Project Gutenberg's The Pioneer Boys on the Mississippi, by Harrison Adams

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most

other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions

whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of

the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at

www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have

to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook.

Title: The Pioneer Boys on the Mississippi

or The Homestead in the Wilderness

Author: Harrison Adams

Illustrator: H. Richard Boehm

Release Date: September 7, 2014 [EBook #46796]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK PIONEER BOYS ON MISSISSIPPI ***

Produced by Beth Baran and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

| THE PIONEER BOYS OF THE OHIO, | |

| Or: Clearing the Wilderness | $1.25 |

| THE PIONEER BOYS ON THE GREAT LAKES, | |

| Or: On the Trail of the Iroquois | 1.25 |

| THE PIONEER BOYS OF THE MISSISSIPPI, | |

| Or: The Homestead in the Wilderness | 1.25 |

Copyright, 1913, by

L. C. Page & Company (INCORPORATED) ———— All rights reserved First Impression, June, 1913 THE COLONIAL PRESS C. H. SIMONDS & CO. BOSTON, U. S. A. |

|

Dear Boys:—Those of you who have read the earlier volumes in this series of backwoods stories may remember that I half-promised to follow the “Pioneer Boys on the Great Lakes” with a third volume. I now have the pleasure of presenting that story to you. In it you will renew your acquaintance with the two stout-hearted lads of the border, Bob and Sandy Armstrong, as well as several other characters you met before, some of whose names have become famous, and are recorded in the history of those early days that “tried men’s souls.” Besides this, there are some new characters introduced, who, I hope, will appeal to your interest.

It was hardly to be expected that such a restless spirit as that of David Armstrong, the Virginia pioneer who built his log cabin on the bank of the beautiful Ohio, would long rest contented when wonderful stories constantly reached his ears concerning the astonishing fertility of the black soil, as well as the[vi] abundance of fur-bearing animals, to be found in the valley of the great river which De Soto had discovered—the mighty Mississippi; and, as you will learn, his first serious set-back caused him to start upon another long pilgrimage toward the “Promised Land.”

It was this constant rivalry among the early settlers, this never-ending desire to find better homesteads in the new country, always toward the setting sun, that gradually peopled our Middle West, and finally reached out far across the plains to the shore of the Pacific.

Trusting that you may enjoy reading the present volume, and that at no distant day we may again renew our acquaintance, believe me, dear readers, to be,

May 1st, 1913.

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| PAGE | |

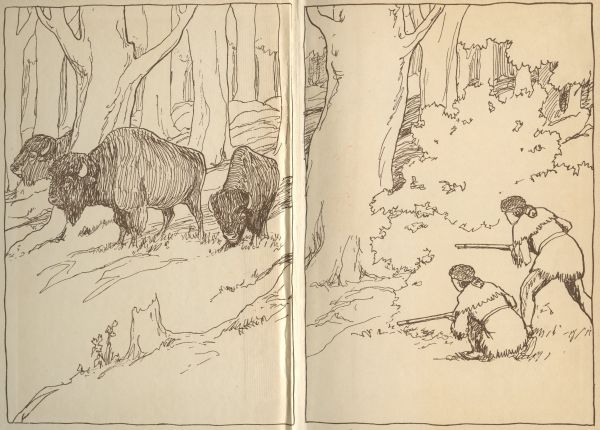

“‘The precious wampum belt, Sandy!’ he cried” (See page 332) |

Frontispiece |

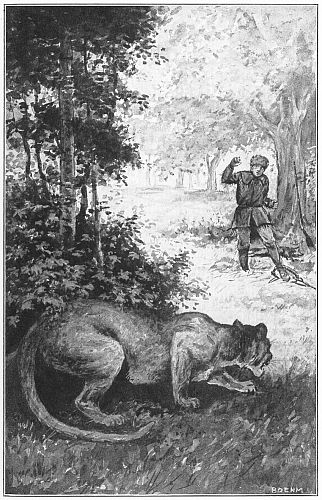

“He was being stalked by one of the most dreaded animals of the forest, a gray panther” |

12 |

“Made a spring for the safety of the log that had done the damage” |

35 |

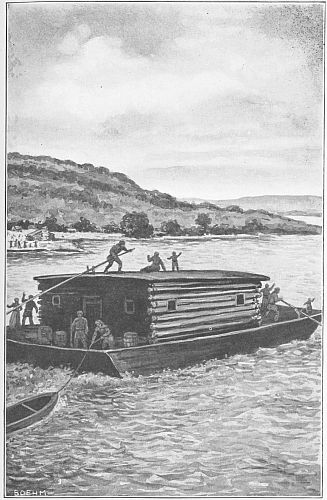

“At last they were afloat on the Ohio, bound into the unknown country that lay far away to the westward” |

136 |

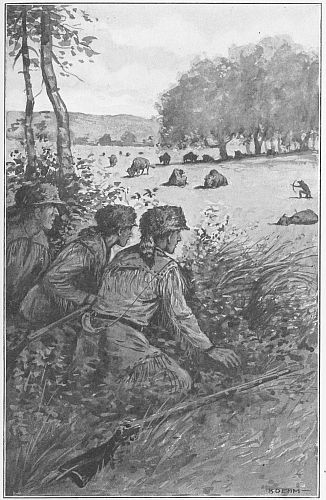

“They could now plainly discern the figure under the wolfskin” |

230 |

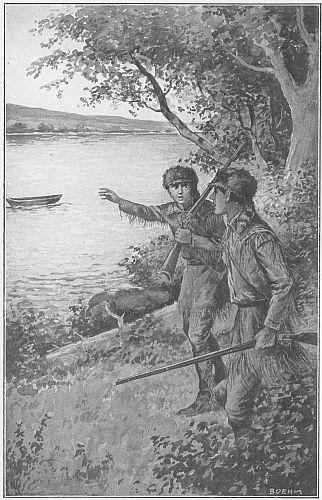

“‘Yes, you are right, Sandy, it is a boat’” |

291 |

“Paddle harder, brother. The current is stronger than I ever knew it to be before.”

“But, Bob, we must be very near the place where we always land when we come over to look after our traps?”

“Once we are in the lee of that point ahead, Sandy, we can go ashore. The river is so high that it’s hard to recognize the old landmarks.”

“Both together, then, Bob. There! that looks like business! and, just as you say, our dugout can lie safely under the shelter of that tongue of land, while we’re off ’tending our traps. Another week, and we must stop setting any snares, for the fur will be getting[2] poor; so Pat O’Mara said the last time he came to the settlement.”

Five minutes later, the two Armstrong boys sprang ashore on the Ohio side of the river, at a little distance below the spot where, across the now unusually wide stream, their parents, together with other bold pioneers from Virginia, had, not more than a year before, started a frontier settlement.[1]

The clumsy, but staunch boat, fashioned from the trunk of a tree, was drawn partly out of the water. They had made the passage of the river with considerable hard labor, because of the vast volume of water which the heavy spring rains had brought out of the hills all the way up to and beyond old Fort Duquesne.[2]

Both boys were dressed after the fashion of that time among hunters and trappers, who, scorning the homespun clothes of the Virginia settlers, found garments made of buckskin, not unlike those worn by many of the Indians, to give them the best service when roaming the great forests that stretched from the Alleghanies, off to the border of the mighty[3] Mississippi, in the “Land of the Setting Sun.”

Having picked up their guns, the brothers started through the thick woods; but not before Sandy, the younger, had cast a last wistful look back at the swollen waters of the Ohio, that, seen in the dull light of the overcast afternoon, flowed steadily toward the west. Truth to tell, that unknown western region was drawing the thoughts of the pioneer boy very much of late; and, even as he tramped along at the side of Bob, his first words told how he envied the rushing waters that were headed into the country he longed to see.

“Abijah Cook is back at the settlement for a short spell, I heard Mr. Harkness say,” he remarked, with a long sigh that caused his brother to turn an uneasy glance in his direction.

“And has he given up ranging the woods with young Simon Kenton?” the older boy asked.

“Oh! no; but he brought his winter’s catch of pelts in for Mr. Harkness to dispose of, when he found the chance,” Sandy replied.

“And I suppose the old woodranger has been talking again about the region of the[4] Mississippi,” remarked Bob, who could guess what was on the mind of his brother.

“Well,” Sandy went on, “Abijah has seen that wonderful country, and he knows how different it is from this hilly place, where the corn washes down the sides of the slopes whenever a big rain comes. Out there it is mostly prairie, and the soil, he says, is black and rich. It will grow maize twice as high as your head. The stories he tells of what he saw on those prairies fairly make my heart ache.”

