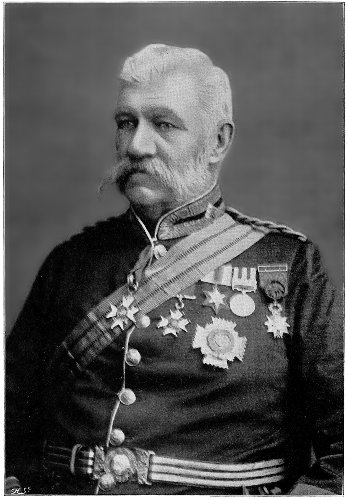

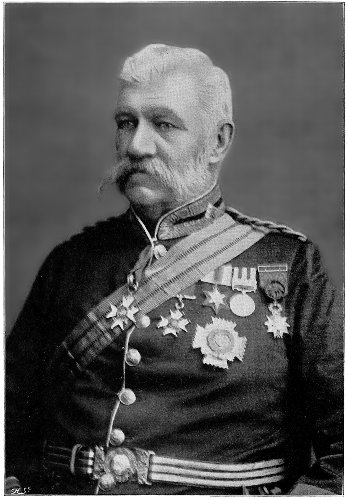

SIR CHARLES A. GORDON, K.C.B., Surgeon-General

(From a Photograph by Mr. A. Bassano, Old Bond Street)

The Project Gutenberg EBook of Recollections of Thirty-nine Years in the Army, by Charles Alexander Gordon This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook. Title: Recollections of Thirty-nine Years in the Army Author: Charles Alexander Gordon Release Date: November 17, 2014 [EBook #47380] Language: English Character set encoding: UTF-8 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK RECOLLECTIONS *** Produced by Brian Coe, Charlie Howard, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

Cover created by Transcriber, using an illustration from the original book, and placed in the Public Domain.

SIR CHARLES A. GORDON, K.C.B., Surgeon-General

(From a Photograph by Mr. A. Bassano, Old Bond Street)

Recollections of Thirty-nine

Years in the Army

GWALIOR AND THE BATTLE OF MAHARAJPORE, 1843

THE GOLD COAST OF AFRICA, 1847–48

THE INDIAN MUTINY, 1857–58

THE EXPEDITION TO CHINA, 1860–61

THE SIEGE OF PARIS, 1870–71

Etc

BY

SIR CHARLES ALEXANDER GORDON, K.C.B.

London

SWAN SONNENSCHEIN & CO., Limd

PATERNOSTER SQUARE

1898

Butler & Tanner,

The Selwood Printing Works,

Frome, and London.

THIS PERSONAL NARRATIVE

IS INSCRIBED TO

MY WIFE AND OUR CHILDREN

| PAGE | |

| CHAPTER I | |

| 1841–1842. Gazetted to the Buffs—Arrive in India | 1 |

| CHAPTER II | |

| 1842–1843. In Progress to Join | 12 |

| CHAPTER III | |

| 1843. At Allahabad | 18 |

| CHAPTER IV | |

| 1843–1844. Campaign in Gwalior | 24 |

| CHAPTER V | |

| 1844–1845. Allahabad to England | 36 |

| CHAPTER VI | |

| 1845–1846. Home Service | 46 |

| CHAPTER VII | |

| 1847–1848. Coast of Guinea—Barbados—England | 55 |

| CHAPTER VIII | |

| 1848–1851. Ireland | 74 |

| CHAPTER IX | |

| 1851–1852. Dublin to Wuzzeerabad | 80 |

| CHAPTER X | |

| 1852–1853. Wuzzeerabad | 86 |

| CHAPTER XI | |

| 1854–1856. Meean-Meer—Aberdeen | 96 |

| CHAPTER XII | |

| 1857. Aberdeen—Dinapore—Outbreak of Sepoy Mutiny | 106 |

| CHAPTER XIII | |

| 1857. Early Months of the Mutiny | 111 |

| CHAPTER XIV | |

| 1857–1858. The Jounpore Field Force | 124 |

| CHAPTER XV | |

| 1858. Capture of Lucknow | 130 |

| CHAPTER XVI | |

| 1858. The Azimghur Field Force | 135 |

| CHAPTER XVII | |

| 1858–1859. Dinapore—Plymouth | 147 |

| CHAPTER XVIIIviii | |

| 1859–1860. Plymouth—Devonport | 154 |

| CHAPTER XIX | |

| 1860. Devonport—Hong-Kong | 160 |

| CHAPTER XX | |

| 1860. Hong-Kong—Tientsin | 166 |

| CHAPTER XXI | |

| 1860–1861. Tientsin | 177 |

| CHAPTER XXII | |

| 1861. Tientsin—Chefoo—Nagasaki—Devonport | 188 |

| CHAPTER XXIII | |

| 1862–1864. Devonport—Calcutta | 201 |

| CHAPTER XXIV | |

| 1865–1868. Calcutta—Portsmouth | 213 |

| CHAPTER XXV | |

| 1868–1870. Portsmouth | 227 |

| CHAPTER XXVI | |

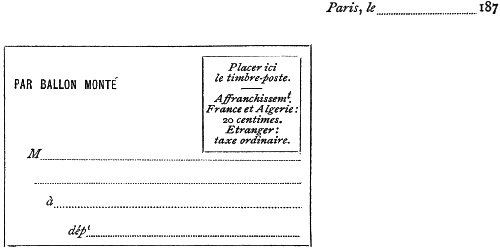

| 1870. July-September. Franco-Prussian War—Siege of Paris | 231 |

| CHAPTER XXVII | |

| 1870. September. Siege of Paris | 242 |

| CHAPTER XXVIII | |

| 1870. October. Siege of Paris | 248 |

| CHAPTER XXIX | |

| 1870. November. Siege of Paris | 259 |

| CHAPTER XXX | |

| 1870. December. Siege continued | 265 |

| CHAPTER XXXI | |

| 1871. January. Siege—Bombardment—Capitulation of Paris | 272 |

| CHAPTER XXXII | |

| 1871. February. Paris after Capitulation | 282 |

| CHAPTER XXXIII | |

| 1871. March. Enemies within Paris | 289 |

| CHAPTER XXXIV | |

| 1871–1874. Dover—Aldershot | 293 |

| CHAPTER XXXV | |

| 1874–1875. Burmah | 297 |

| CHAPTER XXXVI | |

| 1875–1880. Madras Presidency—Finale | 306 |

| Index | 315 |

First Affghan War—Chatham—Fort Pitt—Supernumeraries—How appointed—Gazetted—Breaking in—Orders of readiness—Ship inspected—Embark—First days on board—Typical characters—Warmth—Our “tub”—Reduced allowances—Conditions on board—Amusements for men—For officers—“Speaking” ships—A dismasted vessel—First sense of responsibility—Indiscipline—Neptune—On board—Table Bay—Shore boats—Cape Town—Vicinity—Official duties—The ship Lloyds—An “old friend”—The 25th Regiment—The contractor—Botanic Garden—Eastward—Mutinous crew—Land ahoy—Terrible news—The Hooghly.

In 1841 British and Indian troops occupied Cabul; but throughout Affghanistan the aspect of things political was alarming. In Scinde the Ameers were defiant and hostile. The Punjab in a state of disturbance and convulsion; law and order had ceased; isolated murders and massacres instigated by opposing claimants to the throne left vacant in 1839, and since that time occupied by a prince against whom the insurrectionary movement was now directed by chiefs, some of whom were inimical to British interests.

Military reinforcements on a large scale were dispatched from England. Great, accordingly, the activity at Chatham, then the only depot whence recruits and young officers were sent to regiments serving in India. The depot then at Warley was for soldiers of the Honourable Company’s service.

Into the General Hospital at Fort Pitt were received military invalids from India as from all other foreign stations. There they were treated for their several ailments; thence discharged to join their respective depots, or from the service on such pensions as they were deemed entitled to by length of service and regimental character. Then the period of engagement was for life, otherwise twenty-one years in the infantry, twenty-four in the mounted branches.

2 There young medical men nominated for appointment to the army underwent a course of training, more or less long, according to individual circumstances, for the special duties before them; meanwhile they received no pay, wore no uniform; they dined at mess, paid mess subscriptions, and were subject to martial law.

