THE GIRLS OF

FRIENDLY TERRACE

Or: Peggy Raymond's Success

BY

HARRIET LUMMIS SMITH

ILLUSTRATED BY

JOHN GOSS

BOSTON

L. C. PAGE & COMPANY

MDCCCCXII

Copyright, 1912

BY L. C. PAGE & COMPANY

(INCORPORATED)

All rights reserved

First Impression, April, 1912

Second Impression, November, 1912

Electrotyped and Printed by

THE COLONIAL PRESS

C. H. Simonds & Co., Boston, U.S.A.

CONTENTS

CHAPTER

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

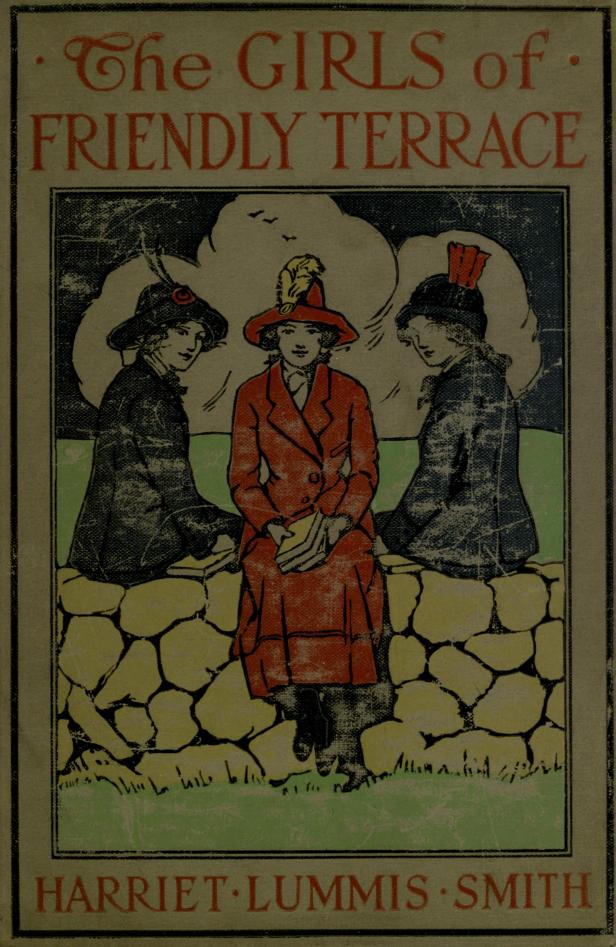

Peggy . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Frontispiece

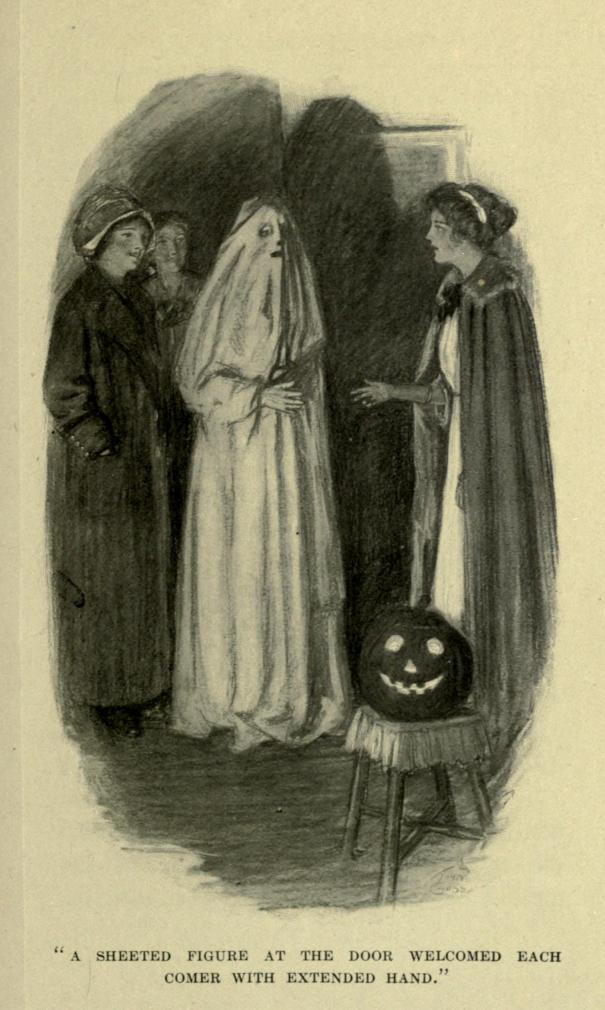

"A sheeted figure at the door welcomed each comer with extended hand"

"The rapidity with which the ice cream disappeared was startling, to say the least"

"Staring with surprise at her brother's crestfallen figure"

"Luncheon was served shortly after their arrival"

The Girls of Friendly Terrace

CHAPTER I

THE RETURN OF PEGGY

The naming of the Terrace was a happy accident. It must have been an accident, for Jenkins Avenue crossed it at right angles, and just to the north ran Sixtieth Street. No one could have guessed when the Terrace was laid out that the name would prove so appropriate, and that the comfortable cottages would have such a cordial, neighborly look, as if nodding greetings to one another across their neat strips of lawn. When the name Friendly Terrace appeared on the street lamps at the corner there were no smiling faces visible at the front windows of the houses, no plump babies rolling over the lawns, no girls gathering on one another's porches, like robins in the boughs of a cherry tree, or strolling along the sidewalk, two by two, with their arms about each other's waists. The naming of the Terrace must have been a happy accident, or else an inspiration.

There was usually a girl in evidence on Friendly Terrace at any hour of the day, and this morning there were three of them. They ranged from tall Priscilla, who was five feet seven, and mortally afraid of growing taller, down to Amy, who was almost as broad as she was long, and who was in a chronic state of announcing her determination to leave off eating candy next week. Ruth, who on this occasion served as the connecting link between the two extremes, was a slender girl, whose alert air told plainly that she was on the watch for something or somebody.

"Once when my Aunt Fanny was coming to make us a visit," Amy observed reminiscently, "her train was six hours late. Just think if Peggy's train--"

"Don't!" exclaimed Priscilla rather fretfully, and Ruth said with decision, "O Peggy's train couldn't be late, she's coming such a tiny bit of a way."

"It might be if there was a wreck," Amy insisted triumphantly. "That was the matter when Aunt Fanny came. A freight train was wrecked just ahead of them, and they had to stand on the track for hours and hours. We waited luncheon for her till I was almost starved."

The other girls exchanged amused smiles. The thought of Amy, undergoing the pangs of starvation, was likely to present itself in a humorous light. Amy saw the look and understood it, but was far from being offended. In point of disposition, Amy was as sweet as the confections she was always on the point of denying herself. An appreciative giggle showed that she understood her friends' point of view.

"That's always the way," she said, with unimpaired cheerfulness. "Fat people never get any sympathy." She stopped abruptly, for Ruth had uttered a stifled scream and was pinching her arm.

"The hack!" cried Ruth. "The hack's coming. Peggy's here."

The non-committal vehicle, rapidly approaching from the direction of the Avenue, was mud-stained and shabby, but the appearance of Cinderella's golden coach would hardly have been the occasion for greater excitement. Ruth clasped her hands, her color coming and going. Tall Priscilla forgot her dignity and capered like a five year old, while Amy went tripping down the street to meet the hack, which, of course, passed her, reducing her to the necessity of following in pursuit, panting and very red in the face. All along the Terrace people came to the windows at the sound of wheels, for from the mothers down to the babies, everyone knew that Peggy Raymond was coming home that morning. Even Taffy, Peggy's dog, bounded out to add his mite to the general welcome.

"Talk of the intelligence of animals," gasped Priscilla, as Taffy shot between Ruth and herself, narrowly avoiding upsetting both. "That dog knows it's Peggy just as well as we do. O why don't the man stop in the right place?"

The mud-splashed vehicle came to a standstill midway between Peggy's home and the vacant cottage next door. Before it had fairly halted the girls were abreast of it.

"Here we are, honey!"

"Hurry up! We're dying for a sight of you."

"O, don't be such a slow-poke. Even Taffy is losing patience." This last comment was unnecessary, as Taffy was speaking for himself, barking uproariously, and leaping about with an air of the keenest anticipation.

The door of the hack opened, and very deliberately a girl stepped out. She was a tall girl, dressed in black, which added to her apparent slenderness. Her lips, which suggested a degree of self-repression, unusual in a girl of her age, were tightly set. She did not look in the direction of the crestfallen trio ranged along the sidewalk.

"Why!" cried Amy, who had an odd fashion of announcing discoveries which had been apparent to everyone for some time, "It isn't Peggy after all."

"We--you--I mean we thought you were somebody else," explained Priscilla, with considerably less than her usual self-confidence.

