THE

Little Cousin Series

L. C. PAGE & COMPANY

53 Beacon Street, Boston, Mass.

OUR LITTLE

By |

||

Copyright, 1913,

By L. C. Page & Company

(INCORPORATED)

———

All rights reserved

First Impression, June, 1913

THE COLONIAL PRESS

C. H. SIMONDS & CO., BOSTON, U. S. A.

In this volume I have endeavored to give my young readers a clearer and a more intimate knowledge than is usually possessed of the vast territory known as the Austro-Hungarian Empire, which is a collection of provinces united under one ruler, and which is, strange to say, the only country of importance in the world that has not a distinctive language of its own, since the various races—German, Slav, Magyar and others—each speak their own tongue.

The northeastern provinces, Galicia and Bukowina, have not been considered in this book, owing to the fact that they are included in Our Little Polish Cousin; and, for a similar reason, Hungary and Bohemia have been omitted, as each is the subject of an earlier volume in The Little Cousin Series. The[vi] book consequently is chiefly devoted to Austria proper and Tyrol, but the other provinces, including Dalmatia and Bosnia, are not neglected.

The publication of Our Little Austrian Cousin is most timely, since the Balkan War, now drawing to a close, has occupied the attention of the world. The Balkan States lie just to the south of the Austrian Empire, and Austria has taken a leading part in defining the terms of peace which the Great Powers of Europe insist shall be granted by the Balkan allies to the defeated Turks.

Our Little Austrian Cousin can well be read in connection with Our Little Bulgarian Cousin and Our Little Servian Cousin, describing two of the principal Balkan States, which volumes have just been added to The Little Cousin Series.

Among others, I am especially indebted to Fr. H. E. Palmer, for much information concerning country customs in Upper Austria.

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| PAGE | |

| "Ferdinand and Leopold . . . would help with the cattle" (See page 100) | Frontispiece |

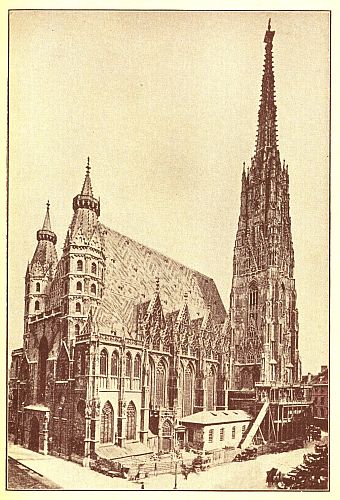

| St. Stephan's Church | 12 |

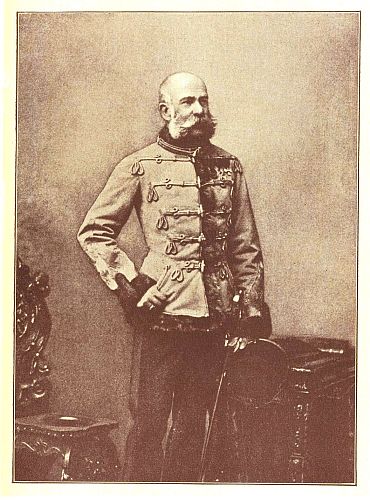

| Emperor Franz-Joseph | 22 |

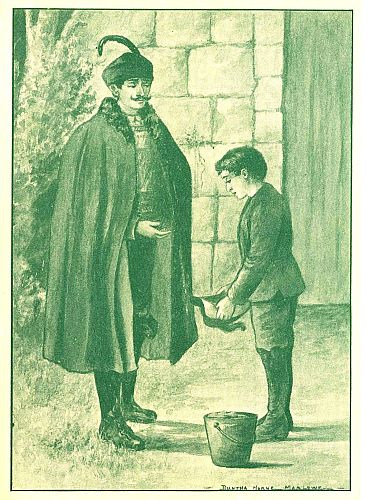

| "'Cheer up, my lad,' said the stranger" | 29 |

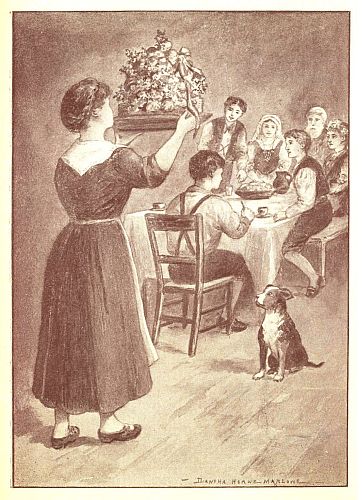

| "It towered high above her head" | 72 |

| Statue of Andreas Hofer, near Innsbruck | 83 |

| "Tramp thus, in vagabond fashion, over the mountains!" | 111 |

| The Rosengarten | 121 |

"Hurrah!" shouted Ferdinand, as he burst into the living-room, just as his mother was having afternoon coffee.

"And what makes my son so joyful?" asked Frau Müller, as she looked up at the rosy cheeks of her young son.

"Hurrah, mother! Don't you know? This is the end of school."

"So it is," replied the mother. "But I had other things in my head."

"And, do you know," the child continued, as he drew up to the table where the hot coffee[2] emitted refreshing odors, "you haven't told me yet where we are to go."

"No, Ferdinand, we've wanted to surprise you. But help yourself to the cakes," and the mother placed a heaping dish of fancy kuchen before the lad.

Ferdinand did not require a second invitation; like all normal boys, he was always hungry; but I doubt very much if he knew what real American-boy-hunger was, because the Austrian eats more frequently than we, having at least five meals a day, three of which are composed of coffee and delicious cakes, so that one seldom has time to become ravenous.

"But, mother," persisted the child, his mouth half filled with kuchen, "I wish I knew. Tell me when we start; will you tell me that?"

"Yes," answered his mother, smiling. "To-day is Wednesday; Saturday morning we shall leave."

"Oh, I just can't wait! I wish I knew."

"Perhaps father will tell you when he comes," suggested the mother. "Do you think you could possibly wait that long?"

"I don't believe I can," answered the lad, frankly; "but I suppose I shall have to."

That evening, when Herr Müller returned from his shop, Ferdinand plied him with questions in an effort to win from him, if possible, the long-withheld secret.

"Well, son, there's no use trying to keep you in the dark any longer. Where do you guess we are going?"

"To see Cousin Leopold in Tyrol."

"Well, that's a very good guess, and not all wrong, either; but guess again."

"Oh, I can't. It must be splendid, if it's better than visiting Cousin Leopold."

"Well, it is better," continued Herr Müller; "for not only are we going to pass a few days with your Tyrolese relations, but we are going to a farm."

The boy's face fell visibly.

"To a farm!" he exclaimed. "Why, Uncle Hofer has a splendid farm in Tyrol; that won't be very new to me, then."

"It won't!" ejaculated his father, a trifle amused. "You wait and see, my boy. This is not to be a tiny farm of a few acres, creeping up the mountain on one side and jumping off into a ravine on the other. We sha'n't have to tie this farm to boulders to keep it from slipping away from us." And Herr Müller chuckled.

"Then it isn't in the mountains?"

"No, it isn't in the mountains; that is, not in any mountains that are like the Tyrolese mountains. But there will be acres and acres of this farm, and you will be miles away from any one. You will see corn growing, too; you've never seen that in Tyrol, my son."

"No," answered the child. After a few moments'[5] silence, he added: "Will there be any young folks, father?"

"Don't let that trouble you, Ferdinand; where there's an Austrian farm there are many children."

"Hurrah for the farm, then!" shouted Ferdinand, much to the astonishment and amusement of his parents, who were unused to such impulsive outbursts. But Ferdinand Müller was a typical boy, even though he had been reared in the heart of the city of Vienna, where the apartment houses stand shoulder to shoulder, and back to back, with no room for play-yards or gardens, even; the outside windows serving the latter duty, while the school building on week-days, and the public parks on holidays, serve the former. Austrian children are never allowed to play on the street; but, as if to make up to their children for the loss of play-space, the Austrian parents take them, upon every available occasion, to the splendid[6] parks where are provided all sorts of amusements and refreshments at a modest sum.

"Father," asked the lad, after a few moments' silence, during which he had sat thinking quietly, "when shall we start?"

"Saturday morning, my son. I believe your mother has everything in readiness, nicht war, meine liebe Frau?" he asked, as he glanced over his paper at his wife.

"Oh, mother, do say you are ready," pleaded the child, who, for all his twelve years, and his finely developed body, was yet a boy, and impulsive.

"Yes, I'm all ready," she replied.

And, for the rest of the evening, silence descended upon the boy, his small brain being filled with visions of the coming pleasure.

