The Project Gutenberg EBook of Memoirs of Joseph Grimaldi, by Joseph Grimaldi

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most

other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions

whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of

the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at

www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have

to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook.

Title: Memoirs of Joseph Grimaldi

Author: Joseph Grimaldi

Editor: Charles Dickens

Illustrator: George Cruikshank

Release Date: August 28, 2014 [EBook #46709]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK MEMOIRS OF JOSEPH GRIMALDI ***

Produced by Carlos Colon, Emmanuel Ackerman, University

of Toronto and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team

at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images

generously made available by The Internet Archive)

MEMOIRS

OF

JOSEPH GRIMALDI

EDITED

By "BOZ"

WITH ILLUSTRATIONS BY GEORGE CRUIKSHANK

LONDON

GEORGE ROUTLEDGE AND SONS

BROADWAY, LUDGATE HILL

NEW YORK: 416 BROOME STREET

GEORGE CRUIKSHANK

Price 2s. each, boards.

The Greatest Plague of Life; or, The Adventures

of a Lady in Search of a Good Servant.

Edited by the Brothers Mayhew. With

Illustrations by George Cruikshank.

Whom to Marry and How to

Get Married; or,

The Adventures of a

Lady in Search of a

Good Husband. Edited

by the Brothers

Mayhew,

and Illustrated

by George

Cruikshank.

Mornings at Bow Street. With

Steel Frontispiece

and 21 Illustrations

by George

Cruikshank.

It is some years now, since we first conceived a strong veneration

for Clowns, and an intense anxiety to know what they

did with themselves out of pantomime time, and off the stage.

As a child, we were accustomed to pester our relations and

friends with questions out of number concerning these gentry;—whether

their appetite for sausages and such like wares was

always the same, and if so, at whose expense they were maintained;

whether they were ever taken up for pilfering other

people's goods, or were forgiven by everybody because it was

only done in fun; how it was they got such beautiful complexions,

and where they lived; and whether they were born

Clowns, or gradually turned into Clowns as they grew up. On

these and a thousand other points our curiosity was insatiable.

Nor were our speculations confined to Clowns alone: they extended

to Harlequins, Pantaloons, and Columbines, all of whom

we believed to be real and veritable personages, existing in the

same forms and characters all the year round. How often have

we wished that the Pantaloon were our god-father! and how

often thought that to marry a Columbine would be to attain the

highest pitch of all human felicity!

The delights—the ten thousand million delights of a pantomime—come

streaming upon us now,—even of the pantomime

which came lumbering down in Richardson's waggons at fair-time

to the dull little town in which we had the honour to be

brought up, and which a long row of small boys, with frills as[Pg vi]

white as they could be washed, and hands as clean as they would

come, were taken to behold the glories of, in fair daylight.

We feel again all the pride of standing in a body on the platform,

the observed of all observers in the crowd below, while

the junior usher pays away twenty-four ninepences to a stout

gentleman under a Gothic arch, with a hoop of variegated lamps

swinging over his head. Again we catch a glimpse (too brief,

alas!) of the lady with a green parasol in her hand, on the outside

stage of the next show but one, who supports herself on

one foot, on the back of a majestic horse, blotting-paper coloured

and white; and once again our eyes open wide with

wonder, and our hearts throb with emotion, as we deliver our

card-board check into the very hands of the Harlequin himself,

who, all glittering with spangles, and dazzling with many

colours, deigns to give us a word of encouragement and commendation

as we pass into the booth!

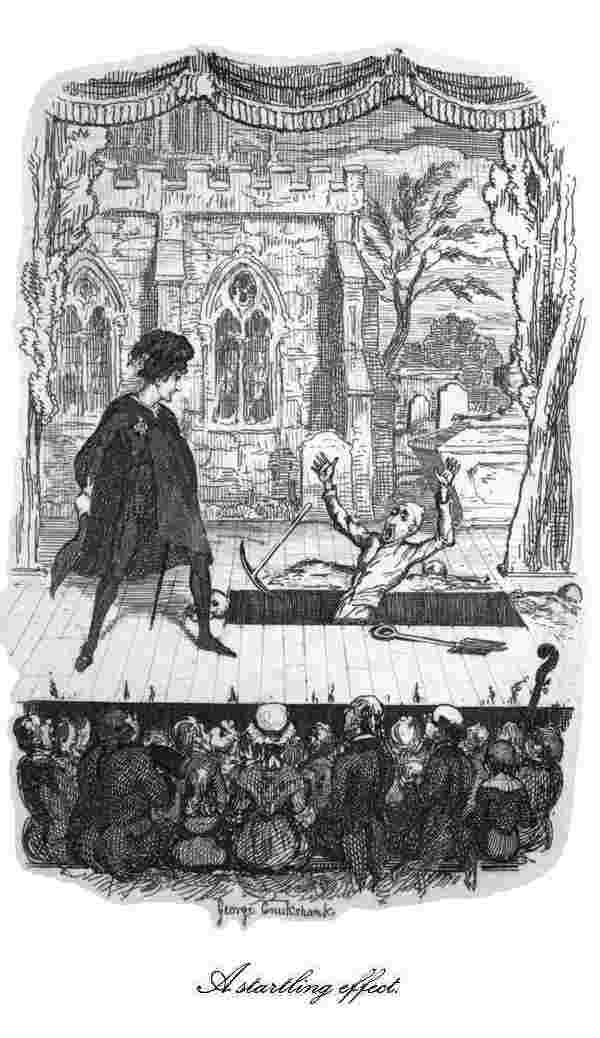

But what was this—even this—to the glories of the inside,

where, amid the smell of saw-dust, and orange-peel, sweeter far

than violets to youthful noses, the first play being over, the

lovers united, the ghost appeased, the baron killed, and everything

made comfortable and pleasant,—the pantomime itself

began! What words can describe the deep gloom of the

opening scene, where a crafty magician holding a young lady

in bondage was discovered, studying an enchanted book to the

soft music of a gong!—or in what terms can we express the

thrill of ecstasy with which, his magic power opposed by superior

art, we beheld the monster himself converted into Clown!

What mattered it that the stage was three yards wide, and four

deep? we never saw it. We had no eyes, ears, or corporeal

senses, but for the pantomime. And when its short career was

run, and the baron previously slaughtered, coming forward

with his hand upon his heart, announced that for that favour

Mr. Richardson returned his most sincere thanks, and the performances

would commence again in a quarter of an hour, what[Pg vii]

jest could equal the effects of the Baron's indignation and surprise,

when the Clown, unexpectedly peeping from behind the

curtain, requested the audience "not to believe it, for it was all

gammon!" Who but a Clown could have called forth the roar

of laughter that succeeded; and what witchery but a Clown's

could have caused the junior usher himself to declare aloud, as

he shook his sides and smote his knee in a moment of irrepressible

joy, that that was the very best thing he had ever heard

said!

We have lost that clown now;—he is still alive, though, for

we saw him only the day before last Bartholomew Fair, eating

a real saveloy, and we are sorry to say he had deserted to the

illegitimate drama, for he was seated on one of "Clark's Circus"

waggons:—we have lost that Clown and that pantomime, but

our relish for the entertainment still remains unimpaired. Each

successive Boxing-day finds us in the same state of high excitement

and expectation. On that eventful day, when new pantomimes

are played for the first time at the two great theatres,

and at twenty or thirty of the little ones, we still gloat as

formerly upon the bills which set forth tempting descriptions of

the scenery in staring red and black letters, and still fall down

upon our knees, with other men and boys, upon the pavement

by shop-doors, to read them down to the very last line. Nay,

we still peruse with all eagerness and avidity the exclusive

accounts of the coming wonders in the theatrical newspapers of

the Sunday before, and still believe them as devoutly as we did

before twenty years' experience had shown us that they are

always wrong.

With these feelings upon the subject of pantomimes, it is no

matter of surprise that when we first heard that Grimaldi had

left some memoirs of his life behind him, we were in a perfect

fever until we had perused the manuscript. It was no sooner

placed in our hands by "the adventurous and spirited publisher,"—(if

our recollection serve us, this is the customary style[Pg viii]

of the complimentary little paragraphs regarding new books

which usually precede advertisements about Savory's clocks in

the newspapers,)—than we sat down at once and read it every

word.

See how pleasantly things come about, if you let them take

their own course! This mention of the manuscript brings us

at once to the very point we are anxious to reach, and which we

should have gained long ago, if we had not travelled into those

irrelevant remarks concerning pantomimic representations.

For about a year before his death, Grimaldi was employed in

writing a full account of his life and adventures. It was his

chief occupation and amusement; and as people who write their

own lives, even in the midst of very many occupations, often

find time to extend them to a most inordinate length, it is no

wonder that his account of himself was exceedingly voluminous.

This manuscript was confided to Mr. Thomas Egerton Wilks:

to alter and revise, with a view to its publication. Mr. Wilks,

who was well acquainted with Grimaldi and his connexions,

applied himself to the task of condensing it throughout, and

wholly expunging considerable portions, which, so far as the

public were concerned, possessed neither interest nor amusement,

he likewise interspersed here and there the substance of such

personal anecdotes as he had gleaned from the writer in desultory

conversation. While he was thus engaged, Grimaldi died.

Mr. Wilks having by the commencement of September concluded

his labours, offered the manuscript to the present publisher,

by whom it was shortly afterwards purchased unconditionally,

with the full consent and concurrence of Mr. Richard

Hughes, Grimaldi's executor.

The present Editor of these Memoirs has felt it necessary to

say thus much in explanation of their origin, in order to establish

beyond doubt the unquestionable authenticity of the

memoirs they contain.

