TRANSCRIBER'S NOTE

The cover image was created by the transcriber and is placed in the public domain.

Obvious typographical errors and punctuation errors have been corrected after careful comparison with other occurrences within the text and consultation of external sources.

More detail can be found at the end of the book.

THE THOUGHTS

OF

BLAISE PASCAL

THE THOUGHTS OF

BLAISE PASCAL

TRANSLATED FROM THE TEXT OF

M. AUGUSTE MOLINIER

BY

C. KEGAN PAUL

Pendent opera interrupta

LONDON

KEGAN PAUL, TRENCH & CO.

MDCCCLXXXV

| Page | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preface |

vii | |

| General Introduction | 1 | |

| Pascal's Profession of Faith | 2 | |

| General Introduction | 3 | |

| Notes for the General Introduction |

11 | |

| The Misery of Man Without God | 15 | |

| Preface to the First Part | 17 | |

| Man's Disproportion | 19 | |

| Diversion | 33 | |

| The Greatness and Littleness of Man | 43 | |

| Of the Deceptive Powers of the Imagination | 51 | |

| Of Justice, Customs, and Prejudices | 61 | |

| The Weakness, Unrest, and Defects of Man |

73 | |

| The Happiness of Man with God | 89 | |

| Preface to the Second Part | 91 | |

| Of the Need of Seeking Truth | 95 | |

| The Philosophers | 105 | |

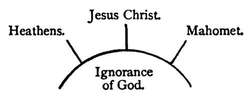

| Thoughts on Mahomet and on China | 115 | |

| Of the Jewish People | 119 | |

| The Authenticity of the Sacred Books | 125 | |

| The Prophecies | 131 | |

| Of Types in General and of their Lawfulness | 157 | |

| That the Jewish Law was Figurative | 167 | |

| Of the True Religion and its Characteristics | 179 | |

| The Excellence of the Christian Religion | 183 | |

| Of Original Sin | 191 | |

| The Perpetuity of the Christian Religion | 197 | |

| [vi] | Proofs of the Christian Religion | 203 |

| Proofs of the Divinity of Jesus Christ | 213 | |

| The Mission and Greatness of Jesus Christ | 225 | |

| The Mystery of Jesus | 231 | |

| Of the True Righteous Man and of the True Christian | 237 | |

| The Arrangement | 253 | |

| Of Miracles in General | 257 | |

| Jesuits and Jansenists | 273 | |

| Thoughts on Style | 301 | |

| Various Thoughts |

307 | |

| Notes |

317 | |

| Index |

339 | |

Those to whom the Life of Pascal and the Story of Port Royal are unknown, must be referred to works treating fully of the subject, since it were impossible to deal with them adequately within the limits of a preface. Sainte-Beuve's great work on Port Royal, especially the second and third volumes, and "Port Royal," by Charles Beard, B.A., London, 1863, may best be consulted by any who require full, lucid, and singularly impartial information.

But for such as, already acquainted with the time and the man, need a recapitulation of the more important facts, or for those who may find an outline map useful of the country they are to study in detail, a few words are here given.

Blaise Pascal was born at Clermont-Ferrand in Auvergne, on June 19, 1623. He sprung from a well-known legal family, many members of which had held lucrative and responsible positions. His father, Etienne Pascal, held the post of intendant, or provincial administrator, in Normandy, where, and at Paris previously, Pascal lived from the age of sixteen to that of twenty-five; almost wholly educated by his father on account of his precarious health. His mother died when he was eight years old. Etienne Pascal was a pious but stern person, and by no means disposed to entertain or allow any undue exaltation in religion, refusing as long as he lived to allow his daughter Jaqueline to take the veil. But he had the usual faiths and superstitions of his time, and believing that his son's ill-health arose from witchcraft, employed the old woman who was supposed to have caused the malady to remove it, by herbs culled before sunrise, and the expiatory death of a cat. This made a great impression on his son, who in the "Thoughts" employs an[viii] ingenious argument to prove that wonders wrought by the invocation of the devil are not, in the proper sense of the term, miracles. At any rate the counter-charm was incomplete, as the child's feeble health remained feeble to the end.

Intellectually, Blaise Pascal grew rapidly to the stature and strength of a giant; his genius showing itself mainly in the direction of mathematics; at the age of fifteen his studies on conic sections were thought worthy to be read before the most scientific men of Paris, and in after years of agonizing pain mathematical research alone was able to calm him, and distract his mind from himself. His actual reading was at all times narrow, and his scholarship was not profound. In 1646, his father, having broken his thigh at Rouen, came under the influence of two members of the Jansenist school of thought at that place, who attended him in his illness, and from that time dated the more serious religious views of the family. Jaqueline was from the first deeply affected by the more rigorous opinions with which she came in contact. Forbidden to enter the cloister, she lived at home as austere a life as though she had been professed, but after her father's death won her brother's reluctant consent to take the veil at Port Royal, and became one of the strictest nuns of that rigid rule.

Blaise Pascal went through a double process of conversion. When the family first fell under Jansenist influence he threw himself so earnestly into the study of theology that he seriously injured his frail health, and being advised to refrain from all intellectual labour, he returned to the world of Paris, where his friends the Duc de Roannez, the Chevalier de Méré and M. Miton were among the best known and most fashionable persons. His father's death put him in possession of a fair fortune, which he used freely, not at all viciously, but with no renunciation of the pleasures of society. There is some evidence of a proposal that he should marry the Duc de Roannez' sister, and no doubt with such a scheme before him he wrote his celebrated "Discours sur les Passions de l'Amour." This, however, resulted only in the conversion of the duke and his sister, the latter of whom for a time, the former for the whole of his life, remained subject to the religious feelings then excited.

In the autumn of 1654, whether after deliverance in a dangerous accident, or from some hidden cause of which nothing can now be even surmised, there came a second sudden conversion from which there was no return. That hour wrought a complete change in Pascal's life; austerity, self-denial, absolute obedience to his spiritual director, boundless alms-giving succeeded to what at most had been a moderate and restrained use of worldly pleasure, and he threw himself into the life, controversy and interests of Port Royal, with all the passion of one who was not only a new convert, but the champion of a society into which those dearest to him had entered even more fully than he. He became, for a time, one of the solitaries of Port Royal before the close of that same year.

The Cistercian Abbey of Port Royal des Champs was situated about eighteen miles from Paris. It had been founded early in the thirteenth century, and would have faded away unremembered but for the grandeur of its closing years. The rule of the community had been greatly relaxed, but it was reformed with extreme rigour by Jaqueline Arnauld, its young abbess, known in religion as La Mère Angélique. The priest chosen as Director of the community was Jean du Vergier de Hauranne, Abbé de St. Cyran, a close friend of Cornelius Jansen, Bishop of Ypres. They had together devoted themselves to the study of Saint Augustine; and the "Augustinus," the work to which Jansen gave his whole life, was planned with the assistance of St. Cyran. Certain propositions drawn from this work were afterwards condemned, and the controversy which raged between the two schools of the Jesuits and the Jansenists divided itself into two parts, first, whether the propositions were heretical, and secondly, whether as a fact they were contained in, or could fairly be deduced from, Jansen's book. The strife, which raged with varying fortunes for many years, need not here detain us.

After the reform of Port Royal, and when the Society, however assailed and in danger, was at the height of its renown, the whole establishment consisted of two convents, the mother house of Port Royal des Champs, and one in Paris to which was attached a school for girls. To Port Royal des Champs, as to a spiritual centre, and to be under the guidance of the three great[x] directors, who in succession ruled the abbey, M. de St. Cyran, M. Singlin, and M. de Saci, there came men and women, not under monastic vows, but living for a time the monastic or even the eremitical life. The women, for the most part, had rooms in the convent, the men built rooms for themselves hard by, or shared between them La Grange, a farm belonging to the abbey. It need scarcely be said that in so strict a community the sexes were wholly separate; a common worship, and the confidence of the same confessor, together with similarity of views in religion, were the ties which bound together the whole society.