Professional education included requirements for diplomas, and in addition, special subjects relating to military medicine, surgery, and management of troops. Nominations for appointments were given by old officers or other men whose social position was a guarantee in regard to character and fitness of their nominees for the position sought by them; certificates by professors and teachers under whom they studied were submitted to the responsible authority1 at the War Office, with whom rested their selection. Thus in effect a combined system of patronage and competition was in force.

With anxious interest a small group of expectants awaited the arrival of the coach by which in those days afternoon letters and evening papers from the metropolis were conveyed. Eagerly was The Gazette scanned when, close upon the hour of midnight, the papers were delivered. Great was the pride and rejoicing with which some of our number read the announcement relating to them; great the disappointment of those who were not so included. The regiment to which I had the honour of being appointed was the 3rd, or “Buffs,” the depot of which formed part of the Provisional Battalion then occupying Forton Barracks.2

The duties assigned to young medical officers were unimportant—initiatory rather than definite in kind. Careful watch and superintendence on the part of official seniors gave us an opportunity of learning various points relative to practice, as well as to routine and discipline, to be turned to account—or otherwise—in the career upon which we were entering. But the process of “breaking in” was not without its disagreeables. Courtesy towards young officers on the part of their seniors, military or medical, was a quality rare at Chatham, but where met with in isolated instances was the more appreciated, and remembered in subsequent years. The “system” of training in force tended rather to break than bend the sapling.

Thus did three months pass away. Then came an order of readiness to embark with the detachment of recruits next to sail. Although about to proceed with those pertaining to what was now “my own regiment,” official regulations required that my appointment to3 charge of them should have the authority of “The Honourable Court of Directors,” and that to obtain it, personal application must be made at their old historical house in Leadenhall Street—a formality which was gone through with ease and success. This is what the appointment in question implied:—Not only did I receive the free passage to which I was entitled, my daily rate of pay3 running on the while, minus £5 deducted “for messing,” but was privileged to occupy the second best cabin on board, and at the end of the voyage to receive in rupees a sum equivalent to fifteen shillings per head for officers and soldiers landed, and half a guinea for each woman and child. In those “golden days” the sterling value of the rupee was at par.

The ordeal of “inspection” was duly performed, the requirements on board declared “satisfactory,” the formal report to that effect transmitted to the authorities. My personal knowledge of those requirements was absolutely nil. How much more definite that of other members of the Inspecting Committee, was soon to be judged of. For example: side or stern ports there were none, deck ventilators being considered sufficient. Food stores comprised casks of salted beef and pork; tins of soup and bouillé, potatoes and other vegetables, some dried, some tinned; pickles and lime juice, bread, otherwise hard biscuit, destined ere many weeks had elapsed to become mouldy and honeycombed by weevils. There were bags of flour, peas, and raisins; an ample supply of tobacco; also of rum and porter, to be issued to the troops as a daily ration. The water tanks and a series of casks on deck had been filled—so it was said—from the Thames below London Bridge, when the tide was at its lowest.

The day of departure arrived. The detachment of which I was an unit marched away from Chatham Barracks, through Rochester, Strood, and so by road to Gravesend. There it was conveyed on board the Indian; twenty-four hours allowed us to settle down on board; the ship then taken in tow by steamer; we are on our voyage.

A fortnight elapsed; we were no farther on our way than off the coast of Spain. The novelties of first experience afforded subject of observation and thought: those which most impressed us, the clear moonlight, the starry galaxy of the heavens, the Milky Way, the cloudless sky, the phosphorescence of the undulating sea through which our ship slowly glided; the masses of living things, chiefly medusæ, that floated fathoms deep in ocean. During daylight many land birds flew over us or rested on the rigging.

Small though our party was, it comprised its proportion of men4 typical in their several ways. The commander of the vessel, soured with life, disappointed in career, tired of sea life, but unable to quit his profession. One of the ship’s officers, a young man of deeply religious convictions. An ancient subaltern, inured to the chagrin of having been several times purchased over by men of less service but more fortunate than himself in worldly means. The lady’s man, pretentious and vapid, given to solos on a guitar; the instrument adorned with many coloured ribbons, to each of which he attached a legend; his cabin decorated with little bits of “work,” cards, and trinkets, for as yet photographs had not been invented. The irascible person, ready to take offence at trifles, and in other ways uncertain.

A month on board; the Canary Islands faintly seen in the distance. Already heat and stuffiness ’tween decks so unpleasant that carpenters were set to work to cut out stern ports for ventilation. Our progress so slow that with all sails set a ship’s boat was launched, in which some of our numbers amused themselves by rowing round the vessel.

Two months, and we still north of the Equator. Various reasons given for tedious progress, among others light airs, contrary winds, adverse currents. But none of these explained the fact of our being passed by vessels, some of which, on the horizon astern of us in the morning, were hull down on that ahead ere daylight vanished. That our ship was alluded to as “a worthless old tub” need now be no matter of surprise.

Not more than one-third of our distance to be run as yet got over; prospects as regarded the remainder by no means happy. The unwelcome announcement made that all hands, including crew and troops, must submit to reduced allowance of food and water. Of the latter, the full allowance per head per day for cooking and all other purposes was seven pints, now to be reduced to six. No wonder that the announcement was not received with tokens of approval.

Looking back to conditions as described in notes taken at the time, the contrast so presented between those which were then deemed sufficient for troops on board ship, and those which now exist may not be without some historical interest. Space ’tween decks so limited,4 that with men’s hammocks slung, those who on duty had to make their way along at night were forced to stoop almost to the attitude of the ordinary quadruped. The “sick bay” on the port side, close to the main hatch, directly exposed to rain from starboard; except a canvas screen, no separation between the quarters of unmarried and those of married; no separate accommodation for sick women or children; no prison set apart for the refractory. All over the ship myriads of cockroaches;5 these insects, especially lively at night, supplied to men and officers excitement and exercise, as, slipper in hand, they hunted them whenever the pale light given by the ship’s lamps enabled them to do so. Cleanliness of decks and fittings was to some extent effected by means of dry scrubbing. The use of Burnett’s Solution5 substituted the odour of the compound so named for that of humanity. By means of iron fumigators in which was burning tar, the atmosphere of ’tween decks was purified, due precautions taken to minimise the risks of fire attending the process. Tubs and hose on deck supplied ample means for the morning “souse.”

A carefully chosen library provided for the use of our men was placed on board by the Indian authorities; it was highly appreciated and generally made use of. Among the troops, games of all sorts were encouraged, their selection left to men’s own choice. In working the ship ready hands were at all times available. Gymnastics and feats of strength were in high favour, and so, with the routine of guards, parades, inspections, and so forth, daytime was filled up. In the evenings, songs, recitations, theatrical performances, and instrumental music were indulged till the bugle sounded “lights out.”

Officers had their ways of passing the time. They included games, gymnastics, bets, practical jokes (of all degrees of silliness), cock fighting, wild and dangerous adventures in the rigging, and on Saturday evenings, toasts, then usual on such occasions, enthusiastically “honoured.” A weekly newspaper was set on foot; the works of Scott, Shakespeare, and Pope, among other authors, carefully studied, and discussions, more or less profitable, held on their contents.

Sighting, signalling, and hailing ships was a favourite amusement as opportunity occurred. By some of those homeward bound we dispatched letters, with passengers on board others we exchanged visits, strange as such ceremonies may seem to those now acquainted only with modern twenty-knot floating steam palaces. While paying such a visit to a ship five months out from China, we learned the “news” that Canton had been captured (on May 25–27, 1841) by the forces under command of Sir Hugh Gough.

In near proximity to the Equator we came upon a ship, the Cambridge, disabled, her topmasts carried away in a sudden squall two nights previous. The resolve to stand by and give assistance was quickly taken. Boats were lowered, parties of sailors and recruits, accompanied by some officers, were soon on board. Within a few hours defects were made good as far as that was practicable; meantime night had closed in, a somewhat fresh breeze sprung up, clouds obscured the sky, and6 so the return to our ship was by no means accomplished without danger.

The distance to be got over was still great before the ship could reach Table Bay and renewed supplies obtained. The health of all on board had so far remained good, notwithstanding all the drawbacks experienced. The likelihood, however, that this happy state of things might suddenly come to an end became to me a source of what was the first sense of official anxiety with which I had been acquainted.