“But Sandy, you must try to forget all that,” returned Bob, who often found it necessary to restrain his impatient young brother. “You are needed at home, for father is not able to hunt and trap, besides taking care of his crops. Nobody in the whole settlement brings in as much game as you do. Wait a few years, and then, when we are grown men, perhaps we may strike out for that country you have been hearing so much about; where De Soto discovered the greatest of rivers, and lies buried under its waters.”

Sandy sighed again.

“I suppose I must wait, just as you say, Bob,” he observed, “but it may not be for years, as you seem to think. Already some of[5] the men are beginning to talk of making a flatboat, and floating down the Ohio until they reach the father of all the waters. They do not like the idea of the rascally French taking possession of all that fine land, which is a part of our own Virginia. And it may not be so very long before we will lose some of our people in that way.” (Note 1.)[3]

These brave men, who had already successfully braved the dangers that beset them on their journey across the mountains to the Ohio valley, had heard stories from the lips of trappers who had penetrated far into the western land in pursuit of the rich skins of otter, beaver, fox, mink and marten. When their crops failed to turn out as well as they had anticipated, a spirit of unrest began to pervade the little community; and these wonderful tales were repeated, from lip to lip, always with a longing to obtain a glimpse of the country that offered such astonishing opportunities.

It was this spirit of unrest that peopled our great West. Those who found themselves out-distanced in the race, unwilling that others should get ahead, gave up their holdings, partly improved as they might be, and once[6] more started out to get in the van of the procession headed toward the setting sun.

“Do you think we will have any trouble getting back to the other shore of the river, this afternoon?” Sandy asked, after they had walked along for a few minutes in silence, headed for the first of their traps.

“I admit that I don’t just like the way we were buffeted around on the voyage over,” replied Bob; “and, if the waters keep on rising to-night, as I think they are going to, we will not be able to visit our traps on this side for several days.”

“Then had we better take them along with us?” asked Sandy.

“No, they would bother us in the dugout,” replied Bob; then, noticing the quick glance his brother shot in his direction, he added: “Yes, I am figuring on the chance of our boat being upset in the flood; and, if that happened, we’d have all we could do to save ourselves and our guns, let alone half a dozen heavy traps. They can stay here until we find a chance to cross again, after the water goes down.”

“But, I wonder if Colonel Boone knew about such a thing as a flood when he led us[7] to where the settlement now stands?” remarked Sandy, with a frown. “Because, if the water rises very much more, we, as well as some of the other settlers, stand to lose our cabin. Already the water has covered the land where open fields lay, ready to be planted in maize this spring. All Mr. Bancroft’s new fence has been taken down, to save it from being swept away.”

“No, I do not believe such a rise has been known for many years,” Bob went on to say. “You know how it flows between banks that are covered with trees. These countless hills are crowned with great forests, and under the trees the ground is carpeted with moss and dead leaves. This is like a great sponge, father says, that soaks up the water during rainy seasons, and lets it out again in time of drought. I heard him say only this morning that the Indians never knew of a flood like this one. They believe that the Great Spirit is angry because they have not driven the palefaces from Kentucky. And there will be a renewal of the fighting, after this rainy spell is over, he fears.” (Note 2.)

“Well, here’s where we set our first trap,” Sandy cried. “And the next is only a short[8] distance along the trail. I’ll take a look at this one, while you go on and attend to the next.”

“That is the best way, Sandy,” returned Bob, with a quick glance toward the darkening heavens. “I do not like the looks of those clouds, and it may be that the rain will set in again. If that happens, we would find it all we could do to make a safe passage across the river, for the darkness will fall early to-night.”

“And we must not forget to keep our eyes open for a sight of those rascally French trappers, Jacques Larue and Henri Lacroix,” remarked Sandy, with a suggestive movement of his gun. “They have been reported as being seen not far away from here of late, and you know, Bob, they have never forgiven us the way we managed to outwit Larue last fall, and bring Henri Lacroix’s brother to justice.”[4]

“But they also know,” Bob replied, “that because you and I were able to do the great Indian sachem, Pontiac, a favor, he gave us his wampum belt, which has served to keep the Indians who were on the war-path away from our little settlement. Those Frenchmen understand that, if either of us were hurt, the Indians[9] would visit vengeance on the head of the guilty party. Larue learned that before he escaped from the Indians.” (Note 3.)

The boys had learned that Jacques Larue had loosened his bonds and escaped from his Indian captors through the connivance of a young buck for whom he had once performed some service, and was again free to work with Henri Lacroix such damage against the latest English settlers as their evil minds might suggest.

“I am convinced it was they who robbed our traps several times this winter, so that we had to change their location,” Sandy declared, indignantly. “And, when that brush was piled up against our cabin, that dark night, and fired, did we not find tracks that were never made by Indian feet? I seem to feel that we have not seen the last of those French trappers. And Pat O’Mara told me that, if ever I had to shoot to defend myself against either of them, to get the full value of my lead!”

“Well, let us hope that they will go elsewhere, and do their trapping,” said Bob, as he turned and left his brother. “I think it is a great pity that, with a string of trading posts all the way from the big lakes down to the sea, these greedy French from the North[10] cannot let us alone here. They seem to want the earth. But I’ll wait for you at the second trap, Sandy. Be as quick as you can.”

Sandy made no reply, but hastened forward to where they had set the first trap. He was filled with thoughts of the stories he had heard connected with the Mississippi country, and he pictured in his mind the loveliest scene that could ever greet the eager eyes of a pioneer—game waiting to be shot and trapped; the earth so rich that it would grow bountiful crops upon being simply stirred; the fields glorious with myriads of wild flowers; and all to be had by simply reaching out a hand and taking possession, in defiance of the French, who claimed everything from the far North to the gulf.

He found in the trap a fine red fox, which he succeeded in knocking on the head without injuring the pelt. Laying his gun aside, Sandy started to reset the trap, believing that, as it seemed to be a lucky place, perhaps the mate of the fox might come along, and also step into the steel circle.

As he began his task, an accident occurred that had never happened to Sandy before in all his trapping experience, and probably never[11] would again. In some manner, which he could not fully explain, in turning around to secure something, he managed to thrust his foot into the set trap, which he had quite forgotten.

There was a snap, and an acute feeling of pain that caused the boy to give a startled cry. His heavy leggings saved him to a great extent from the cruel teeth of the trap, for at that time the smooth jaws now in universal use had not come into vogue; but the boy knew he would have a sore ankle for some days because of his carelessness.

Sandy tried to get at the trap to release himself, and found that, because of the formation of the ground at that particular spot, it would prove a difficult task. He persisted in his efforts, however, and refrained from calling out to his brother, not wishing the more cautious Bob to learn what a foolish thing he had done.

He was still striving to squirm around so as to get at the double spring, and by pressure release his foot, when he heard a sound close by that riveted his attention. Looking up, what was the boy’s dismay to discover a creeping animal gradually drawing closer and closer to him.

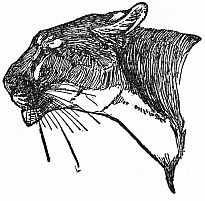

It needed only that one look to tell Sandy[12] that he was being stalked by one of the most dreaded animals of the forest, a gray panther, that had evidently scented the blood of the captured fox, and was bent on securing a supper.

Of course, Sandy’s first thought was of his musket. He remembered placing this against a neighboring tree, and, sure enough, it still stood there; but, when he made a movement to reach the weapon, he found to his dismay that the chain of the fox trap was too short to allow his fingers to come within a foot of the gun!

In vain he writhed and pulled; the trap had been made only too secure, and Sandy realized that there was nothing he could do but lift up his lusty young voice in an appeal for help.

When Bob Armstrong parted from his brother he quickened his steps. The next trap was not very far away; but, as he had just said, he did not like the looks of the cloudy sky, and began to fear that, after all, the break in the heavy rainy spell was going to prove of but short duration.

He knew that the little mother in that cabin on the other side of the swollen water would be worried about her boys, and Bob disliked to give her any more reason for anxiety than could be helped.

