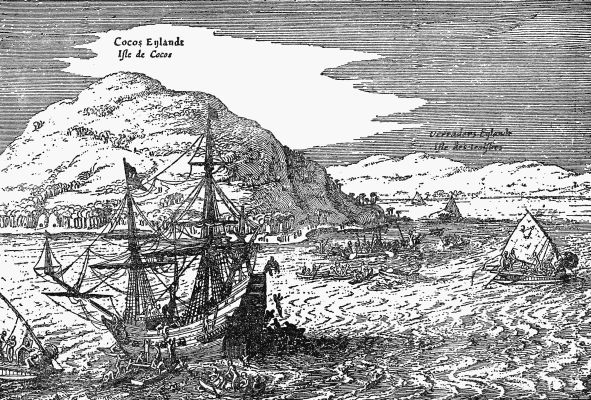

The Cocos Islands

The Cocos Islands

The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Golden Book of the Dutch Navigators, by Hendrik Willem van Loon This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org/license Title: The Golden Book of the Dutch Navigators Author: Hendrik Willem van Loon Release Date: May 28, 2014 [EBook #45799] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE GOLDEN BOOK OF THE DUTCH NAVIGATORS *** Produced by Chris Curnow and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

THE GOLDEN BOOK

OF THE

DUTCH NAVIGATORS

BY

HENDRIK WILLEM van LOON

ILLUSTRATED WITH SEVENTY REPRODUCTIONS OF OLD PRINTS

NEW YORK

THE CENTURY CO.

1916

Copyright, 1916, by

The Century Co.

Published, October, 1916

FOR HANSJE AND WILLEM

This is a story of magnificent failures. The men who equipped the expeditions of which I shall tell you the story died in the poorhouse. The men who took part in these voyages sacrificed their lives as cheerfully as they lighted a new pipe or opened a fresh bottle. Some of them were drowned, and some of them died of thirst. A few were frozen to death, and many were killed by the heat of the scorching sun. The bad supplies furnished by lying contractors buried many of them beneath the green cocoanut-trees of distant lands. Others were speared by cannibals and provided a feast for the hungry tribes of the Pacific Islands.

But what of it? It was all in the day's work. These excellent fellows took whatever came, be it good or bad, or indifferent, with perfect grace, and kept on smiling. They kept their powder dry, did whatever their hands found to do, and left the rest to the care of that mysterious Providence who probably knew more about the ultimate good of things than they did.

I want you to know about these men because they were your ancestors. If you have inherited any of their good qualities, make the best of them; they will prove to be worth while. If you have got your share of their bad ones, fight these as hard as you can; for they will lead you a merry chase before you get through.

Whatever you do, remember one lesson: "Keep on smiling."

Hendrik Willem van Loon.

Cornell University, Ithaca, New York.

February 29, 1916.

CONTENTS

| CHAPTER | Page | |

| I | JAN HUYGEN VAN LINSCHOTEN | 3 |

| II | THE NORTHEAST PASSAGE | 43 |

| III | THE TRAGEDY OF SPITZBERGEN | 87 |

| IV | THE FIRST VOYAGE TO INDIA—FAILURE | 97 |

| V | THE SECOND VOYAGE TO INDIA—SUCCESS | 135 |

| VI | VAN NOORT CIRCUMNAVIGATES THE WORLD | 159 |

| VII | THE ATTACK UPON THE WEST COAST OF AMERICA | 207 |

| VIII | THE BAD LUCK OF CAPTAIN BONTEKOE | 249 |

| IX | SCHOUTEN AND LE MAIRE DISCOVER A NEW STRAIT | 279 |

| X | TASMAN EXPLORES AUSTRALIA | 303 |

| XI | ROGGEVEEN, THE LAST OF THE GREAT VOYAGERS | 325 |

The history of America is the story of the conquest of the West. The history of Holland is the story of the conquest of the sea. The western frontier influenced American life, shaped American thought, and gave America the habits of self-reliance and independence of action which differentiate the people of the great republic from those of other countries.

The wide ocean, the wind-swept highroad of commerce, turned a small mud-bank along the North Sea into a mighty commonwealth and created a civilization of such individual character that it has managed to maintain its personal traits against the aggressions of both time and man.

When we discuss the events of American history we place our scene upon a stage which has an immense background of wide prairie and high mountain. In this vast and dim territory [Pg vii] there is always room for another man of force and energy, and society is a rudimentary bond between free and sovereign human beings, unrestricted by any previous tradition or ordinance. Hence we study the accounts of a peculiar race which has grown up under conditions of complete independence and which relies upon its own endeavors to accomplish those things which it has set out to do.

The virtues of the system are as evident as its faults. We know that this development is almost unique in the annals of the human race. We know that it will disappear as soon as the West shall have been entirely conquered. We also know that the habits of mind which have been created during the age of the pioneer will survive the rapidly changing physical conditions by many centuries. For this reason those of us who write American history long after the disappearance of the typical West must still pay due reverence to the influence of the old primitive days when man was his own master and trusted no one but God and his own strong arm.

The history of the Dutch people during the last five centuries shows a very close analogy. The American who did not like his fate at home went "west." The Hollander who decided that he would be happier outside of the town limits of his native city went "to sea," as the expression was. He always had a chance to ship as a cabin-boy, just as his American successor could pull up stakes at a moment's notice to try his luck in the next county. Neither of the two knew exactly what they might find at the end of their voyage of adventure. Good luck, bad luck, middling luck, it made no difference. It meant a change, and most frequently it meant a change for the better. Best of all, even if one had no desire to migrate, but, on the other hand, was quite contented to stay at home and be buried in the family vault of his ancestral estate, he knew at all times that he was free to leave just as soon as the spirit moved him.

Remember this when you read Dutch history. It is an item of grave importance. It was always in the mind of the mighty potentate [Pg ix] who happened to be the ruler and tax-gatherer of the country. He might not be willing to acknowledge it, he might even deny it in vehement documents of state, but in the end he was obliged to regulate his conduct toward his subjects with due respect for and reference to their wonderful chance of escape. The Middle Ages had a saying that "city air makes free." In the Low Countries we find a wonderful combination of city air and the salt breezes of the ocean. It created a veritable atmosphere of liberty, and not only the liberty of political activity, but freedom of thought and independence in all the thousand and one different little things which go to make up the complicated machinery of human civilization. Wherever a man went in the country there was the high sky of the coastal region, and there were the canals which would carry his small vessel to the main roads of trade and ultimate prosperity. The sea reached up to his very front door. It supported him in his struggle for a living, and it was his best ally in his fight for independence. Half of his family and [Pg x] friends lived on and by and of the sea. The nautical terms of the forecastle became the language of his land. His house reminded the foreign visitor of a ship's cabin.

And finally his state became a large naval commonwealth, with a number of ship-owners as a board of directors and a foreign policy dictated by the need of the oversea commerce. We do not care to go into the details of this interesting question. It is our purpose to draw attention to this one great and important fact upon which the entire economic, social, intellectual, and artistic structure of Dutch society was based. For this purpose we have reprinted in a short and concise form the work of our earliest pioneers of the ocean. They broke through the narrow bonds of their restricted medieval world. In plain American terms, "They were the first to cross the Alleghanies."

They ushered in the great period of conquest of West and East and South and North. They built their empire wherever the water of the ocean would carry them. They laid the foundations [Pg xi] for a greatness which centuries of subsequent neglect have not been able to destroy, and which the present generation may triumphantly win back if it is worthy to continue its existence as an independent nation.

