THE KNIGHTS OF THE ROUND TABLE

THE KNIGHTS OF

THE ROUND TABLE

STORIES OF KING ARTHUR

AND THE HOLY GRAIL

BY

WILLIAM HENRY FROST

ILLUSTRATED BY SYDNEY RICHMOND BURLEIGH

NEW YORK

CHARLES SCRIBNER'S SONS

1897

COPYRIGHT, 1897, BY

CHARLES SCRIBNER'S SONS

TROW DIRECTORY

PRINTING AND BOOKBINDING COMPANY

NEW YORK

BY THE SAME AUTHOR

Each 1 vol., 12mo, Illustrated by SIDNEY

R. BURLEIGH. Price, $1.50

THE KNIGHTS OF THE ROUND TABLE

THE COURT OF KING ARTHUR

THE WAGNER STORY BOOK

To

MY FATHER

John Dudley Frost

CONTENTS

CHAPTER I

CHAPTER II

CHAPTER III

CHAPTER IV

CHAPTER V

"Camelot, that is in English Winchester"

CHAPTER VI

CHAPTER VII

CHAPTER VIII

CHAPTER IX

CHAPTER X

CHAPTER XI

CHAPTER XII

CHAPTER XIII

CHAPTER XIV

CHAPTER XV

CHAPTER XVI

CHAPTER XVII

"And on the Mere the Wailing Died Away"

CHAPTER XVIII

CHAPTER XIX

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

"Percivale saw a ship coming toward the land." . . . Frontispiece

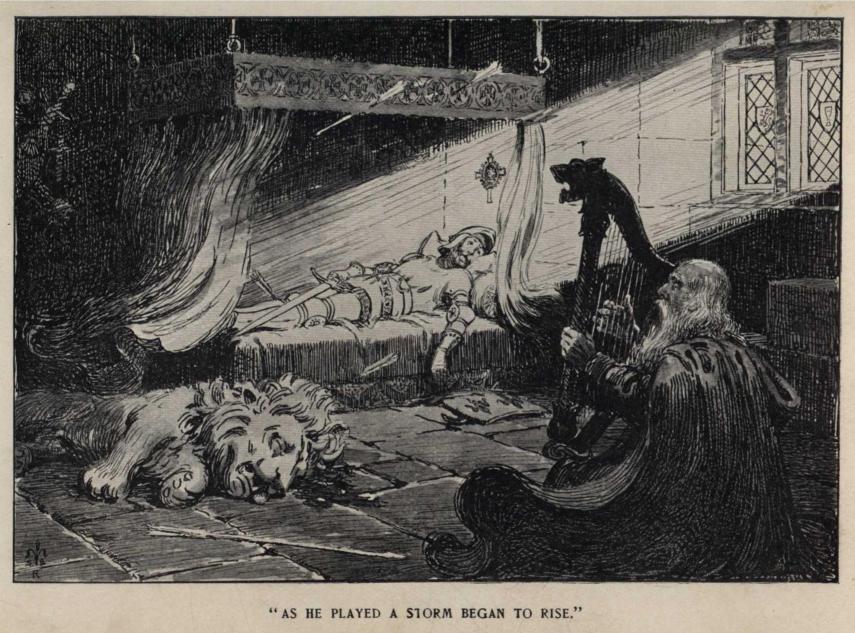

"As he played a storm began to rise"

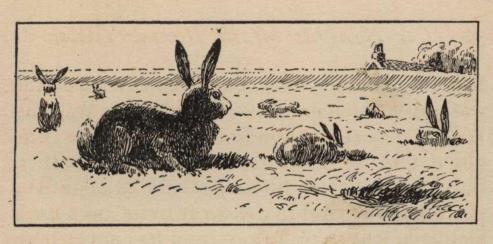

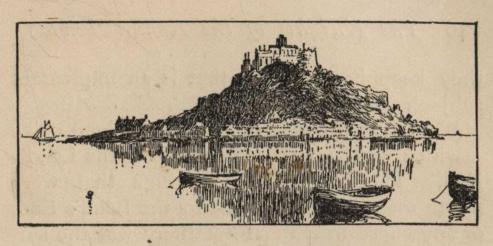

"The city and the fortress of the rabbits"

"Kay's horse galloped back alone" (missing from book)

"The bright spot on the road grew smaller and smaller" (missing from book)

"A pasture where a hundred and fifty bulls were feeding"

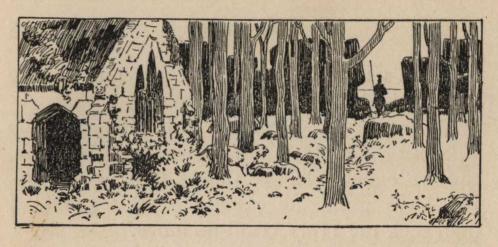

"Through woods where there were scarcely any paths to follow"

"He saw the water before him and a ship"

"'Knight,' she said, 'what are you doing here?'"

"'It was King Evelake's shield'"

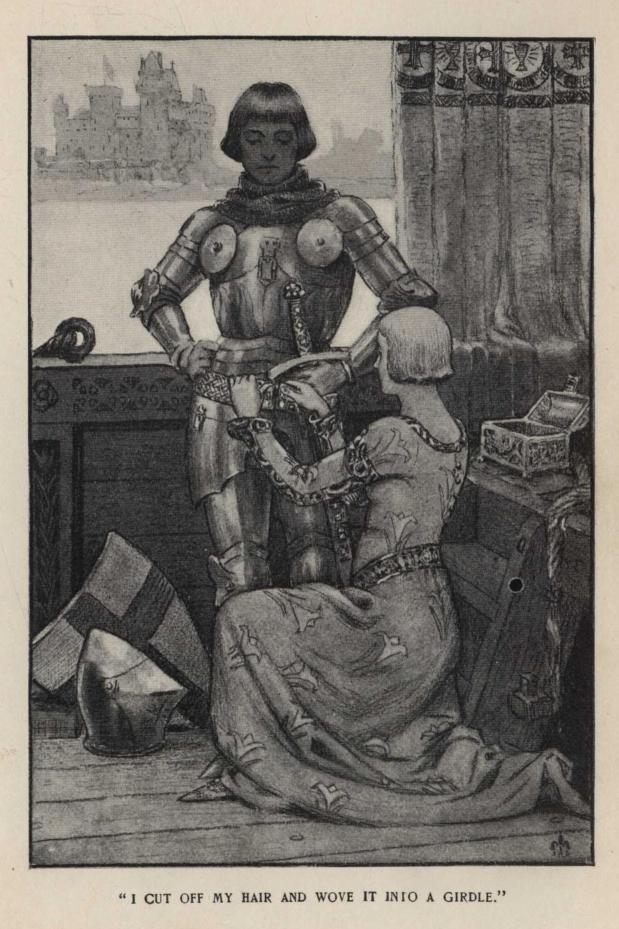

"'I cut off my hair and wove it into a girdle'"

The Dove with the golden censer

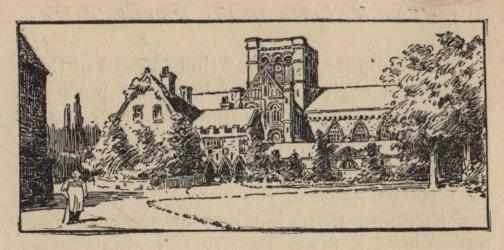

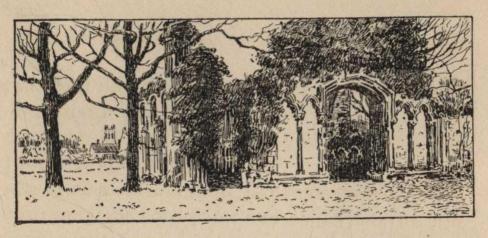

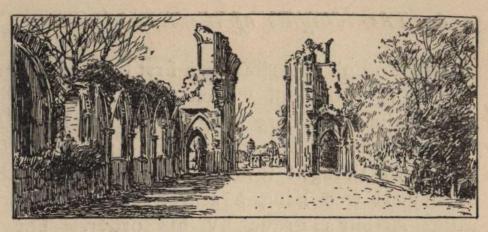

St. Joseph's Chapel, Glastonbury Abbey

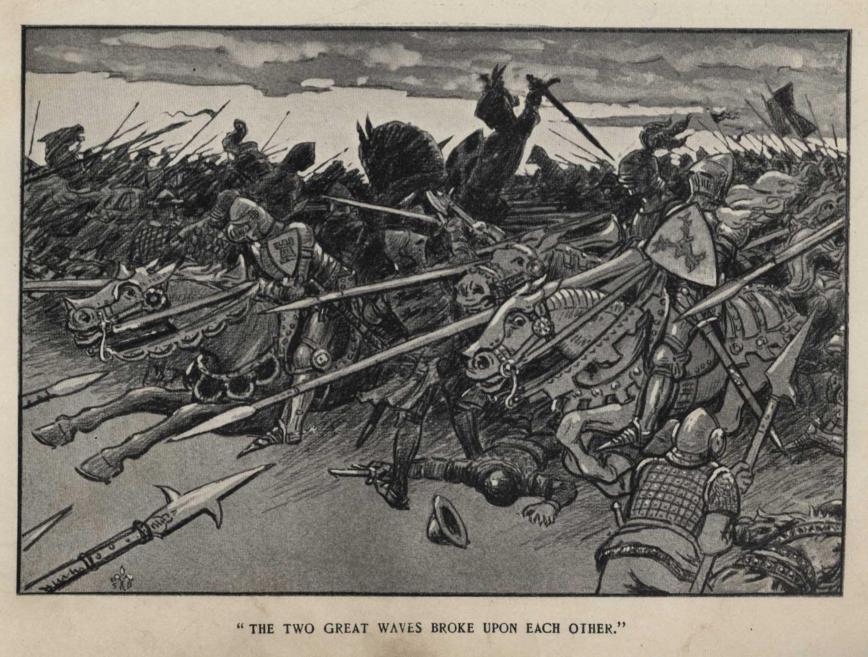

"The two great waves broke upon each other"