His own share in them is stated in a few words. Being much[Pg ix]

struck by several incidents in the manuscript—such as the description

of Grimaldi's infancy, the burglary, the brother's

return from sea under the extraordinary circumstances detailed,

the adventure of the man with the two fingers on his left hand,

the account of Mackintosh and his friends, and many other

passages,—and thinking that they might be related in a more

attractive manner, (they were at that time told in the first

person, as if by Grimaldi himself, although they had necessarily

lost any original manner which his recital might have imparted

to them;) he accepted a proposal from the publisher to edit the

book, and has edited it to the best of his ability, altering its

form throughout, and making such other alterations as he conceived

would improve the narration of the facts, without any

departure from the facts themselves.

He has merely to add, that there has been no book-making in

this case. He has not swelled the quantity of matter, but

materially abridged it. The account of Grimaldi's first courtship

may appear lengthy in its present form; but it has undergone

a double and most comprehensive process of abridgment. The

old man was garrulous upon a subject on which the youth had

felt so keenly; and as the feeling did him honour in both stages

of life, the Editor has not had the heart to reduce it further.

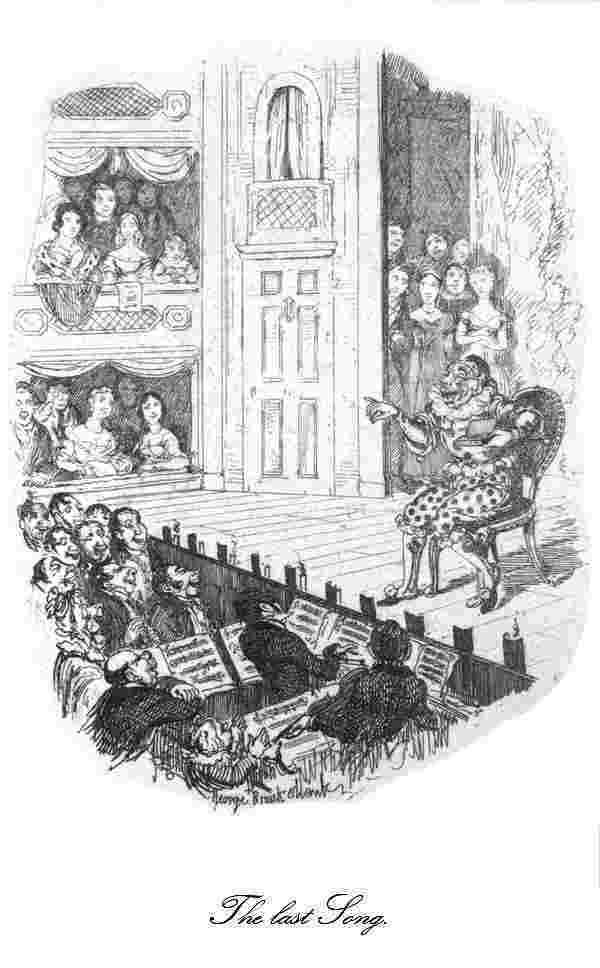

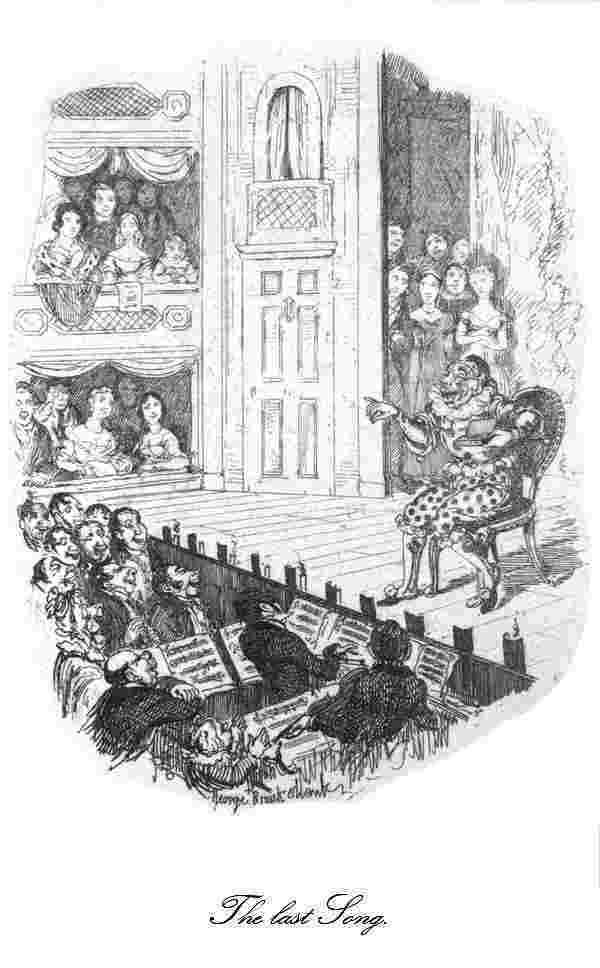

Here is the book, then, at last. After so much pains from so

many hands—including the good right hand of George Cruikshank,

which has seldom been better exercised,—he humbly

hopes it may find favour with the public.

Doughty Street,

February, 1838.

| Introductory Chapter |

page v |

| CHAPTER I. |

| His Grandfather and Father—His Birth and first appearance

at Drury Lane Theatre and at Sadler's Wells—His Father's

severity—Miss Farren—The Earl of Derby and the Wig—the

Fortune-box and Charity's reward—His Father's pretended Death,

and the behaviour of himself and his brother thereupon |

1 |

| CHAPTER II. |

| 1788 to 1794. |

| The Father's real Death—His Will, and failure of the

Executor—Generous conduct of Grimaldi's Schoolmaster,

and of Mr. Wroughton the Comedian—Smart running against

time—Kindness of Sheridan—Grimaldi's industry and

amusements—Fly-catching—Expedition in search of the "Dartford

Blues"—Mrs. Jordan—Adventure on Clapham Common: the piece of

Tin—His first love and its consequences |

17 |

| CHAPTER III. |

| 1794 to 1797. |

| Grimaldi falls in Love—His success—He meets with an accident

which brings the Reader acquainted with that invaluable

specific "Grimaldi's Embrocation"—He rises gradually in his

Profession—The Pentonville Gang of Burglars |

28 |

| CHAPTER IV. |

| 1797 to 1798. |

| The Thieves make a second attempt; alarmed by their perseverance,

Grimaldi repairs to Hatton Garden—Interview with Mr. Trott;

ingenious device of that gentleman, and its result on the third

visit of the Burglars—Comparative attractions of Pantomime and

Spectacle—Trip to Gravesend and Chatham—Disagreeable recognition

of a good-humoured friend, and an agreeable mode of journeying

recommended to all Travellers |

40 |

[Pg xii]

| CHAPTER V. |

| 1798. |

| An extraordinary circumstance concerning himself, with another

extraordinary circumstance concerning his Grandfather—Specimen

of a laconic epistle, and an account of two interviews with Mr.

Hughes, in the latter of which a benevolent gentleman is duly

rewarded for his trouble—Preparations for his marriage—Fatiguing

effects of his exertions at the Theatre |

51 |

| CHAPTER VI. |

| 1798. |

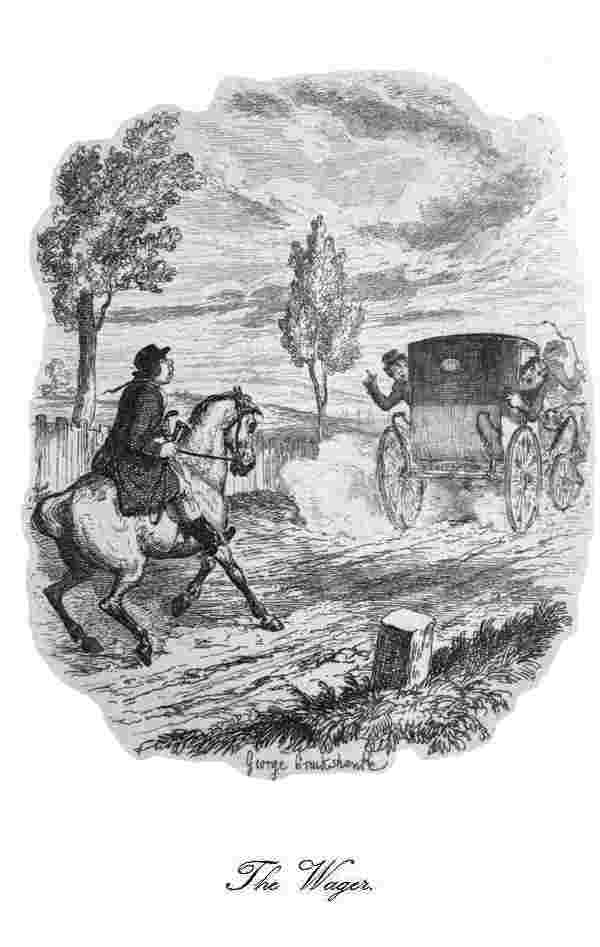

| Tribulations connected with "Old Lucas," the constable, with an

account of the subsequent proceedings before Mr. Blamire, the

magistrate, at Hatton Garden, and the mysterious appearance of a

silver staff—A guinea wager with a jocose friend on the Dartford

Road—The Prince of Wales, Sheridan, and the Crockery Girl |

62 |

| CHAPTER VII. |

| 1798 to 1801. |

| Partiality of George the Third for Theatrical

Entertainments—Sheridan's kindness to Grimaldi—His

domestic affliction and severe distress—The production of

Harlequin Amulet a new era in Pantomime—Pigeon-fancying and

Wagering—His first Provincial Excursion with Mrs. Baker, the

eccentric Manageress—John Kemble and Jew Davis, with a new

reading—Increased success at Maidstone and Canterbury—Polite

interview with John Kemble |

76 |

| CHAPTER VIII. |

| 1801 to 1803. |

| Hard work to counterbalance great gains—His discharge from

Drury Lane, and his discharge at Sadler's Wells—His return to

the former house—Monk Lewis—Anecdote of him and Sheridan, and of

Sheridan and the Prince of Wales—Grimaldi gains a son and loses

all his capital |

88 |

[Pg xiii]

| CHAPTER IX. |

| 1803. |

| Containing a Very Extraordinary Incident Well Worthy of the

Reader's Attention |

97 |

| CHAPTER X. |

| 1803 to 1805. |

| Bologna and his Family—An Excursion into Kent with that

personage—Mr. Mackintosh, the gentleman of landed property,

and his preserves—A great day's sporting; and a scene at the

Garrick's Head in Bow Street, between a Landlord, a Gamekeeper,

Bologna and Grimaldi |

106 |

| CHAPTER XI. |

| 1805 to 1806. |

| Stage Affairs and Stage Quarrels—Mr. Graham, the Bow Street

Magistrate and Drury Lane Manager—Mr. Peake—Grimaldi is

introduced to Mr. Harris by John Kemble—Leaves Drury Lane Theatre

and engages at Covent Garden—Mortification of the authorities at

"the other house"—He joins Charles Dibdin's Company and visits

Dublin—The wet Theatre—Ill success of the speculation, and

great success of his own Benefit—Observations on the comparative

strength of Whisky Punch and Rum Punch, with interesting experiment |

115 |

| CHAPTER XII. |

| 1806 to 1807. |

| He returns to town, gets frozen to the roof of a coach on the

road, and pays his rent twice over when he arrives at home—Mr.