As he walked along he thought of what Sandy had said about his determination, sooner or later, to follow the river down past Fort Washington, and far away to where it united with the greatest of watercourses, the mighty Mississippi. Bob, himself, was not so indifferent to the beckoning finger of adventure as his words to his brother might lead[14] one to believe. He, too, had listened to those marvelous stories told by trappers and traders, and, when twice a flatboat had landed at their rude little float, giving the settlers a chance to talk with the bold souls who were bent on risking the unknown dangers that lay beyond, Bob had hung upon the adventurers’ words, and had longed to join the party as it continued its voyage down the Ohio into the unknown land. He had, however, always thrust aside the thought, feeling that neither he nor Sandy ought to think of leaving the father, mother and sister Kate, who made up the Armstrong household.

As he approached the spot where the trap lay, Bob once more became the trapper, and forgot all else. He saw that success had come to them, for there was certainly some animal in the trap.

It had been set in a certain little gully, where the boys had discovered the tracks of several mink, together with their holes. The tiny stream that had trickled through this same gully in the preceding fall, was now a rushing torrent, and the trap had lately been set high up on the bank, just in front of a particularly inviting opening, where many tracks told of[15] its being a favorite haunt for the wandering males of the furry tribe he hunted.

Yes, it was a mink he had captured, and really the largest and finest of the whole winter’s catch. Bob felt pleased to make this discovery, for every pelt which they could gather meant more comforts in the Armstrong home.

The mink seemed unusually fierce, and put up a savage fight when Bob started to dispose of him; but the young trapper would not be denied, and he quickly put an end to the animal’s sufferings.

As a usual thing the traps for mink and muskrats were set in such fashion that, after being caught, the animals would jump into the water, and be drowned by the weight of the trap; so that it was seldom they found one alive that had to be disposed of in this manner.

Having reset the trap, Bob sat down to wait for the coming of Sandy, and, while sitting there, he drew something out of an inner pocket of his hunting tunic, which he examined with considerable interest, as well as with many shakes of the head, that told of bewilderment.

The object was a soft and pliable piece of[16] clean birch bark, upon the brown side of which were traced several rude drawings, such as a child might make. This had been done with some sharp instrument, possibly the point of a knife.

Bob Armstrong knew well that these crude figures of men, campfires, streams and trails were not intended to express the idle whim of some white child, beginning to draw the things he saw around him.

Bob had looked upon Indian picture-writing before now; indeed, a young Shawanee brave, named Blue Jacket, whose life he had once saved, and whose friendship the brothers prized very much, had shown them how to read these symbols, by means of which the red men communicated after their own fashion, just as the palefaces did by putting all those queer little signs in a line, and calling it writing.

This was the second time that Bob had found a birch-bark letter left mysteriously at the cabin. No one knew whence they came; but, when the characters were deciphered, on each occasion it was found that some one was warning them against danger that hovered over their heads.

On the first occasion, they read that two white men were hanging around near the settlement, and meant to do the Armstrong family harm. The careful mother’s first thought was of Kate, her only daughter, a pretty girl, who had already been once carried away by a young chief of the Delawares, and rescued only after much trouble by her brothers, assisted by Simon Kenton and several of the young woodranger’s comrades.

That very night there had come the alarm of fire, with the greedy flames doing their best to devour the cabin where David Armstrong and his little brood lived. Only through the most valiant labor was the fire conquered before it could do much harm. And, now, Bob had found a second strange warning under the door of the cabin, on that very morning, he being the first to arise.

He traced each symbol with his finger as he sat there and mused. There were the same two men again, whom he believed must stand for the ugly French trappers, because they wore hats, which no Indian ever was known to do; and their feet “toed-out,” which was another sure sign. In addition, he could make out the cabins of the settlers, and the two[18] bent figures appeared to be creeping toward them.

Of course, word of the message had been carried to all the other men in the community, and doubtless there would be a strict watch kept that coming night. If Jacques Larue and his companion, Henri Lacroix, were discovered approaching the settlement, other than erect on their feet, the chances were that they would be given a very warm reception.

But Bob was not puzzling his head just now about what the symbols meant. He had had little difficulty in understanding that some one intended to warn them against the attacks of their old-time enemies. The question that gave both Bob and Sandy cause for speculation was the identity of the friend from whom these two birch-bark warnings came.

It was not Blue Jacket, Bob knew. He had seen the young Shawanee brave draw similar figures, and they were slightly different from those now in front of him; even as one person’s handwriting looks unlike that of another. And yet Bob felt positive that the work must have been done by an Indian.

The mystery piqued his curiosity greatly. He and Sandy had tried to reason it out, and[19] discover the identity of this unknown and unseen friend among the red men; but up to now they had not met with any success.

After looking at the little strip of bark for a minute, Bob shook his head, as though once more compelled to abandon the solution of the puzzle; and, allowing it to roll up again of its own accord, he replaced the message in his pocket.

“I’d give a lot to know who sent those two messages,” he muttered, as he started to take the skin off the mink, not wishing to carry any more burden than seemed necessary, if they were to continue along the line of traps. “But, anyway, it’s nice to feel that we’ve got a good friend among the Indians, who takes delight in upsetting the plans of those two precious rascals. Some day he may see fit to make himself known to us. But, I wonder what keeps Sandy. He surely ought to be here by now, for he had plenty of time to get to that trap, and fix it fresh, if it was sprung. I hope nothing has happened to him.”

He looked eagerly along the back trail, but failed to see any sign of the approaching figure of his younger brother. The afternoon was more than three-quarters past, and in another[20] hour they could expect darkness to swoop down upon the land.

Bob noted this fact when he again looked up toward the darkening heavens.

“We will have to leave the rest of the traps until another day,” he said to himself, uneasily. “I promised mother that I would not take any more chances than necessary, and she did not seem any too well satisfied about our crossing to-day, as it was. But, how queer Sandy does not come! Perhaps I’d better start back after him.”

Once this idea had taken root in his mind, Bob could not remain at ease. He arose to his feet, took the mink in one hand, with his rifle clutched in the other, and started off.

Hardly had he taken ten steps when he heard a call. It was certainly his own name, and coupled with a word that sent a thrill through him.

“Bob! oh! Bob! Help!”

Instantly the boy dropped the mink, utterly unmindful of the value of the fine pelt. He started off at a swift pace, heading in the direction whence the shout came.

If Sandy was in danger, then it must be some of those hateful French trappers again. Bob[21] could remember how they had first met them, and there were three at that time. A fine deer had fallen before the gun of one of the brothers, and, upon rushing forward to bleed the prize, they found themselves confronted by a trio of burly men whose appearance told the lads that they were French trappers, even before they proved this fact by their speech.

These fellows had claimed that they shot the deer, and there was trouble in prospect that might have ended seriously, but for the fortunate coming of Kenton and two companions, who proved the right of the boys to the spoils, and sent the Frenchmen away, with a warning not to look back or they would rue it.

Quickly Bob covered the ground. All the while he had his gun ready for use in case of necessity. Now he could see Sandy, and, when he discovered the other on hands and knees, great was his wonder, until he heard him cry out:

“Take care, Bob, there’s a big panther in the brush close by, and bent on jumping on you! My foot’s fast in the trap, and I can’t get free. Go slow, and be ready to shoot, for he’s savage with hunger, and as fierce as they make them. Look out! there he comes now!”

Bob did not need the warning from Sandy to put him on his guard. The mere fact that there was a panther near by was sufficient reason for his alertness, because no animal that roamed the woods was more respected than this sleek gray beast with the square jaws, the powerful muscles and the sharp claws.

Every slight movement of the bushes caused Bob to turn his eyes in that direction, with his gun half raised, ready to take a quick shot. And, yet, he knew well how important it was that he use extreme care, when the time came for firing. A wounded panther was a thing to be dreaded by even the stoutest-hearted hunter. He had heard many stories told around the family hearth at home about these animals, by such men as Pat O’Mara, the jolly Irish borderer, old Reuben Jacks, the veteran hunter, and others; all of whom agreed that they would sooner face a bear, or a pack of wolves[23] than a big “cat” that was wild with pain and rage.

Bob could see his brother now, on his knees, still struggling to release himself from the hold of the fox trap, that seemed to grip his ankle with a stubborn determination to keep him from reaching his gun, standing there so close, but beyond his itching fingers.

Once Bob thought he saw the beast crouching among some bushes that ran down to the edge of the water; but he dared not waste his one shot on an uncertainty, since he would then be compelled to defend himself with his knife or hatchet. And, as it turned out, he showed considerable wisdom in repressing his boyish desire to fire, for just then there was a movement in an entirely different direction, and he had a glimpse of a gray beast slinking past a small opening.

At this moment, Sandy made a new discovery that added a new note of alarm to his voice:

“Oh! there are two of them, Bob! Be careful what you do, brother! Try to scare them off without shooting, if you can! Oh! if I could only reach my gun, it would be all right; but I’m held here, a prisoner!”

