This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: Romances of Old Japan

Rendered into English from Japanese Sources

Author: Yei Theodora Ozaki

Release Date: June 11, 2014 [eBook #45933]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK ROMANCES OF OLD JAPAN***

| Note: | Images of the original pages are available through Internet Archive. See https://archive.org/details/romancesofoldjap00ozak |

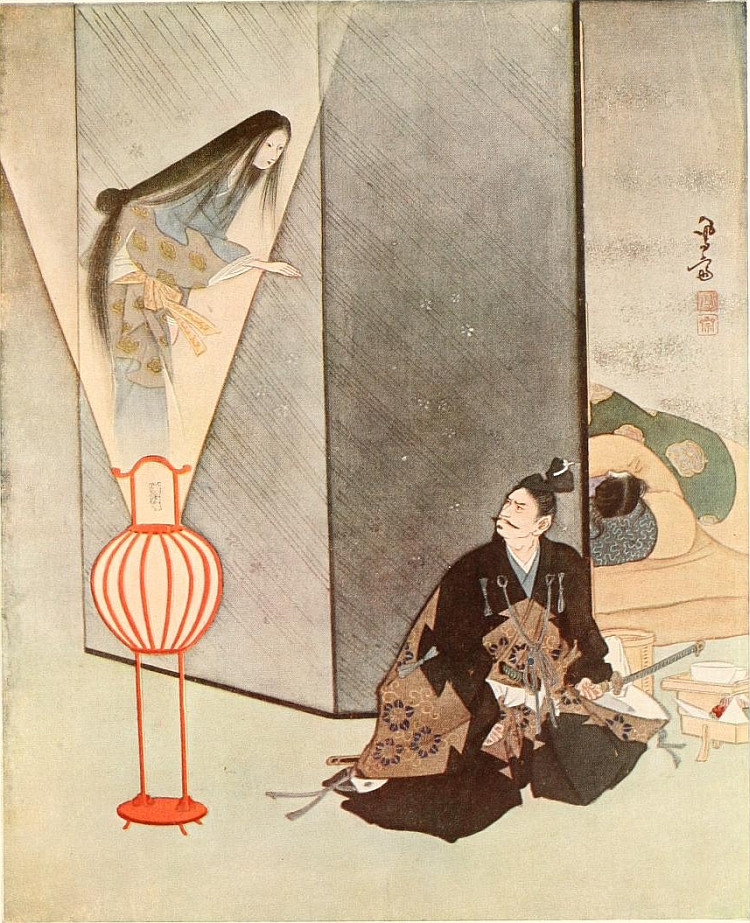

What was his breathless amazement to see that the picture he so much admired had actually taken life ... and was gliding lightly towards him—see here. (Frontispiece)

THE QUEST OF THE SWORD

THE TRAGEDY OF KESA GOZEN

THE SPIRIT OF THE LANTERN

THE REINCARNATION OF TAMA

THE LADY OF THE PICTURE

URASATO, OR THE CROW OF DAWN

TSUBOSAKA

LOYAL, EVEN UNTO DEATH; OR THE SUGAWARA TRAGEDY

HOW KINU RETURNED FROM THE GRAVE

A CHERRY-FLOWER IDYLL

THE BADGER-HAUNTED TEMPLE

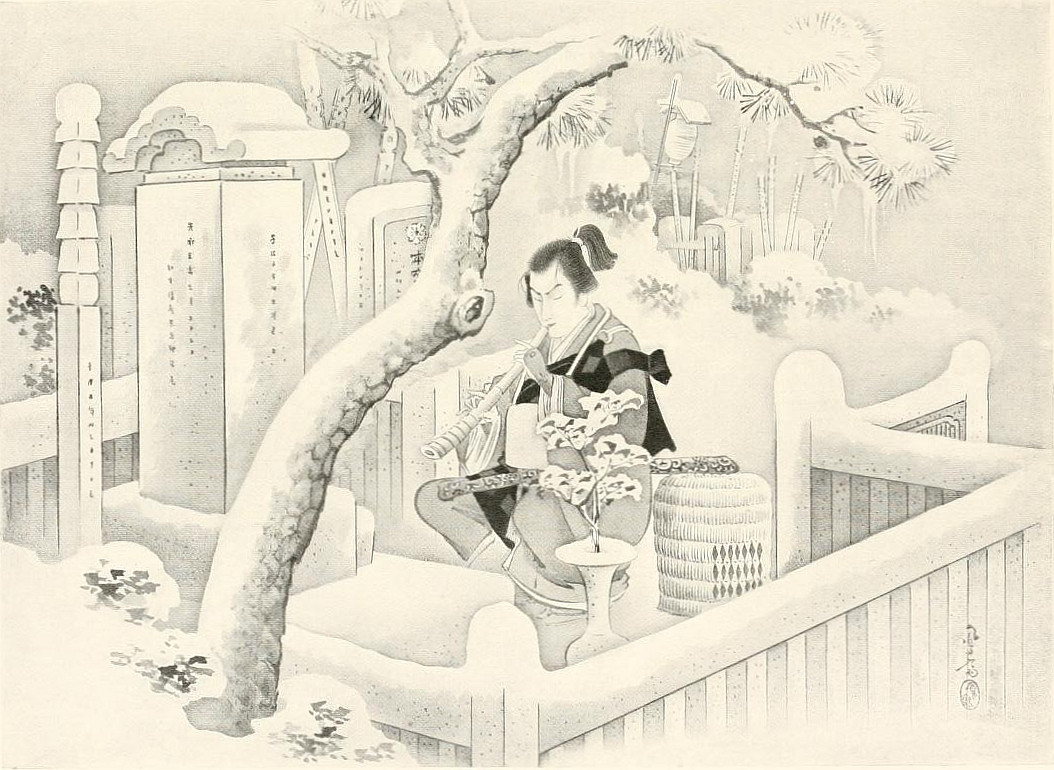

Gunbei had watched the execution of his cruel order from the veranda

Yendo draws his sword, when between him and the victim of his vengeance there darts the lovely Kesa

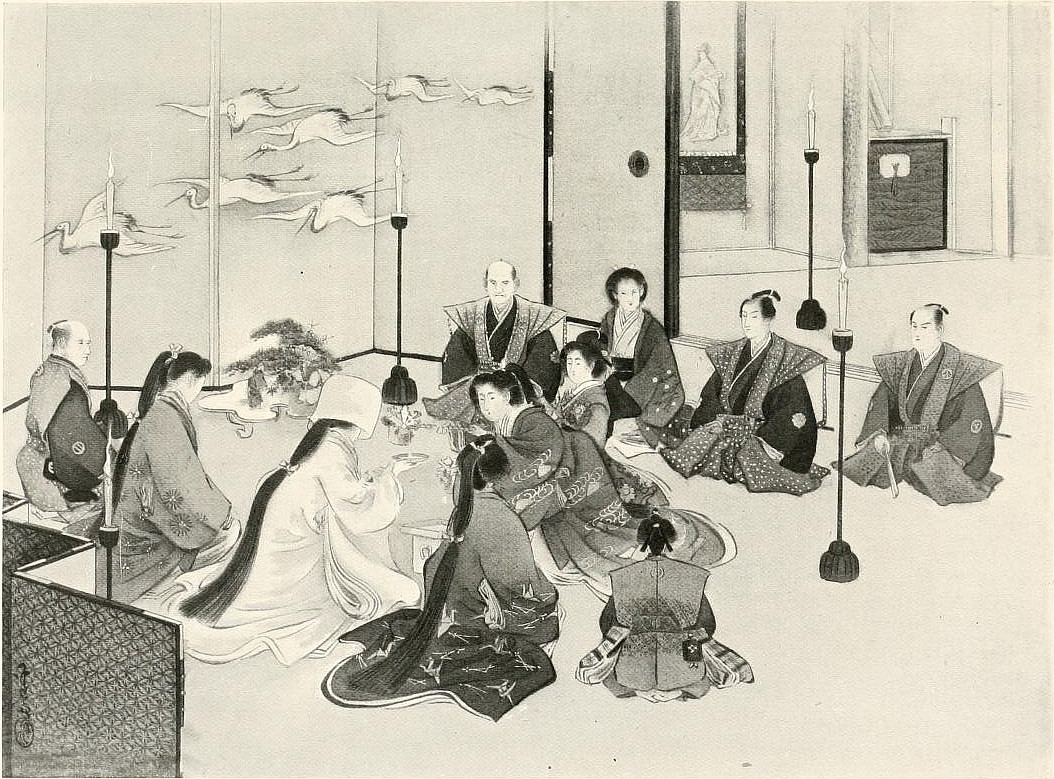

Wataru little dreams that it is the last cup his wife will ever drink with him

To his unspeakable horror and amazement the moonlight reveals the head of Kesa—his love!

He was suddenly startled to see a girlish form coming towards him in the wavering shadows

"When I was eighteen years of age, bandits ... made a raid on our village and ... carried me away"

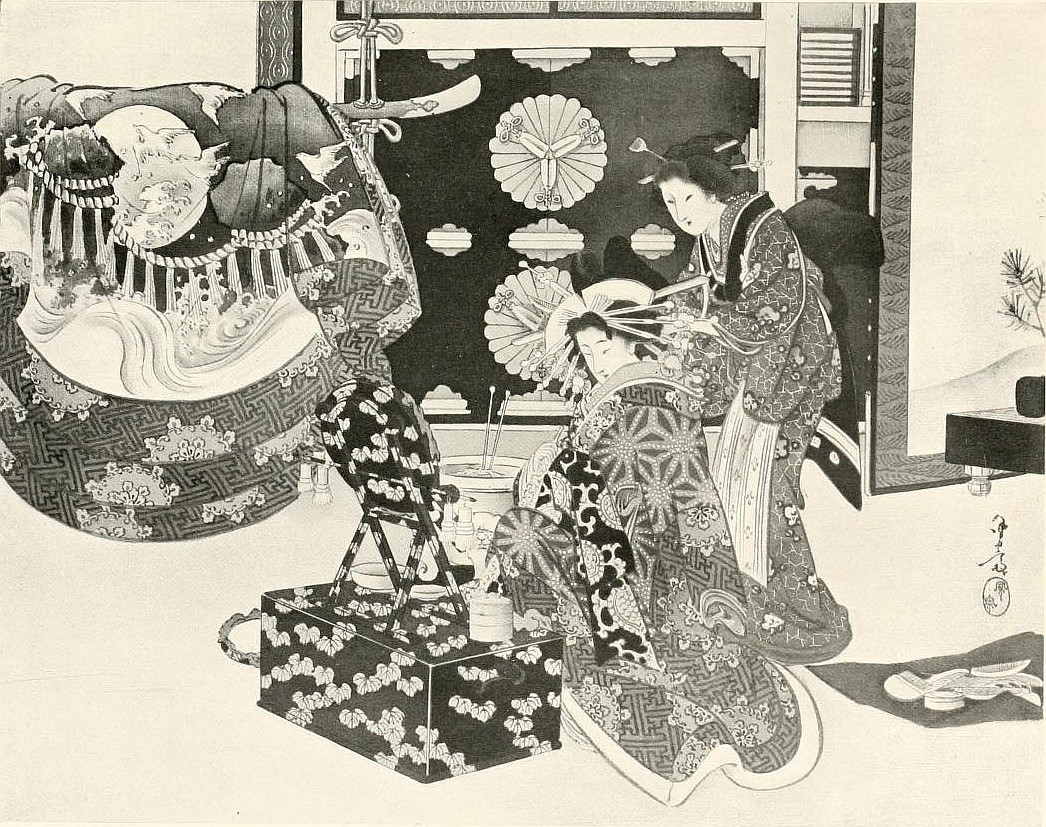

Urasato's escape from the Yamana-Ya

As she spoke, Urasato leaned far out over the balcony, the picture of youth, grace and beauty

"This is the head of Kanshusai, the son of the Lord Sugawara!"