When Pascal formally joined Port Royal, the Abbey and all that was attached to it greatly needed aid from without. A Bull in condemnation of Jansen had been gained from the Pope, and a Formulary, minimising its effect as far as possible, was drawn up by the General Assembly in France, which was ultimately accepted by Port Royal itself. But if the Port Royalists minimized the defeat, and, with great intellectual dexterity, showed that the condemned propositions were not in precise terms what they had held, and were not in Jansen's book, their adversaries exaggerated the victory. A confessor in Paris refused absolution to a parishioner because he had a Jansenist living in his house, and had sent his grand-daughter to school at Port Royal. Antoine Arnauld, known as Le Grand Arnauld, brother of La Mère Angélique, himself in danger of condemnation by the Sorbonne, drew up a statement of the case intended to instruct the public on the points in dispute. On reading this to the Port Royal solitaries before printing it, he saw that it would not do, and turning to Pascal, who had then been a year under M. Singlin's direction, he suggested to him as a younger man with a lighter pen to see what he could do. The next day Pascal produced the first of the "Provincial Letters," or to give it the correct title, "A Letter written to a Provincial by one of his friends." In these Letters Pascal formed his true style, and took rank at once among the great French writers. They contributed largely to turn the scale of feeling against his adversaries; they, and an occurrence in which he saw the visible finger of God, saved Port Royal for a time. But the history of the "Provincial Letters" must be read elsewhere, as must also in[xi] its fulness the miracle of the Holy Thorn, on which a few words are needed.

The "Provincial Letters" were in course of publication, but M. Arnauld had been condemned by the Sorbonne just as the first was issued, and his enemies said he was excommunicated, which was not technically true; he was in danger of arrest, and was in hiding; the solitaries of Port Royal were almost all dispersed; the schools were thinned of their pupils and on the point of closing, the confessors were about to be withdrawn and the nuns sent to various other convents, when the miracle took place. Marguerite Perier, a child of ten years old, daughter of Pascal's elder sister, was one of the pupils at Port Royal in Paris, not as yet dismissed to her home. She was tenderly nursed by the nuns for an ulcer in the lachrymal gland, which had destroyed the bones of the nose, and produced other horrors of which there is no need to speak. A relic of the Saviour, one of the thorns of his crown of mockery, which had been intrusted to the nuns, was specially venerated during a service in its honour, and as it would seem was passed from hand to hand in its reliquary. When the turn of the scholars came, Sister Flavia, their mistress, moved by a sudden impulse said, "My child, pray for your eye," and touched the ulcer with the reliquary. The child was cured, and the effect on the community was immediate. The remaining solitaries were not dispersed, some of those who had gone returned, the confessors were not removed, the school was not closed, and Port Royal was respited.

The miracle was to Pascal at once a solemn matter of religion and a family occurrence; he took henceforward as his cognizance an eye encircled with a crown of thorns and the motto Scio cui credidi, he jotted down various thoughts on the miracle, and the manner in which as it seemed to him God had by it given as by "a voice of thunder" his judgment in favour of Port Royal, and he sketched a plan of a work against atheists and unbelievers. In the year between the spring of 1657, and that of 1658, the last year of his good health, if that can be called good which was at best but feeble, he indicated the plan, and wrote the most finished paragraphs of his intended work. The detached thoughts which make up the bulk of it were[xii] scribbled, as they occurred to him during the last four years of his life, on scraps of paper, or on the margin of what he had already written, often when he was quite incapable of sustained employment. Many were dictated, some to friends, and some to a servant who constantly attended him in his illness.

Towards the end of his life he was obliged to move into Paris again, where he was carefully nursed by his sister Madame Perrier, to whose house he was moved at the last, where he died on August 9th, 1662, at the age of thirty-nine, having spent his last years in an ecstasy of self-denial, of charity, and of aspiration after God.

Not for six years after his death were his family and friends able to consider in what form his unfinished work should be given to the world. Then Port Royal had a breathing space, what was known as the Peace of the Church was established by Clement IX., and it was considered that the time had come to set in order these precious fragments. The duty of giving an author's works to the world as he left them was little understood in those days, and the Duc de Roannez even suggested that Pascal's whole work should be re-written on the lines he had laid down. Some editing was, on all hands, allowed to be needful; thus the arrangement of chapters, and the fragments to be included in chapters, were matter for fair discussion. But the committee of editors went further, and even when the text had been settled by them, it had to undergo a further censorship by various theologians. Finally, in January, 1670, the "Pensées" appeared as a small duodecimo, with a preface by the Perrier family, and no mention of Port Royal in the volume.

For a full account of this and other editions, the reader must be referred to the preface to M. Molinier's edition, Paris, 1877-1879, and to that of M. Faugère, Paris, 1844.

M. Victor Cousin was the first to draw attention to the need of a new edition of Pascal in 1842. He showed that great liberties had been taken with and suppressions made in the text, and the labour to which he invited was first undertaken by M. Prosper Faugère. M. Havet adopting his text departed from his arrangement, reverted in great measure to that of the[xiii] old editors, and accompanied the whole by an excellent commentary and notes, 2nd edition, Paris, 1866. M. Molinier has again consulted the MSS. word for word, and while in a degree following M. Faugère's arrangement has yet been guided by his own skill and judgment. It must always be remembered that each editor must necessarily follow his own judgment in regard to the position he should give to fragments not placed by the writer. But provided that an editor makes no changes merely for the sake of change and that he loyally enters into the spirit of his predecessors, each new comer, till the arrangement is finally fixed, has a great advantage. Such an editor is M. Molinier, and in his arrangement the text of Pascal would seem to be mainly if not wholly fixed; so that for the first time we have not only Pascal's "Thoughts," but we have them approximately arranged as he designed to present them to his readers.

The course of an English translator is clear; his responsibility is confined to deciding which text to follow, he has no right to make one for himself. In the present edition, therefore, M. Molinier's text and arrangement are scrupulously followed except in two places. In regard to one, M. Molinier has himself adopted a different reading in his notes made after the text was printed, the second is an obvious misprint. Pascal's "Profession of Faith," or "Amulet," is transferred from the place it occupies in M. Molinier's edition to serve as an introduction to the work, striking as it does the key-note to the "Thoughts."

Pascal's quotations from the Bible were made of course from the Vulgate, but very often indeed from memory, and incorrectly, while he often gave the substance alone of the passage he used. No one version of the Bible therefore has been used exclusively, but the Authorised Version and the Douai or Rheims versions have been used as each in turn most nearly afforded the equivalent of the quotations made by Pascal.

The notes are mainly based on those of MM. Faugère, Havet, and Molinier.

This year of Grace 1654,

Monday, November 23rd, day of Saint Clement, pope

and martyr, and others in the martyrology,

Eve of Saint Chrysogonus, martyr, and others;

From about half past ten at night, to

about half after midnight,

Fire.

God of Abraham, God of Isaac, God of Jacob,

Not of the philosophers and the wise.

Security, security. Feeling, joy, peace.

God of Jesus Christ

Deum meum et Deum vestrum.

Thy God shall be my God.

Forgetfulness of the world and of all save God.

He can be found only in the ways taught

in the Gospel.

Greatness of the human soul.

O righteous Father, the world hath not known thee,

but I have known thee.

