“Come on, old man.”

Lawrence led the way with a jaunty step that was intended to show his easy footing with the Carters. But Marley lagged behind. Even if calling on girls had not been such a serious business with him, he could not forget that he was just graduated from college and that a certain dignity befitted him. He wished Lawrence would not speak so loud; the girls might hear, and think he was afraid; he wished to keep the truth from them as long as possible. He had already caught a glimpse of the girls, or thought he had, but before he could make sure, the vague white figures on the veranda stirred; he heard a scurrying, and the loose bang of a screen door. Then it was still. Lawrence laughed—somehow, as Marley felt, derisively.

The way from the sidewalk up to the Carters’ veranda was not long, of course, though it seemed long to Marley, and Marley’s deliberation made it seem long to Lawrence. They paused at the steps of the veranda, and Lawrence made a low bow.

“Good evening, Mrs. Carter,” he said. “Ah, Captain, you here too?”

Marley had not noticed the captain, or Mrs. Carter; they sat there so quietly, enjoying the cool of the evening, or such cool as a July evening can find in central Ohio.

“My friend, Mr. Marley, Mrs. Carter—Glenn Marley—you’ve heard of him, Captain.”

Marley bowed and said something. The presentation there in the darkness made it rather difficult for him, and neither the captain nor his wife moved. Lawrence sat down on the steps and fanned himself with his hat.

“Been a hot day, Captain,” he said. “Think there’s any sign of rain?” He sniffed the air. The captain did not need to sniff the air to be able to reply, in a voice that rumbled up from his bending figure, that he had no hope of any.

“Mayme’s home, ain’t she?” asked Lawrence, turning to Mrs. Carter.

“I’ll go see,” said Mrs. Carter, and she rose quickly, as if glad to get away, and the screen door slammed again.

“Billy was in the bank to-day,” Lawrence went on, speaking to Captain Carter. “He said your wheat was ready to cut. Did you get Foose all right?”

“Yes,” said the captain, “he’ll give me next week.”

“Do you have to board the threshers?”

“No, not this year; they bring along their own cook, and a tent and everything.”

“Je-rusalem!” exclaimed Lawrence. “Things are changing in these days, ain’t they? Harvesting ain’t as hard on the women-folks as it used to be.”

“No,” said the captain, “but I pay for it, so much extra a bushel.”

His head shook regretfully, but he would have lost his regrets in telling of the time when he had swung a cradle all day in the harvest field, had not Mrs. Carter’s voice just then been heard calling up the stairs:

“Mayme!”

“Whoo!” answered a high, feminine voice.

“Come down. There’s some one here to see you.”

Mrs. Carter turned into the parlor, and the tall windows that opened to the floor of the veranda burst into light.

“She’ll be right down, John,” said Mrs. Carter, appearing in the door. “You give me your hats and go right in.”

“All right,” said Lawrence, and he got to his feet. “Come on, Glenn.”

Mrs. Carter took the hats of the young men and hung them on the rack, where they might easily have hung them themselves. Then she went back to the veranda, letting the screen door bang behind her, and Lawrence and Marley entered the parlor. Marley took his seat on one of the haircloth chairs that seemed to have ranged themselves permanently along the walls, and Lawrence went to the square piano that stood across one corner of the room, and sat down tentatively on the stool, swinging from side to side.

Marley glanced at the pictures on the walls. One of them was a steel engraving of Lincoln and his cabinet; another, in a black oval frame, portrayed Captain Carter in uniform, his hair dusting the strapped shoulders of a coat made after the pattern that seems to have been worn so uncomfortably by the heroes of the Civil War. There was, however, a later picture of the captain, a crayon enlargement of a photograph, that had taken him in civilian garb. This picture, in its huge gilt frame, was the most aggressive thing in the room, except, possibly, the walnut what-not. Marley had a great fear of the what-not; it seemed to him that if he stirred he must topple it over, and dash its load of trinkets to the floor. Presently he heard the swish of skirts. Then a tall girl came in, and Lawrence sprang to his feet.

“Hello, Mayme. What’d you run for?” he said.

He had crossed the room and seized the girl’s hand. She flashed a rebuke at him, though it was evident that the rebuke was more out of deference to the strange presence of Marley than for any real resentment she felt.

“This is my friend, Mr. Marley, Miss Carter,” Lawrence said. “You’ve heard me speak of him.”

Marley edged away from the what-not, rose and took the hand the girl gave him. Then Miss Carter crossed to the black haircloth sofa and seated herself, smoothing out her skirts.

“Didn’t know what to do, so we thought we’d come out and see you,” said Lawrence.

“Oh, indeed!” said Miss Carter. “Well, it’s too bad about you. We’ll do when you can’t find anybody else to put up with you, eh?”

“Oh, yes, you’ll do in a pinch,” chaffed Lawrence.

“Well, can’t you find a comfortable seat?” the girl asked, still addressing Lawrence, who had gone back to the piano stool.

“I’m going to play in a minute,” said Lawrence, “and sing.”

“Well, excuse me!” implored Miss Carter. “Do let me get you a seat.”

Lawrence promptly went over to the sofa and leaned back in one corner of it, affecting a discomfort.

“Can’t I get you a pillow, Mr. Lawrence?” Miss Carter asked presently. “Or perhaps a cot; I believe there’s one somewhere in the attic.”

“Oh, I reckon I can stand it,” said Lawrence.

Marley had regained his seat on the edge of the slippery chair.

“Where’s Vinie?” asked Lawrence.

“She’s coming,” answered Miss Carter.

“Taking out her curl papers, eh?” said Lawrence. “She needn’t mind us.”

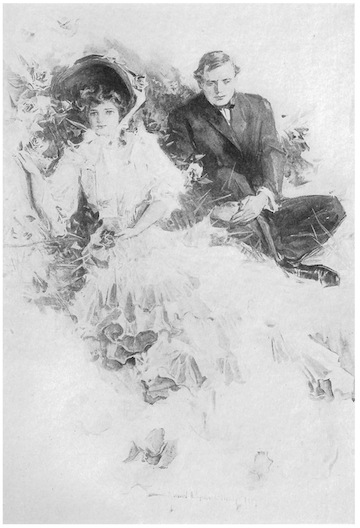

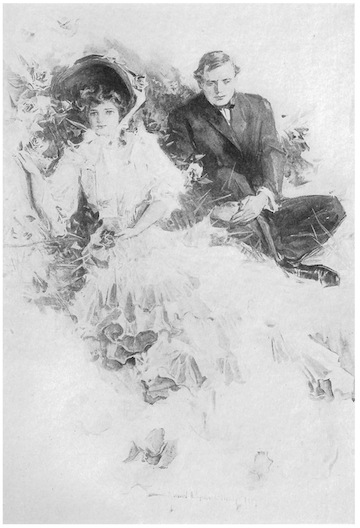

Miss Carter pretended a disgust, but as she was framing a retort, somehow, the eyes of all of them turned toward the hall door. A girl in a gown of white stood there clasping and unclasping her hands curiously, and looking from one to another of those in the room.

“Come in, Lavinia,” said Miss Carter. Something had softened her voice. The girl stepped into the room almost timidly.

“Miss Blair,” said Miss Carter, “let me introduce Mr. Marley.”

The sudden consciousness that he had been sitting—and staring—smote Marley, and he sprang to his feet. Embarrassment overpowered him and he bowed awkwardly. Lawrence had been silent, and his silence had been a long one for him. Seeming to recognize this he hastened to say:

“Well, how’s the world using you, Vinie?”

The girl smiled and answered:

“Oh, pretty well, thank you, Jack.”

It grated on Marley to hear her called Vinie. Lavinia Blair! Lavinia Blair! That was her name. He had heard it before, of course, yet it had never sounded as it did now when he repeated it to himself. The girl had seated herself in a rocking-chair across the room, almost out of range, as it were. He was rather glad of this, if anything. It seemed to relieve him of the duty of talking to her. He supposed, of course, they would pair off somehow. The young people always did in Macochee. He supposed he had been brought there to pair off with Lavinia Blair. He liked the thought, yet the position had its responsibilities. Somehow he never could forget that he could not dance. He hoped they would not propose dancing. He always had a fear of that in making calls, and all the calls he made seemed to come to it soon or late; some one always proposed it.

