or Eleven-penny Madell.

Oxford

HORACE HART, PRINTER TO THE UNIVERSITY

A Glossary of Words

USED IN THE

COUNTY OF WILTSHIRE.

BY

GEORGE EDWARD DARTNELL

AND THE

REV. EDWARD HUNGERFORD GODDARD, M.A.

London:

PUBLISHED FOR THE ENGLISH DIALECT SOCIETY

BY HENRY FROWDE, OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS WAREHOUSE.

AMEN CORNER, LONDON, E.C.

1893.

[All rights reserved.]

The following pages must not be considered as comprising an exhaustive Glossary of our Wiltshire Folk-speech. The field is a wide one, and though much has been accomplished much more still remains to be done. None but those who have themselves attempted such a task know how difficult it is to get together anything remotely approaching a complete list of the dialect words used in a single small parish, to say nothing of a large county, such as ours. Even when the words themselves have been collected, the work is little more than begun. Their range in time and place, their history and etymology, the side-lights thrown on them by allusions in local or general literature, their relation to other English dialects, and a hundred such matters, more or less interesting, have still to be dealt with. However, in spite of many difficulties and hindrances, the results of our five years or more of labour have proved very satisfactory, and we feel fully justified in claiming for this Glossary that it contains the most complete list of Wiltshire words and phrases which has as yet been compiled. More than one-half of the words here noted have never before appeared in any Wiltshire Vocabulary, many of them being now recorded for the first time for any county, while in the case of the remainder much additional information will be found given, as well as numerous examples of actual folk-talk.

The greater part of these words were originally collected by us as rough material for the use of the compilers of the[vi] projected English Dialect Dictionary, and have been appearing in instalments during the last two years in the Wilts Archæological Magazine (vol. xxvi, pp. 84-169, and 293-314; vol. xxvii, pp. 124-159), as Contributions towards a Wiltshire Glossary. The whole list has now been carefully revised and much enlarged, many emendations being made, and a very considerable number of new words inserted, either in the body of the work, or as Addenda. A few short stories, illustrating the dialect as actually spoken now and in Akerman's time, with a brief Introduction dealing with Pronunciation, &c., and Appendices on various matters of interest, have also been added; so that the size of the work has been greatly increased.

As regards the nature of the dialect itself, the subject has been fully dealt with by abler pens than ours, and we need only mention here that it belongs to what is now known as the South-Western group, which also comprises most of Dorset, Hants, Gloucester, and parts of Berks and Somerset. The use of dialect would appear gradually to be dying out now in the county, thanks, perhaps, to the spread of education, which too often renders the rustic half-ashamed of his native tongue. Good old English as at base it is,—for many a word or phrase used daily and hourly by the Wiltshire labourer has come down almost unchanged, even as regards pronunciation, from his Anglo-Saxon forefathers,—it is not good enough for him now. One here, and another there, will have been up to town, only to come back with a stock of slang phrases and misplaced aspirates, and a large and liberal contempt for the old speech and the old ways. The natural result is that here, as elsewhere, every year is likely to add considerably to the labour of collecting, until in another generation or so what is now difficult may become an almost hopeless task. No time should be lost, therefore, in noting down for permanent record every word and phrase, custom or superstition, still current among us, that may chance to come under observation.

The words here gathered together will be found to fall mainly under three heads;—(1) Dialect, as Caddle, (2) Ordinary English with some local shade of meaning, as Unbelieving, and (3) Agricultural, as Hyle, many of the latter being also entitled to rank as Dialect. There may also be noted a small number of old words, such as toll and charm, that have long died out of standard English, but still hold their own among our country people. We have not thought it advisable, as a general rule, to follow the example set us by our predecessors in including such words as archet and deaw, which merely represent the local pronunciation of orchard and dew; nor have we admitted cantankerous, tramp, and certain others that must now rank with ordinary English, whatever claim they may once have had to be considered as provincial. More leniency, however, has been exercised with regard to the agricultural terms, many that are undoubtedly of somewhat general use being retained side by side with those of more local limitation.

The chief existing sources of information are as follows:—(1) the Glossary of Agricultural Terms in Davis's General View of the Agriculture of Wilts, 1809; reprinted in the Archæological Review, March, 1888, with many valuable notes by Prof. Skeat; (2) The Word-list in vol. iii. of Britton's Beauties of Wilts, 1825; collated with Akerman, and reprinted in 1879 for the English Dialect Society, with additions and annotations, by Prof. Skeat; (3) Akerman's North Wilts Glossary, 1842, based upon Britton's earlier work; (4) Halliwell's Dictionary, 1847, where may be found most (but not all) of the Wiltshire words occurring in our older literature, as the anonymous fifteenth-century Chronicon Vilodunense, the works of John Aubrey, Bishop Kennett's Parochial Antiquities, and the collections by the same author, which form part of the Lansdowne MSS.; (5) Wright's Dictionary of Obsolete and Provincial English, 1859, which is mainly a condensation of Halliwell's work, but contains a few additional[viii] Wiltshire words; (6) a Word-list in Mr. E. Slow's Wiltshire Poems, which he has recently enlarged and published separately; and (7) the curious old MS. Vocabulary belonging to Mr. W. Cunnington, a verbatim reprint of which will be found in the Appendix.

Other authorities that must here be accorded a special mention are a paper On some un-noted Wiltshire Phrases, by the Rev. W. C. Plenderleath, in the Wilts Archæological Magazine; Britten and Holland's invaluable Dictionary of English Plant-names, which, however, is unfortunately very weak as regards Wilts names; the Rev. A. C. Smith's Birds of Wiltshire; Akerman's Wiltshire Tales; the Flower-class Reports in the Sarum Diocesan Gazette; the very scarce Song of Solomon in North Wilts Dialect, by Edward Kite, a work of the highest value as regards the preservation of local pronunciation and modes of expression, but containing very few words that are not in themselves ordinary English; the works of Richard Jefferies; Canon Jackson's valuable edition of Aubrey's Wiltshire Collections; and Britton's condensation of the Natural History of Wilts. In Old Country and Farming Words, by Mr. Britten, 1880, much information as to our agricultural terms may be found, gathered together from the Surveys and similar sources. Lastly, the various Glossaries of the neighbouring counties, by Cope, Barnes, Jennings, and other writers, should be carefully collated with our Wiltshire Glossaries, as they often throw light on doubtful points. Fuller particulars as to these and other works bearing on the subject will be found in the Appendix on Wiltshire Bibliography.

We regret that it has been found impossible to carry out Professor Skeat's suggestion that the true pronunciation should in all doubtful cases be clearly indicated by its Glossic equivalent. To make such indications of any practical value they should spring from a more intimate knowledge of that system than either of us can be said to possess. The same remarks will also apply to the short notes on Pronunciation, &c., where our utter inexperience as regards the modern[ix] scientific systems of Phonetics must be pleaded as our excuse for having been compelled to adopt methods that are as vague as they are unscientific.

To the English Dialect Society and its officers we are deeply indebted for their kindness and generosity in undertaking to adopt this Glossary, and to publish it in their valuable series of County Glossaries, as well as for the courtesy shown us in all matters connected with the work. We have also to thank the Wilts Archæological Society for the space afforded us from time to time in their Magazine, and the permission granted us to reprint the Word-lists therefrom.

In our Prefaces to these Word-lists we mentioned that we should be very glad to receive any additions or suggestions from those interested in the subject. The result of these appeals has been very gratifying, not only with regard to the actual amount of new material so obtained, but also as showing the widespread interest felt in a branch of Wiltshire Archæology which has hitherto been somewhat neglected, and we gladly avail ourselves of this opportunity of repeating our expression of thanks to all those who have so kindly responded. To Dr. Jennings we owe an extremely lengthy list of Malmesbury words, from which we have made numerous extracts. We have found it of special value, as showing the influence of Somersetshire on the vocabulary and pronunciation of that part of the county. To Sir C. Hobhouse we are indebted for some interesting words, amongst which the survival of the A.S. attercop is well worth noting. We have to thank Mr. W. Cunnington for assistance in many ways, and for the loan of MSS. and books, which we have found of great service. To Mr. J. U. Powell and Miss Kate Smith we owe the greater part of the words marked as occurring in the Deverill district. Mr. E. J. Tatum has given us much help as regards local Plant-names: Miss E. Boyer-Brown, Mr. F. M. Willis, Mr. E. Slow, Mr. James Rawlence, Mr. F. A. Rawlence, Mr. C. E. Ponting, Mr. R. Coward, the[x] Rev. W. C. Plenderleath, Mr. Septimus Goddard, Mrs. Dartnell, the Rev. C. Soames, and the Rev. G. Hill must also be specially mentioned. We are indebted to Mr. W. Gale, gardener at Clyffe Pypard Vicarage, for valuable assistance rendered us in verifying words and reporting new ones.

We take this opportunity of acknowledging gratefully the assistance which we have throughout the compilation of this Glossary received from H. N. Goddard, Esq., of the Manor, Clyffe Pypard, to whose wide knowledge and long experience of Wiltshire words and ways we owe many valuable suggestions; from the Rev. A. Smythe-Palmer, D.D., who has taken much interest in the work, and to whose pen we owe many notes; from Professor Skeat, who kindly gave us permission to make use of his reprints; and last, but by no means least, from the Rev. A. L. Mayhew, who most kindly went through the whole MS., correcting minutely the etymologies suggested, and adding new matter in many places.

In conclusion, we would say that we hope from time to time to publish further lists of Addenda in the Wilts Archæological Magazine or elsewhere, and that any additions and suggestions will always be very welcome, however brief they may be. The longest contributions are not always those of most value, and it has more than once happened that words and phrases of the greatest interest have occurred in a list whose brevity was its only fault.

George Edward Dartnell,

Abbottsfield, Stratford Road, Salisbury.

Edward Hungerford Goddard,

The Vicarage, Clyffe Pypard, Wootton Bassett.

CONTENTS

| PAGE | |

| Introduction | xiii-xix |

| List of Abbreviations | xx |

| Glossary | 1-186 |

| Addenda to Glossary | 187-204 |

| Specimens of Dialect:— | |

| Extracts from the Remains of William Little | 205-208 |

| The Harnet and the Bittle | 208-209 |

| The Vargeses | 210 |

| Thomas's Wives | 210-211 |

| Manslaughter at 'Vize 'Sizes | 211 |

| How our Etherd got the Pewresy | 211-212 |

| Gwoin' raythur too vur wi' a Veyther | 212-213 |

| Nothen as I likes wusser | 213-214 |

| Putten' up th' Banns | 214 |

| The Cannings Vawk | 214-215 |

| Lunnon avore any Wife | 215-216 |

| Kitchin' th' Influenzy | 216 |

| Appendices:— | |

| I.—Bibliography | 217-223 |

| II.—Cunnington MS. | 224-233 |

| III.—Monthly Magazine Word-List | 234-235 |

The following notes may perhaps serve to give some slight indication as to pronunciation, &c., but without the aid of Glossic it is impossible accurately to reproduce the actual sounds.

