Project Gutenberg's Our Little Grecian Cousin, by Mary F. Nixon-Roulet This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: Our Little Grecian Cousin Author: Mary F. Nixon-Roulet Illustrator: Diantha W. Horne Release Date: August 5, 2014 [EBook #46508] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK OUR LITTLE GRECIAN COUSIN *** Produced by Emmy, Beth Baran and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

(TRADE MARK)

Each volume illustrated with six or more full-page plates in

tint. Cloth, 12mo, with decorative cover,

per volume, 60 cents

LIST OF TITLES

By Mary Hazelton Wade

(unless otherwise indicated)

L. C. PAGE & COMPANY

New England Building, Boston, Mass.

Our Little

|

||

Copyright, 1908

By L. C. Page & Company

(INCORPORATED)

Entered at Stationers' Hall, London

All rights reserved

First Impression, July, 1908

TO

Mary and Julia Rhodus

TWO LITTLE FRIENDS

Of all people in the world the Grecians did most for art, and to the ancient Hellenes we owe much that is beautiful in art and interesting in history. Of modern Greece we know but little, the country of isles and bays, of fruits and flowers, and kindly people. So in this story you will find much of the country, old and new, and of the every-day life of Our Little Grecian Cousin.

| Contents |

| PAGE | |

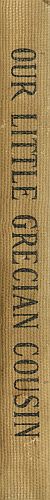

"She took her basket and ran down the hillside" (See page 11) |

Frontispiece |

"Something lay there half covered with earth" |

31 |

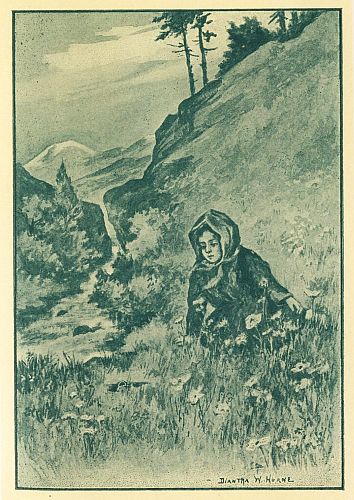

"Papa Petro came riding down from his house on a tiny donkey" |

39 |

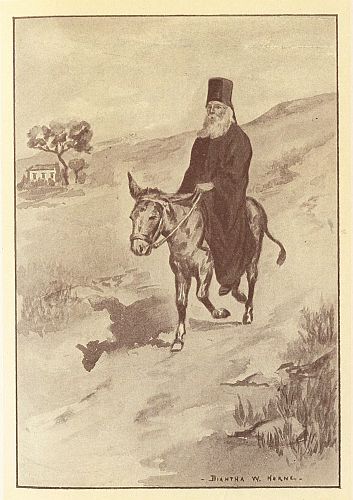

"Stood before them in the beautiful national costume of Greece" |

68 |

"They washed beneath a huge plane tree" |

108 |

"She sprang to her feet, and in so doing pulled the bell-rope" |

125 |

Zoe sat in the doorway tending baby Domna as she lay asleep in her cradle. She was sleeping quietly, as any child should who has the cross on her cradle for good luck. Her skin was as white as milk, and this was because Zoe had taken care of her Marti. On the first day of March she had tied a bit of red ribbon about her little cousin's wrist, for a charm. The keen March winds could not hurt the baby after that, nor could she have freckles nor sunburn.

Early on the morning of April first, Zoe had dressed the baby and carried her out of doors.[2] The dew lay over the flowers, the sun was just up, and his rosy beams turned the blossoming lemon trees to beauty. Zoe had sought the nearest garden and there hung the Marti on a rose bush, plucking a rose and pinning it to Domna's cap.

"Now, Babycoula,"[1] she had said, clapping her hands, "you shall have luck. Your Marti is upon a rose bush kissed with dew before the sun is high. The summer's heat shall not touch you and you shall be cool and well."

It was fortunate for Zoe as well as for the "Joy," which the Greek word for baby means, that Domna was a quiet baby. As most of the little girl's time was taken up with caring for one or another of her aunt's children, when they were cross it left her but little time for thinking and dreaming. Zoe's thoughts were often sad ones, but her dreams were rose-coloured. When the little girl thought, she[3] remembered the home she had once had. It was far in the sunny south where lemon groves lifted golden-fruited arms to the soft winds, and hillsides gleamed with purple and white currants.

Her father had met with ill luck and men had told him of a land beyond the seas, where people had plenty to eat and found gold pieces rolling in the streets. He had sent her mother and herself to live near Zoe's uncle and she had seen no more the bright, gay father whom she loved. Then her mother died, and this, her first great sorrow, made her into a quiet, sober child with a dark, grave face. At ten she was a little old woman, taking such good care of her aunt's babies that that hard-working woman did not begrudge the orphan the little she ate.

Uncle Georgios was a kind man. He loved children, as do all Grecians, who say, "A house without a child is a cold house." He worked too hard to pay much attention to any one of the[4] swarm which crowded his cottage. Aunt Anna had so many children that she never had time to think of any of them except to see that they had food and clothes. Zoe was but another girl for whom a marriage portion must be provided. Every Grecian girl must have a dowry, and it would be a great disgrace if none were ready for her when she was sought in marriage. Fathers and brothers have to earn the necessary money, and the girls themselves make ready their household linens, often beginning when only ten years old.

Zoe had not commenced making her linens because her aunt had not been able to give her thread or even to take time to teach her to spin. So the little maid's hands were idle as she watched the babycoula and that was not good, for a girl's fingers should always be at work, lest she have too much time to think sad thoughts. But, if her thoughts were dark, her dreams were bright, for she saw before her a[5] rosy future in which she lived where the sun shone and everyone was happy.

Baby Domna stirred in her cradle, for flies were crawling over her little nose. Zoe waved them off singing, "Nani, nani, Babycoula, mou-ou-ou!" The baby smiled and patted her hands.

"You are a good child," said Zoe. "The best of tables was set out for you the third night after you came from Heaven. There was a fine feast for the Three Fates, even a bit of sumadhe and a glass of mastika.[2] You must have good fortune.

"Palamakia,[3] play it, dear,

Papa's coming to see you here,

He brings with him loukoumi[4] sweet

For Babycoula now to eat.

"It's time you went to sleep again, Baby," said Zoe, her foot on the rocker, but the babycoula[6] gurgled and waved her fat arms to be taken up, so the patient nurse took up the heavy little child and played with her.

"Little rabbit, go, go, go," she said, making her little fingers creep up the soft little arm, as American children play "creep mousie," with their baby sisters.

"Dear little rabbit, go and take a drink,

Baby's neck is cool and clean and sweet,"

and the little girl's fingers tickled the warm little neck and Domna laughed and gurgled in glee. Zoe danced her up and down on her knee and sang,

"Babycoula, dance to-day,

Alas, the fiddler's gone away,

He's gone to Athens far away,

Find him and bring him back to play."

The pretty play went on, and at last the tiny head drooped on Zoe's shoulder and the babycoula slept again. Then her little nurse gently laid her in the cradle, tucked in the covers and[7] sat slowly waving an olive branch above her to keep away the flies.

Zoe's uncle lived in Thessaly, that part of Northern Greece where splendid grain fields cover the plains, a golden glory of ripened sheaves.

Uncle Georgios worked in the fields in harvest time and the rest of the year he was a shepherd, herding sheep and goats in the highlands. The boys worked with him. There were Marco and Spiridon, well grown boys of eighteen and twenty, working hard for their sisters' marriage portions, which must be earned before they themselves could be married. After Spiridon came Loukas, a sailor, who was always away from home, and then Maria and Anna. Another boy, mischievous Georgios, was next in age to Anna, there were two little girls younger than she, and then Baby Domna, Zoe's especial charge.

It had been a hard summer. The sirocco had[8] blown from Africa and made the days so hot that all field work had to be done at night. Now the threshing-floors were busy and Uncle Georgios was working early and late to get in the grain.

"Zoe!" called Aunt Anna from within the house. "It is time to take your uncle's dinner to him."

"Yes, Aunt," said Zoe, rising from the doorway, and hastening to take the basket Aunt Anna had prepared. There was black bread, fresh garlic and eggs. Then she ran quickly along the path which led to the fields. It was a beautiful day and the air was fresh and sweet.