Charles Farley—His first appearance at Covent Garden—Valentine

and Orson—Production of "Mother Goose," and its immense

success—The mysterious adventure of the Six Ladies and the Six

Gentlemen |

124 |

| CHAPTER XIII. |

| 1807. |

| The mystery cleared up chiefly through the instrumentality of Mr.

Alderman Harmer; and the characters of the Six Ladies and the Six

Gentlemen are satisfactorily explained—The Trial of Mackintosh

for Burglary—Its result |

133 |

[Pg xiv]

| CHAPTER XIV. |

| 1807 to 1808. |

| Bradbury, the Clown—His voluntary confinement in a Madhouse,

to screen an "Honourable" Thief—His release, strange conduct,

subsequent career, and death—Dreadful Accident at Sadler's

Wells—The night-drives to Finchley—Trip to Birmingham—Mr.

Macready, the Manager and his curious Stage-properties—Sudden

recall to Town |

148 |

| CHAPTER XV. |

| 1808 to 1809. |

| Covent Garden Theatre destroyed by fire—Grimaldi makes a trip

to Manchester: he meets with an accident there, and another at

Liverpool—The Sir Hugh Myddleton Tavern at Sadler's Wells, and

a description of some of its frequenters, necessary to a full

understanding of the succeeding chapter |

158 |

| CHAPTER XVI. |

| 1809. |

| Grimaldi's Adventure on Highgate Hill, and its consequences |

165 |

| CHAPTER XVII. |

| 1809 to 1812. |

| Opening of the new Covent Garden Theatre—The great O. P.

Rows—Grimaldi's first appearance as Clown in the public

streets—Temporary embarrassments—Great success at Cheltenham and

Gloucester—He visits Berkeley Castle, and is introduced to Lord

Byron—Fish sauce and Apple Pie |

172 |

| CHAPTER XVIII. |

| 1812 to 1816. |

| A Clergyman's Dinner-party at Bath—First Appearance of Grimaldi's

Son, and Death of his old friend Mr. Hughes—Grimaldi plays at

three Theatres on one night, and has his salary stopped for his

pains—His severe illness—Second journey to Bath—Davidge, "Billy

Coombes" and the Chest—Facetiousness of the aforesaid Billy |

183 |

[Pg xv]

| CHAPTER XIX. |

| 1816 to 1817. |

| He quits Sadler's Wells in consequence of a disagreement with

the Proprietors—Lord Byron—Retirement of John Kemble—Immense

success of Grimaldi in the provinces, and his great gains—A scene

in a Barber's Shop |

194 |

| CHAPTER XX. |

| 1817. |

| More provincial success—Bologna and his economy—Comparative

dearness of Welsh Rare-bits and Partridges—Remarkably odd modes

of saving money |

203 |

| CHAPTER XXI. |

| 1817 to 1818. |

| Production of "Baron Munchausen"—Anecdote of Ellar the Harlequin,

showing how he jumped through the Moon and put his hand

out—Grimaldi becomes a Proprietor of Sadler's Wells—Anecdotes of

the late Duke of York, Sir Godfrey Webster, a Gold Snuff-box, his

late Majesty, Newcastle Salmon, and a Coal Mine |

209 |

| CHAPTER XXII. |

| 1818 to 1823. |

| Profit and Loss—Appearance of his Son at Covent Garden—His

last engagement at Sadler's Wells—Accommodation of the Giants

in the Dublin Pavilion—Alarming state of his health—His

engagement at the Coburg—The liberality of Mr. Harris—Rapid

decay of Grimaldi's constitution, his great sufferings, and last

performance at Covent Garden—He visits Cheltenham and Birmingham

with great success—Colonel Berkeley, Mr. Charles Kemble, and Mr.

Bunn |

218 |

| CHAPTER XXIII. |

| 1823 to 1827. |

| Grimaldi's great afflictions augmented by the dissipation and

recklessness of his Son—Compelled to retire from Covent Garden

Theatre, where he is succeeded by him—New Speculation at Sadler's

Wells—Changes in the system of Management, and their results—Sir

James Scarlett and a blushing Witness |

229 |

[Pg xvi]

| CHAPTER XXIV. |

| 1828. |

| Great kindness of Miss Kelly towards Grimaldi—His farewell

benefit at Sadler's Wells; last appearance, and farewell

address—He makes preparations for one more appearance at Covent

Garden, but, in a conversation with Mr. Charles Kemble, meets with

a disappointment—In consequence of Lord Segrave's benevolent

interference, a benefit is arranged for him at Drury Lane—His

last interview with Mr. Charles Kemble and Fawcett |

236 |

| CHAPTER XXV. |

| 1828 to 1836. |

| The farewell benefit at Drury Lane—Grimaldi's last appearance and

parting address—The Drury Lane Theatrical Fund, and its prompt

reply to his communication—Miserable career and death of his

Son—His Wife dies, and he returns from Woolwich (whither he had

previously removed) to London—His retirement |

183 |

| Concluding Chapter |

253 |

MEMOIRS

OF

JOSEPH GRIMALDI.

CHAPTER I.

His Grandfather and Father—His Birth and first appearance at Drury Lane

Theatre, and at Sadler's Wells—His Father's severity—Miss Farren—The

Earl of Derby and the Wig—The Fortune-box and Charity's reward—His

Father's pretended death, and the behaviour of himself and his brother

thereupon.

The paternal grandfather of Joseph Grimaldi was well known,

both to the French and Italian public, as an eminent dancer,

possessing a most extraordinary degree of strength and agility,—qualities

which, being brought into full play by the constant

exercise of his frame in his professional duties, acquired for him

the distinguishing appellation of "Iron Legs." Dibdin, in his

History of the Stage, relates several anecdotes of his prowess in

these respects, many of which are current elsewhere, though

the authority on which they rest would appear from his grandson's

testimony to be somewhat doubtful; the best known of

these, however, is perfectly true. Jumping extremely high one

night in some performance on the stage, possibly in a fit of enthusiasm

occasioned by the august presence of the Turkish

Ambassador, who, with his suite, occupied the stage-box, he

actually broke one of the chandeliers which in those times hung

above the stage doors; and one of the glass drops was struck

with some violence against the eye or countenance of the Turkish

Ambassador aforesaid. The dignity of this great personage

being much affronted, a formal complaint was made to the

Court of France, who gravely commanded "Iron Legs" to

apologize, which "Iron Legs" did in due form, to the great

amusement of himself, and the court, and the public; and, in

short, of everybody else but the exalted gentleman whose person[Pg 2]

had been grievously outraged. The mighty affair terminated

in the appearance of a squib, which has been thus translated:—

Hail, Iron Legs! immortal pair,

Agile, firm knit, and peerless,

That skim the earth, or vault in air,

Aspiring high and fearless.

Glory of Paris! outdoing compeers,

Brave pair! may nothing hurt ye;

Scatter at will our chandeliers,

And tweak the nose of Turkey.

And should a too presumptuous foe

But dare these shores to land on,

His well-kicked men shall quickly know

We've Iron Legs to stand on.

This circumstance occurred on the French stage. The first

Grimaldi[1] who appeared in England was the father of the subject[Pg 3]

of these Memoirs, and the son of "Iron Legs," who, holding

the appointment of Dentist to Queen Charlotte, came to England

in that capacity in 1760; he was a native of Genoa, and long

before his arrival in this country had attained considerable

distinction in his profession. We have not many instances of

the union of the two professions of dentist and dancing-master;

but Grimaldi, possessing a taste for both pursuits, and a much

higher relish for the latter than the former, obtained leave to

resign his situation about the Queen, soon after his arrival in

this country, and commenced giving lessons in dancing and[Pg 4]

fencing, occasionally giving his pupils a taste of his quality in

his old capacity. In those days of minuets and cotillions, private

dancing was a much more laborious and serious affair than it is

at present; and the younger branches of the nobility and gentry

kept Mr. Grimaldi in pretty constant occupation. In many

scattered notices of OUR Grimaldi's life, it has been stated that

the father lost his situation at court in consequence of the rudeness

of his behaviour, and some disrespect which he had shown

the King; an accusation which his son always took very much to

heart, and which the continual patronage of the King and

Queen, bestowed upon him publicly, on all possible occasions,

sufficiently proves to be unfounded.

His new career being highly successful, Mr. Grimaldi was

appointed ballet-master of old Drury Lane Theatre and Sadler's

Wells, with which he coupled the situation of primo buffo; in

this double capacity he became a very great favourite with the

public, and their majesties, who were nearly every week accustomed

to command some pantomime of which Grimaldi was the

hero. He bore the reputation of being a very honest man, and

a very charitable one, never turning a deaf ear to the entreaties

of the distressed, but always willing, by every means in his

power, to relieve the numerous reduced and wretched persons

who applied to him for assistance. It may be added—and his

son always mentioned it with just pride—that he was never

known to be inebriated: a rather scarce virtue among players

of later times, and one which men of far higher rank in their

profession would do well to profit by.

