HOW PARIS AMUSES ITSELF

Contents

| Page | ||

| Introduction | 7 | |

| Chapter | ||

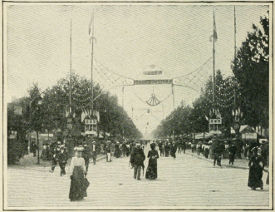

| I. | The Shows of The Champs-Élysées | 17 |

| II. | Paris Dines | 40 |

| III. | Some “Risqué” Curtains with Serious Linings | 78 |

| IV. | Bars and Boulevards | 109 |

| V. | Montmartre | 143 |

| VI. | In the Cabarets | 185 |

| VII. | Circuses and Fêtes Foraines | 222 |

| VIII. | Grease Paint and Powder Puffs | 255 |

| IX. | In Parisian Waters | 285 |

| Envoi | 333 |

Introduction

It is the small boy who crawls under the circus tent who most keenly enjoys the show.

He has watched while the big double-top canvas was being raised and staked taut, transforming the familiar pasture-lot into a magic realm, more alluring and seductive than the best fishing-hole in the town creek.

Following the parade, a cavalcade of golden chariots, caparisoned horses and swaying elephants, the small boy has walked on air, buoyed by the thump and blare of the brass band. Weeks before he had reveled in every detail of the show as revealed in posters on the barn-doors: the lady with the fluffy skirts bounding through the paper hoops from the well-rosined back of her white horse; the merry, painted clown; the immaculate ringmaster in glistening boots; and, last of all, the showman!—generous, genial and big of heart, whose plain black cravat, fitted neatly under his collar as in the lithographs, and whose beaming blue eye seemed an open guaranty of all he promised at the single price of admission.

Should the small boy grow up to be a connoisseur in much that glitters in life besides golden chariots, and yet manage to keep young enough to preserve a kindly feeling toward the lady of perennial youth upon the white horse, should boyish love of the picturesque still abide in him, he will find within the gates of Paris a city after his own heart, a place where gaiety never ceases, where the finesse of amusement has been brought almost to a state of perfection.

To this great pleasure-ground the whole world flocks for amusement. It is upon this exquisitely fashioned spider-web of Europe that many rare butterflies have beaten their pretty wings to tatters, and in it that many an old wasp has entangled itself and died.

Paris! the polished magnet which attracts the spare change of countless thousands in payment for the wares of folly and fashion, of the dressmaker and the cook!

When the sun shines, the city is en fête.

Rows of geraniums flame in the well ordered gardens of the Tuileries. Masses of flowers, gay in color as the ribbons streaming from the bonnets of the nurses, lie in brilliant patches along gravel walks or within the cool shadow of massive architecture. Brown-legged children, in white socks and white dresses fresh from the blanchisseuse, run screaming after runaway hooples, or watch in silent ecstasy the life and exploits of Mr. Punch at the Théâtre Guignol.

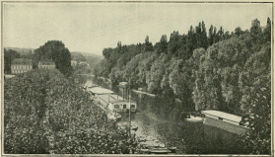

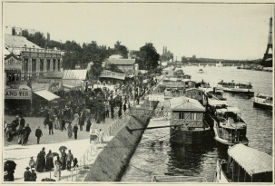

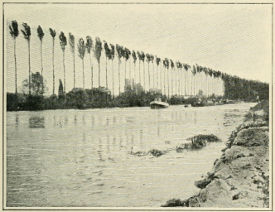

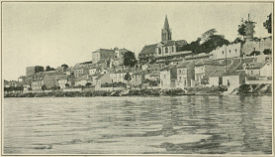

Under a vault of turquoise sky the Alexander Bridge, emblazoned with its golden horses, spans the Seine, crowded with traffic sweeping beneath the great arc. Sturdy steam-tugs with vermilion funnels tow long sausage-like lines of newly varnished canal-boats, whose sunburned captains with their sweethearts or families lounge at déjeuner under improvised awnings stretched from the roofs of cabins shining in fresh paint. Down the great vista of the Seine each successive bridge is choked with thousands of hurrying ant-like humanity. Swift bateaux-mouches dart back and forth to their floating stations. For a few sous these small steamers will take you to St. Cloud or beyond, past feathery green islands, past small rural cafés perched upon grassy banks where all day long old gentlemen wearing white socks and Panama hats wait patiently for a stray nibble.

This bright morning in Paris the boulevards are crowded with a passing throng which is gazed at for hours by those who fill the terraces of the cafés to linger over a morning apéritif. At one café a party of commerçants are transacting business.

It is the fat cognac merchant now who is gesticulating to the rest of the group, pausing at intervals to wipe the perspiration from his oily neck. Near them, four Arabs, swathed in spotless burnooses, their bare feet encased in sandals, sip in silence their steaming petites tasses of café Maure. Omnibuses lumber by. The air is vibrant with strident cries and the cracking of whips. An automobile passes, sputtering and growling through the mêlée of the broad boulevard, taking advantage of every chance space as it threads its way out to the green country beyond with its begoggled occupants to déjeuner at Poissy or perchance to dash farther on at a devilish pace to the sea and Trouville.

At another table on the terrace is a pretty blonde, her dainty feet resting in high-heeled slippers upon the little wooden footstool which the garçon has so thoughtfully tucked under them, and her eyes shaded by the brim of the reddest of hats. She is engrossed in writing a note, which she finally slips in its envelope. Then this dainty Parisienne calls the chasseur, that invaluable messenger attached to every big café, and gives him a few cautionary parting instructions. He springs upon his bicycle and in half an hour returns with another envelope, this one plain and unaddressed and containing a hastily scribbled line in pencil. The corners of the pretty mouth curl upward in a little satisfied smile as the answer is read.

“Madame was in,” explains the chasseur in a low voice. “It was madame’s maid who wrote it for monsieur!”

An hour later, in quite a different café, in a jewel-box of a Louis XVI. room, a well-groomed monsieur gazes in adoration across the snow-white cloth of a breakfast table at a wealth of golden hair, a pair of blue eyes and what is now the sauciest of little mouths. The scarlet hat has been tenderly laid upon the Louis XVI. clock, its brim discreetly covering the dial. The aged garçon allotted to these indiscreet people has just served the hors-d’oeuvre.

There are many other just such déjeuners particuliers in Paris over which no one bothers oneself.

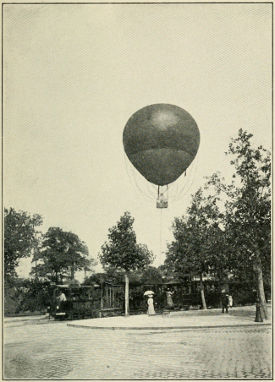

A long line of carriages is ascending the Champs-Élysées. Here and there among them you will see the glitter of smart turnouts. In the cool Bois nearby, the deer from their noon-day hiding-places hear the trot of equestrians passing in the feathery alleys. Upon some grassy corner of the wood a family party have spread themselves and laid out their bread, cheese and wine for a day’s outing. Like a yellow pearl shimmering far up in the azure, a balloon sails briskly toward Vincennes.

All these things happen when the sun shines. When it rains, Paris is in mourning. Cozy corners of café interiors are sought. Here, at least, one can forget for the time the chill, rain-swept city. Somber fiacres, drawn by dejected steeds, splash along the glistening wood pavements, with hoods up, their occupants stowed under huge waterproof aprons, the cocher muffled in his coat to the edge of his yellow, glazed hat.

Susanne, she of the madonna-like eyes, and the painter—their small stove, with its pipe traversing the ceiling, having failed dismally to warm even the cat beneath it—have come from their apartment across the Seine to the café, and are snug in a corner over a game of dominoes. The café is a refuge in raw, dreary weather. Only the wretchedly poor must needs pass by its welcome door. Now and then one does pass: an outcast, pale and hopeless, wrapping her soaking skirts about her shrunken hips with something of her old-time grace; or a man with matted hair, hungry and bitterly cold. Last night, after running a mile behind a closed cab with a trunk strapped on top, he had had the good luck to stagger beneath its weight up five flights of stairs, for which service he had received a franc. He had rushed with it down the winding stairs to the street. Ah, he remembered how happy he was!—how drunk and warm he had been for ten hours! And so among the cheerlessness of leaden roofs and deserted streets the smile of the city has gone.

Suddenly there is a break in the dull gray overhead and the downpour ceases.

“Ah! Sapristi! It is going to clear!” predicts the garçon de café, as he glances up at the scudding clouds, and nods his assurance to those within. Instantly the café becomes animated with good humor. A tall man and a brunette in new high-heeled shoes are the first to venture out. They laugh over the incident of the rain very much as those who have luckily escaped an accident.

In half an hour the boulevards are steaming in warm sunshine. Again the crowd pours by. All Paris is smiling.

