Project Gutenberg's Writing & Illuminating, & Lettering, by Edward Johnston

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most

other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions

whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of

the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at

www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have

to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook.

Title: Writing & Illuminating, & Lettering

8 pp. Examples in Red & Black and 24 pp. of Collotypes.

Author: Edward Johnston

Contributor: A. E. R. Gill

Illustrator: Edward Johnston

Noel Rooke

Release Date: October 10, 2014 [EBook #47089]

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK WRITING, ILLUMINATING, LETTERING ***

Produced by Chris Curnow and RichardW and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive)

See Transcriber's Endnote for details of this transcription. Scans of the original printed book are available from archive.org/details/writingillumina00john.

In issuing these volumes of a series of Handbooks on the Artistic Crafts, it will be well to state what are our general aims.

In the first place, we wish to provide trustworthy text-books of workshop practice, from the points of view of experts who have critically examined the methods current in the shops, and putting aside vain survivals, are prepared to say what is good workmanship, and to set up a standard of quality in the crafts which are more especially associated with design. Secondly, in doing this, we hope to treat design itself as an essential part of good workmanship. During the last century most of the arts, save painting and sculpture of an academic kind, were little considered, and there was a tendency to look on “design” as a mere matter of appearance. Such “ornamentation” as there was was usually obtained by following in a mechanical way a drawing provided by an artist who often knew little of the technical processes involved in production. With the critical attention given to the crafts by [p-viii] Ruskin and Morris, it came to be seen that it was impossible to detach design from craft in this way, and that, in the widest sense, true design is an inseparable element of good quality, involving as it does the selection of good and suitable material, contrivance for special purpose, expert workmanship, proper finish, and so on, far more than mere ornament, and indeed, that ornamentation itself was rather an exuberance of fine workmanship than a matter of merely abstract lines. Workmanship when separated by too wide a gulf from fresh thought—that is, from design—inevitably decays, and, on the other hand, ornamentation, divorced from workmanship, is necessarily unreal, and quickly falls into affectation. Proper ornamentation may be defined as a language addressed to the eye; it is pleasant thought expressed in the speech of the tool.

In the third place, we would have this series put artistic craftsmanship before people as furnishing reasonable occupations for those who would gain a livelihood. Although within the bounds of academic art, the competition, of its kind, is so acute that only a very few per cent. can fairly hope to succeed as painters and sculptors; yet, as artistic craftsmen, there is every probability that nearly every one who would pass through a sufficient period of apprenticeship to workmanship and design would reach a measure of success.

In the blending of handwork and thought in [p-ix] such arts as we propose to deal with, happy careers may be found as far removed from the dreary routine of hack labour as from the terrible uncertainty of academic art. It is desirable in every way that men of good education should be brought back into the productive crafts: there are more than enough of us “in the city,” and it is probable that more consideration will be given in this century than in the last to Design and Workmanship.

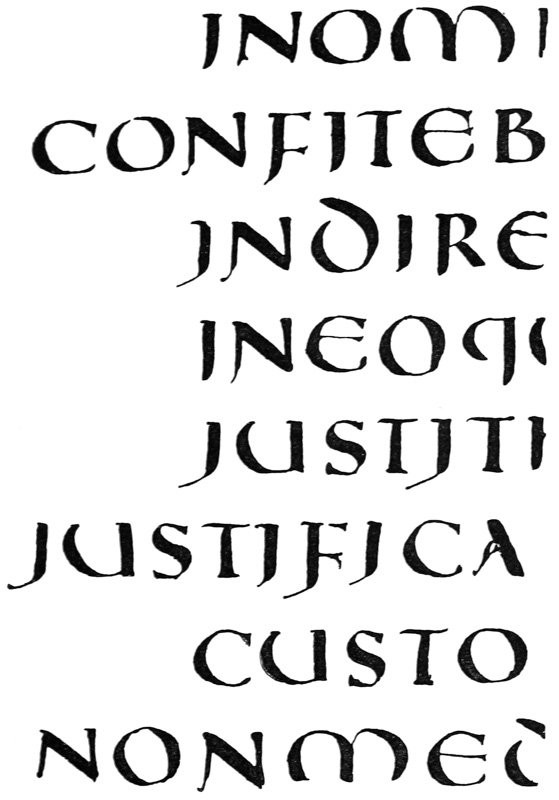

Of all the Arts, writing, perhaps, shows most clearly the formative force of the instruments used. In the analysis which Mr. Johnston gives us in this volume, nearly all seems to be explained by the two factors, utility and masterly use of tools. No one has ever invented a form of script, and herein lies the wonderful interest of the subject; the forms used have always formed themselves by a continuous process of development.

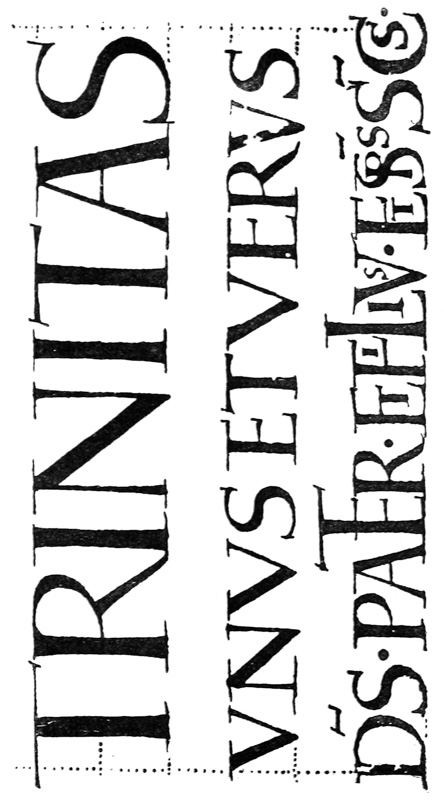

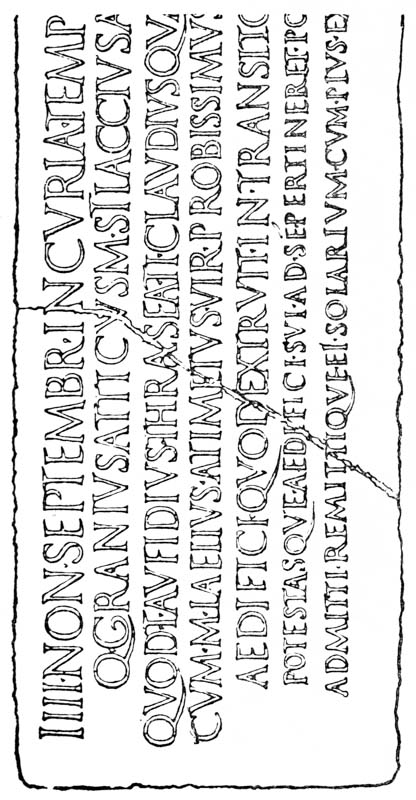

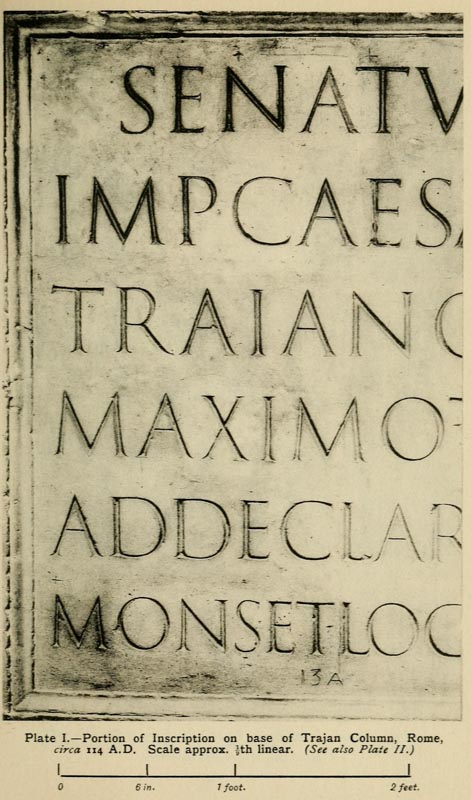

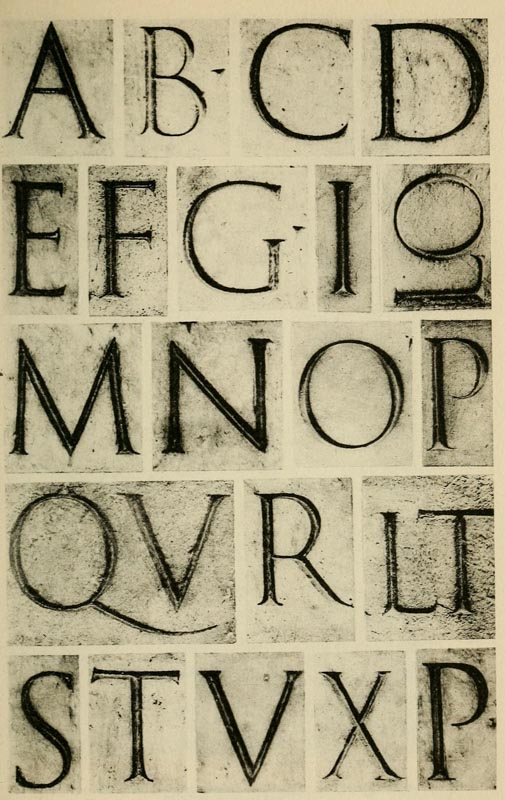

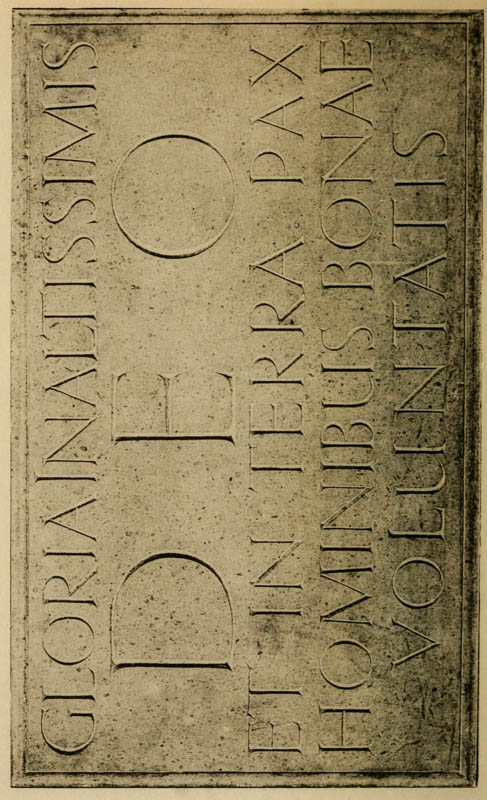

The curious assemblages of wedge-shaped indentations which make up Assyrian writing are a direct outcome of the clay cake, and the stylus used to imprint little marks on it. The forms of Chinese characters, it is evident, were made by quickly representing with a brush earlier pictorial signs. The Roman characters, which are our letters to-day, although their earlier forms have only come down to us cut in stone, must have been formed by incessant practice with a flat, stiff [p-x] brush, or some such tool. The disposition of the thicks and thins, and the exact shape of the curves, must have been settled by an instrument used rapidly; I suppose, indeed, that most of the great monumental inscriptions were designed in situ by a master writer, and only cut in by the mason, the cutting being merely a fixing, as it were, of the writing, and the cut inscriptions must always have been intended to be completed by painting.

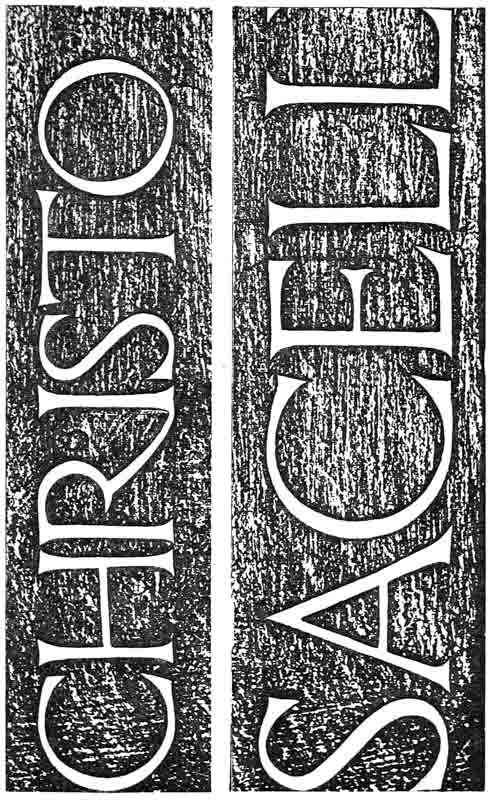

All fine monumental inscriptions and types are but forms of writing modified according to the materials to which they are applied. The Italian type-founders of the fifteenth century sought out fine examples of old writing as models, and for their capitals studied the monumental Roman inscriptions. Roman letters were first introduced into English inscriptions by Italian artists. Torrigiano, on the tombs he made for [p-xi] Henry VII. in Westminster Abbey and for Dr. Young at the Rolls Chapel, designed probably the most beautiful inscriptions of this kind to be found in England.

This volume is remarkable for the way in which its subject seems to be developed inevitably. There is here no collection of all sorts of lettering, some sensible and many eccentric, for us to choose from, but we are shown the essentials of form and spacing, and the way is opened out to all who will devote practice to it to form an individual style by imperceptible variations from a fine standard.

Writing is for us the most universal of the Arts, and most craftsmen have to deal with lettering of a more formal kind. It is a commonplace of historical criticism to point out how much the Italian artists owed to the general practice amongst them of goldsmith’s work, a craft which required accuracy and delicacy of hand. We cannot go back to that, but we do need a basis of training in a demonstrably useful art, and I doubt if any is so generally fitted for the purpose of educating the hand, the eye, and the mind as this one of WRITING.

W. R. LETHABY.

October 1906.

“We must set up the strong present tense against all the rumours of wrath, past or to come. So many things are unsettled which it is of the first importance to settle,—and, pending their settlement, we will do as we do. . . . Expediency of literature, reason of literature, lawfulness of writing down a thought, is questioned; much is to say on both sides, and, while the fight waxes hot, thou, dearest scholar, stick to thy foolish task, add a line every hour, and between whiles add a line. Right to hold land, right of property is disputed, and the conventions convene, and before the vote is taken, dig away in your garden, and spend your earnings as a waif or godsend to all serene and beautiful purposes. Life itself is a bubble and a scepticism, and a sleep within a sleep. Grant it, and as much more as they will,—but thou, God’s darling! heed thy private dream: thou wilt not be missed in the scorning and scepticism: there are enough of them: stay there in thy closet, and toil, until the rest are agreed what to do about it. Thy sickness, they say, and thy puny habit, require that thou do this or avoid that, but know that thy life is a flitting state, a tent for a night, and do thou, sick or well, finish that stint. Thou art sick, but shall not be worse, and the universe, which holds thee dear, shall be the better.”

—Emerson.

“I began to think that if I should discover how to make enamels, I could make earthen vessels and other things very prettily, because God had gifted me with some knowledge of drawing. And thereafter, regardless of the fact that I had no knowledge of drugs, I began to seek for the enamels as a man gropes in the dark.”

—Palissy.

