OUR ENGLISH

TOWNS AND VILLAGES

BY

H. R. WILTON HALL

Library Curator, Hertfordshire County Museum; Sub-Librarian St. Alban's Cathedral, &c. Author of "Hertfordshire: a Reading-Book of the County", &c.

LONDON

BLACKIE & SON, Limited, 50 OLD BAILEY, E.C.

GLASGOW AND DUBLIN

1906

Many things connected with the history of our towns and villages have to be passed over in an ordinary school history reader. In the following pages an attempt is made to call attention in simple language, very broadly and generally, to connecting-links with the past in our towns and villages. There are many relics and customs yet remaining in many places, which, with a little care and attention to local circumstances, may be made helpful in teaching history, so that it shall be something more than a collection of names, dates, battles, and lists of eminent persons.

The book is intended as a reader, not as a text-book to be worked up for examination purposes. Its aim is rather to arouse interest in the "why and the wherefore" of things which can be seen by an intelligent and observant boy or girl in the place in which he or she lives: to do for history, and the subjects connected with it, what "nature-lessons" are intended to do in their "sphere of influence". Attention is being directed to localities, their special history, physical, political, industrial, and commercial, as it has never been before in our Educational history; and all that a special locality can contribute in the way of illustration and exemplification is worth knowing, understanding, and utilising.

It is hoped that this book may be of some service in quickening intelligence in looking out for "things to see". The observation which is directed to noting the numbers on the motor cars, the names of locomotives, and the collection of postage-stamps and picture post-cards, can also be usefully turned, say, to noting the styles of architecture which really mark broadly great periods of our national life and development; and may help us, perhaps more than anything else, to arrange our ideas of the days of old in a proper order and sequence. An old building may be an excellent date-book.

The chapters are intended to be suggestive, not exhaustive, and may be expanded by the teacher in conversational or more formal lessons as his own predilection, taste, and judgment shall direct.

Local and County Histories, Guide-books and Hand-books will be found of great service to the teacher in dealing with special districts. The general subject embraces a very wide range of literature, but amongst books readily accessible may be mentioned English Towns, by E. H. Freeman; English Towns and English Villages, by Rev. P. H. Ditchfield; and the Rev. Dr. Jessopp's Essays in The Coming of the Friars and Studies of a Recluse.

In conclusion, the book is designed for older scholars who already know something of the dry bones of the history of England, and it is hoped that it may do something towards covering those dry bones with flesh, instinct with life and vigour.

H. R. W. H.

St. Alban's, December, 1905.