The newcomer took as little notice of the stammered apology as she had of her boisterous welcome. Silently she assisted a lady draped in mourning to alight, and together they made their way to the empty cottage, which displayed in the front window the sign, "To Rent." The hack driver grinned, fully appreciating the little comedy, while the girls exchanged glances of mingled wrath and humiliation.

Amy was the first to see the humorous side. She shut her eyes and staggered to the fence for support. Her peals of laughter must have been plainly audible to the girl who was trying the key in the front door of the vacant cottage, but the latter only tightened her lips and did not turn her head. Ruth and Priscilla, after staring blankly at Amy for a moment, joined in her laughter, though in a rather half-hearted fashion.

"She looked so out of temper," gasped Amy breathlessly. "And we'd been calling her 'honey' and telling her we were dying to see her. O dear!" She wiped her eyes, and started on another burst of merriment which almost immediately died away in a gurgle of astonishment.

"Peggy!" Three voices pronounced the name at once, with varied intonations of surprise and pleasure. So engrossed had they been that they had not noticed the arrival of a second hack, which with magical suddenness had spilled out upon the sidewalk a large girl and a small one, to say nothing of a motley collection of suit-cases, hand-bags, bundles and umbrellas. Settling with the hackman delayed Peggy a half-minute, and the girls arrived at the gate as soon as she, but she waved them aside.

"First kiss for mother," Peggy cried, and shot straight as an arrow into the arms of the lady who stood waiting on the steps. There was a long clasp and more kisses than one, and none of Peggy's friends thought the less of her for that loyal rush for the one who loved her best.

It was no wonder that Peggy Raymond's return was an event on Friendly Terrace. She was the sort of girl you could not see without wishing you knew her, and could not know without beginning to love her. From her reddish-brown top-knot down to the tips of her toes she was bubbling over with life and joyous energy. It was a nice world, Peggy thought, full of nice people. Every to-morrow was stored for her with wonderful possibilities, as the yesterdays were full of sweet recollections. Complaining, discontented people wakened in her the same sorrowful wonder she felt when she saw a blind man feeling his uncertain way along the street. Indeed, to Peggy discontent seemed another and more dreadful form of blindness.

"Come into the house, all of you." Peggy was making up for the brief delay by kissing everybody twice around. "Hasn't Dorothy grown, girls? Wouldn't you think she was more than four years old? What are you doing, Dorothy darling?"

"I'm wipin' off kisses," Dorothy replied with great distinctness, scrubbing violently at her rosebud of a mouth. "'Cause I don't like kisses to stick on, 'cept my mamma's."

"She says that because she's forgotten you since last year," Peggy explained excusingly.

"She'll be real friendly after a day or two. O Amy, dear, you mustn't try to lift that heavy suit-case. It weighs as much as you do."

"I'm afraid not. I've gained three pounds since you went away," Amy replied dolefully. "Next week I'm going to stop eating candy, and begin to walk ten miles a day."

Everybody laughed, for, when hearts are light, old jokes serve as well as new ones. They streamed into the house, a laden procession, and piled Peggy's belongings in the middle of the living-room. Then they pulled her down on the window-seat, chafing under the undeniable difficulty of evenly dividing one girl among three.

"I'm so glad to see you, I could just eat you up," Amy declared, seating herself on Peggy's knee, as each of the others had preempted a side. "And to think of your staying six weeks, when you said you'd only be gone a month."

"I hated to leave Alice," Peggy's face clouded for a moment, as she spoke her sister's name. "She isn't a bit well. You know we are going to keep Dorothy with us for a while. She's so full of life that she's a tax on her mother."

"I stood on a tacks once," observed Dorothy, suddenly becoming interested. "It sticked into me, and I hollered." She frowned meditatively as she added, "I don't like you to call me a tacks, either."

"It's another kind, darling. O girls, you don't know how good it seems to get back to the Terrace, where people know each other and are real neighbors. I don't see how Alice stands it."

"Is it so bad living in a very big city?" Priscilla asked, rather doubtfully. "I believe I'd love it. I like crowds and noise and something happening every moment."

Peggy shook her head with decision. "Just wait till I tell you. Alice lives in a flat, and there's only one woman in the building whom she'd know if she met her on the street. One morning while I was there we heard the greatest commotion in the flat just over ours. Somebody screamed, and then we could hear somebody else hurrying around right over our heads, and then there was the sound of dreadful crying. The windows were open, you know, and we heard everything as plainly as you hear me."

"Well, what had happened?" Amy demanded, as Peggy paused dramatically.

"That's what we couldn't imagine. I wanted to rush right up first thing, but Alice said people didn't do that way in big cities, and that she didn't know the woman at all, though she thought the name on the letter box was Flemming. Well, the crying kept up till I couldn't stand it any longer. I just walked upstairs and knocked, and when the girl came to the door, I said I lived on the next floor and I was afraid that somebody was in trouble and could I do anything to help.

"O girls!" Peggy's voice grew pensive at the remembrance of that sorrowful scene. "I never imagined anything so dreadful. The poor woman--her name was Fletcher instead of Flemming--had just had word that her little boy had been hurt by an automobile, and taken to a hospital. And she was so upset that she didn't know how to get ready to go to him, and the girl was so stupid that she didn't know how to help her. And I rushed around and found her hat and coat and put on her shoes for her--she was wearing slippers--and did everything, just as if I'd known her all my life. And then she wouldn't let me go, and I went along with her to the hospital. She told me afterward that she had only lived in the city a few years and hadn't made many friends. A few years!" repeated Peggy with fine scorn.

"Why, if anybody on this Terrace was in trouble, even if she hadn't lived here more than six weeks, we'd all be flocking in to see what we could do for her."

"Did the boy die?" asked Amy, missing the moral Peggy was trying to point, in her interest in the story.

"No, indeed. He wasn't hurt as badly as they thought at first. He was home again before I left, such a nice boy, not far from Dick's age. O here's Dick now."

Peggy's younger brother, Dick Raymond, coming in at that moment, said, "Hello, Peggy," in the most matter-of-fact manner imaginable and submitted with apparent resignation to his sister's kiss. But no one was deceived. Dick's admiration of Peggy was an open secret in Friendly Terrace. The boy was hot and perspiring. He had run all the way home from his music teacher's, so impatient was he for a glimpse of the dearest as well as the most remarkable girl in the world, as he firmly believed, and yet at the sight of her, he had only a "hello Peggy," and a shame-faced kiss. Luckily Peggy was not the sort of girl who needed to be told certain things. She understood without any explanation.

"Guess we're going to have some new neighbors," Dick observed, looking out of the window, apparently glad of an opportunity to change the topic of the conversation.

"Who? Where? The next house?" Peggy stood looking over her brother's shoulder, as two people came from the vacant cottage and moved toward the waiting hack. Her eyes dwelt approvingly on the slender figure of a black-gowned girl, carefully assisting the older lady into the carriage.

"Girls!" Peggy's voice fairly tinkled, as she made the pleasant announcement. "It looks as if we might be going to have another girl on the Terrace. Won't that be fine?"

The others exchanged dubious glances. "Always room for one more, I suppose," Priscilla said at last.

"And she looks like such a sweet girl, too," Peggy continued, as the shabby hack rumbled off. "She had such a nice way of helping her mother--that is, I suppose it's her mother."

Amy coughed in an embarrassed fashion, and Ruth said hastily, "We took her for you at first, Peggy. We were watching for your hack, you know, and hers came first."

"I imagine she must have thought us very cordial to strangers," Priscilla added, choking down a laugh, as she remembered the contemptuous indifference of the girl who had received a welcome intended for somebody else.

"I'm glad of that," said the innocent Peggy. "Because that may help them in making up their minds to come here. And I don't like to have a vacant house on the Terrace. It reminds me of a child shedding its first teeth. The more smiling and pleasant it looks, the more you notice that something is missing."

From across the street somebody whistled, a rather peculiar whistle, long and piercing. Ruth jumped to her feet.

"It's Graham," she said. "What is he doing home at this time in the morning? O, I wonder if luncheon really can be ready?"

"Of course it can," Amy cried tragically. "I'm nearly starved. I couldn't eat any breakfast this morning, I was so excited because Peggy was coming."

"You'll be over this afternoon, won't you, Peggy?" Priscilla asked as she rose to go, and her face fell slightly as Peggy answered, "Why, of course. I'll run in to see all of you." It was just a little hard for Priscilla to remember that her claim on Peggy was in no sense superior to that of the other girls. She was one of the people who liked to be first, and, though generous enough with her other possessions, she found it hard to share her friend. Yet there were moments when Priscilla acknowledged to herself that a fraction of Peggy's affection was worth more than the undivided devotion other girls had given her in the fervid friendships which, in a few weeks or months at the outside, had burned themselves out.

