With a Study of Continental Detention Colonies and

Labour Houses.

BY

WILLIAM HARBUTT DAWSON

Author of "The Evolution of Modern Germany,"

"German Socialism and Ferdinand Lassalle,"

"Prince Bismarck and State Socialism,"

"The German Workman," etc., etc.

London:

P. S. KING & SON,

ORCHARD HOUSE, WESTMINSTER.

1910

"In all ways it needs, especially in these times, to be proclaimed aloud that for the idle man there is no place in this England of ours. He that will not work, and save according to his means, let him go elsewhither; let him know that for him the law has made no soft provision, but a hard and stern one; that by the law of nature, which the law of England would vainly contend against in the long run, he is doomed either to quit these habits, or miserably be extruded from this earth, which is made on principles different from these. He that will not work according to his faculty, let him perish according to his necessity; there is no law juster than that....

"Let paralysis retire into secret places and dormitories proper for it; the public highways ought not to be occupied by people demonstrating that motion is impossible. Paralytic;—and also, thank Heaven, entirely false! Listen to a thinker of another sort: 'All evil, and this evil too, is a nightmare, the instant you begin to stir under it, the evil is, properly speaking, gone.'"—Thomas Carlyle, "Chartism."

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I. | THE PROBLEM STATED | 1 |

| II. | THE URBAN LOAFER | 47 |

| III. | DETENTION COLONIES AND LABOUR HOUSES | 62 |

| IV. | THE BELGIAN BEGGARS' DEPOTS | 104 |

| V. | THE GERMAN LABOUR HOUSES | 133 |

| VI. | THE GERMAN TRAMP PRISONS | 147 |

| VII. | THE BERLIN MUNICIPAL LABOUR HOUSE | 166 |

| VIII. | TREATMENT OF VAGRANCY IN SWITZERLAND | 179 |

| IX. | LABOUR HOUSES UNDER THE POOR LAW | 193 |

| X. | LABOUR DEPOTS AND HOSTELS | 212 |

| XI. | RECOMMENDATIONS OF RECENT COMMISSIONS | 229 |

| APPENDIX I.—THE CHILDREN ACT, 1908, AND VAGRANTS | 250 | |

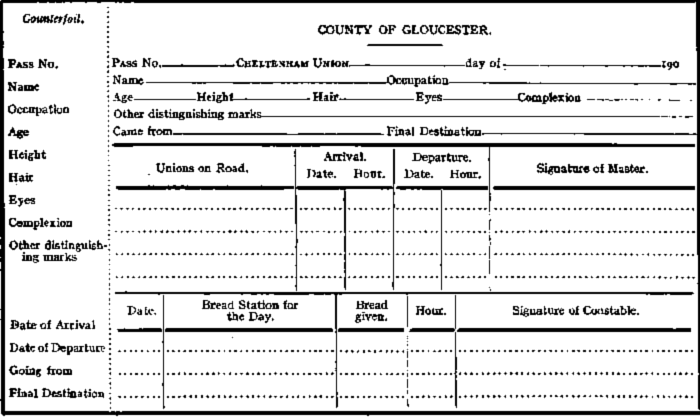

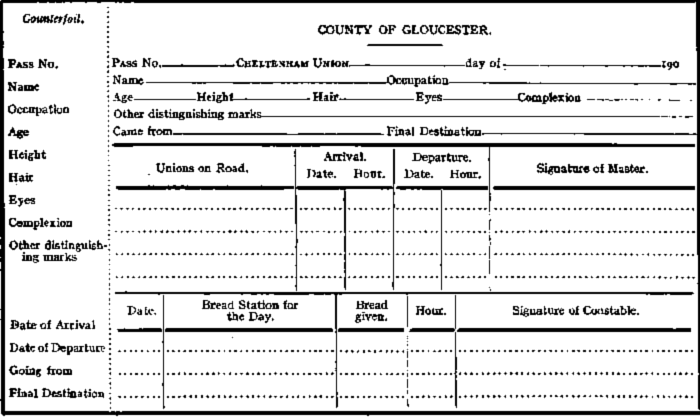

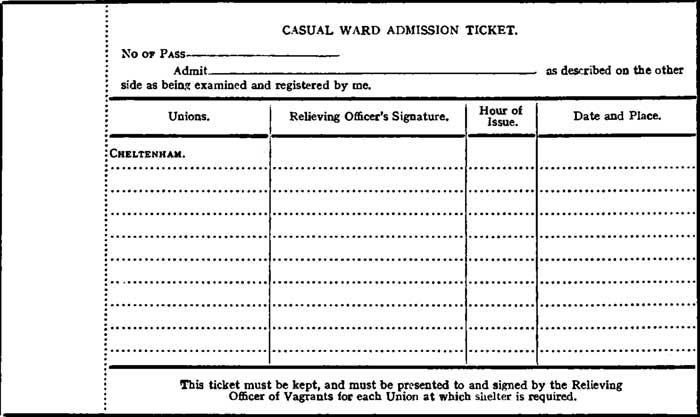

| APPENDIX II.—SPECIMEN WAY TICKETS | 253 | |

| APPENDIX III.—BELGIAN LAW OF NOVEMBER 27, 1891, FOR THE REPRESSION OF VAGRANCY AND BEGGARY | 257 | |

| APPENDIX IV.—REGULATIONS OF THE BERLIN (RUMMELSBURG) LABOUR HOUSE | 263 | |

There is growing evidence that English public opinion is not only moving but maturing on the question of vagrancy and loafing, and its rational treatment. Foreign critics have maintained that we are slow in this country to listen to new ideas, and still slower to appropriate them, partly, it has been inferred, from aversion to innovation of every kind, partly from aversion to intellectual effort. If a national proneness to cautiousness is hereby meant, it is neither possible to deny the accusation nor altogether needful to resent it. Yet while this cautiousness protects us against the evil results of precipitancy and gives balance to our public life, a rough sort of organic unity to our corporate institutions and a certain degree of continuity to our political and social policies, it has also disadvantages, and[Pg viii] one of the chief of these is that it has a tendency to perpetuate hoary anomalies and to maintain in galvanic and artificial life theories of public action which are hopelessly ineffectual and effete, if we would but honestly admit it.

The principles which underlie our treatment of the social parasite afford an illustration of our national conservatism. Alone of Western nations we still treat lightly and almost frivolously this excrescence of civilisation. Other countries have their tramps and loafers, but they regard and treat them as a public nuisance, and as such deny to them legal recognition; only here are they deliberately tolerated and to some extent fostered. Happily we are now moving in the matter, and moving rather rapidly. A few years ago it was still accepted as an axiom by all but a handful of sociologists—men for the most part regarded as amiable faddists, whose eccentric notions it was, indeed, quite fashionable to listen to with a certain indulgent charity, but unwise to receive seriously—that there was really only one[Pg ix] way of dealing with the tramp, and that was the way of the Poor Law. That this was also the rational way was proved by the fact that it had been inherited from our forefathers, and who were we that we should impugn the wisdom of the past? And yet nothing is more remarkable in its way than the strong public sentiment hostile to inherited precept and usage which has of late arisen on this subject.

It is the object of this book to strengthen this healthy sentiment, and if possible to direct it into practical channels. The leading contention here advanced is that society is justified, in its own interest, in legislating the loafer out of existence, if legislation can be shown to be equal to the task.

Further justification this book will hardly be held to require at its writer's hands, but a few words as to its genesis may not be out of place. It is now some twenty years since I first directed attention to the Continental method of treating vagrants and loafers in Detention Colonies and Labour Houses. Repeated visits to in[Pg x]stitutions of this kind, both in Germany and Switzerland, together with active work as a Poor Law Guardian, only served to deepen my conviction that prolonged disciplinary treatment is the true remedy for the social parasite whose besetting vice is idleness.

At the Bradford Meeting of the British Association in September, 1900, I read (before the Economic Section) a paper in which I developed, in such detail as seemed suitable to the occasion, practical proposals based, with necessary modifications, upon the result of a study of Continental methods. This paper was published immediately afterwards in abbreviated form in the Fortnightly Review, and was followed a little later by a second article in the same place, in which the proposals advanced were further elaborated. These proposals attracted great attention at the time; in particular they were discussed by many of the leading London and provincial journals, and it was encouraging and significant that while the novelty of the ideas put forward was admitted, they were all[Pg xi] but unanimously endorsed by the Press and by Poor Law authorities. It is desirable to say that the first three chapters of the present book are based on, and to a large extent embody, these writings of ten years ago, though much illustrative evidence of a later date has been added; the remainder of the volume, with the exception of one chapter, although dealing with phases of the subject which I have frequently expounded before, is published for the first time.

