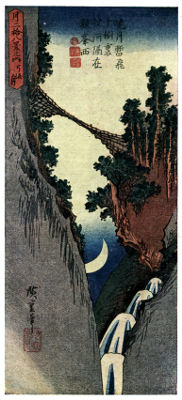

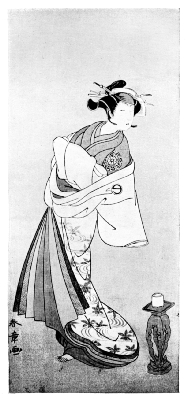

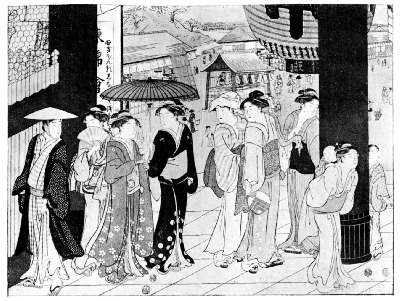

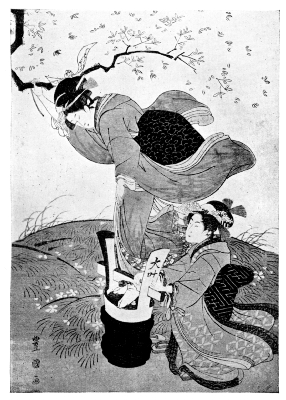

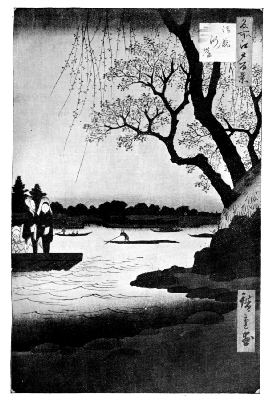

Size 15 × 7. Signed Hiroshige, hitsu.

Frontispiece.

Project Gutenberg's Chats on Japanese Prints, by Arthur Davison Ficke This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook. Title: Chats on Japanese Prints Author: Arthur Davison Ficke Release Date: September 2, 2014 [EBook #46753] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK CHATS ON JAPANESE PRINTS *** Produced by Susan Skinner and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

BOOKS FOR COLLECTORS

With Frontispieces and many Illustrations.

CHATS ON ENGLISH CHINA.

By Arthur Hayden.

CHATS ON OLD FURNITURE.

By Arthur Hayden.

CHATS ON OLD PRINTS.

(How to collect and value Old Engravings.)

By Arthur Hayden.

CHATS ON COSTUME.

By G. Woolliscroft Rhead.

CHATS ON OLD LACE AND NEEDLEWORK.

By E. L. Lowes.

CHATS ON ORIENTAL CHINA.

By J. F. Blacker.

CHATS ON OLD MINIATURES.

By J. J. Foster, F.S.A.

CHATS ON ENGLISH EARTHENWARE.

(Companion volume to "Chats on English China.")

By Arthur Hayden.

CHATS ON AUTOGRAPHS.

By A. M. Broadley.

CHATS ON PEWTER.

By H. J. L. J. Massé, M.A.

CHATS ON POSTAGE STAMPS.

By Fred. J. Melville.

CHATS ON OLD JEWELLERY AND TRINKETS.

By MacIver Percival.

CHATS ON COTTAGE AND FARMHOUSE FURNITURE.

(Companion volume to "Chats on Old Furniture.")

By Arthur Hayden.

CHATS ON OLD COINS

By Fred. W. Burgess.

CHATS ON OLD COPPER AND BRASS.

By Fred. W. Burgess.

CHATS ON HOUSEHOLD CURIOS.

By Fred. W. Burgess.

CHATS ON OLD SILVER.

By Arthur Hayden.

CHATS ON JAPANESE PRINTS.

By Arthur Davison Ficke.

CHATS ON MILITARY CURIOS.

By Stanley C. Johnson.

CHATS ON OLD CLOCKS AND WATCHES.

By Arthur Hayden.

CHATS ON ROYAL COPENHAGEN PORCELAIN.

By Arthur Hayden.

CHATS ON OLD SHEFFIELD PLATE.

(Companion volume to "Chats on Old Silver.")

By Arthur Hayden.

BYE PATHS OF CURIO COLLECTING.

By Arthur Hayden.

With Frontispiece and 72 Full page Illustrations. 9s. net.

LONDON: T. FISHER UNWIN, LTD.

NEW YORK: F. A. STOKES COMPANY.

Chats on

Japanese Prints

BY

ARTHUR DAVISON FICKE

WITH 56 ILLUSTRATIONS AND A COLOURED FRONTISPIECE

T. FISHER UNWIN LTD

LONDON: ADELPHI TERRACE

First published in 1915

Second Impression, 1916

Third Impression, 1917

Fourth Impression, 1922

(All rights reserved)

TO

FREDERICK WILLIAM GOOKIN

AND

HOWARD MANSFIELD

CUSTODIANS, APPRAISERS, AND LOVERS OF BEAUTY

For assistance of many kinds in preparing this book the thanks of the author are gratefully offered to Mr. Frederick William Gookin, Mr. Howard Mansfield, Mr. William S. Spaulding, Mr. John T. Spaulding, Mr. Judson D. Metzgar, Mr. Charles H. Chandler, Mr. John Stewart Happer, Col. Henry Appleton, Mrs. Arthur Aldis, Mr. Ernest Oberholtzer, and Mr. Charles August Ficke. Though many obligations must perforce go unacknowledged, it would be improper to fail to state indebtedness to the writings of Von Seidlitz, Bing, Huish, Anderson, Strange, Binyon, Gookin, Kurth, Morrison, Happer, Koechlin, Vignier, Succo, Field, De Goncourt, Okakura, Edmunds, Perzynski, Wright, Fenollosa, and De Becker.

Many collectors have kindly allowed their prints to be used for illustration in this book. That all the examples are from American collections is due to considerations of convenience, not to any notion of their superiority. All prints not credited to another owner are from the collection of the author. The other collections from which illustrations are drawn are as follows:—

Four of the poems herein printed appeared first in The Little Review. A number of the others are from the author's book "Twelve Japanese Painters." Most of the photographs here reproduced were prepared by Mr. J. H. Paarman, Miss Sarah G. Foote-Sheldon, and Mr. J. D. Metzgar.

Davenport, Iowa, U.S.A.{13}

| PAGE | ||

| PREFACE | 11 | |

| GLOSSARY | 19 | |

| CHAPTER | ||

| I. | PRELIMINARY SURVEY | 23 |

| II. | CONDITIONS PRECEDING THE RISE OF PRINT DESIGNING | 47 |

| III. | THE FIRST PERIOD: THE PRIMITIVES | 61 |

| IV. | THE SECOND PERIOD: THE EARLY POLYCHROME MASTERS | 125 |

| V. | THE THIRD PERIOD: KIYONAGA AND HIS FOLLOWERS | 205 |

| VI. | THE FOURTH PERIOD: THE DECADENCE | 255 |

| VII. | THE FIFTH PERIOD: THE DOWNFALL | 347 |

| VIII. | THE COLLECTOR | 401 |

| INDEX | 449 | |

| Hiroshige: The Bow-moon | Frontispiece | |

| PLATE | PAGE | |

| 1. | Moronobu: A Pair of Lovers | 71 |

| 2. | Sukenobu: A Young Courtesan | 77 |

| 3. | Kwaigetsudō: Courtesan arranging her Coiffure (Spaulding Collection) | 81 |

| 4. | Okumura Masanobu: Courtesans at Toilet | 93 |

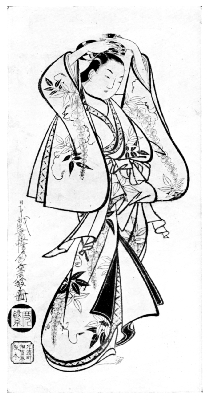

| 5. | Okumura Masanobu: Standing Woman | 97 |

| 6. | Okumura Masanobu: Young Nobleman Playing the Drum (Chandler Collection) | 101 |

| 7. | Toyonobu: Two Komuso, represented by the Actors Sanokawa Ichimatsu and Onoye Kikugoro (Chandler Collection) | 109 |

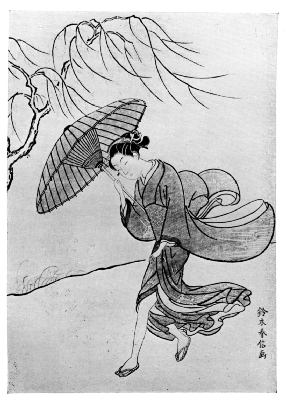

| 8. | Toyonobu: Girl opening an Umbrella (Metzgar Collection) | 113 |

| Toyonobu: Woman dressing | 113 | |

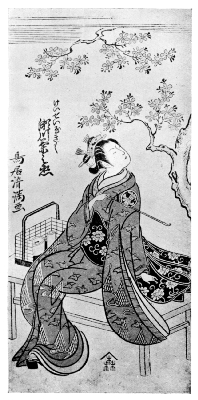

| 9. | Kiyomitsu: The Actor Segawa Kikunojo as a Woman smoking | 117 |

| 10. | Kiyomitsu: Woman with Basket Hat | 121 |

| Kiyomitsu: Woman coming from Bath | 121 | |

| 11. | Harunobu: Young Girl in Wind (Gookin Collection) | 137 |

| 12. | Harunobu: Lady talking with Fan-vendor {16}(Chandler Collection) | 141 |

| 13. | Harunobu: Girl viewing Moon and Blossoms (Chandler Collection) | 145 |

| 14. | Harunobu: Courtesan detaining a passing Samurai | 149 |

| 15. | Harunobu: Shirai Gompachi disguised as a Komuso | 153 |

| Harunobu: Girl playing with Kitten | 153 | |

| 16. | Koriusai: Mother and Boy | 161 |

| Koriusai: Two Lovers in the Fields; Spring Cuckoo | 161 | |

| 17. | Koriusai: Two Ladies | 165 |

| Koriusai: A Game of Tag | 165 | |

| 18. | Shigemasa: Two Ladies | 169 |

| Koriusai: A Courtesan | 169 | |

| 19. | Shunsho: An Actor of the Ishikawa School in tragic rôle | 175 |

| 20. | Shunsho: The Actor Nakamura Matsuye as a Woman in White | 179 |

| 21. | Shunsho: The Actor Nakamura Noshio in Female rôle (Gookin Collection) | 183 |