He appears to have been a very singular and eccentric man.

It would be difficult to account for the little traits of his character

which are developed in the earlier pages of this book,

unless this circumstance were borne in mind. He purchased

a small quantity of ground at Lambeth once, part of which

was laid out as a garden; he entered into possession of it in

the very depth of a most inclement winter, but he was so

impatient to ascertain how this garden would look in full bloom,

that, finding it quite impossible to wait till the coming of

spring and summer gradually developed its beauties, he had

it at once decorated with an immense quantity of artificial[Pg 5]

flowers, and the branches of all the trees bent beneath the weight

of the most luxuriant foliage, and the most abundant crops of

fruit, all, it is needless to say, artificial also.

A singular trait in this individual's character, was a vague

and profound dread of the 14th day of the month. At its approach

he was always nervous, disquieted, and anxious: directly

it had passed he was another man again, and invariably exclaimed,

in his broken English, "Ah! now I am safe for anoder

month." If this circumstance were unaccompanied by any

singular coincidence it would be scarcely worth mentioning;

but it is remarkable that he actually died on the 14th day of

March; and that he was born, christened, and married on the

14th of the month.

There are other anecdotes of the same kind told of Henri

Quatre, and others; this one is undoubtedly true, and it may

be added to the list of coincidences or presentiments, or by

whatever name the reader pleases to call them, as a veracious

and well-authenticated instance.

These are not the only odd characteristics of the man. He

was a most morbidly sensitive and melancholy being, and entertained

a horror of death almost indescribable. He was in the

habit of wandering about churchyards and burying-places, for

hours together, and would speculate on the diseases of which

the persons whose remains occupied the graves he walked

among, had died; figure their death-beds, and wonder how

many of them had been buried alive in a fit or a trance: a possibility

which he shuddered to think of, and which haunted him

both through life and at its close. Such an effect had this fear

upon his mind, that he left express directions in his will that,

before his coffin should be fastened down, his head should be

severed from his body, and the operation was actually performed

in the presence of several persons.

It is a curious circumstance, that death, which always filled

his mind with the most gloomy and horrible reflections, and

which in his unoccupied moments can hardly be said to have

been ever absent from his thoughts, should have been chosen by

him as the subject of one of his most popular scenes in the pantomimes

of the time. Among many others of the same nature,

he invented the well-known skeleton scene for the clown, which

was very popular in those days, and is still occasionally represented.

Whether it be true, that the hypochondriac is most

prone to laugh at the things which most annoy and terrify him

in private, as a man who believes in the appearance of spirits

upon earth is always the foremost to express his unbelief; or

whether these gloomy ideas haunted the unfortunate man's

mind so much, that even his merriment assumed a ghastly hue,

and his comicality sought for grotesque objects in the grave and

the charnel-house, the fact is equally remarkable.

This was the same man who, in the time of Lord George

Gordon's riots, when people, for the purpose of protecting their[Pg 6]

houses from the fury of the mob, inscribed upon their doors the

words "No Popery,"—actually, with the view of keeping in the

right with all parties, and preventing the possibility of offending

any by his form of worship, wrote up "No religion at all;"

which announcement appeared in large characters in front of

his house, in Little Russell-street.[2] The idea was perfectly

successful; but whether from the humour of the description,

or because the rioters did not happen to go down that particular

street, we are unable to determine.

On the 18th of December, 1779, the year in which Garrick

died, Joseph Grimaldi, "Old Joe," was born, in Stanhope-street,[3]

Clare-market; a part of the town then as now, much frequented

by theatrical people, in consequence of its vicinity to the

theatres. At the period of his birth, his eccentric father was

sixty-five years old, and twenty-five months afterwards another

son was born to him—Joseph's only brother.

The child did not remain very long in a state of helpless and

unprofitable infancy, for at the age of one year and eleven

months he was brought out by his father on the boards of Old

Drury, where he made his first bow and his first tumble.[4] The[Pg 7]

piece in which his precocious powers were displayed was the

well-known pantomime of Robinson Crusoe, in which the father

sustained the part of the Shipwrecked Mariner, and the son

performed that of the Little Clown. The child's success was

complete; he was instantly placed on the establishment, accorded

a magnificent weekly salary of fifteen shillings, and every

succeeding year was brought forward in some new and prominent

part. He became a favourite behind the curtain as well

as before it, being henceforth distinguished in the green-room

as "Clever little Joe;" and Joe he was called to the last day of

his life.

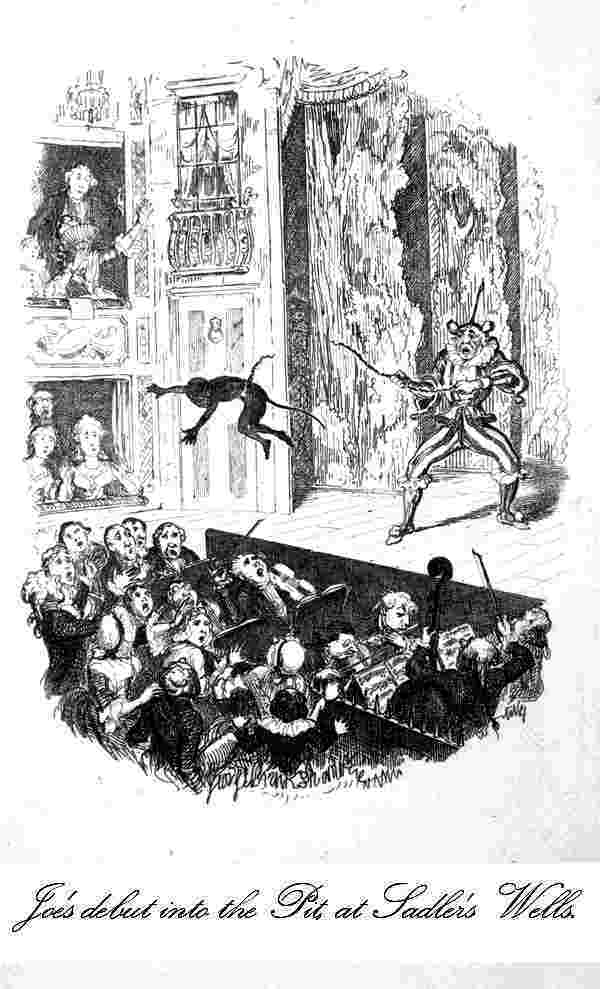

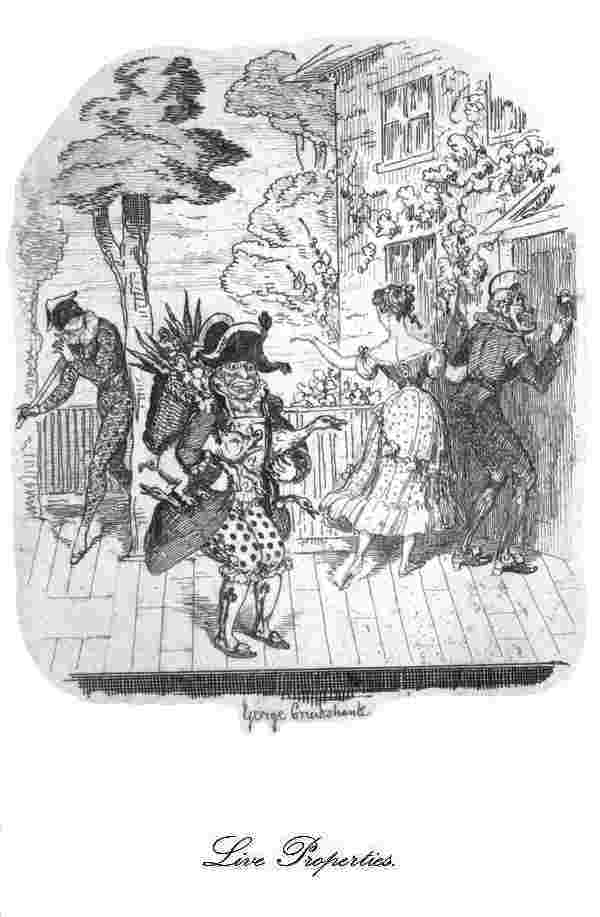

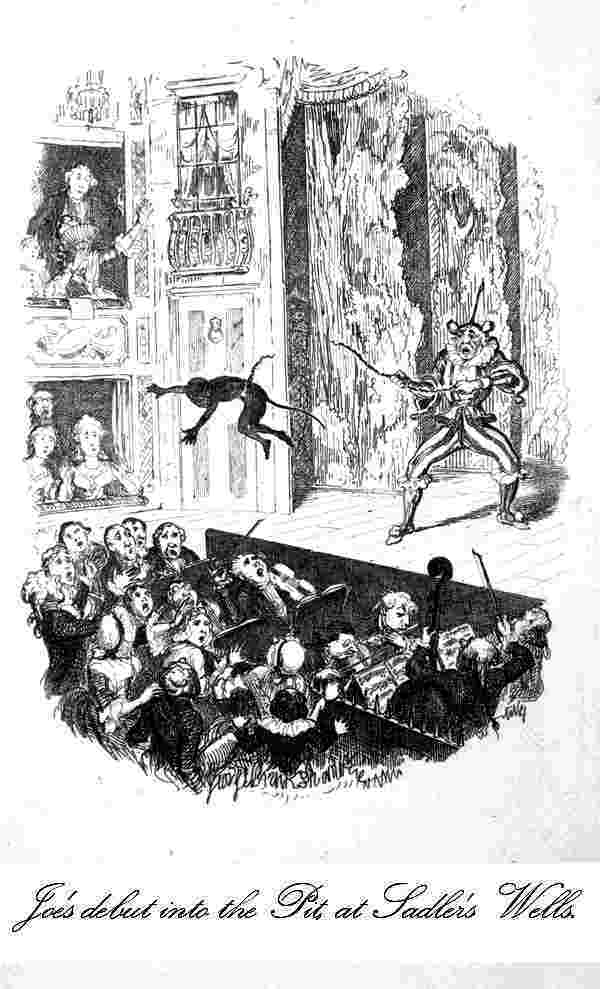

In 1782, he first appeared at Sadler's Wells, in the arduous

character of a monkey; and here he was fortunate enough to

excite as much approbation, as he had previously elicited in

the part of clown at Drury Lane. He immediately became a

member of the regular company at this theatre, as he had done

at the other; and here he remained (one season only excepted)

until the termination of his professional life, forty-nine years

afterwards.