Nevertheless, two of the pleas originally put forward have now disappeared from my argument, inasmuch as the measures to which they related have, in the meantime, been realised—one, the establishment of public labour registries, the other, the prohibition of child vagrancy, which has been dealt with in that humane law the Children Act of 1908.

As a result of the more serious attention given to the vagrancy question at that time, the President of the Local Government Board in 1904 appointed a Departmental Committee of Inquiry, before which[Pg xii] I was invited to give evidence. The reader who takes up this book is strongly urged to study the Report of the Departmental Committee as well; it is a most able exposition of the vagrancy problem by serious investigators who were less concerned to emphasise their individual predilections than to help on the settlement of the question by uniting on broad principles of procedure. As the thorough-going recommendations of the Committee differ but slightly from the proposals which I advocated before them and here repeat, the value of the present volume will consist chiefly in the description which it contains of a series of disciplinary institutions in which other countries are actually carrying out the methods whose feasibility we are still discussing.

Pressure is happily come from other directions, and particularly from the new school of Poor Law reformers. The publication of the Reports of the Poor Law Commission begins a new era in the history of public relief. The realisation of a constructive policy so large and fundamental[Pg xiii] as that which the Commissioners have put forward will probably prove to be the work of many years; yet whether our advance on the lines suggested be fast or slow, it must be obvious to everyone that the question of Poor Law reform is now a living one, and cannot again fall into the background.

As regards the aspect of Poor Law administration with which this volume is concerned, all those who have laboured as path-makers in this undeveloped province of social experiment must derive satisfaction from the fact that the Commission, simply endorsing the recommendations of the Vagrancy Committee, regard the disciplinary treatment of loafers of all kinds as an essential part of any reorganisation of the Poor Law. For if the deserving poor, the genuine unemployed, and the hopeless unemployables are to be treated more systematically and more humanely in the future than they have been in the past, it will be impossible to withhold from the loafers the special attention which they need.

Although the subject of vagrancy is necessarily approached in these pages from the standpoint of repression, I should feel that my advocacy had failed of its purpose if a change of the law simply stamped out the tramp without making ample provision for the bona-fide work seeker. I urge the abolition of the casual wards, not merely because they encourage vagrancy, but also because they are altogether unsuited to the decent workers who are on the road owing to misfortune, and not to fault. While accepting the Vagrancy Committee's conclusion that the retention of the casual wards may be necessary by way of transition, I look to the time when there will be provided for such men in sufficiency, and as part of a national system, hostels or houses of call offering on the easiest possible terms accommodation superior to that of the shelter, the doss-house, or even the so-called model lodging-house. This is done on a large scale in Germany and Switzerland, and it is little creditable to us as an industrial nation that we are so behindhand in a matter of such great social[Pg xv] importance. The new system of labour registries, by increasing the mobility of labour, will probably help to bring home to the public mind the need for these wayfarers' hostels. With co-operation on the part of public authorities, labour organisations, and private philanthropy the cost should not prove deterrent, while the advantage would be incalculable.

January 1, 1910

THE PROBLEM STATED.

There are two large sections of sociologists who to-day strongly advocate, the one a radical reform of the Poor Law, the other the reform of the Prison system. The modern Poor Law reformer would administer public assistance with greater discrimination, showing more consideration in the treatment of the unfortunate poor, more rigour in the treatment of those whose destitution is deliberate and preventable, more care for the children, with a view to helping them past the dangers of demoralisation and lifelong intermittent pauperisation. On the other hand, the prison reformer desires to see the punitive and retaliatory aspect of imprisonment made subsidiary to the reformative, or at least he would give to the latter greater prominence than it receives at present.

Now that concerted endeavours are being made to place both Poor Law and Prison in the crucible, with a view to recasting them in new and improved forms, the time would appear to be specially appropriate for filling up an important gap in our penal system dating from the reorganisation of the Poor Law in 1834.

The reform which is urged in these pages appears to me to be the missing link in that long and unique chain of laws and orders and regulations which has in course of time been constructed for the purpose of casting round the residual elements of society influences at once repressive and benevolent, at once deterrent and remedial. While some of these elements have received attention enough—not always wise, perhaps, and often defeating its object—one element has never yet been treated rationally and systematically. I refer to the large and ever-growing class of idlers, who differ from the genuine unemployed in that they will neither seek work nor accept it when offered: the drones of the social hive, the habitual loafers.

We may distinguish in this parasitic class several clearly-defined types.

(1) There is first the type with which we are most familiar—the nomad of the highway, who is always in motion yet never gets to his journey's end, the unmitigated vagabond, who lives by begging and blackmailing and pillaging.

(2) There is also the settled, resident loafer—an urban type in the main, though the country[Pg 3] village knows him likewise—who haunts the streets year in year out from morning till evening, living no one knows how, and whose only purpose in life might seem to be to offer disproof in his own obtrusive person of that saying of Adam Smith: "As it is ridiculous not to dress, so it is in some measure not to be employed, like other persons."

(3) There is also the intermittent loafer, three-quarters idler, one-quarter worker of a sort, and altogether good-for-nothing, who is almost invariably an inebriate and often has taken upon himself domestic responsibilities which he saddles upon the shoulders of a too-willing community—a character who mostly comes before public notice in connection with Poor Law prosecutions for arrears of maintenance.

(4) Not to exhaust the classification, there is a pitiable type for which we must go to an almost hopeless class of the other sex, a type which the Poor Law system knows likewise in connection with default in parental obligations which, but for our exaggerated notions of the limits of personal liberty, our laws would see to it were never incurred. For the virtual encouragement which the Poor Law offers to promiscuous, illegitimate, and irresponsible maternity amongst the lowest class of society should shock the sense and excite the alarm of all who are concerned for the moral and mental health of the race.

The idlers of the first two classes keep[Pg 4] themselves most persistently before the public gaze, but in any legislative treatment of their shortcomings it is desirable that the other types should not be overlooked, and in these pages the problem of the loafer is viewed as a whole.

What society must do in its own interest, and in the interest of the idlers themselves, is to stamp out, as far as well-devised laws can do it—and we need not be too soft-hearted—the social parasite of every kind. His existence is a positive injury to the State in every way; he robs the State not only of the industry which he owes to it, but he consumes the produce of other people's labour and renders it nugatory, by abstracting from the wealth of society without adding to it; his example scandalises honest workers, for while we preach industry and thrift to the labouring classes, we assiduously foster a huge loafing class, which preaches more eloquently on a very different text, viz., that it pays best to do nothing and sponge on the community; he is a standing menace to public order and safety; and for society to tolerate him is not merely to condone, injury done to itself, but absolutely to place a premium upon social treason of a particularly insidious and vicious kind.

It is only by the veriest abuse of the modern theory of personal liberty that the Legislature, which is not slow to restrict the free action of its citizens in so many ways, has hitherto thrown a paternal and protecting arm over the loafer and[Pg 5] the wastrel. For several generations we have done little but pet and coddle the loafer; we have treated his constitutional laziness not as the personal vice and social crime which it is, but as a venial weakness to be excused and indulged, while the man himself we have surrounded with a nimbus of maudlin sentimentality.

Think what we do for the professional idlers. Take the urban type. While honest men are working we give him the free run of our thoroughfares, and set apart for him the best of our street corners. Should he be a vagrant we make it possible for him to travel through England from the Channel to the Tweed without doing one hour's serious work save for the labour tasks which are imposed by some of the workhouses at which he may call. In these institutions—erected at intervals not too far distant to overtask his strength—food is placed before him night and morning, with a bed thrown in; while outside he can always rely upon the alms which he is able to draw from the pockets of the unwisely charitable whom he deceives with his tales of misery, or the unwillingly charitable whom he terrorises into compliance with his demands.