Excepting two somewhat elderly non-commissioned officers, specially put on board the better to ensure discipline among our recruits, all others were as yet but partly tutored in military duties and order. Unwilling obedience had from the first been shown by several of their number; then came irregularities, quarrels, and fights among themselves. Nor were the few married women on board ideal patterns of gentleness, either in speech or behaviour.

Among the crew were men whose antecedents, so far as they could be ascertained, were of the most questionable kind, and whose conduct on board had, from the first, been suspicious. Between them and kindred spirits among the recruits, it appeared that an understanding had been come to to have what they called “a disturbance” on board. Those intentions having come to the ears of the officers, with the further information that fully ninety men were implicated, preparations were made for emergencies: arm-racks fitted up in the saloon; fire-arms burnished; ammunition seen to; non-commissioned officers instructed as to their duties. But an occurrence which now happened distracted attention from the so-called plot, whether real or imaginary did not transpire.

Our entrance into tropical latitudes, some three weeks previous, had been duly announced by “Neptune,” who, selecting the period of first night watch for the ceremony, welcomed us from amidst a flare of blue lights on the forecastle, on our coming to his dominions. Having done so, he returned to his element; his car a burning tar-barrel, which we continued to watch as it seemed to float astern, until all was darkness again. On board, “offerings” had to be made to the sea-god, half-sovereigns and bottles of rum, sent to the fo’c’s’le, being those most appreciated.

While yet in the first degree of south latitude, the sea-god, accompanied by his court officials, announced their arrival on board, the whole personified by members of the ship’s crew, appropriately attired in accordance with their respective official positions. The ceremony of “initiating” the “children” was quickly in progress, the chief ceremonies connected therewith including shaving, “bathing,” besides some7 others by no means pleasant to their subjects. One of our young recruits strongly resisted the ordeal through which several of his comrades had passed. He succeeded in making his escape from his captors, and quickly mounting the ship’s railing, thence plunged into the sea, to the consternation and horror of us all. The vessel was instantly “put about,” a boat lowered, but search for him was in vain. The occurrence was, indeed, a melancholy outcome of what was intended to be a scene of amusement. But the spirits of young men were light, and ere many hours had elapsed, the song and dance were in progress, as if the event had not occurred. A Court of Inquiry followed in due time, and then the incident was forgotten.

We were now approaching Table Bay. Great was the interest and admiration with which we looked upon Table Mountain, as its grandeur became more and more distinctly revealed. Hardly less was our estimate of the Blue Berg range, by which the distant view was bounded. Soon we were among the shipping, and at anchor.

Our ship was soon surrounded by boats, that seemed to come in shoals from shore; some conveying fruit and curiosities for sale, others suspected of carrying commodities less innocuous in kind. But sentries, already placed at gangways and other points on deck, prevented traffic between our men and the small craft. The aspect of boats and their crews was alike new and strange to most of us: the former, striped with gaudy colours, red, black, and white; the latter, representing several nationalities, including English, Dutch, Malay, East Indian, and typical African, their several styles of costume no less various than themselves.

Some of our number, proceeding ashore, stood for the first time on foreign ground. Cape Town presented a series of wide, regularly arranged streets, intersecting each other, their sides sheltered by foliage trees. Flat-roofed houses, coated with white plaster, were nearly invariable in their uniformity. Great wagons, drawn by teams of oxen, from six to twelve in number—and even more—were being driven along by Malays, armed with whips of alarming proportions; though, fortunately for the beasts of burthen, they were little used. Crowds of pedestrians were on the thoroughfares, interspersed with guardians of the peace, the latter dressed after the manner of their kind in London. It was the month of December; but the temperature was that of summer; the heat oppressive, as we continued our excursion.

Part of that excursion was to Constantia. On the right, the great mountain, rising to a height of three thousand feet; the space between its base and the road along which we drove thickly covered by forest and undergrowth, the whole comprising oaks, silver and other pines,8 geraniums, pomegranates, and heaths, interspersed with herbaceous plants bearing gorgeously coloured flowers. At intervals there were richly cultivated fields and valleys; on or near them attractive-looking houses, many having attached to the latter no less handsome gardens. The road was thickly occupied by vehicles and pedestrians; among the whites, a considerable proportion of well-looking individuals of the fair sex. There was, in fact, a general aspect of activity and of prosperity.

The ordeal of “reporting ourselves” to the authorities was gone through: our reception by one, whose surname indicated Dutch origin, ungracious and supercilious; by the departmental chief so kindly, as by contrast to make an impression upon us, but partially inured to official ways as we then were. Meanwhile, the necessary steps were in progress for placing on board our ship the much-needed supplies of food materials and of water.

Among vessels that anchored in the bay during our detention, there was the ship Lloyds, having on board emigrants from England to New Zealand. When first they began their voyage, they numbered eighty women and 117 children; but so appalling had been the mortality among them that, of the children, fifty-seven had died. In all parts of the space occupied by passengers, sickness and distress in various shapes prevailed. Children, apparently near to death, lay in cots by the side of their prostrate mothers, whose feebleness rendered them unable to give the necessary aid to their infants. A state of indescribable filth existed everywhere; ventilation there was none in the proper sense. Women and children affected with measles in very severe form, that disease having been brought on board in the persons of some of those embarking; others suffered from low fever, and some from scurvy, which had recently appeared among them. The family of the medical man on board had suffered like the others, one of his children having died. On the deck of the ship lay two coffins, containing bodies of the dead, preparatory to being taken on shore for burial. The entire scene presented by the ship, the saddest with which, so far, I had become acquainted.

In Table Bay we again met the Cambridge already mentioned, that vessel arriving shortly after our own had anchored. In a sense we, the passengers of both, greeted each other as old friends; visits were interchanged, then leave was taken of each other with expressions of good wishes. By-and-by there came to anchor the ship Nanking, having on board recruits belonging to the service of the Honourable Company. Greetings and cheers were interchanged; for were we not all alike proceeding on a career, hopeful indeed, but as yet uncertain?

9 In the Castle, a short distance from Cape Town, the 25th Regiment, or Borderers, was stationed, and in accordance with the hospitable custom of the time, an invitation to dinner with the officers was received on board. The party on that festive occasion numbered seventy, the majority guests like ourselves, and now the circumstance is mentioned as showing the scale upon which such entertainments were given.

Invited to the house of an Afrikander Dutchman6, we found ourselves in large airy rooms, destitute of carpets, with polished floors; wall space reduced to a series of intervals between doors and windows; the arrangements new to us, but suited to climatic conditions of the place. Little attentions shown by, added to personal attractions of, lady members of the family naturally enough left their impression on young susceptibilities.

Very interesting also, though in a different way, was our visit to the house of Baron von Ludovigberg. Elegantly furnished, rooms so arranged as to be readily transformed into one large hall, everything in and around marking a life of ease and comfort. His garden, situated in Kolf Street, extensive, elegantly laid out, with large collection of plants indigenous and foreign; at intervals fountains and ornamental lakes. In the latter were thousands of gold fish, so tame as to approach and feed from the hand of an attendant; to the sound of a handbell rung by him they crowded, though on seeing us they kept at a distance. To the sound of the same bell when rung by us they would approach, but not come near the strangers.

Our voyage resumed, away eastward we sailed. Sixteen days without noteworthy incident; then sighted the island of Amsterdam, from which point, as the captain expressed it, he began to make his northing.

Another interval of monotonous sea life. At daybreak we found that in close proximity to us was a barque, the Vanguard, on board of which there was disturbance amounting to mutiny among the crew. The captain7 signalled for assistance. A party of our young soldiers, under command of an officer, proceeded on board, removed the recalcitrant men to our ship, some of our sailors taking their place, and so both vessels continued their way to Calcutta.

Again was the unwelcome announcement made that short allowance of food and water was imminent, to be averted by progress of our vessel becoming more rapid than it had hitherto been. The10 tedium of the voyage had told upon us; idleness had produced its usual effect. Chafing against authority and slow decay of active good fellowship became too apparent; all were tired of each other.