"No, no," said Matsuo ... "this is not the body of my boy. We are going to bury our young lord!"

From earliest times Kinu and Kunizo were accustomed to play together

Her ghastly face and blood-stained garments struck terror to the souls of the petrified spectators

Kunizo, almost beside himself with happiness, did his utmost to minister to his beloved lady

Suddenly a young girl appeared from the gloom as if by magic!

His beautiful hostess, seating herself beside the koto, began to sing a wild and beautiful air

An old priest suddenly appeared ... staff in hand and clad in ancient and dilapidated garments

What was the young man's astonishment to see a pretty young girl standing just within the gate

In one of the dark corners of the temple-chamber, they came upon the dead body of an old, old badger

His old widowed mother would not die happy unless he were rehabilitated, and to this end he knew that she and his faithful wife, O Yumi, prayed daily before the family shrine.

How often had he racked his brains to find some way by which it were possible to prove his unchanging fidelity to Shusen; for the true big-hearted fellow never resented his punishment, but staunchly believed that the ties which bound him to his lord were in no wise annulled by the separation.

At last the long-awaited opportunity had come. In obedience to the mandate of the Shogun Ieyasu that the territorial nobles should reside in his newly established capital of Yedo during six months of the year, the Daimio of Tokushima proceeded to Yedo accompanied by a large retinue of samurai, amongst whom were his chief retainers, the rivals Shusen Sakurai and Gunbei Onota.

Like a faithful watchdog, alert and anxious, jurobei had followed Shusen at a distance, unwilling to let him out of his sight at this critical time, for Gunbei Onota was the sworn enemy of Shusen Sakurai. Bitter envy of his rival's popularity, and especially of his senior rank in the Daimio's service, had always rankled in the contemptible Gunbei's mind. For years he had planned to supplant him, and Jurobei knew through traitors that the honest vigilance of his master had recently thwarted Gunbei in some of his base schemes, and that the latter had vowed immediate vengeance.

Jurobei's soul burned within him as this sequence of thoughts rushed through his brain. The tempest that whirled round him seemed to be in harmony with the emotions that surged in tumult through his heart.

More than ever did it devolve on him to see that his master was properly safeguarded. To do this successfully he must once more become his retainer. So Jurobei with vehement resolution clenched his hands over the handle of his umbrella and rushed onwards.

Now it happened that same night that Gunbei, in a sudden fit of jealous rage and chagrin, knowing that his rival was on duty at the Daimio's Palace, and that he would probably return alone after night-fall, ordered two of his men to proceed to Shusen's house and to waylay and murder Shusen on his road home. Once and for all he would remove Shusen Sakurai from his path.

Meanwhile Jurobei arrived at Shusen's house, and in the heavy gloom collided violently with the two men who were lying in ambush outside the gate.

"Stop!" angrily cried the assassins, drawing their swords upon him.

Jurobei, recognizing their voices and his quick wit at once grasping the situation, exclaimed:

"You are Gunbei's men! Have you come to kill my lord?"

"Be assured that that is our intention," replied the confederates.

"I pray you to kill me instead of my lord," implored Jurobei.

"We have come for your master and we must have his life as well as yours. I have not forgotten how you cut me to pieces seven years ago. I shall enjoy paying back those thrusts with interest," returned one of them sharply.

Jurobei prostrated himself in the mud before them. "I care not what death you deal me, so long as you accept my life instead of my lord's. I humbly beg of you to grant my petition."

Instead of answering, one of the miscreants contemptuously kicked him as he knelt there.

Jurobei, whose ire was now thoroughly provoked, seized the offending leg before its owner had time to withdraw it, and holding it in a clutch like iron, inquired:

"Then you do not intend to grant my request?"

"Certainly not!" sneered the wretches.

Jurobei sprang to his feet and faced them. Without more ado they both set upon him with their weapons.

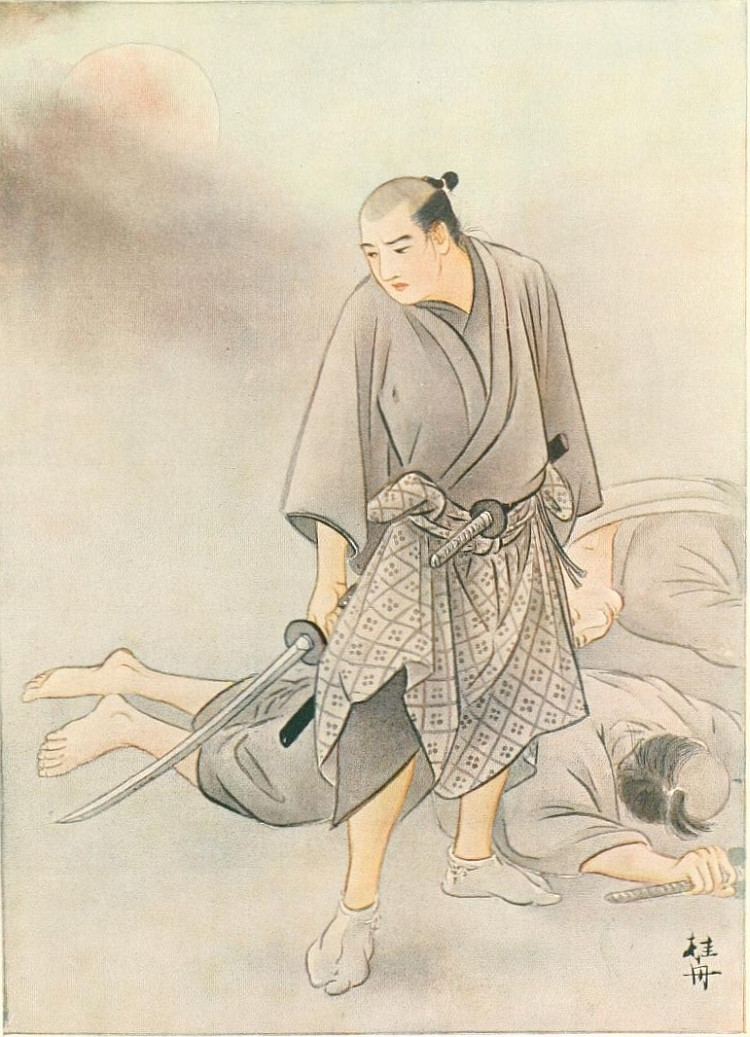

Overhead the storm increased in violence. The floodgates of heaven were opened, peals of heavy thunder shook the earth with their dull reverberations, and the inky skies were riven with blinding flash upon flash of forked lightning, which lit up the dark forms and white faces of the combatants, and glinted on their swords as they parried and clashed together in mortal strife.

Now Jurobei was an expert swordsman of unusual and supple strength. He defended himself with skill and ferocity, and soon his superiority began to tell against the craven couple who were attacking him. It was not long before they realized that they were no match for such a powerful adversary, and turned to flee. But Jurobei was too quick for them, and before they could escape he cut them down.

Mortally wounded, both men fell to the ground, and so fatal had been Jurobei's thrusts that in a few minutes they breathed their last.

By this time, the fury of the storm having spent itself, the sky gradually lifted and the moon shone forth in silver splendour between the masses of clouds as they rolled away, leaving the vast blue vault above clear and radiant and scintillating with stars.

Jurobei raised a jubilant face heavenwards and thanked the gods for the victory. He had rescued his master from death. He felt that the sacrifices that he and O Yumi had made in the past—the breaking up of the old home and the parting from their baby-daughter and the old mother—had not been in vain. The prescience, which had warned him that evil was hanging over Shusen, and which had made him so restless and uneasy of late, had been fulfilled, and he had forestalled the dastardly intention of the treacherous Gunbei and his two scoundrels.

In the stillness after the tumult of the fray, Jurobei's ear caught the sound of approaching footsteps. Turning in the direction from whence they came, there in the bright moonlight he clearly discerned the form of his beloved master, crossing the bridge.

"Oh, my lord! Is it you? Are you safe?" he exclaimed.

"Who is it?" demanded the startled samurai."Ah—it is Jurobei! What brings you here at this hour?" Then noticing the two lifeless bodies lying across the path, he sharply interrogated, "What does this mean? Has there been a fight? What was the cause of the quarrel?"

"They are Gunbei's assassins. They were waiting in ambush for your return, by Gunbei's order. I found them here. They attacked me and I killed them both, the cowards!"

Shusen started. An exclamation of dismay escaped him.

"It is a pity that you should have killed those particular men at this juncture." He mused for a few seconds, gazing at the dead faces of his would-be murderers. "I knew these rascals. My purpose was to let them go free, and to lure them over to our side: they could soon have been persuaded to confess the crimes of their master."

Jurobei realized that he had blundered. Overcome with disappointment, he sank upon the ground in a disconsolate heap.

"The intelligence of inferior men cannot be relied upon," said Jurobei with chagrin. "Alas, they unwittingly err in their judgment. I did not give the matter enough consideration. My sole idea was to save your life at all costs, my lord! I have committed a grave error in slaying them. With the intention of tendering abject apologies for my past misconduct, which has lain upon me like a heavy yoke all these years, I came here to-night. I killed these men to save your life—hoping that for this service you would reinstate me. I beg of you to forgive my stupidity."

Mortally wounded, both men fell to the ground, and so fatal had been Jurobei's thrusts that in a few minutes they breathed their last.

With these words he drew his sword and was about to plunge it into himself and rashly end his life by hara-kiri, by way of expiation.

Shusen seized his arm and stopped him in the act. "This is not the time to die! It would be a dog's death to kill yourself here and now. Perform some deed worthy of a samurai and then I will recall you as my retainer. You are a rash man, Jurobei! In future think more before you act."

"Oh, my lord, do you really forgive me? Will you indeed spare a life forfeited by many errors committed in your service?" and Jurobei gave a sigh of relief.

"Certainly I will," replied Shusen, aware that the affinity existing between lord and retainer is a close relationship not to be lightly severed.

"You were about to throw away your life," he continued, "for what you considered a samurai's duty. I commend that, anyhow! I tell you now to wait until you have accomplished some real work in the world. Listen to what I have to say.

"From generation to generation the Lords of Tokushima have entrusted to the care of our house one of their most valuable treasures and heirlooms, a talisman of the family, the Kunitsugu sword. At the end of last year we gave a banquet and entertained a large number of friends. While the attention of every one was absorbed in waiting upon the guests, some robber must have entered the house and stolen the sword, for on that night it disappeared.

"In my own mind I have strong suspicions as to who the guilty party may be, but as yet there is no proof. While I was pondering in secret over possible ways and means of bringing the theft to light, another complication has arisen.

"It has come to my knowledge that Gunbei, our enemy, is organizing a conspiracy to make an attack upon the life of my lord, the Daimio of Tokushima. My whole attention must be concentrated on this plot, to circumvent which requires very subtle and adroit handling, so that it is impossible for me to take any steps in the matter of the sword at the present time. There is no one to whom I can entrust this important mission except yourself, Jurobei. If you have any gratitude for all that I have done for you, then stake your life, your all, in the search for the lost sword.