| Chapter | Page | ||

| I. | Introduction | 9 | |

| II. | Men who lived in Caves and Pits | 11 | |

| III. | The Pit-Dwellers | 14 | |

| IV. | Earthworks, Mounds, Barrows, etc. | 19 | |

| V. | In Roman Times | 22 | |

| VI. | Early Saxon Times | 26 | |

| VII. | Early Saxon Villages | 28 | |

| VIII. | Anglo-Saxon Tuns and Vills | 32 | |

| IX. | Tythings and Hundreds—Shires | 36 | |

| X. | The Early English Town | 41 | |

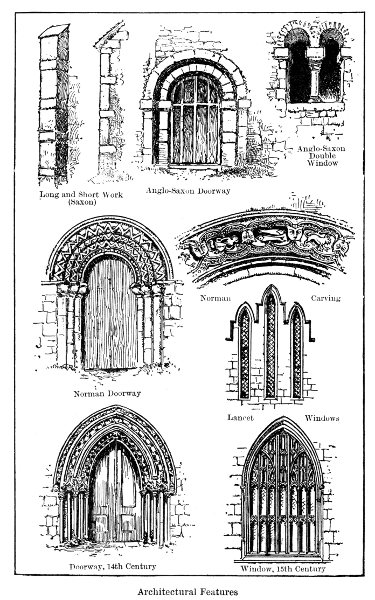

| XI. | In Early Christian Times | 44 | |

| XII. | Monasteries | 46 | |

| XIII. | Towns and Villages in the Time of Cnut the Dane | 51 | |

| XIV. | Churches and Monasteries in Danish and Later Saxon Times | 56 | |

| XV. | Later Saxon Times | 59 | |

| XVI. | In Norman Times | 62 | |

| XVII. | In Norman Times (continued) | 66 | |

| XVIII. | In Norman Times: The Churches | 68 | |

| XIX. | Castles | 71 | |

| XX. | Castles and Towns | 74 | |

| XXI. | In Norman Times: The Monasteries | 78 | |

| XXII. | Early Houses | 81 | |

| XXIII. | Early Houses (continued) | 85 | |

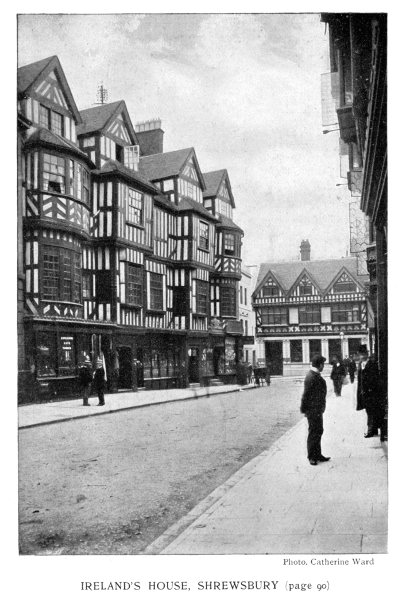

| XXIV. | Early Town Houses | 88 | |

| XXV. | Life in the Towns of the Middle Ages | 92 | |

| XXVI. | The Growing Power of the Towns | 98 | |

| XXVII. | The Villages, Manors, Parishes, and Parks | 102 | [Pg 8] |

| XXVIII. | Traces of Early Times in the Churches | 106 | |

| XXIX. | Traces of Early Times in the Churches (continued) | 110 | |

| XXX. | Clerks | 114 | |

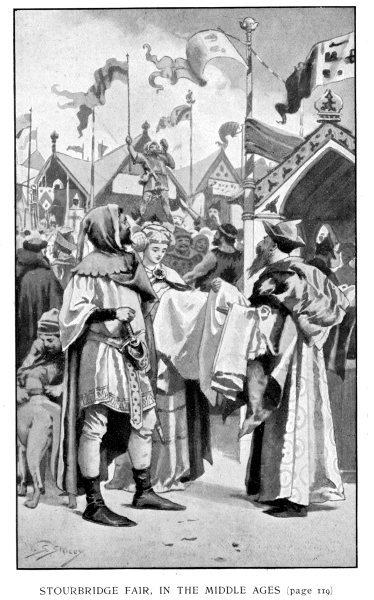

| XXXI. | Fairs | 118 | |

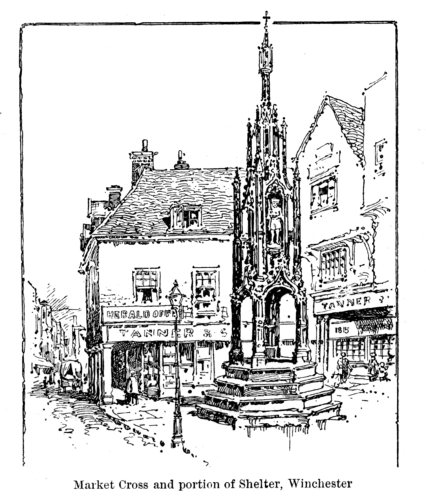

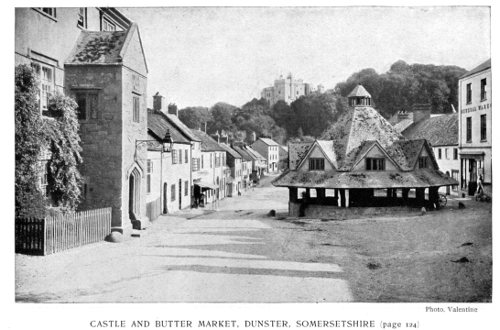

| XXXII. | Markets | 123 | |

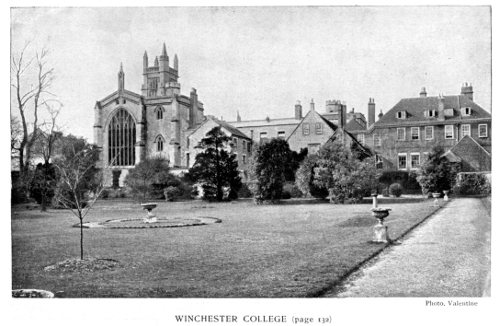

| XXXIII. | Schools | 128 | |

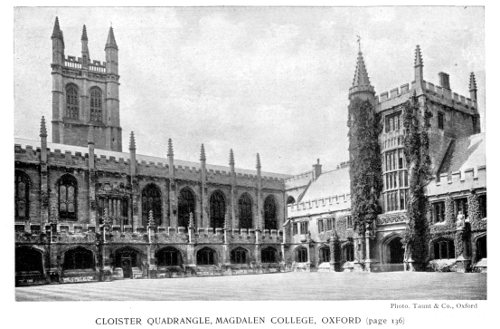

| XXXIV. | Universities | 133 | |

| XXXV. | Changes brought about by the Black Death | 137 | |

| XXXVI. | Wool | 140 | |

| XXXVII. | The Poor | 143 | |

| XXXVIII. | Changes in Houses and House-building | 149 | |

| XXXIX. | The Ruins of the Monasteries and the New Buildings | 153 | |

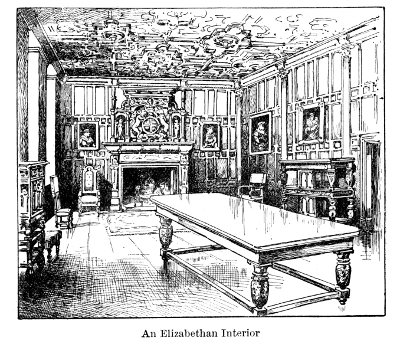

| XL. | The New Houses of the Time of Queen Elizabeth | 158 | |

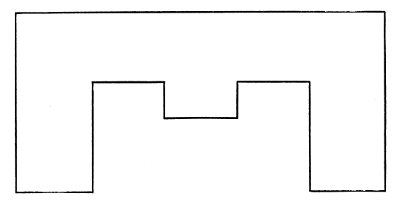

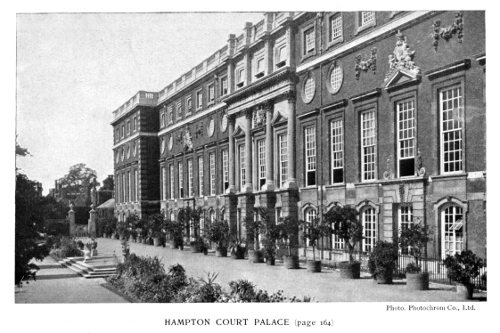

| XLI. | Larger Elizabethan and Jacobean Houses | 162 | |

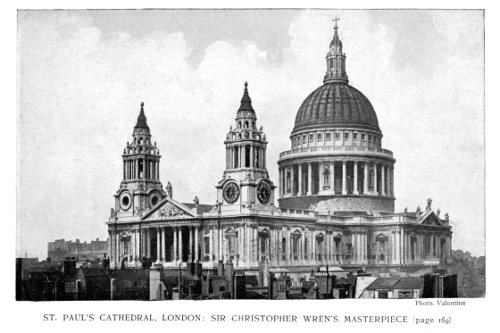

| XLII. | Churches after the Reformation | 166 | |

| XLIII. | Building after the Restoration: Houses | 169 | |

| XLIV. | Building after the Restoration: Churches | 174 | |

| XLV. | Schools after the Reformation | 179 | |

| XLVI. | Apprentices | 183 | |

| XLVII. | Play | 185 | |

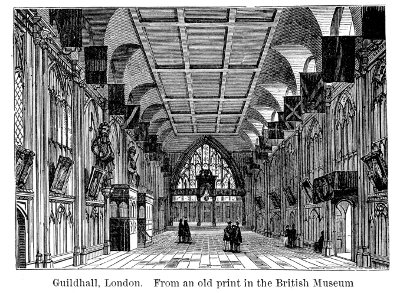

| XLVIII. | Government | 189 | |

| XLIX. | Some Changes | 193 |

1. A little boy, who had been born in a log cabin in the backwoods of Canada, was taken by his father, when he was about eight years old, to the nearest settlement, for the first time in his life. The little fellow had never till then seen any other house than that in which he had been born, for the settlement was many miles away. "Father," he said, "what makes all the houses come together?"

2. Now that sounds a very strange and foolish question to ask; but it is by no means as foolish a question as it seems. Here, in England, there are towns and villages dotted about all over the country. Some of them are near the sea, on some big bay or inlet; others stand a little farther inland on the banks of tidal rivers; others are far away from the sea, in sheltered valleys or on the sunny slopes of hills; some stand in the midst of broad fertile plains, while others are on the verge of bleak lonely moorlands. What has made all the houses [Pg 10] in these towns and villages come together in these particular spots? There must be a reason in every case why a particular spot should have been chosen in the first instance.

3. In trying to find an answer to this question with reference to any town or village in our country we have to go back, far back, into the past. We may have to go back to ages long before there was any written history. As we go back step by step into the past we learn much of the people who have lived before us—of their ways and their doings, and of the part they played in the life and work of the country.

4. The little Canadian boy's question can be asked about every town and village in the land. There are no two places exactly alike; each one has its own history, which, however simple it may be, is quite worth knowing. The busy manufacturing town, with its tens and hundreds of thousands of people, where all is movement and bustle, has its history; and the lonely country village, where everybody knows everybody else, has often a history even more interesting than that of the big town; if we only knew what to look for, and where to look for it.

5. One summer day, a few years ago, a party of tourists was climbing Helvellyn. One of the party was an elderly gentleman, who was particularly active, and anxious to get to the top. After several hours' stiff climbing, the party reached the summit; and there, spread out before them, was a lovely view of hills and dales, of mountains and lakes. [Pg 11] Most of the party gazed upon this fair scene in quiet enjoyment; but our old gentleman, as soon as he had recovered his breath, and mopped his red face with his pocket-handkerchief, gave one look round, and then said in a grieved tone: "Is that all? Nothing to see! Wish I hadn't come."

6. He saw nothing interesting because he did not know what to look for, and he might just as well have stopped at the bottom. He came to see nothing, and he saw it.

Summary.—All towns and villages in England have a history. In every case there is a special reason why that town or village grew up in that particular place. In trying to find out how this came about we learn a great deal of the history of the past, shown in old names, old buildings, old manners and customs.

1. Man is a very ancient creature. It is a curious fact that we have learned most of what we know about the earliest men from the rubbish which they have left behind them. Even nowadays, in this twentieth century, without knowing much about a boy personally, we can tell a good deal about his habits from the treasures he turns out of his pockets. Hard-hearted mothers and teachers call these treasures rubbish, but the contents of a lad's pockets are a pretty sure indication of the boy's tastes.

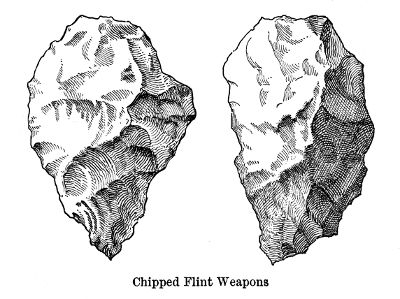

2. The earliest traces of the existence of man in our part of the world are found in beds of gravel, which in some places now are many feet above the level of the sea. There, in the gravel, are the roughly chipped stone tools and weapons which those early men used; tools which they lost or threw away. Almost every other trace has quite disappeared. Remains belonging to the same period have been noticed in caves in various parts of the world.

3. Here, in Britain, caves have been found where these early men have left their stone implements and remains of their rubbish. Some of the best-known of such cave-dwellings in Britain are near Denbigh and St. Asaph in North Wales; at Uphill in Somersetshire; at King's Car and Victoria Cave near Settle; at Robin Hood's Cave and Pinhole in Derbyshire; in Pembrokeshire; in King Arthur's [Pg 13] Cave in Monmouthshire; at Durdham Down near Bristol; near Oban; in the gravels in the valleys of the Rivers Trent, Nore, and Dove; in the Irish River Blackwater; near Caithness; and in a good many other places.

4. So, you see, the remains of these early men cover a pretty wide area. In the course of ages rivers and seas have flowed over the places where these stone tools had been dropped, and year after year throughout the ages the drift brought down by the rivers covered them inch by inch and foot by foot. Great changes have taken place in the surface of the land, some suddenly, but most of them very, very slowly. The land has risen, and sunk again, and long, long ages of sunshine and storm, of ice and snow, of stormy wind and tempest, have altered the surface of the country.

5. Those very ancient men, who lived in the Early Stone Age, are called Cave-Dwellers, because they lived apparently in caves, and River-Drift Men and Lake-Dwellers, because the roughly chipped tools are found in the drift of various rivers and lakes.

Summary.—The earliest remains of man are found in certain beds of gravel and in caves. They consist chiefly of roughly chipped stone implements. Such celts are found in all parts of England, and in caves in North Wales; in Somersetshire at Uphill; in Yorkshire near Settle; in Derbyshire at Robin Hood's Cave and Pinhole; in Pembrokeshire and Monmouthshire; at Durdham Down near Bristol; near Oban; and in the valleys of the Rivers Trent, Nore, and Dove; in the Irish River Blackwater; and near Caithness. These men are known as the River-Drift Men, the Cave-Dwellers, or the Lake-Dwellers.

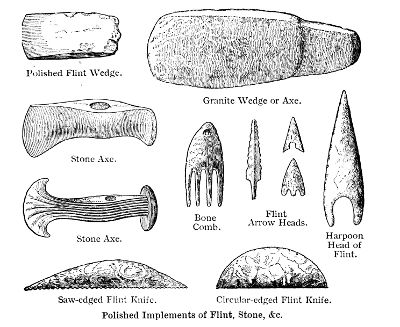

1. Other remains not so ancient as these oldest stone implements, but still very ancient, are found nearer the surface than the remains of the River-Drift Men. They are the remains of people who, like the Drift Men, knew nothing of metals, and used stone weapons and tools, but better made. They had learned to shape and finish their tools by rubbing, grinding, and polishing them, and were, evidently, a more advanced race of men than the Cave or Drift Men.

2. For the most part we have to go to somewhat desolate parts of England to find traces of them now. In fact, those traces would long ago have disappeared had they not been in places which were so wild and difficult to get at, that it was not worth any man's while to cultivate them. The spade and the plough would very soon remove all traces of them. In fact, the plough has removed many traces of these ancient men, and most of the specimens of their tools and weapons, which you can see in museums, were found by men employed in ploughing and preparing the land for crops.

3. You must not suppose that we can fix a date when these men first appeared, as we can fix an exact date for the landing of Julius Cæsar, or the sealing of Magna Carta. Neither can we say for how many centuries they occupied land in what we now call Britain. It was a long period, at any [Pg 15] rate, and during that time their manners and their customs changed very, very slowly.

