We are told by writers of antiquity that elephants have written sentences in Greek, and that one of them was even known to speak. There is, therefore, nothing unreasonable in the supposition that the White Elephant of this history, the famous "Iravata" so celebrated throughout Asia, should have written his own memoirs.

The story of his long existence—at times so glorious, and at other times so full of misfortune—in the kingdom of Siam, and the India of the Maharajahs and the English, is full of most curious and interesting adventure.

After being almost worshipped as an idol, Iravata becomes a warrior; he is made prisoner with his master, whose life he saves, and whom he assists to escape.

Later he is deemed worthy to be the guardian and companion of the lovely little Princess Parvati, for whose amusement he invents wonderful games, and to whom he renders a loving service.

We see how a wicked sentiment having crept into the heart of the faithful Elephant, usually so wise and good, he is separated for a long time from his beloved Princess, and meets with painful and trying experiences.

But at last he once more finds his devoted friend the Princess, and her forgiveness restores him to happiness.

J. G.

My DEAR CHILDREN:—

This Story was written by Mademoiselle Gautier, a French lady who lives in Paris. She is very handsome, and very learned, and is able to write and speak Chinese, which is the most difficult language in the world.

She has also written beautiful tales of Persia, Japan, and other far-away countries.

This Story was meant for French children, but I have made it into English, so that my little American friends can have the pleasure of hearing all about "Iravata" the good and wise Elephant, and his friends, the King and Queen of Golconda, and the charming little Princess Parvati.

Iravata meets with many surprising adventures. At one time he becomes a "War-Elephant," and goes into battle in magnificent armour carrying the King on his back. He fights tremendously, but nevertheless is taken prisoner, and the King, his master, is condemned to death by his cruel enemies. But the clever Elephant finds a way to liberate his Master, and they escape together, and after many adventures reach home safely.

Later on Iravata becomes restless and unhappy, and runs away, and after many wanderings, he joins a Circus. Here he performs many amusing feats. But, growing homesick, he is at last only too glad to return to his home in the Palace of Golconda, where he lives happily ever after.

S. A. B. H.

Atlantic City, 1916.

| I. | THE STUDENT OF GOLCONDA | |

| II. | THE NATIVE FOREST | |

| III. | THE TRIUMPHAL PROCESSION | |

| IV. | ROYAL ELEPHANT OF SIAM | |

| V. | THE DOWRY OF THE PRINCESS | |

| VI. | THE DEPARTURE | |

| VII. | THE LIGHT OF THE WORLD | |

| VIII. | BATTLE | |

| IX. | THE ESCAPE | |

| X. | GANESA | |

| XI. | WE ARE TAKEN FOR ROBBERS | |

| XII. | PARVATI | |

| XIII. | MY PRINCESS | |

| XIV. | ELEPHANT GAMES | |

| XV. | SCIENCE | |

| XVI. | FINE CLOTHES | |

| XVII. | THE ABDUCTION | |

| XVIII. | RETRIBUTION | |

| XIX. | THE HERMIT | |

| XX. | DESPAIR | |

| XXI. | JEALOUSY | |

| XXII. | FLIGHT | |

| XXIII. | THE HERD | |

| XXIV. | THE BRAHMAN | |

| XXV. | THE IRON RING | |

| XXVI. | "THE GRAND CIRCUS OF THE TWO WORLDS" | |

| XXVII. | MY DEBUT | |

| XXVIII. | COMEDIAN | |

| XXIX. | THE RETURN TO PARADISE |

ILLUSTRATIONS

A SPLENDID PROCESSION WAS FORMED AND BEGAN ITS MARCH. I FOLLOWED NEXT AFTER THE KING

TRANSPORTED WITH RAGE I RAN AT HIM, SEIZED HIM WITH MY TRUNK AND DRAGGED HIM FROM THE SADDLE

PARVATI RAN TO HIM, LAUGHING AND QUITE RECOVERED

"WHICH OF YOU HAS BEEN GOOD?" SHE INQUIRED

I UTTERED A SUDDEN ROAR AND AT THE SAME TIME LEAPED TOWARD THE SERPENT

"HE IS WHITE, AND THAT IS ALL THE MORE REASON FOR SENDING HIM OFF"

First of all I must tell you how I learned to write. This knowledge came to me somewhat late in my long life, but it has to be mentioned at the outset, for although you men have taught my race to perform many laborious tasks, you have not been in the habit of sending us to school, and an elephant capable of reading and writing is a phenomenon so rare as to seem almost incredible. I say rare, for I have heard it stated that my case is not entirely unique. During my long association with mankind I have come to understand much of their speech. I am even acquainted with several languages; Siamese, Hindustani, and a little English.

I might have been able to speak; I attempted to do so at times; but I only succeeded in producing such extraordinary sounds as set my teachers laughing, and terrified my companion elephants, if they chanced to hear me; for my utterances resembled neither their own language nor that of mankind!

I was about sixty years old (which is the prime of youth with us), when chance enabled me to learn letters, and eventually to write the words which I was never able to pronounce.

The enclosure reserved for me in the Palace of Golconda, where I was permitted to roam entirely at liberty, was bordered on one side by a wall of bricks enameled in blue and green. It was quite a high wall, but it reached only to my shoulder, so that I could, if inclined, look over the top very easily.

I spent much of my time at this place, owing to some tall tamarind trees, which cast a fresh and delicious shade all around.

I had plenty of leisure, indeed, I was actually idle, for I was rarely called upon except for processions. So, after my morning bath had been taken, my toilet made, and my breakfast finished, my guardians, or rather my servants, were at liberty to sleep, or to go about visiting and amusing themselves—while I stood motionless under the trees, going over in my mind the many experiences of my past life.

Every day there arose from an adjoining courtyard merry shouts and laughter, which would be followed by a silence, and then by a monotonous chanting. It was a class of little boys who were reciting the Alphabet, for a school was being taught there.

Under shady trees, on turf covered here and there with small carpets, a number of children with red caps romped and played, when the Master was not there. As soon as he appeared all was silence, and he seated himself upon a larger rug, under an old tree.

On the trunk of the tree was fastened a white Tablet, on which he wrote with a red pencil.

I looked and listened, at first without much interest, noticing chiefly the mischievous antics of the children, who made faces at me, and glanced over with all sorts of grimaces—exploding suddenly with laughter for which no cause was apparent.... Punishments rained! Tears succeeded laughter! And I, who felt myself somewhat the cause of the disturbance, no longer ventured to show myself. But my curiosity was awakened. The idea of trying to learn what was being taught to the small men became fixed in my mind.

I could not speak—but who knows?—I might learn to write!

Concealed in the foliage from the eyes of the frolicsome little urchins, I gave an extreme attention to the lessons—sometimes making such violent efforts to understand that I trembled from head to foot.

All that was required was simply to pronounce the letters of the Alphabet, one after another, and trace them on the white Tablet.

At night now, instead of sleeping, I exercised my memory; and when in spite of my endeavors I could not recall the form or the sound of a letter, I uttered such cries of despair that my guardians were aroused.

One day there stood before the Tablet a boy who was quite large, but extremely stupid. He had stood for some minutes with his head hanging down, his finger in his mouth, shifting himself from one foot to the other in a sulky manner—He did not know!

All at once an impulse seized me. I extended my trunk over the wall, and taking the pencil gently, with the tip of my trunk, from the hand of the little dunce (somewhat excited by my own audacity), I traced on the white Tablet a gigantic "E"!!!!

The stupefaction was such that it could only be manifested by profound silence, and gaping mouths.

Emboldened by success I seized the wet cloth with which the Tablet was cleaned, and effaced the "E" which I had drawn. Then, in smaller characters, and doing my very best, I wrote the entire Alphabet, from end to end.

This time the Master fell on his face, crying out, "A Miracle" and the children ran away, terrified.

As for me, I expressed my satisfaction by moving backward and forward my big ears.

The Teacher now rose trembling, detached the Tablet (being careful not to obliterate any of the writing), and, after saluting me most humbly, went away. A few moments later I saw my Mahout advancing towards me, and, without mounting, he led me through the great avenues of the park to the Entrance of the Palace.