Another interval. From the mast-head comes the welcome sound, “Land on the starboard bow.” Soon we come in view of low-lying shore, over which hangs a haze in which outlines of objects are indistinct. What is seen, however, indicates that our ship is out of reckoning; that, as for some time past suspected, something has gone wrong with the chronometers. Wisely, the captain determines to proceed no farther for the present, until able to determine our precise position. A day and night pass, then is descried a ship in the distance westward. We proceed in that direction, and ere many hours are over exchange signals with a pilot brig.

Twenty-four weeks had elapsed since the pilot left us in the Downs; now the corresponding functionary boards our ship off the Sandheads. We are eager for news. He has much to tell, but of a nature sad as unexpected. The envoy at Cabul, Sir William Macnaughten, murdered by the hand of Akbar Khan; the 44th Regiment annihilated, part of a force comprising 4,500 fighting men and 12,000 camp-followers who had started on their disastrous retreat from Cabul towards the Khyber Pass; one only survivor, Dr. Bryden, who carried tidings of the disaster to Jellalabad. Another item was that several officers, ladies, and children were in the hands of the Affghan chief.

Progress against the current of Hooghly River was slow, steam employed only while crossing the dreaded “James and Mary” shoal; for then tugs were scarce, their use expensive. Three days so passed; the first experience of tropical scenery pleasant to the eye, furnishing at the same time ample subject for remark and talk. On either side jungle, cultivated plots of ground, palms, bamboos, buffaloes and cattle of other kinds. In slimy ooze gigantic gavials; in the river dead bodies of animals and human beings, vultures and crows perched upon and tearing their decomposing flesh. Native boats come alongside; their swarthy, semi-naked crews scream and gesticulate wildly as they offer for sale fruit and other commodities. Our rigging is crowded with brahminee kites and other birds; gulls and terns swarm around. The prevailing damp heat is oppressive. Now the beautiful suburb of Garden Reach is on our right; on our left the Botanic Garden; the City of Palaces is ahead of us; we are at anchor off Princep’s Ghat.

The “details,” as in official language our troops collectively are called, were transferred to country boats of uncouth look, and so conveyed to Chinsurah, then a depot for newly arrived recruits. Our actual11 numbers so transferred equalled those originally embarked, two lives lost during our voyage being made up for by two births on board. Sanitation, in modern significance of the term, had as substitute the arrangements—or want of them—already mentioned; yet no special illness occurred; my first charge ended satisfactorily.

Chinsurah—Cholera—Start—Omissions—Relics of mortality—Collision—Fire—Panic—Berhampore—The “garrison”—Crime and punishment—Civilities—Progress resumed—A hurricane—Cawnpore—Attached to 50th Regiment—The troops—Agra—Sind—Gwalior—39th Regiment.

First impressions of this our first station in India, recorded at the time, were:—Houses of mud, roofs consisting of reeds, fronts open from end to end; members of families within squatting, infants sprawling, in a state of nudity, upon earthen floors made smooth and polished by means of cowdung applied in a liquid state; while to outside walls cakes of the same material are in process of drying, to be thereafter used as fuel by Hindoos. Gardens and cultivated fields abound; flowering trees and shrubs, cocoa palms, banana bushes, clumps of bamboo, rise above dense undergrowth of succulent plants. A heavy, oppressive atmosphere, pervaded by odours, sweet and otherwise, has a depressing effect, as if conditions were not altogether wholesome. European houses according to Holland model, terraces and gardens giving to them an attractive and elegant appearance, indicating the importance of the place while in the hands of the Dutch, prior to date8 of the treaty in accordance with which it was by them exchanged for Java. An extensive range of spacious barracks and supplementary buildings added much to the beauty of the station.

Before many days were over several of our young lads had fallen victims to cholera. In this our first experience of that disease we had access to no one capable of giving aid and advice; we were left to individual judgment, and it altogether astray as to the appropriate method in our emergency. For a time, out of our small party death claimed several daily victims; young wives were thus left widows, young children orphans.

Glad to receive orders of readiness to resume progress by river to next stage of our journey. Then arrived two senior officers,—13one to take military command;9 the other, departmental charge of our detachment. Country boats provided as before, others of better kind for officers. Our unwieldy fleet started at the appointed time;10 the boats comprising it straggled irregularly across the river, and having gained the opposite bank, there made fast for the night.

Early next morning it was in movement. Mid-day heat became oppressive. One of the soldiers was prostrated by cholera, another by sun fever. Inquiry revealed the unpleasant fact that the “experienced” officer recently appointed for the purpose had made no arrangements whatever for sick. Those fallen ill were now sent in small boats back towards Chinsurah; and so we continued our river progress, steps being taken to have deficient requirements sent on without delay.

Next evening was far advanced ere they arrived. The numbers of our sick had increased, several deaths taken place, some with appalling rapidity in the absence of means of help. The great heat prevailing made early interment necessary. Graves had to be hastily made in groves of trees near the river bank; to them the dead were committed, our fleet continuing its progress, sailing or tracking11 according to wind and current. After night had fallen, the blaze of funeral pyres on the river banks told their tale of pestilence.

For several days mortality was great in our small party, and among the native boatmen. As deaths occurred among the latter, the bodies were simply left on the bank to be devoured by jackals, dogs, and vultures, numbers of which were in wait for prey. Some of our boats sprung leaks, and so became useless; nor was it an easy matter to get them replaced. Men and stores had to be got out as best they could and disposed of among others—proceedings by no means easy under then present circumstances.

At last there came an interval in which the malign influence of our invisible enemy seemed as if withheld. While gliding upwards against the silent river current, suddenly from one of the men’s boats there burst a mass of thick smoke, speedily followed by flame, and within the space of a few minutes nothing except the charred framework remained. How, or by what means, the occupants of the boat escaped did not transpire; that they did so was fortunate for themselves and satisfactory to all, though the accident, subsequently ascertained to have resulted from their own carelessness, destroyed their entire kits and other belongings.

14 Short was our respite. Suddenly and fatally was our detachment again struck, several deaths by cholera occurring in quick succession. Our somewhat eventful “voyage” was near its end, when in mid-stream two of our boats came violently in collision with each other, considerable mutual damage being the result. An unfortunate panic occurred among the recruits on board, one of whom leapt overboard and so disappeared. Soon afterwards our journey was at an end, it having occupied eleven days; we arrived at Berhampore.

Near to the spacious range of barracks in which our young soldiers were accommodated were lines occupied by a native regiment,12—at that time reputed to be of distinguished loyalty to Jân Kompanee, with whose liberal dealings towards its own proper servants all were so well pleased. In others were invalids, soldiers’ wives and children pertaining to regiments13 employed in the war proceeding against China; many as yet unaware that they had been made widows and orphans by the climate of Chusan and coast generally.

Here the conduct of our lads—for they had scarcely become men—became so reckless that military discipline had to be rigidly enforced, while in many instances severe or fatal illness seemed to be the direct result of their own misconduct. As a ready, and as thought at the time effectual, means of coercion, corporal punishment was awarded by courts-martial. The ordeal of being present during its infliction was nauseating; but constituted as the detachment was, the punishment seemed to have been in all cases well deserved.

General Raper was the officer in political charge of the Nawab of Moorshedabad, then a boy of some ten years old. Several civilians high in rank, and a few non-official residents, for the most part connected with the manufacture of tussar14 silk, resided at Berhampore. From several of them we young officers received much attention and kindness, not only in their own houses but on excursions organized by them for our special benefit. Prominent among those who thus befriended us, young “griffs” as we were, General Raper and Charles Du Pré Russell are remembered gratefully—even while these notes are penned, many years after the date and incidents referred to.

In due time the order arrived for us to resume our river journey, our destination Cawnpore; again country-made boats our means of transport. In the early days of August we started on what was to be in many respects a monotonous voyage, though not altogether without its excitement and stirring incidents. The general manner of our15 progress was that with which we were now acquainted. We were doomed, as before, to be at intervals stricken by cholera, which seemed to have its favourite lurking-places, generally at the foot of a somewhat precipitous alluvial bank. Night after night rest was disturbed or altogether banished by the sound of tom-toms, songs, barking of dogs, cries of jackals; sight and smell offended by funeral fires as they blazed in near proximity to us.