"I am Atalanta running for the apple," laughed Zoe to herself, as she sped up the hill, reaching the threshing-place just at noon. The threshing-floor was very old and made of stone. It was thirty feet across, and over its stone floor cattle were driven up and down,[9] with their hoofs beating the grain out of the straw. Zoe stood and watched the patient creatures going back and forth yoked together in pairs.

"Heu! Zoe!" called Marco, with whom she was a great favourite, "Have you brought us to eat?"

"I have, Cousin," she answered, gazing with admiring eyes at the tall fellow, with his slim figure, aquiline nose, oval face, and pleasant mouth shaded by a slight moustache. Marco was a true Thessalonian, handsome and gay. He had served his time in the army and had come home to help his father bring up the younger children.

"Why don't you put muzzles on the oxen, they look so fierce?" said Zoe, looking at the great creatures as they passed and repassed.

"Oh, they are never muzzled," said Marco. "It was not done by our fathers. It reminds me of what I read in Queen Olga's Bible, 'Do[10] not muzzle the ox when he treadeth out the grain.'"

"What is Queen Olga's Bible?" asked Zoe. She was not afraid of Marco. With her other cousins she was as quiet as a mouse, but she chatted with Marco without fear.

"The good queen found that the soldiers had no Holy Scriptures which they could read," said Marco. "Because all the holy books were in the ancient Greek. She had them put into the language we talk and printed for the soldiers. Then she gave one to each man in our regiment and I have mine still."

"How good she was!" cried Zoe. "Did every one love her for her kindness?"

"Not so," said Marco. "Many people were angry at her. They said she was not showing respect to the Scriptures and was trying to bring in new things, as if that was a sin! All new things are not bad, are they, little cousin?"

"I do not know, it is long since I had anything new," said Zoe.

"That is true, poor child," said Marco, kindly as he glanced at her worn dress. "Never mind. When we get Maria married you shall have something new and nice."

"Oh, thank you, I am very well as I am," said Zoe, flushing happily at his kindness, for she was a loving little soul and blossomed like a flower in the sunlight. "I must go home now," she said. "Baby will be awake from her nap and Aunt Anna will need me to tend her."

"Are you never tired of baby?" asked Marco.

"Oh, I love her," said Zoe brightly, as if that was an answer to his question, and nodding gaily, she took her basket and ran down the hillside, where buttercups and bright red poppies nodded in the sun.

Maria was to be married. This was a very great event in the family and all the little Mezzorios were wild with excitement. Maria was the favourite sister, and she was tall and very beautiful. Her hair and eyes were dark and her smile showed through gleaming white teeth. Her marriage chest was ready, her dowry was earned, and a cousin of the family had acted as "go-between" between Uncle Georgios and the father of the young man who wished to marry Maria. His name was Mathos Pappadiamantopoulas, and he had seen Maria as she walked spinning in the fields.

Generally in Greece the parents arrange the marriages and the young people scarcely see[13] each other before the marriage ceremony binds them together. Maria's, however, was quite a love match, for she and Mathos had grown up together and had been waiting only for the dowry to go to housekeeping in a little white cottage near to that of her mother.

Mathos had often been beneath Maria's window and had called his sweetheart all the fond names he could think of. She was in turn "cold water" (always sweet to a Grecian because good water is so scarce in that country), a "lemon tree," and a "little bird." He had sung to her many love songs, among them the Ballad of the Basil.

"If I should die of love, my love, my grave with basil strew,

And let some tears fall there, my life, for one who died for you,

Agape mon-ou-ou!"

Maria's prekas[5] was a fine one. Her father and brothers had determined that.

"She shall not be made ashamed before any man. If I never marry, Maria shall have a good dowry," said Marco.

When the list of what she would give to the furnishing of the little home was made for the groom there was a strange array, a bedstead, a dresser, a chair, sheets and pillowcases, blankets and quilts. There were copper kettles and saucepans of many sizes and shapes, and the lovely homespun linens were beautifully embroidered.

Early in the morning of the wedding day, Mathos' friends helped him carry the praekika[6] from the bride's old home to her new one. Not a single pocket handkerchief but was noted on the list Mathos' best man had made, and it would have been a disgrace to all the family of Mezzorios had there been even a pin missing from all that had been agreed upon when the match was arranged.

Musicians played the guitar and mandolin, as Maria sat straight upright upon a sofa. She was a little white and frightened, but looked very pretty in her white dress embroidered in gold, her yellow embroidered kerchief over her head. Zoe, with the other children, had been flying around the room ready, whenever the mastiche paste was passed on a tray, to take a spoon from the pile and gouge out a taste of the sweet stuff.

"Maria looks lonely," she said to Marco. "I'm glad I'm not in her place."

"She'll be all right now," he said as the cry "He comes!" was heard outside. Zoe ran to the door. She had never seen a wedding in Thessaly and was very curious to see what it was like. Little Yanne Ghoromokos was coming up the street carrying a tray on which rested two wreaths of flowers and two large candles tied with white ribbon. Behind him was Mathos, looking very foolish, surrounded by his friends.

"I shall not marry a man who looks like that," said Zoe to Marco, who stood beside her.

"What is wrong with him?" asked Marco, who liked to hear his little cousin talk, her remarks were so quaint and wise.

"He looks very unhappy, as if this were a funeral," she said, "or as if he were afraid of something. When I marry, my husband shall be glad."

"That he should be," said Marco smiling, and showing his white teeth.

Mathos meanwhile made his way into the house and sat down on the sofa by Maria. He did not look at her, for that would have been contrary to etiquette, but over the girl's face there stole a warm and lovely colour which made her more beautiful than ever.

All the men present looked at her and all the women, old and young, kissed the groom, and each woman made him the present of a silk handkerchief. Then it was time for the wedding[17] ceremony and Zoe's eyes were big with wonder.

On the table were placed a prayer book, a plate of candies, as the priest, old Papa Petro took his stand near by. Maria came forward with her father and Mathos and his best man stood beside her. To the child's great wonder and delight, Zoe was to be bridesmaid, for Maria had said to her mother,

"Let Zoe be bridesmaid. It will please her and she is a good little thing." And Aunt Anna had answered,

"What ever you want, my child."

Zoe, therefore, in a new frock, with a rose pinned in her black hair, stood proudly beside Maria at the altar. She watched the queer ceremony in silence. First Papa Petro gave the groom a lighted candle and asked him if he would take Maria for his wife; then Maria received a candle and was asked if she would take Mathos for her husband, after which the[18] priest sang the Kyrie Eleison and made a long, long prayer.

He blessed the two rings laid on the tray before him, giving one to the bride and one to the groom. The best man quickly took them off the fingers of each, exchanged them, and put the bride's on the groom's finger, giving his to her.

Papa Petro next put a wreath on the head of each and the best man exchanged them, and the ceremony continued, but of it Zoe saw little. She was so overcome by the sight of Mathos' red, perspiring face, surmounted by the wreath of white blossoms, and looking silly but happy, that she had all she could do to keep from laughing.

She was so astonished a moment later that she nearly disgraced herself, for the rest of the ceremony was like nothing she had ever seen before. The priest took the hand of the best man, he took that of the groom, and he held his[19] bride by the hand, and all, priest, best man, groom and bride, danced three times around the altar, while the guests pelted the dancers with candies, and Zoe stood in open-mouthed amazement, until Marco threw a candy into her mouth and nearly choked her. Then the ceremony was over and everybody kissed the bride and her wreath, which brings good luck.

"What do you think of being bridesmaid?" asked Marco.

"It is very nice, but I was afraid I should laugh," answered Zoe. "What do they do now, Marco?"

"Maria must go to her husband's house. She is starting now. Come, let us follow."

They went with the bridal couple down the village street, and at her door lay a pomegranate. Upon this the bride stepped for good fortune with her children. Then Mathos' mother tied the arms of the two together with a handkerchief and they entered their own home. They drank a[20] cup of wine together and turned to receive the congratulations of their friends.

"Marco, it is your turn next. Beware lest a Nereid get you," said Mathos, laughing.

"I am not afraid of a Nereid," said Marco hastily crossing himself.

"Once I saw one upon the hillside when I was watching the sheep," said an old man. "She was so beautiful I crept up to seize her in my arms and behold! she turned into a bear and then a snake. The bear I held but the snake I let go. Then I saw her no more."