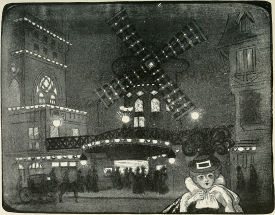

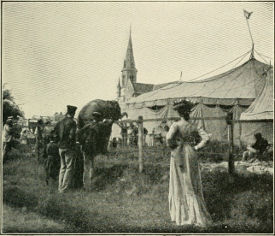

If you are an epicure with a fortune, you will find restaurants whose interiors are marvels of refinement and good taste, whose cellars hold priceless wines, and whose cuisines would grace the table of a king; or, if you are a bohemian, there is good-fellowship and a cheering dish awaiting you at a price within the means of even poets and dreamers. But it is after one dines that Paris throws open the doors of her varied attractions. There are the ever-moving fêtes foraines—mushroom growths of tawdry side-shows springing up in the different Quartiers in a night—with their carrousels and menageries, and the smarter circuses, like the Cirque Médrano, the Nouveau Cirque and the Cirque d’Hiver. There are the cheap shows of the small Bouis-Bouis, and the big open-air café concerts of the Champs-Élysées, the Concert des Ambassadeurs and the Alcazar d’Été, and that exquisite music-hall, the Folies Marigny, the Jardin de Paris, the Folies Bergère, the Casino de Paris and the Olympia, and, in contrast to these, the Opéra, the Opéra Comique and the Bouffes Parisiennes. There are serious concerts and little serious concerts like the Concert Rouge. There are the shows and cabarets of Montmartre and those of the rive gauche, the Noctambules, and the Grillon. There are the cheap dramas of the bourgeois theaters in remote quarters of the city, and the risqué plays of the Palais Royal; the daring, independent Théâtre Libre, and the Châtelet, famous for its scenic wonders; the lighter plays of the day at the Vaudeville, interpreted by Réjane; the splendid new theater of the divine Sarah; and the historic Français, with its finished acting in perfect French. The list is endless.

Where shall it be? To roar with the rest at the latest song of Polin or listen to a sadder tale at the Odéon, or, perchance, enjoy your second cigar in the front row under the sparkling eyes and pert nose of that most charming chanteuse, Odette Dulac, at the Boîte à Fursy!

If you have finished your liqueur and have retained the enthusiasm of the small boy who squirmed his way into the circus tent, raise your finger at a passing cocher. He will take you anywhere.

Paris, 1903.

Chapter One

THE SHOWS OF THE CHAMPS-ÉLYSÉES

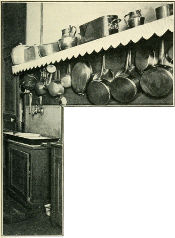

If you wish to buy your tickets in advance for the evening performance at the Alcazar d’Été, the open-air café concert of the Champs-Élysées, you go there some afternoon, and are ushered by a waiter through a narrow corridor of the adjoining restaurant, past little rooms, shining in copper pots and pans, and pungent with steaming sauces, through a pair of swinging doors well worn by hurrying waiters, and into a square room piled high with snow-white linen, pyramids of lump sugar, and rows of glittering silver. Half hidden in a corner among this spotless collection you discover a desk presided over by madame, who greets you pleasantly and produces for your inspection from beneath a litter of dinner checks and bills the seating diagram of the Alcazar.

“Does Monsieur wish seats for the evening, and in what location?” madame asks.

You suggest two in the third row.

“Bon,” replies madame, approvingly. She dips a pen in violet ink and writes carefully upon a checklike document the numbers of the chosen seats, tears this check from its stub, blots it, and scratches the corresponding numbers from the diagram. “Voilà, Monsieur,” and she hands you your ticket. Then she dives into the pocket of her petticoat for the key to a money-drawer from which to make your change. Finally, as you raise your hat to go, she adds, in parting assurance, with a little shrug of her shoulders beneath her worsted shawl: “I am sure Monsieur will find the seats excellent; I should have chosen them myself.”

All this takes time, but I must confess that I like the pantry method better than having my change blown at me through the pigeon-window of a draughty box-office, with the last rear seats in the house slapped out to me, all the desirable ones being in the mercenary hands of a band of sidewalk pirates.

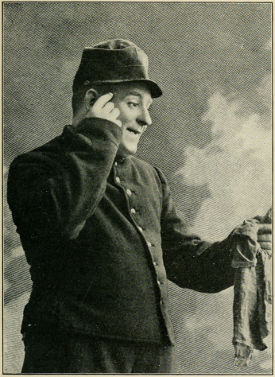

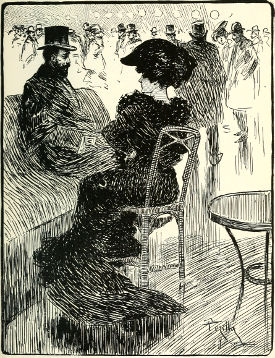

LAMY IN “LA CAROTTE” AT THE PALAIS ROYAL

Drawing by BARRÈRE

Meanwhile, several newcomers are crowding about the table, among them three well-groomed men in top hats and frock coats, evidently having strolled over from their club, and a faultlessly dressed old baron, with a tea rose in his button-hole, who is now leaning over the desk, poring over the diagram through his black-rimmed monocle.

It is the first night of the new revue. This well-fed old baron! His beard is grizzled now and his bald pate shines beneath the rim of his stove-pipe hat. How many revues has he seen in his Parisian life! How many capricious débutantes of café concerts and the theater has he known! How many has he seen flash into brilliant stars and then grow old and fade away! Some of them are staid old concierges now knitting away the short remnant of their lives. Some of them died young as roses will under gas-light. Les petites femmes! Ah! the good old days of the Palais Royal! The Orangerie! or the Tuileries and the Jardin Mabille! The days of brocades, of cashmeres, and pendent jewelry of malachite and old mine diamonds! What famous beauties then! and how they could wear their flounces and furbelows—the little minxes! What a reckless riot of costly gaiety! How much baccarat at the clubs! How many suppers at Bignon’s and the Maison Dorée! How many years of all this! and yet on this sunny afternoon this old baron is as eager as a schoolboy over the new burlesque, and so he strolls out with his ticket up the Champs-Élysées, stopping for a full half hour to watch the Guignol and the children and the nurses. Later you will see him rolling through the Bois in his victoria, a queenly woman in black by his side, the tea-rose stuck jauntily under the turquoise collar of a sleek red spaniel in her lap. The baron is smoking. There is no conversation.

You will hear Polin at the Alcazar. He comes on at the end of a preliminary program of excellent variety before the revue. Fat jolly old Polin, whose song creations portray the happy-go-lucky lot of the common soldier. He reels in from the wings, convulsed with laughter over some recent adventure, the result of which has put him in the guard-house for ten days. He is fairly bursting his red-trousered uniform with merriment as he begins his first verse. He tells you every detail of his experience, painfully even, for he is now crying with laughter, his voice rising in little squeaks like the water in a pump and bubbling over as he reaches the point. He is manipulating the while a red cotton handkerchief, which is never still; now it mops his round genial face, now it is twisted nervously into a rope and jammed into his trousers’ pocket, and as speedily taken out to dust his knees. His last verse is smothered in chuckling glee; little jets of cleverly chosen words manage, however, to get over the footlights to his listeners. The song ends amid a thunder of applause and Polin bows awkwardly and retreats with his back to the audience, his cavalry boots combined with his red trousers flopping as he goes.

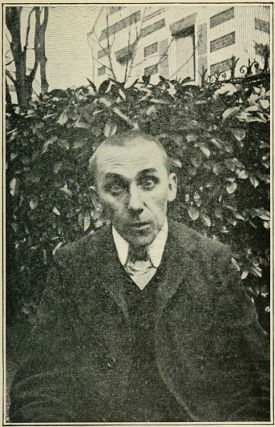

Photo by Reutlinger, Paris

POLIN

Parisians delight in caricature. It is as inborn with them as the art of pantomime. The political topic of the day, a new phase of the law or the government, the latest scandal, all come to the net of the writers of these revues.

Eve, the daughter of Madame Humbert, that shrewdest of modern swindlers, is presented as a Juno-like creature of lisping innocence. Shrewd, politic and extravagant Madame Humbert, the brains of that colossal robbery of millions of francs, steps on the stage. The brother, Daurignac, who posed as a painter, and the famous empty safe which played such an important role in the Humbert ménage, have been the theme for a dozen clever burlesques.

“Les Apaches,” a notorious band of cutthroats, who have lately infested Paris, and their beautiful accomplice, known as Casque d’Or, a term befitting her wealth of golden hair, have also furnished a well-worn topic for the revue writers. So, too, the capture of Miss Stone has inspired a clever revue, containing a whole stageful of pretty and shapely brigands. The book is by de Cottens and the music by Henri José, and it is presented in six tableaux at the Marigny with that idol of Paris, Germaine Gallois, in the principal role.