Peggy was as good as her word. But when she crossed the street that afternoon, on her way to Priscilla's, she noticed that the sign "To Rent" had disappeared from the window of the house next door. "That means new neighbors, certain sure," thought Peggy hopefully. Nor did she guess what a new element her prospective neighbors were to introduce into the cheerful atmosphere of Friendly Terrace.

CHAPTER II

THE GIRL NEXT DOOR

A delicious odor was gradually pervading the Raymond cottage, a spicy fragrance which of itself was suggestive of Peggy's return. For Peggy's accomplishments were of a practical sort. The crayon which adorned the wall of her mother's bed-room, and which represented Peggy's supreme achievement in the field of art, had been the subject of considerable discussion in the family. Dick insisted that a prominent object in the foreground was a Newfoundland dog, while his mother accepted Peggy's assurance that it was a sheep grazing, and refused to listen to the arguments by which Dick supported his position. As a musician, too, Peggy had her obvious limitations, but when it came to transforming the cold potatoes, and the unpromising ends of the roast left from dinner, into an appetizing luncheon, it would be hard to find Peggy's equal; while the fame of her sponge cake and her gingerbread had spread far beyond the confines of the Terrace. And since this is a practical world, with very commonplace needs, there is much to be said in favor of such accomplishments as Peggy cultivated.

She moved about the spotless kitchen with a quick, light step, humming under her breath something which, if not exactly a tune, was, nevertheless, like the chirp of a cricket, or the purring of a tea-kettle, very pleasant to hear. In her blue gingham apron, with her sleeves rolled to the elbow, she looked decidedly businesslike, though the costume was far from being unbecoming. Indeed Dick, sitting on the window-sill, gravely observant of Peggy's occupation, noticed how the heat from the range had deepened the pink on his sister's cheeks, and told himself that Peggy was growing pretty. Not for worlds would he have said as much to Peggy herself, but, for all that, the discovery gave him the greatest satisfaction.

"Put on plenty of sugar and cinnamon now," Dick advised from his precarious perch on the window-sill. "You'd ought to have tasted the cinnamon rolls Sally made while you were gone. She scrimped on the sugar and the cinnamon, you see, and you wouldn't have known what you were eating. What's the good of making cinnamon rolls at all, if you're going to scrimp?"

"That's right, Dick," Peggy agreed. "If you're going to do anything, put enough into it so that it will amount to something when it's done." Peggy was not given to lecturing her younger brother after the fashion of some girls, but she had a habit of hanging little sentence sermons on pegs which chanced to be available--cinnamon rolls, in this instance. And Dick, who would have turned sulky in a moment if he had suspected Peggy of "preaching," looked thoughtful, and stowed the suggestion away for further reference.

Peggy went on rolling, cutting, sifting on cinnamon with lavish hand and adding little dabs of butter until the second pan of rolls was ready for the oven. Then Dorothy, standing by the open door, made a startling announcement. "House is a-fire! House is a-fire!"

"O Dorothy!" Peggy flew to the door, and turned in the direction in which the chubby finger was pointing. As she looked, the kitchen window in the next house was lowered and a cloud of black smoke escaped, accompanied by an odor which caused Dorothy to wrinkle her nose and say disgustedly, "Glad I don't live in that house."

"They let something on the stove burn; beans, I guess," said Peggy, sniffing wisely. "It's dreadful trying to cook while you are getting settled after moving." She looked thoughtfully toward the house next door, which presented the forlorn appearance to be expected considering that the tenants had moved in only the day before. Through the uncurtained windows Peggy caught glimpses of incongruous groups of furniture, of step-ladders standing aimlessly in the midst of the confusion, of pictures leaning precariously against the wall. To Peggy the sight was like an audible appeal for help.

"I might take them some of my cinnamon rolls," she exclaimed, turning to Dick.

"Take who?" As long as Dick made his meaning clear, he was never troubled as to grammatical correctness.

"Why, the next door people. It would make them feel as though they really had neighbors and, of course, I can't go over to see the girl till the house is settled."

"If you'd been going to do that," Dick said rather reprovingly, "you ought to have baked more than two pans. But then," he added with an evident effort to be generous, "I guess they need them more than we do. Go ahead."

The rolls came out of the oven just the golden-brown that Peggy wanted. Peggy might draw a sheep that looked like an own cousin to a Newfoundland dog, but she had the joy of a real artist in her cookery. With shining eyes she gazed upon the work of her hand. "They're perfect," she announced, with an unsuccessful effort at a judicial air.

"They do look good enough to eat," Dick agreed. "Say, give me one. I'm hungry."

"And I'm hungry, too," cried Dorothy, edging close.

"When the next pan comes out," Peggy promised. "I'll run over with these so our neighbors will know what they've got to depend on for luncheon." She set her rolls on a plate, threw a napkin over them, and without stopping to remove her apron, crossed the yard to the next house. The kitchen window was still open, and as Peggy stood upon the steps she heard the sharp tinkle of broken glass.

"There's something gone to smash. Dear me, what a time they're having," thought Peggy, wishing her acquaintance with the new arrivals was sufficiently advanced so that she could offer to lend her aid, for her capable fingers fairly itched to assist in bringing order out of the chaos within. She knocked, and, after waiting for some minutes, knocked again, this time a little louder.

"Elaine!" a voice cried. "Elaine! Somebody's at the back door."

"O dear!" someone else said distinctly, and Peggy's color heightened, even though she felt confident that the speaker's mood would change as soon as she knew her caller's errand. "So her name is Elaine," Peggy thought, as footsteps slow, and seemingly reluctant, sounded on the bare floors. "Such a pretty name."

The door opened violently and a girl looked out. It was the same black-gowned girl Peggy had watched from her window a few days earlier, but, on this occasion, her appearance was decidedly less prepossessing. Apparently she had neglected to comb her hair that morning, or else her forenoon's occupation had been strenuous enough to obliterate all traces of that ceremony. Her apron was soiled. She wore an expression of weary discouragement, which seemed as incongruous with her girlish face as white hair would have done. The eyes she turned upon Peggy were anything but friendly, and yet at the sight of her, Peggy's heart swelled with a sympathy that was almost tender.

"Good morning!" Peggy extended her offering with a cordial smile. "I know how busy you must be getting settled, and I brought you over a plate of rolls. I live--"

"We don't care to buy anything this morning," said the girl, and made a movement as if to close the door. Peggy's face flamed to the roots of her hair.

"O, you don't understand," she cried. "I'm a neighbor of yours. I've brought you over a plate of cinnamon rolls, I've just finished baking. They're not for sale."

Elaine was a rather pale girl. But as Peggy finished her little speech, two spots of red showed in the other's thin cheeks.

"We're not objects of charity, thank you," she said. The door shut with a slam. Peggy, her rejected offering in her hand, stood bewildered on the step. For a moment she battled with the temptation to push open the door and force the girl inside to listen to reason. With a choked laugh, that covered not a little humiliation, she realized the folly of such a proceeding and turned away.

Peggy's eyes were absent as she entered the house. She took the second pan of rolls from the oven without feeling any disposition to gloat over their yellow-brown perfection. Then, remembering her promise to Dick and Dorothy, she put some of the rolls on a plate and carried them into the next room. Her thoughts were still full of the rebuff she had received from her new neighbor, and when she had set the plate of rolls on the table she stood with clasped hands, looking hard at nothing in particular, and frowning over her reflections.

"How glad she is to see us!"

"Yes, just notice her smile."

"Probably those are city manners, girls. We'll have to get used to it."

A volley of mocking laughter followed these observations, and Peggy started guiltily.

"I didn't see you," she apologized, as three girls popped up from the window-seat and approached her.

"Don't try to get out of it, Peggy," teased Priscilla, slipping her arm about Peggy's waist. "You know you can't be glad to see us with such a face."

"O, Peggy! What delicious rolls!" Amy hung over the plate with an ecstatic gasp. "Don't they look as if they'd melt in your mouth."

"Help yourself," Peggy cried. "All of you."

"They'll make you fat, Amy," warned Ruth, extending a slim hand. "Priscilla and I can eat all we want, but you'll have to refuse. You know you're going to leave off eating candy."

"Well, they're not candy, and, besides, I'd rather gain a few ounces than turn down such darlings," Amy replied recklessly. Suiting the action to the word she set her teeth in the golden-brown crust. "They're as good as they look," she announced indistinctly. "Say, Peggy, are these the kind you took over to the house next door? Dick said that was what you went out for."

Peggy nodded, her face betraying the peculiarly guilty expression that sensitive people wear when fearing that they will be forced to betray the wrongdoing of someone else. Priscilla eyed her suspiciously.

"Well, I don't see that there could have been a nicer introduction," Amy remarked with her mouth full. "How lovely it would be if all callers brought cinnamon rolls instead of visiting cards."

"What happened, Peggy?" demanded Priscilla, reading her friend's tell-tale face as if it had been an open book. "Weren't they nice to you?"