Here ordinarily was seated my dear Mistress. But now she had left her couch, and, kneeling on a cushion, was examining the Tablet covered with letters which the Schoolmaster had brought her.

Standing around her were visitors, also looking on—several Hindus and an Englishman.

As soon as she saw me she ran to me, clapping her hands.

"Is it true? Is it true?" cried she. "Iravata, did you really do it?" I replied by winking my eyes and flapping my ears.

"Yes!—He says yes!" said my sweet Mistress, who always understood me.

But the Englishman shook his head, with an air of incredulity.

"In order to believe such a thing," said he, "I should have to see it with my own eyes—hearsay is not enough."

I attempted to efface the writing.

"No, no," said the Schoolmaster, removing it out of my reach.

"I saw the Miracle, and I implore the Royal Soul which inhabits the body of this Elephant to allow me to retain the proofs!"

Upon a sign from the Princess the Scribes were sent for. They came and unrolled before me a long scroll of white satin, and gave me a pencil dipped in gold ink.

The Englishman, with a singular grimace, put a morsel of glass in front of one of his eyes, and became observant.

Secure now of myself, not permitting myself to be embarrassed by the scrutiny of the company, I clasped the pencil firmly with the tip of my trunk, and slowly, and with deliberation, I wrote very neatly the Alphabet, from beginning to end.

"Iravata!—my faithful friend!" said the Princess, "I knew that you were more than our equal!"...

Then, with her lovely white arms she clasped my ugly trunk, and leaned her cheek against my rough skin. I felt her tears falling upon me, and trembling myself with emotion, I knelt down and wept, too.

"Very curious!... Very curious!" murmured the Englishman, who seemed much excited, and continually let fall and replaced the bit of glass in the corner of his eye.

"What have you to say, Milord? You, who are one of the most learned men in England?" inquired the Princess, drying my eyes with the corner of her gauze scarf.

The philosopher recovered his composure.

"Quintus Mucius, who was three times Consul, relates that he saw an elephant draw in Greek characters this sentence. "It is I who have written these words, and have dedicated the Celtic Spoils" And Elien mentions an elephant who was able to write entire phrases, and even talk. I was formerly unable to credit these statements. But it is evident that, such things being possible, we must bow to the authority of the Ancients, our predecessors, and apologize for having doubted their word."

My Princess decided that the Schoolmaster should now be attached to my person, and entrusted with the responsibility of teaching me to write syllables, and words (should that prove possible).

The good man performed his task with reverence, and with a patience worthy of a saint.

For my part, I made such struggles to learn that I grew thin in a way to cause anxiety to those who loved me, and my skin at last floated about my bones, like a mantle that is too large. But when they spoke of interrupting my lessons I uttered such shrieks of despair that it was not to be thought of.

I was compelled, however, to regulate my hours of study, and above all not to omit my meals, which had often happened in the fever of learning which had taken hold of me.

At last I was rewarded for my diligence. I was able at length to write the beloved name of my Princess! It is true it was instantly blotted out by the tears with which I deluged the paper!

From this moment it seemed as if veils had been removed from my understanding. I made rapid progress, and with the greatest ease. So much so, that my Professor was not considered to be sufficiently learned for his position, and a celebrated Brahman was called upon to complete my education.

I learned that all Golconda thought of nothing but me. And it was expected that, when I should become proficient in writing, wonderful revelations would be made by me, concerning the successive migrations of the Royal Soul which at present inhabited my person.

But what I have written has been simply the Story of my Life, portions of which my dear Mistress was unacquainted with.

The work was at once translated from the Hindustani, in which I had written it, into all the languages of Asia and Europe, and sold by hundreds of thousands.

This honour (which has excited much envy in the minds of authors whose works were not so successful), did not inspire me with vanity.

My reward—my recompense—was Her joy, and Her pride: the rest of the world was of no account to me; for all that I had achieved was solely and exclusively for Her.

I was born in the forest of Laos, and regarding my youth I have retained only very confused memories; occasional punishments inflicted by my Mother, when I refused to take my bath, or to follow her in search of food; some gay frolics with elephants of my own age; excessive fear during the great storms; pillage of the enemy's fields—and long beatitudes on the borders of streams, and in the silent glades of the forest. That is all. For in those days the mists rested on my mind, which later on were cleared away.

When I grew large I perceived with surprise that the Elders of the Herd of which I was a member regarded me with disfavour. This pained me, and I would have been glad to think that I was mistaken; but it was evident that no matter what advances were made by me, I was avoided by all. I sought for some cause for this aversion, and soon discovered it by observing my reflection in a pool. I was not like the others!

My skin instead of being like theirs, gray and dingy, was white, and in spots of a pinkish colour.... How did that happen? Mortification overwhelmed me. And I formed the habit of retiring from the Herd which despised me, and of remaining by myself.

One day when I was thus alone, sad and humiliated, at a distance from the Herd, I noticed a slight noise in the thicket, near me. I parted the branches with my trunk, and saw a singular being, who walked on two legs—and yet was not a bird. He wore neither feathers nor fur; but on his skin there shone brilliant stones, and bits of bright colours that made him look like a flower! I beheld for the first time a Man.

An extreme terror seized me; but a curiosity equally intense kept me motionless in the presence of this creature—so small that without the slightest effort I could have crushed him, and who yet in some way appeared to me more formidable and powerful than I.

While I was gazing at him he saw me, and instantly threw himself on the ground, making extraordinary motions, of which I did not comprehend the meaning, but which did not seem to me to be hostile.

After a few moments he rose and retired, bowing at every step, till I lost sight of him.

I returned next day to the same spot, in the hope of seeing him again; the man was there, but this time he was not alone. On seeing me his companions, like himself, performed the same singular movements, throwing themselves on their faces upon the ground, and doubling their bodies backwards and forwards.

My astonishment was great, and my fears diminished. I thought the men so pretty, so light and graceful in their motions, that I could not tire of watching them.

After a while they went away, and I saw them no more.

One day soon after, when alone as usual I descended to the Lake to drink, I saw upon the opposite shore an elephant who looked over at me and made friendly signals. It flattered me that he did not seem to feel repelled by my appearance, but on the contrary seemed to admire me, and was disposed to make my acquaintance. But he was a stranger to me, and certainly did not belong to our Herd.

He gathered some delicate roots, of a kind that we elephants greatly enjoy, and held them out to me, as though to offer them for my acceptance. I hesitated no longer, but began to swim across the Lake.

On reaching the other side I gave the polite stranger to understand that I was attracted, not so much by the sight of the delicacies as by the wish to enjoy his company. He insisted upon my accepting a portion of his hospitality, and began, very sociably, to eat up the rest.

Then, after some gambols, which seemed to me very graceful, he moved off, inviting me by his looks to follow. I did not need urging, and we plunged into the Forest, running, frolicking, pulling fruits and flowers. I was so delighted with the companionship of my new friend that I took no notice of the direction in which he was leading me. But suddenly I stopped. I saw with uneasiness that I was quite lost. We had come out onto a plain that was strange to me, and where, in the distance, singular objects showed against the sky—tall points the colour of snow, and brilliant red mounds, and smoke ... things that seemed to me not natural!

Seeing my hesitation, my companion gave me a friendly blow with his trunk, of sufficient force, however, to show more than ordinary strength.

My suspicions were not allayed by this blow, under which my flank smarted; I refused to go further.

The stranger then uttered a long call, which was answered by similar calls. Seriously frightened now, I turned abruptly towards the Forest. A dozen elephants barred the way.

He who had so duped me (for what reason I could not imagine), fearing the effects of my indignation, now promptly retired. He set off running; but I was so much larger than he that it seemed easy to overtake him. I rushed in pursuit, but just as I caught up with him I was obliged to stop short. He had entered the open door of a formidable stockade, made of the trunks of giant trees. It was inside that he wished to lead me, to make me a prisoner!.

I tried to draw back and escape, but I was surrounded by the accomplices of my false friend, who beat me cruelly with their trunks, and at last forced me into the enclosure—the door being at once shut behind me.

