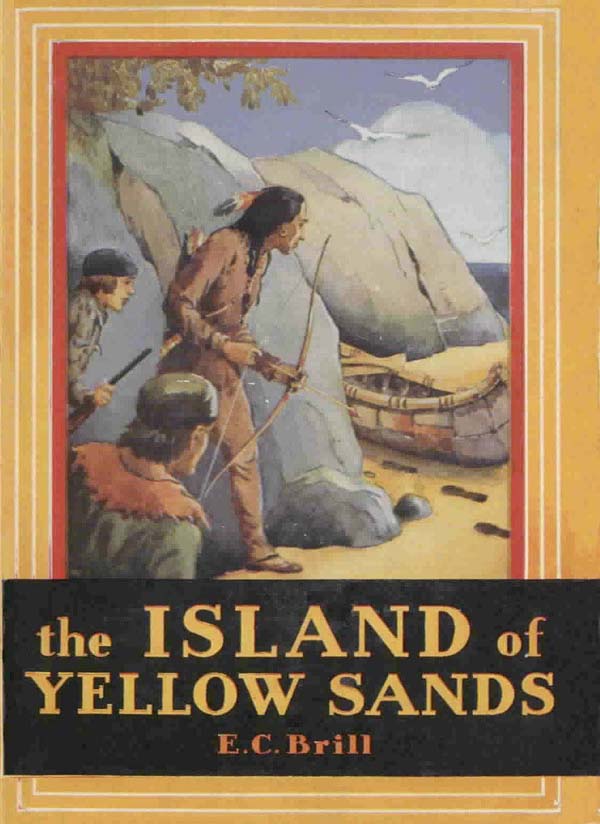

Project Gutenberg's The Island of Yellow Sands, by E. C. [Ethel Claire] Brill

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: The Island of Yellow Sands

An Adventure and Mystery Story for Boys

Author: E. C. [Ethel Claire] Brill

Illustrator: W. A. Wolf

Release Date: July 13, 2014 [EBook #46271]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ASCII

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE ISLAND OF YELLOW SANDS ***

Produced by Stephen Hutcheson, Beth Baran, Rod Crawford,

Dave Morgan and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team

at http://www.pgdp.net

AN ADVENTURE AND MYSTERY

STORY FOR BOYS

BY

E. C. BRILL

ILLUSTRATED

CUPPLES & LEON COMPANY

PUBLISHERS NEW YORK

By E. C. BRILL

Large 12 mo. Cloth. Illustrated.

THE SECRET CACHE

SOUTH FROM HUDSON BAY

THE ISLAND OF YELLOW SAND

Copyright, 1932, by

Cupples & Leon Company

The Island of Yellow Sands

PRINTED IN U. S. A.

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

|---|---|---|

| I. | The Isle with the Golden Sands | 11 |

| II. | The Grande Portage | 19 |

| III. | Ronald Makes an Enemy | 29 |

| IV. | Launched on the Great Adventure | 39 |

| V. | The Grave of Nanabozho | 46 |

| VI. | Along the North Shore | 56 |

| VII. | The Rock of the Beaver | 65 |

| VIII. | Storm and Wreck | 73 |

| IX. | The Home of the Gulls | 81 |

| X. | The Island to the Southwest | 89 |

| XI. | Nangotook Reconnoiters | 98 |

| XII. | Over the Cliffs | 105 |

| XIII. | The Camp in the Cave | 112 |

| XIV. | Lost in the Fog | 122 |

| XV. | Stranded | 132 |

| XVI. | Island or Mainland? | 139 |

| XVII. | A Caribou Hunt | 148 |

| XVIII. | Minong | 158 |

| XIX. | Le Forgeron Tordu Again | 168 |

| XX. | The Northeaster | 178 |

| XXI. | Compelled to Give Up the Search | 186 |

| XXII. | The Indian Mines | 196 |

| XXIII. | Mining and Hunting | 207 |

| XXIV. | Nangotook’s Disappearance | 216 |

| XXV. | The Red Spot Among the Green | 196 |

| XXVI. | The Burning Woods | 207 |

| XXVII. | Nangotook’s Captivity | 216 |

| XXVIII. | Fleeing from Le Forgeron | 255 |

| XXIX. | Near Starvation | 264 |

| XXX. | The End of the Twisted Blacksmith | 271 |

| XXXI. | The Windigo | 278 |

| XXXII. | The Uprooted Tree | 287 |

| XXXIII. | The Mine | 298 |

The Island of Yellow Sands

“My white brother speaks wisdom.”

The two boys were startled. The red-haired one, who had been lying on the ground, scrambled to his feet. The other, a wiry dark-skinned lad, sprang from his seat on a spruce log and seized the newcomer by the hand.

“Etienne, Nangotook,” he cried, “how came you here?”

“Even as you, little brother, over those great waters.” The Indian made a gesture towards the lake, which gleamed between the long point and the island that protected the bay of the Grande Portage from wind and waves. “I have listened to the words of this other white brother and found them good,” he added, with a grave glance at the surprised face of the red-haired boy. “He would deal justly with my people as with his own.”

“That would he, even as I would,” the dark lad exclaimed. “He is my good friend and comrade Ronald Kennedy of Montreal. And this, Ronald,” he added, completing the introduction, “is Nangotook, the Flame, called by the good fathers Etienne, friend of my father and of my own childhood.”

The greetings over, the Indian seated himself on the log beside Jean. “And will my little brother be a trader to steal the wits of the Indian and take his furs away from him?” he asked.

“Not I, Nangotook, unless I can be an honest one and give the trapper and hunter fair return for his pelts. Though,” Jean added more thoughtfully, “I am eager indeed to gain gold, and I know not how it is to be done except through trade with the savages.”

“Gold,” said the Ojibwa thoughtfully. “White men would do all things for gold. Why is my brother Jean in need of it? What could gold give him better than this?” He stretched out his arm with a sweeping gesture that embraced the water, still glowing with the soft light of the afterglow, and the rocky wooded shores.

“It would give back the land and the house on the beautiful St. Lawrence, the house where my father was born,” Jean answered, his face softening. “You know the place, Etienne, and you know how my father loves it. And now, if he had but the money, he could buy it back, but it is a great sum and he has it not.”

The Indian nodded in silence. After a moment, fixing his dark eyes on Jean’s, he said slowly, “How then if some man should lead my brother and his comrade with hair like the maple leaf before it falls, to a place where they can gather much gold and load with it many canoes?”

The two boys stared at him.

“You are making game of us,” cried Jean indignantly.

“Nay, little brother. I will tell you the story.” And the Indian settled himself more comfortably on the log.

“Among my people,” he began, “a tale is told of an island lying far out in the wide waters. On that island is a broad beach of sand, a beach unlike any other, for the sand is of a yellow more bright and shining than the birch leaf when the frost has touched it.”

“Gold?” queried Jean. “I have heard that there is gold on the shores and islands of this lake, but no white man has found it.”

“As the story is told among my people,” Nangotook continued, without heeding the interruption, “many summers ago three braves were driven by the wind on the shore of that island. They loaded their canoe with the sand, and started to paddle away. Then a man, as tall as a pine tree and with a face like the lightning in its fierceness, appeared on the sands and commanded them to bring back the gold. They did not heed, and he waded into the water, and, growing greater and more terrible at every step, gained on them swiftly. Then they were sick with fear, and agreed to return to the land and empty out the yellow sand they had stolen. When not one grain remained in the canoe, the manito of the sands allowed them to go.”

“That is the story of the Island of Yellow Sands,” said Jean, as Nangotook paused. “I recall it now. I heard it in childhood. Many have sought that island, but none has found it. Do you mean that you know where it is and can lead us there?”

The Ojibwa nodded. “My grandfather saw the island once many summers ago, when a storm had driven him far out in the lake. But the wind was wrong and the waves were rolling high on the beach, so he could not land. He was close enough to see the sands gleaming in the sunlight. He knew them for the same as the piece of yellow metal a medicine man of his clan had taken from a Sioux prisoner. The Sioux had bought it from one whose people lived far towards the setting sun. That metal was what the white men call gold, and are always seeking. I heard my grandfather tell the tale while the winter snow whistled around the lodge.”