Marley was aware that Lawrence and Mayme Carter had resumed the exchange of their rude repartee, though he did not know what they had said. They kept laughing, too. Lavinia Blair seemed to join in the laughter if not in the badinage. Marley wished he might join in it. Jack Lawrence was evidently funnier than ever that night; Mayme Carter was convulsed. Now and then Lawrence said something to her in a tone too low for the others to hear, and these remarks pushed her to the verge of hysterics. Marley had a notion they were laughing at him.

Meanwhile Lavinia Blair sat with her hands in her lap, smiling as though she were amused. Marley wondered if he amused her. He felt that he ought to say something, but he did not know what to say. He thought of several things, but, as he turned them over in his mind, he was convinced that they were not appropriate. So he sat and looked at Lavinia Blair, looked at her eyes, her mouth, her hair. He thought he had never seen such a complexion.

Mayme Carter had snatched her handkerchief back from Lawrence, and retreated to her end of the sofa. There she sat up stiffly, folded her hands, and, though her mirth still shook her spasmodically, she said:

“Now, Jack, behave yourself.”

Lawrence burlesqued a surprise, and said:

“I’ll leave it to Vine if I’ve done anything.”

Marley wondered how much further abbreviation Lavinia Blair’s name would stand, but he was suddenly aware that he was being addressed. Miss Carter, with an air of dismissing Lawrence, said:

“You have not been in Macochee long, have you, Mr. Marley?”

Marley admitted that he had not, but said that he liked the town. When Lawrence explained that Marley was going to settle down there and become one of them, Miss Carter said she was awfully glad, but warned him against associating too much with Lawrence. This embarrassed Marley, if it did not Lawrence, and he immediately gave the scene to Lawrence, who guessed he would sing his song. To do so he went to the piano, and began to pick over the frayed sheets of music that lay on its green cover. To forestall him, however, Miss Carter rushed across the room and slid on to the piano stool herself, saying breathlessly:

“Anything to stop that!”

She struck a few vagrant chords, and Marley, glad of a subject on which he could express himself, pleaded with her to play. At last she did so. When she had finished, Lawrence clapped his hands loudly, and stopped only when a voice startled them. It was Mrs. Carter calling through the window:

“Play your new piece, Mayme!”

Miss Carter demurred, but after they had argued the question through the window, the daughter gave in, and played it. The music soothed Lawrence to silence, and when Miss Carter completed her little repertoire, his mockery could recover itself no further than to say:

“Won’t you favor us, Miss Blair?”

When Lavinia Blair declined, he struck an imploring attitude and said:

“Oh, please do! We’re dying to hear you. You didn’t leave your music at home, did you?”

Marley heard the chairs scraping on the veranda, and the screen door slammed once more. Then he heard Captain Carter go up the stairs, while Mrs. Carter halted in the doorway of the parlor long enough to say:

“You lock the front door when you come up, Mayme.”

Mayme without turning replied “All right,” and when her mother had disappeared she said:

“It’s awful hot in here, let’s go outside.”

Marley found himself strolling in the yard with Lavinia Blair. The moon had not risen, but the girl’s throat and arms gleamed in the starlight; her white dress seemed to be a cloud of gauze; she floated, rather than walked, there by his side. They paused by the gate. About them were the voices of the summer night, the crickets, the katydids, far away the frogs, chirping musically. They stood a while in the silence, and then they turned, and were talking again.

Marley did most of the talking, and all he said was about himself, though he did not realize that this was so. He had already told her of his life in the towns where his father had preached before he came to Macochee, and of his four years in college at Delaware. He tried to give her some notion of the sense of alienation he had felt as the son of an itinerant Methodist minister; for him no place had ever taken on the warm color and expression of home. He explained that as yet he knew little of Macochee, having been away at college when his father moved there the preceding fall. It was so easy to talk to her, and as he told her of his ambitions, the things he was going to do became so many, and so easy. He was going to become a lawyer; he thought he should go to Cincinnati.

“And leave Macochee?” said Lavinia Blair.

Marley caught his breath.

“Would you care?” he whispered.

She did not answer. He heard the crickets, the katydids, the frogs again; there came the perfume of the lilacs, late flowering that year; the heavy odor of a shrub almost overpowered him.

“My father is a lawyer,” Lavinia said.

They had turned off the path, and were wandering over the lawn. The dew sparkled on it; and Marley became solicitous.

“Won’t you get your feet wet?” he asked.

The girl laughed at the idea, but she caught up her skirts, and they wandered on in the shade of the tall elms. Marley did not know where they were. The yard seemed an endless garden, immense, unknown, enchanted; the dark trees all around him stood like the forest of some park, and the lawn stretched away to fall over endless terraces; he imagined statues and fountains gleaming in the heavy shadows of the trees. The house seemed lost in the distance, though he felt its presence there behind him.

Once he saw the twinkle of a passing light in an upper story. He could no longer hear the voices of Mayme and Lawrence, but he caught the tinkling notes of a banjo, away off somewhere. Its music was very sweet. They strolled on, their feet swishing in the damp grass, then suddenly there was a rush, a loud barking, and a dog sprang at them out of the darkness. Lavinia gave a little cry. Marley was startled; he felt that he must run, yet he thought of the girl beside him. He must not let her see his fear. He stepped in front of her. He could feel her draw more closely to him, and he thrilled as the sense of his protectorship came to him. He must think of some heroic scheme of vanquishing the dog, but it stopped in its mad rush, and Lavinia, standing aside, said:

“Why, it’s only Sport!”

They laughed, and their laugh was the happier because of the relief from their fear.

“We must have wandered around behind the house,” said Lavinia. “There’s the shed.”

They turned, and went back. The enchantment of the yard had departed. Marley seemed to see things clearly once more, though his heart still beat as he felt the delicious sense of protectorship that had come over him as Lavinia shrank to his side at the moment the dog rushed at them. Nor could he ever forget her face as she smiled up at him in the little opening they came into on the side lawn. The young moon was just sailing over the trees. As they approached the veranda, Lawrence’s voice called out of the darkness:

“Well, where have you young folks been stealing away to?”

Marley halted at the threshold and glanced up at the sign that swung over the doorway. The gilt lettering of the sign had long ago been tarnished, and where its black sanded paint had peeled in many weathers the original tin was as rusty as the iron arm from which it creaked. Yet Macochee had long since lost its need of the shingle to tell it where Wade Powell’s law office was. It had been for many years in one of the little rooms of the low brick building in Miami Street, just across from the Court House; it was almost as much of an institution as the Court House itself, with which its triumphs and its trials were identified. Marley gathered enough courage from his inspection of the sign to enter, but once inside, he hesitated. Then a heavy voice spoke.

“Well, come in,” it said peremptorily.

Wade Powell, sitting with his feet on his table, held his newspaper aside and looked at Marley over his spectacles. Marley had had an ideal of Wade Powell, and now he had to pause long enough to relinquish the ideal and adjust himself to the reality. The hair was as disordered as his young fancy would have had it, but it was thinner than he had known it in his dreams, and its black was streaked with gray. The face was smooth-shaven, which accorded with his notion, though it had not been shaven as recently as he felt it should have been. But he could not reconcile himself to the spectacles that rested on Powell’s nose, and pressed their bows into the flesh of his temples—the eagle eyes of the Wade Powell of his imagination had never known glasses.

When Wade Powell slowly pulled his spectacles from his nose and tossed them on to the table before him, he bent his eyes on Marley, and their gaze, under their heavy brows, somewhat restored him, but it could not atone for the disappointment. Perhaps the disappointment that Marley felt in this moment came from some dim, unrealized sense that Wade Powell was growing old. The spectacles, the gray in his hair, the wrinkles in his face, the looseness of the skin at his jaws and at his throat—where a fold of it hung between the points of his collar—all told that Wade Powell had passed the invisible line which marks life’s summit, and that his face was turned now toward the evening. There was the touch of sadness in the indistinct conception of him as a man who had not altogether realized the ambitions of his youth or the predictions of his friends, and the sadness came from the intuition that the failure or the half-failure was not of the heroic kind.

The office in which he sat, and on which, in the long years, he had impressed his character, was untidy; the floor was dirty, the books on the shelves were dusty and leaning all awry; the set of the Ohio reports had not been kept up to date; one might have told by a study of them at just what period enterprise and energy had faltered, while the gaps here and there showed how an uncalculating generosity had helped a natural indolence by lending indiscriminately to other lawyers, who, with the lack of respect for the moral of the laws they pretended to revere, had borrowed with no thought of returning.