"On toward the gold and the purple in the west"

SOME OLDER STORY-TELLERS

There is really no need, perhaps, for me to tell you that all these stories have been told before. But, though you know it already, I like to say it again, because I can never say often enough how grateful I am to those who told the world first of Arthur, of Guinevere, of Lancelot, and of Gawain; of Galahad, of Percivale, and of Percivale's sister; of the Siege Perilous and of the Holy Grail. If you do not now count Sir Thomas Malory a dear friend, as I do, learn to do it, and you will be the better for it. I do not know who made those wonderful tales the Mabinogion, but I know who gave them to us in our own language—Lady Charlotte Guest. I wish that I knew whom to thank for "The Romance of Merlin" and for the story of "Gawain and the Green Knight." And there were many other noble story-tellers of the old time who passed away and left us no knowledge of themselves and not even their names to call them by. But they left us their stories, and if anything from us can reach them where they are, surely gratitude can, and that they must have from every one of us who loves a story. And the great poet of our own days, Lord Tennyson, must have it too, for teaching us how to read their stories.

Some time you may read these tales and others as they wrote them, and you cannot read them without thinking what a great and marvellous thing it was that they, who lived no longer than other men, could give delight to the people of so many centuries. But some of these stories are not easy to find, and some are not easy to read, when you have found them. I have tried to tell a few of them again in my own way, hoping that thus some might have the stories and know them, for whom the older books might be hard to get or hard to understand.

THE KNIGHTS OF THE ROUND TABLE

CHAPTER I

ON GLASTONBURY TOR

It was when we were making a journey in the South of England one summer that we found ourselves in the midst of the old tales of King Arthur and of the Holy Grail. "We" means Helen, Helen's mother, and me. We wandered about the country, here and there and wherever our fancy led us, and everywhere the stories of King Arthur fell in our way. In this place he was born, in that place he was crowned; here he fought a battle, there he held a tournament. Everything could remind us, when we knew how to be reminded, of the stories of the King and the Queen and the knights of the Round Table.

It was I who told the stories and it was Helen who listened to them. Sometimes Helen's mother listened to them too, and sometimes she had other things to do that she cared about more.

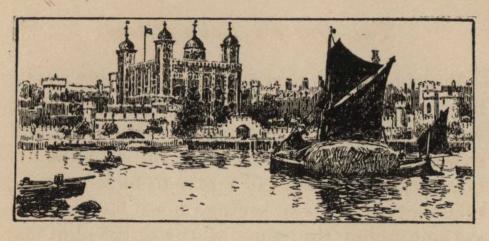

One day we had been riding for many hours on the crooked railways of the Southwest, where you change cars so often that after a little while you cannot remember at all how many trains you have taken. And late in the afternoon, or perhaps early in the evening, we saw from the window of the carriage a big hill, lifting itself high up against the sky, with a lonely tower on the top of it. And that was Glastonbury Tor.

There was no time to try to see anything of Glastonbury that night after dinner, and we were too tired. But that big hill looked so inviting that we decided that we would see it the next day and climb up to the top of it, before we did anything else. I was a little disappointed with Glastonbury, as we walked through the streets on our way to the Tor. The place looked much too prosperous to please me, and not at all too neat.

I cheered up a little when we came to the Abbot's Kitchen. It stands in the middle of a big field, with a fence around it, and we had to borrow a key from a woman who kept it to lend so that we could go in and see it. We even spared a little time from the Tor to see it in. The Abbot's Kitchen belonged to the old abbey of Glastonbury. It is a small, square building, with a fireplace in each corner. It is still in such good repair that it is hardly fair to call it a ruin, but it is a part of old Glastonbury, and we carried back the key feeling glad that we had borrowed it.

It was a good, stiff climb up the side of the Tor, and we stopped more than once to look back at the town behind us and below us. It looked prettier from here. Down there in the streets there was the noise of a busy modern town. The ways were muddy and there were rather frowsy women and children about some of the doors. But up here we were out of sight and hearing of all that. From here the town looked quiet and peaceful and beautiful—just its roofs and chimneys and towers showing through the wide, green masses of the trees, and the sound of a church chime, that rang every quarter of an hour, came to us softened and mellow.

"Down there," I said, "we saw nothing but Glastonbury—to-day's Glastonbury—but here we can see Avalon. That is Avalon down there below us, the Island of Apples, the happy country, the place where there was no sorrow, the place where fairies lived, the place where Joseph brought the Holy Grail and where he built his church. A wonderful old place it was, and it was a wonderful abbey that grew up where Joseph first made his little chapel. Our old friend St. Dunstan, who pinched the devil's nose, was the abbot there once. So was St. Patrick. When he came to Glastonbury he climbed up to the top of this hill where we are now and found, where this old tower is, the ruins of a church of St. Michael. They used to have a way of building churches to St. Michael on the tops of high hills. St. Patrick rebuilt this one and afterwards it was thrown down by an earthquake. I don't know whether St. Patrick built this tower that is here now or not.

"Did I say that fairies used to live here? Another abbot of Glastonbury found that out. He was St. Collen, and he must have lived when there was no church of St. Michael here on the top of the Tor. St. Collen was one of those men who think that they cannot serve God and live in comfort at the same time. When he had been abbot of Glastonbury for a time he thought that he was leading too easy a life, so he gave up his post and went about preaching. But even that did not please him, so he came back here and made a cell in the rock on the side of Glastonbury Tor, and lived in it as a hermit.

"One day he heard two men outside his cell talking about Gwyn, the son of Nudd. And one of them said: 'Gwyn, the son of Nudd, is the King of the Fairies.'

"Then Collen put his head out of the door of his cell and said to the two men: 'Do not talk of such wicked things. There are no fairies, or if there are they are devils. And there is no Gwyn, the son of Nudd. Hold your tongues about him.'

"'Hold your own tongue about him,' one of the men answered, 'or you will hear from him in some unpleasant way.'

"The men went away, and by and by Collen heard a knock at his door, and a voice asked if he were in his cell. 'I am here,' he answered; 'who is it that asks?'

"'I am a messenger from Gwyn, the son of Nudd, the King of the Fairies,' the voice said, 'and he has sent me to command you to come and speak with him on the top of the hill at noon.'

"Collen did not think that he ought to mind what the King of the Fairies said to him, if there really were any King of the Fairies, so he stayed in his cell all day. The next day the messenger came again and said just what he had said before, and again St. Collen stayed in his cell all day. But the third day the messenger came again and said to Collen that he must come and speak with Gwyn, the son of Nudd, the King of the Fairies, on the top of the hill, at noon, or it would be the worse for him.

"Then Collen took a flask and filled it with holy water and fastened it at his waist, and at noon he went up the hill. For a long time Collen had been abbot of Glastonbury and for a long time he had been a hermit and lived in his cell on the side of this very hill, but never before had he seen the great castle that stood that day on the top of Glastonbury Tor. It did not look heavy, as if it were built for war, but it was wonderfully high and graceful and beautiful. It had tall towers, with banners of every color hung from the tops of them and lower down, and there were battlements where ladies and squires in rich dresses stood and looked down at other ladies and squires below. And those below were dancing and jousting and playing games, and all around there were soldiers, handsomely dressed too, guarding the place.

"When Collen came near, a dozen of the people met him and said to him: 'You must come with us to our King, Gwyn, the son of Nudd—he is waiting for you.'

"And they led him into the castle and into the great hall. In the middle of the hall was a table, spread with more delicious things to eat than poor St. Collen, who thought that it was wicked to eat good things, had ever dreamed of. And at the head of the table, on a gold chair, sat a man who wore a crown. 'Collen,' he said, 'I am the King of the Fairies, Gwyn, the son of Nudd. Do you believe in me now? Sit down and eat with me, and let us talk together. You are a learned man, but you did not believe in me. Perhaps I can tell you of other things that so wise a man as you ought to know.'

