WARWICKSHIRE

VOLUMES IN THIS SERIES

| CAMBRIDGE | By W. Matthison and M. A. R. Tuker. |

| OXFORD | By John Fulleylove and Edward Thomas. |

| SCOTLAND | By Sutton Palmer and A. R. Hope Moncrieff. |

| SURREY | By Sutton Palmer and A. R. Hope Moncrieff. |

| WARWICKSHIRE | By Fred Whitehead and Clive Holland. |

| WILD LAKELAND | By A. Heaton Cooper and MacKenzie MacBride. |

Other Volumes to follow.

AGENTS

| America | The Macmillan Company 64 & 66 Fifth Avenue, New York |

| Australasia | The Oxford University Press 205 Flinders Lane, Melbourne |

| Canada | The Macmillan Company of Canada, Ltd. St. Martin’s House, 70 Bond Street, Toronto |

| India | Macmillan & Company, Ltd. Macmillan Building, Bombay 309 Bow Bazaar Street, Calcutta Indian Bank Buildings, Madras |

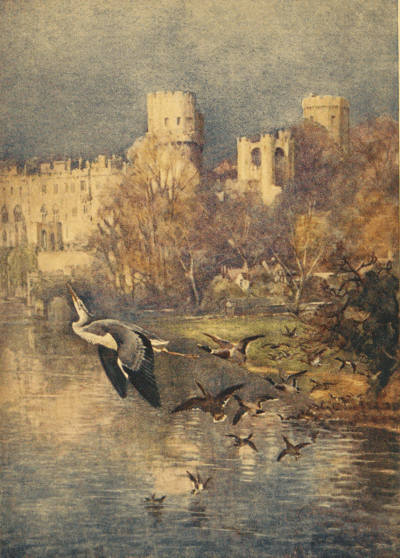

WARWICK CASTLE FROM THE BRIDGE.

First Edition, with 75 Illustrations, published in 1906

Reprinted in 1912

Second Edition, revised, with 32 Illustrations, published in 1922

Printed in Great Britain by R. & R. Clark, Limited, Edinburgh.

Preface to Revised Edition

To those who know Warwickshire well it will be unnecessary to either sing its praises, as not only one of the most historic but also one of the most fascinating of middle–England shires, or to urge its claims for the consideration of those who love the fair, open country, winding roads, and pleasant hills and vales. This county, of whose beauty poets from almost time immemorial have sung, possesses an added interest beyond the romantic elements afforded by its history, its magnificent survivals of bygone ages in castles, manor–houses, churches, and other domestic buildings, in that it is the land of Shakespeare. Around this beautiful district of England still hangs some of the unfading glamour which comes from the association with it of great deeds and great names; from amongst the latter of which that of “the nation’s poet” stands out with undimmed lustre as the centuries pass away.

The wealth of material which confronts both the writer and the artist who seeks to depict with pen and brush some of the most salient features of the county is so embarrassing that selection becomes a task of[viii] extreme difficulty. What to leave out presents itself as a most pressing problem, not easily solved; for, alas! space is not elastic; and even when the question is in a measure disposed of, it is still pregnant with regrets for the many beautiful things, historic places, scenes, and incidents which have had to be omitted for lack of space. To those who know the county only as one of England’s central shires, perhaps the book may give sufficient pleasure to induce them to visit the places described.

C. H.

Ealing, W.5.

June 1922.

Contents

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I. | Warwickshire and its History from the Earliest Times to the close of the Fifteenth Century | 1 |

| II. | Warwickshire and its History from the Fifteenth Century to Modern Times | 24 |

| III. | Fayre Warwick Town: Its History and Romance | 43 |

| IV. | The Story of Warwick Castle | 70 |

| V. | Coventry: Its History, Romance, Churches, and Ancient Buildings | 89 |

| VI. | Kenilworth and its Priory—The Story and Romance of Kenilworth Castle | 125 |

| VII. | Leamington | 144 |

| VIII. | The Story of Birmingham | 154 |

| IX. | The Story of some Ancient Manor–Houses—Baddesley Clinton—Packington Old Hall—Maxstoke Castle—Astley Castle | 174 |

| X. | The Story and Romance of some South Warwickshire Manor–Houses |

189 |

| XI. | Shakespeare’s Life and Shakespeare’s Town | 202 |

| XII. | A Group of Shakespeare’s Villages | 240 |

| Index | 256 |

List of Illustrations

| 1. | Warwick Castle from the Bridge | Frontispiece |

| FACING PAGE | ||

| 2. | Henley–in–Arden | 4 |

| 3. | Salford Priors | 9 |

| 4. | Coughton Court | 16 |

| 5. | Dunchurch | 25 |

| 6. | Southam | 32 |

| 7. | Warwick Castle | 41 |

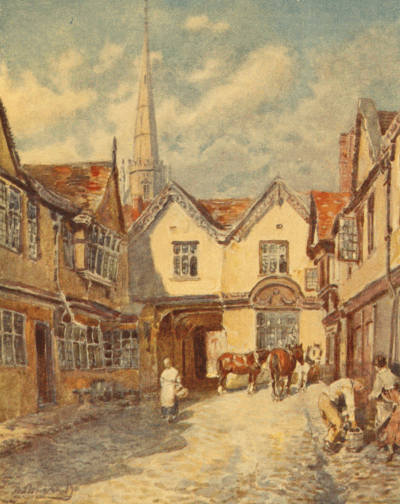

| 8. | Leicester’s Hospital, Warwick | 48 |

| 9. | Beauchamp Chapel, Warwick | 57 |

| 10. | Guy’s Cliffe Mill | 64 |

| 11. | Peeping Tom, Coventry | 73 |

| 12. | Palace Yard, Coventry | 80 |

| 13. | Ufton | 89 |

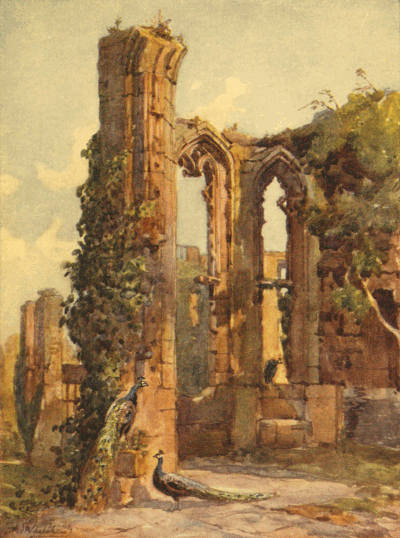

| 14. | Kenilworth Castle | 96 |

| 15. | Stoneleigh Abbey | 105 |

| 16. | The Parade, Leamington | 112 |

| 17. | St. Martin’s Church, Birmingham | 121 |

| 18. | Baddesley Clinton Hall | 128 |

| 19. | Maxstoke Castle | 137 |

| [xi]20. | Compton Wynyates | 144 |

| 21. | Burton Dassett Church | 153 |

| 22. | Little Wolford Manor–House | 160 |

| 23. | Long Compton | 169 |

| 24. | Ann Hathaway’s Cottage | 176 |

| 25. | Shakespeare’s Birthplace | 185 |

| 26. | Stratford–on–Avon. The Grammar School | 192 |

| 27. | Stratford–on–Avon | 201 |

| 28. | “Hungry” Grafton | 208 |

| 29. | Abbots Salford | 217 |

| 30. | Bidford Bridge | 224 |

| 31. | Charlecote | 233 |

| 32. | Rugby School | 240 |

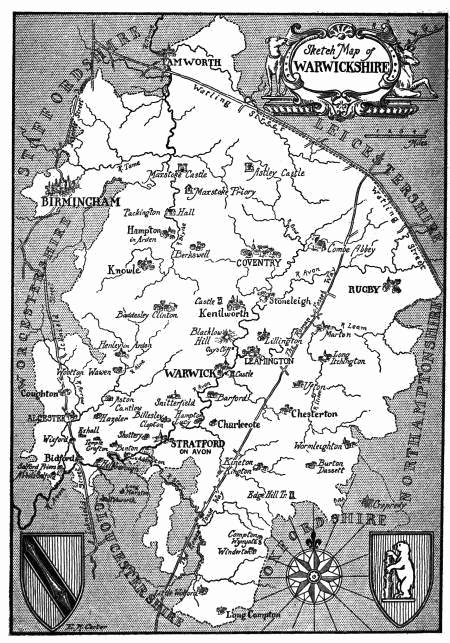

| Sketch Map facing p. 1 | ||

SKETCH MAP OF WARWICKSHIRE.

