BOOKS BY

FRANCES BONKER

AND

JOHN JAMES THORNBER

Copyright, 1932,

By THE MACMILLAN COMPANY.

All rights reserved—no part of this book may be reproduced in any form without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer who wishes to quote brief passages in connection with a review written for inclusion in magazine or newspaper.

Set up and electrotyped.

Published February, 1932

PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

NORWOOD PRESS LINOTYPE, INC.

NORWOOD, MASS., U.S.A.

To the Memory of My Father

JAMES THORNBER

A Seeker After the Odd and

the Beautiful in Nature

J. J. T.

To My Aunt

LIDA PLANT TRUMBULL

A Collector of Rare and Unique Specimens

of the Weird Fantastic Clan

F. B.

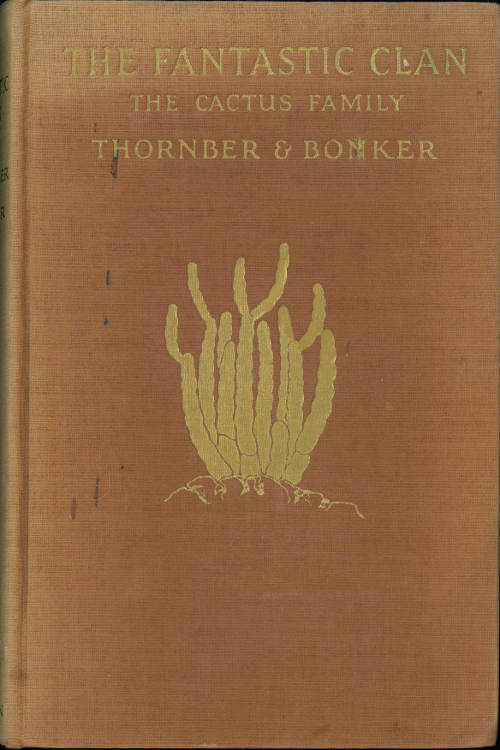

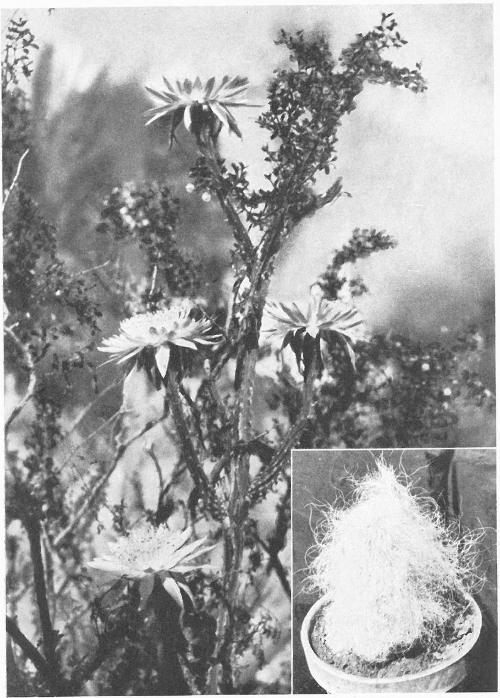

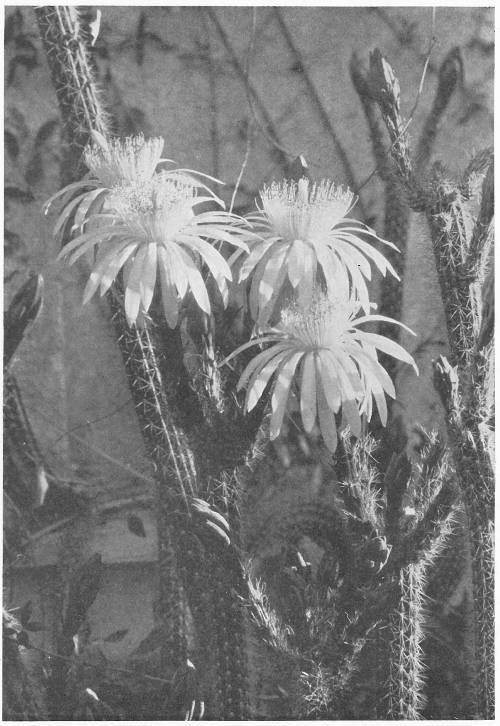

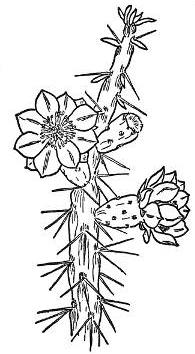

MEXICAN NIGHT BLOOMING CEREUS; REINA DE NOCHE; SERPENT CACTUS (Cereus serpentinus)

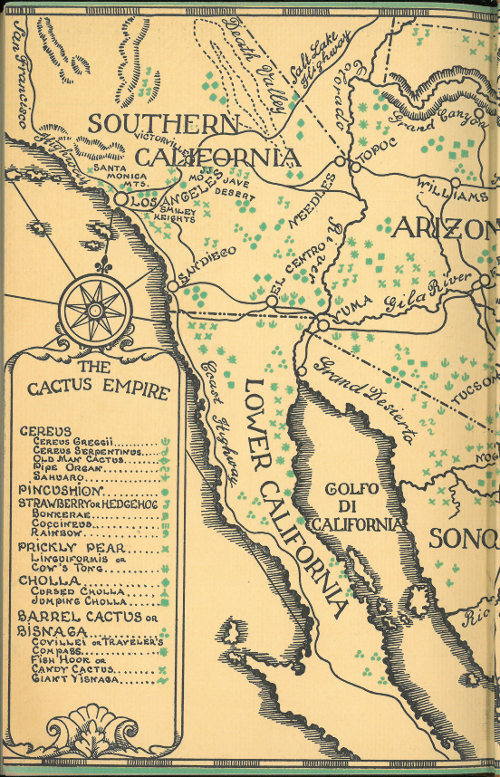

Studies of that unique and fascinating growth, the Cactus plant, treating of all the most important groups of Cacti known, with scientific accuracy, and depicting the charm of the desert land, its magic spell and wondrous lure, in the great Cactus area of the world, the American desert of the Southwest.

By JOHN JAMES THORNBER, A.M.,

Professor of Botany, University of Arizona

and FRANCES BONKER.

THE MACMILLAN COMPANY

NEW YORK MDCCCCXXXII

In this book we are going to introduce something new and interesting to many, the weird cactus plant life of the Southwestern desert—strange and marvelous growths which we call the Fantastic Clan; and to increase the reality and charm of the subject we will take an imaginary trip into the domain of the flowers of the desert. We shall explain here how to come to know them, and how to grow them in gardens; and we hope that, after reading, you will desire to have a cactus garden of your own, for the desert cacti are so different and so beautiful, with their symmetry of filigree and lacework, their fantastic shapes and marvelous colorings, and in many cases with a perfection of design that seems to have just come from the draughting board. We will not attempt to picture all the wondrous beauty of the Night Blooming Cereus, nor to tell how dainty the Arizona Rainbow and the California Pincushion really are. We will try, however, to treat in large measure about them, and about all the most important groups of cacti known to man, here in Mexico and our own Southwest, the great cactus area of the earth. We will show where they live and how they live, and in what manner they grow; and when you actually see them, in traveling across the Great American Desert, you will appreciate the wondrous beauty of desert creations and the flashes of brilliant color, gorgeous beyond description. No artist can paint nor pen describe the weird Fantastic Clan, as they are glimpsed peering out from under the rocks or gathered in clusters and patches surrounded with their [viii] dead-looking, drab-colored neighbors; or rearing their stately heads far above the ordinary walks of life in columnar pillars of towering strength. There is a fascination away out there on the desert; nevertheless, unlike the strange weird members of the cactus clan, we come not to stay, but only to enjoy the charm of the desert, to study and learn, and then to depart on our way.

Without help from the following persons and organizations, it would have been impossible for us to make such careful study of these plants, so widely distributed over the Southwestern deserts:

We thank Dr. James Greenlief Brown and Dr. Rubert Burley Streets of the University of Arizona for numerous photographs; Professor Andrew Alexander Nichol of the University of Arizona for rare species of cacti collected; Dr. Forrest Shreve of the Carnegie Institution of Washington for specimens of plants and photographs; Evelyn Thornber for pen-and-ink drawings of cacti; Miss Frances Hamilton, Mr. William Palmer Stockwell, Mr. Frank Henry Parker, and Mr. Barnard Hendricks for assistance in making careful studies of the cacti; the University of Arizona and the Desert Botanical Laboratory of the Carnegie Institution for help in procuring specimens of cacti for comparative study.

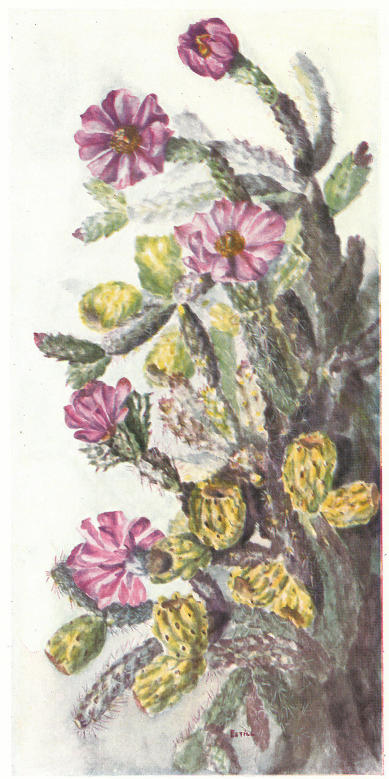

We are deeply indebted to Mrs. John Wilmot Estill of Los Angeles, California, for her exquisite paintings used in this book.

John James Thornber

Tucson, Arizona

Frances Bonker

Pasadena, California

October 1, 1931

We believe that many readers are interested in the mysterious plants and flowers of the desert, especially of the great Southwest. Here in our own back yard, as it were, in sunny California and also over in that great sand pile of southwestern Arizona, sometimes called the “Studio of the Gods,” time has carved and chiseled out wonderful valleys and cañons, and graced their floors with tiny streams of water like threads of molten silver on burnished sands. This desert fairyland is brimful of Nature’s most curious plants and flowers. Here in Nature’s workshop you will find plants and flowers weird and marvelous, of fantastic shapes and grotesque design, of glowing hue and exotic fragrance.

Out where rock and sand and gravel, and sagebrush and mesquite and chaparral struggle hard to hold on to life, the giant cactus, Sahuaro, the Old Man cactus known as Cereus senilis, the Prickly Pear Opuntia, and the wonderful Night Blooming Cereus live on peacefully and quietly and seem to smile down on man and beast and reptile, in the magnificent splendor of their brilliant flowers and fruit in the spring. Drought or rain in plenty seems to make but little difference to most of these, for the reason that Nature, the Great Engineer, has given these plants a unique structure which enables them to store up enough moisture in their reservoir systems to last, in some cases, as long as three years, if the rains should not come. It would tax man’s ingenuity to the utmost to beat that!

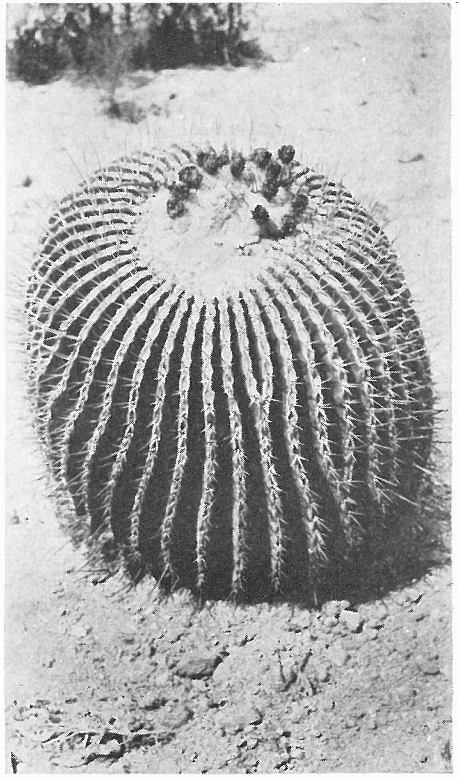

Do you know how the Cursed Cholla gets its name? or why the cactus spines are such a puzzle to the botanist? or the romance Time has woven round the Night Blooming Cereus? or why the Barrel cactus is the Indian’s friend in time of drought, the traveler’s friend when lost? or why the Fishhook cactus is called by that name? Would you know a Pipe Organ cactus if you saw one? Do you know that the Strawberry cactus or Hedgehog is delicious for food?

“The Fantastic Clan” tells you about all these things. In this book we take you on a pleasant journey through a wonderland of plant life, stopping at lonely isolated spots to view the Night Blooming Cereus cactus, whose ethereal beauty vies with the famous orchids of the South American forests. And to see this lovely queen in all her pristine beauty will make you forget the orchid and the rose! We also get a glimpse of the Hawaiian Night Blooming Cereus, so exquisitely beautiful that, for ages, in faraway Hawaii magnificent fiestas have marked the opening of the buds and the blooming of the Night Blooming Cereus.

Then we take you into the presence of the giant cactus, Sahuaro, which in a previous volume we have called the Sage of the desert; steadfast, towering pillarlike fifty feet into the air, he gives a sense of power to all who behold him, some certain realization of the grandeur and the mystery of God’s creations here on Earth.