"But St. Collen only took the flask of holy water from his side and threw some of it upon Gwyn, the son of Nudd, and sprinkled some of it around, and in an instant there was no king there and there was no table. The hall was gone, and the castle. The dances and the games were done, and the squires and the ladies and the soldiers all had vanished. The whole of the fairy palace was gone, and Collen was left standing alone on the top of Glastonbury Tor.

"But Glastonbury has forgotten St. Collen, I suppose. The old town is prouder now of Joseph of Arimathæa than of anybody else—prouder than it is of King Arthur, I think, though King Arthur—but I won't tell you about that now. You know how Joseph of Arimathæa buried the Christ in his tomb after He was taken down from the cross. After He had risen again the Jews put Joseph in prison, because they said that he had stolen the body. But Joseph had with him the Holy Grail, the cup in which he had caught the blood of the Saviour, when He was on the cross. It was the same cup, too, from which the Saviour had drunk at the Last Supper. It was a wonderful thing, that cup, and there are whole volumes of stories about it. The blood that Joseph had caught in it always stayed in it afterwards, and the cup and the blood seemed to have a strange sort of life and knowledge and the power of choosing. One of the wonderful things about the Holy Grail was that it could always give food to any one whom it chose, and those who were fed by the Holy Grail wanted no other food than what it gave them. And so Joseph wanted nothing while he was in prison.

"At last the Emperor had Joseph let out of his prison. And some one asked him how long it had been since he was put there, and he answered: 'I have been here in this prison for nearly three days.'

"Then they all stared at one another and whispered and looked at Joseph, and then they whispered together again. 'Why do you look at one another and at me so,' said Joseph, 'is it not three days, almost, since they put me here?'

"'It is wonderful,' said one of them; 'Joseph, you have been in this prison for forty-two years.'

"'Can it be?' said Joseph; 'it seems to me like only three days, and barely that, and I have never been so happy in my life as I have been for these three days—or these—can it be—forty-two years?'

"And this was because he had had the Holy Grail in the prison with him. Afterwards he came to England. He brought the Holy Grail here to Avalon, and the King of that time gave him some ground to build his church on. They say it was really the island of Avalon then, for it was all surrounded by marsh and water, and there was an opening, a waterway, out to the Bristol Channel. And since it ceased to be an island the sea has twice at least broken through and made it one again for a little while. But the last time was almost two hundred years ago.

"Well, when Joseph and those who were with him first came here, they rested on the hillside and Joseph stuck the staff that he carried into the ground. It was not this hill where we are, but another, Wearyall Hill. And Joseph's staff, where he had set it in the ground, began to bud, and then leaves and branches grew on it. It struck roots into the ground and became a tree. It was a thorn-tree, the Holy Thorn they called it, and always after that it blossomed twice a year, once in the time of other thorn-trees and again at Christmas. The tree was gone, of course, long ago, but other trees had grown from slips of it, and they say that descendants of it are still growing in Glastonbury gardens and that they still bloom at Christmas. I am sorry that we cannot stay here till Christmas to see if it is true.

"So, in the place that the King gave him, Joseph built his chapel of wood and woven twigs, and it was the first Christian church in England. Some of the stories say that the Holy Grail, that Joseph brought here with him, was buried at last under one of these Glastonbury hills, but that is not the story that I like the best. One story says that it was not a cup at all that Joseph brought to Avalon, but two cruets. It says besides that these two cruets were buried with Joseph when he died, and that when his grave is found, and the two cruets in it, there will never again be any drought in England. But according to the story that I like best, Joseph did not die at all, as other men die, but was long kept alive by the Holy Grail, waiting for the best knight of the world, for it was foretold that he should never die till the best knight of the world should come.

"Since it was here that the Grail was brought, I think it must have been not far from here that King Pelles lived, before Balin gave him the wound that was never to heal till the best of all knights should come. And I fancy it was somewhere near here, too, that he lived after that. He was the keeper of the Grail, and he had a castle called Carbonek. When we talk of the Grail it seems to me that everything becomes mysterious and uncertain, so that it is hard to tell where this Castle of Carbonek was. At one time it seems to have been on the seashore and at another time it seems to have been inland. But for that very reason I think that Avalon is as likely a place for it as any, for this place was inland, just as it is now, but then the waters of the sea came in around it. Yet the land around King Pelles's old castle was all laid waste, and I have never heard that the land around Avalon was so. But you see that it is all uncertain and strange, and we cannot be sure of anything about it.

"I think I have told you the story about King Pelles and Balin before, but I will tell you a little of it again, because it fits in so well just here. King Pelles was descended from Joseph of Arimathæa, and, as I said, he was the keeper of the Holy Grail. Once Balin came to his castle, seeking for Garlon, a knight who had the power of riding invisible and who killed other knights, when they could not see him. Balin found him there and killed him, and King Pelles tried to avenge his death, because he was his brother.

"Balin had broken his sword and he fled from King Pelles and ran through the castle till he came to a chamber where Joseph of Arimathæa, who was kept alive by the power of the Holy Grail, was lying in a bed. And beside him was a spear, with drops of blood flowing from the point. It was the spear with which the Roman soldier wounded the side of the Christ when He was on the cross. Balin seized it and turned upon King Pelles and wounded him with it in the side.

"Then the whole castle fell down around them and all the country about it became waste and dry and desolate. Balin lay under the ruins for three days, and then Merlin, the great magician of King Arthur's court, came and woke him and gave him a horse and a sword and sent him on his way. Afterwards Balin met his brother Balan, and they fought, neither of them knowing who the other was, till they killed each other. Then Merlin took the sword with which Balin had killed his brother and drove it into a great stone, up to the hilt, and set the stone floating on the river. And he wrote on the stone that no knight should ever draw this sword out of the stone except the one to whom it should belong, the best knight of the world.

"I cannot tell you how King Pelles got out of the ruins of his castle, but afterwards he had another castle, the one that was called Carbonek. He was still the keeper of the Grail. And it was foretold that the wound in the side that Balin had given to him with the spear would never be healed till the best knight of all the world should come. So for many years King Pelles lived in his castle and bore the pain of a wound that always seemed new and fresh, and waited for the coming of the best knight of the world.

"This is getting to be a rather rambling sort of story, and while we are rambling perhaps I may as well tell you about the adventure that Sir Bors had at the Castle of Carbonek. Bors was a knight of the Round Table. He was one of the best of all of them. He sat at the table in the next seat but one to the Siege Perilous. The Siege Perilous was the seat on the right of the King's. Merlin had made it when he made the Round Table, and he said that no one should ever sit in it without coming to harm, except the best knight of all the world. So for many years no one had sat in that seat. And no one sat in the one next to it either, but Bors sat in the one next to that. Next to him sat his cousin Lancelot. They were the sons of two kings who were brothers, Ban and Bors, who had helped King Arthur, when he first came to his throne.

"Lancelot was counted as the best of all King Arthur's knights. He was the strongest and the bravest of them all, people said, and the best fighter, and the King and the Queen loved him more than any of the others. Nobody could see why he should not sit in the Siege Perilous, but whenever a knight came to the Round Table his name appeared of itself, in gold letters, in the seat that he was to have; and nobody could sit in the Siege Perilous till his name came in it.

"But I set out to tell you about Sir Bors. Once Bors came to the Castle of Carbonek. A wandering knight, in those days, was always welcome in every castle, and so King Pelles welcomed Bors. The King was brought into the hall and Bors was placed at the table between him and his daughter. And there in the hall, too, Bors saw a beautiful child, a boy, with deep eyes and a bright, sweet face and golden hair. He was the son of King Pelles's daughter, and I will tell you more about him another time.

"It was a strange way of entertaining guests that they had here, Bors thought, for, though they were sitting at the table, there was nothing to eat on it. Just as Bors noticed this he saw a white dove fly into the room. It carried a little golden censer, by a chain which it held in its beak. The thin smoke from the censer spread through the hall and filled it with a strange, sweet odor. And while the dove flew about the hall a girl came in, carrying something covered with white silk, which she held high up in her hands. Bors could not see what it was that she carried, but all who were in the hall knelt down and looked up toward it, and Bors did the same. But though the covering of silk hid the thing itself which was under it, there was something about it that it could not hide. For the white silk was all glowing with a rosy light that came from within it, and it shone through it and shed a rosy brightness all through the hall. The dove flew out of the room again and the girl went away too. And this was the Holy Grail that had passed, and Bors had not seen it.

"But when it was gone and Bors looked at the table again it was covered with food, finer and more delicious than Bors had ever tasted or seen before. 'There are strange things to see in your castle, King Pelles,' said Bors.

"'There are stranger things than you have seen yet,' King Pelles answered. 'It is a place of wonders and of danger for knights, and few of them leave here without coming to harm. Only for the best of them is it safe to stay all night in my castle. You, Sir Knight, may stay if you will, but it will be better for you to go, and so I warn you.'