“. . . in that communion only, beholding beauty with the eye of the mind, he will be enabled to bring forth, not images of beauty, but realities (for he has hold not of an image but of a reality), and bringing forth and nourishing true virtue to become the friend of God and be immortal, if mortal man may.”

—Plato.

The arts of WRITING, ILLUMINATING, & LETTERING offer a wide field for the ingenious and careful craftsman and open the way to a number of delightful occupations. Beyond their many uses—some of which are referred to below—they have a very great educational value. This has long been recognized in the teaching of elementary design, and the practice of designing Alphabets and Inscriptions is now common in most Schools of Art. Much would be gained by substituting, generally, WRITING for designing, because writing being the medium by which nearly all our letters have been evolved from the Roman Capital (see p. 35), the use of the pen—essentially a letter-making tool—gives a practical insight into the construction of letters attainable in no other way. The most important use of letters is in the making of books, and the foundations of typography and book decoration may be mastered—as they were laid—by the planning, writing, and illuminating of MSS. in book form. Of this a modern printer (see also p. 368) says:

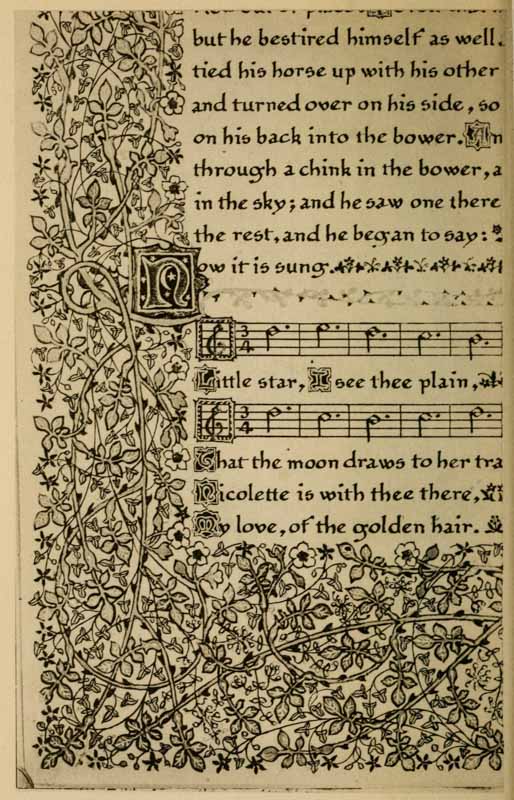

“In the making of the Written Book, . . . . . . the adjustment of letter to letter, of word to word, of picture to text and of text to picture, and of the whole to the subject matter and to the page, admits of great nicety and perfection. The type is fluid, and the letters and words, picture, text, and page are conceived of as one and are all executed by one hand, or by several hands all working together without intermediation on one identical page and [p-xiv] with a view to one identical effect. In the Printed Book this adjustment is more difficult. . . . . . . Yet in the making of the printed book, as in the making of the written book, this adjustment is essential, and should be specially borne in mind, and Calligraphy and immediate decoration by hand and the unity which should be inseparably associated therewith would serve as an admirable discipline to that end.”

And though calligraphy is a means to many ends, a fine MS. has a beauty of its own that—if two arts may be compared—surpasses that of the finest printing. This in itself would justify the transcribing and preservation of much good literature in this beautiful form (besides the preparation of “Illuminated Addresses,” Service Books, Heraldic and other MSS.) and make the practice of formal writing desirable. And furthermore as the old-fashioned notion that a legible hand is a mark of bad breeding dies out, it may be that our current handwriting will take legibility and beauty from such practice. And even the strict utilitarian could not fail to value the benefits that might some day come to men, if children learnt to appreciate beauty of form in their letters and in their writing the beauty of carefulness.

Of the practice of ILLUMINATING—properly associated with writing—it may be observed that, among various ways of acquiring a knowledge of the elements of design & decoration it is one of the most simple and complete. Moreover, a fine illumination or miniature has a beauty of its own that may surpass the finest printed book-decoration. And pictures in books may be as desirable as pictures on the wall—even though like the beautiful household gods of the Japanese they are kept in safe hiding and displayed only now and then. [p-xv]

Magnificent as are the dreams of a fine Decoration based on lettering, the innumerable practical applications of LETTERING itself (see Chap. XVI.) make the study of Letter-Craft not only desirable but imperative. And perhaps I may here be permitted to quote from The Athenæum of Feb. 3, 1906, which says of “the new school of scribes and designers of inscriptions”

“These have attacked the problem of applied design in one of its simplest and most universal applications, and they have already done a great deal to establish a standard by which we shall be bound to revise all printed and written lettering. If once the principles they have established could gain currency, what a load of ugliness would be lifted from modern civilization! If once the names of streets and houses, and, let us hope, even the announcements of advertisers, were executed in beautifully designed and well-spaced letters, the eye would become so accustomed to good proportion in these simple and obvious things that it would insist on a similar gratification in more complex and difficult matters.”

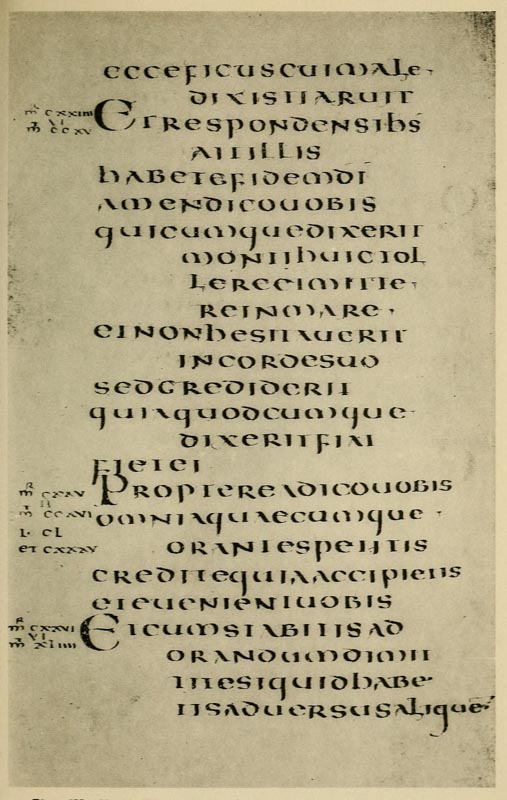

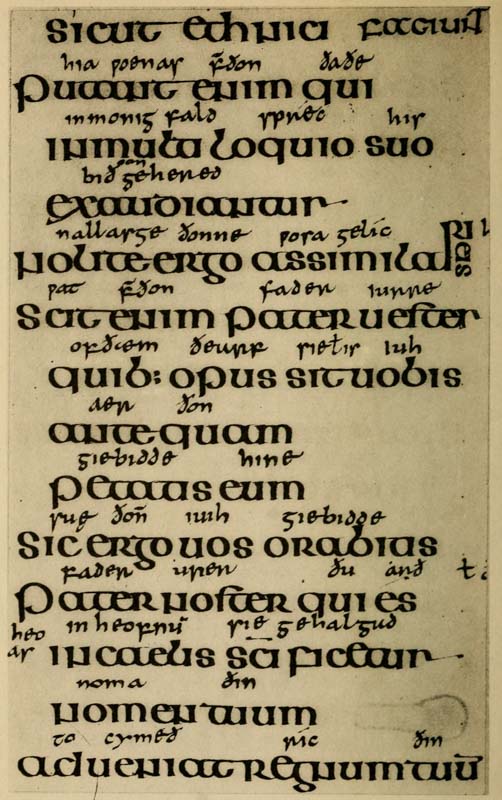

Yet Ordinary Writing and even scribbling has had, and still might have, a good influence on the art of the Letter maker, and at least the common use of pen, ink, & paper makes it a simple matter for any one to essay a formal or ‘book’ hand. A broad nib cut to give clean thick and thin strokes (without appreciable variation of pressure) will teach any one who cares to learn, very clearly and certainly. And though much practice goes to the making of a perfect MS., it is easier than people suppose to make really beautiful things by taking a little pains. As “copy book” hands simple, primitive pen-forms—such as the Uncial & Half-Uncial (pp. 38, 70)—afford the best training and permit [p-xvi] the cultivation of the freedom which is essential in writing: they prepare the way for the mastery of the most practical characters—the ROMAN CAPITAL, roman small-letter, & Italic—and the ultimate development of a lively and personal penmanship.

Developing, or rather re-developing, an art involves the tracing in one’s own experience of a process resembling its past development. And it is by such a course that we, who wish to revive Writing & Illuminating, may renew them, evolving new methods and traditions for ourselves, till at length we attain a modern and beautiful technique. And if we would be more than amateurs, we must study and practise the making of beautiful THINGS and thereby gain experience of Tools, Materials, and Methods. For it is certain that we must teach ourselves how to make beautiful things, and must have some notion of the aim and bent of our work, of what we seek and what we do.