"There is no time to lose! This is January and our Daimio's birthday falls on the third of March. The sword must be laid out in state on that festive occasion in the palace. I shall be disgraced and my house ruined if the sword be not forthcoming that day. My duties at the palace make it impossible for me to undertake the search. Even supposing that I were at liberty to go in quest of the sword, to do so would bring about my undoing, which is just what our enemy Gunbei desires. You are now a ronin [a masterless samurai], you have no master, no duty, no appearances to maintain. Your absence from our midst will cause embarrassment to no one. Therefore undertake this mission, I command you, and restore the sword to our house. If your search is crowned with success, I will receive you back into my household, and all shall be as it was between us in former times."

With this assurance Sakurai took his own sword from his girdle and handed it to Jurobei as a pledge of the compact between them.

Jurobei stretched out both hands, received it with joy, and reverently raised it to his forehead.

"Your merciful words touch my heart. Though my body should be broken to pieces I will surely not fail to recover the sword," replied Jurobei.

He then began to examine the dead men hoping to find their purses, for in his new-formed resolution he realized the immediate need of money in his search for the lost treasure.

"Stop, stop!" rebuked Shusen, "take nothing which does not belong to you, not even a speck of dust."

"Kiritori goto wa bushi no narai" [Slaughter and robbery are a knight's practice], answered Jurobei, "has been the samurai's motto from ancient times. For the sake of my lord I will stop at nothing. I will even become a robber. In token of my determination, from this hour I change my name Jurobei to Ginjuro. Nothing shall deter me in my search for the sword. To prosecute my search I will enter any houses, however large and grand they may be. Rest assured, my lord. I will be responsible for the finding of the sword."

"That is enough," returned his master. "You have taken the lives of these two men—escape before you are seized and delivered up to justice."

"I obey, my lord! May all go well with you till I give you a sign that the sword is found."

"Yes, yes, have no fear for me. Take care of yourself, Jurobei!" answered Shusen.

Jurobei prostrated himself at his master's feet.

"Farewell, my lord!"

"Farewell!"

And Shusen Sakurai and his faithful vassal separated.

On the quest of the lost sword Jurobei and his wife left Yedo buoyant with high hope and invincible courage.

The sword, however, was not to be found so easily. Jurobei was untiringly and incessantly on the alert, and week followed week in his fruitless search; however, his ardour was unabated, and firm was his resolution not to return until he could restore the missing treasure upon which the future of his master depended. Possessing no means of support, Jurobei became pirate, robber, and impostor by turns, for the samurai of feudal times considered that all means were justified in the cause of loyalty. The obstacles and difficulties that lay in his path, which might well have daunted weaker spirits, merely served to inflame his passion of duty to still greater enthusiasm.

After many adventures and hairbreadth escapes from the law, the vicissitudes of his search at last brought him to the town of Naniwa (present Osaka) where he halted for a while and found it convenient to rent a tiny house on the outskirts of the town. Here Jurobei met with a man named Izæmon who belonged to the same clan—one of the retainers of the Daimio of Tokushima and colleague of Shusen Sakurai.

Now it happened that an illegitimate half-sister of the Daimio by a serving-woman had sold herself into a house of ill-fame to render assistance to her mother's family which had fallen into a state of great destitution. As proof of her high birth she had in her possession a Kodzuka[1] which had been bestowed on her in infancy by her father, the Daimio. Izæmon, aware of her noble parentage, chivalrously followed her, and in order to redeem the unfortunate woman borrowed a sum of money from a man named Butaroku, who had proved to be a hard-hearted wretch, continually persecuting and harassing Izæmon on account of the debt. Jurobei was distressed by Butaroku's treatment of his clansman, and magnanimously undertook to assume all responsibility himself. The day had come when the bond fell due and the money had to be refunded. Jurobei was well aware that before nightfall he must manage by some way or another to obtain the means to satisfy his avaricious creditor or both himself and Izæmon would be made to suffer for the delay.

At his wit's end he started out in the early morning, leaving his wife, O Yumi, alone.

Shortly after his departure a letter was brought to the house. In those remote days there was, of course, no regular postal service, and only urgent news was transmitted by messengers. The arrival of a letter was, therefore, looked upon as the harbinger of some calamity or as conveying news of great importance. In some trepidation, therefore, O Yumi tore open the communication, only to find that her fears were confirmed. It proved to be a warning from one of Jurobei's followers with the information that the police had discovered the rendezvous of his men—some of whom had been captured while others had managed to escape. The writer, moreover, apprehended that the officers of law were on the track of Jurobei himself, and begged him to lose no time in fleeing to some place of safety. This intelligence sorely troubled O Yumi. "Even though my husband's salary is so trifling yet he is a samurai by birth. The reason why he has fallen so low is because he desires above all things to succeed in restoring the Kunitsugu sword. As a samurai he must be always prepared to sacrifice his life in his master's service if loyalty demands it, but should the misdeeds he has committed during the search be discovered before the sword is found, his long years of fidelity, of exile, of deprivation, of hardship will all have been in vain. It is terrible to contemplate. Not only this, his good qualities will sink into oblivion, and he will be reviled as a robber and a law-breaker even after he is dead. What a deplorable disgrace! He has not done evil because his heart is corrupt—oh, no, no!"

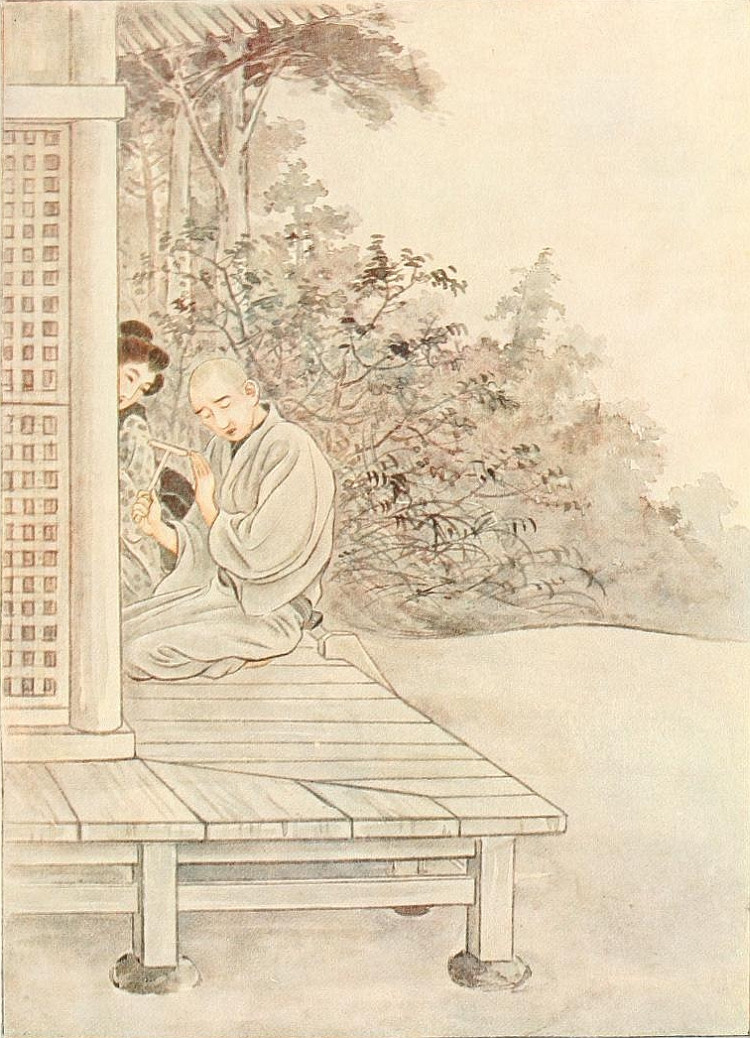

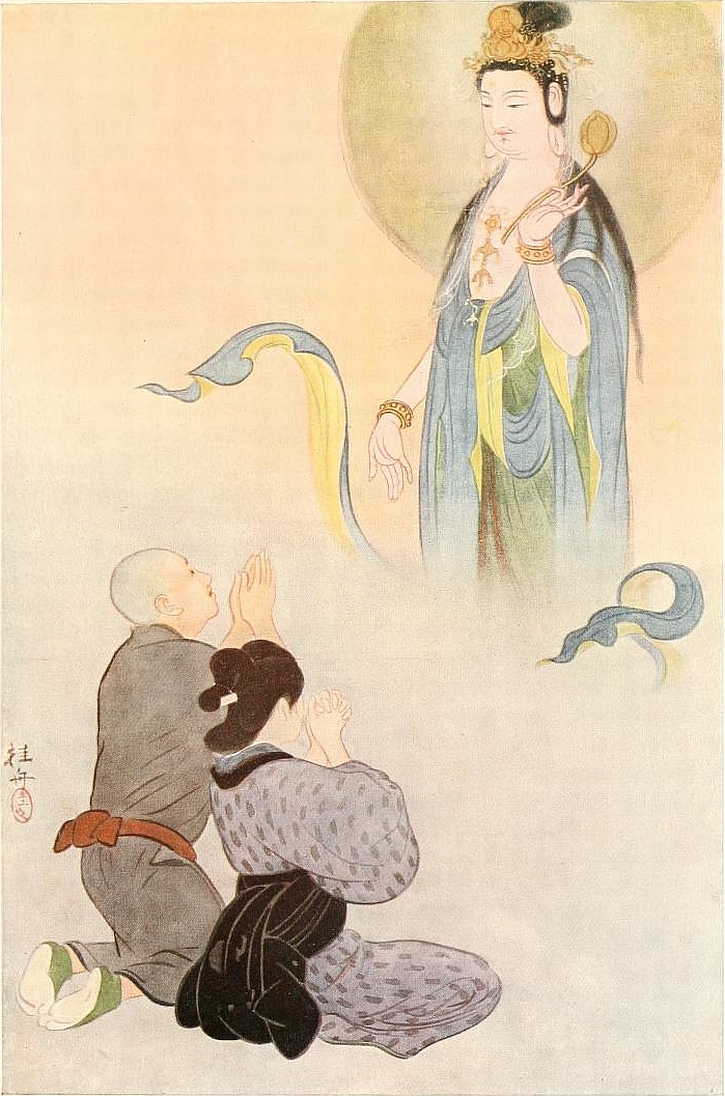

Overcome with these sad reflections, she turned to the corner where stood the little shrine dedicated to Kwannon, the Goddess of Mercy and Compassion, and sinking upon her knees she prayed with the earnestness of a last hope, that the holy Kwannon would preserve her husband's life until his mission should be accomplished and the sword safely returned to its princely owner.

As she was kneeling before the shrine there floated into the room from outside the sound of a pilgrim's song chanted in a child's sweet treble.

Fudaraku ya!

Kishi utsu nami ya

Mi Kumano no

Nachi no oyama ni

Hibiku takitsuse.

Goddess of Mercy, hail!

I call and lo!