A is usually lengthened out or broadened in some way or other.

Thus in hazon and haslet it would be pronounced somewhat as in baa, this being no doubt what the Monthly Magazine means by saying that 'a is always pronounced as r.'

When a is immediately followed by r, as in ha'sh, harsh, and paa'son, parson, the result is that the r appears to be altogether dropped out of the word.

Aw final always becomes aa, as laa, law, draa, draw, thaa, thaw.

In saace, sauce, au becomes aa.

A is also broadened into eä.

Thus garden, gate, and name become geärden, geät, and neäme.

These examples may, however, be also pronounced in other ways, even in the same sentence, as garne, yăt, and naayme, or often ne-um.

A is often softened in various ways.

Thus, thrash becomes draish, and wash, waish or weish.

It is often changed to o, as zot, sat, ronk, rank.

Also to e, as piller, pillar, refter, rafter, pert, part.

In vur, far, the sound is u rather than e.

The North Wilts version of the Song of Solomon gives frequent examples of oi for ai, as choir, chair, foir, fair, moyden, maiden; but this is probably an imported letter-change, chayer or chai-yer, for instance, being nearer the true sound.

E is often broadened into aa or aay.

Thus they gives us thaay, and break, braayke.

In marchant, merchant, and zartin, certain, the sound given is as in tar.

Ei takes the sound of a in fate, as desave, deceive.

Left, smell, and kettle become lift, smill, and kiddle.

In South Wilts ĕ in such words as egg or leg becomes a or ai, giving us aig and laig or lăg. Thus a Heytesbury Rosalind would render—

by 'O-my-poor-vit'n-laigs!' uttered all in one gasp. In N. Wilts the e in these words is not perceptibly so altered.

The ĕ in such words as linnet usually takes the u sound, giving us linnut. In yes it is lengthened out into eece in S. Wilts, and in N. Wilts into cez.

Long e or ee is shortened into i, as ship, sheep, kippur, keeper, wick, week, fit, vit, feet, the latter word sometimes being also pronounced as ve-ut.

Heat becomes het, and heater (a flat-iron), hetter; while hear is usually hire in N. Wilts.

I short becomes e, as breng, bring, drenk, drink, zet, sit, pegs, pigs.

Occasionally it is lengthened into ee, as leetle, little.

In hit (pret.) and if it usually takes the sound of u, as hut and uf or uv; but hit in the present tense is het, and if is often sounded as ef in N. Wilts.

At the beginning of a word, im, in, and un usually become on, as onpossible, ondacent, oncommon.

In present participles the sound given varies between un', en', and in', the g almost invariably being dropped.

O very commonly becomes a, as archet, orchard, tharn, thorn, vant, font, vram, from, carn, corn.

Quite as commonly it takes the au or aw sound, as hawp, hope, aupen, open, cawls, coals, hawle, hole, smawk, smoke.

In such words as cold and four, the sound is ow rather than aw, thus giving us cowld and vower.

Moss in S. Wilts sometimes takes the long e, becoming mēsh, while in N. Wilts it would merely be mawss.

Know becomes either knaw or kneow.

O is often sounded oo, as goold, gold, cwoort, court, mwoor'n or moor'n, more than, poorch, porch.

Oo is sometimes shortened into ŭ, as shut, shoot, sut, soot, tuk, took.

Very commonly the sound given to ō is wo or woä. Thus we get twoad, toad (sometimes twoad), pwoast, post, bwoy, boy, rwoäs, a rose, bwoän, bone, spwoke (but more usually spawk in N. Wilts), spoke.

Oa at the beginning of a word becomes wu, as wuts, oats.

Oi in noise and rejoice is sounded as ai.

In ointment and spoil it becomes ī or wī, giving intment and spile or spwile.

Ow takes the sound of er or y, in some form or other, as vollur and volly, to follow, winder and windy, a window.

U in such words as fusty and dust becomes ow, as fowsty, dowst.

D when preceded by a liquid is often dropped, as veel', field, vine, to find, dreshol, threshold, groun', ground.

Conversely, it is added to such words as miller, gown, swoon, which become millard, gownd, and zownd.

In orchard and Richard the d becomes t, giving us archet[xvi] and Richut or Rich't; while occasionally t becomes d, linnet being formerly (but not now) thus pronounced as linnard in N. Wilts.

D is dropped when it follows n, in such cases as Swinnun, Swindon, Lunnon, London.

Su sometimes becomes Shu, as Shusan, Susan, shoot, suit, shewut, suet, shower, sure, Shukey, Sukey.

Y is used as an aspirate in yacker, acre, yarm, arm, yeppern, apron, yerriwig, earwig. It takes the place of h in yeäd, head, yeldin, a hilding; and of g in yeat or yat, a gate.

Consonants are often substituted, chimney becoming chimbley or chimley, parsnip, pasmet, and turnip, turmut.

Transpositions are very common, many of them of course representing the older form of a word. For examples we may take ax, to ask, apern, apron, girt, great, wopse, wasp, aps, the aspen, claps, to clasp, cruds, curds, childern, children.

F almost invariably becomes v, as vlower, flower, vox, fox, vur, far, vall, fall, vlick, flick, vant, font.

In such words as afterclaps and afternoon it is not sounded at all.

L is not sounded in such words as amwoast, almost, and a'mighty, almighty.

N final is occasionally dropped, as lime-kill, lime-kiln.

P, F, V, and B are frequently interchanged, brevet and privet being forms of the same word, while to bag peas becomes fag or vag when applied to wheat.

R is slurred over in many cases, as e'ath, earth, foc'd, forced, ma'sh, marsh, vwo'th, forth.

It often assumes an excrescent d or t, as cavaltry, horsemen, crockerty, crockery, scholard, scholar.

H has the sound of wh in whoam, home. This word, however, as Mr. Slow points out in the Preface to his Glossary—

Bob. Drat if I dwon't goo wom to marrer.

Zam. Wat's evir waant ta go wimm var.

Bob. Why, they tell's I as ow Bet Stingymir is gwain to be caal'd whoam to Jim Spritely on Zundy.—

is variously pronounced as wom, wimm, and whoam, even in the same village.

As stated at page 72, the cockney misuse of h is essentially foreign to our dialect. It was virtually unknown sixty or seventy years ago, and even so late as thirty years back was still unusual in our villages. Hunked for unked is almost the only instance to be found in Akerman, for instance. But the plague is already fast spreading, and we fear that the Catullus of the next generation will have to liken the Hodge of his day to the Arrius (the Roman 'Arry) of old:—

Touching this point the Rev. G. Hill writes us from Harnham Vicarage as follows:—'I should like to bear out what you say with regard to the use of the letter h in South-West Wilts. When I lived in these parts twenty years ago, its omission was not I think frequent. The putting it where it ought not to be did not I think exist. I find now that the h is invariably dropped, and occasionally added, the latter habit being that of the better educated.'

H becomes y in yeäd, head.

K is often converted into t, as ast, to ask, mast, a mask, bleat, bleak.

T is conversely often replaced by k, as masking, acorn-gathering, from 'mast,' while sleet becomes sleek, and pant, pank.

S usually takes the sound of z, as zee, to see, zaa, a saw, zowl, soul, zaat or zate, soft, zider, cider, zound, to swoon.

Thr usually becomes dr, as dree, three, droo, through, draish, to thrash.

In afurst, athirst, and fust, thirst, we still retain a very ancient characteristic of Southern English.

T is always dropped in such words as kept and slept, which become kep' and slep'.

Liquids sometimes drop the next letter, as kill, kiln; but more usually take an excrescent t or d, as varmint, vermin, steart, a steer, gownd, gown.

W as an initial is generally dropped in N. Wilts in such cases as 'oont, a want or mole, 'ooman, woman, 'ood, wood.

Occasionally in S. Wilts it takes the aspirate, 'ood being then hood.

Final g is always dropped in the present participle, as singin', livin', living; also in nouns of more than one syllable which end in ing. It is, however, retained in monosyllabic nouns and verbs, such as ring and sing.

Pre becomes pur, as purtend, pretend, purserve, preserve.

Sometimes a monosyllabic word will be pronounced as a dissyllable, as we have already mentioned, ne-um, ve-ut, ve-us, and ke-up being used concurrently with naayme, vit or fit, veäce, and kip or keep.

The prefix a is always used with the present participle, as a-gwain', going, a-zettin' up, sitting up.

The article an is never used, a doing duty on all occasions, as 'Gie I a apple, veyther.'

Plurals will be found to be dealt with in the Glossary itself, under En and Plurals.

Pronouns will also be found grouped together under Pronouns.

As is used for who, which, and that.

Active verbs govern the nominative case.

Verbs do not agree with their nominative, either in number or person.

The periphrastic tenses are often used in S. Wilts, as 'I do mind un,' but in N. Wilts the rule is to employ the simple tenses instead, merely altering the person, as 'I minds un.' In S. Wilts you might also say 'It be a vine night,' whereas in N. Wilts ''Tes a vine night' would be more correct.

In conclusion we would mention that we hope in the course of the next year or two to be able to deal with the grammatical and phonological sides of our Dialect in a somewhat more adequate manner than it has been possible to do on the present occasion.

[For full titles of works see Appendix.]

| (A.) | Words given for Wilts in | Akerman. | |

| (B.) | " | " | Britton. |

| (C.) | " | " | Cunnington MS. |

| (D.) | " | " | Davis. |

| (G.) | " | " | Grose. |

| (H.) | " | " | Halliwell. |

| (K.) | " | " | Kennett. |

| (M.) | " | " | Monthly Magazine. |

| (S.) | " | " | Slow. |

| (Wr.) | " | " | Wright. |

N. & S.W. North and South Wilts, the place-names following being those of localities where the word is reported as being in use.

* An asterisk denotes that the word against which it is placed has not as yet been met with by ourselves in this county, although given by some authority or other as used in Wilts.

A. He; she. See Pronouns.

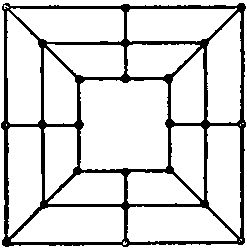

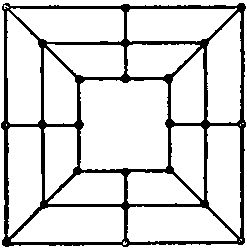

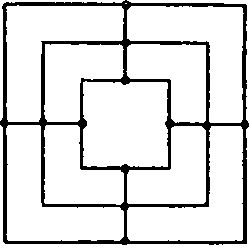

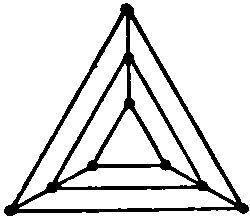

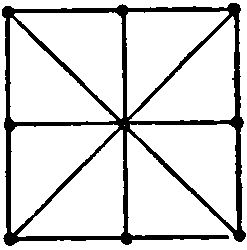

A, pl. As or Ais. n. A harrow or drag (D.); probably from A.S. egethe, M.E. eythe, a harrow (Skeat).—S.W., obsolete. This term for a harrow was still occasionally to be heard some thirty years ago, in both Somerset and Wilts, but is now disused. Davis derives it from the triangular shape of the drag, resembling the letter A.