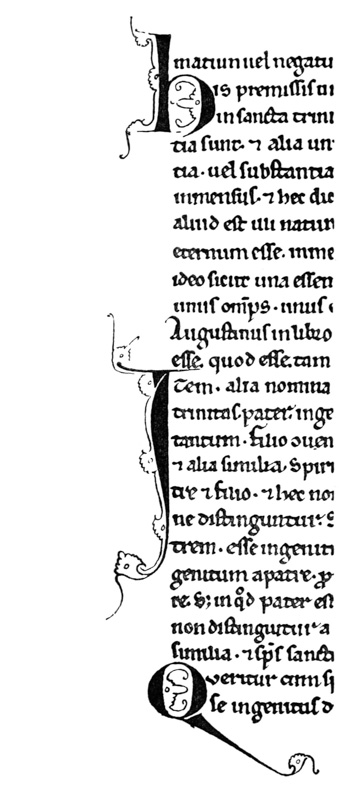

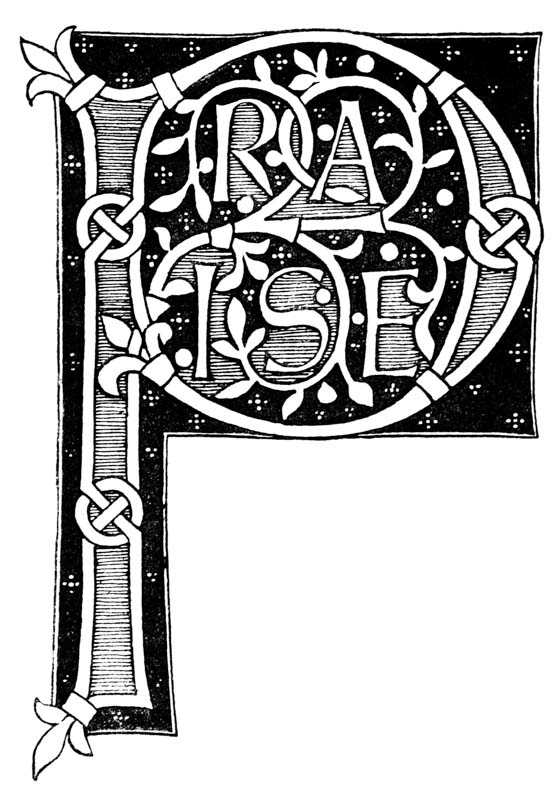

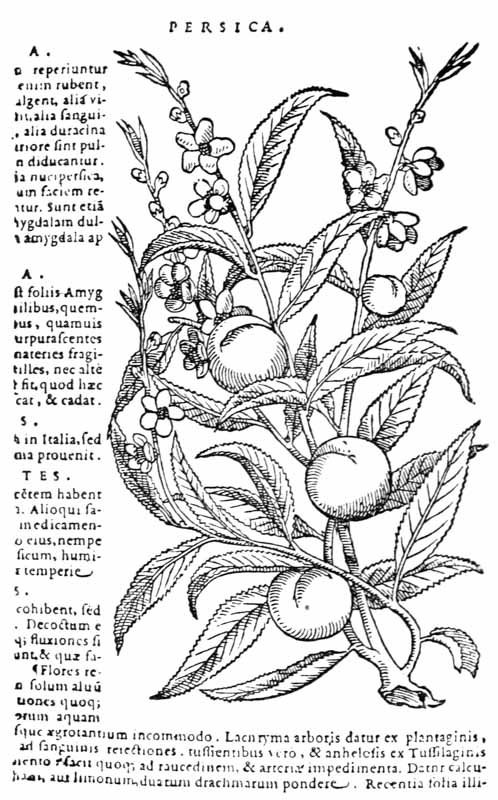

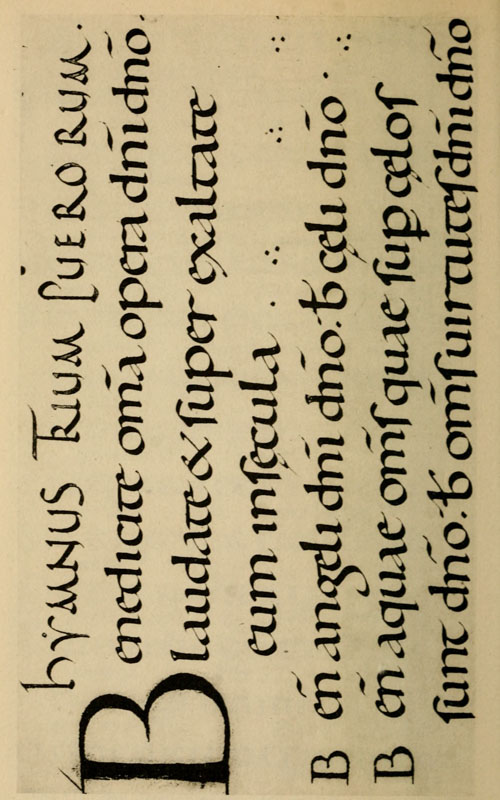

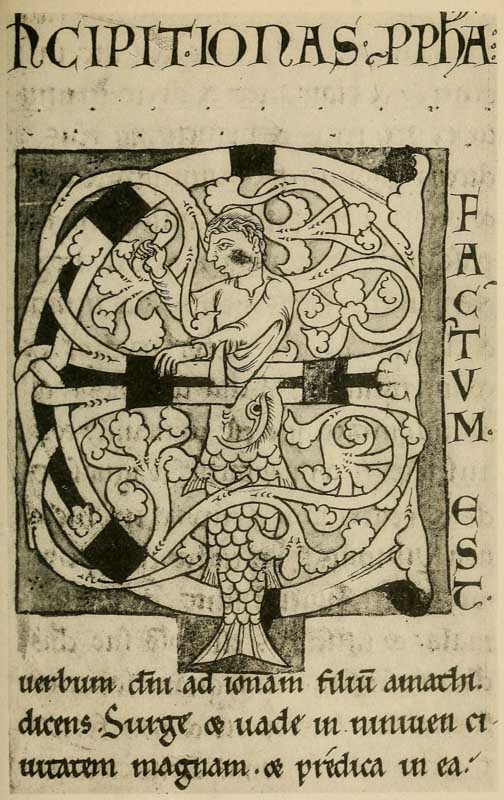

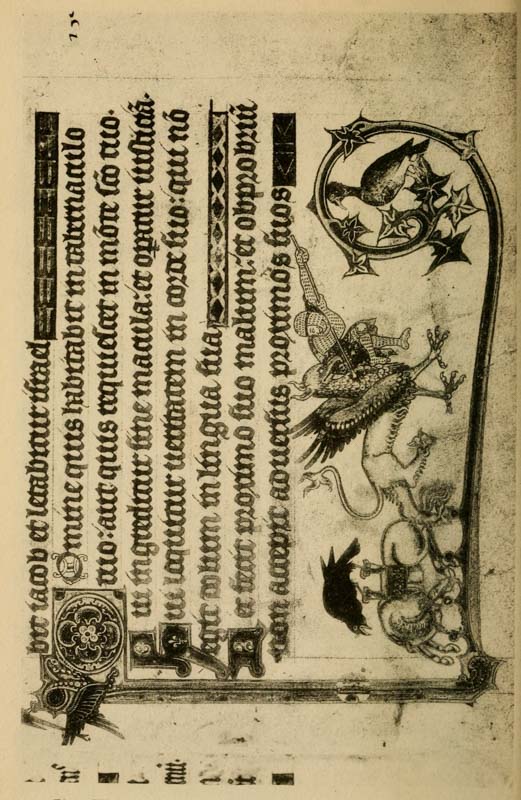

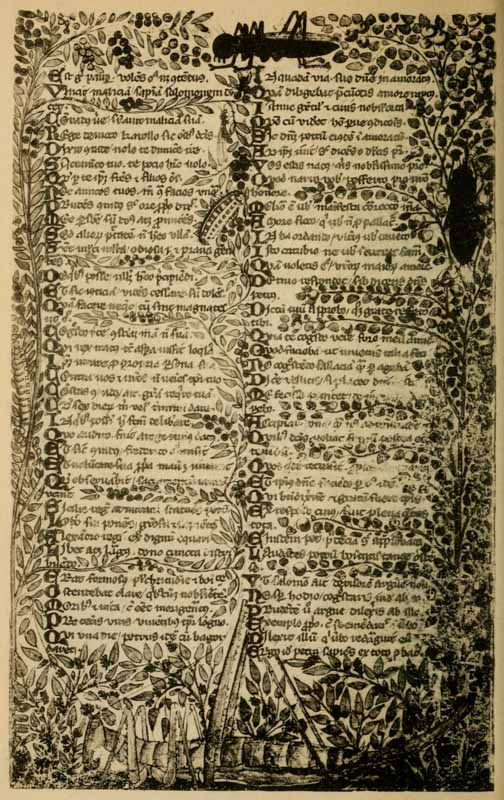

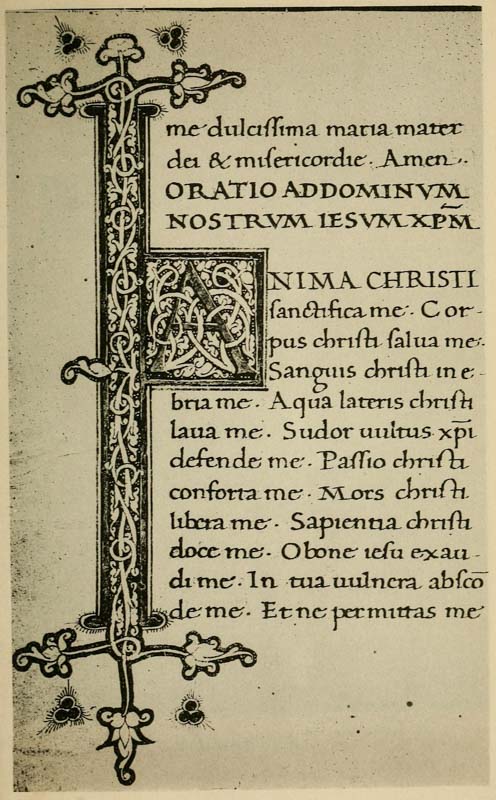

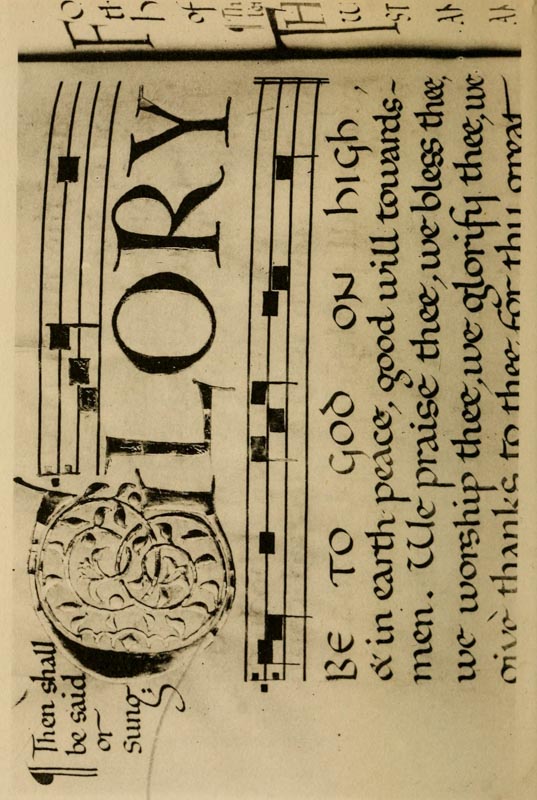

Early illuminated MSS. and printed books with woodcuts (or good facsimiles) may be studied with advantage by the would-be Illuminator, and he should if possible learn to draw from hedgerows and from country gardens. In his practice he should begin as a scribe making MS. books and then decorating them with simple pen & colour work. We may pass most naturally from writing to the decoration of writing, by the making and placing of initial letters. For in seeking first a fine effectiveness we may put readableness before “looks” and, generally, make a text to read smoothly, broken only by its natural division into paragraphs, chapters, and the like. But these divisions, suggesting that a pause in reading is desirable, suggest also that [p-xvii] a mark is required—as in music—indicating the “rest”: this a large capital does most effectively.

A technical division of illumination into Colour-work, Pen-work, and Draughtsmanship is convenient (see Chap. XI.). Though these are properly combined in practice, it is suggested that, at first, it will be helpful to think of their effects as distinct so that we may attain quite definitely some mastery of pure, bright, colours & simple colour effects, of pen flourishing and ornament, and of drawing—whether plain or coloured, that will go decoratively with writing or printing. This distinction makes it easier to devise definite schemes of illumination that will be within our power to carry out at any stage of our development. And while the penman inevitably gains some power of pen decoration it is well for him as an illuminator to practise in bright colours and gold; for illumination may be as brilliant and splendid in its own way as stained glass, enamels, and jewellery are in theirs.1 At first, at any rate, hues that have the least suspicion of being dull or weak are to be avoided as though they were plainly “muddy” or “washed-out.” The more definite we make our work the more definitely will our materials instruct us; and such service must precede mastery.

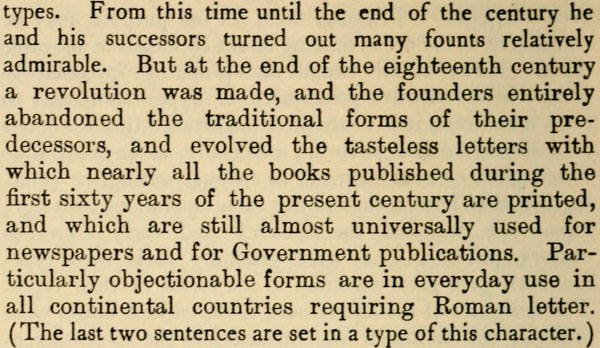

Referring again to good LETTERING: the second part of this book deals with some of its Qualities, Forms—the Roman Capitals & their important pen-derivatives—and Uses. It is written [p-xviii] largely from the penman’s point of view,2 but a chapter on inscriptions in stone has been added and various types and modes of letter making are discussed. The essential qualities of Lettering are legibility, beauty, and character, and these are to be found in numberless inscriptions and writings of the last two thousand years. But since the traditions of the early scribes and printers and carvers have decayed, we have become so used to inferior forms and arrangements that we hardly realize how poor the bulk of modern lettering really is. In the recent “revival” of printing and book decoration, many attempts have been made to design fine alphabets and beautiful books—in a number of cases with notable success. But the study of Palæography and Typography has hitherto been confined to a few specialists, and these attempts to make “” books often shew a vagueness of intention, which weakens their interest and an ignorance of Letter-craft which makes the poorest, ordinary printing seem pleasant by comparison. The development of Letters was a purely natural process in the course of which distinct and characteristic types were evolved and some knowledge of how these came into being will help us in understanding their anatomy and distinguishing good and bad forms. A comparatively little study of old manuscripts and inscriptions will make clear much of the beauty and method of the early work. And we may accustom ourselves to good lettering by carefully studying such examples as we can find, and acquire a practical knowledge [p-xix] of it by copying from them with a pen or chisel or other letter-making tool. A conscientious endeavour to make our lettering readable, and models3 and methods chosen to that end, will keep our work straight: and after all the problem before us is fairly simple—To make good letters and to arrange them well. To make good letters is not necessarily to “design” them—they have been designed long ago—but it is to take the best letters we can find, and to acquire them and make them our own. To arrange letters well requires no great art, but it requires a practical knowledge of letter-forms and of the rational methods of grouping these forms to suit every circumstance.

Generally this book has been planned as a sort of “guide” to models and methods for Letter-craftsmen and Students—more particularly for those who cannot see the actual processes of Writing, Illuminating, &c. carried out, and who may not have access to collections of MSS. Much of, if not all, the explanation is of the most obvious, but that, I hope, gives it more nearly the value of a practical demonstration. In describing methods and processes I have generally used the present tense—saying that they “are—”: this is to be taken as meaning that they are so in early MSS. and inscriptions, and in the practice of the modern school of scribes who found their work on them.

Regarding the copying of early work (see pp. 195, 323, &c.) it is contended that to revive an art [p-xx] one must begin at the beginning, and that, in an honest attempt to achieve a simple end, one may lawfully follow a method4 without imitating a style. We have an excellent precedent in the Italian scribes who went back 300 years for a model and gave us the Roman small-letter as a result (see p. 47). The beginners attitude is largely, and necessarily, imitative, and at this time we should have much to hope from a school of Artist-Beginners who would make good construction the only novelty in their work. We have almost as much—or as little—to be afraid of in Originality as in imitation, and our best attitude towards this problem is that of the Irishman with a difficulty—“to look it boldly in the face and pass on”—making an honest attempt to achieve a simple end. Perhaps we trouble too much about what we “ought to do” & “do”: it is of greater moment to know what we are doing & trying to do. In so far as tradition fails to bound or guide us we must think for ourselves and in practice make methods and rules for ourselves: endeavouring that our work should be effective rather than have “a fine effect”—or be, rather than appear, good—and following our craft rather than making it follow us. For all things—materials, tools, methods—are waiting to serve us and [p-xxi] we have only to find the “spell” that will set the whole universe a-making for us.

Endeavouring to attain this freedom we may make Rules and Methods serve us (see p. 221), knowing that Rules are only Guides and that Methods are suggested by the work itself: from first to last our necessary equipment consists in good models, good tools, & a good will. Within the limits of our craft we cannot have too much freedom; for too much fitting & planning makes the work lifeless, and it is conceivable that in the finest work the Rules are concealed, and that, for example, a MS. might be most beautiful without ruled lines and methodical arrangement (see p. 343). But the more clearly we realize our limitations the more practical our work. And it is rather as a stimulus to definite thought—not as an embodiment of hard and fast rules—that various methodical plans & tables of comparison & analysis are given in this book. It is well to recognize at once, the fact that mere taking to pieces, or analysing, followed by “putting together,” is only a means of becoming acquainted with the mechanism of construction, and will not reproduce the original beauty of a thing: it is an education for work, but all work which is honest and straightforward has a beauty and freshness of its own.

The commercial prospects of the student of Writing & Illuminating—or, indeed, of any Art or Craft—are somewhat problematical, depending largely on his efficiency & opportunities. There is a fairly steady demand for Illuminated Addresses; but the independent craftsman would have to establish himself by useful practice, and by seizing opportunities, and by doing his work well. Only an attempt [p-xxii] to do practical work will raise practical problems, and therefore useful practice is the making of real or definite things. In the special conditions attaching to work which the craftsman is commissioned to do for another person, there is a great advantage. And the beginner by setting himself specific tasks (for example: making a MS. book for a specific purpose—see p. 100) should give reality to his work. As a craftsman in Lettering he might get work in some of the directions mentioned in pp. 337–341.

Although the demand for good work is at present limited, the production of good work will inevitably create a demand; and, finally, the value of Quality is always recognized—sooner or later, but inevitably—and whatever “practical” reasons we may hear urged in favour of Quantity, the value of Quality is gaining recognition every day in commerce and even in art, and there or here, sooner or later we shall know that we can afford the best.

EDWARD JOHNSTON.

October 1906.

My thanks are due to Mr. T. J. Cobden-Sanderson, to Mr. Emery Walker, and to Mr. George Allen for quotations: to Mr. Graily Hewitt, to Mr. Douglas Cockerell, to Mr. A. E. R. Gill, to Mr. C. M. Firth, and to Mr. G. Loumyer, for special contributions on gilding, binding, and inscription-cutting: to Mr. S. C. Cockerell for several of the plates: to Mr. W. H. Cowlishaw, to the Rev. Dr. T. K. Abbott, to Dr. F. S. Kenyon of the New Palæographical Society, to the Vicar of Holy Trinity Church, Hastings, to the Secretary of the Board of Education, S. Kensington, to Mr. H. Yates-Thompson, to Mr. G. H. Powell, and to others, for permission to reproduce photographs, &c.: and to Mr. Noel Rooke and G. J. H. for assistance with the illustrations and many other matters: I should like, moreover, to acknowledge my indebtedness to Mr. W. R. Lethaby and Mr. S. C. Cockerell for encouragement and advice in years past.

E. J.

1 See Chap. XVI. “Of Colour” in “Stained Glass Work” by C. W. Whall, in this Series, and the illuminator might profit by the suggestion (ibid., p. 232) of playing with a home-made kaleidoscope.

2 Dealing with the practical and theoretical knowledge of letter-making and arrangement which may be gained most effectually by the use of the pen.

3 In making choice of a model we seek an essentially legible character, remembering that our personal view of legibility is apt to favour custom and use unduly, for a quite bad, familiar writing may seem to us more readable than one that is far clearer in itself but unfamiliar.

4 Much remains to be found out and done in the matter of improving tools & materials & processes, and it would be preferable that the rediscovery of simple, old methods should precede new & complex inventions. We still find the Quill—for its substance & for shaping it and keeping it sharp—is a better tool than a modern gold or metal pen (see p. 60). The old parchment, paper, ink, gilding-size & colours are all much better than those now obtainable (see pp. 51, 167, 173, 178–179). I should greatly appreciate any advice from illuminators and letter-craftsmen as to materials and methods, and should endeavour to make such information available to others.—E. J.

P. 51. Beginners practising large writing may more easily use a thin, or diluted, ink: in small writing this does not show up the faults with sufficient clearness.

