The Project Gutenberg eBook, The Sanitary Evolution of London, by Henry

Lorenzo Jephson

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States

and most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no

restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it

under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this

eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not

located in the United States, you'll have to check the laws of the

country where you are located before using this ebook.

Title: The Sanitary Evolution of London

Author: Henry Lorenzo Jephson

Release Date: November 7, 2014 [eBook #47308]

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE SANITARY EVOLUTION OF LONDON***

E-text prepared by Chris Curnow, Quentin Campbell,

and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team

(http://www.pgdp.net)

from page images generously made available by

Internet Archive

(https://archive.org)

Transcriber’s Notes

The cover image was created by the transcriber and is placed in the public domain.

For a complete list of corrections, other changes, and notes, please see the end

of this document.

Clickable links to page numbers in the Table of Contents, and the Index, appear as 155

or 213–4 rather than 155 or 213–4.

Similarly, links to footnotes in the text appear like this[3]

rather than being underlined like this[3].

On some devices, clicking the sketch map image below will display a larger version of it.

THE SANITARY EVOLUTION

OF LONDON

THE

SANITARY EVOLUTION

OF LONDON

BY

HENRY JEPHSON, L.C.C.

AUTHOR OF

“THE PLATFORM: ITS RISE AND PROGRESS”

“The discovery of the laws of public health, the determination of

the conditions of cleanliness, manners, water supply, food, exercise,

isolation, medicine, most favourable to life in one city, in one

country, is a boon to every city, to every country, for all can

profit by the experience of one.”

G. Graham, Registrar-General, 1871.

A. WESSELS COMPANY

PUBLISHERS

BROOKLYN, N. Y.

MCMVII

DEDICATED

TO

THE LONDON COUNTY COUNCIL

BY ONE OF ITS MEMBERS

THE AUTHOR

4, Cornwall Gardens,

S.W.

[vii]

CONTENTS

| MAP |

Facing page 1 |

| |

|

| |

PAGE |

| Chapter I |

1 |

| |

|

| Chapter II (1855–1860) |

82 |

| |

|

| Chapter III (1861–1870) |

155 |

| |

|

| Chapter IV (1871–1880) |

221 |

| |

|

| Chapter V (1881–1890) |

288 |

| |

|

| Chapter VI (1891–1901) |

349 |

| |

|

| Chapter VII (1901–1906) |

401 |

| |

|

| INDEX |

435 |

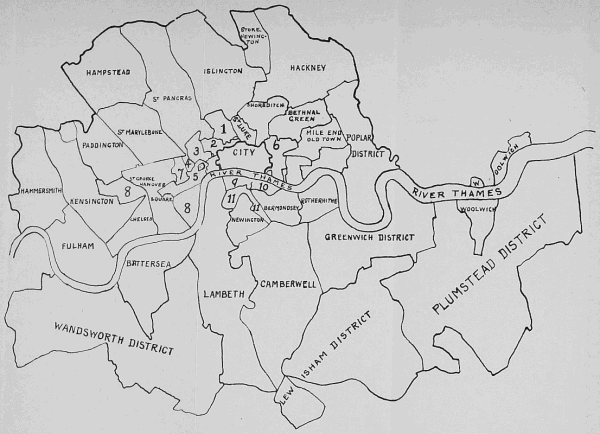

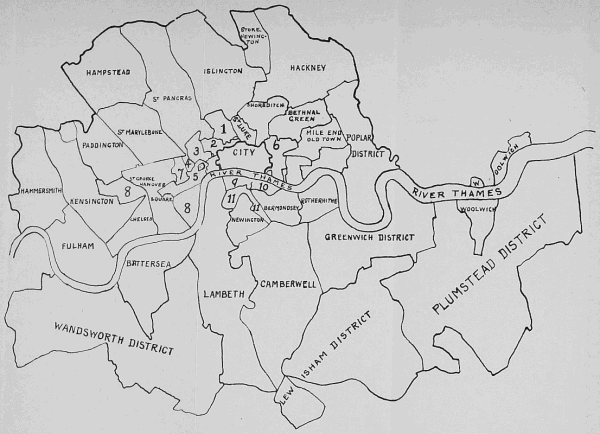

SKETCH MAP OF LOCAL DISTRICTS IN LONDON.

REFERENCE TO NAMES OF PARISHES AND DISTRICTS NUMBERED ON THE MAP.

1. Clerkenwell. 2. Holborn. 3. St. Giles’. 4. Strand.

5. St. Martin-in-the-Fields. 6. Whitechapel. 7. St. James’, Westminster.

8. Westminster. 9. St. Saviour’s, Southwark. 10. St. Olave’s, Southwark.

11. St. George the Martyr, Southwark.

[1]

The Sanitary Evolution of London

CHAPTER I

The health of the people of a country stands foremost in

the rank of national considerations. Upon their health

depends their physical strength and energy, upon it their

mental vigour, their individual happiness, and, in a great

degree, their moral character. Upon it, moreover, depends

the productivity of their labour, and the material prosperity

and commercial success of their country. Ultimately, upon

it depends the very existence of the nation and of the

Empire.

The United Kingdom can claim no exemption from this

general principle; rather, indeed, is it one which, in the

present period of our history, affects us more vitally than it

has ever done before, and in a more crucial manner than

it does many other nations.

The more imperative is it, therefore, that every effort

should be made to raise the health of our people to the

highest attainable level, and to maintain it at the loftiest

possible standard.

The subject is so vast and complicated that it is impossible,

within reasonable limits, to treat more than a portion of it

at a time.

London, the great metropolis, the capital of the Empire

itself, constitutes, by the number of its inhabitants, so large

a portion of the United Kingdom, that the health of its

people is a very material factor in that of the kingdom.

It has a population greater than either Scotland or Ireland,

greater than any of our Colonies, except Canada and

Australasia, greater than that of many foreign States—

[2]

“the greatest aggregate of human beings that has ever

existed in the history of the world in the same area of

space.”

And, in a measure too, it is typical of other of our great

cities.

A narrative of the sanitary history and conditions of life

of the people of London, therefore, would be a material

contribution to the consideration of the general subject

in its national aspect, whilst it cannot but be of special

interest to those more immediately concerned in the

amelioration of the existing condition of the masses of

the people of the great capital.

Such a narrative is attempted in the following pages.

It is, in the main, based upon the experiences, and

inferences, and conclusions, of men who, more than any

others, were in a position closely to observe the circumstances

in which the people lived, their sanitary condition,

and the causes leading thereto and influencing the same.

It includes the principal measures from time to time

passed by the Legislature to create local governing

authorities in sanitary matters—the various measures

designed and enacted to improve the condition of the

people—and the administration of those measures by the

local authorities charged with their administration.

It is a narrative, in fact, of the sanitary—and, therefore,

to a great extent of the social—evolution of this great city.

It is doubtful how long a time would have elapsed before

the condition of the people came into real prominence had

it not been for the oft-recurring invasions of the country by

epidemic disease of the most dreaded and fatal forms. Ever-present

diseases, disastrous and devastating though they

were, did not strike the imagination or appeal to the fears

of the public as did the sudden onslaught of an awe-inspiring

disease such as cholera.

An epidemic of that dreaded disease swept over London

in 1832, and there were over 10,000 cases and nearly 5,000

deaths in the districts then considered as metropolitan—the

population of those districts being close upon 1,500,000.