It was a time for doing the right thing, as[24] Bob well knew. If there were, indeed, a pair of the animals, eager to pounce upon the boy who was so helpless there, he would certainly have his hands full.

Fire would frighten them away, Bob knew; but he had no means of quickly igniting a handful of dead leaves. In those early days, long before matches of any kind had come to be known, the only way to get fire was by the use of flint and steel; and often it was a difficult task, requiring a pinch of powder, the same as was used for priming in the pan of a gun.

In this emergency there flashed into the active mind of the young pioneer a dozen schemes for frightening the panthers away, or, at least, make the brutes hesitate long enough for him to have a chance to hand to his brother the gun that was so tantalizingly close to his eager fingers. Both armed, they might, by two well-directed shots, put an end to both of the panthers.

Each scheme was, however, dismissed as impracticable as soon as thought of, and there remained to Bob only the one thought,—he must, regardless of the danger, reach his brother’s gun!

Believing that a sudden noise might momentarily disconcert the beasts, he gathered himself for a spring, and then, with a shrill, piercing cry, he leaped from the bushes, and dashed forward.

The distance was but a few yards, and was quickly covered. Seizing Sandy’s gun, he, by the same motion, tossed it to his eager brother, and the two lads, back to back, stood with ready weapons, awaiting the spring of the crouching panthers.

Moments passed and, to the boys, the tension was fearful. Suddenly the silence was broken by a sharp, cracking sound, followed by a mighty crash, as a huge dead tree toppled down, its bare, gaunt branches grazing the boys, as they stood alertly eying the surrounding bushes.

This was followed by a slight rustling sound and then all was again still.

For several minutes the lads maintained their tense attitude and then, with a sigh of relief, Bob relaxed his strained muscles.

“I believe, Sandy, the fall of that dead tree scared the brutes away,” he said, at last.

“You are right, Bob,” answered the other, with a ring of disgust in his voice; “I do believe[26] the cowards are slinking off over there, for I saw the brush moving. I wish we could have had a shot at them.”

“Well, for one, I’m glad they’ve taken a notion to let us alone,” Bob remarked. “I was afraid that they would spring at any second, and we might have missed, or only wounded, one or both of the panthers. It was exciting while it lasted, Sandy.”

“Yes, I can say it was,” replied the other, with a shrug of his shoulders. “Just think of me held up here like this, and with the teeth of that old trap biting in deeper every time I pulled, or tried to turn around. Please get me loose, Bob; my ankle will be pretty sore after this, I’m afraid.”

“So you couldn’t turn around to unfasten it yourself,” remarked the other, as he hastened to turn the trap over, so that he might stand on the double spring, and thus throw back the two jaws. “There, does that fix it, Sandy? Looks like those teeth had chewed pretty well into your buckskin legging, too. I hope you won’t be crippled too badly to limp back to the boat.”

Sandy scrambled to his feet, and started to try his left leg. He certainly did limp considerably,[27] but only made a wry face as he said:

“I’ll have to stand it, Bob. And, then, it might have been so much worse. Think how those sharp teeth must have cut into my leg but for the support of that stout deerskin legging. And even they would have been nothing like the teeth of a panther. I honestly believe the savage beasts meant to get me. And, after this, I’m just going to add as many panther skins to our bag as I can, to pay up for the scare they gave me.”

“Well,” Bob replied, “I think we’ll give up all idea of keeping along our line of traps to-day. Not to speak of your lame ankle, it seems to get darker all the while; and, with the river before us, we’d be foolish to stay over here any longer than we can help. You remember what mother told us, Sandy?”

“Oh! I wouldn’t bother my head about any trouble we might have in making the other shore all right,” declared the confident younger boy; “but, then, with this pain in my leg, I don’t see how I could manage to get over much ground. However, if you care to go on alone, I can get back to the boat, and wait there for you to come.”

Bob shook his head resolutely.

“I’ll return with you, Sandy,” he said, “but first we will pick up the mink I dropped, if, indeed, those hungry woods cats have not already found it. It looks as if we will have to be contented with a fox and a mink for this afternoon.”

“With three more traps to hear from,” grumbled Sandy, who hated exceedingly to be kept from doing what he had planned. “This seemed to be our lucky day, Bob; and the chances are we’d have found something in every trap. Now those two panthers will just about run the line, and clean everything out for us.”

“Still, we have a whole lot to be thankful for,” urged the older boy, as he picked up the red fox, threw it over his shoulder, and offered to assist Sandy in walking. The other, however, scorned to appear like a cripple, and managed unaided to limp along close at his brother’s heels, though he made many a wry face, unseen by Bob, as pains shot through the injured ankle.

They were fortunate enough to find the mink just where it had been so hastily dropped when Bob heard the shouts of the trapped boy, and,[29] as soon as this had been secured, they turned their faces toward the point where the dugout had been left.

“You see that I was right about the weather thickening up again,” Bob remarked, leading the way at as fast a pace as he believed the lame member of the expedition could stand.

“It does grow gloomy right along, for a fact. As you say, Bob, perhaps the bad spell was only broken for a short time, and the rains may come on worse than ever. Ouch! that hurt like everything then. I didn’t see that root sticking up in the trail. Don’t I wish I was over home right now, so I could wash that sore spot with hot water, and have mother apply some of that wonderful salve which she makes out of herbs.”

“Only a little way more, and we’ll strike the boat,” called out Bob, encouragingly; “there, I can see the place now.”

“I was just thinking what a fix we’d be in if we found it gone!” remarked Sandy. “With the river booming bank-full, and the current as fierce as a wolf pack, how in the wide world would we ever manage to get across, Bob?”

“I’m not going to bother my head trying[30] to guess,” answered the other. “Time enough to cross a bridge when you come to it. Besides, I happen to know that the boat is still there, for I just had a glimpse of it. But, did you mean you thought the river could have risen enough, since we left, to carry it off?”

“No,” said Sandy, soberly, “I was thinking of that second warning you found under the door of the cabin this very morning, and wondering whether those French trappers could be around on this side of the river. If they saw our boat, and guessed whose it was, they’d be ready to send it adrift, and keep us from getting home to-night.”

“That is just what I think, myself; and they would do even worse than that, if they had the chance. The only thing that keeps them from firing on us as we pass through the forest is their fear of the vengeance of Boone and Kenton, not to speak of Pontiac, whose wampum belt hangs in our cabin, a sign of his protecting hand over the Armstrong family. But, here we are; and now to get started right away.”

One glance out upon the heaving bosom of the flood told Sandy that they had been wise to give up further idea of staying on the further[31] shore. Indeed, with the gathering darkness, it began to look as if, even now, they had taken more chances than were wise or prudent.

The boys pushed out with a fearlessness that was characteristic of their actions. Accustomed to facing perils by land or water, they seldom hesitated, or allowed anything like alarm to influence them, when duty called. And both lads knew that, should they fail to return home on that night, there would be little sleep under the Armstrong roof.

As usual, Sandy sat in the bow of the boat, while his brother managed the stern paddle with considerable dexterity. Until they had come to the Ohio country neither boy had had very much experience in boats; but, after the dugout was built, they spent much of their time on the water, shooting ducks for the family larder, fishing, or crossing over to hunt on the other shore, where, later on in the fall, they had stretched a line of traps that brought them in many a fine pelt.

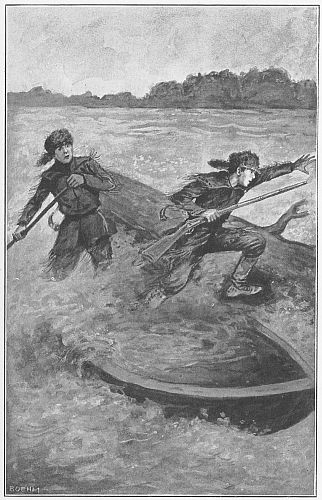

They soon found that, somehow, owing to the trend of the shore, perhaps, it was going to prove an even more difficult task to push the heavy dugout back to the southern side of the river, than it had been in coming across.[32] The current added to their troubles, for it carried them along faster than either of the boys had dreamed possible. For the first time, possibly, they were learning of the power of the flood, once it arose in its tremendous might.

Both lads strained every muscle as they drove the blades deeply into the water. They had, by the hardest kind of work, managed to get about half-way over, though both of them were somewhat winded by their efforts, when they noticed that heavy clouds, rolling up across the heavens, had begun to bring the dusk of night much earlier than even the careful Bob had anticipated.