P. 59. Quills often have a sort of skin (which tends to make a ragged nib), this should be scraped off the back.

P. 63. Until the simple pen-stroke forms are mastered, the pen should be used without appreciable pressure. With practice one gains sleight of hand (pp. 85, 311), and slightly changing pressures & quick movements on to the corners, or points, of the nib are used. The forms in the best MSS. shew such variations; e.g. the Uncials in fig. 5 appear to have been made with varying pressure (perhaps with a soft reed) & their fine finishing-strokes with the nib-point (comp. forms in fig. 146). Versals likewise shew varying, and sometimes uncertain, structures that suggest a form consisting of strokes other than definite pen strokes. [p-xxv]

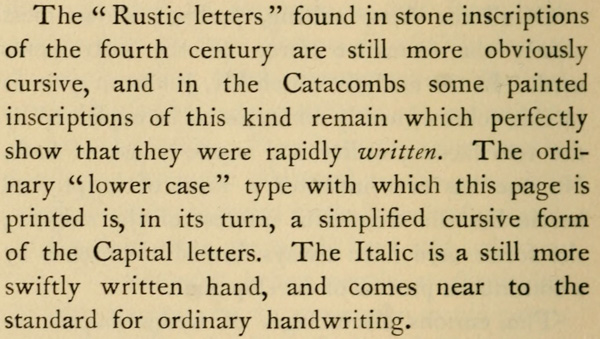

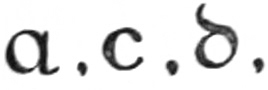

P. 64. A nib may be sharpened several times, before it is re-cut, by paring it underneath (fig. a).

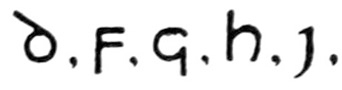

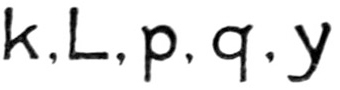

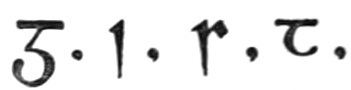

Pp. 73 & 81. The thin finishing-strokes of j, & F, G, J, N, are made with the point of the nib—see note p. 63 above.

P. 99. The plan of a paper scale is shewn in fig. b.

P. 109. The dots for lines were often pricked through the edges of the book-sheets which were cut off after ruling (fig. c).

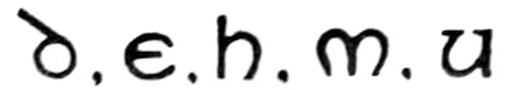

P. 118. The spread or wedge-shaped thin stroke, sometimes very strongly marked, is common in early forms (fig. d).

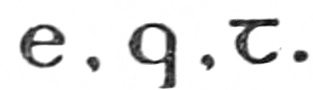

P. 144.

&

&

: better (pen) forms of these are

shewn in fig. e.

: better (pen) forms of these are

shewn in fig. e.

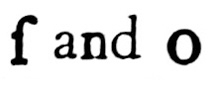

P. 208. Ornamental Letter forms may consist of flourishes, patterns, leaves, flowers, &c. (see fig. f).

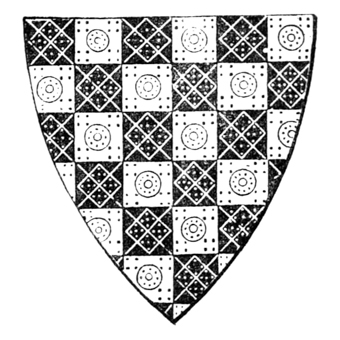

Pp. 215–217. Diapering generally means the variegation, figuring, or flowering, of a plain or patterned surface, with a finer pattern (see fig. 191a). Some diagrams of simple patterns (g–g2 from modern cantagalli ware) are shewn in fig. g. Note: the more solid penwork line-fillings in figs. 87, 126, make effective framing borders (see fig. h).

Pp. 219–220. Note: the principle of breaking straight or long lines, mentioned in regard to background edges (p. 190), and illustrated in the line-finishings (fig. 126) and flourishes (fig. 79), is related to branching out and is re-creative, whereas the prolonged line is tiresome (see figs. k, k1, & comp. k2).

P. 249. The B & D should be round-shouldered—see note p. 280 below. [p-xxvi]

P. 260. It is sometimes better to make narrow forms than to combine wide ones—example fig. l.

Pp. 270–275.

Pp. 280–288.

The large types—“Old Face” (founded on Caslon Type) and “Old French”

(modern) respectively—are used in these pages as reference or index

letters (not as models).

P. 280.

Generally round-shouldered letters have

finer and more stable forms than square-shouldered,

and generally emphasis

should be laid on the strong, thick stroke

running obliquely down from left to right

( ),

while the weak, thin stroke

(

),

while the weak, thin stroke

( )

is rather to be avoided (see

fig. m). The

writing used in the diagrams in this

book, considered as a formal hand,

shews a little too much of the thin

stroke (see p.

485).

)

is rather to be avoided (see

fig. m). The

writing used in the diagrams in this

book, considered as a formal hand,

shews a little too much of the thin

stroke (see p.

485).

P. 324. Commonly letters are made more slender in proportion as they are made larger, and it is generally not desirable (or possible) in practical work to have exactly similar proportions in large and small lettering.

P. 325. g from fig. 173 inaccurate—comp. fig. 173 & see fig. n.

P. 331. Ornamental letters—see note p. 208 above.

P. 481. A small writing is often the most practical—in the matter of speed in reading and less bulk in the MS., besides speed in the writing of it—but it is more difficult for the beginner to write it well and it is apt to lose some of the virtues of formal penmanship (see Fine-pen writing pp. 59, 86, 311, 324, 482).

P. 485. Oblique thin stroke—see note p. 280 above.

ILLUMINATING

ILLUMINATING ILLUMINATING

CHAPTER I

THE DEVELOPMENT OF WRITING

ILLUMINATING

CHAPTER I

THE DEVELOPMENT OF WRITINGNearly every type of letter with which we are familiar is derived from the Roman Capitals, and has come to us through the medium, or been modified by the influence, of the pen. And, therefore, in trying to revive good Lettering, we cannot do better than make a practical study of the best pen-forms, and learn at the same time to appreciate the forms of their magnificent archetypes as preserved in the monumental Roman inscriptions.

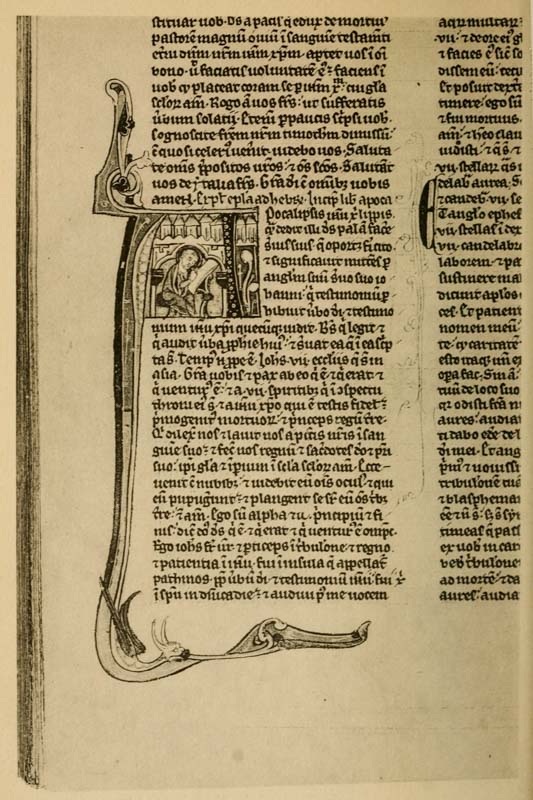

The development and the relations of the principal types of letters are briefly set out in the accompanying “family tree”—fig. 1. When the student has learnt to cut and handle a pen, he can trace this development practically by trying to copy a few words from each example given below. [p036]

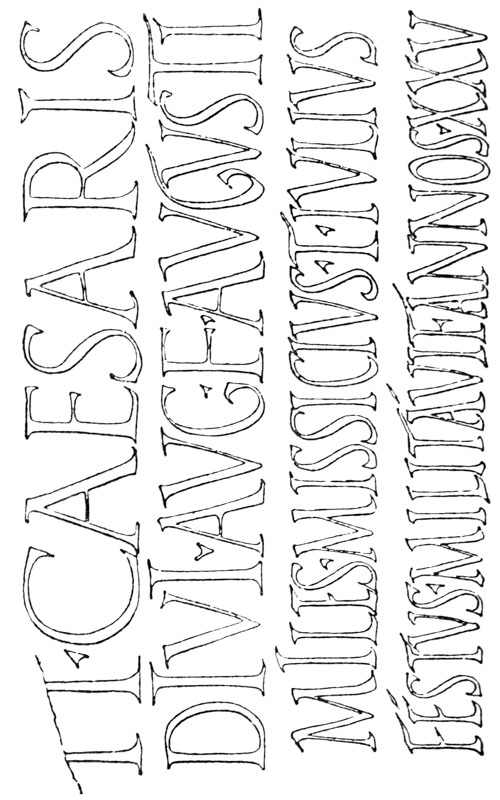

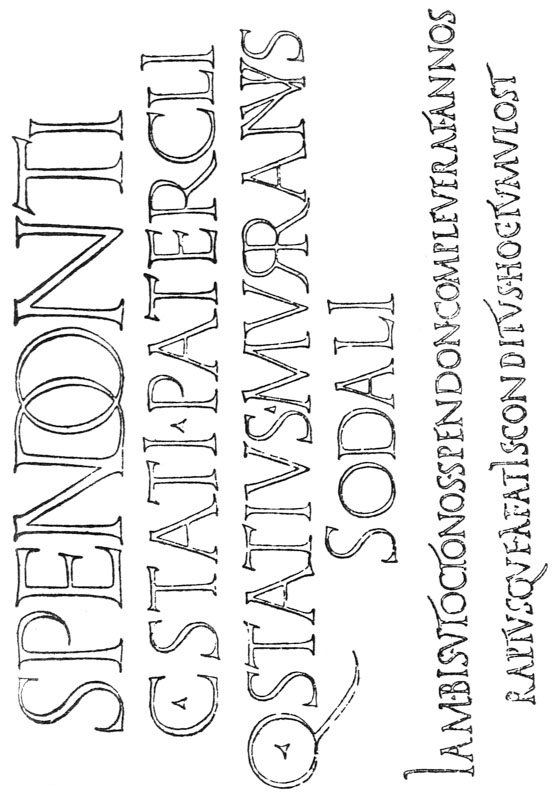

THE ROMAN ALPHABET.—The Alphabet, as we know it, begins with the ROMAN CAPITALS5 (see fig. 2). Their fine monumental forms were evolved by the use of the chisel—probably under the influence of writing—and had reached full development about 2000 years ago (see Plates I., II., and Chapter XV.).

FORMAL WRITING—the “book-hand” or professional writing of the scribes—comes of the careful writing of the Roman Capitals (see also footnote, p. 38, on the beginnings of fine penmanship). It was the—

“literary hand, used in the production of exactly written MSS., and therefore a hand of comparatively limited use. By its side, and of course of far more extensive and general use, was the cursive hand of the time”6 [p037]

In early cursive writing—the running-hand or ordinary writing of the people—

“The Letters are nothing more than the old Roman letters written with speed, and thus undergoing certain modifications in their forms, which eventually developed into the minuscule hand.”7 (See fig. 3.)

Here it is sufficient to trace the history of the formal Latin “hands,” but the continual, modifying influence exerted on them by the ordinary cursive writing should be borne in mind. Notable results of this influence are seen in Half-Uncials and Italics.

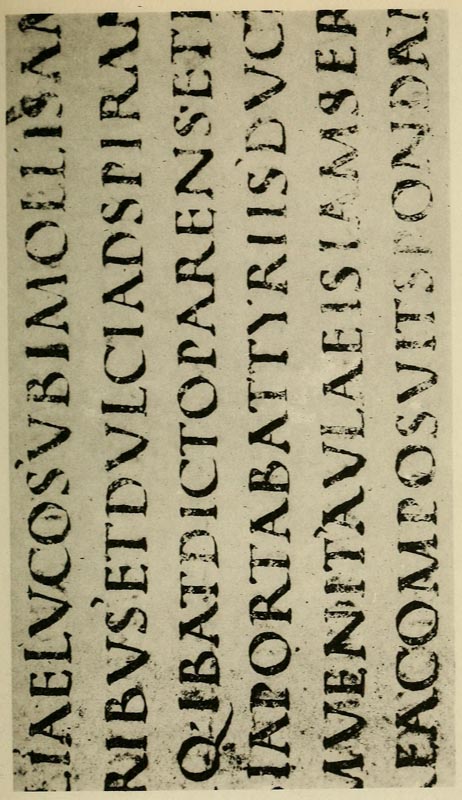

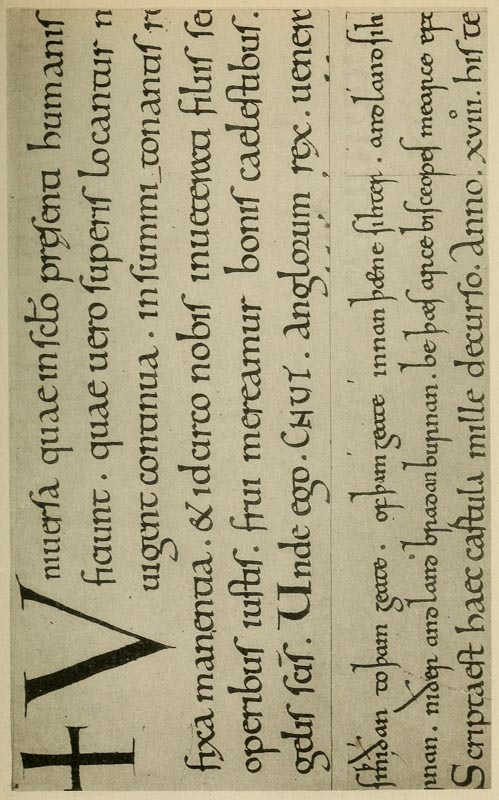

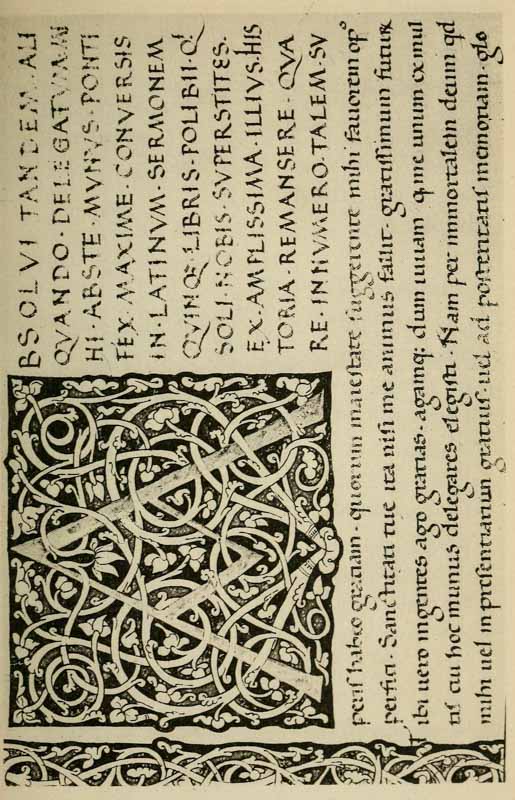

SQUARE CAPITALS were formal, pen-made Roman Capitals, of the monumental type: they were used (perhaps from the second) till about the [p038] end of the fifth century for important books (see Plate III.).