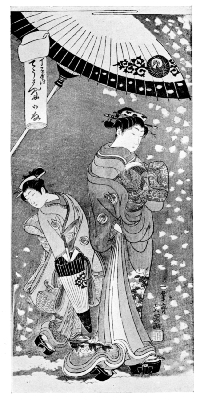

| 22. | Buncho: Courtesan and her Attendant in Snowstorm (Mansfield Collection) | 187 |

| 23. | Shunyei: An Actor | 191 |

| 24. | Shunko: The Actor Ishikawa Monnosuke in Character | 195 |

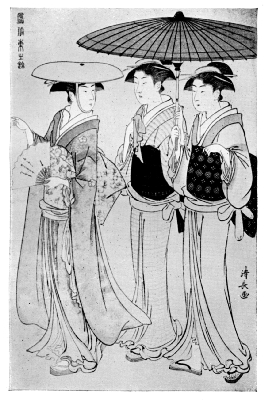

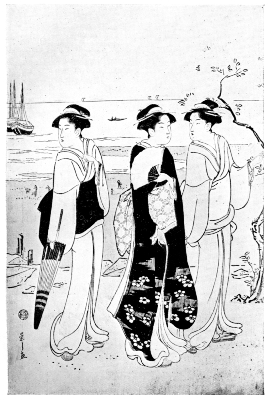

| 25. | Kiyonaga: The Courtesan Hana-ōji with Attendants | 211 |

| 26. | Kiyonaga: Lady with two Attendants (Gookin Collection) | 215 |

| 27. | Kiyonaga: The Courtesan Shizuka with Attendants in the Peony Garden at Asakusa | 219 |

| 28. | Kiyonaga: Two Women and a Tea-house Waitress beside the Sumida River (Gookin {17}Collection) | 223 |

| 29. | Kiyonaga: Yoshitsune Serenading the Lady Jorurihime (Spaulding Collection) | 227 |

| 30. | Kiyonaga: Geisha with Servant carrying Lute-box | 231 |

| Kiyonaga: Woman painting her Eyebrows | 231 | |

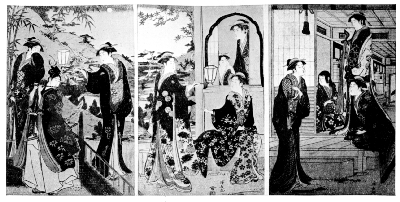

| 31. | Shuncho: Group at a Temple Gate (Mansfield Collection) | 235 |

| 32. | Shuncho: Two Ladies under Umbrella | 239 |

| Shuncho: The Courtesan Hana-ōji; the Sumida River seen through the Window | 239 | |

| 33. | Shuncho: Two Ladies in a Boat on the Sumida River | 243 |

| Yeisho: Two Courtesans after the Bath | 243 | |

| 34. | Kitao Masanobu: The Cuckoo (Spaulding Collection) | 251 |

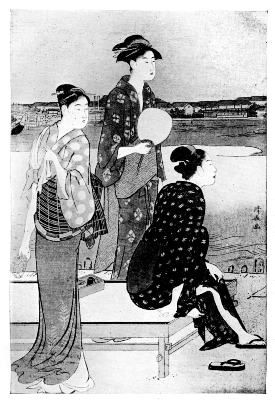

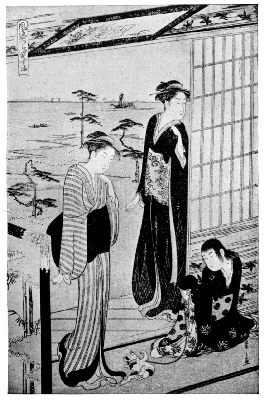

| 35. | Yeishi: Three Ladies by the Seashore | 267 |

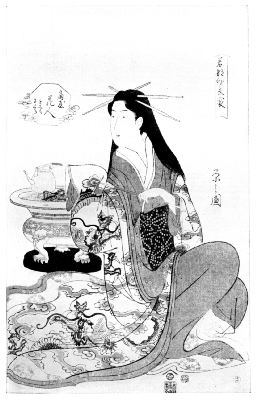

| 36. | Yeishi: Lady with Tobacco-pipe | 271 |

| 37. | Yeishi: Interior opening on to the Seashore (Metzgar Collection) | 275 |

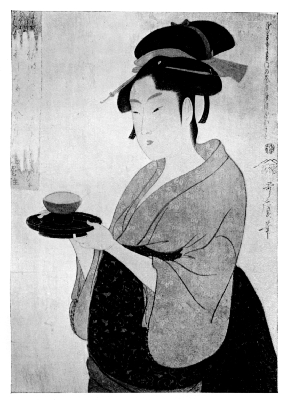

| 38. | Utamaro: Okita of Naniwaya, a Tea-house Waitress (Chandler Collection) | 283 |

| 39. | Utamaro: Two Courtesans | 287 |

| 40. | Utamaro: Woman Seated on a Veranda | 291 |

| 41. | Utamaro: A Youthful Prince and Ladies | 295 |

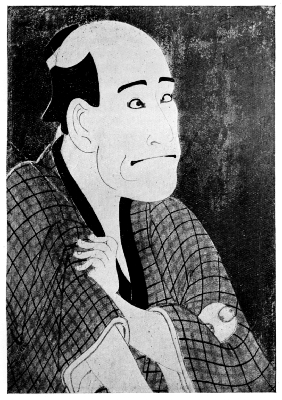

| 42. | Sharaku: The Actor Arashi Ryuzō in the rôle of one of the Forty-seven Ronin (Spaulding Collection) | 301 |

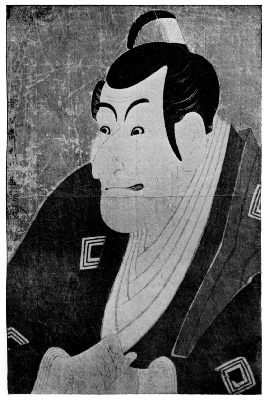

| 43. | Sharaku: The Actor Ishikawa Danjuro in the rôle of Moronao | 309 |

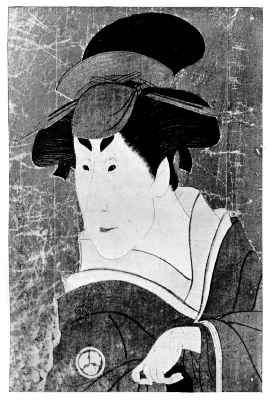

| 44. | Sharaku: The Actor Kosagawa Tsuneyo as a Woman in the Drama of the Forty-seven Ronin (Ainsworth Collection) | 313 |

| 45. | Choki: Courtesan and Attendant | 321 |

| {18}Shunman: Two Ladies under a Maple-tree | 321 | |

| 46. | Choki: A Courtesan and her Lover | 325 |

| Choki: A Geisha and her Servant carrying Lute-box | 325 | |

| 47. | Toyokuni: Ladies and Cherry Blossoms in the Wind (Metzgar Collection) | 333 |

| 48. | Toyohiro: A Daimyo's kite-party | 341 |

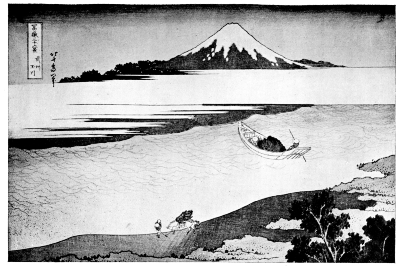

| 49. | Hokusai: Fuji, seen across the Tama River, Province of Musashi | 361 |

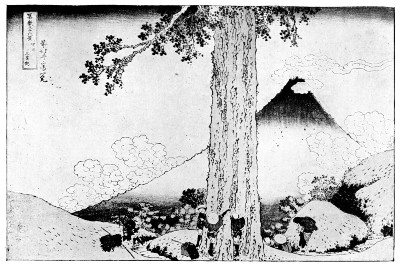

| 50. | Hokusai: Fuji, seen from the Pass of Mishima, Province of Kahi | 367 |

| 51. | Hokusai: The Monkey Bridge; Twilight and Rising Moon | 371 |

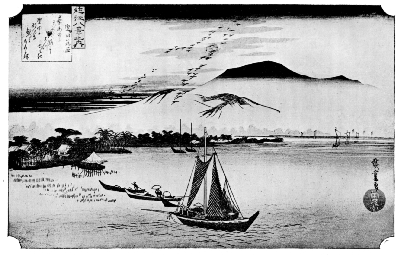

| 52. | Hiroshige: Homing Geese at Katada; Twilight | 377 |

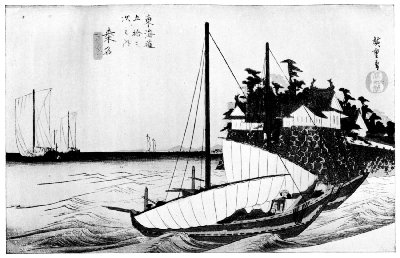

| 53. | Hiroshige: The Seven Ri Ferry, Kuwana, at the Mouth of the Kiso River; Sunset | 383 |

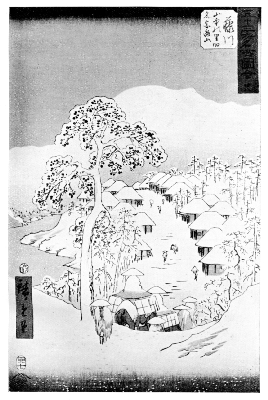

| 54. | Hiroshige: The Village of the Fuji Kawa; Evening Snow | 387 |

| 55. | Hiroshige: The Ommaya Embankment, on the Sumida River at Asakusa; Evening | 391 |

| 56. | Hiroshige: Bird and Flowers | 395 |

Beni.—A delicate pink or red pigment of vegetable origin.