"Upon the river bank of Kephissos," said an old woman, "dwell three Nereids. They are sisters. Two are fair but one is ugly and crippled. My mother lived there and she has often told me that she heard the fays talking and laughing in the reeds along the shore. The pretty sisters like children and love to play with mortals. Sometimes they steal away little folk when they have stayed out at night in disobedience[21] to their mothers. They take them to their home in the reeds, but the lame sister is jealous of pretty children and when she is sent to take them home, she pinches them. My mother has with her two eyes seen the black and blue marks of pinches upon the arms of children who did not always stay in the house after dark. And where my mother lived they say always to naughty children, 'Beware! the lame Nereid will get you!'"

"Be careful, Zoe," said Marco. "Be a good child and keep within when it is dark, else you shall see the Nereid."

"God forbid!" said Zoe, quickly crossing herself, "I should die of fright."

Fall had come with its cool, sunny days and Aunt Anna was cooking beans, symbols of the autumn fruits in honour of the old Feast of Apollo. Olive branches were hung over the door of the house to bring luck, as in the olden times olive boughs hung with figs and cakes, with jars of oil and wine were carried by youths to the temples. Upon the hillsides the vineyards hung, purple with fruit and winter wheat was sown in the fields.

Zoe had begun to go to school and the babycoula wept for her. She did not at all believe in education since it took away her willing slave and devoted attendant, but in Greece all children are compelled to go to school and learn at least to read and write and do simple sums.

Zoe enjoyed the school very much. She liked the walk in the fresh morning air and she liked to learn, but most of all she liked the stories which her teacher told whenever they were good children, stories of the days when Greece was the greatest nation of the earth, her women were famous for beauty and virtue, her men were warriors and statesmen.

She learned of Lycurgus, the great lawgiver, of Pericles, the statesman, of Alexander, the great general, and of the heroes of Thermopylć. All these tales she retold to her cousins and many were the hours she kept them listening spellbound.

"It was not far from here, the Pass of Thermopylć," she said. "Some day I shall ask Marco to take us there. The story tells of how Leonidas was king of Sparta and the cruel Persians came to conquer Greece. Xerxes was the Persian king and he had a big army, oh, ever so many times larger than the Grecian.[24] Well, the only way to keep out the Persians was to keep them from coming through the Pass of Thermopylć, so Leonidas took three hundred men and went to hold the Pass. For two days they held it, and kept the Persians from coming in, and they could have held out longer but for treachery. A miserable man, for money, told the Persians a secret path across the mountains, so they crept up behind the Grecians and attacked them. When Leonidas found they were surrounded, he made up his mind that he and his men must die, but that they should die as brave men. They fought the Persians so fiercely that the Pass ran with blood and several times the Persians fell back; others took their places, but these too turned back, and the Persian king said,

"'What manner of men are these who, but a handful can keep back my whole army?' and one of his men replied,

"'Sire, your men fight at your will; these[25] Grecians, fight for their country and their wives!'

"But at last the end came. Leonidas fell, covered with wounds, and without him his men could withstand no longer. One by one they fell, each with his sword in hand, his face to the foe, and when the last one fell, the Persians, with a great shout, rushed through the Pass over the dead bodies of the heroes."

"That's a fine story," said Georgios. "But I sha'n't wait for Marco. I shall go to see the Pass for myself."

"No, no!" said Zoe. "You must not. Aunt Anna would be angry. It is quite too far and it is in the mountains; you might meet a brigand."

But Georgios said only, "Pooh! I can take care of myself," and looked sulky. It was rather hard for Zoe to look after him. He was a mischievous boy, only a year younger than she was, and he thought himself quite as old. He[26] did not like it at all when his mother told him to mind what Zoe said and often he did things just to provoke her. This particular Saturday he was in bad temper because he had wished to go to the mountains with Marco and his brother would not take him.

"Another time I will take you," said Marco. "But to-day I am in haste. Stay with the girls and be a good little boy."

"Stay with the girls!" muttered Georgios. "It is always stay with the girls. Some day I will show them I am big enough to take care of myself."

So he felt cross and did not enjoy Zoe's stories as much as usual.

"Not long ago," said Zoe, for the other children were listening with rapt interest, "some shepherds were tending their flocks on the hills and one of them dug a hole in the ground to make a fire that they might cook their food. As he placed the stones to make his[27] oven, he saw something sticking out of the ground and leaned down to see what it was. It looked like a queer kettle of some kind and he dug it out and examined it. He cleaned the dirt from it and it turned out to be an old helmet, rusted and tarnished, but still good. He took it and showed it to the teacher in the village and he said it was very, very old and might have belonged to one of Leonidas' men. So the master sent it to Athens and there they said that it was very valuable, and that the writing upon it showed that it had been at Thermopylć. They put it in the great museum at Athens, and paid the shepherd a great many drachmas[7] for it, so many that he could have for himself a house and need not herd sheep for another man, but have his own flocks."

"Wish I could find one," said Georgios. "I heard my father say we needed money very badly. There are so many of us! I wish I was[28] big!" and the boy's face grew dark. Zoe's clouded too.

"I am but another mouth to feed," she thought; but Aunt Anna's voice, calling them to come to the midday meal, put her thoughts to flight.

It was not until after the little siesta they all took after luncheon that she thought of what Georgios had said.

"How I wish I could find something of value," she thought to herself. "I am not of much use except that I try to help with the children. Oh, I wonder what Georgios is doing now!" she thought suddenly. She could not hear him and when Georgios was quiet he was generally naughty.

"Where is Georgios?" she asked the children, but they did not know. Only little Anna had seen him and she said that he had run quickly down the road a little while before.

"You must stay with the babycoula here on[29] the door step," Zoe said to the little girls, calling to her aunt within the house, "Aunt Anna, I am going to find Georgios, he is not here."

"Very well," said her aunt, and Zoe set off down the road. "Georgios!" she called. There was no answer, but she thought she saw the tracks of his feet in the dust of the road.

"Perhaps he has gone to the river," she said to herself, "to try to fish," and hastily she ran to the bank but there was no little boy in a red tasselled cap in sight. She hurried back to the road.

"I am afraid he has tried to go and see the Pass," she thought. "It would be just like him, for he said he would not wait for Marco. Oh, dear! I must find him. Aunt Anna will think it my fault if he is lost or anything happens to him." She hurried onward, calling and looking everywhere but found not a trace of the naughty little boy. It seemed as if he had disappeared from the face of the earth, and she murmured to herself,

"Oh, if he has gone to the river and a Nereid has stolen him! Perhaps he has run to the mountain and a brigand has found him! I must bring him home. Good St. Georgios, who killed the terrible dragon, help me to find your name-child! Oh, dear, of course the saints hear us, but it would be ever so much nicer if they would answer!" she thought. Then she had little time to think more, for her whole mind was bent upon finding the naughty boy whom, with all his naughtiness, she dearly loved. She hurried up the hill, peering under every bush, behind every tree, beginning to think that perhaps something had happened to the child. She went on and on until the shadows of twilight began to gather and she grew more and more frightened. Beneath her on the mountain-side flowed a little stream and she peered into its silver depths wondering if perhaps Georgios could have fallen into it. Then in her eagerness she leaned too far, lost her balance and fell.[31] Down, down she tumbled, rolling over and over on the soft grass until she reached the bottom of the hill. She lay still for a few moments then sat up and looked about her.

She was in a spot in which she had never been before, a pretty little glen, where the silvery stream ran over white pebbles with a soft, murmuring sound. Ferns grew tall and green, delicate wild flowers bloomed among them, the air was fragrant with the pines which grew overhead, and the whole spot was like a fairy dell. She tried to rise, but frowned with pain, for she had hurt her foot. So she sat thinking, "I will rest a minute and then go on and find Georgios."

As she sat thinking she noticed a queer place hollowed out by the water. Something lay there half covered with earth and she stooped to see what it was.

"Perhaps I shall find something like the shepherd did," she thought, but with sharp[32] disappointment she found that the object which had caught her eye was but a queer little cup black with red figures around the rim, and with two handles, one at each side. It had the figure of a woman at one side and Zoe thought it rather pretty.

"It is not of any use," she said to herself, "It is but someone's old cup. But I shall take it home for the babycoula to play with. She will think it is nice." So she tucked it into her pocket and got up to go. Her ankle hurt but not so badly that she could not walk. She wet her kerchief and tied it around the swollen joint and climbed up the hill which she had rolled down so unexpectedly. At the top she stopped and called as loudly as she could, "Georgios, Georgios!"