“And he told you how to reach the island?” asked Ronald. “Why did he not go back and bring away some of the gold?”

“He had no need of the yellow sands, and he feared the manito that was said to guard them.”

“And do not you fear the manito?” Jean questioned.

The Indian shook his head. “I am a Christian,” he said proudly, “and the good fathers have taught me that I need fear no evil spirits, if I remain true in my heart to the great Father above. Then too,” he added in a lower voice, “I have a mighty charm,” his hand touched the breast of his deerskin tunic, “which protects me from all the spirits of the waters and the islands.”

The two lads were not surprised at this strange intermingling of savage superstition and civilized religion. Such a combination did not seem as contradictory to them, in that superstitious age, as it would to a modern boy. Jean merely replied very seriously that he had heard that the golden sands of the island were guarded, not only by the spirit himself, but by gigantic serpents, that came up out of the water, and fierce birds and beasts which, at the command of the manito, attacked the rash man who attempted to land.

At that the Indian smiled and, leaning forward from his log, said in a low voice, “Nay, little brother, many tales are told that are not true. May not the red men wish to keep the white men from the islands of this great water, and so tell them tales to frighten them away? Is it not right that we should keep something to ourselves, not the yellow sands only but the red metal that comes from the Isle Minong? My brother has heard tales of Minong, some white men call it the Isle Royale. Yet I have been there and others with me, and after we had sacrificed to the manito of the island, we carried away pieces of red metal, and no evil befell us.”

“My uncle,” remarked Ronald, “told me of a man he knew, Alexander Henry, once a partner in the Company, and even now connected with it, I believe, who went in search of the Island of Yellow Sands. But when he reached it, there were no golden sands at all, only the bones of dead caribou.”

“He never reached the island,” said Nangotook scornfully. “Those who guided him misled him, and let him think he had been to the right place. The true Island of Yellow Sands is many days’ journey from the island where he landed.”

“And you know where it is?”

“I know in what part of the waters it lies, where to leave the shore and how to head my canoe,” the Ojibwa replied confidently. “If my brothers fear not a hard and dangerous journey, I will take them there. I know not whether the charm I bear will protect them also,” he added more doubtfully.

“We are willing to risk that,” Ronald answered promptly. “We’re not fearing a little danger and hardship, if there is chance of reaching the island with the sands of gold.”

“It is not that we fear to go,” put in Jean, “but how can we find an opportunity? We cannot ask for leave from the fleet, for then we must tell our purpose, and that would never do.”

“No,” Ronald agreed, “we must be keeping our plans secret, so we may be the first to land. Then the gold will be ours by right of discovery. ’Tis not likely we could obtain leave anyway, if we asked for it, whatever our purpose, and——”

He was interrupted by the Indian, who made a gesture of silence. Glancing about, the boys saw several men in the scarlet caps and sashes of canoemen, approaching along the shore. Nangotook rose from the log.

“To-morrow, after the sun has gone to rest, I will speak to my brothers again,” he said in a low voice. “Let them be at this spot.” Without waiting for a reply, he slipped swiftly and silently away among the trees.

Before the canoemen drew near enough to speak to them, the boys were making their way towards the post. They kept back from the shore, in the dusk of the woods, that they might not have to encounter the newcomers, who appeared to be strangers to them.

Jean Havard and Ronald Kennedy had come to the Grande Portage, on the northwest shore of Lake Superior, as canoemen in the service of the Northwest Fur Company. Ronald’s uncle was a partner in the Company, and the boy had been ambitious to follow the life of the fur-trader. Both he and Jean had found the long trip from the Sault interesting and well worth while, in spite of its hardships and strenuous toil. They were outdoor lads, with a plentiful share of the hardihood and adventurous spirit of the outdoor men of their time. Since reaching the Portage, however, they had begun to question whether they really wished to make fur-trading their life-work. Ronald, especially, an honest, straightforward Scot with a strong sense of fair play, had been sickened and roused to indignation by many of the tales told by men from the north and west who had come to the Portage with their loads of furs. It seemed to the boy that most of the traders cared for nothing but gain and were far from honest in their methods. They boasted of giving liquor to the Indians, stealing their wits away, and obtaining their furs, the earnings of a whole winter’s work and hardship, for next to nothing. To the boys this seemed a miserable, heartless way of doing business. Both were eager for the life of the explorer. They longed to push through the wilderness and see strange lands, but the regular work of the fur-trader, carried on as it was by most of these men, had lost its attractiveness.

Ronald, as well as Jean, was poor and had his own way to make. He knew that his uncle had planned to get him into the Northwest Company’s permanent service. From a practical point of view the opportunity would be a good one. He would have a chance to advance. He might even become some day a member of the Company, and make a fortune. But he hated the idea of being compelled to use the methods which seemed a matter of course to most of the “northmen”. He had been vigorously expressing his disgust with the whole sordid business, when Nangotook had interrupted him. The Indian had made it plain that he had been listening to the boy’s remarks and had approved of them.

The Ojibwa’s extraordinary proposition had put the rights and wrongs of the fur trade quite out of the two lads’ heads for the time being. They were fired with a desire to go in quest of the wonderful island. It might be a mere myth indeed, but they were willing to believe that it was not. Nangotook’s grandfather had seen it, and Jean declared that he had never known Nangotook to lie. In those days, even in the last decade of the eighteenth century, very little was known about the islands of Lake Superior. The great central expanse of the lake was unexplored. Who could tell what wonders it might contain?

That night and the next day the two lads’ heads were full of the Island of Yellow Sands. They wanted to be alone to discuss the Indian’s tale, but found it impossible to avoid their companions. Moreover they had few idle moments, for the Northwest Fur Company’s station was a busy place that July day in 179—. Nearly a thousand men were gathered at the post, and there was much work to be done.

The Bay of the Grande Portage, where the station was located, is on the northwest shore of Lake Superior, a few miles south of the Pigeon River. The river forms a part of the line between the United States and the Dominion of Canada. Although the peace treaty that followed the Revolution had been signed, defining the boundary, the Northwest Company, a Canadian organization, still maintained its trading post on United States ground. The place had proved a convenient and satisfactory spot for the chief station, that marked the point of departure from Lake Superior for the country north and west.

Separated from a much larger bay to the northeast by a long point of land, and further cut off from the main lake by an outlying, wooded island, Grande Portage was well screened from all winds except the south. The land at the head of the bay formed a natural amphitheatre and had been cleared of woods. On one side of the open ground, underneath a hill more than three hundred feet high, with higher hills rising beyond, a cedar stockade walled in a rectangular space some twenty-four rods wide by thirty long. Within the stockade were the quarters of the men in charge of the post, clerks, servants, artisans and visiting traders and members of the Company, as well as the buildings where furs, supplies and goods for trade were stored and business transacted. There also was the great dining hall where proprietors, clerks, guides and interpreters messed together.

Outside the stockade were grouped tents and upturned canoes, supported on paddles and poles. The tents were the temporary homes of the “northmen,” the men who went to the far north and west for furs. The “comers and goers” or “pork eaters,” as the canoemen who made the trip between Montreal and the Portage, but did not go on to the west, were called, slept under their canoes. In that queer town of tents and boats, men were constantly coming and going; clerks and other employees from the fort; painted and befeathered Indians, many of them accompanied by squaws and children; and French-Canadians and half-breed voyageurs, strikingly clothed in blanket or leather tunics, leggings and moccasins of tanned skins, and scarlet sashes and caps.

Offshore a small sailing vessel of about fifty tons burden lay at anchor. This boat was to take a cargo of pelts back across the lake, but the main dependence of the Company was placed upon the great fleet of canoes. Other smaller canoes were arriving daily from the northwest or setting out in that direction, the route being up the Rivière aux Tourtres, now known as Pigeon River, the English translation of the French name. The mouth of the stream is about five miles northeast of Grande Portage Bay, and the falls and rapids near the outlet were so many and dangerous that boats could not be paddled or poled through them. So the canoes from the west had to be unloaded several miles above the mouth of the river, and the packages of furs carried on the backs of men over a hard nine-mile portage to the post, while provisions and articles of trade were taken back to the waiting canoes in the same way. This was the long or great portage that gave the place its name.