Now that he had made, or rather that his father had made

for him, two engagements, by which he was bound to appear at

two theatres on the same evening, and at very nearly the same

time, his labours began in earnest. They would have been

arduous for a man, much more so for a child; and it will be

obvious, that if at any one portion of his life his gains were very

great, the actual toil both of mind and body by which they were

purchased was at least equally so. The stage-stricken young

gentlemen who hang about Sadler's Wells, and Astley's, and the

Surrey, and private theatres of all kinds, and who long to

embrace the theatrical profession because it is "so easy," little

dream of all the anxieties and hardships, and privations and

sorrows, which make the sum of most actors' lives.

We have already remarked that the father of Grimaldi was

an eccentric man; he appears to have been peculiarly eccentric,

and rather unpleasantly so, in the correction of his son. The[Pg 8]

child being bred up to play all kinds of fantastic tricks, was as

much a clown, a monkey, or anything else that was droll and

ridiculous, off the stage, as on it; and being incited thereto by

the occupants of the green-room, used to skip and tumble about

as much for their diversion as that of the public. All this was

carefully concealed from the father, who, whenever he did

happen to observe any of the child's pranks, always administered

the same punishment—a sound thrashing; terminating

in his being lifted up by the hair of the head, and stuck in a

corner, whence his father, with a severe countenance and awful

voice, would tell him "to venture to move at his peril."

Venture to move, however, he did, for no sooner would the

father disappear, than all the cries and tears of the boy would

disappear too; and with many of those winks and grins which

afterwards became so popular, he would recommence his pantomime

with greater vigour than ever; indeed, nothing could

ever stop him but the cry of "Joe! Joe! here's your father!"

upon which the boy would dart back into the old corner, and

begin crying again as if he had never left off.

This became quite a regular amusement in course of time, and

whether the father was coming or not, the caution used to be

given for the mere pleasure of seeing "Joe" run back to his

corner; this "Joe" very soon discovered, and often confounding

the warning with the joke, received more severe beatings than

before, from him whom he very properly describes in his manuscript

as his "severe but excellent parent." On one of these

occasions, when he was dressed for his favourite part of the

little clown in Robinson Crusoe, with his face painted in exact

imitation of his father's, which appears to have been part of the

fun of the scene, the old gentleman brought him into the green-room,

and placing him in his usual solitary corner, gave him

strict directions not to stir an inch, on pain of being thrashed,

and left him.

The Earl of Derby, who was at that time in the constant habit

of frequenting the green-room, happened to walk in at the

moment, and seeing a lonesome-looking little boy dressed and

painted after a manner very inconsistent with his solitary air,

good-naturedly called him towards him.

"Hollo! here, my boy, come here!" said the Earl.

Joe made a wonderful and astonishing face, but remained

where he was. The Earl laughed heartily, and looked round

for an explanation.

"He dare not move!" explained Miss Farren, to whom his

lordship was then much attached, and whom he afterwards

married; "his father will beat him if he does."

"Indeed!" said his lordship. At which Joe, by way of confirmation,

made another face more extraordinary than his former

contortions.

"I think," said his lordship, laughing again, "the boy is not[Pg 9]

quite so much afraid of his father as you suppose. Come here,

sir!"

With this, he held up half-a-crown, and the child, perfectly

well knowing the value of money, darted from his corner,

seized it with pantomimic suddenness, and was darting back

again, when the Earl caught him by the arm.

"Here, Joe!" said the Earl, "take off your wig and throw it

in the fire, and here's another half-crown for you."

No sooner said than done. Off came the wig,—into the fire

it went; a roar of laughter arose; the child capered about with

a half-crown in each hand; the Earl, alarmed for the consequences

to the boy, busied himself to extricate the wig with the

tongs and poker; and the father, in full dress for the Shipwrecked

Mariner, rushed into the room at the same moment. It

was lucky for "Little Joe" that Lord Derby promptly and

humanely interfered, or it is exceedingly probable that his

father would have prevented any chance of his being buried

alive at all events, by killing him outright.

As it was, the matter could not be compromised without his

receiving a smart beating, which made him cry very bitterly;

and the tears running down his face, which was painted "an inch

thick," came to the "complexion at last," in parts, and made him

look as much like a little clown as like a little human being, to

neither of which characters he bore the most distant resemblance.

He was "called" almost immediately afterwards, and the father

being in a violent rage, had not noticed the circumstance until the

little object came on the stage, when a general roar of laughter

directed his attention to his grotesque countenance. Becoming

more violent than before, he fell upon him at once, and beat him

severely, and the child roared vociferously. This was all taken

by the audience as a most capital joke; shouts of laughter

and peals of applause shook the house; and the newspapers next

morning declared, that it was perfectly wonderful to see a mere

child perform so naturally, and highly creditable to his father's

talents as a teacher!

This is no bad illustration of some of the miseries of a poor

actor's life. The jest on the lip, and the tear in the eye, the

merriment on the mouth, and the aching of the heart, have

called down the same shouts of laughter and peals of applause a

hundred times. Characters in a state of starvation are almost

invariably laughed at upon the stage—the audience have had

their dinner.

The bitterest portion of the boy's punishment was the being

deprived of the five shillings, which the excellent parent put

into his own pocket, possibly because he received the child's

salary also, and in order that everything might be, as Goldsmith's

Bear-leader has it, "in a concatenation accordingly,"

The Earl gave him half-a-crown every time he saw him afterwards[Pg 10]

though, and the child had good cause for regret when his

lordship married Miss Farren,[5] and left the green-room.

At Sadler's Wells he became a favourite almost as speedily as

at Drury Lane. King, the comedian,[6] who was principal proprietor[Pg 11]

of the former theatre and acting manager of the latter,

took a great deal of notice of him, and occasionally gave the

child a guinea to buy a rocking-horse or a cart, or some toy that

struck his fancy. During the run of the first piece in which he

played at Sadler's Wells, he produced his first serious effect,

which, but for the good fortune which seems to have attended

him in such cases, might have prevented his subsequent appearance

on any stage. He played a monkey, and had to

accompany the clown (his father) throughout the piece. In

one of the scenes, the clown used to lead him on by a chain

attached to his waist, and with this chain he would swing him

round and round, at arm's length, with the utmost velocity.

One evening, when this feat was in the act of performance, the

chain broke, and he was hurled a considerable distance into

the pit, fortunately without sustaining the slightest injury;

for he was flung by a miracle into the very arms of an old

gentleman who was sitting gazing at the stage with intense

interest.

Among the many persons who in this early stage of his career

behaved with great kindness to him, were the famous rope-dancers,

Mr. and Mrs. Redigé, then called Le Petit Diable,[7]

and La Belle Espagnole; who often gave him a guinea to buy

some childish luxury, which his father invariably took away

and deposited in a box, with his name written outside, which

he would lock very carefully, and then, giving the boy the key,

say, "Mind, Joe, ven I die, dat is your vortune." Eventually

he lost both the box and the fortune, as will hereafter appear.

As he had now nearly four months vacant out of every twelve,

the run of the Christmas pantomime at Drury Lane seldom

exceeding a month, and Sadler's Wells not opening until Easter,

he was sent for that period of the year to a boarding-school at

Putney, kept by a Mr. Ford, of whose kindness and goodness of

heart to him on a later occasion of his life, he spoke, when an

old man, with the deepest gratitude. He fell in here with

many schoolfellows who afterwards became connected one way

or another with dramatic pursuits, among whom was Mr. Henry

Harris, of Covent Garden Theatre. We do not find that any

of these schoolfellows afterwards became pantomime actors;

but recollecting the humour and vivacity of the boy, the wonder

to us is, that they were not all clowns when they grew up.[Pg 12]

In the Christmas of 1782, he appeared in his second character[8]

at Drury Lane, called "Harlequin Junior; or, the Magic Cestus,"

in which he represented a demon, sent by some opposing magician

to counteract the power of the harlequin. In this, as in his

preceding part, he was fortunate enough to meet with great

applause; and from this period his reputation was made,

although it naturally increased with his years, strength, and

improvement.

In the following Easter[9] he repeated the monkey at Sadler's

Wells without the pit effect. As the piece was withdrawn at

the end of a month, and he had nothing to do for the remainder

of the season, he again repaired to Putney.

In Christmas 1783, he once more appeared at Drury Lane, in

a pantomime called "Hurly Burly."[10] In this piece he had to

represent, not only the old part of the monkey, but that of a cat

besides; and in sustaining the latter character he met with an

accident, his speedy recovery from which would almost induce

one to believe that he had so completely identified himself with

the character as to have eight additional chances for his life. The

dress he wore was so clumsily contrived, that when it was sewn

upon him he could not see before him; consequently, as he was

running about the stage, he fell down a trap-door, which had

been left open to represent a well, and tumbled down a distance

of forty feet, thereby breaking his collar-bone, and inflicting

several contusions upon his body. He was immediately conveyed

home, and placed under the care of a surgeon, but he did not

recover soon enough to appear any more that season at Drury

Lane, although at Easter he performed at Sadler's Wells as

usual.