This was not, of course, the old English tradition. The very earliest of our Poor Laws drew a very clear distinction between the normal poor—the "aged, poor, and impotent persons compelled to live by alms," as they are described in the Act of 1530—and the idle beggar and vagabond. While provision was made for the due relief of the[Pg 6] former, penal measures were consistently directed against the latter.[1] And when such methods of[Pg 7] repression as the felon irons, the stocks, the whip, serfage, and transportation no longer commended themselves to the public conscience, there remained the method of summary despatch home to the town or village of legal domicile in the custody of zealous parish constables who relieved the monotony of their dignified calling with many a pleasurable jaunt over country in those old leisurely days. But the noteworthy thing about the old laws against vagrants is that their uniform purpose—[Pg 8]whatever their effect—was not the mere restriction of this class within due numerical bounds, or the regulation of its movements within decorous limits of liberty, but its absolute extinction. In those brave days the idea of maintaining the vagrant at the public expense, and of encouraging him in idleness and vice, never occurred to the Legislature.

We have so whittled down the laws on vagrancy and idleness, however, that there are now only two ways in which it is possible to convict and punish the tramp and loafer as such. The law regards as "idle and disorderly persons" such persons, being able wholly or in part to maintain themselves or their families by work or other means, who wilfully refuse or neglect so to do, by which refusal or neglect they or their families whom they may be legally bound to maintain become chargeable to the public funds; also any persons wandering abroad or placing themselves in public places, highways, courts, or passages, to beg or gather alms, or causing or procuring children so to do, and the penalty in such cases is imprisonment with labour up to one calendar month, though should a fine be imposed instead of imprisonment hard labour must not be adjudged for default in payment. The law also regards as "rogues and vagabonds" such persons wandering abroad and lodging in any barn or outhouse, or in any deserted or unoccupied building, or in the open air or under a tent or in any cart or waggon, not having any visible means of subsistence, and not giving a good account of[Pg 9] themselves, and the penalty is imprisonment with labour for a period not exceeding three calendar months, though on a second conviction such offenders may be imprisoned with hard labour as long as one year.

So runs the law, and in theory it does not seem ineffectual; in practice it is wholly so. For the penalties visited on "rogues and vagabonds" are virtually annulled by the care which the Poor Law has taken to allow these offenders to evade apprehension. A vagrant may be as "idle and disorderly" as he likes by day, so long as he pursues his irregular life undetected but at night he has only to present himself at the handiest workhouse, and he is forwith certified to be a deserving citizen, and is lodged and fed at the public expense.

And even about the enforcement of the penal provisions against the tramp, when his native wit and cunning fail him, and he is caught in the meshes of the law, there is an unreality and a frivolity which brings both the statute and its administration into disrepute. Nine-tenths of the "idle and disorderly persons," of the "rogues and vagabonds," who come before the justices of the peace are hardened offenders, who know more about the county gaols of the country than the most experienced of Prison Commissioners; yet the view which most commonly prevails in the police courts is that so long as the itinerant mendicant is sent on his way, and is thus got safely out of the district, expedience if not justice is satisfied. To be fair to our justices,[Pg 10] it should be remembered that this blind-eyed administration of the law is no modern innovation. It is really only a survival of the ancient custom, already alluded to, of harrying vagabonds from parish to parish—often after a rigorous application of the whip, but in any case after a blood-curdling warning from the local justice, duly followed by a special commination from the parish constable on his own account—lest they should by any mischance fall upon poor funds to which they had no domiciliary claim. The result, however, is the same now as of old. The tramp takes his admonition, and, if need be, his punishment, with stoical indifference, and continues a tramp. The offence is condoned or corrected, as the case may be, but the offender knows that he is free to commit it again—at his peril, of course—directly the law has done with him, and that in the bathroom of the casual ward he may each evening purge the day's offences, and so begin anew on the morrow his career of licensed crime.

Who shall wonder, then, that our past indulgent treatment of the vagrant has had the effect of perpetuating and multiplying this class? The dictum of wise Sir Matthew Hale, uttered just two and a half centuries ago, is as true to-day as ever: "A man that has been bred up in the trade of begging will never, unless compelled, fall to industry."

As for the casual ward itself, it was to a large extent an accident of legislation, and certainly it was not contemplated when the Poor Law was[Pg 11] reformed in 1834. The great constructive measure of that year, introducing the existing type of workhouse, made no reference to vagrants. The Act presupposed only the relief by the new Boards of Guardians of the settled poor. "But," the Departmental Committee on Vagrancy write, "when workhouses had been established vagrants applied for admission to them, representing themselves to be in urgent need of relief. The masters of workhouses had no means of investigating the facts and had to deal with each case on their own responsibility. At that time workhouse inmates who had no settlement were maintained at the expense of the parish in which the workhouse happened to be; this made the relief of the vagrant in the workhouse more difficult, and workhouse masters were pressed by the Guardians to refuse such cases altogether. In 1837 the Poor Law Commissioners, on being appealed to by the Commissioners of Metropolitan Police with regard to the question, expressed the opinion that it was the intention of the Act that all cases of destitution should be relieved, irrespective of the fact that the applicant might belong to a distant parish. They stated that it was the duty of the relieving officer to relieve casually destitute wayfarers and of the workhouse master to admit such cases to the workhouse. These cases were distinguished from beggars by profession, who were to be dealt with under the Vagrancy Act of 1824."[2] In 1838 the Commissioners issued[Pg 12] instructions to the Boards of Guardians in the Metropolis pointing out their duties in regard to the relief of the casually destitute, and suggesting the adoption of arrangements for securing the performance by them of task work, and the following year a further Circular threatened with instant dismissal officers who neglected to relieve cases of urgent casual destitution. In this way the right of the vagrant to admittance became asserted: "as a class vagrants came to be recognised by the Central Authority, who from this time issued a series of circulars and orders dealing with them directly or indirectly." As a natural result between 1834 and 1848 vagrancy increased to an alarming extent in all parts of the country.

It is interesting to recall the fact that as late as 1840 the Poor Law Commissioners, though the vagrancy evil was steadily growing, were "convinced that vagrancy would cease to be a burden if the relief given to vagrants were such as only the really destitute would accept." Hence they recommended that the Central Board should be "empowered and directed to frame and enforce regulations as to the relief to be afforded to vagrants." An Act of 1842 empowered Boards of Guardians to prescribe a task of work for persons relieved in the workhouse "in return for the food and lodging afforded," though no one was to be detained against his will for more than four hours after breakfast on the morning following admission, which meant that the casual might do little or much, according to his whim.[Pg 13] The same year the Poor Law Commissioners ordered the setting apart of separate wards for casuals, prescribed special diet for them, and regulated the task-work system. Meantime, the vagrant proved himself more and more the master of the Board of Guardians; his claim to relief having been admitted, he settled down to the view that the casual wards were convenient houses of call, intended the better to facilitate his roaming life, and this view was implicitly accepted by Poor Law authorities. More than anything else, therefore, the casual ward is responsible for the present perplexities of the vagrancy problem.

One of the first acts of the new Poor Law Board of 1848 was to inquire into the extent of the casual pauper nuisance and the causes of the abuse of casual relief; and overlooking the fact that the Boards of Guardians had been forced to accept the vagrant against their will, it blamed these bodies and told them that a remedy must be sought "principally in their own vigilance and energy." Among the measures recommended were (1) the refusal of relief to able-bodied men not actually destitute; (2) the employment of police officers as assistant relieving officers for vagrants, and (3) the adoption of a system of passes and certificates (restricted as to time and route) to be issued "by some proper authority" to persons actually in search of work. The first two of these recommendations were widely acted upon, though lack of uniformity in policy seriously[Pg 14] hampered the efforts of those Boards of Guardians which honestly tried to do their duty.

Of the later measures introduced in the vain hope of checking vagrancy three are specially noteworthy:—

(1) A Poor Law Board Circular of 1868 and a General Order of 1871 recommending the introduction of the separate cell system.

(2) The Pauper Inmates Discharge and Regulation Act of 1871 empowering Boards of Guardians to detain casual paupers for the following times: If a pauper had not previously been admitted within one month, until 11.0 a.m. on the day following admission; if he had already been admitted more than twice within a month, until 9.0 a.m. on the third day after admission. The Casual Poor Act of 1882 extended the periods of detention as follows: First admissions during the month, until 9.0 a.m. on the second day following admission; second and further admissions during the month, until 9.0 a.m. on the fourth day.

(3) An Order of December 18, 1882, making admission to a casual ward dependent upon the order of a relieving officer or an assistant relieving officer, except in urgent cases. In effect it is well known that nearly all cases are urgent.