Busy with their work, and surrounded almost constantly by the other voyageurs, the boys had no opportunity to discuss the prospect of reaching the Island of Yellow Sands, but Jean found a chance to answer some of Ronald’s questions about the tall Ojibwa. The Indian’s gratitude and devotion to Jean’s father dated from fifteen years back, when the elder Havard had saved him from being put to death by white traders at the Sault de Ste. Marie, for a crime he had not committed. Convinced of Nangotook’s innocence, Havard had induced the angry men to delay the execution of their sentence, and had sought out and brought to justice the real offender, a renegade half-breed. For that service the Indian had vowed that his life belonged to his white brother. The Ojibwa and the Frenchman had become fast friends, for Nangotook, or Etienne, as the French priests, in whose mission school he had been trained, had christened him, was one of the higher type of Indians, possessing most of the better and few of the worse traits of his tribe. He visited Havard at his home on the St. Lawrence, and there became the devoted friend of little Jean, then a child of three.

Since that first visit, Nangotook had appeared at the Havard home a number of times, after irregular intervals of absence, sometimes of months, again of years. Although, until the night before, it had been more than four years since Jean had seen him, the Ojibwa had apparently not forgotten either his gratitude to the elder Havard or his affection for the boy. That gratitude and affection had led him to offer to guide the two lads to the wonderful island. Jean and his father needed gold, so Nangotook intended that they should have gold, if it was in his power to help them to it. Ronald was Jean’s friend, and the Indian was willing to include him also. Moreover what he had overheard of the Scotch boy’s remarks about the way some of the traders treated the Indians had pleased Nangotook. He had taken the teachings of the missionary priests seriously and had grasped at least a little of their meaning. By nature moderate and self-controlled, he realized the disasters that were coming upon his people through the physical degradation, idleness and other evils that followed overindulgence in the white man’s liquor. So Ronald’s disgust at the unscrupulousness of many of the traders in their dealings with the savages had met with his approval, and had made the Indian the lad’s friend.

It was nearly sunset when the two boys slipped away from the camp to the secluded spot where they were to meet Etienne. Seating themselves on the fallen tree trunk, they began at once to talk of the subject uppermost in their thoughts. In a week or two the canoes would be ready to start back around the shore of the lake to the Sault, and thence to Montreal, where they would arrive late in September. Jean and Ronald, however, were not obliged to return the whole distance, although, up to the night before, they had intended to do so. They had spent the previous winter at the Sault de Ste. Marie, the falls of the river St. Mary which connects Lake Superior with Lake Huron. Jean had been staying with a French family there, friends of his father, while Ronald, who had made the trip from Montreal with his uncle in the autumn, had remained, after the latter’s return, as a volunteer helper to the Company’s agent at the Sault. Before pledging him to the Company’s service for a term of years, his uncle had wished him to learn whether he really liked the business of fur-trading. When, in the spring, the canoe fleet from Montreal had arrived at the Sault, it had been short handed. Two men had been killed and several seriously injured in an accident on the way. So it happened that Jean and Ronald, expert canoemen and eager to make the Superior trip, had been engaged with three others. Their contracts were only for the voyage from the Sault to the Grande Portage and back again to the Sault, and they were under no obligation to go on with the fleet to Montreal.

Whether there would be time, before cold weather and winter storms set in, to come back to the lake and join the Indian in a search for the Island of Yellow Sands, they could not be sure until they had consulted him. They hoped ardently that they could make the attempt that year, for who could tell what might happen before another spring? As Ronald pointed out, Etienne alone knew how to reach the island. If anything should go wrong with him, they would have no guide. Moreover, in the interval, some other white man might discover the place. Indeed Etienne, though Jean thought that unlikely, might take it into his head to lead some one else there.

They were discussing this question, when, just as the sun was sinking, the Indian joined them. It soon became evident that he was bent on leading them on the adventure, and they were quite as eager to follow him. He seemed certain that there would be ample time, unless they were delayed by unusually bad weather, to make at least one trip from the Sault to the mysterious island and back, before winter set in. He would furnish a small canoe, and would bargain at the trading post for the supplies they would need. He was well known at the Sault, and his arrival there would excite no comment. But he cautioned them to keep their plans secret, lest others should forestall them in the discovery of the gold. They must disappear quietly and join their guide at a spot agreed upon, several miles from the little settlement. As rapidly as possible they would paddle along the north shore of Lake Superior to the place where they must strike out into the open lake. The voyage from shore to island could be undertaken only in the best of weather, but it could be made, he assured them, in a few hours. After they had loaded their canoe with as much sand as it would carry, they would return to the shelter of the shore, and make their way back to the eastern end of the lake. Not far from the Sault he knew a safe, well hidden spot where they could secrete the bulk of their precious cargo, until they could find an opportunity to return to the island for more.

Any scruples the lads might have felt at leaving the Sault without letting their friends know where they were going, were soon overcome by the lure of the adventure as well as of the gold itself. They comforted their consciences with the thought that, once they had found the yellow sands, they would make everything right by taking Jean’s father and Ronald’s uncle into confidence and partnership. Then they would secure, or build, a small sailing vessel, and bring away from the island all the gold they would ever need. M. Havard could buy back the old home on the St. Lawrence that financial reverses had forced him to lose. Jean glowed with the thought of the happiness his father and mother would feel at returning to their dearly loved and much mourned home. Ronald was an orphan, the uncle in Montreal being his only near relative, and the latter was wealthy and not in need of help. But the boy had already planned a great future for himself. First he would go to college in Montreal and perhaps even in England for a time, until he learned all the things an explorer ought to know. Then he would make up an expedition to the north and west, and, not being dependent on trade for gain, would penetrate to new lands and would add, not only to his own glory and renown, but to that of his country as well.

After their plans had been perfected, so far as they could be at that time, Nangotook left them, but the two lads lingered to discuss their hopes and dreams. As they were sitting on the log, watching the moonlight on the peaceful waters of the bay, and talking in low but eager voices, Jean’s keen ears caught the sound of a snapping twig and a slight rustle among the trees behind him. He rose quickly to his feet and peered into the shadows, but could distinguish nothing that could have made the sounds. Ronald also took alarm. They ceased their conversation, and slipped quietly back among the trees and bushes. In the darkness they could find no trace of anything disturbing, but the thread of their thoughts had been broken, and they felt strangely uneasy. With one accord they turned in the direction of the camp, and made their way towards it without speaking. As they approached the edge of the clearing, they saw ahead of them the dark figure of a man slip out from among the trees and go swiftly, but with an awkward gait, across the open. His stiff ankle and out-turning right foot betrayed him.

“Le Forgeron Tordu,” exclaimed Ronald. “Do you suppose he was listening to us?”

“I fear it,” answered Jean. “We were fools not to be more cautious. I would give much to know just what he overheard.”

“He may not have been listening at all,” Ronald returned. “Perhaps he was merely passing through the woods and didn’t hear us, or paid no heed even if he caught the sound of our voices. Unless he were close by he couldn’t have understood, for we were speaking softly.”

Jean shook his head doubtfully. “I hope he heard nothing,” he said. “There is not another man in the fleet I would so fear to have know our plans. He is not to be trusted for one moment. There is nothing evil he would shrink from, if he thought it to his advantage.”

“Well,” was Ronald’s answer, “he’s not fond of you and me, that is certain, but what harm can he do? Since Etienne left, I am sure we have not been saying anything about the island itself or how to reach it. Indeed he told us little enough. He merely said it lies south of a point on the north shore, the Rock of the Beaver he called it, but he didn’t tell us where on the north shore that rock is. Have you ever heard of such a place, Jean?”

The French lad shook his head, then said with an air of relief, “It is true Le Forgeron can have learned nothing of importance, if he has been listening. He was not near when Etienne was there or Etienne would have discovered him. Trust Nangotook not to let an enemy creep up on him without his knowing it. But we must be more careful in the future.”

The camp was ruddy with the light of fires and noisy with the voices of men, talking, laughing, singing, quarreling. Many of the voyageurs were the worse for too much liquor, which flowed far too freely among the canoemen. But the canoe where the boys lodged was near the edge of the camp, and they were able to avoid the more noisy and boisterous groups.