Joy, joy, joy, tears of joy.

I have separated myself from him.

Dereliquerunt me fontem aqua vivæ.

My God, why hast thou forsaken me?...

That I be not separated from thee eternally.

This is life eternal: That they might know thee

the only true God, and him whom thou hast sent, Jesus Christ,

Jesus Christ,

Jesus Christ.

I have separated myself from him; I have fled, renounced, crucified him.

May I never be separated from him.

He maintains himself in me only in the ways taught

in the Gospel.

Renunciation total and sweet.

etc.

Let them at least learn what is the Religion they assail, before they assail it. If this religion claimed to have a clear view of God, and to possess it openly and unveiled, then to say that we see nothing in the world which manifests him with this clearness would be to assail it. But since on the contrary it affirms that men are in darkness and estranged from God, that he has hidden himself from their knowledge, that the very name he has given himself in the Scriptures is Deus absconditus; and if indeed it aims equally at establishing these two points, that God has set in the Church evident notes to enable those who seek him in sincerity to recognise him, and that he has nevertheless so concealed them that he can only be perceived by those who seek him with their whole hearts; what advantages it them, when, in their professed neglect of the search after truth, they declare that nothing reveals it to them? For the very obscurity in which they are, and for which they blame the Church, does but establish one of the points which she maintains, without affecting the other, and far from destroying, establishes her doctrine.

In order to assail it they ought to urge that they have sought everywhere with all their strength, and even in that which the Church proposes for their instruction, but without avail. Did they thus speak, they would indeed assail one of her claims. But I hope here to show that no rational person can thus speak, and I am even bold to say that no one has ever done so. We know well enough how men of this temper behave. They believe they have made great efforts for their instruction, when they have[4] spent a few hours in reading some book of Scripture, and have talked with some Ecclesiastic on the truths of the faith. Whereupon they boast that they have in vain consulted books and men. But indeed I will tell them what I have often said, that such carelessness is intolerable. We are not here dealing with the light interest of a stranger, that we should thus treat it; but with that which concerns ourselves and our all.

The immortality of the soul is a matter of so great moment to us, it touches us so deeply, that we must have lost all feeling if we are careless of the truth about it. Our every action and our every thought must take such different courses, according as there are or are not eternal blessings for which to hope, that it is impossible to take a single step with sense or judgment, save in view of that point which ought to be our end and aim.

Thus our first interest and our first duty is to gain light on this subject, whereon our whole conduct depends. Therefore among unbelievers, I make a vast difference between those who labour with all their power to gain instruction, and those who live without taking trouble or thought for it.

I can have nothing but compassion for all who sincerely lament their doubt, who look upon it as the worst of evils, and who, sparing no pains to escape it, find in that endeavour their principal and most serious occupation.

But as for those who pass their life without thought of the ultimate goal of life, who, solely because they do not find within themselves the light of conviction, neglect to seek it elsewhere and to examine thoroughly whether the opinion in question be among those which are popularly received with credulous simplicity, or among those which, although in themselves obscure, have yet a solid and indestructible basis,—of those, I say, my thoughts are very different.

This neglect of a matter in which themselves are concerned, their eternity, and their all, makes me angry rather than compassionate; it astonishes and terrifies me, it is to me something monstrous. I do not say this out of the pious zeal of a spiritual devotion. I mean on the contrary that such a feeling should spring from principles of human interest and self-love; and for this we need see no more than what is seen by the least enlightened persons.

We need no great elevation of soul to understand that here is no true and solid satisfaction, that all our pleasures are but vanity, our evils infinite, and lastly that death, which threatens us every moment, must infallibly and within a few years place us in the dread alternative of being for ever either annihilated or wretched.

Nothing is more real than this, nothing more terrible. Brave it out as we may, that is yet the end which awaits the fairest life in the world. Let us reflect on this, and then say if it be not certain that there is no good in this life save in the hope of another, that we are happy only in proportion as we approach it, and that as there is no more sorrow for those who have an entire assurance of eternity, so there is no happiness for those who have not a ray of its light.

Assuredly then it is a great evil thus to be in doubt, but it is at least an indispensable duty to seek when we are in such doubt; he therefore who doubts and yet seeks not is at once thoroughly unhappy and thoroughly unfair. And if at the same time he be easy and content, profess to be so, and in fact pride himself thereon; if even it be this very condition of doubt which forms the subject of his joy and boasting, I have no terms in which to describe a creature so extravagant.

Whence come such feelings? What delight can we find in the expectation of nothing but unavailing misery? What cause of boasting that we are in impenetrable darkness? How can such an argument as the following occur to a reasoning man?

"I know not who has sent me into the world, nor what the world is, nor what I myself am; I am terribly ignorant of every thing; I know not what my body is, nor my senses, nor my soul, nor even that part of me which thinks what I say, which reflects on all and on itself, yet is as ignorant of itself as of all beside. I see those dreadful spaces of the universe which close me in, and I find myself fixed in one corner of this vast expanse, without knowing why I am set in this place rather than elsewhere, nor why this moment of time given me for life is assigned to this point rather than another of the whole Eternity which was before me or which shall be after me. I see nothing but infinities on every side, which close me round as an atom, and as a shadow[6] which endures but for an instant and returns no more. I know only that I must shortly die, but what I know the least is this very death which I cannot avoid.

"As I know not whence I come, so I know not whither I go; only this I know, that on departing this world, I shall either fall for ever into nothingness, or into the hands of an offended God, without knowing which of these two conditions shall eternally be my lot. Such is my state, full of weakness and uncertainty; from all which I conclude that I ought to pass all the days of my life without thought of searching for what must happen to me. Perhaps I might find some ray of light in my doubts, but I will not take the trouble, nor stir a foot to seek it; and after treating with scorn those who are troubled with this care, I will go without foresight and without fear to make trial of the grand event, and allow myself to be led softly on to death, uncertain of the eternity of my future condition."

Who would wish to have for his friend a man who should thus speak; who would choose him rather than another for advice in business; who would turn to him in sorrow? And indeed to what use in life could we put him?

In truth, it is the glory of Religion to have for enemies men so unreasoning, whose opposition is so little dangerous to her, that it the rather serves to establish her truths. For the Christian faith goes mainly to the establishment of these two points, the corruption of nature, and the Redemption by Jesus Christ. Now I maintain that if these men serve not to demonstrate the truth of Redemption by the holiness of their morals, they at least serve admirably to show the corruption of nature by sentiments so unnatural.

Nothing is so important to man as his condition, nothing so formidable to him as eternity; and thus it is not natural there should be men indifferent to the loss of their being, and to the peril of an endless woe. They are quite other men in regard to all else; they fear the veriest trifles, they foresee them, they feel them; and the very man who spends so many days and nights in rage and despair for the loss of office or for some imaginary insult to his honour, is the same who, without disquiet and without emotion, knows that he must lose all by death. It is a monstrous[7] thing to see in one and the same heart and at the same time this sensibility to the meanest, and this strange insensibility to the greatest matters. It is an incomprehensible spell, a supernatural drowsiness, which denotes as its cause an all powerful force.

