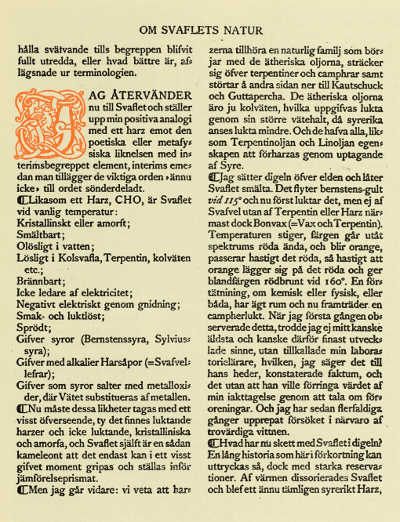

The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Art of the Book, by

Bernard H. Newdigate and Douglas Cockerell and L. Deubner and E. A. Taylor

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: The Art of the Book

A Review of Some Recent European and American Work in

Typography, Page Decoration & Binding

Author: Bernard H. Newdigate

Douglas Cockerell

L. Deubner

E. A. Taylor

Editor: Charles Holme

Release Date: June 14, 2014 [EBook #45968]

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE ART OF THE BOOK ***

Produced by Chris Curnow, Turgut Dincer and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive)

THE ART OF THE BOOK

AXiREVIEWXiOFXiSOME

RECENTXXeeEUROPEAN

ANDeAMERICANeWORK

INeTYPOGRAPHY,ePAGE

DECORATION & BINDING

........................................

CHARLES HOLME, EDITOR

MCMXIV

“THE STUDIO” LTD.

LONDON, PARIS, NEW YORK

THE Editor desires to express his thanks to the following who have kindly assisted in the preparation of this volume:—to the Trustees of the Kelmscott Press for permission to reproduce the pages printed in the three types designed by William Morris, and to Mr. Emery Walker for the valuable assistance he has rendered in the reproductions of these particular pages, and also the page of Proctor's Greek type; to Mr. Lucien Pissarro for allowing the three pages by the Eragny Press to appear; to Mr. C. H. St. John Hornby, whose page by the Ashendene Press has been especially set up for this volume; to Mr. Philip Lee Warner for permission to show two pages by the Riccardi Press; to Messrs. Chatto & Windus for the page by the Florence Press; to Messrs. Methuen & Co. for the page printed in the “Ewell” type; to Messrs. H. W. Caslon & Co. for the page of their new “Kennerley” type; to Messrs. P. M. Shanks & Sons for the page of “Dolphin Old Style” type; to Mr. F. V. Burridge for the two pages especially set up at the London County Council Central School of Arts and Crafts; to Messrs. George Allen & Co. for permission to reproduce the two pages designed by Mr. Walter Crane; to Mr. Percy J. Smith for the book-opening designed by him; to the Cuala Press, the Vincent Press, the Reigate Press, Messrs. B. T. Batsford, Messrs. J. M. Dent & Sons, Messrs. George Routledge & Sons, Messrs. Siegle, Hill & Co., for permission to show various pages from their publications; and to Mr. J. Walter West, R. W. S., for the pages designed by him.

The Editor's thanks are due to the various bookbinders whose work has been lent for illustration, and to Monsieur Emile Lévy for the loan of the photographs of Mr. Douglas Cokerell's bindings; to Mr. John Lane for permission to illustrate the cover designs by Aubrey Beardsley; and to Messrs. George Newnes for the end-paper design by Mr. Granville Fell.

The Editor is also indebted to the various Continental and American publishers, printers, type-founders, bookbinders and book-decorators who have kindly placed at his disposal the examples of their work shown in the foreign sections; particularly to Herren Gebrüder Klingspor, the Bauersche Giesserei, Herr Emil Gursch, Herr D. Stempel, Herren Genzsch and Heyse, MM. G. Peignot et fils, Monsieur L. Pichon, and Monsieur Jules Meynial for the pages of type especially set up for this volume.

| PAGE | ||

| British Types for Printing Books. | By Bernard H. Newdigate | 3 |

| Fine Bookbinding in England. | By Douglas Cockerell | 69 |

| The Art of the Book in Germany. | By L. Deubner | 127 |

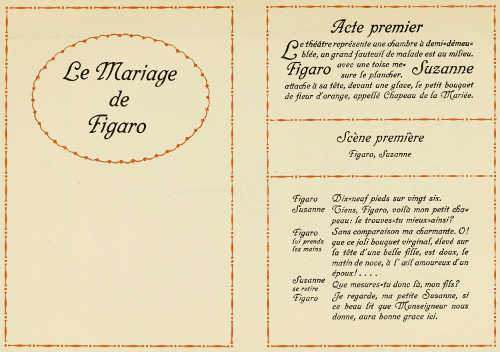

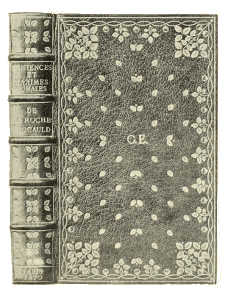

| The Art of the Book in France. | By E. A. Taylor | 179 |

| The Art of the Book in Austria. | By A. S. Levetus | 203 |

| The Art of the Book in Hungary. | —— | 231 |

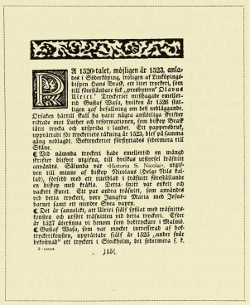

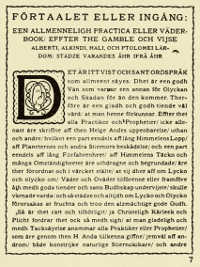

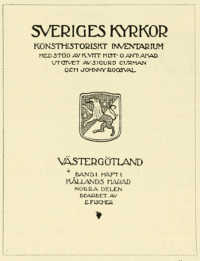

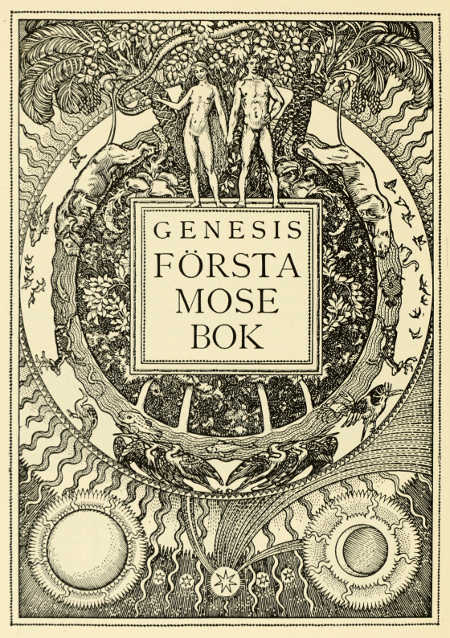

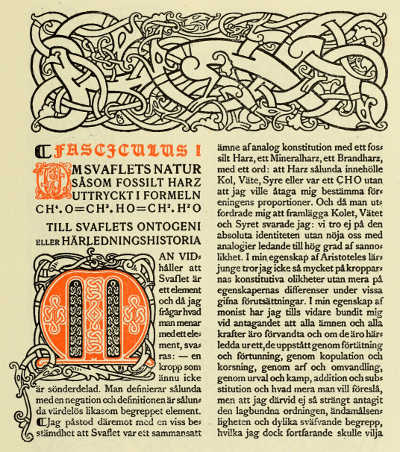

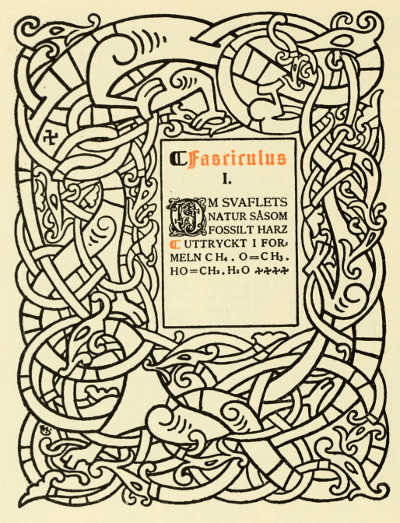

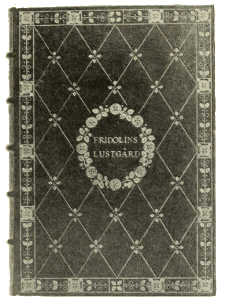

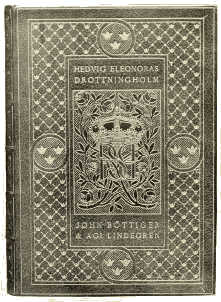

| The Art of the Book in Sweden. | By August Brunius | 243 |

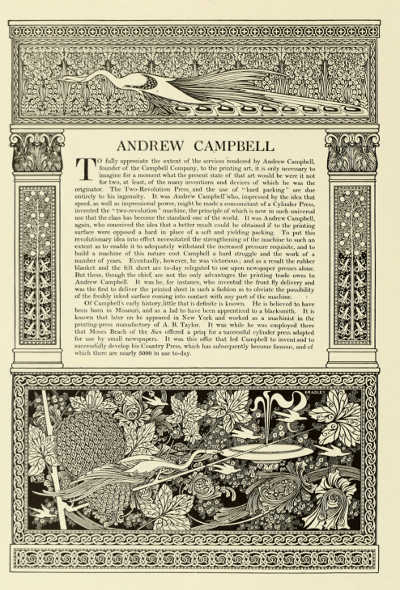

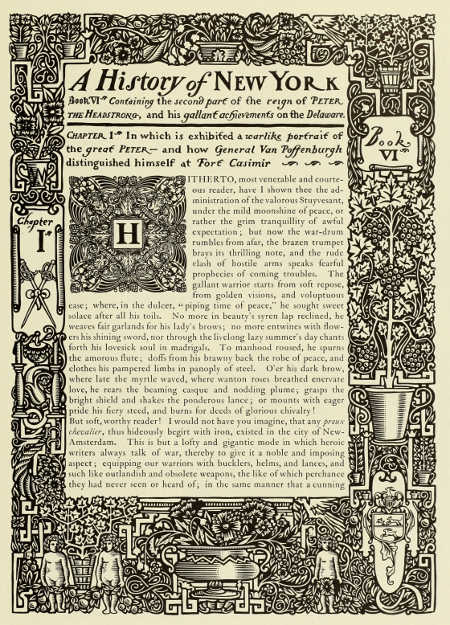

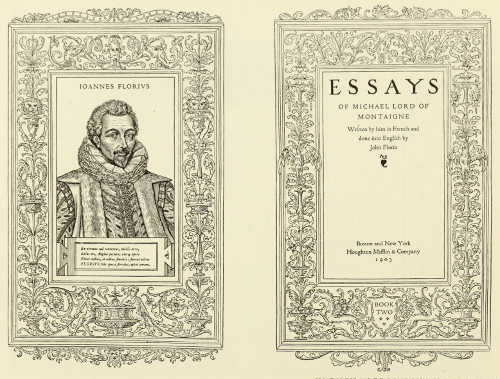

| The Art of the Book in America. | By William Dana Orcutt | 259 |

TO judge rightly of the good or bad features of types used for printing books, we should have some acquaintance at least with the earlier forms from which our modern types have come. Let us therefore glance at the history of the letter from which English books are printed to-day.

The earliest printed books, such as the Mainz Bible and Psalters, were printed in Gothic letter, which in its general character copied the book-hands used by the scribes in Germany, where these books were printed. In Italy, on the other hand, the Gothic hand did not satisfy the fastidious taste of the scholars of the Renaissance, who had adopted for their own a handwriting of which the majuscule letters were inspired, or at least influenced, by the letter used in classical Rome, of which so many admirable examples had survived in the old monumental inscriptions. For the small letters they went back to the fine hand which by the eleventh and twelfth centuries had gradually been formed out of the Caroline minuscules of the ninth and had become the standard book-hand of the greater part of Latin Europe. When the Germans Sweynheim and Pannartz brought printing into Italy, they first printed books in a very beautiful but somewhat heavy Roman letter of strong Gothic tendency. It seems, indeed, to have been somewhat too Gothic for the refined humanistic taste of that day; and when they moved their press to Rome, it was discarded in favour of a letter more like the fashionable scrittura umanistica of the Renaissance. Other Italian printers had founts both of Gothic and of Roman types. The great Venetian printer Jenson, for instance, and many of his fellows printed books in both characters; but the Roman gradually prevailed, first in Italy, then in Spain and France, and later on in England. In Germany, on the other hand, the cradleland of the craft, Gothic letter of a sadly debased type has held its own down to this day. Even in Germany, however, the use of Roman type has gained ground of late years, nationalist feeling notwithstanding.

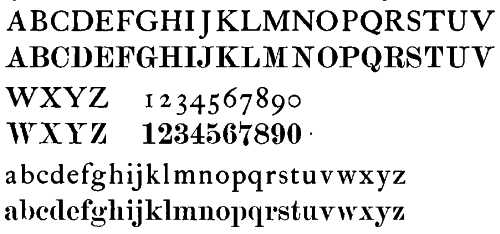

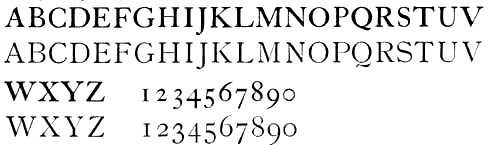

The Roman type used by the early Italian printers is, then, the prototype from which all other Roman founts are descended. Its development may be traced through such Roman type as was used by Aldus at Venice, by Froben at Basle, by the Estiennes in Paris, by Berthelet and Day in London, by Plantin at Antwerp, by the Elzevirs at Leyden and Amsterdam, and by printers generally right through the seventeenth century and the greater part of the eighteenth. Through all these years types still kept what modern printers call their “old-face” character, which they had acquired from the scrittura umanistica of the Italian Renaissance. In the seventeenth century the letters of the Roman[4] alphabet began to acquire certain new features at the hands of the copper-plate engravers, who supplied the book illustrations of the period. Working with the burin instead of the pen, they naturally used a sharper and finer line and also modified somewhat the curves of the letters, which tended to become more stilted and less open. The tail of the “R,” for instance, which in Jenson's type is thrust forward at an angle of about forty-five degrees, at the hands of some of the seventeenth-century engravers tends to drop more vertically, as in the “R” of “modern” type, the development of which we are seeking to trace. How far and how soon the lettering of the engravers of illustrations came to modify the letters cast by the type-founders is a question which invites further research. A material piece of evidence is supplied by the “Horace” printed by John Pine in 1733. Instead of being printed from type, the text of this book, together with the ornaments and illustrations, was printed from engraved copperplates. In date it was some sixty years prior to the earliest books printed in “modern-faced” type in this country; yet in the cut of the lines and the actual shape of the letters many distinguishing features of the “modern” face may already be traced. What these features became may be seen best by comparing an alphabet of the “old” with one of the “modern” face printed below it:

The “modern” tendency may be seen in certain features of the types designed by Baskerville, who printed his first book in 1757; but it is not nearly so pronounced as in Pine's “Horace,” engraved twenty-four years earlier. Baskerville's editions had an enormous vogue, not only in this country but on the Continent also, where they had considerable influence on the style of printing which then prevailed. Amongst those who felt this influence was Giambattista Bodoni, a scholar and printer of Parma, which city has lately kept the centenary of his death. To Bodoni more than anyone else the so-called “modern-face” is due. He cast a large number of founts, narrow in the “set” or width of the letters as com[5]pared with their height, and having the excessively fine lines and the close loops and curves which are characteristic of that face. Like Baskerville he printed his books with very great care on a spacious page in large and heavily-leaded type; and although an occasional protest was raised against the ugliness of his letter, his books caught the taste of his day, and his type was copied by all the English type-founders of the time. The new fashion completely drove out the older tradition, which dated from the very invention of printing; and from the closing years of the eighteenth to the middle of the nineteenth century books were printed almost exclusively in “modern-faced” type.

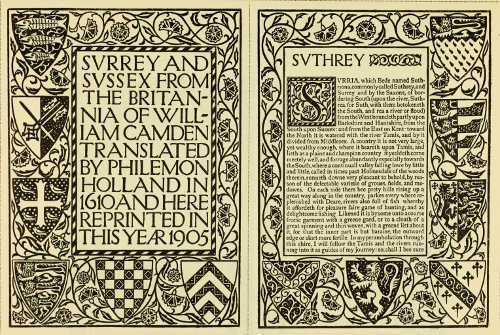

The older and more authentic letter had its revenge in 1843, when the publisher, William Pickering, arranged with his friend Charles Whittingham, the printer, to produce a handsome edition of Juvenal as a “leaving-present” for Eton; and the book was to be printed from the discarded type first cut by William Caslon about the year 1724. Prior to that time English printers had gone to Holland for most of their type; but Caslon's types surpassed in beauty any hitherto used in England, and the best English printing had been done from them till near the end of the century, when they were driven out by the “modern” face. Before the Juvenal was issued, a romance entitled “The Diary of Lady Willoughby,” dealing with the period of the Civil Wars, was also printed in old-faced type cast from William Caslon's matrices, so as to impart to the book a flavour of the period at which the diarist was supposed to be writing. It was the day of Pugin and of the Gothic revival; and the public taste was won by the appearance of this book, printed in old-fashioned guise in the selfsame type which had been cast aside half a century before. Type-founders are generally quick to follow one another's lead in new fashions; and before long every type-founder in England had cut punches and cast letter in that modified form of Caslon's old-faced type which printers call “old-style.” Mr. Adeney of the Reigate Press has used an “old-style” fount in the extract from Camden's “Britannia” reproduced on a very small scale on page 57. The “old-style” character and the points in which it is either like or unlike the more authentic old-faced letter may be seen by comparing the two. The lower of these founts is the “old-style” :

The favour which the revived “old-face” and the new “old-style” letter won for themselves in the middle of last century has suffered no diminution since. The ugly “modern-face,” which we owe to Bodoni, is still used almost exclusively for certain classes of work and alternatively for others; so that the printer is bound to be familiar with all three. For book-printing at the present day the “old style” and the “old-face” are used much more than the modern.

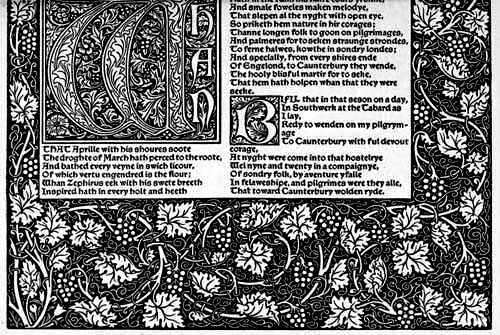

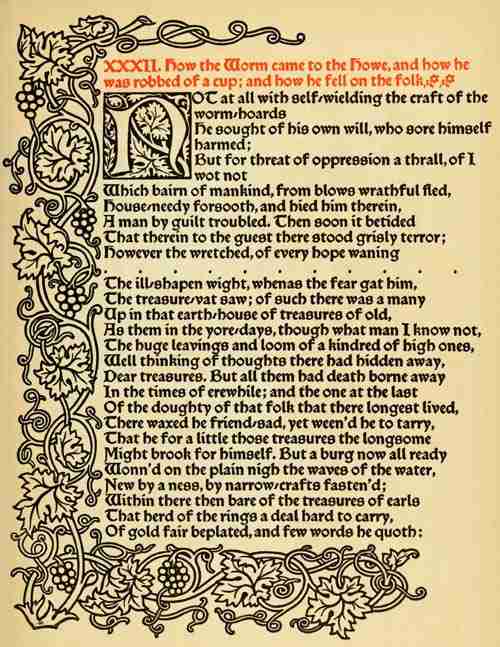

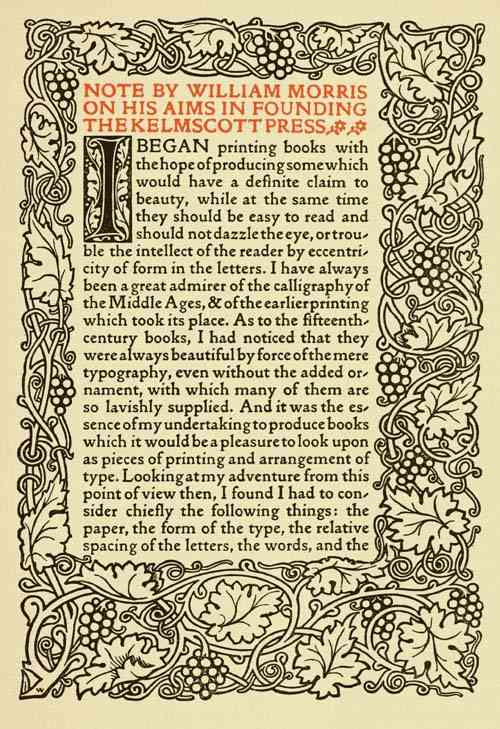

During the fifty years that followed the revived use of Caslon's types by the Whittinghams there is little else to record about the designs of the types used for printing books, until about the year 1890, when William Morris set himself to design type, fired thereto by a lecture, given by Mr. Emery Walker, on the work of the Early Printers, to which he had listened. In the “Note by William Morris on his aims in founding the Kelmscott Press,” printed after his death, he writes of the purpose which led him to print books, and of the character he sought to give his letter: “I began printing books with the hope of producing some which would have a definite claim to beauty, while at the same time they should be easy to read and should not dazzle the eye by eccentricity of form in the letters. I have always been a great admirer of the calligraphy of the Middle Ages and of the earlier printing which took its place. As to the fifteenth-century books, I had noticed that they were always beautiful by force of the mere typography, even without the added ornament with which many of them are so lavishly supplied. And it was the essence of my undertaking to produce books which it would be a pleasure to look upon as pieces of printing and arrangement of type.... Next as to type. By instinct rather than by conscious thinking it over, I began by getting myself a fount of Roman type. And here what I wanted was letter pure in form; severe without needless excrescences; solid without the thickening and thinning of the line, which is the essential fault of the ordinary modern type and which makes it difficult to read; and not compressed laterally, as all later type has grown to be owing to commercial exigencies. There was only one source from which to take examples of this perfected Roman type, to wit, the works of the great Venetian printers of the fifteenth century, of whom Nicholas Jenson produced the completest and most Roman characters from 1470 to 1476. This type I studied with much care, getting it photographed to a big scale, and drawing it over many times before I began designing my own letter; so that, though I think I mastered the[7] essence of it, I did not copy it servilely; in fact, my Roman type, especially in the lower case, tends rather more to the Gothic than does Jenson's. After a while I felt I must have a Gothic as well as a Roman fount; and herein the task I set myself was to redeem the Gothic character from the charge of unreadableness which is commonly brought against it. And I felt that this charge could not be reasonably brought against the types of the first two decades of printing: that Schoeffer at Mainz, Mentelin at Strassburg, and Günther Zainer at Augsburg, avoided the spiky ends and undue compression which lay some of the later types open to the above charge.... Keeping my end steadily in view, I designed a black-letter type which I think I may claim to be as readable as a Roman one, and to say the truth I prefer it to the Roman. This type is of the size called Great Primer (the Roman type is of 'English' size); but later on I was driven by the necessities of the Chaucer (a double-columned book) to get a similar Gothic fount of Pica size.”