Beni-ye.—A print in which beni is the chief colour used. The term is generally employed to describe all those two-colour prints which immediately preceded the invention of polychrome printing.

Chuban.—A vertical print, size about 11 × 8, sometimes called the "medium size" sheet.

Diptych.—A composition consisting of two sheets.

Gauffrage.—Printing by pressure alone, without the use of a pigment, producing an embossed effect on the paper.

Hashira-ye.—A very tall narrow print, size about 28 × 5, used to hang on the wooden pillars of a Japanese house; a pillar-print.

Hashirakake.—See hashira-ye.

Hoso-ye.—A small vertical print, size about 12 × 6.

Kakemono.—A painting mounted on a margin of brocade; hung by its top when in use, and rolled up when not in use.{20}

Kakemono-ye.—A very tall wide print, size about 28 × 10.

Key-block.—The engraved wooden plate from which the black outlines of the print were produced.

Kira-ye.—A print with mica background.

Koban.—A vertical print slightly smaller than the Chuban (q.v.).

Kurenai-ye.—A hand-coloured print in which beni is chiefly used.

Mon.—The heraldic insignia used by actors and others as coat-of-arms; generally worn on their sleeves.

Nagaye.—See hashira-ye.

Nishiki-ye.—Brocade picture—a term used at first to describe the brilliant colour-inventions of Harunobu, but now loosely applied to all polychrome prints.

Oban.—A large vertical print, about 15 × 10—the normal full-size upright sheet.

Otsu-ye.—A rough broadsheet painting, of small size, on paper; the precursor of the print.

Pentaptych.—A composition consisting of five sheets.

Pillar-print.—See hashira-ye.

Sumi.—Black Chinese ink.

Sumi-ye.—A print in black and white only.

Surimono.—A print, generally of small size and on thick soft paper, intended as a festival greeting or memento of some social occasion.{21}

Tan.—A brick-red or orange colour, consisting of red oxide of lead.

Tan-ye.—A print in which tan is the only or chief colour used. Such prints, in which the tan was applied by hand, were among the earliest productions.

Triptych.—A composition consisting of three sheets.

Uchiwa-ye.—A print in the shape of a fan.

Urushi.—Lacquer.

Urushi-ye.—A print in which lacquer is used to heighten the colour. The term is generally employed to describe only the early hand-coloured prints in which lacquer, colours, and metallic dust were applied to the printed black outline.

Yokoye.—A large horizontal print, about 10 × 15—the normal full-size landscape sheet.

I

PRELIMINARY

SURVEY

THE GENERAL NATURE

OF JAPANESE PRINTS

GROWTH OF INTEREST

IN THEM

THE TECHNIQUE OF

THEIR PRODUCTION

THEIR ÆSTHETIC

CHARACTERISTICS

The general nature of Japanese prints—Growth of interest in them—The technique of their production—Their æsthetic characteristics.

That sublimated pleasure which is the seal of all the arts reaches its purest condition when evoked by a work in which the æsthetic quality is not too closely mingled with the every-day human. Poetry, because of its close human ties, is to a certain extent a corrupt art; its medium is that base speech which we use for communicating information, and few are the readers whose minds can absolve words from the work-a-day obligation of conveying, first of all, mere tidings. Music, on the other hand, employing a medium wholly sacred to its own uses, starts with no such handicap; its succession of notes awakens in the listener no expectation of an eventual body of facts to carry home. Between the two extremes lie the graphic arts. These are perhaps most fortunate when they deal with material not familiar to the spectator, for it is then that he most readily accepts them as designs and harmonies, without looking to them for a literal record of things only too well known to him.{26}

The graphic art of an alien race has therefore an initial strength of purely æsthetic appeal that a native art often lacks. It moves free from the demands with which unconsciously we approach the art of our own people. It stands as an undiscovered world, of which nothing can logically be expected. The spectator who turns to it at all must come prepared to take it on its own terms. If it allures him, it will do so by virtue of those qualities of harmony, rhythm, and vision which in these strange surroundings are more perceptible to him than in the art of his own race, where so many adventitious associations operate to distract him. Like a man whom Mayfair bewilders with its fashions, he may find that fundamental verity, that humanity which he seeks only among the Gipsy beggars.

Perhaps this theory best explains the impulse that has of late led many lovers of beauty to turn to the arts of Persia, China, and Japan for their keenest pleasure. Here, in unfamiliar environment, the fundamental powers of design stand forth free. Here the beautiful is discoverable for its own sake, liberated from the oppression of utility.

Toward Japan this impulse has in our own day been strongly directed. The handicrafts of the Japanese people have charmed the Western world, possibly to an undue extent. On the other hand, the great classical schools of Japanese painting have unfortunately been difficult of access. But between the two, half craft and half art, lies the Japanese colour-print—a finer product than mere dexterous artizan work, and more accessible than the paintings{27} of the classic masters. In the print many a Western mind has found its clearest intimation of the universal principles of beauty.

During a period of a little more than a hundred years, roughly delimited by 1742 and 1858, there were produced in Japan large numbers of wood-engravings, printed in colours; these have of late come to occupy an almost unique place in the esteem of European art-lovers. So great is the importance now attached to these works that the Japanese public of earlier days, for whose delectation they were designed, would be astounded could they witness it. Just as obscure Greek potters moulded for common use vases that are to-day treasured in the museums as paradigms of beauty, so the coloured broadsheets, whose immediate purpose was to give pleasure to the crowds of the Japanese capital, have taken in the course of years a distinguished rank among the beautiful things of all time.

The day is passing when the love of these sheets can be looked upon as the badge of a cult, the secret delight of far-searching worshippers of the strange and exotic. Even did the collector desire, he could not long hide this light under a bushel; and the Japanese print is swiftly becoming a general treasure. This is proper and natural. An understanding of the origin of this form of art makes its present popularity in Europe seem like the felicitous rounding of a circle begun on the other side of the world.

It was in Yedo, the teeming capital of Japan, that the art of the colour-print flourished; and the patron sought by the artists was primarily the common man.{28} No art more purely national or more definitely popular and exoterical in its inception has ever existed. The subjects of the prints are alone enough to make this fact evident. In them appear the forms and faces of the popular actors in their admired rôles, fashionable courtesans decked in all the splendour of their unhappy but far-famed days and nights, legendary heroes, dancers, wrestlers, and popular entertainers. In the matter of landscape, the scenes shown are the festival-crowded temples of Yedo, the sunlit tea-gardens and gay midnight boating-parties of the Sumida River, the great highroads of national travel, the famous spots of popular recreation. Only rarely are there episodes from aristocratic life; and the occasional occurrence of these has precisely the significance of a photograph of a royal house-party shown in a penny paper. The Yoshiwara, as the licensed quarter of Yedo is called, appears in these prints more often than do the garden-parties of noble ladies; the vulgar theatre is shown, but not the classic Nō drama of the aristocracy; it is a Japanese Montmartre, not a Japanese Faubourg St. Germain, that is revealed. The artist's sense of beauty subdues these riotous pleasures of the populace to the severe demands of a beautiful pattern; but it is a whimsical vulgar world, a world of the people, a world of passing gaiety, that he portrays.

The purposes of these pictures were various. "To some extent," says Mr. Frederick W. Gookin, "they were used as advertisements. Incidentally they served as fashion plates. Some were regularly published{29} and sold in shops. Others were designed expressly upon orders from patrons, to whom the entire edition, sometimes a very small one, was delivered. The number struck from any block or set of blocks varied widely. Of the more popular prints many editions were printed, each one, as might be expected, inferior to those that preceded it.... Most of the prints were sold at the time of publication for a few sen. The finer ones brought relatively higher prices, and such prints as the great triptychs and still larger compositions by Kiyonaga, Yeishi, Toyokuni, Utamaro, and other leading artists could never have been very cheap. In general, however, the price was small, and they were regarded as ephemeral things. Many were used to ornament the small screens that served to protect kitchen fires from the wind, and in this use were inevitably soiled and browned by smoke. Others, mounted upon the sliding partitions of the houses, perished in the fires by which the Japanese cities have been devastated; or, if in houses that chanced safely to run the gauntlet of fires, typhoons, cloudbursts, and other mishaps, their colours faded, and their surfaces were rubbed until little more than dim outlines were left."