The night was fine, and they had no need of shelter. Wrapping themselves in their blankets, they stretched out, not under the canoe, but in its shadow, a little way from the fire. Around the blaze the rest of the crew were gathered, listening to the tale that one of the Frenchmen was telling with much animation and many gestures. Ordinarily the boys would have paused to hear the story, for they usually enjoyed sitting about the camp-fire to listen to the tales and join in the songs. They had no taste for the excesses and more boisterous merry-making of many of the men and youths who were their companions, but, as both boys were plucky, good-natured, and always willing to do their share of the work, their temperate and quiet ways did them no harm with most of their rough fellows, and they were by no means unpopular. That night, however, they took no interest in song or story. Their minds were too full of the fascinating adventure in which they had enlisted.

During the days that passed before their departure from the Portage, the two lads saw Etienne only twice more and then for but a few minutes. The last of the northmen arrived, the portaging was completed, the furs sorted and made into packages of ninety to one hundred pounds each, and everything was ready for the homeward trip.

One fine morning, when the sky was blue and the breeze light, the first canoes of the great return fleet put out from shore. The birch canoes of the traders were not much like the small pleasure craft we are familiar with to-day. Frail looking boats though they were, each was between thirty and forty feet long, and capable of carrying, including the weight of the men that formed the crew, about four tons. In each canoe were a foreman and a steersman, skilled men at higher wages than the others and with complete authority over the middlemen. The foreman was the chief officer of the boat, always on the lookout to direct the course and passage, but he shared responsibility with the steersman in the stern. Three or four boats made up a brigade, and each brigade had a guide who was in absolute command.

The long, slender, graceful canoes, picturesque in themselves, were filled with even more picturesque canoemen: Indians, French half-breeds, many of them scarcely distinguishable from their full-blooded Indian brothers, and white men, French-Canadians for the most part, in pointed scarlet caps that contrasted strongly with their swarthy, sun-bronzed faces. Singing boat songs, the men dipped their paddles with swift and perfect unison and rhythm, and the canoes slipped over the quiet water as smoothly and easily as if they were themselves alive. The clear depths of the lake reflected the deep blue of the sky, while the rocky shores, crowned or covered to the water’s edge with dark evergreens and bright-leaved birches, made a fitting background.

The canoes of each brigade kept as close together as possible, but all the brigades did not start at the same time. When the last one was ready to put off, the first was apt to be a number of days and many miles ahead. In calm weather the canoes, though heavily loaded, made good speed, four miles an hour being considered satisfactory progress. The trips to and from the Sault were always made as rapidly as wind and waves would permit, but the number of days required depended on the weather encountered. The birch canoes could not plow through the middle of the lake as the steamers of to-day do, but were obliged to skirt the shore and take advantage of its shelter. The daring voyageurs often took chances that would seem reckless to us, and paddled their frail boats through seas that would have swamped or destroyed them, had they not been handled with wonderful skill by the experienced Canadians and Indians. But there were always periods of storm and rough weather when the boats and their precious cargoes could not be trusted to the mercy of the waters. Then the canoemen had to remain in camp on shore or island, sometimes for a few hours, sometimes for days. During the outward trip delays had not disturbed Jean and Ronald, but had been enjoyed as welcome periods of rest from the hard and incessant labor of paddling. On the return journey, however, the two were all impatience.

On the way out the two lads had traveled in the same canoe, but for the trip back, they were assigned, much to their disgust, to different boats. It did not add to Ronald’s satisfaction to find that he had been placed in the same canoe with the man whom he had suspected of listening when he and Jean had been talking over their plans. Le Forgeron Tordu was the steersman. The foreman was Benoît Gervais, Benoît le Gros or Big Benoît he was usually called, a merry giant of a Frenchman, with a strain of Indian blood, who, in spite of his usual good nature, could be trusted to keep his crew in admirable control and to handle even the evil tempered Le Forgeron. The latter was known far and wide throughout the Indian country. He was always called Le Forgeron, the blacksmith, or in Ojibwa, Awishtoya. His real name no one seemed to know, but the nickname had evidently been given him because of his unusual skill as a metal worker. The epithet “tordu” or “twisted” referred to his deformity, his right leg from the knee down being twisted outward, and his ankle stiff. His nose also was twisted to one side, and there was an ugly scar on his chin. It was said that these disfigurements were the marks of the tortures he had suffered, when scarcely more than a boy, at the hands of the Iroquois.

Skilled smith though he was, Le Forgeron Tordu did not choose to settle down and work at his trade. Occasionally he took employment for a short period at one of the trading posts or as a voyageur. He had tremendous physical strength and far more intelligence than the average canoeman, but his violence, ugly temper, and treacherous craftiness made him a dangerous employee or companion. Most of the time he lived with the Indians, among whom he had the reputation of a great medicine man or magician. Yet he professed to be of pure Norman French blood, and did not have the appearance of a half-breed, though cruel enough in disposition for an Iroquois.

For the first two days everything went well with the brigade to which the boys belonged, for the skies were blue and the winds light. To make the most of the good weather the men paddled long hours and slept short ones. On the beaches where they camped, after they had made their fires and boiled their kettles, they needed no shelter but their blankets wrapped about them, as they lay stretched out under the stars.

The two lads’ muscles had been hardened on the outward trip, and they were in too much haste to reach the Sault to complain of the long hours of work. Neither did they have any fault to find with the food, monotonous enough as such meals would seem to boys of to-day. The fare of the voyageurs consisted almost entirely of corn mush. The corn had been prepared by boiling in lye to remove the outer coating of the kernels, which were then washed, crushed and dried. This crushed corn was very much like what is now called hominy, an Indian name. It was mixed with a portion of fat and boiled in kettles hung on sticks over the fire. When time and weather permitted, nets and lines were set at night and taken up in the morning, supplying the canoemen with fish, but there was never any time for hunting or gathering berries, except when bad weather or head winds forced the voyageurs to remain on shore.

The third day of the trip a sudden storm compelled the brigade to seek the refuge of a sheltered bay. The two canoes in which the boys traveled were beached nearly half a mile apart. During the storm, which lasted into the night, the lads were unable to get together. The next morning the sky was clear again, but a violent northwest wind prevented the launching of the boats. Since they could not go on, the canoemen were at liberty to follow their own devices. Some of them sat around the fires they had kindled in the lea of rocks and bushes, mended their moccasins and other clothing, and told long tales of their adventures and experiences. Others wandered about the beach and the adjacent woods, seeking for ripe raspberries or hunting squirrels, hares and wood pigeons. A group of Indian wigwams on a point was visited by a few of the men, who bartered with the natives for fish, maple sugar and deerskin moccasins.

For Ronald the Indian fishing camp had no particular attraction, and he started to walk around the bay to the place where Jean’s canoe was beached. On the way he climbed a bluff a little back from the water, and lingered to eat his fill of the ripe wild raspberries that grew along the top. As he pushed his way through the brush, he heard the sound of voices from the beach below and recognized the harsh, rough tones of Le Forgeron. Just why he turned and went to the edge of the bluff in the direction of the voices, Ronald did not know. Instinct seemed to tell him that the Twisted Blacksmith was up to some mischief. Parting the bushes, he looked down on an Indian lodge. He was surprised to see a wigwam in that place, for it was at least a quarter of a mile from the point where the temporary village stood. Near the wigwam Le Forgeron was sitting cross-legged on a blanket, smoking at his ease, while a squaw, bending over a small cooking fire, was preparing food for him, venison, the boy’s nose told him, as the savory odor rose on the wind.

“Make haste there, thou daughter of a pig,” the Blacksmith was saying roughly, “and take care that the meat is not burned or underdone or I will burn thee alive in thine own fire.”

The Indian woman shrank back as if frightened, and, as she turned her head, Ronald saw that she was old and withered, and, from the way she groped about, he judged her to be nearly if not quite blind. She made a motion to withdraw from the fire the piece of venison she was broiling on a wooden spit, that rested on two sticks driven into the ground, but, whether through fear or blindness, she struck the stick with her hand instead of grasping it, and spit and meat went into the fire.