There must be a strange revolution in the nature of man, before he can glory at being in a state to which it seems incredible that any should attain. Experience however has shown me a large number of such men, a surprising fact did we not know that the greater part of those who meddle with the matter are not as a fact what they declare themselves. They are people who have been told that the manners of good society consist in such daring. This they call shaking off the yoke, this they try to imitate. Yet it would not be difficult to convince them how much they deceive themselves in thus seeking esteem. Not so is it acquired, even among those men of the world who judge wisely, and who know that the only way of worldly success is to show ourselves honourable, faithful, of sound judgment, and capable of useful service to a friend; because by nature men love only what may prove useful to them. Now in what way does it advantage us to hear a man say he has at last shaken off the yoke, that he does not believe there is a God who watches his actions, that he considers himself the sole master of his conduct and accountable for it only to himself. Does he think that thus he has brought us to have henceforward confidence in him, and to look to him for comfort, counsel and succour in every need of life? Do they think to delight us when they declare that they hold our soul to be but a little wind or smoke, nay, when they tell us so in a tone of proud content? Is this a thing to assert gaily, and not rather to say sadly as the saddest thing in all the world?

Did they think on it seriously, they would see that this is so great a mistake, so contrary to good sense, so opposed to honourable conduct, so remote in every respect from that good breeding at which they aim, that they would choose rather to restore than to corrupt those who might have any inclination to follow them. And indeed if they are obliged to give an account of their opinions, and of the reasons they have[8] for doubts about Religion, they will say things so weak and base, as rather to persuade the contrary. It was once happily said to such an one, "If you continue to talk thus you will really make me a Christian." And the speaker was right, for who would not be horrified at entertaining opinions in which he would have such despicable persons as his associates!

Thus those who only feign these opinions would be very unhappy were they to put force on their natural disposition in order to make themselves the most inconsequent of men. If, in their inmost hearts, they are troubled at their lack of light, let them not dissemble: the avowal will bring no shame; the only shame is to be shameless. Nothing betrays so much weakness of mind as not to apprehend the misfortune of a man without God, nothing is so sure a token of an evil disposition of heart as not to desire the truth of eternal promises, nothing is more cowardly than to fight against God. Let them therefore leave these impieties to persons who are so ill-bred as to be really capable of them, let them at least be men of honour if they cannot be Christians, and lastly, let them recognise that there are but two classes of men who can be called reasonable; those who serve God with their whole heart because they know him, or those who seek him with their whole heart because they know him not.

But as for those who live without knowing him and without seeking him, they judge themselves to deserve their own care so little, that they are not worthy the care of others, and it needs all the charity of the Religion they despise, not to despise them so utterly as to abandon them to their madness. But since this Religion obliges us to look on them, while they are in this life, as always capable of illuminating grace, and to believe that in a short while they may be more full of faith than ourselves, while we on the other hand may fall into the blindness which now is theirs, we ought to do for them what we would they should do for us were we in their place, and to entreat them to take pity on themselves and advance at least a few steps, if perchance they may find the light. Let them give to reading these words a few of the hours which otherwise they spend so unprofitably: with whatever aversion they set about it they may perhaps gain something; at least they cannot be great losers. But if any bring[9] to the task perfect sincerity and a true desire to meet with truth, I despair not of their satisfaction, nor of their being convinced of so divine a Religion by the proofs which I have here gathered up, and have set forth in somewhat the following order....

Before entering upon the proofs of the Christian Religion, I find it necessary to set forth the unfairness of men who live indifferent to the search for truth in a matter which is so important to them, and which touches them so nearly.

Among all their errors this doubtless is the one which most proves them to be fools and blind, and in which it is most easy to confound them by the first gleam of common sense, and by our natural feelings.

For it is not to be doubted that this life endures but for an instant, that the state of death is eternal, whatever may be its nature, and that thus all our actions and all our thoughts must take such different courses according to the state of that eternity, as to render it impossible to take a single step with sense and judgment, save in view of that point which ought to be our end and aim.

Nothing is more clear than this, and therefore by all principles of reason the conduct of men is most unreasonable if they do not alter their course. Hence we may judge concerning those who live without thinking of the ultimate goal of life, who allow themselves to be guided by their inclinations and their pleasures without thought or disquiet, and, as if they could annihilate eternity by turning their minds from it, consider only how they may make themselves happy for the moment.

Yet this eternity exists; and death the gate of eternity, which threatens them every hour, must in a short while infallibly reduce them to the dread necessity of being through eternity either nothing or miserable, without knowing which of these eternities is for ever prepared for them.

This is a doubt which has terrible consequences. They are in danger of an eternity of misery, and thereupon, as if the matter were not worth the trouble, they care not to examine whether this is one of those opinions which men in general receive with a too credulous facility, or among those which, themselves obscure, have yet a solid though concealed foundation. Thus they know not whether the matter be true or false, nor if[10] the proofs be strong or weak. They have them before their eyes, they refuse to look at them, and in that ignorance they choose to do all that will bring them into this misfortune if it exist, to wait for death to verify it, and to be in the meantime thoroughly satisfied with their state, openly avowing and even making boast of it. Can we think seriously on the importance of this matter without being revolted at conduct so extravagant?

Such rest in ignorance is a monstrous thing, and they who live in it ought to be made aware of its extravagance and stupidity, by having it revealed to them, that they may be confounded by the sight of their own folly. For this is how men reason when they choose to live ignorant of what they are and do not seek to be enlightened. "I know not," say they....

To doubt is then a misfortune, but to seek when in doubt is an indispensable duty. So he who doubts and seeks not is at once unfortunate and unfair. If at the same time he is gay and presumptuous, I have no terms in which to describe a creature so extravagant.

A fine subject of rejoicing and boasting, with the head uplifted in such a fashion.... Therefore let us rejoice; I see not the conclusion, since it is uncertain, and we shall then see what will become of us.

Is it courage in a dying man that he dare, in his weakness and agony, face an almighty and eternal God?

Were I in that state I should be glad if any one would pity my folly, and would have the goodness to deliver me in despite of myself!

Yet it is certain that man has so fallen from nature that there is in his heart a seed of joy in that very fact.

A man in a dungeon, who knows not whether his doom is fixed, who has but one hour to learn it, and this hour enough, should he know that it is fixed, to obtain its repeal, would act against nature did he employ that hour, not in learning his sentence, but in playing piquet.

So it is against nature that man, etc. It is to weight the hand of God.

Thus not the zeal alone of those who seek him proves God, but the blindness of those who seek him not.

We run carelessly to the precipice after having veiled our eyes to hinder us from seeing it.

Between us and hell or heaven, there is nought but life, the frailest thing in all the world.

If it be a supernatural blindness to live without seeking to know what we are, it is a terrible blindness to live ill while believing in God.

The sensibility of man to trifles, and his insensibility to great things, is the mark of a strange inversion.

This shows that there is nothing to say to them, not that we despise them, but because they have no common sense: God must touch them.

We must pity both parties, but for the one we must feel the pity born of tenderness, and for the other the pity born of contempt.

We must indeed be of that religion which man despises that we may not despise men.

People of that kind are academicians and scholars, and that is the worst kind of men that I know.

I do not gather that by system, but by the way in which the heart of man is made.

To reproach Miton, that he is not troubled when God will reproach him.

Is this a thing to say with joy? It is a thing we ought then to say with sadness.

Nothing is so important as this, yet we neglect this only.

This is all that a man could do were he assured of the falsehood of that news, and even then he ought not to be joyful, but downcast.

... Suppose an heir finds the title-deeds of his house. Will he say, "Perhaps they are forgeries?" and neglect to examine them?

We must not say that this is a mark of reason.

To be so insensible as to despise interesting things, and to become insensible to the point which most interests us.

What then shall we conclude of all these obscurities, if not our own unworthiness?

To speak of those who have treated of the knowledge of self, of the divisions of Charron which sadden and weary us, of the confusion of Montaigne; that he was aware he had no definite system, and tried to evade the difficulty by leaping from subject to subject; that he sought to be fashionable.

His foolish project of self-description, and this not casually and against his maxims, since everybody may make mistakes, but by his maxims themselves, and by his main and principal design. For to say foolish things by chance and weakness is an ordinary evil, but to say them designedly is unbearable, and to say of such that....