It was the year of our Lord 1579, and the eleventh of the glorious revolution of Holland against Spain. Brielle had been taken by a handful of hungry sea-beggars. Haarlem and Naarden had been murdered out by a horde of infuriated Spanish regulars. Alkmaar—little Alkmaar, hidden behind lakes, canals, open fields with low willows and marshes—had been besieged, had turned the welcome waters of the Zuyder Zee upon the enemy, and had driven the enemy away. Alva, the man of iron who was to destroy this people of butter between his steel gloves, had left the stage of his unsavory operations in disgrace. The butter had dribbled away between his [Pg 4] fingers. Another Spanish governor had appeared. Another failure. Then a third one. Him the climate and the brilliant days of his youth had killed.

But in the heart of Holland, William, of the House of Nassau, heir to the rich princes of Orange, destined to be known as the Silent, the Cunning One—this same William, broken in health, broken in money, but high of courage, marshaled his forces and, with the despair of a last chance, made ready to clear his adopted country of the hated foreign domination.

Everywhere in the little terrestrial triangle of this newest of republics there was the activity of men who had just escaped destruction by the narrowest of margins. They had faith in their own destiny. Any one who can go through an open rebellion against the mightiest of monarchs and come out successfully deserves the commendation of the Almighty. The Hollanders had succeeded. Their harbors, the lungs of the country, were free once more, and could breathe the fresh air of the open sea and of commercial prosperity.

On the land the Spaniard still held his own, but on the water the Hollander was master of the situation. The ocean, which had made his country what it was, which had built the marshes upon which he lived, which provided the highway across which he brought home his riches, was open to his enterprise.

He must go out in search of further adventure. Thus far he had been the common carrier of Europe. His ships had brought the grain from the rich Baltic provinces to the hungry waste of Spain. His fishermen had supplied the fasting table of Catholic humanity with the delicacy of pickled herring. From Venice and later on from Lisbon he had carried the products of the Orient to the farthest corners of the Scandinavian peninsula. It was time for him to expand.

The rôle of middleman is a good rôle for modest and humble folk who make a decent living by taking a few pennies here and collecting a few pennies there, but the chosen people of God must follow their destiny upon the broad highway of international commerce [Pg 6] wherever they can. Therefore the Hollander must go to India.

It was easily said. But how was one to get there?

Jan Huygen van Linschoten was born in the year 1563 in the town of Haarlem. As a small boy he was taken to Enkhuizen. At the present time Enkhuizen is hardly more than a country village. Three hundred years ago it was a big town with high walls, deep moats, strong towers, and a local board of aldermen who knew how to make the people keep the laws and fear God. It had several churches where the doctrines of the great master Johannes Calvinus were taught with precision and without omitting a single piece of brimstone or extinguishing a single flame of an ever-gaping hell. It had orphan asylums and hospitals. It had a fine jail, and a school with a horny-handed tyrant who taught the A B C's and the principles of immediate obedience with due reference to that delightful text about the spoiled child and the twigs of a birch-tree.

Outside of the city, when once you had passed the gallows with its rattling chains and aggressive ravens, there were miles and miles of green pasture. But upon one side there was the blue water of the quiet Zuyder Zee. Here small vessels could approach the welcome harbor, lined on both sides with gabled storehouses. It is true that when the tide was very low the harbor looked like a big muddy trough. But these flat-bottomed contraptions rested upon the mud with ease and comfort, and the next tide would again lift them up, ready for farther peregrinations. Over the entire scene there hung the air of prosperity. A restless energy was in the air. On all sides there was evidence of the gospel of enterprise. It was this enterprise that collected the money to build the ships. It was this enterprise, combined with nautical cunning, that pushed these vessels to the ends of the European continent in quest of freight and trade. It was this enterprise that turned the accumulating riches into fine mansions and good pictures, and gave a first-class education to all boys and girls. It walked proudly along [Pg 9] the broad streets where the best families lived. It stalked cheerfully through the narrow alleys when the sailor came back to his wife and children. It followed the merchant into his counting-room, and it played with the little boys who frequented the quays and grew up in a blissful atmosphere of tallow, tar, gin, spices, dried fish, and fantastic tales of foreign adventure.

And it played the very mischief with our young hero. For when Jan Huygen was sixteen years old, and had learned his three R's—reading, 'riting, and 'rithmetic—he shipped as a cabin-boy to Spain, and said farewell to his native country, to return after many years as the missing link in the chain of commercial explorations—the one and only man who knew the road to India.

Here the industrious reader interrupts me. How could this boy go to Spain when his country was at war with its master, King Philip? Indeed, this statement needs an explanation.

Spain in the sixteenth century was a magnificent example of the failure of imperial [Pg 10] expansion minus a knowledge of elementary economics. Here we had a country which owned the better part of the world. It was rich beyond words and it derived its opulence from every quarter of the globe. For centuries a steady stream of bullion flowed into Spanish coffers. Alas! it flowed out of them just as rapidly; for Spain, with all its foreign glory, was miserably poor at home. Her people had never been taught to work. The soil did not provide food enough for the population of the large peninsula. Every biscuit, so to speak, every loaf of bread, had to be imported from abroad. Unfortunately, the grain business was in the hands of these same Dutch Calvinists whose nasal theology greatly offended his Majesty King Philip. Therefore during the first years of the rebellion the harbors of the Spanish kingdom had been closed against these unregenerate singers of Psalms. Whereupon Spain went hungry, and was threatened with starvation.

Economic necessity conquered religious prejudice. The ports of King Philip's domain [Pg 11] once more were opened to the grain-ships of the Hollanders and remained open until the end of the war. The Dutch trader never bothered about the outward form of things provided he got his profits. He knew how to take a hint. Therefore, when he came to a Spanish port, he hoisted the Danish flag or sailed under the colors of Hamburg and Bremen. There still was the difficulty of the language, but the Spaniard was made to understand that this guttural combination of sounds represented diverse Scandinavian tongues. The tactful custom-officers of his Most Catholic Majesty let it go at that, and cheerfully welcomed these heretics without whom they could not have fed their own people.

When Jan Huygen left his own country he had no definite plans beyond a career of adventure; for then, as he wrote many years later, "When you come home, you have something to tell your children when you get old." In 1579 he left Enkhuizen, and in the winter of the next year he arrived in Spain. First of all he did some clerical work in the town of Seville, where [Pg 12] he learned the Spanish language. Next he went to Lisbon, where he became familiar with Portuguese. He seems to have been a likable boy who did cheerfully whatever he found to do, but watched with a careful eye the chance to meet with his next adventure. After three years of a roving existence, with rare good luck, he met Vincente da Fonseca, a Dominican who had just been appointed Archbishop of Goa in the Indies. Jan Huygen obtained a position as general literary factotum to the new dignitary and also acted as purser for the captain of the ship.

At the age of twenty he was an integral member of a bona-fide expedition to the mysterious Indies. Through his account of this trip, printed in 1595, the Dutch traders at last learned to know the route to the Indies. The expedition left Lisbon on Good Friday of the year 1583 with forty ships. During the first few weeks nothing happened. Nothing ever happened during the first weeks on any of those expeditions. The trouble invariably began after the first rough weather. In this instance [Pg 13] everything went well until the end of April, when the coast of Guinea had been reached. Then the fleet entered a region of squalls and severe rainstorms. The rain collected on the decks and ran down the hatchways. A dozen times or so a day the fleet had to come to a stop while all hands bailed out the water which filled the holds. When it did not rain the sun beat down mercilessly, and soon the atmosphere of the soaked wood became unpleasant. To make things worse the drinking water was no longer fresh, and smelled so badly that one could not drink it without closing the unfortunate nose that came near the cup.

On the whole the printed work of Jan Huygen does not show him as an admirer of the Portuguese or their system of navigation. In all his writing he gives us the impression of a very sober-minded young Hollander with a lot of common sense. Portugal had then been a colonial power for many years and showed unmistakable signs of deterioration. The people had been too prosperous. They were no longer willing to defend their own interests against [Pg 14] other and younger nations. They still exercised their Indian monopoly because it had been theirs for so long a time that no one remembered anything to the contrary. But the end of things had come. Upon every page of Jan Huygen's book we find the same evidence of bad organization, little jealousies, spite, disobedience, cowardice, and lack of concerted action.