For the moment, the dread of it stimulated the people,

[3]

and such governing authorities as there were, to inspection,

and cleansings, and purifications, and to plans for vigorous

sanitary reform; but the instant the cholera departed

the good resolutions died down, and the plans disappeared

likewise.

There were, however, some persons upon whom this

visitation made more abiding impression; and they, struck

by the waste of human life, by the frequent recurrence of

epidemics which swept away thousands upon thousands of

victims, and distressed by the perpetual prevalence and

even more deadly destructiveness of various other diseases

among the people, bethought themselves of investigating

the actual existing facts, and the causes of them—so far

at least as London, their own city, was concerned.

And then slowly the curtain began to be raised on the

appalling drama of human life in London, and dimly to be

revealed the circumstances in which the great masses of the

working and labouring classes of the great metropolis lived,

moved, and came to the inevitable end, and the conditions

and surroundings of their existence.

The slowness with which England as a nation awoke to

the idea that the public health was a matter of any concern

whatever is most strange and remarkable. It seems now so

obvious a fact that one marvels that it did not at all times

secure for itself recognition and acknowledgment. But men

and women were growing up amidst the existing surroundings,

foul and unwholesome though those were, and some,

at least, were visibly living to old age; population was

increasing at an unprecedented rate; wealth was multiplying

and accumulating; the nation was reaching greater heights

of power and fame. What, then, was there, what could

there be wrong with the existing state of affairs?

Real social evils, however, sooner or later, force themselves

into prominence. For long they may be ignored,

or treated with indifference by the governing classes; for

long they may be endured by the victims in suffering and

silence; but ultimately they compel recognition, and have

to be investigated and grappled with, and, if possible,

remedied.

[4]

The real beginning of such investigations was not until

near the close of the fourth decade of the nineteenth

century. Information then for the first time was collected,

of necessity very limited in extent, crude in form, and of

moderate accuracy, but none the less illuminating in its

character—information from which one can piece together

in a hazy sort of way a general impression of the condition

of the working and poorer classes in London at that

period.

Foremost among the diseases which worked unceasing

and deadly havoc among the people was fever. By its

wide and constant prevalence and great fatality, it was the

first upon which attention became fixed. The returns

which were collected as regarded it related to twenty

metropolitan unions or parishes, and in them only to the

pauper population, some 77,000 in number. But they

showed that in the single year of 1838, out of those 77,000

persons, 14,000, or very nearly one-fifth, had been attacked

by fever, and nearly 1,300 had died.[1]

Being limited to the technically pauper population this

information related only to one section of the community;

but it nevertheless afforded the means of forming a rough

estimate of the amount of fever among the community as a

whole.

And another fact also at once became apparent, namely,

that certain parts of London were more specially and

persistently haunted or infested by fever than others. In

Whitechapel, Holborn, Lambeth, and numerous other

parishes or districts, fever of the very worst forms was

always prevalent—“typhus, and the fevers which proceed

from the malaria of filth.” The sanitary condition of

those districts was fearful, every sanitary abomination

being rampant therein, whilst certain localities in them

were so bad that “it would be utterly impossible for any

description to convey to the mind an adequate conception

of their state.” And most marvellous and deplorable of all

was the fact that this fearful condition of things was

allowed, not merely to continue, but to flourish without any

attempt being made to remedy, or even to mitigate, some of

the inevitable and most disastrous consequences.

[5]

As regarded the districts in which the wealthier classes

resided, systematic efforts had been made on a considerable

scale to widen the streets, to remove obstructions to

the circulation of free currents of air, and to improve the

drainage—an acknowledgment and appreciation of the

fact that these things did deleteriously affect people’s

health. But nothing whatever had been attempted to

improve the condition of the districts inhabited by the

poor. Those districts were not given a thought to,

though in them annually thousands and tens of thousands

of victims suffered or died from diseases which were

preventable.

Reports such as these attracted some degree of attention,

and awakened a demand for further information,

and in 1840 the House of Commons appointed a Select

Committee to inquire as to the health, not only of

London, but of the large towns throughout the country.

Their report[2] enlarged upon the evils previously in part

portrayed, and emphasised them.

“Your Committee,” they wrote, “would pause, from the

sad statements they have been obliged to make, to observe

that it is painful to contemplate in the midst of what

appears an opulent, spirited, and flourishing community,

such a vast multitude of our poorer fellow-subjects, the

instruments by whose hands these riches were created,

condemned for no fault of their own to the evils so justly

complained of, and placed in situations where it is almost

impracticable for them to preserve health or decency of

deportment, or to keep themselves and their children from

moral and physical contamination. To require them to be

clean, sober, cheerful, contented under such circumstances

would be a vain and unreasonable expectation. There is no

building Act to enforce the dwellings of these workmen

being properly constructed; no drainage Act to enforce their

being properly drained; no general or local regulation to

enforce the commonest provisions for cleanliness and

comfort.”

[6]

Lurid as were the details thus made public of the condition

in which the vast masses of the people in London

were living, neither Parliament nor the Government took

any action beyond ordering successive inquiries by Poor Law

Commissioners, or Committees of the House of Commons,

or Royal Commissions.

Before one of these Commissions[3] the following striking

evidence was given—evidence which it might reasonably

be expected would have moved any Government to immediate

action:—

“Every day’s experience convinces me,” deposed the

witness,[4] “that a very large proportion of these evils is

capable of being removed; that if proper attention were

paid to sanitary measures, the mortality of these districts

would be most materially diminished, perhaps in some places

one-third, and in others even a half.

“The poorer classes in these neglected localities and

dwellings are exposed to causes of disease and death which

are peculiar to them; the operation of these peculiar causes

is steady, unceasing, sure; and the result is the same as if

twenty or thirty thousand of these people were annually

taken out of their wretched dwellings and put to death—the

actual fact being that they are allowed to remain in

them and die. I am now speaking of what silently but

surely takes place every year in the metropolis alone.”

But the Government took no action—beyond a Building

Act which did little as regarded the housing of the people.

No local bodies took action, and years were to pass before

either Government or Parliament stirred in the matter.

In dealing historically with matters relating to London

as a whole, it is to be remembered that for a long time there

had been practically two Londons—that defined and described

as the “City,” and the rest of London—that which

had no recognised boundaries, no vestige of corporate existence,

and which can best be described by the word

“metropolis.”

[7]

The “City” was virtually the centre of London—the

centre of its wealth, its industry, its geographical extent—a

precisely defined area of some 720 acres, or about one

square mile in extent, and originally surrounded by walls.

Its boundaries had been fixed at an early period of our

history, and had never been extended or enlarged. So

densely was it covered with houses at the beginning of the

nineteenth century, and so fully peopled, that there was

practically no room for more, either of houses or people;

and from then to the middle of that century its population

was stationary—being close upon 128,000 at each of those

periods.

Apart altogether from political influences, there were in the

“City” powerful economic forces at work which profoundly

affected the condition and circumstances of the people, not

only of the “City,” but of London.

These, which were by no means so evident at one time,

became more and more pronounced as time went on.

All through the earlier part of the nineteenth century

England was attaining to world pre-eminence by her commerce,

her manufactures, and her wealth. The end of the

great war with France saw her with a firm grip of all the

commercial markets of the world. Her merchants pushed

their trade in every quarter of the globe—her ships enjoyed

almost a monopoly of the carrying trade of the world.