"'It is not for me to say,' Bors answered, 'that I am better than other knights, and indeed I know some who are better than I. But I am not afraid to be in your castle for a night, and here I will stay.'

"'Do as you please,' said the King, 'but I have warned you.'

"So, when it was time to go to bed, Bors was led to a chamber and left alone in it. Nothing that the King had said had made him afraid, but he thought that it would be better not to take off his armor. And as soon as he had lain down in his armor a great beam of light shone upon him. He could not tell where it came from, but suddenly, along in the beam of light, came a spear, with no hand to hold it, and a little stream of blood flowed from the point of the spear. And before Bors could move the spear came upon him and went through his armor as if it had been a cobweb and made a deep wound in his side. The spear was drawn away again, but with the pain Bors fell back upon his pillow and did not see where it went.

"Then there came a knight, all armed, with his sword drawn, and the knight said: 'Sir Bors, arise and fight with me.'

"Bors was almost fainting, because of the wound in his side, but he arose and tried to fight. And when he tried he found that he could fight better than he thought. He fought the other knight till he gave ground before him, little by little, and at last Bors forced him out of the chamber. Then Bors lay down again to rest, and all at once the room was full of falling arrows. He could not see where they came from, any more than he could see where anything else came from, but they fell all around him and upon him. They pierced his armor, just as the spear had done, as if there had been no armor, and they wounded him in many places. And these wounds and the wound that the spear had made burned and smarted more than before, and Bors felt weaker and fainter.

"Then a lion came into the chamber and sprang upon Bors and tore off his shield. But again Bors found that he could fight if he tried, and he struck the lion's head with his sword and killed it.

"And next there came an old man, who had a harp. He sat down and began to play on the harp and to sing, and as he played a storm began to rise outside the castle. At first it was only a rising of the wind that Bors heard, but it grew and grew, till it swept through the halls and the corridors of the castle and through the room where Bors lay. It caught at the curtains and the tapestries of the chamber and almost tore them from their places, and it shook the arms that hung on the walls, till they rattled together with a dull, ghostly clatter. Bors could hear the wind, too, rushing and roaring and screaming up over the towers. And then the rain came, and the thunder, with noises of splitting and crashing as if the hills around were breaking and rolling down into the valleys, and the very walls shuddered and trembled, and the lightning was so fierce that it seemed to shine through the walls, as if they had been made of glass.

"But all through the dreadful noise of the storm Bors could hear the soft voice of the old man who sang, as if there had been no other sound. He sang a song of how Joseph of Arimathæa had come to England and had brought the Holy Grail. When he had finished it he spoke to Bors, and, as he talked and as Bors answered him, the storm grew louder and more terrible. 'Bors,' said the old man, 'leave this place. You have done nobly here. There are few knights in the world who could bear all that you have borne to-night. Tell your cousin Lancelot all that you have seen, and tell him that it is he who should be here and should see these things and more, but that he is not so good a knight as to be allowed to see what you have seen. These things are only for the best of knights.'

"'It is well for you,' said Bors, 'that you are old. I am weary with fighting and I am faint and dizzy with many wounds, but in spite of all, if you were not old and weak, I would not hear you say such things of my cousin Sir Lancelot. Sir Lancelot is the best knight that lives, and what any good knight can do or see Lancelot can do or see.'

"'Bors, Bors,' said the old man again, 'do not think that you can frighten me with loud talk. In the strength of his arm and the sureness of his spear and the power of his sword, Lancelot is the best knight that lives, but, for all that, he is not so good a knight as you, Sir Bors. Bors, what did you, and what did Lancelot swear when King Arthur made you knights of his Round Table?'

"'We swore,' said Bors, 'that we would help the King to guard his people, that we would do right and justice, that in all things we would be true and loyal to God and to the King.'

"'Yes, Bors,' said the old man, 'that was what you swore, and have you kept your oath, both by your deeds and in your heart?'

"'As far as God has given me power,' Bors answered, 'I have kept it.'

"'Yes,' said the old man, 'you have kept it well. But how has Lancelot kept it?'

"'Old man,' said Bors, 'do you dare to say to me, Lancelot's cousin and his friend, that he has not kept his oath?'

"'Bors, Bors,' said the old man again, 'do not try to frighten me. I dare to tell you anything that it is good for you to know. In all his deeds Lancelot has kept his oath, but how has he kept it in his heart? Go and ask him. Ask him if in his heart he has always been true and loyal to the King. Ask him if he has never grown proud of his strength. Ask him if he has not sometimes done his deeds for the Queen's praise, and not for the King's love and the King's glory. Ask him if he has never wished that he himself were such a king, with such a queen. Ask him if that wish was all true and loyal to the King. Bors, Bors, out there in the world, where you and Lancelot live, the strongest knight is the best, and Lancelot is the best knight—out there in the world. But this is the castle of the Holy Grail, and the Holy Grail searches the hearts of men. Here, in this chamber, Sir Bors, Lancelot could not stay as you have stayed and see what you have seen and bear what you have borne.'

"As the old man ceased to speak it seemed to Bors that the burning of his wounds grew less. While he was thinking of this and of what the old man had said, the old man was gone, he could not tell where. Then, he could not tell from where, the white dove flew into the room. It was the same dove that he had seen in the hall, and it held the same little gold censer in its beak, and again there was the sweet odor through the room. And when the dove came the storm was ended. There was no more blinding lightning and the thunder sounded only a little and far off. The rain ceased and all the wind died down.

"Then Bors saw four children pass through the room, carrying four lighted tapers. With the four children was a figure like an old man. It wore a long, white robe, and a hood hung low down over the face, so that all that Bors could see of it was the end of a white beard. In the right hand was that spear, with the little stream of blood flowing from the point. There was no one to tell Bors who this was, but somehow he seemed to know that it was Joseph of Arimathæa.

"They passed through the room, but still Bors could see them in the next chamber. The children knelt around the old man and he held high up in his hands that wonderful thing with the covering of white silk. Again the soft, rosy brightness glowed through the silk, and Bors did not know why it was that when he saw it he felt so peaceful and glad. Then he heard a loud voice that said: 'Sir Bors, leave this place; it is not yet time for you to be here.'

"Then all at once the door was shut and Bors could not see the children or the old man or what he carried. The strange, bright light that had shone upon him all this time was gone. Outside the storm and the clouds were past, and a clear ray of moonlight shone through the chamber. All the pain of his wounds was gone and he sank back upon his pillow and slept.

"When he awoke in the morning it seemed to him that he had never felt so strong and fresh. The wounds that he had had from the spear and the arrows had left no scar. And when King Pelles saw him he said: 'Sir Bors, you have done here what few living knights could do, and I know that you will prove one of the best knights of the world.'

"Then Bors remembered that the voice had told him that it was not time yet for him to be in this place, so he took his horse and rode away toward Camelot, to find Lancelot and to tell him what he had seen."

CHAPTER II

HOW WE DISCOVERED CAMELOT

One of the strangest things about this kind of travel is to find how much more you know about the country than the people do who live in it. Before we came to England at all I had read in certain books that the real Camelot was in the county of Somerset. It was at Camelot that King Arthur lived more than anywhere else and where he had his finest castle. So of course we were anxious to see Camelot. Our trouble did not seem to be that we could not find it; it was that we found it in too many places. We had been to Camelford, a poor little village in Cornwall, earlier in our journey, and they had told us that that was Camelot. We did not really believe it, but neither did I feel quite sure that my books were right about the place in Somerset. We thought that it would be best to see all the Camelots, so that we could make up our minds which one we ought to believe in, or whether we ought to believe in any of them at all.

I had studied the books and I had studied the maps, till I almost felt that I could go straight to this Camelot, without any help. It was still called Camelot, it seemed, and it was a fortified hill, near a place called Queen Camel, some dozen miles to the south of Glastonbury.

It was lucky that I knew all this, because when we asked the people of the hotel in Glastonbury if they could give us a carriage and a driver to take us to Camelot they said that they had never heard of any such place. They had heard of Queen Camel. They did not know just where even that was, but they thought that it might be found. I felt so sure that the books and the maps and I were right about it that I told them that we would take the carriage and go to Queen Camel, and then we would see if we could find Camelot. No doubt they thought that we were insane, but that made no difference to us, and as long as we paid for the carriage it made no difference to them.

Helen's mother is one of those dreadfully sensible people who always want you to take umbrellas and things with you. She was not going with us to discover Camelot, but she said that we must take umbrellas and mackintoshes with us, because it was going to rain. It is always hard to argue with these people, because they are so often right. This time we really had no excuse for not taking them, for they would simply be put in the bottom of the carriage and they would be no trouble. So we took them, and we were scarcely outside Glastonbury before we found that this was one of the times when Helen's mother was right. For then it began to rain. The driver had taken the way that he thought was toward Queen Camel, and we were riding across a great stretch of low, level land. The wind swept across it, and the rain came at us in sheets. We didn't mind it much, with our mackintoshes on, but I did think that it was fair to ask Helen what she thought of the poet who said that this Avalon was a place "Where falls not hail, or rain, or any snow."