A-Drag. A large heavy kind of drag (Agric. of Wilts). Still used in South Wilts for harrowing turnips before the hoers go in.

Abear. To bear, to endure (S.). 'I can't abear to see the poor theng killed.'—N. & S.W.

Abide. To bear, to endure. 'I can't abide un nohow.'—N. & S.W.

About. (1) adv. Extremely. Used to emphasize a statement, as ''T'wer just about cold s'marnin'.'—N. & S.W. (2) At one's ordinary work again, after an illness. 'My missus were bad aal last wick wi' rheumatiz, but she be about agen now.'—N. & S.W.

Acksen. See Axen.

Adder's-tongue. Listera ovata, Br., Twayblade.—S.W.

Adderwort. Polygonum Bistorta, L., Bistort.—S.W. (Salisbury, &c.)

Afeard, Aveard. Afraid (A.B.S.).—N. & S.W.

*Agalds. Hawthorn berries. (English Plant Names.) Aggles in Devon.

Agg. (1) To hack or cut clumsily (A.B.H.S.Wr.); also Aggle and Haggle.—N. & S.W. (2) To irritate, to provoke.—N. & S.W.

Ahmoo. A cow; used by mothers to children, as 'Look at they pretty ahmoos a-comin'!'—S.W. (Som. bord.)

Ailes, Eyles, Iles, &c. The awns of barley (D.); cf. A.S. egle, an ear of corn, M.E. eile. Hail in Great Estate, ch. i.—N. & S.W.

Aisles of wheat. See Hyle.

All-a-hoh. All awry (A.B.C.H.Wr.); also All-a-huh. Unevenly balanced, lop-sided. A.S. awóh. 'That load o' carn be aal-a-hoh.'—N. & S.W.

All-amang, Allemang, All-o-mong. Mingled together, as when two flocks of sheep are accidentally driven together and mixed up (A.B.G.H.S.Wr.). Seldom heard now.—N. & S.W.

All one as. Just like. 'I be 'tirely blowed up all one as a drum.'—N.W. Compare—

All one for that. For all that, notwithstanding, in spite of, as 'It medn't be true all one for that.'—N.W.

Aloud. 'That there meat stinks aloud,' smells very bad.—N.W.

*A-masked. Bewildered, lost (MS. Lansd., in a letter dated 1697: H.Wr.).—Obsolete.

'Leaving him more masked than he was before.'

Fuller's Holy War, iii. 2.

Ameäd. Aftermath. See note to Yeomath.—N.W. (Cherhill.)

*Anan, 'Nan. What do you say? (A.B.); used by a labourer who does not quite comprehend his master's orders. 'Nan (A.B.) is still occasionally used in N. Wilts, but it is almost obsolete.—N. & S.W.

Anbye. adv. Some time hence, presently, at some future time. 'I be main busy now, but I'll do't anbye.'—N.W.

Anchor. The chape of a buckle (A.B.).—S.W.

And that. And all that sort of thing, and so forth. 'Well, he do have a drop tide-times and that.'—S.W.

Aneoust, Aneust, Anoust, Neust, or Noust. Nearly, about the same (A.B.G.).—N. & S.W.

Anighst. Near (A.S.). 'Nobody's bin anighst us since you come.'—N. & S.W.

Anneal. A thoroughly heated oven, just fit for the batch of bread to be put in, is said to be nealded, i.e. annealed.—S.W.

Anoint, 'Nint (i long). To beat soundly. 'I'll 'nint ye when I gets home!' See Nineter.—N.W.

*Anont, Anunt. Against, opposite (A.B.H.Wr.).

Any more than. Except, although, only. 'He's sure to come any more than he might be a bit late.' Usually contracted into Moor'n in N. Wilts.—N. & S.W.

Apple-bout. An apple-dumpling. (Cf. Hop-about.)—N.W. (Clyffe Pypard.)

Apple-owling. Knocking down the small worthless fruit, or 'griggles,' left on the trees after the apple crop has been gathered in. See Howlers, Owlers, and Owling.—N.W.

Aps. Populus tremula, L., Aspen; always so called by woodmen. This is the oldest form of the word, being from A.S. æps, and is in use throughout the south and west of England. In Round About a Great Estate, ch. i. it is misprinted asp.—N.W.

Arg. To argue, with a very strong sense of contradiction implied (S.). 'Dwoan't 'ee arg at I like that! I tell 'ee I zeed 'un!' See Down-arg.—N. & S.W.

Arms. 'The arms of a waggon,' such parts of the axle-tree as go into the wheels (Cycl. of Agric.).—N.W.

Arra, Arra one, Arn. See Pronouns.

Array, 'Ray. To dress and clean corn with a sieve (D.).—N.W.

Arsmart. Polygonum Hydropiper, L., and P. Persicaria, L.—S.W.

Ashore, Ashar, Ashard. Ajar. 'Put the door ashard when you goes out.'—N. & S.W.

Ashweed. Aegopodium Podagraria, L., Goutweed.—N. & S.W.

*Astore. An expletive, as 'she's gone into the street astore' (H.). Perhaps connected with astoor, very soon, Berks, or astore, Hants:—

'The duck's [dusk] coming on; I'll be off in astore.'

A Dream of the Isle of Wight.

It might then mean either 'this moment' or 'for a moment.'

At. (1) 'At twice,' at two separate times. 'We'll ha' to vetch un at twice now.'—N.W. (2) 'Up at hill,' uphill. 'Th' rwoad be all up at hill.'—N.W.

Athin. Within (A.B.).—N. & S.W.

Athout. Without; outside (A.B.S.).—N. & S.W.

*Attercop. A spider. A.S. atter-coppa.—N.W. (Monkton Farleigh), still in use. Mr. Willis mentions that Edderkop is still to be heard in Denmark.

*Attery. Irascible (A.B.).

Away with. Endure. This Biblical expression is still commonly used in Wilts. 'Her's that weak her can't away with the childern at no rate!'

Ax. To ask (A.B.S.).—N. & S.W.

*Axen. Ashes (A.B.); Acksen (MS. Lansd.: G.H.Wr.).—Obsolete.

Babies'-shoes. Ajuga reptans, L., Common Bugle.—S.W.

Bachelor's Buttons. (1) Wild Scabious (A.B.), Scabiosa arvensis, L., S. Columbaria, L., and perhaps S. succisa, L.—N.W. (2) Corchorus Japonica (Kerria Japonica, L.).—N.W. (Huish.)

Back-friends. Bits of skin fretted up at the base of the finger-nails.—N.W.

*Backheave. To winnow a second time (D.).

Backside. The back-yard of a house (A.B.).—N. & S.W., now obsolete.

Backsword. A kind of single-stick play (A.H.Wr.). Obsolete, the game being only remembered by the very old men. For an account of it see The Scouring of the White Horse, ch. vi.—N.W.

Bacon. To 'strick bacon,' to cut a mark on the ice in sliding; cf. to strike a 'candle.'—N.W. (Clyffe Pypard.)

Bacon-and-Eggs. Linaria vulgaris, Mill., Yellow Toadflax. Also called Eggs-and-Bacon.—N. & S.W.

*Bad, Bod. To strip walnuts of their husks (A.B.H.Wr.); cf. E. pod.—N.W., obsolete.

*Badge. v. To deal in corn, &c. See Badger.—Obsolete.

'1576. Md. that I take order of the Badgers that they do name the places where the Badgers do use to badge before they resieve their lycens.... Md. to make pces [process] against all the Badgers that doe badge without licence.'—Extracts from Records of Wilts Quarter Sessions, Wilts Arch. Mag. xx. 327.

*Badger. A corn-dealer (A.B.); used frequently in old accounts in N. Wilts, but now obsolete.

'1620. Itm for stayeinge Badgers & keepinge a note of there names viijd.'—F. H. Goldney, Records of Chippenham, p. 202.

Compare bodger, a travelling dealer (Harrison's Description of England, 1577), and bogging, peddling, in Murray. (Smythe-Palmer).

Bag. (1) v. To cut peas with a double-handed hook. Cf. Vag.

'They cannot mow it with a sythe, but they cutt it with such a hooke as they bagge pease with.'—Aubrey, Nat. Hist. Wilts, p. 51, ed. Brit.

(2) n. The udder of a cow (A.B.).—N.W.

Bake, Beak. (1) v. To chop up with a mattock the rough surface of land that is to be reclaimed, afterwards burning the parings (Agric. of Wilts, ch. xii). See Burn-beak. *(2) n. The curved cutting mattock used in 'beaking' (Ibid. ch. xii). (3) n. The ploughed land lying on the plat of the downs near Heytesbury, in Norton Bavant parish, is usually known as the Beäk, or Bake, probably from having been thus reclaimed. In the Deverills parts of many of the down farms are known as the Bake, or, more usually, the Burn-bake.—S.W.

Bake-faggot. A rissole of chopped pig's-liver and seasoning, covered with 'flare.' See Faggot (2).—N.W.

Ballarag, Bullyrag. To abuse or scold at any one (S.).—N. & S.W.

Balm of Gilead. Melittis Melissophyllum, L., Wild Balm.

Bams. Rough gaiters of pieces of cloth wound about the legs, much used by shepherds and others exposed to cold weather. Cf. Vamplets.—N. & S.W.

'The old man ... had bams on his legs and a sack fastened over his shoulders like a shawl.'—The Story of Dick, ch. xii. p. 141.

Bandy. (1) A species of Hockey, played with bandy sticks and a ball or piece of wood.—N. & S.W. (2) A crooked stick (S.).

Bane. Sheep-rot (D.). Baned. Of sheep, afflicted with rot (A.B.).—N.W.

Bang-tail, or Red Fiery Bang-tail. Phoenicurus ruticilla, the Redstart.—N.W. (Wroughton.)

*Bannet-hay. A rick-yard (H.Wr.).

Bannis. Gasterosteus trachurus, the Common Stickleback (A.B.H.Wr.). Also Bannistickle (A.B.), Bantickle (A.Wr.), and *Bramstickle (S.). 'Asperagus (quoedam piscis) a ban-stykyll.'—Ortus Vocab. A.S. bán, bone, and sticels, prickle. (See N.E.D.).—S.W.

*Bannut. Fruit of Juglans regia, L., the Walnut (A.B.).