"Nice!" cried Ruth, flaring up at the mere suggestion of ill-treating Peggy. "Why shouldn't they be nice?"

"Peggy's blushing," exclaimed Amy, announcing a discovery sufficiently obvious to the least discerning. "She's blushing as red as fire. Peggy Raymond, what has happened?"

"It really wasn't anything," said poor Peggy, fairly cornered. "Only--"

"Well?"

"Only she didn't quite understand."

"Who didn't? That snippy, disagreeable girl, who puts on such ridiculous airs of being better than other people?"

Peggy's eyes widened over the vivid description whose appropriateness she was forced to admit. "I saw the girl," she replied hastily. "Her name's Elaine, I think."

"We don't care about her name, Peggy. What did she do?"

"At first she thought I'd come to sell the rolls, and she said they didn't care to buy anything."

"Peggy a pedler! I never heard anything so funny!" Amy sat down on the floor to laugh, but her amusement did not communicate itself to the others. Ruth's face still wore a protesting frown, and Priscilla's eyes were flashing.

"A pedler!" Priscilla repeated disdainfully. "She must be very observing. Well, Peggy. After you explained--"

"That seemed to make it all the worse," admitted Peggy, finding a little relief, it must be acknowledged, in the sympathy called out by her confession. "She can't have been used to neighbors, that's sure. She said they weren't objects of charity, and shut the door in my face."

An indignant explosion followed, when everybody talked at once. Then Dorothy bobbing up as expectedly as a Jack in a box, poured oil on the troubled waters by offering a suggestion. "Maybe they fought the currants was flies. I did till I bited 'em."

"O, Dorothy, what a killing child you are!" cried Amy, giving way to helpless laughter, and this time she had plenty of company. Peggy was the only one of the quartet who made any effort to conceal her merriment, Peggy having a singular theory that children should be treated just as courteously as older people. She looked regretfully at the small, erect figure marching out of the room with an air of stately displeasure. "O dear!" she sighed. "I'm afraid we've hurt her feelings. Dorothy does hate to be laughed at."

"Then she'd better give up making such speeches," remarked Amy, wiping her eyes. "But to go back to Peggy's new friend--Elaine--"

"Yes, just to think of her slamming the door in Peggy's face," cried Ruth, whose customary gentleness had quite disappeared in resentment over Peggy's snubbing. "If she doesn't want neighbors she needn't have any. I move that we let her alone, just as much as if she lived down town somewhere."

"We didn't tell you, Peggy," Priscilla exclaimed, taking up the tale. "But we found out the sort of girl she was the day you came. We thought it was your hack, you know, and we rushed to grab you the minute you stepped out, and we were all screaming for you to hurry, and when this girl got out we felt cheap enough to go right through the sidewalk."

"Yes, we did," interrupted Amy. "If there had been an open coal-hole handy it would have taken me about five seconds to disappear."

"The way she took it showed the sort of girl she is," insisted Priscilla. "Instead of smiling, or saying that it didn't matter, she acted as if we'd been so many hitching-posts standing in a row. Didn't see us or hear us, either. I knew in a minute that I'd never have any use for her if she lived here a thousand years."

"That's just the way I feel," said Ruth.

"Me, too," exclaimed Amy from the rug, and absent-mindedly she reached for another cinnamon roll.

It was Peggy's turn. "O, girls," she pleaded, in tones of distress. "Let's not be in such a hurry to make up our minds. You see, we've hardly seen anything of her."

"Quite enough," observed Priscilla.

"And things were rather against her both times," continued Peggy, disregarding the interruption. "When we come to know her we may like her awfully well."

A depressing silence implied that no one but Peggy herself thought such a result at all probable.

"And, anyway," concluded Peggy, falling back on the supreme argument, "she hasn't tried living in Friendly Terrace yet. We don't know what that will do for her. Instead of letting her alone, I think we'd better show her what it means to have neighbors of the neighborly kind."

It did not appear that a continuation of the discussion was likely to bring them into agreement. Amy tried changing the subject. "Do you know what this roll reminds me of?" she asked, looking thoughtfully at the fragments in her hand.

No one could imagine.

"The first time I ever tasted one of Peggy's rolls," Amy explained, "it was on a picnic at the Park. It was the time that Ruth fell into the lake, feeding the swans."

"I'd forgotten the rolls, but I remember that picnic," Ruth said. "The picnics this year didn't seem like the real thing," she added disconsolately, "with Peggy gone."

"'Tisn't too late for another," Priscilla cried. "Why not go to-morrow?"

If the quartet had failed to agree on the subject of Peggy's next-door neighbor there was no lack of unanimity as far as the picnic was concerned. In five minutes it was arranged that Ruth was to bring the sandwiches and Amy the fudge, while Peggy had agreed to get up early and make some little sponge cakes.

"You won't mind if I bring Dorothy, will you, girls?" Peggy inquired anxiously. "You see, she really does make a lot of extra work, she's such a mischief, and I don't want to leave too much for mother to do."

It was the general opinion that Dorothy's presence would add to the gaiety of the picnic, and, after completing their plans, the friends parted with looks expressive of cheerful anticipation. But Peggy's bright face clouded over as she glanced a little later toward the next house, and saw, perched upon the top of a step-ladder, a slender, girlish figure, with an indefinable air of dejection and helplessness.

"O dear! I shall be glad when she's lived in the Terrace long enough to be one of us," Peggy thought. "All the trouble is that we don't understand one another. As soon as we're acquainted everything will be all right, and nobody'll have to be left out."

CHAPTER III

MAKING FRIENDS

It was just as well, as things turned out, that Peggy had resolved on an early start the following morning. Dimly through the grey dawn she became aware of an elfish, white-gowned figure perched on the foot of the bed. Her sleepy questionings as to its identity were dispelled by a sweet, high-pitched voice.

"Now this is down to the sea shore, Aunt Peggy, and that's the water where you are. Bime-by I'm going to dive and make a big splash."

Before Peggy could protest, Dorothy had carried out her intention, descending on her shrinking relative like an avalanche. "Kick, Aunt Peggy! Kick hard!" she shouted, disappointed at Peggy's failure to enter into the sport, with the spirit due its dramatic possibilities. "That's what makes the waves."

But Peggy was beyond kicking. When she had succeeded in dislodging Dorothy from a commanding position on her chest, she indulged herself in several deep breaths before saying plaintively, "O, Dorothy, why did you wake so early? It isn't time to get up yet."

"It's time to get up for a picnic day," insisted Dorothy. "And you've got to cook luncheon, Aunt Peggy, and can I wear my rubber boots and take my dolly and my blue celluloid comb?"

Further sleep was out of the question. Making a virtue of necessity, Peggy jumped out of bed, reflecting that this early start would give the frosting on her cakes a chance to harden. Getting Dorothy dressed was a process requiring time and patience, for the child was so excited by the festivities in prospect that she could hardly stand still long enough to allow a button to be popped into its rightful button-hole. Inventors interested in perpetual motion should have made a study of Dorothy. She interrupted the process of getting her fat little legs into their black stockings by so many fantastic capers that Peggy forgot the loss of her morning nap in helpless laughter, and the day began cheerfully after all.

By breakfast time the comfortable odor of sponge cake diffused through the house, told that Peggy had made good use of her time. It penetrated Dick's bed-room, and that young man, under the mistaken impression that he was sniffing the fragrance of waffles, rose in haste and reached the breakfast table on time, an unusual feat for Dick, who dearly loved the last minutes in bed, and, as a rule, needed to be called three times before responding.

Dorothy was too excited to eat. She had made a collection of cherished belongings to take with her to the Park, and tact, as well as logic, was needed to convince her that the occasion did not call for a pink parasol or a tooth brush. A compromise was finally reached by virtue of which Dorothy agreed to leave all her belongings at home, with the exception of her "shut-eye doll," on the understanding that she was to be allowed to help in packing the lunch basket. This ordinarily prosaic task proved quite exciting that morning, owing to Dorothy's propensity to smuggle in such articles from the sideboard as appealed to her as attractive and desirable.

A little after nine the girls began to arrive. Priscilla and Ruth came up the walk at almost the same minute, and they all settled themselves to wait for Amy. It was understood that they must always wait for Amy, though, singularly enough, Amy always had a brand-new reason for her invariable delays. Either her shoe-string broke at the last minute or someone called her up on the telephone, or her hat pins had disappeared, or some other unforeseen event interfered with her innate propensity to promptness. Amy's friends listened with cheerful disrespect to her latest excuses, and Amy was the only one of them all who accepted them at their face value, and honestly believed herself the soul of punctuality.

At quarter of ten Amy appeared, puffing a little, to show how she had hurried, and explaining that the fudge had refused to harden. The other baskets were grouped upon the porch and the girls sat in a row on the steps, discussing some of the interesting events which had taken place along the Terrace during Peggy's absence. At Amy's approach Peggy jumped briskly to her feet.