4. The lowest forms of savage life seem very much alike, all the world over. Savages are hunters, and do not as a rule cultivate the soil. Now hunters must follow their prey from place to place, so that we should expect these early men to have no settled homes. But even the earliest Pit Men had advanced beyond this lowest stage, for they had flocks and herds and dogs. No doubt they hunted as well; but they were mainly a pastoral people, and at first did not till the soil. Races of men who did not till the soil are called [Pg 16] Non-Aryan. They chose for their settlements the tops of hills, and avoided the narrow valleys and low-lying lands.

5. The Pit-Dwellers are so called from the simple fact that they had their homes in pits—not, however, dug anywhere and anyhow. The hole in the ground is the simplest notion of a house. When in your summer holiday by the sea you see the little boys and girls digging deep holes in the sand to make "houses", they are doing in play what the early Pit-Dwellers did in real earnest.

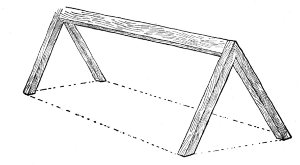

6. The pits were usually some six or eight feet in diameter; and they probably had cone-shaped roofs, formed by poles tied together, and covered with peat. In the centre of the hut was the hearth, which was made of flints carefully placed together. The hut would hold two or three people, and the fire on the hearth was its most important feature. The hut in the centre of the group belonged to the head of the family, and other huts were ranged round it.

7. Surrounding the group was an earthen rampart for further protection; and these earthworks can still be traced in many parts of the country. The huts have gone, of course, and all that can be seen in most cases now is a number of circular patches in the turf, slightly hollowed. People living in the neighbourhood will very likely speak of them as "fairy rings". It is from a careful examination of these hollows that learned men have been able to gather much information concerning the habits of these Pit-Dwellers.

8. We English folk speak proudly of "hearth and home"; they are the centre of our social life, and the idea has come down to us through all these long, long ages. The hearth and the fire upon it was the centre of the life of these men, and the head of a family was also its priest.

9. Some of the best known of these pit-dwellings are found near Brighthampton, in Oxfordshire; at Wortebury, near Weston-super-Mare; and along the Cotswolds, looking over the Severn Valley; and at Hurstbourne, in Hampshire.

10. In the course of time this race seems to have learned something in the way of cultivating the ground. The hilltops, where they built their huts, were only suited for their cattle, and in order to find soil which they could till they had to go outside their earthwork, and some distance down the hill-slope. By their way of digging the ground they gradually, in the course of many years, carved broad terraces, one below the other, on the hillsides. There are some very marked traces of such terraces still to be seen near Hitchin and Luton.[1]

11. In the course of time—how long ago it is still quite impossible to say—a race of men, more advanced than these early Pit-Dwellers, found their way to this part of the world. They were more civilized, and were Aryans; that is, they were cultivators of the soil. You may be pretty sure that fighting took place between the two races.

12. The newer race preferred to make their settlements near running streams. In the middle of each settlement there would be an open space, or meeting-ground, usually a small hill or a mound, round which their huts were built. Beyond this was the garden-ground, then the ground where the grain was grown, and beyond that the grazing-lands. These men began cultivating at the bottom of the hillsides and valleys, and as they required more ground they would advance higher up the slopes.

13. Gradually to this race came the knowledge of metals, and we reach the Bronze Age, and so, step by step, we come to the Iron Age.

Summary.—The remains of the Pit-Dwellers are found on desolate heaths and moorlands. These men used stone weapons, which they smoothed and polished. They had a greater variety of tools than the Drift Men. They were a non-Aryan race; that is, they did not till the soil. They were a pastoral people; that is, they kept cattle. Their settlements were on the hilltops. Their houses were pits, covered with a rough kind of roof, and were placed in clusters. In the centre of each dwelling was a hearth made of stones. All that can be seen of them now are circular hollows, often called "fairy rings". The clusters of huts were usually enclosed by an earthen wall or rampart. In course of time they learned to cultivate the ground. They worked downhill, and carved out many hillsides into broad terraces, which can still be traced in some places, as between Hitchin and Luton. An Aryan race also found its way here. These cultivated the soil, but their settlements were in the valleys, near running streams. An Aryan settlement had an open space in the centre, or meeting-ground. The huts were built round this. Then came the garden-ground, and then the grazing-lands. They began cultivating from the bottom of the hills, and worked upwards. In time they learned the [Pg 19] use of metal—bronze,—and gradually also they came to know the value of iron.

1. There are still remaining, in many parts of the country, curious mounds and stones. We can say very little about them here; but though learned men have discovered much, there is still a good deal to be explained concerning them. Old-world stories put most of these strange objects down to the work of witches, fairies, or giants; some ascribe them to the Romans, or to Oliver Cromwell; others even to the devil. But most of them really belong to this period of which we are speaking—the very early part of our history, of which there is no written record.

2. Earthworks are of many kinds, but the very earliest are usually found on hilltops. There are some which enclose considerable spaces of ground, bounded by an earthen rampart, with a ditch outside. Sometimes there are two such ramparts. Frequently they are spoken of as British Towns or British Camps. They appear to have been enclosures into which the cattle were driven in time of danger, and in which a whole tribe could take refuge and hold out against their enemies.

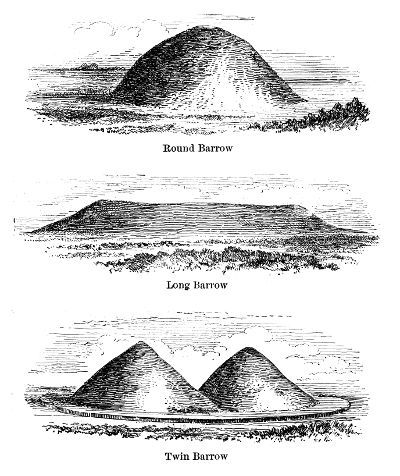

3. Then there are big mounds or heaps, called Barrows. Some of these are oval in shape, and are called Long Barrows; others are round, and are called [Pg 20] Round Barrows. The Long Barrows are thought to be the older kind, and were apparently the burial-places of great leaders. The Round Barrows were also burial-places; but those who raised them burned their dead. The great pyramids of Egypt are barrows, only they are made of stone, not of earth.

4. The circles of stones at Stonehenge and Avebury seem to have been connected with the worship of these early people. There are many single stones, especially in Cornwall and Wales, which also seem to have been connected with religious rites; but of this we know nothing for certain. In later times they have served as boundary marks.

5. In various parts of England there are deep lanes or cuttings, which have received curious local names. There are no less than twenty-two such cuttings in different parts of England all known as Grim's Ditch. These, no doubt, formed boundaries, separating various tribes.

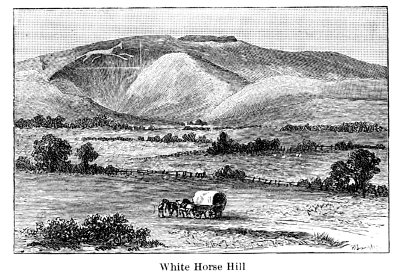

6. The White Horse, cut out of the slope of Uffington Hill, and several similar objects in Wiltshire, as well as the crosses—also cut in the turf—at Whiteleaf and Bledlow, may also belong to this [Pg 22] period. Some learned men, however, have thought that they are of a later date.

7. From these early men then the Ancient Britons appear to have descended, and they were settled here a good many centuries before the coming of the Romans. Many of the wild tales and legends, still told in country villages, about giants and fairies, have come down to us from these early times.

Summary.—There are many curious mounds and stones, about which wild tales are told. Earthworks are of various kinds. Those enclosed by an earthen wall or rampart are often called British towns or camps. They were places of refuge. There are two kinds of mounds, called Long Barrows and Round Barrows. Both were burial-places. The Long Barrows belonged to the older race. Stone circles, like those at Stonehenge and Avebury, had something to do with worship, and there are many stones in Cornwall and Devon which most likely were put to the same use. There are twenty-two old trackway boundaries in England all called Grim's Ditch. The White Horse and several other cuttings in the turf possibly belong to this same period. The old legends and tales about all these are worth keeping in mind, though at present we do not understand them.

1. Here, then, at the time the Romans first came to Britain were tribes of Britons who had been established in the country for centuries, living their lives according to the customs of their forefathers, and more or less cultivating the land. The Romans [Pg 23] invaded the country, and, in time, subdued the people. They remained masters here for nearly four hundred years, but they did not make such a permanent impression on this country as they did in some countries which they conquered—as on France and Spain, for instance.

2. We are to-day masters of India; but we have not made India English, nor are we trying to do so. The natives there go on cultivating the land according to their custom from time out of mind. They preserve their own manners, customs, and religions. In places where they come much in contact with our fellow-countrymen, they are influenced to a certain degree; but in India to-day the English and the natives lead their own lives, each race quite apart from the others.

3. So it was with the Romans in Britain. They formed colonies in various places and built towns all over the land; they had country villas dotted here and there, some little distance from the chief towns, and built strong military stations in suitable districts. These posts were kept in communication by means of good roads. Many Britons must in the course of time have adopted Roman ways and Roman civilization; but the bulk of the Britons, living away from the Roman centres, kept to their own customs, and cultivated the ground in the way their ancestors had done. They prospered, on the whole, as the Romans kept the various tribes from fighting with one another.