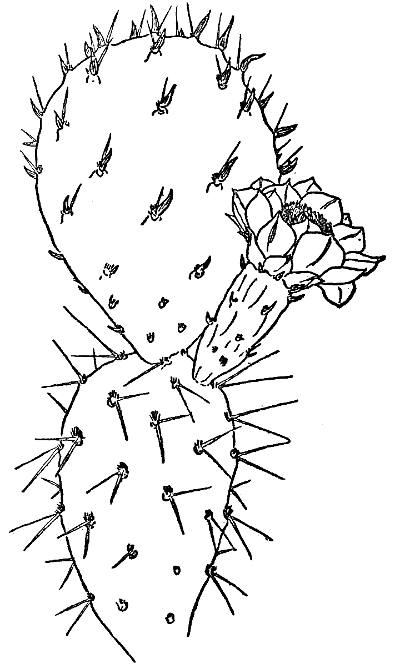

The Serpent cacti, with their grotesque angular arms projecting like so many sinuous tentacles, claim our attention next; and the Prickly Pears, advance guard for the entire cactus clan, pass before our gaze. Many, many others, of fantastic shapes and distorted growth, freaks of nature, also numbers of God’s glorious creations, flowers of ethereal beauty, trees, majestic and noble, crowd into this picture stretched before our eyes in one vast scene of limitless sand, the Great American Desert.

Kipling once said, “When you’ve heard the East a-calling, you won’t have anything else.” And this is true of the desert. The charm of the desert, once it gets its hold on you, always brings you back. There are no fears nor dreads out there; it is the place where mankind can go and rest.

When springtime comes it is time to be on the move, to see new places, new things, to enjoy, to learn. Early in April we start on a trek or trip by automobile across the Giant Amphitheater of the Sun, somewhere on the great desert along the Mexico-California frontier and thence on into Southern California; seeking out the plants and flowers which appear now in gay spring tints and hues, scrutinizing their wondrous beauty, their colorings and fantastic shapes, their scientific make-up and their dwelling places, and occasionally their grotesque appearance.

The desert is an enormous caldron of burning sand, rolling and rising and sinking here and there. But in the spring these arid lands present a striking parade of beautiful flowers—a veritable fashion show! It is early in the morning of a cloudless April day; the night dew is on most of the blossoms, and they are fresh from its bath. There is no dust and their colors are still bright as we inhale the fragrant scent. The desert glow is brightening, for the sun is rising just over the eastern rim of the foothills, and we stop to gaze upon the first of a colony of cacti called the Cereus Group. The name Cereus is musical; we find that it is from the [2] Latin, meaning torch, and is given to this genus in the family of Cactaceæ because of the beautiful candelabralike branching of some of its members.

They are trees, shrubs, or climbers, growing erect or spreading out with ribbed branches; they are the tallest and largest of the Cactaceæ. The flowers are funnel-form, some are elongated and very showy, and we find that they bloom mostly in the darkness of the desert night. Perhaps this night blooming accounts for the softness and brilliance of their delicate colorings, as of the orchids, the most gorgeous of which as you know come from the deep shaded forests of the South American jungles. The genus Cereus is very large, comprising more than two hundred varieties. Their native habitats are in South America, Central America, the West Indies, Mexico, and southern United States.

Lower California, Magdalena Island

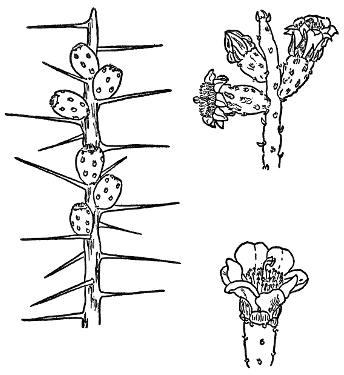

The first of these growths to attract our attention is the weird Creeping Devil cactus! How apropos is this nomenclature! We see it here in Lower California, Cereus eruca, creeping along the coastal lands and over the fine drifted sands of the seashore like countless thousands of caterpillars crawling over the ground, worming their way slowly across the sandy plains to the sea. This remarkable cactus grows on the coastal plains of Lower California and is abundant on Magdalena Island in very sandy soil, preferring the softer sand for its habitat and particularly the wind-drifted material, over small areas of which it forms a more or less continuous covering, broken here and there by dead stems. In [3] the clumps of this cactus the desert foxes live; for in its natural habitat it prevents the sand from drifting and offers homes for the little animals of the region.

The stems lie flat on the ground with their tips somewhat upturned, thus resembling huge caterpillars, head and body; they grow along on the ground, rooting from their lower surfaces, elongating at the tips, and dying back behind, which results in a slow forward movement of the whole plant. When this cactus meets with a log or stone the stem with its upraised tip gradually grows over this hindrance, up one side and down the other, and by the dying back of the rear end, in time passes over the obstruction. The stems, varying from three to nine feet in length and nearly as large as a man’s arm, are very spiny, with fifteen to twenty radial and central thorns of a dark brownish hue and dull tan, turning to grayish white with age, the tips translucent yellow. The flowers are bright yellow, the fruit delicious and relished by Indians and Mexicans both as a salad and as a preserve.

Lower California, Sonora, and Southwestern Arizona

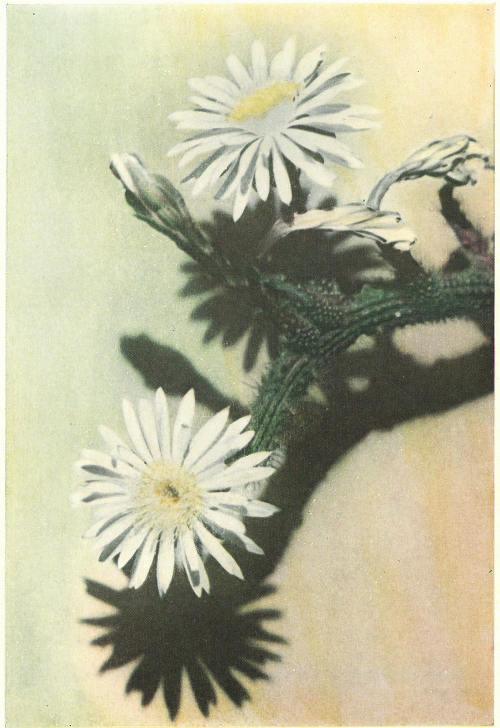

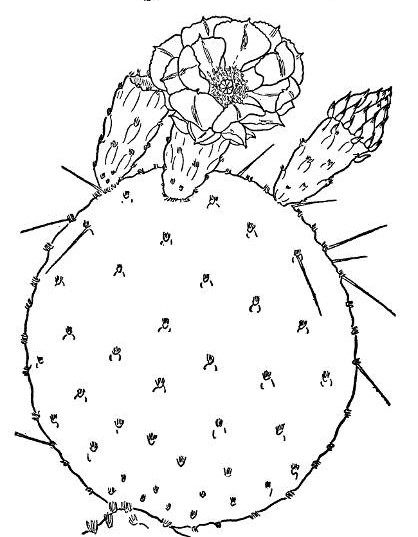

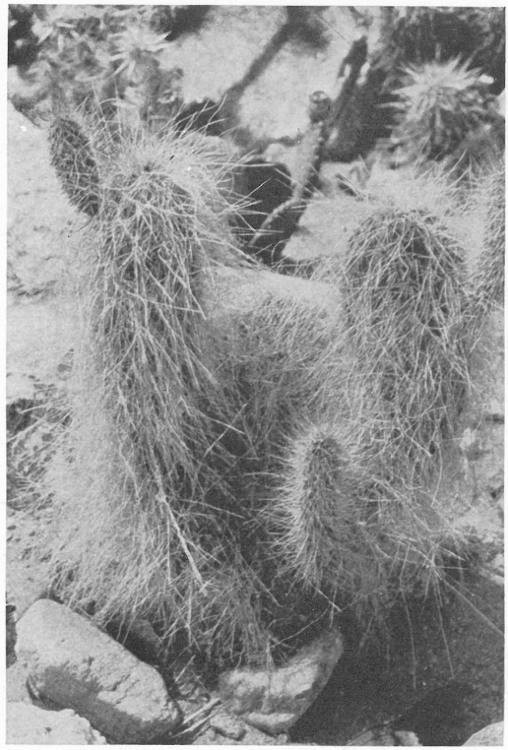

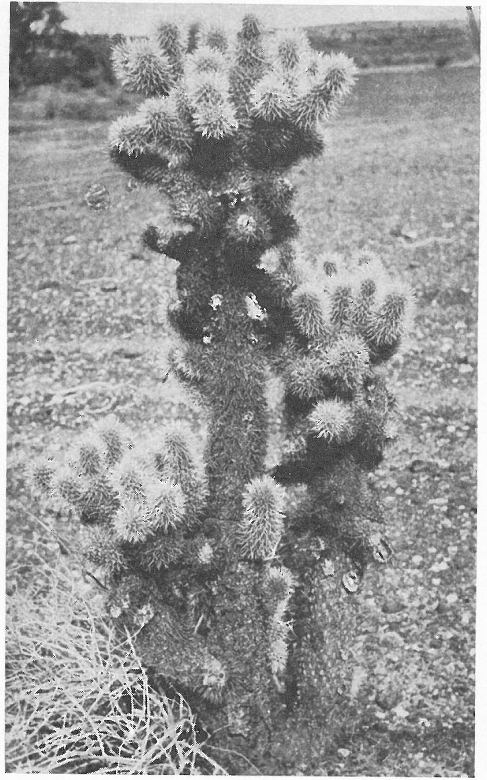

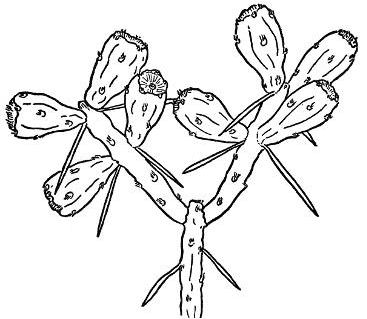

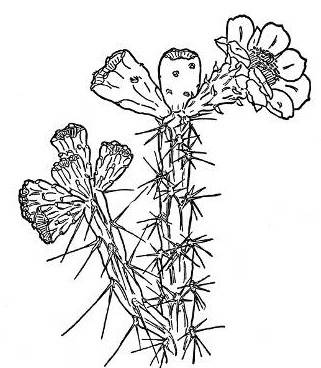

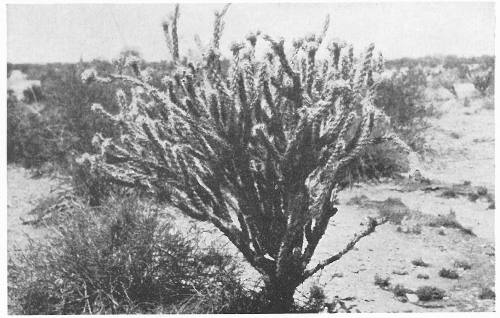

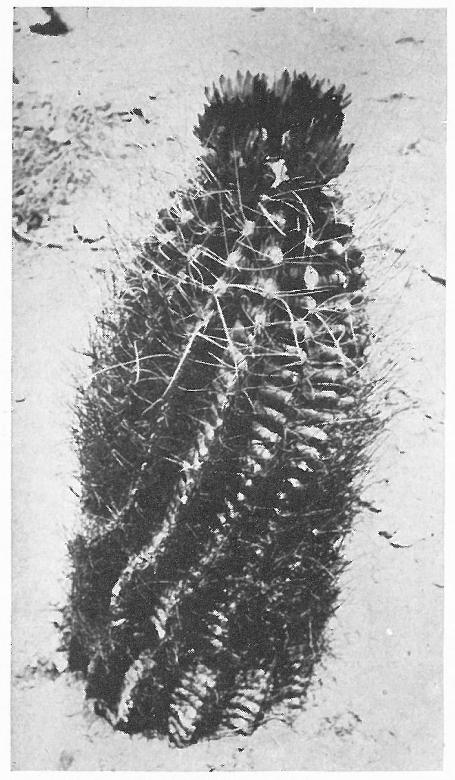

SENITA, ZINA, OR SINA (Cereus Schottii)

The next growth to attract our notice is that called by botanists Cereus Schottii or Lophocereus Schottii. It is named also for convenience Senita, Zina, and Sina. This is a remarkable cactus found in Sonora (a state of Northern Mexico), southwestern Arizona, and Lower California under the most arid conditions. It grows commonly in colonies and patches in the mountain cañons and there enjoys protection that the individual plants do not have. The young plants are equipped with silvery, short, stout spines, and the old ones with slender, long, flexible bristles, grayish or purplish gray, giving the appearance of old age—hence the [5] common popular name of Senita. At a little distance these bristlelike thorns appear like fine purplish bands, from their symmetrically twisted spiral arrangement on the five- to twenty-foot yellow-green stems, which are supported by wooden cores or scalloped cylinders. Senita plants are very striking on the arid mountain slopes, along the foothills, and in protected valleys and cañons where the winter is warm and the summer hot, their dense branches often interlocking in huge clumps twenty feet across and twenty-five feet high. Their bristly stems resemble somewhat a squirrel’s tail or bottle brush, and in Mexico the plants are grown for fences which are unique and effective. The flowers are about an inch and a half long and as wide, shaped like a bell, with very lovely cream-white and pale pink petals shading into deep pink at the tips. The fruit is a greenish brown changing to dull red when mature, and globose. The blossoms and fruit of this species are rather small for the Cereus; the flowers open in the evening and close in the morning, and while delicate are not at all showy.