When Herr Müller returned to his home the following evening, he found a letter, postmarked "Linz," awaiting him.

"Hello," he said, half aloud, "here's word[7] from our friend Herr Runkel. Wonder if there's anything happened to upset our plans?"

"Oh, father, please don't say it," pleaded the boy; "I shall be so disappointed."

"Well, cheer up," replied his father, "there's better news than you thought for. We shall leave on Saturday morning as planned; but to-morrow Herr Runkel's sister from the convent will come to us. He asks us to take charge of her, as the Sisters find it very inconvenient this year to send an escort with her; and, as we are coming up in a day or two, perhaps we would not mind the extra trouble."

"Oh, father, won't it be fine! How old is she?"

"I believe about your age."

Friday morning Frau Müller and Ferdinand jumped into a fiaker and drove to the railroad station to meet Teresa Runkel. She was a fine-looking child, with round, rosy cheeks; quite tall, with the fair complexion, sunny hair, and[8] soft, Austrian blue eyes that makes the women of that land famed for their beauty. She was overjoyed at this unexpected pleasure of spending a day or two in the city of Vienna, which she had never seen, although she had passed through several times on her way to and from the convent. She enjoyed the brisk drive to the tall apartment house in the Schwanengasse, and she fairly bubbled with chatter.

"After luncheon, my dear," observed Frau Müller, "we shall have Herr Müller take you about our city; for Vienna is vastly different from Linz."

Herr Müller joined the party at luncheon at eleven o'clock, which was really the breakfast hour, because Austrian families take only coffee and cakes or rolls in the early morning, eating their hearty breakfast toward the middle of the day, after which they rest for an hour or two, before beginning their afternoon duties.

At two o'clock the three were ready for the[9] walk, for Frau Müller was not to accompany them. Joseph, the portier, an important personage in Viennese life, nodded "A-b-e-n-d" to them, as they passed out the front door of the building, over which he presided as a sort of turnkey. No one may pass in or out without encountering the wary eye of Joseph, who must answer to the police for the inmates of the building, as also for the visitors. And this is a curious custom, not only in Vienna, but other European cities, that immediately upon one's arrival at an hotel, or even a private home, the police are notified, unawares to the visitor, of his movements and his object in being in the city, which reduces chances of crime to a minimum; burglary being almost unknown, picking pockets on the open streets taking its place in most part.

"Of course you know, children," said Herr Müller, as they passed along the broad Kärtnerstrasse, where are the finest shops of Vienna,[10] "you've been taught in school the history of our city, so I need not tell you that."

"Oh, but please do, father," said Ferdinand. "Teresa may not know it as well as I do,"—he hesitated, for he noticed the hurt look in the girl's eyes, and added—"although she may know a lot more about other things."

"Well," began the father, "away back in the times before Christ, a body of rough men came from the northern part of France and the surrounding countries. They were called Celts. They were constantly roving; and so it chanced they came to this very spot where we now are, and founded a village which they called Vindobona. But about fourteen years after Christ, the Romans worked their way northward; they saw the village of the Celts and captured it. They built a great wall about it, placed a moat outside of these fortifications and settled down to retain their conquest. They built a forum, which was a public square where all the business[11] of the city was transacted; and, on one side, they placed their camp or praetorium. To-day, we call the Roman forum the Hohermarkt, just here where we stand now," continued Herr Müller, "and here, where the Greek banker Sina has built this fine palace, stood the Roman praetorium; while here, you see the street is named for Marcus Aurelius, the Roman emperor who was born in Spain and died in this city so many hundreds of years ago."

"I've heard that ever so many times, father," said Ferdinand, "but I never realized it before; somehow it seems as if I could almost see the Celts driven out and the great wall and moat of the Romans."

Meanwhile they had walked on, down the Bauermarkt and reached the St. Stephanienplatz, with St. Stephan's Church in the middle.

"There," said Herr Müller, pointing to the beautiful edifice, "is the oldest monument we[12] have in Vienna, begun in 1144. Duke Heinrich Jasomirgott founded it."

"Oh, he was our first duke," spoke up Teresa, who also wished to prove that she knew her Austrian history as well as her friend.

"Yes, Teresa," answered Herr Müller. "But it's a long jump from the Romans to Duke Heinrich. Several hundred years after the expulsion of the Celts from Vindobona, Charlemagne, the undaunted conqueror of the age, absorbed it into the German Empire; he distinguished it from the rest of the German Empire by giving it the name of the Eastmark or border of the empire (Oesterreich), hence Austria. He placed a lord or margrave over it; and when Conrad III of Germany became emperor, he appointed Heinrich Jasomirgott ruler over the Eastmark, giving him, at the same time, the adjoining territory of Bavaria. But he had no right to dispose of these Bavarian[13] lands as he chose, just because he was angry with the Bavarians; and when his son, Frederick Redbeard (Barbarossa) came to the throne, he gave it back to the Bavarians. But Frederick Redbeard was a politic ruler; he did not wish to offend any of his subjects; in order to make up to Henry Jasomirgott for the loss of Bavaria, he raised him to the rank of duke, and thus Oesterreich or the Eastmark became a duchy. This was about 1100; then, being such an important personage, Duke Heinrich determined to make his home in Vienna. He built himself a strong castle, surrounded it with a high stone wall and a moat, as was the custom at that time, and included within it the confines of the city, so that he and his people might not be molested by neighboring princes.

"Here," continued Herr Müller, as they passed to the end of the Platz, "is the Graben. To-day it is our most fashionable shopping district; but in the time of Duke Heinrich it was[14] a moat filled with water; and here, where these rows of modern houses stand, were the ancient walls which protected the city."

"Isn't it great!" cried Teresa, who, girl though she was, could appreciate the ancient struggles of her ancestors for liberty and defence.

"Oh, father, there is Der Stock im Eisen!" said Ferdinand. "Tell Teresa about that, please; she doesn't know."

"Der Stock im Eisen?" repeated Teresa. "What is it?"

"That old tree with the iron hoop around it, at the corner of the Graben," replied her companion.

"We will reserve that tale for the evening," answered Herr Müller; "it is getting toward coffee hour, and we want to visit many places yet."

As he spoke, they walked slowly along the Graben, which means Moat in German, and,[15] at the end of several minutes, they reached a large open square called Platz am Hof.

"Here is what remains of the palace of the House of Babenberg, which Duke Heinrich built," said Herr Müller; "and here before it you see the Tiefe-graben, or deep moat, which amply protected the stronghold from attack. And there," he continued, moving as he spoke toward the building, "stands the Schottenhof."

"The Schottenhof?" exclaimed Teresa, astonished. "Why is it called a Scottish palace in Austria?"

"Because it was originally built and occupied by some monks from Scotland in the year 1158, whom Duke Heinrich had asked to come and instruct the citizens, not only in religion, but in the educational arts, there being no schools in those days; all the teaching was done by the Holy Fathers. But later on, the Scottish monks were dispossessed by a German order of monks; yet the Hof still bears the name of its founders.[16] And even to-day the Church owns all this most valuable property, right in the very heart of our city, which was given to them so many years ago."

"That's the first time I thought about the Hof being Scottish," admitted Ferdinand, between whom and Teresa there was much rivalry and jealousy as to the amount of knowledge possessed by each; but the lad was generous enough to admit his ignorance, because he did not wish to assume too superior airs before his guest.

"Here runs the tiny lane, the Schotten-gasse, which separates the Schottenhof from the smaller Molkerhof just across the land; and here are the ancient bastions which protected them; to-day, you notice, these same names are retained; the bastions are no longer required, but history preserves their memory in preserving their names, the Schotten-bastei and the Molker-bastei, now streets of the city of Vienna[17] instead of bastions. But we have had quite enough of history," continued Herr Müller, "I am quite certain our little convent friend is tired."

"Oh, no indeed," spoke up Teresa. "At the convent we take long walks every day; and in the country at Linz, we do much walking, too; it does not tire me at all."

"But walking about city streets is quite different from country lanes, my girl," observed Herr Müller.

"Yes, but we do not have the interesting places to visit, nor the tales to hear, in the lanes," wisely answered the child.

"Well, then, if you are quite certain you are not too tired, we will walk home. We will go by the way of the Ring, here behind the Schottenhof; and we will walk over the old walls, which were erected in later years as the original city of Duke Heinrich grew. Of course, we have no use for these fortifications in these days,[18] so we have changed them into a magnificent boulevard."

No one, not knowing the original use of the Ring, would ever have suspected the mission it had fulfilled; so broad and handsome was the avenue encircling what is called the Inner-Stadt (Inner City), planted with magnificent trees, and bubbling over with life, color and gayety.