Two or three pictures hung crookedly on the walls; the table at which Powell sat was old and scarred; its ink-stand had long ago gone dry and been abandoned; a cheap bottle, with its cork rolling tipsily by its side, had taken the ink-stand’s place. The papers scattered over the table had an air of hopelessness, as though they had grown tired, like the clients they represented, in waiting for Powell’s attention. The half-open door at the back led into a room that had been, and possibly might yet be, used as a private office or consulting room, should any one care to brave its darkness and its dust; but as for Wade Powell, it was plain that he preferred to sit democratically in the outer office, where all might see him, and, what was of more importance to him, where he might see all.

The one new thing in the room was a typewriter, standing on its little sewing-machine table, in the corner of the room. There was no stenographer nor any chair for one; Marley imagined Powell, whenever he had occasion to write, sitting down to the machine himself, and picking out his pleadings painfully, laboriously and slowly, letter by letter, using only his index fingers. And this somehow humbled his ideal the more. Marley almost wished he hadn’t come.

“What’s on your mind, young man?” said Wade Powell, leaning back in his chair and dropping his long arm at his side until his newspaper swept the floor. Marley had seated himself in a wooden chair that was evidently intended for clients, and he began nervously.

“Well, I—”

Here he stopped, overcome again by an embarrassment. A smile spread over Wade Powell’s face, a gentle smile with a winning quality in it, and his face to Marley became young again.

“Tell your troubles,” he said. “I’ve confessed all the young men in Macochee for twenty-five years. Yes—thirty-five—” He grew suddenly sober as he numbered the years and then exclaimed as if to himself:

“My God! Has it been that long?”

He took out his watch and looked at it as if it must somehow correct his reckoning. For a moment, then, he thought; his gaze was far away. But Marley brought him back when he said:

“I only want—I only want to study law.”

“Oh!” said Powell, and he seemed somehow relieved. “Is that all?”

To Marley this seemed quite enough, and the disappointment he felt, which was a part of the effect Wade Powell’s office had had on him, showed suddenly in his face. Powell glanced quickly at him, and hastened to reassure him.

“We can fix that easily enough,” he said. “Have you ever read any law?”

“No,” said Marley.

“Been to college?”

Marley told him that he had just that summer been graduated and when he mentioned the name of the college Powell said:

“The Methodists, eh?”

He could hardly conceal a certain contempt in the tone with which he said this, and then, as if instantly regretting the unkindness, he observed:

“It’s a good school, I’m told.”

He could not, however, evince an entire approval, and so seeming to desert the subject he hastened on:

“What’s your name?”

“Glenn Marley.”

“Oh!” Wade Powell dropped his feet to the floor and sat upright. “Are you Preacher Marley’s son?”

Marley did not like to hear his father called “Preacher,” and when he said that he was the son of Doctor Marley, Powell remarked:

“I’ve heard him preach, and he’s a damn good preacher too, I want to tell you.”

Marley warmed under this profane indorsement. He had always, from a boy, felt somehow that he must defend his father’s position as a preacher from the world, as with the little world of his boyhood and youth he had always had to defend his own position as the son of a preacher.

“Yes, sir, he’s a good preacher, and a good man,” Powell went on. He had taken a cigar from his pocket and was nipping the end from it with his teeth. He lighted it, and leaned back comfortably again to smoke, and then in tardy hospitality he drew another cigar from his waistcoat pocket and held it toward Marley.

“Smoke?” he said, and then he added apologetically, “I didn’t think; I never do.”

Marley declined the cigar, but Powell pressed it on him, saying:

“Well, your father does, I’ll bet. Give it to him with Wade Powell’s compliments. He won’t hesitate to smoke with a publican and sinner.”

Marley smiled and put the cigar away in his pocket.

“I don’t know, though,” Powell went on slowly, speaking as much to himself as to Marley, while he watched the thick white clouds he rolled from his lips, “that he’d want you to be in my office. I know some of the brethren wouldn’t approve. They’d think I’d contaminate you.”

Marley would have hastened to reassure Powell had he known how to do so without seeming to recognize the possibility of contamination; but while he hesitated Powell avoided the necessity for him by asking:

“Did your father send you to me?”

He looked at Marley eagerly, and with an expression of unfounded hope, as he awaited the answer.

“No,” replied Marley, “he doesn’t know. I haven’t talked with him at all. I have to do something and I’ve always thought I’d go into the law. I presume it would be better to go to a law school, but father couldn’t afford that after putting me through college. I thought I could read law in some office, and maybe get admitted that way.”

“Sure,” said Powell, “it’s easy enough. You’ll have to learn the law after you get to practising anyway—and there isn’t much to learn at that. It’s mostly a fake.”

Marley looked at him in some alarm, at this new smiting of an idol.

“I began to read law,” Powell went on, “under old Judge Colwin—that is, what I read. I used to sit at the window with a book in my lap and watch the girls go by. Still,” he added with a tone of doing himself some final justice, “it was a liberal education to sit under the old judge’s drippings. I learned more that way than I ever did at the law school.”

He smoked on a moment, ruminating on his lost youth; then, bringing himself around to business again, he said:

“How’d you happen to come to me?”

“Well,” said Marley, haltingly, “I’d heard a good deal of you—and I thought I’d like you, and then I’ve heard father speak of you.”

“You have?” said Powell, looking up quickly.

“Yes.”

“What’d he say?”

“Well, he said you were a great orator and he said you were always with the under dog. He said he liked that.”

Powell turned his eyes away and his face reddened.

“Well, let’s see. If you think your father would approve of your sitting at the feet of such a Gamaliel as I, we can—” He was squinting painfully at his book-shelves. “Is that Blackstone over there on the top shelf?”

Marley got up and glanced along the backs of the dingy books, their calfskin bindings deeply browned by the years, their red and black labels peeling off.

“Here’s Blackstone,” he said, taking down a book, “but it’s the second volume.”

“Second volume, eh? Don’t see the first around anywhere, do you?”

Marley looked, without finding it.

“Then see if Walker’s there.”

Marley looked again.

“Walker’s American Law,” Powell explained.

“I don’t see it,” Marley said.

“No, I reckon not,” assented Powell, “some one’s borrowed it. I seem to run a sort of circulating library of legal works in this town, without fines—though we have statutes against petit larceny. Well, hand me Swan’s Treatise. That’s it, on the end of the second shelf.”

Marley took down the book, and gave it to Powell. While Marley dusted his begrimed fingers with his handkerchief, Powell blew the dust off the top of the book; he slapped it on the arm of his chair, the dust flying from it at every stroke. He picked up his spectacles, put them on and turned over the first few leaves of the book.

“You might begin on that,” he said presently, “until we can borrow a Blackstone or a Walker for you. This book is the best law-book ever written anyway; the law’s all there. If you knew all that contains, you could go in any court and get along without giving yourself away; which is the whole duty of a lawyer.”

He closed the book and gave it to Marley, who was somewhat at a loss; this was the final disappointment. He had thought that his introduction into the mysteries of the noble profession should be attended by some sort of ceremony. He looked at the book in his hand quite helplessly and then looked up at Powell.

“Is that—all?” he said.

“Why, yes,” Powell answered. “Isn’t that enough?”

“I thought—that is, that I might have some duties. How am I to begin?”

“Why, just open the book to the first page and read that, then turn over to the second page and read that, and so on—till you get to the end.”

“What will my hours be?”

“Your hours?” said Powell, as if he did not understand. “Oh, just suit yourself.”

Marley was looking at the book again.

“Don’t you make any entry—any memorandum?” he asked, still unable to separate himself from the idea that something formal, something legal, should mark the beginning of such an important epoch.

“Oh, you keep track of the date,” said Powell, “and at the end of three years I’ll give you a certificate. You may find that you can do most of your reading at home, but come around.”

Marley looked about the office, trying to imagine himself in this new situation.

“I’d like, you know,” he said, “to do something, if I could, to repay you for your trouble.”

“That’s all right, my boy,” said Powell. Then he added as if the thought had just come to him:

“Say, can you run a typewriter?”

“I can learn.”

“Well, that’s more than I can do,” said Powell, glancing at his new machine. “I’ve tried, but it would take a stationary engineer to operate that thing. You might help out with my letters and my pleadings now and then. And I’d like to have you around. You’d make good company.”

“Well,” said Marley, “I’ll be here in the morning.” He still clung to the idea that he was to be a part of the office, to be an identity in the local machinery of the law. As he rose to go, a young man appeared in the doorway. He was tall, and the English cap and the rough Scotch suit he wore, with the trousers rolled up over his heavy tan shoes, enabled Marley to identify him instantly as young Halliday. He was certain of this when Powell, looking up, said indifferently:

“Hello, George. Raining in London?”