An answering shout of "Zoe!" came from below and her heart gave a glad leap. She turned her steps downward and Marco met her ere she was half way down.

"Child, what are you doing here?" he asked.

"Is Georgios found? I came to seek him!" she cried.

"He was not lost, that bad boy!" said Marco. "When I reached home I found my mother disturbed in her mind because you had disappeared and the little girls said you had gone to the mountain to find Georgios. Him I found by the river fishing and he said that you had called but that he had not answered. He will answer the next time," and Marco's voice told Zoe that he had made it unpleasant for Georgios. "Then I came on to seek you. Poor child! you must have had a hard climb."

"Oh, I did not mind," said Zoe. "Only I fell and hurt my ankle. I am glad Georgios was not lost. He might have answered me, though," and her lip quivered.

"He was a bad boy," said Marco, "and did it just to tease you. Let me see your ankle. It is badly bruised, but not sprained, I think.[34] Come, I will help you home," and he put his arm around her.

It took Zoe some time to get home for walking on the lame ankle tired her and often Marco stopped her to rest.

"What is it you have in your hand?" he asked her, as they sat down to rest beneath a giant fir.

"Oh, it is nothing," she said. "Just a queer little cup I found and thought Baby Domna might like to play with."

"Let me see it," said Marco, and he examined it carefully. "Where did you find it?" he asked at length and Zoe answered,

"When I fell by the river it lay in the dirt. Is it too dirty for the babycoula?"

"Zoe," Marco looked strangely excited. "I believe this old cup is of great value."

"Oh Marco!" the little girl could say no more.

"Yes," he said. "I may be mistaken, but[35] I think it is very old and that it is like some cups I saw in Athens. They were sold for many drachmas. They were black like this with a little red on them, in lines and figures, and with two handles. A man in my regiment said they were of ancient pottery and that they were dug up out of the earth. He said the museum at Athens paid good prices for such things."

"Oh Marco!" Zoe's eyes were like stars. "If it would only turn out that this was worth something, even a little, how happy I should be! I want money so badly."

"What do you want it for?" Marco looked surprised.

"To give to Aunt Anna, of course," said Zoe, surprised in her turn. "Georgios said to-day that your father needed money and Aunt Anna needs many things." The child said it so simply that one would have supposed she never needed anything for herself, and Marco caught her hand with a sudden impulse.

"You are a strange little one," he said. "If this turns out to be worth any money, you shall have it all to spend, every cent."

"For whatever I want?" asked Zoe in surprise.

"Yes, indeed," said Marco.

"Then I shall buy a dress for Aunt Anna and for each of the little girls a new one that has not been made over from someone's else. And something I shall buy for each one of the family, most of all for the babycoula, since I meant to take the cup to her. And all the rest I shall give to Uncle Georgios, for I am such an expense to him."

"That you are not," said Marco. "My mother said but yesterday that she did not know how she would ever get along without you."

"Did she really?" Zoe's face flushed with pleasure. "My foot is much better, we must go on now, it grows so late."

So they hastened home and Zoe met a warm[37] welcome, even Georgios hugging her and saying he was sorry he had sent her on such a wild goose chase. Her cup was displayed and wondered at, and later, when Papa Petro sent it to a priest in Athens and he sold it for many drachmas, Zoe was delighted and insisted upon giving the money to her uncle for all of them to share. Many comforts it brought for the family, besides paying the debts which had been worrying her uncle. And mischievous Georgios said airily,

"It was all due to me that the cup was found; for, if Zoe had not gone to find me, she would never have fallen down the hill on top of it."

"Nevertheless," said Marco sternly, "do not let me catch you playing any such tricks on your cousin again, or you will find something not so pleasant as antique cups. She's too good a little girl to tease."

And Zoe said in her soft little voice, "Oh, Marco."

Maria had a little son. Mathos was almost beside himself with delight, and the young mother was beautiful in her happiness. Her pretty face, always sweet, took on a deeper loveliness as she gazed on the little creature, so pink and white and dear, and Zoe thought she had never seen anything sweeter than her cousin and the baby together. Zoe had cared for her Aunt's babies so well that she was quite an authority and Maria trusted her with the little treasure when she would look anxiously at anyone else who took him up. He was indeed a joy. Serene and healthy, he lay all day, quite happy in the fact that he was able to get his tiny thumb in his mouth.

Maria had made her visit at Church on the fortieth day after the baby was born and Papa Petro had taken the little angel in his arms and walked thrice around the altar with him. Now the time had come when the good old priest was to christen the baby, and all the relatives and friends assembled to see the ceremony.

Papa Petro came riding down from his house on a tiny donkey. He was a dear old man with a wise, kindly face. He had been all his priestly life over the one parish, and his people were dear to him. They in turn loved him devotedly and he was always welcomed joyfully at any festivity.

Before the christening he blessed the house, performing the agiasmo or blessing, with great earnestness. First he took off his tall hat and let down his hair which was long and snowy white and usually worn in a knob at the back of his head. Then he set a basin of water and some incense before the eikon which was hung[40] in a corner of the room. Every Grecian home has its eikon or picture of a saint or the Blessed Virgin. The incense he placed in a bowl and lighted it, the smoke rising and filling the room with a strong perfume. He read the prayers which keep off the evil spirits in an impressive manner, and then turned his attention to the christening.

Baby Mathos, very cunning in his new cap, was set down before the eikon which bore the pictured face of the saint to whom he was to be dedicated. That was the signal for all the women present to rush for his cap, the one who secured the coveted bit of lace and muslin being the godmother. Zoe was the lucky one, and she stood proudly up beside Maria and the godfather, who had been Mathos' best man. The nounos[8] had given baby his fine new dress and had come prepared for all that a godfather must do.

The babycoula was then undressed and held up to the priest in Zoe's proud arms for Papa Petro to cut three hairs from the tiny head and throw them into the baptismal font. This was filled with water into which the godfather had poured a little olive oil.

Baby Mathos was then held to the west, to represent the kingdom of darkness, and Papa Petro asked three times, "Do you renounce the devil and all his works?" To this the godfather replied, "I do renounce them." At this the priest and godfather turned toward the east with the baby and the baby was plunged three times into the water. Baby squealed and kicked, and Zoe smiled, for if a baby does not cry at the water it is very bad luck, showing that the Evil One has not gone out of him. The babycoula did his little best to assure the company that he had no evil spirit left within, howling wrathfully after he was dried and anointed with holy oils, refusing to stop even when prayed[42] over at length, only smiling when, the ceremony over, the nounos gave some drachmas to his parents and threw a whole handful of lepta[9] among the children present.

"He is generous with his witness money," whispered Zoe to Maria and she smiled happily.

"Our little one will have the best of godparents," Maria said sweetly. "You to love him and Loukas to think of his welfare."

Papa Petro dipped an olive branch in holy water and sprinkled the rooms of the little cottage, then he sat down beside Maria, tied up his hair and took a cup of coffee. Everyone was served to glasses of water and sweets and everybody talked and laughed and said what a beautiful little Christian the babycoula was! As each one admired the baby Maria coloured and looked anxious and fingered the blue beads about her darling's neck.

"What have you for a charm against the evil[43] eye?" asked Papa Petro, kindly. "Ah, I see, the blue beads. Well, that is good. Blue is the Blessed Virgin's colour and the Panageia[10] will be your help. However, I have brought you a bit of crooked coral which I have always found good."

"It is most kind of you," said Maria prettily, as she hung the precious spray of coral at the babycoula's throat. Zoe smiled to herself. She had not intended to run any risk that her cousin's little baby should be marked with the evil eye, which can be put on a child just by admiring it. So, for the baby was so pretty she had felt sure it would be admired all day, she had put a bit of soot behind his ear, for that will ward off any evil eye. It is a sure charm. Therefore she felt quite satisfied even though every one present did say that the baby was perfectly beautiful. Then she held the little thing up before a mirror, for that would insure[44] another baby in the family before the close of the year, and as the Grecians love children dearly they are glad to have many of them.

The baby had so many pieces of white stuff given to him that the little house looked as if it had been in a snow storm. No polite person would come to see a new baby and not give it something white, even if it were only an egg, for such a gift insures to the infant a lovely fair complexion.

Thus was Baby Mathos started on his journey as a Christian with all good omens, and his little godmother went home in the cool of the evening, happy in all of the pleasures of the day.