Montaigne.—Montaigne's defects are great. Lewd expressions. This is bad, whatever Mademoiselle de Gournay may say. He is credulous, people without eyes; ignorant, squaring the circle, a greater world. His opinions on suicide and on death. He suggests a carelessness about salvation, without fear and without repentance. Since his book was not written with a religious intent, it was not his duty to speak of religion; but it is always a duty not to turn men from it. We may excuse his somewhat lax and licentious opinions on some relations of life, but not his thoroughly pagan opinions on death, for a man must give over piety altogether, if he does not at least wish to die like a Christian. Now through the whole of his book he looks forward to nothing but a soft and indolent death.

What good there is in Montaigne can only have been[18] acquired with difficulty. What is evil in him, I mean apart from his morality, could have been corrected in a moment, if any one had told him he was too prolix and too egoistical.

Not in Montaigne, but in myself, I find all that I see in him.

Let no one say I have said nothing new, the disposition of my matter is new. In playing tennis, two men play with the same ball, but one places it better.

It might as truly be said that my words have been used before. And if the same thoughts in a different arrangement do not form a different discourse, so neither do the same words in a different arrangement form different thoughts.

This is where our intuitive knowledge leads us. If it be not true, there is no truth in man; and if it be, he finds therein a great reason for humiliation, because he must abase himself in one way or another. And since he cannot exist without such knowledge, I wish that before entering on deeper researches into nature he would consider her seriously and at leisure, that he would examine himself also, and knowing what proportion there is.... Let man then contemplate the whole realm of nature in its full and exalted majesty, and turn his eyes from the low objects which hem him round; let him observe that brilliant light set like an eternal lamp to illumine the universe, let the earth appear to him a point in comparison with the vast circle described by that sun, and let him see with amazement that even this vast circle is itself but a fine point in regard to that described by the stars revolving in the firmament. If our view be arrested there, let imagination pass beyond, and it will sooner exhaust the power of thinking than nature that of giving scope for thought. The whole visible world is but an imperceptible speck in the ample bosom of nature. No idea approaches it. We may swell our conceptions beyond all imaginable space, yet bring forth only atoms in comparison with the reality of things. It is an infinite sphere, the centre of which is every where, the circumference no where. It is, in short, the greatest sensible mark of the almighty power of God, in that thought let imagination lose itself.

Then, returning to himself, let man consider his own being compared with all that is; let him regard himself as[20] wandering in this remote province of nature; and from the little dungeon in which he finds himself lodged, I mean the universe, let him learn to set a true value on the earth, on its kingdoms, its cities, and on himself.

What is a man in the infinite? But to show him another prodigy no less astonishing, let him examine the most delicate things he knows. Let him take a mite which in its minute body presents him with parts incomparably more minute; limbs with their joints, veins in the limbs, blood in the veins, humours in the blood, drops in the humours, vapours in the drops; let him, again dividing these last, exhaust his power of thought; let the last point at which he arrives be that of which we speak, and he will perhaps think that here is the extremest diminutive in nature. Then I will open before him therein a new abyss. I will paint for him not only the visible universe, but all that he can conceive of nature's immensity in the enclosure of this diminished atom. Let him therein see an infinity of universes of which each has its firmament, its planets, its earth, in the same proportion as in the visible world; in each earth animals, and at the last the mites, in which he will come upon all that was in the first, and still find in these others the same without end and without cessation; let him lose himself in wonders as astonishing in their minuteness as the others in their immensity; for who will not be amazed at seeing that our body, which before was imperceptible in the universe, itself imperceptible in the bosom of the whole, is now a colossus, a world, a whole, in regard to the nothingness to which we cannot attain.

Whoso takes this survey of himself will be terrified at the thought that he is upheld in the material being, given him by nature, between these two abysses of the infinite and nothing, he will tremble at the sight of these marvels; and I think that as his curiosity changes into wonder, he will be more disposed to contemplate them in silence than to search into them with presumption.

For after all what is man in nature? A nothing in regard to the infinite, a whole in regard to nothing, a mean between nothing and the whole; infinitely removed from understanding either extreme. The end of things and their beginnings are invincibly[21] hidden from him in impenetrable secrecy, he is equally incapable of seeing the nothing whence he was taken, and the infinite in which he is engulfed.

What shall he do then, but discern somewhat of the middle of things in an eternal despair of knowing either their beginning or their end? All things arise from nothing, and tend towards the infinite. Who can follow their marvellous course? The author of these wonders can understand them, and none but he.

Of these two infinites in nature, the infinitely great and the infinitely little, man can more easily conceive the great.

Because they have not considered these infinities, men have rashly plunged into the research of nature, as though they bore some proportion to her.

It is strange that they have wished to understand the origin of all that is, and thence to attain to the knowledge of the whole, with a presumption as infinite as their object. For there is no doubt that such a design cannot be formed without presumption or without a capacity as infinite as nature.

If we are well informed, we understand that nature having graven her own image and that of her author on all things, they are almost all partakers of her double infinity. Thus we see that all the sciences are infinite in the extent of their researches, for none can doubt that geometry, for instance, has an infinite infinity of problems to propose. They are also infinite in the number and in the nicety of their premisses, for it is evident that those which are finally proposed are not self-supporting, but are based on others, which again having others as their support have no finality.

But we make some apparently final to the reason, just as in regard to material things we call that an indivisible point beyond which our senses can no longer perceive any thing, though by its nature this also is infinitely divisible.

Of these two scientific infinities, that of greatness is the most obvious to the senses, and therefore few persons have made pretensions to universal knowledge. "I will discourse of the all," said Democritus.

But beyond the fact that it is a small thing to speak of it simply, without proving and knowing, it is nevertheless impossible[22] to do so, the infinite multitude of things being so hidden, that all we can express by word or thought is but an invisible trace of them. Hence it is plain how foolish, vain, and ignorant is that title of some books: De omni scibili.

But the infinitely little is far less evident. Philosophers have much more frequently asserted they have attained it, yet in that very point they have all stumbled. This has given occasion to such common titles as The Origin of Creation, The Principles of Philosophy, and the like, as presumptuous in fact though not in appearance as that dazzling one, De omni scibili.

We naturally think that we can more easily reach the centre of things than embrace their circumference. The visible bulk of the world visibly exceeds us, but as we exceed little things, we think ourselves more capable of possessing them. Yet we need no less capacity to attain the nothing than the whole. Infinite capacity is needed for both, and it seems to me that whoever shall have understood the ultimate principles of existence might also attain to the knowledge of the infinite. The one depends on the other, and one leads to the other. Extremes meet and reunite by virtue of their distance, to find each other in God, and in God alone.

Let us then know our limits; we are something, but we are not all. What existence we have conceals from us the knowledge of first principles which spring from the nothing, while the pettiness of that existence hides from us the sight of the infinite.

In the order of intelligible things our intelligence holds the same position as our body holds in the vast extent of nature.

Restricted in every way, this middle state between two extremes is common to all our weaknesses.

Our senses can perceive no extreme. Too much noise deafens us, excess of light blinds us, too great distance or nearness equally interfere with our vision, prolixity or brevity equally obscure a discourse, too much truth overwhelms us. I know even those who cannot understand that if four be taken from nothing nothing remains. First principles are too plain for us, superfluous pleasure troubles us. Too many concords are unpleasing in music, and too many benefits annoy, we wish to have wherewithal to overpay our debt. Beneficia eo usque læta sunt dum[23] videntur exsolvi posse; ubi multum antevenere, pro gratia odium redditur.