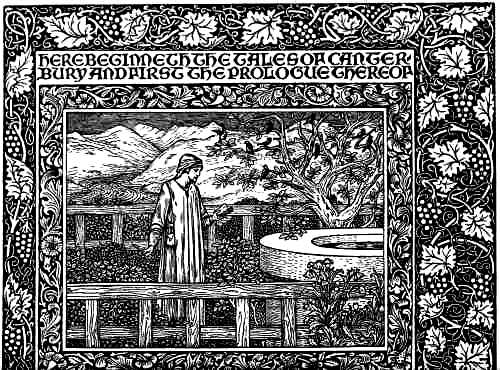

Pages printed in each of Morris's three founts of type are reproduced here on pages 14, 15, 17 and 19. It is interesting to compare Morris's “Golden” type—so he called his Roman fount after the “Golden Legend,” which he printed from it—with the Roman letter of the Italian printers, which he studied with so much care before he began to design his type. The “Golden” type is much heavier in face than, say, that of Jenson; and it certainly lacks the suppleness and grace of the Italian types generally. As a point of detail we may notice especially the brick-bat serifs used on Morris's capital “M” and “N,” giving a certain clumsiness to these letters. The two Gothic letter founts which Morris designed, on the other hand, must be regarded as amongst the most beautiful ever cast. William Morris's types should be judged on the setting of richly decorated borders which he designed for his pages. Adding to these the designs of Sir Edward Burne-Jones, engraved on wood by W. H. Hooper, we have in the Kelmscott “Chaucer” the most splendid book which has ever been printed.

The “Golden” type of the Kelmscott Press was copied freely in America and sent back to the country of its birth under several different names. In somewhat debased forms it had a vogue for a time as a “jobbing” fount amongst printers who knew little or nothing of the Kelmscott Press; but the heaviness of its line and also its departure from accepted forms kept it from coming into general use for printing books. The interest awakened by the books printed by William Morris at Hammersmith tempted many more to set up private presses or to design private founts of type when the work of the Kelmscott Press came to an end after Morris's death, which took place in 1896. Most of such founts and the best of them followed more or less closely the letter of the early Italian printers, which, as we have seen, are the prototypes of our book letter of to-day. Even before the founding[8] of the Kelmscott Press Mr. Charles Ricketts had designed books, using some of the “old style” faces which were in general use. When the Kelmscott Press books appeared, he too was won over by what he called the “golden sunny pages” of the early Italian printers, and designed for himself the “Vale” type. In weight and general appearance it bears considerable likeness to Morris's “Golden” type, and in some ways is an improvement on it. Mr. Ricketts afterwards had the same letter cast in a smaller size for his edition of Shakespeare, whence its name of the “Avon” type. He also designed another letter, the interest of which lies in certain experiments towards the reform of the alphabet which it embodies. In the “King's” type, as Mr. Ricketts called it, many of the minuscule letters, such as e, g, t, are replaced by small majuscules. Such a departure from traditional use is too violent to give pleasure, and only two or three books were printed in this letter. The three Vale Press founts and also the punches and matrices were destroyed when the Press ceased publishing.

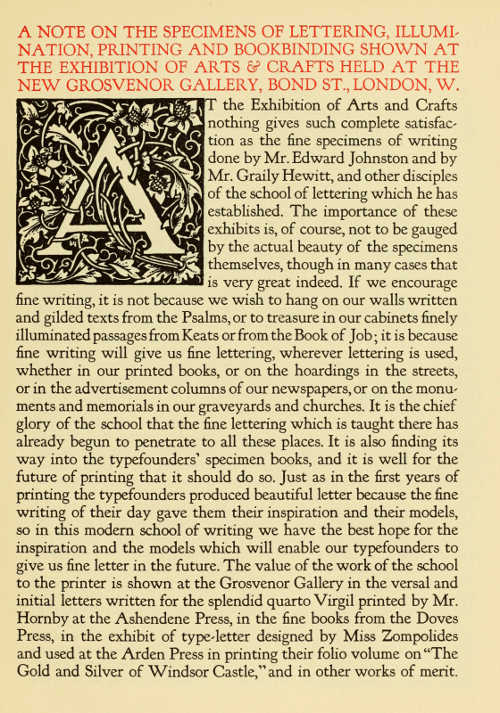

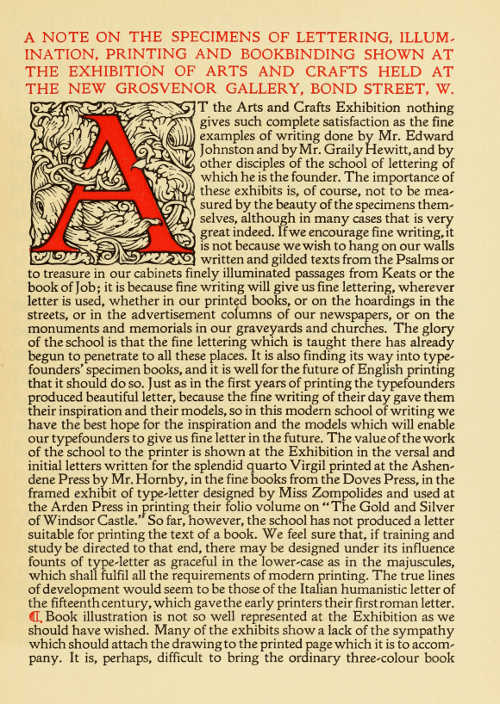

Mr. T. J. Cobden-Sanderson and Mr. Emery Walker set up the Doves Press at Hammersmith in 1900, and designed and got cast for themselves a fount of type which follows Jenson's Roman type very closely. It differs from it chiefly in the greater regularity of its lines, and also in the squareness and brick-bat shape of some of the serifs, which are, however, less conspicuous than in Morris's “Golden” type. The Doves Press books, unlike those of the Kelmscott Press, are entirely free from ornament or decoration, and owe their remarkable beauty to what Morris styled the architectural goodness of the pages and also to the fine versal and initial letters done by Mr. Edward Johnston and Mr. Graily Hewitt. Later on we shall have something more to say about the work of these men and their school.

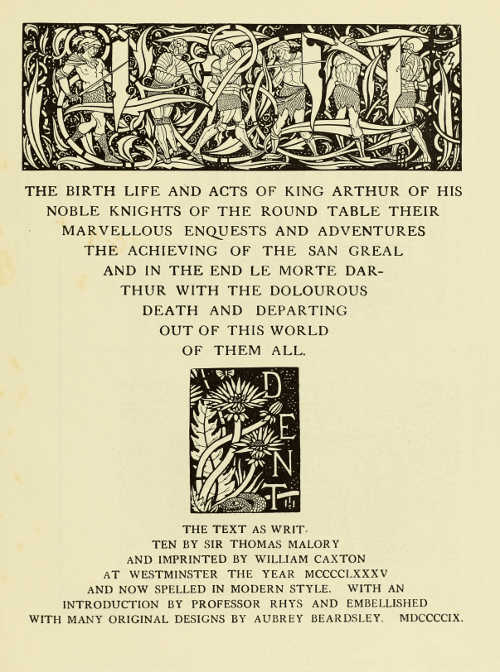

The type of the Ashendene Press (p. 23) is modelled from that in which Sweynheim and Pannartz printed books at Subiaco, and which, as we have seen, they replaced by a purer Roman letter more in accord with the humanistic taste of their day. Morris himself designed, but never carried out, a fount of letter after the same fine model. It is a Roman type, with many Gothic features. The folio “Dante,” the “Morte Darthur,” the Virgil and the other books which Mr. St. John Hornby has printed from it in black and red, with occasional blue and gold, are superb examples of typography.

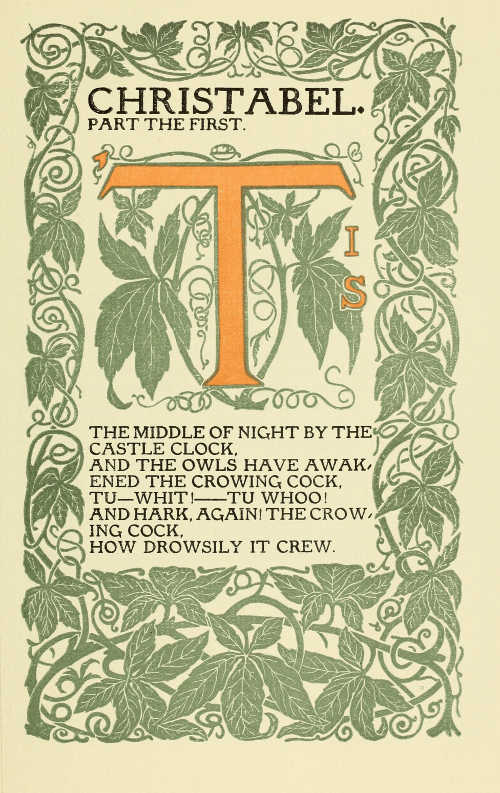

Mr. Lucien Pissarro's little octavos have a certain personal charm of their own distinct from anything that is found in the more weighty volumes which have issued from the other private presses. The first books which he produced at his Eragny Press were printed from the Vale type belonging to his friend Mr. Ricketts. In 1903 he began printing from the “Brook” type (pp. 25 to 29), which he had designed. Although in this article we are concerned chiefly with his types, it is impossible to withhold a tribute of praise for the graceful beauty of[9] these little books, which they owe even more to the admirable way in which their different elements have been combined—type, wood-engraving, colour, printing and binding, all of them the work of Mr. and Mrs. Pissarro themselves—than to the individual excellence of any one of them.

Mr. C. R. Ashbee's “Endeavour” type was designed by him for use at the Essex House Press, which he first established at Upton in the eastern suburbs of London and afterwards removed to Chipping Campden in Gloucestershire. It owes nothing to the types of the early printers, and taken by itself is not pleasing; but it makes a very handsome page when printed in red and black, as in the Campden Song Book. The type was also cut in large size for King Edward's Prayer Book, one of the most ambitious ventures of any private press.

Mr. Herbert P. Horne has designed three founts, all of them inspired by the Roman letter of the early Italian printers. The “Montallegro” type (p. 265), the first in order of date, was designed for Messrs. Updike and Co., of the Merrymount Press, Boston, and hardly falls within the scope of this article. In 1907 he designed for Messrs. Chatto and Windus a fount called the “Florence” type (p. 31), from which editions of “The Romaunt of the Rose,” “The Little Flowers of St. Francis,” A. C. Swinburne's “Songs before Sunrise,” R. L. Stevenson's “Virginibus Puerisque” and also his Poems have been printed at the Arden Press on behalf of the publishers. It is a letter of a clean, light face, and in many ways might serve as a model for a book type for general use. The capital letters used in continuous lines, as Aldus and other great Venetians delighted to use them, are especially charming. Mr. Horne's Riccardi Press type (pp. 33 and 35) was designed for the Medici Society, and many fine editions, amongst them a Horace, Malory's “Morte Darthur,” and “The Canterbury Tales,” have been printed from it. It is a little heavier in face than its predecessor, the “Florence,” and is a little further removed from the humanistic character. The type has also been cast successfully in a smaller size.

To the number of privately owned founts of type we must add the “Ewell” (p. 37), designed by Mr. Douglas Cockerell for Messrs. Methuen and Co., who will shortly publish the first book to be printed from it, an edition of the “Imitatio Christi.” It is a heavy but very graceful letter, based on one used by the Roman printer Da Lignamine.

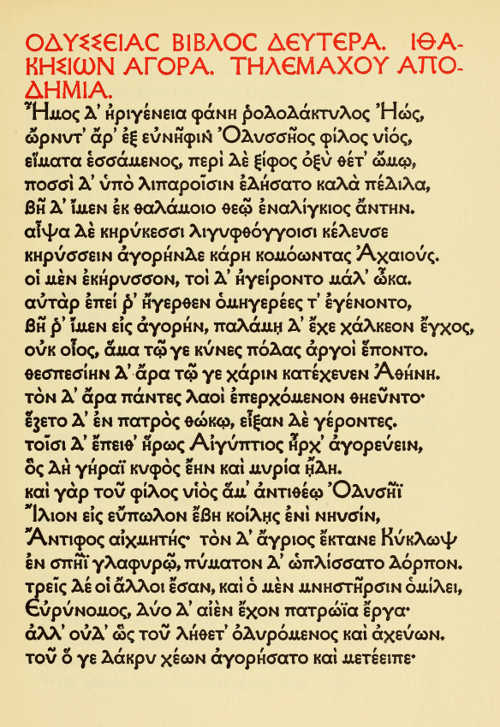

One of the most interesting of the privately owned founts is the “Otter” Greek type designed by the late Mr. Robert Proctor, and shown in the page from the Odyssey printed on page 43. The Greek letter from which most of our school classics are printed is a descendant of the cursive type introduced by Aldus at the beginning of the sixteenth century, and has the merit neither of beauty nor of clearness. The majuscules are especially ugly, being nearly always of the “modern” type which we owe to Bodoni. Proctor took[10] as his model the finest of the old Greek founts, which was that used in the Complutensian Polyglot printed in 1514.

Amongst the types sold by the founders for general use none have enjoyed such successive favour as Caslon's “Old-Face” in its various sizes; and it is a splendid tribute to the excellence of this letter that at this day, nearly two centuries since it was first cut, it is being used more than any other face of type for printing fine books. This Special Number of The Studio is printed from Caslon's “Old-Face” type, as well as the pages, set up at the Central School of Arts and Crafts, which are shown on pages 45 and 47. The fame of Caslon's letter brought other rivals into the field besides Baskerville. One of these was Joseph Fry, a Bristol physician, who took to letter-founding in the year 1764, and cut a series of type somewhat like Baskerville's. A few years later, however, the Caslon character seems again to have recovered its old ascendancy, and Fry put on the market a new series in acknowledged imitation of Caslon's. Both these series of Fry's have been reissued within the last few years by Messrs. Stephenson and Blake, of Sheffield, who, in 1906, bought the type-founding business of Sir Charles Reed and Son, to whom Fry's business had eventually come. Like the revived Caslon “Old-Face” in 1843, these founts were cast from the old matrices, or from matrices struck from the old punches, so far as these had survived.

Since the “old-style” founts were designed about the middle of last century, what new book types have been cast by the founders for use by the printing trade generally have as a rule been mere variations of letter already in vogue. The founders have drawn but little on the wealth of beautiful book types which in the early printed books of Italy are offered to anyone who has the good taste and the skill to adapt them to modern needs. Messrs. Shanks and Sons, the type-founders of Red Lion Square, have, however, gone to this source for their “Dolphin” series (p. 41), which has many features of beauty to commend it. It is based on Jenson's Roman letter, somewhat thickened in the line. The punches were cut by Mr. E. P. Prince, who also cut the Kelmscott type and many others of the private founts.

Intelligent study of Italian models also gives us the “Kennerley” type (p. 39), designed by the American Mr. Goudy, which Messrs. Caslon will shortly put on the English market. This type is not in any sense a copy of early letter—it is original; but Mr. Goudy has studied type design to such good purpose that he has been able to restore to the Roman alphabet much of that lost humanistic character which the first Italian printers inherited from their predecessors, the scribes of the early Renaissance. Besides being beautiful in detail his type is beautiful in the mass; and the letters when set into words seem to lock into one another with a closeness which is common in the letter of early printers, but is rare in modern type. The[11] “Kennerley” type is quite clear to read and has few features which by their strangeness are likely to waken the prejudice of the modern reader. Since the first Caslon began casting type about the year 1724, no such excellent letter has been put within reach of English printers.

So large is the proportion of books which are now set in type by machinery that, however much our sympathies may make us prefer the hand-set book, we cannot but be concerned for the characters used in machine composition. Type set by machinery generally seems to be inferior in design to that set by hand; but the inferiority is in the main accidental, and is probably due to a lesser degree of technical skill shown either in the designing or in the process of punch-cutting, which is itself done by machinery. One or two admirable faces of type have, however, been produced by the Lanston Monotype Company for setting by the monotype machine. One of these is the “Imprint” type, adapted from one of the founts used by Christopher Plantin, the famous printer of Antwerp, in the late sixteenth century. The letters are bold and clear, and pages set in them are both pleasant to look at and easy to read. At the same time the type is sufficiently modern in character not to offend by any features unfamiliar to the ordinary reader.

No art can live by merely reviving and reproducing past forms, and in reviewing the share taken by the type-founders of the past and of the present in the art of the book one cannot help considering by what means and from what quarter good types are to be designed and cut in the future. We have seen that the early printers took their inspiration from the best of the contemporary book-hands. The invention of printing, however, killed the art of the scribe, and with it perished the source whence during the ages past life and beauty had been given to the letters of the alphabet and to the pages in which they were gathered. Henceforth the letters were cast in lead, and there was no influence save the force of tradition to make or keep them beautiful. Whatever change they underwent was for the worse, unless indeed it was a mere reversion to forms or features which for a while had been abandoned.

Conscious of this downward tendency, which he seems to look upon as inevitable and irresistible, Mr. Guthrie, of the Pear-tree Press at Bognor, has renounced type altogether, and now prints books, like William Blake, from etched plates inscribed with his own fine book-hand. Such a method is, of course, not practicable for the vast majority of books, even if we were willing to forgo the many fine qualities which are presented in a well-printed book. Neither is any such counsel of despair warranted, for of late years the art of the scribe itself has been renewed; and most readers of The Studio know something of the fine work done by the school of calligraphy established some ten years since by Mr. Edward Johnston, and still carried on by his pupil Mr. Graily Hewitt at the Central School[12] of Arts and Crafts in Southampton Row, London. May not the printer look to that school as the source whence the type-designer and type-founder shall learn to design and cut beautiful letter for his books? Not indeed that type-letter should be a mere reproduction of any written hand; rather must it bear nakedly and shamelessly all the qualities which the steel of the punch-cutter and the metal from which it is cast impose upon it. It must be easy to read as well as fair to look on, and besides carrying on the traditions of the past must respect the prejudices of the present. But only a calligrapher whose eye and hand have been trained to produce fine letter for the special needs of the printed book can have knowledge of the manifold subtleties of such letter and power to provide for them in the casting of types. If the writing schools can turn out such men, they will deserve well of all those who are interested in the art of the book. That our hope need not be vain is shown by the fact that calligraphers trained in the methods of the school have gone to Germany, and have there profoundly influenced the production of modern types; and the supreme irony of it all is that German type-founders are sending to England new types which draw their inspiration from a London school of which the English and Scottish type-founders seem never even to have heard.

Note—In the course of the preceding article the writer has had occasion to refer frequently to the type of Nicholas Jenson in its relation to the modern British founts. The Editor has therefore included amongst the examples shown a page from the “Pliny,” printed by Jenson in 1476, for purposes of comparison and reference. It will be found on page 21.