The beat of surf on shore

Suffers a heaven-change

To the great cataract's roar

On Nachi's holy range

In hallowed Kumano.[2]

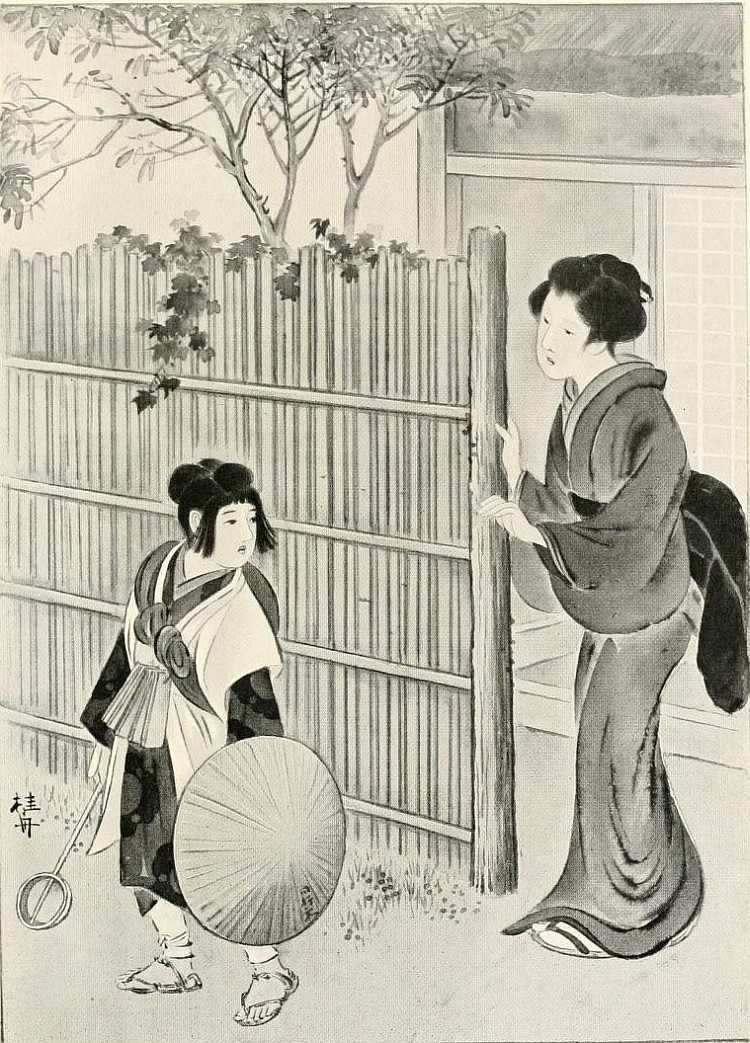

O Yumi arose from her knees and went out to ascertain who the singer could be. A little girl about nine years of age was standing in the porch. On her shoulders was strapped a pilgrim's pack. Again she sang:

Furusato wo

Harubaru, kokoni

kii—Miedera

Hana no Miyako mo

Chikaku naruran.

From home and birth

Far ways of earth

Forwandered here

Kii's holy place

A sojourn's space

Receives me, ere

Anon thy bowers,

City of Flowers,[3]

(Life's goal) draw near.

When she saw that some one had appeared, her song ceased, and she plaintively added:

"Be kind enough to give alms to a poor little pilgrim."

"My pretty little pilgrim," answered O Yumi, "I will gladly give you some alms," and placing a few coins in a fold of paper she handed it out to her.

"I thank you from my heart!" responded the child in grateful accents. By the manner in which these words were uttered, and in spite of the travel-stained dress and the dust of the road, it was apparent to O Yumi that the little girl before her was no common beggar, but a beautiful and well-born child. Naturally of a fair complexion, her eyes were clear and bright, her dishevelled hair was long and jet black. The hardships of the pilgrimage had left their mark upon the child, she was thin and seemed so weary, that it filled the heart with pity. O Yumi found her thoughts carried back to the infant she had been compelled to leave behind in the old home seven long years before, when she and Jurobei had followed their lord Shusen Sakurai to Yedo.

For some inexplicable reason she felt strangely touched by the plight of the little girl before her, and reflected sadly that her own child—so far away, and deprived at such an early age of her mother's love and care—would now be somewhat of the same age and size as the little pilgrim.

"Dear child," said O Yumi, "I suppose you are travelling with your parents. Tell me what province you came from?"

"My native province is Tokushima of Awa," was the reply.

"What?" exclaimed O Yumi. "Did you say Tokushima? That is where I was born, too! My heart thrills at hearing the beloved name of the place of my birth. And so you are making a pilgrimage with your parents?"

The woman's question was a reasonable one, for a Buddhist pilgrim wanders around from temple to temple all over the country to worship the founder of their faith and patron saints, and it was most unlikely that a child of such tender years should set out alone upon so long and arduous a journey. It was, indeed, a great distance from Tokushima, in the Island of Shikoku, to the town of Naniwa. But the little girl shook her head and answered in forlorn accents:

"No, no. I have not seen my parents for seven years. I have left my home in Awa and come upon this long pilgrimage entirely in the hope of finding them."

On hearing these words O Yumi became agitated in mind. Perchance this child might prove to be her own daughter! Drawing near the little pilgrim and scanning her features eagerly, she asked:

"Why do you go on this pilgrimage to seek your parents? Tell me their names?"

"When I was only two years of age my parents left our native place. I have been brought up entirely by my grandmother. For several months now we have had no news of them, since they followed our lord to Yedo; they seem to have left Yedo, but no one knew whither they went. I am wandering in search of them: my one wish being to look upon their faces if but once again in this life. My father's name is Jurobei of Awa and my mother is called O Yumi."

"What? Your father is Jurobei and your mother O Yumi?" stammered out the astonished parent, greatly taken aback by this statement. "And they parted from you when you were two years of age, and you were brought up by your grandmother?"

Oh! there was no room for doubt. An angel must have guided the wandering footsteps of the little pilgrim, for it was indeed her own little daughter, the sole blossom of her youth and early married life. The more carefully O Yumi regarded the child, the more her memory convinced her that in the young face before her she could trace the baby features so sadly missed for seven long years—and finally her eager eyes detected an undeniable proof of her identity—a tiny mole high up on the child's forehead.

The poor mother was on the verge of bursting into tears and crying out: "Oh, oh! You are indeed my own, O Tsuru!" But with a painful effort she realized what such a disclosure would mean to the child.

"Who knows!" reflected the unhappy woman. "My husband and I may be arrested at any moment. I am indeed prepared for the worst that may befall us—even to be thrown into prison—but if I disclose my identity to O Tsuru, she must inevitably share our misery.[4] It is in the interest of my poor child's welfare that I send her away without revealing the truth which would expose her to untold trouble and disgrace."

In those ancient times the criminal law enacted that innocent children should be implicated in the offences of the parents, and that the same sentence of punishment should cover them also. Love gave clearness to the workings of her mind, and in a moment O Yumi remembered what was threatening them and the inexorable decrees of the law. Involuntarily her arms were extended with the mother's instinct to gather the child to her heart, but she quickly controlled her emotion and did her best to address the little girl in a calm voice:

"Oh, yes, I understand. For one so young you have come a long, long way. It is wonderful that alone and on foot you could traverse such a great and weary distance, and your filial devotion is indeed worthy of praise. If your parents could know of this they would weep for joy. But things are not as we wish in this sad world, life is not as the heart of man desires, alas! You say your father and mother had to leave you, their little babe, for whose sake they would gladly sacrifice their own souls and bodies. My poor child, they must have had some very urgent reason for parting from you in this way. You must not feel injured nor bear them any resentment on that account."

"No, no," replied the little one intelligently, "it would be impious even to dream of such a feeling. Never have I felt resentment even for a single moment against my parents, for it was not their wish or intention to forsake me. But as they left me when I was only a baby I have no recollection of their faces, and whenever I see other children being tended and cherished by their mothers, or at night hushed to rest in their mother's arms, I cannot help envying them. I have longed and prayed ever since I can remember that I might be united to my own mother, and know what it is to be loved and cherished like all the other children! Oh, when I think that I may never see her again, I am very, very sad!"

The lonely child had begun to sob while pouring out the grief that lay so near her heart, and the tears that she could no longer restrain were coursing, porori, porori, down her cheeks.

O Yumi felt as though her heart was well-nigh breaking. Indeed, the woman's anguish at being an impotent witness of the sorrows of her forsaken child was of far greater intensity than the woes of the little girl's narration, yet as she answered, the mother's heart felt as though relentless circumstances had transformed her into a monster of cruelty!

"In this life there is no deeper Karma-relation than that existing between parent and child, yet children frequently lose their parents, or the child sometimes may be taken first. Such is the way of this world. As I said before, the desire of the heart is seldom gratified. You are searching for your parents whose faces you could not even recognize, and of whose whereabouts you are entirely ignorant. All the hardships of this pilgrimage will be endured in vain unless you are able to discover them, which is very improbable. Take my advice. It would be much better for you to give up the search and to return at once to your native province."

"No, no, for the sake of my beloved parents," expostulated the child, "I will devote my whole life to the search for them, if necessary. But of all my hardships in this wandering life the one that afflicts me most is that, as I travel alone, no one will give me a night's lodging, so that I am obliged to sleep either in the fields or on the open mountain-side; indeed, at times I seek an unwilling shelter beneath the eaves of some house, from whence I am often driven away with blows. Whenever I go through these terrible experiences I cannot help thinking that if only my parents were with me I should not be treated in this pitiless way. Oh! some one must tell me where they are! I long to see them ... I long ..." and the poor little vagrant burst out into long wailing sobs.

The distracted mother was torn between love and duty. Oblivious of everything, for one moment she lost her presence of mind and clasped her daughter to her heart.

She was on the point of exclaiming:

"My poor little stray lamb! I cannot let you go! Look at me, I am your own mother! Is it not marvellous that you should have found me?"

But only her lips moved silently, for she did not dare to let the child know the truth. She herself was prepared for any fate however bitter, but the innocent O Tsuru must be shielded from the suffering which would ultimately be the lot of her father and mother as the penalty for breaking the law. Fortified by this resolution, the Spartan mother regained her self-control and managed to repress the overwhelming tide of impulse which almost impelled her, in spite of all, to reveal her identity.

Holding the little form closely to her breast she murmured tenderly:

"I have listened to your story so carefully that your troubles seem to have become mine own, and there are no words to express the sorrow and pity I feel for your forlorn condition. However, 'while there is life there is hope' [inochi atte monodane]. Do not despair, you may some day be united to your parents. If, however, you determine to continue this pilgrimage, the hardships and fatigues you must undergo will inevitably ruin your health. It is far better for you to return to the shelter of your grand-mother's roof than to persist in such a vague search and with so little prospect of success. It may be that before long your parents will return to you, who knows! My advice is good, and I beg you to go back to your home at once, and there patiently await their coming."

Thus O Yumi managed to keep up the pretence of being a stranger, and at the same time to give to her own flesh and blood all the help and comfort that her mother's heart could devise. But nature would not be disguised, and although she knew it not, a passion of love and yearning thrilled in her voice and manner and communicated itself to the child's heart.

"Yes, yes," answered the little creature in appealing tones. "Indeed, I thank you. Seeing you weep for me, I feel as if you were indeed my own mother and I no longer wish to go from here. I pray you to let me stay with you. Since I left my home no one has been so kind to me as you. Do not drive me away. I will promise to do all you bid me if only you will let me stay."

"Do you wish to make me weep with your sad words?" was all that O Yumi could stammer out, her voice broken with agitation. After a moment she added: "As I have already told you, I feel towards you as though you were indeed my own daughter, and I have been wondering if by any means it would be possible to keep you with me. But it cannot be. I am obliged to seem cold-hearted and to send you away, and all that I can tell you is that for your own sake you must not remain here. I hope you fully understand and will return to your home at once."

With these words O Yumi went quickly to an inner room, and taking all the silver money she possessed from her little hoard she offered it to O Tsuru, saying:

"Although you are travelling in this solitary and unprotected state you will always find some one ready to give you a night's lodging if you can offer them money. Take this. It is not much, but receive it as a little token of my sympathy. Make use of it as best you can and return to your native province without delay."

"Your kindness makes me very happy, but as far as money is concerned I have many koban [coins of pure gold used in ancient times], I am going now. Thank you again and again for all your goodness to me," replied O Tsuru in wounded accents, and showing by a gesture that she refused the proffered assistance.

"Even if you have plenty of money—take this in remembrance of our meeting. Oh ... you can never know how sad I am at parting from you, you poor little one!"