Seeing myself caught, I uttered my war-cry, and charged the palisades, throwing all my weight against them, in the hope of breaking through. I ran madly round the enclosure, thrusting my tusks into the walls, and seizing the timbers with my trunk, endeavouring to wrench them apart. It was against the door that I strove most furiously.... But all was useless. My enemies had prudently disappeared; they did not return till I was exhausted, paralyzed by my impotent rage, and until, motionless, and with drooping head, I owned myself vanquished!

Then he who had lured me into this trap reappeared and approached me, dragging enormous chains, which he wound around my feet. Groaning deeply, I reproached him with his perfidy; but he gave me to understand that I was in no danger, and that if I would be submissive I would have no cause to regret my lost liberty.

The night came. I was left alone, chained in this manner. I strove with desperation to break my manacles, but without success.

At last, worn out with grief and fatigue, I threw myself on the ground, and after a time fell asleep.

When I opened my eyes the sun was up, and I saw, all standing around the stockade, the elephants of the day before—but out of my reach!

They were fastened by the foot, by means of a rope which they could have broken without the slightest effort. They were eating with great relish the fine roots and grasses piled up in front of them.

I was too sad and mortified to feel hungry, and I looked gloomily at these prisoners, whose happiness and contentment I could not understand.

After they had finished eating some men arrived, and far from showing fear, they saluted them by flapping their ears—giving every sign of joy. Each man seemed to be welcomed by one special elephant to whom he gave his sole attention. He loosened the rope from the foot, and rubbed the rough skin with an ointment, and then, upon a signal, the captive bent back one of his fore-legs to enable the man to mount upon his colossal back. I looked at all this with such astonishment that I almost for the moment forgot my own sufferings.

And now, each man being seated upon the neck of an elephant, they, one after another, fell into line and marched out of the enclosure, and the gate was shut behind them.

I was alone; abandoned. The day was long and cruel. The sun scorched me, and hunger and thirst began to cause me suffering.

I struggled no more. My legs were lacerated by the vain efforts I had made. I was prostrate—hopeless!—and considered myself as one already dead!...

At sunset the elephants returned, each one bearing a ration of food; and again I saw them eat joyously, while hunger gnawed my stomach and no one noticed me.

The night again descended. I could no longer suppress my screams, which were more of misery than of rage. Hunger and thirst prevented me from sleeping, even for a moment.

In the morning a man came towards me. He stopped at some distance, and began to speak to me. I could not, of course, understand what he said to me, but his voice was gentle, and he did not appear to threaten me.

When he had finished speaking he uncovered a bowl that he carried filled with some unfamiliar food, the appetizing odour of which made me fairly quiver!

Then he came near, and kneeling, held out the bowl to me.

I was so famished that I forgot all pride, and even all prudence (for what was offered me might have been poisoned)! At any rate, I never had tasted anything so delicious; and when the basin was empty I carefully picked up the smallest crumbs that had fallen on the ground.

The elephant who had captured me now drew near, bearing a man on his back; he made me understand by little slaps of his trunk that I should bend back one of my fore-legs to allow the man who had fed me to get upon my neck. I obeyed, resigned to anything, and the man sprang up very lightly and placed himself near my head. Then he pricked me with an iron—but very gently—just to let me know that he was armed, and that he could hurt me terribly at this point, so sensitive with us, at the least sign of rebellion.

Sufficiently warned, I allowed myself to show no impatience. Then they removed my manacles; the other elephant took up the march, and I followed quietly.

We left the stockade, and they led me to a pool in which I was permitted to bathe and drink. After the privations I had suffered the bath seemed so delightful that I could not make up my mind to leave it when the time came; but a prick on the ear told me plainly that I must obey, and I was so afraid of being again deprived of food and drink that I rushed out of the water, determined to do all I was bid.

We now went towards the strange objects that I had seen in the distance on the plain, on the day I was made prisoner. I learned later that it was the city of Bangok, the capital of Siam. I had never yet beheld a city, and my curiosity was so aroused that I was anxious to reach it. As we drew near men appeared on the sides of the road, more and more numerously, so that the way was crowded. They stood on each side of the pathway, and to my great surprise, I at last discovered that it was I whom they were expecting, and had come out to see!

At my approach they uttered shouts of joy; and when I passed before them they threw themselves, face-downward, upon the earth, with extended arms, then rose and followed me.

At the gates of the city a Procession appeared, with cloth of gold, and arms, and streamers of silk on long poles.

All at once there was a noise—so wonderful that I stopped short. One would have said it was composed of shrieks and groans, and claps of thunder, and whistling winds, mingled with the songs of birds! I was so terrified that I turned to escape, but found myself trunk to trunk with my companion, who was following me. His perfect tranquility, and the roguish wink that he gave me, reassured me, and I felt mortified to have exhibited less courage than others before so many spectators, and I wheeled about so promptly that the man on my head did not have time to prick my ear.

I was ordered to stop in front of the leader of the Procession, who saluted me, and made an address.

The great and fearful noise had ceased, but began again as soon as this personage had finished his speech. The Procession turned around now and preceded me, and we again moved on. I then saw that it was men who were making all this noise. They struck various objects—they tapped them—they whistled into them—and seemed to take the greatest trouble! That which they made was called "Music." I grew used to it in time, and even came to think it agreeable. I was no longer afraid, and all that I saw interested me, and delighted me greatly.

In the city the crowds were even denser, and the rejoicings more noisy. They spread carpets on the route I was to traverse; the houses were wreathed with garlands of flowers, and from the windows they threw phials of perfume, which my rider caught, flying, and sprinkled over me.

Why were they so glad to see me? Why were all these honours showered upon me? I, who in my own Herd had been repulsed and disdained....

I could find no reply at the time, but later on I learned that it was the whiteness of my skin which alone was responsible for all this enthusiasm. That which seemed to elephants a defect, seemed admirable to men, and made me more valuable than a treasure.

They believed my presence was a sign of Happiness—of Victory—of Prosperity to the Kingdom—and they treated me accordingly.

We had now reached a great square in front of a magnificent building which might well cause amazement to a "wild" elephant. Often since then I have seen this Palace, and with better understanding, but always with the same astonishment and admiration. It was like a mountain of snow, carved into domes and great stairways, with painted statues, and columns encrusted with jewels, and tipped with globes of crystal that dazzled the eyes. The tall golden points rose higher than the domes, and in many places red standards floated, and on all of them there was the figure of a White Elephant!

All the Court, in costume of ceremony was assembled on the lower steps of the stairway. Above, on the platform, on either side of a doorway of red and gold, elephants covered with superb housings were ranged—eight to the right, eight to the left, all standing motionless.

They summoned me to the foot of the stair, and there I was told to stop. A great silence fell upon all. One would have said that there was nobody there. The crowd which had been so noisy now was mute.

The red and gold doorway was opened wide, and all the people prostrated themselves, resting their foreheads upon the earth.

The King of Siam appeared.

He was borne by four porters in a pavilion of gold, in which he sat with crossed legs. His robe was covered with jewels, and scattered blinding rays. Before him walked young boys dressed in crimson, who waved great bunches of feathers attached to long sticks; others carried silver basins out of which came clouds of perfumed smoke.

I am able to describe all this now, with words which I have learned since then; but at that time I admired without understanding, and I felt as if I was looking upon all the Stars of Heaven, and the Sun at Noonday, and all the Flowers of the loveliest Spring—at one and the same time!...

The bearers of the King descended the steps in front of me. His Majesty approached. Then my conductor pricked my ear, and my companion struck my leg with his trunk, indicating that I was to kneel.

I did so voluntarily, in the presence of such splendour, which seemed to me as if it might burn any one who should touch it!

The King inclined his head slightly.... THE KING OF SIAM HAD SALUTED ME! (I learned afterwards that I was the only one who had ever been honoured in such fashion. And I was soon able to return the King's salute, or rather to anticipate it.)

His Majesty addressed me with a few words which had an agreeable sound. He bestowed on me the name of "King-Magnanimous" with the rank of Mandarin of the First Class. He placed upon my head a chaplet of pearls set with gold and precious stones, and then retired to his Palace.