(Reproduced by permission of the Trustees of the

Kelmscott Press)

KELMSCOTT PRESS: PAGE FROM “THE WORKS OF GEOFFREY CHAUCER” PRINTED IN

THE “CHAUCER” TYPE DESIGNED BY WILLIAM MORRIS. ILLUSTRATION BY SIR

EDWARD BURNE-JONES, BART., BORDER AND INITIAL LETTER BY WILLIAM MORRIS

KELMSCOTT PRESS: PAGE FROM “THE TALE OF BEOWULF” PRINTED IN THE “TROY” TYPE DESIGNED BY WILLIAM MORRIS (REPRODUCED BY PERMISSION OF THE TRUSTEES OF THE KELMSCOTT PRESS)

KELMSCOTT PRESS: PAGE PRINTED IN THE “GOLDEN” TYPE DESIGNED BY WILLIAM MORRIS (REPRODUCED BY PERMISSION OF THE TRUSTEES OF THE KELMSCOTT PRESS)

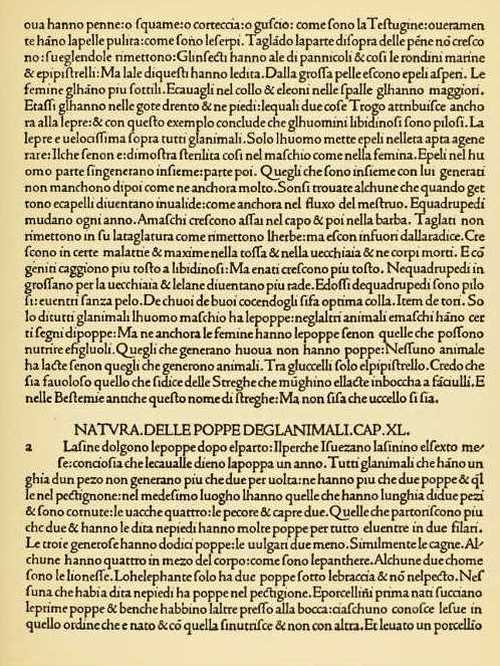

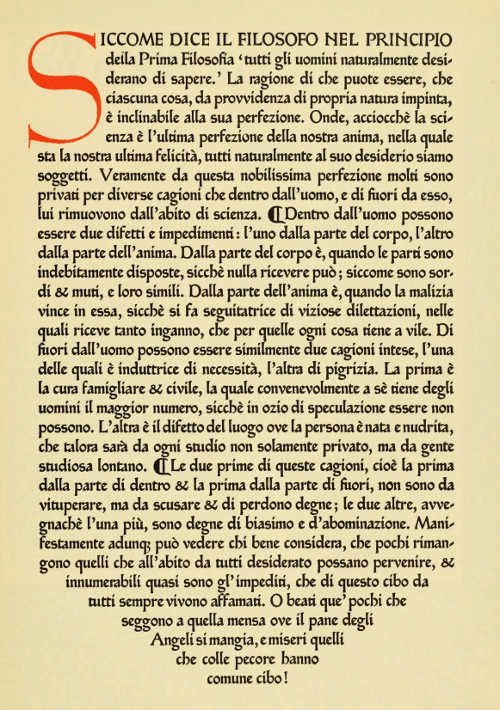

PAGE FROM THE “PLINY” PRINTED AT VENICE BY NICOLAS JENSON IN 1476

ASHENDENE PRESS: PAGE PRINTED IN GREAT PRIMER TYPE MODELLED UPON THE TYPE USED BY SWEYNHEIM AND PANNARTZ AT SUBIACO IN 1465

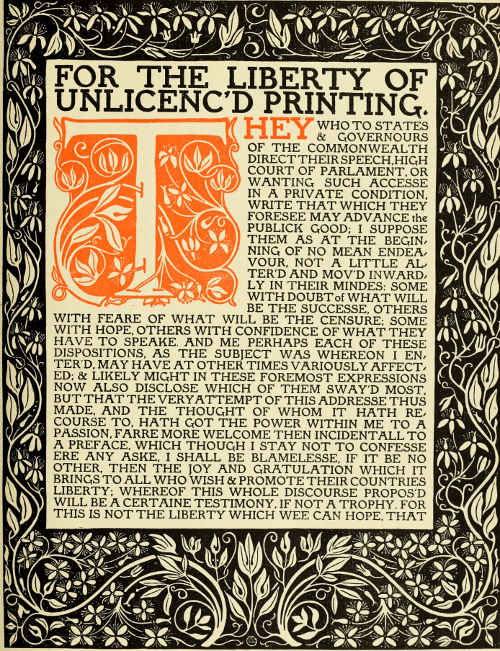

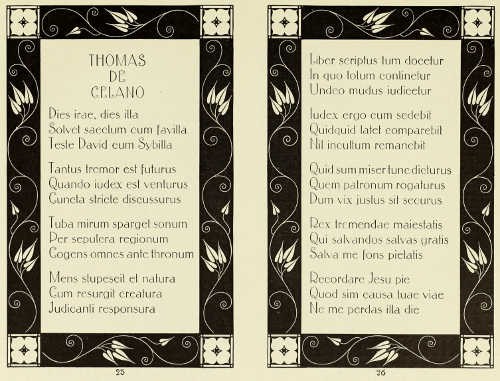

ERAGNY PRESS: OPENING PAGE OF THE “AREOPAGITICA” PRINTED IN THE “BROOK” TYPE, WITH BORDER AND INITIAL LETTER DESIGNED BY LUCIEN PISSARRO

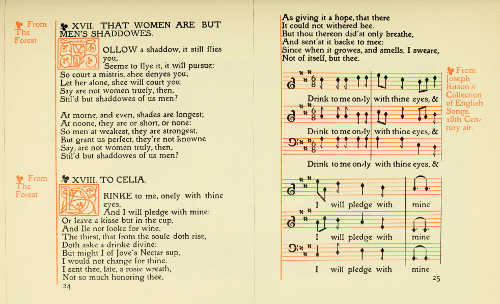

ERAGNY PRESS: PAGES FROM “SONGS BY BEN JONSON” PRINTED IN THE “BROOK” TYPE DESIGNED BY LUCIEN PISSARRO

ERAGNY PRESS: OPENING PAGE OF COLERIDGE'S “CHRISTABEL” PRINTED IN THE “BROOK” TYPE, WITH BORDER AND INITIAL LETTER DESIGNED BY LUCIEN PISSARRO

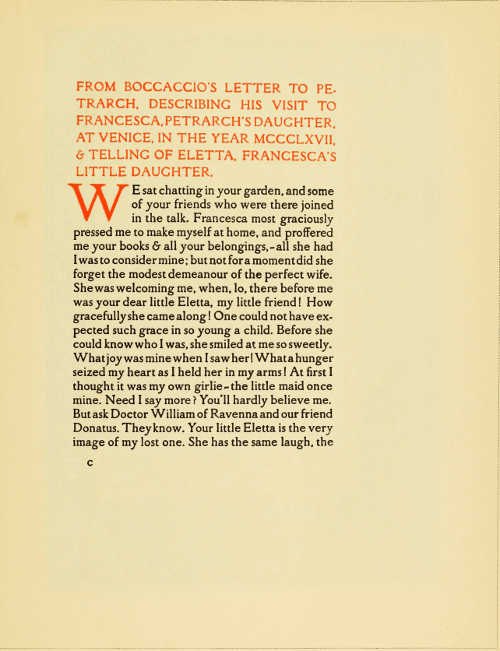

FLORENCE PRESS: PAGE FROM BOCCACCIO'S “OLYMPIA” SET IN ENGLISH TYPE DESIGNED BY HERBERT P. HORNE, AND PRINTED AT THE ARDEN PRESS, LETCHWORTH, FOR MESSRS. CHATTO AND WINDUS

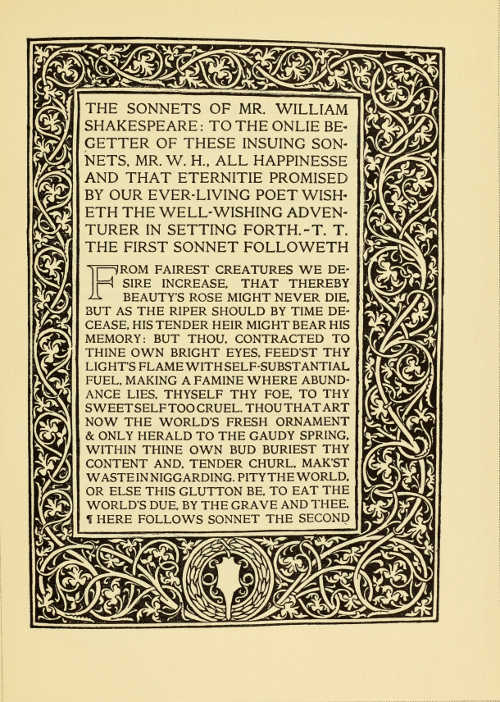

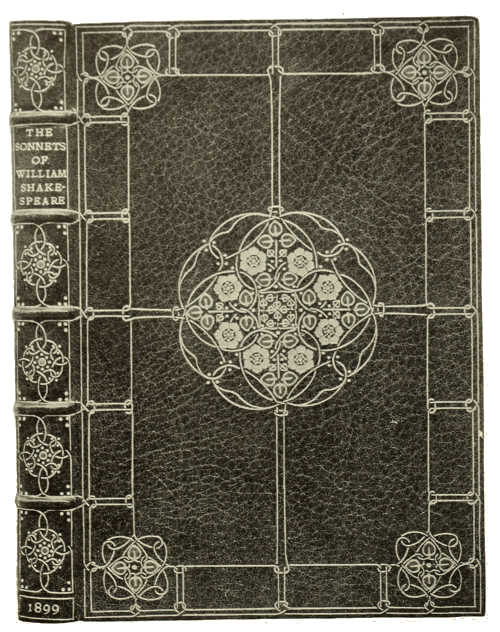

RICCARDI PRESS: PAGE FROM “SONNETS OF SHAKESPEARE” PRINTED IN 14 AND 11 POINT CAPITALS DESIGNED BY HERBERT P. HORNE. BORDER FROM BERNARD PICTOR AND ERHARDT RATDOLT'S “APPIANUS,” 1477

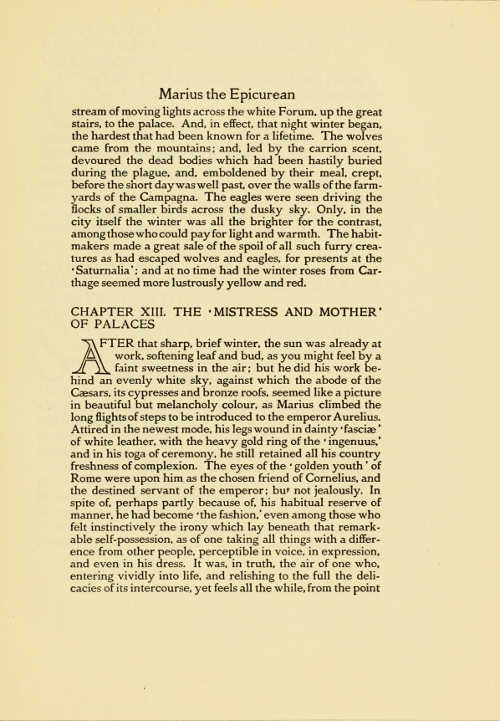

RICCARDI PRESS: PAGE FROM WALTER PATER'S “MARIUS THE EPICUREAN,” PRINTED IN 11 POINT FOUNT DESIGNED BY HERBERT P. HORNE

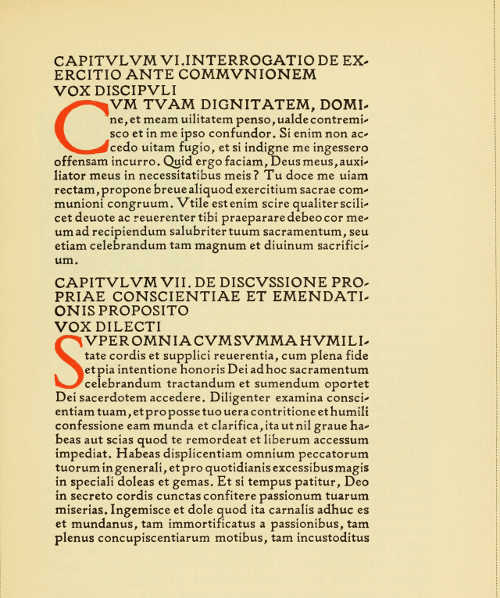

ABERDEEN UNIVERSITY PRESS: PAGE FROM THE “DE IMITATIONE CHRISTI” PRINTED IN THE “EWELL” TYPE DESIGNED BY DOUGLAS COCKERELL FOR MESSRS. METHUEN AND CO.

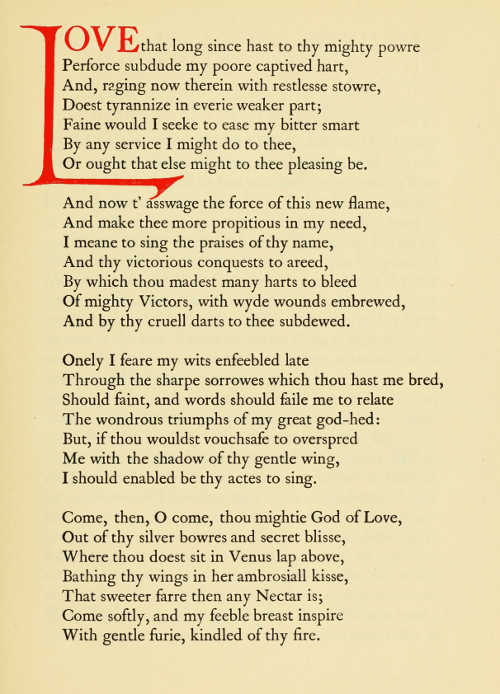

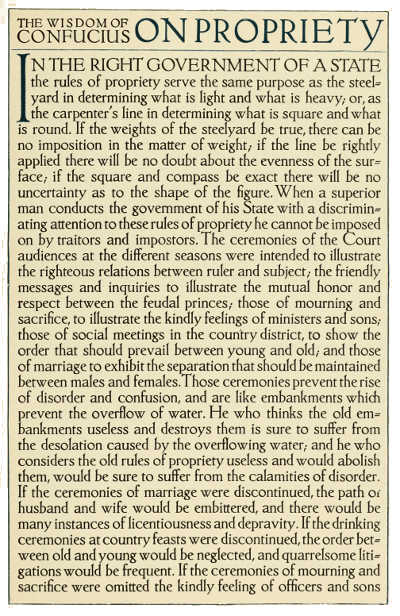

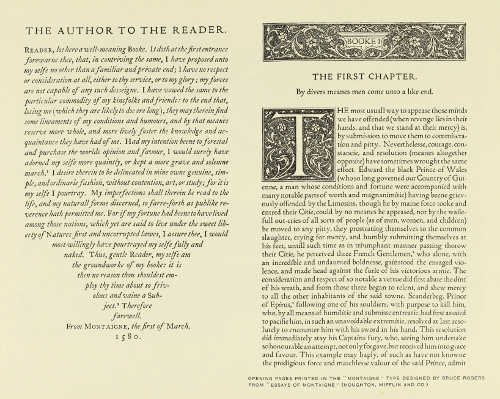

PAGE PRINTED IN THE “KENNERLEY” TYPE, 14 POINT, DESIGNED BY FREDERICK W. GOUDY AND CAST BY H. W. CASLON AND CO. LTD. INITIAL LETTER BY PAUL WOODROFFE, LENT BY THE ARDEN PRESS

PAGE PRINTED IN THE “DOLPHIN OLD STYLE” TYPE, 12 POINT DESIGNED AND CAST BY P. M. SHANKS AND SONS

OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS: PAGE FROM THE “ODYSSEY,” PRINTED IN THE “OTTER” TYPE DESIGNED BY ROBERT W. PROCTOR

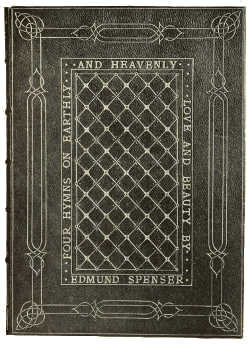

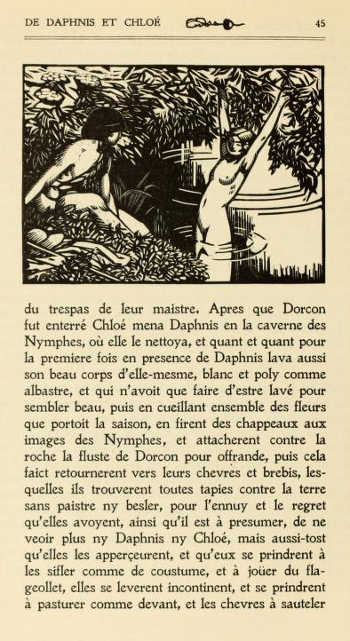

LONDON COUNTY COUNCIL CENTRAL SCHOOL OF ARTS AND CRAFTS: PAGE FROM EDMUND SPENSER'S “FOUR HYMNS ON EARTHLY AND HEAVENLY LOVE AND BEAUTY” PRINTED IN CASLON TYPE. WOODCUT INITIAL BY W. F. NORTHEND, STUDENT

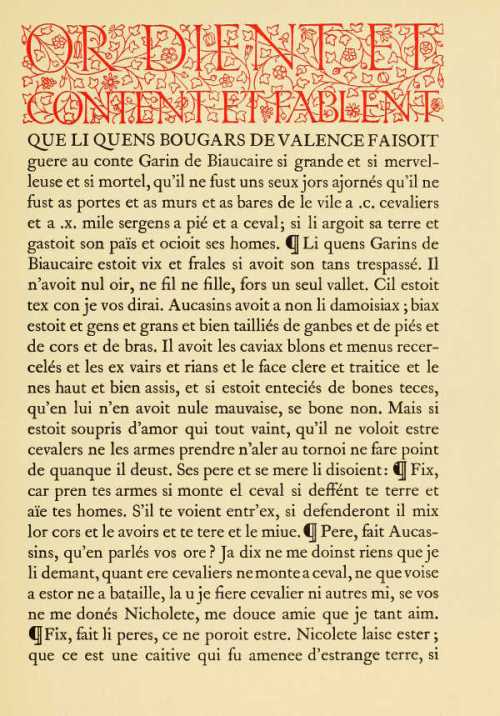

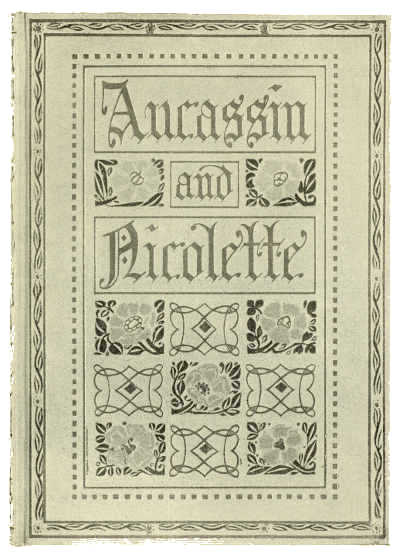

LONDON COUNTY COUNCIL CENTRAL SCHOOL OF ARTS AND CRAFTS: PAGE FROM “AUCASSIN AND NICOLETTE,” IN OLD FRENCH, PRINTED IN CASLON TYPE, WITH DECORATIVE HEADING

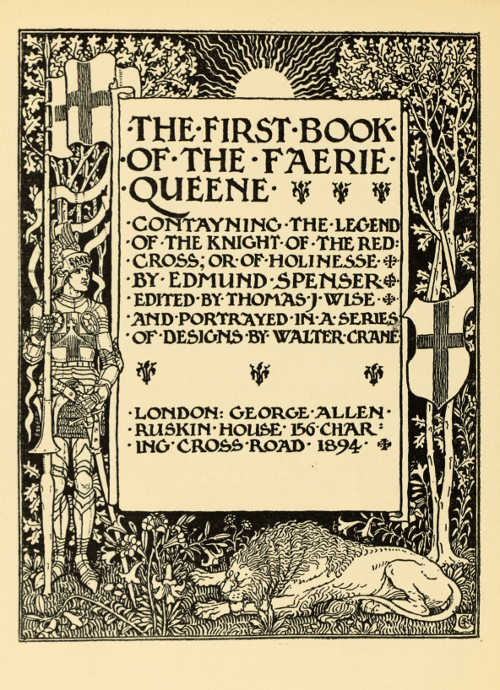

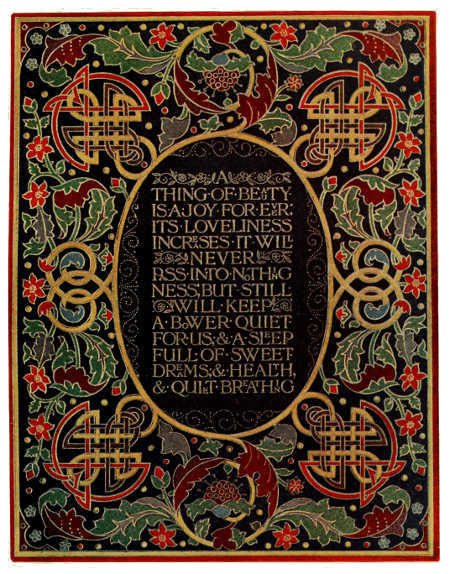

(Reproduced by permission of Messrs. George Allen and Co. Ltd.)

TITLE-PAGE BY WALTER CRANE FOR THE FIRST BOOK OF “THE

FAERIE QUEENE” (SIZE OF ORIGINAL WOOD-ENGRAVING 10 × 7-1/2 INCHES)

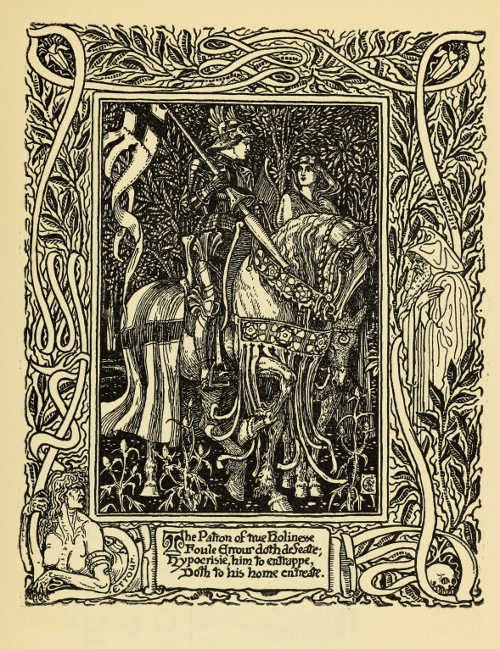

(Reproduced by permission of Messrs. George Allen and

Co. Ltd.)