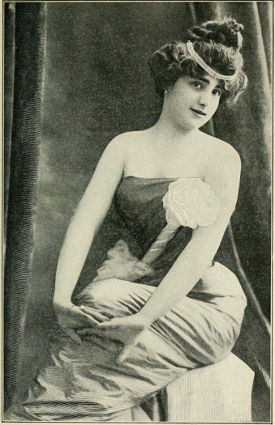

Photo by Stebbing, Paris

LISE FLEURON OF THE ALCAZAR D’ÉTÉ

The Parisian revue is in structure traditionally ever the same, and the receipt for these musical puddings is never altered. There are two important characters which are never to be departed from—the commère and the compère. The first fifteen minutes are occupied with the introduction of a young man of leisure, the compère, who has just inherited a colossal fortune from a dying uncle. He brings with him an exaggerated outfit of clothes, all brand new, consisting of a sack suit of dove gray, lined with red satin; a voluminous red satin tie to match the suit, clasped with a heavy turquoise-studded ring; a gold-buttoned embroidered vest; a soft gray felt traveling hat; lemon kid gloves, and a rattan cane. He stalks about the stage, smiling—the stage picture of good health—and squaring his shoulders and curling the ends of his long mustache with that debonair air supposed to be consistent with good luck. His ecstasy over what fortune has bestowed upon him would put in the shade even the enthusiasm of the “found at last!” gentlemen of the Eureka advertisements.

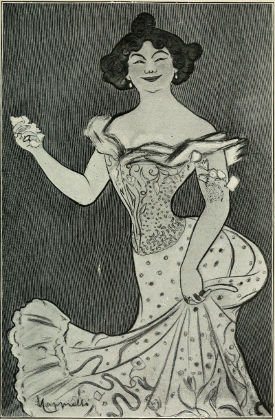

Photo by Reutlinger, Paris

GERMAINE GALLOIS OF THE MARIGNY

Before he gets half way down the village street of the first act, the commère, a statuesque fairy queen in silk tights, with real gems that are the talk of Paris, who has been hunting for him all over the town, suddenly comes upon him in the village square, and, touching him with her wand, makes him her protégé.

The compère may come upon the stage as an old roué, weighted with years and careworn. In this case, the good fairy immediately bestows upon him joyous youth and the satin apparel. She is running over with benefactions and, causing to appear suddenly a score of comely young grisettes and hard-working peasant girls who have been loitering around the town pump, arrayed in silk hose of assorted lengths, she urges him to select from these his mate. Just at this moment a plain little seamstress, in passing, runs into this barricade of village beauties, and at once becomes the victim of their badinage. Our youthful Crœsus, seeing her distress, straightway chooses her for his bride, amid the discontented reproaches of the rest of the girls and to the inward satisfaction of the good fairy.

Photo by Cautin & Berger, Paris

A COMMÈRE

The plain little seamstress turns out to be superlatively beautiful, and as naïve and witty as she is charming, especially if it is Lise Fleuron who plays the part.

It takes only a short time, in the second act, to clothe this stray Cinderella in a Paquin or a Worth creation, while her old gray and white clothes are neatly folded and laid away in the basket with which that very morning she had started early to market to buy a poulet and a salade for her sick grandmama. After this public shopping the happy pair is ready to start upon the honeymoon. Cinderella adds to her wardrobe a blue silk parasol, stuck in a rolled up traveling rug, while her happy companion decorates himself with a field-glass and dons an English shooting hat of impossible plaids.

In the third act they are joined by the good fairy and the revue passes before them. This is a hodgepodge of burlesques upon the topics of the day, ballets representing flowers and perfumes and the history of fashion, and choruses representing the different journals, the arts, inventions and manufactures. The costumes are superb and the massing of color exquisite.

Before the finale, an apotheosis of gorgeous color, with a stageful of kicking, giggling, romping gaiety, I catch a glimpse of the old baron. He has bowed to someone on the stage and is applauding vigorously. So, too, is the young vicomte with a scar across his cheek where a ball ploughed itself one chilly morning on the outskirts of Surennes, all on account of just such a cocotte as the good fairy who is now glancing under her stenciled eyelids at a swarthy little Italian in the front row.

And the Comte de B—— is shouting “Bravo!” from his box. It is he who has paid so highly to see Ninette included nightly in the program. She has been permitted by the amiable management, after the transfer of certain crisp bank-notes from the purse of the count to the pocket of the manager, to announce, in the third act, the approach of the soldiers, “as a personal favor to the Comte and because Madame is so beautiful.” To be in a revue and flattered by the press is as necessary to Ninette as to have a new gown for the Grand Prix. For, tho she is fair to look upon and has little bills springing up along the Rue de la Paix as thick as a field of bachelor’s-buttons, Ninette is not an actress. But Ninette enjoys her theatrical career. She takes the stage seriously, enjoying even the rigid discipline, because of its complete novelty. The old playgoers come to her salon, gravely kiss the tips of her fingers, and tell her how charming she has been in the revue. Then the journalists! Ah! how amiable they are! For the crisp bank-notes of the Comte which placed the crown of Thespis upon the blond head of Ninette did not all of them go into managerial pockets. But Ninette has begun to sing; listen! Yes, it is the line faintly announcing the soldiers. A final chorus, the curtain falls and the crowd rises and pours slowly out under the trees.

Photo by Reutlinger, Paris

A BEAUTY OF THE REVUE

It is starlight. Passing and repassing like fire-flies the cabs go trundling by. Here and there in the shadow one is stopped and a fluff of lace and sheen of silk is bundled in. The baron walks home, the end of his cigar glowing cheerily. The revue is a success.

The Concert des Ambassadeurs with its revue and variety adjoins the Alcazar. One can dine leisurely on the balconies of either of the two restaurants adjoining these cafés, and watch the performance during dinner.

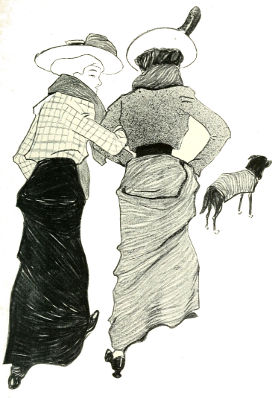

Near by is the Jardin de Paris enclosed by lattice and hedge, and ablaze at night with festoons of colored lights and crimson lanterns. Within, the crowd pours round the promenade thronged with demi-mondaines, in décolleté gowns flashing in jet, in picture hats flaming in scarlet, their white hands glittering to the knuckles in showy rings. Some of these women are pretty and gowned in chic simplicity, some of them are coarsely bedizened and heavily rouged, with small cruel eyes and strident voices.

The variety performance at the end of the garden has just ended, and a fanfare of hunting horns announces the quadrille. The passing throng crowds about the estrade to watch the dancing. Another fanfare from the horns, and the orchestra commences a lively can-can. The crowd presses close against the low balustrade. “Grille d’Égout” gathers up her skirts, and a second later her black stockings are silhouetted in billows of cheap lingerie. The band crashes on. The other dancers execute pas seuls with their traditionally voluminous display, which, from its very boldness, is neither suggestive nor vulgar—it is if anything rather a common exhibition from which all illusion has vanished. They are a type unto themselves, these can-can dancers; half of them might easily pass for middle-aged housemaids, but there are some who unmistakably have been gathered from the riff-raff of such places as the “Ange Gabriel” and the cabaret of the “Rat Mort” in Montmartre.

An old man in a long coat of rusty black and a straight-brimmed top hat now joins the quartet. He is tall, square-jawed and clean-shaven, with twinkling gray eyes. He is seventy years old and has been a professional quadrille dancer all his life. Laying the smoldering stump of his cigarette in a safe corner of the balustrade, he flings himself into the measure. His gaunt Mephistophelian frame seems tireless as if hardened by the dancing of a lifetime. He executes with a certain precision and gravity the steps of a pas seul. When he finishes, he recovers the butt of his cigarette, smiles sardonically at the applauding crowd, and sits down to refresh himself over a “bock.” “Grille d’Égout,” passing, good-humoredly tips his hat sideways with the toe of her slipper, and his satanic majesty rises and leads her into a maze of steps, evidently in revenge, since she begs off, exhausted at the end of a quarter of an hour. The crowd cheers.

A shooting-gallery pops and cracks away at one end of the promenade, while next to it a much-mirrored bar dispenses so-called English and American drinks, villainous all, with a bottle of warm champagne, on tap and sold by the glass, as a questionable alternative.

Below the level of the garden, almost immediately under the orchestra, is the Crypte, where there are varied attractions.

There are two ways of getting down to this Crypte; one is by the stairs, and the other by a polished board-chute. Both are free, but the chute is the more popular. Here an amused crowd stands about waiting for some Mimi or Cora or Faustine to plant her neat patent leather boots on the board and slide to the subterranean regions beneath. Here there are living pictures, two pink samples of which stand guard at the entrance of this side-show, while within, a gray-haired pianist thumps out the incidental music to the tableaux from an ancient piano with a sleighbell tone.

At intervals the sentinels without change guard with Spring and Summer, while Autumn and Winter pass the hat, and Venus rising from the Sea tarries in the dressing-room to curl her hair and gossip with the leading victims of the Deluge.

Certain tremulous cries emerge from the other side of the Crypte to the accompaniment of a desert tom-tom and the tread and sway of Oriental dancing.

Yes, the Jardin de Paris with all its noise and glare was built especially to attract most of the smoking-room list of the incoming ships. It appeals in some mysterious way to that natural prey of the Parisian landlord, the traveler who allows himself to be held as a hostage in exchange for his pocket-book at one of the large dismal hotels built solely for his capture. Here in a heavily upholstered and silent reading-room he may read the papers and watch other unfortunates of his kind prowl about him, until at seven he is ushered by an overbearing maître d’hôtel into an even more elaborate hall of fame to the table d’hôte, an occasion representing in gaiety a feast of refugees after a flood. If during his stay in Paris he has the good fortune to see anything Parisian he may count himself lucky.