In this progress to greatness London took the foremost

part, and became the greatest port and trade emporium of

the kingdom, a great manufacturing city, and the financial

centre of the world’s trade.

It was upon this commerce that the prosperity and glory

of London were built: it was by this commerce that the

great bulk of the people gained their livelihood, and that a

broad highway was opened to comfort, to opulence, and

power. And so the commercial spirit—the spirit of acquiring

and accumulating wealth—got ever greater possession

of London.

[8]

That spirit had long been a great motive power in London;

it became more and more so as the century wore on, until

almost everything was subordinated to it.

That indisputable fact must constantly be borne in mind

as one reviews the sanitary and social condition of the people

of London at and since that time. Other constant factors

there were, also exercising vast influence—the constant

factors of human passions and human failings—but widespread

as were their effects, they were second to the all-powerful,

the all-impelling motive and unceasing desire—commercial

prosperity and success.

Synchronous with the rise in importance of the port of

London, and with its trade and business assuming ever

huger volume and variety, a noteworthy transformation took

place.

The “City,” by the very necessities of its enormous

business, became gradually more and more a city of offices

and marts, of warehouses and factories, of markets and exchanges,

and houses long used as residences were pulled

down, and larger and loftier ones erected in their place

for business purposes.

In some places, moreover, ground was entirely cleared of

houses for the construction of docks, or for the erection of

great railway termini.

How marked were the effects of these changes is evidenced

by the fact that from 17,190 inhabited houses in the “City”

in 1801, the number had sunk to 14,575 in 1851.

The explanation was the simple economic one, that land

in the “City” yielded a much larger income when let for

business than for residential purposes. Offices and warehouses

were absolutely essential in the “City” for business.

What did it matter if people had to look for a residence in

some other place? London was large. They could easily

find room. And the process, without control of any sort or

kind, and wholly unimpeded by legislation or governmental

regulation, went on quite naturally—entailing though it

did consequences of the very gravest character, then quite

unthought of, or, if thought of, ignored or regarded as

immaterial.

[9]

This then was, at that time, and still is, one of the

great, if not indeed the greatest of the economic forces

at work which has unceasingly dominated the housing of

the people not only in the “City,” but in the metropolis

outside and surrounding the “City,” and, in dominating their

housing, powerfully affected also their sanitary and social

condition.

The “City” was in the enjoyment of a powerful local

governing body—namely, the Lord Mayor and Corporation,

or Common Council, elected annually by the ratepayers;

and numerous Acts of Parliament and Royal Charters had

conferred sundry municipal powers upon them.

For that important branch of civic requirements—the

regulation of the thoroughfares and the construction of

houses and buildings—they had certain powers. The vastly

more important sphere of civic welfare—namely, the

matters affecting the sanitary condition of the inhabitants—was

delegated by the Corporation to a body called the

Commissioners of Sewers, annually elected by the Common

Council out of their own body, some ninety in number.

And these Commissioners had, in effect, authority in the

City, directly or indirectly, over nearly every one of the

physical conditions which were likely to affect the health

or comfort of its inhabitants. They could also appoint a

Medical Officer of Health to inform and advise them upon

public health matters, and Inspectors to enforce the laws

and regulations.

The “City” was thus in happy possession of a powerful

local authority, and a large system of local government.

And it stood in stately isolated grandeur, proud of, and

satisfied with, its dignity, and privileges, and wealth;

glorying in its own importance and splendour; content

with its own system of government, and its powers for

administering its municipal affairs, and indifferent to the

existence of the greater London which had grown up

around it, and which was ever becoming greater.

Greater indeed. The population of the “City” in 1851

was 128,000; that of the metropolis not far short of

2,500,000.

[10]

The number of inhabited houses in the “City” was

hundreds short of 15,000. In the metropolis it was over

300,000.

The “City” was 720 acres in extent: what in 1855 was

regarded as the metropolis was about 75,000 acres in

extent.

And here, with no visible boundary of separation between

them, were what were still “Parishes,” but what were in

reality great towns; not merely merged or rapidly merging

into each other, but already merged into one great

metropolis. Some of them even had a greater population

than the “City” itself. St. Pancras, for instance, with

167,000 persons; St. Marylebone with 157,000, and Lambeth

with 139,000.

Of that greater London—or, in effect, of London itself—there

is a complicated and tangled story to tell.

Long before the middle of the nineteenth century had

been reached, the time had passed when the “City” could

contain the trade, and commerce, and manufactures, and

business, which had grown up. They had overflowed into

London outside the walls, and just as in the “City” the

great economic forces produced certain definite changes in

the circumstances and sanitary condition of the people

living therein, so, in the greater London, the commercial

spirit radiating gradually outwards, produced precisely

similar results, only on a far wider scale, and with more

potent effect.

Trade, and commerce, and wealth, and population, were

increasing by leaps and bounds; and like the rings which

year by year are added to the trunk of a tree, so year by

year, decade by decade, London—the metropolis—spread

out, and grew, and grew. From something under one

million of inhabitants in 1801, the population increased to

nearly two and a half millions in 1851, partly by natural

increase, due to the number of those who were born being

greater than of those who died, partly by immigration from

the country.

This was London, in the large sense of the title—London,

the great metropolis which had never received recognition

[11]

by the law as one great entity, and whose boundaries

had never been fixed, either by enactment, charter, or

custom.[5]

Dependent as is the public health, or sanitary and social

condition of the people, upon the circumstances in which

they find themselves placed, and the economic forces which

are constantly at work moulding those circumstances, it is

in as great a degree dependent on the system of local

government in existence at the time, upon the scope and

efficacy of the laws entrusted to the local authorities to

administer, and upon the administration of those laws by

those authorities.

As for local government—unlike the “City”—this greater

London was without form and almost void. With the

exception of the Poor Law Authority—the Boards of

Guardians—whose sphere of duty was distinctly limited,

there was, outside the boundaries of the “City,” not even

the framework of a system of such government; and the

confusion and chaos became ever greater as years went on

and London grew.

There was no authority so important as to have any

extended area for municipal purposes under its control and

management except certain bodies, five in number, entitled

“Commissioners of Sewers,” charged with duties in

connection with the sewerage of their districts.

In some parishes some of the affairs of the parish were

managed by the parishioners in open vestry assembled, at

which assembly Churchwardens, Overseers of the Poor, and

Surveyors of Highways were appointed to carry out certain

limited classes of work. In others, the parishioners elected

a select vestry to do the work of the parish.

But for many of the vitally important municipal affairs

there were no authorities at all.

As the non-City and out-districts became more thickly

peopled, and streets and houses increased in number, the

inconvenience of there being practically no local government

at all made itself felt.

In some cases, the owners of the estates which were

[12]

being so rapidly absorbed into London and being built

upon, applied to Parliament for powers to regulate those

estates.

In other cases, persons with interests in a special locality

associated themselves together and obtained a private Act

of Parliament giving them authority, under the name of

Commissioners or Trustees, to tax and in a very limited way

to govern a particular district or group of streets forming

part of a parish. Thus it happened that a large number of

petty bodies of all sorts and kinds came into existence.