Lower California, Northern Mexico, and Southwestern California

Bergorocactus Emoryi, as he is sometimes called, is a little fellow to have such a long name. He is odd and rather humble, and very much resembles the Hedgehog Cactus, another group of Cereus, entirely. He grows well on the arid hillsides near the southern coast in San Diego County, California, and in Lower California; perhaps we should call him the “Prohibition cactus,” for he likes his home place dry. A foot or two high, he grows in thick impenetrable masses ten to twenty feet across, and covered with a dense spiny coating; fifteen to thirty slender, yellowish, needlelike but stiff [6] thorns, half an inch to an inch long or longer; pale yellowish brown flowers, quite small and clustering toward the tips of the stems. As we stop a moment here in Lower California to view him, we see that he is somewhat interesting, but though a member of the noble tribe of Cereus not attractive to us as a weird cactus, having little to suggest the dignity and grandeur of the giant Sahuaro, the uniqueness of the Pipe Organ with its finest of fruit, or the exquisite blossoms of la Reina de Noche, queen among desert flowers.

Mexico

Next in line of our fashion parade comes the Cereus senilis, sometimes called by the botanists Cephalocereus senilis (a polite way of saying “old man”). For a long time he has been one of the most popular of the Cactus Clan. He grows well in cactus gardens and conservatories, here and in Europe, and is greatly in demand on both continents; his habitat is the limestone foothills and mountains in northern and central Mexico, and is rather inaccessible. We find that the radial spines of the young plants are transformed into coarse white translucent hairs from four to twelve inches long, and, being deflexed like long gray hairs, suggest the name of “Old Man Cactus.” In the varying conditions and locations where he grows, he is sometimes called the “Bunny” or the “White Persian Cat” cactus. All the spines are fragile and break easily, and hence the Old Man cactus should not be handled more than is necessary. In maturity he grows around his head a dense mass of tawny wool, sometimes longer on one side suggesting a hat cocked to left or right, which gives the tall plant a most grotesque and rakish appearance. This cactus is columnar and little branched; in some instances he grows to a height of forty-five feet, and [7] is a very imposing sight in the landscape. The stems and branches are pale green or yellow-green with a scurfy waxy coating over the surface, are not tough, and sometimes a large tree can be cut down with a small pocketknife! The rose-colored flowers are bell-shaped or funnel-shaped and night-blooming, appearing only on the older plants. The inch-long fruit is rose-colored and covered with scales and tufts of hair or short wool! How strangely at times Nature does her work!

Lower California, Sonora, and Southern Arizona

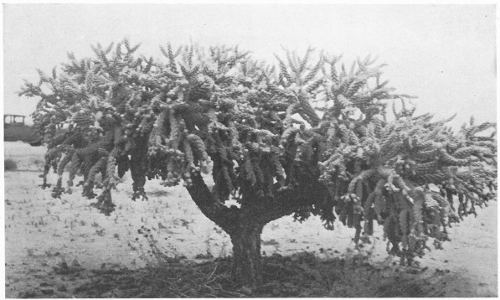

An aristocrat of the Cactaceæ claims our attention next, Cereus Thurberi, called also the “Pipe Organ” cactus. It grows well in the arid mountain regions, on the lower mountains and flats of Lower California and from Sonora in Mexico to southern Arizona, usually in colonies, seeking the rocky, gravelly soil in foothills and along the mountain cañons. Notice how it branches near the base and grows from ten to twenty feet tall; very erect and stately, the plant makes quite an appearance in green armor with a thin waxy coat. Surrounded by smaller patches of cacti where it towers well over them all, Thurberi presents a very striking picture in this setting of old Mexico or Lower California. We note that its great columns of yellow-green cuticle look much like the pipes of a giant organ silhouetted against the sky away out on the desert; hence the name Pipe Organ cactus or Pitahaya. We might even fancy that the rush of the wind through mountain and cañon, with its piercing shriek or duller roar, the song of the desert, is music emanating from the giant pipes of this great Organ cactus of Arizona and Lower California. The flowers, like those of many others of its kind, bloom in the night and are usually closed [8] by nine o’clock in the morning; growing in the tops of clusters of slender spreading grayish spines, lining the fifteen or twenty ridges of the stems, and, it is to be noted, appearing only on the tips of the stems; beautiful blooms three inches long with white margins, the delicate petals light pink with green and white bands along their edges, the innermost petals satiny white with some pink above, gradually toning into the purple-red of the sepals. The fruit of “Pitahaya dulce” as the Indians call the plant, globose, olive-green, with a crimson sweet fleshy pulp when ripe, is a rare delicacy and is highly prized by Indians and Mexicans for the making of jellies and jams, conserves, syrups, and sweetmeats. From the syrup they also make wine.

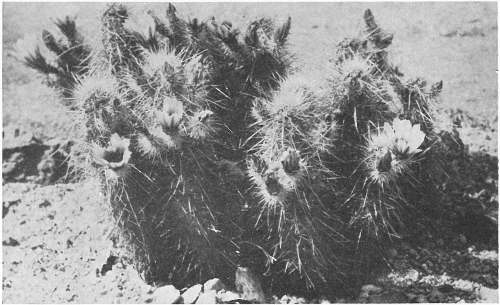

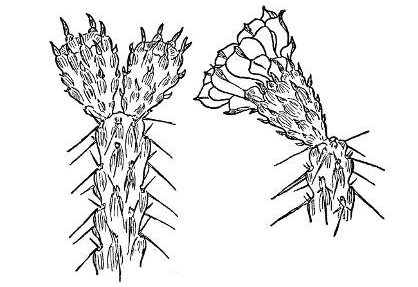

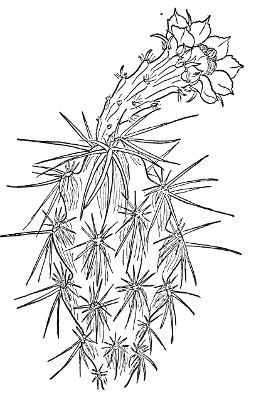

Mexico

In one of the cultivated gardens of Northern Mexico we are introduced by the hospitable natives (half Mexican, half Spanish), to that weird and striking growth, the Cereus serpentinus, known also in the realm of botany as Nyctocereus serpentinus. Any one of its long sinuous tentacles, the six to fifteen entangled stems, might easily remind one of the twisted body of a serpent springing at its intended victim! This is a Night Blooming Cereus cactus, supposed to be a native of eastern Mexico, where it grows half wild in hedges and over walls, but its habitat is uncertain. The stems, eight to fifteen feet long, grow erect for about ten feet, and then bend over or are pendent for several feet; on top of the ridges running along them are clusters of slender spreading cream-white and reddish brown spines, flexible and not stiff like those of most cacti.

NIGHT BLOOMING CEREUS; GODDESS OF THE NIGHT; LA REINA DE NOCHE; THE QUEEN OF NIGHT (Cereus Greggii)

You must come to the desert in the soft shadows of the moonlit night to see the ethereal beauty of this rare and exquisite flower. For only one night in each year does the flower queen come forth into bloom, scenting the warm sweet air of the desert land for miles and miles, while thousands of people, Indian and white, gather for the brilliant spectacle of hundreds of thousands of waxy white blossoms. Then no more may the eye of man behold the lovely colorings, nor sense the exotic perfume of the Goddess of the Night, until her appointed time comes yet again in the Desert Land of Plants and Flowers.

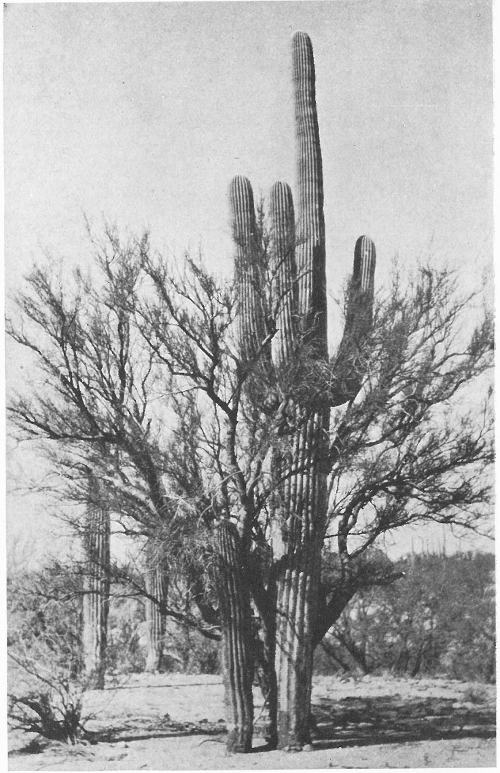

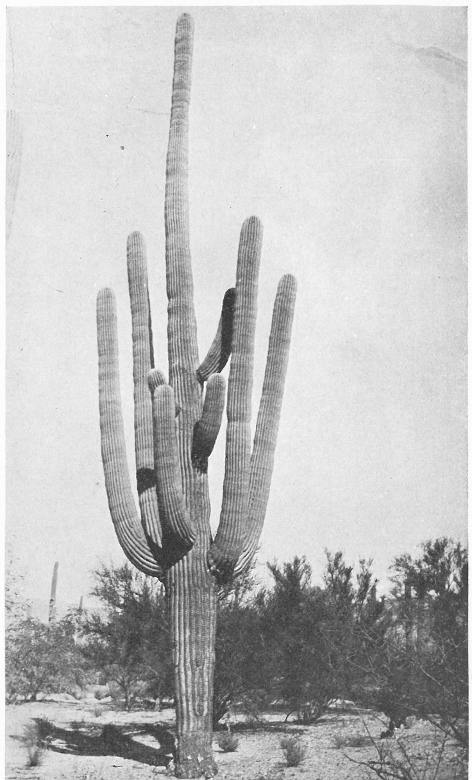

SAHUARO OR GIANT CACTUS (Cereus giganteus); AND PALO VERDE

The noble “Sage of the Desert,” towering fifty feet into the air, oldest and largest of the American Cacti, often attaining the age of two hundred and fifty years, entwining with the Palo Verde.

Why are such names as la Reina de Noche (the Queen of Night), Mexican Night Blooming Cereus, Junco Espinoso, given to this Cereus? We see the answer in the large bloom nearly a foot long and over seven inches wide, of a delicate tan-pink in background, shading into the soft cream-white of the petals, then the corona of stamens, a symphony of pale yellow and white; touches of green grace the bases of the sepals, and the whole forms a lovely picture against the background of old adobe dwellings, evanescent and brilliant in the white rays of the southern moon. And the fragrance of this lovely Cereus! The perfume from a single blossom will fill a large room or a whole yard: a pronounced spicy odor somewhat like that of a tuberose. This beautiful flower resembles that of the Cereus Greggii, our own Night Blooming Cereus. Its delicate colorings and poignancy of perfume make it one of the finest blossoms of the flower kingdom, much in demand for cactus gardens and window decoration. The showy beauties are highly prized by Mexicans and Spaniards as well, both in Mexico and abroad. Strictly night-blooming, and opening but one night in a season, the beautiful blossoms begin to unfold soon after sundown, having increased rapidly in size the day before, the loosened sepals and petals giving the flower the appearance of an inverted flask; the blossoms close soon after sunrise unless the day is cloudy, when they remain open until late afternoon. This blossoming, however, continues on different plants during April, May, and even into June. With favorable conditions the weird serpent plants run wild and grow luxuriantly, forming very striking hedges; and they are most attractive as climbers over the Mexican adobe walls.

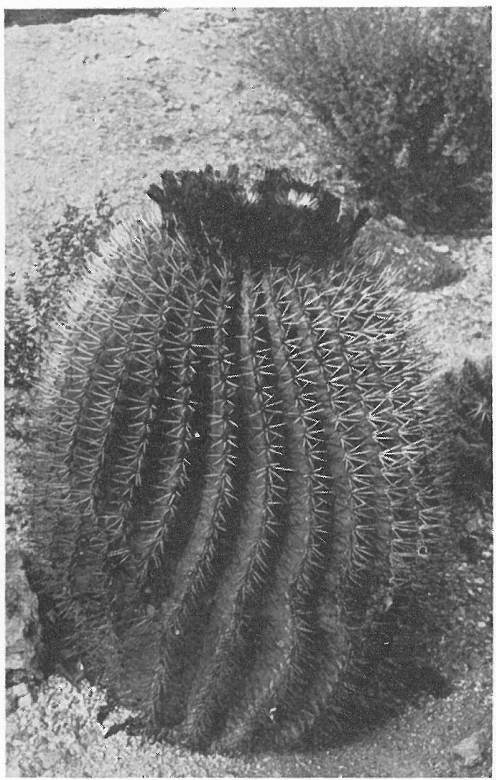

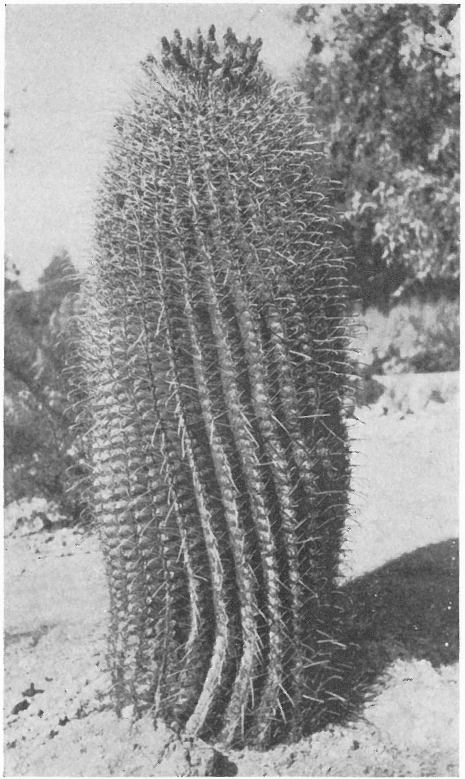

Southern California, Southern Arizona, and Mexico

That fellow over yonder is Cereus giganteus, or Carnegiea gigantea; he is “old Sahuaro” (pronounced “sa-wáh-ro”), [10] Saguaro, or Giant cactus. Sahuaro is the “Sage of the Desert” because of the great age he attains, often two hundred fifty years or more. He is the giant tree of the cactus clan. There are Sahuaro out on the Great American Desert that were old when the thirteen colonies became a nation in 1776. Proud and dignified and stately they stand out there in the great alone, silent sentinels of a long gone past still hardy in the towering strength of their great age, with yesterday gone forever and looking to the day that is yet to come.