The Théâtre Marigny is to the Jardin de Paris what a cozily lit dinner-table glowing in shaded candles is to a bar-room, aglitter with brass and glass and electric lights. This jewel-box of a theater in the Champs-Élysées was fashioned for all seasons, but in summer it is in full bloom.

Photo by Reutlinger, Paris

ÉLISE DE VÉRE OF THE MARIGNY

The approach to it among the trees is much the same as to the others, only that the roadway in front is packed at night with private carriages. Here a Parisian équipage de luxe of an eastern prince crowds a new coupé, with a rhinestone clock and hidden cases of doeskin lined with silk, a tiny mirror, a diminutive powder-puff in a box with a golden top, a little of this and a little of that. It is the carriage of Julie la Drôlesse; with this gilt encased arsenal one feels safe to look one’s best in any emergency thinks Julie—that is, if Julie ever really does any thinking. Does the little golden-puff remind her, I wonder, of the days when two sous of poudre de riz applied in a jiffy with a corner of her jupon sufficed to charm the habitués of the Rue Blanche? Ah! mes enfants!

Seen through the trees the Théâtre Marigny looms like some gigantic flower of light, the reflection from the edge of its circular promenade illuminating in a hazy light the surrounding foliage. And such a promenade!—aglow with fairy lamps thrust in a setting of shining leaves, and with comfortable rattan chairs encircling the mosaic floor which during the intermission is brilliant with the passing throng.

“Mar-ga-rita” sing gayly the Neapolitans to the strum of guitars. A woman with an olive skin whose lithe body seems to have been poured into a delicate mold of Valenciennes lace, glides by on the arm of a Russian. Her jewels have bankrupted a prince.

Sundry old Frenchmen, in straight-brimmed hats with ribbons in their button-holes, pass; one is a senator, another a famous sculptor. At one’s elbows is a pretty blonde, her white neck encircled by a band of turquoise reaching nearly to her small pink ears, ever listening like tiny shells to the flattering murmur of the human sea about her.

Pop! goes a bottle of champagne in the bar. Crack! rips the spangled train of Thérèse Derval under the clumsy heel of her admirer. “Fifty louis for your awkwardness, idiot!” snaps the quick-tempered Thérèse.

“Mar-ga-rita” strum the guitars. But the bell is ringing for the curtain. The spectacular revue following the excellent variety is quite different from the revues of the other café concerts; at the Marigny they are poems of color—costumes which are the creation of artists. Nowhere is scenic art brought to a higher perfection than at the Marigny.

One sees a ballet in tones of violet and gray that is as delicate as an orchid. Again the stage is blazing in Spanish yellow and red as rich as a pomegranate crushed in the sun. Now the tableau changes to a scenic night bathed in pale moonlight with a ruined château harboring purple shadows and framed in a grove of cypresses.

From this grove may flutter a ballet of bats, or the summer night may vanish in a twinkling and in its place appear a garden of Maréchal Niel roses blooming at a signal into another ballet.

Now enters a procession representing the history of fashion. Here are the exaggerated costumes of the Middle Ages, ermine and miniver, and those impossible head-dresses, the cornettes, hennins, and escoffions of the time of “Louis the Fair.” Then follow the grand apparel of the Medicis, and the transparent sheath-like tunics of the merveilleuses of the Directory, slit at the side and fastened with a cameo brooch, and the toilettes of the balls of the Restoration. Even more ridiculous costumes were worn, you remember, by women of society a hundred years ago openly in this very Champs-Élysées, the days when all Paris went mad over the costumes of the Athenian maidens. What a contrast are the creations of the present age to those seen during the Reign of Terror at Frascati’s! And yet I am sure that if any of the celebrated beauties of the Marigny had entered the court of Louis XVI. in a perfect gown of to-day, she would have been welcomed with wonder and delight.

The curtain falls on the revue, smart equipages outside are being shouted for by the chasseur. Julie la Drôlesse has just stepped in her boudoir-like coupé. It has begun to drizzle. I call my own conveyance, a dingy fiacre with a green light and a jingly bell, the cocher swathed about his middle with a yellow horse-blanket. He wheels his raw-boned steed to the door.

“Chez Maxime, cocher!”

“Bien, Monsieur!”

Chapter Two

PARIS DINES

The famous chef, Vatel, before a dinner given to Louis XIV., killed himself because the fish was late.

Nowadays he might simply have shrugged his shoulders in apology, a mode of reply most popular in France, and against which all argument is as useless as so much steam in the air.

Boil with rage if you will; plead with the ingenuity of a defending lawyer, or berate him in language which would inspire renewed effort in a government mule, the Frenchman’s shrug will disarm you as neatly as an expert duelist sends your foil spinning out of your grip, and you will be conscious of how useless your tirade has been only when you perceive the delinquent monsieur with the elevated shoulders bowing himself politely out through the door.

A year ago the veteran chef of a celebrated Parisian restaurant resigned his position. Prices had been affixed to the menu. With this deplorable change the famous maison had sunk below the dignity of this august personage. To attach to so noble a creation as a “filet d’ours à la François-Joseph” a fixed price as one would to a pound of butter, made his further connection with the house an impossibility. “Parbleu!” he cried, “Had Paris become a gargotte for the grand monde that he should have lived to see this?”

There still remain a few smart restaurants where there are no prices on the menu, but even in these there is a second edition of the bill of fare with the prices thereon which the maître d’hôtel will apologetically hand you when he discovers you are neither a millionaire nor a fool, even tho your French may be not so good as his own. If you have the leisure, the best plan is to order your dinner for a partie carrée in advance and for a certain fixed sum, as most Parisians do.

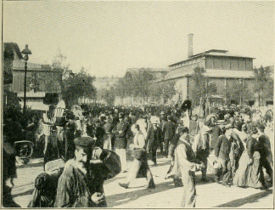

AROUND THE HALLES

In no city in the world are there so many and so varied places to dine as in Paris. One can hardly look right or left from any corner of any street and not find restaurants, from little boîtes, where a plat du jour and a bottle of wine are to be had for a few sous, to those whose cuisine and rare vintages are adapted only to the well-filled purse of an epicure. There are numberless resorts frequented by the vast army of bohemians, some the rendezvous for students and grisettes, others for the poets, the pensive, long-haired devotees of the symbolistic school, and kindred souls in the realm of art. There are those patronized by jolly, devil-may-care young doctors, sleepless night-owls, who discuss till graying dawn their latest operations with a complacent sense of superiority over the other half of the human world, who, they are convinced, without their medical aid would be left as helpless as a mass of struggling white bait in a net. And there, too, buried away in the dingy alley of Montmartre and fringing the ill-reputed neighborhoods of La Butte and the great Halles, are the feeding places of thieves, reeking from the odor of decaying vegetables and bad cheeses, yet, they say, supplied with some of the rarest wines.

A BUSY MORNING

It was a famous French sociologist who declared, from extended personal investigations of the private life of the Parisian mendicants, that the best champagne brut he had yet encountered he had found on the dinner tables of professional beggars.

Along the lighted streets and boulevards are the great brasseries for Munich beer and German dishes, and the richly decorated taverns, some of them in black oak shining in pewter and ornate with medieval decoration and stained glass. These are swarming with eddies from the passing world until long after midnight. Many of these are the habitual rendezvous of journalists, like the Café Navarin. Others, like the Café des Variétés and the Taverne de la Capitale, are the favorite places for actors, and still others for painters and musicians. There is hardly a resort in Paris which has not its distinct clientèle, from the buvettes of the cochers to Maxime’s.

And of soberer kind are the innumerable, perfectly kept establishments created by Duval and imitated by Boulant. They are big places for small purses; everything is of excellent quality, well cooked, and served by respectable women in spotless white caps and aprons.

There are hundreds of other restaurants besides, with dîners and déjeuners at a prix fixe, in which a secondary quality of food is turned into a clever imitation of the best, and where the wine is plain and harmless and included with a course dinner au choix for two francs fifty and less. On fête days and Sundays these well patronized petits dîners de Paris are crowded with bourgeois folk: clerks with their sweethearts, commerçants and their families, economical bachelors, and others, frugal-minded, from out of Paris who have come into the metropolis to spend a long-anticipated holiday.

And in contrast to all these dining places are the smart restaurants, filled with the correct grand monde and the chic demi-monde—the Café de Madrid, the Maison Anglaise, Paillard, Arménonville, La Rue, Joseph, Ledoyen, Voisin and the Café de Paris. There are serious old places, such as the Tour d’Argent, plain and unadorned, where all the wealth is in the casserolles and the cobwebbed bottles. Then, too, there is the ancient Restaurant Foyot, with its clientèle of senators, academicians and military officers, and the Restaurant La Pérouse on the quay of the Seine, where resort savants and magistrates and others less grave—an old-fashioned place with a narrow stairway leading to quaint, low-ceiled cabinets particuliers and excellent things simmering over the kitchen fires below stairs and certain rare old Burgundy lining the walls of the cellar.