WARWICKSHIRE

CHAPTER I

WARWICKSHIRE AND ITS HISTORY FROM THE EARLIEST TIMES TO THE CLOSE OF THE FIFTEENTH CENTURY

Warwickshire has rightly been termed “leafy Warwickshire,” for although deficient in scenery cast in a large mould, which may be described as grand or magnificent, it is undoubtedly one of the most lovely of English counties. Though lacking the peaks and deep–set dales of its near neighbour, Derbyshire, which it touches at its northern limit, it is essentially a county of pleasant hills, uplands, and fertile well–watered vales. Some of the richest meadow–land and most picturesque woodland scenery in the Midlands lie within the confine of Shakespeare’s shire.

Few English counties present greater attractions for the student of the past, the archæologist, the rambler, and the tourist than Warwickshire. Through it gently–flowing rivers, unagitated by sudden drops from highland sources, pass on their placid ways by rich pasture–land and fields of waving corn, or wind in tortuous convolutions through wide–spread parks, and past historic castles and mansions rich in traditions of[2] the stirring times when the shire played its part in the affairs of national history.

Warwickshire, although possessing few ranges of considerable hills, and no very high eminences, the chief ranges being on its north, eastern and south–eastern borders, has just that type of scenery which was so delightfully described by Mrs. Browning in “Aurora Leigh”:—

The ground’s most gentle dimplement

(as if God’s finger touched, but did not press,

In making England!), such an up and down

Of verdure—nothing too much up or down;

A ripple of land; such little hills, the sky

Can stoop to tenderly and the wheat fields climb;

Such nooks and valleys, lined with orchises,

Fed full of noises by invisible streams;

And open pastures, where you scarcely tell

White daisies from white dew; at intervals

The mythic oaks and elm trees standing out

Self–poised upon their prodigy of shade—

I thought my father’s land was worthy too

Of being my Shakespeare’s.

Few better descriptions of the charms of this delightful county have ever been written, although many poets have sung them. An Elizabethan singer, Michael Drayton, said of his native shire, “We the heart of England well may call.”

It was well, indeed, for English literature that such an one as the Bard of Avon should have been born and have lived in this land of pleasant pastures, leafy woodlands, and placid and beautiful streams, and should have treasured early memories of vagrant days amid[3] her sylvan solitudes and river banks with which to gem his after work with sweet imageries of rural beauties, of flowers, and the songs of birds.

Shakespeare loved his native town, and he put into almost all of his plays some glimpses or description of the natural and unfailing beauties of Stratford and its immediate surroundings. And still, in the meadows in which long ago he loved to muse and wander, are found those “daisies pied,” “pansies that are for thoughts,” the “blue–veined violets,” and “ladies’ smocks all silver white,” of which Shakespeare’s maidens often sing. And there are also the willow–hung brooks, and the orchards in spring beauteous in white and pink blossom, and in autumn rich with sun–kissed fruit.

In few parts of rural England are richer and more beautiful meadows to be found than round Stratford. These, through which the placid–moving Avon flows, are in spring and early summer gay with the glistening gold of kingcups and humbler buttercups, and fragrant with meadowsweet. And a little later on the meadow grass is shot and diapered with mauve orchises, tall horse daisies, yellow rattlegrass, blue and white milkwort, and frail bluebells. In the woodlands, which engirdle Stratford a little way beyond the town, there is in spring a rich carpet of the mingled yellow of primroses and vivid ultramarine of wild hyacinths, and a blended odour of awakening earth and flowers. Few counties have been better sung by poets of the past and present than Warwickshire. And much verse[4] which has never been traced to Warwickshire writers doubtless owes its origin to a district which, “beautiful as some dreamland of flowers and fruits, and kingdom of elfish people,” is taken to the heart of all who sojourn within its borders, be it only for a brief period.

Beautiful, however, as the county is, it has interests quite as fascinating for the historian, student, and archæologist as for the wayfarer and artist. There is, indeed, no lack of historical associations and of famous houses, connected with which are many of the traditions and gallant deeds of past ages, which give an added interest to much that is beautiful in itself.

The history of Warwickshire contains much which is also that of England. Its life throughout the varying ages has been a part of that of the kingdom at large. Although the traces of the earliest of all inhabitants are comparatively few, sufficient exist, or have been discovered from time to time, to enable both historical and archæological students to construct with some certainty the life of the district in far remote times.

Of the history of Warwickshire in pre–Roman times unfortunately little is known. Even the very name of the county itself is of obscure origin, although it most probably has a distinct connection with that of the tribe Hwicci, who, in common with another tribe, the Cornavii, dwelt in the district, which was a part of the great central kingdom of Mercia, before the Roman occupation.

HENLEY–IN–ARDEN.

Of the Roman occupation, which lasted nearly 470 years, fortunately many memorials and relics have survived. Traces of three of those great highways which exerted so puissant a civilising influence whilst Romans dwelt in Britain, are still to be seen in the portions of the Icknield–Way, Watling Street, and the Fosse–Way, which are to be found in different parts of the county. Indeed, the second of these has given its name to one of Birmingham’s most important streets. Along a portion of the county’s western border, too, runs the Ridgeway; and Alcester, Mancetter, and many other spots were once Roman stations or Roman encampments. But although the Roman occupation doubtless affected Warwickshire with the rest of the kingdom, it was of a more partial character than in many other districts, and appears to have been largely confined to the immediate vicinity of the roads which the invaders constructed. The character of the country, which was at that time densely wooded, permitted the inhabitants to hold it against their conquerors with some success, attacking when the opportunity served, and then retiring into ambush afforded by the nature of the ground.

Details of the early years of the Roman Conquest are fragmentary, and it is not, indeed, till about A.D. 50 that one finds Ostorius Scapula, who was the second governor, erecting a string of military posts and forts on the Severn, indicating at all events the partial subjugation of the British. Ultimately the district of which Warwickshire formed a part became incorporated in the province known by the name of Flavia Cæsariensis, and latterly was called Britannia Secunda.

Comparatively few architectural traces of the days[6] of Roman rule have been found, and of these most have been upon the lines of the two great roads, the Icknield–Way and Watling Street, and then chiefly in the immediate vicinity of the camps or “stations.” Very little history, too, relating to this interesting period has survived the effluxion of time.

The immediate successor of Ostorius appears to have made terms with the leaders of the Hwicci, granting to them certain concessions, and some measure of independence, but these British chiefs later on joined with the Silures in resisting the Romans, and an era of greater severity on the part of the latter ensued.

Under Suetonius Paulinus the domination over this portion of Britain was extended and ultimately rendered complete. At this period “Arden,” which is the general Celtic name for a forest, was to all intents Warwickshire. It certainly was the largest of all British forests, and extended from the Avon as far northward as the Trent, and probably stretched to the banks of the Severn on the west. Its eastern boundary is more uncertain, but there appears considerable reason for believing that it lay approximately along a line drawn from the town of Burton–on–Trent to High Cross, where the Fosse–Way and Watling Street intersect. The early inhabitants of the southern portion of this thickly–wooded and well–timbered district were principally if not entirely belonging to the tribe of herdsmen known as the Hwiccian Ceangi, and this district of Arden was known as the “Feldon,” whilst the northern portion of the county beyond the Avon[7] was then known as the Woodland. The first–named district was of the nature of more open country, with pasture lands and possessing wide cultivated areas, although well–wooded in places; whilst the second named was thickly timbered and scarcely penetrated to any extent by the Roman conquerors. In later times, when England was ultimately divided into shires or counties, in those of Warwick and Stafford were incorporated various portions of the wilder Arden of those ancient days. The name is, however, now only preserved in Warwickshire, where it survives in Hampton–in–Arden and Henley–in–Arden, situated in the Woodland district.

Partial as the subjection to the Roman yoke of what is now known as Warwickshire undoubtedly was, considerable remains of the occupation have from time to time been discovered in the shape of coins, implements, pottery, and other antiquities at Warwick, Alcester, Lapworth, Hampton–in–Arden, Milverton, Birmingham, and other places.

The departure of the Romans affected Warwickshire less than some other portions of the country at first. But there is little doubt that the usual policy of the conquerors of drafting the bravest, best, and youngest men into their own legions for service abroad left “the heart of England” as badly prepared to resist the invasion of other tribes as was the rest of the country. Depleted of many of its bravest warriors, England was, after several centuries of reliance upon an alien power for defence, when the Roman conquerors[8] departed left at the mercy of any who chose to attack. Not only were all the legions required at home to resist the Saxon invasion under Alaric, who poured his hosts of barbarians over the wide–spread Roman Empire, but the British youth who had been drafted abroad returned not, and thus, as Gildas says, Britain, despoiled of her soldiers, arms, and youth, who had followed Maximus to return no more to their native shores, and being ignorant of the art of war, groaned for many years under the constant incursions and ruthlessness of the Picts and Scots.