"We're all ready now," she said. "Where's Dorothy disappeared to? O, Dorothy! We're going to start now."

There was no answer. "Dorothy!" Peggy called again, "Come quick. The picnic's going to begin."

This assurance was effective. At the end of the hall appeared a mysterious figure which moved toward the door with hesitating and uncertain steps. A weird, white drapery concealed its face, and fell in flowing folds to its shoulders. Amy was the first to perceive its appearance and she let fall her basket and squealed.

"What is it?" she cried wildly, as Peggy, at the other end of the porch, turned upon her a startled countenance, "O, what is it?"

"What's what?" Peggy flew to answer her own question. At the sight which had alarmed Amy she stood as if petrified, her lips apart, and broken fragments of sentences escaping at intervals.

Meanwhile the slow-moving figure had reached the door. From beneath the mysterious drapery came the sound of a stifled wail. Peggy came to herself with a start.

"Dorothy!" she cried. "What have you got over yourself?" She touched the drapery with shrinking fingers. It was sticky, clinging. The fragment she touched fell off at her feet.

"I smell--yeast," exclaimed Peggy sniffing. "Yeast!" She looked about her wildly. "Girls, it's bread-sponge."

"She'll smother," exclaimed the practical Priscilla, and forthwith clawed an opening in the sticky mass, through which Dorothy's face looked out. It was a solemn face at that moment. A suspicious trembling of the lips told that the tears were not far away.

"I--I don't like Sally," faltered Dorothy. "She put somefing in a pan, up high. And when I pulled, it covered me all up."

"That's the end of the picnic, girls." Peggy spoke with forced calm. "The end, as far as I'm concerned. Bread-sponge all the way from here to the kitchen. Bread-sponge in her hair and her eyebrows."

"I don't care, Aunt Peggy," cried poor little Dorothy. "I'd just as soon go to the picnic all sticky."

It was a melancholy ending for so many cheerful plans. The girls protested that the picnic without Peggy would only be an aggravation. They suggested putting it off till another day. But Peggy, usually distinguished for her sweet reasonableness, was not in a mood to make the best of things.

"She'd only get into something else, girls," she insisted. "The glue pot or the molasses jug. Even if the fudge would be just as good to-morrow, you can't say as much for the sandwiches. Go along and enjoy yourselves."

While three girls wended their disconsolate way toward the Park car, a still more dejected procession of two climbed the stairs to the Raymond bathroom. Mrs. Raymond, hearing the sound of Dorothy's stifled crying, came out to inquire the cause of the trouble, and uttered a horrified exclamation at the sight of her small granddaughter. Although divested of the greater part of the mass of bread-sponge, enough adhered to Dorothy's plump person, to give her a most unique appearance. Mrs. Raymond patted the round, tear-stained cheek, and cast a comprehending glance at Peggy's overcast face.

"I wish you had gone with the girls, dear," she said. "I could have attended to this little mischief, and it's hardly fair that you should lose your fun."

"Just as fair as that you should spend your morning scrubbing Dorothy," Peggy returned. "You ought to know I wouldn't leave it for you." Then with the honesty which was one of Peggy Raymond's charms, she added, "I suppose I might better have gone than stay at home and act like a martyr. Never mind, mother. There'll be more picnics some day."

The process of repairing damages was a slow and tedious one. At intervals Dorothy wept copiously into the bath tub, and uttered broken promises to the effect that next time she would stand in a corner and not move till the hour of starting arrived, "And I sha'n't like Sally never any more," sobbed Dorothy, who had a habit, not unknown among older girls, of holding other people responsible for her escapades, "'cause she put that up high where it could fall all over me."

The last traces of glutinous matter were at last removed from Peggy's charge. Arrayed in a clean gingham, with a bath towel over her shoulders, Dorothy was set out on the porch, where the sun could dry her golden hair. Peggy gave her attention to repairing damages elsewhere, and when she returned after twenty minutes' absence, Dorothy's hair was curling all over her head, in a flossy yellow snarl, while in her hand she held a typewritten sheet of paper.

"What's that, Dorothy?" Peggy asked, feeling the curly head for signs of dampness.

Dorothy reflected. "It's a letter, I fink," she replied, obviously giving the explanation which seemed most plausible, but speaking doubtfully.

"Let me see!" Peggy took the sheet in her hand, and began its perusal, her eyes opening wide and wider as she read.

"'honor is at stake,' replied the earl, his hand seeking his sword. The Lady Vivian uttered a cry of anguish, and sank fainting into the arms of her attendant."

"Why, how funny," Peggy broke off in the midst of the thrilling narrative to ask a practical question. "Where did this come from?"

"I guess a angel brought it," replied Dorothy, after due reflection.

"O, you goosie!" Peggy's laughter rang out blithely, and Mrs. Raymond upstairs, overheard and drew a relieved sigh. For to have Peggy low-spirited produced much the same effect as when the sun goes under a cloud.

"Where did you find the paper, dearie?" coaxed Peggy. "The wind blew it from somewhere, didn't it?"

Dorothy shook her head with vehemence, causing extreme agitation among her frizzled locks. "No, it didn't blow from anywhere. It just camed." It was evident that little information could be extracted from this source and Peggy fell back upon her own wits.

"It's typewritten. There isn't anybody around here who has a typewriter, except Harry Rind, and he wouldn't be writing about earls and swords and things. I wonder--"

Peggy broke off, and stared at the next house. The windows upstairs were open. It would be an easy matter for a sheet of paper, more enterprising than its associates, to take a little excursion into the outer world. At the same time, Peggy disliked the idea of facing Elaine again, to inquire if the typewritten sheet was her property. If it happened to belong to someone else, the chances were that Elaine would be as uncompromisingly disagreeable as she had been the day before. And to be snubbed twice in two days was too much, even for Peggy.

"I don't believe it's worth anything anyway," thought Peggy, glancing at the sheet in her hand. Lurid sentences caught her eye. The ladies in the narrative seemed given to shrieking and fainting, while the gentlemen had a propensity for deadly combat. A sturdy strain of common sense in Peggy's make-up caused her lips to twitch over this cheap tragedy.

"It sounds silly," was Peggy's final verdict. "I don't believe it's worth anything, but, after all, it belongs to somebody, and whoever wrote it thinks it's nice, I suppose. And--well, at the worst, she can't do more than shut the door in my face."

She marched down the yard, head up and shoulders back, in soldier fashion. Indeed Peggy felt very much as if she were leading a charge. Like most popular people, Peggy shrank from discourtesy. She was so accustomed to being liked that any indication of unfriendliness came with a sense of shock. The girl who had refused one neighborly kindness in so unpleasant a fashion was not likely to have undergone a change of heart in a little over twenty-four hours.

With a sense of bracing herself to face the worst, Peggy knocked at the kitchen door and stood waiting. Elaine herself answered the summons. The look which crossed her face seemed to say, "What, you here again?" but Peggy did not wait for her to put the ungracious sentiment into words.

"I don't know whether this belongs to you or not," she said hastily, "but I thought perhaps it did, because hardly anybody on the Terrace has a typewriter." She handed the sheet to Elaine and prepared to back away.

But Elaine's formality had vanished with the understanding of Peggy's errand. "Page six," she exclaimed in tones of dismay, "O, I wonder where the rest are."

"I didn't see but this one, but then, I didn't really look. When I came out on the porch my little niece had it in her hand. She said an angel brought it."

"An angel?" Elaine forgot her anxiety for a moment and laughed outright; a little bubbling laugh which did wonders in advancing the acquaintance of the two. Then her thoughts reverted to the paper, which in Peggy's opinion she prized unduly. "They must have blown out of one of the upstairs windows," she exclaimed.

"Perhaps only that one blew out. You look upstairs, and I'll see if there are any more scattered over the grass," Peggy suggested obligingly. As it happened, the search of both girls was successful. Elaine came downstairs, her hands full of sheets she had gathered from the floor, and out of the number only one proved to be missing. This one, numbered four, Peggy had found winding itself about the trunk of a spindling young peach tree in the front yard.

"Now let's count them again and be sure they're all here," Elaine said eagerly. "One, two, three, four."

"Five, six, seven, eight," concluded Peggy. "That's all, isn't it?"

"Yes, that's all. O, how lucky I am to find them."

"O, isn't it splendid."

The door opened and a tall lady looked in. A white veil was tied over her grey hair, and she wore black gloves. In one hand she carried a feather duster, and the helpless air with which she handled this domestic implement, caught Peggy's attention at once. The sight of Elaine and Peggy, beaming at each other across the typewritten sheets, seemed to startle the new-comer. She made a movement as if to draw back, halted irresolutely, and murmured something unintelligible. Elaine came to the rescue, blushing vividly, quite as if, Peggy said to herself, she had been caught doing something out of the way.