The plebeian origin of the prints explains why the cultivated Japanese have not, as a rule, looked upon them with much enthusiasm. Only now, when the greatest print treasures have gone out of Japan, are a few Japanese collectors beginning to buy back at high prices works which they allowed to leave the country for a song. The admiration of Europe and America has awakened them to a realization of the{30} distinction of the prints, in spite of the undistinguished nature of their subjects; and the day will come when the Japanese themselves will be the most formidable bidders at the sales of great Western collections.

The interest of Western collectors in Japanese prints is of comparatively recent origin. As late as 1861 it was possible for a writer on Japan to regard them with blank indifference. There is a rare little book by Captain Sherard Osborne, printed in that year in London, called "Japanese Fragments." It contains six hand-coloured reproductions of prints and a number of uncoloured cuts, all from prints which Captain Osborne had purchased in Japan. In the following words he makes reference to Hiroshige, who is now generally ranked as one of the supreme landscape artists of all time: "Even the humble artists of that land have become votaries of the beautiful, and in such efforts as the one annexed strive to do justice to the scenery. Their appreciation of the picturesque is far in advance, good souls, of their power of pencil, but our embryo Turner (i.e. Hiroshige) has striven hard ..." etc. In 1861, perhaps, few people would have believed it possible that to-day many serious judges might question whether any product of European art has ever matched the designs of these "humble artists."

The earliest of European collectors was, according to Mr. Edward F. Strange, a certain M. Isaac Titsingh, who died in Paris in 1812. M. Titsingh had for fourteen years served the Dutch East India Company in Nagasaki; and among his effects were{31} "nine engravings printed in colours." Doubtless he had acquired them merely as curiosities, without any perception of their artistic importance. Mr. Strange notes that four prints were reproduced in Oliphant's "Account of the Mission of Lord Elgin to China and Japan" (1859); and, as we have seen, Osborne devoted some desultory attention to prints in 1861. These are, perhaps, the chief evidences of early European interest.

Subsequently such events as the International Exhibition in London, 1862, the Paris Exposition of 1867 and that of 1878, and the Centennial Exhibition in Philadelphia, 1876, served to bring a few prints to the notice of Western amateurs. Particularly in Paris was intense interest in them aroused among painters and literary men. From 1889 to 1891, S. Bing was bringing out in Paris his magazine Le Japon Artistique, whose pages contain many fine reproductions of notable prints. In 1891, Edmond de Goncourt issued his volume on Utamaro. Other books followed rapidly. In 1895, Professor Anderson issued his small but important monograph on "Japanese Wood Engraving." In 1896, Fenollosa's epoch-making catalogue, "Masters of Ukioye," was published in New York, establishing for the first time the foundations of all our present knowledge of this field, and pronouncing judgments from which the consensus of later opinion has, in the main, never departed. The same year brought forth de Goncourt's "Hokusai." Mr. Strange's "Japanese Colour Prints" appeared in 1897. In the same year, Von Seidlitz issued his "Geschichte des japanischen Farbenholzschnittes"{32} (published in England as "A History of Japanese Colour Prints" in 1900), which remains to-day the most comprehensive and accurate single treatise on the subject.

Of recent years, the growth of interest and the increase of books has been rapid. Eager collectors have scoured the world to bring to light new masterpieces; Japan has been ransacked so thoroughly that the would-be purchaser can perhaps more wisely go to London or Paris or New York than to Tokyo or Kyoto in his search for prizes; and the places of honour accorded these sheets in the portfolios of discriminating collectors and great museums leaves no doubt as to the esteem with which they are regarded. Values have been multiplied by tens and hundreds, so that to-day the supreme rarities among prints are beyond the reach of the ordinary purchaser.

All this is due neither to accident nor to any strange freak of whimsical tastes. It has come about because the prints are in fact artistic treasures. Commonplace and trivial as the subjects of most of them are, they rise by virtue of the quality of their execution to a very high point—masterpieces of composition, triumphs of colour, monuments of the power of human genius to impose its sense of rhythm, form, and harmony on the appearances of the seen world.

But as is true in the case of any art, the content of the colour-prints is not to be grasped at a first glance by the casual passer-by. Familiarity with the aims selected, the conventions employed, and{33} the achievements possible is necessary before the specific charm of these works makes itself manifest. It is the experience of most print-lovers that, starting with perhaps a mere casual liking for a certain landscape design, they progress gradually, in the course of years, to an unmeasured delight in the whole body of prints, and eventually find in them a unique source of repose and exaltation.

There are certain peculiarities, common not only to prints but to Japanese art as a whole, that require a special effort of the Western mind before they become acceptable. The first and most vital of these is the absence of realism. "Throughout the course of Asian painting," writes Mr. Laurence Binyon, "the idea that art is the imitation of Nature is unknown, or known only as a despised and fugitive heresy.... A Chinese critic of the sixth century, who was also an artist, published a theory of æsthetic principles which became a classic and received universal acceptance, expressing as it did the deeply rooted instincts of the race. In this theory, it is rhythm that holds the paramount place; not, be it observed, imitation of Nature, or fidelity to Nature, which the general instinct of the Western races makes the root-concern of art. In this theory every work of art is thought of as an incarnation of the genius of rhythm manifesting the living spirit of things with a clearer beauty and intenser power than the gross impediments of complex matter allow to be transmitted to our senses in the visible world around us. A picture is conceived as a sort of apparition from a more real world of essential life."{34}

It will, therefore, be vain to expect in Japanese designs any production that will astonish the spectator by its life-likeness, its fidelity to an actual scene. Eastern art has never attempted to compete with the work of photography. Its function is the function which the European public grants to poets but not always to painters—the seeking out of subtle and invisible relations in things, the perception of harmonies and rhythms not heard by the common ear, the interpretation of life in terms of a finer and more beautiful order than practical life has ever known.

All Asian art has recognized for centuries the fact that vision and imagination are the faculties by which the painter as well as the poet must grapple with reality. In the words of Mr. Binyon once more—"It is always the essential character and genius of the element that is sought for and insisted on: the weight and mass of water falling, the sinuous, swift curves of a stream evading obstacles in its way, the burst of foam against a rock, the toppling crest of a slowly arching billow; and all in a rhythm of pure lines. But the same principles, the same treatment, are applied to other subjects. If it be a hermit sage in his mountain retreat, the artist's efforts will be concentrated on the expression, not only in the sage's features, but in his whole form, of the rapt intensity of contemplation; toward this effect every line of drapery and of surrounding rock or tree will conspire, by force of repetition or of contrast. If it be a warrior in action, the artist will ensure that we feel the tension of nerve, the heat of{35} blood in the muscles, the watchfulness of the eye, the fury of determination. That birds shall be seen to be, above all things, winged creatures rejoicing in their flight; that flowers shall be, above all things, sensitive blossoms unfolding on pliant, up-growing stems; that the tiger shall be an embodiment of force, boundless in capacity for spring and fury—this is the ceaseless aim of these artists, from which no splendour of colour, no richness of texture, no accident of shape diverts them. The more to concentrate on this seizure of the inherent life in what they draw, they will obliterate or ignore at will half or all of the surrounding objects with which the Western painter feels bound to fill his background. By isolation and the mere use of empty space they will give to a clump of narcissus by a rock, or a solitary quail, or a mallow plant quivering in the wind, a sense of grandeur and a hint of the infinity of life."

This almost symbolic quality is the chief element of the pleasure to be derived from Japanese art. Japanese designs are metaphors; they depict not any object, but remote and greater powers to which the object is related. Often the artist produces his effect by the exaggeration of certain aspects, or by expressing particular qualities in the terms of some kindred thing. If his subject happens to be an actor in some great and tragic rôle, he will not hesitate to prolong the lines of the drapery unconscionably, to give the effect of solemn dignity, slow movement, and monumental isolation. Westerners may smile at the distortion of such a figure; but they must{36} acknowledge that an atmosphere of lofty and special destiny surrounds the form, precisely because the artist has dared to use these devices. The Japanese artist will draw a woman as if she were a lily, a man as if he were a tempest, a tree as if it were a writhing snake, a mountain as if it were a towering giant. This is the very essence of poetical imagination; and the result of it is to endow a picture with obscure suggestions and overtones of infinite power. Symbols of existence beyond themselves, these designs are charged with an almost mystical command upon the emotions of the spectator. Western art has employed such a method comparatively little in painting. In poetry it appears frequently. The poet, when he wishes to convey the impression of a beautiful woman, does not set out her features and her stature and all the details of her aspect. He tries to awaken some realization of her by a bold and fantastic leap of the imagination straight to the heart of the matter—he makes her a perfume, a light, a music, a memory of goddesses.

The prosaic mind will never greatly care for work produced in accordance with this principle; the conventions will seem distortions, the imaginative generalizations will seem inaccuracies, and the transcending of reality to shape a more universal and significant statement will appear nothing more than ineptitude in grappling with fact. But to the poetical mind, all these things will come with a unique and irresistible fascination; and far more delightful than the novelty and interest of the scenes represented will be the manner of their representation.{37} As one enters into the spirit of these paintings and prints, it is as if one saw the world from a new angle, or had acquired the power to assemble into new intellectual combinations those sensory impressions which our own art has taught us to combine in a manner now grown a little dull and stereotyped.