4. No doubt, in districts such as that which we now call Hampshire, and along the Thames valley, [Pg 24] where wealthy Romans had their country villas, Roman methods of farming were in use. The Britons would see something of Roman ways of doing things, and, perhaps, tried to copy them.

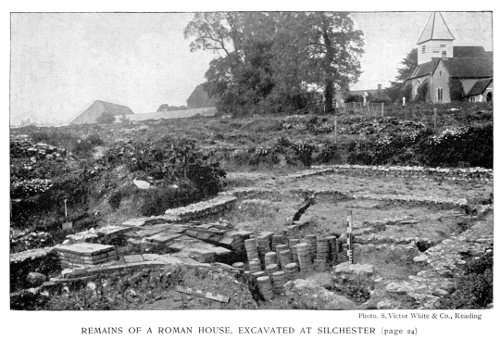

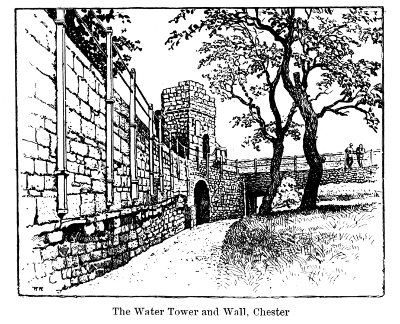

5. But the Romans have not left many marks upon our towns and villages. It is quite true that a large number of our present towns and cities are on the sites of, or near, Roman towns; but, in most cases, we have to dig down into the earth to find Roman remains. The most important Roman city, Verulam, has quite disappeared; and the most complete remains of a Roman town, Silchester, are near to what is now a quiet country village. The present cities of London, Winchester, Gloucester, Lincoln, Chester, Carlisle, and the towns of Colchester and Leicester, and several others, can hardly be said to have sprung from Roman towns, though they stand on their sites.

6. Most of the Roman cities were built in districts where the Britons had been strong, or where they were likely to give trouble. Carlisle and Gloucester were, for instance, military towns, because they were on the borders of the Roman territory. London and Winchester were trading cities, and they developed much in Roman times.

7. But, when the Roman power was withdrawn, there was, in those cities at any rate, a British population, which had adopted very extensively Roman customs and ideas. For a time things went on much as they had done while the Romans were here; in fact, until the struggles with the Saxons began.

8. As a matter of fact, the coming of the Saxons began a good while before the Romans actually left. Various tribes of Saxons attacked different parts of the coast. Colchester had to keep a sharp look-out for them on the east coast; and the Romans built Portchester Castle, in Hampshire, to guard the south coast.

9. Christianity had found its way to Britain during Roman times, and that helped in the work of civilizing the Britons. But we do not know very much of the early British Church. Christianity probably made more headway among the population in and near the Roman towns than in the wilder districts. The foundations of an early Christian church have been found at Silchester.

Summary.—The Romans held Britain much as we hold India. They did not interfere with the manners and customs, or the religion, of the Britons. The Romans lived in their towns and villas, the Britons in their own settlements. Britons in and near Roman towns gradually adopted Roman ways. Verulam was the chief Roman city, and there were others at London, Winchester, Gloucester, Lincoln, Chester, Carlisle, Colchester, &c. These modern cities, though on the sites of these Roman towns, have not sprung from the Roman cities. The Saxons began to give trouble before the Romans left. Christianity came in Roman times, and the remains of a church have been found at Silchester, in Hants.

1. The conquest of Britain by the Saxons took a long time—considerably over one hundred and fifty years. A great many people are born, and live their lives, and die, in such a period of time as that. It was only little by little that the various tribes of Saxons got a footing in England. They were the stronger and fiercer race, and the Britons were gradually subdued or driven into the mountainous regions by them.

2. Those early tribes of Saxons, who came to Britain, brought with them their own special manners and customs. As they settled down, the face of the country was gradually changed by them. They disliked and suspected everything Roman, and destroyed the towns and villas. They hated the idea of walled towns. These, therefore, were left in ruins; and the great highways, being neglected in most places, were, in the course of years, overgrown with brushwood and hidden in thick forests.

3. In some parts of the country the Saxons seem to have completely swept the Britons away, and almost all traces of them vanished; but, in other parts, there certainly were some of them left, because we have still their marks upon our language. Although most of the place-names in use now are Saxon or Danish, there are still a good many of British, or partly British, origin.

4. The names of many of our rivers are British [Pg 27] or Celtic, such as Axe, Exe, Stour, Ouse, and Yare. So are many names of hills; and, in some parts of the country, the names of the villages are partly British and partly Saxon. Take, for instance, such a common name as Ashwell. Some learned men think that it is made up of two words, Ash and Well, both meaning pretty much the same thing, ash being British for "water", and well being Saxon for "watering-place". Now, if the Saxons had quite got rid of the Britons, they would not have known that a particular place was called "Ash"—they learned to call it "Ash" from the natives, but they did not know what it meant. They knew that there was a spring of water there, which they called a "well"; and so, to distinguish it from other wells in the neighbourhood, they got into the habit of calling it "Ashwell"—and the name has stuck to the place.

5. In some such way as this many other place-names, partly British and partly Saxon, were formed; and they teach us this, that Saxons and Britons must have lived near each other closely enough for the Saxons to take up and use some British names.

6. There are some English counties in which you will hardly find one place-name which is not Saxon. This shows us that the Britons were either killed or completely driven away. That is the case in Hertfordshire. But in Hampshire, while most of the names are Saxon, there are many partly Saxon and partly British. This same thing can be noticed in the county of Gloucester. The Britons, then, [Pg 28] must have been in these districts long enough for the Saxons to pick up a good many place-names. They did not understand the meaning of them, and so tacked on to them names which they did understand.

7. The Saxons made their settlements at first away from the Roman towns and British villages. In the course of time, in a good many cases, they made settlements very close to these old sites, and we know that Saxons lived in such places as Winchester, Gloucester, and London. We find, especially in Hampshire and Gloucestershire, that near, or in, certain villages with Saxon names, Roman remains have from time to time been dug up.

Summary.—The Saxon conquest was gradual. At first the invaders destroyed and avoided the remains of Roman cities. In some parts of the country the Britons were swept quite away, and British names forgotten. The old place names in some places show that the Britons and Saxons must have lived side by side, as was the case in Hampshire and Gloucestershire. In others, as in Hertfordshire, the Britons quite disappeared, as nearly all the place-names are Saxon. Roman remains have been found in some places with Saxon names, which seems to show that after a time the Saxons took to some old Roman sites for their dwelling-places.

1. It is with the coming of the Saxons that the history of our towns and villages really begins. For, though there are not a few places which show [Pg 29] some connection with Romans, Britons, and Pit-Dwellers, it is mainly from Saxon times that we can follow the history of the places in which we live, with any certainty.

2. When the Saxons came to Britain they brought their own ideas with them, of course. Nowadays, when English folk go to settle in a distant land, they take their English notions with them. They find, however, in the course of time, that they have to modify or alter them somewhat, according to the circumstances in which they are placed. They may find that roast beef and plum-pudding do not at all suit them in the new climate. If they are wise, they will see whether the foodstuffs used by the natives, and by folk who have lived out there for many years, are not more suitable, even though they are inclined to despise such food at first.

Now the Saxon tribes who first settled in England in the fifth century belonged to a race of people, bold, strong, fierce, and free. But they could not make their new homes exactly what their old ones had been in the land from whence they had come.

3. Like those other Aryan people, who had made their way to Britain in the Stone Age, they lived together in families. When the family became too large, some of the members had to turn out, like bees from a hive, though not in such great numbers, and set out on their travels to form new settlements, or village communities.

4. This idea of a village community had come down to them through many generations. The [Pg 30] early Saxon idea of a village community was something of this sort:—

5. All the men of the family had equal rights; though there was one who was the head of the family, and who took the lead. The affairs of the family were discussed and settled at open-air meetings, called folk-moots. The spot where these were held was regarded as a sacred place. The tilling of their land, their marriages, their quarrels, their joining with other villages to make war or peace, were all settled at the folk-moot. The question whether the younger branches of the family should leave the village and go out and form another was fixed by the folk-moot also. In the course of time many such little swarms left the parent hive, and settled farther away. But they always looked back upon the old settlement as their home, and the head of the family as their chief. They were all of one kin, and in the course of time they began to look upon their chief as their king.

6. Now what was the nature of the old Saxon village settlement? In its general arrangement it was very like the old Pit-Dwellers' settlement. There was the open space where the men of the village met, the sacred mound where the folk-moot was held. The houses in which the family dwelt were placed close together, round the hut of the head of the family.

Outside these was a paling of some sort, so that all the houses were within the enclosure, or "tun", as it was called; and here calves and other [Pg 31] young stock were reared near the houses. Beyond the enclosure, or tun, was the open pasture-ground and the arable land, or land under cultivation. Beyond these would be the untouched forest-land, or open moorland.

7. Each man of the tun had a share in these lands; not to deal with as he liked, but to use according to the custom of his family. The arable land was divided into strips, and shared amongst the men. However many strips of land a man might have, he could not have them for all time. The strips were apparently chosen by lot, and changed from time to time, so that all had an equal chance of having the best land. In the same way the number of cattle a man might turn out to graze on the pasture-land was regulated. The folk-moot, or meeting of the people, was a very important assembly, and through it the little community was governed.

8. Such was the mode of life to which the Saxons who came to England had been used; but they were not nearly as free individually when they landed here as their ancestors had been. More and more power had come into the hands of the chief or king, and to him the people looked for protection and guidance. In times of war, or when the tribe was invading new lands, the power of the king increased. By the time, then, that the Saxon tribes began their conquest of England, they were very much under the rule of their chiefs or kings. The kings had rights and power over their followers, which had gradually grown up by long custom, [Pg 32] and none of those followers ventured to dispute such rights and powers.