Any district, however small, was suffered to obtain a local

Act of Parliament for the purpose of managing some of its

affairs, and this, too, without any reference to the interests

of the immediate neighbours, or of the metropolis as a

whole. Most of the limited and somewhat primitive

powers possessed by them were derived from an Act

passed in 1817,[6] and related to the paving of streets and

the prevention of nuisances therein. Some of these bodies

were authorised to appoint surveyors or inspectors; also

“scavengers, rakers, or cleaners” to carry away filth from

streets and houses, but the exercise of such powers was, of

course, purely optional. Indeed, there were scarcely any

two parishes in London governed alike.

What the exact number of these various petty authorities

was is unknown. Of paving boards alone, it is said that

about the middle of the last century there were no less than

eighty-four in the metropolis—nineteen of them being in

one parish. The lighting of the parish of Lambeth was

under the charge of nine local trusts. The affairs of St.

Mary, Newington, were under the control of thirteen Boards

or trusts, in addition to two turnpike trusts.[7]

In Westminster:—

“The Court of Burgesses and the Vestry retained general

jurisdiction over the whole parish for certain purposes; but

the numerous local Acts so effectually subdivided the

control and distributed it among boards, commissioners,

trustees, committees, and other independent bodies, that

[13]

uniformity, efficiency, and economy in local administration

had become impossible.”[8]

There were authorities exclusively for paving; authorities

for street improvements; authorities for lighting; even

authorities for a bridge across the river. In the course of

years, several hundred such bodies had been created, without

any relation one to the other, and without any central

controlling authority, good, bad, or indifferent, by as many

Acts of Parliament. They were mostly self-elected, or

elected for life, or both; and were wholly irresponsible to

the ratepayers, or indeed to any one else; nor were their

proceedings in any way open to the public. Many of them

had large staffs of well paid officials; and there were

perpetual conflicts of jurisdiction between them, and an

absolute want of anything approaching to municipal administration.

It has been roughly stated—roughly because there are no

reliable figures—that there were about three hundred such

bodies in London—“jostling, jarring, unscientific, cumbrous,

and costly”—the very nature of many of them being “as

little known to the rest of the community as that of the

powers of darkness.”

Add to these numerous, clashing, and incompetent

authorities, various great public companies or corporations—the

water companies, and gas companies, and dock

companies, each with its own special rights—which were

far more favourably and generously regarded by Parliament

than were the rights of the public, and one has fairly

enumerated the local governing bodies then existing in

London.

In fact, in no parish of the great metropolis of London

was there a local authority possessed of powers to deal in

its own area with the multitudinous affairs affecting the

health and well-being of the people.

Nor was there in the metropolis any central authority—no

single body, representative or even otherwise—to attend

to the great branches of municipal administration which

affected and concerned the metropolis as a whole, and

which could only be dealt with efficiently by the metropolis

being treated as a whole.

[14]

The consequences to the inhabitants of London of the

absence of any efficient form of local government were dire

in character, terrible in extent, and unceasing in operation.

The higher grades of society suffered in some degree, as

disease, begotten in filth and nurtured in poverty, often

invaded with disastrous consequences the homes of the

well-to-do; but it was by the great mass of the industrial

classes and the poorer people that the terrible burden of

insanitation had to be borne, and upon them that it fell

with the deadliest effect.

The non-existence of a central authority, or of any capable

local authorities whose function it would have been to

protect them from the causes of disease, had resulted in an

insanitary condition which year after year entailed the

waste of thousands upon thousands of lives. And the

people, in the cruel circumstances of their position, were

absolutely powerless to help themselves, and had no possible

means of escape from the ever-present, all-surrounding

danger.

The first absolute necessity of any sanitation whatever is

the getting rid by deportation or destruction of all the filth

daily made or left by man or beast, for such filth or refuse

breeds all manner of disease, from the mildest up to the

very worst types and sorts, and promptly becomes not only

noxious to health, but fatal to life. The more rapidly and

thoroughly, therefore, this riddance is effected, the better is

it in every way for the general health of the public.

So far as the metropolis was concerned, this necessity had

for generation after generation been very lightly regarded;

and when at last it so forced itself upon public notice that

it could no longer be ignored, the measures taken were

wholly inadequate and ineffective.

What system there was in London as to the disposal of

sewage throughout the earlier half of last century was based

upon a Statute dating so far back as Henry VIII.’s reign,

amended by another in William and Mary’s reign. Under

these Statutes certain bodies had been constituted by the

[15]

Crown as Commissioners of Sewers for certain portions of

London, and charged with the duty of providing sewers and

drains in their respective districts, and maintaining the same

in proper working order.

But what might have been good enough for London in

the sixteenth or seventeenth centuries was certainly not

adequate in the nineteenth, when London had extended

her borders in every direction, and her population had

reached almost two and a half millions. Successive Parliaments

had not troubled themselves about such a matter;

and this neglect, which now appears almost incredible, was

typical of the habitual attitude of the governing classes to

the sanitary requirements of the masses of the population of

the metropolis.

In the eighteen hundred and forties, five such bodies of

Commissioners were in existence in London, each with a

separate portion of the metropolis under its charge and

exercising an independent sway in its own district; and

when we collect the best testimony of that time as to their

work and that of their predecessors, we have the clearest

demonstration of their glaring incapacity, and of the utter

inadequacy and inefficiency of the sewerage in their

respective districts.

Many miles of sewers had, it is true, in process of time

been constructed, and did exist, but much of the work had

been so misdone that the cure was little better than the

disease.

A river is always a great temptation to persons to get rid

of things they want to get rid of, particularly when the

things are nasty and otherwise not easily disposed of.

Londoners only followed the general practice when they

constructed their sewers so that they discharged their

contents direct into the Thames. The majority of these

sewers emptied themselves only at the time of low water;

for as the tide rose the outlets of the sewers were closed,

and the sewage was dammed back and became stagnant.

When the tide had receded sufficiently to afford a vent for

the pent-up sewage, it flowed out and deposited itself along

the banks of the river, evolving gases of a foul and offensive

[16]

character. And then the sewage was not only carried up

the river by the rising tide, but it was brought back again

into the heart of the metropolis, there to mix with each

day’s fresh supply of sewage; the result being that “the

portion of the river within the metropolitan district became

scarcely less impure and offensive than the foulest of the

sewers themselves.”

This was bad enough, but there were miles of sewers

which, through defects of construction or disrepair, did not

even carry off the sewage from the houses and streets to

the river, but had become “similar to elongated cesspools,”

and, as such, actual sources and creators of disease.

Incredible almost were the stupidities perpetrated by

these Commissioners in regard to the construction of the

sewers. At even so late a date as 1845 no survey had been

made of the metropolis for the purposes of drainage; there

was a different level in each of the districts, and no attempt

was made to conform the works of the several districts to

one general plan. Large sewers were made to discharge

into smaller sewers. Some were higher than the cesspools

which they were supposed to drain, whilst others had been

so constructed that to be of any use the sewage would have

had to flow uphill!

It might reasonably have been expected that in the nineteenth

century, at least, the twenty parishes which formed

the district of the Westminster Commissioners of Sewers

would have been equal to producing an enlightened and

capable body as Commissioners, but the Westminster Court

of Sewers was certainly not such. Even their own chief

surveyor, in 1847, stigmatised it as a body “totally incompetent

to manage the great and important works committed

to their care and control.”

Upon it were builders, surveyors, architects, and district

surveyors—a class of persons whose opinions “might certainly

be biassed with relation to particular lines of drains

and sewers.”