“Oh, I say, Powell,” replied Halliday, ignoring a taunt that had grown familiar to him, “that Zeller case—we would like to have that go over to the fall term, if you don’t mind.”

“Why don’t you settle it?” asked Powell.

Halliday was leaning against the door-post, and had drawn a short brier pipe from his pocket. Before he answered, he paused long enough to fill it with tobacco. Then he said:

“You’ll have to see the governor about that—it’s a case he’s been looking after.”

“Oh, well,” said Powell, with his easy acquiescence, “all right.”

Halliday had pressed the tobacco into the bowl of the pipe and struck a match.

“Then, I’ll tell old Bill,” he said, pausing in his sentence to light his pipe, “to mark it off the assignment.”

Marley watched Halliday saunter away, with a feeling that mixed admiration with amazement. He could not help admiring his clothes, and he felt drawn toward him as a college man from a school so much greater than his own, though he felt some resentment because Halliday had never once given a sign that he was aware of Marley’s presence. His amazement came from the utter disrespect with which Halliday referred to Judge Blair. Old Bill! Marley had caught his breath. He would have liked to discuss Halliday with Powell, but the lawyer seemed to be as indifferent to Halliday’s existence as Halliday had been to Marley’s, and when Marley saw that Powell was not likely to refer to him, he started toward the door. As he went Powell resumptively called after him:

“I’ll get a Blackstone for you in a day or two. Be down in the morning.”

Marley went away bearing Swan’s Treatise under his arm. He looked up at the Court House across the way; the trees were stirring in the light winds of summer, and their leaves writhed joyously in the sun. The windows of the Court House were open, and he could hear the voice of some lawyer arguing a cause to the jury. Marley thought of Judge Blair sitting there, the jury in its box, the sleepy bailiff drowsing in his place, the accustomed attorneys and the angry litigants, and his heart began to beat a little more rapidly, for the thought of Judge Blair brought the thought of Lavinia Blair. And in the days to come, when he should be arguing a cause to a jury, as that lawyer, whose voice came pealing and echoing in sudden and surprising shouts through the open windows, was arguing a cause now, would Lavinia Blair be interested?

He had imagined that a day so full of importance for him would be marked by greater ceremonials, and yet while he was disappointed, he was reassured. He had solved a problem, he had done with inaction, he had made a beginning, he was entered at last upon a career. As all the events of the recent years rushed on him, the years of college life, the decisions and indecisions of his classmates, their vague troubles about a career, he felt a pride that he had so soon solved that problem. He felt a certain superiority too, that made him carry his head high, as he turned into Main Street and marched across the Square. It required only decision and life was conquered. He saw the years stretching out prosperously before him, expanding as his ambitions expanded. He was glad that he had tackled life so promptly, that he had come so quickly to an issue with it; it was not so bad, viewed thus close, as it had been from a distance. He laughed at the folly of all the talk he had heard about the difficulty of young men getting a start in these days; he must write to his fraternity fellows at once, and tell them what he had done and how he was succeeding. They would surely see that at the bar he would do, not only himself, but them, the greatest credit, and they would be proud.

The girls, flitting about with nervous laughter and now and then little screams, had spread long cloths over the table of plain boards that had served so many picnic parties at Greenwood Lake; the table-cloths and the dresses of the girls gleamed white in the amber light that streamed across the little sheet of water, though the slender trees, freshened by the morning shower that threatened to spoil the outing, were beginning to darken under the shadows that diffused themselves subtly through the grove, as if there were exudations of the heavy foliage.

Lawrence, in his white ducks, stood by the table, assuming to direct the laying of the supper. His immense cravat of blue was the only bit of color about him, unless it were his red hair, which he had had clipped that very morning, and his shorn appearance intensified his comic air. Marley, sitting apart on the stump of a small oak, could hear the burlesque orders Lawrence shouted at the girls. The girls were convulsed by his orders; at times they had to put their dishes down lest in their laughter they spill the food or break the china; just then Marley saw Mayme Carter double over suddenly, her mass of yellow hair lurching forward to her brow, while the woods rang with her laughter. The other men were off looking after the horses.

Lavinia moved quickly here and there, smiling joyously, her face flushed; though she laughed as the others did at Lawrence’s drollery, she did not laugh as loudly, and she did not scream. Just now she rose from bending over the table, and brushed her brown hair from her brow with the back of her hand, while she stood and surveyed the table as if to see what it lacked. When she raised her hand the sleeve of her muslin gown fell away from her wrist and showed her slender forearm, white in the calm light of evening. Marley could not take his eyes from her. She ran into the pavilion, her little low shoes flashed below her petticoats, and he grew sad; when she reappeared, all her movements seemed to be new, to have fresh beauties. Then he suspected that the girls were laughing at him and he felt miserable.

He thought of himself sitting alone and apart, an awkward, ungainly figure. He longed to go away, yet he feared that, if he did, he would not have the courage to come back. He shifted his position, only to make matters worse. Then suddenly his feeling took the form of a rage with Lawrence; he longed to seize Lawrence and kick him, to pitch him into the lake, to humiliate him before the girls. He thought he saw all at once that Lawrence had been making fun of him, surreptitiously; that was what had made the girls laugh so.

There was some little consolation in the thought that Lavinia did not laugh as much as the others; perhaps, if she did not care to defend him, she at least pitied him. And then he began to pity himself. The whole evening stretched before him; pretty soon he would have to move up to the table, and sit down on the narrow little benches that were fastened between the trees; then after supper they would begin their dancing and when that came he did not see what he could do.

The only pleasure he had had that afternoon had been on the way out; he had been alone with Lavinia, and the four miles of pleasant road that lay between the town and Greenwood Lake were too short for all the happiness Marley found in them. He could feel Lavinia again by his side, her hands folded on the thin old linen lap-robe. He could not recall a word they had said, but it seemed to him that the conversation had flowed on intimately and tranquilly; she had been so close and sympathetic; and he would always remember how her eyes had been raised to his. The fields with the wheat in shock had swept by in the beauty of harvest time; the road, its dust laid by the morning shower, had rolled under the wheels of the buggy softly, smoothly and noiselessly; the air had been odorous with the scent of green things freshened by the rain, and had vibrated with the sounds of summer.

Then suddenly his reverie was broken. The men were gathering about the table with the girls; all of them looked at him expectantly.

“Here, you!” called Lawrence. “Do you think we’re going to do all the work? Come, get in the game, and don’t look so solemn—this ain’t a funeral.”

They all laughed, and Marley felt his face flame, but he rose and went over to the table, halting in indecision.

“Run get some water,” ordered Lawrence, imperatively waving his hand. “Mayme,” he shouted, “hand him the pitcher! Step lively, now. The men-folks are hungry after their day’s work. Has any one got a pitcher concealed about his person? What did you do with the pitcher, Glenn? Take it to water your horse?”

They were laughing uproariously, and Marley was plainly discomfited. But Lavinia stepped to his side, a large white pitcher in her hand. “I’ll show you,” she said.

They started away together, and Marley felt a protection in her presence. A little way farther he suddenly thought of the pitcher, which Lavinia still was bearing, and he took it from her. As he seized the handle their fingers became for an instant entangled.

“Did I hurt you?” he asked.

“Oh, no!” she assured him, and as they walked on, out of the sight of the laughing group behind them, an ease came over him.

“Do you know where the well is?” he asked.

“Oh, yes,” she answered. “It’s down here. I could have come just as well as not.”

“I’m glad to come,” he said; and then he added, “with you.”

They had reached the wooden pump behind the pavilion. The little sheet of water curved away like a crescent, following the course of the stream of which it was but a widening. Its little islands were mirrored in its surface. The sun was just going down, the sky beyond the lake was rosy, and the same rosy hue now suffused everything; the waters themselves were reddened.

It was very still, and the peace of the evening lay on them both. Lavinia stood motionless, and looked out across the water to the little Ohio hills that rolled away toward the west. She stood and gazed a long time, her hands at her sides, yet with their fingers open and extended, as if the beauty of the scene had suddenly transfixed her. Marley did not see the lake or the sun, the islands or the hills; he saw only the girl before him, the outline of her cheek, the down on it showing fine in the pure light, the hair that nestled at her neck, the curve from her shoulder to her arms and down to her intent fingers. At last she sighed, and looked up at him.

“Isn’t it all beautiful?” she said solemnly.

“Beautiful?” he repeated, as if in question, not knowing what she said.