There were many obstructions that had to be avoided. Trees were floating on the surface of the water in places, and logs seemed plentiful. Altogether, it was an entirely new sight to both Bob and his brother, for, until now, they had never known the beautiful Ohio to rise to a point that could be called dangerous.

“Take care, and keep away from that tree!” warned Bob, as he saw a particularly ugly snag, with broken branches sticking out along its sides, bearing down upon them on the left.

They had to paddle furiously in order to keep[33] clear of this threatening object, and, possibly, in his eagerness, Sandy may have bent too heavily on his paddle, for, just as they reached a point where they would be safe from the floating tree, there was a sharp snap.

“What happened?” cried Bob, alarmed more than he would have liked to confess.

For reply Sandy held up the stump of his paddle. It had broken off clean, and, from that time on, only one could paddle at a time. This catastrophe was sure to delay their passage, and doubtless cause them to be swept some miles down-stream before they could land; but the boys were hardy, and would not mind walking back, though doubtless Sandy might complain a little on account of his lame leg.

Bob set to work again with a good will, and was making fair progress when yet another peril came booming along, this time in the shape of a heavy log that was sweeping with the speeding current.

Bob saw the danger and strove the best he could to avoid it; but, in the clutch of the current, the little dugout seemed but a plaything, and the log, driving three times as fast as they were going, bore straight down upon them.[34] When Bob saw that a collision was unavoidable, he called at the top of his voice to his brother:

“It’s going to strike us, Sandy. Hold on to your gun if you can, and climb aboard the log as they come together; for I fear that the boat will sink. Quick! jump now!”

In that moment of alarm Sandy forgot all about his lame ankle. He realized, as soon as the crash came, that the dugout was about to sink, for water began to pour in over the side. So he obeyed the cry of his brother, and made a spring for the safety of the log that had done the damage.

How he managed to scramble on it he could never afterwards explain; but, when he had done so, and looked around, it was to discover Bob sitting astride the rolling log, close by, and the half-sunken boat just vanishing from sight in the gathering gloom.

“How is it, Sandy; are you all right?” anxiously asked Bob.

“I’m on the log, if that is what you mean,” gasped the younger boy, noticing, however, that their strange craft began to roll less, now that they had settled down upon its broad back.

“And I hope you held on to your gun?” Bob went on; for even in that terrible moment[36] he could remember such a thing. This was hardly to be wondered at, because it had taken both of the boys many a long month’s work with their first traps, away off in Virginia, to gather together enough money to purchase the flint-lock muskets they owned, and which had always served their purpose well. To lose one meant another expenditure of hard-earned shillings, and even pounds.

“I have it here, safe and sound,” replied Sandy, not without a touch of pride in his voice; for to have managed to get aboard that rolling log in such a hurry, and to keep a grasp upon the long musket, was no trifling task.

“That was a close shave,” said the elder brother, with a long-drawn sigh; since he had been terribly alarmed for the moment, more on account of Sandy than for himself.

“We never had a more exciting time,” admitted his brother, frankly.

“And we have much to be thankful for,” continued Bob.

“For this old floating log, you mean?” observed Sandy, not without a touch of sarcasm in his voice.

“Yes, because even an old log may turn out to be a pretty good friend,” Bob went on,[37] positively. “I’ve heard father declare that a sailor is thankful for any port in a storm; and, only for this log, we might have been swimming our level best right now, brother, to keep our heads above water.”

“That may be,” answered Sandy, still unconvinced; “but you forget that, only for this same log, we would have been safe and sound in our dugout, and paddling as nice as anything for the bank. As it is, we’ve lost our boat, paddle and all, as well as the fox and mink; and will have to borrow Alexander Hodgson’s craft until we can build another.”

“Let us shout as loud as we can,” proposed Bob. “Perhaps some of the settlers will hear us, if they are down near the edge of the river, watching how fast it keeps on rising.”

Accordingly both lads sent out sturdy calls at the top of their voices; but there came back no answering, reassuring shout. Only the murmur of the flood could be heard, or it might be a grinding noise as the log came in contact with other floating stuff.

So finally the boys, as if by mutual consent, gave up hallooing.

For a little time they sat there in silence, both looking uneasily toward the shore which[38] marked the connecting link between themselves and their home, though it could only be faintly seen, where the tree-crowned hills stood out against the dull, darkening heavens.

Bob suddenly aroused himself. This was no time for vain regrets. They must be up and doing, if they hoped to cope with the new and strange situation into which a freak of fortune had so suddenly thrust them.

“We must try to do something to get ashore, Sandy,” he said, firmly.

“I was just thinking that way, myself,” admitted the other; “but, since we have no paddles, and this log chooses to remain out here in the middle of the river, I’m bothered to know how it can be done.”

As usual, Sandy was depending part upon his brother to suggest some way out of their difficulty; not that he did not possess a bright mind himself, but when it came to quick thinking, and the suggesting of a reasonable plan, Bob was always to be relied on.

“Paddles would do us little good just now, I fear,” said Bob. “We are both of us good swimmers, and might be able to make the shore; but the water is very cold, and there would be danger of a cramp catching one of us.[39] For that reason I don’t like the idea of deserting this friendly log. We are at least safe as long as we have it to cling to.”

“But, Bob, what if we keep on floating all night? We will be chilled to the marrow with this cold wind, and the rain that promises to fall. Besides, when the dawn breaks, we will find ourselves many miles down the river. And what would mother think?”

“Well, I’ve got a plan in my mind that might help us,” the other went on. “We don’t want to lose our guns, to begin with; and, once we took to the water in that way, how could we hold on to them? So here’s what I was thinking. Let us fasten the guns, and our clothes, as far as we can, to this log. I always carry some buckskin thongs in the pocket of my tunic, and there are knobs here and there, where branches have been broken off.”

Sandy broke out laughing.

“But, what good would that do us?” he demanded. “If ever we did get ashore, think how cold we should be, and likely to starve to death. I think I’d rather take my chances sitting right here, than try that.”

“But you don’t understand the whole of the plan yet, Sandy,” the other went on, steadily,[40] for he was quite used to having his impatient brother break in upon him in this way.

“Oh! if there is more of it, I’m glad to hear it,” Sandy remarked. “After we’ve tied our guns, and part of our clothes, to the log, what do we expect to do then, Bob—fly away to the shore away over yonder? We might,—if only we had wings!”

“Listen, then,” Bob pursued. “We’ll slip down into the water, and, one on either side of the log, start steering it in the direction of land. Do you understand now, brother?”

Sandy gave a shout, for he was always enthusiastic, once he discovered any reason for being so.

“It is a great idea, Bob,” he said, warmly. “And I never would have thought it out in an hour. Just as you say, we can, by slow stages, push the log ashore. Even if it is miles below the settlement, we will have our clothes with us, and tinder bags to start a fire with. But why, do you think, did no one answer our shouts back there?”

“In the first place,” replied Bob, who was beginning to fumble around, in a hunt for the best nubbin of a broken branch, to which he might secure his valuables, consisting of his[41] precious musket, powder horn, bullet pouch, tinder bag, and last, if not least of all, his clothes, which the loving fingers of their mother had fashioned out of pliable deerskin; “in the first place, we must have been some distance below the settlement at the time of our accident.”

“Yes,” added Sandy, at once, seeing how reasonable this sounded, “I think you are right about that, Bob.”

“And,” continued the other, “even if they had guessed that the cries came from down the river, what could they have done to help us? There is no better boat than the one we owned; and, with night at hand, and the sky as black as it is now, the women would not have let the men venture out upon the water. They are always in mortal fear lest the wily Indians lay some plan for the undoing of our settlement, and begin with luring some of its defenders away.”

Sandy, too, was beginning to secure some of his things to the novel craft which a strange decree of fate had made them accept as a means of riding the flood in safety. When he had received the several buckskin thongs which his brother passed over to him, the task of securing[42] the gun to the two knobs he had selected was first of all begun, because with that in his hands he could accomplish little.

But Sandy, dearly loved to talk. It was indeed hard to keep him quiet, for he was always either seeking information from another, or else desirous of imparting his own views upon various subjects.

So, even as he worked, he must needs start afresh.

“How far do you believe we will be from home when we get to land?” was what he first of all asked his brother, just as though the other was a knowledge box upon which he could draw at will.

“That would be hard to say,” replied Bob. “It all depends on how long we are in landing. This flood must be going anywhere from six to seven miles an hour; and, even if we are lucky, we would find ourselves perhaps ten miles below our home.”