We feel neither extreme heat nor extreme cold. Qualities in excess are inimical to us and not apparent to the senses, we do not feel but are passive under them. The weakness of youth and age equally hinder the mind, as also too much and too little teaching....

In a word, all extremes are for us as though they were not; and we are not, in regard to them: they escape us, or we them.

This is our true state; this is what renders us incapable both of certain knowledge and of absolute ignorance. We sail on a vast expanse, ever uncertain, ever drifting, hurried from one to the other goal. If we think to attach ourselves firmly to any point, it totters and fails us; if we follow, it eludes our grasp, and flies from us, vanishing for ever. Nothing stays for us. This is our natural condition, yet always the most contrary to our inclination; we burn with desire to find a steadfast place and an ultimate fixed basis whereon we may build a tower to reach the infinite. But our whole foundation breaks up, and earth opens to the abysses.

We may not then look for certainty or stability. Our reason is always deceived by changing shows, nothing can fix the finite between the two infinites, which at once enclose and fly from it.

If this be once well understood I think that we shall rest, each in the state wherein nature has placed him. This element which falls to us as our lot being always distant from either extreme, it matters not that a man should have a trifle more knowledge of the universe. If he has it, he but begins a little higher. He is always infinitely distant from the end, and the duration of our life is infinitely removed from eternity, even if it last ten years longer.

In regard to these infinites all finites are equal, and I see not why we should fix our imagination on one more than on another. The only comparison which we can make of ourselves to the finite troubles us.

Were man to begin with the study of himself, he would see how incapable he is of proceeding further. How can a part know[24] the whole? But he may perhaps aspire to know at least the parts with which he has proportionate relation. But the parts of the world are so linked and related, that I think it impossible to know one without another, or without the whole.

Man, for instance, is related to all that he knows. He needs place wherein to abide, time through which to exist, motion in order to live; he needs constituent elements, warmth and food to nourish him, air to breathe. He sees light, he feels bodies, he contracts an alliance with all that is.

To know man then it is necessary to understand how it comes that he needs air to breathe, and to know the air we must understand how it has relation to the life of man, etc.

Flame cannot exist without air, therefore to know one, we must know the other.

All that exists then is both cause and effect, dependent and supporting, mediate and immediate, and all is held together by a natural though imperceptible bond, which unites things most distant and most different. I hold it impossible to know the parts without knowing the whole, or to know the whole without knowing the parts in detail.

I hold it impossible to know one alone without all the others, that is to say impossible purely and absolutely.

The eternity of things in themselves or in God must also confound our brief duration. The fixed and constant immobility of Nature in comparison with the continual changes which take place in us must have the same effect.

And what completes our inability to know things is that they are in their essence simple, whereas we are composed of two opposite natures differing in kind, soul and body. For it is impossible that our reasoning part should be other than spiritual; and should any allege that we are simply material, this would far more exclude us from the knowledge of things, since it is an inconceivable paradox to affirm that matter can know itself, and it is not possible for us to know how it should know itself.

So, were we simply material, we could know nothing whatever, and if we are composed of spirit and matter we cannot perfectly know what is simple, whether it be spiritual or material. For[25] how should we know matter distinctly, since our being, which acts on this knowledge, is partly spiritual, and how should we know spiritual substances clearly since we have a body which weights us, and drags us down to earth.

Moreover what completes our inability is the simplicity of things compared with our double and complex nature. To dispute this point were an invincible absurdity, for it is as absurd as impious to deny that man is composed of two parts, differing in their nature, soul and body. This renders us unable to know all things; for if this complexity be denied, and it be asserted that we are entirely material, it is plain that matter is incapable of knowing matter. Nothing is more impossible than this.

Let us conceive then that this mixture of spirit and clay throws us out of proportion....

Hence it comes that almost all philosophers have confounded different ideas, and speak of material things in spiritual phrase, and of spiritual things in material phrase. For they say boldly that bodies have a tendency to fall, that they seek after their centre, that they fly from destruction, that they fear a void, that they have inclinations, sympathies, antipathies; and all of these are spiritual qualities. Again, in speaking of spirits, they conceive of them as in a given spot, or as moving from place to place; qualities which belong to matter alone.

Instead of receiving the ideas of these things simply, we colour them with our own qualities, and stamp with our complex being all the simple things which we contemplate.

Who would not think, when we declare that all that is consists of mind and matter, that we really understood this combination? Yet it is the one thing we least understand. Man is to himself the most marvellous object in Nature, for he cannot conceive what matter is, still less what is mind, and less than all how a material body should be united to a mind. This is the crown of all his difficulties, yet it is his very being: Modus quo corporibus adhæret spiritus comprehendi ab homine non potest et hoc tamen homo est.

These are some of the causes which render man so totally unable to know nature. For nature has a twofold infinity, he[26] is finite and limited. Nature is permanent, and continues in one stay; he is fleeting and mortal. All things fail and change each instant, he sees them only as they pass, they have their beginning and end, he conceives neither the one nor the other. They are simple, he is composed of two different natures. And to complete the proof of our weakness, I will finish by this reflection on our natural condition. In a word, to complete the proof of our weakness, I will end with these two considerations....

The nature of man may be considered in two ways, one according to its end, and then it is great and incomparable; the other according to popular opinion, as we judge of the nature of a horse or a dog, by popular opinion which discerns in it the power of speed, et animum arcendi; and then man is abject and vile. These are the two ways which make us judge of it so differently and which cause such disputes among philosophers.

For one denies the supposition of the other; one says, He was not born for such an end, for all his actions are repugnant to it; the other says, He cannot gain his end when he commits base deeds.

Two things instruct man about his whole nature, instinct and experience.

Inconstancy.—We think we are playing on ordinary organs when we play upon man. Men are organs indeed, but fantastic, changeable, and various, with pipes not arranged in due succession. Those who understand only how to play upon ordinary organs make no harmonies on these. We should know where are the....

Nature.—Nature has placed us so truly in the centre, that if we alter one side of the balance we alter also the other. This makes me believe that there is a mechanism in our brain, so adjusted, that who touches one touches also the contrary spring.

Lustravit lampade terras.—The weather and my moods have little in common. I have my foggy and my fine days within me, whether my affairs go well or ill has little to do with the matter. I sometimes strive against my luck, the glory of subduing it makes me subdue it gaily, whereas I am sometimes wearied in the midst of my good luck.

It is difficult to submit anything to the judgment of a second person without prejudicing him by the way in which we submit it. If we say, "I think it beautiful, I think it obscure," or the like, we either draw the imagination to that opinion, or irritate it to form the contrary. It is better to say nothing, so that the other may judge according to what really is, that is to say, as it then is, and according as the other circumstances which are not of our making have placed it. We at least shall have added nothing of our own, except that silence produces an effect, according to the turn and the interpretation which the other is inclined to give it, or as he may conjecture it, from gestures or countenance, or from the tone of voice, if he be a physiognomist; so difficult is it not to oust the judgment from its natural seat, or rather so rarely is it firm and stable!

The spirit of this sovereign judge of the world is not so independent but that it is liable to be troubled by the first disturbance about him. The noise of a cannon is not needed to break his train of thought, it need only be the creaking of a weathercock or a pulley. Do not be astonished if at this moment he argues incoherently, a fly is buzzing about his ears, and that is enough to render him incapable of sound judgment. Would you have him arrive at truth, drive away that creature which holds his reason in check, and troubles that powerful intellect which gives laws to towns and kingdoms. Here is a droll kind of god! O ridicolosissimo eroe!

The power of flies, which win battles, hinder our soul from action, devour our body.

When we are too young our judgment is at fault, so also when we are too old.