Bantickle. See Bannis.

*Barber's Brushes. Dipsacus sylvestris, L., Wild Teasel (Flower's Flora of Wilts). Also Brushes.—N.W.

Bargain. A small landed property or holding. 'They have always been connected with that little bargain of land.'—N.W., still in use. Sir W. H. Cope, in his Hants Glossary, gives 'Bargan, a small property; a house and garden; a small piece of land,' as used in N. Hants.

Barge. (1) n. The gable of a house. Compare architectural Barge-boards.—N.W. (Clyffe Pypard.) (2) v. Before a hedge can be 'laid,' all its side, as well as the rough thorns, brambles, &c., growing in the ditch, must be cut off. This is called 'barging out' the ditch.—N.W.

Barge-hook. The iron hook used by thatchers to fasten the straw to the woodwork of the gable.—N.W. (Clyffe Pypard.)

Barge-knife. The knife used by thatchers in trimming off the straw round the eaves of the gable.—N.W. (Clyffe Pypard.)

Bargin. The overgrowth of a hedge, trimmed off before 'laying.'—N. & S.W.

Barken. The enclosed yard near a farm-house (A.B.); Rick-Barken, a rick-yard (A.), also used without prefix in this sense (Wilts Tales, p. 121).

'Barken, or Bercen, now commonly used for a yard or backside in Wilts ... first signified the small croft or close where the sheep were brought up at night, and secured from danger of the open fields.'—Kennett's Parochial Antiquities.

Barton was formerly in very common use, but has now been displaced by Yard.—N. & S.W.

*Barley-bigg. A variety of barley (Aubrey's Wilts MS., p. 304).

*Barley-Sower. Larus canus, the Common Gull (Birds of Wilts, p. 534).

Barm. The usual Wilts term for yeast (A.B.M.S.).—N. & S.W.

*Barn-barley. Barley which has never been in rick, but has been kept under cover from the first, and is therefore perfectly dry and of high value for malting purposes (Great Estate, ch. viii. p. 152).

Basket. In some parts of S. Wilts potatoes are sold by the 'basket,' or three-peck measure, instead of by the 'sack' or the 'bag.'

Baskets. Plantago lanceolata, L., Ribwort Plantain.—S.W. (Little Langford.)

Bat-folding net. The net used in 'bird-batting,' q.v. (A.): more usually 'clap-net.'

Bat-mouse. The usual N. Wilts term for a bat.—N. & S.W.

Batt. A thin kind of oven-cake, about as thick as a tea-cake, but mostly crust.—N.W.

*Battledore-barley. A flat-eared variety of barley (Aubrey's Wilts MS., p. 304: H.Wr.).

Baulk. (1) Corn-baulk. When a 'land' has been accidentally passed over in sowing, the bare space is a 'baulk,' and is considered as a presage of some misfortune.—N.W. (2) A line of turf dividing a field.—N.W.

'The strips [in a "common field"] are marked off from one another, not by hedge or wall, but by a simple grass path, a foot or so wide, which they call "balks" or "meres."'—Wilts Arch. Mag. xvii. 294.

Bavin. An untrimmed brushwood faggot (A.B.S.): the long ragged faggot with two withes, used for fencing in the sides of sheds and yards; sometimes also applied to the ordinary faggot with one withe or band.—N. & S.W.

*Bawsy, Borsy, or Bozzy. Coarse, as applied to the fibre of cloth or wool. 'Bozzy-faced cloth bain't good enough vor I.'—S.W. (Trowbridge, &c.)

Bay. (1) n. A dam across a stream or ditch.—N.W. (2) v. 'To bay back water,' to dam it back.—N.W. (3) n. The space between beam and beam in a barn or cows' stalls.—N.W.

*Beads. Sagina procumbens, L., Pearlwort.—N.W. (Lyneham.)

Beak. See Bake and Burn-bake.

Bearsfoot. Hellebore.—N.W. (Huish, &c.)

Beat. 'To beat clots,' to break up the hard dry lumps of old cow-dung lying about in a pasture.—N.W.

Becall. To abuse, to call names. 'Her do becall I shameful.'—N. & S.W.

Bed-summers. See Waggon.

Bedwind, Bedwine. Clematis Vitalba, L., Traveller's Joy.—S.W.

Bee-flower. Ophrys apifera, Huds., Bee Orchis.—S.W.

Bee-pot. A bee-hive.—S.W.

Been, Bin. Because, since; a corruption of being (B.S.). 'Bin as he don't go, I won't.'—N.W.

Bees. A hive is a Bee-pot. Bee-flowers are those purposely grown near an apiary, as sources of honey. Of swarms, only the first is a Swarm, the second being a Smart, and the third a Chit. To follow a swarm, beating a tin pan, is Ringing or Tanging.—N.W.

*Beet. To make up a fire (A.B.C.G.). A.S. bétan, to better; to mend a fire (Skeat).—N.W., obsolete.

Beetle. (1) The heavy double-handed wooden mallet used in driving in posts, wedges, &c. Bittle (A.H.). Bwytle (S.). Also Bwoitle.—N. & S.W.

'On another [occasion] (2nd July, 25 Hen. VIII) ... William Seyman was surety ... for the re-delivery of the tools, "cuncta instrumenta videlicet Beetyll, Ax, Matock, and Showlys."'—Stray Notes from the Marlborough Court Books, Wilts Arch. Mag. xix. 78.

(2) The small mallet with which thatchers drive home their 'spars.'—S.W.

*Beggar-weed. Cuscuta Trifolii, Bab., Dodder; from its destructiveness to clover, &c. (English Plant Names).

Bellock. (1) To cry like a beaten or frightened child (A.B.).—N.W., rarely. (2) To complain, to grumble (Dark, ch. x.).—N.W.

*Belly vengeance. Very small and bad beer.—N.W.

'Beer of the very smallest description, real "belly vengeance."'—Wilts Tales, p. 40.

Cf.:—

'I thought you wouldn't appreciate the widow's tap.... Regular whistle-belly vengeance, and no mistake!'—Tom Brown at Oxford, xl.

Belt. To trim away the dirty wool from a sheep's hind-quarters.—N.W.

*Bennet. v. Of wood-pigeons, to feed on bennets (A.).

'They have an old rhyme in Wiltshire—

"Pigeons never know no woe

Till they a-benetting do go;"

meaning that pigeons at this time are compelled to feed on the seed of the bent, the stubbles being cleared, and the crops not ripe.'—Akerman.

Bennets, Bents. (1) Long coarse grass or rushes (B.).—N.W. (2) Seed-stalks of various grasses (A.); used of both withered stalks of coarse grasses and growing heads of cat's-tail, &c.—N. & S.W. (3) Seed-heads of Plantain, Plantago major, L., and P. lanceolata, L.—N. & S.W.

Bents. See Bennets.

Bercen (c hard). See Barken. 'This form of the word is given in MS. Gough, Wilts, 5, as current in Wilts' (H.K.Wr.).

Berry. The grain of wheat (D.); as 'There's a very good berry to-year,' or 'The wheat's well-berried,' or the reverse. See Old Country Words, ii. and v.—N.W.

Berry-moucher. (1) A truant. See Blackberry-moucher and Moucher (A.).—N. & S.W. (2) Fruit of Rubus fruticosus, L., Blackberry. See Moochers.—N.W. (Huish.) Originally applied to children who went mouching from school in blackberry season, and widely used in this sense, but at Huish—and occasionally elsewhere—virtually confined to the berries themselves: often corrupted into Penny-moucher or Perry-moucher by children. In English Plant Names Mochars, Glouc., and Mushes, Dev., are quoted as being similarly applied to the fruit, which is also known as Mooches in the Forest of Dean. See Hal., sub. Mich.

Besepts. Except.—N. & S.W.

'Here's my yeppurn they've a'bin and scarched, and I've a-got narra 'nother 'gin Zunday besepts this!'—Wilts Tales, p. 138.

Besom, Beesom, Bissom, &c. A birch broom (A.B.S.).—N. & S.W.

*Betwit. To upbraid (A.B.).

Bide. (1) To stay, remain (A.S.). 'Bide still, will 'ee.'—N. & S.W. (2) To dwell (A.). 'Where do 'ee bide now, Bill?' 'Most-in-general at 'Vize.'—N. & S.W.

Bill Button. Geum rivale, L., Water Avens.—S.W.

Bin. See Been.

Bird-batting. Netting birds at night with a 'bat-folding' or clap-net (A.B., Aubrey's Nat. Hist. Wilts, p. 15, ed. Brit.). Bird-battenen (S.).—N. & S.W.

Bird's-eye. (1) Veronica Chamaedrys, L., Germander Speedwell.—N. & S.W. (2) Anagallis arvensis, L., Scarlet Pimpernel.—S.W. (3) Veronica officinalis, L., Common Speedwell.—S.W. (Barford.)

Bird's-nest. The seed-head of Daucus Carota, L., Wild Carrot.—N. & S.W.

'The flower of the wild carrot gathers together as the seeds mature, and forms a framework cup at the top of the stalk, like a bird's-nest. These "bird's-nests," brown and weather-beaten, endured far into the winter.'—Great Estate, ch. vii. p. 137.

'The whole tuft is drawn together when the seed is ripe, resembling a bird's nest.'—Gerarde.

Bird-seed. Seed-heads of Plantain.—N. & S.W.

Bird-squoilin. See Squail (S.).

Bird-starving. Bird-keeping.—N.W.

'This we call bird-keeping, but the lads themselves, with an appreciation of the other side of the case, call it "bird-starving."'—Village Miners.

Birds'-wedding-day. St. Valentine's Day.—S.W. (Bishopstone.)

Bishop-wort. Mentha aquatica, L., Hairy Mint.—S.W. (Hants bord.)

Bissom. See Besom.

Bittish. adj. Somewhat. ''Twer a bittish cowld isterday.'—N. & S.W.

Bittle. See Beetle.

Biver. To tremble, quiver, shiver as with a cold or fright (S.). Cp. A.S. bifian, to tremble.—N. & S.W.

'Bless m' zoul, if I dwon't think our maester's got the ager! How a hackers an bivers, to be zhure!'—Wilts Tales, p. 55.

Bivery. adj. Shivery, tremulous. When a baby is just on the verge of crying, its lip quivers and is 'bivery.'—N.W.

Blackberry-moucher. (1) A truant from school in the blackberry season (H.). See Berry-moucher, Mouch, &c.—N.W. (Huish, &c.)

'A blackberry moucher, an egregious truant.'—Dean Milles' MS., p. 180.

(2) Hence, the fruit of Rubus fruticosus, L., Blackberry. See Berry-moucher, Moochers, &c.—N.W. (Huish, &c.)

*Blackberry-token. Rubus caesius, L., Dewberry (English Plant Names).

Black-Bess. See Black-Bob.

