WITH THE FRENCH FLYING CORPS

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at http://www.gutenberg.org/license.

Title: With the French Flying Corps

Author: Carroll Dana Winslow

Release Date: July 16, 2014 [EBook #46299]

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK WITH THE FRENCH FLYING CORPS ***

Produced by Al Haines.

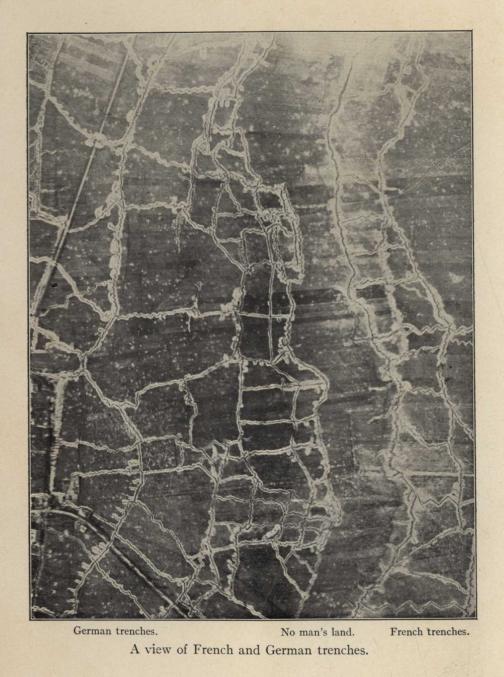

A view of French and German trenches.

WITH THE FRENCH

FLYING CORPS

BY

CARROLL DANA WINSLOW

OF THE FRENCH FLYING CORPS

NEW YORK

CHARLES SCRIBNER'S SONS

1917

COPYRIGHT, 1917, BY

CHARLES SCRIBNER'S SONS

Published January, 1917

TO

MY FATHER

CONTENTS

My Enlistment

First Principles

Learning to Fly

The School at Chartres

Passing the Final Tests

The Zeppelin Raid over Paris

At the Ecole de Perfectionnement

The Réserve Générale De l'Aviation

Ordered to the Front

In the Verdun Sector

My First Flight over the Lines

Co-operating with the Artillery

All in the Day's Work

July 14th, 1916

The Finishing Touches

ILLUSTRATIONS

A view of the French and German trenches . . . Frontispiece

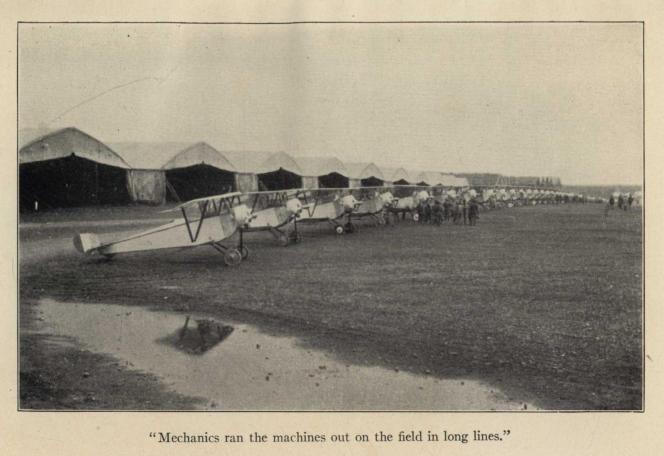

"Mechanics ran the machines out on the field in long lines"

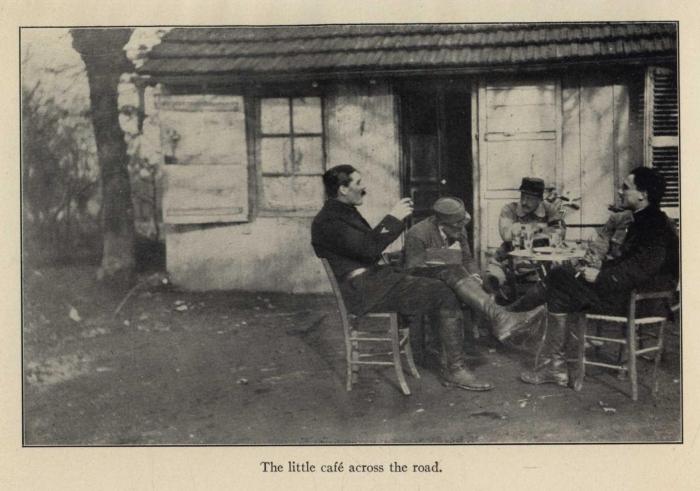

The little café across the road

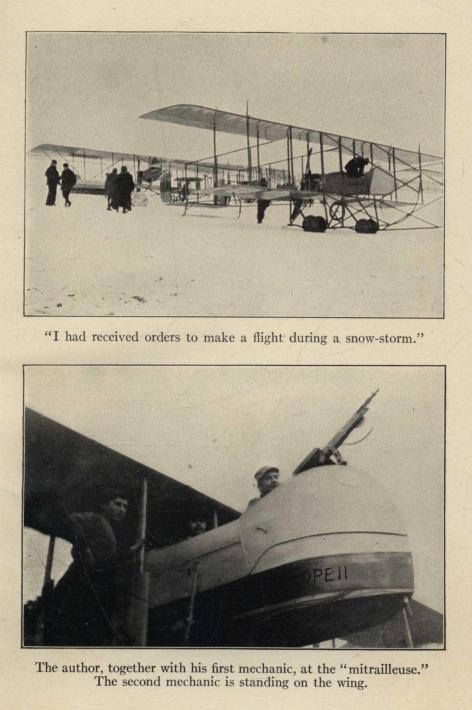

"I had received orders to make a flight during a snow-storm"

The author, together with his first mechanic, at the "mitrailleuse"

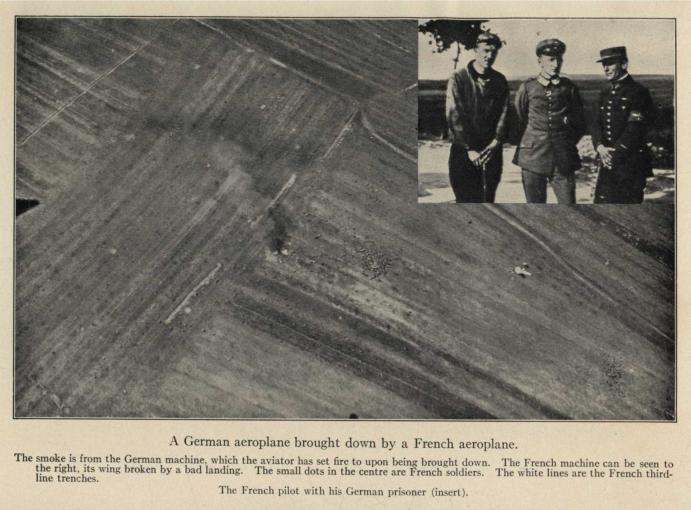

A German aeroplane brought down by a French aeroplane

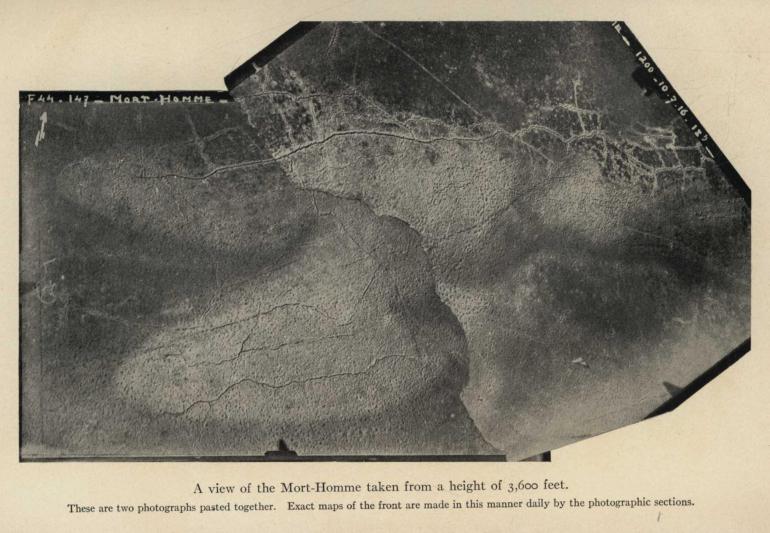

A view of the Mort-Homme taken from a height of 3,600 feet

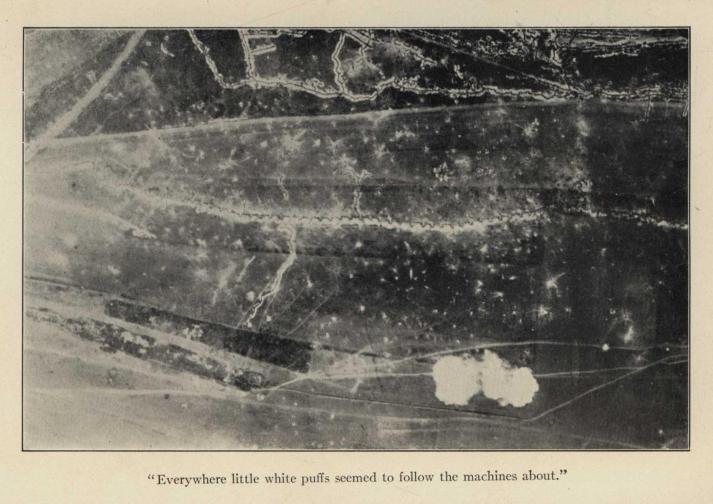

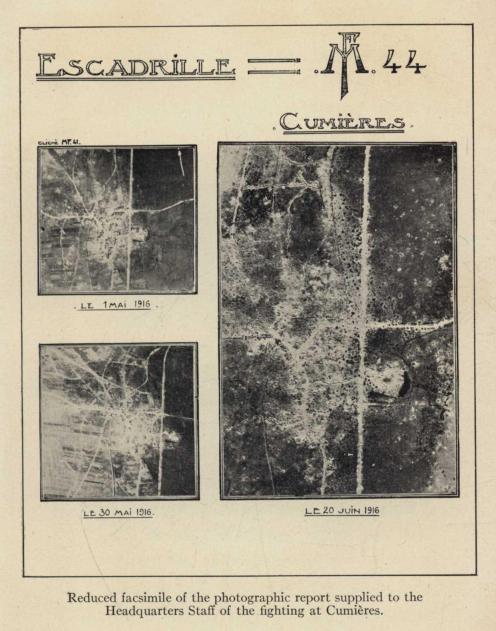

"Everywhere little white puffs seemed to follow the machines about"

MY ENLISTMENT

In the last two years aviation has become an essential branch of the army organization of every country. Daily hundreds of pilots are flying in Europe, in Africa, in Asia Minor; flying, fighting, and dying in a medium through which, ten years ago, it was considered impossible to travel. But though the air has been mastered, the science of aero-dynamics is still in its infancy, and theory and practice are unproved so often that even the best aviators experience difficulty in keeping abreast of the times.