For some considerable period after the departure of the Romans few historical records relating to Warwickshire exist. And if, as George Eliot wrote in The Mill on the Floss, “the happiest nations have no history,” then the county which gave her and the “Bard of Avon” birth must have been a pleasant spot for a long period. There is probably a reasonable explanation of this circumstance when its position is considered. Situated in the centre of England, and far removed from the seaboard, it naturally escaped much of the storm and stress of invasion and attack from which less happily placed districts in those wild, early periods of national history so constantly suffered. Except for a record that one Credda, a Saxon commander of note, successfully penetrated into the wooded solitudes of Warwickshire, there are few data obtainable for the construction of an historic sketch of this region until the time of the Saxon Heptarchy. Then it became a part and parcel of the wide–spread kingdom of Mercia, and not only enjoyed a share of its rule and barbaric pomp and circumstance, but also played a not inconsiderable part in the wars and feuds of the various Mercian rulers.

SALFORD PRIORS.

The capital of several of these monarchs was Tamworth; which anciently enjoyed the distinction of standing in both Staffordshire and Warwick, concerning which the Saxon Chronicle of 913 records, “This year, by the help of God, Æthelflæd, lady of the Mercians, went with all the Mercians to Tamworth, and there builded a burgh early in the summer.” In those times Kingsbury, on the Tame, was also a place of importance as a royal residence, and, according to Dugdale, the farmhouse, formerly the Hall, stands on the spot where stood the palace of the Mercian kings. Tamworth was destined to play its part in one of those fierce and lurid conflicts between the Saxons and the Danish invaders which took place after the town had been burned by the latter. Near by, too, in A.D. 757, another battle took place between Ethelbald, the tenth king of Mercia, and Cuthred, King of the West Saxons, when the former was slain by one of his own followers. At Seckington, about five miles to the north–east of Tamworth, is a tumulus, which not only marks the site of the battle, but also the burial–place of those who fell.

In the latter half of the eighth century Offa, who ultimately became the greatest ruler of the West of those times, raised the kingdom of Mercia to a height of greatness and prosperity that it had never before[10] enjoyed,—an importance which it continued to hold for a period under the rule of his son Cenwulf. Warwickshire, as a part of Mercia, must naturally have benefited by its greatness and progress, but during the reign of Cenwulf the seeds of a far–reaching revolution were being sown, the fruits of which were the uniting of the kingdoms of Wessex and Mercia by Ecgberht or Egbert, King of the West Saxons, who has been sometimes incorrectly described as the first king of England.

The incursions of the Danish invaders, which had been of frequent occurrence prior to the reign of Egbert, assumed a much more formidable aspect almost ere the King had succeeded in welding together the separate kingdoms under one head. Their first unwelcome visitations had begun in 787, some thirteen years before Egbert’s accession.

In 868 they once again invaded and seriously ravaged Mercia. Two years later they conquered East Anglia. A year later their triumphant progress extended into Wessex, where they at first achieved some successes, although that kingdom was ruled by a wise and heroic ruler in the person of Æthelred, the brother of Alfred the Great, who succeeded him. In the following year, 871, no less than nine pitched battles were fought between the Danes and the Saxons.

It is supposed that Mercia about this time was only a portion of the kingdom of Burhred, the last native king of central England, who had succeeded Ceolwulf. This in 874 had been divided by the victorious Danes, and committed as a tributary state to Ceolwulf.[11] Be this as it may, the whole of Warwickshire, there is little reason to doubt, came into the hands of Alfred the Great by the Treaty of Wedmore in 878, made between him and Guthrun the Danish leader, and was ultimately formed by him into a duchy under his daughter Æthelflæd and her husband Æthelred.

The effects of the Danish settlement were important on the future history of the kingdom, for it was that of a new people with different customs, modes of life, and traditions. How far–reaching the occupation was can be traced in local nomenclature, and the counties which were anciently West Saxon still retain the names and boundaries of the divisions founded by the successors of Cerdic. Mercia, in contradistinction to the local divisions of Wessex, which were evolved naturally, was apparently mapped out, and the extent of the Danish settlement of the county of Warwick may be traced from the fact that Rugby is the southernmost town possessing the Danish affix by, whilst there are a considerable number of places so distinguished in the more northern part of the county.

In the several massacres of the Danes which took place during the period comprised by the last few years of the tenth and first years of the eleventh centuries, the part played by Mercia, and, as a consequence, by the district afterwards to be known as Warwickshire, was considerable. The ultimate vengeance for these massacres, which was taken by Swend in 1013, was shared by the Mercians as well as by the other inhabitants of East Anglia and central England. And[12] the coming of Canute three years later was destined to have a far–reaching effect upon the history of the district, and of England generally.

Arriving with his army and Eadric, the Saxon Earldorman, who had betrayed his fellow–countrymen previously, and had, so the Chronicles state, fled from England to escape their vengeance, Canute crossed the Thames at Cricklade and entered and ravaged Mercia, proceeding into Warwickshire during mid–winter’s tide, where the Danes ravaged and burned and slew all that they could come across. Afterwards Canute and his forces besieged London. “But,” says the Chronicler, “Almighty God saved it.” Failing to capture the city, the Danes once more returned into Mercia, and carried fire and sword into its vales and woodlands, slaying and burning whatever they overran.

On the death of Æthelred the Unready two years later, in 1016, Canute was chosen king at Southampton, and Edmund, surnamed Ironside, in London. The latter’s reign was short but glorious; several battles were fought with the Danes and victories won, in consequence of which Canute agreed to a division of the kingdom between Edmund and himself. In this division Canute took Mercia and Northumbria, and Edmund the rest of England. In a few months the latter died in London, and Canute became by common consent King of England.

The Danish leader’s reign brought peace and a large degree of prosperity for the people over whom he had been destined to rule. And during his sovereignty[13] Warwickshire at least experienced immunity from ravishment by fire and sword, and enjoyed a measure of good government. In the years which immediately followed little happened to disturb the peace of the county, although bloody feuds occasionally wrought destruction in contiguous localities.

With the death of Edward the Confessor a brief period of unrest ensued, whilst Harold was engaged in a struggle to retain the throne he had ascended and in resisting the invasion of William of Normandy, who claimed that the crown of England had been left him by Edward the Confessor.

In the fierce Battle of Hastings, waged on the heights of Sussex, Harold fell fighting, and with him ended the history of the country under its Anglo–Saxon kings.

Under them England had gained a foretaste of those principles of individual and personal liberty, in comparison with which all other so–called freedom can be but a mockery.

The extent of the occupation of Warwickshire by the Saxons can be easily traced by the curious from the number of marks, as their early settlements were called. Thirty–one of the large number of thirteen hundred and twenty–nine names of settlements, which have been traced throughout the land, belong to Warwickshire. Some few of the most notable were Leamingas (Leamington), Beormingas (Birmingham), Ludingas (Luddington), Whittingas (Whittington), Poeccingas (Packington), Ælmingas (Almington), Secingas (Seckington), and Eardingas (Erdington).

Warwickshire is not possessed of many Saxon remains. Of architecture dating from before the Conquest the fragments of round–headed door cases at Kenilworth, Stretton–on–Dunsmoor, Ryton, Honingham, Badgeley, and Burton Dassett may be mentioned. While at Polesworth nunnery, the ruins of Merevale Abbey, and in the churches at Salford Priors and Beaudesert there are some fragments. Occasionally Saxon jewels have been turned up in the soil. Perhaps amongst the most interesting of these relics are the two Saxon jewels of cut gold, one set with an opal and rubies, and the other adorned on both sides with a cross between two rudely–fashioned human figures, each holding a lance or sword in one hand, found more than a century and a quarter ago at Walton Hall, near Compton Verney. Tumuli, of course, exist in different parts of the country, from which at various times bones, skulls, and small ornaments have been excavated.

Until the coming of William the Conqueror Warwickshire was almost without historians or records, although an attempt at a survey and the accumulation of historical data had been made in the previous reign of Edward the Confessor. Though the Saxon Chronicle gives many interesting and valuable details concerning lands, places, and incidentally also of the life of the people of the period, it is to the Domesday Book, that monumental work of the Conqueror, all historians and students have to go when in search of information regarding the English counties at the time of, immediately prior to, and after the Conquest. The value[15] of this truly wonderful work as regards Warwickshire in particular is considerably enhanced by reason of its containing a comparative report of the nature, extent, and value of the different estates, names of towns, and position of roads in the reign of Edward the Confessor. From its pages one is enabled to gain a more or less vivid idea of the extent of the county, its inhabitants, and its peculiarities at a time when English history and that of Warwickshire was in the making.