Summary.—The history of our present towns and villages really begins with the Saxons. The Saxons had been used to a settlement very like the early Aryan settlement. All the men had equal rights, and the business of the community was settled in the folk-moot. When new settlements were formed they looked back to the early settlement as their home: they were all of one kin. Gradually the chief man of the first home was looked upon as their chief or king. The land was shared amongst the men in strips in the common field, and the shares changed from time to time.

When the Saxons came to England they were less free than they had been; more power was in the hands of the chief or king, and they looked to him for leadership in battle, and he had certain rights which had grown up by long custom.

1. A good many Britons no doubt settled down with the Saxons as slaves, and that probably accounts for so many of the natural features of the country—the rivers and hills—keeping their old British names. The British villages must have had names, but those villages were apparently destroyed, and the slaves would be settled near the homesteads which their conquerors set up.

2. In fixing on a place for a "tun" the Saxons would choose a valley rather than a hill, usually near a running stream, or a plentiful supply of water. At the present time nearly all over England [Pg 33] we can find villages which have not been touched by modern improvements and alterations; and most of these show something even now of their Saxon origin.

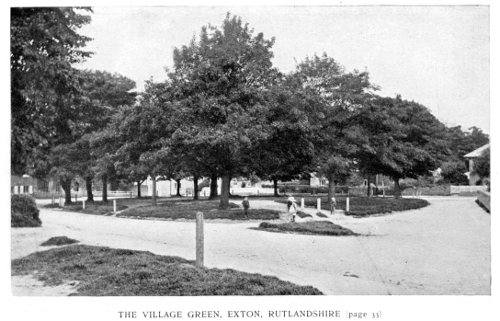

3. For instance, in the county of Rutland there is a village named Exton, which has for many centuries kept several features which show its connection with Saxon days. Its name Ex-ton seems to be compounded of the British word "ex", which means "water", and the Saxon "ton" or "tun", which means the "enclosure"—"the tun by the water". There, sure enough, flowing by the village, is the River Gwash; just such a stream as the Saxons loved. In the middle of the village is the triangular open space, or village green. Round it the houses are thickly clustered together, with hardly any garden ground at the back or in front, and most of them with none at all. Outside the ring of houses are small grass fields or closes, where calves and cows feed, and poultry run. These little fields form a kind of ring round the village, and the hedges enclosing them represent the old fence of Saxon days, which formed the "tun". Beyond this are wider pasture-grounds and big plough-lands, stretching away in several directions up the gentle slopes.

4. You will be able to find a good many villages which have some resemblance to Exton; they answer very closely to the Anglo-Saxon vill and the Anglo-Saxon town, for town and village were laid out on the same principle.

5. Now look at some little sleepy country town, [Pg 34] and you will see much the same arrangement as in the village. The wide open space in the middle, where the town pump stands, and where the market is held, answers to the village green. Though this is often spoken of as the Market Square, it is usually more like a triangle in shape than a square.

6. The old houses round the market square are built very closely one into the other, and with queer narrow alleys leading to houses behind those in front; much in the same way as the houses are clustered round the village green. Round the outskirts of the town, at the back of the houses, are small green closes or paddocks. Beyond them are the larger meadows and pastures; then the wide corn-lands and woods; and, not far away, the heath or common.

7. The Saxon settlements, the "tuns" or "vills", whether they afterwards became what we now understand as "towns" or "cities", or remained what we call villages, had all the same chief features. Just as ordinary school-rooms are all pretty much alike, because they all have to serve much the same purpose, so the Saxon settlements were very similar in their general plan.

8. There was the open place, where people met and the folk-moot was held, surrounded by the houses of stone or wood, in which the people lived. Around these lay the grass yards or common homestead; and, beyond them, the arable and pasture lands, with patches of moorland and forest.

9. But outside the actual "tun" there would be something connected with the Saxon settlement [Pg 35] which you would be sure to notice. After you had passed the boundary to the tun, you would see no hedgerows, or walls, dividing the land into fields. The arable land was one huge field. Its position would depend, of course, upon the nature of the soil and the lie of the land. You would not expect to find it down in the water-meadows, through which the river flowed; it would be higher up, out of the reach of floods; perhaps on the hillsides.

10. Then, you would see the huge field, ploughed in long strips, about a furlong in length, that is, a "furrow long", and one or two perches in breadth. Between the ploughed strips would be narrow unploughed strips, on which, in places, brambles would grow. The heath-lands and moorlands were uncultivated tracts, where rough timber and underwood grew, which was cut and lopped by the people of the vill under certain conditions. There were no formal spinneys [2], nor wide stretches of old timber, such as we nowadays expect to see in a forest. In places the forests contained old timber, and were thick with undergrowth, and infested with wild animals, such as wolves and boars. The name forest was often given to an uncultivated district, not much differing from a rough common, where sheep, cattle, and swine could pick up a living.

Summary.—Anglo-Saxons tuns and vills were usually in a valley near a stream, with a meeting-place or green in the middle, and the houses built round it. At the back were small closes, and all was surrounded by a fence. Outside was the big common field, reaching up the slope, and beyond [Pg 36] these the wide pasture-grounds. In many old villages and towns something of this arrangement can still be seen.

1. Though the Saxons, as they settled down in England, formed "tuns", which at first had very little to do with one another, that state of things probably did not last a very long time. In fighting the Britons they had had to act together; and, for the sake of protection and help, these separate communities had to combine. Somewhat in this way ten families in a district would form a tything; and the heads of the villages would, from time to time, meet together, to consult on various matters in which they were interested.

2. Then larger areas would need to be covered, as the country became more settled. Ten tythings would make a hundred; and, from time to time, men from all the places in the hundred would meet together and hold hundred courts. Most of the English counties are still divided into hundreds. In those days the hundreds were not all of the same size, because, owing to the nature of the soil, some tuns were far apart from one another, and a tything might cover a wide district, and a hundred a much larger area. If the hundred was small, that would show that the tuns were pretty close together, and that the district was populous. If, [Pg 37] on the other hand, the tythings and hundreds were large, that would show that the district was thinly peopled.

3. We have seen that new settlements were formed by portions of the family leaving the old home, and making a new tun in the most suitable place they could find. It would happen, no doubt, in favourable districts, that new tuns would spring up not very far from the mother tun; and, in the course of time, there would be a good many more tuns in the tything than there were originally. The fact seems to be, that when once the boundaries had been roughly agreed upon, they were not often altered. From being a combination of families, or tuns, the tything got to be a district; and it kept its name of tything long after the number of tuns in it had increased.

4. It was much the same with the hundreds. In time they were represented by certain districts, whose borders were known to the people living in them. The hundreds all over the country have not altered their boundaries to any great extent until quite recently. In Hampshire to-day there are thirty-seven hundreds; in Hertfordshire there are only eight; and Middlesex has now the same six hundreds which it had twelve centuries ago when a good part of the county was forest land.

5. As to the time when the hundreds became grouped into shires we cannot say much: the change was brought about gradually, and quite naturally. It is not at all likely that all the various kingdoms in England came together on [Pg 38] some particular occasion and said: "Now we'll divide all our kingdoms into shires". But the hundreds did become grouped into shires, doubtless because it was necessary that they might act together in matters which concerned all.

6. There is nothing like a threatened danger from without to draw men together. In the tun, no doubt, the villagers fell out with each other; however fairly the strips of land were shared somebody was sure to get what he did not like, and to grumble about it. Some of his fellow-villagers would take his side, and say it was a shame; and others would take the opposite side. But if the cattle belonging to the tun over the hills, or on the other side of the marsh, had been seen on the wrong side of the mark, or boundary which separated the lands of the two tuns, the dispute about the strips in the field would be forgotten, and away the people would go in a body towards the offending tun "to see about it".

7. In much the same way, when the boundaries of a tything or hundred were invaded by another tything or hundred, the differences between the tuns would be dropped, in order to preserve the rights which they had in common.

8. There was strife among the Saxon kingdoms which lasted for many years, especially between the three great rivals, Wessex, Mercia, and Northumbria. The lesser kingdoms were under the dominion, sometimes of one, sometimes of another of these rivals. All this fighting and settling down put more and more power into the hands of the [Pg 39] kings. Instead of each village fighting for itself, and leaving all the others to fight for themselves, it was found to be a much safer and wiser policy to join together for common protection. Now if people join together, whether in peace or war, to win a football match, or to take a city, somebody must be in authority to give the necessary orders. Hence the power of the king, and the officers acting under him, grew up by custom, until the overlordship of the king was so firmly established that no one dared call it in question.

9. Apparently from the smaller Saxon kingdoms [Pg 40] we get our older shires. Whether the overlord happened to be the King of Mercia, or the King of Wessex, the under-king continued to rule over his old kingdom, or share. When, at length, in the ninth century, the King of Wessex was acknowledged as the overlord or King of England, Wessex and Mercia, and a part of Northumbria, were gradually divided into shares, or shires, over each of which the King of England appointed a reeve to look after his interests—the shire-reeve or sheriff. The King of England still appoints the high sheriff of each county. An eorlderman, who, in the case of the older shires, was at first no doubt a descendant of the old under-king, looked after the business of the shire itself.

10. Amongst the older shires we have Kent, Surrey, Sussex, Essex, Middlesex; while the newer ones were all named after some important central town, which in each case gave its name to the shire; such are Hertfordshire and Bedfordshire.