"Maybe it is," she answered, pulling her water-proof hood down so that scarcely a bit of her could be seen, except the tip of her nose; "this rain doesn't fall; it just comes against us sideways." So the poet's reputation was saved.

It could not rain so hard as this very long, and by and by it stopped altogether. Then it began again, and there were showers all day. Sometimes it looked as if it were going to stop for good, but we could scarcely get our waterproofs off before it began all over.

"Isn't it curious," I said, "that a storm coming up just here should remind me of a story? It is about a time when Gawain had to go out in bad weather. This is the right time to tell the story, too, while we are looking for this particular Camelot. For the story begins at Camelot, and the learned man who first dug it out of its old manuscript and printed it says that Camelot was in Somerset.

"King Arthur was keeping Christmas at Camelot with his knights. The feast lasted for many days. On New Year's Day, as they all sat in the hall, the King and the Queen and the knights, there rode in the most wonderful-looking man whom they had ever seen. He was dressed all in green, and the big horse that he rode was green. And that was not all, for the hair that hung down upon his shoulders was like long, waving grass, and the beard that spread over his breast was like a green bush. He wore no helmet and he carried no shield or spear. In one hand he held a branch of holly and in the other a battle-axe. It was sharp and polished so that it shone like silver. 'Who is the chief here?' he cried.

"'I am the chief,' Arthur answered; 'sit down with us and help us keep our feast.'

"'I have not come to eat and drink,' said the man in green. 'I have come to see if it is true that you have brave knights in your court, King Arthur.'

"'Then sit and eat with us first,' Arthur answered, 'and afterwards you shall have as many good knights to joust with you as you can wish, and you shall see whether they are brave.'

"'It is not for jousting that I have come, either,' said the man in green. 'Do you see this axe of mine? I will lend it to any knight in this hall who dares to strike me one blow with it, only he must promise that afterwards I may strike him one blow with it, too. He shall strike me with the axe now, and I will strike him with it a year from this day.'

"This was such a new way of proving whether they were brave or not that for a minute none of the knights answered. Then the King himself rose and went toward the man in green. 'Give me your axe,' he said; 'none of us here is afraid of your big talk; I will strike you with the axe myself, and you shall strike me with it whenever you like.'

"Then Gawain sprang from his seat. Gawain was the King's nephew. And he cried: 'My lord, let me try this game with him! You are the King, and if any harm should come to you it would be the harm of all the country, but one knight more or less will count but little.'

"Then many other knights begged the King to do as Gawain had said, and the King thought of it a moment, and then gave the axe, which he had taken from the man in green, to Gawain.

"Sir Knight,' said the man in green, 'will you tell me who you are?'

"'I am Gawain,' he said, 'the nephew of King Arthur.'

"'I have heard of you,' said the other, 'and I am glad that I shall receive my blow from so great a knight. But will you promise that a year from now you will seek me and find me, so that I may give you your blow in return?'

"'I do not know who you are or where you live,' Gawain answered. 'If you will tell me your name and where to find you, I will come to you when the year is over.'

"'I will tell you those things,' said the man in green, 'after you have struck me. If I cannot tell you then, you will be free of your promise and you need not seek me.'

"Then the man in green came down from his horse, knelt on the floor before Gawain, put his long, green hair aside from his neck, and told Gawain to strike. Gawain swung the axe above his head and brought it down upon the neck of the man in green, and his head was cut cleanly off and rolled upon the floor. Instantly the green man sprang after it and caught it in his hands, by the long, green hair. He sprang upon his horse again and held up the head, with its face toward Gawain. 'Sir Gawain,' it said 'seek for me till you find me, a year from now, so that I may return your good blow. Bring the axe with you, and ask, wherever you go, for the Knight of the Green Chapel.' Then he rode out of the hall and away, still carrying the head in his hands.

"Of course Gawain and the King and all the rest thought that this was the strangest adventure that they had ever seen. They were all sorry for Gawain and they all wondered what would become of him, but there was no danger for a year, and that always seems a long time, at the beginning of it. So, as the time went on, they almost forgot about the Knight of the Green Chapel, and even Gawain himself seemed to have no dread of him. And the year went past like other years. Yet Gawain was not forgetting his promise, and, as the time came near when he must keep it, he began to wonder more and more who this Knight of the Green Chapel could be and where he must go to look for him. 'It may take me a long time to find him,' he said to the King at last, 'and so I mean to leave the court and to begin my search on All Saints' Day.'

"'Yes,' said the King,' that will be best. And we know all the places and nearly all the knights here in the South and in the West of England, and over in the East, but we have never heard of this Knight of the Green Chapel, so it will be best for you to seek him in the North.'

"So, on All Saints' Day, King Arthur made a feast, that all the knights of the court might be together and bid Gawain good-by. They called it a feast, but there was no happiness in it. They were all sad at the parting and with the fear that Gawain would never come back.

"And when the time came they helped Gawain to put on the finest armor that could be found for him and he mounted his horse and left them. He rode slowly at first, and as soon as he came to places that he did not know he began to ask the people whom he met if they could tell him where to find the Green Chapel and the Knight of the Green Chapel. But no one had ever heard of such a place or of such a person.

"He went farther and farther into the North, and as his time grew shorter he tried to travel faster, for he felt that it would be a shame to him if he did not find the Knight of the Green Chapel by New Year's Day. Up great hills he went and down into deep valleys, across wide, lonely plains, with freezing winds sweeping over them, and through dark forests, where the wind cried up among the treetops and the trees groaned and sighed in answer. Often he met wild beasts, wolves that barked and leaped and sprang about him and tried to pull down his horse. But he killed them or beat them and drove them away. Then he came to plains where for many miles he saw no houses and no people. Often he had to sleep in his armor, lying on the ground. Often he had to go so long without food that he was faint with hunger, as well as weary.

"As the days went by the winter came on rougher and stormier and colder. Then the winds that swept across the plains were full of driving rain and sleet and snow. They cut against his face and almost blinded him, and his horse could scarcely labor through the drifts and stand against the storm. The wet sleet found its way into the joints of his armor and froze there, and it froze into the chains of his mail and choked them up, so that it was all rigid and hard, and it was as if all that he wore were one solid piece of iron or ice. So terrible it was that he almost forgot why he had come, and all that he wanted was to find some place where he and his horse could rest and be warm. But at night he must get off his horse, though he could scarcely bend his limbs, in his frozen armor, and lie down in it, with no shelter but a tree, or perhaps a high rock, and try to sleep till the light came, so that he could go on again.

"Yet wherever he saw any people he asked them if they knew of the Knight of the Green Chapel, and always they answered no. Then he told them how the knight looked, but they all shook their heads or stared at him or laughed, and they all said that they had never seen such a knight. Some of them thought that he must be mad, to be wandering all by himself and asking for a knight with green hair and a green beard, and sometimes Gawain himself almost thought that he must be mad. Sometimes he thought: 'I will hunt for him only till New Year's Day. If I have not found him then it is his fault that he did not tell me where to come, and I shall be free of my promise.' And then at other times he thought: 'I will not count my promise as so small a thing; I will seek this knight as long as I live, if I do not find him, for the honor of King Arthur and the Round Table.'

"And the cold and the storm and the long, rough journey seemed worst of all to Gawain on Christmas Eve, for then he thought most of the King and the Queen and the knights whom he had left at Camelot. He knew that they were all together in the great hall now, that the fires were blazing, that the minstrels were singing, and that a noble feast was spread upon the Round Table. He thought of his own place at that table, where he had sat a year ago, empty now. Did the others look at that seat and think of him and wonder where he was? It was a common thing, he knew, for Arthur's knights to be away from the hall seeking adventures, and he knew that those who were left behind went on with their feasting at such times as these, just as if all were there. No, it was a little thing to them that he was gone, he thought. They were laughing together and eating and drinking, and perhaps some one was telling them some strange old tale, and they were warm and happy; and the light of the fires and the torches was shining on the windows of the hall, so that the people of the country miles away could see it and could say: 'King Arthur and his knights are at Camelot to-night keeping the Christmas feast.' And here was he alone, cold, hungry, weary, riding over the rough ways and through the rough night, to find a man who was to kill him.

"Then there came another thought that made him stronger: 'The honor of the Round Table to-night is not all with those who sit about it; it is here with me too. I am here because it was I who dared to come, for the King and for all of them. If I never go back the King and all of them will know that, and they will not forget. And now my time is short and I must not rest any more. I will ride all night and go as far as I can to find the Knight of the Green Chapel by New Year's Day.'