Black-Bob. A cockroach (S.). Black-Bess on Berks border.—S.W.

Black-boys. (1) Flower-heads of Plantain.—N.W. (Huish.) (2) Typha latifolia, L., Great Reedmace.—N.W. (Lyneham.)

*Black Couch. A form of Agrostis that has small wiry blackish roots (D). Agrostis stolonifera.

Black Sally. Salix Caprea, L., Great Round-leaved Sallow, from its dark bark (Amateur Poacher, ch. iv). Clothes-pegs are made from its wood.—N.W.

*Black Woodpecker. Picus major, Great Spotted Woodpecker (Birds of Wilts, p. 253). Also known as the Gray Woodpecker.

Blades. The shafts of a waggon (S.).—S.W.

Blare, Blur. To shout or roar out loudly (S.).—N. & S.W.

Blatch. (1) adj. Black, sooty (A.B.).—N.W. (2) n. Smut, soot. 'Thuc pot be ael over blatch.'—N.W. (3) v. To blacken. 'Now dwon't 'ee gwo an' blatch your veäce wi' thuc thur dirty zoot.'—N.W.

Bleachy. Brackish.—S.W. (Som. bord.)

Bleat. Bleak, open, unsheltered. 'He's out in the bleat,' i.e. out in the open in bad weather. See K for examples of letter-change.—N.W. (Clyffe Pypard.)

Bleeding Heart. Cheiranthus Cheiri, L., the red Wallflower (A.B.).—N.W.

Blind-hole. n. A rabbit hole which ends in undisturbed soil, as opposed to a Pop-hole, q.v. (Gamekeeper at Home, ch. vi. p. 120).—N.W.

Blind-house. A lock-up.

'1629. Item paied for makeing cleane the blind-house vijd.'—Records of Chippenham, p. 204.

Blind-man. Papaver Rhoeas, L., &c., the Red Poppy, which is locally supposed to cause blindness, if looked at too long.—S.W. (Hamptworth.)

*Blink. A spark, ray, or intermittent glimmer of light (A.B.). See Flunk.

*Blinking. This adjective is used, in a very contemptuous sense, by several Wilts agricultural writers.

'A short blinking heath is found on many parts [of the downs].'—Agric. of Wilts, ch. xii.

Compare:—

''Twas a little one-eyed blinking sort o' place.'—Tess of the D'Urbervilles, vol. i. p. 10.

*Blissey. A blaze (A.H.Wr.). A.S. blysige, a torch.

Blobbs, Water Blobs. Blossoms of Nuphar lutea, Sm., Yellow Water Lily (A.B.); probably from the swollen look of the buds. Cf. Blub up.

Blood-alley. A superior kind of alley or taw, veined with deep red, and much prized by boys (S.).—N. & S.W.

Bloody Warr The dark-blossomed Wallflower, Cheiranthus Cheiri, L. (A.B.S.).—N. & S.W.

Blooens. See Bluens.

Bloom. Of the sun; to shine scorchingly (B.); to throw out heat as a fire. 'How the sun do bloom out atween the clouds!'—N.W.

Blooming. Very sultry, as ''Tis a main blooming day.'—S.W. (Salisbury.)

Bloomy. Sultry. Bloomy-hot. Excessively sultry (A.B.).—S.W.

Blooth, Blowth. Bloom or blossom.—S.W.

Blossom. A snow-flake. 'What girt blossoms 'twer to the snow isterday!'—N. & S.W.

'Snow-flakes are called "blossoms." The word snow-flake is unknown.'—Village Miners.

Blow. Sheep and cattle 'blow' themselves, or get 'blowed,' from over-eating when turned out into very heavy grass or clover, the fermentation of which often kills them on the spot, their bodies becoming terribly inflated with wind. See the description of the 'blasted' flock, in Far from the Madding Crowd, ch. xxi.—N. & S.W.

Blowing. A blossom (A.B.H.Wr.). See Bluen.—N.W.

Blowth. See Blooth.

Blub up. To puff or swell up. A man out of health and puffy about the face is said to look 'ter'ble blubbed up.' Cf. Blobbs.—N.W. Compare:—

'My face was blown and blub'd with dropsy wan.'—Mirror for Magistrates.

Blue Bottle. Scilla nutans, Sm., Wild Hyacinth.—S.W.

Blue Buttons. (1) Scabiosa arvensis, L., Field Scabious.—S.W. (2) S. Columbaria, L., Small Scabious.—S.W.

Blue Cat. One who is suspected of being an incendiary. 'He has the name of a blue cat.' See Lewis's Cat.—S.W. (Salisbury.)

Blue Eyes. Veronica Chamaedrys, L., Germander Speedwell.—N.W.

Blue Goggles. Scilla nutans, Sm., Wild Hyacinth. Cf. Greygles or Greggles.—S.W.

Bluen or Blooens. pl. Blossoms (S.). Also used in Devon.—N. & S.W.

Blue-vinnied. Covered with blue mould. See Vinney. Commoner in Dorset as applied to cheese, &c.—N. & S.W.

Blunt. 'A cold blunt,' a spell of cold weather. See Snow-blunt. Compare Blunk, a fit of stormy weather, which is used in the East of England.—N.W.

Blur. See Blare. In Raleigh's account of the fight in Cadiz Bay, he says that as he passed through the cross-fire of the galleys and forts, he replied 'with a blur of the trumpet to each piece, disdaining to shoot.'

Board. To scold, to upbraid. 'Her boarded I just about.'—S.W. (occasionally.)

Boar Stag. A boar which, after having been employed for breeding purposes for a time, is castrated and set aside for fattening (D.). Cf. Bull Stag.—N.W.

Boat. Children cut apples and oranges into segments, which they sometimes call 'pigs' or 'boats.'

Bob. In a timber carriage, the hind pair of wheels with the long pole or lever attached thereto.—N.W. In Canada 'bob-sleds' are used for drawing logs out of the woods.

*Bobbant. Of a girl, romping, forward (A.B.H.Wr.).—N.W.

Bobbish. In good health (A.B.S.). 'Well, an' how be 'ee to-day?' 'Purty bobbish, thank 'ee.'—N. & S.W.

Bob-grass. Bromus mollis, L.—S.W.

*Bochant. The same as Bobbant (A.B.G.H.Wr.).

Bod. See Bad.

Boistins. The first milk given by a cow after calving (A.). See N.E.D. (s.v. Beestings).—N.W.

Bolt. In basket-making, a bundle of osiers 40 inches round. (Amateur Poacher, ch. iv. p. 69).

Boltin, Boulting. A sheaf of five or ten 'elms,' prepared beforehand for thatching. 'Elms' are usually made up on the spot, but are occasionally thus prepared at threshing-time, and tied up and laid aside till required, when they need only be damped, and are then ready for use. Cf. Bolt.—N.W.

Bombarrel Tit. Parus caudatus, the Long-tailed Titmouse (Great Estate, ch. ii. p. 26). Jefferies considers this a corruption of 'Nonpareil.'—N.W.

Book of Clothes. See Buck (Monthly Mag., 1814).

Boon Days. Certain days during winter on which farmers on the Savernake estate were formerly bound to haul timber for their landlord.

*Boreshore. A hurdle-stake (S.).—S.W.

'This is a kind of hurdle stake which can be used in soft ground without an iron pitching bar being required to bore the hole first for it. Hence it is called bore-shore by shepherds.'—Letter from Mr. Slow.

*Borky. (Baulky?) Slightly intoxicated.—S.W.

*Borsy. See *Bawsy.

Bossell. Chrysanthemum segetum, L., Corn Marigold (D.). Bozzell (Flowering Plants of Wilts).—N. & S.W.

Bossy, Bossy-calf. A young calf, whether male or female.—N.W.

Bottle. The wooden keg, holding a gallon or two, used for beer in harvest-time (Wild Life, ch. vii).—N. & S.W.

Bottle-tit. Parus caudatus, L., the Long-tailed Titmouse.—N.W.

Bottom. A valley or hollow in the downs.—N. & S.W.

Boulting. See Boltin.

Bounceful. Masterful, domineering. See Pounceful.—N.W.

Bourne. (1) n. A valley between the chalk hills; a river in such a valley; also river and valley jointly (D.).—N. & S.W.

'In South Wilts they say, such or such a bourn: meaning a valley by such a river.'—Aubrey's Nat. Hist. Wilts, p. 28. Ed. Brit.

(2) v. In gardening, when marking out a row of anything with pegs, you 'bourne' them, or glance along them to see that they are in line.—N.W.

Box or Hand-box. The lower handle of a sawyer's long pit-saw, the upper handle being the Tiller.—N.W. (Clyffe Pypard.)

Boy's-love. Artemisia Abrotanum, L., Southernwood (A.B.).—N. & S.W.

Boys. The long-pistilled or 'pin-eyed' flowers of the Primrose, Primula vulgaris, Huds. See Girls.—N.W. (Clyffe Pypard.)

Bozzell. See Bossell.

*Bozzy. See *Bawsy.

Brack. n. A fracture, break, crack (S.). 'There's narra brack nor crack in 'un.'—N. & S.W.

Brain-stone. A kind of large round stone (Aubrey's Nat. Hist. Wilts, p. 9, ed. Brit., H.Wr.). Perhaps a lump of water-worn fossil coral, such as occasionally now bears this name among N. Wilts cottagers.

*Bramstickle. See Bannis (S.).

Brandy-bottles. Nuphar lutea, Sm., Yellow Water-lily.—S.W. (Mere, &c.)

Brave. adj. Hearty, in good health (A.B.).—N.W.

Bread-and-Cheese. (1) Linaria vulgaris, Mill., Yellow Toadflax.—N. & S.W. (2) Fruit of Malva sylvestris, L., Common Mallow (S.).—S.W. (3) Young leaves and shoots of Crataegus Oxyacantha, L., Hawthorn, eaten by children in spring (English Plant Names).—S.W. (Salisbury.)

Bread-board. The earth-board of a plough (D.). Broad-board in N. Wilts.

Break. To tear. 'She'll break her gownd agen thuc tharn.' You still break a bit of muslin, but to tear a trace or a plate now grows obsolete.—N.W. Similarly used in Hants, as

'I have a-torn my best decanter ... have a-broke my fine cambrick aporn.'—Cope's Hants Glossary.

Brevet, Brivet. (1) To meddle, interfere, pry into.—N.W.

'Who be you to interfere wi' a man an' he's vam'ly? Get awver groundsell, or I'll stop thy brevettin' for a while.'—Dark, ch. xix.

(2) To brevet about, to beat about, as a dog for game (A.).—N.W. Also Privet.—N.W. (Clyffe Pypard; Castle Eaton, &c.)

'Brivet, a word often applied to children when they wander about aimlessly and turn over things.'—Leisure Hour, Aug. 1893.

*(3) To pilfer. 'If she'll brevet one thing, she'll brevet another.'—N.W. (Mildenhall.)