When only a few weeks from home this fleet of forty ships encountered a single small French vessel. Part of the Portuguese crew of the fleet was sick. The others made ready to flee at once. After a few hours it was seen that the Frenchman had no evil intentions, and continued his way without a closer inspection of his enemies. Then peace returned to the fleet of Fonseca.

A few days later the ship reached the equator. The customary initiation of the new sailors, followed by the usual festivities and a first-class drunken row, took place. The captain was run down and trampled upon by his men, tables and chairs were upset, and the crew fought one another [Pg 15] with knives. This quarrel might have ended in a general murder but for the interference of the archbishop, who threw himself among the crazy sailors, and with a threat of excommunication drove them back to work. Half a dozen were locked up, others were whipped, and the ships continued their voyage in this happy-go-lucky fashion. Then it appeared that nobody knew exactly where they were. Observations finally showed that the fleet was still fifty miles west of the Cape of Good Hope. As a matter of fact, they had passed the cape several days before, but did not discover their error until a week later. Then they sailed northward until they reached Mozambique, where they spent two weeks in order to give the crew a rest and to repair the damages of the equatorial fight. On the twentieth of August they continued their voyage until the serpents which they saw in the water showed them that they were approaching the coast of India. From that time on luck was with the expedition. The ships reached the coast near the town of destination. After a remarkably [Pg 16] short passage of only five months and thirteen days the fleet landed safely in Goa.

Jan Huygen was very proud of the record of his ship. Only thirty people had died on the voyage. It is true that all the people on board had been under a doctor's care, and every one of the sailors and passengers had been bled a few times; but thirty men buried during so long a voyage was a mere trifle. In the sixteenth century, if fifty per cent. of the men returned from an Indian voyage, the trip was considered successful.

The next five years Jan Huygen spent in Goa with his ecclesiastical master. He was intrusted with a great deal of confidential work, and became thoroughly familiar with all the affairs of the colony. In Goa he heard wonderful tales about the great Chinese Empire, many weeks to the north. He began to collect maps for an expedition to that distant land, but lack of funds made him put it off, and he never went far beyond the confines of the small Portuguese settlement.

Unfortunately, at the end of five years the [Pg 17] archbishop died, and Jan Huygen was without a job. As he had had news that his father had died, he now decided to go back to Enkhuizen to see what he could do for his mother. Accordingly, in January of the year 1589, he sailed for home on board the good ship Santa Maria. It was the same old story of bad management: The ships of the return fleet were all loaded too heavily. The handling of the cargo was left entirely to ship-brokers, and these worthies had developed a noble system of graft. Merchandise was loaded according to a regular tariff of bribes. If you were willing to pay enough, your goods went neatly into the hold. If you did not give a certain percentage to the brokers, your bags and bales were stowed away somewhere on a corner of a wharf exposed to the rain and the sea. Very likely, too, the first storm would wash your valuable possessions overboard.

When the Santa Maria left, her decks were stacked high with disorderly masses of colonial products. The sailors on duty had to make a path through this accumulated stuff, and the [Pg 18] captain lacked the authority to put his own ship in order. A few days out a cabin-boy fell overboard. The sea was quiet, and it would have been possible to save the child, but when the crew ran for a boat, it was found to be filled with heavy boxes. By the time the boat was at last lowered the boy had drowned.

The Santa Maria sailed direct for the Cape. There it fell in with another vessel called the San Thome, and it now became a matter of pride which ship could round the cape first. Severe western winds made the Santa Maria wait several days. The San Thome, however, ventured forth to brave the gale. When finally the storm had abated and the Santa Maria had reached the Atlantic Ocean, the bodies and pieces of wreckage which floated upon the water told what had happened to the other vessel. This, however, was only the beginning of trouble. On the fifth of March the Santa Maria was almost lost. Her rudder broke, and it could not be repaired. A storm, accompanied by a tropical display of thunder and lightning, broke loose. For more than forty-eight [Pg 19] hours the ship was at the mercy of the waves. The crew spent the time on deck absorbed in prayer. When little electric flames began to appear upon the masts and yards (the so-called St. Elmo's fire, a spooky phenomenon to all sailors of all times), they felt sure that the end of the world had come. The captain commanded all his men to pray the "Salvo corpo Sancto," and this was done with great demonstrations of fervor. The celestial fireworks, however, did not abate. On the contrary the crew witnessed the appearance of a five-pointed crown, which showed itself upon the mainmast, and was hailed with cries of the "crown of the Holy Virgin." After this final electric display the storm went on its way.

In his sober fashion Jan Huygen had looked

on. He did not take much stock in this sudden

piety, and called it "a lot of useless noise."

Then he watched the men repairing the rudder.

It was discovered that there was no anvil on

board the ship, and a gun was used as an anvil.

A pair of bellows was improvised out of some

old skins. With this contrivance some sort of

[Pg 20]

[Pg 21]

steering-gear was finally rigged up, and the

voyage was continued. After that, except for

occasional and very sudden squalls, when all the

sails had to be lowered to save them from being

blown to pieces, the Santa Maria was past her

greatest danger, though the heavy seas caused

by a prolonged storm proved to be another obstacle.

No further progress was possible until

the ship had been lightened. For this purpose

the large boat and all its valuable contents were

simply thrown overboard.

The recital of Jan Huygen's trip is a long epic of bungling. The captain did not know his job; the officers were incompetent; the men were unruly and ready to mutiny at the slightest provocation; and everybody blamed everybody else for everything that went wrong. The captain, in the last instance, accused the good Lord, Who "would not allow His own faithful people to pass the Cape of Good Hope with their strong and mighty ships," while making the voyage an easy one for "the blasphemous English heretics with their little insignificant schooners." In this statement there was more [Pg 22] wisdom than the captain suspected. The English sailors knew their business and could afford to take risks. The Portuguese sailors of that day hastened from one coastline and from one island to the next, as they had done a century before. As long as they were on the high seas they were unhappy. They returned to life when they were in port. Every time the Santa Maria passed a few days in some harbor we get a recital of the joys of that particular bit of paradise. If we are to believe Portuguese tradition, St. Helena, where the ship passed a week of the month of May of the year 1589, was placed in its exact geographical position by the Almighty to serve His faithful children as a welcome resting-point upon their perilous voyage to the far Indies. The island was full of goats, wild pigs, chickens, partridges, and thousands of pigeons, all of which creatures allowed themselves to be killed with the utmost ease, and furnished food for generations of sailors who visited those shores.

Indeed, this island was so healthy a spot that it was used as a general infirmary. After a few [Pg 23] days on shore even the weakest of sufferers was sufficiently strong to catch specimens of the wild fauna of the island. Often, therefore, the sick sailors were left behind. With a little salt and some oil and a few spices they could support themselves easily until the next ship came along and picked them up. We know what ailed most of these stricken sailors. They suffered from scurvy, due to a bad diet; but it took several centuries before the cause of scurvy was discovered. When Jan Huygen went to the Indies the crew of every ship was invariably attacked by this most painful disease. Therefore the islands were of great importance.

Nowadays St. Helena is no longer a paradise. Three centuries ago it was the one blessed point of relief for the Indian traders. The diary of Jan Huygen tells of attempts made to colonize the island. The King of Portugal, however, had forbidden any settlement upon this solitary rock. For a while it had harbored a number of runaway slaves. Whenever a ship came near they had fled to the mountains. Finally, however, they had been caught and taken back to [Pg 24] Portugal and sold. For a long time the island had been inhabited by a pious hermit. He had built a small chapel, and there the visiting sailors were allowed to worship. In his spare time, however, the holy man had hunted goats, and he had entered into an export business of goat-skins. Every year between five and six hundred skins were sold. Then this ingenious scheme was discovered, and the saintly hunter was sent home.