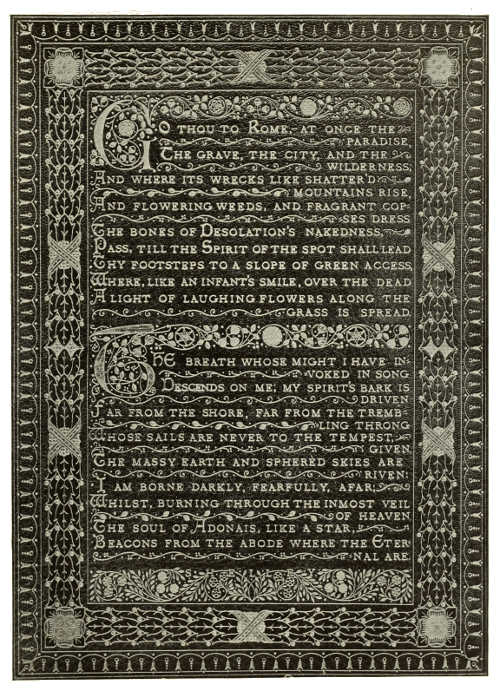

FULL-PAGE ILLUSTRATION BY WALTER CRANE FOR THE FIRST BOOK OF “THE

FAERIE QUEENE.” (SIZE OF ORIGINAL WOOD-ENGRAVING 9½ × 7½ INCHES)

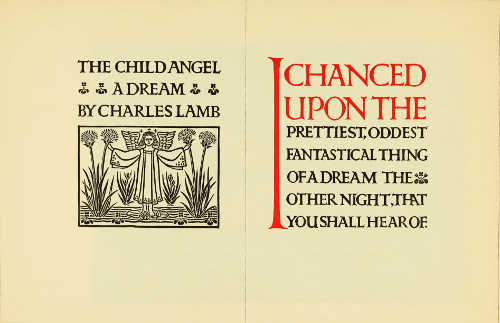

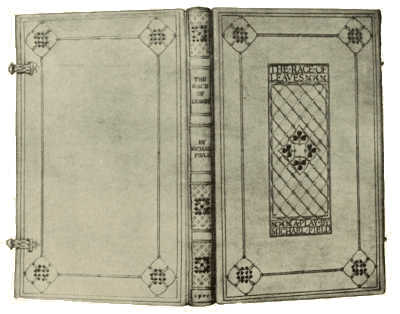

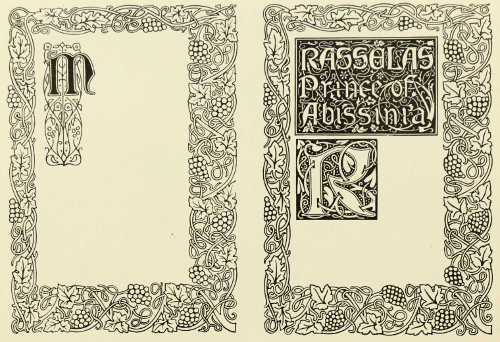

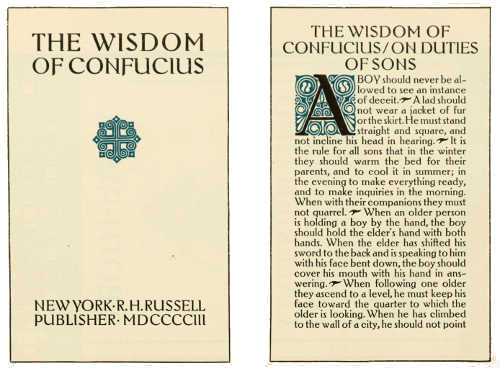

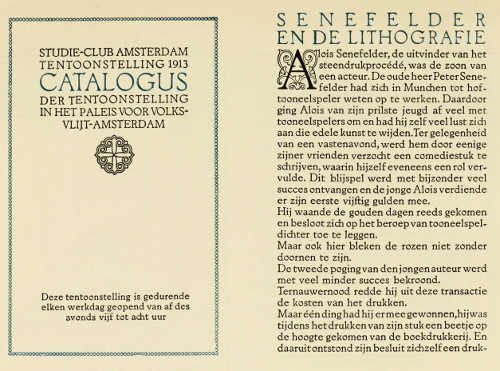

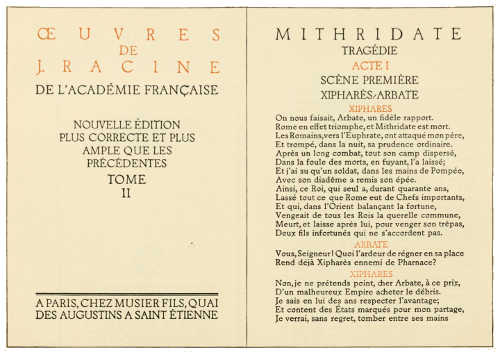

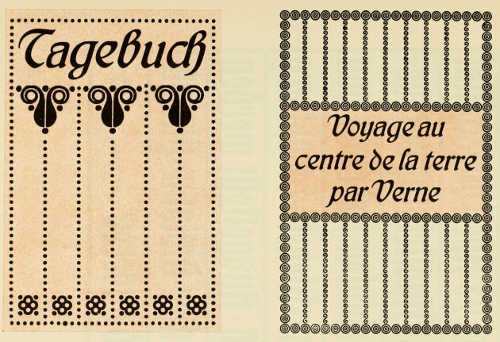

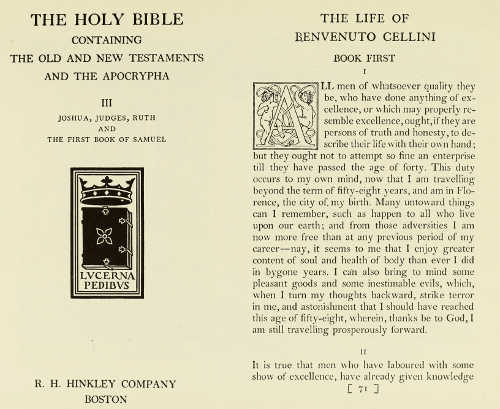

BOOK OPENING DESIGNED BY PERCY J. SMITH

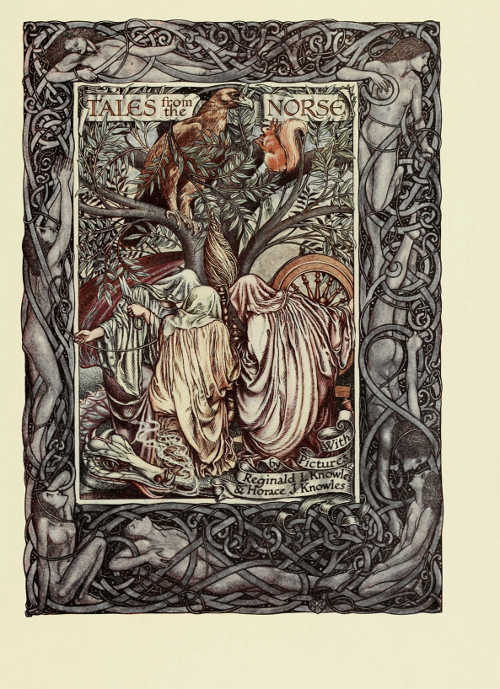

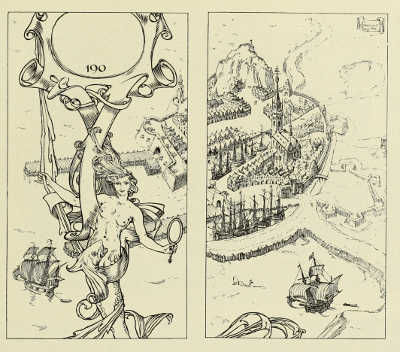

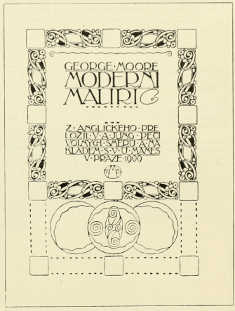

DESIGN FOR A TITLE-PAGE BY REGINALD L. KNOWLES. PUBLISHED BY MESSRS. GEORGE ROUTLEDGE AND SONS, LTD.

REIGATE PRESS: TITLE AND OPENING PAGES DESIGNED BY W. BERNARD ADENEY

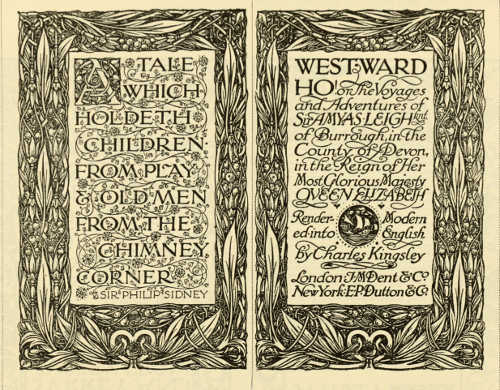

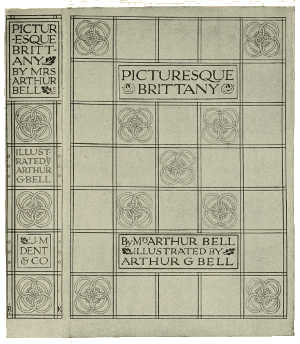

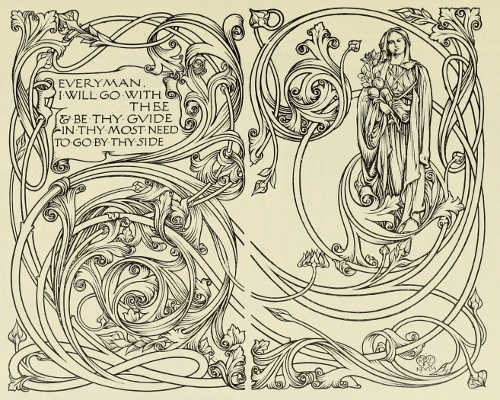

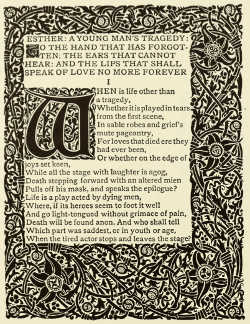

TITLE-PAGE OPENING OF THE FICTION SECTION OF “EVERYMAN'S LIBRARY” DESIGNED BY REGINALD L. KNOWLES FOR MESSRS. J. M. DENT AND SONS LTD.

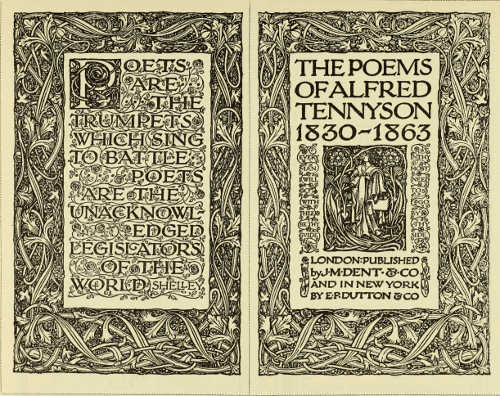

TITLE-PAGE OPENING OF THE POETRY SECTION OF “EVERYMAN'S LIBRARY” DESIGNED BY REGINALD L. KNOWLES FOR MESSRS. J. M. DENT AND SONS LTD.

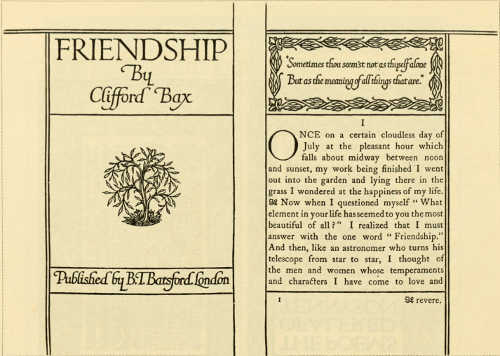

“FELLOWSHIP” BOOK. TITLE AND OPENING PAGES DESIGNED BY JAMES GUTHRIE LETTERING BY PERCY J. SMITH. PUBLISHED BY MESSRS. B. T. BATSFORD LTD.

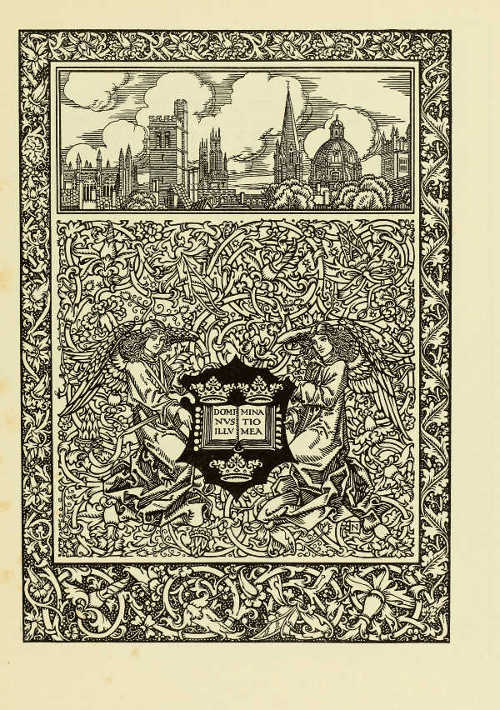

FRONTISPIECE TO AYMER VALLANCE'S “OLD COLLEGES OF OXFORD” DESIGNED BY HAROLD NELSON FROM SUGGESTIONS BY AYMER VALLANCE PUBLISHED BY MESSRS. B. T. BATSFORD LTD.

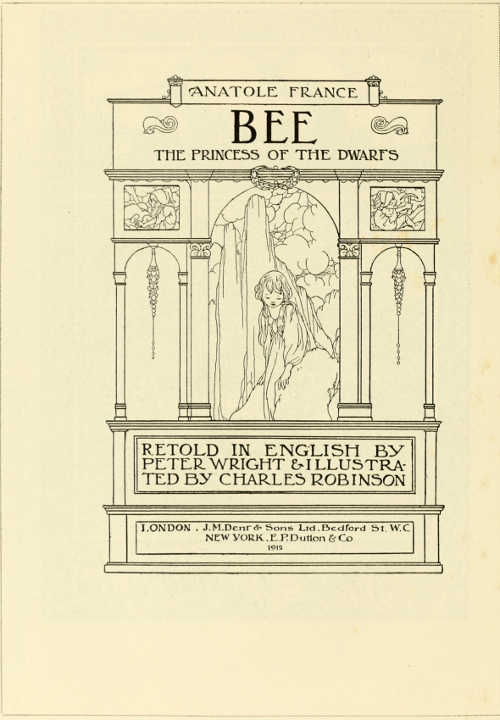

TITLE-PAGE DESIGNED BY CHARLES ROBINSON FOR MESSRS J. M. DENT AND SONS LTD.

TITLE-PAGE DESIGNED BY AUBREY BEARDSLEY FOR MESSRS. J. M. DENT AND SONS LTD.

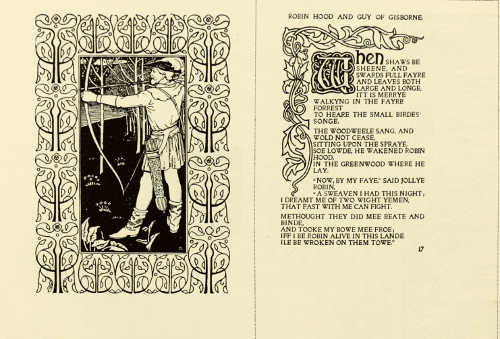

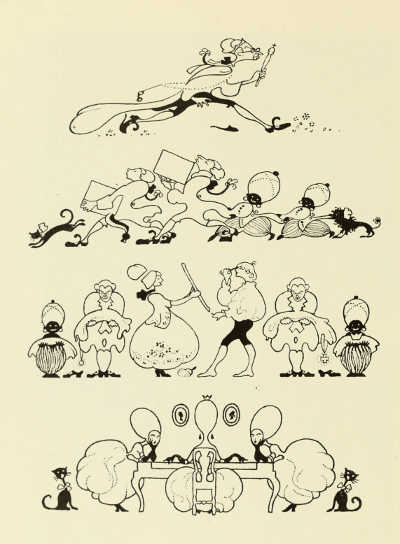

ILLUSTRATION AND PAGE OF TEXT FROM “ROBIN HOOD BALLADS.” DESIGNED BY R. JAMES WILLIAMS. PUBLISHED BY THE VINCENT PRESS

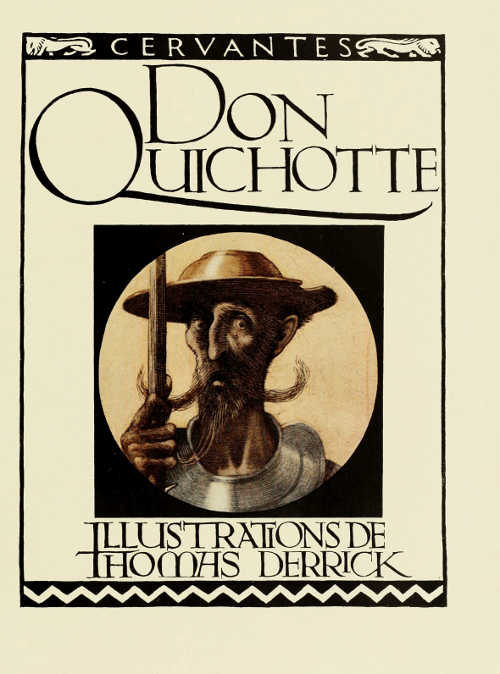

DESIGN FOR A TITLE-PAGE. BY THOMAS DERRICK. PUBLISHED BY MESSRS. SIEGLE, HILL AND CO.

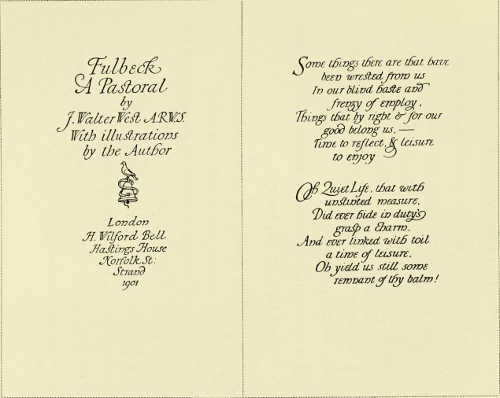

TITLE-PAGE AND PAGE OF TEXT DESIGNED BY J. WALTER WEST

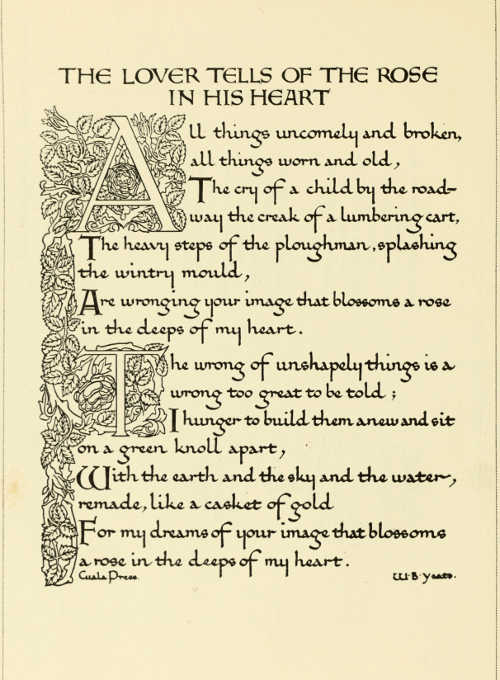

CUALA PRESS: PAGE DESIGNED BY CHARLES BRAITHWAITE

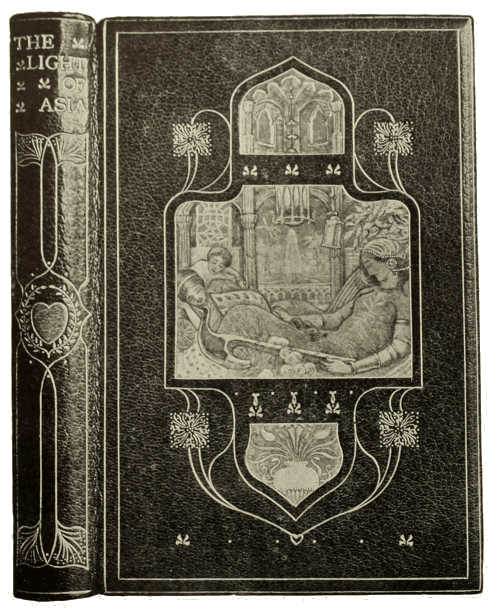

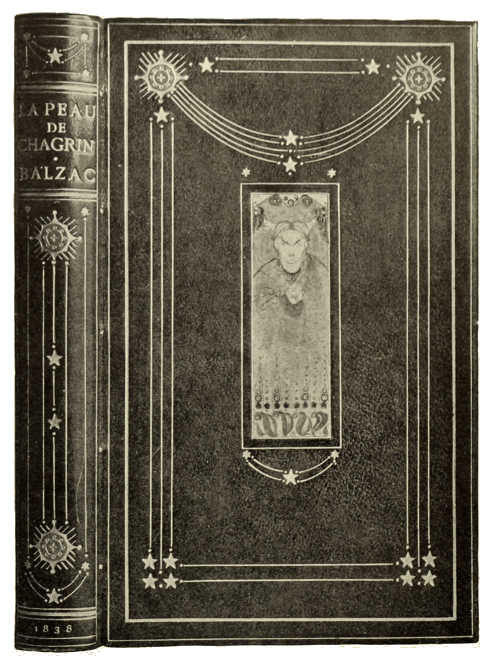

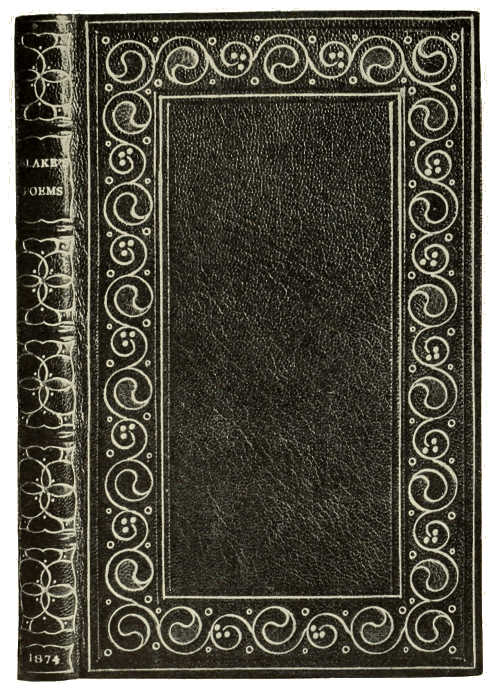

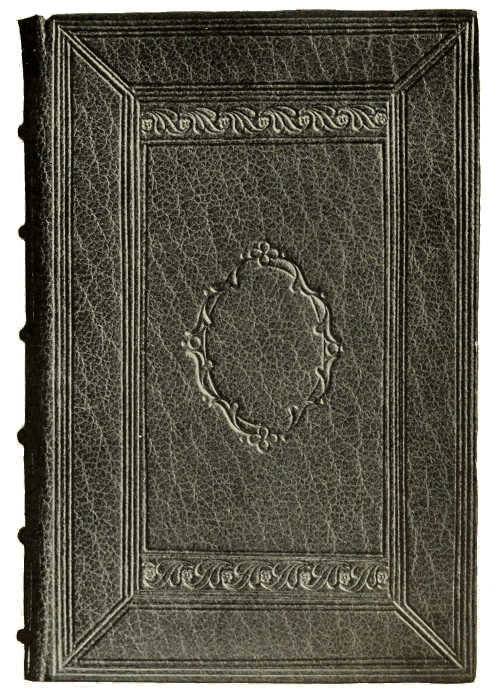

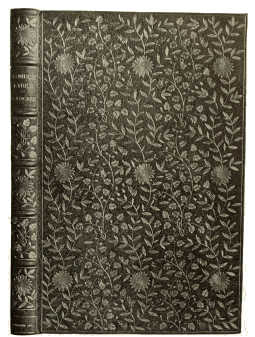

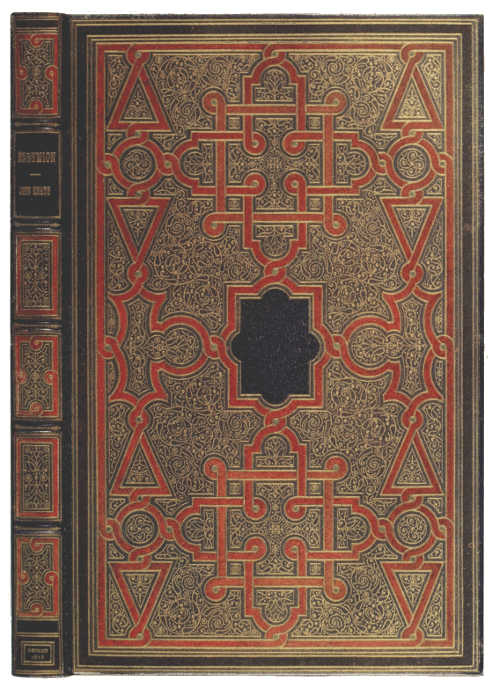

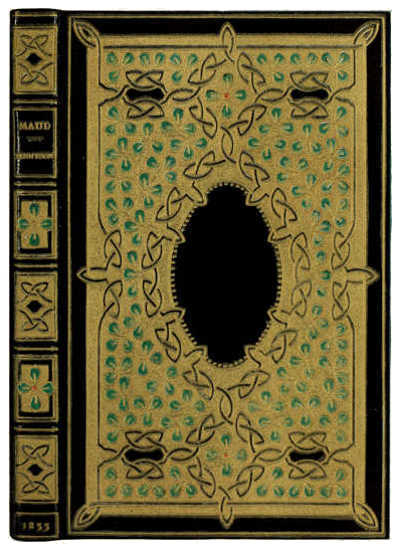

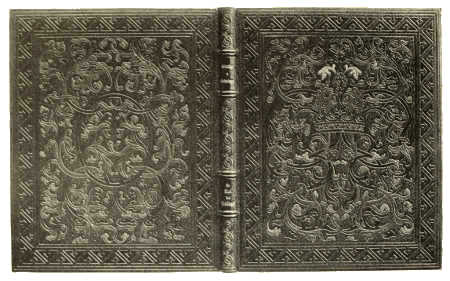

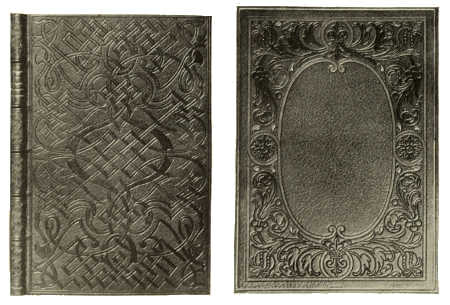

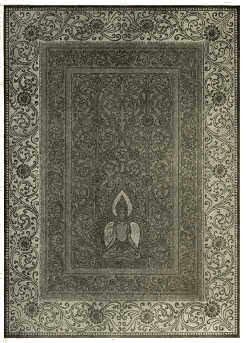

FINE or “extra” binding as it is called in the trade implies that the craftsman has done his best with the best materials. It may be plain or decorated, but whatever work there is should be the best of which the craftsman is capable. Printed books are largely machine-made productions, and it would seem reasonable that machine-made books should have machine-made covers, and it is in such covers or “cases” that most of our books are issued. There is a general feeling that the cost of the binding should bear some relation to the cost of the book; but since books are turned out by the thousand from the printing press, and fine bindings can only be made singly and laboriously by hand, it is inevitable that in most cases such a binding costs much more than the book it covers. This has probably been the case since the invention of printing cheapened books, and yet there have always been people who valued certain books highly enough to have them well bound and decorated. For a true book-lover does not value a book at the price it costs, and he may wish to have the words of a favourite author enshrined in a precious cover. Some books by their nature and use call for lavish treatment. Books used for important ceremonies, such as altar books or lectern Bibles, can quite well be covered with ornament, provided this ornament is good. They will be but a spot of gorgeousness in a great church or cathedral, and should be judged in relation to their surroundings and not as isolated articles.

