick and mortar elysium, where it was all play and no work. “Oho!” said the board, looking very knowing; “we are the fellows to set this to rights; we’ll stop it all in no time.” So, they established the rule, that all poor people should have the alternative (for they would compel nobody, not they,) of being starved by a gradual process in the house, or by a quick one out of it. With this view, they contracted with the waterworks to lay on an unlimited supply of water, and with a corn-factor to supply periodically small quantities of oatmeal; and issued three meals of thin gruel a-day, with an onion twice a week, and half a roll on Sundays. They made a great many other wise and humane[26] regulations having reference to the ladies, which it is not necessary to repeat; kindly undertook to divorce poor married people, in consequence of the great expense of a suit in Doctors’ Commons; and, instead of compelling a man to support his family as they had theretofore done, took his family away from him, and made him a bachelor! There is no telling how many applicants for relief under these last two heads would not have started up in all classes of society, if it had not been coupled with the workhouse. But they were long-headed men, and they had provided for this difficulty. The relief was inseparable from the workhouse and the gruel, and that frightened the people.

For the first six months after Oliver Twist was removed, the system was in full operation. It was rather expensive at first, in consequence of the increase of the undertaker’s bill, and the necessity of taking in the clothes of all the paupers, which fluttered loosely on their wasted, shrunken forms, after a week or two’s gruel. But the number of workhouse inmates got[27] thin as well as the paupers, and the board were in ecstasies.

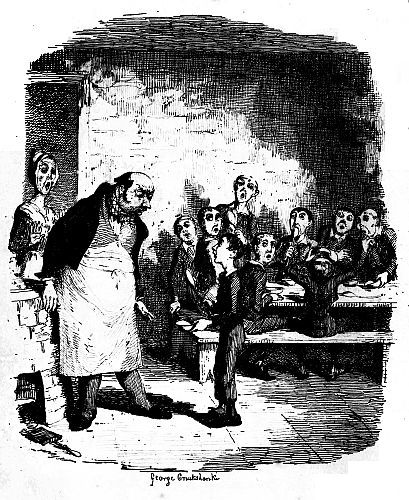

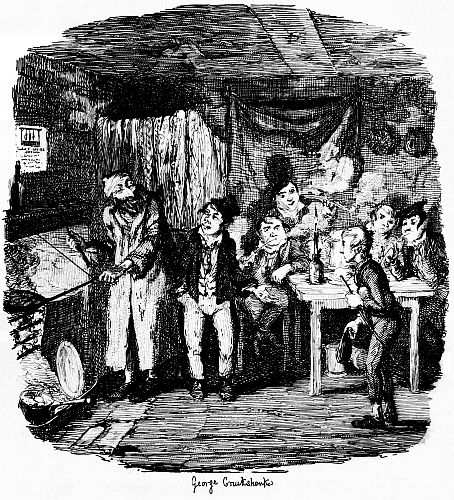

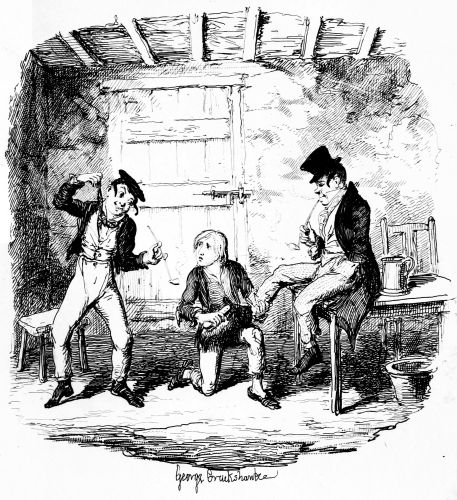

The room in which the boys were fed was a large stone hall, with a copper at one end, out of which the master, dressed in an apron for the purpose, and assisted by one or two women, ladled the gruel at meal-times; of which composition each boy had one porringer, and no more—except on festive occasions, and then he had two ounces and a quarter of bread besides. The bowls never wanted washing—the boys polished them with their spoons till they shone again; and when they had performed this operation, (which never took very long, the spoons being nearly as large as the bowls,) they would sit staring at the copper with such eager eyes as if they could devour the very bricks of which it was composed; employing themselves meanwhile in sucking their fingers most assiduously, with the view of catching up any stray splashes of gruel that might have been cast thereon. Boys have generally excellent appetites. Oliver Twist and[28] his companions suffered the tortures of slow starvation for three months; at last they got so voracious and wild with hunger, that one boy, who was tall for his age, and hadn’t been used to that sort of thing, (for his father had kept a small cook’s shop,) hinted darkly to his companions, that unless he had another basin of gruel per diem, he was afraid he should some night eat the boy who slept next him, who happened to be a weakly youth of tender age. He had a wild, hungry eye, and they implicitly believed him. A council was held; lots were cast who should walk up to the master after supper that evening, and ask for more; and it fell to Oliver Twist.

The evening arrived: the boys took their places; the master in his cook’s uniform stationed himself at the copper; his pauper assistants ranged themselves behind him; the gruel was served out, and a long grace was said over the short commons. The gruel disappeared, and the boys whispered each other and winked at Oliver, while his next neighbours nudged him. Child as he was, he was desperate with[29] hunger and reckless with misery. He rose from the table, and advancing, basin and spoon in hand, to the master, said, somewhat alarmed at his own temerity—

“Please, sir, I want some more.”

The master was a fat, healthy man, but he turned very pale. He gazed in stupefied astonishment on the small rebel for some seconds, and then clung for support to the copper. The assistants were paralysed with wonder, and the boys with fear.

“What!” said the master at length, in a faint voice.

“Please, sir,” replied Oliver, “I want some more.”

The master aimed a blow at Oliver’s head with the ladle, pinioned him in his arms, and shrieked aloud for the beadle.

The board were sitting in solemn conclave when Mr. Bumble rushed into the room in great excitement, and addressing the gentleman in the high chair, said—

“Mr. Limbkins, I beg your pardon, sir;—Oliver Twist has asked for more.” There was[30] a general start. Horror was depicted on every countenance.

“For more!” said Mr. Limbkins. “Compose yourself, Bumble, and answer me distinctly. Do I understand that he asked for more, after he had eaten the supper allotted by the dietary?”

“He did, sir,” replied Bumble.

“That boy will be hung,” said the gentleman in the white waistcoat; “I know that boy will be hung.”