O Yumi stooped down and was brushing away the dust which covered the hem of O Tsuru's dress.

"Oh, you must never think that I want to let you go.... Your little face reminds me of one who is the most precious to me in all the world, and whom I may never see again."

Overcome with the passion of mother-love, she enfolded the poor little wayfarer in a close embrace, and the little girl, nestling in the arms of her own mother, thought she was merely a stranger whose pity was evoked by the recital of her sufferings.

Instinct, however, stirred in her heart, and she could not bear the thought of leaving her new-found friend. But since it was impossible for her to stay with this compassionate woman, nothing remained but for her to depart. Slowly and reluctantly she passed out from the porch, again and again wistfully looking back at the kind face, and as O Tsuru resumed her journey down the dusty road she murmured a little prayer:

"Alas! Shall I ever find my parents! I implore thee to grant my petition, O great and merciful Kwannon Sama!" and her tremulous voice grew stronger with the hopefulness of childhood as she chanted the song of the pilgrim.

Chichi haha no

Megumi mo fukahi

Kogawa-dera

Hotoke no chikai

Tanomoshiki Kana.

Father-love, mother-love,

Theirs is none other love

Than in these Courts is mine.

Safe at Kogawa's shrine,

Yea, Buddha's Vows endure,

Verily a refuge sure.

Meanwhile, from the gate, the unhappy mother sadly followed with her eyes the pathetic little figure disappearing on her unknown path into the gathering twilight, while the last glow of sunset faded from the sky. The little song of faith and hope sounded like sardonic mockery in her ears. In anguish she covered her face with her sleeves and sobbed:

"My child—my child—turn back and show me your face once more! As by a miracle her wandering footsteps have been guided to the longed-for haven from far across the sea and the distant mountains. Oh, to have ruthlessly driven her away! What must our Karma-relation have been in previous existences! What retribution is this! What must have been my sin to receive such punishment!"

While these torturing reflections voiced themselves in broken utterance her daughter's shadow had vanished in the gloom, and O Yumi, standing at the gate, felt her grief become unbearable.

Vividly there arose before her mind the bitter pangs of leaving the old home and her baby child, and the misfortunes and poverty which had come upon them ever since Jurobei's discharge; the weariness and disappointment of the months of fruitless search for the lost sword; the homesickness of the exile banished from his own province and his lord's service by cruel circumstances; the disgrace which had now fallen upon her husband; all the accumulated pain of the past hushed to rest by the narcotic necessity of bearing each day's burden and meeting with courage and resource the ever-recurring difficulties and dangers of their hunted life. All these cruel phantom shapes arose to haunt the unhappy woman with renewed poignancy, sharpened by the agony of repression which her mother-love had been enduring for the past hour. Neither the arrow of hope which pierces the looming clouds of the future, nor the shield of resignation, would ever defend her again in this sorrow of sorrows. Suddenly a new resolve stirred her to action. "I can bear this no longer!" she cried frantically. "If we part now we may never meet again. I cannot let her go! From the fate that threatens us there may still be some way of escape. I must find her and bring her back."

Hastily gathering up the lower folds of her kimono she rushed out into the road that wound between the rice-fields and the dark gnarled pines. The evening wind had begun to moan through the heavy branches, and as it tossed them to and fro, to her fevered imagination they seemed to be warning her to retrace her steps and to wave her back with ominous portent. On and on she sped along the lonely road into the shadowy vista beyond which her child had disappeared into the darkness....

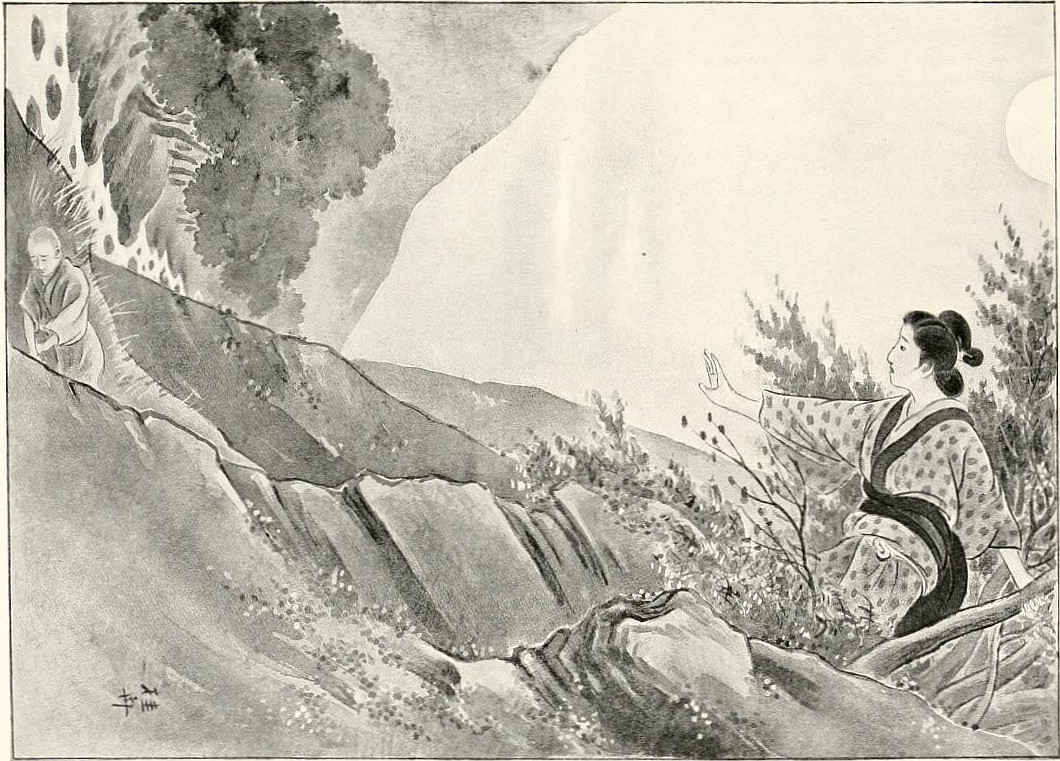

The unhappy mother sadly followed with her eyes the pathetic little figure disappearing on her unknown path.

The temple bell was booming the hour of parting day as Jurobei disconsolately hurried home. All his attempts had failed to procure the money wherewith to pay Izæmon's debt to Butaroku, and knowing that Butaroku was the kind of man to take a merciless revenge, he was in a mood of profound depression.

Suddenly in the road he came upon a group of beggars surrounding a little girl dressed as a pilgrim. The wretches, thinking her an easy prey to their cupidity, were tormenting the poor little wayfarer and trying to wrest from her the contents of her wallet, but she was bravely defending herself and resisting their attacks with great spirit.

Seeing how matters stood, Jurobei promptly drove the beggars away with his stick, and then, to avoid the return of her assailants, he compassionately took the child by the hand and led her home with him.

But alas! by a fatal mischance they had taken a different road to that chosen by O Yumi.

As soon as they reached the porch he called out:

"I have come back, O Yumi!"

Contrary to his expectation there was no response, and entering hastily he found the cottage empty and in darkness.

"How is it that the place is deserted? Where can O Yumi have gone to at this hour?" he grumbled as he groped his way across the room and set light to the standing lantern.

Then by its fitful glow he sank down upon the mats in gloomy abstraction and the lassitude of disappointment, and pondered seriously on the desperate straits to which he and his wife were reduced: the situation seemed hopeless, for well he knew that no clemency could be expected from the enemy and unless some money was forthcoming that very night he was a lost man. All at once a thought struck him. He beckoned the little pilgrim to draw near.

"Come here, my child! Those rascally beggars from whom I rescued you were trying to steal your wallet. Tell me, have you much money with you?"

"Yes, I have what several kind people have given me," was her reply.

"Let me see how much you have?" demanded Jurobei peremptorily.

O Tsuru, for indeed it was she, took out a little bag, and reluctantly offered a few coins for her inquisitor's inspection.

"Is this all you have, child?" he persisted impatiently.

"No, no, I have several koban[5] besides," answered the girl, her childish mind exaggerating the amount.

"Oh, indeed, so you have many koban?" Jurobei mused for a few minutes. Here was an unexpected opportunity to satisfy the avarice of Butaroku. "Let me take care of the koban for you. It is not safe for you to keep them," said Jurobei, stretching out his hand towards her.

"No, no!" replied O Tsuru, shaking her head with decision. "When my grandmother was dying she made me promise faithfully never to show the money to any one, as it is tied together with a very precious thing. I must not give or show the bag to any one."

Jurobei, who saw deliverance from his debt of honour in the money he supposed the child to carry, tried to frighten her into giving it up to him, but she was firm in her refusal, and rose to her feet with the intention of escaping from her persecutor.

"Oh, I will stay here no longer. You frighten me!" she exclaimed, moving towards the porch.

Jurobei, in fear lest his last hope should fail, seized her by the collar of her dress.

"Oh, oh, help, help!" loudly screamed the girl in terror.

"What a noise, what a noise!" exclaimed Jurobei in exasperation, and alarmed lest the neighbours should overhear the child's cries, he roughly attempted to stifle her screams with his hand across her mouth.

For a few minutes, as a snared bird flutters in the net of its captor, the hapless O Tsuru put forth all her strength and endeavoured desperately to disengage herself; her struggles then subsided and she grew still.

Jurobei began to reason with her without removing his hold:

"There is nothing whatever to fear! The truth is I am in pressing need of some money. I do not know how much you have, but lend it to me for a few days. During that time stay here quietly. I will take you to visit the Temple of Kwannon Sama, and we will go every day to see the sights of the city near by and amuse ourselves. Never fear, only lend me all you have like a good child."

As he freed her she fell to the ground.

"What is the matter?" said Jurobei, anxiously bending over her little form.

There was no answer. She lay quite still with no sign of life or motion.

"Oh, oh!" exclaimed Jurobei. Thinking that she had fainted, he fetched water and sprinkled her pale face and tried to force a few drops between her closed lips, but there was not even a flicker of response.

The child lay dead before him. Worn out with the hardships and fatigues of the long, long pilgrimage, as a frail light flickers out before a rough gust of wind, her waning strength had failed in that last struggle. The griefs of earth were left behind and the brave little soul had set out on its longer journey to the Meido (Hades).

Jurobei was thoroughly alarmed. In that tragic moment he knew not what to do. However, hearing his wife's returning footsteps, he hastily moved the body to one side of the room and covered it with a quilt.

O Yumi entered the room in great perturbation.

"Oh, oh! Help me to look for her, help me! While you were out this afternoon, wonderful to tell! who should come here in search for us but our own child, O Tsuru. How I longed to reveal myself to her, the poor, poor little one! But the knowledge that she must share our miserable fate when we are arrested, which may be at any moment now, forced me to send her away without telling her that I was her mother. After she had gone I could not bear the thought of never seeing her again. I ran after her, but she had disappeared! She cannot have gone far. I came back to fetch you. Let us look for her together."

Jurobei was dumbfounded at this totally unexpected intelligence. He stood up as though ready to start out into the night.

"How was she clothed? What kind of dress did she wear?" he asked hurriedly.

"She wore a long-sleeved robe brightly patterned with designs of spring blossoms, and on her shoulders she carried a pilgrim's pack."

"She carried a pilgrim's pack!" echoed Jurobei forlornly, and seized with an icy trembling. The frightful truth had flashed upon his brain. He knew that he had killed his own child!

O Yumi, wondering at his hesitation, prepared to start out again.

"You need not go to look for our child!" Jurobei hoarsely muttered. "She is already here!"