Near sunset we may fancy them in silent meditation as if determining some mooted question of time or weather. For in case of long continued drought the reservoir systems of these great trees store up enough moisture to last them for three years, and they will blossom and fruit just the same without fail and on time! Over the entire length of these giants, run long ridges or flutings, which serve the plants as miraculous reservoirs for water: as the ridges expand, the plant becomes water-filled; and as the great tree uses up its moisture, these flutings contract into proper position, thereby exhibiting but one of the many marvels in engineering consummated by Nature, the Great Engineer. Along his twenty or twenty-five flutings she has given Sahuaro a formidable array of long sharp spikes which defy the approach of man and beast alike: grayish black spines, clustering on the lower ridges of the plant and never bearing flowers, and clusters of yellowish thorns, on the upper part of stem and branches, that bear the blossoms and fruit.

Thirty to fifty feet tall, these sentinels of the desert tower above the baby Pincushion, the Cholla, the Creosote and Desert Sagebrush, and the other Cerei, which seem but tiny dwarfs in comparison. Columns of their massive trunks grow singly for a distance of ten to fifteen feet, then curve abruptly erect in candelabralike branches, terminating in [11] masses of waxy white blossoms, the whole giving strongly the effect of a lighted candelabra in the dazzling sunlight. Full-grown Sahuaro weigh six tons or more; they are very sturdily constructed, vigorous and hardy, caring not for wind or weather or time. Woodpeckers make their homes in the waxy green trunks of old Sahuaro, and the injuries made by birds are sealed over by a coating of tissue from the plant itself. These coverings often take form of water containers and are so used by the Indians. The spiked armor causes Sahuaro to be feared by man and bird and beast, and the bold woodpecker and the hawk are almost alone in venturing to nest in their trunks.

In flower time the blossoms are produced in abundance on the tips of stem and branches, large satiny blooms four inches or so long and half as wide, growing solitary but in such great masses of waxy white bloom as to give the effect of being clustered; as usual with the Cereus, remaining open all night and closing in the forenoon. The Department of Commerce at Washington is taking steps to develop the fruit of the giganteus as an article of commerce. Shaped like an egg and about the same size, its crimson red pulp is made into wine by native Indians and Mexicans, preserved as jam and fruit in clay ollas, and after drying in the sun served as delicious sweetmeats to the whites trading near by. In June, when the sun is blazing hot, the Papago Indians camp in forests and harvest the fruit of old Sahuaro, while the dead plants furnish material for the building of their huts and adobe dwellings, the “ribs” used for rafters and poles, and even for fuel. The ceilings of many old buildings in Tucson, Arizona, were made of Giant cactus ribs, several layers deep. Many an Indian life has been saved by old Sahuaro in time of severe drought. Is it any wonder that the Papago begins his New Year in June with the fruiting of the Giant cactus?

The beautiful blossom of the Sage of the Desert is the [12] state flower of Arizona. A hundred miles west of Tucson, Arizona, is a great forest of these noble cacti, the Papago Sahuaro Forest of Arizona, while another forest of the great trees is a little to the east of the state capital, Phoenix. The Giant cactus thrives best in the rocky valleys and foothills along the low mountain slopes and cañons, and prefers a southern exposure. He likes a sandy, rocky soil where the roots can go down deep, or run long distances underground. He begins his life under the protection of some other plant or shrub, and in time crowds out even his protectors. Near Victorville in Southern California, in northern Mexico, and through all of southern Arizona, “constellations” of huge massive Sahuaro, viewed by the traveler for the first time in the ghostly light of the moon, are a sight never to be forgotten. Like apparitions they seem in the white rays, strange and noble figures of another world appearing before us in these fantastic desert plants; it is as if a graveyard had suddenly delivered its dead! Silent and mute and still they stand; waiting and watching and never seeming to die. And here we must leave these majestic plants to their heritage of the desert, above whose blazing sands they tower serene and untouched by the life struggle silently going on around them.

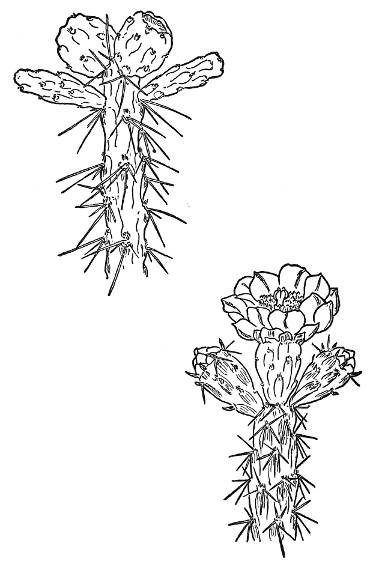

Southern California, Mexico, Southern Arizona, and Texas

The fashion show of the desert is about to close, for we see approaching us in southeastern California the Cereus Greggii, the typical night blooming cereus. Have you been in the Hawaiian Islands? Have you attended any of the early Spanish fiestas? Have you heard the stories of the Night Blooming Cereus? If so, you have heard about the most beautiful, the most fragrant of flowers! No flower garden [13] or conservatory is complete without this graceful queen of the desert, whose evanescent beauty surpasses the orchid and the rose; for the delicate shadings and exquisite colorings of the South American orchid are no finer than those of this night blooming cactus. Pen or brush in the hand of the genius scarce can do justice to the loveliness of Nature’s handiwork, the Goddess of the Night. Most popular of all the cacti, she delights to grow wild on the desert mesas, where the sensuous spicy fragrance of her beautiful blossoms perfumes the air for miles around, along the bajadas in western Texas and Southern California, over the mesas of southern Arizona and far down into old Mexico. Never in abundance, this rare flower grows in twos and threes under a creosote, cat’s-claw, or other desert shrub, which affords the flower goddess protection from the hot desert winds that at times sweep over the mesas and down the cañons, and from the blazing heat of the noonday sun. She prefers a deep sandy loam along the swales or draws of the desert, at altitudes of twenty-five hundred feet and more, though sometimes she appears on the mountains as far up as forty-five hundred feet; and related varieties, Cereus pentagonus and Deeringii, even grace the plains at sea level in the swampy lands of Lake Okechobee down in the south of Florida. Another cousin, the Cereus undatus, grows wild all over the tropics, and is a great favorite among natives and whites in Honolulu; around Punahou College there, in Punahou Valley, the hedge of this Night Blooming Cereus is a half-mile long, and on a single night five thousand blossoms have unfolded! This bloom, often twelve inches long, is the best known of all the Night Blooming Cereus flowers.

Two to eight feet in height, the blackish green angular grotesque stems bearing the lovely flower queen, almost like a crooked stick or dead snake in their fantastic appearance, form a strange contrast to the ethereal beauty and fragrance [14] of her blossoms. Often mistaken for a dead stick, these loosely branched and densely fine hairy stems of the Cereus Greggii are rarely noticed on the desert; but we who are fortunate enough to have a guide can perceive that the thin half-inch base of the trunk is narrower here than a few inches higher up, almost like the slim neck of a snake. Each slender trunk consists of a central woody core one-fourth inch in diameter, covered by a series of furrows to draw up the moisture which is stored in the fleshy beetlike root, weighing fifty to a hundred pounds and buried deep in the ground where it forms a reservoir of water and food lasting for more than two years. Thus, rain or shine, the delicate flower goddess may bring forth her lovely blossoms at their appointed time. Then too, Nature has provided her favorite with finely barbed, stout stiff hairy spines, about one-eighth inch long, growing on the areola so as to resemble a small insect of the desert.

The flowers are from seven to ten inches long and about six inches across, with a delightfully spicy fragrance, which at times is quite strong. The colorings of the Greggii are a wondrous harmony of tint and hue. The background of color forms a corona of waxy white and rich creamy yellow that looks as if it had been chiseled out of a rare old marble, with no duplicate in all the world; shading beautifully into the white of the petals, with their hint of pale lavender diffused throughout with touches of tan and pink; sepals and petals recurving into a graceful cornucopia.

It is no wonder that Indians and Mexicans revere their lovely “Queen of Night,” Reina de Noche, or that, across the sea in Honolulu, a grand celebration marks the opening of the blossoms of the Hawaiian variety, which occurs but once a year! During Queen Liliuokalani’s reign many were the ceremonies to Pau on occasions of the flowering of the Night Blooming Cereus.

You must come to the desert in the soft shadows of the moonlit night to see the ethereal beauty of this rare and exquisite flower. For only one night in each year does the Cereus Greggii come forth into bloom, scenting the warm sweet air of the desert land for miles and miles with poignant fragrance. When the shadows begin to lengthen and the deepening glow of sunset approaches, the satiny blossoms begin to open (having already loosened and expanded); in an hour or so they are fully opened, and as one stands watching them curiously one can actually see them moving and lifting from minute to minute, the petals seeming to tremble, so forcibly is Nature causing them to expand. One can detect the lovely fragrance as soon as the blooms start to unfold. During the night thousands of people, Indian and white, gather for the brilliant spectacle of hundreds of thousands of waxy white blossoms; others celebrate in the popular fiestas of the Southwest in old Mexico, or the luaus of far-away Hawaii. At sunrise of the day following, or shortly thereafter, the goddess flowers begin to fold, and by nine or ten o’clock on a cloudless morning they are entirely closed. No more may the eye of man behold the lovely colorings, nor sense the exquisite perfume of the Goddess of the Night, until her appointed time comes yet again in the Desert Land of Plants and Flowers.

And now the parade of the Desert’s Fashion Show is over and night is closing in. But if you wish to see the real show and to appreciate the real beauties of the desert land in flower-time, you must go into the silent sandy wastes when the sun is gone and the moon is coming over the mountains, spreading its gossamer silvery sheen over the floor of the desert in crazy shadow-patch, and watch the blossoms come slowly open, one by one, to receive the kiss of the night dew and the gentle caress of the newborn breeze. For you have [16] not looked upon matchless beauty nor sensed the sweetest perfume, till you have been out there in the great alone, where Beauty comes and fades and dies, and is born again in the ceaseless tide of God’s evolution of men and things, in the great Eternity of Being.

In general cacti like warm or hot sunny southern exposures; they grow best in sandy, gravelly, or rocky loam or clay soils, according to the habits of the species; they succeed best with good drainage, a moderate or limited rainfall or a limited amount of moisture in the soil. They should have occasional dry periods to harmonize growth with their original desert habitats, and also all the summer heat possible. This produces the contracted growth characteristic of cacti with all their desert beauty and symmetry of colors and arrangement of spines, and their fine large showy flowers. Cacti do best in regions of limited rainfall and maximum sunshine, blazing-hot summers, and mild winters where the temperatures keep well above zero.

The bad effects of heavy rainfall can be overcome largely by including in the soil a large proportion of sand or gravel or cobblestones and by growing the plants on ridges or raised borders. The effects of fog and extreme humidity can be corrected somewhat by growing them in dry conservatories. Where the temperatures fall below the lowest temperatures given in the section on “How to Grow” for each species, cacti must be grown in warm greenhouses in winter and preferably throughout the year—with the exception of the hedgehog cacti, which rarely grow successfully in greenhouses. With the specific information given under the heading “How to Grow” for each species, it is possible to grow cacti successfully in the tropics and over a large part of the [17] temperate zone. The important things are: warm sunshine, protection from too low temperatures, the right kind of soil, and limited watering or irrigation.

Cacti may be grown out of doors in the entire southwestern section of the United States, in Mexico, Central America, and South America (except the southern part), where the temperatures are never colder than fifteen to twenty-five degrees below freezing. Also, they can be grown successfully out of doors in parts of Spain and Portugal, and in the region immediately bordering the Mediterranean Sea, over much of Africa lying at the lower altitudes, in Arabia, Persia, India, southern China, extreme southern Japan, and the northern half of Australia, in addition to the islands of the Pacific, nearly all of which lie between the 33° parallels, north and south (except where the temperatures are modified by mountains or other natural features).

They can be grown indoors generally in the north and south temperate zones between the 34° and 54° parallels, north and south, where the temperatures reach as low as twenty to thirty degrees below zero. This includes the northern two-thirds of the United States, the lower half of the Dominion of Canada, Great Britain, Ireland, France, Germany, Austria, the northern half of the Chinese Republic, Japan, and the southern part of South America.

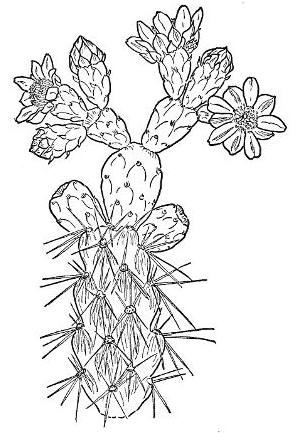

Many species of this group can be identified by the beautiful candelabralike branching of the plants. They are trees, [18] shrubs, or climbers, and grow erect or spread out, the tallest and largest trees or plants of the cactus family. They are the “torch flower” cacti, are tropical or subtropical, the stems growing single or clustered, with prominent ridges or flutes which in many instances expand or contract as the plant fills with water or loses its moisture. The tubercles are not conspicuous and grow in rows on the ridges. There are no leaves nor spicules. The spines are of one or two kinds, sharp and dangerous in some species, inconspicuous in others, growing from one-fourth inch to twelve inches in length. The flowers are funnel-form, of brilliant or delicate colorings, large and showy, and unlike many cactus blossoms are fragrant, often with a pronounced spicy odor. In some instances they crown the candelabralike branches in a becoming aureola of light, giving the effect of a lighted candelabrum; hence the designation “torch flower” cacti. Most species bloom only at night. As a rule the calyx tube is found to be very long. The fruit is usually quite large, has shallow tubercles, and is covered with many scales, but is rarely spiny.