More than half our journey was got over without special mishap. Our boatmen observe that signs of coming storm appear in the sky; they prepare as best they can, but soon the hurricane is upon us. Boats are dashed against each other, and against the river bank; waves break over them, tearing away their flimsy gear, battering some to pieces, their inmates obliged to escape and save themselves as best they could. After a time there came a downpour of rain; then gradually the storm ceased, leaving several of our number boatless, and destitute of greater or smaller portions of our respective kits. Among others, I suffered considerably. A friend in need, more fortunate than myself, gave me hospitality on his boat until sometime thereafter, when, with others similarly situated, I chartered a budgerow. A few days after our mishap news reached us that a similar fleet to our own, with troops,15 some thirty miles ahead of us, suffered very severely from the same hurricane that had struck us, a considerable number of the men in it having perished in the river.

Without further incident of importance we arrived at Cawnpore in the early days of November, our journey by river having occupied more than two months and a half, the date fourteen years before the terrible year 1857, when that station was to acquire the sad memory ever since associated with it. Anticipating the return to India of the force commanded by General Pollock from Jellalabad, the march to which place had restored British prestige from the temporary eclipse at Jugdulluck, orders were issued to honour that army by an appropriate military display on the left bank of the Sutlej. Among the regiments assembled for that purpose, at Ferozepore, the then frontier station, were the Buffs. Orders had also directed that on completion of that duty they should march towards Allahabad and there occupy the fort, the detachment with which I was connected joining headquarters en route. For the time being we were attached to the 50th Regiment, and so continued during the remaining four months of the cold season.

Here took place the first initiation into their several duties connected16 with regimental life of the young men belonging to our detachment, myself among them. Among the officers in the “Dirty Half-Hundred” who had served with it during the Peninsular War, when, on account of the continuous severe work performed by it, the corps obtained its honourable soubriquet, three16 remained, looked up to with the respect due to, and then accorded to, distinguished veterans. Alternate with duties assigned to us, amusements filled up our time pleasantly. Gaiety was in full flow. Many were the joyous gatherings by which were filled the Assembly rooms—some years thereafter to be the scene of very terrible doings. Outdoor games and sports were the order of the day, the tract of jungle in Oude that stretched along the opposite river bank proving our most happy hunting ground. So it was that time passed pleasantly, if in an intellectual sense not very profitably. At the time alluded to traffic and communication with Oude was by means of a long bridge of boats, that bridge from their attack on which in subsequent days the Gwalior mutineers were to be driven by the forces under Sir Colin Campbell.17

A large force, comprising all arms, then occupied that important station. The impression made upon us, as for the first time we beheld the magnificent spectacle presented by general field-day parades and exercises, was never to be forgotten. The swarthy visages of the sepoys; their quaint uniforms attracted our notice. The solidarity of the 50th gave the impression of irresistible force. The rush of cavalry, as, like a whirlwind, they went at full charge, to a great extent concealed in a cloud of dust raised by their horses’ hoofs; the magnificent and unsurpassed Bengal Horse Artillery, in performing the evolutions pertaining to them,—these incidents struck us with amazement and admiration. Little did we think that not many months thereafter we were to be even more struck with admiration at the brilliant performance of some of those very troops in actual fight.

A trip to Agra18 introduced me to the experiences of palkee dâk. Travelling by night, the distance got over was about fifty miles; alongside trotted torch-carriers, the odours from those “pillars of flame” foul and offensive. During the day a halt was made at bungalows provided by Government for the use of travellers. Thus were four days occupied in making a journey of two hundred miles. In and near Agra various excursions were made and places of interest visited. In the fort had recently been deposited the gates of Somnath,1719 in connection with the removal of which from Ghuznee the bombastic proclamation by Lord Ellenborough was still subject of comment. The tomb of Akbar20 and the exquisite Taj Mahal21 were visited on several occasions. The scene presented by the latter, more especially as seen by moonlight, was extremely beautiful. The minarets and domes of the mausoleum, consisting of pure white marble; the long avenue of cypress trees by which it is approached; the fountains in full play; the ornamental flower pots,—made upon us an impression never afterwards to be forgotten.

With the regiments returned recently from Kandahar, aided by troops from Bombay and Bengal, Sir Charles Napier undertook an expedition against the disaffected Ameers of Scinde. In February, 1843, the battles of Meeanee and Hyderabad ended in defeat of their forces, Hyderabad occupied, the country being conquered during the succeeding month of March. Of that war it was said: “The Muhamadan rulers of Sind, known as the Ameers, whose chief fault was that they would not surrender their independence, were crushed.”

In the neighbouring State of Gwalior events were in progress, the issue of which was destined to affect the 39th, the 50th, and the Buffs in a way not at the moment anticipated by either of those regiments. Early in February, the distant boom of heavy guns intimated to us at Agra that the Maharajah of Gwalior was dead, and had been succeeded on his throne by his adopted son22 in the absence of a lineal heir. In such events there did not appear anything to interfere with the routine of pleasure in which so many young officers indulged; that routine went on uninterruptedly, for as yet with them the serious business of life was in the future.

Those were indeed the days of India’s hospitality, alike in respect to individuals and regiments. For example: Three weeks had I been an honorary member of the “Dorsets’” mess, when the time of my departure arrived; yet to my request for my mess bill I received the reply, “There is none.” Among the officers whose hospitality I had so long unconsciously enjoyed were two, father and son, both of whom I was shortly to meet under circumstances very different from those in which I had made their acquaintance.

I join the Buffs—An execution parade—Remnants of 44th Regiment—Allahabad—Sickness—Papamow—Cobra bite—Accident—Natural history—Agriculture—Locusts—Hindoo girl’s song—Society—Lord Sahibs—Their staffs—Rumours of war—Preparations—The start—Affairs in Gwalior—The Punjab.

Eighteen months had elapsed since the day when we left Chatham to that on which we joined the distinguished regiment23 of which I was a member, the manner of my reception kind and friendly. As the regiment passed through Cawnpore, a short halt was ordered to take place; the camp to be pitched on that part of the parade ground, afterwards to be occupied by the defences in connection with which the story of General Wheeler and his party has left so many sad associations. The object of that halt appeared in Division Orders—the carrying into execution of sentence of death passed by General Court-Martial on a soldier of the regiment convicted of murdering a comrade. This was to be the first regimental parade on which I was to appear. By sunrise the troops were in their places, so as to form three sides of a square, the fourth being partly occupied by the construction above which the fatal beam and its supports stood prominent. The procession of death began its march, the regimental band wailing forth the Dead March; then came the coffin, carried by low-caste natives; then the condemned man, ghastly pale, strongly guarded. Thus did they proceed until they arrived at the place of execution. The eyes of most of us were averted, and so we saw not the further details of the sad drama. Regiment after regiment marched past the structure, from which dangled the body of a man; thence to their respective barracks or tents, their bands playing “rollicking” tunes.

Pleasant as novel were the incidents of our march eastward along that most excellent highway, the Grand Trunk Road. The early rouse, “striking” tents, the “fall in,” the start while as yet stars glistened in the sky and dawn had not appeared; then came the wild note of the coel24 as herald of coming day; the gleam of blazing fire far ahead, indicating where the midway halt was to take place, and19 morning coffee with biscuits was in readiness for all. Resuming the day’s journey, we reached the appointed camp ground by 8 a.m. Tents were quickly pitched on lines previously drawn by the Quarter-master and his staff. Bath, a hearty breakfast, duty, shooting, and other excursions occupied the day, then early dinner, early to bed, and so ready to undergo similar routine on the morrow. In our progress we passed through Futtehpore, a place to be subsequently the scene of stubborn fight against mutineers in 1857.

Attached to the Buffs were the remnants of what had been the 44th Regiment, now consisting of a few men of whom the majority were mutilated or suffering from bodily illness; the party under command of Captain Souter, by whose gallant devotion to duty the regimental colour was saved two years previous when our force was annihilated near the Khyber by Affghans, directed by Akbar Khan.

Pârâg, as the locality of Allahabad was anciently called, is closely connected with Hindoo tradition, and still retains a sacred character. At the date referred to in the Ramayana it was a residence of a Rajah of “the powerful Kosalas,” whose capital was Ajudyia, their country the modern Oude. Here it was that Rama and Seeta crossed the Ganges in their progress to the jungles of Dandaka, where shortly afterwards she was captured by Ravana and carried away by him to Lunka, otherwise Ceylon. Within the fort, now occupied by our regiment, is an underground temple dedicated to Siva, its position believed to indicate the point where the mythical Suruswatee joins the still sacred Ganges. On an enclosed piece of ground stands one of six pillars assigned to Asoka, B.C. 240, bearing an inscription of the period of Samudra Gupta, 2nd century A.D. That pillar, having fallen, was restored by Jehangir, A.D. 1605; the fort itself captured by the English from Shah Alum, A.D. 1765.