"It was lovely, Aunt Anna!" she said to her aunt. "Was it not? Maria's baby is a dear little fellow. He is my own godchild and I love him dearly, but of course not more than our own babycoula," and she buried her face in Baby Domna's neck. The baby crowed and cooed and patted Zoe's face with her tiny chubby[45] hands and pulled her hair and acted in the entrancing way in which only a baby can act and Zoe laughed back at her and hugged her tight.

"You're my own babycoula," she said. "And I love you better than anything."

"Better than you do me? Oh shame!" said Marco teasing, while Aunt Anna, like every other good mother pleased with the attention her baby received, smiled upon her. Marco, however, looked very solemn and said reproachfully,

"I thought you would never like any baby better than me!"

"But you are not a baby," said Zoe, and Aunt Anna said,

"I am not so sure that he is not. But do not mind him, he is only teasing. You are a good child, Zoe," and little Zoe went happily to bed her heart warm at the thought that everybody seemed to love her, if she was an orphan and far away from home.

"It is only love that counts," she murmured[46] to herself sleepily and fell asleep with a smile on her face, as the silver moon streamed through her window and the air came in soft and kind, fragrant with the breath of spring.

The winter passed quietly to Zoe and spring came with its glories of cloud and flower and sunshine. Men began to plough in the fields with quaint old-fashioned, one-handled ploughs, drawn by great strong oxen. Snows still crested Ossa and Pelion, and beautiful Olympus, in snow-crowned grandeur golden in the morning's glow, turned to rose in the evening sunset.

Marco had gone far up the mountain side to herd for a rich farmer who had many goats. He watched the herds all day and, when they were safely housed for the night, camped in a rough little hut on the hillside.

Zoe missed him from the cottage, for of all her cousins she most loved Marco. She was very[48] happy therefore when her Aunt Anna told her one day that she might carry a basket of food to the mountain.

She started off happily, running along the village street into the open country, going more slowly up the hillside, where the early wildflowers were beginning to bloom.

She reached the little hut where Marco slept, nearly at sundown but he was not there, so she sat down to wait for him. The sun was streaming in a golden glory and the Vale of Tempe opened before her as fair as when the god Apollo slept beneath its elms and oaks, wild figs and plane trees. Zoe loved everything beautiful and she sat and looked eagerly at the lovely scene.

"It is almost as pretty as my own Argolis," she said aloud, and then gave a little sigh.

"Still homesick, little one?" Marco's voice said close behind her, and she sprang to her feet in astonishment. He seemed to have sprung from the ground, so quickly had he come upon her.

"Oh, Marco!" she said. "I did not hear you come. I am so glad to see you. It has been lonely at home without you."

"I have missed you, too. It is good of you to come to see me," he said.

"Aunt Anna sent me with fresh cheese and eggs and bread for your supper," she told him. "This is a beautiful place isn't it, Marco?"

"It is indeed," he answered. "Like a fine old man, Mt. Olympus always has snow upon his head. See how the clouds float about the summit; you know that was the home of the gods in the old days. 'Not by wind is it shaken nor ever wet with rain, but cloudless upper air is spread about it and a bright radiance floats over it.'"

"Papa Petro says we must not talk of the gods of olden times, for they were heathen," said Zoe primly. "But they were interesting. Where did you learn so much, Marco?"

"It is not much I know," he said with a[50] laugh. "But when I was in Athens I took service with a man from America. He knew much. He read ancient Greek and when I told him I was a Grecian from near Mt. Olympus, he asked many questions about Thessaly and the way we live here. In return he told me much of our Ancient Grecian stories. He told me of Jason and his adventures after the Golden Fleece, of Perseus and Theseus and many others."

"Tell me some of them," demanded Zoe eagerly.

"Well, Perseus was the son of Danae, and a god was his father. He was taller and stronger and handsomer than any of the princes of the court and the king hated him. But Pallas Athene, the beautiful goddess of wisdom, loved him and helped him and took him under her protection. She gave him a task to perform, to rid the land of the horrible Gorgon Medusa, whose hair was a thousand snakes and whose[51] face was so horrible that no man could look upon it and live. That Medusa might not kill Perseus, Athene gave him a magic shield and told him to look into the shield and seeing there the Gorgon's image, strike! He was to wrap the head in a goat's skin and bring it back. She gave him also Herme, the magic sword, and sandals with which he might cross the sea and even float through the air. They would guide him, too, for they knew the way and could not lose the path.

"So Perseus started out, and he flew through the air like a bird. And many were the dangers which he met, but all he overcame. Far was the journey, but he made it with a light heart. He went until he came to Atlas, the giant who holds the world on his shoulders, and of his daughters, the gentle Hesperides, he asked his way. And they said to him, 'You must have the hat of darkness so that you can see but not be seen.'

"'And where is that hat?' he asked. And Atlas said to him,

"'No mortal can find it, but if you will promise me one thing, I will send one of my daughters, the Hesperides for it.'

"'I will promise,' said Perseus. 'If it is a thing I may do.'

"'When you have cut off the Gorgon's head, which turns all who see it into stone,' said Atlas, 'promise me that you will bring it here that I may see it and turn to stone. For I must hold up the world till the end of time, and my arms and legs are so weary that I should be glad never to feel again.' So Perseus promised, and one of the Hesperides brought him the hat of darkness, which she found in the region of Hades. Then Perseus went on and on until at last he came to the Gorgons' lair. And he put on the hat of darkness and came close to the evil beasts. There were three of them, but Medusa was the worst, for he saw in the mirror that her[53] head was covered with vipers. He struck her quickly with his sword, cut off her head and wrapped it in the goat's skin. Then, flying upward with his magic sandals, he fled from the wrath of the other two Gorgons, who followed fast. They could not catch him, for the sandals bore him too swiftly. Remembering his promise he came to Atlas, and Atlas looked but once upon the face of Medusa and he was turned to stone. They say that there he sits to this day, holding up the earth. Then Perseus said farewell to the Hesperides, thanking them, and he turned away toward his home.

"He flew over mountains and valleys by sea and land for weary days and nights. As he came to the water of the blue Aegean sea, there he found a strange thing, for, chained to a rock, was a maiden, beautiful as day, who wept and called aloud to her mother.

"'What are you doing here?' demanded Perseus, and she answered,

"'Fair youth, I am chained here to be a victim to the Sea God, who comes at daybreak to devour me. Men call me Andromeda, and my mother boasted that I was fairer than the queen of the fishes, so that the queen is angry and has sent storm and earthquake upon my people. They sacrifice me thus to appease her wrath. Depart, for you can be of no help to me and I would not that you see the monster devour me.'

"'I shall help you, and that right promptly,' said Perseus, who loved her for her beauty and her sweetness. So he took his sword and cut her chains in two, and he took her in his arms and said,

"'You are the fairest maiden I have ever seen. I shall free you from this monster and then you shall be my wife.' And she smiled upon him, for she loved him for his strength and for his brave words.

"The sea monster was a fearful beast. His jaws were wide open and his tail lashed the[55] waters as he rushed toward the maiden. She screamed and hid her face, but Perseus dropped down from the rock, right on the monster's back, and slew him with his gleaming sword. Then Perseus took Andromeda and flew to her home, and her parents received him with joy, giving him their daughter and begging him to stay with them. That he could not do, because of his promise to Pallas Athene. So he took his bride, and her father gave him a great ship and he returned to his mother like a hero, with his galley and much gold and treasure, the marriage portion of Andromeda. The wicked king was not glad to see him and would have had him killed, but Perseus held up to him the head of Medusa and it turned the king to stone. Then Perseus reigned in his stead, and one night in a dream Pallas Athene came to him and said,

"'You have kept your promise and brought back the Gorgon's head. Give back to me the sword, the sandals, the shield and the hat of[56] darkness, that I may give each to whom it belongs.' And when he awoke they were all gone.

"Then he went home to his own land of Argos and there he lived in happiness with Andromeda, and they had fair sons and daughters, and men say that when they died they were borne by the gods to the heavens, and that there one can still see, on fair nights of summer, Andromeda and her deliverer Perseus."

"Oh!" exclaimed Zoe, with a long drawn breath of delight. "What a lovely story! But, Marco, why don't people do such brave things as that now days?"