Just then they heard Lawrence hallooing, and Marley began to pump vigorously. He rinsed out the pitcher, then filled it, and they went back, walking closely side by side, and they did not speak all the way.

Mayme Carter, who, as it seemed, had a local reputation as a compounder of lemonade, had the lemons and the sugar all ready when Marley and Lavinia rejoined the group, and Lawrence, as he seized the pitcher, said:

“I see that, between you, you’ve spilled nearly all of the water, but I guess Mayme and I’ll have to make it do.”

The others laughed at this, as they did at all of Lawrence’s speeches, and then they turned and laughed at Marley and Lavinia, though the men, who as yet did not feel themselves on terms with Marley, had a subtile manner of not including him in their ridicule, however little they spared Lavinia.

The supper was eaten with the hunger their spirits and the fresh air had given them and Marley, placed, as of course, by Lavinia’s side, felt sheltered by her, as he felt sheltered by all the talk that raged about him. He wished that he could join in the talk, but he could not discover what it was all about. Once, in a desperate determination to assert himself, he did mention a book he had been reading, but his remark seemed to have a chilling effect from which they did not recover until Lawrence, out of his own inexhaustible fund of nonsense, restored them to their inanities. He tried to hide his embarrassment by eating the cold chicken, the ham and sardines, the potato chips and pickles, the hard-boiled eggs and sandwiches that went up and down the board in endless procession, and he was thankful, when he thought of it, that Lawrence seemed to forget him, though Lawrence had forgotten no one else there. He seemed to note accurately each mouthful every one took.

“Hand up another dozen eggs for Miss Winters, Joe,” he called to one of the men, and then they all laughed at Miss Winters.

When the cake came, Lawrence identified each kind with some remark about the mother of the girl who had brought it, and tasted all, because, as he said, he could not afford to show partiality. The fun lagged somewhat as the meal neared its end, but Lawrence revived it instantly and sensationally by rising suddenly, bending far over toward Lavinia in a tragic attitude and saying:

“Why, Vine, child, you haven’t eaten a mouthful! I do believe you’re in love!”

The company burst into laughter, but they suddenly stopped when they saw Marley. His face showed his anger with them, and he made a little movement, but Lavinia smiled up at Lawrence, and said:

“Well, Jack, it’s evident that you’re not.”

And then they all laughed at Lawrence, and the girls clapped their hands, while Marley, angry now with himself, tried to laugh with them.

When they stopped laughing Lawrence produced his cigarettes, and tossing one to Marley in a way that delicately conveyed a sense of intimacy and affection, he said:

“When you girls get your dishes done up we’ll be back and see if we can’t think up something to entertain you,” and then he called Marley and with him and the other men strolled down to the lake.

The dance was proposed almost immediately. Marley had hoped up to the very last minute that something, possibly a miracle, would prevent it, but scarcely had the men finished their first cigarettes before Howard was saying:

“Well, let’s be getting back to the girls. They’ll want to dance.”

Howard spoke as if the dancing would be a sacrifice on the part of the men to the pleasure of the girls, but they all turned at once, some of them flinging their cigarettes into the water, as if to complete the sacrifice, and started back. When they reached the pavilion, Payson and Gallard took instruments out of green bags, Payson a guitar and Gallard a mandolin, and Lawrence, bustling about over the floor, shoving the few chairs against the unplastered wooden walls, was shouting:

“Tune ’em up, boys, tune ’em up!”

The first tentative notes of the strings twanged in the hollow room, and Lawrence was asking the girls for dances, scribbling their names on his cuff with a disregard of its white polished linen almost painful.

“I’ll have to divide up some of ’em, you know, girls,” he said. “Jim and Elmer have to play, and that makes us two men shy. But I’ll do the best I can—wish I could take you all in my arms at once and dance with you.”

The girls, standing in an expectant, eager little group, clutched one another nervously, and pretended to sneer at Lawrence’s patronage.

Marley was standing with Lavinia near the door. He was trying to affect an ease; he knew by the way the other girls glanced at him now and then that they were speculating on his possibilities as a partner; he tried just then to look as if he were going to dance as all the other men were, yet he felt the necessity of confessing to Lavinia.

“You know,” he said contritely, “that I don’t dance.”

She looked up, a disappointment springing to her eyes too quickly for her to conceal it. She was flushed with pleasure and excitement, and tapping her foot in time with the chords Payson and Gallard were trying on their instruments. Marley saw her surprise.

“I ought not to have come,” he said; “I’ve no business here.”

The look of disappointment in Lavinia’s eyes had gone, and in its place was now an expression of sympathy.

“It makes no difference,” she said. And then she added in a low voice: “I’ll not dance either; there are too many of us girls anyway.”

“Oh, don’t let me keep you from it,” said Marley, and yet a joy was shining in his eyes. She turned away and blushed.

“I’ll give you all my dances,” she said; “we can sit them out.”

“But it won’t be any fun for you,” protested Marley. And just then Lawrence came up.

“Say, Glenn,” he said, “if you don’t want to dance I’ll take Lavinia for the first number.”

The guitar and mandolin, after a long preliminary strumming to get themselves in tune, suddenly burst into The Georgia Campmeeting, and the couples were instantly springing across the floor.

“Come on, Vine,” said Lawrence, his fingers twitching. And Lavinia, eager, trembling, alive, casting one last glance at Marley, said “Just this one!” and went whirling away with Lawrence.

Marley moved aside, awkwardly, when the couples, sweeping in a long oval stream around the little room, whirled past him. Lavinia danced with a grace that almost hurt him; she was laughing as she looked up into Lawrence’s face, talking to him as they danced. Marley felt a gloom, almost a rage, settle on him. He looked up and down the room. At the farther end, through the door by which the musicians sat swinging their feet over their knees in time to the tune they played, he could see the man who kept the grounds at the lake, looking on at the dance; his wife was with him, and they smiled contentedly at the joy of the young people.

Marley could not bear their joy, any more than he could bear the joy of the dancers, and he looked away from them. Glancing along the wall he saw a girl, sitting alone. It was Grace Winters; she was older than the others, and she sat there sullenly, her dark brows contracted under her dark hair. Marley felt drawn toward her by a common trouble, and he thought, instantly, that he might appear less conspicuous if he went and sat beside her. As he approached, her sallow face brightened with a brilliant smile of welcome and she drew aside her skirts to make a place for him, though there was no one else on all that side of the room. Marley sat down.

“It’s warm, isn’t it?” he said.

“Yes,” Miss Winters replied, “almost too warm to dance, don’t you think?”

Marley tried to express his acquiescence in the polite smile he had seen the other men use before the dance began, but he did not feel that he carried it off very well.

“I should think you’d be dancing, Mr. Marley,” Miss Winters said. “I hear you are a splendid dancer. Don’t you care to dance this evening?”

“I can’t dance,” said Marley, crudely.

He was looking at Lavinia, following her young figure as it glided past with Lawrence. Miss Winters turned away. Her face became gloomy again, and she said nothing more. Marley was absorbed in Lavinia, and they sat there together silent, conspicuous and alone, in a wide separation.

Marley thought the dance never would end. It seemed to him that the dancers must drop from fatigue; but at last the mandolin and guitar ceased suddenly, the girls cried out a disappointed unisonant “Oh!” and then they all laughed and clapped their hands. Lavinia and Lawrence were coming up, glowing with the joy of the dance.

“Oh, that was splendid, Jack!” Lavinia cried, putting back her hair with that wave of her hand.

Lawrence’s face was redder than ever. He leaned over and in a whisper that was for Lavinia and Marley together he said:

“Lavinia, you’re the queen dancer of the town.” And then he turned to Miss Winters.

“Grace,” he said, distributing himself with the impartiality he felt his position as a social leader demanded, “you’ve promised me a dance for a long time. Now’s my chance.”

“Why certainly, Jack,” Miss Winters said, with her brilliant smile, and then she took Lawrence’s arm and drew him away, as if otherwise he might escape.

“Take me outdoors!” said Lavinia to Marley. “Those big lamps make it so hot in here.”

Marley was glad to leave, and they went out on to the little piazza of the pavilion. Lavinia stood on the very edge of the steps, and drank in the fresh air eagerly.

“Oh!” she said. “Oh! Isn’t it delicious!”

The darkness lay thick between the trees. The air was rich with the scent of the mown fields that lay beyond the grove. The insects shrilled contentedly. Marley stood and looked at Lavinia, standing on the edge of the steps, her body bent a little forward, her face upturned. She put back her hair again.