Only a few of the different kinds of the Cereus Group grow well from cuttings, including Cereus serpentinus. Set the cuttings of such plants as this Serpent Cactus a few inches deep in moist sandy soil and irrigate sufficiently to keep the soil moist. The cuttings grow best in part shade. Cereus plants grow readily from seeds sown in sandy loam mixed with a small amount of pulverized charcoal and some leaf mold; plant in pots or flats one-fourth inch to one inch deep in the soil in partial shade, and keep the soil moist. The young plants can be transplanted to pots when one-half inch to one inch tall. They grow indoors or out; a southern exposure is preferable, being warmer and more sunny.

(Named “eruca,” or “caterpillar cactus,” because the stems turn upward at their tips, resembling a caterpillar, head and body)

The prostrate stems, three to nine feet long, lie flat on the ground with their tips upturned, resembling huge caterpillars. They grow in light sandy soils or sand, and root from below, the tips of the stems elongating and growing forward, the bases of the stems dying; thus the plant slowly moves forward over the sand. These prostrate stems, two or three inches in diameter, are very spiny, with fifteen radial and four central spines clustering an inch or so apart on the twelve to seventeen ridges which run lengthwise on the stems. These fierce, sharp thorns are dark brown and dull tan and turn white with age; the tips are translucent yellow. The radials are less than an inch long and flattened, the centrals grow to two inches in length, one very stout and strongly flattened, resembling a dagger and with a white body. The large flowers are bright yellow and grow four or five inches in length, narrow and funnel-shaped, about two inches across. The fruit is very spiny; but the thorns fall away at maturity, and it becomes quite edible and is relished by Indians and Mexicans.

Plant in sand or sandy soil, preferably fine sand, with the tips slightly upward, and keep the sand lightly moist. The plant requires a hot, sunny location and will grow out of doors in the Southwest where the temperatures do not drop more than a few degrees below freezing, and in hot dry [20] conservatories and greenhouses where the temperatures drop lower.

(Named from its appearance of old age, and for F. A. Schott, a botanical explorer of western United States)

These plants grow in colonies or patches in the mountain cañons, twenty to fifty stems in a clump, the dense branches interlocking in huge clusters twenty-five feet high and twenty feet or more across. The yellow-green stems are scalloped and cylindric, five or six inches in diameter, growing four to twenty feet or more in height, with five to nine ridges running lengthwise from top to bottom. On these ridges cluster the spines, silvery stout thorns about one-fourth inch long on the young plants; the older spines are really dense bristles, slender, flexible, symmetrically twisted, appearing like fine purplish gray bands, one and one-half to three inches long, and giving the appearance of old age. The flowers are shaped like a bell an inch and a half long and about as broad, pale pink and cream-white petals shading into deep pink at their tips, opening only at night. The fruit is globose, an inch or more in diameter, of a deep reddish tinge, and fleshy.

Plants may be grown from seed in sandy soil in flats or pots; young plants may be transplanted in spring in sandy, gravelly, or rocky soil. Water during dry weather enough to moisten the soil well. The plants can be grown out of doors only where the coldest winter temperatures are but a few degrees below freezing. In other parts of the country, grow in hot, dry conservatories or greenhouses.

(Named in honor of Lieutenant Colonel Emory, who was in charge of the Mexican Boundary Survey)

This is a low-branched plant a foot or two high, growing prostrate with erect branches in thick impenetrable masses ten to twenty feet across. Numerous stiff, needlelike thorns form a dense spiny yellowish coating over the entire mass. There are many pale yellow to yellow-brown flowers an inch and a half long which cluster near the tips of the stems. The fruit is globose and densely spiny, an inch or so in diameter. The plant is not attractive nor very cereus-like.

This species can be transplanted in the spring by digging rooted stems, planting in gravelly clay soil, and irrigating sufficiently to moisten the soil in dry periods; or by digging a shallow hole and partly covering the stems with soil kept moist but not wet. The plants will grow out of doors and endure only a few degrees of frost; where the temperature drops more than fifteen degrees below freezing they must be protected outside, or grown indoors or in a warm, sunny greenhouse.

(Named from the long white hairs or beards found on young plants)

This cactus is columnar, and some mature plants reach a height of forty-five feet. It is native to Mexico and not [22] easily accessible. The trunk is usually unbranched, cylindrical in young plants, two or three inches in diameter, yellow-green with a scurfy waxy coating; and it is not tough. A large tree can be cut down with a small pocketknife in some instances. The twenty or twenty-five radial spines are changed over into long coarse white hairs, four to twelve inches long or even longer, and form a dense covering; hence the common and specific names, Old Man Cactus and senilis. These radials are crooked, flattened, and twisted, while the one to four central thorns are easily pulled out, all spines very fragile. In maturity a dense mass of tawny wool appears around the head of the plant. The rose-colored blossoms are two inches long, shaped like a bell or funnel, and appear only on the older cacti. They open at night and close in the early morning. The fruit is about the size of a large strawberry; it, too, is rose-colored and covered with scales and tufts of wool.

Plants may be grown from seed in flats or pots, but the seed is rare and difficult to get. Commonly young plants are purchased and grown in pots in gravelly, sandy limestone soil. Water sufficiently to keep the soil slightly moist. A bright sunny location is best. The plants are tender to frost and thrive best in warm conservatories or greenhouses. The Old Man Cactus is a popular plant for rock gardens and is found in many homes both in this country and abroad.

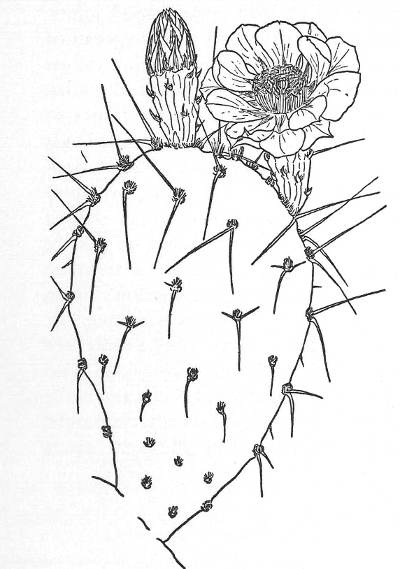

(Named in honor of George Thurber, botanist of the Mexican Boundary Commission)

These are large, columnar, symmetrical plants ten to twenty feet tall; the large columns of yellow-green stems, [23] in six to thirty branches ascending from near the base, look much like the pipes of a great organ at a distance. The stems are from six inches to nearly two feet in diameter and are cylindrical, with fifteen to nineteen ridges lined with clusters of slender, spreading, grayish spines. The flowers, which appear only at the tips of the stems, are three inches long and half as wide, and open always at night; their delicate pink petals are suffused with green and banded in white or green, and their purple sepals are tinged with red. The fruit is very delicious, sweet and juicy, olive-green, globular, with scarlet fleshy pulp. The Pipe Organ Cactus is shown on the cover of this book. It is one of the finest of the Cactus Clan.

Sow seed in sandy soil in pots or flats with partial shade; young plants may be transplanted in spring or early summer in rocky or gravelly soil and watered during dry spells once a month to moisten the soil well. The plants can be grown out of doors in the Southwest where the lowest winter temperatures are only a few degrees below freezing. In other parts of the country they may be grown indoors in rock gardens or in warm sunny conservatories.

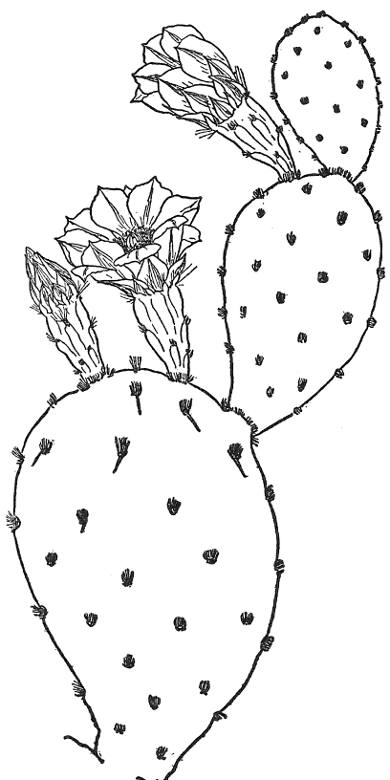

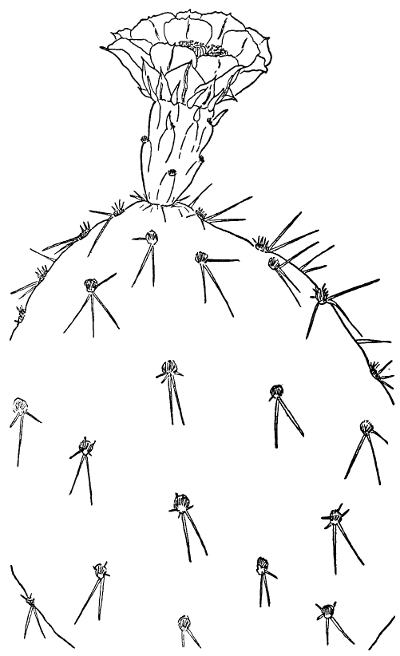

(Named specifically from the snakelike stems)

The six to fifteen entangled stems of this weird cactus resemble a serpent. They are eight to fifteen feet tall, about an inch in diameter, generally growing erect for about [24] ten feet, then bending over and climbing for several feet. Each bears a dozen or so low ridges lined with clusters of slender spines a half-inch or so long, translucent white or dull cream color. The large brilliant blooms are eight to nine inches long and when fully open five to seven inches across, with soft cream-white petals and pink and tan sepals touched with green, both strongly reflexed. The strong spicy fragrance is much like that of a tuberose. Each plant blooms at night and only one night in the year. The different plants blossom from April into June. The plants run wild in Mexico and form a luxuriant growth; they are prized as rare beauties by the Mexicans and Indians.

Set cuttings about a foot long in moist soil, and water weekly; or lay the stems down and cover with moist sand or soil. When grown outside in sunny exposures but in the protection of dwellings the plants are not injured by twenty degrees of frost. In colder weather than this they may be grown in warm, sunny conservatories.

These are majestic trees thirty to fifty feet tall, with columnar massive trunks which grow singly ten to fifteen feet, then curve sharply erect in branches like a giant candelabrum. Twenty to twenty-five ridges run the entire length of the trunk, and these flutings expand as the plant fills with water and contract as it loses its moisture. They are covered with long sharp spikes which stick out like diminutive swords closely packed along the tops of the ridges. The flowers are night blooming, four or five inches long and [25] half as wide, growing solitary but in such masses as to appear clustered, with large satiny, waxy white petals strongly reflexed. The fruit is about the shape and size of an egg, with crimson pulp, palatable and prized highly by the Indians. The Giant Cactus is one of the largest cacti in the world and can blossom and bear fruit for three years without rain, using the reservoir of water that Nature provides.

The plants grow readily from seed sown in sandy soil in pots or flats and may be transplanted when a half-inch tall. The soil should be kept moist but never wet. Transplant young plants one to six feet high in spring, taking two feet of the roots with care not to injure them, and set in gravelly clay soil, irrigating once a month during dry seasons. Giant cactus plants one foot tall or taller thrive out of doors and will endure a temperature twenty degrees below freezing without injury. Where the weather is colder than this they must be protected in winter, or grown in dry sunny conservatories or indoor rock gardens.

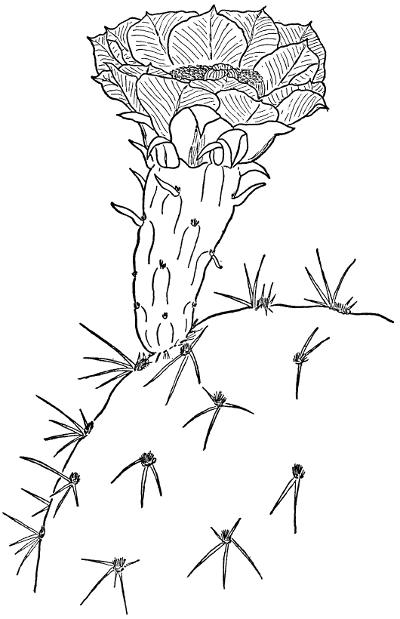

(Named in honor of Dr. J. Gregg, student of cacti and plant explorer of Northern Mexico)

One of the most beautiful of all cactus flowers. The plants grow two to three feet tall, rarely eight feet, the blackish grotesque stems densely fine hairy and loosely branched, resembling a crooked stick or a snake. They are very slender, a half-inch or so in diameter, and are fluted with four to six blackish gray-green ridges, lined with spines [26] less than a fourth-inch long. The latter are arranged in such manner as to resemble a small insect, and have thick bulbous bases. Each slender trunk is supported by a central woody core. There is a fleshy root a foot or so below the ground, weighing fifty to a hundred pounds, which acts as a reservoir for water and food, so that the Greggii blossoms every year, rain or no rain. The flowers are from seven to ten inches long and about six inches across, showing a beautiful combination of coloring, a background of soft waxy white shading into pale lavender in the forty or more petals, with touches of pink and tan in the sepals, forming into a cornucopia. The stamens form a corona extending beyond the petals. The fragrance is delightfully spicy, strong, and persistent; the plants blossom only one night each year, generally in the latter part of June. This most beautiful of all the cacti in our Southwest usually grows in the lee of a creosote or other desert shrub in sandy loam.