"Mamma, this is a neighbor of ours, Miss--I don't know your name, do I?" She looked a little surprised at the discovery.

"Peggy Raymond," said the owner of the name with promptness.

"And this is my mother, Mrs. Marshall." The introduction completed, Elaine hastened to explain Peggy's presence, and the other girl could not free herself of the feeling that she found it necessary to excuse as well as to explain.

"Just think, mamma! One of the sheets of my--I mean one of these sheets flew out of the window, and she brought it back to me. Wasn't I fortunate? And wasn't she kind?"

"We certainly are much indebted to Miss Raymond," Mrs. Marshall remarked with a stateliness which took Peggy's breath away. "I regret that it is necessary," she continued impressively, "to apologize for my appearance. After being accustomed to the supervision of a house full of servants throughout married life it is extremely humiliating to me to be discovered engaged in the work of a parlor maid."

Peggy could think of no suitable reply to this speech. She perceived that Mrs. Marshall was one of the people who, having "come down in the world," persist in flaunting in the face of their acquaintances recollections of their past grandeur. She said hastily that nobody ever called her Miss Raymond, and she wanted to be Peggy to her new neighbors as well as to the rest of the Terrace. Then she excused herself, on the ground that she must look after Dorothy, while Elaine followed her to the door to say again, "I'm so much obliged. I can't tell you how much I thank you."

Dorothy was sitting on the porch steps, a subdued little figure. Her hair, crinkling tightly after its recent washing, stood out in all directions, giving it the appearance of a tuft of thistle-down just ready to fly away.

Peggy felt the fluffy golden crown thoughtfully. "Dry as the Desert of Sahara, isn't it?"

Dorothy compressed her lips and blinked. She strongly objected to being addressed in language beyond her comprehension, perhaps because she always suspected the people who used these terms of trying to make fun of her.

"And as long as your hair is dry, and your dress is clean, I've an idea, Dorothy darling. How would you like to go to the Park and hunt up the girls? They'll have had luncheon before we get there, but there'll be a-plenty left. There always is."

"Aunt Peggy!" screamed Dorothy, climbing to her feet with undignified haste. "I like you better'n butter-scotch, and better'n pink tooth-powder. Let's hurry."

And hurry they did. And which of the two enjoyed the gaieties of the picnic more, the big girl or the little one, it would be hard to say. But underneath Peggy's lightness of heart, and whole-souled participation in the afternoon's fun, a pleasant undercurrent of thought ran like a hidden stream, the consciousness that at last she had succeeded in establishing friendly relations with the girl next door.

CHAPTER IV

A BUSY AFTERNOON

The breeze which had lingered by the honeysuckle, climbing over the back porch of the Raymond cottage, did not carry to the next-door neighbors any whiffs of refreshing fragrance. For before it crossed the hedge, which marked the boundary line between the two places, it had picked up an odor very different. And Peggy Raymond's paint-pot was responsible.

Peggy was arrayed in what she called her regimentals. They consisted of an old shirtwaist, the sleeves cut off at the elbows, a calico skirt, and a pair of shabby shoes, all of which articles were splashed with paint of different colors. The landscape which hung in Peggy's mother's room, and which had been the cause of so much discussion in the family, was not responsible for any part of this rainbow effect. When Peggy donned her "regimentals," her artistic instincts took an entirely different turn.

Standing upon several newspapers, spread out for the protection of the grass in the Raymond back yard, was a chair. It was a rather dilapidated chair, judged from the standpoint of an unbiassed spectator. Its cane seat had long ceased to be practical for purposes of support, and its battered, scarred appearance suggested that it had been used as a target for missiles singularly effective. But Peggy regarded it with a look of pleased anticipation, not unmixed with pride.

The can of paint, which, lending its odor to the breeze, had quite submerged the fragrance of the honeysuckle, stood conveniently near the chair, and Peggy was absorbed in transferring the contents of the one to the battered surface of the other. The first results of the transference did not impress the beholder as successful, for the chair had been painted black in the first place, and the original hue, showing distinctly through the coat of paint, suggested a brown cheek veiled in white. But, undisturbed by her failure to produce the effect she wanted, without any irritating delays, Peggy worked away cheerily, humming a tune under her breath, and so absorbed was she in her task that she did not hear a light step coming across the grass. Her first intimation that she was not alone was when a somewhat hesitating voice said, "I beg your pardon."

With a start Peggy looked up. At the sight of Elaine her face crinkled into a smile of such unmistakable pleasure that only a very peculiar person could have felt indifferent to being its exciting cause.

"Why, it's you, isn't it?" exclaimed Peggy radiantly, springing from her knees with a haste which came near to overturning the can of paint. "I can't ask you to take a chair, because the only chair there is is pretty well covered with paint by now. But I'll pull out the wheelbarrow--"

"O, I can't stay long enough to sit down," Elaine said hastily. She was on the point of saying more, but quite unconscious that she was interrupting, Peggy broke in.

"I suppose you wondered what I was doing. You see one of the chairs in my bed-room went to pieces the other day. Amy was sitting on it at the time, and she was quite mortified. Amy is plump, and she decided right away that she wouldn't eat any more candy for six months, if she was getting so big that ordinary furniture wouldn't bear her weight." Peggy interrupted herself by an infectious laugh and chattered on, "And so I've got to have a new chair--"

"A new chair," repeated Elaine, surprise causing her to give a rather impolite emphasis to the adjective.

Peggy laughed again. "The new things for my room are a good deal like some folks' new dresses, the made-over, new kind, you know. But I almost think I like them all the better. Take this chair, for instance." Peggy indicated the article in question by a sweeping gesture of her paint brush. "It isn't much to look at just now."

"No!" Elaine acknowledged, apparently glad to find a point on which she could agree with Peggy. "It isn't."

"It'll have to have quite a number of coats," Peggy explained. "And when the paint is thick enough, so that the black doesn't show through, I'll tack a square of blue denim over the seat. If you put it on with braid and gilt-headed tacks, it is quite effective."

Elaine's start was not due to admiration for the glowing picture Peggy's words had conjured up, but rather to consternation over her own negligence. "O, I forgot!" she exclaimed, and hesitated. She was so plainly embarrassed that Peggy felt vaguely uncomfortable herself. But she did not have time to wonder why, before Elaine was launched on an explanation.

"Mamma sent me over to say that she objects to the smell of paint, and to ask if you would mind--"

Elaine hesitated again. Her air of confusion did not seem consistent with the impression Peggy had formed of her. As for Peggy herself, she was equally divided between sympathy for the bearer of the message, and regret over her interrupted task.

"I suppose I should have stopped to think which way the wind was blowing," she said quickly. "But somehow I never can remember that some people dislike the smell of paint. It seems so clean, and it always makes me think how nice things are going to look when you are done." She studied the unfinished chair, and suppressed a sigh. "I'll just dab a little more paint on this round, and then I'll set it in the woodshed and wait till the wind is from the east."

Peggy gave her attention to a particularly battered portion of the chair's anatomy, till she was aroused from her absorption by a question. The voice which asked it was intense, almost tragically so, in striking contrast to the serenity of the afternoon.

"Don't you hate, hate, hate to be poor?"

A big spot of white paint added itself to the decoration of the calico skirt, as Peggy stared up at her interrogator. "Why, I don't know," she acknowledged, "I guess I never thought about it."

"Not thought about it? Why, how can you help it when you have to do things like this?" Elaine made a scornful gesture, in the direction of the woe-begone chair. "Just suppose that all you had to do when you wanted something new was to go and buy it."

Peggy laughed a little. "I'm afraid my imagination isn't equal to that," she replied cheerily. "And, anyway, this sort of thing is such fun!"

"Fun!" echoed Elaine, with an incredulous gasp.

"Why, yes! To take something like this chair and fix it up so that it is useful and pretty is real fun. And so are lots of things about housework. There's cooking, now."

"I don't know a thing about cooking." Elaine had moved a little nearer Peggy, as if afraid of losing something. Her air of interest was unmistakable.

"Well, I love it all, but the nicest part, I think, is taking the left-overs, you know, the cold potatoes, and the ends of the steak, and fixing them up into real nice appetizing dishes."

"I tried getting luncheon to-day," Elaine acknowledged. "I was going to make an omelette because I thought that would be easy. It burned to start with, and then instead of puffing up light, it flattened out till it was just like india-rubber. And Mamma can't cook any better. I don't know what we are going to do."

Peggy looked sympathetically at the troubled face beside her. "Why, if you'd like," she began, then hesitated, remembering her past experience. But having started the sentence there seemed no way out of finishing it. "I'll be glad to show you all I know," she ended with a gulp.

Apparently the present Elaine, staring moodily at Peggy's handiwork, bore little resemblance to the Elaine who had frigidly declined the cinnamon rolls. She drew a long, sighing breath, "I'd like to learn," she replied. "But I'm afraid I'd be dreadfully stupid about it."