“Let’s go on down!” she said, a little adventurous quality in her tone. She ran lightly down the steps, Marley after her.

“Won’t you take cold?” he asked, bending close to her.

She looked up and laughed. They were walking on, unconsciously making their way toward the edge of the little lake. Marley felt the white form floating there beside him and a happiness, new, unknown before, came to him. They were on the edge of the little lake. Before them the water lay, dark now, and smooth. A small stage was moored to the shore and a boat was fastened to it. They could hear the light lapping of the water that barely stirred the boat. Presently Lavinia ran out on to the stage. She gave a little spring, and rocked it up and down; then smiled up at Marley like a child venturing in forbidden places. Marley stepped carefully on to the stage.

“Isn’t it a perfect night?” Lavinia said, looking up at the dark purple sky, strewn with all the stars. Marley looked at her white throat.

“The most beautiful night I ever knew!” he said. He spoke solemnly, devoutly, and Lavinia turned and gazed on him. Marley touched the boat with the toe of his shoe.

“We might row,” he said almost timidly.

“Could we?” inquired Lavinia.

“If we may take the boat.”

“Oh, of course—anybody may. Can you row?”

Marley laughed. He had rowed in the college crew on the old Olentangy at Delaware. His laugh was a complete answer to Lavinia. She approached the boat, and Marley bent over and drew it alongside the stage.

“Get in,” he said. It was good to find something he could do. He helped her carefully into the boat, and held it firmly until she had arranged herself in the stern, her feet against the cleats, and her white skirts tucked about her. Then he took his seat, shipped the oars and shoved off. He swept the boat out into the deep water, and rowed away up the lake. He rowed precisely, feathering his oars, that she might see how much a master he was. They did not speak for a long time. First one, then the other, of the little islands swept darkly by; the water slapped the bow of the boat as Marley urged it forward. The lights of the pavilion on the shore twinkled an instant, then went out behind the trees. They could hear the distant mellow thrumming of the guitar and the tinkle of the mandolin.

“Are you too cool?” he asked presently.

“Oh, no, not at all!” said Lavinia.

“Hadn’t you better take my coat?” Marley persisted. The idea of putting his coat about her thrilled him.

“You’ll need it,” she said.

“No, I’ll be warm rowing.”

She shook her head, and smiled. They drifted on. Still came the distant strumming of the guitar and the tinkle of the mandolin. Marley thought of the young people dancing, and then, noting Lavinia’s silence, he asked, out of the doubt that was his one remaining annoyance:

“Wouldn’t you rather be back there dancing?”

“No, no!” she answered softly.

“I’m ashamed of myself.”

“Why?” She started a little.

“Because I can’t dance!” There was guilt in his tone.

“You mustn’t feel that way about it,” Lavinia said. “It’s nothing.”

“Isn’t it?”

“No. It’s easy to learn.”

“I never could learn.”

Lavinia was still, and Marley thought she assented to this. But in another moment she spoke again.

“I—” she began, and then she hesitated.

Marley stopped rowing and rested on his oars. The water lapped the bows of the boat as it slackened its speed.

“I could teach you,” Lavinia went on.

“Could you?” Marley leaned forward eagerly.

“I’d like to.” She was trailing one white hand in the water.

“Will you?”

“Yes,” she said. “We can do it over at Mayme’s—any time. She’ll play for us.”

Marley felt a great gratitude, and he wondered how he could pour it forth upon her.

“You are too good to me,” he exclaimed.

Then, suddenly, a change came over the dark surface of the waters. A mellow quality touched them; they seemed to tremble ecstatically, then they broke into sparkling ripples; the air quivered with a luminous beauty and a light flooded the little valley. Marley and Lavinia turned instinctively and looked up, and there, over the tops of the trees, black a moment before, now rounded domes of silver, rose the moon. They gazed at it a long time. Finally Marley turned and looked at Lavinia. Her white dress had become a drapery, her arms gleamed, her eyes were lustrous in the transfiguration of the moonlight. He could see that her lips were slightly parted, and her fingertips, dipped in the cool water over the gunwale of the boat, trailed behind them a long narrow thread of silver. They looked into each other’s eyes, and neither spoke. They drifted on. At last, Marley said:

“Lavinia!”

She stirred.

“Do you know—” he began, and then he stopped. “Don’t you know,” he went on, “can’t you see, that I love you?”

He rested his arms on the oars, and leaned over toward her.

“I’ve loved you ever since that first night—do you remember? I know—I know I’m not good enough, but can’t you—can’t I—love you?”

He saw her eyelids fall, and as she turned and looked over the side of the boat, she put forth her hand, and he took it.

They were awakened from the dream by a call, and after what seemed to Marley a long time, he finally remembered the voice as Lawrence’s.

“We must go back,” he said reluctantly. “How long have we been gone?”

“I don’t know,” said Lavinia. He heard her sigh.

Marley pulled the boat in the direction whence came the hallooing voice; he had quite lost all notion of their whereabouts. But presently they saw the lights of the pavilion, and then the dark figures of the men, and the white figures of the girls on shore.

As they pulled up and Marley sprang out of the boat to the landing stage, Lawrence said:

“Well, where have you babes been?”

Marley helped Lavinia out of the boat.

“We’ve been rowing,” he said.

“We thought you’d been drowned,” said Lawrence.

Marley and Lavinia drove home together in silence. In the light of the moon, the road was silver, and the fields with their shocks of wheat were gold.

“I don’t know what ails Lavinia,” said Mrs. Blair to her husband as he sat on the veranda after dinner the next day. The judge laid his paper in his lap, and looked up at his wife over his glasses.

“Isn’t she well?” he asked.

“M—yes,” replied Mrs. Blair, prolonging the word in her lack of conviction, “I guess so.”

“Don’t you know?” the judge demanded in some impatience with her uncertainty.

“She says she feels all right.”

“Well, then, what makes you think she isn’t?”

“Oh, I don’t know,” replied Mrs. Blair, “she seems so quiet, that’s all.”

“Lavinia is not a girl given to excitement or demonstration,” said the judge, lapsing easily into the manner of speech he had cultivated on the bench.

“No, that’s so,” assented Mrs. Blair. “But she’s always cheerful and bright.”

“Is she gloomy?”

“No, I wouldn’t exactly call it that, but she seems preoccupied—rather wistful I should say, yes—wistful.” She seemed pleased to have found the right word.

“Oh, she’s all right. That picnic last night may have fatigued her. I presume there was dancing.”

“Yes.”

“I don’t know that we should let her go out that way.” The judge took off his glasses and twirled them by their black cord while he gazed across the street, apparently at some dogs that were tumbling each other about in the Chenowiths’ yard. The judge had a subconscious anxiety that they would get into Mrs. Chenowith’s flower beds.

“You and I used to go to them; they never hurt us,” argued Mrs. Blair.

“No, I suppose not. But then—that was different.”

Mrs. Blair laughed lightly, and the laugh served to dissipate their cares. She went to the edge of the veranda and pulled a few leaves from the climbing rose-vine that grew there, and the judge put on his glasses and spread out his paper.

“I’ll take her out for a drive this afternoon,” said Mrs. Blair, turning to go indoors.

“She’ll be all right,” said the judge, already deep in the political columns.

That night at supper, the judge looked at Lavinia closely, and after a while he said:

“You’re not eating, Lavinia. Don’t you feel well?”

Lavinia turned to her father and smiled.

“Oh, I’m all right.”

Her smile perplexed the judge.

“You look pale,” he said.

Mrs. Blair glanced warningly at him the length of the table.

“My girl’s losing her color,” he forged ahead.

Lavinia dropped her eyelids, and a look of pain appeared in her face, causing it to grow paler.

“Please don’t worry about me, papa,” she said.

Mrs. Blair divined Lavinia’s dislike of this personal discussion. She tried to catch her husband’s eye again, but he was looking at Lavinia narrowly through his glasses.

“Did you go riding this afternoon?” he asked as if he were examining a witness whom counsel had not drawn out properly.

“Yes,” Mrs. Blair hastened to say. “We drove out the Ludlow a long way.”

“She was riding last night, too,” said Connie.

“Who with?” demanded Chad, turning to Connie with the challenge he always had ready for her.

“Who with?” retorted Connie. “Why, Glenn Marley, of course. Who else?”

“Well, what of it?” demanded Chad. “What’s it to you?”

“Oh, children, children!” protested Mrs. Blair, wearily. “Do give us a little peace!”

“Well, she began it,” said Chad.