Of another of the courts—namely, the Finsbury Court

of Sewers—one of the Commission had been outlawed;

another was a bankrupt.

[17]

It was stated at the time that “jobbery and favouritism

and incompetence were rampant,” and that the system was

“radically wrong and rotten to the core.” Certain it is that

these bodies failed completely to cope with the requirements

of the time. London was spreading out in all directions,

and the increase of houses and population was very rapid.

Practically no effort, however—certainly no adequate effort—was

made by the various bodies of Commissioners to provide

these new and growing districts with the means of getting

rid of their sewage. And then, inasmuch as the sewage had

somehow or other to be got rid of, and some substitute for

sewers devised, the surface drains, and millstreams, and

ditches were appropriated to use and converted into open

sewers or “stagnant ponds of pestilential sewage.”

London was “seamed with open ditches.”

According to contemporary reports there were in Lambeth

numerous open ditches of the most horrible description.

Bermondsey was intersected by ditches of a similar character,

and abounded with fever nests. Rotherhithe was

the same. Hackney Brook, formerly “a pure stream,” had

become “a foul open sewer.”[9] In St. Saviour’s Union the

sewers were in a dreadful condition … “the receptacle of

all kinds of refuse, such as putrid fish, dead dogs, cats, &c.

Greenwich was not drained or sewered.”

What certainly was conclusively demonstrated was that

the existence of several bodies of Commissioners, each with

a district to itself, presented an insuperable obstacle to any

general system of sewerage for greater London; and that

one capable central authority was the first essential of an

adequate and efficient system for London as a whole.

Thus, then, in this first essential of all sanitation—one

might say of civilisation—no adequate provision was made

by Parliament for the safety of the metropolis; whilst as to

other essentials of sanitation, there were no laws for the

prevention of the perpetration of every sanitary iniquity;

and such authorities as there were failed absolutely to use

even the few powers they possessed.

The defective and inefficient sewerage of the metropolis

[18]

precluded the possibility of any proper system of house

drainage, for there being few sewers there were few drains,

and consequently instead of drains from the houses to the

sewers there were cesspools under almost every house. At

the census of 1841 there were over 270,000 houses in the

metropolis. It was known, then, that most houses had a

cesspool under them, and that a large number had two,

three, or four under them. Some of them were so huge

that the only name considered adequate to describe them

was “cess-lake.” In many districts even the houses in

which the better classes lived had neither drain nor sewer—nothing

but cesspools; and many of the very best portions

of the West End were “literally honeycombed” with them.

And so jealous was the law as regarded the rights of private

property that so late as 1845 owners were not to be interfered

with as regarded even their cesspools, no matter how

great the nuisance might be to their neighbours, no matter

how dangerous to the community at large. Indeed, the

Commissioners of Sewers had no power to compel landlords

or house-owners to make drains into the sewers, and of

their own motion the landlords would take no action.

In the lower part of Westminster the Commissioners of

Sewers had actually carried sewers along some of the streets,

but they found “very little desire on the part of the

landlords” to use them. “So long as the owners get their

rent they do not care about drainage…. The landlords

will not move; their property pays them very well; they

will not put themselves to any expense; they are satisfied

with it as it stands.”

Strange level of satisfaction! when one reads the

following evidence given two years later before the

Metropolitan Sewers Commission:—

“There are hundreds, I may say thousands, of houses in

this metropolis which have no drainage whatever, and the

greater part of them have stinking, overflowing cesspools.

And there are also hundreds of streets, courts, and alleys,

that have no sewers; and how the drainage and filth is

cleared away, and how the poor miserable inhabitants live

in such places it is hard to tell.

[19]

“In pursuance of my duties, from time to time, I have

visited very many places where filth was lying scattered

about the rooms, vaults, cellars, areas, and yards, so thick,

and so deep, that it was hardly possible to move for it. I

have also seen in such places human beings living and

sleeping in sunk rooms with filth from overflowing cesspools

exuding through and running down the walls and over the

floors…. The effects of the stench, effluvia, and poisonous

gases constantly evolving from these foul accumulations

were apparent in the haggard, wan, and swarthy countenances,

and enfeebled limbs, of the poor creatures whom

I found residing over and amongst these dens of pollution

and wretchedness.”[10]

And this witness was unable to refrain from passing a

verdict upon what he had seen:—

“To allow such a state of things to exist is a blot

upon this scientific and enlightened age, an age, too, teeming

with so much wealth, refinement, and benevolence.

Morality, and the whole economy of domestic existence,

is outraged and deranged by so much suffering and misery.

Let not, therefore, the morality, the health, the comfort of

thousands of our fellow creatures in this metropolis be in

the hands of those who care not about these things, but let

good and wholesome laws be enacted to compel houses to

be kept in a cleanly and healthy condition.”

There were, it was said, “a formidable host of difficulties”

as regarded the execution of improved works of

house drainage.

There was the opposition of the proprietors on the

ground of expense; there were the provisions of the Act of

Parliament,[11] which were so intricate as to be almost

unintelligible and unworkable; there was the want of

a proper outfall for the sewage; and the want of a supply

of water to wash away the filth—a possible explanation for

the existing state of abomination, but certainly not a

justification for the prolonged inaction of successive

Parliaments and Governments in allowing affairs to reach

so frightful a pass, and for dooming the people to a

condition of things which it was entirely beyond their

power to remedy even as regarded the single house they

inhabited.

[20]

Just as everything connected with sewerage and drainage

was so placidly neglected, and so fearfully bad, so also was

it as regarded another matter of even more vital necessity,

namely, the supply of water to the inhabitants of

London for drinking, or for domestic, trade, or sanitary

purposes.

“Water is essential as an article of food. Water is

necessary to personal cleanliness. Water is essential to

external cleansing, whether of houses, streets, closets, or

sewers.”

Manifestly, the supply of water was not a matter which

the individual in a large community such as London could

in any way make provision for by his own independent

effort. And yet there was no public body in London,

central or local, representative or otherwise, charged with

the duty of securing to the people even the minimum

quantity necessary for life.

Early in the seventeenth century the New River Company

was formed for the supply of water to London. And as

years went on Parliament evidently considered it fulfilled

its obligations in this respect by making over to sundry

private companies the right of supplying to the citizens of

London this vital requirement, or, as it has been termed,

this “life-blood of cities”; and Parliament had done this

without even taking any guarantee or security for a proper

distribution to the people, or for the purity of the water, or

the sufficiency of its supply.

Practically, a generous Parliament had bestowed as a

free gift upon these Water Companies the valuable monopoly,

so far as London was concerned, of this necessity

of life.

Although by the middle of the nineteenth century there

was no portion of the metropolis into which the mains and

pipes of some of the companies had not been carried, yet,

as the companies were under no compulsion to supply it to

[21]

all houses, large numbers of houses, and particularly those

of the poorer classes, received no supply. Indeed, in many

parts of London there were whole streets in which not a

single house had water laid on to the premises.

In the district supplied by the New River Company,

containing about 900,000 persons, about one-third of the

population were unsupplied; and in the very much smaller

area of the Southwark Company’s district about 30,000

persons had no supply.

Even in 1850 it was computed that 80,000 houses in

London, inhabited by 640,000 persons, were unsupplied

with water.

A very large proportion of the people could only obtain

water from stand-pipes erected in the courts or places, and

that only at intermittent periods, and for a very short time

in the day; sometimes, indeed, only on alternate days, and

not at all on Sunday.