My experience in the French Aviation Service early taught me what a difficult and scientific task it is to pilot an aeroplane. By piloting I mean flying understandingly, skilfully; not merely riding in a machine after a few weeks' training in the hope that a safe landing may be made. In America many aviators holding pilot's licenses are in reality only conductors. Some pilots have received their brevets in the brief period of six weeks. I can only say that I feel sorry for them. My own training in France opened my eyes. It showed me how exhaustive is the method adopted by the belligerents of Europe for making experienced aviators out of raw recruits. Time and experience are the two factors essential in the training of the military pilot. Even in France, where the Aviation Service is constantly working under the forced draught of war conditions, no less than from four to six months are devoted to the training of finished pilots.

Although I have just come from France, the progress of aviation is so rapid that much of my own knowledge may be out of date before I again return to the front. But interest in flying is becoming so general among Americans that the way the aviators of France are trained, and what they are accomplishing, should attract more than passing attention. Surely, what France has done, and is doing, should be an object-lesson to our own government.

Through a special channel only recently open to Americans I enlisted in the French Air Service. As is usual in governmental matters, there were many formalities to be complied with, but in my case a friendly official in the Foreign Office came to the rescue and arranged them for me. After a few days I received the necessary permit to report for duty. Without delay I hurried to the recruiting office, which is located in the Invalides, that wonderfully inspiring monument of martial France. As I entered the bureau I met a crowd of men who had been declared unfit for the front, either on account of their health, or because they had been too seriously wounded. But to a man they were anxious to serve "la patrie," and were seeking to be re-examined for any service in which physical requirements were not so stringent. For an "embusqué" (a shirker) is looked upon as pariah in France.

When I had signed a contract to "obey the military laws of France and be governed and punished thereby," I received permission to join the French Air Service. With about thirty other men I marched to the doctor's office, where I was put through the eye, lung, and heart test. I was then ordered to report to the sergeant who had charge of the men who had passed the examination.

Among those accepted I noticed a young man of the working class. He had been particularly nervous while the roll was called. But the moment he heard his own name he seemed overjoyed. Outside, on the sidewalk, his wife was waiting. He dashed out to tell her the news. Instead of bursting into tears, as I had rather expected, she seized his hands and they danced down the street as joyfully as two children. It was typical of the spirit of the French women, willing to sacrifice everything, to help bring victory to their country.

I received my service-order to proceed immediately to Dijon, the headquarters of the Flying Corps. I took the first train and arrived there at about three in the morning. I discovered that the offices did not open until seven, and, as I had nothing to do and was hungry, I sought the military buffet at the railway-station. It was filled with men on leave and others who had been discharged from the hospitals, all waiting to return to the front. Officers and men mingled in a spirit of democracy and "camaraderie." This made a deep impression upon me, for, while discipline in the French army is very strict, there is an entire absence of that snobbishness which the average civilian so often associates with a military organization.

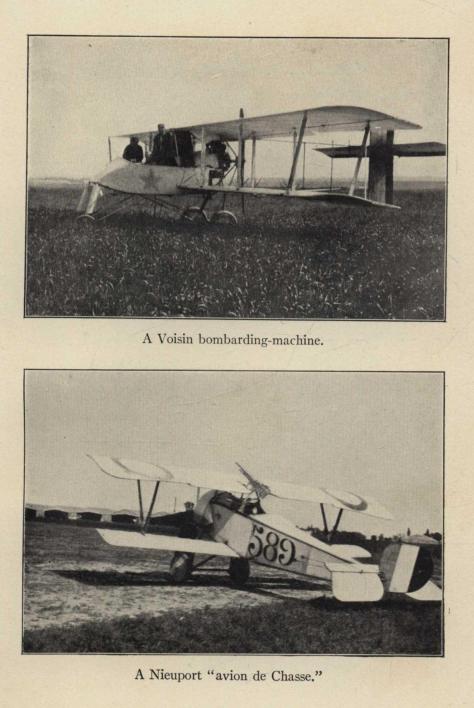

A Nieuport "avion de Chasse."

About seven o'clock I made my way to the camp. A sentry challenged me, but after I had proved my identity he sent me to the adjutant, who took my papers and, after reading them, addressed me in perfect English. I was surprised and asked him how he happened to speak English so well. It seems that he had lived in New York for twelve years, but on the outbreak of the war had returned at once to serve. I was then given in charge of a corporal. After this I was put through another "questionnaire." One officer asked for my pedigree; to another I gave the name and address of my nearest relative, to be notified in the event of my death. After this came the "vestiaire." Each "dépôt," or headquarters, has one of these, where every soldier is completely outfitted by the government. I received a uniform, two pairs of shoes, two pairs of socks, an overcoat, two suits of underwear, two hats, a knapsack, and a tin cup, bowl, and spoon. The recruit may buy his own outfit if he wishes, but the government offers it to him gratis if he is not too particular. I was now a full-fledged French soldier of the second class, second because there was no third. My satisfaction was only exceeded by my embarrassment. I felt very self-conscious in my uniform, but, as a matter of fact, I was less conspicuous in this garb than I was before I gave up my civilian clothing.

The adjutant now gave me three cents, my first three days' pay as a soldier, and warned me "not to spend it all in one place." Aviators receive extra pay, but I was still only a simple "poilu." He then handed me a formal order to study aviation—to be an "élève pilote," as they say in France—and also a pass to proceed to Pau.

My time was now my own, so I decided to take a look around the hangars, and before long two "élèves pilotes" greeted me and inquired whether I was entering the Aviation Corps. When they heard that I was, and that I was an American they told me that they also, and several of their friends to whom they afterward introduced me, had lived for some time in the United States. With all this welcome I became conscious of the understood but inexplicable freemasonry that binds all aviators together. I was greeted everywhere as a comrade and shown everything. I was amazed at the vastness of it all and at the scale of the organization. In one corner of the establishment they were teaching mechanics how to repair motors, in another how to regulate aeroplanes. Beyond were classes for chauffeurs, and countless other courses. There must have been several thousand men, and all of them were merely learning to serve the national heroes, the "aviateurs."

In the evening we all went to Dijon together. We dined and went to the theatre. The theatre was full of soldiers, and every little while the provost marshal's guard, composed of gendarmes, would enter and make an arrest. Any one who does not produce papers explaining his absence from the army is hustled off immediately. There are very few Frenchmen who attempt to dodge their service, but this system of supervision has been found necessary to keep down their number and to discover any German spies who may be about.

After the play I went to the station. The road was clogged with troop-trains carrying reinforcements to the Near-Eastern front. During the four hours I spent in the station twelve trains of British artillery passed by. The entente between the Tommies and the French was very cordial. As the trains came to a stop the men would make a rush for the station buffet, and the French would exchange all sorts of pleasantries with them. Right here I had a lot of fun with the Tommies, for they could not understand how a Frenchman could speak English so fluently.

Then came my train, and I found myself en route for Pau. As there were already several American "élèves pilotes" at the aviation school, I had no difficulty in learning the ropes. It was all very simple. But it was well to know what to expect, especially when it came to the question of discipline, which was very strict until one became a full-fledged aviator. It was just like going back to school and I settled down for the long grind.

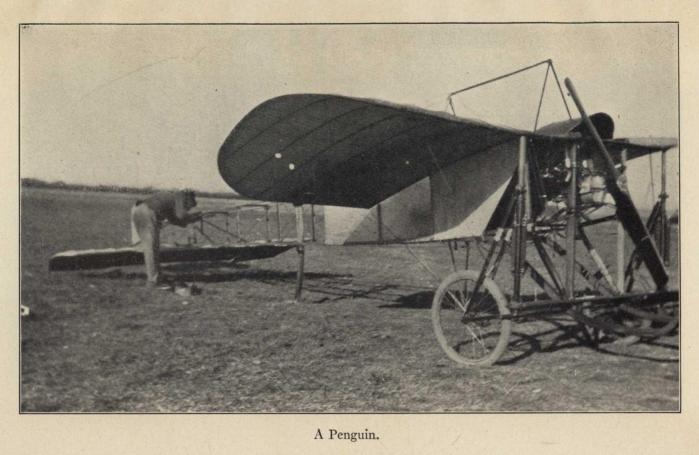

FIRST PRINCIPLES

I have rarely been as much impressed as when I first saw the flying school at Pau. It is situated eight miles beyond the town on the hard meadow-lands granted in the sixteenth century to the villages of Osseau by Henri IV. The grant is still in effect, and the fields now in use are only rented by the government. They make a perfect aviation-ground. Four separate camps and a repair-station lie about a mile from one another and are named—Centre, Blériot, etc. At Centre I saw the low, gray hangars that house the aeroplanes, the tall wireless mast over which the communiqués from Paris are daily received, the office-building for the captain and monitors of the school, and the little café across the road where every one goes when off duty. Beyond were the Boche prisoners working on the road, building fences, or cutting wood, under direction of their non-commissioned officers and decrepit old territorials—grim reminders that this flying business is not all play. It was early morning—the mists were slowly lifting—when the "élèves pilotes" gathered for their daily work. Mechanics ran the machines out on the field in long lines, and the motors woke to motion with startling roars. One by one the pilots stepped in, and one by one the little biplanes moved swiftly across the field, rose, dipped slightly, rose again, and then mounted higher and higher into the gray sky. In the distance the snowy peaks of the Pyrenees formed an impressive background. At almost any time during training hours one can see from ten to twenty machines in the air. There are over three hundred men training. The repair-shops are like a large manufacturing plant. Five hundred mechanics are continually employed there. Among these are little Indo-Chinese, or "Anamites," as the French call them, who have come from distant Asia to help France in her struggle for liberty. As French citizens they are mobilized and wear the military uniform, but their tasks are usually of the monotonous, routine variety.