"Has she come back?" cried O Yumi in excitement. "Tell me where she is."

"She is lying there under that quilt," he replied, pointing to where the body lay.

O Yumi quickly crossed the room and drew back the coverlet. "My child! Oh, my child! At last, at last I may call you so!" cried the delighted mother sinking on her knees in a transport of joy.

Long and tenderly she gazed at the little figure, lying prone before her. But how strange that her clothes were still unloosened and the heavy pack had not been unstrapped from the tired shoulders. O Yumi touched her hands and found them cold. Panic-stricken, she listened at the child's breast only to find her fears confirmed and that the little form was still and lifeless.

"Oh, oh, oh!" wailed O Yumi, "She is dead! She is dead!"

The shock was too deep for tears. For a moment the unhappy woman was paralysed.

Then turning to her husband:

"You must know how she died. Tell me! Tell me!" she gasped distractedly.

The half-dazed Jurobei related as well as he could all the events of that fatal afternoon. He finished his recital:

"I put my hand over her mouth to stop her screaming, and on releasing her she fell to the ground. I had no intention of killing her and pitied the poor unfortunate girl, though I had no idea that she was my little Tsuru. That I should have slain our own child must be the result of sin committed in one of the former states of existence, alas! Forgive me, O Yumi! Forgive me!" and the stricken man broke down and wept.

"Was it you, her father, who killed her?" cried O Yumi, in horror.

"Oh, my child, my own child!" she sobbed. "It was your fate to come in search of such cruel, unnatural parents. When you told me of the hardships you had suffered in looking for them, my soul was pierced with woe. When I refrained from making myself known to you I felt as though my heart must break. It was only the depth of my love for you that made me drive you away from our door. If only I had kept you here this would never have happened. This calamity has come upon us as a result of my driving you away. Forgive me, oh, forgive me! O Tsuru, O Tsuru!" and the miserable mother gathered the lifeless form of her little daughter to her breast and rocked herself to and fro in the frenzy of grief unutterable.

"Words are useless. What is done can never be undone. If only I had not known that she possessed the money to help me out of this crisis it would never have happened. Money is a curse!" he said in broken accents, as he took out from the folds of the child's dress the bag containing the coins. Opening it only three ryo[6] were disclosed.

"What a miserable pittance! Can this be all? I made a mistake in thinking she had a great deal. This certainly must be retribution for some bad action in my previous existence!"

His hand still searching the bag came upon a letter. He drew it forth and read the address:

"To Jurobei and his Wife!"

"Ah! this is my mother's handwriting!"

Jurobei tore it open and began to read:

"Ever since the day you left home we must have felt mutual anxiety concerning each other's health and welfare. This is the natural feeling between parent and child, so I shall not write more upon this subject, but inform you of the real reason for this letter without further detail.

"First of all what I wish to tell you is, that it has come to my knowledge that Onota Gunbei has the lost Kunitsugu sword in his possession. Immediately I tried to obtain indisputable evidence of this fact, but as I am only a stupid woman, on second thoughts I feared that were I to take any steps in this direction it might result in more harm than good.

"Intending, therefore, to seek you out and let you proceed in this matter, I began to prepare myself and O Tsuru for the journey. But at the last moment I was suddenly taken with a mortal illness and was compelled to relinquish all hope of setting out to find you. I write this letter instead. As soon as it reaches your hands return home at once.

"Restore the sword to its rightful owner and earn your promotion—for this I shall wait beneath the flowers and the grass."

"Oh," exclaimed Jurobei, "then it was Gunbei who stole the sword. How grateful I am to my mother for this discovery. But what a cruel blow to think that she is dead!"

O Yumi took the letter from his hand and continued to read aloud:

"My greatest anxiety now is concerning little O Tsuru left helpless and friendless, and about to start alone on this journey. If by the mercy and help of the Gods she reaches you safely, bring her up tenderly and carefully. She is a clever child. She writes and plays the koto well, besides being clever at her needle, and can skilfully sew crêpe and silken robes. I myself have taken pains to instruct her, and am proud of my pupil. Give her an opportunity of showing her handiwork, and then praise her both of you.

"She brings with her the medicine which I have found by experience to suit her best. Should she ail at any time, fail not to administer it. Although repetition is irksome, yet again I beg you to take every care of my precious grandchild."

Here O Yumi, unable to read further, broke down in lamentations and cried aloud.

Now the spiteful Butaroku, finding that Jurobei did not come to pay Izæmon's debt according to agreement, was highly incensed. Knowing that the authorities were on the alert to seize Jurobei, he maliciously went and lodged information of his whereabouts.

Just at the moment they had finished reading the momentous letter the officers of the law arrived outside the house with a great noise, shouting and clamouring.

Jurobei and O Yumi, to gain a few minutes' time, snatched up the body of O Tsuru and quickly concealed themselves in a back room.

The police entered and a scene of wild confusion ensued. Confident of finding their prey hidden somewhere in the cupboards, they broke down the walls, the shoji, the boards of the ceiling, and even the little shrine dedicated to the Goddess Kwannon.

Jurobei had in those few moments braced himself up for a desperate fight. He would rather die than surrender to the law before his mission of finding the sword had been accomplished. Like a whirlwind he rushed into the room where his adversaries were battering down all before them, and like a demon of fury he attacked them, mortally slashing with his sword each man that attempted to lay hands on him.

The savage bravery of his onslaught was terrific, and so dexterous and unerring was his aim that he seemed possessed of superhuman strength: his opponents were terror-stricken, and in a few minutes, like a spider's nest, when the threads of the binding web are broken by rough contact, they fled for their very lives and rushed scattered in all directions.

"Now is our time! Let us escape!" cried O Yumi.

Both began to run from the wrecked house.

"You have forgotten our child!" Jurobei whispered brokenly.

"She needs our anxiety no more. She is safe beyond the suffering of this world. We will bury her here before we leave."

Hurriedly retracing their steps they re-entered the house, and seizing the debris that lay strewn in all directions, placed it in a heap upon the little corpse. It was the work of a few moments to light the torches: this was the sole alternative that was left them to prevent their beloved dead from falling into the desecrating hands of callous strangers.

It was impossible to carry the body with them in their flight.

As the flames crackled and blazed up, Jurobei and O Yumi stood side by side, praying for the departed soul with uplifted hands placed palm to palm, while they watched the burning of their child's funeral pyre.

It was springtime, and in the town of Tokushima the cherry-blossoms were bursting into bloom. The second of March[7] had come, and Onoto Gunbei was secretly rejoicing in the wicked thought that his schemes for the disgrace of his rival had been successful. Sakurai once removed from his path, his own advancement would be certain. To-morrow Sakurai must take the Kunitsugu sword to the palace and lay it in state before the Daimio. For reasons of his own Gunbei knew that this would be a matter of impossibility. Sakurai would therefore be suspected of having stolen it and his degradation would be the certain result.

Gunbei's sinister features relaxed into a malignant smile as he proudly stalked along the road on his way to the shrine at the western end of the town.

Two of his retainers were following at a respectful distance in his rear.

He had reached the precincts of the temple when one of these men came hurrying up:

"My lord! Jurobei, the man for whom you are constantly on the look out, is in that tea-house close by. I have just recognized him. What steps shall we take?"

"Very good!" said his master. "You have done well. Let us hide ourselves, and when he leaves the place rush upon him unawares and seize him."

Jurobei, after a short time, walked out from the hostelry. His mind was entirely engrossed with the thought that the sword must be retrieved from Gunbei's possession before the morrow, the third of the third month.

As he abstractedly strolled along, the enemy lying in ambush pounced upon him from behind. But his years of ronin's hard and reckless life had trained his muscles to such phenomenal strength that in the tussle that followed, within a few rounds, he came off triumphantly the victor.

Gunbei, who had been a spectator of this unequal contest, drew his sword.

Jurobei, noting his action, caught up one of Gunbei's men and used him as a shield to ward off the blows.

The news of the fight was soon carried to Sakurai, who immediately hurried to the spot.

Directly he became aware of the identity of Gunbei's opponent, he shouted:

"What presumption to stand up and attack your superior. Surrender at once!"

He then turned to Gunbei.

"I will take him, therefore put up your sword."

Jurobei, who understood that this was strategy on his master's part, obediently allowed himself to be bound. Sakurai then handed him over to Gunbei, who gave him in charge of his henchmen and bade them conduct him to his house.

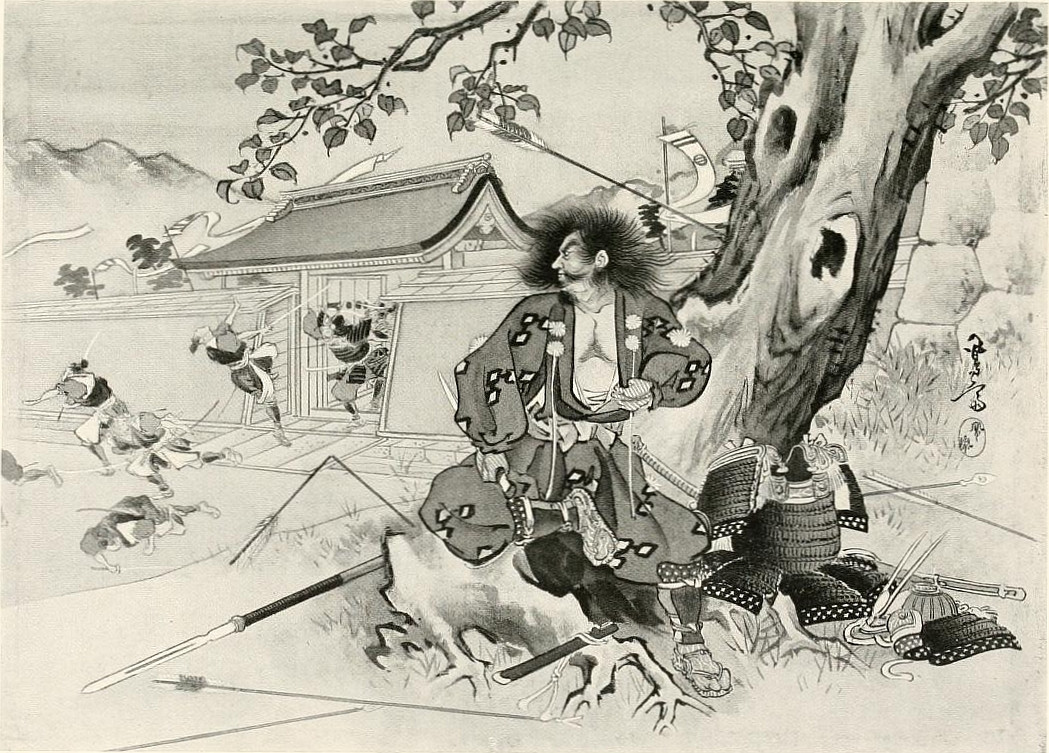

Gunbei's joy was extreme at having Jurobei in his power. He ordered him to be secured to a tree in the inner garden while he stood and mocked at him.

"Ho, Jurobei! I have a grudge to pay off against you. Why did you kill two of my men three months ago—tell me that?"

"I slew them because they intended to murder my master," replied Jurobei.

"Indeed! I believe that you are also the man who stole the sword for which your master is responsible—ho, ho, ho! You are both robbers, you must have connived at the theft of the sword together—confess!"

"You may say what you like of me, but you lie with regard to Shusen."

In a rage Gunbei and his accomplices put their sheathed swords beneath the ropes which bound Jurobei, and twisted them round and round so that they cut into the flesh and inflicted great torture on their victim.