Le Forgeron uttered an ugly oath and sprang to his feet. “I’ll teach you how to broil meat, old witch,” he cried. Before Ronald could free himself from the bushes, the Blacksmith had seized the frightened old woman and had thrust her moccasined foot and bare ankle, for she wore no leggings, into the fire. She gave a scream of pain and terror, and Ronald, without pausing to think, launched himself over the edge of the bluff in a flying leap. He landed on the sand close to where the old squaw was struggling in Le Forgeron’s grasp, and brought a stout stick, that he had used a few moments before to kill a snake, down on the Blacksmith’s neck and shoulder. Surprised at the attack, Le Forgeron flung the squaw from him and turned on the boy, reaching for his knife as he did so. He made a quick lunge at Ronald, who jumped aside just in time and seized him by the arm that held the knife. At the same moment he heard a shout from beyond the lodge and recognized Jean’s voice. Ronald, though a strong and sturdy lad, was no match for Le Forgeron, but he hung on to the Frenchman’s right arm like a bulldog. The Blacksmith flung his left arm out and around the boy’s waist, to crush him in his iron grasp. Ronald heard Jean’s shout close by, and then, just as he thought his body would be crushed in the Blacksmith’s terrible grip, there came from the top of the bluff a roar like that of a mad bull, and Benoît le Gros launched his great body down on the struggling pair as if to bury them both.

But Big Benoît did not bury Ronald. The boy went down on the sand, found himself loose, rolled completely over and picked himself up, just in time to see the giant foreman hurl his steersman into the breakers that were rolling on the beach. Then he strode in after him, seized him by the back of the neck and pulled him out again, dazed, bloody, choking with the water he had swallowed. Le Forgeron Tordu was beaten. There was no fight left in him for the time being, but he was far from being subdued. He cast an ugly look at the two boys, but for the moment he was unable even to swear. With an imperious gesture Big Benoît motioned him to go back down the beach towards camp. Le Forgeron went, but as he passed Ronald he gave him a look so full of vindictive hatred it fairly chilled the lad’s blood. There was no need of voice or words to express the threat of vengeance. That look was enough.

In the meantime the Indian woman had disappeared, and, though the boys sought for her to discover how badly she had been burned and to see if they could do anything to relieve her suffering, they could not find her. When Ronald returned to the camping place of his own crew, he found the brigade guide in conversation with Big Benoît. The boy was summoned to tell his story, and did so in a few words. He admitted having attacked Le Forgeron first and gave his reason. Benoît added his evidence, for he had seen the Indian woman crawl away and thrust her smoking, blackened moccasin into the water. The guide grunted a malediction upon Le Forgeron, whom he called the “king of fiends,” and dismissed the boy. Later Benoît informed him that he had been transferred to the canoe where Jean was, and added, with a grin, that he was sorry to lose a lad who was not afraid to attack the Blacksmith, but that it was best the two should be separated. “Look to yourself, my son,” he said, laying a kindly hand on the boy’s shoulder. “Le Forgeron does not forget a grudge.”

For two days strong winds prevented the continuance of the journey, but Ronald, having been transferred to the same canoe with Jean, kept clear of Le Forgeron.

The delay vexed the impatient boys, who felt that every lost hour was shortening the time they could give to the search for the strange island. At last, during the night, the wind changed to another quarter and went down, and for the remainder of the voyage the weather was generally favorable. There were several delays, but none so long as the first, and the Sault was reached in fairly good time.

The visits of the brigades were the great events of the year at the trading post of Sault de Ste. Marie. The few whites and half-breeds that formed the little settlement, and most of the Indians of the Ojibwa village near by, were on hand to receive the voyageurs. But Nangotook, who should have been awaiting the boys, was nowhere to be seen.

The Northwest Company’s agent and Jean’s friends had expected the lads to go on to Montreal with the fleet, and the two were hard put to it to find excuses for lingering. The men who had been injured in the accident of the spring before, and who had been left behind to recover, were strong enough to resume their places at the paddles, so the lads’ services were not actually needed, and no pressure was put upon them to go on. As day after day of impatient waiting passed without any sign of their Indian guide, Jean and Ronald began to wonder if they had been foolish to remain behind. Until the prospect of adventure and riches had opened before them, they had not dreamed of spending another winter at the Sault. Even when they had decided not to go on with the fleet, they had hoped that they might accomplish their treasure-seeking trip in time to allow them to return to Montreal or at least to Michilimackinac, under Etienne’s guidance, before winter set in.

On the morning of the third day after the departure of the last brigade of the fleet, Etienne appeared at the Sault. At the post he purchased a supply of corn, a piece of fat pork, some ammunition and tobacco and two blankets, and was given credit for them, promising to pay in beaver skins from his next winter’s catch. Of the two lads he took no notice whatever, but his behavior did not surprise them. They knew exactly what was expected of them, and in the afternoon of the day he made his purchases, they left the post quietly. Wishing to give the impression that they were going for a mere ramble, they took no blankets, but each had concealed about him fish lines, hooks, as much ammunition as he could carry comfortably and various other little things. The fact that they were carrying their guns, hunting knives and small, light axes, did not excite suspicion. Game was extremely scarce, especially at that time of year, in the vicinity of the post, the Indians and whites living largely on fish. One of the half-breeds laughed at the boys for going hunting, but they answered good-naturedly that they were not looking for either bears or moose.

While in sight of the post and the Indian camp, the two lads went at a deliberate pace, as if they had no particular aim or purpose, but as soon as a patch of woods had hidden the houses and lodges from view, they increased their speed and made directly for the place where they were to meet Etienne. The spot agreed upon was above the rapids, out of sight of the post, where a thick growth of willows at the river’s edge made an excellent cover. There they found the Ojibwa, in an opening among the bushes, going over the seams of his canoe with a piece of heat-softened pine gum. He grunted a welcome, but was evidently not in a talkative mood, and the boys, knowing how an Indian dislikes to be questioned about his affairs, forbore to ask what had caused his long delay. They had expected to start at once, but Etienne seemed in no hurry. When he had made sure that the birch seams were all water-tight, he settled himself in a half reclining position on the ground, took some tobacco from his pouch, cut it into small particles, rubbed them into powder and filled the bowl of his long-stemmed, red stone pipe. He struck sparks with his flint and steel, and, using a bit of dry fungus as tinder, lighted the tobacco. After smoking in silence for a few minutes, he went to sleep.

“He thinks it best not to start until dark,” whispered Jean to his companion. “Doubtless he is right. We might meet canoes on the river and have to answer questions.”

Ronald nodded, but inaction made him restless, and presently he slipped through the willows and started to make his way along the shore of the river. In a few moments Jean joined him, and they rambled about until the sun was setting. When they returned to the place where Etienne and the canoe were concealed, they found the Indian awake. He had made a small cooking fire and had swung his iron kettle over it. As soon as the water boiled, he stirred in enough of the prepared corn and fat to make a meal for the three of them. While they ate he remained silent and uncommunicative.

Dusk was changing into darkness when the three adventurers launched their canoe. They carried it into the water, and Ronald and Jean held it from swinging around with the current while Nangotook loaded it. To distribute the weight equally he placed the packages of ammunition, tobacco, corn and pork, a birch-bark basket of maple sugar he had provided, the blankets, guns, kettle and other things on poles resting on the bottom and running the entire length of the boat. A very little inequality in the lading of a birch canoe makes it awkward to manage and easy to capsize. When the boat was loaded Ronald held it steady, while the Indian and Jean stepped in from opposite sides, one in the bow, the other in the stern. Ronald took his place in the middle, and they were off up the River Ste. Marie, on the first stage of their adventure.

Where the river narrows opposite Point aux Pins, which to this day retains its French name meaning Pine Point, there was a group of Indian lodges, but the canoe slipped past so quietly in the darkness that even the dogs were not disturbed. The voyageurs rounded the point and, turning to the northwest, skirted its low, sandy shore. The water was still, and in the clear northern night, traveling, as long as they kept out from the shore, was as easy as by daylight.

As they neared Gros Cap, the “Big Cape,” which, on the northern side, marks the real entrance from Ste. Mary’s River into Whitefish Bay, Nangotook, in the bow, suddenly made a low hissing sound, as a warning to the boys, and ceased paddling, holding his blade motionless in the water. The others instantly did the same, while the Indian, with raised head, listened intently. Evidently he detected some danger ahead, though no unusual sound came to the blunter ears of the white boys.