Teresa would like to have stopped at every fine building and park, but Herr Müller promised to ask her brother to allow her a few days with them in Vienna before returning to the convent in the fall, that she might see all there was not time now to show her. For the present must suffice a cursory glance at the Burghof or imperial residence, the royal theatre, the Hofgarten and the Volksgarten, gay with the scarlet skirts and gold cloth caps of hundreds of nurse-maids watching over their youthful cares.

"Wouldn't it be splendid to be an emperor,"[19] remarked Teresa to her companion, "and live in such a fine palace?"

"Oh, that isn't much of a palace," remarked Ferdinand, somewhat contemptuously, "that's just like a prison to me; you ought to see Schönbrunn, the summer home of the Emperor."

"Oh, I've been to Schönbrunn," returned the girl with disdain in her voice. "The Sisters took us all there once; they showed us the room where the Duke of Reichstadt died, and where his father, Napoleon, lived when he took Vienna."

"Well, I'll bet you haven't seen the celebration on Maundy Thursday, when the Emperor sends his twenty-four gorgeous gala coaches with their magnificent horses and mounted escorts in uniform to bring the four and twenty poor men and women to his palace, that he might humble himself to wash their feet?"

"No, I haven't seen that," admitted Teresa. "Tell me about it. Have you seen it?"

"I've heard father tell about it a number of times," continued the lad. "The Emperor sends his wonderful holiday coaches with the escorts in gorgeous uniforms; they bring the poor men and women to the palace and set a splendid banquet before them; then they go to the royal chapel and hear Mass, at which the Emperor and the royal family, and the entire Court are present; after that, the poor folks are led to the banquet hall and here they are served from silver platters which the Emperor and his royal family present to them. After that, the Emperor kneels before them and wipes their feet with a wet cloth."

"He does that himself?" asked Teresa, who had listened spellbound, that her beloved emperor should conduct such a ceremony.

"Indeed he does! And, furthermore," added the boy, with ineffable pride, "he is the only monarch, so father tells me, who preserves[21] the ancient custom. But that isn't all; the Emperor sends these astonished poor people home again in the gorgeous coaches; he gives them each a purse in which is about fifteen dollars; he sends a great basket filled with the remains of the banquet which they have left untouched, together with a bottle of wine and a fine bouquet of flowers;—and, what do you think, Teresa?"

"I'm sure I couldn't guess," admitted the child.

"He gives them the silver platters from which he served them."

"What a splendid emperor!" cried Teresa. Then she added, "I've seen the Emperor."

"Oh, that's nothing," most ungallantly replied the boy. "Franz-Joseph walks about our streets like Haroun-al-Raschid used to in the Arabian Nights. Any one can see the Emperor; he allows even the poorest to come and see him in his palace every week; and he talks to them[22] just as if he was a plain, ordinary man and not an emperor at all."

"Well, I've had him speak to me," answered Teresa. "At the convent he praised my work."

There was a dead silence. Herr Müller walked along, not a muscle in his face betraying the fact that he had overheard this juvenile conversation, for fear of interrupting a most entertaining dialogue.

"Has he ever spoken directly to you?" demanded the girl, seeing that Ferdinand did not reply.

"No."

Again a dead silence.

"The Emperor needs our love and sympathy," said Herr Müller, after waiting in vain for the children to renew their talk; "his beloved empress Elizabeth has been taken from him by an assassin's hand; his favorite brother Maximilian went to his doom in the City of Mexico, the victim of the ambition of a Napoleon;[23] even his heir, the crown-prince is dead; and when our beloved king shall be no more, the very name of Habsburg will have passed away."

"He is a very kind man," replied Teresa. "He comes often to the convent; and he makes us feel that he is not an emperor but one of us."

Herr Müller touched his hat in respect. "Long live our beloved emperor, our most sympathetic friend," he said.

By this time they had gained the entrance of their home; Joseph opened the public door to admit them to the corridor, and they ascended to the third floor to the apartment of Herr Müller.

That evening, after a hearty dinner, the children called for the story of Der Stock im Eisen. And so Herr Müller began:

"Many hundreds of years ago, in the old square known as the Horsemarket, lived Vienna's most skilful master-locksmith, Herr Erhanrd Marbacher. Next door to him, stood a baker-shop owned by the Widow Mux. The widow and Herr Marbacher were good neighbors, and were fond of chatting together outside the doors of their homes, as the evening came on; Herr Marbacher smoking his long, quaintly-painted pipe, and the Widow Mux relating the sprightly anecdotes of the day.

"But, one evening, Herr Marbacher found[25] the widow in great distress; as she usually wore a merry smile upon her jolly face this change in temperament greatly affected the spirits of the locksmith, and he demanded the cause of her unhappiness. With tears in her eyes, the widow confided to her neighbor the dreadful fact that her younger son, Martin, a worthless, idle fellow, had refused to do any work about the shop, and had even used harsh words.

"'Sometimes it happens,' suggested the master-locksmith, 'that a lad does not take to his forced employment; it may be that Martin is not cut out for a baker; let me have a hand with him; perhaps he will make a first-rate locksmith.'

"'A locksmith!' exclaimed the widow in astonishment. 'How can he become a locksmith, with its attendant hard work, when he will not even run errands for the baker-shop! No, Herr Marbacher, you are very kind to suggest it, and try to help me out of my trouble,[26] but Martin would never consent to become a locksmith's apprentice. He is downright lazy.'

"'Well, you might let me have a trial with him,' said the locksmith; 'I am loved by all my workmen, yet they fear me, too; they do good work under my direction, and I am proud of my apprentices. Martin, I am certain, would also obey me.'

"'Well, have your way, good neighbor,' replied the widow, 'I can only hope for the best.'

"Evidently Herr Marbacher knew human nature better than the widow, for Martin was delighted with the prospect of becoming an apprentice-locksmith, with the hope of earning the degree of master-locksmith, like Herr Marbacher, and he worked hard and long to please his master. His mother was overjoyed at the change in the lad, and Herr Marbacher himself was very well pleased.

"Now, it chanced that some little time after Martin's apprenticeship, Herr Marbacher[27] handed him a tin pail and directed him to a certain spot on the edge of the forest, without the city walls, where he should gather clay with which to mould a certain form, for which he had had an order. As the commission was a particular one, and somewhat out of the ordinary, it required a peculiar sort of clay which was only to be found in this particular spot.

"With light heart, and whistling a merry tune, Martin, swinging his tin pail, set out upon his errand. The day was perfect; Spring was just beginning; the trees were clothed in their fresh greenness, light clouds flitted across a marvelously blue sky, the birds twittered noisily in the treetops and Martin caught the Spring fever; he fairly bounded over the green fields, and reached the forest in a wonderfully short time.

"Having filled his pail, he started homewards. But, instead of keeping to the path by which he had come, he crossed through the[28] meadows, his heart as light as ever. Suddenly he espied through the trees figures of men or boys; then voices came to his ears; he stopped and listened. Boy-like, he was unable to resist the temptation—the lure of the Spring—so he changed his course and made toward the bowlers, his old-time cronies, who were engaged in their old-time sport. Slower moved his feet,—his conscience prompted him in vain—he forgot the admonition of his master not to loiter on the way, for fear the city gates would be shut at the ringing of the curfew; he forgot all about the time of day, and that it was now well on toward evening. The fever of the Spring had gotten into his veins; Martin paused, set down his bucket of clay, and, picking up a bowl, joined in the sport of his comrades.

"Suddenly the curfew bell reached his ears; he recalled his errand, the warning of his master, and his heart stopped still in fright. He dropped the bowl in his hands, grasped his[29] bucket of clay, and ran with beating heart toward the city gate, but he was too late; the gate was closed and the gate-keeper either would not or could not hear his call.

"Fear now seized Martin, in very truth. The woods about the city were infested with robbers and dangerous men; there was no way in which to protect himself; yet he had nothing about him which any one would care to have, and that thought gave him some comfort. As he was planning how he might get within the walls, a tall man dressed in scarlet feathered cap and a long black velvet cloak upon his shoulders, stood before him.

"'Cheer up, my lad,' said the stranger. 'What is the use of crying?'

"'But I am locked out for the night,' replied Martin.

"'That is nothing to fret about,' answered the tall man. 'Here is some gold. Take it, it will open the gate for you.'

"'Oh, thank you,' said Martin, overjoyed. Then he hesitated. 'But I shall never be able to repay you,' he added. 'I have never seen so much gold.'