Just such a place of seclusion and good cooking is the “Père La Thuille” in Montmartre. It is often a pleasure to dine in a room devoid of gilt and tinsel. The Père La Thuille is restful in this respect. The cuisine is perfect and the wine very old.

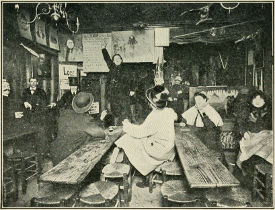

THE KITCHEN OF A CHEAP TABLE D’HÔTE

At one of the tables in the rectangular dining-room a celebrated diva whose bodice glitters in gems is dining with monsieur, the aged director of a gas company. Several empty tables away another elderly gentleman is filling Mademoiselle Fifi’s glass of champagne. Half hidden in another corner of the long leather settee a lady with delicate features and frank, intelligent eyes pours forth her soul and the remainder of a bottle to a well-groomed man at her side. The light from the shaded candles shows more clearly his strong fine hands. Now the little finger of his companion touches his seal ring quite unconsciously, as one would give an accent by a gesture to a confession. For a moment he covers her tiny hand with his own. Poor devil! he must return to his regiment to-morrow and, what is still sadder, the lady is married.

The New York Dairy Lunch, with its mirrored and marbled bathroom decoration, its elevating Bible texts, and depressing “sinkers,” and its dyspeptic griddle-cakes cooked in the window, would never make a success with Parisians. One of the most doleful sights I have seen in Paris was a sad-looking gentleman in black sitting at a cold marble-topped table of an expensive patisserie lunching on a weak cup of tea and a plate of cream-puffs—Chacun son goût!

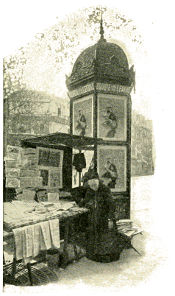

There exist here, however, “Express Bars” along the boulevards, where by dropping two sous in a slot you are permitted to rob the nickel-plated chicken house installed beneath of any of a dozen different articles, from a baba au rhum to a glass of beer. But Parisians stop at these places very much as they would to hear a phonograph, or as French children stop for their goûter at four o’clock in the cake shops, or as men and women of all classes drop in for the celebrated fruits in spirits dispensed at the famous solid silver bar of La Mère Moreau.

The French never hurry over dinner. The pleasure of dining must not be spoiled by haste. It is an hour which nothing postpones. If anything serious is to be decided upon, Parisians dine first and then think the matter over. Perhaps after all they are right, for are we not at our best in heart and spirit when we have dined wisely? Anger, hatred, even the green monster jealousy, fade away with the progress of a good dinner.

Drawn by Sancha

LE PLONGEUR

Into the Restaurant Weber comes an old bon-vivant growling. He stands for a brief moment surveying the tables, chooses one of the few unoccupied ones and plants himself savagely in front of the snow-white cloth. “The devil!” he mutters to himself. “She’ll get my letter to-morrow. Bon Dieu! to think I have been imbecile enough to trust her!”

“Has monsieur le comte ordered?” interrupted quietly the maître d’hôtel Léon.

The count glowers over the menu.

“Some filets de hareng saurs.”

“Parfaitement, monsieur,” replies Léon, and he repeats the order to a waiter.

There follows a pause, during which the count’s irate eye (the one not occupied with his monocle) wanders absently over the list.

“Perhaps monsieur would like an excellent purée of peas to follow?” Léon naïvely suggests.

“Bon!” gruffly accepts the comte. “And a homard, and a roast partridge with a good salad, and a bottle of Veuve Clicquot, ’93,” adds the count.

“Bien, monsieur, I will season the salad myself.” And Léon, with an authoritative gesture, claps his hands twice, stirring into increased activity the already alert waiters, gives a final touch to the appointments of the count’s table, and hurries off to attend to another dinner, a jolly party of four who need no further cheering up.

Drawing by Sancha

LE MAÎTRE D’HÔTEL

“She has the innocent eyes of a child when she lies!” mutters the count, returning to his thoughts.

But the tiny filets de hareng, with their tang of the sea, sharpen his appetite, and the wine quiets his nerves and refreshes his brain, and the purée warms him and the lobster steaming in its thick, spicy sauce cheers him. The hatred within him is growing less. That lump of jealousy buried so deep half an hour ago has so diminished that, when the fat little partridge arrives, garnished and sunk in its nest of fresh watercress, this gives the fatal coup to ill humor. Again the champagne is rattled out of its cooler. Léon, whose watchful eye is everywhere and whose intuition tells him when a patron wishes to talk, now comes to the count’s table.

The count has by this time become the soul of good humor. He compliments Léon on the dinner and Léon compliments him on his taste in selection of viands, and so they talk on until Léon goes himself for a special liqueur.

The count gazes peacefully on those about him and admires, with the critical eye of a connoisseur of beauty, the pretty woman at the corner table. Silent waiters lay the fresh cloth and bring him an extensive choice of Havanas. All these final accessories have little by little taken away the remnants of his ill feeling. He puffs reminiscently at his cigar. His very spirit of revenge seems to have been steamed, sautéed and grilled out of him. Now he takes from his waistcoat pocket a thin gold watch—the one he bought at a round sum in Geneva years ago and which has been faithfully ticking away the seconds of his turbulent life so long that he has come to regard it somewhat with awe, as one would the change from his last dollar.

The delicate hands have crept to nine o’clock and two tiny bells within strike the hour. The count writes upon his visiting card a short line, seals it in its envelope, calls the chasseur and, giving him the note, directs: “Stop on your way at Véton’s for the red roses.”

LE CHASSEUR

Drawn by Sancha

Ah, mesdames et messieurs, how many of your little troubles have been settled by the doctor with the cordon bleu and the shining saucepans!

The Taverne Pousset is famous for its beer, its écrevisses (crawfish boiled scarlet and served steaming), and its soupe à l’ognon, a bouillon redolent with onions and smothered beneath a coverlet of brown cheese.

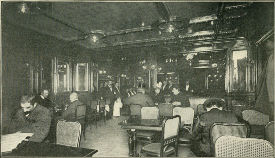

Parisians flock to Pousset after the theater. At night its richly decorated interior is ablaze with light and crowded with those who have stopped for supper after the play.

There are dozens of just such tavernes and brasseries. These German institutions have oddly enough become most popular with the French, who have grown in recent years critically fond of good beer. I might add, however, that it is the only thing German that has become popular. That little affair of Sedan is still in the gorge.

The Coq d’Or, on the rue Montmartre, is one of the oldest taverns in Paris. Its clientèle during dinner is composed of commerçants and a mixture of bourgeoisie and Bohemia, but after midnight, as happens in scores of other such places, the Coq d’Or is filled by a veritable avalanche of demi-mondaines of the surrounding quarter.

If you dine at Marguery’s, order a sole au vin blanc and let Étienne bring it to you.

If it is summer you will find a table in the covered portico brilliant with hanging flowers, or you may choose a snug corner behind the cool green hedge that skirts the entrance of this famous rendezvous of rich bourgeois and commerçants.

The restaurant Marguery is unique. It is a magnificent establishment, perfect in its cooking, its wines, and its service. I know of no restaurant where for this perfect ensemble one pays so moderate and just a price; the proof of this is that here you will see the true Parisian; neither is there any supplementary charge for any of the cabinets particuliers or the private dining-rooms. It is the only maison de premier ordre I know of which does not tax one more or less heavily for the right of seclusion.

You will have hardly finished your sole before a distinguished old gentleman with a decoration in his lapel and a crumpled napkin in one hand, will pass your table, bowing graciously to you if you are a stranger and stopping to say a few pleasant words if you are a friend. He is slightly bent with age, massive of frame, with silvery locks combed back from a broad forehead, and his face is illumined with kindliness and intelligence.

“VOILÀ, MONSIEUR!”

Drawn by Sancha

Such a personage is Monsieur Marguery, whom the French government has decorated in recognition of his skill as a restaurateur, a man who still directs personally every detail of this superb establishment where one can dine for a few francs with an excellent bottle of wine, or give a dinner fit for an emperor, including, I have not the slightest doubt, the famous peacock tongues should you wish them, and with a choice of wines from a cellar whose contents are valued at three millions of francs.

In a corner a fat merchant, flushed with a heavy dinner, is ready for his chat with the sommelier. He tells him with some fervor that he is proud to say that when he was eighteen he dined on a sou’s worth of bread on the stones of the Place de la Bastille. “Men of that time were ready to begin at the foot of the ladder,” he continues, puffing at his cigar, “but nowadays our sons, who see us in comfort, want to obtain money and luxuries without going through the mill.”

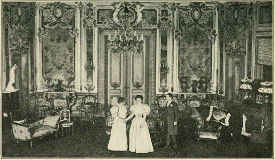

“Par ici! monsieur,” says Étienne, and he leads the way up a carved stairway to the floor above, past little cabinets particuliers whose cozy interiors are marvels of good taste. Here is one with walls of rich brocade of the time of Louis XVI. Another is in early French, with its adaptation of Chinese ornaments. Another is paneled in ebony inlaid with mother-of-pearl; still another in pale lilac brocade and teakwood. Each of these private rooms has its serving pantry across a narrow hallway where the linen and glass and silver are kept spotless, in readiness at a moment’s notice. A superb private stairway in white marble and stained glass connects this portion of the restaurant with a dignified courtyard leading out to a gray little side street. But these are the little rooms.