As the hot season advanced, severe and fatal disease prevailed alarmingly among our men, cholera and heat fever claiming victims after a few hours’ illness. Treatment applied by the younger medical officers in accordance with theoretical school teaching was useless, nor was it till the regimental surgeon (Dr. Macqueen) directed us to more practical methods that anything approaching favourable results were attained. In these notes, however, the intention is to omit professional matters.

A full company of our men was sent to Papamow, situated on the right bank of the Ganges, six miles distant, the object being to afford additional space to those within the fort. Captain Airey, in command of the detachment, had been one of the hostages in Affghanistan to Akbar Khan, and utilised on that occasion his culinary talents by acting as20 cook to the party. For a time the men enjoyed, and benefited by their change to country quarters. Towards the end of the rainy season, however, malarial diseases attacked them to a degree larger in proportion than their comrades in the fort; consequently our detachment was ordered to rejoin Headquarters.

A good deal of freedom was allowed to the soldiers when first sent to the country place above mentioned, one result being that crime was next to absent from among them. A favourite amusement was shooting in the adjoining woods and fields, and, unhappily for some of them, of bathing, notwithstanding strict orders to the contrary, in the Ganges, then in full flood. On one of those shooting excursions a soldier got bitten in the hand by a cobra, the reptile being immediately killed, and brought in with him. That the teeth penetrated was manifest by the wounds; yet, strange to say, no serious results followed—a circumstance accounted for only by supposing that the poison sacs must by some means have been emptied immediately previous. Of those who insisted on entering the river, some fell victims to their temerity.

The pursuit and study of subjects relative to natural history furnished those of us whose leanings were in those directions with continuous enjoyment and profitable occupation. Visits by friends and small attempts at hospitality came in as so many pleasant interludes. When neither of these was practicable, a good supply of books and papers gave us variety in the way of reading.

So time passed until the month of September, when the cultivated fields were covered by heavy crops special to this part of India. A sudden outburst of discordant noises induces us to quit our quarters in search of the wherefore. A dense cloud is seen in rapid advance from the south-east; myriads of locusts, for of those insects it is composed, alight upon and by their accumulated weight bear down the stems to which they cling. Next day a similar flight is upon us, devouring every green thing; eight days thereafter, a third, but it passed over the locality, obscuring the sky as it did so.

The regimental mess house occupied an elevated position adjoining and overlooking the Jumna, a short distance above the confluence of that river with the Ganges, a terrace pertaining to the building being a favourite resort whereon, in the cool of the evening, it was usual for the officers to enjoy the refreshing breeze, when there was any, and contemplate the unrippled surface of the deep stream as it glided past. On one such evening, while a number of us were so enjoying the scene, watching the lights of native boats secured for the night to either bank, and listening to that strange mixture of sounds to which natives give the name of music, a series of what appeared to be floating lamps21 emerged from where the boats lay thickest and glided along the stream. Here we witnessed the scene alluded to, and so graphically described by L.E.L.25 in her version of “The Hindoo Girl’s Song.”26 It was, in fact, the Dewalee Festival.27

Allahabad was the chief civil station in the provinces; the principal courts were situated there, the higher officials connected with criminal and with revenue administration having their residences scattered over what was an extensive and ornamental settlement. Some of their houses were noted for hospitality, and for more homely entertainments given for the special benefit of the younger officers. Of the latter, that of Mrs. Tayler28 has left most pleasant recollections, the good influence exerted by that lady making its mark on some of us who might otherwise have had remembrances very different in kind. Among the most esteemed of the residents was Dr. Angus, “The Good Samaritan,” as he was called. Hospitable to all; considerate to juniors; his good advice, and help in other ways, readily given to all who in difficulties applied to him.

Early in October, the Commander-in-Chief, Sir Hugh Gough, arrived en route north-westward. New colours were presented by His Excellency to a native regiment29 of distinguished service in Affghanistan, the event celebrated by festive gatherings, in accordance with customary22 usage. On the staff of His Excellency were two officers, both of whom subsequently attained high military distinction; the one Sir Harry Smith, the other Sir Patrick Grant.

Reports were “in the air” that a Camp of Exercise was about to assemble at Agra, as an experiment then tried in India for the first time. Bazaar report had it that the Buffs were about to be ordered on service, the scene and nature of which did not just then transpire. Meanwhile, responsible officers “saw to” the state of “brown Bess,” with which weapon our men were then armed; to that of ammunition, and other necessary items of equipment. The arrival of part of the 29th Regiment, to take our place, next followed, and, simultaneously, came an order directing the Buffs to proceed to Kalpee, on the Jumna, thirteen days’ march distant. A few days thereafter, published orders directed the organization of “the Army of Exercise” into divisions and brigades; still, there was no inkling of what was about to happen.

For some time previous evidences were manifest that all was not right in Gwalior; latterly report said that things in that State had settled down, terms having been come to between the young Maharajah and leaders of the disaffected. A few days thereafter, our preparations were renewed; our weakly men, together with soldiers’ wives and children, arranged for to be left behind, and with a fighting strength of 739 powerful and seasoned soldiers, the regiment started fit and ready for whatever service might be required of it.

The actual state of affairs, above referred to, was briefly this:—The young Maharajah, known as “Ali Jah Jyajee Scindia,” owed his selection to the widow of the deceased monarch of the same name, who died childless, she a girl aged thirteen, named Tara Bye. To the post of Regent, Mama Sahib, an uncle of the deceased monarch, was acknowledged by Lord Ellenborough through the Resident, against the wishes of the Maharanee; Dada Khasjee, steward of the Household, by the Maharanee. Thereupon, the Resident was ordered by His Excellency to quit Gwalior, and the Dada prepared his troops to oppose forces of the Company, if sent against him; hence the campaign now about to take place.

In the Punjab, conditions were at the same time most serious, giving rise to expectations of armed intervention there. For example:—On the 15th of September, 1843, was perpetrated the double murder of the Maharajah Shere Singh30 and his son Pertab, at the northern gate of Lahore, the conspiracy which led up to that deed having been formed23 by Dyhan Singh.31 Next day Ajeet Singh, by whose hand the crime was committed, together with his followers, were attacked and put to death by Heera Singh, son of the deceased vizier, and his party. For a time a state of anarchy, with its attendant slaughter and rapine, prevailed within the capital. These having run their course, Dhuleep Singh, only surviving son of Runjeet, was placed upon the throne of his father, Heera Singh making himself vizier. Meanwhile, the Sikh or Khalasa army had become formidable under Lal Singh, a favourite of the Ranee;32 as an outcome of a conspiracy among them, Heera was murdered, his place taken by Lal.33 Nothing could then restrain their ardour but an expedition into British territory, for which it was well understood that preparations were in progress. The proceedings thus alluded to supplied ample subject for comment in the papers, and talk at social gatherings.

16th Lancers—Delhi—The city—Kutub—Feroze’s Lath—Divers—Muttra—Affairs in Gwalior—Army of Exercise—Halt—City of Krishna—River Chumbul—Across—Sehoree—Before the battle—Battle of Maharajpore—The 16th—“The Brigadier”—Search for wounded—General Churchill—Lieutenant Cavanagh—The muster-roll—Next night—The killed and wounded—Resume the advance—News of Punniar—Queen Regent—Around our camp—Gwalior—The fort—Disarming the conquered—Breaking up—Repassing the field of battle—Meerut—The welcome—Writing to the papers—Native troops—Hurdwar—Religious festival—The Dhoon—Return—Batta—A native regiment disbanded—Unrest in Punjab—Rejoin the Buffs.

On the day the Buffs began their march, I proceeded to join the 16th Lancers, to which distinguished regiment I had been, by General Orders, attached for duty. Ten nights were passed in travelling by palkee dâk. In early morning of the eleventh day the Kutub was seen in bold relief against the indistinct horizon, for the atmosphere was laden with dust. After a little time, the Jumna was crossed by a bridge of boats; then another interval, and I was hospitably received by Dr. Ross, to whom I had an introduction.