"'Oh, do not fret yourself about repaying me,' answered the stranger. 'I have plenty of gold, and do not need the little I have given you. Still, if you are really anxious to repay me, you might give me your soul when you have finished with it.'

"'My soul?' cried the boy aghast. 'I can't give it to you. One cannot sell his soul?'

"'Oh, yes,' replied the malicious stranger, smiling grimly, 'many people do sell their souls; but you need not give it me until you are dead.'

"'Much good would it do you then,' replied Martin; 'I cannot see what you would want with it after I am dead?'

"'That is the bargain,' retorted the tall man.[31] And he made as if to move away and leave Martin to his fate.

"'Oh, very well,' said Martin, fearing to throw away this chance for deliverance. 'I will take your gold, and you may have my soul when I have finished with it; the bargain is made.'

"'And I shall be lenient with you,' continued the stranger. 'I will give you a chance to redeem your soul.'

"'You will?' exclaimed Martin in delight. 'And how?'

"'Only this, if you forget to attend divine service even once, during all the rest of your days, then shall I claim my bargain. Now, am I not fair?'

"Martin was very glad to be released, even with this proviso, and laughed as he moved away, for Martin had been brought up religiously by a pious mother, and he knew he should not forget his Sabbath duty.

"As the stranger had said, the gold gained entrance for Martin Mux through the closed city gate, and he straightway made his way to his room and to bed before his master should discover his absence.

"Some days later, as the apprentices were hard at work in the shop under the scrutinizing eye of Herr Marbacher, a tall man in a black velvet cloak and a red plumed cap, stood in the doorway. Martin recognized his erstwhile friend and feared he knew not what. But the stranger had come to order an iron hoop with padlock so intricate that it could not be unlocked.

"Herr Marbacher hesitated; the order was certainly unusual, and even he, the master-locksmith of Vienna, was uncertain whether he could accomplish such a commission. But, seeing Marbacher's hesitation, the stranger cast his glance about the shop full of young apprentices,[33] and fixing his regard upon Martin, he said, in a loud voice:

"'Among all these workmen, is there not one who can make the lock?'

"Whether impelled by fear, or feeling that having assisted him once, the devil would assist him yet a second time, Martin spoke out,

"'I will do it.'

"All eyes turned toward the young apprentice.

"'You?' cried Marbacher, and he laughed very loud and very long, so excellent did he consider the joke. 'You? You are my very youngest apprentice.'

"'Let him try,' suggested the stranger warily, fearing the master would deny Martin the privilege. 'Who knows what he may be able to accomplish?'

"And so it was agreed.

"Martin worked all that day until the evening shadows compelled him to quit his work.[34] He racked his brain; he thought and thought; yet no lock could he imagine which could not be unlocked. He carried his paper and pencil to his room with him, thinking that in the stillness of the night he might think of some design. But, although he worked conscientiously, no ideas came to him, and he fell asleep. With visions of locks and bolts and bars in his head, it was no wonder that Martin dreamed of robbers' castles and dungeons and locks and bolts. He dreamed about a mighty robber in a fortress-castle; he was a prisoner there, he, Martin; but what his crime he did not know. He rushed toward the door to make his escape; it was locked; he tried to undo it, but in vain; then he looked about him, and the room seemed filled with padlocks, some small, some large, some handsomely wrought, some very simple; but among them he found one that looked like a huge spider. It interested him so much that he took out his pencil and mechanically reproduced[35] it; then he felt himself sinking, sinking, down, down. With a start he awoke, he had tossed himself out of bed and lay sprawling upon the floor of his room. Rather piqued, Martin picked himself up and jumped into bed. But there upon his pillow lay a drawing. He examined it by the feeble rays of the candle, which was still burning; it was the design of the spider lock he had seen in the robber's castle in his dream.

"Impatient for the morning, Martin was at his bench early working upon the design of the lock; and when the end of the sixth day arrived, the time appointed by the stranger for the delivery of the work, Martin had the lock completed. Evidently it proved entirely satisfactory to the stranger, for he paid Marbacher the money agreed upon, and left the shop.

"At the corner of the square he stopped before the larch-tree, bound the iron hoop about[36] the tree, locked it, put the key in his pocket and disappeared.

"Time passed. Martin, for some inexplicable reason, had left Vienna and gone to the city of Nuremburg where he continued in his profession. But, one day, he heard that the Burgomaster of Vienna had offered the title of master-locksmith to the one who would make a key which would unlock the iron hoop about the larch-tree. It was a small task for Martin to make a duplicate of the key he had once made, and with it in his pocket he travelled to Vienna and presented it to the Burgomaster.

"It was a great holiday when the hoop was to be unbound. Dressed in robes of state, glistening all over with gold thread and medals, the Burgomaster and the City Fathers gathered in the Horsemarket, where stood the Stock im Eisen; the lock was unfastened and Martin was created a master-locksmith, much to the[37] joy of his mother and to the overwhelming pride of his former master, Herr Marbacher.

"But, although Martin Mux had now acquired fortune and fame, he was far from being happy. His bargain with the devil haunted him; day and night it was with him, for he feared Sunday morning might come and he would forget to attend Mass. And then he would be irretrievably lost. What would he not give to be able to recall his bargain. He enjoyed no peace of mind; at his bench he thought ever of the dreaded day when he must pay; he could no longer work; he must not think; he joined his old-time idle companions; hour after hour was spent in gambling; night after night he frittered his wealth away; the more he lost the more desperate he became; poor Martin Mux was paying dearly for his game of bowls and his disobedience to his master.

"One Saturday evening Martin joined his[38] comrades quite early, but luck had deserted him; he lost and lost. One by one the other habitués of the place had gone until there was no one left but Martin and his few friends at the table with him. He paid no heed to time; all he thought of was to regain some of his lost money. Suddenly, as had happened some years before, out on the bowling green, Martin heard the deep tones of a bell. But this was not the curfew; it was the church bell calling to Mass.

"Martin looked up from his cards and saw the sun shining brightly through the curtained windows. His heart stood still with fright, for his bargain flashed through his mind; he threw down the cards and fled into the street, like a mad man.

"On and on he ran. He brushed past a tall man, but heeding him not, Martin rushed on.

"'Hurry, my friend,' called out the stranger, whom he had jostled. 'Hurry, the church bell has rung; the bargain is paid.'

"A malicious laugh rang in Martin's ear. He turned and saw the evil-eyed stranger, him of the black velvet cloak and red-plumed cap.

"Mad with fear, Martin bounded up the church steps. He entered the house of worship; but the stranger had said truly it was too late; the bargain was due for the service was ending. Martin Mux turned to leave the church, but at the threshold he fell dead; the stranger had claimed his soul.

"Since that time it has been the custom for every locksmith apprentice, whether he comes into Vienna to seek his fortunes, or whether he goes out from Vienna to other parts, to drive a nail into the stump of the larch-tree and offer up a prayer for the peace of Martin Mux's soul. That is why the old tree is so studded with nails."

"What a dreadful bargain for Martin to make!" said Teresa fearfully. "How could he have given his soul away?"

"He chose the easier way out of a small difficulty, and he paid dearly for it," replied Herr Müller. "It is not always the easiest way which is the wisest, after all."

The following morning the Müller family and Teresa Runkel boarded the boat in the Canal which should take them up current to Linz. It was most exciting for Ferdinand, who had never been on the Danube before, but to Teresa it was quite usual, for she always made the journey to and from her home by way of the river.

There was a great deal of excitement upon the quay—the fish boats had come in with their supply for the day, and fishermen were shouting themselves hoarse in their endeavors to over-shout their competitors.

The children seated themselves in the bow of the boat that they might miss nothing of the scenery which is so delightful near Vienna, with[42] its green banks, its thick forests and its distant mountains.

"Do you know what that grim castle is, over there on the left?" asked Herr Müller.

"Oh, yes," replied Teresa quickly. "That is the Castle of Griefenstein."

"Then you know its history?" asked Herr Müller.

"Yes, indeed," answered the child. "Sometimes the Sister who takes me home tells me, and sometimes father; but doesn't Ferdinand know it?"

"No," answered the boy. "I haven't been on the river before." As if it required some explanation for his seeming ignorance.

"Then tell it to him, please," said Teresa, "for it is a splendid tale."

"Long ages ago, this castle belonged to a lord who was, like all noblemen of that time, very fond of adventure. Whenever the least opportunity offered to follow his king, he would[43] take up his sword and his shield and his coat-of-mail, and hie him off to the wars.

"Now, the lord of the castle had a young and beautiful wife whose wonderful golden locks were a never-ending delight to him. Having a great deal of time upon her hands, and neighbors being few and far between, the lady of the castle passed her time in arranging her magnificent hair in all sorts of fashions, some very simple, while others were most intricate and effective.