The repair-shops are continually working under pressure, as accidents occur daily.

It is estimated that the average cost to France of training each pilot is five thousand dollars. Most of the accidents, however, are caused by carelessness, stupidity, or overconfidence. The day I joined the school two of the members lost their lives in a curious accident. They were flying at a great height, but thoughtlessly allowed their machines to approach too closely. Before they could change direction there was a crash, and both came tumbling to earth. When two aeroplanes come too near to each other the suction of their propellers pulls them together and they become uncontrollable. That is what happened to these two unfortunate "élèves." The officer in charge of the school explained at length just how this accident happened. We were cautioned against overlooking the fact that the speed of an aeroplane is always spoken of in reference to the body of the air in which the machine is moving. Thus an aeroplane travelling eighty miles an hour with a twenty-mile breeze is travelling at a speed of a hundred miles an hour in reference to the ground. The two machines at the time of the accident were flying east and west, but, while both were travelling at the same speed with reference to the ground, the plane moving in the direction of the wind was making about ninety miles an hour, while the other was covering barely fifty miles at the same time. The speed at which they were approaching one another was, however, approximately one hundred and forty miles an hour, or more than two miles a minute. What, under ordinary circumstances, would have been a safe distance became a danger zone, and before either pilot realized his mistake it was too late to steer clear.

The scene of the accident lay over a part of the field where Wright's Barn stands. This little red building was the workshop of the Wright brothers when they astonished the world by their first aerial flights. To-day that little red barn stands as a monument to American stupidity, for when we allowed the Wrights to go abroad to perfect their ideas instead of aiding them to carry on their work at home, we lost a golden opportunity. Now the United States, which gave to the world the first practical aeroplane, is the least advanced in this all-important science.

Although I came to Pau with a little preliminary experience, and had the "feel" for engines and steering, I was obliged to begin, with the others, at the bottom of the primary class. It was nearly two months before I was allowed to make my first flight. The French idea is that before a pupil commences his apprenticeship as a pilot he must understand thoroughly the machine he is going to handle and know just what he is trying to do in the air. Together with twenty-five other men, who began their studies at about the same time, I was ordered to attend the theoretical courses. When not in the classroom we were stationed on the aviation-field where we could watch the more advanced "élèves" fly, thus familiarizing ourselves by observation with all the details of our profession. Class-room work and field-practice go hand in hand.

At first I did not realize how important these courses were, or how strict was the discipline under which we lived. One day, when my thoughts were a little more intent upon an expected week-end at Biarritz than upon what was being explained on the blackboard, the lecturer suddenly asked me a question. I could not answer and forthwith my forty-eight-hour leave was retracted. My Sunday was spoiled, but I considered myself lucky not to have received a "consigne," which involves sleeping in the guard-house every night for a week.

The first subject we took up was mechanics. We were made to mount and dismount motors, and were familiarized with every part of their construction. Carburetors and magnetos came next, and then we learned what made a motor "go." At the front a pilot always has two "mecaniciens" to take care of his machine, but if on account of a breakdown he should have to land in hostile territory he must be able to make the necessary repairs himself, and make them quickly, or else run the risk of being taken prisoner. When flying, the pilot can usually tell by the sound of his motor whether it is running perfectly or not. Many a life has been saved in this way—the pilot knowing in time what was out of order before being forced to land in a forest, on a mountain peak, or in some other equally impossible place.

When we had become "apt," we were promoted to a course in aeroplane construction. This is an extremely technical course, and at first we were asked to know only simple subjects, such as the incidence of the wings, the angle of attack of the cellule, the carrying force of the tail in reference to the size of the propeller. By the incidence of the wings is meant their upward slope. This is an extremely important matter, for the stability and climbing propensities of the machine depend entirely upon their model. The angle of attack of the cellule is the angle of the different wings in reference to each other. For instance, the incidence of one side must be greater than that of the other on account of the rotary movement of the propeller. There are also certain fixed ratios between the upper and lower planes. Still more important is the carrying power of the tailplane, for if it has too much incidence it lifts the rear end and makes the machine dive, while if it has too little the reverse happens. If any part of the aeroplane is not correctly regulated it becomes dangerous and difficult for the pilot to control. All this becomes more important as one reaches the close of the apprenticeship. One then appreciates this intimate knowledge acquired at the school. Often a pilot is compelled to land in a field many miles from his base. If something is wrong with his motor he must be able to find out immediately what the trouble is, for if a part is broken the camp must be called up on the telephone, so that a new piece may be sent to the spot by motor, with a mechanic to adjust it.

When a pilot starts on a cross-country trip he is always given blank requisitions, signed by his commanding officer. When he is forced to land he therefore is able to call upon authorities, whether military or civilian, for any service or assistance he may need, and this "scrap of paper" is sufficient in every case to obtain food, lodging, and even transportation to the nearest aviation headquarters for both the pilot and his machine.

Map-reading and navigation were the next subjects we studied. First we were taught how to read a map, how to judge the height of hills and the size of towns, so that when flying we would know at a glance just where we were. This, we later appreciated, is a very important matter. When passing through clouds or mist an aviator may become momentarily lost, and the instant he again sees the ground he must locate on his map the country he views or else land and ask where he is. Aerial navigation may not be as complicated as that employed by mariners upon the high seas, but it is not easily mastered by any means. One must learn to calculate the direction a straight line takes between two points, and translate this direction into degrees on the compass. Secondly, and more important, is the estimation of the drift caused by the wind. If the wind is from the west and the pilot is attempting to go north, the machine will go "en crabe" (sideways like a crab). The machine will be pointing north by the compass, but in reality it will be moving northeast. After the pilot has laid out his course on the map, and is tearing through the air, he must immediately take into consideration his drift. By watching landmarks selected beforehand the drift is calculated very quickly. The course by the compass is altered, and, though the machine is speeding due north, the compass informs the pilot that he is pointing northwest, a fact very confusing for a beginner.

LEARNING TO FLY

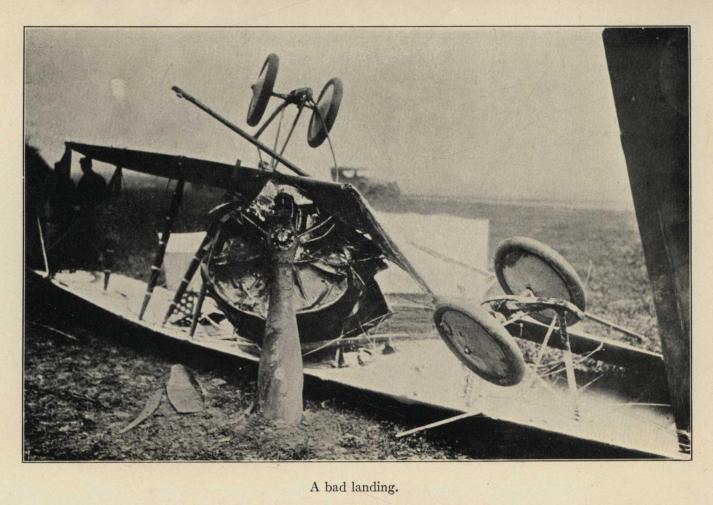

During the lecture course we always spent several hours a day on the aviation-field. We were not allowed to fly, but our presence was insisted upon. We would observe the things to avoid, so that when our turn came to go up we should be familiar with all the dangers. Every start, flight, and landing was made a subject of special study. Every time a pupil made a mistake his fault was explained to us, and we were usually impressed with the fact that he had barely escaped a bad smash and perhaps death. The pupils who made the mistakes, were immediately made examples. If the fault was corrected they escaped with a long and loud lecture for the benefit of the onlookers, but if, on the other hand, an accident followed the mistake the offenders were immediately punished with a ten days' "consigne." If a pupil continued to make mistakes he was "vidé," and sent back to his former regiment.

Loss of speed—"perte de vitesse," the French call it—is the most common and probably the greatest danger an aviator meets with—it is his "bête noire." There is a minimum speed capable of holding an aeroplane in the air which varies inversely with the spread of the wings. While in line of flight, the force of the motor will maintain the speed, but when the motor is shut off and the pilot commences to volplane the force of gravity produces the same result. There are two ways of knowing when you are approaching the danger-point—by closely watching the speed-indicator and by feeling your controls. The moment the controls become lifeless and have no resistance you must act instinctively and regain your momentum, or it is all up with you. While climbing you may lose speed by forcing the motor and climbing too rapidly. When a "perte de vitesse" is produced the aeroplane "goes off on the wing," sliding down sideways in such a manner and with such force that the rudders cannot right you or that the propeller cannot pick up your forward speed. This can happen also if, when making a vertical turn, the speed is not sufficiently increased to carry you around the corner. Occurring near the ground a loss of speed is certain to result in a smash-up. If high in the air a "vrille," or tail spin, is generally the result. By this is meant coming down in a whirlpool, spinning like a match in the waste of a basin. The machine takes as a pivot the corner of one wing and revolves about it. The first turn is very slow, but the speed increases with each revolution. The only hope of escape is to dive into the centre of the whirlpool. Even then, if the motor is turned on, the planes will fold up like a book. Among the accidents to beginners this, next to faulty landing, is the most common.