Nobody controverted the prophetic gentleman’s opinion. An animated discussion took place. Oliver was ordered into instant confinement; and a bill was next morning pasted on the outside of the gate, offering a reward of five pounds to anybody who would take Oliver Twist off the hands of the parish. In other words, five pounds and Oliver Twist were offered to any man or woman who wanted an apprentice to any trade, business or calling.

“I never was more convinced of anything in my life,” said the gentleman in the white waistcoat, as he knocked at the gate and read the[31] bill next morning—“I never was more convinced of anything in my life, than I am that that boy will come to be hung.”

As I purpose to show in the sequel whether the white-waistcoated gentleman was right or not, I should perhaps mar the interest of this narrative (supposing it to possess any at all) if I ventured to hint just yet, whether the life of Oliver Twist had this violent termination or no.

For a week after the commission of the impious and profane offence of asking for more, Oliver remained a close prisoner in the dark and solitary room to which he had been consigned by the wisdom and mercy of the board. It appears, at first sight, not unreasonable to suppose, that, if he had entertained a becoming feeling of respect for the prediction of the gentleman in the white waistcoat, he would have established that sage individual’s prophetic character, once and for ever, by tying one end of his pocket handkerchief to a hook in the wall, and attaching himself to the other. To the performance of this feat, however, there was one obstacle, namely, that pocket-handkerchiefs[33] being decided articles of luxury, had been, for all future times and ages, removed from the noses of paupers by the express order of the board in council assembled, solemnly given and pronounced under their hands and seals. There was a still greater obstacle in Oliver’s youth and childishness. He only cried bitterly all day; and when the long, dismal night came on, he spread his little hands before his eyes to shut out the darkness, and crouching in the corner, tried to sleep: ever and anon waking with a start and tremble, and drawing himself closer and closer to the wall, as if to feel even its cold hard surface were a protection in the gloom and loneliness which surrounded him.

Let it not be supposed by the enemies of “the system,” that, during the period of his solitary incarceration, Oliver was denied the benefit of exercise, the pleasure of society, or the advantages of religious consolation. As for exercise, it was nice cold weather, and he was allowed to perform his ablutions every morning under the pump, in a stone yard, in the presence of Mr. Bumble, who prevented his[34] catching cold, and caused a tingling sensation to pervade his frame, by repeated applications of the cane; as for society, he was carried every other day into the hall where the boys dined, and there sociably flogged as a public warning and example; and so far from being denied the advantages of religious consolation, he was kicked into the same apartment every evening at prayer-time, and there permitted to listen to, and console his mind with, a general supplication of the boys, containing a special clause therein inserted by authority of the board, in which they entreated to be made good, virtuous, contented, and obedient, and to be guarded from the sins and vices of Oliver Twist, whom the supplication distinctly set forth to be under the exclusive patronage and protection of the powers of wickedness, and an article direct from the manufactory of the devil himself.

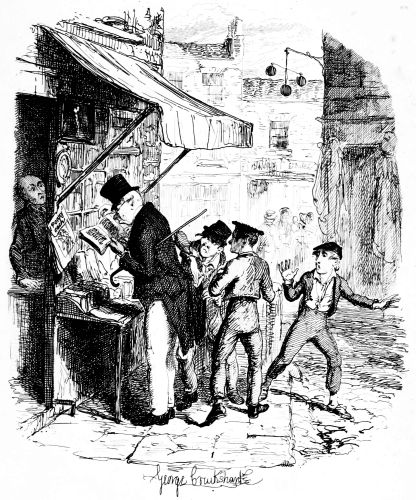

It chanced one morning, while Oliver’s affairs were in this auspicious and comfortable state, that Mr. Gamfield, chimney-sweeper, was wending his way adown the High-street, deeply cogitating in his mind his ways and means of[35] paying certain arrears of rent, for which his landlord had become rather pressing. Mr. Gamfield’s most sanguine calculation of funds could not raise them within full five pounds of the desired amount; and, in a species of arithmetical desperation, he was alternately cudgelling his brains and his donkey, when, passing the workhouse, his eyes encountered the bill on the gate.

“Wo—o!” said Mr. Gamfield to the donkey.

The donkey was in a state of profound abstraction,—wondering, probably, whether he was destined to be regaled with a cabbage-stalk or two, when he had disposed of the two sacks of soot with which the little cart was laden; so, without noticing the word of command, he jogged onwards.

Mr. Gamfield growled a fierce imprecation on the donkey generally, but more particularly on his eyes; and, running after him, bestowed a blow on his head, which would inevitably have beaten in any skull but a donkey’s; then, catching hold of the bridle, he gave his jaw a sharp wrench, by way of gentle reminder[36] that he was not his own master: and, having by these means turned him round, he gave him another blow on the head, just to stun him till he came back again; and having done so, walked up to the gate to read the bill.

The gentleman with the white waistcoat was standing at the gate with his hands behind him, after having delivered himself of some profound sentiments in the board-room. Having witnessed the little dispute between Mr. Gamfield and the donkey, he smiled joyously when that person came up to read the bill, for he saw at once that Mr. Gamfield was exactly the sort of master Oliver Twist wanted. Mr. Gamfield smiled, too, as he perused the document, for five pounds was just the sum he had been wishing for; and, as to the boy with which it was encumbered, Mr. Gamfield, knowing what the dietary of the workhouse was, well knew he would be a nice small pattern, just the very thing for register stoves. So he spelt the bill through again, from beginning to end, and then, touching his fur cap in token of humility, accosted the gentleman in the white waistcoat.

“This here boy, sir, wot the parish wants to ’prentis,” said Mr. Gamfield.

“Yes, my man,” said the gentleman in the white waistcoat, with a condescending smile, “what of him?”

“If the parish vould like him to learn a light pleasant trade, in a good ’spectable chimbley-sweepin’ bisness,” said Mr. Gamfield, “I wants a ’prentis, and I’m ready to take him.”

“Walk in,” said the gentleman in the white waistcoat. Mr. Gamfield having lingered behind, to give the donkey another blow on the head, and another wrench of the jaw, as a caution not to run away in his absence, followed the gentleman with the white waistcoat into the room where Oliver had first seen him.

“It’s a nasty trade,” said Mr. Limbkins when Gamfield had again stated his wish.

“Young boys have been smothered in chimneys before now,” said another gentleman.

“That’s acause they damped the straw afore they lit it in the chimbley to make ’em come down again,” said Gamfield; “that’s all smoke, and no blaze; vereas smoke ain’t o’ no use at[38] all in makin’ a boy come down, for it only sinds him to sleep, and that’s wot he likes. Boys is wery obstinit, and wery lazy, gen’lmen, and there’s nothink like a good hot blaze to make ’em com down vith a run; it’s humane too, gen’lmen, acause, even if they’ve stuck in the chimbley, roastin’ their feet makes ’em struggle to hextricate theirselves.”