“That would be further than we have ever wandered down the river,” remarked Sandy, for their trapping and hunting had all been done within the immediate vicinity of the settlement, since game could often be found inside of ten minutes’ walk.

Once only had the brothers been tempted to take a long journey. This was when their sister Kate, at a time when their father had gone in Virginia on urgent business, had been carried off by a young chief of the Delawares; and a pursuit was undertaken by the brothers that led them to the far distant great lakes.[5]

“Well, if we can make the bank in safety, I, for one, will not complain of the distance,” declared Bob. “How is your gun fixed now; are you sure that it will hold safe, even if we should knock up against another log?”

“Yes, it is fast to the tree trunk, and can never slip loose,” returned Sandy. “The more I think of this plan of yours, the better I like it, Bob. Once we are in the water, and swimming, we can urge the log toward the shore, a foot at a time, it may be, but with a constant pressure, until at last we find that we can touch bottom. Then for a fire, and warming up, for I fear by that time both of us will be chilled to the bone.”

“And if your lame ankle is so bad that it prevents our getting back to-night, why, Sandy, what should hinder us from making camp in the forest, under some ledge, where we can[44] keep out of the rain? Then, when morning comes, we can follow up the river until we reach our home again.”

“It makes me feel better to hear you talk like that, Bob,” declared the younger of the two. “I wonder what I would have done without you?”

“Perhaps just what we mean to do right now,” Bob went on to say. “The trouble is, Sandy, you will not think for yourself, when you have me to depend on. You must remember what father told you once, that every tub ought to stand on its own bottom. But Simon Kenton tells me he was just such a youngster, until he found himself thrown on his own resources. It was the making of him, he declares; because such things are apt to bring out all there is in a boy.”

Both of them were still diligently working to secure their possessions safely to the friendly trunk, which, having been the means of their disaster, now seemed willing to make reparation as best it could by offering them an asylum for those things which otherwise must have gone into the river with them.

It had, by now, grown so dark that all they could see was a stretch of about thirty feet or[45] so of surging water on either side of them. Ahead, a similar unending panorama opened up, and, had they chosen to turn their heads in order to cast a backward glance, they would have looked upon the same dismal spectacle.

“There,” said Sandy at last, “that job is done, and I’m ready to pull off my tunic, hunting shirt, and coonskin cap, which I’ll make up into a bundle, and fasten with this last long thong. But, Bob, before we do that, and go overboard, it seems to me we ought to give a last shout for help. There is about one chance in a thousand that some person in a boat may hear us.”

“We’ll take that chance, then, Sandy,” echoed Bob. “So, ready now, and shout when I do, with all your might!”

Again did their lusty young voices ring out over the flood. Once, twice, thrice they gave tongue, and then, pausing, listened to see if by chance there came any welcome reply. Immediately Sandy gave a low bubbling cry of satisfaction.

“Did you hear that?” he demanded. “Some one certainly answered us; unless it was an echo from the hills away off yonder.”

“It was no echo, Sandy,” replied Bob.[46] “Shout again, and louder than before. There is hope of a rescue even now. That one chance looks better! Now, let go!”

This time the answering hail seemed somewhat closer, as though they were sweeping down toward the spot where the unknown must be sitting in his boat, holding it to some degree against the rushing current.

Sandy became wild with excitement. He had almost despaired of assistance coming to them before, and, now that this sudden chance loomed up, the horizon seemed to brighten visibly.

“Oh! I can hear the sound of paddles, Bob!” he exclaimed.

“Yes, that is what I was just listening to,” answered the other, and Sandy was surprised to note a lack of the same enthusiasm about Bob that reigned in his own heart.

“What ails you?” he demanded. “We are in a fair way of being taken safely ashore, and yet you do not seem to be happy. Is there anything wrong, do you think, about that answer to our shouts? Surely it could not be an echo, for by now we can make out the dip of paddles plainly. Tell me what worries you?”

“That is just it,” replied Bob, soberly;[47] “the dip of the paddles, as you say, which tells us that others are on the flood as well as ourselves. But I have never heard a white man handle a paddle just like that, and there are many who have tried it all their lives.”

Sandy asked no more questions. Doubtless, if his face could have been seen just then, it would be found to have taken on a sudden pallor, as he muttered to himself the one significant word:

“Indians!”

There was really nothing that could be done.

In a choice between two evils, Bob Armstrong could always be depended on to take that which seemed the less. To go on down the flood was a dreadful outlook; and almost anything was to be preferred to facing the unknown perils of the river, especially in the pitch darkness that prevailed.

The sound of the paddles drew constantly nearer. Then they heard voices, as if those in the canoe were asking each other whence it could be that they had heard that last shout for help.

To the astonishment of the floating boys the words came in English, though evidently one of the speakers was an Indian who had apparently learned the tongue of the palefaces.

“Oh! it’s Pat O’Mara, I do believe!” exclaimed Sandy, in his amazement speaking loud enough for his voice to carry some distance away; for immediately, even before Bob could[49] add any words of his own to the declaration, there came a hail out of the gloom.

“Avast there! Be ye the Arrmstrong byes I’m afther hearin’ out on this roarin’, tearin’ flood this night?”

“Yes, yes, that’s who it is, Pat; and precious glad to hear the sound of your voice, because we need help the worst way!” cried Sandy, always impulsive.

“All right, we’ll be wid yees in a jiffy, depind on it,” came the answer from a point close at hand. “Give us another few digs at the paddle, chief, an’, by the same token, we’ll soon be alongside, so we will.”

A minute later the anxious boys began to detect some moving object, as they strained their eyes to see. Then this turned out to be a long canoe, in which two persons were sitting, the one in the stern using a paddle with that grace and dexterity which only an Indian could exhibit, just as Bob had wisely said.

Sandy craned his head forward to see better through the darkness. Doubtless there must have been something familiar about the movements of this paddler, for he certainly did not have enough light to recognize his features, or even the feather that adorned his scalplock.

“Surely that must be Blue Jacket!” he ejaculated, with a thrill of delight, as well as surprise noticeable in his quivering voice.

“Uh! that so, Sandy,” came in a voice he knew almost as well as he did that of his brother.

“What luck!” cried Sandy. “To think that such good friends should happen to be on the river this night of all times, when we are in such sore need.”

Perhaps, had Bob Armstrong been asked his opinion, he might have declared that it was something much higher than mere luck that brought about such a happy conclusion to their adventure. Bob was a much more serious fellow than his younger brother, and imbibed some of the sentiments that influenced his gentle mother. To him there was something especially Providential in this coming of help when the two boys were in so great need, just as there had been in the falling of the dead tree just as the panthers were about to attack them.

Quickly the canoe worked up alongside the log, to which both the Irish trapper and his native companion fastened a firm grip.

“Come aboord, and be sinsible,” said Pat[51] O’Mara, who was one of the oldest friends the Armstrong family had; and whom they had known away back in Old Virginia, before the thought of daring the perils of the unknown wilderness had ever entered David Armstrong’s mind. “Sure, ’tis a mighty poor sort av a craft ye do be havin’, if I might make so bowld.”

“But it was better than nothing,” said Sandy, as he carefully placed his musket in the canoe before even thinking of attempting to get aboard himself.

Bob did not make a single move until he had seen his brother safely over the side. Indeed, to judge from his actions, one might be inclined to think that he even kept himself in readiness to clutch Sandy, should the other manage to slide down the side of the log into the water, instead of gaining a lodgment in the boat. Then Bob copied the other’s actions, his precious gun being first made secure before he would think of himself.

It was rather a ticklish business leaving the log, and entering the canoe that, being made of birch bark, was so light in build that it careened under the passage of the boys, and might have tipped over had not both Pat and[52] the young Shawanee brave leaned far to the opposite side while the embarkation was taking place.

“Good-bye, old log!” said Sandy, now in an exultant frame of mind that contrasted strangely with his recent gloomy spirits. “We hope you will have a good voyage down to the great Mississippi. Tell them that, perchance, the Armstrong boys will be navigating that way to see some of the wonders they have so long been hearing about. You were a pretty fair kind of a log, though we are not sorry to part with you.”

Already was the paddle, in the expert hands of Blue Jacket, busily employed in sending the craft toward the southern shore of the swollen river. Pat O’Mara had his share of curiosity, and he was not the one to keep silent when desirous of knowing the true facts.