On the twenty-first of May the Santa Maria continued her northward course. Again bad food and bad water caused illness among the men. A score of them died. Often they hid themselves somewhere in the hold, and had been dead for several days before they made their presence noticeable. It was miserable business; and now, with a ship of sick and disabled men, the Santa Maria was doomed to fall in with three small British vessels. At once there was a panic among the Portuguese sailors. The British hoisted their pennant, and opened with a salvo of guns. The Portuguese fled below decks, and the English, in sport, shot [Pg 25] the sails to pieces. The crew of the Santa Maria tried to load their heavy cannon, but there was such a mass of howling and swearing humanity around the guns that it took hours before anything could be done. The ships were then very near one another, and the British sailors could be heard jeering at the cowardice of their prey. But just when Jan Huygen thought the end had come the British squadron veered around and disappeared. The Santa Maria then reached Terceira in the Azores without further molestation.

Like all other truthful chroniclers of his day, Jan Huygen speculates about the mysterious island of St. Brandon. This blessed isle was supposed to be situated somewhere between the Azores and the Canary Islands, but nearer to the Canaries. As late as 1721 expeditions were fitted out to search for the famous spot upon which the Irish abbot of the sixth century had located the promised land of the saints. Together with the recital of another mysterious bit of land consisting of the back of a gigantic fish, this story had been duly chronicled by a [Pg 26] succession of Irish monks, and when Jan Huygen visited these regions he was told of these strange islands far out in the ocean where the first travelers had discovered a large and prosperous colony of Christians who spoke an unknown language and whose city could disappear beneath the surface of the ocean if an enemy approached.

Once in the roads of Terceira, however, there was little time for theological investigations. Rumor had it that a large number of British ships were in the immediate neighborhood. Strict orders had come from Lisbon that all Portuguese and Spanish ships must stay in port under protection of the guns of the fortifications. Just a year before that the Armada had started out for the conquest of England and the Low Countries. The Invincible Armada had been destroyed by the Lord, the British, and the Dutch. Now the tables had been turned, and the Dutch and British vessels were attacking the Spanish and Portuguese colonies. The story of inefficient navigation is here supplemented by a recital of bad military management. [Pg 27] The roads of Terceira were very dangerous. In ordinary times no ships were allowed to anchor there. A very large number of vessels were now huddled together in too small a space. These vessels were poorly manned, for the Portuguese sailors, whenever they arrived in port, went ashore and left the care of their ship to a few cabin-boys and black slaves. The unexpected happened; during the night of the fourth of August a violent storm swept over the roads. The ships were thrown together with such violence that a large number were sunk. In the town the bells were rung, and the sailors ran to the shore. They could do nothing but look on and see how their valuable ships were driven together and broken to splinters, while pieces of the cargo were washed all over the shore, to be stolen by the inhabitants of the greedy little town. When morning came, the shore was littered with silk, golden coin, china, and bales of spices. Fortunately the wind changed later in the morning, and a good deal of the cargo was salved. But once on shore it was immediately confiscated [Pg 28] by officials from the custom-house, who claimed it for the benefit of the royal treasury. Then there followed a first-class row between the officials and the owners of the goods, who cursed their own Government quite as cheerfully as they had done their enemies a few days before.

To make a long story short, after a lawsuit of two years and a half the crown at last returned fifty per cent. of the goods to the merchants. The other half was retained for customs duty. Jan Huygen, who was an honest man, was asked to remain on the island and look after the interests of the owners while they themselves went to Lisbon to plead their cause before the courts. He now had occasion to study Portuguese management in one of the oldest of their colonies. The principles of hard common sense which were to distinguish Dutch and British methods of colonizing were entirely absent. Their place was taken by a complicated system of theological explanations. The disaster that befell these islands was invariably due to divine Providence. The local authorities were always up [Pg 29] against an "act of God." While Jan Huygen was in Terceira the colony was at the mercy of the British. The privateers waited for all the ships that returned from South America and the Indies, and intercepted these rich cargoes in sight of the Portuguese fortifications. When the Englishmen needed fresh meat they stole goats from the little islands situated in the roads. Finally, after almost an entire year, a Spanish-Portuguese fleet of more than thirty large ships was sent out to protect the traders. In a fight with the squadron of Admiral Howard the ship of his vice-admiral, Grenville, was sunk. The vice-admiral himself, mortally wounded, was made a prisoner and brought on board a Spanish man-of-war. There he died. His body was thrown overboard without further ceremonies.

At once, so the story ran, a violent storm had broken loose. This storm lasted a week. It came suddenly, and when the wind fell only thirty ships were left out of a total of one hundred and forty that had been in the harbors of the islands. The damage was so great that the [Pg 30] loss of the Armada itself seemed insignificant. Of course it was all the fault of the good Lord. He had deserted His own people and had gone over to the side of the heretics. He had sent this hurricane to punish the unceremonious way in which dead Grenville had been thrown into the ocean. And of course this unbelieving Britisher himself had at once descended into Hades, had called upon all the servants of the black demon to help him, and had urged this revenge. Evidently the thing worked both ways.

This clever argument did not in the least help the unfortunate owners of the shipwrecked merchandise. One fine day they were informed that they could no longer expect royal protection for the future. Jan Huygen was told to come to Lisbon as best he could. He finally found a ship, and after an absence of nine years returned to Lisbon. On his trip to Holland he was almost killed in a collision. Finally, within sight of his native land, he was nearly wrecked on the banks of one of the North Sea islands. On the third of September [Pg 31] of the year 1592, however, after an absence of thirteen years, he returned safely to Enkhuizen. His mother, brother, and sisters were there to welcome him.

He did not at once rush into print. It was not necessary. The news of his return spread quickly to the offices of the Amsterdam merchants. They had been very active during the last dozen years and they had conducted an efficient secret organization in Portugal, trying to buy up maps and books of navigation and, perhaps, even a pilot or two. They knew a few things, and guessed at many others. A man who had actually been there, who knew concrete facts where other people suspected, such a man was worth while. Jan Huygen became consulting pilot to Dutch capital.

The Dutch merchants still found themselves in a very difficult position. They had to enter this field of activity when their predecessors had been at work for almost two centuries. These predecessors, judging by outward evidences, were fast losing both ability and energy. But prestige before an old and well-established name [Pg 32] is a strong influence in the calculations of men. Those who directed the new Dutch Republic did not lack courage. All the same, they shrank from open and direct competition with the mighty Spanish Empire. Besides, there were other considerations of a more practical nature.

The Middle Ages, both late and early, dearly

loved monopoly. Indeed, the entire period between

the days of the old Roman Empire and

the latter part of the eighteenth century, when

the French Revolution destroyed the old system,

was a time of monopolies or of quarrels about,

and for, monopolies. The Dutch traders wondered

whether they could not obtain a little

private route to India, something that should be

Dutch all along the line, and could be closed at

will to all outsiders. What about the Northeastern

Passage? There seem to have been

vague rumors about a water route along the

north of Siberia. That part of the map was

but little known. The knowledge of Russia had

improved since the days when Moscow was situated

upon the exact spot where the ocean between

[Pg 33]

[Pg 34]

Iceland and Norway is deepest. The

White Sea was fairly well known, and Dutch

traders had found their way to the Russian port

of Archangel. What lay beyond the White Sea

was a matter of conjecture. Whether the Caspian

Sea, like the White Sea, was part of the

Arctic Sea or part of the Indian Ocean no one

knew. But it appeared that farther to the

north, several days beyond the North Cape,

there was a narrow strait between an island

which the Russians called the New Island

(Nova Zembla) and the continent of Asia.

This might prove to be a shorter and less dangerous

route to China and the Indies. Furthermore,

by building fortifications on both sides of

the narrows between the island and the Siberian

coast, the Hollanders would be the sole owners

of the most exclusive route to India. They

could then leave the long and tedious trip around

the Cape of Good Hope, with its perils of

storms, scurvy, royal and inquisitorial dungeons,

savage negroes, and several other unpleasant incidents,

to their esteemed enemies.