Summary.—In time ten free families or tuns joined together for protection, formed a tything. Gradually the name tything was given to the district, though many more tuns had grown up upon it. Then the tythings had to join together, and ten of these formed the hundred. These, too, got to be the names of districts, and these are still in use in most counties. The divisions known as shires, or shares, came later. The earliest formed were those which had been little kingdoms, like Kent, Sussex, Essex, Middlesex, and Surrey. When the bigger kingdoms were broken up, they were named after important towns in the district, like Hertfordshire, Gloucestershire, Northamptonshire, &c. The king's officer, or reeve, in each county in time was called the shire-reeve, or sheriff.

1. At first, as we have seen, the Saxons were an agricultural people, and each village or tun produced all that it needed for its own support. But in peaceful times a tun might produce more than it needed; and, by and by, something like trade and exchange between one place and another would begin. There were many places, as for example London, which in Roman times had been great places for commerce, to which ships had come bringing various kinds of goods. In time, as the Saxons settled down, they began to have new wants, and some of them began to be attracted towards places where there were more people than in their native tuns. Some men found that they could make certain articles of common use better than their neighbours could. Thus certain trades took their rise. Those who worked at them would gradually give up the agricultural labour in which everybody else in the tun was employed. We do not know the causes which led certain of these agricultural tuns to become trading-places; but it is quite certain that they did gradually grow to be what we now call towns.

2. We find Saxon towns springing up near the places where some of the Roman towns had been; in some cases on the actual site of the Roman city. In Gloucester and Lincoln, for instance, some of the streets to-day follow the actual lines of the [Pg 42] Roman streets. These towns are, however, really Saxon towns, not old Roman towns turned into Saxon towns. The men of these Saxon towns had lands on the outskirts of the towns, just as the village men had. Even to-day you will notice that there are many towns which possess lands called by such names as the Townlands, Townfield, or Lammas Land.

3. The men in these towns were, from the very first, more inclined to hold out against an overlord than the men in the villages were. In the first place, their numbers were greater; and then they had more varieties of occupation than the villagers, or, as we may say, had wider interests. In the trading towns, like London and Southampton, they came in contact with traders from other lands, and trade brought them more wealth. They, too, had their folk-moots, and they had more business to transact in them than the country villagers had. They were very particular to keep a tight hold on their rights, and were always on the look-out to gain fresh privileges if they possibly could.

4. The fence or wall, which surrounded the town, was made much stronger than that round the village; and men saw the use now of the thick walls of the old Roman cities which their ancestors had despised, for they had wealth and goods which needed protection.

5. We have seen that the power of the king gradually increased; and, as it did so, the king and the town became more necessary to each other. The town was wealthy; but it could not stand by [Pg 43] itself against all the rest of the country. The king had the power of the country at his back, and could protect it if he would. The town had to give something to the king in return for this protection. But we shall presently see more of the relations between king and town.

Summary.—Trading towns, like London, gradually arose: the Saxons took to trades and trading; and towns sprang up over the land. The townsmen were jealous of any overlord, and better able to make a stand against him than the men in the vills. Their folk-moots were important, and the men held very tightly to any privileges which the town had, and were always on the look-out to secure fresh rights. Gradually they became rich, and needed the king's protection, and both the king and the town had to depend a great deal upon each other.

1. One great and important factor in the making of Saxon England was Christianity. The first Saxons who came were heathen, and they wiped out the British Christianity, where they settled, as completely as they wiped out Roman civilization. Towards the end of the sixth century Christian missionaries were at work in the north and in the south of what we now call England; and, from that time onwards, the Church played an important part in the making of the nation.

2. So, side by side with the development and political growth of the country, came the spread of Christianity and the organization of the Church. We find that the Saxon kingdoms, following the lead of their kings, became Christian as a matter of course. Over and over again we find the kings giving up Christianity and going back to paganism, and their people following them, also as a matter of course. The conversion of England took many years to accomplish, and mixed up with the Christianity was much paganism, which was not overcome for many centuries. The Dioceses [3] of the early Saxon bishops were, roughly speaking, of the same extent as the early kingdoms, and the bishops and their clergy travelled about as missionaries.

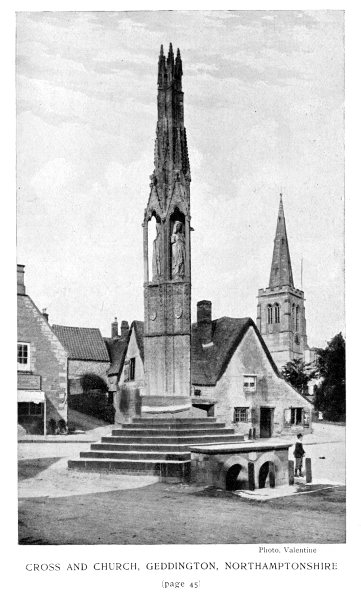

3. As the lords or thanes of the various vills, following the example of their kings, accepted [Pg 45] Christianity, their people followed their example. In the open places of the tuns and vills, where the folk-moots were held, Christianity was preached and the cross set up. That, probably, was the origin of most of the village and market crosses. Then, in the course of time, in some cases, a church was built on a part of the old sacred open spaces. You cannot help noticing to-day how in many towns the chief church is by the market-place, and in the villages by the village green. In other cases we find the church and manor-house are outside the present village. That may be because the thane's or lord's land was outside the vill or tun, and he built the church on his own land, not on the common public land in the middle of the tun. It may have happened, also, that at the time the church was first built the houses were there also; but, owing to changes, many years afterwards, the people have removed to another spot some distance away—possibly to the side of a busy main road. Then the original village has dwindled away; the houses, having fallen into ruin, have been pulled down, and no traces of them left.

4. A priest would be appointed to work in a tun, and a portion of land would be set apart in the common fields to maintain him and to aid in carrying on the services of the church. In course of time there were certain dues and fees given to him, the paying of which became a recognized custom. Somewhat in this way glebe lands and tithes took their rise, and became a part of the land system of the Saxon people.

5. Along with the growth of churches in the tuns and vills was the founding of monasteries. Small bodies of men bound themselves by simple rules to live and work and worship together. Frequently they made their settlements in lonely, desolate places, which they worked to bring under cultivation. So there sprang up settlements, or convents, of these religious people, living under their own rules. Work and worship went side by side. It was a new kind of life, different from the life in the "tun" which the early Saxons were used to; but, in time, it had a mighty influence in the land, and played an important part in the making of England.

Summary.—At the end of the sixth century Christian missionaries were working in the north and in the south of England, but the progress made was very slow. The early bishops and their clergy travelled about as missionaries. In time churches were built in the vills and tuns, and a priest left in charge, who had his share in the strips of land, and in the course of time had other dues paid to him. Monasteries, too, sprang up. These were bodies of religious people living together to work and worship.

1. The Saxons learned to respect the quiet simple lives of the early monks. They saw them toiling hard in their fields, bravely facing many difficulties and hardships, and turning the wilderness into a [Pg 47] garden. At first each monk, from the abbot downwards, had to take his share in the toil, wherever it was, and the monastery, as well as the vill, had to produce all that it needed.

2. Men, who were not very good or very religious, began to respect the lives and works of the monks. We find thanes and kings not only allowing monks to settle on some of their unoccupied land, but making over to them some of their own land, on condition that they and their children after them might always have a share in the prayers of these good men. We see, too, that whole vills came gradually into the hands of some monasteries; so that the convent became the lord of the vill, instead of a thane or a king.

3. Some convents made rapid progress, while others never prospered, but in the course of time disappeared. We have seen that the vill and the "town" grew up in much the same way, and were formed on the same plan. There are, however, a good many towns which grew up round monasteries in the first instance.

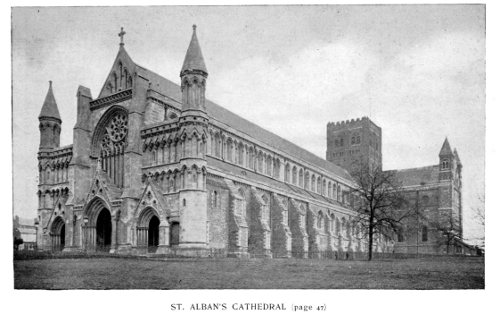

4. For example, King Offa II, at the end of the eighth century, founded the monastery of St. Alban, giving to it a wide extent of land round the ruins of the old city of Verulam. The monastery was built, and much land brought under cultivation. We find the sixth abbot, Ulsinus, two centuries later, encouraging people to settle round the walls of the monastery. That monastery lay near one of the great roads of England; many people were coming and going; so houses were built and a [Pg 48] market was established. Churches, too, were erected for the use of the people who settled in the town. The abbot was the lord of this "town", and the people dwelling in it were his tenants. He, like any other lord of a "tun", or "vill", was responsible for the keeping of order and good government on his land.

5. St. Edmund's Bury, or Bury St. Edmund's, grew up round a monastery which had been established in a lonely place; and there, also, arose in time a flourishing town, under the rule of the abbot.

6. A number of towns, which to-day are cathedral cities, grew up round the churches where the bishop and his principal clergy had their homes and chief centres of work.

7. These things only came about very gradually. The monks who settled first at Bury, or those whom King Offa settled by the ruins of Verulam, never dreamed that in the years to come their convents would be great land-owners, with many hundreds of tenants. But it was so; and the monasteries at length formed one of the most important classes of land-owners in the country; their special rights and privileges coming to them so gradually, and so naturally, that no one realized exactly what was taking place.