"So Gawain rode all night. In the morning he was in a great forest, where it would have been too dark for him to ride, but for the snow that lay everywhere, so that he could dimly see the black trunks of the trees against it. And before the first cold light of the late morning fell into the forest, he saw it touch the top of a high hill before him, and there he saw a castle. It was one of the greatest castles he had ever seen, with strong towers and thick walls and high ramparts. And as soon as he saw it, it seemed to him as if the last strength went out of him and his horse too, so that they could scarcely climb the hill to come to the gate and ask if they might come in.

"But they reached the gate and the porter said: 'Come in, Sir Knight; the lord of the castle will welcome you and you can stay as long as you will.' And the lord of the castle did welcome him and Gawain let his men lead him to a chamber, where they took off his armor and gave him a rich robe to wear. Then they led him back to the hall and placed him at the table with the lord and his wife and his daughter.

"They asked him who he was, and he told them that he was Gawain, a knight of the Round Table. 'It is a proud day for us,' said the lord, 'so far away up here in the North, when a knight comes to us from the court of King Arthur, and now you will stay with us and help us keep our Christmas.'

"'No,' said Gawain, 'I cannot stay, for I must go on and find the Knight of the Green Chapel,' and then he told them all that he knew about this knight and why he had made this journey.

"'Then you will stay with us,' said the lord, 'for the Green Chapel is only two miles from here, and on New Year's Day some one of my servants shall show you the way there.'

"So Gawain stayed, and, on the third day after he had come to the castle, the lord told him that on the next day he was going hunting and asked Gawain if he would go too. 'No,' Gawain answered, 'it is only four days now before I must go to the Knight of the Green Chapel. I have no magic, such as he has, to guard myself against him, and he will kill me. It is not a time now for me to think of hunting or of other pleasures. I must think of more solemn things.'

"'Then shall we make a bargain?' said the lord. 'I will go to the hunt to-morrow, and you shall stay here at the castle. When I come home I will give you all that I have got in the hunt, and you shall give me all that you have got by staying here.'

"'It shall be so, if you wish it,' said Gawain.

"The next morning the lord and his men were away early at the hunt. Gawain breakfasted with the lady of the castle and her daughter, and afterward they left him and he sat alone in the hall. Then the lord's daughter came back, without her mother, and sat on the seat beside him. 'Sir Knight,' she said, 'will you tell me about King Arthur's court?'

"'What shall I tell you?' he asked.

"'We are so far away from all the world here!' she said. 'We never see a town or a court or any people, except those who live here with us. But sometimes we hear strange things and beautiful things about Camelot and Caerleon and London and the court of King Arthur. They say that we cannot believe how grand it is, and they say that there are such feasts and tournaments, and that all the knights and the ladies are so happy there in King Arthur's court! And oh! will you tell me one thing! Is it true that every knight of King Arthur's has some lady whom he loves more than anybody else, and is it true that every lady has some knight whom she loves, who fights for her and wears something that she gave him, a sleeve or a chain or a jewel, and tells everybody that she is the most beautiful lady in the world?'

"'There are many knights,' Gawain answered, 'who have ladies whom they love and who love them, and they do all the things that you have said.'

"The girl looked at Gawain and was silent for a little while, and then she said: 'Sir Knight, is it too much that I am going to ask? I would not ask you to be my knight, for there must be many ladies in King Arthur's court more beautiful and more noble than I am. You would have to love some one of them, I suppose. Only do not tell me so, and I will not ask you. But after you have gone let me remember you and love you, and I will try not to think whether you love me or not.'

"'My child,' said Gawain, 'I am here in your father's castle and he trusts me, and it is not right that I should talk to you of such things without his leave. And besides that, it is not right for me to think of such things now. You know that I am going to find the Knight of the Green Chapel. Your father has promised that on New Year's Day he will send me to him. Then the Knight of the Green Chapel will kill me. I have only three days more to live, and it is no time for me to think of love.'

"'But why must you find this wicked Knight of the Green Chapel?' she asked. 'Go back to Camelot and tell the King and the knights that you fought him and that he could not hurt you. Nobody will know but us. We never go to court and we never would tell anybody what you had done.'

"'No, no,' said Gawain, 'I promised him that I would find him. Now I must find him or I never could go back to King Arthur's court or be one of his knights again.'

"Then the girl started to go out of the hall, but when she was at the door she turned and came back to Gawain. 'Will you let me kiss you just once?' she said. And Gawain let her kiss him and she went away.

"At night, when the lord of the castle came home from the hunt, he brought with him a deer that he had killed. He gave it to Gawain and said: 'This is what I got in the hunt; now give me what you got by staying behind.'

"Then Gawain gave him a kiss. 'Indeed,' said the lord, 'I think that you have done better than I. Where did you get this?'

"'It was not in our bargain,' said Gawain, 'that I should tell you that.'

"'Very well, then,' said the lord, 'shall we make the same bargain for to-morrow?'

"'Yes,' said Gawain, 'if you wish it.'

"So the next day the lord rode to the hunt again and Gawain stayed behind, as he had done before. And again the lord's daughter came to him as he sat in the hall. 'Sir Knight,' she said, 'is it because you have some other lady whom you love that you will not let me be your lady? I do not ask you to love me, you know, only to let me love you.'

"'No,' Gawain answered, 'I have no lady, and if I might have any now, I could love you as well as any other, but I have only two more days to live and I must not think of such things.'

"Then the girl kissed him twice and went away. When the lord came back that evening he brought the head and the sides of a wild boar that he had killed. He gave these to Gawain and Gawain gave him two kisses. 'You always have better luck than I,' said the lord.

"Then they made the same bargain for the third day, and in the morning the lord rode to the hunt and Gawain stayed behind. As he sat in the hall the lord's daughter came to him again. 'Sir Knight,' she said, 'since you will do nothing else, will you not wear something of mine, as the knights at King Arthur's court do for their ladies? See, this is it, my girdle of green lace. And it is good for a knight to wear, for while you have this around your body you can never be wounded.'

"Then Gawain thought that such a girdle as this would indeed be of use to him, when the time came for the Knight of the Green Chapel to strike him with his axe. So he took the girdle and thanked her for it, and she kissed him three times and went away.

"That night the lord of the castle brought home the skin of a fox. He gave it to Gawain and Gawain gave him three kisses. 'Your luck grows better every day,' said the lord.

"Early the next morning Gawain rose and called for his armor and his horse. One of the lord's servants was to show him the way to the Green Chapel. The snow was falling again and there was a fierce, cold wind. It was not daylight yet. They rode over rough hills and through deep valleys for a long time, and at last, when it had grown as light as it would be at all on such a dull, dreary day, the servant stopped. 'You are not far now,' he said, 'from the Green Chapel. I can go with you no farther. Ride on into this valley. When you are at the bottom of it look to your left and you will see the chapel.'

"Then the servant turned back and left Gawain alone. He rode to the bottom of the valley and looked about, but nothing like a chapel did he see. But at last he saw a hole in a great rock, a cave, with vines, loaded down with snow, almost hiding its mouth. Then it seemed to Gawain that he heard a sound inside the cave, and he called aloud: 'Is the Knight of the Green Chapel here? Gawain has come to keep his promise to him. He has brought his axe, so that he may pay back the blow that he received a year ago. Is the Knight of the Green Chapel here?'

"Then a voice from the cave said: 'I am here, Sir Gawain, and I am waiting for you. You have kept your time well.'

"And then out of the cave came the Green Knight. It seemed to Gawain that he looked stronger and fiercer than when he was at Arthur's court, and that his hair and beard were longer and of a brighter green. 'Give me my axe,' he cried, 'and take off your helmet and be ready for my stroke. Let us not delay!'

"'I want no delay,' said Gawain, and he took off his helmet, knelt down on the snow and bent his neck, ready for the knight to strike. The Green Knight raised his axe, and then, in spite of himself, Gawain drew a little away from him.

"'How is this?' said the Green Knight; 'are you afraid? I did not flinch when you struck me, a year ago.'

"'I shall not flinch again,' said Gawain; 'strike quickly.'

"Then the knight raised his axe a second time and Gawain was as still as a stone. But this time the axe did not fall. 'Now I must strike you,' said the Green Knight.

"'Strike, then, and do not talk about it,' said Gawain; 'I believe you yourself are losing heart.'

"This time the knight swung the axe quickly up over his head and brought it down with a mighty force upon Gawain's neck, and it made only a little scratch. The girdle of green lace would not let him be wounded. Then he sprang up and drew his sword and cried: 'Now, Knight of the Green Chapel, take care of yourself. I have kept my promise and let you strike me once, but I warn you that if you strike again I shall resist you.'

"'Put up your sword,' the Knight of the Green Chapel answered; 'I do not want to harm you. I could have used you much worse than I have, if I had wished. I tried only to prove you, and you are the bravest and the truest knight that I have ever found. I am the lord of the castle where you have stayed for this last week. I knew where you got your kisses, for I myself sent my daughter to you to try you, and you would not do what you thought would not be right toward me, and you would not let any thoughts of love turn you aside from your promise to the Knight of the Green Chapel. You were well tried and you proved most true. It was because of that and because you kept your word to me on the first two days that I went to the hunt, that I did not strike you the first or the second time that I raised my axe. But the third time I did strike you, because you were untrue to me in one little thing. For you said that you would give me all that you got by staying in the castle, yet you did not give me the girdle of green lace. It was I who sent that to you by my daughter, too. But you kept it only to save your life, and so I forgive you, and to show you that I forgive you, you may keep it now always.'