Japanese art has certain conventions that are highly individual. Some of these may trouble and repel the Western eye. For example, the Japanese artist draws his figures without shadows, and makes no attempt to represent the play of light and shade over them. The scene is painted as if in a clear, cold vacuum, where the diffusion of illumination is almost perfectly uniform. In the Japanese view, a shadow is something ephemeral and transitory—a mere accident and illusion, and as such unworthy of perpetuation in art. The pattern of the object itself, freed from this momentary tyranny, should be the sole theme of the artist. Similarly, high-lights or chiaroscuro are not attempted; nor is modelling by means of these employed. A universal flatness is the result—a result deliberately aimed at.

Most of the European ideas of perspective are ignored in these works. In accordance with the ancient Chinese canon—based upon an imaginative and not upon a visual perception—the linear perspective of the Japanese exactly reverses that of Western painting. In their system, parallel lines converge as they approach the spectator. Different planes of distance may be suggested merely by placing the remote plane higher up in the picture; and sometimes no attempt is made to diminish the{38} size of the figures in the upper plane. These devices may seem very naïve to the European. But in aerial perspective—the power to give to objects a colouring appropriate to their relative distance from the eye—the Japanese indisputably employ the utmost subtlety. When these artists differ from European custom, it is not because of ignorance, but because their way seems to them the more expressive—the better adapted to the creation of those peculiar impressions of beauty which are their aim. The longer one examines the products of these alien theories of drawing, the less certain one is likely to be of the superiority of our more scientific Western conventions.

In all Japanese art, the element of pure brushwork is of greater importance than in the art of Europe. The people, trained from childhood in the handling of the brush as a pencil for the drawing of the complex forms of written characters, acquire a facility and accuracy unknown in other lands. Fine caligraphy is esteemed an art in itself. And the Japanese painter, whose life is devoted to further exercises with the brush, may achieve a unique degree of skill. His power to sweep, guide, and modulate the width and intensity of his line is developed into a sixth sense. He can make his brush-stroke smooth-flowing as a violin-note, or splintered as a broken branch, or wavering like the flow of a river, or coldly hard and sharp as flint; sometimes it has the edge of a knife; at other times it dies away into imperceptible gradations; its blacks are dazzling in their intensity, its greys are like veils of mist. The mystery of the{39} expression of pure personality in art is nowhere more strikingly exemplified than here. To the accustomed eye the line-work of the Japanese artist is vibrant with intimate connection between hand and spirit. This command of the brush, so perfect that the passion of the artist's soul flows out through it, is one of the vital characteristics of Japanese painting.

The colour-print is one small and peculiar division of the larger field of Japanese pictorial design; besides being subject to the general laws of Japanese æsthetics, it is distinguished by certain special characteristics that grow out of the nature of the technique employed. Of this technique, Mr. F. W. Gookin gives an illuminating exposition:—

"None but the most primitive methods—or what from our point of view may seem such—were employed. The most wonderful among all the prints is but a 'rubbing' or impression taken by hand from wood blocks. The artist having drawn the design with the point of a brush in outline upon thin paper, it was handed over to the engraver, who began his part of the work by pasting the design face downward upon a flat block of wood, usually cherry, sawn plank-wise as in the case of the blocks used by European wood-engravers in the time of Dürer. The paper was then carefully scraped at the back until the design showed through distinctly in every part. Next, the wood was carefully cut away, leaving the lines in relief, care being taken to preserve faithfully every feature of the brush strokes with which the drawing was executed. A number of impressions were then taken in Chinese ink from this{40} 'key block' and handed to the artist to fill in with colour. This ingenious plan, which is manifestly an outgrowth of the early custom of colouring the ink-prints (sumi-ē) by hand, and which perhaps would never have been thought of had not the colour itself been an afterthought, enabled the artist to try many experiments in colour arrangement with a minimum amount of labour. The colour scheme and ornamentation of the surfaces having been determined, the engraver made as many subsidiary blocks as were required, the parts meant to take the colour being left raised and the rest cut away. Accurate register was secured by the simplest of devices. A right-angled mark engraved at the lower right-hand corner of the original block, and a straight mark in exact line with its lower arm at the left, were repeated upon each subsequent block, and in printing, the sheets were laid down so that their lower and right-hand edges corresponded with the marks so made. The defective register which may be observed in many prints was caused by unequal shrinking or swelling of the blocks. In consequence of this, late impressions are often inferior to the early ones, even though printed with the same care, and from blocks that had worn very little. The alignment will usually be found to be exact upon one side of the print, but to get further out of register as the other side is approached.

"The printing was done on moist paper with Chinese ink and colour applied to the blocks with flat brushes. A little rice paste was usually mixed with the pigments to keep them from running, and to{41} increase their brightness. Sometimes dry rice flour was dusted over the blocks after they were charged. To this method of charging the blocks much of the beauty of the result may be attributed. The colour could be modified, graded, or changed at will, the blocks covered entirely or partially. Hard, mechanical accuracy was avoided. Impressions differed even when the printer's aim was uniformity. Sometimes in inking the 'key block,' which was usually the last one impressed, some of the lines would fail to receive the pigment, or would be overcharged. This was especially liable to happen when the blocks were worn and the edges of the lines became rounded. A little more or a little less pigment sometimes made a decided difference in the tone of the print, and, it may be noted, has not infrequently determined the nature and extent of the discoloration wrought by time.

"In printing, a sheet of paper was laid upon the block and the printer rubbed off the impression, using for the purpose a kind of pad called a baren. This was applied to the back of the paper and manipulated with a circular movement of the hand. By varying the degree of pressure the colour could be forced deep into the paper, or left upon the outer fibres only, so that the whiteness of those below the surface would shine through, giving the peculiar effect of light which is seen at its best in some of the surimono (prints designed for distribution at New Year's or other particular occasion) by Hokusai. Uninked blocks were used for embossing portions of the designs. The skill of the printer was a large{42} factor in producing the best results. Even the brilliancy of the colour resulted largely from his manipulations of the pigments and various little tricks in their application. The first impressions were not the best, some forty or fifty having to be pulled before the blocks would take the colour properly. Many kinds of paper were used. For the best of the old prints it was thick, spongy in texture, and of an almost ivory tone. The finest specimens were printed under the direct personal supervision of the artists who designed them. Every detail was looked after with the utmost care. No pains were spared in mixing the tints, in charging the blocks, in laying on the paper so as to secure perfect register, in regulating the pressure so as to get the best possible impressions. Experiments were often tried by varying the colour schemes. Prints of important series, as for example Hokusai's famous 'Thirty-six Views of Fuji,' are met with in widely divergent colourings."

The results produced by this technique, as it was employed in the great period of the art, have no parallel. When Dürer, in the fifteenth century, brought wood and steel engraving to such brilliant perfection, he determined the future history of European engraving, fixing the line of greatest development in the region of black-and-white, where, except for sporadic excursions of debatable merit, it has continued ever since. Fortunately, in Japan, colour and line did not part company, but in combination progressed toward a unique triumph.

A print produced by this technique is simply a{43} sheet of paper upon which are impressed, by means of hand-charged wood blocks, a series of patches of colour that combine into a design. In general, each of these patches is flat and unshaded; its edges are sharp, definite, bounded by a line as distinct as the line of the lead used in stained glass. In the print, as in the stained-glass window, only major lines and important colour-masses can be shown; thus elimination of the incidental and selection of what is vital are imperatively demanded of the designer. Salient curves and expressive outlines are the essential requisite. One reason why these prints seem classic is that they are purged of the thousand unimportant and meaningless gradations of tone that are easy to use in a painting and impossible here. Singular purity and loftiness of effect is the result, together with a certain abstract aloofness from reality that has a high æsthetic value.

Into the drawing of these few lines, and into the construction of these few flat colour-spaces, went all the artist's sense of proportion and rhythm, grace and dignity, movement and tone. On the flat wall of his printed sheet he devised a pattern that should weave, out of figures and objects, a decorative design upon whose harmonious mosaic the eye would willingly linger. There he played his music to allure and beguile and absorb the spectator.

Like his fellow-painters of all Asia, the print-designer did not feel that literal accuracy greatly concerned him. If the figures moved with a stately godlike grace in rhythmic procession, what matter if they were taller or shorter than real beings? If{44} their faces were expressive of a noble calm or a sublime fury, why ask for a detailed mirroring of a real face? If the landscape was beautiful, was it important that the real scene could never look exactly thus?

As an example of the curious conventions that dominate this art, the observer will note the way in which heads are drawn by these artists. With very rare exceptions, the angle from which all the heads are seen is the same. In the print, as in the Egyptian wall-carvings, the head is held in a poise dictated by a traditional formula. The face is turned half-way between profile and full-face; the nose approaches but does not intersect the line of the cheek; the outline of the nose is shown, and also the broad sweep of the brow, while at the same time both eyes are visible. For two centuries, with only occasional variations, this formula for drawing the face persisted; and in the submission to this wisely chosen type—admirably adapted as it was to exhibit most expressively the whole map of the features—is revealed something of that willingness to accept discipline, style, and conventionalization which in these artists went side by side with so much originality.

A magic world—a pure creation of the imagination in its search for beauty! This convention in the drawing of the faces has much to do with the unreal quality we find there. Something in the repetition and uniformity of the heads produces a delicate visionary impression, a trance-like mood—as does the rhythm of poetry or music. Under its spell{45} the emotion of the spectator comes forth free from its daily bonds and preoccupations, in the liberation that only art can give.