Considering now the extent of the vagrant population, using the term in its wider signification, and not confining it to the casual paupers[Pg 15][3] who are particularly enumerated in Poor Law statistics, the admission must be made at the outset that the data available are very inconclusive. It seems desirable first to call attention to the limitations of strictly official information on the subject. Since 1848 a count of the vagrants relieved in casual wards has been made by order of the Local Government Board on January 1 and July 1 in each year; since 1890 there has also been a count of vagrants relieved on the nights of January 1 and July 1; and since 1904 a count has been taken each Friday night.

According to the Annual Report of the Local Government Board for 1908 the average number of casual paupers relieved in England and Wales on each Friday night of that year was 11,491, comparing with an average of 10,401 for the year 1907; the maximum number was 13,798 on August 22 and the minimum 8,341 on July 4. The average relieved on Friday nights in London alone during the year was 1,114. A further return of the number of persons in England and Wales in receipt of relief on January 1, 1909, shows that the casual paupers numbered 15,852, 1,420 being relieved in London unions and 14,432 in provincial unions. As to these numbers, however, the Local Government Board state:—

"These are the total numbers of casual paupers entered in the returns as relieved on January 1, 1909. The total number relieved on the night of January 1, was 9,747. To what extent the former totals include twice over persons who received relief in more than one union on the same day is not ascertainable, and it is[Pg 16] possible that the total of the paupers relieved on the night of January 1, although omitting many casual paupers who, after their discharge from the workhouse in the morning, did not again have recourse to the Poor Law on the same day, is the more reliable."[4]

That the vagrant population, even enumerated in this partial manner, is increasing is shown by the following table, showing for a period of ten years the number of casuals relieved during day and night on January 1:—

| Year | Casual Paupers Relieved. | |||

| At any time during January 1. |

On the night of January 1. |

|||

| 1899 | 13,366 | 7,499 | ||

| 1900 | 9,841 | 5,579 | ||

| 1901 | 11,658 | 6,795 | ||

| 1902 | 13,178 | 7,840 | ||

| 1903 | 14,475 | 8,266 | ||

| 1904 | 15,634 | 8,519 | ||

| 1905 | 17,524 | 9,768 | ||

| 1906 | 16,823 | 9,708 | ||

| 1907 | 14,957 | 8,346 | ||

| 1908 | 17,083 | 10,436 | ||

It would appear from these figures that a certain relationship exists between vagrancy and trade cycles. Of the years of maximum vagrancy, 1904, 1905, and 1908 were years of more or less acute unemployment, while those of minimum vagrancy, 1900, 1901, and 1902, were years of[Pg 17] good or fairly good trade. That the fact of an inter-relationship between vagrancy and the state of trade cannot be pressed unduly, however, is proved by the comparatively narrow limits within which, allowing for increase of population, the figures move. Certainly the figures afford no prima facie justification for supposing that trade depression causes any considerable number of genuine workmen to join the highway population.

Poor Law statistics, however, fail entirely to do justice to the extent of the vagrancy problem. They show the number of vagrants relieved at one time and in one way only; but all vagrants do not receive public help at the same time, and the total number on the road is far larger than the number who call at the workhouses. As to this the testimony of Poor Law Inspectors and all who have studied the vagrancy question at close quarters is unanimous. "A very large number, probably the majority, of vagrants seldom come to the vagrant wards," wrote Mr. J. S. Davy, as Poor Law Inspector for Sussex, Kent, and part of Surrey.[5] "It ought to be remembered," says another Inspector, "that the vagrants admitted to the vagrant wards represent only a very small percentage of the vagrants of the country."[6]

The Departmental Committee on Vagrancy of 1904 endorse this view:—

"The returns of pauperism published annually by the Local Government Board give figures relating to[Pg 18] casual paupers, that is, vagrants relieved in casual wards, but these represent only a small portion of the total number of vagrants.... The vagrant is to be found in many places—on the road, in casual wards, common lodging houses, public or charitable shelters, and prisons, besides which he has many other resorts, such as barns, brickworks, etc. Then, again, the number of homeless wayfarers varies greatly from time to time, and at different periods of the year, owing to conditions of trade, the state of the weather, or the attraction of seasonal employments."[7]

Although a simultaneous census of the entire vagrant population has never been taken, certain data exist which furnish the basis for at least an approximate estimate. Several of these will be mentioned.

(1) Up to 1868 yearly returns were collected by the Home Office from the different police forces of England and Wales showing the number of vagrants of all kinds known to them. The number on the latest date, April 1, 1868, was 38,179, against 32,528 on April 1, 1867. The number of persons relieved in the casual wards of the country on January 1, 1867, was 5,027, and on January 1, 1868, 6,129, showing that the "casual paupers" at that date represented only about one-sixth of the total vagrant class. If the same proportion to population still held good to-day the number of vagrants of all kinds, based on the mean of the known number of casual paupers on January 1 of the five years 1904-8, viz., 9,355, would be about 56,000.

(2) In the county of Gloucester a count has been made for many years on a night of April of the numbers sleeping in casual wards and in common lodging houses, and the results show that the lodging-houses contain five times as many vagrants as the casual wards. Allowing for vagrants who sleep out of doors, the ratio would not seriously differ from that shown by the police enumeration already mentioned. Applying to the whole country the number of vagrants per thousand of the population of Gloucestershire, the nomad army would be shown to be 30,000. It should be remembered, however, that Gloucestershire is a county of small towns, and lies away from the great streams of population; hence it should not feel the full effect of the vagrant movement.[8]

(3) An enumeration made on March 17, 1905, by the chief constable of Northumberland, by means of police officers placed at the most important points, of vagrants on the roads between the hours of 7.0 a.m. and 7 p.m. gave a total of 300 (exclusive of Newcastle and Tynemouth), equal to about 1 per 1,000 of the population of the area covered. On this basis he placed the number of vagrants in England and Wales at 36,000. Here the omission of two important towns largely invalidates computation; their[Pg 20] inclusion would unquestionably give a much higher ratio.

(4) A careful census of vagrants, beggars, migratory poor, etc., is taken by the police for each county, city, and burgh police district in Scotland on two nights in the year, in June and December, showing the number of these persons in (1) prisons or police cells, (2) homes and refuges, hospitals and poorhouses, (3) common lodging-houses or other houses, (4) public parks, gardens or streets, outhouses, sheds, barns, or about pits, brick and other works. The two counts of 1908 gave the following result:—

| Men. | Women. | Children. | Total. | |

| June 21 | 6,815 | 1,843 | 1,541 | 10,199 |

| December 27 | 6,129 | 1,391 | 1,541 | 8,506 |

This was equal to 2.1 and 1.8 per 1,000 of the population respectively, and if these ratios were applied to England and Wales they would represent aggregates of 76,000 and 63,000.

(5) An enumeration of homeless persons in the administrative County of London, made by the London County Council on the night of January 15, 1909, showed a total of 2,088. On that night there were also 1,188 persons in the casual wards of London, and 21,864 in the common lodging-houses and shelters, of whom 10 per cent. were supposed to belong to the vagrant class. This would give a total of 5,462 vagrants as follows:—homeless (sleeping out and walking the streets), 2,088; in casual wards, 1,188; in common lodging-houses and shelters, 2,186;[Pg 21] total, 5,462. As the population of the administrative County of London at the date named was estimated at 4,795,757, this total is equal to a ratio of 1.14 per 1,000 of the population. The same ratio for England and Wales would give a vagrant population of about 41,000.

(6) Dr. J. R. Kaye, Medical Officer of Health for the West Riding of Yorkshire, in a report upon the influence of vagrancy in the dissemination of disease, published in 1904, estimated the roving population at 36,000. He has, at my request, explained the basis of his calculation as follows:—

"The estimate of 36,000 refers to England and Wales, and it includes the inmates of casual wards and nomads of the same class who inhabit alternately the casual wards and the common lodging houses according to the state of their pockets. The county police here (West Riding), make an annual census of tramps, and the figure comes out at about 1,000 persons, of whom about 200 are in the casual wards on any given night. Now the Local Government Board reports give the casual-ward population of England and Wales at about 10,000, so that if the same proportions hold good there should be about 50,000 wanderers. Or, on the other hand, if you take our ascertained 1,000 in the county area in relation to our population of 1,249,685, and apply the ratio to the population of England and Wales, we get a figure of 26,000. My figure of 36,000 comes about mid-way between the two estimates given above."