The multitude, who until now had remained prostrated, now rose up, and with shouts and cries of joy, accompanied me to my own palace, where I was to dwell.

It was in a garden, in the midst of an immense lawn. The walls were of sandal wood, and the great roofs extended far out on all sides; they were lacquered in red and glistened in the sunlight, with here and there globes of copper, and carved likenesses of elephants' heads.

I was taken into an immense Hall, so high that the red rafters which interlaced overhead and supported the roof made me think of the branches of my native Forest, when the sunset reddens them.

An old elephant was walking slowly about the Hall. As soon as he saw me he advanced towards me, flapping his ears in welcome. His tusks were ornamented with rings and golden bells, and he wore on his head a diadem like that which the King had just placed on mine. But all this did not improve his appearance. His skin was mottled with dingy patches, like dried earth, and cracked in spots; his eyes and ears were encircled with rednesses; his tusks were yellow and broken, and he walked with difficulty. But he seemed amiable, and I returned his courtesies.

My conductor descended from my neck, while officers and servants prostrated themselves before me as they had done before the King himself.

Then they led me to a huge table of marble, where in great bowls and vessels of silver and gold were bananas, sugar-canes, all sorts of delicious fruits, and choice grasses—and cakes—and rice—and melted butter.... What a feast!

Ah! how I wished that those of my Herd who had made a mock of me could see how I was treated by Men!

My heart swelled with pride, and I no longer regretted my liberty and my native Forest.

Prince-Formidable, for such was the name of my ancient companion, reclining not far from me upon a bed of fragrant branches, now told me something of his history, and also instructed me as to my duties of Royal Elephant.

"I have been here rather more than one hundred years," said he. "I am very old, and I am sick, in spite of the white monkeys that you see frisking about up there in the rafters. They are kept here to preserve us from evil diseases; but all those who were here with me in this palace died within a few days of each other, of some ailment which they seemed to take from each other, and I, the oldest of all of them, am the only survivor.

"For several years I have been alone—the only White Elephant—and the greatest anxiety has been felt in Court Circles on this account. No others could be discovered, notwithstanding the incessant hunts which were made throughout the forests. It was thought that great misfortunes menaced the Kingdom, and your arrival has caused rejoicings throughout the country."

"Why is it that they consider us so important?" asked I. "What is there extraordinary about us? Among elephants they seem rather to despise us!"

"I understand," said Prince-Formidable, "that men, when they die are transformed into animals; the noblest into elephants, and Kings into White Elephants. We are therefore ancient Kings; though, for my part, I have no recollection of having been either a man or a King." "Nor I either," said I. "I don't remember anything at all! But is it then on account of envy that the gray elephants dislike us?"

"No," said Prince-Formidable. "Those of us who have not lived among men are mere brutes, and don't know anything. They think the colour of our skin results from disease, and so consider us inferior to themselves; while on the contrary it is really a sign of Royalty.... You see what poor ignorant creatures they are!"

I admired the wisdom and experience of my new friend, who had lived so long and seen so much. I never tired of asking him questions, and he replied with an inexhaustible good nature.

To-day I am able to translate in words what he was obliged to tell me in the very limited language of elephants. Over and over he had to begin again and repeat; but he was never impatient, although he was himself so superior, and had long understood the language of men.

"Attention!" said he to me, upon hearing the sound of distant music. "Here are the Talapoins, who are coming to give you their benediction." He tried to make me understand who they were, but although I pretended out of politeness to do so, I had not in reality the least idea of what was meant, except that it was some new honour that was to be conferred upon me.

The Talapoins had shaven heads, and their ears stood out, and they wore long yellow gowns with big sleeves.

On entering they did not prostrate themselves—and I confess this shocked me somewhat! The oldest marched in the centre. He stopped before me, and began talking in a queer voice, very high and unpleasant; then, without stopping his remarks, he took from the hand of one of his followers a mop with an ivory handle, while another one held a basin of water, in which he dipped the mop, and commenced to sprinkle me in a way that displeased me exceedingly. He squirted the water in my eyes and ears, and as it lasted longer than I thought needful, I seized the mop out of his hand, and sousing it well in the water I shook it over all three of them—giving as good as I had received!

They escaped, laughing and wiping their faces with their-long sleeves, and I gave a loud scream of triumph, to proclaim my victory, and my satisfaction!... But Prince-Formidable did not approve my conduct—he thought it lacked dignity.

Soon after this they came to take us to the bath. A slave marched in front, striking cymbals in order to make way for us, and others held over our heads magnificent umbrellas. It was in our own park that the beautiful pond was situated, and I was allowed this time to plunge and swim, and roll over as long as I wanted.

A repast as plentiful as it was delicious ended the day, which had certainly been to me in every way most satisfactory.

It continued in this manner, from day to day, with the exception of the Talapoins, who never returned.

Only one hour in the day was somewhat distressing to me. It was my daily lesson, which I had to take each evening, before going to bed.

The man who had first sat upon my head remained my principal guardian—my "Mahout," and he had to teach me, and make me understand the indispensible words of command, such as "Forward," "Backward," "Kneel," "Rise," "Right," "Left," "Halt," "Faster," "Slower," "That's Right," "That's Wrong," "Do It Again," "That's Enough," "Salute the King."

Prince-Formidable assisted me by translating these orders to me in elephant-speech, so that I soon knew all that was needful.

Several years passed in this way very pleasantly, but rather monotonously. Prince-Formidable died the second year after my arrival. They gave him a Royal Funeral and all the Court went into mourning.

For a while I was alone. Then other White Elephants came in; but the new ones were very ignorant, and seemed sulky and rebellious in their dispositions—so that I took but little notice of them.

One day my Mahout, who like all others of his class, had the habit of making long discourses (which I finally grew to understand), came and stood before me, as he always did when he wished me to listen.

I at once became attentive, for I saw from his agitated air that something of importance was concerned.

"King-Magnanimous," said he, "ought we to rejoice—or ought we to weep? Is a new life for us a good, or an evil thing? Should one dread change, or should one welcome it? These are questions which are being balanced in my mind, like the weights in a pair of scales! You, who are now an elephant, but were once a King could tell me, if only you could speak. You could tell me if the numerous transformations, the changes, have brought you most joy or sorrow. Your wisdom could put an end to my anxiety, perhaps; But perhaps, on the other hand, you can look no further into the future than I; and you would say to me, "Let us resign ourselves to what we cannot help, and wait to either weep or rejoice, till events prove good or ill."... Well! so will we do. We will resign ourselves, and wait.

"That which is about to happen you know not—and that is what I am going to tell you.

"Our great King, Phra, Puttie, Chucka, Ka, Rap, Si, Klan, Si, Kla, Mom, Ka, Phra, Puttie, Chow (for I cannot mention the King's name without giving him all his titles—I who am only a simple Mahout—when the Prime Minister, himself durst not do so!)—our great King is the father of several Princes, and also of a Princess—a beautiful Princess—who is of a marriageable age.... Well! that is it! She is about to be married. The King Phra, Puttie, Chucka has bestowed the hand of the Princess Saphire-of-Heaven upon a Hindu, the Prince of Golconda: and this marriage, which at first would seem of little interest to us, is going to overturn our whole existence.

"Know, King-Magnanimous, that your glorious person is to form part of the Dowry of the Princess. Yes! even so. Without asking your pleasure in this affair, they have made a gift of you to a stranger Prince, who may not have for your Majesty the respect due you.

"And I—poor Mahout—what am I without the noble elephant whom I attend? And what is your Majesty without me?

"Therefore they have also made a gift of me, and I am now a fragment of the royal dowry. We are bound to each other till death—we are but one! You go where I conduct you, and I must go where you go. Oh! King-Magnanimous, ought we to weep or rejoice?"

Really, I could not say. And I was greatly disturbed at what had been told me.

To leave this life, so sweet and tranquil, but which sometimes wearied me by its monotony and inaction.... Abandon this beautiful home so abundantly provided with good things!... Surely this was cause for weeping! But then, to see new countries, new cities, meet with new adventures—that was perhaps something to rejoice at! ...