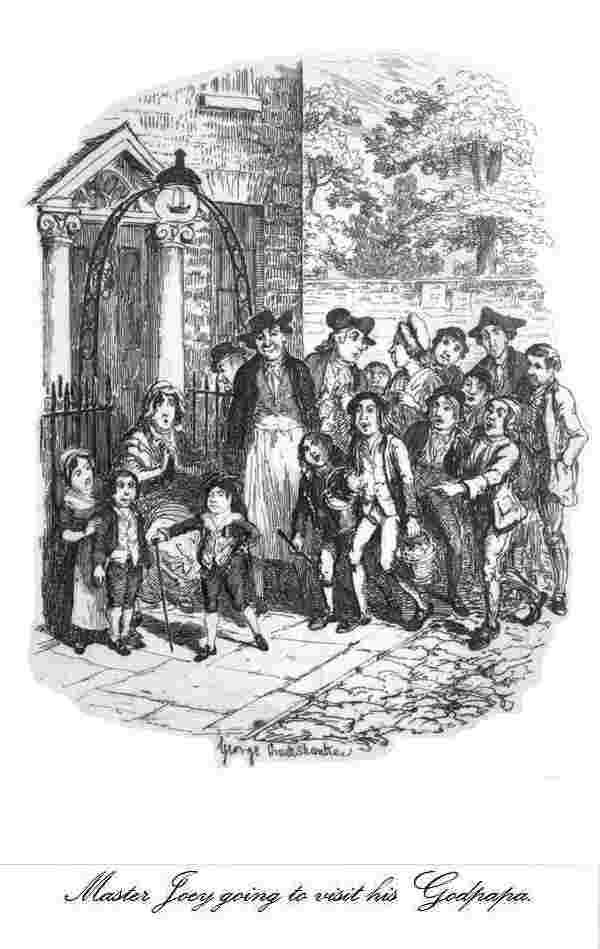

In the summer of this year, he used to be allowed, as a mark

of high and special favour, to spend every alternate Sunday at

the house of his mother's father, "who," says Grimaldi himself,

"resided in Newton-street, Holborn, and was a carcase butcher,

doing a prodigious business; besides which, he kept the Bloomsbury

slaughter-house, and, at the time of his death, had done

so for more than sixty years." With this grandfather, "Joe"

was a great favourite; and as he was very much indulged and

petted when he went to see him, he used to look forward to

every visit with great anxiety. His father, upon his part, was

most anxious that he should support the credit of the family

upon these occasions, and, after great deliberation, and much

consultation with tailors, the "little clown" was attired for one

of these Sunday excursions in the following style. On his back

he wore a green coat, embroidered with almost as many artificial

flowers as his father had put in the garden at Lambeth; beneath

this there shone a satin waistcoat of dazzling whiteness; and

beneath that again were a pair of green cloth breeches (the word

existed in those days) richly embroidered. His legs were fitted

into white silk stockings, and his feet into shoes with brilliant

paste buckles, of which he also wore another resplendent pair at

his knees: he had a laced shirt, cravat, and ruffles; a cocked-hat

upon his head; a small watch set with diamonds—theatrical,

we suppose—in his fob; and a little cane in his hand, which he

switched to and fro as our clowns may do now.

Being thus thoroughly equipped for starting, he was taken in

for his father's inspection: the old gentleman was pleased to

signify his entire approbation with his appearance, and, after

kissing him in the moment of his gratification, demanded the

key of the "fortune-box." The key being got with some difficulty

out of one of the pockets of the green smalls, the bottom of

which might be somewhere near the buckles, the old gentleman

took a guinea out of the box, and, putting it into the boy's

pocket, said, "Dere now, you are a gentleman, and something

more—you have got a guinea in your pocket." The box having

been carefully locked, and the key returned to the owner of the

"fortune," off he started, receiving strict injunctions to be home

by eight o'clock. The father would not allow anybody to attend

him, on the ground that he was a gentleman, and consequently

perfectly able to take care of himself; so away he went, to walk

all the way from Little Russel-street, Drury-lane, to Newton-street,

Holborn.

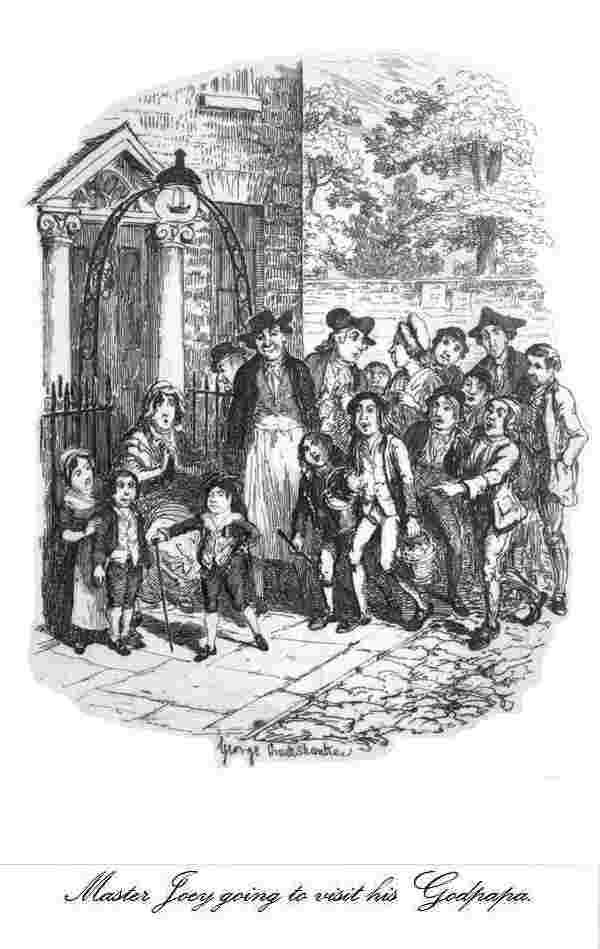

The child's appearance in the street excited considerable

curiosity, as the appearance of any other child, alone, in such a

costume, might very probably have done; but he was a public

character besides, and the astonishment was proportionate.

"Hollo!" cried one boy, "here's 'Little Joe!'" "Get along,"

said another, "it's the monkey." A third, thought it was the

"bear dressed for a dance," and the fourth suggested "it might[Pg 14]

be the cat going out to a party," while the more sedate passengers

could not help laughing heartily, and saying how ridiculous it

was to trust such a child in the streets alone. However, he

walked on, with various singular grimaces, until he stopped to

look at a female of miserable appearance, who was reclining on

the pavement, and whose diseased and destitute aspect had

already collected a crowd. The boy stopped, like others, and

hearing her tale of distress, became so touched, that he thrust

his hand into his pocket, and having at last found the bottom of

it, pulled out his guinea, which was the only coin he had, and

slipped it into her hand; then away he walked again with a

greater air than before.

The sight of the embroidered coat, and breeches, and the

paste buckles, and the satin waistcoat and cocked-hat, had

astonished the crowd not a little in the outset; but directly it

was understood that the small owner of these articles had given

the woman a guinea, a great number of people collected around

him, and began shouting and staring by turns most earnestly.

The boy, not at all abashed, headed the crowd, and walked on

very deliberately, with a train a street or two long behind him,

until he fortunately encountered a friend of his father's, who

no sooner saw the concourse that attended him, than he took

him in his arms and carried him, despite a few kicks and struggles,

in all his brilliant attire, to his grandfather's house, where

he spent the day very much to the satisfaction of all parties

concerned.

When he got safely home at night, the father referred to his

watch, and finding that he had returned home punctual to the

appointed time, kissed him, extolled him for paying such strict

attention to his instructions, examined his dress, discovered

satisfactorily that no injury had been done to his clothes, and

concluded by asking for the key of the "fortune-box," and the

guinea. The boy, at first, quite forgot the morning adventure;

but, after rummaging his pockets for the guinea, and not finding

it, he recollected what had occurred, and, falling upon the

knees of the knee-smalls, confessed it all, and implored forgiveness.

The father was puzzled; he was always giving away money

in charity himself, and he could scarcely reprimand the child

for doing the same. He looked at him for some seconds with a

perplexed countenance, and then, contenting himself with simply

saying, "I'll beat you," sent him to bed.

Among the eccentricities of the old gentleman, one—certainly

not his most amiable one—was, that whatever he promised he

performed; and that when, as in this case, he promised to thrash

the boy, he would very coolly let the matter stand over for

months, but never forget it in the end. This was ingenious,

inasmuch as it doubled, or trebled, or quadrupled the punishment,

giving the unhappy little victim all the additional pain[Pg 15]

of anticipating it for a long time, with the certainty of enduring

it in the end. Four or five months after this occurrence, and

when the child had not given his father any new cause of

offence, he suddenly called him to him one day, and communicated

the intelligence that he was going to beat him forthwith.

Hereupon the boy began to cry most piteously, and faltered

forth the inquiry, "Oh! father, what for?"—"Remember the

guinea!" said the father. And he gave him a caning which he

remembered to the last day of his life.

The family consisted at this time of the father, mother, Joe,

his only brother John Baptist, three or four female servants,

and a man of colour who acted as footman, and was dignified

with the appellation of "Black Sam."

The father was extremely hospitable, and fond of company;

he rarely dined alone, and on certain gala days, of which

Christmas-eve was one, had a very large party, upon which

occasions his really splendid service of plate, together with various

costly articles of bijouterie, were laid out for the admiration

of the guests. Upon one Christmas-eve, when the dining-parlour

was decorated and prepared with all due gorgeousness and

splendour, the two boys, accompanied by Black Sam, stole into

it, and began to pass various encomiums on its beautiful appearance.

"Ah!" said Sam, in reply to some remark of the brothers,

"and when old Massa die, all dese fine things vill be yours."

Both the boys were much struck with this remark, and especially

John, the younger, who, being extremely young, probably

thought much less about death than his father, and accordingly

exclaimed, without the least reserve or delicacy, that he should

be exceedingly glad if all these fine things were his.