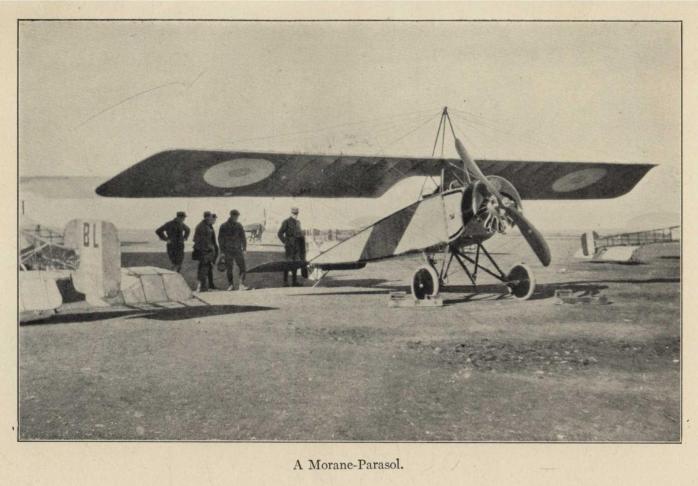

I witnessed one very sad example. A young lieutenant had just been brevetted and was ready to leave the school. Just as he was saying good-by to his comrades, a "Morane Parasol" was brought out on the field. These machines are very tricky and dangerous. He had never piloted one, but wanted to show off. The monitors begged him not to take it up, but he insisted on doing so. When he had reached an altitude of about five hundred metres he shut off his motor to come down, not realizing that monoplanes do not volplane well. He did not dive enough and had a "perte de vitesse." The machine slipped off the wing. We all held our breaths and prayed that he would recover control before he engaged in the fatal corkscrew spiral. Our hopes were of no avail. The machine started to turn, and approached the earth spinning like a chip caught in a whirlpool. I turned my back, but I could hear the machine whistling through the air till it came to the ground with a sickening crash.

Faulty landings are also very common causes of accidents. It takes a beginner a long time to train his eye to make a perfect landing, and even experienced men now and then smash up on the "atterrissage." A few inches sometimes make a great difference. If the pilot does not check his speed in time he will crash into the ground and "capote," that is, turn over. If he pulls up too soon he will slip off on the wing or land so hard that the machine collapses. Not only the manner of landing but gaining the exact place of landing is difficult. If the pilot misjudges his distance, and lands either beyond or short of a given spot, he may collide with some object that will wreck the aeroplane.

Just before leaving the ground is another critical moment. If the tail is lifted too high in an effort to gain speed the wheels are liable to hit some small obstacle and the machine turns a somersault. Often one is forced to lift the tail very high to gain flying speed in a short distance, and it always results in an uncomfortable few seconds until the pilot knows he is clear. Still another mishap against which aviators are powerless may occur while rolling along the ground. The machine may be caught by a cross wind, which will turn it completely around, a "chevaux-de-bois," a merry-go-round, the French call it. If the machine is going fast when this happens it means touching the ground with a wing and a first-class smash.

For two months I studied and watched, and the result was a profound respect for the air. During this time it seems that I also had been the object of study and observation on the part of my teachers, for one day I was told that I was to receive my "baptême de l'air," my first flight as a passenger. Words cannot describe my joy or my sensations.

I walked over to the double-seater. The pilot had already taken his seat, and the propeller was turning. I had hardly climbed in and fastened my belt than we were off. I could hear the wheels bounding along the ground. Suddenly the noise stopped—we were in the air. I was sure I would have vertigo, as I often had had in high places. I did not look out of the machine until we were about five hundred feet up. Then, to my surprise, I experienced not the slightest sensation of height. The ground seemed to be merely moving slowly under and away from me. We kept climbing. I could see the country for miles. Never had I viewed the horizon from so far. The snow-clad Pyrenees were literally at my feet. Trees looked like weeds and roads like white ribbons. It was a marvellous sight. At about two thousand feet we struck some wind and "remous" (whirlpools). Each time we struck one we would drop about fifty feet, and the sensation was like being in a descending express elevator. At the end of the drop we would stop, the biplane would shiver and roll like a ship in a heavy sea, and then it would shoot up until we struck the solid air again. This was real flying.

After a while my instructor cut off the motor, and we started to come down. We were going fast enough on the level, but now the wind just roared past my ears. The ground appeared to be rushing up to meet us. We were pointing down so straight that my whole weight was on my feet, and I was literally standing up. I thought that the pilot had forgotten to redress, and that we would go head first into the ground, but he finally pulled up, and before I knew it we were rolling along the ground at a speed of about forty miles an hour.

With this preliminary experience I was ready to commence my final studies for a pilot's brevet.

Some people seem to think that the two months devoted merely to first principles are time lost, but I now realize that this is not so. I seemed to have much more confidence on account of this intelligent understanding of every detail. I felt that I knew just what I was to avoid, and just how to do the correct thing in case an emergency arose.

Perhaps I might say here that military aviators have four distinct duties to perform at the front: they must fight, reconnoitre the enemy's positions, control the fire of their own batteries, or make distant bombarding raids over the enemy's bases of supplies.

The fighting pilots do nothing but combat work. Their machines are the very small and fast Nieuports, designed especially for quick manoeuvring. They are called the "appareils de chasse," on account of their great speed—over one hundred miles an hour. Their armament consists of a mitrailleuse, which is carried in a fixed position. In order to aim it, the pilot must point his machine. The principal task assigned to the Nieuports is to do sentry duty over our own lines, in order to prevent the enemy aeroplanes from crossing over for observation purposes.

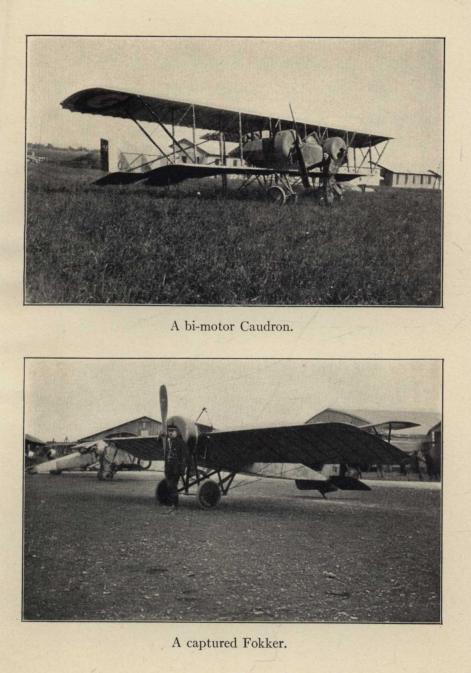

Heavier and somewhat slower, and too cumbersome for fighting, are the machines used for reconnoissance duty. They are large bimotor Caudrons, very stable and capable of carrying two men, an observer and a pilot. In addition they carry a wireless apparatus, powerful photographing instruments, and other equipment essential to their work of observing, recording, and reporting the enemy's movements and the disposition of his batteries. If attacked, they can fight, being armed with a machine gun mounted in front of the observer's seat; but attacking the enemy is not the rôle they are intended to play.

Next come the Farman artillery machines. They are like the reconnoissance machines, too cumbersome for fighting, but are best equipped for the purpose of "réglage"—controlling the fire of batteries. While the small Nieuports have a carrying capacity of only two hundred and twenty pounds, these unwieldy creatures are able to take on over five hundred pounds, which includes the weight of the two men, their clothes, cameras, the wireless, and the gun and its ammunition. In this branch of aviation the weight of the pilot does not matter so very much, whereas in the case of the little Nieuports, if the aviator exceeds the prescribed weight, he has to choose between not piloting the machine or starting on his flight with a supply of gasolene reduced by the amount of his excess weight.

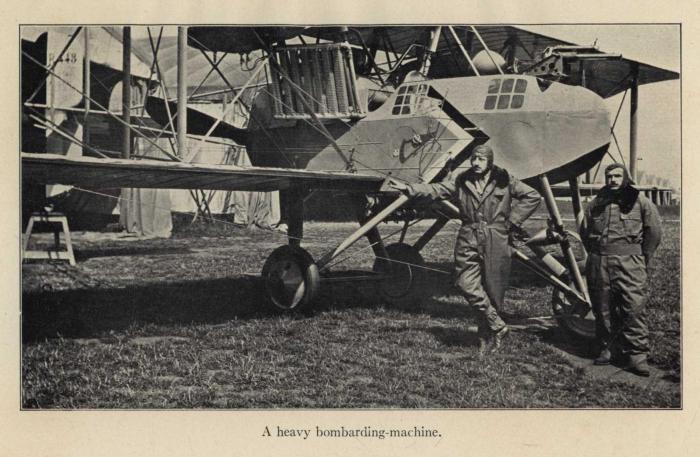

Finally, there are the heavy-armored bombardment machines, with a carrying capacity of over one thousand pounds. They are the slowest machines of all, and their work is both tiring and tiresome, as their flights are made mostly by night. They are armed with mitrailleuses or small, non-recoil cannon, but on account of their low speed their daylight flights are attended by "escadrilles de chasse." They are also detailed for guarding cities.