(7) A final estimate which may be quoted is that made at the request of the Departmental Committee on Vagrancy on the night of July 7, 1905, by the various police forces in England and Wales of persons without a settled home or visible means of subsistence: (a) in common lodging-houses; and (b) elsewhere than in common[Pg 22] lodging-houses or casual wards. The result was as follows:—

| (a) | In common lodging-houses | 47,588 |

| (b) | Elsewhere than in common lodging-houses or casual wards | 14,624 |

| 62,212 |

These totals were made up of:—

| (a) | (b) | |

| Men | 41,439 | 10,750 |

| Women | 4,869 | 2,436 |

| Children | 1,280 | 1,438 |

| Children | 47,588 | 14,624 |

In the opinion of the Vagrancy Committee, a considerable deduction must be made from the number returned for common lodging-houses, though, on the other hand, it appears from some of the returns that many vagrants, who would otherwise have been in tramp wards or common lodging-houses, were at the time engaged in temporary work such as fruit-picking and harvesting, and so were not included in the count. Further, an addition of about 10,000 is necessary to include the vagrants in casual wards. The Committee came to the conclusion that the census could not be accepted as "a trustworthy guide to the actual number of vagrants," and their Report contains the following guarded verdict:—

"The number of persons with no settled home and no visible means of subsistence probably reaches, at times of trade depression, as high a total as 70,000 or 80,000, while in times of industrial activity (as in 1900) it might not exceed 30,000 or 40,000. Between these limits the number varies, affected by the conditions of trade, weather, and economic causes. In our Inquiry[Pg 23] we are more concerned with the habitual vagrant, that is, the class whom trade conditions do not affect. Of this class there is always an irreducible minimum, though successive depressions of trade may increasingly swell the numbers. No definite figures as to this permanent class can be obtained, but we are inclined to think that the total number would not exceed 20,000 to 30,000."[9]

It may be added that the estimates of the vagrant population made by witnesses who gave evidence before this Committee ranged from 25,000 to 70,000.

The mean of all the seven estimates put forward above, as approximations only, is about 50,000, which is probably below rather than above the actual number in normal times. The estimates differ so widely, however, as to shake one's faith in the possibility of arriving at a safe figure except by a special census on even more comprehensive lines than those which underlay the Home Office enumerations up to 1868.

But even when the casual wards, model lodging-houses, shelters, and other resorts of the roaming poor have been enumerated, the full extent of the vagrant population is not told.

According to a statement made by the Prison Commissioners to the Vagrancy Committee, 3,736 out of 12,369 convicted male prisoners on February 28, 1905, were, in the opinion of the prison governors, "persons with no fixed place of abode and no regular means of subsistence"; and of 2,595 convicted female prisoners, 372 answered the same description. In other words,[Pg 24] one-fourth of the prison population belonged at that date to the vagrant and loafing class.

The prosecutions in England and Wales for vagrancy offences in the narrower sense—begging, sleeping out, misbehaviour by paupers, and theft or destruction of workhouse clothes—fluctuated as follows during the ten years 1898-1907:—

| Year. | Begging. | Sleeping-out. | Misdemeanour by Paupers. | Theft or Destruction of Workhouse Clothes. | ||||

| 1898 | 15,474 | 9,582 | 3,769 | 589 | ||||

| 1899 | 12,659 | 8,515 | 3,632 | 615 | ||||

| 1900 | 11,339 | 7,452 | 3,717 | 457 | ||||

| 1901 | 14,492 | 9,101 | 5,118 | 576 | ||||

| 1902 | 16,184 | 9,598 | 5,959 | 726 | ||||

| 1903 | 19,283 | 10,349 | 6,496 | 841 | ||||

| 1904 | 23,036 | 11,785 | 7,436 | 937 | ||||

| 1905 | 26,386 | 12,636 | 6,314 | 1,005 | ||||

| 1906 | 25,083 | 11,540 | 5,176 | 1,016 | ||||

| 1907 | 23,023 | 11,164 | 4,633 | 852 | ||||

At whatever figure we place the vagrant population, there is little doubt that the number tends to increase. The Vagrancy Committee frankly accept this view.

"The army of vagrants has increased in number of late years," they state, "and there is reason to fear that it will continue to increase if things are left as they are. It is mainly composed of those who deliberately avoid any work, and depend for their existence on almsgiving and the casual wards; and for their benefit the industrious portion of the community is heavily taxed. We are convinced that the present system of treating casual paupers neither deters the vagrant nor affords any means of reclaiming him, and we are unanimously of opinion that a thorough reform is necessary."[10]

As to the class of men who frequent the casual wards the great mass, both in town and country, are unquestionably unskilled labourers, though[Pg 25] nearly all trades contribute a share, larger or smaller, to the sum total of vagrancy. A classification of the men relieved in the casual wards of Hitchin and Brixworth during twelve months ending September, 1906, showed the following result:—[11]

| Occupations. | Hitchin. | Brixworth. | ||

| Labourers | 3,830 | 222 | ||

| Painters | 226 | 14 | ||

| Grooms | 157 | 12 | ||

| Bricklayers | 144 | 13 | ||

| Shoemakers | 133 | 13 | ||

| Fitters | 123 | 9 | ||

| Rivetters | 123 | — | ||

| Boilermakers | 123 | — | ||

| Tailors | 108 | 5 | ||

| Carpenters and joiners | 106 | 9 | ||

| Printers and compositors | 74 | — | ||

| Stokers, firemen, etc. | 70 | 3 | ||

| Seamen | 60 | 4 | ||

| Moudlers and drillers | 58 | — | ||

| Gardeners | 37 | — | ||

| Clerks | 36 | — | ||

| Engineers | 34 | — | ||

| Bakers | 33 | — | ||

| Harnessmakers and saddlers | 31 | — | ||

| Porters | 27 | — | ||

| Blacksmiths, etc. | 25 | — | ||

| Sawyers | 25 | — | ||

| Plasterers | 24 | — | ||

| Plasterers | 22 | — | ||

| Silversmiths | — | 3 | ||

| Other trades | 446 | 16 | ||

| Total | 5,829 | 322 | ||

The following classification of the casuals admitted into the wards of a rural union, unnamed, is published by the Poor Law Commission:—[12]

| Occupations. | 1905 | 1906 | 1907 | |||

| Navvies | 552 | 772 | 613 | |||

| General labourers | 404 | 485 | 489 | |||

| Carters | 62 | 56 | 61 | |||

| Carpenters | 42 | 6 | 37 | |||

| Masons | 38 | 42 | 48 | |||

| Grooms | 37 | 40 | 60 | |||

| Seamen | 34 | 28 | 48 | |||

| Fitters | 24 | — | 20 | |||

| Shoemakers | 23 | 24 | 36 | |||

| Firemen | 15 | 21 | 31 | |||

| Tailors | 13 | 16 | 11 | |||

| Gardeners | 12 | 12 | 8 | |||

| Miners | 12 | — | — | |||

| Bakers | 4 | 13 | 13 | |||

| clerks | 11 | 8 | 38 | |||

| Ironmoulders | 11 | 5 | 16 | |||

| Blacksmiths | 9 | — | 13 | |||

| Other occupations | 142 | 57 | 69 | |||

| Professional tramps | 79 | 25 | 66 | |||

| Total | 1,512 | 1,610 | 1,673 | |||

Of 450 men admitted into the casual wards of the Skipton-in-Craven workhouse during the period September 1 to November 12, 1904, 50 were aged and infirm, while 250 described themselves as general labourers, and 150 as tradesmen.

The classification of the latter was as follows:—

| Tailors | 30 |

| Joiners | 15 |

| Mechanics | 12 |

| Bricklayers | 12 |

| Painters | 12 |

| Masons | 12 |

| Spinners | 12 |

| Weavers | 12 |

| Butchers | 9 |

| Colliers | 8 |

| Printers | 8 |

| Shoemakers | 8 |

It must be granted, of course, that every highway wanderer is not a loafer, and that the workhouse casual ward itself offers a rude hospitality to many a decent wayfarer who is deserving of a better fate, though a good deal of misapprehension exists on this subject. There is no means of learning the percentage of bona-fide work-seekers amongst that section of the vagrant population which fights shy of poor relief, but when one enters the casual ward it is possible at once to divide the sheep from the goats. Those who theorise upon the basis of intuition, and much more those who confuse the voting of other people's money with Christian charity, are apt to conclude that, as a matter of course, the casuals "in a lump" are not "bad," but only unfortunate, and deserve all such relief as is afforded them. It would be futile to deny to the most habitual of vagrants the power to impress even the case-hardened listener by fiction which is a good deal stranger than truth, by doubtful emotions and still more doubtful morals. Let appeal be made, however, to the trained observation of the Poor Law clerk and the weather-beaten soul of the workhouse master, and a different story will be learned. Some years ago I questioned all the[Pg 28] Poor Law authorities of Yorkshire on the subject; half the answers placed the number of the genuine work-seekers at 5 per cent. of the whole, though in special cases a much higher percentage was allowed. The Vagrancy Committee, on the evidence placed before them, estimated the proportion of genuine work-seekers at 3 per cent. of all casual paupers.