"There are just as brave men now as there were in the old times," said Marco, his eyes kindling. "In my regiment they tell a story of a Grecian soldier in our War for Independence. Beside him marched a comrade, a man from his own island. They had played together as boys and had always been friends. But the other[57] fellow had married the girl whom Spiro loved, and he had a sore heart about that. The regiment was up in the mountains and was attacked by the Turks and Spiro's friend captured. Spiro wept, but that was not all. He went to his captain and begged that he might be sent to the Turks in exchange for his friend. His captain said it was impossible, that the Turks would not accept him in exchange, but would kill both. Spiro said, 'My captain, if they did accept me it would be well. Let me go.'

"'You are a silly fellow,' said the captain. 'I cannot give you any permission. If you can get word to the Turks and they will accept you, then you may go.' This he said because he was sure the Turks would but laugh at such an idea of Spiro. But Spiro thanked him with tears of joy. Then he went to a man in the regiment who could write. 'Will you write a letter just as I say it?' he asked and his friend said that he would. Here is the letter,

"'To the most noble general of the Turks,' it began,

"'I am Spiro Rhizares of the —— Grecian Infantry. I salute your Worship. You have captured a man of my regiment, one Yanne Petropoulas. He is a better man than I am but I am good enough to kill. I am taller than he so there is more of me to die. He has a wife and I have not, so there is more need for him to live. Wives take money; he should not be killed, for then there is no one to buy bread and garlic and embroidered kerchiefs for Evangoula. She is a good wife, but even good women must have loukoumi and coloured kerchiefs to keep them good. I ask you therefore to have the great kindness to kill me, Effendi, in place of Yanne, and I think he would not object. If therefore, your Worship will consent send me word, but do not speak of it to Yanne, since he might feel a disappointment that he might not die for his country at your most worshipful hands. Asking[59] your Graciousness to send me word when I shall have to the pleasure to be killed, I sign myself, through the hands of a comrade, since I am too ignorant a fellow to write (you see I am fit only to kill),

"This letter Spiro sent through the mountain passes by a shepherd boy and awaited an answer. At last one came. It was short.

"'To one Spiro Rhizares, —th, Grecian Infantry.

"'Sir:—Since you are wishing to feel the edge of a Turkish scimiter, come and be killed. When you are dead your friend shall go free. This on the honour of a Turk. I promise because I know you will not come. You thought to work on my heart. I have no heart for Greeks. As we will kill all your men in a few months, you may as well die now if you like. Your friend I will send back.

"Spiro was like a fellow mad with joy. He sent all his money to Evangoula, gave his things to his comrades, and, lest he be hindered, stole off in the night. He reached the Turkish camp and smilingly asked to die quickly that Yanne might quickly go home. But the Turks had other ideas. They tried to buy Spiro to talk about his regiment and tell secrets of the army, promising that both he and his comrade should live, but he said only that he came to die and not to talk, and they could get nothing out of him though they tried in many ways. So at last they cut off his head and set Yanne free. He was in a terrible rage. He said that he never would have consented had they told him. But they only laughed at him and set him outside the camp. And he came back to the regiment, but he was not happy. He grieved for Spiro and made himself ill. Then the captain spoke with him. He told Yanne that Spiro had died for him and that now he must make the life that[61] Spiro had saved of some account. His time in the army was nearly up. He should go home and care for his wife and thus do what Spiro would wish.

"'This will be the only way to win happiness,' said the captain. 'For if you do not do this, your wife will say that Spiro was the better man and that he should not have died, but you.' And Yanne wept, but he did what the captain had said. And that is the end of the story. But all the regiment drink to the eternal health of Spiro Rhizares, the hero."

"Oh, the brave splendid fellow!" cried Zoe. "Indeed, he was as poor, as Perseus. That is the nicest story I ever heard. Thank you so much for telling it to me.

"How did there come to be war with Turkey, Marco?"

"That is a long story, child, but one that you should know. Once, you know, Greece included Macedonia and all the strip of land along the[62] sea as far as Constantinople. But the Turks always wanted Greece and in the year 1453 they came down upon us in a frightful war and took the land. The Turkish rule was horrible. Their rulers knew nothing but to wring money out of our poor people and many Grecians fled to the mountains and became klephts.[11] These fought always against the Turks and kept ever within them the spirit of freedom. At last they formed the Hetaeria, or Revolutionary Secret Society, and soon Greece was fighting for her independence. Such terrible battles as came; such heroes as there were! It makes one want to shout at the very name of Marco Bozzaris, who surprised the Turks one night at Karpenisi and overcame them.

"Our people fought like the ancient heroes, but they could not get money to carry on the war. The Turks brought in hordes of soldiers; Greece was plundered and burned; people starved by[63] the roadside, women and children were murdered. At last the nations of Europe said that such things could no longer be, and they joined together to compel the Turks to allow Greece to be free. This the Turks did not wish to do; but France, Russia and England compelled them to permit Greece to have her own government. The Turks gave us back a part of our country and a king was chosen to reign over us.

"This was better than belonging to Turkey, but it was not enough. We wanted all the land that belonged to us and this we could not get. The island of Crete especially wanted to be Grecian but the Turks would not let it go.

"At last in 1897, came the war in Macedonia, in which our poor soldiers were shot down by the hundred and we had to turn our backs upon the foe. It was then that Spiro Rhizares fought and died, and many, many splendid fellows[64] as brave as he. It was a terrible war, Little One. War is easy when a man marches toward the foe. He is never tired or hungry or footsore. But when he is ordered back and must march away, his knapsack grows heavier at each step; he is hungry and cold and weary, and his heart is within him like lead. Our men could have fought like heroes and Macedonia would now be ours; but the orders came always, 'Retreat! Back to Velestino!' and what could they do?

"The Powers forbade the Turks to conquer further, or we might be slaves again. Never mind, the day will come when every Grecian shall arm himself, and the detestable Turks shall be swept from our borders and all Greece shall once more be free!"

Marco's eye kindled and his face flushed.

"Thank you so much for telling me about it, Marco, I hope you'll never have to go to fight, but I wish Greece could have all the land[65] that belongs to her. I am afraid I must go now. Aunt Anna will be displeased if I am late. It is growing dark. Are you not afraid all alone here in the mountains?"

"Afraid of what, Little One?" asked Marco, his hand on the hunting-knife which he carried in the soft sash at his waist. "You see I am not alone, I have a good friend here."

"Yes, but you might see a bear or a brigand!" she said. "Oh, Marco, what is that?" A tall figure appeared as she spoke from out of the rocks above them. "It is a brigand I am sure!" she whispered and clung close to her cousin.

"Nonsense," he answered. "Nobody ever sees brigands now, Zoe," but as he spoke he tightened his grasp on his dagger and put his arm around his cousin, for every Grecian knows there are brigands in the mountains of Thessaly, though they are much less frequently seen than they used to be.

Zoe gave a frightened gasp, "It is, I know it is! Pana yea,[12] save me!" she said as the stranger approached, but Marco said pleasantly,

"Kalos orsesate!"[13]

The stranger replied to Marco with "Tee Kamnete"[14] and came up close to them. Zoe blessed herself and said not a word.

"Kala,"[15] Marco said briefly, and the stranger said,

"It is late for you and your sister to be on the mountain. She is a pretty child."

"Na meen avosgothees,"[16] whispered Marco to Zoe, then to the stranger, "Not later than for you."

"But I have business here," he said with a smile.

"And so have we," and Marco's tone was a little curt.

"My business is to eat supper," said the man. "Will you join me?"

Marco was surprised, but Zoe whispered, "Do not make him angry," so he said,

"Thank you. Zoe has brought me to eat also. Will you not share with us?"

"We will eat together," said the stranger, so they seated themselves upon the green grass and Marco took from the basket Zoe had brought, black bread and cheese for all three.

"This is the best I have, but I am glad to give," he said, for he thought to himself, "He has not a bad face now that one sees him close. In any case it is best to be civil, for bees are not caught with sour wine."

The stranger threw aside his cloak and stood before them in the beautiful national costume of Greece. Zoe thought that she had never seen anything so fine as his clothes.[69] He wore a white shirt, a little black jacket and fustanellas, the full white petticoat reaching to the knees, to which Grecian men cling in spite of the fact that it can be soiled in ten minutes while it takes a woman almost as many hours to make it clean again.

He carried a leather bag over one shoulder, and from this he took a parcel, seating himself beside Zoe and opening it with a gay smile.