If we take not thought enough, or too much, on any matter, we are obstinate and infatuated.

He that considers his work so soon as it leaves his hands, is prejudiced in its favour, he that delays his survey too long, cannot regain the spirit of it.

So with pictures seen from too near or too far; there is but one[28] precise point from which to look at them, all others are too near or too far, too high or too low. Perspective determines that precise point in the art of painting. But who shall determine it in truth or morals?

When I consider the short duration of my life, swallowed up in the eternity before and after, the small space which I fill, or even can see, engulfed in the infinite immensity of spaces whereof I know nothing, and which know nothing of me, I am terrified, and wonder that I am here rather than there, for there is no reason why here rather than there, or now rather than then. Who has set me here? By whose order and design have this place and time been destined for me?—Memoria hospitis unius diei prætereuntis.

It is not well to be too much at liberty. It is not well to have all we want.

How many kingdoms know nothing of us!

The eternal silence of these infinite spaces alarms me.

Nothing more astonishes me than to see that men are not astonished at their own weakness. They act seriously, and every one follows his own mode of life, not because it is, as a fact, good to follow, being the custom, but as if each man knew certainly where are reason and justice. They find themselves constantly deceived, and by an amusing humility always imagine that the fault is in themselves, and not in the art which all profess to understand. But it is well there are so many of this kind of people in the world, who are not sceptics for the glory of scepticism, to show that man is thoroughly capable of the most extravagant opinions, because he is capable of believing that his weakness is not natural and inevitable, but that, on the contrary, his wisdom comes by nature.

Nothing fortifies scepticism more than that there are some who are not sceptics. If all were so, they would be wrong.

Two infinites, a mean. If we read too quickly or too slowly, we understand nothing.

Too much and too little wine. Give a man none, he cannot find truth, give him too much, the same.

Chance gives thoughts, and chance takes them away; there is no art for keeping or gaining them.

A thought has escaped me. I would write it down. I write instead, that it has escaped me.

In writing down my thought it now and then escapes me, but this reminds me of my weakness, which I constantly forget. This teaches me as much as my forgotten thought, for my whole study is to know my nothingness.

Are men so strong, as to be insensible to all which affects them? Let us try them in the loss of goods or honour. Ah! the charm is worked.

To fear death out of danger, and not in danger, for we must be men.

Sudden death is the only thing to fear, therefore confessors live in the houses of the great.

We know ourselves so little, that many think themselves near death when they are perfectly well, and many think themselves well when they are near death, since they do not feel the fever at hand, or the abscess about to form.

Why is my knowledge so restricted, or my height, or my life to a hundred years rather than to a thousand? What was nature's reason for giving me such length of days, and for choosing this number rather than another, in that infinity where there is no reason to choose one more than another, since none is preferable to another?

The nature of man is not always to go forward, it has its advances and retreats.

Fever has its hot and cold fits, and the cold proves as well as the hot how great is the force of the fever.

The inventions of men from age to age follow the same plan. It is the same with the goodness and the wickedness of the world in general.

Plerumque gratæ principibus vices.

The strength of a man's virtue must not be measured by his occasional efforts, but by his ordinary life.

Those great spiritual efforts to which the soul sometimes attains are things on which it takes no permanent hold. It leaps to them, not as to a throne, for ever, but only for an instant.

I do not admire the excess of a virtue as of valour, unless I see at the same time the excess of the opposite virtue, as in Epaminondas, who had exceeding valour and exceeding humanity, for otherwise we do not rise, but fall. Grandeur is not shown by being at one extremity, but in touching both at once, and filling the whole space between. But perhaps this is only a sudden motion of the soul from one to the other extreme, and in fact it is always at one point only, as when a firebrand is whirled. Be it so, but at least this marks the agility if not the magnitude of the soul.

We do not remain virtuous by our own power, but by the counterpoise of two opposite vices, we remain standing as between two contrary winds; take away one of these vices, we fall into the other.

When we would pursue the virtues to their extremes on either side, vices present themselves, which insinuate themselves insensibly there, in their insensible course towards the infinitely great, so that we lose ourselves in vices, and no longer see virtues.

It is not shameful to man to yield to pain, and it is shameful to yield to pleasure. This is not because pain comes from without us, while we seek pleasure, for we may seek pain, and yield to it willingly without this kind of baseness. How comes it then that reason finds it glorious in us to yield under the assaults of pain, and shameful to yield under the assaults of pleasure?[31] It is because pain does not tempt and attract us. We ourselves choose it voluntarily, and will that it have dominion over us. We are thus masters of the situation, and so far man yields to himself, but in pleasure man yields to pleasure. Now only mastery and empire bring glory, and only slavery causes shame.

All things may prove fatal to us, even those made to serve us, as in nature walls may kill us and stairs may kill us, if we walk not aright.

The slightest movement affects all nature, the whole sea changes because of a rock. Thus in grace, the most trifling action has effect on everything by its consequences; therefore everything is important.

Provided we know each man's ruling passion we are sure of pleasing him; yet each man has his fancies, contrary to his real good, even in the very idea he forms of good; a strange fact which puts all out of tune.

When our passions lead us to any act we forget our duty. If we like a book we read it, when we should be doing something else. But as a reminder we ought to propose to ourselves to do something distasteful; we then excuse ourselves that we have something else to do, and thus remember our duty.

Sneezing absorbs all the faculties of the soul, as do certain bodily functions, but we do not draw therefrom the same conclusions against the greatness of man, because it is against his will. And if we make ourselves sneeze we do so against our will. It is not in view of the act itself, but for another end, and so it is not a mark of the weakness of man, and of his slavery to that act.

Scaramouch, who thinks of one thing only.

The doctor, who speaks for a quarter of an hour after he has said all he has to say, so full is he of the desire of talking.

The parrot's beak, which he dries though it is clean already.

The sense of falseness in present pleasures, and our ignorance of the vanity of absent pleasures, are the causes of inconstancy.

He no longer loves the person he loved ten years ago. I can well believe it. She is no longer the same, nor is he. He was young, and so was she; she is quite different. He would perhaps love her still were she what she then was.

Reasons, seen from afar, appear to restrict our view, but not when we reach them; we begin to see beyond.

... We look at things not only from other sides, but with other eyes, and care not to find them alike.

Diversity is so ample, that all tones of voice, all modes of walking, coughing, blowing the nose, sneering. We distinguish different kinds of vine by their fruit, and name them the Condrieu, the Desargues, and this stock. But is this all? Has a vine ever produced two bunches exactly alike, and has a bunch ever two grapes alike? etc.

I never can judge of the same thing exactly in the same way. I cannot judge of my work while engaged on it. I must do as the painters, stand at a distance, but not too far. How far, then? Guess.

Diversity.—Theology is a science; but at the same time how many sciences! Man is a whole, but if we dissect him, will man be the head, the heart, the stomach, the veins, each vein, each portion of a vein, the blood, each humour of the blood?

A town, a champaign, is from afar a town and a champaign; but as we approach there are houses, trees, tiles, leaves, grass, emmets, limbs of emmets, in infinite series. All this is comprised under the word champaign.

We like to see the error, the passion of Cleobuline, because she is not aware of it. She would be displeasing if she were not deceived.

What a confusion of judgment is that, by which every one puts himself above all the rest of the world, and loves his own advantage and the duration of his happiness or his life above those of all others.