In the early months of the war each aviator was usually assigned to any one of these types of machines at hazard. At the school which he attended the instruction he received was specialized for the work which that particular machine could perform. Since then, however, it has been found more advisable to train all beginners on one of the heavier machines. The reason is this: Fighting, although the safest work, requires the most experienced pilot. It is the most important work of all—or rather it calls for greater attributes of skill, courage, and knowledge. The famous aviators of whom we read in the daily communiqués, like Navarre, Nungesser, Vialet, and Guynemer, all gained their reputation with the small, fighting Nieuports. A pilot is consequently promoted from a reconnoissance machine to an "appareil de chasse" after he has had two or three months' experience at the front and his captain has indorsed his application.

There are exceptions to this rule. The most notable is the American Escadrille, which consists entirely of fighting machines. The volunteers from the United States who applied for this duty were considered such naturally good aviators that they were accorded the exceptional honor of being assigned immediately to the fighting Nieuports.

When I first reported at the aviation headquarters they offered to let me go directly to the combat school because I was an American. I refused. "When in Rome, do as the Romans do," I thought, and so expressed my preference for a French escadrille. I knew that by doing so I would put in a longer apprenticeship, but that in the end it would make a much better fighting pilot of me. Having chosen this course, I was ordered to report to the school at Chartres.

THE SCHOOL AT CHARTRES

Most Americans know Chartres only for its beautiful Gothic cathedral, which, since its construction in the eleventh century, has been regarded as one of the finest edifices of France. Those of us who, since the war began, have had occasion to visit Chartres, have found there other interests besides the little, straggling streets, the historic old houses, and the beautiful monuments and memorials to men, like Pasteur and Marceau, who brought fame to their native city in peace as well as in war. Not far from the centre of the town lie the vast aviation-fields—close by the little village of Bretigny, where the treaty of peace which concluded the One Hundred Years' War was signed over five centuries ago. Little did the soldiers who met on that historic battle-field dream that to-day their descendants would be training for an even greater conflict, in which the combatants not only clinch below ground but also fight aerial battles high above the clouds.

As Chartres was a great cavalry headquarters of the French army before the war, to-day many of the horses shipped over from the western plains of North America are sent there the moment they are unloaded from the steamers at Bordeaux. Many a morning from my window I have seen the square below filled with a moving mass of animals on their way to the near-by remount depots. Twice I saw whole regiments of cavalry leaving for the front. So steadily and so quietly did those mounts move in ranks that it seemed as if they had acquired some of their riders' dogged determination and sense of responsibility.

The aviation school at Chartres is as large as the one I had recently left, and its organization is the same. In fact, it is only one of a dozen equally large and important schools located in various parts of France—all of which is bound to make a great impression upon Americans when they appreciate the insufficiency of aviation schools in our own country. At Chartres there are three fields. Two of these are reserved for the use of the double-control machines, while the third, the "Grande Piste," serves as a practice-field for the élèves who are about to come up for their pilots' examinations. As soon as I had reported my arrival to the officer in charge, and had complied with the usual formalities, I was assigned to an "équipe," which in English means a "team." There were twelve of these "équipes" under instruction at all times, comprising a dozen pupils apiece, and each having its own double-control machine and an instructor. Half of the number are always making use of one of the two smaller fields, while the remaining six use the other.

The instruction in this way progresses rapidly. The "moniteur" first takes each pupil for a few rides to see how the latter takes to the air. The élève must follow every move of his pilot, until he appears perfectly at home in the machine, and then he is allowed to hold the controls alone. Each flight lasts only about five minutes, the French theory being that an aviator must take his instruction in small doses. In the interim, as in the preliminary courses, he remains on the field, observing and studying the mistakes of his comrades. If the progress of the instruction is too rapid, the pupil has not the time to grasp each step that has been passed and cannot, therefore, become an expert pilot.

The double control works in this way: The controls and the pedals of the pupil are a duplicate set of those of the "moniteur," or instructor, and have the same connections with the engine and steering apparatus. Either set will steer the machine. The pupil takes hold of the controls and places his feet on the pedals. Every motion of the instructor is reproduced in the pupil's control and pedals—their hands and feet move together. In this way the pupil develops a reflex action and instinct for doing the right thing. Each day, weather permitting, at least half a dozen flights are made by a pupil. Gradually the "moniteur" allows him to control the machine. Suddenly he finds himself running the biplane alone, with his instructor riding as a passenger behind him and merely giving him a word of advice or caution from time to time.

Landing is the most difficult part of aviation to master. A great many of the accidents occur because the aviator has made a poor contact with the ground. In fact, in the early days of aviation most of the accidents occurred near the ground, and this led people to speculate on the peculiar action of the lower air currents. These, in reality, had little to do with it. The cause lay in the inability of the pilots to know how to make proper contacts and to appreciate the fact which we now know to be a fundamental principle, that the engine should be shut off before a machine catches the air and volplanes down against the wind. There are exceptions to this rule, but not for a beginner. Sometimes it is necessary for the pilot to descend against a strong wind. In order to maintain the required speed the motor must be left partially turned on. Generally it is most important to turn off the motor, because if the landing is made with the wind, even in the gentlest breeze, the aeroplane, on account of the speed of the tail wind, is likely to turn a somersault and be completely smashed up. Even then another manoeuvre has to be mastered. Just before alighting the pilot must make a quick upward turn, so that at the moment of contact the machine may be travelling parallel with the ground. Formerly the importance of this little upward turn of the rudder was not fully appreciated by aviators, and many a machine was wrecked by a sudden hard compact with the earth.

When the "moniteur" sees that his pupil has acquired the knack of making a landing he passes on to the all-important manoeuvre of volplaning, and the dreaded "perte de vitesse" is tackled. Lastly, but not least, comes the "virage"—turn, or bank, as we say in English. These rudimentary principles are all that are required of the élève before he may go up alone, or be "lâché."

During this phase of my instruction it was repeatedly impressed upon me that, if anything ever happened to me when I was in the air and I did not immediately realize what to do, I was to let go of the controls, turn off the motor, and let the machine take charge of itself. The modern aeroplane is naturally so stable that, if not interfered with, it will always attempt to right itself before the dreaded "vrille" occurs, and fall "en feuille morte." Like a leaf dropping in an autumn breeze is what this means, and no other words explain the meaning better.

A curious instance of this happened one day as I was watching the flights and waiting for my turn. I was particularly interested in a machine that had just risen from the "Grande Piste." It was acting very peculiarly. Suddenly its motor was heard to stop. Instead of diving it commenced to wabble, indicating a "perte de vitesse." It slipped off on the wing and then dove. I watched it intently, expecting it to turn into the dreaded spiral. Instead it began to climb. Then it went off on the wing, righted itself, again slipped off on the wing, volplaned, and went off once more. This extraordinary performance was repeated several times, while each time the machine approached nearer and nearer to the ground. I thought that the pilot would surely be killed. Luck was with him, however, for his slip ceased just as he made contact with the ground, and he settled in a neighboring field. It was a very bumpy landing, but the aeroplane was undamaged.

The officers rushed to the spot to find out what was the matter. They found the pilot unconscious but otherwise unhurt. Later, in the hospital, he explained that the altitude had affected his heart and that he had fainted. As he felt himself going he remembered his instructions and relinquished the controls, at the same moment stopping his motor. His presence of mind and his luck had saved his life—his luck, I say, for had the machine not righted itself at the moment of touching the ground it would have been inevitably wrecked.

This was a practical demonstration of the expediency of the French method of instruction, and before long it was to serve me also in good stead.

One day, after I had flown for several hours in the double-control machine, my "moniteur" told me that he thought me qualified to be "lâché," and that I was to go up alone the following morning. I felt very proud and confided my feelings to one of my friends who had been qualified a few hours earlier. While we were talking he was called upon to make his first independent flight. We watched him leave the ground, rise, and then make his turns. He was doing remarkably well for a beginner, but when he came down for his landing he did not redress his machine in time and it crushed him to the ground, with fatal result. This completely unnerved me. I lost all desire to fly the following day, and prayed earnestly for rain. The next morning, however, was beautifully clear. The captain was there to watch my flight. I was loath to go up, but I had no alternative. The mechanics rolled out a single-control biplane for my use and I climbed in. The motor was started. With its crackling noise my nerve almost deserted me again. I should have felt less frightened, probably, had no one been looking on, but my "moniteur," my captain, and all my comrades stood there, interested to see how I would handle myself. I had to see the thing through, so I opened the throttle. The machine began to roll along the ground, then to bounce, and then, in response to a pull on the control, to fly. I was flying alone. The thought filled me with alarm. I rose to less than two hundred feet, but it seemed prodigious. Then I made a turn. When I found that I was flying smoothly and easily I felt a little more confident. As I turned back toward the field I could see my masters and comrades below looking up at me. Another machine was about to leave the field. It seemed no larger than a huge insect as it glided across the ground. I made up my mind that I was going to make good. If others could do it, I could. I volplaned down, and made my landing safely but somewhat bumpily. The captain told me that I would do, but he would like me to make another turn. I went up again. This time I made a faultless landing. I had passed my test satisfactorily. I felt happy and confident. I was now qualified to "conduct" an aeroplane alone, and in a few weeks I would be allowed to try for a brevet as military pilot.

There were several other pilots whose turns to pass to the "Grande Piste" came before mine. I had, therefore, to wait for several days, which I used to advantage in taking up the old "double-control" machine alone. In this way I was able to make several ascensions and landings every morning and every night. This was to be of the greatest service to me later, for during these practice flights I acquired perfect confidence in myself. At other times, both before and after working hours, my "moniteur" would take me up with him as a passenger for a newly discovered sport. We would rush along the ground, barely two feet above it, and put up partridges, which abounded in the greatest numbers. Our speed would enable us to overtake and hit them with the wires of the machine and kill them. Running along the ground in this way is always attended with danger, but it was real sport. One morning in twenty minutes we killed six partridges in this novel manner.