These figures are in keeping with all we know of the experience of the Poor Law Inspectors who report from year to year to the Local Government Board upon the vagrancy question. To quote one opinion only by way of illustration:—

"The more I see of the vagrant class the more strongly I am impressed with the conviction that the number of those really in search of work is relatively very small. Over and over again I have gone into the casual wards and have, in answer to my question, been told by the vagrants that they were all seeking work but could not find any; but when I have pointed out that farmers were everywhere advertising for hands, they had nothing to say, except, perhaps, that farm labour did not suit them. In the agricultural districts it may be said, generally, that enough labourers can rarely be obtained, and the local newspapers are scarcely ever without advertisements for them. No doubt some of the able-bodied paupers know nothing of farm work, and if they can be enticed to labour colonies, which would teach them, agriculture may gain, but there is a large demand for absolutely unskilled men which they refuse to supply. For example, last summer, a tradesman in a small town in Somerset asked the master of the workhouse to send him half-a-dozen labourers, to whom he would give permanent employment for 18s. a week. Six of the occupants of the casual wards professed themselves as eager to accept this offer, but, on leaving the workhouse in the morning, all but one slipped away. That one remained, and has been earning his 18s. a week[Pg 29] ever since, but the other five have presumably found begging more profitable."[13]

The Local Government Board, as we have seen, have endeavoured to check vagrancy by urging Boards of Guardians to adopt the cell system, and to impose upon the casuals systematic labour tasks proportioned to the frequency of their visits. Yet though the cell system has been pressed upon workhouse authorities since 1868, so far only two-thirds of them have adopted it. As to the labour task, the Local Government Board advise that vagrants should, as a rule, be detained for two nights and required to perform a full day's work, but that the period of detention should be extended to four nights in the case of those who seek admission twice within the same month.

There is no general practice to this effect, however, for every union follows its own devices for making the life of the tramp hard or easy as the case may be, and in the absence of a uniform policy, few unions take the question of vagrant regulations seriously. The average Board of Guardians attacks all its problems on the line of least resistance, and the line of least resistance in dealing with the tramp is to follow the advice of the incomparable constable Dogberry, and get him out of sight as soon as possible, thanking God that it is rid of a knave.

The reports of Poor Law Inspectors have for years abounded with complaints of absence of uniformity in the treatment of vagrants and of the evil results of the existing state of anarchy. To quote several of recent date:—

"While many unions have adopted the Local Government Board's suggestions, others have ignored them. It is useless for one union to take steps for driving casuals away from their workhouses simply to plant them on others."[14]

"There is a want of uniformity as regards detention and the task of work in the various casual wards, and it is worthy of notice that at Loughborough, where the guardians, after a short trial of two nights' detention, decided to revert to a one night's detention only, the number of vagrants has increased from 10,751 in 1906 to 12,058 in 1907."[15]

"There is a great want of uniformity in the treatment of vagrants as regards accommodation, detention, diet and tasks of work, and guardians are naturally averse to taking any action involving expense pending legislation on the subject."[16]

"Some mitigation of the evils of vagrancy might be possible if guardians fully exercised the powers possessed by them. No uniform practice prevails. The system of a two nights' detention, with the imposition of an adequate task, is uncommon in this district. Some kind of task is prescribed in the majority of vagrant wards, but for the most part vagrants are released the following morning after admission. Here and there the regulations are enforced with beneficial results. Guardians are, perhaps, apathetic or disinclined to detain more often, because they are not enabled to deal effectively with this class owing to insufficient[Pg 31] accommodation. A system of two nights' detention, combined with proper discretion and supervision on the part of the workhouse master, has generally been followed by a diminution in the number of vagrants, but an absence of any such similar practice in neighbouring unions largely defeats these good results. Vagrants simply avoid these wards, and pass on to those where the restrictions are less severe."[17]

As the Departmental Committee on Vagrancy say:—

"It is much easier for a workhouse master, or the superintendent of the casual ward, to allow vagrants to discharge themselves on the morning after admission without labour, than to detain them, and insist upon their doing the regulation task of work, and the discretion which is left to the officers with respect to the discharge of certain classes of vagrants results in a complete variety of practice."[18]

Again:—

"Where a union carries out the regulations as to detention and task of work there is always a reduction in the number of admissions to their casual wards, but the evidence before us shows that severity of discipline in one union may merely cause the vagrants to frequent other unions."[19]

In London, according to the evidence given before that Committee:—

"Some guardians do not detain, some give one task, some another, and some practically none at all.... Some Boards of Guardians say the casuals are working-men honestly looking for work, and there is no doubt they are, but they know where they are going to get it. When they leave, they know to what casual ward they are going, and whether they are going to break stones or pick oakum. The consequence is, that the London vagrants flock to Poplar, Thavies Inn, and the other[Pg 32] wards where detention and work are not enforced, or where only a light task is given."[20]

All experience shows that the frequency with which vagrants visit given parts of the country is in exact proportion to the comfort or otherwise of the casual wards, and a change either way means a difference in the number of loafers entertained. "If a tramp likes the ward he is there again within the month, and perhaps in a fortnight," was the verdict of a witness before the Poor Law Commission.

"The slightest relaxation with reference to the quantity or quality of food given in workhouses leads immediately to an increase of vagrants," writes a Poor Law Inspector.[21]

Another Inspector, explaining decreases in the numbers of vagrants in some of his districts, says:—

"A small cause will apparently divert the vagrant stream from its usual course. Where a change of master has taken place, or where gruel has been substituted for bread and water, or vice versa, there has frequently occurred, very rapidly, a large increase or decrease in the numbers applying for admission to the casual wards where these changes have taken place."[22]

An illustration of tramp susceptibility to the attractions of the dietary is related by the Poor Law Inspector for Cumberland, Lancashire, and Westmorland, as follows:—

"In 1908 ... the guardians of the Leigh Union decided in the autumn to make an improvement in the dietary at their casual wards, a proceeding in which they did not invite the co-operation of other Boards of Guardians. The result was an influx of vagrants into the union, which swamped the accommodation, and rendered administration impossible. The admission to the Leigh casual wards for the first six months of the year had shown an increase of 33 per cent., as compared with 1907; in the second half of the year, the comparative increase was 164 per cent. The comparative increase for the latter half year in Lancashire as a whole was under 30 per cent., and none of the unions adjoining Leigh showed an increase greater than 60 per cent."[23]

Only those who have had practical experience of Poor Law work know how fastidious the tramp is in the choice of his involuntary tasks. In connection with the casual wards of a Board of Guardians of which I was for many years a member the task imposed was breaking 13 cwts. of stone. We added to this task the riddling and wheeling away of the stone. The result was that many tramps would come to the door, read the regulations, and walk off, while others, who entered and asked what they would have to do, would at once leave with "No, thank you." Several tramps resolutely argued the illegality of the extra task with the master, and tried to evade it.

It may be said that the case advanced against the vagrant up to this point rests upon negative grounds. Even were he an idler and a parasite and nothing worse, however, he has no claim to be tolerated. Those who tell us that vagabonds and loafers form, after all, an insignificant pro[Pg 34]portion of the population, and that the Poor Law holds out severer problems for our solution, forget or undervalue the fact that every one of these people is a centre of moral contagion. To ignore them because they are a small minority in society is just as rational as it would be to ignore gangrene because its effects are local only, or a plague because its victims are as yet few in number. Each of these loafers creates imitators. On the highways he is a walking advertisement of the advantages of idleness; in the model lodging-house, the night shelter, the wayside inn, he acts the part of recruiting sergeant for the great army of sloth and vice.