To these regions of pure æsthetic experience the amateur turns with delight—not only as an escape from practical life, but as an escape from much that is known to the Western world as art. The childish mind loves pictures that tell a story; but the more sophisticated intelligence goes to a work of art for those elements which lie far beyond the region of episodic narration—elements that are allied to the principles of geometry, the laws of motion, the excursions of pure music, the visions of religious faith. Though these manifestations are difficult to correlate, they all arise from one fountainhead; and the best of the Japanese prints lie very close to the source of the stream.{47}

II

CONDITIONS

PRECEDING THE RISE

OF PRINT-DESIGNING:

THE BIRTH OF

THE UKIOYE SCHOOL

At the outset of the seventeenth century was inaugurated the Tokugawa Dynasty of Shoguns or military dictators, by the victories of the great warrior and statesman Iyeyasu over rival factions. Upon acquiring the Shogunate—a position which had for long eclipsed the power of the Emperor—Iyeyasu laid a wise but iron hand upon Japan, forcing all departments of industry, society, and even art into rigid forms whose pattern was laid down by his far-seeing mind. The same policy guided his successors of the Tokugawa Dynasty; so that during the whole period of print production Japan was a land of gorgeous feudal splendour, regulated by inflexible rules of conduct and manners that amounted almost to caste regulations.

That subtle interpreter of the ideals of the East, the late Kakuzo Okakura, thus analyses the state of society at that time: "The Tokugawas," he writes, "in their eagerness for consolidation and discipline, crushed out the vital spark from art and life....{50} In their prime of power, the whole of society—and art was not exempt—was cast in a single mould. The spirit which secluded Japan from all foreign intercourse, and regulated every daily routine, from that of the daimyo to that of the lowest peasant, narrowed and cramped artistic creativeness also. The Kano academies of painting—filled with the disciplinary instincts of Iyeyasu—of which four were under the direct patronage of the Shogun and sixteen under the Tokugawa Government, were constituted on the plan of regular feudal tenures. Each academy had its hereditary lord, who followed his profession, and, whether or not he was an indifferent artist, had under him students who flocked from various parts of the country, and who were, in their turn, official painters to different daimyos in the provinces. After graduating at Yedo (Tokyo), it was de rigueur for these students, returning to the country, to conduct their work there on the methods, and according to the models given them during their instruction. The students who were not vassals of daimyos were, in a sense, hereditary fiefs of the Kano lords. Each had to pursue the course of studies laid down by Tannyu and Tsunenobu, and each painted and drew certain subjects in a certain manner. From this routine, departure meant ostracism, which would reduce the artist to the position of a common craftsman."

Yet it would convey a wrong impression of the Tokugawa period to suggest that bureaucratic tightness of regime was its sole or most vital characteristic. The age was marked as strongly by its{51} expansive powers as by the restraints that attempted to direct them. For in this epoch, the common people, set apart in a class distinct from the warriors and aristocracy, rose to a vigour and cultivation that was almost a new thing in Japanese history. "It was," writes Fenollosa, "like the rise of the industrial classes in the free cities of Europe in those middle centuries when the old feudal system was breaking up. There, too, could be seen armoured lords of castles flourishing side by side with burghers and guilders. It is the same duality which forms the keynote of Tokugawa culture taken as a whole.... The keynote of Tokugawa life and art is their broad division into two main streams—the aristocratic and the plebeian. These two flowed on side by side with comparatively little intermingling. On the one side select companies of gentlemen and ladies congregated in gorgeous castles and yashikis, daimyos and samurai, exercising, studying their own and China's past, weaving martial codes of honour, surrounding themselves with wonderful utensils of lacquer, porcelain, embroidery, and cunningly wrought bronze; and on the other side great cities like Osaka, Nagoya, Kyoto, and Yedo, swarming with manufacturers, artizans, and merchants, sharing little in the castle privileges, but devising for themselves methods of self-expression in local government, schools, science, literature, and art."

Examining into the history of Japanese colour-prints, one must leave entirely aside the interesting and sometimes sublime art of the cultivated and aristocratic classes and their tradition-hallowed{52} schools of painting. The prints were solely the product of the popular school; they were in a way allied to those delicate Japanese handicrafts, such as bronze and lacquer, which are characteristically the output of the common people.

The Tokugawa regime was one of national peace. The country, long disturbed by both internal and external wars, settled down at last under the strong Tokugawa banner to two centuries and a half of tranquillity. The vital activity of this time was not diffused and scattered over the whole country, but was chiefly centred upon one spot, the ancient "Capital of the East," Yedo, now called Tokyo. Here, under the dominance of the great Iyeyasu, the life of the empire was brought to a focus. Iyeyasu forced all the great nobles, living customarily on their estates scattered throughout the empire, to come to Yedo and remain there in residence for at least half of each year, in order that he might keep his hand upon them and prevent them from springing up to rival power. The natural effect of this regulation was to give Yedo a supreme importance in the realm, and to cultivate in Yedo the growth of every form of popular activity. There, in the metropolitan centre, all the agencies of pleasure burst into luxurious bloom; the tea-houses, the theatres, the riverside gardens, and the Yoshiwara or courtesans' quarter, all took on a new and alluring splendour; and Yedo became the great city and the great art centre of Japan.

At this time, aristocratic art, in the hands of the later generations of the Kano School of painters,{53} was not only largely inaccessible to the common people, but was also no longer in its prime. The giants of the Kano School were long since dead. In the place of their vigorous inspiration only superficiality and formalism remained. Long since dead was that lofty idealistic art, best known to us in the work of Sesshu, which had distinguished the preceding Ashikaga Period—an art which, to quote Mr. Laurence Binyon, "deals little in human figures and has no concern with the physical beauty of men and women, contenting itself mainly with the contemplation of wide prospects over lake and mountain, mist and torrent, or a spray of sensitive blossoms trembling in the air." Yet even though the earlier greatness of the aristocratic schools of painting was passing or had passed in this seventeenth and eighteenth century epoch, still the authority derived by the Kano painters from their connection with the court of the Shogun gave them dictatorship over matters of art; and their academy imposed its technique upon all aspirants for the favour of the aristocracy. The rival school of the Tosas, associated closely with the court of the Emperor in Kyoto, was no less careful of tradition and discipline. Thus the moribund art of the upper classes stood alone like a little island, shut out from the art of the people, unable to influence it or to be influenced by it.

Therefore Japan, at the time when the popular school came into existence, was in a curious state: subject to a strict disciplinary system that kept the common people and the aristocracy apart; enjoying{54} a period of peace and a centralization of resources that gave the common people in their isolation a favourable opportunity to develop a culture of their own; and suffering from a growing degeneracy in the classical schools of painting that might be counted on to drive at least an occasional aristocratic artist out into the ranks of the people were any interesting opportunity offered there.

At this juncture, early in the seventeenth century, there arose in Yedo a new movement which later was to produce the colour-print.

This new movement was called the Ukioye School. The real gap between it and the older classical schools has been by many writers grossly exaggerated. One might well gather from them that the Ukioye artists were the first in all Japanese art to draw subjects selected from real life and to paint with vivid humanism. This is by no means the fact. All the subjects treated by the Ukioye painters had been at some time used by the painters of the older schools; and certainly the usual subject of the Kano or Tosa painter was as real and vivid to him as were any of the themes of the popular artists to these creators. Each painted his customary environment—what was closest to his experience and dearest to his æsthetic perceptions: on the one hand, traditionary and religious figures, scenes from poetry, reflections of Chinese or old Japanese art; and on the other hand, the pulsing life of Yedo streets, the tea-gardens of the Sumida River, the theatres, and the brilliant houses of pleasure. Yet having suggested that the gap between{55} the two was not immeasurable, we may grant that it was nevertheless real. Ukioye concerned itself with contemporary plebeian life, its shows and festivals and favourites of the hour, to an extent alien to the more restrained and almost monastic tradition of the older art. Ukioye means "Passing-world Picture"; there is implied in the word a reproach and an accusation of triviality. It suggests values not recognized by that orthodox Buddhistic attitude of contemplation which regards life as a show of shadows, a region of temporal desire and illusion and misery, a vigil to be endured only by keeping fixedly before the vision pictures of the desireless calm of Nirvana. But no such profound philosophy of despair and abnegation as this could find real root in the hearts of a lively populace like that of Japan; in that nation, the lonely minds of sequestered aristocrats alone could give it more than nominal habitation. The Ukioye School, since it was a popular school, remained as unshadowed by Buddhism as modern French poster-art is by Christianity; and the distance between the spiritual attitudes of Giotto and Aubrey Beardsley is no greater than that between the attitudes of Kanaoka and Utamaro. All that aureole of moral idealism which hallowed the classical Japanese art was abandoned by the popular school for a frank acceptance of the joy of the world and its enthralling lures.

The style adopted by the new school in portraying the life of the multitude allowed itself a certain keen realism, often tinged with humour and sometimes with mild obscenity. This realism appears only{56} occasionally, and it is generally so completely subordinated to the decorative impulse that realism is the last word by which a Western observer would describe it. Only by way of contrasting it with the idealism of the older schools can one thus classify the arbitrary attitudes, mask-like faces, and fanciful colour schemes of Ukioye. This arbitrariness indicates another characteristic of the new manner. It was a flippant style which took nothing seriously except itself. Its technique departed from the sacred traditions of Kano and Tosa brushwork and the inheritance of Chinese painting canons. It developed a novel use of clear, hard outline, unrestrained sweep, brilliantly fresh colour, and strong contrast, that relied on no precedent for their appeal and awakened no sanctioning echo from the classic masters.