Now it happened that Takao, the Daimio's illegitimate half-sister, whom Izæmon had been enabled to rescue from the infamous quarter through Jurobei's help, had been taking refuge in Sakurai's home. Here she had been seen by Gunbei, who had fallen madly in love with her beauty, and had planned to make her his mistress. One day in the absence of Sakurai he had sent his retainer, Dotetsuke, to carry her off by force.

Takao, now installed beneath Gunbei's roof, was obliged to listen to his dishonourable advances, but so far had managed to repel them. She was in the secret of the lost sword, and her purpose was to use the present occasion as an opportunity of laying hands on it if possible.

On hearing the commotion she opened the shoji and eagerly scanned the direction whence it arose. To her astonishment and distress she recognized in the bound and helpless form none other than her valiant friend Jurobei. The thought that she owed her deliverance from her wretched past to his chivalrous generosity flashed through her mind. Trained to resource and intrigue, on the spur of the moment she resolved to pretend that Jurobei was her brother. This feigned relationship would afford them facilities for consultation concerning the sword. Impetuously advancing to the edge of the veranda, she looked earnestly at the captive and uttered a piteous cry:

"Oh, oh! it is my brother! Oh! my poor brother!"

"This is interesting!" jeered Gunbei. "Are you really brother and sister?"

Takao implored Gunbei to release Jurobei.

"If you listen to me I will set him free," replied Gunbei, whose desire was all the more inflamed by her rejection of his suit. "But if you refuse to obey me, I will torture him with both fire and water."

Takao wept with her face hidden in her sleeves. "Is it possible that you are a samurai?" she sobbed.

"Does your heart know no sympathy—no mercy? This is unendurable! I cannot bear to see it!"

"It is you who know no sympathy either for me or your brother. I have made conditions with you, Takao. It rests entirely with you. Accept my love and you are both free."

"Such a matter cannot be decided of my own will. I am a woman and not a free agent. I must consult my elder brother."

"Very well," responded Gunbei, "if you cannot decide this by yourself, by all means consult with your elder brother Jurobei—and come to a good understanding. I will leave you both for a while."

At a sign Gunbei's henchmen released Jurobei. "Persuade your sister to obey me and I will forgive you all and set you free. I must have Takao's affection. Think well, and give me an answer that will gladden me."

Then turning to Takao he continued:

"If you finally reject my proposals you shall both be cruelly put to death. Your two lives depend upon your will. I shall await your decision in the inner part of the house."

Here Gunbei retired. Blinded by his wild passion for the unfortunate girl he was unable to see the resolution expressed on both their faces. Both his mind and soul were clouded by the desire to possess at all costs the beautiful woman who defied him. Unaware of her high birth, the knowledge of which would have abashed him in his pursuit of her, he considered that she was the legitimate prey to his will.

Takao and Jurobei were left alone. They entered the room, crossing the veranda. Seating themselves, Jurobei made a profound obeisance at a respectful distance from Takao.

"Even though it is for the sake of the Kunitsugu sword, it is a sacrilege that the close relative of our noble Daimio should for one moment be called the sister of such a poor fellow as myself."

"It is not worth while to trouble your mind about these trifles while the finding of the sword is at stake. Think not of who is master or servant. We must find the sword this very night."

"Yes, yes," replied Jurobei, "I have the same purpose as yourself. Now is a good opportunity. Gunbei is madly in love with you. For a time pretend to listen to his wooing—whatever he may say do not let it anger you—then while he is off his guard draw out the sword he is wearing from its sheath: if the habaki (the ring which secures the guard to the blade) is of gold, ornamented with carven butterflies and flowers, and the markings on the edge of the blade is the midare-yake,[8] be sure that it is the missing Kunitsugu sword. Then give me a sign. Till that moment I will be waiting in concealment close at hand."

"Yes, yes," answered Takao. "Although Gunbei's attentions are hateful to me, it is my duty, for the sake of the sword, to pretend to yield to him for a short time. In this way Sakurai will be saved. Let us agree upon a signal. I will go to the stream and, throwing some cherry flowers into it, I will repeat:

Hana wa sakura:

Hito wa bushi.

The cherry is first among flowers:

The warrior first among men."

They separated quietly. Takao sank upon the mats, musing sadly. The prospect that lay before her was utterly revolting to her mind. Meanwhile Gunbei, eager to know the result of the conference he had permitted between the two, quietly entered the room from behind.

Her attitude of dejection greatly enhanced her pale and aristocratic beauty, and Gunbei thought that she looked more ravishingly lovely than he had ever seen her before. The sight of her inflamed his longing to possess her as his own.

"What a woman!" he thought to himself. "She shall be mine!"

As he moved across the room, Takao, who was hitherto unaware of his presence, started to her feet.

"No, no," remonstrated Gunbei in seductive accents, "I cannot allow you to run away—do not deceive yourself for one moment. I have come for your answer, Takao. It is 'Yes,' is it not?"

He thought that as he found her alone and in this pensive frame of mind that Jurobei must have persuaded her to become his paramour. His pulses throbbed and the blood in his veins ran fire. In his overmastering passion he did not notice that his would-be victim shuddered as he took her hand and drew her close to him till she was reclining on his knees. Dreamily he whispered:

"Takao, you are as beautiful as an angel. Yield to my desire and I will make you my wife. Only listen to me, and all shall be as you wish both for yourself and your brother, Jurobei.—Come, come! Let us belong to each other!" and he endeavoured to draw her towards the inner room.

Takao, in the meantime, had rested her hand on the hilt of his sword and was about to draw it from its sheath.

"What are you doing, Takao! Why do you touch my sword?" asked Gunbei sharply, roused out of his reverie of love.

"Think of me no more! With this sword I will cut off my hair and become a nun. You may rest assured that never shall another man touch me all my life."

With these words she attempted to draw the sword from his girdle.

Gunbei, thwarted in his longing for the beautiful woman, now lost his temper. He pushed her roughly to one side:

"You scorn my love then? You are an obstinate creature! Instead of forgetting you I will torture Jurobei. You shall soon know what my hatred means." Clapping his hands, he called his confidential servant:

"Dotetsuke! Dotetsuke!"

When the man appeared his master wrathfully gave the imperious command:

"Tie up that woman to yonder cherry-tree."

Dotetsuke obediently dragged Takao into the garden and bound her with the rope that had a little time before made Jurobei a prisoner to the same tree.

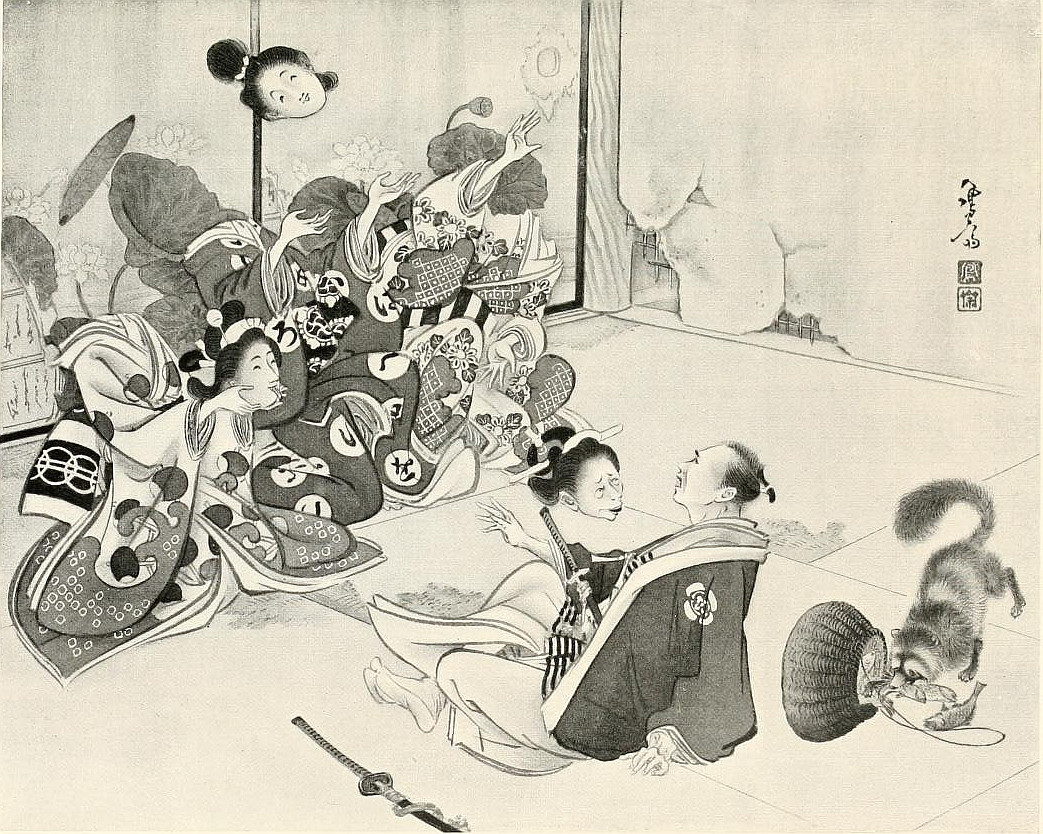

Gunbei, who had watched the execution of his cruel order from the veranda, retired into the room to meditate sulkily on his ill-success. His heart was bitter within him with chagrin and baffled desire.

Suddenly, through a small side gate, there appeared a priest of sinister appearance who, approaching the balcony, saluted Gunbei.

"According to your wishes I have prayed seven days in succession for the Daimio of Tokushima to be seized with mortal illness. Where is my reward?"

"Do not speak so loudly!" reproved Gunbei. "You may be overheard! You shall be duly compensated for your services later. This is not the time. Return at once!"

"Yes, yes, I will obey you, but do not forget to let me have the money soon."

And Kazoin, the wicked priest, fingering his rosary and praying for evil, departed as stealthily as he had come.

Meanwhile the unhappy Takao was left alone. She struggled to free her hands from the cords that cut into her tender flesh, but in vain.

"What shall I do?" she sobbed. "Jurobei must be waiting for my answer. I must find some means of letting him know my condition. Is there no way by which I can get free? I am powerless to find the sword or to help Shusen."

She struggled desperately against the tree and in her anguish she murmured:

"Gunbei is surely a devil in human form. He has stolen the sword himself in order to incriminate others. Shusen will be lost and his house ruined unless we can recover it this very night."

In her violent efforts to wrench herself free the cherry-tree was shaken and several blossoms fell into the stream. The falling flowers brought hope and comfort to Takao's heart.

"The holy Buddha has come to our aid," she reflected. "Jurobei will surely see the flowers in the water, and think that it is the pre-arranged signal."

Meanwhile Jurobei, from his hiding-place, was watching the stream, waiting with impatience for the promised sign. Just as he was beginning to chafe at the unexpected delay he caught sight of a cluster of white blossoms floating down the current of the rivulet.

"Ah, then it was the Kunitsugu sword which Gunbei stole and wore on his person, never letting it out of his sight night or day."

Creeping along within the shadow of the trees he stealthily made his way across the inner garden towards the room where he expected to find Takao.

But what was his surprise when he came upon her bound to the cherry-tree.

"Jurobei, at last you have come!" she gasped.

"Takao Sama, whatever has happened? Why are you treated like this?"

"It is because I could not endure Gunbei's hateful attentions," she answered, weeping. "Help me, I cannot move!"

Jurobei set to work to unfasten the ropes and in a few minutes Takao was released.

"Leave this matter to me!" advised Jurobei. "I will find some means of outwitting Gunbei yet."

And Jurobei, followed by Takao who was endeavouring to arrange her disordered robes, boldly strode into the room of his enemy.