Finally my turn came. I graduated from the beginners' class at "La Mare de Grenouille" to the company of the more finished pilots of the "Grande Piste." The beginners' field is called the "frog's meadow," because the landings are so hoppy. On the "Grande Piste" we had newer and faster machines, and we could fly alone and go practically anywhere we wished. Six pilots were assigned to one aeroplane. We had to divide up the time equally between each pilot, so as to give every one an opportunity of making at least two flights both morning and afternoon. A maximum height was imposed upon each "équipe," and this was gradually increased from five hundred feet to a thousand, and then to one thousand five hundred, as we became more and more adept.

Most of our time was given to making landings and to accustoming ourselves to volplaning. The motor had to be reduced at a predetermined distance from the field, and the rest of the descent made by volplaning to a given spot. Spirals were also made during each flight. We would select our landing-places and prepare ourselves for the "atterrissage" by reducing our motor, making due allowance for the drive of the wind. At about two hundred feet from the ground we would suddenly turn on the motor again, tilt up the tail, and resume our flights. This was excellent practice and gave us more and more confidence in our own ability to come down wherever we wished. The average layman cannot understand why aviators spend so much time turning in spirals as they approach the ground. It is because they are manoeuvring for position to hold their headway and land against the wind, as does a sailing ship when beating up a harbor against wind and tide.

Every day I took my machine up higher and higher until I had gradually increased my altitude to two thousand feet. Here, one day, I had a narrow escape. I had received orders to make a flight during a snow-storm. I rose to the prescribed height and then prepared to make my descent. A whirling squall caught me in the act of making a spiral. I felt the tail of my machine go down and the nose point up. I had a classical "perte de vitesse." I looked out and saw that I was less than eight hundred feet above the ground, and approaching it at an alarming rate of speed. I had already shut off the motor for the spiral, and turning it on, I knew, would not help me in the least. Suddenly I remembered the pilot who fainted. I let go of everything, and with a sickening feeling I looked down at the up-rushing ground. At that instant I felt the machine give a lurch and right itself. I grabbed the controls, turned on the motor and resumed my line of flight only two hundred feet in the air. All this happened in a few seconds, but my helplessness seemed to have lasted for hours. I had had a very close call—not as close as the man who fainted, but sufficiently so for me.

The author, together with his first mechanic, at the "mitrailleuse."

The second mechanic is standing on the wing.

Since that day I have seen several other pilots experience a loss of speed under similar circumstances. Thanks to the thorough instruction which we had received previous to our being allowed to fly alone, their lives, as well as my own, were saved. Later we learned how the very dangers which we had experienced as new aviators often become the safety of expert pilots.

PASSING THE FINAL TESTS

My équipe was now making flights at three thousand feet and was remaining up for an hour at a time. We had all flown alone for thirty hours and were ready for our "épreuves."

The weather was cloudy, however, and as our first examination was to be a height test, we had to wait until it cleared. It would have been extremely difficult—in fact, almost impossible—for us to go up under existing conditions. The first two tests which we were required to pass involved ascensions of six thousand feet; then an hour at ten thousand. If we passed these satisfactorily we would next be required to take a triangular voyage of one hundred and fifty miles, making a landing at each corner of the triangle. Lastly, there was the ordeal of going up to an altitude of one thousand five hundred feet, where the motor had to be cut off and the descent made by spirals to a previously determined spot.

The day on which we were required to begin our altitude flights the captain assigned three machines to our équipe—that is, one aero-biplane for each pair. My chum, a sous-lieutenant, and I were assigned to the same machine. We matched to see which one of us should use it first. He won and I helped him prepare for the test. I fastened on his recording barometer, which indicates the altitude reached by a machine, and he climbed in. Waving us a cheery "Au revoir," he started off. His machine climbed fast. To us he seemed to be going too steeply. We felt like shouting to him to be careful, but we knew it was useless. Suddenly his machine slipped off on the wing. For some unknown reason he failed to shut off his motor. His biplane engaged in the fatal spiral. There was a loud report, like a cannon-shot, and the machine collapsed. The strain had been too great. The top plane fell one way, the lower another, while my friend and the motor dropped like stones.

I would have given anything to put off my own test for a few days, but within twenty-four hours I received orders that my turn had come; and orders were orders. I made up my mind to be very careful and to take my time about the climb.

That first flight at six thousand feet gave me a thrilling sensation. I remembered my first flight alone, when I had barely reached two hundred feet. It seemed now as if I was going to mount to an indescribable height. Since that day I have had to go up that high often, and even higher; but it has all become commonplace, for familiarity breeds contempt in the air as well as on land.

I was so very cautious about mounting that twenty minutes elapsed before the needle on my registering barometer marked six thousand feet. It was very cold. The wind struck my face with icy blasts, but I was so excited that I did not really mind it. After a while I shut off the motor and started to volplane to earth. I came down a little too rapidly and made a very bad landing. In fact, for a moment I thought that I had broken my machine. I was wet all through from the sudden rise in temperature and stone-deaf. It was ten minutes before I could hear again. Then I received my call-down. It seems that when a pilot has been up to a very great height, he loses his sense of altitude—his "sens de profondeur," as the French call it. When approaching the ground he cannot tell whether he is twenty-five or fifty feet in the air. He must take every care, before making contact, to train his eye for "depths" again by flying a few minutes fairly close to the ground. It is only a question of a few moments, but it is a necessary precaution.

My next climb to six thousand feet was better. In fact, I felt a certain degree of confidence. It took me somewhat longer to mount to the required height, because some clouds came up and I had to search for a hole through which to pass. Everywhere below me, as far as my eyes could reach, was a sea of clouds. The sun was shining on their snowy-white crests. It looked for all the world as though I was looking down upon an enormous bowl of froth.

The following morning was the day fixed for my ten-thousand-foot ascension. The atmosphere was remarkably clear, and I felt an extraordinary sense of freedom and power as I rose from the ground. The earth below me was bright with color. As I climbed higher the shades became less brilliant. At ten thousand feet all color had vanished. The only hue visible was a varying degree of shading, gray and black. Below me I could make out the city of Chartres. Forty miles away lay Orléans. To one side, the Loire wound its course in a gray, ribbon-like band. On all sides the straight, white roads were merely blurred streaks in the murky mass.

A few days later I started on my endurance test, the triangle, in company with five other machines. In this flight of two hundred and fifty kilometres I had to make landings at two towns where there were aviation-fields, and the third my own field. At each place I had to report to the aviation officer in charge and have my papers signed. In case of a breakdown on this flight I had forty-eight hours in which to make the necessary repairs and complete the test.

The day of my triangle was a poor one for flying. It was the first warm morning of early spring and the sun was just soaking the moisture out of the ground. The air was, in consequence, spotty and there were many "remous," or whirlpools. These whirlpools often cause a sudden "perte de vitesse" and are therefore very dangerous. The machine is sailing along quietly and smoothly, when suddenly the controls become lifeless. You glance at your speed-indicator and at your engine-speed. Both show that the machine is travelling well above the minimum safety speed. This is apt to puzzle the beginner, for without warning there follows a sudden jolt. Your machine trembles like a frightened horse and unexpectedly leaps forward again. On a day like this you have to fight the machine all the time to maintain its equilibrium.

The first leg of the triangle was accomplished without incident. As I was starting my motor for the second stage, however, I noticed that the ignition was faulty. A spark-plug had become fouled with oil, and I had to change it before venturing up again. My companions started without me, calling out that I could catch up with them at Versailles, where they intended to lunch. I hurriedly screwed on a new spark-plug and threw my tool-bag back into the box under the extra seat, but in my hurry to be off I neglected to fasten it down. I was later to regret my carelessness.

I soon found that in trying to catch up with the others I had no easy task before me. The day was well advanced, and the "remous" which I encountered were countless. I climbed and climbed. To no avail. The cloud ceiling was at eighteen hundred metres, and I could not escape the "remous" so low. The country below me was all wooded and interspersed with lakes both large and small. There was not a landing-place in view. Suddenly I felt a hard blow on the back of my head and a weight pushing against me. "Ça y est," I thought; "the machine can't stand the buffeting and has given way." I ventured a look back. To my surprise, everything seemed intact—everything except the observer's seat, which was leaning against my head! It was the seat which I had forgotten to hook down at Châteaudun! I was greatly relieved, and fastened it back into place.

Just then I came within sight of Versailles. I looked for the aviation-field at which I was supposed to land. Instead of one I saw three, lying about two miles apart. This was indeed a puzzle. From the height at which I was flying I could not make out which was the school. I picked out one which I thought should probably be the haven of refuge for my storm-tossed aeroplane and spiralled down. I climbed out of my machine. No one seemed to be about. No mechanics ran out to assist me, as is usually the case at the schools. "It must be the luncheon-hour," I thought, "and all the mecaniciens are at déjeuner." I glanced over to where the machines were ranged in line. To my surprise, they were not of the model I had seen at Pau and Chartres, but the latest and fastest "avions de chasse." Somewhat uncertain as to my whereabouts, I walked over to the office. I was not left long in ignorance of my error. I had landed on a secret testing-field, access to which was obtained only by special permit. The sergeant advised me to lose no time in leaving, for if the captain saw me I would be speedily punished in accordance with the military regulations. I needed no second urging, and within five minutes I was on the right field, explaining to my comrades why I had been so long rejoining them. It seems that they had experienced a very pleasant flight all the way, for the hour's start they had had over me had enabled them to escape most of the "remous," which are always at their worst in the middle of the day.

Late in the afternoon we returned to Chartres. This was the most enjoyable part of the day's flying. The aerial conditions were perfect and we were able to allow ourselves the pleasure of appreciating all the interesting places we passed over. First we saw the beautiful valley of the Chevreuse; then Rambouillet, with its wonderful hunting and fishing preserves. Next I caught a glimpse of the imposing palace and gardens of Maintenon. The time passed all too quickly; yet when we reached home it was almost dark. We all felt quite tired, but before putting our machines away, however, we asked permission to make our spirals, so that we might complete every requirement of the brevet before night set in. We were anxious to do this, so that we might obtain our "permissions" immediately. We did not wish to lose a moment. A four days' leave is always accorded each pilot the moment he has satisfactorily fulfilled all the requirements of the course. Our request was granted and the final test was successfully passed.