Not unnaturally the aristocracy were repelled by the plebeian and vulgar nature of the subjects of the new school. Their sensibilities were injured by the throwing overboard of traditions of style that stretched back through many centuries to the founders of the art in China, and by the genuine lack of distinction in the spiritual attitude and outlook of many of these new painters. The modern European, bred of a different artistic lineage, may regard these objections as negligible; but he must remember that it is perhaps his own ignorance of Japanese classics that makes him so tolerant; and he may properly hesitate to condemn hastily the aristocratic Japanese opinion.

The aristocratic opinion is readily comprehensible. The Ukioye School without doubt lacks that almost{57} religious idealism by which the earlier Japanese schools of painting attained a subtlety perhaps excessively rarefied, an allusiveness almost too remote, a sublimation of intangible spiritual values that very nearly reaches the vanishing-point. No such serene cultivation of feeling is to be found in the Ukioye painters. "Great art is that before which we long to die," says Okakura; and the overstrained intensity of his words conveys to the Westerner some conception of the passionate spirituality which the cultivated Japanese desires and finds in the works of the older painters. The Japanese connoisseur misses in Ukioye that exaltation which, in the creations of Sesshu or Yeitoku or Kanaoka, leads him up to heights whence he surveys mountain and lake lying like a visionary incantation before him, or feels the giant loneliness of pines upon a snowy crest, or enters into the ineffable spirit of the white goddess Kwannon meditating in a measureless void of clouds and streams.

These things are not to be found in Ukioye—these ultimate reaches of the Oriental spirit; but there is here a more human and lovable beauty, and a power of design no less notable than that of the aristocratic masters.

It must be granted that the colour-prints of this school constitute the fullest and most characteristic expression ever given to the temper of the Japanese people. Asia—the region of measureless, overwhelming spaces, innumerable lives, and immemorial antiquity—Asia speaks in the older paintings; but in the amiable prints, the one voice is the defined,{58} circumscribed, and beguiling voice of Japan. The colour-print constitutes almost the only purely Japanese art, and the only graphic record of popular Japanese life. Therefore it may be regarded as the most definitely national of all the forms of expression used by the Japanese—an art which they alone in the history of the world have brought to perfection.

The beginnings of the Ukioye School antedated by many years the beginnings of colour-printing. Iwasa Matabei, the founder of the school, was born in 1578 and died in 1650. At first it was the aristocracy that applauded this pioneer, who was not yet alienated from them; then some vital element in Matabei's manner kindled enthusiasm outside this circumscribed region and set in motion the forces which eventually resulted in a popular school of art.

After Matabei, the Ukioye School did not take any immediate turn toward notable development. In fact, it is doubtful whether its importance could have been far-reaching had its activity been always, as in its earliest days, confined to painting. It was, however, the destiny of the school to come into a relation with the hitherto undeveloped art of wood-engraving; and its alliance with this popular medium increased a thousand-fold the breadth of its appeal and the force of its sway.

The art of wood-engraving in Japan originated some time between the twelfth and fourteenth centuries. Legend associates the first use of it with the great priest Nichiren, who lived from 1222 to 1282. Ryokin, also a priest, produced a woodcut which is dated 1325. No date earlier than this last can{59} be fixed upon with any confidence. The few specimens of early woodcuts that have survived are pious Buddhistic representations of religious paintings or statues, which were probably sold to pilgrims as mementoes of their visit to some famous shrine. In artistic merit these earliest woodcuts have no interest; their importance is entirely historical.

By the end of the sixteenth century the process of wood-engraving had come into use as a means of illustrating books. From this time on, mythological, romantic, and legendary works, such as the "Ise Monogatari," were frequently so embellished. Most of the designs were very crude, and the cutting of the wood blocks displayed only elementary skill. These early books were in no way connected with the Ukioye School, which they in fact antedated; they were wholly the product of the old classical tradition. Contemporaneously with them were produced fairly vigorous but clumsy broadsides, representing historical scenes. Occasionally a few spots of coarse colour were applied by hand to these designs.

By the middle of the seventeenth century there began to appear illustrated books in which the rudimentary elements of artistic pictorial feeling are visible. A few have a slight Ukioye cast. Not until the last quarter of the century, however, did wood-engraving achieve the dignity of a fine art and the scope of a popular method of expression. That it then did so was due to the genius of Moronobu, an Ukioye painter, the first of the great print-designers.{61}

III

THE FIRST

PERIOD:

THE PRIMITIVES

FROM MORONOBU

TO THE INVENTION

OF POLYCHROME PRINTING

(1660-1764)

From Moronobu to the Invention of Polychrome Printing (1660-1764).

The Primitive Period, first of those epochs into which the history of Japanese prints may be roughly divided, begins about 1660 with the appearance of the work of Moronobu. The period ends a century later when, after many experiments, the technique of the art had been developed from the black-and-white print to the full complexity of multi-colour printing.

The commonly accepted name of "the Primitives" requires some explanation when applied to these artists lest it create the impression that we are dealing with designers in whose works are to be found the naïve efforts of unsophisticated and groping minds. Nothing could be farther from the truth. Thousands of years of artistic experience and tradition lay back of these productions; and the level of æsthetic sophistication implied in them was high. The word Primitive applies to these men only in so{64} far as they were workers in the technique of wood-engraving. As producers of prints they were indeed pioneers and experimenters; but as designers they were part of a long succession that had reached full maturity centuries earlier.

Whether it be that a new technical form, like an unexplored country, tends to exclude from entrance all but bold and vigorous spirits, or whether it be that the stimulus of difficulty and discovery inspirits the adventurer with keener powers, these Primitives were as a group surpassed by none of their successors in force and lofty feeling. They seized the freshly available medium with an exuberance of vitality that had not yet lost itself in the deserts of a fully mastered technique.

"These Primitives," says Von Seidlitz, "are now held in far higher esteem than formerly. We recognize in them not only forerunners, but men of heroic race, who, without being able to claim the highest honours paid to the gods, still exhibit a power, a freshness, and a grace that are hardly met with in the same degree in later times. Despite the imperfections that necessarily attach to their works, despite their lack of external correctness, their limitations to few and generally crude materials, and their conventionalism, there clings to their work a charm such as belongs to the works neither of the most brilliant nor of the pronouncedly naturalistic periods. For, in the singleness of their efforts to make their drawing as expressive as possible, without regard to any special kind of beauty or truth, these Primitives discover a power of idealization and{65} a stylistic skill which, at a later period and with increased knowledge, are quite unthinkable."

To the new Ukioye School these Primitives gave the first great opening for popularity. Their broadsides and albums disseminated among the millions of Yedo the product of the new and vigorous art-impulse. They were the river-streams through which the lake reservoirs of Ukioye art returned to the sea of popular life whence the waters had come.

Fenollosa's picture of the popular life during a portion of this Primitive Period, the Genroku Era (1688-1703), is not without its significance in this connection. "This was the day when population and arts had largely been transferred to Yedo, and both people and samurai were becoming conscious of themselves. The populace of the new great city, already interested in the gay pleasures of the tea-houses and the dancing-girls' quarter, were just elaborating a new organ for expression, namely the vulgar theatre, with plays and acting adapted to their intelligence. They had just caught hold, too, of the device of the sensational novel. Now here was an army of young samurai growing up in the neighbouring squares, who were just on the qui vive to slip out into these nests of popular fun. For the time being, freedom for both sides was in the air. Anybody could say or do what he pleased. Fashions and costumes were extravagant. Everybody joined good-naturedly in the street dances. It was like a world of college boys out on a lark; to speak more exactly, it had much resemblance to the gay, roistering, unconscious mingling of lords and people in the{66} Elizabethan days of Shakespeare, before the duality of puritan and cavalier divided them."

The subjects depicted by the Primitive artists for the pleasure of this populace are drawn from the flourishing life thus described. First and foremost, the stage is represented; and the greatest prints of this period are, as a rule, the single figures of actors portrayed in their rôles. But social and domestic scenes also find place here; and all the play of fashion and recreation, the occupations and amusements of the ladies, the boating-parties and tea-house scenes, the street and the festival, appear in brilliant succession.

In the general style of their designs the Primitives were all controlled by one fundamental aim—that of decoration. This dominating quality appears most clearly in the large actor-prints which we associate with the names of Kwaigetsudō, Kiyonobu, Masanobu, and Toyonobu. To an extent greater than the artists of any succeeding period they eschewed minuteness of detail and accuracy of representation, sacrificing these things for the sake of achieving broad decorative effects combined with vigorous movement. A certain unique simplicity and grandeur in the spacial and linear conceptions of these men gives to the whole Primitive Period a Titanic character that distinguishes it. In the best works of this time the stylistic finish of the drawing is masterful. It translates motion into sweeping caligraphic lines, and creates imposing calm by the poise and balance of severe black-and-white masses. Just as in opera the flow of music induces in the{67} auditor a state of semi-trance that makes him oblivious to the patent absurdities and unrealities of the action, so in these pictures the rhythmic flow of the composition lifts the consciousness of the spectator to a plane where it ceases to take note of the incorrect report of Nature and loses itself in the enjoyment of the noble decorative conceptions that actuate the creating hand.