The men who were most interested in this [Pg 35] northern enterprise were two merchants who lived in Middleburg, the capital of the province of Zeeland. The better known of the two was Balthasar de Moucheron, an exile from Antwerp. When the Spanish Government reconquered this rich town it had banished all those merchants who refused to give up their Lutheran or Calvinistic convictions. Their wealth was confiscated by the state. They themselves were forced to make a new start in foreign lands. The foolishness of this decree never seems to have dawned upon the Spanish authorities. They felt happy that they had ruined and exiled a number of heretics. What they did not understand was that these heretics did not owe their success to their wealth, but to the sheer ability of their minds, and before long these penniless pilgrims had laid the foundations for new fortunes. Then they strove with all their might to be revenged upon the Government which had ruined them.

De Moucheron, one of this large group which had been expelled, had begun life anew in the free Republic and was soon among the [Pg 36] greatest promoters of his day. Of tireless energy and of a very bitter ambition, none too kindly to the leading business men of his adopted country, he got hold of Jan Huygen and decided to try his luck in a great gamble. He interested several of the minor capitalists of Enkhuizen, and on the fifth of June of the year 1594 Jan Huygen went upon his first polar exploration with two ships, the Mercurius and the Lwaan. Without adventure the ships passed the North Cape, sailed along the coast of the Kola peninsula, where Willoughby had wintered just forty years before, and reached the Straits of Waigat, the prospective Gibraltar of Dutch aspirations. The conditions of the ice were favorable.

On the first of August of the year 1594 the two ships entered the Kara Sea, which they called the New North Sea. Then following the coast, they entered Kara Bay. After a few days Jan Huygen discovered the small Kara River, the present frontier between Russia and Siberia. He mistook it for the Obi River, and thought that he had gone sufficiently eastward to be certain [Pg 37] of the practicability of the new route which he had set out to discover. The ice had all melted. As far as he could see there was open water. He cruised about in this region for several weeks, discovered a number of little islands, and sprinkled the names of all his friends and his employers upon capes and rivers and mountains. Finally, contented with what had been accomplished, he returned home. On the sixteenth of September of the same year he came back to the roads of Texel.

After that he was regarded as the leader in all matters of navigation. The stadholder, Prince Maurice, who had succeeded his father William after the latter had been murdered by one of King Philip's gunmen, sent for Jan Huygen to come to The Hague and report in person upon his discoveries. John of Barneveldt, the clever manager of all the financial and political interests of the republic, discussed with him the possibility of a successful northeastern trading company. Before another year was over Jan Huygen, this time at the head of a fleet of seven ships, was sent northward for a second voyage. [Pg 38] Everybody, from his Highness the stadholder down to the speculator who had risked his last pennies, had the greatest expectations. Nothing came of this expedition. As a matter of fact, Jan Huygen had met with exceptionally favorable weather conditions upon his first voyage; on the second he came in for the customary storms and blizzards. His ships were frozen in the ice, and for weeks they could not move. Scurvy attacked the crew and many men died.

In October of the same year he was back in Holland. The only result of the costly expedition was a dead whale that the captain had towed home as an exhibit of his good intentions. He was still a young man, not more than forty-five, but he had had his share of adventures. He did not join the third trip to the North in the next year, about which we shall give a detailed account in our next chapter. He was appointed treasurer of his native city. There he lived as its most respected citizen until the year 1611, when he died and was buried with great solemnity. His work had been done.

In the year 1595 the "Itinerary of His Voyage [Pg 39] to the East Indies" had been published. By this book he will always be remembered. For a century it provided a practical handbook of navigation which guided the Dutch traders to the Indies, allowed them to attack the Spaniards and Portuguese in their most vulnerable spot, and gave them the opportunity to found a colonial empire which has lasted to this very day.

Amsterdam, the capital of the new Dutch commonwealth, the rich city which alone counted more people within her wide walls than all of the country provinces put together, had ever been the leader in all matters which offered the chance of an honest penny. Her intellectual glory was a reflected one, her artistic fame was imported from elsewhere; but her exchange dictated its own terms to the rest of the country and to the rest of the world. When the Estates of the Republic gave up the hope of finding the route to India through the frozen Arctic Ocean, Amsterdam had the courage of her nautical convictions, and at her own expense she equipped a last expedition to proceed northward and discover this famous route, which had the advantage of being short and safe.

Out of this expedition grew the famous voyage of Barendsz and Heemskerk to Nova Zembla, the first polar expedition of which we possess a precise account. There were two ships. They were small vessels, for no one wished to risk a large investment on an expedition to the dangerous region of ice and snow. Fewer than fifty men took part, and all had been selected with great care. Married men were not taken; for this expedition might last many years, and it must not be spoiled by the homesick discontent of fathers of families.

Jan Corneliszoon de Ryp was captain of the smaller vessel. The other one was commanded by Jacob van Heemskerk, a remarkable man, an able sailor who belonged to an excellent family and entered the merchant marine at a time when the sea was reserved for those who left shore for the benefit of civic peace and sobriety. He had enjoyed a good education, knew something about scientific matters, and had been in the Arctic a year before with the last and unfortunate expedition of Linschoten. The real leader of this expedition, however, was a very simple [Pg 45] fellow, a pilot by the name of Willem, the son of Barend (Barendsz, as it is written in Dutch). He was born on the island of Terschelling and had been familiar with winds and tides since early childhood. Barendsz had two Northern expeditions to his credit, and had seen as much of the coast of Siberia as anybody in the country. A man of great resource and personal courage, combined with a weird ability to guess his approximate whereabouts, he guided the expedition safely through its worst perils. He died in a small open boat in the Arctic Sea. Without his devoted services none of the men who were with him would ever have seen his country again.

There was one other member of the ship's staff who must be mentioned before the story of the trip itself is told. That was the ship's doctor. Officially he was known as the ship's barber, for the professions of cutting whiskers and bleeding people were combined in those happy days. De Veer was a versatile character. He played the flute, organized amateur theatrical performances, kept everybody happy, and finally [Pg 46] he wrote the itinerary of the trip, of which we shall translate the most important part.

From former expeditions the sailors had learned what to take with them and what to leave at home. Unfortunately, contractors, then as now, were apt to be scoundrels, and the provisions were not up to the specifications. During the long night of the Arctic winter men's lives depended upon the biscuits that had been ordered in Amsterdam, and these were found to be lacking in both quality and quantity. There were more complaints of the same nature. As the leaders of the expedition fully expected to reach China, they took a fair-sized cargo of trading material, so that the Hollanders might have something to offer the heathen Chinee in exchange for the riches of paradise which this distant and mysterious land was said to possess. On the eighteenth of May everything was ready. Without any difficulty the Arctic Circle was soon reached and passed. Then the trouble began. When two Dutch sailors of great ability and equal stubbornness disagree about points of the compass there is little chance for an agreement. [Pg 47] The astronomical instruments of that day allowed certain calculations, but in a rather restricted field. As long as land was near it was possible to sail with a certain degree of precision, but when they were far away from any solid indications of charted islands and continent the captains of that day were often completely at a loss as to their exact whereabouts.

The reason why two of the previous expeditions had failed was known: the ships had been driven into a blind alley called the Kara Sea. In order to avoid a repetition of that occurrence it was deemed necessary to try a more northern [Pg 48] course. Barendsz, however, wanted to go due northeast, while De Ryp favored a course more to the west. For the moment the two captains compromised and stayed together. On the fifth of June the sailor on watch in the crow's-nest called out that he saw a lot of swans. The swans were soon found to be ice, the first that was seen that year.