"I did not think this morning, when I had this put up, that I should eat it with so dear a little girl," he said. "Perhaps I should have put in Syrian loukoumi had I known that you would be here instead of halva[17] and tarama.[18] Should I not?"

"Halva is very nice," said Zoe shyly. "And I have never tasted loukoumi of Syria."

"Have you not? Poor child! Tell me[70] where you live and I will send you a packet of it."

"I live in Karissa, near to Volo," said Zoe with a sweet smile. "The gentleman takes too much trouble."

"I shall certainly do it," he said, "unless I am wrestling with Charos."[19]

"When your soul shall be a Petalouda[20] and your dust shall become myrrh," said Zoe. "On the third day I shall carry raw wheat and a candle to Papa Petro, that he may say prayers for you."

"You are an angel of a child!" there were tears in the man's eyes. "It matters little when Charos comes, since God sends Charos to take souls. It is well if we leave behind us some grateful hearts to say 'may your dust become myrrh.' Come, let us eat. Here is[71] a bottle of resinato,[21] bread and tarama, with olives and garlic and halva for dessert. It is a feast for the gods, yet the best Christian may eat it in Lent."

They ate, the two men chatting together, Zoe listening in silence. It had been long since she had seen such a feast, for bread and eggs were often all that was to be had in her aunt's house, and sometimes there were no eggs.

They sat beneath a giant tree on a carpet of maiden-hair fern; scarlet anemones and heath, orchids and iris bloomed beside them, and the silver tinkle of a waterfall came softly through the evening air. The fragrance of violets was there, and a few early asphodel raised their star-like blooms toward heaven.

"There is no place in all the world like Greece," said the stranger, as he looked down over the beautiful valley. "It was near to[72] here that Cheiron's cave lay, and one can almost see Olympus, home of the gods."

"Who was Cheiron?" asked Zoe.

"Do you not know the story of the Golden Fleece?" said the stranger. "Shall I tell it while we eat?"

"Oh, if you only would?" cried Zoe, and he began.

"Long, long ago, when the gods lived on Olympus, there was a cave in the depths of old Mount Pelion and it was called the cave of Cheiron, the Centaur. Cheiron was a strange being, half horse and half man, for he had the legs of a horse but the upper part of his body was that of a man. He was wise and kind and men called him 'the Teacher.' Many men sent their sons to him to be taught, for he knew not only all the things of war, but music and to play the lyre, and of all the healing herbs, so that he could cure the wounds of men. Among his pupils was a lad named Jason, whose father[73] was Ćson, king of Iolcos, by the sea. The wicked brother of Ćson had cast him forth from his kingdom, and fearing that Jason would be killed, the father left the lad with Cheiron. Cheiron taught him much, and he learned quickly. He learned to wrestle and box, to ride and hunt, to wield the sword, to play the lyre, and even all that Cheiron knew of healing herbs Jason learned. Jason was happy with Cheiron and loved him, and the youths who dwelt in the Centaur's cave, these he loved as brothers. He was quite content until one day he looked forth over the plains of Thessaly to the south, and as he saw the white-walled town beside the sea, something stirred within him, and he said to Cheiron,

"'There lies my home. Now I am grown, I am a hero's son, let me go forth and take my heritage from that bad man who cast forth my father, for I know that one day I shall be king in Iolcos.'

"'That day is far, far away,' said Cheiron, who could read the future. 'But it will come. Eagles fly from the nest, so must you fly hence. Go, but promise me this. Speak kindly to each one that you meet and keep always your promises.'

"'I promise you and I will perform,' said Jason, and he bade Cheiron farewell. Then he hurried down the mountain-side, through the sweet-smelling groves where grew the wild thyme and arbutus, beyond the vineyards green in the sun, and the olive groves in fragrant bloom. He came to the river bank, a stream swollen with spring rains and foaming to the sea. Upon the bank was an old woman, wrinkled and gray, and she cried to Jason,

"'Good sir, carry me across this stream.'

"Jason looked at her, and at first he thought to leave her, for the stream was broad and it roared over cruel rocks and was heavy with the[75] mountain's melting snow. But she cried pitifully,

"'Fair youth, for Hera's sake, carry me across.'

"Now Hera was queen of all the gods who lived on Olympus, and Jason said,

"'For Hera's sake will I do much. Cling upon my back and I will carry you across. That I promise you.' Then he remembered Cheiron's word and was glad he had answered her softly. He struggled through the foam, but the old woman was heavy and she clung about his neck and seemed to grow heavier. He buffeted the waves and struggled, and twice he thought he must let the old woman go, but he remembered his promise and held her fast, and at last he reached the farther shore and scrambled up the bank. And as he gently set his burden down, lo! she was a fair young woman, and she smiled upon him and said,

"'I am that Hera for whose sake you have done this deed of kindness. I will repay you, for whenever you need help call upon me, and I will not forget you.' Then she rose up from the earth into the clouds, and with awe and wonder, Jason watched her fade from his sight.

"Then he went on to Iolchis, but he walked slowly, for he had lost one sandal in the flood. He went into the city and spoke with the king, demanding his realm, and the king was afraid of him, for soothsayers had foretold that a man wearing one sandal should take the kingdom away from him.

"But the king spoke to him kindly and gave him food, and said to him, 'Your father gave me the kingdom of his own free will. See him and ask him if this is not true.' Jason said that he would do so, and he ate with his uncle, and at last the king said,

"'There is a man in my kingdom whom[77] I am afraid will cause me trouble if he stays here. What would you do with him were you I? I ask because I know you are wise.'

"'I think I would send him to bring home the Golden Fleece,' said Jason.

"'Will you go?' said the king, and Jason saw that he was caught in a trap, and that his uncle had meant him.

"'I will go, and when I return I will take the kingdom,' he said, and straightway he made ready. He made sacrifice to Hera, for in those days people killed a lamb in honour of the gods, as we to-day burn a candle at a shrine. Then he fitted up a ship and sent word to all those princes who had been with him in Cheiron's cave that they come with him on this glorious quest. And they came and all the youths set forth upon a mighty ship. Of the many things that happened to them I have no time to tell, but at last Jason came to the shores of Cutaia, where the Colchians lived. There was the[78] Golden Fleece, but guarded so that no man might take it. There it had been for many years, since King Phrixus had slain the Golden Ram and offered it in sacrifice, and since then all the world had longed to possess the wonderful Golden Fleece.

"Medea, the king's daughter, saw Jason, and loved him because he was fearless and brave. She was a witch and she helped him with her witchcraft, giving him a magic salve with which he rubbed himself so that no weapon could hurt him, and his strength was as the strength of mighty hills. He who would possess the Fleece must first wrestle with two terrible bulls, then he must sow serpent's teeth in a ploughed field. From the teeth sprang up a field of armed men, and these must be overcome, and then the deadly serpent which guarded the Fleece must be slain. All these things Medea's magic helped Jason to do. He fought with the bulls and conquered them;[79] he harnessed them to the plough and ploughed the field. He hewed down the armed men as if they were stalks of wheat and last of all he sought to slay the serpent. Orpheus, who had been with Jason in Cheiron's cave, went with him to the tree where hung the Golden Fleece. He was the sweetest singer in all the world, and he played soft and sweet upon his lyre and sang of sleep, and the serpent closed his eyes and slumber stole upon him. Then Jason stepped across his body and tore the Fleece from the tree, and he and Orpheus and Medea fled to the ship and away they sailed to Greece again."

As he finished a sudden sound reached their ears and Marco sprang to his feet.

"A wolf is at my goats!" he cried. "I must go. Zoe, fly quickly down the mountain; but no—it is too late for you to go alone, there are wild beasts abroad. You should not have stayed so late!"

"Go quickly to your goats, Marco. That is your duty. I shall be safe, for I shall pray to the saints and the Holy Virgin, and I shall run very fast."

"Go to your herd, good shepherd, and I will take your sister home," said the stranger, putting up the remains of his meal, but Marco did not look reassured. He looked helplessly from one to the other. "I may be out all night," he said, when another squeal, sharp and shrill, came through the air.

"Go at once, Marco, I shall be quite safe with this gentleman," said Zoe.

"I will promise that she shall go straight home," said the stranger, and Marco unwillingly turned to the mountain.

Zoe and her strange companion walked hastily down the steep path which led to the village.

"Child," said the stranger, "why did you tell your brother to go? Are you not afraid of me?"