"It chanced that one day, after an absence of several months, the lord of the castle returned. Hastening to his wife's boudoir, he found her before her mirror dressing her hair in most bewitching fashion.

"After greeting her, he remarked about her elaborate head-dress, and laughingly the young wife asked her husband how he liked it.

"'It is much too handsome,' he replied, 'for a young woman whose husband is away to the[44] wars. It is not well for a woman to be so handsome.'

"And without further word, he seized the sword which hung at his side, removed it from its scabbard, and with one stroke cut off the beautiful golden locks of his young wife. But no sooner had he done so than he was angry with himself, for his display of temper. He rushed from the room to cool his anger, when, whom did he run into, in the corridor, but the castle chaplain. The poor young lord was so ashamed of himself for his ungovernable temper, that, with even less reason than before, he seized the frightened and astonished chaplain by the two shoulders, dragged him down the castle steps and threw him into the dungeon.

"'Now,' said he, after bolting the door securely, 'pray, my good man, that the day may be hastened when the balustrade of my castle steps may become so worn by the hands of[45] visitors that it may hold the hair of my wife, which I have cut off in my folly.'

"There is nothing so unreasonable as a man in anger; I presume had the cook of the castle chanced to come in the way of milord's anger, he, too, would have been thrown into the dungeon, and all would have starved, just to appease the temper of the impossible lord. Fortunately, the cook, or the hostler or any of the knights or attendants of the castle did not appear, and thus was averted a great calamity.

"When the lord had had time to calm down a bit, he realized how unjust had been his actions. It was impossible to restore his wife's hair, but at least he might release the chaplain. A castle without a priest is indeed a sorry place; in his haste to descend the steps to the dungeon the lord caught his foot; perhaps his own sword, which had been the means of his folly, tripped him; in any event, he fell down the entire flight and was picked up quite dead."

"It served him quite right," interrupted Ferdinand.

"Oh, but that wasn't the end of the lord, by any means," continued Herr Müller, smiling. "He is doomed to wander about his castle until the balustrade has been worn so deep that it will hold two heads of hair like those he cut from his wife. The penitent lord has roamed about the castle for many a year crying out to all who pass, 'Grief den Stein! Grief den Stein!' (Grasp the stone). Long ago he realized how foolish had been his actions, but although he has heartily repented, yet may he never know the rest of his grave until the balustrade has been worn hollow."

"And does he yet wander there?" asked Ferdinand.

"So they say; but one cannot see him except at night. There are many who claim to have heard him calling out, 'Grief den Stein,' but although I have been up and down the river[47] many times, sometimes in the daytime and sometimes at night, I, myself, have never heard the ghostly voice."

"I've always felt sorrier for the poor lady without her beautiful golden hair," observed Teresa, after a moment's silence, "and I always felt glad to think the lord had to be punished for his wickedness; but, somehow, hearing you tell the story, Herr Müller, I wish his punishment might not last much longer. For he was truly sorry, wasn't he?"

Herr Müller looked quizzically at his wife, and they both turned their heads from the earnest faces of the children.

"Do you find the old legends of the Danube interesting, Teresa?" asked Herr Müller, as the boat sped along, and the children maintained silence.

"Oh, I love all sorts of tales," the child replied. "Father tells us some occasionally, but I am home so little of the time now I do not[48] hear as many as I used to. In the summer-days we are always so busy at the farm we do not have the time for story-telling as we do in the winter-days."

"Austria is full of tales about lords and ladies, ghosts and towers, but the Danube legends are not as well known as those of the Rhine. Have you ever heard that story concerning the Knight of Rauheneck near Baaden?"

"No, Herr Müller," replied Teresa.

"Well, it isn't much of a tale when you compare it with the Habsburg legends and the Griefenstein, and Stock im Eisen, but then it is worth telling."

"Begin," commanded the young son, in playful mood.

"Well, near Baaden there stands a formidable fortress called Rauheneck where lived a knight in former years. As he was about to go to war, and might return after many years[49] and perhaps never, he decided to hide the treasures of the castle and place a spell upon them so that none might touch them but those for whom they were intended. So, in secrecy, he mounted to the summit of the great tower of the castle and on the battlement he planted a cherry stone, saying, as he did so:

"'From this stone shall spring forth a tree; a mighty cherry-tree; from the trunk of the tree shall be fashioned a cradle; and in that cradle shall be rocked a young baby, who, in later years, shall become a priest. To this priest shall my treasure belong. But even he may not be able to find the treasure until another cherry-tree shall have grown upon the tower, from a stone dropped by a bird of passage. When all these conditions have been complied with, then shall the priest find the treasure at the foot of my tree, and not until then.'

"Then the careful knight, fearing for the[50] safety of his treasure, even after such precautions, called upon a ghost to come and watch over the castle tower, that peradventure, daring robbers who might presume to thrust aside the spells which bound the treasure, would fear to cope with a ghost."

"And did the priest ever come?" queried Teresa.

"Not yet, child; the cherry-tree at the top of the tower is but yet a sapling; there are long years yet to wait."

"But we don't believe in ghosts, father," interrupted Ferdinand. "Why could not some one go and dig at the root of the tree and see if the treasure were really there?"

"One could if he chose, no doubt," answered Herr Müller, "but no one has."

"Would you, Ferdinand?" asked Teresa.

"Oh, I might, if I were a grown man and had a lot of soldiers with me."

"Do you know another legend, Herr Müller?" asked Teresa, shortly.

"Well, there is the legend of Endersdorf in Moravia.

"A shepherd once lived in the neighborhood, and although he had always been exceedingly poor, often almost to the verge of starvation, yet, one morning, his neighbors found that he had suddenly become exceedingly rich. Every one made conjectures concerning the source of his wealth, but none of them became the confidante of the shepherd, so that none were ever the wiser. The erstwhile poor shepherd left his humble cot and built himself a magnificent estate and palace upon the spot; he surrounded himself with retainers and sportsmen and gave himself up quite naturally to a life of ease and indolence. Most of his time was spent in following the hounds; but with all his newly-acquired wealth, and notwithstanding the memory of days when a few pence meant a fortune to[52] him, the shepherd lost all sense of pity, and none about the country-side were quite so penurious and selfish as he. To such poor wayfarers as accosted him, in mercy's name, to befriend them, he turned a deaf ear, until his name was the synonym for all that was miserable and hard-hearted.

"Now, it happened, that one day a poor beggar came to the gate of the rich shepherd, asking for alms. The shepherd was about to leave the gate in company with a noisy crowd of hunters and followers, on his way to the chase. Taking no pity on the poor man's condition, he suddenly conceived the idea of making the beggar his prey.

"'Here is sport for us, good men,' he cried. 'Let us drive the beggar before us with our whips, and see him scamper lively.'

"Whereupon, following the action of their host, the entire company raised their whips, set spurs to their horses, and drove the trembling,[53] frightened, outraged man from before them.

"'Now has your hour come,' cried out the old man, as he turned and defied his assailants. 'May all the curses of Heaven fall upon your heads, ye hard-hearted lot of roysterers!'

"At the word, the sky, which had before been cloudless, grew suddenly black; the lightning flashed; the thunder rolled; the very ground under their feet, shook, cracked and opened, swallowing the shepherd, his followers, their horses, dogs, and every vestige of the estate vanished. In its place arose a lake whose dark waters tossed and moaned in strange fashion.

"On stormy days, even to this present day, when the waters of the lake are lashing themselves in fury, the shepherd of the hard heart can be seen passing across the waves, his whip raised to strike some unseen object, a black hunting dog behind him. How long his punishment[54] may last, no one knows, but he can always be seen just as he was when the earthquake swallowed him up."

"Isn't it strange," observed Teresa, "but every one of the tales end in the punishment of the wicked knight."

"Of course," remarked Ferdinand. "They wouldn't be tales at all if the wrong-doer was allowed to go free. Would they, father?"

"Indeed not; but now it's time for breakfast. Would you like to eat on deck? It is so perfect a day, it is a pity to go indoors."

This suggestion appealed wonderfully to the children, and Herr Müller left them to order the meal served upon the deck.

As night fell, the boat docked at Linz. Herr Runkel was waiting on the quay with a heavy wagon and a team of horses to drive them to the farm. It was a beautiful drive in the bright moonlight, and the lights of Linz twinkled below[55] them, while the Danube sparkled in the distance, just like a fairy world.

It was very late when they reached the farm-house; Frau Runkel greeted them cordially, and immediately after helping them off with their wraps, poured out steaming hot coffee to warm them up, the night air having been a trifle chilly.