Four days later a new island was discovered. Barendsz thought it must be part of Greenland. After all, he argued, he had been right; the ships had been driven too far westward. De Ryp denied this, and his calculation proved to be true. The ships were still far away from Greenland. The islands belonged to the Spitzbergen Archipelago. On the nineteenth of June they discovered Spitzbergen. The name (steep mountains) describes the island. An expedition was sent ashore, after which we get the first recital of one of the endless fights with bears that greatly frightened the good people in those days of blunderbusses. Nowadays polar bears, while still far removed from harmless kittens, offer no grave danger to modern guns. But the bullets [Pg 49] of the small cannon which four centuries ago did service as a rifle refused to penetrate the thick hide of a polar bear. The pictures of De Veer's book indicate that these hungry mammals were not destroyed until they had been attacked by half a dozen men with gunpowder, axes, spears, and meat-choppers.

A very interesting discovery was made on this new island. Every winter wild geese came to the Dutch island of the North Sea. Four centuries ago they were the subject of vague ornithological speculations, for, according to the best authorities of the day, these geese did not behave like chickens and other fowl, which brought up their families out of a corresponding number of eggs. No, their chicks grew upon regular trees in the form of wild nuts. After a while these nuts tumbled into the sea and then became geese. Barendsz killed some of the birds and he also opened their eggs. There were the young chicks! The old myth was destroyed. "But," as he pleasantly remarked, "it is not our fault that we have not known this before, when these birds insist upon breeding so far northward."

On the twenty-fifth of June, Spitzbergen was left behind, and once more a dispute broke out between the two skippers over the old question of the course which was to be taken. Like good Dutchmen, they decided that each should go his own way. De Ryp preferred to try his luck farther to the north. Barendsz and Heemskerk decided to go southward. They said farewell to their comrades, and on the seventeenth of July reached the coast of Nova Zembla. The coast of the island was still little known; therefore the usual expediency of that day was followed. They kept close to the land and sailed until at [Pg 51] last they should find some channel that would allow them to pass through into the next sea. They discovered no channel, but on the sixth of August the northern point of Nova Zembla, Cape Nassau, was reached. There was a great deal of ice, but after a few days open water appeared.

The voyage was then continued. Their course then seemed easy. Following the eastern coast downward they were bound to reach the Strait of Kara. Avoiding the Kara Sea, they made for the river Obi and hoped that all would be well. But before the ship had gone many days the cold weather of winter set in, and before the end of August the ship was solidly frozen into the ice. Many attempts were made to dig it out and push it into the open water. The men worked desperately; but the moment they had sawed a channel through the heavy ice to the open sea more ice-fields appeared, and they had to begin all over again. On the thirtieth of August a particularly heavy frost finally lifted the little wooden ship clear out of the ice. Then came a few days of thaw, [Pg 52] during which they hoped to get the vessel back into shape and into the water. But the next night there was a repetition of the terrible creakings. The ship groaned as if it were in great agony, and all the men rushed on shore.

The prospect of spending the winter in this desolate spot began to be more than an unspoken fear. Any night the vessel might be destroyed by the violent pressure of the ice. An experienced captain knew what to do in such circumstances. All provisions were taken on shore, and the lifeboats were safely placed on the dry land. They would be necessary the next summer to reach the continent. Another week passed, and the situation was as uncertain as before. By the middle of September, however, all hope had to be given up. The expedition was condemned to spend the winter in the Arctic. The ship's carpenter became a man of importance. Near the small bay into which the vessel had been driven he found a favorable spot for a house. A little river near by provided fresh water. On the whole it was an advantageous spot for shipwrecked sailors, for a short [Pg 53] distance towards the north there was a low promontory. The western winds had carried heavy trees and pieces of wood from the Siberian coast, and this promontory had caught them. They were neatly frozen in the ice. All the men needed to do was to take these trees out of their cold storage and drag them ashore which, however, did not prove to be so easy a task as it sounds. There were only seventeen men on the ship, and two of them were too ill to do any work. The others were not familiar with the problem of how to saw and plane water-soaked and frozen logs into planks. Even [Pg 54] when this had been done the wood must be hauled a considerable distance on home-made sleighs, clumsy affairs, and very heavy on the soft snow of the early winter.

Unfortunately, after two weeks the carpenter of the expedition suddenly died. It was not easy to give him decent Christian burial. The ground was frozen so hard that spades and axes could not dig a grave; so the carpenter was reverently laid away in a small hollow cut in the solid ice and covered with snow.

When their house was finished it did not offer many of the comforts of home, but it was a shelter against the ever-increasing cold. The roof offered the greatest difficulty to the inexperienced builders. At last they hit upon a scheme that proved successful: they made a wooden framework across which they stretched one of the ship's sails. This they covered with a layer of sand. Then the good Lord deposited a thick coat of snow, which gradually froze and finally made an excellent cover for the small wooden cabin which was solemnly baptized "Safe Haven." There were no windows—fresh [Pg 55] air had not yet been invented—and what was the use of windows after the sun had once disappeared? There was one door, and a hole in the roof served as a chimney. To make a better draft for the fire of driftwood which was kept burning day and night in the middle of the cabin floor, a large empty barrel was used for a smoke-stack. Even then the room was full of smoke during all the many months of involuntary imprisonment, and upon one occasion the lack of ventilation almost killed the entire expedition.

While they were at work upon the house the men still spent the night on board their ship. When morning came, with their axes and saws [Pg 56] and planes they walked over to the house. But hardly a day went by without a disturbing visit from the much-dreaded polar bears. After some of the provisions had been removed from the ship to the house the bears became more insistent than ever. Upon one occasion when the bears had gone after a barrel of pickled meat, as shown with touching accuracy in the picture, the concerted action of three sailors was necessary to save the food from the savage beasts. Another time, when Heemskerk, De Veer, and one of the sailors were loading provisions upon a sleigh they were suddenly attacked by three huge bears. They had not brought their guns, [Pg 57] but they had two halberds, with which they hit the foremost bear upon the snout; and then they fled to the ship and climbed on board. The bears followed, sat down patiently, and laid siege to the ship. The three men on board were helpless. Finally one of them hit upon the idea of throwing a stick of kindling-wood at the bears. Like a well-trained dog, the animal that was struck chased the stick, played with it, and then came back to ask for further entertainment. At last all the kindling-wood laid strewn across the ice, and the bears had had enough of this sport. They made ready to storm the ship, but a lucky stroke with a halberd hit one of them so severely upon the sensitive tip of his nose that he turned around and fled. The others followed, and Heemskerk and his companions were saved.

When the month of November came and the sun had disappeared, the bears also took their departure, rolled themselves up under some comfortable shelter, and went to sleep for the rest of the winter. Now the sailors could wander about in peace, for the only other animal that kept awake all through the year was the polar [Pg 58] fox. He was a shy beastie and never came near a human being. The sailors, however, hunted him as best they could. Not only did they need the skins for their winter garments, but stewed fox tasted remarkably like the domestic rabbit and was an agreeable change from the dreary diet of salt-flesh. In Holland before the introduction of firearms rabbits were caught with a net. The same method was tried on Nova Zembla with the more subtle fox. Unfamiliar with the wiles of man, he actually allowed himself to be caught quite easily. Later on traps were also built. But the method with the net was more popular, for the men had the greatest aversion to the fresh air of the freezing polar night and never left the house unless they were ordered to do some work. When they went hunting with the net they could pass the string that dropped the mechanism right under the door and stay inside, where it was warm and cheerful, and yet catch their fox.