Connie was eating savagely, but she whirled on Chad, speaking with difficulty because her mouth was filled with food:

“You shut up, will you?”

Chad laughed with a contempt almost theatrical, waved his hand lightly and said:

“Run away, little girl, run away.”

Mrs. Blair asked the judge why he did not correct his children, and though the sigh he gave expressed the hopelessness, as it seemed to him, of bringing the two younger members of his train into anything like decorous behavior, he laid his knife and fork in his plate.

“This must cease,” he said. “It is scandalous. One might conclude that you were the children of some family in Lighttown.”

“It is very trying,” said Mrs. Blair, acquiescing in her husband’s reproof. “They are just like fire and tow.” She said this quite impersonally and then turned to Connie: “If you can’t behave yourself, I’ll have to send you from the table.”

“That’s it!” wailed Connie. “That’s it! Blame everything on to me!”

Mrs. Blair looked severely at her, and Connie’s face reddened. She glanced angrily at her mother and began again:

“Well, I—”

The judge rapped the table smartly with his knuckles.

“Now I want this stopped!” he said. “And right away. If it isn’t I’ll—” He was about to say if it wasn’t he would clear the room, as he was fond of saying whenever the idle spectators in his court showed signs of being human, but he did not finish his sentence. Chad was subdued and decorous, and Connie drooped her head, and began to gulp her food. Her eyes were filling with tears and the tears began to fall, slowly, one by one, splashing heavily into her plate.

Lavinia was trembling; she tried to control herself, tried to lift her glass, but when she did, her hand shook so that the water was likely to spill. This completed the undoing of her nerves, her eyes suddenly flooded with tears, and she snatched her handkerchief from her lap, rose precipitately, and hurried from the room, dropping her napkin as she went. They heard her going up the stairs, and presently the door of her room closed.

Connie had followed Lavinia with her misty eyes as she left the table and now she too prepared to leave. She felt a sudden pity springing from her great love of her older sister, and her great pride in her, and she felt a contrition, though she tried to convict Chad, as the latest object of her fiery and erratic temper, by glowering at him.

“I’ll go to her,” she said, “I can comfort her!”

“No, stay where you are,” said her mother. “Just leave her alone.”

The evening light of the summer day flooded into the dining-room; outside a robin was singing. In the room there was constraint and heavy silence, broken only by the slight clatter of the silver or the china. But after a while the judge spoke:

“Did Lavinia go to the picnic with young Marley?” he asked. He regretted instantly that he had revived the topic that had given rise to the difficulty, but as it lay on the minds of all, it was impossible, just then, to escape its influence.

“I believe so,” said Mrs. Blair. “He really seems like a nice young man.”

The judge scowled.

“I don’t know,” he said. “He’s in the office of Wade Powell—I suppose he is the one, isn’t he?” He thought it unbecoming that a judge should show an intimate knowledge of the relations of young men who were merely studying law.

“Yes, sir,” said Chad, maintaining his own dignity.

“Everybody seems to speak well of him,” said Mrs. Blair.

“But I can’t quite reconcile that with his selecting Wade Powell as a preceptor. I would hardly consider his influence the best in the world, and I would imagine that Doctor Marley would hold to the same opinion.”

Judge Blair spoke with a certain disappointment in Doctor Marley. He had gone to hear him preach once or twice, and found, as he said, an intellectual quality in his utterances that he missed in the sermons Mr. Hill had been preaching for twenty years in the Presbyterian church.

“Perhaps he doesn’t know Wade Powell,” said Mrs. Blair. “Doctor Marley is comparatively a stranger here, you know.”

“Yes, I presume that explains it. But—” he shook his head. He could not forgive any one who showed respect for Wade Powell. “Powell has little business except a certain criminal practice, and now and then a personal injury case.”

“Is there anything wrong in personal injury cases?” asked Mrs. Blair.

The judge looked at his wife in surprise.

“Well, I suppose you know, don’t you,” he said, “that such cases are taken on contingent fees?” He spoke with the natural judicial contempt of the poor litigant.

“Of course, dear,” she replied, “I shall not undertake to defend Mr. Powell. He’s a wild sort.”

“Yes; a drunkard, practically,” said Judge Blair, “and an infidel besides. The moral environment there is certainly not one for a young man—”

“Is he really an infidel?” asked Mrs. Blair, abruptly dropping her knife and fork.

“Well,” replied the judge with the judicial affectation of fairness, “he’s at least a free-thinker. Perhaps agnostic were the better word. That is one reason why I can not understand Doctor Marley’s permitting his son to be associated with him. It seems to me to argue a weakness, or a lack of observation in the doctor, as it does a certain depravity of taste in his son.”

They discussed Marley until the meal was done, and Connie and Chad had gone out of doors. Judge Blair followed his wife into the sitting-room.

“I’m worried, I’ll admit,” said the judge. “What could it have been that so distressed her?”

“Oh well, the children’s little quarrels were too much for her nerves.”

“I suppose so.”

They were silent and thoughtful, sitting together, rocking gently in their chairs as the twilight stole into the room.

“It’s too bad he’s going to study law,” the judge said after a while.

He shook his gray head dubiously.

“But you always say that about any one who’s going to study law,” Mrs. Blair argued. “You even said it about George Halliday when his father took him into partnership.”

“Well, it’s bad business nowadays unless a young man wants to go to the city, and it’s hard to get a foothold there.”

“But you began as a lawyer,” she urged, as though he had finished as something else.

“It was different in my day.”

“And you’ve always done well in the law,” Mrs. Blair went on, ignoring his distinction.

“Oh yes,” the judge said in a tone that expressed a sense of individual exception. “But I went on the bench just in time to save my bacon. There’s no telling what might have become of us if I had remained in the practice.”

They were silent long enough for him to feel the relief he had always found in his salaried position, and then he said:

“You don’t suppose—”

“Oh, certainly not!” his wife hastened to assure him.

“Well, I think it would be well, perhaps, to watch her closely. I don’t just like the notion.”

“But his father is—”

“Yes, but after all, we really know nothing about him.”

“That is true.”

“And then Lavinia’s so young.”

“Yes.”

“I’d go to her.”

“After a while,” Mrs. Blair said.

They heard steps on the veranda, and then the voices of Mr. and Mrs. Chenowith who had run across, as Mrs. Chenowith said, when Mrs. Blair met them in the darkness that filled the wide hall, to see how they all were. The Chenowiths begged Mrs. Blair not to light the gas; they preferred to sit out of doors. The Chenowiths remained all the evening. When they had gone, the judge drew the chairs indoors, while Mrs. Blair rolled up the wide strip of red carpet that covered the steps of the veranda. And when they had gone up to their room, Mrs. Blair stole across to Lavinia, softly closing the door behind her.

She found the girl stretched on her bed, her face buried in the pillows, which were wet with her tears.

“What is troubling my little girl?” she asked. She sat down on the side of the bed, and lightly stroked Lavinia’s soft hair. The girl stirred, and drew herself close to her mother. Mrs. Blair did not speak, but continued to stroke her hair, and waited. Presently Lavinia cried out:

“Oh, mama! mama!”

And then she was in her mother’s arms, weeping on her mother’s breast.

“I’ve never kept anything from you before, mama,” Lavinia cried.

“No,” Mrs. Blair whispered. “Can’t you tell mama now?”

And then with her mother’s arms about her Lavinia told her all. When she had finished she lay tranquilly. Mrs. Blair was relieved and yet her troubles had but grown the more complicated. She saw all the intricate elements with which she would have to deal, and she quailed before them, realizing what tact would be required of her.

“The coming of love should be a time of joy, dear,” she said presently. Even in the darkness, she could see the white blur of Lavinia’s face change its expression. A smile had touched it.

“It should, shouldn’t it, mama?”

“Yes, indeed.”

“But I never kept anything from you before.”

Mrs. Blair laughed.

“But you kept this only a day, dear. That doesn’t count.”

“It was a long day.”

“I know, sweetheart.” The mother kissed her, and they were silent a while.

“I do love him so,” said Lavinia, presently. “And you’ll love him too, mama, I know you will.”

“I’m sure of that, dear.”

“But what of papa?”

Mrs. Blair felt the girl grow tense in her arms.

“That will all come right in time,” said Mrs. Blair.

“Will you tell him?”

“Not just now, dear. We’ll have this for a little secret of our own. There’s plenty of time. You are young, you know, and so is Glenn.”

“I love to hear you call him Glenn.”

Mrs. Blair remained with Lavinia until she had tucked her into her bed.