8. Those who entered a monastery, or embraced "the religious life", intended to keep out of the world, and apart from its cares and worries as much as they could. But the lands left to them had to be looked after and cultivated. These did [Pg 49] not always lie close round the monastery—very frequently they were tracts of land in distant counties,—and somebody had to look after them. New possessions mean new responsibilities; and so we find that the monasteries had not only to attend to the daily round of worship and work inside the walls of the monastery, but had to carry on all the business belonging to great estates as well.

9. So in time a monastery had to use the services of many men besides monks; the monks became great employers of labour one way and another, and this attracted to their towns a good many skilled workmen.

10. The times when the Danes ravaged the greater part of the country were very trying to the life of English villages and towns. These sea-rovers came, at first, as plunderers, and the destruction of towns, churches, and monasteries was very great. Some monasteries, like Crowland [4], suffered several times, and many were never rebuilt. But, gradually, the invaders settled in England. They did not bring with them an entirely new land system. As they settled down to farming and village life, we find that land was held in almost exactly the same manner as under Saxon customs.

11. Of course there were some differences, and those who have studied the subject closely can indicate a good many points in which the Saxon and Danish land customs differed from each other. The dangers to which the Saxons had been exposed by the attacks of the Danes had put a great deal [Pg 50] of power into the hands of the thanes and the king. Thus, by the time the Danes had settled in England, every vill and tun had got into the hands of some lord or thane, or was in the king's hands. In Danish settlements there seems always to have been an overlord, who led his people in war and ruled in time of peace; though there was a class of freemen amongst them which had special rights and privileges.

12. But the Danes were something more than tillers of the soil; they were traders too, and "tuns" became in many places more like our "towns" and trading-places than ever they had been before. In time we find the largest towns in the Danish part of England—Leicester, Lincoln, Derby, Nottingham, and Stamford—binding themselves together to protect their trading interests.

Summary.—Land was gradually left to monasteries by kings and nobles on condition that they and their families should always be prayed for. The monasteries became holders of lands, often far away from their houses, which had to be attended to. Towns grew up round many monasteries, like St. Alban's and Bury St. Edmund's, and the monastery was their overlord.

The Danes brought no new land system with them to England, though amongst them there was a class of freemen. Towns grew to be greater trading-places in Danish times.

1. Now let us see what an ordinary village was like in the time of King Cnut, when Saxon and Dane were living pretty comfortably together, side by side, under good government.

2. We find that each vill or tun had a lord, an eorl, or thane, who practically owned the place and everything in it, though he could not do entirely as he liked. There was the land which belonged to him, and which was in his own hands, or occupation, as we say; that was called his demesne. The rest of the land was also his, but it was let out to people who had lived on the land from time out of mind—the cheorls or villeins. The lord's house was on his demesne. The villeins' houses were all together in the tun, with the grass yards for the cattle close to them, and the open fields and pasture-lands outside the tun, just as they had been in the olden days.

3. There seem to have been two classes of villeins—geburs and cottiers.

4. The geburs were the higher class. They seem very frequently to have held about 120 acres of land; they had to work on the lord's home farm two or three days a week, or pay him certain produce of the land as a rent; and they had to provide one or more oxen for the village plough, when there was ploughing to be done on the lord's farm, or in the common field.

5. In the Danish part of the country there appears to have been a class of freeholders in some places, called socmen, but there were not very many of them. They, no doubt, had had their rights granted to them for distinguished service in the Danish wars.

6. The cottiers held only about 5 acres of land. They had to work for the thane or lord on certain days of the week; but, as they had no oxen, they had no ploughing to do for him.

7. Below the geburs and the cottiers were the theows, thralls, or slaves, who could be bought and sold. They were captives taken in war; or men who, for their crimes, had been doomed to slavery.

8. We must remember that the overlord might be the king, or a bishop; a monastery, or a thane. Their rights over their vills and tuns were much the same in each case, and their duties to those vills and tuns were also similar.

9. A very large number of vills and tuns were under the lordship of the various bishops and monasteries. It was so with towns like Winchester, Reading, Bury St. Edmund's, and St. Alban's. The custom had grown up quite naturally and in the course of many years.

10. It is pretty clear that the overlord did not always reside in his vill or tun. The tuns or vills [Pg 53] of the bishopric of Winchester, for instance, were scattered about in various parts of the diocese. It was the same with other overlords. But we find in every place a steward, and in each town the king's reeve or the lord's reeve. These acted for the overlord, whoever he was, and saw that the villeins and cottiers did their proper proportion of work at the right time; they saw that the lord's tolls at the markets, fairs, and ferries, were properly enforced. The steward was a most important officer in every town and village, and a great deal of power was in his hands.

11. Then in the ordinary country vill there was the faber, or smith; the mason; the pundar, or man who looked after the fences and hedges and drove stray cattle into the pound. The simple ordinary trades were found in the country villages then, as they are now; but the craftsmen, the most skilled workmen, had become for the most part dwellers in the towns. Even in very early times we find craftsmen in towns formed into trades' unions or guilds, to protect their special trades.

12. Now the land was shared amongst the villeins and cottiers in strips, usually containing an acre or a half-acre, in the common fields of which we have heard before. The villein did not have all the strips belonging to his holding set out side by side—they lay in different parts of the great open field. Crops had to be sown according to the custom of the vill or tun, and according to a fixed order. Wheat and rye would be sown one year on a part of the great field; barley, oats, and beans the next [Pg 54] year; and the third year the land must be left fallow. The lord's land had to be treated in the same way.

13. On the pasture-land and in the meadows the villein and cottier had the right to turn out a certain number of cattle, according to the size of their holdings. The crops, whether of hay or corn, had to be cleared from the fields by certain fixed days, so that cattle might be turned out to graze. You will still find, in some towns, that certain of the freeholders, or burgesses, have the right to turn a certain number of cattle on certain lands for a part of the year between fixed dates.

14. Then, on the rough commons or heaths, there were also grazing rights for the lord and his tenants. The tenants might "top and lop" the trees growing there at certain times, but they might not cut the trees down—that was the lord's right. There were also rights of cutting turf and heather, and the turning of hogs into the forest; all these rights were ruled by "custom", which bound both the lord and the tenants.

15. The lord, or steward, or reeve, held courts or meetings at regular intervals. At first these took place in the open air, like the old folk-moots; but in time they came to be held in a court-house. The court was a meeting, presided over by the lord or his steward, to see that the customs of the place were kept up; to call to account those tenants who had failed to do their share of the work; to put new tenants into the places of those who had removed or died; and to punish offenders.

16. This last right, of punishing offenders, was one thought to be of vast importance. In the early days the men of the tun were bound together to keep the peace, and to see that it was kept; and they were strong enough to keep evil-doers in check. In the trading tuns or towns especially, the right was valued very highly; but, at the time we are now treating of, the right to exercise punishment was in the hands of the overlord, though the men of the place had still some voice in the government of their town. The right to have a gallows was one eagerly sought for, and held very firmly; not because people particularly wanted to hang one another, but because the gallows represented to them the highest power of government. The towns had lost most of their rights in this respect, but they had never forgotten those they had had, and were always on the alert to get back any lost right, or to gain a new one, which should help them to obtain the privilege of self-government.

Summary.—Each vill had an overlord, who might be the king, a bishop, a noble, or a monastery. Land held by the lord was his demesne. Those who lived on the land were villeins or cheorls. Villeins were divided into geburs and cottiers. Geburs held about 120 acres each, did so many days' work on the lord's land, and supplied an ox for the village plough. Cottiers had only 5 acres. In Danish districts there were some socmen, or freemen. The thralls, or serfs, were a lower class still. Each vill and tun had a steward, who looked after the lord's interests, and courts were held regularly in each. The right of a gallows was a sign of right to govern, and so it was much valued, especially by the trading towns. The faber or smith, mason, and pundar were the common trades in the vills.

1. In speaking of our towns and villages we are obliged to make mention frequently of churches and monasteries. At the time when Cnut was king, each vill or tun had its church and its priest to minister in it. There were parts of the land, in the common fields and pasture, mixed up with the villeins' strips, set apart for the support of the services of the Church, the maintenance of the priest, and the care of the poor. In time various dues and customs were also paid to the priest for certain things which he was expected to do.

2. There are very few churches still standing which have any parts of their structure dating from before the time of King Cnut. In the early days churches were very simple buildings, built mainly of wood, and in the Danish wars most of them were destroyed.

3. In the tenth century there was a very general belief that the world was coming to an end at the end of the thousand years after the establishment of Christianity; so there was not much actual church-building going on. But in King Cnut's time a revival of interest in church-building took place, and there are in a good many of the old churches of England little bits of work in the walls, or very rude carvings over the doorways, which belong to this time. Unless such work is pointed [Pg 57] out to you by one who understands something about these matters, you will not be likely to discover it for yourself, any more than you are likely to discover the traces of the pit-dwellings, of which we spoke in an early chapter.

4. These parish churches and parish priests were under the control of the bishop, who had his chief church or cathedral in some important place in his diocese. Those cathedrals were generally served by colleges of clergy, called canons.

5. These were the public churches. But besides them there were colleges and monasteries, which were private societies of men living together. Some of the religious houses were in towns, as we have seen, and others were in wild desolate places. Every religious house, whether a monastery for men or a nunnery for women, had its church, which was the private chapel of the house, and not open to the public. In the course of years these private chapels were built as huge churches, much larger than the parish church. Even now you may see close to a big college church a much smaller parish church, as for example St. Margaret's Church, which stands by the side of Westminster Abbey. As more land came into the possession of these religious houses, the monks had more business with the outside world, for, as landlords, they had to see that their lands were turned to good account, and cultivated according to the notions of the day.