On the sixth of November the sun was seen for the last time. On the seventh, when it was quite dark, the clock stopped suddenly in the [Pg 59] middle of the night, and when the men got up in the morning they had lost the exact time. For the rest of the winter they were obliged to guess at the approximate hour; not that it mattered so very much, for life had become an endless night: one went to bed and got up through the force of habit acquired by thousands of previous generations. If the men had not been obliged to, they never would have left their comfortable beds. They had but one idea, to keep warm. The complaint about the insufferable cold is the main motive in this Arctic symphony. Lack of regular exercise was chiefly to blame for this "freezing feeling"—lack of exercise and the proper underwear. It is true that the men dressed in many layers of heavy skins, but their lower garments, which nowadays play a great part in the life of modern explorers, were sadly neglected. In the beginning they washed their shirts regularly, but they found it impossible to dry them; for just as soon as the shirt was taken out of the hot water it froze stiff. When they carried the frozen garment into the house to thaw it out before the fire it was either singed and burned in [Pg 60] spots or it refused absolutely to melt back into the shape and aspect of a proper shirt. Finally the washing was given up, as it has been on many an expedition, for cleanliness is a costly and complicated luxury when one is away from the beaten track of civilization.

The walls of the house had been tarred and calked like a ship. All the same, when the first blizzards occurred, the snow blew through many cracks, and every morning the men were covered [Pg 61] with a coat of snow and ice. Hot-water bottles had not yet been invented, but at night large stones were roasted in the fire until they were hot, and then were placed in the bunks between the fur covers. They helped to keep the men warm, and incidentally they burned their toes before they knew it. Not only did the men suffer in this way. That same clock which I have already mentioned at last succumbed to the strain of alternating spells of heat and cold. It began to go slower and slower. To keep it going at all, the weight was increased every few days. At last, however, a millstone could not have coaxed another second out of the poor mechanism. From that moment on an hour-glass was used. One of the men had to watch it, and turn it over every sixty minutes.

All this time, while the men never ceased their complaint about feeling cold, the heating problem had been solved by fires made of such kindling-wood as the thoughtful ocean had carried across from the Siberian coast and deposited upon the shore. Finally, however, in despair at ever feeling really warm again, if only for a [Pg 62] short while, it was decided, as an extra treat, to have a coal fire. There was some coal on board the ship, but it had been saved for use upon the homeward trip in the spring, when the men would be obliged to travel in open boats. The coal was brought to the house. The worst cracks in the walls were carefully filled with tar and rope, and somebody climbed to the roof and closed the chimney; not an ounce of the valuable heat must be lost. As a result the men felt comfortable for the first time in many months; they also came very near losing their lives. Having dozed off in the pleasant heat they had not noticed that their cabin was filling with coal-gas until finally some of them, feeling uncomfortable, tried to get up, grew dizzy, and fainted. Our friend the barber, possessed of more strength than any of the others, managed to creep to the door. He kicked it open and let in the fresh air. The men were soon revived, and the captain treated them all to a glass of wine to celebrate the happy escape. No further experiments with coal were made during that year.

December was a month of steady blizzards. The snow outside piled up in huge drifts which soon reached to the roof. The hungry foxes, attracted by the smell of cookery wafted abroad through the barrel-chimney, used to gallop across the roof, and at night their dismal and mean little bark kept the men in their bunks awake. At the same time their close proximity made trapping easier, and the skins were now doubly welcome; for the shoes, bought in Holland, had been frozen so often and had been thawed out too near the fire so frequently that they were leaking like sieves and could no longer be worn. New shoes were cut out of wood and covered with fox-fur. They provided comfortable, though far from elegant, footwear.

New Year's day was a dreary feast, for all the men thought of home and were melancholy and sad. Outside a terrible snow-storm raged. It continued for an entire week. No one dared to go outside to gather wood, fearing the wind and cold would kill them. In this extremity they were obliged to burn some of their home-made furniture. On the fifth of January the blizzard [Pg 64] stopped. The door was opened, the cabin was put in order, wood was brought from the woodpile, and then one of the men suddenly remembered the date and how at home the feast of the Magi was being celebrated with many happy and innocent pastimes. The barber decided to organize a little feast. The first officer was elected to be "King of Nova Zembla." He was crowned with due solemnity. A special dinner of hot pancakes and rusks soaked in wine was served, and the evening was such a success that many imagined themselves safely home in their beloved fatherland. A new blizzard reminded them that they were still citizens of an Arctic island.

On the sixteenth of January, however, the men who had been sent out to look after the traps and bring in wood suddenly noticed a glimmer of red on the horizon. It was a sign of the returning sun. The dreary months of imprisonment were almost over. From that moment the heating problem became less difficult. On the contrary, the roof and the walls now began to leak, and the expedition had its first taste of the thaw [Pg 65] which would be even more fatal than the cold weather had proved to be. As has been remarked, these men had been leading a very unhealthy life. While it was still light outside they had sometimes played ball with the wooden knob of the flagpole of the ship, but since early November they had taken no exercise of any sort. A few minutes spent out of doors just long enough to kill the foxes in the traps was all the fresh air they ever got. Out of a barrel they had made themselves a bath-tub, and once a week every man in turn had climbed through the little [Pg 66] square opening into that barrel (see the picture) to get steamed out. But this mode of living, combined with bad food, brought half a year before from Holland, together with the large quantity of fox-meat, now caused a great deal of scurvy, and the scurvy caused more dangerous illness. Barendsz, the man upon whom they depended to find the way home, was already so weak that he could not move. He was kept near the fire on a pile of bearskins. On the twenty-sixth of January another man who had been ill for some time suddenly died. His comrades had done all they could to save him. They had cheered him with stories of home, but shortly after midnight of that day he gave up the ghost. Early the next morning he was buried near the carpenter. A chapter of the Bible was read, a psalm was sung, and his sorrowful companions went home to eat breakfast.

None of the men were quite as strong as they had been. Among other things, they hated the eternal bother of keeping the entrance to the door clear of snow. Why should they not abolish the door, and like good Eskimos enter and leave [Pg 67] their dwelling-place through the chimney? Heemskerk wanted to try this new scheme and he got ready to push himself through the narrow barrel. At the same time one of the men rushed to the door to go out into the open and welcome the skipper when he should stick his head through the barrel; but before he espied the eminent leader of the expedition he was struck by another sight: the sun had appeared above the horizon. Apparently Barendsz, who had tried to figure out the day and week of the year after they had lost count of the calendar, had been wrong in his calculation. According to him, there were to be two weeks more of darkness. And now, behold! there was the shining orb, speedily followed by a matutinal bear. The lean animal was at once killed and used to replenish the oil of the odorous little lamp which for more than three months had provided the only light inside the cabin.

February came and went, but as yet there were no signs of the breaking up of the ice. During the first day of March a little open water was seen in the distance, but it was too far away to [Pg 68] be of any value to the ship. An attempt was made to push the ship out of its heavy coat of ice, but the men at once complained that they were too weak to do much work. Some of them had had their toes frozen and could not walk. Others suffered from frost-bite on their hands and fingers and were unable to hold an ax. When they went outside only incessant vigilance saved them from the claws of the skinny bears that were ready to make up for the long winter's fast. Once a bear almost ate the commander, who was just able to jump inside the house and slam the door on bruin's nose. Another time a bear climbed on the roof, and when he could not get into the chimney, he got hold of the barrel and rocked that architectural contrivance until he almost ruined the entire house. It was very spooky, for the attack took place in the middle of the night, and it was impossible to go out and shoot the monster.

March passed, and the ship, which had been seventy yards away from the water when it was deserted in the autumn of 1595, was now more than five hundred yards away from the open sea. [Pg 69] The intervening distance was a huge mass of broken ice and snow-drifts. It seemed impossible to drag the boats quite so far. When on the first of May the last morsel of salt meat had been eaten, the men appeared to be as far away from salvation as ever. There was a general demand that something be done. They had had enough of one winter in the Arctic, and would rather risk a voyage in an open boat than another six months of cold bunks and tough fox-stew, and reading their Bible by the light of a single oil-lamp.