Bribe. To taunt, to bring things up against any one, to scold. 'What d'ye want to kip a-bribing I o' that vur?'—N.W.

Brit, Brittle out. (1) To rub grain out in the hand.—N.W. (2) To drop out of the husk, as over-ripe grain (D.).—N.W.

Brivet. See Brevet.

Brize. To press heavily on, or against, to crush down (S.). A loaded waggon 'brizes down' the road.—N. & S.W.

Broad-board. See Bread-board.

Broke-bellied. Ruptured.—N.W.

Brook-Sparrow. Salicaria phragmitis, the Sedge Warbler; from one of its commonest notes resembling that of a sparrow (Great Estate, ch. vii; Wild Life, ch. iii).—N.W.

'At intervals [in his song] he intersperses a chirp, exactly the same as that of the sparrow, a chirp with a tang in it. Strike a piece of metal, and besides the noise of the blow, there is a second note, or tang. The sparrow's chirp has such a note sometimes, and the sedge-bird brings it in—tang, tang, tang. This sound has given him his country name of brook-sparrow.'—Jefferies, A London Trout.

Brow. (1) adj. Brittle (A.B.C.H.Wr.); easily broken. Vrow at Clyffe Pypard. Also Frow.—N.W. *(2) n. A fragment (Wilts Arch. Mag. vol. xxii. p. 109).—N.W. (Cherhill.)

Brown. 'A brown day,' a gloomy day (H.Wr.).—N.W.

Bruckle. (Generally with off or away.) v. To crumble away, as some kinds of stone when exposed to the weather (Wilts Arch. Mag. vol. xxii. p. 109); to break off easily, as the dead leaves on a dry branch of fir. Compare brickle=brittle (Wisdom, xv. 13), A.S. brucol=apt to break.—N.W.

Bruckley. adj. Brittle, crumbly, friable, not coherent (S.).—N. & S.W.

Brush. 'The brush of a tree,' its branches or head.—N.W.

Brushes. Dipsacus sylvestris, L., Wild Teasel. See Clothes-brush.—N. & S.W.

Bubby-head. Cottus gobio, the Bullhead.—N. & S.W.

Buck. A 'buck,' or 'book,' of clothes, a large wash—N.W.

Bucking. A quantity of clothes to be washed (A.).—N.W.

*Buddle. To suffocate in mud. 'There! if he haven't a bin an' amwoast buddled hisel' in thuck there ditch!' Also used in Som.—N.W. (Malmesbury.)

Budgy. Out of temper, sulky. A softened form of buggy, self-important, churlish, from the Old English and provincial budge, grave, solemn, &c. See Folk-Etymology, p. 42 (Smythe-Palmer).—N.W. Cp. Milton,

'Those budge doctors of the stoic fur.'—Comus.

Bullpoll, Bullpull. Aira caespitosa, L., the rough tufts of tussocky grass which grow in damp places in the fields, and have to be cut up with a heavy hoe (Great Estate, ch. ii; Gamekeeper at Home, ch. viii).—N.W.

Bull Stag. A bull which, having been superannuated as regards breeding purposes, is castrated and put to work, being stronger than an ordinary bullock. Cf. Boar Stag.—N.W., now almost obsolete.

Bulrushes. Caltha palustris, L., Marsh Marigold; from some nursery legend that Moses was hidden among its large leaves.—S.W., rarely.

Bumble-berry. Fruit of Rosa canina, L., Dog-rose.—N.W.

Bunce. (1) n. A blow. 'Gie un a good bunce in the ribs.'—N.W. (2) v. To punch or strike.—N.W.

Bunch. Of beans, to plant in bunches instead of rows (D.).—N. & S.W.

Bunny. A brick arch, or wooden bridge, covered with earth, across a 'drawn' or 'carriage' in a water-meadow, just wide enough to allow a hay-waggon to pass over.—N.W.

Bunt. (1) v. To push with the head as a calf does its dam's udder (A.); to butt; to push or shove up.—(Bevis, ch. x.) N.W. (2) n. A push or shove.—N.W. (3) n. A short thick needle, as a 'tailor's bunt.' (4) n. Hence sometimes applied to a short thickset person, as a nickname.—S.W.

Bunty. adj. Short and stout.—N.W.

Bur. The sweetbread of a calf or lamb (A.).—N.W.

Bur', Burrow, or Burry. (1) A rabbit-burrow (A.B.).—N. & S.W. (2) Any place of shelter, as the leeward side of a hedge (A.C.). 'Why doesn't thee coom and zet doon here in the burrow?'—N. & S.W.

Burl. (1) 'To burl potatoes,' to rub off the grown-out shoots in spring.—N.W. (2) The original meaning was to finish off cloth or felt by removing knots, rough places, loose threads, and other irregularities of surface, and it is still so used in S. Wilts (S.).

Burn. 'To burn a pig,' to singe the hair off the dead carcase.—N. & S.W.

*Burn-bake (or -beak). (1) To reclaim new land by paring and burning the surface before cultivation (Agric. of Wilts, ch. xii). See Bake. (2) To improve old arable land by treating it in a similar way (Ibid. ch. xii). Burn-beke (Aubrey's Nat. Hist. Wilts, p. 103. Ed. Brit., where the practice is said to have been introduced into S. Wilts by Mr. Bishop of Merton, about 1639). (3) n. Land so reclaimed. See Bake.—S.W.

Burrow. See Bur'.

Burry. See Bur'.

'Buseful. Foul-mouthed, abusive.—N.W.

Bush. (1) n. A heavy hurdle or gate, with its bars interlaced with brushwood and thorns, which is drawn over pastures in spring, and acts like a light harrow (Amateur Poacher, ch. iv).—N.W. (2) v. To bush-harrow a pasture.—N.W.

Butchers' Guinea-pigs. Woodlice. See Guinea-pigs.—S.W.

Butter-and-Eggs. (1) Narcissus incomparabilis, Curt., Primrose Peerless.—N. & S.W. (2) Linaria vulgaris, Mill., Yellow Toadflax (Great Estate, ch. v).—N. & S.W.

Buttercup. At Huish applied only to Ranunculus Ficaria, L., Lesser Celandine, all other varieties of Crowfoot being 'Crazies' there.

Butter-teeth. The two upper incisors.—N.W.

Buttons. Very young mushrooms.—N. & S.W.

Buttry. A cottage pantry (A.B.).—N.W., now almost obsolete.

Butt-shut. (1) To join iron without welding, by pressing the heated ends squarely together, making an imperceptible join (Village Miners). See Shut. (2) Hence a glaringly inconsistent story or excuse is said 'not to butt-shut' (Village Miners).

Butty. A mate or companion in field-work (S.).—N. & S.W.

*By-the-Wind. Clematis Vitalba, L., Traveller's Joy.—S.W. (Farley.)

*Caa-vy (? Calfy). A simpleton (S.).—S.W.

Cack. See Keck.

*Cack-handed, *Cag-handed. Extremely awkward and unhandy: clumsy to the last degree (Village Miners). Other dialect words for 'awkward' are Dev., cat-handed, Yorks., gawk-handed, and Nhamp., keck-handed. Cf. Cam-handed.

Caddle. (1) n. Dispute, noise, row, contention (A.); seldom or never so used now.—N. & S.W.

'What a caddle th' bist a makin', Jonas!'—Wilts Tales, p. 82.

'If Willum come whoam and zees two [candles] a burnin', he'll make a vi-vi-vine caddle.'—Wilts Tales, p. 42.

(2) n. Confusion, disorder, trouble (A.B.C.S.).—N. & S.W.

'Lawk, zur, but I be main scrow to be ael in zich a caddle, alang o' they childern.'—Wilts Tales, p. 137.

(3) v. To tease, to annoy, to bother (A.B.C.). See Caddling. 'Now dwoan't 'e caddle I zo, or I'll tell thee vather o' thee!' 'I be main caddled up wi' ael they dishes to weish.'—N. & S.W.

''Tain't no use caddlin I—I can't tell 'ee no more.'—Greene Ferne Farm, ch. viii.

(4) v. To hurry. 'To caddle a horse,' to drive him over-fast.—N.W. (5) v. To loaf about, only doing odd jobs. 'He be allus a caddlin' about, and won't never do nothin' reg'lar.'—N. & S.W. (6) v. To mess about, to throw into disorder. 'I don't hold wi' they binders [the binding machines], they do caddle the wheat about so.'—N. & S.W.

Caddlesome. Of weather, stormy, uncertain. ''T 'ull be a main caddlesome time for the barley.'—S.W.

Caddling. (1) adj. Of weather, stormy, uncertain.—N. & S.W. (2) adj. Quarrelsome, wrangling (C.).—N. & S.W.

'His bill was zharp, his stomack lear, Zo up a snapped the caddlin pair.'—Wilts Tales, p. 97.

'A cadling fellow, a wrangler, a shifting, and sometimes an unmeaning character.'—Cunnington MS.

(3) adj. Meddlesome (S.), teasing (Monthly Mag., 1814); troublesome, worrying, impertinent (A.B.).—N. & S.W.

'Little Nancy was as naisy and as caddlin' as a wren, that a was'.—Wilts Tales, p. 177.

*(4) Chattering (Monthly Mag., 1814): probably a mistake.

Caffing rudder. See Caving rudder.

*Cag-handed. See Cack-handed.

Cag-mag. Bad or very inferior meat (S.).—N. & S.W.

Cains-and-Abels. Aquilegia vulgaris, L., Columbine.—S.W. (Farley.)

*Calf-white. See White.

Call. Cause, occasion. 'You've no call to be so 'buseful' [abusive].—N. & S.W.

Call home. To publish the banns of marriage (S.).—S.W.

'They tells I as 'ow Bet Stingymir is gwain to be caal'd whoam to Jim Spritely on Zundy.'—Slow.

*Callow-wablin. An unfledged bird (A.).—S.W.

Callus-stone. A sort of gritty earth, spread on a board for knife-sharpening (Wilts Arch. Mag. vol. xxii. p. 109).—N. & S.W. (Cherhill, &c.)

Calves'-trins. Calves' stomachs, used in cheese-making. A.S. trendel. See Trins. Halliwell and Wright give 'Calf-trundle, the small entrails of a calf.'—N.W.

*Cam. Perverse, cross. Welsh cam, crooked, wry.—N.W.

'A 's as cam and as obstinate as a mule.'—Wilts Tales, p. 138.

'They there wosbirds [of bees] zimd rayther cam and mischievul.'—Springtide, p. 47.

Cam-handed. Awkward.—N.W.

*Cammock. Ononis arvensis, L., Restharrow (D.).

Cammocky. Tainted, ill-flavoured, as cheese or milk when the cows have been feeding on cammock. See Gammotty (2).—S.W.

Canary-seed. Seed-heads of Plantain.—N. & S.W.