"But Gawain tore off the girdle and threw it at the feet of the Knight of the Green Chapel. 'Take it back!' he cried, 'I do not deserve ever to be called an honorable knight again! I came here for the honor of the Round Table, and then I broke my promise to you. Tell me why you came to our court and why you brought me to this shame, and then I will go back to King Arthur and tell him that I am not worthy any longer to be one of his knights. He will ask me why you did this, so tell me and let me go away, for now I have lied to you and I cannot look you in the face.'

"'I did it,' said the Knight of the Green Chapel, 'because the great enchantress, Queen Morgan-le-Fay, King Arthur's sister, who hates him, told me that all his knights were cowards. She said that all who praised them lied or were themselves deceived and that some good knight ought to go and prove them to be the cowards that they were. So I went to try whether they were brave or not, and it was by the magic of Queen Morgan-le-Fay that I was not killed when you cut off my head. But now I see that what I did was wrong. It was Morgan-le-Fay, I see now, who hoped to bring shame on King Arthur's court, because she hated him. And you have shown me that Arthur's knights are brave and true, for you took my challenge and came up here into the North to find me and to let me kill you. Now come back with me to my castle and help us to keep the festival of the New Year. Take up your girdle and come.'

"But Gawain was still filled with shame and horror at what he had done. 'I will not go back with you,' he said, 'but I will keep the girdle to remind me of this time. If I ever feel that I am doing better things and if I ever begin to grow proud of them, I will look at this girdle and it will make me remember how I broke my word.'

"And Gawain would not listen to anything more that the knight said, but he mounted his horse and turned him toward the south and rode away. Gawain never knew what happened to him on that journey back to Camelot. Perhaps the nights were as cold and the ways as rough as they had been before. Perhaps the wild beasts came against him again. Perhaps the storms still drove the snow and the sleet against him, so that they cut him in the face and froze into his armor. He cared for none of these things and he remembered none of them afterwards. His one thought was to get back to Camelot and tell the King that he was no longer worthy to be his knight, and then to go where no one who had known him should ever see him again.

"And so he rode on, as fast as he could, for he did not know how many days, and at last, in the early winter evening, he saw the glow in the windows of the castle at Camelot. Once more he hurried his horse till he reached the gate. He threw himself down from the saddle and hastened to the hall, where a great shout went up: 'Gawain is alive and he has come back!' and the knights and the ladies crowded around him to ask him where he had been and what he had seen and done. He pushed his way through them all and threw himself down upon the floor before the King. He told all of his story, how he had gone out for the honor of the Round Table and how he had broken his word and been shamed, and at the end he held up the girdle of green lace and said: 'My lord, I shall leave you now and I shall never see you again, for I am not worthy to be your knight, but I shall carry this with me, and shall always wear it, so that I never can forget my shame."

"And the King answered: 'Gawain, you are still among the best of my knights. You failed a little at last, but it was no coward and no false knight who went up there to seek his death and to keep a promise that he need not have kept. Wear your girdle, but it shall be no shame to you. And that it may be none all my knights shall wear girdles of green lace like it.

"So the story says that all of King Arthur's knights wore green lace girdles in honor of Gawain. I don't know what became of the girdles afterwards, but they cannot have worn them always, or at least Gawain cannot have worn his. For you know he could never be wounded while he had it on, and he certainly was wounded afterwards. But I will tell you about that when I get to it."

About the time that we got to the end of this story we came to a place which the driver said was as far from Glastonbury as he had ever been in this direction. We stopped at a little inn by the road, and the driver asked the way to Queen Camel. We also asked the man who told him if he had ever heard of a hill or of any sort of place about here called Camelot, but he never had. So we went on to find it for ourselves. After more riding and more asking of the way and more showers, we came to Queen Camel. It was past luncheon-time then, and, what was more to the point, it was past the horse's luncheon-time. So we decided that we would not go any farther till we had all had something to eat.

The Bell looked like the best hotel in the place, so we went there and astonished the proprietor and all the servants by asking for something to eat. But we got it, and while we were at luncheon the driver put the horse in the stable and then talked with the proprietor, to find out whether he knew anything about Camelot. Now the keeper of this bit of an hotel must have been a remarkably intelligent man, for he really did know something about it. He came in to see us and he said that he thought that it must be Cadbury Castle that we were looking for. Then a great light shone upon me and I remembered what I ought to have remembered before, that one of my books at home had said that it was called Cadbury Castle now. "But do they not call it Camelot too?" I asked him. I did not like to give up that name.

"Oh, yes, sir," he said, "they call it Camelot too."

"And do they say that King Arthur lived there?"

"No, sir, he didn't live there; he placed his army there."

Then the landlord went away and came back with a big book, a history of Somersetshire, or something of that sort, to show us what it had to say about Cadbury Castle. It did not say much that I did not know before, but it said enough to prove what I wanted to know most of all. And that was that this Cadbury Castle was without any doubt the place that we were looking for. We finished our luncheon, the landlord showed us our way, and we went on again.

It was only a little way now. We were to find a steep road that led up the side of the hill to Cadbury Castle. It was too steep, we were told, to take our carriage up, and we should have to leave it at the bottom and walk. And so it proved. We found the hill and the steep little track up its side. We got down from the carriage, and, while we waited for the driver to find a safe place to leave the horse, we gazed up the hill, along the rough little road, and knew that at last we were before the gates of Camelot.

CHAPTER III

THE BOY FROM THE FOREST

We walked up the steep road, and just before we came to the top of the hill the rain began again. There was one little house near the top and we decided to let Camelot wait for a few minutes longer and go into the house and stay till the rain stopped.

The woman of the house seemed to be glad to see us, and she asked us to write our names in her visitors' book. The names and the dates in the book showed that Camelot had some six or eight visitors a year. Of course we tried to get the woman to tell us something about the place, and of course we failed. She knew that it was called Cadbury Castle and sometimes Camelot and sometimes the Camp. She knew that the well close by her house was called King Arthur's Well, but she did not know why. The water in it was not good to drink, and in dry times they could not get water from it at all. She got drinking-water and in dry times all the water that she used from St. Anne's Wishing Well, a quarter of a mile around the hill. She did not know what that name meant either. She used to have a book that told all about the place, but she couldn't show it to us, because it had been lent to somebody and had never been returned. The vicar had studied a good deal about the place too, and he knew all about it. Could we find the vicar and get him to tell us about it? Oh, no, it wasn't the present vicar, it was the old vicar, and he was dead.

So we gave up learning anything and waited for the rain to stop, and then went out to see as much as we could for ourselves. The hilltop was broad and level. I can't tell just how broad, because I am no judge of acres, but I believe it was several. It had a low wall of earth around it, covered with grass, of course, like all the rest of the place. When we stood on the top of this wall and looked down, we saw that the ground sloped away from us till it made a sort of ditch, and then rose again and made another earth wall, a little way down the hillside. Then it did the same thing again, and yet once more. So in its time this hilltop must have had four strong walls around it. It really looked much more like a fort or camp than like a city. It seemed too small for a city, though it might have been a pretty big camp. If we had been looking for hard facts, I think we should have believed what the hotel-keeper had said, that this was not where King Arthur lived, but where he placed his army.

I remembered reading somewhere that the Britons and the Romans and the Saxons had all held this place at different times. I had read, too, I was sure, that parts of old walls, of a dusky blue stone, and old coins had been found here. It was a fine place for a camp or a castle. It was so high and breezy and we could see for so many miles across the country, that we could understand how useful and pleasant it must have been for either or for both. It was pleasant enough now, this broad, grassy hilltop, with its four grassy walls and the woodland sloping away from it all around. But nobody lived here now to enjoy it—nobody, that is to say, but the rabbits. For the place is theirs now, and they dig holes in the ground and make their houses where King Arthur's castle stood, where he and his knights sat in the hall about the Round Table, and where all the greatest of the world came to see all that was richest and noblest and best for kings and knights to be and to enjoy.

The rabbits scuttled across our way, as we walked about, and leaped into their holes, when we came near, and then looked timidly out again, when we had gone past, and wondered what we were doing and what right we had here in their Camelot. There were only these holes now, where once there were palaces and churches, and no traces of old glories, but the walls of earth and turf. Yet it seemed better to me that Camelot should be left alone and forgotten, like this, the city and the fortress of the rabbits, but still high and open and fresh and free, than that it should be a poor little town, full of poor little people, like Camelford. Helen said that she thought so too, when I asked her, and she was willing that this should be Camelot, if I thought that it really was.