Suddenly resuming his strokes, Nangotook swerved the canoe to the right, the lads lifting their blades and leaving the paddling to the Ojibwa. As they drew near the shadow of the shore, the boys discovered the reason for the sudden change of direction. Very faintly at first, then with increasing clearness, came the sound of a high tenor voice, singing. It was an old song, brought from old France many years before, and Jean knew it well.

“Chante, rossignol, chante,

Toi qui a le cocur gai;

Tu as le coeur a rire,

Moi je l’ai-t-a pleurer,”

sang the tenor voice. Then other voices joined in the chorus.

“Lui ya longtemps que je t’aime,

Jamais je ne t’oublierai.”

A rough translation would be something like this:

“Sing, nightingale, sing,

Thou who hast a heart of cheer,

Hast alway the heart to laugh,

But I weep sadly many a tear.

A long, long time have I loved thee,

Never can I forget my dear.”

By the time these words could be heard distinctly, the adventurers had reached a place of concealment in the dark shadow of the tree-covered shore. There they remained silent and motionless, while three canoes, each containing several men, passed farther out on the moonlit water. They were headed for the Sault, and were evidently trappers or traders from somewhere along the north shore, coming in to sell or forward their furs and to buy supplies. Not until the strangers were out of sight and hearing, did the treasure-seekers put out from the shadows again.

At sunrise they made a brief halt at Gros Cap for breakfast, entering a narrow cove formed by a long, rocky point, almost parallel with the shore. There, well hidden from the lake among aspen trees and raspberry and thimbleberry bushes, they boiled their corn and finished the meal with berries. The thimbleberries, which are common on the shores and islands of Superior, are first cousins to the ordinary red raspberry, though the bushes, with their large, handsome leaves and big, white blossoms, look more like blackberry bushes. The berries are longer in shape than raspberries, and those the boys gathered that morning, with the dew on them, were acid and refreshing. Later, when very ripe, they would become insipid to the taste.

Anxious to take advantage of the good weather, the three delayed only long enough for a short rest. The sun was bright and a light breeze rippled the water, when they paddled out from the cove. Jean started a voyageur’s song.

“La fill’ du roi d’Espagne,

Vogue, marinier, vogue!

Veut apprendre un metier,

Vogue, marinier!

Veut apprendre un metier.

Vogue, marinier!

“The daughter of the king of Spain,

Row, canoemen, row!

Some handicraft to learn is fain,

Row, canoemen!

Some handicraft to learn is fain,

Row, canoemen.”

Ronald joined in the chorus, though his voice, not yet through changing from boy’s to man’s, was somewhat cracked and quavering. The Indian remained silent, but his paddle kept time to the music.

They were still in the shadow of the cliff of Gros Cap, rising abruptly from the lake, while to the north, eight or ten miles away across the water, they could see a high point of much the same general appearance, Goulais Point, marking the northern and western side of a deep bay. The water was so quiet that, instead of coasting along the shores of Goulais Bay, they risked running straight across to the point, saving themselves about fifteen miles of paddling.

The traverse, as the voyageurs called such a short cut across the mouth of a bay, was made safely, although the wind had risen before the point was gained. They proceeded along Goulais Point, past the mouth of a little bay where they caught a glimpse of Indian lodges, and through a channel between an island and the mainland. The lodges doubtless belonged to Indians who had camped there to fish, but the travelers caught no glimpse of them and were glad to escape their notice.

The wind, which was from the west, was steadily rising, and by the time the point now called Rudderhead was reached, was blowing with such force that the traverse across the wide entrance to Batchewana Bay was out of the question. The voyageurs were obliged to take refuge within the mouth of the bay, running into a horseshoe shaped indentation at the foot of a high hill. There a landing was made and a meal of mush prepared.

By that time the adventurers were far enough away from the Sault not to fear discovery. Any one going out from the post in search of them might easily follow the two boys’ trails to the spot where they had met Etienne. The lads chuckled to think how their aimless wanderings after that, while they were waiting for darkness, might confuse a search party. It was unlikely, however, that any one would worry about them or make any thorough search for them, until several days had passed. They were now fairly launched on their adventure and their hopes were high.

The sun set clear in a sky glowing with flame-red and orange, but the wind blew harder than ever, and forced the adventurers to camp in the cove. They were tired enough to roll themselves in their blankets as soon as darkness came, for they had not taken a wink of sleep the night before. Protected from the wind, they needed no overhead shelter.

When the complaining cries of the gulls waked the lads at dawn, the wind was still strong, but from a more southerly direction. While the open lake was rough, the bay might be circled without danger, so, without waiting for breakfast, the three launched the canoe. Jean, who was in the stern, baited a hook with a piece of pork, and, fastening the line to his paddle, let the hook, which was held down by a heavy sinker, trail through the water, the motion of the paddle keeping the line moving.

As they were passing a group of submerged rocks at the mouth of a stream, a sudden pull on the line almost jerked the paddle out of his hands. The fish made a hard fight, but Etienne handled the canoe skilfully, giving Jean a chance to play his catch. He finally succeeded in drawing it close enough so that Ronald, leaning over the side of the boat, while the Indian balanced by throwing his body the other way, managed to reach the fish with his knife. It proved to be a lake trout of about six pounds. Landing on a sandy point that ran out from the north shore of the bay, the boys prepared breakfast. Broiled trout was a welcome change from corn, and the three ate every particle that was eatable.

The wind continuing to blow with force, they camped on the point, and spent the rest of the day fishing and hunting. Fishing was fairly successful, but they found no game, not even a squirrel. The only tracks observed were those of a mink at the edge of a stream. An abundance of ripe raspberries helped out their evening meal, however. The wind lessened after sunset, but the lake was too rough for night travel. So the treasure-seekers laid their blankets on the sand for another good night’s sleep.

Nangotook woke at dawn and roused the boys. The sky, dappled with soft white clouds and streaked with pink, was reflected in the absolutely still water. So the three got away at once and, making a traverse of five or six miles across an indentation in the shore to the end of another point, were soon out of Batchewana Bay.

Going on up the shore, the travelers rounded Mamainse Point, and ran among rock islets, some of them bare, some with a tuft of trees or bushes at the summit. The islands they had passed in the southeast corner of the lake had been flat and sandy. From Mamainse on, although many of the larger islands and the margin of the shore continued low, the general appearance of the land was very different. High cliffs formed a continuous rampart a little back from the water and were covered with trees down to the beach, the silvery stems and bright green of the birches and aspens standing out against the darker colors of spruce and balsam. This was true north shore country, contrasting strongly with most of the south shore.

All day the wind was light, and the voyageurs made upwards of forty miles, reaching Montreal River before dark. As the canoe turned towards the broad beach where the stream enters the lake, the boys ceased paddling, leaving Etienne to make the landing. The Indian took a long stroke, then held his paddle motionless, edge forward and blade pressed against the side of the boat, until the momentum slackened, made another stroke, held the blade still again, then a third and rested until the bow ran gently on the sand. The moment it struck, before the onward motion ceased, the three rose as with one movement, threw their legs over the sides, Etienne and Jean to the right, Ronald to the left, and stepped out into the water without tipping the canoe. Then the boys lifted it by the cross bars and carried it beyond the water line.

The beach jutted out across the mouth of the river, partly closing it, while a bar, about six feet below the surface, extended clear across. Farther back were large trees, and the place was in every way a satisfactory camping ground.

After the evening meal, the boys, hoping to secure a fish or two for breakfast, went out in the canoe to set some lines. Trolling had been unsuccessful that day. In the meanwhile Etienne was examining an old trail that led up-stream. The deep, clear, brown waters emptied into the lake through a kind of delta, partly tree covered, but farther up they raced down with great force through a steep-walled, rock chasm. The trail, which proved that Indians were in the habit of frequenting the place, interested Nangotook for it bore signs of recent use. So he followed it.

Suddenly, as he rounded a clump of birches, he saw two men coming towards him. Luckily they were both looking in the other direction at the moment when the Ojibwa caught sight of them. Before they could turn their heads, he was out of view, squatted in the dark shadow behind an alder bush. Though he had but a glimpse of them, he recognized one, a white man with twisted nose and a scar on his chin. The other was an Indian, a stranger to him. As soon as the two men had passed, Nangotook rose and followed them cautiously, making his way among trees and bushes at the edge of the trail. The long twilight was deepening to darkness, and it was not difficult to keep hidden. The men went on along the trail for a way, then turned from it and struck off into the woods. Nangotook did not pursue them farther. Satisfied that they were not headed for the camp on the beach, he went on rapidly and joined the boys at the fire. In a few words he told them of the encounter.