I was now a full-fledged aviator, with the rank of corporal, with the regular pay of eight cents a day and an additional indemnity of forty-five cents as a member of the Flying Corps.

THE ZEPPELIN RAID OVER PARIS

I decided to spend my four days' "permission" in Paris, the rendezvous of all aviators when not on active service. From the first I felt conscious of unusual attention. People seemed to treat me with deference and with more respect than I had ever before experienced. I could not account for it. Then, of a sudden, I chuckled to myself. The envied stars and wings on my collar were the cause. I was a "pilote aviateur," a full-fledged member of the aerial light cavalry of France.

For most "permissionnaires" Paris usually offers only the distractions of its theatres and restaurants, its boulevards, and its beautiful monuments. These pleasures I also had looked forward to, but in the first thirty-six hours of my visit occurred another, more startling diversion—two Zeppelin raids. It was my first real experience of the war.

The first alarm occurred as we were leaving a restaurant after dinner. A motor fire-engine rushed by, sounding the alert for the approaching enemy. Pandemonium reigned in the streets. I hastened to find a way to reach the aviation-field at Le Bourget, where I felt that duty called me. The concierge hailed a taxi. I jumped in and gave the address to the chauffeur. "Le Bourget! Oh, mais non," exclaimed the man; "monsieur must think me a fool." He flatly refused me as a fare. He was the father of a family, and he certainly would not go to the very spot where all the bombs were certain to be dropped; besides—he did not have enough gasolene in his tank for so long a run. We talked and argued. In desperation I thrust my hand in my pocket and handed him a generous retainer. At the sight of the money he wavered. I followed up my advantage and promised him a handsome tip if he started at once. He threw in his clutch. I had won my first "engagement."

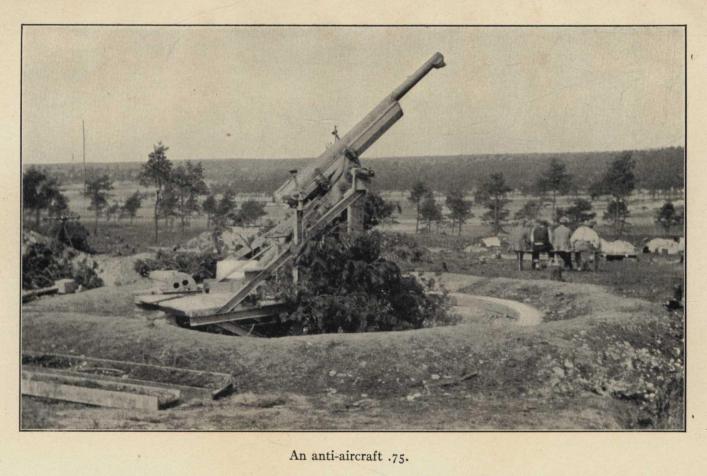

The streets were pitch-dark and jammed with people, all staring heavenward. The feeble oil-lights of the taxicab barely lit up their faces as we wound our way in and out. At breakneck speed we swung right and left, sounding the horn and crying out warning "attentions." Near the outskirts of the city we could see search-lights flashing against the heavy mist. There was so much fog, however, that they could not pierce the veil which hung over the city. At one thousand five hundred feet the sky was opaque. The anti-aircraft batteries were barking and sending off deep-red flashes into the impenetrable murkiness in answer to wireless signals from the invisible air guards above. Now and then a military automobile dashed by.

As we neared Le Bourget, there was a deep detonation. A bomb had been dropped. The Zeppelin had arrived. My chauffeur in panic jammed on the brakes. I was literally thrown out of the taxi and into the arms of a waiting sentinel who flashed an electric torch into my face. The sergeant of the guard rushed up and escorted me to the guard-house, where an officer proceeded to question me. I immediately realized that I was an object of suspicion. Who was I and what was I doing here? Here I was, a foreigner in the French uniform, and unknown to them. Instead of being welcomed at the post of danger I found to my amusement that I was temporarily under arrest.

Several more explosions were heard. Then a deathlike silence. The cannon ceased their angry roar, the search-lights put out their blinding rays. Through the window I noticed a large fire in the middle of the "piste," where several cans of gasolene had been ignited. It was the signal for the searching aeroplanes to return. The Zeppelin had left.

As soon as the electric current had been switched on again the captain returned. He seemed surprised at my "enthusiasm." "Just like you Americans," he said smiling. "A man en permission, however, should never look for trouble." He then explained that this night guarding required special training. Even had he needed my services, I would have been helpless, as I had never before flown after sundown.

One by one the defenders of Paris returned. At two thousand feet they were invisible, though we could hear the humming of their motors. Then, as they came nearer and nearer we saw little indefinite lights moving in the mist above us, and finally the machines, their dimmed search-lights yet staring like two great eyes.

About fifty aeroplanes are in the air around Paris all the time. Each pilot remains up three hours, when he is relieved by another flier. When the Zeppelins are known to have crossed the front, some eighty miles away, the whole defense squadron of two hundred takes to the air. The organization of the aerial defense of Paris is admirable, and it is this, together with the efficient anti-aircraft posts in the environs, which prevents the "Boches" from raiding Paris more often.

I was allowed to examine everything at my leisure, and took advantage of this opportunity to gain as much information as I could about the lighting systems and the new models of small cannon which had recently been installed on the aeroplanes. Presently I was greeted by one of the pilots who had just landed. He proved to be an old acquaintance.

It seems that the Zeppelin had profited by the mist to slip by our watchers at the front, and had reached the very outskirts of the city before it was sighted by the air guards of Paris. The Boches dropped several bombs near the Gare du Nord and in the vicinity of Le Bourget. Then they had vanished into the mist. "How could they ever find the railway-station in the dark?" I asked. "That's easy," he answered. "The Zeppelins are equipped with a small observation-car that hangs down on a long cable. It is built something like an aeroplane and travels about five thousand feet below the dirigible. This evening the raider flew at an altitude of seven thousand feet, while the car moved along only two thousand feet from the ground. Its passenger could, therefore, locate everything easily and telephone the directions to the commander above." "But," I insisted, "how did they ever locate the freight-yards in the dark?" "Easily," replied my companion; "their spies had arranged all that. They simply hung a series of blue lights in the chimneys of houses and laid out a path directly to the spot." These spies in all probability had been already caught, but I was angry, very angry, to realize that their "espionage" was still so efficient.

On the way home Paris seemed surprisingly normal again. The street-lamps were glowing peaceably and the cafés were crowded with talkative men and women. I could not help thinking how wonderful those people were, how fearless and forgetful of danger.

The actual damage done by the bombs during that raid was insignificant. The photographs published in the daily press bore witness to this. A few civilians were killed, but no military damage was done. It was only an attempt at terrorism. I visited one of the "craters" the next morning. The bomb had landed directly over the subway and had blown a huge hole in the pavement. The tracks below lay open to view. Gangs of laborers were already at work, not repairing the damage but enlarging the hole. I asked them what this was for. "Why, monsieur, it is this way. The health authorities always insisted that a ventilator was needed in this part of the 'Metropolitain.' The Boches obligingly saved us the trouble and expense. We are now merely going to put a fence around it."

That night there was another alarm. We were spending the evening with friends in the Latin Quarter when the pompiers startled us with their wailing sirens. From every direction came the "Alerte! the Zeppelins are coming. Lights out!" One by one the street-lamps faded, apartments were darkened, and the street-cars stopped where they were, plunged into darkness. It was thrilling. In the velvety gloom the outlines of people and motors could be seen moving about. The corner of the rue d'Assas alone remained illuminated. A "bec de gaz" was still burning brightly, to the rage of an old infantry colonel who was too short to reach it himself. To our amusement, a little girl clad in a red kimono and bedroom slippers ran out into the street and volunteered her aid. The old soldier blurted out a word or two, then lifted her up in his arms while she extinguished the light. "Thanks, mademoiselle. Now, quick!" he gasped; "run back to bed."

We saw some of the people climb down into their cellars. The majority, however, gathered in the streets, looking up at the search-light swept sky. Tiny, starlike lights moved about above us and we knew that aeroplanes of the "Garde de Paris" were searching for the venturesome raider. "I don't believe the sales Boches and their sausage balloon are coming this evening to beg food," remarked one man. "Oh, no," answered another, "it is clear and they well know that a Zeppelin over Paris to-night is a Zeppelin less for Germany." Just then we heard the firemen coming back. Their bugles were playing a jubilant call. The Zeppelins had been frightened away. Everywhere lights were again lit. The people laughed good-naturedly at their neighbors' strange attire. "Quelle guerre!" yawned the old officer at my elbow; "down in the ground, under the sea, and over our homes! Quelle guerre!"

AT THE ECOLE DE PERFECTIONNEMENT

From Chartres I was sent to Châteauroux to continue my studies and perfect myself in flying. Châteauroux is a small provincial town situated half-way between the château country and the beautiful valley of the river Creuse. It was originally founded by the Romans, and before the war had a large "caserne." All this is forgotten to-day in the glory of the stream of air pilots that pass through the "Ecole deviation militaire." Soldiers are to be found everywhere, but not aviators, and the residents of Châteauroux are very conscious of the honor conferred upon their town.