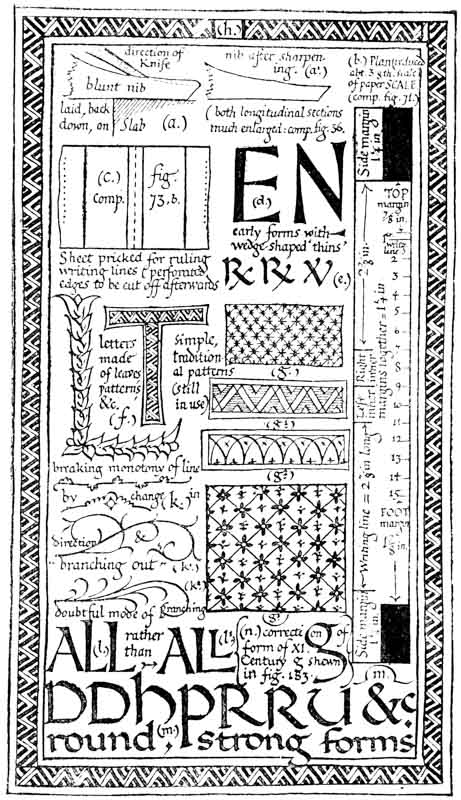

RUSTIC CAPITALS were probably a variety of the “Square Capitals,” and were in use till about the end of the fifth century (fig. 4; see also p. 297).

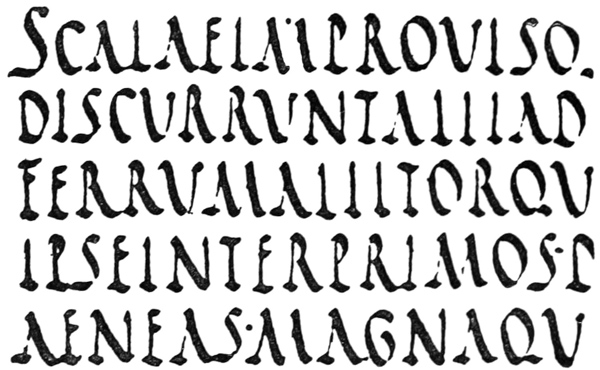

ROMAN UNCIALS were fully developed by the fourth century, and were used from the fifth till the eighth century for the finest books (fig. 5).

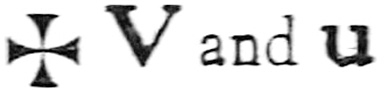

Uncials are true pen-forms8—more quickly written than the “Square,” and clearer than the “Rustic” Capitals—having the characteristic, simple strokes and beautiful, rounded shapes which flow from the rightly handled reed or quill. The [p040] typical Uncial letters are the round D, E, H, M, U (or V), and A and Q (see p. 300).

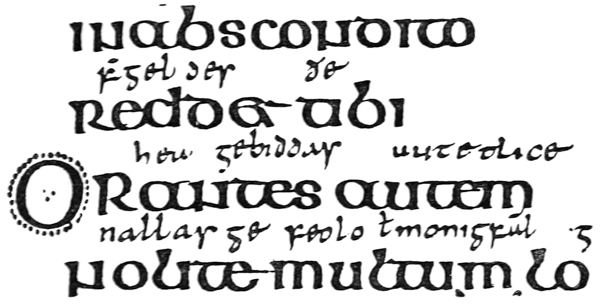

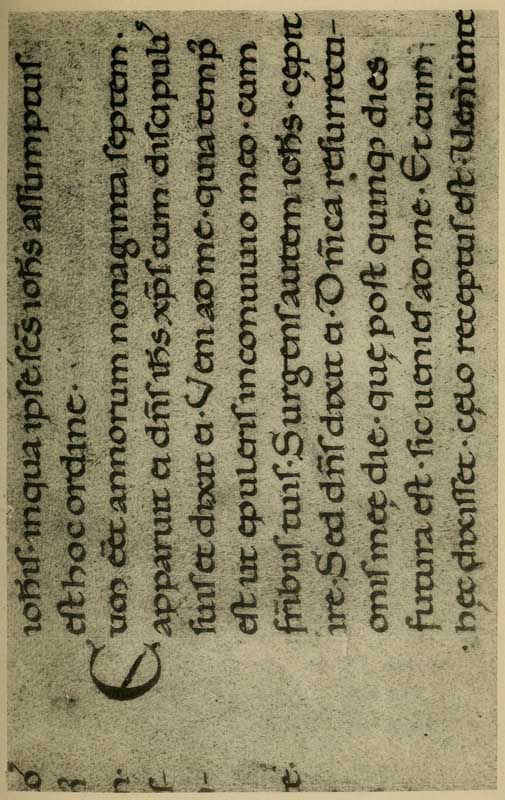

ROMAN HALF-UNCIALS—or Semi-Uncials—(fig. 6) were mixed Uncial and Cursive forms adopted by the scribes for ease and quickness in writing. Their evolution marks the formal change from Capitals to “Small-Letters.”

They were first used as a book-hand for the less important books about the beginning of the sixth century.

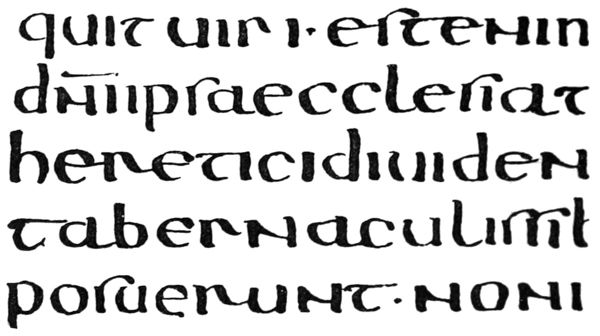

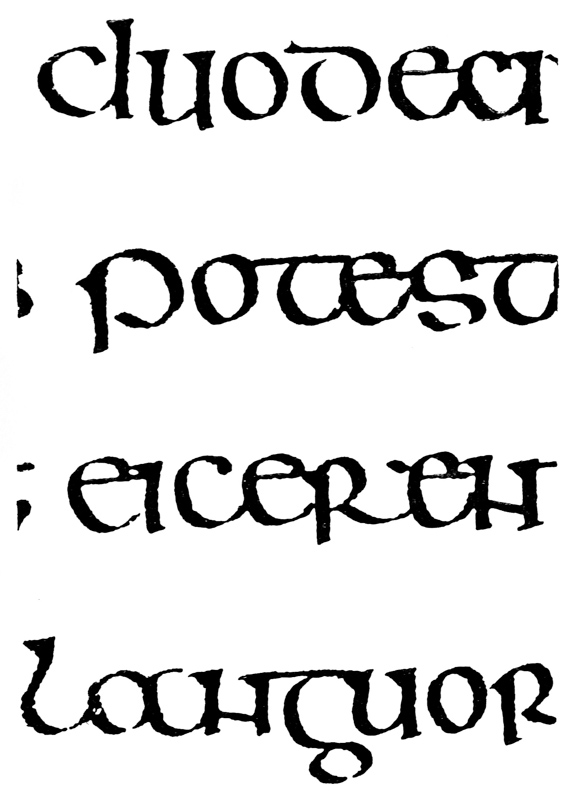

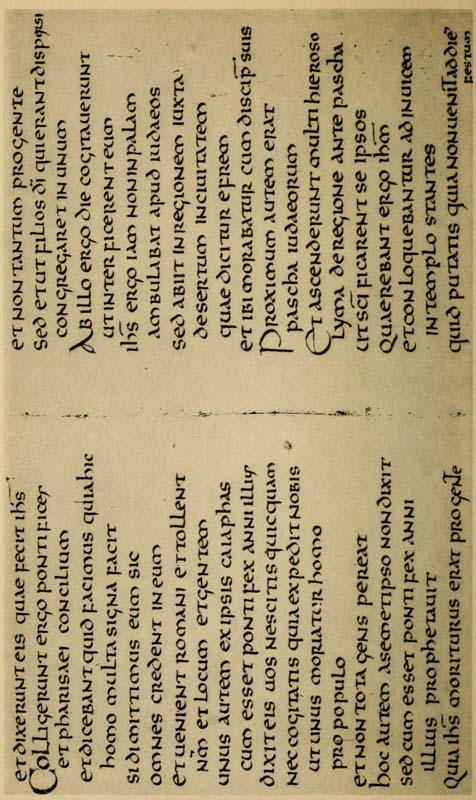

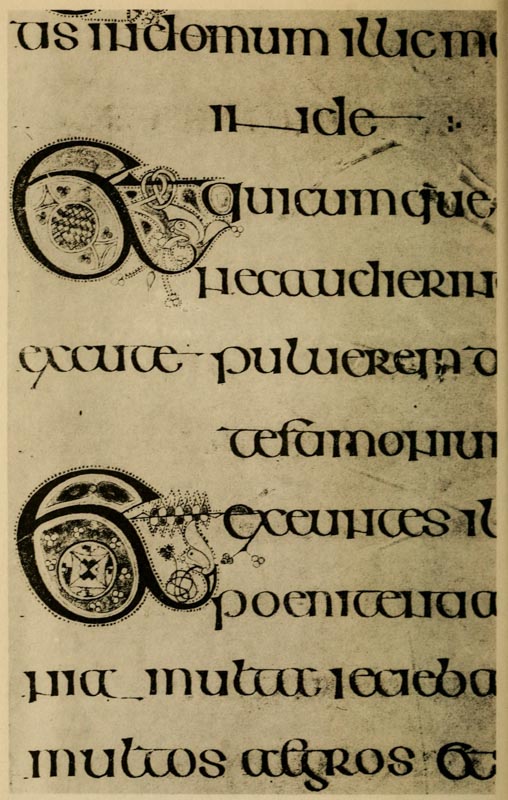

IRISH HALF-UNCIALS were founded on the Roman Half-Uncials (probably brought to Ireland by Roman missionaries in the sixth century). As a beautiful writing, they attained in the seventh century a degree of perfection since unrivalled (see Plate VI.).

They developed in the eighth and ninth centuries into a “pointed” writing, which became the Irish national hand.

ENGLISH HALF-UNCIALS (fig. 7) were modelled on the Irish Half-Uncials in the seventh [p041] century. They also developed in the eighth and ninth centuries into a “pointed” writing.

CAROLINE (or CARLOVINGIAN) WRITING.—While English and Irish writing thus came from Roman Half-Uncial, the Continental hands were much influenced by the rougher Roman Cursive, and were, till near the end of the eighth century, comparatively poor.

“The period of Charlemagne is an epoch in the history of the handwritings of Western Europe. With the revival of learning naturally came a reform of the writing in which the works of literature were to be made known. A decree of the year 789 called for the revision of church books; and this work naturally brought with it a great activity in the writing schools of the chief monastic centres of France. And in none was there greater activity than at Tours, where, under the rule of Alcuin of York, who was abbot of St. Martin’s from 796 to 804, was specially developed the exact hand which has received the name of the Caroline Minuscule.”9 [p042]

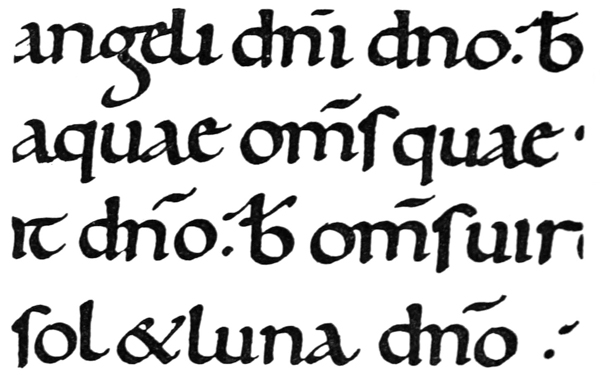

The influence of the Caroline hands (see fig. 8) presently spread throughout Europe. The letters in our modern copy-books may be regarded as their direct, though degenerate, descendants.

SLANTED-PEN or TILTED WRITING.—The forms of the letters in early writing indicate an easily held pen—slanted away from the right shoulder. The slanted pen naturally produced oblique thick strokes and thin strokes, and the letters were “tilted” (see fig. 9).

In the highly finished hands—used from the sixth to the eighth centuries—such as the later Uncials and the Roman, Irish, and English Half-Uncials, the pen was manipulated or cut so that the thin strokes were approximately horizontal, and the thick strokes vertical (fig. 10). The earlier and easier practice came into fashion again in the eighth and ninth centuries, and the round Irish and English hands became “pointed” as a result of slanting the pen.

The alteration in widths and directions of pen strokes, due to the use of the “slanted pen,” had these effects on the half-uncial forms (see fig. 11):—

1. The thin strokes taking an oblique (upward) direction (a) (giving a sharp angle with the verticals (d, a)) led to angularity and narrower forms (a1), and a marked contrast between thick and thin strokes—due to the abrupt change from one to the other (a2).

2. The thick strokes becoming oblique (b) caused a thickening of the curves below on the left (b1), and above on the right (b2), which gave heavy shoulders and feet.

3. The horizontal strokes becoming thicker (c) gave stronger and less elegant forms. [p044]

4. The vertical strokes becoming thinner (d) (with oblique or pointed ends—not square ended) increased the tendency to narrow letters.

It is to be noted that the Caroline letters—though written with a “slanted pen”—kept the open, round appearance of the earlier forms. [p046]

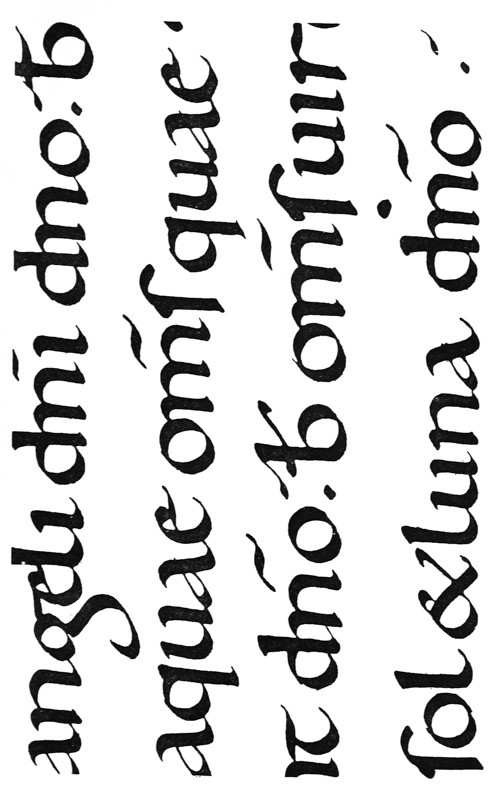

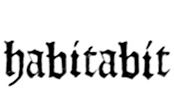

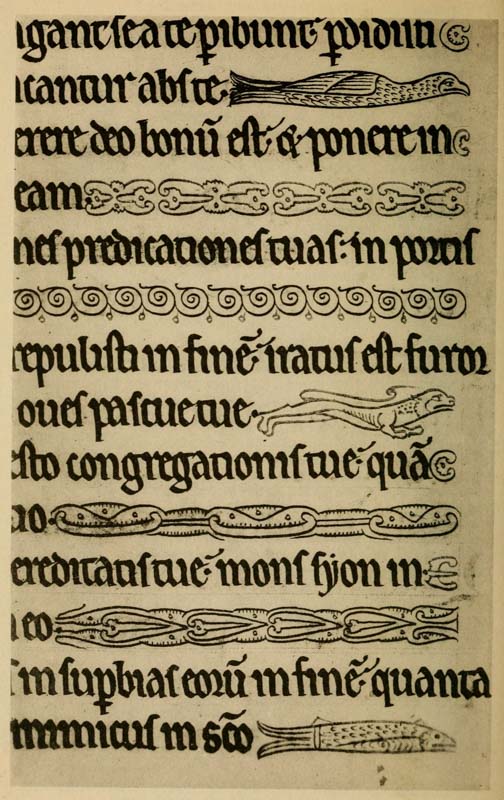

TENTH, ELEVENTH, AND TWELFTH CENTURY WRITING.—The easy use of the slanted pen, and the lateral compression of the letters which naturally followed, resulted in a valuable economy of time and space in the making of books. This lateral compression is strongly marked in the tenth century (see fig. 12), and in the eleventh and twelfth centuries it caused curves to give place to angles, and writing to become “Gothic” in character (see Plate XI.).