The gentleman in the white waistcoat appeared very much amused by this explanation; but his mirth was speedily checked by a look from Mr. Limbkins. The board then proceeded to converse among themselves for a few minutes, but in so low a tone, that the words “saving of expenditure,” “look well in the accounts,” “have a printed report published,” were alone audible: and they only chanced to be heard on account of their being very frequently repeated with great emphasis.

At length the whispering ceased, and the members of the board having resumed their seats and their solemnity, Mr. Limbkins said,

“We have considered your proposition, and we don’t approve of it.”

“Not at all,” said the gentleman in the white waistcoat.

“Decidedly not,” added the other members.

As Mr. Gamfield did happen to labour under the slight imputation of having bruised three or four boys to death already, it occurred to him that the board had perhaps, in some unaccountable freak, taken it into their heads that this extraneous circumstance ought to influence their proceedings. It was very unlike their general mode of doing business, if they had; but still, as he had no particular wish to revive the rumour, he twisted his cap in his hands, and walked slowly from the table.

“So you won’t let me have him, gen’lmen,” said Mr. Gamfield, pausing near the door.

“No,” replied Mr. Limbkins; “at least, as it’s a nasty business, we think you ought to take something less than the premium we offered.”

Mr. Gamfield’s countenance brightened, as, with a quick step he returned to the table, and said,

“What’ll you give, gen’lmen? Come, don’t[40] be too hard on a poor man. What’ll you give?”

“I should say three pound ten was plenty,” said Mr. Limbkins.

“Ten shillings too much,” said the gentleman in the white waistcoat.

“Come,” said Gamfield; “say four pound, gen’lmen. Say four pound, and you’ve got rid of him for good and all. There!”

“Three pound ten,” repeated Mr. Limbkins, firmly.

“Come, I’ll split the difference, gen’lmen,” urged Gamfield. “Three pound fifteen.”

“Not a farthing more,” was the firm reply of Mr. Limbkins.

“You’re desp’rate hard upon me, gen’lmen,” said Gamfield, wavering.

“Pooh! pooh! nonsense!” said the gentleman in the white waistcoat. “He’d be cheap with nothing at all, as a premium. Take him, you silly fellow! He’s just the boy for you. He wants the stick now and then; it’ll do him good; and his board needn’t come very expensive, for he hasn’t been overfed since he was born. Ha! ha! ha!”

Mr. Gamfield gave an arch look at the faces round the table, and, observing a smile on all of them, gradually broke into a smile himself. The bargain was made, and Mr. Bumble was at once instructed that Oliver Twist and his indentures were to be conveyed before the magistrate for signature and approval that very afternoon.

In pursuance of this determination, little Oliver, to his excessive astonishment, was released from bondage, and ordered to put himself into a clean shirt. He had hardly achieved this very unusual gymnastic performance, when Mr. Bumble brought him with his own hands a basin of gruel, and the holiday allowance of two ounces and a quarter of bread; at sight of which Oliver began to cry very piteously, thinking, not unnaturally, that the board must have determined to kill him for some useful purpose, or they never would have begun to fatten him up in this way.

“Don’t make your eyes red, Oliver, but eat your food and be thankful,” said Mr. Bumble, in a tone of impressive pomposity. “You’re a-going to be made a ’prentice of, Oliver.”

“A ’prentice, sir!” said the child, trembling.

“Yes, Oliver,” said Mr. Bumble. “The kind and blessed gentlemen which is so many parents to you, Oliver, when you have none of your own, are a-going to ’prentice you, and to set you up in life, and make a man of you, although the expense to the parish is three pound ten!—three pound ten, Oliver!—seventy shillin’s!—one hundred and forty sixpences!—and all for a naughty orphan which nobody can’t love.”

As Mr. Bumble paused to take breath after delivering this address in an awful voice, the tears rolled down the poor child’s face, and he sobbed bitterly.

“Come,” said Mr. Bumble, somewhat less pompously, for it was gratifying to his feelings to observe the effect his eloquence had produced, “come, Oliver, wipe your eyes with the cuffs of your jacket, and don’t cry into your gruel; that’s a very foolish action, Oliver.” It certainly was, for there was quite enough water in it already.

On their way to the magistrates, Mr. Bumble[43] instructed Oliver that all he would have to do, would be to look very happy, and say, when the gentleman asked him if he wanted to be apprenticed, that he should like it very much indeed; both of which injunctions Oliver promised to obey, the rather as Mr. Bumble threw in a gentle hint, that if he failed in either particular, there was no telling what would be done to him. When they arrived at the office, he was shut up in a little room by himself, and admonished by Mr. Bumble to stay there until he came back to fetch him.

There the boy remained with a palpitating heart for half an hour, at the expiration of which time Mr. Bumble thrust in his head, unadorned with the cocked hat, and said aloud,

“Now, Oliver, my dear, come to the gentleman.” As Mr. Bumble said this, he put on a grim and threatening look, and added in a low voice, “Mind what I told you, you young rascal.”

Oliver stared innocently in Mr. Bumble’s face at this somewhat contradictory style of address; but that gentleman prevented his[44] offering any remark thereupon, by leading him at once into an adjoining room, the door of which was open. It was a large room with a great window; and behind a desk sat two old gentlemen with powdered heads, one of whom was reading the newspaper, while the other was perusing, with the aid of a pair of tortoise-shell spectacles, a small piece of parchment which lay before him. Mr. Limbkins was standing in front of the desk on one side, and Mr. Gamfield, with a partially washed face, on the other, while two or three bluff-looking men in top-boots were lounging about.

The old gentleman with the spectacles gradually dozed off over the little bit of parchment, and there was a short pause, after Oliver had been stationed by Mr. Bumble in front of the desk.

“This is the boy, your worship,” said Mr. Bumble.

The old gentleman who was reading the newspaper raised his head for a moment, and pulled the other old gentleman by the sleeve, whereupon the last-mentioned old gentleman woke up.

“Oh, is this the boy?” said the old gentleman.

“This is him, sir,” replied Mr. Bumble. “Bow to the magistrate, my dear.”

Oliver roused himself, and made his best obeisance. He had been wondering, with his eyes fixed on the magistrates’ powder, whether all boards were born with that white stuff on their heads, and were boards from thenceforth on that account.

“Well,” said the old gentleman, “I suppose he’s fond of chimney-sweeping?”