In this wonderful work, commenced in 1081 and completed in 1086, are to be found records of all the original Saxon landowners (many of whom were afterwards dispossessed by their conquerors), and the value and extent of their estates. The original holders of the Saxon manors and estates in Warwickshire suffered severely at the hands of the Norman invader; and the pages of the Domesday Book afford interesting evidence of how wide–spread these confiscations were. The population of the county at that time was a few less than seven thousand, all told.

The period immediately succeeding the Conquest was one of great suffering for the vanquished. Year after year the Saxon Chronicle sets down a tale of wars, pestilences, storms, and famines, and although there is no direct reference to Warwickshire, it is certain that the county bore its part in “the sufferings inflicted by the acts of tyrannous man and the wisdom of God.”

From the tangle of the history of this period it is no easy task to seek to justly estimate the part played by Warwickshire in the history of the country at large.

But towards the end of Henry III.’s reign it was the scene of some of the most stirring and momentous episodes of the Barons’ War. The struggle between the King and the Barons under the leadership of Simon de Montfort, Earl of Leicester, centred, so far as Warwickshire was concerned, round Kenilworth and Warwick. De Montfort at the outset of the war garrisoned the former castle and placed Sir John Gifford in command. The latter and the troops of the garrison promptly ravaged the country round about, destroying the manor–houses and farms of those who were well–affected to the King. And finding that the Earl of Warwick had espoused the Royal cause the Kenilworth garrison, under the leadership of its governor, surprised and made a vigorous attack upon Warwick, taking the Earl and Countess prisoners.

In the year following the Battle of Lewes was fought, on May 14, 1264, in which the Barons under De Montfort were victorious. Prince Edward and his troops afterwards made a forced march and appeared before Kenilworth and routed De Montfort and dispersed his force. De Montfort took refuge in the castle, and ultimately effected his escape. With the small force at his command Prince Edward felt unable to successfully attack a fortress of such strength, but in a skirmish hard by he succeeded in capturing much booty, and no less than fifteen of the Barons’ standards, which were destined a short time later to prove of peculiar service to the victor.

COUGHTON COURT.

Abandoning all intention of reducing Kenilworth Castle Edward and his troops pushed on their way towards Evesham, just over the border, in the neighbouring county of Worcestershire, bearing the captured standards in the van. At Evesham lay the Earl of Leicester, awaiting his son De Montfort, who, at the time of his defeat near Kenilworth by Prince Edward, had been on his way to join the Earl, then in Wales. Deceived by the standards the forces of the Barons prepared not to resist the advancing army, but to welcome it, under the mistaken impression that the force was that of their expected friends.

After the fierce engagement, fought on a torrid August day in 1265, on the high ground known as Green Hill, between the roads to Birmingham and Worcester, and about a mile outside the town, in which not only was the Earl of Leicester, Henry de Montfort and many nobles slain, but the power of the Barons finally broken, Simon de Montfort, who had escaped, fled to Kenilworth and afterwards to France.

After the conclusion of the Barons’ war, for almost two centuries this most lovely of English counties rested in the tranquillity which during that period marked the years as they passed in central England, whatever happenings fell to dwellers on the coasts.

Only the merest echoes of the French wars of Edward III. and the glorious victories of Crecy and Poitiers seem to have reached the peaceful vales of Warwickshire; though old Records and Chronicles bear witness that the country contributed of her money[18] and her sons to uphold the might of England. And the same may be said of the brave doings at Agincourt, Crevant, Verneuil, and Herrings; and the defeat sustained at Patay which counted for so much in the future history of the race. At most the disturbing influence of these wars was represented by the rumours, which travelled not fast in those times, the visits of the recruiting officers of the day, the appeal for followers made by some manorial lord, or the breathless tales told by returned wounded, or veterans from the “stricken fields” of fair France.

The religious life of the county was, as in other parts of England at this time, ministered to by the monks of foundations, such as Warwick Priory; Stoneleigh Abbey, a Cistercian monastery founded by the monks of Radmore, Staffordshire, who relinquished their estates in that county to Henry II. in exchange for those of Stoneleigh; Temple Balsall, near Knowle, erected by the Knights Templars in the reign of Richard II.; Combe Abbey, near Coventry, the second Cistercian foundation in the county, built in the reign of Stephen; Merevale Abbey, near Atherston, founded and richly endowed by Robert, Earl Ferrers, in the middle of the twelfth century in one of the most beautiful spots in the northern part of the county; and the once magnificent Maxstoke Priory, built in 1336 by William de Clinton for an establishment of the Augustines. From these and other religious houses emanated what of learning and religion the countryfolk knew in the Middle Ages, and with the passing[19] away of the monkish owners at the time of the Dissolution, although abuses had undoubtedly crept in which called loudly for and needed stringent action and redress, Warwickshire was the poorer. It was to the monasteries and religious orders, rightly or wrongly, that the humble folk had looked for salvation, protection, and healing in the ancient days when almost all learning as well as knowledge of physic was to be found within cloistered walls.

With the accession of Henry VI. of Winchester, weak and totally unfitted to govern during the turbulent times which lay in the immediate future, trouble soon manifested itself amongst the powerful nobles; these the King proved quite unable to reduce to order. To make matters worse nearly the whole of the vast possessions held by England in France, which had been won by the triumphant arms of Henry V., were lost, adding to the bitterness and discontent which already was bringing the country at large to a state bordering upon anarchy. The serious family quarrels which had commenced whilst the King was still a minor, involving many of the noble houses, either in support of the claims of the House of York or the House of Lancaster, became acute. Shakespeare, in “Henry VI.,” well and vividly pictures the historic scene in the Temple Gardens, in front of which in those days flowed a “clear, reed–begirt Thames,” which was destined to give the coming contest its name, and describes the quarrel between the Earl of Somerset and Richard Plantagenet. The Earl of Warwick,[20] whilst in the company of the latter, by tradition is stated to have plucked a white rose, which was afterwards adopted as the badge of the Yorkists, and whilst doing so he makes the following speech:—

This blot that they object against your house

Shall be wiped out in the next parliament,

Call’d for the truce of Winchester and Gloster;

And, if thou be not then created York,

I will not live to be accounted Warwick.

Meantime, in signal of my love for thee,

Against proud Somerset and William Pole,

Will I upon thy party wear this rose:

And here I prophesy,—This brawl to–day,

Grown to this faction, in the Temple Garden,

Shall send, between the red rose and the white,

A thousand souls to death and deadly night.

In the bloody struggle, which lasted intermittently for a period of thirty years, and was foreshadowed so accurately by Warwick’s speech, his own county was destined to play a far more intimate and important rôle than many other parts of England where, indeed, the battle royal between the houses of York and Lancaster was regarded with comparatively slight interest. With the final rupture of the parties, which took place in 1455, Warwickshire entered upon another period of unrest, such as had afflicted its peace, progress, and prosperity during the Barons’ War.

The struggle was possibly rendered the more disastrous from the fact that the county was divided in opinion regarding the merits of the “rival Roses.” The supporters of the House of York numbered many[21] of the most powerful families in Warwickshire, in addition to that of Richard Neville, Earl of Warwick, destined to go down to posterity as “the King Maker.” But while the town of Warwick was for York, this advantage was somewhat counterbalanced by the strong Lancastrian sympathies of Coventry, but twelve miles distant.

Henry of Lancaster and his Queen, Margaret, had sedulously wooed the latter town by frequent visits, and also by making it and several adjoining parishes a separate county. Coventry saw a good deal of the Red Rose faction, and at the re–commencement of the war, which had languished after the first battle of St. Albans in 1455, at the time the Earls of Warwick and March (the latter of whom was afterwards made Edward IV.) set out for London in search of the King’s forces, the Lancastrians were actually quartered at Coventry. The troops, however, did not remain long in the town, but marching south–east under the command of the Duke of Buckingham, encountered the Yorkist forces at Northampton on July 10, 1460, suffering a disastrous defeat, when Henry himself was captured. Amongst the more notable Warwickshire adherents of the King who fell was Sir Henry Lucy, of Charlecote, near Stratford–on–Avon.