When a pilot has received his "brevet" he has really only begun his professional education. This I soon found out at Châteauroux. The day after my arrival I was set to work making daily flights and attending the various courses and lectures on artillery-fire, bomb-dropping, war aviation, "liaison," and the design of enemy aircraft. The daily flights were very short, lasting only fifteen minutes each. We made three or four of them each day, and their purpose was chiefly to give us greater confidence in making our landings. We were allowed to take up passengers, and we often paired off and took each other up. In this connection it was amusing to see how every one avoided being taken up by certain pilots. Some men cannot fly: their temperaments prevent it, and try as they will they cannot improve. This is generally due to sheer stupidity or to lack of nerve. One thing is certain, and that is that these men will kill themselves sooner or later if they persist in their efforts to fly.

An incident occurred shortly after my arrival at the school. About thirty pilots were receiving practical instruction on the aviation-field and were standing around two aeroplanes. About a hundred feet away another machine was making ready to start. When the mechanic spun the propeller at the word from the aviator the motor started, not slowly as it should, but with a roar. The machine began to roll toward the group of men. Instead of cutting off the ignition—we found out later that the wire connecting the throttle and the carburetor was broken and that the throttle was therefore turned on full—the pilot lost his head. He tried to steer around the group of men in front of him. The ground was muddy and very slippery, which made escape almost impossible. In their hurry to get away several men lost their footing and fell down in the very path of the onrushing biplane. We thought that at least a dozen would be crushed or else decapitated by the rapidly revolving propeller. Fortunately no one was seriously injured. Even the stupid pilot escaped unscathed. The three machines, however, were completely wrecked. Needless to say, the offender was immediately dismissed from the aviation school and sent back to his regiment. His escapade had cost the government about ten thousand dollars. Even had there been no damage to the machines it is doubtful whether any further chances would have been taken with a man of such a temperament.

There is not much to tell of the daily flights which we made. The weekly trips, however, proved extremely interesting. We usually covered at least a hundred miles and flew at a height of over six thousand feet.

My first trip was to the aviation school near Bourges, situated on the estates of the Count d'Avord, who has lent the ground to the government for the duration of the war. It is a much larger school than any I had attended, and its instruction covers every type of machine. The most important course given is that in night flying. All the aviators who have been selected for the bombarding-machines and for the work of guarding cities are sent here. Their life is the exact opposite of that led by the average pilot, for they sleep all day and work all night. All this was so new to me that I found much of interest. What surprised me most was to learn that night flying is really easier than day work. The reason given is that after sunset there are no "remoux," and that, when it comes to making landings, the aviation-fields are so well lighted that the pilots have no more difficulty making contact than in the daytime. It is another matter, of course, if an aviator meets with a mishap and is forced to alight elsewhere. Under those circumstances the story is usually a sad one.

One of the longest flights I made was to Tours. Since then I have often thought how strange it was to be flying over this historic region of France. We took it as a matter of course, but what would the ancient heroes of France have thought had they seen us? One week we were over Bourges, called the source of the French nation, for it was from here that the Duke de Berry sallied forth and conquered the English hosts, bringing to a close the struggle which had lasted for a century. The next week we were over Lorraine and the châteaux of the Bourbon kings, who did many great deeds, but had surely never thought of flying.

The lectures which we attended every day were extremely important. The first subject covered had reference to artillery-fire and the theory of trajectories. It is essential that aviators be familiar with the parabola described by the shells fired by cannon of various calibers. If they are not, some day they may unconsciously fly in the very path of shells sent by their own guns and be killed by projectiles not meant for them. The "seventy-five" field-guns, when firing at long ranges, have to elevate their muzzles so much that their shells describe a high parabola before they explode over the enemy's trenches. The very heavy shells, on the other hand, like those of the 420-centimetre French pieces and the famous German "Big-Berthas," rise to a point almost over their target and then drop suddenly. Aviators must become familiar with this and with a hundred other peculiarities of artillery-fire. When flying over the front it is too late to acquire this knowledge. Information has to be gained beforehand or you stand the chance of being annihilated with your machine. An aviator I know involuntarily got into the path of a seventy-seven or seventy-five caliber shell. He is alive to-day, but he lost his left foot in the "collision." He just managed to come down within our lines before he had bled too much to recover.

Our next subject for study was "liaison," which means the science of maintaining communication between the several branches of an army. During an attack upon the enemy's position each arm of the service has its own part to play. The artillery has to prepare the way for the infantry, and at a given signal the infantry must be ready to rush forward to the attack. As the infantry carry the positions before them and move forward the artillery-fire must be correspondingly lengthened; the supply-trains have to keep the necessary amount of ammunition and shells and other material supplied to the infantry and artillery; while the cavalry must be ready to charge the moment a favorable opening presents itself. For all this co-ordination there are various "agents de liaison." There are messengers on foot, and despatch-bearers on horseback, and motor-cycles; there are visual signals, such as the signal-flags, the semaphore, and the colored fires and star shells; and there are the telephone and the telegraph. None of these are depended upon by the army headquarters as much as the aviation corps, the "agent de liaison par excellence." It is one of the most important rôles that aviators are called upon to play at the front, and we were being prepared for this work by very special instruction.

Under the subject of "war aviation" we studied the designs of the various enemy aircraft, and the pitfalls which are encountered at the front. Then followed a course in bomb-dropping. This was a practical course, and our method of learning was as peculiar as it was ingenious. A complete bomb-dropping apparatus was mounted on stakes about twenty-five feet above the ground. Under this there was a miniature landscape painted to scale on canvas. It was a regular piece of theatrical scenery mounted on rollers so that it could be revolved to represent the passage of the earth under your machine. We would climb into the seat on the stilts and consider ourselves flying at some arbitrary height. Through our range-finder we would gaze down at the "land," and as a town appeared we would make allowances through the system of mirrors arranged by the range-finder for our speed and height and for an imaginary wind. At the calculated moment the property bombs would be loosed.

When I came to Châteauroux I thought that I knew something about aviation because I had obtained my "brevet." I soon realized how very little of the ground I had actually covered. In fact, after four weeks of this advanced work I felt as if I would never acquire all the knowledge required for work at the front. Just then about twenty of us were selected to go into the reserve near the front, to fill vacancies caused by casualties. At last! We were off for the front!

I left Châteauroux for the reserve at Plessis-le-Belleville with a certain feeling of uneasiness, yet with the certainty that in case of emergency I knew almost instinctively what to do. In addition, I had become thoroughly familiar with the perils of the air which pilots are called upon to meet most often. These dangers are the same as those encountered on the high seas by sailors: fog, fire, and a lee shore. Take fog, for example. The most difficult operation in flying is the "atterrissage" (landing). Now, in a fog you must land almost by chance. You cannot see the ground until it is too late for your eyesight to be of any use. Your altimetre is supposed to register your height above the ground, but no altimetre is delicate enough to keep up with the rapid descent of an aeroplane. It is always from fifteen to twenty yards behind your real height. Nor is this all. The altimetre "begins at the ground"; it registers your height above the altitude from which you started. Now, since all ground is more or less irregular, you may be coming down on a spot lower—or, much worse, higher—than that from which you started. Besides, when a fog comes up the atmospheric pressure changes and, as the altimetre is a barometer, it becomes from that moment unregulated. Then, of course, on landing you may strike bad ground—houses or shrubbery or fences, all of which adds to the uncertainty and risk.

The danger from fire has never been entirely eliminated, although it is not to-day as great as it was before aeroplane engines reached their present perfection. The greatest danger lies in the propeller. The slightest obstacle will break it, and if the motor cannot be stopped instantly the increased revolutions are certain to force the flame back into the carburetor and you are "grillé" before you can land. Aviators are from the first instructed to leave nothing loose about the machine or their clothing. Many pilots have been killed because their caps blew off, caught in the propeller, and broke it. So fast and powerful is the motion of the propeller that I have seen machines come out of a hail-storm with the blades all splintered from striking the hailstones. There have been experiments made with fire-proof machines, but none have yet proved successful. Fireproofing is apt to make a machine too heavy and cumbersome.

The last peril of the air we were warned against was that of the lee shore. In landing you should always do so against the wind. This is the first principle drummed into the beginners at the schools. If you make an "atterrissage" with the wind behind you, you roll along the ground so fast and so far that you are apt to meet an obstacle which will either wreck your machine or else cause it to turn a somersault. Yet, when making a landing against the wind, the force of the breeze blowing toward you will sometimes prevent you from coming down where you had planned. On many occasions I have seen aeroplanes remain practically stationary in the air, while descending, and sometimes even move backward in reference to the ground. This has to be considered by the pilot and grasped on the instant, or else he will surely come to grief by hooking some object in his descent.

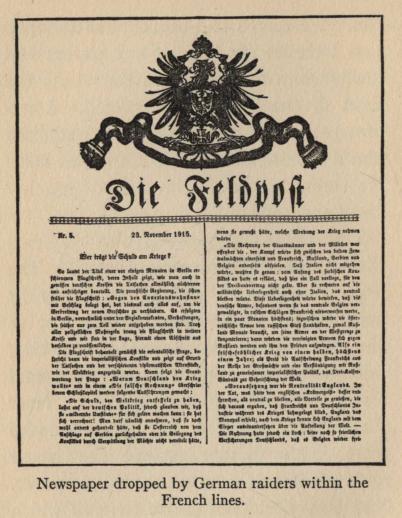

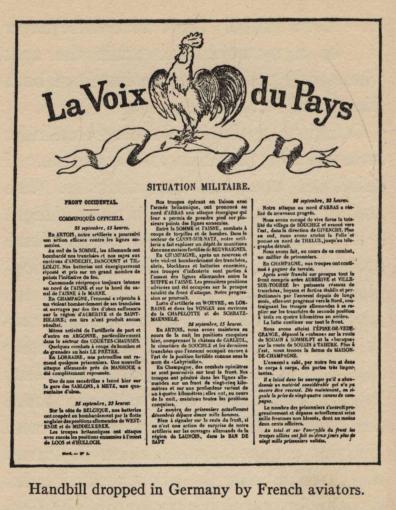

THE RÉSERVE GÉNÉRALE DE L'AVIATION