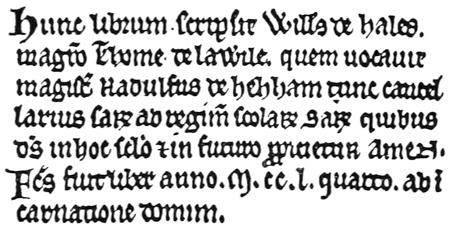

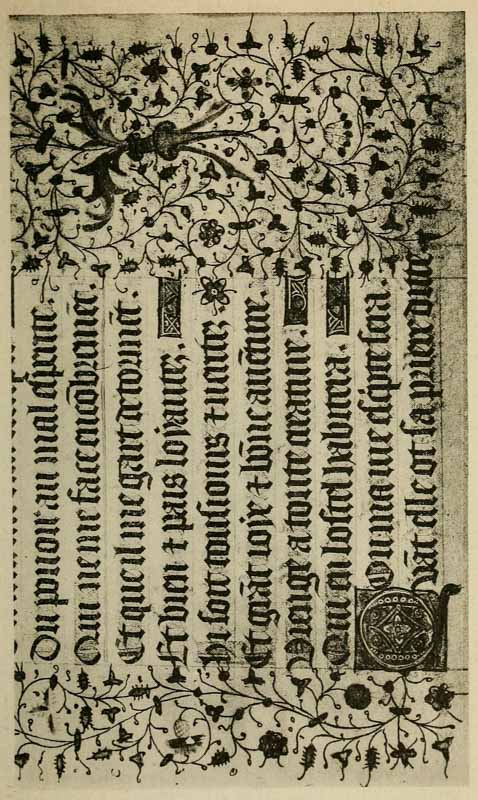

THIRTEENTH, FOURTEENTH, AND FIFTEENTH CENTURY WRITING.—The tendency to compression continued, and a further economy of space was effected in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries by the general use of much smaller writing (see fig. 13). In the fifteenth century writing grew larger and taller again, but the letters had steadily become [p047] narrower, more angular, and stiffer, till the written page consisted of rows of perpendicular thick strokes with heads and feet connected by oblique hair-lines—which often look as if they had been dashed in after with a fine pen—all made with an almost mechanical precision (see Plate XVII.).

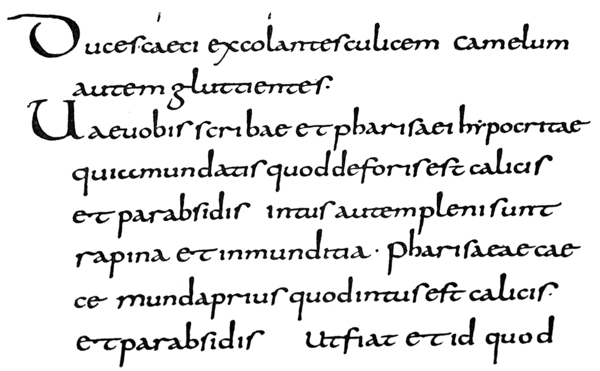

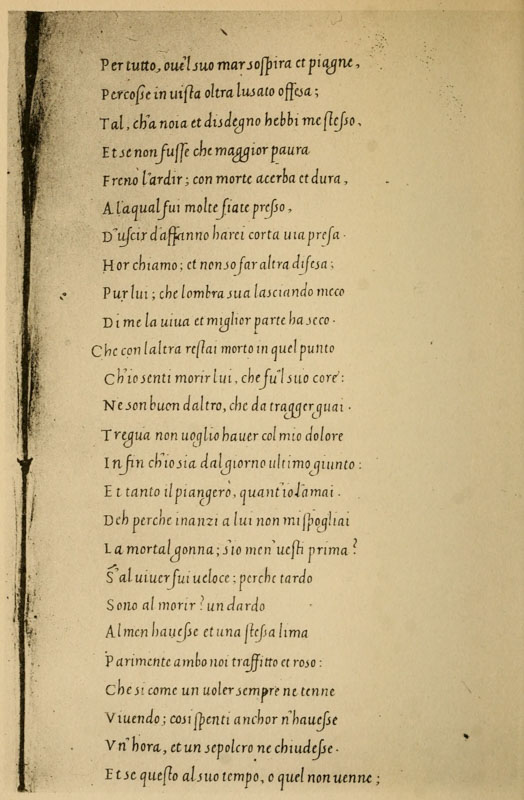

ITALIAN WRITING.—In Italy alone the roundness of the earlier hands was preserved, and though in course of time the letters were affected by the “Gothic” tendency, they never lost the curved forms or acquired the extreme angularity which is seen in the writings of Northern Europe (compare Plates X. and XI.).

At the time of the Renaissance the Italian scribes remodelled their “hands” on the beautiful Italian writing of the eleventh and twelfth centuries (see Plates X. and XVIII., XIX., XX.). The early Italian printers followed after the scribes and modelled their types on these round clear letters. And thus the fifteenth century Italian formal writing became the foundation of the “Roman” small letters, which have superseded all others for the printing of books. [p048]

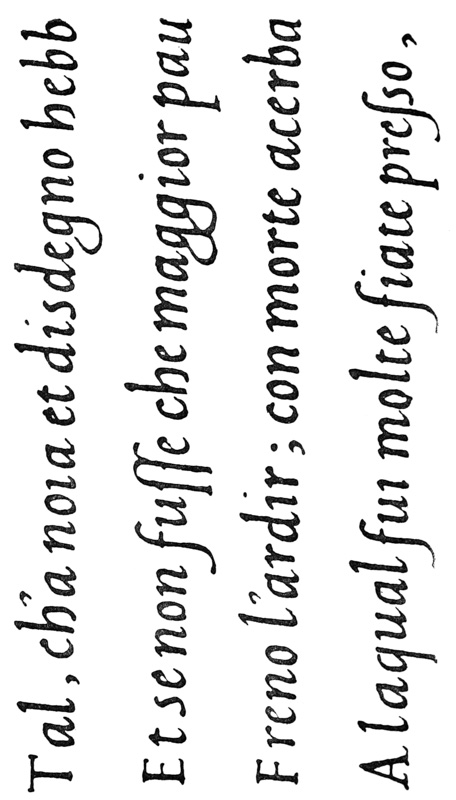

ITALICS.—The Roman Letters, together with the cursive hand of the time, gave rise to “Italic” letters (see fig. 1, & pp. 311, 316, 483).

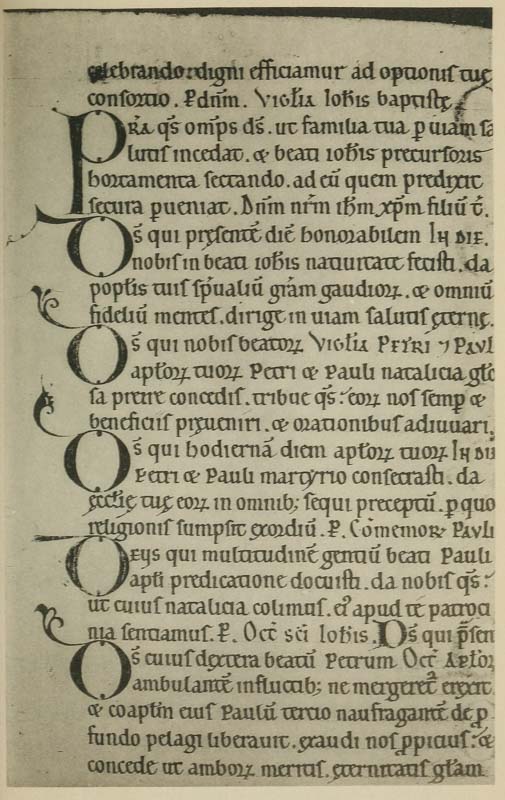

ORNAMENTAL LETTERS originated in the simple written forms, which were developed for special purposes, and were made larger or written in colour (see Versals, &c., fig. 1, 189).

Their first object was to mark important words, or the beginnings of verses, chapters, or books. As Initial Letters they were much modified and embellished, and so gave rise to the art of Illumination (see pp. 113, 114).

The simplest way of learning how to make letters is to acquire a fine formal hand. To this end a legible and beautiful writing (see p. 70) should be chosen, and be carefully copied with a properly cut pen.

For learning to write, the following tools and materials are required:—

An ordinary desk or drawing-board can be used, but the best desk is made by hinging a drawing-board (“Imperial” size) to the edge of a table. The board may be raised and supported at any desired angle by a hinged support, or by a round tin set under it (fig. 14). For a more portable [p050] desk two drawing-boards may be similarly hinged together and placed on a table (fig. 15).

A tape or string is tightly stretched—horizontally—across the desk to hold the writing-paper (which, as a rule, is not pinned on). The lower part of the writing-paper is held and protected by a piece of stout paper or vellum fixed tightly, with drawing-pins, across and over it (fig. 16). Under the writing-paper there should be a “writing-pad,” consisting of one or two [p051] sheets of blotting-paper, or some other suitable substance.10

It is a good plan to have the lower, front edge of the desk bevelled or rounded, so that the tail part of a deep sheet, which may hang below the table, does not become accidentally creased by being pressed against it. A curved piece of cardboard fixed on the edge will answer the same purpose.

For “practice” any smooth—not glazed—paper will do. For careful work a smooth hand-made paper is best (pp. 103, 111).

A good, prepared, liquid (carbon) ink is best. It should be as black as possible, without being too thick. A jet-black ink will test the quality of the writing by “showing up” all the faults; “pale” or “tinted” inks rather conceal the faults, and lend a false appearance of excellence (p. 322). A thin ink greatly adds to the ease of writing (see Addenda, p. 23). Waterproof inks, as a rule, are too thick or gummy, and do not flow freely enough.

The ink-bottle is kept corked when not in use, to keep the ink clean and prevent evaporation. Thick or muddy ink should be put away: it is not worth while trying to use it.

A small brush is used for filling the pen.

V. A pencil or brush-handle is held under the nib, and is gently twitched upwards to lengthen the slit (fig. 21). An ordinary reed should have a slit about 34 inch long. A very stiff pen may have in addition a slit on either side of the centre.

The left thumb nail is pressed against the back of the pen—about 1 inch from the tip—to prevent it splitting too far up (see also fig. 27).

VII. A strip of thin metal (very thin tin, or clock spring with the “temper” taken out by heating and slowly cooling) is cut the width of the nib and about 2 inches long. This is folded into a “spring” (fig. 23).

The loop a b c is “sprung” into place, and holds the spring in the right position. The loop c d, which should be rather flat, holds the ink in the pen. The point d should be about 18 inch from the end of the nib.

THE QUILL.—A Turkey’s Quill is strong, and suitable for general writing. As supplied by the stationers it consists of a complete wing-feather, about 12 inches long, having the quill part cut for ordinary use. For careful writing it should be re-made thus:—

I. The quill should be cut down to 7 or 8 inches (fig. 25); the long feather if left is apt to be in the way.

II. The “barbs” or filaments of the feather are stripped off the shaft (fig. 26). [p055]

III. The nib already has a slit usually about 14 inch long. This is sufficient in a fairly pliant pen; in a very stiff pen (see p. 60) the slit may be lengthened to 38 inch. This may be done with care by holding a half-nib between the forefinger [p056] and thumb of each hand, but the safest way is to twitch the slit open (fig. 27), using the end of another pen (or a brush-handle) as explained under Reed, V. (see p. 53).

IV. The sides of the nib are pared till the width across the tip is rather less than the width desired12 (fig. 28).

V. The nib is laid, back up, on the glass slab, and the extreme tip is cut off obliquely to the slit, the knife blade being slightly sloped, and its edge forming an angle of about 70° with the line of the shaft (fig. 29; see also fig. 36). [p057]

The shaft rests lightly in the left hand (not gripped and not pressed down on slab at all), and the knife blade is entered with a steady pressure.

If the nib is then not wide enough it may be cut again; if too wide, the sides may be pared down.

Cut very little at a time off the tip of the nib; a heavy cut is apt to force the pen out of shape and spoil the edge of the nib.

VI. The nib should then be examined with the magnifying glass. Hold the pen, back down, over a sheet of white paper, and see that the ends of the two half-nibs are in the same straight line a–b (fig. 30).

The nib should have an oblique chisel-shaped tip, very sharply cut (fig. 31).

A magnifying glass is necessary for examining a fine pen; a coarse pen may be held up against [p058] the light from a window—a finger-tip being held just over the nib to direct the eye (fig. 32).

VII. The Spring (see Reed, VII.) (about 332 inch by 112 inch) is placed so that the point is about 116 inch from the end of the nib. The long loop should be made rather flat to hold plenty of ink (A, fig. 35)—neither too much curved (B: this holds only a drop), nor quite flat (C: this draws the ink up and away from the nib).

For ordinary use the nib may be cut with a fairly steep angle, as shown (magnified) at (a) (fig. 36).

But it is better for fine, sharp writing that the angle be made very sharp: the knife blade is laid back (much flatter than is shown in fig. 29) and the quill is cut quite thin; the knife blade is then held vertical and the extreme tip of the nib is cut off sharp and true (b, fig. 36).

For large writing, the curved inside of the quill is pared flat (c, d, fig. 36) [p060] to give full strokes. If the nib be left curved and hollow underneath (e), it is apt to make hollow strokes.

The pen may be made more pliant by scraping it till it is thinner, or by cutting the “shoulder” (a–b, fig. 29) longer, or stiffer by cutting the nib back until the “shoulder” is short.

Goose and Crow Quills (see p. 172).

The main advantages of a quill over a metal pen are, that the former may be shaped exactly as the writer desires, and be re-cut when it becomes blunt.

A metal pen may be sharpened on an oilstone, but the process takes so much longer that there is no saving in time: it is not easily cut to the exact shape, and it lacks the pleasant elasticity of the quill.

A gold pen is probably the best substitute for a quill, and if it were possible to have a sharp, “chisel-edged” iridium tip on the gold nib, it would be an extremely convenient form of pen. A “fountain pen” might be used with thin ink.

THE KNIFE.—Quill makers use a special knife. A surgical scalpel makes an excellent pen-knife. The blade should be fairly stout, as the edge of a thin blade is easily damaged. It should be ground almost entirely on the right side of the blade (fig. 37) and kept very sharp. [p061]

THE SLAB.—A piece of glass (preferably white) may be used for fine quills; hard wood, bone, or celluloid for reed and cane pens.

SHARPENING STONE.—A “Turkey” (fine) or “Washita” (fine or coarse grained) stone.