Candle. 'To strike a candle,' to slide, as school-boys do, on the heel, so as to leave a white mark along the ice.—S.W.

Cank. To overcome (H.Wr.): perhaps a perversion of conquer. The winner 'canks' his competitors in a race, and you 'cank' a child when you give it more than it can eat.—N.W.

Canker. Fungus, toadstool (A.B.).—N. & S.W.

Canker-berries. Wild Rose hips. Conker-berries (S.).—S.W. (Salisbury, &c.).

Canker-rose. The mossy gall on the Dog-rose, formed by Cynips rosae; often carried in the pocket as a charm against rheumatism (Great Estate, ch. iv).—N.W.

*Cappence. The swivel-joint of the old-fashioned flail, Capel in Devon.—N. & S.W.

Carpet. To blow up, to scold; perhaps from the scene of the fault-finding being the parlour, not the bare-floored kitchen. 'Measter carpeted I sheamvul s'marning.' 'I had my man John on the carpet just now and gave it him finely.'—N.W.

Carriage. A water-course, a meadow-drain (A. B. G. H. Wr.). In S. Wilts the carriages bring the water into and through the meadow, while the drawn takes it back to the river after its work is done.—N. & S.W.

Carrier, Water-carrier. A large water-course (Wild Life, ch. xx).—N. & S.W.

Carry along. To prove the death of, to bring to the grave. 'I be afeard whe'er that 'ere spittin' o' blood won't car'n along.'—N.W.

Cart. 'At cart,' carrying or hauling, as 'We be at wheat cart [coal-cart, dung-cart, &c.] to-day.—N.W.

Casalty. See Casulty.

Cass'n. Canst not (A.S.).—N. & S.W.

Cassocks. Couch-grass.—S.W. (Som. bord.).

Casulty. (1) adj. Of weather, unsettled, broken (Green Ferne Farm, ch. i). Casalty (Wilts Arch. Mag. vol. xxii. p. 109).—N. & S.W. (2) Of crops, uncertain, not to be depended on. Plums, for instance, are a 'casalty crop,' some years bearing nothing.—N.W.

*Cat-gut. The ribs of the Plantain leaf; so called by children when drawn out so as to look like fiddle-strings (Great Estate, ch. ii).

Cat-Kidney. A game somewhat resembling cricket, played with a wooden 'cat' instead of a ball.—N.W. (Brinkworth.)

Cat's-ice. White ice, ice from which the water has receded.—N. & S.W. (Steeple Ashton, &c.).

'They stood at the edge, cracking the cat's-ice, where the water had shrunk back from the wheel marks, and left the frozen water white and brittle.'—The Story of Dick, ch. xii. p. 153.

Cats'-love. Garden Valerian, on which cats like to roll.—S.W.

*Cats'-paws. Catkins of willow while still young and downy.—S.W. (Deverill.)

Cats'-tails. (1) Equisetum, Horse-tail (Great Estate, ch. ii).—N.W. (2) The catkin of the willow.—N.W. (Lyneham.) (3) The catkin of the hazel.—N.W. (Clyffe Pypard.)

Catch. (1) Of water, to film over, to begin to freeze. Keach, Keatch, Kitch, or Ketch (A.B.C.H.Wr.).—N. & S.W.

'A bright clear moon is credited with causing the water to "catch"—that is, the slender, thread-like spicules form on the surface, and, joining together, finally cover it.'—Wild Life, ch. xx.

Also see Bevis, ch. xl. (2) To grow thick, as melted fat when setting again.—N. & S.W. *(3) 'To catch and rouse,' to collect water, &c.

'In the catch-meadows ... it is necessary to make the most of the water by catching and rousing it as often as possible.'—Agric. of Wilts, ch. xi.

*(4) n. The same as Catch-meadow (Ibid. ch. xii).

*Catch-land. The arable portion of a common field, divided into equal parts, whoever ploughed first having the right to first choice of his share (D.).—Obsolete.

*Catch-meadow, Catch-work meadow, or Catch. A meadow on the slope of a hill, irrigated by a stream or spring, which has been turned so as to fall from one level to another through the carriages (Agric. of Wilts, ch. xii).

Catching, Catchy. Of weather, unsettled, showery (Agric. of Wilts, ch. iii. p. 11).—N. & S.W.

Caterpillar. A cockchafer.—N.W.

Cattikeyns. Fruit of the ash.—N.W. (Clyffe Pypard.)

Cave. (1) n. The chaff of wheat and oats (D.): in threshing, the broken bits of straw, &c. Cavin, Cavings, or Keavin in N. Wilts.—N. & S.W. (2) v. To separate the short broken straw from the grain.—N. & S.W.

Cavin, Cavings. See Cave (1).

*Caving-rake. The rake used for separating cavings and grain on the threshing-floor.

Caving (or Caffing) rudder, or rudderer. *(1) The winnowing fan and tackle (D.).—S.W. (2) A coarse sieve used by carters to get the straw out of the horses' chaff.—N. & S.W.

Cawk, Cawket. To squawk out, to make a noise like a hen when disturbed on her nest, &c. 'Ther's our John, s'naw [dost know?]—allus a messin' a'ter the wenchin, s'naw—cawin' an' cawkettin' like a young rook, s'naw,—'vore a can vly, s'naw,—boun' to coom down vlop he war!' Caa-kinn (S.).—N. & S.W. (Clyffe Pypard; Seagry, &c.)

*Centry. Anagallis tenella, L., Bog Pimpernel.—S.W. (Barford.)

Cham. To chew (A.B.C.S.). 'Now cham thee vittles up well.' An older form of Champ.—N. & S.W.

Champ. To scold in a savage snarling fashion. 'Now dwoan't 'ee gwo an' champ zo at I!' Used formerly at Clyffe Pypard.—N.W.

Chan-Chider. See Johnny Chider.—S.W.

Chap. (1) v. Of ground, to crack apart with heat.—N & S.W. (2) n. A crack in the soil, caused by heat.—N. & S.W.

Charm. (1) n. 'All in a charm,' all talking loud together. A.S. cyrm, clamour (A.H.S.), especially used of the singing of birds. See Kingsley's Prose Idylls, i. Also used of hounds in full cry.—N. & S.W.

'Thousands of starlings, the noise of whose calling to each other is indescribable—the country folk call it a "charm," meaning a noise made up of innumerable lesser sounds, each interfering with the other.'—Wild Life, ch. xii.

Cp, Milton,

'Charm of earliest birds.'—P. L., ii. 642.

(2) v. To make a loud confused noise, as a number of birds, &c., together.—N. & S.W. (3) v. 'To charm bees,' to follow a swarm of bees, beating a tea-tray, &c.—N.W. (Marlborough).

Chatter-mag, Chatter-pie. A chattering woman.—N. & S.W.

Chawm, Chawn. A crack in the ground (A.).—N.W.

Cheese-flower. Malva sylvestris, L., Common Mallow.—S.W.

Cheeses. Fruit of Malva sylvestris, L., Common Mallow.—N. & S.W.

*Chemise. Convolvulus sepium, L., Great Bindweed.—S.W. (Little Langford.) This name was given us as Chemise, but would probably be pronounced as Shimmy.

Cherky. Having a peculiar dry taste, as beans (Village Miners).—N. & S.W.

Cherry-pie. Valeriana officinalis, L., All-heal, from its smell.—S.W.

Cheure. See Choor.

Chevil (or Chevril) Goldfinch. A large variety of goldfinch, with a white throat. See Birds of Wilts, p. 203, for a full description of the bird.—N. & S.W.

Chewree. See Choor.

Chib. 'Potato-chibs,' the grown-out shoots in spring. See Chimp.—S.W.

Chiddlens, Chiddlins. Pigs' chitterlings (H.S.Wr.).—N. & S.W.

Children of Israel. *(1) A small garden variety of Campanula, from the profusion of its blossoms (English Plant Names). (2) Malcolmia maritima, Br., Virginian Stock, occasionally.

Chilver, Chilver-lamb. A ewe lamb (A.).—N.W.

Chilver-hog. A ewe under two years old (D.). The word hog is now applied to any animal of a year old, such as a hog bull, a chilver hog sheep. 'Chilver' is a good Anglo-Saxon word, 'cilfer,' and is related to the word 'calf.' A chilver hog sheep simply means in the dialect of the Vale of Warminster, a female lamb a year old. See Wilts Arch. Mag. xvii. 303.—N. & S.W.

Chimney-sweeps. Flowering-heads of some grasses.—N.W. (Lyneham.)

Chimney-sweepers. Luzula campestris, Willd., Field Wood-rush.—N.W.

Chimp. (1) n. The grown-out shoot of a stored potato (S.); also Chib.—S.W. (2) v. To strip off the 'chimps' before planting.—S.W.

Chink. Fringilla coelebs, the Chaffinch; from its note.—S.W.

Chinstey. n. The string of a baby's cap.—N.W. (Clyffe Pypard.) A horse's chin-strap.—S.W. Compare:—

'Oh! Mo-ather! Her hath chuck'd me wi' tha chingstey [caught me by the back-hair and choked me with the cap-string].'—The Exmoor Scolding, p. 17.

Chip. The fore-shoot of a plough.—S.W.

Chipples. Young onions grown from seed. Cf. Gibbles and Cribbles.—S.W.

Chisley. adj. Without coherence, as the yolk of an over-boiled egg, or a very dry cheese. When land gets wet and then dries too fast, it becomes chisley. Compare:—'Chizzly, hard, harsh and dry: East,' in Hal.—S.W.

Chism. To germinate, to bud (A.B.C.). 'The wheat doesn't make much show yet, John.' 'No, zur, but if you looks 'tes aal chisming out ter'ble vast.'—N. & S.W.

Chit. (1) n. The third swarm of bees from a hive.—N.W. (2) v. To bud or spring (A.B.C.). 'The whate be chitting a'ter thease rains.'—N.W.

Chitchat. Pyrus Aucuparia, Gærtn., Mountain Ash.—S.W.

Chitterlings. Pigs' entrails when cleaned and boiled (A.B.); Chiddlens (H.S.Wr.).—N. & S.W.

Chivy. Fringilla coelebs, the Chaffinch.—S.W. (Som. bord.).

Choor. (1) v. To go out as a charwoman (A.); Cheure, Chewree-ring (H.Wr.); Char (A.S.). Still in use.—N.W. (2) n. A turn, as in phrase 'One good choor deserves another' (A.). Still in use.—N.W.

Chop. To exchange (A.B.S.). 'Wool ye chop wi' I, this thing for thuck?' (B.).—N. & S.W.

*Chore. A narrow passage between houses (MS. Lansd. 1033, f. 2); see N.E.D. (s.v. Chare).

Christian Names. The manner in which a few of these are pronounced may here be noted:—Allburt, Albert; Allfurd, Alfred; Charl or Chas, Charles; Etherd, Edward; Rich't or Richet, Richard; Robbut, Robert; &c.