Grow plants from seed in pots or flats, in sandy loam with partial shade, or transplant without injuring the large fleshy root, setting the top of the root about a foot below the surface in loamy soil in the protection of shrubs; mature plants will blossom within two years of transplanting. Water well during the growing season, in dry weather about once a month. Do not cultivate. Plants grow out of doors or indoors and will endure a temperature of twenty-five degrees below freezing without injury. In localities where the winter weather is colder than this the plants must be protected or grown under glass.

And now we will pause in our trip across Cactus Land to take up the many peculiar features which characterize and differentiate these odd desert plants, and to tell of those individual and unique growths, the terrible swordlike thorns of the strange Fantastic Clan.

Cacti are not closely related to any other family of plants, and there is no certainty as to which group of plants they developed from. Their immediate ancestors perhaps have disappeared in the hazy past. They stand, therefore, alone. In this respect few other plants resemble them; only one or two other families, for instance the Ocotillos or Fouquieriaceæ, are in a like position.

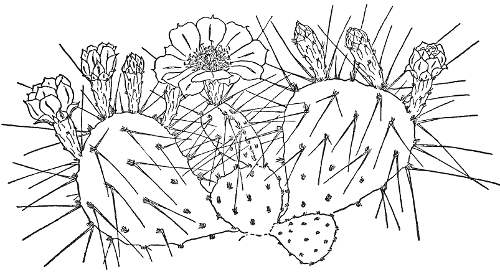

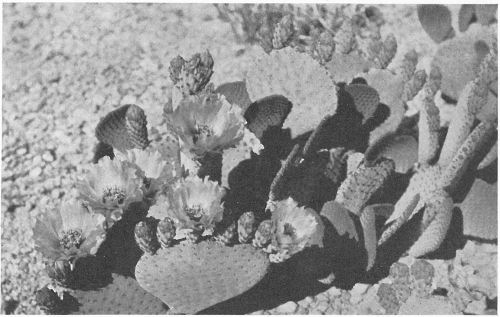

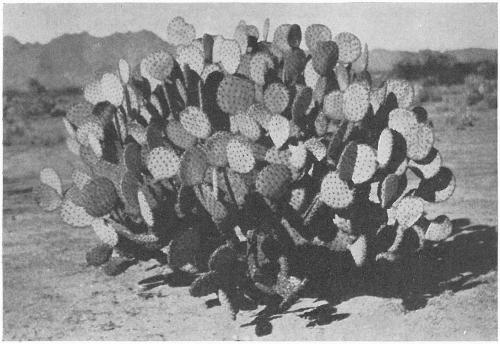

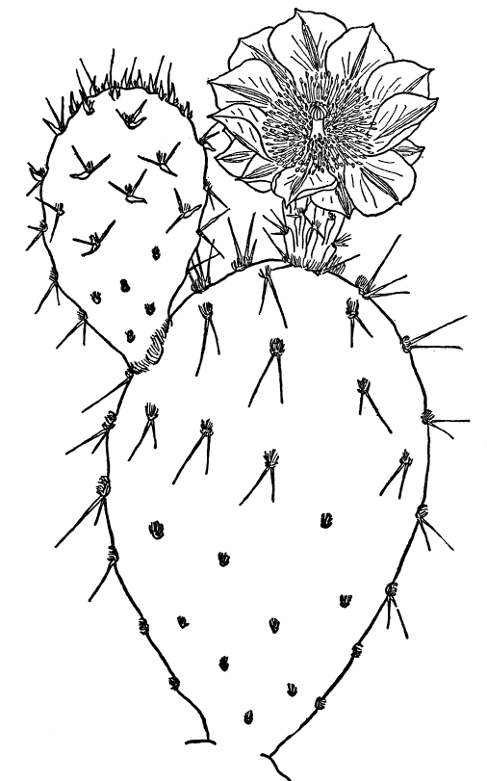

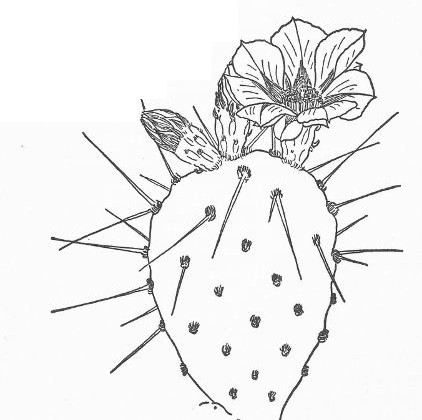

Cacti are generally thought of as limited to North and South America and the outlying islands. However, about eleven species of one genus, Rhipsalis, grow, apparently native, in South Africa, Madagascar, and Ceylon, though these are identical with the same species growing in South America. There is a strong belief that these species were distributed in Africa by birds eating their ripe fruit in South America and then flying across the ocean to Africa, and there dropping the seeds, which germinated and grew into plants on another continent. The most widely distributed of the various groups of cacti is the prickly pear group of the genus [28] Opuntia. The prickly pears grow wild from Argentina through Central America, Mexico, and the United States to British Columbia, within four or five hundred miles of the Arctic Circle. Prickly pears may be regarded as the advance guard of the cactus invasion of the United States from Mexico, and there are nearly as many kinds in our country as in Mexico. Prickly pears are most abundant in the temperate zones; the species grow larger in tropical parts than in cooler temperate regions.

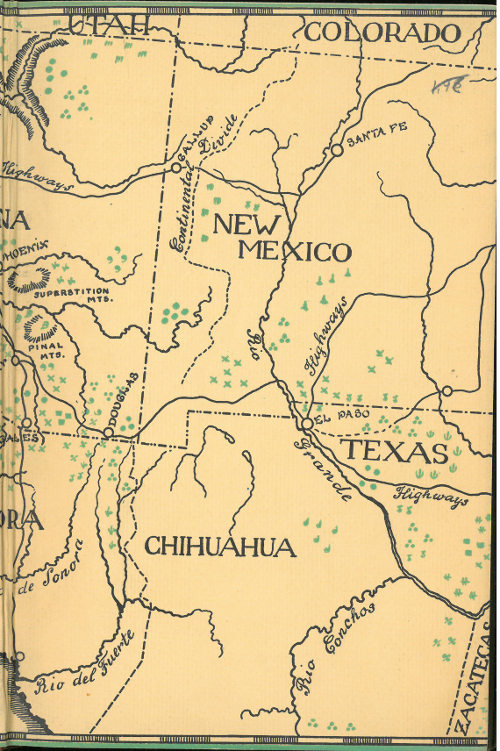

All told, there are more than twelve hundred species or kinds of cacti, of which about two hundred twenty-five occur in the United States and the rest in Mexico, Central America, South America and outlying islands. Of the two hundred twenty-five species occurring in the United States, about one hundred are native of Arizona, the premier cactus state, and nearly two hundred grow in the four southwestern states, California, Arizona, New Mexico, and Texas, with a few in Nevada and Utah. Arizona contains almost one-tenth of the cacti of the entire earth. Our four southwestern states together with Mexico constitute the great cactus area of the world, not alone in numbers but in variety and weirdness of types, containing many of the most peculiar and fantastic forms of these grotesque plants.

Doubtless because the cacti are such odd, weird, fantastic growths, they have been popular with mankind since the earliest times. To-day forty or fifty species are known only in cultivation; and they have been under culture so long that their native habitats and original distribution have been forgotten, and are no longer known. This is due largely to the fact that several very popular species have been dug up and removed from their own haunts to cultivated lands, or planted in gardens to such an extent that the last specimens have been taken and they no longer grow wild or under natural conditions. This uprooting is taking place continuously, [29] doubtless much faster now than formerly, and in future we shall have many additional instances to record, as it is quite likely that new species are originating under experimentation through careful selection and ingenious plant breeding.

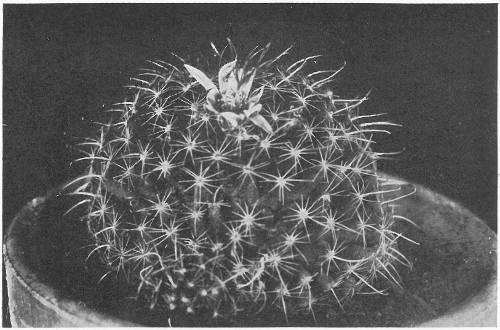

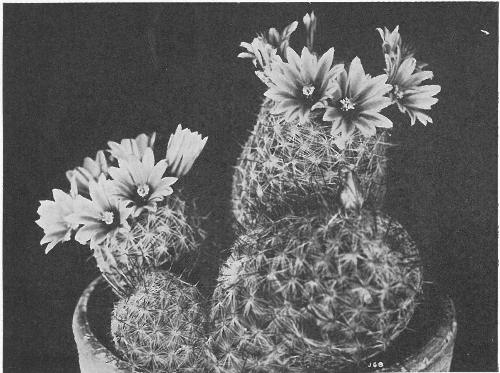

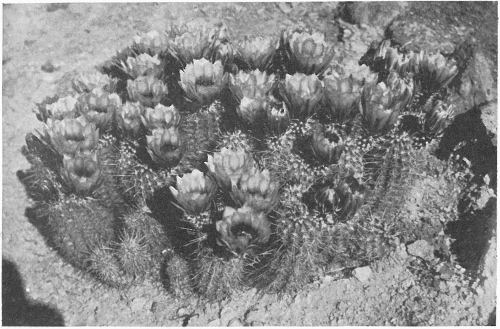

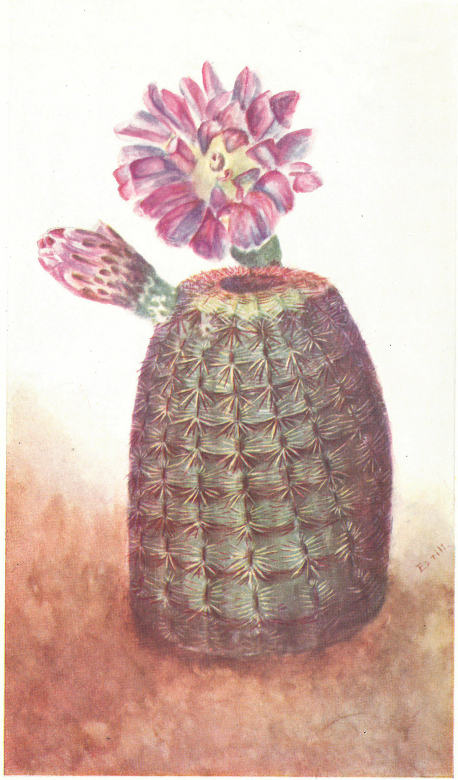

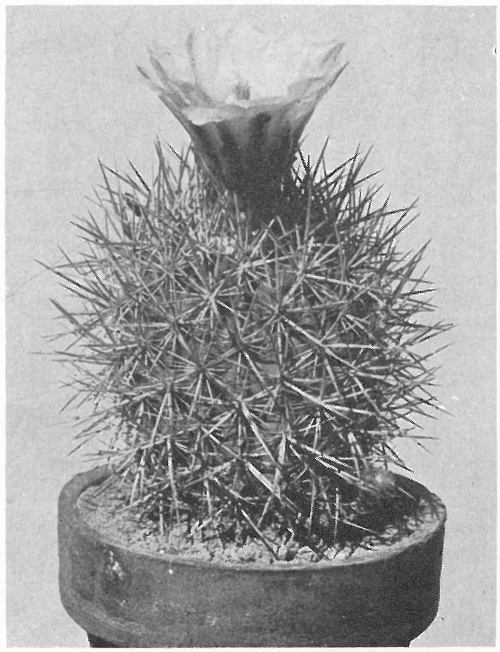

SHORT SPINED STRAWBERRY CACTUS (Echinocereus Bonkeræ)

A new and handsome little strawberry cactus, named in honor of Frances Bonker for her writings depicting the beauty and charm of the desert land.

The spines of cacti are ever an interesting subject for study, and the very name “cactus” is suggestive of thorns. It is generally known that cactus spines develop from their bases and that they are impregnated with resin or a resinlike substance, while the spines of nearly all other plants (as for instance the plum) grow from their tips and are not resinous in character. A young growing cactus spine has a very soft yielding base while the tip is hard and sharp, and the sides retrorsely barbed. Because of their resinous nature the thorns persist on the desert long after the cactus body has disappeared, and often fragments of the thick cuticle remain with them, still firm, sharp and translucent. Such spines about a spot where a noble Sahuaro or Giant Cactus has fallen and gone back to Nature as dust may persist for a long period unchanged, without crumbling or otherwise disintegrating; this is true also of those of the bisnaga or barrel cactus. Thorns grow on the Giant Cacti for a hundred, even two hundred years, unalterable, sharp and hard and dangerous. Some species of cactus have as many as three kinds of spines: centrals, the inner thorns, usually the largest and stoutest; radials, the outer spines; and what are termed “bristles” but are more accurately described as “antennalike” spines. In some groups, as the bisnaga, the spines are cross-ridged or marked transversely, with the tips smooth, straight, or hooked. Many cactus spines are marked with brilliant colorings, and some are transversely banded with bright variegated “zones” of color. When held to the light they [30] are translucent and show beautiful colorings: red, orange, yellow, brown, and purple. Generally cactus spines are glabrous, that is, smooth and without hairs, but the spines of some cacti are densely fine-hairy or distinctly hairy; and this can be seen easily with a pocket lens or the unaided eye: their pubescence commonly produces a grayish layer overlying the true color of the spines beneath. The thorns of Cholla differ from those of other cacti in that they are covered with sheaths which can be removed very easily, and then are not replaced. The significance of these sheaths is not clear, except that they help form a barrier against the intense heat of the sun and the burning desert sands.