Various places of interest in the imperial city were visited in turn. The Jumna Musjid, or chief mosque, its domes and minarets imposing in their grandeur; the balcony in the Chandee Chouk, whereon, in 1739, Nadir Shah sat witnessing the massacre of the inhabitants; the palace of the once “Great Mogul”; the smaller building in its garden, within which had stood “the Peacock Throne”; the remnants of the crystal seat upon which, in ancient times, monarchs were crowned; those of numerous fountains; the Persian inscription, to the effect that “If there is an Elysium upon earth, it is this.” But from the ruins around, frogs and lizards stared at us; the once gorgeous palaces, and all that pertained to them, were smeared over with filth.

At a distance of twelve miles from the city stands the Kutub, surrounded by numerous remains of buildings, the road through all that way being along a space covered by ruins of various kinds. The Cashmere gate of Delhi by which we emerged was then noted as the place where Mr. Fraser, Resident at the Court of the Emperor, was murdered, and where Shumshoodeen, the instigator of that crime, was25 executed; it was to become famous as the scene of severe but victorious struggle against the mutineers in 1857. About two miles onwards stood the ruins of an astronomical observatory, one of two of their kind in India, the other being at Benares. A little farther on was the tomb of Sufter Jung, minister to the princes of Delhi; then continuous ranges of ruins until we arrive at Feroze’s Lath, a metal pillar, the history of which is somewhat obscure, but on which marks of shot indicate attempts by Nadir Shah to destroy it. Now we reach the Kutub, a pillar sixty-five yards in circumference at the base, the ascent within it comprising three hundred and twenty-nine steps, the exterior interrupted by four terraces. Legend relates that it is Hindoo in origin; history that its exterior ornamentation was seriously damaged by the Mahomedan conquerors. Not far from it are the ruins of what would seem to have been a tower of still larger dimensions. In the vicinity of the latter a deep well, into which from a height of sixty feet natives dived, performing strange evolutions in mid-air as they did so.

From Delhi to Muttra the journey was made along by-paths across country. In camp near the latter-named city were the 16th, commanded by Colonel Cureton, and there I joined them. The fact had meantime been promulgated that the destination of “the Army of Exercise” was to be Gwalior. The force so named, 30,000 strong, was to be divided into two wings or corps, to enter that State simultaneously from two directions. That from the south and eastward comprised the Buffs, 50th Regiment, 9th Lancers, Artillery, Native Cavalry, and Native Infantry; that from the west, the 16th Lancers, 39th and 40th Regiments, a strong force of Artillery, 1st and 10th Regiments of Native Cavalry, 4th Irregulars, and several regiments of Native Infantry.

While arrangements for active movements were being matured, those of us on whom as yet cares of office had not descended, passed our time in visiting places of interest in and near the cities of Muttra and Bindrabund, both held sacred by Hindoos in relation to the life of Krishna. In the last-named city we were only permitted to approach the principal temple that stood close to its entrance gate, but from the distance we could see, stretching far away as it seemed to us, the vista of its interior, dimly lighted by hanging lamps; at its extreme end the emblem of the deity to whom it was dedicated, resplendent with gems and precious stones. Everywhere along the narrow streets and from the flat roofs of their houses armies of “sacred” baboons grinned and chattered at us. A picnic to some characteristically Indian gardens34 adjoining the banks of the Jumna furnished us with another pleasant interlude.

26 The division of the force of which the 16th were part resumed its march; in three days arrived at its assigned position not far from Agra and there encamped, pending the result of an ultimatum dispatched by the Governor-General to the disaffected Gwalior leaders. Meanwhile, arrivals of the high civil and military officials, additions to the force, salutes and festivities afforded all of us pleasant occupation and variety.

The answer of the chiefs arrives; its terms are defiant. War against the State immediately proclaimed35 by Lord Ellenborough; portions of the force put in motion towards the river Chumbul, among them the 16th. The appointed rendezvous near Dholpore is speedily reached, and there we encamp.

A vakeel arrives in camp, bearer of a dispatch by which the leaders of Gwalior rebels submit proposals for peace, on their own terms. They are at once refused. By daybreak next morning the force is in motion. Three hours suffice for crossing the Chumbul, an operation effected without important incident; establishments follow without delay; camp is pitched on hostile territory. The aspect of our position and immediate vicinity presents uneven ground, intersected by deep ravines, destitute of roadways. Our halt is of short duration. Early next morning the force emerged on open country; in due time arrived in near proximity to the village of Sehoree, and there encamped.

Meanwhile, information was received that Gwalior forces were rapidly concentrating in our front. Officers on the staff of our Quartermaster-General reconnoitred the country to a radius of ten miles and more around our camp. Soon the “Chief”36 issued orders that the march should be resumed next day, and the Mahrattas attacked if met with.

Conversation at mess turned upon the probable events so soon to transpire; extemporised plans by individual officers indicated the several views they entertained of what was to happen. The very young expressed hopes that the enemy would show good fight; some of their number speculated on the chances of promotion before them. Then broke in one of the seniors, who had gained experience of war in Affghanistan: “I have just been employed in making a few little arrangements in case of accidents.” “Highly proper,” remarked another “for no one knows what to-morrow may bring forth.”

At daylight on December 29 our force began its advance, its manner of distribution to make an attack simultaneously on front and flank of the position known to have been occupied by the Mahrattas27 the previous evening. But during the night they had taken up a new position, considerably in advance, and from it unexpectedly opened fire on our leading columns. The general force was at once directed upon the new position. Horse Artillery commanded by Captain Grant37 at full gallop rode directly at the Gwalior battery; opened fire upon it with crushing effect, and within the space of a few minutes reduced it to silence. Having done so, away again at full gallop Captain Grant led his battery against one on the left of the former, that had meanwhile opened upon us, our infantry columns plodding their way, slowly but steadily, against its line of fire. Very soon that battery also was silenced. The infantry were at work with the bayonet with terrible effect upon the enemy, with very heavy loss to our own forces, in men, horses, and ammunition. A third battery began its deadly work upon other bodies of infantry, in motion onwards. Again Captain Grant led his troop against it with the same result; then arrived the infantry, including the 39th and 40th British regiments; then hand-to-hand conflict, and then—the positions were in the grasp of our forces.

While thus the conflict raged fiercely, the 16th, led by Colonel Rowland Smyth,38 together with the two cavalry regiments39 brigaded with them, were ordered to sweep round the rebel camp, cut off, destroy, or disperse those who, driven from their guns, might take to flight. The Lancers dashed onwards at the charge, the bright steel and showy pennants of their weapons seeming to skim the ground, while at intervals stray rebels fell lifeless. The Gwalior men, anticipating such a manœuvre, had taken precautions against its complete success; the position for heaviest guns selected by them had along its front a ravine of great breadth and depth. Upon its edge the cavalry suddenly came, nor is it clear by what means they escaped being precipitated into it. There was for a moment some confusion as the halt was sounded; eighteen guns directly in front, six others in flank sent their missiles through our ranks or high above them. To remain exposed to risks of more perfect practice would serve no good purpose; there was no alternative but to retire. The infantry were seen advancing; down one side of the ravine, lost to sight; up the further side, then onwards, into the batteries, and then—the fight was won.

When at first the 16th took the position assigned to them on the field, it may have been that my endeavours to discover what was subsequently called “the first line of assistance” were unsuccessful; it may have been28 that they were not very keenly made, at any rate “the Brigadier”—for so was named the troop horse I rode—knew his right place in the ranks, and so enabled me to witness the events now described.

Returning to my proper duties, I joined the parties who traversed the field of battle in search of wounded. Great, alas! was the number who lay prostrate,—many dead, many more suffering from wounds. Among the latter was General Churchill, his injuries of a nature to make him aware that speedy death was inevitable. While being attended to with all possible care, he requested me to take charge of the valuable watch he wore, and after his demise to send it to his son-in-law, Captain Mitchell40 of the 6th Foot, at that time serving in South Africa. During the night he died, and his request was carried out by me.