“He doats on it, your worship,” replied Bumble, giving Oliver a sly pinch, to intimate that he had better not say he didn’t.

“And he will be a sweep, will he?” inquired the old gentleman.

“If we was to bind him to any other trade to-morrow, he’d run away simultaneously, your worship,” replied Bumble.

“And this man that’s to be his master—you, sir—you’ll treat him well, and feed him, and do all that sort of thing,—will you?” said the old gentleman.

“When I says I will, I means I will,” replied Mr. Gamfield doggedly.

“You’re a rough speaker, my friend, but you look an honest, open-hearted man,” said the old gentleman, turning his spectacles in the direction of the candidate for Oliver’s premium, whose villanous countenance was a regular stamped receipt for cruelty. But the magistrate was half blind and half childish, so he couldn’t reasonably be expected to discern what other people did.

“I hope I am, sir,” said Mr. Gamfield with an ugly leer.

“I have no doubt you are, my friend,” replied the old gentleman, fixing his spectacles more firmly on his nose, and looking about him for the inkstand.

It was the critical moment of Oliver’s fate. If the inkstand had been where the old gentleman thought it was, he would have dipped his pen into it and signed the indentures, and Oliver would have been straightway hurried off. But as it chanced to be immediately under his nose, it followed as a matter of course that he[47] looked all over his desk for it, without finding it; and happening in the course of his search to look straight before him, his gaze encountered the pale and terrified face of Oliver Twist, who, despite all the admonitory looks and pinches of Bumble, was regarding the very repulsive countenance of his future master with a mingled expression of horror and fear, too palpable to be mistaken even by a half-blind magistrate.

The old gentleman stopped, laid down his pen, and looked from Oliver to Mr. Limbkins, who attempted to take snuff with a cheerful and unconcerned aspect.

“My boy,” said the old gentleman, leaning over the desk. Oliver started at the sound—he might be excused for doing so, for the words were kindly said, and strange sounds frighten one. He trembled violently, and burst into tears.

“My boy,” said the old gentleman, “you look pale and alarmed. What is the matter?”

“Stand a little away from him, beadle,” said the other magistrate, laying aside the paper,[48] and leaning forward with an expression of interest. “Now, boy, tell us what’s the matter: don’t be afraid.”

Oliver fell on his knees, and clasping his hands together, prayed that they would order him back to the dark room—that they would starve him—beat him—kill him if they pleased—rather than send him away with that dreadful man.

“Well!” said Mr. Bumble, raising his hands and eyes with most impressive solemnity,—“Well! of all the artful and designing orphans that ever I see, Oliver, you are one of the most bare-facedest.”

“Hold your tongue, beadle,” said the second old gentleman, when Mr. Bumble had given vent to this compound adjective.

“I beg your worship’s pardon,” said Mr. Bumble, incredulous of his having heard aright,—“did your worship speak to me?”

“Yes—hold your tongue.”

Mr. Bumble was stupefied with astonishment. A beadle ordered to hold his tongue! A moral revolution!

The old gentleman in the tortoise-shell spectacles looked at his companion; he nodded significantly.

“We refuse to sanction these indentures,” said the old gentleman, tossing aside the piece of parchment as he spoke.

“I hope,” stammered Mr. Limbkins—“I hope the magistrates will not form the opinion that the authorities have been guilty of any improper conduct, on the unsupported testimony of a mere child.”

“The magistrates are not called upon to pronounce any opinion on the matter,” said the second old gentleman sharply. “Take the boy back to the workhouse, and treat him kindly. He seems to want it.”

That same evening the gentleman in the white waistcoat most positively and decidedly affirmed, not only that Oliver would be hung, but that he would be drawn and quartered into the bargain. Mr. Bumble shook his head with gloomy mystery, and said he wished he might come to good; whereunto Mr. Gamfield replied, that he wished he might come to him,[50] which, although he agreed with the beadle in most matters, would seem to be a wish of a totally opposite description.

The next morning the public were once more informed that Oliver Twist was again to let, and that five pounds would be paid to anybody who would take possession of him.

In great families, when an advantageous place cannot be obtained, either in possession, reversion, remainder, or expectancy, for the young man who is growing up, it is a very general custom to send him to sea. The board, in imitation of so wise and salutary an example, took counsel together on the expediency of shipping off Oliver Twist in some small trading vessel bound to a good unhealthy port, which suggested itself as the very best thing that could possibly be done with him; the probability being, that the skipper would either flog him to death in a playful mood some day after dinner, or knock his brains out with an iron bar—both pastimes being, as is pretty generally known,[52] very favourite and common recreations among gentlemen of that class. The more the case presented itself to the board in this point of view, the more manifold the advantages of the step appeared; so they came to the conclusion, that the only way of providing for Oliver effectually, was to send him to sea without delay.

Mr. Bumble had been despatched to make various preliminary inquiries, with the view of finding out some captain or other who wanted a cabin-boy without any friends; and was returning to the workhouse to communicate the result of his mission, when he encountered just at the gate no less a person than Mr. Sowerberry, the parochial undertaker.

Mr. Sowerberry was a tall, gaunt, large-jointed man, attired in a suit of thread-bare black, with darned cotton stockings of the same colour, and shoes to answer. His features were not naturally intended to wear a smiling aspect, but he was in general rather given to professional jocosity; his step was elastic, and his face betokened inward pleasantry, as he advanced to Mr. Bumble and shook him cordially by the hand.

“I have taken the measure of the two women that died last night, Mr. Bumble,” said the undertaker.

“You’ll make your fortune, Mr. Sowerberry,” said the beadle, as he thrust his thumb and forefinger into the proffered snuff-box of the undertaker, which was an ingenious little model of a patent coffin. “I say you’ll make your fortune, Mr. Sowerberry,” repeated Mr. Bumble, tapping the undertaker on the shoulder in a friendly manner with his cane.

“Think so?” said the undertaker in a tone which half admitted and half disputed the probability of the event. “The prices allowed by the board are very small, Mr. Bumble.”

“So are the coffins,” replied the beadle, with precisely as near an approach to a laugh as a great official ought to indulge in.

Mr. Sowerberry was much tickled at this, as of course he ought to be, and laughed a long time without cessation. “Well, well, Mr. Bumble,” he said at length, “there’s no denying that, since the new system of feeding has come in, the coffins are something narrower and[54] more shallow than they used to be; but we must have some profit, Mr. Bumble. Well-seasoned timber is an expensive article, sir; and all the iron handles come by canal from Birmingham.”