Nothing more was said upon the subject. Black Sam went

to his work, the boys commenced a game of play, and nobody

thought any more of the matter except the father himself, who,

passing the door of the room at the moment the remarks were

made, distinctly heard them. He pondered over the matter for

some days, and at length, with the view of ascertaining the

dispositions of his two sons, formed a singular resolution, still

connected with the topic ever upwards in his mind, and determined

to feign himself dead. He caused himself to be laid out

in the drawing-room, covered with a sheet, and had the room

darkened, the windows closed, and all the usual ceremonies

which accompany death, performed. All this being done, and

the servants duly instructed, the two boys were cautiously informed

that their father had died suddenly, and were at once

hurried into the room where he lay, in order that he might hear

them give vent to their real feelings.[11]

When Joe was brought into the dark room on so short a notice,

his sensations were rather complicated, but they speedily resolved

themselves into a firm persuasion that his father was not dead.

A variety of causes led him to this conclusion, among which the

most prominent were, his having very recently seen his father in

the best health; and, besides several half-suppressed winks and

blinks from Black Sam, his observing, by looking closely at the

sheet, that his deceased parent still breathed. With very little

hesitation the boy perceived what line of conduct he ought to adopt,

and at once bursting into a roar of the most distracted grief,

flung himself upon the floor, and rolled about in a seeming

transport of anguish.

John, not having seen so much of public life as his brother,

was not so cunning, and perceiving in his father's death nothing

but a relief from flogging and books (for both of which he had

a great dislike), and the immediate possession of all the plate

in the dining room, skipped about the room, indulging in various

snatches of song, and, snapping his fingers, declared that he was

glad to hear it.

"O! you cruel boy," said Joe, in a passion of tears, "hadn't

you any love for your dear father? Oh! what would I give to

see him alive again!"

"Oh! never mind," replied the brother; "don't be such a fool

as to cry; we can have the cuckoo-clock all to ourselves now."

This was more than the deceased could bear. He jumped

from the bier, opened the shutters, threw off the sheet, and

attacked his younger son most unmercifully; while Joe, not

knowing what might be his own fate, ran and hid himself in

the coal-cellar, where he was discovered some four hours afterwards,

by Black Sam, fast asleep, who carried him to his father,

who had been anxiously in search of him, and by whom he was

received with every demonstration of affection, as the son who

truly and sincerely loved him.

From this period, up to the year 1788, he continued regularly

employed upon the same salaries as he had originally received

both at Drury Lane and Sadler's Wells.

[Pg 17]

CHAPTER II.

1788 to 1794.

The Father's real Death—His Will, and failure of the Executor—Generous conduct

of Grimaldi's Schoolmaster, and of Mr. Wroughton, the Comedian—Kindness

of Sheridan—Grimaldi's industry and amusements—Fly catching—Expedition

in search of the "Dartford Blues"—Mrs. Jordan—Adventure

on Clapham Common: the piece of Tin—His first love and its consequences.

It has been stated in several publications that Grimaldi's father

died in 1787. It would appear from several passages in the

memoranda dictated by his son, that he expired on the 14th of

March, 1788, of dropsy, in the seventy-eighth year[12] of his age,

and that he was interred in the burial-ground attached to Exmouth-street

Chapel; a spot of ground in which, if it bore any

resemblance at that time to its present condition, he could have

had very little room to walk about and meditate when alive.

He left a will, by which he directed all his effects and jewels to

be sold by public auction, and the proceeds to be added to his

funded property, which exceeded 15,000l.; the whole of the gross

amount, he directed should be divided equally between the two

brothers as they respectively attained their majority. Mr.

King,[13] to whom allusion has already been made, was appointed[Pg 18]

co-executor with a Mr. Joseph Hopwood, a lace manufacturer in

Long-acre, at that time supposed to possess not only an excellent

business, but independent property to a considerable amount

besides. Shortly after they entered upon their office, in consequence

of Mr. King declining to act, the whole of the estate fell

to the management of Mr. Hopwood, who, employing the whole

of the brothers' capital in his trade, became a bankrupt within

a year, fled from England, and was never heard of afterwards.

By this unfortunate and unforeseen event, the brothers lost the

whole of their fortune, and were thrown upon their own resources

and exertions for the means of subsistence.

It is very creditable to all parties, and while it speaks highly

for the kind feeling of the friends of the widow, and her two

sons, bears high testimony to their conduct and behaviour, that

no sooner was the failure of the executor known than offers of

assistance were heaped upon them from all quarters. Mr. Ford,

the Putney schoolmaster, offered at once to receive Joseph into

his school and to adopt him as his own son; this offer being

declined by his mother, Mr. Sheridan, who was then proprietor

of Drury Lane Theatre, raised the boy's salary, unasked, to one

pound per week, and permitted his mother, who was and had

been from her infancy a dancer at that establishment, to accept

a similar engagement at Sadler's Wells, which was, in fact,

equivalent to a double salary, both theatres being open together

for a considerable period of the year.

At Sadler's Wells, where Joseph appeared as usual in 1788,[14]

shortly after his father's death, they were not so liberal, nor was

the aspect of things so pleasing, his salary of fifteen shillings

a-week being very unceremoniously cut down to three, and his

mother being politely informed, upon her remonstrating, that if[Pg 19]

the alteration did not suit her, he was at perfect liberty to

transfer his valuable services to any other house. Small as the

pittance was, they could not afford to refuse it; and at that

salary he remained at Sadler's Wells for three years, occasionally

superintending the property-room, sometimes assisting in the

carpenter's, and sometimes in the painter's, and, in fact, lending

a hand wherever it was most needed.

When the defalcation of the executor took place, the family

were compelled to give up their comfortable establishment, and

to seek for lodgings of an inferior description. His mother

knowing a Mr. and Mrs. Bailey, who then resided in Great

Wild-street, and who let lodgings, applied to them, and there

they lived, in three rooms on the first floor, for several years.

The brother could not be prevailed upon to accept any regular

engagement, for he thought and dreamt of nothing but going to

sea, and evinced the utmost detestation of the stage. Sometimes,

when boys were wanted in the play at Drury Lane, he was sent

for, and attended, for which he received a shilling per night;

but so great was his unwillingness and evident dissatisfaction

on such occasions, that Mr. Wroughton, the comedian, who, by

purchasing the property of Mr. King, became about this period[15]

proprietor of Sadler's Wells, stepped forward in the boy's behalf,

and obtained for him a situation on board an East-Indiaman,

which then lay in the river, and was about to sail almost immediately.

John was delighted when the prospect of realizing his ardent

wishes opened upon him so suddenly; but his raptures were

diminished by the discovery that an outfit was indispensable,

and that it would cost upwards of fifty pounds: a sum which,

it is scarcely necessary to say, his friends, in their reduced position,

could not command. But the same kind-hearted gentleman

removed this obstacle, and with a generosity and readiness

which enhanced the value of the gift an hundredfold, advanced,

without security or obligation, the whole sum required, merely

saying, "Mind, John, when you come to be a captain you must

pay it me back again."

There is no difficulty in providing the necessaries for a voyage

to any part of the world when you have provided the first and

most important—money. In two days, John took his leave of

his mother and brother, and with his outfit, or kit, was safely

deposited on board the vessel in which a berth had been procured

for him; but the boy, who was of a rash, hasty, and inconsiderate

temper, finding, on going on board, that a delay of

ten days would take place before the ship sailed, and that a

king's ship, which lay near her, was just then preparing to

drop down to Gravesend with the tide, actually swam from his[Pg 20]

own ship to the other, entered himself as a seaman or cabin-boy

on board the latter in some feigned name,—what it was his

friends never heard,—and so sailed immediately, leaving every

article of his outfit, down to the commonest necessary of wearing

apparel, on board the East-Indiaman, on the books of which he

had been entered through the kindness of Mr. Wroughton. He

disappeared in 1789, and he was not heard of, or from, or seen,

for fourteen years afterwards.

At this period of his life, Joseph was far from idle; he had to

walk from Drury Lane to Sadler's Wells every morning to

attend rehearsals, which then began at ten o'clock; to be back

at Drury Lane to dinner by two, or go without it; to be back

again at Sadler's Wells in the evening, in time for the commencement

of the performances at six o'clock; to go through

uninterrupted labour from that time until eleven o'clock, or

later; and then to walk home again, repeatedly after having

changed his dress twenty times in the course of the night.

Occasionally, when the performances at Sadler's Wells were

prolonged so that the curtain fell very nearly at the same time

as the concluding piece at Drury Lane began, he was so pressed

for time as to be compelled to dart out of the former theatre at

his utmost speed, and never to stop until he reached his dressing-room

at the latter. That he could use his legs to pretty good advantage

at this period of his life, two anecdotes will sufficiently show.

On one occasion, when by unforeseen circumstances he was

detained at Sadler's Wells beyond the usual time, he and Mr.

Fairbrother (the father of the well-known theatrical printer),

who, like himself, was engaged at both theatres, and had agreed

to accompany him that evening, started hand-in-hand from

Sadler's Wells theatre, and ran to the stage-door of Drury Lane

in eight minutes by the stop watches which they carried.

Grimaldi adds, that this was considered a great feat at the time;

and we should think it was.

Another night, during the time when the Drury Lane company

were playing at the Italian Opera-house in the Haymarket,

in consequence of the old theatre being pulled down and a new

one built, Mr. Fairbrother and himself, again put to their

utmost speed by lack of time, ran from Sadler's Wells to the

Opera-house in fourteen minutes, meeting with no other interruption

by the way than one which occurred at the corner of

Lincoln's Inn Fields, where they unfortunately ran against and

overturned an infirm old lady, without having time enough to

pick her up again. After Grimaldi's business at the Opera-house

was over, (he had merely to walk in the procession in

Cymon,) he ran back alone to Sadler's Wells in thirteen minutes,

and arrived just in time to dress for Clown in the concluding

pantomime.