“To these pipes,” wrote a contemporary, “the inhabitants

have to run, leaving their occupation, and collecting

their share of this indispensable commodity in vessels of

whatever kind might be at hand. The water is then kept

in the close, ill-ventilated tenements they occupy until it is

required for use.”[12]

The quality of the water which was supplied by the companies

left much to be desired. That supplied by the New

River Company was, as a rule, fairly good in quality; but

that supplied by the other companies was very much the

reverse. Financial profit being their first and principal

consideration, they got it from where it was obtainable at

least capital outlay or cost, regardless of purity or impurity;

and almost without exception took it from the Thames—“the

great sewer of London”—took it, too, from precisely

the places where the river was foulest and most contaminated

by sewage and other filth; and as there were no

filtering beds in which it could have been to some extent

purified before its distribution to householders, its composition

can best be imagined.

Looking at the great river even now in its purified state,

as it sweeps under Westminster Bridge, any one would

shudder at the idea of being compelled to drink its water

in its muddy and unfiltered state, and of one’s health and

life being dependent on the supply from such a source.

How infinitely more repugnant it must have been when

the river was “the great sewer” of the metropolis.

[22]

The great shortage of company-supplied water compelled

large numbers of people to have recourse to the pumps

which still existed in considerable numbers in many parts

of London, the water from which was drawn from shallow

wells.

The water of these “slaughter wells,” as they have

been termed, appears to have combined all the worst

features of water, and to have contained all the ingredients

most dangerous to health.

“If,” wrote a Medical Officer of Health some years later,

“the soil through which the rain passes be composed of the

refuse of centuries, if it be riddled with cesspools and the

remains of cesspools, with leaky gas-pipes and porous

sewers, if it has been the depository of the dead for generation

after generation, the soil so polluted cannot yield water

of any degree of purity.”[13]

As all these “ifs” were grim actualities, the water of such

wells was revolting in its impurity and deadly in its composition.

Of Clerkenwell it was indeed stated positively that “the

shallow-well water of the parish received the drainage

water of Highgate cemetery, of numerous burial grounds,

and of the innumerable cesspools in the district.”

On the south side of the river the water in most of the

shallow wells was tidal—from the Thames, which is a

sufficient description of the quality thereof—and where

people did not live close enough to the river to draw water

from it for their daily wants, they took it from these tidal

wells. Vile as it was, it had to be used in default of any

better.

[23]

Where such wells were not available, the water for all

household consumption was taken from tidal ditches which

were to all intents and purposes only open sewers. A contemporary

report gives a graphic picture of this form of

supply[14]:—

“In Jacob’s Island (in Bermondsey) may be seen at any

time of the day women dipping water, with pails attached

by ropes to the backs of the houses, from a foul, fœtid ditch,

its banks coated with a compound of mud and filth, and

with offal and carrion—the water to be used for every purpose,

culinary ones not excepted.”

An adequate supply of wholesome water has for very long

been recognised as of primary sanitary importance to all

populations, but with a densely crowded town population

the need of care as to the quality of the supplies is peculiarly

urgent. And yet, through the indifference of successive

Governments, the people of the great metropolis of London

were most inadequately supplied with water, and what water

was supplied to the great mass of them, or was available for

them, was of the foulest and most dangerous description.

The inadequacy of supply not alone put a constant premium

upon dirt and uncleanliness, both in house and person, but

it intensified the evils of the existing sewers and drains, as

without water efficient drainage was impossible. And

the horrible impurity of the water affected disastrously

and continuously the health of the great mass of the

people.

Many dire lessons, costing thousands upon thousands of

lives, were needed before it was borne in on the Government

of the country that the arrangements regarding the supply

of water for the people of London required radical amendment.

Much of the health of a city depends upon the width of

its thoroughfares, the free circulation of air in its streets

and around its buildings, and the sound and sanitary construction

of its houses.

[24]

In every one of these respects all the central parts of

London were remarkably defective. The great metropolis

had grown, and had been permitted to grow, mostly at

haphazard. Large parks and open spaces there were in the

richer and more well-to-do parts, and some handsome

thoroughfares; but “there were districts in London

through which no great thoroughfares passed, and which

were wholly occupied by a dense population composed of

the lowest class of persons, who, being entirely secluded

from the observation and influence of better educated

neighbours, exhibited a state of moral degradation deeply

to be deplored.”[15]

Parliament had taken some interest as to the width of

the streets, and had shown some anxiety for improvements

in them. Hence, much local and general legislation was

from time to time directed to control the erection of buildings

beyond the regular lines of buildings. Thus the Metropolitan

Paving Act, 1817, contained stringent provisions

as to projections which might obstruct the circulation

of air and light, or be inconvenient or incommodious to

passengers along carriage or foot ways in certain parts of

the metropolis.

In 1828 the Act for Consolidating the Metropolis Turnpike

Trusts, also, contained certain restrictive provisions, but

these were rendered futile by the construction put upon its

terms by the magistrates.

Again, in 1844, further enactments were made by the

Metropolitan Building Act to restrain projections from

buildings; but after a short administration of its provisions

it was found that shops built on the gardens in front of the

houses, or on the forecourts of areas, did not come within

the terms of the Act. And so the Act, in that very important

respect, was useless.

The action of Parliament had been mainly prompted by

the necessity for increased facilities of communication, and

by the desire to safeguard house property from destruction

by fire; whilst the most important of all aspects of the

housing of the people—namely, the sanitary aspect—received

no consideration, and was completely ignored as

a thing of no consequence.

[25]

But whatever the motive of action by Parliament, the

ensuing legislation was in the main inoperative or ineffective.

The resolution of landowners to secure the highest

prices for their property, and the determination of builders,

once they got possession of any land, to utilise every inch of

it for building, and so to make the utmost money they could

out of it, defeated the somewhat loosely drawn enactments.

Means of evading the legislative provisions were promptly

discovered, and, in despite of legislation, builders, architects,

and surveyors of the metropolis were unrestrained in their

encroachments upon areas and forecourts—at times even

were successful in breaking the existing lines of buildings in

metropolitan streets or roads by encroachments which were

only discovered too late to be prevented.

Nor was there anything to prevent houses being built on

uncovered spaces at the backs of existing buildings, thus

taking up whatever air-space had been left between the

previous buildings. Hence, great blocks of ground absolutely

covered with buildings, back to back, side to side,

any way so long as a building could by any ingenuity be

fitted in. Hence the culs-de-sac, the small and stifling

courts and alleys. Nor were there any regulations forbidding

certain kinds of buildings which would be injurious

to the health of their inhabitants. Hence the mean and

flimsy and insanitary houses which were being erected in

the outer circle of the metropolis, and which wrought havoc

with the health and lives of the people. Hence, too, the

erection, on areas and forecourts, of buildings which

narrowed the streets, diminished the air-spaces and means

of ventilation, and destroyed the appearance of the localities.

And once up they had come to stay; for years were to

pass before the Legislature created any effective means for

securing their amelioration, and for generations they were

permitted to exercise their evil and deadly sway over the

people, and to scatter broadcast throughout the community

the seeds of disease and death.

The then existing actual state of the case was summed

up by Dr. Southwood Smith in his evidence before the

Select Committee of the House of Commons in 1840:—

[26]

“At present no more regard is paid in the construction

of houses to the health of the inhabitants than is paid to

the health of pigs in making sties for them. In point of

fact there is not so much attention paid to it.”