Ten years later saw Warwick “the King Maker” espousing the cause of Lancaster. After his quarrel with Edward IV. he had fled to France, and there at the Court of Louis XI. had met with and been reconciled to Margaret, and exiled Queen of Henry VI. of[22] Windsor, and Edward’s own brother the Duke of Clarence. In the same year (1470) Warwick and Clarence made a descent upon England, and Edward fled to Flanders. On the landing of Warwick, Henry VI., who although deposed was still alive, was proclaimed; and for a short period the Lancastrian dynasty may be said to have been restored.

On the return of Edward in the following year the Earl of Warwick took the field at the head of the Lancastrian forces. He was not long destined, however, to profit by his change of sides, for, encountering the army which Edward, who had been rejoined by the Duke of Clarence, had hastily gathered together at Barnet, “the King Maker” was utterly defeated and slain on April 14, 1471. The landing of Margaret, which had taken place at Weymouth on the same day, caused the Lancastrian forces to rally after the battle of Barnet, but they were finally overthrown on May 4 at Tewkesbury, after which Edward, son of Henry and Margaret, was treacherously assassinated by the King and his brother; and the Duke of Somerset, who had been captured, executed.

With the defeat and death of “the King Maker” Warwickshire’s active participation in the struggles of the rival Roses may be said to have come to an end.

A few years later the House of Warwick became allied to that of York by the marriage of Richard III. with Anne, daughter of the Earl of Warwick, and widow of the unhappy Edward V., who had been murdered by Richard, his uncle.

The final struggle between the rival Roses took place not in Warwickshire, but in its sister county Leicestershire at Market Bosworth, in the sanguinary battle of August 22, 1485, which by the defeat and death of Richard III. brought the Plantagenet line of English sovereigns to an end.

Upon the accession of Henry of Richmond after the battle of Bosworth, the Earl of Warwick, son of the Duke of Clarence, was imprisoned in the Tower. And on the advent of Perkin Warbeck, who represented himself to be Richard, Duke of York, son of Edward IV., the fact of Warwick’s imprisonment was used by King Henry VII.’s enemies to his injury and disparagement.

The fate of Warbeck was destined ultimately to involve that of the unfortunate Earl of Warwick. Bacon puts the position in a brief phrase, which cannot be easily surpassed for vivid imagery. He says, “it was ordained that the winding ivy of a Plantagenet should kill the true tree itself.”

By the execution of the Earl upon Tower Hill in 1499 the male line of the Plantagenets, which had flourished in great royalty, power, and renown from the time of Henry II., came to an end; and there was no other Earl of Warwick for a period of nearly half a century.

CHAPTER II

WARWICKSHIRE AND ITS HISTORY FROM THE FIFTEENTH CENTURY TO MODERN TIMES

For many years after the decisive battle of Bosworth the history of Warwickshire was marked rather by peaceful and steady progress than by events of intense interest. No great occurrence of a military or catastrophic character disturbed its sunny hills and fertile vales. And even during the reign of Edward VI., which witnessed the historical struggle between the Duke of Somerset and Earl of Warwick for power, Warwickshire enjoyed a period of rest and tranquillity, unaffected by the schemes and plotting of John Dudley, who had been created Earl of Warwick by the King.

On the death of Edward VI., however, the county became involved in the attempt of Warwick, who had been made Duke of Northumberland, to place Lady Jane Grey, who had just married his son Lord Guildford Dudley, on the throne to the exclusion of Mary, half–sister of the late King. The attempt completely failed and resulted in Warwick’s execution as a traitor on Tower Hill on August 22, 1553, his death being followed the next year by that of the unfortunate lady who had been made the innocent instrument of his over–weening ambition.

DUNCHURCH.

During Mary’s reign Warwick’s grandson, Ambrose, was restored to favour, and although the county was involved in the rising of the Duke of Suffolk and Sir Thomas Wyatt in February 1554 to depose the Queen and prevent her marriage with Philip of Spain, the House of Warwick was not concerned in the rebellion, which was speedily quashed.

Warwickshire was not permitted to escape the cruelties and persecutions which distinguished the disastrous reign of Mary, and among the historical memories which the county should for ever honour and cherish with undying love are those of the martyrdom of Robert Glover and Mrs. Joyce Lewis, both of Mancetter, and of others; the former of whom was burned at the stake in Coventry on September 19, 1555, in company with Cornelias Bungey.

In the succeeding reign of Elizabeth the county had its part in the general progress and prosperity of the nation at large. The fear of the threatened Armada of 1585 found Warwickshire, as other counties, ready and willing to furnish its quota of men and money for the defence of England. And as the time of danger drew nearer and the designs of Philip of Spain became a reality, the numbers of the levies made in the county increased, until in December 1587 the Lord–Lieutenant received orders from the Queen to provide 600 men, properly selected and equipped. Large loans were also successfully raised,[26] although from the State Papers one gathers that there were a considerable number of families, probably Catholics, who objected to contribute. One great happening only in the county marked this period as one destined to be ultimately regarded as of worldwide interest and importance. On April 23, 1564, at Stratford–on–Avon, William Shakespeare, one of the greatest poets of any age, was born. A genius not alone destined to reflect undying lustre upon the literature of the wonderfully rich Elizabethan age, but to survive through succeeding centuries of change in men, modes of thought and fashion as no other writer has.

Rather less than half a century after Shakespeare’s birth the county was once more brought into prominence by the famous Gunpowder Plot. Not only were many of the chief conspirators members of well–known Warwickshire families, but much of the plotting took place in the county. The conspiracy, which was intended to compass the death of King James and his eldest son Prince Henry, and other Protestant noblemen on the opening of the Parliament in November 1605, was in the beginning largely the work of one Robert Catesby, of Bushwood Hall, near Lapworth. Catesby had taken part in the abortive rebellion of the Earl of Essex in the previous reign, but had been pardoned after having paid a fine amounting to £3000. He would appear to have been “the born plotter” he was called by an historian of the period, for he was mixed up in numerous conspiracies previous to the “gunpowder[27] treason,” which cost him his life. At one time he was probably a Protestant, as he married a daughter of Sir Thomas Leigh, of Stoneleigh Abbey.

Catesby and his fellow conspirators, in addition to compassing the death of King James and the heir to the throne, proposed to seize the person of Prince Charles or that of the Princess Elizabeth, then living at Combe Abbey, near Coventry, which had been but recently erected by Lord Harrington. The ultimate intention being to marry the Princess to some Catholic nobleman. Catesby’s mother was a Roman Catholic, a Miss Throckmorton of Coughton Court, near Alcester. His father, originally a Protestant, had been frequently brought to book and fined for recusancy. It was probably the persecution of his father that turned Robert Catesby’s undoubted gifts for plotting into the channel of the famous Gunpowder Conspiracy. He at first associated himself with three desperadoes, and ultimately with Guido Fawkes. The plotters met to arrange the details of their plan chiefly at Bushwood, Clopton, Coughton Court, and the ancient manor–house of Norbrook, not far from Warwick, the home of John Grant, one of the chief conspirators. This latter place was the magazine where the arms were stored, and also a general rendezvous, but the headquarters were the Lion Inn, at Dunchurch.

At this time Catesby himself was residing at Ashby St. Ledgers, Northamptonshire, after he had sold his Warwickshire estates. The plan was to have a hunting match at Dunsmore, near Dunchurch, and then the[28] conspirators, on receiving the news that Guido Fawkes’ portion of the work had been faithfully accomplished, and the Houses of Parliament blown up, were to ride off to Combe Abbey and seize the person of the Princess Elizabeth.

On the 5th of November there was a large muster of people—invited by Sir Everard Digby, whose part in the plot it was to bring about a “rising” in the Midlands—concerned at Dunchurch, ostensibly for a hunting party. All day they hung about the street of the little town, or sat in the parlour of the low–gabled Lion Inn, hungering for news. Towards midnight these were thrown into a panic by the arrival of Catesby, Rokewood, Percy, the Wrights, and others who had fled from London on the arrest of Guido Fawkes the night before, whilst he was at work in the vaults beneath the Houses of Parliament laying the train that was to explode the gunpowder on the following day.

The principal conspirators, who, instead of fleeing the country on Fawkes’ arrest, had proceeded post–haste to Dunchurch, in the hope of still seizing the Princess and raising a rebellion in her name, on reaching the village decided to continue their flight, with others who joined them, on the news of the failure of the plot.

It was ultimately decided to make a stand at Holbeach House, Staffordshire, the residence of Stephen Littleton, who had only recently joined the conspiracy. To reach it they had to ford a river, and in doing so their arms and ammunition became damp. Whilst drying the powder in front of the fire a spark fell[29] amongst it; an explosion occurred, and Catesby, Morgan, Rokewood, and Grant were badly burned; and several of those who had thrown in their lot with the fugitives took advantage of the confusion to escape.