“Well, well,” said Mr. Bumble, “every trade has its drawbacks, and a fair profit is of course allowable.”

“Of course, of course,” replied the undertaker; “and if I don’t get a profit upon this or that particular article, why, I make it up in the long-run, you see—he! he! he!”

“Just so,” said Mr. Bumble.

“Though I must say,”—continued the undertaker, resuming the current of observations which the beadle had interrupted—“though I must say, Mr. Bumble, that I have to contend against one very great disadvantage, which is, that all the stout people go off the quickest—I mean that the people who have been better off, and have paid rates for many years, are the first to sink when they come into the house: and let me tell you, Mr. Bumble, that three or[55] four inches over one’s calculation makes a great hole in one’s profits, especially when one has a family to provide for, sir.”

As Mr. Sowerberry said this, with the becoming indignation of an ill-used man, and as Mr. Bumble felt that it rather tended to convey a reflection on the honour of the parish, the latter gentleman thought it advisable to change the subject; and Oliver Twist being uppermost in his mind, he made him his theme.

“By the bye,” said Mr. Bumble, “you don’t know anybody who wants a boy, do you—a porochial ’prentis, who is at present a dead-weight—a millstone, as I may say—round the porochial throat? Liberal terms, Mr. Sowerberry—liberal terms;”—and, as Mr. Bumble spoke, he raised his cane to the bill above him, and gave three distinct raps upon the words “five pounds,” which were printed thereon in Roman capitals of gigantic size.

“Gadso!” said the undertaker, taking Mr. Bumble by the gilt-edged lappel of his official coat; “that’s just the very thing I wanted to[56] speak to you about. You know—dear me, what a very elegant button this is, Mr. Bumble; I never noticed it before.”

“Yes, I think it is rather pretty,” said the beadle, glancing proudly downwards at the large brass buttons which embellished his coat. “The die is the same as the porochial seal—the Good Samaritan healing the sick and bruised man. The board presented it to me on New-year’s morning, Mr Sowerberry. I put it on, I remember, for the first time, to attend the inquest on that reduced tradesman who died in a doorway at midnight.”

“I recollect,” said the undertaker. “The jury brought in, ‘Died from exposure to the cold, and want of the common necessaries of life,’—didn’t they?”

Mr. Bumble nodded.

“And they made it a special verdict, I think,” said the undertaker, “by adding some words to the effect, that if the relieving officer had——”

“Tush—foolery!” interposed the beadle angrily. “If the board attended to all the[57] nonsense that ignorant jurymen talk, they’d have enough to do.”

“Very true,” said the undertaker; “they would indeed.”

“Juries,” said Mr. Bumble, grasping his cane tightly, as was his wont when working into a passion—“juries is ineddicated, vulgar, grovelling wretches.”

“So they are,” said the undertaker.

“They haven’t no more philosophy nor political economy about ’em than that,” said the beadle, snapping his fingers contemptuously.

“No more they have,” acquiesced the undertaker.

“I despise ’em,” said the beadle, growing very red in the face.

“So do I,” rejoined the undertaker.

“And I only wish we’d a jury of the independent sort in the house for a week or two,” said the beadle; “the rules and regulations of the board would soon bring their spirit down for them.”

“Let ’em alone for that,” replied the undertaker. So saying, he smiled approvingly to[58] calm the rising wrath of the indignant parish officer.

Mr. Bumble lifted off his cocked hat, took a handkerchief from the inside of the crown, wiped from his forehead the perspiration which his rage had engendered, fixed the cocked hat on again; and, turning to the undertaker, said in a calmer voice,

“Well; what about the boy?”

“Oh!” replied the undertaker; “why, you know, Mr. Bumble, I pay a good deal towards the poor’s rates.”

“Hem!” said Mr. Bumble. “Well?”

“Well,” replied the undertaker, “I was thinking that if I pay so much towards ’em, I’ve a right to get as much out of ’em as I can, Mr. Bumble; and so—and so—I think I’ll take the boy myself.”

Mr. Bumble grasped the undertaker by the arm, and led him into the building. Mr. Sowerberry was closeted with the board for five minutes, and it was arranged that Oliver should go to him that evening “upon liking,”—a[59] phrase which means, in the case of a parish apprentice, that if the master find, upon a short trial, that he can get enough work out of a boy without putting too much food in him, he shall have him for a term of years, to do what he likes with.

When little Oliver was taken before “the gentlemen” that evening, and informed that he was to go that night as general house-lad to a coffin-maker’s, and that if he complained of his situation, or ever came back to the parish again, he would be sent to sea, there to be drowned, or knocked on the head, as the case might be, he evinced so little emotion, that they by common consent pronounced him a hardened young rascal, and ordered Mr. Bumble to remove him forthwith.

Now, although it was very natural that the board, of all people in the world, should feel in a great state of virtuous astonishment and horror at the smallest tokens of want of feeling on the part of anybody, they were rather out in this particular instance. The simple fact[60] was, that Oliver, instead of possessing too little feeling, possessed rather too much, and was in a fair way of being reduced to a state of brutal stupidity and sullenness for life by the ill usage he had received. He heard the news of his destination in perfect silence, and, having had his luggage put into his hand—which was not very difficult to carry, inasmuch as it was all comprised within the limits of a brown paper parcel, about half a foot square by three inches deep—he pulled his cap over his eyes, and once more attaching himself to Mr. Bumble’s coat cuff, was led away by that dignitary to a new scene of suffering.

For some time Mr. Bumble drew Oliver along without notice or remark, for the beadle carried his head very erect, as a beadle always should; and, it being a windy day, little Oliver was completely enshrouded by the skirts of Mr. Bumble’s coat as they blew open, and disclosed to great advantage his flapped waistcoat and drab plush knee-breeches. As they drew near to their destination, however, Mr. Bumble[61] thought it expedient to look down and see that the boy was in good order for inspection by his new master, which he accordingly did, with a fit and becoming air of gracious patronage.

“Oliver!” said Mr. Bumble.

“Yes, sir,” replied Oliver, in a low, tremulous voice.

“Pull that cap off your eyes, and hold up your head, sir.”

Although Oliver did as he was desired at once, and passed the back of his unoccupied hand briskly across his eyes, he left a tear in them when he looked up at his conductor. As Mr. Bumble gazed sternly upon him, it rolled down his cheek. It was followed by another, and another. The child made a strong effort, but it was an unsuccessful one; and, withdrawing his other hand from Mr. Bumble’s, he covered his face with both, and wept till the tears sprung out from between his thin and bony fingers.