Like my Mahout, I concluded the best way was to wait—and for the present to be resigned.

The day of our departure arrived, and very early in the morning the Slaves came to make my toilet. They rubbed me all over several times with a pomade perfumed with magnolia and santal; they placed on my back a mantle of purple and gold, and upon my head a chaplet of pearls and the royal diadem. They fastened heavy gold bracelets on my legs, and on my tusks gold rings set with jewels; from each of my ears there hung down a great tail of horse-hair, white and silky. Arrayed thus, I was conscious of my magnificence, and longed to show myself to the People.

Still, I gave a backward glance at the Palace I was leaving, and sounded a few notes of farewell to the elephants who were remaining, with whom I had begun to be quite friendly. They replied by thundering outbursts of trumpeting, the noise of which followed me for a long way. All the inhabitants of Bangok were out, as on the day of my triumphal entry. They were in holiday costume, and were moving towards the palace of the King. There a splendid procession was formed and began its march, preceded by one hundred musicians dressed in green and crimson.

The King was seated in a howdah of gold fillagree, on a colossal black elephant—a giant among elephants. On his right and on his left were the Prince and Princess, on mounts of more than ordinary size.

The howdah of the Bride was enclosed by a fringe of jewels which rendered her invisible. The Prince was young and handsome; he had a charming expression, which at once inspired me with confidence.

I followed next after the King, conducted by my Mahout, who walked on foot beside me. And after me came the Mandarins, Ministers, and other high functionaries, according to rank, and mounted on elephants or horses, followed by their servants, who carried behind each noble lord the Tea-pot of Honour, which in Siam is an insignia of nobility, the greater or less richness of which indicates the importance of the owner.

Then came the baggage of the Princess, consisting of numberless boxes of teak wood, marvelously carved.

The ceremony of the marriage had already taken place, and had occupied eight days. This was the "farewell" of the King, the Princes and the people to their Princess, whom they were escorting to the shore, whence she was to depart.

We stopped on the way at the richest Pagoda in the city, where they worship a Buddha carved out of a single emerald, which has not its equal in the world, for it is three feet tall, and as thick as the body of a man.

After this we descended by narrow streets, traversed by bridges and canals to the shores of the river—the broad and beautiful Mei-nam.

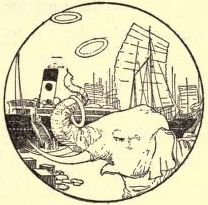

In the distance were seen the deep blue mountains against the brilliant sky—the chain of "The-Hundred-Peaks"—the "Rameau-Sabad"—the "Hill-of-Precious-Stones" and others. But the spectacle of the river, all covered with shipping bearing flags, and decorated with flowers, was incomparable!

There were great Junks of red and gold, with their sails of matting spread out like fans, their masts carrying pennants, and their prows rounded and made to imitate the head of a gigantic fish with goggle eyes; all sorts of boats, sampans, and rafts, supporting tents of silk which looked like floating summer-houses! All laden to the water's edge with a gay and noisy crowd, and with bands of music and singers, who played and sang by turns.

Salvos of artillery, louder than thunder, burst forth when the King appeared, and the people gave such a deafening shout that I should have died of fright, had I not learned by this time to permit nothing to startle me.

The vessel which was to convey us to India lay at the wharf with steam up, and splendidly decorated.

It was here we were to part.

The King and the Bride and Groom descended from their elephants. The Mandarins formed a circle; and all the people kept silence.

Then the King, "Sacred Master of Heads, Sacred Master of Lives, Possessor of Everything, Lord of the White Elephants, Infallible, and All-Powerful," made a speech, while chewing Betel, which stained his mouth crimson, and obliged him to spit frequently into a silver basin, which was held by a slave.

The Prince, kneeling before his royal father-in-law, also made a speech, less long—chewing nothing! The Bride wept behind her veils.

When it was time to embark there was some confusion on account of the Princess's innumerable boxes of teak wood, and because of the horses, whom my presence terrified greatly. A long whistle was heard; the musicians played; the cannon boomed; a swaying movement made me feel dizzy—and the shore receded.

All the boats followed us at first with oars and sails, but were soon left behind. The King stood on the wharf as long as he could see us. I was deeply moved at leaving this city, where I had at first suffered so severely, but where my existence afterwards had been so happy and glorious.

My Mahout, leaning against me, we both looked back. At a turn of the river all disappeared; our eyes met, and both were full of tears.

"King-Magnanimous," said he, after a moment of silence, "let us wait before we either weep or rejoice. Let us see what Fate has in store for us!"

Soon the river grew so broad that the banks could no longer be seen. The water began to move in a singular manner, and the ship also, causing me most unpleasant sensations. Little by little we put out to sea.... Then it was horrible! My head spun round; my legs failed me; an atrocious misery twisted me in the stomach. I was shamefully sick, and thought a thousand times that I was dying! I can, therefore, say nothing of this voyage, which is the most distressing memory of my life.

Never, never would I go again to sea—except it might be to serve Her. But for any other reason I would massacre whoever should compel me to put foot on a boat!...

The Rajah of Golconda, my new master, was called Alemguir, which signifies, "The Light of the World."

He certainly did not show me the respect to which I was accustomed; he did not prostrate himself, nor even salute me; but he did better than either—he loved me.

From the first he spoke kind words to me, not in my quality of "White Elephant," which is a distinction much less thought of in India than in Siam, but because he found me intelligent, good-tempered, and obedient—more so than any of his other elephants. He remembered me and came to see me every day, and saw to it that I was not allowed to lack anything.

He had changed my name from "King-Magnanimous" to "Iravata," which is the name of the elephant who bears the God Indra. The title was certainly sufficiently honourable, and I was easily consoled for being no longer worshipped as an idol by the pleasure of being treated as a friend.

Alemguir would have preferred that his Queen, Saphire-of-Heaven should always use me as her mount; but she never would consent to install herself on my back.... "It would be a sacrilege!" said she, "and a grave offence to one of my Ancestors!"

She was persuaded that I was one of her forefathers, undergoing a transformation for the time being.

Her husband rallied her good-naturedly upon the subject, but she would not yield.

So he gave her a black elephant, and kept me for his own service.

I was proud to carry my Prince in promenades, in festivals, and in Tiger hunting, which he taught me.

My life was much less indolent than in Siam, and much more varied and interesting. My Mahout, in spite of the trouble that this stirring existence imposed upon him also found it pleasanter than the monotony of the old life—and as usual he confided his sentiments to me!

I was also instructed in the art of war, for during the year following the marriage of Alemguir with Saphire-of-Heaven grave anxieties came to darken the happiness of the young married couple.

A powerful neighbour, the Maharajah of Mysore sought without ceasing to fasten a quarrel upon the Prince of Golconda, concerning certain questions of boundaries.

Alemguir did all in his power to avoid hostilities, but the ill-will of his opponent was evident, and in spite of the conciliatory efforts of the ambassadors, a war seemed imminent. The Princess wrote to her father, the King of Siam, who sent cannon, and a few soldiers; but the enemy was formidable, and the apprehensions of all increased from hour to hour.

One day the Ambassadors returned in dismay; diplomacy had failed, negotiations were at an end, and the Maharajah of Mysore declared war. The necessary preparations were made in haste; and one morning I was invested with my armour. A sheathing of horn covered me and descended below my knees; on my head was a helmet of metal, with a visor of iron, perforated with holes for the eyes, and a point projected from the middle of the forehead. My crupper and flanks were defended by flexible armour, as was my trunk, which had a ridge running down the centre armed with pointed teeth of metal; and upon my tusks were steel casings, sharp and cutting, which lengthened them greatly and made of them terrific weapons.

Thus accoutred, my Mahout, who was also in armour, and weighed more heavily than usual upon my neck, guided me to the portico of the Palace overlooking the great Courtyard, where were assembled all the chiefs of the army. Prince Alemguir appeared at the entrance, and the officers saluted him by clashing their arms.