For some years his life went on quietly enough, possessing very

little of anecdote or interest beyond his steady and certain rise[Pg 21]

in his profession and in the estimation of the public, which,

although very important to him from the money he afterwards

gained by it, and to the public from the amusement which his

peculiar excellence yielded them for so many years, offers no

material for our present purpose. This gradual progress in the

good opinion of the town exercised a material influence on his

receipts; for, in 1794, his salary at Drury Lane was trebled,

while his salary at Sadler's Wells had risen from three shillings

per week to four pounds. He lodged in Great Wild-street with

his mother all this time: their landlord had died, and the

widow's daughter, from accompanying Mrs. Grimaldi[16] to Sadler's

Wells theatre, had formed an acquaintance with, and married

Mr. Robert Fairbrother, of that establishment, and Drury Lane,

upon which Mrs. Bailey, the widow, took Mr. Fairbrother into

partnership as a furrier, in which pursuit, by industry and perseverance,

he became eminently successful.

This circumstance would be scarcely worth mentioning, but

that it shows the industry and perseverance of Grimaldi, and

the ease with which, by the exercise of those qualities, a very

young person may overcome all the disadvantages and temptations

incidental to the most precarious walk of a precarious

pursuit, and become a useful and respectable member of society.

He earned many a guinea from Mr. Fairbrother by working at

his trade, and availing himself of his instruction in his leisure

hours; and when he could do nothing in that way, he would go

to Newton-street, and assist his uncle and cousin, the carcase

butchers, for nothing; such was his unconquerable antipathy to

being idle. He does not inform us, whether it required a practical

knowledge of trade, to display that skill and address with

which, in his subsequent prosperity, he would diminish the

joints of his customers as a baker, or increase the weight of their

meat as a butcher, but we hope, for the credit of trade, that his

morals in this respect were wholly imaginary.

These were his moments of occupation, but he contrived to

find moments of amusement besides, which were devoted to

the breeding of pigeons, and collecting of insects, which latter

amusement he pursued with such success, as to form a cabinet

containing no fewer than 4000 specimens of flies, "collected," he

says, "at the expense of a great deal of time, a great deal of

money, and a great deal of vast and actual labour,"—for all of

which, no doubt, the entomologist will deem him sufficiently

rewarded. He appears in old age to have entertained a peculiar

relish for the recollection of these pursuits, and calls to mind a

part of Surrey where there was a very famous fly, and a part of

Kent where there was another famous fly; one of these was

called the Camberwell Beauty (which he adds was very ugly),

and another, the Dartford Blue, by which Dartford Blue he

seems to have set great store; and which were pursued and[Pg 22]

caught in the manner following, in June, 1794, when they regularly

make their first appearance for the season.

Being engaged nightly at Sadler's Wells, he was obliged to

wait till he had finished his business upon the stage: then he

returned home, had supper, and shortly after midnight started

off to walk to Dartford, fifteen miles from town. Here he

arrived about five o'clock in the morning, and calling upon a

friend of the name of Brooks, who lived in the neighbourhood,

and who was already stirring, he rested, breakfasted, and sallied

forth into the fields. His search was not very profitable, however,

for after some hours he only succeeded in bagging, or bottling, one

"Dartford Blue," with which he returned to his friend perfectly

satisfied. At one o'clock he bade his friend good by, walked

back to town, reached London by five, washed, took tea, and

hurried to Sadler's Wells. No time was to be lost—the fact of

the appearance of the "Dartford Blues" having been thoroughly

established—in securing more specimens; so on the same night,

directly the pantomime was over, and supper over, too, off he

walked down to Dartford again, found the friend up again,

took a hasty breakfast again, and resumed his search again.

Meeting with better sport, and capturing no fewer than four

dozen Dartford Blues, he hurried back to the friend's; set them—an

important process, which consists in placing the insects in

the position in which their natural beauty can be best displayed—started

off with the Dartford Blues in his pocket for London

once more, reached home by four o'clock in the afternoon,

washed, and took a hasty meal, and then went to the theatre for

the evening's performance.

As not half the necessary number of Blues had been taken,

he had decided upon another visit to Dartford that same night,

and was consequently much pleased to find that, from some unforeseen

circumstance, the pantomime was to be played first.

By this means he was enabled to leave London at nine o'clock,

to reach Dartford at one, to find a bed and supper ready, to

meet a kind reception from his friend, and finally to turn into

bed, a little tired with the two days' exertions. The next day was

Sunday, so that he could indulge himself without being obliged

to return to town, and in the morning he caught more flies than

he wanted; so the rest of the day was devoted to quiet sociality.

He went to bed at ten o'clock, rose early next morning, walked

comfortably to town, and at noon was perfect in his part, at the

rehearsal on the stage at Drury Lane theatre.

It is probable that by such means as these, united to temperance

and sobriety, Grimaldi acquired many important bodily

requisites for the perfection which he afterwards attained. But

his love of entomology, or exercise, was not the only inducement

in the case of the Dartford Blues; he had, he says, another

strong motive, and this was, the having promised a little collection

of insects to "one of the most charming women of her[Pg 23]

age,"—the lamented Mrs. Jordan, at that time a member of the

Drury Lane company.

Upon one occasion he had held under his arm, during a morning

rehearsal, a box containing some specimens of flies: Mrs.

Jordan was much interested to know what could possibly be in

the box that Grimaldi carried about with him with so much

care, and would not lose sight of for an instant, and in reply to

her inquiry whether it contained anything pretty, he replied by

exhibiting the flies.

He does not say whether these particular flies, which Mrs.

Jordan admired, were Dartford Blues, or not; but he gives us

to understand, that his skill in preserving and arranging insects

was really very great; that all this trouble and fatigue

were undertaken in a spirit of respectful gallantry to the most

winning person of her time; and that, having requested permission

previously, he presented two frames of insects to Mrs.

Jordan, on the first day of the new season, and immediately

after she had finished the rehearsal of Rosalind in "As you like

it;" that Mrs. Jordan was delighted, that he was at least

equally so, that she took the frames away in her carriage, and

warmed his heart by telling him that his Royal Highness the

Duke of Clarence considered the flies equal, if not superior, to

any of the kind he had ever seen.

His only other companion in these trips, besides his Dartford

friend, was Robert Gomery, or "friend Bob," as he was called

by his intimates, at that time an actor at Sadler's Wells,[17] and

for many years afterwards a public favourite at the various

minor theatres of the metropolis; who is now, or was lately,

enjoying a handsome independence at Bath. With this friend

he had a little adventure, which it was his habit to relate with

great glee.

One day, he had been fly-hunting with his friend, from early

morning until night, thinking of nothing but flies, until at

length their thoughts naturally turning to something more substantial,

they halted for refreshment.

"Bob," said Grimaldi, "I am very hungry."

"So am I," said Bob.

"There is a public-house," said Grimaldi.

"It is just the very thing," observed the other.

It was a very neat public-house, and would have answered

the purpose admirably, but Grimaldi having no money, and

very much doubting whether his friend had either, did not

respond to the sentiment quite so cordially as he might have

done.

"We had better go in," said the friend; "it is getting late—you

pay."

[Pg 24]

"No, no! you."

"I would in a minute," said his friend, "but I have not got

any money."

Grimaldi thrust his hand into his right pocket with one of his

queerest faces, then into his left, then into his coat pockets, then

into his waistcoat, and finally took off his hat and looked into

that; but there was no money anywhere.

They still walked on towards the public-house, meditating

with rueful countenances, when Grimaldi spying something

lying at the foot of a tree, picked it up, and suddenly exclaimed,

with a variety of winks and nods, "Here's a sixpence."

The hungry friend's eyes brightened, but they quickly resumed

their gloomy expression as he rejoined, "It's a piece of

tin!"

Grimaldi winked again, rubbed the sixpence or the piece of

tin very hard, and declared, putting it between his teeth by

way of test, that it was as good a sixpence as he would wish to

see.

"I don't think it," said the friend, shaking his head.

"I'll tell you what," said Grimaldi, "we'll go to the public-house,

and ask the landlord whether it's a good one, or not.

They always know."

To this the friend assented, and they hurried on, disputing all

the way whether it was really a sixpence, or not; a discovery

which could not be made at that time, when the currency was

defaced and worn nearly plain, with the ease with which it

could be made at present.

The publican, a fat, jolly fellow, was standing at his door,

talking to a friend, and the house looked so uncommonly comfortable,

that Gomery whispered as they approached, that

perhaps it might be best to have some bread and cheese first,

and ask about the sixpence afterwards.

Grimaldi nodded his entire assent, and they went in and

ordered some bread and cheese, and beer. Having taken the

edge off their hunger, they tossed up a farthing which Grimaldi

happened to find in the corner of some theretofore undiscovered

pocket, to determine who should present the "sixpence." The

chance falling on himself, he walked up to the bar, and with a

very lofty air, and laying the questionable metal down with a

dignity quite his own, requested the landlord to take the bill

out of that.

"Just right, sir," said the landlord, looking at the strange

face that his customer assumed, and not at the sixpence.

"It's right, sir, is it?" asked Grimaldi, sternly.

"Quite," answered the landlord; "thank ye, gentlemen."

And with this he slipped the—whatever it was—into his pocket.

Gomery looked at Grimaldi, and Grimaldi, with a look and

air which baffle all description, walked out of the house, followed

by his friend.

[Pg 25]

"I never knew anything so lucky," he said, as they walked

home to supper—"it was quite a Providence—that sixpence."

"A piece of tin, you mean," said Gomery.

Which of the two it was, is uncertain, but Grimaldi often

patronised the same house afterwards, and as he never heard

anything more about the matter, he felt quite convinced that it

was a real good sixpence.

In the early part of the year 1794, they quitted their lodgings

in Great Wild-street, and took a six-roomed house, in Penton-place,

Pentonville, with a garden attached; a part of this they

let off to a Mr. and Mrs. Lewis, who then belonged to Sadler's

Wells; and in this manner they lived for three years, during

the whole of which period his salaries steadily rose in amount,

and he began to consider himself quite independent.