“Well!” exclaimed Mr. Bumble, stopping short, and darting at his little charge a look of[62] intense malignity,—“well, of all the ungratefullest and worst-disposed boys as ever I see, Oliver, you are the——”

“No, no, sir,” sobbed Oliver, clinging to the hand which held the well-known cane; “no, no, sir; I will be good indeed; indeed, indeed I will, sir! I am a very little boy, sir; and it is so—so—”

“So what?” inquired Mr. Bumble in amazement.

“So lonely, sir—so very lonely,” cried the child. “Everybody hates me. Oh! sir, don’t, don’t pray be cross to me.” The child beat his hand upon his heart, and looked into his companion’s face with tears of real agony.

Mr. Bumble regarded Oliver’s piteous and helpless look with some astonishment for a few seconds, hemmed three or four times in a husky manner, and, after muttering something about “that troublesome cough,” bid Oliver dry his eyes and be a good boy; and, once more taking his hand, walked on with him in silence.

The undertaker had just put up the shutters of his shop, and was making some entries in his[63] day-book by the light of a most appropriately dismal candle, when Mr. Bumble entered.

“Aha!” said the undertaker, looking up from the book, and pausing in the middle of a word; “is that you, Bumble?”

“No one else, Mr. Sowerberry,” replied the beadle. “Here, I’ve brought the boy.” Oliver made a bow.

“Oh! that’s the boy, is it?” said the undertaker, raising the candle above his head to get a full glimpse of Oliver. “Mrs. Sowerberry! will you come here a moment, my dear?”

Mrs. Sowerberry emerged from a little room behind the shop, and presented the form of a short, thin, squeezed-up woman, with a vixenish countenance.

“My dear,” said Mr. Sowerberry, deferentially, “this is the boy from the workhouse that I told you of.” Oliver bowed again.

“Dear me!” said the undertaker’s wife, “he’s very small.”

“Why, he is rather small,” replied Mr. Bumble, looking at Oliver as if it were his fault that he was no bigger; “he is small,—there’s[64] no denying it. But he’ll grow, Mrs. Sowerberry,—he’ll grow.”

“Ah! I dare say he will,” replied the lady pettishly, “on our victuals and our drink. I see no saving in parish children, not I; for they always cost more to keep than they’re worth: however, men always think they know best. There, get down stairs, little bag o’ bones.” With this, the undertaker’s wife opened a side door, and pushed Oliver down a steep flight of stairs into a stone cell, damp and dark, forming the ante-room to the coal-cellar, and denominated “the kitchen,” wherein sat a slatternly girl in shoes down at heel, and blue worsted stockings very much out of repair.

“Here, Charlotte,” said Mrs. Sowerberry, who had followed Oliver down, “give this boy some of the cold bits that were put by for Trip: he hasn’t come home since the morning, so he may go without ’em. I dare say he isn’t too dainty to eat ’em,—are you, boy?”

Oliver, whose eyes had glistened at the mention of meat, and who was trembling with eagerness to devour it, replied in the negative[65] and a plateful of coarse broken victuals was set before him.

I wish some well-fed philosopher, whose meat and drink turn to gall within him, whose blood is ice, and whose heart is iron, could have seen Oliver Twist clutching at the dainty viands that the dog had neglected, and witnessed the horrible avidity with which he tore the bits asunder with all the ferocity of famine:—there is only one thing I should like better, and that would be to see him making the same sort of meal himself, with the same relish.

“Well,” said the undertaker’s wife, when Oliver had finished his supper, which she had regarded in silent horror, and with fearful auguries of his future appetite, “have you done?”

There being nothing eatable within his reach, Oliver replied in the affirmative.

“Then come with me,” said Mrs. Sowerberry, taking up a dim and dirty lamp, and leading the way up stairs; “your bed’s under the counter. You won’t mind sleeping among the coffins, I suppose?—but it doesn’t much[66] matter whether you will or not, for you won’t sleep anywhere else. Come; don’t keep me here all night.”

Oliver lingered no longer, but meekly followed his new mistress.

Oliver, being left to himself in the undertaker’s shop, set the lamp down on a workman’s bench, and gazed timidly about him with a feeling of awe and dread, which many people a good deal older than he was will be at no loss to understand. An unfinished coffin on black tressels, which stood in the middle of the shop, looked so gloomy and death-like that a cold tremble came over him every time his eyes wandered in the direction of the dismal object, from which he almost expected to see some frightful form slowly rear its head to drive him mad with terror. Against the wall were ranged in regular array a long row of elm boards cut[68] into the same shape, and looking in the dim light like high-shouldered ghosts with their hands in their breeches-pockets. Coffin-plates, elm chips, bright-headed nails, and shreds of black cloth, lay scattered on the floor; and the wall behind the counter was ornamented with a lively representation of two mutes in very stiff neckcloths, on duty at a large private door, with a hearse drawn by four black steeds approaching in the distance. The shop was close and hot, and the atmosphere seemed tainted with the smell of coffins. The recess beneath the counter in which his flock mattress was thrust, looked like a grave.

Nor were these the only dismal feelings which depressed Oliver. He was alone in a strange place; and we all know how chilled and desolate the best of us will sometimes feel in such a situation. The boy had no friends to care for, or to care for him. The regret of no recent separation was fresh in his mind; the absence of no loved and well-remembered face sunk heavily into his heart. But his heart was heavy, notwithstanding; and he wished,[69] as he crept into his narrow bed, that that were his coffin, and that he could be laid in a calm and lasting sleep in the churchyard ground, with the tall grass waving gently above his head, and the sound of the old deep bell to soothe him in his sleep.

Oliver was awakened in the morning by a loud kicking at the outside of the shop-door, which, before he could huddle on his clothes, was repeated in an angry and impetuous manner about twenty-five times; and, when he began to undo the chain, the legs left off their volleys, and a voice began.

“Open the door, will yer?” cried the voice which belonged to the legs which had kicked at the door.

“I will, directly, sir,” replied Oliver, undoing the chain, and turning the key.

“I suppose yer the new boy, a’n’t yer?” said the voice, through the key-hole.

“Yes, sir,” replied Oliver.

“How old are yer?” inquired the voice.

“Ten, sir,” replied Oliver.

“Then I’ll whop yer when I get in,” said[70] the voice; “you just see if I don’t, that’s all, my work’us brat!” and having made this obliging promise, the voice began to whistle.

Oliver had been too often subjected to the process to which the very expressive monosyllable just recorded, bears reference, to entertain the smallest doubt that the owner of the voice, whoever he might be, would redeem his pledge most honourably. He drew back the bolts with a trembling hand, and opened the door.