We find, too, that the cacti with most pronounced thorny growth live in the hottest parts of the desert, where the thermometer often registers 130° Fahrenheit during the long summer days and sometimes up to 150°! Their dense layer of spines becomes a shield of lacework, protecting the plants by cutting off over twenty per cent of the light, and reducing the terrible heat by raising the humidity within the network of spines, which in turn reduces evaporation from the plant. If it were not for their thorns and sheaths cacti would be scalded by the burning temperatures of even one summer day in the great desert amphitheater of the sun. Being resinous, cactus thorns are very inflammable, and if ignited they all burn to a cinder before the fire ceases, for one cluster of spines will set others aflame and so the fire sweeps over the entire plant, rapidly changing the beautifully colored, symmetrical and translucent spines into ugly charred masses.

The cactus is encased in a thick cuticle which is continuous over the whole surface of the plant, except at the numerous, small, rounded or oval areas of growth called areolas. In the cactus all growth, of leaves, spines, spicules, flowers, and even roots (in the case of cuttings) and branches, takes place from these areolas, which are truly areas or centers of [31] growth; and if all these areolas are cut away on the stem and its tip cut off, the plant ceases to grow and dies. Spines are generally understood to represent branches, since they grow from the tissues of the plant under the epidermis and not from the epidermis. The inordinate multiplication of spines in cacti is not well understood by botanists. Some cacti add thorns to their spine clusters in the areolas each year, and thus in time the cluster may come to have as many as fifty or even a hundred spines on old stems and large branches. Occasionally cactus spines replace themselves in areolas after the former thorns have been destroyed or burned off. The thorns of some cacti may grow as long as six inches and even longer, and as broad as one-fourth inch at their bases. After they complete their growth toward the close of the season and the bases become hard and firm, they do not elongate farther nor make further growth.

The flowers of cacti are generally large and showy and are quite responsive to light in their opening and closing. They have many stamens, from thirty or fifty to as many as three thousand in the Giant Cactus. This development of stamens is rare among flowering plants, and is due to a splitting process that takes place early in the development of the stamens of the embryo flower. The stamens of many cacti are sensitive to touch and when being worked by insects for pollen are constantly moving backward and forward. Cactus flowers differ also from nearly all other flowers in the number of sepals and petals, which is variable and relatively large, and in the fact that their sepals and petals are not distinct in character. Rather there is a gradual transition between the bracts of the ovary, if such are present, and the sepals; and likewise a gradual gradation in form, color, and size between the sepals and petals. There are usually several whorls or circles of petals in the flower; commonly such flowers are spoken of as being double.

Out in the vast desert land in ages long gone by, the stifling sun had burned everything to a cinder. This seeming annihilation was but part of that great plan wherein the desert regions of the earth have been transformed into the greatest flower garden of all creation; where Time has chiseled out the filigree of lacework and pattern for the hills and valleys; where erosion has painted the beautiful pictures on the faces of mountains and hills; where volcanic action has juggled the rocks and mountain sides into fantastic shapes and designs, piling them up and leveling them out again for ages untold, until the Divine decree was accomplished. For God has walked amidst all this seeming turbulence, and with infinite patience has brought forth verdure and flowers the like of which do not exist anywhere else on earth; and to-day when Man ventures into the great arid wastes it would seem that he little anticipates the hidden loveliness to be found there—the wonder of desert creations, flowers and then more flowers, blossoms of rare and seductive beauty, of exotic and sensuous fragrance. Flowers that cannot be painted by brush or in coloring to do justice to the delicate waxlike originals. Flowers that seem like delicate souls wrapped in somber lifeless bodies, trying to gain expression through their beautiful colorings and evanescent perfume in the dry atmosphere of their monotonous existence, out in the great [33] stillness of the arid spaces with only the midnight blue of the heavens to caress them, and the dew of the night zephyrs to kiss them when the torrid sun has gone.

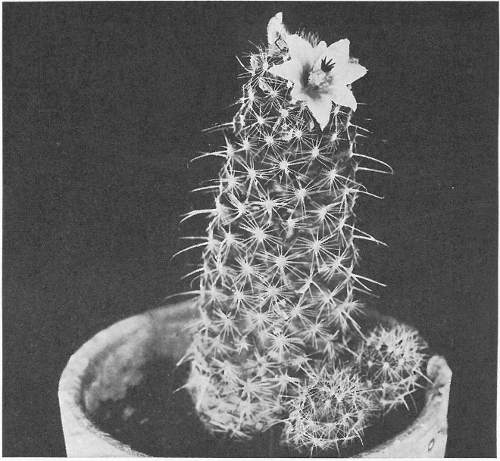

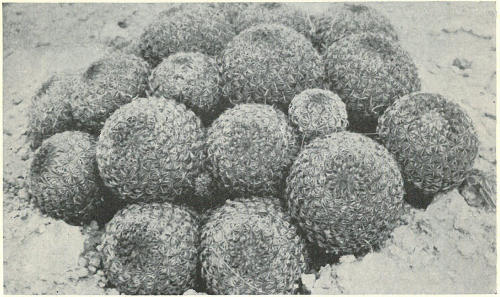

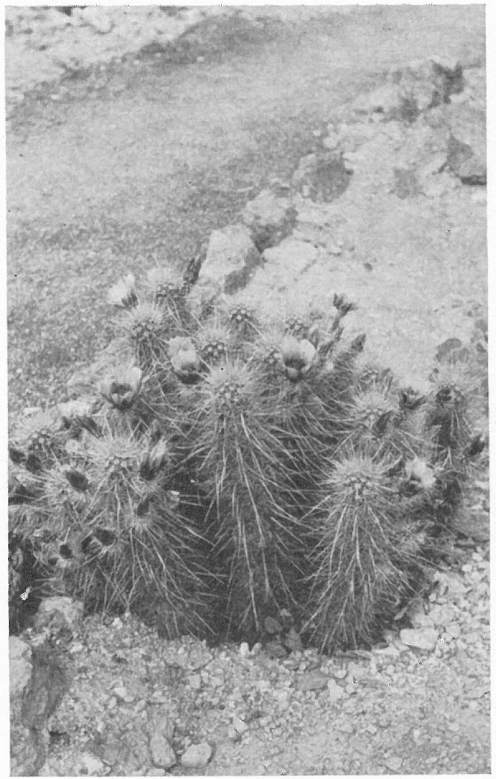

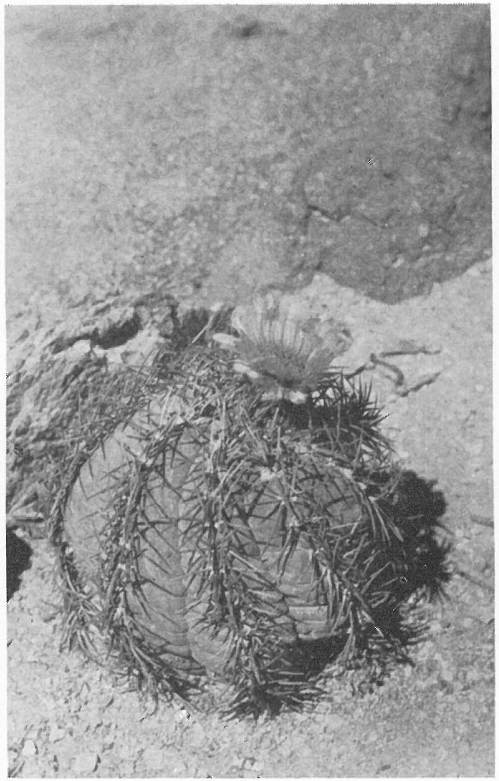

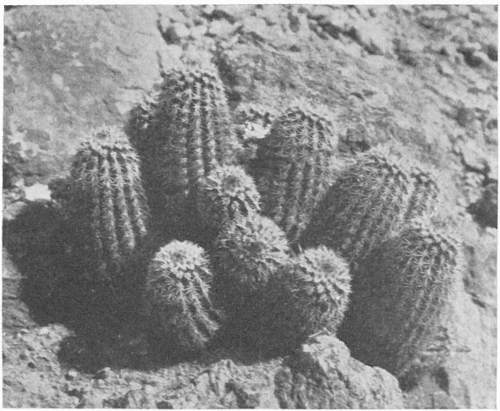

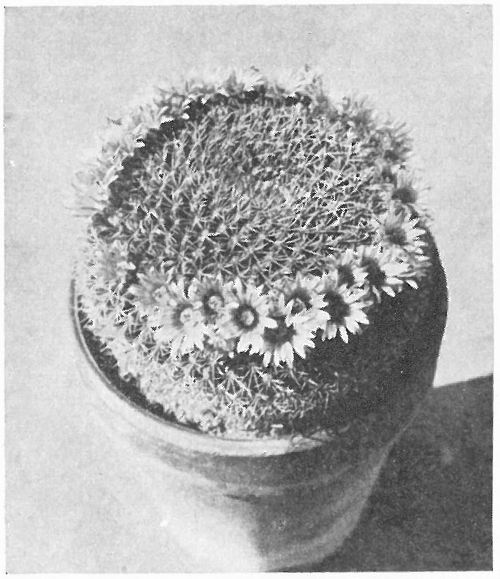

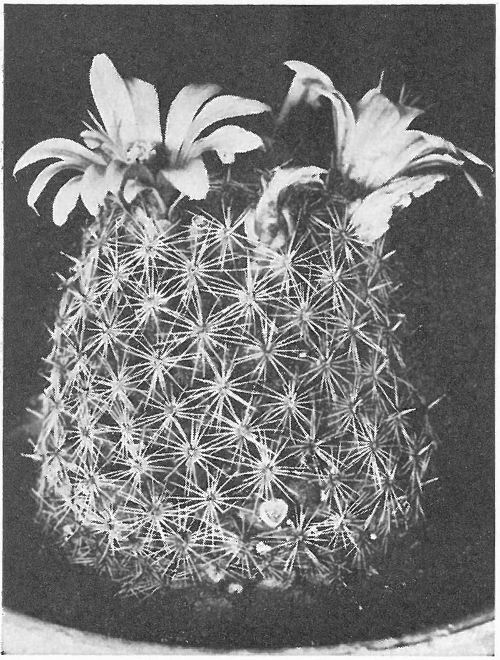

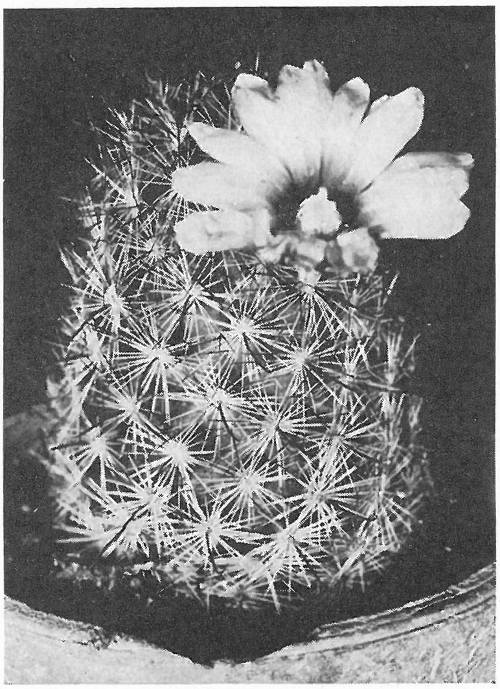

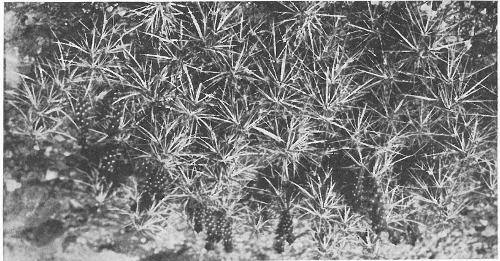

Early in the morning of a fine April day near Needles, California, on the Arizona border, we continue our journey into the desert. Before us stretches a panorama the like of which few among us have ever beheld; a picture majestic, tremendous, suggestive of the grandeur of Nature’s workshop, the vastness of those great sweeps of arid lands, covered with symmetrical, cross-patch, lacework, fantastic growths, of every size and shape and color imaginable. The Cholla are there, Giant Sahuaro rear their great trunks high into the air, and fantastic Joshua Trees lean toward us, their weird grotesque arms with long grasping fingers all pointing in one direction as if to guide the weary traveler on his way. And peering forth from among rocks, in the lee of a Giant Sahuaro or growing in a forest of the grotesque Joshua whose fantastic arms seem to engulf these tiny cacti, we find the Baby Pincushion, our Mammillaria (Coryphantha) or Cactus Mammillaria. He is a funny little ball-like plant, two or three inches in diameter, full of star-shaped spines, with an extra-long one in each star cluster and rather hooked over on the ends. These little aristocrats of the desert often cling together in groups, like a colony of sea urchins, and are very dainty when in bloom in the balmy month of April, when all the desert life is arraying itself in gay spring color and blossom.