There is a fashion now to value decoration in inverse ratio to its quantity, and demand that it should be concentrated on spots, leaving the greater part of the surface of articles bare. This is quite a reasonable way to treat a binding, but it is not the only way. A satisfactory binding can be made with little or no ornament, and there is then little fear of a disastrous failure. To cover a book all over with gold-tooled decoration is a more difficult thing to do satisfactorily, but it can be done, and, if well done, is well worth doing.

At the present time there are many binders working in England who are capable of turning out work of the highest class, and fortunately there are book-lovers here and in America with the taste and means to commission such work. Probably, if a man were bold enough to spend five or ten thousand pounds on binding the finest books that are being produced at the present time, he would find, if the money were wisely spent, that he had got a library that would be celebrated all over the world. There is an interesting revival in the use of arms-blocks on bindings, and when certain modern libraries come to be dispersed their owners will be remembered by their books in the same way as are the original owners of the many armorial bindings that have[70] come down to us from the past.

There are some qualities that are common to all well-bound books. Of course abnormal books have to be treated specially, but it may generally be said that every leaf of a book should open right to the back. This means that all single leaves and plates should be attached by guards, and that no overcasting or pasting-in should be allowed, and it also means that the back should be truly flexible. The sections should be sewn to flexible cords or tapes, the ends of these should be firmly attached to the boards, and the back should be covered with some flexible material, such as leather, which, while protecting the sewing-thread or cord, shall itself add to the strength of the binding. A fine binding will have many other features added by way of refinement or elaboration, but unless it has these qualities it is likely to be an unsatisfactory piece of work. A well-bound book should open well and stay open, and shut well and stay shut. The binder can bind any book so that it will not open, but there are some books that he cannot bind so that they will open and shut “sweetly.”

Bookbinding is only one part of the larger craft of book production, and to obtain a perfect book it is necessary that the workers in each branch of the craft should have a common ideal of what a book should be, and that each should do his part in such a way that this ideal may be attained. Unfortunately it too often happens that the printers are quite content if their printing looks perfect as it comes from the press, with the result—through errors in the choice of paper or the number of leaves to a section—that the bookbinder has unnecessary and sometimes unsurmountable obstacles put in his way. A book that will not open freely and that gapes like a dead oyster when it ought to be shut is not pleasant to use, and when these faults are noticed the binder generally gets the blame. Sometimes he deserves the blame, for the fault may be his, but more often than not the fault lies with the paper. To open a book a certain number of leaves of paper must be bent, and if the paper is so stiff that a single leaf will not fall over by its own weight, the book cannot be made to open quite satisfactorily if bound in the ordinary way. By swinging each leaf on a guard it is possible to bind a pack of playing-cards into something like a book which will open and shut freely, but that this can be done is no excuse for the production of books which necessitate this drastic treatment before they can be bound satisfactorily.

William Morris, when he founded the Kelmscott Press, did more than revive fine book-printing; he established a tradition for books that were eminently bindable, and the presses that followed his lead kept up the tradition; so that we have in England a large number of beautifully printed books that are worthy of the best binding, and that impose no unnecessary difficulties on the binder.

Mr. Cobden-Sanderson did much to revive the use of the tight or flexible back. In this style[71] the leather is attached directly to the back of the sections, and so helps to hold them firmly together. All leather-bound books had tight backs until about a hundred years ago, when the hollow back came into general use. A tight back should throw up when the book is opened; that is to say the back, convex when the book is shut, should become concave on the book being opened. This causes a certain amount of creasing in the leather, and this creasing is not good for gold tooling; but with a well-bound book the damage is not serious, and important constructional features must not be sacrificed for the sake of the decoration.

The hollow back does not crease the leather, and so is preferred by finishers, and besides it is easier to cover a hollow back neatly than a tight one; but the strain of opening and shutting, which should be distributed evenly across the back, is in the hollow back thrown on the joints, with the result that the leather is apt to break at these places unless specially strengthened, as is the case with well-bound account books.

While “flexible” backs that are truly flexible are undoubtedly the best, some binders line up their backs so stiffly under the leather as to allow little or no movement when the book is opened. This avoids the creasing of the leather and leaves the decoration uninjured, but the book will not open freely, and there is no virtue in such a tight back. Leather is chosen for binding because of its toughness and flexibility, yet binders deliberately sacrifice this last quality in order to obtain extreme neatness or to hide faults in the forwarding.

It is the fashion in some quarters to admire as the perfection of craftsmanship an exact and hard square edge to the boards of a book. This can only be got by paring the leather down till it is as thin as paper and has consequently very little strength. A softer, rounder edge is natural to a leather-covered article, and it is unreasonable to expect the qualities of a newly planed board in a material so wholly different in character. The edges of the leather-covered board should have a distinctly flat face, and clumsiness will be avoided by any good craftsman. It is only the extreme sharpness, so much admired by unknowing people, that is objectionable.

In the treatment of the edges of the leaves fashion has gone to two extremes: some book-lovers demand that the edges should be entirely uncut, while others require them to look like a solid piece of metal. The rough edges, or “deckle,” on hand-made paper is a necessary defect due to the way the paper is made. These rough edges were always trimmed off by the early binders because they were unsightly, difficult to turn over, and harboured dust. Some of the shorter leaves would usually be left untrimmed. Such short leaves are known in the trade as “proof,” i.e. proof that the book has not been unduly cut down. To gild a book-edge absolutely solid the binder must cut down to the shortest leaves and so often has to reduce the size of the book unreasonably; but an accept[72]able compromise between entirely uncut edges and solid gilding can be arrived at if the sections of a book to be finely bound are trimmed singly and gilt “in the rough” before sewing. This enriches the edges but does not disguise their nature nor necessitate their being unduly cropped.

In recent times there has been much good work done in England in the investigation of bookbinding materials. The Royal Society of Arts Committee on “Leather for Bookbinding” has established standards of leather that have made it possible for binders to procure skins that are uninjured in the process of manufacture, and bookbinding leather of the very highest class is now being produced in England. The leather manufacturers are able to dye leather any reasonable shade without the use of sulphuric acid, and it is only some of the lighter fancy colours that are unprocurable in “acid free” leather. That these “fancy” shades are unprocurable in uninjured leather is a distinct gain, as they mostly fade, and books bound in such leather seldom look as if they were intended to be used.

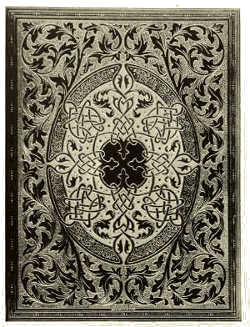

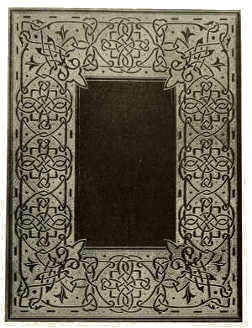

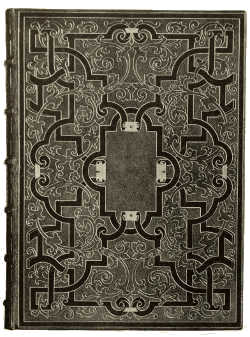

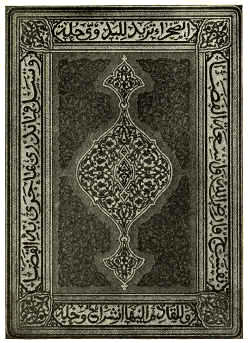

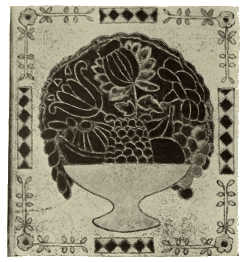

There are various ways by which leather-bound books may be decorated, but tooling, either in gold or blind, is by far the commonest, and it is tooled bindings that we are considering here. “Blind” tooling is the impression of hot tools on the leather. The most satisfactory tools for blind work are those cut die-sunk like a seal. These, by depressing the ground, leave the ornament in relief. Tools for gold work are cut so that the ornament with the gold is depressed below the surface of the leather. These tools may be used without gold, but blind tooling produced in this way has little of the character associated with this work when it was at its best, i.e. up to the end of the fifteenth century. Gold-tooling came to Europe from the East, and preserved a tradition of Eastern design for a very long period. The English gold-tooled bindings of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries are often strangely Eastern in the style of the decoration.

The ornamentation of fine bindings reached almost its lowest ebb in England about the middle of last century. Of technical skill there was never any lack, but decoration had lost vitality, and the ornamental bindings of this time are for the most part copies or parodies of the work of earlier binders. William Morris designed a few very beautiful gold-tooled bindings which were covered all over with the impressions of tools, each one of which represented a complete plant. His friend, Mr. Cobden-Sanderson, who gave up the practice of the law to learn the binder's craft, produced books that are unsurpassed in the delicate beauty of their decoration. Before his time there had been few attempts to combine tools to form organic patterns. Mr. Cobden-Sanderson's tools were very elementary in character, each flower, leaf or bud being the impression of a separate tool. These impressions were combined in such a way as to give a sense of growth, and yet in no way overlapped the traditional limitations and conventions[73] of the craft. Mr. Cobden-Sanderson got his results by sheer genius in the right use of simple elements. He used inlays very sparingly, and his finest bindings depend entirely on the effect of gold on leather. The style of design which he founded has spread throughout the trade, mainly through the teaching at the various technical schools, and it is now comparatively rare to find an elaborate binding of recent date without some attempt having been made to connect the tools so that they together form an organic whole.

The use of composite tools (that is, tools which form a whole design in themselves and do not bear any definite relationship to one another) is now restricted to cheap bindings. The corners and centres on the backs of school prizes are familiar, if degraded, examples of the use of such tools. Together with the Cobden-Sanderson style of decoration there has been a marked revival of the use of interlacement in gold-tooled designs. Interlaced gold lines, if not so intricate as to be bewildering, may be very beautiful, but in this, as in most other crafts, the highly-skilled workman loves to attempt the almost impossible, and some of the recent interlaced patterns fail on account of their over-elaboration and consequent restlessness.

Mr. Charles Ricketts designed some very notable gold-tooled bindings for the Vale Press. These bindings have hardly received the attention they deserve, and the style has not spread to any extent, possibly because Mr. Ricketts' refinement and delicacy in the use of fine lines are not easy to acquire. These bindings have an architectural quality that places them in a class by themselves. Mr. Cobden-Sanderson and Mr. Ricketts, in their entirely different styles, have shown that gold-tooling may be extremely beautiful as decoration without overstepping the traditional limits of the craft, and in the case of the most successful bindings now being produced these traditional limits have been recognised. Gold-tooling is by its nature a limited means of expression, though exactly where the limits lie must be a matter of feeling and taste rather than of knowledge. Certainly in some of the elaborate bindings now being produced the limits of the craft have been passed, and while serving to show amazing dexterity on the part of the finisher, these bindings are less successful artistically than many that are less ambitious in technique.

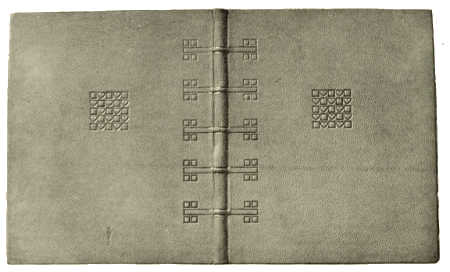

There is no clearly marked school of blind-tooling at present, though here and there the method has been used with success. Mr. William Morris designed a notable binding in white pigskin for the Kelmscott “Chaucer.” Many copies were so bound at the Doves Bindery, but most of the attempts that have been made to carry out work in the same style have been comparatively unsuccessful.

There have been a good many efforts made to revive modelled leather-work as a means of decorating books, but although this method is capable of producing very fine results, most of the binding in modelled leather shown in recent[74] exhibitions cannot be said to be successful. Any work that has to be done on the leather before the book is bound is almost doomed to failure, because leather which is modelled before binding cannot be handled by the binder with the freedom that is necessary if he is to make a workmanlike job of the covering. It is, however, possible to put quite sufficient relief in modelled leather after a book is bound, if the leather be reasonably thick; indeed high relief for most books is objectionable.

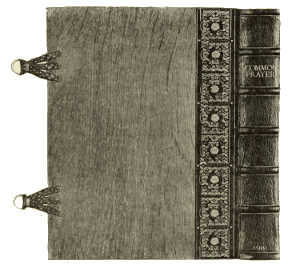

Many of the old bindings had fine metal mounts and clasps. If clasps are used on modern books, as a rule they should be flush with the sides, so as not to scratch their neighbours when taken in and out of shelves. Raised clasps and bosses are only suitable for books that are expected to stand permanently on a lectern.

In criticising decorated bindings there is a danger of falling into the common error of generalising from isolated instances. You cannot put too much ornament on a thing as small as a bookcover if the ornament is good enough. A book well bound in beautiful leather may be perfectly satisfactory and beautiful by virtue of good workmanship, fine material and colour. A binding covered with fine gold-tooling may be just as restful and far more beautiful, but while there is comparatively little scope for failure in the plain binding, there are appalling pitfalls if the cover be lavishly decorated. There are, of course, all sorts of degrees of decoration between an absolutely plain binding and one covered entirely with gold, but there are some qualities common to most successful tooled ornament.

There are few bindings that are quite successful unless the ornament is arranged on a symmetrical plan. Any attempt to portray landscape, human figures or naturalistic flowers is almost doomed to failure. Gold-tooling is not a suitable medium for rendering such subjects.

Lettering should be well designed and free from eccentricities. The problem of lettering a long title across a narrow back may necessitate ungainly breaking of words, but where this is done it should only be done from obvious necessity, and the reasonable necessity for this fault should be apparent. To letter books in type so small as to be quite illegible, lettering that looks from a short distance like a gold line, is more unreasonable than almost any breaking of words that allows the use of letters of a larger size.

Fine binding is an expensive luxury but not an unreasonable one compared with many others. We have now in England a school of really fine binding, and the most reasonable and unobjectionable form that luxury can take is the use of beautiful things in everyday life. If a book is well bound and well decorated it is fit to use, and in choosing a book to be expensively bound it would be better to choose the book most often used than one which would be put away unopened. Most fine bindings would be greatly improved by use, and the reasonable using of them would give immense pleasure, a pleasure that would justify the binder's care and trouble and the purchaser's outlay. The use of a beautiful thing gives a far higher form of pleasure than does the mere sense of ownership.

|

|

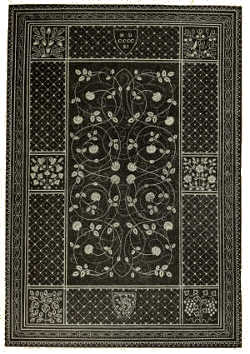

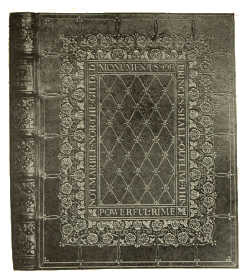

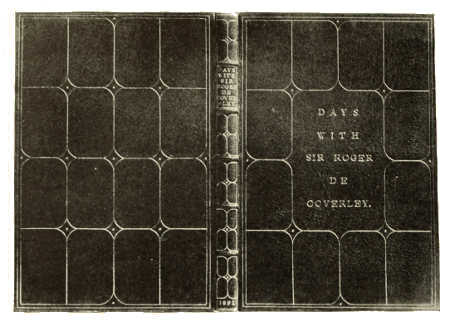

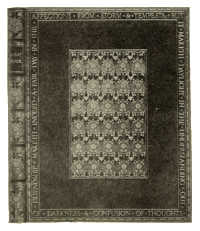

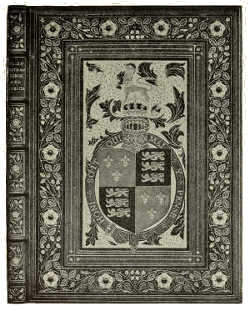

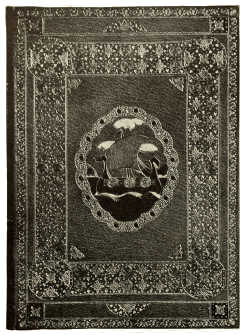

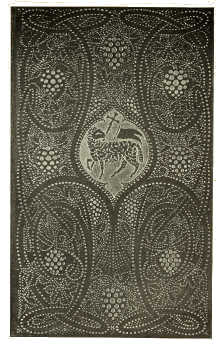

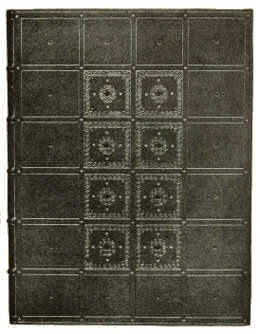

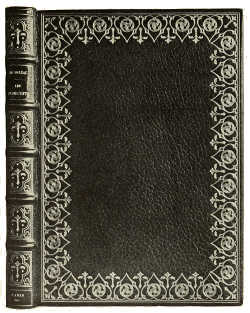

BOOKBINDING IN BLUE PIGSKIN, WITH HERALDIC BORDER ENCLOSING A PANEL OF FLORAL DESIGN AND BACKGROUND OF POINTILLÉ. BY KATHARINE ADAMS |

|

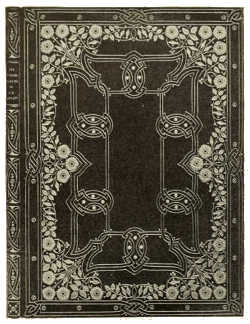

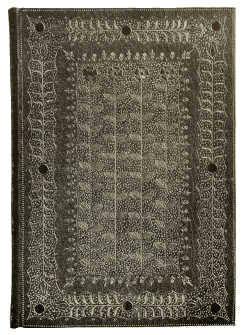

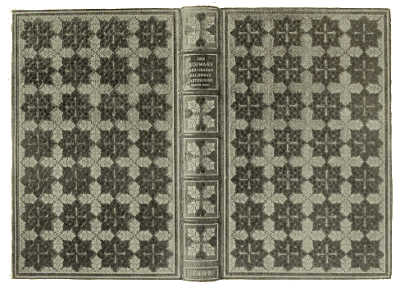

BOOKBINDING WITH GEOMETRICAL BORDER IN POINTILLÉ BY KATHARINE ADAMS

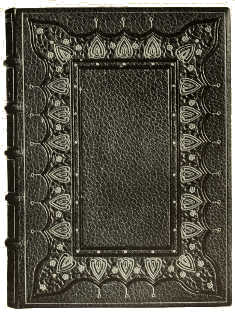

BOOKBINDING IN BROWN MOROCCO, WITH INLAY, GOLD TOOLING,

OAK SIDES AND LEATHER CLASPS. DESIGNED AND TOOLED BY L. HAY-COOPER

FORWARDED BY W. H. SMITH AND SON

(In the possession of the Grey Coat Hospital, Westminster)

(In the possession of Lambeth Parish Church)