For a second or two Oliver glanced up the street, and down the street, and over the way, impressed with the belief that the unknown, who had addressed him through the key-hole, had walked a few paces off to warm himself, for nobody did he see but a big charity-boy sitting on a post in front of the house, eating a slice of bread and butter, which he cut into wedges, the size of his mouth, with a clasp-knife, and then consumed with great dexterity.

“I beg your pardon, sir,” said Oliver, at length: seeing that no other visitor made his appearance; “did you knock?”

“I kicked,” replied the charity-boy.

“Did you want a coffin, sir?” inquired Oliver, innocently.

At this the charity-boy looked monstrous fierce, and said that Oliver would stand in need of one before long, if he cut jokes with his superiors in that way.

“Yer don’t know who I am, I suppose, Work’us?” said the charity-boy, in continuation; descending from the top of the post, meanwhile, with edifying gravity.

“No sir,” rejoined Oliver.

“I’m Mister Noah Claypole,” said the charity-boy, “and you’re under me. Take down the shutters, yer idle young ruffian!” With this, Mr. Claypole administered a kick to Oliver, and entered the shop with a dignified air, which did him great credit. It is difficult for a large-headed, small-eyed youth, of lumbering make and heavy countenance, to look dignified under any circumstances; but it is more especially so, when superadded to these personal attractions are a red nose and yellow smalls.

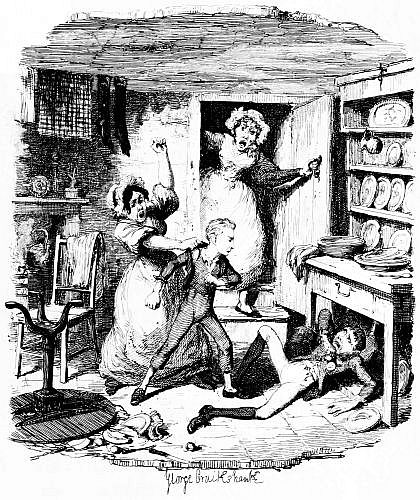

Oliver having taken down the shutters, and broken a pane of glass in his efforts to stagger[72] away beneath the weight of the first one to a small court at the side of the house in which they were kept during the day, was graciously assisted by Noah, who, having consoled him with the assurance that “he’d catch it,” condescended to help him. Mr. Sowerberry came down soon after, and, shortly afterwards, Mrs Sowerberry appeared; and Oliver having “caught it,” in fulfilment of Noah’s prediction, followed that young gentleman down stairs to breakfast.

“Come near the fire, Noah,” said Charlotte. “I saved a nice little piece of bacon for you from master’s breakfast. Oliver, shut that door at Mister Noah’s back, and take them bits that I’ve put out on the cover of the bread-pan. There’s your tea; take it away to that box, and drink it there, and make haste, for they’ll want you to mind the shop. D’ye hear?”

“D’ye hear, Work’us?” said Noah Claypole.

“Lor, Noah!” said Charlotte, “what a rum creature you are! Why don’t you let the boy alone?”

“Let him alone!” said Noah. “Why[73] every body lets him alone enough, for the matter of that. Neither his father nor mother will ever interfere with him: all his relations let him have his own way pretty well. Eh, Charlotte? He! he! he!”

“Oh, you queer soul!” said Charlotte, bursting into a hearty laugh, in which she was joined by Noah; after which they both looked scornfully at poor Oliver Twist, as he sat shivering upon the box in the coldest corner of the room, and ate the stale pieces which had been specially reserved for him.

Noah was a charity-boy, but not a workhouse orphan. No chance-child was he, for he could trace his genealogy all the way back to his parents, who lived hard by; his mother being a washerwoman, and his father a drunken soldier, discharged with a wooden leg and a diurnal pension of twopence-halfpenny and an unstateable fraction. The shop-boys in the neighbourhood had long been in the habit of branding Noah in the public streets with the ignominious epithets of “leathers,” “charity,”[74] and the like; and Noah had borne them without reply. But now that fortune had cast in his way a nameless orphan, at whom even the meanest could point the finger of scorn, he retorted on him with interest. This affords charming food for contemplation. It shows us what a beautiful thing human nature sometimes is, and how impartially the same amiable qualities are developed in the finest lord and the dirtiest charity-boy.

Oliver had been sojourning at the undertaker’s some three weeks or a month, and Mr. and Mrs. Sowerberry, the shop being shut up, were taking their supper in the little back-parlour, when Mr. Sowerberry, after several deferential glances at his wife, said,

“My dear—” He was going to say more; but, Mrs. Sowerberry looking up with a peculiarly unpropitious aspect, he stopped short.

“Well,” said Mrs. Sowerberry, sharply.

“Nothing, my dear, nothing,” said Mr. Sowerberry.

“Ugh, you brute!” said Mrs. Sowerberry.

“Not at all, my dear,” said Mr. Sowerberry[75] humbly. “I thought you didn’t want to hear, my dear. I was only going to say——”

“Oh, don’t tell me what you were going to say,” interposed Mrs. Sowerberry. “I am nobody; don’t consult me, pray. I don’t want to intrude upon your secrets.” And, as Mrs. Sowerberry said this, she gave an hysterical laugh, which threatened violent consequences.

“But, my dear,” said Sowerberry, “I want to ask your advice.”

“No, no, don’t ask mine,” replied Mrs. Sowerberry, in an affecting manner: “ask somebody else’s.” Here there was another hysterical laugh, which frightened Mr. Sowerberry very much. This is a very common and much-approved matrimonial course of treatment, which is often very effective. It at once reduced Mr. Sowerberry to begging as a special favour to be allowed to say what Mrs. Sowerberry was most curious to hear, and, after a short altercation of less than three quarters of an hour’s duration, the permission was most graciously conceded.

“It’s only about young Twist, my dear,” said Mr. Sowerberry. “A very good-looking boy that, my dear.”

“He need be, for he eats enough,” observed the lady.

“There’s an expression of melancholy in his face, my dear,” resumed Mr. Sowerberry, “which is very interesting. He would make a delightful mute, my dear.”

Mrs. Sowerberry looked up with an expression of considerable wonderment. Mr. Sowerberry remarked it, and, without allowing time for any observation on the good lady’s part, proceeded.

“I don’t mean a regular mute to attend grown-up people, my dear, but only for children’s practice. It would be very new to have a mute in proportion, my dear. You may depend upon it that it would have a superb effect.”