On the arrival of the sheriff of Worcestershire and his posse at Holbeach, the house—which had been seriously damaged by the explosion—was attacked, and Catesby and Percy, a member of the Northumberland family, were shot in the courtyard, where they had intentionally exposed themselves. Rokewood was severely wounded and taken prisoner with Winter, Grant, Morgan, and several less known plotters who had retreated into the house. Others were afterwards taken whilst hiding in the cover afforded by Snitterfield Bushes, some six or seven miles to the south–west of Warwick.

Thus ended one of the most notable conspiracies in English history, the heinousness of which has been the subject of much controversy both in the period immediately following its failure and in recent times. With the capture and death of the chief participants, and the ultimate trial and punishment of those who had not succeeded in making good their escape, Warwickshire once more relapsed into its normal condition of peace and quietude, from which it was, however, destined to be rudely awakened by the yet more stirring events of the great Civil War.

At the outbreak of the struggle between Charles I. and his parliament the county generally declared itself[30] strongly on the side of the latter; the then owner of Warwick Castle, Robert Greville, Lord Brooke, being one of the most powerful and bitter of the early opponents of the King. Prominent upon the side of Charles, however, was found Sir William Dugdale of Blythe Hall, the antiquary and historian, who, holding office as one of the royal heralds and as Garter King–at–Arms, journeyed with the King to Nottingham and made the proclamation when the royal standard was set up on August 22, 1642. The disastrous Civil War may be said to have then begun, notwithstanding that two days previously a hot skirmish had taken place at Long Itchington, some ten miles to the east of Warwick, between the King’s forces and those of the Parliament under Lord Brooke and Lord Grey.

Although the first serious encounter between the opposing parties took place in the neighbouring county of Worcester on September 23, when Prince Rupert gained an advantage over a body of Parliamentarian troops, what may be called the first battle of the war took place just a month later, a little to the south of Kineton, on the plain below Edge Hill, by which latter name the engagement is known.

Following hard upon the raising of the Royal standard at Nottingham, Lord Essex at the head of the Parliamentarian forces seized Worcester. About the middle of September the King and the army which had flocked to his standard marched to Shrewsbury, from which town on the 12th of the following month they set out for London. On the 18th of October Charles[31] was quartered at Packington Old Hall, the home of Sir Robert Fisher, about ten miles to the north–west of Coventry. On the 19th and 20th the Royal forces were at Kenilworth, next day at Southam, and on Saturday, 22nd, Charles was the guest of Mr. Toby Chauncy at Edgecote House, near Cropredy, just over the border in Oxfordshire; whilst Prince Rupert and a body of troops were encamped a few miles to the north at Wormleighton House, the main body of the Royalist army being gathered at Edgecote and Cropredy.

Essex, who had left Worcester upon hearing of the Royalist move towards the capital, reached Kineton on the eve of the 22nd of October with a portion of his army, numbering about 13,000 foot and regular horse, with some 700 dragoons. He was thus numerically inferior to the Royalists, whose forces numbered about two thousand more foot. The intention of the Parliamentary leader was to rest his men on the following day (Sunday), so as to allow the remainder of his troops to come up with him. These consisted of two regiments of foot, eleven troops of horse, and seven pieces of ordnance.

The approach of Essex, the number of his forces and his intentions became known to Prince Rupert, through the pickets which he had judiciously stationed on the high ground at Burton Dassett. A hasty council of war was held at Cropredy, at which it was decided to attempt to check the Parliamentary advance, and to give Essex battle.

Throughout the night of Saturday October 22,[32] the whole district was astir with the movements of troops, the little town of Kineton, the Tysoe villages, Butler’s Marston, Burton Dassett, Warmington, Cropredy, and Wormleighton being terror–struck with the massing of the rival forces and passage of swiftly–travelling messengers.

Almost before it was light the main body of the Royal army struck camp, and marched by way of Mollington and Warmington to a position on the Edge Hills extending from Edge Hill House on the south to Knowle End on the north, the King’s standard being placed and displayed on the site now occupied by the Round Tower. The Royal Line was well protected both on its flanks and in the rear; whilst a complete view of the Parliamentarian army, then disposed in three lines of battle on the plain below in front of the little town of Kineton, was obtainable, the ground in front of the Parliamentarians being even more “open” than it is at the present time.

There would appear to have been good hope on the Royalist side of a successful issue to the impending battle. The advantage of position certainly lay with Charles’ troops. The King, after reconnoitring the enemy through a telescope from Knowle End, where now stands a crown–shaped mound planted with trees, rode along the lines of his army clad in steel, wearing a star and garter, and a black velvet mantle over his suit of armour. He afterwards addressed the officers, gathered in his tent for last instructions, in these words, “Come life or death, your King will bear you company.” It was the Earl of Lindsey, the King’s Lieutenant–General, who acted as impromptu chaplain and offered up a quaint and brief prayer in these words: “O Lord, Thou knowest how busy I must be to–day! If I forget Thee, do not Thou forget me. March on, boys!”

SOUTHAM.

Through that long Sunday morning, on October 23, 1642 (November 2, new style), the forces of Lord Essex lay and watched the enemy on the heights above them, and distant from them scarcely more than a couple of miles; showing no disposition to risk an attack upon a position which was undoubtedly so advantageous as to be worth several thousand men. At about one o’clock it was decided by the King and his officers to descend the steep face of the cliff, and make a frontal attack upon the Parliamentarians disposed in a long line passing through Battle and Thistle Farms. In Essex’s own regiment commanding a troop was Oliver Cromwell, then forty–one, who was destined to ultimately crush the Royal cause on the fields of Marston Moor and Naseby.

Prince Rupert, who, earlier in the day, had caused embarrassment by his refusal to serve under orders save those of King Charles himself, led the cavalry on the right, Lord Wilmot on the left, whilst the command of the centre was vested in Sir Jacob Astley and General Ruthven, with the King and reserves of pensioners in the rear. Although the day was fine overhead the ground was wet and miry, and proved heavy “going” for troops already fatigued by several days of rapid marching. Close upon two o’clock the[34] muffled boom of two cannon fired by the Parliamentarians rolled across the plain and reverberated amid the cliffs of the Edge Hills. The momentous opening of the great Civil War had come.

The Royalists’ cavalry on the left swept round, and charged upon the body of Parliamentarian troops located at what is now known as Battle Farm, where Essex had placed some of his artillery. They were repulsed with considerable loss. Prince Rupert’s charge along the right wing met with more success as it drove back Sir James Ramsay and the force under his command. But unhappily for the King the Prince rushed onwards towards Kineton with characteristic heedlessness to plunder the Parliamentarian baggage train, unmindful of the fact that his help was needed, as the Royalists were losing ground on other parts of the field.

At this hour of the day, although the Parliamentary left was crumpled up and forced back, the right wing held its own, as did also the centre; and when Rupert returned from his impetuous pursuit, it was too late to retrieve his error of judgment. The enemy’s centre had not only stood firm but had advanced, forcing the Royalists to retreat. The arrival of John Hampden, with a body of troops who promptly opened fire upon the Prince’s horsemen, causing them to flee in great confusion, completed the disaster, Rupert himself having to throw away his hat and plumes lest they should offer a mark to the enemy’s musketeers.

The Royal army was now indeed, for some considerable time, in imminent danger of a disastrous and[35] crushing defeat, owing to the severe pressure on its left front.

Both armies suffered severely, almost equally so, states a contemporary account, but inasmuch as the Parliamentarians had held their ground and the Royalists had been compelled to retire from the assault, the advantage was with some justness claimed by the former. The number of killed was very large, but contemporary estimates are so contradictory that it is almost impossible to obtain figures of any exactness. Probably Sir William Dugdale, who, present during the engagement, afterwards went over the field and estimated the number of those actually slain to have been rather more than 1100, is approximately correct.

Although the enclosures have altered the general appearance of the field of battle from that which it bore on that disastrous Sunday of October 23, 1642, the main lines can even nowadays be traced with considerable clearness and accuracy. And the “Sun Rising,” a fine, old stone house, has survived the course of the years, as has also the old Beacon Tower, at Burton Dassett, on the summit of which the first signal fire was kindled in the cresset by the Parliamentarians to send the news of the battle London–wards to the next station at Ivinghoe, some forty miles distant, and thence to Harrow–on–the–Hill.