6. The monasteries, especially in their early days, were great centres of good and useful work. Those who founded them, or gave them lands, did so because [Pg 58] they felt they were doing excellent service for the people, and they wanted to have a share in the work, and to be remembered in the prayers of the monks. Founders of religious houses believed that they were getting something worth having in return for the lands which they gave.

7. In the wild times of the Danish invasions the monasteries were looked upon as places of safety for the weak and helpless. But they were not always safe places. People sometimes, when the country was in a disturbed state, would send their valuables to the nearest monastery. In time the Danes got to know of this, and many a religious house was attacked and sacked by them on account of the tales they had heard of the marvellous wealth hidden there.

8. A story is told of a worthy person living near St. Alban's monastery at a time when a visit from marauding Danes was expected. One market-day he sent a number of heavy iron-bound chests, guarded by armed men, through the market to the monastery. Everybody, of course, turned to look, and talked about the affair. As a matter of fact the chests only contained stones; the treasure was carefully hidden somewhere else, till all danger was thought to be over. That plan was used to put the Danes "off the scent", as we should say.

9. All the land that did not go with the tuns and vills in early days was apparently regarded as belonging to the people, and was called the folk-land. The king came to be regarded as the custodian or guardian of these folk-lands. Little by [Pg 59] little they became the property of the king, until practically he could do what he pleased with them. It was from these folk-lands—which in early times were probably scraps of land which nobody thought to be worth very much, since the nearest vills and tuns had never taken them in—that kings gave land to bishoprics and monasteries. By and by these rough lands became very valuable; but in most cases it was the labour, the skill, and the brains of the monks of the early days which turned the waste lands into fruitful fields.

Summary.—Each vill had its church, but there are none of these old churches now standing. Bits of stone-work belonging to that time are sometimes found built into old church walls. The early churches were mostly of wood. The monastery churches were often very large, but they were not public churches. In times of danger, monasteries were looked upon as places of safety. The waste lands which did not belong to any tun or vill in early times were called folk-land, and belonged to the people. The king was regarded as the guardian of these lands, but in time they were looked upon as his private property. Land given to monasteries was often very rough, but the care the monks gave to it in time made it fertile.

1. Every old town and village has got its oldest house, of course. You will most likely have heard people trying to be funny about it, and saying they think it must have been built in the year One. [Pg 60] There is, we may pretty safely say, no house now standing exactly as it was in the days of King Cnut and the later Saxon times. But even yet there are some buildings standing, and still in use, which have certain parts which were erected in those times. These buildings are mostly churches, and in various parts of the country, indeed in almost every county, something belonging to this age can be pointed out.

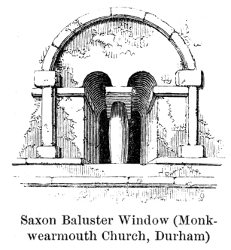

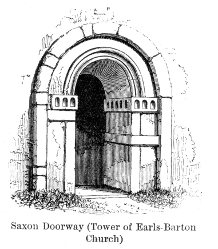

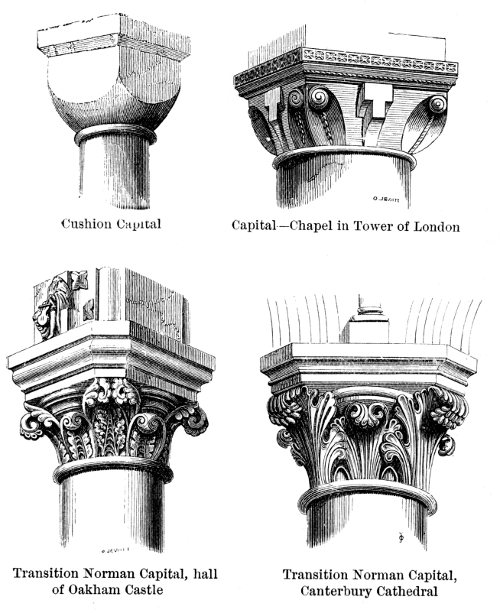

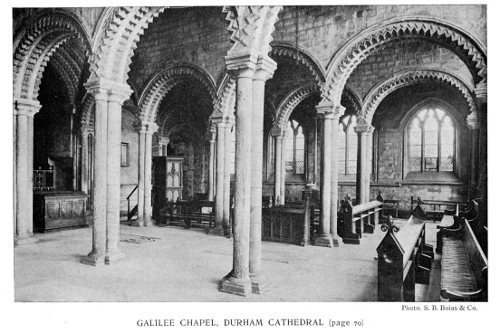

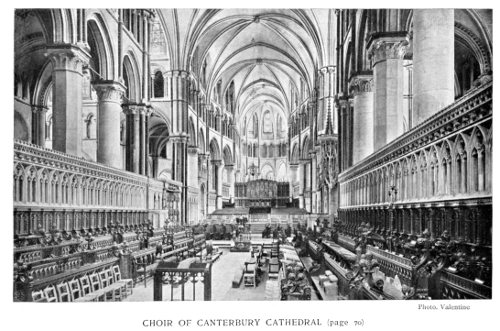

2. Churches built of stone in those days had very thick walls with very small windows. The east end of the chancel was usually semicircular, forming an apse. The wall between the chancel and the nave was pierced by a narrow, low, round-headed arch. Most of the windows had plain, round-headed arches, and in some of them, dividing the opening into two parts or "lights", were stone pillars with bulging stems. Some of the doorways had triangular heads, others had round heads. There are some very curious bits of sculpture over some of these doorways. The meaning of them was quite plain, no doubt, to the people who carved them, but they are very difficult for us to understand. They represent the ideas which the Saxons had of good and evil, and of the strife going on between them.

3. King Edward the Confessor had been brought [Pg 61] up in Normandy, where church-building was in advance of anything in England. He encouraged Norman ideas in building, as well as in other directions, and so prepared the way for the coming of the Normans. Some parts of the buildings connected with Westminster Abbey were built at that time.

4. We do not know much of Saxon castles, though the Saxons had their strongholds and fortified places.

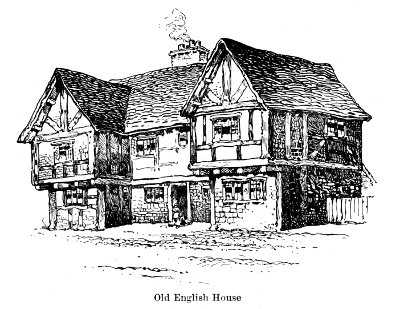

5. The houses in which the people lived were most of them in those days built of wood. There was not much difference, except in size, between the house of the king, the thane, and the villein. There was the hearth, on which was the fire; and the room or hall in which it was placed was the chief building, close to which, very gradually, other buildings arose. Apparently the buildings had a framework of timber, filled in with wood, wattled together like hurdles. In the more important buildings, stone gradually came into use.

6. The monasteries and convents each had the buildings in which the monks lived grouped round the church. After the Danish wars the buildings improved, stone taking the place of wood.

7. Even in the towns wood was chiefly used for the ordinary house; though, as we should expect, stone was used in the more important buildings, and in the wall round the town.

8. What we understand by comfort in a house was absent. There was the fire on the hearth in the middle of the floor; in this room the people of the house, from the highest to the lowest, had their meals; and there, on the floor, most of them slept at night. Cooking was almost entirely done in the open air.

Summary.—In most towns and villages the oldest building now in use is usually the church. Some churches have remains of Saxon [5] work in them. The style was very plain: the chancel usually had an apse or semicircular end; the windows were round-headed and sometimes had pillars with bulging shafts; doorways were round-headed or triangular. King Edward the Confessor prepared the way for Normans and Norman ways of building. The Saxons had strongholds, but they were not castle-builders. Ordinary houses were usually of wood, and consisted of a room or hall, with a hearth in the middle; in this room the family slept. Most of the cooking was done in the open air.

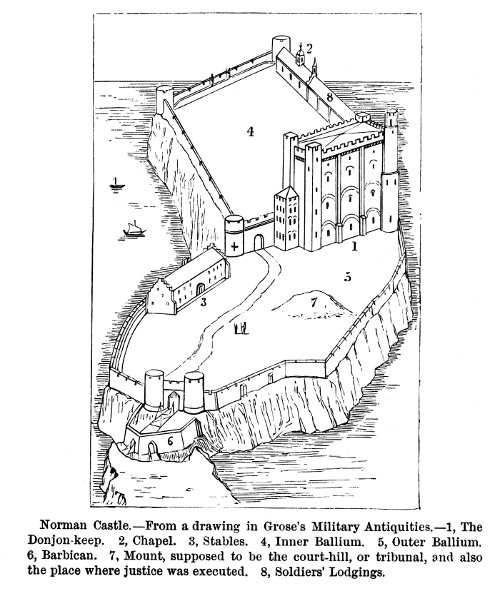

1. When Duke William of Normandy became King of England, the power of the Crown was [Pg 63] greater than it had ever been before. All the old folk-land had become king's land. Many knights had followed Duke William from Normandy into England, and expected to be provided for by their leader. The lands belonging to King Harold, and those of the Saxon eorls who had died fighting at Senlac, King William regarded as his own. These he granted to his followers, on condition that they acknowledged him as their overlord, and followed him in war when required. This was a stricter condition than had ever before been required in England. The Normans were used to it, and it did not seem at all strange to them.