Mrs. Sowerberry, who had a good deal of taste in the undertaking way, was much struck by the novelty of this idea; but, as it would have been compromising her dignity to have[77] said so under existing circumstances, she merely inquired with much sharpness why such an obvious suggestion had not presented itself to her husband’s mind before. Mr. Sowerberry rightly construed this as an acquiescence in his proposition; it was speedily determined that Oliver should be at once initiated into the mysteries of the profession, and, with this view, that he should accompany his master on the very next occasion of his services being required.

The occasion was not long in coming; for, half an hour after breakfast next morning, Mr. Bumble entered the shop, and supporting his cane against the counter, drew forth his large leathern pocket-book, from which he selected a small scrap of paper, which he handed over to Sowerberry.

“Aha!” said the undertaker, glancing over it with a lively countenance; “an order for a coffin, eh?”

“For a coffin first, and a porochial funeral afterwards,” replied Mr. Bumble, fastening the strap of the leathern pocket-book, which, like himself, was very corpulent.

“Bayton,” said the undertaker, looking from the scrap of paper to Mr. Bumble; “I never heard the name before.”

Bumble shook his head as he replied, “Obstinate people, Mr. Sowerberry, very obstinate; proud, too, I’m afraid, sir.”

“Proud, eh?” exclaimed Mr. Sowerberry with a sneer.—“Come, that’s too much.”

“Oh, it’s sickening,” replied the beadle; “perfectly antimonial, Mr. Sowerberry.”

“So it is,” acquiesced the undertaker.

“We only heard of them the night before last,” said the beadle; “and we shouldn’t have known anything about them then, only a woman who lodges in the same house made an application to the porochial committee for them to send the porochial surgeon to see a woman as was very bad. He had gone out to dinner; but his ’prentice, which is a very clever lad, sent ’em some medicine in a blacking-bottle, off-hand.”

“Ah, there’s promptness,” said the undertaker.

“Promptness, indeed!” replied the beadle.[79] “But what’s the consequence; what’s the ungrateful behaviour of these rebels, sir? Why, the husband sends back word that the medicine won’t suit his wife’s complaint, and so she shan’t take it—says she shan’t take it, sir. Good, strong, wholesome medicine, as was given with great success to two Irish labourers and a coalheaver only a week before—sent ’em for nothing, with a blackin-bottle in,—and he sends back word that she shan’t take it, sir.”

As the flagrant atrocity presented itself to Mr. Bumble’s mind in full force, he struck the counter sharply with his cane, and became flushed with indignation.

“Well,” said the undertaker, “I ne—ver—did——”

“Never did, sir!” ejaculated the beadle,—“no, nor nobody never did; but, now she’s dead, we’ve got to bury her, and that’s the direction, and the sooner it’s done the better.”

Thus saying, Mr. Bumble put on his cocked hat wrong side first, in a fever of parochial excitement, and flounced out of the shop.

“Why, he was so angry, Oliver, that he forgot[80] even to ask after you,” said Mr. Sowerberry, looking after the beadle as he strode down the street.

“Yes, sir,” replied Oliver, who had carefully kept himself out of sight during the interview, and who was shaking from head to foot at the mere recollection of the sound of Mr. Bumble’s voice. He needn’t have taken the trouble to shrink from Mr. Bumble’s glance, however; for that functionary, on whom the prediction of the gentleman in the white waistcoat had made a very strong impression, thought that now the undertaker had got Oliver upon trial, the subject was better avoided, until such time as he should be firmly bound for seven years, and all danger of his being returned upon the hands of the parish should be thus effectually and legally overcome.

“Well,” said Mr. Sowerberry, taking up his hat, “the sooner this job is done the better. Noah, look after the shop. Oliver, put on your cap, and come with me.” Oliver obeyed, and followed his master on his professional mission.

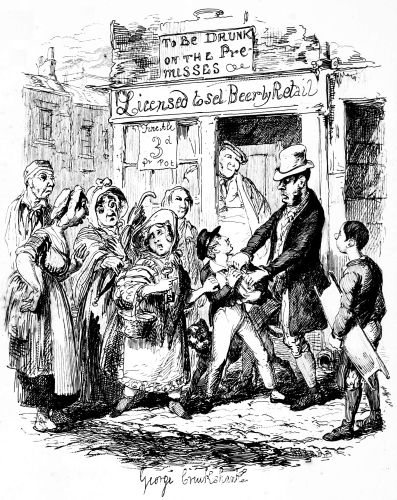

They walked on for some time through the[81] most crowded and densely inhabited part of the town, and then striking down a narrow street more dirty and miserable than any they had yet passed through, paused to look for the house which was the object of their search. The houses on either side were high and large, but very old, and tenanted by people of the poorest class, as their neglected appearance would have sufficiently denoted without the concurrent testimony afforded by the squalid looks of the few men and women who, with folded arms and bodies half doubled, occasionally skulked along. A great many of the tenements had shop-fronts; but they were fast closed, and mouldering away: only the upper rooms being inhabited. Others which had become insecure from age and decay, were prevented from falling into the street by huge beams of wood which were reared against the walls, and firmly planted in the road; but even these crazy dens seemed to have been selected as the nightly haunts of some houseless wretches, for many of the rough boards which supplied the place of door and window were wrenched from their[82] positions to afford an aperture wide enough for the passage of a human body. The kennel was stagnant and filthy; the very rats which here and there lay putrefying in its rottenness, were hideous with famine.

There was neither knocker nor bell-handle at the open door where Oliver and his master stopped; so, groping his way cautiously through the dark passage, and bidding Oliver keep close to him and not be afraid, the undertaker mounted to the top of the first flight of stairs, and stumbling against a door on the landing, rapped at it with his knuckles.

It was opened by a young girl of thirteen or fourteen. The undertaker at once saw enough of what the room contained, to know it was the apartment to which he had been directed. He stepped in, and Oliver followed him.

There was no fire in the room; but a man was crouching mechanically over the empty stove. An old woman, too had drawn a low stool to the cold hearth, and was sitting beside him. There were some ragged children in another corner; and in a small recess opposite[83] the door there lay upon the ground something covered with an old blanket. Oliver shuddered as he cast his eyes towards the place, and crept involuntarily closer to his master; for though it was covered up, the boy felt that it was a corpse.

The man’s face was thin and very pale; his hair and beard were grizzly, and his eyes were bloodshot. The old woman’s face was wrinkled, her two remaining teeth protruded over her under lip, and her eyes were bright and piercing. Oliver was afraid to look at either her or the man,—they seemed so like the rats he had seen outside.