It was Peggy's habit to strike while the iron was hot. "It's Sally's day out," she said. "I'm going to get supper. Wouldn't you like a lesson this afternoon?"

"Are you sure it wouldn't be a bother?"

Peggy's ears had not deceived her. The friendly offer had not been declined. With a face as radiant as if she had just received notification of a legacy, she hurried to make arrangements with her prospective pupil.

"Come over about four. That'll give us lots of time for experiments." She carried the half-painted chair into the woodshed in a jubilant mood, which was rather remarkable considering that she had been prevented from finishing the task on which she had started. Like all energetic people Peggy detested interruptions. But this was too much of a red-letter day for her to allow herself to be depressed by trifles.

Promptly at four Elaine presented herself, wearing over her black serge dress a little embroidered apron, about the size of a pocket-handkerchief. Peggy regarded the lace-edged affair with an amazement which Elaine mistook for admiration.

"Pretty, isn't it?" she said, glancing down at it complacently. "It was a Christmas present."

"It would be fine for a chafing-dish supper," Peggy returned, feeling that if she were to act as Elaine's instructor she must begin with the fundamentals. "Chafing dishes and the aprons that go with them are all right for fun, but, when it comes to real business, there's nothing like a good range and a big apron. I'll lend you one of mine."

Elaine, enveloped in a long apron which fell to the bottom of her skirt, was soon being initiated into some of the preliminary mysteries of household economy. "There are five of us Raymonds to get supper for," Peggy said counting them off on her fingers. "And Dick's always so hungry that he counts for two. You'll stay, won't you?"

"O, I'd better not. I don't know anybody but you."

"That'll be the best way to get acquainted. And, besides, if you help with the cooking, you ought to help eat the things. That's half the fun. I don't know how anybody can be a good cook who hasn't got a good appetite. I simply adore the things I make."

After a careful examination of the refrigerator the supper was planned. There had been baked fish for dinner, and the remnants, Peggy explained to the respectfully attentive Elaine, arranged in a baking dish, with cream sauce between the layers and crumbs on top, would be even more delicious than the fish in its original state. Peggy also decided on baking powder biscuits. "They're such handy things," she said. "And you can stir them up so quickly and keep on baking as long as anybody is hungry; so they're one of the very first things you should learn to make."

Working with Peggy, Elaine began to understand why she found everything "fun." The neat, pleasant kitchen had a charm of its own. There was an agreeable excitement about the business of evolving a palatable supper from materials which the eye of inexperience had found unpromising. Elaine asked a great many questions, helped a little, in an awkward fashion, which unkind critics would have pronounced a hindrance rather than an aid, and was conscious of a steadily increasing respect for this deft-handed girl who knew so well what she wanted to do and how to do it.

The telephone bell rang while Peggy was sifting out the flour for the biscuits. She dusted her hands, and went to answer it. "Very well, father," Elaine heard her say, and she was smiling when she came running back.

"We're going to have company," she announced to Elaine as if the news were pleasant. "A Mr. White, one of father's friends." She reflected a moment, frowning thoughtfully. "I guess we'll put some potatoes in the oven to bake. There'll be time enough if we pick out small ones, and there's plenty of the fruit cake."

The potatoes were washed hastily and consigned to the oven, and Peggy sifted out a little more flour. Then the door bell rang and there was a sound of voices in the hall. A moment later Peggy's mother slipped into the kitchen and shut the door behind her.

"Peggy, old Mr. and Mrs. Andrews have just come. I suppose they'll stay for supper. Have you got enough for two more?"

"O, yes. We'll have enough," Peggy answered blithely.

"Don't you want me to help you?"

"O, I'm getting on finely with my neighbor's assistance. You can go back and entertain the company." As her mother slipped away, looking relieved, Peggy added to Elaine, "I didn't know what I was getting you into when I asked you over this afternoon."

"Will there really be enough for so many?" demanded Elaine, feeling rather oppressed by the weight of these unusual responsibilities.

"I've had a brilliant idea; I'm going to heat some maple syrup. People like it with hot biscuit, and, besides, it takes off the edge of their appetite," Peggy explained shamelessly. "But we shall have to put an extra leaf in the table, I'm afraid."

At six o'clock everything was ready. A pleasant mixture of odors pervaded the house, the fragrance of coffee being most in evidence. Peggy had just taken a pan of biscuit from the oven, and was calling Elaine's attention to their flaky lightness, when Dick put his head through the door.

"Say, Peg--"

"O, is that you, Dick? This is our new neighbor, Elaine Marshall."

Dick gave a shy little bob of his head in Elaine's direction. "Say, Peg," he repeated.

"Yes, dear."

"Looney Batezell's mother has gone somewhere to supper, and his father, too, and the hired girl won't fuss to fix him anything decent, and so I just told him to come over here to supper."

Elaine waited for the explosion that did not come. "Very well," Peggy said resignedly. As the door closed and Dick's footsteps echoed along the hall, she flung a twinkle in Elaine's direction. "It never rains but it pours," she quoted.

"Why, I don't see--" Elaine checked herself, reflecting that it was not necessary for the matter to be explained to her satisfaction. But Peggy took it on herself to reply to the unspoken remonstrance.

"I suppose I might have told Dick he couldn't have Looney to-night. But it's only one more and it doesn't really make much difference. Besides we like to have Dick feel that his friends are welcome. When you are bringing up a boy," concluded Peggy, laughing, and still very much in earnest, "you have to think of so many things."

Peggy did not eat her supper that evening till the others had finished. She waited on the table, and baked biscuit, and if there was anything more remarkable than the celerity with which the biscuit plates were cleared, it was the promptness with which they were refilled, each time with flaky, smoking-hot biscuits, which fairly melted in one's mouth. Only in one respect had Peggy miscalculated, and that was when she remarked that the maple syrup would take off the edge of her guests' appetites. To all appearances it only whetted them to a more razor-like keenness.

But everybody was satisfied at last, and Peggy ate her own supper, her cheerfulness unimpaired by the fact that the baking dish had been scraped clean before her turn came, and that her baked potato was overdone. She protested against Elaine's determination to stay and help her with the dishes, but Elaine was firm.

"It's only fair, as part payment for my lesson. And, besides, I dare say I need to learn things about washing dishes as well as cooking."

As a matter of fact, Elaine had learned several things that afternoon, and the secret of making baking-powder biscuits was not perhaps the most important. She had seen a girl not far from her own age equal to an emergency which older housekeepers would have found trying, keeping her head clear and temper unruffled. Elaine was beginning to understand that it was not what Peggy did, so much as her way of doing it, that set her apart.

"I feel real selfish keeping you so long," Peggy declared, when the last dish was in its place. "Your poor mother will have been awfully lonely."

"O, no, she--" Elaine paused with an air of checking herself on the verge of an admission. "Mamma doesn't mind being alone," she ended, but Peggy was quite sure that this was not what she had intended to say.

Peggy stood in the doorway while her new friend and pupil crossed the yard, passed through the opening in the hedge and tried her own door. It was locked, and Elaine knocked and waited till her mother came to let her in. As the door opened Elaine turned and waved a good night to the figure framed in light, watching to be sure that she was safely home.

As Peggy returned the greeting, something odd happened. In the room above a shade was lowered. All that Peggy saw was an extended arm and a white hand pulling down the shade, but she stood staring as if this had been a most out-of-the-way proceeding.

"Queer thing," mused Peggy. "Elaine and her mother are downstairs at the door, and they haven't any servant, and I'm sure I thought Mrs. Marshall was alone this evening."

She looked blankly at the non-committal shade, then remembered her morning's lessons, and, closing the door, ran upstairs to her school books. By bed-time she had forgotten to wonder whose hand had lowered the shade in that upstairs room.

CHAPTER V

A HALLOWE'EN PARTY

While Peggy's acquaintance with Elaine had been steadily progressing, the other girls were little farther along than on the memorable morning when they welcomed the wrong hack. Priscilla had begun to speak of "Peggy's friend" with an intonation which showed resentment.

"It's because we live next to each other, I suppose," said Peggy, who never imagined that her own sunniness of disposition could prove a magnet to attract friends and was always devising explanations for their abundance. "You haven't had a fair chance. I believe I'll give a Hallowe'en party, so that Elaine can get acquainted with the rest of you."

The suggestion awakened an enthusiasm that had little connection with Elaine. Peggy's parties were simple affairs, old-fashioned, one might call them. There was no orchestra playing behind a screen of palms, no elaborate refreshments, no display of pretty frocks. Indeed Peggy very often said, "Don't put on your good clothes; you might hurt them." Many a girl of Peggy's age who regards herself as a young lady would turn up her nose at one of Peggy's parties, where everybody came at eight o'clock and went home correspondingly early, and where nobody made an effort to appear grown up. But since Peggy's guests invariably had a good time, "the best time ever," they were likely to declare, Peggy was entirely satisfied.