The vices of the vagrant, however, are by no means all of a negative order. From the standpoint of public security and order it is intolerable that the known criminals, which the majority of tramps are, should be afforded every facility for following their irregular calling. Incidents like the following, cited at random, are of weekly and almost daily occurrence in all parts of the country, and bring home better than argument the folly of our present method, or lack of method, of treating the tramp and loafer:—

"An attack on a lady in a lonely country road, between the Potteries and Leek, has been reported to the local police. The lady, who lives near Dunwood Hall, had been visiting an invalid, and on her way home was waylaid by a tramp, who attempted to rob her. A severe struggle took place, during which the lady was viciously handled. In the end the tramp was frightened by something and decamped."

"At the Mansion House, a plasterer was charged[Pg 35] with vagrancy and assault. On Tuesday night the prisoner knocked at the door of St. Mary Aldermary Rectory, and applied for assistance. The rector's butler, after consulting the rector, told him to go away, whereupon he struck him in the mouth, cutting it, and loosening two of his teeth. The rector went to his man's assistance, and the prisoner placed himself in a menacing attitude and attempted to strike him, saying that he would have his rights. The prisoner placed his shoulder against the door and prevented it being shut. Ultimately he was given into custody.... Sentenced to six weeks' hard labour."

The reports of Poor Law Inspectors frequently illustrate this aspect of the vagrancy problem. To quote from one only:—

"Another aspect of vagrancy, peculiar to rural districts, is the sense of insecurity which is created in the minds of people living in remote localities. Sometimes methods of threats and intimidation are resorted to to enforce demands when it is safe to do so. Truculent and insubordinate, as is proved by his frequent appearances before the magistrates for refusing to perform his allotted task, he is a burden to the community, and a nuisance alike to the police and to the Poor Law authorities."[24]

The laxity with which the law against mendicancy is enforced is notorious, and upon this question also the reports of Poor Law Inspectors contain interesting reading. "It is impossible," wrote Mr. J. S. Davy several years ago, "to deal adequately with the question (of vagrancy) without having regard to the mode in which the police carry out their obligations under the statute, and the action of magistrates when[Pg 36] vagrants are charged before them. There are obvious difficulties in the way of the police laying too much stress either on the apprehension of beggars or the prevention of sleeping out, and these difficulties affect magistrates, who occasionally discourage the police from proceeding against offenders under the Vagrancy Act."[25]

Another Poor Law Inspector wrote in 1906:—

"With regard to the punishment of vagrant offenders, it is very unfortunate that there is so little uniformity in the sentences in Leeds. While the stipendiary magistrate gives, as a rule, lenient sentences, the West Riding magistrates deal more rigorously with those who come before them. There seem to be no fixed principles governing the cases."[26]

The following extract is taken from a Yorkshire newspaper of April, 1903:—

"Three labourers of no fixed abode (it is the police constable's well-known euphemism for a vagrant), were charged at Skipton with begging at Kelbrook. The prisoners fairly took the village by storm. They were singing and shouting, and swore at women who would not relieve them. One of them kicked a door, and their conduct generally was altogether disgraceful. After they had collected 3½d., they went to the public-house and asked to be supplied with a quart of beer for that amount. The girl who was in supplied them for the sake of quietness, and after drinking the beer the men went out, collected the same amount, came back, and demanded another quart for 3½d. The men were sent to gaol for fourteen days each."

Very outrageous, of course, yet very common, and also very natural. For given the implicit[Pg 37] licence to beg, why not give the tramp also the licence to spend the proceeds of begging in his own way, and if he gets drunk and is violent, is it not the fault of those who furnished the money? But "fourteen days!" There is the true irony of the incident. For the same men probably served fourteen days a month before, and would serve fourteen days a month later, since the vagrant's time is notoriously divided pretty equally between the gaol and the highway. If, however, our penal laws are intended to be not merely punitive, but also, and mainly, reformatory, a system which consists of sending men into and out of prison at more or less regular intervals is obviously futile and childish. It is the obligation to work which these men, and tens of thousands like them, need to come under. Dislike of regular labour makes them tramps, tramping makes them criminals—the two conditions are inseparably connected as cause and effect, for their kinship lies in the very constitution and instincts of human nature, and the police laws which ignore it are engaged in an encounter from which they must of necessity emerge foiled and beaten. They may hide the tramp for a time from view, but they will not cure him; the very iteration of the futile penalties which are imposed upon him only confirms him in the conviction that vagrancy, mendicancy, rowdyism, and blackmailing are venial offences, the commission of which society almost takes for granted, since it has arranged that they may be compounded[Pg 38] for upon terms so easy as to amount to open incitement to illegality.

"Evidence is available on all hands, both from magistrates and from those connected with the administration of the Poor Law," the Vagrancy Committee of the Lincolnshire Quarter Sessions of 1903 write, "that the present short-term sentences, especially in view of the improved prison dietary, are a treatment of no deterrent value.... If the present methods are not deterrent, the evidence is also clear that neither are they reformatory. If the man bona-fide out of work and seeking work be excluded, a very large proportion of those convicted for vagrancy are found to be habituals. Many of these cases are either mentally or physically below the normal standard, and it is obvious that such cases cannot be successfully dealt with during the very short periods for which they are brought under the prison influence."

The Committee cite one notorious case in which between December 8, 1881, and October 23, 1903, a period of under twenty-two years, a man of thirty-seven years had been sentenced to imprisonment thirty-one times in Lincolnshire, and after he had done all continued an unprofitable servant. His sentences were as follows:—

| Sentence of | seven days | 5 | times |

| " | ten days | 2 | " |

| " | fourteen days | 9 | " |

| " | three months | 12 | " |

| " | six months | 1 | " |

| " | twelve months | 2 | " |

An interesting feature of these sentences was the way in which shorter and longer sentences alternated. In another case a man of thirty years had been sentenced twenty-three times within five years, viz., between July 14, 1898, and June 29, 1903, as follows:—

| Sentence of | seven days | 6 | times |

| " | ten days | 3 | " |

| " | fourteen days | 4 | " |

| " | one month | 2 | " |

| " | six weeks | 1 | " |

| " | three months | 5 | " |

| " | six months | 2 | " |

To quote the words of the Prison Commissioners:—

"The elaborate and expensive machinery of a prison, whose object is to punish and at the same time to improve by a continuous discipline and applied labour, cannot fulfil its object in the case of this hopeless body of men who are here to-day and gone to-morrow, and who, from long habit and custom, are hardened against such deterrent influences as a short detention in prison may afford."[1]

Moreover, our medical authorities are at last on the track of the tramp, and none too soon, for several recent epidemics have convinced them that he is one of the most proficient disseminators of disease. The following incidents, all relating to the last wide-spread epidemic of small-pox, are typical of his services to society in this respect:—

[27]"A tramp who was making his way through the Lake District was found lying by the roadside near Ullswater on Sunday evening in an advanced state of smallpox. He was removed to a smallpox hospital, and it was[Pg 40] ascertained that he had been infected by another tramp, who is now in the Penrith Hospital." (March 5, 1903.)

"At Northwich three more begging cases were dealt with. The chairman said tramps were mainly responsible for the smallpox prevalent in the district. Cheshire was infested, and if vagrancy could be put down they intended to do it."

"Smallpox has broken out in a somewhat serious form at Barking, and several families have been removed to the isolation hospital. The outbreak is attributed to a tramp, who was found lying in the roadway at Ripplesdale with a severe attack of the disease."—(May 19, 1903.)

How disease is disseminated by tramps is graphically told in the following newspaper paragraph relating to the epidemic above referred to:—

"On December 20, 1902, a tramp named —— entered Doncaster Workhouse. He said he came from Worksop way; had been sleeping out; had not had any food for three days; and complained of aches and pains all over him. He was isolated as much as possible in an end ward of the Workhouse Infirmary. On December 26, he was found to be suffering from small-pox, and immediately removed to the Small-pox Hospital. Four inmates who had been in contact with the case were isolated and re-vaccinated, and a nurse, also re-vaccinated, was told off to attend to them, and not allowed to go near the other inmates.

"On January 8, a second case of small-pox occurred in the workhouse. This inmate, it appears, had sorted the clothing of the first case. He complained of illness on January 4, and developed the disease on January 8. The amount of trouble that was given in isolation, re-vaccination, and disinfection must have been very considerable, and must all be debited to the tramp who introduced the disease."