The months immediately succeeding the first struggle at Edge Hill saw some great happenings. Warwick had held out when called upon by Sir William Dugdale to surrender in the King’s name, though[36] Banbury yielded. But at Coventry the anti–Royalist faction was all powerful, the “rebels,” “sectaries,” and “schismatics” gathered thick within its walls, where they deemed immunity from molestation more certain than in unprotected towns. Kenilworth at the commencement of the war had been garrisoned for the King, but the defenders were soon stealthily withdrawn as the rebels in the district increased in numbers; a fight between them and a body of Parliamentarian troops from Coventry taking place at Curdworth near Coleshill, just prior to the battle of Edge Hill.

So far as Warwickshire’s part in the Civil War is concerned the most stirring and memorable event after the battle of Edge Hill was the attack upon and the destruction of a part of Birmingham by Prince Rupert on Easter Monday of the year 1643.

Although many echoes of the struggle which was fiercely waged, and with varying fortune to the contending parties, up and down the country for a further period of two and a half years, reached Warwickshire, and although several severe engagements were fought in the neighbouring counties of Oxfordshire, Northamptonshire, and Berkshire, no very considerable fighting took place in Warwickshire itself after the burning of Birmingham. It was, however, so near the field of other actions that its peace was perpetually disturbed during the succeeding years, until the final crushing of the Royalist adherents at Naseby on June 14, 1645, and the surrender of the King to the Scots in the following year at Newark. Troops passed[37] along its peaceful lanes on many occasions, and manor–houses were raided by detached bodies of Royalists and Parliamentarians, producing a feeling of unrest and insecurity amongst the inhabitants, and imparting an element of romance to many a time–worn building.

With the return of Charles II. in the early years of the Commonwealth, and during the brief campaign succeeding his invasion of England to assert his kingship, which ended so disastrously on “Cromwell’s day,” September 3, 1651, at the battle of Worcester, Warwickshire once more knew the presence of troops within its peaceful confines, and the hurrying to and fro along its lanes and by–ways of fugitive Royalists and armed pursuers.

After the battle Charles, whilst escaping in disguise, in company with Miss Jane Lane, fled into Warwickshire, narrowly escaping capture by some of the Lord Protector’s men near Bearley Cross. It was in the kitchen of a house at Long Marston that the royal fugitive, to render his disguise more effective, took his turn at the kitchen spit! And Packington Old Hall also sheltered him and his companion during their flight.

Warwickshire played no very prominent part in the history of the half century immediately succeeding the Restoration, and although the intervening years between the latter and the Napoleonic Wars saw many changes, the life of the county was on the whole placid and uneventful. Situated far inland, the wars of the closing years of the eighteenth and early years of the nineteenth century made little impression[38] on a county then so agricultural in its interests and pursuits.

During the first quarter of the nineteenth century Warwick grew little, though remaining the county town; and even the anciently renowned city of Coventry had but an uneventful history, and progress chiefly remarkable for its development of the ribbon industry.

Birmingham was as yet almost unthought of as a great industrial centre of population.

The history of Warwickshire during the middle and latter years of the nineteenth century is chiefly industrial, although the period which has seen the rise of Birmingham has not been entirely without an underlying element of romance. The “hardware town” had from early times, as we have already pointed out, attracted many artisans, skilled workmen, and ingenious inventors to itself by reason of its freedom from corporate restrictions. And at the end of the eighteenth century it had commenced to grow and expand, not, of course, at first with the rapidity that was later on to mark its advance; but, nevertheless, with an expansion which was notable and also marked in the character of its industries. The gun and sword trades, which had existed at the time of the Civil War, grew steadily; and to these were added others connected with iron, steel, and brass, and in the days of Edmund Burke the rise of the jewellery trade, and that of other ornaments, had made it what he described as “the toy shop of Europe.”

Indeed, the growth and progress of Birmingham[39] has shed upon Warwickshire almost all the lustre which it has enjoyed for more than a century, and since the passing away of the more stirring days of internecine strife. As was but natural the town, now become a centre of a vast unrepresented population, took an active and prominent part in the agitation which preceded the passing of the great Reform Bill of 1832; and its famous public meetings in support of that measure not only may be said to have represented the county as well as Birmingham itself, but also the Midlands generally.

Defeated in 1831, the measure was reintroduced in the following year, and was read a third time on the 19th of March, and on the 26th of the same month was sent up to the Lords. It passed its second reading, but there were grave fears that it would be thrown out at the third. An enormous gathering of the Birmingham Union on New Hall Hill, at which 200,000 people were stated to be present, took place in support of the Bill. In the petition to the House of Lords, sent by this great gathering, it was prayed that they would not mutilate the Bill, and that they “would not drive to despair a high–minded, a generous, and fearless people.”

The news that the Bill was defeated and that Lord Grey had resigned stirred up the whole population—timid and fearless, enthusiasts and apathetics alike—whose anger and determination to see this measure become law were manifested in no uncertain way. Still treasured in some households are copies of the[40] placards that were exhibited, which bore these words:—

NOTICE.

No Taxes paid here

Until

The Reform Bill is Passed.

In the subsequent agitation for the repeal of the Corn Laws Birmingham also took its part, and in connection with this there was once more serious rioting.

The political prominence of Birmingham, first earned in the reign of Charles I., has continued of steady growth, although its “great fame for hearty, wilful affected disloyalty” asserted by Clarendon happily no longer abides with it.

Warwickshire, as we have stated, was in ancient times largely an agricultural county, and, indeed, may still be reckoned so. Its well–watered meads and pleasant valleys providing pasturage for cattle, and its rich soil being productive of excellent crops.

The war, however, brought about a great change in the nature of its industries. The men were in large numbers called off the land to supply the needs of man power in the army; their places were taken by older men who were above military age, by boys, women, and girls of all ranks in society.

WARWICK CASTLE.

The temporary growth in population of such towns as Coventry and Birmingham was another noticeable effect of the necessities of war. On the outskirts of the latter town temporary dwellings were erected in large numbers to accommodate the munitions workers drawn to Birmingham from all parts of the country, and in the case of the former town enormous building operations were undertaken to provide factories and to house the workers engaged in the same.

Coventry in war time was a very different place to the town of even the period immediately preceding the outbreak of hostilities; and different from the city of to–day which has gradually tended to return to the normal.

The development of the munitions industries in the county formed one of the most significant features of its life from the spring of 1915 to the autumn of 1918. Not only was the very face of the countryside greatly altered in many districts, but the very lives of the people underwent a radical though temporary change.

Unfortunately industrial unrest, which immediately followed the armistice and extended into several of the succeeding years, prevented Warwickshire from making full use of the enormously increased facilities for output of manufactured articles for which the county has long been famous. Even factories which only needed conversion in comparatively unimportant details to fit them for the struggle to capture the world–trade that waited to be won by enterprise and hard work were left idle or were very imperfectly adapted to the needs of peaceful production.

But that there is a great future for this county in the very heart of England when industry has learned its lesson, and enterprise is once more harnessed to the chariot wheels of commerce no one can doubt.

To–day Warwickshire has largely recovered from the temporary dislocation of its life by war, and has returned to its more normal occupations and mode of living.

Its war record, to be read in the gallant deeds of its fighting sons, and in the amazing work performed by its women, girls, lads, and older men, gives it a place of honour among the counties of central England, as its natural loveliness has given it one of compelling charm among the most beautiful.

CHAPTER III

FAYRE WARWICK TOWN: ITS HISTORY AND ROMANCE

The town of Warwick is undoubtedly of very ancient origin, and from the earliest period of its existence has been considered the chief town of the shire. It is situated upon a rocky plateau on the north side of the river Avon, and blessed with a dry and fertile soil, with luxuriant meadows on one side and well–wooded and well–cultivated lawns on the other.

It seems not unlikely indeed that Gutherline or Kimberline, one of the British kings who lived in the time of Christ, was the founder of the first settlement at Warwick, and that Guiderius, the former’s son, enlarged the town and bestowed upon it considerable privileges. Originally, according to Rous, it was known as Cær–guthleon, contracted into Cær–leon, derived from Cær, a fortress, and Guthline, the name of its founder.

It was upon the site of an ancient church of All Saints founded by St. Dubritius that the first castle was ultimately built; and about this time that King Vortigern gave his ill–judged invitation to the[44] Saxons, who, arriving nominally to assist him against the Picts and Scots, turned their swords against the nation to whose assistance they had come.

St. Dubritius fled during these disorders to Wales for safety, and abandoned Warwick, his cathedral, and his see to the mercy of the invaders.

One ancient historian gives a vivid description of the rapine and destruction to which the centre of England in general, and Warwick in particular, was at that time subjected. And in his pages one sees the surging hosts of Picts and Scots and Britons and Saxons contending for the mastery of what was, even in those days, one of the most fertile and desirable districts of all England.