BOOKBINDING IN GREEN MOROCCO, WITH INLAY AND GOLD TOOLING DESIGNED AND

TOOLED BY L. HAY-COOPER, BOUND BY S. BARNARD

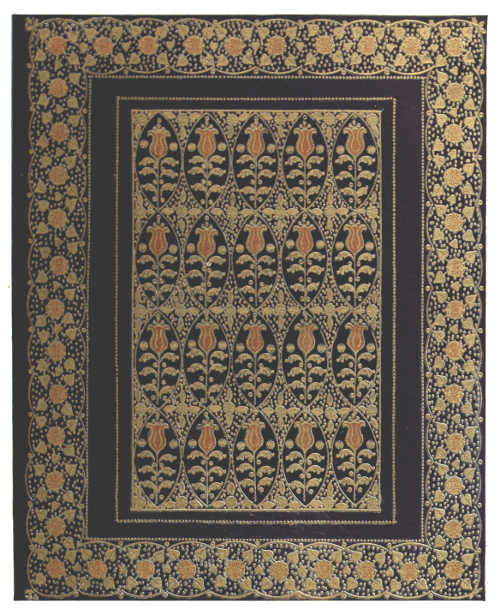

BOOKBINDING IN WHOLE CRUSHED CRIMSON LEVANT MOROCCO, WITH VELLUCENT PANELS AND GOLD TOOLING. DESIGNED BY H. GRANVILLE FELL, EXECUTED BY CEDRIC CHIVERS OF BATH

BOOKBINDING IN DONKEY HIDE, WITH VELLUCENT PANEL AND GOLD TOOLING DESIGNED BY O. CARLETON SMYTH, EXECUTED BY CEDRIC CHIVERS OF BATH

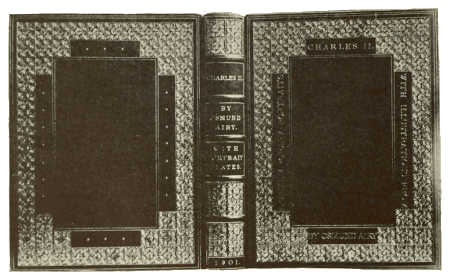

BOOKBINDING IN NIGER MOROCCO, WITH INLAY AND GOLD TOOLING BY R. DE COVERLY AND SONS

BOOKBINDING IN APPLE-GREEN LEVANT MOROCCO, WITH BLIND AND GOLD TOOLING. BY R. DE COVERLY AND SONS

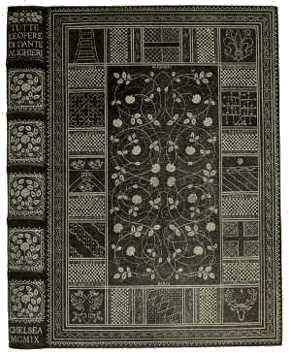

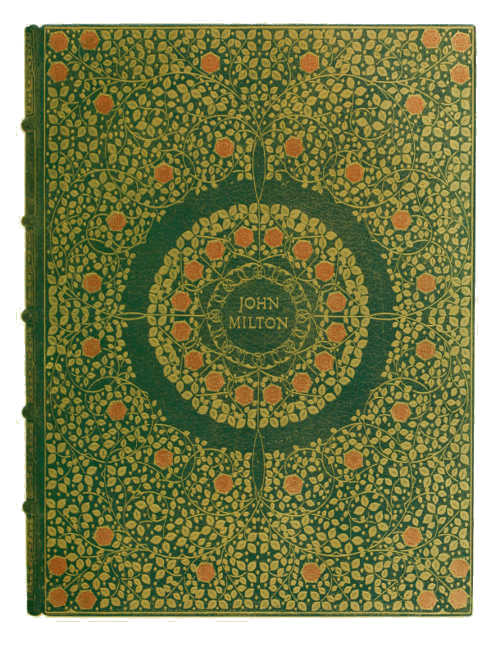

BOOKBINDING IN GREEN MOROCCO, WITH INLAY AND GOLD

TOOLING BY DOUGLAS COCKERELL

(Photo. lent by Mons. Emile Lévy)

BOOKBINDING IN GREEN MOROCCO, WITH INLAY AND GOLD

TOOLING BY DOUGLAS COCKERELL

(Photo. lent by Mons. Emile Lévy)

BOOKBINDING IN GREEN MOROCCO, WITH INLAY AND GOLD TOOLING. BY DOUGLAS COCKERELL

(Photo. lent by Mons. Emile Lévy)

BOOKBINDING IN DARK RED MOROCCO, WITH INLAY AND GOLD TOOLING. BY

DOUGLAS COCKERELL

BOOKBINDING IN RED NIGER MOROCCO, WITH GOLD TOOLING BY FRANK G. GARRETT

BOOKBINDING IN VELLUM, WITH GOLD AND GREEN TOOLING. BY FRANK G. GARRETT

BOOKBINDING IN MAUVE MOROCCO, WITH INLAY AND GOLD TOOLING. BY HON. NORAH HEWITT

BOOKBINDING IN SAGE GREEN MOROCCO, WITH INLAY AND GOLD TOOLING. BY HON. NORAH HEWITT

BOOKBINDING IN POWDER BLUE MOROCCO, WITH GOLD TOOLING. BY HON. NORAH HEWITT

BOOKBINDING IN NIGER MOROCCO, WITH GOLD TOOLING. BY HON. NORAH HEWITT

|

|

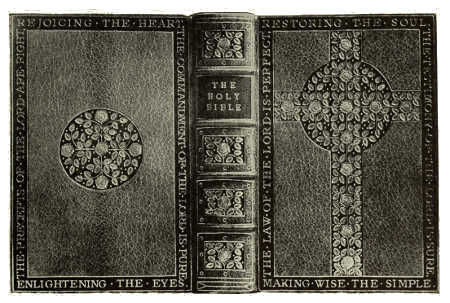

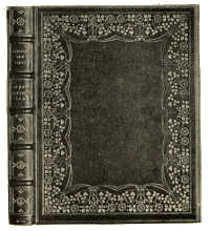

BOOKBINDING IN RED LEVANT MOROCCO, WITH INLAY AND GOLD TOOLING DESIGNED BY J. GREEN, EXECUTED BY S. TOUT (OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS) |

BOOKBINDING IN BLUE LEVANT MOROCCO, WITH INLAY AND GOLD TOOLING DESIGNED BY T. TURBAYNE, EXECUTED BY J. GREEN (OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS) |

BOOKBINDING IN MAROON LEVANT MOROCCO, WITH INLAID PANEL. DESIGNED BY J. GREEN, EXECUTED BY P. WARD (OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS)

BOOKBINDING IN GREEN LEVANT MOROCCO, WITH GOLD TOOLING. DESIGNED BY T. TURBAYNE, EXECUTED BY P. WARD (OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS)

BOOKBINDING IN PURPLE LEVANT MOROCCO, WITH INLAY AND GOLD TOOLING. DESIGNED BY E. SPARKES EXECUTED BY J. GREEN (OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS)

BOOKBINDING IN GREEN LEVANT MOROCCO, WITH INLAY AND GOLD TOOLING. DESIGNED BY J. GREEN EXECUTED BY P. WARD (OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS)

|

|

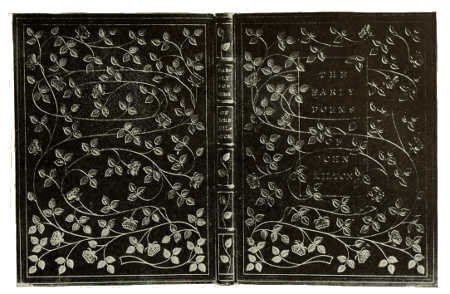

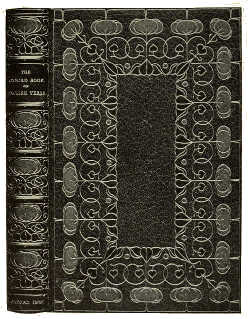

TOOLED LEATHER BOOKBINDING. BY S. T. PRIDEAUX |

TOOLED LEATHER BOOKBINDING. BY S. T. PRIDEAUX |

|

|

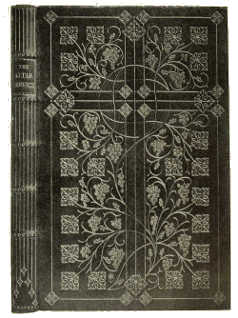

TOOLED LEATHER BOOKBINDING. BY S. T. PRIDEAUX |

TOOLED LEATHER BOOKBINDING. BY S. T. PRIDEAUX |

BOOKBINDING IN GREEN SEALSKIN, WITH INLAY AND GOLD TOOLING BY MARY E. ROBINSON

|

|

BOOKBINDING IN CRUSHED GREEN LEVANT MOROCCO WITH GOLD TOOLING. BY ALICE PATTINSON (MRS. RAYMUND ALLEN) |

BOOKBINDING IN CRUSHED DARK BLUE LEVANT MOROCCO WITH INLAY AND GOLD TOOLING. BY ALICE PATTINSON (MRS. RAYMUND ALLEN) |

|

|

BOOKBINDING IN WHITE PIGSKIN, WITH BLIND AND GOLD TOOLING BY SYBIL PYE |

BOOKBINDING IN WHITE PIGSKIN, WITH BLIND AND GOLD TOOLING BY SYBIL PYE |

|

|

DOUBLURE IN LEVANT MOROCCO, WITH POINTILLÉ AND INLAY BY ROBERT RIVIERE AND SON |

FLY-LEAF IN GREEN LEVANT MOROCCO, WITH POINTILLÉ AND INLAY BY ROBERT RIVIERE AND SON |

DOUBLURE IN LEVANT MOROCCO, WITH INLAY AND TOOLING. BY ROBERT RIVIERE AND SON

FLY-LEAF IN GREEN LEVANT MOROCCO, WITH INLAY AND GOLD TOOLING. BY F. SANGORSKI AND G. SUTCLIFFE

|

|

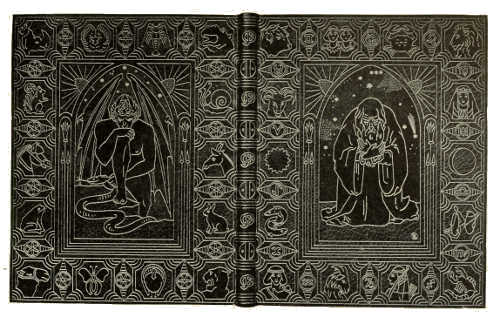

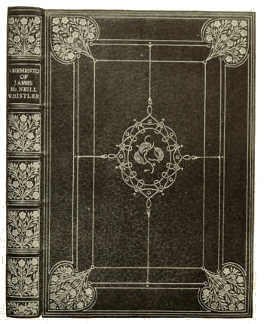

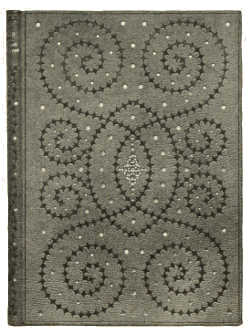

BOOKBINDING IN BLUE LEVANT MOROCCO, WITH GOLD TOOLING BY F. SANGORSKI AND G. SUTCLIFFE |

BOOKBINDING IN BLUE LEVANT MOROCCO, WITH GOLD TOOLING BY F. SANGORSKI AND G. SUTCLIFFE |

|

|

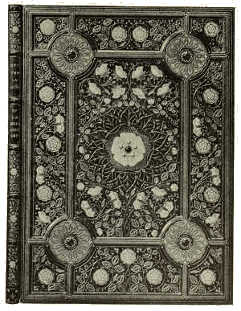

BOOKBINDING IN GREEN LEVANT MOROCCO, WITH INLAY AND GOLD TOOLING BY F. SANGORSKI AND G. SUTCLIFFE |

BOOKBINDING IN BROWN LEVANT MOROCCO, WITH INLAY AND GOLD TOOLING BY F. SANGORSKI AND G. SUTCLIFFE |

|

|

BOOKBINDING IN BLUE LEVANT MOROCCO, WITH INLAY AND GOLD TOOLING BY F. SANGORSKI AND G. SUTCLIFFE |

BOOKBINDING IN GREEN LEVANT MOROCCO, WITH GOLD TOOLING BY F. SANGORSKI AND G. SUTCLIFFE |

BOOKBINDING IN OLIVE MOROCCO, WITH GOLD TOOLING. CENTRE PANEL OF RED INLAY. BY A. DE SAUTY

BOOKBINDING IN OLIVE MOROCCO, WITH GOLD TOOLING. BY A. DE SAUTY

|

|

BOOKBINDING IN BLUE MOROCCO, WITH INLAY AND GOLD TOOLING BY SIR EDWARD SULLIVAN, BART. |

BOOKBINDING IN PINK MOROCCO, WITH INLAY AND GOLD TOOLING BY SIR EDWARD SULLIVAN, BART. |

BOOKBINDING IN BLUE MOROCCO, WITH INLAY AND GOLD TOOLING. BY SIR EDWARD SULLIVAN, BART.

|

|

BOOKBINDING IN YELLOW LEVANT MOROCCO, WITH INLAY AND GOLD TOOLING. BY ZAEHNSDORF |

BOOKBINDING IN OLIVE GREEN LEVANT MOROCCO, WITH INLAY AND GOLD TOOLING. BY ZAEHNSDORF |

|

|

BOOKBINDING IN BLUE LEVANT MOROCCO, WITH INLAY AND GOLD TOOLING. BY ZAEHNSDORF |

BOOKBINDING IN GREEN LEVANT MOROCCO, WITH INLAY AND GOLD TOOLING. BY ZAEHNSDORF |

BOOKBINDING IN BLUE LEVANT MOROCCO, WITH INLAY AND GOLD TOOLING. BY ZAEHNSDORF

BOOKBINDING IN BLUE LEVANT MOROCCO, WITH INLAY AND GOLD TOOLING. BY ZAEHNSDORF

|

|

BOOKBINDING IN GREEN ENGLISH MOROCCO, WITH GOLD TOOLING BOUND BY B. BENKOSKI, DECORATED BY W. F. MATTHEWS (L.C.C. CENTRAL SCHOOL OF ARTS AND CRAFTS) |

BOOKBINDING IN GREEN LEVANT MOROCCO, WITH INLAY AND GOLD TOOLING BOUND BY S. H. COLE, DECORATED BY W. H. GIFFARD (L.C.C. CENTRAL SCHOOL OF ARTS AND CRAFTS) |

|

|

|

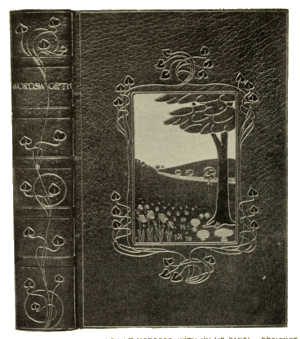

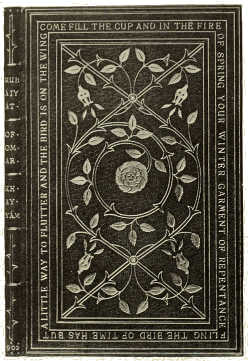

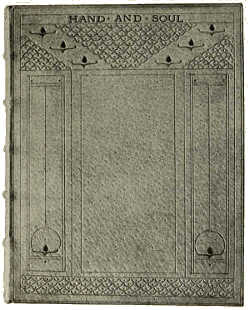

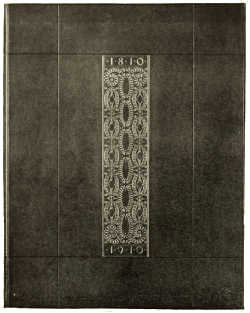

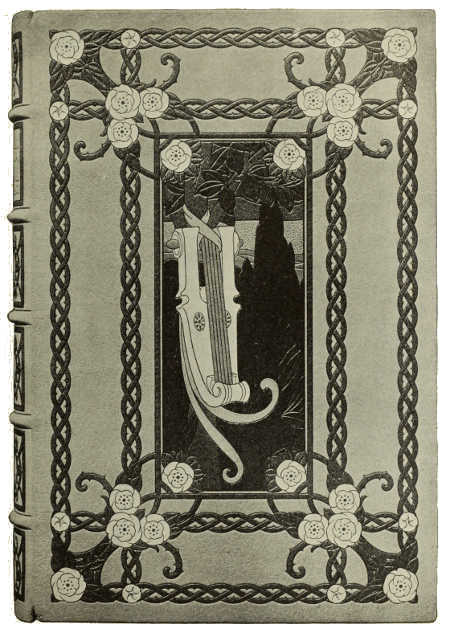

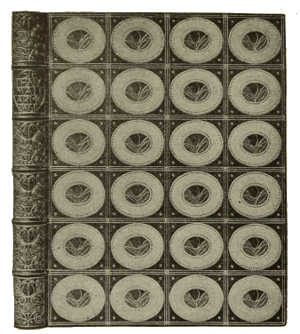

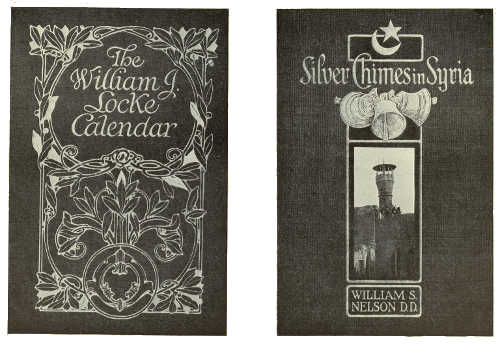

BINDING-CASE DESIGNED BY LAURENCE HOUSMAN FOR MR. JOHN LANE |

BINDING-CASE DESIGNED BY WILL BRADLEY FOR MR. JOHN LANE |

|

|

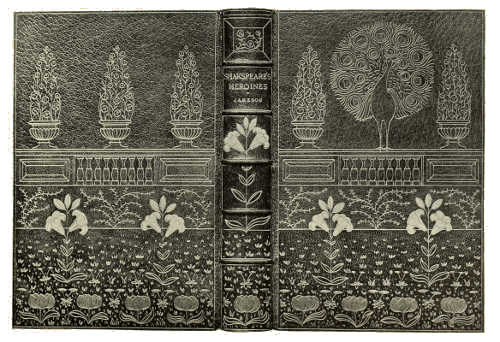

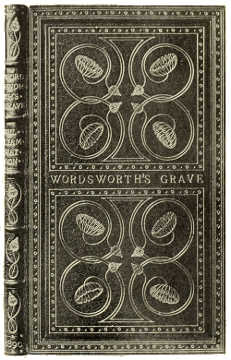

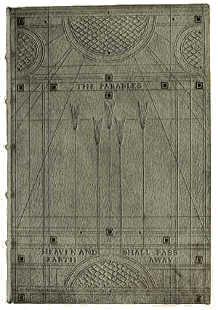

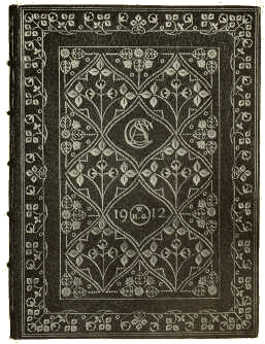

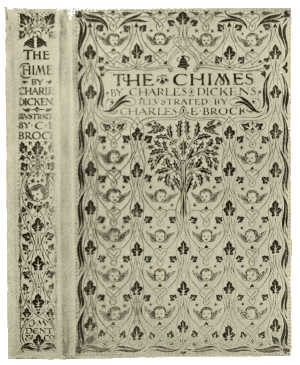

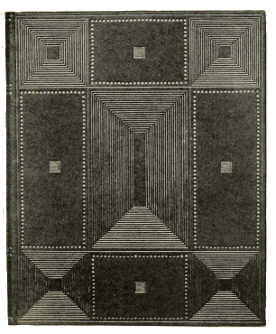

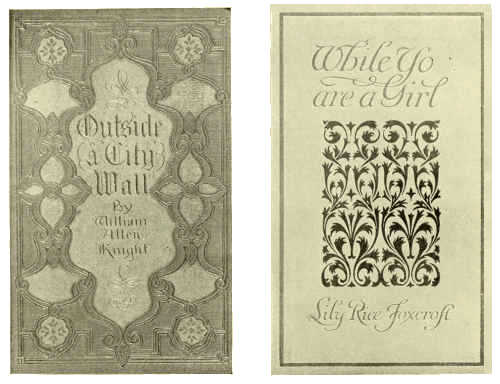

BINDING-CASE DESIGNED BY REGINALD L. KNOWLES FOR MESSRS. J. M. DENT AND SONS LTD. |

BINDING-CASE DESIGNED BY REGINALD L. KNOWLES FOR MESSRS. J. M. DENT AND SONS LTD. |

|

|

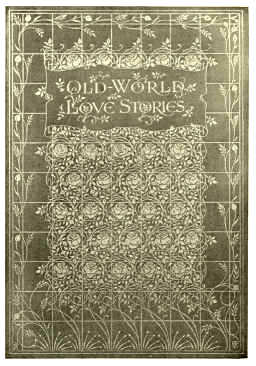

BINDING-CASE DESIGNED BY REGINALD L. KNOWLES FOR MESSRS. J. M. DENT AND SONS LTD. |

BINDING-CASE DESIGNED BY REGINALD L. KNOWLES FOR MESSRS. J. M. DENT AND SONS LTD. |

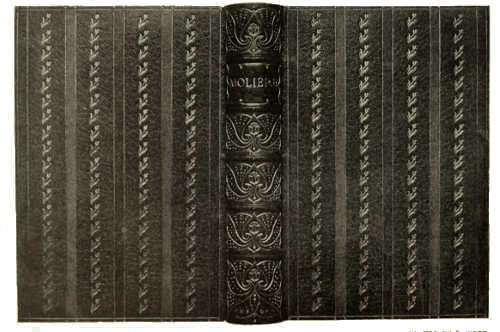

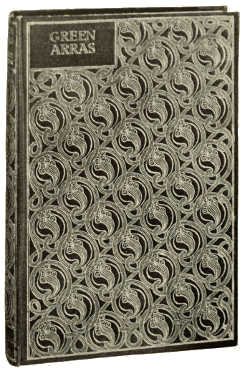

BINDING-CASE DESIGNED BY R. P. GOSSOP FOR MESSRS. J. M. DENT AND SONS LTD.

|

|

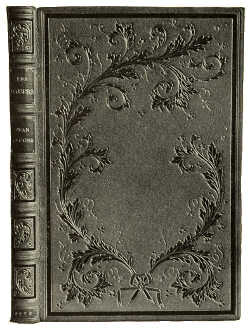

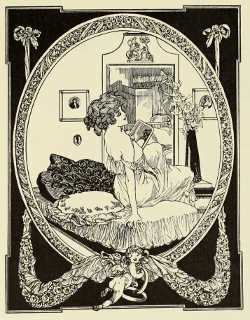

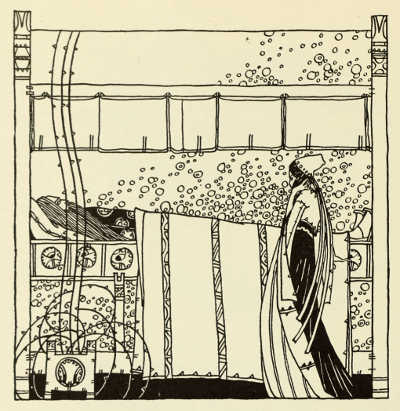

DESIGN FOR COVER OF “THE WOMAN WHO DID” BY AUBREY BEARDSLEY |

DESIGN FOR TITLE-PAGE OF “PAGAN PAPERS” BY AUBREY BEARDSLEY |

(By permission of Mr. John Lane) |

|

|

|

DESIGN FOR COVER OF “THE MOUNTAIN LOVERS” BY AUBREY BEARDSLEY |

DESIGN FOR COVER OF “NOBODY'S FAULT” BY AUBREY BEARDSLEY |

(By permission of Mr. John Lane) |

|

|

|

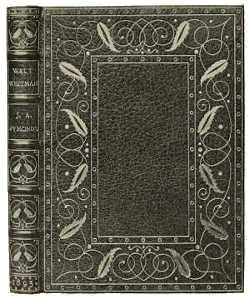

BINDING-CASE DESIGN BY REGINALD L. KNOWLES FOR MESSRS. J. M. DENT AND SONS LTD. |

BINDING-CASE DESIGN BY REGINALD L. KNOWLES FOR MESSRS. J. M. DENT AND SONS LTD. |

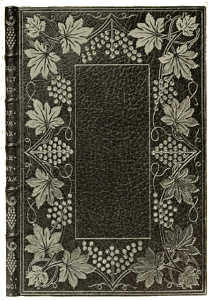

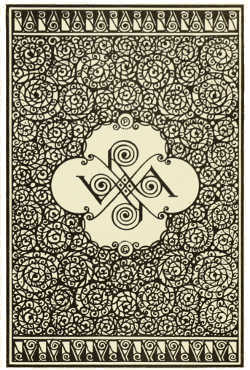

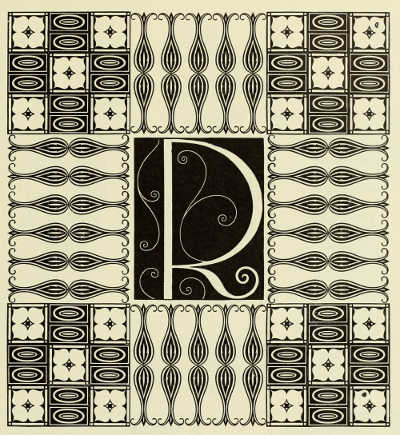

END-PAPER DESIGN BY REGINALD L. KNOWLES FOR “EVERYMAN'S LIBRARY.” FOR MESSRS. J. M. DENT AND SONS LTD.