“Sure, ’tis a quare thing to be findin’ the two av yees adrift on a tree out on this high water,” he started to say; “and, by the same token, if yees have no objection, ’tis mesilf wud like to know how the same came about.”

“That is easy enough to tell, Pat,” burst out Sandy. “Of course, you mustn’t think we started from the shore, to cross over on an old[53] log. It was just an accident, and that’s all. My paddle broke under the strain; and, when this log came whirling down on our boat, Bob alone could not get it out of the way. So it was upset, and we were lucky enough to scramble aboard, guns and all.”

The Irish trapper was loud in his exclamations of wonder.

“It do bate iverything how ye two lads always manage to chate the ould Reaper whin he thinks he has ye in the hollow av his hand,” he declared. “I warrant ye that nine out av tin min would have at laste taken a dip in the water afore crawling aboord the log; and, be the powers, ye do not same to be wit at all, at all.”

“We were wondering how we could manage to get ashore, so as to head for home,” Sandy went on to say, “when Bob thought of a way. Just when we heard your answer to our last shout we were about to fasten our guns and clothing to the log, slip overboard, and, by swimming, push it toward the shore.”

“A cliver ijee, by me troth,” remarked Pat, who was a great admirer of both young pioneers; of Bob on account of his steady ways and quick mind in emergencies, and of Sandy[54] because he had a winning, sunny disposition, which appealed especially to the genial, roving Irish trapper. “But, afther all, ’tis just as will that Blue Jacket and mesilf came upon the sane at the time we did, since ’tis a wet back ye’d be havin’, not to spake of many miles more to thramp back home. And ’tis also will that ye are off the river before this same night is many hours older.”

Bob noticed that there was a peculiar significance to these last words of their old friend, who had been many times tried, and found as true as steel.

“What brings you and Blue Jacket here, and on your way to our cabin, as I reckon you are from the way you head across the river?” he asked, desirous of drawing the other out, and learning what new peril now threatened the little settlement on the southern bank of the Ohio.

More than once had Pat brought news of the coming of Indians on the warpath, so that the pioneers had learned to look upon him as their best guardian. As he was forever roaming the great forests, sometimes in the company of such noted men as Daniel Boone, Simon Kenton or Harrod the surveyor, Pat was in a position[55] to pick up intelligence that could be obtained by no one else. (Note 4.)

And so Bob wondered whether it could be something of this character that was now causing him to hasten to the relief of the struggling settlement.

“Sure, ’twas by sheer accident that we came togither,” the trapper observed, as he bent his supple body quickly to one side, so as to better balance the frail canoe, which at that instant was being buffeted about in a swirl of waters, not unlike a miniature whirlpool. “An’, whin I larned that the chief was aven thin on his way to warrn the white settlers as fast as he could go, I made up me mind to accompany him. So that’s how it happens we wor abroad on the river jist at the same time ye naded hilp so bad. Troth, as Sandy jist said, ’twas a lucky thing all around.”

“But, Pat,” Bob continued, “of what danger was Blue Jacket about to warn our people? Have the Indians again taken to the warpath, after their professions of peace, and after saying that the hatchet was buried ever so deep?”

“Sure, there be always danger av that same,” remarked the other, grimly; “but, on[56] this occasion, ’tis a peril av another color intirely. The flood is bearin’ down upon yees like a race horse, and, befoor the dawn av another day, it may be the risin’ water wull be afther swapin’ away some av the cabins in the settlement!”

“Oh! but how could Blue Jacket learn about that, when it must be many miles up the river, and coming much faster than any Indian could run?” demanded Sandy.

“Ye must know,” went on the Irish trapper, impressively, “that these rid hathen have a way av communicatin’ news by manes av smoke signals in the day time, and fires at night. From hill to hill, many miles away, they sind these smokes; and, so I’ve been towld at laist, the missage can be carried as much as a hundred miles in less time than it wud take a horse to run tin.”

“Yes, that is something I knew about, but had forgotten,” admitted Sandy.

“And this flood, does it come from the last rain, or has there been what I heard my father call a cloud-burst?” asked Bob, anxiously; for his thoughts were upon the little community some miles up the river, which had already grappled with more perils than the settlers had[57] ever dreamed could be met with in this new country.

“That I do not chanct to know, me bye,” replied Pat. “’Tis enough to learn that the flood is comin’ tearin’ along down the river, and that the water will rise in a way niver known before. The Injuns are wild with alarrm. Their ould medicine-min do be on the rampage, and kape tillin’ thim they do be sufferin’ from the anger av the Great Spirit, becase av their allowin’ the white trispassers till remain on the sacred land that was given till their ancestors long years ago. It all manes hapes av trouble for the pioneers, from Boonesborough till Fort Washington, and all the way along the Ohio.”

“I can see the shore again,” called out Sandy at this moment; for, while he had been listening with deep anxiety to what the trapper said, at the same time his keen young eyes had been on the watch to detect the first signs of land ahead.

A minute later, and Sandy again broke out with an exclamation, and this time there was a note of wonder, not unmixed with anxiety, in his voice.

“Look! there is a fire burning on the shore[58] below, and just about where we will come to the land!” he cried out.

“And I can see one or two white men beside it; yes, with an Indian also,” added Bob, who had as sharp vision as his brother.

“And they must hear us talking, for they have jumped to their feet, and seem to be looking this way. Can it be some of our friends from above, brother?” asked the younger boy, eagerly.

“I do not think so,” Bob answered. “They are not in the broad firelight now; but, from the glimpse I had, I took them to be woodrangers like Pat here, and some of the others we know.”

“Oh! perhaps, then, it may be Boone and Kenton themselves,” remarked Sandy, who had secretly always admired the forest ranger, Kenton, and aspired to follow in the footsteps of the daring young man, when he grew older.

“Well, we shall soon know,” Bob went on, “for Blue Jacket is heading straight in to that point where they have built their fire, as though he means to land on the lower side, where the current does not run so fiercely.”

Already they were in less turbulent waters,[59] for, near the shore, the river did not attain anything like the swiftness that marked the middle of the stream. Under the skillful guidance of the sturdy young Shawanee brave, whose name, although not very well known just then, was fated later on to be on the lips of every settler who had built a cabin in the wilderness along the Ohio, the canoe presently came against the shore.

Sandy, as usual, was the first to jump on to the bank; but he was careful to take his gun along with him. The Irish trapper quickly reached his side, and then came Bob, and the dusky Blue Jacket, who certainly could never be accused of being a talkative fellow, though capable of expressing himself freely on occasion.

As if instinctively they allowed the young Shawanee to lead the way toward the burning campfire, because the presence of an Indian would seem to indicate that he might be better able to conduct the intercourse with the strangers; for already Bob and Sandy had discovered that the two white men were totally unknown to them. Besides, since it was Blue Jacket’s canoe, he seemed to be conducting the expedition to the settlement, the others having[60] just been taken on as he happened to come across them.

But Bob Armstrong felt a new uneasiness creep over him when he heard the Irish trapper mutter something half under his breath, and caught the one significant word:

“Traitor!”

“Who are they, Pat?” asked Bob, half under his breath, as he saw Blue Jacket gravely salute the other Indian, whom he knew to be a chief among the fierce Miamis, both by the feathers he wore in his scalplock, and by the trimmings on his buckskin hunting shirt and nether garments.

“The Injun is Little Turtle, the greatest chief among the Miamis,” replied the Irish trapper, also lowering his voice, for he saw the two white men frowning in his direction. Bob noticed that his old friend kept his long-barrelled rifle close under his arm, and his finger touching the trigger.

“And the two others?” Bob went on. “I have never met either of them before, that I can remember; and yet I have seen most of the white men who roam the woods in this region of the Ohio.”

“Wull,” whispered Pat, “ye niver missed much, thin, for, by the same token, there niver[62] lived greater rascals than the same precious pair ye say before yees this minute. The wan ag’inst the tree, wid the scowl on his black face, is none ither than the infamous Simon Girty; while his frind’s name it do be McKee; and there are hapes av people thot say he be the blackest renegade that iver wint over till the Injuns, to wage war on his own kind.” (Note 5.)

Both boys heard what Pat said, although he had lowered his voice to a whisper; and, of course, they were chilled to the marrow at the idea of looking upon such notorious persons, for already their names were being held up to execration among all honest settlers. Both Girty and McKee had been seen in the ranks of the hostile Shawanees when attacks were made on frontier settlements; and there were threats going the rounds as to what fate awaited them should the fortunes of war ever throw them into the hands of the whites.