Legislation against some of the evils which had already

reached huge proportions, and which, as London grew,

were spreading and developing, was not alone ineffective,

but earlier legislation, in one notorious Act, had been the

direct incentive to, and cause of evils. This was the Act

which imposed a tax upon windows.[16] In effect this Act

said to the builder, “Plan your houses with as few openings

as possible. Let every house be ill-ventilated by shutting

out the light and air, and as a reward for your ingenuity

you shall be subject to a less amount of taxation.”[17]

The builder acted upon this counsel, and the tax operated

as a premium upon the omission from a building of every

window which could by any device be spared; with the

result that passages, closets, cellars, and roofs—the very

places where mephitic vapours were most apt to lodge—were

left almost entirely without ventilation.[18]

In effect, the window duties compelled multitudes to live

and breathe in darkened rooms and poisoned air, and with

a rapidly increasing population the evils resulting therefrom

were being steadily intensified.

Admirable was the comment passed upon the tax in

1843:—

“Health is the capital of the working man, and nothing

can justify a tax affecting the health of the people, and

especially of the labouring community, whose bodily health

and strength constitute their wealth, and, oftentimes, their

only possession. It is a tax upon light and air, a tax more

vicious in principle and more injurious in its practical consequences

than a tax upon food.”

Not until 1851 was the tax abandoned, but its evil consequences,

wrought in stone and embodied in bricks and

mortar, endured many a long year after.

[27]

The existing laws or regulations as to building were

wholly inadequate to secure healthy houses. And there

was no public authority with power to compel attention to

the internal condition of houses so as to prevent their continuance

in such a filthy and unwholesome state as to endanger

the health of the public. There was no power to

compel house owners to make drains and carry them to the

common sewer where it existed. No persons were appointed

to carry into effect such communication. No persons were

authorised to make inspection and to report upon these

matters.

The poor, or, indeed, the working classes generally, were

powerless to alter or amend the construction of the dwellings

in which they were compelled to reside, still less to alter

their surroundings. Any improvement in the condition of

their dwellings could only be by voluntary action on the

part of the landlords, or of interference by Government to

compel that measure of justice to the poor, and of economy

to the ratepayers.

Parliament failed to interfere with any effect; and as to

the landlords or house-owners, their interest ran all the

other way.

Few persons of large capital built houses as a speculation,

or had anything to do with them. Many, however, who

were desirous of making the highest possible interest on

their money acquired either freehold or leasehold land, and

built cheap and ill-constructed houses upon it without the

least regard to the health of the future inmates.

And the small landlords were often the most unscrupulous

with regard to the condition of the houses they let, and

exacted the highest rents.

Inasmuch as this freedom as regarded house construction

had been going on almost from time immemorial, it was not

only the newly-built houses which were bad. Earlier built

houses had rapidly fallen into disrepair and semi-ruin, and

were steadily going from bad to worse, and becoming ever

less and less suitable for human dwellings.

[28]

The following description[19] of parts of St. Giles’ and

Spitalfields shows what, under a state of freedom as to

building, had been attained to in 1840, and is typical of

what so extensively prevailed in the central parts of

London:—

“Those districts are composed almost entirely of small

courts, very small and very narrow, the access to them

being only under gateways; in many cases they have been

larger courts originally, and afterwards built in again with

houses back to back, without any outlet behind, and only

consisting of two rooms, and almost a ladder for a staircase;

and those houses are occupied by an immense number of

inhabitants; they are all as dark as possible, and as filthy

as it is possible for any place to be, arising from want of

air and light.”

Here is another description—that of “Christopher

Court,” a cul-de-sac in Whitechapel—given, in 1848, by

Dr. Allison, one of the surgeons of the Union:—

“This was one of the dirtiest places which human

beings ever visited—the horrible stench which polluted

the place seemed to be closed in hermetically among the

people; not a breath of fresh air reached them—all was

abominable.”

It is needless to multiply instances. There is a dreadful

unanimity of testimony from all parts of London as to the

miserable character and condition of the houses in which in

the middle of the nineteenth century the industrial and the

lower classes were forced to live; the deficiency or total

absence of drainage, the universal filth and abomination of

every kind, the fearful overcrowding, the ravages of every

type of disease, and the absolute misery in which masses

struggled for existence.

The density of houses upon an area has long been recognised

as one of the great contributing causes to the ill-health

of a community, but when coupled with the

overcrowding of human beings in those houses, the combined

results are always disastrous in the extreme.

[29]

Overcrowding had been a long-standing evil in London;

had existed far back in history.

As London had grown, the evil had grown; and about

the middle of the last century it was immeasurably greater

than ever before, and its disastrous consequences were on

a vastly larger scale.

The great economic forces which resulted, in certain

districts of London, in the destruction of houses and great

clearances of ground, had largely reduced the available

accommodation for dwellings, and the expelled inhabitants,

chained to the locality by the fact of their livelihood being

dependent upon their residence being close by, were forced

to invade the yet remaining places in the neighbourhood

suited to their means. As the circle of possible habitations

contracted, while the numbers seeking accommodation

therein increased, a larger population was crowded into an

ever-diminishing number of houses.

It was also a most unfortunate but apparently inevitable

consequence that once a beginning was made to improve

some of the streets and thoroughfares of London, and to

substitute in any district a better class of houses and shops

for those actually existing, the improvements necessarily

involved increased overcrowding in that particular locality

and in those adjoining it. But so it was.

Thus, in the eighteen hundred and forties a new street—New

Oxford Street—was formed. It was driven through

“a hive of human beings, a locality overflowing with human

life.” Evidence given before the Commission in 1847

described the results:—

“The effect has been to lessen the population of my

neighbourhood by about 5,000 people, and therefore to

improve it at the expense of other parts of London. Some

have gone to the streets leading to Drury Lane, some to

St. Luke’s, Whitechapel, but more to St. Marylebone and

St. Pancras. The vestries of St. Marylebone and St. Pancras

disliked this very much. Places in the two latter

parishes which were before bad enough are now intolerable,

owing to the number of poor who formerly lived in

St. Giles’.”

[30]

And a year or so later, from across the river, came the

complaint from Lambeth that “owing to the number of

houses pulled down in Westminster and other places, there

had been a great influx of Irish and other labourers which

necessarily caused a great overcrowding of the miserable

domiciles already overfull.”

This Lambeth complaint is specially interesting, as it

refers to another great cause of overcrowding—the constant

immigration into London of labourers and poor people

in search of work or food.

Owing to the ever increasing and urgent demand for

house accommodation for the working and poorer classes,

it became a very remunerative proceeding for the occupier

of a house to sub-let it in portions to separate families or

individuals, and the practice gradually extended to and

absorbed streets hitherto belonging to the better class.

The owner of a property let his whole house to a tenant;

this tenant, seeing an easy way of making money, sub-let

the rooms in it in twos or threes, or even separately, at a

very profitable rate to individual tenants. Nor did the

sub-letting end here, for these tenants let off even the sides

or corners of their room or rooms to individuals or families

who were unable to bear the expense of a whole room.

And so the house sank at once into being a “tenement

house”—that prolific source of the very worst evils,

sanitary, physical, and moral, to those who inhabited

them.