"He is not my brother, but my cousin, and I am not at all afraid," she said.

"But you were afraid at first," he said. "You thought I was a brigand."

"That was before I had seen your face," said the little girl. "And now that I have seen you and heard you talk, I know that you are not."

"How do you know?" he asked.

"You are a good man, because you keep the Lenten fast, you speak well of God and you are kind to a little girl. So I know you have a white heart. You may perhaps be a brigand, but you are a good one."

He threw back his head and laughed aloud.

"You are a strange little one," he said. "Tell me your name."

"I am Zoe Averoff, of Argolis."

"Zoe Averoff of Argolis! Child, what are you doing here?"

She looked at him in wonder as she answered,[82] "My mother is dead, my father is gone and comes no more; he must be dead too. I live here with my uncle, the father of Marco."

The stranger's eyes were fixed upon her and she saw them fill with hot tears.

"Child," he said, "I believe you are my little niece. I am Andreas Averoff, and your father was my brother. I feared that I would fail to find you, since all they could tell me at your old home was that you had gone to Thessaly. Do you remember me, since I went to your house once long ago?"

"I know that I had an Uncle Andreas," said Zoe, scarce believing her ears. "But I do not remember him."

"I am that uncle," he said, "and I have come to take you with me to my home. I have a wife and son in Argolis, but our little girl we lost. Will you come and be our daughter, or are you too happy here?"

"I am not too happy," said Zoe, "but it[83] would be hard to leave Marco. He is so good to me."

"Perhaps your Marco will come with us, for I have money and we can find him better things to do than to fly to the mountains with the shepherds each St. George's Day. Now, take me to your home and tell your aunt what has come of your taking tea with a brigand."

The next few days seemed to Zoe to pass as in a dream. So many things happened which she had never supposed could come to her, that she was almost dazed. Uncle Andreas was such an energetic person that he carried everything his own way. He silenced all objections to his plans, and before the child fairly knew what was happening she had said good-bye to her Thessalonian relatives, and with her new-found uncle and Marco was sailing out of the harbour of Volo on her uncle's ship. She wept a little at leaving her cousins, especially the babycoula, but that Marco was to be with her robbed the separation of half its sting. The future opened before her with much of[85] interest. Unknown lands were to be explored, and to Zoe this in itself was charming.

"Do you feel as if you were setting out to find the Golden Fleece?" asked Marco as the two sat upon the deck and watched the hills of Thessaly fade in the distance, as they sailed over the blue Gulf of Velos.

"I feel very strange and full of wonder as to what will come next," she said.

"Well, Little One," said Uncle Andreas' hearty voice, "what kind of a sailor are you going to make?"

"Oh, I like it on the sea," she answered brightly. "When we came to Thessaly, Mother was very ill, but I was not at all. I love the salt air, the spray and the feel of the wind on my cheek. It is like a kiss."

"Good girl," her uncle smiled at her. "You are just the one to have a sailor uncle. Many a fine sail shall we have together when we reach our own Argolis. Marco shall be a fisherman[86] and we three shall sail and sail in the roughest weather. They do not know the sea who know her only when she is calm. She is most beautiful when angry. Shall you tire of your long voyage?"

"Oh, no, Uncle Andreas, I could sail for ever."

The time passed pleasantly for Marco told Zoe pleasant tales of their own beautiful Greece, and her uncle told of rovings from shore to shore. He had been a sailor for many years and now owned his own sloop, in which he sailed over the Mediterranean with cargoes of currants and lemons. He had had many adventures, had been shipwrecked upon one of the little islands of the sea and in his youth had even sailed to America.

"I do not believe that your father is dead," he said to Zoe one day. "He may have written letters which you have never received, but I think if he were dead we would have heard[87] of it. Some day he will come back or we will go and hunt him up."

Zoe's eyes grew large and tender.

"If my father would only come back," she said, "I should never ask the saints for anything so long as I live. But I know I will be very happy with you and Aunt Angeliké."

"Especially as Marco will be there," laughed her uncle, and Zoe laughed too.

"Marco has been so good to me that I would be a strange girl could I be happy without him," she said.

When they sailed into the Gulf of Athens and, rounding the point, she saw the "City of Sails," as it is called from the many boats in the harbour, the little girl could hardly contain herself. She saw for the first time the wonderful marble buildings of the city of Athens, with the Acropolis and the Areopagus, where gleamed the famous ruins of the Parthenon; and to the child, her mind filled with the lore of the long[88] ago, every marble was peopled with heroes, every leaf and bud and bird sang of Pericles and other famous Athenians, as Mt. Olympus and Tempe's Vale had whispered of the gods of old.

Athens is perhaps one of the most interesting cities in the world. The ship anchored in the harbour of Pireas and the three landed in a small boat rowed by Uncle Andreas' stout sailors. Then they drove in a cab between the long rows of pepper trees, Zoe bouncing from one window of the cab to the other in a frantic effort to see both sides of the street at once. The driver drove very fast, calling "Empros!" to any passer who chanced to cross his path, and Zoe wished he would go slowly so that she might see all the wonderful things they passed.

"Oh, Uncle, what is that?" she cried as they passed a procession of men carrying something on a bier.

"It is a funeral," he said.

"Why isn't the coffin covered?" she asked, for as they drew nearer she saw that there was no cover and the dead man lay covered only with flowers.

"The custom of burying the dead without cover arose in the time of the first Turkish war," he said. "The Turks feared that soldiers would get outside of the wall by pretending to be dead and being carried out in coffins. Several famous leaders got out of the city in that manner and stirred up the country people to revolt. So they made a law that people who died must be carried through the streets uncovered and a lid put on the coffin only as it was lowered into the grave. Miserable Turks!" and Uncle Andreas spat on the ground, as every good Grecian does when mentioning the name of his hated enemy. The Turks have always coveted Greece and in the bitter wars between the two countries has been bred a hatred which does not die out as the countries grow older.

"Oh, Marco!" cried Zoe from the other window, "See them cooking in the street! I never heard of such a thing."

"That is quite common," said Marco. "It is not good to have fire in the house, you know, so men make their living by taking stoves around from house to house and cooking whatever people wish for dinner. You see many of the houses are built without any chimneys for the smoke, and when they have stoves in them they have to let the smoke out through a pane of the window. Often it blows back into the room, and so people do not care for stoves. Heat in the house is very bad for the health, you know, so these travelling stove-men make a good living."

"Nearly everything is brought to your door in Athens," said Uncle Andreas. "The street sellers peddle not only everything to eat, but dry goods, notions, hats, shoes, and nearly everything else, from trays hung around their necks."

Suddenly their cab stopped and drew up at the edge of the sidewalk. Zoe wondered what was the matter as she saw the driver take off his cap, and her uncle exclaimed,

"Well, Zoe, you are in luck! Here comes the royal carriage."

"Oh, Uncle, is it the King?" she cried, bouncing up and down with excitement.

"His Majesty, the Queen and Prince Constantine," said her uncle as a handsome carriage drove by. Zoe had a glimpse of a fine-looking man, and a sweet-faced woman gave her a bright smile. Then the cab drove on again and she sat down with a gasp of astonishment.

"Is that all?" she said. "Why, Uncle, it was only a two-horse carriage, and there wasn't any music or soldiers or crowns on their heads or anything!" Her uncle and Marco laughed heartily.

"You are all mixed up, Little One," said Marco. "Crowns on whose head—the horses?[92] Our king is the most democratic monarch in Europe. He often walks around Athens without any one with him at all. He is quite safe, for every one likes him. He likes a joke and does not care at all for fuss and ceremony. They tell a story that one day he was out walking and met an American, who stopped him to ask if it was permitted to see the royal gardens. Of course the American did not know to whom he was talking, but the king said, 'Certainly, sir, I will show them to you;' and he took him all around the gardens, talking with him pleasantly and telling him many interesting things about Athens. At last the American said,

"'What kind of a woman is the queen?'

"'She is beautiful and good as she is beautiful,' answered the king.

"'What about the king?' asked the stranger.

"'Oh, he isn't of much account,' said King George. 'He hasn't done much for the country.'

"'That's strange,' said the American. 'You are the first person I have met in Greece who did not speak well of the king.'

"'Indeed,' said the king with a laugh. 'Well, I know him better than most people.' The man found out afterwards that he had been talking to the king, and he was very much astonished.