MAGNIFYING GLASS.—A magnifying glass (about 1 inch in diameter) is necessary for examining fine pen nibs to see if they are “true.” A “pocket” glass is the most suitable for general use, and for the analysis of small writing, &c.

RULE.—A 2, or 3-foot wood rule having brass strips let in to protect the edges, or a metal rule.

LINEN PEN-WIPER.—A piece of an old linen handkerchief may be used to keep the pen clean.

Always write at a slope. This enables you to sit up comfortably at your work, and to see the MS. clearly as though it were on an easel—and, by the resulting horizontal position of the pen, the ink is kept under control. It may be seen from ancient pictures that this was the method of the scribes (see Frontispiece). Never write on a flat table; it causes the writer to stoop, the MS. is seen foreshortened, and the ink flows out of the pen too rapidly. [p062]

The slope of the desk may be about, or rather less than, 45° to begin with: as the hand becomes accustomed to it, it may be raised to about 60° (fig. 38).

The “heel” of the right hand may be tired at first, but it soon grows used to the position. A rest for the left arm, if necessary, can be attached to the left side of the board.

Lighting. The desk is placed very near to a window, so that a strong light falls on it from the left. Direct sunlight may be cut off by fixing a sheet of thin white paper in the window. Careful work should be done by daylight. Work done by artificial light always appears faulty and unsatisfactory when viewed by day.

Each penman will find for himself the writing level along which his pen will move most naturally and conveniently (see figs. 39 and 16). The paper guard should be pinned on about 1 inch below the [p063] writing level: the tape is fixed across about 3 inches above the guard. In the case of very large writing the space between the tape and the guard is greater, and in the case of a very small MS. it is less.

The writing level is kept constant. When one line has been written, the writing paper—which is placed behind the tape and the guard—is pulled up for another line.

For the practical study of pen-forms use a cane or a reed pen—or a quill cut very broad—giving a broad, firm, thick stroke. It is the chisel edge (p. 57) of the nib which gives the “clean cut” thick and thin strokes and the graduated curved strokes characteristic of good writing (fig. 40).

Therefore, let the nib glide about on the surface with the least possible pressure, making natural pen-strokes the thickness of which is only varied [p064] by the different directions in which the nib moves (see Addenda, p. 23).

It is very important that the nib be cut “sharp,” and as often as its edge wears blunt it must be resharpened. It is impossible to make “clean cut” strokes with a blunt pen (see Addenda, p. 25).

When the nib is cut back, the “shoulder” should be cut back to preserve the elasticity of the pen (p. 60).

The hand holds the pen lightly and easily. A good method is to loop the thumb and forefinger over, and slightly gripping, the shaft of the pen, and support the shaft from below with the second finger. The third and fourth fingers are tucked, out of the way, into the palm (figs. 41, 45).

The pen should be so lightly held that the act of writing should draw the edge of the nib into perfect contact with the paper, both the half-nibs touching the surface. (To make sure that the contact is perfect, make experimental thick strokes on a scrap of paper—pinned at the right-hand side of the desk—and see that they are “true,” i.e. that they are of even width, with “clean cut” edges and ends.) The writer should be able to feel what the nib is doing. If the pen be gripped stiffly the edge of the nib cannot be felt on the paper; and it will inevitably be forced out of shape and prematurely blunted.

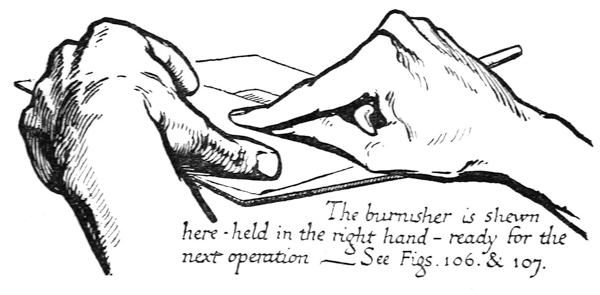

A thin slip of bone—a “folder” or the handle of the pen-knife will do—is commonly held in the left hand to keep the paper flat and steady (see fig. 41). [p065]

THE CUSTOMARY MANNER.—The ancient scribe probably held his pen in the manner most convenient to himself; and we, in order to write with freedom, should hold the pen in the way to which, by long use, we have been accustomed; provided that, for writing an upright round-hand, the pen be so manipulated and cut as to make fine horizontal thin strokes and clean vertical thick strokes (see fig. 40, & footnote, p. 304).

SLANTED SHAFT, &c.—Most people are accustomed to holding a pen slanted away from the right shoulder. The nib therefore is cut at [p066] an oblique angle13 to the shaft, so that, while the shaft is slanted, the edge of the nib is parallel with the horizontal line of the paper, and will therefore produce a horizontal thin stroke and a vertical thick stroke. For example: if the shaft is held slanted at an angle of 70° with the horizontal, the nib is cut at an angle of 70° with the shaft (fig. 42). The angle of the nib with the shaft may vary from 90° (at right angles) to about 70°, according to the slant at which the shaft is held (fig. 43).

If the writer prefers an extremely slanted shaft, to cut the nib correspondingly obliquely would weaken it, so it is better to counteract the slant by slightly tilting the paper (fig. 44).

To produce the horizontal thin stroke, therefore:

must be so adjusted, one to another, that the chisel edge of the nib is parallel to the horizontal line of the paper. Before writing, make trial strokes on a scrap of paper to see that this is so: the vertical thick strokes should be square ended and the full width of the nib, the horizontal strokes as fine as possible.

HORIZONTAL SHAFT, &c.—The pen shaft is held approximately horizontal. This will be found the natural position for it when the slope [p068] of the desk is about 50° or 60°. It gives complete control of the ink in the pen, which can be made to run faster or slower by slightly elevating or depressing the shaft (fig. 45).

The writing-board may be slightly lowered or raised with the object of elevating or depressing the pen shaft (fig. 46 & p. 118).

The pen makes a considerable angle with the writing surface, so that the ink, which is held in the hollow of the nib, comes in contact with the paper at the very extremity of the nib, making very fine strokes (a, fig. 47).

It is convenient to stand the ink, &c., beside the desk on the left, and for this purpose a little cup-shaped bracket or clip may be attached to the edge of the writing-board. The filling-brush stands in the ink-bottle (p. 51) or pot of colour (p. 176), and is taken up in the left hand; the pen, retained in the right hand, being brought over to the left to be filled.

The back of the nib is kept dry (a, fig. 48). A very convenient and perfectly clean method, when care is taken, of removing any ink on the back of the pen is to draw it across the back of the left fore-finger.

In careful work the pen should be tried, on a [p070] scrap of paper, almost every time it is filled (to see that it is not too full and that the ink is flowing rightly).

The nib is kept clean. A carbon ink (p. 51), through gradual evaporation, is apt to clog the nib (especially in hot weather); therefore every now and then, while the nib is in use, the spring is taken out and the whole thoroughly cleaned. It is impossible to write well with a dirty pen.

The best training is found in the practice of an upright round-hand (p. 302). Having mastered such a writing, the penman can acquire any other hands—sloping or angular—with comparative ease (p. 323).

The English Half-Uncial writing in Plate VII. is an excellent model. Those who have sufficient time to spare for the careful study of this, or any other legible and beautiful round-hand, should obtain access to the MSS. in a museum, or procure good facsimiles (see Plates at end of Book, & p. 388).

Those who have not sufficient time for a careful and thorough study of an early MS. will find it [p071] easier to begin with a simplified and modernised writing, such as Script I. (fig. 49).

Before copying a hand it is well to examine carefully the manuscript from which it is taken: observe its general appearance: note the character and mode of the ruling, and the sizes and relative proportions of page, text, margins, and ornaments. With regard to the actual forms of the letters and the mode of their arrangement, such a method of analysis as the following will be found useful, as an aid to accuracy in copying, and definiteness in self-criticism. [p072]

A METHOD OF ANALYSIS. |

Example: Analysis of Script I. (as in fig. 50). | |

|---|---|---|

| 1. THE WRITING | general character: | Modernized Half-Uncial. |

| (Ruling) | Double or single lines, &c. (see pp. 304, 305): | Double lines (see figs. 59, 65). |

| Letters | round or angular: | round. |

| upright or sloping: | upright. | |

| coupled or separate: | coupled. | |

| 2. THIN STROKES: | horizontal or oblique (see figs. 10, 9): | horizontal. |

| 3. THICK STROKES: | heavy, medium, or light (see fig. 183): | medium. |

| 4. “HEADS” & “FEET”: | character (see fig. 145): | solid, triangular, &c. |

| 5. STEMS (ascending & descending): | short, medium, or long (see fig. 183): | medium. |

| 6. SPACING (Letters, Words, Lines): | close or wide (see fig. 154): | fairly close (see figs. 54, 55). |

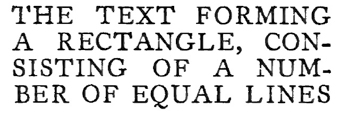

| 7. ARRANGEMENT: | in mass (of equal lines), or in column (of unequal lines) (see fig. 154): | in mass of equal lines (see fig. 66). |

| 8. MEASUREMENTS (& proportions see pp. 324, 327): | width of thick stroke (see p. 83): | l = about 332″ wide. |

| height of o and d (see pp. 82, 84): |

| |

| writing lines, distance apart (see p. 82): | Lines 1″ apart. | |

| 9. COMPONENT PARTS: | number and forms (see pp. 75, 81, 84): |

|

The pen generally is held so as to give approximately horizontal thin strokes (see p. 66), but in making v (w, y) and x, parts of z, &c., it is “slanted.” In figs. 51 and 57 these forms are marked with a small diagonal cross × (see also p. 25).

Most of the strokes begin as down-strokes, but at the end of a down-stroke, when the ink is flowing freely, the stroke may be continued in an upward direction (as in coupling-strokes, &c., the feet of letters, the thin stroke of x, and, if preferred, in making the last stroke of g, s, and y).

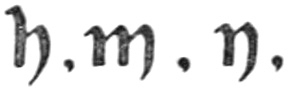

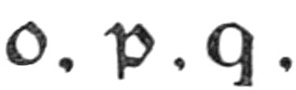

While the ink is still wet in a down-stroke, the nib may be replaced on it and be pushed upward and outward to form the round arch in b, h, m, n, p, and r. This stroke, reversed, is also used for the top of t.

The making of these UP-strokes is shown diagrammatically in fig. 51.

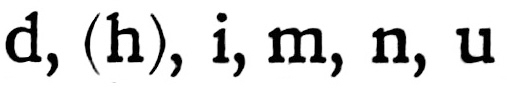

Note.—The forms +oin× in fig. 51 contain all the principal strokes in this alphabet, and are therefore useful for early practice.

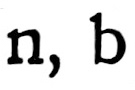

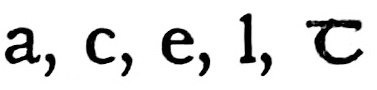

The letters are joined together by means of their coupling-strokes, which for this purpose may be slightly drawn out, and forward, from the naturally round forms of the letters (see c, e, &c., fig. 52 & fig. 59).

The coupling-strokes are finishing strokes—and as such are akin to serifs (p. 244)—growing out of or added to such stems as need “finishing.”

Coupling enables one to write faster and with [p076] more freedom, the concluding or “coupling” stroke not being slowed down, but written with a dash, which is covered by the first stroke of the succeeding [p077] letter. It keeps the individual words more distinct, and therefore permits closer spacing of the text. Coupling is for convenience and legibility, and where it tends to interfere with legibility, we must be careful. The freer and more cursive the hand, the greater is the tendency to join and run letters together, as in ordinary writing.

It is preferable to couple letters below, if possible. Couplings above are sometimes apt to confuse the reading; for example, the cross-bar of t (though the most natural coupling for the scribe to use—see petatis, Plate VII.) should generally be made to pass over or fall short of the succeeding letter (see fig. 52).

The letters of a word are fitted together so that there is a general effect of evenness. This evenness is only to be attained by practice: it is characteristic of rapid skilful writing, and cannot be produced satisfactorily by any system of measurement while the writer’s hand is still slow and uncertain. It is worth noting, however, that the white interspaces vary slightly, while the actual distances between the letters vary considerably, according to whether the adjacent strokes curve (or slant) away or are perpendicular (figs. 53, 152).

It is sufficient for the beginner to take care that two curved letters are made very near each other, and that two straight strokes are spaced well apart.

If the curves are too far apart there will be spots of light, and where several heavy stems are made too close together, “blots” of dark, marring the evenness of the page. [p078]

Words are kept as close as is compatible with legibility. The average space between two words is the width of the letter o (fig. 54). [p079]

The Lines in massed writing (see p. 262) are kept as close together as is compatible with legibility. The usual distance apart of the writing-lines is about three times the height of the letter o (see also p. 327).

The descending strokes of the upper line must “clear” the ascending strokes of the lower line. Interlocking of these strokes may be avoided by the experimental placing of p over d (fig. 55).

These modernised Uncials (see fig. 56, & p. 300) are intended to go with Script I., and their analysis and mode of construction are almost identical with those of Script I. (see pp. 72, 73). [p082]

Grouping: Uncials have no coupling-strokes; when several are used together, they are not joined, but evenly grouped, allowing as before for curves and straight strokes (see p. 77).

Note.—The height of Uncial o is about equal to the height of the Half-Uncial d.

These are best made with a “slanted” pen (fig. 9).

When writing “Arabic numerals,” 1 and 0 may be made on the line, 2468 ascending, and 3579 descending.

When copying a MS. it is best to choose a complete page—or part of a page—to be copied in facsimile.

Two or three lines are copied to begin with; then the composition of the individual letters and words is studied by means of a large pen; and finally the whole page is copied in facsimile. (Of practising, see pp. 85, 86).

Make a general examination and analysis as suggested at p. 71. Accurate measurements will be found helpful.

Take the heights of the o and the d, and the distance apart of the writing-lines with dividers [p083] The width of the thick stroke is best found by making experimental thick strokes—the full width of the pen nib—on a scrap of paper: cut the paper in half across the thick strokes, and place the cut edge on the thickest strokes in the original MS., you will then find whether the pen nib should be cut wider or narrower.

The direction of the thickest strokes is approximately at right angles to the direction of the thin strokes; which commonly approaches the horizontal in early round hands, and is oblique in other hands (see fig. 9 and 10). The positions both of these strokes in the model, and of your pen, determine the angle of the nib. Therefore, cut the nib across at such an angle to the shaft of the pen that, when you hold the pen naturally, the direction of the thin strokes which it makes on the writing paper will coincide with the direction of the thin strokes in the model; but

may all be slightly varied, so that the direction of the thin strokes can be followed exactly (see p. 66).

The writing paper is cut and ruled exactly in accordance with the model; and the heights of the letters and the widths of the thick strokes in the copy agree as nearly as possible with those in the original. It is therefore a good test for accuracy—when a few lines of writing have been copied—to measure and compare their lengths. If they correspond with their originals, it goes far to prove the copy a good one.

Before copying more of the page, the construction of the letters should be carefully studied. The number and the forms of pen-strokes in each letter [p084] are found by examination—with a magnifying glass if necessary—and by the experimental putting together of strokes, to form a similar letter. For this a large pen, such as a reed, is useful, and it is a good plan to write individual letters and words exactly two, three, or four times their height in the model: both the pen nib and the individual letters are made correspondingly two, three, or four times as wide as in the original.