Even the underground kitchens and cellars, which were

never intended for human habitation, were let to tenants,

and thus turned to financial profit.[20] It mattered not that

they were without air or ventilation, or even light; it

mattered not that they were damp, or sometimes even

inundated with the overflow of cesspools; it mattered

not that they were inhabited contrary to the provisions

of Section 53 of the Building Act of 1844, for that section

was of no operative effect whatever. It is true that “Overseers”

were to report to the “Official Referees,” who were

to give notice to and inform the owners and occupiers of

such dwellings as to the consequences of disobeying the

Statute, and the “District Surveyor” was to carry out the

directions of the Referees. But nothing was ever done—Overseers,

District Surveyors, and Referees, all neglected

their duties.

[31]

Overcrowding was usually at its worst in one-room

tenements, and in an immense number of cases in the

metropolis one room served for a family of the working

or of the labouring classes. It was their bedroom, their

kitchen, their wash-house, their sitting-room, their eating-room,

and, when they did not follow any occupation elsewhere,

it was their workroom and their shop. In this one

room they were born, and lived, and slept, and died amidst

the other inmates.

And still worse, in innumerable cases, more than one

family lived in one room.

When this one room was in a badly drained, damp, ill-constructed,

and unventilated house, reeking with a polluted

atmosphere, and that house was in a narrow and hemmed-in,

unventilated “court” or “place” or “alley”—as an

immense number of them were—the maximum of evil

consequences was attained.

The evils of overcrowding cannot be summed up in a

phrase, nor be realised by the description, however graphic,

of instance upon instance. The consequences to the individual

living in an overcrowded room or dwelling were

always disastrous, and, through the disastrous consequences

to great masses of individuals, the whole community was

affected in varying degree.

Physically, mentally, and morally, the overcrowded people

suffered. Not a disease, not a human ill which flesh is heir

to, but was nurtured and rendered more potent in the human

hothouse of the overcrowded room; and the ensuing ill-health

and diseases not alone doubled the death rate, but

increased from ten to twenty-fold, at least, the number of

victims of disease of one sort or another—diseases dealing

rapid death, or slowly but surely sapping human strength

and vitality.

[32]

In the report of the London Fever Hospital for 1845

a certain overcrowded room in the neighbourhood was

described—a room which was filled to excess every night,

sometimes from 90 to 100 men being in it; a room 33 feet

long, 20 feet wide, and 7 feet high. From that one room

alone no fewer than 130 persons affected with fever were

received into the hospital in the course of the year.[21]

One, whose very close experience of the conditions of life

and circumstances of the poorer classes of London at the

time of the cholera epidemic of 1848–9 entitled him to speak

with special authority on the subject, thus summed up his

views and conclusions:—

“The members of the medical profession, in the presence

of these physical evils, when they are, as so often happens,

concentrated, find their science all but powerless; the

minister of religion turns from these densely crowded and

foul localities almost without hope; whilst the administrators

of the law, especially the chaplains and governors

of prisons, see that crime of every complexion is most rife

where material degradation is most profound.”[22]

And he quoted from the report of the Governors of the

Houses of Correction at Coldbath Fields and Westminster

the following passage:—

“The crowning cause of crime in the metropolis is, in my

opinion, to be found in the shocking state of the habitations

of the poor, their confined and fœtid localities, and the consequent

necessity for consigning children to the streets for

requisite air and exercise. These causes combine to produce

a state of frightful demoralisation. The absence of cleanliness,

of decency, of all decorum—the disregard of any

needful separation of the sexes—the polluting language and

the scenes of profligacy hourly occurring, all tend to foster

idleness and vicious abandonment. Here I beg emphatically

to record my conviction that this constitutes the

monster mischief.”

And then he himself adds:—

[33]

“If to considerations like these regarding the moral and

religious aspect of this great question, be added those suggested

by the indescribable physical sufferings inflicted on

the labouring classes by the existing state of the public

health in the metropolis, the conviction must of necessity

follow, that the time is come when efforts in some degree

commensurate with these great and pervading evils can no

longer with safety be deferred.”[23]

This opinion was expressed three years after the Royal

Commissioners of 1847 had said in their report:—

“There appears to be no available (legal) means for the

immediate prevention of overcrowding; all we can do is

to point it out as a source of evil to be dealt with hereafter.”

One gets a clue to the unceasing insanitary condition of

the greater part of London and to the inhuman conduct of

so many tenement house-owners when one realises that

there was no legal punishment whatever for the perpetration

and perpetuation of the insanitary abominations, no

matter how noxious or dangerous they were, nor how

rapidly or directly they led to disease or death. An order

to abate a nuisance (which usually was not obeyed) appears

to have been the only penalty, and it was only obtainable at

great trouble and after great delays; and, even if obtained

and the nuisance abated, there was nothing to prevent the

offender at once starting the nuisance again. Offences of

the most heinous description—amounting morally to deliberate

murder—were perpetrated with absolute impunity.

Houses which were scarcely ever free from fever cases were

allowed to continue year after year levying their heavy death

tax from the unfortunate inhabitants.

In Whitechapel one house, inhabited by twelve or fourteen

families, was mentioned as scarcely free from fever cases for

as many years.

“It is also a fearful fact that in almost every instance

where patients die from fever, or are removed to the hospital

or workhouse, their rooms are let as soon as possible to new

tenants, and no precautions used, or warning given; and in

some houses, perfect hotbeds of fever probably, where a

patient dies or is removed, the first new-comer is put into

the sick man’s bed.”

[34]

Sanitary improvement was almost a hopeless task.

There was a dead weight of opposition to it in the ignorance

and recklessness and indifference of the poorer

classes, the very hopelessness of being able to improve

their condition. And there was an active and bitter

opposition from those house-owners or lessees who for

their own financial profit exploited the poorer classes.

“There is one house in Spitalfields,” said Dr. Lynch,

“which has been the constant habitation of fever for fifteen

years. I have enforced upon the landlord the necessity of

cleansing and lime-washing it, but it has never been done!!…

There are many landlords with whom nothing but

immediate interest has any effect.”[24]

The favourite principle that an Englishman’s house was

his castle was used as a defence against any suggestion

that the malpractices committed therein should be curbed.

Others argued, “I am entitled to do what I like with

my own.”

“We everywhere find people ready to declare in respect

to every evil: There is not any law that could compel

its removal, the place complained of being private property.”

All sorts of far-fetched and strained arguments were

devised by them in the efforts to evade responsibility for

the infamous condition of their property, and to defend

and justify inaction.

Fortunately some voices began to be raised as to the

persons upon whom both equitably and morally the

responsibility lay of improving the condition of things.

“I would suggest,” said a voice in 1837, “the idea of the

landlords of many of the wretched filthy tenements being

held responsible for their being tenantable, healthy, and

cleanly.”

And the Commissioners in 1844 reported:—

“There are some points on which the public safety

demands the exercise of a power on the part of a public

authority to compel attention to the internal condition of

houses so as to prevent their continuance in such a filthy

and unwholesome state as to endanger the health of the

public.”

[35]

And they recommended that:—

“On complaint of the parish, medical, or other authorised

officer, that any house or premises are in such a filthy and

unwholesome state as to endanger the health of the public,

the local authority have power to require the landlord to

cleanse it properly without delay.”

But ideas or recommendations were alike ignored by the

Government and Parliament, and several years were to pass

before any legislation was attempted which would make