There is, besides, a great banquet hall in medieval Gothic that might have been carried bodily out of some feudal castle in Touraine with a carved minstrel gallery, a superb ceiling and rare stained glass. Here wedding breakfasts and dinners are given with cotillions to follow. And there are two other salons paneled in rare carving and inlaid woods. At the bottom of another stairway Étienne directs me across the mosaic floor of a spacious hall and into a grotto-like cave. Here is another dining-room. It is resplendent in stalactites with green ferns growing from walls of moss-grown rocks and a cascade talking to itself and purling into a green pool.

Music? no, indeed. People who come here have too good a time to need to be waltzed through the soup or polkaed through the entrée.

It is four o’clock and they are laying the round table in the center of the grotto with twenty covers. It might be for a state dinner in the presence of a king, so perfectly is the table appointed and in such rare taste. A bed of violet orchids forms the center of the table.

I look up and catch sight of the venerable Monsieur Marguery on the stairway, peering interestedly into the room to watch the laying of the service. He has suddenly entered through some hidden door—a panel in the wall which Étienne afterwards shows me. “He is everywhere, as you see,” said Étienne, quietly.

LE GÉRANT

Drawn by Sancha

“Ah! it is you, monsieur,” says Monsieur Marguery, cheeringly, as he approaches. “And have you found this grotto room charming with the pale orchids and the cool water? You know in summer,” he continues, “it is quite as cool here as in the Bois”—and he might have added, quite as beautiful, for this fairy corner needed only the setting of wit and beauty to make it a paradise.

“And you see, my friend,” he continues, “you have seen only the upstairs of my restaurant. Come between seven and eight some evening and I will put you in a corner of my kitchen when it is busiest,” and he adds, with smiling good humor, “I won’t warn them you are coming.”

I was the guest of the chef in the Marguery kitchen at eight o’clock one Saturday evening. There were a dozen wedding banquets going on upstairs, and scores of hidden dîners particuliers, while the restaurant, screened from the kitchen by a swinging door, was filled to overflowing.

I passed through this door and met my host with the cordon bleu, who looked more like the director of a railroad than a cook. He placed me in a safe corner connecting the meat room and the kitchen, from which I could observe and still be out of the way of the rush, for the famous cuisine was as busy as a stage during a spectacle.

A long counter ran the length of the room, serving as a barrier against hurrying waiters. Back of this counter lay the culinary plant. Five great ranges were in full blast.

At one a cloud of steam rose from some entrée, on the second range a great copper saucepan was suddenly lifted and the fire beneath it sent up a lurid flare which went slipping up the hooded chimney.

The room was in a state of bedlam with the cries of meat cooks, vegetable cooks, soup cooks and waiters hurrying for their orders. The system beneath all this was perfect.

THE VEGETABLE COOK

Drawn by Sancha

A waiter sprang through the swinging door shouting his order. He never was forced to repeat it, so alert were the staff of cooks that they seemed to have been awaiting him.

“Un Chateaubriand aux pommes!” cries a garçon.

“Un Chateaubriand aux pommes!” corroborates a chief cook.

Instantly a man dodges out of the meat room, a second later the steak is sizzling over the fire, the vegetable cook stands ready with his potatoes, a fourth prepares the sauce, a fifth attends to the plates, and the sixth looks after the garnishing of the dish.

“I am glad you find it interesting,” said my host the chef, as he joined me for a moment’s rest.

I bowed my compliments.

“And is this the only kitchen for so large an establishment?” I ventured, in surprise.

“Yes, the only one; we do it all here. It is the organization which counts, not the space. With these five ranges and this force of men we are competent to handle as many dinners as come under the roof.”

The chef’s eye seemed everywhere. When the rush was over, his private coupé would call for him, but at present he was on guard.

I marveled at this man’s memory. What a catalog of sauces, each one containing scores of ingredients, he must carry in his head! What a list of dishes, each one prepared in a dozen different ways! I imparted to him the fact that my culinary skill was limited to boiling an egg, and he laughed good-humoredly, his intelligent face, with its white mustache, glowing under his white cap in the glare of a nearby fire.

“Precisely, monsieur, but you see it is the same in every profession; one must learn the minute parts which tend to make something which in itself pleases, whether it be through the mind, the pocket, or the stomach,” and, asking me to excuse him for a moment, he disappeared in the direction of a cloud of mushroom steam to overlook an entrée.

A cook near me was busy with the final sizzle of a duck en casserole.

The man was an artist in the way he stirred his sauce. Even in the very handling of the burnished copper batterie of saucepans about him.

I fully expected this culinary prestidigitator would produce the lady’s ring from the duck he had just finished cooking and discover the rabbit in my overcoat pocket, but the duck was smothered so quickly in a rich brown sauce, with a dash of this and a pinch of that from the magician, and finally thrust for a final magic touch over the crackling blaze, that, before I could guess what might happen next, it was on its way to some cabinet particulier, where a quiet little man with gray hair was waiting to carve it.

It was he who won the grand prize for his skill in getting sixty slices from a single duck. He has quite the air of a dignified surgeon who has been called in consultation.

He carves with a plain knife sharpened upon the back of a plate. The duck seems to fall apart under his expert touch. He mashes into a paste the liver and heart, pouring over the whole the red blood gravy. Voilà! It is done; and, passing the first dish to one of the group of garçons at his elbow who have been watching him, he bows and leaves the room. The group of waiters about him are deeply interested in this object lesson, and it is this willingness to learn which makes in Paris so many good garçons de café.

The famous old Maison Dorée has closed its doors. The business of this celebrated restaurant had fallen off so seriously that its death was but a question of days. Paris had deserted it in its old age and dined elsewhere.

Many of the waiters, who had spent their lifetime beneath its roof, hoped against hope, and continued to serve the few habitués who remained faithful to the end.

Occasionally a party of strangers would open the door, and, finding the restaurant deserted, close it apologetically and go on their way to a gayer place.

THE MAGICIAN

In encouraging moments like these the veteran waiters ceremoniously took their places and the dignified maître d’hôtel advanced to greet the newcomers bravely, as if the ruin of the old house were not an open secret. There is something pathetic about the death of an establishment like the Maison Dorée.

How much gaiety it has seen in its lifetime!

How faithfully it has cheered those who entered its doors!

Here the vie Parisienne that Grévin and Cham drew so inimitably, came to dine in the old days; the courtezans of Balzac; the belles and beaux of the Empire.

Just as the Maison Dorée lived in thoroughbred dignity so did it die. Yesterday morning the shades of the windows were drawn down. The end had come. A simple card on the door bore the words:

And one felt like laying a wreath on its threshold.

THE VERSEUR

Drawn by Sancha

On Saturdays the Café de la Cascade, in the Bois, is taken possession of by bourgeois wedding parties, with brides in white satin gowns and grooms and their friends in dress-suits, which they had donned early in the morning and in which they have sung and cheered, and drunk the bride’s health and the groom’s health, and that of les belles soeurs and les petits nephews and all the innumerable enfants, cousins and cousines, comrades and amis connected by blood, marriage or friendship with the happy pair.

No wonder that by midnight, after such a day of continuous festivity, the poor bride is wild-eyed, flushed, exhausted and demoralized! For this bourgeois wedding had started at ten A. M. with the civil ceremony at the City Hall, the civil wedding being the only one legally recognized in France. From the hall the party proceeded to the church, where most brides insist on going after the civil ceremony. Here occurs another long function, including an address by the priest or minister. Then the bridesmaids, accompanied by the men of honor, garçons d’honneur, of which there are three classes, make two collections among the assemblage: one for the poor and the other for the church. This procession is headed by a gorgeously dressed major-domo, “Le Suisse,” who pounds the floor with his heavy baton as he strides solemnly through the aisles warning everyone to get their donations ready. The collections referred to are made either in a butterfly net, which discreetly hides the sous from view, or in purses made to match the gowns of the bridesmaids and carried ostensibly open for the expected louis.

There are several classes of weddings, just as there are several classes of funerals, their magnificence progressing in proportion to the money paid. You can be married at the little altar or the big one, enter under a spangled canopy at the front door or by an unadorned modest side one.

Now comes another ordeal for the bride; having gone to the sacristy after the ceremony, she is obliged to shake hands with everyone present and be kissed on both cheeks by cousins, friends or even acquaintances. Then the procession of carriages drives up, each being given its precedence in line. They are filled and start off for the wedding breakfast at the restaurant. This means a well-to-do wedding; many couples can afford only one huge stage which alternately serves in going to and from the races, while others go on foot, often six or seven arm-in-arm romping through the streets, singing or stopping at some little buvette for a glass of wine. The poor bride walks on and on, holding her satin train. She is half exhausted, but is expected to be bright and gay. Poor victim, the day has only begun for her!

After the wedding breakfast at the restaurant, trains are taken to some nearby country place like St. Cloud, or carriages to the Café de la Cascade. Here occurs the indispensable dinner, a feast of uproarious camaraderie, where dishes succeed dishes, and where each one is expected to be rollicking and witty and sing his song. In accordance with an old custom, to the first man of honor is allotted the privilege of trying to steal the garter of the bride.