Chuffey. Chubby. 'What chuffey cheeks he've a got, to be showr!'—S.W.

Chump. A block of wood (A.B.); chiefly applied to the short lengths into which crooked branches and logs are sawn for firewood (Under the Acorns).—N. & S.W.

Ciderkin, 'Kin. The washings after the best cider is made.—N. & S.W.

Clacker. The tongue (S.).—S.W.

Clackers. A pair of pattens (S.).—S.W.

Clangy, Clengy, or Clungy. Of bad bread, or heavy ground, clingy, sticky.—N.W.

Claps. n. and v. clasp (A.).—N. & S.W.

Clat. See Clot.

Clattersome, Cluttersome. Of weather, gusty.—S.W. (Hants bord.)

Claut. Caltha palustris, L., Marsh Marigold (A.H.Wr.).—N.W. (Clyffe Pypard, &c.)

Clavy, Clavy-tack. A mantelpiece (A.B.C.).—N.W., now almost obsolete. Strictly speaking, clavy is merely the beam which stretches across an old-fashioned fireplace, supporting the wall. Where there is a mantelpiece, or clavy-tack, it comes just above the clavy.

Clean. 'A clean rabbit,' one that has been caught in the nets, and is uninjured by shot or ferret, as opposed to a 'broken,' or damaged one. (Amateur Poacher, ch. xi. p. 212).—N. & S.W.

Cleat, Cleet. (1) The little wedge which secures the head of an axe or hammer.—N.W. *(2) n. A patch (A.B.C.).—N.W. *(3) v. To mend with a patch (A.B.C.)—N.W. *(4) Occasionally, to strengthen by bracing (C.).—N.W.

Cleaty. Sticky, clammy; applied to imperfectly fermented bread, or earth that will not work well in ploughing.—N.W.

Cleet. See Cleat.

Clengy. See Clangy.

Clim. To climb (A.S.). A cat over-fond of investigating the contents of the larder shelves is a 'clim-tack,' or climb-shelf.—N. & S.W.

Clinches. The muscles of the leg, just under the knee-joint.—N. & S.W.

Clinkerbell. An icicle.—S.W. (Som. bord.) occasionally.

Clitch. The groin.—N.W.

Clite, Clit. (1) n. 'All in a clite,' tangled, as a child's hair. A badly groomed horse is said to be 'aal a clit.'—N. & S.W. (2) v. To tangle. 'How your hair do get clited!'—N. & S.W.

Clites, Clytes. Galium Aparine, L., Goosegrass (A.). Usually pl., but Jefferies has sing., Clite, in Wild Life, ch. ix.—N. & S.W.

Clitty. Tangled, matted together.—S.W.

Clock. A dandelion seed-head, because children play at telling the time of day by the number of puffs it takes to blow away all its down.—N. & S.W.

Cloddy. Thick, plump, stout (H.Wr.).—S.W.

Clog-weed. Heracleum Sphondylium, L., Cow-parsnip (Amateur Poacher, ch. vi).—N.W.

Clot. A hard lump of dry cow-dung, left on the surface of a pasture. See Cow-clat.—N.W.

'On pasture farms they beat clots or pick up stones.'—R. Jefferies, Letter to Times, Nov. 1872.

'1661. Itm pd Richard Sheppard & Old Taverner for beating clatts in Inglands, 00. 04. 08.'—Records of Chippenham, p. 226.

*Clote. n. Verbascum Thapsus, L., Great Mullein (Aubrey's Wilts MS.).—Obsolete.

Clothes-brush. Dipsacus sylvestris, L., Wild Teasel. Cf. Brushes.—S.W.

Clottiness. See Cleaty. Clottishness (Agric. Survey).

'The peculiar churlishness (provincially, "clottiness") of a great part of the lands of this district, arising perhaps from the cold nature of the sub-soil.'—Agric. of Wilts, ch. vii. p. 51.

Clout. (1) n. A box on the ear, a blow (A.B.C.S.). See Clue. 'I'll gie thee a clout o' th' yead.'—N. & S.W. (2) v. To strike.—N. & S.W.

Clue. 'A clue in the head,' a knock on the head (Village Miners). A box on the ear. Cf. clow, Winchester College. See Clout.—N.W.

Clum. To handle clumsily (A.B.), roughly, boisterously, or indecently (C.).—N.W.

Clumbersome. Awkward, clumsy.—N.W.

Clumper, Clumber. A heavy clod of earth.—N.W. (Marlborough.)

Clums. pl. Hands. 'I'll keep out o' thee clums, I'll warnd I will!'—N.W. Clumps is used in S. Wilts in a similar way, but generally of the feet (S.), and always implies great awkwardness, as 'What be a treadin' on my gownd vor wi' they girt ugly clumps o' yourn?'

Clungy. See Clangy.

*Cluster-of-five. The fist. Cluster-a-vive (S.).—S.W.

Clutter. n. Disorder, mess, confusion. 'The house be ael in a clutter to-day wi' they childern's lease-carn.'—N. & S.W.

Cluttered. (1) 'Caddled,' over-burdened with work and worry.—N. & S.W.

'"Cluttered up" means in a litter, surrounded with too many things to do at once.'—Jefferies, Field and Hedgerow, p. 189.

*(2) Brow-beaten. Said to have been used at Warminster formerly.

Cluttersome. See Clattersome.

Cluttery. Showery and gusty.—S.W.

*Clyders. Galium Aparine, L., Goosegrass.—S.W.

*Clyten. *(1) n. An unhealthy appearance, particularly in children (A.B.C.).—N.W., obsolete. *(2) n. An unhealthy child (C.).—N.W., obsolete.

*Clytenish. adj. Unhealthy-looking, pale, sickly (A.B.C.H.Wr.).—N.W., obsolete.

Clytes. See Clites.

*Coath. Sheep-rot (D.S.).—N. & S.W.

Cobbler's-knock. 'To do the cobbler's knock,' to slide on one foot, tapping the ice meanwhile with the other.—S.W.

*Cob-nut. A game played by children with nuts (A.B.).—S.W.

Cockagee, Cockygee (g hard). A kind of small hard sour cider apple. Ir. cac a' gheidh, goose-dung, from its greenish-yellow colour (see N.E.D., s.v. Coccagee).—S.W. (Deverill, &c.)

Cocking-fork. A large hay-fork, used for carrying hay from the cock into the summer-rick.—S.W.

*Cocking-poles. Poles used for the same purpose.—N.W.

Cockles. Seed-heads of Arctium Lappa, L., Burdock.—N.W. (Clyffe Pypard).

Cock's Egg. The small eggs sometimes first laid by pullets.—N. & S.W.

Cock-shot. A cock-shy: used by boys about Marlborough and elsewhere. 'I say, there's a skug [squirrel]—let's have a cock-shot at him with your squailer.'—N. & S.W.

*Cock's-neckling. 'To come down cock's-neckling,' to fall head foremost (H.Wr.).—Obsolete.

Cock's-nests. The nests so often built and then deserted by the wren, without any apparent cause.—N.W.

*Cock-sqwoilin. Throwing at cocks at Shrovetide (A.Wr.). See Squail.—N.W., obsolete.

'1755. Paid expenses at the Angel at a meeting when the By Law was made to prevent Throwing at Cocks, 0.10.6.'—Records of Chippenham, p. 244.

Cocky-warny. The game of leap-frog.—N.W. (Clyffe Pypard.)

*Cod-apple. A wild apple (Wilts Arch. Mag. xiv. 177).

Codlins-and-cream. Epilobium hirsutum, L., Great Hairy Willow-herb; from its smell when crushed in the hand. Cf. Sugar-Codlins.—S.W.

*Coglers. The hooks, with cogged rack-work for lifting or lowering, by which pots and kettles were formerly hung over open fireplaces. Now superseded by Hanglers.—N.W., obsolete.

Colley. (1) A collar.—N. & S.W. *(2) Soot or grime from a pot or kettle (A.B.). Compare:—

'Brief as the lightning in the collied night.'—Midsummer Night's Dream.

'Thou hast not collied thy face enough.'—Jonson's Poetaster.

Colley-maker. A saddler. See Colley (1).—N. & S.W.

Colley-strawker. A milker or 'cow-stroker.'—N.W. (Clyffe Pypard.)

Colt's-tail. A kind of cloud said to portend rain.—N.W.

'The colt's tail is a cloud with a bushy appearance like a ragged fringe, and portends rain.'—Great Estate, ch. viii.

*Comb, Coom. (1) n. The lower ledge of a window (Kennett's Paroch. Antiq.). (2) n. Grease from an axle-box, soot, dirt, &c. Koomb (S.).—S.W.

Comb-and-Brush. Dipsacus sylvestris, L., Wild Teasel.—S.W.

Combe, Coombe. (1) The wooded side of a hill (D.); used occasionally in this sense in both Wilts and Dorset.—N. & S.W. (2) A narrow valley or hollow in a hillside. This is the proper meaning.—N. & S.W. Used of a narrow valley in the woodlands in Gamekeeper at Home, ch. i.

Come of. To get the better of, to grow out of. 'How weak that child is about the knees, Sally!' 'Oh, he'll come o' that all right, Miss, as he do grow bigger.'—N. & S.W.

Come to land. Of intermittent springs, to rise to the surface and begin to flow (Agric. of Wilts, ch. xii).—S.W.

Comical. (1) Queer-tempered. 'Her's a comical 'ooman.'—N. & S.W. (2) Out of health. 'I've bin uncommon comical to-year.'—N. & S.W. (3) Cracky, queer. 'He's sort o' comical in his head, bless 'ee.'—N. & S.W. 'A cow he's a comical thing to feed; bin he don't take care he's very like to choke hisself.'—N.W. (Marlborough.) It should be noted that Marlborough folk are traditionally reputed to call everything he but a bull, and that they always call she!

Coney-burry. A rabbit's hole.—S.W. (Amesbury.)

Coniger, Conigre. This old word, originally meaning a rabbit-warren, occurs frequently in Wilts (as at Trowbridge) as the name of a meadow, piece of ground, street, &c. See Great Estate, note to ch. ix.

Conker-berries. See Canker-berries.

Conks, Conkers (i.e. conquerors). (1) A boy's game, played with horse-chestnuts strung on cord, the players taking it in turn to strike at their opponent's conk, in order to crack and disable it.—N.W. (Marlborough.) (2) Hence, the fruit of Aesculus Hippocastanum, L., Horse-chestnut.—N.W.

Coob. A hen-coop (H.): invariably so pronounced.—N. & S.W.

Cooby. A snug corner. See Cubby-hole.—N. & S.W.

Coom. See Comb.

*Coombe-bottom. A valley in a hillside (Great Estate, ch. iv). See Combe.

Coom hedder. (A.S.). See Horses.