Out on the desert mesas and along the bajadas, or mountain slopes, we find so many fantastic objects that it is hard to decide just where to start. Nature has provided many wonderful mysterious growths for her desert land of plants and flowers, and she has been careful to place them where they will be able to thrive and to evolve. Many will be found hidden away under rocks and in deep cañon recesses; others out [34] on the foothills, where it would seem that the sun would burn them up; still others are placed boldly on the mesas where wind and rain and sandstorms play hide and seek around them. Naturally the question of growth, which is next to the most vital problem of all “Where do they get their moisture?” now presents itself. We will begin at the bottom of the ladder, to-day, and will select the Baby Pincushion, the smallest of the cactus family.

Several natural groups or genera go to make up the Pincushion Cacti, and of these the two most important in the great desert of the Southwest are the interesting plants of Coryphantha and Mammillaria. The name “Coryphantha” alludes to the plant’s habit of bearing the flowers at its top; Mammillaria is from mammilla, a nipple, referring to the tubercles or knobs of the plant. They are the smallest of the large and important cactus family (Cactaceæ), the Fantastic Clan, and their stems are single or in clusters and from one to twelve inches in height and diameter, often as broad as long, or broader. Often, too, the upper surface is almost flattened, while the main part of the plant is a carrot-shaped fleshy root, which Nature, the great Builder, has made a reservoir of food and water for this, her baby of the Fantastic Clan, to withstand the drying desert winds that sweep across the mesas and up the cañons, and the months of drought and fiery heat in the desert sun, when no rains come to freshen and beautify the earth and to gladden the hearts of native dwellers on the desert. The stem is studded with tubercles spirally arranged, and each crowned with an areola bearing a cluster of slender but stout spines, often hooked like the tines on a spear; and usually with hairs. This spiral arrangement gives the plant a very attractive appearance. Some [35] species have a thick milky juice in their stems, others a colorless watery sap.

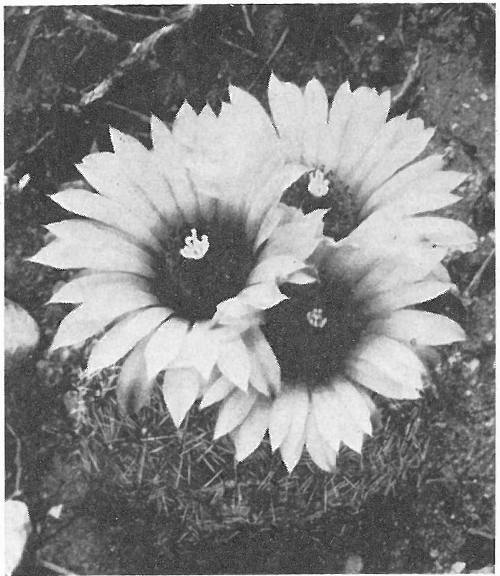

The flowers are day-blooming, both opening and closing with surprising rapidity. Mammillaria blossoms are relatively small, while those of Coryphantha are much larger, often two or three inches across; yellowish, white, pink, rose, red, or purple. There are usually many sepals, petals, and stamens, all beautifully and symmetrically arranged, and the harmony of color in the flowers is often commented upon with delight. While the flowers last at most but a few days, many of the different plants are in bloom for a considerable length of time, and some blossom two or three times a year during the spring and summer. The fruit of Pincushion Cacti are naked and smooth, rarely with a few scales in some species, and when mature red, green, yellowish, or dull purplish, and club-shaped or nearly globose. They are borne at the bases of the tubercles; in Coryphantha, at the bases of young tubercles near the top of the plant, so that they appear terminal; in Mammillaria, at the bases of old tubercles some distance from the top of the plant.

Pincushion Cacti are very popular for window gardens and miniature cactus gardens on account of their smallness, their symmetry and beauty, their fantastic shapes and designs, and their bright-colored dainty flowers. They are considered to be among the most highly developed of the cacti, inasmuch as the greatest reduction of the plant body has taken place, the plants having no leaves nor even trace of leaves. In the evolution of cacti the tendency of the different groups and species is to become leafless, and most cacti either are without leaves or have leaflets that soon disappear.

Baby cacti grow readily from seed, preferably new seed, which is Nature’s method for their reproduction. For this gallon tin cans or large flower pots, with holes in the [36] bottom for drainage, half or two-thirds filled with gravel and sand and the remainder with light sandy soil, or wooden flats twelve by twelve inches or larger and three inches deep, filled to a depth of two and a half inches with fine light sandy soil, answer well. The soil must be free from alkali, but may contain some finely divided organic matter. Level the surface of the soil firmly to prevent water from collecting, sow the seed an eighth of an inch deep, cover carefully, set in a sunny location, and give just enough water to keep the surface moist but not wet. (Out in the open, cover the frame with glass painted white or with white cheesecloth, and raise the glass slightly to insure ventilation.) The seeds should be sown in warm weather, and they should begin growth within one to three or four weeks. After the plants have grown a half-inch or more, transplant to two-inch pots, using paper pots or the usual flower pot, and with the soil somewhat heavier but drainage good. From this time their growth is more rapid and far more interesting, and they should be kept in a sunny location and given frequent light waterings, and, later, less frequent but heavier waterings. Do not attempt to force growth by heavy watering or heavy fertilizing. Once established and having grown to a considerable size, many of the Pincushion Cacti propagate by means of offshoots from the axils of tubercles below the surface of the ground, and thus form clumps of several larger plants with numerous smaller ones about them.

Southern California, Northwestern Arizona, and Southern Nevada

The desert is noted for its many forms of mirage, and because of the rarefied or clear atmosphere due to lack of moisture, things are not always what they seem there. In the [37] distance ahead numberless baby foxes appear to be moving slowly toward us, their heads and bodies hidden from view, their white and reddish tails waving in the hot desert breezes. Now our guide smiles, and as we drive closer and stop he points out several clumps of short cylindric Foxtail Cacti, covered with dense masses of stiff radiating spines, white or whitish with darker tips, and stout central spines white at their bases, then black, shading into reddish brown, the whole resembling a fox’s tail and creating a striking appearance. Light pink are the dainty flowers, and when full open (only in the brightest sunlight) nearly an inch and a half wide and long, the sepals hairy and the beautiful petals narrowly lance-shaped. It is no wonder that our baby cacti are so popular for winter rock gardens with their almost perfect symmetry, and their wonderful uniformity of spines so often beautifully mottled, with exquisite patterns of color and design, brilliant, cross-patch, symmetrical, running through the individual thorns. Care should be taken that such rock gardens are arid gardens, and that the soil is not enriched, with just sufficient water to encourage a natural, compact, symmetrical growth. A heavy flooding occasionally is good. If over-watered, or fertilized too much, or if shaded, these tiny cacti make a rapid artificial growth, usually non-symmetrical in part, called “storied” or “zoned.”

Western and Southern Arizona, and Northern Sonora

Especially is this true of the Cream Cactus, a very odd and interesting Pincushion, with a thick conical fleshy root which transplants easily and grows with little care from the hand of man. This fellow is broader than he is tall, four to ten inches in diameter, only two to six inches high, having a flat head around which radiate his clusters of thirteen or so [38] cream-white short stout spines, and one or two pale red central thorns with purplish brown curved tips and yellow bulbous bases; into this harmony of color come the flowers in bloom, twenty-five or more cream-colored or light yellow petals recurving into a lovely cornucopia effect, very pretty in the dazzling sun of spring and summer on the desert. When injured by small rodents or other enemies, MacDougalii yields a thick creamy fluid which immediately heals the wounds, and is pleasant to taste. Hence his name.

Southern Arizona and Northern Sonora

Hidden under a crevice in the rocks along our dusty track, we spy that little fellow, Coryphantha recurvata, with his dense coat of interlocking thorns, stout but slender and often hooked on the ends, recurving downward and inward toward the plant body with yellow and orange-brown hooks, and almost hiding the plants from our view. Rightly are the Pincushion Cacti named: with their tiny compactness and beautiful symmetry, they resemble nothing so much as an old-fashioned pincushion, with twenty or more sharp stout needles stuck into each brilliantly colored, soft downy cushion. Although among the larger Pincushion Cacti, this little fellow grows only six inches tall, more often four inches, and is three to six inches wide, a broad and rounded dwarf, flattened and depressed on top; often as many as fifty of his companions, their heads occasionally peering over one another, grow in a clump two or three feet across and half a foot high. The blossoms with their tan and brownish sepals and the inner petals lemon-yellow, tone into the brown and orange-brown spines, the sharp needles of our pretty [39] pincushion; the whole producing a happy symphony in brown and orange, so that many feel tempted to purloin this prize and take it back to adorn conservatories at home. And how many are transported and grown in our homes in lovely rock gardens! For recurvata is much in demand for cactus collections and is very easy to transplant. Plant him in sand or among rocks, and let him have plenty of bright sunshine and occasionally a little water, and he will thrive with neither care nor trouble to any one.

Southern Arizona, Southwestern New Mexico, and Northern Sonora

The Devil’s Pincushion is our largest and finest, resembling a pineapple in color and appearance, with his cone-shaped stems three to nine inches tall and three to six inches across, his big tubercles in spirals of thirteen or more rows, coarse yellowish thorns, and large fruit and seeds. The dozen or so spines in a comb-like radial arrangement from a common center, the areola, and graduated, are not alone beautiful and symmetrical, but provide a coat of mail for robustispina protecting him against excessive light or heat and cold. It is from this armament of stout wide-spreading thorns that he is so aptly named “The Devil’s Pincushion.” However, this cactus is endowed not only with a strong set of needles, but with lovely patterns in flower array as well: beautiful, showy blossoms, two or three inches long and wide, of a brilliant yellow against their reddish brown background of thorns, coming forth in one glorious splash of color for but [40] a day, then fading away from eye of man, and no more to be seen until another year has passed.

Southern Arizona

The Slender Pincushion Cactus, typical native of the desert, is commonly so called because of the tiny slender stems an inch or less in diameter and seven or eight inches tall, growing in dense clumps of fifty to two hundred or more plants of all sizes; some growing from seed, some from offshoots of the axils near their bases. Out from the dozen or so rows of tubercles spring the white thorns with their black tips, and the central hooked spine twisted from its bulbous base; then the funnel-shaped pale purple and pink blossoms, giving a decidedly pinkish cast to this whole lovely pincushion. The bright scarlet berries, while they are odd, are pretty and also are edible. This plant was first discovered by Lieutenant Colonel Emory in 1846; it was never seen again until 1902, when it was rediscovered by one of the writers and Mr. Orcutt, along the Gila River in Arizona, from which the Gila monster is named.

Southern Arizona and Northern Sonora

This gayly decorated Pincushion we see peering over solitary rocks and gladdening the hearts of the tired travelers along the desert track, with his pink and white daintiness of blossom and comb of brown and white thorns is another “Cream Cactus”; for it is said many an Indian has owed his life to the thick milk-white fluid which this unique growth yields to those who know the secret. This fat fellow looks like a huge coconut, with a green body, and stout thorns curved both upward and downward. Little bells are the flowers peeping out in a circle at the bases of the old tubercles and laughing up at us gayly as we motor slowly along the hot dusty road.

HORNED TOAD CACTUS (Mammillaria Mainæ)

SLENDER PINCUSHION CACTUS (Mammillaria fasciculata)

SUNSET CACTUS (Mammillaria Grahamii)

The bright pink and rose tints of the bell-like blossoms tone into the pink glow of the desert sunset in a circle of full open, brilliant flowers, their many brightly glowing segments spreading out like so many iridescent rays of the setting sun.

BENT SPINE PINCUSHION (Coryphantha recurvata)

Southern Arizona, Western Texas, Southern California, Southern Utah, and Mexico

We have come more than two hundred miles on this second springtime trek across the ocean of sand and sagebrush and mesquite, with its brilliant flashes of color and fragrance, and still the clumps of dainty pincushions attract us almost against our will. As the sun completes his journey across the western skies, one of the most beautiful of all Nature’s creations claims our attention; this pincushion has earned a title appropriate to its lovely self, the bright pink and rose tints of its bell-like blossoms toning into the pink glow of the desert sunset in a circle of full open brilliant flowers, their many brightly glowing segments spreading out like so many iridescent rays of the setting sun. What name could be more apropos than “Sunset Cactus”? With her evanescent beauty and delicate perfume she is one of the most popular as well as the most abundant of the Mammillaria, ranging from Mexico through Southern California and Arizona to southern Utah. From two to ten inches tall, only a little more than two inches in breadth, she grows more slender than her brothers; her twenty rows of compact tubercles are set in a beautiful gray-green symmetrical spiral, and bear twenty or so slender grayish white radiating spines with dark tips, a half-inch long or less, and two central thorns sticking out stouter than the others, their bodies pale pink and their sharp [42] tips curving upward in a transparent golden fringe of color.

Southern and Southeastern Arizona

The Brown Pincushion is one of the most attractive of the southwestern cacti, and is a rare creation indeed. This tiny cactus is two or three inches tall and about as broad, with a beautiful halo of red-brown thorns covering the whole plant, the hooked central spines and whitish radials slender, sharp, needlelike, with pointed tips. Through these the tiny flowers peep in two rows of thirty-five or forty bright purple or pink petals, recurved into the pretty cornucopia effect that we have seen so often among the clumps of Pincushions on our way across the desert. But beware of pressing the fingers against this dainty pincushion too hard, for if the sharp points of the central spines get hooked into the hand it is only with great difficulty and discomfort that one can get free. When the first offenders are released other spines hook into the flesh, and the plant seems to play with the victim for some time to see just how far it can go in provoking one so lacking in desert knowledge.

Southern Arizona and Northern Sonora