A profound formalism dominates these works. The figures are purely one-dimensional; the picture is a flat pattern of lights and darks bounded by the sharp outline of great curves. In the actor-pieces no real portraiture of the actor as an individual is essayed; the artist's aim is rather to convey some sense of the dynamic power of the rôle in which the actor appears. He succeeds so well that his pictures, though not representations of individuals, stand as abstract symbols of grace or of power.

Historically, one of the chief interests in this period centres upon the notable developments in technique. Wood-engraving was, as we have seen, already known when the period opened; but it had not yet been subjected to the purposes of the artist. Confined almost exclusively to crude book illustrations, it had as little artistic significance as the cheap hand-painted sketches called otsu-ye, which, produced by hundreds, were sold for the amusement of the populace.

With the advent of the gifted Moronobu, the book-illustration was transformed into an important and beautiful creation. Going further, Moronobu and his successors produced single-sheet prints of large size,{68} in black and white only, that served all the purposes of paintings and were capable of being reproduced without limit. These black-and-white prints were called sumi-ye (Plate 1). Books and albums by him appeared at various earlier dates, but the first of his single-sheet prints was issued about 1670.

The second step in development came with the realization that the brilliant colour of the older otsu-ye could easily be imparted to the new prints. So some of the sheets of Moronobu and his contemporaries were coloured by hand with orange, yellow, green, brown, and blue, somewhat after the manner used by the painters of the classical Kano School. In the actor-prints there began to appear, shortly after 1700, solid masses of orange-red pigment. These sheets were called tan-ye, from the tan or red lead used in them. About 1710 citrine and yellow were used in connection with the tan (Plate 2). By 1715 or a little later, beni, a delicate red colour of vegetable origin, was discovered, and almost entirely replaced the cruder tan. Prints thus coloured were called kurenai-ye.

About 1720 it was found that the intensity of the colouring could be enhanced by the addition of lacquer. Red, yellow, blue, green, brown, and violet were used in brilliant combination; and their tone was heightened by painting glossy black lacquer on the black portions of the picture, and sprinkling some of the colours with sparkling powdered gold or mother-of-pearl. Such prints were called urushi-ye, or lacquer-prints (Plate 5).{69}

These various methods of hand-colouring prevailed up to about the year 1742. At this time, a method was perfected by which two colour-blocks could be used in printing; and the true colour-print came into existence. Masanobu is generally credited with being the inventor of the new technique. The first colours employed were green and the red known as beni; and from this the prints derived their common name of beni-ye (Plate 6). Later many varieties of colour were tried. To some print-lovers, these two-colour prints seem unequalled in beauty.

About 1755 a method was devised by which a third colour-block could be employed, and blue was the colour at first selected to accompany the original green and red. Then blue, red, and yellow were used, and other variations; and in the hands of such men as Toyonobu and Kiyomitsu, rich decorative effects resulted (Plate 7).

To the end of the period hand-colouring was still occasionally used for large and important pieces such as pillar-prints; but the old method lost ground steadily, and the day of the polychrome-print was at hand.

To give in more detail the history of this period, the strict chronological method must be abandoned; and each of the important artists must be taken up in turn as an independent creator.

Hishikawa Moronobu, born probably in 1625, was the son of a famous embroiderer and textile designer who lived in the province of Awa. Moronobu worked{70} at the trade of his father during his youth, obtaining thus a training in decorative invention that is traceable in all his later work. Upon the death of his father, he came to Yedo and took up the study of painting under the masters of the Tosa and Kano Schools. Gradually, however, the Ukioye style, introduced by Matabei some years before, became his chosen province; and from painting he turned to the designing of woodcuts for book illustrations and broadsheets. Later in life he became a monk; and died probably in 1695, though some authorities say 1714.

Moronobu's importance in the history of Japanese prints is twofold. He inspirited the Ukioye School with a new vitality; and he turned wood-engraving into an art.

The Ukioye movement, when Moronobu appeared, was still indeterminate. A great personality was needed to crystallize the vague tendencies then in solution. This Moronobu accomplished; and the far-reaching effect of his work was due to the fact that he did not confine his work to painting, but took up the hitherto unexplored field of woodcuts. As we have seen in the previous chapter, there had been produced up to Moronobu's time no illustrated book that could lay claim to artistic value. The little that had been done in this field was crude{73} artizan work without charm. Now Moronobu seized this medium and transformed it. Into his woodcuts he poured that powerful sense of design which he so notably possessed, creating real pictures of striking decorative beauty. These books and prints, widely circulated, carried to the eyes of the masses a new and delightful diversion, spreading far and near the contagious fascination of this lively Ukioye manner of drawing and awakening in the populace a thirst for more of these productions. Matabei had devised the new popular style, but it was Moronobu who threw open the gates of this region to the people.

Moronobu's first books appeared about 1660, and from that date to the time of his retirement he brought out more than a hundred books and albums and an unknown number of broadsheets. In all of these his vigorous, genial personality and his strong sense of decoration make themselves felt. Such a print as the album-sheet reproduced in Plate 1 exhibits his characteristic simplicity of sweeping line, the masterly use he makes of black and white contrasts, and the vivid force of his rendering of movement. The firm lines live; the composition is grouped to form a harmonious picture; a dominating sense of form has entered here to transform the chaotic raggedness of his predecessors' attempts. Distorted as these figures may appear to unaccustomed Western eyes, they have unmistakable style and their bold command of expression is the first great landmark in Japanese print history.

All of Moronobu's work was printed in black and white only, but occasionally the sheets were roughly{74} coloured by hand after they had been printed. His designs have little detail; as a rule the scene surrounding his main figures is barely suggested by a few lines; and the figures themselves are hardly more than intense shorthand notations of a theme. But how much life he gives them! No wonder that the populace loved his work, and that his many pupils bore away with them to their own productions the impress of his strong personality and animated style.

Certain of Moronobu's large single-sheet compositions (such as the Lady Standing Under a Cherry Tree, in the Buckingham Collection, Chicago, or the noble Figure of a Woman in the Morse Collection, Evanston), display so fine a power of composition and so unsurpassable a mastery of rhythmic line that there can be no hesitancy in judging him, quite apart from his historical significance, to be an artist of the first order. Nothing that he ever did was undistinguished.

The collector will not find it easy to procure adequate specimens of this artist's work. Moronobu's large single sheets are unobtainable to-day; they could never have been numerous, and the few that have survived the vicissitudes of almost three centuries are now in the hands of museums or collectors who will never part with them. Even his smaller single sheets are uncommon. His work is seldom signed.

The powerful impetus of Moronobu's art communicated itself to many pupils.{75}

Morofusa was the eldest son of Moronobu; he collaborated with his father, and produced designs that are in exact imitation of his father's style. His work comprises book illustrations and some large single sheets, and is very rare.

Additional pupils or contemporaries were: Moromasa, Moronaga, Morikuni, Masanojo, Moroshige, Morobei, Masataka, Osawa, Morotsugi, Moromori, Hishikawa Masanobu, Tomofusa, Shimbei, Toshiyuki, Furuyama, Morotane, Ryujo, Hasegawa Toun, Ishikawa Riusen, Ishikawa Riushu, Wowo, Kawashima Shigenobu, Kichi, Yoshimura Katsumasa, and Tsukioka Tange. Many of these are obscure figures, of whose work little is known. Most of them were chiefly book-illustrators.

The name of Nishikawa Sukenobu brings to mind that long procession of charming girl figures which year by year came from his hand—figures whose sweet monotonous faces and delicately poised bodies move with a pure grace that is perpetually delighting. Lacking the powerful decorative sense of Moronobu, whose lead he in general followed, and never attempting the massive blacks of the master's dashing brush-stroke, Sukenobu yet achieved effects that are more gracious and appealing than those of his great predecessor. Nothing{76} could surpass the delicate harmony of line in such a design as the one reproduced in Plate 2; the willowyness of the young body, the naïve innocence of the head, the movement and rhythm of the flowing garments, are admirably depicted. This was Sukenobu's characteristic note; he lingers in one's memory by virtue of it and none other; he was the least versatile of artists.

He lived between the years 1671 and 1751. During the period of his activity his popularity must have been enormous. The single-sheet prints which he produced were not many, and only a small proportion of these have come down to us. His main work was in the field of illustrated books and albums. More than forty of these are known to-day. They contain chiefly scenes from the lives of women and figures of young girls. Most of them date from 1713 to 1750. They constitute Sukenobu's claim to rank as Moronobu's most important successor in the field of book-illustration. Generally they are printed in black and white only; a few are embellished with colour added by hand. It is not always possible to tell whether this colouring was done when the books were published or whether it was the work of some subsequent owner of the volume.

The delicacy of Sukenobu's designs, and the absence of those peculiar mannerisms and exaggerations which characterize much of the work of this period, serve to make him, of all the Primitives, perhaps the most comprehensible and pleasing to the European taste. To the Japanese connoisseur he recommends himself because of the refinement of{79} his work both in subject and in manner, and because of a certain classic dignity that pervades it.

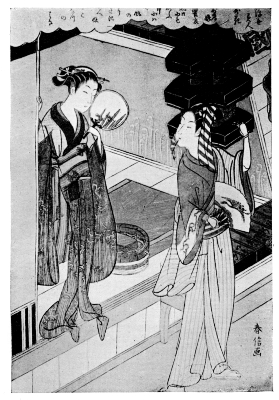

Plate 2.