At a short distance lay, in the growing crop that covered the field of battle, Lieutenant Cavanagh of the 4th Irregulars, loudly calling to attract attention, supporting by his hands a limb from which dangled the foot and part of the leg, his other limb grazed by a round shot which inflicted both wounds, and passed through his horse, now lying dead beside him. He was taken to the hospital tents, where meanwhile wounded soldiers and officers in considerable numbers had accumulated. The surgeons’ work begun, three41 of us mutually assisted each other. The turn of Lieutenant Cavanagh to be attended to having come, he made a request that we should “just wait a bit while he wrote to his wife,” for he had recently been married. This done, he submitted to amputation, and during that process uttered no cry or groan, though nothing in the shape of anæsthetic was given, nor had chloroform as such been discovered; then, during the interval purposely permitted to elapse between the operation and final dressing, he continued his letter to his young wife, these circumstances illustrating the courage and endurance so characteristic among men (and women) at the time referred to. His case was one of many men who had to be succoured that day.

Meanwhile the force was in process of encamping on the field so gallantly won; the 16th paraded for roll call, the band of the regiment playing “The Convent Bells,” the notes of which long years thereafter recalled the day and occasion. Casualties42 among the men were only29 nine; but among the horses more numerous than they had been at Waterloo, where as Light Dragoons the 16th so highly distinguished themselves.43

The arduous and responsible work of the day over, those of us who could do so withdrew to our tents, our hearts full of gratitude to the Almighty for individual safety, there to obtain such measure of rest and quiet as under the circumstances was procurable; for all through the evening and early hours of night the bright glare from burning villages, the dense smoke from others, the dull heavy sound of exploding mines made the hours hideous. Such was the battle of “Maharajpore.”

During the evening the mangled remains of what in the morning had been a band of brave men were committed to earth. With returning daylight the same sad task was continued, all possible honour being shown to the dead according to the rank they had held, from that of General Officer in the person of General Churchill, who had succumbed in the course of the night, to that of the private soldier. Meantime, in tents the work of attending to the wounded went steadily on. There, officers and men whom we personally knew, lay helpless; among them Major Bray, of the 39th, and his son in adjoining cots, the former terribly burnt by the explosion of a mine, the life-blood of the latter ebbing through a bullet-wound in his chest.44 And there were many other very painful instances, to the aid of whom our best endeavours had to be directed.

It was for the time being impossible to carry on with the army, in its further advance, the large number of wounded with which it was now encumbered. A guard sufficiently strong to protect the extemporised field hospital having been detailed, the general force resumed its march, the intention being to press on as rapidly as possible to the capital. Along a tract of soft sandy country, oppressed by heat, exhausted by the fatigue of the previous day, the troops plodded their weary way, in their progress passing many relics of the recent fight, including shot, arms, shreds of clothing, dead bodies of animals and of men, etc.

At last the halt resounded from trumpet and bugle; for a time we rested as best we could, and then the tents having arrived we30 encamped. Some further delay was rendered necessary by circumstances. During that and the succeeding day information was received in camp that while the battle was proceeding in the vicinity of Maharajpore, an engagement equally formidable took place between the Mahrattas and the force under General Grey at Punniar, on the eastern border of the Gwalior State; that in it the Buffs had sustained a loss in killed of one officer and thirteen men, in wounded of three officers and sixty men,—the casualties in the 50th being equally numerous.

The arrival in camp of the Queen Regent, together with her Sirdars, and the young Maharajah, the salute on the accession of whom some ten months previous has been already mentioned, caused no little excitement, and at the same time much speculation among us. Later on, however, the report spread that the result of their interview with the Governor-General was by both parties deemed satisfactory.

As some among us took rides in different directions around our camp, not an armed man was met with. In some of the villages visited individuals who had escaped the carnage of the previous day were found lying more or less completely stripped of clothing, and wounded, some of them dead. The villagers had fallen upon the fugitives, robbed them of all they possessed, then turned them adrift. They had failed, and they paid the penalty of failure.

The march resumed, the force in due time reached the immediate vicinity of Gwalior, and there encamped. The huge fortress seemed to tower above us, while the neighbouring hills looked as if from their summits a well-directed fire could have swept the country to a considerable distance around. Within a couple of days arrived the force under General Grey and the Seepree contingent under Brigadier Stubbs. Negotiations had so far advanced that the latter took possession of the fort, the camp of the former adding very considerably to the dimensions of the great canvas city already existing. Rapidly and completely did the routine of life to which for some time past we had been accustomed undergo a change: complimentary visits and entertainments, each regiment entertaining every one else and being in turn entertained by them. By the high officials durbars and receptions were held, to which ceremonials Representatives of Gwalior having given their presence, the fact that they did so indicated that the end of our expedition was approaching.

Connected with the strong fortress by which the city of Gwalior is dominated were many points of interest; among them the general aspect of decay as seen from without, the tortuous narrow lane that leads to it, the steep and difficult flight of stone steps by which the ascent31 must be made, and powerful gates that seemed to lead but to a mass of ruins. Within the defences we were face to face with remains of temples, pillars, and arches pertaining to edifices of the Jains;45 there were remains of what had been reservoirs of large dimensions and beautiful workmanship, in some portions of which clear water glistened in the sunlight. Only one piece of ordnance was met with; it was an ancient gun, seventeen feet in length, and apparently capable of discharging a fifty-eight pound shot.

The process of disarming the Gwalior troops was next performed—somewhat slowly at first, and not without some risk of difficulty, but more rapidly as information circulated among them that they were to receive all arrears of pay due, and a certain number of them taken into the service of “the Company.”46 Then did they march to the places assigned to them in battalions, their bands playing what was intended to be “God Save the Queen”; finally laying down their arms and surrendering their colours, all of which, packed on elephants, were taken to the fort. The artillery and cavalry gave theirs up elsewhere.

The wounded from different regiments were collected in camp, those among them fit to undergo the journey towards Allahabad being dispatched thither by means of doolies and native carts (hackeries),—the orders of the Commander-in-Chief, as expressed by himself, being that their progress thither should be by “easy stages and intermediate halts.” From Allahabad they were to be conveyed by means of native boats to Calcutta, and there embarked on board one or more of the most comfortably and well-equipped ships proceeding viâ the Cape to England. For those whose condition was more serious, accommodation was provided in camp, and in public buildings outside the city of Gwalior. Among those so left were three respected officers of the Buffs. Of these, Captain Chatterton and Dr. Macqueen shortly afterwards succumbed to the disease—induced by the trials of active service. The death of the third—namely, Captain Magrath—was attended by a little circumstance which showed that the spirit of romance persisted to the last in him. During the battle at Punniar, he, together with thirteen men of his company, were blown up by the explosion of a tumbril that they were in the act of capturing. Captain Magrath and twelve of the soldiers with him speedily succumbed, or were instantly killed. When his body was being prepared for burial, there,32 over the region of the heart, was found a lady’s glove; nor was it difficult, bearing in mind some of the most pleasant incidents at Allahabad already recorded, to indicate the hand to which the memento originally pertained.

A general parade of the combined forces now took place. On that occasion the young Maharajah accompanied the Governor-General, by whom, in the course of his address, sufficient was expressed to raise hopes that further service on the Punjab frontier was to be immediately undertaken. But this was not to be.

Disintegration of “the Army of Exercise” forthwith began, in obedience to orders issued. Starting on their return march, the 16th traversed the field on which, twenty-nine days previous, the battle already mentioned had taken place. At short distances over its extent lay bodies of men and horses far advanced in decomposition; fragments of natives and equipments everywhere. The village of Maharajpore reduced to charred ruins; in their midst numbers of dead bodies of those who had so manfully stood their ground and perished as they did so. In what had been a room or enclosure a confused heap of what had been men further testified to the obstinacy of the defence. In some places miserable-looking inhabitants were searching among the ruins for property and houses. Such was the wreck of battle.

Thence to Meerut the march of the Lancers was uneventful. Halts for a day were made respectively at Hattras and Alighur, associated as those places are with early campaigns of the century. At the latter fortress we visited the gate and approach thereto through which was made the historic charge by the 76th Regiment;47 then the monument to officers and men who fell on that occasion, and at Laswaree soon thereafter. Twenty days en route; the 16th re-enter Meerut, whence they had started on service now happily performed. Very touching were meetings between wives and their husbands; though to younger and less thoughtful men the full significance of husband and father restored to those dependent on him had yet to be realized.