To the eyes of the pioneer boys they looked doubly ugly on this night, when met so unexpectedly in company with a noted Miami chief, whose hostility towards the invading palefaces was so well known.

Meanwhile the two Indians were engaged in[63] a conversation that by degrees became more and more heated. Indeed, neither Bob nor Sandy could ever remember seeing their young friend, Blue Jacket, quite so worked up. He made dramatic gestures when he talked, and seemed to be replying to the taunts of the older chief.

It began to look as though there might be trouble, and Sandy fingered the lock of his gun, taking a sly look down to make sure that there was powder in the pan, for the spark from flint and steel to reach, in case it became necessary for him to depend on a quick discharge of the musket.

“What are they talking about, Pat?” asked Sandy; for he knew that the Irish trapper was able to follow what the two Indians said in their warm discussion.

“Sure, thot scum av the aarth, Little Turtle, do be taunting Blue Jacket wid bein’ frinds-like wid the palefaces,” the other replied, cautiously, keeping one eye all the while upon the pair of treacherous renegades, whom he would not trust for a single second to get behind his back. “He tills him thot ivery ridskin ought to be the mortual foe av the palefaces who would stale their land away from thim. He[64] kapes on sayin’ thot he hates the white men as hotly as the sun shines in summer, and will niver, niver make frinds wid the same.” (Note 6.)

“But, no matter what he says, it will not cause Blue Jacket to turn against the Armstrong family, even if he some day takes up the hatchet against the whites,” Sandy went on to say, with a confidence born of an intimate acquaintance with the young Shawanee brave, whose name was also fated to figure in the history of the times.

“Av yees could but hear what he do be sayin’ this blissed minit,” declared Pat, “sure, it’s on a good foundation ye build yer faith. Listen to him till that he was sore wounded, and how ye two byes did bring him intil yees own wigwam, h’alin’ his hurts, so that instead av dyin’ he lived. Now, it is av thot same kind mither av yees that he do be spakin’, and how she bound up his bullet wound wid salve, an’ trated him as though he might be her own boy. For thot he can niver be anything but the frind av the Arrmstrong family. An’ already has he parrt convinced Little Turtle, becase, ye know, gratitude is the bist trait av the ridskins.”

“But now the other seems to be changing his[65] talk, and appealing to him in another way. Tell us what he is saying, Pat, please,” insisted Sandy.

The Irish trapper listened for a minute, and then nodded.

“That wor a cliver shot av Blue Jacket, on me worrd,” he muttered. “Yees say, the ould chief he do be tillin’ him that his brothers, the Shawanees, are always on the warpath aginst the palefaces; and that, while it may be all right for him to keep frinds wid yer family, he ought to take up arrms aginst the rist av the sittlement. But Blue Jacket replied by tillin’ him av what ye byes did for the great sachem, Pontiac, only last autumn, and what it meant for the sacred wampum belt of the same to be hangin’ in the Arrmstrong cabin.”

“Oh! yes,” Sandy went on; “that ought to convince Little Turtle that Pontiac is the friend of our settlement, just because we live there; and an injury to one would be an injury to all. All these months, now, while other places have been attacked, there has come no evil against our neighbors. Much though they feared the coming of the Indians, not once has a hostile shot been fired since that day when Pontiac gave us his wonderful belt.”

“Do you notice, Pat,” remarked Bob just then, in a whisper intended only for the ears of the one he addressed, “that the man you called Simon Girty is edging off to the left, a little at a time? I do not like the look in his eye. He scowls as though he meant us harm.”

“’Tis mesilf that do be after watchin’ the sarpint av the forest,” replied the trapper. “And yees spake rightly whin ye say he has evil in his mind; but me finger is on the trigger, an’, be the powers, wan hostile move on his parrt manes for me to fire. I cud hit the eye av a rid squirrel at this distance, and surely must find his black heart wid me bullet.”

He spoke louder than before, and for a reason. Evidently his words must have reached the ear of the renegade, for he no longer tried to keep on moving, a little at a time, toward the left. Doubtless Girty knew well what a splendid shot Pat O’Mara was; and also that the trapper would willingly rid the border of such a pest, if given half an excuse.

The two Indians had by this time come to an understanding. What Blue Jacket had told concerning the gratitude of Pontiac, and the bestowing of his wampum belt on the young pioneers, because of their saving his life, must[67] have impressed the Miami chief greatly. At that time Pontiac’s name was one to conjure with among the confederated red men of the region lying between the Alleghenies and the Mississippi; while Little Turtle had not yet come to the zenith of his fame.

Turning to his white allies the Miami chieftain spoke in a rapid tone. Although Bob could understand only a word or two, nevertheless he grasped the meaning of what Little Turtle said; and knew that he was warning Girty and McKee not to think of injuring either of the boys who had been taken under the especial protection of Pontiac, the master schemer.

“Are they going to let us pass on, or do they mean to start a fight?” asked Sandy, whose manner showed that he was by no means averse to trying conclusions with the two ugly desperadoes who had thrown their fortunes in with the Indians, so that they could no longer find a friendly greeting at the cabin of a single white settler.

“No danger of our being halted,” Bob hastened to reply, fearful lest the impulsive Sandy might attempt some sort of play that would open hostilities, when there was no necessity.

“Come, we’d bist be on our way, av we hope to rach the sittlement before the flood arrives,” said Pat, beginning to retreat, still keeping watch on the renegades; for no white man who had his senses about him would ever be so foolish as to turn his back on such a treacherous snake in the grass as Simon Girty.

They were soon far enough away from the camp to feel safe, especially since the keen eyes of Blue Jacket saw that not one of the three whom they had left there had made any move toward following them.

“How is your ankle going to hold out, Sandy?” asked Bob, who feared the worst.

“It’s just got to do,” was the determined reply. “I mean to go on until I drop; but I shall keep up with you. If the worst comes, you can leave me behind somewhere, and the rest push on, for, unless the warning is received, our people may be caught asleep in their cabins, and carried away, like that log was.”

Sandy was possessed of considerable grit, inherited from his sturdy Scotch ancestors, no doubt. When he set those teeth of his firmly together it meant that he was just bound to do, or die. And in many a tight hole that stubborn[69] trait served him a good turn, just as it had also gotten the boy into heaps of trouble.

When he limped, Bob threw an arm around him; or it might be the genial trapper gave him such assistance as lay in his power. Indeed, deep down in his own mind, though he did not say as much, Pat O’Mara was determined that if he had to take the lame boy upon his broad back, as an Indian squaw would her little papoose, he was bound to see to it that Sandy reached his home with the rest of them.

But Blue Jacket was familiar with every trail of the forest. He could lead them over cut-offs that even the trapper did not know and which saved many a weary step.

The boys began to recognize their surroundings after a while, although the night was so dark that only the general conformation of the country could be noticed.

“We’re getting there, Bob,” said Sandy, hopefully.

“To be sure we are!” declared the other. “See, that must be the tree we shot the wildcat from, when he was eating the mink taken from our trap.”

“And that means only another mile or so to go before we reach home,” remarked the[70] younger boy gladly; for Sandy was fast reaching a point where even his remarkable grit could not carry him along, and he must admit defeat.

But every step he knew took him that much closer to home. Even the thought of his mother and father, as well as Kate, anxiously awaiting news of the two who had crossed the raging river on the preceding afternoon, buoyed him up, and lent him new strength.

By degrees they were coming near the settlement. This had been built along a small elevation on the bank of the Ohio, from which the pioneers were afforded a magnificent view up and down the river. At the time of its selection by Daniel Boone, who had long admired the site as an ideal place for a growing town, no one had so much as dreamed that a flood might sooner or later come sweeping down from the hills away beyond Fort Duquesne, and threaten the little colony with disaster. But it had come, and this night was likely to prove the blackest in the history of the settlement.

Now they could see the blockhouse that had been erected on the very crown of the ridge, so that in times of danger all those having cabins lower down along the face of the hill might flee[71] thither for refuge. And the wily Indians could not find any higher point whence to send their arrows, winged with flame, to stick in the roof of the fort, and set it ablaze.

“I can see a light in our cabin window,” declared Sandy, presently, his voice trembling with eagerness. “See, it is on the side that looks down the river. I am sure mother must have put it there to serve as a guide for her boys, if they chanced to be afloat on the dark waters. Oh! how glad we will be to see her again.”

The roar of the river was in their ears as they advanced further; but their coming must have been detected by some sentinel, for a minute later a harsh voice rang out, calling upon them to halt and explain who they were, on pain of being fired on.