The dance which follows this dinner lasts until morning, and lucky are the bride and groom if they can escape by midnight.

But mild indeed are these bourgeois weddings of the city compared with those of the well-to-do peasants! These include festivities which last three days, most of which time is spent at table, where beef is followed by veal, veal by mutton, mutton by rabbit, rabbit by chicken, and chicken by pork, and so on through the list of viands. This continuous feast is only made possible by consuming from time to time a stiff glass of applejack.

“Vive la mariée!” cry a dozen overjoyous ones in front of a café at St. Cloud as my voiture tries to pass. My cocher grins and cracks his whip. The best man, a soldier, the groom and a dozen others, noisy with the sound wine of Touraine, link arms in front of my rawboned steed, yelling:

“You cannot pass, monsieur, unless you cry Vive la mariée!”

“Vive la mariée!” I cry, loudly as I can, in my ineradicable accent.

There is a welcoming shout from the wedding party. The bride throws me a kiss. The little cousins and cousines and the beau-frère and belle-mère wave their handkerchiefs in acknowledgment, a dozen tumblers of red wine are offered to me, and as many are thrust at the fat cocher who is now waving his glazed hat in the air with enthusiasm.

“Vive la République! Vive la mariée! Vive la France!” come from a score of throats as I am allowed to proceed. As we rattle up a crooked street, the din of the festivity grows fainter and fainter in the distance, now I hear faintly the indistinct blare of the band playing below for the dance, and now and then a cheer, stronger than the others, floats up from the far-away café: “Vive la mariée!”

Dining in the open air is brought to its perfection in the Bois de Boulogne.

The Chalet du Touring Club, at the entrance of the Bois, is a popular rendezvous for the bicycling Mimis and the Faustines, and their admirers. At the apéritif hour in the afternoon, this cosmopolitan café under the trees is crowded with a mixed assemblage. It is an excellent place in which to breakfast well and at a moderate price.

The Pavillon Chinois, with its picturesque pagoda-like roof, is frequented by a richer class.

During the season, between five and seven, all of smart Paris may be seen at the Pavillon d’Armenonville. At this hour the tables in the garden are filled with pretty women in chic toilettes, accompanied by faultlessly dressed gentlemen whose bank accounts have managed thus far to survive.

By six, the scene resembles a garden party. There is a mixture of nature and artifice, of exquisite toilettes, of gay flowers blooming in beds under the shadows of sturdy trees up in whose branches the birds flutter and sing. One’s ears are filled with babble of voices and the soft laughter of those whose life for the moment is happy. The sun has sunk in an opalescent haze, its rays reflect upon the glass of the pavilion and the edge of the tiny kiosks whence come the chatter and laughter of some jolly partie carrée still at table over a late déjeuner. Above the hum drones the rhythm of the Tziganes; their violins cry in some plaintive gipsy song. Now the strings rush into the most seductive of Viennese waltzes, melting away, to begin afresh in some mad Hungarian czardas.

Smart turnouts and little private victorias with tinkling bells are constantly arriving and departing. Now there is a sound of prancing hoofs and the clink of harness at the entrance of the garden, and in rumbles a break perfectly driven by a well-groomed gentleman posed in faultless style on the box seat. By his side sits a Parisienne of Parisiennes—from the glossy undulations of her black hair to the tips of her tiny patent leather boots, both of which are now occupied in daintily descending the steps of the break. She is a famous beauty who sings at one of the cafés concerts, quite young, with pretty white teeth and an olive skin.

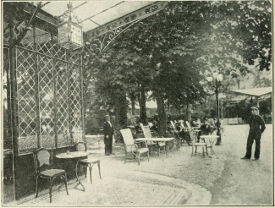

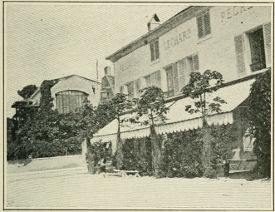

ENTRANCE OF THE CAFÉ DE MADRID

THE GARDEN OF THE CAFÉ DE MADRID

Her companion leaves his turnout to the care of his grooms, and the break with its shining red wheels rumbles away in the direction of the carriage shed. The charming brunette is radiant from the drive; they have been nearly to Poissy and back. She will now have a gaufrette and a coupe de fruits au champagne, and the gentleman who drove so cleverly a cigarette and a long brandy and soda. This dainty Parisienne insists on preparing this “drôle de boisson anglaise” herself, and, with a rippling laugh, puts in the ice and the brandy and then the soda, and, as a final touch, in a spirit of deviltry, adds a cherry from her own coupe, for which archness she is scolded by her companion, to whom she blows a kiss in return.

A RESTAURANT ON THE CHAMPS-ÉLYSÉES

At eight, the Pavillon d’Armenonville will be brilliant with a throng of diners—men in spotless shirt-fronts and women in toilets of lace and jewels—and crisp notes of the Bank of France will change hands for rich food and sparkling wine. The season for these delightful retreats of the Bois being short, the rents for them are exorbitant, and so the monde must pay the fiddler accordingly.

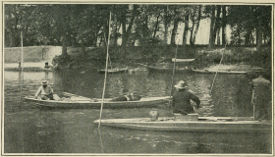

At the end of the Bois is the Chalet du Cycle, another restaurant with a superb garden flaming in flowers, and dotted with cozy thatched kiosks like the huts of some jungle village and dotted with tables shaded by huge red umbrellas. Here at the apéritif hour the crowd comes en bicyclette and automobile, and at night the hurrying waiters serve parties dining cozily in the glow of shaded candles. The Chalet du Cycle is a charming place in which to breakfast some sunny morning with the Seine gliding close by under the trees.

Another segment of fairy-land, even more exquisite in its mise en scène, is the Café de Madrid. Here a low, rambling, half-timbered house forms a courtyard which is as brilliant at night with the haut monde at dinner. Here, too, as at Armenonville, the carriages, entering under a gateway smothered in trailing vines, drive in past the tables. Everywhere about you there are flowers—banks of geraniums and fragrant roses. When you have dined, you can turn your armchair and watch the beauty about you and the victorias coming and going.

It is characteristic for Parisians to sit for hours over dinner. The Café de Madrid at night resembles closely a garden party given at the château of some private estate. It is the absence of the feeling of publicity that makes it so charming.

And after all this restful luxury there is the cool Bois to drive in, through forest alleys with the smell of the fresh woods all about and the sparkle of stars overhead.

Who will ever tell the history of this famous playground of rich and poor? How many of its silent trees have sheltered and kept secret the romances of the world! How much honor has been risked for the sake of cruel, triumphant women whose hearts were tender in proportion to their needs! And how many real loves have sought it as a refuge!

If all this is sad, turn back in your drive towards the sparkling lights of the city, to Paris who is now wearing all her jewels. Some of her strings of diamonds are glittering through the vista of black trees ahead—or are these only the footlights of the great stage whereon so many comedies, so many tragedies, and so many light farces, have been played?

Chapter Three

SOME “RISQUÉ” CURTAINS WITH SERIOUS LININGS

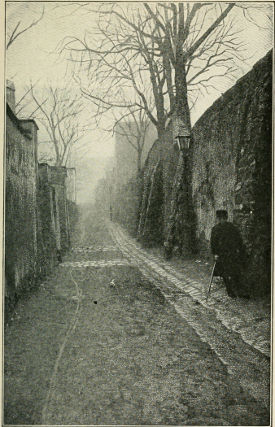

Snug in the corner of an ancient alley called the Cité d’Antin is the “Théâtre de la Robinière.” Its official address is “3 (bis) Rue La Fayette,” that is, you are requested to enter there and, following your nose around the corner, grope your way in the obscurity over the cobbles and make a second turn to the right. At last a green lantern over the doorway glimmers ahead of you. It is the Robinière now installed in what was once the Théâtre Mondain.

The Robinière once existed on the first platform of the Tour Eiffel; since then its proprietor, Monsieur François Robin, has moved it to its permanent address, all of which speaks well for its success. It is filled nightly with Parisians of the vicinity.

Much of the success of this tiny theater is due to the indefatigable effort of its director, Monsieur Robin, who literally passes his life in his playhouse, assisted in its management by his wife. These two, without help, without even a secretary, run the theater, often working from early morning until long past midnight, writing their own posters, watching the rehearsals of their excellent small company (in which Madame plays), attending to press notices, receiving authors and artists, and, in short, making a success of this old “Salle d’Antin” where all its preceding owners met with ruin.

There is nothing elaborate about this stuffy little bandbox of a theater. Its narrow auditorium is plain, dingy and old-fashioned. A piano serves for the orchestra, but the comedies are clever and the acting excellent—two things which Parisians demand first of all.

The Robinière is but one of a number of miniature theaters in Paris beginning at eight-thirty or nine o’clock, and producing each night four short realistic comedies, often with some clever chansonnier singing his creations during the entr’actes. No two of these theaters are alike, and in all of them there is good acting; even in the smallest of these so-called bouis-bouis you will find the actors to be men and women who have worked patiently through the National Conservatoire studying their art under the best masters.