“Just my little child,” the mother whispered over the girl. “Just my little child.”

“Yes, always that,” said Lavinia. And her mother kissed her again and again, and left her in the dark.

When Mrs. Blair rejoined her husband, he laid down the book he always read before retiring, and looked up with the question in his eyes.

“She’s just a little nervous and tired,” Mrs. Blair said. “She’ll be all right in the morning. I think it best not to notice her.”

“Do you think we’d better have Doctor Pierce see her?”

“Oh, not at all!” Mrs. Blair laughed, and the judge, reassured, went back to his book.

They were awakened from their first doze that night by voices singing.

“It’s some of the darkies from Gooseville,” said Mrs. Blair. “They’re out serenading.”

“Yes,” said the judge. “It is sweet to fall asleep by.”

At the sound of the singing Lavinia had crept from her bed and crouched in her white night-dress before the open window; the shutters were closed. She heard the melody from far down the street. The singing ceased, then began again, drawing nearer and nearer. Presently she heard the fall of feet on the sidewalk before the house, and the low tones of voices in hurried consultation. And then a clear baritone voice rose, and she heard it begin the song:

She knew the voice. Her heart swelled and the tears came again and there alone in the fragrant night she opened her arms and stretched them out into the darkness.

The days following the picnic had been no easier for Marley than they had been for Lavinia. As he looked back on that night, a fear took hold of him; the whole experience, the most wonderful of his life, grew more and more unreal. Much as he longed to see Lavinia again, he was afraid to go to her home; he wondered whether he should write her a note; perhaps she would think him false, perhaps she would think he had already forgotten her; the idea tormented him; he did not know what to do. He had seen her but once, and then at a distance; the Blairs’ well-known surrey had stopped in the middle of the Square, and George Halliday stood leaning into the carriage chatting with Lavinia. Marley had but a glimpse of Lavinia’s face, pink in the shadow of the surrey-top. As they drove away she had turned with a smile and a nod at Halliday. The sight had affected Marley strangely.

He felt himself so weak and incapable in this affair that he longed to discuss it with some one, and on Sunday afternoon he found his mother at her window with the Christian Advocate, which replaced, in her case, the nap nearly every one else took at that hour.

“How old was father when you were married, mother?” he began.

He spoke out of that curious ignorance of the lives of their parents so common to children; he had never been able to realize his parents as having separate and independent existences before his own. Mrs. Marley laid her paper by, and a smile came to her face.

“He was twenty-two,” she said.

“Just my age,” observed Marley.

Mrs. Marley looked up hastily.

“You’re not thinking of getting married, are you, Glenn?” she asked.

“No.” he said with a laugh.

“My goodness! You’re just a boy!”

“But I’m as old as father was.”

“Y—es,” said Mrs. Marley, “but then—”

“But then, what?”

“That was different.”

Marley smiled.

“Had father entered the ministry yet?” he said presently.

“Yes, we were married in his first year. He had been teaching school, and the fall he was admitted to the conference he was sent out to the Gibsonburg circuit in Green County. We were married in the spring.”

Her face flushed, and she turned the pages of her paper with a dreamy deliberation.

“Ah, but your father was a handsome young man, Glenn!” she said presently.

“He’s handsome yet,” Marley replied with the pride he always felt in his father. And then he asked:

“Did he have any money?”

“Yes,” she said, and she laughed, “just a hundred dollars!”

“A hundred dollars! Well, he had nerve, didn’t he? And so did you!”

“We had more than that,” said Mrs. Marley, solemnly.

Marley looked at his mother suddenly. Her face seemed for an instant to be transfigured in the afternoon glow.

He might have told her then; he was on the point of it, but a footfall on the brick walk outside caused him to look up, and he saw Lawrence coming into the yard. Lawrence beckoned him and he went out.

“Come on,” said Lawrence. “Let’s go out to Carters’.”

Marley looked a question at him, and the smile which Lawrence never could repress long at a time was twitching at the corners of his large mouth.

“She’ll be there.”

“How do you know?” asked Marley.

Lawrence smiled a little more significantly.

When they got to the Carters’ they found Mayme and Lavinia together in the yard, strolling about in apparent aimlessness, yet with an expectancy in their manner that belied its quality of mere idleness. In the look Lavinia gave him all of Marley’s perplexities vanished. Lawrence stood by with a grin on his red face, and Mayme Carter’s eyes danced. She and Lawrence assumed almost immediately an elder, paternal manner, and looked on at the lovers’ meeting as from far heights that were to be reached only after all such youthful experiences had long since become possible in retrospect alone. Still smiling, they edged away, and left the lovers alone.

“Is it really true?” Marley asked.

Lavinia colored a little as she smiled up at him.

“And you are happy?” he asked.

“So happy!” she said.

And then all at once a cloud came over her eyes. She closed them an instant.

“What is it?” he asked in alarm.

“Nothing.”

“Tell me.”

“It’s nothing.” She was smiling again, as if to show that her happiness was complete. “See?” Her eyes were blinking rapidly.

“I’m glad,” he said.

As they turned and walked across the yard Marley looked at her nervously.

“Do you know,” he said, “that I couldn’t remember what color your eyes were?” He spoke with all the virtue there is in confession.

“What color are they?” she asked, suddenly closing her eyes.

“They’re blue,” Marley replied, saying the word ecstatically, as if it had a new, wonderful meaning for him.

“Connie says they’re green.”

“Connie?”

“Yes, don’t you know? She’s my younger sister.”

“Oh.” He did not know any of her family, and the baffling sense of unreality came over him again.

“You’ll know her,” said Lavinia, and added thoughtfully: “I hope she’ll like you. Then there’s Chad, my little brother.”

Marley was growing alarmed at the intricacies of an introduction into a large family, the characters of which were as yet like the characters in the first few chapters of a novel, but he thought it would not reflect on him to admit that he did not know Chad, seeing that he was merely a little brother.

“He admires you immensely,” said Lavinia.

“Does he?” said Marley, eagerly, instantly loving Chad. “How does he know me?”

“He says you were a football player at college.”

Marley laughed a modest deprecation of his own prowess.

“But I knew your voice,” said Lavinia.

“Did you? When did you hear it?”

“As if you didn’t know!”

“Honestly,” he protested. “Tell me.”

“Why, that night that you serenaded me.”

He was regretting that she had outdone him in observation, but she suddenly looked up and said:

“Oh, Glenn! What a beautiful voice you have!”

It was the first time she had ever called him Glenn, and it produced in him a wonderful sensation.

They had come to a little bench, and, sitting there, they could only look at each other and smile. Marley noticed that a little line of freckles ran up over the bridge of Lavinia’s nose. They were very beautiful, he thought, and yet he had never heard of freckles as one of the elements of a woman’s beauty. Then he leaned back and looked about the yard.

He had always thought of it as it seemed that first night, enormous, enchanted, with wide terraces and fountains, and white statues gleaming through the green shrubbery. But now he saw no terraces, no statuary, no fountains, and no wide lawns; nothing but a cramped little yard crowded with bushes and trees, and surrounded by a weathered fence that had lost several pickets. He looked around behind the house where he had fancied long stables with big iron lamps over the doors, but now he saw nothing but an old woodshed and a barn on the rear end of the lot. The cracks in the barn were so wide that he could see the light of day between them as through a kinetoscope. He heard a horse stamping fretfully at the flies.

“It was here,” he said, “that I first saw you.” He did not speak his whole thought.

“Yes,” she answered. “I remember.”

“That was a wonderful night, the most wonderful of my life, except the one at the lake.”

He drew close to her. “I loved you at first sight,” he whispered.

“Did you?” She looked at him in reverence.

“Yes,—from the very first moment. When you came into the room, I knew that—”

“What?”

“That you were the woman I had always loved and waited for; that I had found my ideal. And yet they say we never discover our ideals in this life!”

He laughed at this philosophical absurdity.

“What did you think then?” he asked.

She cast down her eyes, and probed the turf with the toe of her little shoe.

“I loved you then too.”

He gazed at her tenderly, rapturously.

“Isn’t it wonderful?” he said presently, “this love of ours? It came to us all at once!”

She looked at him suddenly. Her short upper lip was raised.

“It was love at first sight, wasn’t it?”

“Yes. We were intended for each other.”

They sat there, and went over that first night of their meeting and that other night at Greenwood Lake, finding each moment some new and remarkable feature of their love, something that proved its divine and providential quality, something that convinced them that no one before had ever known such a remarkable experience. They marveled at the mystery of it.