Raided, burned, with many of the inhabitants put to the sword, Warwick lay in ruins until the coming of King Warremund, the forbear of the kings of Mercia, who rebuilt the town. Under his rule and that of his descendants the town is stated to have flourished and grown in size and importance until the coming of the Danes.

After some years, in which it once more lay in ruins, Warwick rose phœnix–like from its ashes under the hand of Lady Æthelflæd, daughter of King Alfred the Great and wife of King Æthelred. This princess in the year 915 built the first castle and a fortification called the Dungeon (donjon or keep?), and this building served as a residence of the earls from that date for a century and a half, until the coming of William the Conqueror.

In the early years of William the Conqueror, Turchill, a Saxon, was Earl of Warwick, a man of great power, possessions, and influence; and he it was who was commanded by William the Conqueror to fortify the town more strongly by means of walls and ditches, and to add to and strengthen the existing castle.

A little later King William gave to his Norman favourite Henry de Newburgh the title of Earl of Warwick and a grant of the castle, town, and suburbs, to be held in capite per Servitum Comitatus. The new Earl conferred upon one of his priests one–tenth of his tolls, as an offering for the health of his soul. And Roger de Newburgh, his son, who succeeded him, £4:10s. rent for a similar purpose to his priest.

In 1261, in the reign of Henry III., John de Plessetis, who had married Margery, the last heiress of the De Newburghs, and thereby had succeeded to the earldom, granted to the burgesses a charter to enable them to hold each year a fair lasting three days, for which privilege they paid no toll,—a concession of far more value and importance than appears to the uninitiated.

The male branch of the De Newburghs failing, the family was succeeded by that of Mauduit, and one of these, William, who was a supporter of Henry III., was surprised and taken prisoner during the wars of the barons, and, in consequence of the capture, the walls of Warwick Castle were destroyed. He was also obliged to pay for the ransom of himself and his[46] Countess the then large sum of 1900 marks (about £1250). He died childless, and was succeeded by his sister’s husband, William de Beauchamp, who in the reign of Edward I. possessed the borough in chief in 1279, and also held annually a fair, which lasted for sixteen days, commencing on the eighth day before the Feast of St. Peter ad Vincula, and a weekly market on Wednesdays.

A strange sidelight on these days is thrown by the record that there was a pillory and tumbril as well as assize of bread in connection with this fair. De Beauchamp also instituted a fifteen days’ fair, which commenced on the eve of the Feast of St. Peter and Paul.

In the year 1290 William de Beauchamp’s successor, Guy, finding it necessary to undertake considerable works for the walling in of the town and the paving of its streets, was granted a patent by Edward I. by which he was entitled to receive a toll during seven years on all vendible articles. But the works not having been completed within that period, he and his successor Thomas obtained an extension of the original or similar patents for ten years longer.

A very interesting circumstance in connection with the Thomas de Beauchamp we have just referred to, who had in 1351 a charter of free warren at Warwick, is that he “at the suit of his lady, and for the health of his own soul and his ancestors’ souls,” freed the traders resorting hither for the future from terrage, stallage, and all other sorts of toll. The petition[47] having been made because the said traders had been, by the heavy exactions of previous holders of the title, driven away from the market at Warwick, to the great detriment of the town.

The Municipal history of Warwick is unfortunately very obscure, although there seems little or no doubt that the town was anciently incorporated and had the privilege of returning members to Parliament, but when it was first incorporated, and whether such incorporation and privilege continued without interruption is not ascertainable. A record, however, exists that there was a Mayor in 1279, in the reign of Edward I., and that twenty–one years later the Mayor of the day and bailiffs were ordered to allow Phillip de Rout and William de Serdely reasonable expenses for their services as members of Parliament for that year. Afterwards, however, in the reign of Edward III., the King’s mandate for the same purpose was, strange to tell, addressed to the bailiffs only.

The earliest known date of incorporation under royal charter with the designation of bailiff and burgesses occurs in the reign of Philip and Mary, but it is certain that letters patent were granted by Henry VIII. in 1546 to the borough under the Municipal title of “burgesses only.” This grant of letters patent was confirmed by one from James I. in 1613, and was again followed by another during the reign of William and Mary, bearing the date of March 5, 1694, which remains the governing charter of the borough down to the present time.

The history of the town of Warwick has, as we have remarked in a previous chapter, been largely that of the county itself, and during the ages when wars and revolts swayed parties in England the town played its part in the romantic and tragic happenings of those times.

The old stone cross, which stood at the intersection of the two ancient and principal streets as late as the reign of James I., has long ago disappeared, but in few towns in England are there more notable survivals of ancient times to be found than in Warwick. One of the most interesting buildings is the ancient Chapel of St. James, now known as the West Gate, and formerly as the Hongyn Gate, standing where the High Street terminates, on the crest of the hill, supported for its entire length by a lofty groined archway, itself placed on the bed–rock which rises several feet above the road surface. This structure anciently formed a defensive gateway to the old and fortified town.

In the reign of Henry I. this chapel was given by Roger, Earl of Warwick, to the Church of St. Mary. That it was of very small value is proved by the fact that in 1368, in the reign of Edward III., the latter was estimated at only £1.

LEICESTER’S HOSPITAL, WARWICK.

In 1383, in the reign of Richard II., the advowson was given to the Guild of St. George, and the fraternity established in Warwick the same year was founded by a license granted to Robert Dynelay, Hugh Cooke, and William Russell on the 20th of April, giving them privilege to extend their numbers by admission of other inhabitants of the borough, and to build a chantry for two priests to sing mass every day in the Chapel, which stood over the west gate, for the good estate of King Richard and his consort Ann; of his mother, also Michael de la Pole, and all the brothers and sisters of the said Guild during their lives in this world, and for the everlasting happiness of their souls, as also for the souls of King Edward III., Edward Prince of Wales, the father of Richard II., and their royal progenitors, and all the faithful departed.

Thomas de Beauchamp, Earl of Warwick, eventually had license to give the advowson of the Church of St. James at the same time that the Guild brethren purchased two houses, a loft, and the quarry in Warwick for their use.

At length, however, the Guild of St. George the Martyr and the Guild of the Holy Trinity and the Virgin, in the early part of Henry VI.’s reign, became one, and four priests belonging to the Guilds sang masses; two of them at “Our Lady’s Chapel” in St. Mary’s, and the others in the two chapels built over the gates. This Guild also paid in part the secular canons attached to St. Mary’s Church, gave a weekly dole of alms to eight poor people of the Guild, and also assisted in maintaining the great bridge over the Avon.

After the Dissolution of the Monasteries the establishment was granted by Edward VI., on July 23, 1551, to Sir Nicholas l’Estrange, Kt. and his heirs. And from him it passed into the possession of Robert[50] Dudley, Earl of Leicester, who made it in 1571, in the reign of Elizabeth, a hospital for twelve men, called brethren, and a master, who must be a clergyman of the Church of England; the preference being given to the Vicar of St. Mary’s if he offered himself for the post. The appointment of these brethren is vested in the heirs of the founder, now represented by Lord D’Lisle and Dudley, of Penhurst Place, in the county of Kent, who is a descendant of Mary, the sister of Robert Dudley, who married Sir Henry Sidney, of the same place.

The brethren elected to this foundation must, according to the statutes, be either tenants or servants of the founder or his heirs, and resident in the county of Warwick, or soldiers of the Sovereign, more especially those who had been wounded on active service; the latter to be chosen from the parishes of Warwick, Kenilworth, and Stratford–on–Avon, or from those of Wooton–under–Edge and Erlingham, in the county of Gloucester.

Of recent years radical changes have been made in the charity, one of these being that provision is now made for the housing and maintenance in the hospital itself of twelve women, wives of the brethren. Nowadays, as none of the founder’s heirs have tenants resident in either of the two counties, the brethren are chosen under the second provision we have mentioned, and all of them have been soldiers of the Crown. Here now dwell in comfort and peace the master and the twelve brethren, the former having a salary of £400 and a residence; and the latter pensions amounting to[51] £80 each, with separate apartments, consisting of bedroom, sitting–room, and pantry, with the use of a common kitchen and the services of a cook and housekeeper.

There are many interesting customs in connection with the hospital; one of which is that the brethren must daily attend service in the chapel, and are obliged when they appear in public to wear a blue gown, on the sleeve of which is worn a silver badge with the crest of the bear and ragged staff. With one exception these badges are the ancient ones originally provided; the exception being a modern reproduction in facsimile of the badge which was stolen many years ago.