Ferdinand went directly to his room after coffee was served. It was on the opposite side of the house, on the ground floor; the farm-house was but one story high, with a lofty attic above. In one corner of the large bedroom stood a canopied bed of dark wood, elaborately painted in bright colors, on head and foot board, with designs of flowers and birds. There were two small, stiff-backed wooden chairs, a night-table, upon which stood a brass candlestick, and an enormous wardrobe or chest for his clothes. All the furnishings of the room, even to the rug by the bed, were the handiwork of the occupants[56] of the farm-house, for no true Austrian peasant would condescend to purchase these household necessities from a shop. Between two voluminous feather beds Ferdinand slept soundly, nor did he stir until he heard voices in the garden. Hastily dressing, he made his way into the living-room, where breakfast had already been partaken of by the others.

"I'm so sorry to be late," he apologized, shamefacedly. "Why didn't you call me, mother?" he asked, as he turned to the one who must naturally share the responsibility of her children's shortcomings.

"We thought to let you have your rest," answered Frau Müller. "Your day will be very full. You evidently enjoyed your downy bed."

"Oh, it was great; let us get one, mother."

"I used to sleep under one when I was a girl," replied Frau Müller, "but no one in the[57] city uses them any more; the woolly blankets have quite superceded them."

"You may take yours home with you, if you like," said Frau Runkel, "we have geese enough to make more."

"Now," said Herr Runkel, "if you are all ready, we'll go over and pay our respects to father and mother."

"Then your parents do not live with you?" asked Herr Müller, a little astonished.

"No, that is not the custom among us. You see, when I got married, father made over the farm and all its appurtenances to me, being the eldest son; then he built himself another home, just over in the field, there," and Herr Runkel pointed to a tiny, cosy cottage some few hundred paces away.

"What a splendid thing to be the eldest son," remarked Herr Müller.

"Perhaps it is," replied his host, "but it entails a great responsibility, as well. You see,[58] after the ceremony of deeding the farm away to me, I am called upon to settle an allowance upon my parents during their lifetime."

"That's but right," assented Herr Müller, "seeing that they have given you everything they possess, and which they have acquired with such toil and privation."

"Yes, but father received the farm from his father, in just the same manner; although he has enlarged it, so that it is bigger and better. But, in addition to father and mother," continued the farmer, "I have all my brothers and sisters to look after. There is Teresa at the convent in Vienna; there is Frederick at the Gymnasium in Linz; and there is Max an apprentice in Zara; these must all be cared for; and, I can tell you, Müller, it's a responsible position, that of being the eldest son."

"But you weren't called upon, Franz," replied his friend, "to provide so bountifully for each."

"No, but what would you have?" he replied. "I have tried to be a dutiful son; and," he added, his eyes twinkling as he glanced at his wife, "I've been sort of lenient towards father and the children, because father let me off so lightly when he boxed my ears for the last time."

"Boxed your ears?" exclaimed Herr Müller, in astonishment. "What had you done to deserve such disgrace?"

"Well, that was part of the ceremony. When the farm was made over to me, it's the custom, before signing the deed, for the owner to make the rounds of his estate with his family; when he comes to each of the four corner-posts, he boxes the ears of the new owner. Now, father might have boxed mine roundly, had he chosen, for I was somewhat of a rollicker in my youth," and the genial farmer chuckled softly, "but father was sparing of my feelings. Don't you believe he deserved a recompense?"

"He certainly did," answered his friend, and they all laughed heartily over the matter.

Meanwhile they had gained the entrance to the dower-house, as the home of the aged couple was called. As Herr Müller had not seen the parents of his friend since childhood there were many years of acquaintanceship to bridge over; and Ferdinand, fascinated, listened to the conversation, for this old couple were most interesting persons to talk with.

After returning from church the family gathered on the wide verandah under the eaves, the women with their knitting, which is not considered improper even on Sundays among Austrian women.

This verandah in the peasant home in Upper Austria is a most important part of the house. It is protected from the elements by the enormous overhanging eaves above, running the entire side of the house; heavy timbers support it, green with growing vines which climb[61] from the porch boxes filled with gayly blossoming flowers. It is a tiny garden brought to one's sitting-room; the birds twitter in the sunlight, as they fly in and out of their nests under the eaves; and here the neighbors gossip and drink coffee and munch delicious cakes. In fact, it is the sole sitting-room of the family during warm days, for no peasant woman would think of shutting herself in a room to do her work. One can always work to better advantage in the sunlight and open air.

The children rambled about the farm and outbuildings. The farm-house was very long and deep and low, with a long, slanting roof. The front door was of heavy timbers upon which was a design of St. Martin outlined in nails, the work of the farmer, while small crosses at either side of the door were considered sufficient protection from the evil spirits who might wish to attack the family within.

The interior of the farm-house was very simple; a large vestibule called the Laube or bower served as a means of communication between the different parts of the house; the sleeping-rooms were ranged on one side, while the dining and living-room occupied the other, with the kitchen just beyond.

The Gesindestube, or living-room, was very plain, with its bare floors and darkened walls; a tile stove in one corner, benches about the walls and chests, some plain, some elaborately decorated and carved, occupied whatever space was left. Here were kept the household linens and the wardrobes for the family, as no Austrian peasant home is built with closets as we have in America.

That evening, Herr Runkel said to Ferdinand:

"To-morrow, my boy, we work. Would you like to help?"

"Oh, it would be jolly," replied the lad.[63] After a moment's hesitation, he added: "What kind of work? Hoeing potatoes or weeding the garden?"

These two tasks were the only ones the lad was familiar with upon his uncle's farm in Tyrol.

The farmer laughed. "No, we won't do that," he said. "We'll leave that to the servants; but we'll make shoes."

"Make shoes!" exclaimed the child, incredulously. "Really make them yourself? I've never made shoes," he added, doubting whether he might be allowed now to assist.

"Why not?" answered Herr Runkel. "You know we are very old-fashioned here; and, as we have so far to go to the shops, why we don't go; we let the workmen come to us. This is an off-time of the season; so we have the tailors and the shoemakers and all sorts of folk come and help us with such things as we can't do ourselves, for, you know, we make[64] everything we use on the farm, and everything we wear."

"Oh, how fine," said Ferdinand.

"Yes, and we have jolly times, too," continued the farmer, "for when work is over we play. Isn't that right?"

Ferdinand went to bed that night with visions of tailors and shoemakers and harnessmakers and whatnot, in his head, until he fell asleep.

Ferdinand needed no call to arouse him in the morning. He was awake and up long before any of his family, but he did not catch Herr Runkel nor his buxom wife, napping.

"Come along, Ferdinand, and help me get the leather ready for the men," said the farmer, and he led the way across the garden to a great timber building, two stories in height. He opened the door, and they entered a very large room, with a decided smoky smell about it.

"What is this?" asked Ferdinand.

"This is our Feld-kasten (field-box) where we keep all our supplies. Here are the seeds for planting when the time comes; here are the hams and bacons and dried meat for use during the winter; here is the lard for the[66] year;" and Herr Runkel took off the lids of the great casks and showed the white lard to the child, astonished beyond expression, at this collection of supplies.

"And what's in the loft?" asked the boy, seeing the substantial ladder leading thereto.

"Oh, that's for the women-folks," he replied. "We keep all sorts of things there. Let's go up."

And they ascended.

The loft was a room full of shelves; in most delightful order were ranged bundles of white cotton cloth, bundles of flax for spinning, bundles of woolen goods for making up into apparel, some dyed and some in the natural wool; there were rows and rows of yarn for embroidering the garments of the peasants, and upon the floor in one corner was a great heap of leather, with all sorts of machinery, and harness, and Ferdinand never could learn what there was not here, so overwhelmed was he.

"Here we are," said Herr Runkel, as he tugged at the pile of leather. "We must get this out, for the shoemakers start after breakfast. Give us a lift, child," and he half dragged, half lifted the leather to the trap-door and let it slide down the ladder.

For days afterwards Ferdinand was in a fever of excitement. First he would help cut out the leather for the heavy farm shoes, working the best he could with his inexperience; the main thing being to keep busy, and he certainly accomplished it. Then he helped the tailors, for every one who could be spared about the farm joined in the tasks of the journeymen, that they might finish their work and move on to another farm, before the busy season should begin for the farmers.

It is customary in addition to the low wages of about twelve cents a day for servants to receive their clothing, as part payment, so that upon a large farm, of the extent of Herr[68] Runkel's, there were many to be provided for. Frau Müller assisted Frau Runkel in the kitchen, where Teresa, too, was kept busy; even Ferdinand not disdaining to make himself useful in that department.