He was magnificent in his warlike array. He wore a tunic of gold-linked armour, under a light breastplate studded with diamonds; he carried a round shield that blazed with jewels, and his helmet was gold with a diamond crest.

Standing upon the upper steps of the portico he harangued his troops; but as I did not then understand Hindustani I do not know what he said.

When he was about to mount, the Princess Saphire-of-Heaven rushed out of the Palace, followed by all her women, and threw herself, sobbing into the arms of her husband.

"Alas!" cried she, "what will become of me, separated from you? How shall I endure the continual anguish of knowing you exposed to wounds and death? The heir which we hoped would be born in joy and festivity, now will enter life amid tears and despair! Perhaps he will be born an orphan—for if the father is killed, the mother will not survive!"

I listened to this and felt my heart ache under my coat of horn.

The Prince, much affected, could hardly restrain his tears. He made an effort, however, to master his emotion, and replied with calmness.

"Every man," said he, "owes his life to his Country; and the Prince more than any other man. Our honour, and the welfare of our people are more dear to us than our own happiness. We must set an example of courage and self-sacrifice, instead of allowing ourselves to be softened by tears.

"If the war proves cruel to me—and I die—you, my beloved Wife, will live to bring up our Child; and hereafter we shall find each other, and be forever happy in the life to come!"

He gently disengaged the clasp of her delicate arms. The veil of the Princess caught on the breastplate of the Prince and was torn. The Prince gathered a fragment, and kept it as a talisman.

And now Alemguir was in the howdah, and it was to me that the Princess appealed, with breathless sobs.

"Iravata, thou who art strong, and who lovest thy Master, and who ought to love me, for thou hast the soul of one of my Ancestors.... Guard the Prince! Protect him, and bring him back to me living—for if he comes not back I shall die!"

Speaking these words the Princess became as pale as snow, and fell fainting into the arms of her servants.

I made a resolve in my heart to defend my Master with all my might, and not to fail in risking my life for the safety of his.

Taking advantage of the swoon of the Princess, which made her unconscious, Alemguir gave the signal to depart.

We left the Palace, and then the City, to join the main army, which was encamped outside on the plains.

The Artillery and the Elephants were placed in the centre; the Horsemen on the right and left, and the foot-soldiers in front and at the rear.

The trumpets sounded a warlike march; the drums beat; the whole army gave a shout—and we marched on the enemy.

What a fearful thing is a battle! How terrible—how grand! It intoxicates, and stuns you. The music, the roar of the cannon, the firing, the shouts of the combatants; the tumult, the smoke, the dust—excite in you a strange madness, which makes you hate the creatures which you can scarcely see—whom you have never known, and who, for no other reason, are filled with the same murderous rage towards you!

At first I, who had never killed anything but tigers, shuddered at the thought of shedding human blood. I hesitated—I avoided giving blows. But suddenly I saw my Master in danger; a horseman was aiming at him at close range. He had not time to fire—my armed tusks disappeared in the belly of the horse, which I lifted high up in the air, and whose bleeding carcass I tossed, with its rider, into the ranks of the enemy.

From that moment it was carnage where I went. I pierced. I cut. I disembowelled all before me—making corpses of the living, and crushing to pulp the dead under my great feet, which soon were shod with blood.

The Prince encouraged me by his voice, and pushed constantly forward. His gun, which a soldier behind him reloaded as fast as it was discharged, was never silent, and his aim was so sure that he never missed. The Enemy's ranks crumbled before us. And Alemguir, full of ardour urged me on and on! He desired to reach the Maharajah of Mysore, who in the centre of his army directed the battle.

At last he found him, shouted defiance at him, and defied him to meet him in single combat.

The Maharajah smiled scornfully and did not answer.

All at once my Mahout, who, being occupied with guiding me, and less carried away by the fury of the battle, had a better opportunity of observing the situation, cried out in a voice of horror, "Back!—Back!—or you are lost!"

But the Prince continued to shout "Forward!" And my Mahout could jab my ear as much as he chose—I refused to obey!

"Prince! Prince! You are lost!" groaned the unhappy slave. "The army of Golconda is in retreat, and we are surrounded! It is too late to escape!"

A ball struck him. With a groan he rolled off my neck, clinging an instant, deluging me with blood, then he fell.

Dead. He was dead!

I stopped, horrified; turning the body gently over with the tip of my trunk—he did not move; he did not breathe; it was the end.

My poor Mahout had breathed his last so quickly—almost without pain. This then, was what "Fate" had in store for him!

I could see him off there, at Bangok, saying so gravely to me, "Ought we to rejoice, or weep?" Alas! he was dead; he could neither weep or rejoice any more!...

But around me were shouts of triumph. My Master still fought.

"Take him alive!" cried the Maharajah from his elephant. "He shall die by the hand of the executioner!"

I tried to rush forward but my feet were entangled in running knots which they had thrown around me, and my furious efforts only drew them tighter.

All was ended. I was taken; and my Master with me.

Poor Princess Saphire-of-Heaven! In her desolate Palace she was suffering a thousand times more from fear and anxiety than we from our misfortune. For her also it was Fate!

I could hear her sweet voice entreating me to bring back to her her beloved husband; and behold! we were vanquished—prisoners—and the Prince, loaded with chains, was now listening to the sentence that condemned him to die a shameful death at dawn on the morrow!

I was of value. I made part of the "spoils." And they had no intention of killing me. But I had been so terrible in battle that they dared not come near me.

I set to thinking with all the powers of my poor, feeble mind. It seemed as if I had best pretend to submit. I began to feel the smart of my wounds, and the fatigue of the combat; and my heavy armour weighed on me painfully.

I began to utter plaintive moans—as if imploring assistance from those standing about.

One of them, seeing me so quiet, ventured to approach. I redoubled my moans, making them very soft.

"He must be hurt," said the man. "We must look after him, and take care of him, for he is an animal of great price!"

All drew near. They took off my armour, I helping them as well as I could. When it was off I sank on the ground, as if exhausted.

I had received a great many wounds, but only one was of any consequence; it was near the shoulder.

They brought a doctor who dressed my wounds. Meanwhile; I thought of my Master, who, perhaps, was also wounded, but who was receiving no care!

I had not failed to watch him, out of the corner of my eye, without seeming to do so, while I was performing my little comedy!

I saw that they had chained him to a stake, and that soldiers with arms in their hands guarded him.

Grief tore my heart: and the groans that I gave were most sincere—but it was not my wounds that caused them!

However, I feigned an indifference to my Master. I appeared to give no thought to anything but myself. And I took pains to be so grateful to the surgeon for his services that he was quite touched, and ordered them to take off the running knots which were murdering my legs.

"This elephant is remarkably gentle," said he, "Give him some food and drink, for he seems very tired and feeble—no doubt from the blood he has lost!"

He went off to attend others; and presently they brought me a good ration of forage; vegetables, and rice, and fresh water in a great vessel. I thought of Prince Alemguir, who was perhaps also suffering from thirst—and my throat grew tight!...

However, we are slaves to our enormous appetite; hunger soon subdues and enfeebles us. I must eat, in order to be strong, and ready for whatever was to come.

I gave myself the airs of an invalid, disinclined for food, and did not raise myself up from the ground.

So, giving no more thought to me, they put a light rope on my foot and fastened it to a peg, and left me.

Night came; fires dotted with their red flames the entire extent of the camp; the smoke mounted straight in the tranquil air; I saw around the camp-kettles the men crouching, their forms showing dark against the light; then there were dances, songs, and music. They were celebrating the victory by drinking, shouting and quarrelling; they even acted over again their hand-to-hand struggles, which grew so furious that blood flowed.

Then, little by little, silence fell; all was dark; a heavy sleep weighed upon the evening of the battle!

Then I rose up on my feet.

There was no moon, only the great stars palpitated in the sky. I listened; I peered into the obscurity. The tents formed little dark hillocks, undulating away, as far as the eye could reach. No sound, but the intermittent call of distant sentinels, who could not be seen. Before the tent where my Master was imprisoned two soldiers in white tunics marched slowly with guns on their shoulders. I could see clearly their long white robes, and their muslin turbans. Sometimes the barrel of their gun sparkled, reflecting the ray of a star.