The screens were pushed aside and Gunbei appeared. He glared fiercely at the intruding couple.

"How dare you release that woman without my permission?"

"It is my intention to counsel her to comply with your wishes," replied Jurobei, "therefore have I set her free—to give her to you as my sister."

"Ya, Jurobei, have your powers of persuasion induced your sister to consent to my proposals?" inquired Gunbei in mocking tones.

"Yes, I know not which I am, an elder brother or a go-between. If you have any other work for me, I am at your service."

"Ha, ha!" sneered Gunbei, "then as your sister agrees to please me we shall now be members of the same family. As a sign that we are closely related, take this by way of congratulation," and suddenly drawing his sword, he slashed at Jurobei.

Jurobei's keen eye forestalled the action, and, skilled fencer that he was, like lightning he seized a bucket close at hand and, holding it up, adroitly parried the rain of blows with this improvised shield.

"What does this mean?" he exclaimed. "This is too much attention even from a relative. It is troublesome. Surely so much ceremony between members of the same family is unnecessary. Please take it back."

Gunbei's answer was another wild attack on Jurobei, who nimbly avoided the thrusts.

While his whole attention was engrossed in trying to cut down Jurobei, Takao stole behind him and snatched the long sword hanging at his side from its sheath.

"Here is the Kunitsugu sword," she joyfully exclaimed.

On hearing these words, Gunbei turned like a demon of fury upon her.

"If you have found it I will kill you both," shouted Gunbei.

But before he could execute his threat Jurobei seized him from behind.

Dotetsuke, a secret supporter of Shusen Sakurai, and who all this time has acted the part of a spy and pretended accomplice in Gunbei's vile schemes, now escorted his real master upon the scene.

Sakurai loftily addressed his unmasked foe.

"Your villainous plots are all laid bare, and it is impossible for you to escape justice. Confess all and pray for mercy."

Gunbei, choking with rage, flung off Jurobei and rushed upon his abhorred rival.

Sakurai skilfully parried the onslaught, seized Gunbei, and with a prodigious effort hurled him out into the garden.

"Dotetsuke!" called Sakurai, "come and help us!"

"Yes, yes!" answered the man, as he ran to Jurobei's assistance in holding the wretch down.

Gunbei started.

"What? Are you also on Shusen's side?" and he gnashed his teeth in impotent fury.

"You have won!" He turned to Shusen. "It is useless for me to attempt to conceal the truth. I stole the sword, thereby hoping to bring about your ruin. I can say no more. Take the sword and return to your house. Does not that suffice?"

"The sword is but a small part of the crimes you have committed. Listen, villain that you are! You have done a much greater wrong. Our Lord, the Daimio of Tokushima, has loaded you with favours, and you, like a dastardly traitor, have requited his kindness by conspiring to compass the death of your benefactor."

"Silence, Shusen! That is a lie. I have always hated you as my rival, but I have borne no spite towards our Lord. What proof could you possibly have for such base allegations?" and Gunbei stared hard at his accuser.

Shusen smiled superciliously as he clapped his hands. In answer to the summons, Izæmon led in a prisoner, Kazoin, the wicked priest.

"Here are my witnesses of your schemes against the life of the Lord of Tokushima."

Gunbei realized his checkmate: there was nothing to be gained by lying further. He was a declared traitor. In desperation he attempted to rally his strength and attack Sakurai again, but he was promptly seized and again thrown down into the garden.

"You are a bad man, Gunbei. Our Lord shall judge you." Then turning to the men he gave the command:

"Bind him, hand and foot!"

When the mortified Gunbei lay helpless and cringing at his mercy, Shusen turned to his trusty vassal and addressed him, saying:

"Jurobei, I promote you in my service. You are a true and faithful knight. Let us rejoice, for we have triumphed and our enemy will receive his deserts—he is defeated!"

Takao here brought forward the sword and placed it slowly and ceremoniously before Jurobei who had staked his life, his house, his all, and lost his only child in the tragic search.

"It is found in time!" she said. "Look, the dawn breaks! It is the morning of the third of March!"

Receiving the weapon with a profound bow, Jurobei, on bended knees, raised it aloft in both hands and presented it to his feudal master, saying:

"To your keeping is at last restored the stolen treasure of our Daimio!" and thus ended the

Quest of the Lost Sword

NOTE.—Kunitsugu was the name of a famous swordsmith who lived at the end of the Kamakura Period, 1367.

[1] A small knife which fits into the hilt of a sword.

[2] The Shrines of Kumano or The Three Holy Places date from the first century B.C., and are famous for their healing powers. The Nachi waterfall is the third of these ancient shrines, and is No. 1 of the thirty-three places sacred to Kwannon, the Goddess of Mercy.

[3] Lit. Flower-Capital = Kyoto.

[4] In old Japan the sentence of imprisonment, execution, and even crucifixion fell on the wife as well as all the children, even to the youngest babe of the criminal.

[5] Koban = the name of an ancient pure gold coin elliptical in shape, worth about one Yen, but the purchasing value perhaps a hundred times what it is in the present day.

[6] Ryo = Yen, about two shillings, but in those times equal to perhaps a hundred times its present value.

[7] March by the old calendar fell a month later than the present way of reckoning.

[8] Swords of different smiths were distinguished by the marks on their blades, formed by the different methods of welding. The midare-yake is an undulating line like the waves of the sea.

The beautiful tragedy of Kesa Gozen has been familiar to me since the days of my early youth, when hand in hand I walked the school garden with Fumiko, my friend, and listened with the ardour of a romance-loving nature to the many stories of old Japan, and more especially of its heroines of antiquity, with which she loved to make me familiar.

Fumiko was the daughter of a naval officer, well versed in the literature of her own land, and a good English scholar. I had only just come to Japan, an Anglo-Japanese girl who had been brought up in England, knowing nothing of my fatherland. "Friendships are discovered, not made," says a philosopher, and in our case this was true. In her delightful and sympathetic companionship I began to forget the heart-aching homesickness for my motherland, and to learn to accustom myself to the strange country to which fate and my father had brought me. There is nothing more pitiful than the abysmal loneliness and utter hopelessness of the young, cut off from those they love, and planted in antipodal surroundings; they have no experience to tell them that misery, like joy, is but a condition of time, and that both pass and alternate. Who can say what drew us together? Yet never was I happier than when she put her hand in mine and made me her confidante, and great was my sorrow when she married and left me to pace the garden alone and to the memory of all the stories she had told me. To her I owe my awakening to the beauty of Japanese romance and the love of those old tragedies.

Many years have passed since then, but when I was told that Danjiro was acting the drama of Kesa Gozen at the Kabukiza Theatre my mind flashed back to those convent-like days when Fumiko and I

Lo, as some innocent and eager maiden

Leans o'er the wistful limit of the world,

Dreams of the glow and glory of the distance,

Wonderful wooing and the grace of tears,

Dreams with what eyes and what a sweet insistence

Lovers are waiting in the hidden years,

stirred to life stories of love and duty, old as the dawn which first broke upon the island empire, yet ever new and living while hearts throb to the music of the ideal.

But I am long in coming to the story of Kesa Gozen. This beautiful and touching story of the Japanese ideal of woman's character and morals is told in the drama called Nachi-No-Taki Chikai No Mongaku, "The Priest Mongaku at the Waterfall of Nachi" (it is characteristic of the Japanese that they have ignored the heroine in the title of the drama), which was acted by Danjiro Ichikawa, the star of the Japanese stage, at the Kabukiza Theatre during the month of October 1902. The heights of romance and tragedy are scaled, and the pathos of a woman's unflinching and voluntary sacrifice of life, rends the heart. The heroine is not a Francesca da Rimini, caught up by the whirlwind of passion and blown whithersoever it listeth, but a woman who finds herself confronted by a vehement and determined love, out of the toils of which she sees no escape, and so, in the prime of youth and beauty, to save her husband's name, her mother's life, and her own virtue, she calmly arranges by stratagem to die by the hand of her impetuous and would-be lover.

These tragic events took place in the year 1160, and a full account of them may be found in the "Gempei Seisuiki," a record of the rise and fall of the two great rival clans, the Taira[1] and the Minamoto, whose struggles for supremacy disturbed Japan for many years, and find a parallel in the conflicts of the White and Red Roses in England.

What is known historically of the story is this. Kesa, the heroine, was the only child of a widowed mother called Koromogawa, after the place of her residence during her married life. The word "Koromo" means the vestments of a priest, and her daughter was consequently called "Kesa," which means the "stole," her real name being Atoma. Both her father and grandfather were knights. The mother and daughter led a secluded life, always bordering on poverty, and at times menaced by actual want.

Koromogawa took charge of an orphaned nephew, a boy, a few years older than Kesa, and the two young cousins grew up together, with the old-fashioned result that the lad fell in love with the lass. At the age of sixteen, Yendo Morito, called away probably on business connected with his clan, had to leave Kesa, just then budding into exquisite beauty. Before leaving he entreated his aunt to promise him Kesa in marriage. Koromogawa complied. Yendo did not return for five years, and in the meantime, Watanabe Wataru, a wealthy and handsome young warrior, proposed for the hand of Kesa. The mother, probably in consideration of the advantages of the match from a worldly point of view, neglected her promise to Yendo, and married Kesa to Wataru, who also was the girl's cousin. After they have been married two years Yendo Morito returns and sees his lovely young cousin by accident. His boy's love, cherished fondly during long years of absence, flames into a man's overmastering passion at sight of her. He learns, to his despair, that she is married to another, and in his wrath determines to kill his aunt who, by her faithlessness to her promise, has made his life a misery. He rushes out and entering his aunt's house draws his sword upon her. She, to gain time, weakly promises that he shall see Kesa that very evening. Yendo, fain to be content with this hope, retires, and Koromogawa summons her daughter by a letter.

When Kesa arrives she finds that her mother has made all arrangements to kill herself, and on learning the circumstances she undertakes to see her cousin, and quiets her distressed parent. Then she interviews Morito and tells him that she has always loved him, but before she can be his he must first put her husband out of the way. To this he willingly consents. She bids him come that night to the house, where she will make her husband wash his hair and drink wine so that he may sleep soundly. Yendo is to steal in at midnight and, by feeling for the damp hair, find and slay his rival. Kesa returns home, washes her own hair, and sleeps in the room she has pointed out to Yendo, having carefully put her husband to sleep in an inner room.

This is an interesting psychological point, and is perhaps obscure to the Western reader. The ethical training of a Japanese woman teaches her that in any great crisis she is the one to be sacrificed. Kesa, rather than be the cause of a quarrel which would involve her husband and her mother in a blood-feud with Yendo, puts herself out of the way, and by doing so not only saves the lives of all concerned, but preaches a silent and moving sermon to her kinsman, whose ungoverned conduct is contrary to the teaching of all Japanese moralists.

The mad and reckless lover comes, but when he thinks to gaze with triumph on the severed head of his hated rival he is stricken with horror to find that he has murdered the woman he loved so passionately. He confesses his crime to the husband and they both become monks. Years after, from the obscurity of the monastery, having survived a long interval of austere life and self-inflicted penances, there rises into the prominence of political life a monk called Mongaku, who is the friend and counsellor of the great Shogun, Yoritomo, the head of the Minamoto clan. Mongaku, the monk, is the knight Yendo Morito.

It is the opinion of some that Kesa really loved Yendo, but her filial obedience obliged her to marry the man whom her mother chose for her. Then, when she found how great was her cousin's love for her, and knowing that in her heart she returned his love, but that she could not be his without sin, she went gladly to her death, rejoicing, doubtless, that it was by the sword of her beloved she should perish.[2]