Diversion.—When I have set myself now and then to consider the various distractions of men, the toils and dangers to which they expose themselves in the court or the camp, whence arise so many quarrels and passions, such daring and often such evil exploits, etc., I have discovered that all the misfortunes of men arise from one thing only, that they are unable to stay quietly in their own chamber. A man who has enough to live on, if he knew how to dwell with pleasure in his own home, would not leave it for sea-faring or to besiege a city. An office in the army would not be bought so dearly but that it seems insupportable not to stir from the town, and people only seek conversation and amusing games because they cannot remain with pleasure in their own homes.

But upon stricter examination, when, having found the cause of all our ills, I have sought to discover the reason of it, I have found one which is paramount, the natural evil of our weak and mortal condition, so miserable that nothing can console us when we think of it attentively.

Whatever condition we represent to ourselves, if we bring to our minds all the advantages it is possible to possess, Royalty is the finest position in the world. Yet, when we imagine a king surrounded with all the conditions which he can desire, if he be without diversion, and be allowed to consider and examine what he is, this feeble happiness will never sustain him; he will necessarily fall into a foreboding of maladies which threaten him, of revolutions which may arise, and lastly, of death and inevitable diseases; so that if he be without what is called diversion he is unhappy, and more unhappy than the humblest of his subjects who plays and diverts himself.

Hence it comes that play and the society of women, war,[34] and offices of state, are so sought after. Not that there is in these any real happiness, or that any imagine true bliss to consist in the money won at play, or in the hare which is hunted; we would not have these as gifts. We do not seek an easy and peaceful lot which leaves us free to think of our unhappy condition, nor the dangers of war, nor the troubles of statecraft, but seek rather the distraction which amuses us, and diverts our mind from these thoughts.

Hence it comes that men so love noise and movement, hence it comes that a prison is so horrible a punishment, hence it comes that the pleasure of solitude is a thing incomprehensible. And it is the great subject of happiness in the condition of kings, that all about them try incessantly to divert them, and to procure for them all manner of pleasures.

The king is surrounded by persons who think only how to divert the king, and to prevent his thinking of self. For he is unhappy, king though he be, if he think of self.

That is all that human ingenuity can do for human happiness. And those who philosophise on the matter, and think men unreasonable that they pass a whole day in hunting a hare which they would not have bought, scarce know our nature. The hare itself would not free us from the view of death and our miseries, but the chase of the hare does free us. Thus, when we make it a reproach that what they seek with such eagerness cannot satisfy them, if they answered as on mature judgment they should do, that they sought in it only violent and impetuous occupation to turn their thoughts from self, and that therefore they made choice of an attractive object which charms and ardently attracts them, they would leave their adversaries without a reply. But they do not so answer because they do not know themselves; they do not know they seek the chase and not the quarry.

They fancy that were they to gain such and such an office they would then rest with pleasure, and are unaware of the insatiable nature of their desire. They believe they are honestly seeking repose, but they are only seeking agitation.

They have a secret instinct prompting them to look for diversion and occupation from without, which arises from the sense[35] of their continual pain. They have another secret instinct, a relic of the greatness of our primitive nature, teaching them that happiness indeed consists in rest, and not in turmoil. And of these two contrary instincts a confused project is formed within them, concealing itself from their sight in the depths of their soul, leading them to aim at rest through agitation, and always to imagine that they will gain the satisfaction which as yet they have not, if by surmounting certain difficulties which now confront them, they may thereby open the door to rest.

Thus rolls all our life away. We seek repose by resistance to obstacles, and so soon as these are surmounted, repose becomes intolerable. For we think either on the miseries we feel or on those we fear. And even when we seem sheltered on all sides, weariness, of its own accord, will spring from the depths of the heart wherein are its natural roots, and fill the soul with its poison.

The counsel given to Pyrrhus to take the rest of which he was going in search through so many labours, was full of difficulties.

A gentleman sincerely believes that the chase is a great, and even a royal sport, but his whipper-in does not share his opinion.

Dancing.—We must think where to place our feet.

But can you say what object he has in all this? The pleasure of boasting to-morrow among his friends that he has played better than another. Thus others sweat in their closets to prove to the learned world that they have solved an algebraical problem hitherto insoluble, while many more expose themselves to the greatest perils, in my judgment as foolishly, for the glory of taking a town. Again, others kill themselves, by their very application to all these studies, not indeed that they may grow wiser, but simply to prove that they know them; these are the most foolish of the band, because they are so wittingly, whereas it is reasonable to suppose of the others, that were they but aware of it, they would give over their folly.

A man passes his life without weariness in playing every day[36] for a small stake. Give him each morning, on condition he does not play, the money he might possibly win, and you make him miserable. It will be said, perhaps, that he seeks the amusement of play, and not the winnings. Make him then play for nothing, he will not be excited over it, and will soon be wearied. Mere diversion then is not his pursuit, a languid and passionless amusement will weary him. He must grow warm in it, and cheat himself by thinking that he is made happy by gaining what he would despise if it were given him not to play; and must frame for himself a subject of passion and excitement to employ his desire, his wrath, his fear, as children are frightened at a face they themselves have daubed.

Whence comes it that a man who within a few months has lost his only son, or who this morning was overwhelmed with law suits and wrangling, now thinks of them no more? Be not surprised; he is altogether taken up with looking out for the boar which his hounds have been hunting so hotly for the last six hours. He needs no more. However full of sadness a man may be, he is happy for the time, if you can only get him to enter into some diversion. And however happy a man may be, he will soon become dispirited and miserable if he be not diverted and occupied by some passion or pursuit which hinders his being overcome by weariness. Without diversion no joy, with diversion no sadness. And this forms the happiness of persons in high position, that they have a number of people to divert them, and that they have the power to keep themselves in this state.

Take heed to this. What is it to be superintendent, chancellor, first president, but to be in a condition wherein from early morning a vast number of persons flock in from every side, so as not to leave them an hour in the day in which they can think of themselves? And if they are in disgrace and dismissed to their country houses, though they want neither wealth nor retinue at need, they yet are miserable and desolate because no one hinders them from thinking of themselves.

Thus man is so unhappy that he wearies himself without cause of weariness by the peculiar state of his temperament, and he is so frivolous that, being full of a thousand essential causes[37] of weariness, the least thing, such as a cue and a ball to strike with it, is enough to divert him.

Diversions.—Men are charged from infancy with the care of their honour, their fortunes, and their friends, and more, with the care of the fortunes and honour of their friends. They are overwhelmed with business, with the study of languages and bodily exercises; they are given to understand that they cannot be happy unless their health, their honour, their fortune and that of their friends be in good condition, and that a single point wanting will render them unhappy. Thus we give them business and occupations which harass them incessantly from the very dawn of day. A strange mode, you will say, of making them happy. What more could be done to make them miserable? What could be done? We need only release them from all these cares, for then they would see themselves; they would think on what they are, whence they come, and whither they go, and therefore it is impossible to occupy and distract them too much. This is why, after having provided them with constant business, if there be any time to spare we urge them to employ it in diversion and in play, so as to be always fully occupied.

How comes it that this man, distressed at the death of his wife and his only son, or who has some great and embarrassing law suit, is not at this moment sad, and that he appears so free from all painful and distressing thoughts? We need not be astonished, for a ball has just been served to him, and he must return it to his opponent. His whole thoughts are fixed on taking it as it falls from the pent-house, to win a chase; and you cannot ask that he should think on his business, having this other affair in hand. Here is a care worthy of occupying this great soul, and taking away from him every other thought of the mind. This man, born to know the Universe, to judge of all things, to rule a State, is altogether occupied and filled with the business of catching a hare. And if he will not abase himself to this, and wishes always to be highly strung, he will only be more foolish still, because he wishes to raise himself above humanity; yet when all is said and done he is only a man,[38] that is to say capable of little and of much, of all and of nothing. He is neither angel nor brute, but man.