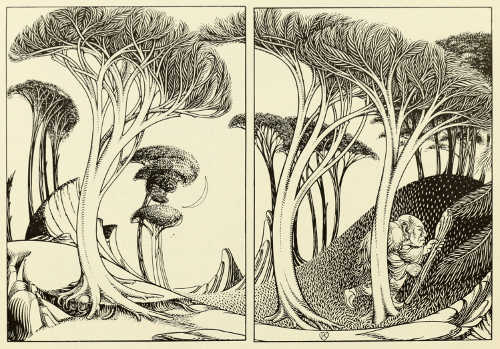

“THE HAUNT OF THE TROLL” —END-PAPER DESIGN BY REGINALD L. KNOWLES FOR “TALES FROM THE NORSE.” PUBLISHED BY MESSRS. GEORGE ROUTLEDGE AND SONS, LTD.

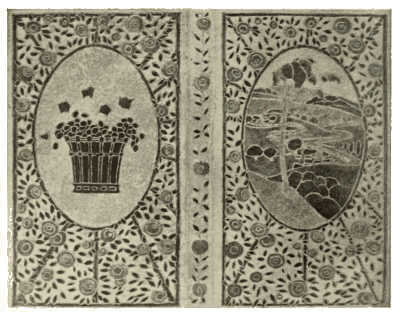

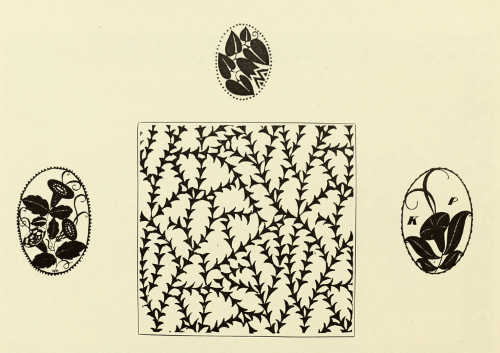

END-PAPER DESIGN BY H. GRANVILLE FELL FOR MESSRS. GEORGE NEWNES, LTD.

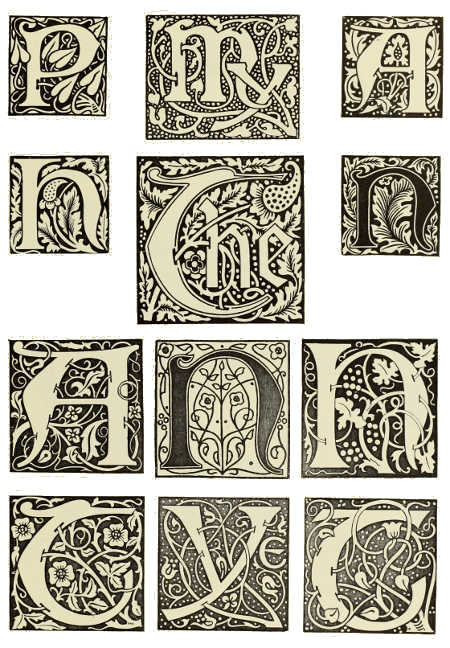

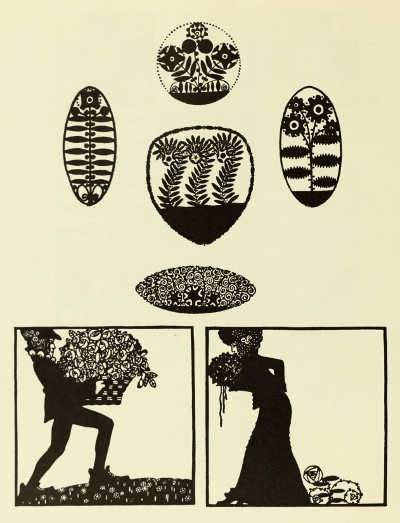

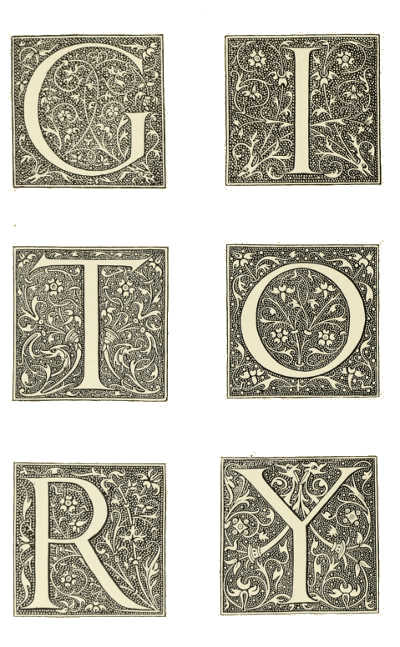

BORDER, INITIAL LETTERS, AND HEADPIECE DESIGNED BY R. JAMES WILLIAMS. FOR THE VINCENT PRESS

INITIAL LETTERS DESIGNED BY R. JAMES WILLIAMS. FOR THE VINCENT PRESS

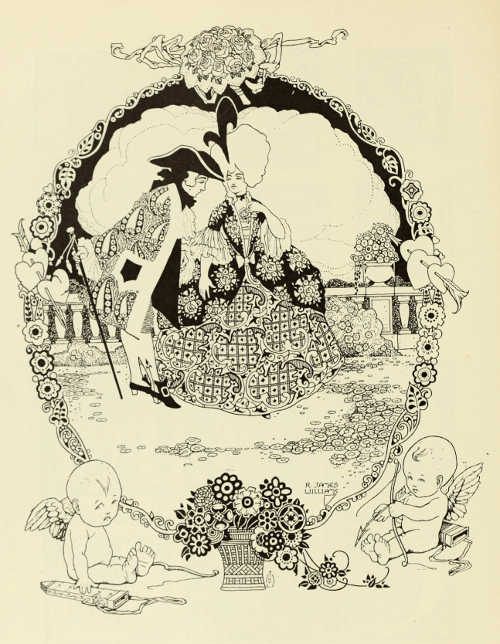

“COÛTE QUE COÛTE” —DECORATIVE DRAWING BY R. JAMES WILLIAMS

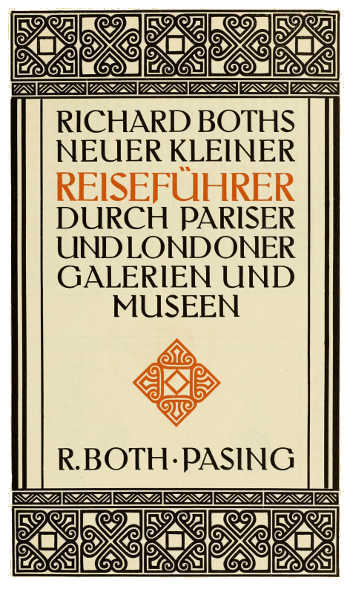

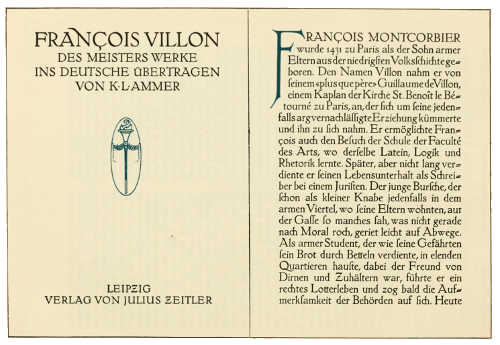

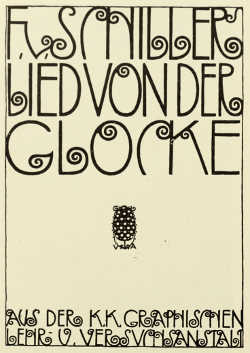

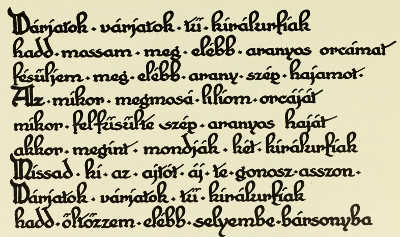

THE ART OF THE BOOK IN GERMANY. BY L. DEUBNER

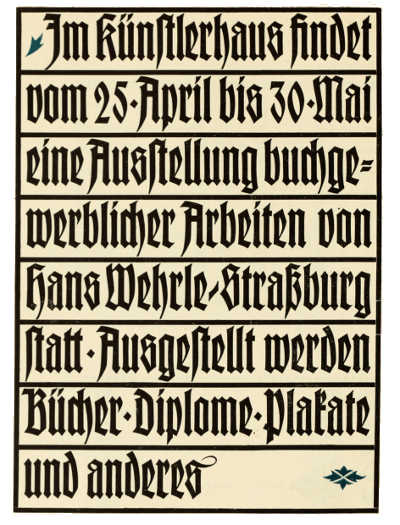

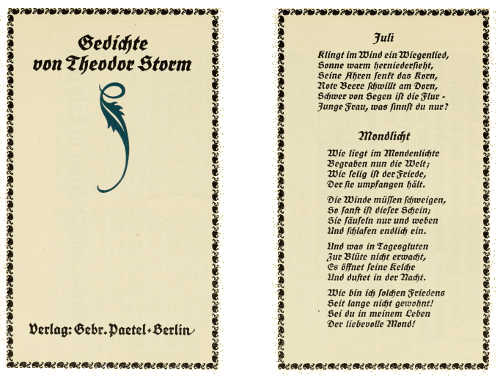

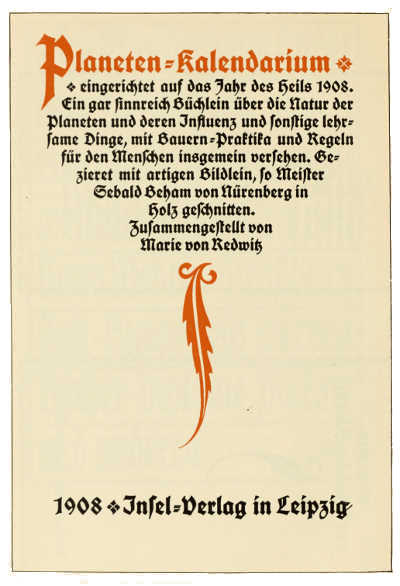

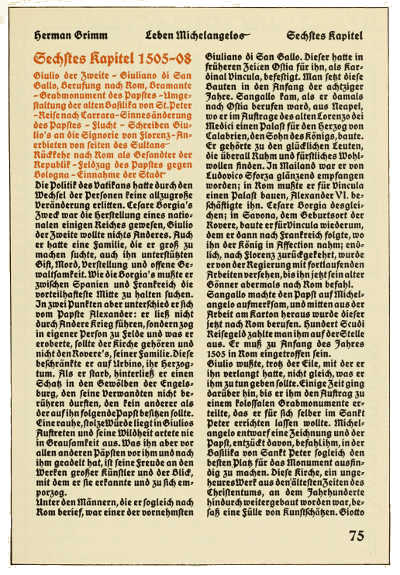

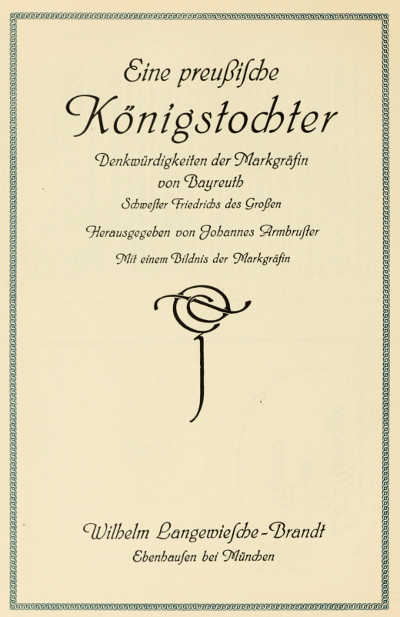

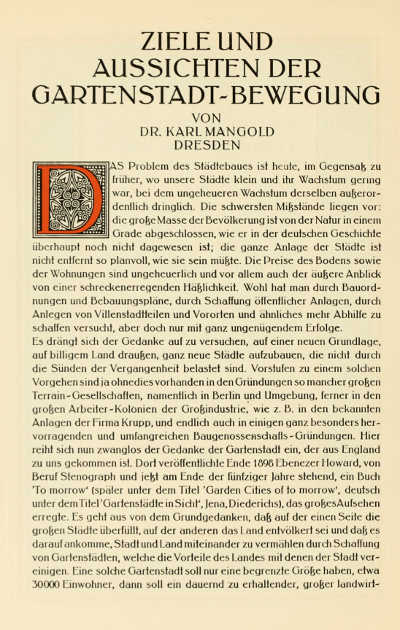

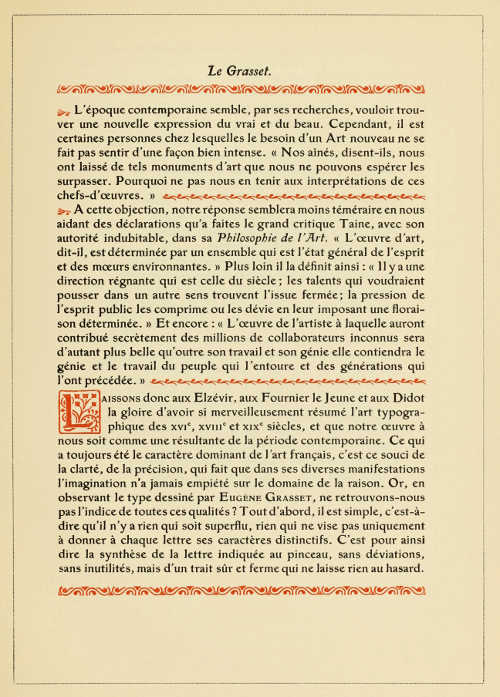

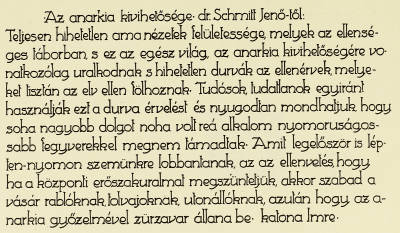

“LETTERPRESS printing, even in the edition de luxe, is not an art, and neither the compositor nor the printer is an artist.” This is what was written in the year 1887 by Ludwig Nieper, at that time Director of what is now the Royal Academy of the Graphic Arts and Book Industry at Leipzig, a city which in the present year has in its International Exhibition, embracing every conceivable aspect of the industry as well as the arts most closely bound up with it, furnished such a convincing and impressive demonstration of the culture uniting the nations as perhaps has never been offered before. The conviction expressed in the passage just quoted, repudiating the existence of any influence of art on industrial labour, belongs to a period bereft of any real feeling for art and content with the imitation and repetition of historic styles while eschewing any contact with the practical requirements of the industry. Nowadays we know how beneficial and fruitful for both has been the reciprocal influence of art and industry in every sphere of activity, and that only by this means have we been able to proceed from mere external embellishment to artistic form, from book adornment to a true art of the book. Thus in the space of barely twenty-five years our views of what art really is and what are its functions have radically changed, and it must be left to those who come after us to estimate more correctly than we are able to at the present day, the immense labour which has been accomplished in the space of a generation. The incipient stages in the growth of the new movement in Germany date back some twenty years. At that time we looked with envy at the publications which issued from the private presses of England, and could boast of nothing that could compare with the far-famed “Faust” of the Doves Press; and if to-day we are at length able to stand on our own feet, it would yet be false to assert that the modern art of book production in Germany has developed from within, and to disavow the valuable stimulus and knowledge we owe especially to the English books of that period. And clearly as we perceived that the book in its entirety, with its harmonious co-ordination of type, decoration, composition, paper and binding, should form a work of art, yet only after many mistakes and deviations have we arrived at the goal. Thus nowadays no one would seriously seek to defend such a production as the official catalogue of the German section at the Paris Exhibition of 1900; and so, too, the so-called “Eckmann” type, which at one time was taken up with unexampled enthusiasm—a type in which the designer had contrived to adapt the ancient forms of the “Antiqua” type to the sinuous lines of modern[128] ornament—is now almost completely forgotten. These and many other things which at that time were acclaimed as creative achievements, belong to that class of errors which are really nothing but exaggerated truths. But in the absence of such excesses and that exuberance of feeling which was so violently manifested, it would have been quite impossible to accomplish in so short a time what as a matter of fact was accomplished, and in spite of shortcomings has even now lost none of its importance in the history of the development of a new art of the book.

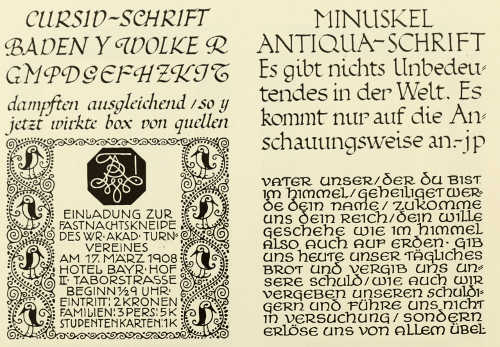

The first event of significance which followed the renewed recognition of the decorative value of the printed letter was the issue of some new types designed by Otto Eckmann and Peter Behrens respectively, the former slender, delicate, and round, the latter bold, distinguished, and angular, but both alike quite free, natural, and easily legible. It was these founts that really inaugurated the new development; and the foundry of the Gebr. Klingspor which issued them, placed itself by so doing at the head of all those enterprising type-foundries which have since enriched our printing press with a wealth of new and valuable founts. It had come to be recognised that lettering and ornament were closely correlated; that the ornamentation of printed matter could not be regarded as an end in itself, but must be adapted to the character of the lettering in order that the rectangular space of a page should be so filled as to achieve a good general effect and satisfy the sensitive eye. Nothing remained, therefore, but to entrust the designing of new types to artists who had already accomplished good and original work as book decorators; and as none of the numerous German type-foundries desired or indeed could afford to be behindhand in a movement of this kind, it resulted that in the course of a few years the printing presses of the country were inundated with a flood of new “artist” types, of which, nevertheless, only relatively few have been able to survive till now. To design a new type or to re-mould the old forms of “Antiqua” (Roman) or “Fraktur” (German Gothic), so that the new forms should not only have a good black-and-white effect but that the eye should be able to grasp with ease the sequence of “word-pictures” as well as each individual letter and to read the lines quickly and comfortably, is a task of extraordinary difficulty which many who have attempted to grapple with have under-estimated. To obtain an idea of the multitude of difficulties that have to be overcome, one must bear in mind that the fundamental forms of the individual letters are fixed, and that only small changes are possible in the general shape, in the proportions of the component parts, in the alternation of the upright, horizontal, and oblique lines, in the curvature of the so-called “versal” or capital letters, in the serifs, and in the sweep of preliminary or terminal flourishes; that the printed letter, unlike manuscript, is bound up with fixed laws,[129] and that in order to justify its claim to consideration it should, while expressing the artistic individuality of its designer, not be too original and personal if it is to be employed for general use. Further, it should conform to the spirit and ideas of the age, and yet again it ought not to be wholly conditioned by contemporary considerations if it is to survive to a later age, as have many fine founts which the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries have bequeathed to us.

As already said, only a few among our modern German designers of printed types have mastered all these difficulties, and among these few the names of Behrens, Tiemann, Koch, Kleukens, Weiss, and Wieynk are pre-eminent. In the course of some thirteen years that born architect, Peter Behrens, who began as a painter of easel pictures and a decorator of books, and now builds palaces, factory buildings, and gigantic business-houses, has himself designed four founts in which the whole artistic evolution of this strong-willed nature is reflected, and which yet seem so entirely the product of a natural growth that one is quite unconscious of the years of labour spent on their improvement and perfection in the interval between the preparation of the designs and the actual casting of the founts. As compared with the architectonic character of the austere, angular forms of the first Behrens type, the italic or “Kursiv” fount (p. 141) which made its appearance six years later looks more decorative with the gentle sweep and uniform flow of its lines, and in the most successful of the Roman founts the full vigour and monumentality of his later period of activity is clearly expressed; while the most recent of all, the “Mediæval” (p. 140), which was only issued a few weeks ago, is again more ornamental with its uniformly fine lines, and admirably answers to its designation as a type embodying the characteristics of the Italian Renaissance script.