Kill these two men? Deliver my Master? and escape with him? Would such a thing be possible?...

The sentinels marched slowly around the prisoner's tent, walking in opposite directions from each other, so that all sides of the tent were constantly under observation.

How to seize them without their being able to give the alarm?... Standing motionless in the darkness, I followed them with my eyes, striving to understand their movements, and the different positions they occupied while coming and going.

I observed that one soldier in crossing his companion turned his back to me, and then disappeared behind the tent, and at the same instant the other soldier also had his back to me, while making the circuit. A short moment only elapsed before the first one would reappear and be facing me.

I could not strike the two guards at one time; and if one saw me attack the other he would have time to give the alarm, and awaken the whole camp.

It was, then, during this one brief moment that I must act.

About twenty paces separated me from the tent, and this was an added difficulty—shortening still more the available time during which I would be unseen; but the attempt must be made.

I tried to undo the rope that tethered my foot. I could not succeed; but with a single jerk I pulled up the stake to which I was attached.

I was free.

Choosing a favourable moment I took some steps towards the tent. Then I waited for the soldiers to make another turn—and moved still nearer. I preserved the attitude of a sleeping elephant; and they failed to notice in the darkness that I had drawn closer.

Now was the time. I must make the attempt—at the next turn, thought I.

But my heart beat so violently that I was compelled to wait. My one fear was that I might not succeed; then, too, I felt a repugnance to slaying—by treachery as it seemed—these two unknown human beings. But after all, was it not men who had set me the example of ferocity? To save my Master I would have destroyed without remorse the entire army of the enemy!

My self-possession returned; and it was with the greatest coolness that I executed my plan.

The first soldier was seized by my trunk and strangled, with no sound except the cracking of his bones. I had just thrown aside his corpse when the other came face to face with me.

He did not cry out—terror prevented him; but he instinctively jumped backward, and so hastily that he fell.... The unfortunate man never rose; my enormous foot falling upon him crushed him to a bloody mass.

I drew a long breath; then I listened; in the distance could still be heard the occasional call of the sentinels who guarded the outskirts of the camp, of which we occupied the centre; no doubt they would soon be relieved—and perhaps also the guards of the Prince; there was not a moment to spare.

Yet I dared not approach my Master suddenly, lest he might utter an exclamation of surprise.

Was he sleeping, the dear Prince, worn out with fatigue? Or was he grieving silently over the loss of his liberty, and his life?

I was at a loss what to do; and the anguish of knowing that the moments were slipping by made my skin creep!

All at once an idea came to me. I pulled up on one side the stakes that held the tent, and taking the canvas by the lower edge, I turned it half-way over, just as a strong wind might have done. There remained nothing between us, and I saw the Prince seated on the ground, his elbow on his knee, his head resting on his hand. He raised his head quickly, and saw my giant form outlined against the starry sky.

"Iravata! my friend, my companion in misfortune!" murmured he.

Tears came to my eyes; but there was no time for anything of that kind! I touched the chains of my Master, feeling them to judge of their weight. They were nothing for me. With one blow they were broken—first those on the feet, and finally the heavier one, which, attached to a belt of iron, chained the Prince to a gallows.

"What are you doing? How is it that you are free?" said Alemguir, who, by degrees, was recovering from his prostration.

All at once he understood; he sprang to his feet.

"Why! you are liberating me!—You are going to save me!"

I made a sign that it was so, but that we must be quick. Calm and resolute now, he cast off the remnants of his shackles. I showed him the tether on my foot, and the stake that dragged after it. He stooped down and unfastened the cord; then I helped him to mount up on my neck.... Oh! what joy to feel him there again! But we were far from being out of danger.

He spoke no more. He concentrated all his attention upon directing our flight through the darkness.

Coming out of the obscurity of the tent, he could see all the better, and from on high he could look about him, listen to the voices of the sentinels, and ascertain something of the arrangement of the camp, and of its extent, and its nearest limits.

He bent forward, darting his looks in every direction; but it was impossible to pierce the darkness for more than a hundred feet in advance.

Avenues had been formed between the tents, which had been placed in fairly even lines; but these pathways would naturally be guarded, and the Prince judged it would be safer to glide behind the tents in their confused and indistinct shadows.

Notwithstanding our appearance of heaviness, and our massive corpulence, we have the faculty of walking as noiselessly as a cat or a panther. A whole herd of elephants on the march, if they suspect any danger, can avoid snapping a twig, or rustling a leaf. The most acute hearing will fail to detect the sound of their footsteps; and whoever sees them filing past by hundreds would take them for phantoms. It would be quite proper to say "as light as an elephant"—but I imagine the idea never occurred to any one.

This peculiarity explains how I was enabled to circulate between these thousands of tents, scarcely seeing my way, and obliged very often to pass through an opening barely larger than my own person, without running against, or overturning anything, and without making a noise that would have betrayed us.

We had now reached the limits of the encampment, which were by no means easy to pass, for they had been rapidly fortified, ditches had been dug, and entrenchments thrown up. But the work having been hastily done was not very solid.

The Prince leaned down close to my ear, and said to me:

"Try to break down the earth wall, and turn it into the ditch so as to fill it up."

I understood, and went to work. The ground was still soft and yielded readily; but I could not prevent a dull thud when it fell into the ditch. It was a very feeble smothered sound ... and yet to me it seemed tremendous!

At last the opening was made. I passed through, plodded across the mud in the bottom of the ditch, and succeeded in climbing up the other side.

We were out of the camp, and I joyfully quickened my pace.

But a cry resounded—a cry of alarm. They had seen us in the open space, which I was crossing now at full speed.... "Beware, Master!" I seized him and placed him cross-wise upon my tusks, supporting him with my trunk, and without slackening my pace. My quick ear had detected the sound of loading guns—they were going to fire upon us; but my Prince, protected by the bulk of my great body would be in no danger.

A sudden light flashed in the darkness; there was a rattling volley of shots, and a shower of bullets struck my crupper. They bounded off, for these little leaden pellets are incapable of penetrating the tough hide of an elephant. They merely stung me like little pricks of red-hot iron.

A second discharge fell short, with the exception of a single ball which grazed my ear, and carried off a small piece.

I ran still faster, hoping to gain the shelter of a thicket which at least would protect us from the bullets.

Just as I reached it I heard the sound of galloping horses.

"We are pursued," said Alemguir. He had resumed his place on my neck. I plunged into the thickest of the woods, making a pathway by the aid of my tusks, crushing the branches under my feet. But this delayed us; it also betrayed our course, and left an open road for our enemies.

There seemed no way of meeting this danger, and I trembled with an anxiety that for the moment paralyzed me.

My Master, full of courage, spoke soothingly to me.

"Calm yourself," said he, "there is no cause for despair; you know how horses fear you; if they reach us you have only to turn and fall upon them to terrify them, and put them to flight!"

But although I could not say so in words, my thought was, The shots can reach my Master!

However, I took courage, and managed to push on still faster. The day, which comes so early in summer, began to break. A dull continuous noise now became audible, and drowned the sound of the horses' hoofs.

"That must be a river," said Alemguir. "If we can but reach it and put it between us and our pursuers, we shall be saved."

I raised my trunk, snuffing the air to discover the direction of the water, and changed my course. The wood now became less dense; I advanced more easily between the young trees and saplings which I crushed under foot; and we soon found ourselves beside a rapid river which flowed in the depths of a ravine. The water, which boiled in places and ran with a dizzy swiftness, had dug for itself a bed in the clayey soil, and flowed as it were between two walls.

"Alas!" said the Prince; "that which I hoped would be our salvation is going to be our ruin! It will never be possible to descend to the level of this river."

To my mind it was difficult—but not impossible. And as there was no time to waste in reflection, I went to work at once digging the clay with my tusks, stamping it down with my feet, and throwing it right and left, in a way to form a sort of incline; but when I thought I might risk myself upon it the earth crumbled away, and, sliding down the sticky mud, I shot into the water more quickly than I had intended, with a tremendous splash that sent the water up into the air to an amazing height. Luckily, my Master had been able to cling to my ear, and was none the worse. So I was soon relieved, though astounded at my sudden descent.