The report for 1903 of Dr. J. R. Kaye, the West Riding of Yorkshire Medical Officer of Health, stated:—

"Yorkshire towns have had such a visitation of smallpox, that we read with interest the part played by the tramp genus in spreading it. Last year there were 144 cases of the disease in the West Riding. In nearly every centre affected, the tramp was responsible for its introduction. Thus we find at Keighley, where the greatest number of cases occurred, the infection was brought by a man who had been 'on tramp' seeking employment. The 15 cases at Barnsley were attributed to tramps of the lodging-house class. A recent investigation has shown that out of 138 towns having cases of small-pox, in no less than 100 its introduction was attributed to persons of the same class. At Sheffield, out of 28 importations, 21 were brought about by tramps, and at Huddersfield, 8 out of 13 invasions were traced to similar channels. It is significant, that in districts away from the main roads trodden by these nomads, small-pox was unknown. Clearly something will have to be done with this highly objectionable person if we are not to have small-pox always with us."

In a paper on "Tramps and the Part they Play in the Dissemination of Smallpox," read in July of the same year at the Sanitary Institute's meeting, Dr. Kaye said:—

"In the recent prevalence of small-pox, some 12,000 cases have occurred in the provinces (since January, 1902), and experience all over the country shows that the most subtle agency of distribution is not to be found in the close commercial intercourse of our communities, but in the wanderings of the relatively insignificant number of people whom we designate tramps."

As a result of the discussion which followed, it was resolved to request the Government to "take into consideration the necessity for legislation to deal more effectually with those resorting to common lodging-houses and workhouse tramp-wards, as a constant and dangerous element in the propagation and dissemination of smallpox."

The following year Dr. H. E. Armstrong,[Pg 42] Medical Officer of Health for Newcastle-upon-Tyne, published an elaborate report on the same epidemic, based upon inquiries addressed to the Medical Officers of Health throughout the country. As a result of the epidemic, which began in the latter part of 1901, and lasted the two following years, 25,341 cases occurred. As to their origin, Dr. Armstrong came to the following conclusions:—

(1) Of the 126 districts from which returns were received, 111 had been invaded by small-pox in the epidemic, and in 57 or 51 per cent. of these, the disease was first introduced by vagrants. In 25 of these latter districts spread of infection from vagrants occurred.

(2) Small-pox was introduced secondarily by vagrants into 58 districts, and, perhaps, into two other, at least 305 times. Such secondary introductions of infection took place with the following frequency:—

Number of Times

Infection was

Introduced.Number of

Districts.1 11 or 12 1 or 2 1 2 11 or 12 3 5 4 5 5 3 6 3 7 2 8 7 9 7 9 or 10 7 11 7 12 7 13 7 23 4 24 4 31 4 34 4 (3) It was found that the vagrants were housed in the workhouse in 41 districts, and in common lodging-houses in 58. The number of cases of small-pox occurring in these lodging-houses was 'at least 606,' and probably more, though 19 districts reported that the disease was introduced into common lodging-houses (169 with 165 cases) otherwise than by vagrants.

(4) In 35 districts there was reason to believe or suspect that infection had been carried elsewhere by vagrants leaving those districts—in most cases twice or more.

(5) Infection was first introduced by vagrants into 58 per cent. of the 63 large towns to which the inquiries extended, and was carried sooner or later into 72 per cent. of these towns, and on an average about five times to each. The disease had been taken to 30 workhouses and about 70 common lodging-houses, causing a large number of fresh cases, but had been of comparatively slight prevalence in such houses when not brought there by vagrants.[28]

So, too, at the meeting of the Sanitary Institute, held on February 7, 1903, at Manchester, Dr. E. Sergeant, Medical Officer of Health to the Lancashire County Council, reported that "The spread of smallpox was owing most largely to the vagrant class," and he claimed that "these parasites should not be allowed to go about the country spreading disease, and it was very little to ask that they should be vaccinated," for it seems that under present legislation, while the parasite can require you to support him, you cannot require him to protect himself, much less you, against infectious disease!

Furthermore, guardians of the poor have[Pg 44] become increasingly alive to the fact that one of the most difficult tasks which they have hitherto had to discharge, in the administration of the existing law, will compel them before long to face this wider problem: I refer to the question of child vagrancy. For oftentimes the tramp has both wife and children, and unless a benevolent public interposes and relieves him of their maintenance, they accompany him on his wanderings. Passing over the humane aspect of the question, I would ask: What does this ghastly parody of family life mean? It implies that where there is one vagrant now there will in all human probability be two, three, four, a few years hence. Calling attention to the fact that during the year 1908 3,899 children were admitted to vagrant wards, the Report of the Local Government Board remarks:—

"Debarred from education and all that is essential to the formation of settled habits, they are subjected to great hardships, and it would be strange if, under such conditions, they did not become bound to the road."[29]

Our forefathers recognised three and a half centuries ago that vagrancy was hereditary, for an Act of 3 & 4 Edward VI. (1550), reciting that "many men and women going begging carried children about with them, which, being once brought up in idleness, would hardly be brought afterwards to any good kind of labour or service," gave carte blanche to any person willing to appropriate such children and bring[Pg 45] them up to honest labour till the age of eighteen years if boys, or fifteen if girls. It may be said that this was legalised kidnapping, and that our modern way of dealing with the children of tramps is better. For we have got so far as to recognise that the liberty of vagrant parents to drag their offspring round the country is a vicious liberty, and should not be tolerated, though we are not agreed on preventive measures. The Poor Law Acts of 1889 and 1899 empower Boards of Guardians, under certain specified circumstances, to assume and exercise parental rights over the children of pauper parents, and the Children Act, 1908, prohibits child vagrancy under penalty, and makes provision for placing in public or other suitable custody the children of persons who are unfit to discharge parental duty.[30] These statutes do not interfere with parents' liability to maintain their children, though in other hands, yet the enforcement of that liability will prove difficult, if not impossible, in the case of a vagrant. Unless such a parent voluntarily abandoned a roaming life, the Poor Law and police authorities would have to choose between the alternatives of perpetually chevying him from pillar to post or letting him go scot free. Obviously, legislation which leaves the[Pg 46] question of parental responsibility in so unsatisfactory a position cannot be the final word on the child vagrancy problem.

Viewing the question of vagrancy from all sides, we shall be compelled to endorse the verdict of the Lindsey Quarter Sessions Committee:—

"The cost to the community of this class is immense, for they produce nothing, they necessitate large additions to our workhouses, involving heavy cost to the rates, and they overcrowd our prisons. At the same time they form a ready recruiting ground for the criminal classes, they are a continual nuisance to rich and poor alike, and they leave behind them families worse than themselves."

THE URBAN LOAFER.

The vagrant is only one type of social parasite, however, and in some respects he is not the most obnoxious. When we leave the casual wards and enter the workhouses themselves, a further loafing element confronts us, adding to the difficulty of our problem. For though these institutions nominally exist for the reception of people who are not only destitute but are unable to prevent their destitution, we find that the able-bodied pauper is to a large extent in possession.

It is interesting to recall the fact that when workhouses were established, the tendency which the Poor Law authorities fought against was, that the aged and infirm of the labouring class regarded them as infirmaries for their permanent maintenance. A Report of the Poor Law Commissioners of 1840 protested against the idea that workhouses should be placed on the same footing as almshouses.

"If the condition of the inmates of a workhouse," they wrote, "were to be so regulated as to invite the aged and infirm of the labouring classes to take refuge in it, it would immediately be useless as a test between indigence and[Pg 48] indolence or fraud—it would no longer operate as an inducement to the young and healthy to provide support for their later years, or as a stimulus to them, whilst they have the means, to support their aged parents and relatives. The frugality and forethought of a young labourer would be useless if he foresaw the certainty of a better asylum for his old age than he could possibly provide by his own exertions...."

Nowadays, the difficulty of Poor Law Guardians is to prevent, not the aged and infirm, but the middle-aged and able-bodied from making the workhouse their permanent home.

"Once admitted into the workhouse in England," says the Majority Report of the Poor Law Commission, "the pauper is usually left undisturbed, the Guardians seldom exercising their power of discharge." This generalisation is unjust, yet what is said certainly holds good of a large number of workhouses. While, however, Boards of Guardians are mainly to blame, the laws which they have to administer are also, in part, responsible. In the absence of institutions for the detention of loafers such as exist in Continental countries, these loafers are able to abuse the Poor Law at will, and snap their fingers at the police. Within the workhouse they are a cause of perpetual annoyance, and their presence and example are a fruitful source of demoralisation and disorder.

Speaking of this class of able-bodied paupers in relation to the Sheffield Union, Mr. P. H. Bagenal,[Pg 49] Poor Law Inspector for the West Riding, reports:—