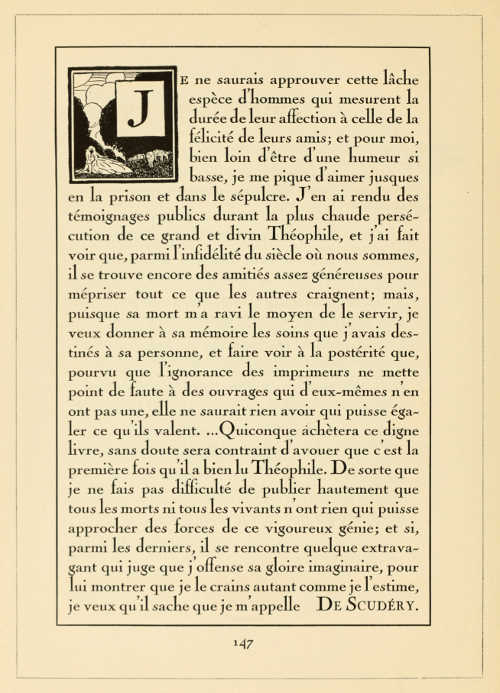

Another “Mediæval” type which even excels that just mentioned in clearness and beauty of form has been designed by Walter Tiemann (pp. 146 and 147), who holds the position of instructor at the Royal Academy of Graphic Arts at Leipzig, and devotes himself almost exclusively to the improvement of the art of lettering and book production. Like all the other types designed by this artist, it has less of a personal character about it, and reason more than sentiment has been the guiding motive in the design; but its cool, distinguished reticence gives it a quite exceptional merit. It is, moreover, completely independent of its classical prototypes and their Romanesque imitations; very effective in all its gradations, the use of it is not restricted to the limited editions of our private presses, and in fact it is now one of the most popular founts we have.

The fine Roman types by F. W. Kleukens (pp. 151, 153 and 156) rank among the most gratifying achievements of our new school. They are free from eccentricity of any kind, there is a seductive charm in their unassuming yet distinguished[130] forms, and even the ornamental slender kinds are agreeably clear. In spite of the thinness of their lines the letters belonging to this slender fount combine to make easily legible lines. The Kleukens types are practical as well as attractive, and in conjunction with specially designed borders, initials and decorative devices of all kinds, they are well adapted for the most diverse uses.

Of a far more personal character, but at the same time of a more restricted range of use, are the graceful types by Heinrich Wieynk (pp. 149 and 150). It is the spirit of the Rococo that dwells therein—that epoch to which, with its playful charm and light-hearted grace, we owe so many masterpieces of French typography. Even the superfluous loops and flourishes which were characteristic of that period are encountered again, with many bizarre peculiarities, in the “Kursiv” and “Trianon” of Wieynk, and yet there is a remarkable fluidity and vitality in each stroke; the general effect is highly artistic, and, as the examples now reproduced show, the founts are admirably adapted to numerous purposes.

Many attempts have been made to modernise the old “Schwabacher” type, which dates from the middle of the fifteenth century, and differs from German Gothic, or “Fraktur,” by being more compact. The most successful in this direction so far has been Rudolf Koch, whose “German Script,” in the three different forms here shown (pp. 142 to 145), has once more revealed the rich beauty and massive power inherent in the various kinds of German type. In these boldly designed letters is expressed a manly earnestness and also a simple grandeur which, in the sweeping, powerful forms of the initials, becomes truly monumental. They are, moreover, carefully thought out in all their details, and notwithstanding the strength of the lines, even in the smallest sizes, they are very expressive in their beauty.

Heinz König, too, has had good fortune with his “Schwabacher” type (p. 152). This is remarkably clear, and in its amalgamation of Roman forms with the characteristics of German founts it has proved both sound and serviceable, and it is one, moreover, which offers no difficulty whatever to the foreigner. The curls and loops which the champions of “Antiqua,” or Roman, find fault with in the German styles of type are absent; it is a Gothic purged of all unnecessary details and is at once dignified and decorative.

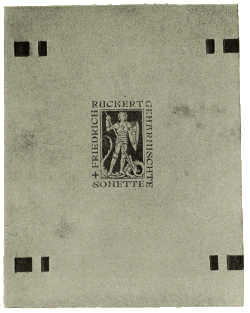

Among the new “Fraktur” or German Gothic types mention should first of all be made of that known as “Weiss-Fraktur,” which, designed by E. R. Weiss, has been perfected by him after many years of untiring collaboration with the Type Foundry of Bauer and Co. It has remained a purely German type, but is without the flourishes bequeathed by the old German Gothic. The light and open appearance of matter composed with it imparts to it a clarity which is distinctly agreeable, so that one can follow it with ease and comfort while deriving quiet pleasure from the simplicity and[131] definiteness of a type which satisfies in equal degree the requirements of use and æsthetic susceptibility. The Tempel Verlag, in common with a number of other important German publishing houses, has adopted the “Weiss-Fraktur” for its model editions of German classics.

When new desires call for satisfaction and new forms begin to develop, it is always those spheres of activity which offer easy and pleasant possibilities of accomplishment that are selected for experimenting. Thus some fifteen years ago the designing of book-bindings was a favourite occupation of the artists who interested themselves in the reform of industrial art, and many who have now attained to clear and definite ideas do not want to be reminded of the sort of work that was done in those days. Under the influence of Van de Velde's precept that every line is a force, the wrappers and bindings of books were among the things that were covered with a nervous labyrinth of lines which was expressive only of an attitude of mind radically at variance with all that had gone before. But many who at first occupied themselves with this kind of work in a more or less dilettante spirit, have by quiet, serious labour and steady development mastered its problems and have come to devote themselves almost exclusively to the graphic arts and the industry of book production, so that we now possess an important organisation of the workers in this field—the “Verein deutscher Buchgewerbekünstler” —whose collective exhibition at the International Exhibition now being held at Leipzig is one of the most interesting sections of this great display. Of the artists whose work is represented among the accompanying illustrations, Cissarz, Ehmcke, Kleukens, Köster, Koch, Renner, Steiner-Prag, Tiemann, Weiss and Wieynk belong to this group.

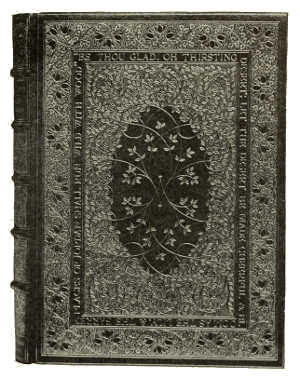

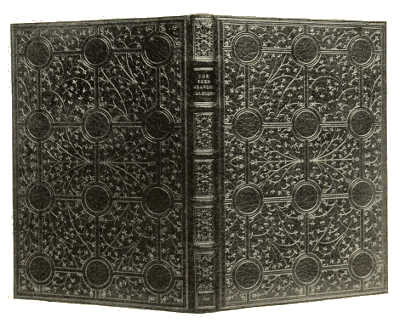

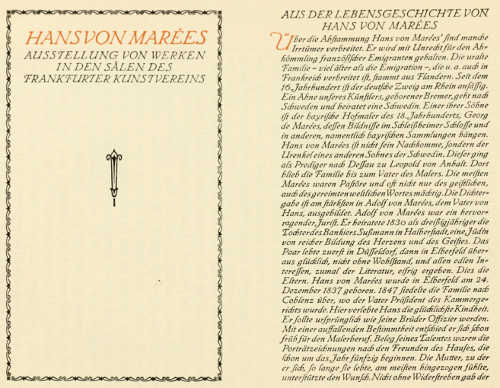

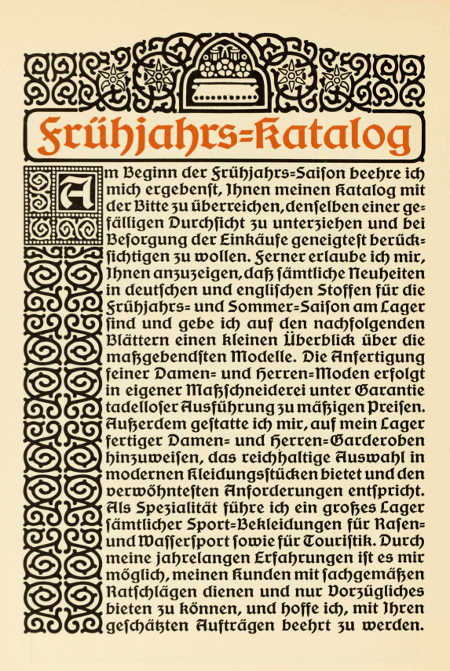

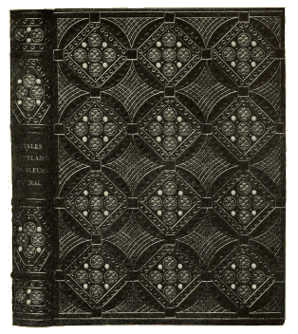

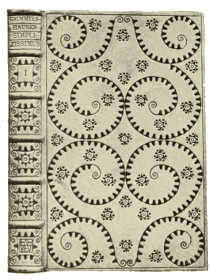

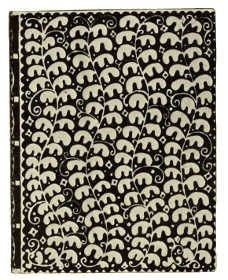

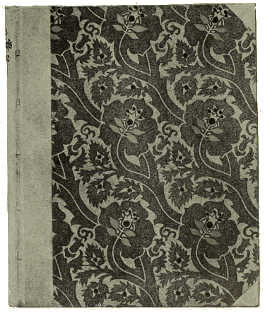

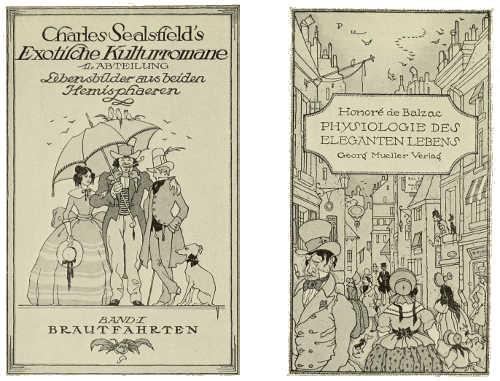

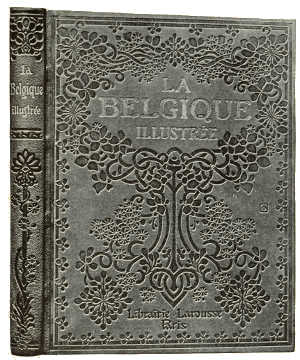

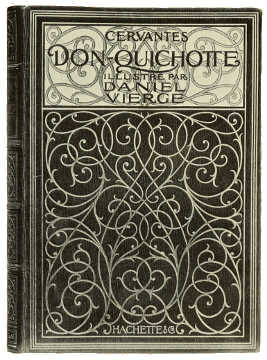

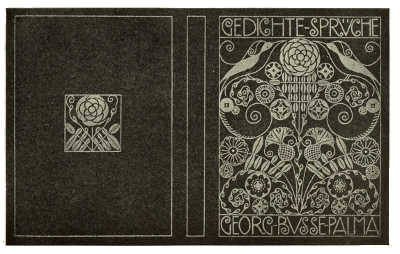

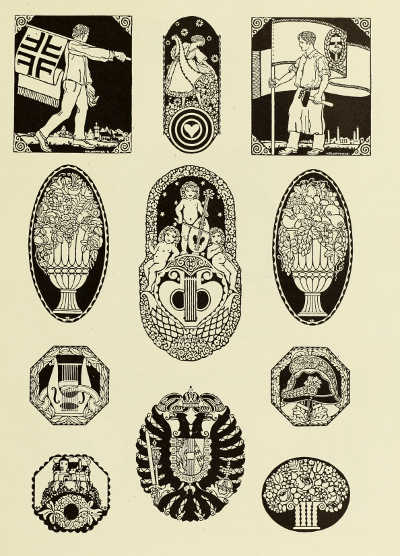

Johann Vincenz Cissarz had in 1900 already advanced to such prominence in this branch of work that the artistic arrangement of the German Typographical Section at the Paris Universal Exhibition was entrusted to him. A long way behind as this catalogue now is, it was nevertheless at that date an exemplary achievement as regards type, ornament, printing, and binding; and to the large number of commissions it brought the artist may be due the fact that thereafter his chief attention was bestowed on the art of the book, in spite of his penchant and decided genius for painting of a decorative and even monumental character and his particular partiality for the etching-needle. From Dresden Cissarz migrated, first to Darmstadt and then to Stuttgart, where as teacher at the Royal School of Applied Art he found a welcome opportunity of communicating to others his own sound principles in regard to the internal and external arrangement of books, and already he is able to look back upon a teaching career which has been very successful. And here, too, many grateful tasks have fallen to him, not only in connection with special events, such as jubilees, presentation addresses, and such things, but[132] more especially in the course of work undertaken for the publishing houses of Stuttgart. Though the luxurious binding executed by hand in costly materials may be superior in an artistic sense, yet from the economic and cultural point of view the tastefully designed bindings produced in large quantities by the publishing houses are of greater importance. A series of these publishers' cases of diverse design is illustrated on pages 168 and 172, and it shows how successfully the designer has utilised the space to display his boldly lettered title or to cover the whole field with becoming ornament.

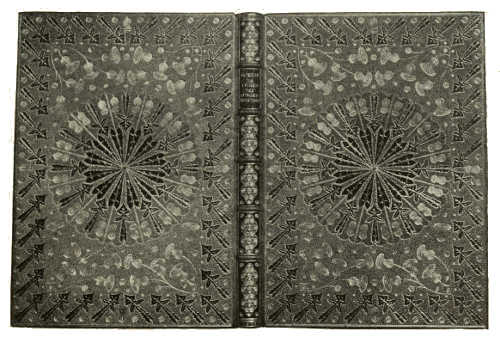

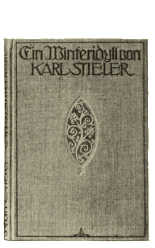

Hugo Steiner-Prag, who first became known through his poetic drawings for children's fairy tales and books of verses, has also for some years past taught at the Royal Academy of Graphic Arts at Leipzig. His chief successes have been won as an illustrator, but from the bindings now reproduced (pp. 166 and 167) it will be seen that he has a marked talent for the embellishment of the book. By means of simple lines and decorative ornament, usually confined to a well-proportioned centre field, he achieves really charming effects.

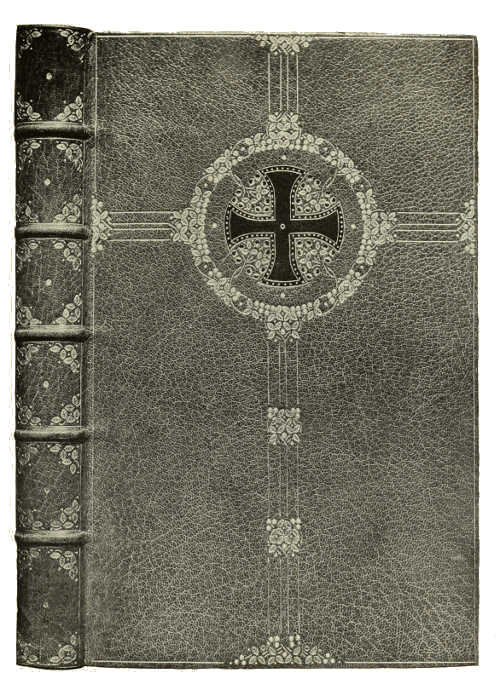

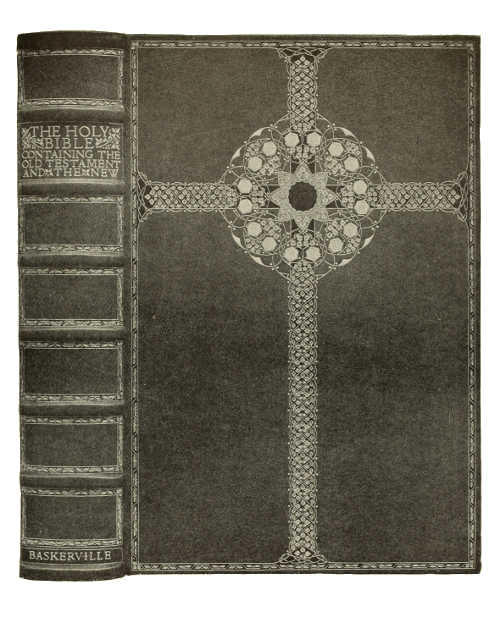

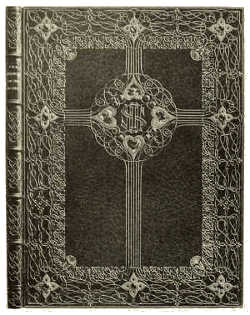

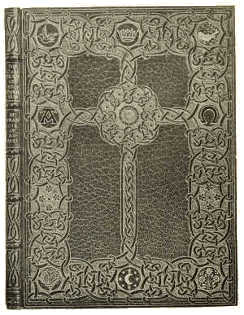

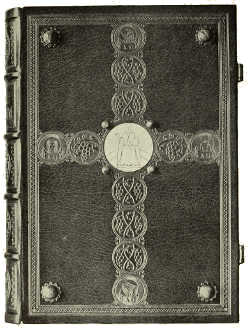

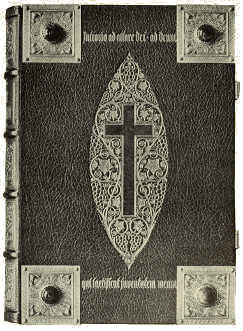

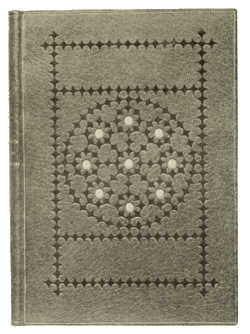

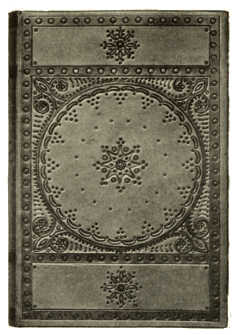

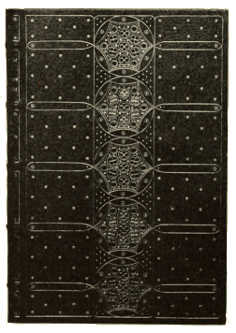

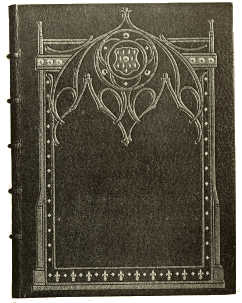

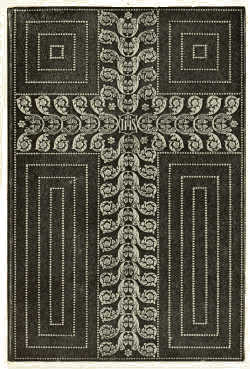

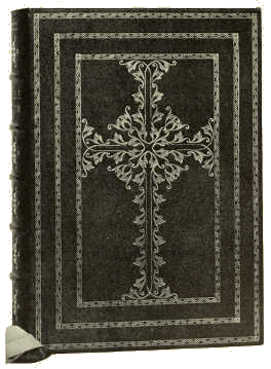

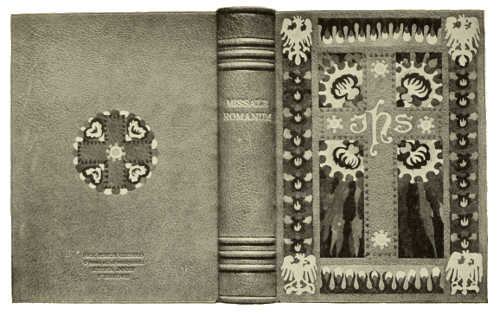

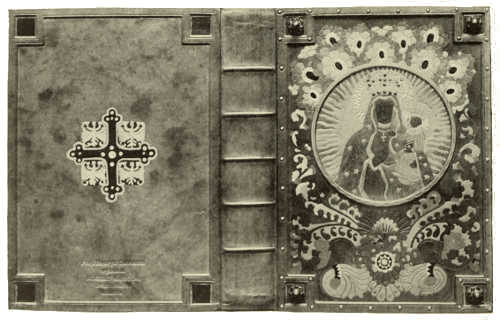

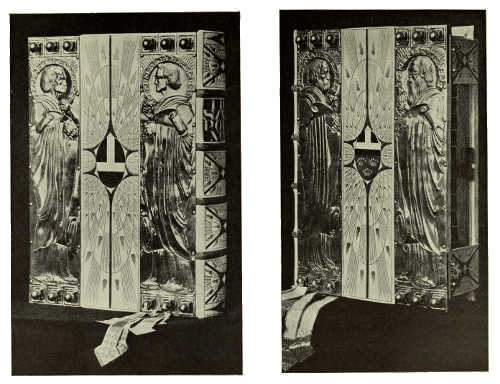

Karl Köster was at one time a pupil of Peter Behrens, and in order to be able to take advantage of all the possibilities open to the bookbinder he has not shrunk from learning the craft in the regular way. Thus in the course of his work he has not been wholly concerned with the external embellishment of the book, which he always endeavours to harmonise with its contents, but has also kept in view the practical purpose of the binding as a protective covering for the book. His great skill in achieving delightful effects with the simplest means is amply demonstrated by the numerous bindings he has designed for publishers. Thus in the bindings here illustrated, “Heimkehr” and “Buch Joram” (p. 169), three lines of lettering suffice to animate and decorate the entire surface; but he is quite capable of employing much richer decorative devices with discretion and good taste. From the way in which he has placed a simple cross of violet leather in the richly ornamented middle field of his red missal binding (p. 163), to show to the greatest advantage the colour of the amethysts set in the silver mounts, it may be inferred that he is capable of producing new and peculiar arrangements of form and colour without breaking with the best traditions. In his second missal binding the form of the cross which dominates the entire space is distributed over twelve circular panels or fields, of which the middlemost is worked with a white leather inlay and gold-tooling. The other circles are lined with violet leather, and with the four amethysts of the corner rosettes, the sea-green morocco, and the rich gilding, produce a splendid effect of colour.