Fortunately—and this is a great compliment to a dozen men who have been cooped up in a small cabin for six months of dark and cold—the spirit of the sailors had been excellent, and discipline had been well maintained. They did not make any direct demands upon the captain. The question of going or staying they discussed first of all with the sick Barendsz, and he in turn mentioned it to Heemskerk. Heemskerk himself was in favor of waiting a short while. He reasoned that the ice might melt soon, and then the ship could be saved. He, as captain, was responsible for his craft. He asked that they wait two weeks more. If the condition of the ice was still unsatisfactory at the end of that time, they would give up the ship and try to reach home in the boats. Meanwhile the men could get ready for the trip. They set to work at once cleaning and repairing their fur coats, sharpening their tools, and covering their shoes with new skins to keep their feet from freezing during the long weeks in the open boats.

An eastern storm on the last day of May filled their little harbor with more ice, and all hope of [Pg 71] saving the ship was given up. The return trip must be made in the open boats. There were two, a large and a small one. They had been left on land in the autumn, and were now covered with many feet of frozen snow. A first attempt to dig them out failed. The men were so weak that they could not handle their axes and spades. The inevitable bear attacked them, drove them post-haste back to the safe shelter of the house, and so put an end to the first day's work.

The next morning the men went back to their work. Regular exercise and fresh air soon gave them greater strength, while the dire warning of Heemskerk that, unless they succeeded, they would be obliged to end their days as citizens of Nova Zembla provided an excellent spur to their digging enthusiasm. The two boats were at last dragged to the house to be repaired. They were in very bad condition, but since there was no further reason for saving the ship there was sufficient wood with which to make good the damage. From early to late the men worked, the only interruptions being the dinner-hour and [Pg 72] the visits of the bears. "But," as De Veer remarked in his pleasant way, "these animals probably knew that we were to leave very soon, and they wanted to have a taste of us before we should have gone for good." Before that happy hour arrived the expedition was threatened with a novel, but painful, visitation. To vary the monotonous diet of bearsteak, the men had fried the liver. Three of them had eaten of this dish and fell so ill that all hope was given up of saving their lives. The others, who knew that they could not handle the boats if three more sailors were to die, waited in great anxiety. Fortunately on the fourth day the patients showed signs of improvement and finally recovered. There were no further experiments with scrambled bear's liver.

After that the work on the two boats proceeded with speed, and by the twelfth of June everything was ready. The boats, now reinforced for the long trip across the open water of the Arctic Ocean, had to be hauled to the sea, and the ever-shifting wind had once more put a high ice-bank between the open water and the [Pg 73] shore. A channel was cut through the ice with great difficulty, for there were no tools for this work. After two days more the survivors of this memorable shipwreck were ready for the last part of their voyage. Before they left the house Barendsz wrote three letters in which he recounted the adventures of the expedition. One of these letters was placed in a powder-horn which was left hanging in the chimney, where it was found two hundred and fifty years later.

On the morning of the fourteenth, Barendsz and another sick sailor who could no longer walk were carried to the boats. With a favorable [Pg 74] wind from the south they set sail for the northern cape of Nova Zembla, which was soon reached. Then they turned westward, and followed the coast until they should reach the Siberian continent. The voyage along the coast was both difficult and dangerous. The two boats were not quite as large as the life-boats of a modern liner. Being still too weak to row, the men were obliged to sail between huge icebergs, often being caught for hours in the midst of large ice-fields. Sometimes they had to drag the boats upon the ice while they hacked a channel to open water. After a week the condition of the ice forced them to pull the boats on shore and wait for several days before they could go [Pg 75] any farther. Great and tender care was taken of the sick pilot and the dying sailor, but those nights spent in the open were hard on the sufferers. On the morning of the twentieth of June the sailor, whose name was Claes Andriesz, felt that his end was near. Barendsz, too, said he feared that he would not last much longer. His active mind kept at work until the last. De Veer, the barber, had drawn a map of the coast, and Barendsz offered suggestions. Capes and small islands off the coast were definitely located, placed in their correct geographical positions, and baptized with sound Dutch names.

The end of Barendsz came very suddenly. Without a word of warning he turned his eyes toward heaven, sighed, and fell back dead. A few hours later he was followed by the faithful Claes. They were buried together. Sad at heart, the survivors now risked their lives upon the open sea. They had all the adventures not uncommon to such an expedition. The boats were in a rotten condition; several times the masts broke, and most of the time the smaller boat was half full of water. The moment they [Pg 76] reached land and tried to get some rest, there was a general attack by wild bears. And once a sudden break in a field of ice separated the boats from the provisions, which had just been unloaded. In their attempt to get these back several men broke through the ice. They caught cold, and on the fifth of July another sailor, a relative of Claes, who had died with Barendsz, had to be buried on shore.

During all this misery we read of a fine example of faithful performance of duty and of devotion to the interest of one's employers. You will remember that this expedition had been sent out to reach China by the Northeast Passage and to establish commercial relations with the merchants of the great heathen kingdom. For this purpose rich velvets and other materials agreeable to the eyes of Chinamen had been loaded onto the ship when they left Amsterdam. Heemskerk felt it his duty to save these goods, and he had managed to keep them in safety. Now that the sun shone with some warmth, the packages were opened and their contents dried. When Heemskerk came back to Amsterdam the [Pg 77] materials were returned to their owners in good condition.

On the eleventh of June of the year 1597 the boats were approaching the spot where upon previous voyages large colonies of geese had been found. They went ashore and found so many eggs that they did not know how to take them all back to the boats. So two men took down their breeches, tied the lower part together with a piece of string, filled them with eggs, and carried their loot in triumph back to the others on board.

That was almost their last adventure with polar fauna, except for an attack by infuriated seals whose quiet they had disturbed. The seals almost upset one of the boats. The men had no further difficulties, however. On the contrary, from now on everything was plain sailing; and it actually seemed to them that the good Lord himself had taken pity upon them after their long and patient suffering, for whenever they came to a large ice-field it would suddenly separate and make a clear channel for their boats; and when they were hungry they found that the [Pg 78] small islands were covered with birds that were so tame that they waited to be caught and killed.

At last, on the twenty-seventh of July, they arrived in open water where they discovered a strong eastern current. They decided that they must be near Kara Strait. The next morning they hoped to find out for certain. When the next morning came they suddenly beheld two strange vessels near their own boats. They were fishing-smacks, to judge by their shape and size, but nothing was known about their nationality, for they flew no flags, and it was well to be careful in the year of grace 1597. Therefore a careful approach was made. To Heemskerk's great [Pg 79] joy, the ships were manned by Russians who had seen the fleet of Linschoten several years before and remembered some of the Hollanders. There were familiar faces on both sides, and this first glimpse of human beings did more to revive the courage of the men than the doubtful food which the Russians forced with great hospitality upon their unexpected guests. The following day the two fishing-boats set sail for the west, and Heemskerk followed in their wake. But in the afternoon they sailed into a heavy fog and when it lifted no further trace of the Russians could be found. Once more the two small boats were alone, with lots of water around them and little hope before them.

By this time all of the men had been attacked by scurvy and they could no longer eat hard-tack, which was the only food left on board. Divine interference again saved them. They found a small island covered with scurvy-grass (Cochlearia officinalis) the traditional remedy for this painful affliction. Within a few days they all recovered, and could row across the current of the straits which separated them from [Pg 80] the continent. Here they found another Russian ship. Then they discovered that their compass, on account of the proximity of heavy chests and boxes covered with iron rings, had lost all track of the magnetic pole and that they were much farther toward the east than they had supposed. They deliberated whether they should continue their voyage on land or on sea. Finally they decided to stick to their boats and their cargo. Once more they closely followed the coast until they came to the mouth of the White Sea. That meant a vast stretch of dangerous open water, which must be crossed at great risk. The first attempt to reach the other shore failed. The two boats lost sight of each other, and they all worried about the fate of their comrades. On the eighteenth of August the second boat managed to reach the Kola peninsula after rowing for more than thirty hours.