It is particularly important, in copying, to preserve accurately the proportion of the thick stroke to the height and width of a letter (see p. 324). These are conveniently measured by the pen nib itself, or by the estimated width of the thick stroke; thus, in the writing shown in fig. 50, the width of the o is approximately five, and the height approximately four, times the width of the thick stroke.

Not only must the copier ascertain what the forms are like and what are their proportions, but he must try to find out how they were made. This is of the greatest importance, for the manner of making a letter, or even a single stroke, affects its form and character with a definite tendency (see p. 416 & fig. 172). And this becomes more marked the faster the writing. An apparently right form may yet be wrongly—if slowly—made; but in rapid writing, a wrong manner of handling the pen will inevitably produce wrong forms. As the real virtue of penmanship is attained only when we can write quickly, it is well worth training the hand from the beginning in the proper manner.

Patient and careful examination should be made of the changing pen-strokes, and of the mode in which they join—to form letters—and begin and end—to form “heads” and “feet.” This, accompanied [p085] by practical experiments in cutting and handling the pen, will bring out details of the utmost technical value. A certain amount of legitimate “faking” (p. 246), play of the pen, and sleight of hand (p. 311), may be found, but, in the main, the regular, natural, thick and thin strokes of the pen, and the orderly arrangement of the writing, give to a manuscript its beauty and character.

Then having cut the nib rightly, you may, in a sense, let the pen do the writing, while you merely follow the strokes of the model, and you will, in course of time, have the pleasure of seeing the same beautiful writing—in the very manner of the ancient scribes—growing under your own hand.

In acquiring a formal writing the penman should have two paper books constantly in hand: one for the study of the forms of letters, the other for both the letters and their arrangement. The first should contain large and very carefully made writing—with perhaps only one word to the line; the second [p086] should have smaller and quicker writing, neatly arranged on the pages, with four or five words to the line. (See MS. Books, Chap. VI.)

A broad nib is used in preference to a narrow one, so that the characteristics of true pen-work are brought out and the faults made clear. A fine, light handwriting is often very pretty, but it is certain to mislead the novice in penmanship (see p. 324).

Having acquired a formal hand the penman may modify and alter it, taking care that the changes are compatible, and that they do not impair its legibility or beauty. Such letters as are obsolete he replaces by legible forms akin to them in feeling, and, the style of the selected type becoming very naturally and almost unconsciously modified by personal use, he at length attains an appropriate and modern Formal-Handwriting. The process of “forming” a hand requires time and practice: it resembles the passage of “Copy-book” into “Running” hand, familiar to us all (see p. 323).

Having cut

the nib of a

reed or large

quill to the

exact width required for the thick stroke, copy the

component strokes of the letter

(Script I.), and

[p087]

immediately make the complete letter: go through

the whole alphabet in this way several times (fig.

58). Next join the letters together (see p.

73)

[p088]

to form words—writing always between ruled lines

(fig.

59 & p.

414).

(Script I.), and

[p087]

immediately make the complete letter: go through

the whole alphabet in this way several times (fig.

58). Next join the letters together (see p.

73)

[p088]

to form words—writing always between ruled lines

(fig.

59 & p.

414).

Script II. is similarly practised: the letters are grouped (p. 82) to form words (fig. 60).

Next make a neat page of large writing, and, if possible, write such a page every day. The more definite and methodical practice is, the better. “Practising” anyhow, on scraps of paper, does more harm than good.

The size of an inscription is commonly settled before the arrangement of the text is planned out, being determined by considerations of its future position and office, or by custom and use (see pp. 100–103 & 351). [p089]

The proportions of the writing, spacing, and margins will likewise properly settle themselves (see pp. 265, 103, 107), but where the size of the sheet only is fixed, we have, broadly speaking, to decide between “large” writing with “small” margins (fig. 61), and “small” writing with “large” margins (fig. 62).

Generally a compromise is arrived at and the proportions are more evenly balanced (fig. 63).

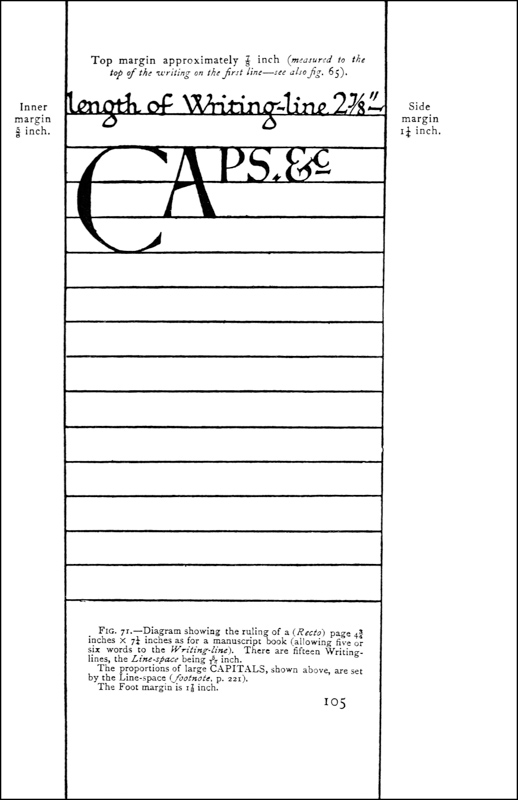

Ruling (see also pp. 258, 99).—The mode of ruling marginal lines and writing lines is shown in fig. 65. The ruling should be light, but firm and accurate. A fine pen, or hard pencil, or a blunt point may be used. Where the writing lines are double (as for round hands, p. 304), it is best to have a double ruling point (see fig. 77). Two hard pencils firmly [p090] lashed together make a convenient tool for large work: the distance between the points is easily adjusted by means of a small wedge.

To write out the Pater noster (50 words) in a formal round-hand (arranged in “mass” of equal lines) on a sheet of “foolscap” (i.e. 17 inches high and 1312 inches wide).

If the size of the writing be considered of the first importance, a few words are written out in a script chosen to suit the subject, the space, &c., and these are measured to find the area which the whole text so written would occupy (fig. 64). The size of the script is then modified, if necessary, to suit the available area. [p091]

Frequently it is desirable first to determine the sizes of the margins. These depend on various considerations of the position and office of the MS., but more particularly on the size of the sheet and the character of its future environment14 (see p. 351).

The top and side margins may be of equal width—or the top may be a little less (see a, fig. 70). Ample space should be allowed for the foot margin, which is generally about twice the width of the top, but may vary in different cases, according as the text falls short of or encroaches upon it (see pp. 352, 342). For a plain foolscap sheet: sides (each) 212 inches, top (approx.) 2 inches, and foot (approx.) 4 inches, may be taken as suitable margins (fig. 65).

The width of the sheet (1312 inches) less the two side margins (212 inches each) gives the length of the writing lines (1312 – 5 = 812 inches). One or two such lines are written experimentally in a suitable script (say, 516 inch), and the average number of words per line (four) is found.

The number of words in the complete text (fifty) will determine the number of lines: an extra line or so may be allowed for safety (504 = 1212, say, thirteen). The spacing of these is calculated—

516 in. writing requires about 78 in. (close) spacing (p. 79): Thirteen lines at 78 in. gives 1138 in. = depth of text: 1138 in. from 17 in. leaves 558 in.15 for head and foot margins

—and if the space is not sufficient, the writing is made a little smaller. If, on the other hand, the [p095] marginal depth left over were excessive, the writing might be made a little larger in order to fill up the space.

To write out “He that is down, needs fear no fall,” in a formal round-hand on a sheet of foolscap (i.e. 17 inches high × 1312 inches wide).

Here there are three verses of four lines each: these with two space lines, left between the verses, give a total of fourteen lines (fig. 67).

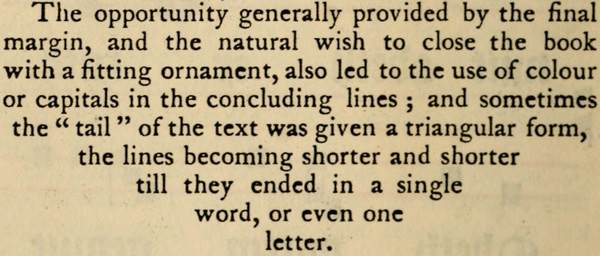

A poem has a given number of lines of various lengths, and only very strong reason or necessity can justify our altering its proper form (e.g. by breaking up the lines) in order to make a mass of equal lines. Such theoretical margins as are possible in the treatment of prose can therefore seldom be observed in writing out a poem, and, unless the height or the width of the sheet can be altered, there is apt to be an excess of margin in one or the other direction. When such excess margin is obviously unavoidable, no objection can be made to its appearance. Poetry may conveniently be treated as “fine writing” (see p. 263).

If the size of the writing be considered of the first importance, several of the longer lines (e.g. the first and the eleventh in the poem given) are written on a piece of paper in the size of writing preferred (say, 14 inch). By laying this paper on the given sheet, it is seen whether such lines would allow of sufficient side margins. (If they would not, the writing may be made smaller.)

The height of the writing (14 inch) must allow of the full number of lines (fourteen) being properly [p097] spaced on the sheet (17 inches) with sufficient head and foot margins. This is calculated—

14 in. writing requires approximately 34 in. spacing (p. 79): Fourteen lines at 34 in. gives 1012 in. = depth of text: 1012 in. from 17 in. leaves 612 in. for head and foot margins

—and if the space were not sufficient, the lines might be made a little closer, or the writing a little smaller (or, if necessary, the blank lines might be left out between the verses; p. 123).

The Sizes of the Margins.—It will be seen that the above method is primarily for settling a length of line which will allow of sufficient side margins. The process can be reversed; if necessary, the side margins are made of a given width, thus determining the exact length of the line, the size of writing which this line allows being found experimentally.

Note.—The extra long lines may slightly encroach on the right-hand margin: the effect of this is balanced by the falling short of other lines.

In penmanship great nicety of spacing and arrangement is possible. The ascending and descending strokes may be shortened or drawn out, the spaces between letters and words may be slightly increased or decreased, the lines may be written near or far apart, and the letters may be written with a broader or narrower nib.

Elaborate spacing and planning, however, should not be attempted at first, and straightforward, undesigned work is often the best. The student is apt to waste time writing out an elaborate draft [p098] in order to ascertain how to space the matter. This is a mistake, because if written well, it is a waste of good writing on a mere draft; if written ill, it is bad practice. The briefer experiments and calculations are, the better, though the simplest problem always requires for its solution a calculation or process of guess and trial (such as suggested in the preceding pages). Practice will make people very good guessers, and the best work of all is done when the worker guesses rightly, and follows his guesses with the actual work, itself the trial and proof of accuracy.

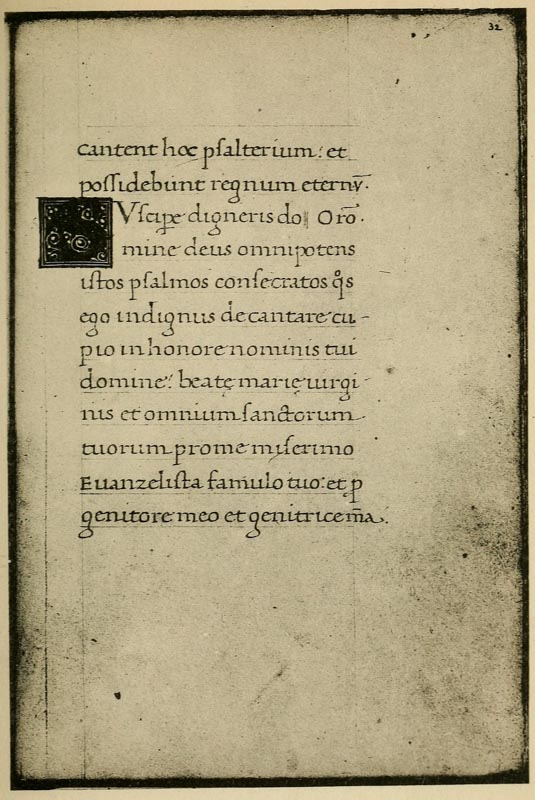

The making of manuscript books, based on a study of the early MSS., offers the best training to the scribe and illuminator in writing, lettering, rubricating, gilding, illuminating initials and borders, and miniature painting, and is the best means of mastering the foundations of Book Typography and Decoration.

Materials, &c. for MS. Books; Paper (see pp. 51, 103, 111, 317); Vellum and Parchment and Pounce [p099] (see pp. 110, 167, 173–5).—Cut a small sheet the size of a page of the book, and clip the long edge between two flat pieces of wood (holding it as it would be if bound). If the page will bend over and stay down by its own weight, it is thin enough (R fig. 68); if it stands up (W), it is too stiff.

Cutting Sheets.—A frame or template (the size of the sheet desired) is used by parchment makers. It is useful for cutting out the sheets for a common size of parchment book. They are cut on the end-grain of wood, or on card or glass.

Folding.—A Folder, as used by bookbinders (or a bone paper-knife), is useful, and also a Set or T-Square for testing right angles, &c. The fold and the top edge of each book-sheet are commonly squared by proper folding.

Ruling, &c. (see p. 343).—For marking distances of lines, a carefully prepared paper17 scale or pattern (p. 25) and an awl (p. 109), or a [p100] “star-wheel”—having regular intervals between the spikes—may be used. Or the ruling—of the writing lines—may be simplified by using a stout card frame (internally the size of the text-column) with strips glued across it: for a common size of book this might be made in stout tin or other metal. The lines are commonly ruled with a ruling stylus (see figs. 72, 77), or a sort of “rake” may be made to rule six lines at once.

Writing, Colouring, Gilding, Binding (Chaps. II., X., IX., XVI.).

Having to make a manuscript book for a specific purpose, the scribe formulates in his mind a general plan of the work, and decides approximately the respective sizes of page and of writing which seem most suitable.

He endeavours to fashion the book in accord with its use, and therefore allows the (most suitable) material, the subject-matter and the office of the book, and the way in which it will be read and handled, to determine as far as is possible the proportions of its parts, and its treatment as a whole.

Its material may be vellum, parchment, or paper, on which a variety of pens, brushes, and other tools, with inks, colours, and metal foils, may be employed. Its office may be “useful” or “ornamental”; its contents may be long or short, weighty or light, and of greater or less worth; it may be for public or for private use; and the book may be intended to be placed on a lectern, to be held in the hand, or to be carried in a coat pocket.

In following out such natural indications, the [p101] practised craftsman relies greatly on his working methods, preferring a direct mode of treatment to one which is too ingenious or subtle. In deciding a doubtful point, a common-sense of proportion is a sufficient guide, and one may generally assume that great works are best “writ large,” and that large letters look best on an ample page, and vice versâ.

The main proportions which have to be considered are interdependent, and follow one another in their natural order (see p. 256), thus—

And the methodical scribe makes his books of certain definite and regular sizes, each size having corresponding and regular proportions of margins and writing. Though these may greatly depend on individual taste and experience, it is suggested that—like all good designs—they should be allowed as far as possible to settle and arrange themselves.

A book is thought of by the scribe chiefly as an open book, and the width and height of its pages are chosen with a view to its convenient shape and pleasant appearance when open. The most economical sizes into which a suitable sheet of paper can be folded (or a skin of parchment can be cut) may commonly be allowed to decide these proportions.