"Really and truly and honestly," I said, "I think that this is as likely to have been Camelot as any place that we have seen or shall see. It is lucky for us that we know more about it than the people who live about here do. If we did not I am afraid it would not interest us much. I think that I have read somewhere that the King and his knights were still here on the hilltop, kept here and made invisible by some enchantment, that at certain times they could be seen, and that some people had really seen them. I don't believe this story, but while we are here let us believe at least, with all our might, that we are really and truly in Camelot.

"Now here is a story, with Camelot in it, that you ought to hear. You must not mind if it makes you think of a story that we saw once in the fire. There are different ways of telling the same story, you know, and this is a different way of telling that same story.

"Once, when Arthur was first King of England, he had a good knight called Sir Percivale. He was killed in a tournament by a knight whom no one knew. Some who saw the fight said that it was not a fair one and that Sir Percivale was as good as murdered. The knight who killed him wore red armor, and once, when his visor was up, Arthur saw his face. No one knew where the knight went afterward and Arthur could never find him to make him answer for the death of Sir Percivale.

"Now this Sir Percivale had seven sons and a daughter, and six of his sons were killed also, in tournaments or battles. But the youngest of the sons was not old enough yet to be a knight, and when his mother had lost her husband and all her sons but him, she resolved that he should never be a knight. His name was Percivale, like his father's. It was right, she thought, for her to keep this last son that she had safe and not to let him fight and be killed, as his father and his brother's had been. And she feared so much that when he grew up he would want to be a knight, like the others, that she resolved that he should never know anything about knights or tournaments or wars or arms.

"She took him far away from the place where they had lived, and made a home in the woods. It was far from the towns and the tournaments and the courts, and it was even away from the roads that led through the country. It was a lonely place that the mother chose, and she hoped that no one would ever come to it from the world that she had left. She brought her daughter with her, I suppose, though the story says nothing about her just here, and she brought nobody else but servants—women and boys and old men. Nobody in her house was ever allowed to speak of knights or arms or battles or anything that had to do with them. She would not even have any big, strong horses kept about the place, because they reminded her of the war horses that knights rode. She tried to bring up her boy so that he should know only of peaceful things. He should know the trees and the flowers of the woods, she thought; he should know the goats and the sheep and the cows that they kept, how the fruits grew in the orchard, how the birds lived in the trees and the bees in their hive; but he should never know the cruel ways of men out in the world. He should see the axe of the woodman, not the battle-axe; the scythe, not the sword; the crook of the shepherd, not the spear.

"So the boy grew up in the forest and ran about wherever he would and climbed the trees and followed the squirrels and studied the nests of the birds and knew all the plants that grew and all the animals that lived about him. If it had not been for many things that his mother taught him he would have been almost like one of the animals of the wood himself. He could run almost as fast as the deer and he could climb almost as well as the squirrel, and he could sing as well as some of the birds.

"When he grew a little older his mother let him have a bow and arrows to play with and shoot at marks, but nobody told him that men used bows and arrows to shoot at one another or that men ever wanted to harm one another. But he began to shoot at the birds with his arrows, and at last he hit one of them and killed it. Then he looked at the dead bird lying at his feet and he heard the other birds singing all around him. And he thought: 'I have done a dreadful thing; a little while ago this bird was singing too, and was as happy as the rest of them, and now it can never sing any more or be happy any more, because I have killed it.' And he broke his bow and threw it away and he threw himself down on the ground beside the little dead bird and cried at what he had done. And when his mother saw how grieved he was she said that all the birds should be driven away, so that they should not trouble him. But Percivale begged her to let them stay. He liked to hear them sing, and to drive them off would be a crueler thing than he had done already. And his mother thought: 'The boy is right; I brought him here to find peace and safety for both of us, and why should I not let the poor birds stay in peace and safety too?'

"But it was foolish for the poor woman to think that she could keep her boy so that he would never know anything of the world. The world was all around him, no matter how far off, and it was sure some time to come where he was. And so, one day, as he was wandering in the wood, he saw three horses coming, larger and stronger and finer than any horses he had ever seen before. And on their backs, he thought, were three men, but he could not feel sure, for they did not look like any men whom he had ever seen. They seemed to be all covered with iron, which was polished so that it glistened where the light touched it, and they wore many gay and beautiful colors besides. He stood and looked at them till they came close to him, and then one of them said: 'My boy, have you seen a knight pass this way?'

"'I do not know what a knight is,' Percivale answered.

"'We are knights,' the man on the horse said; 'have you seen anyone like us?'

"But Percivale was wondering so much at what he saw that he could not answer. 'What is this?' he asked, touching the knight's shield.

"'That?' the knight answered, 'that is my shield.'

"'And what is it for?'

"'To keep other knights from hitting me with their spears or their swords.'

"'Spears? What are they?'

"'This is a spear,' the knight answered, showing him one.

"'And what is this?'

"'That is a saddle.'

"'And what is this?'

"'A sword.'

"And so Percivale asked the knights about everything that they wore and everything that they carried and all that was on their horses. 'And where did you get these things?' he asked. 'Did you always wear them?'

"'No,' the knight answered; 'King Arthur gave me these arms when he made me a knight.'

"'Then you were not always a knight?' Percivale asked again.

"'Why, no, I was a squire, a young man, like you, and King Arthur made me a Knight and gave me these arms.'

"'Who is King Arthur, and where is he?'

"'He is the King of the country, and he lives at Camelot.'

"Then Percivale ran home as fast as he could and said to his mother: 'Mother, I saw some knights in the forest, and one of them told me that he was not a knight always, but King Arthur made him one, and before that he was a young man like me. And now I want to go to King Arthur, too, and ask him to make me a knight, so that I can wear bright iron things like them and ride on a big horse.'

"The instant that she heard the word 'knights' the mother knew that all her care was lost. The boy was a man now. He had seen what other men were like and she knew that he would never be happy again till he was like the rest of them. Before her mind, all at once, everything came back—the court, the field of the tournament, the men all dressed in steel, with their sharp, cruel spears, the gleaming lines charging against each other, the knights falling from their horses and rolling on the ground. Her brain whirled around as she thought of all this, and her one last son in the midst of it, to be killed, perhaps, as the rest had been. But she knew that he must go—that he would go—nothing could keep him with her now.

"'My son,' she said, 'if you will leave me and be a knight, like those that you have seen, go to King Arthur. His are the best of knights and among them you will learn all that you ought to know. Before you are a knight the King will make you swear that you will be always loyal and upright, that you will be faithful, gentle, and merciful, and that you will fight for the right of the poor and the weak. Percivale, some knights forget these things, after they have sworn them, but you will not forget. Remember them the more because I tell them to you now. Be ready always to help those who need help most, the poor and the weak and the old and children and women. Keep yourself in the company of wise men and talk with them and learn of them. Percivale, the King will make you swear, too, that you will fear shame more than death. And I tell you that. I have lost your father and your brothers, but I would rather lose you, too, than not to know that you feared shame more than death.'

"Then, from the horses that his mother had, Percivale chose the one he thought the best. It was not a war horse, of course, and it was not even a good saddle horse, but it would carry him. He put some old pieces of cloth on the horse's back, for a saddle, and with more of these, and bits of cord and woven twigs he tried to make something to look like the trappings that he had seen on the horses of the knights. Then he found a long pole and sharpened the end of it, to make it look like a spear. When he had done all that he could he got on the back of the horse, bade his mother good-by, and rode away to find the court of King Arthur.

"The King and the Queen and their knights were in the great hall of the castle at Camelot, when a strange knight, dressed in red armor, came in and walked straight to where the King and the Queen sat. A page was just offering to the Queen a gold goblet of wine. The red knight seized the goblet and threw the wine in the Queen's face. Then he said: 'If there is any one here who is bold enough to avenge this insult to the Queen and to bring back this goblet, let him follow me and I will wait for him in the meadow near the castle!' Then he left the hall, took his horse, which he had left at the door, and went to the meadow.

"In the hall all the knights jumped from their places. But for an instant they only stood and stared at one another. They remembered the Green Knight, and they thought that this other knight would never dare to do what he had done, unless he had some magic to guard him against them. I am sure that in a moment some one of them would have gone after him, but just in that moment a strange-looking young man rode straight into the hall, on a poor, old, boney horse. He looked so queer, with his simple dress and the saddle and trappings that he had made himself, and his rough pole for a spear, that the knights almost forgot the insult to the Queen in looking at him, and some of them laughed as they saw him ride through the hall toward the King, with no more thought of fear than if he had been a king himself. He came to where Kay, King Arthur's seneschal, stood, and said to him: 'Tall man, is that King Arthur who sits there?'

"'What do you want with King Arthur?' said Kay.

"'My mother told me,' the young man answered, 'to come to King Arthur and be made a knight by him.'

"'You are not fit to be a knight,' said Kay; 'go back to your cows and your goats.' Kay was a rough sort of fellow and he was always saying unpleasant things without waiting to find out what he was talking about.