The current now carried us along, and I floated with it. It saved me all exertion, and I reposed deliciously in the cool refreshing water, which restored my strength. The Prince also was invigorated. He leaned over several times to drink out of the hollow of his hand.

Suddenly he turned his head.

"Here come our enemies!" said he.

The horsemen, following the pathway which I had made in the woods, had reached the banks of the river; they saw us, and riding along the borders they started in pursuit of us.

The Prince watched them closely.

"They are taking aim," cried he, "give your War-cry!"

I tore up from the bottom of my lungs the most terrible yell in my power! It was a success; and the echoes repeated it as if they would never stop. It did not fail to produce the effect my Master expected. The horses were terrified and reared in disorder, and the shots scattered, without reaching us.

"We know how to defend ourselves for the present," said Alemguir; "some of the men are unhorsed, and the others have all they can do to control their animals."

Having my back turned, I could see nothing, but was greatly rejoiced at what I heard.

The current continued to carry us on, and there was no way of landing on the other side, which presented only a straight wall, while on the side of our foes the shore was becoming less and less steep.

The soldiers of Mysore, having succeeded in quieting their steeds, now gained rapidly upon us; but it was a peril of another kind that suddenly alarmed me. I felt the water beginning to draw me on with increasing swiftness, as though being attracted towards a gulf. I struggled vigorously against the current, endeavouring to draw backwards, but I could affect but little its course, which had become fearful in its rapidity. The Prince shared my anxiety.

"Help me," said he, "to stand upright on your neck, so that I can see what is this new danger."

I held up my trunk, and he leaned against it, steadying himself by means of it.

"Don't hesitate," shouted he in a trembling voice. "Throw yourself onto the shore where our enemies are—the river is going to fall in a cataract down into a horrible abyss!"

I swam with all my might towards the shore; but a force greater than mine drew me towards the fall, from which we were now distant only about a hundred yards.

"Courage! courage!" called my Master.

I made a desperate effort, straining every muscle, and putting forth every ounce of strength that I possessed. But I was out of breath, stunned by the fearful roar of the cataract, now so near, and blinded by the spray of the boiling waters.

I felt that hope was at an end. And I was about to abandon effort when I felt the ground under my feet. That revived me; in two strokes I was within a few yards of the shore, standing on a bottom of solid rock, my flanks panting with a cruel lack of breath.

The Prince, whose limbs I could feel still trembled, stroked me with his hand and spoke gently to me. The water ran foaming between my legs as though they were the piers of a bridge; but it could no longer carry me away.

The soldiers now rode up with shouts of joy, and were preparing to aim at their ease, when "Charge them!" ordered my Master.

I thundered my war-cry, and rushed at them from the water, with my trunk uplifted.

The horses took fright, plunging and seizing the bit; a number of them ran off "ventre-à-terre."

The captain of the soldiers was furious; mastering his horse by means of the spurs, he fired. The ball passed so close to the head of Alemguir that it singed his hair. At this, transported with rage, I ran at him; I seized him with my trunk, and dragged him out of the saddle. At the shriek which he uttered his companions, instead of coming to his rescue, left him and fled.

For a moment I balanced him in the air, like a trophy; then I tossed him into the middle of the river, where he fell with a splash almost as great as the one I myself had made recently.

The wretch struggled for a moment, and then was swept on and dashed over the cataract.

The sun was shining now, and dried us with its warmth. We were saved. And this joy compensated for all the sufferings we had endured.

The Prince dismounted; standing before me, he gazed gratefully upon me.

"Had it not been for thee," he said, "at this moment my head would be rolling in blood!

"During our flight our safety depended on each moment as it passed—not an instant could be spared—and I have only been able to thank thee in my heart. But now, before this shining Sun, I desire to express the feelings that thy devotion, thy heroism, have inspired in me. Oh! Iravata, had it pot been for thee, Saphire-of-Heaven, in robes of mourning, would have wept my death; without thee I should never have lived to behold my child! My name would have been dishonoured by a disgraceful death, my Kingdom conquered and ravaged—whereas, my life being saved, all can be regained. And this I owe to a being whom men deem inferior to themselves! Ah! the Princess of Siam was right. It is indeed a Royal Soul that is hidden in thy rough body!"

I was greatly embarrassed by so much praise: and I could not make it understood that if I had a "Soul," it was simply a good, plain, elephant soul—all full of affection for him who had been the first to treat me as a friend.

He stroked me softly with his hand, and gazing at me smiled kindly; while I by all the means in my power—flapping my ears—snorting—and shuffling my feet, expressed my delight.

"I swear to you," said the Prince, "that hereafter you shall always be treated as an equal, and looked upon as my best friend!...

"But let us move on; our enemies may return in force, now that my escape must be known to all."

We descended a steep hill, parallel with the waterfall, and found ourselves in a beautiful fertile plain, through which the river, grown tranquil and shallow, ran gently over a bed of rocks and pebbles. I was able to wade across with ease a short distance below the cataract, which fell, scattering itself in snowy foam, which the sunlight filled with sparkling rainbows. Here was the leap we had so nearly taken! One could but tremble to look at it, in spite of the loveliness with which Nature had adorned it.

I looked for the horseman who had been dashed to pieces there, but not a trace of him was left.

When we reached the other side we found the plain covered with fresh grass, growing in thick tufts. My Master told me to eat.

"See! there is a fine meal for you," said he, "which you should take advantage of at once. I am sorry that I cannot, like you, breakfast on green bushes!... For it is a long time since I have tasted food!"

But how could I eat when he was suffering the pangs of hunger? I continued on my way, as though I had not heard.

"I understand you well, Iravata," said the Prince. "You are refusing to eat because I am compelled to go fasting. But this will not do. I know the requirements of your vast stomach—those of men are more patient!"

I was above all tortured with thirst, and I drank my fill from the river.

"Eat", Iravata—"your stomach being empty will not fill mine!"

I pulled off here and there bunches of leaves and grass, but without stopping. I looked everywhere for signs of some houses or villages.

"That is useless," said the Prince, who devined my thoughts. "They robbed me of all I had, and did not leave me a diamond, or a rupee; and I am not yet so vanquished by misfortune as to be willing to beg! I have only succeeded in saving my royal Signet. The idea came to me to remove from my finger the ring on which it is engraved, and conceal it in my mouth. But I cannot barter this Seal, which will serve to identify me, for the sake of food. I must wait till we find people who are capable of understanding the significance of my ring, and who will furnish me with the means of reaching my Kingdom."

My Master was right. He could not sell his ring.

I hurried my steps to get out of this detestable prairie, which seemed to have no end. But though I travelled on and on, the same fresh grass and herbage surrounded us, with from time to time a few tall trees which bore no fruit; and not a sign of any human habitation was to be seen.

The Prince had gathered some large leaves with which to cover his head, and protect it from the burning rays of noon, and had also placed some on mine, knowing how the heat distresses us.

Some cultivated fields now appeared, and presently a group of giant bamboos, and in their midst an edifice of stone, in the form of a bee-hive.

"It is a Shrine," said Alemguir. "Let us not fail to render homage to the God it shelters, who meets us thus on our way, before going any further. Our prayers finished it will be well to rest ourselves in the shade of the trees."

What a surprise when I stood before the entrance of the Chapel! The stone God which appeared in the depths on a dais of velvet was a Man with the head of an Elephant!

"Ganesa! the God of Wisdom!" cried the Prince. "It is no chance that has brought us here before Him, to whom more than to all the others I should offer thanks!"

He knelt at the foot of the altar and prayed in a low voice. During this time I, who could not enter the small and narrow building, examined this strange God, who on the body of a Man bore a head like mine, and held the tip of his trunk in his right hand!

I could see the upper part of the altar which was hidden from my Master, being above his head. There were fresh offerings in plates and bowls—Oh! joy! Cakes, melted butter, and various fruits—enough to feed a man for three days!

My trunk reached the Altar. As the Prince finished his prayers I placed, one after another, the plates and dishes before him.