The lads were amazed. At first they could scarcely believe it was really Le Forgeron Tordu Etienne had seen. The Blacksmith had left the Sault with his brigade for Montreal nearly two weeks before. He must have deserted below the Sault, have returned past the post and come on to the northeast shore. Desertion from the fleet was a serious matter, for the canoemen were under strict contract, and the guilty man was liable to heavy punishment. Le Forgeron had been a steersman too, and that made his offense worse. It was scarcely possible that he could have been discharged voluntarily, but if he had taken the risk of desertion, it must have been for some very important or desperate purpose.

The knowledge that the evil Frenchman was so near made the lads uneasy. Remembering the look of bitter hatred the Blacksmith had given him, and Big Benoit’s warning to look to himself, Ronald felt, for the first time in his life, the chill dread that comes to one who is followed by a relentless enemy. He pulled himself together in a moment, however. If Le Forgeron was following them, it could not be merely to obtain vengeance for the blow the lad had given him. That cause seemed altogether too slight to account for desertion and the long trip back to Superior. It was probable that he had heard more of their plans that night at the Grande Portage than they had believed he could have heard, and was bent on securing the gold for himself.

While Ronald was pondering these things, Jean was telling Nangotook of their suspicions that Le Forgeron had overheard them, of his treatment of the squaw, of Ronald’s attack on him and of Big Benoit’s fortunate appearance. Nangotook listened silently, and nodded gravely when the boy had finished his tale, but the two could not read in his impassive face whether he shared their fears or not.

From a tree overhead a screech owl uttered its eerie cry, the long drawn closing tremolo on one note sounding like a threat of disaster. Perhaps the Indian took the sinister sound for a warning, for he rose from the log where he was sitting and went down to the water’s edge. When he returned, he said decisively, “Sleep now little while. Then go on in dark.”

The boys concluded he was as anxious as they to get away from the neighborhood of Le Forgeron.

Ronald could not sleep much that night, and when he did drop off for a few moments, the slightest sound was enough to arouse him. By midnight the water was still, and, at Nangotook’s command, the boys launched the canoe. The Indian in the bow, the three paddled noiselessly away from their camping ground, going slowly at first for fear of striking a bar or reef. Though they scanned the shore, they could see no sign of Le Forgeron’s camp-fire. Had he gone on ahead of them, they wondered.

All the rest of the night they traveled steadily, and did not make a landing until the sun had been up for more than an hour. Then they stopped long enough to boil the kettle and eat their breakfast of corn and pork.

The wind had come up with the sun, and before they had gone far from the little island where they had breakfasted, the gale threatened to dash the canoe on the shore, where breakers were rolling. The travelers were driven to seek refuge behind a sand-bar at the mouth of a small stream. Then the wind began to shift about from one point to another. Rain clouds appeared, and a succession of squalls and showers kept the impatient gold-seekers on shore until the following morning.

The sky was still cloudy and threatening, but the water was not dangerously rough, when they put out from the shelter of the sand-bar. A head wind made progress slow, as they went on up the shore and around the great cape which some early explorer had named Gargantua, because of a fancied resemblance to the giant whose adventures were told by Rabelais, a French writer of the first half of the sixteenth century.

A short distance east of the Cape, Nangotook directed the canoe towards a small rock island, one of a group. “Land there,” he said laconically.

“Why should we be landing on that barren rock?” questioned Ronald in surprise.

“Grave of great manito, Nanabozho,” the Indian answered seriously.

Ronald opened his mouth to speak again, but Jean punched him with his paddle as a warning to ask no further questions. Nangotook ran the canoe alongside a ledge of rock only slightly above the water. There he stepped out. The others followed and lifted the boat up on the ledge. Without waiting for them, Nangotook climbed swiftly over the rocks. Ronald would have followed him, but Jean took the Scotch boy by the arm.

“He goes to make an offering to the manito,” the French lad said, “and to ask him to send us fair weather and favorable winds for our voyage.”

“But Nangotook says he’s a Christian,” the other replied. “Why is he making sacrifices to heathen gods then?”

Jean shrugged his shoulders. “A savage does not so easily forget the gods of his people,” he said. “I have heard of this place before. Let us look around a bit while he is offering his sacrifices.”

The island proved to be a mere rock, barren of everything but moss, lichens, a few trailing evergreens, and here and there such scattering, stunted plants as will grow with almost no soil. Part of the rock looked as if it had been artificially cut off close to the water line, while the rest ran up steeply to a height of thirty or forty feet. At several spots the two lads found the remains of offerings made by passing Indians, strands of sun-dried or decaying tobacco, broken guns, rusty kettles and knives, bits of scarlet cloth, beads and trinkets. Evidently the savages reverenced the place deeply and believed that the spirit of the great manito made it his abode.

What interested the boys more than Indian offerings was several clearly defined veins of metal running through the rock. Here and there in the veins were holes indicating that some one, white man or Indian, had made an attempt to mine. Moss and stunted bushes growing in the holes proved that the prospecting must have been done a number of years before. Ronald, who knew a little of geology, said there was certainly copper in the rock, and he thought there might be lead, and perhaps silver, which, he explained, was sometimes found in conjunction with copper.

“The man I was telling you about,” Ronald concluded, “old Alexander Henry, who looked for the Island of Yellow Sands, but who went to the wrong place Etienne says, did some mining along this east and north shore. Perhaps he opened these veins, but if he did, it must have been twenty or thirty years ago.”

The three did not remain long on the island. Around Cape Gargantua the shore had become more abrupt and more broken, with sheer cliffs, deep chasms, ragged points and islands. The rocks were painted with a variety of tints, caused by the weathering of metallic substances and by lichens that ranged in color from gray-green to bright orange. It was slow work paddling in the rough water, but before night the travelers reached a good camping ground, among birch trees, above a steep, terraced beach in the shadow of the high cliffs of Cape Choyye.

Near their landing place the boys came upon a broad sheet of red sandstone sloping gradually into the water. The rock was scored with shallow, winding channels and peppered with smooth holes, some of them three or four feet deep. Many of the cavities were nearly round, but one was in the shape of a cloven hoof. When the Indian saw the place he looked awed and muttered, “Manito been here.” Jean, too, was much impressed, and hastened to make the sign of the cross over the cloven footprint, but Ronald laughed at him. The holes were perfectly natural, he said. He pointed out in many of them loose stones of a much harder rock, and suggested that, at some previous period when the lake level must have been much higher, the friction of such stones and boulders against the softer sandstone, as they were washed and churned about by the waves, might have ground out the cavities. The shallow channels were probably chiseled by the grating of sand and small pebbles. Nangotook paid no attention whatever to Ronald’s explanation, and even Jean did not seem entirely convinced. He shook his head doubtfully over the cloven hole.

Apparently the great Nanabozho looked upon the treasure-seekers with favor, for the next morning dawned bright, clear and with a favorable breeze. They started early to the tune of

“Fringue, fringue, sur la rivière,

Fringue, fringue, sur l’aviron.”

“Speed, speed on the river,

Speed, speed with the oar.”

Making good time, they continued northward into Michipicoten Bay. On the Michipicoten River, which empties into the head of the bay, was a trading station. They did not wish to land there, but hoped to pass unobserved and to avoid any one going to or coming from the post. It was late in the season for white men to be traveling towards the western end of the lake, and questions or even unspoken curiosity might be embarrassing.

So, on reaching a beach, the only one they noticed along that bold, steep stretch of shore, they decided to land and wait for darkness before running past the post.

The manito continued to be kind to them, for during the afternoon a haze spread over the sky. When the fog on the water became thick enough to furnish cover, the adventurers set out again, paddling along the steep shore, gray and indistinct in the mist, the Indian keeping a sharp lookout for detached rocks. As they neared the mouth of the Michipicoten, they went farther out, and passed noiselessly, completely hidden in the fog. Not caring to risk traveling in the thick obscurity of a foggy night, they made camp before dark a few miles beyond the river.