Fortunately in France the woman who has become suddenly notorious through her divorce or the latest scandal is not snapped up by theatrical managers as a star before the ink is dry on the Sunday papers detailing her disgrace. In Paris there are music hall revues to receive these meteors when they fall and where they may parade their beauty and their clothes, or their lack of them, with the rest of the demi-mondaines.

During the intervals between the plays at the Robinière a single aged “garçon de café” takes the orders for the refreshments in the cold, stuffy little “fumoir,” while behind the bar one of the leading ladies of the comedy graciously assists him by opening the bottled beer and attending to the drinks, very much as a good-natured woman would help by cutting the cake at a children’s party.

When the bell rings for the curtain Madame hurries out of her apron and back to her part in “Les Deux Jarretières,” a farce so replete with amusing complications that the small audience is kept in a continual titter of good humor. In the comedy following, entitled “Le Sofa de Monsieur Dupré,” the story is even more simple. A respectable widow, Madame Dupré, living alone in her old age, is attended by her maid Pauline, whom she has come to regard as an indispensable companion. Pauline makes the old lady comfortable in her favorite chair, tucks under her feet her foot-warmer, and, leaving her mistress, goes out to post a letter.

In the interval which elapses before her return a neighbor calls and kindly informs Madame Dupré that the indispensable Pauline has been the mistress of Madame Dupré’s revered husband. When Pauline returns, Madame, in her indignation, turns her out of the house. The foot-warmer grows cold, the fire in the grate goes out, a thousand little comforts have not been attended to, and the old lady decides to send for Pauline and forgive her, preferring that her few remaining years should pass in peace and comfort.

Quite different is the Théâtre de la Bodinière, founded by Monsieur Bodin, the former secretary of the historic Comédie Française. The Bodinière is devoted to interpreting the work of young authors by celebrated artists. It is a theater where respectable jeunes filles may be taken in safety. The plays are as harmless as the Rollo books.

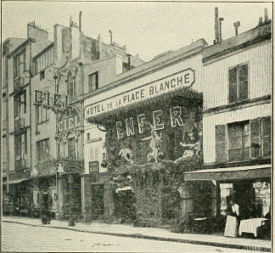

The playwright, Aimé Ducrocq, is the founder and manager of a cozy blue-and-gold bonbonnière of a theater called the “Rabelais,” in Montmartre. Here, as the title suggests, the comedies and farces are thoroughly Rabelaisian. It might even be averred that they are more so than elsewhere, which is saying a great deal. Here farces like “La Vertu De Nini,” “La Journée d’une Demi-Mondaine” and “Le Corset de Germaine” pack the small auditorium nightly. Many of these are written to a point where the curtain discreetly drops upon the situation, but none of them harbors a line or a gesture of vulgarity. It is not worth while having trouble with the police, and happily the French policeman is both broad-minded and discreet in enforcing an arbitrary rule. When you ask a policeman here why a thing is prohibited he will shrug his shoulders, stare at you in astonishment, and reply brusquely: “It is prohibited because it is prohibited!”

Which settles all further argument.

There are but two things which I find absolutely interdicted: malicious satires against the Government, and breaking the Parisian peace. The rest, which has merely to do with “l’Amour,” seems to the policemen not worth bothering their heads about.

A “’Cipal” (municipal guard) is detailed during a performance of any kind in Paris in every theater, music-hall or cabaret, to jot down in a small black-covered book anything which may offend his sense of delicacy, but he is generally too hugely amused in watching the stage to do so. During moments like these his ruddy visage, with its bristly mustache, at other times so stern, is wreathed in wrinkles of delight, and his formidable short sword sleeps peacefully in its scabbard. These are the lighter hours of his existence; where he is needed you will find him brave as a bulldog and quick as a cat, and intelligent and honest as well. You cannot bribe a French policeman.

The one who generously offered me half his seat at a crowded performance the other night poured forth his opinions sotto voce during the second act of a risqué comedy. He was sincere and enthusiastic in his praise of our President and struck his brass-buttoned chest as he pronounced him a good man and a brave soldier; however, I regret that some of his views of La Fayette are unfit for publication, as he regarded him as a traitor to France.

“Oui, monsieur,” he said, savagely; “a man who gave his strength and knowledge and power to another country when that man belonged to our army was a traitor.” He said other things, too, about the gentleman, but they will not bear a graceful translation.

Below the Rabelais, past an iron grill and at the end of a cobbled court in the Rue Chaptal, is the “Grand Guignol.” Its oak interior in carved Gothic was once the studio of the celebrated painter, Rochegrosse, and resembles at first glance, except for the boxes running beneath the low choir gallery, the lecture room of a modern Episcopal church. The prevailing tone of the room, gray corduroy and oak, is thoroughly restful. From the spandrelled ceiling hang iron chandeliers of ecclesiastical design. A paneled frieze of allegorical paintings, representing the human passions—envy, hate and jealousy—enrich the cove. Carved angels support the corbels of the ceiling beams, and a square of rare Gobelins tapestry enriches the wall back of the gallery. A simple proscenium, in keeping with the rest of this exquisite interior, fills the end of the room.

Drawing by F. Berkeley Smith

PAULINE

There is a small foyer, too, with a Gothic stairway, which contains a unique collection of steel engravings of players of bygone days. Snug in an alcove beside this interesting promenoir there is a tiny bar. At nine the boxes beneath the Sunday-school gallery are brilliant with women’s toilets, framed by the white shirt-fronts and sombre black of their well-groomed escorts. Such is this charming after-dinner theater, which has been so appropriately named “The Big Punch and Judy,” where very cleverly constructed short plays are presented, such as “Scrupules,” “Une Affaire de Mœurs,” “La Coopérative” and “La Fétiche.”

They are plays of dramatic incident rather than of plots. Some of them are as risqué as the most daring at the Rabelais. Some are full of pathos, others screamingly funny, and still others revolting in their realism.

Photo by F. Berkeley Smith

LA FÉTICHE AT THE GRAND GUIGNOL

Enter the Murderer

Of the last class is “Une Affaire de Mœurs.” In this the identity of a famous judge of the high court is discovered by two demi-mondaines who are dining with him in a cabinet particulier. The judge has at one time sentenced the lover of one of the women and she threatens to expose him in revenge. He offers money, and finally half his fortune to quiet her, but the woman is determined to avenge her lover. Then his terror at the thought of scandal and disgrace brings on a stroke of apoplexy. The two women, now thoroughly frightened, send the old waiter out for a doctor. He hurries back with a young physician whom he finds carousing with his friends in the café below. The young man stands aghast as he recognizes the form in the chair; it is his father. He listens at the heart, then buries his head in his hands. The judge is dead. The women huddle in a corner terrified. The room is in disorder, reeking with the odor of cigarettes and spilled wine.

“Come, monsieur,” gently urges the aged garçon. “Pull yourself together, we must get the body into a cab unnoticed.”

The realization of the disgrace and publicity of the affaire when it will be known in the café below, braces the son to act quickly. He suggests to the garçon that the body be removed by the back stairs.

“There is no back stairs, monsieur,” confesses the garçon. “The only way out is by the main stairway and through the café. We will walk monsieur out and support him between us. I have helped to do it once before that way; no one will suspect—they will think monsieur is drunk.”

Together they put on the Inverness and, adjusting the opera hat of the deceased and supporting the body beneath the arms, walk slowly with it to the door leading to the stairs, the two women preceding them, singing hysterically the marche des pompiers!

As the curtain fell the audience seemed in a stupor. A woman beside me sat staring at the floor, crying. Men coughed and remained silent. Not until the pianist in the foyer struck up a lively polka did they leave their seats for a little cognac and a breath of air.

Just such realism is typical of the Grand Guignol.

Even smaller than the Grand Guignol is the cozy “Théâtre des Mathurins,” with a pretty foyer twice the size of its small auditorium, which scarcely holds two hundred.

Here short plays like “Monsieur Camille,” “Le Quadrille” and “Les Deux Courtisanes” are played with rare finish by De Marcy, Cora Lapercerie, and other famous beauties of the Parisian stage.

During the entr’actes a shutter over an archway of the foyer opens and the head of a celebrated singing satirist is thrust out from the dark closet like the punctual cuckoo in the clock. During the intermission he sings his original songs to the listening throng, a mixture of the grand- and the demi-monde promenading below.

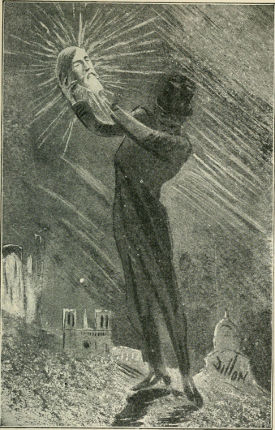

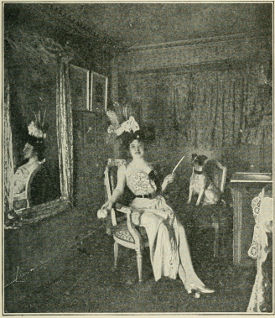

Photo by Reutlinger, Paris

CARMEN DEVILLERS

“Gil Blas,” First Prize Beauty