At length the journeymen were finished, and Herr Müller spoke about leaving in a few days for Tyrol.

"We shall have a merrymaking, then, before you go," said his host. "But I presume parties are not a novelty to you; are they, Ferdinand? City folks, especially Viennese, are very gay."

"Oh, we never have parties in Vienna," replied the lad. "That is, private parties; they cost too much. But we have our masked balls and ice festivals. Of course I can't go to those; they are only for grown folks."

Herr Müller took up the thread of conversation at this point. "Vienna, with all its glitter, is but a poor city, after all," he said. "Living[69] is very costly; the rich and the aristocracy have impoverished themselves by their extravagant ways of living. They dwell in fine homes, wear gorgeous uniforms and gowns, but cannot pay for these extravagances. They have shooting-lodges in the mountains, country villas for the summer, besides their town homes, but they have the fear constantly over their heads that these will be taken from them, to redeem the mortgages upon them."

"I am more than ever thankful," replied the farmer, "that I have my farm and my family, and owe no man."

"You are certainly right," answered his friend. "It is to such men as you that Austria must look in the future."

"But about the party, Herr Runkel," interrupted Ferdinand, who feared that his host might forget his suggestion.

"Oh, yes. Well, we'll have that Saturday night; so run along and help the women-folks[70] get ready for it, for you never saw such feasts as we do have at our parties, child."

Ferdinand, being just a boy, rushed off to the kitchen to provide for the "spread" that was to come, and he and Teresa chattered like two magpies over the splendid prospect.

Although Ferdinand Müller did not quite believe that Saturday afternoon would ever come, it eventually did come; and a perfect day, too. Teresa was dressed in her most shining silver buckles and her whitest of homespun stockings, while Frau Runkel outshone every one in the room with her gayly embroidered apron over her dark skirt, and her overwhelming display of hand-made silver ornaments in her ears, upon her arms, about her neck, and on her fingers. And her head-dress was a marvel to behold, glistening with gold thread and shining with tiny beads of various colors.

The table was set in the Gesindestube; there were roast ducks, and geese and chickens, roast[71] meats and stewed meats, and Wienerschnitzel (veal cutlet), without which no Austrian home is complete. There were sausage and cheese and black bread and noodles; there were cakes with white frosting and pink frosting, and some were decorated with tiny colored seeds like caraway-seeds. Never had Ferdinand beheld such a sight before; but truly the Austrian peasant knows how to enjoy life.

The reception over, the host and hostess led the way to the dining-table, the men placing themselves on the bench on one side while the women sat opposite them on the other. With bowed heads, the host said the grace; then began the gayety. There was no constraint; each helped himself and his neighbor bountifully. Meanwhile, the two young children, at the foot of the board, were not neglected, but kept up a lively conversation of their own, utterly oblivious of their elders.

"Wait until the dessert comes," said Teresa.[72] "Did you ever see one of these nettle-cakes?"

"Nettle-cakes?" repeated the lad. "What is that?"

"Oh, you will see," replied the young lady, looking wise. "But be careful, I warn you, not to prick your fingers. Perhaps, though," she added, "mother may not allow us to join in, for this is a special feast-day, in honor of you and your parents."

Ferdinand was not kept long in suspense. The viands having been disposed of to the satisfaction of every one, the maid brought in the "pièce de resistance." It towered high above her head, and had she not been brought up in the open air of the country she certainly never would have had the strength to manage such a burden. Upon a huge wooden dish was piled high fresh fruits from the orchard, cakes with delicious frosting, nuts and bright flowers. It was a medley of color, set off by great streamers[73] of gay ribbons and bows; quite like a bridal cake, but vastly more interesting.

Tongues wagged fast, you may be sure; all wished to get a chance at the gorgeous centrepiece, nevertheless, they all waited for their host's approval, and, waiting his opportunity, when many were not on the alert, he raised his hand, and then such a scramble you never saw in all your days. The men rose out of their seats and grabbed for one particular sweetmeat, which might appeal to the palate of his fair partner; but for all their precautions, knowing the hidden secrets of the dessert, many emerged from the battle with scratched hands or bleeding fingers, for these delicious cakes and luscious fruits covered prickly nettles, a trap for the unskilful.

But what mattered these trifles to the happy-hearted peasant folk. They chatted and laughed and dived for fruit and decked the hair of their favorites with gay flowers, or cracked[74] nuts with their knife handles and fed them to their lady loves. With the coffee, the feast ended.

Carrying the benches to the sides of the room, where they ordinarily reposed, the table was cleared as if by magic. Now the dance was on. Zithers and violins appeared, and the darkened rafters of the Gesindestube rang with the clatter of many feet.

By ten o'clock all was quiet at the farm-house; the guests had complimented their host and hostess upon the success of the evening, and the elaborateness of the table; they bade farewell to the Müller family, and saying good night to all, made their way over the fields, singing with hearty voices, their tuneful folk-songs; and thus Ferdinand heard the last of them ere he fell asleep.

The following morning Herr and Frau Müller and Ferdinand bade their kind host and hostess good-by and they set out for Linz, where they would take the train to Innsbruck, the capital of Upper Tyrol. Ferdinand was very loth to leave the farm, he had had such a splendid time there, and felt that he had not seen half of the farm-life; but Herr Runkel promised that he should come again the following summer and spend the entire vacation with them, to which his parents consented, so the child was content. However, he was to visit his cousin Leopold, and that was always a treat, for Tyrol is so charming and so different from other spots in Austria, it would be a difficult[76] child, indeed, to please, who would not be content with a trip to Tyrol.

Herr Hofer and his son Leopold met them at the station in Innsbruck, with a heavy wagon and two strong horses; the Hofers lived in Volders in the Unter-Innthal or valley of the Lower Inn River, some distance in the mountains; all the country to the north of the Inn being designated as the Upper and that to the south, as the Lower valley.

"Have you had your luncheon?" asked Herr Hofer, as soon as the greetings were over.

"Oh, yes, we lunched on board the train," replied Herr Müller.

"Then, let's get off," said Herr Hofer, "for we have a long drive before us." He pulled his horses' reins and the beasts started off at a good pace.

Leaving the station, they turned down the Margareth-platz with its fountain of dragons and griffins, where young women were filling[77] their pitchers, for Innsbruck is very primitive in many of its customs. Down the broad and splendid Maria-Theresa Strasse the carriage turned, and stopped before a most gorgeous palace, whose roof shone in the bright sunshine like molten metal.

"Oh, uncle, who can live in such a beautiful house?" asked Ferdinand.

"That is the Goldne Dachl, or the House with the Golden Roof," replied his uncle. "It was built ever so many years ago by our beloved Count Frederick of Tyrol. You've heard of him?" he queried.

"Oh, yes," replied the lad. "But I don't know about this house of his."

"Well, Count Frederick was a most generous man; he would lend to all his friends who were not always very prompt in repaying him, and sometimes forget they owed him anything at all. At length, his enemies began to call him the Count of the Empty Pockets. This was[78] very unjust, for poor Friedl (that's what we call him, who love him, you know) had had a very hard time of it, indeed. His own brother had driven him from his throne and usurped it himself, and made it a crime for any one to even shelter poor Friedl, who wandered about from place to place like the veriest vagabond. But, at length, he discovered that he had many friends who longed to show their devotion to him; he made a stand for his rights and secured his throne. But still, the nickname did not leave him. So, just to prove to his people that he was unjustly called the Count of the Empty Pockets, he ordered this wonderful roof of gold to be put on his palace. They say it cost him $70,000, which certainly was a great sum for a man with empty pockets."

Turning the horses' heads in the opposite direction, Herr Hofer conducted them through the Triumphal Arch and gained the country road.

"I thought to show the boys the Abbey of Wilten," explained Herr Hofer, as they trotted along, "and perhaps stop at Schloss Amras, as we may not have an opportunity soon again."

"Oh, uncle," cried Ferdinand, "I love to see old ruins and castles. We have a lot of fine ones about Vienna, but they are all alike."

"Well, these will be quite different, I can assure you," replied his uncle.

The two boys occupied the rear seat with Frau Müller, while the fathers sat upon the front. And verily the little tongues wagged as only boys' tongues can do. In the midst of their spirited conversation, the carriage stopped before a splendid old church.

"Oh, father," exclaimed Ferdinand, "what queer looking men!"

Herr Müller looked about, but saw no one.

"Where?" he asked.

"Why, there, by the sides of the church door."

Both men laughed.