The next morning they embarked at dawn and went on under cover of the fog, but the rising sun soon dispersed it. They were now traveling directly west. After passing Point Isacor, they could see clearly, ten or twelve miles to the south, Michipicoten Island or Isle de Maurepas, as the French named it, after the Comte de Maurepas, minister of marine under Louis XV. Alexander Henry the elder visited that island, and it was the Indians who guided him there who told him of another isle farther to the south, where the sands were yellow and shining. According to Nangotook, those Indians had deliberately deceived the white man, taking him intentionally to the wrong island. The boys gazed with new interest at the high pile of rock and forest, and Jean related to Ronald a legend that one of the old French missionaries had heard from the savages more than a century before and had written down.

“The savages told the good Father,” began Jean, “that four braves were lost in a fog one day, and drifted to that island. Wishing to prepare food, they began to pick up pebbles, intending to heat them in the fire they had lighted, and then drop them into their basket-ware kettle to make the water boil. But they were surprised to find that all the pebbles and slabs on the beach were of pure copper. At once they began to load their canoe with the copper rocks, when they were startled by a terrible voice calling out in wrath. ‘Who are you,’ roared the great voice, ‘you robbers who carry away my papoose cases and the playthings of my children?’ The slabs, it seems, were the cradles, and the round stones, the toys, of the children of the strange race of manitos or supernatural beings who dwelt, like mermen and mermaids, in the water round about the island. The frightful voice terrified the savages so they dropped the copper stones, and put out from the shore in haste. One of them died of fright on the way to the mainland. A short time later a second died, and then, after he had returned to his own people and told the story, the third. What became of the fourth the savages did not say. It is said,” concluded Jean, “that the island is rich in copper and other metals, so it well may be, as Etienne suggests, that such tales were told to frighten the white men and keep them from the place.”

That night the eager gold-seekers traveled until after midnight, pausing at sundown only long enough for supper and a brief rest. As the darkness deepened, the wavering flames of the aurora borealis, or northern lights, began to glow in the northern and western sky. From the sharply defined edge of bank of clouds below, bands and streamers of white and pale green stretched upwards, flashing, flickering and changeable. Sometimes glowing spots appeared in the dark band, again streamers of light shot up to the zenith, the center of brightness constantly shifting, as the flames died out in one place to flare up in another.

The Ojibwa hailed the “dancing spirits” as a good omen, and the boys were inclined to agree with him. All the evening the lights flashed and glowed, but when, after midnight, the travelers rounded the cape known as Otter’s Head, from the upright rock surmounting it, the streaks and bands were growing faint, and by the time a landing had been made in the cover beyond, they had faded out entirely.

Whether the aurora borealis was to be considered a good sign or not, fortune continued to favor the voyageurs the next day. They put up a blanket sail attached to poles, and ran before a favorable wind most of the twenty-five miles to the mouth of White Gravel River. There they remained until nightfall, for they were anxious to avoid another trading post some twenty miles farther up the shore, near the mouth of the Pic River.

Glad of exercise after being cramped in the canoe, the boys made their way along the bank of White Gravel River for about two miles, where they discovered a round, deep, shaded pool, alive with darting shadows. They cut fishing poles and had an hour of fine sport. As they were going on up-stream, they heard the calling and cooing of wood pigeons, and soon came upon a great flock of the birds. The trees were covered with them, and the air fairly full of them, flying up, darting down, and wheeling about in the open spaces, singly and in squads and small flocks. So plentiful were the pigeons, and so little disturbed by the lads’ presence, that the two might have killed hundreds had they chosen, but they were not greedy or wanton sportsmen, and shot only as many as they thought they could eat for supper, reserving the trout for breakfast.

A grove of trees and bushes hid the camp, and the canoe was beached on the inner side of the sand-bar that partly concealed the entrance to the stream. Ever since Etienne had seen Le Forgeron Tordu at Montreal River, he had taken precautions to select camping places where the three would not be noticed by any one passing on the lake. If the Twisted Blacksmith were coming up the shore on some business of his own that had nothing to do with them, the gold-seekers had no wish to attract his attention. If he was following them, they hoped to give him the slip. Just as the sun was setting that night, as Jean was plucking the pigeons and Ronald was preparing to kindle the cooking fire, their attention was attracted by the harsh screaming of gulls. Looking out through their screen of bushes, the lads saw a canoe, about the size of their own, passing a little way out. It was going north, and contained two men, one evidently an Indian, the other from his dress a white man or half-breed. The boys could not see him plainly enough to be sure, but they had little doubt the white man was Le Forgeron. Etienne was some distance away gathering bearberry leaves to dry and mix with his smoking tobacco to make kinni-kinnik. So he did not see the canoe go by.

The sight of the passing voyageurs caused the three to delay going on until twilight had deepened to darkness, and then they traveled in silence, and watched the shore closely for signs of a camp. They saw none, however, ran past the mouth of the Pic without encountering any one, and landed in a bay a few miles farther on. Ahead of them lay a very irregular shore with many islands, rocks and reefs, which they did not dare to try to thread in the darkness.

In spite of their night run, they embarked early and passed through a labyrinth of islands. In a winding passage they met a canoe containing an Indian, his squaw, three children and two pointed-nosed, fox-eared dogs. The boys thought this Indian family particularly unattractive looking savages. They had very flat faces and large mouths and were ragged and disgustingly dirty, but they were evidently good-natured and ready to be friendly, for man, woman and children grinned broadly as they called out “Boojou, boojou,” the Indian corruption of the French “Bonjour.” The man held up some fish for sale, but Nangotook treated him with dignified contempt, grunting an unsmiling greeting, shaking his head at the proffered fish, and passing by without slowing the strokes of his paddle. As he left the Indian canoe astern, he growled out a name that Ronald could not make out, but that Jean understood.

“Gens de Terre,” the boy exclaimed. “These are the shores where they belong. They seldom go as far south as the Sault. Some call them Men of the Woods. They are dirty, but very honest. The traders say it is always safe to give them credit, for rarely does one of them fail to pay in full. They are good tempered too, but when food is scarce I have heard they sometimes turn Windigo.” The lad shuddered and crossed himself. Windigo is the Indian name for a man who has eaten human flesh and has learned to like it. Both Indians and white men believed that such a savage was taken possession of by a fiend. Men suspected of being Windigos were shunned and feared by red men and white alike.

The voyageurs made a traverse of several miles, and ran among a cluster of little islands abreast of Pic Island, a rock peak rising about seven hundred feet from a partly submerged ridge. Fog, blown by a raw, gusty wind delayed them considerably that day. After running on a hidden rock and starting a seam in the canoe, they were finally compelled to camp on a rock islet near shore. There they dined on blueberries, and slept on thick beds of moss and low growing blueberry and bearberry plants.

The following day, after a sharp north wind had driven away the fog, they went on, and passed the Slate Islands, high and blue, seven or eight miles across the water. At supper time they entered a little cove, where they were horrified to find signs of a recent tragedy. A canoe was floating bottom up, the beach at the head of the cove was strewn with pelts, the sand trampled and blotched with dark patches. Near by were the ashes of a camp-fire.

Nangotook looked the place over carefully, then remarked, “Awishtoya been here.”

“Why do you say that?” exclaimed Jean. “What makes you think so?”

“Trapper going to Pic with winter’s catch,” the Indian explained. “Awishtoya found him, attacked him, killed him maybe,” and he pointed to the blood stains in the sand. “Broke open his packs and took best furs. These no good,” touching one of the abandoned skins with his foot.

“Something of the kind must have happened here,” Ronald agreed, “and Le Forgeron would not be above such a deed. Do you see anything to prove he did it, Etienne?”

The Ojibwa shook his head. “No need to prove it,” he said. “Awishtoya came this way. Always there are evil deeds where he goes.”

From the ashes of the fire and the condition of the sand, the Indian thought the deed a recent one, committed not longer ago than the night before, perhaps that very day. The three righted the canoe, but found nothing about it to show its owner. Though they searched the shores of the cove, they did not discover the body of the murdered man, if he had been murdered, or any further traces of him or of the man or men who had attacked him. The marks in the sand were so confused, indicating a desperate struggle, that not much could be read from them, but Nangotook thought there had been at least three men in the affray.