Elaine, being new to the traditions of the Terrace, opened her eyes when Peggy tendered her an invitation across the hedge. "A Hallowe'en party," she repeated, a question in her voice. "Isn't that rather--"

"Rather what?" inquired Peggy with such good-natured curiosity that Elaine almost regretted her beginning.

"O, nothing. Only a Hallowe'en party seems rather childish, don't you think?"

"I didn't think anything about it, except that it was fun," Peggy answered tranquilly. And then she added the warning so likely to accompany Peggy's invitations, "Don't wear your good clothes."

"What!"

"I mean don't wear anything good enough to hurt."

"I haven't anything particularly nice," said Elaine with dignity, "but if I'm going to a party where I'll meet a lot of strangers I naturally shall wear my best." She looked at Peggy half resentfully, half perplexedly, reflecting as she did so that Peggy was the sort of girl who could wear an old dress to a party and have a good time in spite of it. But, then, Peggy wasn't like other people. A very short residence on the Terrace had been long enough to bring Elaine to this conclusion.

Peggy was very busy the next ten days. She had never been accustomed to much spending money, and she had early learned that for the drawback of a slender purse there is abundant compensation in cleverness and ingenuity. Whatever pleasure Peggy's parties gave her friends, she enjoyed them doubly, for she had the pleasure of preparation along with the other. If a bubbling laugh escaped over the transom of Peggy's room, when she was supposed to be abed and asleep, some member of the household was sure to say, "Peggy's got a new idea," and to smile in sympathy.

That some busy brain had been evolving ideas, and that busy hands had been carrying them out, was evident enough on the night of the thirty-first. The light was turned low in the hall, and a sheeted figure at the door welcomed each comer with extended hand. The ceremony of hand-shaking was generally followed by little shrill squeals on the part of the arrivals, and voluble exclamations.

Elaine, coming in alone, and holding her head very high, distinguished herself by not screaming when the clammy hand touched hers, though she jumped, without any question. There was an unearthly chill about that hand, which, coupled with the sepulchral white garments and the dark eyes showing through holes edged with red, produced a singular shivery feeling along Elaine's spine.

"It's Dick, I guess," said the girl who had entered just ahead of Elaine, plunging into conversation without waiting for an introduction. "He's got on gloves, wet chamois-skin gloves, but who would imagine that it would feel so ghastly? Don't you love to have your blood run cold?" Fortunately Elaine was spared the necessity of answering that question by encountering Peggy, who gave both arrivals a rapturous squeeze and bore them off to her room to remove their wraps.

The Raymond living-room had been transformed in honor of Peggy's party. Jack-o'-lanterns grinned from the mantel and the book-cases. A tub of water, Elaine noticed with disapproval, occupied the centre of the room. Hung over the grate was an old iron kettle, in whose depths something silvery bubbled responsive to the heat below. The chairs set back against the wall were filled with laughing girls; for, in spite of Peggy's repeated warnings that Elaine was not to be late, she was the last arrival.

"We'll start with the lead, that's boiling so nicely, and perhaps lead boils away, just as water does." Peggy brought out a long-handled tin spoon, and a basin filled with water. "Come, Ruth," she commanded.

"O, let somebody else take her turn first," pleaded Ruth, but half a dozen hands pushed her forward. Cautiously she ladled a little of the melted lead into the water. Hissing it fell to the bottom of the basin, taking shape as it cooled. The girls crowded about to read the augury.

"Ruth!" Peggy's voice was preternaturally solemn. "It's awful, but it looks to me like three balls. Do you suppose you are going to marry a pawn-broker?"

"O, horrors!" cried Ruth, aghast. Milly Weston patted her shoulder comfortingly.

"Don't you believe it. I can see leaves and branches, too. Those three balls are fruit; oranges probably. That means you're going to have an orange ranch in California or Florida, and make lots of money."

The rest of the fortune telling proved equally cheerful. The fantastic shapes assumed by the lead in cooling could be interpreted in a variety of ways. While Priscilla insisted that fate had moulded the lead she let fall into the shape of the horn of plenty, which, of course, would signify prosperity, Peggy was positive that the lead had taken the form of a ship, and signified a voyage, while some of the girls saw a fish in the curved shape, and advanced ingenious theories as to its meaning.

There was no disagreement as to Elaine's fortune. The lead took the form of a violin, and Peggy triumphantly prophesied that her new friend would make a success in music. Elaine smiled with a sense of superiority, as one who has outgrown childish things, but she could not help being glad of the violin, in place of the rolling-pin Peggy had claimed for herself, and which she considered argued skill in the domestic arts. Though Elaine was trying hard to put Peggy's lessons into execution she had not got beyond the point of regarding housework as drudgery.

By the time the supply of lead was exhausted the company was ready for something else. Into the tub filled with water Peggy dropped three apples, which bobbed against one another sociably and then went sailing off in different directions.

"O, dear me, Peggy," Amy cried reproachfully, "I've got the loveliest wave in my hair, and it would have lasted a week if it wasn't for you. I always get down to the bottom of the tub when I bob for apples and look like a wet kitten for the rest of the evening."

"I've had pity on your hair, honey," Peggy laughed, with an approving pat of Amy's fair locks. "It looks much too nice to spoil." She brought a bow and arrow from the adjoining room. "Instead of bobbing for apples," she explained, "you try to hit them with the arrow. The yellow apple stands for wealth, the red one for health, and the green for happiness. See! Dick fixed something sharp in the end of the arrow so it would stick."

The girls gathered around to admire, then drew off, while Amy made her first attempt in archery. The cord twanged as the arrow sped on its way. There was a shriek from the girls on Amy's right.

"Oh! Oh!" screamed Blanche Estabrook cowering and clutching frantically at the girl who stood next her. "She's hit me."

It was only too true, and considerable argument was needed to convince Blanche that the injury was not serious. As a matter of fact, the arrow had pierced the bow of blue ribbon surmounting her knot of yellow curls, and hung dangling. What with the agonized exclamations of Amy, horrified over the thought of what might have happened, and the chatter of the other girls, trying to explain to Blanche that she couldn't possibly be hurt, Peggy had some difficulty in restoring order.

"The trouble was just here, Amy," she explained to her friend. "You took aim as carefully as could be, and then, just at the last, you shut your eyes. Now, it stands to reason you can't hit a mark with your eyes shut."

"You can hit a mark," corrected Priscilla, "but not the right one."

Poor Amy submitted to her friend's mild reproof without attempting to defend herself, and withdrew to the corner in a very subdued mood. The following archers were more successful. Many times, it is true, the arrow fell splashing into the water, or stuck quivering in the sides of the tub, but, occasionally, it pierced one of the three lucky targets, and on such occasions the whole company shouted joyfully. Elaine was one of the fortunate archers. When her arrow pierced the apple which stood for happiness her lips curled a trifle; yet down in her heart she was conscious of an inconsistent wish that the green apple might be a true prophet. Happiness! With a little ungirlish sigh Elaine wondered if she was to find it on Friendly Terrace.

It was Amy's unlucky night. A little later, twelve colored candles, each standing upright in its own tiny candle-stick, were ranged the length of the long hall, at intervals of two or three feet, burning away like so many miniature light-houses. "These stand for the months," explained Peggy; "the first one is November, and then December, and so on around the year. If you jump over them without putting them out, you'll have good luck all the year."

"And if you put them out?" inquired Amy anxiously.

"Every candle that goes out means bad luck for that particular month. Come, Priscilla. You try it first."

In spite of her height, Priscilla was as light on her feet as a fairy. Drawing her skirts around her, she went hopping down the hall so lightly that she left the whole twelve candles burning behind her. The applause this feat called forth was less enthusiastic than it would have been a little later, when the other girls had learned by experience the difficulties in the way of duplicating Priscilla's performance.

While Blanche was lamenting over the fact that the three candles which stood for the summer months had been extinguished, which she interpreted to mean that she was to be disappointed in certain cherished vacation plans, Amy came forward to try her fate. Clutching her skirts frantically, she jumped over the first candle, coming down with a thump which fairly shook the house, while the cheery little flame which stood for November blinked in astonishment and promptly went out. Ten times did Amy repeat this feat. When she reached the end of the hall only one of the twelve candles remained lighted, and the girls were in peals of laughter.

"''Tis the last rose of summer left blooming alone,'" Peggy quoted tragically, but Amy was in no mood to see the humor of the situation.

"Did you ever hear of anything so dreadful?" she moaned. "What a year! Only one lucky month in it."

The girls laughed again at her horrified tone, and Peggy crossed the room and shook her playfully.

"You're actually pale, you ridiculous, superstitious creature," she said severely. "As if it wasn't all a joke. I guess we'll have some refreshments now to revive you."