"They are queer looking, aren't they?" said Uncle Hofer. "But you would think it a lot queerer did you know how they came to be here."

"Oh, tell us," the boy exclaimed.

"Well, once upon a time, way back in the Middle Ages, there were two giants who lived in different parts of the earth. Each of them was twelve feet or more tall; one was called Haymo and the other Tirsus. Now, in those times, giants did not remain quietly in their strongholds; they set out on adventures; so it chanced that, in the course of their travels, these two mighty giants encountered each other, right on this spot where this abbey stands. But of course, there was no abbey here then; the ancient Roman town of Veldidena was hereabouts.

"Now, when the two giants met, they stopped, looked one at the other and measured his strength. Well, it naturally fell about that they decided to prove their strength; in the struggle, sad to tell, Haymo killed Tirsus. Poor giant Haymo. Big as he was, he wept, for he had not meant to harm his giant comrade. At length, to ease his mind, he determined to build an abbey on the spot, as that seemed to be the solace for all evils, in those days. And then Haymo would become a monk, and for eighteen whole years he would weep and weep as penance for the deed.

"But poor Haymo had more than he bargained for. He did not know that the Devil had claimed this same spot; no sooner did Haymo bring the stones for the foundation of his church than the Devil came and pulled them down. But Haymo persisted, for he really must keep his vow; and evidently he conquered the Devil himself, for the abbey stands, as you[82] see, and these are the two statues of the giants guarding the portal of the church, so that the Devil may not come, I suppose."

"Poor Haymo," said Ferdinand. "What a hardship to weep for eighteen years, nicht wahr, Leopold?"

"Yawohl," came the stolid reply, while the two men chuckled softly.

It is a peculiarity of Tyrol that, not until one attains middle age at least, does he begin to appreciate humor the least bit. Children are always too serious to admit of "fun" in their prosaic lives, so that, were it not for the elderly people, humor might eventually die out altogether in Tyrol, so serious a nation are they.

"Shall we go inside, father?" asked Leopold.

"We have not time; night will overtake us, and we must go on to Schloss Amras yet. There really is little to see, however."

And while the lads strained their necks and eyes to catch a glimpse of the beautiful paintings[83] upon the outside walls of the abbey, the wonderful gilding and stucco, the horses disappeared around a bend in the road, and it was lost to sight.

Now they commenced to climb, for the road is always up and up in Tyrol. Below them lay the wonderful view of Innsbruck, with the Inn running gayly along; there, too, was the fair abbey with its two giants carved in stone, watching ever at the portal.

"Have you boys any idea where we are?" asked Herr Hofer.

Both shook their heads negatively.

"All this country hereabouts is alive with interest attaching to Andreas Hofer, our patriot," replied he. "Here, at this very Gasthaus (inn) was where he made his last effort against the enemy. We shall learn more of it as we go along," he continued, "but there is not much use to stop here now. We go a few steps further to the Schloss."

Truly it was a delightful old place, this castle of Amras, one of the few feudal castles left. There was an old courtyard paved with great stones, there were battlements and towers and relics of Roman invasions. The guide led them through the castle, room after room, filled with most interesting articles of every description pertaining to ancient times and wars, all of which intensely absorbed the boys' attention.

"Oh, what an immense bowl!" cried Ferdinand. "And of glass. What is it for?"

"That is the welcome bowl," replied the attendant. "We call it, nowadays, the loving cup. In every castle there were many like this; there was a gold one for ladies, a silver one for princes and a glass one for knights, which latter was the largest of all. When guests came to the castle, the welcome bowl was brought out, filled to the brim and handed to the guest, who was supposed to drink it off at a draught, if he was at all of a hazardous or knightly disposition.[85] To his undoing, it sometimes happened he did not survive the ordeal; but that mattered not at all to him; he had displayed his bravery and that was worth life itself. After the bowl was drained, a great book was brought out, in which the guest was requested to write his name, no doubt as a test as to his real station, for no one but the highest and noblest were able to write or read in those times, and it often chanced even they were unable to do so."

"Why, that is what they do in hotels!" said Ferdinand.

"Yes," replied the guide, "and probably that is where the custom originated, for the manager of a hotel but preserves the ancient custom of registering the names of his guests."

All too soon the visit came to an end; the party made its way to the near-by inn to spend the night.

The inn-keeper, Herr Schmidt, was a big, raw-boned man with a red face and a jolly air. He was a genuine Wirthe or inn-keeper of the old-time; and after supper, as they all sat in the great sitz-saal together, he told them wonderful tales of the country round about, which so abounded in legends and folk-lore. As the position of Wirthe descends from father to son, for generations back, as long as there remains any sons to occupy that honored position, naturally, too, the legends are passed from one to the other, so that no one is quite so well able to recite these as our hearty friend Herr Schmidt.

"If it were not so late," remarked Herr Hofer, while the men sat and smoked their[87] long, curious pipes, "I should continue on to Volders, for it looks as if to-morrow might be stormy."

"Oh, you need have no fear as to that," replied the host. "I noticed Frau Hütte did not have her night-cap on."

Ferdinand looked at his little cousin with his face so puckered up with glee and merriment, that Leopold laughed outright.

"Do tell Ferdinand about Frau Hütte, father!" said the child.

"No, I think Herr Wirthe better able to do that. Bitte," and he saluted the inn-keeper in deference.

"And have you never heard of Frau Hütte, my boy?" asked the host.

"No, sir," replied the boy. "You know I live in Vienna."

"Well, everybody knows her," replied the inn-keeper; "but then, you are a little young yet, so I will tell you."

"Very long ago, in the time of giants and fairies,— But then you don't believe in fairies, do you?" and the fellow's eyes sparkled keenly.

"Oh, yes, I do," exclaimed the boy hastily, for fear if he denied the existence of such beings, he should miss a good story.

"Well, then, there was a queen over the giants who was called Frau Hütte."

"Oh," interrupted the lad, "then she isn't a real person?"

"Oh, yes, she was; but that was long ago," continued the story teller. "Well, Frau Hütte had a young son who was very much like any other little child; he wanted whatever he wanted, and he wanted it badly. One day, this giant child took a notion he should like to have a hobby horse. Without saying a word to any one, he ran off to the edge of the forest and chopped himself a fine large tree. But evidently the child did not know much about felling[89] trees, for this one fell over and knocked him into the mud. With loud cries, he ran home to his mother. Instead of punishing him, she bade the nurse wipe off the mud with a piece of white bread. No one but the very richest could afford the luxury of white bread, black bread being considered quite good enough for ordinary consumption, so no wonder the mountain began to shake and the lightning to flash, just as soon as the maid started to obey her mistress' command.

"Frau Hütte was so frightened at this unexpected storm that she picked up her son in her arms and made for the mountain peak some distance from her palace. No sooner had she left the palace than it disappeared from view, even to the garden, and nothing was ever seen of it again. But even in her retreat the wasteful queen was not secure. When she had seated herself upon the rock, she became a stone image, holding her child in her arms. And[90] there she sits to this day. When the clouds hover about her head then we know there will be a storm, but when Frau Hütte does not wear her night-cap," and the Wirthe's eyes sparkled, "then we are certain of clear weather."

"Ever since then, the Tyrolese have made Frau Hütte the theme of a proverb 'Spart eure Brosamen fur die Armen, damit es euch nicht ergehe wie der Frau Hütte,' which really means 'Spare your crumbs for the poor, so that you do not fare like Frau Hütte,' a lesson to the extravagant."

There were endless more stories, all of which delighted the boys immensely, but we could not begin to relate them all, for Tyrol is so overladen with the spirit of the past, and with the charm of legend, that the very air itself breathes of fairies and giants, and days of yore, so that in invading its territory one feels he is no longer in this work-a-day world, but in some enchanted spot.

Early the next morning, up with the sun, all were ready for the drive home. As Herr Wirthe had predicted, the day was fair; as they drove away from the Inn, they caught a glimpse of Frau Hütte in the distance beyond Innsbruck, and, sure enough, there she sat on her mountain peak, with her great son safely sheltered in her arms.

"Shall we go to the salt mines, father?" asked Leopold, as they made their way along the mountain road.

"No, we cannot take the time; mother will be waiting for us and the women folks are impatient to visit, I know."

"They have wonderful salt mines at Salzburg," said Ferdinand. "Perhaps we may go there some time to visit them."

"Perhaps," replied his father. "But, while we are on the subject, did it ever occur to you that Salzburg means the 'town or castle of salt?'—for, in the old times, all towns were[92] within castle-walls, to protect them from depredations of the enemy."

"Isn't it curious?" meditated Ferdinand.